キリスト教哲学と神学と「女神学」

Christian philosophy and Theology, with Thealogy

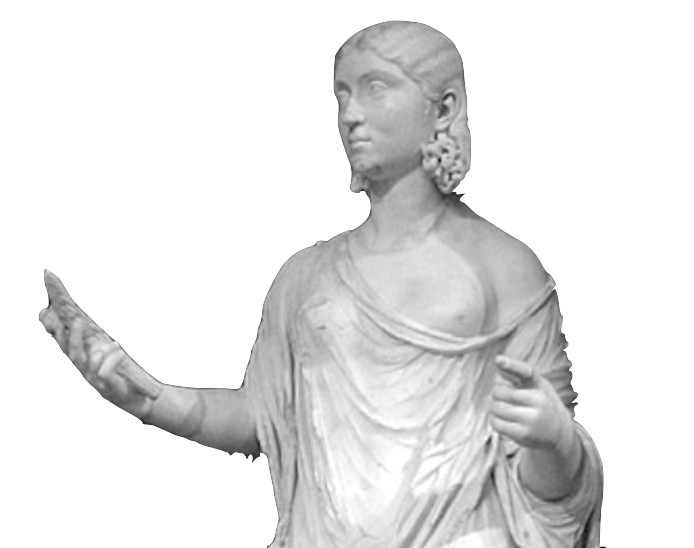

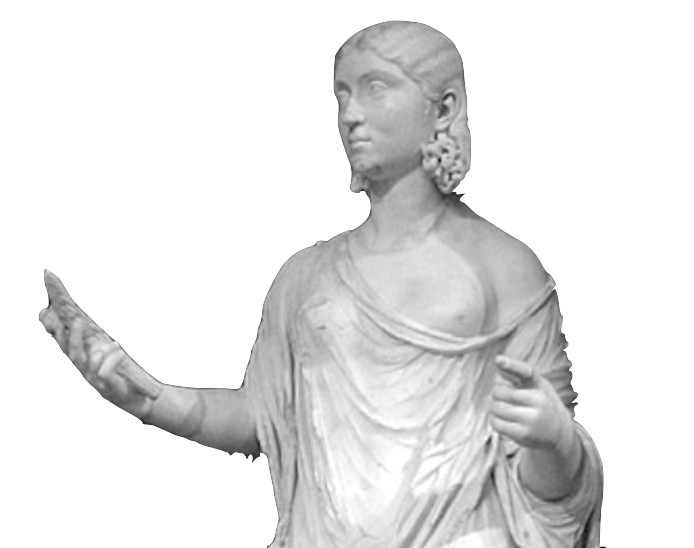

Statue of Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture

★ キリスト教哲学(Christian philosophy)は、キリスト教徒によって、あるいはキリスト教という宗教に関連して行われたすべての哲学を含む。キリスト教哲学は、科学 と信仰を調和させることを目的とし、キリスト教の啓示の助けを借りて、自然の合理的説明から出発した。アレクサンドリアのオリゲンやアウグスティヌスのよ うな数人の思想家は、科学と信仰の間には調和した関係があると信じていたが、テルトゥリアヌスのように矛盾があると主張する者もいれば、両者を区別しよう とする者もいた。 キリスト教哲学の存在自体を疑問視する学者もいる。これらの学者は、キリスト教思想には独自性がなく、その概念や思想はギリシャ哲学から受け継いだものだ と主張する。したがって、キリスト教哲学は、すでにギリシア哲学によって決定的に精緻化された哲学的思想を保護することになる。 しかし、ベーナーとジルソンは、キリスト教哲学は、プラトン、アリストテレス、新プラトン主義者たちによって開発された知識をギリシア科学に負っていると はいえ、古代哲学の単純な反復ではないと主張している。彼らは、キリスト教哲学においては、ギリシャ文化が有機的な形で存続しているとさえ主張している。

★ 神学(Theology)とは、宗教的観 点から宗教的信念を研究する学問である。より狭義には、神の本質を研究する学問である。超自然的なものを分析するという独特な内容を扱うが、宗教的認識論 も扱い、啓示の問題に問いかけ、答えようとする。啓示とは、神、神々、あるいは神々が、自然界を超越した存在であるだけでなく、自然界と相互作用し、人類 に自らを明らかにする意思と能力を持つ存在であることを受け入れることに関係する。 神学者たちは、さまざまな形式の分析や議論(経験的、哲学的、民俗学的、歴史的、その他)を用いて、無数の宗教的トピックの理解、説明、検証、批判、擁 護、推進に役立てている。倫理哲学や判例法のように、論証は多くの場合、以前に解決された疑問の存在を前提とし、そこから類推して新たな状況における新た な推論を導き出すことによって発展する。 神学の研究は、神学者が自らの宗教的伝統[や他の宗教的伝統をより深く理解するのに役立つこともあれば、特定の伝統に言及することなく神性の本質を探求す ることを可能にすることもある。…… 神学の研究は、神学者が自らの宗教的伝統や他の宗教的伝統をより深く理解するのに役立つこともあれば、特定の伝統に言及することなく神性の本質を探 求することを可能にすることもある。神学は宗教的伝統を広めたり改革したり正当化したりするために用いられることもあれば、宗教的伝統や世界観を比較した り挑戦したり(聖書批判など)、反対したり(無宗教など)するために用いられることもある。神学はまた、宗教的伝統を通して神学者が現在の状況や必要性に 対処したり、世界を解釈する可能な方法を探求したりするのに役立つかもしれないのである(→キリスト教神学)。

★

女神学([をんなしんがく]あるいは女神論、Thealogy)は、フェミニズムに限らず、女性的な視点を通して神的な事柄を捉える。ヴァレリー・サイヴィング、アイザッ

ク・ボネヴィッツ(1976年)、ナオミ・ゴールデンバーグ(1979年)は、この概念を新造語(新しい言葉)として紹介した。

その後、その用法は聖なるものに対する女性的な考え方全般を意味するようになり、1993年にシャーロット・キャロンが「女性的あるいはフェミニスト的な

用語による神的なものへの考察」と有益な説明をした。 1996年にメリッサ・ラファエルが『Thealogy and

Embodiment』を出版する頃には、この用語はすっかり定着していた[3]。

新造語として、この用語は2つのギリシア語に由来している:テア、θεάは「女神」を意味し、テオス、「神」(PIE語源*dhes-から)の女性的な等

価語である[4]。ロゴス、λόγος、複数形のlogoiは、しばしば英語では接尾辞-logyとして見出され、「言葉、理性、計画」を意味し、ギリシ

ア哲学と神学では、宇宙に内在する神の理性である[5][6]。

女神学はフェミニスト神学と共通する部分があり、フェミニストの視点からの神の研究であり、しばしば一神教を強調する。女神学は(その語源にもかかわら

ず)一つの神に限定されるものではないため、その関係は重複している。

| Christian

philosophy

includes all philosophy carried out by Christians, or in relation to

the religion of Christianity. Christian philosophy emerged with the aim

of reconciling science and faith, starting from natural rational

explanations with the help of Christian revelation. Several thinkers

such as Origen of Alexandria and Augustine believed that there was a

harmonious relationship between science and faith, others such as

Tertullian claimed that there was contradiction and others tried to

differentiate them.[1] There are scholars who question the existence of a Christian philosophy itself. These claim that there is no originality in Christian thought and its concepts and ideas are inherited from Greek philosophy. Thus, Christian philosophy would protect philosophical thought, which would already be definitively elaborated by Greek philosophy.[2] However, Boehner and Gilson claim that Christian philosophy is not a simple repetition of ancient philosophy, although they owe to Greek science the knowledge developed by Plato, Aristotle and the Neo-Platonists. They even claim that in Christian philosophy, Greek culture survives in organic form.[3] |

キリスト教哲学(Christian

philosophy)は、キリスト教徒によって、あるいはキリスト教という宗

教に関連して行われたすべての哲学を含む。キリスト教哲学は、科学と信仰を調和させることを目的とし、キリスト教の啓示の助けを借りて、自然の合理的説明

から出発した。アレクサンドリアのオリゲンやアウグスティヌスのような数人の思想家は、科学と信仰の間には調和した関係があると信じていたが、テルトゥリ

アヌスのように矛盾があると主張する者もいれば、両者を区別しようとする者もいた[1]。 キリスト教哲学の存在自体を疑問視する学者もいる。これらの学者は、キリスト教思想には独自性がなく、その概念や思想はギリシャ哲学から受け継いだものだ と主張する。したがって、キリスト教哲学は、すでにギリシア哲学によって決定的に精緻化された哲学的思想を保護することになる[2]。 しかし、ベーナーとジルソンは、キリスト教哲学は、プラトン、アリストテレス、新プラトン主義者たちによって開発された知識をギリシア科学に負っていると はいえ、古代哲学の単純な反復ではないと主張している。彼らは、キリスト教哲学においては、ギリシャ文化が有機的な形で存続しているとさえ主張している [3]。 |

| Historical aspects Christian philosophy began around the 3rd century. It arises through the movement of the Christian community called Patristics,[4] which initially had as a main objective the defense of Christianity. As Christianity spread, patristic authors increasingly engaged with the philosophical schools of the hellenized Roman Empire, and ultimately learned from some aspects of these surrounding ideas how to better articulate Christianity's own revelation of Jesus Christ as God incarnate and one with God the Father and God the Spirit. Many scholars consider Origen of Alexandria to be the first Christian teacher to fully present Christian philosophy and metaphysics as a stronger alternative to other schools (especially Platonism). See Origen Against Plato by Mark J. Edwards and the introduction to Origen: On First Principles translated and introduced by John Behr as two prominent examples of this history of a specifically Christian philosophy and metaphysics. From the 11th century onwards, Christian philosophy was manifested through Scholasticism. This is the period of medieval philosophy that extended until the 15th century, as pointed out by T. Adão Lara. From the 16th century onwards, Christian philosophy, with its theories, started to coexist with independent scientific and philosophical theories. The development of Christian ideas represents a break with the philosophy of the Greeks, bearing in mind that the starting point of Christian philosophy is the Christian religious message. Lara divides Christian philosophy into three eras: Early philosophy: Patristics (2nd–7th centuries) Medieval philosophy: Scholastics (9th–13th centuries) Pre-modern (14th–15th centuries)[5] |

歴史的側面 キリスト教哲学は3世紀頃に始まった。キリスト教哲学は、キリスト教を擁護することを主な目的とした、キリスト教共同体のパトリスティク[4]と呼ばれる 運動を通じて生まれた。キリスト教が広まるにつれて、教父学の著者たちはヘレニズム化したローマ帝国の哲学学派との関わりを増やし、最終的には、受肉した 神であり、父なる神と聖霊なる神と一体であるイエス・キリストについてのキリスト教自身の啓示をより明確に表現する方法を、これらの周辺の思想のいくつか の側面から学んだ。多くの学者が、アレクサンドリアのオリゲンを、キリスト教哲学と形而上学を他の学派(特にプラトン主義)に対するより強力な選択肢とし て完全に提示した最初のキリスト教教師であると考えている。マーク・J・エドワーズ著『プラトンに対するオリゲン』、および『オリゲン入門』を参照: 特にキリスト教哲学と形而上学のこのような歴史の2つの顕著な例として、ジョン・ベーアによって翻訳・紹介された『第一原理について』を参照されたい。 11世紀以降、キリスト教哲学はスコラ哲学を通して顕在化した。これは、T.アダオ・ララが指摘するように、15世紀まで続いた中世哲学の時代である。 16世紀以降、キリスト教哲学はその理論とともに、独立した科学的・哲学的理論と共存するようになる。 キリスト教哲学の出発点がキリスト教の宗教的メッセージであることを念頭に置くと、キリスト教思想の発展はギリシャ哲学との決別を意味する。 ララはキリスト教哲学を3つの時代に分けている: 初期哲学 教父学(2~7世紀) 中世哲学: スコラ哲学(9~13世紀) 前近代(14世紀から15世紀)[5]。 |

| Characteristics Natural demonstration See also: Metaphysics § Epistemological foundation The philosophical starting point of Christian philosophy is logic, not excluding Christian theology.[6] Although there is a relationship between theological doctrines and philosophical reflection in Christian philosophy, its reflections are strictly rational. On this way of seeing the two disciplines, if at least one of the premises of an argument is derived from revelation, the argument falls in the domain of theology; otherwise it falls into philosophy's domain.[7][8] Justification of truths of faith Fundamentally, Christian philosophical ideals are to make religious convictions rationally evident through natural reason. The Christian philosopher's attitude is determined by faith in matters relating to cosmology and everyday life. Unlike the Secular philosopher, the Christian philosopher seeks conditions for the identification of eternal truth, being characterized by religiosity[9] There is criticism of Christian philosophy because the Christian religion is hegemonic at this time and centralizes the elaboration of all values. The coexistence of philosophy and religion is questioned, as philosophy itself is critical and religion founded on revelation and established dogmas. Lara believes that there was questioning and writings with philosophical characteristics in the Middle Ages, although religion and theology predominated.[10] In this way it was established by dogmas, in some aspects, which did not prevent significant philosophical constructions. Tradition A Christian philosophy developed from predecessor philosophies. Justin is based on Greek philosophy, an academy in Augustine and Patristics. It is in the tradition of Christian philosophical thought or Judaism, from whom it was inherited from the Old Testament and more fundamentally in the Gospel message, which records or at the center of the message advocated by Christianity. Scholasticism received influence from both Jewish philosophy and Islamic philosophy. This Christian Europe did not remain exclusively influenced by itself, but it suffered strong influences from other cultures.[11] Systematizing view The 'Divine Unity' (attempts) 'intercedes' to systematically and comprehensively systematize the problems of 'global/worldly' reality 'on' a 'cosmic-harmonic-balance' whole. There is a lack of creative 'Divine Spirit',[citation needed] which is compensated by the overall vision. Christian Revelation itself provides the Christian with an overview.[12] |

特徴 自然なデモンストレーション も参照: 形而上学§認識論的基礎 キリスト教哲学の哲学的出発点は論理学であり、キリスト教神学を除外するものではない。この2つの学問の捉え方において、議論の前提の少なくとも1つが啓 示に由来する場合、その議論は神学の領域に入り、そうでない場合は哲学の領域に入る[7][8]。 信仰の真理の正当化 基本的にキリスト教哲学の理想は、宗教的確信を自然理性によって合理的に明らかにすることである。キリスト教哲学者の態度は、宇宙論や日常生活に関する事 柄において信仰によって決定される。世俗の哲学者とは異なり、キリスト教の哲学者は宗教性を特徴とし、永遠の真理を識別するための条件を求める[9]。 キリスト教哲学に対する批判があるのは、キリスト教がこの時代において覇権的であり、あらゆる価値の精緻化を一元化しているからである。哲学は批判的であ り、宗教は啓示と確立された教義に基づいているため、哲学と宗教の共存が疑問視されている。ララは、宗教と神学が支配的であったとはいえ、中世には哲学的 な特徴をもった問いかけや著作があったと考えている[10]。このように、中世はドグマによって確立されていた面もあるが、それは重要な哲学的構築を妨げ るものではなかった。 伝統 キリスト教哲学は先行する哲学から発展した。ユスティヌスはギリシア哲学、アウグスティヌスやパトリスティクスのアカデミーに基づいている。キリスト教哲 学思想の伝統、あるいはユダヤ教哲学の伝統の中にあり、旧約聖書から受け継がれ、より根本的には福音書のメッセージの中にあり、キリスト教が提唱したメッ セージの記録、あるいは中心にある。 スコラ哲学は、ユダヤ哲学とイスラム哲学の両方から影響を受けた。このキリスト教ヨーロッパは、自分たちだけの影響にとどまることなく、他の文化からの強 い影響を受けた[11]。 体系化された見解 神聖なる統一」(の試み)は、「地球的/世界的」現実の問題を「宇宙的-調和的-均衡的」な全体として体系化し、包括的に体系化するために「執り成す」。 創造的な「神の霊」[要出典]の欠如があるが、それは全体的なヴィジョンによって補われる。キリスト教の啓示そのものが、キリスト教徒に概観を提供してい る[12]。 |

| Arguments for the existence of

God Biblical studies Christian apologetics Christian humanism Catholic theology Ethics in the Bible Judeo-Christian ethics Sobornost Theism Thomism |

神の存在の論拠 聖書学 キリスト教弁証論 キリスト教ヒューマニズム カトリック神学 聖書における倫理 ユダヤ教倫理学 ソボルノスト 有神論 トミズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_philosophy |

|

| Theology is the

study of

religious belief from a religious perspective. More narrowly it is the

study of the nature of the divine. It is taught as an academic

discipline, typically in universities and seminaries.[1] It occupies

itself with the unique content of analyzing the supernatural, but also

deals with religious epistemology, asks and seeks to answer the

question of revelation. Revelation pertains to the acceptance of God,

gods, or deities, as not only transcendent or above the natural world,

but also willing and able to interact with the natural world and to

reveal themselves to humankind. Theologians use various forms of analysis and argument (experiential, philosophical, ethnographic, historical, and others) to help understand, explain, test, critique, defend or promote any myriad of religious topics. As in philosophy of ethics and case law, arguments often assume the existence of previously resolved questions, and develop by making analogies from them to draw new inferences in new situations. The study of theology may help a theologian more deeply understand their own religious tradition,[2] another religious tradition,[3] or it may enable them to explore the nature of divinity without reference to any specific tradition. Theology may be used to propagate,[4] reform,[5] or justify a religious tradition; or it may be used to compare,[6] challenge (e.g. biblical criticism), or oppose (e.g. irreligion) a religious tradition or worldview. Theology might also help a theologian address some present situation or need through a religious tradition,[7] or to explore possible ways of interpreting the world.[8] |

神学(Theology)とは、宗教的観点から宗教

的信念を研究する学問である。より狭義に

は、神の本質を研究する学問である。超自然的なものを分析するという独特な内容を扱うが、宗教的認識論も扱い、啓示の問題に問いかけ、答えようとする。啓

示とは、神、神々、あるいは神々が、自然界を超越した存在であるだけでなく、自然界と相互作用し、人類に自らを明らかにする意思と能力を持つ存在であるこ

とを受け入れることに関係する。 神学者たちは、さまざまな形式の分析や議論(経験的、哲学的、民俗学的、歴史的、その他)を用いて、無数の宗教的トピックの理解、説明、検証、批判、擁 護、推進に役立てている。倫理哲学や判例法のように、論証は多くの場合、以前に解決された疑問の存在を前提とし、そこから類推して新たな状況における新た な推論を導き出すことによって発展する。 神学の研究は、神学者が自らの宗教的伝統[2]や他の宗教的伝統[3]をより深く理解するのに役立つこともあれば、特定の伝統に言及することなく神性の本 質を探求することを可能にすることもある。神学は宗教的伝統を広めたり[4]改革したり[5]正当化したりするために用いられることもあれば、宗教的伝統 や世界観を比較したり[6]挑戦したり(聖書批判など)、反対したり(無宗教など)するために用いられることもある。神学はまた、宗教的伝統を通して神学 者が現在の状況や必要性に対処したり[7]、世界を解釈する可能な方法を探求したりするのに役立つかもしれない[8]。 |

| Etymology Main article: History of theology The term derives from the Greek theologia (θεολογία), a combination of theos (Θεός, 'god') and logia (λογία, 'utterances, sayings, oracles')—the latter word relating to Greek logos (λόγος, 'word, discourse, account, reasoning').[9][10] The term would pass on to Latin as theologia, then French as théologie, eventually becoming the English theology. Through several variants (e.g., theologie, teologye), the English theology had evolved into its current form by 1362.[11] The sense that the word has in English depends in large part on the sense that the Latin and Greek equivalents had acquired in patristic and medieval Christian usage although the English term has now spread beyond Christian contexts.  Plato (left) and Aristotle in Raphael's 1509 fresco The School of Athens Classical philosophy Greek theologia (θεολογία) was used with the meaning 'discourse on God' around 380 BC by Plato in The Republic.[12] Aristotle divided theoretical philosophy into mathematike, physike, and theologike, with the latter corresponding roughly to metaphysics, which, for Aristotle, included discourse on the nature of the divine.[13] Drawing on Greek Stoic sources, the Latin writer Varro distinguished three forms of such discourse:[14] mythical, concerning the myths of the Greek gods; rational, philosophical analysis of the gods and of cosmology; and civil, concerning the rites and duties of public religious observance. Later usage Some Latin Christian authors, such as Tertullian and Augustine, followed Varro's threefold usage.[14][15] However, Augustine also defined theologia as "reasoning or discussion concerning the Deity".[16] The Latin author Boethius, writing in the early 6th century, used theologia to denote a subdivision of philosophy as a subject of academic study, dealing with the motionless, incorporeal reality; as opposed to physica, which deals with corporeal, moving realities.[17] Boethius' definition influenced medieval Latin usage.[18] In patristic Greek Christian sources, theologia could refer narrowly to devout and/or inspired knowledge of and teaching about the essential nature of God.[19] In scholastic Latin sources, the term came to denote the rational study of the doctrines of the Christian religion, or (more precisely) the academic discipline that investigated the coherence and implications of the language and claims of the Bible and of the theological tradition (the latter often as represented in Peter Lombard's Sentences, a book of extracts from the Church Fathers).[citation needed] In the Renaissance, especially with Florentine Platonist apologists of Dante's poetics, the distinction between 'poetic theology' (theologia poetica) and 'revealed' or Biblical theology serves as stepping stone for a revival of philosophy as independent of theological authority.[citation needed] It is in the last sense, theology as an academic discipline involving rational study of Christian teaching, that the term passed into English in the 14th century,[20] although it could also be used in the narrower sense found in Boethius and the Greek patristic authors, to mean rational study of the essential nature of God, a discourse now sometimes called theology proper.[21] From the 17th century onwards, the term theology began to be used to refer to the study of religious ideas and teachings that are not specifically Christian or correlated with Christianity (e.g., in the term natural theology, which denoted theology based on reasoning from natural facts independent of specifically Christian revelation)[22] or that are specific to another religion (such as below). Theology can also be used in a derived sense to mean "a system of theoretical principles; an (impractical or rigid) ideology".[23][24] |

語源 主な記事 神学の歴史 語源はギリシャ語のtheologia(θεολογία)で、theos(Θεός、「神」)とlogia(λογία、「発言、言明、託宣」)を組み 合わせたものである。 [9][10]この用語はラテン語のtheologia、フランス語のthéologieへと受け継がれ、最終的には英語のtheologyとなった。 英語のtheologyは、いくつかの変種(theologie、teologyeなど)を経て、1362年までに現在の形に進化した[11]。英語にお けるこの語の意味は、ラテン語とギリシャ語の同等語が教父時代や中世のキリスト教の用法で獲得した意味に大きく依存しているが、英語の用語は現在ではキリ スト教の文脈を超えて広まっている。  ラファエロの1509年のフレスコ画『アテネの学派』に描かれたプラトン(左)とアリストテレス 古典哲学 ギリシャ語のtheologia(θεολογία)は、紀元前380年頃にプラトンが『共和国』で「神についての言説」という意味で使用した[12]。 アリストテレスは理論哲学をmathematike(数学的)、physike(物理学的)、theologike(神学的)に分け、後者はアリストテレ スにとって神の本質に関する言説を含む形而上学にほぼ相当する[13]。 ラテン語の作家ヴァロは、ギリシアのストア派の典拠をもとに、そのような言説を次の3つの形態に区別した[14]。 神話的:ギリシア神話の神々に関するもの; 理性的な、神々と宇宙論の哲学的分析 民俗的なもので、公的な宗教的儀礼や義務に関するもの。 後の用法 テルトゥリアヌスやアウグスティヌスといったラテン・キリスト教の著者の中には、ヴァッロの三重の用法に従った者もいた[14][15]が、アウグスティ ヌスもまたテオロギアを「神に関する推論や議論」と定義していた[16]。 6世紀初頭に書かれたラテン語の作家ボエティウスは、身体的で動く現実を扱うフィジカとは対照的に、動かない、無体な現実を扱う、学問的研究の対象として の哲学の細目を示すためにテオロギアを使用した[17]。 教父的なギリシアのキリスト教資料では、テオロギアは神の本質的な性質についての敬虔で霊感に満ちた知識と教えを狭義に指すことがあった[19]。 スコラ哲学ラテン語資料では、この用語はキリスト教の教義の理性的な研究、または(より正確には)聖書と神学的伝統の言語と主張の首尾一貫性と含意を調査 する学問を示すようになった(後者はしばしば教父からの抜粋を集めたペテロ・ロンバールの『文』に代表される)[要出典]。 ルネサンス期、特にダンテの詩学を擁護するフィレンツェのプラトン主義者たちにおいて、「詩的神学」(theologia poetica)と「啓示された」神学、あるいは聖書神学との区別は、神学的権威から独立した哲学の復活への足がかりとなった[citation needed]。 キリスト教の教えを理性的に研究する学問としての神学という最後の意味において、この用語は14世紀に英語に使われるようになった[20]が、ボエティウ スやギリシアの教父言行録に見られるような、神の本質に関する理性的な研究という狭い意味でも使われるようになり、現在では神学と呼ばれることもある。 17世紀以降、神学という用語は、特にキリスト教的でなかったり、キリスト教と関連していなかったりする宗教的な考え方や教え(例えば、自然神学という用 語では、特にキリスト教的な啓示から独立した自然的事実からの推論に基づく神学を示す)[22]、あるいは他の宗教に特有のもの(例えば、以下のようなも の)を指すのに使われ始めた。 神学は「理論的原則の体系;(非実用的または硬直的な)イデオロギー」を意味する派生的な意味で用いられることもある[23][24]。 |

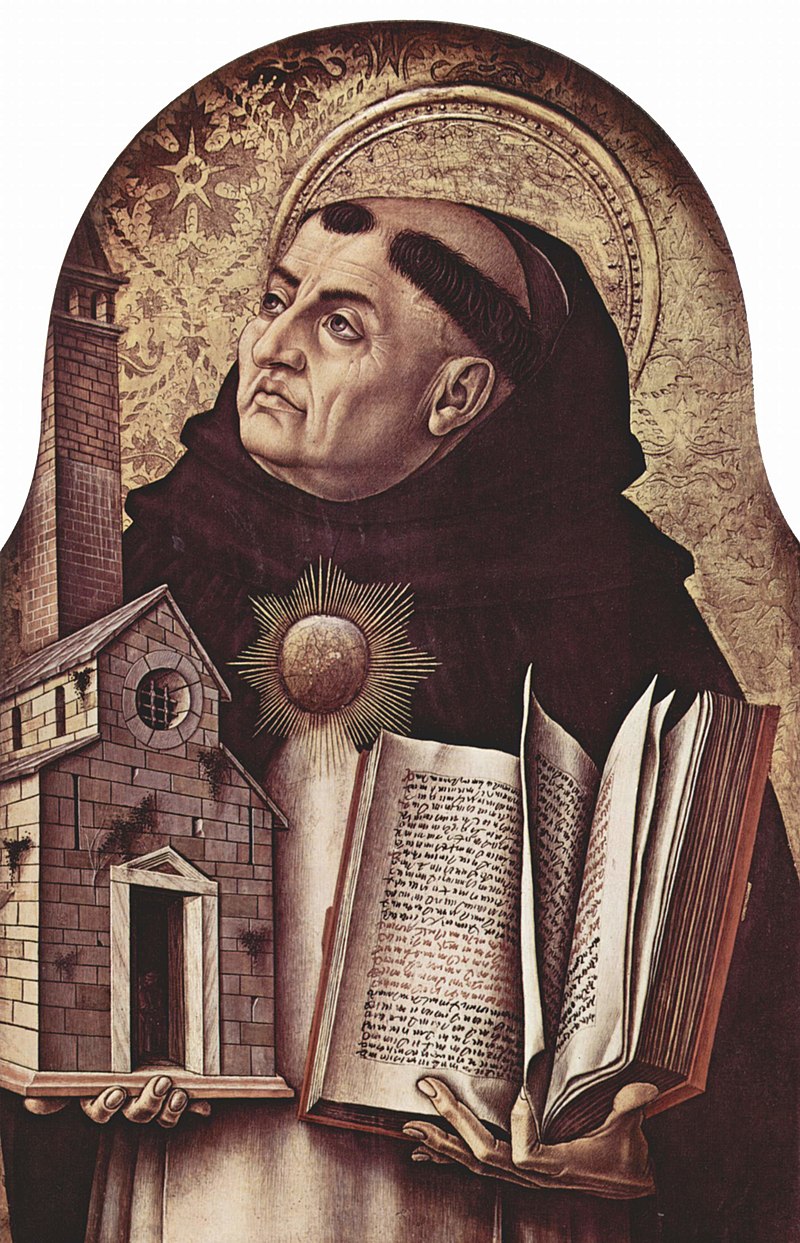

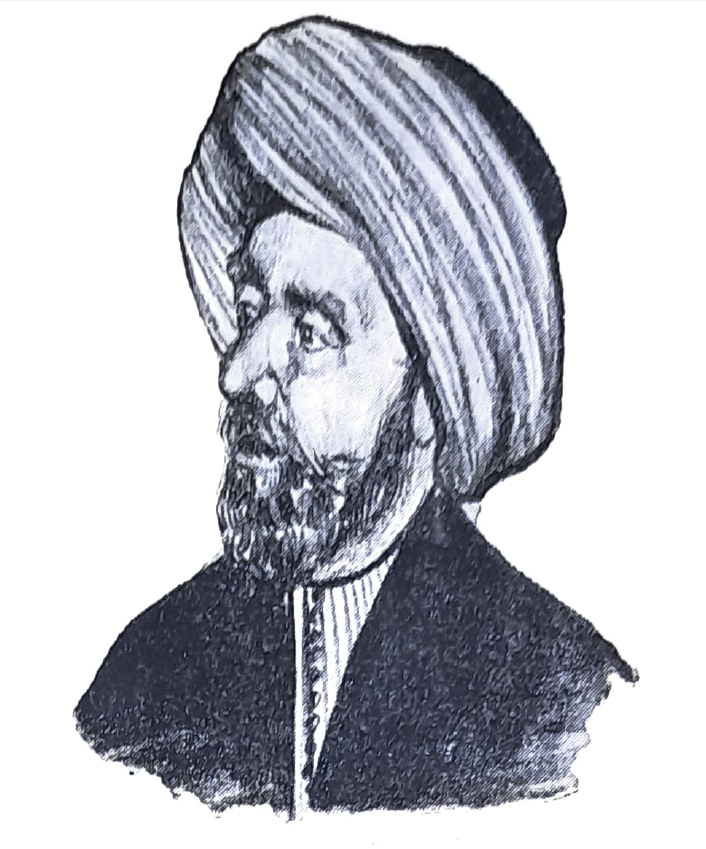

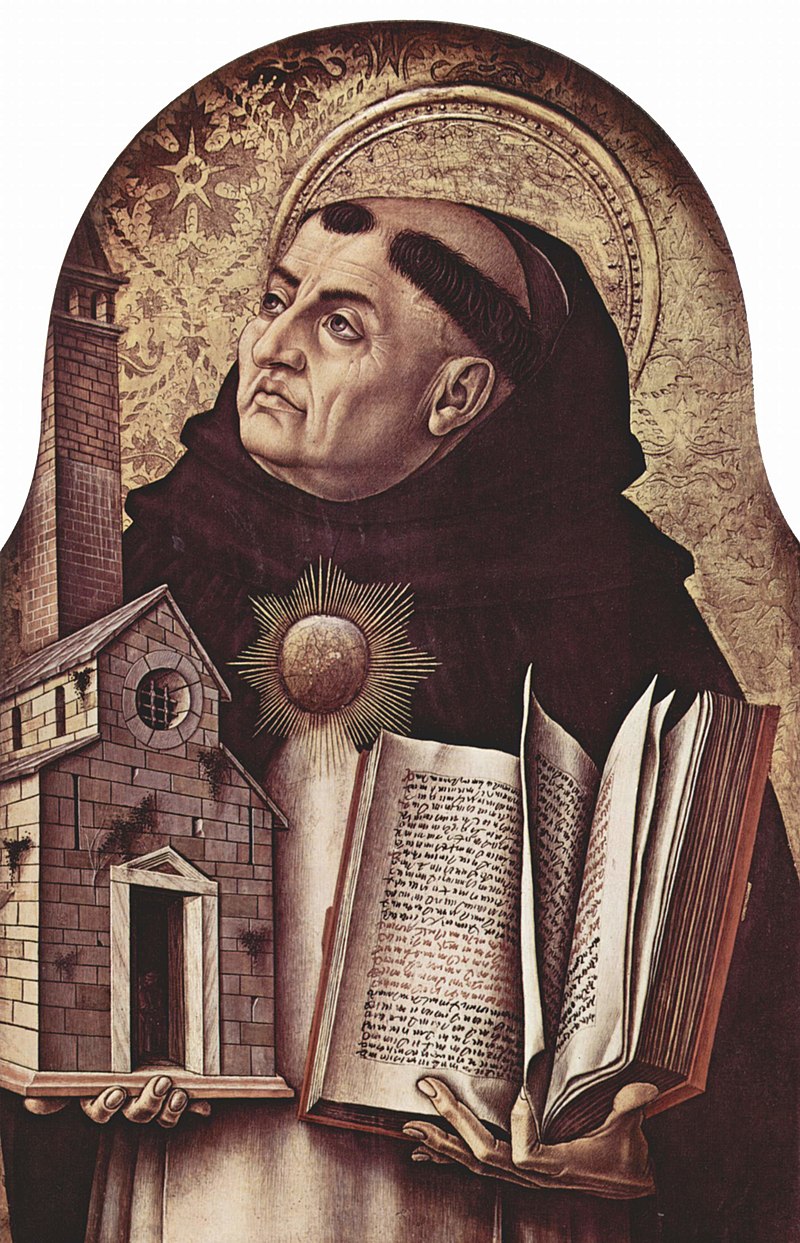

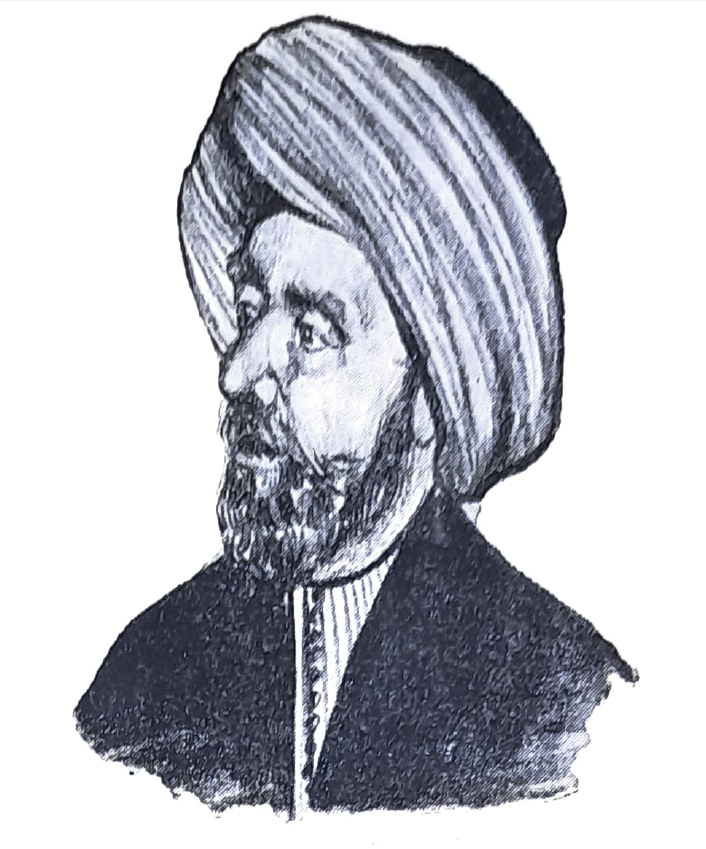

| In religion The term theology has been deemed by some as only appropriate to the study of religions that worship a supposed deity (a theos), i.e. more widely than monotheism; and presuppose a belief in the ability to speak and reason about this deity (in logia). They suggest the term is less appropriate in religious contexts that are organized differently (i.e., religions without a single deity, or that deny that such subjects can be studied logically). Hierology has been proposed, by such people as Eugène Goblet d'Alviella (1908), as an alternative, more generic term.[25] Abrahamic religions Christianity Main articles: Christian theology and Neoplatonism Further information: Diversity in early Christian theology, Great Apostasy, Nontrinitarianism, Son of God (Christianity), and Trinity  Thomas Aquinas, an influential Roman Catholic theologian As defined by Thomas Aquinas, theology is constituted by a triple aspect: what is taught by God, teaches of God, and leads to God (Latin: Theologia a Deo docetur, Deum docet, et ad Deum ducit).[26] This indicates the three distinct areas of God as theophanic revelation, the systematic study of the nature of divine and, more generally, of religious belief, and the spiritual path. Christian theology as the study of Christian belief and practice concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and the New Testament as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theologians use biblical exegesis, rational analysis and argument. Theology might be undertaken to help the theologian better understand Christian tenets, to make comparisons between Christianity and other traditions, to defend Christianity against objections and criticism, to facilitate reforms in the Christian church, to assist in the propagation of Christianity, to draw on the resources of the Christian tradition to address some present situation or need, or for a variety of other reasons. Islam  The famous Islamic scholar, jurist and theologian Malik Ibn Anas Main article: Aqidah Further information: Kalam, List of Muslim theologians, and Schools of Islamic theology Islamic theological discussion that parallels Christian theological discussion is called Kalam; the Islamic analogue of Christian theological discussion would more properly be the investigation and elaboration of Sharia or Fiqh.[27] Kalam...does not hold the leading place in Muslim thought that theology does in Christianity. To find an equivalent for 'theology' in the Christian sense it is necessary to have recourse to several disciplines, and to the usul al-fiqh as much as to kalam. — translated by L. Gardet Some Universities in Germany established departments of islamic theology. (i.e. [28]) Judaism  Sculpture of the Jewish theologian Maimonides Main article: Jewish theology In Jewish theology, the historical absence of political authority has meant that most theological reflection has happened within the context of the Jewish community and synagogue, including through rabbinical discussion of Jewish law and Midrash (rabbinic biblical commentaries). Jewish theology is also linked to ethics, as it is the case with theology in other religions, and therefore has implications for how one behaves.[29][30] Indian religions Buddhism Some academic inquiries within Buddhism, dedicated to the investigation of a Buddhist understanding of the world, prefer the designation Buddhist philosophy to the term Buddhist theology, since Buddhism lacks the same conception of a theos. Jose Ignacio Cabezon, who argues that the use of theology is in fact appropriate, can only do so, he says, because "I take theology not to be restricted to discourse on God.... I take 'theology' not to be restricted to its etymological meaning. In that latter sense, Buddhism is of course atheological, rejecting as it does the notion of God."[31] Hinduism See also: Krishnology Within Hindu philosophy, there is a tradition of philosophical speculation on the nature of the universe, of God (termed Brahman, Paramatma, and/or Bhagavan in some schools of Hindu thought) and of the ātman (soul). The Sanskrit word for the various schools of Hindu philosophy is darśana ('view, viewpoint'). Vaishnava theology has been a subject of study for many devotees, philosophers and scholars in India for centuries. A large part of its study lies in classifying and organizing the manifestations of thousands of gods and their aspects. In recent decades the study of Hinduism has also been taken up by a number of academic institutions in Europe, such as the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies and Bhaktivedanta College.[32] Other religions Shinto In Japan, the term theology (神学, shingaku) has been ascribed to Shinto since the Edo period with the publication of Mano Tokitsuna's Kokon shingaku ruihen (古今神学類編, 'categorized compilation of ancient theology'). In modern times, other terms are used to denote studies in Shinto—as well as Buddhist—belief, such as kyōgaku (教学, 'doctrinal studies') and shūgaku (宗学, 'denominational studies'). Modern Paganism English academic Graham Harvey has commented that Pagans "rarely indulge in theology".[33] Nevertheless, theology has been applied in some sectors across contemporary Pagan communities, including Wicca, Heathenry, Druidry and Kemetism. As these religions have given precedence to orthopraxy, theological views often vary among adherents. The term is used by Christine Kraemer in her book Seeking The Mystery: An Introduction to Pagan Theologies and by Michael York in Pagan Theology: Paganism as a World Religion. |

宗教の内部における神学 神学という用語は、想定される神(テオス)を崇拝する宗教、すなわち一神教よりも広範な宗教の研究にのみ適切であり、この神について(ロギアにおいて) 語ったり推論したりする能力を信じることを前提とする、と考える人もいる。この用語は、異なる組織(すなわち、単一の神を持たない宗教、またはそのような 主題が論理的に研究されることを否定する宗教)の宗教的文脈ではあまり適切ではないことを示唆している。ヒエロジーは、ウジェーヌ・ゴブレ・ダルヴィエラ (Eugène Goblet d'Alviella)(1908年)などによって、代替的な、より一般的な用語として提案されている[25]。 アブラハムの宗教 キリスト教 主な記事 キリスト教神学と新プラトン主義 さらに詳しい情報 初期キリスト教神学における多様性、大背教、非三位一体主義、神の子(キリスト教)、三位一体  ローマ・カトリックの神学者トマス・アクィナス トマス・アクィナスによって定義されたように、神学は、神によって教えられるもの、神について教えるもの、神へと導くもの(ラテン語:Theologia a Deo docetur, Deum docet, et ad Deum ducit)という三重の側面によって構成されている[26]。これは、神智学的啓示としての神、神の性質、より一般的には宗教的信仰の性質に関する体系 的な研究、霊的な道という3つの異なる領域を示している。キリスト教の信仰と実践の研究としてのキリスト教神学は、主に旧約聖書と新約聖書のテキストとキ リスト教の伝統に集中している。キリスト教神学者は聖書の釈義、合理的な分析、議論を用いる。神学は、神学者がキリスト教の教義をよりよく理解するため、 キリスト教と他の伝統との比較を行うため、異論や批判からキリスト教を守るため、キリスト教会の改革を促進するため、キリスト教の布教を支援するため、現 在の状況や必要性に対処するためにキリスト教の伝統のリソースを活用するため、またはその他のさまざまな理由で行われる。 イスラム教  有名なイスラム学者、法学者、神学者マリク・イブン・アナス 主な記事 アキーダ さらなる情報 カラーム、イスラム神学者リスト、イスラム神学の学派 キリスト教の神学的議論に類似するイスラームの神学的議論はカラームと呼ばれる。 カラームは...キリスト教における神学のように、ムスリム思想において主導的な地位を占めてはいない。キリスト教的な意味での「神学」に相当するものを 見出すためには、いくつかの学問分野、そしてカラームと同様にウスル・アル・フィクに頼る必要がある。 - L.ガーデ著 ドイツのいくつかの大学では、イスラム神学部が設置されている。(すなわち[28])。 ユダヤ教  ユダヤ教の神学者マイモニデスの彫刻 主な記事 ユダヤ神学 ユダヤ教神学では、歴史的に政治的権威が存在しなかったため、神学的考察のほとんどはユダヤ教共同体やシナゴーグの中で行われてきた。ユダヤ教の神学もま た、他の宗教の神学と同様に倫理と結びついており、それゆえ人がどのように行動するかに影響を及ぼしている[29][30]。 インドの宗教 仏教 仏教には神という概念がないため、仏教哲学という呼称の方が仏教神学という呼称よりも好まれる。ホセ・イグナシオ・カベゾンは、神学の使用は実際適切であ ると主張するが、そうすることができるのは、「私は神学を神に関する言説に限定したものではないと考える。私は『神学』を語源的な意味に限定しない。後者 の意味で、仏教はもちろん無神論的であり、神という概念を否定している」[31]。 ヒンドゥー教 以下も参照: クリシュノロジー ヒンドゥー哲学の中には、宇宙の本質、神(ヒンドゥー思想の学派によってはブラフマン、パラマートマ、バガヴァンと呼ばれる)、アートマン(魂)に関する 哲学的思索の伝統がある。ヒンドゥー哲学の様々な学派を表すサンスクリット語はdarśana(「見解、視点」)である。ヴァイシュナヴァ神学は、何世紀 にもわたってインドの多くの帰依者、哲学者、学者の研究対象であった。その研究の大部分は、何千もの神々の顕現とその様相を分類・整理することにある。こ こ数十年、ヒンドゥー教の研究は、オックスフォード・センター・フォー・ヒンドゥーやバクティヴェーダンタ・カレッジなど、ヨーロッパの多くの学術機関で も取り上げられている[32]。 その他の宗教 神道 日本では、江戸時代に真野時綱の『古今神学類編』が出版されて以来、神学という用語が神道に当てられてきた。現代では、教学や宗学など、仏教だけでなく神 道に関する学問を指す言葉も使われている。 現代の異教 イギリスの学者グラハム・ハーヴェイは、異教徒は「神学に耽溺することはほとんどない」とコメントしている[33]。それにもかかわらず、神学はウィッ カ、異教、ドルイド教、ケメティズムなど、現代の異教徒のコミュニティ全体のいくつかの分野で適用されている。これらの宗教は正神教を優先しているため、 神学的見解はしばしば信者の間で異なる。この用語はクリスティン・クレーマー(Christine Kraemer)の著書『Seeking The Mystery: また、マイケル・ヨークは『異教の神学』の中でこの言葉を用いている: また、マイケル・ヨークは『異教の神学:世界宗教としての異教』を執筆している。 |

| Topics Further information: Outline of theology Richard Hooker defines theology as "the science of things divine".[34] The term can, however, be used for a variety of disciplines or fields of study.[35] Theology considers whether the divine exists in some form, such as in physical, supernatural, mental, or social realities, and what evidence for and about it may be found via personal spiritual experiences or historical records of such experiences as documented by others. The study of these assumptions is not part of theology proper, but is found in the philosophy of religion, and increasingly through the psychology of religion and neurotheology. Theology's aim, then, is to record, structure and understand these experiences and concepts; and to use them to derive normative prescriptions for how to live our lives. |

トピックス さらに詳しい情報 神学の概要 リチャード・フッカーは神学を「神的なものに関する科学」と定義している[34]が、この用語はさまざまな学問分野や研究領域に対して使われることがある [35]。神学は、神的なものが物理的、超自然的、精神的、社会的現実などの何らかの形で存在するかどうか、また、個人的な霊的体験や他者によって記録さ れたそのような体験の歴史的記録を通じて、神的なものに対する、また神的なものに関するどのような証拠が見つかるかどうかを考察する。このような仮定の研 究は神学には含まれないが、宗教哲学や、最近では宗教心理学や神経神学にも見られるようになっている。神学の目的は、これらの経験や概念を記録し、構造化 し、理解することである。 |

| History of academic discipline The history of the study of theology in institutions of higher education is as old as the history of such institutions themselves. For instance: Taxila was an early centre of Vedic learning, possible from the 6th-century BC or earlier;[36][37]: 140–2 the Platonic Academy founded in Athens in the 4th-century BC seems to have included theological themes in its subject matter;[38] the Chinese Taixue delivered Confucian teaching from the 2nd century BC;[39] the School of Nisibis was a centre of Christian learning from the 4th century AD;[40][41] Nalanda in India was a site of Buddhist higher learning from at least the 5th or 6th century AD;[37]: 149 and the Moroccan University of Al-Karaouine was a centre of Islamic learning from the 10th century,[42] as was Al-Azhar University in Cairo.[43] The earliest universities were developed under the aegis of the Latin Church by papal bull as studia generalia and perhaps from cathedral schools. It is possible, however, that the development of cathedral schools into universities was quite rare, with the University of Paris being an exception.[44] Later they were also founded by kings (University of Naples Federico II, Charles University in Prague, Jagiellonian University in Kraków) or by municipal administrations (University of Cologne, University of Erfurt). In the early medieval period, most new universities were founded from pre-existing schools, usually when these schools were deemed to have become primarily sites of higher education. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by monasteries.[45] Christian theological learning was, therefore, a component in these institutions, as was the study of church or canon law: universities played an important role in training people for ecclesiastical offices, in helping the church pursue the clarification and defence of its teaching, and in supporting the legal rights of the church over against secular rulers.[46] At such universities, theological study was initially closely tied to the life of faith and of the church: it fed, and was fed by, practices of preaching, prayer and celebration of the Mass.[47] During the High Middle Ages, theology was the ultimate subject at universities, being named "The Queen of the Sciences". It served as the capstone to the Trivium and Quadrivium that young men were expected to study. This meant that the other subjects (including philosophy) existed primarily to help with theological thought.[48] In this context, medieval theology in the Christian West could subsume fields of study which would later become more self-sufficient, such as metaphysics (Aristotle's "first philosophy",[49][50] or ontology (the science of being).[51][52] Christian theology's preeminent place in the university started to come under challenge during the European Enlightenment, especially in Germany.[53] Other subjects gained in independence and prestige, and questions were raised about the place of a discipline that seemed to involve a commitment to the authority of particular religious traditions in institutions that were increasingly understood to be devoted to independent reason.[54] Since the early 19th century, various different approaches have emerged in the West to theology as an academic discipline. Much of the debate concerning theology's place in the university or within a general higher education curriculum centres on whether theology's methods are appropriately theoretical and (broadly speaking) scientific or, on the other hand, whether theology requires a pre-commitment of faith by its practitioners, and whether such a commitment conflicts with academic freedom.[53][55][56][57] Ministerial training In some contexts, theology has been held to belong in institutions of higher education primarily as a form of professional training for Christian ministry. This was the basis on which Friedrich Schleiermacher, a liberal theologian, argued for the inclusion of theology in the new University of Berlin in 1810.[58][53]: ch.14 For instance, in Germany, theological faculties at state universities are typically tied to particular denominations, Protestant or Roman Catholic, and those faculties will offer denominationally-bound (konfessionsgebunden) degrees, and have denominationally bound public posts amongst their faculty; as well as contributing "to the development and growth of Christian knowledge" they "provide the academic training for the future clergy and teachers of religious instruction at German schools."[59] In the United States, several prominent colleges and universities were started in order to train Christian ministers. Harvard,[60] Georgetown,[61] Boston University, Yale,[62] Duke University,[63] and Princeton[64] all had the theological training of clergy as a primary purpose at their foundation. Seminaries and bible colleges have continued this alliance between the academic study of theology and training for Christian ministry. There are, for instance, numerous prominent examples in the United States, including Phoenix Seminary, Catholic Theological Union in Chicago,[65] The Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley,[66] Criswell College in Dallas,[67] The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville,[68] Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois,[69] Dallas Theological Seminary,[70] North Texas Collegiate Institute in Farmers Branch, Texas,[71] and the Assemblies of God Theological Seminary in Springfield, Missouri. The only Judeo-Christian seminary for theology is the 'Idaho Messianic Bible Seminary' which is part of the Jewish University of Colorado in Denver.[72] As an academic discipline in its own right In some contexts, scholars pursue theology as an academic discipline without formal affiliation to any particular church (though members of staff may well have affiliations to churches), and without focussing on ministerial training. This applies, for instance, to the Department of Theological Studies at Concordia University in Canada, and to many university departments in the United Kingdom, including the Faculty of Divinity at the University of Cambridge, the Department of Theology and Religion at the University of Exeter, and the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of Leeds.[73][74] Traditional academic prizes, such as the University of Aberdeen's Lumsden and Sachs Fellowship, tend to acknowledge performance in theology (or divinity as it is known at Aberdeen) and in religious studies. Religious studies In some contemporary contexts, a distinction is made between theology, which is seen as involving some level of commitment to the claims of the religious tradition being studied, and religious studies, which by contrast is normally seen as requiring that the question of the truth or falsehood of the religious traditions studied be kept outside its field. Religious studies involves the study of historical or contemporary practices or of those traditions' ideas using intellectual tools and frameworks that are not themselves specifically tied to any religious tradition and that are normally understood to be neutral or secular.[75] In contexts where 'religious studies' in this sense is the focus, the primary forms of study are likely to include: Anthropology of religion Comparative religion History of religions Philosophy of religion Psychology of religion Sociology of religion Sometimes, theology and religious studies are seen as being in tension,[76] and at other times, they are held to coexist without serious tension.[77] Occasionally it is denied that there is as clear a boundary between them.[78] |

学問分野の歴史 高等教育機関における神学研究の歴史は、高等教育機関そのものの歴史と同じくらい古い。例えば タキシラは紀元前6世紀かそれ以前からヴェーダ学問の中心地であった可能性がある[36][37]: 140-2 紀元前4世紀にアテネに設立されたプラトンアカデミーは、その主題に神学的テーマを含んでいたようである[38]。 中国の太学は紀元前2世紀から儒教の教えを伝えていた[39]。 ニシビス学派は紀元4世紀からのキリスト教の学問の中心地であった[40][41]。 インドのナーランダは、少なくとも紀元後5~6世紀から仏教の高等教育の場であった[37]: 149と モロッコのアル・カラウイーン大学は、カイロのアル・アズハル大学と同様に、10世紀からのイスラムの学問の中心地であった[42]。 最古の大学は、ラテン教会の庇護の下、ローマ教皇の勅令によって一般大学(Studia Generalia)として、またおそらくは大聖堂の学校から発展したものであった。しかし、カテドラル・スクールが大学に発展することは、パリ大学を例 外として、極めて稀であった可能性がある[44]。 その後、王によって(ナポリ・フェデリコ2世大学、プラハ・カレル大学、クラクフのヤギェウォ大学)、あるいは自治体によって(ケルン大学、エアフルト大 学)設立された。 中世初期には、ほとんどの新しい大学は既存の学校から設立され、これらの学校が主に高等教育の場となったとみなされたときに設立された。多くの歴史家は、 大学やカテドラル・スクールは修道院が推進した学問への関心を受け継ぐものであったと述べている[45]。したがって、キリスト教神学は、教会法やカノン 法の研究と同様に、これらの機関の構成要素であった。大学は、教会の役職に就く人材の育成、教会の教えの解明と擁護のための支援、世俗の支配者に対する教 会の法的権利の支援において重要な役割を果たした。 [そのような大学では、神学研究は当初、信仰生活や教会生活と密接に結びついていた。神学研究は、説教、祈り、ミサの祭儀の実践を養い、またそれによって 養われていた[47]。 中世には、神学は大学における究極の科目であり、「科学の女王」と呼ばれていた。トリヴィウムとクアドリヴィウムの頂点に位置する科目であり、若者は神学 を学ぶことが期待されていた。この文脈では、キリスト教西方における中世の神学は、形而上学(アリストテレスの「最初の哲学」)[49][50]や存在論 (存在の科学)など、後に自立的なものとなる学問分野を包含していた[51][52]。 キリスト教神学の大学における卓越した地位は、ヨーロッパの啓蒙主義の時代、特にドイツにおいて挑戦され始めた[53]。 19世紀初頭以来、西洋では学問としての神学に対して様々な異なるアプローチが出現してきた。神学の大学における位置づけや一般的な高等教育カリキュラム における位置づけに関する議論の多くは、神学の方法が適切に理論的であり、(大まかに言えば)科学的であるかどうか、あるいは他方で神学がその実践者に信 仰の事前コミットメントを要求するかどうか、またそのようなコミットメントが学問の自由と相反するかどうかに集中している[53][55][56] [57]。 牧師養成 ある文脈においては、神学は主としてキリスト教宣教のための専門的訓練の一形態として高等教育機関に属するとされてきた。リベラルな神学者であったフリー ドリヒ・シュライアーマッハーが1810年に新設されたベルリン大学に神学が含まれることを主張した根拠はここにあった[58][53]。 例えばドイツでは、国立大学の神学部は一般的にプロテスタントやローマ・カトリックといった特定の教派に縛られており、それらの学部は教派に縛られた学位 (konfessionsgebunden)を提供し、教員には教派に縛られた公職がある。彼らは「キリスト教の知識の発展と成長」に貢献するだけでな く、「将来の聖職者やドイツの学校における宗教教育の教師のための学問的訓練を提供している」[59]。 アメリカでは、キリスト教の聖職者を養成するために、いくつかの著名な大学が設立された。ハーバード大学[60]、ジョージタウン大学[61]、ボストン 大学、イェール大学[62]、デューク大学[63]、プリンストン大学[64]はいずれも、聖職者の神学的養成を創立時の主要な目的としていた。 神学校や聖書学院は、神学の学問的研究とキリスト教宣教のための訓練との間のこの提携を続けてきた。例えば、フェニックス神学校、シカゴのカトリック神学 連合[65]、バークレーの大学院神学連合[66]、ダラスのクリスウェル・カレッジ[67]、ルイビルの南部バプテスト神学校[68]など、米国には数 多くの著名な例がある、 [68]イリノイ州ディアフィールドのトリニティ福音神学校、[69]ダラス神学校、[70]テキサス州ファーマーズブランチのノース・テキサス・カレッ ジ・インスティテュート、[71]ミズーリ州スプリングフィールドのアッセンブリーズ・オブ・ゴッド神学校。神学のための唯一のユダヤ教神学校は、デン バーにあるユダヤ教コロラド大学の一部である「アイダホ・メシアン・バイブル・セミナリー」である[72]。 学問としての神学 特定の教会に正式に所属することなく(スタッフの中には教会に所属している者もいるが)、また牧師養成に力を入れることなく、神学を学問として追求する学 者もいる。例えば、カナダのコンコーディア大学の神学研究学科や、ケンブリッジ大学の神学部、エクセター大学の神学・宗教学科、リーズ大学の神学・宗教学 科など、イギリスの多くの大学の学科がこれに該当する[73][74]。アバディーン大学のラムスデン・フェローシップやサックス・フェローシップなどの 伝統的な学術賞は、神学(またはアバディーン大学では神学と呼ばれる)や宗教学の業績を評価する傾向にある。 宗教学 現代的な文脈では、神学は、研究対象の宗教的伝統の主張に対するある程度のコミットメントを含むと見なされ、宗教学は、対照的に、研究対象の宗教的伝統の 真偽の問題は、その分野の外に置かれることが通常必要と見なされ、区別されます。この意味での「宗教学」が焦点となる文脈では、研究の主な形態として以下 のようなものが考えられる: 宗教人類学 比較宗教学 宗教史 宗教哲学 宗教心理学 宗教社会学 神学と宗教学は緊張関係にあると見なされることもあれば[76]、深刻な緊張関係なしに共存していると見なされることもある[77]。 |

| Criticism See also: Criticism of religion Pre-20th century Whether or not reasoned discussion about the divine is possible has long been a point of contention. Protagoras, as early as the fifth century BC, who is reputed to have been exiled from Athens because of his agnosticism about the existence of the gods, said that "Concerning the gods I cannot know either that they exist or that they do not exist, or what form they might have, for there is much to prevent one's knowing: the obscurity of the subject and the shortness of man's life."[79][80]  Baron d'Holbach Since at least the eighteenth century, various authors have criticized the suitability of theology as an academic discipline.[81] In 1772, Baron d'Holbach labeled theology "a continual insult to human reason" in Le Bon sens.[81] Lord Bolingbroke, an English politician and political philosopher, wrote in Section IV of his Essays on Human Knowledge, "Theology is in fault not religion. Theology is a science that may justly be compared to the Box of Pandora. Many good things lie uppermost in it; but many evil lie under them, and scatter plagues and desolation throughout the world."[82] Thomas Paine, a Deistic American political theorist and pamphleteer, wrote in his three-part work The Age of Reason (1794, 1795, 1807):[83] The study of theology, as it stands in Christian churches, is the study of nothing; it is founded on nothing; it rests on no principles; it proceeds by no authorities; it has no data; it can demonstrate nothing; and it admits of no conclusion. Not anything can be studied as a science, without our being in possession of the principles upon which it is founded; and as this is the case with Christian theology, it is therefore the study of nothing. The German atheist philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach sought to dissolve theology in his work Principles of the Philosophy of the Future: "The task of the modern era was the realization and humanization of God – the transformation and dissolution of theology into anthropology."[84] This mirrored his earlier work The Essence of Christianity (1841), for which he was banned from teaching in Germany, in which he had said that theology was a "web of contradictions and delusions".[85] The American satirist Mark Twain remarked in his essay "The Lowest Animal", originally written in around 1896, but not published until after Twain's death in 1910, that:[86][87] [Man] is the only animal that loves his neighbor as himself and cuts his throat if his theology isn't straight. He has made a graveyard of the globe in trying his honest best to smooth his brother's path to happiness and heaven.... The higher animals have no religion. And we are told that they are going to be left out in the Hereafter. I wonder why? It seems questionable taste. 20th and 21st centuries A. J. Ayer, a British former logical-positivist, sought to show in his essay "Critique of Ethics and Theology" that all statements about the divine are nonsensical and any divine-attribute is unprovable. He wrote: "It is now generally admitted, at any rate by philosophers, that the existence of a being having the attributes which define the god of any non-animistic religion cannot be demonstratively proved.... [A]ll utterances about the nature of God are nonsensical."[88] Jewish atheist philosopher Walter Kaufmann, in his essay "Against Theology", sought to differentiate theology from religion in general:[89] Theology, of course, is not religion; and a great deal of religion is emphatically anti-theological.... An attack on theology, therefore, should not be taken as necessarily involving an attack on religion. Religion can be, and often has been, untheological or even anti-theological. However, Kaufmann found that "Christianity is inescapably a theological religion."[89] English atheist Charles Bradlaugh believed theology prevented human beings from achieving liberty,[90] although he also noted that many theologians of his time held that, because modern scientific research sometimes contradicts sacred scriptures, the scriptures must therefore be wrong.[91] Robert G. Ingersoll, an American agnostic lawyer, stated that, when theologians had power, the majority of people lived in hovels, while a privileged few had palaces and cathedrals. In Ingersoll's opinion, it was science that improved people's lives, not theology. Ingersoll further maintained that trained theologians reason no better than a person who assumes the devil must exist because pictures resemble the devil so exactly.[92] The British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins has been an outspoken critic of theology.[81][93] In an article published in The Independent in 1993, he severely criticizes theology as entirely useless,[93] declaring that it has completely and repeatedly failed to answer any questions about the nature of reality or the human condition.[93] He states, "I have never heard any of them [i.e. theologians] ever say anything of the smallest use, anything that was not either platitudinously obvious or downright false."[93] He then states that, if all theology were completely eradicated from the earth, no one would notice or even care. He concludes:[93] The achievements of theologians don't do anything, don't affect anything, don't achieve anything, don't even mean anything. What makes you think that 'theology' is a subject at all? |

神学に対する批判 こちらもご覧ください: 宗教批判 20世紀以前 神についての理性的な議論が可能かどうかは、長い間論争の的であった。紀元前5世紀には、神々の存在について不可知論を唱えたためにアテナイを追放された とされるプロタゴラスが、「神々については、存在することも存在しないことも、またどのような形を持っているかも知ることができない。  ドルバック男爵 少なくとも18世紀以降、さまざまな著者が神学の学問としての適性を批判してきた。 1772年、ドルバック男爵は『Le Bon sens』の中で神学を「人間の理性に対する絶え間ない侮辱」とレッテルを貼っている[81]。イギリスの政治家であり政治哲学者であったボリングブロー ク卿は、『人間の知識に関する論考』の第4節で「神学は宗教に非ず。神学はパンドラの箱に例えられるにふさわしい科学である。しかし、その下には多くの悪 が潜んでおり、世界中に災いと荒廃を撒き散らす」[82]。 トマス・ペインは、神道主義的なアメリカの政治理論家であり、パンフライターであったが、3部構成の著作『理性の時代』(1794年、1795年、 1807年)の中で次のように書いている[83]。 神学の研究は、キリスト教の教会で行われているように、何も研究していない。そして、キリスト教神学がそうであるように、無の学問なのである。 ドイツの無神論哲学者ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハは、その著作『未来の哲学の原理』の中で神学を解体しようとした: 「近代の課題は神の実現と人間化であり、神学の人間学への変容と溶解である。 [アメリカの風刺作家であるマーク・トウェインは、1896年頃に書かれ、1910年にトウェインが亡くなった後まで出版されなかったエッセイ『最下層の 動物』の中で次のように述べている[86][87]。 [人間は)隣人を自分のように愛し、自分の神学がまっすぐでなければその喉をかき切る唯一の動物である。弟の幸福と天国への道をスムーズにするために正直 なベストを尽くそうとして、地球上の墓場を作ってしまった......。高等動物には宗教がない。彼らは来世では見捨てられると言われている。なぜだろ う?趣味が悪いとしか思えない。 20世紀と21世紀 A. イギリスの元論理実証主義者であるA. J. Ayerは、そのエッセイ『倫理学と神学の批判』の中で、神に関するすべての記述は無意味であり、いかなる神的属性も証明不可能であることを示そうとし た。現在、哲学者たちの間では、どのような非宗教的な神であっても、その神を定義する属性を持つ存在の実証的な証明は不可能であることが一般的に認められ ている。[神の本質に関するあらゆる発言は無意味である」[88]。 ユダヤ人無神論者の哲学者であるウォルター・カウフマンは、そのエッセイ『神学に抗して』の中で、神学を一般的な宗教と区別しようと努めている[89]。 神学はもちろん宗教ではない。したがって、神学に対する攻撃は、必ずしも宗教に対する攻撃を含んでいると考えるべきではない。宗教は神学的でないこともあ るし、反神学的であることさえある。 しかし、カウフマンは「キリスト教は不可避的に神学的な宗教である」と見なしている[89]。 イギリスの無神論者チャールズ・ブラッドローは、神学が人間の自由達成を妨げていると考えていたが[90]、彼はまた当時の多くの神学者が、現代の科学研 究が聖典と矛盾することがあるため、聖典は間違っているに違いないと考えていたことにも言及している[91]。 アメリカの不可知論者である弁護士ロバート・G・インガソルは、神学者が権力を握っていた時代、大多数の人々は掘っ立て小屋に住んでいたが、一部の特権階 級は宮殿や大聖堂を持っていたと述べている。インガソールの考えでは、人々の生活を向上させたのは科学であり、神学ではなかった。インガソルはさらに、訓 練された神学者は、絵が悪魔にそっくりだから悪魔は存在するはずだと思い込んでいる人と同じように推論することはできないと主張した[92]。 イギリスの進化生物学者であるリチャード・ドーキンスは神学を率直に批判している[81][93]。1993年に『インディペンデント』紙に掲載された記 事の中で、彼は神学を全く役に立たないものとして厳しく批判しており[93]、神学は現実の本質や人間の状態に関するいかなる疑問にも完全に、そして何度 も答えることができなかったと宣言している[93]。 [そして、もしすべての神学が地球上から完全に根絶されたとしても、誰も気づかないし、気にも留めないだろうと述べている。彼は次のように結んでいる [93]。 神学者の業績は何もしないし、何も影響を与えないし、何も達成しないし、何の意味もなさない。神学』が主題であると考える根拠は何ですか? |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theology |

|

| Thealogy views divine matters

through feminine perspectives including but not limited to feminism.

Valerie Saiving, Isaac Bonewits (1976) and Naomi Goldenberg (1979)

introduced the concept as a neologism (new word).[1] Its use then

widened to mean all feminine ideas of the sacred, which Charlotte Caron

usefully explained in 1993: "reflection on the divine in feminine or

feminist terms".[2] By 1996, when Melissa Raphael published Thealogy

and Embodiment, the term was well established.[3] As a neologism, the term derives from two Greek words: thea, θεά, meaning 'goddess', the feminine equivalent of theos, 'god' (from PIE root *dhes-);[4] and logos, λόγος, plural logoi, often found in English as the suffix -logy, meaning 'word, reason, plan'; and in Greek philosophy and theology, the divine reason implicit in the cosmos.[5][6] Thealogy has areas in common with feminist theology – the study of God from a feminist perspective, often emphasizing monotheism. The relation is an overlap, as thealogy is not limited to one deity (in spite of its etymology);[7][8] the two fields have been described as both related and interdependent.[9] |

女神学(あるいは女神論、Thealogy)は、フェミニズムに限ら

ず、女性的な視点を通して神的な事柄を捉える。ヴァレリー・サイヴィング、アイザック・ボネヴィッツ(1976年)、ナオミ・ゴールデンバーグ(1979

年)は、この概念を新造語(新しい言葉)として紹介した[1]。

その後、その用法は聖なるものに対する女性的な考え方全般を意味するようになり、1993年にシャーロット・キャロンが「女性的あるいはフェミニスト的な

用語による神的なものへの考察」と有益な説明をした[2]。 1996年にメリッサ・ラファエルが『Thealogy and

Embodiment』を出版する頃には、この用語はすっかり定着していた[3]。 新造語として、この用語は2つのギリシア語に由来している:テア、θεάは「女神」を意味し、テオス、「神」(PIE語源*dhes-から)の女性的な等 価語である[4]。ロゴス、λόγος、複数形のlogoiは、しばしば英語では接尾辞-logyとして見出され、「言葉、理性、計画」を意味し、ギリシ ア哲学と神学では、宇宙に内在する神の理性である[5][6]。 女神学はフェミニスト神学と共通する部分があり、フェミニストの視点からの神の研究であり、しばしば一神教を強調する。女神学は(その語源にもかかわら ず)一つの神に限定されるものではないため、その関係は重複している[7][8]。 |

History of the term Statue of Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture The term's origin and initial use is open to ongoing debate. Patricia 'Iolana traces the early use of the neologism to 1976, crediting both Valerie Saiving and Isaac Bonewits for its initial use.[10] The coinage of thealogian on record by Bonewits in 1976 has been promoted.[11][12] In the 1979 book Changing of the Gods, Naomi Goldenberg introduces the term as a future possibility with respect to a distinct discourse, highlighting the masculine nature of theology.[13] Also in 1979, in the first revised edition of Real Magic, Bonewits defined thealogy in his Glossary as "Intellectual speculations concerning the nature of the Goddess and Her relations to the world in general and humans in particular; rational explanations of religious doctrines, practices and beliefs, which may or may not bear any connection to any religion as actually conceived and practiced by the majority of its members". In the same glossary, he defined "theology" with nearly identical words, changing the feminine pronouns with masculine pronouns appropriately.[14] Carol P. Christ used the term in Laughter of Aphrodite (1987), claiming that those creating thealogy could not avoid being influenced by the categories and questions posed in Christian and Jewish theologies.[15] She further defined thealogy in her 2002 essay, "Feminist theology as post-traditional thealogy", as "the reflection on the meaning of the Goddess".[16] In her 1989 essay "On Mirrors, Mists and Murmurs: Toward an Asian American Thealogy", Rita Nakashima Brock defined thealogy as "the work of women reflecting on their experiences of and beliefs about divine reality".[17] And again in 1989, Ursula King notes thealogy's growing usage as a fundamental departure from traditional male-oriented theology, characterized by its privileging of symbols over rational explanation.[18] In 1993, Charlotte Caron's inclusive and clear definition of thealogy as a "reflection on the divine in feminine and feminist terms" appeared in To Make and Make Again.[19] By this time, the concept had gained considerable status among Goddess adherents. |

用語の歴史 ローマ神話の農業の女神ケレス像 この用語の起源と最初の使用については、現在も議論が続いている。パトリシア・イオラナ(Patricia 'Iolana)はこの新語の初期の使用を1976年まで遡り、ヴァレリー・サイヴィング(Valerie Saiving)とアイザック・ボネヴィッツ(Isaac Bonewits)の両名にその功績を認めている[10]。 1979年の著書『Changing of the Gods』において、ナオミ・ゴールデンバーグは神学の男性的性質を強調しながら、明確な言説に関する将来の可能性としてこの用語を紹介している。 [13] また1979年、『Real Magic』の最初の改訂版で、ボーンウィッツはその用語集でthealogyを「女神の性質と世界一般および人間との関係に関する知的思索、宗教的教 義、実践、信念の合理的説明。同じ用語集で、彼はほぼ同じ言葉で「神学」を定義し、女性代名詞を男性代名詞に適切に変えている[14]。 キャロル・P・クライストは『アフロディーテの笑い』(1987年)の中でこの用語を使用し、系図を創造する者はキリスト教やユダヤ教の神学において提起 されるカテゴリーや問いかけから影響を受けずにはいられなかったと主張している[15]。 彼女はさらに2002年のエッセイ「ポスト・トラディショナルな系図としてのフェミニスト神学」の中で、系図を「女神の意味についての考察」と定義してい る[16]。 1989年のエッセイ「鏡と霧と独り言について」では、「アジア系アメリカ人の女神学に向けて」と定義している[16]: リタ・ナカシマ・ブロックは1989年のエッセイ「鏡、霧、独り言について:アジア系アメリカ人の女神学に向けて」において、系譜学を「神的実在について の経験や信念を考察する女性の仕事」と定義している[17]。また1989年にはアーシュラ・キングが、合理的な説明よりも象徴の特権化によって特徴づけ られる、伝統的な男性中心の神学からの根本的な逸脱として、女神学が使用されるようになってきていることを指摘している[18]。 1993年には、シャルロット・キャロンが『To Make and Make Again』において、「女性的でフェミニスト的な用語における神についての考察」として、女神学の包括的で明確な定義を発表した[19]。 |

| As academic discipline Situated in relationship to the fields of theology and religious studies, thealogy is a discourse that critically engages the beliefs, wisdom, practices, questions, and values of the Goddess community, both past and present.[20] Similar to theology, thealogy grapples with questions of meaning, include reflecting on the nature of the divine,[21] the relationship of humanity to the environment,[22] the relationship between the spiritual and sexual self,[23] and the nature of belief.[24] However, in contrast to theology, which often focuses on an exclusively logical and empirical discourse, thealogy embraces a postmodern discourse of personal experience and complexity.[25] The term suggests a feminist approach to theism and the context of God and gender within Paganism, Neopaganism, Goddess Spirituality and various nature-based religions. However, thealogy can be described as religiously pluralistic, as thealogians come from various religious backgrounds that are often hybrid in nature. In addition to Pagans, Neopagans, and Goddess-centred faith traditions, they are also Christian, Jewish, Buddhist, Muslim, Quakers, etc. or define themselves as Spiritual Feminists.[26] As such, the term thealogy has also been used by feminists within mainstream monotheistic religions to describe in more detail the feminine aspect of a monotheistic deity or trinity, such as God/dess Herself, or the Heavenly Mother of the Latter Day Saint movement. In 2000, Melissa Raphael wrote the text Introducing Thealogy: Discourse on the Goddess for the series Introductions in Feminist Theology. Written for an academic audience, it purports to introduce the main elements of thealogy within the context of Goddess feminism. She situates thealogy as a discourse that can be engaged with by Goddess feminists—those who are feminist adherents of the Goddess who may have left their church, synagogue, or mosque—or those who may still belong to their originally established religion.[27] In the book, Raphael compares and contrasts thealogy with the Goddess movement.[28] In 2007, Paul Reid-Bowen wrote the text "Goddess as Nature: Towards a Philosophical Thealogy", which can be regarded as another systematic approach to thealogy, but which integrates philosophical discourse.[29] In the past decade, other thealogians like Patricia 'Iolana and D'vorah Grenn have generated discourses that bridge thealogy with other academic disciplines. 'Iolana's Jungian thealogy bridges analytical psychology with thealogy, and Grenn's metaformic thealogy is a bridge between matriarchal studies and thealogy.[30] Contemporary thealogians include Carol P. Christ, Melissa Raphael, Asphodel Long, Beverly Clack, Charlotte Caron, Naomi Goldenberg, Paul Reid-Bowen, Rita Nakashima Brock, and Patricia 'Iolana. |

学問分野として 神学や宗教学の分野に関連して、女神学は、過去と現在の女神の共同体の信念、知恵、実践、疑問、価値観に批判的に関わる言説である。 [20]神学と同様に、系譜学は意味の問題に取り組んでおり、その中には神の本質、[21]環境と人間の関係、[22]精神的自己と性的自己の関係、 [23]信念の本質について考察することが含まれる。[24]しかしながら、専ら論理的で経験的な言説に焦点を当てることが多い神学とは対照的に、女神学 は個人的な経験と複雑性のポストモダンの言説を受け入れている。 この用語は、ペイガニズム、ネオペイガニズム、女神のスピリチュアリティ、様々な自然に基づく宗教における神論と神とジェンダーの文脈に対するフェミニス ト的なアプローチを示唆している。しかし、女神学は宗教的に多元的であると言うことができ、それは系図学者が様々な宗教的背景を持ち、しばしばハイブリッ ドであるからである。異教徒、ネオペイガン、女神を中心とする信仰伝統に加えて、キリスト教、ユダヤ教、仏教、イスラム教、クエーカー教徒などであった り、スピリチュアル・フェミニストと定義していたりする[26]。そのため、系図という用語は、主流の一神教内のフェミニストたちによって、神/女神その ものや末日聖徒運動の天の母など、一神教の神や三位一体の女性的側面をより詳細に記述するためにも使われてきた。 2000年、メリッサ・ラファエルは『女神学入門』という文章を書いた: フェミニスト神学入門』シリーズのために。学術的な読者に向けて書かれたこの本は、女神フェミニズムの文脈の中で、女神学の主要な要素を紹介することを意 図している。この本の中でラファエルは、女神学と女神運動を比較対照している[28]。 2007年、ポール・リード=ボーエンは、「自然としての女神: 哲学的系譜学に向けて "は、女神学へのもう一つの体系的アプローチとみなすことができるが、哲学的言説を統合している[29]。 過去10年の間に、パトリシア・イオラナやディヴォラ・グレンのような他の女神学者たちが、女神学と他の学問分野との架け橋となるような言説を生み出して きた。イオラナのユングの女神学は分析心理学と女神学の架け橋であり、グレンのメタ形式の女神学は母系制研究と女神学の架け橋である[30]。 現代の女神学者には、キャロル・P・クライスト、メリッサ・ラファエル、アスフォデル・ロング、ビバリー・クラック、シャーロット・キャロン、ナオミ・ゴールデンバーグ、ポール・リード=ボーエン、リタ・ナカシマ・ブロック、パトリシア・イオラナなどがいる。 |

| Criticisms At least one Christian theologian dismisses thealogy as the creation of a new deity made up by radical feminists.[31] Paul Reid-Bowen and Chaone Mallory point out that essentialism is a problematic slippery slope when Goddess feminists argue that women are inherently better than men or inherently closer to the Goddess.[32][33] In his book Goddess Unmasked: The Rise of Neopagan Feminist Spirituality, Philip G. Davis levies a number of criticisms against the Goddess movement, including logical fallacies, hypocrisies, and essentialism.[34] Thealogy has also been criticized for its objection to empiricism and reason.[35] In this critique, thealogy is seen as flawed by rejecting a purely empirical worldview for a purely relativistic one.[36] Meanwhile, scholars like Harding[37] and Haraway[38] seek a middle ground of feminist empiricism. |

批判 少なくとも一人のキリスト教神学者は、女神学は急進的なフェミニストたちによって作り上げられた新たな神の創造であると否定している[31]。 ポール・リード=ボーエンとチャオーン・マロリーは、女神フェミニストたちが、女性は男性よりも本質的に優れている、あるいは女神に本質的に近いと主張す るとき、本質主義は問題のある滑りやすい斜面であると指摘している[32][33]: The Rise of Neopagan Feminist Spirituality(ネオペイガン・フェミニスト・スピリチュアリティの台頭)』において、フィリップ・G・デイヴィスは女神運動に対して、論理的 誤り、偽善、本質主義を含む多くの批判を行なっている[34]。 この批判において、女神学は純粋に相対主義的なもののために純粋に経験的な世界観を拒絶することによって欠陥があると見なされている[36]。 一方、ハーディング[37]やハラウェイ[38]のような学者はフェミニスト経験主義の中間点を模索している。 |

| Art and culture Artist Edwina Sandys' 250-pound (110 kg) bronze statue of a bare-breasted female Crucifixion statue, Crista, was removed from the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine at the order of the Jesus Suffragan Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York during Holy Week in 1984. The bishop accused the Cathedral Dean of "descrating our symbols" even though viewer reaction had been "overwhelmingly positive."[39] In 2016, Sandy's Crista was reinstalled at the cathedral, on the altar, as the centerpiece of the "groundbreaking" The Christa Project: Manifesting Divine Bodies.[40] The Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York wrote an article for the cathedral's booklet stating, "In an evolving, growing, learning church, we may be ready to see 'Christa' not only as a work of art but as an object of devotion, over our altar, with all of the challenges that may come with that for many visitors to the cathedral, or indeed, perhaps for all of us."[41] This exhibition of more than 50 contemporary works that "interpret – or reinterpret – the symbolism associated with the image of Jesus", in order to provide "an excellent vehicle for thinking about sacred incarnation, and one that reaches out to humans of all genders, races, religions and sexual orientations" included work by Fredericka Foster, Kiki Smith, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and Eiko Otake.[42][43][44] |

芸術と文化 芸術家エドウィナ・サンディスの250ポンド(110キロ)のブロンズ像である裸の女性の磔刑像「クリスタ」は、1984年の聖週間の間、ニューヨークの エピスコパル教区のジーザス・サフラガン司教の命令により、聖ヨハネ大聖堂から撤去された。司教は、視聴者の反応が「圧倒的に肯定的」であったにもかかわ らず、「私たちのシンボルを神聖化している」と大聖堂の学長を非難した[39]。2016年、サンディのクリスタは、「画期的な」クリスタ・プロジェクト の目玉として、大聖堂の祭壇に再設置された: 進化し、成長し、学習する教会において、私たちは『クリスタ』を芸術作品としてだけでなく、私たちの祭壇の上にある献身の対象として見る準備ができている のかもしれない。 「聖なる受肉について考えるための優れた手段であり、あらゆる性別、人種、宗教、性的指向の人間に手を差し伸べるもの 」を提供するために、「イエスのイメージに関連する象徴主義を解釈(あるいは再解釈)」した50以上の現代作品を展示したこの展覧会には、フレデリッカ・ フォスター、キキ・スミス、ジェネシス・ブレイヤー・P・オリッジ、大竹英子の作品が含まれていた[42][43][44]。 |

| Devi (Hindu goddess) God and gender Goddess movement Goddess worship Matriarchal religion Matriarchy Mother goddess |

Devi (Hindu goddess) God and gender Goddess movement Goddess worship Matriarchal religion Matriarchy Mother goddess |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thealogy |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆