アブラハム・イェシャヤフ・カレリッツ

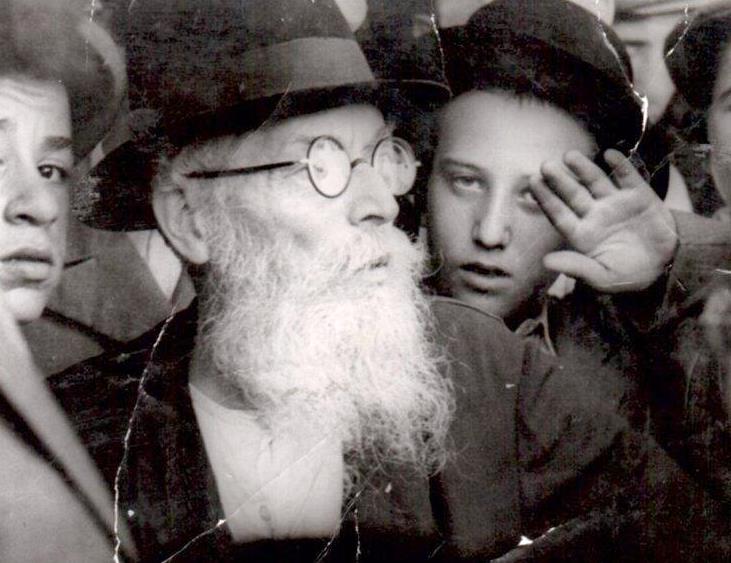

Avraham Yeshayahu Karelitz, the Chazon Ish

1878-1953 (Hebrew: החזון איש)

☆ アブラハム・イェシャヤフ・カレリッツ(ヘブライ語: אברהם ישעיהו קרליץ; 1878年11月7日 - 1953年10月24日)は、その代表作にちなんで「ハゾン・イシュ」(ヘブライ語: החזון איש)とも呼ばれる。ベラルーシ生まれの正統派ラビであり、後にイスラエルにおけるハレディ・ユダヤ教の指導者の一人となった。1933年から1953 年までの最後の20年間をイスラエルで過ごした。

| Avraham Yeshayahu

Karelitz (Hebrew: אברהם ישעיהו קרליץ; 7 November 1878 – 24 October

1953), also known as the Chazon Ish (Hebrew: החזון איש) after his

magnum opus, was a Belarusian-born Orthodox rabbi who later became one

of the leaders of Haredi Judaism in Israel, where he spent his final 20

years, from 1933 to 1953. |

アブラハム・イェシャヤフ・カレリッツ(ヘブライ語: אברהם

ישעיהו קרליץ; 1878年11月7日 - 1953年10月24日)は、その代表作にちなんで「ハゾン・イシュ」(ヘブライ語:

החזון

איש)とも呼ばれる。ベラルーシ生まれの正統派ラビであり、後にイスラエルにおけるハレディ・ユダヤ教の指導者の一人となった。1933年から1953

年までの最後の20年間をイスラエルで過ごした。 |

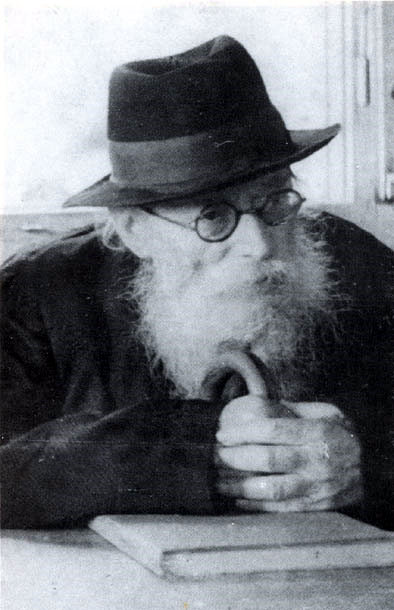

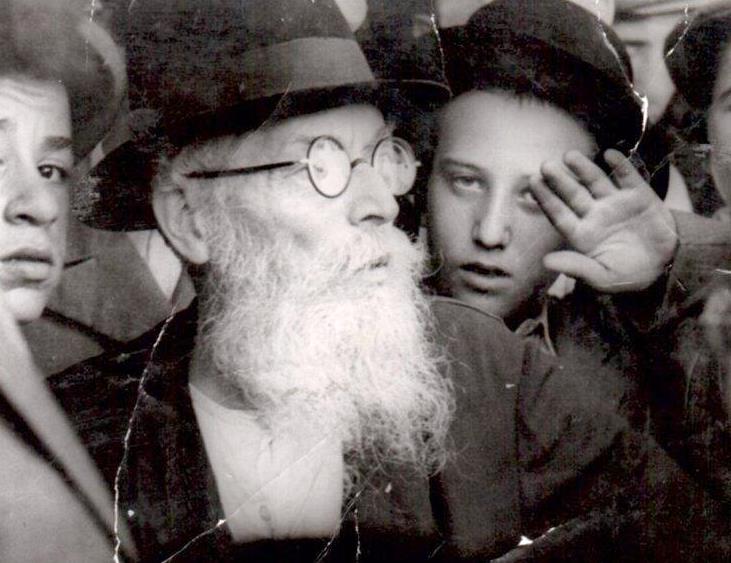

| Biography Youth  Kosava, 1930  The Chazon Ish in his youth Born in the town of Kosava in the Grodno Governorate of the Russian Empire (today in Belarus). His father, Rabbi Shmaryahu Yosef Karelitz, served as the town's rabbi. His mother, Rashe Leah, was the daughter of the previous town rabbi, Rabbi Shaul Katzenelnbogen, who left his position for the rabbinate of Kobrin. Except for a short period in which he studied in the "kibbutz" of R' Chaim Ozer Grodzinski in Vilna,[1] Avraham Yeshayahu Karelitz did not study in a cheder or yeshiva, and apparently was never officially ordained as a rabbi. His Torah education was received from his father and a private melamed named R' Moshe Tuvia. The Chazon Ish quotes Torah teachings from this teacher in several places in his writings. According to David Frankel,[2] the Chazon Ish related that his father hired a private melamed to keep him away from the company of children his age and idle chatter. For most of his life, he was self-taught. His mother later told Rebbetzin Malka Finkel, wife of Rabbi Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, that even in childhood he studied with great diligence. According to her, he told her several times that he did not enjoy studying, but he studied out of the recognition that "this is a good thing," hoping that the sweetness would come later.[3] His brother, Rabbi Meir Karelitz, said in his eulogy that at his bar mitzvah he committed to devote all his strength to Torah. According to a common story, his talents were not noticeable in childhood, though some deny this detail.[4] Binyamin Brown accepts both versions and speculates that although he was indeed talented, he was regarded in his environment as average due to his different study method, which did not meet the accepted criteria of yeshiva-style scholarship.[5] Nevertheless, Brown, a scholar of the Chazon Ish’s life and thought, claims that there is a noticeable influence of Jewish Enlightenment literature in his writings and also in a few surviving poems he wrote. This influence is expressed in his florid and stylistic writing, and in his strict use of Hebrew free of foreign words, unlike other rabbis of his time.[6] In contrast, Shlomo Havlin claimed that the evidence for this assumption is anachronistic, since rabbinic literature had always been written in Hebrew, whereas Yiddish literature was then in its heyday.[7] The Chazon Ish was known from a young age as a quiet person. To one of his associates, Yitzhak Gerstenkorn, founder of the city Bnei Brak, he explained that in his teens he decided not to utter anything that wasn't fully formed in his mind, but since he tends to write well-formed ideas, it is rare that he has anything to say aloud.[8] In the year 5651 (1891), his grandfather Rabbi Shimshon Karelitz died. His son, Rabbi Shmaryahu Yosef Karelitz, was absent from the town that day, and the grandsons Meir and Avraham Yeshayahu, aged 16 and 12 respectively, prepared eulogies themselves, which the elder brother Meir read at the funeral.[9] In his youth the Chazon Ish traveled to study in Brisk. Binyamin Brown also discusses the version that his journey was to Volozhin Yeshiva,[10] but this seems mistaken, in light of testimony by Rabbi Isser Yehuda Unterman that the Chazon Ish studied in Brisk,[11] but did not find his place there and returned home to Kosava. The reason for the trip was to study from Rabbi Yosef Dov HaLevi Soloveitchik of Brisk, who taught in Brisk after leaving Volozhin Yeshiva until his death in 5652 (1892).[12] Several speculations have been raised about his quick return home: from homesickness, to halachic issues (Chadash prohibition, which was treated leniently in Brisk based on the ruling of Rabbi Joel Sirkis, who once served as the local rabbi), and even poor spiritual environment in Brisk.[13][14] In the year 5661 (1901), several responses under the name of the Chazon Ish were published in the journal "HaPeles", under the pen name "A.Ya.SH. from Kassava [=Kosava]". In one of them he defended the accepted calculation in the Hebrew calendar against a possible objection raised by another rabbi.[15] These were, as far as is known, his first printed words. In the winter of 5665 (1905), the Chazon Ish stayed for an extended time in the city of Vilna and studied in the kibbutz of Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski there. He may have remained there due to travel disruptions caused by the 1905 Russian Revolution, which lasted the entire year.[16] |

伝記 青年期  コサヴァ、1930年  若き日のハゾン・イシュ ロシア帝国グロドノ県(現在のベラルーシ)のコサヴァ村に生まれた。父はラビ・シュマリアフ・ヨセフ・カレリッツで、町のラビを務めていた。母ラシェ・レ アは、前任の町ラビであるラビ・シャウル・カッツェネルンボーゲンの娘であった。父はコブリンのラビ職に就くため、この職を離れた。 ヴィルナのラビ・ハイム・オゼル・グロジンスキーの「キブツ」で短期間学んだ時期を除き、 [1] アブラハム・イェシャヤフ・カレリッツはヘダーやイェシーバーで学ばず、正式にラビの資格を得たこともなかったようだ。彼のトーラー教育は父と、モー シェ・トゥヴィアという名の個人教師から受けた。ハゾン・イシュは著作の複数箇所でこの教師の教えを引用している。デイヴィッド・フランケルによれば [2]、ハゾン・イシュは、父親が同年代の子供たちとの付き合いや無駄話から遠ざけるため、個人教師を雇ったと語っていた。彼は生涯の大半を独学で過ごし た。母親は後に、ラビ・エリエゼル・イェフダ・フィンケルの妻であるレベツィン・マルカ・フィンケルに、幼少期から彼は非常に熱心に学んでいたと語った。 彼女によれば、彼は何度か「勉強は好きではないが、『これは良いことだ』と認識して勉強している。後でその甘さが訪れることを願って」と語っていたという [3]。弟のラビ・メイル・カレリッツは追悼演説で、彼がバル・ミツヴァの時に「全力をトーラーに捧げる」と誓ったと述べた。一般的な話では、彼の才能は 幼少期には目立たなかったとされるが、この詳細を否定する者もいる。[4] ビニャミン・ブラウンは両説を認めつつ、彼は確かに才能があったものの、イェシーバー式の学問の基準に合致しない独自の学習法のため、周囲からは平均的な 存在と見なされていたと推測している。[5] しかしながら、ハゾン・イッシュの生涯と思想を研究する学者ブラウンは、彼の著作や現存する数少ない詩作に、ユダヤ啓蒙主義文学の影響が顕著に見られると 主張する。この影響は、彼の華麗で様式的な文章表現や、当時の他のラビとは異なり外来語を一切排除した厳格なヘブライ語使用に表れている。[6] これに対し、シュロモ・ハヴリンはこの仮定の根拠は時代錯誤だと主張する。ラビ文学は常にヘブライ語で書かれたが、イディッシュ語文学は当時全盛期にあっ たからだ。[7] ハゾン・イシュは若い頃から物静かな人物として知られていた。彼の知人であるベニ・ブラク市の創設者イツハク・ゲルステンコーンに対し、彼は十代の頃に 「頭の中で完全に形作られていないことは口にしない」と決めたと説明している。しかし、彼はよく練られた考えを文章にすることが多いため、口に出して話す ことは稀だという。[8] 5651年(1891年)、祖父のラビ・シムション・カレリッツが死去した。その日、父であるラビ・シュマリアフ・ヨセフ・カレリッツは町を離れていたた め、16歳と12歳の孫であるメイアとアブラハム・イェシャヤフが自ら追悼の辞を準備し、兄のメイアが葬儀で朗読した。[9] 若き日のハゾン・イシュはブリスクへ学びに赴いた。ビニャミン・ブラウンは彼の旅先がヴォロジン・イェシーヴァであったとする説も論じている[10]が、 ラビ・イッサー・イェフダ・ウンターマンの証言によれば、ハゾン・イシュは確かにブリスクで学んだ[11]ものの、そこに居場所を見出せず故郷コサヴァへ 戻ったことから、この説は誤りと思われる。この旅の目的は、ブリスクのヨセフ・ドヴ・ハレヴィ・ソロヴェイチク師に学ぶためであった。同師はヴォロジン・ イェシーヴァを去った後、5652年(1892年)に亡くなるまでブリスクで教鞭を執っていた。[12] 彼の早急な帰郷については、郷愁、ハラハー上の問題(ブリスクでは元現地ラビであるヨエル・シルキス師の裁定に基づき寛大に扱われた「チャダシュ禁 止」)、さらにはブリスクの霊的環境の悪さなど、いくつかの推測がなされている。[13] [14] 5661年(1901年)、雑誌「ハペレス」に「カサヴァ(=コサヴァ)のA.Ya.SH.」という筆名で、ハゾン・イシュ名義の回答が数点掲載された。 その一つで彼は、別のラビが提起した可能性のある異議に対して、ヘブライ暦における通説の計算法を擁護している。[15] これらは、現時点で知られている限り、彼の最初の印刷物である。 5665年(1905年)の冬、ハゾン・イシュはヴィルナ市に長期滞在し、現地のハイム・オゼル・グロジンスキー師のキブツで学んだ。1905年のロシア革命による交通障害が一年中続いたため、滞在が延長された可能性がある。[16] |

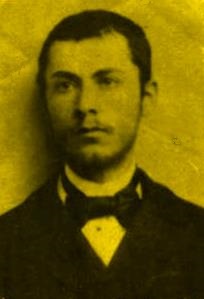

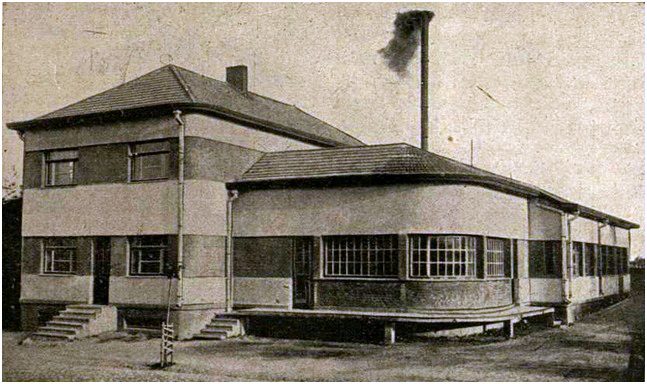

Period of Kvedarna The dairy cooperative of Kvedarna (1938)  Title page of the book "Chazon Ish", first edition, Vilna 1911 In the winter of 5666 (end of 1905), at the age of 27, he became engaged to Batya (Basha), daughter of Mordechai Bay, a merchant from the town of Kvedarna (Yiddish: Kovidan) in western Lithuania, who was significantly older than him. Exact details about her year of birth, and thus about their age gap, are unknown. According to the author Chaim Grade,[17] her age was twice his; however, it may be that the fictional character “Machazeh Avraham”, undoubtedly based on the Chazon Ish, is not identical in all its details. The Karelitz family agreed to the match because she was considered an industrious and God-fearing woman, and also because their son Avraham Yeshayahu was known to be a heart patient and stringent in halacha, and was seeking a wife who would take on the burden of livelihood and allow him to study Torah.[18] After the "Tna'im” (conditions) were signed, it became clear that the father-in-law would not be able to meet his financial obligations and that the intended bride was older than thought; because of this, the family of the Chazon Ish sought to withdraw from the match, but he refused, arguing that one must not shame a daughter of Israel under any circumstance and once terms were agreed upon, one should not back out.[19] The wedding took place three months after the engagement, on 11 Shevat 5666 (6 February 1906),[20] in Kovidan, and the couple made their home in that town. Batya opened a fabric shop there and supported the family, and the Chazon Ish devoted his time to Torah study. Rabbi Avraham Horowitz reports that Batya testified her husband sometimes helped her manage the household accounts,[21] but still, when the Chazon Ish needed something, he had to ask her for money.[22] The Kovidan period is mentioned by the Chazon Ish's biographers as his "golden era", during which he studied Torah undisturbed. He studied in chavruta with the town’s rabbi, Rabbi Moshe Rozin, author of Nezer HaKodesh, and delivered Gemara lessons in the local synagogue. He would be in the beit midrash from early morning until night.[23] Rabbi Rozin held the Chazon Ish in high esteem and told Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski of him in Vilna. According to Brown, this was the point when the connection between the two men was formed.[24] Among his study companions in Kovidan were Rabbi Moshe Ilovitzky, Rabbi David Nachman Koloditzky,[25] and his future brother-in-law Rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu Kahan, with whom the Chazon Ish studied Tractate Niddah for a time, and through this connection arranged a match between him and his sister Badana. In Kovidan, the Chazon Ish founded a yeshiva with the local rabbi.[26] In the year 5671 (1911), the first book in the series "Chazon Ish" was published, on topics of "Orach Chayim", "Kodashim", and the laws of Niddah. The book was published anonymously and only the name of the publisher, his brother Rabbi Moshe Karelitz, appeared on the title page, with no approbations. His books were not particularly popular, likely due to the difficult and concise writing style and the interpretive method that differed from the analytic method common in the Lithuanian Torah world. According to Brown, the difficulty in understanding his words stems from the fact that the author assumes the reader has already studied the sugya with its commentaries and is aware of the difficulties it raises, which the Chazon Ish seeks to solve.[27] The Chazon Ish's nephew, Rabbi Eliezer Alpha, once asked him, comparing it to Rabbi Chanokh Eigesh’s Marcheshet, published at the same time: "Your book is hard, and his is easy. And if we're already making an effort, we may as well study the works of the Rashba!" It is told that the Chazon Ish replied: "Once one toils over the Rashba, there’s no need to toil over the Chazon Ish."[28] Due to the blood libel against Mendel Beilis and the Beilis trial (1911–1913), during which the defense submitted to the Russian court expert testimony disproving the blood libel in both private and general terms, Rabbi Karelitz, then age 34, wrote a treatise published in his letters collection under the title "To a Foreign Minister".[29] In this treatise, of which only the initial parts survived, there are twenty-six short chapters,[30] in which he surveys the Jewish outlook regarding the sanctity of human life and seeks to prove that ritual murder contradicts the fundamental principles of Judaism. Brown speculates that the missing parts of the treatise were never written, as it eventually became clear to him that his words would not receive the court's attention.[31] |

クヴェダルナの時代 クヴェダルナ酪農協同組合(1938年)  『ハゾン・イシュ』初版表紙、ヴィルナ1911年 5666年冬(1905年末)、27歳の時に彼は、リトアニア西部のクヴェダルナ(イディッシュ語:コヴィダン)出身の商人モルデハイ・ベイの娘バティア (バーシャ)と婚約した。彼女は彼よりかなり年上だった。彼女の正確な生年、つまり二人の年齢差については不明である。作家ハイム・グラードによれば [17]、彼女の年齢は彼の倍であった。しかし、架空の人物「マハゼ・アブラハム」(明らかにハゾン・イシュをモデルとしている)の描写が細部まで正確と は限らない。カレリッツ家は、彼女が勤勉で敬虔な女性と見なされていたこと、また息子のアブラハム・イェシャヤフが心臓病を患い、律法に厳格な人物として 知られ、生計の負担を引き受け、彼がトーラーの勉強に専念できる妻を求めていたことから、この縁談に同意した。[18] 「トナイム」(婚約条件)の調印後、義父が経済的義務を果たせないこと、また花嫁予定者が想定より年上であることが判明した。このためハゾン・イシュの家 族は婚約破棄を望んだが、彼は拒否した。いかなる状況でもイスラエルの娘を辱めてはならず、一度条件が合意された以上、撤回すべきではないと主張したので ある。[19] 結婚式は婚約から3か月後の5666年シェバト月11日(1906年2月6日)[20]にコヴィダンで行われ、夫妻はその町に居を構えた。バティアはそこ で布地店を開き家計を支え、ハゾン・イシュはトーラー研究に専念した。ラビ・アブラハム・ホロヴィッツによれば、バティアは夫が家計簿の管理を手伝うこと もあったと証言している[21]。それでもハゾン・イシュが何かを必要とする時は、彼女にお金を頼まねばならなかった。[22] コヴィダン時代は、ハゾン・イシュの伝記作家たちによって「黄金期」と評されている。この期間、彼は妨げられることなくトーラーを学んだ。町のラビであり 『ネツァール・ハコデシュ』の著者であるモーシェ・ロージンとハヴルータ(学友)を組み、地元のシナゴーグでゲマラの講義を行った。彼は早朝から夜までベ イト・ミドラシュ(学びの家)にいた。[23] ラビ・ロジンはハゾン・イシュを高く評価し、ヴィルナにいるラビ・ハイム・オゼル・グロジンスキーに彼について語った。ブラウンによれば、この時が二人の 間に絆が生まれた瞬間であった。[24] コヴィダンでの彼の学友には、ラビ・モシェ・イロヴィツキー、ラビ・ダヴィド・ナフマン・コロディツキー[25]、そして後に義理の兄弟となるラビ・シュ ムエル・エリヤフ・カーハンがいた。ハゾン・イシュはカーハンと共に一時的に『ニダ』の巻を学び、この縁でカーハンの妹バダナとの縁談が成立した。コヴィ ダンでは、ハゾン・イシュは地元のラビと共にイェシーバーを設立した[26]。 5671年(1911年)、「ハゾン・イシュ」シリーズの第一巻が刊行された。内容は「オラフ・ハイム」「コダシム」、そしてニダ法の規定に関するもので あった。この書は匿名で出版され、表紙には出版者である兄ラビ・モーシェ・カレリッツの名のみが記され、推薦文は一切なかった。彼の著作は特に人気を博さ なかったが、その理由は難解で簡潔な文体と、リトアニアのトーラー界で一般的な分析的手法とは異なる解釈方法にあったと考えられる。ブラウンによれば、彼 の言葉を理解するのが難しいのは、著者が読者が既にそのスギヤ(律法主題)と注釈書を学び、そこで生じる難点を認識していることを前提としているためだ。 チャゾン・イシュはそれらの難点を解決しようとしているのである[27]。チャゾン・イシュの甥であるラビ・エリエゼル・アルファは、同時期に出版された ラビ・ハノク・エイゲシュの『マルケシェット』と比較して、彼にこう尋ねたことがある。「あなたの書物は難しいが、彼の書物は易しい。努力するのなら、ラ シュバの著作を学んだ方がましだ!」と。チャゾン・イシュはこう答えたという:「ラシュバに労力を費やせば、チャゾン・イシュに労力を費やす必要はない」 と。[28] メンデル・ベイリスに対する血の誹謗とベイリス裁判(1911-1913年)において、弁護側はロシアの法廷に、私的・一般的な観点から血の誹謗を否定す る専門家証言を提出した。当時34歳だったラビ・カレリッツは、この裁判を受けて論文を執筆し、書簡集に「外務大臣へ」という題名で収録した。[29] この論文は冒頭部分のみが現存しているが、26の短い章で構成されている[30]。そこでは、ユダヤ教における人命の尊厳に関する見解を概観し、儀式殺人 (血の誹謗)がユダヤ教の基本原理に矛盾することを証明しようとしている。ブラウンは、論文の欠落部分は結局書かれなかったのではないかと推測している。 なぜなら、彼の言葉が裁判所の注意を引くことはないと最終的に理解したからだという。[31] |

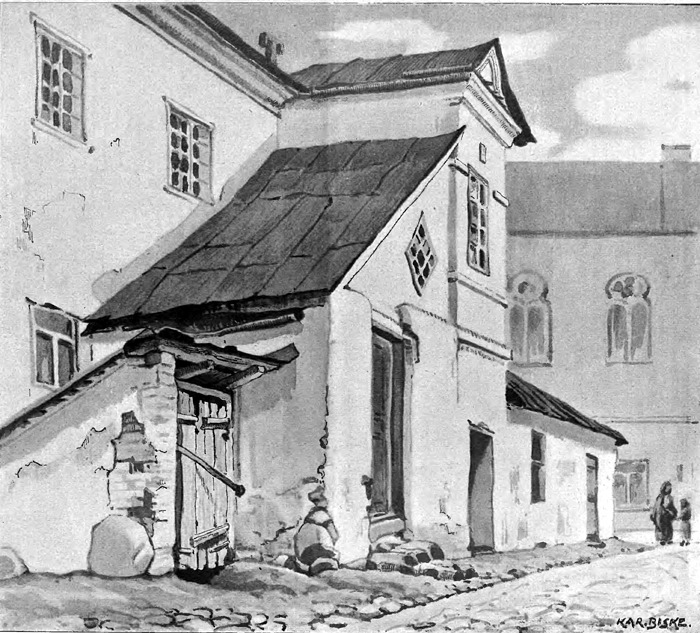

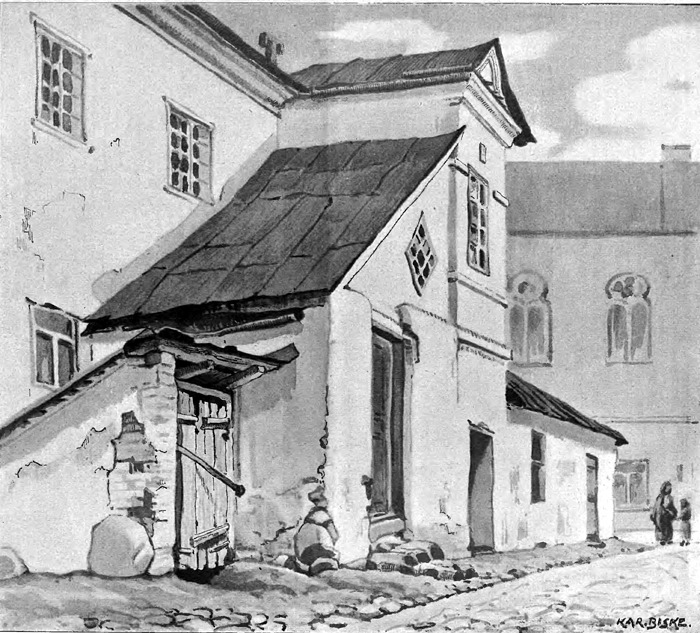

| Period of World War I Stoybtz  The great Beit Midrash in Stoybtz during the Chazon Ish’s stay in the town During the course of Eastern Front (World War I), the Imperial German Army occupied large swaths of historical Lithuania, and many residents from battle areas fled their homes and became refugees. The Chazon Ish and his wife, like many Jews of Kovidan, also fled to Russian-controlled territory and settled in the town of Stoybtz (Stołpce). Batya Karelitz opened a fabric shop in Stoybtz as well,[32] and the Chazon Ish continued his studies. Although the Chazon Ish opposed holding a rabbinic post all his life, when the town’s rabbi, Rabbi Yoel Sorotzkin, was forced to leave by Russian orders, the Chazon Ish unofficially replaced him at his request, until he returned.[33] According to another version,[34] the residents begged Rabbi Karelitz to take the position after Rabbi Sorotzkin left, but he refused. According to one source, the Chazon Ish declined to bear communal responsibility, except in one case, when he joined efforts to restore the local mikveh that burned down in a fire.[35] That fire is described in a rare heading to one of the Chazon Ish’s commentaries on Tractate Kelim: Stoybtzi, where nearly the whole town burned on Monday, 25 Sivan, and all its residents under pressure and distress with no home to live in and no place to lodge.[36] Rabbi Shmaryahu Greineman recounted that when a plague broke out in town and the members of the chevra kadisha feared burial due to contagion, the Chazon Ish took it upon himself to bury the dead out of respect for the deceased. As a provocative act, he took one of the corpses on his shoulders and carried it to the cemetery, which caused the chevra kadisha members to return to their role. He later explained that his rationale was that if the dead were not buried, the entire town would be in mortal danger.[37] In Stoybtz, the Chazon Ish hosted a group of young Jewish refugees in his home, among them Mordechai Shulman, who later founded Slabodka Yeshiva (Bnei Brak) and was one of his close associates.[38] Among the exiles to Stoybtz were also students of the Mir Yeshiva, along with their mashgiach Rabbi Yerucham HaLevi Leibowitz, and a connection was formed between them.[39] There are recorded cases of students from the Stoybtz area who came there to converse in Torah with the Chazon Ish.[40] Minsk  Minsk 1918, painting by Karol Biske The Chazon Ish and his wife lived in Stoybtz during the first four years of the war, but at some point moved to the city of Minsk. After the October Revolution in 1917, the Belarusian Democratic Republic was declared. This state, which lacked broad international recognition, lasted briefly, and in 1919 the Communists took over and turned it into the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. At first, the Chazon Ish moved alone to Minsk and lived in an apartment provided by Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin, while Batya continued managing the fabric store in Stoybtz and traveled to Minsk for Sabbaths. His cousin Shaul Lieberman described those days in Minsk: In those years he sat in his home in Minsk and studied all day and night. On Shabbat his wife came from Stoybtzi… I believe those were his best days, because he was still unknown… the public generally did not know of his existence, and he enjoyed that very much. He could seclude himself and study. Jews did not disturb him, and his mouth did not cease from learning. His wife would send him enough for sustenance, and he sufficed with little, from one Sabbath to the next. — Shaul Lieberman, "In the Company of Rabbis"[41] On 21 Iyar 5677 (1917), his father Rabbi Shmaryahu Yosef Karelitz died in Kosava, and was succeeded as town rabbi by his son-in-law, Rabbi Abba Swiatycki. The news of his father's death reached the Chazon Ish only four months later, on 29 Elul 5677,[42] via the Red Cross.[43] From then on, the Chazon Ish made a practice of studying the entire Tractate Chullin on his father's yahrtzeit, as his father had written the work Beit Talmud on that tractate.[44] The Chazon Ish's seclusion for continuous Torah study during his time in Minsk was so complete that he did not go to prayers at the synagogue except on Shabbat and on Monday and Thursday, when there is Torah reading.[45] In those days, he wrote the commentaries later published on Tractate Eruvin and other topics in Orach Chayim and Yoreh De’ah. In Minsk, the Chazon Ish met leading Torah sages who were also staying there because of the war, including Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel, and Rabbi Yeruchom Levovitz. |

第一次世界大戦期 ストイブツ  ハゾン・イシュが町に滞在した際の、ストイブツの大ベイト・ミドラシュ 東部戦線(第一次世界大戦)の過程で、ドイツ帝国軍は歴史的なリトアニアの大部分を占領し、戦域の多くの住民は家を離れ難民となった。コヴィダンの多くの ユダヤ人同様、ハゾン・イシュとその妻もロシア支配地域へ逃れ、ストイブツ(ストープツェ)に定住した。バティヤ・カレリッツもストイブツで布地店を開い た[32]。ハゾン・イシュは学問を続けた。 チャゾン・イシュは生涯にわたりラビ職の就任を拒んでいたが、町のラビであるヨエル・ソロツキン師がロシア軍の命令で退去を余儀なくされた際、ソロツキン 師の要請により非公式に後任を務めた。ソロツキン師が復帰するまでの間である[33]。別の説によれば[34]、ソロツキン師の退去後、住民がカレリッツ 師にラビ職を引き受けるよう懇願したが、彼はこれを拒否したという。ある情報源によれば、ハゾン・イシュは共同体の責任を担うことを拒んでいたが、一つの 例外があった。それは火災で焼失した地元のミクヴェ(浸礼場)を修復する取り組みに参加した時である[35]。その火災は、ハゾン・イシュの『ケリム篇』 注釈書に稀に見られる見出しで記述されている: ストイブツィでは、シヴァン月25日月曜日に町の大半が焼失し、住民は住む家も宿る場所もなく、苦痛と圧迫に苛まれている。[36] ラビ・シュマリアフ・グライネマンによれば、町に疫病が流行した際、ヘヴラー・カディシャー(埋葬団体)のメンバーが感染を恐れ埋葬を拒んだ。チャゾン・ イシュは故人への敬意から自ら死者を埋葬することを引き受けた。挑発的な行為として、彼は遺体の一つを肩に担ぎ墓地まで運んだ。これによりヘヴラー・カ ディシャーのメンバーは職務に復帰したのである。彼は後に、死者を埋葬しなければ町全体が死の危険に晒されると考えたからだと説明した。[37] ストイブツでは、ハゾン・イシュが自宅に若いユダヤ人難民の一団を招き入れた。その中には後にスラボドカ・イェシーバ(ブネイ・ブラク)を設立し、彼の側 近の一人となったモルデハイ・シュルマンも含まれていた。[38] ストイブツに追放された者の中には、ミール・イェシーバの学生たちとその指導者であるラビ・イェルフアム・ハレヴィ・ライボヴィッツも含まれており、彼ら との間に繋がりが生まれた[39]。ストイブツ地域から来た学生たちが、ハゾン・イシュとトーラーについて議論するためにそこを訪れた事例も記録されてい る[40]。 ミンスク  ミンスク 1918年、カロル・ビスケ作 ハゾン・イシュとその妻は戦争最初の4年間をストイブツで過ごしたが、ある時点でミンスク市へ移った。1917年の十月革命後、ベラルーシ民主共和国が宣 言された。この国家は国際的な認知を得られず短命に終わり、1919年に共産主義者が掌握しベラルーシ・ソビエト社会主義共和国へと変貌した。 当初、ハゾン・イシュは単身ミンスクに移り、ラビ・ザルマン・ソロツキンが提供したアパートに住んだ。一方、妻バティアはストイブツで布地店を経営し続け、安息日にはミンスクへ通った。彼の従兄弟シャウル・リーバーマンは、ミンスクでの日々をこう語っている: あの頃、彼はミンスクの自宅で昼夜を問わず学びに没頭していた。安息日には妻がストイブツィから訪ねてきた…おそらくあの頃が彼にとって最良の日々だっ た。まだ無名だったからだ…世間は彼の存在を知らず、彼はそれを大いに楽しんでいた。隠遁して学問に専念できたのだ。ユダヤ人たちは彼を煩わせず、彼の口 は学びを絶やさなかった。妻が生活費を送ってくれ、彼はわずかなもので満足し、安息日から次の安息日まで過ごした。 ―シャウル・リーバーマン『ラビたちの交わり』[41] 5677年(1917年)イヤール月21日、父シュマリアフ・ヨセフ・カレリッツがコサヴァで死去し、娘婿のアッバ・スヴィャティツキが町ラビを継いだ。 父の死の知らせは赤十字を通じて、わずか4か月後の5677年エルル月29日[42]にようやくチャゾン・イシュのもとに届いた[43]。それ以来、チャ ゾン・イシュは父の命日に『フリン』全巻を学ぶ習慣を身につけた。父がこのトラクタートについて『ベイト・タルムード』を著していたからである[44]。 ミンスク滞在中、ハゾン・イシュはトーラー研究に没頭し、安息日とトーラー朗読が行われる月曜日・木曜日以外はシナゴーグの礼拝にも行かなかった。この期 間に彼は『エルーヴィン』や『オラフ・ハイーム』『ヨレ・デーア』の諸主題に関する注釈を執筆し、後に刊行された。ミンスクでは、戦争のため同地に滞在し ていた主要なトーラーの賢者たちと出会った。ハイム・ソロヴェイチク師、ノッソン・ツヴィ・フィンケル師、イェルフーム・レヴォヴィッツ師らがその例であ る。 |

Vilna period The Chazon Ish around the time of his arrival in Vilna, circa 1920  Interior of the Great Synagogue of Vilna, around 1920 After the war, the Karelitz family returned to Stoybtz, which was in Soviet territory, and later crossed the border into Lithuania intending to return to Kovidan. Upon arrival, they found the town had not yet recovered from its destruction, and they turned to the Chazon Ish’s siblings (two brothers and a sister) who were living in Vilna to arrange their relocation there. An apartment with two rooms was rented for the couple in the Vilna suburb of Zaretshe, one of which was dedicated to Batya’s fabric shop.[46] In 1920, the Karelitz family settled in the city of Vilna (then the capital of the short-lived state of Central Lithuania; in 1922 it was annexed by the Second Polish Republic), where he became close to the city’s rabbi, Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski. According to assessments, his exposure to Vilna’s Torah greats, even though he was not yet central in public affairs, contributed to the leadership ability he would later demonstrate as a Gadol Hador in the Land of Israel after the war.[47] In the mornings, the Chazon Ish would walk to another suburb called Paplaujos (Paplauja), where his brother-in-law, Rabbi Shmuel Greineman, gave him a room in his apartment, simply furnished with a bed, chair, table, and basic sefarim. In this room, he studied alone, as was his custom, until evening, sometimes until collapse, for a period of three years.[48] It was said that during this time he delved into a specific Mishnah in Tractate Mikvaot for three months, about 15 hours a day.[49] During the 13 years he lived in Vilna, three more volumes of Chazon Ish were published. His brother-in-law Rabbi Greineman and his brother Rabbi Moshe managed their printing. Binyamin Brown writes that although the Chazon Ish secluded himself for learning, he was “pleasant in manner, very kind, loved people, smiling, optimistic, and even possessed a subtle sense of humor,” and loved to offer advice and help people. He attributes his withdrawal from social interaction to natural shyness.[50] In 5683 (1923), the second volume of his work on Orach Chayim was published, including his comprehensive treatment of the laws of muktzeh, Kuntres HaMuktzeh. That summer, the Chazon Ish collapsed and was forced to take a break from his intensive study. He wrote to his friend Rabbi Moshe Ilovitzky: “I suffered from nervous weakness and stopped learning.”[51] During that time, Rabbi Yoel Kloft recounted in his name: “Idleness was difficult for me; I felt like I was wandering the streets of Vilna like a madman because I couldn’t study.”[52] After this breakdown, he abandoned his habit of solitary all-day study and began learning with young students as chavruta. In late summer 5683 (1923), he recuperated in the resort town of Valkenik near Vilna, where Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski also stayed. There he began learning with a young man named Shlomo Cohen, grandson of Rabbi Shlomo HaCohen, one of Vilna’s rabbis. Cohen became his close student and later headed the semi-official biography project of the Chazon Ish.[53] Their joint study continued until the Chazon Ish immigrated to Eretz Yisrael in 5693 (1933), nearly 10 years after their acquaintance began. Later during his time in Vilna, Chaim Grade, who would become a prominent Yiddish author, also lived in his home. He too studied with the Chazon Ish in chavruta for about seven years.[54] Some speculate that the Chazon Ish preferred to study with young students because he saw them as a substitute for children he never had, or because he preferred to shape their learning style rather than study with those already “corrupted” by standard yeshiva methods.[55] Paplaujos Bridge over the Vilnia River, Vilna, 2008 In Vilna, the Chazon Ish made one final attempt to persuade his wife Batya to accept a get (Jewish divorce), so he could marry a younger woman who could bear children. Batya later recounted this to her friend, the mother of Chaim Kolitz. According to her, it happened on their way home across the Vilnia River (Vilnia); she answered: “Alright, but on my way home from the beit din, I will jump from the bridge straight into the water.” The Chazon Ish ceased all attempts and accepted the situation. However, according to Kolitz’s account, he then practiced the halakhic Niddah restrictions with her, such as not handing objects directly into her hand.[56] In the 1930s, the Torah monthly Knesset Yisrael was published in Vilna, edited by his brother Rabbi Moshe. The Chazon Ish published insights there under pseudonyms. In one instance, he used the name of his student “Shlomo Cohen” to publish a critique of novellae written by Rabbi Joseph Dov Soloveitchik of Boston (then a student at Humboldt University of Berlin). According to the Chazon Ish’s brother-in-law, Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky (“the Steipler”), the Chazon Ish believed that the novellae were not the young Soloveitchik’s work, but that of his father, Rabbi Moshe Soloveichik, then Rosh yeshiva at Yeshiva University. Nonetheless, he chose to attack them ideologically, due to their association with Religious Zionist and Mizrachi circles.[57] According to Rabbi Soloveitchik’s son, Prof. Haym Soloveitchik, the novellae were indeed his father’s, not his grandfather’s, and the Chazon Ish sought to refute them even with weak arguments “to show that there is no Torah in him or his kind.”[58] At this stage, the Chazon Ish was involved in several heated public issues, including: A. The rabbinate controversy in Vilna,[59] a struggle that developed over the spiritual leadership of the city. The Mizrachi faction in Vilna sought to appoint Rabbi Yitzchak Rubinstein, who until then had been the official "government rabbi", as chief rabbi of the city. The Agudat Yisrael faction opposed, claiming that Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski was the natural spiritual leader of the community. The Chazon Ish led, behind the scenes, the effort to block Rubinstein’s appointment. The campaign failed, and the Chazon Ish’s brother, Rabbi Meir Karelitz, who was openly involved in the effort, was forced to resign from his seat on the “Rabbinical Council” of Vilna.[60] B. A dispute between the Novardok Yeshiva network and the Vaad HaYeshivot regarding the share of funding to which the network was entitled. The leadership of the network argued that the Vaad should calculate each of the network’s branches as an independent institution when allocating the overall budget. The Vaad, for its part, decided due to financial constraints to treat the network as a single entity. Rabbi Grodzinski, who served as president of the Vaad, recused himself from the matter and imposed upon the Chazon Ish, in the presence of several prominent rabbis from Lithuania and beyond,[note 1] to issue a ruling. After deliberation, the Chazon Ish was compelled to decide. He heard both sides and ruled that the Novardok Yeshiva network would be entitled to 10% of the Vaad’s total budget. He was unaccustomed to such a position and quickly exited the hall after delivering the ruling. It is told that Rabbi Grodzinski summed up the meeting with the words: Do you not know who the Chazon Ish is? The Chazon Ish is “truth” – and in the face of truth, one must yield![61] In the year 5691 (1931), Rabbi Moshe Blau, at the recommendation of Rabbi Grodzinski, proposed that the Chazon Ish be appointed his deputy and eventual successor to Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, the leader of the Edah HaChareidis in Jerusalem, who was by then struggling to fulfill his role. The Chazon Ish declined, saying he had no objection to the title, but was unwilling to judge monetary cases – a central part of the proposed position – thereby disqualifying the candidacy. In 5692 (1932), after Rabbi Sonnenfeld's death, Rabbi Grodzinski wrote to Jacob Rosenheim[62] that the Chazon Ish was not among the "fearful of issuing rulings" regarding matters of kashrut laws, but in monetary matters he hesitated to rule “out of great righteousness.”[63] In his final years in Vilna, he studied in the mornings in chavruta with his acquaintance from Stoybtz, Rabbi Mordechai Shulman, then the young son-in-law of Rabbi Yitzchak Isaac Sher and later head of the Slabodka Yeshiva (Bnei Brak).[64] In the spring of 5693 (1933), following a theft of merchandise from his wife’s fabric store,[65] the Chazon Ish decided to immigrate to the Land of Israel. He informed Rabbi Grodzinski, who hurried to arrange an immigration certificate for him and his wife. He turned to Moshe Blau, a leader of Agudat Yisrael in Eretz Yisrael, requesting that he handle the matter. Blau hinted that the Chazon Ish’s agreement to serve in the Edah HaChareidis Rabbinate in Jerusalem might ease the certificate process. The Chazon Ish again refused, and the process was handed to the secretary of Agudat Yisrael in Jerusalem, Moshe Porush. Before even receiving the Chazon Ish’s reply, Porush approached the British Mandate authorities, stating that there was a possibility that the Chazon Ish would be appointed head of the rabbinical court of the Edah, and that Agudat Yisrael guaranteed he would not be a public burden. The certificate was quickly arranged and sent to Rabbi Grodzinski.[66] At Rabbi Grodzinski’s special request on behalf of the Chazon Ish, the Jerusalem activists arranged a special exemption for him from the quarantine then in force at ports to prevent disease transmission.[67]  Vilna railway station The Chazon Ish and his wife left Vilna on Sunday, 8 Tammuz 5693, 2 July 1933. On Saturday night, they were accompanied to the train station by a small group, including Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski and Rabbi Chanokh Eigesh.[68] The Karelitz family traveled by train to Warsaw, and from there to the port city of Constanța on the shores of the Black Sea in Romania. From the port of Constanța, they sailed to the Land of Israel aboard the ship USS Martha Washington. |

ヴィルナ時代 ヴィルナ到着当時のハゾン・イシュ、1920年頃  ヴィルナ大シナゴーグの内部、1920年頃 戦後、カレリッツ家はソ連領内のストイブツに戻り、後にリトアニア国境を越えてコヴィダンへ戻るつもりだった。到着すると、町はまだ破壊から回復しておら ず、彼らはヴィルナに住んでいたハゾン・イシュの兄弟姉妹(二人の兄と一人の姉)に頼み、ヴィルナへの移住を手配した。夫婦のためにヴィルナ郊外のザレ チェに二部屋のアパートが借りられ、その一つはバティアの布地店に充てられた。[46] 1920年、カレリッツ家はヴィルナ市(当時は短命に終わった中央リトアニア共和国の首都。1922年に第二ポーランド共和国に併合)に定住し、彼は同市 のラビであるハイム・オゼル・グロジンスキーと親交を深めた。評価によれば、彼はまだ公的な活動の中心ではなかったものの、ヴィルナのトーラーの偉人たち との接触が、戦後イスラエルの地でガドル・ハドール(時代の偉人)として示した指導力の一因となった。[47] 朝になると、ハゾン・イシュはパプラウジャス(パプラウジャ)と呼ばれる別の郊外へ歩いて行った。そこでは義兄のラビ・シュムエル・グライネマンが、ベッ ド、椅子、机、基本的なセファリム(聖典)だけが置かれた部屋をアパートの一室に提供していた。この部屋で彼は、いつものように一人で夕暮れまで、時には 倒れるまで、三年間にわたり学び続けた。[48] この期間、彼は『ミクヴォート』の特定のミシュナーを3か月間、1日約15時間も掘り下げたと言われる。[49] ヴィルナに13年間住んだ間に、『ハゾン・イシュ』のさらに3巻が出版された。義理の兄弟であるグレインマン師と実の兄弟であるモーシェ師が印刷を管理し た。 ビニャミン・ブラウンは記す。ハゾン・イシュは学問のために世を避けたが、「気立てが良く、非常に親切で、人を愛し、笑顔を絶やさず、楽観的で、微妙な ユーモアのセンスさえ持っていた」と。彼は助言を与え、人を助けることを好んだ。社交から遠ざかったのは、生まれつきの内気さによるものだとブラウンは分 析する。[50] 5683年(1923年)、彼の『オラハ・ハイム』に関する著作の第2巻が刊行された。これにはムクツェの律法に関する包括的な論考『クントレス・ハ・ム クツェ』が含まれていた。その夏、ハゾン・イシュは体調を崩し、集中的な学習を中断せざるを得なかった。彼は友人であるラビ・モシェ・イロヴィツキーにこ う書き送っている。「神経衰弱に苦しみ、学習を中断した」 [51] この時期について、ヨエル・クロフト師は彼の言葉をこう伝えている。「怠惰は耐え難かった。学べないため、ヴィルナの街を狂人のように彷徨っている気がし た」[52] この病後、彼は終日独学する習慣を捨て、若い学生たちとハヴルータ(学友)として学ぶようになった。5683年(1923年)の夏の終わり、彼はヴィルナ 近郊の保養地ヴァルケニクで療養した。そこにはラビ・ハイム・オゼル・グロジンスキーも滞在していた。そこで彼はシュロモ・コーヘンという青年と学び始め た。シュロモはヴィルナのラビの一人、ラビ・シュロモ・ハコーヘンの孫であった。コーヘンは彼の親しい弟子となり、後にハゾン・イシュの準公式伝記プロ ジェクトを率いることになった。[53] 彼らの共同学習は、知り合ってからほぼ10年後となる5693年(1933年)にハゾン・イシュがエレツ・イスラエルに移住するまで続いた。 後にヴィルナ時代、後に著名なイディッシュ語作家となるハイム・グラードも彼の家に住んでいた。彼もまたハゾン・イシュと約7年間ハヴルータで学んだ。 [54] チャゾン・イシュが若い学生との学習を好んだ理由について、彼には子供がいなかったため彼らをその代わりと見なしていたとか、あるいは既存のイェシーバ教 育法に「汚染」された者たちとの学習よりも、彼らの学習スタイルを自ら形成したいと考えていたからだと推測する者もいる。[55] ヴィルニャ川に架かるパプラウジョス橋、ヴィルナ、2008年 ヴィルナで、ハゾン・イシュは妻バティアにゲト(ユダヤ教離婚)を受け入れさせ、子供を産める若い女性と再婚しようと最後の説得を試みた。バティアは後に この出来事を友人であるハイム・コリッツの母に語った。彼女によれば、それはヴィルニア川を渡って帰宅途中での出来事だった。彼女はこう答えた: 「わかったわ。でも、ベイト・ディン(宗教裁判所)から帰る途中で、私は橋からまっすぐ川に飛び込むわ」チャゾン・イシュはそれ以上の試みを止め、現状を 受け入れた。しかしコリッツの記述によれば、彼はその後、彼女に対してニダ(月経中の女性)の律法上の制限を実践した。例えば、物を直接彼女の手に渡さな いといったことだ。[56] 1930年代、ヴィルナでは兄のモーシェ師が編集する月刊トーラー誌『クネセト・イスラエル』が刊行された。ハゾン・イシュはそこでペンネームを用いて見 解を発表した。ある事例では、弟子の「シュロモ・コーヘン」名義で、当時ベルリン・フンボルト大学に在籍していたボストンのヨセフ・ドヴ・ソロヴェイチク 師のノヴェラ批判を掲載している。チャゾン・イシュの義兄であるラビ・ヤアコブ・イスラエル・カニエフスキー(「シュテイプラー」)によれば、チャゾン・ イシュはこれらの新解釈が若きソロヴェイチクの著作ではなく、当時イェシーバ大学のロシュ・イェシーバであった父ラビ・モーシェ・ソロヴェイチクの著作で あると信じていた。それにもかかわらず、彼はこれらの論考が宗教的シオニストやミズラヒ派のサークルと結びついていることを理由に、イデオロギー的に攻撃 することを選んだ[57]。ラビ・ソロヴェイチクの息子であるハイム・ソロヴェイチク教授によれば、これらの論考は確かに祖父ではなく父親のものであり、 ハゾン・イシュは「彼や彼のような者にはトーラーの精神が欠けていることを示すため」に、たとえ弱い論拠であっても反駁しようとしたという[58]。 この段階において、ハゾン・イシュはいくつかの激しい公的論争に関与していた。具体的には: A. ヴィルナにおけるラビ職論争[59]。これは都市の精神的指導権を巡る争いだった。ヴィルナのミズラヒ派は、それまで公式の「政府ラビ」であったイッツハ ク・ルビンシュタインを首席ラビに任命しようとした。アグダト・イスラエル派はこれに反対し、ハイム・オゼル・グロジンスキーがコミュニティの当然の精神 的指導者だと主張した。ハゾン・イシュは、ルービンシュタインの任命阻止運動を水面下で主導した。この運動は失敗に終わり、公然と関与していたハゾン・イ シュの弟であるメイル・カレリッツ師は、ヴィルナの「ラビ評議会」の議席を辞任せざるを得なかった。[60] B. ノヴァルドク・イェシーバ・ネットワークとイェシーバ評議会(ヴァアド・ハ・イェシーボット)の間で、ネットワークが受けるべき資金配分比率を巡る争いが 生じた。ネットワーク指導部は、予算配分において各支部を独立した機関として計算すべきだと主張した。一方、ヴァアドは財政的制約からネットワークを単一 組織として扱うことを決定した。ヴァアド議長を務めていたグロジンスキー師はこの件から身を引くとともに、リトアニア内外の著名なラビ数名[注1]を同席 させ、ハゾン・イシュに裁定を下すよう要請した。審議の末、ハゾン・イシュは決断を迫られた。双方の主張を聞いた彼は、ノヴァルドク・イェシーバ・ネット ワークがヴァアド総予算の10%を配分されるべきだと裁定した。彼はこのような立場に慣れておらず、裁定を下すとすぐに会場を後にした。ラビ・グロジンス キーはこの会合を次のように締めくくったという: 「チャゾン・イシュが誰か知らないのか?チャゾン・イシュとは『真実』そのものだ。真実の前では、誰もが屈服せざるを得ないのだ!」 [61] 西暦5691年(1931年)、ラビ・モシェ・ブラウはラビ・グロジンスキーの推薦を受け、当時職務遂行に苦慮していたエルサレムのエダー・ハハレディス 指導者ラビ・ヨセフ・ハイム・ゾンネンフェルトの後継者として、ハゾン・イシュを副代表兼後継者に任命するよう提案した。チャゾン・イシュはこれを辞退し た。称号自体には異論はないが、提案された職責の中核をなす金銭訴訟の裁定には従いたくないと述べた。これにより立候補資格を失ったのである。5692年 (1932年)、ラビ・ゾンネンフェルトの死後、ラビ・グロジンスキーはヤコブ・ローゼンハイム[62]に書簡を送り、ハゾン・イシュはカシュルート(食 の律法)に関する裁定を下すことを「恐れる者」には含まれないが、金銭問題に関しては「非常に正しい心から」裁定を下すことを躊躇していると記した [63]。 ヴィルナでの晩年、彼は毎朝、ストイブツ時代の知人であるラビ・モルデハイ・シュルマンとハヴルータで学んだ。シュルマンは当時、ラビ・イッツハク・イサク・シェルの若い娘婿であり、後にスラボドカ・イェシーバ(ブネイ・ブラク)の学長となった人物である。[64] 5693年(1933年)の春、妻の布地店から商品が盗まれた事件[65]を受け、ハゾン・イシュはイスラエルの地への移住を決意した。彼はグロジンス キー師にその旨を伝え、師は急いで夫妻の移住証明書の手配に取りかかった。彼はエルサレムのアグダト・イスラエル指導者モーシェ・ブラウに、この件の処理 を依頼した。ブラウは、ハゾン・イシュがエルサレムのエダー・ハハレディス・ラビナート(宗教裁判所)で職務に就くことに同意すれば、証明書取得が容易に なる可能性を示唆した。ハゾン・イシュは再びこれを拒否し、手続きはエルサレムのアグダト・イスラエル書記モーシェ・ポルシュに引き継がれた。ポーラッ シュはハゾン・イシュの返答を待たず、英国委任統治当局に接触した。ハゾン・イシュがエダーのラビ法廷長に任命される可能性があり、アグダット・イスラエ ルが彼が公的負担とならないことを保証すると述べたのだ。証明書は迅速に手配され、グロジンスキー師に送付された。[66] ラビ・グロジンスキーがチャゾン・イシュに代わって特別に要請したため、エルサレムの活動家たちは、疾病伝播防止のため当時港湾で施行されていた検疫から 彼を特別に免除する手配をした。[67]  ヴィルナ駅 チャゾン・イシュとその妻は、5693年タムーズ月8日(1933年7月2日)の日曜日にヴィルナを出発した。土曜日夜、ハイム・オゼル・グロジンスキー師やハノク・エイゲシュ師ら少数のグループが駅まで見送りに来た。[68] カレリッツ一家は列車でワルシャワへ移動し、そこからルーマニアの黒海沿岸にある港湾都市コンスタンツァへ向かった。コンスタンツァ港から、彼らはUSSマーサ・ワシントン号でイスラエルの地へと航海した。 |

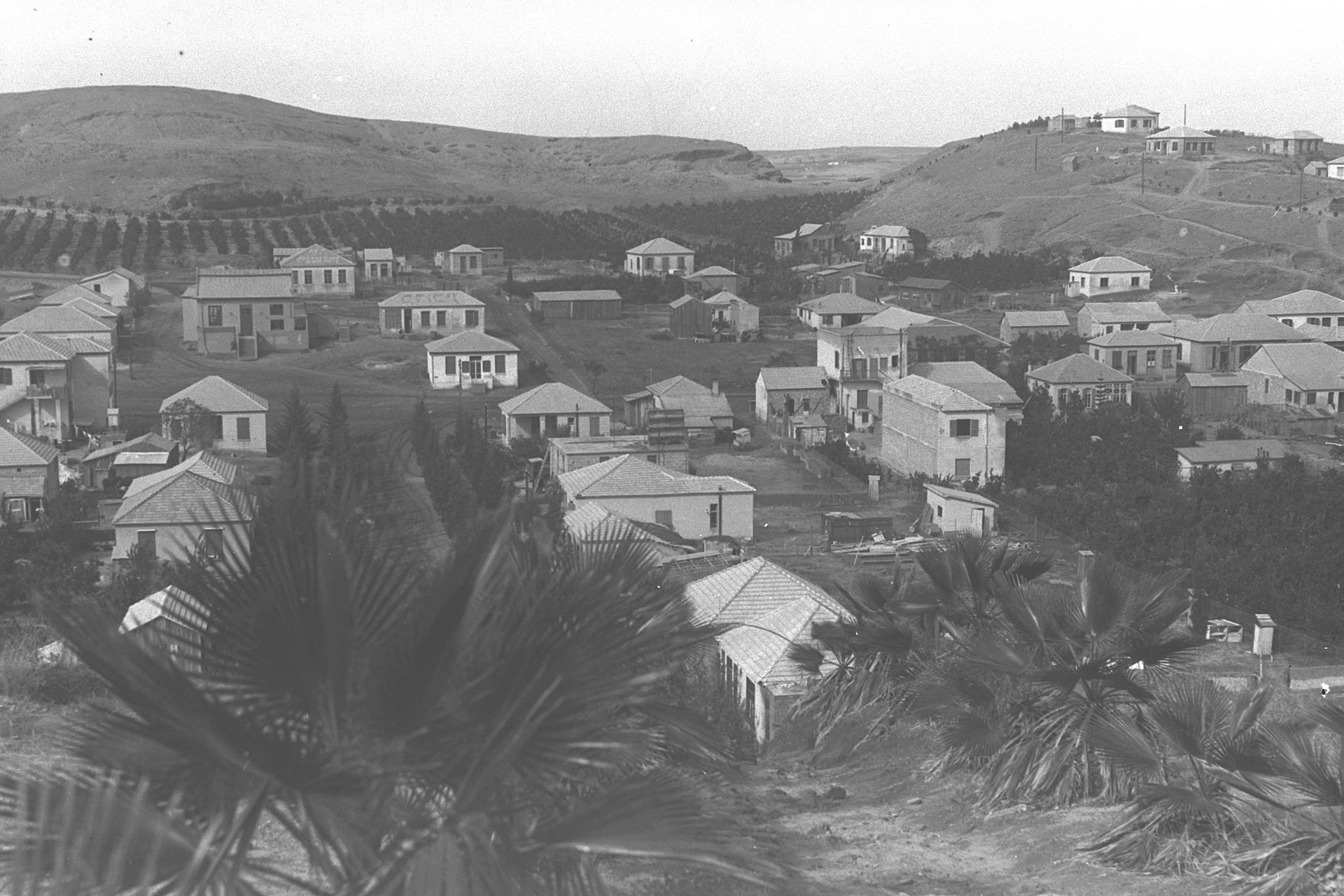

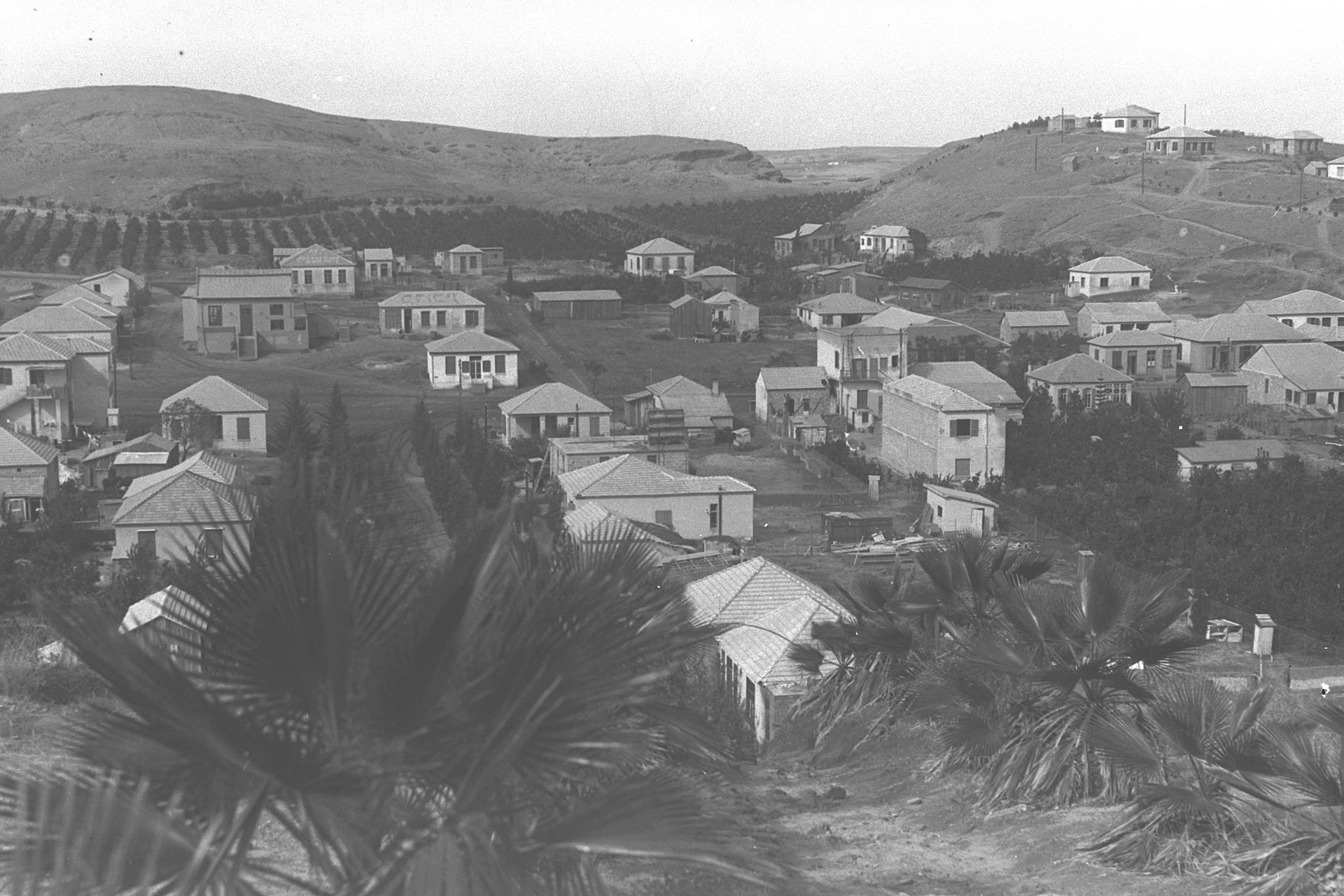

| In Mandatory Palestine I contemplate... and reflect on that wondrous man... the ideal type of the halachic man, who drew his authority from his intellectual capability and his personality, and not from the position he held. It seems he is one of the only figures about whom it is impossible not to speak in superlatives—and this is indeed what lexicon and encyclopedia writers, usually restrained in tone, do. — Chaim Be’er, Report from Another World[69]  Bnei Brak as it looked in the year the Chazon Ish arrived, 1933  The Chazon Ish serving as sandek at a brit milah, Tel Aviv, late 1940s  The Chazon Ish, early 1950s  The Chazon Ish, 1952 On 16 Tammuz 5693 (10 July 1933), the Chazon Ish and his wife immigrated to Mandatory Palestine. At the Port of Jaffa, they were greeted by members of Agudat Yisrael, at the request of Rabbi Grodzinski. In their early days in the Land of Israel, they stayed at the home of Rabbi David Potaš in Tel Aviv. After some time, they rented a room on Geula Street in the city. Rabbi Mattityahu Stigl, who had founded Beit Yosef Novardok Yeshiva in the new settlement of Bnei Brak, visited him in his apartment and invited him to move there. The Chazon Ish replied that he would come after the Three Weeks.[note 2] When the couple eventually arrived, they settled on the hill of Har Shalom. The air there pleased the Chazon Ish,[70] and he decided to settle in the area. Rabbi Shmuel Halevi Wosner related that he told him on the matter: Jerusalem is full of righteous and great Torah scholars, but in the new settlement I found a wilderness; I wanted to plant seeds of Torah in it—therefore I came to Bnei Brak. If I do not succeed in planting? Then I will go to Gehinnom with its inhabitants like one of them.[71] At first, he rented a two-room apartment from Rabbi Nachman Shmuel Yaakov Miyodser, rabbi of Bnei Brak and later head of the settlement council. After a short time, he moved to another apartment in Givat Rokach, where the rent was cheaper. Near his home was the Beit Yosef Yeshiva, and from time to time, the Chazon Ish would deliver lessons to its students. A few years later, he moved into a house built for him in eastern Bnei Brak.[72] In this house also lived his sister Miriam and her husband, Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky. Bnei Brak later became, to a large extent due to the Chazon Ish, one of the strongholds of Haredi Judaism in Israel. At first, he was joined in Bnei Brak by a small circle of members of Poalei Agudat Yisrael, who followed his halachic guidance on agricultural matters, mainly after Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski referred them to him. Later, he became widely known and became a halachic authority among broader circles in the country. An attempt by Batya Karelitz to reopen a textile shop failed, and she had to close it. A wealthy man who offered monthly financial support, at the request of Rabbi Yechezkel Abramsky, was declined by the Chazon Ish,[73] who resolved to support himself through the sale of his books, even though this income was neither profitable nor steady; the Chazon Ish had not yet achieved national fame, and buyers came only gradually. In 5694 (1934), Rabbi Grodzinski put forward the Chazon Ish as one of the candidates for the Council of Torah Sages of Agudat Yisrael in the Land of Israel. After consulting with the Chazon Ish, Rabbi Grodzinski wrote: Rabbi A.Y. Karelitz does not want to accept any official title or responsibility, but is willing to be consulted.[74] That summer, the Chazon Ish spent an extended period in Safed for health reasons. During that time, he primarily studied in the Beit Midrash of Rabbi Yosef Karo in the Old City. In 5696 (1936), he worked to establish the “Torah Education Center in the Land of Israel,”[75] and he founded a kollel in the Zikhron Meir neighborhood in Bnei Brak. This kollel, one of the first in the New Yishuv, became a model for many other institutions.[76] After his death, the institution was named "Kollel Chazon Ish". In December 1936 (winter 5697), the Chazon Ish fell ill, apparently due to appendicitis, and required removal of the appendix (appendectomy).[77] Later that year, ahead of the upcoming Shmita year 5698 (1937–38), his brother-in-law Rabbi Shmuel Greineman printed for the first time in Jerusalem his book "Chazon Ish" on Tractate Shevi'it and the laws of shmita. In the following years, several more volumes in the series were published, especially from Seder Taharot, which scholars had previously studied little due to the lack of both Babylonian Talmud and Jerusalem Talmud on it. At the beginning of winter 5701, on 19 Cheshvan, his mother Rashe Leah died in Jerusalem. In her final years she had lived with her son Rabbi Meir Karelitz and was buried on the Mount of Olives. The Chazon Ish ascended to Jerusalem for the second time in his life; the first had been a year earlier, for the wedding of Shlomo Shimshon Karelitz, son of his older brother Rabbi Meir. After the deaths of the great rabbis of Eastern European Judaism, some of whom perished in the Holocaust, many saw him as their successor. During this time, his status as Gadol Hador began to take shape.[78] In the years prior to the founding of the State, the Chazon Ish was involved in several public issues, most with a religious background. He helped establish new yeshivot following the destruction of European Jewry and its yeshivot, encouraged both ideologically and financially farmers who kept Shmita, and wrote letters requesting financial aid for Haredi educational institutions that were in crisis (1947). Shmita and Heter Mechira When the Chazon Ish arrived in the Land of Israel, nearly all farmers (except a few in the Petah Tikva area) relied during the Sabbatical year on the Heter Mechira. He worked to change this situation. In 5698, when the treasurer of the Haredi settlement of Machane Yisrael (Jezreel Valley) came to consult with him on the matter, the Chazon Ish ruled that they should refrain from relying on the heter. In accordance with his ruling, Kibbutz Hafetz Haim and other settlements of Poalei Agudat Yisrael also acted.[79] To enable farmers to keep shmita without heter mechira, the Chazon Ish permitted certain labors aimed at preserving the fruit ("le-okmei peira"), and allowed marketing the produce via Otzer Beit Din. The international date line controversy During World War II, when students of the Mir Yeshiva and others fled to East Asia, the "Shabbat controversy in Japan" arose, in which many halachic authorities debated the question of determining which day the Shabbat and festivals fall on in that region of the globe. On the eve of Yom Kippur 5702 (early October 1941), the issue intensified among the Jewish refugees in Japan. Until then, those who wished to be stringent avoided a decision by observing two consecutive days as Shabbat. However, a two-day fast was not a viable solution for most of the refugees, especially under wartime living conditions. The exiles sent telegrams to rabbis in the Land of Israel and elsewhere, asking how to proceed. The Chazon Ish, who had already dealt with this issue in the past,[80] was also asked about the matter, and his response[81] was published in a well-known halachic ruling, which opposed the view of Jerusalem’s rabbis and rabbis affiliated with the Chief Rabbinate. According to his ruling, the Halachic date line passes west of Japan, and therefore Shabbat there falls on Sunday, contrary to the practice of the local Jewish community. The Chazon Ish dictated his position on the date line to his student Rabbi Kalman Kahana on the night of Yom Kippur eve. On the morning of Yom Kippur eve, he sent Rabbi Kalman Kahana to Jerusalem to Rabbi Yitzchok Zev Soloveitchik to request that the two of them send a telegram to Japan instructing people to eat on Wednesday (according to their reckoning) and to fast on Thursday. The Brisker Rav refused to send the telegram, arguing that it would arrive in Japan after Wednesday evening and some people would surely have already accepted the fast of Yom Kippur and would not want to interrupt it; seeing the telegram, they might fast again on Thursday and thus endanger themselves. He also added that the Av Beit Din of Brisk, Rabbi Simcha Zelig Riger, had already ruled, before their departure, that they should fast on Thursday. Even before Rabbi Kalman Kahana returned from Jerusalem to Bnei Brak, the Chazon Ish sent a telegram to Japan instructing: "Eat on Wednesday and fast Yom Kippur on Thursday, and do not be concerned about anything." Rabbi Yechezkel Levenstein, who was the spiritual authority among the Mir Yeshiva students at the time, ruled to follow the Chazon Ish’s opinion even against the majority of dissenters. This position was printed in Kuntres Shemoneh Esreh Sha’ot (“Pamphlet of Eighteen Hours”), initially as a separate booklet,[82] and later included in his book on Orach Chayim. |

委任統治下のパレスチナにおいて 私は思う…あの驚くべき人物について…律法的な理想像であり、その権威は地位ではなく知性と人格から引き出された人物について。彼ほど最高級の賛辞を禁じ得ない人物は稀だろう——実際、通常は抑制的な語調の辞書や百科事典の執筆者たちでさえ、そうしている。 ―ハイム・ビール『異世界からの報告』[69]  ハゾン・イシュが到着した1933年のブネイ・ブラク  割礼の儀式でサンデクを務めるハゾン・イシュ、テルアビブ、1940年代後半  1950年代初頭のハゾン・イシュ  1952年のハゾン・イシュ 5693年タムーズ月16日(1933年7月10日)、ハゾン・イシュとその妻は委任統治下のパレスチナに移住した。ヤッファ港では、グロジンスキー師の 要請によりアグダット・イスラエルのメンバーが出迎えた。イスラエルの地での初期の頃、彼らはテルアビブのラビ・ダヴィド・ポタシュの家に滞在した。しば らくして、彼らは市内のゲウラ通りで部屋を借りた。新開拓地ブネイ・ブラクにベイト・ヨセフ・ノヴァルドク・イェシーヴァを設立したラビ・マティティヤ フ・スティグルが彼のアパートを訪れ、そこに移るよう勧めた。ハゾン・イシュは三週間の断食期間が終わってから行くと言った。夫妻がようやく到着した時、 彼らはハル・シャロムの丘に定住した。その地の空気がハゾン・イシュの気に入ったため、彼はその地域に定住することを決めた。ラビ・シュムエル・ハレ ヴィ・ヴォスナーは、この件について彼がこう語ったと伝えている: エルサレムには義人であり偉大なトーラーの学者たちが満ちているが、この新しい入植地には荒野を見つけた。そこにトーラーの種を蒔きたかった——だから私 はブネイ・ブラクに来たのだ。もし蒔くことに成功しなければ? ならば私はゲヘノムへ行き、その住人たちと共に、彼らの一人となるだろう。[71] 当初、彼はベニ・ブラクのラビであり後に定住者評議会議長となるナフマン・シュムエル・ヤアコブ・ミヨドセルから二部屋のアパートを借りた。間もなく、家 賃が安いギヴァト・ロカフの別のアパートへ移った。自宅近くにはベイト・ヨセフ・イェシーヴァがあり、時折ハゾン・イシュはその生徒たちに講義を行った。 数年後、彼はブネイ・ブラク東部に建てられた自宅に移った[72]。この家には妹のミリアムとその夫であるラビ・ヤアコブ・イスラエル・カニエフスキーも 同居していた。 ブネイ・ブラクは後に、主にハゾン・イシュの影響により、イスラエルにおけるハレディ派ユダヤ教の拠点の一つとなった。当初、ベニ・ブラクにはポアレイ・ アグダト・イスラエルの小さなグループが彼に加わった。彼らは主にラビ・ハイム・オゼル・グロジンスキーの紹介で、農業問題に関する彼のハラハー的指導に 従った。後に彼は広く知られるようになり、国内のより広い層におけるハラハー的権威となった。 バティア・カレリッツが織物店を再開しようとした試みは失敗に終わり、閉店せざるを得なかった。ラビ・イェヘズケル・アブラムスキーの依頼で月々の資金援 助を申し出た裕福な人物も、ハゾン・イシュによって断られた[73]。彼は書籍の販売で生計を立てる決意を固めたが、この収入は利益も安定性もなかった。 ハゾン・イシュはまだ全国的な名声を得ておらず、買い手は徐々にしか現れなかったのである。 5694年(1934年)、グロジンスキー師はイスラエルの地におけるアグダット・イスラエルのトーラー賢者評議会の候補者としてチャゾン・イシュを推挙した。チャゾン・イシュと協議した後、グロジンスキー師は次のように記している: A.Y.カレリッツ師は公式の称号や責任を引き受けることを望んでいないが、相談役となることは承諾している。[74] その夏、チャゾン・イシュは健康上の理由でサフェドに長期滞在した。その間、主に旧市街にあるラビ・ヨセフ・カロのベイト・ミドラシュで学んだ。 5696年(1936年)、彼は「イスラエル地におけるトーラー教育センター」[75]の設立に尽力し、ブネイ・ブラクのジクロン・メイル地区にコレルを 創設した。このコッレルは新ユダヤ入植地(ニュー・イシュブ)初のコッレルの一つであり、後に多くの機関のモデルとなった[76]。彼の死後、この機関は 「コッレル・ハゾン・イシュ」と命名された。 1936年12月(5697年冬)、ハゾン・イシュは虫垂炎と思われる病気にかかり、虫垂切除術(アペンデクテミー)を必要とした。[77] その年の後半、迫り来るシュミタ年5698年(1937-38年)を前に、義弟であるラビ・シュムエル・グライネマンがエルサレムで初めて彼の著書『ハゾ ン・イシュ』を刊行した。この書は『シェビイット』篇とシュミタの律法に関するものである。 その後数年間で、このシリーズのさらに数巻が刊行された。特に『浄化の律法』の巻は、バビロニア・タルムードとエルサレム・タルムードの双方が欠けていたため、これまで学者たちがほとんど研究していなかった分野であった。 5701年冬のはじめに、ケシュヴァン月19日、彼の母ラシェ・レアがエルサレムで死去した。晩年は息子のラビ・メイル・カレリッツと同居しており、オ リーブ山に埋葬された。ハゾン・イシュは生涯で二度目のエルサレム訪問を果たした。一度目は一年前、兄ラビ・メイルの息子シュロモ・シムション・カレリッ ツの結婚式のためであった。 東欧ユダヤ教の偉大なラビたちが亡くなり、その一部がホロコーストで命を落とした後、多くの人々が彼を後継者と見なした。この時期に、彼の「ガドル・ハドール(時代の偉人)」としての地位が形作られ始めた。[78] 国家建国前の数年間、ハゾン・イシュはいくつかの公共問題に関与した。そのほとんどは宗教的背景を持つものであった。彼はヨーロッパのユダヤ人とそのイェ シーバが破壊された後、新たなイェシーバの設立を支援し、シュミタを守る農民たちを思想的にも経済的にも励まし、危機に瀕していたハレディ教育機関への財 政援助を求める書簡を書いた(1947年)。 シュミタとヘテル・メヒラ ハゾン・イシュがイスラエルの地に着いた時、ペタ・ティクバ地域の一部の農家を例外として、ほぼ全ての農家が安息年にヘテル・メヒラに依存していた。彼は この状況を変えるために尽力した。5698年(1938年)、マハネ・イスラエル(エズレル谷)のハレディ入植地の会計係がこの件について相談に来た際、 ハゾン・イシュはヘテル・メヒラに依存すべきではないと裁定した。この裁定に従い、キブツ・ハフェツ・ハイムやポアレイ・アグダト・イスラエルの他の入植 地も同様の行動を取った。[79] 農民がヘテル・メヒラなしでシュミタを守れるようにするため、ハゾン・イシュは果実の保存を目的とした特定の労働(「レ・オクメイ・ペイラ」)を許可し、産物をオツァル・ベイト・ディンを通じて販売することを認めた。 国際日付変更線をめぐる論争 第二次世界大戦中、ミール・イェシーバの学生らが東アジアへ逃れた際、 「日本における安息日論争」が発生した。この論争では、地球のその地域において安息日や祭日が何日に当たるかを定める問題について、多くのハラハー権威が 議論を交わした。5702年(1941年10月初旬)のヨム・キプール前夜、日本にいるユダヤ人難民の間でこの問題は深刻化した。それまで厳格に守りたい 者は、二日連続で安息日として過ごすことで判断を避けていた。しかし、二日間の断食は、特に戦時下の生活環境では、ほとんどの難民にとって現実的な解決策 ではなかった。亡命者たちはイスラエルの地や各地のラビに電報を送り、対応を尋ねた。 過去にこの問題を取り上げていたハゾン・イシュ[80]にも質問が寄せ られ、彼の回答[81]は有名なハラハー的裁定として公表された。これはエルサレムのラビや首席ラビ庁所属のラビたちの見解に反するものであった。彼の裁 定によれば、ハラハ上の日付変更線は日本西側を通るため、現地ユダヤ人コミュニティの慣行とは異なり、同地の安息日は日曜日となる。 ハゾン・イシュはヨム・キップル前夜の夜、弟子であるカルマン・カハナ 師に日付変更線に関する見解を口述した。ヨム・キップル前夜の日中、彼はカルマン・カハナ師をエルサレムのイッツハク・ゼヴ・ソロヴェイチク師のもとへ派 遣し、二人で日本へ電報を送り、現地の人々に(彼らの計算では)水曜日に食事をし、木曜日に断食するよう指示するよう要請した。 ブリスクのラビは電報送付を拒否した。その理由は、電報が水曜日の夜を 過ぎて日本に届くため、既にヨム・キプルの断食を受け入れた人々がいる可能性があり、彼らが断食を中断したがらないだろうと考えたからだ。電報を見て木曜 日も断食を続ける可能性があり、それが命の危険につながる恐れがあると主張した。さらに彼は、ブリスクの裁判長であるラビ・シンハ・ゼリグ・リガーが、彼 らが日本へ向かう前に既に木曜日に断食すべきとの裁定を下していたと付け加えた。 カルマン・カハナ師がエルサレムからブネイ・ブラクに戻る前に、ハゾン・イシュ師は既に電報を日本に送り「水曜日は食事をし、木曜日に贖罪の日の断食を行え。何も心配するな」と指示していた。 当時ミール・イェシーバの学生たちの精神的指導者であったイェヘズケル・レヴェンシュタイン師は、反対多数派に抗してさえもハゾン・イシュの見解に従うべきだと裁定した。 この見解は『クントレス・シェモーネ・エスレー・シャオット(十八時間の小冊子)』に印刷された。当初は別冊として[82]、後に彼の『オラハ・ハイム』に関する書物に収録された。 |

| The holocaust and his attitude toward it During the Holocaust, the rabbi did not imagine the extent of the disaster and refused to believe the reports arriving about the extermination of millions of Jews. Eventually, when the scope of the destruction became known, the rabbi lamented: "From Heaven, the calamity that befell the Jews of Europe was concealed from us—even prayer efforts to annul the harsh decree were lacking."[83] Various reports circulated regarding his statements on the cause of the Holocaust, including: that it could not be explained, that it was a punishment for the sins of the generation and its secular leaders, or that it was due to the weakness of the generation after the deaths of previous Gedolei Yisrael. He also claimed that despite everything, God's punishment was given with abundant mercy. Aharon Surasky reports that he likened the period to the work of tailoring, in which the tailor must "cut the fabric into shreds… in preparation for sewing a new garment"—destruction as a precursor to creation.[84] In light of all this, it seems he avoided providing a structured and systematic theological doctrine.[85] Before the establishment of the state, a proposal was made to institute a perpetual public fast day and a collective shiv'ah. The rabbi responded with a lengthy letter opposing additions to what the Sages already instituted, especially in a generation he viewed as spiritually diminished. He did not see the Holocaust as an exceptionally unique catastrophe compared to the disasters that befell the Jewish people throughout history. Binyamin Brown assesses that this response also reflects hidden anxieties about accusations toward the Haredi world, which was surprised and unprepared for the devastation.[86] Blaming the rabbis for the destruction of European Jewry was, in his view, heresy—even if said by someone otherwise observant.[87] The establishment of the state of Israel and his attitude toward it The rabbi instructed R’ Jacob Rosenheim, president of Agudat Yisrael Worldwide, to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state as much as possible.[88] Even after the state became a reality, he expressed reservation and hostility toward its ruling institutions and did not believe the state would last long.[89] Upon the establishment of the State of Israel, he supported Agudat Yisrael's participation in the United Religious Front for the elections to the Knesset, in contrast to the position of the Edah HaChareidis. He explained that such participation did not imply recognition of the state and likened it to a man facing a robber and reaching an agreement with him to avoid being killed; this is not recognition of “authority” but an acknowledgment of reality.[90] He opposed Zionism and Religious Zionism, and insisted that Tachanun be recited in his study hall on Yom HaAtzmaut. In one case where he was sandek on that day, he publicly announced it to prevent misunderstanding.[91] Two years later, he ruled that even when a brit was held in his study hall, Tachanun should be said—so no one would mistakenly think it was omitted due to Yom HaAtzmaut.[92] After the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, he addressed the halachic implications of its outcomes. In his book on Tractate Sanhedrin, he discusses regarding the olives taken from Arab trees that they abandoned and [then] left, and regarding the question of Arab land ownership in the Land of Israel, he proposed that since all foreign ownership in the Land of Israel after the exile derives its legal validity from the laws of "kinyan kibush", which halachically regulate a conqueror’s ownership of captured land, then when a new conqueror (Israel) arrives, the previous ownership expires on its own. This has important halachic implications for the obligation of terumot and ma’aserot on agricultural produce from captured territories.[93] National service law affair In 1952, the issue of the conscription of religious women into national service arose. In the background of the controversy was an attempt to obligate women to serve military service, an obligation that even the vast majority of the Religious Zionist public opposed. Subsequently, due to this opposition, a clause was established in the law exempting women from military service for religious reasons, and in a second stage, an attempt was made to determine a national service alternative for women within the framework of the Security Service Law. The Chief Rabbinate and Haredi rabbis and others strongly opposed this, contrary to the position of the Religious Kibbutz Movement and the “Lamifneh” faction in HaPoel HaMizrachi, who supported the law. This issue was considered very essential in the eyes of the Chazon Ish. He wrote on the matter: “The stirring of my soul instructs and comes forth that it is a matter of ‘be killed and not transgress’, and perhaps also from the point of halacha it is so.”[94] In this context, "Agudat Yisrael" left the coalition at the end of 1952.[95] Eventually, in 1953, the "National Service Law" was legislated, stipulating that any religious woman who received exemption from military service in Israel is obligated to national service. This law was passed with the agreement of the Chief Rabbinate and the support of the Mafdal representatives. Shlomo Zalman Shragai wrote that Minister Haim-Moshe Shapira and Deputy Minister Zerach Warhaftig received the Chazon Ish’s principled consent to their step.[96] However, due to the opposition, the law was not implemented in practice. |

ホロコーストとその態度 ホロコーストの最中、ラビはその惨事の規模を想像できず、何百万ものユダヤ人が虐殺されているという報告を信じようとしなかった。やがて破壊の規模が明ら かになると、ラビは嘆いた。「天より、ヨーロッパのユダヤ人に降りかかった災いは我々から隠されていた。厳しい裁きを無効にするための祈りの努力さえも欠 けていたのだ」[83] ホロコーストの原因に関する彼の発言については様々な報告が流れた。説明のつかない出来事であるとか、その世代と世俗的指導者たちの罪に対する罰であると か、あるいは過去の偉大なイスラエルの指導者たちが亡くなった後の世代の弱さによるものだというものだ。彼はまた、あらゆることに拘わらず、神の罰は豊か な慈悲をもって下されたとも主張した。アハロン・スラスキーによれば、彼はこの時代を仕立て屋の作業に例えた。仕立て屋は「新しい衣服を縫う準備として、 布を細切れに裁断しなければならない」——創造の前段階としての破壊である[84]。こうした事情を踏まえると、彼は体系化された神学的教義の提供を避け たようだ。[85] 国家樹立以前、恒久的な公的断食日と集団的シヴァ(喪)を制定する提案がなされた。ラビは長文の手紙で、特に彼が霊的に衰退したと見なした世代において、 賢者たちが既に定めたものに追加することを反対する回答をした。彼はホロコーストを、ユダヤ民族が歴史を通じて被った災厄と比較して、例外的に特異な大惨 事とは見なしていなかった。ビニャミン・ブラウンは、この反応には、壊滅的な被害に驚き、準備不足だったハレディ世界への非難に対する潜在的な不安も反映 されていると評価している。[86] 欧州ユダヤ人虐殺の責任をラビに帰することは、たとえ敬虔な者による発言であっても、彼の見解では異端であった。[87] イスラエル国家の樹立とそれに対する彼の態度 ラビはアグダト・イスラエル世界総連合の会長であるヤコブ・ローゼンハイム師に対し、可能な限りユダヤ人国家の樹立を阻止するよう指示した。[88] 国家が現実となった後も、彼はその統治機構に対して留保と敵意を示し、国家が長く存続するとは信じていなかった。[89] イスラエル建国後、彼はエダー・ハハレディスの立場とは対照的に、クネセト選挙に向けた宗教統一戦線へのアグダー・イスラエル参加を支持した。その参加は 国家承認を意味せず、強盗に殺されないよう合意する行為に例え、「権威」の承認ではなく現実の容認だと説明した。[90] 彼はシオニズムと宗教的シオニズムに反対し、独立記念日に自身の学習室でタハヌンを唱えることを主張した。ある事例では、その日にサンデク(割礼の立会 人)を務めることになり、誤解を避けるため公に発表した。[91] 2年後、彼は自身の学習堂で割礼式が行われた場合でも、タハヌンを唱えるべきだと裁定した。これにより、独立記念日のために省略されたと誤解されることを 防ぐためである。[92] 1948年のアラブ・イスラエル戦争後、彼はその結果がもたらすハラーハー上の含意について論じた。『サンヘドリン篇』の著書では、アラブ人が放棄して 去った木から採取されたオリーブについて論じ、イスラエルの地におけるアラブ人の土地所有権問題に関しては、流刑後のイスラエルの地における全ての外国人 の所有権は、征服者が占領地を所有する権利を規定するハラーハー「キヤン・キブシュ」の法理に基づくものであるため、新たな征服者 (イスラエル)が現れた時点で、以前の所有権は自動的に消滅すると主張した。これは占領地における農産物へのテルモート(初穂税)とマアセロット(十分の 一税)の義務に関して、重要なハラーハー上の含意を持つ。[93] 国民奉仕法問題 1952年、宗教的女性を国民奉仕に徴兵する問題が浮上した。論争の背景には、女性にも兵役義務を課そうとする動きがあった。この義務化には、宗教的シオ ニストの大多数さえ反対した。その後、この反対を受けて、宗教的理由による女性の兵役免除条項が法律に設けられた。第二段階では、保安サービス法の枠組み 内で女性向けの国民奉仕代替案を定める試みが行われた。首席ラビ庁やハレディ派ラビらはこれに強く反対したが、宗教的キブツ運動やハポエル・ハミズラヒ内 の「ラミフネ」派は法律を支持した。この問題はハゾン・イシュにとって極めて重要視されていた。彼はこの件について次のように記している: 「我が魂の揺れ動きが教えるところによれば、これは『殺されても律法を破るな』という事柄であり、おそらく律法上の観点からもそうである」[94] こうした状況下で、「アグダト・イスラエル」は1952年末に連立政権から離脱した[95]。結局1953年、「国民奉仕法」が制定され、イスラエルで兵 役免除を受けた宗教的女性は国民奉仕を義務付けられることとなった。この法律は最高ラビ会議の合意とマフダル代表者の支持を得て可決された。シュロモ・ザ ルマン・シュラガイによれば、ハイム・モシェ・シャピラ大臣とゼラフ・ワルハフィグ副大臣は、ハゾン・イシュからこの措置に対する原則的な同意を得ていた という[96]。しかし反対運動のため、この法律は実際には施行されなかった。 |

| His death Condolence notice published by the Municipality of Bnei Brak in the press on the day of the Chazon Ish's funeral  Grave of the Chazon Ish in the Shomrei Shabbat Cemetery in Bnei Brak The Chazon Ish died of a heart attack on Friday night, the 15th of Cheshvan 5714, October 24, 1953, after midnight.[97] He died at 2:30 a.m., with his student Yechezkel Bartler at his side.[98] The rumor of his death spread throughout Bnei Brak in the morning hours. By midday on Shabbat, the Chazon Ish’s room was closed due to the crowding. According to Rafael Halperin, thousands stood in the courtyard reciting Psalms. With the conclusion of Shabbat, the news of his death was broadcast on "Kol Yisrael".[99] The municipalities of Bnei Brak and Ramat Gan declared a suspension of work during the funeral hours. At the opening of the government meeting on Sunday morning, Prime Minister Ben-Gurion delivered remarks in the rabbi's memory.[100] At the funeral procession, which was held on Sunday afternoon, tens of thousands of men, women, and children walked behind his bier. He was buried in the Shomrei Shabbat Cemetery in Bnei Brak.[101] The Chazon Ish's grave serves as a pilgrimage site throughout the year, especially on the anniversary of his death. Nearby, his brother-in-law Rabbi Shmuel Greineman purchased a special burial compound for members of the Chazon Ish’s family. After his death, his brother-in-law Rabbi Shmuel Greineman revealed the amounts of charity money the Chazon Ish distributed annually to the needy, from funds given to him by Jewish philanthropists from Israel and abroad. According to him, in the last year of his life, the Chazon Ish distributed over one hundred thousand Israeli lira. After his death, a charity fund was established in his name to continue this work.[102] |

彼の死 ハゾン・イシュの葬儀当日、ブネイ・ブラク市が新聞に掲載した弔意表明  ブネイ・ブラクのショムレイ・シャバット墓地にあるハゾン・イシュの墓 チャゾン・イシュは、5714年ケシュヴァン月15日金曜日夜、1953年10月24日深夜過ぎに心臓発作で死去した[97]。午前2時30分に息を引き取り、その傍らには弟子イェヘズケル・バルトラーがいた[98]。 彼の死の噂は朝方までにブネイ・ブラク中に広まった。安息日の正午までに、チャゾン・イシュの部屋は人混みのため閉鎖された。ラファエル・ハルペリンによ れば、数千人が中庭に立ち詩篇を唱えていた。安息日が終わると、その死の知らせは「コル・イスラエル」で放送された[99]。ブネイ・ブラクとラマト・ガ ンの自治体は、葬儀時間中の業務停止を宣言した。日曜朝に開かれた政府会議の冒頭で、ベン=グリオン首相はラビを追悼する言葉を述べた。[100] 日曜午後に執り行われた葬列では、数万人の男女と子供たちが棺の後を歩いた。彼はブネイ・ブラクのショムレイ・シャバット墓地に埋葬された。[101] ハゾン・イシュの墓は年間を通じて巡礼地となっており、特に命日には多くの参拝者が訪れる。近くには義弟のシュムエル・グライネマン師がハゾン・イシュの家族専用の墓地を購入した。 死後、義弟のシュムエル・グライネマン師は、国内外のユダヤ人慈善家から寄せられた資金を基に、ハゾン・イシュが毎年貧しい人々に配った慈善金の額を明ら かにした。彼によれば、ハゾン・イシュは最期の年に10万イスラエルリラ以上を配ったという。死後、この活動を継続するため、彼の名を冠した慈善基金が設 立された。[102] |

| His thought and work Halakha His method of study, and his attitude toward the rulings of his predecessors A central element in the teaching and halakhic rulings of the Chazon Ish was his attitude toward “dina degemara” — laws explicated in the Talmud — as those that may not be questioned, must not be deviated from even in the slightest, and must be fulfilled even if they were not mentioned by later halakhic authorities after the sealing of the Talmud: “A law that is clarified explicitly from the Gemara is, to me, the foundation of halakhic decision.”[103] Even in some cases where the reality from which the Talmudic law was derived had changed over the generations, the Chazon Ish maintained that the law remained in force. His reason was that halakha for future generations was meant to be sealed according to the words of the sages of the “two thousand years of Torah,” which ended in the time of Chazal. Thus he wrote about the laws of terefot (non-kosher animals): “And behold, it was necessary that during the two thousand years of Torah, as it says in Avodah Zarah 9a and Bava Metzia 86a — Rabbi and R. Natan are the end of the Mishnah, Rav Ashi and Ravina are the end of the hora’ah — there should be a fixed determination of terefot. There is no new Torah after them. The terefot were determined by Divine Providence at that time, and even if medicine later develops cures for these conditions, they remain the terefot that the Torah forbade, both then and in future generations.”[104] On the other hand, there were other Talmudic rulings, such as those relating to human terefot, that the Chazon Ish did not see as dependent on the conditions of Hazal’s time: “Indeed, regarding marrying off his wife, as long as there is a treatment in his time, we do not prevent him from doing so.” Regarding later periods recognized in halakhic discourse, the Chazon Ish believed that although Torah scholars had accepted the authority of earlier generations, halakhic clarification must still derive from the original sources — i.e., the tradition of Hazal. Therefore, he maintained that someone who does not know how to derive halakhic conclusions from the Talmudic discussions may not issue rulings, even from works like the Shulchan Aruch, as he would be unable to match specific real-life cases to the abstract cases presented in halakhic literature. As a result of this outlook, he shaped his study method to first derive halakhic conclusions from the Talmudic sugya (discussion), and only afterward to compare the conclusions to those in halakhic codes. Although in general he nullified his own opinion before that of the Rishonim (early authorities), he held that each person is required to exhaust his intellect in Torah study. Incorporating the greatness of the Rishonim into one’s own analytical process could hinder the understanding of the roots of halakha. Their words should be taken into account only when not understood, and in practical halakhic rulings — when it is clear that the Rishonim were addressing the same case. He summed up this approach in a letter: “To take hold of the rope of Torah is a difficult matter, and manifold. I took upon myself to investigate the Gemara as much as possible, even if it contradicts the Rishonim — and to suffice with the knowledge that the words of our sages are fundamental, and we are ‘orphans of orphans.’ Nevertheless, not to refrain from clarifying and analyzing what we can in our smallness, and also to rule accordingly in cases where there is no explicit contrary ruling in halakha. Otherwise, I would lack the engagement of Torah.”[105] Nevertheless, the Chazon Ish generally did not permit himself to rule against the Shulchan Aruch in cases where the opinion of the Rema was clear. Regarding the Vilna Gaon (Gra), he considered his status — especially in Lithuanian Jewry — to be like that of the Rishonim. This allowed accepting rulings from the Gra even when they contradicted the Shulchan Aruch. In one of his letters, he placed the Gra in a row alongside Moses, Ezra the Scribe, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, Rav Ashi, and the Rambam: “We relate to the Gra in the same category as Moshe Rabbeinu, Ezra, Rabbeinu HaKadosh, Rav Ashi, the Rambam, and the Gra, through whom Torah was revealed as one sanctified for that purpose, who illuminated that which had not been illuminated before him and took his portion. He is counted as one of the Rishonim, and therefore disagrees with them in many places with great strength — even with the Rif and the Rambam. His stature in divine spirit, piety, wisdom, diligence, and mastery of the entire Torah cannot be fathomed. Therefore it is not surprising that he disagrees with the Shulchan Aruch — and the places where he does so are many.”[106] Despite this, and according to his principle that one must “investigate the Gemara as much as possible, even if it contradicts the Rishonim,” he himself was eventually forced to interpret sugyot differently even from the revered Gra. Rabbi Shlomo Cohen recounted that in 1920, when the Chazon Ish was 41, he said that throughout his life he had tried to avoid disagreeing with the Gra, but had finally been compelled to interpret one grave sugya differently.[107] A representative example of his approach — “to interpret and clarify what we can... and also to rule accordingly when there is no explicit contrary view” — that also highlights his social sensitivity, can be found in the case of an agunah that was brought before his nephew, Rabbi Shlomo Shimon Karelitz, head of the rabbinical court in Petah Tikva. The nephew struggled to find a solution to the dire situation and turned to his uncle. The Chazon Ish delved into the relevant sugyot and ruled leniently in that specific case. The judges accepted his opinion and signed a marriage permit for the woman. The nephew, still uneasy with the ruling, came to him the next morning and reiterated his strong objections. Under those circumstances, he argued, how could they allow it? The Chazon Ish reconsidered his arguments and then replied: “It is true that it is difficult to permit — but it is more difficult to forbid!”[108] Precision in Halakha “The Lithuanian genius, whose greatness at first glance is expressed in his intellectual achievements, [but in truth is revealed] as a great and multifaceted personality, full of imagination, emotion, and soul"[109] One of the banners of the "Chazon Ish" worldview is the matter of meticulous adherence to the minutest detail in fulfilling halakha in all its details and refinements. The Chazon Ish viewed this exacting behavior as a guarantee of Yirat Shamayim (fear of Heaven) and dedicated to it the third section of his philosophical work "Emunah uVitachon", titled "Ethics and Halakha." His great independence as a halakhic authority led him to extreme precision even in the details of laws he deduced from halakhic discussion in the relevant Talmudic sugyot. These refinements became identified with him and his students. Most well-known are his stringencies, dating back to his time in Europe, especially in the following areas: The laws of Eruvin: Writing Torah scrolls, tefillin, and mezuzot – with special emphasis on the shape of the letters according to the ruling of the Beit Yosef. According to his approach, which contradicts the custom of the Ari, the right “leg” of the letter tzadi should be shaped like a regular yud (as in contemporary Hebrew fonts), not an inverted yud, as is customary among Sephardic and Hasidic Jews;[110] Baking matzot – he insisted on baking them personally so he could supervise every step of the process in accordance with his stringencies; The Four Species – into which he invested much money and effort to obtain them in their optimal halakhic form. It is told that once, in midsummer, he saw beautiful myrtle branches that met halakhic standards in a local non-Jew’s garden. He paid the man in advance to guard and care for them until Sukkot to add them to his lulav;[111] Laws of mikvaot: the infusion of drawn water into rainwater (zeriah) to render it a valid mikveh – the Chazon Ish had his own unique position on this matter.[112] Mitzvot between man and his fellow were also, in his view, included in halakhic precision, and he was very careful that one not come at the expense of the other. His close associate Rabbi Shlomo Cohen related that once the Chazon Ish instructed him not to say the usual verses before the shofar blowing but to blow without delay and finish prayers quickly. The reason for the haste became clear after prayers: the Chazon Ish had overheard a weak elderly man tell his son, who urged him to eat for health reasons: "No, I have never eaten before the shofar blowing." So that he would not be forced to prolong his fast, the Chazon Ish shortened the traditional ritual.[113] The Chazon Ish instituted the reading of Megillat Esther in Bnei Brak also on Shushan Purim, out of doubt that the city might be considered "adjacent and visible" to the ancient city of Jaffa.[114] Etrogim of the “Chazon Ish” strain: A well-known case of the Chazon Ish’s halakhic stringency was his search for a native Israeli etrog variety that grew wild, to avoid the suspicion that etrogim might be grafted with another botanical species, which would render the etrog halakhically invalid for the Four Species. The etrog tree is prone to grafting due to its weakness. The etrogim he found were slightly lacking in aesthetic beauty and symmetry. In the Haredi public, his approach was widely accepted, and there is high demand for etrogim descended from trees whose fruits the Chazon Ish used. His method for identifying the ancient Israeli etrog was accepted by several researchers.[115] Some etrogim come from a tree planted by Rabbi Michel Yehuda Lefkowitz in his yard, from seeds given to him by the Chazon Ish. These are called the "Lefkowitz strain," from which additional varieties have developed. There are also "Halperin etrogim of the Chazon Ish strain." |

彼の思想と業績 ハラハー 彼の研究方法と、先人の裁定に対する姿勢 ハゾン・イシュの教えとハラハー的裁定における中心的な要素は、「ディナー・デゲマラ」―タルムードで明示された法―に対する彼の態度であった。すなわ ち、それらは疑問を呈してはならず、わずかな逸脱も許されず、タルムード完成後に後代のハラハー的権威者によって言及されなかった場合でも履行されねばな らないという立場である: 「ゲマラから明示的に導かれた法は、私にとってハラーカ決定の基盤である」[103] たとえタルムードの法が導かれた現実が時代と共に変化した場合でも、ハゾン・イシュはその法が依然として有効であると主張した。その理由は、将来の世代の ためのハラハーは、「二千年のトーラー」の時代——すなわちハザール(タルムード編纂者)の時代に終焉した——の賢者たちの言葉に従って封印されるべきも のだったからである。彼はテレフォート(非コーシャー動物)に関する法についてこう記している: 「見よ、トーラーの二千年の間、アヴォダー・ザラー9aとババ・メツィア86aに記されている通り――ラビとラビ・ナタンはミシュナーの終焉であり、ラ ビ・アッシとラビナはホラーア(裁定)の終焉である――テレフォットの確定的な規定が必要であった。彼ら以降に新たなトーラーは存在しない。当時の神のご 意思によって定められたテレフォットは、たとえ後に医学が治療法を開発しても、トーラーが禁じたテレフォットとして、当時も将来の世代も変わらず存在する のだ。」[104] 一方で、人間のテレフォットに関する規定など、ハザールの時代の状況に依存しないとハゾン・イシュが考えたタルムードの裁定もあった: 「確かに、妻を嫁がせることに関しては、その時代に治療法がある限り、我々はそれを妨げない。」 ハラーハー的議論で認められる後世の時代について、ハゾン・イシュは、トーラー学者たちが先代の権威を受け入れてきたとはいえ、ハラーハー的解釈は依然と して原典、すなわちハザールの伝統に由来しなければならないと信じていた。したがって彼は、タルムードの議論からハラーハー的結論を導き出せない者は、 シュルハーン・アールーフのような著作からでさえ裁定を下してはならないと主張した。なぜなら、現実の具体的な事例をハラーハー文献に記された抽象的な事 例と照合できないからである。 この見解に基づき、彼はまずタルムードの議論(スギヤ)からハラーハー的結論を導き出し、その後で初めてハラーハー法典の結論と比較する学習方法を確立し た。一般的に彼はリショニム(初期権威者)の見解を自らの意見より優先させたが、各人がトーラー研究において知性を尽くすことが求められるとも主張した。 リショニムの偉大さを自らの分析過程に取り入れることは、ハラハーの根源を理解する妨げとなりうる。彼らの言葉は、理解できない場合にのみ考慮すべきであ り、実践的なハラハーの裁定においては、リショニムが同じ事例を扱っていたことが明らかな場合に限り適用すべきである。 彼はこのアプローチを手紙にこう要約している。「トーラーの綱を掴むことは困難であり、複雑である。私はゲマラを可能な限り調査することを自らに課した。 たとえそれがリショニムと矛盾する場合でも――そして、我々の賢者たちの言葉が根本であり、我々は『孤児の中の孤児』であるという認識で満足することを。 しかしながら、我々の小ささの中で可能な限り明確化し分析することを控えず、また、ハラハーに明示的な反対の裁定がない場合にはそれに従って裁定すること も怠らない。さもなければ、私はトーラーへの関与を欠くことになる。」[105] しかしながら、ハゾン・イシュは、レマの見解が明確な場合、シュルハン・アルーフに反する裁定を下すことを概して自らに許さなかった。ヴィルナ・ガオン (グラ)に関しては、特にリトアニア系ユダヤ社会における彼の地位をリショニム(初期ラビ学者)と同等と見なした。これにより、シュルハン・アルーフと矛 盾する場合でもグラの裁定を受け入れることが可能となった。 ある書簡の中で、彼はグラをモーセ、書記官エズラ、ラビ・イェフダ・ハナーシ、ラビ・アッシ、ラムバムと同列に位置づけている: 「我々はグラをモーシェ・ラベヌ、エズラ、ラベヌ・ハカドシュ、ラヴ・アッシ、ラムバム、そしてグラと同列に位置づける。彼を通じてトーラーは啓示され、 そのために聖別された者であり、彼以前に照らされなかったものを照らし、自らの分担を果たした者である。彼はリショニムの一人と数えられ、ゆえに多くの箇 所で彼らと激しく対立する――リフやラビ・マイモン(ラムバム)とさえもだ。彼の神聖な霊性、敬虔さ、知恵、勤勉さ、そしてトーラー全体の掌握における高 みは測り知れない。だから彼がシュルハン・アルーフと対立するのも驚くに当たらない――そしてその対立箇所は数多い。」[106] それにもかかわらず、彼の「たとえリショニムと矛盾しても、可能な限りゲマラを調査せよ」という原則に従い、彼自身も最終的には、尊敬されるグラでさえも 異なる解釈を余儀なくされた。ラビ・シュロモ・コーヘンは、1920年、ハゾン・イシュが41歳の時、生涯を通じてグラに異議を唱えることを避けてきた が、ついに一つの重大なスギュアについて異なる解釈をせざるを得なかったと語っている。[107] 彼のアプローチ――「解釈し、可能な限り明確化し…また、明確な反対意見がない場合にはそれに従って裁定する」――の代表的な例であり、同時に彼の社会的 感受性を浮き彫りにする事例が、ペタ・ティクヴァのラビ法廷長である甥、ラビ・シュロモ・シモン・カレリッツのもとに持ち込まれたアグナー(離婚が成立し ない女性)のケースに見られる。甥はこの深刻な状況の解決策を見出せず、叔父に相談した。ハゾン・イシュは関連するスギョット(律法論議)を精査し、この 特定の事例において寛容な裁定を下した。裁判官たちは彼の意見を受け入れ、女性への婚姻許可証に署名した。しかし甥は依然として裁定に不安を抱き、翌朝ハ ゾン・イシュのもとを訪れ、強い異議を改めて申し立てた。このような状況下で、どうしてそれを許せるのか?と彼は主張した。ハゾン・イシュは自身の論拠を 再考し、こう答えた。「確かに許可するのは難しい。だが、禁止するのはさらに難しいのだ!」[108] ハラハーにおける精密さ 「リトアニアの天才は、一見すると知的な業績にその偉大さが表れているが、[真実は]想像力、感情、魂に満ちた偉大で多面的な人格として現れている」[109] 「ハゾーン・イシュ」世界観の旗印の一つは、ハラハーの細部に至るまで、そのあらゆる詳細と精緻さを厳密に遵守する姿勢である。ハゾーン・イシュはこの厳 格な行動をヤリート・シャマイム(天への畏敬)の保証と見なし、その哲学的著作『エムナー・ウヴィターホン』の第3章「倫理とハラハー」をこの主題に捧げ た。彼のハラーハー権威としての卓越した独立性は、関連するタルムードの議論から導き出した法細則においても、極端な精密さを追求させた。これらの精緻な 解釈は彼と弟子たちの代名詞となった。最もよく知られているのは、ヨーロッパ時代から続く以下の分野における厳格な解釈である: エルーヴィンの法: トーラー巻物、テフィリン、メズーザの書写――特にベイト・ヨセフの裁定に基づく文字の形状に重点を置いた。彼のアリ(エカ・ハ・アリ)の慣習と矛盾する 見解によれば、ツァディ文字の右「脚」は、セファルディ系やハシディズムのユダヤ人の慣習である逆さユドではなく、現代ヘブライ文字フォントのように通常 のユドの形とすべきである。[110] マッツォの焼成――彼は自らの厳格な規定に従い、工程の全段階を監督するため、自ら焼成することを固執した。 四種の植物――彼はこれらを最適なハラハー的形態で入手するため多額の資金と労力を注いだ。ある夏の真っ只中、地元の非ユダヤ人の庭でハラハー基準を満た す美しいミルトの枝を見つけたという。彼はその男に前金を渡し、仮庵祭まで枝を守り手入れさせ、自身のルラーブに加えるようにした; [111] ミクワーの律法:汲み上げた水を雨水に混ぜる(ツェリア)ことで有効なミクワーとする行為について、ハゾン・イシュはこの問題に独自の立場を持っていた。[112] 人間同士の間にある戒律も、彼の見解では律法の厳密さに含まれており、一方を犠牲にして他方を達成しないよう細心の注意を払っていた。彼の側近ラビ・シュ ロモ・コーエンによれば、ある時ハゾン・イシュは彼に、ショファル吹奏前の慣例的な詩句を唱えず、遅滞なく吹奏し祈りを速やかに終えるよう指示した。この 急ぎの理由は祈りの後に明らかになった。ハゾン・イシュは、健康上の理由で食事を勧める息子に、衰弱した老人が「いや、俺はショファル吹奏前に食べたこと など一度もない」と答えるのを耳にしていたのだ。断食を延長させないため、彼は伝統的な儀式を短縮したのである。[113] チャゾン・イシュはベニ・ブラクにおいて、シュシャン・プリム(シュシャン・プーリム)にもエステル記の朗読を定めた。この街が古代都市ヤッファに「隣接し視認可能」と見なされる可能性を疑ったためである。[114] 「ハゾン・イシュ」系統のエトログ: ハゾン・イシュの律法上の厳格さが知られる事例として、イスラエル原産の野生エトログ品種を探すことが挙げられる。これはエトログが他の植物種と接ぎ木さ れている疑いを避けるためであり、接ぎ木されたエトログは律法上「四種の植物」として無効となる。エトログの木は弱いため接ぎ木されやすい性質がある。彼 が発見したエトログは、美観と対称性にやや欠けていた。ハレディ派のコミュニティでは彼の手法が広く受け入れられ、チャゾン・イシュが使用した木の子孫で あるエトログへの需要は高い。古代イスラエル産エトログを特定する彼の方法は、複数の研究者にも認められている。[115] 一部のエトログは、ラビ・ミシェル・イェフダ・レフコヴィッツが庭に植えた木から採れる。その木はチャゾン・イシュから授かった種から育ったものだ。これ らは「レフコヴィッツ系統」と呼ばれ、そこからさらに様々な品種が派生している。「チャゾン・イシュ系統のハルペリン・エトログ」も存在する。 |

| Land-dependent commandments The Chazon Ish especially acted to instill broad awareness for the observance of land-dependent commandments, particularly the commandment of Shemitah. He demanded of the kibbutzim of Poalei Agudat Yisrael to observe the Sabbatical year without relying on the heter mechirah (permitted sale of the land to a non-Jew) by the Chief Rabbinate, which he rejected. As part of his activity for the observance of land-dependent commandments, he went out to the field several times to conduct experiments and trial examinations of halakhic concepts. The Chazon Ish also acted in matters of terumot and ma'aserot (tithes and offerings). He was meticulous to tithe at home even foods that had already been tithed, out of concern that they had not been tithed properly. He also innovated the matter of the perutah chamurah, which was not practiced before him; he encouraged and spurred the study of Seder Zera'im among Torah scholars, and answered many inquiries on these topics. The issue of halakhic measurements The name of the Chazon Ish is also associated with a fundamental disagreement on the issue of "shiurim" (halakhic measures) mentioned in the Bible and the Talmud (cubit, span, fingerbreadth, olive-size, egg-size, etc.). Rabbi Avraham Chaim Naeh (the GaRa"Ch Naeh) published these measures in modern units (meters and grams), and according to his approach, a handbreadth is eight centimeters and a revi'it (liquid measure) is 86 cc. The Chazon Ish disagreed with this view, and claimed that the true measures are much greater — a handbreadth is about ten centimeters, and a revi'it is approximately 150 cc. The main point of disagreement is whether to base the other measures on the volume of eggs or on the width of the thumb. Rabbis Naeh and Karelitz were not the first to differ on this point, they were preceded by great Acharonim, the Chatam Sofer and the Noda BiYehuda. Rabbi Naeh sought to preserve the custom of the Old Yishuv in Jerusalem, while the Chazon Ish held that the tradition he had received from his father’s home and the greats of Lithuania regarding measurements was accepted by Torah scholars with higher halakhic authority than that of popular custom. As part of this approach, the Chazon Ish relied on the measurement of the finger of his student Rabbi Kalman Kahana, whom he considered an average person for the purpose of measures and sizes.[116] In practice, in the Lithuanian sector, the Chazon Ish’s method on this issue is the widespread norm. The spread of this practice began among graduates of Lithuanian yeshivas and from there extended to the broader sector. Even among the rest of the Haredi public, who follow their ancestral tradition with the smaller measure, some are stringent in Torah-level commandments according to the larger measurement due to concern for the opinions of the Chatam Sofer and the Chazon Ish, as recommended by the Mishnah Berurah.[117][118] The philosophy of halakha The Chazon Ish held that, beyond the essential obligation on every Jew to obey the Torah's directives as they are, their goal is to place a person in the position of a subject standing before his king and submitting to his authority. For this purpose, what is required on one hand is absolute submission and obedience to every detail; and on the other hand, the performance of mitzvot under all circumstances — even when it is clear to a person that he cannot precisely assess what is required of him for the full performance of the mitzvah. This is because the main thing is fulfilling the king’s command, and man’s limitations and assessments were taken into account with the command. Or in the words of the Chazon Ish: "The halakha was given to be calculated approximately, for the mitzvot were given only to purify the creatures, and to be precise in His commandments [i.e., God’s] to accept His sovereignty, and also to fulfill the wisdom of the Torah contained in all the laws of the commandment and its inner secret. And for all of these, nothing is lost if the fixing of boundary lines is approximate, so that even those of weak understanding can fulfill the practical commandments."[119] |

土地に依存する戒律 ハゾン・イシュは特に、土地に依存する戒律、とりわけシェミター(安息年)の戒律の遵守に対する広範な認識を浸透させるために活動した。彼はポアレイ・ア グダト・イスラエルのキブツに対し、最高ラビ会議によるヘテル・メヒラー(土地を非ユダヤ人に売却することを許可する制度)に依存せず、安息年を遵守する よう要求した。彼はこの制度を拒否していたのである。土地に依存する戒律の遵守活動の一環として、彼は何度か畑に出向き、ハラハー的概念の実験や試験的検 証を行った。 ハゾン・イシュはまた、テルーモットとマアセロット(十分の一税と献げ物)の問題にも取り組んだ。彼は、既に十分の一税が納められていた食品でさえ、適切 に納められていない可能性を懸念し、自宅で細心の注意を払って十分の一税を納めた。また、彼以前には実践されていなかったペルトゥア・ハムーラ(厳格なペ ルトゥア)の概念を新たに提唱した。さらに、トーラー学者たちによる『種子の順序』(セデル・ゼライム)の研究を奨励し促進し、これらの主題に関する多く の質問に答えた。 ハラハ的測定単位の問題 ハゾン・イシュの名は、聖書やタルムードに記された「シウリム」(ハラハ的測定単位:キュビット、スパン、指幅、オリーブ大、卵大など)に関する根本的な 意見の相違とも結びついている。ラビ・アブラハム・ハイム・ナエ(ガラーハ・ナエ)はこれらの単位を現代単位(メートルとグラム)で公表し、彼の見解によ れば手のひらは8センチメートル、レヴィート(液体量)は86ccである。しかしハゾン・イシュはこの見解に反対し、真の単位ははるかに大きいと主張し た。すなわち手のひらは約10センチメートル、レビットは約150ccである。 主な論点は、他の単位を卵の体積に基づくか、親指の幅に基づくかである。ナエとカレリッツのラビがこの点で意見が分かれたのは初めてではなく、彼らより前 に、偉大なアハロニムであるハタム・ソフェルとノダ・ビイェフダが同様の議論を展開していた。ナエ師はエルサレムの古きユダヤ人定住区(イシュブ)の慣習 を守ろうとしたが、ハゾン・イシュ師は、自身の父の家やリトアニアの偉人たちから受け継いだ測定に関する伝統が、民間の慣習よりも高いハラハー的権威を持 つトーラー学者たちに受け入れられていると主張した。この立場の一環として、ハゾン・イシュは弟子であるラビ・カルマン・カハナの手指の測定値を拠り所と した。彼はカハナを、測定やサイズの基準として平均的な人物と見なしていたのである。[116] 実際、リトアニア派の領域では、この問題に関するハゾン・イシュの方法が広く普及した規範となっている。この慣行の普及はリトアニア系イェシーバの卒業生 から始まり、そこからより広範な地域へ広がった。祖先の伝統に従い小さい測定値を用いる他のハレディ派コミュニティにおいても、ミシュナー・ベルーラーの 推奨通り、ハタム・ソフェルとハゾン・イシュの見解を重視する者たちは、律法レベルの戒律に関しては大きい測定値を厳格に守る場合がある[117]。 [118] ハラハーの哲学 ハゾン・イシュは、ユダヤ人一人ひとりがトーラーの指示をそのまま従うという本質的な義務を超えて、その目的は人を王の前に立つ臣下の立場に置き、その権 威に服従させることにあると主張した。この目的のためには、一方であらゆる細部への絶対的な服従と従順が求められ、他方であらゆる状況下での戒律の履行が 求められる。たとえ人が戒律の完全な履行に必要なことを正確に評価できないと自覚している場合でも同様である。なぜなら、重要なのは王の命令を全うするこ とであり、人間の限界や評価は命令の中に考慮されているからである。あるいはハゾン・イシュの言葉によれば:「律法はおおむね計算されるために与えられ た。なぜなら戒律は被造物を清めるためだけに与えられ、その命令(すなわち神の命令)において正確であることは、神の主権を受け入れるためであり、また戒 律の全ての法とその内なる秘義に込められたトーラーの知恵を成就するためである。これら全てにおいて、境界線を大まかに定めることで何も失われることはな い。そうすれば理解力の弱い者でさえ、実践的な戒律を履行できるのだ。」[119] |