クリスチャン・ヴォルフ

Christian Wolff, 1679-1754

☆ クリスティアン・ヴォルフ(Christian Wolff、1679年1月24日 - 1754年4月9日)は、ドイツの哲学者、近世自然法論者。ライプニッツからカントへの橋渡し的存在。パン屋の息子としてブレスラウに生まれる。最初に神 学を学び、イェーナ大学・ライプツィヒ大学で哲学と数学を修め、1704年からライプニッツと交わり、その推薦で1707年にハレ大学の数学・自然学教 授、1709年に哲学教授となる。従来の習慣を破ってドイツ語で著作し講義をした。1723年に孔子を賞賛した演説が無神論という言いがかりを招き、プロ イセン王フリードリヒ・ウィルヘルム1世の退去命令によりマールブルクに逃亡した。有名な教師であったヴォルフに嫉妬した神学者がヴォルフの予定調和説を 歪めて伝え、「兵隊が脱走しても宿命がそうさせたので、兵を罰することは不当である」と主張しているかのように王に告げ口したせいともいわれる。ハレ大学 を訪れる人が激減し、間接国税が減る結果に驚いた王がヴォルフを呼び戻そうとしたが応じず、マールブルク大学の哲学科主任教授となり、ロンドン王立協会・ パリ・ストックホルムの科学アカデミーの会員資格を与えられ、ロシアのピョートル1世からは新設のペテルスブルク・アカデミーの副会長に指名されるという 全ヨーロッパ的な名声を享受した。フリードリヒ2世即位後の1740年にハレ大学に復帰、1745年に学長となる。晩年にはさすがの令名も色あせ、最後に は聴講席はがら空きだったという。

☆ ヴォルフはそれまで固有の語彙体系をもたずラテン語による著述や借用語がほとんどだったドイツ語圏の思想界において、ドイツ語の哲学用語を確立した。ヴォ ルフが造語した哲学用語の多くは現在もなお使われている。またライプニッツの表象概念を基礎にした体系的な形而上学を構想し、もって哲学を神学から独立さ せた。したがって彼とその後継者の哲学はライプニッツ=ヴォルフ学派といわれることがある。ヴォルフは数学を学問の典型とし概念的厳密性を重んじ、分析的 思考に基づく哲学を構築した。 彼の哲学は啓蒙思想の代表の一つであり、ドイツの大学で17世紀から18世紀にかけて講じられた、いわゆる講壇哲学の基礎をなした。17世紀後半のドイツ の形而上学者は、多くヴォルフの弟子筋にあたり、彼らの著述は18世紀半ばまで広く教科書として使われた。ヴォルフはまたカントに影響を与えた。カントは ヴォルフ学派の体系性をそれとしては高く評価しており、自身の批判によって「独断論」と位置づけたヴォルフ学派への批判を行い形而上学の再構築を図った が、大学での講義では、自著ではなくヴォルフ学派の哲学者たちの形而上学の書を教科書として指定していた。 しかし他方、ヴォルフはドイツ人にとっての哲学を退屈にしたとも批判されうる。ライプニッツのモナド論と弁神論以外のもっとも興味ある側面は受け継がず、 ライプニッツ流の退屈でもったいぶった文体をドイツの学界に広めた。ハイネは「ヴォルフは体系的というよりは百科全書的な頭脳をもち、ある学説の統一性を 完成した形でしか理解できなかった。彼は一種の小間壁細工で満足した。各小間をできるかぎり美しく配列し、うまく充填して、明瞭なレッテルを貼り付ける。 かくしていわゆるヴォルフの独断論が生まれた」と説明する。スピノザの『エチカ』に見られる数学的形式は、ヴォルフの手にかかるとそれ以上の探求を許さな い図式となった。ヘーゲルはヴォルフについて「アリストテレスと同じく、万人に対して意識の世界を定義した人」だが「アリストテレスと違って、哲学的思考 を用いず分析的な思考しか用いない」から、思考概念はバラバラに固定されてしまうと批評している。ヴォルフ哲学の根底にあるのは「常識」であり、常識を単 純化したものが「定義」とされる。ヘーゲルは「このような野蛮な厳密主義は通俗化されて、やがて信用をなくし廃れていく」と述べた。

| Christian Wolff

(less correctly Wolf,[5] German: [vɔlf]; also known as Wolfius;

ennobled as Christian Freiherr von Wolff in 1745; 24 January 1679 – 9

April 1754) was a German philosopher. Wolff is characterized as one of

the most eminent German philosophers between Leibniz and Kant. His life

work spanned almost every scholarly subject of his time, displayed and

unfolded according to his demonstrative-deductive, mathematical method,

which some deem the peak of Enlightenment rationality in Germany.[6] Wolff wrote in German as his primary language of scholarly instruction and research, although he did translate his works into Latin for his transnational European audience. A founding father of, among other fields, economics and public administration as academic disciplines,[citation needed] he concentrated especially in these fields, giving advice on practical matters to people in government, and stressing the professional nature of university education.[citation needed] |

クリスティアン・

ヴォルフ(Christian Wolff、正しくはヴォルフ、[5] ドイツ語: [vɔlf];

ヴォルフィウス、1745年にクリスティアン・フライヘル・フォン・ヴォルフに改名、1679年1月24日 -

1754年4月9日)はドイツの哲学者である。ヴォルフは、ライプニッツとカントの間に位置する最も著名なドイツ人哲学者の一人である。彼の生涯の業績

は、当時のほとんどすべての学問的主題に及び、彼の実証的演繹的、数学的方法に従って表示され、展開され、ドイツにおける啓蒙的合理性のピークとみなす人

もいる[6]。 ヴォルフは学問の指導と研究の主要言語としてドイツ語で執筆したが、国境を越えたヨーロッパの読者のために著作をラテン語に翻訳した。特に経済学と行政学 を学問分野として確立した創始者であり[要出典]、これらの分野に特に力を注ぎ、行政に携わる人々に実務的な事柄について助言を与え、大学教育の専門的な 性質を強調した[要出典]。 |

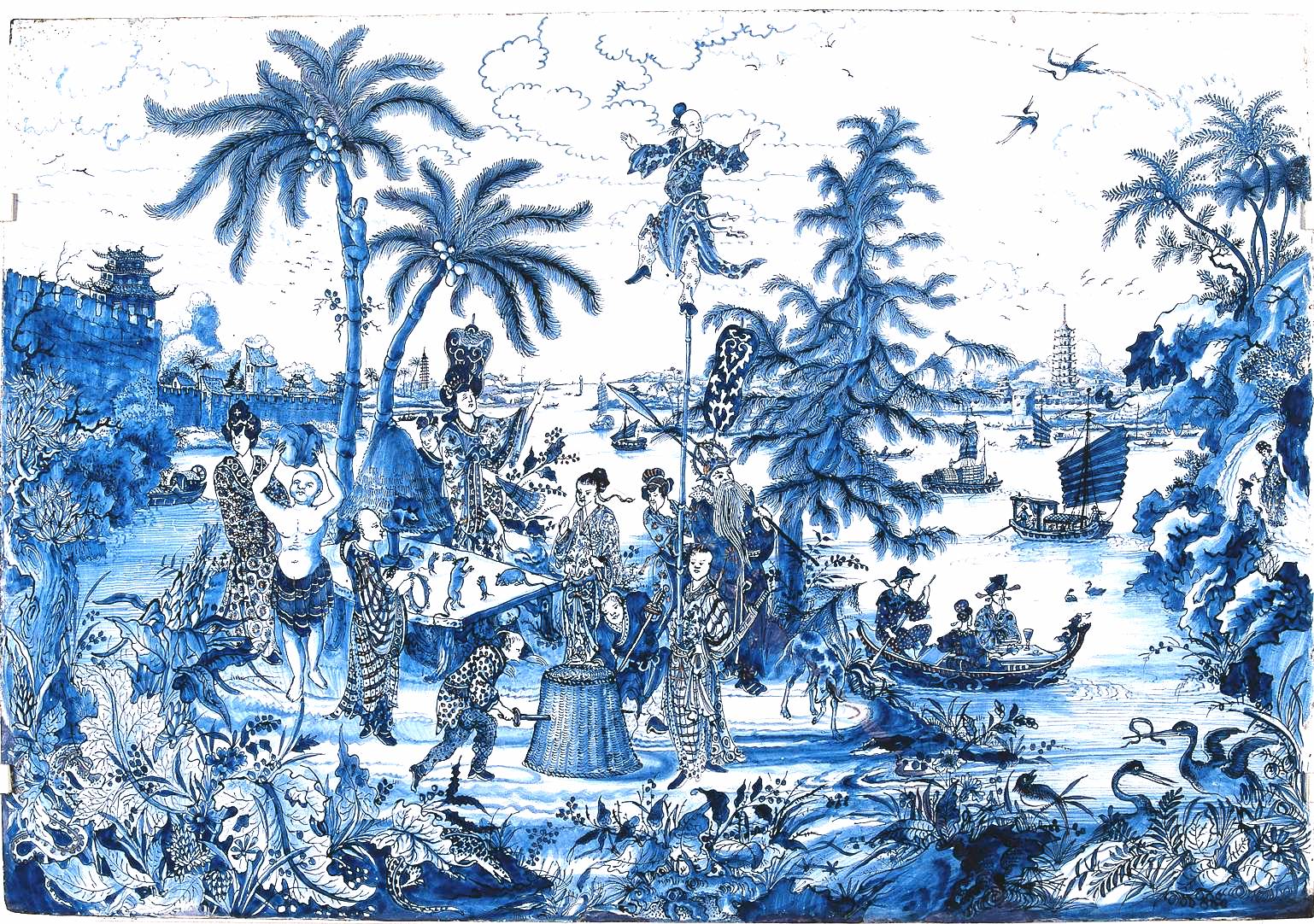

Life Plaque on building in Wrocław (Breslau) where Wolff was born and lived, 1679–99 Wolff was born in Breslau, Silesia (now Wrocław, Poland), into a modest family. He studied mathematics and physics at the University of Jena, soon adding philosophy. In 1703, he qualified as Privatdozent at Leipzig University,[7] where he lectured until 1706, when he was called as professor of mathematics and natural philosophy to the University of Halle. By this time he had made the acquaintance of Gottfried Leibniz (the two men engaged in an epistolary correspondence[8]), of whose philosophy his own system is a modified version. At Halle, Wolff at first restricted himself to mathematics, but on the departure of a colleague, he added physics, and soon included all the main philosophical disciplines.[5] However, the claims Wolff advanced on behalf of philosophical reason appeared impious to his theological colleagues. Halle was the headquarters of Pietism, which, after a long struggle against Lutheran dogmatism, had assumed the characteristics of a new orthodoxy. Wolff's professed ideal was to base theological truths on mathematically certain evidence. Strife with the Pietists broke out openly in 1721, when Wolff, on the occasion of stepping down as pro-rector, delivered an oration "On the Practical Philosophy of the Chinese" (Eng. tr. 1750), in which he praised the purity of the moral precepts of Confucius, pointing to them as an evidence of the power of human reason to reach moral truth by its own efforts.[5]  Delftware plaque with chinoiserie, 17th century On 12 July 1723, Wolff held a lecture for students and the magistrates at the end of his term as a rector.[9] Wolff compared, based on books by the Flemish missionaries François Noël (1651–1729) and Philippe Couplet (1623–1693), Moses, Christ, and Mohammed with Confucius.[10] According to Voltaire, Prof. August Hermann Francke had been teaching in an empty classroom but Wolff attracted with his lectures around 1,000 students from all over.[11] In the follow-up, Wolff was accused by Francke of fatalism and atheism,[12] and ousted in 1723 from his first chair at Halle in one of the most celebrated academic dramas of the 18th century. His successors were Joachim Lange, a pietist, and his son, who had gained the ear of the king Frederick William I. (They claimed to the king if Wolff's determinism were recognized, no soldier who deserted could be punished as he would have acted only as it was necessarily predetermined that he should, which so enraged the king that he immediately deprived Wolff of his office, and ordered Wolff to leave Prussian territory within 48 hours or be hanged.)[5] The same day, Wolff passed into Saxony, and presently proceeded to Marburg, Hesse-Kassel, to whose university (the University of Marburg) he had received a call even before this crisis, which was now renewed. The Landgrave of Hesse received him with every mark of distinction, and the circumstances of his expulsion drew universal attention to his philosophy. It was everywhere discussed, and over two hundred books and pamphlets appeared for or against it before 1737, not reckoning the systematic treatises of Wolff and his followers.[5] According to Jonathan I. Israel, "the conflict became one of the most significant cultural confrontations of the 18th century and perhaps the most important of the Enlightenment in Central Europe and the Baltic countries before the French Revolution."[13] Prussian crown prince Frederick defended Wolff against Joachim Lange and ordered the Berlin minister Jean Deschamps, a former pupil of Wolff, to translate Vernünftige Gedanken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt into French.[14] Frederick proposed to send a copy of Logique ou réflexions sur les forces de l'entendement humain to Voltaire in his first letter to the philosopher from 8 August 1736. In 1737, Wolff's Metafysica was translated into French by Ulrich Friedrich von Suhm (1691–1740).[15] Voltaire got the impression Frederick had translated the book himself.[citation needed] In 1738, Frederick William began the hard labour of trying to read Wolff.[16] In 1740, Frederick William died, and one of the first acts of his son and successor, Frederick the Great, was to acquire him for the Prussian Academy.[17] Wolff refused,[18] but accepted on 10 September 1740 an appointment in Halle. [citation needed] His entry into the town on 6 December 1740 took on the character of a triumphal procession. In 1743, he became chancellor of the university, and in 1745, he received the title of Freiherr (Baron) from the Elector of Bavaria, possibly the first scholar to have been created hereditary Baron of the Holy Roman Empire on the basis of his academic work.[citation needed] When Wolff died on 9 April 1754, he was a very wealthy man, owing almost entirely to his income from lecture-fees, salaries, and royalties. He was also a member of many academies. His school, the Wolffians, was the first school in the philosophical sense to be associated with a German philosopher. It dominated Germany until the rise of Kantianism.[citation needed] Wolff was married and had several children.[19] |

人生 ヴォルフが生まれ住んだヴロツワフ(ブレスラウ)の建物のプレート(1679-99年 ヴォルフはシレジアのブレスラウ(現ポーランドのヴロツワフ)で質素な家庭に生まれた。イエナ大学で数学と物理学を学び、やがて哲学を加えた。 1703年、ライプツィヒ大学でプライヴァトドーゼントの資格を得[7]、1706年にハレ大学に数学と自然哲学の教授として招かれるまで講義を行った。この頃、彼はゴットフリート・ライプニッツと知り合い(二人は書簡のやり取りをしていた[8])。 ハレでは、ヴォルフは当初数学に限定していたが、同僚の退去に伴い物理学を加え、やがてすべての主要な哲学的分野を含むようになった[5]。 しかし、ヴォルフが哲学的理性のために主張したことは、神学部の同僚には不敬に映った。ハレは、ルター派の教条主義に対する長い闘争の末、新しい正統派の 特徴を備えた敬虔主義の総本山であった。ヴォルフの公言する理想は、神学の真理を数学的に確かな証拠に基づかせることであった。1721年、ヴォルフが学 長を退任する際に「中国人の実践哲学について」(1750年、英文訳)という演説を行い、孔子の道徳訓の純粋さを賞賛し、人間の理性が自らの努力によって 道徳的真理に到達する力の証拠であると指摘したことから、敬虔主義者との争いが公然と勃発した[5]。  シノワズリをあしらったデルフト焼きのプレート、17世紀 1723年7月12日、ヴォルフは学長としての任期を終えるにあたり、学生や判事の前で講義を行った[9]。ヴォルフは、フランドルの宣教師フランソワ・ ノエル(1651-1729)とフィリップ・クープレ(1623-1693)の著書をもとに、モーセ、キリスト、モハメッドと孔子を比較した[10]。 ヴォルテールによれば、アウグスト・ヘルマン・フランケ教授は誰もいない教室で教えていたが、ヴォルフは彼の講義で各地から1,000人ほどの学生を集めた[11]。 その後、ヴォルフはフランケから運命論と無神論で非難され[12]、1723年に18世紀で最も有名な学問のドラマのひとつであるハレの最初の椅子から追 放された。彼の後継者は敬虔主義者のヨアヒム・ランゲとその息子で、彼は国王フレデリック・ウィリアム1世の耳目を集めていた(彼らは国王に対し、もし ヴォルフの決定論が認められれば、脱走した兵士は必然的に定められた通りに行動したに過ぎず、処罰されることはないと主張したため、国王は激怒し、直ちに ヴォルフの職を剥奪し、48時間以内にプロイセン領内から退去しなければ絞首刑に処すよう命じた)[5]。 同日、ヴォルフはザクセンに入り、すぐにヘッセン=カッセルのマールブルクに向かった。マールブルクの大学(マールブルク大学)には、この危機の以前から 召集がかかっていたが、それが今回新たに召集されたのである。ヘッセン州知事は、あらゆる栄誉をもって彼を迎え入れたが、彼が追放された経緯から、彼の哲 学に世界中の注目が集まった。この哲学はいたるところで議論され、ヴォルフとその追随者たちの体系的な論考を除いても、1737年までに200冊以上の本 やパンフレットが出版された。 ジョナサン・I・イスラエルによれば、「この対立は18世紀における最も重要な文化的対立のひとつとなり、おそらくフランス革命以前の中央ヨーロッパとバルト諸国における啓蒙主義の最も重要な対立となった」[13]。 プロイセンの皇太子フリードリヒはヨアヒム・ランゲからヴォルフを擁護し、ヴォルフの元教え子であったベルリンの大臣ジャン・デシャンに 『Vernünftige Gedanken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt』をフランス語に翻訳するよう命じた[14]。フリードリヒは1736年8月8日、哲学者に宛てた最初の手紙の中で、『Logique ou réflexions sur les forces de l'entendement humanain』のコピーをヴォルテールに送ることを提案した。1737年、ヴォルフの『メタフィシカ』はウルリッヒ・フリードリヒ・フォン・スーム (1691-1740)によってフランス語に翻訳された[15]。ヴォルテールはフレデリックが自分で翻訳したという印象を受けた[要出典]。 1740年、フリードリヒ・ウィリアムは死去し、息子で後継者のフリードリヒ大王が最初に行ったことのひとつが、ヴォルフをプロイセン・アカデミーに迎えることだった[17]。[要出典]。 1740年12月6日、ヴォルフは凱旋行進のようにハレに入った。1743年には大学の総長に就任し、1745年にはバイエルン選帝侯からフライヘル男爵の称号を授与された。 1754年4月9日にヴォルフが死去したとき、彼は非常に裕福な人物であり、その収入のほとんどすべてが講演料、給料、印税によるものであった。また、多 くのアカデミーの会員でもあった。彼の学派であるヴォルフ派は、哲学的な意味でドイツの哲学者に関連する最初の学派であった。カント主義の台頭までドイツ を支配した[要出典]。 ヴォルフは結婚しており、数人の子供がいた[19]。 |

| Philosophical work Wolffian philosophy has a marked insistence everywhere on a clear and methodic exposition, holding confidence in the power of reason to reduce all subjects to this form. He was distinguished for writing copies in both Latin and German. Through his influence, natural law and philosophy were taught at most German universities, in particular those located in the Protestant principalities. Wolff personally expedited their introduction inside Hesse-Cassel.[20] The Wolffian system retains the determinism and optimism of Leibniz, but the monadology recedes into the background, the monads falling asunder into souls or conscious beings on the one hand and mere atoms on the other. The doctrine of the pre-established harmony also loses its metaphysical significance (while remaining an important heuristic device), and the principle of sufficient reason is once more discarded in favor of the principle of contradiction which Wolff seeks to make the fundamental principle of philosophy.[5] Wolff had philosophy divided into a theoretical and a practical part. Logic, sometimes called philosophia rationalis, forms the introduction or propaedeutics to both.[5] Theoretical philosophy had for its parts ontology or philosophia prima as a general metaphysics,[21] which arises as a preliminary to the distinction of the three special metaphysics[22] on the soul, world and God:[23][24] rational psychology,[25][26] rational cosmology,[27] and rational theology.[28] The three disciplines are called empirical and rational because they are independent of revelation. This scheme, which is the counterpart of religious tripartition in creature, creation, and Creator, is best known to philosophical students by Kant's treatment of it in the Critique of Pure Reason.[5] In the "Preface" of the 2nd edition of Kant's book, Wolff is defined as "the greatest of all dogmatic philosophers."[29] Wolff was read by Søren Kierkegaard's father, Michael Pedersen. Kierkegaard himself was influenced by both Wolff and Kant to the point of resuming the tripartite structure and philosophical content to formulate his own three Stages on Life's Way.[30] Wolff saw ontology as a deductive science, knowable a priori and based on two fundamental principles: the principle of non-contradiction ("it cannot happen that the same thing is and is not") and the principle of sufficient reason ("nothing exists without a sufficient reason for why it exists rather than does not exist").[31][32] Beings are defined by their determinations or predicates, which can't involve a contradiction. Determinates come in 3 types: essentialia, attributes, and modes.[31] Essentialia define the nature of a being and are therefore necessary properties of this being. Attributes are determinations that follow from essentialia and are equally necessary, in contrast to modes, which are merely contingent. Wolff conceives existence as just one determination among others, which a being may lack.[33] Ontology is interested in being at large, not just in actual being. But all beings, whether actually existing or not, have a sufficient reason.[34] The sufficient reason for things without actual existence consists in all the determinations that make up the essential nature of this thing. Wolff refers to this as a "reason of being" and contrasts it with a "reason of becoming", which explains why some things have actual existence.[33] Practical philosophy is subdivided into ethics, economics and politics. Wolff's moral principle is the realization of human perfection[5]—seen realistically as the kind of perfection the human person actually can achieve in the world in which we live. It is perhaps the combination of Enlightenment optimism and worldly realism that made Wolff so successful and popular as a teacher of future statesmen and business leaders.[35] |

哲学作品 ヴォルフ哲学は、あらゆる対象をこのような形に還元する理性の力に自信を持ち、明晰で整然とした説明へのこだわりが随所に見られる。彼はラテン語とドイツ 語の両方で文献を書いた。彼の影響により、自然法と哲学はドイツのほとんどの大学、特にプロテスタント諸侯国の大学で教えられるようになった。ヴォルフは 自らヘッセン=カッセルへの導入を推進した[20]。 ヴォルフの体系はライプニッツの決定論と楽観主義を維持しているが、モナド論は背景に退いており、モナドは一方では魂や意識のある存在に、他方では単なる 原子に分裂している。既成調和の教義も(重要な発見的装置であることに変わりはないが)その形而上学的意義を失い、十分理性の原理は、ヴォルフが哲学の基 本原理としようとしている矛盾の原理に取って代わられ、再び捨て去られた[5]。 ヴォルフは哲学を理論的な部分と実践的な部分に分けていた。論理学は、時にフィロソフィア・ラリヴァーシスと呼ばれ、両者の導入部あるいはプロペデュティックスを形成している[5]。 理論哲学は、魂、世界、神に関する3つの特殊な形而上学[22]、すなわち合理的な心理学[23][24]、合理的な宇宙論[25][26]、合理的な神 学[27]を区別する前段階として生じる一般的な形而上学[21]として、存在論またはフィロソフィア・プリマをその部分に有していた。この図式は、被造 物、被造物、創造主における宗教的三分割と対をなすものであり、哲学を学ぶ者にとって最もよく知られているのは、『純粋理性批判』におけるカントの扱いで ある[5]。 カントの著書の第2版の「序文」において、ヴォルフは「すべての教条主義哲学者の中で最も偉大な哲学者」[29]と定義されている。キルケゴール自身は ヴォルフとカントの両方から影響を受け、三部構成と哲学的内容を再開して彼自身の『人生の道程』における3つの段階を定式化した[30]。 ヴォルフは存在論を演繹的な科学とみなし、先験的に知ることが可能であり、2つの基本原理、すなわち非矛盾の原理(「同じものが存在することも存在しない こともありえない」)と十分理由の原理(「存在しないのではなく、なぜ存在するのかという十分な理由なしに存在するものはない」)に基づいていると考えた [31][32]。決定には本質、属性、態様の3種類がある[31]。本質とはある存在の性質を定義するものであり、したがってこの存在の必要な性質であ る。属性は本質的なものから導かれる決定であり、モードとは対照的に同様に必要なものである。ヴォルフは存在を、存在者が欠く可能性のある他の決定事項の うちの一つに過ぎないと考えている[33]。しかし、実際に存在するか否かにかかわらず、すべての存在は十分な理由を持っている[34]。実際に存在しな い事物の十分な理由は、この事物の本質的な性質を構成するすべての決定から成り立っている。ヴォルフはこれを「存在の理由」と呼び、あるものが実際に存在 する理由を説明する「なりゆきの理由」と対比している[33]。 実践哲学は倫理学、経済学、政治学に細分化される。ヴォルフの道徳原理は人間の完全性[5]の実現であり、人間が生きている世界で実際に達成できる完全性 の種類として現実的に捉えられている。おそらく、啓蒙主義的な楽観主義と世俗的な現実主義の組み合わせが、ヴォルフを将来の政治家やビジネスリーダーの教 師として成功させ、人気を博させたのであろう[35]。 |

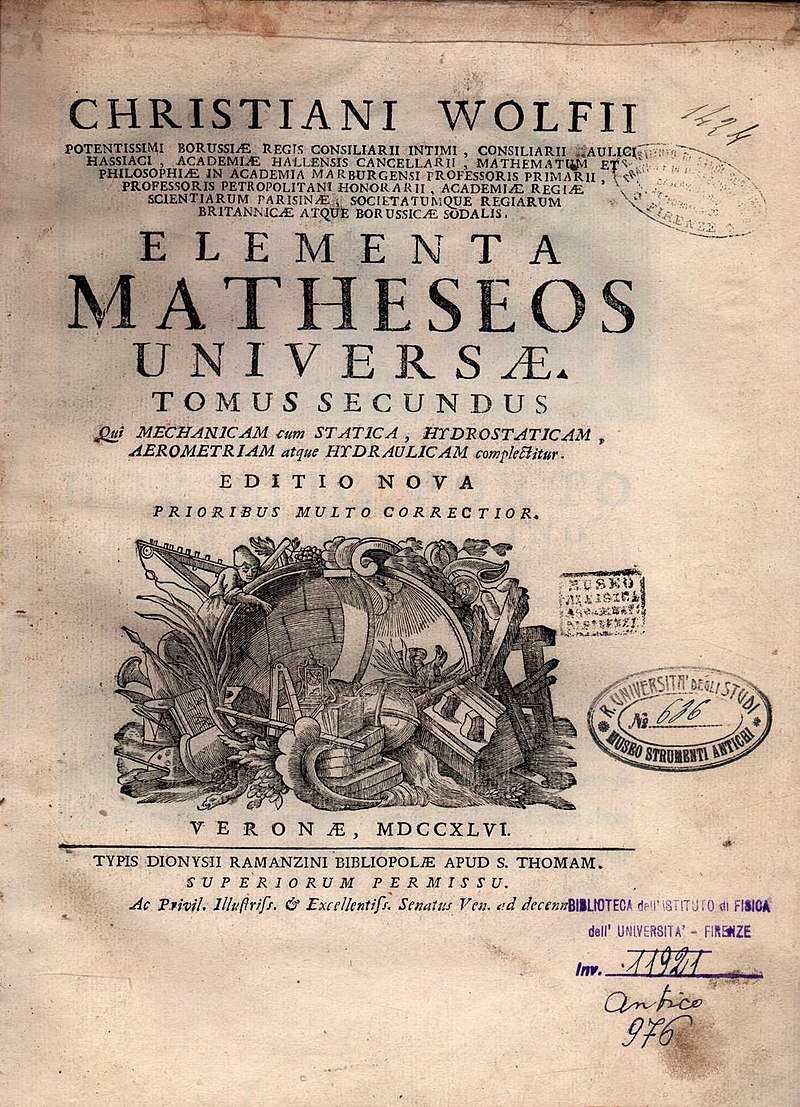

Works Elementa matheseos universae, 1746 Wolff's most important works are as follows:[5] Dissertatio algebraica de algorithmo infinitesimali differentiali (Dissertation on the Algebra of Solving Differential Equations Using Infinitesimals; 1704)[36] Anfangsgründe aller mathematischen Wissenschaften (1710); in Latin, Elementa matheseos universae (1713–1715) Vernünftige Gedanken von den Kräften des menschlichen Verstandes (1712). French translation by Jean Des Champs, Logique, Berlin: 1736. English translation by anonymous, Logic, London: 1770. Unfortunately, the English version is a translation of Des Champs's French edition instead of the original German of Wolff's Vernünftige Gedanken. Vern. Ged. von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt (1719) Vern. Ged. von der Menschen Thun und Lassen (1720) Vern. Ged. von dem gesellschaftlichen Leben der Menschen (1721) Vern. Ged. von den Wirkungen der Natur (1723) Vern. Ged. von den Absichten der natürlichen Dinge (1724) Vern. Ged. von dem Gebrauche der Theile in Menschen, Thieren und Pflanzen (1725); the last seven may briefly be described as treatises on logic, metaphysics, moral philosophy, political philosophy, theoretical physics, teleology, physiology Philosophia rationalis, sive logica (1728) Philosophia prima, sive Ontologia (1730). Part 1 translated as First Philosophy, or Ontology, a translation with critical introduction and annotation by Klaus Ottmann, Thompson: Spring Publications (2022). Cosmologia generalis (1731) Psychologia empirica (1732) Psychologia rationalis (1734) Theologia naturalis (1736–1737) Kleine philosophische Schriften, collected and edited by G.F. Hagen (1736–1740). Philosophia practica universalis (1738–1739) Jus naturae and Jus Gentium. Magdeburg, 1740–1748. English trans.: Marcel Thomann, trans. Jus naturae. NY: Olms, 1972. Wolff, Christian (1746). Elementa matheseos universae (in Latin). Vol. 2. Verona: Dionigi Ramanzini. Wolff, Christian (1746). Elementa matheseos universae (in Latin). Vol. 3. Verona: Dionigi Ramanzini. Wolff, Christian (1751). Elementa matheseos universae (in Latin). Vol. 4. Verona: Dionigi Ramanzini. Jus Gentium Methodo Scientifica Pertractum (The Law of Nations According to the Scientific Method) (1749) Philosophia moralis (1750–1753). Wolff's complete writings have been published since 1962 in an annotated reprint collection: Gesammelte Werke, Jean École et al. (eds.), 3 series (German, Latin, and Materials), Hildesheim-[Zürich-]New York: Olms, 1962–. This includes a volume that unites the three most important older biographies of Wolff. An excellent modern edition of the famous Halle speech on Chinese philosophy is: Oratio de Sinarum philosophia practica / Rede über die praktische Philosophie der Chinesen, Michael Albrecht (ed.), Hamburg: Meiner, 1985. |

著作 Elementa matheseos universae, 1746年 ヴォルフの最も重要な著作は以下の通りである[5]。 Dissertatio algebraica de algorithmo infinitesimali differentiali(無限小数を用いた微分方程式の代数学に関する学位論文、1704年)[36]。 1710年、ラテン語でElementa matheseos universae (1713-1715)。 1712年、『人間的立場の起源に関する哲学的考察』(邦訳『人間的立場の起源に関する哲学的考察』)。ジャン・デシャンによるフランス語訳、『論理 学』、ベルリン、1736年。英訳はanonymous, Logic, London: 1770。残念なことに、英語版はヴォルフのVernünftige Gedankenの原文ドイツ語ではなく、デ・シャンのフランス語版の翻訳である。 Vern. Vern. von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt (1719) Vern. トゥーンとラッセンの諸神について (1720) Vern. 人びとの社会生活から (1721) Vern. 自然の作用に関する研究 (1723) Vern. 自然界の諸行無常について (1724) Vern. Ged. von dem Gebrauche der Theile in Menschen, Thieren und Pflanzen (1725); 最後の7つを簡単に説明すると、論理学、形而上学、道徳哲学、政治哲学、理論物理学、目的論、生理学に関する論文である。 理性哲学、論理学 (1728) Philosophia prima, sive Ontologia (1730)。第1部は、クラウス・オットマンによる批評的序論と注釈を付した翻訳『第一哲学、あるいは存在論』(Thompson: Spring Publications (2022))として翻訳されている。 宇宙一般論(1731年) 経験的心理学 (1732) 合理的心理学 (1734) 自然神学 (1736-1737) G.F.ハーゲンが収集・編集したKleine philosophische Schriften (1736-1740). 普遍哲学(1738-1739年) Jus naturaeとJus Gentium。Magdeburg, 1740-1748. 英語訳: Marcel Thomann, trans. Jus naturae. NY: Olms, 1972. Wolff, Christian (1746). Elementa matheseos universae (in Latin). Verona: Dionigi Ramanzini. Wolff, Christian (1746). Elementa matheseos universae (in Latin). 第3巻: Dionigi Ramanzini. Wolff, Christian (1751). Elementa matheseos universae (in Latin). 第4巻: Dionigi Ramanzini. Jus Gentium Methodo Scientifica Pertractum(科学的方法による国民法) (1749) 道徳哲学(1750-1753)。 ヴォルフの全著作は1962年以降、注釈付きの復刻版として出版されている: Gesammelte Werke, Jean École et al., 3 series (German, Latin, and Materials), Hildesheim-[Zürich-]New York: Olms, 1962-. これには、ヴォルフの最も重要な3つの伝記を統合した巻も含まれている。 中国哲学に関する有名なハレ講演の優れた現代版がある: Oratio de Sinarum philosophia practica / Rede über die praktische Philosophie der Chinesen, Michael Albrecht (ed.), Hamburg: Meiner, 1985. |

| Mueser,

Benjamin (2024). "The Privilege of Territory: Christian Wolff at the

Origins of Statist International Thought". Political Theory. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_Wolff_(philosopher) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆