文明化の使命

Civilizing mission

☆文

明化の使命(スペイン語:misión civilizadora、ポルトガル語:Missão

civilizadora、フランス語:Mission civilisatrice)とは、先住民、特に 15 世紀から 20

世紀にかけての期間に、その文化の同化を促進することを目的とした軍事介入や植民地化を行う政治的根拠のことだ。西洋文化の原則として、この用語は15世

紀後半から20世紀半ばにかけてのフランス[1]の植民地化を正当化する際に最も頻繁に使用された。文明化の使命は、フランス領アルジェリア、フランス西

アフリカ、フランス領インドシナ、ポルトガル領アンゴラ、ポルトガル領ギニア、ポルトガル領モザンビーク、ポルトガル領ティモールを含む植民地化に対する

文化的正当化として用いられた。文明化の使命は、イギリス[2]とドイツ[3][4]の植民地主義を正当化する一般的な根拠としても用いられた。ロシア帝

国では、中央アジアの征服と、その地域のロシア化とも関連していた[5][6][7]。西洋の植民地支配国は、キリスト教国として、異教徒であり原始的な

文化であると見なした国々に西洋文明を広める義務があると主張した。この概念は、朝鮮を植民地化した日本帝国にも適用された[8][9]。

| The civilizing mission

(Spanish: misión civilizadora; Portuguese: Missão civilizadora; French:

Mission civilisatrice) is a political rationale for military

intervention and for colonization purporting to facilitate the cultural

assimilation of indigenous peoples, especially in the period from the

15th to the 20th centuries. As a principle of Western culture, the term

was most prominently used in justifying French[1] colonialism in the

late-15th to mid-20th centuries. The civilizing mission was the

cultural justification for the colonization of French Algeria, French

West Africa, French Indochina, Portuguese Angola and Portuguese Guinea,

Portuguese Mozambique and Portuguese Timor, among other colonies. The

civilizing mission also was a popular justification for the British[2]

and German[3][4] colonialism. In the Russian Empire, it was also

associated with the Russian conquest of Central Asia and the

Russification of that region.[5][6][7] The Western colonial powers

claimed that, as Christian nations, they were duty bound to disseminate

Western civilization to what they perceived as heathen, primitive

cultures. It was also applied by the Empire of Japan, which colonized

Korea.[8][9] |

文明化の

使命(スペイン語:misión civilizadora、ポルトガル語:Missão civilizadora、フランス語:Mission

civilisatrice)とは、先住民、特に 15 世紀から 20

世紀にかけての期間に、その文化の同化を促進することを目的とした軍事介入や植民地化を行う政治的根拠のことだ。西洋文化の原則として、この用語は15世

紀後半から20世紀半ばにかけてのフランス[1]の植民地化を正当化する際に最も頻繁に使用された。文明化の使命は、フランス領アルジェリア、フランス西

アフリカ、フランス領インドシナ、ポルトガル領アンゴラ、ポルトガル領ギニア、ポルトガル領モザンビーク、ポルトガル領ティモールを含む植民地化に対する

文化的正当化として用いられた。文明化の使命は、イギリス[2]とドイツ[3][4]の植民地主義を正当化する一般的な根拠としても用いられた。ロシア帝

国では、中央アジアの征服と、その地域のロシア化とも関連していた[5][6][7]。西洋の植民地支配国は、キリスト教国として、異教徒であり原始的な

文化であると見なした国々に西洋文明を広める義務があると主張した。この概念は、朝鮮を植民地化した日本帝国にも適用された[8][9]。 |

| Origins In the eighteenth century, Europeans saw history as a linear, inevitable, and perpetual process of sociocultural evolution led by Western Europe.[10] From the reductionist cultural perspective of Western Europe, colonialists saw non-Europeans as "backward nations", as people intrinsically incapable of socioeconomic progress. In France, the philosopher Marquis de Condorcet formally postulated the existence of a European "holy duty" to help non-European peoples "which, to civilize themselves, wait only to receive the means from us, to find brothers among Europeans, and to become their friends and disciples".[11] Modernization theory – progressive transition from traditional, premodern society to modern, industrialized society – proposed that the economic self-development of a non-European people is incompatible with retaining their culture (mores, traditions, customs).[12] That breaking from their old culture is prerequisite to socioeconomic progress, by way of practical revolutions in the social, cultural, and religious institutions, which would change their collective psychology and mental attitude, philosophy and way of life, or to disappear.[13]: 302 [14]: 72–73 [15] Therefore, development criticism sees economic development as a continuation of the civilizing mission. That to become civilized invariably means to become more "like us", therefore "civilizing a people" means that every society must become a capitalist consumer society, by renouncing their native culture to become Westernized.[16] Cultivation of land and people has been a similarly employed concept, used instead of civilizing in German speaking colonial contexts to press for colonization and cultural imperialism through "extensive cultivation" and "culture work".[17] According to Jennifer Pitts, there was considerable skepticism among French and British liberal thinkers (such as Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham, Edmund Burke, Denis Diderot and Marquis de Condorcet) about empire in the 1780s. However, by the mid-19th century, liberal thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville endorsed empire on the basis of the civilizing mission.[18] |

起源 18 世紀、ヨーロッパ人は、歴史を、西ヨーロッパが主導する直線的で必然的かつ永続的な社会文化の進化過程と捉えていました[10]。西ヨーロッパの還元主義 的な文化観から、植民地主義者は、ヨーロッパ人以外の民族を「後進国」であり、社会経済の発展が本質的に不可能な人々として見なしていました。フランスで は、哲学者コンドルセ侯爵が、非ヨーロッパの人々を「文明化するために、私たちから手段を受け取り、ヨーロッパ人に兄弟を見出し、彼らの友人や弟子となる ことを待ち望んでいる」と表現し、彼らを支援するヨーロッパの「神聖な義務」の存在を正式に提唱した。[11] 近代化理論(伝統的な前近代社会から近代的な工業化社会への漸進的な移行)は、非ヨーロッパの人々の経済的自立は、彼らの文化(慣習、伝統、習慣)の維持 と両立しないことを提唱した。[12] 古い文化からの断絶は、社会的、文化的、宗教的機関における実践的な革命を通じて、集団の心理や精神態度、哲学、生活様式を変えるか、または消滅するかを 条件として、経済社会的な進歩の前提条件であるとされた。[13]: 302 [14]: 72–73 [15] したがって、開発批判は経済発展を文明化の使命の継続と見なす。文明化とは、必ず「私たちのように」なることを意味するため、「人民を文明化」するという ことは、すべての社会が、自国の文化を放棄して西洋化することで、資本主義的な消費社会にならなければならないことを意味する。[16]土地と人々の育成 は、ドイツ語圏の植民地時代において、文明化に代わって「広範な耕作」や「文化活動」を通じて植民地化や文化帝国主義を推進するために用いられた、同様の 概念である。[17] ジェニファー・ピッツによると、1780年代のフランスとイギリスの自由主義思想家(アダム・スミス、ジェレミー・ベンサム、エドマンド・バーク、デニ ス・ディドロ、コンドルセ侯爵など)の間では、帝国主義に対してかなりの懐疑論があった。しかし、19世紀半ばまでに、ジョン・スチュワート・ミルやアレ クシス・ド・トクヴィルなどの自由主義思想家は、文明化の使命を理由に帝国主義を支持するようになった。 |

| By state Britain Although the British did not invent the term, the notion of a "civilizing mission" was equally important for them to justify colonialism. It was used to legitimatize British rule over the colonized, especially when the colonial enterprise was not very profitable.[2] The British used their sports as a tool to spread their values and culture among native populations, as well as a way of emphasizing their own dominance, as they were the owners of the rules of these sports and were naturally more experienced at playing these games. Test cricket, for example, was seen as a sport that inherently involved values of fair play and civilizedness. In some cases, British sports served a purpose of providing exercise and integration across social boundaries for native populations.[19] The growth of British sports led to a natural decline of the colonized peoples' sports, creating fear amongst some that a loss of their native culture might hamper their ability to resist colonial rule. Over time, colonized peoples ended up seeing British sports as a venue to prove their equality to the British, and victories against the British in sports gave momentum to nascent independence movements.[20][21][22] The idea that the British were bringing civilization to the uncivilized areas of the world is famously expressed in Rudyard Kipling's poem The White Man's Burden. |

国別 イギリス イギリス人はこの用語を発明したわけではないが、「文明化の使命」という概念は、植民地主義を正当化するために彼らにとっても同様に重要だった。これは、特に植民地事業があまり利益をもたらさない場合に、イギリスによる植民地支配を正当化するために用いられた。[2] イギリス人は、スポーツを、先住民に自分たちの価値観や文化を広めるためのツールとして、また、スポーツのルールを所有し、当然そのスポーツに熟練してい たことから、自分たちの優位性を強調する手段としても利用した。例えば、テストクリケットは、フェアプレーと文明的な価値観を本質的に含むスポーツと見な されていた。場合によっては、イギリスのスポーツは、先住民に運動の機会を提供し、社会的な境界を越えた統合を図る目的も果たしていた。[19] イギリスのスポーツの成長は、植民地の人々のスポーツの自然な衰退につながり、自国の文化を失うことで植民地支配に抵抗する能力を失うのではないかと一部 の人々に不安を抱かせた。時が経つにつれて、植民地の人々は、イギリスのスポーツをイギリス人に対する平等を証明する場とみなすようになり、スポーツでイ ギリスに勝利することは、誕生したばかりの独立運動に弾みをつけた。[20][21][22] イギリス人が世界の未開の地域に文明をもたらしたという考えは、ラドヤード・キップリングの詩『白人の負担』で有名に表現されている。 |

| France Alice Conklin explained in her works that the French colonial empire coincided with the apparently opposite concept of "Republic".[citation needed] |

フランス アリス・コンクリンは、彼女の著作の中で、フランスの植民地帝国は、一見相反する「共和国」という概念と一致していたと説明している。[要出典] |

| United States The concept of a "civilizing mission" would also be adopted by the United States during the age of New Imperialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Such projects would include US annexation of the Philippines during the aftermath of the Spanish-American War in 1898. The McKinley administration would declare that the US position within the Philippines was to “oversee the establishment of a civilian government” on the model of the United States.[23] That would be done through adopting a civilizing process that would entail a "medical reformation" and other socioeconomic reforms.[24] The Spanish health system had broken down after the 1898 war and was replaced with an American military model, which was made up of public health institutions.[25] The "medical reformation" was done with "military rigor"[25] as part of a civilizing process in which American public health officers set out to train native Filipinos the "correct techniques of the body."[26] The process of "rationalized hygiene" was a technique for colonizing in the Philippines, as part of the American physicists assurance that the colonized Philippines was inhabited with propriety. Other "sweeping reforms and ambitious public works projects" [27] would include the implementation of a free public school system, as well as architecture to develop "economic growth and civilizing influence" as an important component of McKinley's "benevolent assimilation."[28] Similar "civilizing" tactics were also incorporated into the American colonization of Puerto Rico in 1900. They would include extensive reform such as the legalization of divorce in 1902 in an attempt to instill American social mores into the island’s populace to "legitimatize the emerging colonial order."[29] Purported benefits for the colonized nation included "greater exploitation of natural resources, increased production of material goods, raised living standards, expanded market profitability and sociopolitical stability". [30] However, the occupation of Haiti in 1915 would also show a darker side to the American "civilizing mission." The historian Mary Renda has argued that the occupation of Haiti was solely for the "purposes of economic exploitation and strategic advantage,"[31] rather than to provide Haiti with "protection, education and economic support."[32] |

アメリカ合衆国 「文明化の使命」という概念は、19 世紀後半から 20 世紀初頭の新帝国主義時代にもアメリカ合衆国によって採用された。そのようなプロジェクトには、1898 年の米西戦争後のフィリピン併合などが含まれる。マッキンリー政権は、フィリピンにおける米国の立場は、米国をモデルとした「文民政府の設立を監督するこ と」であると宣言した。[23] これは、「医療改革」をはじめとする社会経済改革を含む文明化プロセスを採用することで実現されることになった。[24] 1898年の戦争後に崩壊したスペインの保健制度は、公衆衛生機関で構成されるアメリカの軍事モデルに置き換えられた。[25] 「医療改革」は、「軍事的厳格さ」[25] を伴って、アメリカの公衆衛生担当官がフィリピン先住民に「正しい身体技術」を訓練するという文明化プロセスの一環として実施された。[26] 「合理化された衛生」のプロセスは、フィリピンにおける植民地化の手法の一つであり、アメリカ人物理学者が植民地化されたフィリピンが適切に管理されてい ることを保証する一環として行われた。その他の「広範な改革と野心的な公共事業プロジェクト」[27]には、無料の公立学校制度の導入、および「経済成長 と文明化の影響」を重要な要素とする建築物の建設が含まれ、これはマッキンリー大統領の「慈悲深い同化政策」の一環として位置付けられていた。[28] 同様の「文明化」戦術は、1900年のプエルトリコのアメリカ植民地化にも取り入れられた。これには、1902年の離婚の合法化など、島の住民にアメリカの社会規範を植え付け、「新興の植民地秩序を正当化」するための広範な改革が含まれていた。[29] 植民地化された国民に期待された恩恵としては、「天然資源のより一層の搾取、物質的な生産の増加、生活水準の向上、市場の収益性の拡大、社会政治的安定」などが挙げられた。[30] しかし、1915年のハイチ占領は、アメリカの「文明化の使命」の暗い側面も露呈することになった。歴史家のメアリー・レンダは、ハイチ占領は「保護、教 育、経済支援」を提供するためではなく、「経済的搾取と戦略的優位性の目的」のみのために行われたと主張している[31]。 |

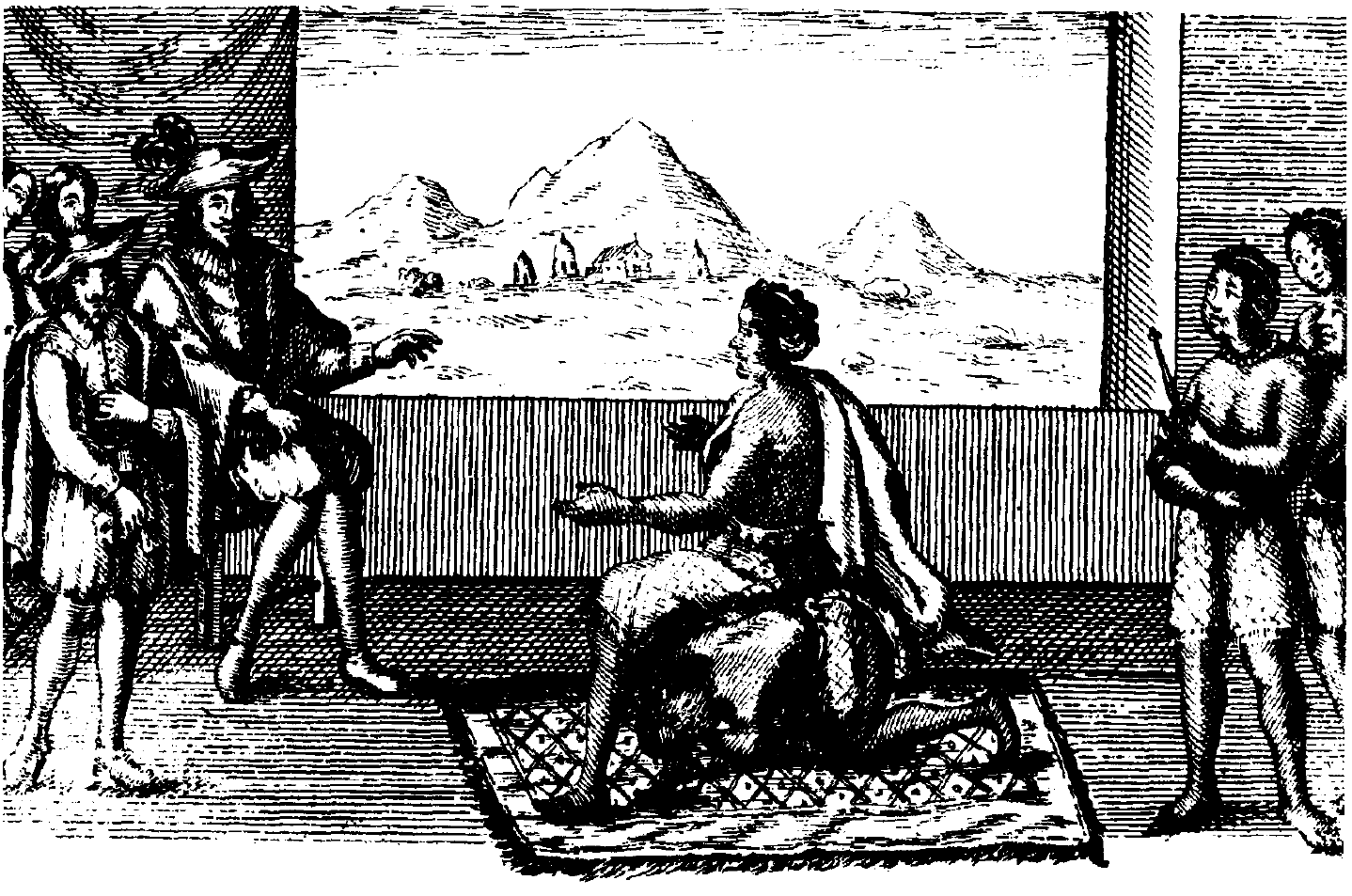

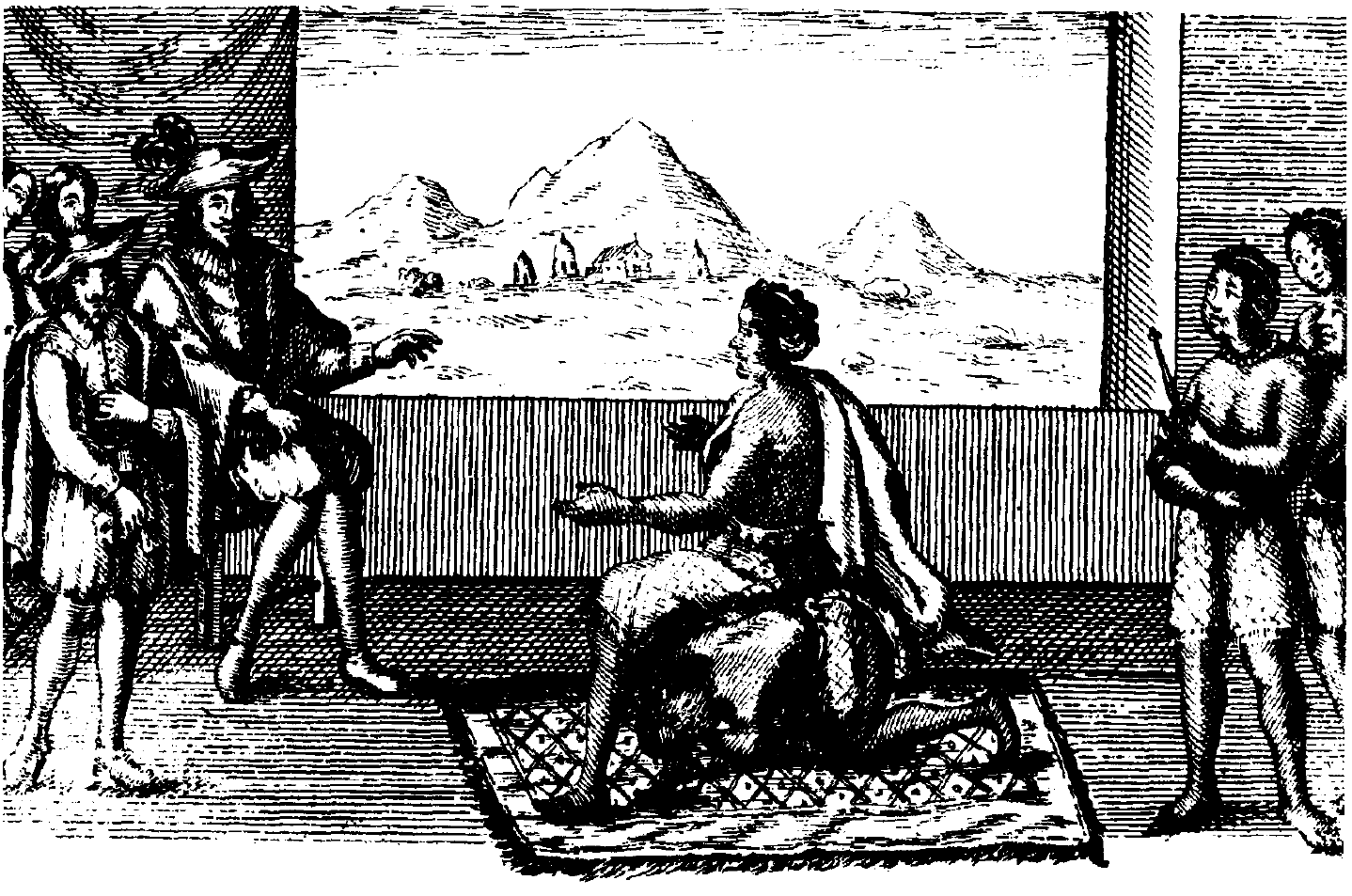

| Portugal After consolidating its territory in the 13th century through a Reconquista of the Muslim states of Western Iberia, the Kingdom of Portugal started to expand overseas. In 1415, Islamic Ceuta was occupied by the Portuguese during the reign of John I of Portugal. Portuguese expansion in North Africa was the beginning of a larger process eventually known as the Portuguese Overseas Expansion, under which the Kingdom's goals included the expansion of Christianity into Muslim lands and the desire of nobility for epic acts of war and conquest with the support of the Pope. As the Portuguese extended their influence around the coast to Mauritania, Senegambia (by 1445) and Guinea, they created trading posts. Rather than become direct competitors to the Muslim merchants, they used expanding market opportunities in Europe and the Mediterranean to increase trade across the Sahara.[33] In addition, Portuguese merchants gained access to the African interior via the Senegal and Gambia rivers, which crossed long-standing trans-Saharan routes. The Portuguese brought in copper ware, cloth, tools, wine and horses. Trade goods soon also included arms and ammunition. In exchange, the Portuguese received gold (transported from mines of the Akan deposits), pepper (a trade which lasted until Vasco da Gama reached India in 1498) and ivory. It was not until they reached the Kongo coast in the 1480s that they moved beyond Muslim trading territory in Africa. Forts and trading posts were established along the coast. Portuguese sailors, merchants, cartographers, priests and soldiers had the task of taking over the coastal areas, settling, and building churches, forts and factories, as well as exploring areas unknown to Europeans. A Company of Guinea was founded as a Portuguese governmental institution to control the trade, and called Casa da Guiné or Casa da Guiné e Mina from 1482 to 1483, and Casa da Índia e da Guiné in 1499. The first of the major European trading forts, Elmina, was founded on the Gold Coast in 1482 by the Portuguese. Elmina Castle (originally known as the "São Jorge da Mina Castle") was modeled on the Castelo de São Jorge, one of the earliest royal residences in Lisbon. Elmina, which means "the port", became a major trading center. By the beginning of the colonial era, there were forty such forts operating along the coast. Rather than being icons of colonial domination, the forts acted as trading posts – they rarely saw military action – the fortifications were important, however, when arms and ammunition were being stored prior to trade.[34] The 15th-century Portuguese exploration of the African coast, is commonly regarded as the harbinger of European colonialism, and also marked the beginnings of the Atlantic slave trade, Christian missionary evangelization and the first globalization processes which were to become a major element of the European colonialism until the end of the 18th century. Although the Portuguese Empire's policy regarding native peoples in the less technologically advanced places around the world (most prominently in Brazil) had always been devoted to enculturation, including teaching and evangelization of the indigenous populations, as well as the creation of novel infrastructure to openly support these roles, it reached its largest extent after the 18th century in what was then Portuguese Africa and Portuguese Timor. New cities and towns, with their Europe-inspired infrastructure, which included administrative, military, healthcare, educational, religious, and entrepreneurial halls, were purportedly designed to accommodate Portuguese settlers.  Queen Ana de Sousa Nzingha Mbande in peace negotiations with the Portuguese governor in Luanda, 1657 The Portuguese explorer Paulo Dias de Novais founded Luanda in 1575 as "São Paulo de Loanda", with a hundred families of settlers and four hundred soldiers. Benguela, a Portuguese fort from 1587 which became a town in 1617, was another important early settlement they founded and ruled. The Portuguese would establish several settlements, forts and trading posts along the coastal strip of Africa. In the Island of Mozambique, one of the first places where the Portuguese permanently settled in Sub-Saharan Africa, they built the Chapel of Nossa Senhora de Baluarte, in 1522, now considered the oldest European building in the southern hemisphere. Later the hospital, a majestic neo-classical building constructed in 1877 by the Portuguese, with a garden decorated with ponds and fountains, was for many years the biggest hospital south of the Sahara.[35] |

ポルトガル 13世紀に西イベリア半島のイスラム諸国を征服し、領土を統合したポルトガル王国は、海外への拡大を開始した。1415年、ポルトガル王ジョン1世の治世 中に、イスラム教徒の支配下にあったセウタがポルトガル軍によって占領された。北アフリカにおけるポルトガルの拡大は、最終的に「ポルトガル海外拡大」と して知られるようになったより大きなプロセスの始まりだった。この拡大では、王国はイスラム教徒の土地へのキリスト教の拡大と、教皇の支援を受けた貴族た ちの壮大な戦争と征服の願望を目標としていた。 ポルトガルは、沿岸部からモーリタニア、セネガル・ガンビア(1445年までに)、ギニアへと影響力を拡大し、交易拠点を設立した。イスラム商人との直接 的な競争を避けるため、彼らはヨーロッパと地中海における拡大する市場機会を活用してサハラ砂漠を越えた貿易を拡大した。[33] さらに、ポルトガル商人はセネガル川とガンビア川を通じてアフリカの内部地域へのアクセスを獲得した。これらの川は、長年存在するサハラ横断ルートと交差 していた。ポルトガル人は銅製品、布、工具、ワイン、馬を輸入した。貿易品にはやがて武器や弾薬も加わった。その見返りに、ポルトガル人は金(アカン鉱山 から運ばれた)、胡椒(この貿易は1498年にヴァスコ・ダ・ガマがインドに到着するまで続いた)、象牙を受け取った。ポルトガル人がアフリカにおけるイ スラム教徒の貿易地域を越えて進出したのは、1480年代にコンゴ海岸に達した時だった。 沿岸部に要塞と交易拠点が設立された。ポルトガル人水兵、商人、地図製作者、神父、兵士は、沿岸地域を支配し、定住し、教会、要塞、工場を建設する任務を 負った。また、ヨーロッパ人にとって未知の地域を探検した。貿易を管理するポルトガル政府機関として「ギニア会社」が設立され、1482年から1483年 までは「カサ・ダ・ギネ」、1499年には「カサ・ダ・インディア・エ・ダ・ギネ」と改称された。 ヨーロッパの主要な貿易要塞の最初のひとつであるエルミナは、1482年にポルトガル人によってゴールド・コーストに設立された。エルミナ城(当初は「サ ン・ジョルジェ・ダ・ミナ城」と呼ばれていた)は、リスボンの最も古い王室別邸の一つであるサン・ジョルジェ城をモデルに建設された。エルミナ(意味は 「港」)は主要な貿易中心地となった。植民地時代のはじめには、沿岸部に40の要塞が運営されていた。これらの要塞は植民地支配の象徴ではなく、貿易拠点 として機能し、軍事行動に巻き込まれることはほとんどなかった。ただし、貿易前の武器や弾薬の貯蔵には重要な役割を果たしていた。[34] 15世紀のポルトガルによるアフリカ沿岸の探検は、ヨーロッパの植民地主義の先駆けと見なされており、大西洋奴隷貿易、キリスト教宣教の始まり、そして 18世紀末までヨーロッパの植民地主義の主要な要素となる最初のグローバル化プロセスを画する出来事だった。 ポルトガル帝国は、技術的に後進的な地域(特にブラジル)の先住民に対して、先住民への教育やキリスト教の布教、そしてこれらの役割を公然と支援するため の新しいインフラの構築など、文化の同化に専心してきたが、その取り組みは 18 世紀以降、当時のポルトガル領アフリカとポルトガル領ティモールで最大規模に達した。ヨーロッパを模倣したインフラを備えた新しい都市や町が建設され、行 政、軍事、医療、教育、宗教、商業の施設が整備された。これらの施設は、ポルトガル人入植者を収容するために設計されたとされている。  1657年、ルアンダでポルトガル総督との和平交渉を行うアナ・デ・ソウザ・ンジンガ・ムバンデ女王 ポルトガル人探検家パウロ・ディアス・デ・ノヴァイスの手により、1575年に「サン・パウロ・デ・ロアンダ」としてルアンダが設立された。この都市には 100家族の入植者と400人の兵士が移住した。1587年にポルトガル要塞として建設され、1617年に町となったベンゲラも、彼らが設立し支配した重 要な初期の植民地の一つだ。ポルトガル人はアフリカ沿岸地帯に複数の植民地、要塞、貿易拠点を設立した。モザンビーク島は、ポルトガル人がサハラ以南のア フリカで最初に永久定住した場所の一つで、1522年に「ノッサ・セニョーラ・デ・バウアルテ礼拝堂」が建設され、現在では南半球で最も古いヨーロッパ建 築物とされている。その後、1877年にポルトガル人によって建設された壮麗な新古典主義建築の病院は、池と噴水で飾られた庭園を擁し、長年サハラ以南で 最大の病院として機能した。[35] |

| Estatuto do Indigenato The establishment of a dual, racialized civil society was formally recognized in Estatuto do Indigenato (The Statute of Indigenous Populations) adopted in 1929, and was based in the subjective concept of civilization versus tribalism. Portugal's colonial authorities were totally committed to develop a fully multiethnic "civilized" society in its African colonies, but that goal or "civilizing mission", would only be achieved after a period of Europeanization or enculturation of the native black tribes and ethnocultural groups. It was a policy which had already been stimulated in the former Portuguese colony of Brazil. Under Portugal's Estado Novo regime, headed by António de Oliveira Salazar, the Estatuto established a distinction between the "colonial citizens", subject to Portuguese law and entitled to citizenship rights and duties effective in the "metropole", and the indigenas (natives), subject to both colonial legislation and their customary, tribal laws. Between the two groups, there was a third small group, the assimilados, comprising native blacks, mulatos, Asians, and mixed-race people, who had at least some formal education, were not subjected to paid forced labor, were entitled to some citizenship rights, and held a special identification card that differed from the one imposed on the immense mass of the African population (the indigenas), a card that the colonial authorities conceived of as a means of controlling the movements of forced labor (CEA 1998). The indigenas were subject to the traditional authorities, who were gradually integrated into the colonial administration and charged with solving disputes, managing the access to land, and guaranteeing the flows of workforce and the payment of taxes. As several authors have pointed out (Mamdani 1996; Gentili 1999; O'Laughlin 2000), the Indigenato regime was the political system that subordinated the immense majority of native Africans to local authorities entrusted with governing, in collaboration with the lowest echelon of the colonial administration, the "native" communities described as tribes and assumed to have a common ancestry, language, and culture. After World War II, as communist and anti-colonial ideologies spread out across Africa, many clandestine political movements were established in support of independence. Regardless it was exaggerated anti-Portuguese/anti-"Colonial" propaganda,[36] a dominant tendency in Portuguese Africa, or a mix of both, these movements claimed that since policies and development plans were primarily designed by the ruling authorities for the benefit of the territories' ethnic Portuguese population, little attention was paid to local tribal integration and the development of its native communities. According to the official guerrilla statements, this affected a majority of the indigenous population who suffered both state-sponsored discrimination and enormous social pressure. Many felt they had received too little opportunity or resources to upgrade their skills and improve their economic and social situation to a degree comparable to that of the Europeans. Statistically, Portuguese Africa's Portuguese whites were indeed wealthier and more skilled than the black indigenous majority, but the late 1950s, the 1960s and principally the early 1970s, were being testimony of a gradual change based in new socioeconomic developments and equalitarian policies for all.[citation needed] |

先住民法 人種差別的な二重の市民社会の確立は、1929年に採択された先住民法(Estatuto do Indigenato)で正式に認められ、文明対部族主義という主観的な概念に基づいていました。ポルトガルの植民地当局は、アフリカ植民地において完全 に多民族的な「文明化された」社会を築くことに完全にコミットしていたが、その目標または「文明化の使命」は、先住の黒人部族や民族文化集団のヨーロッパ 化または同化を経て初めて達成されることになった。この政策は、かつてのポルトガル植民地であるブラジルでもすでに推進されていた。アントニオ・デ・オリ ベイラ・サラザール率いるポルトガルのエスタド・ノヴォ政権下、エスタトゥートは、ポルトガル法に服し、「大都市」で市民権と義務を享受する「植民地市 民」と、植民地法と慣習法、部族法の両方に服する「先住民」とを区別した。 この2つのグループの間には、先住民の黒人、ムラート(混血)、 アジア人、混血の人々で構成され、少なくともある程度の正式な教育を受けており、強制労働の対象とはならず、一部の市民権を有し、アフリカ系住民(先住 民)の大多数に課せられたものとは異なる特別な身分証明書を所持していた。この身分証明書は、植民地当局が強制労働者の移動を管理するための手段として考 案したものだった(CEA 1998)。インディジェナスは、徐々に植民地行政に統合され、紛争の解決、土地へのアクセス管理、労働力の流動と税金の支払いの保証を担当する伝統的権 威の支配下に置かれていた。複数の研究者が指摘するように(Mamdani 1996; Gentili 1999; O'Laughlin 2000)、インディジェナート制度は、植民地行政の最下層と協力して「部族」と称され、共通の祖先、言語、文化を持つと仮定された「原住民」コミュニ ティを統治する地方当局に、アフリカ原住民の圧倒的多数を従属させる政治体制だった。 第二次世界大戦後、共産主義と反植民地主義の思想がアフリカに広まる中、独立を支援する多くの秘密政治運動が設立された。それは、ポルトガル支配に対する 反感や反「植民地」の宣伝が誇張されていた[36] ためか、あるいはその両方が混ざり合ったためか、これらの運動は、政策や開発計画は主に、その領土のポルトガル系住民のために支配当局によって策定されて いるため、現地の部族の統合や先住民コミュニティの発展にはほとんど注意が払われていないと主張した。ゲリラの公式声明によると、このことは、国家による 差別と大きな社会的圧力の両方に苦しむ先住民の大半に影響を及ぼした。多くの人々は、ヨーロッパ人と同等のスキルや経済・社会状況を向上させるための機会 や資源が、あまりにも少なすぎると感じていた。統計上、ポルトガル領アフリカのポルトガル系白人は、黒人先住民の多数派よりも裕福で技能が高かったが、 1950年代後半、1960年代、特に1970年代前半は、新たな社会経済的発展とすべての住民を対象とした平等主義的政策に基づく漸進的な変化の証左と なっていた。[出典が必要] |

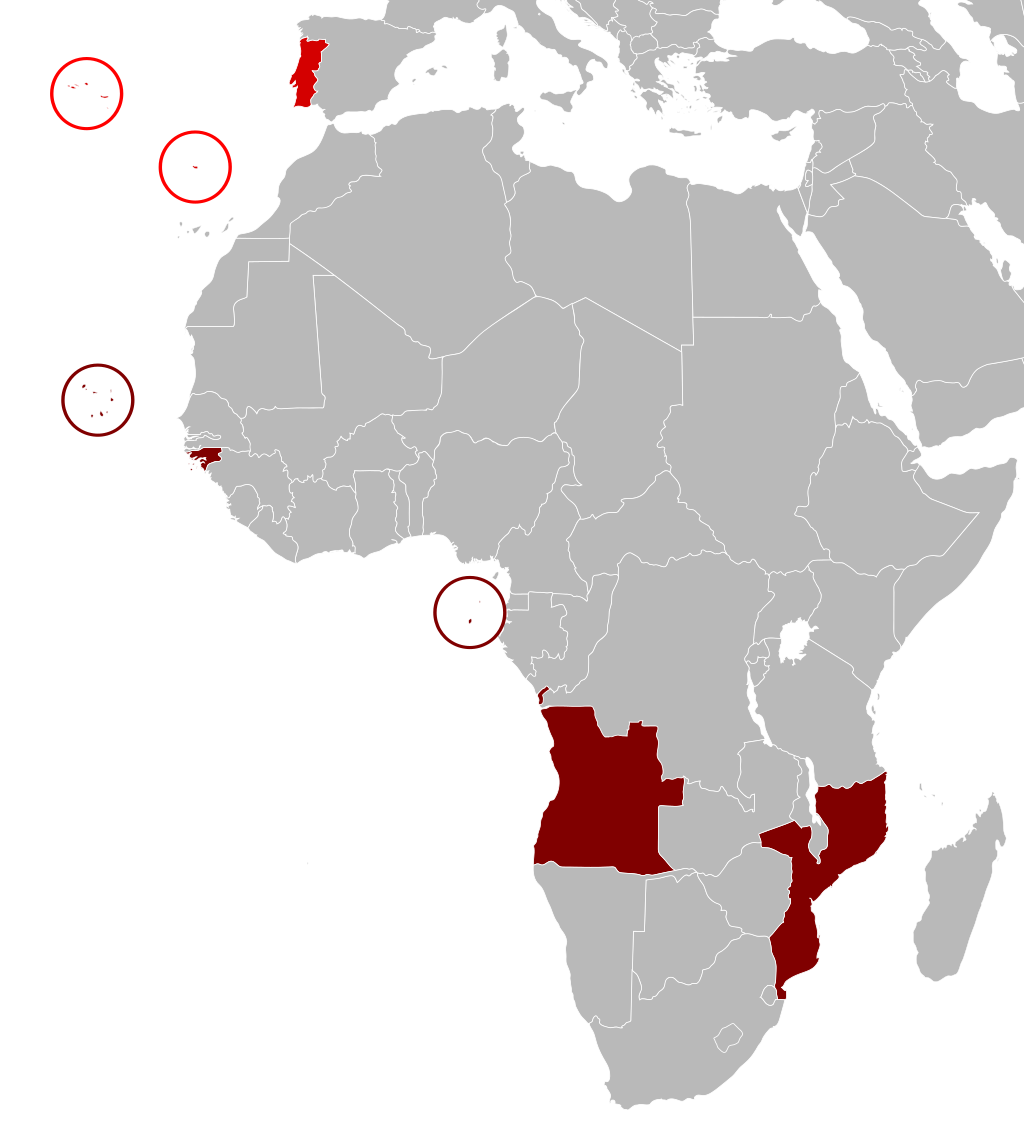

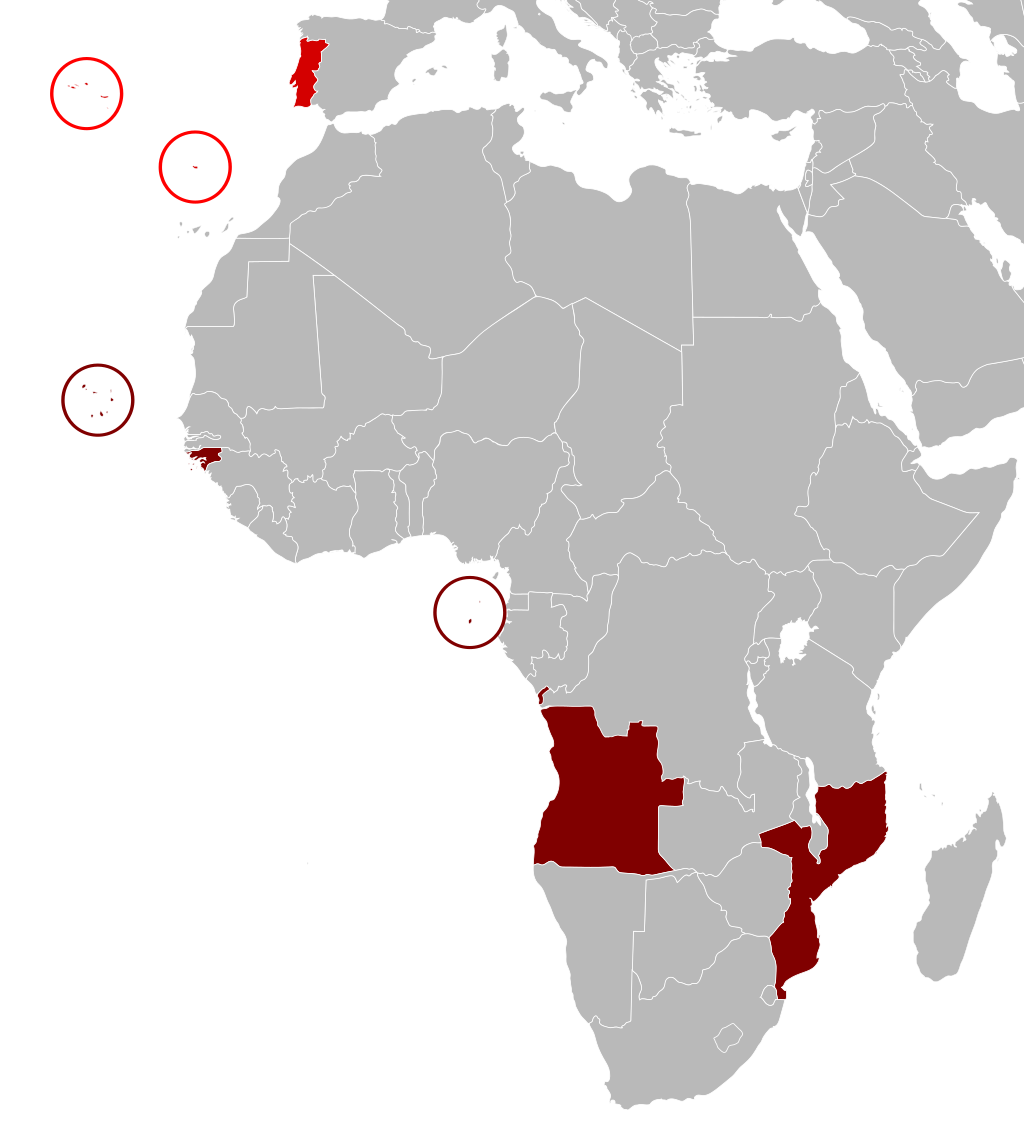

Colonial wars Portuguese overseas territories in Africa during the Estado Novo regime (1933–1974): Angola and Mozambique were by far the two largest of those territories The Portuguese Colonial War began in Portuguese Angola on 4 February 1961, in an area called the Zona Sublevada do Norte (ZSN or the Rebel Zone of the North), consisting of the provinces of Zaire, Uíge and Cuanza Norte. The U.S.-backed UPA wanted national self-determination, while for the Portuguese, who had settled in Africa and ruled considerable territory since the 15th century, their belief in a multi-racial, assimilated overseas empire justified going to war to prevent its breakup and protect its populations.[37] Portuguese leaders, including António de Oliveira Salazar, defended the policy of multiracialism, or Lusotropicalism, as a way of integrating Portuguese colonies, and their peoples, more closely with Portugal itself.[38] For the Portuguese ruling regime, the overseas empire was a matter of national interest. In Portuguese Africa, trained Portuguese black Africans were allowed to occupy positions in several occupations including specialized military, administration, teaching, health, and other posts in the civil service and private businesses, as long as they had the right technical and human qualities. In addition, intermarriage of black women with white Portuguese men was a common practice since the earlier contacts with the Europeans. The access to basic, secondary, and technical education was being expanded and its availability was being increasingly opened to both the indigenous and European Portuguese of the territories. Examples of this policy include several black Portuguese Africans who would become prominent individuals during the war or in the post-independence, and who had studied during the Portuguese rule of the territories in local schools or even in Portuguese schools and universities in the mainland (the metropole) – Samora Machel, Mário Pinto de Andrade, Marcelino dos Santos, Eduardo Mondlane, Agostinho Neto, Amílcar Cabral, Joaquim Chissano, and Graça Machel are just a few examples. Two large state-run universities were founded in Portuguese Africa in the early 1960s (the Universidade de Luanda in Angola and the Universidade de Lourenço Marques in Mozambique, awarding a wide range of degrees from engineering to medicine[39]), during a time that in the European mainland only four public universities were in operation, two of them in Lisbon (which compares with the 14 Portuguese public universities today). Several figures in Portuguese society, including one of the most idolized sports stars in Portuguese football history, a black football player from Portuguese East Africa named Eusébio, were other examples of assimilation and multiracialism. Since 1961, with the beginning of the colonial wars in its overseas territories, Portugal had begun to incorporate black Portuguese Africans in the war effort in Angola, Portuguese Guinea, and Portuguese Mozambique based on concepts of multi-racialism and preservation of the empire. African participation on the Portuguese side of the conflict ranged from marginal roles as laborers and informers to participation in highly trained operational combat units, including platoon commanders. As the war progressed, the use of African counterinsurgency troops increased; on the eve of the military coup of 25 April 1974, Africans accounted for more than 50 percent of Portuguese forces fighting the war. Due to the technological gap between both civilizations and the centuries-long colonial era, Portugal was a driving force in the development and shaping of all Portuguese Africa since the 15th century. In the 1960s and early 1970s, in order to counter the increasing insurgency of the nationalistic guerrillas and show to the Portuguese people and the world that the overseas territories were totally under control, the Portuguese government accelerated its major development programs to expand and attempted to upgrade the infrastructure of the overseas territories in Africa by creating new roads, railways, bridges, dams, irrigation systems, schools and hospitals to stimulate an even higher level of economic growth and support from the populace.[40] As part of this redevelopment program, construction of the Cahora Bassa Dam began in 1969 in the Overseas Province of Mozambique (the official designation of Portuguese Mozambique by then). This particular project became intrinsically linked with Portugal's concerns over security in the overseas colonies. The Portuguese government viewed the construction of the dam as a testimony to Portugal's "civilizing mission"[41] and intended for the dam to reaffirm Mozambican belief in the strength and security of the Portuguese colonial government. |

植民地戦争 エスタド・ノヴォ政権(1933年~1974年)時代のポルトガルのアフリカ海外領土:アンゴラとモザンビークは、これらの領土の中で群を抜いて最大の2つだった ポルトガル植民地戦争は、1961年2月4日、ポルトガル領アンゴラの「北反乱地域」(Zona Sublevada do Norte、ZSN)と呼ばれる地域で始まった。この地域はザイール、ウイゲ、クアンザ・ノルテの3州から成っていた。米国が支援する UPA は、民族の自己決定を望んでいたが、15 世紀以来アフリカに定住し、広大な領土を支配していたポルトガル人は、多民族が融合した海外帝国を信奉しており、その崩壊を防ぎ、住民を守るために戦争を 行うことは正当であると主張した。[37] アントニオ・デ・オリベイラ・サラザールをはじめとするポルトガルの指導者たちは、多民族主義、すなわち「ルソトロピカリズム」を、ポルトガルの植民地と その住民をポルトガル本体とより緊密に統合するための政策として擁護した。[38] ポルトガルの支配政権にとって、海外帝国は国益の問題だった。ポルトガル領アフリカでは、訓練を受けたポルトガル系アフリカ人は、適切な技術的および人間 的資質を備えている限り、専門的軍事、行政、教育、保健、その他の公務員や民間企業の職に就くことが認められていた。さらに、ヨーロッパ人との接触が始 まった当初から、黒人女性と白人ポルトガル人男性の間の婚姻は一般的な慣習だった。基礎教育、中等教育、技術教育へのアクセスが拡大され、その利用は、領 土内の先住民とヨーロッパ系ポルトガル人の双方にますます開放されていった。 この政策の例としては、戦争中や独立後に著名な人物となった、ポルトガル領で現地の学校、あるいは本土のポルトガル学校や大学で学んだ、複数の黒人ポルト ガル系アフリカ人が挙げられる。(本土)で学んだ黒人ポルトガル系アフリカ人が挙げられる。サモラ・マシェル、マリオ・ピント・デ・アンドラーデ、マルセ リーノ・ドス・サントス、エドゥアルド・モンドラーネ、アゴスティーニョ・ネト、アミルカル・カブラル、ジョアキン・チサノ、グラサ・マシェルなどはその 一部だ。1960年代初頭、ポルトガル領アフリカに2つの大規模な国立大学が設立された(アンゴラのルアンダ大学とモザンビークのロレンソ・マルケス大 学。工学から医学まで幅広い学位を授与していた[39])。この当時、ヨーロッパ本土では4つの公立大学しか存在せず、そのうち2つはリスボンにありまし た(現在のポルトガル公立大学は14校)。ポルトガル社会におけるいくつかの著名人、特にポルトガルサッカー史上最も崇拝されるスポーツ選手の1人であ る、ポルトガル東アフリカ出身の黒人サッカー選手エウゼビオは、同化と多民族主義の他の例として挙げられる。 1961 年、海外領土での植民地戦争が始まって以来、ポルトガルは多民族主義と帝国維持の概念に基づき、アンゴラ、ポルトガル領ギニア、ポルトガル領モザンビーク での戦争に、黒人のポルトガル系アフリカ人を参加させるようになった。紛争におけるポルトガル側のアフリカ人の参加は、労働者や情報提供者といった周辺的 な役割から、小隊長を含む高度な訓練を受けた作戦部隊への参加まで多岐にわたった。戦争が進むにつれ、アフリカ人反乱鎮圧部隊の活用が増加し、1974年 4月25日の軍事クーデター直前に、戦争に従事するポルトガル軍兵士の50%以上がアフリカ人だった。両文明の技術的格差と数百年に及ぶ植民地支配の時代 背景から、ポルトガルは15世紀以来、ポルトガル領アフリカの発展と形成に主導的な役割を果たしてきた。 1960年代から1970年代初頭にかけて、ナショナリストのゲリラの反乱の高まりに対抗し、ポルトガル国民と世界に対して海外領土が完全に支配下にある ことを示すため、ポルトガル政府は、大規模な開発プログラムを加速し、アフリカにある海外領土のインフラ整備を推進した。ダム、灌漑システム、学校、病院 などを建設し、より一層の経済成長と民衆の支持の獲得を図った[40]。この再開発プログラムの一環として、1969年にモザンビーク海外州(当時のポル トガル領モザンビークの正式名称)でカホラ・バサダムの建設が開始された。このプロジェクトは、ポルトガルの海外植民地の治安に対する懸念と密接に関連し ていた。ポルトガル政府はダムの建設をポルトガルの「文明化の使命」の証と見なし、ダムがモザンビークの住民にポルトガル植民地政府の力と安全保障への信 頼を再確認させることを意図していた。 |

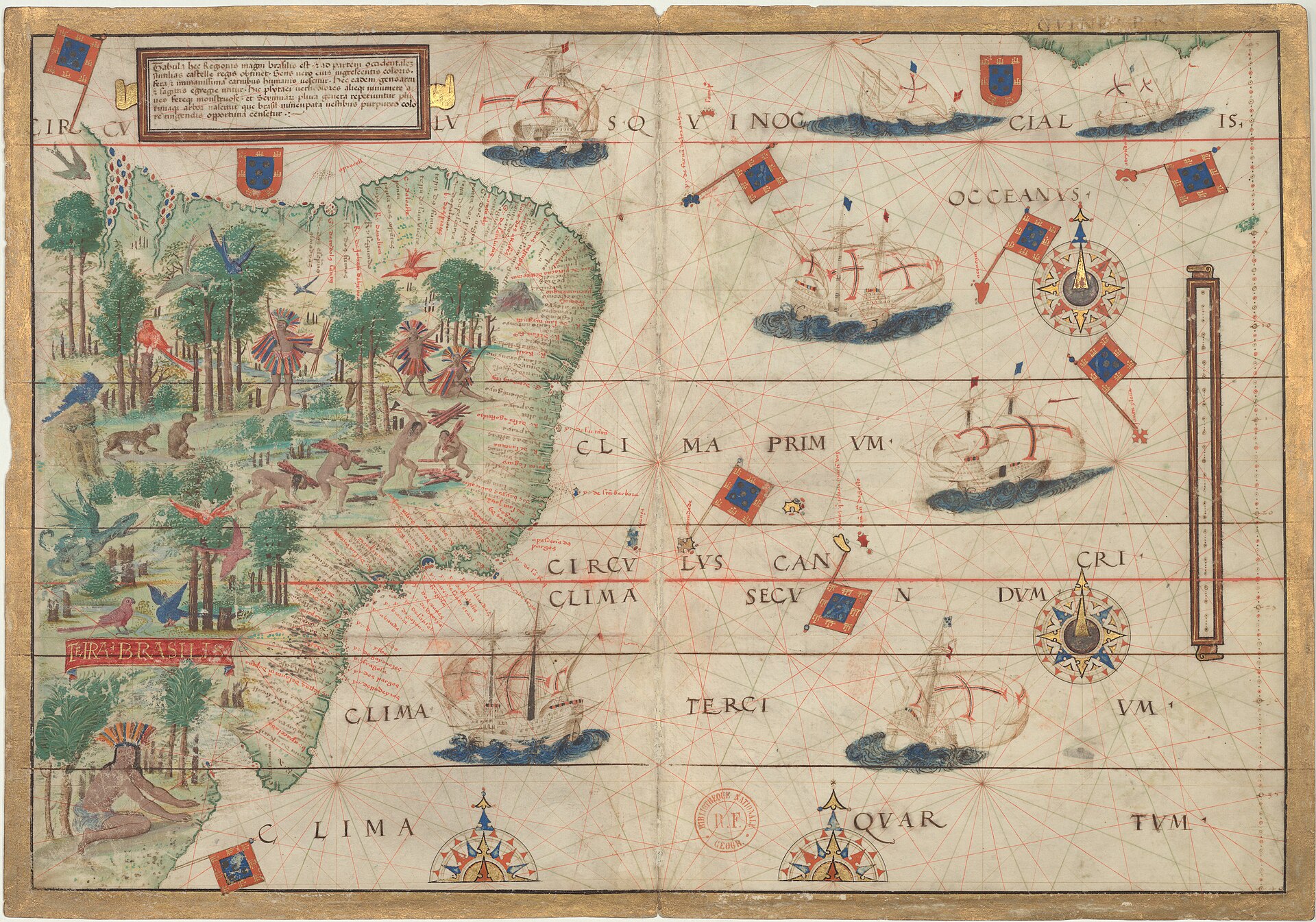

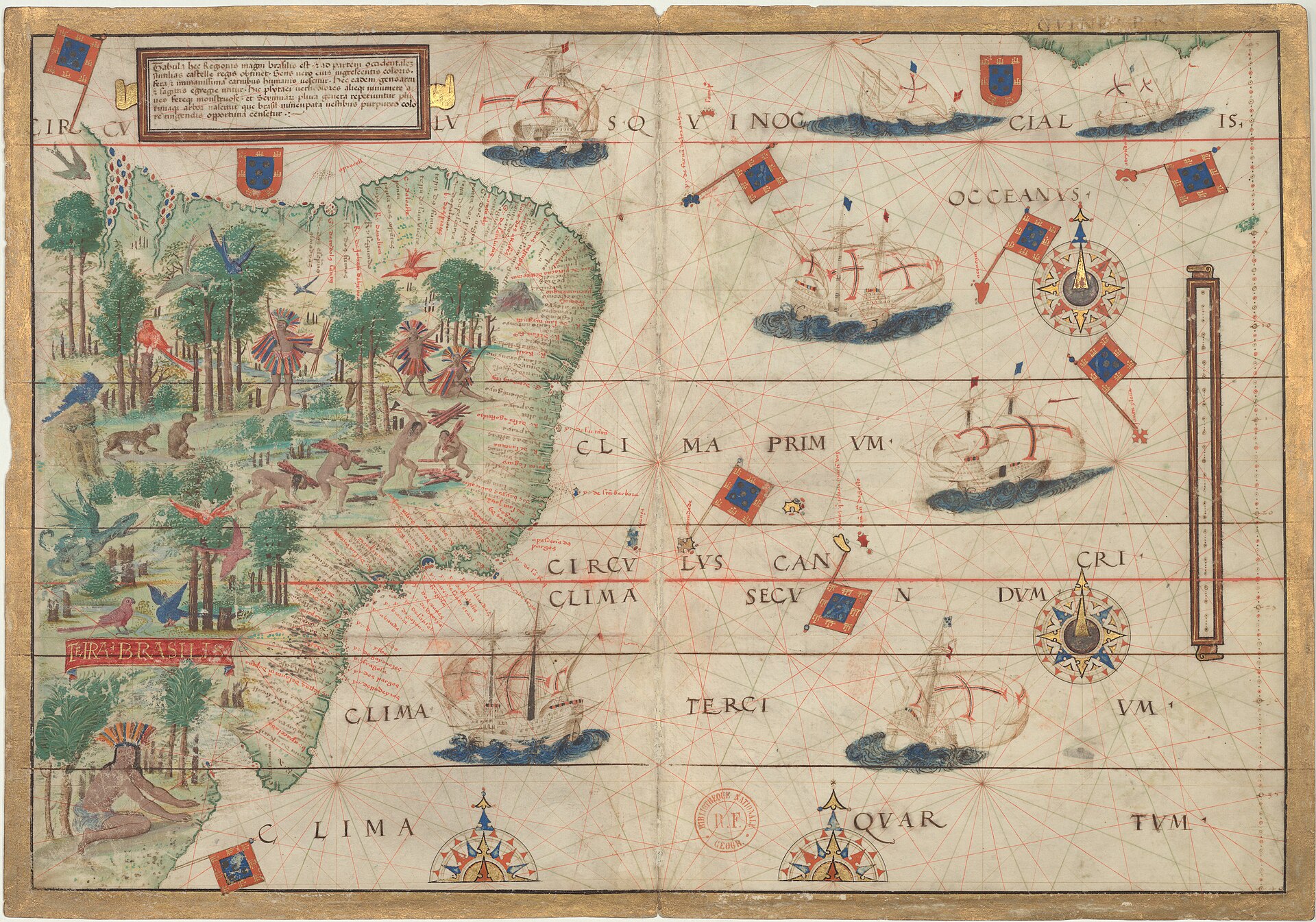

Brazil Portuguese map by Lopo Homem (c. 1519) showing the coast of Brazil and natives extracting brazilwood, as well as Portuguese ships When the Portuguese explorers arrived in 1500, the Amerindians were mostly semi-nomadic tribes, with the largest population living on the coast and along the banks of major rivers. Unlike Christopher Columbus who thought he had reached India, the Portuguese sailor Vasco da Gama had already reached India sailing around Africa two years before Pedro Álvares Cabral reached Brazil. Nevertheless, the word índios ("Indians") was by then established to designate the peoples of the New World and remains so (it is used to this day in the Portuguese language, the people of India being called indianos). Initially, the Europeans saw the natives as noble savages, and miscegenation began straight away. Tribal warfare and cannibalism convinced the Portuguese that they should "civilize" the Amerindians,[42] even if one of the four groups of Aché people in Paraguay practiced cannibalism regularly until the 1960s.[43] When the Kingdom of Portugal's explorers discovered Brazil in the 15th century and started to colonize its new possessions in the New World, the territory was inhabited by various indigenous peoples and tribes which had developed neither a writing system nor school education. The Society of Jesus (Jesuits) has been since its founding in 1540 as a missionary order. Evangelization was one of the primary goals of the Jesuits; however, they were also committed to an education both in Europe and overseas. Their missionary activities, both in the cities and in the countryside, were complemented by a strong commitment to education. This took the form of the opening of schools for young boys, first in Europe, but soon extended to both America and Asia. The foundation of Catholic missions, schools, and seminaries was another consequence of the Jesuit involvement in education. As the spaces and cultures where the Jesuits were presently varied considerably, their evangelizing methods diverged by location. However, the Society's engagement in trade, architecture, science, literature, languages, arts, music, and religious debate corresponded, in fact, to the common and foremost purpose of Christianization. By the middle of the 16th century, the Jesuits were present in West Africa, South America, Ethiopia, India, China, and Japan. In a period of history when the world had a largely illiterate population, the Portuguese Empire, was home to one of the first universities founded in Europe – the University of Coimbra, which currently is still one of the oldest universities. Throughout the centuries of Portuguese rule, Brazilian students, mostly graduated in the Jesuit missions and seminaries, were allowed and even encouraged to enroll at higher education in mainland Portugal. By 1700, and reflecting a larger transformation of the Portuguese Empire, the Jesuits had decisively shifted their activity from the East Indies to Brazil. In the late 18th century, the Portuguese minister of the kingdom Marquis of Pombal attacked the power of the privileged nobility and the church and expelled the Jesuits from Portugal and its overseas possessions. Pombal seized the Jesuit schools and introduced educational reforms all over the empire. In 1772, even before the establishment of the Science Academy of Lisbon (1779), one of the first learned societies of both Brazil and the Portuguese Empire, the Sociedade Scientifica, was founded in Rio de Janeiro. Furthermore, in 1797, the first botanic institute was founded in Salvador, Bahia. During the late 18th century, the Escola Politécnica (then the Real Academia de Artilharia, Fortificação e Desenho) of Rio de Janeiro was created in 1792 through a decree issued by the Portuguese authorities as a higher education school for the teaching of the sciences and engineering. It belongs today to the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro and is the oldest engineering school of Brazil, and one of the oldest in Latin America. A royal letter of November 20, 1800 by the King John VI of Portugal established in Rio de Janeiro the Aula Prática de Desenho e Figura, the first institution in Brazil dedicated to teaching the arts. During colonial times, the arts were mainly religious or utilitarian and were learned in a system of apprenticeship. A Decree of August 12, 1816, created an Escola Real de Ciências, Artes e Ofícios (Royal School of Sciences, Arts and Crafts), which established an official education in the fine arts and was the foundation of the current Escola Nacional de Belas Artes. In the 19th century, the Portuguese royal family, headed by João VI, arrived in Rio de Janeiro escaping from the Napoleon's army invasion of Portugal in 1807. João VI gave impetus to the expansion of European civilization in Brazil.[44] In a short period between 1808 and 1810, the Portuguese government founded the Royal Naval Academy and the Royal Military Academy, the Biblioteca Nacional, the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden, the Medico-Chirurgical School of Bahia, currently known as the "Faculdade de Medicina" under the purview of the Universidade Federal da Bahia and the Medico-Chirurgical School of Rio de Janeiro which is the modern-day Faculdade de Medicina of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. |

ブラジル ロポ・オメム(1519年頃)によるポルトガル語の地図。ブラジルの海岸と、ブラジルの木を伐採する先住民、そしてポルトガル船が描かれている。 1500年にポルトガルの探検家が到着したとき、アメリカ先住民は主に半遊牧の部族で、その大部分は海岸や主要な川の河岸沿いに住んでいた。インドに到達 したと信じていたクリストファー・コロンブスとは異なり、ポルトガルの航海士ヴァスコ・ダ・ガマは、ペドロ・アルヴァレス・カブラルがブラジルに到達する 2 年前に、アフリカを周航してすでにインドに到達していました。それにもかかわらず、「インディオ(インディアン)」という言葉は、新大陸の人々を指す言葉 として定着し、現在もその意味のまま使用されています(ポルトガル語では、インドの人々は「インディアーノス」と呼ばれています)。 当初、ヨーロッパ人は先住民を「高貴な野蛮人」と見なし、すぐに人種混交が始まった。部族間の戦争や人食いの習慣から、ポルトガル人はアメリカ先住民を 「文明化」すべきだと確信した[42]が、パラグアイの 4 つのアチェ族のうち 1 つは 1960 年代まで人食いの習慣を定期的に続けていた。[43] 15 世紀、ポルトガル王国の探検家がブラジルを発見し、新大陸の新しい領土の植民地化を開始したとき、この地域には、文字や学校教育を発達させていなかったさ まざまな先住民や部族が住んでいた。 イエズス会(イエズス会)は、1540年の設立以来、宣教修道会として活動してきた。宣教はイエズス会の主要な目標の一つだったが、彼らはヨーロッパと海 外の両方で教育にも尽力した。都市部と農村部での宣教活動は、教育への強いコミットメントによって補完された。これは、まずヨーロッパで少年向けの学校を 開校する形で始まり、やがてアメリカとアジアにも拡大した。カトリックの宣教基地、学校、神学校の設立は、イエズス会の教育への関与のもう一つの結果だっ た。イエズス会が活動していた地域や文化は多岐にわたり、その伝道方法は場所によって異なっていました。しかし、イエズス会が貿易、建築、科学、文学、言 語、芸術、音楽、宗教論争などに携わっていたことは、実際にはキリスト教化という共通かつ最優先の目標と一致していたのです。 16世紀半ばまでに、イエズス会は西アフリカ、南アメリカ、エチオピア、インド、中国、そして日本にその足跡を残していました。世界の大部分が文盲だった 時代、ポルトガル帝国にはヨーロッパで最初に設立された大学の一つであるコインブラ大学があり、現在も最も古い大学の一つとして存続している。ポルトガル 統治の時代を通じて、イエズス会の宣教活動や神学校で学んだブラジル人学生は、ポルトガル本土の高等教育機関への入学が許可され、甚至い奨励されていた。 1700年までに、ポルトガル帝国の大きな変革を反映して、イエズス会は東インドからブラジルへの活動を決定的に移行した。18世紀後半、ポルトガル王国 の大臣であるポンバル侯爵は、特権貴族と教会の権力を攻撃し、イエズス会をポルトガルとその海外植民地から追放した。ポンバルはイエズス会の学校を接収 し、帝国全土で教育改革を導入した。 1772年、リスボン科学アカデミー(1779年設立)よりも前に、ブラジルとポルトガル帝国で最初の学術団体の一つである「科学協会」がリオデジャネイ ロに設立された。さらに、1797年には、サルバドール(バイア州)に最初の植物研究所が設立された。18世紀後半、ポルトガル当局の勅令により、科学と 工学の高等教育機関として、リオデジャネイロにエスクーラ・ポリテクニカ(当時、レアル・アカデミア・デ・アルティリアリア、フォルティフィカサオ・エ・ デゼニョ)が設立された。現在、リオデジャネイロ連邦大学に属し、ブラジル最古の工学学校であり、ラテンアメリカでも最も古い工学学校の一つだ。1800 年11月20日、ポルトガル王ジョン6世の勅令により、リオデジャネイロにブラジル初の美術教育機関である「アウラ・プラティカ・デ・デセンホ・エ・フィ グーラ」が設立された。植民地時代、美術は主に宗教的または実用的な目的で、徒弟制度によって学ばれていた。1816年8月12日の勅令により、王立科 学・芸術・工芸学校(Escola Real de Ciências, Artes e Ofícios)が設立され、美術の公式教育が開始され、現在の国立美術学校(Escola Nacional de Belas Artes)の基礎となった。 19世紀、ポルトガル王室は、1807年のナポレオン軍によるポルトガル侵攻から逃れてリオデジャネイロに避難した。ジョアン6世は、ブラジルにおける ヨーロッパ文明の拡大に拍車をかけた。[44] 1808年から1810年の短い期間に、 ポルトガル政府は、王立海軍アカデミー、王立陸軍士官学校、国立図書館、リオデジャネイロ植物園、バイア医科大学(現在はバイア連邦大学傘下の 「Faculdade de Medicina」として知られている)、リオデジャネイロ医科大学(現在のリオデジャネイロ連邦大学医学部)を設立した。 |

| Chile Nineteenth century elites of South American republics also used a civilizing mission rhetoric to justify armed actions against indigenous groups. On January 1, 1883, Chile refounded the old city of Villarrica, thus formally ending the process of the occupation of the indigenous lands of Araucanía.[45][46] Six months later, on June 1, president Domingo Santa María declared:[47] The country has with satisfaction seen the problem of the reduction of the whole Araucanía solved. This event, so important to our social and political life, and so significant for the future of the republic, has ended, happily and with costly and painful sacrifices. Today the whole Araucanía is subjugated, more than to the material forces, to the moral and civilizing force of the republic ... Chileans also deployed a "civilizatory crusade" discourse against Peru and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific (1879–1884). Along these lines Peru and Bolivia were seen as representatives of a backward Ancien régime that fought its wars with armies of indigenous barbarians.[48] Negative views of this types also occurred among Peruvians as after the war, the indigenous peoples in Peru became scapegoats in the narratives of Peruvian criollo elites, exemplified in the writing of Ricardo Palma: The principal cause of the great defeat is that the majority of Peru is composed of that wretched and degraded race that we once attempted to dignify and ennoble. The Indian lacks patriotic sense; he is born enemy of the white and of the man of the coast. It makes no difference to him whether he is a Chilean or a Turk. To educate the Indian and to inspire him a feeling for patriotism will not be the task of our institutions, but of the ages.[49] |

チリ 19世紀の南米諸共和国のエリートたちは、先住民グループに対する武力行使を正当化するために、文明化の使命のレトリックを用いた。1883年1月1日、 チリは旧ヴィラリカ市を再建し、アラウカニアの先住民土地の占領を正式に終結させた。[45][46] 6か月後の6月1日、ドミンゴ・サンタ・マリア大統領は次のように宣言した。[47] 国は、アラウカニア全体の縮小の問題が解決されたことを満足して受け止めている。私たちの社会および政治生活にとって非常に重要であり、共和国の将来に とっても非常に意味のあるこの出来事は、多大な犠牲と苦痛を伴ったものの、幸いなことに終結した。今日、アラウカニア全体は、物質的な力よりも、共和国の 道徳的かつ文明化力によって征服されている... チリ人は、太平洋戦争(1879年~1884年)でも、ペルーとボリビアに対して「文明化十字軍」という言説を展開した。この考えに沿って、ペルーとボリ ビアは、先住民である野蛮人の軍隊で戦争を行う、後進的な旧体制の代表者と見なされた。[48] このような否定的な見方は、戦争後もペルー人の間でも見られ、ペルーの先住民は、リカルド・パルマの著作に代表されるペルーのクリオージョ(植民地支配 層)のエリートたちの物語の中で、スケープゴートにされた。 大敗の主な原因は、ペルーの大部分が、かつて私たちが尊厳と高貴さを与えた、惨めで堕落した人種で構成されていることにある。インディアンには愛国心がな い。彼らは白人や海岸の住民を敵として生まれ、チリ人であろうとトルコ人であろうと、彼らには何の違いもない。インディアンを教育し、愛国心を植え付ける ことは、私たちの機関の仕事ではなく、何世紀にもわたる仕事だ。[49] |

| Modern day See also: Western values (West) Pinkwashing, the strategy of promoting LGBT rights protections as evidence of liberalism and democracy, has been described as a continuation of the civilizing mission used to justify colonialism, this time on the basis of LGBT rights in Western countries.[50][51] |

現代 参照:西洋の価値観(西洋) ピンクウォッシングとは、LGBT の権利保護を自由主義や民主主義の証拠として宣伝する戦略のこと。これは、植民地主義を正当化するために用いられた文明化の使命の継続であり、今回は西洋諸国における LGBT の権利を根拠としていると評されている。[50][51] |

| Christian mission – Organized effort to spread Christianity Cultural assimilation – Adoption of features of another culture Cultural backwardness – Soviet political term Cultural imperialism – Cultural aspects of imperialism Blaise Diagne – Senegalese and French politician (1872–1934) Development theory – Theories about how desirable change in society is best achieved Discourse on Colonialism – Essay by Aimé Césaire Ethnocide – Extermination of a culture Faccetta Nera French law on colonialism Forced assimilation – Involuntary cultural assimilation of minority groups Indoctrination – Inculcating a person with certain ideas Lusotropicalism – Historical concept of Portuguese suitability as a coloniser Macaulayism – Education policy introduced in British colonies Manifest destiny – Cultural belief of 19th-century American expansionists Postcolonial amnesia Western education – Education from the Western world White savior – Sarcastic or critical description The White Man's Burden – Poem by the English poet Rudyard Kipling |

キリスト教の布教活動 – キリスト教を広めるための組織的な取り組み 文化同化 – 他の文化の特徴を採用すること 文化の遅滞 – ソビエトの政治用語 文化帝国主義 – 帝国主義の文化的側面 ブレース・ディアネ – セネガルとフランスの政治家(1872–1934) 開発理論 – 社会における望ましい変化を最もよく達成する方法に関する理論 植民地主義に関する言説 – エメ・セゼールによるエッセイ 民族自滅 – 文化の絶滅 ファチェッタ・ネラ 植民地主義に関するフランスの法律 強制同化 – 少数民族の非自発的な文化同化 教化 – ある考えを人格に植え付けること ルソトロピカリズム – ポルトガルが植民地支配に適しているとする歴史的概念 マコーレー主義 – イギリスの植民地で導入された教育政策 マニフェスト・デスティニー – 19世紀のアメリカ拡張主義者の文化的信念 ポストコロニアル・アメーニア 西洋教育 – 西洋世界における教育 ホワイト・セイバー – 皮肉的または批判的な表現 ホワイト・マンズ・バーデン – イギリスの詩人ルディヤード・キップリングの詩 |

| Adas, Michael (2006). Dominance

by Design: Technological Imperatives and America's Civilizing Mission.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Aldrich, Robert (1996). Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 0-312-16000-3. Anderson, Warwick (1995). "Excremental Colonialism: Public Health or the Poetics of Pollution". Critical Inquiry. 21 (3): 640–669. doi:10.1086/448767. ISSN 0093-1896. S2CID 161471633. Conklin, Alice L. (1998). A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa 1895–1930. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2999-4. Conklin, Alice L. (1998). "Colonialism and Human Rights, A Contradiction in Terms? The Case of France and West Africa, 1895–1914". The American Historical Review. 103 (2): 419–442. doi:10.2307/2649774. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 2649774. Costantini, Dino (2008). Mission civilisatrice. Le rôle de l'histoire coloniale dans la construction de l'identité politique française (in French). Paris: La Découverte. Daughton, J. P. (2006). An Empire Divided: Religion, Republicanism, and the Making of French Colonialism, 1880–1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537401-8. Falser., Michael (2015). Cultural Heritage as Civilizing Mission. From Decay to Recovery. Heidelberg, New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-13638-7. Findlay, Eileen J. Suarez (1999). Imposing Decency: The Politics of Sexuality and Race in Puerto Rico, 1870–1920. Durham: Duke University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv125jpk1. ISBN 978-0-8223-2375-4. Retrieved February 20, 2022. Jerónimo, Miguel Bandeira (2015). The 'civilizing mission' of Portuguese colonialism. Houndsmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137355904. Manning, Patrick (1998). Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa, 1880–1995 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64255-8. Mitchell, Timothy (1991). Colonizing Egypt. Berkeley: University of California Press. Olstein, Diego; Hübner, Stefan, eds. (2016). "Preaching the Civilizing Mission and Modern Cultural Encounters" (special issue). Journal of World History. 27 (2). ISSN 1527-8050. Renda, Mary (2001). "Moral Breakdown". Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940. Chapel Hill. pp. 131–181. Jean Suret-Canale. Afrique Noire: l'Ere Coloniale (Editions Sociales, Paris, 1971) Eng. translation, French Colonialism in Tropical Africa, 1900–1945. (New York, 1971). Tezcan, Levent (2012). Das muslimische Subjekt: Verfangen im Dialog der Deutschen Islam Konferenz. Konstanz: Konstanz University Press. Thurman, Kira (2016). "Singing the Civilizing Mission in the Land of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms: The Fisk Jubilee Singers in Nineteenth-Century Germany". Journal of World History. 27 (3): 443–471. doi:10.1353/jwh.2016.0116. ISSN 1527-8050. S2CID 151616806. Retrieved February 19, 2022. Young, Crawford (1994). The African Colonial State in Comparative Perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06879-4. |

アダス、マイケル (2006)。『デザインによる支配:技術的要請とアメリカの文明化の使命』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。 アルドリッチ、ロバート (1996)。『大フランス:フランス海外拡大の歴史』。パームグレイブ・マクミラン。ISBN 0-312-16000-3。 アンダーソン、ワーウィック (1995)。「排泄物による植民地主義:公衆衛生か、それとも汚染の詩学か」。クリティカル・インクワイアリー。21 (3): 640–669. doi:10.1086/448767. ISSN 0093-1896. S2CID 161471633. コンクリン、アリス L. (1998)。文明化への使命:フランスと西アフリカにおける共和主義の帝国思想 1895-1930。スタンフォード:スタンフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8047-2999-4。 コンクリン、アリス L. (1998)。「植民地主義と人権、用語上の矛盾?フランスと西アフリカの場合、1895–1914年". アメリカ歴史評論. 103 (2): 419–442. doi:10.2307/2649774. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 2649774. コスタンティーニ、ディノ(2008)。文明化の使命。フランス政治のアイデンティティ構築における植民地史の役割(フランス語)。パリ:ラ・デクーヴェルト。 ダウトン、J. P.(2006)。分裂した帝国:宗教、共和主義、そしてフランス植民地主義の形成、1880-1914。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-537401-8。 ファルサー、マイケル(2015)。『文化遺産としての文明化の使命。衰退から回復へ』。ハイデルベルク、ニューヨーク:スプリンガー。ISBN 978-3-319-13638-7。 ファインレイ、アイリーン・J・スアレス(1999)。良識の押し付け:1870年から1920年のプエルトリコのセクシュアリティと人種の政治。ダーラ ム:デューク大学出版。doi:10.2307/j.ctv125jpk1。ISBN 978-0-8223-2375-4。2022年2月20日取得。 ジェロニモ、ミゲル・バンデイラ (2015)。ポルトガル植民地主義の「文明化の使命」。ハウンドミルズ、ベージングストーク、ハンプシャー:パームグレイブ・マクミラン。ISBN 978-1137355904。 マニング、パトリック (1998)。フランス語圏のサハラ以南アフリカ、1880-1995 (第 2 版)。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-64255-8。 ミッチェル、ティモシー(1991)。『エジプトの植民地化』。バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局。 オルスタイン、ディエゴ、ヒュブナー、ステファン(編)(2016)。「文明化の使命の説教と現代文化の出会い」(特別号)。世界史ジャーナル。27 (2)。ISSN 1527-8050。 レンダ、メアリー (2001)。「道徳的崩壊」。ハイチ占領:軍事占領と米国帝国主義の文化、1915-1940。チャペルヒル。131-181 ページ。 ジャン・シュレ・カナレ。Afrique Noire: l'Ere Coloniale (Editions Sociales, Paris, 1971) 英訳、French Colonialism in Tropical Africa, 1900–1945. (New York, 1971). テズカン、レベント (2012). Das muslimische Subjekt: Verfangen im Dialog der Deutschen Islam Konferenz. コンスタンツ: コンスタンツ大学出版局。 サーマン、キラ(2016)。「バッハ、ベートーヴェン、ブラームスの地で文明化の使命を歌う:19 世紀ドイツのフィスク・ジュビリー・シンガーズ」。世界史ジャーナル。27 (3): 443–471。doi:10.1353/jwh.2016.0116。ISSN 1527-8050。S2CID 151616806。2022年2月19日取得。 ヤング、クロフォード (1994)。比較の視点から見たアフリカの植民地国家。ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版局。ISBN 0-300-06879-4。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civilizing_mission |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099