コミュニタリアニズム

Communitarianism; 共同体主義

☆ コミュニタリアニズムすなわち共同体主義(Communitarianism) は、個人と共同体のつながりを重視する哲学である。その最も重要な哲学は、人の社会的アイデンティティと人格は、共同体との関係によって大きく形成される という信念に基づいており、個人主義の発展の度合いは小さい。共同体は家族であるかもしれないが、共同体主義は通常、より広い、哲学的な意味で、ある場所 (地理的な場所)の人々の共同体、あるいは関心を共有する、あるいは歴史を共有する共同体の間の相互作用の集まりとして理解される。共同体主義は通常、極 端な個人主義に反対し、共同体全体の安定を優先する極端な自由放任政策を拒否する。

| Communitarianism

is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual

and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based on the belief

that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by

community relationships, with a smaller degree of development being

placed on individualism. Although the community might be a family,

communitarianism usually is understood, in the wider, philosophical

sense, as a collection of interactions, among a community of people in

a given place (geographical location), or among a community who share

an interest or who share a history.[1] Communitarianism usually opposes

extreme individualism and rejects extreme laissez-faire policies that

deprioritize the stability of the overall community. |

コ

ミュニタリアニズムすなわち共同体主義は、個人と共同体のつながりを重視する哲学である。その最も重要な哲学は、人の社会的アイデンティティと人格は、共

同体との関係によって大きく形成されるという信念に基づいており、個人主義の発展の度合いは小さい。共同体は家族であるかもしれないが、共同体主義は通

常、より広い、哲学的な意味で、ある場所(地理的な場所)の人々の共同体、あるいは関心を共有する、あるいは歴史を共有する共同体の間の相互作用の集まり

として理解される。共同体主義は通常、極端な個人主義に反対し、共同体全体の安定を優先する極端な自由放任政策を拒否する。 |

| Terminology The philosophy of communitarianism originated in the 20th century, but the term "communitarian" was coined in 1841, by John Goodwyn Barmby, a leader of the British Chartist movement, who used it in referring to utopian socialists and other idealists who experimented with communal styles of life. However, it was not until the 1980s that the term "communitarianism" gained currency through association with the work of a small group of political philosophers. Their application of the label "communitarian" was controversial, even among communitarians, because, in the West, the term evokes associations with the ideologies of socialism and collectivism; so, public leaders—and some of the academics who champion this school of thought—usually avoid the term "communitarian", while still advocating and advancing the ideas of communitarianism. The term is primarily used in two senses:[2][attribution needed] Philosophical communitarianism considers classical liberalism to be ontologically and epistemologically incoherent, and opposes it on those grounds. Unlike classical liberalism, which construes communities as originating from the voluntary acts of pre-community individuals, it emphasizes the role of the community in defining and shaping individuals. Communitarians believe that the value of community is not sufficiently recognized in liberal theories of justice. Ideological communitarianism is characterized as a radical centrist ideology that is sometimes marked by socially conservative and economically interventionist policies. This usage was coined recently. When the term is capitalized, it usually refers to the Responsive Communitarian movement of Amitai Etzioni and other philosophers. Czech and Slovak philosophers like Marek Hrubec,[3] Lukáš Perný[4] and Luboš Blaha[5] extend communitarianism to social projects tied to the values and significance of community or collectivism and to various types of communism and socialism (Christian, scientific, or utopian), including: Historical roots of collectivist projects from Plato, through François-Noël Babeuf, Pierre Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, Charles Fourier, Robert Owen to Karl Marx Contemporary theoretical communitarianism (Michael J. Sandel, Michael Walzer, Alasdair MacIntyre, Charles Taylor), originating in the 1980s Pro-liberal, pro-multicultural (Walzer, Taylor) Anti-liberal, pro-national (Sandel, MacIntyre) The vision of practical, self-sustaining communities as described by Thomas More (Utopia), Tommaso Campanella (Civitas solis) and practised by Christian Utopians (Jesuit Reduction) or utopian socialists like Charles Fourier (List of Fourierist Associations in the United States), Robert Owen (List of Owenite communities in the United States). This line includes various forms of cooperatives, self-help institutions, or communities (Hussite communities, The Diggers, Habans, Hutterites, Amish, Israeli kibbutz, Slavic community; examples include the Twelve Tribes communities, Tamera (Portugal), Marinaleda (Spain), the monastic state of Mount Athos[6] and the Catholic Worker Movement). |

用語解説 コミュニタリアニズムの哲学は20世紀に生まれたが、「コミュニタリアン」という言葉は1841年にイギリスのチャーティスト運動の指導者であったジョ ン・グッドウィン・バームビーによって作られた。しかし、「コミュニタリアニズム」という言葉が、政治哲学者の小グループの仕事と結びついて広まったの は、1980年代に入ってからのことである。欧米では、「コミュニタリアン」という言葉は社会主義や集団主義のイデオロギーを連想させるため、公的指導者 やこの学派を支持する学者の一部は、通常「コミュニタリアン」という言葉を避けながら、コミュニタリアニズムの思想を提唱し、推進している。 この用語は主に以下の2つの意味で使われる[2][要出典]。 哲学的コミュニタリアニズムは、古典的自由主義を存在論的にも認識論的にも支離滅裂であるとみなし、それを理由に反対する。共同体が共同体以前の個人の自 発的な行為に由来すると解釈する古典的自由主義とは異なり、共同体が個人を定義し形成する役割を強調する。コミュニタリアンは、リベラルの正義理論では共 同体の価値が十分に認識されていないと考えている。 イデオロギー的コミュニタリアニズムは、時に社会的に保守的で経済的に介入主義的な政策を特徴とする急進的中道主義イデオロギーとして特徴づけられる。こ の用法は最近の造語である。この用語が大文字で表記される場合は、通常、アミタイ・エツィオーニやその他の哲学者によるレスポンシブ・コミュニタリアニズ ム運動を指す。 マレク・フルベック[3]、ルカーシュ・ペルニー[4]、ルボシュ・ブラハ[5]のようなチェコやスロバキアの哲学者は、共同体や集団主義の価値や意義と 結びついた社会的プロジェクトや、様々なタイプの共産主義や社会主義(キリスト教的、科学的、ユートピア的)などにもコミュニタリアニズムを拡張してい る: プラトンから、フランソワ・ノエル・バブーフ、ピエール・ジョゼフ・プルードン、ミハイル・バクーニン、シャルル・フーリエ、ロバート・オーウェンを経てカール・マルクスに至るまで、集団主義的プロジェクトの歴史的ルーツ。 1980年代に生まれた現代の理論的共同体主義(マイケル・J・サンデル、マイケル・ウォルツァー、アラスデア・マッキンタイア、チャールズ・テイラー)。 プロリベラル、プロ多文化主義(ウォルツァー、テイラー) 反自由主義、親国家主義(サンデル、マッキンタイア) トマス・モア(ユートピア)、トマソ・カンパネラ(Civitas solis)によって記述され、キリスト教ユートピアン(イエズス会還元)、またはシャルル・フーリエ(米国におけるフーリエ主義者団体のリスト)、ロ バート・オーウェン(米国におけるオーウェン派共同体のリスト)のようなユートピア社会主義者によって実践された、実践的で自立した共同体のビジョン。こ の系統には、様々な形態の協同組合、自助施設、または共同体(フス派共同体、ディガー、ハバン、ハッタイト、アーミッシュ、イスラエルのキブツ、スラブ共 同体、例として十二部族共同体、タメラ(ポルトガル)、マリナレダ(スペイン)、アトス山の修道院国家[6]、カトリック労働者運動)が含まれる。 |

| Origins While the term communitarian was coined only in the mid-nineteenth century, ideas that are communitarian in nature appeared much earlier. They are found in some classical socialist doctrines (e.g. writings about the early commune and about workers' solidarity), and further back in the New Testament. Communitarianism has been traced back to early monasticism. A number of early sociologists had strongly communitarian elements in their work, such as Ferdinand Tönnies in his comparison of Gemeinschaft (oppressive but nurturing communities) and Gesellschaft (liberating but impersonal societies), and Emile Durkheim's concerns about the integrating role of social values and the relations between the individual and society. Both authors warned of the dangers of anomie (normlessness) and alienation in modern societies composed of atomized individuals who had gained their liberty but lost their social moorings. Modern sociologists saw the rise of mass society and the decline of communal bonds and respect for traditional values and authority in the United States as of the 1960s. Among those who raised these issues were Robert Nisbet (Twilight of Authority),[7] Robert N. Bellah Habits of the Heart,[8] and Alan Ehrenhalt (The Lost City: The Forgotten Virtues Of Community In America).[9] In his book Bowling Alone (2000), Robert Putnam documented the decline of "social capital" and stressed the importance of "bridging social capital," in which bonds of connectedness are formed across diverse social groups.[10] In the twentieth century communitarianism also began to be formulated as a philosophy by Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker movement. In an early article the Catholic Worker clarified the dogma of the Mystical Body of Christ as the basis for the movement's communitarianism.[11] Along similar lines, communitarianism is also related to the personalist philosophy of Emmanuel Mounier. Responding to criticism that the term 'community' is too vague or cannot be defined, Amitai Etzioni, one of the leaders of the American communitarian movement, pointed out that communities can be defined with reasonable precision as having two characteristics: first, a web of affect-laden relationships among a group of individuals, relationships that often crisscross and reinforce one another (as opposed to one-on-one or chain-like individual relationships); and second, a measure of commitment to a set of shared values, norms, and meanings, and a shared history and identity – in short, a particular culture.[12] Further, author David E. Pearson argued that "[t]o earn the appellation 'community,' it seems to me, groups must be able to exert moral suasion and extract a measure of compliance from their members. That is, communities are necessarily, indeed, by definition, coercive as well as moral, threatening their members with the stick of sanctions if they stray, offering them the carrot of certainty and stability if they don't."[12] What is specifically meant by "community" in the context of communitarianism can vary greatly between authors and periods. Historically, communities have been small and localized. However, as the reach of economic and technological forces extended, more expansive communities became necessary to provide effective normative and political guidance to these forces, prompting the rise of national communities in Europe in the 17th century. Since the late 20th century there has been some growing recognition that the scope of even these communities is too limited, as many challenges that people now face, such as the threat of nuclear war and that of global environmental degradation and economic crises, cannot be handled on a national basis. This has led to the quest for more encompassing communities, such as the European Union. Whether truly supra-national communities can be developed is far from clear. More modern communities can take many different forms, but are often limited in scope and reach. For example, members of one residential community are often also members of other communities – such as work, ethnic, or religious ones. As a result, modern community members have multiple sources of attachments, and if one threatens to become overwhelming, individuals will often pull back and turn to another community for their attachments. Thus, communitarianism is the reaction of some intellectuals to the problems of Western society, an attempt to find flexible forms of balance between the individual and society, the autonomy of the individual and the interests of the community, between the common good and freedom, rights, and duties.[13][14] |

起源 コミュニタリアンという言葉が生まれたのは19世紀半ばのことだが、コミュニタリアン的な考え方はもっと以前から存在していた。古典的な社会主義の教義 (初期のコミューンや労働者の連帯に関する著作など)や、新約聖書にも見られる。共同体主義は、初期の修道士主義にまで遡ることができる。 初期の社会学者の中には、ゲマインシャフト(抑圧的だが育成的な共同体)とゲゼルシャフト(解放的だが非人間的な社会)を比較したフェルディナント・テー ニースや、社会的価値の統合的役割や個人と社会の関係についてのエミール・デュルケムの懸念のように、共同体主義的な要素を強く持つ者が少なくない。両者 とも、自由は手に入れたが社会的な拠り所を失った孤立化した個人で構成される近代社会におけるアノミー(無規範性)と疎外の危険性を警告していた。現代の 社会学者たちは、1960年代の時点で、アメリカにおいて大衆社会が台頭し、共同体の絆や伝統的な価値観や権威に対する敬意が衰退していることを見抜いて いた。このような問題を提起した人々の中には、ロバート・ニスベット(『権威の黄昏』)[7]、ロバート・N・ベラ(『心の習慣』)[8]、アラン・エー レンハルト(『失われた都市:アメリカにおけるコミュニティの忘れられた美徳』)[9]などがいる。ロバート・パットナムはその著書『ボウリング・アロー ン』(2000年)において、「社会関係資本」の衰退を記録し、多様な社会集団を超えてつながりの絆が形成される「橋渡し的社会関係資本」の重要性を強調 している[10]。 20世紀には、ドロシー・デイとカトリック労働者運動によって、共同体主義も哲学として定式化され始めた。カトリック労働者は初期の論文で、運動の共同体 主義の基礎としてキリストの神秘体の教義を明確にしている[11]。同様の路線で、共同体主義はエマニュエル・ムニエの個人主義哲学とも関連している。 アメリカのコミュニタリアニズム運動の指導者の一人であるアミタイ・エツィオーニは、「コミュニティ」という用語は漠然としすぎていて定義できないという 批判に対して、コミュニティは2つの特徴を持つものとして合理的な精度をもって定義することができると指摘した。 [12]さらに、著者のデイヴィッド・E・ピアソンは、「『共同体』という呼称を得るためには、集団は道徳的な説得力を発揮し、メンバーから一定のコンプ ライアンスを引き出すことができなければならない。つまり、共同体は必然的に、実に定義上、道徳的であると同時に強制的であり、メンバーが逸脱すれば制裁 という棒で脅し、逸脱しなければ確実性と安定というニンジンを提供する」[12]。 共同体主義の文脈における「共同体」が具体的に何を意味するかは、著者や時代によって大きく異なることがある。歴史的に、コミュニティは小規模で地域的な ものであった。しかし、経済的・技術的な力が拡大するにつれて、これらの力に対して効果的な規範的・政治的指針を提供するために、より拡大的な共同体が必 要となり、17世紀にはヨーロッパで国民的共同体が台頭した。20世紀後半以降、核戦争の脅威や地球環境の悪化、経済危機など、現在人々が直面している多 くの課題は、国家単位では対処できないため、こうした共同体の範囲さえも限定的であるという認識が広まりつつある。そのため、EUのような、より包括的な 共同体が求められている。真に超国家的な共同体を発展させることができるかどうかは、まだ明らかではない。 より現代的なコミュニティは、さまざまな形をとることができるが、その範囲や範囲は限定的であることが多い。たとえば、ある居住コミュニティのメンバー は、しばしば他のコミュニティ(職場、民族、宗教など)のメンバーでもある。その結果、現代の共同体構成員は複数の愛着源を持ち、1つの愛着源が圧倒的に なりそうになると、個人は愛着源を引き戻し、別の共同体に目を向けることが多い。したがって、共同体主義とは、西洋社会の問題に対する一部の知識人の反応 であり、個人と社会、個人の自律性と共同体の利益、共通善と自由、権利、義務の間に柔軟なバランスの形を見出そうとする試みである[13][14]。 |

| Academic communitarianism Whereas the classical liberalism of the Enlightenment can be viewed as a reaction to centuries of authoritarianism, oppressive government, overbearing communities, and rigid dogma, modern communitarianism can be considered a reaction to excessive individualism, understood as an undue emphasis on individual rights, leading people to become selfish or egocentric.[15] The close relation between the individual and the community was discussed on a theoretical level by Michael Sandel and Charles Taylor, among other academic communitarians, in their criticisms of philosophical liberalism, especially the work of the American liberal theorist John Rawls and that of the German Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant. They argued that contemporary liberalism failed to account for the complex set of social relations that all individuals in the modern world are a part of. Liberalism is rooted in an untenable ontology that posits the existence of generic individuals and fails to account for social embeddedness. To the contrary, they argued, there are no generic individuals but rather only Germans or Russians, Berliners or Muscovites, or members of some other particularistic community. Because individual identity is partly constructed by culture and social relations, there is no coherent way of formulating individual rights or interests in abstraction from social contexts. Thus, according to these communitarians, there is no point in attempting to found a theory of justice on principles decided behind Rawls' veil of ignorance, because individuals cannot exist in such an abstracted state, even in principle.[15] Academic communitarians also contend that the nature of the political community is misunderstood by liberalism. Where liberal philosophers described the polity as a neutral framework of rules within which a multiplicity of commitments to moral values can coexist, academic communitarians argue that such a thin conception of political community was both empirically misleading and normatively dangerous. Good societies, these authors believe, rest on much more than neutral rules and procedures—they rely on a shared moral culture. Some academic communitarians argued even more strongly on behalf of such particularistic values, suggesting that these were the only kind of values which matter and that it is a philosophical error to posit any truly universal moral values. In addition to Charles Taylor and Michael Sandel, other thinkers sometimes associated with academic communitarianism include Michael Walzer, Alasdair MacIntyre, Seyla Benhabib, and Shlomo Avineri.[15] Social capital Beginning in the late 20th century, many authors began to observe a deterioration in the social networks of the United States. In the book Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam observed that nearly every form of civic organization has undergone drops in membership exemplified by the fact that, while more people are bowling than in the 1950s, there are fewer bowling leagues. This results in a decline in "social capital", described by Putnam as "the collective value of all 'social networks' and the inclinations that arise from these networks to do things for each other". According to Putnam and his followers, social capital is a key component to building and maintaining democracy.[10] Communitarians seek to bolster social capital and the institutions of civil society. The Responsive Communitarian Platform described it thus:[16] Many social goals require partnerships between public and private groups. Though the government should not seek to replace local communities, it may need to empower them by strategies of support, including revenue-sharing and technical assistance. There is a great need for study and experimentation with creative use of the structures of civil society, and public-private cooperation, especially where the delivery of health, educational and social services are concerned. Positive rights Important to some supporters of communitarian philosophy is the concept of positive rights, which are rights or guarantees to certain things. These may include state-subsidized education, state-subsidized housing, a safe and clean environment, universal health care, and even the right to a job with the concomitant obligation of the government or individuals to provide one. To this end, communitarians generally support social security programs, public works programs, and laws limiting such things as pollution. A common objection is that by providing such rights, communitarians violate the negative rights of the citizens; rights to not have something done for you. For example, taxation to pay for such programs as described above dispossesses individuals of property. Proponents of positive rights, by attributing the protection of negative rights to the society rather than the government, respond that individuals would not have any rights in the absence of societies—a central tenet of communitarianism—and thus have a responsibility to give something back to it. Some have viewed this as a negation of natural rights. However, what is or is not a "natural right" is a source of contention in modern politics, as well as historically; for example, whether or not universal health care, private property or protection from polluters can be considered a birthright. Alternatively, some agree that negative rights may be violated by a government action, but argue that it is justifiable if the positive rights protected outweigh the negative rights lost. Still, other communitarians question the very idea of natural rights and their place in a properly functioning community. They claim that instead, claims of rights and entitlements create a society unable to form cultural institutions and grounded social norms based on shared values. Rather, the liberalist claim to individual rights leads to a morality centered on individual emotivism, as ethical issues can no longer be solved by working through common understandings of the good. The worry here is that not only is society individualized, but so are moral claims.[17] |

アカデミックな共同体主義 啓蒙主義の古典的な自由主義が、何世紀にもわたる権威主義、抑圧的な政府、威圧的な共同体、硬直した教義に対する反動とみなすことができるのに対し、現代 のコミュニタリアニズムは、個人の権利を過度に強調し、人々を利己主義や自己中心主義に導くと理解される過剰な個人主義に対する反動とみなすことができる [15]。 個人と共同体との密接な関係は、他のアカデミックなコミュニタリアンの中でもマイケル・サンデルやチャールズ・テイラーによって、哲学的自由主義、特にア メリカの自由主義理論家ジョン・ロールズやドイツの啓蒙主義哲学者イマヌエル・カントの研究に対する批判の中で理論的なレベルで議論された。彼らは、現代 のリベラリズムは、現代世界のすべての個人が属している複雑な社会関係を説明できていないと主張した。リベラリズムは、一般的な個人の存在を前提とし、社 会的包摂性を説明できない存在論に根ざしている。それどころか、一般的な個人など存在せず、ドイツ人かロシア人か、ベルリン人かムスコヴィッツ人か、ある いは他の特殊な共同体のメンバーしか存在しないと彼らは主張した。個人のアイデンティティは部分的には文化や社会関係によって構築されるため、社会的文脈 から抽象化して個人の権利や利益を定式化する首尾一貫した方法は存在しない。したがって、これらのコミュニタリアンによれば、ロールズの無知のヴェールの 向こうで決定された原理に基づいて正義の理論を確立しようとすることには意味がなく、そのような抽象化された状態では個人は原理的にも存在し得ないからで ある[15]。 アカデミック・コミュニタリアンはまた、政治的共同体の本質がリベラリズムによって誤解されていると主張している。リベラルの哲学者たちが政治を、道徳的 価値に対する多様なコミットメントが共存できる中立的なルールの枠組みとして説明したのに対し、アカデミック・コミュニタリアンは、このような政治的共同 体の薄い概念は経験的に誤解を招き、規範的にも危険であると主張する。良い社会とは、中立的なルールや手続き以上のものであり、共有された道徳文化に依拠 しているのだ。一部のアカデミックなコミュニタリアンは、このような特殊な価値観をさらに強く主張し、重要なのはこのような価値観だけであり、真に普遍的 な道徳的価値観を措定するのは哲学的に誤りであると示唆した。 チャールズ・テイラーやマイケル・サンデルに加えて、アカデミック・コミュニタリアニズムと関連付けられることのある思想家には、マイケル・ウォルツァー、アラスデア・マッキンタイア、セイラ・ベンハビブ、シュロモ・アヴィネリなどがいる[15]。 社会資本 20世紀後半から、多くの著者が米国の社会的ネットワークの劣化を観察し始めた。ロバート・パットナムは、『Bowling Alone』という本の中で、1950年代よりも多くの人々がボウリングをしている一方で、ボウリング・リーグの数は減っているという事実に代表されるよ うに、ほとんどあらゆる形態の市民団体が会員数の減少を経験していると観察した。 この結果、「ソーシャル・キャピタル」が減少している。パットナムは、「すべての『ソーシャル・ネットワーク』の集合的価値と、これらのネットワークから 生じる、互いのために何かをしようとする傾向」と表現している。パトナムとその支持者たちによれば、ソーシャル・キャピタルは民主主義を構築し維持するた めの重要な要素である[10]。 コミュニタリアンは、ソーシャル・キャピタルと市民社会の制度を強化しようとしている。レスポンシブ・コミュニタリアン・プラットフォームはそれを次のように説明している[16]。 多くの社会的目標には、公共団体と民間団体のパートナーシップが必要である。政府は地域コミュニティに取って代わろうとすべきではないが、収入分配や技術 支援を含む支援戦略によって、地域コミュニティに力を与える必要があるかもしれない。特に保健、教育、および社会サービスの提供に関しては、市民社会の構 造を創造的 に利用し、官民協力について研究し、実験することが大いに必要である。 積極的権利 共同体主義哲学を支持する一部の人々にとって重要なのは、特定のものに対する権利や保証である積極的権利の概念である。これには、国が補助する教育、国が 補助する住宅、安全で清潔な環境、国民皆保険、さらには政府や個人が仕事を提供する義務を伴う仕事を得る権利などが含まれる。この目的のために、コミュニ タリアンは一般的に、社会保障制度、公共事業プログラム、公害などを制限する法律を支持する。 よくある反論は、このような権利を提供することで、コミュニタリアンは市民の否定的権利、つまり自分のために何かをされない権利を侵害するというものだ。 例えば、上記のようなプログラムの費用を賄うための課税は、個人の財産を奪うことになる。積極的権利の支持者は、消極的権利の保護を政府ではなく社会に帰 属させることで、社会がなければ個人はいかなる権利も持たないことになり、したがって社会に何かを還元する責任があると反論する。これを自然権の否定とみ なす向きもある。しかし、何が「自然権」であり、何が「自然権」でないかは、歴史的にも現代政治においても論争の種となっている。例えば、国民皆保険、私 有財産、汚染者からの保護が生まれながらの権利と言えるかどうかなどである。 あるいは、政府の行為によって否定的権利が侵害される可能性があることに同意する人もいるが、保護される肯定的権利が失われる否定的権利を上回る場合は正当化されると主張する。 さらに、自然権という考え方や、適切に機能する共同体における自然権の位置づけを疑問視するコミュニタリアンもいる。彼らは、権利や資格の主張が、共有さ れた価値観に基づく文化制度や社会規範を形成できない社会を生み出すと主張する。むしろ、個人の権利に対するリベラリストの主張は、個人の感情主義を中心 とした道徳をもたらし、倫理的な問題はもはや善についての共通理解を通じて解決することができないからである。ここで懸念されるのは、社会が個人化されて いるだけでなく、道徳的主張も個人化されているということである[17]。 |

| Responsive communitarianism movement In the early 1990s, in response to the perceived breakdown in the moral fabric of society engendered by excessive individualism, Amitai Etzioni and William A. Galston began to organize working meetings to think through communitarian approaches to key societal issues. This ultimately took the communitarian philosophy from a small academic group, introduced it into public life, and recast its philosophical content. Deeming themselves "responsive communitarians" in order to distinguish the movement from authoritarian communitarians, Etzioni and Galston, along with a varied group of academics (including Mary Ann Glendon, Thomas A. Spragens, James Fishkin, Benjamin Barber, Hans Joas, Philip Selznick, and Robert N. Bellah, among others) drafted and published The Responsive Communitarian Platform[18] based on their shared political principles, and the ideas in it were eventually elaborated in academic and popular books and periodicals, gaining thereby a measure of political currency in the West. Etzioni later formed the Communitarian Network to study and promote communitarian approaches to social issues and began publishing a quarterly journal, The Responsive Community. The main thesis of responsive communitarianism is that people face two major sources of normativity: that of the common good and that of autonomy and rights, neither of which in principle should take precedence over the other. This can be contrasted with other political and social philosophies which derive their core assumptions from one overarching principle (such as liberty/autonomy for libertarianism). It further posits that a good society is based on a carefully crafted balance between liberty and social order, between individual rights and personal responsibility, and between pluralistic and socially established values. Responsive communitarianism stresses the importance of society and its institutions above and beyond that of the state and the market, which are often the focus of other political philosophies. It also emphasizes the key role played by socialization, moral culture, and informal social controls rather than state coercion or market pressures. It provides an alternative to liberal individualism and a major counterpoint to authoritarian communitarianism by stressing that strong rights presume strong responsibilities and that one should not be neglected in the name of the other. Following standing sociological positions, communitarians assume that the moral character of individuals tends to degrade over time unless that character is continually and communally reinforced. They contend that a major function of the community, as a building block of moral infrastructure, is to reinforce the character of its members through the community's "moral voice," defined as the informal sanction of others, built into a web of informal affect-laden relationships, which communities provide. Influence Responsive communitarians have been playing a considerable public role, presenting themselves as the founders of a different kind of environmental movement, one dedicated to shoring up society (as opposed to the state) rather than nature. Like environmentalism, communitarianism appeals to audiences across the political spectrum, although it has found greater acceptance with some groups than others. Although communitarianism is a small philosophical school, it has had considerable influence on public dialogues and politics. There are strong similarities between communitarian thinking and the Third Way, the political thinking of centrist Democrats in the United States, and the Neue Mitte in Germany. Communitarianism played a key role in Tony Blair's remaking of the British socialist Labour Party into "New Labour" and a smaller role in President Bill Clinton's campaigns. Other politicians have echoed key communitarian themes, such as Hillary Clinton, who has long held that to raise a child takes not just parents, family, friends and neighbors, but a whole "village".[19] It has also been suggested[14] that the compassionate conservatism espoused by President Bush during his 2000 presidential campaign was a form of conservative communitarian thinking, although he did not implement it in his policy program. Cited policies have included economic and rhetorical support for education, volunteerism, and community programs, as well as a social emphasis on promoting families, character education, traditional values, and faith-based projects. President Barack Obama gave voice to communitarian ideas and ideals in his book The Audacity of Hope,[20] and during the 2008 presidential election campaign he repeatedly called upon Americans to "ground our politics in the notion of a common good," for an "age of responsibility," and for foregoing identity politics in favor of community-wide unity building. However, for many in the West, the term communitarian conjures up authoritarian and collectivist associations, so many public leaders – and even several academics considered champions of this school – avoid the term while embracing and advancing its ideas. Reflecting the dominance of liberal and conservative politics in the United States, no major party and few elected officials openly advocate communitarianism. Thus there is no consensus on individual policies, but some that most communitarians endorse have been enacted. Nonetheless, there is a small faction of communitarians within the Democratic Party; prominent communitarians include Bob Casey Jr., Joe Donnelly, and Claire McCaskill. Many communitarian Democrats are part of the Blue Dog Coalition. It is quite possible[according to whom?] that the United States' right-libertarian ideological underpinnings have suppressed major communitarian factions from emerging.[21] Dana Milbank, writing in The Washington Post, remarked of modern communitarians, "There is still no such thing as a card-carrying communitarian, and therefore no consensus on policies. Some, such as John DiIulio and outside Bush adviser Marvin Olasky, favor religious solutions for communities, while others, like Etzioni and Galston, prefer secular approaches."[22] In August 2011, the right-libertarian Reason Magazine worked with the Rupe organization to survey 1,200 Americans by telephone. The Reason-Rupe poll found that "Americans cannot easily be bundled into either the 'liberal' or 'conservative' groups". Specifically, 28% expressed conservative views, 24% expressed libertarian views, 20% expressed communitarian views, and 28% expressed liberal views. The margin of error was ±3.[23] A similar Gallup survey in 2011 included possible centrist/moderate responses. That poll reported that 17% expressed conservative views, 22% expressed libertarian views, 20% expressed communitarian views, 17% expressed centrist views, and 24% expressed liberal views. The organization used the terminology "the bigger the better" to describe communitarianism.[23] The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party, founded and led by Imran Khan, is considered the first political party in the world which has declared communitarianism as one of their official ideologies.[24] |

レスポンシブ・コミュニタリアニズム運動 1990年代初頭、行き過ぎた個人主義がもたらした社会のモラルの崩壊を受け、アミタイ・エツィオーニとウィリアム・A・ガルストンは、重要な社会問題に 対するコミュニタリアニズム的アプローチについて考えるワーキングミーティングを組織し始めた。これは最終的に、共同体主義哲学を小さな学術グループから 一般社会に導入し、その哲学的内容を再構成することになった。 エツィオーニとガルストンは、この運動を権威主義的コミュニタリアンと区別するために、自らを「応答的コミュニタリアン」と称し、メアリー・アン・グレン ドン、トーマス・A・スプラゲンス、ジェームズ・フィッシュキン、ベンジャミン・バーバー、ハンス・ヨース、フィリップ・セルズニック、ロバート・N・ベ ラなど、さまざまな学者たちとともに、共同体主義的な理念の草案を作成した。エッツィオーニは、自分たちが共有する政治的原則に基づき、『レスポンシブ・ コミュニタリアン・プラットフォーム』[18]を起草・出版した。エッツィオーニはその後、社会問題に対するコミュニタリアン的アプローチを研究・促進す るためにコミュニタリアン・ネットワークを結成し、季刊誌『The Responsive Community』の発行を開始した。 反応的共同体主義の主要なテーゼは、人々は2つの主要な規範の源に直面しているということである。すなわち、共通善と自律性と権利である。これは、一つの 包括的な原理(リバタリアニズムにおける自由/自律など)から中核的な前提を導き出す他の政治哲学や社会哲学と対照的である。さらに、良い社会とは、自由 と社会秩序の間、個人の権利と個人の責任の間、多元的価値観と社会的に確立された価値観の間の、注意深く作り上げられたバランスの上に成り立っているとす る。 責任共同体主義は、他の政治哲学がしばしば重視する国家や市場以上に、社会とその制度の重要性を強調する。また、国家の強制や市場の圧力よりも、社会化、 道徳文化、インフォーマルな社会統制が果たす重要な役割を強調する。強力な権利は強力な責任を前提とし、他方の名において一方がないがしろにされるべきで はないと強調することで、自由主義的個人主義に代わる選択肢を提供し、権威主義的共同体主義への主要な対抗策となる。 社会学的な立場を踏襲し、コミュニタリアンは、個人の道徳的人格は、その人格が継続的かつ共同的に強化されない限り、時間の経過とともに低下する傾向があ ると仮定する。彼らは、道徳的基盤の構築物としてのコミュニティの主要な機能は、コミュニティが提供する「道徳的声」(インフォーマルな他者からの制裁と 定義され、コミュニティが提供する、インフォーマルな感情を伴う人間関係の網の目の中に構築される)を通して、その構成員の人格を強化することであると主 張する。 影響力 レスポンシブ・コミュニタリアンは、自然よりもむしろ社会(国家とは対照的)を支えることに専念する、異なる種類の環境運動の創始者として自らを提示し、 かなりの公的役割を果たしてきた。環境保護主義と同様、コミュニタリアニズムは政治的なスペクトルを超えて聴衆にアピールしているが、一部のグループには 他のグループよりも受け入れられている。 共同体主義は小さな哲学学派だが、公的な対話や政治に大きな影響を与えてきた。共同体主義的思考と第三の道、アメリカの中道民主党の政治的思考、ドイツの ノイエ・ミッテには強い類似性がある。コミュニタリアニズムは、トニー・ブレアがイギリスの社会主義労働党を「新労働党」に作り変える際に重要な役割を果 たし、ビル・クリントン大統領のキャンペーンでは小さな役割を果たした。ヒラリー・クリントンのように、子供を育てるには両親、家族、友人、隣人だけでな く、「村」全体が必要であると長い間主張してきた政治家もいる[19]。 また、2000年の大統領選挙キャンペーン中にブッシュ大統領が唱えた思いやりのある保守主義は、彼の政策プログラムでは実施されなかったものの、保守的 な共同体主義的思考の一形態であったことが示唆されている[14]。引用された政策には、教育、ボランティア活動、コミュニティ・プログラムに対する経済 的・修辞的支援や、家族促進、人格教育、伝統的価値観、信仰に基づくプロジェクトなどの社会的重点が含まれている。 バラク・オバマ大統領は、著書『The Audacity of Hope(希望の大胆さ)』[20]の中で共同体主義的な考えや理想を表明し、2008年の大統領選挙キャンペーンでは、「共通善の概念に政治を根付かせ る」こと、「責任の時代」であること、地域全体の団結構築を優先してアイデンティティ政治を見送ることを、アメリカ人に繰り返し呼びかけた。しかし、欧米 の多くの人々にとって、コミュニタリアンという言葉は権威主義や集団主義を連想させるため、多くの公的指導者たち、そしてこの学派の擁護者とされる学者た ちでさえも、この言葉を避けながら、その考えを受け入れ、推進している。 米国ではリベラルと保守の政治が支配的であることを反映して、どの主要政党も、また選挙で選ばれた議員の中にも、公然とコミュニタリアニズムを標榜する者 はほとんどいない。したがって、個々の政策についてのコンセンサスは存在しないが、コミュニタリアンの多くが支持するいくつかの政策は制定されている。と はいえ、民主党内にはコミュニタリアンの小派閥が存在する。著名なコミュニタリアンには、ボブ・ケーシー・ジュニア、ジョー・ドネリー、クレア・マッカス キルなどがいる。共産主義者の民主党議員の多くは、ブルードッグ連合の一員である。米国の右派リバタリアンのイデオロギー的基盤が、主要なコミュニタリア ン派閥の台頭を抑制している可能性は十分にある[21]。 ダナ・ミルバンクは『ワシントン・ポスト』紙に寄稿し、現代のコミュニタリアンについて次のように述べている。ジョン・ディウリオやブッシュの外部アドバ イザーであるマービン・オラスキーのように、共同体に対する宗教的な解決策を支持する者もいれば、エツィオーニやガルストンのように、世俗的なアプローチ を好む者もいる」[22]。 2011年8月、右派リベタリアンの『リーズン』誌は、ルーピー組織と協力して1,200人のアメリカ人を対象に電話調査を行った。リーズン-ルーペの世 論調査では、「アメリカ人は簡単に『リベラル派』にも『保守派』にも括れない」ことがわかった。具体的には、28%が保守派、24%がリバタリアン、 20%がコミュニタリアン、28%がリベラル派であった。誤差は±3であった[23]。 2011年のギャラップ社の同様の調査では、中道/中庸の回答も含まれていた。その世論調査では、17%が保守的な意見、22%がリバタリアン的な意見、 20%がコミュニタリアン的な意見、17%が中道的な意見、24%がリベラルな意見であった。同団体は「大は小を兼ねる」という用語を使って共同体主義を 表現した[23]。 イムラン・カーンが創設し率いるパキスタン・テヒリーク・エ・インサフ党は、共産主義を公式イデオロギーの一つとして宣言した世界初の政党と考えられている[24]。 |

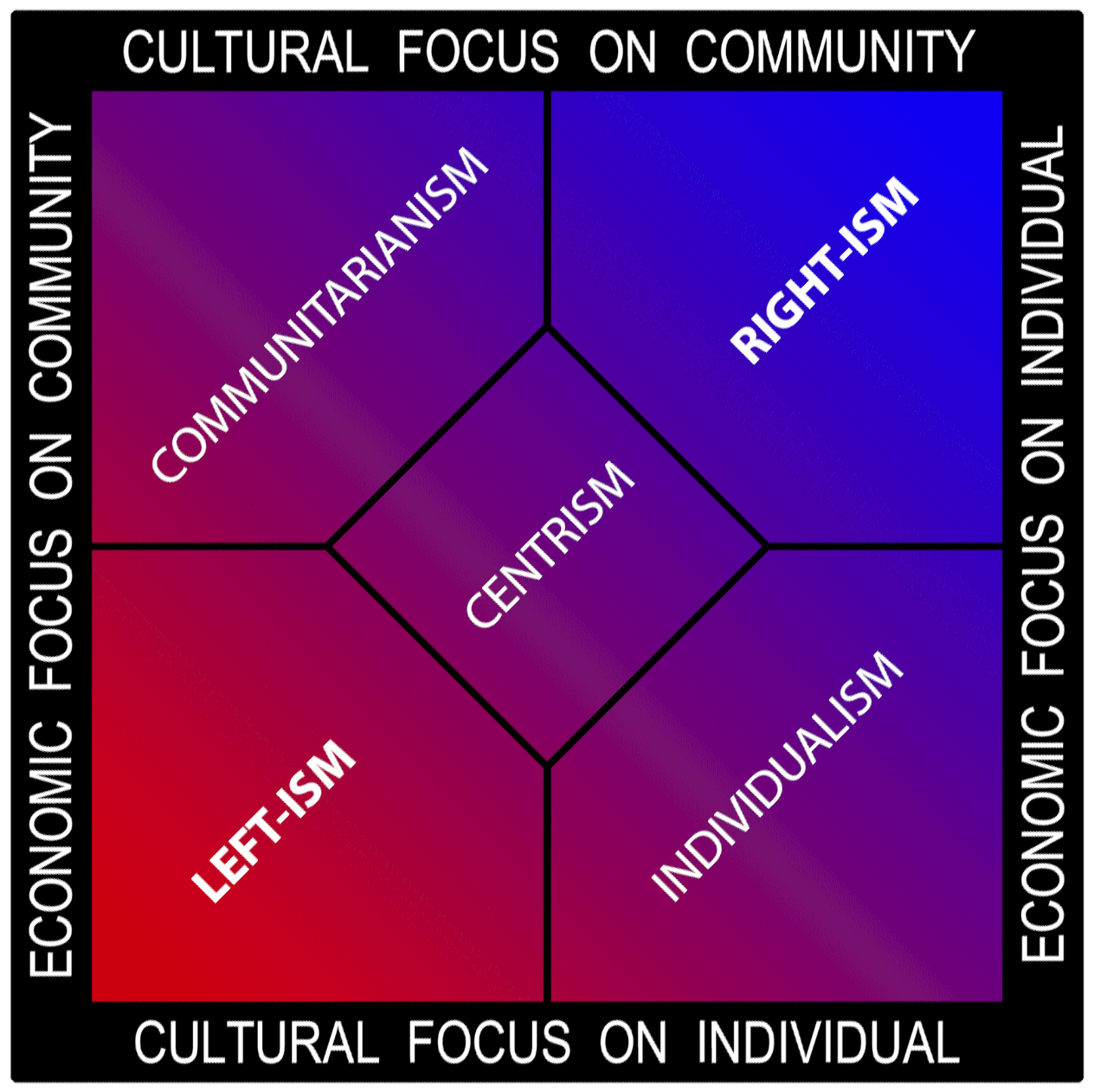

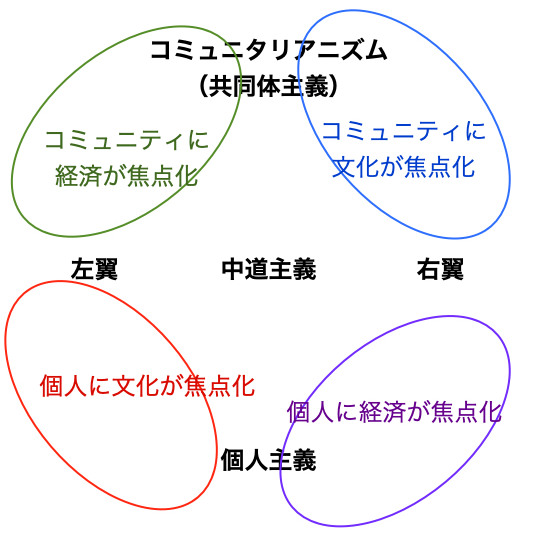

Comparison to other political philosophies A variant of the Nolan chart using traditional political color coding (red leftism versus blue rightism) with communitarianism on the top left Early communitarians were charged with being, in effect, social conservatives. However, many contemporary communitarians, especially those who define themselves as responsive communitarians, fully realize and often stress that they do not seek to return to traditional communities, with their authoritarian power structure, rigid stratification, and discriminatory practices against minorities and women. Responsive communitarians seek to build communities based on open participation, dialogue, and truly shared values. Linda McClain, a critic of communitarians, recognizes this feature of the responsive communitarians, writing that some communitarians do "recognize the need for careful evaluation of what is good and bad about [any specific] tradition and the possibility of severing certain features . . . from others."[25] And R. Bruce Douglass writes, "Unlike conservatives, communitarians are aware that the days when the issues we face as a society could be settled on the basis of the beliefs of a privileged segment of the population have long since passed."[26] One major way the communitarian position differs from the social conservative one is that although communitarianism's ideal "good society" reaches into the private realm, it seeks to cultivate only a limited set of core virtues through an organically developed set of values rather than having an expansive or holistically normative agenda given by the state. For example, American society favors being religious over being atheist, but is rather neutral with regard to which particular religion a person should follow. There are no state-prescribed dress codes, "correct" number of children to have, or places one is expected to live, etc. In short, a key defining characteristic of the ideal communitarian society is that in contrast to a liberal state, it creates shared formulations of the good, but the scope of this good is much smaller than that advanced by authoritarian societies."[27] |

他の政治哲学との比較 伝統的な政治的色分け(赤の左派対青の右派)を用いたノーラン・チャートの変形で、中央上にコミュニタリアニズムがある。 初期のコミュニタリアンは、事実上、社会的保守主義者であるとして告発された。しかし、現代のコミュニタリアンの多く、特に自らをレスポンシブ・コミュニ タリアンと定義する人々は、権威主義的な権力構造、厳格な階層化、マイノリティや女性に対する差別的慣行を持つ伝統的なコミュニティに戻ろうとはしていな いことを十分に理解し、しばしば強調している。レスポンシブ・コミュニタリアンは、開かれた参加、対話、真に共有された価値観に基づくコミュニティの構築 を目指す。コミュニタリアンを批判しているリンダ・マクレーン(Linda McClain)は、反応的コミュニタリアンのこの特徴を認め、コミュニタリアンの中には「(特定の)伝統の良いところと悪いところを注意深く評価する必 要性と、ある種の特徴を他から切り離す可能性を認識している者もいる」と書いている[25]。また、R.ブルース・ダグラスは、「保守派とは異なり、コ ミュニタリアンは、社会として直面する問題が、人口の特権階級の信念に基づいて解決されうる時代はとうに過ぎ去ったことを認識している」と書いている [26]。 コミュニタリアンの立場が社会的保守主義の立場と異なる大きな点のひとつは、コミュニタリアニズムが理想とする「良い社会」は私的な領域にまで及ぶもの の、国家が与える拡大的で全体論的な規範的アジェンダを持つのではなく、有機的に発展した価値観の集合を通して、限られた核となる美徳の集合のみを育成し ようとする点である。たとえば、アメリカ社会は無神論者であることよりも宗教的であることに好意的だが、特定の宗教を信仰することに関しては中立的であ る。国家が規定するドレスコード、「正しい」子供の数、住むべき場所などは存在しない。要するに、理想的な共同体主義社会の重要な特徴は、自由主義国家と は対照的に、善の共有化を生み出すが、この善の範囲は権威主義社会が進めるそれよりもはるかに小さいということである」[27]。 |

| Criticism Liberal theorists, such as Simon Caney,[28] disagree that philosophical communitarianism has any interesting criticisms to make of liberalism. They reject the communitarian charges that liberalism neglects the value of community, and holds an "atomized" or asocial view of the self. According to Peter Sutch the principal criticisms of communitarianism are: that communitarianism leads necessarily to moral relativism; that this relativism leads necessarily to a re-endorsement of the status quo in international politics; and that such a position relies upon a discredited ontological argument that posits the foundational status of the community or state.[29] He argues that such arguments cannot be leveled against the particular communitarian theories of Michael Walzer and Mervyn Frost.[citation needed] Other critics emphasize close relation of communitarianism to neoliberalism and new policies of dismantling the welfare state institutions through development of the third sector.[30] Opposition Bruce Frohnen – author of The New Communitarians and the Crisis of Modern Liberalism (1996) Charles Arthur Willard – author of Liberalism and the Problem of Knowledge: A New Rhetoric for Modern Democracy, University of Chicago Press, 1996. |

批判 サイモン・ケイニー[28]のようなリベラルの理論家は、哲学的コミュニタリアニズムがリベラリズムに対して興味深い批判を行うことに同意しない。彼ら は、リベラリズムが共同体の価値を軽視し、「原子化された」あるいは非社会的な自己観を持っているという共同体主義者の主張を否定している。 ピーター・サッチによれば、共同体主義に対する主な批判は以下の通りである: 共同体主義は必然的に道徳的相対主義につながる; この相対主義は、国際政治における現状の再推薦に必然的につながる。 そのような立場は、共同体や国家の基礎的地位を措定する不信任な存在論的議論に依存していることである[29]。 彼はそのような議論はマイケル・ウォルツァーやマーヴィン・フロストの特定のコミュニタリアン理論に対して行うことはできないと主張している[要出典]。 他の批評家は、共同体主義が新自由主義や第三セクターの発展を通じて福祉国家制度を解体するという新しい政策と密接な関係があることを強調している[30]。 反対派 ブルース・フローネン - 『新コミュニタリアンと現代リベラリズムの危機』(1996年)の著者。 チャールズ・アーサー・ウィラード - 『リベラリズムと知識の問題』の著者: A New Rhetoric for Modern Democracy, University of Chicago Press, 1996. |

| Earlier theorists and writers[citation needed] Aristotle Martin Buber Confucius Charles Fourier T. H. Green Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel L. T. Hobhouse J. A. Hobson Niccolò Machiavelli Robert Owen Jean-Jacques Rousseau Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America Contemporary theorists Benjamin Barber Gad Barzilai Robert N. Bellah Phillip Blond Amitai Etzioni William Galston Mark Kuczewski Alexandre Marc Stephen Marglin Emmanuel Mounier Michael Sandel Non-conformists of the 1930s Costanzo Preve Robert Putnam Jose Perez Adan Joseph Raz Charles Taylor Michael Walzer Yoram Hazony |

初期の理論家および作家[要出典] アリストテレス マルティン・ブーバー 孔子 シャルル・フーリエ T. H. グリーン ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル L. T. ホブハウス J. A. ホブソン ニッコロ・マキャベリ ロバート・オーウェン ジャン=ジャック・ルソー アレクシス・ド・トクヴィル著『アメリカの民主主義』 現代の理論家 ベンジャミン・バーバー ガド・バルザイ ロバート・N・ベラー フィリップ・ブロンド アミタイ・エッツィオーニ ウィリアム・ガルストン マーク・クチェスキー アレクサンドル・マーク スティーブン・マーグリン エマニュエル・ムニエ マイケル・サンデル 1930年代の非順応主義者たち コンスタンゾ・プレヴェ ロバート・パットナム ホセ・ペレス・アダン ジョセフ・ラズ チャールズ・テイラー マイケル・ウォルツァー ヨラム・ハゾニー |

| Civics Civil religion Classical republicanism Corporatism Corporate statism Communalism (South Asia) Dark Enlightenment Distributism List of Fourierist Associations in the United States List of Owenite communities in the United States Medieval commune Nationalism National Conservatism One-nation conservatism Postliberalism Public sphere Radical centrism Singaporean communitarianism Statism Third Way Tribalism Ubuntu philosophy Venezuelan Communal Councils Yellow socialism |

公民 市民宗教 古典的共和主義 コーポラティズム 企業国家主義 共同体主義(南アジア) 暗黒啓蒙主義 分配主義 アメリカのフーリエ主義団体のリスト 米国のオウエナイト派共同体のリスト 中世のコミューン ナショナリズム 国家保守主義 一国保守主義 ポスト自由主義 公共圏 急進中道主義 シンガポール共同体主義 国家主義 第三の道 トライバリズム ウブントゥ哲学 ベネズエラの共同体評議会 黄色い社会主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communitarianism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆