消費

Consumption, Konsum

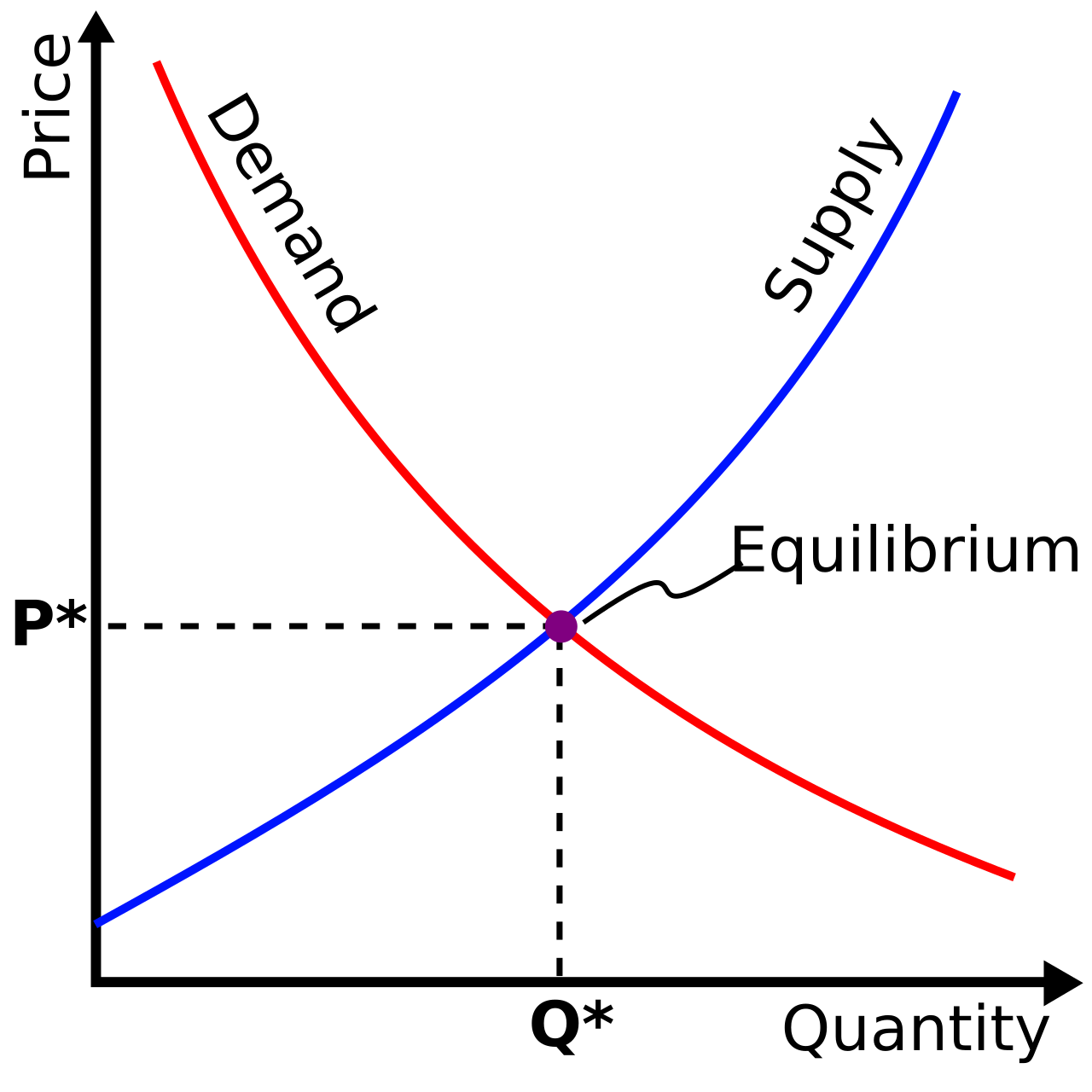

☆ 経済学における消費(Consumption) とは、現在の欲求や欲望を満たすために資源を使うことを指す[1]。将来の収入を得るために支出する投資とは対照的である[2]。消費は経済学の主要な概 念であり、他の多くの社会科学でも研究されている。 経済学者の異なる学派は、消費を異なるように定義している。主流派の経済学者によれば、個人が新たに生産した財やサービスをすぐに使用するために最終的に 購入することのみが消費であり、それ以外の支出、個別主義では固定投資、中間消費、政府支出は別のカテゴリーに分類される(消費者選択を参照)。他の経済 学者は、消費をより広義に定義し、財・サービスの設計、生産、マーケティングを伴わない全ての経済活動の総体(例えば、財・サービスの選択、採用、使用、 廃棄、リサイクル)としている[3]。 経済学者は、消費関数でモデル化された消費と所得の関係に個別主義的な関心を寄せている。同様の現実主義的構造観は消費理論にも見出すことができ、フィッ シャー的時間間選択の枠組みを消費関数の現実的構造として捉えている。帰納的構造実在論に具現化された構造の受動的戦略とは異なり、経済学者は介入下での 不変性の観点から構造を定義する[4]。

★社

会学における消費(consumption):

消費に関する理論は、19世紀半ばから後半にかけてのカール・マルクスの研究に少なくとも暗黙のうちに遡り、その初期から社会学の分野の一部であった。社

会学者は、消費は日常生活、アイデンティティ、社会秩序の中心であると見なしている。多くの社会学者は、消費を社会階級、アイデンティティ、集団の構成

員、年齢、階層化と関連付けており、それは近代性において大きな役割を果たしている[1]。こうした初期のルーツにもかかわらず、消費に関する研究は20

世紀後半にヨーロッパ、特にイギリスで本格的に始まった。米国の主流の社会学者の間でこのテーマへの関心が高まるのはずっと遅く、多くの米国の社会学者に

とっては、いまだに中心的な関心事とはなっていない[2]。現在[いつ]、米国社会学会に消費研究に特化したセクションを形成するための努力が進められて

いる。

しかし、ここ20年の間に、消費の領域に関する社会学的研究は、同分野、特にグローバル・スタディーズやカルチュラル・スタディーズにおいて急成長してい

る:

グローバリゼーションに伴うプロセスは、文化的形態や実践が、それらが最初に考案され生産された固有の場所や空間をはるかに超えて移動する、これまで想像

もできなかった機会を生み出した。ある空間から別の空間への文化的な移動と流れは常にあったが、グローバルとローカルが交差する現代の激しさと容易さに

よって、学者たちは文化が消費される、つまり使い尽くされ、理解され、受け入れられ、探求される無数の方法を注意深く見ることを余儀なくされている

[3]。

現代の消費の理論家には、ジャン・ボードリヤール、ピエール・ブルデュー、ジョージ・リッツァーなどがいる。

| Consumption

refers to the use of resources to fulfill present needs and desires.[1]

It is seen in contrast to investing, which is spending for acquisition

of future income.[2] Consumption is a major concept in economics and is

also studied in many other social sciences. Different schools of economists define consumption differently. According to mainstream economists, only the final purchase of newly produced goods and services by individuals for immediate use constitutes consumption, while other types of expenditure — in particular, fixed investment, intermediate consumption, and government spending — are placed in separate categories (see consumer choice). Other economists define consumption much more broadly, as the aggregate of all economic activity that does not entail the design, production and marketing of goods and services (e.g., the selection, adoption, use, disposal and recycling of goods and services).[3] Economists are particularly interested in the relationship between consumption and income, as modelled with the consumption function. A similar realist structural view can be found in consumption theory, which views the Fisherian intertemporal choice framework as the real structure of the consumption function. Unlike the passive strategy of structure embodied in inductive structural realism, economists define structure in terms of its invariance under intervention.[4] |

経済学における消費とは、現在の欲求や欲望を満たすために資源を使うこ

とを指す

[1]。将来の収入を得るために支出する投資とは対照的である[2]。消費は経済学の主要な概念であり、他の多くの社会科学でも研究されている。 経済学者の異なる学派は、消費を異なるように定義している。主流派の経済学者によれば、個人が新たに生産した財やサービスをすぐに使用するために最終的に 購入することのみが消費であり、それ以外の支出、個別主義では固定投資、中間消費、政府支出は別のカテゴリーに分類される(消費者選択を参照)。他の経済 学者は、消費をより広義に定義し、財・サービスの設計、生産、マーケティングを伴わない全ての経済活動の総体(例えば、財・サービスの選択、採用、使用、 廃棄、リサイクル)としている[3]。 経済学者は、消費関数でモデル化された消費と所得の関係に個別主義的な関心を寄せている。同様の現実主義的構造観は消費理論にも見出すことができ、フィッ シャー的時間間選択の枠組みを消費関数の現実的構造として捉えている。帰納的構造実在論に具現化された構造の受動的戦略とは異なり、経済学者は介入下での 不変性の観点から構造を定義する[4]。 |

| Behavioural economics, Keynesian

consumption function Main article: Consumption function The Keynesian consumption function is also known as the absolute income hypothesis, as it only bases consumption on current income and ignores potential future income (or lack of). Criticism of this assumption led to the development of Milton Friedman's permanent income hypothesis and Franco Modigliani's life cycle hypothesis. More recent theoretical approaches are based on behavioural economics and suggest that a number of behavioural principles can be taken as microeconomic foundations for a behaviourally-based aggregate consumption function.[5] Behavioural economics also adopts and explains several human behavioural traits within the constraint of the standard economic model. These include bounded rationality, bounded willpower, and bounded selfishness.[6] Bounded rationality was first proposed by Herbert Simon. This means that people sometimes respond rationally to their own cognitive limits, which aimed to minimize the sum of the costs of decision making and the costs of error. In addition, bounded willpower refers to the fact that people often take actions that they know are in conflict with their long-term interests. For example, most smokers would rather not smoke, and many smokers willing to pay for a drug or a program to help them quit. Finally, bounded self-interest refers to an essential fact about the utility function of a large part of people: under certain circumstances, they care about others or act as if they care about others, even strangers.[7] |

行動経済学、ケインズの消費関数 主な記事 消費関数 ケインズの消費関数は絶対所得仮説とも呼ばれ、現在の所得のみを消費の基礎とし、将来の潜在的所得(またはその欠如)を無視する。この仮定に対する批判か ら、ミルトン・フリードマンの永続所得仮説やフランコ・モディリアーニのライフサイクル仮説が発展した。 より最近の理論的アプローチは行動経済学に基づくものであり、行動経済学に基づく総消費関数のためのミクロ経済学的基礎として、多くの行動原理を取り入れ ることができることを示唆している[5]。 行動経済学はまた、標準的な経済モデルの制約の中で、いくつかの人間の行動特性を採用し、説明している。これには、束縛合理性、束縛意志力、束縛利己主義 が含まれる[6]。 束縛合理性はハーバート・サイモンによって最初に提唱された。これは、人民が、意思決定のコストと誤りのコストの合計を最小化することを目指した自らの認 知限界に合理的に対応することがあることを意味する。さらに、束縛された意志力とは、人民がしばしば自分の長期的利益と相反する行動をとるという事実を指 す。例えば、ほとんどの喫煙者はタバコを吸いたくないと考えるが、多くの喫煙者は禁煙のための薬やプログラムにお金を払うことを厭わない。最後に、束縛さ れた自己利益とは、多くの人民の効用関数に関する本質的な事実を指す。ある状況下では、人民は他人を気にかけるか、見知らぬ人であっても他人を気にかける かのように行動する。 |

| Consumption and household

production Aggregate consumption is a component of aggregate demand.[8] Consumption is defined in part by comparison to production. In the tradition of the Columbia School of Household Economics, also known as the New Home Economics, commercial consumption has to be analyzed in the context of household production. The opportunity cost of time affects the cost of home-produced substitutes and therefore demand for commercial goods and services.[9][10] The elasticity of demand for consumption goods is also a function of who performs chores in households and how their spouses compensate them for opportunity costs of home production.[11] Different schools of economists define production and consumption differently. According to mainstream economists, only the final purchase of goods and services by individuals constitutes consumption, while other types of expenditure — in particular, fixed investment, intermediate consumption, and government spending — are placed in separate categories (See consumer choice). Other economists define consumption much more broadly, as the aggregate of all economic activity that does not entail the design, production and marketing of goods and services (e.g., the selection, adoption, use, disposal and recycling of goods and services).[citation needed] Consumption can also be measured in a variety of different ways such as energy in energy economics metrics. |

消費と家計生産 総消費は総需要の構成要素である[8]。 消費は、部分的には生産との比較によって定義される。新家庭経済学としても知られるコロンビア学派の家計経済学の伝統では、商業消費は家計生産の文脈で分 析されなければならない。時間の機会費用は、家庭で生産される代替品のコストに影響し、したがって商業財やサービスに対する需要に影響する[9] [10]。消費財に対する需要の弾力性はまた、誰が家庭で家事を行うか、そしてその配偶者が家庭生産の機会費用をどのように補償するかの関数でもある [11]。 経済学者の異なる学派は、生産と消費を異なるように定義している。主流派の経済学者によれば、個人が財やサービスを最終的に購入することのみが消費を構成 し、他の種類の支出、特に固定投資、中間消費、政府支出は個別のカテゴリーに分類される(消費者選択参照)。他の経済学者は、消費をより広義に定義してお り、財・サービスの設計、生産、マーケティングを伴わない全ての経済活動の総体(例えば、財・サービスの選択、採用、使用、廃棄、リサイクル)と定義して いる[要出典]。 消費はまた、エネルギー経済学の指標におけるエネルギーなど、様々な異なる方法で測定することができる。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consumption_(economics) |

|

| Theories of consumption have

been a part of the field of sociology since its earliest days, dating

back, at least implicitly, to the work of Karl Marx in the mid-to-late

nineteenth century. Sociologists view consumption as central to

everyday life, identity and social order. Many sociologists associate

it with social class, identity, group membership, age and

stratification as it plays a huge part in modernity.[1] Thorstein

Veblen's (1899) The Theory of the Leisure Class is generally seen as

the first major theoretical work to take consumption as its primary

focus. Despite these early roots, research on consumption began in

earnest in the second half of the twentieth century in Europe,

especially Great Britain. Interest in the topic among mainstream US

sociologists was much slower to develop and it is still not[when?] a

focal concern of many American sociologists.[2] Efforts are

currently[when?] underway to form a section in the American

Sociological Association devoted to the study of consumption. However, over the last[when?] twenty years, sociological research into the area of consumption has burgeoned in cognate fields, particularly in global and cultural studies: The processes associated with globalization have created hitherto unimaginable opportunities for cultural forms and practices to travel far beyond the indigenous sites and spaces in which they were first conceived and produced. While there have always been cultural movements and flows from one space to another, the intensity and ease of contemporary intersections of the global and the local have forced scholars to look closely at the myriad ways in which culture is consumed – used up, made sense of, embraced, and explored.[3] Modern theorists of consumption include Jean Baudrillard, Pierre Bourdieu, and George Ritzer. |

消費に関する理論は、19世紀半ばから後半にかけてのカール・マルクス

の研究に少なくとも暗黙のうちに遡り、その初期から社会学の分野の一部であった。社会学者は、消費は日常生活、アイデンティティ、社会秩序の中心であると

見なしている。多くの社会学者は、消費を社会階級、アイデンティティ、集団の構成員、年齢、階層化と関連付けており、それは近代性において大きな役割を果

たしている[1]。こうした初期のルーツにもかかわらず、消費に関する研究は20世紀後半にヨーロッパ、特にイギリスで本格的に始まった。米国の主流の社

会学者の間でこのテーマへの関心が高まるのはずっと遅く、多くの米国の社会学者にとっては、いまだに中心的な関心事とはなっていない[2]。現在[い

つ]、米国社会学会に消費研究に特化したセクションを形成するための努力が進められている。 しかし、ここ20年の間に、消費の領域に関する社会学的研究は、同分野、特にグローバル・スタディーズやカルチュラル・スタディーズにおいて急成長してい る: グローバリゼーションに伴うプロセスは、文化的形態や実践が、それらが最初に考案され生産された固有の場所や空間をはるかに超えて移動する、これまで想像 もできなかった機会を生み出した。ある空間から別の空間への文化的な移動と流れは常にあったが、グローバルとローカルが交差する現代の激しさと容易さに よって、学者たちは文化が消費される、つまり使い尽くされ、理解され、受け入れられ、探求される無数の方法を注意深く見ることを余儀なくされている [3]。 現代の消費の理論家には、ジャン・ボードリヤール、ピエール・ブルデュー、ジョージ・リッツァーなどがいる。 |

| Definitions of Consumption The sociology of consumption is a field within sociology specifically about the social, economic, and cultural dimensions of consumer behavior. It studies how and why individuals and groups acquire and use goods and services in a given society, as well as the cultural meanings and social norms associated with these practices. When defining consumption, there must be a focus on the consumer, their relationships, and the process of consumption itself. When considering the consumer’s role in consumption, there is an emphasis on the moment of exchange of a good or service as well as stressing the importance of considering the consumer as an individual within a socially constructed environment. The process of consumption itself takes into account how activities are socially constructed and organized. Other definitions of consumption necessitate a process that creates utility, agency, and appropriation (in the sense that a raw material is processed, handled, or transformed by humans). For instance, infants cannot consume because they lack agency; instead, their parents consume for them. An example of appropriation is purchasing a Christmas tree–although it is a natural object, it has been processed by others and therefore consumed by those who purchase it. On the other hand, if one were to go into their backyard, chop a fir themselves, and then bring it into the home, arguably, that is not an act of consumption. The academic debate surrounding definitions of consumption include whether or not consumption is an active choice or an action carried out simply due to habit or circumstance. Though individualism and identity is highly intertwined with practices of consumption, so are the economic conditions that obstruct agency for marginalized groups and individuals. In "Consumption, Food and Taste" (1997), sociologist Alan Warde defines consumption as "the process by which goods and services are acquired, used and disposed of by households and other economic actors" (p. 3). He emphasizes that consumption involves not just the physical act of purchasing and consuming goods, but also the cultural meanings and social norms that are associated with these practices, including economic conditions, new technologies, and cultural trends. Moreover, consumption has significant implications for social inequality, as patterns of consumption are often tied to broader patterns of social stratification. |

消費の定義 消費社会学は社会学の一分野であり、特に消費行動の社会的、経済的、文化的側面について研究する。消費社会学は、ある社会で個人や集団がどのように、そし てなぜ商品やサービスを手に入れ、利用するのか、また、こうした行為に関連する文化的意味や社会規範を研究するものである。 消費を定義する際には、消費者、消費者との関係、消費のプロセスそのものに焦点を当てなければならない。消費における消費者の役割を考える場合、財やサー ビスの交換の瞬間に重点を置くとともに、社会的に構築された環境の中で消費者を個人として考えることの重要性を強調する。消費のプロセスそのものが、どの ように社会的に構築され、組織化されているかを考慮に入れている。消費の他の定義では、効用、主体性、充当(原材料が人間によって加工され、扱われ、変化 するという意味での)を生み出すプロセスが必要とされる。例えば、乳幼児は主体性がないため消費することができず、代わりに親が消費する。クリスマスツ リーは自然物であるが、他者によって加工されたものである。一方、裏庭に行って自分でモミの木を切り、家に持ち込むとしたら、それは間違いなく消費行為で はない。 消費の定義をめぐる学術的な議論には、消費が能動的な選択なのか、それとも単に習慣や状況によって行われる行為なのかが含まれる。個人主義やアイデンティティは消費の実践と密接に絡み合っているが、境界を置かれた集団や個人の主体性を阻害する経済状況もまた同様である。 社会学者のアラン・ウォードは、『消費、食品、嗜好』(1997年)の中で、消費を「財やサービスが家計やその他の経済主体によって獲得され、使用され、 廃棄される過程」(p.3)と定義している。彼は、消費には単に商品を購入し消費するという物理的な行為だけでなく、経済状況、新しい技術、文化的傾向な ど、こうした行為に関連する文化的意味や社会的規範も含まれると強調している。さらに、消費のパターンはしばしば、より広範な社会階層のパターンと結びつ いているため、消費は社会的不平等に重大な意味を持っている。 |

| History of Consumption Consumption patterns have a direct link to ways in which people interact with the environment. What people eat and wear, what types of homes people live in, and where people even buy groceries all have impacts on the environment. This immense stratification of impact has a long and rich history that has roots in the Industrial Revolution, imperialism, the World Wars, and much more especially as the global population has grown exponentially in recent centuries. Pre–Industrial Revolution  Watermill Before the Industrial Revolution, consumption looked very different. Around the world, consumption patterns revolved largely around what food could be grown and brought into the villages, towns, and cities of the day. Additionally, prior to the Industrial Revolution, the steam engine had yet to be invented and fossil fuels had yet to truly be revolutionizing. So, production was significantly limited to the fuel that could be found consisting of wood, peat, or possibly watermill power. Collectively, these limitations prohibited a majority of the global population from being able to consume in excess. Excess consumption was reserved for the global elites.[4] |

消費の歴史 消費パターンは、人民と環境との関わり方に直結している。人民が何を食べ、何を身につけ、どのような家に住み、どこで食料品を買うかさえも、すべて環境に 影響を与えている。産業革命、帝国主義、世界大戦、そして特にここ数世紀で世界人口が飛躍的に増加したことに根ざした、この影響の巨大な階層化には、長く 豊かな歴史がある。 産業革命以前  水車小屋 産業革命以前は、消費の様相は大きく異なっていた。世界中で、消費パターンは主に、どのような食料を栽培し、当時の村や町、都市に持ち込むことができるか を中心に展開されていた。さらに、産業革命以前は、蒸気機関はまだ発明されておらず、化石燃料はまだ本当の意味で革命を起こしていなかった。そのため、生 産は薪や泥炭、あるいは水車から得られる燃料に大きく制限されていた。これらの制限を総称して、世界人口の大多数が過剰に消費することを禁じていた。過剰 な消費は、世界のエリートたちだけのものであった[4]。 |

| During the Industrial Revolution Starting during the Industrial Revolution, consumption patterns changed drastically around the world. For the countries getting industrialized first, cheap mass-produced goods combined with new steady and rising wages. People in countries like England, the United States, and France began to be able to buy more commodities with the more expendable income they had. This pattern only grew exponentially as time moved toward the present. In contrast to the individuals in industrializing countries, people in the colonies of the colonial industrializing powers became dumping grounds for the overproduction of commodities.[5] Subsequently, production overall grew exponentially as industrial production transitioned into the backbone of the global economy. Everyday people began having more things and more specifically, more uniform mass-produced things. As more and more people began having more and more things, the raw resources and the consequences of production grew as well. These production-based consequences include but are in no way limited to immense deforestation, overhunting of different animal populations (beaver hunting), and exploitative and destructive mining and resource extraction processes.[6][7] |

産業革命期 産業革命が始まると、消費パターンは世界中で劇的に変化した。最初に工業化された国々では、安価な大量生産品と新しい安定した賃金の上昇が結びついた。イ ギリス、アメリカ、フランスといった国々の人民は、より多くの商品を、より多くの支出可能な収入で購入できるようになった。このパターンは、時代が現代に 進むにつれて指数関数的に拡大していった。工業化国の個人とは対照的に、植民地工業化国の植民地の人民は、過剰生産された商品の捨て場となった[5]。 その後、工業生産が世界経済の基幹へと移行するにつれて、生産全体が飛躍的に増大した。人民はより多くのものを持つようになり、より具体的には、より画一 的な大量生産品を持つようになった。より多くの人民がより多くのモノを持つようになると、原材料と生産がもたらす結果も同様に増大した。こうした生産に基 づく結果には、莫大な森林伐採、異なる動物個体群の乱獲(ビーバー狩り)、搾取的で破壊的な採掘や資源抽出プロセスなどが含まれるが、これらに限定される わけではない[6][7]。 |

Post-Industrial Revolution Tank assembly during WWII From the time of the Industrial Revolution until World War II, there were significant differences in consumption patterns between those in the industrialized world and those in the unindustrialized world. Yet, those differences got exacerbated during World War II and in the immediate postwar years. Driven by the United States’ monumental industrial capacity, the world exited the Second World War with a new jump in industrialization and mass production. Consumption during World War II was altered globally due to so many resources going to the war effort.[8] However, after the war, the factories still intact switched to consumer goods to avoid an economic slowdown. For the United States with all of its industrial capacity unharmed, the United States became an industrial titan producing mass-consumption goods for the whole world. Additionally through the Marshall Plan, an American foreign policy aid program aimed at preventing broken European nations from becoming Communist by supporting a capitalist revitalization with immense economic support from the United States, European nations rebuilt extremely quickly and were able to modernize their industrial systems toward mass production as well.[9] People all around the world, in every corner, in every nation, had American and Western European goods flowing in during the second half of the 20th century. The cheap Western goods enabled a new level of consumption where people could now have cheap American corn and Spam, cheap Ford cars, and American electronics. While people around the world were seeing the “Made in America” stamp more and more frequently, a mirrored impact is that Americans of all classes were becoming richer in comparison. This increase in wealth allowed for the increase in stratification between Americans and largely the rest of the world. Americans could now afford to consume gluttonous amounts of everything.[10] |

ポスト産業革命 第二次世界大戦中の戦車組み立て 産業革命から第二次世界大戦までは、先進国と非先進国の消費パターンには大きな違いがあった。しかし、第二次世界大戦中と戦後間もない時期に、その差異は さらに悪化した。第二次世界大戦後、アメリカの巨大な工業力に後押しされ、世界は工業化と大量生産の新たな飛躍を遂げた。第二次世界大戦中の消費は、多く の資源が戦争に投入されたため、世界的に変化した[8]。しかし戦後は、経済の停滞を避けるため、工場はそのまま消費財に切り替わった。すべての工業能力 が無傷であったアメリカにとって、アメリカは全世界のために大量消費財を生産する工業の巨人となった。さらに、アメリカからの莫大な経済支援によって資本 主義の復興を支援することで、崩壊したヨーロッパ諸国の共産主義化を防ぐことを目的としたアメリカの外交援助プログラムであるマーシャル・プランによっ て、ヨーロッパ諸国は極めて迅速に復興し、大量生産に向けて産業システムを近代化することができた[9]。 20世紀後半には、世界中の人民が、あらゆる場所で、あらゆる国民が、アメリカや西欧の商品を流入させていた。安価な欧米製品は、人民が安価なアメリカ産 トウモロコシやスパム、安価なフォード車、アメリカ製電子機器を手にすることができるようになり、新たなレベルの消費を可能にした。世界中の人民が 「Made in America 」のスタンプを目にする機会が増える一方で、それに比べてアメリカ人はあらゆる階層で豊かになっていった。この富の増加によって、アメリカ人とそれ以外の 国々との間に階層化が進んだ。アメリカ人はあらゆるものを大量に消費する余裕ができたのだ[10]。 |

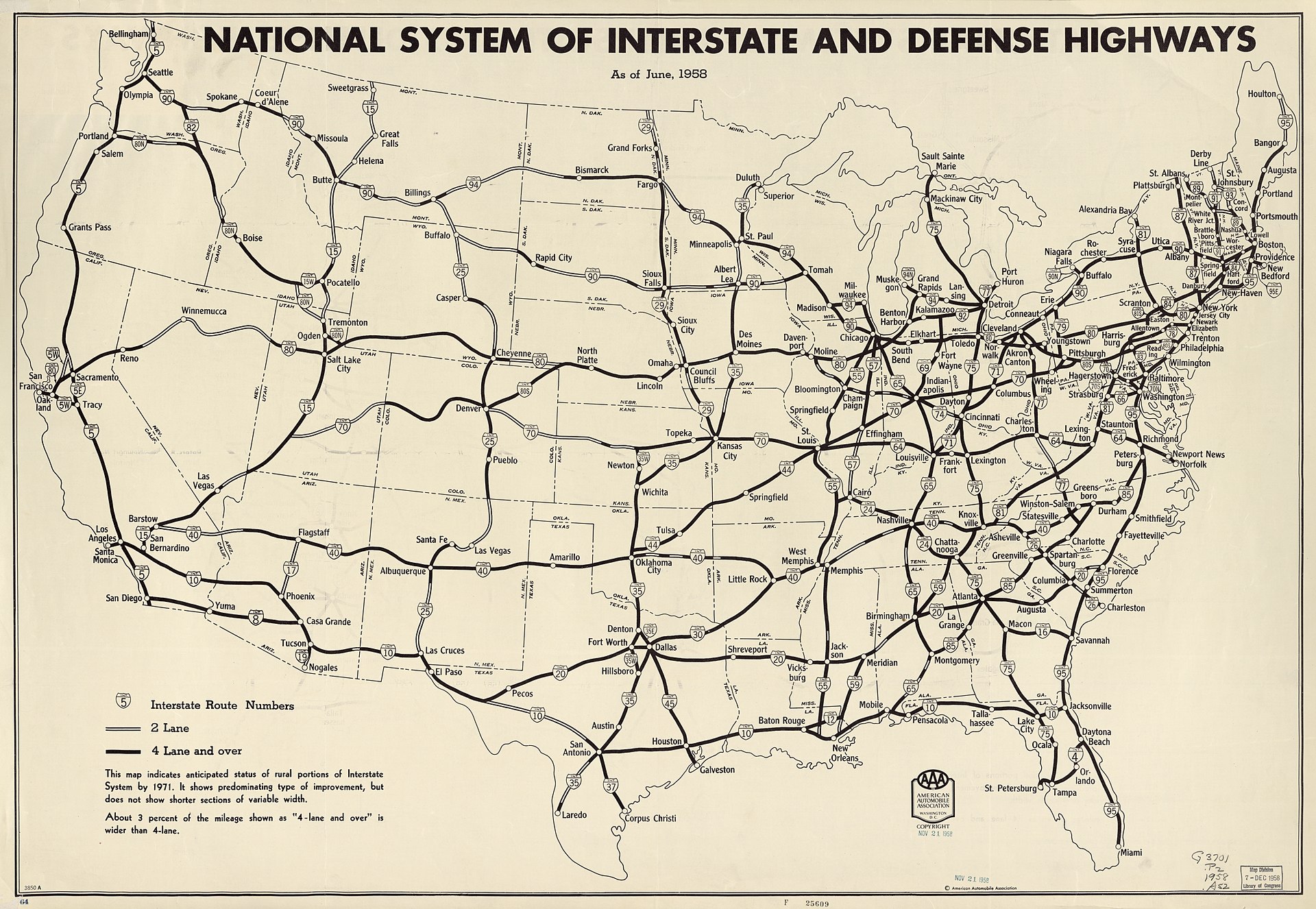

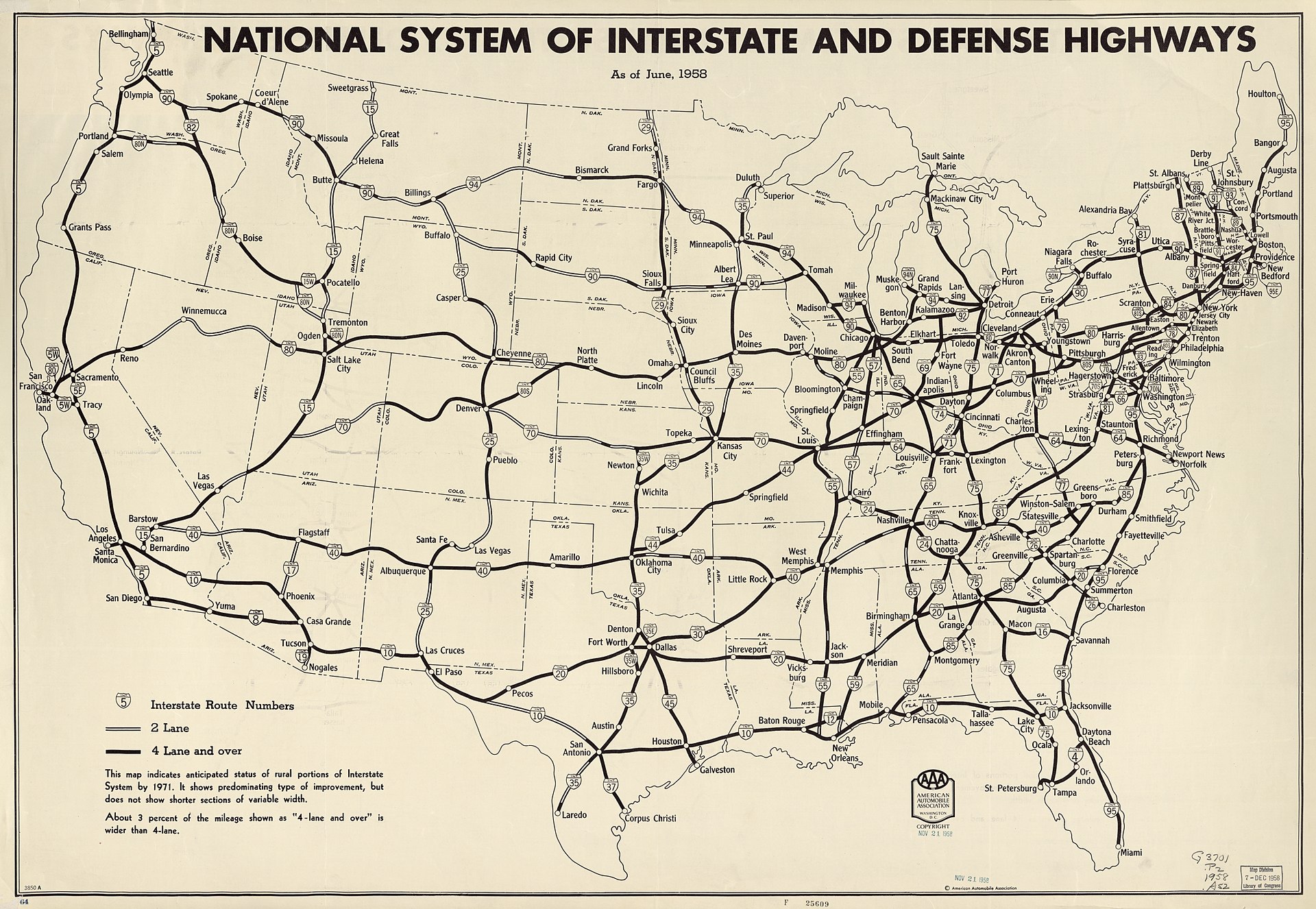

Divergence in American consumption vs European consumption Map of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, June of 1958 When looking at American cities, they look remarkably different to cities around the world. These drastic differences have a lot of causes yet they all lead to cities that have on average significantly higher levels of per capita consumption than others around the world.[11] Stemming largely from the post-World War II divergence, the United States built much of its prosperity on its national demand for mass-consumption goods whereas Europe built theirs largely around exports.[12] This divergence is exhibited in how American and European cities function and look. Americans, and subsequently American economic trends, tend to be significantly more self-centered and personal while European economic trends tend to be more community-based. These differences can best be seen in governmental policy toward taxation and public spending. In the United States, people tend to dislike public spending and taxation while Europeans tend to support higher rates of taxation for spending on the public good.[13] Additionally, when looking at how American cities look vs European cities, this divergent ideology around public vs private living and responsibility is extremely clear. Look at how Americans have embraced suburbia as a major way of living. With suburbia comes single-family homes, private cars, and massive supermarkets. All entities that prioritize and enable hyper-individualized (and often redundant) consumption. American living is epitomized by urban sprawl, where cities have grown outwards rather than upwards. Various American governmental policies have enabled and encouraged urban sprawl. For example, President Eisenhower implemented the Federal Aid Highway Act in 1956 and paved the way for a substantial highway system to be implemented across the nation. These highways, coupled with the uniquely American ability at the time for the average family to afford a car, provided the necessary infrastructure to accelerate and accommodate a massive shift into the suburbs.[14] In the suburbs, families could have their own private single-family house, a backyard, and personal appliances such as refrigerators, dishwashers, and laundry machines. This focus on personal single-family homes led to this very individualistic and socially repetitive pattern of consumption in the United States. Conversely, Europe embraced a more collectivist community-based approach to living that does not necessitate the same level of hyper-consumption. Europe has a much higher population density prioritizing multi-family units. This polar opposite urban planning allowed most European cities to subside off less consumption per capita. Whereas in America, strict urban planning restrictions limited who could live where and where businesses could be, in Europe, there was a much more lenient system that allowed for and encouraged a much higher population density.[15] |

アメリカの消費とヨーロッパの消費の乖離 1958年6月、州間高速道路と国防高速道路の国民システム地図 アメリカの都市を見ると、世界の都市とは著しく異なっている。第二次世界大戦後の乖離に起因するところが大きいが、アメリカは大量消費財の国民需要によっ て繁栄の多くを築いたのに対し、ヨーロッパは輸出を中心に繁栄を築いた[12]。アメリカ人、ひいてはアメリカの経済動向は、自己中心的で人格的な傾向が 著しく強いのに対して、ヨーロッパの経済動向は、より地域社会に根ざした傾向が強い。こうした違いは、税制や公共支出に対する政府の政策に最もよく表れて いる。アメリカでは、人民は公共支出や課税を嫌う傾向があるのに対し、ヨーロッパでは、公共の利益のために支出する高い税率を支持する傾向がある [13]。さらに、アメリカの都市とヨーロッパの都市の様子を見比べてみると、公共と私的な生活や責任をめぐるこのイデオロギーの相違は極めて明確であ る。アメリカ人がいかに郊外を主要な生活様式として受け入れているかを見てみよう。郊外には一戸建て住宅、自家用車、巨大なスーパーマーケットがある。こ れらはすべて、超個人化された(そしてしばしば冗長な)消費を優先し、可能にするものだ。アメリカの暮らしは都市のスプロール化に象徴され、都市は上へ上 へと成長するのではなく、外へと広がってきた。アメリカ政府のさまざまな政策が、都市のスプロールを可能にし、奨励してきた。例えば、アイゼンハワー大統 領は1956年に連邦補助高速道路法を施行し、国民全体に大規模な高速道路システムを導入する道を開いた。これらの高速道路は、当時のアメリカ特有の一般 家庭が自動車を購入する余裕と相まって、郊外への大規模なシフトを加速させ、受け入れるために必要なインフラを提供した[14]。郊外では、家族は自分だ けの人格的な一戸建て住宅、裏庭、冷蔵庫、食器洗い機、洗濯機などの個人的な電化製品を持つことができた。このような人格的な一戸建て住宅への集中が、ア メリカにおける非常に個人主義的で社会的に反復的な消費パターンにつながった。 逆にヨーロッパでは、同じレベルの超消費を必要としない、より集団主義的な共同体ベースの生活アプローチが受け入れられている。ヨーロッパは人口密度が高 く、集合住宅を優先している。この正反対の都市計画によって、ほとんどのヨーロッパの都市は一人当たりの消費量を抑えている。アメリカでは、厳しい都市計 画の制限によって、誰がどこに住み、どこでビジネスを行うことができるかが制限されていたのに対し、ヨーロッパでは、はるかに高い人口密度を許容し、奨励 する、はるかに寛大な制度があった[15]。 |

| Consumer Culture This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) One major area of research within the sociology of consumption is the study of consumer culture. This includes analyzing the ways in which consumer goods and services are marketed, consumed, and integrated into social identities and cultural practices. Scholars in this area have examined the role of advertising, branding, and other forms of commercial communication in shaping consumer desires and preferences. Consumer Culture Theory (CCT) maintains that consumption practices contribute to the creation and maintenance of an identity, contrary to Bourdieu’s theory that one’s consumption patterns are rooted in their upbringing and environment. Consumption through the lens of CCT is not only shaped by external factors (such as socioeconomic status, marketing, and upbringing) but also is rooted in individual agency. However, even though CCT credits individual agency to influence patterns of consumption, relationships, networks, and changing societal norms are also sources of influence.[citation needed] CCT also relates to the idea of the “extended self” which is a construction of identity created with external objects. For instance, a fashion blogger may consider their clothes to be an extension of themself. They chose clothes that they liked, bought them (or made them), and wear them to signal their identity. In this way, the “you are what you eat” sentiment can be extended to other things that you consume, whether it be clothes, art, books, computers, etc. Sociologist Alan Warde suggests that goods and services can be understood as a form of cultural capital, in which individuals use these products to signal their social status and cultural tastes to others. He argues that the consumption of goods and services is often driven by a desire to participate in particular cultural scenes or communities, and to gain recognition and approval from others within these contexts. In this sense, goods and services are seen as part of a broader system of cultural signifiers, in which individuals use a range of material and symbolic objects to communicate their identity and social position. Warde suggests that the meanings and values associated with particular goods and services can change over time, and that these meanings are often contested and negotiated. Considering advertisements and branding, Jens Beckert’s Imagined Futures sheds light on the potency of symbolic value. Symbolic value is defined as the value derived from the symbolic meaning of an object. For instance, a stuffed animal from childhood has little physical value (in that the toy itself is not necessarily worth much or do much), but can have high symbolic value to the owner because they have ascribed emotions of comfort and nostalgia to the toy. Advertising and branding has tapped into how consumers value products, and ascribe non-function related meanings to the goods and services. For instance, many dog food commercials symbolize their product to be a lifeforce for pets, keeping them happy and healthy for as long as possible, when in reality pet food is just pet food. Branding in itself can be considered as a construction of symbolic meaning attached to an entity, whether it be a company or a person. For example, Nike as a brand represents perseverance and athletic achievement, especially through their tagline, “just do it,” even though they cannot sell perseverance or athletic success. They sell athletic products, but are successful as a brand because of their advertising with some of the greatest athletes of all time and through imbuing their brand with meaning that permeates through the general public. |

消費者文化 このセクションでは出典を引用していない。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは、異議を唱えられ削除される可能性がある。(2024年10月) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 消費社会学における主要な研究分野の一つは、消費文化の研究である。これには、消費財やサービスがどのように市場化され、消費され、社会的アイデンティ ティや文化的実践に組み込まれているかを分析することも含まれる。この分野の研究者は、消費者の欲望や嗜好を形成する上で、広告やブランディング、その他 の形態の商業的コミュニケーションが果たす役割を検証してきた。 消費者文化理論(CCT)は、人の消費パターンは生い立ちや環境に根ざしているというブルデューの理論に反して、消費慣行はアイデンティティの創造と維持 に寄与すると主張している。CCTのレンズを通した消費は、外的要因(社会経済的地位、マーケティング、生い立ちなど)によって形成されるだけでなく、個 人の主体性に根ざしている。しかし、CCTが消費のパターンに影響を与える個人の主体性を信用するとしても、人間関係、ネットワーク、社会規範の変化もま た影響力の源泉である。例えば、ファッションブロガーは自分の服を自分自身の延長だと考えるかもしれない。彼らは気に入った服を選び、それを買い(あるい は作り)、自分のアイデンティティを示すために身につける。このように、「you are what you eat 」という感情は、洋服、アート、本、コンピューターなど、消費する他のものにも拡張することができる。 社会学者のアラン・ウォードは、商品やサービスを文化資本の一形態として理解することができ、個人がこれらの商品を使って、自分の社会的地位や文化的嗜好 を他者に示すことができると提案している。彼は、商品やサービスの消費は多くの場合、個別的な文化的場面や共同体に参加し、その中で他者から認められ、承 認されたいという欲求によって引き起こされると主張する。この意味で、商品やサービスは、個人が自分のアイデンティティや社会的立場を伝えるために、さま ざまな物質的・象徴的なものを使用する、より広範な文化的シニフィエのシステムの一部とみなされる。Wardeは、個別商品やサービスに付随する意味や価 値は時代とともに変化する可能性があり、こうした意味はしばしば争われたり交渉されたりすることを示唆している。 広告やブランディングを考える上で、イェンス・ベッカート(Jens Beckert)の『Imagined Futures』は象徴的価値の効力に光を当てている。象徴的価値とは、ある物体の象徴的意味から得られる価値と定義される。例えば、子供の頃のぬいぐる みは、物理的な価値はほとんどないが(そのおもちゃ自体に大した価値があるわけでもないし、何かをしてくれるわけでもない)、持ち主にとっては、そのおも ちゃに安らぎや懐かしさといった感情が付与されているため、高い象徴的価値を持つことがある。広告やブランディングは、消費者がどのように商品に価値を見 出し、商品やサービスに機能とは関係のない意味を付与しているかに着目している。例えば、多くのドッグフードのコマーシャルは、その製品がペットの生命力 であり、できるだけ長くペットの幸せと健康を維持するものであることを象徴しているが、実際にはペットフードは単なるペットフードである。ブランディング それ自体は、企業であれ人格であれ、ある実体に付けられた象徴的な意味の構築と考えることができる。例えば、ナイキというブランドは、忍耐力や運動での成 功を売ることはできないが、特に「やってみなはれ」というキャッチフレーズを通して、忍耐力や運動での成功を表している。ナイキはアスレチック製品を販売 しているが、ブランドとして成功しているのは、史上最高のアスリートたちを起用した広告や、一般大衆に浸透する意味をブランドに吹き込んでいるからであ る。 |

| Consumer theory Consumerism Hypermobility (travel) Overconsumption Waste |

消費者論 消費主義 ハイパーモビリティ(旅行) 過剰消費 廃棄物 |

| Further reading Bourdieu, Pierre (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-21277-0. James, Paul; Szeman, Imre (2010). Globalization and Culture, Vol. 3: Global-Local Consumption. London: Sage Publications. Rey, P; Ritzer, G.(2011) "The Sociology of Consumption", The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Sociology, pp. 444. Stebbins, Robert A. Leisure and Consumption: Common Ground, Separate Worlds. Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. |

さらに読む Bourdieu, Pierre (1984). 区別: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. ケンブリッジ: ハーバード大学出版局. ISBN 0-674-21277-0. James, Paul; Szeman, Imre (2010). Globalization and Culture, Vol.3: Global-Local Consumption. London: Sage Publications. Rey, P; Ritzer, G.(2011) 「The Sociology of Consumption」, The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Sociology, pp.444. Stebbins, Robert A. Leisure and Consumption: Common Ground, Separate Worlds. Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consumption_(sociology) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆