コロンブスの交換

Columbian exchange

☆ コロンブス交換(コロンブスこうかん、英: Columbian exchange)とは、15世紀後半以降、西半球の新世界(アメリカ大陸)と東半球の旧世界(アフロ・ユーラシア大陸)の間で、植物、動物、貴金属、商 品、文化、人口、技術、病気、思想などが広範囲に渡って交換されたことである。 [イタリアの探検家クリストファー・コロンブスにちなんで命名され、彼の1492年の航海後のヨーロッパの植民地化と世界貿易に関連している。旧世界に由 来する伝染病は、15世紀以降、アメリカ大陸の先住民の数を80~95%減少させる結果となり、カリブ海地域では最も深刻だった。ヨーロッパ人入植者とア フリカ人奴隷は、程度の差こそあれ、アメリカ大陸の先住民に取って代わった。新大陸に連れて行かれたアフリカ人の数は、コロンブス後の最初の3世紀に新大 陸に移動したヨーロッパ人の数をはるかに上回っていた。 世界人口の新たな接触は、多種多様な作物や家畜の交流をもたらし、旧世界における食糧生産と人口の増加を支えた。トウモロコシ、ジャガイモ、トマト、タバ コ、キャッサバ、サツマイモ、唐辛子といったアメリカの作物は、世界中で重要な作物となった。旧世界の米、小麦、サトウキビ、家畜などの作物は、新世界で も重要な作物となった。アメリカで生産された銀は世界中に溢れ、特に帝国中国で硬貨に使われる標準的な金属となった。 この言葉は、1972年にアメリカの歴史家であり教授でもあるアルフレッド・W・クロスビーが環境史の著書『コロンブス交換』の中で初めて使用した。

左は、新大陸から旧大陸に渡った植物産品/右は旧大陸から新大陸にわたった植物産品である()

| The Columbian

exchange The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World (the Americas) in the Western Hemisphere, and the Old World (Afro-Eurasia) in the Eastern Hemisphere, in the late 15th and following centuries.[1] It is named after the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus and is related to the European colonization and global trade following his 1492 voyage.[1] Some of the exchanges were purposeful while others were unintended. Communicable diseases of Old World origin resulted in an 80 to 95 percent reduction in the number of Indigenous peoples of the Americas from the 15th century onwards, most severely in the Caribbean.[1] The cultures of both hemispheres were significantly impacted by the migration of people, both free and enslaved, from the Old World to the New. European colonists and African slaves replaced Indigenous populations across the Americas, to varying degrees. The number of Africans taken to the New World was far greater than the number of Europeans moving to the New World in the first three centuries after Columbus.[2][3] The new contacts among the global population resulted in the interchange of a wide variety of crops and livestock, which supported increases in food production and population in the Old World. American crops such as maize, potatoes, tomatoes, tobacco, cassava, sweet potatoes, and chili peppers became important crops around the world. Old World rice, wheat, sugar cane, and livestock, among other crops, became important in the New World. American-produced silver flooded the world and became the standard metal used in coinage, especially in Imperial China. The term was first used in 1972 by the American historian and professor Alfred W. Crosby in his environmental history book The Columbian Exchange.[1][4] It was rapidly adopted by other historians and journalists. |

コロンブス交換(コロンブスこうかん、英: Columbian

exchange) コロンブス交換(コロンブスこうかん、英: Columbian exchange)とは、15世紀後半以降、西半球の新世界(アメリカ大陸)と東半球の旧世界(アフロ・ユーラシア大陸)の間で、植物、動物、貴金属、商 品、文化、人口、技術、病気、思想などが広範囲に渡って交換されたことである。 [イタリアの探検家クリストファー・コロンブスにちなんで命名され、彼の1492年の航海後のヨーロッパの植民地化と世界貿易に関連している[1]。旧世 界に由来する伝染病は、15世紀以降、アメリカ大陸の先住民の数を80~95%減少させる結果となり、カリブ海地域では最も深刻だった[1]。ヨーロッパ 人入植者とアフリカ人奴隷は、程度の差こそあれ、アメリカ大陸の先住民に取って代わった。新大陸に連れて行かれたアフリカ人の数は、コロンブス後の最初の 3世紀に新大陸に移動したヨーロッパ人の数をはるかに上回っていた[2][3]。 世界人口の新たな接触は、多種多様な作物や家畜の交流をもたらし、旧世界における食糧生産と人口の増加を支えた。トウモロコシ、ジャガイモ、トマト、タバ コ、キャッサバ、サツマイモ、唐辛子といったアメリカの作物は、世界中で重要な作物となった。旧世界の米、小麦、サトウキビ、家畜などの作物は、新世界で も重要な作物となった。アメリカで生産された銀は世界中に溢れ、特に帝国中国で硬貨に使われる標準的な金属となった。 この言葉は、1972年にアメリカの歴史家であり教授でもあるアルフレッド・W・クロスビーが環境史の著書『コロンブス交換』の中で初めて使用した[1] [4]。 |

| Etymology In 1972, Alfred W. Crosby, an American historian at the University of Texas at Austin, published the book The Columbian Exchange,[4] and subsequent volumes in the 1970s. His primary focus was mapping the biological and cultural transfers that occurred between the Old and New Worlds. He studied the effects of Columbus's voyages between the two – specifically, the global diffusion of crops, seeds, and plants from the New World to the Old, which radically transformed agriculture in both regions.[5] His research made a lasting contribution to the way scholars understand the variety of contemporary ecosystems that arose due to these transfers.[5] The term has become popular among historians and journalists and has since been enhanced with Crosby's later book in three editions, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900. Charles C. Mann, in his book 1493 further expands and updates Crosby's original research.[6] |

語源 1972年、テキサス大学オースティン校のアメリカ人歴史家であるアルフレッド・W・クロスビーは、『コロンブス交換』[4]という本を出版し、1970 年代にはそれに続く本を出版した。彼の主な焦点は、旧世界と新世界の間で起こった生物学的・文化的移転のマッピングであった。具体的には、新世界から旧世 界への作物、種子、植物の世界的な拡散を研究し、両地域の農業を根本的に変えた[5]。 彼の研究は、このような移転によって生じた多様な現代の生態系を理解する学者たちの方法に、永続的な貢献をした[5]。この用語は歴史家やジャーナリスト の間で広まり、後にクロスビーが出版した3版の著書『生態学的帝国主義』によってさらに強化された: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900』である。チャールズ・C・マンは著書『1493』において、クロスビーの当初の研究をさらに拡大し、更新している[6]。 |

| Background The weight of scientific evidence is that humans first came to the New World from Siberia thousands of years ago. There is little additional evidence of contacts between the peoples of the Old World and those of the New World, although the literature speculating on pre-Columbian trans-oceanic journeys is extensive. The first inhabitants of the New World brought with them domestic dogs and, possibly, a container, the calabash, both of which persisted in their new home.[7] The medieval explorations, visits, and brief residence of the Norsemen in Greenland, Newfoundland, and Vinland in the late 10th century and 11th century had no known impact on the Americas.[8] Many scientists accept that possible contact between Polynesians and coastal peoples in South America around the year 1200 resulted in genetic similarities and the adoption by Polynesians of an American crop, the sweet potato.[9] However, it was only with the first voyage of the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus and his crew to the Americas in 1492 that the Columbian exchange began, resulting in major transformations in the cultures and livelihoods of the peoples in both hemispheres.[1] |

背景 人類が最初にシベリアから新大陸にやってきたのは数千年前であるというのが、科学的証拠の大部分である。旧世界の人々と新世界の人々が接触したことを示す 証拠はほとんどないが、コロンブス以前の大洋横断旅行を推測する文献は数多くある。新大陸の最初の住民は、家畜である犬と、おそらく容器であるカラバッ シュを持ち込んだが、この2つは新天地でも存続した[7]。10世紀後半から11世紀にかけてグリーンランド、ニューファンドランド、ヴィンランドで行わ れた北欧人の中世の探検、訪問、短期間の滞在は、アメリカ大陸に影響を与えたことは知られていない[8]。 しかし、1492年にイタリアの探検家クリストファー・コロンブスとその乗組員たちがアメリカ大陸に初めて航海して以来、コロンブス交流が始まり、両半球の人々の文化や生活に大きな変化をもたらした[1]。 |

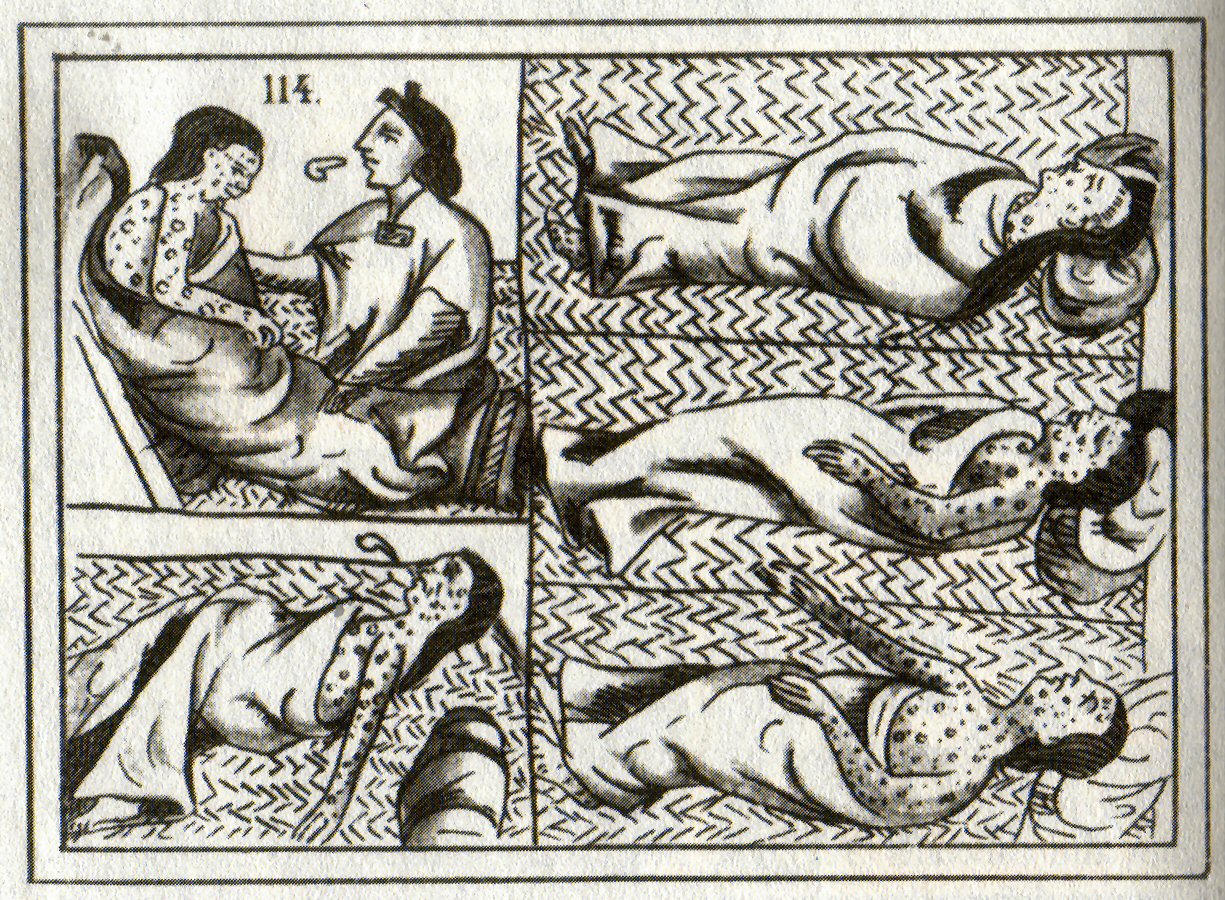

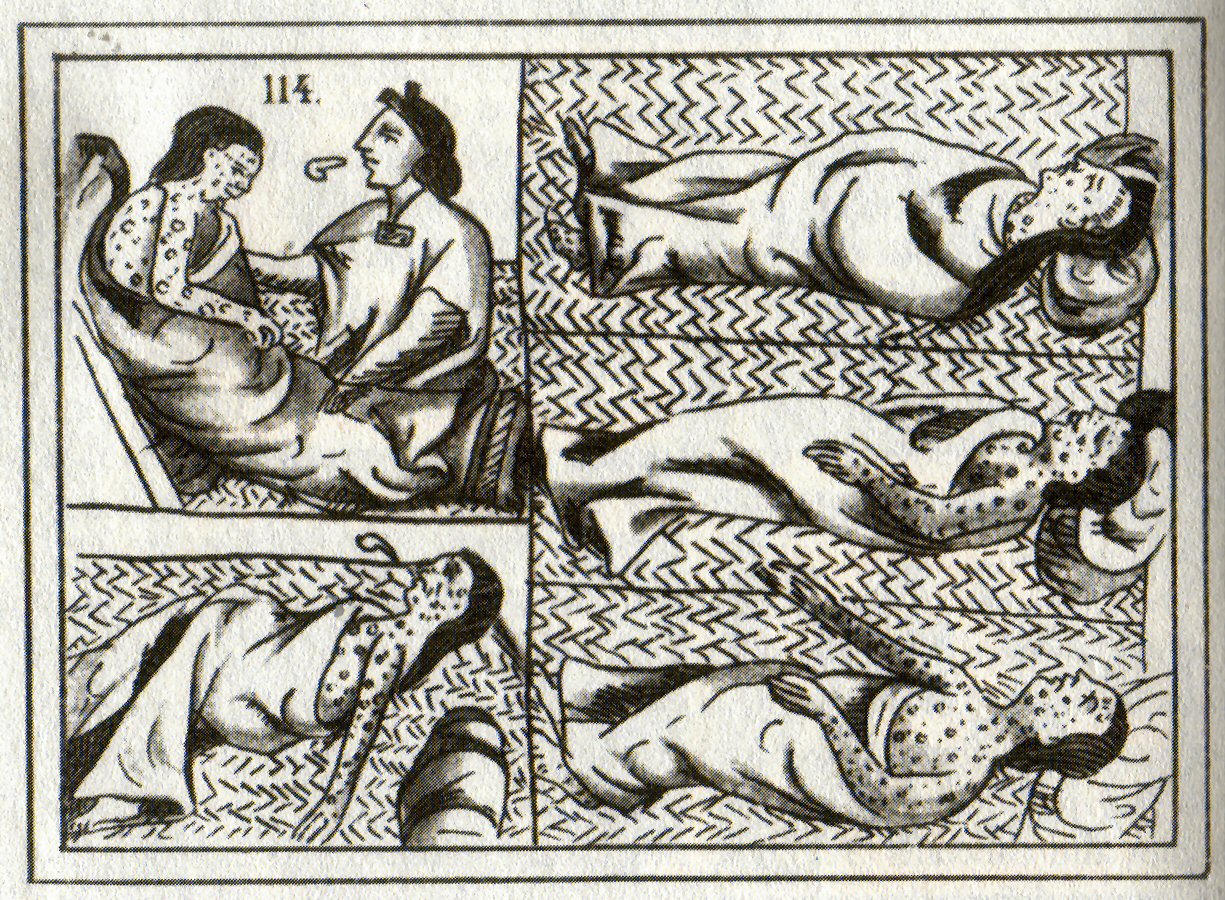

| Diseases Further information: Native American disease and epidemics, Influx of disease in the Caribbean, Virgin soil epidemic, and Cocoliztli epidemics  Sixteenth-century Aztec drawings of victims of smallpox The first manifestation of the Columbian exchange may have been the spread of syphilis from the native people of the Caribbean Sea to Europe. The history of syphilis has been well-studied, but the origin of the disease remains a subject of debate.[10] There are two primary hypotheses: one proposes that syphilis was carried to Europe from the Americas by the crew of Christopher Columbus in the early 1490s, while the other proposes that syphilis previously existed in Europe but went unrecognized.[11] The first written descriptions of syphilis in the Old World came in 1493.[12] The first large outbreak of syphilis in Europe occurred in 1494–1495 among the army of Charles VIII during its invasion of Naples.[11][13][14][15] Many of the crew members who had served with Columbus had joined this army. After the victory, Charles's largely mercenary army returned to their respective homes, thereby spreading "the Great Pox" across Europe and killing up to five million people.[16][17] The Columbian exchange of diseases in the other direction was by far deadlier. The peoples of the Americas previously had no exposure to European and African diseases and little or no immunity.[18] An epidemic of swine influenza beginning in 1493 killed many of the Taino people inhabiting Caribbean islands. The pre-contact population of the island of Hispaniola was probably at least 500,000, but by 1526, fewer than 500 were still alive. Spanish exploitation was part of the cause of the near-extinction of the native people.[19] In 1518, smallpox was first recorded in the Americas and became the deadliest imported Old World disease. Forty percent of the 200,000 people living in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, later Mexico City, are estimated to have died of smallpox in 1520 during the war of the Aztecs with conquistador Hernán Cortés.[20] Epidemics, possibly of smallpox and spread from Central America, devastated the population of the Inca Empire a few years before the arrival of the Spanish.[21] The ravages of Old World diseases and Spanish exploitation reduced the Mexican population from an estimated 20 million to barely more than a million in the 16th century.[22] The indigenous population of Peru decreased from about 9 million in the pre-Columbian era, to 600,000 in 1620.[23] An estimated 80–95 percent of the Native American population died in epidemics within the first 100–150 years following 1492. Nunn and Qian also refer to the calculations of the scientist David Cook, in which in some cases no one survived due to diseases. The deadliest Old World diseases in the Americas were smallpox, measles, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague, typhus, and malaria.[24] |

疾患 さらに詳しい情報 アメリカ先住民の病気と伝染病、カリブ海における病気の流入、処女地の伝染病、Cocoliztliの伝染病  天然痘の犠牲者を描いた16世紀のアステカの絵 コロンブス交流の最初の現れは、カリブ海の先住民からヨーロッパへの梅毒の伝播であったかもしれない。梅毒の歴史はよく研究されているが、その起源につい ては議論が続いている[10]。1つは、1490年代初頭にクリストファー・コロンブスの乗組員によって梅毒がアメリカ大陸からヨーロッパに持ち込まれた という仮説であり、もう1つは、梅毒は以前からヨーロッパに存在していたが認識されていなかったという仮説である[11]。 旧世界における梅毒に関する最初の記述は1493年にもたらされた[12]。 ヨーロッパにおける最初の大規模な梅毒の発生は、1494年から1495年にかけて、ナポリ侵攻中のシャルル8世の軍隊の間で起こった。勝利の後、シャル ルの傭兵部隊はそれぞれの故郷に戻ったが、それによって「大痘瘡」がヨーロッパ全土に広がり、500万人もの人々が命を落とした[16][17]。 一方、コロンブスによる疫病の交換は、はるかに致命的であった。1493年に始まった豚インフルエンザの流行により、カリブ海の島々に住むタイノ族の多く が死亡した。接触以前のヒスパニョーラ島の人口はおそらく少なくとも50万人であったが、1526年までに生存していたのは500人以下であった。スペイ ンの搾取は、先住民が絶滅寸前になった原因の一部であった[19]。 1518年、天然痘がアメリカ大陸で初めて記録され、最も致命的な輸入旧世界病となった。1520年、アステカの首都テノチティトラン(後のメキシコシ ティ)に住んでいた20万人のうち40パーセントが、征服者エルナン・コルテスとの戦争中に天然痘で死亡したと推定されている。 [20] スペイン人が到着する数年前には、天然痘と思われる中米からの伝染病がインカ帝国の人口を壊滅させた[21]。旧世界の伝染病とスペインの搾取によって、 メキシコの人口は16世紀には推定2,000万人からかろうじて100万人以上にまで減少した[22]。 ペルーの先住民の人口は、コロンブス以前の時代には約900万人であったが、1620年には60万人にまで減少した[23]. ナンとチアンは、科学者デビッド・クックの計算にも言及している。アメリカ大陸で最も致命的だった旧世界の病気は、天然痘、麻疹、百日咳、水疱瘡、ペス ト、チフス、マラリアであった[24]。 |

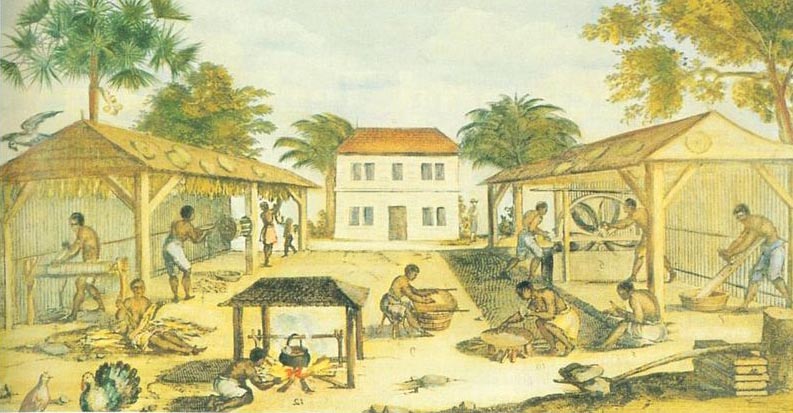

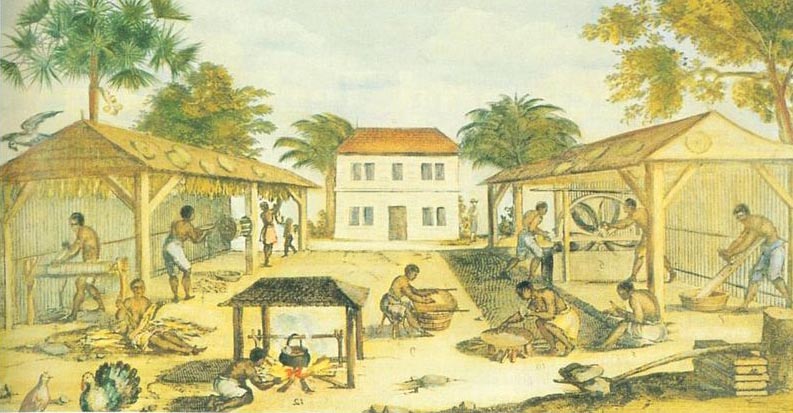

Enslavement of Africans A depiction of slaves working at a plantation in Virginia, 1670 The Atlantic slave trade consisted of the involuntary immigration of 11.7 million Africans, primarily from West Africa, to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries, far outnumbering the about 3.4 million Europeans who migrated, most voluntarily, to the New World between 1492 and 1840.[25] The prevalence of African slaves in the New World was related to the demographic decline of New World peoples and the need of European colonists for labor. Another reason for the demand for slaves was the cultivation of special crops, for example, sugar cane, which were suitable for the climatic conditions of the new lands and were very popular.[26] The Africans had greater immunities to Old World diseases than the New World peoples, and were less likely to die from disease. The journey of enslaved Africans from Africa to America is commonly known as the "middle passage".[27] Enslaved Africans helped shape an emerging African-American culture in the New World. They participated in both skilled and unskilled labor. For example, according to the work of James L. Watson, slaves were involved in handicraft production. They could also work as ordinary workers, and as managers of small enterprises in the commercial or industrial sphere.[28] Their descendants gradually developed an ethnicity that drew from the numerous African tribes as well as European nationalities.[29][26] The descendants of African slaves make up a majority of the population in some Caribbean countries, notably Haiti and Jamaica, and a sizeable minority in most American countries.[30] According to the scholar Jean MacGregor, in the New World there was denial and rebellion against slavery. The rebels went into the rainforests, fought the colonizers, refusing to stop until the signing of agreements, or gathered in settlements. Conscious preservation of ethnic characteristics was considered an unspoken manifestation of resistance. This applied to both men and women, but women had a greater influence on the transmission of ethnic culture to future generations as they were engaged in the upbringing of children. [31] A movement for the abolition of slavery, known as abolitionism, developed in Europe and the Americas during the 18th century. The efforts of abolitionists eventually led to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833, the United States in 1865, and Brazil in 1888. |

アフリカ人の奴隷化 ヴァージニアの農園で働く奴隷の絵(1670年) 大西洋奴隷貿易は、16世紀から19世紀にかけて、主に西アフリカからアメリカ大陸に1,170万人のアフリカ人が非自発的に移住したものであり、 1492年から1840年の間にほとんどが自発的に新大陸に移住した約340万人のヨーロッパ人をはるかに上回っていた[25]。アフリカ人は新世界の人 々よりも旧世界の病気に対する免疫力が高く、病気で死亡する可能性は低かった。アフリカからアメリカへの奴隷にされたアフリカ人の旅は、一般に「ミドル・ パッセージ」として知られている[27]。 奴隷にされたアフリカ人は、新世界で出現したアフリカ系アメリカ人の文化の形成に貢献した。彼らは熟練労働にも非熟練労働にも参加した。例えば、ジェーム ズ・L・ワトソンの研究によれば、奴隷は手工業の生産に携わっていた。彼らの子孫は次第に、ヨーロッパの国籍だけでなく、多数のアフリカの部族から引き出 された民族性を発展させていった[29][26]。 アフリカ人奴隷の子孫は、ハイチやジャマイカをはじめとするカリブ海諸国の一部では人口の過半数を占め、ほとんどのアメリカ諸国ではかなりの少数派である [30]。 学者のジーン・マクレガーによれば、新世界では奴隷制に対する否定と反抗があった。反逆者たちは熱帯雨林に入り、植民者と戦い、協定が結ばれるまで止める ことを拒否し、あるいは入植地に集まった。民族の特徴を意識的に守ることは、抵抗の暗黙の表れと考えられていた。これは男性にも女性にも当てはまったが、 女性は子供の養育に従事していたため、民族文化を後世に伝える上でより大きな影響力を持っていた。[31] 奴隷制度廃止主義として知られる奴隷制度廃止運動は、18世紀にヨーロッパとアメリカ大陸で発展した。奴隷廃止論者の努力により、最終的に1833年に大英帝国、1865年にアメリカ合衆国、1888年にブラジルで奴隷制度が廃止された。 |

Silver A figurine featuring the New World's independently invented wheel. Among the places where wheeled toys were found, Mesoamerica is the only one where the wheel was never put to practical use before the 16th century. The New World produced 80 percent or more of the world's silver in the 16th and 17th centuries, most of it at Potosí in Bolivia, but also in Mexico. The founding of the city of Manila in the Philippines in 1571 for the purpose of facilitating trade in New World silver with China for silk, porcelain, and other luxury products has been called by scholars the "origin of world trade."[32] China was the world's largest economy and in the 1570s adopted silver, which China did not produce in any quantity, as its medium of exchange.[33] China had little interest in buying foreign products, so trade consisted of large quantities of silver coming into China to pay for the Chinese products that foreign countries desired. Silver made it to Manila either through Europe and by ship around the Cape of Good Hope or across the Pacific Ocean in Spanish galleons from the Mexican port of Acapulco. From Manila, the silver was transported onward to China on Portuguese and later Dutch ships. Silver was also smuggled from Potosi to Buenos Aires, Argentina to pay slavers for African slaves imported into the New World.[33] The enormous quantities of silver imported into Spain and China created vast wealth but also caused inflation and the value of silver to decline. In 16th century China, six ounces of silver was equal to the value of one ounce of gold. In 1635, it took 13 ounces of silver to equal in value one ounce of gold. Taxes in both countries were assessed on the weight of silver, not its value. The shortage of revenue due to the decline in the value of silver may have contributed indirectly to the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644. Silver from the Americas financed Spain's attempt to conquer other countries in Europe. The decline in the value of silver left Spain faltering in the maintenance of its world-wide empire and retreating from its aggressive policies in Europe after 1650.[34][35] |

シルバー 新世界で独自に発明された車輪をモチーフにした置物。車輪玩具が発見された場所の中で、16世紀以前に車輪が実用化されなかったのはメソアメリカだけである。 新世界は16世紀から17世紀にかけて世界の銀の80%以上を生産し、そのほとんどはボリビアのポトシで生産されたが、メキシコでも生産された。1571 年にフィリピンにマニラ市が設立されたのは、絹、磁器、その他の贅沢品と交換するために、新世界の銀の中国との貿易を促進するためであり、学者たちは「世 界貿易の起源」と呼んでいる[32]。中国は世界最大の経済大国であり、1570年代には、中国が生産していなかった銀を交換媒体として採用した [33]。 中国は外国製品を買うことにほとんど関心がなかったため、貿易は、外国が欲しがる中国製品の代金を支払うために中国に入ってくる大量の銀で成り立ってい た。銀はヨーロッパを経由して喜望峰を回る船か、メキシコのアカプルコ港からスペインのガレオン船で太平洋を渡ってマニラに運ばれた。マニラから銀はポル トガル船、後にはオランダ船で中国へと運ばれた。銀はまた、ポトシからアルゼンチンのブエノスアイレスへも密輸され、新大陸に輸入されたアフリカ人奴隷の 奴隷商人に支払われた[33]。 スペインと中国に輸入された膨大な量の銀は、莫大な富を生み出したが、同時にインフレを引き起こし、銀の価値を下落させた。16世紀の中国では、6オンス の銀は1オンスの金の価値に等しかった。1635年には、金1オンスの価値に等しい銀13オンスが必要だった。両国とも、税金は銀の価値ではなく重さに対 して課された。銀の価値下落による歳入不足は、1644年の明王朝滅亡に間接的に貢献したのかもしれない。アメリカ大陸の銀は、スペインがヨーロッパ諸国 を征服するための資金となった。銀の価値の下落により、スペインは世界的な帝国の維持に挫折し、1650年以降はヨーロッパにおける攻撃的な政策から後退 した[34][35]。 |

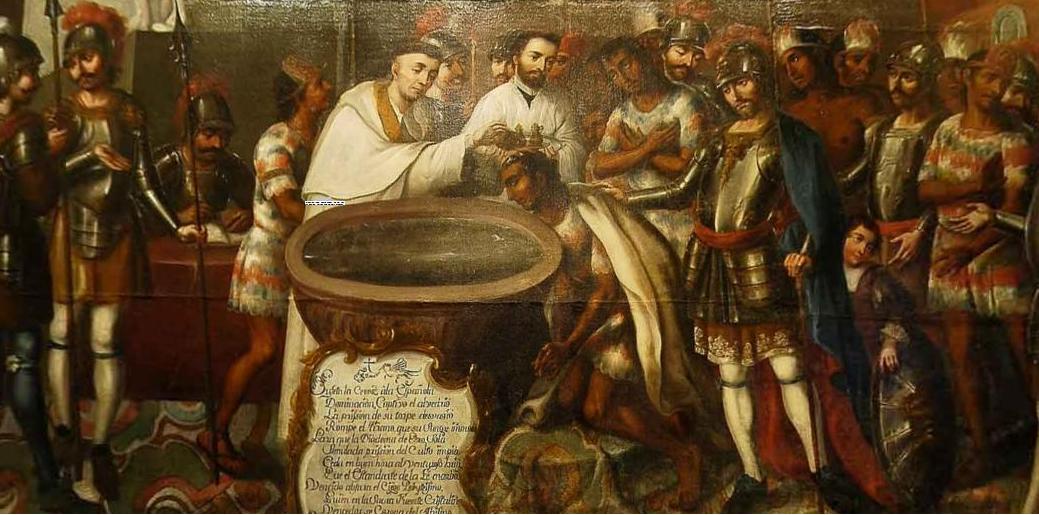

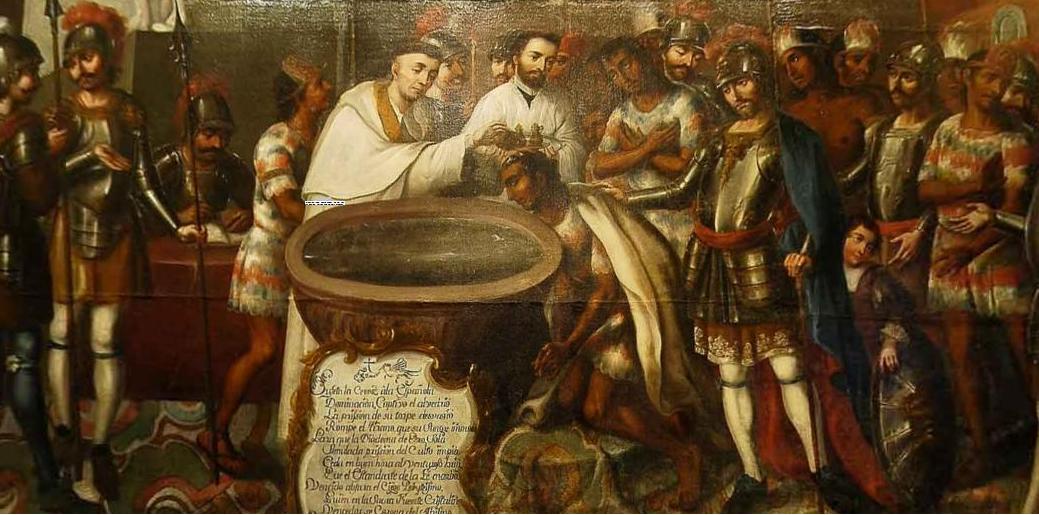

| Effects Crops  Andenes on Taquile are used to grow traditional Andean staples such as quinoa and potatoes, alongside wheat—a European introduction. Because of the new trading resulting from the Columbian exchange, several plants native to the Americas have since spread around the world, including potatoes, maize, tomatoes, and tobacco.[36] Before 1500, potatoes were not grown outside of South America. By the 18th century, they were cultivated and consumed widely in Europe and had become important crops in both India and North America. A highly caloric crop,[37] potatoes eventually became an important staple food in the diets of many Europeans, contributing to an estimated 25% of the population growth in Afro-Eurasia between 1700 and 1900.[38] Many European rulers, including Frederick the Great of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia, encouraged the cultivation of the potato.[39] Despite their lack of some essential nutrients such as vitamins D and A, potatoes came to satisfy major portions of the nutritional needs of people around the world. According to one study, the introduction of potatoes to the Old World correlates with a subsequent 47 percent increase in urbanization and a 12 percent increase in population.[2] Maize and cassava were introduced from South America by the Portuguese in the 16th century,[40] and gradually replaced sorghum and millet as Africa's most important food crops.[41] Spanish colonizers of the 16th century introduced new staple crops to Asia from the Americas, including maize and sweet potatoes, and thereby contributed to population growth in Asia.[42] On a larger scale, the introduction of potatoes and maize to the Old World "resulted in caloric and nutritional improvements over previously existing staples" throughout the Eurasian landmass,[43] enabling more varied and abundant food production.[44] Despite the popularity of maize, cassava was in greater demand in the Old World. These crops also have negative consequences when overused (for example, the nutritional diseases pellagra and konzo), but this has not diminished the importance of maize and cassava to human nutrition.[2] Tomatoes, which came to Europe from the New World via Spain, were initially prized in Italy mainly for their ornamental value. Starting in the 19th century, tomato sauces became typical of Neapolitan cuisine and, ultimately, Italian cuisine in general.[45] The discovery of the Americas brought the Old World not only many previously unknown plant species but also new arable landscapes with favorable soils for growing highly valued Old World crops, such as sugarcane and coffee. Sugar had long been important to Old World populations and found even greater importance when cultivated in the New World, as it is high-calorie and inexpensive. It was actively used in cooking and is thought to have increased the well-being of its consumers.[43] Coffee, introduced in the Americas circa 1720 from Africa and the Middle East, and sugarcane, introduced from the Indian subcontinent to the Spanish West Indies, subsequently became the primary commodity crops and exported goods of extensive Latin American plantations. Introduced to India by the Portuguese, chili peppers and potatoes from South America in turn became integral parts of Indian cuisine.[46] The discovery and spread of chili peppers in particular contributed to the creation of many well-known dishes and spices which are now intimately identified with Old World locales, including Korean kimchi, Indian curry, and Hungarian paprika. Because crops traveled widely but at least initially their endemic fungi did not, for a limited time yields were somewhat higher in the new regions to which they were introduced due to a form of ecological release. Dark & Gent (2001) termed this the "yield honeymoon". However, as globalization has continued, the exchange of pathogens has also continued, and crops have declined back toward their endemic yields.[47] Nunn and Qian mention chocolate and vanilla in their work. The Spanish were the first Europeans to grow cacao, in 1590. Though cacao was usually consumed by European populations in the form of sweets and was at first treated as an expensive luxury item, it helped to cope with fatigue and add strength and energy. As for vanilla, the pods of the plant after chemical treatment acquired an aroma, which was then used both in cooking and in perfumery.[2] Rice See also: Rice production in the United States Rice was another crop that became widely cultivated during the Columbian exchange. As the demand in the New World grew, so did the knowledge of how to cultivate it. The two primary species used were Oryza glaberrima and Oryza sativa, originating from West Africa and Southeast Asia, respectively. European planters in the New World relied upon the skills of African slaves to cultivate both species.[48] Georgia, South Carolina, Cuba, and Puerto Rico were major centers of rice production during the colonial era. Enslaved Africans brought their knowledge of water control, milling, winnowing, and other agrarian practices to the fields. This widespread knowledge among African slaves eventually led to rice becoming a staple food in the New World.[5][49] Fruits Citrus fruits and grapes were brought to the Americas from the Mediterranean. At first planters struggled to adapt these crops to New World climates, but by the late 19th century they were cultivated more consistently.[50] Bananas were introduced into the Americas in the 16th century by Portuguese sailors, who came across the fruits in West Africa while engaged in commercial ventures and the slave trade. Despite this early introduction they were consumed in minimal amounts in the Americas as late as the 1880s. The U.S. did not see major increases in banana consumption until large plantations were established in the Caribbean.[51] Tomatoes It took three centuries after their introduction in Europe for tomatoes to become a widely accepted food item. Nunn & Qian claim that, according to experts, long before the arrival of the Spaniards, wild tomatoes came from Central America to South America, thereby initiating the cultivation of tomatoes in different parts of the Americas.[2] Tobacco, potatoes, chili peppers, tomatillos, and tomatoes are all members of the nightshade family. Similar to some European nightshade varieties, tomatoes and potatoes can be harmful or even lethal if the wrong part of the plant is consumed in excess. Physicians in the 16th century had good reason to suspect that this native Mexican fruit was poisonous; they suspected it of generating "melancholic humours".[citation needed] In 1544, Pietro Andrea Mattioli, a Tuscan physician and botanist, suggested that tomatoes might be edible, but no record exists of anyone consuming them at this time. In 1592, the head gardener at the botanical garden of Aranjuez near Madrid, under the patronage of Philip II of Spain, wrote, "it is said [tomatoes] are good for sauces". In spite of these comments, tomatoes remained exotic plants grown for ornamental purposes, but rarely for culinary use.[citation needed] On October 31, 1548, the tomato was given its first name anywhere in Europe when a house steward of Cosimo I de' Medici, Duke of Florence, wrote to the Medici's private secretary that the basket of pomi d'oro "had arrived safely". At this time, the label pomi d'oro was also used to refer to figs, melons, and citrus fruits in treatises by scientists.[52] In the early years, tomatoes were mainly grown as ornamentals in Italy. For example, the Florentine aristocrat Giovan Vettorio Soderini wrote that they "were to be sought only for their beauty" and were grown only in gardens or flower beds. Tomatoes were grown in elite town and country gardens in the fifty years or so following their arrival in Europe, and were only occasionally depicted in works of art.[citation needed] Tomatoes are very useful, as they contain significant amounts of the essential vitamins C and A. Even despite the small number of calories they provide, tomatoes have become regular contributors to the diets of Western consumers.[2] The first Italian cookbook to include tomato sauce, Lo Scalco alla Moderna ("The Modern Steward"), was written by Italian chef Antonio Latini and was published in two volumes in 1692 and 1694. In 1790, the use of tomato sauce with pasta appeared for the first time, in the Italian cookbook L'Apicio Moderno ("The Modern Apicius"), by chef Francesco Leonardi.[53] Today around 32,000 acres (13,000 ha) of tomatoes are cultivated in Italy.[52] The most problematic thing about eating tomatoes was their storage conditions. In hot weather, tomatoes deteriorated in just a few days. Canning solved this problem by allowing the product to be stored for months. Although canning was expensive in the beginning, after the introduction of mechanical labor, tomatoes became available to everyone.[2] Canned tomatoes contain a useful antioxidant, lycopene, which reduces the risk of developing serious diseases.[2] Livestock Further information: Plains Indians § Horses  Native Americans learned to use horses to chase bison, dramatically expanding their hunting range. Initially, the Columbian exchange of animals largely went in one direction, from Europe to the New World, as the Eurasian regions had domesticated many more animals. Horses, donkeys, mules, pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, chickens, large dogs, cats, and bees were rapidly adopted by native peoples for transport, food, and other uses.[54] One of the first European exports to the Americas, the horse, changed the lives of many Native American tribes. The mountain tribes shifted to a nomadic lifestyle, based on hunting bison on horseback. They largely gave up settled agriculture.[citation needed] Horse culture was adopted gradually by Great Plains Indians. The existing Plains tribes expanded their territories with horses, and the animals were considered so valuable that horse herds became a measure of wealth.[citation needed] This transfer reintroduced horses to the Americas, as the species had died out there prior to the development of the modern horse in Eurasia. While mesoamerican peoples, Mayas in particular, already practiced apiculture,[55] producing wax and honey from a variety of bees, such as Melipona or Trigona,[56] European bees (Apis mellifera)—were more productive, delivering a honey with less water content and allowing for an easier extraction from beehives—were introduced in New Spain, becoming an important part of farming production.[57] The effects of the introduction of European livestock on the environments and peoples of the New World were not always positive. In the Caribbean, the proliferation of European animals consumed native fauna and undergrowth, changing habitat. If free ranging, the animals often damaged conucos, plots managed by indigenous peoples for subsistence.[58] The Mapuche of Araucanía were fast to adopt the horse from the Spanish, and improve their military capabilities as they fought the Arauco War against Spanish colonizers.[59][60] Until the arrival of the Spanish, the Mapuches had largely maintained chilihueques (llamas) as livestock. The Spanish introduction of sheep caused some competition between the two domesticated species. Anecdotal evidence of the mid-17th century show that by then both species coexisted but that the sheep far outnumbered the llamas. The decline of llamas reached a point in the late 18th century when only the Mapuche from Mariquina and the Huequén next to Angol raised llamas.[61] In the Chiloé Archipelago the introduction of pigs by the Spanish proved a success. They could feed on the abundant shellfish and algae exposed by the large tides.[61] In the other direction, the turkey, guinea pig, and the Muscovy duck were New World animals that were transferred to Europe.[62] Medicines European exploration of tropical areas was aided by the New World discovery of quinine, the first effective treatment for malaria. Cinchona trees from the Andes were processed and quinine was obtained from their bark.[2] Europeans suffered from this disease, but some indigenous populations had developed at least partial resistance to it. In Africa, resistance to malaria has been associated with other genetic changes among sub-Saharan Africans and their descendants, which can cause sickle-cell disease.[63] The resistance of sub-Saharan Africans to malaria in the southern United States and the Caribbean contributed greatly to the specific character of the Africa-sourced slavery in those regions.[64] Similarly, yellow fever is thought to have been brought to the Americas from Africa via the Atlantic slave trade. Because it was endemic in Africa, many people there had acquired immunity. Europeans suffered higher rates of death than did African-descended persons when exposed to yellow fever in Africa and the Americas, where numerous epidemics swept the colonies beginning in the 17th century and continuing into the late 19th century. The disease caused widespread fatalities in the Caribbean during the heyday of slave-based sugar plantation. The replacement of native forests by sugar plantations and factories facilitated its spread in the tropical area by reducing the number of potential natural mosquito predators. The means of yellow fever transmission was unknown until 1881, when Carlos Finlay suggested that the disease was transmitted through mosquitoes, now known to be female mosquitoes of the species Aedes aegypti.[65] Cultural exchanges  The evangelization of Mexico One of the results of the movement of people between New and Old Worlds were cultural exchanges. For example, in the article "The Myth of Early Globalization: The Atlantic Economy, 1500–1800", Pieter Emmer makes the point that "from 1500 onward, a 'clash of cultures' had begun in the Atlantic".[66] This clash of culture involved the transfer of European values to indigenous cultures. As an example, the emergence of the concept of private property in regions where property was often viewed as communal, concepts of monogamy (although many indigenous peoples were already monogamous), the role of women and children in the social system, and different concepts of labor, including slavery,[67] although slavery was already a practice among many indigenous peoples and was widely practiced or introduced by Europeans into the Americas. Another example included the European abhorrence of human sacrifice, a religious practice among some indigenous populations.[citation needed] During the initial stages of European colonization of the Americas, Europeans encountered fence-less lands. They believed that the land was unimproved and available for their taking, as they sought economic opportunity and homesteads. However, when European settlers arrived in Virginia, they encountered a fully established indigenous people, the Powhatan. The Powhatan farmers in Virginia scattered their farm plots within larger cleared areas. These larger cleared areas were a communal place for growing useful plants. As the Europeans viewed fences as hallmarks of civilization, they set about transforming "the land into something more suitable for themselves".[68][page needed] Tobacco was a New World agricultural product, originally a luxury good spread as part of the Columbian exchange. As is discussed in regard to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the tobacco trade increased demand for free labor and spread tobacco worldwide. In discussing the widespread uses of tobacco, the Spanish physician Nicolas Monardes (1493–1588) noted that "The black people that have gone from these parts to the Indies, have taken up the same manner and use of tobacco that the Indians have".[69] As Europeans traveled to other parts of the world, they took with them the practices related to tobacco. Demand for tobacco grew in the course of these cultural exchanges among peoples.[citation needed] Tobacco was used in the Old World as medicine and currency.[2] In the New World, tobacco was the subject of religious customs.[2] Tobacco was in great demand until 1950, when the disastrous effect of tobacco on the human body were first widely publicized. Although tobacco use is in decline today, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), it still remains "the single greatest cause of preventable death globally."[70][2] One of the most clearly notable areas of cultural clash and exchange was that of religion, often the lead point of cultural conversion. In the Spanish and Portuguese dominions, the spread of Catholicism, steeped in a European values system, was a major objective of colonization. Europeans often pursued it via explicit policies of suppression of indigenous languages, cultures and religions. In British America, Protestant missionaries converted many members of indigenous tribes to Protestantism. The French colonies had a more outright religious mandate, as some of the early explorers, such as Jacques Marquette, were also Catholic priests. In time, and given the European technological and immunological superiority which aided and secured their dominance, indigenous religions declined in the centuries following the European settlement of the Americas. While the Mapuche of Araucania adopted the horse, sheep, and wheat, the over-all scant adoption of Spanish technology and adherence to ancestral customs by Mapuche was a means of cultural resistance.[71] According to Caroline Dodds Pennock, in Atlantic history indigenous people are often seen as static recipients of transatlantic encounters. But thousands of Native Americans crossed the ocean during the sixteenth century, some by choice.[72] |

効果 作物  タキーレのアンデス山脈では、ヨーロッパから導入された小麦と並んで、キヌアやジャガイモといったアンデスの伝統的な主食が栽培されている。 コロンブス交換による新たな交易の結果、ジャガイモ、トウモロコシ、トマト、タバコなど、アメリカ大陸原産の植物が世界中に広まった。18世紀までには、 ヨーロッパで広く栽培され消費されるようになり、インドと北米でも重要な作物となった。プロイセンのフリードリヒ大王やロシアのエカテリーナ大王を含む多 くのヨーロッパの支配者たちは、ジャガイモの栽培を奨励した[39]。ビタミンDやビタミンAなどの必須栄養素を欠いているにもかかわらず、ジャガイモは 世界中の人々の栄養需要の大部分を満たすようになった。ある研究によると、旧世界へのジャガイモの導入は、その後の都市化の47パーセントの増加と人口の 12パーセントの増加と相関している[2]。 トウモロコシとキャッサバは、16世紀にポルトガル人によって南米から導入され[40]、次第にアフリカの最も重要な食用作物としてソルガムとキビに取っ て代わった[41]。 [より大きなスケールでは、旧世界へのジャガイモとトウモロコシの導入は、ユーラシア大陸全体で「以前からあった主食よりもカロリーと栄養が改善された」 [43]結果、より多様で豊富な食料生産を可能にした[44]。これらの作物も、過剰に使用されると(例えば、栄養疾患であるペラグラやコンツォなど)否 定的な結果をもたらすが、それでもトウモロコシとキャッサバの人類の栄養における重要性が低下することはなかった[2]。 新大陸からスペインを経由してヨーロッパに伝わったトマトは、当初イタリアでは主に観賞用として珍重されていた。アメリカ大陸の発見は、旧世界にそれまで 知られていなかった多くの植物種をもたらしただけでなく、サトウキビやコーヒーといった旧世界で高く評価されていた作物を栽培するのに適した土壌を持つ新 しい耕作地をもたらした。砂糖は古くから旧世界の人々にとって重要なものであったが、新世界で栽培されるようになると、高カロリーで安価であることから、 その重要性はさらに高まった。砂糖は料理に積極的に使われ、消費者の幸福度を高めたと考えられている[43]。 1720年頃にアフリカと中東からアメリカ大陸に導入されたコーヒーと、インド亜大陸からスペイン領西インド諸島に導入されたサトウキビは、その後、ラテ ンアメリカの大規模なプランテーションの主要な商品作物および輸出品となった。特に唐辛子の発見と普及は、韓国のキムチ、インドのカレー、ハンガリーのパ プリカなど、現在では旧世界の土地と密接に結びついた多くの有名な料理や香辛料の創造に貢献した。 農作物は広範囲に移動したが、少なくとも当初は固有の菌類は移動しなかったため、限られた期間ではあったが、生態学的放出の一形態により、農作物が導入さ れた新しい地域では収量が多少高くなった。Dark & Gent(2001)はこれを「収量ハネムーン」と呼んでいる。しかし、グローバリゼーションが進むにつれて、病原菌の交換も続き、作物は固有収量に向 かって減少している[47]。 NunnとQianは、チョコレートとバニラについて言及している。スペイン人は1590年にヨーロッパ人として初めてカカオを栽培した。カカオは通常、 お菓子の形でヨーロッパの人々に消費され、当初は高価な贅沢品として扱われていたが、疲労に対処し、力とエネルギーを加えるのに役立った。バニラについて は、化学処理後の植物のさやに香りがつき、料理にも香水にも使われるようになった[2]。 米 以下も参照のこと: アメリカのコメ生産 米もまた、コロンブス交換の間に広く栽培されるようになった作物である。新世界での需要が高まるにつれて、栽培方法の知識も広がった。主に使われたのは、 西アフリカ原産のオリザ・グラベリマと東南アジア原産のオリザ・サティバだった。ジョージア、サウスカロライナ、キューバ、プエルトリコは植民地時代、米 生産の主要な中心地であった。奴隷にされたアフリカ人たちは、治水、精米、唐箕、その他の農耕に関する知識を田畑に持ち込んだ。アフリカ人奴隷の間に広 まったこの知識は、最終的に米が新世界の主食となるきっかけとなった[5][49]。 果物 柑橘類とブドウは地中海からアメリカ大陸にもたらされた。当初、プランターたちはこれらの作物を新世界の気候に適応させるのに苦労したが、19世紀後半にはより安定的に栽培されるようになった[50]。 バナナは、16世紀にポルトガルの船員によってアメリカ大陸に導入された。彼らは、商業事業と奴隷貿易に従事している間に、西アフリカでこの果物に出会っ た。このように早くから導入されていたにもかかわらず、アメリカ大陸では、1880年代後半にはごく少量しか消費されていなかった。アメリカでは、カリブ 海に大規模なプランテーションが設立されるまで、バナナの消費量が大きく増加することはなかった[51]。 トマト トマトが広く受け入れられる食品になるまでには、ヨーロッパで導入されてから3世紀を要した。NunnとQianは、専門家によると、スペイン人が到着す るずっと前に、野生のトマトが中央アメリカから南アメリカに渡り、それによってアメリカ大陸の様々な地域でトマトの栽培が始まったと主張している[2]。 タバコ、ジャガイモ、唐辛子、トマティーヨ、トマトはすべてナイトシェード科の植物である。ヨーロッパのナイトシェード種と同様、トマトやジャガイモも、 間違った部位を過剰に摂取すると、有害であったり、死に至ることさえある。16世紀の医師たちは、このメキシコ原産の果実に毒があると疑う十分な理由が あった。 1544年、トスカーナの医師であり植物学者であったピエトロ・アンドレア・マッティオリは、トマトが食用になる可能性を示唆したが、この時点でトマトを 食した人の記録は残っていない。1592年、スペインのフィリップ2世の庇護を受けたマドリード近郊のアランフェス植物園の庭師長は、「(トマトは)ソー スに適していると言われている」と記している。1548年10月31日、フィレンツェ公コジモ1世デ・メディチ家の執事が、ポミ・ドーロのバスケットが 「無事に到着した」とメディチ家の私設秘書に書き送ったことで、トマトはヨーロッパで初めてその名を与えられた。この頃、ポミ・ドーロというラベルは、科 学者の論文でイチジク、メロン、柑橘類を指す場合にも使われていた[52]。 初期の頃、イタリアではトマトは主に観賞用として栽培されていた。例えば、フィレンツェの貴族ジョヴァン・ヴェットリオ・ソデリーニは、トマトは「その美 しさのためにのみ求められる」と記しており、庭や花壇でのみ栽培されていた。トマトがヨーロッパに渡ってから50年ほどは、エリートの町や田舎の庭で栽培 されていたが、芸術作品に描かれることはまれだった。トマトが提供するカロリーは少ないにもかかわらず、トマトは西洋の消費者の食生活の常連となっている [2]。トマトソースを含む最初のイタリア料理本『Lo Scalco alla Moderna』(「現代の執事」)は、イタリア人シェフ、アントニオ・ラティーニによって書かれ、1692年と1694年に2巻で出版された。1790 年、シェフであるフランチェスコ・レオナルディによるイタリアの料理本『L'Apicio Moderno(現代のアピシウス)』において、パスタにトマトソースが初めて使用された[53]。現在、イタリアでは約32,000エーカー (13,000ヘクタール)のトマトが栽培されている[52]。 トマトを食べる上で最も問題だったのは、その保存状態だった。暑い気候では、トマトはわずか数日で劣化してしまう。缶詰は、製品を数ヶ月間保存できるよう にすることで、この問題を解決した。缶詰は当初高価であったが、機械労働が導入された後、トマトは誰にでも手に入るようになった[2]。トマトの缶詰には 有用な抗酸化物質であるリコピンが含まれており、重篤な病気にかかるリスクを軽減する[2]。 家畜 さらに詳しい情報 平原インディアン§馬  アメリカ先住民はバイソンを追うために馬を使うことを学び、彼らの狩猟範囲を劇的に広げた。 当初、ユーラシア大陸ではより多くの動物が家畜化されていたため、コロンブスによる動物の交流は、ヨーロッパから新世界へという一方向のものであった。 馬、ロバ、ラバ、ブタ、ウシ、ヒツジ、ヤギ、ニワトリ、大型犬、ネコ、ミツバチは、輸送、食料、その他の用途のために、先住民によって急速に採用された [54]。ヨーロッパからアメリカ大陸への最初の輸出品のひとつである馬は、多くのアメリカ先住民の生活を変えた。山岳部族は、馬に乗ってバイソンを狩猟 する遊牧生活に移行した。彼らは定住農業をほとんど放棄した[要出典]。 馬の文化は大平原インディアンによって徐々に取り入れられた。既存の平原部族は馬によって領土を拡大し、馬は非常に貴重な動物とみなされたため、馬の群れ は富の指標となった[要出典]。ユーラシア大陸で現代の馬が開発される前に、アメリカ大陸では馬の種が絶滅していたため、この移動によってアメリカ大陸に 馬が再導入された。 中米の人々、特にマヤ族はすでに養蜂を実践しており[55]、メリポナやトリゴナといった様々なミツバチから蝋や蜂蜜を生産していた[56]が、ヨーロッ パミツバチ(Apis mellifera)はより生産性が高く、水分の少ない蜂蜜を生産し、蜂の巣からより簡単に蜂蜜を採取することができたため、ニュー・スペインに導入さ れ、農業生産の重要な一部となった[57]。 ヨーロッパからの家畜の導入が新世界の環境や人々に与えた影響は、必ずしも肯定的なものばかりではなかった。カリブ海では、ヨーロッパ産の家畜の繁殖が在 来の動物相や下草を食い荒らし、生息地を変えた。放し飼いにされていた場合、動物はしばしばコヌコ(先住民が自給自足のために管理していた耕作地)を傷つ けた[58]。 アラウカニアのマプーチェ族はスペイン人からいち早く馬を導入し、スペインの植民者とアラウコ戦争を戦いながら軍事力を向上させた[59][60]。スペ イン人が到着するまで、マプーチェ族は家畜として主にチリフエケ(ラマ)を飼育していた。スペイン人が羊を導入したことで、2つの家畜種が競合することに なった。17世紀半ばの逸話によると、その頃には両種は共存していたが、リャマよりもヒツジの方が圧倒的に多かったという。リャマの衰退は18世紀後半に 達し、マリキナのマプチェ族とアンゴルの隣のフエケン族だけがリャマを飼育するようになった[61]。チロエ群島では、スペイン人による豚の導入が成功し た。彼らは大潮によって露出した豊富な貝類や藻類を食べることができた[61]。 一方、七面鳥、モルモット、マスコビーアヒルは、ヨーロッパに移入された新世界の動物であった[62]。 医薬品 ヨーロッパによる熱帯地域の探検は、マラリアに対する最初の有効な治療薬であるキニーネの新世界での発見によって助けられた。アンデス山脈のキナノキが加 工され、その樹皮からキニーネが得られた[2]。ヨーロッパ人はこの病気に苦しんだが、先住民の中には少なくとも部分的な耐性を獲得している者もいた。ア フリカでは、マラリアに対する耐性は、サハラ以南のアフリカ人とその子孫の間で、鎌状赤血球症を引き起こす可能性のある他の遺伝的変化と関連している [63]。米国南部とカリブ海地域におけるサハラ以南のアフリカ人のマラリアに対する耐性は、これらの地域におけるアフリカを起源とする奴隷制の特異な性 格に大きく寄与していた[64]。 同様に、黄熱病は大西洋奴隷貿易を通じてアフリカからアメリカ大陸にもたらされたと考えられている。アフリカでは風土病であったため、多くの人々が免疫を 獲得していた。ヨーロッパ人はアフリカやアメリカ大陸で黄熱病にかかると、アフリカ系住民よりも高い死亡率に苦しんだ。この病気は、奴隷による砂糖プラン テーションの全盛期だったカリブ海で広範な死者を出した。原生林が砂糖プランテーションや工場に取って代わられたことで、蚊の天敵が減り、黄熱病が熱帯地 域に蔓延しやすくなった。1881年にカルロス・フィンレイが黄熱病が蚊によって伝染することを示唆するまで、黄熱病の伝染手段は不明であったが、現在で はアカイエカという種の雌の蚊であることが知られている[65]。 文化交流  メキシコの福音化 新大陸と旧大陸の間で人々が移動した結果のひとつに、文化交流があった。例えば、「初期グローバリゼーションの神話: 大西洋経済、1500-1800年」において、ピーテル・エマーは「1500年以降、大西洋において『文化の衝突』が始まった」と指摘している[66]。 一例として、財産を共同的なものとみなすことが多かった地域における私有財産の概念の出現、一夫一婦制の概念(多くの先住民はすでに一夫一婦制であった が)、社会システムにおける女性と子どもの役割、奴隷制を含む労働に関する異なる概念などが挙げられる[67]。別の例としては、一部の先住民の間で宗教 的な慣習として行われていた人身御供をヨーロッパ人が忌み嫌ったことが挙げられる[要出典]。 ヨーロッパ人がアメリカ大陸を植民地化した初期の段階で、ヨーロッパ人は柵のない土地に遭遇した。彼らは経済的な機会と住居を求めたため、その土地は改良 されておらず、手に入れることができると信じていた。しかし、ヨーロッパ人入植者がヴァージニアに到着したとき、彼らは完全に確立された先住民であるパウ ハタン族に遭遇した。ヴァージニアのパウハタン族の農民たちは、より広大な更地の中に農地を点在させていた。これらの耕作地は、有用な植物を栽培するため の共同場所であった。ヨーロッパ人は柵を文明の象徴とみなし、「土地を自分たちにとってより適したものに変える」ことに着手した[68][要ページ]。 タバコは新世界の農産物であり、もともとはコロンブス交換の一環として広まった贅沢品であった。大西洋横断奴隷貿易に関して議論されているように、タバコ 貿易は自由労働の需要を高め、タバコを世界中に広めた。スペインの医師ニコラス・モナルデス(Nicolas Monardes, 1493-1588)は、タバコの広範な使用について論じる中で、「この地域からインド諸島に行った黒人は、インディアンが行っているのと同じようにタバ コを使用し、タバコの使い方をした」と述べている[69]。 ヨーロッパ人が世界の他の地域を旅するにつれて、彼らはタバコに関する習慣を持ち出した。旧世界ではタバコは薬や通貨として使用され、新世界ではタバコは 宗教的習慣の対象であった[2]。タバコの人体への悲惨な影響が初めて広く知られるようになった1950年まで、タバコは大きな需要があった。世界保健機 関(WHO)によれば、今日ではタバコの使用は減少しているものの、依然として「世界的に予防可能な死亡の唯一最大の原因」である[70][2]。 文化的衝突と交流の最も顕著な分野のひとつは宗教であり、しばしば文化的転換の主導的な役割を果たした。スペインとポルトガルの領地では、ヨーロッパの価 値観に染まったカトリックの普及が植民地化の主要な目的であった。ヨーロッパ人はしばしば、土着の言語、文化、宗教を抑圧する明確な政策によって、それを 追求した。イギリス領アメリカでは、プロテスタントの宣教師が先住民族の多くをプロテスタントに改宗させた。フランスの植民地では、ジャック・マルケット のような初期の探検家がカトリックの司祭であったため、より明白な宗教的使命があった。やがて、ヨーロッパ人の技術的、免疫学的優位性が彼らの支配を助 け、確保したことから、ヨーロッパ人のアメリカ大陸入植後数世紀で、先住民の宗教は衰退していった。 アラウカニアのマプチェは馬、羊、小麦を取り入れたが、全体的にスペインの技術をほとんど取り入れず、マプチェが先祖伝来の習慣を守ることは文化的抵抗の手段であった[71]。 キャロライン・ドッズ・ペノックによれば、大西洋の歴史において先住民は大西洋横断的な出会いの静的な受け手として見られることが多い。しかし、16世紀には何千人ものアメリカ先住民が海を渡り、そのうちの何人かは自ら望んで渡ったのである[72]。 |

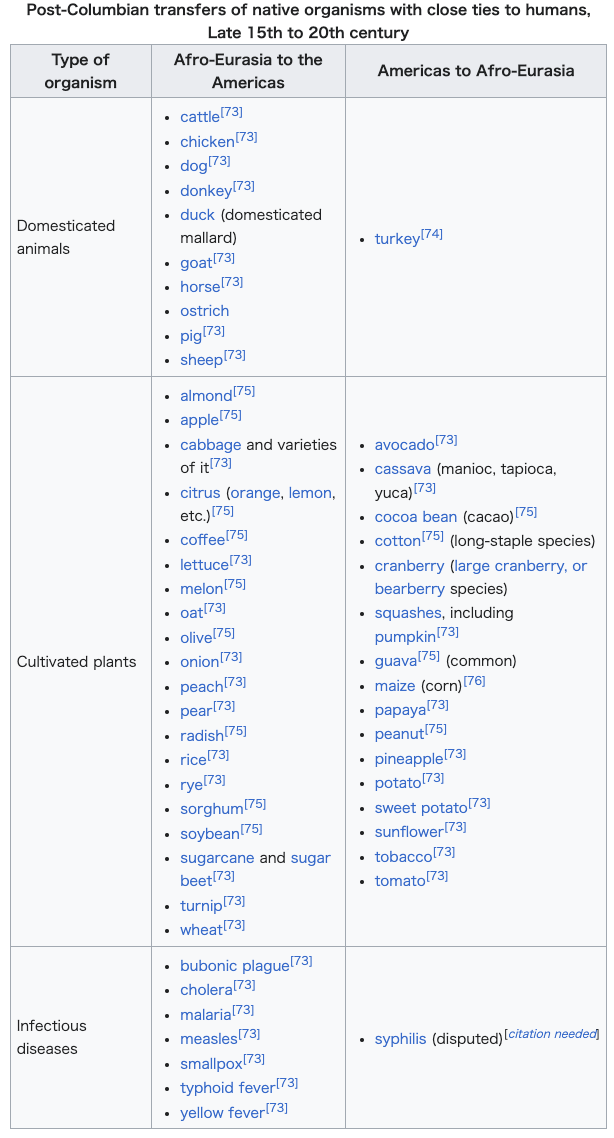

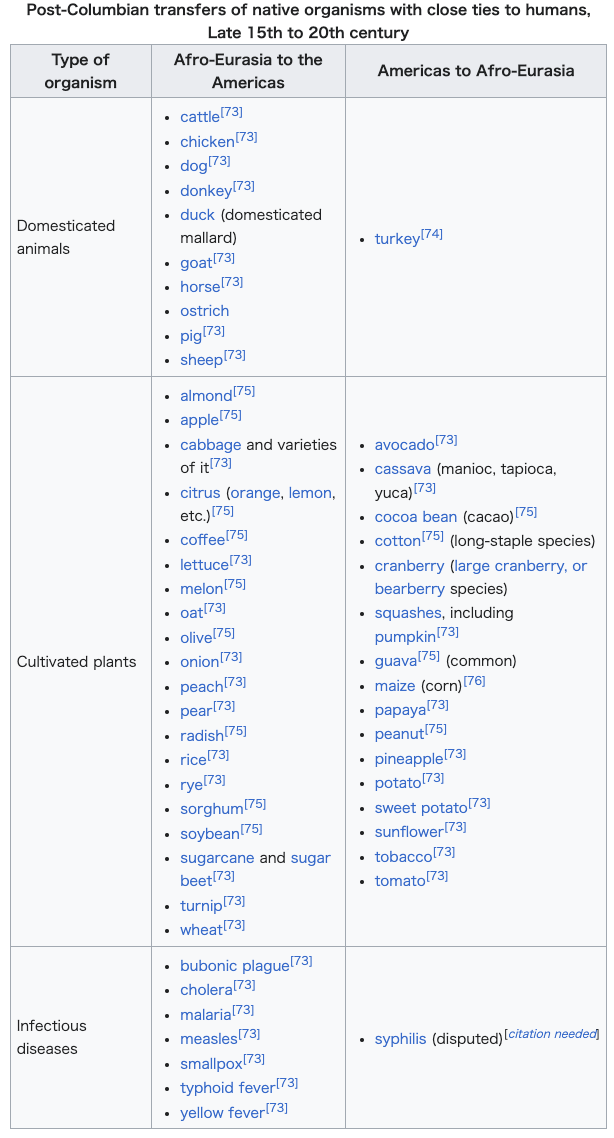

Post-Columbian transfers of native organisms with close ties to humans, Late 15th to 20th century |

15世紀後半から20世紀にかけて、人類と密接な関係を持つ在来生物がコロンブス後に移入された。 |

| Later history Further information: Introduced species, Invasive species, and Lists of invasive species Plants that arrived by land, sea, or air in the times before 1492 are called archaeophytes, and plants introduced to Europe after those times are called neophytes. Invasive species of plants and pathogens also were introduced by chance, including such weeds as tumbleweeds (Salsola spp.) and wild oats (Avena fatua). Some plants introduced intentionally, such as the kudzu vine introduced in 1894 from Japan to the United States to help control soil erosion, have since been found to be invasive pests in the new environment.[citation needed] Fungi have been transported, such as the one responsible for Dutch elm disease, killing American elms in North American forests and cities, where many had been planted as street trees. Some of the invasive species have become serious ecosystem and economic problems after establishing in the New World environments.[77][78] A beneficial, although probably unintentional, introduction is Saccharomyces eubayanus, the yeast responsible for lager beer now thought to have originated in Patagonia.[79] Others have crossed the Atlantic to Europe and have changed the course of history. In the 1840s, Phytophthora infestans crossed the oceans, damaging the potato crop in several European nations. In Ireland, the potato crop was totally destroyed. The Great Famine of Ireland caused millions to starve to death or emigrate.[citation needed] Many animals were introduced to new habitats on the other side of the world either accidentally or incidentally. These include such animals as brown rats and zebra mussels, which arrived on ships.[80] Escaped and feral populations of non-indigenous animals have thrived in both the Old and New Worlds, often negatively impacting or displacing native species. In the New World, populations of feral European cats, pigs, horses, and cattle are common, and the Burmese python and green iguana are considered problematic in Florida. In the Old World, the Eastern gray squirrel has been particularly successful in colonising Great Britain, and populations of raccoons can now be found in some regions of Germany, the Caucasus, and Japan. Fur farm escapees such as coypu and American mink have extensive populations.[citation needed] |

その後の歴史 さらなる情報 移入種、侵入種、侵入種のリスト 1492年以前の時代に陸路、海路、空路で渡来した植物は考古植物と呼ばれ、それ以降にヨーロッパに持ち込まれた植物は新植物と呼ばれる。外来種の植物や 病原菌も偶然持ち込まれたもので、タンブルウィード(Salsola spp.)やワイルドオーツ(Avena fatua)などの雑草がある。1894年に土壌浸食を防ぐために日本から米国に持ち込まれたクズの蔓のように、意図的に持ち込まれた植物もあるが、その 後、新しい環境では侵略的な害虫であることが判明している[要出典]。 ダッチ・エルム病の原因菌のように、北米の森林や街路樹として植えられていた都市のアメリカニレを枯らす菌が運ばれてきた。侵入種の中には、新世界の環境 に定着した後、生態系や経済面で深刻な問題となったものもある[77][78]。おそらく意図的ではないにせよ、有益な移入種として、現在ではパタゴニア が起源と考えられているラガービールの酵母、サッカロマイセス・ユーバヤヌスがある[79]。1840年代、Phytophthora infestansが海を渡り、ヨーロッパのいくつかの国でジャガイモの収穫に被害を与えた。アイルランドではジャガイモが全滅した。アイルランドの大飢 饉は、何百万人もの餓死者や移住者を出した[要出典]。 多くの動物が、偶然または偶発的に、地球の裏側の新しい生息地に持ち込まれた。これらの動物には、船で到着したヒメネズミやシマイガイなどが含まれる [80]。旧世界と新世界の両方で、逃げ出したり野生化したりした非固有動物の個体群が繁栄し、しばしば在来種に悪影響を与えたり、駆逐したりした。新世 界では、野良化したヨーロッパネコ、ブタ、ウマ、ウシの個体群が一般的であり、ビルマニシキヘビとグリーンイグアナはフロリダで問題視されている。旧世界 では、東部灰色リスがイギリスの植民地化に特に成功しており、アライグマの個体群は現在、ドイツ、コーカサス、日本の一部の地域で見られる。コイプーやア メリカミンクのような毛皮農場からの逃亡動物も広範囲に生息している[要出典]。 |

| Arab Agricultural Revolution Early impact of Mesoamerican goods in Iberian society First contact (anthropology) Great American Interchange List of food plants native to the Americas Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact theories Global silver trade from the 16th to 19th centuries Transformation of culture |

アラブの農業革命 イベリア社会におけるメソアメリカ商品の初期影響★ ファースト・コンタクト(人類学)★ アメリカ大陸間大交差(Great American Interchange) アメリカ大陸原産の食用植物のリスト コロンブス以前の大洋横断接触説 16世紀から19世紀にかけての世界銀貿易★ 文化の変容 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbian_exchange |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆