時計仕掛けのオレンジ

A Clockwork Orange

☆ 時計じかけのオレンジ』は、アンソニー・バージェスの1962年の同名小説を基に、スタンリー・キューブリックが脚色・製作・監督した1971年のディス トピア犯罪映画。ディストピア的な近未来のイギリスを舞台に、精神医学、少年非行、青少年ギャング、その他の社会的、政治的、経済的テーマについて、不穏 で暴力的な映像を用いて論評している。中心人物のアレックス(マルコム・マクダウェル)はカリスマ的な[5]反社会的不良で、その趣味はクラシック音楽 (特にベートーヴェン)、強姦、窃盗、 「超暴力」。彼は、ピート(マイケル・ターン)、ジョージー(ジェームズ・マーカス)、ディム(ウォーレン・クラーク)という小さなチンピラ集団を率いて おり、彼らをドロッグス(ロシア語のдруг、「友達」「相棒」から)と呼んでいる。この映画は、内務大臣(アンソニー・シャープ)が推進する実験的な心 理条件付け技術("ルドヴィコ・テクニック")によって、一味のおぞましい犯罪の数々、彼の逮捕、そして更生の試みを描いている。アレックスは映画の大半 を、スラブ語(特にロシア語)、英語、コックニーの韻を踏んだスラングで構成された、分裂した思春期のスラングであるナッドサットでナレーションしてい る。

| A Clockwork Orange

is a 1971 dystopian crime film adapted, produced, and directed by

Stanley Kubrick, based on Anthony Burgess's 1962 novel of the same

name. It employs disturbing, violent images to comment on psychiatry,

juvenile delinquency, youth gangs, and other social, political, and

economic subjects in a dystopian near-future Britain. Alex (Malcolm McDowell), the central character, is a charismatic,[5] anti-social delinquent whose interests include classical music (especially Beethoven), committing rape, theft, and "ultra-violence". He leads a small gang of thugs, Pete (Michael Tarn), Georgie (James Marcus), and Dim (Warren Clarke), whom he calls his droogs (from the Russian word друг, which is "friend", "buddy"). The film chronicles the horrific crime spree of his gang, his capture, and attempted rehabilitation via an experimental psychological conditioning technique (the "Ludovico Technique") promoted by the Minister of the Interior (Anthony Sharp). Alex narrates most of the film in Nadsat, a fractured adolescent slang composed of Slavic languages (especially Russian), English, and Cockney rhyming slang. The film premiered in New York City on 19 December 1971 and was released in the United Kingdom on 13 January 1972. The film was met with polarised reviews from critics and was controversial due to its depictions of graphic violence. After it was cited as having inspired copycat acts of violence, the film was withdrawn from British cinemas at Kubrick's behest, and it was also banned in several other countries. In the years following, the film underwent a critical re-evaluation and gained a cult following. It received several awards and nominations, including four nominations at the 44th Academy Awards, including Best Picture. In the British Film Institute's 2012 Sight & Sound polls of the world's greatest films, A Clockwork Orange was ranked 75th in the directors' poll and 235th in the critics' poll. In 2020, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". |

時計じかけのオレンジ』は、アンソニー・バージェスの1962年の同名

小説を基に、スタンリー・キューブリックが脚色・製作・監督した1971年のディストピア犯罪映画。ディストピア的な近未来のイギリスを舞台に、精神医

学、少年非行、青少年ギャング、その他の社会的、政治的、経済的テーマについて、不穏で暴力的な映像を用いて論評している。 中心人物のアレックス(マルコム・マクダウェル)はカリスマ的な[5]反社会的不良で、その趣味はクラシック音楽(特にベートーヴェン)、強姦、窃盗、 「超暴力」。彼は、ピート(マイケル・ターン)、ジョージー(ジェームズ・マーカス)、ディム(ウォーレン・クラーク)という小さなチンピラ集団を率いて おり、彼らをドロッグス(ロシア語のдруг、「友達」「相棒」から)と呼んでいる。この映画は、内務大臣(アンソニー・シャープ)が推進する実験的な心 理条件付け技術("ルドヴィコ・テクニック")によって、一味のおぞましい犯罪の数々、彼の逮捕、そして更生の試みを描いている。アレックスは映画の大半 を、スラブ語(特にロシア語)、英語、コックニーの韻を踏んだスラングで構成された、分裂した思春期のスラングであるナッドサットでナレーションしてい る。 この映画は1971年12月19日にニューヨークでプレミア上映され、1972年1月13日にイギリスで公開された。批評家からは賛否両論の評価を受け、 生々しい暴力描写が物議を醸した。模倣的な暴力行為を誘発したとの指摘を受け、キューブリックの意向でイギリスの映画館から撤去され、他の数カ国でも上映 禁止となった。その後、この映画は再評価され、カルト的な人気を得た。第44回アカデミー賞では作品賞を含む4部門にノミネートされた。 英国映画協会(British Film Institute)が2012年に実施した世界の名作映画投票「Sight & Sound」では、『時計じかけのオレンジ』は監督投票で75位、批評家投票で235位にランクされた。2020年、この作品は「文化的、歴史的、美学的 に重要である」として、米国議会図書館により米国国立フィルム登録簿に保存されることが決まった。 |

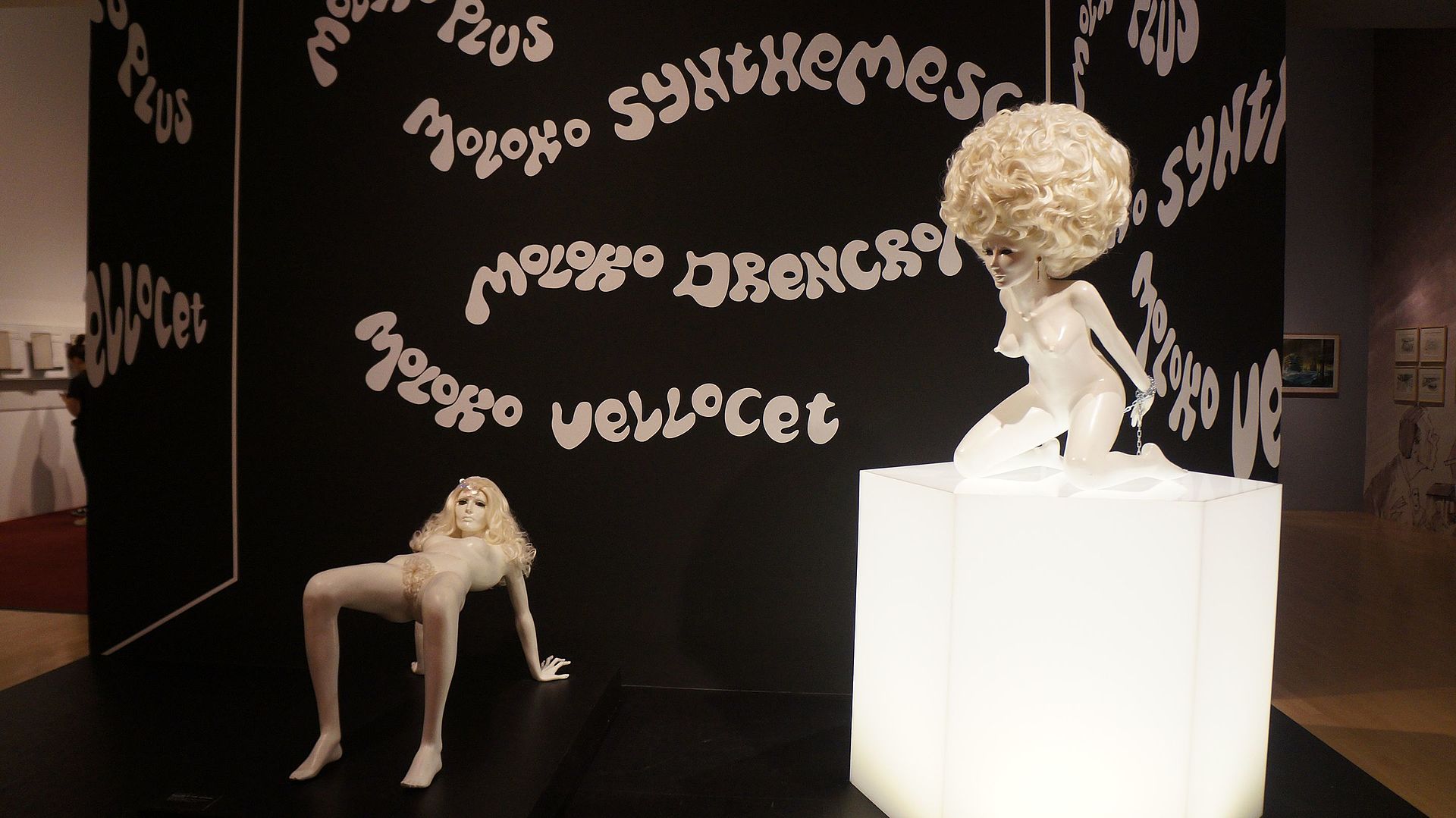

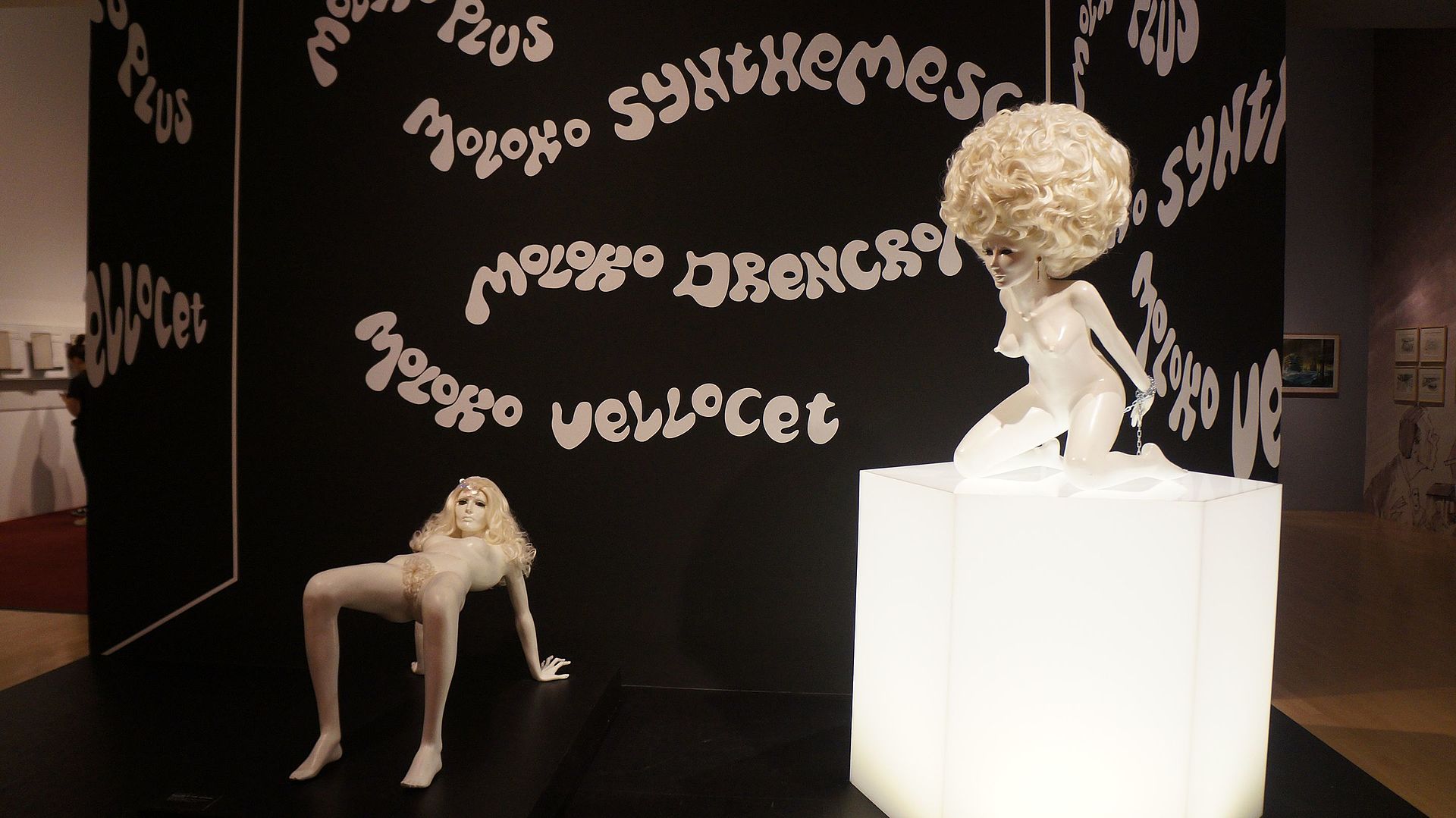

Plot Human furniture from the Korova milk bar, where the "milk-plus" was served In a futuristic Britain, Alex DeLarge is the leader of a gang of "droogs": Georgie, Dim and Pete. One night, after getting intoxicated, they engage in an evening of "ultra-violence", which includes a fight with a rival gang. They drive to the country home of writer Frank Alexander and trick his wife into letting them inside. They beat Alexander to the point of crippling him, and Alex violently rapes Alexander's wife while singing "Singin' in the Rain". The next day, while truant from school, Alex is approached by his probation officer, PR Deltoid, who is aware of Alex's activities and cautions him. Alex's droogs express discontent with petty crime and want more equality and high-yield thefts, but Alex asserts his authority by attacking them. Later, Alex invades the home of a wealthy "cat-lady" and bludgeons her with a phallic sculpture while his droogs remain outside. On hearing sirens, Alex tries to flee, but Dim smashes a bottle in his face, stunning Alex and leaving him to be arrested. Deltoid brings word that the woman has died of her injuries, and Alex is convicted of murder and sentenced to 14 years in prison. Two years into the sentence, Alex eagerly takes up an offer to be a test subject for the Minister of the Interior's new Ludovico technique, an experimental aversion therapy for rehabilitating criminals within two weeks. Alex is strapped to a chair, his eyes are clamped open, and he is injected with drugs. He is then forced to watch films of sex and violence, some of which are accompanied by the music of his favourite composer, Ludwig van Beethoven. Alex becomes nauseated by the films and, fearing the technique will make him sick upon hearing Beethoven, begs for an end to the treatment. Two weeks later, the Minister demonstrates Alex's rehabilitation to a gathering of officials. Alex is unable to fight back against an actor who taunts and attacks him and becomes ill upon seeing a topless woman. The prison chaplain complains that Alex has been robbed of his free will; the Minister asserts that the Ludovico technique will cut crime and alleviate crowding in prisons. Alex is released from prison, only to find that the police have sold his possessions to provide compensation to his victims and his parents have let out his room. Alex encounters an elderly vagrant whom he attacked years earlier, and the vagrant and his friends attack him. Alex is saved by two policemen but is shocked to find they are his former droogs Dim and Georgie. They drive him to the countryside, beat him, and nearly drown him before abandoning him. Alex barely makes it to the doorstep of a nearby home before collapsing. Alex wakes up to find himself in the home of Mr Alexander, who is now using a wheelchair. Alexander does not recognise Alex from the previous attack, but knows of him and the Ludovico technique from the newspapers. He sees Alex as a political weapon and prepares to present him to his colleagues. While bathing, Alex breaks into "Singin' in the Rain", causing Alexander to realise that Alex was the person who assaulted his wife and him. With help from his colleagues, Alexander drugs Alex and locks him in an upstairs bedroom. He then plays Beethoven's Ninth Symphony loudly from the floor below. Unable to withstand the sickening pain, Alex attempts suicide by jumping out of the window. Alex survives the attempt and wakes up in hospital with multiple injuries. While being given a series of psychological tests, he finds that he no longer has aversions to violence and sex. The Minister arrives and apologises to Alex. He informs Alex that the government has had Mr Alexander institutionalised. He offers to take care of Alex and get him a job in return for his co-operation with his election campaign and public relations counter-offensive. As a sign of goodwill, the Minister brings in a stereo system playing Beethoven's Ninth. Alex then contemplates violence and has vivid thoughts of having sex with a woman in front of an approving crowd, thinking to himself, "I was cured, all right!" |

プロット 「ミルク・プラス」が提供されていたコロヴァのミルク・バーの人間家具 近未来のイギリスで、アレックス・デラージは "ドロッグ "ギャングのリーダーだった: ジョージー、ディム、ピート。ある夜、酒に酔った彼らは、敵対するギャングとの戦いを含む "超暴力 "の夜を繰り広げる。彼らは作家フランク・アレクサンダーの田舎の家に車を走らせ、彼の妻を騙して中に入れてもらう。彼らはアレクサンダーを動けなくなる ほど殴り、アレックスは「雨に唄えば」を歌いながらアレクサンダーの妻を激しくレイプする。翌日、学校を無断欠席していたアレックスは、保護観察官のPR デルトイドに声をかけられる。彼はアレックスの行動を知っており、彼を注意する。 アレックスの部下たちは軽犯罪に不満を示し、もっと平等で高利回りの窃盗を望むが、アレックスは彼らを攻撃することで自分の権威を主張する。その後、ア レックスは裕福な "猫女 "の家に侵入し、男根の彫刻で彼女を殴打する。サイレンを聞いたアレックスは逃げようとするが、ディムが彼の顔に瓶をぶつけ、アレックスは気絶し、逮捕さ れる。デルトイドは、女性が負傷して死亡したとの知らせをもたらし、アレックスは殺人罪で有罪判決を受け、懲役14年を言い渡される。 刑期が始まって2年後、アレックスは内務大臣の新しいルドヴィコ・テクニック(2週間以内に犯罪者を更生させる実験的嫌悪療法)の被験者となるオファーを 熱心に受ける。アレックスは椅子に縛り付けられ、目を開かされ、薬を注射される。その後、セックスと暴力の映画を強制的に見せられ、その中には彼の好きな 作曲家ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンの音楽が流れるものもある。アレックスは映画で吐き気を催し、ベートーベンを聴くと気分が悪くなることを恐 れ、この治療をやめてほしいと懇願する。 2週間後、大臣はアレックスのリハビリを関係者の前で披露する。アレックスは、自分を嘲弄し攻撃してくる俳優に対して反撃することができず、トップレスの 女性を見て病気になる。刑務所の牧師は、アレックスは自由意志を奪われたと訴える。大臣は、ルドヴィコのテクニックは犯罪を減らし、刑務所の混雑を緩和す ると主張する。 アレックスは出所するが、警察が被害者への補償のために彼の所持品を売り払い、両親が彼の部屋を解放していることに気づく。アレックスは、数年前に自分が 襲った年老いた浮浪者に出会い、その浮浪者と仲間に襲われる。アレックスは2人の警官に助けられるが、彼らがかつての部下ディムとジョージーであることに ショックを受ける。彼らはアレックスを田舎に追いやり、殴りつけ、溺れさせそうになったところで彼を捨てた。アレックスは倒れる前に、かろうじて近くの家 の玄関先までたどり着く。 アレックスが目を覚ますと、そこは車椅子に乗ったアレクサンダー氏の家だった。アレクサンダーは前回の襲撃でアレックスに見覚えがなかったが、新聞で彼と ルドヴィコ・テクニックを知っていた。彼はアレックスを政治的な武器と見なし、同僚に紹介する準備をする。入浴中、アレックスが『雨に唄えば』を歌い出 し、アレクサンダーはアレックスが妻と自分を襲った犯人だと気づく。アレクサンダーは同僚の助けを借りてアレックスに薬を飲ませ、2階の寝室に閉じ込め る。そして、下の階からベートーベンの交響曲第九番を大音量で流す。気持ちの悪い痛みに耐えられなくなったアレックスは、窓から飛び降りて自殺を図る。 一命を取り留めたアレックスは、病院で目を覚ます。一連の心理テストを受けるうちに、暴力やセックスに対する嫌悪感がなくなっていることに気づく。大臣が 到着し、アレックスに謝罪する。彼はアレックスに、政府がアレクサンダー氏を施設に収容したことを告げる。大臣は、選挙キャンペーンと広報活動への協力の 見返りとして、アレックスの面倒を見、仕事を紹介すると申し出る。大臣は好意のしるしとして、ベートーヴェンの第九を流すステレオシステムを持ち込む。そ してアレックスは暴力を考え、群衆の前で女性とセックスすることを思い浮かべる。 |

| Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge Patrick Magee as Frank Alexander Michael Bates as Chief Guard Barnes Warren Clarke as Dim John Clive as stage actor Adrienne Corri as Mary Alexander Carl Duering as Dr Brodsky Paul Farrell as tramp Clive Francis as Joe the Lodger Michael Gover as prison governor Miriam Karlin as "Catlady" Weathers James Marcus as Georgie Aubrey Morris as P. R. Deltoid Godfrey Quigley as prison chaplain Sheila Raynor as mum Madge Ryan as Dr Branom John Savident as conspirator Dolin Anthony Sharp as Frederick, Minister of the Interior Philip Stone as dad Pauline Taylor as Dr Taylor Margaret Tyzack as conspirator Rubinstein Michael Tarn as Pete The film provided early roles for Steven Berkoff, David Prowse, and Carol Drinkwater, who appeared as a police officer, Mr Alexander's attendant Julian, and a nurse, respectively.[6] |

Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge |

| Themes Morality The film's central moral question is the definition of "goodness" and whether it makes sense to use aversion therapy to stop immoral behaviour.[7] Stanley Kubrick, writing in Saturday Review, described the film: "A social satire dealing with the question of whether behavioural psychology and psychological conditioning are dangerous new weapons for a totalitarian government to use to impose vast controls on its citizens and turn them into little more than robots."[8] Similarly, on the production's call sheet, Kubrick wrote: "It is a story of the dubious redemption of a teenage delinquent by condition-reflex therapy. It is, at the same time, a running lecture on free-will." After aversion therapy, Alex behaves like a good member of society, though not through choice. His goodness is involuntary; he has become the titular clockwork orange—organic on the outside, mechanical on the inside. After Alex has undergone the Ludovico technique, the chaplain criticises his new attitude as false, arguing that true goodness must come from within. This leads to the theme of abusing liberties—personal, governmental, civil—by Alex, with two conflicting political forces, the Government and the Dissidents, both manipulating Alex purely for their own political ends.[9] The story portrays the "conservative" and "leftist" parties as equally worthy of criticism. The writer Frank Alexander, a victim of Alex and his gang, wants revenge against Alex and sees him as a means of definitively turning the populace against the incumbent government and its new regime. He fears the new government and, in a telephone conversation, he says: "Recruiting brutal young roughs into the police; proposing debilitating and will-sapping techniques of conditioning. Oh, we've seen it all before in other countries; the thin end of the wedge! Before we know where we are, we shall have the full apparatus of totalitarianism." On the other side, the Minister of the Interior (the Government) jails Mr Alexander (the Dissident Intellectual) on the excuse of his endangering Alex (the People), rather than the government's totalitarian regime (described by Mr Alexander). It is unclear whether he has been harmed; however, the Minister tells Alex that the writer has been denied the ability to write and produce "subversive" material that is critical of the incumbent government and meant to provoke political unrest. Psychology  Ludovico technique apparatus The film critiques the behaviourism or "behavioural psychology" propounded by psychologists John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner. Burgess disapproved of behaviourism, calling Skinner's book Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971) "one of the most dangerous books ever written". Although behaviourism's limitations were conceded by its principal founder, Watson, Skinner argued that behaviour modification—specifically, operant conditioning (learned behaviours via systematic reward-and-punishment techniques) rather than the "classical" Watsonian conditioning—is the key to an ideal society. The film's Ludovico technique is widely perceived as a parody of aversion therapy, which is a form of operant conditioning.[10] Author Paul Duncan said: "Alex is the narrator so we see everything from his point of view, including his mental images. The implication is that all of the images, both real and imagined, are part of Alex's fantasies."[11] Psychiatrist Aaron Stern, the former head of the MPAA rating board, believed that Alex represents man in his natural state, the unconscious mind. Alex becomes "civilised" after receiving his Ludovico "cure" and the sickness in the aftermath Stern considered to be the "neurosis imposed by society".[12] Kubrick told film critics Philip Strick and Penelope Houston: "Alex makes no attempt to deceive himself or the audience as to his total corruption or wickedness. He is the very personification of evil. On the other hand, he has winning qualities: his total candour, his wit, his intelligence, and his energy; these are attractive qualities and ones, I might add, which he shares with Richard III."[13] Society The society depicted in the film was perceived by some as Communist (as Michel Ciment pointed out in an interview with Kubrick) due to its slight ties to Russian culture. The teenage slang has a heavily Russian influence, as in the novel; Burgess explains the slang as being, in part, intended to draw a reader into the world of the book's characters and to prevent the book from becoming outdated. There is some evidence to suggest that the society is a socialist one, or perhaps a society evolving from a failed socialism into an authoritarian society. In the novel, streets have paintings of working men in the style of Russian socialist art, and the film shows a mural of socialist artwork with obscenities drawn on it. As Malcolm McDowell points out on the DVD commentary, Alex's residence was shot on failed municipal architecture and the name "Municipal Flat Block 18A, Linear North" alludes to socialist-style housing.[14][15] When the new right-wing government takes power, the atmosphere is certainly more authoritarian than the anarchist air of the beginning. Kubrick's response to Ciment's question remained ambiguous as to what kind of society it is. Kubrick asserted that the film held comparisons between both ends of the political spectrum and that there is little difference between the two. Kubrick stated: "The Minister, played by Anthony Sharp, is clearly a figure of the Right. The writer, Patrick Magee, is a lunatic of the Left... They differ only in their dogma. Their means and ends are hardly distinguishable."[14] |

テーマ 道徳 この映画の中心的な道徳的問題は、"善 "の定義と、不道徳な行動をやめさせるために嫌悪療法を用いることに意味があるかどうかである[7]: 「行動心理学と心理的条件付けは、全体主義政府が市民に膨大な統制を課し、彼らをロボットに変えるために使う危険な新兵器なのかという疑問を扱った社会風 刺である」[8]。同様に、キューブリックはこの作品のコールシートにこう書いている。これは同時に、自由意志についての連続講義でもある」。 嫌悪セラピーの後、アレックスは善良な社会人のように振舞う。彼の善良さは不随意的なものであり、彼は時計仕掛けのオレンジになったのである。アレックス がルドヴィコ・テクニックを受けた後、牧師は彼の新しい態度を偽りだと批判し、真の善良さは内面から生まれるものだと主張する。これは、アレックスによる 個人的、政府的、市民的な自由の濫用というテーマにつながり、政府と反体制派という対立する2つの政治勢力が、純粋に自らの政治的目的のためにアレックス を操っている。アレックスとその一味の犠牲者である作家のフランク・アレクサンダーは、アレックスへの復讐を望んでおり、アレックスを現政権とその新政権 に対して民衆を決定的に敵対させる手段と見なしている。彼は新政権を恐れており、電話での会話の中でこう語っている。「残忍な若い荒くれ者を警察に採用 し、衰弱させ、意志を奪うような条件付けのテクニックを提案する。ああ、私たちは他の国でも見たことがある!どこにいるかわからないうちに、全体主義の完 全な装置を手に入れることになる」。 他方で、内務大臣(政府)は、アレクサンダー氏(反体制知識人)を、政府の全体主義体制(アレクサンダー氏の説明)ではなく、アレックス(国民)を危険に さらしたという口実で投獄する。アレグザンダー氏に危害が加えられたかどうかは不明だが、大臣はアレグザンダー氏に対し、現政権に批判的で政治不安を誘発 するような「破壊的」資料を執筆・制作する能力を否定されたと告げる。 心理学  ルドヴィコのテクニック この映画は、心理学者のジョン・B・ワトソンとB・F・スキナーが提唱した行動主義、あるいは「行動心理学」を批判している。バージェスは行動主義を否定 し、スキナーの著書『自由と尊厳を越えて』(1971年)を「これまで書かれた中で最も危険な本のひとつ」と呼んだ。行動主義の限界はその主要な創始者で あるワトソンも認めていたが、スキナーは行動修正、具体的にはワトソン的な「古典的」条件付けではなくオペラント条件付け(体系的な報酬と罰の技法による 学習行動)こそが理想社会への鍵であると主張した。この映画のルドヴィコのテクニックは、オペラント条件づけの一種である嫌悪療法のパロディとして広く受 け止められている[10]。 作者のポール・ダンカンは言う: 「アレックスは語り手なので、私たちは彼の心象風景を含め、すべてを彼の視点から見ている。その意味するところは、現実のイメージも想像上のイメージも、 すべてアレックスの空想の一部であるということだ」[11]。 MPAAレーティング委員会の元委員長である精神科医アーロン・スターンは、アレックスは人間の自然な状態、無意識の心を表していると考えていた。アレッ クスはルドヴィコの "治療 "を受けて "文明化 "し、その余波の病は「社会によって押し付けられた神経症」であるとスターンは考えた[12]。 キューブリックは映画評論家のフィリップ・ストリックとペネロープ・ヒューストンにこう語っている: 「アレックスは、自分の完全な堕落や邪悪さについて、自分自身や観客を欺こうとはしない。彼はまさに悪の擬人化だ。その一方で、彼には魅力的な資質もあ る。率直さ、機知、知性、行動力。 社会 この映画で描かれる社会は、ロシア文化とのわずかな結びつきから(ミシェル・シメントがキューブリックとのインタビューで指摘したように)共産主義的と受 け止められることもあった。ティーンエイジャーのスラングは、小説と同様にロシア語の影響を色濃く受けている。バージェスはこのスラングについて、読者を この本の登場人物の世界に引き込み、この本が時代遅れになるのを防ぐ目的もあったと説明している。この社会が社会主義社会であること、あるいは失敗した社 会主義から権威主義社会へと進化している社会であることを示唆する証拠もある。小説では、ロシアの社会主義芸術のスタイルで描かれた働く男たちの絵が通り に描かれており、映画では、卑猥な言葉が描かれた社会主義芸術の壁画が映し出されている。DVDの解説でマルコム・マクダウェルが指摘しているように、ア レックスの住居は破綻した市営建築で撮影されており、「市営フラット・ブロック18A、リニア・ノース」という名前は社会主義スタイルの住宅を暗示してい る[14][15]。 右派の新政府が権力を握ると、冒頭のアナーキスト的な空気よりも権威主義的な雰囲気になるのは確かだ。シメントの質問に対するキューブリックの回答は、ど のような社会なのか曖昧なままだった。キューブリックは、この映画は政治的スペクトラムの両端を比較するものであり、両者の間にはほとんど違いはないと断 言した。キューブリックはこう述べている: 「アンソニー・シャープ演じる大臣は明らかに右派の人物だ。作家のパトリック・マギーは左翼の狂人だ。両者の違いは教義の違いだけだ。彼らの手段と目的は ほとんど区別できない」[14]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Clockwork_Orange_(film) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆