「芸術のための芸術」批判

Critique for Art for art's sake

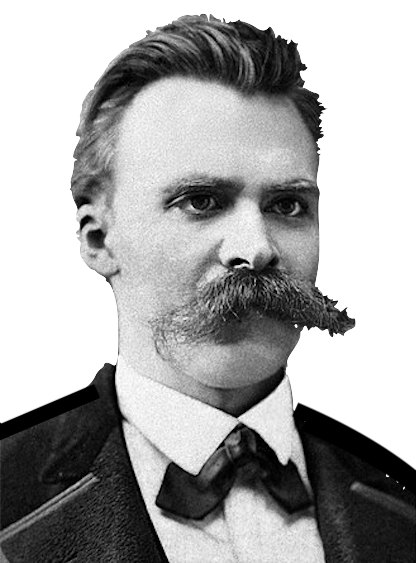

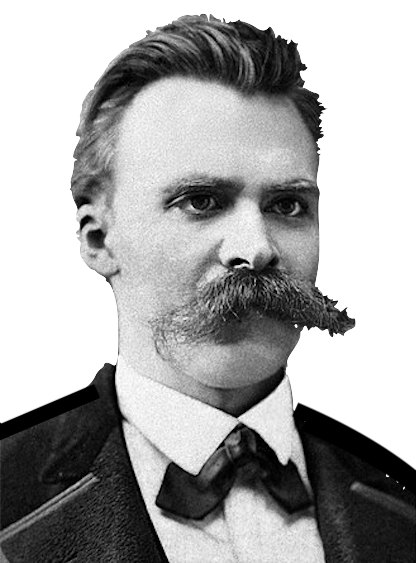

☆フ リードリヒ・ニーチェは、「芸術のための芸術は存在しない」と主張した。すなわち「道徳を説き、人間を向上させるという目的が芸術から排除されたとして も、芸術がまっ たく無目的、無目的、無分別であるということにはならない。"道徳的な目的より、むしろ目的がまったくない方がいい!" - というのは、単なる情熱の話である。一方、心理学者は問う。「すべての芸術は何をしているのか?このすべてによって、芸術は特定の評価を強めたり弱めたり する。これは単なる「おまけ」なのか、偶然なのか、芸術家の本能が関与していないことなのか。それとも、芸術家の能力の前提そのものではないのか?彼の基 本的な本能は、芸術を、いやむしろ芸術の感覚を、人生を、人生の望みを目指しているのだろうか?芸術は人生に対する偉大な刺激である。芸術を無目的なも の、無目的なもの、芸術のための芸術として理解することができるだろうか?」

| Art for art's

sake—the usual English rendering of l'art pour l'art (pronounced [laʁ

puʁ laʁ]), a French slogan from the latter half of the 19th century—is

a phrase that expresses the philosophy that 'true' art is utterly

independent of any and all social values and utilitarian function, be

that didactic, moral, or political.[1] Such works are sometimes

described as autotelic (from Greek: autoteles, 'complete in

itself'),[2] a concept that has been expanded to embrace

"inner-directed" or "self-motivated" human beings.[1] The term is sometimes used commercially. A Latin version of this phrase, ars gratia artis , is used as a motto by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and appears in the film scroll around the roaring head of Leo the Lion in its iconic motion picture logo. |

芸術のための芸術(l'art pour

l'art、19世紀後半のフランスのスローガンの通常の英語表記)とは、「真の」芸術は、教訓的、道徳的、政治的であれ、あらゆる社会的価値や功利的機

能から完全に独立しているという哲学を表す言葉である。

[このような作品はオートテレス(ギリシャ語:autoteles、「それ自体で完結する」から)と表現されることもあり[2]、この概念は「内面的な方

向性」や「自発的な」人間を包含するように拡張されている[1]。 この言葉は商業的に使われることもある。この言葉のラテン語版であるars gratia artisは、メトロ・ゴールドウィン・メイヤーのモットーとして使用されており、その象徴的な映画ロゴであるレオ・ザ・ライオンの咆哮する頭の周りにあ る映画の巻物に描かれている。 |

| The phrase "l'art pour l'art"

('art for art's sake') had been floating around the intellectual

circles of Paris since the beginning of the 19th century, but it was

Théophile Gautier (1811–1872), who first fully articulated its

metaphysical meaning (as we now understand it) in the prefaces of his

1832 poetry volume Albertus, and 1835 novel, Mademoiselle de Maupin.[3] Gautier was not the first nor the only one to use that phrase: it appeared in the lectures and writings of Victor Cousin[1] and Benjamin Constant. In his essay "The Poetic Principle" (1850) Edgar Allan Poe argues: We have taken it into our heads that to write a poem simply for the poem's sake ... and to acknowledge such to have been our design, would be to confess ourselves radically wanting in the true poetic dignity and force:– but the simple fact is that would we but permit ourselves to look into our own souls we should immediately there discover that under the sun there neither exists nor can exist any work more thoroughly dignified, more supremely noble, than this very poem, this poem per se, this poem which is a poem and nothing more, this poem written solely for the poem's sake.[4] "Art for the sake of art" became a bohemian creed in the 19th century; a slogan raised in defiance of those—from John Ruskin to the much later Communist advocates of socialist realism—who thought that the value of art was to serve some moral or didactic purpose. It was a rejection of the Marxist aim of politicising art. Art for the sake of art affirmed that art was valuable as art in itself; that artistic pursuits were their own justification; and that art did not need moral justification, and indeed, was allowed to be morally neutral or subversive.[citation needed] As such, James McNeill Whistler wrote the following in which he discarded the accustomed role of art in the service of the state or official religion, which had adhered to its practice since the Counter-Reformation of the 16th century: "Art should be independent of all claptrap – should stand alone...and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism and the like."[5] Such a brusque dismissal also expressed the artist's distancing of himself from sentimentalism. All that remains of Romanticism in this statement is the reliance on the artist's own eye and sensibility as the arbiter. The explicit slogan is associated, in the history of English art and letters, with Walter Pater and his followers in the Aesthetic Movement, which was self-consciously in rebellion against Victorian moralism. It first appeared in print in English in two works published simultaneously in 1868: in Pater's review of William Morris's poetry in the Westminster Review, and the other in William Blake by Algernon Charles Swinburne. However, William Makepeace Thackeray had used the term privately in an 1839 letter to his mother in which he recommended Thomas Carlyle's Miscellanies, writing that Carlyle had done more than any other to give "art for art's sake . . . its independence."[6] A modified form of Pater's review appeared in his Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873), one of the most influential texts of the Aesthetic Movement.[7] Arnold Bennett made a facetious remark on the issue: "Am I to sit still and see other fellows pocketing two guineas apiece for stories which I can do better myself? Not me. If anyone imagines my sole aim is art for art's sake, they are cruelly deceived."[8] In Germany, the poet Stefan George was one of the first artists to translate the phrase ('Kunst für die Kunst') and adopt it for his own literary programme which he presented in the first volume of his literary magazine Blätter für die Kunst (1892). He was inspired mainly by Charles Baudelaire and the French Symbolists whom he had met in Paris, where he was friends with Albert Saint-Paul and consorted with the circle around Stéphane Mallarmé.[citation needed] |

芸術のための芸術」(l'art pour

l'art)というフレーズは、19世紀初頭からパリの知識人界隈を漂っていたが、1832年の詩集『アルベルトゥス』と1835年の小説『マドモアゼ

ル・ド・モーパン』(Mademoiselle de

Maupin)の序文で、その形而上学的な意味(現在私たちが理解している意味)を初めて明確にしたのは、テオフィル・ゴーティエ(1811-1872)

であった[3]。 この言葉を使ったのはゴーティエが最初でも唯一でもなく、ヴィクトル・クザン[1]やベンジャミン・コンスタン[2]の講義や著作にも登場する。エド ガー・アラン・ポーはそのエッセイ『詩的原理』(1850年)の中でこう論じている: われわれは、単に詩のために詩を書くということを頭に入れている。しかし、単純な事実として、われわれが自分自身の魂を覗き込むことを許すならば、太陽の 下には、まさにこの詩、この詩そのもの、詩でありそれ以上の何ものでもないこの詩、詩のためだけに書かれたこの詩ほど、徹底的に品格のある、至高に高貴な 作品は存在しないし、存在し得ないことを、直ちにそこで発見するはずである[4]。 「芸術のための芸術」は19世紀にボヘミアンの信条となり、ジョン・ラスキンからずっと後の社会主義リアリズムの共産主義者まで、芸術の価値は道徳的ある いは教訓的な目的を果たすことだと考える人々に反抗して掲げられたスローガンだった。それは、芸術を政治化するというマルクス主義の目的を否定するもの だった。芸術のための芸術は、芸術はそれ自体が芸術として価値があること、芸術的追求はそれ自体で正当化されること、芸術は道徳的正当化を必要としないこ と、そして実際、道徳的に中立であったり破壊的であったりすることが許されることを肯定した[要出典]。 そのようなものとして、ジェームズ・マクニール・ホイッスラーは、16世紀の反宗教改革以来、その実践に固執してきた、国家や公的宗教に奉仕する芸術の慣 例的な役割を破棄して、次のように書いた: 「芸術は、あらゆる戯言から独立したものであるべきであり、目や耳といった芸術的感覚に訴えかけるものであるべきであり、献身、憐れみ、愛、愛国心といっ た、芸術とはまったく異質な感情と混同してはならない」[5] 。この声明にロマン主義が残っているのは、裁定者として芸術家自身の目と感性に頼っていることだけである。 この露骨なスローガンは、イギリスの美術と文学の歴史において、ウォルター・ペイターとその支持者たちによる美学運動と結びついている。ペイターが『ウェ ストミンスター・レビュー』誌に発表したウィリアム・モリスの詩の批評と、アルジャーノン・チャールズ・スウィンバーンの『ウィリアム・ブレイク』の批評 である。しかし、ウィリアム・メイクピース・サッカレーは1839年に母親に宛てた手紙の中で、トマス・カーライルの『雑学』を推薦し、カーライルは「芸 術のための芸術......その独立性」を与えるために誰よりも貢献したと書いており、この言葉を私的に使用していた[6]。 アーノルド・ベネットは、この問題について皮肉交じりの発言をしている: 「自分でももっとうまく書けるような物語を、他の連中が1本2ギニーで買っているのを、私はじっと見ていなければならないのだろうか?私は違う。もし私の 唯一の目的が芸術のための芸術であると想像する人がいるとしたら、それはひどい欺瞞である」[8]。 ドイツでは、詩人のシュテファン・ジョルゲがこのフレーズ('Kunst für die Kunst')を翻訳した最初の芸術家の一人であり、自身の文学雑誌『Blätter für die Kunst』(1892年)の第1巻で発表した自身の文学プログラムに採用した。アルベール・サン・ポールと親交があり、ステファン・マラルメを中心とす るサークルと交流があった。 |

| Criticism By Nietzsche Friedrich Nietzsche argued that there is 'no art for art's sake', the arts always expresses human values, communicate core beliefs: When the purpose of moral preaching and of improving man has been excluded from art, it still does not follow by any means that art is altogether purposeless, aimless, senseless — in short, l'art pour l'art, a worm chewing its own tail. "Rather no purpose at all than a moral purpose!" — that is the talk of mere passion. A psychologist, on the other hand, asks: what does all art do? does it not praise? glorify? choose? prefer? With all this it strengthens or weakens certain valuations. Is this merely a "moreover"? an accident? something in which the artist's instinct had no share? Or is it not the very presupposition of the artist's ability? Does his basic instinct aim at art, or rather at the sense of art, at life? at a desirability of life? Art is the great stimulus to life: how could one understand it as purposeless, as aimless, as l'art pour l'art?[9] By Marxists and socialists Marxists have argued that art should be politicised for the sake of transmitting the socialist message.[10] George Sand, who was not a Marxist but a socialist writer,[11][12] wrote in 1872 that L'art pour l'art was an empty phrase, an idle sentence. She asserted that artists had a "duty to find an adequate expression to convey it to as many souls as possible," ensuring that their works were accessible enough to be appreciated.[13] Senegalese president, head of the Socialist Party of Senegal, and co-founder of Negritude Leopold Sedar Senghor and anti-colonial Africanist writer Chinua Achebe have both criticised the slogan as being a limited and Eurocentric view on art and creation. Senghor argued that, in "black African aesthetics," art is "functional" and that in "black Africa, 'art for art's sake' does not exist."[14] Achebe is more scathing in his collection of essays and criticism entitled Morning Yet on Creation Day, in which he asserts that "art for the sake of art is just another piece of deodorised dog shit [sic]."[15] Walter Benjamin, one of the developers of Marxist hermeneutics,[16] discusses the slogan in his seminal 1936 essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction". He first mentions it in regard to the reaction within the realm of traditional art to innovations in reproduction, in particular photography. He even terms the "L'art pour l'art" slogan as part of a "theology of art" in bracketing off social aspects. In the Epilogue to his essay, Benjamin discusses the links between fascism and art. His main example is that of Futurism and the thinking of its mentor Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. One of the slogans of the Futurists was "Fiat ars – pereat mundus" ('Let art be created, though the world perish'). Provocatively, Benjamin concludes that as long as fascism expects war "to supply the artistic gratification of a sense of perception that has been changed by technology," then this is the "consummation," the realization, of "L'art pour l'art."[17] Diego Rivera, who was a member of the Mexican Communist Party and "a supporter of the revolutionary cause," claims that the art for the sake of art theory would further divide the rich from the poor. Rivera goes on to say that since one of the characteristics of so called "pure art" was that it could only be appreciated by a few superior people, the art movement would strip art from its value as a social tool and ultimately make art into a currency-like item that would only be available to the rich.[18] Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong said: "There is in fact no such thing as art for art's sake, art that stands above classes, art that is detached from or independent of politics. Proletarian literature and art are part of the whole proletarian revolutionary cause; they are, as Lenin said, cogs and wheels in the whole revolutionary machine."[19] |

批評 ニーチェ フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、「芸術のための芸術は存在しない」と主張した: 道徳を説き、人間を向上させるという目的が芸術から排除されたとして も、芸術がまったく無目的、無目的、無分別であるということにはならない。"道徳的な目的より、むしろ目的がまったくない方がいい!" - というのは、単なる情熱の話である。一方、心理学者は問う。「すべての芸術は何をしているのか?このすべてによって、芸術は特定の評価を強めたり弱めたり する。これは単なる「おまけ」なのか、偶然なのか、芸術家の本能が関与していないことなのか。それとも、芸術家の能力の前提そのものではないのか?彼の基 本的な本能は、芸術を、いやむしろ芸術の感覚を、人生を、人生の望みを目指しているのだろうか?芸術は人生に対する偉大な刺激である。芸術を無目的なも の、無目的なもの、芸術のための芸術として理解することができるだろうか? マルクス主義者と社会主義者 マルクス主義者たちは、社会主義のメッセージを伝えるために芸術は政治化されるべきであると主張してきた[10]。 マルクス主義者ではなく社会主義者の作家であったジョージ・サンドは、1872年にL'art pour l'artは空虚な言葉であり、無為な文章であると書いている[11][12]。彼女は、芸術家には「できるだけ多くの魂に伝えるための適切な表現を見つ ける義務」があると主張し、彼らの作品が評価されるのに十分なアクセス可能性を保証した[13]。 セネガル大統領、セネガル社会党党首、ネグリチュードの共同創設者であるレオポルド・セダール・センゴールと反植民地主義のアフリカ人作家チヌア・アチェ ベは、芸術と創造に対する限定的でヨーロッパ中心的な見方であるとして、このスローガンを批判した。センゴールは、「アフリカの黒人の美学」において芸術 は「機能的」であり、「アフリカの黒人には『芸術のための芸術』は存在しない」と主張した[14]。アチェベは、『Morning Yet on Creation Day』と題されたエッセイと批評のコレクションで、「芸術のための芸術は、脱臭された犬の糞にすぎない」と主張している[15]。 マルクス主義的解釈学の発展者の一人であるヴァルター・ベンヤミン[16]は、1936年の代表的なエッセイ「機械的複製時代における芸術作品」の中でこ のスローガンを論じている。彼が最初にこのスローガンに言及したのは、複製、特に写真の技術革新に対する伝統芸術の領域における反応についてであった。彼 は「L'art pour l'art(芸術は芸術のために)」というスローガンを「芸術の神学」の一部とさえ言い、社会的側面を除外している。エピローグで、ベンヤミンはファシズ ムと芸術の関係について論じている。彼の主な例は、未来派とその指導者フィリッポ・トマソ・マリネッティの考え方である。未来派のスローガンのひとつは、 "Fiat ars - pereat mundus"(「世界は滅びても、芸術を創造しよう」)であった。挑発的に、ベンヤミンは、ファシズムが戦争に「技術によって変化した知覚の感覚を芸術 的に満足させる」ことを期待している限り、これは「芸術のための芸術」の「完成」であり、実現であると結論づけている[17]。 メキシコ共産党員であり、「革命的大義の支持者」であったディエゴ・リベラは、芸術論のための芸術は、貧富の差をさらに拡大すると主張する。リベラはさら に、いわゆる「純粋芸術」の特徴のひとつは、少数の優れた人々によってのみ評価されうるということであるため、芸術運動は芸術から社会的道具としての価値 を剥奪し、最終的に芸術を富裕層のみが利用できる通貨のようなアイテムにしてしまうと述べている[18]。 中国共産党の指導者、毛沢東は言った: 「芸術のための芸術、階級の上に立つ芸術、政治から切り離された、あるいは政治から独立した芸術などというものは、実際には存在しない。プロレタリア文学 と芸術は、プロレタリア革命の大義全体の一部であり、レーニンが言ったように、革命機械全体の歯車である」[19]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_for_art%27s_sake |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099