コード・ノワール

Code Noir; 黒人法, 1685-1789

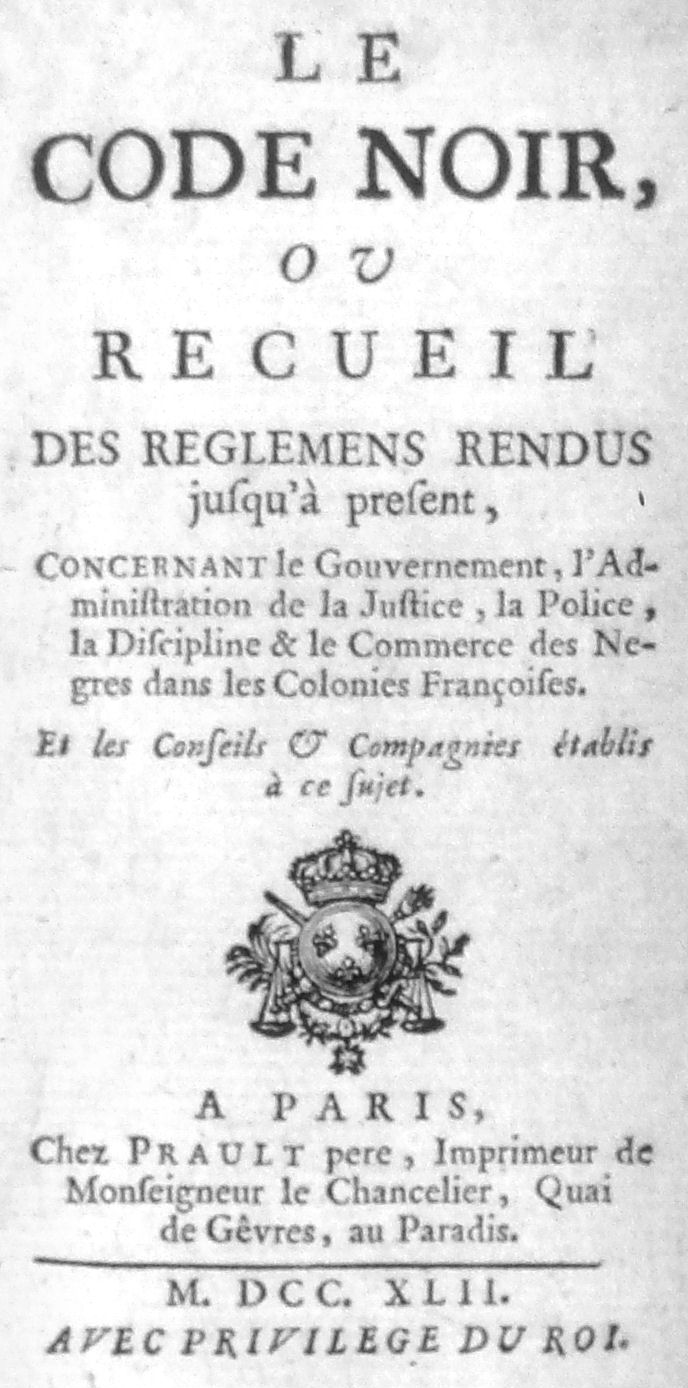

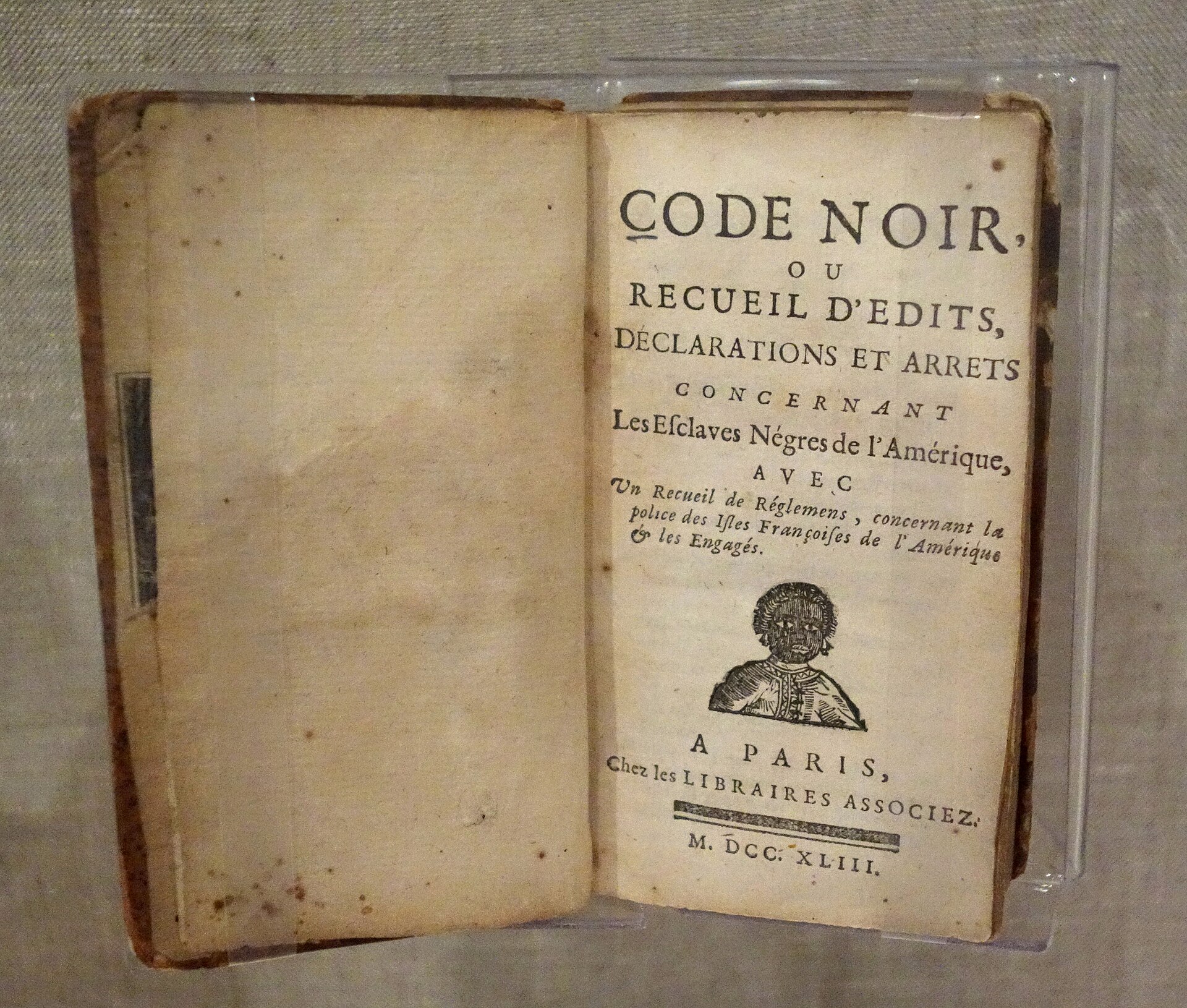

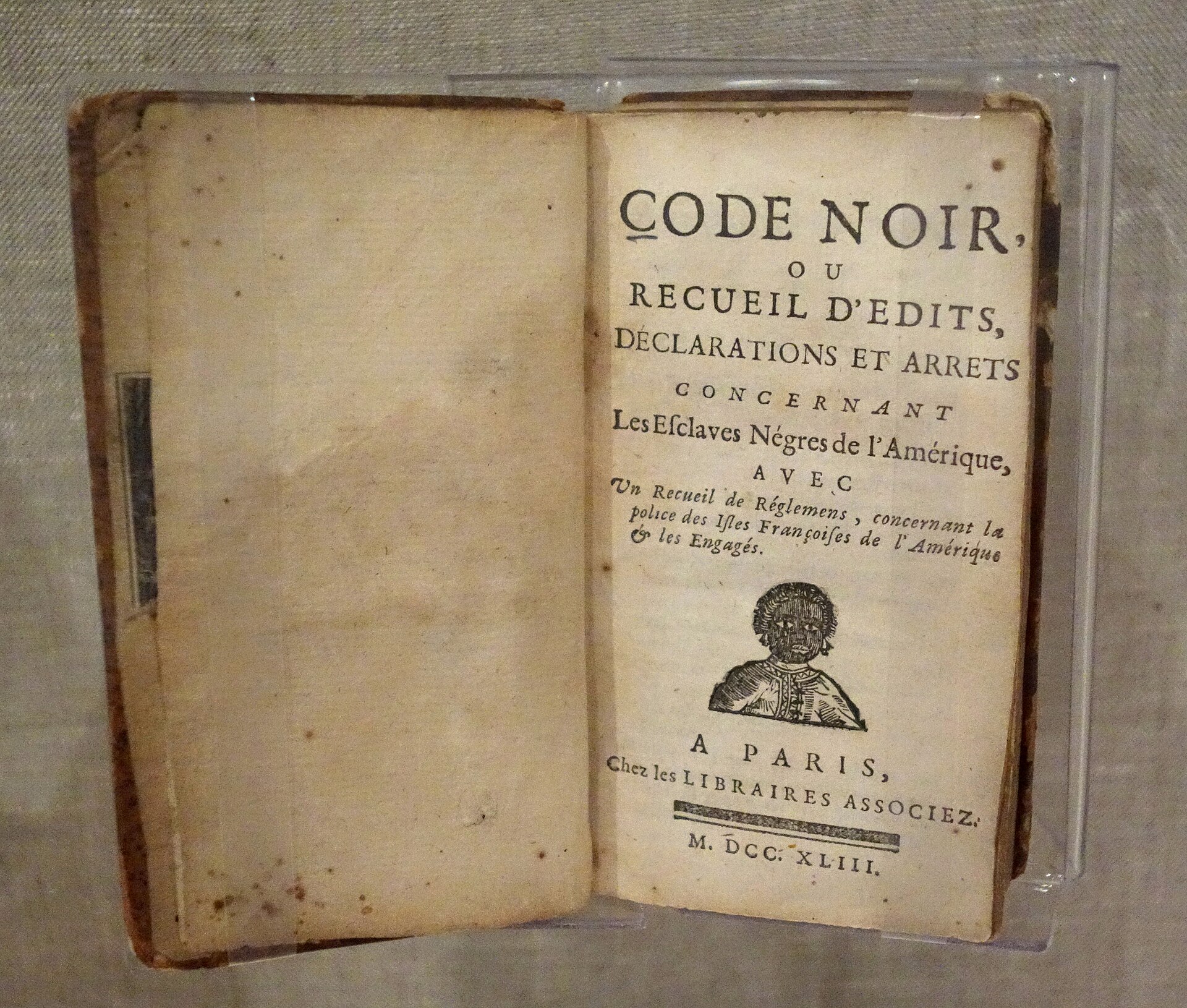

1742 edition; and A copy of the 1743 edition of Code noir, now in New Orleans (Historic New Orleans Collection)

☆ 黒人法(Code noir; フ ランス語発音:[kɔd nwaʁ]、Black code)は、1685年にフランス王ルイ14世が発布した勅令であり、フランス植民地帝国における奴隷制の条件を規定した。この勅令は、フランス革命の 始まりを告げる年となった1789年まで、フランス植民地における奴隷制の行動規範として機能した。この法令は自由な有色人種の活動を制限し、帝国内の全 ての奴隷に対してカトリックへの改宗を義務付け、彼らに科される処罰を定め、フランスの植民地から全てのユダヤ人の追放を命じた。 この法典がフランス植民地帝国の奴隷人口に与えた影響は複雑かつ多面的であった。この法典により、所有者が奴隷に与えることのできる最悪の処罰が禁止さ れ、自由民の人口が増加した。しかし、それでも奴隷は所有者の手による厳しい扱いを受けることには変わりなく、ユダヤ人の追放はフランス王国における反ユ ダヤ主義の傾向の延長であった。 自由な有色人種は、黒人法によって依然として制限を受けていたが、それ以外では自由に自分のキャリアを追求することができた。アメリカ大陸における他の ヨーロッパの植民地と比較すると、フランス植民地帝国における自由有色人種は、読み書きができる可能性が非常に高く、事業や不動産、さらには自分の奴隷を 所有する可能性も高かった。[1][2][3] この法典は、近代フランス史の専門家であるタイラー・ストヴァル氏によって、「人種、奴隷制、自由に関する最も広範な公式文書であり、ヨーロッパで作成さ れたものの中で最も広範な公式文書である」と評されている。[4]

| The Code noir

(French pronunciation: [kɔd nwaʁ], Black code) was a decree passed by

King Louis XIV of France in 1685 defining the conditions of slavery in

the French colonial empire and served as the code for slavery conduct

in the French colonies up until 1789 the year marking the beginning of

the French Revolution. The decree restricted the activities of free

people of color, mandated conversion to Catholicism for all enslaved

people throughout the empire, defined the punishments meted out to

them, and ordered the expulsion of all Jewish people from France's

colonies. The code's effects on the enslaved population of the French colonial empire were complex and multifaceted. It outlawed the worst punishments owners could inflict upon their slaves, and led to an increase in the free population. Despite this, enslaved persons were still subject to harsh treatment at the hands of their owners, and the expulsion of Jews was an extension of antisemitic trends in the Kingdom of France. Free people of color were still placed under restrictions via the Code noir, but were otherwise free to pursue their own careers. Compared to other European colonies in the Americas, a free person of color in the French colonial empire was highly likely to be literate, and had a high chance of owning businesses, properties and even their own slaves.[1][2][3] The code has been described by historian of modern France Tyler Stovall as "one of the most extensive official documents on race, slavery, and freedom ever drawn up in Europe".[4] |

黒人法(フランス語発音:[kɔd nwaʁ]、Black

code)は、1685年にフランス王ルイ14世が発布した勅令であり、フランス植民地帝国における奴隷制の条件を規定した。この勅令は、フランス革命の

始まりを告げる年となった1789年まで、フランス植民地における奴隷制の行動規範として機能した。この法令は自由な有色人種の活動を制限し、帝国内の全

ての奴隷に対してカトリックへの改宗を義務付け、彼らに科される処罰を定め、フランスの植民地から全てのユダヤ人の追放を命じた。 この法典がフランス植民地帝国の奴隷人口に与えた影響は複雑かつ多面的であった。この法典により、所有者が奴隷に与えることのできる最悪の処罰が禁止さ れ、自由民の人口が増加した。しかし、それでも奴隷は所有者の手による厳しい扱いを受けることには変わりなく、ユダヤ人の追放はフランス王国における反ユ ダヤ主義の傾向の延長であった。 自由な有色人種は、黒人法によって依然として制限を受けていたが、それ以外では自由に自分のキャリアを追求することができた。アメリカ大陸における他の ヨーロッパの植民地と比較すると、フランス植民地帝国における自由有色人種は、読み書きができる可能性が非常に高く、事業や不動産、さらには自分の奴隷を 所有する可能性も高かった。[1][2][3] この法典は、近代フランス史の専門家であるタイラー・ストヴァル氏によって、「人種、奴隷制、自由に関する最も広範な公式文書であり、ヨーロッパで作成さ れたものの中で最も広範な公式文書である」と評されている。[4] |

| Context, origin and scope International and trade context Codes governing slavery had already been established in many European colonies in the Americas, such as the 1661 Barbados Slave Code. At this time in the Caribbean, Jews were mostly active in the Dutch colonies, so their presence was seen as an unwelcome Dutch influence in French colonial life.[5] French Plantation owners largely governed their land and holdings in absentia, with subordinate workers dictating the day-to-day running of the plantations. Because of their enormous population, in addition to the harsh conditions facing slaves, small-scale slave revolts were common. Although the Code Noir contained a few, minor humanistic provisions, the Code noir was generally flaunted, in particular regarding protection for slaves and limitations on corporal punishment.[6] In his 1987 analysis of the Code noir's significance, French philosopher Louis Sala-Molins claimed that its two primary objectives were to assert French sovereignty in its colonies and to secure the future of the cane sugar plantation economy.[7] The Code Noir aimed to provide a legal framework for slavery, to establish protocols governing the conditions of the slaves in the French colonies, and appears to make an attempt at ending the illegal slave trade. Strict religious morals were also imposed in the crafting of the Code noir; in part a result of the influence of the influx of Catholic leaders arriving in the Antilles between 1673 and 1685. Legal context The title Code noir first appeared during the regency of Philippe II, Duke of Orleans, (1715–1723) under minister John Law, and referred to a compilation of two separate ordinances of Louis XIV from March and August 1685.[8] One of the two regulated black slaves in the French islands of the Americas, while the other established the Sovereign Council of Saint-Domingue. Subsequently, starting in 1723, two supplementary texts were added that instituted the code in the Mascarene Islands and Louisiana.[6] The earliest of these constituent ordinances was drafted by the Naval Minister (secrétaire d'État à la Marine) Marquis de Seignelay and promulgated in March 1685 by King Louis XIV with the title "Ordonnance ou édit de mars 1685 sur les esclaves des îles de l'Amérique". The only known manuscript of this law to have been preserved is currently in the Archives nationales d'outre-mer (French National Overseas Archives). The Marquis de Seignelay wrote the draft using legal briefs written by the first intendant of the French islands of the Americas, Jean-Baptiste Patoulet [fr], as well as those of his successor Michel Bégon. Legal historians have debated whether other sources, such as Roman slavery laws, were consulted in the drafting of this original text. Studies of correspondence from Patoulet suggest that the 1685 ordinance drew mostly on local regulations provided in the colonial intendant's memoranda.[6][8] The later two supplemental texts concerning the Mascarene Islands and Louisiana were drafted during Phillippe II's regency and ratified by King Louis XV (a minor of thirteen) in December 1723 and March 1724 respectively.[9] It was also during the Régence, that the first royal authorizations to practice the slave trade were given to shipowners in French ports.[10] From the 18th century onward, the term Code noir was used not only to describe edits and additions to the original code, but also came to refer broadly to compilations of laws and other legal documents applicable to the colonies. Over time, the foundational ordinances and their associated texts were amended to meet the evolving needs of each colony.[6] The New Orleans planters relaxed and adapted the slave regime towards the end of French administration.[11] |

背景、起源、範囲 国際および貿易の背景 1661年のバルバドス奴隷法など、多くのヨーロッパのアメリカ大陸植民地ではすでに奴隷制度を規定する法律が制定されていた。この当時、カリブ海ではユ ダヤ人が主にオランダの植民地で活動していたため、彼らの存在はフランス植民地生活に好ましくないオランダの影響をもたらすものと見なされていた。[5] フランスのプランテーションの所有者は、不在のまま主に自分たちの土地と所有地を管理し、下位の労働者がプランテーションの日常業務を指示していた。奴隷 が直面する過酷な状況に加え、人口が膨大であったため、小規模な奴隷の反乱が頻繁に起こっていた。黒人法典には、いくつかの些細な人道的な規定が含まれて いたが、黒人法典は一般的に軽視され、特に奴隷の保護や体罰の制限に関して軽視されていた。[6] 1987年に黒人法典の意義を分析したフランスの哲学者ルイ・サラ=モランは、その主な目的は2つあり、植民地におけるフランスの主権を主張することと、サトウキビ農園経済の将来を確保することであると主張した。[7] 黒人法は、奴隷制の法的枠組みを提供し、フランス植民地における奴隷の条件を規定する手順を確立することを目的としており、また違法な奴隷貿易を終結させ ようとする試みも見られる。 また、黒人法の策定においては厳格な宗教的モラルも課せられたが、これは1673年から1685年の間にアンティル諸島に到着したカトリック指導者たちの 影響によるものである。 法的背景 「黒人法典」という名称は、オルレアン公フィリップ2世の摂政時代(1715年~1723年)に、ジョン・ローの大臣の下で初めて登場し、1685年3月 と8月のルイ14世による2つの別個の法令の集成を指していた。[8] 2つのうちの1つは、アメリカ大陸のフランス領の島々における黒人奴隷を規制するものであり、もう1つは、サン=ドマングの最高会議を設立するものであっ た。その後、1723年より、マスカリン諸島とルイジアナにおける法規を制定する2つの補足文書が追加された。 これらの構成条例の中で最も古いものは、海軍大臣(secrétaire d'État à la Marine)であったセニュレ侯爵(Marquis de Seignelay)によって起草され、1685年3月にルイ14世によって「1685年3月の奴隷に関する条例」というタイトルで公布された。この法律 の唯一の現存する写本は、現在、フランス国立海外公文書館(Archives nationales d'outre-mer)に保管されている。セニュレイ侯爵は、アメリカ大陸のフランス領の初代総督ジャン=バティスト・パトゥレ(Jean- Baptiste Patoulet)や、その後任のミシェル・ベゴン(Michel Bégon)が作成した法的要約を基に草案を書いた。法学者の間では、ローマの奴隷法など他の資料がこの原典の起草に参照されたかどうかについて議論され ている。パトゥレの書簡の研究によると、1685年の条例は主に植民地総督の覚書に記載された現地の規制を参考にしていることが示唆されている。 マスカリーン諸島とルイジアナに関する後の2つの補足条項は、フィリップ2世の摂政時代に起草され、それぞれ1723年12月と1724年3月にルイ15 世(13歳の未成年者)によって批准された。[9] また、摂政時代には、奴隷貿易を認める最初の王令がフランスの港の船主に対して出された。[10] 18世紀以降、コード・ノワールという用語は、元の法典に対する編集や追加を説明するだけでなく、広く植民地に適用される法律やその他の法的文書の集成を 指すようにもなった。時が経つにつれ、各植民地の進化するニーズに対応するために、基本条例とその関連文書は改正された。[6] ニューオーリンズのプランテーション主たちは、フランス統治の終わり頃には奴隷制度を緩和し、適応させていった。[11] |

Summary A copy of the 1743 edition of Code noir, now in New Orleans (Historic New Orleans Collection) In 60 articles,[12] the document specified the following: Legal status and incapacity of slaves In the Code noir, the slave ( of any race, color or gender) is considered property immune from seizure (article 44), yet also criminally liable (article 32). Article 48 stipulates that, in the case of a seizure of person (physical seizure), this is an exception to article 44.[12][8] Should the human nature of the slave confer certain rights, the slave was nevertheless denied a true civil personality before the reforms adopted under the July Monarchy. According to French colonial legal historian Frédéric Charlin, an individual's legal capacity was fully dissociable from her humanity under old French law.[13] Additionally, the legal status of slaves was further distinguished by the separation of field slaves (esclave de jardin), the main workforce, from domestic slaves "of culture" (esclave de culture).[14] Before the institution of the Code noir, slaves other than those "of culture" were considered fixtures (immeubles par destination). The new status was adopted with such great reluctance on the part of local jurisdictions that it was necessary for a ruling of the King's Council of 22 August 1687 to take a position on the capacity of slaves because of the rules of succession applicable to the new status.[13] Despite the 1804 creation of the Napoleonic Code and its partial promulgation in the Antilles, the re-institution of slavery in 1802 had led to the reinstatement of parts of Code noir which precluded Napoleonic rights.[13] In the 1830s, under the civil code of the July Monarchy, slaves were explicitly given a civil personality while also considered as being fixtures, that is, personal property legally attached to and/or part of real estate or businesses.[14] The status of the slave in Code noir is legally different from that of a serf primarily in that serfs could not be bought. According to anthropological historian Claude Massilloux, it is the mode of reproduction that distinguishes slavery from serfdom: while a serf cannot be purchased, they reproduce through demographic growth.[15] In Roman law (the Digest), a slave could be sold, given away, and legally passed to another owner as part of an estate or a legacy, but this could not be done with a serf. Contrary to serfdom, slaves were considered in Roman law to be objects of personal property that could be owned, usufruct, or used as a part of a pledge. In general, a slave could be said to have a much more restricted legal capacity than does a serf, simply due to the fact that serfs were considered right-holding individuals whereas slaves, although recognized as human beings, were not. Swiss Roman law scholar Pahud Samuel explains this paradoxical status as "the slave being a person in the natural sense and a thing in the civil law sense".[16] The Code noir provided that slaves might lodge complaints with local judges in the case of mistreatment or being under-provided with necessities (article 26), but also that their statements should be considered only as reliable as that of minors or domestic servants.[8] Religion The first article of the Code noir enjoins a Catholic expulsion of all Jews residing in the colonial territories due to their being "sworn enemies of the Christian faith" (ennemis déclarés du nom chrétien), within three months under penalty of the confiscation of person and property. The Antillean Jews targeted by the Code noir were mainly descendants of families of Portuguese and Spanish origin who had come from the Dutch colony of Pernambuco in Brazil.[17][5] The writers of the code believed that slaves of all races were human persons, endowed with a soul and receptive to salvation. The Code noir encouraged that slaves be baptized and educated in the Apostolic and Roman Catholic religion (article 2).[6][8] Slaves had the right to marry (articles 10 and 11), provided the master allowed them to do so, and had to be buried in consecrated ground if they were baptized (article 14). The code prohibited slaves from publicly practicing any religion other than the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman Catholic religion (article 3), including the practice of the Protestant faith (article 5) and particularly "pagan religions" practiced by indigenous Indians who were routinely forced into slavery in Mexico and the Americas. The code extends the punishment of pagan slave conventicles to masters who allowed pagan beliefs and practices performed by their slaves, thus encouraging quick indoctrination into Catholicism on threat of the outright punishment of lenient slave holders. Sexual relations, marriage, and progeny Weddings between slaves strictly required the master's permission (art. 10) but also required the slave's own consent (art. 11) Children born to married slaves were also slaves, belonging to the female slave's master (art. 12) Children of a male slave and a free woman were free; children of a female slave and a free man were slaves(art. 13; compare partus sequitur ventrem) Sexual relationships between a free man and a female slave were deemed adulterous. A free man fathering children with a slave, and the slave's master who had allowed it to happen, were fined 2000 pounds of sugar. If the slave's master was the father, the slave and her children were confiscated and couldn't be freed, unless the master agreed to marry the slave, making her and her children free (art.9) Maternal Impact Code Noir acknowledged the existence of slave families and marriages. The Code recognized slaves marriages provided they were contracted according to the Catholic rite and attempted to regulate family life among slaves. Mothers played a central role in maintaining family structures, and the Code addressed issues related to the separation of families through sales or other means. The status of a child's freedom was dependent on the mother's status at the time of birth. Article XIII cites that "...if a male slave has married a free woman, their children, either male or female, shall be free as is their mother, regardless of their father's condition of slavery. And if the father is free and the mother a slave, the children shall also be slaves". Article XII precises that "the children born in marriage to a male and a female slave will belong to the mother's master if they are owned by two different masters".[18] [19] This reliance upon the mother's status for the identification of the consequent child's status placed the majority of the slave-producing burden upon the enslaved women of the French colonies. Prohibitions This section relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this section by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: "Code Noir" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Slaves must not carry weapons except with the permission of their masters for hunting (art. 15) Slaves belonging to different masters must not gather at any time under any circumstance (art. 16) Slaves should not sell sugar cane, even with permission of their masters (art. 18) Slaves should not sell any other commodity without permission of their masters (art. 19–21) Masters must give food (quantities specified) and clothes to their slaves, even to those who were sick or old (art. 22–27) Slaves couldn't work, nor be sold, on Sunday or on catholic's holy days. The penalty was the confiscation of the slave and of the product of his work (art. 6) Slaves could testify in court but their testimony couldn't be considered a proof or be the basis for a ruling (art.30) A slave who struck his or her master, his wife, mistress or children would be executed (art. 33) A slave husband and wife and their prepubescent children under the same master were not to be sold separately (art. 47) Punishments Fugitive slaves absent for a month should have their ears cut off and be branded. For another month their hamstring would be cut and they would be branded again. A third time they would be executed (art. 38) Free blacks who harboured fugitive slaves would be beaten by the slave owner and fined 300 pounds of sugar per day of refuge given; other free people who harboured fugitive slaves would be fined 10 livres tournois per day (art. 39) If a master had falsely accused a slave of a crime and as a result, the slave had been put to death, the master would be fined (art. 40) Masters might chain and beat slaves but might not torture nor mutilate them (art. 42) Masters who killed their slaves would be punished (art. 43) Slaves were community property and could not be mortgaged, and must be equally split between the master's heirs, but could be used as payment in case of debt or bankruptcy, and otherwise sold (art. 44–46, 48–54) Freedom Slave masters 20 years of age (25 years without parental permission) could free their slaves (art. 55) Slaves who were declared to be sole legatees by their masters, or named as executors of their wills, or tutors of their children, should be considered as freed slaves (art. 56) Freed slaves had to show a special respect for their former master and were punished more severely for any offense against him. However, they were deemed free of any other obligation the former master could claim (art. 58) Freed slaves were French subjects, even if born elsewhere (art. 57) Freed slaves had the same rights as French colonial subjects (art. 58, 59) Fees and fines paid with regard to the Code noir must go to the royal administration, but one third would be assigned to the local hospital (art. 60) Délits and punishments The Code Noir permitted corporal punishment for slaves and provides for disfigurement by branding with an iron, as well as for the death penalty (articles 33-36 and 38). Runaway slaves who had disappeared for a month were to have their ears cut off and be branded with the fleur-de-lis. In the case of recidivism, the slave's hamstring would be cut. Should there be a third attempt, the slave would be put to death. It is important to note that these kinds of punishments (branding by iron, mutilation, etc.) also existed in metropolitan France's penological practice at the time.[20] Punishments were a matter of public or royal law, where the disciplinary power over slaves could be considered more severe than that for domestic servants yet less severe than that for soldiers. Masters could only chain and whip slaves "when they believe that their slaves deserved it" and cannot, at will, torture their slaves, or put them to death. The death penalty was reserved for those slaves who had struck their master, his wife, or his children (article 33) as well as for thieves of horses or cows (article 35) (larceny by domestic servants was also punishable by death in France).[21] The third attempt to escape (article 38) and the congregation of recidivist slaves belonging to different masters (article 16) were also offenses punishable by death. Although it was forbidden for the master to mistreat, injure, or kill his slaves, he nevertheless possessed disciplinary power (article 42) according to the Code. "Masters shall only, when they believe that their slaves so deserve, be able to chain them and have them beaten with rods or straps", similar to pupils, soldiers, or sailors. Article 43 addresses itself to judges: "to punish murder while taking into account the atrocity of the circumstances; in the case of absolution, our officers will…” The most serious punishments, such as the cutting of the ears or of the hamstring, branding, and death are prescribed by a criminal court in the case of conviction and imposed by a magistrate rather than by the slave's master. However, in reality, the conviction of masters for the murder or torture of slaves was very rare. Seizure and slaves as chattels With respect to the inheritance of property, estate, and seizures, slaves were considered to be personal property (article 44), that is, considered separate from the estate on which they live (which was not the case with serfs). Despite this, slaves could not be seized by a creditor as property independent of the estate, with the exception of compensating the seller of the slaves (article 47). According to the Code, slaves can be bought, sold, and given like any chattels. Slaves were provided no name or civil registration, rather, starting in 1839, they were given a serial number. Following the 1848 abolition of slavery under the French Second Republic, a name was assigned to each former slave.[22] Slaves could testify, have a proper burial (for those baptized), lodge complaint, and, with the master's permission, have savings, marry, etc. Nevertheless, their legal capacity was still more restrictive than that of minors or domestic servants (articles 30 and 31). Slaves had no right to personal possessions and could not bequeath anything to their families. Upon the death of the slave, all remained property of the master (article 28). Married slaves and their prepubescent children could not be separated through seizure or sale (article 47). Emancipation / manumission Slaves could be manumitted by their owner (article 55), in which case no naturalization records were required for French citizenship, even if the individual was born abroad (article 57). However, starting in the 18th century, manumission required authorization as well as the payment of an administrative tax. The tax was first instituted by local officials, but later affirmed by the edict of 24 October 1713 and the royal ordinance of 22 May 1775.[23] Manumission was considered de jure if a slave was designated the sole legatee of the master (article 56). |

概要 現在ニューオーリンズに所蔵されている1743年版の黒人法(Historic New Orleans Collection)の写本 60の条項[12]で、この文書は以下の内容を規定している。 奴隷の法的地位と無能力 黒人法では、奴隷(人種、肌の色、性別を問わず)は差し押さえが不可能な財産とみなされている(第44条)が、同時に刑事責任も問われる(第32条)。第 48条では、人身の差し押さえ(物理的な差し押さえ)の場合、これは第44条の例外であると規定している。[12][8] 奴隷の人としての本質が一定の権利を付与するとしても、7月王政下で採択された改革以前には、奴隷は真の市民的人格を否定されていた。フランス植民地法の 歴史家であるフレデリック・シャルランによると、旧フランス法の下では個人の法的資格は人間性とは完全に切り離されたものであるとされていた。[13] さらに、奴隷の法的地位は、主な労働力である畑の奴隷(esclave de jardin)と「教養のある」家事奴隷(esclave de culture)に区別されていた。[14] 黒人法が制定される前は、「教養のある」奴隷以外の奴隷は不動産(immeubles par destination)とみなされていた。この新しい身分は、地方当局の側から非常に強い抵抗を受けて採用されたため、この身分に適用される継承の規則 をめぐって、1687年8月22日の王の評議会が奴隷の地位について見解を示す必要があった。[13] 1804年にナポレオン法典が制定され、アンティル諸島でもその一部が公布されたにもかかわらず、 1802年の奴隷制復活により、ナポレオン法典の権利を排除する黒人法典の一部が復活した。[13] 1830年代、七月王政下の民法典では、奴隷は明確に市民権を与えられたが、同時に不動産や事業に法的に結び付けられた、つまり不動産や事業の所有物であ るとみなされた。[14] 黒人法における奴隷の地位は、農奴のそれとは主に、農奴は売買できないという点で法的に異なる。人類学者クロード・マシルーによると、奴隷制と農奴制を区 別するのは再生産の様式である。農奴は購入できないが、人口増加によって再生産される。ローマ法(法大全)では、奴隷は売却、贈与、あるいは遺産や財産の 一部として別の所有者に合法的に譲渡することができたが、農奴の場合はそうすることはできなかった。奴隷制とは対照的に、ローマ法では奴隷は所有、用益、 担保の一部として利用できる個人所有物とみなされていた。一般的に、奴隷は農奴よりもはるかに制限された法的資格しか持たなかったと言える。これは、農奴 は権利を有する個人とみなされていたのに対し、奴隷は人間として認められていたものの、そうではなかったという事実によるものである。スイスのローマ法学 者パ・サミュエルは、この逆説的な地位を「奴隷は自然法上は人であり、民法上は物である」と説明している。[16] 黒人法は、虐待や必需品の不足があった場合、奴隷は地元の裁判官に苦情を申し立てることができると規定していたが(第26条)、奴隷の証言は未成年者や使用人の証言と同程度の信頼性しか持たないとされていた。[8] 宗教 黒人法の第1条では、キリスト教の「公敵」であるとして、植民地に居住するすべてのユダヤ人のカトリック教への改宗を命じ、3か月以内に改宗しなければ、 本人および財産を没収すると定めている。黒人法の対象となったアンティル諸島のユダヤ人は、主にブラジルのオランダ植民地ペルナンブーコから来たポルトガ ル系およびスペイン系の家系の末裔であった。 この法典の起草者たちは、あらゆる人種の奴隷は人間であり、魂を持ち、救済を受け入れることができると考えていた。黒人奴隷法は、奴隷に洗礼を受けさせ、ローマ・カトリックの宗教教育を施すことを奨励していた(第2条)。[6][8] 奴隷は、主人から許可が下りれば結婚する権利があり(第10条および第11条)、洗礼を受けた場合は聖地に埋葬されなければならなかった(第14条)。 この法典は、カトリック、使徒、ローマ・カトリック以外の宗教を公に信仰することを奴隷に禁じていた(第3条)。これにはプロテスタントの信仰(第5条) の実践、および特に、メキシコやアメリカ大陸で日常的に奴隷にされていた先住アメリカ人が信仰していた「異教の宗教」が含まれていた。この法典は、異教徒 の奴隷が異教の信仰やそのパフォーマティビティを実践することを許した主人にも処罰を課すものであり、これにより、甘い処罰を下す主人に対して、迅速なカ トリックへの改宗を促すことができた。 性的関係、結婚、子孫 奴隷間の結婚は、厳密には主人の許可が必要であったが(第10条)、奴隷自身の同意も必要であった(第11条)。 結婚した奴隷の間に生まれた子供も奴隷であり、女性奴隷の主人に属する(第12条) 男性奴隷と自由の身の女性の間に生まれた子供は自由人であり、女性奴隷と自由の身の男性の間に生まれた子供は奴隷である(第13条;比較:partus sequitur ventrem) 自由人と女性奴隷の性的関係は不倫と見なされた。自由人が奴隷との間に子供をもうけた場合、およびそれを許した奴隷の主人には砂糖2000ポンドの罰金が 科せられた。奴隷の主人が父親であった場合、奴隷とその子供は没収され、奴隷の主人が奴隷と結婚し、奴隷とその子供を自由の身にすることを承諾しない限 り、解放されることはなかった(第9条) 母系への影響 奴隷法典は奴隷の家族や結婚の存在を認めていた。この法典は、カトリックの儀式に従って結ばれた結婚を認め、奴隷の家族生活を規制しようとした。母親は家 族構造を維持する上で中心的な役割を果たし、この法典は売却やその他の手段による家族の離散に関する問題を取り扱っている。子供の自由の地位は、出生時の 母親の地位に依存していた。第13条には、「...もし男性奴隷が自由の身の女性と結婚した場合、彼らの子供たちは、父親が奴隷であるかどうかに関わら ず、母親と同じように自由の身となる。また、父親が自由の身で母親が奴隷である場合、子供たちも奴隷となる」と記載されている。第12条では、「男女の奴 隷の婚姻により生まれた子供は、両親が異なる主人に所有されている場合、母親の主人に帰属する」と明確に規定されている。[18][19] 結果として生じる子供の身分を特定するにあたり、母親の身分に依存するというこの規定により、奴隷生産の負担の大部分がフランス植民地の奴隷女性に課せら れることとなった。 禁止事項 この節は一次資料への言及に過度に依存している。 二次資料または三次資料を追加して、この節を改善してください。 出典を見つける:「黒人法典」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学者 · JSTOR (2022年11月) (このメッセージをいつどのように削除するかについて学ぶ) 奴隷は、狩猟のための主人からの許可がある場合を除き、武器を携帯してはならない(第15条) 異なる主人に属する奴隷は、いかなる状況下でも集まってはならない(第16条) 奴隷は、主人の許可があっても、サトウキビを売ってはならない(第18条) 奴隷は、主人の許可なしに他の商品を売ってはならない(第19~21条) 主人は、病気や高齢の奴隷に対しても、定められた量の食料と衣服を与えなければならない(第22条~第27条) 奴隷は、日曜日やカトリックの祝祭日には労働することも、売却されることもできなかった。罰則は奴隷と奴隷の労働の成果の没収であった(第6条) 奴隷は法廷で証言することはできるが、その証言は証拠とは見なされず、判決の根拠ともなりえない(第30条) 主人、その妻、愛人、またはその子供を殴った奴隷は死刑となる(第33条) 同じ主人に仕える奴隷夫婦とその未成年の子供たちは、別々に売買されてはならない(第47条) 処罰 逃亡した奴隷が1か月間見つからなかった場合、その奴隷の耳を切り落とし、焼き印を押す。さらに1か月間見つからなかった場合、その奴隷のハムストリングを切り落とし、再度焼き印を押す。3度目に逃亡した場合は死刑とする(第38条) 逃亡奴隷をかくまった自由黒人は、逃亡奴隷をかくまった日数につき、奴隷所有者に殴打され、砂糖300ポンドの罰金を科せられる。逃亡奴隷をかくまったその他の自由人は、1日につき10リーヴル・トゥルノワの罰金を科せられる(第39条) 主人がある奴隷を犯罪者として虚偽の告発をし、その結果、その奴隷が死刑に処せられた場合、主人は罰金を科せられる(第40条) 主人は奴隷を鎖でつなぎ、鞭打つことはできるが、拷問や身体切断は禁じられていた(第42条) 奴隷を殺した主人は処罰される(第43条) 奴隷は共同所有財産であり、抵当に入れることはできず、主人の相続人たちで均等に分割しなければならなかったが、債務や破産の場合にはその支払いに充てることができ、それ以外の場合には売却することができた(第44条~第46条、第48条~第54条) 自由 奴隷 主人が20歳に達した場合(親の許可なしに25歳に達した場合)、奴隷を解放することができる(第55条) 主人から唯一の遺言執行者と指定されたり、遺言執行者に指名されたり、子供の家庭教師に指名されたりした奴隷は、解放された奴隷とみなされるべきである(第56条) 解放された奴隷は、以前の主人に対して特別な敬意を示さなければならず、主人に対する違反行為に対してはより厳しく処罰された。しかし、彼らは元の主人が主張できるその他の義務からは解放されているとみなされた(第58条) 解放された奴隷は、たとえ他の場所で生まれたとしても、フランス国民である(第57条) 解放された奴隷は、フランス植民地の国民と同じ権利を有した(第58条、第59条) 黒人法に関連して支払われる料金や罰金は王政行政に支払われなければならないが、その3分の1は地元の病院に割り当てられる(第60条) 犯罪と刑罰 黒人法典は奴隷に対する体罰を認め、鉄による焼き印による外観の損傷、および死刑を規定していた(第33条から第36条、および第38条)。 1か月間行方がわからなくなった逃亡奴隷は、耳を切り落とされ、百合の紋章の焼き印を押された。 犯罪を繰り返す場合は、奴隷のハムストリングを切断した。3度目の犯罪を犯した場合は、奴隷は死刑となる。 ここで注目すべきは、こうした処罰(鉄による焼きごての烙印、身体の一部の切断など)は、当時、フランス本土の刑罰の慣行にも存在していたということであ る。[20] 刑罰は公法または王法の問題であり、奴隷に対する懲戒権は、使用人に対するものよりも厳しく、兵士に対するものよりも緩やかであった。主人は「奴隷がそれ に値すると信じる場合」にのみ、奴隷を鎖でつなぎ鞭打つことができ、また、自分の意思で奴隷を拷問したり、死刑にしたりすることはできなかった。 死刑は、主人、その妻、またはその子供を殴った奴隷(第33条)や、馬や牛を盗んだ者(第35条)(フランスでは、使用人の窃盗も死刑に値した)に科せら れた。[21] 3度目の逃亡未遂(第38条)や、異なる主人に属する常習犯の奴隷の結託(第16条)も、死刑に値する犯罪であった。 主人は奴隷を虐待したり、傷つけたり、殺したりすることは禁じられていたが、それでもなお、法典によれば、主人には懲戒権(第42条)が与えられていた。 「主人は、奴隷がそれに値すると信じる場合にのみ、奴隷を鎖でつなぎ、鞭や革紐で打つことができる」とあり、これは生徒、兵士、船員の場合と同様であっ た。 第43条は裁判官に向けられたものであり、 「状況の残虐性を考慮した上で殺人を処罰する。無罪となった場合は、当職らが...」 最も重い処罰、例えば耳や腓腹筋の切断、焼き印、死刑などは、有罪判決が下された場合、刑事裁判所によって規定され、奴隷の主人ではなく、判事によって科 される。しかし、実際には、奴隷の殺人や拷問に対する主人の有罪判決は非常にまれであった。 奴隷の差し押さえと動産 財産、遺産、差し押さえに関する相続について、奴隷は動産(第44条)とみなされ、つまり、奴隷が生活する遺産とは別個のものと考えられていた(農奴の場 合はそうではなかった)。にもかかわらず、奴隷は債権者によって遺産とは別個の財産として差し押さえられることはなく、奴隷の売り手に補償金を支払う場合 を除いては(第47条)。 奴隷法によると、奴隷は他の動産と同様に売買や贈与が可能であった。奴隷には名前も市民登録も与えられず、1839年から通し番号が付けられるようになっ た。1848年のフランス第二共和制下での奴隷制度廃止後、元奴隷にはそれぞれ名前が割り当てられた。[22] 奴隷は証言することができ、洗礼を受けた者には適切な埋葬が与えられ、苦情を申し立てることができ、また、主人の許可があれば貯蓄をしたり結婚したりする こともできた。しかし、彼らの法的権利は未成年者や使用人よりもさらに制限されていた(第30条および第31条)。奴隷には個人所有財産の権利はなく、家 族に遺産を残すこともできなかった。奴隷が死亡した場合、その所有権はすべて主人に残った(第28条)。 結婚した奴隷とその未成年の子供は、差し押さえや売却によって引き離されることはなかった(第47条)。 解放 / 解放奴隷 奴隷は所有者の手によって解放されることができた(第55条)。その場合、たとえその個人が外国で生まれたとしても、フランス国籍取得のための帰化記録は 必要なかった(第57条)。しかし、18世紀に入ると、解放には当局の許可と行政税の支払いが義務付けられた。この税は当初は地方当局によって課されてい たが、その後1713年10月24日の勅令および1775年5月22日の王令によって確認された。[23] 奴隷が主人の唯一の遺産相続人に指定された場合、解放は法的に有効とみなされた(第56条)。 |

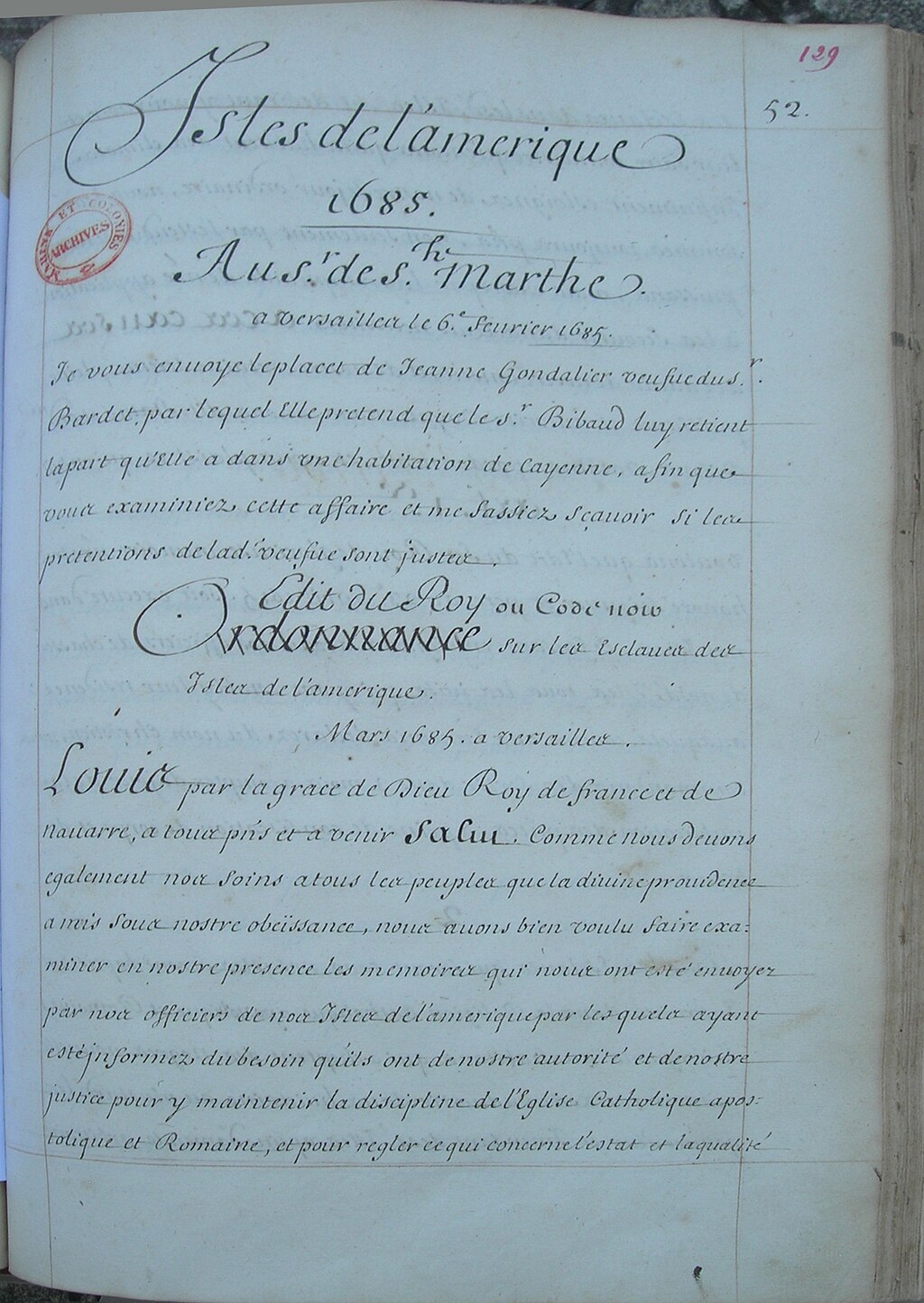

Adoptive territories Manuscript of the Royal Ordinance, Edict of the King or Code Noir of March 1685 Pertaining to the Slaves in the Isles of French America Based on the fundamental law that any man who sets foot on French soil is free, various parliaments refused to pass the original Ordonnance ou édit de mars 1685 sur les esclaves des îles de l'Amérique which was ultimately instituted only in the colonies for which the edict was written: the Sovereign Council of Martinique on 6 August 1685, Guadeloupe on 10 December of the same year, and in Petit-Goâve before the Council of the French colony of Saint-Domingue on 6 May 1687.[24] Finally, the Code was passed before the councils of Cayenne and Guiana on 5 May 1704.[24] While the Code Noir was also applied in the colony of Saint Christopher, the date of its institution is unknown. The edicts of December 1723 and March 1724 were instituted in the islands of Réunion (Île Bourbon) and Mauritius (Île de France) as well as in the colony and province of Louisiana, in 1724.[25] The Code Noir was not originally intended for northern New France (present day Canada) which followed the general principle of French law that Indigenous peoples of lands conquered or surrendered to the Crown should be considered free royal subjects (régnicoles) upon their baptism. Various local indigenous customs were collected to create the Custom of Paris. However, on 13 April 1709, an ordinance created by Acadian colonial intendant Jacques Raudot imposed regulations on slavery thereby recognizing, de facto, its existence in the territory. The ordinance elaborated little on the legal status of slaves, but generally characterized slavery as "a kind of convention" that is "very useful for this colony", proclaiming that "all Panis (native slaves and indigenous members of First Nation/Pawnee) and Negroes who have been purchased or who will be purchased at some time, will belong to those who have purchased them as their full property and be known as their slaves".[26][27][28] After the Revolution The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 articulated the principle of equal rights from birth for all, but under the lobbying influence of the Massiac Club of plantation and slave owners, the National Constituent Assembly and the Legislative Assembly decided that this equality applied only to the inhabitants of metropolitan France, where there were no slaves and where serfdom had been abolished for centuries. The American territories were excluded. After Saint-Domingue (present day Haiti) abolished slavery locally in 1793, the French National Convention did the same on 4 February 1794, for all French colonies. This would only be effective, however, in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Guiana, because Martinique was, at this time, a British colony and Mascarene colonists forcibly opposed the institution of the 1794 decree when it finally arrived to the isle in 1796. Napoleon Bonaparte reinstated slavery on 20 May 1802 in Martinique and the Mascarenes, as the islands had been returned by the British after the Treaty of Amiens. Soon after, he reestablished slavery in Guadeloupe (on 16 July 1802) and Guiana (in December 1802). Slavery was not reestablished in Saint-Domingue due to the resistance of the Haitians against the expeditionary corps sent by Bonaparte, a resistance which eventually resulted in the independence of the colony and the formation of the Republic of Haiti on 1 January 1804. The Code Noir coexisted for forty-three years with the Napoleonic code despite the contradictory nature of the two texts, but this arrangement became increasingly difficult due to the French Court of Cassation rulings on local jurisdictions' decisions following the 1827 and 1828 ordinances on civil procedures. According to historian Frédéric Charlin, in metropolitan France, "the two decades of the July Monarchy were characterized by a political trend to endow the slave with a certain level of humanity… [and to] encourage a slow assimilation of the slave into other workforces of French society through moral and family values".[29] The jurisprudence of the Court of Cassation under the July Monarchy was marked by a gradual recognition of a legal personhood for slaves. Accordingly, the 1820s saw a general abolitionist trend, but one that was mainly preoccupied with a gradual emancipation that paralleled improved conditions for slaves.[29] The revolution of February 1848 and the creation of the Second Republic brought prominent abolitionists such as Cremieux, Lamartine, and Ledru-Rollin to power. One of the first acts of the Provisional Government of 1848 was to establish a commission to "prepare for the act of emancipation of slaves of the colonies of the Republic". The commission was completed and presented to the government in less than two months and subsequently instituted on 27 April 1848. The enslavement of black people in French colonies was definitively abolished on 4 March and 27 April 1848. Due in large part to the actions of Victor Schoelcher,[30][unreliable source?] the slave trade had already been abolished in 1815, following the Congress of Vienna. Article 8 of the decree of 27 April 1848 extended the Second Republic's ban on slavery to all French citizens residing in foreign countries where the possession of slaves was legal, while according them a grace period of three years to conform to the new law. In 1848, there numbered around 20,000 French nationals in Brazil, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and in the U.S. state of Louisiana. Louisiana was, by far, the region home to the most slave owning French, who, despite the 1803 sale of the territory to the U.S. government, retained citizenship. Article 8 forbade all French citizens "to buy, sell slaves, or to participate, whether directly or indirectly, in any traffic or exploitation of this nature". The application of this law was not accomplished without difficulty in these regions, with Louisiana being particularly problematic.[31] |

領有地域 1685年3月の奴隷に関する王令、王令、黒人法の原稿 フランス領土に足を踏み入れた者は自由であるという基本法に基づき、さまざまな議会が1685年3月の奴隷に関する条例の可決を拒否した。最終的にこの条 例は、その条例が書かれた植民地のみで施行された。1685年8月6日のマルティニーク最高会議、同年12月10日のグアドループ最高会議 同年12月10日、そして1687年5月6日、サン・ドマングのフランス植民地評議会に先立ってプチ・ゴーヴで制定された。[24] 最終的に、この法典は1704年5月5日、カイエンヌとギアナの評議会で可決された。[24] 黒人法典はセント・クリストファー植民地でも適用されたが、制定日は不明である。1723年12月と1724年3月の勅令は、1724年に、レユニオン島 (ブルボン島)とモーリシャス島(フランス領マリシャス)の植民地およびルイジアナ州でも施行された。 黒人法は、征服または降伏した土地の先住民は洗礼を受けると自由な王の臣民(régnicoles)とみなされるというフランス法の一般原則に従う北部の ヌーベルフランス(現在のカナダ)を当初の対象としていなかった。さまざまな現地の先住民の慣習が収集され、パリ条例が作成された。しかし、1709年4 月13日、アカディア植民地総督ジャック・ロードーが制定した条例により、奴隷制に関する規定が設けられ、事実上、その領土における奴隷制の存在が認めら れた。この条例では奴隷の法的地位についてはほとんど言及されていないが、一般的に奴隷制は「この植民地にとって非常に有益な慣習」であるとされ、「購入 された、あるいは将来購入されるパニス(先住民奴隷およびファースト・ネーション/ポーニー族の土着民)および黒人は、購入者の完全な所有物となり、購入 者の奴隷となる」と宣言された。[26][27][28] 革命後 1789年の「人権宣言」は、すべての人間が生まれながらにして平等であるという原則を明確にしたが、プランテーションと奴隷所有者のマシアック・クラブ のロビー活動の影響により、国民制憲議会と立法議会は、この平等は奴隷が存在せず、何世紀も前から農奴制が廃止されていたフランス本土の住民のみに適用さ れると決定した。アメリカ領土は除外された。 1793年にサン・ドマング(現在のハイチ)が現地での奴隷制度を廃止した後、1794年2月4日、フランス国民公会はすべてのフランス植民地において同 様の措置を講じた。しかし、この措置が有効だったのは、サン・ドマング、グアドループ、ギアナのみであった。なぜなら、この当時マルティニークはイギリス の植民地であり、1796年にようやくこの島に1794年の法令が届いた際には、マスカリン諸島の入植者たちがこの制度に強硬に反対したからである。 ナポレオン・ボナパルトは、アミアン条約により島々が英国に返還されたため、1802年5月20日にマルティニークとマスカリン諸島で奴隷制を復活させ た。その後まもなく、彼はグアドループ(1802年7月16日)とギアナ(1802年12月)でも奴隷制を復活させた。サン・ドマングでは、ボナパルトが 派遣した遠征軍に対するハイチ人の抵抗により、奴隷制は復活しなかった。この抵抗は最終的に植民地の独立につながり、1804年1月1日にハイチ共和国が 成立した。 黒人法典は、その内容に矛盾があるにもかかわらず、ナポレオン法典と43年間共存していたが、1827年と1828年の民事訴訟手続きに関する条例に続い て、現地の司法権の決定に関するフランス破棄院の判決により、この体制は次第に困難になっていった。歴史家のフレデリック・シャーリンによると、フランス 本土では、「七月王政の20年間は、奴隷に一定の人間性を付与する政治的傾向が特徴的であった…[そして、]道徳的価値観や家族の価値観を通じて、奴隷を フランス社会の他の労働力にゆっくりと同化させることを奨励した」[29]。七月王政期の破棄院の判例法は、奴隷の法的主体性を徐々に認めるという特徴が あった。それゆえ、1820年代には奴隷制度廃止の機運が高まったが、それは主に奴隷の待遇改善と平行して徐々に奴隷を解放していくというものであった。 1848年2月の革命と第二共和制の樹立により、クレミュー、ラマルティーヌ、ルドルー・ロランといった著名な奴隷制度廃止論者が権力を握った。1848 年の臨時政府の最初の行動のひとつは、「共和国の植民地の奴隷解放の準備」を行う委員会を設立することだった。委員会は2か月足らずで作業を終え、政府に 提出し、1848年4月27日に発足した。 フランス植民地における黒人の奴隷制度は、1848年3月4日と4月27日に最終的に廃止された。ヴィクトール・シュルケールの行動が大きく影響したため、[30][信頼できない情報源?]奴隷貿易はウィーン会議に続いて1815年にすでに廃止されていた。 1848年4月27日の法令第8条は、奴隷所有が合法である外国に居住するフランス国民全員に第二共和制の奴隷禁止令を拡大適用し、新法に適合するための 猶予期間として3年間を認めた。1848年当時、ブラジル、キューバ、プエルトリコ、および米国ルイジアナ州には約2万人のフランス国民がいた。ルイジア ナは、フランス人奴隷所有者が最も多く住む地域であり、1803年に米国政府に売却されたにもかかわらず、市民権を保持していた。第8条は、すべてのフラ ンス市民に対して、「奴隷の売買、または直接的・間接的に関わらず、この種の取引や搾取への参加」を禁じた。この法律の適用は、これらの地域では困難を伴 うものであり、特にルイジアナ州では問題が多かった。[31] |

| The development of slavery in the French Antilles The origins of enslaved populations  Definition of the Code noir in Lettres sur la profession d’avocat by Armand-Gaston Camus, 1772 The edict of 1685 bridged a legal void, because, while slavery had existed in the French Caribbean since at least 1625, it was nonexistent in metropolitan France. The first official French establishment in the Antilles was the Company of Saint Christopher and neighboring islands (Compagnie de Saint-Christophe et îles adjacentes) which was founded by Cardinal Richelieu in 1626. In 1635, 500-600 slaves were acquired, through what was essentially a seizure of a slave shipment from the Spanish. Later, the number was increased by slaves brought from Guinea aboard Dutch or French ships. With the island becoming overpopulated, there were efforts to colonize Guadeloupe with the aid of French recruits in 1635, as well as Martinique with the aid of 100 "old residents" of Saint Christopher in the same year. In Guadeloupe, the influx of slaves started in 1641 with the Company of Saint Christopher (by this date renamed Company of the American Isles and owner of multiple islands) importing 60 enslaved people. Then, in 1650, the company imported 100 more.[32] Starting in 1653-1654 the population greatly increased with the arrival of 50 Dutch nationals to the French isles, who had been run out of Brazil, taking with them 1200 black and métis slaves.[33] Subsequently, 300 people composed mainly of a few Flemish families and a great many slaves, settled in Martinique.[34] Many of these immigrants were Sephardic Jewish planters from Bahia, Dutch Pernambuco, and Suriname, who brought sugarcane infrastructure to French Martinique and English Barbados.[35] Although colonial authorities were hesitant to allow entry to the Jewish families, the French decided that their capital and proficiency in cane cultivation would benefit the colony. Some historians suggest that these Jewish planters, such as Benjamin da Costa d'Andrade, were responsible for introducing commercial sugar production to the French Antilles.[36] After the Da Costa family founded the first synagogue of Martinique in 1676, the visible Jewish presence in Martinique and Saint-Domingue led Jesuit missionaries to petition for the expulsion of Jews and other non-Catholics to both local and metropolitan authorities.[36][37] This precipitated an edict expelling Jews from the colonies in 1683, which would be incorporated into the Code Noir.[37] The Jewish population of Martinique was likely the specific target of the antisemitic clause (article 1) of the original 1685 Code. These settlers' arrival in the 1650s marked the second stage of colonization. Until then, tobacco and indigo cultivation had been the mainstay of colonial efforts and had required more laborers than slaves, but this trend was reversed around 1660 with the development of cane cultivation and large plantation estates.[38] Thereafter, the French State made the facilitation of the slave trade a matter of primary concern and worked to undercut foreign competition, particularly Dutch slavers. It is undeniable that the French East India Company, as the owner of slaveholding isles, took part in the slave trade, even though commercial slavery was not explicitly stated in the 1664 edict that chartered the company. The word "trade" was generally defined as any form of trade or commerce and did not exclude commerce in slaves as it might today. Despite the creation of various incentive plans in 1670, 1671, and 1672, the company went bankrupt in 1674 and the islands in its possession became crown lands (domaine royal). The monopoly on the Caribbean trade was given to the Senegal Company (Première compagnie d'Afrique ou du Sénégal) in 1679. To amend what was seen as an insufficient supply, Louis XIV created the Company of Guinea (Compagnie de Guinée—not to be confused with the 17th century English colonial enterprise Guinea Company) to provide a yearly supplement of 1000 black slaves to the French isles. To solve the "negro shortage", in 1686, the King personally chartered a slave ship for operation in Cape Verde.[citation needed] At the time of the first official census of Martinique, taken in 1660, there were 5259 inhabitants, 2753 of which were white and already 2644 were black slaves. There were only 17 Indigenous Caribbeans and 25 mulattoes. Twenty years later, in 1682, the number of inhabitants had tripled to 14,190 with a white population that had barely doubled, but with a slave population that had grown to 9634, and with the Indigenous population at a mere 61, slaves made up 68% of the total population.[39] In all of the colonies, there was a great disparity between the number of men and women which led to men having children with Indigenous women, who were free persons, or with slaves. With white women being rare and black women seeking to improve their circumstances, by 1680 the census showed 314 métis people in Martinique (twelve times the count in 1660), 170 in Guadeloupe, and 350 in Barbados where the slave population was eight times that of Guadeloupe but where miscegenation (métissage) was illegalized after the rise of sugarcane cultivation. To mitigate the deficit of women in the Antilles, Versailles enacted a similar measure to the King's Daughters of New France and sent 250 girls to Martinique and 165 to Saint-Domingue.[40] Compared to its English counterpart, which sent condemned criminals and exiled populations, the French migration was voluntary. Creolization was unavoidable due to basic endogamous tendencies, with colored women being preferred as many colonists considered the new arrivals to be foreigners.[41] The authorities were not concerned with miscegenation per se, but rather the resulting manumission of mulatto children.[42] For this reason, the Code inverted basic patrimonial French custom in maintaining that even if the father is free, the children of an enslaved woman shall be slaves unless they are rendered legitimate through the marriage of the parents, which was a rare occurrence. In subsequent regulation, marriage between free and slave populations would be further limited. The Code Noir also more sharply defined the status of métis people. In 1689, four years after its promulgation, around one hundred mulattoes left the French Antilles for New-France, where all men were considered free. |

フランス領アンティル諸島における奴隷制の発展 奴隷人口の起源  1772年、アルマン=ガストン・カミュ著『弁護士の職業に関する手紙』における黒人法典の定義 1685年の勅令は、法的空白を埋めるものとなった。なぜなら、少なくとも1625年からフランス領カリブ海地域では奴隷制が存在していたが、本土のフラ ンスでは奴隷制は存在していなかったからである。アンティル諸島における最初の公式なフランス人入植は、1626年にリシュリュー枢機卿によって設立され たサン・クリストフおよび近隣諸島会社(Compagnie de Saint-Christophe et îles adjacentes)であった。1635年には、スペインからの奴隷輸送船を実質的に接収し、500~600人の奴隷を獲得した。その後、オランダ船や フランス船でギニアから連れてこられた奴隷によって、その数はさらに増えた。人口過密となったため、1635年にはフランス人入植者の支援を受けてグアド ループ島への入植が試みられ、同じ年にセントクリストファーの「古くからの住民」100人の支援を受けてマルティニークへの入植も試みられた。 グアドループでは、1641年にサン・クリストフ会社(この時点でアメリカ諸島会社と改名され、複数の島を所有)が60人の奴隷を輸入したことから、奴隷 の流入が始まった。その後、1650年にはさらに100人が輸入された。[32] 1653年から1654年にかけて、ブラジルから追放された50人のオランダ国民が到着し、人口が大幅に増加した。彼らは1200人の黒人と混血奴隷を連 れていた。[33] その後、主に少数のフランドル人家族と多数の奴隷で構成される300人が 少数のフランドル人家族と多数の奴隷を中心に構成された300人が、マルティニークに定住した。[34] これらの移民の多くは、バイーア、オランダ領ペルナンブーコ、スリナムから来たセファルディ系ユダヤ人のプランテーション経営者であり、彼らはフランス領 マルティニークとイギリス領バルバドスにサトウキビのインフラストラクチャーをもたらした。[35] 植民地当局はユダヤ人家族の入植を許可することにためらいを見せたが、フランスは彼らの資本とサトウキビ栽培の熟練が植民地に利益をもたらすだろうと判断 した。一部の歴史家は、ベンジャミン・ダ・コスタ・ダンドラーデ(Benjamin da Costa d'Andrade)などのユダヤ人プランテーション経営者が、フランス領アンティル諸島に商業的な砂糖生産を導入したと指摘している。[36] ダ・コスタ家が1676年にマルティニーク初のシナゴーグを設立した後、マルティニークとサン・ドマングにユダヤ人が目に見える形で存在したため、イエズ ス会の宣教師たちは、ユダヤ人とその他の非 地元および本国当局に、ユダヤ人およびその他の非カトリック教徒の追放を嘆願した。[36][37] これが引き金となって、1683年に植民地からのユダヤ人追放令が発令され、これが黒人法典に組み込まれることとなった。[37] マルティニークのユダヤ人人口は、おそらく1685年の黒人法典の反ユダヤ主義条項(第1条)の具体的な標的となった。1650年代にこれらの入植者が到 着したことは、植民地化の第二段階の始まりを意味した。それまでは、タバコや藍の栽培が植民地化の主な柱であり、奴隷よりも多くの労働者を必要としていた が、1660年頃にサトウキビ栽培と大規模なプランテーション農園の開発により、この傾向は逆転した。 その後、フランス政府は奴隷貿易の促進を最重要事項とし、特にオランダの奴隷商人ら外国の競争相手を出し抜こうと努めた。フランス東インド会社が奴隷所有 の島々の所有者として奴隷貿易に関与していたことは否定できない。「貿易」という言葉は、あらゆる形態の貿易や商業を意味するものと一般的に定義されてお り、現代のように奴隷貿易を除外するものではなかった。1670年、1671年、1672年にはさまざまな奨励策が講じられたにもかかわらず、1674年 には会社は倒産し、所有していた島々は王領地(ドメーヌ・ロワイヤル)となった。1679年には、カリブ貿易の独占権がセネガル会社(Première compagnie d'Afrique ou du Sénégal)に与えられた。供給不足と見なされた状況を改善するために、ルイ14世はギニア会社(Compagnie de Guinée)を設立し、フランス領諸島に毎年1000人の黒人奴隷を補充した。「黒人不足」を解消するため、1686年には国王が自ら奴隷船をチャー ターし、カーボベルデで活動させた。[要出典] 1660年に実施されたマルティニークの最初の公式国勢調査では、人口5259人のうち、白人は2753人、黒人奴隷はすでに2644人に達していた。先 住民のカリブ人はわずか17人、混血は25人であった。20年後の1682年には、人口は3倍の14,190人に増加し、白人の人口はかろうじて2倍に増 えただけだったが、奴隷の人口は9634人にまで増加し、先住民の人口はわずか61人であった。奴隷は総人口の68%を占めていた。 すべての植民地において、男女の人口に大きな格差があり、男性は自由民である先住民の女性や奴隷との間に子供をもうけた。白人女性はまれであり、黒人女性 は境遇の改善を求めていたため、1680年の国勢調査では、マルティニークに314人の混血児(1660年の12倍)、グアドループに170人、奴隷人口 がグアドループの8倍であったものの、サトウキビ栽培の隆盛後に混血(メティス)が非合法化されたバルバドスに350人が確認された。 アンティル諸島における女性不足を緩和するために、ヴェルサイユはヌーベルフランス(ニューフランス)のキングズ・ドーターズ(王女会)と同様の措置を講 じ、250人の少女をマルティニークに、165人をサン・ドマング(ハイチ)に送った。[40] 死刑囚や追放された人々を送ったイギリスと比較すると、フランスの移民は自主的なものであった。混血化は、多くの入植者が新参者を外国人とみなすなど、基 本的な同種婚の傾向により避けられなかった。 当局は混血そのものには関心がなく、むしろ混血の結果として生じる混血児の解放に懸念を抱いていた。[42] このため、法典では、父親が自由人であっても、奴隷の女性との間に生まれた子供は、両親の結婚によって嫡出子と認められない限り、奴隷のままとするとい う、フランスにおける基本的な家産相続の慣習を覆す内容となっていた。この慣習はまれにしか見られなかった。その後の規定では、自由人と奴隷の間の結婚は さらに制限されることとなった。 また、黒人法典では混血の人々の地位もより厳密に定義された。1689年、公布から4年後、およそ100人の混血が、すべての男性が自由民とみなされていたヌーベルフランス(ニューフランス)を目指してフランス領アンティル諸島を後にした。 |

| Development Goals The Code Noir was a multifaceted legal document designed to govern every aspect of the lives of enslaved and free African people under French colonial rule. While Enlightenment thinking about liberty and tolerance prevailed dominantly in French society, it became necessary to clarify that people of African descent did not belong under this umbrella of understanding. It was essential to the preservation of France's economy and colonial interests that Black people residing in French colonies maintain their status as property rather than become French subjects.[43] The Code Noir was also conceived to “maintain the discipline of the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman church”[44] in the French colonies. It required that all enslaved people of African descent in the French colonies receive baptism, religious instruction, and the same practices and sacraments for slaves as it did for free persons. While it did grant enslaved people the right to rest on Sundays and holidays, to formally marry through the church, and to be buried in proper cemeteries, forced religious conversion was just one of the many methods that France used to attempt to 'civilize' and exert their imperial control over the Black population in the French colonies. The Code thus gave a guarantee of morality to the Catholic nobility that arrived in Martinique between 1673 and 1685.[45] Of these, were Knight Charles François d'Angennes, the marquis of Maintenon and his nephew Jean-Jacques Mithon de Senneville, the colonial intendant Jean-Baptiste Patoulet, Charles de Courbon, the count of Blénac, and the militia captain Nicolas de Gabaret. Juridical origins and similar legislation English colonies In the English colonies, the Barbados Lifetime Slavery Decree of 1636 was instituted by governor Henry Hawley on his return to England after having entrusted Barbados to his deputy governor Richard Peers.[46] In 1661, the Barbados Slave Code reiterated this 1636 decree and the 1662 Virginia slave law passed by governor William Berkeley under the reign of Charles II used similar jurisprudence. The 1661 law held that a slave could only produce enslaved children[47] and that mistreatment of a slave could be justified in certain cases.[48] The law also incorporated the Elizabeth Key case (a mulatto slave, daughter of a white plantation owner, who converted to Christianity and successfully sued for her freedom) which was contested by the white aristocracy who held that paternity and conversion were unable to confer freedom. French colonies Contrary to the thinking of legal theorists such as Leonard Oppenheim,[49] Alan Watson,[50] and Hans W. Baade,[51] it was not slave legislation from Roman law that served as inspiration for the Code Noir, but rather a collection and codification of the local customs, decisions, and regulations used in the Antilles. According to legal scholar Vernon Palmer, who has described the lengthy four-year decision-making process that led to the original 1685 edict, the project consisted of 52 articles for the first draft and preliminary report, as well as the instructions of the King.[6][52] In 1681, the King decided to create a statute for the black population of the French Caribbean and delegated its writing to Colbert, who, in turn, requested memoranda from the colonial intendant of Martinique, Jean-Baptiste Patoulet and later from his replacement, Michel Bégon, as well as the governor general of the Caribbean, Charles de Courbon, comte de Blenac (1622–1696). The Mémoire (memorandum) of 30 April 1681 from the King to the intendant (who was probably Colbert), expressed the utility of making an ordinance specific to the Antilles. The study, which incorporated local legal customs, decisions, and jurisprudence of the Sovereign Council, as well as a number of rulings by the King's Council, was challenged by the members of the Sovereign Council. When negotiations settled, the draft was sent to the chancellery, which retained what was essential and only reinforced or streamlined the articles such that they were compatible with preexisting laws and institutions. At the time, there were two common law statutes in effect in Martinique: that pertaining to French nationals, which was the Custom of Paris as well as laws for foreigners, which did not include rules particular to soldiers, nobles, or clergy. These statutes were included in the Edict of May 1664 that established the French West India Company. The American Isles were enfeoffed or conceded to the company, whose formation had replaced the Company of Saint Christopher (1626–1635), but would eventually be succeeded by the Company of the American Isles (1635–1664). The Indigenous population, called Caribbean Indians (Indiens caraïbes), were seen as naturalized French subjects, and were provided the same rights as French nationals upon their baptism. It was forbidden to enslave Indigenous peoples, or to sell them as slaves. Two populations were provided for: natural populations and native French, as the Edict of 1664 did not describe slaves or the importation of a black population. The French West India Company had gone bankrupt in 1674, with its commercial activities having been transferred to the Senegal Company and its territories returned to the Crown. The rulings of the Sovereign Council of Martinique patched the legal hole concerning slave populations. In 1652, at the behest of Jesuit missionaries, the Council reified the rule that slaves, like domestic servants, shall not be made to work on Sundays and in 1664, held that slaves would be required to be baptized and to attend catechism.[37][53] The edict of 1685 ratified the practice of slavery despite the conflicting legislation of the Kingdom of France[54] and canon law. In fact, an Edict bringing emancipation in exchange for payment to the serfs of the King's domain, had been introduced on 11 July 1315, by Louis X the Stubborn, but had limited effect due to a lack of control of the King's officers and/or the fact that few serfs possessed sufficient funds to buy their liberty.[55] Such forms of indentured servitude existed up until the Edict for the suppression of the right of mortmain and of servitude in the domains of the King of 8 August 1779, which was passed by Louis XVI, intended for certain regions that had recently become part of the kingdom.[56] The edict was not concerned with personal servitude, but rather real servitude or mortmain, which is to say that the denizen/owner could not sell or bequeath the land, as if the denizen/owner were only a renter. The lord possessed the droit de suite, meaning that the lord could retain any fee or proceeds resulting from the passing of the censive (the right to live on the estate and to pay tribute or cens to the lord).[57] The King's order through Colbert and the centrality of Martinique Sick since 1681, Colbert died in 1683, less than two years after having transmitted the King's order to the two successive intendants of Martinique, Patoulet and Bégon. Colbert's son, the Marquis of Seignelay, signed the ordinance two years after his death.[58] The colonial intendants' work was centered in Martinique, where multiple nobles of the royal entourage had received estates and where Patoulet had requested Louis XIV to ennoble the plantation owners who owned more than one hundred slaves. The opinions recorded in the memoranda were entirely from Martinicans with no one from Guadeloupe, where métis and the large plantation owners were fewer. The first letter from Colbert to intendant Patoulet and governor general of the Antilles Charles de Courbon, count of Blénac, reads: "His Majesty finds it necessary to regulate, by declaration, all that concerns the negros of the isles, both for the punishment of their crimes and for all that might concern the justice to be dealt them. It is for this that it be necessary for you to create a memorandum as precise and extensive as possible, which considers all the cases having to do with said negros and which might merit regulation by an order. You must be well acquainted with the present customs of the isles as well as what should be customary in the future".[59][60] |

開発 目標 黒人法典は、フランス植民地支配下における奴隷および自由のアフリカ人の生活のあらゆる側面を管理するために策定された多面的な法文書であった。啓蒙思想 の自由と寛容の考え方がフランス社会で優勢を占める中、アフリカ系の人々はこうした理解の枠組みに属さないことを明確にする必要が生じた。フランス植民地 の黒人がフランス国民となるのではなく、所有物としての地位を維持することが、フランスの経済と植民地利益の維持に不可欠であった。 また、黒人法はフランス植民地における「カトリック、使徒、ローマ教会の規律を維持する」[44] ことも目的としていた。フランス植民地における奴隷としての人種がアフリカ系である人々全員に洗礼を受けさせ、宗教教育を受けさせ、奴隷にも自由民と同様 の慣習や秘跡を行うことを義務付けた。奴隷の人々には、日曜や祝日に休む権利、教会を通じて正式に結婚する権利、適切な墓地に埋葬される権利が与えられた が、強制的な改宗は、フランスがフランス植民地の黒人人口を「文明化」し、帝国支配を及ぼそうとした数多くの方法のひとつに過ぎなかった。 この法典により、1673年から1685年の間にマルティニークに到着したカトリックの貴族たちに道徳的な保証が与えられた。[45] その中には、ナイトのシャルル・フランソワ・ダンジェンヌ(マントノン侯爵)、甥のジャン=ジャック・ミトン・ド・セヌヴィル、植民地行政官ジャン=バ ティスト・パトゥレ、シャルル・ド・クールボン(ブレナック伯爵)、民兵隊長ニコラ・ド・ガバレットなどがいた。 法的な起源と類似した法律 イギリスの植民地 イギリスの植民地では、1636年のバルバドス終身奴隷令は、バルバドスを代理知事のリチャード・ピアーズに委ねた後、イングランドに帰国したヘンリー・ ホーリー知事によって制定された。[46] 1661年には、バルバドス奴隷法がこの1636年の法令を繰り返し、チャールズ2世の治世下でウィリアム・バークレー知事によって可決された1662年 のバージニア奴隷法も同様の法理を用いた。1661年の法律では、奴隷は奴隷の子孫しか生み出せないとされ[47]、また、特定のケースでは奴隷に対する 虐待が正当化される可能性があるとした[48]。この法律には、エリザベス・キー事件(プランテーションの白人所有者の娘で、キリスト教に改宗し、自由を 求めて訴訟を起こし成功した混血奴隷)も盛り込まれたが、白人貴族階級は、父性や改宗は自由を付与するものではないと主張し、これに異議を唱えた。 フランス植民地 レナード・オッペンハイム(Leonard Oppenheim)[49]、アラン・ワトソン(Alan Watson)[50]、ハンス・W・バーデ(Hans W. Baade)[51]などの法理論家の考えとは逆に、黒人法典のインスピレーションとなったのはローマ法の奴隷法ではなく、むしろアンティル諸島で用いら れていた現地の慣習、決定、規制の収集と体系化であった。1685年の最初の勅令に至るまでの4年間にわたる長い意思決定プロセスを記述した法学者の ヴァーノン・パーマーによると、このプロジェクトは、最初の草案と予備報告書、そして王の指示からなる52の条項から構成されていた。[6][52] 1681年、国王はフランス領カリブ海の黒人住民のための法令を制定することを決定し、その起草をコルベールに委任した。コルベールは、まずマルティニー クの植民地行政官ジャン=バティスト・パトゥレに、その後後任のミシェル・ベゴンに、さらにカリブ海総督シャルル・ド・クールボン、コンテ・ド・ブレナッ ク(1622年-1696年)に覚書を作成するよう要請した。1681年4月30日付の国王から財務総監(おそらくはコルベール)宛の覚書(メモワール) には、アンティル諸島に特化した条例を制定することの有用性が述べられている。 この研究には、現地の法律慣習、決定、最高評議会の判例法、および王の評議会による多数の裁定が盛り込まれていたが、最高評議会のメンバーから異議が唱え られた。交渉が妥結すると、草案は官房に送られ、官房は本質的な部分を維持し、既存の法律や制度と矛盾しないよう、条項を補強したり簡素化したりした。 当時、マルティニークでは2つのコモンロー法が施行されていた。フランス国民に関するもの、つまりパリ慣習法と、外国人に関する法律で、兵士、貴族、聖職 者に関する規定は含まれていなかった。これらの法は、フランス西インド会社を設立した1664年5月の勅令に盛り込まれた。アメリカ諸島は、会社に封土ま たは譲歩された。この会社の設立により、セントクリストファー会社(1626年~1635年)は廃止されたが、最終的にはアメリカ諸島会社(1635年 ~1664年)に引き継がれることとなった。カリブ・インディアン(Indiens caraïbes)と呼ばれる先住民は、帰化フランス国民と見なされ、洗礼を受けるとフランス国民と同等の権利が与えられた。先住民を奴隷にしたり、奴隷 として売買することは禁じられていた。1664年の勅令では奴隷や黒人人口の輸入については言及されていなかったため、先住民とフランス系住民の2つの集 団が規定された。フランス領西インド会社は1674年に倒産し、その商業活動はセネガル会社に移管され、その領土は王冠に返還された。マルティニークの最 高会議の裁定により、奴隷人口に関する法的な穴が埋められた。1652年、イエズス会の宣教師の要請により、最高会議は、奴隷は使用人と同様に日曜日に労 働させてはならないという規則を制定し、1664年には、奴隷には洗礼を受け、カテキズムに参加することが義務付けられた。 1685年の勅令は、フランス王国の法律[54]や教会法の規定に反するものであったにもかかわらず、奴隷制度を承認するものであった。実際、1315年 7月11日には、ルイ10世(頑固王)によって、王領地の農奴に解放と引き換えに支払いを命じる勅令が発布されていたが、王の役人の管理不足や、農奴のほ とんどが自由を手に入れるのに十分な資金を持っていなかったことなどにより、その効果は限定的であった。[55] このような形態の年季奉公は、 1779年8月8日にルイ16世によって発布されたこの勅令は、王国の一部となったばかりの特定の地域を対象としていた。[56] この勅令は、個人的な隷属ではなく、むしろ実質的な隷属、つまり、土地の所有者はその土地を売却したり遺贈したりできないという、土地の所有者は借地人で あるかのように扱うものであった。領主は権利継承権(censive)を保有しており、これは、権利継承権(censive)の譲渡から生じる料金や収益 を領主が保持できることを意味する。権利継承権(censive)とは、領地に住み、領主に貢ぎ物や年貢を納める権利である。[57] コルベールを通じて王が命じたこととマルティニークの中心性 1681年以来病に苦しんでいたコルベールは、マルティニークの2人の代々の総督、パトゥレとベゴンに王の命令を伝えてから2年も経たないうちに、1683年に死去した。コルベールの息子であるセニュレ侯爵は、彼の死から2年後に条例に署名した。 植民地総督の業務はマルティニークに集中しており、王の側近の貴族たちが多数土地を所有していた場所であり、パトゥレがルイ14世に100人以上の奴隷を 所有する農園主の貴族化を要請した場所でもあった。覚書に記録された意見はすべてマルティニーク出身者によるもので、混血や大農園主が少なかったグアド ループ出身者の意見は含まれていなかった。 コルベールからパトゥレ行政長官とアンティル総督シャルル・ド・クーボン・ド・ブレナック伯爵に宛てた最初の書簡には、次のように書かれている。 「陛下は、この島の黒人に関するすべての事項を布告によって規制する必要があると判断された。それは、彼らの犯罪に対する処罰のためであり、また、彼らに 与えられるべき正義に関するすべての事項のためである。このため、できる限り正確かつ広範な覚書を作成し、黒人に関するすべての事例を検討し、命令による 規制に値するものを特定する必要がある。また、島の現在の習慣と、今後取るべき習慣についても熟知していなければならない。[59][60] |

| Impact Opinions In his 1987 analysis of the Code Noir and its applications, Louis Sala-Molins, professor emeritus of political philosophy at Paris 1, argues that the Code Noir is the "most monstrous juridical text produced in modern times".[61] According to Sala-Molins, the Code Noir served two purposes: to affirm "the sovereignty of the State in its farthest territories" and to create favorable conditions for the sugarcane commerce. "In this sense, the Code Noir foresaw a possible sugar hegemony for France in Europe. To achieve this goal, it was first necessary to condition the tool of the slave".[62] Sala-Molin's theories have been critiqued by historians[who?] for lacking historical rigor and for relying on a selective reading of the Code.[63][better source needed] Nevertheless, the precise content of the 1685 edict remains uncertain, because, on one hand, the original has been lost[64] and on the other, there are often important variations between the surviving versions. Thus, it is necessary to compare them and understand which version was applicable to which colony or to each case, in order to accurately measure the impact of the Code Noir.[65] Denis Diderot, in a passage of Histoire des deux Indes, denounces slavery and imagines a large slave revolt orchestrated by a charismatic leader that leads to a complete reversal of the established order. "Everywhere will the name of the hero who has restored the rights of the human species be blessed, everywhere will monuments be erected in his honor. And so the black code will disappear, but how terrible the white code shall be, should the victor consult only the law of reprisal!”[66] Bernardin de Saint Pierre, who stayed in Ile de France from 1768 to 1770, highlighted the lag that existed between the creation of legislation and its institution.[67] Enlightenment historian Jean Ehrard notes a typically colbertist method of regulating a phenomenon in the Code.[68] Slavery had been widespread in the colonies long before royal powers provided a legal framework for it. Ehrard noted that during the same era, one can find similar or equivalent dispositions to those in the Code Noir for other categories like for sailors, soldiers, and vagrants. Colonists were opposed to the Code because they were now compelled to provide slaves with a means of subsistence, which they normally were not required to guarantee. French Revolution impact During the French Revolution, which began in 1789, the ideals of liberty, equality, and society influenced the thinking of many revolutionaries. The revolutionaries sought to apply these principles not only to the people of France but also to the colonies. As a result, the status of slavery and the rights of enslaved individuals became a topic of debate.[69] In 1794, the French National Convention, under the influence of revolutionary ideals, issued the "Decree of 16 Pluviôse, Year II" (February 4, 1794), which effectively abolished slavery in all French colonies.[70] This decree marked a radical departure from the Code Noir's provisions that had supported and regulated the institution of slavery. The ideas of the revolution in France began to inspire revolutionary minds across the world, particularly in colonies of the French. Namely, the Haitian Revolution was a radical rebellion and the first in the area to successfully gain independence from a large European power. Controversies about its legacy Upon the 2015 release of his work Le Code noir. Idées reçues sur un texte symbolique, colonial law historian Jean-François Niort was attacked for his position that the authors of the Code intended for "a mediation between master and slave" by minor Guadeloupean political organizations self-styled as "patriotic" and accused of "racial discrimination" and denialism by some members of the Guadeloupean independentist movement who threatened to expel him from Guadeloupe.[71] He has been roundly supported by the historical community[who?] which has denounced the verbal and physical intimidation of specialists in the colonial history of the region.[72] The controversy continued in an argument in the opinions section of the French newspaper Le Monde between Niort and the philosopher Louis Sala-Molins.[73] In popular culture The Code Noir is mentioned in the action-adventure video game Assassin's Creed IV: Freedom Cry, as it is mainly set in Port-au-Prince. The assassin Adéwalé, formerly an escaped slave turned pirate, aids local Maroons in freeing the enslaved population of Saint-Domingue (now the Republic of Haiti). It is mentioned during the main story of Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag and has its own database entry in the game, which provides background on the Code Noir. |

影響 意見 1987年の黒人法とその適用に関する分析において、パリ第1大学の政治哲学名誉教授ルイ・サラ=モランは、黒人法は「近代において生み出された最もおぞ ましい法文」であると論じている。[61] サラ=モランによると、黒人法には2つの目的があった。「最果ての領土における国家の主権」を確立すること、そしてサトウキビ貿易に有利な条件を作り出す ことである。「この意味において、黒人法典はヨーロッパにおけるフランスによる砂糖覇権の可能性を予見していた。この目標を達成するには、まず奴隷という 手段を整える必要があった」[62]。 サラ=モランの理論は、歴史的な厳密さを欠き、黒人法典の選択的な解釈に依拠しているとして、歴史家たちから批判されている[誰?]。[63][より良い情報源が必要] しかし、1685年の勅令の正確な内容は依然として不明である。なぜなら、一方では原本が失われている[64]し、他方では現存する版の間にはしばしば重 要な相違があるからである。したがって、それらを比較し、どの版がどの植民地や各事例に適用されたかを理解することが必要である。そうすることで、黒人奴 隷法の影響を正確に測定することができるのである。[65] デニ・ディドロは『インドの二つの歴史』の一節で奴隷制を非難し、カリスマ的指導者によって指揮された大規模な奴隷反乱が、確立された秩序を完全に覆すことを想像している。 「人間としての権利を回復させた英雄の名は、あらゆる場所で称賛され、あらゆる場所にその栄誉をたたえる記念碑が建てられるだろう。そして、黒人法は消滅するだろう。しかし、報復の法のみに頼るのであれば、白人法はどれほど恐ろしいものになるだろうか!」[66] 1768年から1770年までイル・ド・フランスに滞在していたベルナール・ド・サン・ピエールは、法律の制定と施行の間に存在する遅れを強調した。[67] 啓蒙思想史家のジャン・エラールは、コルベール主義的な現象の規制方法を指摘している。[68] 奴隷制は、王権が法的な枠組みを定めるはるか以前から、植民地で広く行われていた。エラールは、同じ時代に、船員、兵士、浮浪者など他のカテゴリーについ ても、黒人奴隷法と同様の規定または同等の規定が見られることを指摘している。入植者たちは、黒人奴隷に生活手段を保証しなければならなくなったため、黒 人奴隷法に反対した。 フランス革命の影響 1789年に始まったフランス革命では、自由、平等、社会という理想が多くの革命家の考え方に影響を与えた。革命家たちは、これらの原則をフランス国民だけでなく植民地にも適用しようとした。その結果、奴隷制度の地位と奴隷の権利が議論の対象となった。 1794年、革命の理想の影響下にあったフランス国民公会は、「第2年プラヴィオース16日の布告」(1794年2月4日)を発布し、これにより事実上、 すべてのフランス植民地における奴隷制度が廃止された。[70] この布告は、奴隷制度を支持し、規制してきた黒人法典の規定から急進的に離れるものであった。フランス革命の理念は、世界中の革命家たち、特にフランス植 民地の人々を鼓舞し始めた。すなわち、ハイチ革命は急進的な反乱であり、ヨーロッパの大国から独立を勝ち取った最初の地域であった。 その遺産をめぐる論争 2015年に著書『Le Code noir. Idées reçues sur un texte symbolique』を出版したところ、植民地法の歴史家であるジャン=フランソワ・ニオールは、その著者が「主人と奴隷の仲介」を意図していたという 自身の立場を理由に、自称「愛国者」のグアドループの小規模な政治団体から攻撃を受け、「人種差別」と否定論を非難されたグアドループ独立運動の一部のメ ンバーから、 彼をグアドループから追放すると脅した。[71] 歴史学界からは全面的に支持されているが、この地域の植民地史の専門家たちによる言葉や肉体による威嚇を非難している。[72] 論争は、ニオールと哲学者ルイ・サラ=モランとの間で、フランスの新聞『ル・モンド』の意見欄で続いた。[73] 大衆文化において 『黒人法典』は、主にポルトープランスが舞台となっているアクションアドベンチャーゲーム『アサシン クリード IV フリーダムクライ』で言及されている。かつて逃亡奴隷から海賊となった暗殺者アデワレは、サン・ドマング(現在のハイチ共和国)の奴隷人口の解放に地元の マローン族を支援する。これは『アサシン クリード IV ブラック フラッグ』のメインストーリーで言及されており、ゲーム内には独自のデータベースエントリがあり、コード・ノワールの背景が説明されている。 |

| Palmer, Vernon Valentine (1996). "The Origins and Authors of the Code Noir". Louisiana Law Review. 56: 363–408. | Palmer, Vernon Valentine (1996). "The Origins and Authors of the Code Noir". Louisiana Law Review. 56: 363–408. |

| History of slavery in Louisiana Slavery in the French West Indies Slavery in Canada Slavery in Haiti Slave codes Slave rebellions Black Codes Slave Trade Acts Panis |

ルイジアナ州における奴隷制の歴史 フランス領西インド諸島における奴隷制 カナダにおける奴隷制 ハイチにおける奴隷制 奴隷法 奴隷の反乱 ブラックコード 奴隷貿易法 パン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_Noir |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆