嘘つきに関するキリスト教の見解

Christian views on lying

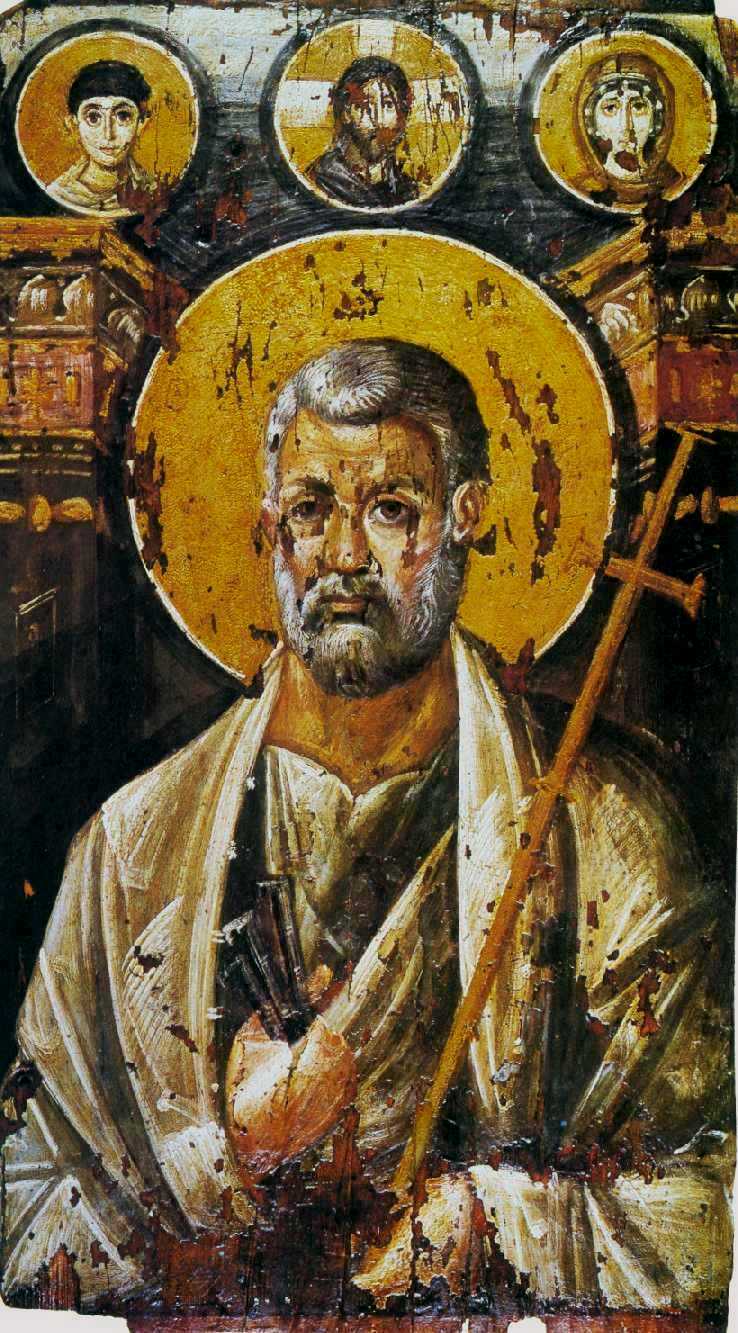

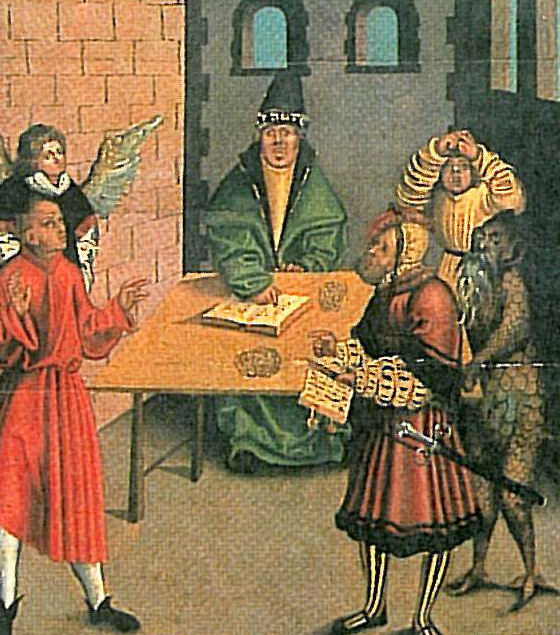

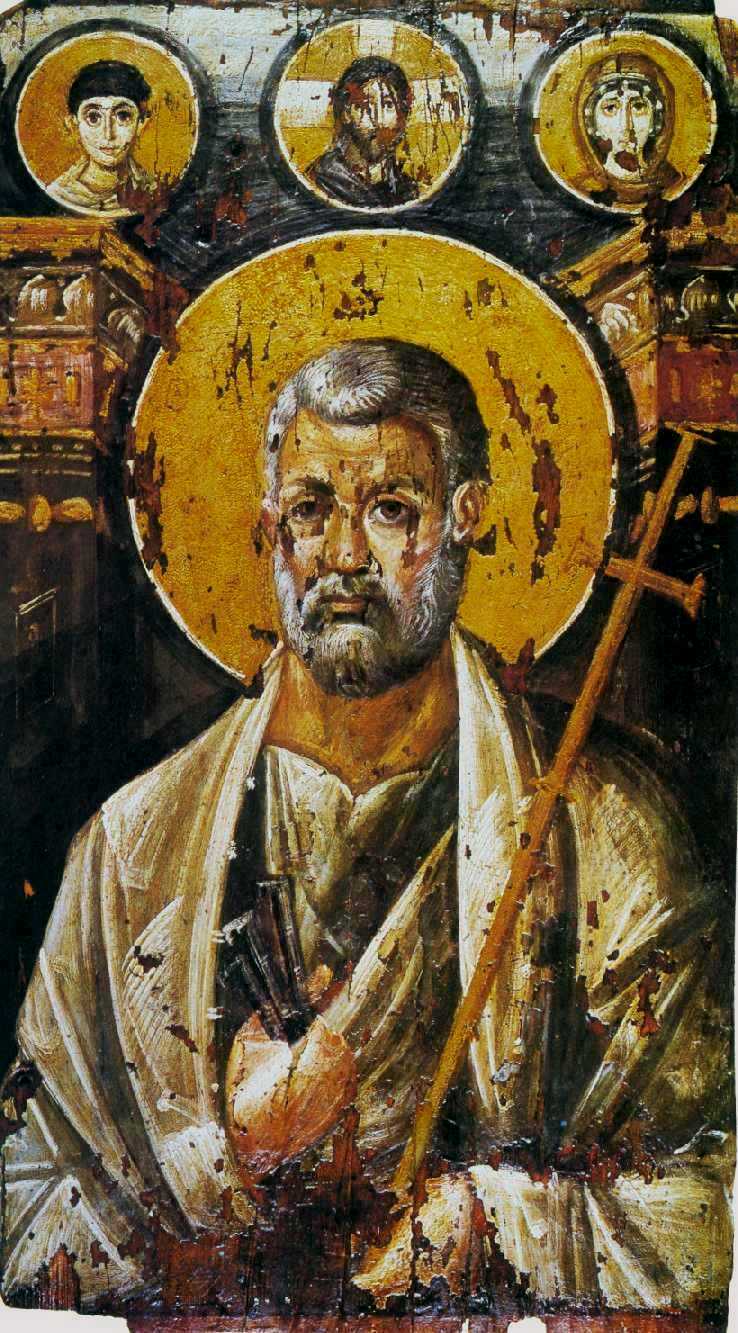

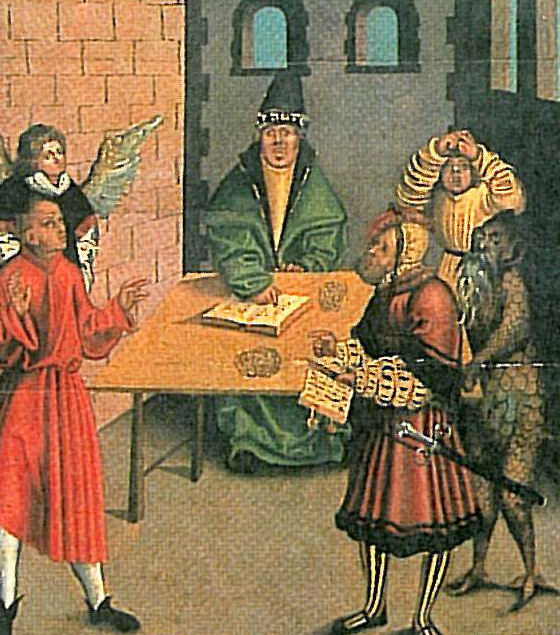

Saint Peter, a 6th-century encaustic icon from Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai/隣人に対して偽りの証言をしてはならない 、長老ルーカス・クラナッハ

☆ キリスト教のほとんどの解釈では、嘘をつくことは強く戒められ、禁じられている。その論拠は、聖書の様々な箇所、特に十戒の一つである「汝、隣人に対して 偽りの証言をしてはならない」に基づいている。キリスト教の神学者たちの間でも、「嘘」の正確な定義や、それが許されるかどうかについては意見が分かれて いる。

| Lying is strongly

discouraged and forbidden by most interpretations of Christianity.

Arguments for this are based on various biblical passages, especially

"Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour", one of the

Ten Commandments. Christian theologians disagree as to the exact

definition of "lie" and whether it is ever acceptable. |

キリスト教のほとんどの解釈では、嘘をつくことは強く戒められ、禁じら

れている。その論拠は、聖書の様々な箇所、特に十戒の一つである「汝、隣人に対して偽りの証言をしてはならない」に基づいている。キリスト教の神学者たち

の間でも、「嘘」の正確な定義や、それが許されるかどうかについては意見が分かれている。 |

| Biblical passages One of the Ten Commandments is "Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour"; for this reason, lying is generally considered as a sin in Christianity.[1] The story of Naboth in 1 Kings 21 provides an example where false witness leads to an unjust outcome.[2] The exact interpretation of the commandment is disputed:[3][4] "Does the commandment pertain only to court or does it prohibit lying in general? Is it only a prohibition (not to lie in court, not ever to lie) or does it imply a positive injunction (truth-telling in court, truth-telling in general)? If positive, is one enjoined only to truth-telling or to veracity and honesty also?"[3] Other statements in the Bible express a negative view of lying, such as "You shall not steal, nor deal falsely, nor lie to one another" (Leviticus 19:11) and "Cursed is he who does the work of the Lord deceitfully" (Jeremiah 48:10).[5] In the Hebrew Bible, those who practice lying and deceit are seemingly rewarded for their actions, posing problems for an exegesis that upholds a categorical prohibition.[6] Examples include the Hebrew midwives who lie after Pharaoh commands them to kill all newborn boys (Exodus 1:17–21), and Rahab (Joshua 2:1–7; cf. Hebrews 11:31), an innkeeper who lies to soldiers while hiding spies in her inn. The midwives appear to be rewarded for their actions (God "dealt well with the midwives” and "gave them families"). James 2:25 appears to praise Rahab as an example of good works: "And in the same way was not also Rahab the prostitute justified by works when she received the messengers and sent them out by another way?"[7][8] In the Book of Judith, Judith deceives Holofernes in order to assassinate him.[9] Both Abraham and Isaac claimed that their wives were their sisters.[10] |

聖書の一節 十戒のひとつに「汝、隣人に対して偽りの証言をしてはならない」というものがある。戒律は法廷にのみ関係するものなのか、それとも嘘をつくこと全般を禁止 するものなのか」[3][4]。もし肯定的であるなら、人は真実を語ることだけを命じられているのか、それとも真実さや正直さも命じられているのか。」 [3] 聖書には他にも、「盗みをしたり、偽りの取引をしたり、互いに嘘をついたりしてはならない」(レビ記19:11)、「主の業を偽って行う者は呪われる」 (エレミヤ48:10)など、嘘をつくことに否定的な見解を示す記述がある[5]。 ヘブライ語聖書では、嘘や偽りを行う者は、その行為によって報われているように見えるが、これは、断言的な禁止を支持する釈義には問題がある[6]。その 例としては、ファラオが生まれたばかりの男の子を皆殺しにするように命じた後に嘘をつくヘブライ人の助産婦(出エジプト記1:17-21)や、宿屋にスパ イを隠している間に兵士に嘘をついた宿屋の主人ラハブ(ヨシュア記2:1-7、ヘブライ人への手紙11:31参照)などが挙げられる。助産婦たちは、その 行為に対して報いを受けているように見える(神は「助産婦たちをよく扱われ」、「彼らに家族を与えられた」)。ヤコブ2:25は、ラハブを良い行いの模範 として賞賛しているように見える: ヤコブ2:25は、ラハブを善い行いの例として称賛しているように見える。「同じように、娼婦ラハブも、使者を受け取り、別の道を通って彼らを送り出した とき、行いによって義とされたのではなかったか」[7][8] ユディト書では、ユディトはホロフェルネスを暗殺するために彼を欺いた[9]。 アブラハムとイサクはともに、自分の妻は姉妹であると主張した[10]。 |

| Early Christian views Among early Christian writers, there existed differing viewpoints regarding the ethics of deception and dishonesty in certain circumstances. Some argued that lying and dissimulation could be justified for reasons such as saving souls, convincing reluctant candidates to accept ordination, or demonstrating humility by refraining from boasting about one's virtues. Supporters of this position often referred to Paul's statement about becoming all things to all men in order to win them over as a basis for their arguments.[11][12][13] |

初期キリスト教の見解 初期キリスト教の著述家たちの間では、特定の状況下における欺きや不正直さの倫理について、異なる見解が存在した。ある者は、嘘をついたり偽ったりするこ とは、魂を救うため、聖職に就くことに消極的な候補者を説得するため、あるいは自分の美徳を自慢することを控えて謙遜さを示すためなどの理由で正当化され ると主張した。この立場の支持者たちは、その主張の根拠として、パウロの「すべての人を味方につけるために、すべての人にすべてのことをするようになる」 という言葉をしばしば引用していた[11][12][13]。 |

| Patristic views Augustine devoted much attention to lying, which he contended was always wrong. He discussed the topic in four works (De magistro, De doctrina christiana, De trinitate, and Enchiridion) and wrote two treatises, De mendacio and Contra mendacium, specifically on the subject of lies.[1] According to Augustine, only four types of falsehood were not lies, because there was no desire to deceive: explanation of someone else's viewpoint, repetition of memorized words, a slip of the tongue, or misspeaking.[14] Augustine distinguished different situations of lying by blameworthiness, but argued that every lie was a sin.[15] The consensus among scholars is that Augustine did not accept any lies as necessary or justified, even to save an innocent life.[16] However, there was an equally strong patristic tradition that defended lying for a worthwhile cause and considered it necessary or even righteous in some cases. Exponents of this view include Pseudo-Maximus, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Hilary of Poitiers, John Cassian, John Chrysostom, Dorotheus of Gaza, Palladius of Antioch, John Climacus, and Paulinus of Nola.[17] This second patristic tradition was summarized by Ambrose of Milan, whose argument, based on scripture, held that Judith's action was meritorious because "she undertook for religion, not love... she served religion... and the fatherland".[1] |

教父の見解 アウグスティヌスは、常に間違っていると主張する嘘に多くの注意を払った。彼は4つの著作(De magistro, De doctrina christiana, De trinitate, Enchiridion)の中でこのテーマについて論じており、特に嘘というテーマについて『De mendacio』と『Contra mendacium』という2つの論考を書いている[1]。 アウグスティヌスによれば、他人の見解の説明、暗記した言葉の繰り返し、滑舌の悪さ、言い間違いという4つのタイプの偽りだけが嘘ではなかった。 [14]アウグスティヌスは、罪の重さによって嘘をつく状況を区別していたが、すべての嘘は罪であると主張していた[15]。学者たちの間では、アウグス ティヌスは、たとえ罪のない命を救うためであっても、どんな嘘も必要なもの、正当なものとして認めなかったというのがコンセンサスである[16]。 しかし、価値ある大義のために嘘をつくことを擁護し、場合によってはそれが必要であり、正義であるとさえ考える、同様に強力な教父の伝統があった。この見 解の支持者には、マクシムス偽書、アレクサンドリアのクレメンス、オリゲン、ポワチエのヒラリー、ヨハネ・カシアヌス、ヨハネ・クリュソストム、ガザのド ロテウス、アンティオキアのパラディウス、ヨハネ・クライマコス、ノーラのパウリヌスなどがいる。 [17] この第二の教父の伝統はミラノのアンブローズによって要約され、その聖句に基づく論証では、ユディトの行為は「愛ではなく宗教のために引き受け た......彼女は宗教と祖国に仕えた」[1]から功徳があったとされた。 |

| Later views Notable Christian theologians who argued that lying was never permissible for Christians include Thomas Aquinas and John Calvin.[18][19] Both Augustine and Aquinas held that it was always possible to take a correct and blameless action in any circumstance. Some Waldensians weren't strongly opposed to lying if necessary for survival.[20] Defenders of lying in some cases, such as Cassian and H. Tristram Engelhardt, tended to hold the opposite view: that sometimes true moral dilemmas arise.[21] Martin Luther argued that it is permissible to go as far as swearing an Oath in a lie in his commentary on Matthew.[22] where taking an oath of any sort, even if followed through is deemed impermissible, possibly using Paul's oath (1 Cor. 9:20), or unhonored oaths from the Crusades for his reasoning.[23] So that some have stretched their conscience so tightly, that one doubts whether one ought to take a solemn oath not to avenge himself when he is set free from prison, or whether we are by an oath to make peace and a treaty with the Turks... As, if it should come to pass, that we would make a treaty and concord with our enemies or the Turks. — Martin Luther, Commentary on the Sermon on the Mount, [24] In the twentieth century, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Reinhold Niebuhr also took a non-absolutist position.[18] In Ethics, Bonhoeffer discusses Kantian ethics and contests the Kantian view of lying, because "Treating truthfulness as a principle leads Kant to the grotesque conclusion that if asked by a murderer whether my friend, whom he was pursuing, had sought refuge in my house, I would have to answer honestly in the affirmative."[25] Although he maintained that one should lie to save his friend in that situation, Bonhoeffer argued that either option incurred guilt.[25] In a later essay, “What Does It Mean to Tell the Truth?”, Bonhoeffer argued that "Lying … is and ought to be understood as something plainly condemnable" and that it did not always incur guilt.[25] Professor Allen Verhey argued that lying is not always wrong, because "We live the truth not for its own sake, but for God's sake and for the neighbor's sake."[19] The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that lying is always wrong.[26] Different definitions of lying exist, such that Christians do not agree that all deception counts as "lying". Catholic writer and new natural law philosopher Christopher Tollefsen has also argued that lying is never permissible for Christians.[18][27] In a review of Tollefsen's book, John Skalko stated that this is an unpopular and widely criticized view.[26] |

後の見解 キリスト教徒にとって嘘は決して許されないと主張した著名なキリスト教神学者には、トマス・アクィナスやジョン・カルヴァンがいる[18][19]。アウ グスティヌスもアクィナスも、どのような状況においても常に正しく非のない行動をとることは可能であるとした。ワルデン派の中には、生存のために必要であ れば嘘をつくことに強く反対しない者もいた[20]。カッシアヌスやH・トリストラム・エンゲルハルトのように、場合によっては嘘をつくことを擁護する者 たちは、時には真の道徳的ジレンマが生じるという逆の見解を持つ傾向があった[21]。 マルティン・ルターは『マタイによる福音書』注解の中で、嘘の誓いをすることまでは許されると主張した[22]。そこでは、ある種の誓いを立てることは、 たとえそれが守られたとしても、許されないとみなされており、おそらくパウロの誓い(1コリント9:20)や十字軍での名誉なき誓いを理由に用いている [23]。 そのため、良心の呵責に耐えかねて、牢獄から解放されたときに仇を討たないという厳粛な誓いを立てるべきかどうか、あるいは、トルコ人と和平条約を結ぶと いう誓いを立てるべきかどうかを疑う者もいる。もしそうなれば、われわれは敵やトルコ人と条約を結び、和睦することになるであろう。 - マルティン・ルター『山上の説教の注解』[24]。 20世紀には、ディートリッヒ・ボンヘッファーとラインホルト・ニーバーもまた、非絶対主義の立場をとっていた[18]。 倫理学』の中で、ボンヘッファーはカント倫理学について論じており、「真実性を原理として扱うと、カントは、殺人者に、彼が追っている私の友人が私の家に 避難してきたかどうかを尋ねられたら、私は正直に肯定的に答えなければならないというグロテスクな結論に至る。 「そのような状況では、友人を救うために嘘をつくべきだと主張したが、ボンヘッファーは、どちらの選択肢を選んでも罪が生じると主張した[25]。後の エッセイ「真実を語るとはどういうことか」において、ボンヘッファーは、「嘘をつくことは......明白に非難されるべきこととして理解され、理解され るべきである」と主張し、常に罪が生じるわけではないと主張した[25]。 アレン・ヴァーヘイ教授は、「私たちが真実に生きるのは、それ自身のためではなく、神のため、隣人のためである」[19]から、嘘は常に悪いことではない と主張した。 カトリック教会のカテキズムは、嘘は常に悪いことであると述べている[26]。カトリックの作家であり、新しい自然法の哲学者であるクリストファー・トレ フセンも、キリスト教徒にとって嘘は決して許されないと主張している[18][27]。 ジョン・スカルコはトレフセンの本の書評の中で、これは不人気で広く批判されている見解であると述べている[26]。 |

| Public opinion According to a 2016 Pew Research Center survey, 67% of Christians in the United States, including 81% of those who defined themselves as "highly religious", agreed that "Being honest at all times" was "essential" to their Christian identity.[28] According to the 2014 Pew Religious Landscape study in the US, the Christian group that had the highest rate of telling white lies were Black Protestants.[29] |

世論調査 2016年のピュー・リサーチ・センターの調査によると、米国のキリスト教徒の67%(うち、自らを「宗教心が強い」と定義する人の81%)は、「常に正 直であること」がキリスト教的アイデンティティにとって「不可欠」であることに同意していた[28]。 2014年の米国のピュー宗教景観調査によると、白い嘘をつく割合が最も高いキリスト教グループは、黒人プロテスタントであった[29]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_views_on_lying |

|

| In Jewish tradition, lying is generally forbidden but is required in certain exceptional cases, such as to save a life. |

ユダヤ教の伝統では、嘘をつくことは一般的に禁じられているが、命を救うためなど、ある例外的な場合には必要とされる。 |

| Hebrew Bible See also: Christian views on lying § Biblical passages The Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) forbids perjury in at least three verses: "You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor" (Exodus 20:12, part of the Ten Commandments), also phrased "Neither shall you bear false witness against your neighbor" (Deuteronomy 5, see Deut 5:16), and another verse "Keep yourself far from a false matter; and the innocent and righteous do not kill; for I will not justify the wicked" (Exodus 23, see Ex 23:7). According to Deuteronomy 19 (see Deut 19:16–21), false witnesses should receive the same punishment that they sought to mete out on the unjustly accused.[1] A similar prohibition, "You shall not steal; neither shall you deal falsely, nor lie one to another" (Leviticus 19, see Lev 19:11) relates to business dealings.[1] There are also passages which condemn lying in general: "He that does deceit shall not dwell within My house; he that speaks false-hood shall not be established before My eyes" (Psalm 101:7), "There are six things which the Lord hates, indeed, seven which are an abomination unto Him: Haughty eyes, a lying tongue, and hands that shed innocent blood" (Proverbs 6, see Prov 6:16–17, 19) and "Lying lips are an abomination to the Lord; but they who deal truly are His delight" (Proverbs 12, see Prov 12:22),[2] "The remnant of Israel shall not do iniquity, nor speak lies, neither shall a deceitful tongue be found in their mouth" (Zephaniah 3, see Zeph 3:13), "And if any prophets appear again, their fathers and mothers who bore them will say to them, “You shall not live, for you speak lies in the name of the Lord”; and their fathers and their mothers who bore them shall pierce them through when they prophesy." (Zechariah 13, see Zech 13:3) "They have taught their tongue to speak lies, they weary themselves to commit iniquity" (Jeremiah 9, see Jer 9:5).[3] However, in various biblical stories, those who lie and mislead are not necessarily condemned, and in some cases are praised. Biblical figures that engaged in deception include Abraham, Isaac, Simeon, and Levi.[4] The Torah does not prohibit lying if no one is harmed.[5] |

ヘブライ語聖書 も参照のこと: 嘘に関するキリスト教の見解 § 聖書の箇所 タナフ(ヘブライ語聖書)は、少なくとも3つの節で偽証を禁じている: 「隣人に対して、偽りの証言をしてはならない」(出エジプト20:12、十戒の一部)、「隣人に対して、偽りの証言をしてはならない」(申命記5章、申命 記5:16参照)、「偽りの事柄から遠ざかりなさい。申命記19章によれば(申命記19:16-21参照)、偽りの証人は、不当に訴えられた者に与えよう としたのと同じ罰を受けるべきである[1]。同様の禁止事項である「盗んではならない。また、偽りの取引をしてはならず、互いに嘘をついてはならない」 (レビ記19章、レビ記19:11参照)は、商取引に関するものである: 「偽りを言う者は、わたしの目の前に立てられない」(詩篇101:7)、「主が憎まれるものは六つあり、実に七つもある: 高慢な目、うそをつく舌、罪のない血を流す手である」(箴言6章16~17節、19節参照)、「うそをつくくちびるは主にとって憎むべきものであるが、ま ことに正しい者は主の喜びである」(箴言12章22節参照)、[2] 「イスラエルの残党は、不義を行うことなく、うそを言うこともなく、その口に欺く舌を見いだすこともない」(ゼパニヤ3章: また、もし預言者が再び現れたなら、彼らを産んだ父と母とは、彼らに言うであろう。 」 (ゼカリヤ13章、ゼカリヤ13:3参照)「彼らは舌に偽りを語ることを教え、不義を犯すことに疲れ果てる」(エレミヤ9章、エレ9:5参照)[3]。 しかし、聖書の様々な物語では、嘘をついたり、人を惑わしたりする者は必ずしも非難されず、賞賛される場合もある。聖書で欺きを行った人物には、アブラハ ム、イサク、シメオン、レビなどがいる[4]。トーラーでは、誰も傷つかないのであれば、嘘をつくことを禁じていない[5]。 |

| Talmud The Talmud forbids lying or deceiving others: "The Holy One, blessed be He, hates a person which says one thing with his mouth and another in his heart" (Pesahim 113b) and also forbids fraud in business dealings: "As there is wronging in buying and selling, there is wronging with words. A man must not ask: ‘How much is this thing?” if he has no intention of buying it" (Bava Metzia 4:10).[3] Bava Metzia 23b-24a lists three exceptions where lying is permitted:[3][6][7] It is permissible for a scholar to state he is unfamiliar with part of the Talmud, even if he is familiar (out of humility) It is permissible to lie in response to intimate questions regarding one's marital life (as such things should be kept private) Lying about hospitality received (to protect the host) Yevamot 65b states that "It is permitted to stray from the truth in order to promote peace", and Rabbi Natan further argues that this is obligatory.[8] |

タルムード タルムードでは、嘘や他人を欺くことを禁じている: 「聖なる方は、口ではあることを言い、心では別のことを言う者を憎まれる」(ペサヒム113b): 「売買に不正があるように、言葉にも不正がある。買う意図がないのに、『これはいくらですか』と聞いてはならない」(バヴァ・メツィア4:10)[3]。 Bava Metzia 23b-24aは、嘘が許される3つの例外を挙げている[3][6][7]。 タルムードに精通している学者であっても、タルムードの一部を知らないと述べることは許される(謙遜から)。 結婚生活に関する親密な質問に対して嘘をつくことは許される(そのようなことは秘密にされるべきであるから)。 受けたもてなしについて嘘をつく(ホストを守るため) イエヴァモト65bには、「平和を促進するために真実から外れることは許される」と書かれており、ラビ・ナタンはさらに、これは義務であると主張している[8]。 |

| Later views Due to the principle of saving a life, in Jewish law it is required to lie to save a life, such as withholding a diagnosis from a seriously ill patient[9] or concealing one's Jewish faith in a time of persecution of Jews.[10] It may also be required to lie in other cases where a positive commandment would be violated by telling the truth, as positive commandments in Judaism usually take precedence against negative ones.[9] Even in the cases where lying is acceptable, it is preferable to tell a technically true but deceptive statement or employ half-truth. It is also completely forbidden to lie habitually, to lie to a child (which would teach them that it was acceptable), and to lie in the court system.[5] Rabbi Eliyahu Dessler redefined "truth" to mean any statement which serves God and "falsehood" to mean any statement that harms God's interests. This would radically change Jewish views on lying.[11] According to Conservative rabbi Louis Jacobs, "the main thrust in the appeals for Jews to be truthful is in the direction of moral truth and integrity" although there is also "great significance to intellectual honesty".[3] Reconstructionist rabbi Fred Scherlinder Dobb stated in an interview, "There is no justification whatsoever in Jewish tradition for lies which are either sloppy, systemic or self-serving... every word we utter should reflect our values, and one of the highest of those values is truth."[12] |

後の見解 救命の原則から、ユダヤ教では、重病患者の診断を保留したり[9]、ユダヤ人迫害の時代にユダヤ教信仰を隠したりするなど、救命のために嘘をつくことが義 務付けられている[10]。また、ユダヤ教では通常、否定的な戒律よりも肯定的な戒律が優先されるため、真実を告げると肯定的な戒律に違反するような場合 にも嘘をつくことが求められることがある[9]。また、常習的に嘘をつくこと、子供に嘘をつくこと(それが許されることを教えることになる)、裁判制度で 嘘をつくことは完全に禁じられている[5]。 エリヤフ・デスラー師は、「真実」とは神に奉仕するあらゆる発言を意味し、「虚偽」とは神の利益を害するあらゆる発言を意味すると再定義した。これはユダヤ教の嘘に対する見解を根本的に変えることになる[11]。 保守派のラビであるルイス・ジェイコブズによれば、「ユダヤ人が真実であることを訴える際の主な方向性は、道徳的な真実と誠実さである」という。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_views_on_lying |

|

| In Islam, Taqiyya (Arabic: تقیة,

romanized: taqiyyah, lit. 'prudence')[1][2] is a dissimulation and

secrecy of religious belief and practice.[1][3][4][5] Generally, taqiyya is regarded as the action of maintaining secrecy or mystifying one's beliefs. Hiding one's beliefs in non-Muslim nations has been practiced since the early days of Islam and early Muslims used it to avoid torture or getting killed by non-Muslims and tyrants with authority; it used to be acknowledged by Muslims of virtually all persuasions.[6][7] The use of taqiyya has varied in recent history, especially between Sunni and Shia Muslims. Sunni Muslims gained political supremacy over time and therefore only occasionally found the need to practice taqiyya. On the other hand, Shia Muslims, as well as Sufi Muslims developed taqiyya as a method of self-preservation and protection in hostile environments.[8] A related term is kitmān (lit. "action of covering, dissimulation"), which has a more specific meaning of dissimulation by silence or omission.[9][10] This practice is emphasized in Shi'ism whereby adherents are permitted to conceal their beliefs when under threat of persecution or compulsion.[3][11] Taqiyya was initially practiced under duress by some of Muhammad's companions.[12] Later, it became important for Sufis, but even more so for Shias, who often experienced persecution as a religious minority.[11][13] In Shia theology, taqiyya is permissible in situations where life or property are at risk and whereby no danger to religion would occur.[11] Taqiyya has also been politically legitimised in Twelver Shi'ism, to maintain unity among Muslims and fraternity among Shia clerics.[14][15] |

イスラームでは、タキーヤ(アラビア語: تقیة, ローマ字表記: taqiyyah, 「慎重さ」)[1][2]とは、宗教的な信念や実践を偽り、秘密にすることである[1][3][4][5]。 一般的に、タキーヤは自分の信念を秘密にしたり、神秘化したりする行為とみなされている。非ムスリム国民において自分の信念を隠すことはイスラームの初期から行われており、初期のムスリムは非ムスリムや権力を持つ暴君による拷問や殺害を避けるためにそれを用いていた。 タキーヤの使用は近年の歴史において、特にスンニ派とシーア派のイスラム教徒の間で様々であった。スンニ派ムスリムは時代とともに政治的優位性を獲得した ため、タキーヤを実践する必要性は時折しか見出されなかった。一方、シーア派ムスリムやスーフィー派ムスリムは、敵対的な環境における自己防衛や保護の方 法としてタキーヤを発展させた[8]。 この実践はシーア派において強調されており、迫害や強制の脅威にさらされている場合、信者は自らの信念を隠すことが許されている[3][11]。 タキーヤは当初、ムハンマドの教友の何人かが強迫の下で実践していた[12]。その後、スーフィズムにとって重要なものとなったが、宗教的少数派として迫 害をしばしば経験していたシーア派にとってはなおさらであった。 [11][13]シーア派の神学では、タキーヤは生命や財産が危険にさらされ、宗教への危険が生じない状況において許される[11]。 |

| Etymology and related terms Taqiyya The term taqiyya is derived from the Arabic triliteral root wāw-qāf-yā denoting "caution, fear",[1] "prudence, guarding against (a danger)",[16] "carefulness, wariness".[17] In the sense of "prudence, fear" it can be used synonymously with the terms tuqa(n), tuqāt, taqwá, and ittiqāʾ, which are derived from the same root.[9] These terms also have other meanings. For example, the term taqwá generally means "piety" (lit. "fear [of God]") in an Islamic context.[18] Kitmān A related term is kitmān (Arabic: كتمان), the "action of covering, dissimulation".[9] While the terms taqiyya and kitmān may be used synonymously, kitmān refers specifically to the concealment of one's convictions by silence or omission.[10] Kitman derives from Arabic katama "to conceal, to hide".[19] Ibadis used kitmān to conceal their Muslim beliefs in the face of persecution by their enemies.[20] |

語源と関連用語 タキーヤ タキーヤ(taqiyya)という用語は、アラビア語で「注意、恐れ」[1]「慎重さ、(危険に対する)警戒」[16]「用心深さ、警戒心」を表す三連語 根wāw-qāf-yāに由来する。 [17]「用心深さ、恐れ」という意味では、同じ語源を持つtuqa(n)、tuqāt、taqwá、ittiqām_2BEと同義に使われることもある [9]。例えば、taqwáという用語は一般的にイスラム教の文脈では「敬虔」(「(神を)畏れる」)を意味する[18]。 キトマーン 関連する用語として、kitmān(アラビア語: كتمان)があり、「覆い隠す、偽る行為」を意味する[9]。タキーヤとkitmānは同義語として使われることもあるが、kitmānは特に沈黙や省 略によって自分の信念を隠すことを指す。 [10]キットマンはアラビア語のkatama「隠す、隠蔽する」に由来する[19]。イバディ教徒は敵からの迫害に直面した際、ムスリムの信念を隠すた めにキットマンを用いた[20]。 |

| Quranic basis The technical meaning of the term taqiyya is thought[by whom?] to be derived from the Quranic reference to religious dissimulation in Sura 3:28: Believers should not take disbelievers as guardians instead of the believers—and whoever does so will have nothing to hope for from Allah—unless it is a precaution against their tyranny. And Allah warns you about Himself. And to Allah is the final return. (illā an tattaqū minhum tuqāt). — Surah Al Imran 3:28 The two words tattaqū ("you fear") and tuqāt "in fear" are derived from the same root as taqiyya, and the use of taqiyya about the general principle described in this passage is first recorded in a Qur'anic gloss by Muhammad al-Bukhari in the 9th century.[citation needed] Regarding 3:28, ibn Kathir writes, "meaning, except those believers who in some areas or times fear for their safety from the disbelievers. In this case, such believers are allowed to show friendship to the disbelievers outwardly, but never inwardly." He quotes the Companion of the Prophet Abu al-Darda, who said "we smile in the face of some people although our hearts curse them," and Hasan ibn Ali, who said, "the tuqyah is acceptable till the Day of Resurrection."[21] A similar instance of the Qur'an permitting dissimulation under compulsion is found in Surah An-Nahl 16:106 [22] Sunni and Shia commentators alike observe that verse 16:106 refers to the case of 'Ammar b. Yasir, who was forced to renounce his beliefs under physical duress and torture.[10] |

コーランの根拠 タキーヤという言葉の専門的な意味は、クルアーン第3章28節にある宗教的偽りに関する言及に由来すると考えられている: 信者たちは、信者たちの代わりに不信心者たちを守護者として迎えてはならない。そのようなことをする者は、アッラーから何も望めないであろう。アッラーは 御自身について,あなたがたに警告なされる。アッラーにこそ,最後の帰りがある。(illā an tattaqū minhum tuqāt)。 - アル・イムラーン 3章28節 tattaqū(「あなたがたは恐れる」)とtuqāt(「恐れている」)はtaqiyyaと同じ語源であり、この箇所で述べられている一般的な原理につ いてtaqiyyaが使用されていることは、9世紀のムハンマド・アル=ブハーリーによるクルアーンの注釈に初めて記録されている[要出典]。 3:28についてイブン・カティールは、「ある地域や時代において、不信心者から身を守ることを恐れている信者を除くという意味である。この場合、そのよ うな信者は、外面的には不信心者に友好を示すことが許されるが、内面的には決して友好を示すことはできない」と書いている。また、預言者さま(祝福と平安 を)の仲間であったアブー・アル=ダルダは、「私たちは、心の中では彼らを呪っていても、ある人々の顔には微笑む」と言い、ハサン・イブン・アリーは、 「トゥッキヤは復活の日まで受け入れられる」と言った[21]。 スンニ派もシーア派も、16:106節は、肉体的な強要と拷問によって信仰を捨てることを強要されたアンマル・b・ヤシールのケースを指していると述べている[10]。 |

| Sunni Islam view The basic principle of taqiyya is agreed upon by scholars, though they tend to restrict it to dealing with non-Muslims and when under compulsion (ikrāh), while Shia jurists also allow it in interactions with Muslims and in all necessary matters (ḍarūriyāt).[23] In Sunni jurisprudence protecting one's belief during extreme or exigent circumstances is called idtirar (إضطرار), which translates to "being forced" or "being coerced", and this word is not specific to concealing the faith; for example, under the jurisprudence of idtirar one is allowed to consume prohibited food (e.g. pork) to avoid starving to death.[24] Additionally, denying one's faith under duress is "only at most permitted and not under all circumstances obligatory".[25] Al-Tabari comments on sura XVI, verse 106 (Tafsir, Bulak 1323, xxiv, 122): "If any one is compelled and professes unbelief with his tongue, while his heart contradicts him, in order to escape his enemies, no blame falls on him, because God takes his servants as their hearts believe." This verse was recorded after Ammar Yasir was forced by the idolaters of Mecca to recant his faith and denounce the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Al-Tabari explains that concealing one's faith is only justified if the person is in mortal danger, and even then martyrdom is considered a noble alternative. If threatened, it would be preferable for a Muslim to migrate to a more peaceful place where a person may practice their faith openly, "since God's earth is wide."[25] In Hadith, in the Sunni commentary of Sahih al-Bukhari, known as the Fath al-Bari, it is stated that:[26] أجمعوا على أن من أكره على الكفر واختار القتل أنه أعظم أجرا عند الله ممن اختار الرخصة ، وأما غير الكفر فإن أكره على أكل الخنزير وشرب الخمر مثلا فالفعل أولى Which translates to: There is a consensus that whomsoever is forced into apostasy and chooses death has a greater reward than a person who takes the license [to deny one's faith under duress], but if a person is being forced to eat pork or drink wine, then they should do that [instead of choosing death]. Al-Ghazali wrote in his The Revival of the Religious Sciences: Safeguarding of a Muslim's life is a mandatory obligation that should be observed; and that lying is permissible when the shedding of a Muslim's blood is at stake. Ibn Sa'd, in his book al-Tabaqat al-Kubra, narrates on the authority of Ibn Sirin: The Prophet (S) saw 'Ammar Ibn Yasir (ra) crying, so he (S) wiped off his (ra) tears, and said: "The nonbelievers arrested you and immersed you in water until you said such and such (i.e., bad-mouthing the Prophet (S) and praising the pagan gods to escape persecution); if they come back, then say it again." Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti, in his book al-Ashbah Wa al-Naza'ir, affirms that: It is acceptable (for a Muslim) to eat the meat of a dead animal at a time of great hunger (starvation to the extent that the stomach is devoid of all food); and to loosen a bite of food (for fear of choking to death) by alcohol; and to utter words of unbelief; and if one is living in an environment where evil and corruption are the pervasive norm, and permissible things (Halal) are the exception and a rarity, then one can use whatever is available to fulfill his needs. Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti, in his book al-Durr al-Manthoor Fi al-Tafsir al- Ma'athoor,[27] narrates that: Abd Ibn Hameed, on the authority of al-Hassan, said: "al-Taqiyya is permissible until the Day of Judgment." The practice of taqiyya is not limited to any one sect within Islam. It is observed and referenced in Sunni texts of law, hadith collections, and Quranic exegesis. Although historically more extensively practiced and referenced by Shii Muslims, taqiyya is doctrinally available to Sunni Muslims as well. This challenges the negative notion that taqiyya is exclusively associated with one community or confined to a specific group.[28] Niyya In Sunni Islamic law, as in Islamic law in general, the concept of intention (niyya) holds great importance. Merely performing an act without the right intention is considered insufficient. A fatwa issued by Ibn Abi Juma highlights the significance of one's inner state and intention in determining their identity as a Muslim. According to this fatwa, if taqiyya is practiced with the right intention, it is not considered sinful but rather a pious act. The fatwa emphasizes that God values the intention of believers over their outward actions, and taqiyya can be seen as a form of outward expression aligned with the correct intention.[28] |

スンニ派の見解 タキーヤの基本原則は学者によって合意されているが、学者たちはタキーヤを非ムスリムとのやりとりや強制された場合(ikrāh)に限定する傾向があり、 シーア派の法学者はムスリムとのやりとりや必要な事柄(ḍarūriyāt)においてタキーヤを認めている。 [23]スンニ派の法学では、極端な状況や緊急の状況下で信仰を守ることをイディラー(إضطرار)と呼び、これは「強制される」または「強要される」 と訳される。 24]また、強要されて信仰を否定することは「せいぜい許されるだけであり、あらゆる状況において義務ではない」[25]。 アル=タバリは、スーラ16章106節について次のようにコメントしている(Tafsir, Bulak 1323, xxiv, 122): 「もし、敵から逃れるために、舌で不信仰であることを強要され、その心で不信仰であることを公言したとしても、神はその心の信ずるままにそのしもべを召さ れるからである。この一節は、アンマル・ヤシールがメッカの偶像崇拝者たちによって信仰を撤回させられ、イスラムの預言者ムハンマドを非難した後に記録さ れた。アル=タバリは、信仰を隠すことが正当化されるのは、その人に死活的な危険が迫っている場合だけであり、その場合でも殉教は立派な代替案と見なされ ると説明している。もし脅かされるのであれば、ムスリムは「神の地は広いのだから」、公然と信仰を実践できるような、より平和な場所に移住することが望ま しいだろう[25]。ハディースでは、ファト・アル=バリとして知られる『サヒーフ・アル=ブハーリ』のスンニ派の注釈書の中で、次のように述べられてい る[26]。 أجمعوا على أن من أكره على الكفر واختار القتل أنه أعظم أجرا عند الله من اختار الرخصة الكفر فإن أكره على أكل الخنزير وشرب الخمر مثلا فالفعل أولى 直訳すればこうなる: 背教を強要され、死を選ぶ者は、(強要されて信仰を否定する)許可を取る者よりも大きな報いを受けるというコンセンサスがあるが、もし豚肉を食べることやワインを飲むことを強要されているのであれば、(死を選ぶ代わりに)そうすべきだ。 アル=ガザーリは『宗教科学の復興』の中でこう書いている: ムスリムの生命を守ることは、守るべき義務であり、ムスリムの血が流される危険がある場合には、嘘をつくことが許される。 イブン・サードは、その著書『アル・タバカト・アル・クブラ』の中で、イブン・シリンの権威に基づいて次のように語っている: 預言者さま(祝福と平安を)は、アンマール・イブン・ヤシール(ラー)が泣いているのを見て、涙を拭われ、こう言われた: 「不信心者たちはあなたを逮捕し、あなたがそのようなこと(迫害を逃れるために預言者さま(祝福と平安を)を悪く言い、異教の神々を賛美すること)を言う まで、あなたを水に浸した。"もし彼らが戻って来たら、もう一度言ってみなさい。 ジャラール・アル=ディン・アル=スユーティは、その著書『アル・アシュバ・ワ・アル=ナザイル』の中で次のように述べている: もし、悪と堕落が蔓延し、許されるもの(ハラール)が例外であり、希少なものであるような環境に住んでいるならば、自分の必要を満たすために利用できるものは何でも利用することができる。 ジャラール・アルディン・アル・スユーティは、その著書『アル・ドゥル・アル・マントゥール・フィ・アル・ターフシール・アル・マースィール』[27]の中で次のように語っている: アブド・イブン・ハミードは、アル・ハッサンの権威に基づき、次のように語った: 「タキーヤは審判の日まで許される。 タキーヤの実践はイスラームのどの宗派にも限定されない。スンニ派の法学書、ハディース集、コーランの釈義書において、タキーヤの実践が観察され、言及さ れている。歴史的にはシーア派のイスラム教徒がより広範に実践し、参照してきたが、タキーヤはスンニ派のイスラム教徒にも教義上利用可能である。このこと は、タキーヤがある共同体のみに関連するものであるとか、特定の集団に限定されたものであるといった否定的な概念に疑問を投げかけるものである[28]。 ニーヤ スンニ派イスラーム法では、一般的なイスラーム法と同様に、意図主義(ニヤ)の概念が非常に重要である。正しい意図なしに行為を行うだけでは不十分である とみなされる。イブン・アビー・ジュマが発表したファトワーは、ムスリムとしてのアイデンティティを決定する上で、人の内面的な状態や意図の重要性を強調 している。このファトワによれば、もしタキーヤが正しい意図のもとに行われるのであれば、それは罪深い行為ではなく、むしろ敬虔な行為であると考えられて いる。このファトワは、神は外面的な行動よりも信者の意図を重視し、タキーヤは正しい意図に沿った外面的な表現の一形態とみなすことができると強調してい る[28]。 |

| Examples A 19th-century painting of a mass baptism of Moors in 1500. Muslim clerics permitted them to use taqiyya and become outwardly Christian, to save their lives. When Mamun became caliph (813 AD), he tried to impose his religious views on the status of the Qur'an over all his subjects, in an ordeal called the mihna, or "inquisition". His views were disputed, and many of those who refused to follow his views were imprisoned, tortured, or threatened with the sword.[29] Some Sunni scholars chose to affirm Mamun's view that the Qur'an was created, in spite of their beliefs,[10] though a notable exception to this was scholar and theologian Ahmad ibn Hanbal, who chose to endure torture instead.[30] Following the end of the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula in 1492, Muslims were persecuted by the Catholic Monarchs and forced to convert to Christianity or face expulsion. The principle of taqiyya became very important for Muslims during the Inquisition in 16th-century Spain, as it allowed them to convert to Christianity while remaining crypto-Muslims, practicing Islam in secret. In 1504, Ubayd Allah al-Wahrani, a Maliki mufti in Oran, issued a fatwā allowing Muslims to make extensive use of concealment to maintain their faith.[5][31][32] This is seen as an exceptional case, since Islamic law prohibits conversion except in cases of mortal danger, and even then requires recantation as quickly as possible,[33] and al-Wahrani's reasoning diverged from that of the majority of earlier Maliki Faqīhs such as Al-Wansharisi.[32] |

例 1500年に行われたムーア人の集団洗礼を描いた19世紀の絵画。イスラム教の聖職者たちは、彼らの命を守るために、タキーヤを使い、外見上はキリスト教徒になることを許可した。 マムンがカリフになった時(西暦813年)、彼はミハ(異端審問)と呼ばれる試練で、コーランの地位に関する自分の宗教的見解をすべての臣下に押し付けよ うとした。彼の見解には異論があり、彼の見解に従うことを拒否した者の多くは投獄されたり、拷問を受けたり、剣で脅されたりした[29]。スンニ派の学者 の中には、彼らの信念にもかかわらず、クルアーンは創作されたというマムンの見解を肯定することを選んだ者もいた[10]。 1492年にイベリア半島のレコンキスタが終わると、イスラム教徒はカトリックの君主によって迫害され、キリスト教に改宗するか追放されるかを迫られた。 タキーヤの原則は、16世紀スペインの異端審問の間にイスラム教徒にとって非常に重要なものとなった。1504年、オランのマリキ派ムフティーであったウ バイド・アッラー・アル=ワーラーニーは、ムスリムが信仰を維持するために隠匿を広範に利用することを認めるファトワーフを発表した[5][31] [32]。イスラム法では、致命的な危険がある場合を除いて改宗を禁じており、その場合でも可能な限り速やかに撤回することを求めているため[33]、こ れは例外的なケースであると考えられており、アル=ワーラーニーの推論は、アル=ワーンシャリージなどそれ以前の大多数のマリキ派ファキーとは異なってい た[32]。 |

| Shia Islam view Minority Shi‘a communities, since the earliest days of Islam, were often forced to practice pious circumspection (taqiyya) as an instinctive method of self-preservation and protection, an obligatory practice in the lands which became known as the realm of pious circumspection (dār al-taqiyya). Therefore, the recurring theme is that during times of danger feigning disbelief is allowed.[34] Two primary aspects of circumspection became central for the Shi‘a: not disclosing their association with the Imams when this could put them in danger and protecting the esoteric teachings of the Imams from those who are unprepared to receive them. While in most instances, minority Shi‘a communities employed taqiyya using the façade of Sunnism in Sunni-dominated societies, the principle also allows for circumspection as other faiths. For instance, Gupti Ismaili Shi‘a communities in the Indian subcontinent circumspect as Hindus to avoid caste persecution. In many cases, the practice of taqiyya became deeply ingrained into practitioners' psyche. If a believer wished, he/she could adopt this practice at moments of danger, or as a lifelong process.[35] Prudential Taqiyya Kohlberg has coined the expression “prudential taqiyya” to describe caution due to fear of external enemies. It can be further categorized into two distinct forms: concealment and dissimulation. For instance, historical accounts narrate how some Imams concealed their identities as a protective measure. In one story, the Imam Jafar al-Sadiq commended the behavior of a follower who chose to avoid direct interaction with the Imam, even though he recognized him on the street, rather than exposing him, and even cursed those who would call him by his name.[34] Kohlberg identifies the second type of prudential taqiyya as dissimulation, characterized by using deceptive words or actions intended to mislead opponents. It is typically employed by individuals possessing secret information. It is not solely confined to Imami Shi'ism but has been observed among various Muslim individuals or groups with minority views. During times of danger, the recurring theme is that taqiyya permits individuals to utter words of disbelief as a means of self-preservation. Prudential taqiyya is considered essential for safeguarding the faith and may be lifted when the political climate no longer poses a threat. Therefore, one way to discern the motivation behind a specific type of taqiyya is to determine whether it ceases once the danger has subsided.[34] Non-Prudential Taqiyya Kohlberg coined the expression “non-prudential taqiyya” for when there is a need to conceal secret doctrines from the uninitiated. Non-prudential taqiyya is employed by believers when they possess secret knowledge and are obligated to conceal it from those who have not attained the same level of initiation. This hidden knowledge encompasses diverse aspects, including profound insights into specific Quranic verses, interpretations of the Imam's teachings, and specific religious obligations. The obligation to conceal arises when individuals acquire such exclusive knowledge emphasizing the importance of preserving its secrecy within the initiated community.[34] Twelver Shia view If coupled with mental reservation, religious dissimulation is considered lawful in Twelver Shi'ism whenever life or property is at serious risk.[36][37] In Twelver theology, taqiyya also refers to hiding or safeguarding the esoteric teachings of Shia imams,[38][39][40] a practice intended to “protect the truth from those not worthy of it.”[41] This esoteric knowledge (of God), taught by imams to their (true) followers, is said to distinguish them from other Muslims.[42] Historically, the Twelver doctrine of taqiyya was developed by Muhammad al-Baqir (d. c. 732), the fifth of the twelve imams,[43][44][45] and later by his successor, Ja'far al-Sadiq (d. 765).[46] At the time, this doctrine was likely intended for the survival of Shia imams and their followers, for they were being brutally molested and persecuted.[47][48][49] Indeed, taqiyya is particularly relevant to Twelver Shias, for until about the sixteenth century they lived mostly as a minority among an often-hostile Sunni majority.[50][36] Traditions attributed to Shia imams thus encourage their followers to hide their faith for their safety, some even characterizing taqiyya as a pillar of faith.[47][51][52] Theological and legal statements of Shia imams were also influenced by taqiyya.[53][38][54] For instance, al-Baqir is not known to have publicly reviled the first two caliphs, namely, Abu Bakr and Umar,[55][56] most likely because the imam exercised taqiyya.[57] Indeed, al-Baqir's conviction that the Islamic prophet had explicitly designated Ali ibn Abi Talib as his successor implies that Abu Bakr and Umar were usurpers.[57] More generally, whenever contradictory statements are attributed to Shia imams, those that are aligned with Sunni positions are discarded, for Shia scholars argue that such statements must have been uttered under taqiyya.[54] |

シーア派イスラームの見解 少数派のシーア派共同体は、イスラームの初期から、しばしば自己保存と保護の本能的な方法として敬虔な周旋(taqiyya)の実践を余儀なくされ、敬虔 な周旋の領域(dār al-taqiyya)として知られるようになった土地では義務的な実践であった。そのため、危険な時には不信仰を装うことが許されるというテーマが繰り 返されている[34]。 それは、イマームたちとの関係が危険に晒される可能性がある場合にはそれを公表しないことと、イマームたちの難解な教えを、それを受け取る準備ができてい ない人々から守ることである。ほとんどの場合、少数派のシーア派共同体はスンニ派が支配する社会でスンニ派を装ってタキーヤを行ったが、この原則は他の信 仰と同じように周到に行うことも認めている。例えば、インド亜大陸のグプティ・イスマイール派シーア派コミュニティは、カーストによる迫害を避けるために ヒンズー教徒として隠遁していた。多くの場合、タキーヤの実践は信者の精神に深く刻み込まれた。信者が望めば、危険が迫ったときに、あるいは生涯のプロセ スとして、この実践を採用することができた[35]。 プルデンシャル・タキヤ コールバーグは「慎重なタキーヤ」という表現を作り出し、外敵を恐れることによる警戒心を表現している。それはさらに、「隠蔽」と「偽り」という2つの異なる形態に分類することができる。 例えば、歴史的な証言によれば、イマームたちの中には、身を守るために自分の正体を隠した者がいる。ある物語では、イマーム・ジャファル・アル=サーディ クは、イマームを街で見かけたにもかかわらず、イマームを晒すのではなく、イマームとの直接の交流を避けることを選んだ従者の行動を称賛し、さらにはイ マームの名前を呼ぶ者を罵った[34]。 コールバーグは、慎重なタキーヤの第二のタイプとして、相手を惑わすことを意図した欺瞞的な言動を用いることを特徴とするディシミュレーション (dissimulation)を挙げている。これは通常、秘密情報を持つ個人が用いる。これはイマーム派シーア派だけに限ったことではなく、少数派の意 見を持つ様々なムスリム個人やグループの間でも観察されている。危険な時には、タキーヤは自己防衛の手段として、個人が不信の言葉を口にすることを許すと いうことが繰り返される。慎重なタキーヤは信仰を守るために不可欠であり、政治情勢が脅威でなくなれば解除されることもある。したがって、特定のタイプの タキーヤの背後にある動機を見分ける1つの方法は、危険が収まるとそれが止まるかどうかを判断することである[34]。 非慎重なタキーヤ コールバーグは、秘密の教義を不慣れな人々から隠す必要がある場合について、「非本質的タキーヤ」という表現を生み出した。非実践的タキーヤとは、信者が 秘密の知識を持っており、同じレベルのイニシエーションに達していない人々からそれを隠す義務がある場合に用いられる。この隠された知識には、コーランの 特定の箇所に関する深い洞察、イマームの教えの解釈、特定の宗教的義務など、様々な側面が含まれる。個人がこのような排他的な知識を得た場合、秘匿する義 務が生じるが、これはイニシエーションを受けた共同体の中でその秘密を守ることの重要性を強調するものである[34]。 シーア派の見解 トゥエルバー・シーア派では、生命や財産が深刻な危険にさらされている場合には、精神的な留保と相まって、宗教的な偽りが合法であると考えられている [36][37]。 [36][37]トゥエルヴァーの神学では、タキーヤはシーア派のイマームの秘教を隠したり保護したりすることも指しており[38][39][40]、 「真理をそれに値しない者から保護する」ことを意図した実践である[41]。イマームが(真の)信者に教えるこの(神についての)秘教の知識は、イマーム を他のムスリムから区別するものであると言われている[42]。 歴史的には、トゥエルバーにおけるタキーヤの教義は、12人のイマームのうち5番目のイマームであるムハンマド・アル=バキール(732年頃没)[43] [44][45]によって、また後に彼の後継者であるジャファル・アル=サーディク(765年没)によって発展させられた[46]。当時、この教義はシー ア派のイマームとその信者が残忍な虐待や迫害を受けていたため、彼らの生存を目的としていたと思われる。 [16世紀頃まで、シーア派はしばしば敵対的なスンニ派が大多数を占める中で、少数派として生活していたからである[50][36]。シーア派のイマーム に起因する伝承は、このように彼らの信者が安全のために信仰を隠すことを奨励しており、中にはタキーヤを信仰の柱とするものさえある。 [例えば、アル・バキールは最初の2人のカリフ、すなわちアブ・バクルとウマルを公に非難したことは知られていないが[55][56]、それはイマームが タキーヤを行使したからであろう。 [57]実際、イスラムの預言者がアリー・イブン・アビ・ターリブを後継者として明確に指名したというアル=バキールの確信は、アブ・バクルとウマルが簒 奪者であったことを暗示している[57]。より一般的には、シーア派のイマームに矛盾した発言が帰結される時は常に、スンニ派の立場に沿った発言は破棄さ れる。シーア派の学者は、そのような発言はタキーヤの下で発せられたに違いないと主張しているからである[54]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taqiyya | |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆