気候変動

Climate change, or Global warming

☆ 一般的な用法では、気候変動(climate change)は地球温暖化、つまり地球の平均気温の継続的な上昇と、それが地球の気候システムに及ぼす影響について説明している。より広い 意味での気候変動には、地球の気候に対する過去の長期的な変化も含まれる。化石燃料の使用、森林伐採、農業や工業の一部は、温室効果ガス[5]を増加させ る。これらのガスは、地球が太陽光によって暖まった後に放射する熱の一部を吸収し、大気下部を暖める。地球温暖化を促進する主要な温室効果ガスである二酸 化炭素は、約50%増加し、数百万年前には見られなかったレベルになっている[6]。

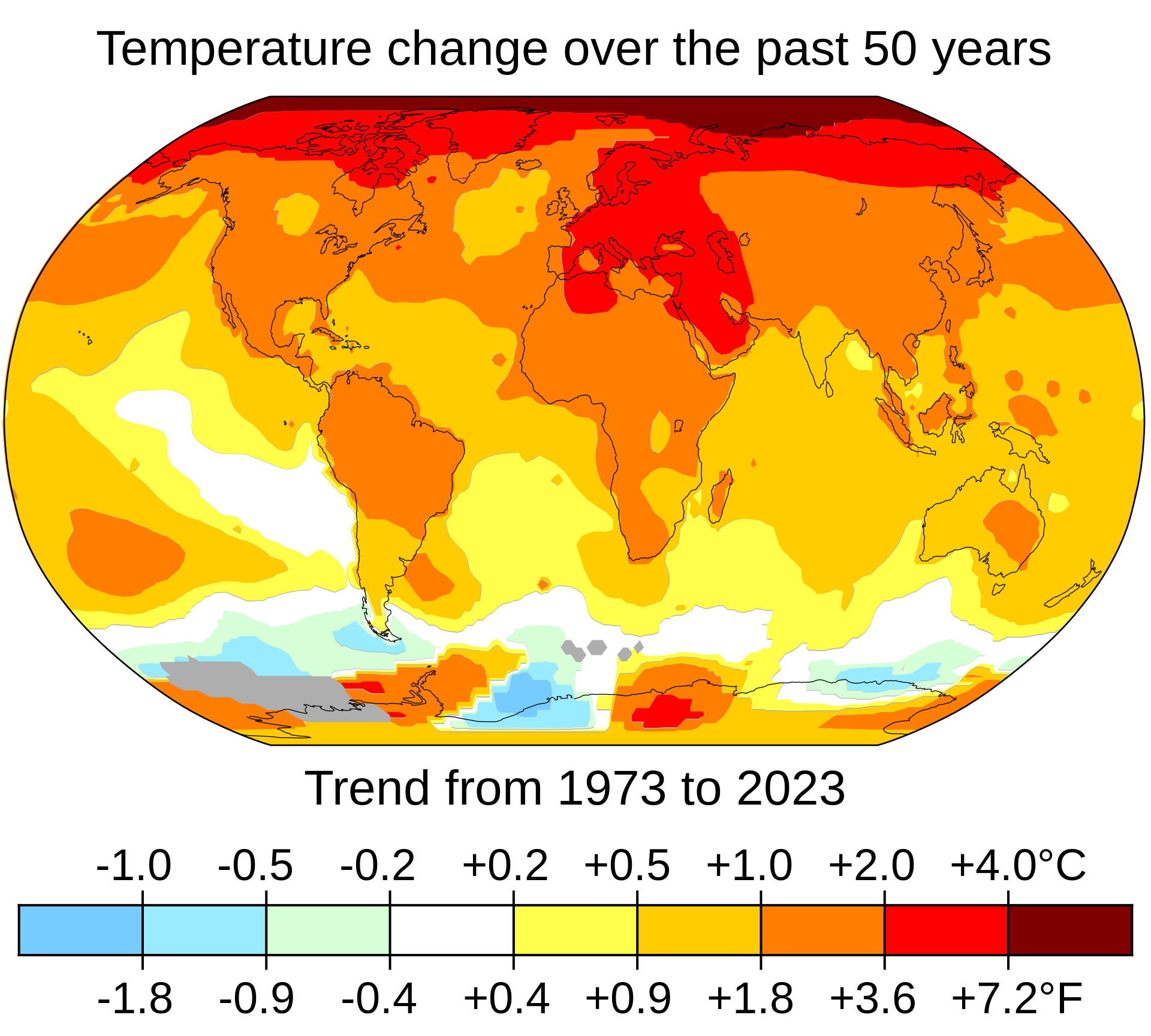

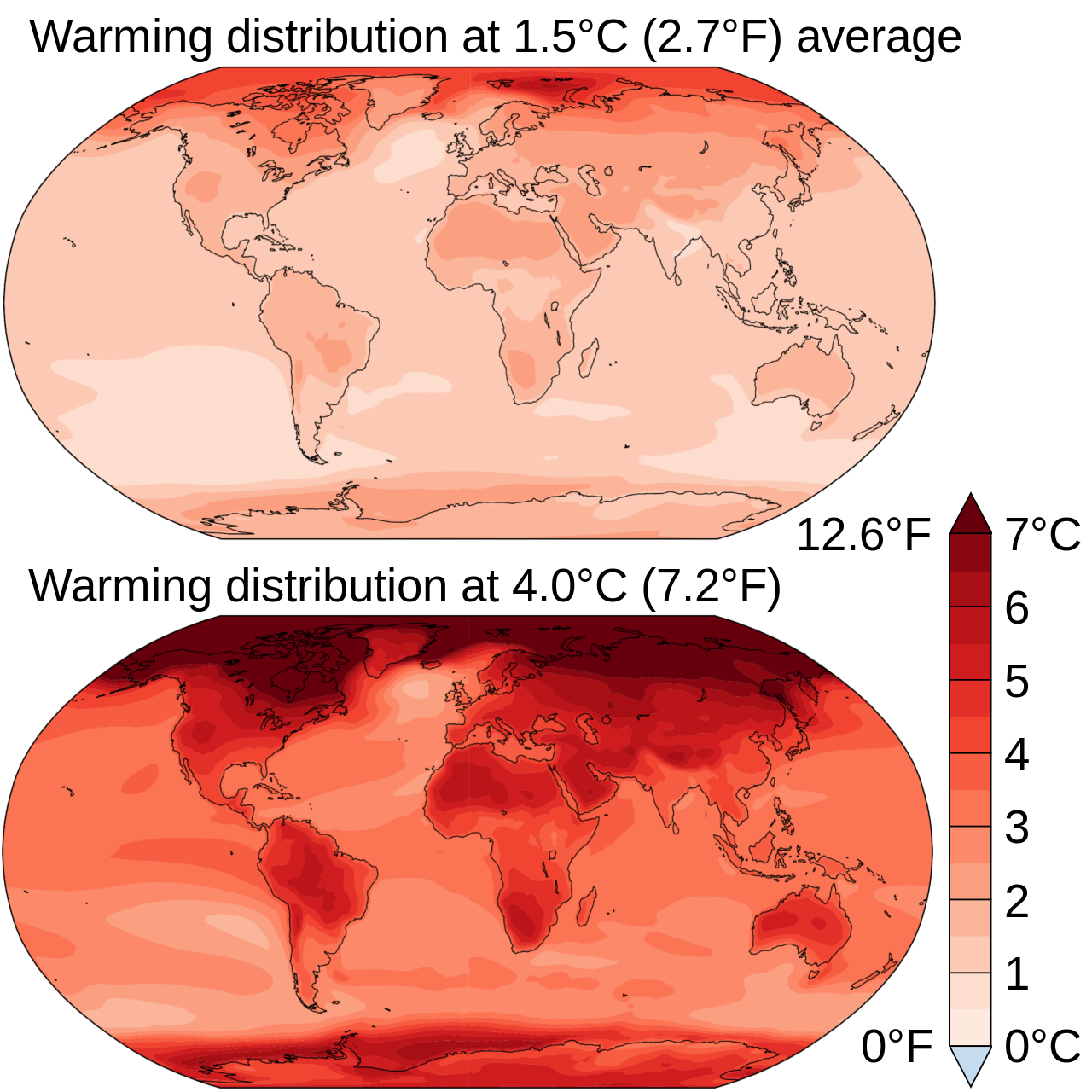

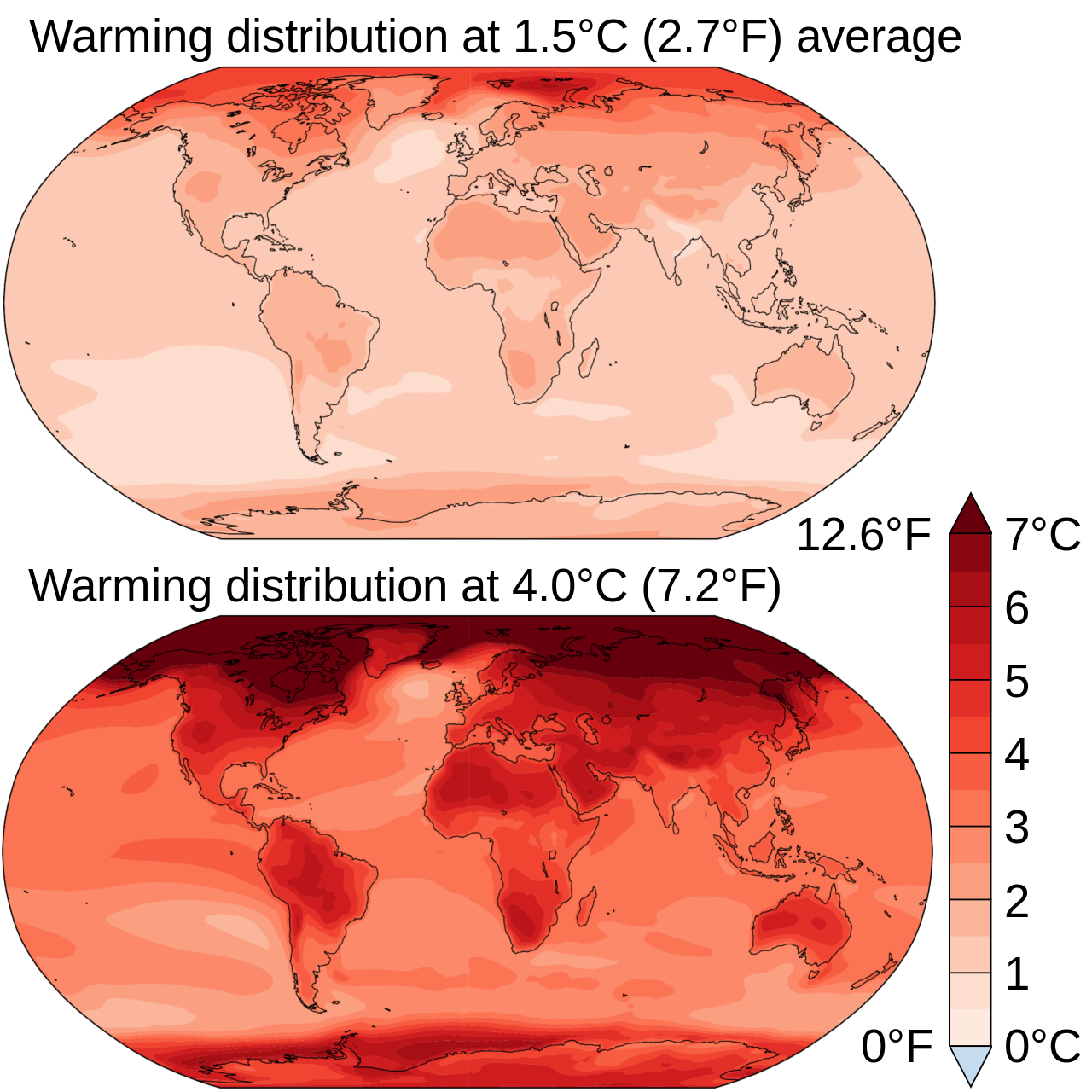

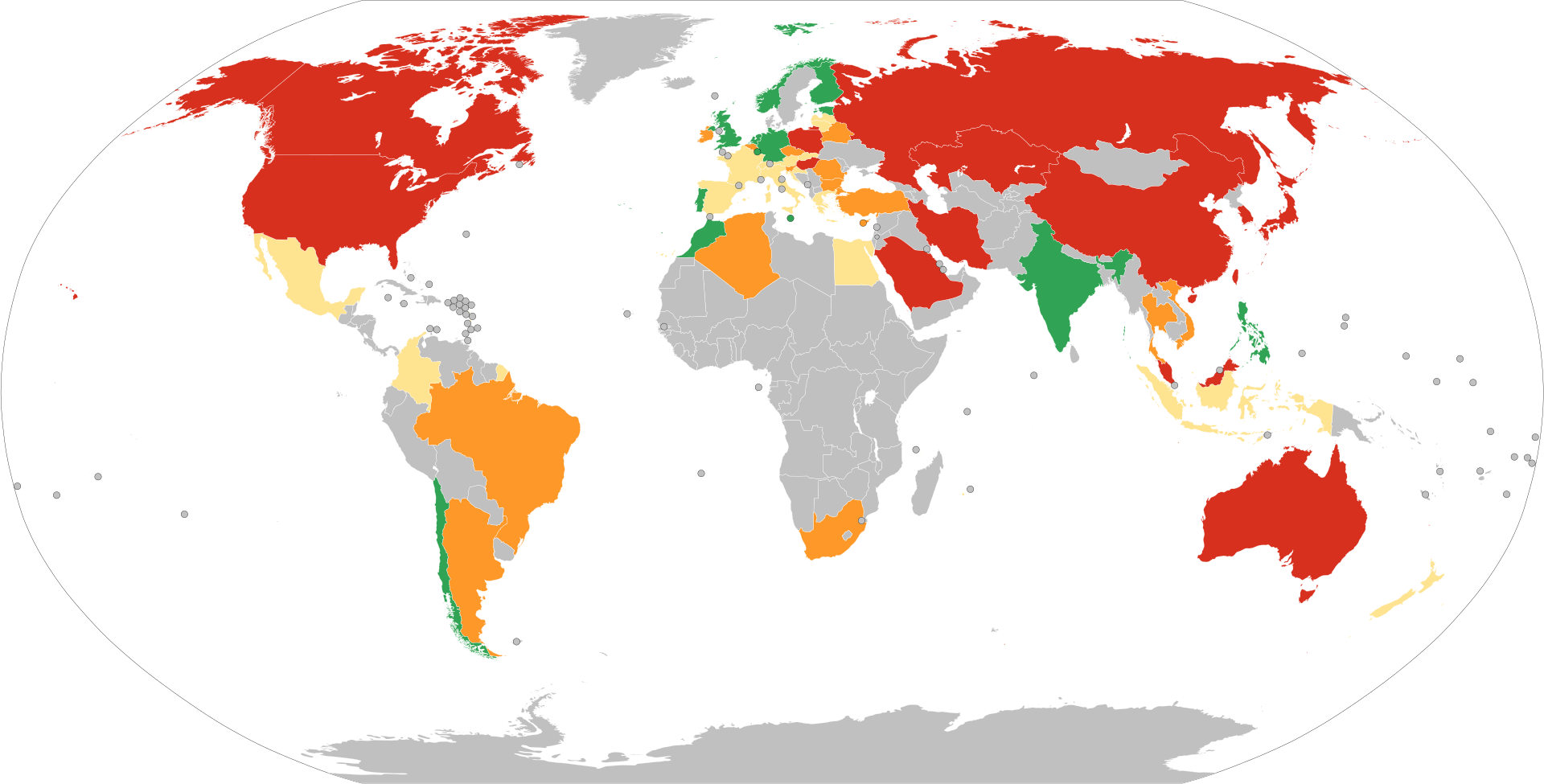

Changes in surface air temperature over the past 50 years.[1] The Arctic has warmed the most, and temperatures on land have generally increased more than sea surface temperatures. 過去50年間の地表気温の変化[1]。北極圏が最も温暖化し、陸地の気温は一般的に海面温度よりも上昇している。

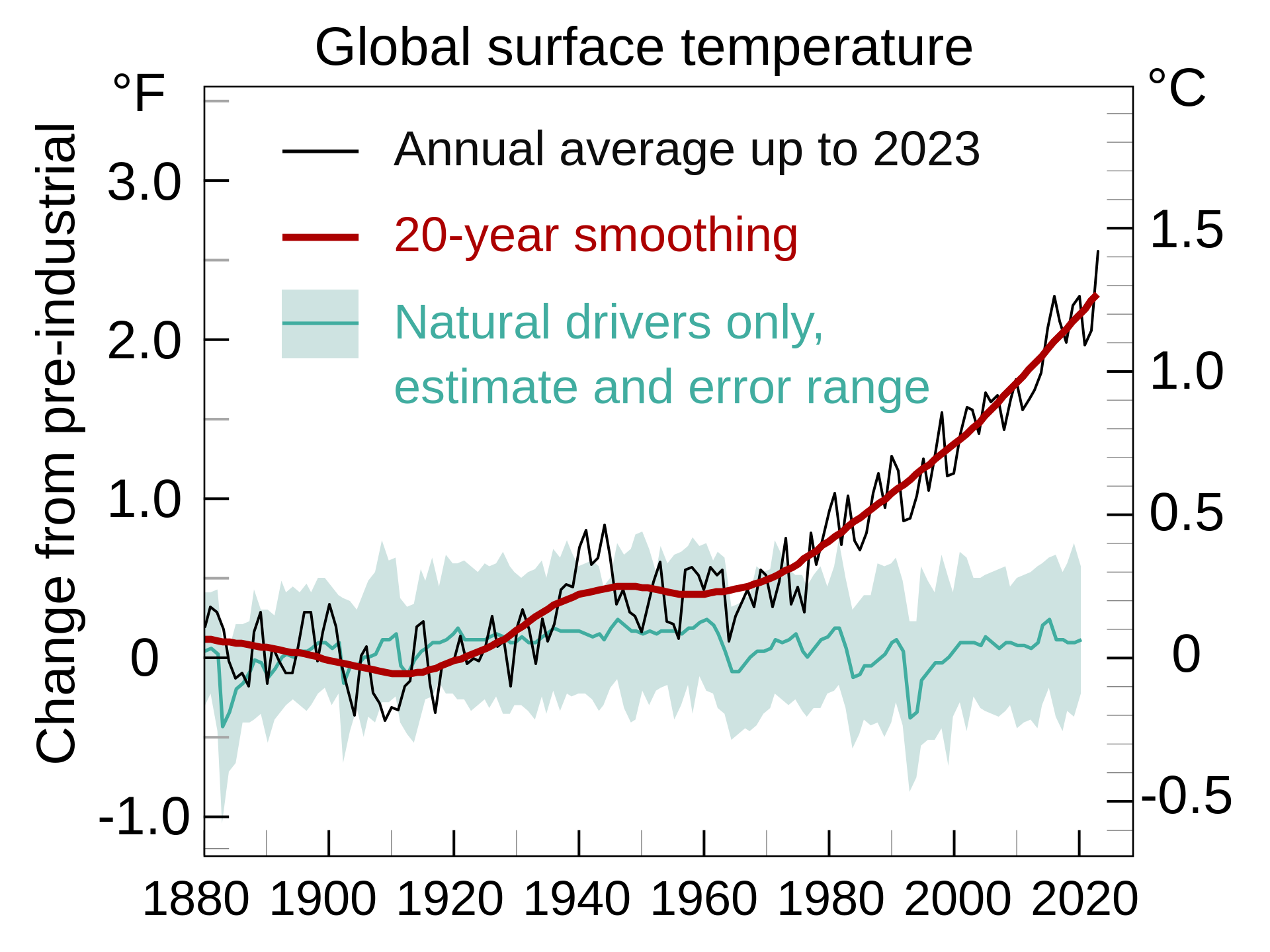

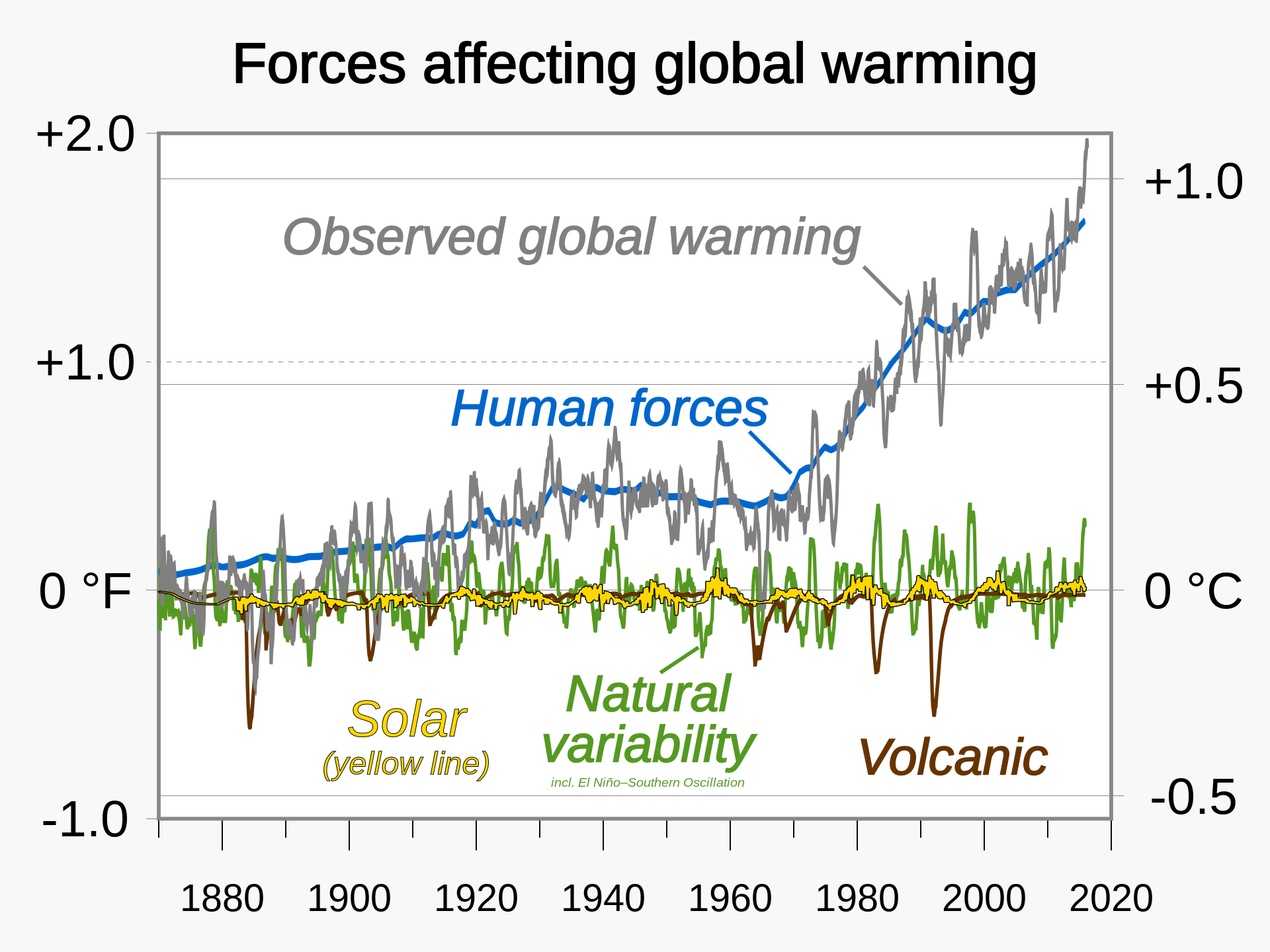

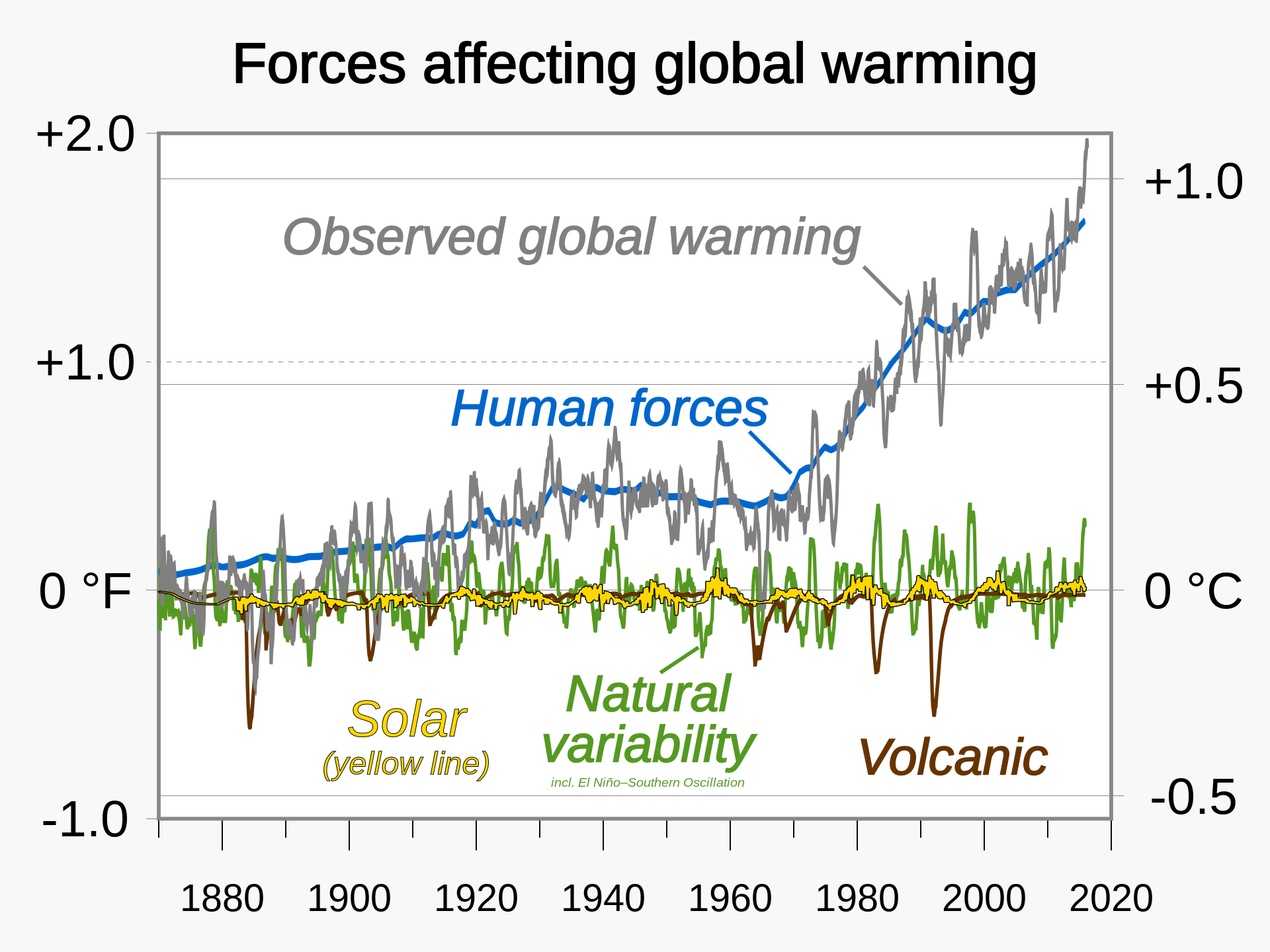

Earth's

average surface air temperature has increased almost 1.5 °C (about 2.5

°F) since the Industrial Revolution. Natural forces cause some

variability, but the 20-year average shows the progressive influence of

human activity.[2]産業革命以降、地球の平均気温はほぼ1.5℃上昇した。自然の力による変動もあるが、20年間の平均を見ると、人間活動の影響が進行していることがわかる[2]。

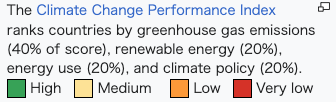

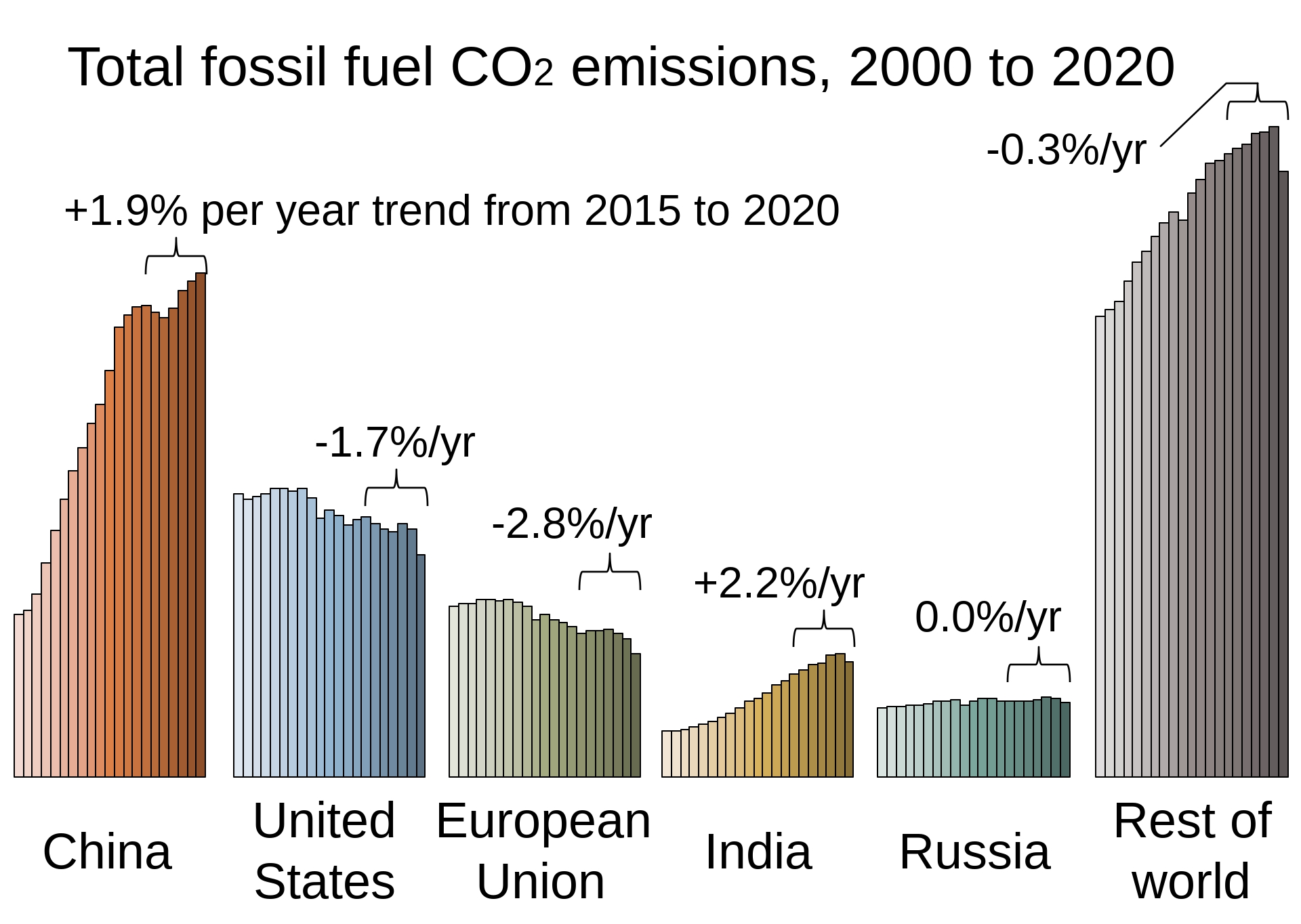

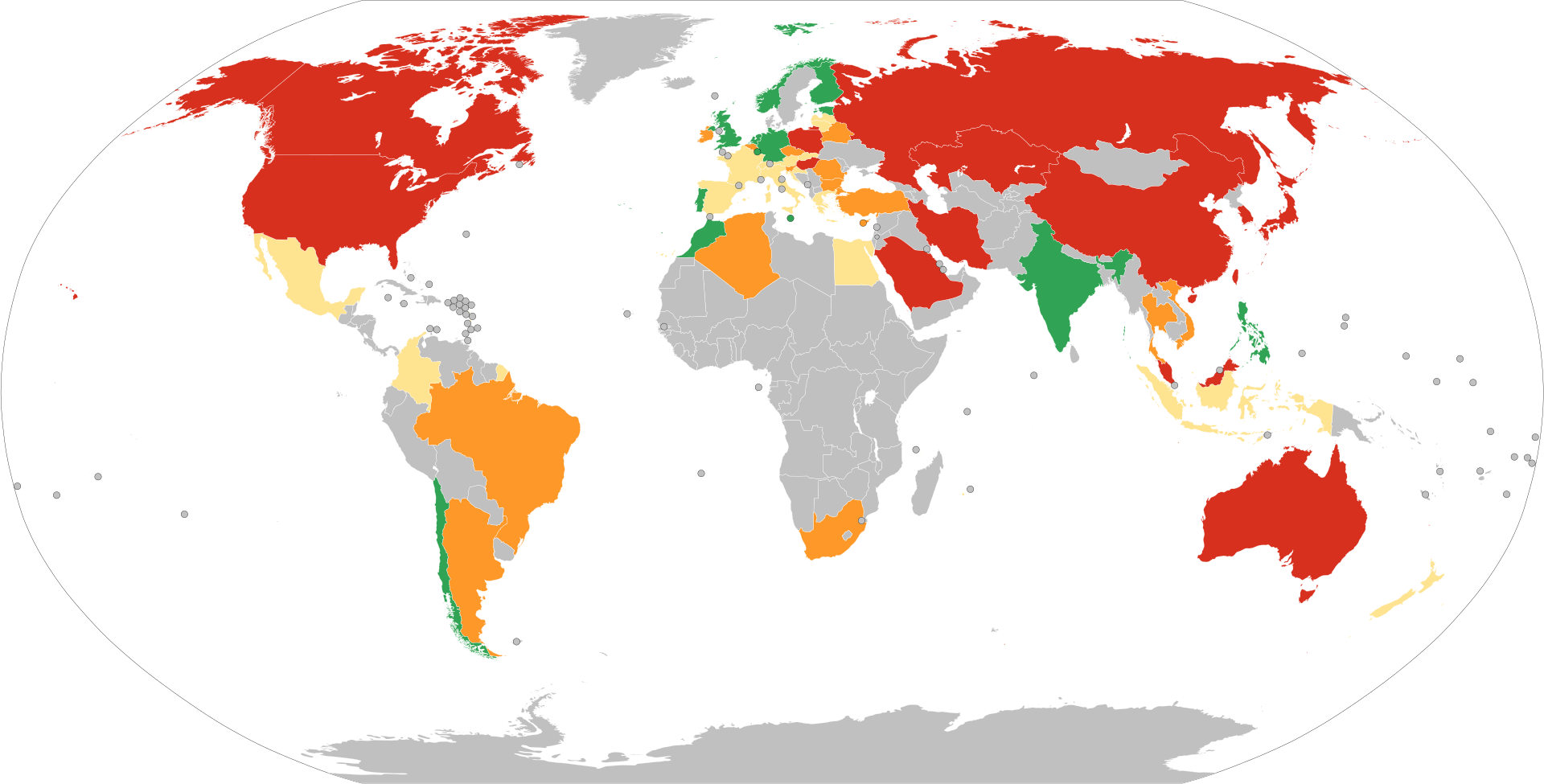

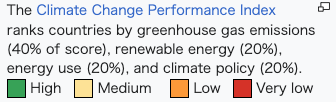

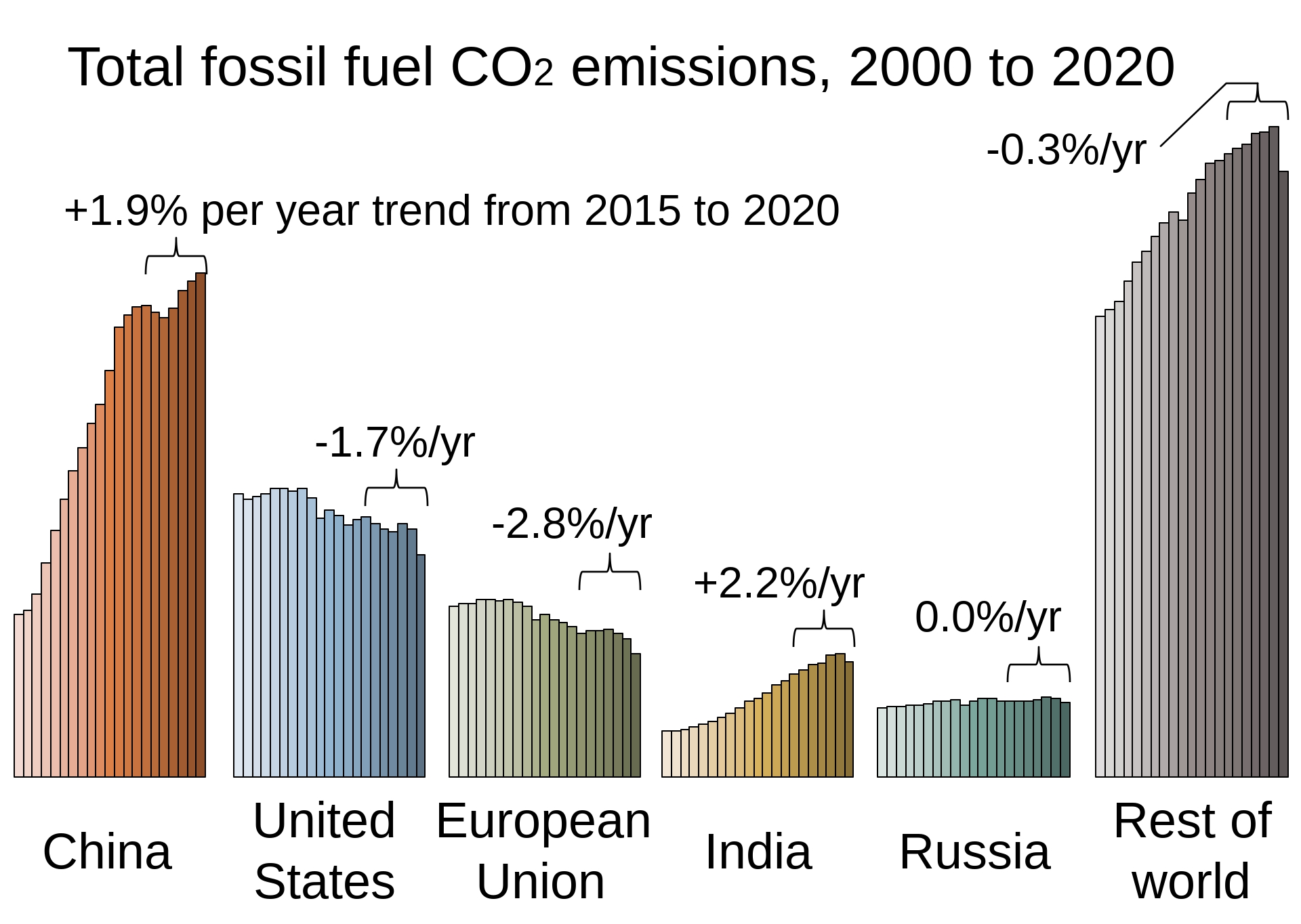

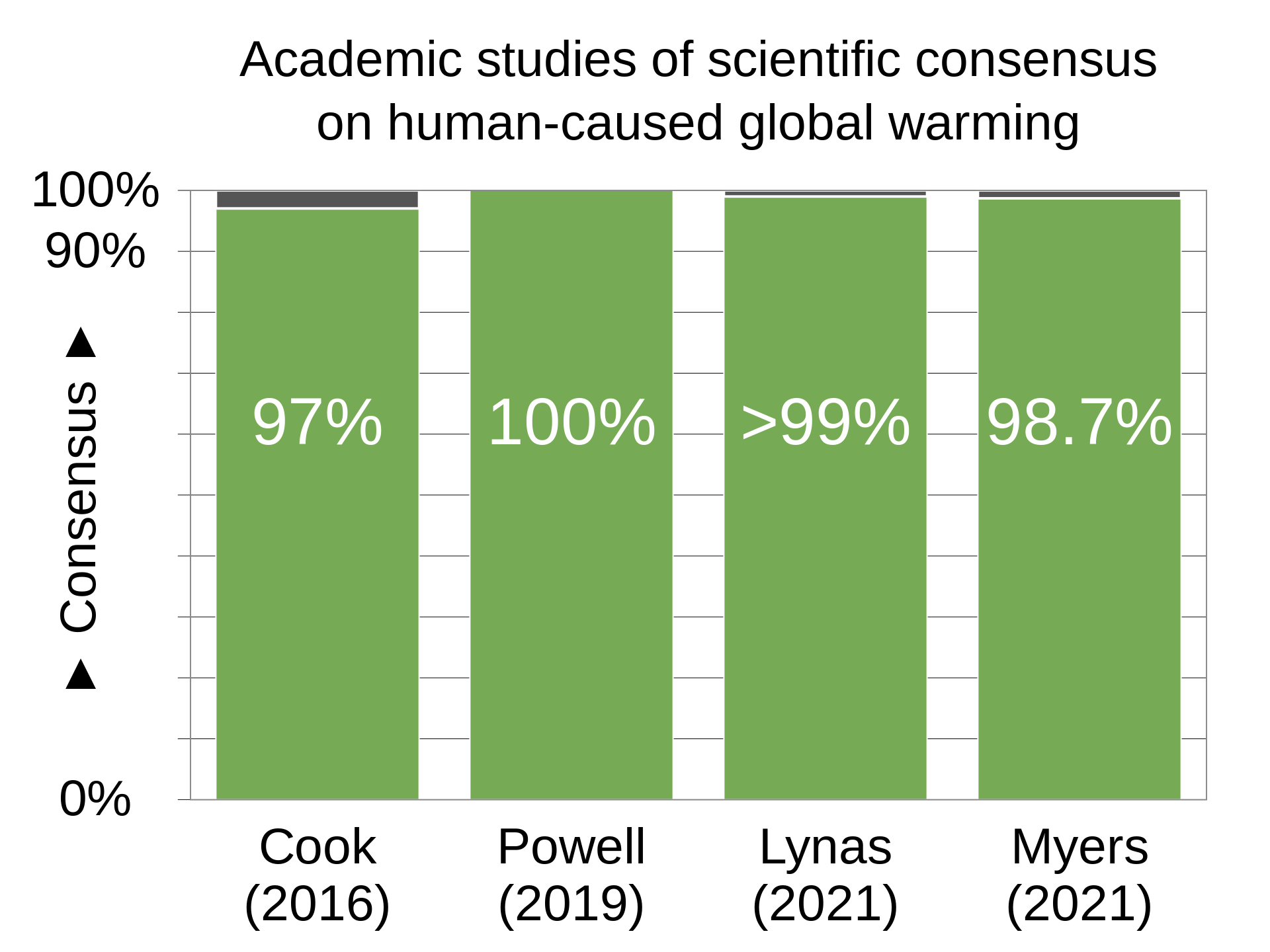

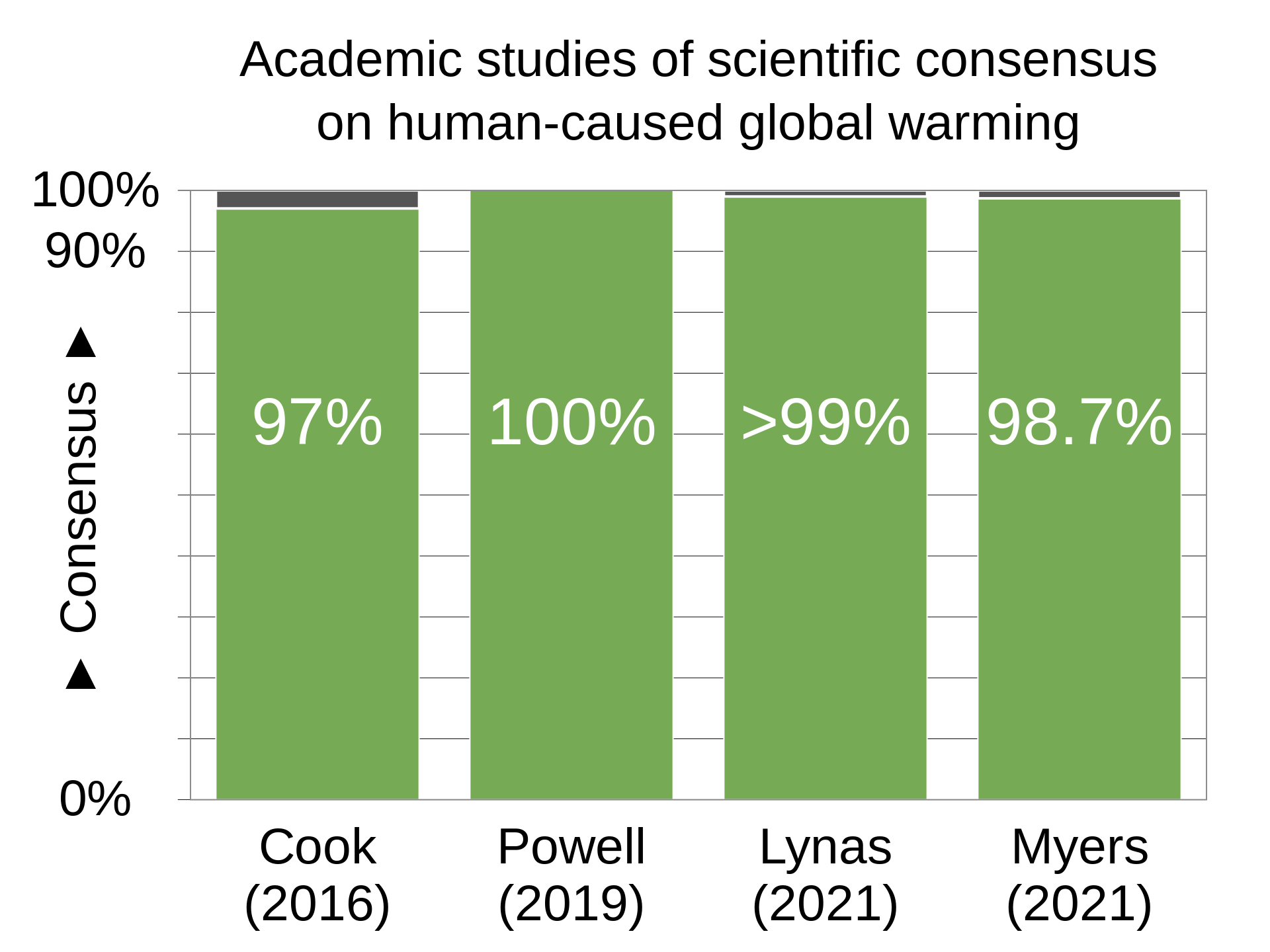

| In common usage, climate change

describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average

temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change

in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to Earth's

climate. The current rise in global average temperature is primarily

caused by humans burning fossil fuels since the Industrial

Revolution.[3][4] Fossil fuel use, deforestation, and some agricultural

and industrial practices add to greenhouse gases.[5] These gases absorb

some of the heat that the Earth radiates after it warms from sunlight,

warming the lower atmosphere. Carbon dioxide, the primary greenhouse

gas driving global warming, has grown by about 50% and is at levels

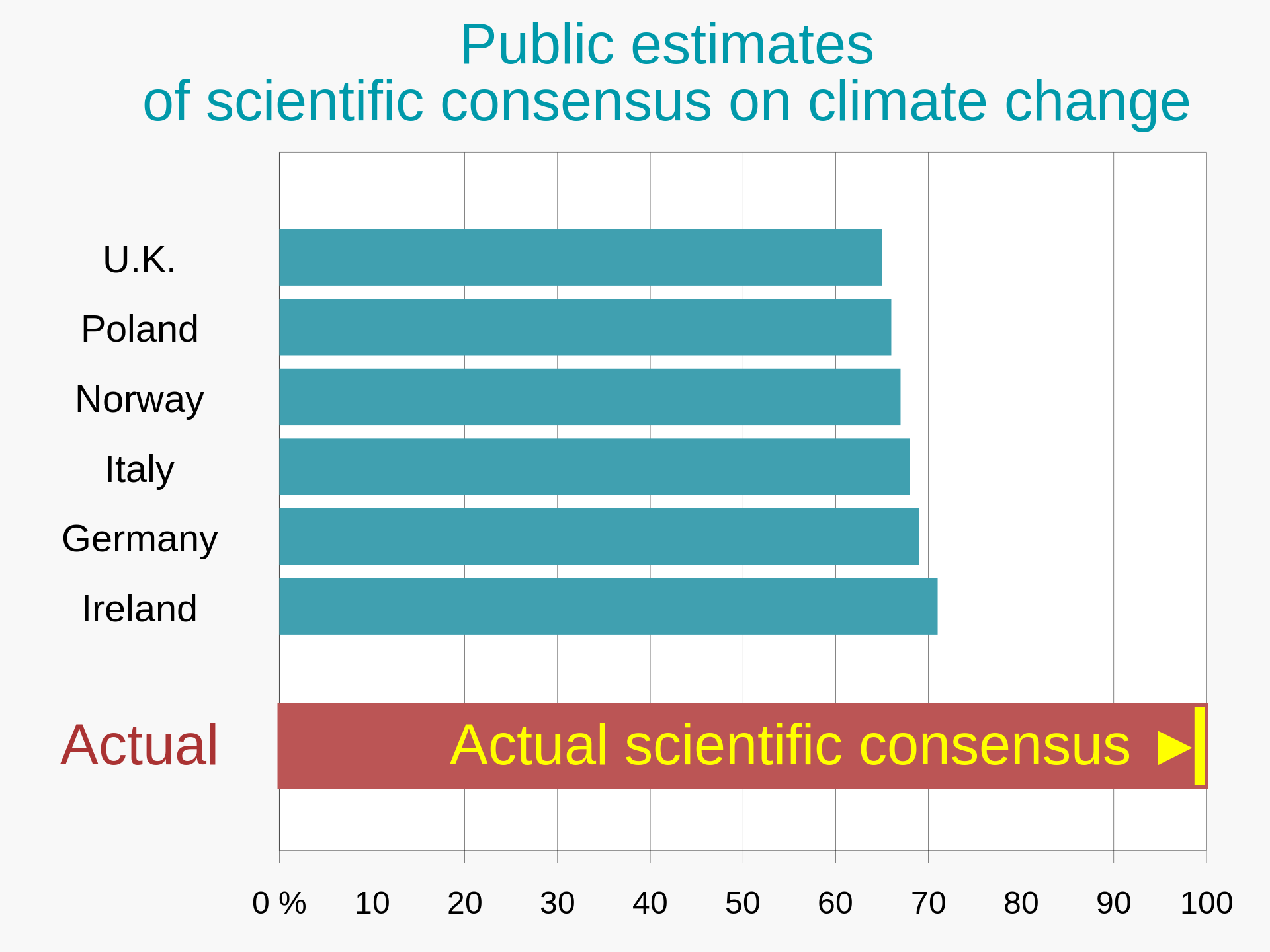

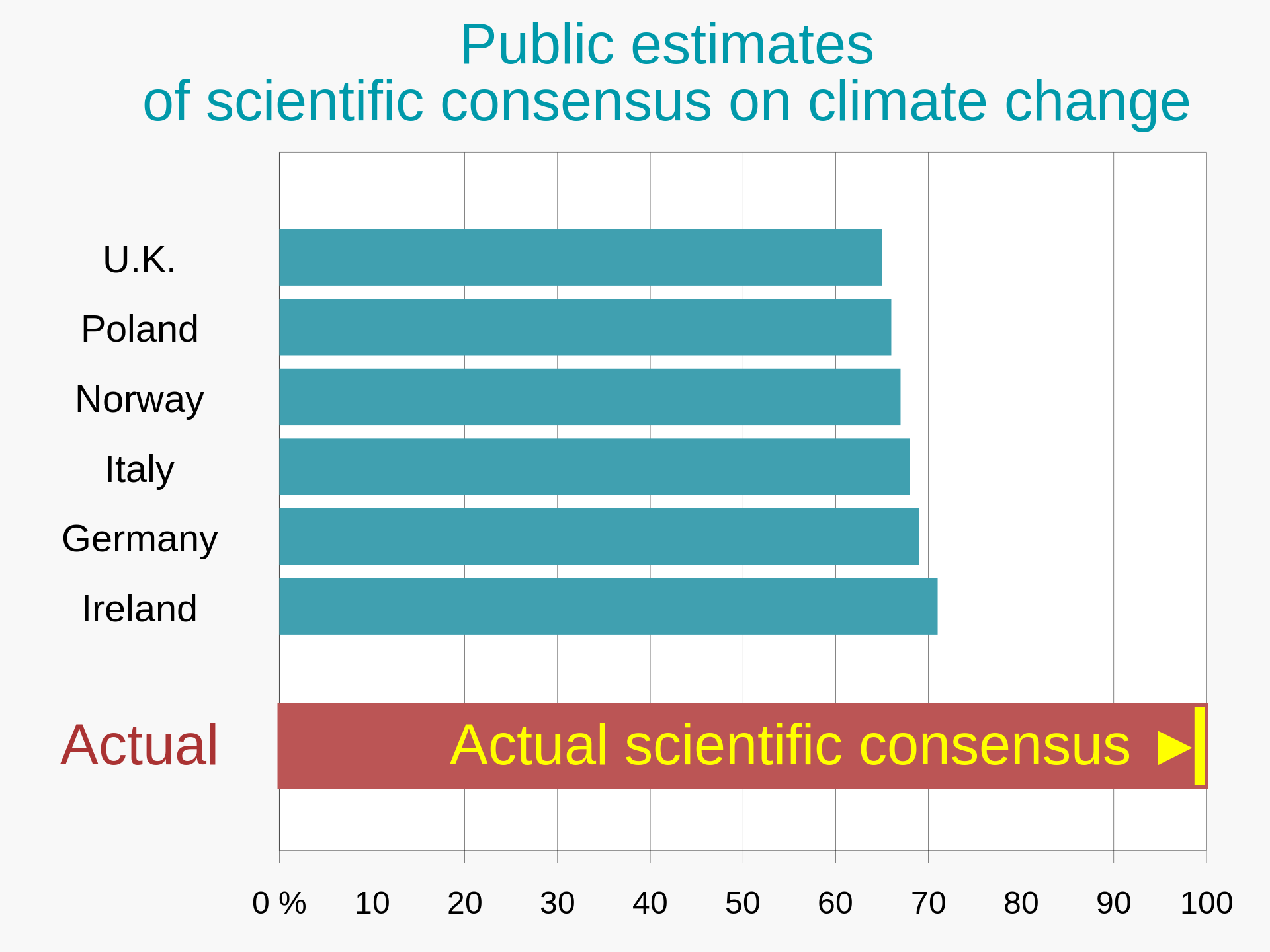

unseen for millions of years.[6] Climate change has an increasingly large impact on the environment. Deserts are expanding, while heat waves and wildfires are becoming more common.[7] Amplified warming in the Arctic has contributed to thawing permafrost, retreat of glaciers and sea ice decline.[8] Higher temperatures are also causing more intense storms, droughts, and other weather extremes.[9] Rapid environmental change in mountains, coral reefs, and the Arctic is forcing many species to relocate or become extinct.[10] Even if efforts to minimise future warming are successful, some effects will continue for centuries. These include ocean heating, ocean acidification and sea level rise.[11] Climate change threatens people with increased flooding, extreme heat, increased food and water scarcity, more disease, and economic loss. Human migration and conflict can also be a result.[12] The World Health Organization (WHO) calls climate change the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century.[13] Societies and ecosystems will experience more severe risks without action to limit warming.[14] Adapting to climate change through efforts like flood control measures or drought-resistant crops partially reduces climate change risks, although some limits to adaptation have already been reached.[15] Poorer communities are responsible for a small share of global emissions, yet have the least ability to adapt and are most vulnerable to climate change.[16][17]  Bobcat Fire in Monrovia, CA, September 10, 2020 Bleached colony of Acropora coral A dry lakebed in California, which is experiencing its worst megadrought in 1,200 years.[18] Examples of some effects of climate change: Wildfire intensified by heat and drought, bleaching of corals occurring more often due to marine heatwaves, and worsening droughts compromising water supplies. Many climate change impacts have been felt in recent years, with 2023 the warmest on record at +1.48 °C (2.66 °F) since regular tracking began in 1850.[19][20] Additional warming will increase these impacts and can trigger tipping points, such as melting all of the Greenland ice sheet.[21] Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, nations collectively agreed to keep warming "well under 2 °C". However, with pledges made under the Agreement, global warming would still reach about 2.7 °C (4.9 °F) by the end of the century.[22] Limiting warming to 1.5 °C will require halving emissions by 2030 and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.[23] Fossil fuel use can be phased out by conserving energy and switching to energy sources that do not produce significant carbon pollution. These energy sources include wind, solar, hydro, and nuclear power.[24][25] Cleanly generated electricity can replace fossil fuels for powering transportation, heating buildings, and running industrial processes.[26] Carbon can also be removed from the atmosphere, for instance by increasing forest cover and farming with methods that capture carbon in soil.[27][28] |

一般的な用法では、気候変動(climate change)

は地球温暖化、つまり地球の平均気温の継続的な上昇と、それが地球の気候システムに及ぼす影響について説明している。より広い意味での気候変動には、地球

の気候に対する過去の長期的な変化も含まれる。化石燃料の使用、森林伐採、農業や工業の一部は、温室効果ガス[5]を増加させる。これらのガスは、地球が

太陽光によって暖まった後に放射する熱の一部を吸収し、大気下部を暖める。地球温暖化を促進する主要な温室効果ガスである二酸化炭素は、約50%増加し、

数百万年前には見られなかったレベルになっている[6]。 気候変動が環境に与える影響はますます大きくなっている。砂漠は拡大し、熱波や山火事が頻発するようになっている[7]。北極圏では温暖化が加速し、永久 凍土の融解、氷河の後退、海氷の減少を引き起こしている[8]。気温の上昇はまた、より激しい嵐、干ばつ、その他の極端な気象現象を引き起こしている [9]。山岳地帯、サンゴ礁、北極圏における急激な環境変化は、多くの生物種に移住や絶滅を迫っている[10]。これには、海洋加熱、海洋酸性化、海面上 昇などが含まれる[11]。 気候変動は、洪水の増加、猛暑、食料・水不足の増加、疾病の増加、経済的損失などで人々を脅かす。世界保健機関(WHO)は、気候変動を21世紀における 世界の健康に対する最大の脅威と呼んでいる[13]。 [14] 洪水対策や干ばつに強い作物などの取り組みを通じて気候変動に適応することで、気候変動リスクは部分的に軽減されるが、適応の限界に達しているものもある [15]。貧しい地域社会は、世界の排出量のわずかな割合しか担っていないにもかかわらず、適応能力が最も低く、気候変動に対して最も脆弱である[16] [17]。  2020年9月10日、カリフォルニア州モンロビアのボブキャット火災 白化したアクロポラサンゴのコロニー 過去1,200年で最悪の大干ばつに見舞われているカリフォルニア州の乾燥した湖底[18]。 気候変動の影響の一例: 暑さと干ばつによる山火事の増加、海洋熱波によるサンゴの白化現象の頻発、干ばつの悪化による水供給の悪化などである。 2023年は、1850年に定期的な追跡が始まって以来、+1.48 °Cという記録的な高温となった[19][20]。さらなる温暖化はこうした影響を増大させ、グリーンランドの氷床がすべて溶けるなどの転換点を引き起こ す可能性がある[21]。2015年のパリ協定では、各国は「2 °C未満」に温暖化を抑えることに合意した。しかし、同協定に基づく約束では、今世紀末までに地球温暖化は依然として約2.7℃に達するだろう[22]。 温暖化を1.5℃に抑えるには、2030年までに排出量を半減させ、2050年までにネットゼロ排出を達成する必要がある[23]。 化石燃料の使用は、エネルギーを節約し、大幅な炭素汚染をもたらさないエネルギー源に切り替えることで、段階的に削減することができる。こうしたエネル ギー源には、風力、太陽光、水力、原子力が含まれる[24][25]。クリーン発電された電力は、輸送、建物の暖房、工業プロセスの運転に使用する化石燃 料に取って代わることができる[26]。炭素はまた、例えば森林被覆を増やしたり、土壌中の炭素を回収する農法を用いたりすることによって、大気中から除 去することもできる[27][28]。 |

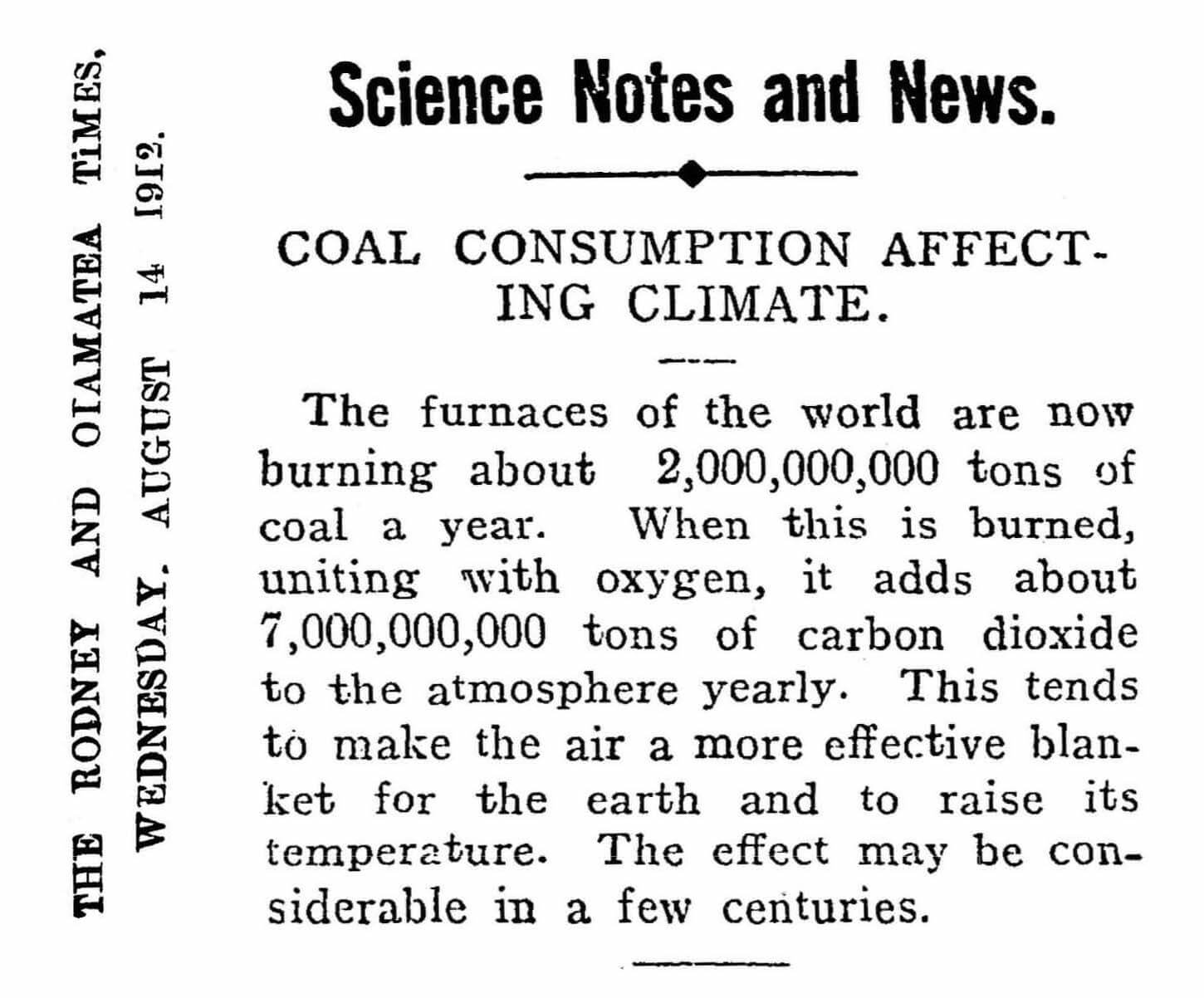

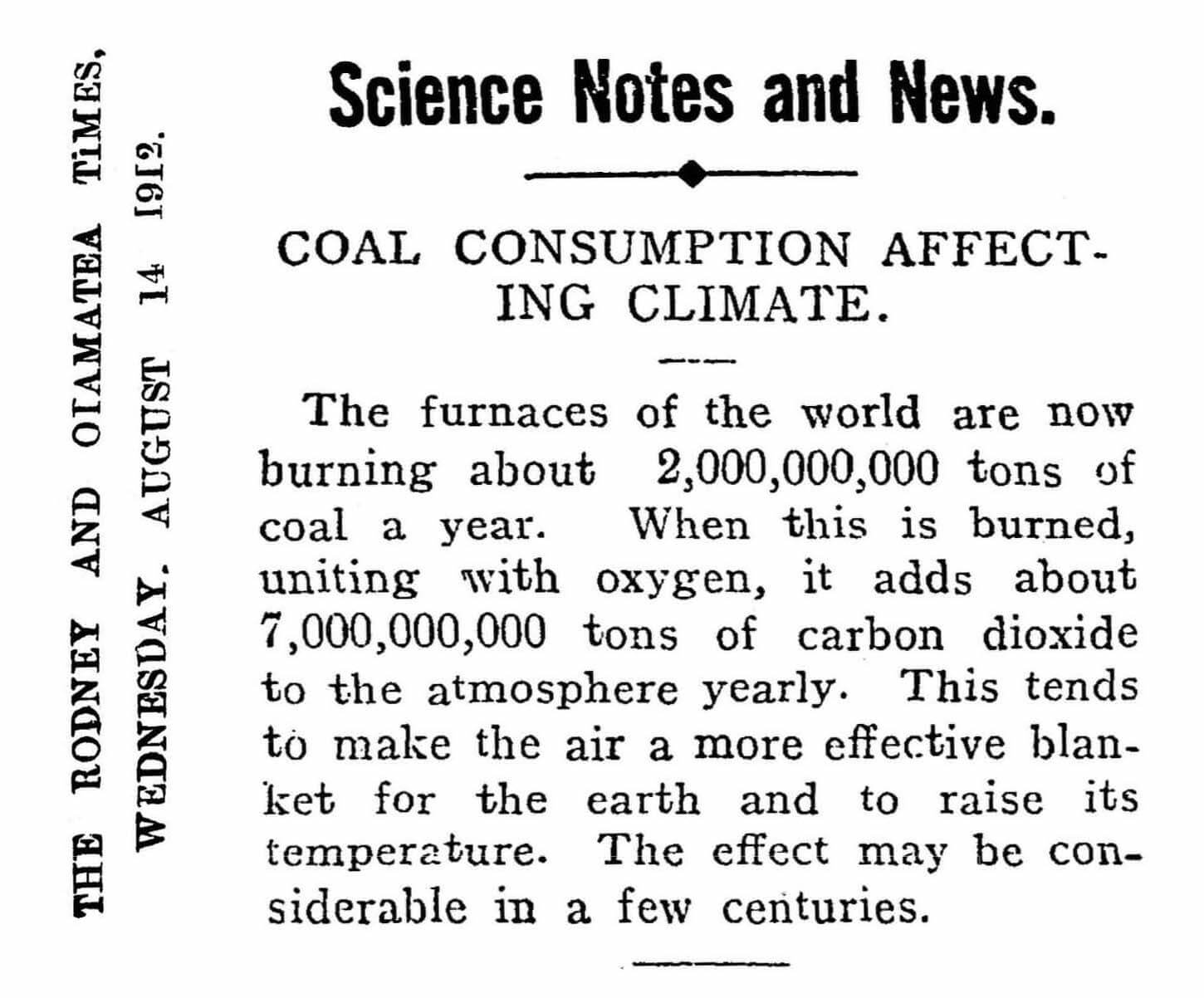

| Terminology Before the 1980s it was unclear whether the warming effect of increased greenhouse gases was stronger than the cooling effect of airborne particulates in air pollution. Scientists used the term inadvertent climate modification to refer to human impacts on the climate at this time.[29] In the 1980s, the terms global warming and climate change became more common, often being used interchangeably.[30] Scientifically, global warming refers only to increased surface warming, while climate change describes both global warming and its effects on Earth's climate system, such as precipitation changes.[29] Climate change can also be used more broadly to include changes to the climate that have happened throughout Earth's history.[31] Global warming—used as early as 1975[32]—became the more popular term after NASA climate scientist James Hansen used it in his 1988 testimony in the U.S. Senate.[33] Since the 2000s, climate change has increased usage.[34] Various scientists, politicians and media now use the terms climate crisis or climate emergency to talk about climate change, and global heating instead of global warming.[35] |

用語解説 1980年代以前は、温室効果ガスの増加による温暖化効果が、大気汚染に含まれる空気中の微粒子による冷却効果よりも強いかどうかは不明であった。 1980年代には、地球温暖化と気候変動という用語がより一般的になり、しばしば同じ意味で使われるようになった[30]。科学的には、地球温暖化は地表 面の温暖化の増加のみを指し、気候変動は地球温暖化と降水量の変化など地球の気候システムへの影響の両方を表す[29]。 気候変動はまた、地球の歴史を通じて起こった気候の変化を含むために、より広義に使用されることもある[31]。 地球温暖化は1975年には早くも使用されていたが[32]、NASAの気候科学者であるジェームズ・ハンセンが1988年の米国上院での証言で使用した 後、より一般的な用語となった[33]。 2000年代以降、気候変動は使用されるようになった[34]。現在、様々な科学者、政治家、メディアは、気候変動について話すために気候危機や気候緊急 事態という用語を使用し、地球温暖化の代わりに地球温暖化という用語を使用している[35]。 |

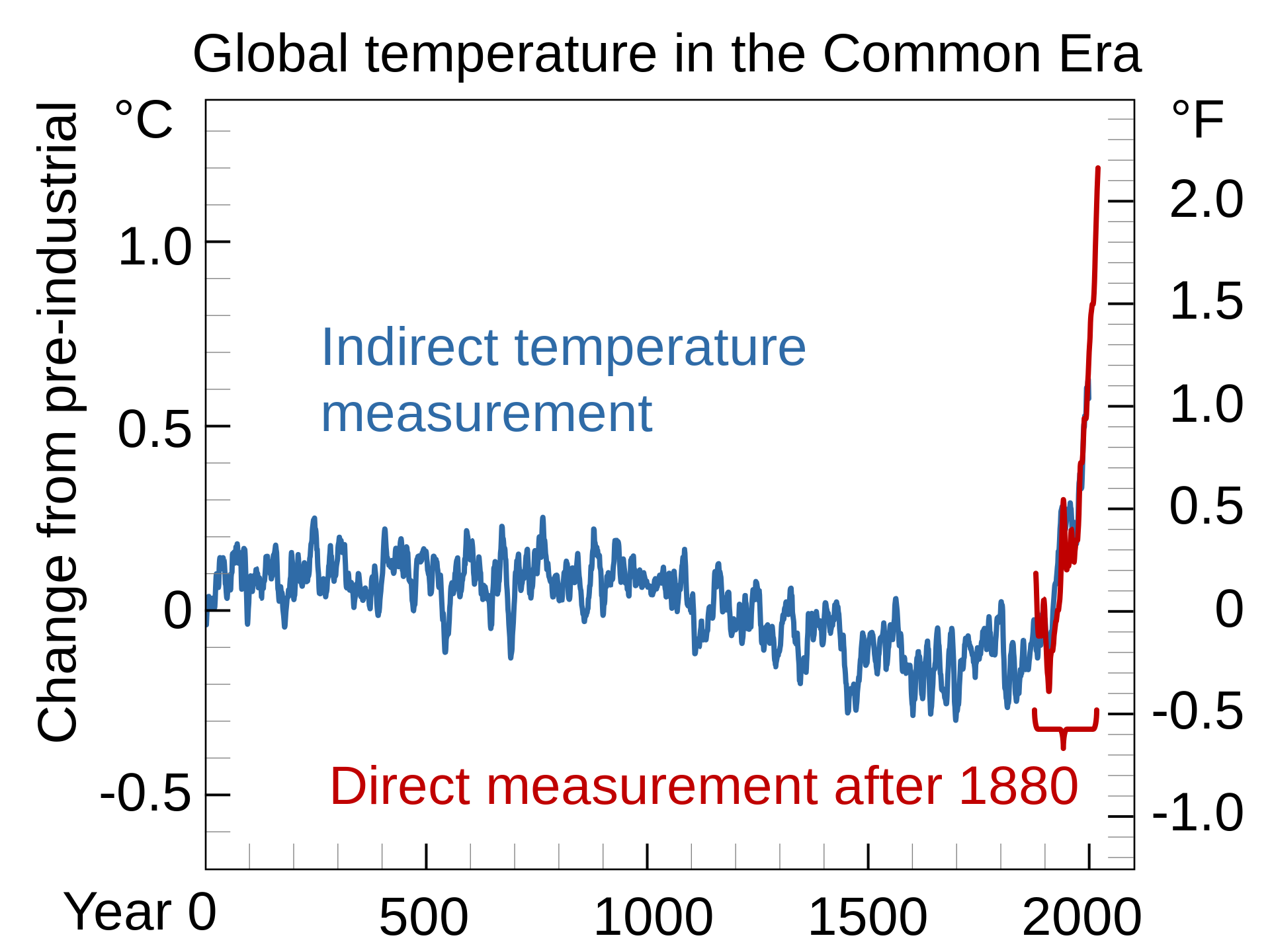

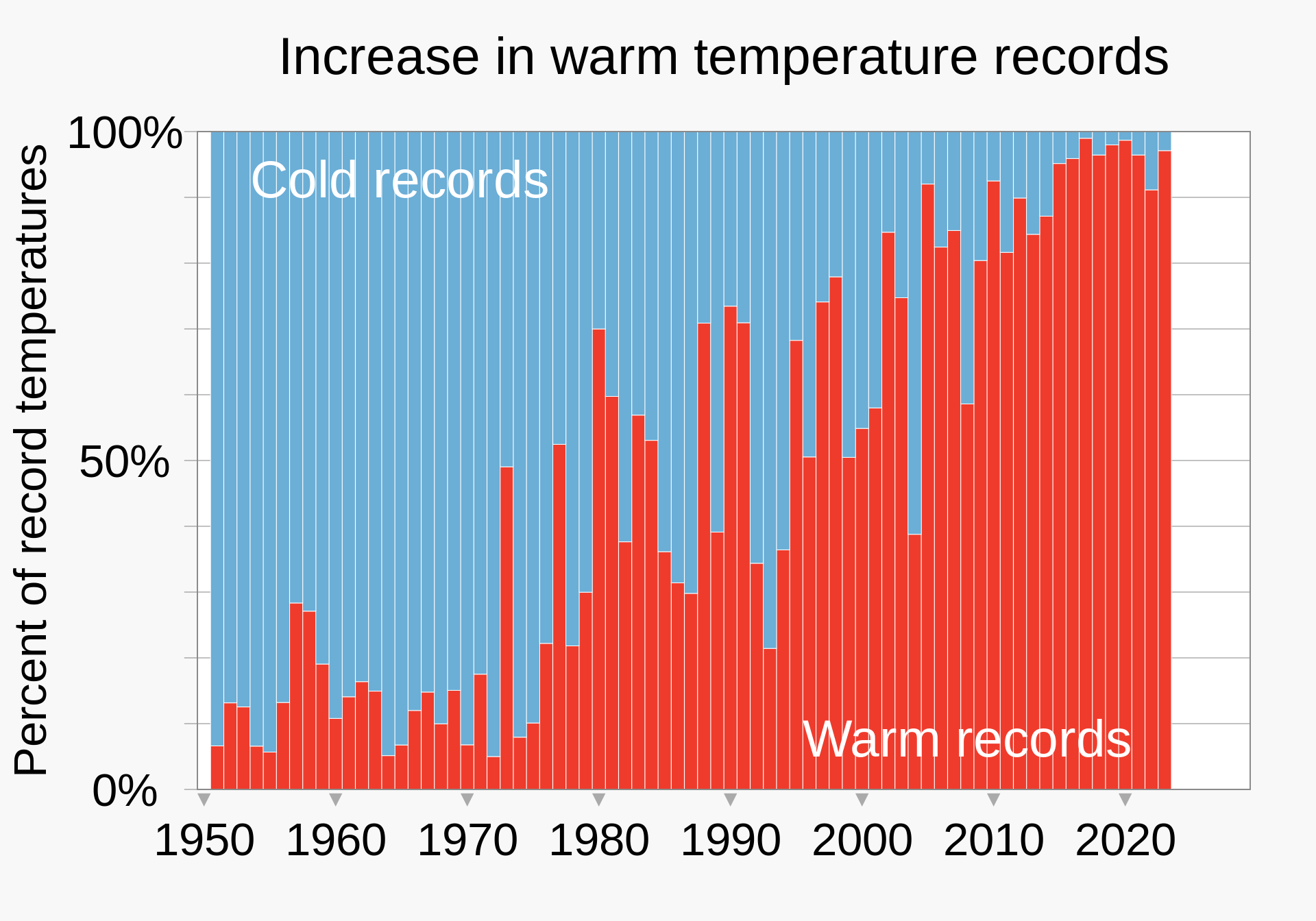

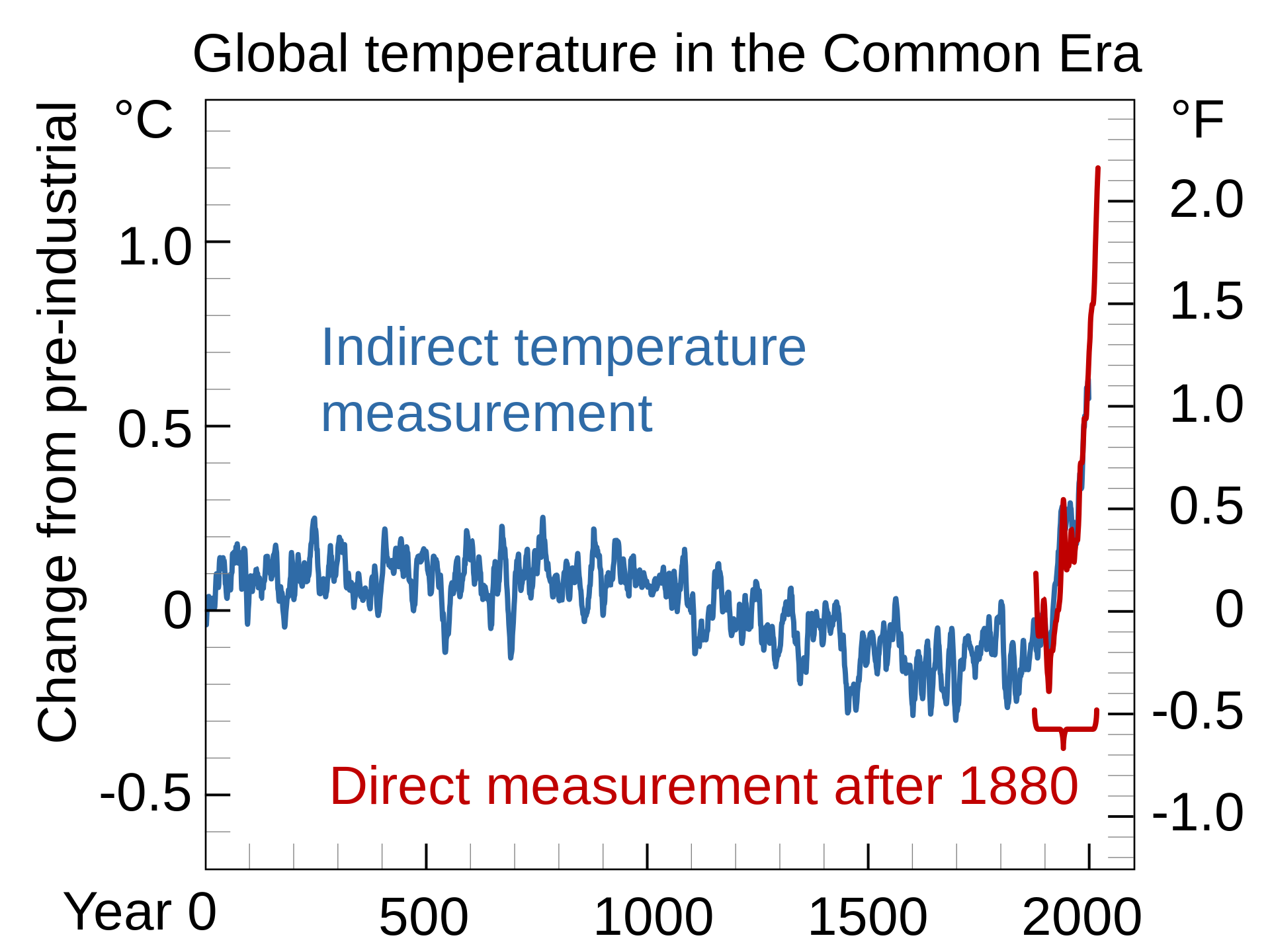

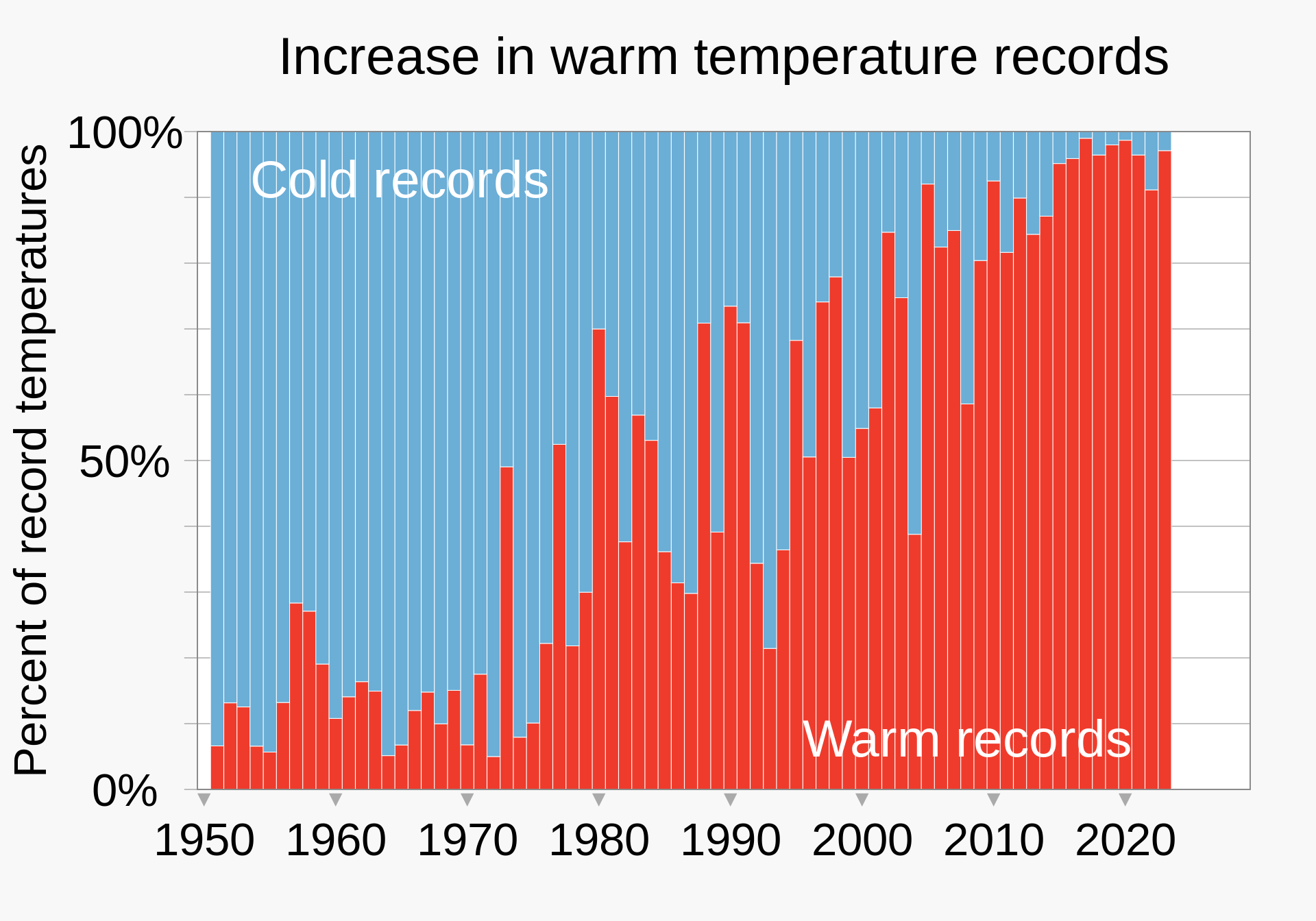

| Global temperature rise Global surface temperature reconstruction over the last 2000 years using proxy data from tree rings, corals, and ice cores in blue.[36] Directly observed data is in red.[37] Temperature records prior to global warming Main articles: Climate variability and change; Temperature record of the last 2,000 years; and Paleoclimatology Over the last few million years human beings evolved in a climate that cycled through ice ages, with global average temperature ranging between 1 °C warmer and 5–6 °C colder than current levels.[38][39] One of the hotter periods was the Last Interglacial between 115,000 and 130,000 years ago, when sea levels were 6 to 9 meters higher than today.[40] The most recent glacial maximum 20,000 years ago had sea levels that were about 125 meters (410 ft) lower than today.[41] Temperatures stabilized in the current interglacial period beginning 11,700 years ago.[42] Historical patterns of warming and cooling, like the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age, did not occur at the same time across different regions. Temperatures may have reached as high as those of the late 20th century in a limited set of regions.[43] Climate information for that period comes from climate proxies, such as trees and ice cores.[44] Warming since the Industrial Revolution Main article: Instrumental temperature record  In recent decades, new high temperature records have substantially outpaced new low temperature records on a growing portion of Earth's surface.[45]  There has been an increase in ocean heat content during recent decades as the oceans absorb over 90% of the heat from global warming.[46] Around 1850 thermometer records began to provide global coverage.[47] Between the 18th century and 1970 there was little net warming, as the warming impact of greenhouse gas emissions was offset by cooling from sulfur dioxide emissions. Sulfur dioxide causes acid rain, but it also produces sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere, which reflect sunlight and cause so-called global dimming. After 1970, the increasing accumulation of greenhouse gases and controls on sulfur pollution led to a marked increase in temperature.[48][49][50] Multiple independent datasets all show worldwide increases in surface temperature,[51] at a rate of around 0.2 °C per decade.[52] The 2013–2022 decade warmed to an average 1.15 °C [1.00–1.25 °C] compared to the pre-industrial baseline (1850–1900).[53] Not every single year was warmer than the last: internal climate variability processes can make any year 0.2 °C warmer or colder than the average.[54] From 1998 to 2013, negative phases of two such processes, Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO)[55] and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)[56] caused a so-called "global warming hiatus".[57] After the hiatus, the opposite occurred, with years like 2023 exhibiting temperatures well above even the recent average.[58] This is why the temperature change is defined in terms of a 20-year average, which reduces the noise of hot and cold years and decadal climate patterns, and detects the long-term signal.[59]: 5 [60] A wide range of other observations reinforce the evidence of warming.[61][62] The upper atmosphere is cooling, because greenhouse gases are trapping heat near the Earth's surface, and so less heat is radiating into space.[63] Warming reduces average snow cover and forces the retreat of glaciers. At the same time, warming also causes greater evaporation from the oceans, leading to more atmospheric humidity, more and heavier precipitation.[64] Plants are flowering earlier in spring, and thousands of animal species have been permanently moving to cooler areas.[65] Differences by region Different regions of the world warm at different rates. The pattern is independent of where greenhouse gases are emitted, because the gases persist long enough to diffuse across the planet. Since the pre-industrial period, the average surface temperature over land regions has increased almost twice as fast as the global average surface temperature.[66] This is because oceans lose more heat by evaporation and oceans can store a lot of heat.[67] The thermal energy in the global climate system has grown with only brief pauses since at least 1970, and over 90% of this extra energy has been stored in the ocean.[68][69] The rest has heated the atmosphere, melted ice, and warmed the continents.[70] The Northern Hemisphere and the North Pole have warmed much faster than the South Pole and Southern Hemisphere. The Northern Hemisphere not only has much more land, but also more seasonal snow cover and sea ice. As these surfaces flip from reflecting a lot of light to being dark after the ice has melted, they start absorbing more heat.[71] Local black carbon deposits on snow and ice also contribute to Arctic warming.[72] Arctic surface temperatures are increasing between three and four times faster than in the rest of the world.[73][74][75] Melting of ice sheets near the poles weakens both the Atlantic and the Antarctic limb of thermohaline circulation, which further changes the distribution of heat and precipitation around the globe.[76][77][78][79] Future global temperatures Further information: Carbon budget and Earth's energy budget  CMIP6 multi-model projections of global surface temperature changes for the year 2090 relative to the 1850–1900 average. The current trajectory for warming by the end of the century is roughly halfway between these two extremes.[22][80][81] The World Meteorological Organization estimates a 66% chance of global temperatures exceeding 1.5 °C warming from the preindustrial baseline for at least one year between 2023 and 2027.[82][83] Because the IPCC uses a 20-year average to define global temperature changes, a single year exceeding 1.5 °C does not break the limit. The IPCC expects the 20-year average global temperature to exceed +1.5 °C in the early 2030s.[84] The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (2023) included projections that by 2100 global warming is very likely to reach 1.0-1.8 °C under a scenario with very low emissions of greenhouse gases, 2.1-3.5 °C under an intermediate emissions scenario, or 3.3-5.7 °C under a very high emissions scenario.[85] In the intermediate and high emission scenarios, the warming will continue past 2100.[86][87] The remaining carbon budget for staying beneath certain temperature increases is determined by modelling the carbon cycle and climate sensitivity to greenhouse gases.[88] According to the IPCC, global warming can be kept below 1.5 °C with a two-thirds chance if emissions after 2018 do not exceed 420 or 570 gigatonnes of CO2. This corresponds to 10 to 13 years of current emissions. There are high uncertainties about the budget. For instance, it may be 100 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent smaller due to CO2 and methane release from permafrost and wetlands.[89] However, it is clear that fossil fuel resources need to be proactively kept in the ground to prevent substantial warming. Otherwise, their shortages would not occur until the emissions have already locked in significant long-term impacts.[90] |

地球の気温上昇 樹木の年輪、サンゴ、氷床コアからのプロキシデータを用いた過去2000年間の地球表面温度の再構築(青色)[36] 直接観測されたデータは赤色である[37]。 地球温暖化以前の気温記録 主な記事 気候変動と変化、過去2,000年の気温記録、古気候学 過去数百万年間、人類は氷河期を周期的に繰り返す気候の中で進化してきた。 20,000年前の氷河期の最盛期は、海面が現在よりも約125メートル低かった[41]。11,700年前に始まった現在の間氷期では、気温は安定した [42]。中世温暖期や小氷期のような歴史的な温暖化と寒冷化のパターンは、異なる地域で同時に起こったわけではない。この時期の気候情報は、樹木や氷床 コアなどの気候プロキシから得られている[44]。 産業革命以降の温暖化 主な記事 機器による気温記録  ここ数十年、地球表面の大部分において、新しい高温記録が新しい低温記録を大幅に上回っている[45]。  地球温暖化による熱の90%以上を海洋が吸収しているため、ここ数十年の間に海洋の熱量が増加している[46]。 1850年頃に温度計の記録が世界的な範囲をカバーするようになった[47]。18世紀から1970年の間は、温室効果ガスの排出による温暖化の影響が二 酸化硫黄の排出による冷却によって相殺されたため、正味の温暖化はほとんどなかった。二酸化硫黄は酸性雨の原因となるが、大気中に硫酸塩エアロゾルを発生 させ、これが太陽光を反射していわゆる地球温暖化を引き起こす。1970年以降、温室効果ガスの蓄積と硫黄汚染の抑制が進み、気温は著しく上昇した [48][49][50]。 2013年から2022年の10年間は、産業革命以前のベースライン(1850年から1900年)と比較して、平均1.15℃ [1.00-1.25 ℃]まで温暖化した[53]。気候の内部変動プロセスによって、どの年も平均より0.2℃暖かくなったり寒くなったりする。 [1998年から2013年にかけて、太平洋十年規模振動(PDO)[55]と大西洋十年規模振動(AMO)[56]という2つの気候変動プロセスの負の 位相が、いわゆる「地球温暖化の休止」を引き起こした。 [58]。このため、気温の変化は20年平均で定義され、暑い年や寒い年、10年ごとの気候パターンのノイズを減らし、長期的なシグナルを検出する: 5 [60] 温室効果ガスが地表付近の熱を閉じ込めているため、大気上層部が冷却しており、宇宙への熱放射が減少している[63]。同時に、温暖化は海洋からの蒸発量 を増加させ、大気中の湿度を増加させ、降水量を増加させ、降水量を増加させる[64]。植物が春に早く開花し、何千もの動物種が恒久的に涼しい地域に移動 している[65]。 地域による違い 世界の地域によって、温暖化の速度は異なる。温室効果ガスは地球全体に拡散するのに十分な期間持続するため、このパターンは温室効果ガスが排出される場所 とは無関係である。産業革命以前の時代から、陸地の平均地表面温度は、世界の平均地表面温度のほぼ2倍の速さで上昇している[66]。 これは、海洋が蒸発によってより多くの熱を失い、海洋が多くの熱を蓄えることができるためである[67]。少なくとも1970年以降、地球気候系の熱エネ ルギーはわずかな休止を挟んで増加しており、この余分なエネルギーの90%以上が海洋に蓄えられている[68][69]。 北半球と北極は、南極と南半球よりもはるかに速く温暖化した。北半球は陸地が多いだけでなく、季節的な積雪や海氷も多い。これらの表面は、多くの光を反射 することから、氷が溶けた後は暗くなるため、より多くの熱を吸収し始める[71]。雪や氷に堆積した局所的な黒色炭素も北極の温暖化に寄与している [72]。 北極の地表温度は、世界の他の地域よりも3倍から4倍の速さで上昇している。 [73][74][75]。極付近の氷床の融解は、熱塩循環の大西洋側と南極側の両縁を弱め、地球上の熱と降水の分布をさらに変化させる[76][77] [78][79]。 将来の世界の気温 さらなる情報 炭素収支と地球のエネルギー収支  1850年から1900年の平均に対する2090年の世界の地表面温度の変化のCMIP6マルチモデル予測。今世紀末までの温暖化の現在の軌跡は、この2つの極端のほぼ中間にある[22][80][81]。 世界気象機関は、2023年から2027年の間に少なくとも1年間は、世界の気温が産業革命以前のベースラインから1.5℃の温暖化を超える可能性が 66%あると見積もっている[82][83]。IPCCは世界の気温の変化を定義するために20年平均を使用しているため、1.5℃を超える年が1年あっ たとしても、限界は破られない。 IPCCは、2030年代初頭に世界の20年平均気温が+1.5 °Cを超えると予想している[84]。IPCC第6次評価報告書(2023年)には、2100年までに地球温暖化が、温室効果ガスの排出量が非常に少ない シナリオでは1.0~1.8 °C、中間排出シナリオでは2.1~3.5 °C、超高排出シナリオでは3.3~5.7 °Cに達する可能性が非常に高いという予測が含まれている[85]。中間排出シナリオと高排出シナリオでは、温暖化は2100年以降も続く[86] [87]。 IPCCによれば、2018年以降の排出量が420または570ギガ トンのCO2を超えなければ、3分の2の確率で地球温暖化を 1.5℃未満に抑えることができる。これは、現在の排出量の10~13年分に相当する。予算については不確実性が高い。例えば、永久凍土や湿地からの CO2やメタンの放出により、CO2換算で100ギガトン少なくなる可能性がある[89]。しかし、大幅な温暖化を防ぐためには、化石燃料資源を積極的に 地中に留めておく必要があることは明らかである。そうでなければ、その不足は、排出がすでに重大な長期的影響を固定化するまで起こらないだろう[90]。 |

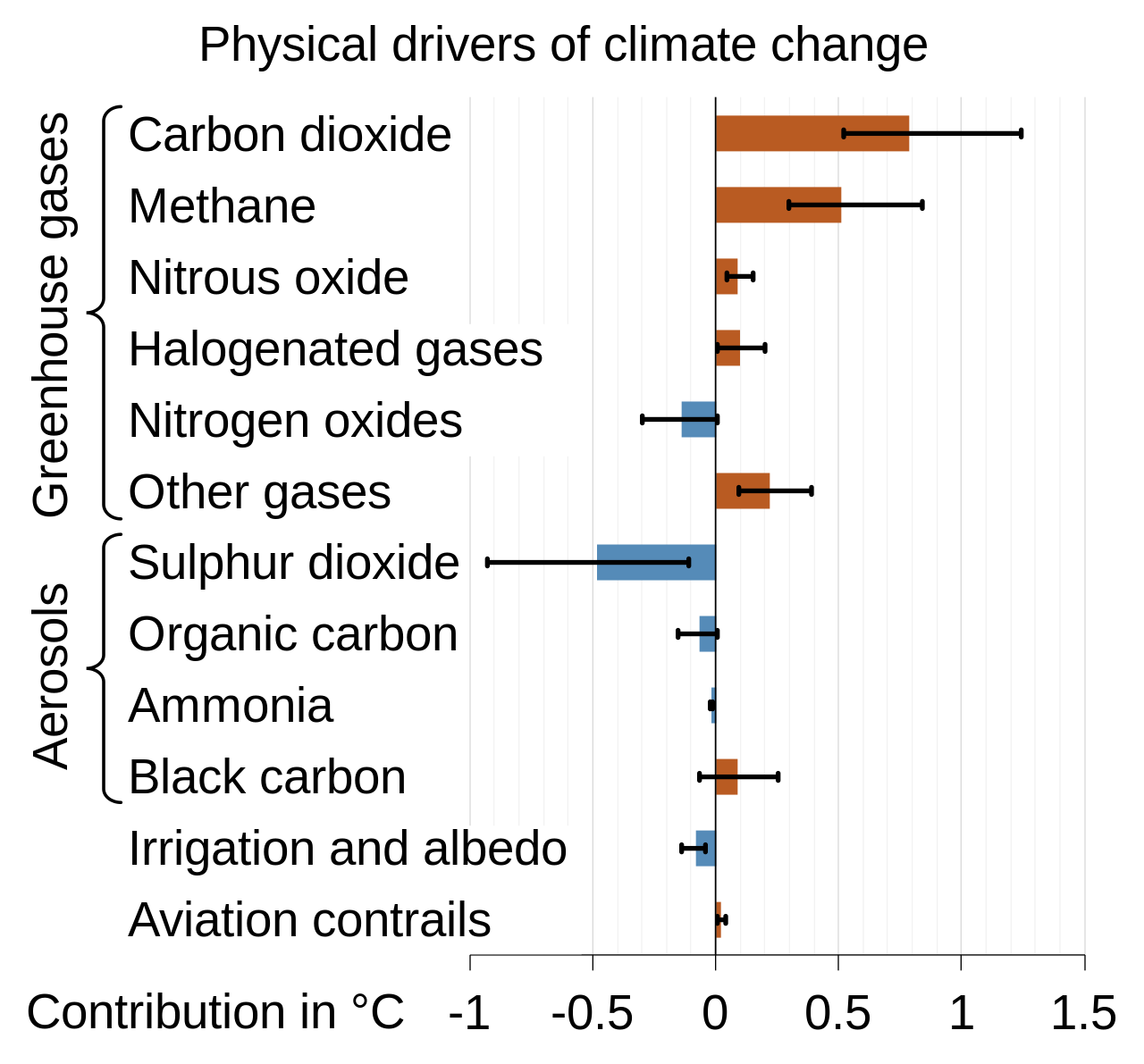

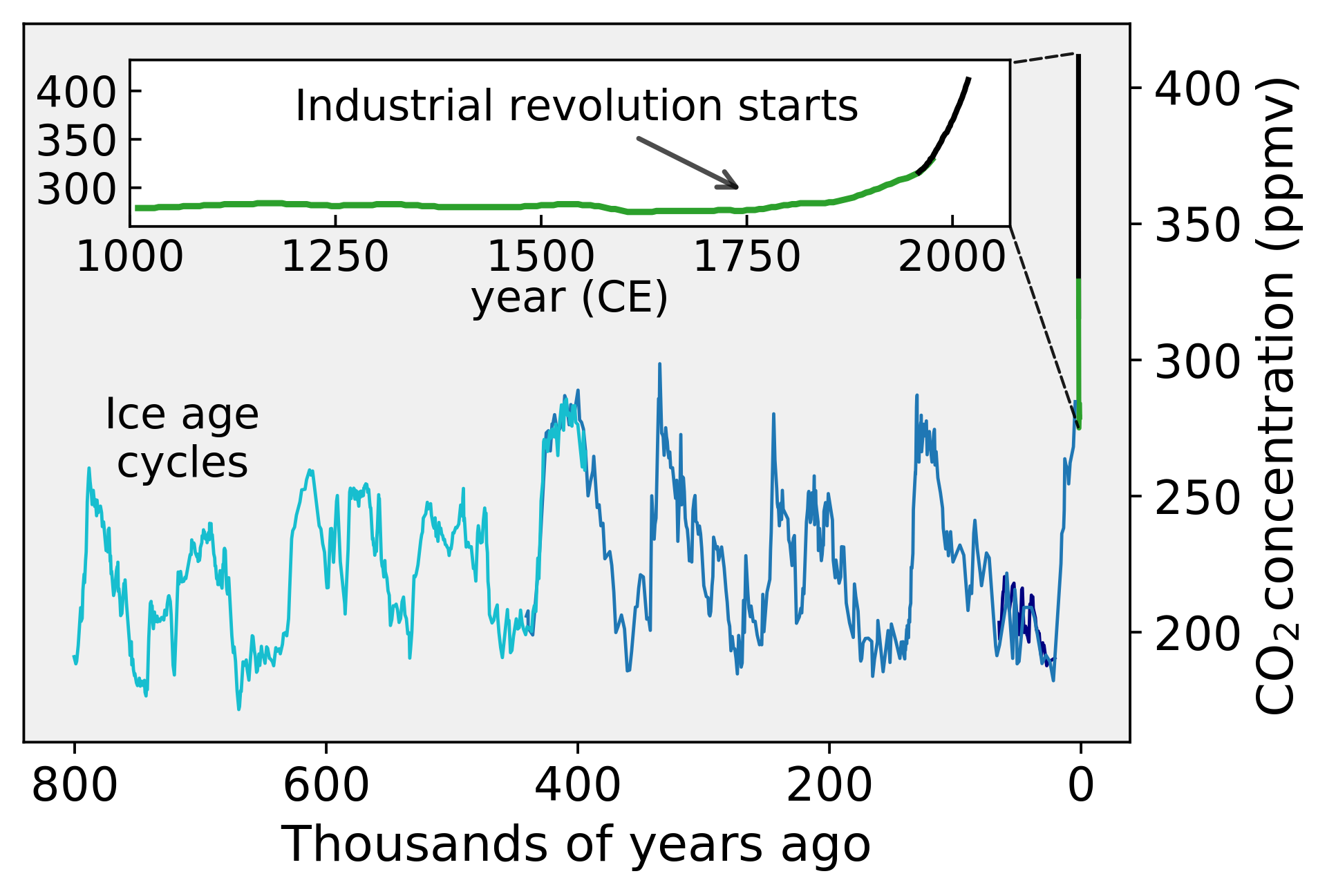

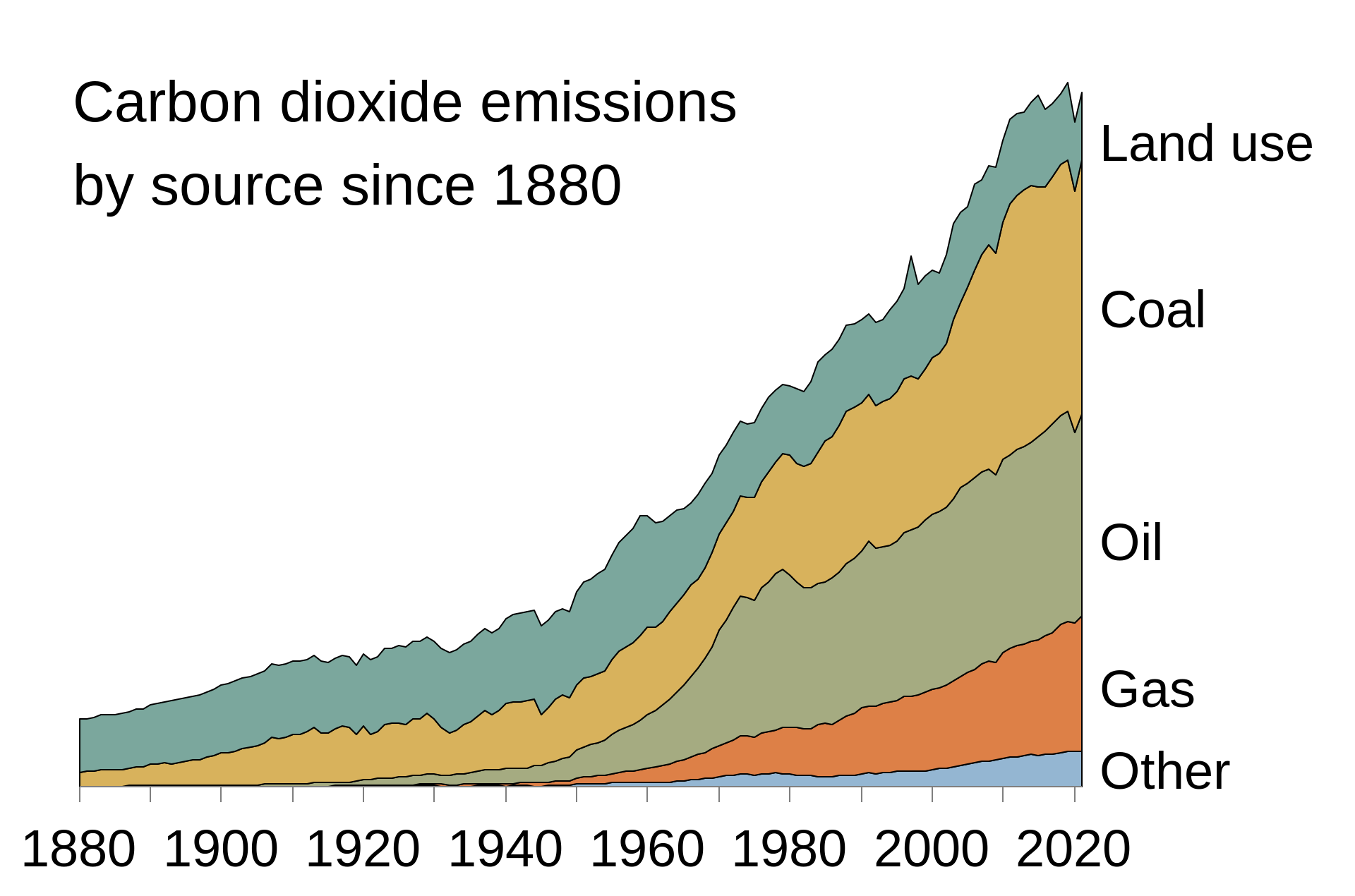

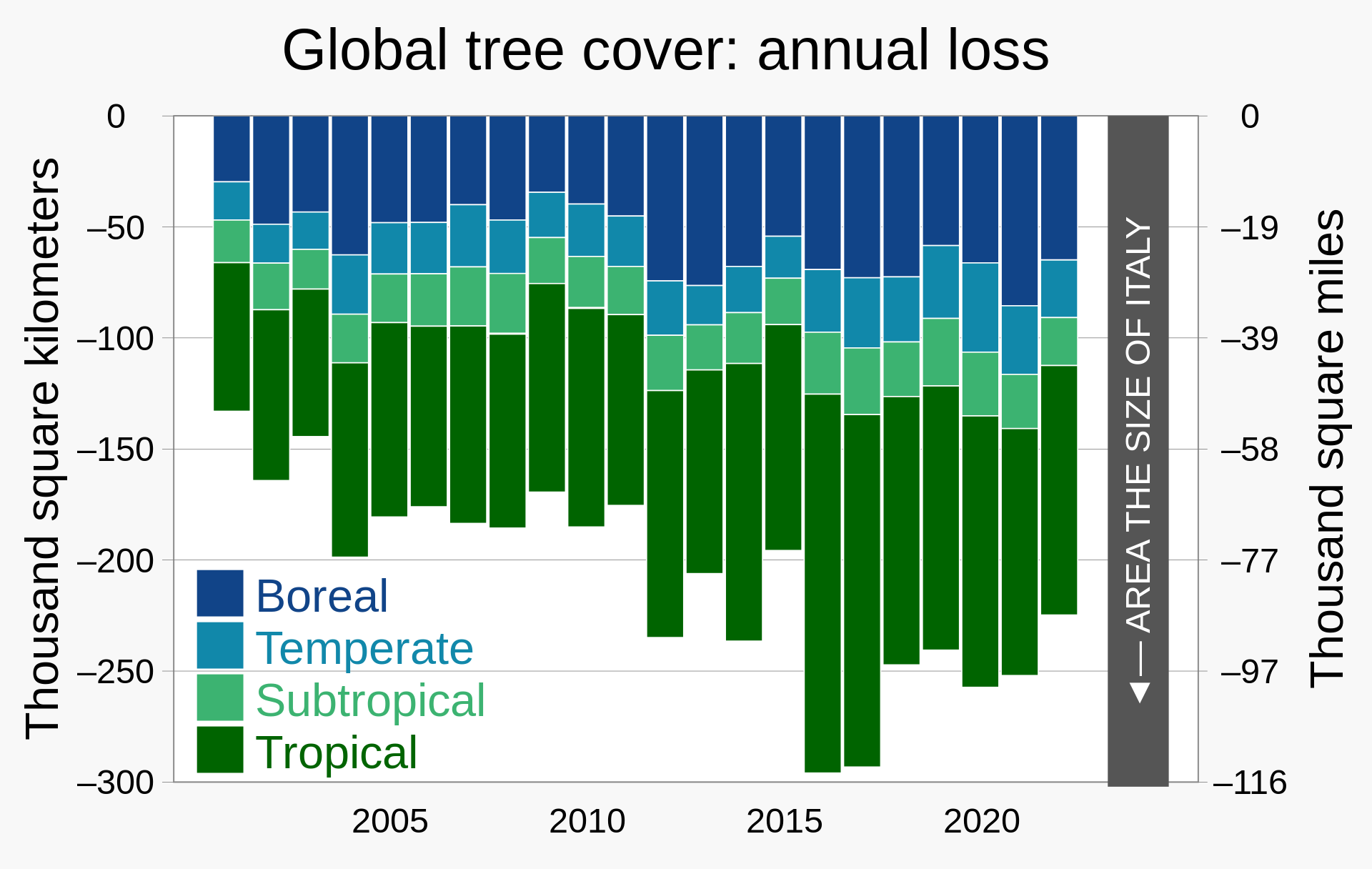

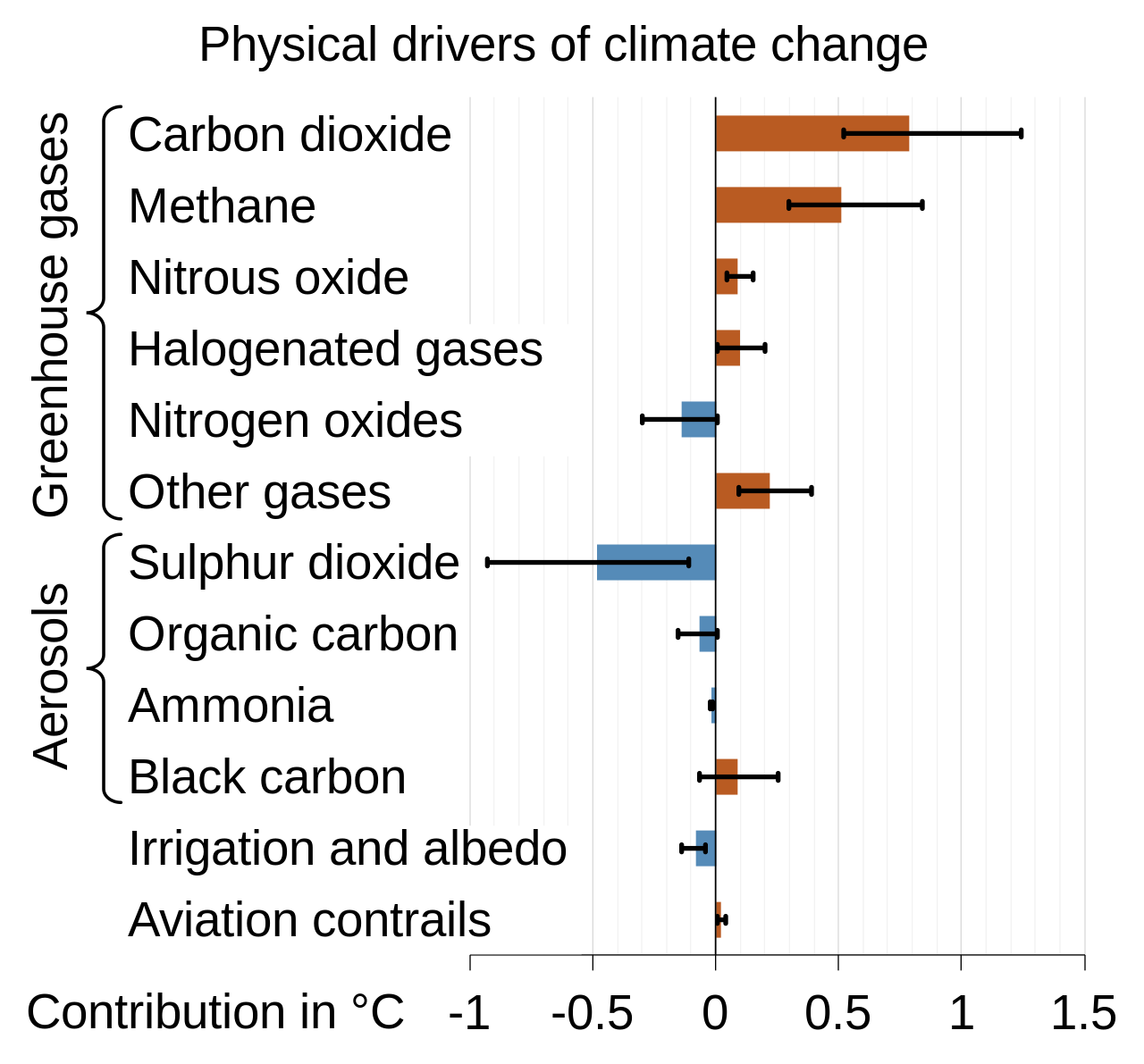

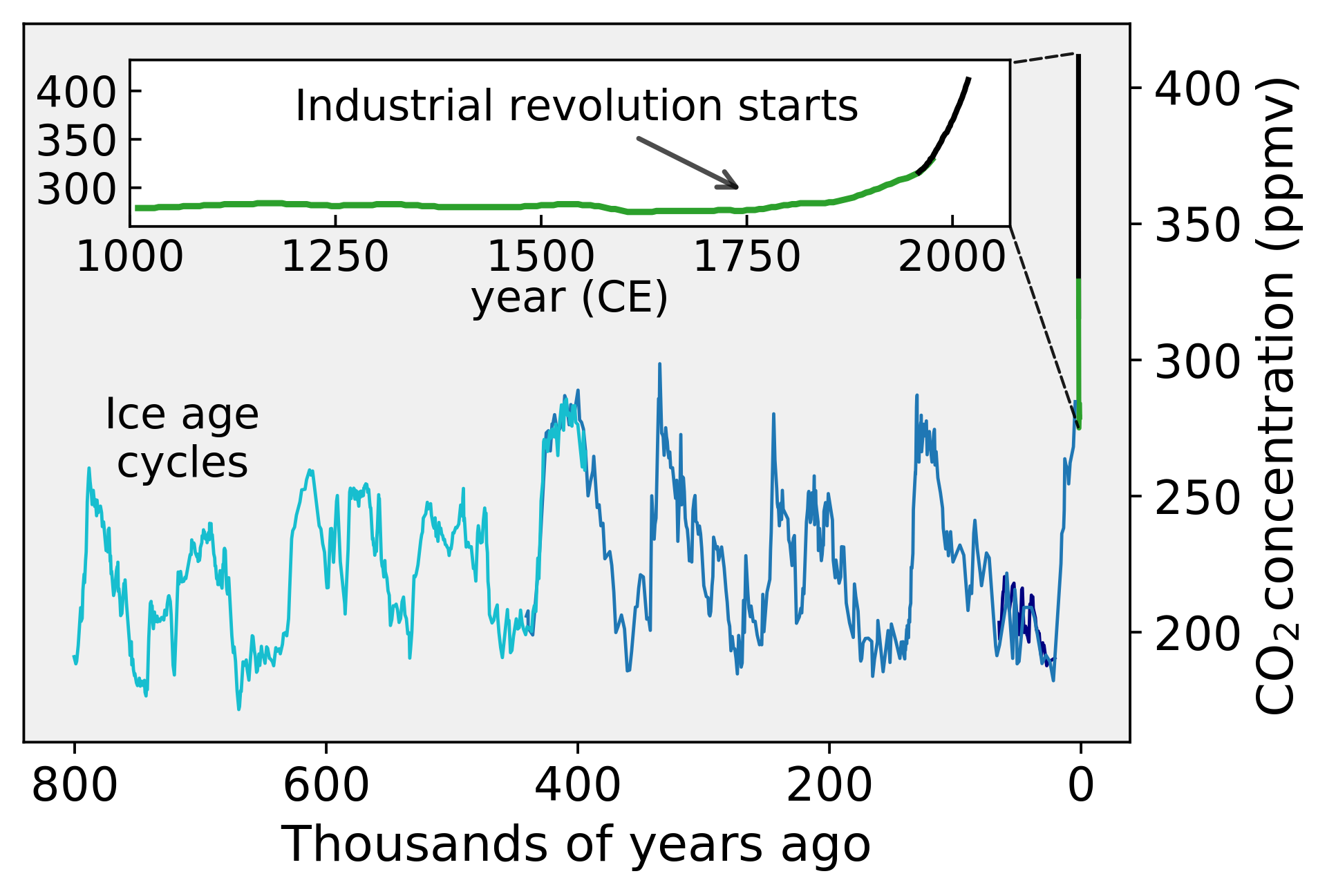

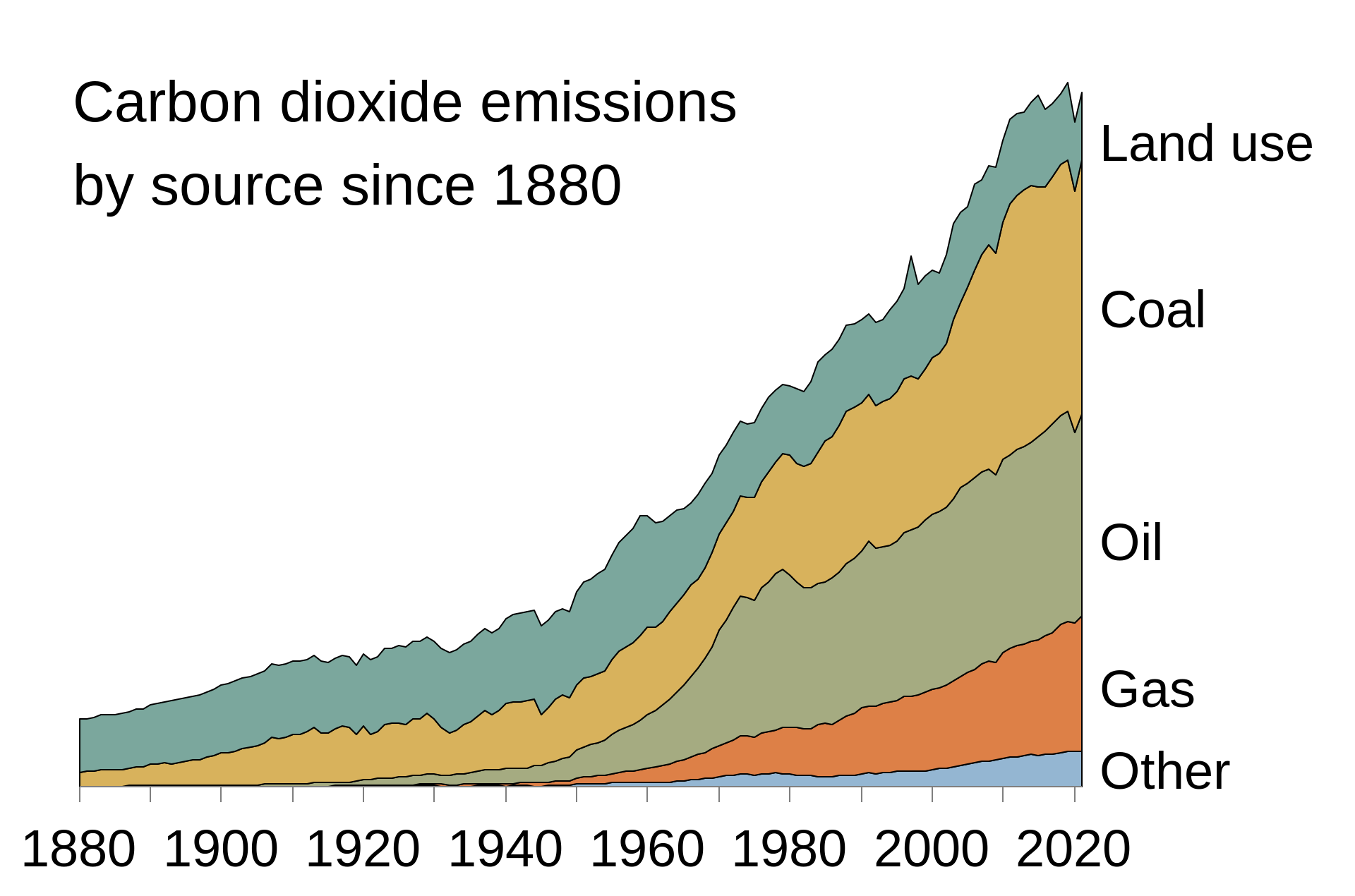

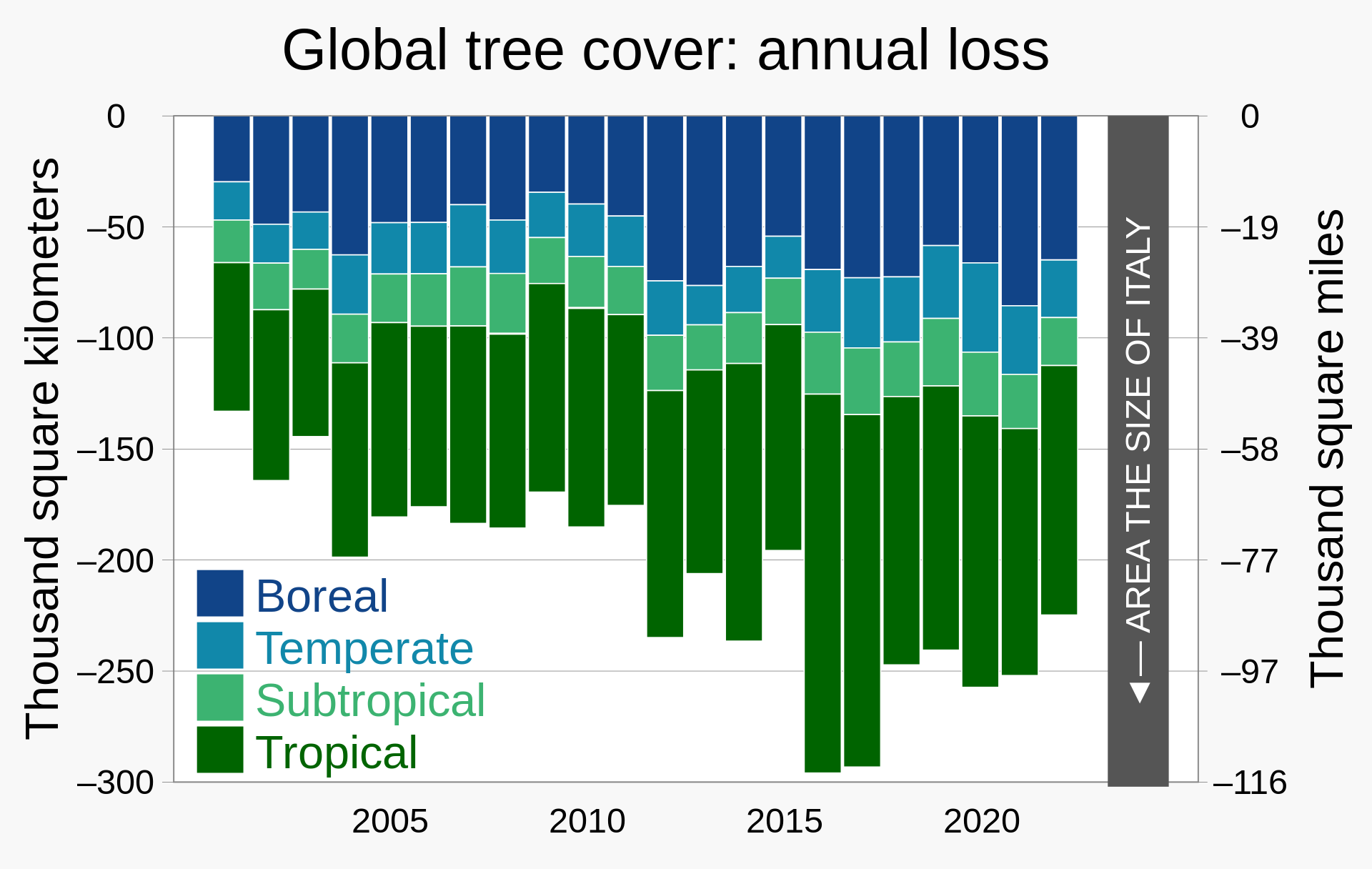

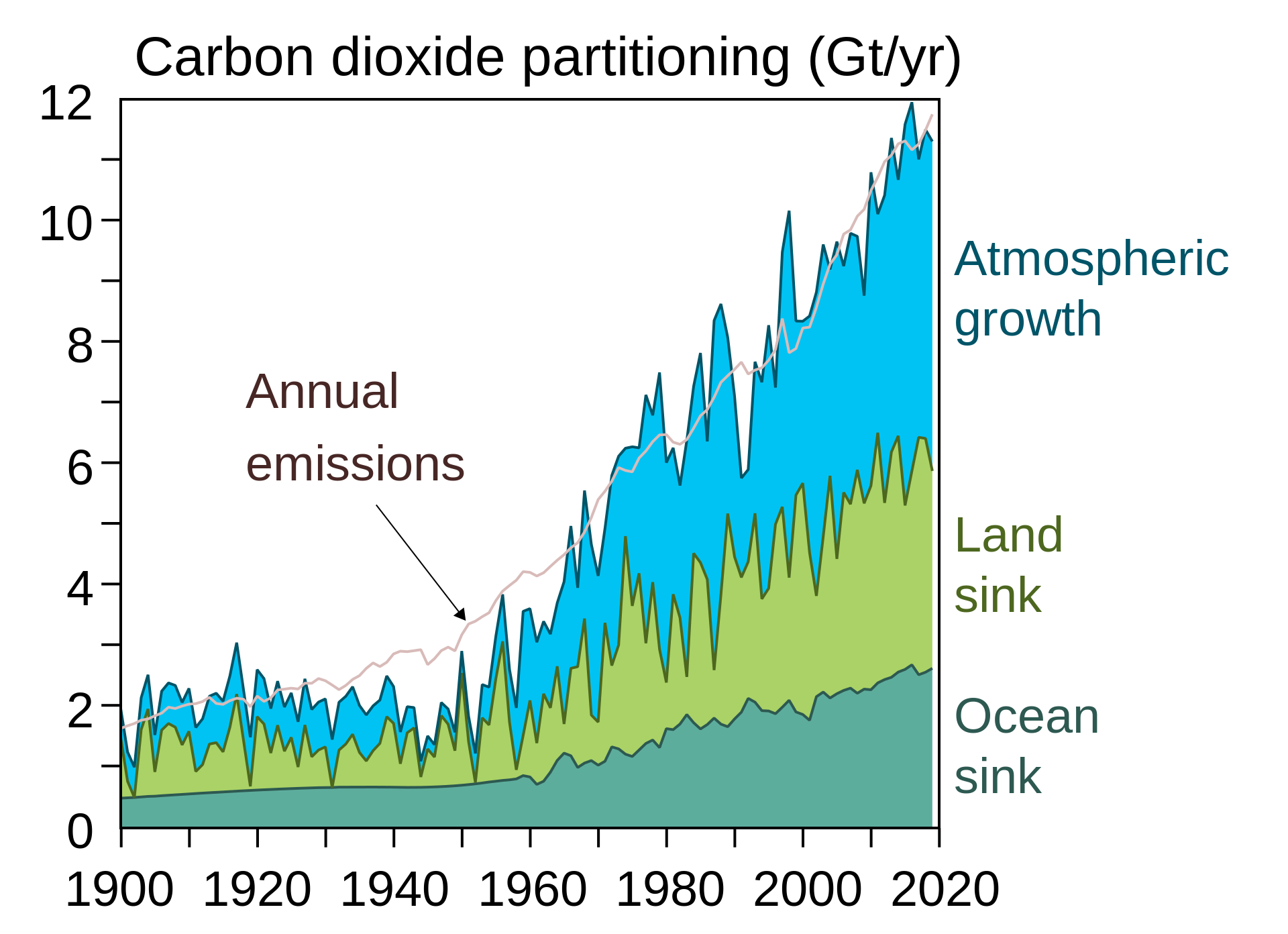

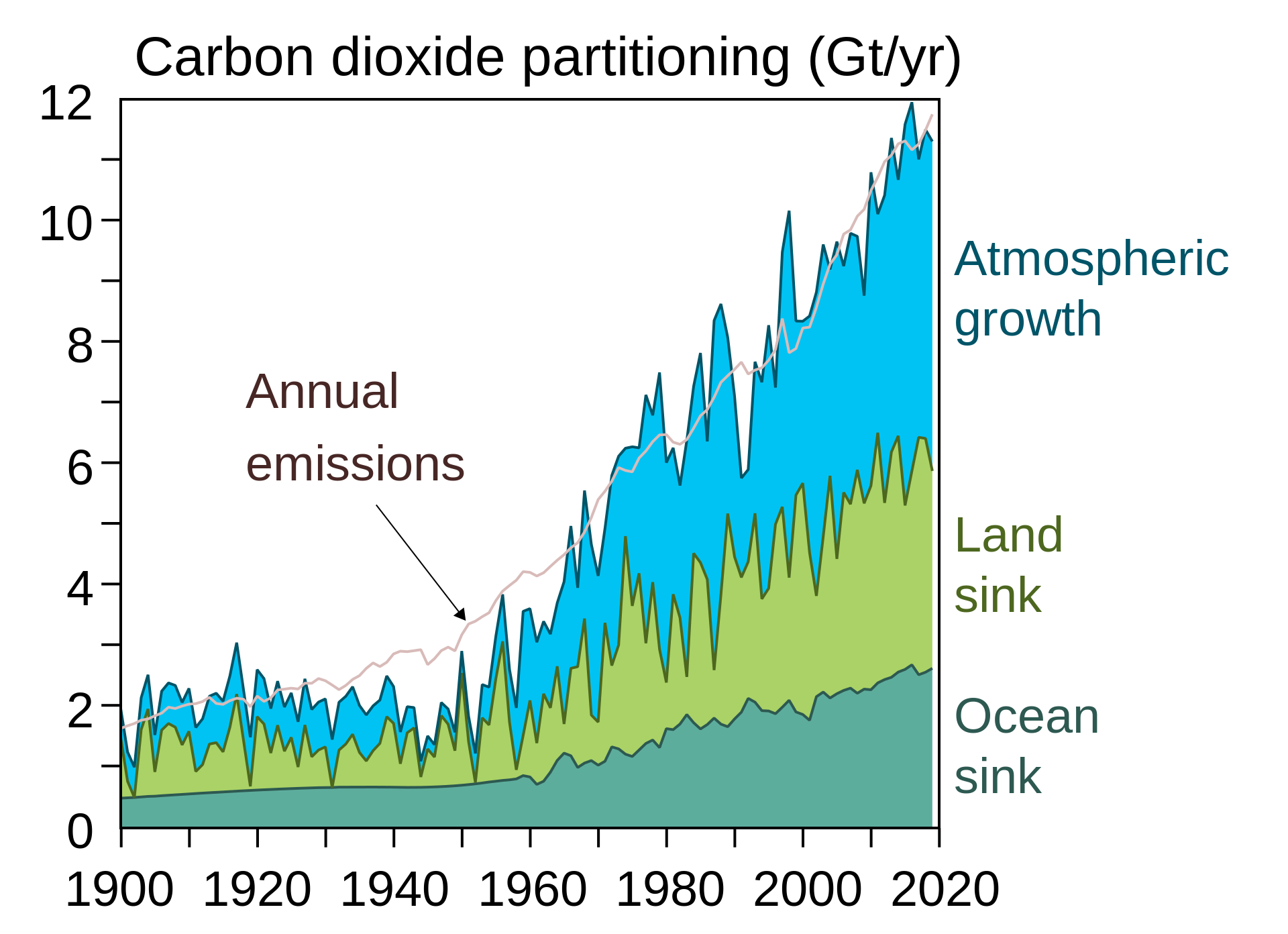

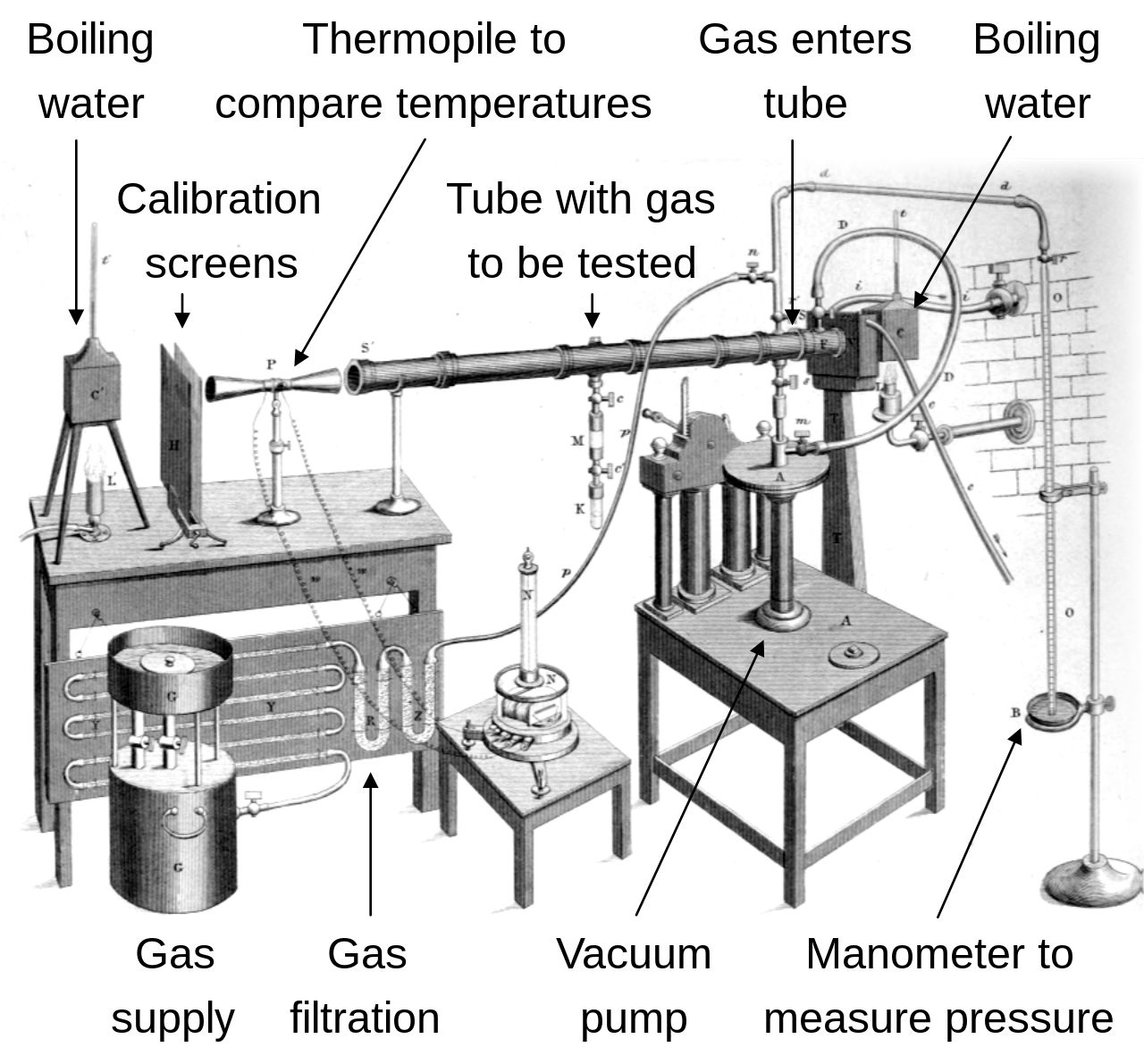

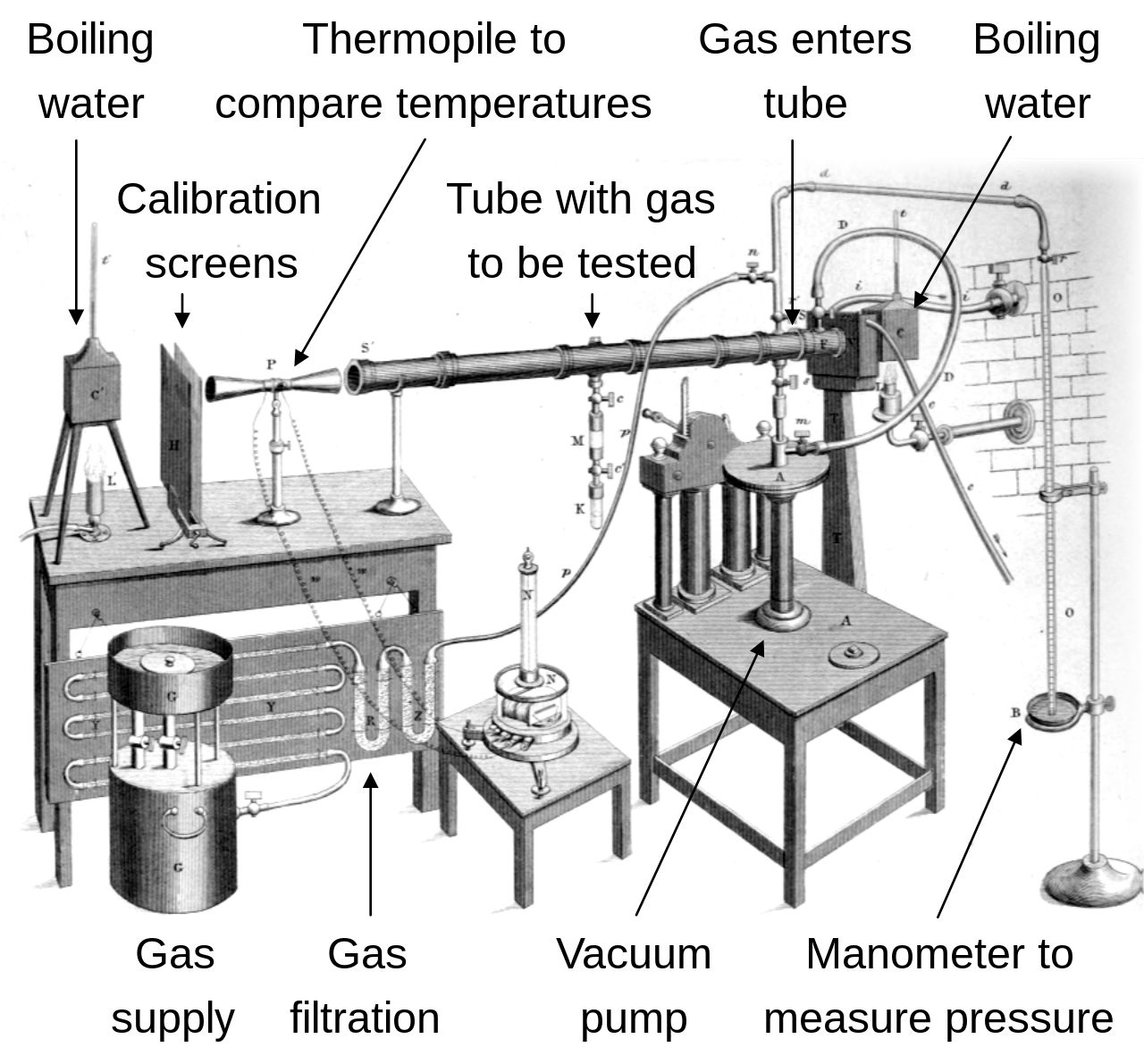

| Causes of recent global temperature rise Main article: Causes of climate change  Drivers of climate change from 1850–1900 to 2010–2019. There was no significant contribution from internal variability or solar and volcanic drivers. The climate system experiences various cycles on its own which can last for years, decades or even centuries. For example, El Niño events cause short-term spikes in surface temperature while La Niña events cause short term cooling.[91] Their relative frequency can affect global temperature trends on a decadal timescale.[92] Other changes are caused by an imbalance of energy from external forcings.[93] Examples of these include changes in the concentrations of greenhouse gases, solar luminosity, volcanic eruptions, and variations in the Earth's orbit around the Sun.[94] To determine the human contribution to climate change, unique "fingerprints" for all potential causes are developed and compared with both observed patterns and known internal climate variability.[95] For example, solar forcing—whose fingerprint involves warming the entire atmosphere—is ruled out because only the lower atmosphere has warmed.[96] Atmospheric aerosols produce a smaller, cooling effect. Other drivers, such as changes in albedo, are less impactful.[97] Greenhouse gases Main articles: Greenhouse gas, Greenhouse gas emissions, Greenhouse effect, and Carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere  CO2 concentrations over the last 800,000 years as measured from ice cores[98][99][100][101] (blue/green) and directly[102] (black) Greenhouse gases are transparent to sunlight, and thus allow it to pass through the atmosphere to heat the Earth's surface. The Earth radiates it as heat, and greenhouse gases absorb a portion of it. This absorption slows the rate at which heat escapes into space, trapping heat near the Earth's surface and warming it over time.[103] While water vapour (≈50%) and clouds (≈25%) are the biggest contributors to the greenhouse effect, they primarily change as a function of temperature and are therefore mostly considered to be feedbacks that change climate sensitivity. On the other hand, concentrations of gases such as CO2 (≈20%), tropospheric ozone,[104] CFCs and nitrous oxide are added or removed independently from temperature, and are therefore considered to be external forcings that change global temperatures.[105] Before the Industrial Revolution, naturally-occurring amounts of greenhouse gases caused the air near the surface to be about 33 °C warmer than it would have been in their absence.[106][107] Human activity since the Industrial Revolution, mainly extracting and burning fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas),[108] has increased the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, resulting in a radiative imbalance. In 2019, the concentrations of CO2 and methane had increased by about 48% and 160%, respectively, since 1750.[109] These CO2 levels are higher than they have been at any time during the last 2 million years. Concentrations of methane are far higher than they were over the last 800,000 years.[110]  The Global Carbon Project shows how additions to CO2 since 1880 have been caused by different sources ramping up one after another. Global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 were equivalent to 59 billion tonnes of CO2. Of these emissions, 75% was CO2, 18% was methane, 4% was nitrous oxide, and 2% was fluorinated gases.[111] CO2 emissions primarily come from burning fossil fuels to provide energy for transport, manufacturing, heating, and electricity.[5] Additional CO2 emissions come from deforestation and industrial processes, which include the CO2 released by the chemical reactions for making cement, steel, aluminum, and fertiliser.[112] Methane emissions come from livestock, manure, rice cultivation, landfills, wastewater, and coal mining, as well as oil and gas extraction.[113] Nitrous oxide emissions largely come from the microbial decomposition of fertiliser.[114] While methane only lasts in the atmosphere for an average of 12 years,[115] CO2 lasts much longer. The Earth's surface absorbs CO2 as part of the carbon cycle. While plants on land and in the ocean absorb most excess emissions of CO2 every year, that CO2 is returned to the atmosphere when biological matter is digested, burns, or decays.[116] Land-surface carbon sink processes, such as carbon fixation in the soil and photosynthesis, remove about 29% of annual global CO2 emissions.[117] The ocean has absorbed 20 to 30% of emitted CO2 over the last 2 decades.[118] CO2 is only removed from the atmosphere for the long term when it is stored in the Earth's crust, which is a process that can take millions of years to complete.[116] Land surface changes  The rate of global tree cover loss has approximately doubled since 2001, to an annual loss approaching an area the size of Italy.[119] According to Food and Agriculture Organization, around 30% of Earth's land area is largely unusable for humans (glaciers, deserts, etc.), 26% is forests, 10% is shrubland and 34% is agricultural land.[120] Deforestation is the main land use change contributor to global warming,[121] as the destroyed trees release CO2, and are not replaced by new trees, removing that carbon sink.[27] Between 2001 and 2018, 27% of deforestation was from permanent clearing to enable agricultural expansion for crops and livestock. Another 24% has been lost to temporary clearing under the shifting cultivation agricultural systems. 26% was due to logging for wood and derived products, and wildfires have accounted for the remaining 23%.[122] Some forests have not been fully cleared, but were already degraded by these impacts. Restoring these forests also recovers their potential as a carbon sink.[123] Local vegetation cover impacts how much of the sunlight gets reflected back into space (albedo), and how much heat is lost by evaporation. For instance, the change from a dark forest to grassland makes the surface lighter, causing it to reflect more sunlight. Deforestation can also modify the release of chemical compounds that influence clouds, and by changing wind patterns.[124] In tropic and temperate areas the net effect is to produce significant warming, and forest restoration can make local temperatures cooler.[123] At latitudes closer to the poles, there is a cooling effect as forest is replaced by snow-covered (and more reflective) plains.[124] Globally, these increases in surface albedo have been the dominant direct influence on temperature from land use change. Thus, land use change to date is estimated to have a slight cooling effect.[125] Other factors Aerosols and clouds Air pollution, in the form of aerosols, affects the climate on a large scale.[126] Aerosols scatter and absorb solar radiation. From 1961 to 1990, a gradual reduction in the amount of sunlight reaching the Earth's surface was observed. This phenomenon is popularly known as global dimming,[127] and is primarily attributed to sulfate aerosols produced by the combustion of fossil fuels with heavy sulfur concentrations like coal and bunker fuel.[50] Smaller contributions come from black carbon, organic carbon from combustion of fossil fuels and biofuels, and from anthropogenic dust.[128][49][129][130][131] Globally, aerosols have been declining since 1990 due to pollution controls, meaning that they no longer mask greenhouse gas warming as much.[132][50] Aerosols also have indirect effects on the Earth's energy budget. Sulfate aerosols act as cloud condensation nuclei and lead to clouds that have more and smaller cloud droplets. These clouds reflect solar radiation more efficiently than clouds with fewer and larger droplets.[133] They also reduce the growth of raindrops, which makes clouds more reflective to incoming sunlight.[134] Indirect effects of aerosols are the largest uncertainty in radiative forcing.[135] While aerosols typically limit global warming by reflecting sunlight, black carbon in soot that falls on snow or ice can contribute to global warming. Not only does this increase the absorption of sunlight, it also increases melting and sea-level rise.[136] Limiting new black carbon deposits in the Arctic could reduce global warming by 0.2 °C by 2050.[137] The effect of decreasing sulfur content of fuel oil for ships since 2020[138] is estimated to cause an additional 0.05 °C increase in global mean temperature by 2050.[139] Solar and volcanic activity Further information: Solar activity and climate  The Fourth National Climate Assessment ("NCA4", USGCRP, 2017) includes charts illustrating that neither solar nor volcanic activity can explain the observed warming.[140][141] As the Sun is the Earth's primary energy source, changes in incoming sunlight directly affect the climate system.[135] Solar irradiance has been measured directly by satellites,[142] and indirect measurements are available from the early 1600s onwards.[135] Since 1880, there has been no upward trend in the amount of the Sun's energy reaching the Earth, in contrast to the warming of the lower atmosphere (the troposphere).[143] The upper atmosphere (the stratosphere) would also be warming if the Sun was sending more energy to Earth, but instead, it has been cooling.[96] This is consistent with greenhouse gases preventing heat from leaving the Earth's atmosphere.[144] Explosive volcanic eruptions can release gases, dust and ash that partially block sunlight and reduce temperatures, or they can send water vapor into the atmosphere, which adds to greenhouse gases and increases temperatures.[145] These impacts on temperature only last for several years, because both water vapor and volcanic material have low persistence in the atmosphere.[146] volcanic CO2 emissions are more persistent, but they are equivalent to less than 1% of current human-caused CO2 emissions.[147] Volcanic activity still represents the single largest natural impact (forcing) on temperature in the industrial era. Yet, like the other natural forcings, it has had negligible impacts on global temperature trends since the Industrial Revolution.[146] Climate change feedbacks Main articles: Climate change feedbacks and Climate sensitivity  Sea ice reflects 50% to 70% of incoming sunlight, while the ocean, being darker, reflects only 6%. As an area of sea ice melts and exposes more ocean, more heat is absorbed by the ocean, raising temperatures that melt still more ice. This is a positive feedback process.[148] The response of the climate system to an initial forcing is modified by feedbacks: increased by "self-reinforcing" or "positive" feedbacks and reduced by "balancing" or "negative" feedbacks.[149] The main reinforcing feedbacks are the water-vapour feedback, the ice–albedo feedback, and the net effect of clouds.[150][151] The primary balancing mechanism is radiative cooling, as Earth's surface gives off more heat to space in response to rising temperature.[152] In addition to temperature feedbacks, there are feedbacks in the carbon cycle, such as the fertilising effect of CO2 on plant growth.[153] Uncertainty over feedbacks, particularly cloud cover,[154] is the major reason why different climate models project different magnitudes of warming for a given amount of emissions.[155] As air warms, it can hold more moisture. Water vapour, as a potent greenhouse gas, holds heat in the atmosphere.[150] If cloud cover increases, more sunlight will be reflected back into space, cooling the planet. If clouds become higher and thinner, they act as an insulator, reflecting heat from below back downwards and warming the planet.[156] Another major feedback is the reduction of snow cover and sea ice in the Arctic, which reduces the reflectivity of the Earth's surface.[157] More of the Sun's energy is now absorbed in these regions, contributing to amplification of Arctic temperature changes.[158] Arctic amplification is also thawing permafrost, which releases methane and CO2 into the atmosphere.[159] Climate change can also cause methane releases from wetlands, marine systems, and freshwater systems.[160] Overall, climate feedbacks are expected to become increasingly positive.[161] Around half of human-caused CO2 emissions have been absorbed by land plants and by the oceans.[162] This fraction is not static and if future CO2 emissions decrease, the Earth will be able to absorb up to around 70%. If they increase substantially, it'll still absorb more carbon than now, but the overall fraction will decrease to below 40%.[163] This is because climate change increases droughts and heat waves that eventually inhibit plant growth on land, and soils will release more carbon from dead plants when they are warmer.[164][165] The rate at which oceans absorb atmospheric carbon will be lowered as they become more acidic and experience changes in thermohaline circulation and phytoplankton distribution.[166][167][77] |

最近の世界気温上昇の原因 主な記事 気候変動の原因  1850-1900年から2010-2019年までの気候変動の要因。内部変動や太陽・火山活動による大きな寄与はなかった。 気候システムは、数年、数十年、あるいは数百年にわたる様々なサイクルを経験している。例えば、エルニーニョ現象は地表面温度 の短期的な急上昇を引き起こし、ラニーニャ現象は短期的な冷え 込みを引き起こす[91]。それらの相対的な頻度は、10年単位 の時間スケールで世界の気温の傾向に影響を与える[92]。 気候変動に対する人為的な寄与を決定するために、すべての潜在的な原因に対する固有の「フィンガープリント」が開発され、観測されたパターンおよび既知の 気候内部変動の両方と比較される[95]。例えば、大気全体を暖めることを含むフィンガープリントを持つ太陽強制は、低層大気のみが温暖化したため除外さ れる[96]。アルベドの変化のような他の要因の影響は小さい[97]。 温室効果ガス 主な記事 温室効果ガス、温室効果ガス排出量、温室効果、地球大気中の二酸化炭素。  氷床コア[98][99][100][101](青/緑)と直接[102](黒)から測定された過去80万年間のCO2濃度。 温室効果ガスは太陽光に対して透明であるため、太陽光が大気を通過して地表を暖める。地球はそれを熱として放射し、温室効果ガスはその一部を吸収する。こ の吸収により、熱が宇宙空間に逃げる速度が遅くなり、地表付近に熱が閉じ込められ、時間の経過とともに温暖化する[103]。 水蒸気(約50%)と雲(約25%)が温室効果に最も寄与しているが、これらは主に気温の関数として変化するため、気候感度を変化させるフィードバックで あると考えられている。他方、CO2(約20%)、対流圏オゾン[104]、フロン[105]、亜酸化窒素のようなガスの濃度は、気温とは無関係に付加さ れたり除去されたりするため、地球の気温を変化させる外部強制力であると考えられている[105]。 産業革命以前は、自然に存在する量の温室効果ガスによって、地表付近の空気は、それらが存在しない場合よりも約33℃暖かくなっていた[106] [107]。 産業革命以降の人間活動、主に化石燃料(石炭、石油、天然ガス)の採掘と燃焼[108]は、大気中の温室効果ガスの量を増加させ、放射の不均衡をもたらし た。2019年、CO2とメタンの濃度は、1750年以降、それぞれ約48%と160%増加した[109]。これらのCO2濃度は、過去200万年間のど の時期よりも高い。メタンの濃度は、過去80万年間の濃度よりもはるかに高い[110]。  グローバル・カーボン・プロジェクトは、1880年以降のCO2増加が、異なる発生源が次々と増加することによって引き起こされたことを示している。 2019年の世界の人為起源の温室効果ガス排出量は、590億トンのCO2に相当する。これらの排出量のうち、75%がCO2、18%がメタン、4%が亜 酸化窒素、2%がフッ素系ガスであった[111]。CO2排出は主に、輸送、製造、暖房、電力にエネルギーを供給するために化石燃料を燃焼させることに起 因する[5]。追加のCO2排出は、森林伐採と工業プロセスからもたらされ、これにはセメント、鉄鋼、アルミニウム、肥料を製造するための化学反応によっ て放出されるCO2が含まれる。 [メタンの排出は、家畜、糞尿、稲作、埋立地、廃水、石炭採掘、石油・ガス採掘から生じる[113]。亜酸化窒素の排出は、主に肥料の微生物分解から生じ る[114]。 メタンは大気中で平均12年しか存在しないが[115]、CO2はもっと長く存在する。地球表面は、炭素循環の一部としてCO2を吸収している。陸上と海 洋の植物は、毎年排出されるCO2の大半を吸収しているが、生物学的物質が消化、燃焼、または腐敗すると、そのCO2は大気中に戻される[116]。土壌 での炭素固定や光合成などの陸上の炭素吸収プロセスは、地球全体の年間CO2排出量の約29%を除去している[117]。 [海洋は過去20年間で、排出されたCO2の20~30%を吸収している[118]。CO2が長期的に大気から除去されるのは、それが地殻に蓄積された時 だけであり、このプロセスが完了するまでに数百万年かかることもある[116]。 地表面の変化  世界の樹木被覆の減少率は2001年以降およそ2倍になり、年間ではイタリアの面積に匹敵するほどになっている[119]。 食糧農業機関によると、地球の土地面積の約30%が人間にとってほとんど使用不可能な土地(氷河、砂漠など)であり、26%が森林、10%が低木林、 34%が農地である[120]。破壊された樹木はCO2を放出し、新しい樹木に取って代わられないため、炭素吸収源が取り除かれ、森林伐採は地球温暖化の 主な土地利用変化である[121]。2001年から2018年の間に、森林伐採の27%は、作物や家畜のための農業拡大を可能にするための恒久的な伐採に よるものであった。別の24%は、焼畑農業システムの下での一時的な伐採によって失われた。26%は木材と派生製品のための伐採によるもので、残りの 23%は山火事によるものである[122]。一部の森林は完全に伐採されていないが、これらの影響によってすでに劣化している。これらの森林を回復させる ことで、炭素吸収源としての可能性も回復する[123]。 地域の植生被覆は、太陽光がどれだけ宇宙空間に反射され(アルベド)、蒸発によってどれだけ熱が失われるかに影響を与える。例えば、暗い森林から草地への 変化は、地表を明るくし、より多くの太陽光を反射させる。森林伐採はまた、雲に影響を与える化学物質の放出を変化させ、風のパターンを変化させることもあ る[124]。熱帯や温帯地域では、正味の効果は著しい温暖化をもたらし、森林の回復は地域の気温をより低くすることができる[123]。極地に近い緯度 では、森林が雪に覆われた(より反射率の高い)平野に置き換わるため、冷却効果がある[124]。したがって、今日までの土地利用の変化は、わずかに冷却 効果を持つと推定される[125]。 その他の要因 エアロゾルと雲 エアロゾルの形をした大気汚染は、大規模に気候に影響を与える[126]。1961年から1990年にかけて、地表に届く太陽光の量が徐々に減少している ことが観測された。この現象は地球減光として一般的に知られており[127]、主に石炭やバンカー燃料のような硫黄濃度が高い化石燃料の燃焼によって生成 される硫酸塩エアロゾルに起因している。 [50]より小さい寄与は、ブラックカーボン、化石燃料やバイオ燃料の燃焼による有機炭素、人為起源の塵によるものである[128][49][129] [130][131]。世界的に見ると、エアロゾルは1990年以降、公害規制のために減少しており、温室効果ガスの温暖化をそれほどマスクしなくなった ことを意味している[132][50]。 エアロゾルはまた、地球のエネルギー収支に間接的な影響を及ぼしている。硫酸塩エアロゾルは雲凝結核として働き、雲粒がより多く、より小さい雲をもたら す。このような雲は、水滴が少なくて大きい雲よりも、太陽放射をより効率的に反射する[133]。また、エアロゾルは雨滴の成長を抑え、雲を入射する太陽 光に対してより反射しやすくする[134]。 エアロゾルは通常、太陽光を反射することで地球温暖化を抑制するが、雪や氷に降り積もった煤に含まれる黒色炭素は、地球温暖化に寄与する可能性がある。こ れは太陽光の吸収を増加させるだけでなく、融解と海面上昇を増加させる[136]。北極圏における新たな黒色炭素の堆積を制限することは、2050年まで に地球温暖化を0.2℃減少させる可能性がある[137]。2020年以降の船舶用燃料油の硫黄含有量の減少の影響[138]は、2050年までに世界の 平均気温をさらに0.05℃上昇させると推定されている[139]。 太陽活動と火山活動 更なる情報 太陽活動と気候  第4次国家気候評価報告書(「NCA4」、USGCRP、2017年)には、太陽活動も火山活動も観測された温暖化を説明できないことを示す図表が含まれている[140][141]。 太陽は地球の主要なエネルギー源であるため、入射する太陽光の変化は気候システムに直接影響する[135]。太陽放射照度は人工衛星によって直接測定され ており[142]、1600年代初頭以降は間接的な測定が可能である。 [1880年以降、下層大気(対流圏)の温暖化とは対照的に、地球に到達する太陽のエネルギー量に上昇傾向は見られない[143]。太陽が地球に多くのエ ネルギーを送っていれば上層大気(成層圏)も温暖化しているはずだが、その代わりに冷却している[96]。これは、温室効果ガスが地球の大気圏から熱が出 るのを妨げていることと一致している[144]。 爆発的な火山噴火は、太陽光を部分的に遮って気温を下げるガス、塵、灰を放出したり、温室効果ガスに加えて気温を上げる水蒸気を大気中に送り込んだりする [145]。 [146]火山によるCO2排出はより持続性が高いが、現在の人為的なCO2排出の1%未満に相当する。[147]火山活動は、工業化時代の気温に対する 唯一最大の自然影響(強制力)を依然として代表している。しかし、他の自然強制力と同様に、産業革命以降、世界の気温トレンドに与えた影響はごくわずかで ある[146]。 気候変動のフィードバック 主な記事 気候変動のフィードバックと気候感度  海氷は入射する太陽光の50%から70%を反射するが、海は暗いため6%しか反射しない。海氷が溶けてより多くの海が露出すると、より多くの熱が海に吸収され、気温が上昇してさらに多くの海氷が溶ける。これは正のフィードバックプロセスである。 初期強制に対する気候システムの応答は、「自己強化型」または「正」の フィードバックによって増加し、「均衡型」または「負」のフィードバックに よって減少するというように、フィードバックによって修正される[149]。 [150][151]主要な平衡メカニズムは放射冷却であり、地球表面は温度上昇に反応してより多くの熱を宇宙に放出する[152]。温度フィードバック に加えて、植物の成長に対するCO2の肥沃化効果のような炭素循環におけるフィードバックがある[153]。 フィードバック、特に雲量[154]に関する不確実性は、気候モデルによって、ある排出量に対する温暖化の大きさが異なると予測される主な理由である [155]。強力な温室効果ガスである水蒸気は、大気中に熱を保持する[150]。雲が増えれば、より多くの太陽光が宇宙空間に反射され、地球を冷却す る。雲が高くなり薄くなると、雲は断熱材として働き、下からの熱を下方に反射して地球を暖める。 もう1つの主要なフィードバックは、北極圏における積雪と海氷の減少であり、これは地球表面の反射率を低下させる[157]。北極圏の増幅はまた、永久凍土を融解し、メタンとCO2を大気中に放出する[159]。 人為的に排出されたCO2の約半分は、陸上植物と海洋によって吸収されてきた[162]。この割合は一定ではなく、将来のCO2排出量が減少すれば、地球 は約70%まで吸収できるようになる。気候変動によって干ばつや熱波が増加し、最終的に陸上での植物の成長が阻害され、土壌が暖かくなると枯死した植物か らより多くの炭素が放出されるからである[164][165]。海洋が大気中の炭素を吸収する割合は、海洋が酸性化し、熱塩循環や植物プランクトンの分布 に変化が生じると低下する[166][167][77]。 |

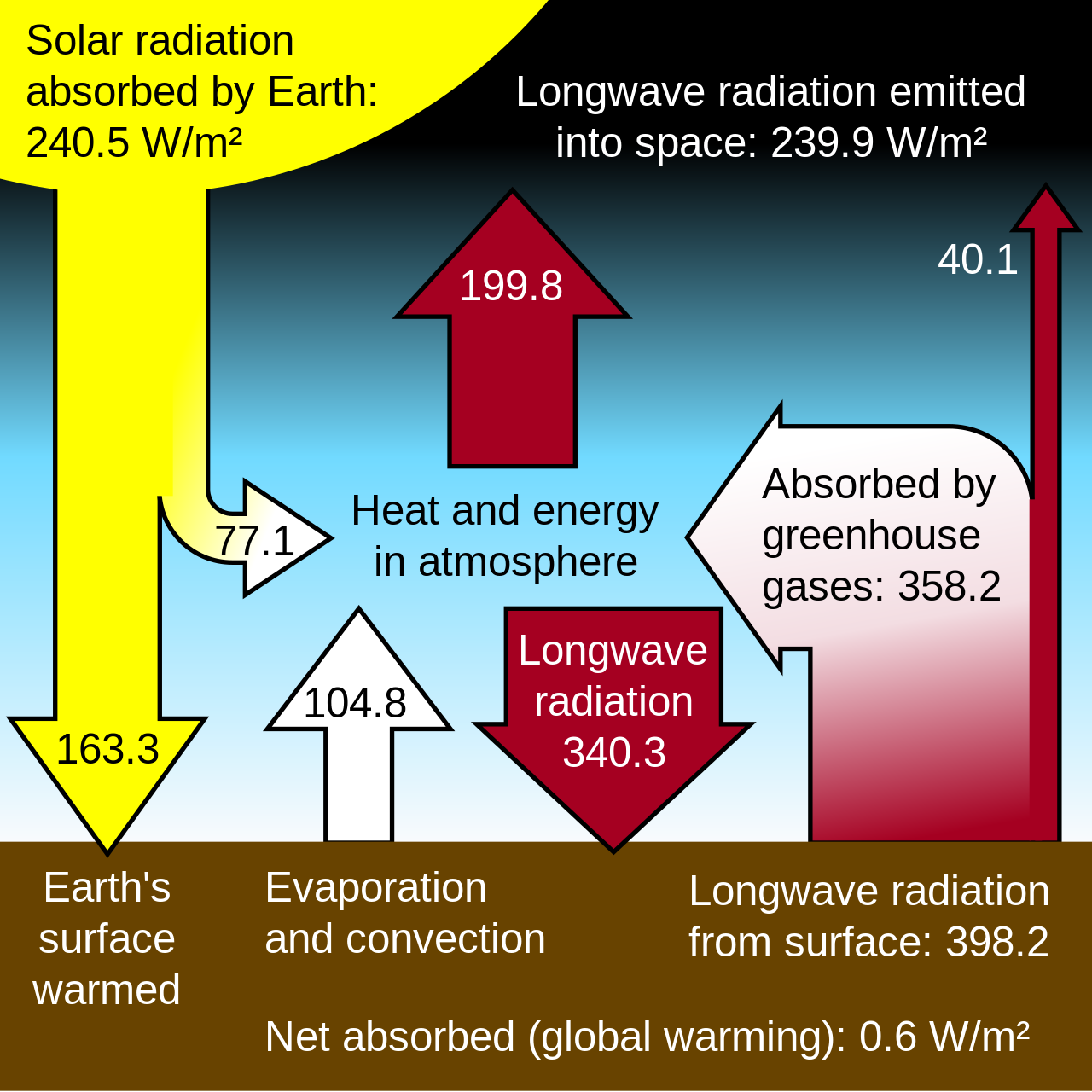

| Modelling Further information: Climate model and Climate change scenario  Energy flows between space, the atmosphere, and Earth's surface. Most sunlight passes through the atmosphere to heat the Earth's surface, then greenhouse gases absorb most of the heat the Earth radiates in response. Adding to greenhouse gases increases this insulating effect, causing an energy imbalance that heats the planet up. A climate model is a representation of the physical, chemical and biological processes that affect the climate system.[168] Models include natural processes like changes in the Earth's orbit, historical changes in the Sun's activity, and volcanic forcing.[169] Models are used to estimate the degree of warming future emissions will cause when accounting for the strength of climate feedbacks.[170][171] Models also predict the circulation of the oceans, the annual cycle of the seasons, and the flows of carbon between the land surface and the atmosphere.[172] The physical realism of models is tested by examining their ability to simulate contemporary or past climates.[173] Past models have underestimated the rate of Arctic shrinkage[174] and underestimated the rate of precipitation increase.[175] Sea level rise since 1990 was underestimated in older models, but more recent models agree well with observations.[176] The 2017 United States-published National Climate Assessment notes that "climate models may still be underestimating or missing relevant feedback processes".[177] Additionally, climate models may be unable to adequately predict short-term regional climatic shifts.[178] A subset of climate models add societal factors to a physical climate model. These models simulate how population, economic growth, and energy use affect—and interact with—the physical climate. With this information, these models can produce scenarios of future greenhouse gas emissions. This is then used as input for physical climate models and carbon cycle models to predict how atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases might change.[179][180] Depending on the socioeconomic scenario and the mitigation scenario, models produce atmospheric CO2 concentrations that range widely between 380 and 1400 ppm.[181] |

モデリング さらに詳しい情報 気候モデル、気候変動シナリオ  エネルギーは宇宙、大気、地表の間を流れている。ほとんどの太陽光は大気を通過して地表を暖め、温室効果ガスが地球が放射する熱の大部分を吸収する。温室効果ガスを増やすと、この断熱効果が高まり、地球を温めるエネルギーの不均衡を引き起こす。 気候モデルとは、気候システムに影響を与える物理的、化学的、生物学的プロセスを表現したものである[168]。モデルには、地球の軌道の変化、太陽活動 の歴史的変化、火山強制力などの自然プロセスが含まれる[169]。モデルは、気候フィードバックの強さを考慮した場合に、将来の排出が引き起こす温暖化 の程度を推定するために使用される[170][171]。モデルはまた、海洋の循環、季節の年周期、地表と大気間の炭素の流れを予測する[172]。 モデルの物理的な現実性は、現代または過去の気候をシミュレートする能力を調べることによって検証される[173]。過去のモデルは、北極の縮小の速度を 過小評価し[174]、降水量の増加速度を過小評価している[175]。1990年以降の海面上昇は、古いモデルでは過小評価されていたが、最近のモデル は観測結果とよく一致している。 [176]。2017年に米国で公表された国家気候評価報告書では、「気候モデルは依然として、関連するフィードバック過程を過小評価しているか、見逃し ている可能性がある」と指摘している[177]。さらに、気候モデルは、短期的な地域的気候変動を適切に予測できない可能性がある[178]。 気候モデルのサブセットは、物理的気候モデルに社会的要 因を追加している。これらのモデルは、人口、経済成長、エネル ギー利用が物理的気候にどのような影響を与え、相互作用す るかをシミュレートしている。この情報を用いて、これらのモデルは、将来の温室効果ガス排出のシナリオを作成することができる。これは、温室効果ガスの大 気中濃度がどのように変化するかを予測するために、物理的気候モデルや炭素循環モデルの入力として使われる[179][180]。社会経済シナリオと緩和 シナリオに応じて、モデルは、380~1400ppmの間の広い範囲の大気中CO2濃度を作り出す[181]。 |

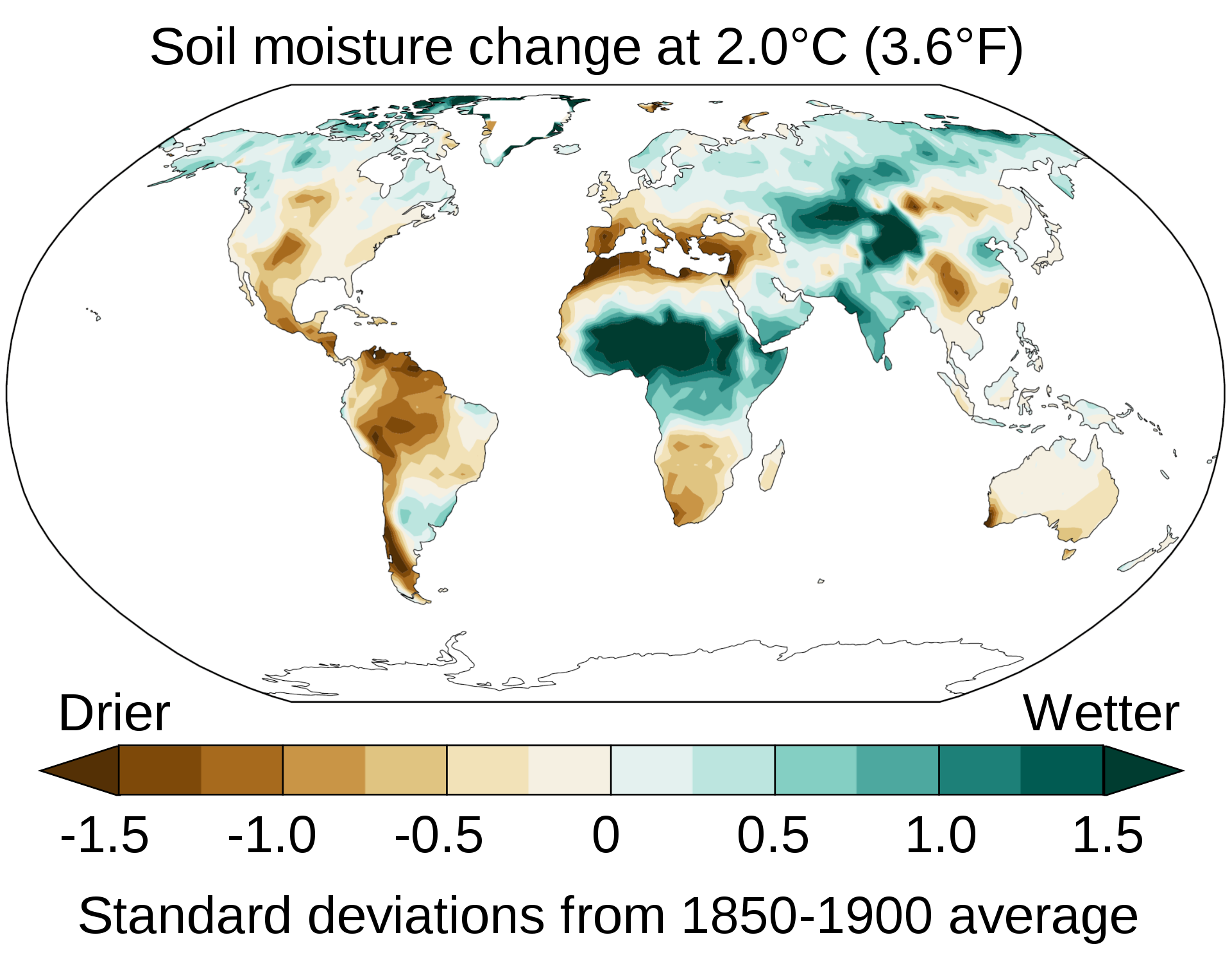

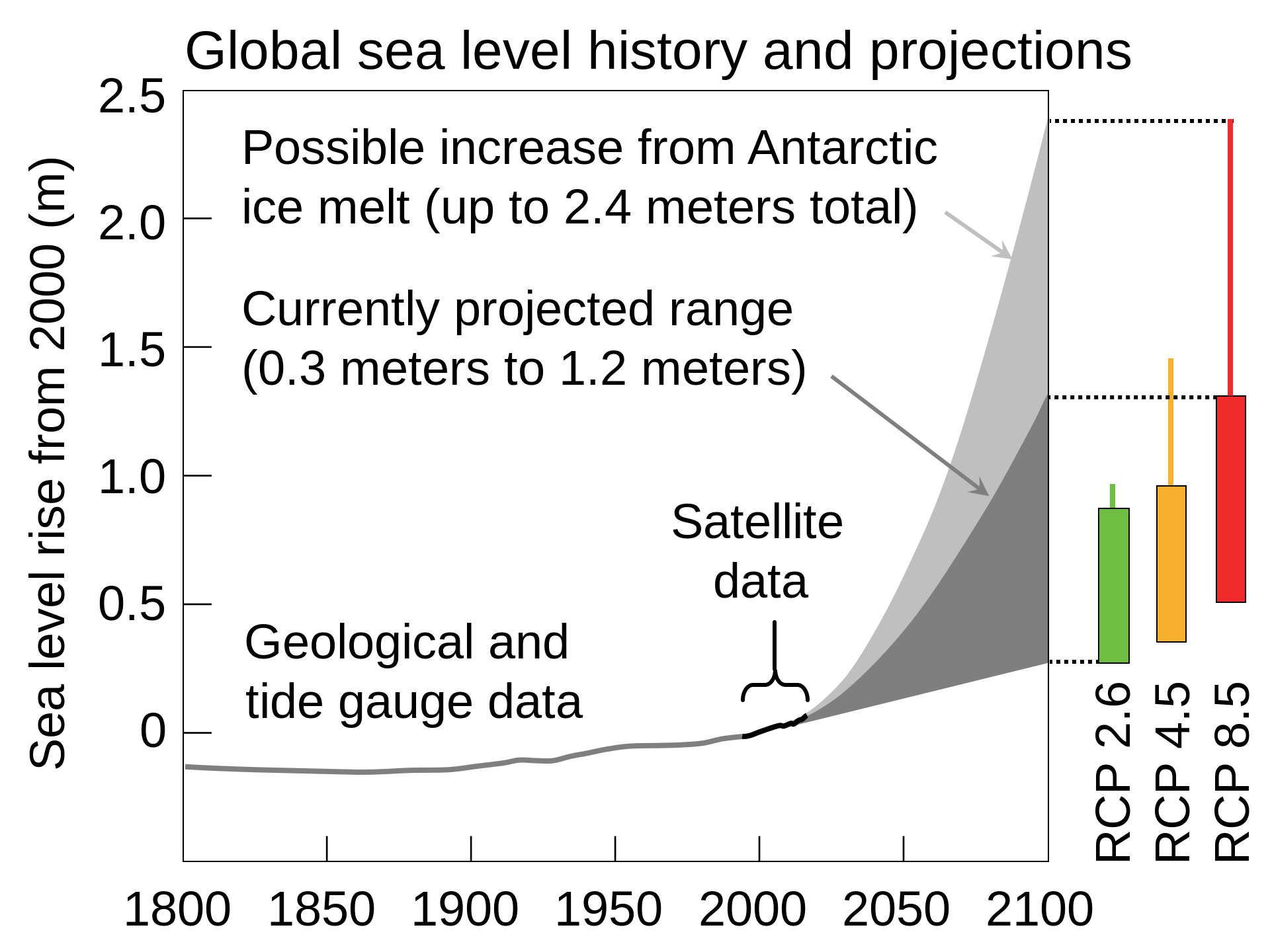

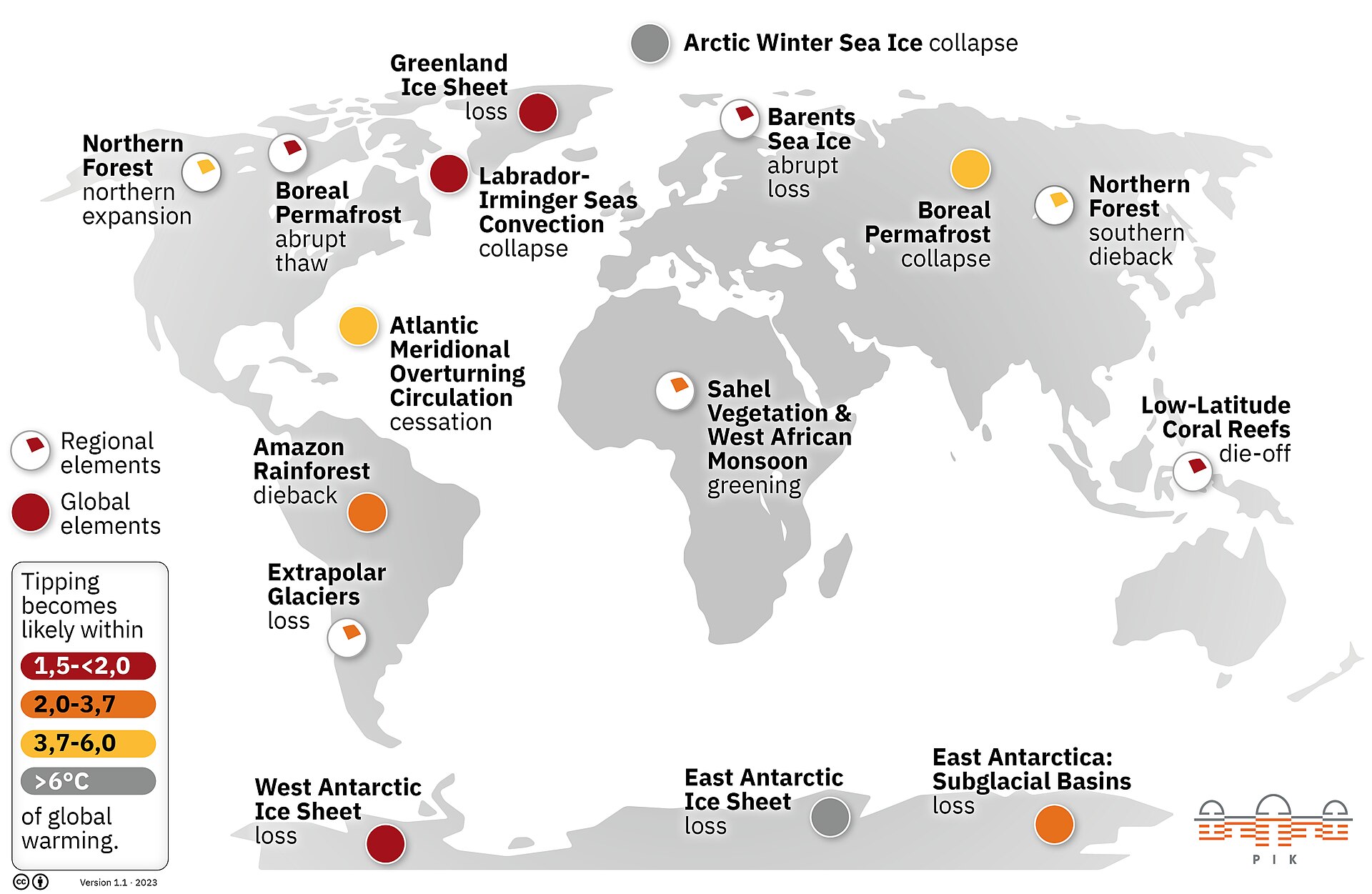

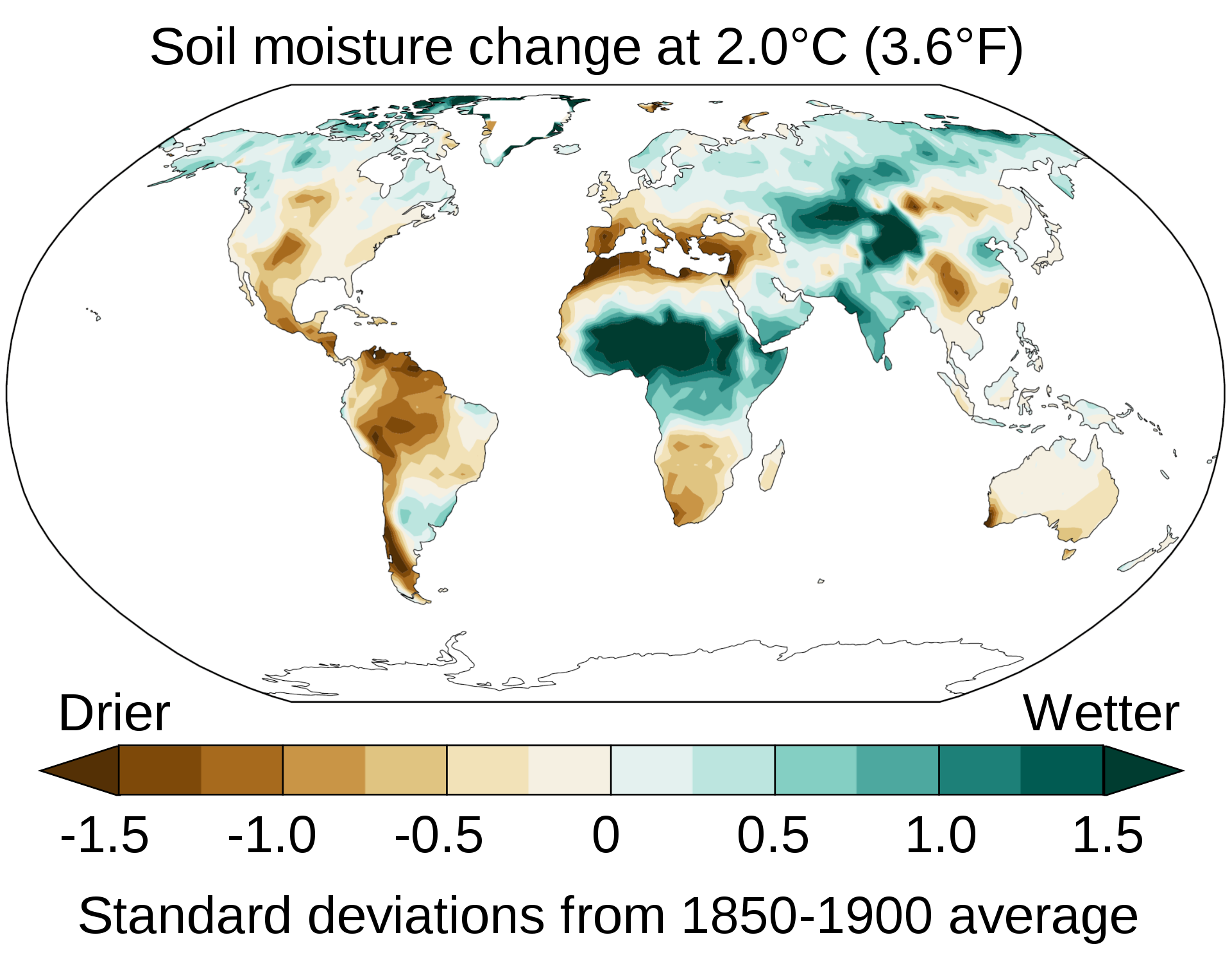

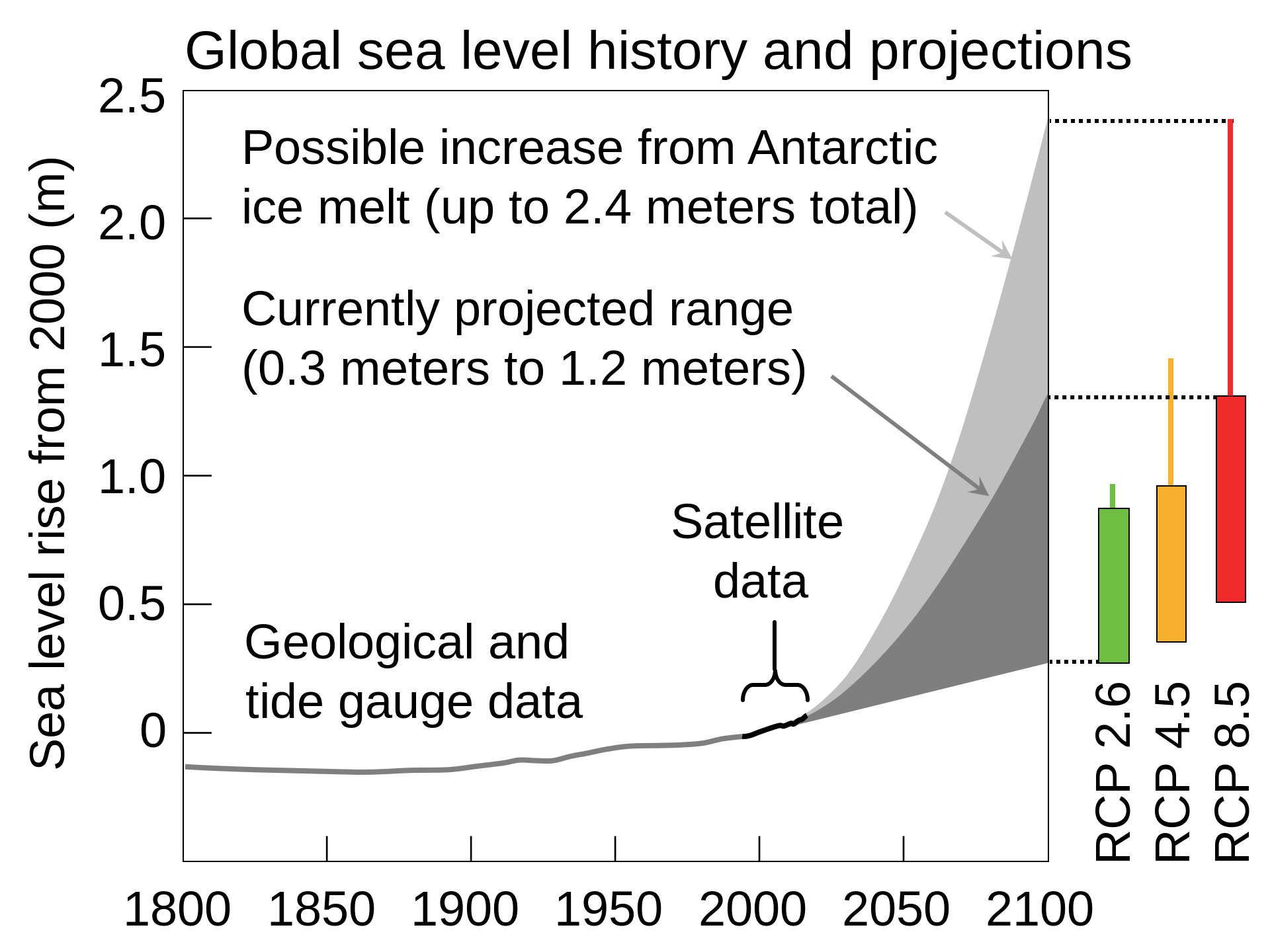

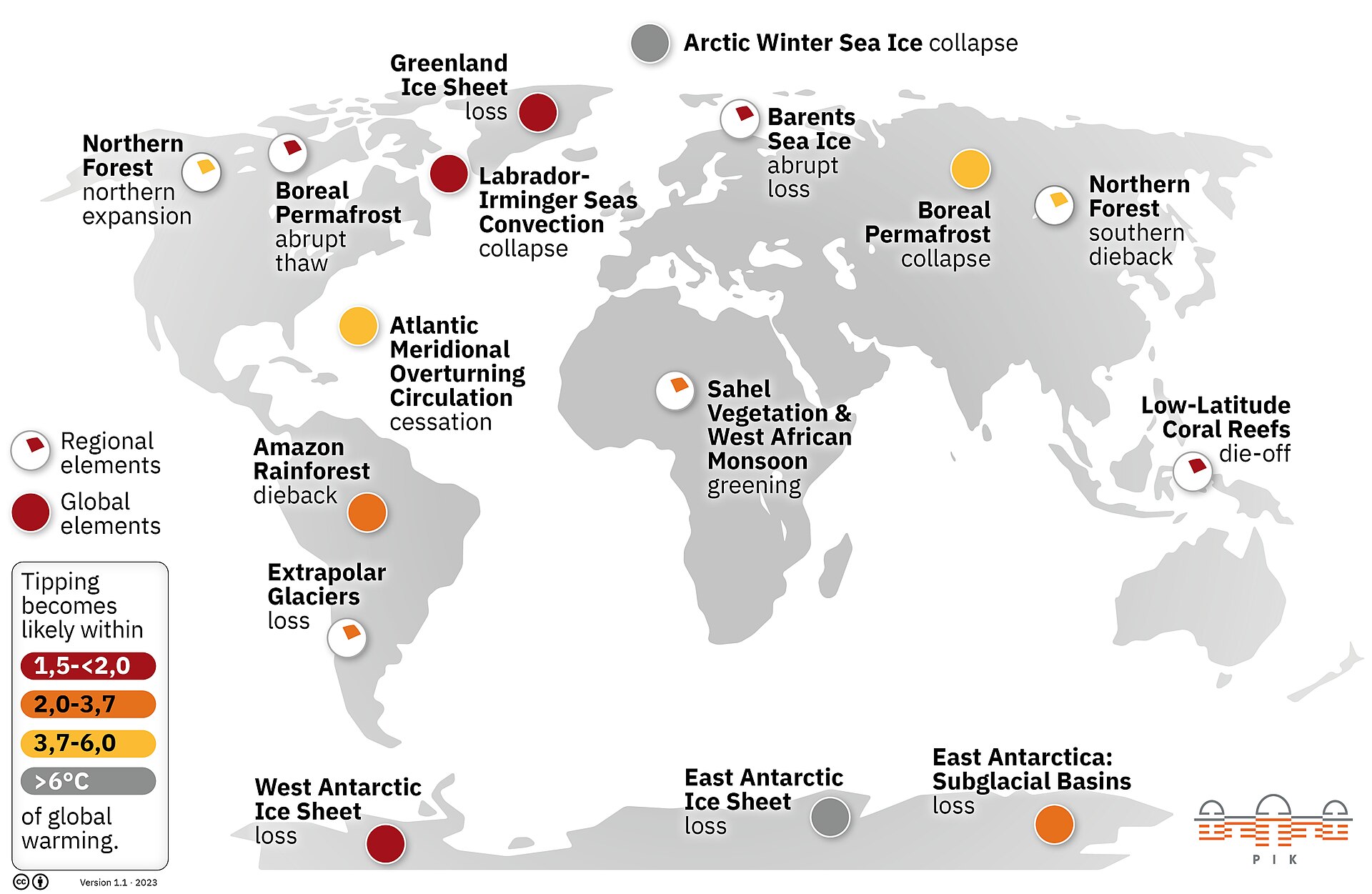

| Impacts Main article: Effects of climate change  The sixth IPCC Assessment Report projects changes in average soil moisture at 2.0 °C of warming, as measured in standard deviations from the 1850 to 1900 baseline. Environmental effects Further information: Effects of climate change on oceans and Effects of climate change on the water cycle The environmental effects of climate change are broad and far-reaching, affecting oceans, ice, and weather. Changes may occur gradually or rapidly. Evidence for these effects comes from studying climate change in the past, from modelling, and from modern observations.[182] Since the 1950s, droughts and heat waves have appeared simultaneously with increasing frequency.[183] Extremely wet or dry events within the monsoon period have increased in India and East Asia.[184] Monsoonal precipitation over the Northern Hemisphere has increased since 1980.[185] The rainfall rate and intensity of hurricanes and typhoons is likely increasing,[186] and the geographic range likely expanding poleward in response to climate warming.[187] Frequency of tropical cyclones has not increased as a result of climate change.[188]  Historical sea level reconstruction and projections up to 2100 published in 2017 by the U.S. Global Change Research Program[189] Global sea level is rising as a consequence of thermal expansion and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets. Between 1993 and 2020, the rise increased over time, averaging 3.3 ± 0.3 mm per year.[190] Over the 21st century, the IPCC projects 32–62 cm of sea level rise under a low emission scenario, 44–76 cm under an intermediate one and 65–101 cm under a very high emission scenario.[191] Marine ice sheet instability processes in Antarctica may add substantially to these values,[192] including the possibility of a 2-meter sea level rise by 2100 under high emissions.[193] Climate change has led to decades of shrinking and thinning of the Arctic sea ice.[194] While ice-free summers are expected to be rare at 1.5 °C degrees of warming, they are set to occur once every three to ten years at a warming level of 2 °C.[195] Higher atmospheric CO2 concentrations cause more CO2 to dissolve in the oceans, which is making them more acidic.[196] Because oxygen is less soluble in warmer water,[197] its concentrations in the ocean are decreasing, and dead zones are expanding.[198] Tipping points and long-term impacts  Different levels of global warming may cause different parts of Earth's climate system to reach tipping points that cause transitions to different states.[199][200] Main article: Tipping points in the climate system Greater degrees of global warming increase the risk of passing through 'tipping points'—thresholds beyond which certain major impacts can no longer be avoided even if temperatures return to their previous state.[201][202] For instance, the Greenland ice sheet is already melting, but if global warming reaches levels between 1.7 °C and 2.3 °C, its melting will continue until it fully disappears. If the warming is later reduced to 1.5 °C or less, it will still lose a lot more ice than if the warming was never allowed to reach the threshold in the first place.[203] While the ice sheets would melt over millennia, other tipping points would occur faster and give societies less time to respond. The collapse of major ocean currents like the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), and irreversible damage to key ecosystems like the Amazon rainforest and coral reefs can unfold in a matter of decades.[200] The long-term effects of climate change on oceans include further ice melt, ocean warming, sea level rise, ocean acidification and ocean deoxygenation.[204] The timescale of long-term impacts are centuries to millennia due to CO2's long atmospheric lifetime.[205] When net emissions stabilise surface air temperatures will also stabilise, but oceans and ice caps will continue to absorb excess heat from the atmosphere. The result is an estimated total sea level rise of 2.3 metres per degree Celsius (4.2 ft/°F) after 2000 years.[206] Oceanic CO2 uptake is slow enough that ocean acidification will also continue for hundreds to thousands of years.[207] Deep oceans (below 2,000 metres (6,600 ft)) are also already committed to losing over 10% of their dissolved oxygen by the warming which occurred to date.[208] Further, West Antarctic ice sheet appears committed to practically irreversible melting, which would increase the sea levels by at least 3.3 m (10 ft 10 in) over approximately 2000 years.[200][209][210][211][212][213][214][215] Nature and wildlife Further information: Effects of climate change on oceans and Effects of climate change on biomes Recent warming has driven many terrestrial and freshwater species poleward and towards higher altitudes.[216] For instance, the range of hundreds of North American birds has shifted northward at an average rate of 1.5 km/year over the past 55 years.[217] Higher atmospheric CO2 levels and an extended growing season have resulted in global greening. However, heatwaves and drought have reduced ecosystem productivity in some regions. The future balance of these opposing effects is unclear.[218] A related phenomenon driven by climate change is woody plant encroachment, affecting up to 500 million hectares globally.[219] Climate change has contributed to the expansion of drier climate zones, such as the expansion of deserts in the subtropics.[220] The size and speed of global warming is making abrupt changes in ecosystems more likely.[221] Overall, it is expected that climate change will result in the extinction of many species.[222] The oceans have heated more slowly than the land, but plants and animals in the ocean have migrated towards the colder poles faster than species on land.[223] Just as on land, heat waves in the ocean occur more frequently due to climate change, harming a wide range of organisms such as corals, kelp, and seabirds.[224] Ocean acidification makes it harder for marine calcifying organisms such as mussels, barnacles and corals to produce shells and skeletons; and heatwaves have bleached coral reefs.[225] Harmful algal blooms enhanced by climate change and eutrophication lower oxygen levels, disrupt food webs and cause great loss of marine life.[226] Coastal ecosystems are under particular stress. Almost half of global wetlands have disappeared due to climate change and other human impacts.[227] |

影響 主な記事 気候変動の影響  IPCC第6次評価報告書では、2.0℃の温暖化における土壌水分の平均値の変化を、1850年から1900年の基準値からの標準偏差で測定している。 環境への影響 さらに詳しい情報 気候変動が海洋に及ぼす影響と気候変動が水循環に及ぼす影響 気候変動による環境への影響は広範囲に及び、海洋、氷、気象に影響を及ぼす。変化は徐々に起こることもあれば、急速に起こることもある。これらの影響に関 する証拠は、過去の気候変動の研究、モデリング、および現代の観測から得られている[182]。1950年代以降、干ばつと熱波が同時に発生する頻度が増 加している[183]。 [184]北半球のモンスーン性降水量は1980年以降増加し ている[185]。ハリケーンや台風の降雨量と強度はおそらく増 加しており[186]、地理的範囲は気候温暖化に対応して北極 方向に拡大している可能性が高い[187]。熱帯低気圧の頻度は 気候変動の結果として増加していない[188]。  米国の地球変動研究プログラム[189]によって2017年に公表された過去の海面の復元と2100年までの予測。 世界の海面は、熱膨張と氷河・氷床の融解の結果として上昇している。1993年から2020年にかけて、上昇幅は経時的に増加し、年平均3.3± 0.3mmであった[190]。21世紀にかけて、IPCCは、低排出シナリオの下で32~62cm、中間シナリオの下で44~76cm、超高排出シナリ オの下で65~101cmの海面上昇を予測している[191]。南極大陸の海洋氷床の不安定化プロセスは、高排出シナリオの下で2100年までに2mの海 面上昇の可能性を含め、これらの値に大幅に加わる可能性がある[192]。 気候変動は、数十年にわたる北極海の海氷の縮小と薄 層化をもたらしている[194]。氷のない夏は、1.5℃の温暖化では稀であ ると予想されるが、2℃の温暖化では3年から10年に一度の頻度で 発生すると設定されている。 [195]。大気中のCO2濃度が高くなると、より多くのCO2が海洋に溶解し、海洋をより酸性にする[196]。 転換点と長期的影響  地球温暖化のレベルが異なると、地球の気候システムの異なる部分が、異なる状態への移行を引き起こす転換点に達する可能性がある[199][200]。 主な記事 気候システムにおける転換点 地球温暖化の度合いが大きくなると、「転換点」-気温が以前の状態に戻ったとしても、特定の重大な影響がもはや回避できない閾値-を通過するリスクが高ま る[201][202]。例えば、グリーンランドの氷床はすでに溶けているが、地球温暖化が1.7℃~2.3℃のレベルに達すると、その氷床は完全に消滅 するまで溶け続ける。その後、温暖化が1.5℃以下に抑えられたとしても、温暖化が最初に閾値に達することを許されなかった場合よりも、多くの氷が失われ ることになる[203]。氷床は数千年かけて溶けるだろうが、他の転換点はより早く発生し、社会が対応する時間をより短くするだろう。大西洋の子午面循環 (AMOC)のような主要な海流の崩壊や、アマゾンの熱帯雨林やサンゴ礁のような主要な生態系への不可逆的なダメージは、数十年のうちに展開する可能性が ある[200]。 気候変動が海洋に及ぼす長期的影響には、さらなる氷の融解、海洋温暖化、海面上昇、海洋酸性化、海洋脱酸素化が含まれる[204]。長期的影響のタイムス ケールは、CO2の大気寿命が長いため、数世紀~数千年である[205]。その結果、2000年後の海面上昇の総量は、摂氏1度あたり2.3メートル(摂 氏4.2フィート/°F)と見積もられる[206]。海洋のCO2吸収は十分に遅いため、海洋酸性化も数百年から数千年続くだろう[207]。深海 (2,000メートル(6,600フィート)以下)もまた、現在までに起こった温暖化によって、すでに溶存酸素の10%以上を失うことが確定している。 [208]さらに、西南極の氷床は、実質的に不可逆的な融解を約束されているようであり、これは約2000年の間に海面を少なくとも3.3m(10フィー ト10インチ)上昇させるだろう[200][209][210][211][212][213][214][215]。 自然と野生生物 更なる情報 気候変動が海洋に及ぼす影響と気候変動が生物群に及ぼす影響 近年の温暖化は、多くの陸生種や淡水生物を極地や高地へと移動させている[216]。例えば、北米の数百種類の鳥類の生息域は、過去55年間で平均 1.5km/年の割合で北上している[217]。しかし、熱波や干ばつによって生態系の生産性が低下している地域もある。これらの相反する効果の将来的な バランスは不明である[218]。 気候変動によって引き起こされる関連した現象は、木本植物の侵入であり、全世界で最大5億ヘクタールに影響を及ぼしている[219]。 気候変動は、亜熱帯における砂漠の拡大など、より乾燥した気候帯の拡大に寄与している[220]。 地球温暖化の規模と速度は、生態系の急激な変化をより起こりやすくしている[221]。 全体として、気候変動は多くの種の絶滅をもたらすと予想されている[222]。 海洋は陸上よりもゆっくりと加熱してきたが、海洋の動植物は陸上の種よりも速く寒冷な極地へと移動してきた[223]。陸上と同様に、気候変動によって海 洋でも熱波が頻繁に発生し、サンゴ、コンブ、海鳥など幅広い生物に害を与えている。 [224]海洋の酸性化は、ムール貝、フジツボ、サンゴなどの海洋石灰化生物が貝殻や骨格を作りにくくし、熱波はサンゴ礁を白化させている[225]。気 候変動と富栄養化によって増加した有害藻類は、酸素濃度を低下させ、食物網を混乱させ、海洋生物の大きな損失を引き起こしている[226]。沿岸生態系は 特にストレス下にある。気候変動やその他の人為的影響により、世界の湿地帯のほぼ半分が消滅している[227]。 |

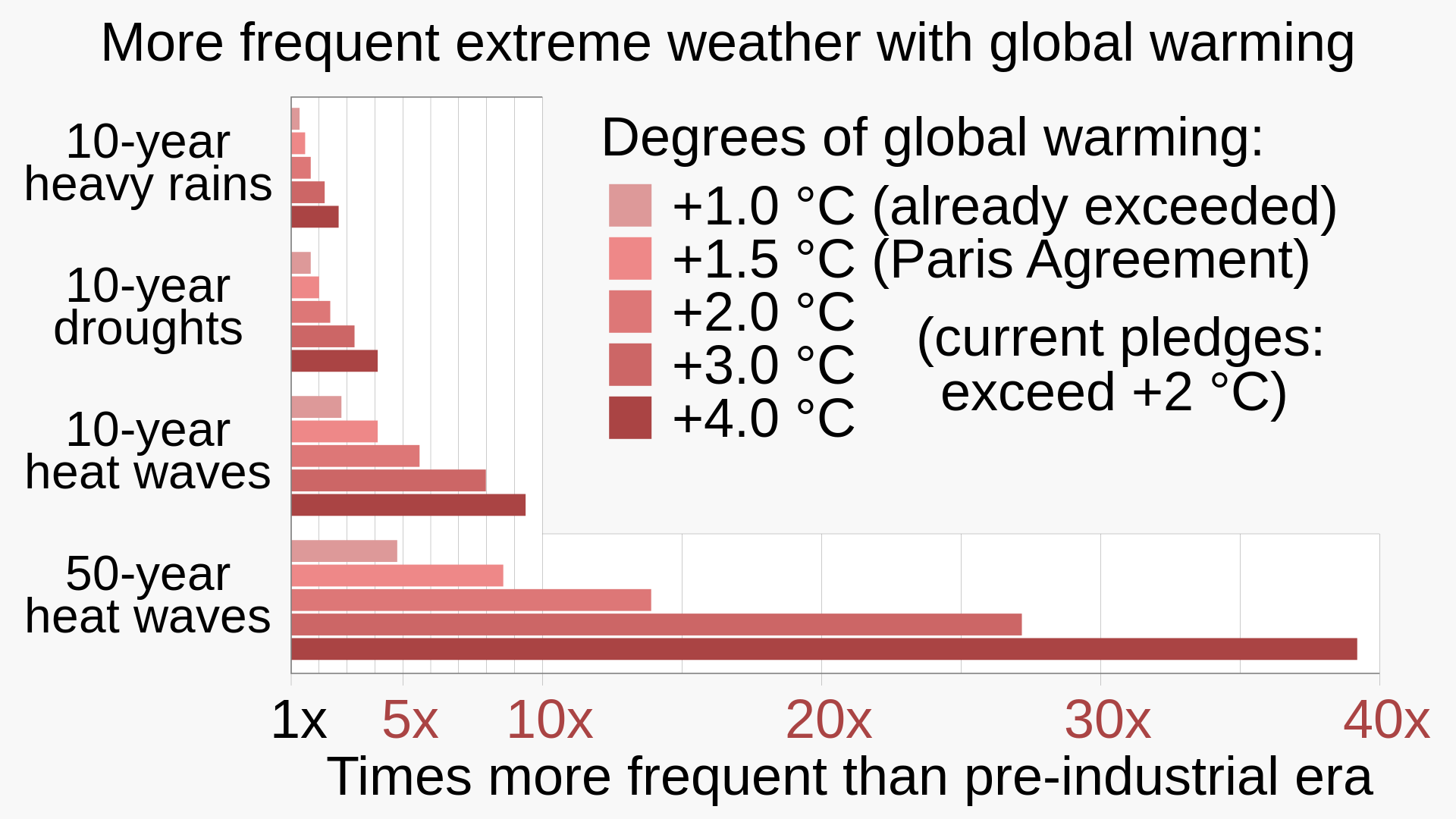

| Humans Main article: Effects of climate change  Extreme weather will be progressively more common as the Earth warms.[232] The effects of climate change are impacting humans everywhere in the world.[233] Impacts can be observed on all continents and ocean regions,[234] with low-latitude, less developed areas facing the greatest risk.[235] Continued warming has potentially "severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts" for people and ecosystems.[236] The risks are unevenly distributed, but are generally greater for disadvantaged people in developing and developed countries.[237] Food and health Main articles: Effects of climate change on agriculture § Global food security and undernutrition, and Effects of climate change on human health The World Health Organization (WHO) calls climate change the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century.[238] Extreme weather leads to injury and loss of life.[239] Various infectious diseases are more easily transmitted in a warmer climate, such as dengue fever and malaria.[240] Crop failures can lead to food shortages and malnutrition, particularly effecting children.[241] Both children and older people are vulnerable to extreme heat.[242] The WHO has estimated that between 2030 and 2050, climate change would cause around 250,000 additional deaths per year. They assessed deaths from heat exposure in elderly people, increases in diarrhea, malaria, dengue, coastal flooding, and childhood malnutrition.[243] By 2100, 50% to 75% of the global population may face climate conditions that are life-threatening due to combined effects of extreme heat and humidity.[244] Climate change is affecting food security. It has caused reduction in global yields of maize, wheat, and soybeans between 1981 and 2010.[245] Future warming could further reduce global yields of major crops.[246] Crop production will probably be negatively affected in low-latitude countries, while effects at northern latitudes may be positive or negative.[247] Up to an additional 183 million people worldwide, particularly those with lower incomes, are at risk of hunger as a consequence of these impacts.[248] Climate change also impacts fish populations. Globally, less will be available to be fished.[249] Regions dependent on glacier water, regions that are already dry, and small islands have a higher risk of water stress due to climate change.[250] Livelihoods and inequality Further information: Economic analysis of climate change and Climate security Economic damages due to climate change may be severe and there is a chance of disastrous consequences.[251] Severe impacts are expected in South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where most of the local inhabitants are dependent upon natural and agricultural resources.[252][253] Heat stress can prevent outdoor labourers from working. If warming reaches 4 °C then labour capacity in those regions could be reduced by 30 to 50%.[254] The World Bank estimates that between 2016 and 2030, climate change could drive over 120 million people into extreme poverty without adaptation.[255] Inequalities based on wealth and social status have worsened due to climate change.[256] Major difficulties in mitigating, adapting, and recovering to climate shocks are faced by marginalised people who have less control over resources.[257][252] Indigenous people, who are subsistent on their land and ecosystems, will face endangerment to their wellness and lifestyles due to climate change.[258] An expert elicitation concluded that the role of climate change in armed conflict has been small compared to factors such as socio-economic inequality and state capabilities.[259] While women are not inherently more at risk from climate change and shocks, limits on women's resources and discriminatory gender norms constrain their adaptive capacity and resilience.[260] For example, women's work burdens, including hours worked in agriculture, tend to decline less than men's during climate shocks such as heat stress.[260] Climate migration Main article: Climate migration Low-lying islands and coastal communities are threatened by sea level rise, which makes urban flooding more common. Sometimes, land is permanently lost to the sea.[261] This could lead to statelessness for people in island nations, such as the Maldives and Tuvalu.[262] In some regions, the rise in temperature and humidity may be too severe for humans to adapt to.[263] With worst-case climate change, models project that almost one-third of humanity might live in Sahara-like uninhabitable and extremely hot climates.[264] These factors can drive climate or environmental migration, within and between countries.[12] More people are expected to be displaced because of sea level rise, extreme weather and conflict from increased competition over natural resources. Climate change may also increase vulnerability, leading to "trapped populations" who are not able to move due to a lack of resources.[265] |

人間 主な記事 気候変動の影響  地球が温暖化するにつれて、異常気象は徐々に一般的になる[232]。 気候変動の影響は、世界中のあらゆる場所で人間に影響を及ぼしている[233]。影響はすべての大陸と海洋地域で観察することができ[234]、低緯度の 低開発地域が最大のリスクに直面している[235]。継続的な温暖化は、人々と生態系にとって潜在的に「深刻で広範かつ不可逆的な影響」をもたらす [236]。リスクは不均等に分布しているが、発展途上国や先進国の恵まれない人々にとっては一般的に大きい[237]。 食品と健康 主な記事 気候変動が農業に及ぼす影響§世界の食料安全保障と栄養不良、及び気候変動が人間の健康に及ぼす影響 世界保健機関(WHO)は、気候変動を21世紀における世界の健康に対する最大の脅威と呼んでいる[238]。異常気象は、負傷や人命の損失につながる [239]。 [240]。農作物の不作は、食糧不足と栄養失調を引き起こし、特に子どもたちに影響を及ぼす。 241]。子どもたちも高齢者も猛暑に弱い。WHOは、2030年から2050年の間に、気候変動によって年間約25万人の死者が増加すると推定してい る。WHOは、高齢者の暑さによる死亡、下痢、マラリア、デング熱、沿岸 での洪水、小児期の栄養失調の増加を評価している[243]。2100年ま でに、世界人口の50%から75%が、猛暑と湿度の複合的な影響によ り、生命を脅かす気候条件に直面する可能性がある[244]。 気候変動は、食料安全保障に影響を及ぼしている。気候変動は、1981年から2010年にかけて、トウモロコシ、小麦、大豆の世界的な収量減少を引き起こ している[245]。将来の温暖化は、主要作物の世界的な収量をさらに減少させる可能性がある[246]。作物生産は、おそらく低緯度の国々で悪影響を受 けるだろうが、北緯度での影響はプラスになることもあればマイナスになることもある[247]。これらの影響の結果として、世界中でさらに最大1億 8,300万人の人々、特に所得の低い人々が飢餓のリスクにさらされている[248]。気候変動はまた、魚の個体数にも影響を与える。氷河の水に依存して いる地域、すでに乾燥し ている地域、小さな島々は、気候変動による水ストレスのリ スクが高い[250]。 生活と不平等 さらなる情報 気候変動の経済分析と気候の安全保障 気候変動による経済的損害は深刻であり、悲惨な結末を もたらす可能性がある[251]。地域住民の大半が自然資源や農業資 源に依存している東南アジアやサハラ以南のアフリカでは、深刻 な影響が予想される[252][253]。世界銀行は、2016年から2030年の間に、気候変動が適応なしに1億2,000万人以上の人々を極度の貧困 に追い込む可能性があると見積もっている[255]。 富や社会的地位に基づく不平等は、気候変動によって悪化している[256]。 気候ショックの緩和、適応、回復において大きな困難に直面しているのは、資源の支配力が弱い周縁化された人々である。 [257][252]自分たちの土地と生態系で生計を立てている先住民は、気候変動によって自分たちの健康や生活様式が危険にさらされることに直面するだ ろう[258]。専門家による聞き取り調査では、武力紛争における気候変動の役割は、社会経済的不平等や国家能力などの要因に比べると小さいと結論付けら れている[259]。 女性が本質的に気候変動やショックからより多くのリスクを負 っているわけではないが、女性の資源に対する制限や差別的なジェ ンダー規範は、女性の適応能力や回復力を制約している[260]。 例えば、農業における労働時間を含む女性の労働負担は、暑熱 ストレスのような気候ショックの間、男性よりも減少しない傾向があ る[260]。 気候移民 主な記事 気候による移住 低平地の島々や沿岸地域社会は、海面上昇の脅威にさらされており、都市部の洪水がより一般的になっている。このことは、モルディブやツバルなどの島国の人 々にとっては無国籍につながる可能性がある[262]。地域によっては、気温と湿度の上昇は、人類が適応するにはあまりに厳しいかもしれない[263]。 最悪の場合の気候変動では、人類のほぼ3分の1が、サハラ砂漠のような居住不可能な極端に暑い気候の地域に住むかもしれないとモデルは予測している [264]。 このような要因は、国内外を問わず、気候変動や環 境変動による移住を促進する可能性がある[12]。気候変動はまた、脆弱性を増大させ、資源不足のために移動することができない「閉じ込められた人口」をもたらす可能性もある[265]。 |

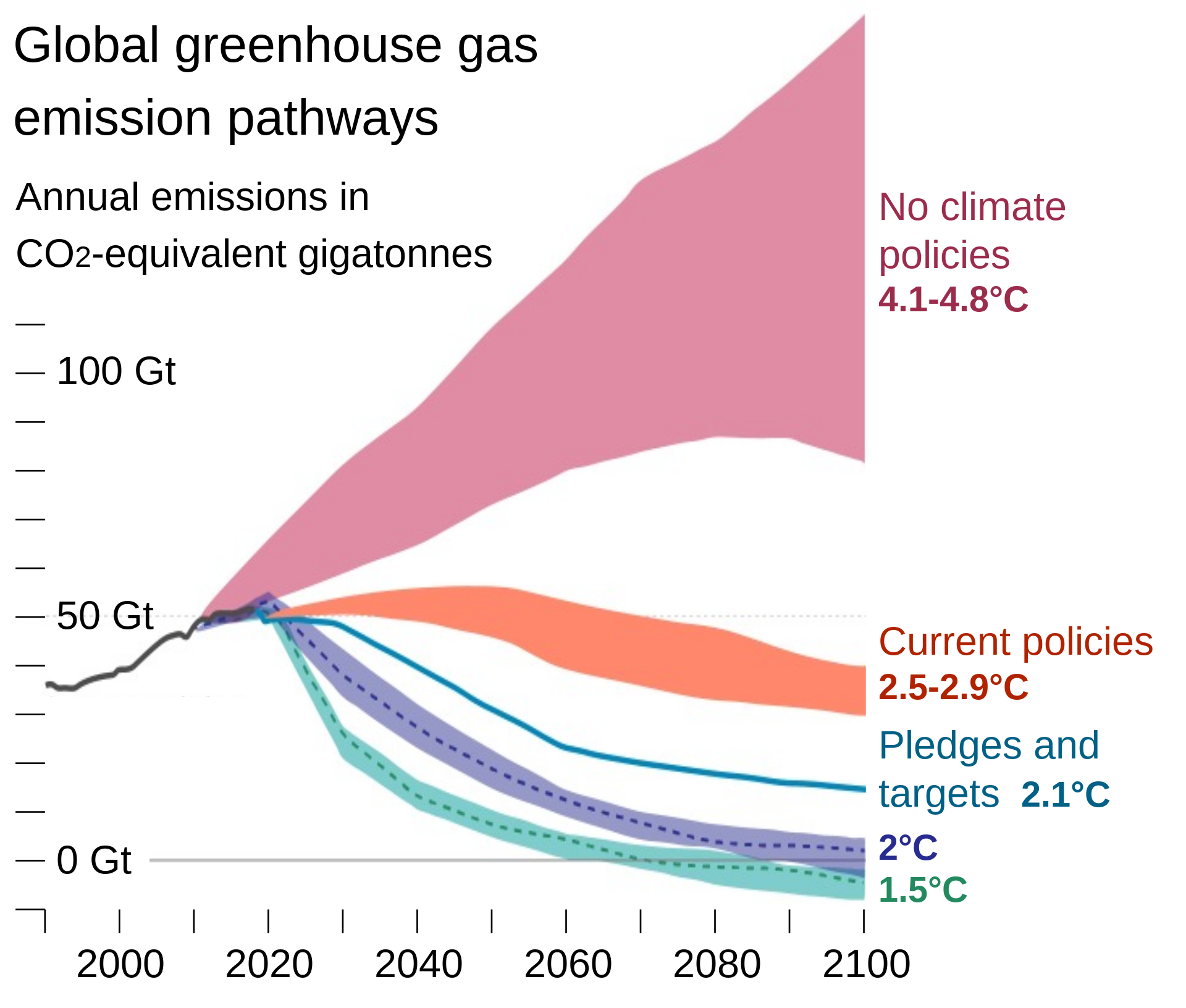

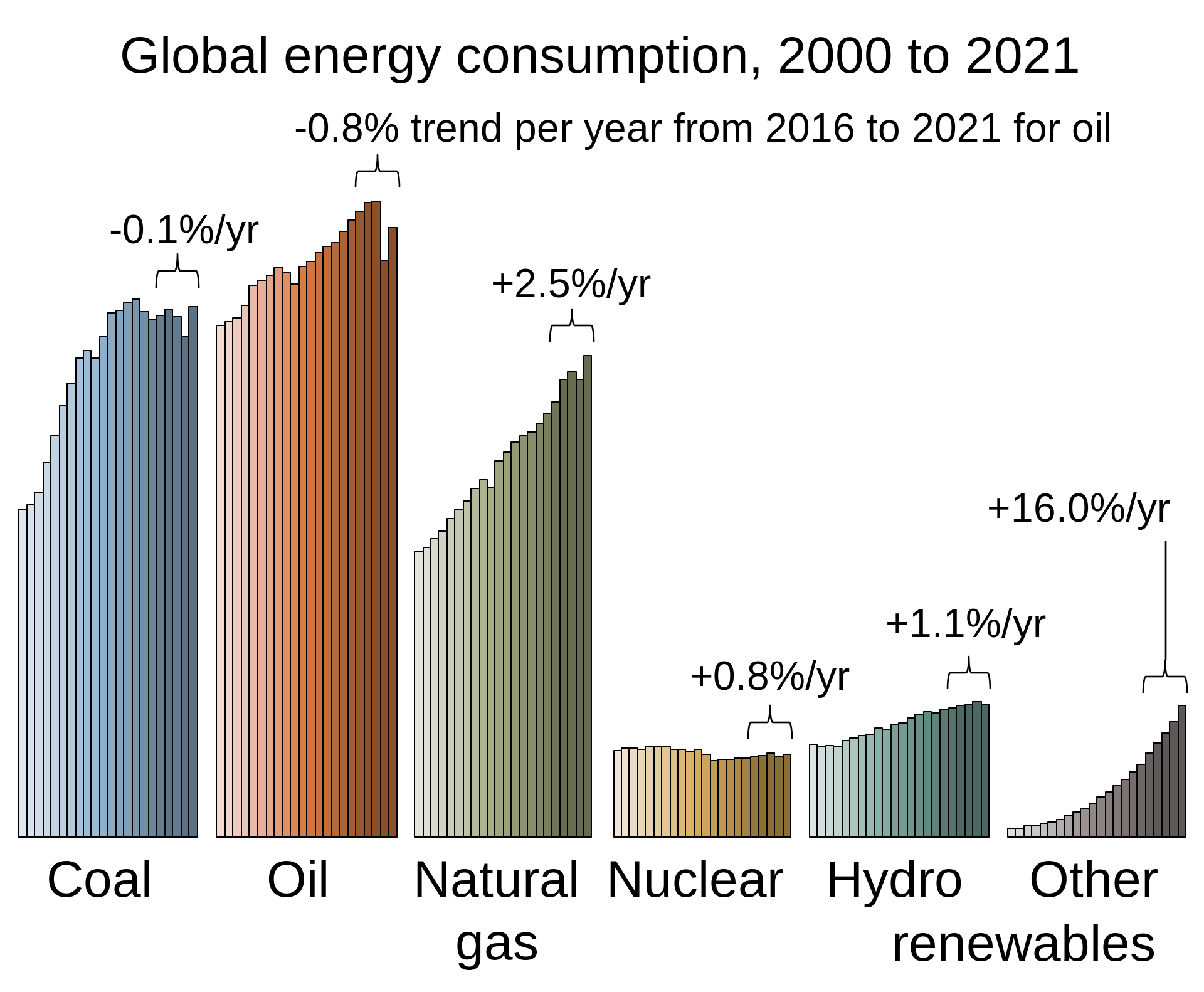

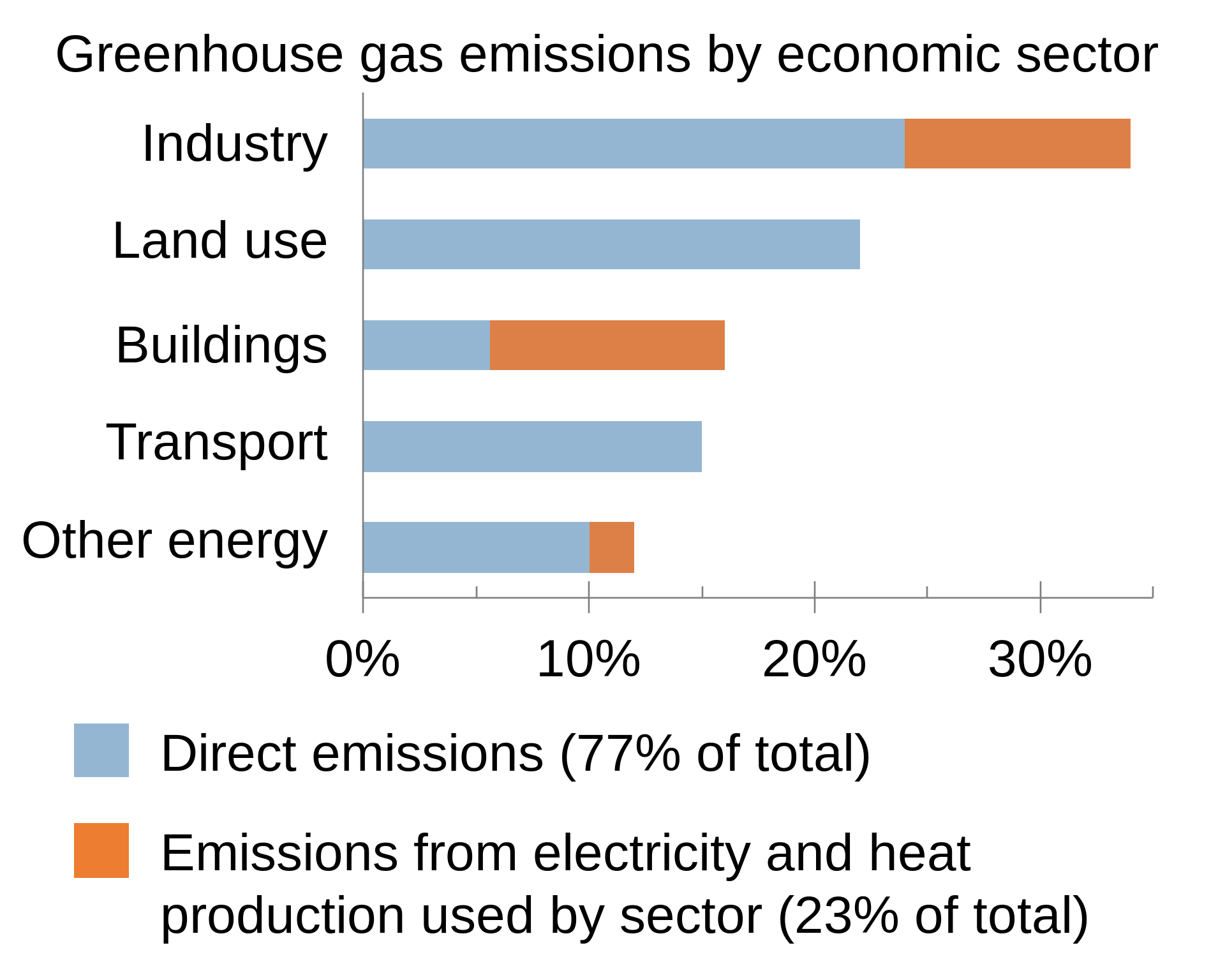

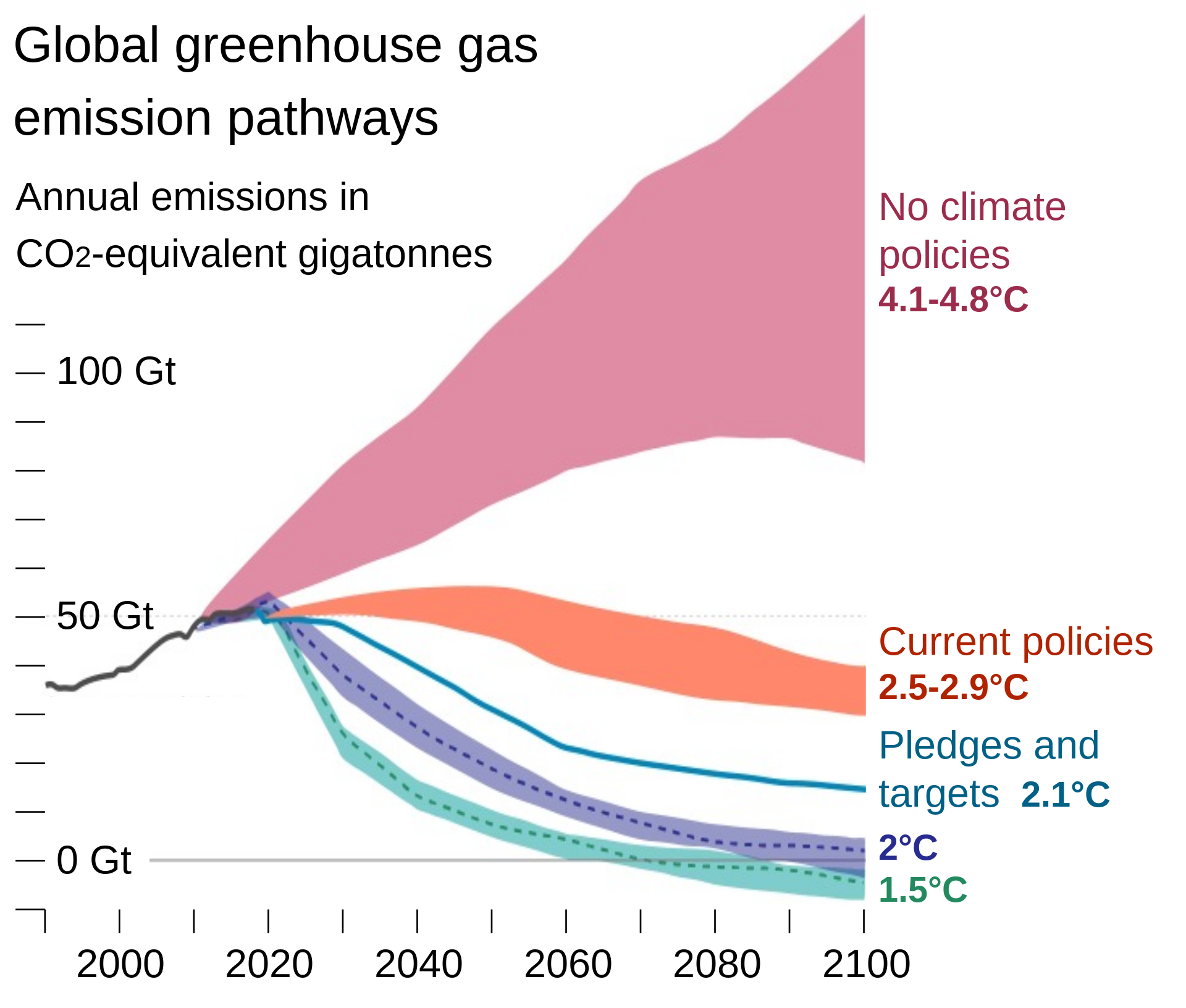

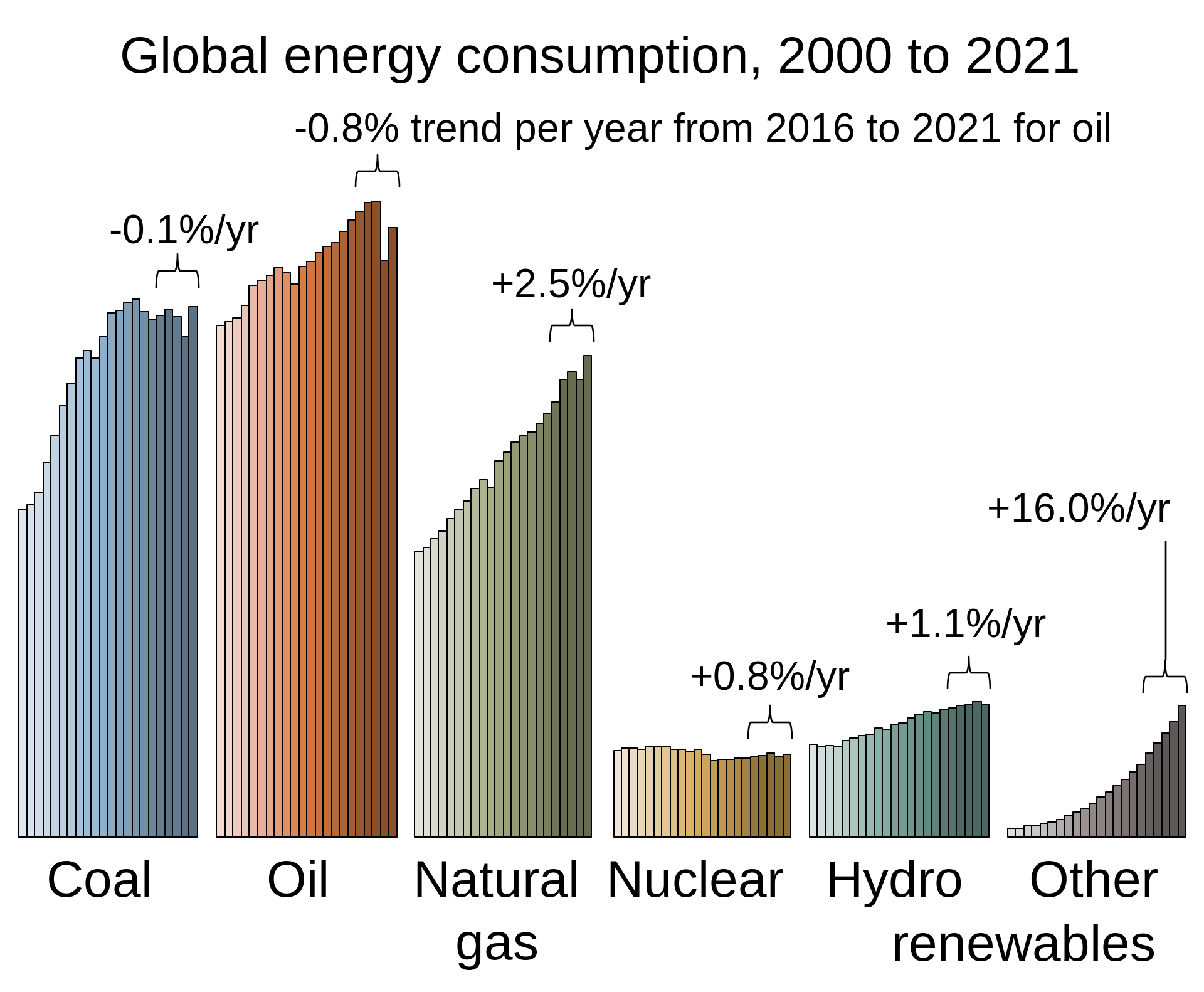

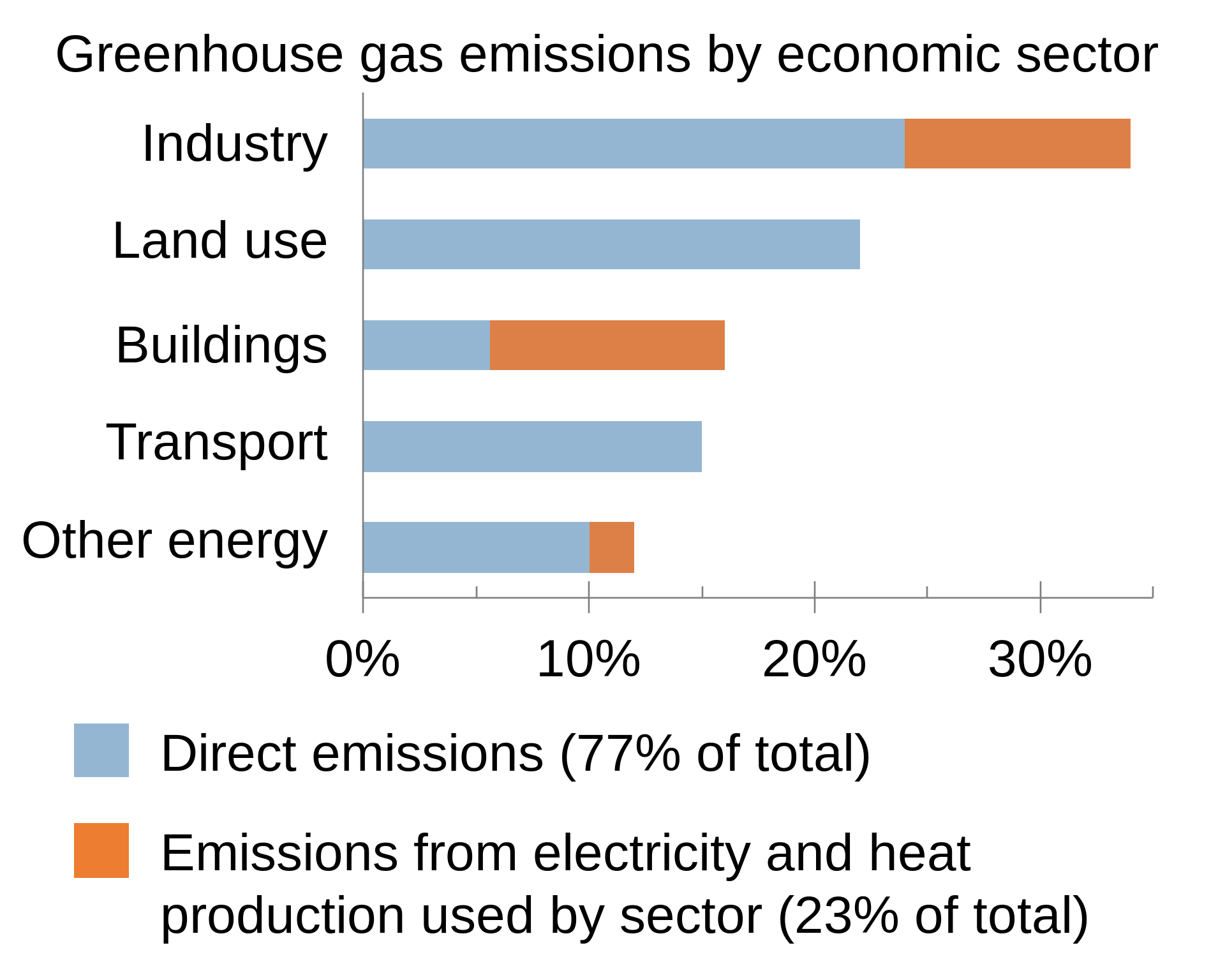

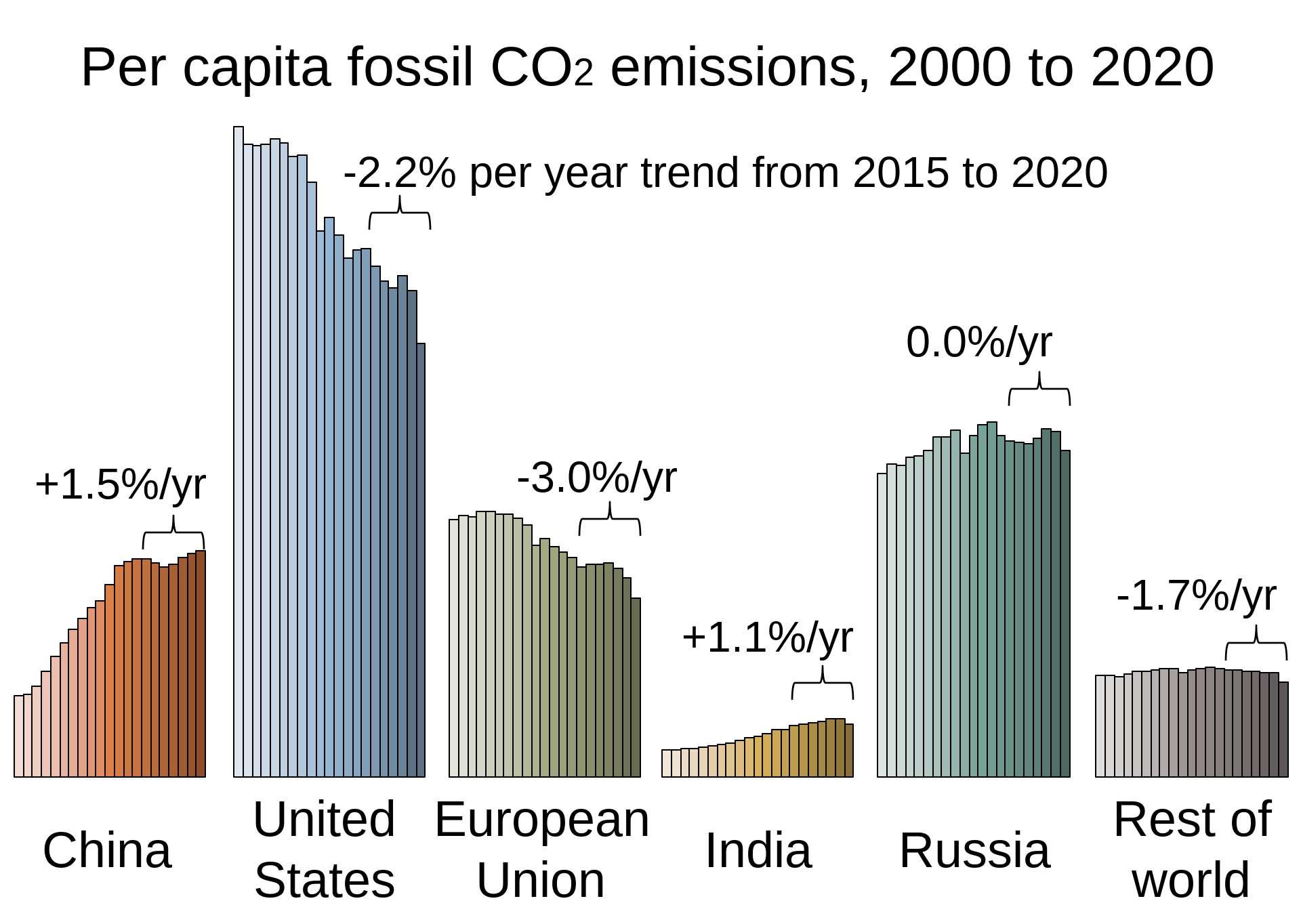

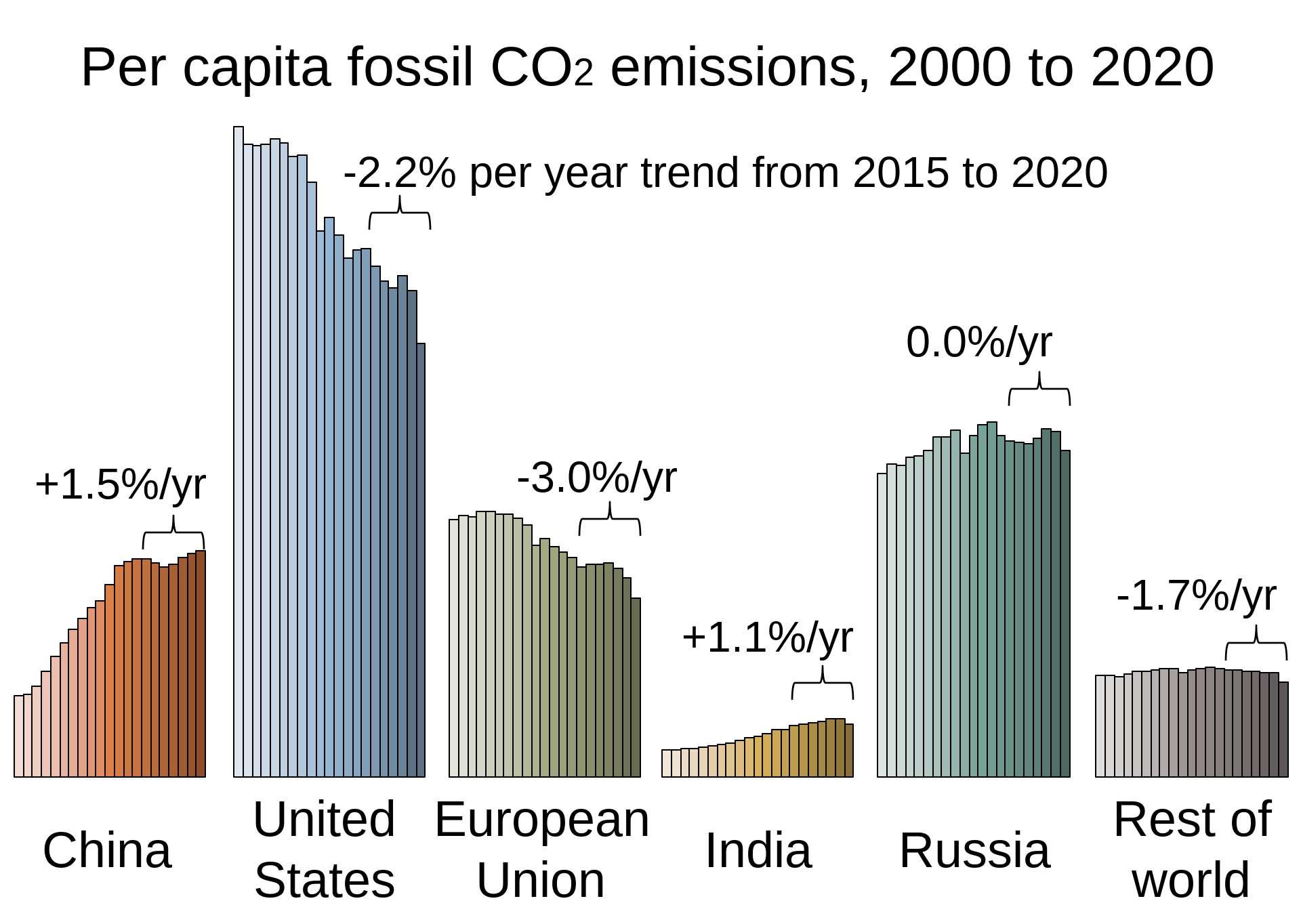

| Reducing and recapturing emissions Main article: Climate change mitigation  Global greenhouse gas emission scenarios, based on policies and pledges as of November 2021 Climate change can be mitigated by reducing the rate at which greenhouse gases are emitted into the atmosphere, and by increasing the rate at which carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere.[271] In order to limit global warming to less than 1.5 °C global greenhouse gas emissions needs to be net-zero by 2050, or by 2070 with a 2 °C target.[89] This requires far-reaching, systemic changes on an unprecedented scale in energy, land, cities, transport, buildings, and industry.[272] The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that countries need to triple their pledges under the Paris Agreement within the next decade to limit global warming to 2 °C. An even greater level of reduction is required to meet the 1.5 °C goal.[273] With pledges made under the Paris Agreement as of October 2021, global warming would still have a 66% chance of reaching about 2.7 °C (range: 2.2–3.2 °C) by the end of the century.[22] Globally, limiting warming to 2 °C may result in higher economic benefits than economic costs.[274] Although there is no single pathway to limit global warming to 1.5 or 2 °C,[275] most scenarios and strategies see a major increase in the use of renewable energy in combination with increased energy efficiency measures to generate the needed greenhouse gas reductions.[276] To reduce pressures on ecosystems and enhance their carbon sequestration capabilities, changes would also be necessary in agriculture and forestry,[277] such as preventing deforestation and restoring natural ecosystems by reforestation.[278] Other approaches to mitigating climate change have a higher level of risk. Scenarios that limit global warming to 1.5 °C typically project the large-scale use of carbon dioxide removal methods over the 21st century.[279] There are concerns, though, about over-reliance on these technologies, and environmental impacts.[280] Solar radiation modification (SRM) is also a possible supplement to deep reductions in emissions. However, SRM raises significant ethical and legal concerns, and the risks are imperfectly understood.[281] Clean energy Main articles: Sustainable energy and Sustainable transport  Coal, oil, and natural gas remain the primary global energy sources even as renewables have begun rapidly increasing.[282]  Wind and solar power, Germany Renewable energy is key to limiting climate change.[283] For decades, fossil fuels have accounted for roughly 80% of the world's energy use.[284] The remaining share has been split between nuclear power and renewables (including hydropower, bioenergy, wind and solar power and geothermal energy).[285] Fossil fuel use is expected to peak in absolute terms prior to 2030 and then to decline, with coal use experiencing the sharpest reductions.[286] Renewables represented 75% of all new electricity generation installed in 2019, nearly all solar and wind.[287] Other forms of clean energy, such as nuclear and hydropower, currently have a larger share of the energy supply. However, their future growth forecasts appear limited in comparison.[288] While solar panels and onshore wind are now among the cheapest forms of adding new power generation capacity in many locations,[289] green energy policies are needed to achieve a rapid transition from fossil fuels to renewables.[290] To achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, renewable energy would become the dominant form of electricity generation, rising to 85% or more by 2050 in some scenarios. Investment in coal would be eliminated and coal use nearly phased out by 2050.[291][292] Electricity generated from renewable sources would also need to become the main energy source for heating and transport.[293] Transport can switch away from internal combustion engine vehicles and towards electric vehicles, public transit, and active transport (cycling and walking).[294][295] For shipping and flying, low-carbon fuels would reduce emissions.[294] Heating could be increasingly decarbonised with technologies like heat pumps.[296] There are obstacles to the continued rapid growth of clean energy, including renewables. For wind and solar, there are environmental and land use concerns for new projects.[297] Wind and solar also produce energy intermittently and with seasonal variability. Traditionally, hydro dams with reservoirs and conventional power plants have been used when variable energy production is low. Going forward, battery storage can be expanded, energy demand and supply can be matched, and long-distance transmission can smooth variability of renewable outputs.[283] Bioenergy is often not carbon-neutral and may have negative consequences for food security.[298] The growth of nuclear power is constrained by controversy around radioactive waste, nuclear weapon proliferation, and accidents.[299][300] Hydropower growth is limited by the fact that the best sites have been developed, and new projects are confronting increased social and environmental concerns.[301] Low-carbon energy improves human health by minimising climate change as well as reducing air pollution deaths,[302] which were estimated at 7 million annually in 2016.[303] Meeting the Paris Agreement goals that limit warming to a 2 °C increase could save about a million of those lives per year by 2050, whereas limiting global warming to 1.5 °C could save millions and simultaneously increase energy security and reduce poverty.[304] Improving air quality also has economic benefits which may be larger than mitigation costs.[305] Energy conservation Main articles: Efficient energy use and Energy conservation Reducing energy demand is another major aspect of reducing emissions.[306] If less energy is needed, there is more flexibility for clean energy development. It also makes it easier to manage the electricity grid, and minimises carbon-intensive infrastructure development.[307] Major increases in energy efficiency investment will be required to achieve climate goals, comparable to the level of investment in renewable energy.[308] Several COVID-19 related changes in energy use patterns, energy efficiency investments, and funding have made forecasts for this decade more difficult and uncertain.[309] Strategies to reduce energy demand vary by sector. In the transport sector, passengers and freight can switch to more efficient travel modes, such as buses and trains, or use electric vehicles.[310] Industrial strategies to reduce energy demand include improving heating systems and motors, designing less energy-intensive products, and increasing product lifetimes.[311] In the building sector the focus is on better design of new buildings, and higher levels of energy efficiency in retrofitting.[312] The use of technologies like heat pumps can also increase building energy efficiency.[313] Agriculture and industry See also: Sustainable agriculture and Green industrial policy  Taking into account direct and indirect emissions, industry is the sector with the highest share of global emissions. Data as of 2019 from the IPCC. Agriculture and forestry face a triple challenge of limiting greenhouse gas emissions, preventing the further conversion of forests to agricultural land, and meeting increases in world food demand.[314] A set of actions could reduce agriculture and forestry-based emissions by two thirds from 2010 levels. These include reducing growth in demand for food and other agricultural products, increasing land productivity, protecting and restoring forests, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural production.[315] On the demand side, a key component of reducing emissions is shifting people towards plant-based diets.[316] Eliminating the production of livestock for meat and dairy would eliminate about 3/4ths of all emissions from agriculture and other land use.[317] Livestock also occupy 37% of ice-free land area on Earth and consume feed from the 12% of land area used for crops, driving deforestation and land degradation.[318] Steel and cement production are responsible for about 13% of industrial CO2 emissions. In these industries, carbon-intensive materials such as coke and lime play an integral role in the production, so that reducing CO2 emissions requires research into alternative chemistries.[319] Carbon sequestration Main articles: Carbon dioxide removal and Carbon sequestration  Most CO2 emissions have been absorbed by carbon sinks, including plant growth, soil uptake, and ocean uptake (2020 Global Carbon Budget). Natural carbon sinks can be enhanced to sequester significantly larger amounts of CO2 beyond naturally occurring levels.[320] Reforestation and afforestation (planting forests where there were none before) are among the most mature sequestration techniques, although the latter raises food security concerns.[321] Farmers can promote sequestration of carbon in soils through practices such as use of winter cover crops, reducing the intensity and frequency of tillage, and using compost and manure as soil amendments.[322] Forest and landscape restoration yields many benefits for the climate, including greenhouse gas emissions sequestration and reduction.[123] Restoration/recreation of coastal wetlands, prairie plots and seagrass meadows increases the uptake of carbon into organic matter.[323][324] When carbon is sequestered in soils and in organic matter such as trees, there is a risk of the carbon being re-released into the atmosphere later through changes in land use, fire, or other changes in ecosystems.[325] Where energy production or CO2-intensive heavy industries continue to produce waste CO2, the gas can be captured and stored instead of released to the atmosphere. Although its current use is limited in scale and expensive,[326] carbon capture and storage (CCS) may be able to play a significant role in limiting CO2 emissions by mid-century.[327] This technique, in combination with bioenergy (BECCS) can result in net negative emissions as CO2 is drawn from the atmosphere.[328] It remains highly uncertain whether carbon dioxide removal techniques will be able to play a large role in limiting warming to 1.5 °C. Policy decisions that rely on carbon dioxide removal increase the risk of global warming rising beyond international goals.[329] |

排出量の削減と回収 主な記事 気候変動の緩和  2021年11月時点の政策と誓約に基づく世界の温室効果ガス排出シナリオ 気候変動は、温室効果ガスが大気中に排出される割合を削減し、二酸化炭素が大気中から除去される割合を増加させることによって緩和することができる [271]。地球温暖化を1.5℃未満に抑えるためには、2050年までに世界の温室効果ガス排出量を正味ゼロにする必要があり、2℃の目標であれば 2070年までにゼロにする必要がある[89]。このためには、エネルギー、土地、都市、交通、建物、産業において、前例のない規模で広範囲に及ぶ体系的 な変化が必要である[272]。 国連環境計画は、地球温暖化を2℃に抑えるためには、今後10年 以内にパリ協定の下での誓約を3倍にする必要があると見積もって いる。1.5℃の目標を達成するためには、さらに大きなレベルの削減が必要である[273]。2021年10月時点のパリ協定の下での誓約では、今世紀末 までに地球温暖化が約2.7℃(範囲:2.2~3.2℃)に達する可能性は依然として66%である[22]。世界的に、温暖化を2℃に抑えることは、経済 コストよりも高い経済的利益をもたらす可能性がある[274]。 地球温暖化を1.5℃または2℃に抑制するための単一の道筋は存在しないが[275]、ほとんどのシナリオや戦略では、必要な温室効果ガスの削減を生み出 すために、エネルギー効率向上策と組み合わせて再生可能エネルギーの利用を大幅に増加させることが考えられている[276]。 生態系への圧力を低減し、炭素隔離能力を強化するためには、森林伐採の防止や再植林による自然生態系の回復など、農業や林業[277]における変化も必要 であろう[278]。 気候変動を緩和するための他のアプローチには、より高いレ ベルのリスクがある。地球温暖化を1.5℃に抑えるシナリオでは、一般的に、21 世紀にわたって二酸化炭素除去方法を大規模に利用することが予測されている[279]。しかし、こうした技術への過度の依存や環境への影響には懸念がある [280]。 太陽放射修正(SRM)も、排出量を大幅に削減するための補完手段となりうる。しかし、SRMは倫理的・法的な重大な問題を提起しており、そのリスクは不 完全に理解されている[281]。 クリーンエネルギー 主な記事 持続可能なエネルギーと持続可能な輸送  石炭、石油、天然ガスは、再生可能エネルギーが急速に増加し始めているにもかかわらず、依然として世界の主要なエネルギー源である[282]。  ドイツの風力発電と太陽光発電 再生可能エネルギーは、気候変動を抑制する鍵である[283]。 数十年間、化石燃料は世界のエネルギー使用のおよそ80%を占めてきた[284]。 [285]化石燃料の使用は、絶対量では2030年以前にピークに達し、その後減少に転じ、石炭の使用が最も急激に減少すると予想されている[286]。 再生可能エネルギーは、2019年に設置されたすべての新規発電の75%を占め、ほぼすべてが太陽光と風力であった[287]。しかし、それらに比べて将 来の成長予測は限られているように見える[288]。 ソーラーパネルと陸上風力は、現在、多くの場所で新しい発電容量を追加する最も安価な形態の一つであるが[289]、化石燃料から再生可能エネルギーへの 急速な移行を達成するためには、グリーンエネルギー政策が必要である[290]。2050年までにカーボンニュートラルを達成するためには、再生可能エネ ルギーが発電の主要な形態となり、いくつかのシナリオでは2050年までに85%以上に上昇する。石炭への投資は排除され、石炭の使用は2050年までに ほぼ段階的に廃止されるだろう[291][292]。 再生可能な資源から発電された電力も、暖房や輸送のための主要なエネルギー源になる必要がある[293]。 輸送は、内燃機関自動車から、電気自動車、公共交通機関、アクティブトランスポート(自転車や徒歩)へと転換することができる[294][295]。海運 や飛行機については、低炭素燃料が排出量を削減する[294]。 自然エネルギーを含むクリーンエネルギーの継続的な急成長には障害がある。風力発電や太陽光発電の場合、新規のプロジェクトには環境面や土地利用面での懸 念がある[297]。従来は、変動するエネルギー生産量が少ない場合に、貯水池を持つ水力ダムや従来型の発電所が利用されてきた。バイオエネルギーはカー ボンニュートラルでないことが多く、食料安全保障に悪影響を及ぼす可能性がある[298]。原子力発電の成長は、放射性廃棄物、核兵器の拡散、事故をめぐ る論争によって制約を受けている[299][300]。水力発電の成長は、最良の立地が開発されてしまったという事実によって制限されており、新しいプロ ジェクトは社会的・環境的懸念の高まりに直面している[301]。 低炭素エネルギーは、気候変動を最小化するだけでなく、2016年に年間700万人と推定された大気汚染による死亡者[302]を削減することによって、 人間の健康を改善する[303]。温暖化を2℃の上昇に抑えるというパリ協定の目標を達成すれば、2050年までに年間約100万人の命を救うことができ るが、温暖化を1.5℃に抑えれば、数百万人を救うことができると同時に、エネルギー安全保障を向上させ、貧困を削減することができる[304]。 省エネルギー 主な記事 効率的なエネルギー利用と省エネルギー エネルギー需要の削減は、排出量削減のもう一つの主要な側面である[306]。必要なエネルギーが少なければ、クリーンエネルギー開発のための柔軟性が増 す。また、送電網の管理が容易になり、炭素集約的なインフラ整備を最小限に抑えることができる[307]。気候変動目標を達成するためには、再生可能エネ ルギーへの投資水準に匹敵する、エネルギー効率投資の大幅な増加が必要となる[308]。エネルギー使用パターン、エネルギー効率投資、資金調達における COVID-19に関連するいくつかの変化が、この10年間の予測をより困難で不確実なものにしている[309]。 エネルギー需要を削減するための戦略は、部門によって異なる。運輸部門では、旅客と貨物は、バスや列車などのより効率的な移動手段に切り替えたり、電気自 動車を利用したりすることができる[310]。エネルギー需要を削減する産業戦略には、暖房システムやモーターの改善、エネルギー集約度の低い製品の設 計、製品寿命の延長などが含まれる[311]。建築部門では、新築建物のより良い設計と、改修におけるより高いレベルのエネルギー効率に重点が置かれてい る[312]。 農業と工業 以下も参照: 持続可能な農業とグリーン産業政策  直接排出と間接排出を考慮すると、産業は世界の排出量に占める割合が最も高い部門である。IPCCによる2019年時点のデータ。 農業と林業は、温室効果ガスの排出を抑制し、森林のさらなる農地への転換を防ぎ、世界の食糧需要の増加に対応するという3つの課題に直面している [314]。これらには、食料およびその他の農産物の需要増加の削減、土地生産性の向上、森林の保護と回復、農業生産からの温室効果ガス排出量の削減が含 まれる[315]。 需要側では、排出量削減の重要な要素は、人々を植物ベースの食生活に移行させることである[316]。食肉と酪農のための家畜の生産をなくせば、農業とそ の他の土地利用からの排出量の約3/4をなくすことができる[317]。家畜はまた、地球上の不凍土地の37%を占め、作物に使用される土地の12%から 飼料を消費し、森林破壊と土地の劣化を促進している[318]。 鉄鋼とセメント生産は、産業界からのCO2排出量の約13%を占めている。これらの産業では、コークスや石灰のような炭素を大量に消費する材料が生産に不可欠な役割を果たしているため、CO2排出量の削減には代替化学物質の研究が必要である[319]。 炭素隔離 主な記事 二酸化炭素除去、炭素隔離  排出されたCO2のほとんどは、植物の成長、土壌への吸収、海洋への吸収などの炭素吸収源によって吸収されてきた(2020年世界炭素収支)。 自然の炭素吸収源を強化することで、自然に存在するレベルを大幅に超える量のCO2を隔離することができる[320]。森林再生と植林(以前は何もなかっ た場所に森林を植えること)は、最も成熟した隔離技術の一つであるが、後者は食糧安全保障上の懸念を引き起こす[321]。農家は、冬期被覆作物の使用、 耕起の強度と頻度の低減、土壌改良としての堆肥や肥料の使用などの実践を通じて、土壌への炭素の隔離を促進することができる。 [森林や景観の復元は、温室効果ガス排出の隔離や削減など、気候に対して多くの利益をもたらす[123]。沿岸湿地帯、大草原、海草草原の復元・再生は、 炭素の有機物への取り込みを増加させる[323][324]。炭素が土壌や樹木などの有機物に隔離された場合、土地利用の変化、火災、生態系のその他の変 化によって、後に炭素が大気中に再放出されるリスクがある[325]。 エネルギー生産やCO2を多量に消費する重工業が、廃棄物であるCO2を排出し続ける場合、そのガスは大気中に放出されるのではなく、回収・貯蔵すること ができる。この技術は、バイオエネルギー(BECCS)と組み合わせることで、CO2が大気から取り出されるため、正味でマイナスの排出量になる可能性が ある[327]。二酸化炭素除去に依存する政策決定は、地球温暖化が国際目標を超えて上昇するリスクを増大させる[329]。 |

| Adaptation Main article: Climate change adaptation Adaptation is "the process of adjustment to current or expected changes in climate and its effects".[330]: 5 Without additional mitigation, adaptation cannot avert the risk of "severe, widespread and irreversible" impacts.[331] More severe climate change requires more transformative adaptation, which can be prohibitively expensive.[332] The capacity and potential for humans to adapt is unevenly distributed across different regions and populations, and developing countries generally have less.[333] The first two decades of the 21st century saw an increase in adaptive capacity in most low- and middle-income countries with improved access to basic sanitation and electricity, but progress is slow. Many countries have implemented adaptation policies. However, there is a considerable gap between necessary and available finance.[334] Adaptation to sea level rise consists of avoiding at-risk areas, learning to live with increased flooding, and building flood controls. If that fails, managed retreat may be needed.[335] There are economic barriers for tackling dangerous heat impact. Avoiding strenuous work or having air conditioning is not possible for everybody.[336] In agriculture, adaptation options include a switch to more sustainable diets, diversification, erosion control, and genetic improvements for increased tolerance to a changing climate.[337] Insurance allows for risk-sharing, but is often difficult to get for people on lower incomes.[338] Education, migration and early warning systems can reduce climate vulnerability.[339] Planting mangroves or encouraging other coastal vegetation can buffer storms.[340][341] Ecosystems adapt to climate change, a process that can be supported by human intervention. By increasing connectivity between ecosystems, species can migrate to more favourable climate conditions. Species can also be introduced to areas acquiring a favorable climate. Protection and restoration of natural and semi-natural areas helps build resilience, making it easier for ecosystems to adapt. Many of the actions that promote adaptation in ecosystems, also help humans adapt via ecosystem-based adaptation. For instance, restoration of natural fire regimes makes catastrophic fires less likely, and reduces human exposure. Giving rivers more space allows for more water storage in the natural system, reducing flood risk. Restored forest acts as a carbon sink, but planting trees in unsuitable regions can exacerbate climate impacts.[342] There are synergies but also trade-offs between adaptation and mitigation.[343] An example for synergy is increased food productivity, which has large benefits for both adaptation and mitigation.[344] An example of a trade-off is that increased use of air conditioning allows people to better cope with heat, but increases energy demand. Another trade-off example is that more compact urban development may reduce emissions from transport and construction, but may also increase the urban heat island effect, exposing people to heat-related health risks.[345] |

適応/ 適用 主な記事 気候変動への適応 適応とは、「気候およびその影響における現在または予想される変化に適応するプロセス」である[330]: 5 さらに緩和策を講じなければ、適応によって「深刻で広範かつ不可逆的」な影響のリスクを回避することはできない[331]。気候変動がより深刻になればな るほど、より変革的な適応が必要となるが、これには法外な費用がかかる可能性がある[332]。 人間の適応能力と潜在能力は、地域や人口によって不均等に分布しており、開発途上国は一般に低い[333]。多くの国が適応政策を実施している。しかし、 必要な資金と利用可能な資金との間にはかなりのギャップがある[334]。 海面上昇への適応は、リスクのある地域を回避し、増加する洪水と共存することを学び、洪水調節施設を建設することから成る。それに失敗した場合、管理され た退去が必要になる可能性がある[335]。危険な暑さの影響に取り組むためには、経済的な障壁がある。農業では、より持続可能な食生活への転換、多角 化、侵食防 止、気候変動への耐性を高めるための遺伝的改良などが適応のオプ ションとして挙げられる[337]。 生態系は気候変動に適応するが、このプロセスは人間の介 入によって支援することができる。生態系間の連結性を高めることで、種はより好ましい気候条件へと移動することができる。また、好ましい気候を獲得した地 域に種を導入することもできる。自然地域や半自然地域の保護と修復は、生態系が適応しやすくなるよう、回復力を高めるのに役立つ。生態系における適応を促 進する行動の多くは、生態系に基づく適応を通じて人間の適応にも役立つ。例えば、自然の火災体制を回復させることで、壊滅的な火災が発生しにくくなり、人 間が火災にさらされる可能性が低くなる。河川にゆとりを持たせることで、自然系により多くの水を蓄えることができ、洪水リスクを軽減することができる。復 元された森林は炭素吸収源として機能するが、適さない地 域に植林すると気候への影響を悪化させる可能性がある[342]。 適応と緩和の間には相乗効果もあるが、トレードオフもある[343] 。相乗効果の例としては、食料生産性の向上が挙げられ、これは適応と緩和の双方に大きな便益をもたらす[344] 。トレードオフの例としては、エアコンの使用が増えることで、人々は暑さによりよく対処できるようになるが、エネルギー需要は増加する。もう一つのトレー ドオフの例として、よりコンパクトな都市 開発は、輸送や建設による排出を削減するかもしれないが、 都市のヒートアイランド効果を増大させ、人々を暑さに関連する 健康リスクにさらすかもしれない[345]。 |