コンラッド・ワディントン

Conrad Hal Waddington, 1905-1975

☆ コンラッド・ハル・ワディントン CBE FRS FRSE(1905年11月8日 - 1975年9月26日)は、発生生物学、エピジェネティクス、進化発生学の基礎を築いたイギリスの発生生物学者、古生物学者、遺伝学者、発生学者、哲学者 である。 彼の遺伝的同化説はダーウィン主義的な説明であったが、セオドア・ドブジャンスキーやエルンスト・メイアなどの著名な進化生物学者は、ワディントンが遺伝 的同化説をいわゆるラマルク遺伝説、すなわち生物の生涯における環境の影響による遺伝形質の獲得を支持するために利用しているとみなした。 ワディントンは詩や絵画など幅広い分野に関心を抱き、また左翼的な政治的傾向も持っていた。著書『科学的態度』(1941年)では、中央計画などの政治的 な話題にも触れ、マルクス主義を「深遠な科学的哲学」と称賛している。[1]

| Conrad Hal

Waddington CBE FRS FRSE (8 November 1905 – 26 September 1975) was a

British developmental biologist, paleontologist, geneticist,

embryologist and philosopher who laid the foundations for systems

biology, epigenetics, and evolutionary developmental biology. Although his theory of genetic assimilation had a Darwinian explanation, leading evolutionary biologists including Theodosius Dobzhansky and Ernst Mayr considered that Waddington was using genetic assimilation to support so-called Lamarckian inheritance, the acquisition of inherited characteristics through the effects of the environment during an organism's lifetime. Waddington had wide interests that included poetry and painting, as well as left-wing political leanings. In his book The Scientific Attitude (1941), he touched on political topics such as central planning, and praised Marxism as a "profound scientific philosophy".[1] |

コンラッド・ハル・ワディントン CBE FRS

FRSE(1905年11月8日 -

1975年9月26日)は、発生生物学、エピジェネティクス、進化発生学の基礎を築いたイギリスの発生生物学者、古生物学者、遺伝学者、発生学者、哲学者

である。 彼の遺伝的同化説はダーウィン主義的な説明であったが、セオドア・ドブジャンスキーやエルンスト・メイアなどの著名な進化生物学者は、ワディントンが遺伝 的同化説をいわゆるラマルク遺伝説、すなわち生物の生涯における環境の影響による遺伝形質の獲得を支持するために利用しているとみなした。 ワディントンは詩や絵画など幅広い分野に関心を抱き、また左翼的な政治的傾向も持っていた。著書『科学的態度』(1941年)では、中央計画などの政治的 な話題にも触れ、マルクス主義を「深遠な科学的哲学」と称賛している。[1] |

| Life Conrad Waddington, known as "Wad" to his friends and "Con" to family, was born in Evesham to Hal and Mary Ellen (Warner) Waddington, on 8 November 1905. His family moved to India and until nearly three years of age, Waddington lived in India, where his father worked on a tea estate in the Wayanad district of Kerala. In 1910, at the age of four, he was sent to live with family in England including his aunt, uncle, and Quaker grandmother. His parents remained in India until 1928. During his childhood, he was particularly attached to a local druggist and distant relation, Dr. Doeg. Doeg, whom Waddington called "Grandpa", introduced Waddington to a wide range of sciences from chemistry to geology.[2] During the year following the completion of his entrance exams to university, Waddington received an intense course in chemistry from E. J. Holmyard. Aside from being "something of a genius of a [chemistry] teacher," Holmyard introduced Waddington to the "Alexandrian Gnostics" and the "Arabic Alchemists." From these lessons in metaphysics, Waddington first gained an appreciation for interconnected holistic systems. Waddington reflected that this early education prepared him for Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy in the 1920s and 30s and the cybernetics of Norbert Wiener and others in the 1940s.[3] He attended Clifton College and Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. He took the Natural Sciences Tripos, earning a First in Part II in geology in 1926.[4] In 1928, he was awarded an Arnold Gerstenberg Studentship in the University of Cambridge, whose purpose was to promote "the study of Moral Philosophy and Metaphysics among students of Natural Science, both men and women."[5] He took up a Lecturership in Zoology and was a Fellow of Christ's College until 1942. His friends included Gregory Bateson, Walter Gropius, C. P. Snow, Solly Zuckerman, Joseph Needham, and John Desmond Bernal.[6][7] His interests began with palaeontology but moved on to the heredity and development of living things. He also studied philosophy. During World War II he was involved in operational research with the Royal Air Force and became scientific advisor to the Commander in Chief of Coastal Command from 1944 to 1945. After the war, in 1947, he replaced Francis Albert Eley Crew as Professor of Animal Genetics at the University of Edinburgh.[8] He would stay at Edinburgh for the rest of life with the exception of one year (1960–1961) when he was a Fellow on the faculty in the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.[9] His personal papers are largely kept at the University of Edinburgh library. He died in Edinburgh on 26 September 1975. |

生涯 コンラッド・ワディントンは、友人からは「ワッド」、家族からは「コン」と呼ばれていた。彼は1905年11月8日、ハルとメアリー・エレン(ワーナー)ワディントンの間にイーブシャムで生まれた。 彼の家族はインドに移住し、ワディントンは3歳近くまでインドで暮らした。父親がケララ州ワヤナド地区の茶園で働いていたためである。1910年、4歳に なった彼は、叔母、叔父、クエーカー教徒の祖母を含む英国の家族のもとへ送られた。両親は1928年までインドに残った。幼少期、彼は地元の薬屋で遠縁の 親戚であるドクター・ドゥグを特に慕っていた。ドゥーグはワディントンに「おじいちゃん」と呼ばれていたが、化学から地質学まで幅広い科学をワディントン に教えた。[2] 大学入学試験終了後の1年間、ワディントンはE. J. ホルミヤードから集中的に化学を学んだ。ホルミヤードは「化学の天才教師」であっただけでなく、ワディントンに「アレクサンドリアのグノーシス派」と「ア ラビアの錬金術師」を紹介した。形而上学の授業から、ワディントンは相互に結びついた全体論的システムに対する理解を初めて得た。ワディントンは、この初 期の教育が、1920年代と30年代のアルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドの哲学、および1940年代のノーバート・ウィーナーらのサイバネティクスへ の準備となったと振り返っている。 彼はクリフトン・カレッジとケンブリッジ大学シドニー・サセックス・カレッジに通った。自然科学トライポスを受講し、1926年には地質学で第2部の第1 位を獲得した。[4] 1928年にはケンブリッジ大学アーノルド・ゲルステンバーグ奨学生に選ばれ、 「自然科学を専攻する男女学生を対象とした道徳哲学と形而上学の研究」を促進することを目的としていた。[5] 彼は動物学の講師職に就き、1942年までキリスト・カレッジの研究員を務めた。彼の友人には、グレゴリー・ベイトソン、ヴァルター・グロピウス、 C.P.スノー、ソリー・ザッカーマン、ジョセフ・ニーダム、ジョン・デスモンド・バーナルなどがいた。[6][7] 彼の関心は古生物学から始まったが、やがて生物の遺伝と発達へと移っていった。彼は哲学も学んだ。 第二次世界大戦中には英国空軍でオペレーションズ・リサーチに従事し、1944年から1945年にかけては沿岸部司令部の最高司令官の科学顧問を務めた。 戦後、1947年に彼はフランシス・アルバート・エリー・クルーの後任としてエディンバラ大学の動物遺伝学教授に就任した。[8] 彼は生涯のほとんどをエディンバラで過ごしたが、1960年から1961年にかけてはコネチカット州ミドルタウンのウェスリアン大学先端研究センターの研 究員として過ごした。[9] 彼の個人資料は主にエディンバラ大学の図書館に保管されている。 彼は1975年9月26日にエディンバラで死去した。 |

| Family Waddington was married twice. His first marriage produced a son, C. Jake Waddington, professor of physics at the University of Minnesota, but ended in 1936. He then married architect Margaret Justin Blanco White, daughter of the writer Amber Reeves, with whom he had two daughters, the anthropologist Caroline Humphrey (1943–) and mathematician Dusa McDuff (1945–).[10][11] |

家族 ワディントンは2度結婚した。最初の結婚では、ミネソタ大学で物理学の教授を務めるC・ジェイク・ワディントンという息子が生まれたが、1936年に離婚 した。その後、作家アンバー・リーブスの娘で建築家のマーガレット・ジャスティン・ブランコ・ホワイトと結婚し、人類学者のキャロライン・ハンフリー (1943年生まれ)と数学者のドゥサ・マクダフ(1945年生まれ)という2人の娘をもうけた。[10][11] |

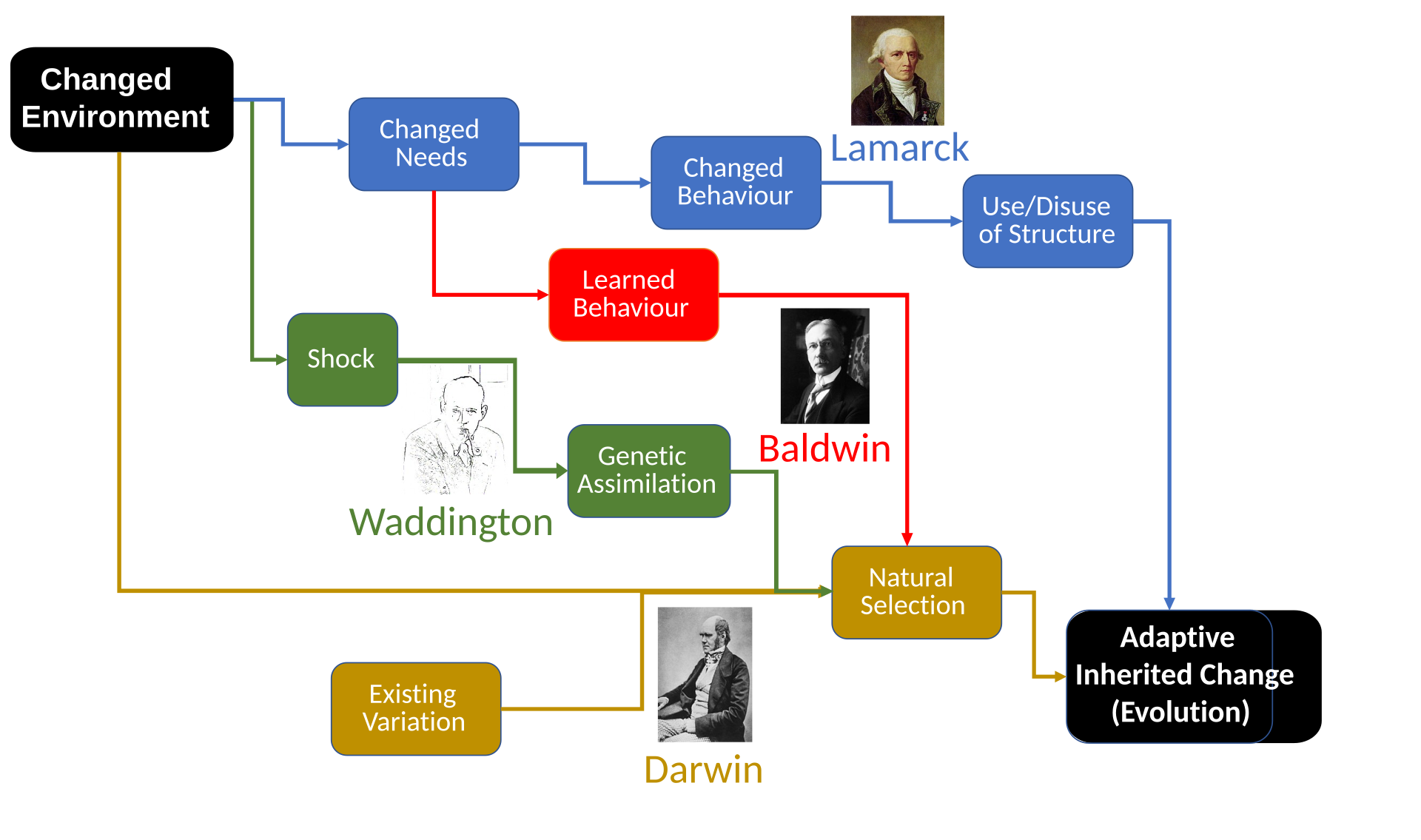

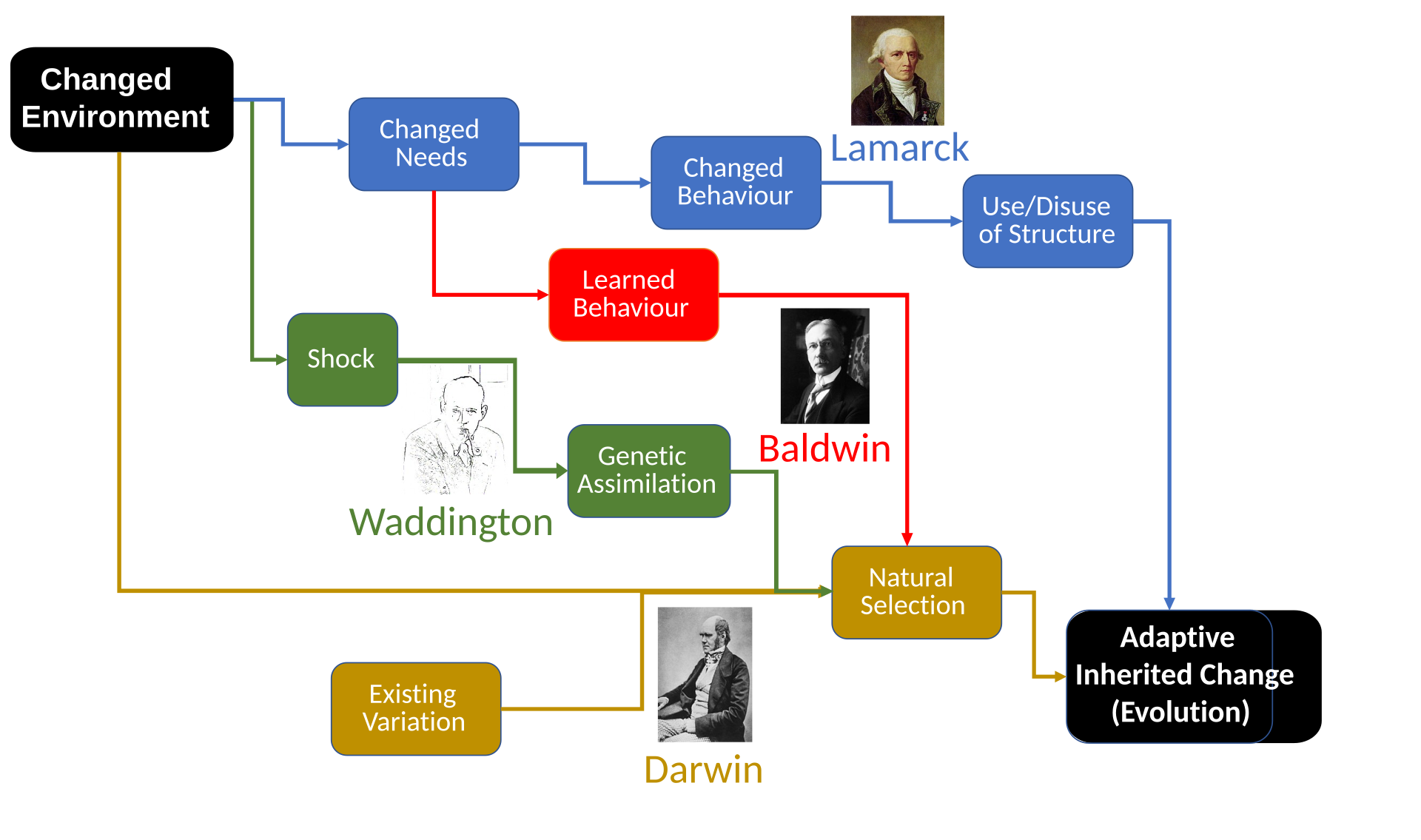

| Evolution In the early 1930s, Waddington and many other embryologists looked for the molecules that would induce the amphibian neural tube. The search was beyond the technology of that time, and most embryologists moved away from such deep problems. Waddington, however, came to the view that the answers to embryology lay in genetics, and in 1935 went to Thomas Hunt Morgan's Drosophila laboratory in California, even though this was a time when most embryologists felt that genes were unimportant and just played a role in minor phenomena such as eye colour. In the late 1930s, Waddington produced formal models about how gene regulatory products could generate developmental phenomena, showed how the mechanisms underpinning Drosophila development could be studied through a systematic analysis of mutations that affected the development of the Drosophila wing.[a] In a period of great creativity at the end of the 1930s, he also discovered mutations that affected cell phenotypes and wrote his first textbook of "developmental epigenetics", a term that then meant the external manifestation of genetic activity. Waddington introduced the concept of canalisation, the ability of an organism to produce the same phenotype despite variation in genotype or environment. He also identified a mechanism called genetic assimilation which would allow an animal's response to an environmental stress to become a fixed part of its developmental repertoire, and then went on to show that the mechanism would work. In 1972, Waddington founded the Centre for Human Ecology in the University of Edinburgh.[14] Epigenetic landscape Waddington's epigenetic landscape is a metaphor for how gene regulation modulates development.[15] Among other metaphors, Waddington asks us to imagine a number of marbles rolling down a hill.[16] The marbles will sample the grooves on the slope, and come to rest at the lowest points. These points represent the eventual cell fates, that is, tissue types. Waddington coined the term chreode to represent this cellular developmental process. The idea was based on experiment: Waddington found that one effect of mutation (which could modulate the epigenetic landscape) was to affect how cells differentiated. He also showed how mutation could affect the landscape, and used this metaphor in his discussions on evolution—he emphasised (like Ernst Haeckel before him) that evolution mainly occurred through mutations that affected developmental anatomy. Genetic assimilation  Waddington's genetic assimilation compared to Lamarckism, Darwinian evolution, and the Baldwin effect. All the theories offer explanations of how organisms respond to a changed environment with adaptive inherited change. Main article: Genetic assimilation Waddington proposed an evolutionary process, "genetic assimilation", as a Darwinian mechanism that allows certain acquired characteristic to become heritable. According to Navis, (2007) "Waddington focused his genetic assimilation work on the crossveinless trait of Drosophila. This trait occurs with high frequency in heat-treated flies. After a few generations, the trait can be found in the population, without the application of heat, based on hidden genetic variation that Waddington asserted had been "assimilated".[17][18] Neo-Darwinism versus Lamarckism Waddington's theory of genetic assimilation was controversial. The evolutionary biologists Theodosius Dobzhansky and Ernst Mayr both thought that Waddington was using genetic assimilation to support Lamarckian inheritance. They denied that genetic assimilation had taken place, and asserted that Waddington had simply observed the natural selection of genetic variants that already existed in the study population.[19] Other biologists such as Wallace Arthur disagree, writing that "genetic assimilation, looks, but is not Lamarckian. It is a special case of the evolution of phenotypic plasticity".[20] Adam S. Wilkins wrote that "[Waddington] in his lifetime... was widely perceived primarily as a critic of Neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory. His criticisms ... were focused on what he saw as unrealistic, 'atomistic' models of both gene selection and trait evolution." In particular, according to Wilkins, Waddington felt that the Neo-Darwinians badly neglected the phenomenon of extensive gene interactions and that the "randomness" of mutational effects, posited in the theory, was false.[21] Even though Waddington became critical of the neo-darwinian synthetic theory of evolution, he still described himself as a Darwinian, and called for an extended evolutionary synthesis based on his research.[21][22] Reviewing the debate in 2015, the systems biologist Denis Noble writes however that [Waddington] did not describe himself as a Lamarckian, but by revealing mechanisms of inheritance of acquired characteristics, I think he should be regarded as such. The reason he did not do so is that Lamarck could not have conceived of the processes that Waddington revealed. Incidentally, it is also true to say that Lamarck did not invent the idea of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. But, whether historically correct or not, we are stuck today with the term 'Lamarckian' for inheritance of a characteristic acquired through an environmental influence.[23] |

進化 1930年代初頭、ワディントンをはじめとする多くの発生学者たちは、両生類の神経管を誘導する分子の探索を行っていた。しかし、当時の技術ではその探索 は不可能であり、ほとんどの発生学者たちはそのような難問から離れていった。しかし、ワディントンは発生学の答えは遺伝学にあるという考えに至り、 1935年には、ほとんどの発生学者が遺伝子は重要ではなく、目の色などの些細な現象にしか関与していないと考えていた時代にもかかわらず、カリフォルニ アのトーマス・ハント・モーガンのショウジョウバエ研究所を訪れた。 1930年代後半、ワディントンは遺伝子制御産物がどのように発生現象を生み出すかについての正式なモデルを提示し、ショウジョウバエの翅の発生に影響を 与える突然変異の系統的分析を通じて、ショウジョウバエの発生を支えるメカニズムを研究する方法を示した 。1930年代末の創造性の高い時代に、彼は細胞の表現型に影響を与える突然変異を発見し、遺伝子活動の外部的な発現を意味する「発生エピジェネティク ス」という用語を用いた最初の教科書を執筆した。 ワディントンは、遺伝子型や環境に変化があっても生物が同じ表現型を作り出す能力である「運河化」という概念を導入した。また、遺伝的同化と呼ばれるメカ ニズムを特定し、動物が環境ストレスに対する反応をその発達レパートリーの固定された一部とすることが可能であることを示し、そのメカニズムが機能するこ とを証明した。 1972年、ワディントンはエディンバラ大学に人間生態学センターを設立した。 エピジェネティック・ランドスケープ ワディントンのエピジェネティック・ランドスケープは、遺伝子調節がどのように発生を調節するかを説明する比喩である。[15] ワディントンは、他の比喩とともに、丘を転がり落ちる多数のビー玉を想像するようにと私たちに求めている。[16] ビー玉は斜面の溝を試しながら転がり、最も低い位置で静止する。これらの位置は最終的な細胞の運命、すなわち組織の種類を表している。ワディントンは、こ の細胞発生プロセスを表すために「クレオード」という用語を考案した。この考えは実験に基づくもので、ワディントンは突然変異(エピジェネティックランド スケープを変化させる可能性がある)が細胞分化に影響を与えることを発見した。また、突然変異がランドスケープに影響を与える可能性があることを示し、こ のメタファーを自身の進化論に関する議論で使用した。彼は、進化は主に発生解剖学に影響を与える突然変異によって起こることを強調した(エルンスト・ヘッ ケルと同様に)。 遺伝的同化  ラマルク説、ダーウィン進化論、ボールドウィン効果と比較したワディントンの遺伝的同化。これらの理論はすべて、生物が環境の変化に適応して変化した形質を遺伝させる仕組みを説明している。 詳細は「遺伝的同化」を参照 ワディントンは、ある種の獲得形質が遺伝するようになるというダーウィン進化論のメカニズムとして、「遺伝的同化」という進化プロセスを提唱した。 Navis (2007)によると、「ワディントンは遺伝的同化の研究をショウジョウバエの無横脈形質に焦点を当てて行った。この形質は熱処理されたハエに高い頻度で 発生する。数世代を経ると、ワディントンが「同化」したと主張する隠れた遺伝的変異に基づいて、熱処理を行わなくてもその形質が集団内で見られるようにな る。[17][18] ネオ・ダーウィニズム対ラマルク主義 ワディントンの遺伝的同化説は論争を呼んだ。進化生物学者のセオドア・ドブジャンスキーとエルンスト・マイヤーは、ワディントンが遺伝的同化説をラマルク 遺伝説の裏付けとして利用していると考えた。彼らは遺伝的同化が起こったことを否定し、ワディントンは研究対象集団にすでに存在していた遺伝的多型の自然 淘汰を観察しただけだと主張した。[19] ウォーレス・アーサーなどの他の生物学者はこれに反対し、「遺伝的同化はラマルク説のように見えるが、ラマルク説ではない。それは表現型の可塑性の進化の 特殊なケースである」と書いている。[20] アダム・S・ウィルキンスは、「ワディントンは生涯を通じて...主にネオ・ダーウィン進化論の批判者として広く認識されていた。彼の批判は、遺伝子選択 と形質進化の両方において、非現実的であると彼が考えた「原子論的」モデルに焦点を当てたものだった」と述べている。特に、ウィルキンスによると、ワディ ントンはネオ・ダーウィニアンが遺伝子の広範な相互作用という現象を著しく軽視していると感じており、その理論で仮定されている突然変異効果の「ランダム 性」は誤りであると考えていた。ワディントンは、新ダーウィン合成進化論に批判的になった後も、自らをダーウィニストと称し、自身の研究に基づく拡張進化 論の統合を呼びかけた。[21][22] 2015年の論争を振り返り、システム生物学者のデニス・ノーブルは、 ワディントンは自らをラマルキストとは称さなかったが、獲得形質の遺伝のメカニズムを明らかにしたことで、彼をラマルキストとみなすべきだと私は考える。 彼がそうしなかった理由は、ラマルクがワディントンが明らかにしたプロセスを想像できなかったからである。ちなみに、ラマルクが獲得形質の遺伝という考え を発明したわけではないというのもまた事実である。しかし、歴史的に正しいかどうかは別として、環境の影響によって獲得された形質の遺伝を「ラマルク的」 という言葉で表現する以外にないのが現状である。[23] |

| As an organiser Waddington was very active in advancing biology as a discipline. He contributed to a book on the role of the sciences in times of war, and helped set up several professional bodies representing biology as a discipline.[24] A remarkable number of his contemporary colleagues in Edinburgh became Fellows of the Royal Society during his time there, or shortly thereafter.[25] Waddington was an old-fashioned intellectual who lived in both the arts and science milieus of the 1950s and wrote widely. His 1969 book Behind Appearance; a Study of the Relations Between Painting and the Natural Sciences in This Century (MIT press) not only has wonderful pictures but is still worth reading.[26] Waddington was, without doubt, the most original and important thinker about developmental biology of the pre-molecular age and the medal of the British Society for Developmental Biology is named after him.[27] Waddington co-founded The Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh in 1969 with Professor John MacQueen, Professor of Scottish Literature and Oral Tradition.[28] |

オーガナイザーとして、 ワディントンは生物学という学問分野の発展に非常に積極的に取り組んだ。彼は、戦争時の科学の役割に関する書籍に寄稿し、生物学という学問分野を代表する複数の専門機関の設立に貢献した。 エディンバラ時代の同僚のなかには、彼の在職中、あるいはその後まもなく、英国王立協会のフェローとなった者が非常に多い。[25] ワディントンは、1950年代の芸術と科学の両方の環境に身を置き、幅広い執筆活動を行った古風な知識人であった。1969年に出版された著書 『Behind Appearance; a Study of the Relations Between Painting and the Natural Sciences in This Century』(MIT press)は、素晴らしい絵画が掲載されているだけでなく、今でも読む価値のある本である。[26] ワディントンは、分子生物学以前の発展生物学において、最も独創的で重要な思想家であったことは疑いようがなく、英国発生生物学会のメダルは彼の名にちな んで名付けられている。[27] ワディントンは、1969年にスコットランド文学および口承伝承の教授であるジョン・マックイーン教授とともに、エジンバラ大学高等人文科学研究センターを共同設立した。[28] |

| Books Waddington, C. H. (1939). An Introduction to Modern Genetics. London : George Alien & Unwin. ––– (1940). Organisers & Genes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ––– and others Science and Ethics. George Allen & Unwin. 1942 – via Internet Archive. ––– (1946). How Animals Develop. London : George Allen & Unwin. ––– The Scientific Attitude (2nd ed.). Pelican Books. 1948 – via Internet Archive. ––– (1953). The Epigenetics of birds. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. ––– (1956). Principles of Embryology. London : George Allen & Unwin. ––– (1957). The Strategy of the Genes. London : George Allen & Unwin. ––– (1959). Biological Organisation Cellular and Subcellular : Proceedings of a Symposium. London: Pergamon Press. ––– (1960). The Ethical Animal. London : George Allen & Unwin. ––– (1961). The Human Evolutionary System. In: Michael Banton (Ed.), Darwinism and the Study of Society. London: Tavistock. ––– (1961). The Nature of Life. London : George, Allen, & Unwin. ––– (1962). New Patterns in Genetics and Development. New York: Columbia University Press. ––– (1966). Principles of Development and Differentiation. New York: Macmillan Company. ––– (1970). 72). Behind Appearance : A Study in the Relationship Between Painting and the Natural Sciences in this Century. The MIT Press. –––, ed. (1968–72). Towards a Theoretical Biology. 4 vols. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. –––, Kenny, A., Longuet-Higgins, H.C., Lucas, J.R. (1972). The Nature of Mind, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press (1971-3 Gifford Lectures in Edinburgh, online) –––, Kenny, A., Longuet-Higgins, H. C., Lucas, J. R. (1973). The Development of Mind, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press (1971-3 Gifford Lectures in Edinburgh, online) ––– (1973) O.R. in World War 2: Operational Research Against the U-Boat. London: Elek Science. –––, & Jantsch, E. (Eds.). (1976). (published posthumously). Evolution and Consciousness: Human Systems in Transition. Addison-Wesley. ––– (1977) (published posthumously). Tools for Thought. London: Jonathan Cape. Papers Waddington, C. H. (1942). Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature 150 (3811):563–565. --- (1946). Human Ideals and Human Progress. World Review August:29-36. ––– & Carter T. C. (1952). Malformations in mouse embryos induced by trypan blue. Nature 169 (4288):27-28. ––– (1952). Selection of the Genetic Basis for an Acquired Character. Nature 169 (4294):278. ––– (1953). Genetic assimilation of an acquired character. Evolution 7:118–126. ––– (1953). Epigenetics and evolution. Symposia of the Society of Experimental Biology 7:186–199. ––– (1956). Genetic assimilation of the bithorax phenotype. Evolution 10:1–13. ––– (1961). Genetic assimilation. Advances in Genetics 10:257–290. ––– (1974). A Catastrophe Theory of Evolution. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 231:32–42. ––– (1977).(published posthumously). Whitehead and Modern Science. Mind in Nature: The Interface of Science and Philosophy. Ed. John B. Cobb and David R. Griffin. University Press of America. |

書籍 ワディントン、C. H. (1939). 現代遺伝学入門. ロンドン : ジョージ・エイリアン&アンウィン. ––– (1940). オーガナイザーと遺伝子. ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ––– ほか. 科学と倫理. ジョージ・エイリアン&アンウィン. 1942 – インターネットアーカイブ経由. ––– (1946). 動物はいかにして進化するか. ロンドン : ジョージ・エイリアン&アンウィン. ――『科学の態度』(第2版)。ペリカンブックス。1948年 – インターネットアーカイブ経由。 ――(1953年)。鳥類のエピジェネティクス。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ――(1956年)。発生学の原理。ロンドン:ジョージ・アレン・アンド・ユニウィン。 ――(1957年)。遺伝子の戦略。ロンドン:ジョージ・アレン・アンド・ユニウィン。 ―――(1959年)『生物学的組織:細胞および細胞小器官:シンポジウム議事録』ロンドン:Pergamon Press。 ―――(1960年)『倫理的な動物』ロンドン:George Allen & Unwin。 ―――(1961年)『ヒトの進化系』マイケル・バントン編『ダーウィニズムと社会研究』ロンドン:Tavistock。 ―――(1961年)『生命の本質』ロンドン:ジョージ・アレン・アンド・アンウィン ―――(1962年)『遺伝学と発生学における新たなパターン』ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版局 ―――(1966年)『発生と分化の原理』ニューヨーク:マクミラン社 ―――(1970年)『72)外見の背後にあるもの:今世紀における絵画と自然科学の関係についての研究』 マサチューセッツ工科大学出版局。 編著(1968-72)。理論生物学への道。4巻。エジンバラ大学出版局。 編著、ケニー、A.、ロングuet-ヒギンズ、H.C.、ルーカス、J.R.(1972)。心の性質、エジンバラ大学出版局(1971-3年エジンバラ・ギフォード講演、オンライン) ―――、ケニー、A.、ロングエト・ヒギンズ、H. C.、ルーカス、J. R. (1973). 心の発達、エジンバラ:エジンバラ大学出版(1971-3年のエジンバラでのギフォード・レクチャー、オンライン) ――― (1973) 第2次世界大戦におけるOR:Uボートに対するオペレーションズ・リサーチ。ロンドン:エレク・サイエンス。 ―――、およびJantsch, E. (編). (1976). (死後出版). 進化と意識:変遷する人間システム。Addison-Wesley. ――― (1977) (死後出版). 思考の道具。ロンドン:Jonathan Cape. 論文 ワディントン、C. H. (1942年). 発育の単一路化と獲得形質の遺伝. Nature 150 (3811):563–565. --- (1946年). 人間の理想と人間の進歩. World Review 8月:29-36. ––– & カーター T. C. (1952年). トリパンブルーによるマウス胚の奇形。Nature 169 (4288):27-28. ――― (1952). 後天的形質の遺伝的基礎の選択。Nature 169 (4294):278. ――― (1953). 後天的形質の遺伝的同化。Evolution 7:118–126. (1953年)。エピジェネティクスと進化。実験生物学学会シンポジウム7:186–199。 (1956年)。胸郭表現型の遺伝的同化。進化10:1–13。 (1961年)。遺伝的同化。遺伝学の進歩10:257–290。 ―――(1974年)。進化のカタストロフィー理論。ニューヨーク科学アカデミー紀要 231:32–42。 ―――(1977年)(死後出版)。ホワイトヘッドと現代科学。自然における心:科学と哲学の接点。ジョン・B・コブ、デビッド・R・グリフィン編。アメリカ大学出版。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C._H._Waddington | |

ラマルク説、ダーウィン進化論、ボールドウィン効果と比較したワディントンの遺伝的同化。これらの理論はすべて、生物が環境の変化に適応して変化した形質を遺伝させる仕組みを説明している。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆