コメディア・デラルテ

Commedia dell'arte

Commedia

dell'arte troupe I Gelosi in a late 16th-century Flemish painting

☆ コメディア・デラルテ(Commedia dell'arte 職業喜劇」)は、16世紀から18世紀にかけてヨーロッパ全土で流行した、イタリア演劇を起源とする初期の職業演劇の形態である。かつては英語でイタリア 喜劇と呼ばれ、コメディア・アッラ・マシェラ、コメディア・インプロヴィーゾ、コメディア・デッラルテ・アッルインプロヴィーゾとも呼ばれる。 仮面を被った「タイプ」によって特徴づけられるコメディアは、イザベッラ・アンドレイニのような女優の台頭や、スケッチやシナリオに基づいた即興のパ フォーマンスを生み出した 。コメディアのもう一つの特徴はパントマイムであり、アルレッキーノ(現在ではハーレクインとしてよく知られている)というキャラクターが主に使用する 。 コメディアの登場人物は通常、愚かな老人、小悪魔的な使用人、虚勢に満ちた軍人など、固定的な社会的タイプやストックキャラクターを表している。 イザベッラ・アンドレイニとその夫フランチェスコ・アンドレイニなどの俳優を擁したイ・ジェローシ(I Gelosi)、コンフィデンティ(Confidenti)一座、デジオイ(Desioi)一座、フェデーリ(Fedeli)一座など、コメディ アの上演のために多くの劇団が結成された。 コメディアの起源は、ヴェニスの カーニバルに関係していると思われ、作者であり俳優であったアンドレア・カルモは、1570年までにヴェッキオ(「老人」)パンタローネの前身であるイ ル・マニフィコのキャラクターを創作していた。例えば、フラミニオ・スカラのシナリオでは、イル・マニフィコは17世紀までパンタローネと入れ替わること なく存続している。カルモの登場人物(スペインのカピターノやイル・ドットーレのようなタイプもいた)は仮面をつけていなかったが、どの時点で仮面をつけ たのかは不明である。しかし、カーニバル(公現祭から 灰の水曜日までの期間)に関連していることから、仮面はカーニバルの慣習であり、ある時点で適用されたと考えられる。北イタリアの伝統は、フィレンツェ、 マントヴァ、ベネチアを中心とするもので、主要なカンパニーは各公爵の保護下にあった。ナポリの伝統は南部で生まれ、著名な舞台役者プルチネッラを登場さ せた。プルチネッラは長い間ナポリと結びついており、他の地域でもさまざまなタイプに派生している。最も有名なのは、イギリスの人形劇『パンチとジュ ディ』のキャラクター、パンチである。

A commedia dell'arte street play during the Carnival of Venice/ Commedia dell'arte Troupe on a Wagon in a Town Square by Jan Miel (1640)

| Commedia dell'arte

(/kɒˈmeɪdiə dɛlˈɑːrteɪ, kə-, -ˈmɛdiə, -ˈɑːrtiː/ kom-AY-dee-ə

del-AR-tay, kəm-, -ED-ee-ə, -AR-tee,[1][2] Italian: [komˈmɛːdja

delˈlarte]; lit. 'comedy of the profession')[3] was an early form of

professional theatre, originating from Italian theatre, that was

popular throughout Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries.[4][5] It

was formerly called Italian comedy in English and is also known as

commedia alla maschera, commedia improvviso, and commedia dell'arte

all'improvviso.[6] Characterized by masked "types", commedia was

responsible for the rise of actresses such as Isabella Andreini[7] and

improvised performances based on sketches or scenarios.[8][9] A

commedia, such as The Tooth Puller, is both scripted and

improvised.[8][10] Characters' entrances and exits are scripted. A

special characteristic of commedia is the lazzo, a joke or "something

foolish or witty", usually well known to the performers and to some

extent a scripted routine.[10][11] Another characteristic of commedia

is pantomime, which is mostly used by the character Arlecchino, now

better known as Harlequin.[12] The characters of the commedia usually represent fixed social types and stock characters, such as foolish old men, devious servants, or military officers full of false bravado.[8][13] The characters are exaggerated "real characters", such as a know-it-all doctor called Il Dottore, a greedy old man called Pantalone, or a perfect relationship like the innamorati.[7] Many troupes were formed to perform commedia, including I Gelosi (which had actors such as Isabella Andreini and her husband Francesco Andreini),[14] Confidenti Troupe, Desioi Troupe, and Fedeli Troupe.[7][8] Commedia was often performed outside on platforms or in popular areas such as a piazza (town square).[6][8] The form of theatre originated in Italy, but travelled throughout Europe – sometimes to as far away as Moscow.[15] The genesis of commedia may be related to Carnival in Venice, where the author and actor Andrea Calmo had created the character Il Magnifico, the precursor to the vecchio ("old man") Pantalone, by 1570. In the Flaminio Scala scenario, for example, Il Magnifico persists and is interchangeable with Pantalone into the 17th century. While Calmo's characters (which also included the Spanish Capitano and a Il Dottore type) were not masked, it is uncertain at what point the characters donned the mask. However, the connection to Carnival (the period between Epiphany and Ash Wednesday) would suggest that masking was a convention of Carnival and was applied at some point. The tradition in Northern Italy is centred in Florence, Mantua, and Venice, where the major companies came under the protection of the various dukes. Concomitantly, a Neapolitan tradition emerged in the south and featured the prominent stage figure Pulcinella, which has been long associated with Naples and derived into various types elsewhere—most famously as the puppet character Punch (of the eponymous Punch and Judy shows) in England. |

Commedia dell'arte (/kɒˈmeɪdiə

dɛlˈɑːrteɪ, kə-, -ˈmɛdiə, -ˈɑːrtiː/ kom-AY-dee-ə del-AR-tay, kəm-,

-ED-ee-ə, -AR-tee,[1][2] Italian: [komˈmɛːdja delˈlarte];

lit.

職業喜劇」)[3]は、16世紀から18世紀にかけてヨーロッパ全土で流行した、イタリア演劇を起源とする初期の職業演劇の形態である[4][5]。かつ

ては英語でイタリア喜劇と呼ばれ、コメディア・アッラ・マシェラ、コメディア・インプロヴィーゾ、コメディア・デッラルテ・アッルインプロヴィーゾとも呼

ばれる[6]。 仮面を被った「タイプ」によって特徴づけられるコメディアは、イザベッラ・アンドレイニ[7]のような女優の台頭や、スケッチやシナリオに基づいた即興の パフォーマンスを生み出した[8][9] 。コメディアのもう一つの特徴はパントマイムであり、アルレッキーノ(現在ではハーレクインとしてよく知られている)というキャラクターが主に使用する [12]。 コメディアの登場人物は通常、愚かな老人、小悪魔的な使用人、虚勢に満ちた軍人など、固定的な社会的タイプやストックキャラクターを表している[8] [13]。 [7] イザベッラ・アンドレイニとその夫フランチェスコ・アンドレイニなどの俳優を擁したイ・ジェローシ(I Gelosi)、[14]コンフィデンティ(Confidenti)一座、デジオイ(Desioi)一座、フェデーリ(Fedeli)一座など、コメディ アの上演のために多くの劇団が結成された[7][8]。 コメディアの起源は、ヴェニスの カーニバルに関係していると思われ、作者であり俳優であったアンドレア・カルモは、1570年までにヴェッキオ(「老人」)パンタローネの前身であるイ ル・マニフィコのキャラクターを創作していた。例えば、フラミニオ・スカラのシナリオでは、イル・マニフィコは17世紀までパンタローネと入れ替わること なく存続している。カルモの登場人物(スペインのカピターノやイル・ドットーレのようなタイプもいた)は仮面をつけていなかったが、どの時点で仮面をつけ たのかは不明である。しかし、カーニバル(公現祭から 灰の水曜日までの期間)に関連していることから、仮面はカーニバルの慣習であり、ある時点で適用されたと考えられる。北イタリアの伝統は、フィレンツェ、 マントヴァ、ベネチアを中心とするもので、主要なカンパニーは各公爵の保護下にあった。ナポリの伝統は南部で生まれ、著名な舞台役者プルチネッラを登場さ せた。プルチネッラは長い間ナポリと結びついており、他の地域でもさまざまなタイプに派生している。最も有名なのは、イギリスの人形劇『パンチとジュ ディ』のキャラクター、パンチである。 |

| History See also: Theatre of Italy  Claude Gillot (1673–1722), Four Commedia dell'arte Figures: Three Gentlemen and Pierrot, c. 1715 Although commedia dell'arte flourished in the Italian theatre during the Mannerist period, there has been a long-standing tradition of trying to establish historical antecedents in antiquity. While it is possible to detect formal similarities between the commedia dell'arte and earlier theatrical traditions, there is no way to establish certainty of origin.[16] Some date the origins to the period of the Roman middle republic (Plautine types) or the early republic (Atellan Farces). The Atellan Farces of the early Roman republic featured crude "types" wearing masks with grossly exaggerated features and an improvised plot.[17] Some historians argue that Atellan stock characters, Pappus, Maccus+Buccus, and Manducus, are the primitive versions of the commedia characters Pantalone, Pulcinella, and Il Capitano.[18][19][20] More recent accounts establish links to the medieval jongleurs, and prototypes from medieval moralities, such as Hellequin (as the source of Harlequin, for example).[21]  Pulcinella, drawn by Maurice Sand The first recorded commedia dell'arte performances came from Rome as early as 1551.[22] Commedia dell'arte was performed outdoors in temporary venues by professional actors who were costumed and masked, as opposed to commedia erudita,[a] which were written comedies, presented indoors by untrained and unmasked actors.[24] This view may be somewhat romanticized since records describe the Gelosi performing Tasso's Aminta, for example, and much was done at court rather than in the street. By the mid-16th century, specific troupes of commedia performers began to coalesce, and by 1568 the Gelosi became a distinct company. In keeping with the tradition of the Italian Academies, the Gelosi adopted as their impress (or coat of arms) the two-faced Roman god Janus. Janus symbolized both the comings and goings of this travelling troupe and the dual nature of the actor who impersonates the "other". The Gelosi performed in Northern Italy and France, where they received protection and patronage from the King of France. Despite fluctuations, the Gelosi maintained stability for performances with the "usual ten": "two vecchi (old men), four innamorati (two male and two female lovers), two Zanni, a captain and a servetta (serving maid)".[25] Commedia often performed inside in court theatres or halls, and also as some fixed theatres such as Teatro Baldrucca in Florence. Flaminio Scala, who had been a minor performer in the Gelosi, published the scenarios of the commedia dell'arte around the start of the 17th century, really in an effort to legitimize the form—and ensure its legacy. These scenarios are highly structured and built around the symmetry of the various types in duet: two Zanni, vecchi, innamorate and innamorati, etc. In commedia dell'arte, female roles were played by women, documented as early as the 1560s, making them the first known professional actresses in Europe since antiquity. Lucrezia Di Siena, whose name is on a contract of actors from 10 October 1564, has been referred to as the first Italian actress known by name, with Vincenza Armani and Barbara Flaminia as the first primadonnas and the first well-documented actresses in Italy (and Europe).[26] In the 1570s, English theatre critics generally denigrated the troupes with their female actors (some decades later, Ben Jonson referred to one female performer of the commedia as a "tumbling whore"). By the end of the 1570s, Italian prelates attempted to ban female performers; however, by the end of the 16th century, actresses were standard on the Italian stage.[27] The Italian scholar Ferdinando Taviani has collated a number of church documents opposing the advent of the actress as a kind of courtesan, whose scanty attire and promiscuous lifestyle corrupted young men, or at least infused them with carnal desires. Taviani's term negativa poetica describes this and other practices offensive to the church, while giving us an idea of the phenomenon of the commedia dell'arte performance.  Harlequin in a 19th-century Italian print By the early 17th century, the Zanni comedies were moving from pure improvisational street performances to specified and clearly delineated acts and characters. Three books written during the 17th century—Cecchini's [it] Fruti della moderne commedia (1628), Niccolò Barbieri's La supplica (1634) and Perrucci's Dell'arte rapresentativa (1699)—"made firm recommendations concerning performing practice". Katritzky argues that, as a result, commedia was reduced to formulaic and stylized acting; as far as possible from the purity of the improvisational genesis a century earlier.[28] In France, during the reign of Louis XIV, the Comédie-Italienne created a repertoire and delineated new masks and characters, while deleting some of the Italian precursors, such as Pantalone. French playwrights, particularly Molière, gleaned from the plots and masks in creating an indigenous treatment. Indeed, Molière shared the stage with the Comédie-Italienne at Petit-Bourbon, and some of his forms, e.g. the tirade, are derivative from the commedia (tirata). Commedia dell'arte moved outside the city limits to the théâtre de la foire, or fair theatres, in the early 17th century as it evolved toward a more pantomimed style. With the dispatch of the Italian comedians from France in 1697, the form transmogrified in the 18th century as genres such as comédie larmoyante gained in attraction in France, particularly through the plays of Marivaux. Marivaux softened the commedia considerably by bringing in true emotion to the stage. Harlequin achieved more prominence during this period. It is possible that this kind of improvised acting was passed down the Italian generations until the 17th century when it was revived as a professional theatrical technique. However, as currently used the term commedia dell'arte was coined in the mid-18th century.[29] Commedia dell'arte was equally if not more popular in France, where it continued its popularity throughout the 17th century (until 1697), and it was in France that commedia developed its established repertoire. Commedia evolved into various configurations across Europe, and each country acculturated the form to its liking. For example, pantomime, which flourished in the 18th century, owes its genesis to the character types of the commedia, particularly Harlequin. The Punch and Judy puppet shows, popular to this day in England, owe their basis to the Pulcinella mask that emerged in Neapolitan versions of the form. In Italy, commedia masks and plots found their way into the opera buffa, and the plots of Rossini, Verdi, and Puccini. During the Napoleonic occupation of Italy, instigators of reform and critics of French Imperial rule (such as Giacomo Casanova) used the Carnival masks to hide their identities while fueling political agendas, challenging social rule and hurling blatant insults and criticisms at the regime. In 1797, in order to destroy the impromptu style of Carnival as a partisan platform, Napoleon outlawed the commedia dell'arte. It was not reborn in Venice until 1979 because of this.[30] |

歴史[編集] 以下も参照のこと: イタリアの劇場  クロード・ジロ(1673-1722)、4人のコメディア・デラルテの人物像: 三人の紳士とピエロ、1715年頃 コメディア・デラルテは マニエリスム期にイタリア演劇界で花開いたが、古代に歴史的な先例を確立しようとする伝統は古くからある。コメディア・デラルテとそれ以前の演劇の伝統と の間に形式的な類似性を見出すことは可能であるが、起源を確定する方法はない[16]。起源をローマ中共和制の時代(プラウティン型)や共和制初期の時代 (アッテラン・ファルセス)とする説もある。ローマ共和国初期のアテラン・ファルスは、粗雑な「タイプ」が仮面をつけ、著しく誇張された特徴と即興的な筋 書きを特徴としていた[17]。アテランのストックキャラクターであるパッポス、マッカス+ブッカス、マンドゥクスは、コメディアのキャラクターであるパ ンタローネ、プルチネッラ、イル・カピターノの原始版であると主張する歴史家もいる[18][19]。 [18][19][20]最近の説明では、中世のジョングルールや、ヘルカン(例えばハーレクインの源流)のような中世のモラリティの原型との関連が確立 されている[21]。  モーリス・サンドが描いたプルチネルラ コメディア・デラルテは、仮装し仮面をつけたプロの役者たちによって仮設の会場で演じられるものであり、コメディア・エルディータ[a]とは対照的であ る。16世紀半ばになると、コメディアの特定の集団が結成されるようになり、1568年にはジェローシが独立した劇団となった。イタリア・アカデミーの伝 統に倣い、ジェローシはローマ神話の二面神ヤヌスを印象(紋章)として採用した。ヤヌスは、この旅一座の行き来と、「他者」になりすます俳優の二面性を象 徴していた。ジェローシ一座は北イタリアとフランスで公演を行い、フランス国王から保護と後援を受けた。変動はあったものの、ジェローシは「いつもの10 人」で安定した公演を維持した: 「2人のヴェッキ(老人)、4人のインナモラーティ(男女2人の恋人)、2人のザンニ、隊長、1人のセルヴェッタ(給仕係)」[25]。コメディアは宮廷 劇場やホールで上演されることが多く、フィレンツェのバルドルッカ劇場のような固定劇場でも上演された。ジェローシ劇場で小芝居を演じていたフラミニオ・ スカラは、17世紀初頭頃にコメディア・デラルテのシナリオを出版した。これらのシナリオは高度に構造化されており、二重唱における様々なタイプの対称性 (二人のザンニ、ヴェッキ、イナモラーテと イナモラーティなど)を中心に組み立てられている。 コメディア・デラルテでは、1560年代には女性によって女性の役が演じられたことが記録されており、古代以来ヨーロッパで初めてプロの女優として知られ るようになった。1564年10月10日の俳優契約書に名前があるルクレツィア・ディ・シエナは、ヴィンチェンツァ・アルマーニと バルバラ・フラミニアが最初のプリマドンナであり、イタリア(およびヨーロッパ)で最初に文書化された女優である。1570年代、イギリスの演劇批評家た ちは、女性俳優を擁する一座を一般的に否定していた(数十年後、ベン・ジョンソンは、コメディアのある女性パフォーマーを「転落する娼婦」と呼んだ)。イ タリアの学者フェルディナンド・タヴィアーニは、一種の宮廷女官として女優の出現に反対する教会文書を数多く収集した。タヴィアーニのネガティヴァ・ポエ チカという用語は、このような教会にとって不快な行為やその他の慣習を説明するものであり、同時にコメディア・デラルテの演目という現象を私たちに教えて くれるものでもある。  19世紀のイタリアの版画に描かれたハーレクイン(アルレッキーノ) 17世紀初頭までに、ザンニ喜劇は、純粋な即興の大道芸から、演技と登場人物が明確に定義されたものへと移行していた。17世紀に書かれた3冊の本- チェッキーニの[it]Fruti della moderne commedia(1628)、ニッコロ・バルビエリの La supplica(1634)、ペルッチのDell'arte rapresentativa(1699)-は、「上演の実践に関して確固たる提言を行った」。カトリツキーは、その結果、コメディアは定型化され、様式 化された演技になり、1世紀前の即興の純粋性から可能な限り遠ざかったと論じている[28]。 フランスでは、ルイ14世の治世に、コメディ=イタリエンヌがレパートリーを作り、新しい仮面と登場人物を定義した。フランスの劇作家たち、特にモリエー ルは、プロットや仮面からヒントを得て、独自の舞台を作り上げた。実際、モリエールはプチ・ブルボンのイタリ ア劇団と舞台を共にしており、コメディア(ティラータ)から派生した形式もある。 コメディア・デラルテは、よりパントマイム的なスタイルに進化するにつれて、17世紀初頭には、市外にあるテアトル・ド・ラ・フォワール(見世物小屋)に 移った。1697年にイタリア人喜劇役者がフランスから追放されると、18世紀には、特にマリヴォーの戯曲を通じて、フランスでコメディー・ラルモワイヤ ントのようなジャンルが人気を博し、形式が変容した。特にマリヴォーの戯曲によって、コメディー・ラルモワイヤントのようなジャンルがフランスで注目され るようになった。この時期、ハーレクインがさらに脚光を浴びた。 このような即興演技は、17世紀にプロの演劇技法として復活するまで、イタリアの世代に受け継がれていた可能性がある。しかし、現在使われているコメディア・デラルテという言葉は、18世紀半ばに作られたものである[29]。 コメディア・デラルテは、17世紀を通じて(1697年まで)人気を博したフランスでも同じように、あるいはそれ以上に人気があり、コメディアが確立され たレパートリーを発展させたのもフランスであった。コメディアはヨーロッパ全土でさまざまな形態に発展し、それぞれの国が自国の好みに合うように様式を馴 染ませていった。たとえば、18世紀に盛んになったパントマイムは、コメディアのキャラクター、特にハーレクインにその起源を求める。イギリスで今日まで 親しまれている「パンチとジュディ」の人形劇は、ナポリで生まれたプルチネッラの仮面に起源を持つ。イタリアでは、コメディアの仮面や戯曲はオペラ・ブッ ファや、ロッシーニ、ヴェルディ、プッチーニの戯曲に取り入れられた。 ナポレオン支配下のイタリアでは、改革の扇動者やフランス帝政の批評家(ジャコモ・カサノヴァなど)が、カーニバルの仮面を使って正体を隠しながら政治的 な意図を煽り、社会的支配に異議を唱え、露骨な侮辱や体制批判を浴びせた。1797年、ナポレオンはパルチザンのプラットフォームとしての即興的なカーニ バルのスタイルを破壊するために、コメディア・デラルテを非合法化した。このため、1979年までヴェネツィアで復活することはなかった[30]。 |

Companies Commedia dell'arte troupe I Gelosi in a late 16th-century Flemish painting Compagnie, or companies, were troupes of actors, each of whom had a specific function or role. Actors were versed in a plethora of skills, with many having joined troupes without a theatre background. Some were doctors, others priests, others soldiers, enticed by the excitement and prevalence of theatre in Italian society. Actors were known to switch from troupe to troupe "on loan", and companies would often collaborate if unified by a single patron or performing in the same general location.[31] Members would also splinter off to form their own troupes, such was the case with the Ganassa and the Gelosi. These compagnie travelled throughout Europe from the early period, beginning with the Soldati, then, the Ganassa, who travelled to Spain,[32] and were famous for playing the guitar and singing—never to be heard from again—and the famous troupes of the Golden Age (1580–1605): Gelosi, Confidenti, Accessi. These names which signified daring and enterprise were appropriated from the names of the academies—in a sense, to lend legitimacy. However, each troupe had its impresse (like a coat of arms) which symbolized its nature. The Gelosi, for example, used the two-headed face of the Roman god Janus, to signify its comings and goings and relationship to the season of Carnival, which took place in January. Janus also signified the duality of the actor, who is playing a character or mask, while still remaining oneself. Magistrates and clergy were not always receptive to the travelling compagnie ("companies"), particularly during periods of plague, and because of their itinerant nature. Actors, both male and female, were known to strip nearly naked, and storylines typically descended into crude situations with overt sexuality, considered to teach nothing but "lewdness and adultery...of both sexes" by the French Parliament.[33] The term vagabondi was used in reference to the comici, and remains a derogatory term to this day (vagabond). This was in reference to the nomadic nature of the troupes, often instigated by persecution from the Church, civil authorities, and rival theatre organisations that forced the companies to move from place to place.  Statues of Pantalone and Harlequin, two stock characters from the commedia dell'arte, in the Museo Teatrale alla Scala, Milan A troupe often consisted of ten performers of familiar masked and unmasked types, and included women.[25] The companies would employ carpenters, props masters, servants, nurses, and prompters, all of whom would travel with the company. They would travel in large carts laden with supplies necessary for their nomadic style of performance, enabling them to move from place to place without having to worry about the difficulties of relocation. This nomadic nature, though influenced by persecution, was also largely due in part to the troupes requiring new (and paying) audiences. They would take advantage of public fairs and celebrations, most often in wealthier towns where financial success was more probable. Companies would also find themselves summoned by high-ranking officials, who would offer patronage in return for performing in their land for a certain amount of time. Companies in fact preferred to not stay in any one place too long, mostly out of a fear of the act becoming "stale". They would move on to the next location while their popularity was still active, ensuring the towns and people were sad to see them leave, and would be more likely to either invite them back or pay to watch performances again should the troupe ever return.[34] Prices were dependent on the troupe's decision, which could vary depending on the wealth of the location, the length of stay, and the regulations governments had in place for dramatic performances. List of known commedia troupes Compagnia dei Fedeli: active 1601–1652, with Giambattista Andreini Compagnia degli Accesi: active 1590–1628 Compagnia degli Uniti [it]: active 1578–1640 Compagnia dei Confidenti: active 1574–1599; reformed under Flaminio Scala, operated again 1611–1639 I Dedosi: active 1581–1599 I Gelosi: active 1568–1604 Signora Violante and Her Troupe of Dancers: active 1729–1732[35] Zan Ganassa: active 1568–1610[36] |

カンパニー(一座) 16世紀末のフランドル絵画に描かれたコメディア・デラルテ一座イ・ジェローシ カンパニー(Compagnie)とは俳優の一座のことで、各俳優は特定の役割や役割を担っていた。俳優たちは様々な技術に精通しており、演劇の経歴を持 たずに劇団に参加した者も少なくない。ある者は医者であり、ある者は司祭であり、またある者はイタリア社会における演劇の興奮と普及に魅せられた兵士で あった。俳優たちは劇団から劇団へと "出向 "することで知られており、一人のパトロンによって団結させられたり、同じ場所で上演されたりする場合には、しばしば協力し合うこともあった[31]。こ れらの劇団は、初期からヨーロッパ中を駆け巡り、ソルダーティに始まり、スペインに渡ったガナッサ[32]、そして黄金時代(1580年~1605年)の 有名なギターと歌の劇団であった: Gelosi、Confidenti、Accessiである。これらの名前は、ある意味で正統性を持たせるために、アカデミーの名前から転用されたもの で、大胆さと大胆さを意味する。しかし、それぞれの劇団は、その性格を象徴するインプレス(紋章のようなもの)を持っていた。例えば、ジェローシはローマ 神話の神ヤヌスの双頭の顔を使い、その出入りや1月に行われるカーニバルの季節との関係を意味していた。ヤヌスはまた、役者の二面性をも意味し、役者は役 柄や仮面を演じながら、なおも自分自身であり続けた。 特に疫病が流行した時期や、旅芸人という性格から、奉行や聖職者たちは、旅するカンパニー(「劇団」)に対して必ずしも好意的ではなかった。男女を問わ ず、役者はほぼ裸になることで知られ、ストーリーは通常、あからさまな性描写を伴う下品な状況に陥り、フランス議会は「男女の淫行と姦淫」以外の何もので もないと見なした[33]。ヴァガボンディ(vagabondi)という用語はコミチについて使われ、今日でも蔑称(放浪者)として残っている。これは、 劇団の遊牧民的な性質を指しており、しばしば教会や市民当局、ライバル劇団からの迫害によって、劇団は各地を転々とすることを余儀なくされた。  ミラノの スカラ座博物館にあるコメディア・デラルテの登場人物、パンタローネと ハーレクインの像。 一座は、おなじみの仮面や仮面を外したタイプの10人の演者で構成されることが多く、女性も含まれていた[25]。劇団は、大工、小道具係、使用人、看護 婦、宣伝係などを雇い、全員が劇団とともに移動した。彼らは遊牧民のようなスタイルのパフォーマンスに必要な物資を積んだ大きな荷車で移動し、移動の難し さを心配することなく、あちこちに移動することができた。このような遊牧民的な性質は、迫害の影響もあったが、劇団が新たな(お金を払ってくれる)観客を 必要としていたことも大きく影響している。劇団は、経済的な成功が見込める裕福な町での見本市や祝祭を利用することが多かった。また、劇団は高位の役人に 呼び出されることもあり、その役人は一定期間その土地で公演を行う見返りとして後援を申し出た。実際、カンパニーはひとつの場所に長く留まることを好まな かったが、その理由のほとんどは、演目が「陳腐化」してしまうことを恐れてのことだった。一座は人気があるうちに次の土地に移り、町や人々が一座の退団を 惜しみ、一座が再び戻ってくることがあれば、再び一座を招いたり、公演を見るためにお金を払ったりする可能性が高くなるようにしたのである[34]。料金 は一座の決定次第であり、その土地の裕福度、滞在期間、政府が演劇公演に対して設けている規制などによって異なる。 知られているコメディア劇団のリスト[編集]。 コンパニア・デイ・フェデーリ:1601年から1652年まで活動、ジャンバッティスタ・アンドレイニがいた。 コンパーニャ・デッリ・アッチェージ(Compagnia degli Accesi):1590年から1628年に活動した。 コンパーニャ・デイ・ウニティ(Compagnia degli Uniti):1578年~1640年に活動 コンフィデンティ会:1574-1599年活動、フラミニオ・スカラの下で改革、1611-1639年再び活動 イ・デドージ: 1581年から1599年まで活動 イ・ジェローシ:1568-1604年に活動 シニョーラ・ヴィオランテとその一座:1729-1732年に活動[35]。 ザン・ガナッサ:1568-1610年に活動[36]。 |

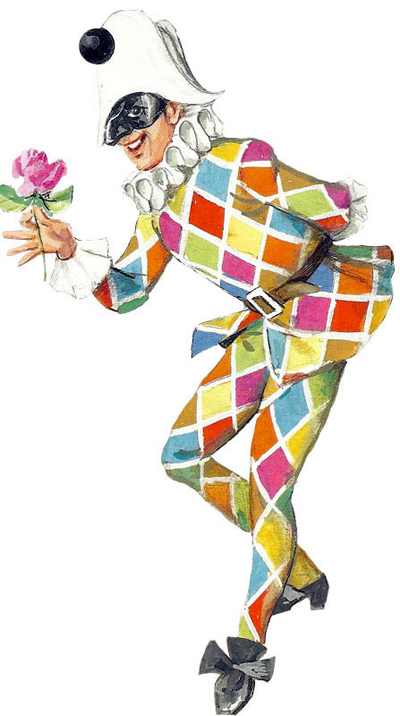

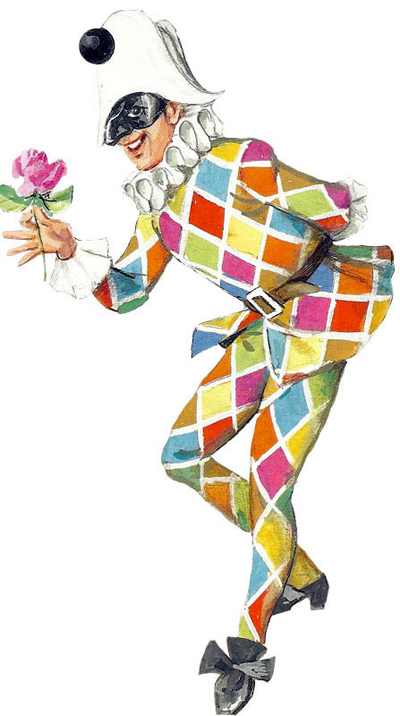

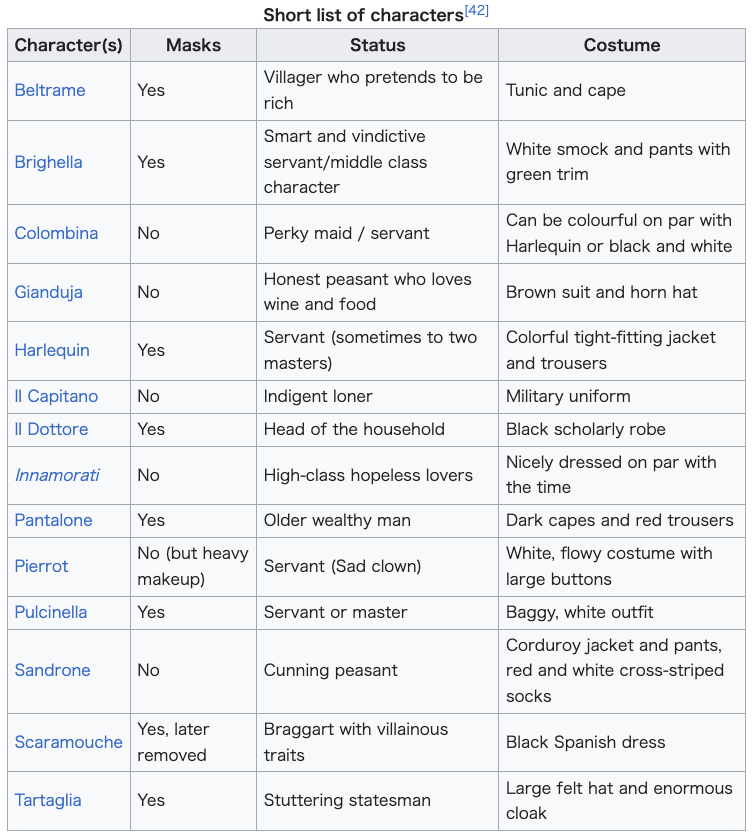

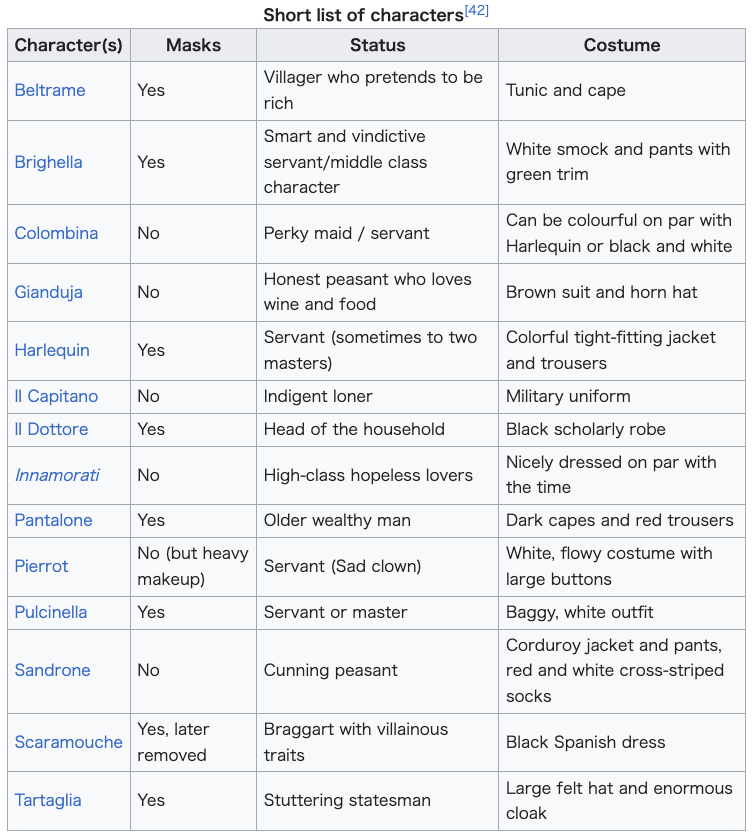

Characters Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), Commedia dell'arte player of Pierrot, c. 1718–19, identified as "Gilles". Louvre, Paris. Generally, the actors playing were diverse in background in terms of class and religion, and performed anywhere they could. Castagno posits that the aesthetic of exaggeration, distortion, anti-humanism (as in the masked types), and excessive borrowing as opposed to originality was typical of all the arts in the late Italian Renaissance.[37] Theatre historian Martin Green points to the extravagance of emotion during the period of commedia's emergence as the reason for representational moods, or characters, that define the art. In commedia, each character embodies a mood: mockery, sadness, gaiety, confusion, and so forth.[38] According to 18th-century London theatre critic Baretti, commedia dell'arte incorporates specific roles and characters that were "originally intended as a kind of characteristic representative of some particular Italian district or town" (archetypes).[29][39] The character's persona included the specific dialect of the region or town represented. Meaning that on stage, each character was performed in its own dialect. Characters would often be passed down from generation to generation, and characters married onstage were often married in real life as well, seen most famously with Francesco and Isabella Andreini. This was believed to make performances more natural, as well as strengthening the bonds within the troupe, who emphasized complete unity between every member. Additionally, each character has a singular costume and mask that is representative of the character's role.[29]  Harlequin and Pantalone in a 2011 play in Tallinn, Estonia Commedia dell'arte has four stock character groups:[13] Zanni: servants, clowns; characters such as Arlecchino (also known as Harlequin), Brighella, Scapino, Pulcinella and Pedrolino[40] Vecchi: wealthy old men, masters; characters such as Pantalone and Il Dottore Innamorati: young upper class lovers; who would have names such as Flavio and Isabella Il Capitano: self-styled captains, braggarts (Scaramuccia); can also be La Signora if a female Masked characters are often referred to as "masks" (in Italian: maschere), which, according to John Rudlin, cannot be separated from the character. In other words, the characteristics of the character and the characteristics of the mask are the same.[41] In time however, the word maschere came to refer to all of the characters of the commedia dell'arte whether masked or not. Female characters (including female servants) are most often not masked (female amorose are never masked). The female character in the masters group is called Prima Donna and can be one of the lovers. There is also a female character known as The Courtisane who can also have a servant. Female servants wore bonnets. Their character was played with a malicious wit or gossipy gaiety. The amorosi are often children of a male character in the masters group, but not of any female character in the masters group, which may represent younger women who have e.g. married an old man, or a high-class courtesan. Female characters in the masters group, while younger than their male counterparts, are nevertheless older than the amorosi. Some of the better known commedia dell'arte characters are Pierrot and Pierrette, Pantalone, Gianduja, Il Dottore, Brighella, Il Capitano, Colombina, the innamorati, Pedrolino, Pulcinella, Arlecchino, Sandrone, Scaramuccia (also known as Scaramouche), La Signora, and Tartaglia.  In the 17th century, as commedia became popular in France, the characters of Pierrot, Columbina and Harlequin were refined and became essentially Parisian, according to Green.[43] |

登場人物[編集] ジャン=アントワーヌ・ワトー(1684-1721)、ピエロの コメディア・デラルテ奏者、1718-19年頃、「ジル」と確認される。ルーヴル、パリ。 一般に、演じる役者は、階級や宗教の面で多様な背景を持ち、どこでも演じることができた。カスタニョは、誇張、歪曲、反人間主義(仮面型に見られるよう な)、独創性とは対照的な過剰な借用という美学は、イタリア・ルネサンス後期のあらゆる芸術の典型であったと仮定している[37]。演劇史家のマーティ ン・グリーンは、コメディアが出現した時期の感情の奔放さが、この芸術を特徴づける表象的な気分やキャラクターの理由であると指摘している。コメディアで は、それぞれの登場人物が、嘲笑、悲しみ、陽気、混乱などの気分を体現する[38]。 18世紀のロンドンの演劇批評家バレッティによれば、コメディア・デラルテには特定の役柄やキャラクターが組み込まれており、それらは「もともとイタリア の特定の地域や町を代表する一種の特徴的なものとして意図された」(原型)ものであった[29][39]。つまり、舞台上では、それぞれのキャラクターが それぞれの方言で演じられた。キャラクターは世代から世代へと受け継がれることが多く、舞台上で結婚したキャラクターは実生活でも結婚していることが多 く、フランチェスコ・アンドレイニとイザベッラ・アンドレイニが有名である。これは、公演をより自然なものにすると同時に、団員全員の完全な団結を重視す る劇団内の絆を強めるためだと考えられていた。さらに、各キャラクターは、その役を代表する衣装と仮面を持っている[29]。  2011年にエストニアのタリンで上演された劇におけるハーレクインとパンタローネ コメディア・デラルテには4つのキャラクターグループがある[13]。 ザンニ:使用人、道化師。アルレッキーノ(ハーレクインとしても知られる)、ブリゲッラ、スカピーノ、プルチネッラ、ペドロリーノなどの登場人物[40]。 ヴェッキ:裕福な老人、主人;パンタローネ、イル・ドットーレなどの登場人物 イナモラーティ:上流階級の若い恋人たち。 イル・カピターノ:自称船長、自慢屋(スカラムッチャ);女性の場合はラ・シニョーラとも呼ばれる。 仮面をかぶった登場人物はしばしば「仮面」(イタリア語では「マスチェーレ」)と呼ばれるが、ジョン・ラドリンによれば、これはキャラクターと切り離すこ とはできない。言い換えれば、キャラクターの特徴と仮面の特徴は同じである[41]。しかし、やがてマスチェーレという言葉は、仮面の有無にかかわらず、 コメディア・デラルテのすべてのキャラクターを指すようになった。女性の登場人物(女性使用人を含む)は仮面をつけないことがほとんどである(女性のアモ ローゼが仮面をつけることはない)。主人グループの女性キャラクターはプリマ・ドンナと呼ばれ、恋人たちの一人であることもある。宮廷女官と呼ばれる女性 キャラクターもおり、彼女も使用人を持つことができる。女性使用人はボンネットを被っている。彼女たちのキャラクターは、悪意のあるウィットやゴシップ好 きな陽気さで演じられる。アモローシは、主人グループの男性キャラクターの子供であることが多いが、主人グループの女性キャラクターにはいない。名人グ ループの女性キャラクターは、男性キャラクターよりは若いが、アモローシよりは年上である。コメディア・デラルテの登場人物でよく知られているのは、ピエ ロとピエレット、パンタローネ、ジャンドゥーヤ、イル・ドットーレ、ブリゲッラ、イル・カピターノ、コロンビーナ、インナモラーティ、ペドロリーノ、プル チネッラ、アルレッキーノ、サンドローネ、スカラムッチャ(スカラムーシュとも呼ばれる)、ラ・シニョーラ、タルターリアなどである。  17世紀、フランスでコメディアが流行すると、ピエロ、コロンビーナ、ハーレクインのキャラクターは洗練され、本質的にパリジャン的なものになったとグリーンは言う[43]。 |

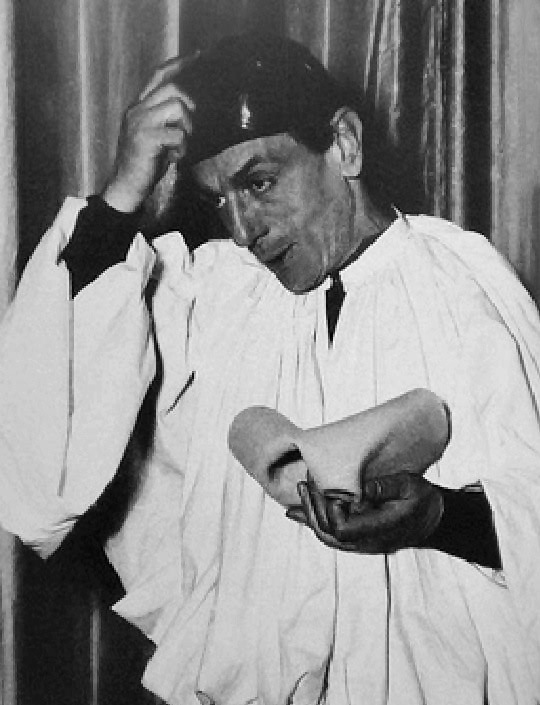

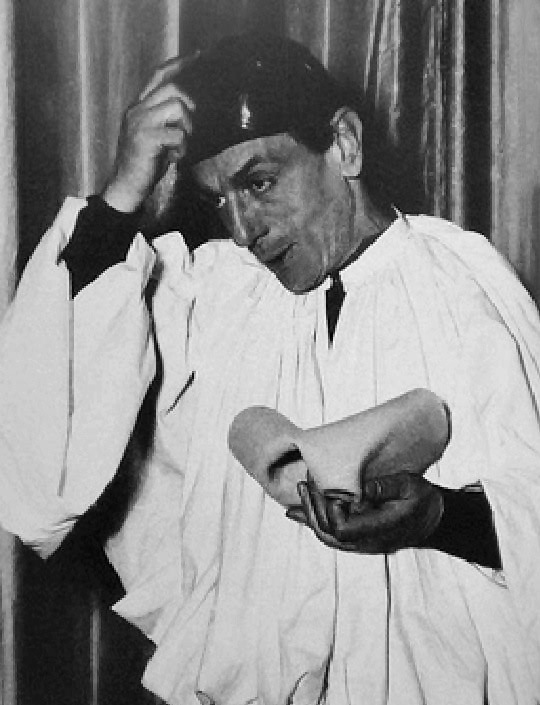

| Costumes Main articles: Costumes in commedia dell'arte and Commedia dell'arte masks  Eduardo De Filippo as Pulcinella Each character in commedia dell'arte has a distinct costume that helps the audience understand who the character is. Arlecchino originally wore a tight fitting long jacket with matching trousers that both had numerous odd shaped patches, usually green, yellow, red, and brown.[44][45] Usually, there was a bat and a wallet that would hang from his belt.[45] His hat, which was a soft cap, was modeled after Charles IX or after Henri II, and almost always had a tail of a rabbit, hare or a fox with the occasional tuft of feathers.[45][44] During the 17th century, the patches turned into blue, red, and green triangles arranged in a symmetrical pattern.[45] The 18th century is when the iconic Arlecchino look with the diamond shaped lozenges took shape. The jacket became shorter and his hat changed from a soft cap to a double pointed hat.[45]  Masks of Il Capitano (left) and Il Dottore (right) Il Dottore's costume was a play on the academic dress of the Bolognese scholars.[45][44] Il Dottore is almost always clothed entirely in black.[45] He wore a long black gown or jacket that went below the knees.[45][44] Over the gown, he would have a long black robe that went down to his heels, and he would have on black shoes, stockings, and breeches.[45][44] In 1653, his costume was changed by Augustin Lolli who was a very popular Il Dottore actor. He added an enormous black hat, changed the robe to a jacket cut similarly to Louis XIV, and added a flat ruff to the neck.[45] Il Capitano's costume is similar to Il Dottore's in the fact that it is also a satire on military wear of the time.[44] This costume would therefore change depending on where the Capitano character is from, and the period the Capitano is from.[44][45] Pantalone has one of the most iconic costumes of commedia dell'arte. Typically, he would wear a tight-fitting jacket with a matching pair of trousers. He usually pairs these two with a big black coat called a zimarra.[45][44] Women, who usually played servants or lovers, wore less stylized costumes than the men in commedia. The lovers, innamorati, would wear what was considered to be the fashion of the time period. They would normally not wear masks but would be heavily makeuped. |

コスチューム[編集] 主な記事 コメディア・デラルテの衣装、コメディア・デラルテの仮面  プルチネッラ役のエドゥアルド・デ・フィリッポ コメディア・デラルテの各キャラクターは、観客にそのキャラクターが誰であるかを理解させるために、特徴的な衣装を持っている。 アルレッキーノはもともと、ぴったりとした長い上着とそれに合うズボンを着用しており、どちらも通常は緑、黄色、赤、茶色などの多数の奇妙な形のワッペン が付いていた[44][45]。通常、ベルトから吊るされるバットと財布があった。 [17世紀には、ワッペンは青、赤、緑の三角形を左右対称に並べたものに変わった[45]。上着は短くなり、帽子はソフト帽からダブルポインテッドハット に変わった[45]。  イル・カピターノ(左)とイル・ドットーレ(右)の仮面 イル・ドットーレの衣装は、ボローニャの学者たちのアカデミックな服装を模したものだった[45][44]。 [1653年、イル・ドットーレの人気俳優であったアウグスティン・ロッリによって衣装が変更された。彼は巨大な黒い帽子を加え、ローブをルイ14世と同 じようなカットのジャケットに変え、首に平らなフリルを付けた[45]。 イル・カピターノの衣装は、当時の軍服に対する風刺でもあるという点で、イル・ドットーレと似ている[44]。したがって、この衣装は、カピターノのキャラクターがどこから来たのか、カピターノがどの時代から来たのかによって変わる[44][45]。 パンタローネはコメディア・デラルテを象徴する衣装の一つである。パンタローネは、コメディア・デラルテを象徴する衣装のひとつである。彼は通常、この2つにツィマーラと呼ばれる大きな黒いコートを合わせる[45][44]。 通常、使用人や恋人役を演じる女性は、コメディアの男性よりも様式化された衣装を着ていなかった。恋人役であるイナモラーティは、その時代のファッションとされるものを着ていた。通常、仮面はつけないが、厚化粧をする。 |

Subjects Harlequin and Colombina. Paint by Giovanni Domenico Ferretti. Conventional plot lines were written on themes of sex, jealousy, love, and old age. Many of the basic plot elements can be traced back to the Roman comedies of Plautus and Terence, some of which were themselves translations of lost Greek comedies of the 4th century BC. However, it is more probable that the comici used contemporary novella or traditional sources, and drew from current events and local news of the day. Not all scenarios were comic, there were some mixed forms and even tragedies. Shakespeare's The Tempest is drawn from a popular scenario in the Scala collection, his Polonius (Hamlet) is drawn from Pantalone, and his clowns bear homage to the Zanni. Comici performed written comedies at court. Song and dance were widely used, and a number of innamorati were skilled madrigalists, a song form that uses chromatics and close harmonies. Audiences came to see the performers, with plotlines becoming secondary to the performance. Among the great innamorate, Isabella Andreini was perhaps the most widely known, and a medallion dedicated to her reads "eternal fame". Tristano Martinelli achieved international fame as the first of the great Arlecchinos, and was honoured by the Medici and the Queen of France. Performers made use of well-rehearsed jokes and stock physical gags, known as lazzi and concetti, as well as on-the-spot improvised and interpolated episodes and routines, called burle (sg.: burla, Italian for 'joke'), usually involving a practical joke. Since the productions were improvised, dialogue and action could easily be changed to satirize local scandals, current events, or regional tastes, while still using old jokes and punchlines. Characters were identified by costumes, masks, and props, such as a type of baton known as a slapstick. These characters included the forebears of the modern clown, namely Harlequin (Arlecchino) and the Zanni. Harlequin, in particular, was allowed to comment on current events in his entertainment.[46] The classic, traditional plot is that the innamorati are in love and wish to be married, but one elder (vecchio) or several elders (vecchi) are preventing this from happening, leading the lovers to ask one or more Zanni (eccentric servants) for help. Typically the story ends happily, with the marriage of the innamorati and forgiveness for any wrongdoings. While generally personally unscripted, the performances often were based on scenarios that gave some semblance of a plot to the largely improvised format. The Flaminio Scala scenarios, published in the early 17th century, are the most widely known collection and representative of its most esteemed compagnia, I Gelosi. |

テーマ[編集] ハーレクインとコロンビーナ ジョヴァンニ・ドメニコ・フェレッティ作。 従来の筋書きは、セックス、嫉妬、愛、老いをテーマに書かれていた。基本的な筋書きの多くは、プラウトゥスや テレンスのローマ喜劇にまで遡ることができる。しかし、コミチが現代の小説や伝統的な資料を利用し、その時々の時事問題や地元のニュースを題材にした可能 性の方が高い。すべてのシナリオが喜劇であったわけではなく、混成形式や悲劇もあった。シェイクスピアの『テンペスト』はスカラ座の人気シナリオから、ポ ローニアス(ハムレット)はパンタローネから、道化師はザンニにオマージュを捧げている。 コミチは宮廷で書き下ろしの喜劇を上演した。歌と踊りは広く用いられ、多くのインナモラーティは、半音階と緊密なハーモニーを用いる歌曲形式であるマドリ ガルに長けていた。観客は演者を見に来たのであり、筋書きは二の次だった。偉大なインナモラーティの中でも、イザベッラ・アンドレイニはおそらく最も広く 知られており、彼女に捧げられたメダイには「永遠の名声」と記されている。トリスターノ・マルティネッリは、偉大なアルレッキーノの第一人者として国際的 な名声を獲得し、メディチ家やフランス王妃から栄誉を受けた。演者たちは、ラッツィ(lazzi)やコンチェッティ(concetti)と呼ばれる、よく 練習されたジョークやストックされたギャグを使うだけでなく、ブッレ(burle、イタリア語で「冗談」の意)と呼ばれる、その場で即興的に挿入されるエ ピソードやルーティンも使った。 即興であったため、台詞やアクションは簡単に変更することができ、その土地のスキャンダルや時事問題、地域の嗜好を風刺することができた。登場人物は、衣 装や仮面、スラップスティックと呼ばれる警棒などの小道具によって識別された。これらのキャラクターには、現代のピエロの前身であるハーレクイン(アル レッキーノ)やザンニが含まれる。特にハーレクインは、娯楽において時事問題についてコメントすることが許されていた[46]。 古典的で伝統的な筋書きは、恋人たちが愛し合っていて結婚を望んでいるが、一人の年長者(vecchio)または数人の年長者(vecchi)がそれを妨 げているため、恋人たちは一人または複数のザンニ(風変わりな使用人)に助けを求めるというものである。通常、物語は幸せな結末を迎え、恋人たちは結婚 し、不義は許される。 個人的には台本に書かれていないことが多いが、即興劇という形式に筋書きのようなものを持たせるために、シナリオに基づいて演じられることもあった。17 世紀初頭に出版されたフラミニオ・スカラのシナリオは、最も広く知られたコレクションであり、最も尊敬されたカンパニー、イ・ジェローシを代表するもので ある。 |

Influence in visual art Jean-Antoine Watteau, Italian Comedians, 1720 The iconography of the commedia dell'arte represents an entire field of study that has been examined by commedia scholars such as Erenstein, Castagno, Katritzky, Molinari, and others. In the early period, representative works by painters at Fontainebleau were notable for their erotic depictions of the thinly veiled innamorata, or the bare-breasted courtesan/actress. The Flemish influence is widely documented as commedia figures entered the world of the vanitas genre, depicting the dangers of lust, drinking, and the hedonistic lifestyle. Castagno describes the Flemish pittore vago (wandering painters) who assimilated themselves within Italian workshops and even assumed Italian surnames: one of the most influential painters, Lodewyk Toeput, for example, became Ludovico Pozzoserrato and was a celebrated painter in the Veneto region of Italy. The pittore vago can be attributed with establishing commedia dell'arte as a genre of painting that would persist for centuries.  Johann Joachim Kändler's commedia dell'arte figures in Meissen porcelain, c. 1735–44 While the iconography gives evidence of the performance style (see Fossard collection), it is important to note that many of the images and engravings were not depictions from real life, but concocted in the studio. The Callot etchings of the Balli di Sfessania (1611) are most widely considered capricci rather than actual depictions of a commedia dance form, or typical masks. While these are often reproduced in large formats, it is important to note that the actual prints measured about 2×3 inches. In the 18th century, Watteau's painting of commedia figures intermingling with the aristocracy were often set in sumptuous garden or pastoral settings and were representative of that genre. Pablo Picasso's 1921 painting Three Musicians is a colorful representation of commedia-inspired characters.[47] Picasso also designed the original costumes for Stravinsky's Pulcinella (1920), a ballet depicting commedia characters and situations. Commedia iconography is evident in porcelain figurines many selling for thousands of dollars at auction. |

視覚芸術における影響[編集] ジャン=アントワーヌ・ワトー《イタリアの喜劇役者たち》1720年 コメディア・デラルテの図像学は、エレンシュタイン、カスタニョ、カトリツキー、モリナーリなどのコメディア研究者たちによって研究されてきた分野であ る。初期、フォンテーヌブローの画家たちによる代表的な作品は、ベールの薄いイナモラータ、つまり裸の花魁や女優をエロティックに描いたことで注目され た。 欲望、飲酒、快楽主義的なライフスタイルの危険性を描いたヴァニタスというジャンルの世界に、コメディアの人物が入り込んだことは、フランドルの影響が広 く記録されている。カスターニョは、フランドル人のピットーレ・ヴァーゴ(放浪画家)がイタリアの工房に同化し、イタリアの姓を名乗るようになったと述べ ている。例えば、最も影響力のあった画家の一人、ロデウィク・トープットは、ルドヴィコ・ポッツォセラートとなり、イタリアのヴェネト地方で有名な画家と なった。ピットーレ・ヴァーゴは、コメディア・デラルテを何世紀にもわたって存続する絵画のジャンルとして確立させたと言える。  マイセン磁器に描かれたヨハン・ヨアヒム・ケンドラーの コメディア・デラルテの人物像、1735-44年頃 図像は上演スタイルの証拠となるが(フォッサール・コレクションを参照)、多くの図像やエングレーヴィングは実生活からの描写ではなく、アトリエで練り上 げられたものであることに注意することが重要である。バッリ・ディ・スフェッサニア(Balli di Sfessania)』(1611年)のカロの銅版画は、コメディア舞踊の形式や典型的な仮面を実際に描いたものではなく、カプリッチと考えられている。 これらはしばしば大判で複製されるが、実際の版画の大きさは2×3インチ程度であったことに注意する必要がある。18世紀、貴族と交わるコメディアの人物 を描いたワトーの絵は、豪華な庭園や牧歌的な舞台を舞台にしたものが多く、そのジャンルを代表するものだった。 パブロ・ピカソが1921年に描いた『三人の音楽隊』は、コメディアにインスパイアされた登場人物を色彩豊かに表現したものである[47]。ピカソはま た、コメディアの登場人物や状況を描いたストラヴィンスキーのバレエ『プルチネルラ』(1920年)のオリジナル衣装をデザインした。コメディアの図像 は、オークションで数千ドルで取引される磁器の置物にも見られる。 |

Influence in performance art Peeter van Bredael, commedia dell'arte Scene in an Italian Landscape The expressive theatre influenced Molière's comedy and subsequently ballet d'action, thus lending a fresh range of expression and choreographic means. An example of a commedia dell'arte character in literature is the Pied Piper of Hamelin who is dressed as Harlequin. Music and dance were central to commedia dell'arte performance, and most performances had both instrumental and vocal music in them.[48] Brighella was often depicted with a guitar, and many images of the commedia feature singing innamorati or dancing figures. In fact, it was considered part of the innamorati function to be able to sing and have the popular repertoire under their belt. Accounts of the early commedia, as far back as Calmo in the 1570s and the buffoni of Venice, note the ability of comici to sing madrigali precisely and beautifully. The danzatrice probably accompanied the troupes and may have been in addition to the general cast of characters. For examples of strange instruments of various grotesque formations, see articles by Tom Heck, who has documented this area. The works of a number of playwrights have featured characters influenced by the commedia dell'arte and sometimes directly drawn from it. Prominent examples include The Tempest by William Shakespeare, Les Fourberies de Scapin by Molière, The Servant of Two Masters (1743) by Carlo Goldoni, the Figaro plays of Pierre Beaumarchais, and especially The Love for Three Oranges, Turandot and other fiabe by Carlo Gozzi. Influences appear in the lodgers in Steven Berkoff's adaptation of Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis. Pierrot as "Pjerrot" in Denmark Through their association with spoken theatre and playwrights commedia figures have provided opera with many of its stock characters. Mozart's Don Giovanni sets a puppet show story and comic servants like Leporello and Figaro have commedia precedents. Soubrette characters like Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro, Zerlina in Don Giovanni and Despina in Così fan tutte recall Columbina and related characters. The comic operas of Gaetano Donizetti, such as L'elisir d'amore, draw readily upon commedia stock types. Leoncavallo's tragic melodrama Pagliacci depicts a commedia dell'arte company in which the performers find their life situations reflecting events they depict on stage. Commedia characters also figure in Richard Strauss's opera Ariadne auf Naxos. The piano piece Carnaval by Robert Schumann was conceived as a kind of masked ball that combined characters from commedia dell'arte with real world characters, such as Chopin, Paganini, and Clara Schumann, as well as characters from the composer's inner world.[49][50] Movements of the piece reflect the names of many characters of the commedia, including Pierrot, Harlequin, Pantalon, and Columbine. Stock characters and situations also appear in ballet. Igor Stravinsky's Petrushka and Pulcinella allude directly to the tradition. Commedia dell'arte is performed seasonally in Denmark on the Peacock Stage of Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, and north of Copenhagen at Dyrehavsbakken.[51] Tivoli has regular performances, while Bakken has daily performances for children by Pierrot and a puppet version of Pulcinella resembling Punch and Judy.[52][53] The characters created and portrayed by English comedian Sacha Baron Cohen (most famously Ali G, Borat, and Bruno) have been discussed in relation to their potential origins in commedia, as Baron Cohen was trained by French master clown Philippe Gaulier, whose other students have gone on to become teachers and performers of commedia.[54] |

パフォーマンス・アートへの影響[編集] ピーテル・ヴァン・ブレダール『イタリアの風景の中のコメディア・デラルテの情景 コメディア・デラルテは、モリエールの喜劇やバレエ・アクションに影響を与え、新鮮な表現と振付を可能にした。文学におけるコメディア・デラルテの登場人物の一例は、ハーレクインに扮したハーメルンの笛吹き男である。 音楽と舞踊はコメディア・デラルテの中心的な要素であり、ほとんどの演目には器楽と声楽の両方が含まれていた[48]。ブリゲッラはしばしばギターを持っ て描かれ、コメディアのイメージの多くには歌うイナモラティや踊る人物が登場する。実際、歌えること、ポピュラーなレパートリーを持っていることは、イナ モラーティの機能の一部と考えられていた。1570年代のカルモやヴェネツィアのブッフォーニにさかのぼる初期のコメディアに関する記述には、コミーチが マドリガリを正確かつ美しく歌えることが記されている。ダンツァトリーチェはおそらく一座の伴奏を務め、登場人物に加えていたのだろう。様々なグロテスク な造形の奇妙な楽器の例については、この分野を記録したトム・ヘックの記事を参照のこと。 多くの劇作家の作品には、コメディア・デラルテの影響を受けたキャラクターが登場し、時にはそこから直接描かれたものもある。ウィリアム・シェイクスピア の 『テンペスト』、モリエールの『スカパンの四人組』、カルロ・ゴルドーニの 『二人の主人の召使い』(1743年)、ピエール・ボーマルシェの『フィガロ』、特にカルロ・ゴッツィの 『3つのオレンジへの恋』、『トゥーランドット』などのフィアベがその代表例である。フランツ・カフカの 『変身』をスティーヴン・ベルコフが脚色した作品では、下宿人たちにその影響が見られる。 ピエロはデンマークで "Pjerrot "と呼ばれる。 コメディアの人物は、口語劇や劇作家との関わりを通して、オペラに多くの定番キャラクターを提供してきた。モーツァルトの『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』は、人形 劇の物語であり、レポレッロやフィガロのような滑稽な召使いは、コメディアに先行している。フィガロの結婚』のスザンナ、『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』のツェル リーナ、『コジ・ファン・トゥッテ』のデスピーナのようなスーブレットのキャラクターは、コロンビーナやそれに関連するキャラクターを思い起こさせる。ガ エターノ・ドニゼッティの喜歌劇『愛の妙薬』(L'elisir d'amore)は、コメディアのストック・タイプを容易に利用している。レオンカヴァッロの悲劇的メロドラマ『パリアッチ』は、コメディア・デラルテの 劇団を描いている。コメディアの登場人物は、リヒャルト・シュトラウスのオペラ『ナクソス島のアリアドネ』にも登場する。 ロベルト・シューマンのピアノ曲『カルナヴァル』は、コメディア・デラルテの登場人物と、ショパン、パガニーニ、クララ・シューマンといった現実世界の登 場人物、さらには作曲者の内面世界の登場人物を組み合わせた仮面舞踏会の一種として構想された[49][50]。曲の動きには、ピエロ、ハーレクイン、パ ンタロン、コロンビーヌなど、コメディアの多くの登場人物の名前が反映されている。 また、バレエにも登場するキャラクターやシチュエーションがある。イーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキーの『ペトルーシュカ』や『プルチネルラ』は、この伝統に直接言及している。 コメディア・デラルテは、デンマークではコペンハーゲンのチボリ公園のピーコック・ステージと、コペンハーゲンの北にあるダイレハヴスバッケンで季節ごと に上演されている[51]。チボリでは定期的に公演が行われ、バッケンではピエロによる子供向けの公演と、パンチとジュディに似たプルチネルラの人形劇が 毎日上演されている[52][53]。 イギリスのコメディアンであるサシャ・バロン・コーエンが創作し、演じているキャラクター(最も有名なのはアリ・G、ボラット、ブルーノ)については、コメディアに起源がある可能性が議論されている。 |

| Costumes in commedia dell'arte Theatre of Italy |

コメディア・デラルテの衣装 イタリアの劇場 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commedia_dell%27arte |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆