クレマンス・ロワイエ

Clémence Royer, 1930-1902

☆ クレマンス・ロワイエ(Clémence Royer,1830年4月21日-1902年2月6日)は独学で学んだフランスの学者で、経済学、哲学、[1]科学、フェミニズムについて講 義や執筆を行った。1862年にチャールズ・ダーウィンの『種の起源』をフランス語に翻訳し、物議を醸したことで知られる。

| Clémence Royer (21

April 1830 – 6 February 1902) was a self-taught French scholar who

lectured and wrote on economics, philosophy,[1] science and feminism.

She is best known for her controversial 1862 French translation of

Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. Early life Augustine-Clémence Audouard was born on 21 April 1830 in Nantes, Brittany, the only daughter of Augustin-René Royer and Joséphine-Gabrielle Audouard.[2] When her parents married seven years later her name was changed to Clémence-Auguste Royer. Her mother was a seamstress from Nantes while her father came from Le Mans and was an army captain and a royalist legitimist. After the failure of a rebellion in 1832 to restore the Bourbon monarchy the family were forced to flee to Switzerland where they spent 4 years in exile before returning to Orléans. There her father gave himself up to the authorities and was tried for his part in the rebellion but was eventually acquitted.[3] Royer was mainly educated by her parents until the age of 10 when she was sent to the Sacré-Coeur convent school in Le Mans. She became very devout but was unhappy and spent only a short time at the school before continuing her education at home.[4] When she was 13 she moved with her parents to Paris. As a teenager she excelled at needlework and enjoyed reading plays and novels. She was an atheist.[5] Her father separated from her mother and returned to live in his native village in Brittany, leaving mother and daughter to live in Paris. She was 18 at the time of 1848 revolution and was greatly influenced by the republican ideas and abandoned her father's political beliefs. When her father died a year later, she inherited a small piece of property. The next 3 years of her life were spent in self-study which enabled her to obtain diplomas in arithmetic, French and music, qualifying her to work as a teacher in a secondary school.[6] In January 1854 when aged 23 she took up a teaching post at a private girls’ school in Haverfordwest in south Wales.[7] She spent a year there before returning to France in the spring of 1855 where she taught initially at a school in Touraine and then in the late spring of 1856 at a school near Beauvais. According to her autobiography, it was during this period that she began to seriously question her Catholic faith.[8] Ernest Renan called Royer "almost a man of genius" reflecting the bias of the 19th century that a woman could not be called a genius.[9] |

クレマンス・ロワイエ(1830年4月21日-1902年2月6日)は

独学で学んだフランスの学者で、経済学、哲学、[1]科学、フェミニズムについて講義や執筆を行った。1862年にチャールズ・ダーウィンの『種の起源』

をフランス語に翻訳し、物議を醸したことで知られる。 生い立ち オーギュスティーヌ=クレマンス・オードゥアールは1830年4月21日、オーギュスタン・ルネ・ロワイエとジョゼフィーヌ=ガブリエル・オードゥアール の一人娘としてブルターニュのナントで生まれた[2]。母親はナント出身の裁縫師で、父親はル・マン出身の陸軍大尉で王党派の正統派であった。1832 年、ブルボン王政復古のための反乱が失敗すると、一家はスイスへの亡命を余儀なくされ、オルレアンに戻るまでの4年間を亡命生活で過ごした。そこで父親は 当局に自首し、反乱に加担した罪で裁判にかけられたが、最終的には無罪となった[3]。 ロワイエは、10歳の時にル・マンにあるサクレ・クール修道院に送られるまで、主に両親から教育を受けた。13歳のとき、両親とともにパリに移り住む。 10代の頃は針仕事が得意で、戯曲や小説を読むのが好きだった。彼女は無神論者だった[5]。 父親は母親と別居し、故郷のブルターニュの村に戻った。1848年の革命当時18歳であった彼女は、共和主義思想に大きな影響を受け、父の政治的信条を捨 てた。1年後に父親が亡くなると、彼女は小さな財産を相続した。その後の3年間は独学に費やし、算数、フランス語、音楽の免状を取得し、中等学校の教師と して働く資格を得た[6]。 1854年1月、23歳の彼女は南ウェールズのハヴァフォードウェストにある私立女子校で教鞭をとることになった[7]。そこで1年を過ごした後、 1855年春にフランスに戻り、最初はトゥーレーヌの学校で、1856年晩春にはボーヴェ近郊の学校で教鞭をとった。自伝によれば、この時期、彼女はカト リックの信仰に真剣に疑問を抱き始めたという。[8] アーネスト・ルナンは、女性は天才とは呼べないという19世紀の偏見を反映して、ロワイエを「ほとんど天才的な男」と呼んだ[9]。 |

| Lausanne In June 1856 Royer abandoned her career as a teacher and moved to Lausanne in Switzerland where she lived on the proceeds of the small legacy that she had received from her father. She borrowed books from the public library and spent her time studying, initially on the origins of Christianity and then on various scientific topics.[10] In 1858, inspired by a public lecture given by the Swedish novelist Frederika Bremer, Royer gave a series of 4 lectures on logic which were open only to women.[11] These lectures were very successful. At about this time she began meeting a group of exiled French freethinkers and republicans in the town. One of these was Pascal Duprat, a former French deputy living in exile, who taught political science at the Académie de Lausanne (later the university) and edited two journals. He was 15 years older than Royer and married with a child. He was later to become her lover and the father of her son.[12] She began to assist Duprat with his journal Le Nouvel Économiste and he encouraged her to write. He also helped her to advertise her lectures. When she began another series of lectures for women, this time on natural philosophy in the winter of 1859-1860, Duprat's Lausanne publisher printed her first lecture Introduction to the Philosophy of Women.[13][14] This lecture provides an early record of her thoughts and her attitudes to the role of women in society. Duprat soon moved with his family to Geneva but Royer continued to write reviews of books for his journal and herself lived in Geneva for a period during the winter of 1860-1861.[15] When in 1860 the Swiss canton of Vaud offered a prize for the best essay on income tax, Royer wrote a book describing both the history and the practice of the tax which was awarded second prize. Her book was published in 1862 with the title Théorie de l'impôt ou la dîme social.[16][17] It included a discussion on the economic role of women in society and the obligation of women to produce children. It was through this book that she first became known outside Switzerland. In the spring of 1861 Royer visited Paris and gave a series of lectures. These were attended by the Countess Marie d'Agoult who shared many of Royer's republican views. The two women became friends and started corresponding with Royer sending long letters enclosing articles that she had written for the Journal des Économistes.[18] |

ローザンヌ 1856年6月、ロワイエは教師としてのキャリアを捨て、スイスのローザンヌに移り住み、父親から受け取ったわずかな遺産を元手に生活した。公立図書館で本を借り、最初はキリスト教の起源について、その後はさまざまな科学的テーマについて勉強に明け暮れた[10]。 1858年、スウェーデンの小説家フレデリカ・ブレマーが行った公開講座に触発され、ロワイエは女性のみに公開された論理学の講義を4回シリーズで行った [11]。この頃、ロワイエは、亡命したフランスの自由思想家や共和主義者のグループと町で出会うようになる。その一人が亡命中の元フランス代議士で、 ローザンヌ大学(後の大学)で政治学を教え、2つの雑誌を編集していたパスカル・デュプラであった。彼はロワイエより15歳年上で、結婚して子供もいた。 彼は後に彼女の恋人となり、息子の父親となった[12]。 彼女はデュプラの雑誌『Le Nouvel Économiste』を手伝い始め、彼は彼女に執筆を勧めた。彼はまた、彼女の講演会の宣伝にも協力した。1859年から1860年の冬に、今度は自然 哲学をテーマとした女性向けの講義シリーズを始めると、デュプラのローザンヌの出版社は彼女の最初の講義『女性の哲学入門』を印刷した[13][14]。 この講義は、社会における女性の役割に対する彼女の考えや態度を示す初期の記録となっている。デュプラはすぐに家族とともにジュネーヴに引っ越したが、ロ ワイエは自分の雑誌に書評を書き続け、彼女自身も1860年から1861年の冬の間、ジュネーヴに住んでいた[15]。 1860年、スイスのヴォー州が所得税に関する最も優れた論文に賞を与えた際、ロワイエは所得税の歴史と慣行について述べた本を執筆し、2位に選ばれた。 この本には、社会における女性の経済的役割や、女性の出産義務に関する議論も含まれていた[16][17]。ロワイエがスイス国外に知られるようになった のは、この本がきっかけであった。 1861年の春、ロワイエはパリを訪れ、一連の講演を行った。この講演会には、ロワイエの共和主義的な考え方に共感したマリー・ダグール伯爵夫人も出席し た。二人の女性は友人となり、ロワイエが『ジャーナル・デ・エコノミスト』誌に書いた記事を同封した長い手紙を送るなど、文通を始めた[18]。 |

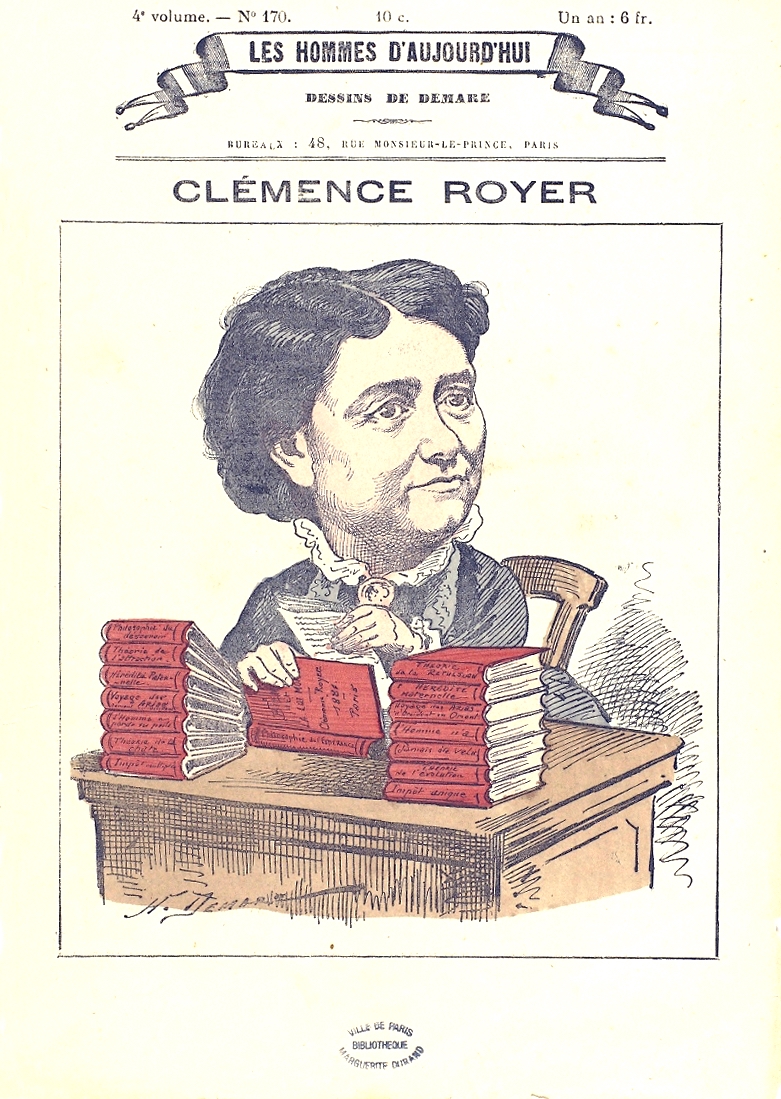

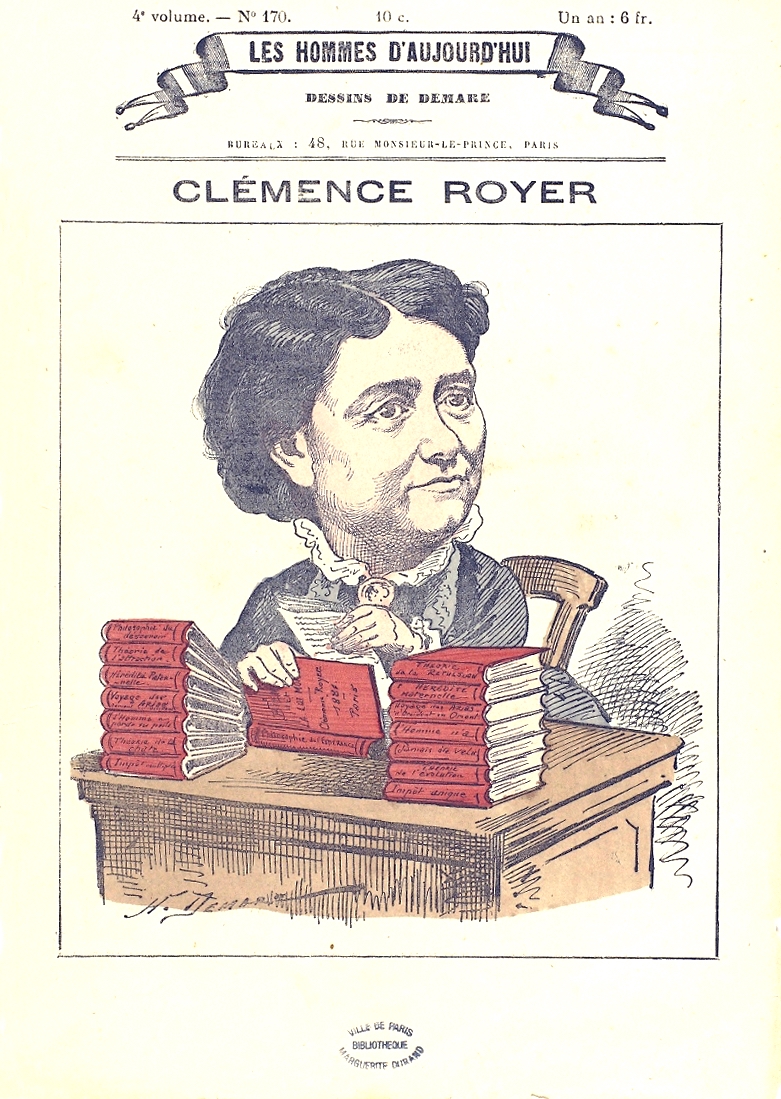

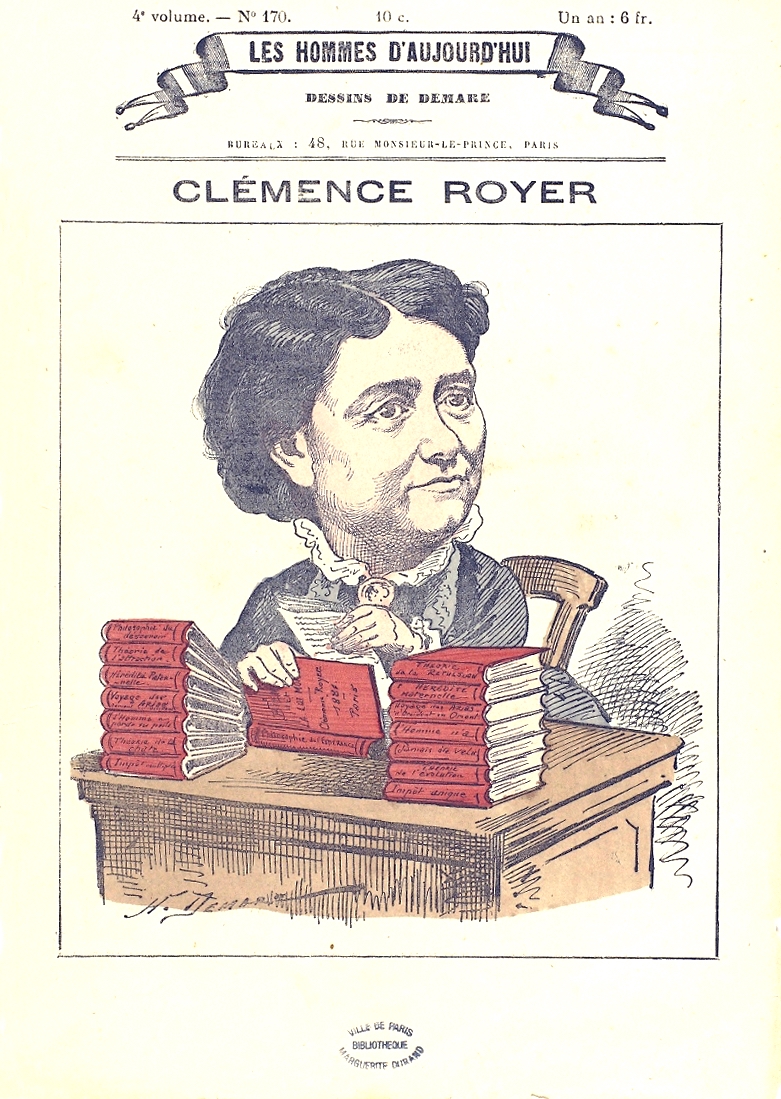

| ranslation of On the Origin of Species First edition  Caricature of Clémence Royer from Les Hommes d’aujourd’hui published in 1881. It is not known exactly how the arrangement was made for Royer to translate Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species.[19][20] Darwin was anxious to have his book published in French. His first choice of translator had been Louise Belloc, but she had declined his offer as she considered the book to be too technical. Darwin had been approached by the Frenchman Pierre Talandier but Talandier had been unable to find a publisher to handle the book. Royer was familiar with the writings of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Thomas Malthus and realized the significance of Darwin's work. She was also probably helped by having close links with a French publisher, Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin. We know from a letter dated 10 Sep 1861 that Darwin asked his English publisher Murray to send a copy of the third edition of the Origin to "Mlle Clémence-Auguste Royer 2. Place de la Madeline Lausanne Switzerland; as she has agreed with a publisher for a French translation".[21] René-Édouard Claparède, a Swiss naturalist who lectured at the University of Geneva and who had favourably reviewed the Origin for the Revue Germanique,[22] offered to help her with the technicalities of the biology. Royer went beyond her role as a translator and included a long (60 page) preface and detailed explanatory footnotes. In her preface she challenged the belief in religious revelation and discussed the application of natural selection to the human race and what she saw as the negative consequences of protecting the weak and the infirm. These eugenic ideas were to gain her notoriety.[23] The preface also promoted her concept of progressive evolution which had more in common with the ideas of Lamarck than with those of Darwin.[24][25] In June 1862, soon after Darwin received a copy of the translation he wrote in a letter to the American botanist, Asa Gray: I received 2 or 3 days ago a French translation of the Origin by a Madelle. Royer, who must be one of the cleverest & oddest women in Europe: is ardent deist & hates Christianity, & declares that natural selection & the struggle for life will explain all morality, nature of man, politicks &c &c!!!. She makes some very curious & good hits, & says she shall publish a book on these subjects, & a strange production it will be.[26] However, Darwin appears to have had doubts as a month later in a letter to the French zoologist Armand de Quatrefages he wrote: "I wish the translator had known more of Natural History; she must be a clever, but singular lady; but I never heard of her, till she proposed to translate my book."[27] He was unhappy with Royer's footnotes and in a letter to the botanist Joseph Hooker he wrote: "Almost everywhere in Origin, when I express great doubt, she appends a note explaining the difficulty or saying that there is none whatever!! It is really curious to know what conceited people there are in the world,..."[28] Second and third editions For the second edition of the French translation published in 1866, Darwin suggested some changes and corrected some errors.[29][30] The words "des lois du progrès" (laws of progress) were removed from the title to more closely follow the English original. Royer had originally translated "natural selection" by "élection naturelle" but for the new edition this was changed to "sélection naturelle" with a footnote explaining that although "élection" was the French equivalent of the English "selection", she was adopting the incorrect "sélection" to conform with the usage in other publications.[31] In his article in Revue Germanique Claparède had used the word "élection" with a footnote explaining that the element of choice conveyed by the word was unfortunate but had he used "sélection" he would have created a neologism.[32] In the new edition Royer also toned down her eugenic statements in the preface but added a foreword championing freethinkers and complaining about the criticism she had received from the Catholic press.[33] Royer published a third edition without contacting Darwin. She removed her foreword but added an additional preface in which she directly criticised Darwin's idea of pangenesis introduced in his Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868).[34] She also made a serious error by failing to update her translation to reflect the changes that Darwin had incorporated in the 4th and 5th English editions. When Darwin learnt of this he wrote to the French publisher Reinwald and to the naturalist Jean-Jaques Moulinié in Geneva who had translated Variation to arrange for a new translation of his 5th edition of the Origin. In November 1869 Darwin wrote to Hooker: I must enjoy myself and tell you about Madame C. Royer who translated the Origin into French and for which 2d edition I took infinite trouble. She has now just brought out a 3d edition without informing me so that all the corrections to the 4th and 5th editions are lost. Besides her enormously long and blasphemous preface to the 1st edition she has added a 2nd preface abusing me like a pick-pocket for pangenesis which of course has no relation to Origin. Her motive being, I believe, because I did not employ her to translate "Domestic animals". So I wrote to Paris; & Reinwald agrees to bring out at once a new translation for the 5th English Edition in Competition with her 3e edition — So shall I not serve her well? By the way this fact shows that "evolution of species" must at last be spreading in France.[35] In spite of Darwin's misgivings, he wrote to Moulinié suggesting that he should carefully study Royer's translation.[36] Publication of the new edition was delayed by the Franco-Prussian war, the Paris Commune and by the death in 1872 of Moulinié. When the new French translation finally appeared in 1873 it included an appendix describing the additions made to the sixth English edition which had been published the previous year.[37][38] |

種の起源』の翻訳 初版  1881年に出版された『Les Hommes d'aujourd'hui』に掲載されたクレマンス・ロワイエの風刺画。 ロワイエがチャールズ・ダーウィンの『種の起源』を翻訳することになった経緯は正確には分かっていない[19][20]。ダーウィンが最初に選んだ翻訳者 はルイーズ・ベロックだったが、彼女はこの本が専門的すぎると考え、彼の申し出を断っていた。ダーウィンはフランス人のピエール・タランディエに声をかけ たが、タランディエはこの本を扱ってくれる出版社を見つけることができなかった。ロワイエはジャン=バティスト・ラマルクやトマス・マルサスの著作に精通 しており、ダーウィンの著作の意義を理解していた。また、フランスの出版社ジルベール・ウルバン・ギョーミンと密接なつながりがあったことも、彼女を助け たと思われる。1861年9月10日付の手紙によると、ダーウィンはイギリスの出版社マレーに『起原』第3版のコピーを「クレマンス=オーギュスト・ロワ イエ嬢 2. Place de la Madeline Lausanne Switzerland; as she has agreed with a publisher for a French translation」[21] ジュネーブ大学で講義をし、『Revue Germanique』誌で『起源』を好意的に批評していたスイスの博物学者ルネ=エドゥアール・クラパレードは、生物学の技術的な面で彼女を手助けする ことを申し出た[22]。 ロワイエは翻訳者としての役割を超えて、長い序文(60ページ)と詳細な脚注をつけた。序文で彼女は、宗教的啓示への信仰に異議を唱え、自然淘汰の人類へ の適用と、弱者や病弱者を保護することの否定的な結果について論じた。これらの優生思想は彼女の悪評を高めることになった[23]。序文はまた、ダーウィ ンの思想よりもラマルクの思想と共通する彼女の漸進的進化の概念を宣伝した[24][25]。 1862年6月、ダーウィンが翻訳のコピーを受け取った直後、彼はアメリカの植物学者アサ・グレイに宛てた手紙にこう書いた: 2、3日前、マデル・ロワイエという人物の『起源』のフランス語訳を受け取った。マデルは熱心な神学者でキリスト教を嫌い、自然淘汰と生命のための闘争が すべての道徳、人間の本質、政治などを説明すると宣言している。彼女は非常に好奇心をそそられる良いヒットをいくつか出し、これらのテーマについて本を出 版すると言っているが、それは奇妙な作品になるだろう[26]。 しかし、ダーウィンは疑念を抱いていたようで、その1ヵ月後、フランスの動物学者アルマン・ド・キャトルファージュに宛てた手紙の中で、「訳者が自然史に ついてもっと知っていればよかったのだが。 彼はロワイエの脚注に不満で、植物学者ジョセフ・フッカーに宛てた手紙の中で、「『起源』のほとんどあらゆる箇所で、私が大きな疑念を表明すると、彼女は その難点を説明する注を付けたり、何もないと言ったりする!世の中にどんなうぬぼれ屋がいるのか、実に興味深い......」[28]。 第2版と第3版 1866年に出版されたフランス語訳の第2版では、ダーウィンはいくつかの変更を提案し、いくつかの誤りを訂正した[29][30]。 より英語の原文に忠実にするために、タイトルから「des lois du progrès」(進歩の法則)という言葉が削除された。ロワイエは当初、「自然淘汰」を「élection naturelle」と訳していたが、新版では「élection」が英語の「淘汰」に相当するフランス語であるにもかかわらず、他の出版物の用法に合わ せるために誤った「淘汰」を採用していることを説明する脚注を付して、これを「sélection naturelle」に変更した[31]。 [31]クラパレードは『Revue Germanique』誌の記事で「élection」という単語を使い、その単語が伝える選択の要素は残念なものだが、「sélection」を使って いたら新造語を生み出したことになると脚注で説明していた[32]。新版ではロワイエは序文で優生学的な記述をトーンダウンさせたが、自由思想家を擁護 し、カトリックの新聞社から受けた批判について苦言を呈する序文を加えた[33]。 ロワイエはダーウィンに連絡することなく第3版を出版した。彼女は序文を削除したが、ダーウィンの『家畜化された動植物の変異』(1868年)に導入され たパンゲネシスの考え方を直接批判する序文を追加した[34]。彼女はまた、ダーウィンが第4版と第5版の英語版に取り入れた変更を反映させるために翻訳 を更新しないという重大なミスを犯した。これを知ったダーウィンは、フランスの出版社ラインワルドと、『変種』を翻訳したジュネーヴの博物学者ジャン= ジャック・ムリニエに、『起原』第5版の新訳を手配するよう手紙を書いた。1869年11月、ダーウィンはフッカーに手紙を書いた: 原点』をフランス語に翻訳したマダムC.ロワイエのこと、そしてその第2版のために私が多大な苦労をしたことを、楽しんで話さなければならない。彼女は私 に知らせずに第3版を出したので、第4版と第5版の修正はすべて失われてしまった。第1版への非常に長く冒涜的な序文に加え、第2版への序文が追加され、 もちろん『オリジン』とは何の関係もないパンゲネシスのことで私をスリみたいに罵倒している。彼女の動機は、私が『家畜』の翻訳に彼女を起用しなかったか らだと思う。そこで私はパリに手紙を書いた。そしてラインヴァルトは、彼女の3e版と競合する形で、英語版第5版のための新訳をすぐに出すことに同意し た。ところでこの事実は、「種の進化」がついにフランスで広まりつつあることを示している[35]。 ダーウィンの不安にもかかわらず、ダーウィンはムリニエに手紙を書き、ロワイエの翻訳を注意深く研究するよう勧めた[36]。新版の出版は普仏戦争、パ リ・コミューン、そして1872年のムリニエの死によって遅れた。1873年にようやく新フランス語訳が出版されたときには、前年に出版された英語版第6 版に追加された内容を記した付録が含まれていた[37][38]。 |

Italy, Duprat and motherhood Portrait ca. 1880 of Pascal Duprat (1815-1885). Royer's translation of On the Origin of Species led to public recognition. She was now much in demand to give lectures on Darwinism and spent the winter of 1862-1863 lecturing in Belgium and the Netherlands. She also worked on her only novel Les Jumeaux d’Hellas,[39] a long melodramatic story set in Italy and Switzerland, which was published in 1864 to no great acclaim.[40] She continued to review books and report on social-science meetings for the Journal des Économistes. During this period she would regularly meet up with Duprat at various European meetings.[41] In August 1865 Royer returned from Lausanne to live in Paris while Duprat, proscribed by the Second Empire, joined her and secretly shared her apartment. Three months later in December they went to live together openly in Florence (then the capital of Italy) where her only son, René, was born on 12 March 1866.[42] With a small child to care for she could no longer easily travel but she continued to write, contributing to various journals and publishing a series of three articles on Jean-Baptiste Lamarck.[43] She also worked on a book on the evolution of human society, L’origine de l’homme et des sociétés,[44] published in 1870. This was a subject that Darwin had avoided in On the Origin of Species but was to address in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex published a year later.[45] In it, she expressed her views that the struggle for existence was inescapable, between not only separate species but individuals and groups within the same species. Royer felt this was especially acute in so-called "savage" societies, contra the rosier view of Rousseau. She argued human biology and society had evolved from that time progressively to higher stages. Inequality, she felt, was innate due to differing evolution, with some races definitely higher than others in ability as a result. She argued it was perfectly right for superior races to wage war on and exterminate lesser ones, unless the latter had some usefulness as laborers. Although she conceded that races mixing could be beneficial, Royer felt this generally immoral. Within and between advanced societies though Royer opposed waging war, seeing competition there taking a more peaceful form, but she did not go into detail on it.[46] Royer advocated maximal liberty to aid natural selection, since then individuals would be free to adapt and thus advance humanity. Simultaneously though, she opposed egalitarian schemes of any kind, along with charity or welfare that would keep the "unfit" alive. However, in spite of her generally anti-egalitarian views, Royer did maintain that there was no biological basis of patriarchy, seeing women's subordinate position as an only an aberration from original equality between genders that she believed had prevailed. A society that denied women's participation in full, she felt, would fall behind others which allowed it, and thus go against its own interests. Royer supported anti-religious and anti-clerical views as well by arguing that religion (particularly Christianity) stifled this progress. She has been characterized as an early leading Social Darwinist in Europe due to these views, which Royer termed a "semiotics of nature".[47] At the end of 1868 Duprat left Florence to report on the Spanish revolution for the Journal des Économistes,[48] and in 1869, with the relaxing of the political climate at the end of the Second Republic, Royer returned to Paris with her son. The move would allow her mother to help with raising her child.[49] Paris and the Société d’Anthropologie Although Darwin had withdrawn his authorization for Royer's translation of his book, she continued to champion his ideas and on her arrival in Paris resumed giving public lectures on evolution.[50] Darwin's ideas had made very little impact on French scientists and very few publications mentioned his work. A commonly expressed view was that there was no proof of evolution and Darwin had not offered any new evidence.[51] In 1870 Royer became the first woman in France elected to a scientific society,[52] when she was elected to the prestigious all-male Société d’Anthropologie de Paris founded and headed by Paul Broca whose membership included many leading French anthropologists. Although the society included free-thinking republicans such as Charles Jean-Marie Letourneau and the anthropologist Gabriel de Mortillet, Royer was nominated for membership by the more conservative Armand de Quatrefages and the physician Jules Gavarret. She remained the only woman member for the next 15 years.[53] She became an active member of the society and participated in discussions on a wide range of subjects. She also submitted articles to the society's journal, the Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris.[54] From the reports of discussions published by the society, it would appear that the majority of the members accepted that evolution had occurred. However the discussions rarely mentioned Darwin's most original contribution, his proposed mechanism of natural selection; Darwin's ideas were considered as an extension to those of Lamarck.[55] In contrast, even the possibility that evolution had occurred was rarely mentioned in the discussions of other learned societies such as the Société Botanique, the Société Zoologique, the Société Géologique and the Académie des Sciences.[56] Royer was always ready to challenge the current orthodoxy and in 1883 published a paper in La Philosophie Positive questioning Newton's law of universal gravitation and criticising the concept of "action at a distance".[57] The editors of the journal included a footnote distancing themselves from her ideas.[58] Duprat died suddenly in 1885 aged 70 and under French law, neither Royer nor her son had any legal claim on his estate.[59] Royer had very little income and had a son who was studying at the École Polytechnique. Her contributions to prestigious journals such as the Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris and the Journal des Économistes brought in no income. She found herself in a difficult financial situation and applied to the Ministère de l'Instruction Publique for a regular pension but instead was given a small lump sum. She was therefore obliged to reapply each year.[60] The Société d’Anthropologie organised a series of annual public lectures. In 1887, as part of this series, Royer gave two lectures entitled L’Évolution mentale dans la série organique.[61][62] She was already suffering from ill health and after these lectures she rarely participated in the affairs of the society. In 1891 she moved to the Maison Galignani,[63] a retirement home in Neuilly-sur-Seine which had been established with an endowment from the will of the publisher William Galignani.[64] She remained there until her death in 1902. |

イタリア、デュプラと母性 1880年頃の肖像画。1880年 パスカル・デュプラ(1815-1885)。 ロワイエは『種の起源』の翻訳で世間に知られるようになった。1862年から1863年の冬にかけて、ベルギーとオランダで講演を行った。また、イタリア とスイスを舞台にしたメロドラマ風の長編小説『Les Jumeaux d'Hellas』[39]の執筆にも取り組んだが、これは1864年に出版され、大きな評判は得られなかった[40]。この時期、彼女はヨーロッパのさ まざまな会合でデュプラと定期的に会っていた[41]。 1865年8月、ロワイエはローザンヌからパリに戻り、第二帝政によって禁止されていたデュプラは彼女と合流し、彼女のアパートを密かにシェアした。3ヶ 月後の12月、二人はフィレンツェ(当時はイタリアの首都)で公然と一緒に暮らすようになり、1866年3月12日に一人息子のルネが誕生した[42]。 小さな子供の世話で、彼女はもはや容易に旅行することはできなかったが、執筆を続け、様々な雑誌に寄稿し、ジャン=バティスト・ラマルクに関する3つの論 文シリーズを出版した[43]。これはダーウィンが『種の起源』で避けていたテーマであったが、その1年後に出版された『人間の下降と性による選択』で取 り上げられることになった[45]。 その中で彼女は、別々の種だけでなく、同じ種内の個体や集団の間でも、生存のための闘争は避けられないという見解を示した。ロワイエは、ルソーの楽観的な 見方とは対照的に、いわゆる「未開人」の社会ではこのことが特に深刻であると感じていた。ロイヤーは、人間の生物学と社会は、その時代から徐々に高い段階 へと進化してきたと主張した。不平等は進化の違いによる生得的なものであり、その結果、ある種族は他の種族よりも確実に高い能力を持っていると彼女は考え た。彼女は、優れた種族が劣った種族に戦争を仕掛け、絶滅させるのは完全に正しいと主張した。人種間の混血が有益であることは認めたが、ロイヤーはこれを 一般的に不道徳なことだと考えた。ロイヤーは先進的な社会内や社会間においては戦争をすることに反対していたが、そこでの競争はより平和的な形を取ってい ると見ていたが、それについて詳しくは述べていなかった[46]。 ロイヤーは自然淘汰を助けるために最大限の自由を提唱していた。しかし同時に彼女は、「不適格者」を生かすような慈善や福祉とともに、いかなる平等主義的 な計画にも反対した。しかし、一般的には反平等主義的な見解であるにもかかわらず、ロイヤーは家父長制には生物学的根拠はないと主張し、女性が従属的な立 場にあるのは、彼女が信じていた本来の男女平等から逸脱したものに過ぎないと考えていた。女性の参画を否定する社会は、女性の参画を認める社会に遅れをと り、自国の利益に反すると彼女は考えた。ロイヤーは、宗教(特にキリスト教)がこの進歩を阻害していると主張し、反宗教的、反宗教的見解をも支持した。彼 女は、ロワイエが「自然の記号論」と呼んだこれらの見解により、ヨーロッパにおける初期の代表的な社会ダーウィン主義者として特徴づけられている [47]。 1868年末、デュプラはフィレンツェを離れ、『Journal des Économistes』誌にスペイン革命について寄稿した[48]。1869年、第二共和政末期の政治情勢の緩和とともに、ロワイエは息子とともにパリ に戻った。この引っ越しによって、母親は子育てを手伝うことができるようになった[49]。 パリと人類学協会 ダーウィンはロワイエの著書の翻訳に対する承認を取り下げていたが、彼女は彼の考えを支持し続け、パリに到着すると進化論に関する公開講演を再開した [50]。ダーウィンの考えはフランスの科学者にほとんど影響を与えず、彼の研究に言及した出版物はほとんどなかった。1870年、ロワイエは、ポール・ ブロカが創設し、フランスを代表する人類学者を多数擁する権威ある男性だけのパリ人類学会の会員に選出され、フランスで初めて科学学会に選出された女性と なった[52]。この協会には、シャルル・ジャン=マリー・ルトゥルノーや人類学者ガブリエル・ド・モルティレのような自由思想の共和主義者も含まれてい たが、ロワイエはより保守的なアルマン・ド・キャトルファージュや医師のジュール・ガヴァレから会員に推薦された。ロワイエは、その後15年間、唯一の女 性会員であり続けた[53]。彼女はまた、学会の機関誌『Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris』に記事を投稿した[54]。 同学会が発表した議論の報告書から、会員の大多数は進化が起こったことを受け入れていたように思われる。対照的に、進化が起こったという可能性さえ、植物学協会、動物学協会、地理学協会、科学アカデミーといった他の学会の議論ではほとんど言及されなかった[56]。 ロワイエは常に現在の正統主義に異議を唱える用意があり、1883年には『La Philosophie Positive』にニュートンの万有引力の法則に疑問を投げかけ、「遠距離作用」の概念を批判する論文を発表した[57]。同誌の編集者は脚注で彼女の 考えから距離を置く旨を記している[58]。 デュプラは1885年に70歳で急死したが、フランスの法律では、ロワイエも彼女の息子も彼の遺産に対して法的な請求権を持たなかった[59]。パリ人類 学協会会報』や『経済学雑誌』といった権威ある雑誌への寄稿も、収入にはつながらなかった。経済的に苦境に立たされた彼女は、公的教育省に年金の支給を申 請したが、わずかな一時金しか支給されなかった。そのため、彼女は毎年再申請しなければならなかった[60]。 人類学協会(Société d'Anthropologie)は毎年、公開講座のシリーズを開催した。1887年、このシリーズの一環として、ロワイエは『L'Évolution mentale dans la série organique』と題する2つの講義を行った[61][62]。彼女はすでに健康を害しており、これらの講義の後、学会の活動に参加することはほとん どなかった。 1891年、彼女はヌイイ=シュル=セーヌにあるメゾン・ガリニャーニに移り住む[63]。メゾン・ガリニャーニは、出版者ウィリアム・ガリニャーニの遺言による寄付によって設立された老人ホームであった[64]。 |

| Feminism and La Fronde Royer attended the first International Congress on Woman's Rights in 1878 but did not speak.[65] For the Congress in 1889 she was asked by Maria Deraismes, to chair the historical section. In her address she argued that the immediate introduction of women's suffrage was likely to lead to an increase in the power of the church and that the first priority should be to establish secular education for women. Similar elitist views were held by many French feminists at the time who feared a return to the monarchy with its strong links to the conservative Roman Catholic Church.[66][67] When in 1897, Marguerite Durand launched the feminist newspaper La Fronde, Royer became a regular correspondent, writing articles on scientific and social themes. In the same year her colleagues working on the newspaper organised a banquet in her honour and invited a number of eminent scientists.[68] Her book La Constitution du Monde on cosmology and the structure of matter was published in 1900.[69] In it she criticized scientists for their over specialization and questioned accepted scientific theories. The book was not well received by the scientific community and a particularly uncomplimentary review in the journal Science suggested that her ideas "... show at every point a lamentable lack of scientific training and spirit."[70][71] In the same year that her book was published she was awarded the Légion d'honneur.[72] Royer died in 1902 at the Maison Galignani in Neuilly-sur-Seine. Her son, René, died of liver failure 6 months later in Indochina.[73] |

フェミニズムとラ・フロンド ロワイエは、1878年の第1回女性の権利に関する国際会議に出席したが、演説はしなかった[65]。1889年の会議では、マリア・デライスムから歴史 部門の議長に任命された。演説の中で彼女は、女性参政権の即時導入は教会の権力拡大につながる可能性が高く、女性のための世俗教育を確立することを第一に 考えるべきだと主張した。当時、保守的なローマ・カトリック教会との結びつきが強い王政への回帰を恐れていたフランスのフェミニストの多くも、同様のエ リート主義的な見解を抱いていた[66][67]。 1897年、マルグリット・デュランがフェミニスト新聞『ラ・フロンド』を創刊すると、ロワイエは定期的な特派員となり、科学や社会をテーマにした記事を 書いた。同じ年、この新聞に携わっていた同僚たちはロワイエに敬意を表し、著名な科学者たちを招いて宴会を開いた[68]。 宇宙論と物質の構造に関する著書『La Constitution du Monde』は1900年に出版された[69]。その中で彼女は、科学者が専門化しすぎていることを批判し、受け入れられている科学理論に疑問を呈した。 この本は科学界からの評判は芳しくなく、特に『サイエンス』誌に掲載された批評では、彼女の考えは「...あらゆる点で科学的訓練と精神の嘆かわしい欠如 を示している」と指摘されている[70][71]。 ロワイエは1902年にヌイイ=シュル=セーヌのメゾン・ガリニャーニで死去した。息子のルネは6ヵ月後にインドシナで肝不全のため死去した[73]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cl%C3%A9mence_Royer |

|

| La traduction de L'Origine des espèces Première édition (1862) Charles Darwin était impatient de voir son livre traduit en français, mais on ne connaît pas le détail des négociations qui ont attribué la première traduction de L'Origine des espèces à Clémence Royer. Darwin avait d’abord sollicité Louise Belloc, qui avait décliné son offre, considérant le livre comme trop technique. Darwin a été également démarché par Pierre Talandier, mais ce dernier fut incapable de trouver un éditeur. Clémence Royer connaissait bien les ouvrages de Lamarck et de Malthus et a saisi l'importance de l'ouvrage de Darwin. Elle fut probablement encouragée par ses étroites relations avec l'éditeur Guillaumin, qui publia les trois premières éditions françaises de L'Origine des espèces. Par une lettre du 10 septembre 1861, Darwin demande à Murray, son éditeur en Angleterre, d'envoyer une copie de la troisième édition originale de L'Origine des espèces à « Mlle Cl. Royer […] en vue d'un accord avec un éditeur pour une traduction française ». René-Édouard Claparède, un naturaliste suisse de l'université de Genève qui avait fait une recension favorable de L'Origine des espèces pour la Revue Germanique, offre d'aider Clémence Royer pour la traduction des termes techniques de biologie. Elle va largement au-delà du rôle de traductrice en ajoutant à l’édition française une préface de 64 pages1,13 dans laquelle elle livre son interprétation personnelle de l’ouvrage, ainsi que des notes de bas de page où elle commente le texte de Darwin1. Dans sa préface, véritable pamphlet positiviste consacré au triomphe du progrès de la science sur l’obscurantisme, elle s’attaque vigoureusement aux croyances religieuses et au christianisme, argumente en faveur de l’application de la sélection naturelle aux races humaines et s’alarme de ce qu’elle considère comme les conséquences négatives résultant de la protection accordée par la société aux faibles. Elle dénonce une société où le faible prédomine sur le fort sous prétexte d’une « protection exclusive et inintelligente accordée aux faibles, aux infirmes, aux incurables, aux méchants eux-mêmes, à tous les disgraciés de la nature ». Ces idées eugénistes avant l’heure (le terme est inventé par le cousin de Darwin, Francis Galton, en 1883) lui valent alors une certaine notoriété. Elle modifie également le titre pour le faire correspondre à ses vues sur la théorie de Darwin : l’édition de 1862 est ainsi intitulée De l'origine des espèces ou des lois du progrès chez les êtres organisés. Ce titre, ainsi que la préface, mettent en avant l’idée d’une évolution tendant vers le « progrès », ce qui est en fait plus proche de la théorie de Lamarck que des idées contenues dans l’ouvrage de Darwin. Clémence Royer a donc projeté sur L'Origine des espèces (qui ne traite nullement des origines de l’homme, de l’application de la sélection naturelle aux sociétés humaines et moins encore du progrès dans la société industrielle du xixe siècle) ses propres idées et aspirations. En juin 1862, après avoir reçu un exemplaire de la traduction française, Darwin écrit une lettre au botaniste américain Asa Gray : « J’ai reçu il y a deux ou trois jours la traduction française de L'Origine des espèces par Mlle Royer, qui doit être une des plus intelligentes et des plus originales femmes en Europe14 : c’est une ardente déiste qui hait le christianisme, et qui déclare que la sélection naturelle et la lutte pour la vie vont expliquer toute la morale, la nature humaine, la politique, etc. !!! Elle envoie quelques sarcasmes curieux et intéressants qui portent, et annonce qu’elle va publier un livre sur ces sujets, et quel étrange ouvrage cela va être. » (Lettre de Ch. Darwin à Asa Gray du 10-20 juin 1862). En revanche, un mois plus tard, Darwin fait part de ses doutes au zoologiste français Armand de Quatrefages : « J’aurais souhaité que la traductrice connaisse mieux l’histoire naturelle14 ; ce doit être une femme intelligente, mais singulière ; mais je n’avais jamais entendu parler d’elle avant qu’elle se propose de traduire mon livre. » (Lettre de Ch. Darwin à Armand de Quatrefages du 11 juillet 1862). Darwin était insatisfait des notes de bas de page de Clémence Royer, et s’en est plaint dans une lettre au botaniste anglais Joseph Hooker : « Presque partout dans L'Origine des espèces, lorsque j’exprime un grand doute, elle ajoute une note expliquant le problème ou disant qu’il n’y en a pas ! Il est vraiment curieux de voir quelle sorte de vaniteux personnages il y a dans le monde… » (Lettre de Ch. Darwin à Joseph Hooker du 11 septembre 1862). Deuxième et troisième éditions (1866, 1870) Pour la deuxième édition de la traduction française, publiée en 1866, Darwin obtient de Clémence Royer de nombreuses modifications et corrige plusieurs erreurs15. L’expression « les lois du progrès » est retirée du titre pour la rapprocher de l’original anglais : L'Origine des espèces par sélection naturelle ou des lois de transformation des êtres organisés. Dans la première édition, Clémence Royer avait traduit natural selection par « élection naturelle », mais pour cette nouvelle édition, cela est remplacé par « sélection naturelle » avec une discussion (p. XII-XIII) où la traductrice explique toutefois qu’« élection » était en français l’équivalent de l’anglais selection et qu’elle adoptait finalement le terme « incorrect » de « sélection » pour se conformer à l’usage établi par d’autres publications. Dans l’avant-propos de cette deuxième édition, Clémence Royer tente d’adoucir les positions eugénistes exposées dans la préface de la première édition (reproduite en intégralité), mais ajoute un plaidoyer en faveur de la libre pensée et s’en prend aux critiques qu’elle avait reçues de la presse catholique. En 1867, le jugement de Darwin est déjà nettement plus négatif : « L’introduction a été pour moi une surprise totale, et je suis certain qu’elle a nui à mon livre en France. » (cité par D. Becquemont in Ch. Darwin, L’Origine de espèces, éd. Flammarion-GF, 2008). Clémence Royer publie une troisième édition16 en 1870 sans en avertir Darwin15. Elle y ajoute encore une préface où elle critique vertement la « théorie de la pangénèse » que Darwin avait avancée dans son ouvrage de 1868, Les variations des animaux et des plantes à l’état de domestication. Cette nouvelle édition n’inclut pas les modifications introduites par Darwin dans les 4e et 5e éditions anglaises15. Lorsque Darwin apprend l’existence de cette troisième édition, il écrit à l’éditeur français Reinwald et au naturaliste genevois Jean-Jacques Moulinié qui avaient déjà traduit et publié Les variations… pour mettre au point une nouvelle traduction à partir de la 5e édition. Toutefois, si Darwin considère qu'elle a abusé de sa confiance en agrémentant sa traduction de considérations personnelles et de hors sujet, et si le philosophe Charles Lévêque l'accuse d'avoir trahi le texte d'origine, nombreux sont ceux qui préfèrent sa traduction à celle de Moulinié, jugée mal écrite. Clémence Royer se défend des accusations de Lévêque, lettres de Darwin à l'appui, et l'affaire se règle au sein de l'Académie des sciences morales et politiques, qui tranche en sa faveur avec les excuses de son président17. Quatrième édition (1882)  Clémence Royer en première page des Hommes d'aujourd'hui, 1882, dessin d'Henri Demare. En 1882, l'année de la mort de Darwin, Clémence Royer publie une quatrième édition chez Flammarion15. Elle y inclut la préface de la première édition et ajoute un court « avertissement aux lecteurs de la quatrième édition » (5 pages). Cette édition sera publiée jusqu'en 1932, soit trente ans après sa mort15. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cl%C3%A9mence_Royer |

『種の起源』の翻訳 初版(1862年) チャールズ・ダーウィンは自分の著書がフランス語に翻訳されるのを待ち望んでいたが、『種の起源』の最初の翻訳がクレマンス・ロワイエに決まった交渉の詳 細はわかっていない。ダーウィンは当初、ルイーズ・ベロックに声をかけたが、彼女はこの本が専門的すぎると考えて断った。ダーウィンはピエール・タラン ディエにも声をかけたが、タランディエは出版社を見つけることができなかった。 クレマンス・ロワイエはラマルクとマルサスの著作に精通しており、ダーウィンの著作の重要性を理解していた。彼女はおそらく、『種の起源』の最初の3冊のフランス語版を出版した出版社ギヨミンとの親密な関係に後押しされたのだろう。 1861年9月10日付の手紙の中で、ダーウィンはイギリスの出版社であるマレーに、『種の起源』第3版の原版のコピーを「フランス語訳の出版社との契約 を視野に入れて」「Cl.ロワイエ嬢[...]に送るよう依頼している。ルネ=エドゥアール・クラパレードは、『種の起源』の好意的な書評を『Revue Germanique』誌に寄稿したジュネーブ大学のスイス人博物学者で、クレマンス・ロワイエに生物学の専門用語の翻訳を手伝うことを申し出た。 彼女は翻訳者としての役割をはるかに超え、フランス語版に64ページに及ぶ序文1,13を加え、その中で作品についての個人的な解釈を述べ、脚注でダー ウィンの文章についてコメントした1。科学的進歩の蒙昧主義に対する勝利に捧げられた、まさに実証主義のパンフレットともいうべき序文の中で、彼女は宗教 的信念とキリスト教を激しく攻撃し、自然淘汰の人類への適用を支持し、社会が弱者を保護することの否定的な結果に警鐘を鳴らしている。彼女は、「弱者、病 弱な者、不治の病にかかった者、邪悪な者、自然の恥辱を受けた者すべてを排他的かつ非知的に保護する」という口実のもとに、弱者が強者よりも優位に立つ社 会を非難した。こうした初期の優生思想(この言葉は、1883年にダーウィンの従兄弟であるフランシス・ガルトンが作った造語である)によって、彼女は一 定の悪評を得た。 1862年版のタイトルは『De l'origine des espèces ou des lois du progrès chez les êtres organisés』となった。このタイトルと序文は、進化が「進歩」に向かうという考え方を提唱したもので、実際にはダーウィンの著作に含まれる考え方 よりもラマルクの理論に近い。 そのためクレマンス・ロワイエは、彼女自身の考えや願望を『種の起源』に投影したのである(『種の起源』は、人間の起源や、人間社会への自然淘汰の適用、さらには19世紀の産業社会における進歩についてはまったく触れていない)。 1862年6月、フランス語訳を受け取ったダーウィンは、アメリカの植物学者アサ・グレイに宛てて手紙を書いた。「2、3日前、ヨーロッパで最も知的で独 創的な女性の一人に違いないロワイエ女史14から『種の起源』のフランス語訳を受け取った!彼女は好奇心をそそる面白い皮肉をいくつか送ってきて、これら のテーマに関する本を出版するつもりであり、それは何とも奇妙な作品になりそうだと予告している」(Ch.ダーウィンからの手紙14)。(Ch.ダーウィ ンからエイサ・グレイへの手紙、1862年6月10-20日)。 しかし、その1ヵ月後、ダーウィンはフランスの動物学者アルマン・ド・キャトルファージュに次のような疑念を表明した。「訳者には自然史の知識がもっとあ ればよかったのだが14。(しかし、彼女が私の本の翻訳を提案するまで、私は彼女のことを聞いたことがなかった」(1862年7月11日、Ch.ダーウィ ンからアルマン・ド・キャトルファージュへの手紙)。ダーウィンはクレマンス・ロワイエの脚注に不満を抱いており、イギリスの植物学者ジョセフ・フッカー に宛てた手紙の中で、脚注について次のように不満を述べている!世の中にどんなうぬぼれ屋がいるのか、実に興味深い...」。(Ch.ダーウィンからジョ セフ・フッカーへの手紙、1862年9月11日)。 第2版と第3版(1866年、1870年) 1866年に出版されたフランス語訳の第2版では、ダーウィンはクレマンス・ロワイエから多くの変更を受け、いくつかの誤りを訂正した15。自然淘汰によ る種の起源あるいは組織化された生物の変容の法則』という英語の原文に近づけるため、タイトルから「進歩の法則」という表現が削除された。初版では、クレ マンス・ロワイエは 「自然選択 」を 「élection naturelle 」と訳していたが、この新版では 「sélection naturelle 」に置き換えられており、訳者は、「élection 」が 「selection 」に相当するフランス語であり、他の出版物によって確立された用法に合わせるために、最終的に 「sélection 」という 「正しくない 」用語を採用したと説明している(XII-XIII頁)。 この第2版の序文で、クレマンス・ロワイエは、第1版の序文(全文再録)にある優生主義的な立場を和らげようとしたが、自由な思想を訴え、カトリックの新 聞から受けた批判を攻撃した。1867年、ダーウィンの判断はすでにずっと否定的だった。「この序文は私にとってまったくの驚きであり、フランスで私の本 に害を及ぼしたことは間違いない。(D.ベックモンがCh.Darwin, The Origin of Species, ed. Flammarion-GF, 2008で引用)。 クレマンス・ロワイエは1870年、ダーウィンに告げずに第3版16を出版した15。彼女は序文を加え、ダーウィンが1868年の著作『家畜動植物の変 異』で提唱した「パンゲネシスの理論」を徹底的に批判した。この新版には、第4版と第5版でダーウィンが導入した変更は含まれていない15。この第3版を 知ったダーウィンは、フランスの出版社ラインワルドと、すでに『変種...』を翻訳出版していたジュネーブの博物学者ジャン=ジャック・ムリニエに、第5 版に基づく新訳をまとめるよう手紙を出した。しかし、ダーウィンは、ムーリエの翻訳が個人的な考えや無関係な事柄で飾られており、ダーウィンの信頼を濫用 したと考え、哲学者のシャルル・レヴェックは、ムーリエが原典を裏切っていると非難したが、多くの人々は、稚拙だと考えるムーリエの翻訳よりも、彼女の翻 訳を好んだ。クレマンス・ロワイエはダーウィンからの手紙でレヴェックの非難をかわし、この問題は道徳・政治科学アカデミーによって解決された。 第4版(1882年)  Hommes d'aujourd'hui』誌一面のクレマンス・ロワイエ、1882年、アンリ・ドゥマール作画。 ダーウィンが亡くなった1882年、クレマンス・ロワイエはフラマリオンと第4版を出版した15。彼女は初版の序文を掲載し、短い「第4版の読者への警告」(5ページ)を付け加えた。この版は、ダーウィンの死から30年後の1932年まで出版された15。 |

| クレマンス・ロワイエ(Clémence Royer, 1830年4月21日 – 1902年2月6日)は、フランスの女性科学者である。ダーウィンの『種の起源』を、自らの注釈をつけてフランス語に翻訳した。 ナントに生まれた。父は王党派の陸軍の将校で、母は針子であった。父は1832年のレジティミスト(ブルボン派)の反乱の失敗で、家族とともにスイスに4 年間の亡命生活をした。オルレアンに戻った後、父は当局に出頭して無罪となった。7歳の時からクレマンスは父の姓を名乗るようになった。子供時代には両親 からの教育を受けることを好んだ。 13歳の時にパリに移り、針仕事に優れ、読書を楽しんだ。18歳の時に起きた1848年革命で、共和派の思想に影響を受けた。父は妻子をパリに残して故郷 に戻っていたが、1850年に死去した。クレマンスは多少の遺産を得て、教師の資格を得るための勉強に3年間を費やした。1854年1月に南ウェールズの 私設の女学校に教師として赴任したが、翌1855年春にフランスへ戻って教師を続けた。自伝によれば、この時期ロワイエはカトリックの哲学に疑念を抱きは じめたとしている。、 1856年に教師を辞め、スイスのローザンヌに移って父の遺産からの収入で暮らし始めた。図書館から本を借り、キリスト教の起源や、自然科学の事項の勉強 をして過ごした。1858年にスウェーデンの小説家フレドリカ・ブレーメルの公開講義に啓発されて、女性たちに4回の論理学の講義を行い、成功を収めた。 この時までに、ロワイエは亡命しているフランスの自由主義者や共和主義者のグループの会合に加わるようになっていた。ローザンヌのアカデミーで政治学を教 え、2つの雑誌を編集していた亡命者のパスカル・デュプラ(Pascal Duprat)と知り合い、後に15歳年上のデュプラの愛人なった。 デュプラの助手として、雑誌 "Le Nouvel Économiste" の発行を手伝い、デュプラに励まされて執筆生活を始めた。また、デュプラに助けられて女性のための自然科学に関する講義を行い、講義録はローザンヌの出版 社から出版された。1860年にスイスのヴォー州が行った税に関する論文の募集に応募し、2位となった。これは "Théorie de l'impôt ou la dîme social" として出版され、その中で社会における女性の経済的役割について論じている。この著書によってスイス以外でもロワイエは知られるようになった。 ロワイエが『種の起源』を翻訳することになった経緯は明確になっていないが、フランスでの出版を望んだダーウィンが初めに選んだルイーズ・ベロック (Louise Belloc)はその内容が技術的すぎる事から断り、次の候補ピエール・タランディエール(Pierre Talandier)は出版社を見つけることができなかった。1861年には翻訳のためにロワイエに『種の起源』の3訂版を送るように依頼するダーウィン の手紙が残されている。スイスの自然科学者家でジュネーブ大学の講師ルネ=エドゥアール・クラパレード(René-Édouard Claparède)が生物学の専門知識のサポートすることを申し出た。 ロワイエは翻訳するだけでなく、60ページに及ぶ長文を序文と詳しい脚注をつけて『種の起源』を出版した。序文でロワイエは反宗教的な立場を述べ、自然淘汰の考え方を社会の分野に適用されることに異論を述べたことによって、ダーウィンを困惑させた。 1870年にパリの人類学協会に入会を許された。 |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆