キューバ革命

Cuban Revolution

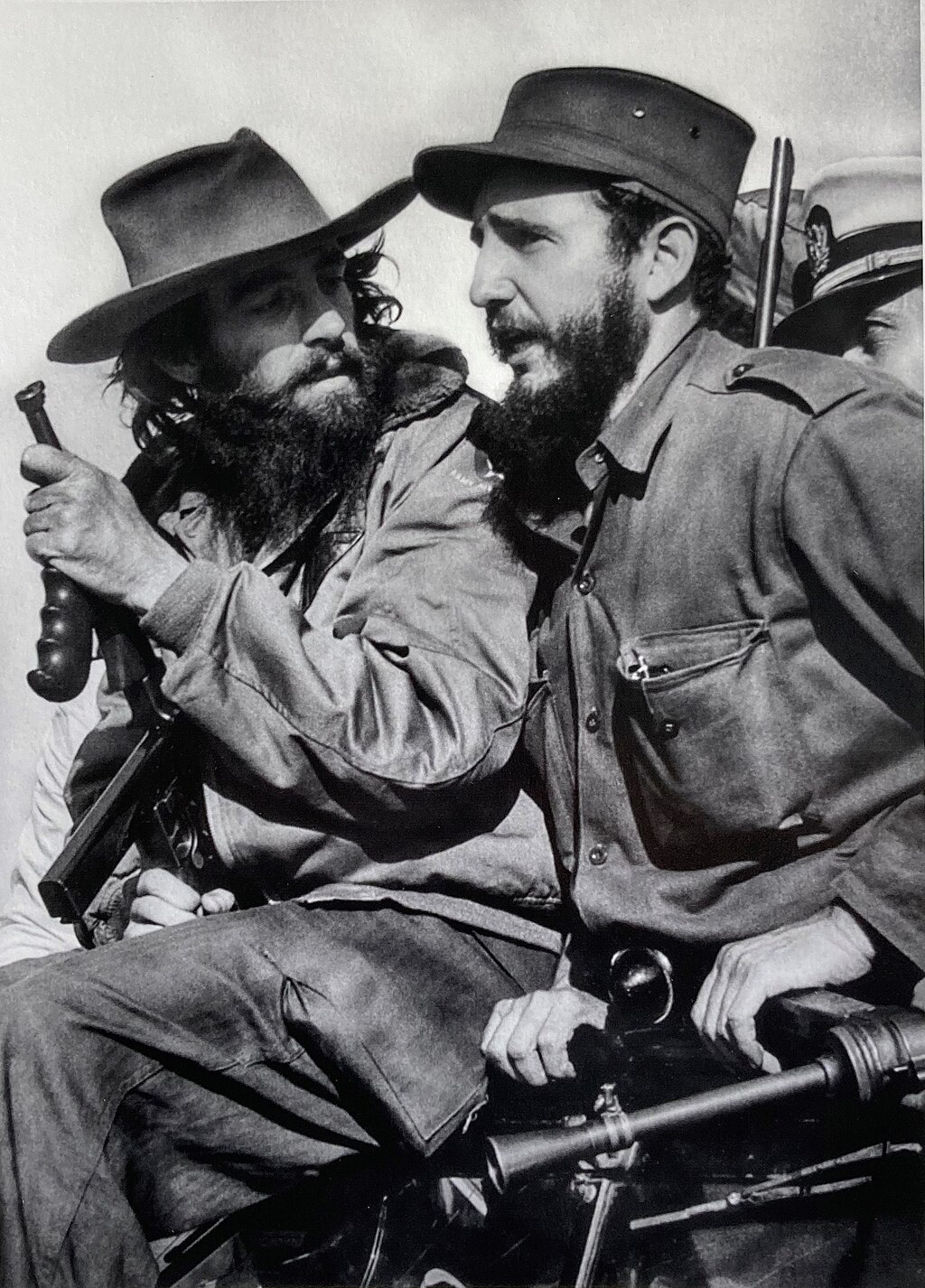

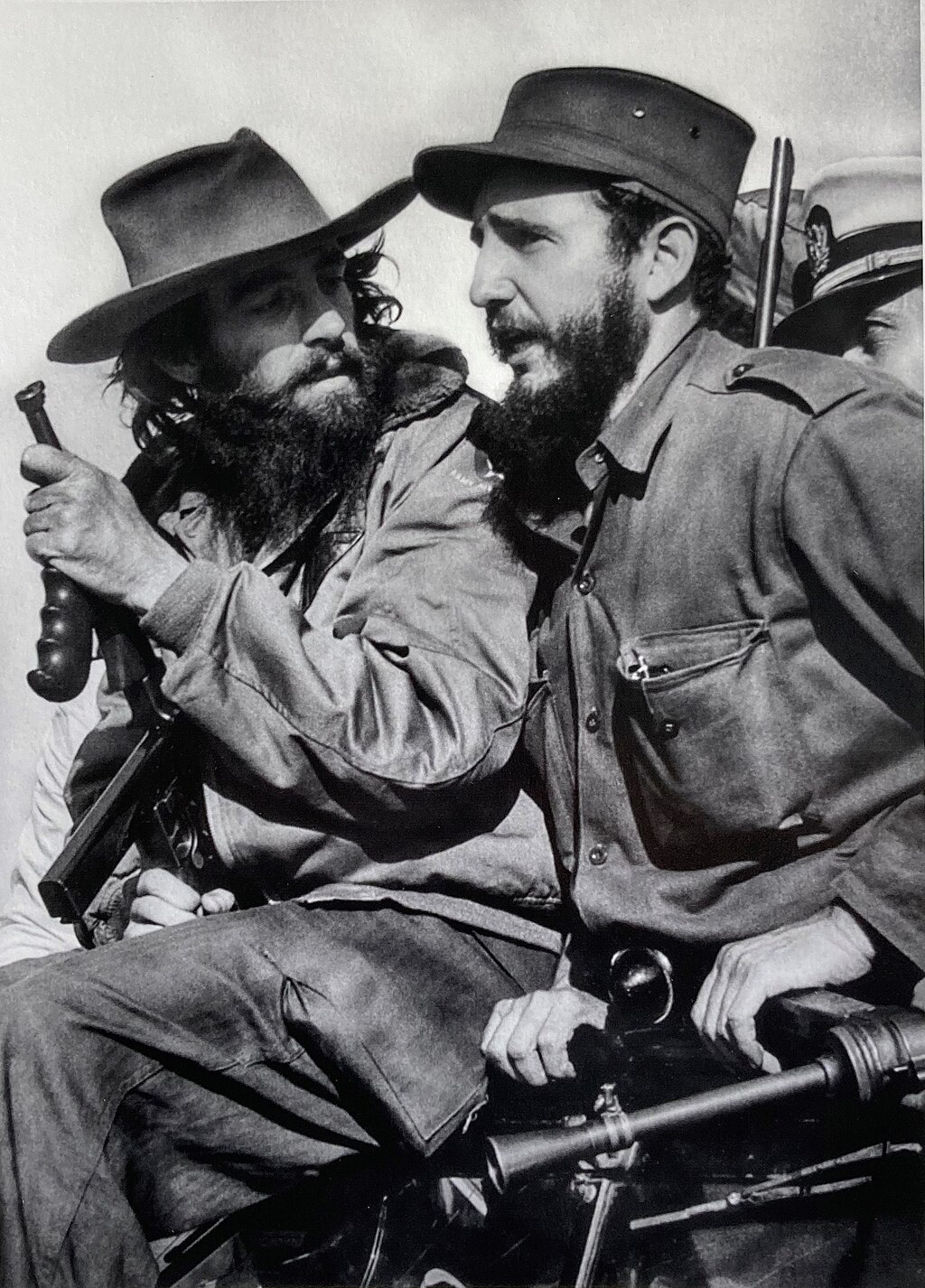

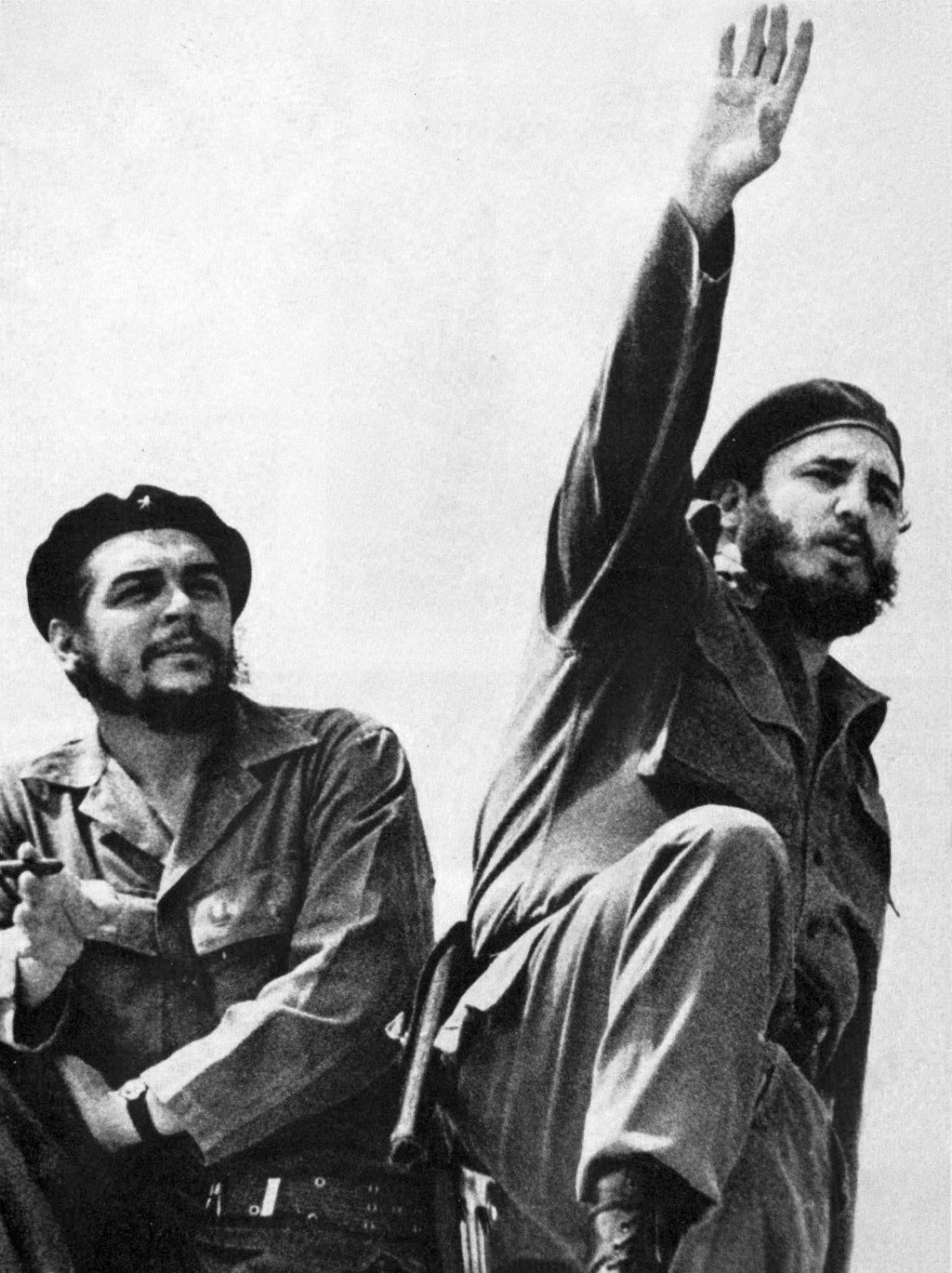

Fidel

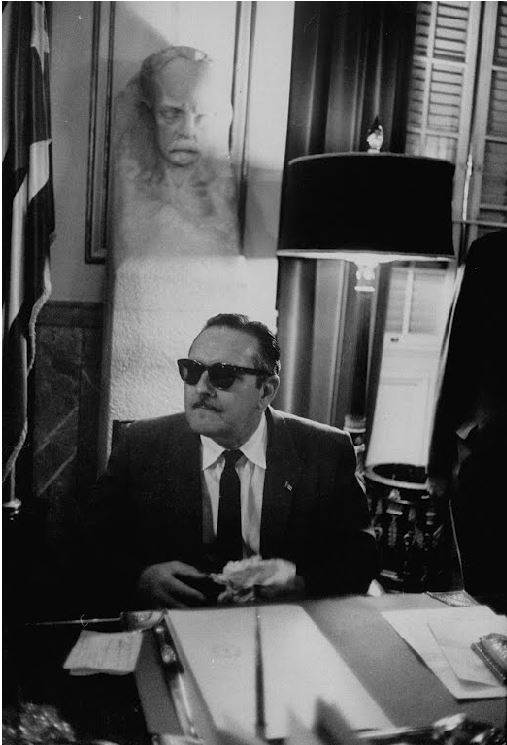

Castro and his men in the Sierra Maestra. From left: Guillermo García,

w:Ernesto "Che" Guevara, Universo Sánchez, w:Raúl Castro (kneeling),

Castro, Crescentio Pérez, Jorge Sotus, and w:Juan Almeida.

☆ キューバ革命(スペイン語:Revolución cubana)は、1953年から1959年にかけてキューバ政府を転覆させようとした軍事的・政治的活動である。1952年のクーデターによりフルヘン シオ・バティスタが国家元首となった後に始まった。裁判でバティスタと争うことに失敗したフィデル・カストロ(1926 -2016)は、1953年7月26日にキューバ軍のモンカダ兵舎への武装攻撃を組織した。反乱軍は逮捕され、獄中で7月26日運動(M-26-7)を結 成した。恩赦を得たM-26-7反乱軍は、メキシコからグランマ号でキューバに侵攻する遠征隊を組織した。その後の数年間、M-26-7反乱軍は農村部で 徐々にキューバ軍を打ち負かす一方、都市部では破壊工作や反乱軍のリクルートに従事した。当初は批判的で両義的だった人民社会党も、やがて1958年後半 には7月26日運動を支持するようになる。反乱軍がバティスタを追放するころには、革命は人民社会党、7月26日運動、3月13日革命総局によって推進さ れていた[7]。 反乱軍は1959年1月1日、ついにバティスタを追放し、政権を交代させた。1953年7月26日は、キューバでは「革命の日(Día de la Revolución)」として祝われる。7月26日運動は後にマルクス・レーニン主義の路線に沿って改革され、1965年10月にキューバ共産党となっ た[8]。 キューバ革命は国内外に大きな影響を与えた。革命直後、カストロ政権は国有化、報道の一元化、政治的強化のプログラムを開始し、キューバの経済と市民社会 を一変させた[13][14]。 [13][14]革命はまた、アフリカ、ラテンアメリカ、東南アジア、中東における対外紛争にキューバが介入する時代の先駆けとなった[15][16] [17][18]。1959年以降の6年間、主にエスカンブライ山脈でいくつかの反乱が発生したが、革命政府によって鎮圧された[19][20][21] [22]。

| The Cuban

Revolution

(Spanish: Revolución cubana) was a military and political effort to

overthrow the government of Cuba between 1953 and 1959. It began after

the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of

state. After failing to contest Batista in court, Fidel Castro

organized an armed attack on the Cuban military's Moncada Barracks on

July 26, 1953. The rebels were arrested and while in prison formed the

26th of July Movement (M-26-7). After gaining amnesty the M-26-7 rebels

organized an expedition from Mexico on the Granma yacht to invade Cuba.

In the following years the M-26-7 rebel army would slowly defeat the

Cuban army in the countryside, while its urban wing would engage in

sabotage and rebel army recruitment. Over time the originally critical

and ambivalent Popular Socialist Party would come to support the 26th

of July Movement in late 1958. By the time the rebels were to oust

Batista the revolution was being driven by the Popular Socialist Party,

26th of July Movement, and the Revolutionary Directorate of March 13.[7] The rebels finally ousted Batista on 1 January 1959, replacing his government. 26 July 1953 is celebrated in Cuba as Día de la Revolución (from Spanish: "Day of the Revolution"). The 26th of July Movement later reformed along Marxist–Leninist lines, becoming the Communist Party of Cuba in October 1965.[8] The Cuban Revolution had powerful domestic and international repercussions. In particular, it transformed Cuba–United States relations, although efforts to improve diplomatic relations, such as the Cuban thaw, gained momentum during the 2010s.[9][10][11][12] In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, Castro's government began a program of nationalization, centralization of the press and political consolidation that transformed Cuba's economy and civil society.[13][14] The revolution also heralded an era of Cuban intervention in foreign conflicts in Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East.[15][16][17][18] Several rebellions occurred in the six years following 1959, mainly in the Escambray Mountains, which were suppressed by the revolutionary government.[19][20][21][22] |

キューバ革命(スペイン語:Revolución

cubana)は、1953年から1959年にかけてキューバ政府を転覆させようとした軍事的・政治的活動である。1952年のクーデターによりフルヘン

シオ・バティスタが国家元首となった後に始まった。裁判でバティスタと争うことに失敗したフィデル・カストロ(1926-2016)は、1953年7月26日にキューバ軍のモン

カダ兵舎への武装攻撃を組織した。反乱軍は逮捕され、獄中で7月26日運動(M-26-7)を結成した。恩赦を得たM-26-7反乱軍は、メキシコからグ

ランマ号でキューバに侵攻する遠征隊を組織した。その後の数年間、M-26-7反乱軍は農村部で徐々にキューバ軍を打ち負かす一方、都市部では破壊工作や

反乱軍のリクルートに従事した。当初は批判的で両義的だった人民社会党も、やがて1958年後半には7月26日運動を支持するようになる。反乱軍がバティ

スタを追放するころには、革命は人民社会党、7月26日運動、3月13日革命総局によって推進されていた[7]。 反乱軍は1959年1月1日、ついにバティスタを追放し、政権を交代させた。1953年7月26日は、キューバでは「革命の日(Día de la Revolución)」として祝われる。7月26日運動は後にマルクス・レーニン主義の路線に沿って改革され、1965年10月にキューバ共産党となっ た[8]。 キューバ革命は国内外に大きな影響を与えた。革命直後、カストロ政権は国有化、報道の一元化、政治的強化のプログラムを開始し、キューバの経済と市民社会 を一変させた[13][14]。 [13][14]革命はまた、アフリカ、ラテンアメリカ、東南アジア、中東における対外紛争にキューバが介入する時代の先駆けとなった[15][16] [17][18]。1959年以降の6年間、主にエスカンブライ山脈でいくつかの反乱が発生したが、革命政府によって鎮圧された[19][20][21] [22]。 |

| Background Corruption in Cuba Main article: Corruption in Cuba  Estrada Palma in 1899 The Republic of Cuba at the turn of the 20th century was largely characterized by a deeply ingrained tradition of corruption where political participation resulted in opportunities for elites to engage in wealth accumulation.[23] Cuba's first presidential period under Don Tomás Estrada Palma from 1902 to 1906 was considered to uphold the best standards of administrative integrity in the history of the Republic of Cuba.[24] However, a United States intervention in 1906 resulted in Charles Edward Magoon, an American diplomat, taking over the government until 1909. Although Magoon's government did not condone corrupt practices, there is debate as to how much was done to stop what was widespread especially with the surge of American money coming into the small country. Hugh Thomas suggests that while Magoon disapproved of corrupt practices, corruption still persisted under his administration and he undermined the autonomy of the judiciary and their court decisions.[25][page needed] On January 29, 1909, the sovereign government of Cuba was restored, and José Miguel Gómez became president. No explicit evidence of Magoon's corruption ever surfaced, but his parting gesture of issuing lucrative Cuban contracts to U.S. firms was a continued point of contention. Cuba's subsequent president, José Miguel Gómez, was the first to become involved in pervasive corruption and government corruption scandals. These scandals involved bribes that were allegedly paid to Cuban officials and legislators under a contract to search the Havana harbour, as well as the payment of fees to government associates and high-level officials.[24] Gómez's successor, Mario García Menocal, wanted to put an end to the corruption scandals and claimed to be committed to administrative integrity as he ran on a slogan of "honesty, peace and work".[24] Despite his intentions, corruption actually intensified under his government from 1913 to 1921.[25][page needed] Instances of fraud became more common while private actors and contractors frequently colluded with public officials and legislators. Charles Edward Chapman attributes the increase of corruption to the sugar boom that occurred in Cuba under the Menocal administration.[26] Furthermore, the advent of World War One enabled the Cuban government to manipulate sugar prices, the sales of exports and import permits.[24] While in office, García Menocal hosted his college fraternity, in the 1920 Delta Kappa Epsilon National Convention, the first international fraternity conference outside the US, which took place in Cuba. He was responsible for creating the Cuban Peso; until his presidency Cuba used both the Spanish Real and US Dollar. President Menocal left the Cuban national treasury in overdraft and therefore in precarious financial situation. Menocal supposedly spent $800 million during his 8 years in office and left a floating debt of $40 million. Alfredo Zayas succeeded Menocal from 1921 to 1925 and engaged in what Calixto Masó refers to as the "maximum expression of administrative corruption".[24] Both petty and grand corruption spread to nearly all aspects of public life and the Cuban administration became largely characterized by nepotism as Zayas relied on friends and relatives to illegally gain greater access to wealth.[25][page needed] Gerardo Machado succeeded Zayas from 1925 to 1933, and entered the presidency with widespread popularity and support from the major political parties. However, his support declined over time. Due to Zayas' previous policies, Gerardo Machado aimed to diminish corruption and improve the public sector's performance under his successive administration from 1925 to 1933. While he was successfully able to reduce the amounts of low level and petty corruption, grand corruption still largely persisted. Machado embarked on development projects that enabled the persistence of grand corruption through inflated costs and the creation of "large margins" that enabled public officials to appropriate money illegally.[27] Under his government, opportunities for corruption became concentrated into fewer hands with "centralized government purchasing procedures" and the collection of bribes among a smaller number of bureaucrats and administrators.[27] Through the development of real estate infrastructures and the growth of Cuba's tourism industry, Machado's administration was able to use insider information to profit from private sector business deals.[27] Many people objected to his running again for re-election in 1928, as his victory violated his promise to serve for only one term. As protests and rebellions became more strident, his administration curtailed free speech and used repressive police tactics against opponents. Machado unleashed a wave of violence against his critics, and there were numerous murders and assassinations committed by the police and army under Machado's administration. The extent of his involvement in these is disputed, but in the end, Machado is described as a dictator. In May 1933, Machada was forced out as newly appointed US ambassador Sumner Welles arrived in Cuba and initiated negotiation with the opposition groups for a government to succeed Machado's. A provisional government headed by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada (son of Cuban independence hero Carlos Manuel de Céspedes) and including members of the ABC was brokered; it took power in August 1933 amidst a general strike in Havana. Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada subsequently was offered the position of President by ambassador Sumner Welles. He took office on August 13, 1933, and Welles proposed that "general elections may be held approximately 3 months from now so that Cuba may once more have a constitutional government in the real sense of the word." Céspedes agreed, and declared that a general election would be held on February 24, 1934, for a new presidential term to begin on May 20, 1934. However, on September 4–5, 1933, the Sergeants' Revolt took place while Céspedes was in Matanzas and Santa Clara after a hurricane had ravaged those regions. The junta of officers led by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista and students proclaimed that it had taken power in order to fulfill the aims of the revolution; it briefly described a program which included economic restructuring, punishment of wrongdoers, recognition of public debts, creation of courts, political reorganization, and any other actions necessary to construct a new Cuba based on justice and democracy.[28] Only five days after the coup, Batista and the Student Directory promoted Ramón Grau to the role of President. The ensuing One Hundred Days Government issued a number of reformist declarations but never gained diplomatic recognition from the US; it was overthrown in January 1934 under pressure from Batista and the US ambassador. Grau was replaced by Carlos Mendieta, and within five days the U.S. recognized Cuba's new government. The corruption was not curtailed under Mendieta and he resigned in 1935 after unrest continued, and their followed a number of interim and weak presidents under the guidance of Batista and the US. Batista, supported by the Democratic Socialist Coalition which included Julio Antonio Mella's Communist Party, defeated Grau in the first presidential election under the new Cuban constitution in the 1940 election, and served a four-year term as President of Cuba. Batista was endorsed by the original Communist Party of Cuba (later known as the Popular Socialist Party), which at the time had little significance and no probability of an electoral victory. This support was primarily due to Batista's labor laws and his support for labor unions, with which the Communists had close ties. In fact, Communists attacked the anti-Batista opposition, saying Grau and others were "fascists" and "reactionaries".  Senator and anti-corruption crusader Eduardo René Chibás Ribas Senator Eduardo Chibás dedicated himself to exposing corruption in the Cuban government, and formed the Partido Ortodoxo in 1947 to further this aim. Argote-Freyre points out that Cuba's population under the Republic had a high tolerance for corruption. Furthermore, Cubans knew and criticized who was corrupt, but admired them for their ability to act as "criminals with impunity".[29] Corrupt officials went beyond members of congress to also include military officials who granted favours to residents and accepted bribes.[29] The establishment of an illegal gambling network within the military enabled army personnel such as Lieutenant Colonel Pedraza and Major Mariné to engage in extensive illegal gambling activities.[29] Mauricio Augusto Font and Alfonso Quiroz, authors of The Cuban Republic and José Martí, say that corruption pervaded in public life under the administrations of Presidents Ramón Grau and Carlos Prío Socarrás.[30] Prío was reported to have stolen over $90 million in public funds, which was equivalent to one fourth of the annual national budget.[31] Prior to the Communist revolution, Cuba was ruled under the elected government of Fulgencio Batista from 1940 to 1944. Throughout this time period, Batista's support base consisted mainly of corrupt politicians and military officials. Batista himself was able to heavily profit from the regime before coming into power through inflated government contracts and gambling proceeds.[29] In 1942, the British Foreign Office reported that the U.S. State Department was "very worried" about corruption under President Fulgencio Batista, describing the problem as "endemic" and exceeding "anything which had gone on previously". British diplomats believed that corruption was rooted within Cuba's most powerful institutions, with the highest individuals in government and military being heavily involved in gambling and the drug trade.[32] In terms of civil society, Eduardo Saenz Rovner writes that corruption within the police and government enabled the expansion of criminal organizations in Cuba.[32] Batista refused U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt's offer to send experts to help reform the Cuban Civil Service. Batista didn't run in the 1944 election, and Partido Auténtico party member Ramón Grau was elected president,[33] and oversaw extensive corruption during his administration. He had Carlos Prío Socarrás serve turns as Minister of Public Works, Minister of Labor and Prime Minister. On the next election July 1, 1948, Prio was elected president of Cuba as a member of the Partido Auténtico which presided over corruption and irresponsible government of this period. [34][35] Prío was assisted by Chief of the Armed Forces General Genobebo Pérez Dámera and Colonel José Luis Chinea Cardenas, who had previously been in charge of the Province of Santa Clara. The eight years under Grau and Prío, were marked by violence among political factions and reports of theft and self-enrichment in the government ranks.[36] The Prío administration increasingly came to be perceived by the public as ineffectual in the face of violence and corruption, much as the Grau administration before it. With elections scheduled for the middle of 1952, rumors surfaced of a planned military coup by long-shot presidential contender Fulgencio Batista. Prío, seeing no constitutional basis to act, did not do so. The rumors proved to be true. On March 10, 1952, Batista and his collaborators seized military and police commands throughout the country and occupied major radio and TV stations. Batista assumed power when Prío, failing to mount a resistance, boarded a plane and went into exile. Batista, after his military coup against Prío Socarras, again took power and ruled until 1959. Under his rule, Batista led a corrupt dictatorship that involved close links with organized crime organizations and the reduction of civil freedoms of Cubans. This period resulted in Batista engaging in more "sophisticated practices of corruption" at both the administrative and civil society levels.[23] Batista and his administration engaged in profiteering from the lottery as well as illegal gambling.[23] Corruption further flourished in civil society through increasing amounts of police corruption, censorship of the press as well as media, and creating anti-communist campaigns that suppressed opposition with violence, torture and public executions.[37] The former culture of toleration and acceptance towards corruption also dissolved with the dictatorship of Batista. For instance, one citizen wrote that "however corrupt Grau and Prío were, we elected them and therefore allowed them to steal from us. Batista robs us without our permission."[38] Corruption under Batista further expanded into the economic sector with alliances that he forged with foreign investors and the prevalence of illegal casinos and criminal organizations in the country's capital of Havana.[38] Batista regime Main article: 1952 Cuban coup d'état In the decades following the United States' invasion of Cuba in 1898, and formal independence from the U.S. on 20 May 1902, Cuba experienced a period of significant instability, enduring a number of revolts, coups and a period of U.S. military occupation. Fulgencio Batista, a former soldier who had served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944, became president for the second time in 1952, after seizing power in a military coup and canceling the 1952 elections.[39] Although Batista had been relatively progressive during his first term,[40] in the 1950s he proved far more dictatorial and indifferent to popular concerns.[41] While Cuba remained plagued by high unemployment and limited water infrastructure,[42][unreliable source?] Batista antagonized the population by forming lucrative links to organized crime and allowing American companies to dominate the Cuban economy, especially sugar-cane plantations and other local resources.[42][43][44] Although the US armed and politically supported the Batista dictatorship, later US president John F. Kennedy recognized its corruption and the justifiability of removing it.[45] During his first term as president, Batista was supported by the original Communist Party of Cuba (later known as the Popular Socialist Party),[40] but during his second term he became strongly anti-communist.[42][46] Batista developed a rather weak security bridge as an attempt to silence political opponents. In the months following the March 1952 coup, Fidel Castro, then a young lawyer and activist, petitioned for the overthrow of Batista, whom he accused of corruption and tyranny. However, Castro's constitutional arguments were rejected by the Cuban courts.[47] After deciding that the Cuban regime could not be replaced through legal means, Castro resolved to launch an armed revolution. To this end, he and his brother Raúl founded a paramilitary organization known as "The Movement", stockpiling weapons and recruiting around 1,200 followers from Havana's disgruntled working class by the end of 1952. |

背景 キューバの汚職 主な記事 キューバの汚職  1899年のエストラーダ・パルマ 20世紀初頭のキューバ共和国は、政治参加によってエリートが富の蓄積に従事する機会を得るという、腐敗の伝統が深く根付いていることが大きな特徴であっ た[23]。1902年から1906年までのドン・トマス・エストラーダ・パルマによるキューバ初の大統領時代は、キューバ共和国の歴史の中で最も優れた 行政の誠実さの基準を維持していると考えられていた[24]。しかし、1906年のアメリカの介入によって、アメリカの外交官であったチャールズ・エド ワード・マグーンが1909年まで政府を引き継いだ。マグーンの政府は腐敗行為を容認していなかったが、特にアメリカの資金が小国キューバに急増する中 で、蔓延していた腐敗行為を阻止するためにどれだけのことが行われたかについては議論がある。ヒュー・トーマスは、マグーンが腐敗行為を容認していたとは いえ、彼の政権下では腐敗は依然として続いており、彼は司法の自治とその判決を弱体化させたと指摘している[25][要出典]。1909年1月29日、 キューバの主権政府が復活し、ホセ・ミゲル・ゴメスが大統領に就任した。マグーンの汚職に関する明確な証拠は表面化しなかったが、米国企業にキューバの有 利な契約を発行するという彼の餞別は、継続的な争点となった。キューバのその後の大統領、ホセ・ミゲル・ゴメスは、蔓延する汚職と政府の腐敗スキャンダル に巻き込まれた最初の人物だった。これらのスキャンダルには、ハバナ港の捜索契約に基づいてキューバ政府高官や議員に支払われたとされる賄賂や、政府関係 者や高官への報酬の支払いが含まれていた[24]。ゴメスの後継者であるマリオ・ガルシア・メノカルは、汚職スキャンダルに終止符を打つことを望んでお り、「正直、平和、仕事」をスローガンに掲げて出馬したことから、行政の誠実さを主張した。 [24]彼の意図とは裏腹に、1913年から1921年にかけて彼の政権下で汚職は実際に激化した[25][要出典]。民間業者や請負業者が公務員や議員 と頻繁に結託する一方で、不正行為はより一般的になった。チャールズ・エドワード・チャップマンは、汚職の増加はメノカル政権下でキューバに起こった砂糖 ブームに起因するとしている[26]。 さらに、第一次世界大戦の到来によって、キューバ政府は砂糖の価格、輸出品の販売、輸入許可証を操作することが可能となった[24]。 ガルシア・メノカルは在任中、1920年にキューバで開催されたアメリカ国外初の国際友愛会議であるデルタ・カッパ・エプシロン全国大会に、大学時代の友 愛会を主催した。彼はキューバ・ペソを創設した責任者であり、彼が大統領に就任するまで、キューバはスペイン・レアルと米ドルの両方を使用していた。メノ カル大統領はキューバ国庫を当座借越の状態にしたため、不安定な財政状況に陥った。メノカルは8年間の在任中に8億ドルを費やし、4000万ドルの負債を 残したとされる。 アルフレド・サヤスは1921年から1925年までメノカルの後を継ぎ、カリクスト・マソが言うところの「行政腐敗の最大表現」に取り組んだ[24]。小 汚職と大汚職の両方が公共生活のほぼすべての側面に広がり、サヤスが友人や親族を頼って不法に富へのアクセスを拡大したため、キューバ行政は縁故主義に よって大きく特徴付けられるようになった[25][要出典]。ジェラルド・マチャドは1925年から1933年までサヤスの後を継ぎ、幅広い人気と主要政 党からの支持を得て大統領に就任した。しかし、彼の支持は時間の経過とともに低下した。1925年から1933年までの歴代政権において、ジェラルド・マ チャドは、ザヤスのそれまでの政策に起因する汚職を減らし、公共部門の業績を向上させることを目指した。彼は、低レベルの汚職や小汚職を減らすことに成功 したが、大汚職はまだ大部分残っていた。マチャドは、膨れ上がったコストと、公務員が違法に金銭を収受することを可能にする「大きなマージン」の創出を通 じて、大汚職の存続を可能にする開発プロジェクトに着手した[27]。マチャドの政権下では、「政府の購買手続きの一元化」と、より少数の官僚と行政官に よる賄賂の収受によって、汚職の機会はより少数の手に集中するようになった。 [27]不動産インフラの整備やキューバの観光産業の成長を通じて、マチャド政権はインサイダー情報を利用して民間部門のビジネス取引から利益を得ること ができた[27]。1928年に再選を目指して出馬したマチャドの勝利は、1期だけ務めるという公約に違反するとして、多くの人々が反対した。抗議や反乱 がより激しくなると、彼の政権は言論の自由を制限し、反対派に対して抑圧的な警察戦術を用いた。マチャドは批判者に対する暴力の波を解き放ち、マチャド政 権下で警察や軍隊による殺人や暗殺が数多く行われた。これらにマチャドがどの程度関与していたかは議論の余地があるが、結局のところ、マチャドは独裁者と 評されている。1933年5月、新たに任命されたアメリカ大使サムナー・ウェルズがキューバに到着し、マチャドの政権を引き継ぐための反対派との交渉を開 始したため、マチャダは追放された。カルロス・マヌエル・デ・セスペデス・イ・クエサダ(キューバ独立の英雄カルロス・マヌエル・デ・セスペデスの息子) を首班とし、ABCのメンバーを含む臨時政府が仲介され、ハバナでゼネストが起こる中、1933年8月に政権を奪取した。 その後、カルロス・マヌエル・デ・セスペデス・イ・クエサダは、サムナー・ウェルズ大使から大統領職のオファーを受けた。彼は1933年8月13日に大統 領に就任し、ウェルズは「今から約3ヵ月後に総選挙を実施し、キューバが再び本当の意味での立憲政府を持つようにしよう」と提案した。セスペデスはこれに 同意し、1934年2月24日に総選挙を行い、1934年5月20日に新大統領の任期が始まることを宣言した。しかし、1933年9月4日から5日にかけ て、セスペデスがマタンサスとサンタクララに滞在している間に、ハリケーンの被害を受けた軍曹たちの反乱が起こった。フルヘンシオ・バティスタ軍曹と学生 たちが率いる将校団は、革命の目的を達成するために政権を奪取したと宣言し、経済再建、不正行為者の処罰、公的債務の承認、裁判所の設立、政治的再編成、 その他正義と民主主義に基づく新しいキューバを建設するために必要なあらゆる行動を含むプログラムを簡潔に説明した[28]。クーデターからわずか5日 後、バティスタと学生名簿はラモン・グラウを大統領に昇格させた。続く百日政府は多くの改革派宣言を発表したが、アメリカからの外交的承認は得られず、バ ティスタとアメリカ大使の圧力で1934年1月に打倒された。グラウの後任にはカルロス・メンディエタが就任し、5日以内にアメリカはキューバの新政府を 承認した。メンディエタ政権下でも腐敗は収まらず、騒乱が続いた後、彼は1935年に辞任し、その後、バティスタとアメリカの指導の下、暫定的で弱体な大 統領が何人も続いた。フリオ・アントニオ・メラ共産党を含む民主社会主義連合に支持されたバティスタは、1940年のキューバ新憲法下初の大統領選挙でグ ラウを破り、4年間キューバ大統領を務めた。バティスタは、当時は存在意義が薄く、選挙で勝利する見込みもなかったキューバ共産党(後の人民社会党)の支 持を得た。この支持の主な理由は、バティスタが労働法を制定し、共産党と密接な関係にあった労働組合を支持したことにあった。実際、共産主義者たちは、グ ラウらを「ファシスト」や「反動主義者」だと言って、反バティスタの野党を攻撃した。  上院議員で反汚職運動家のエドゥアルド・レネ・チバス・リバス 上院議員エドゥアルド・チバスは、キューバ政府の腐敗を暴くことに専念し、1947年、この目的を推進するためにパルティード・オルトドコドを結成した。 アルゴテ=フレアは、共和制下のキューバの人々は汚職に寛容だったと指摘する。さらに、キューバ国民は誰が汚職に手を染めているのかを知っており、批判し ていたが、「犯罪者として堂々と」行動できる彼らを賞賛していた[29]。汚職に手を染めていたのは議会議員にとどまらず、住民に便宜を図り、賄賂を受け 取っていた軍関係者も含まれていた[29]。軍内に違法賭博ネットワークが構築されたことで、ペドラサ中佐やマリネ少佐のような軍関係者が大規模な違法賭 博活動に従事することが可能となった。 [29]『キューバ共和国とホセ・マルティ』の著者であるマウリシオ・アウグスト・フォントとアルフォンソ・キロスは、ラモン・グラウ大統領とカルロス・ プリオ・ソカラス大統領の政権下で汚職が公共生活に蔓延したと述べている[30]。この期間を通じて、バティスタの支持基盤は主に腐敗した政治家と軍関係 者で構成されていた。1942年、イギリス外務省は、アメリカ国務省がフルヘンシオ・バティスタ大統領の下での汚職について「非常に心配している」と報告 し、この問題を「風土病」と表現し、「以前続いていたもの」を超えていると述べた[29]。イギリスの外交官は、汚職はキューバで最も強力な機関に根ざし ており、政府や軍の最高権力者はギャンブルや麻薬取引に深く関わっていると考えていた[32]。市民社会に関しては、エドゥアルド・サエンス・ロブナー は、警察や政府内の汚職がキューバにおける犯罪組織の拡大を可能にしたと書いている[32]。バティスタは、キューバの公務員改革を支援するために専門家 を派遣するというフランクリン・ルーズベルト米大統領の申し出を拒否した。バティスタは1944年の選挙に出馬せず、党員であったラモン・グラウが大統領 に選出され[33]、その政権下で大規模な腐敗を監督した。彼はカルロス・プリオ・ソカラスに公共事業大臣、労働大臣、首相を兼任させた。1948年7月 1日の次の選挙で、プリオはこの時期の汚職と無責任な政府を統率していたパルティド・アウテンティコのメンバーとしてキューバ大統領に選出された。 [34][35]プリオを補佐したのは、軍総司令官のジェノベボ・ペレス・ダメラ将軍と、以前サンタ・クララ州を担当していたホセ・ルイス・チネア・カル デナス大佐であった。 グラウとプリオのもとでの8年間は、政治的派閥間の暴力や、政府内での窃盗や私利私欲の報告が目立った[36]。プリオ政権は、その前のグラウ政権と同 様、暴力と汚職に直面し、国民から無能な政権とみなされるようになった。 1952年半ばに選挙が予定される中、大統領選の有力候補であったフルヘンシオ・バティスタによる軍事クーデター計画の噂が浮上した。プリオは、憲法上の 根拠がないと判断し、行動を起こさなかった。噂は事実であった。1952年3月10日、バティスタとその協力者たちは国中の軍と警察を掌握し、主要なラジ オ局とテレビ局を占拠した。バチスタが権力を握ったのは、抵抗に失敗したプリオが飛行機に乗り亡命したときだった。 プリオ・ソカラスに対する軍事クーデターの後、バティスタは再び政権を握り、1959年まで統治した。バティスタの統治下で、バティスタは腐敗した独裁政 権を率い、組織犯罪組織と密接な関係を持ち、キューバ人の市民的自由を削減した。この時期、バティスタは行政レベルでも市民社会レベルでも、より「洗練さ れた腐敗の慣行」に従事することになった[23]。 バティスタとその政権は、宝くじや違法賭博から利益を得ることに従事した[23]。腐敗は、警察の汚職の増加、報道機関やメディアの検閲、暴力や拷問、公 開処刑で反対派を弾圧する反共キャンペーンを行うことで、市民社会でさらに盛んになった[37]。腐敗に対するかつての寛容で受容的な文化も、バティスタ の独裁によって解消された。例えば、ある市民は、「グラウとプリオがどんなに腐敗していたとしても、私たちは彼らを選んだのだから、彼らが私たちから盗む ことを許したのだ。バティスタは私たちの許可なく私たちから奪う」[38]。バティスタ政権下の汚職は、彼が外国人投資家と結んだ提携や、首都ハバナでの 違法カジノや犯罪組織の蔓延によって、経済分野にもさらに拡大した[38]。 バティスタ政権 主な記事 1952年キューバ・クーデター 1898年に米国がキューバに侵攻し、1902年5月20日に米国から正式に独立した後の数十年間、キューバは多くの反乱、クーデター、米軍の占領に耐 え、大きな不安定期を経験した。1940年から1944年まで選挙でキューバの大統領を務めた元軍人のフルヘンシオ・バティスタは、軍事クーデターで権力 を掌握し、1952年の選挙を中止した後、1952年に2度目の大統領に就任した[39]。 バティスタは1期目は比較的進歩的であったが[40]、1950年代には独裁的で民衆の関心に無関心であることが証明された[41]。 米国はバティスタ独裁政権を武装し政治的に支援していたが、後のジョン・F・ケネディ大統領はその腐敗と排除の正当性を認識していた[45]。 バティスタは大統領としての最初の任期中、キューバ共産党(後に人民社会党として知られる)によって支持されていたが[40]、2期目には強く反共主義的 になった[42][46]。1952年3月のクーデター後の数ヶ月間、当時若い弁護士であり活動家であったフィデル・カストロは、汚職と専制政治を非難す るバティスタの打倒を請願した。しかし、カストロの憲法上の主張は、キューバの裁判所によって却下された[47]。合法的な手段ではキューバの政権を交代 させることはできないと判断したカストロは、武力革命を起こすことを決意した。この目的のために、カストロは弟のラウルとともに「運動」として知られる準 軍事組織を設立し、武器を備蓄し、1952年末までにハバナの不満を持つ労働者階級から約1,200人の信者を集めた。 |

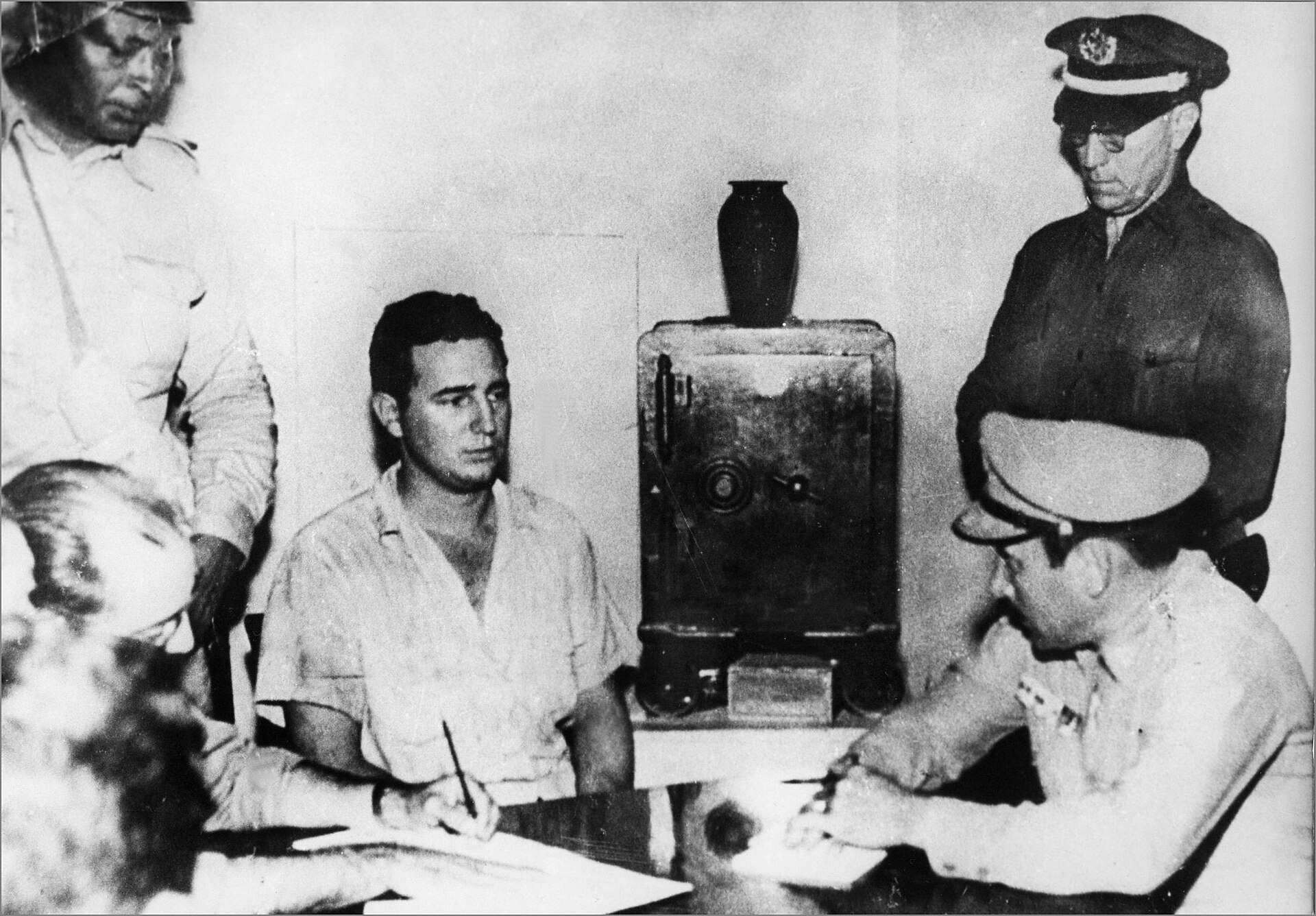

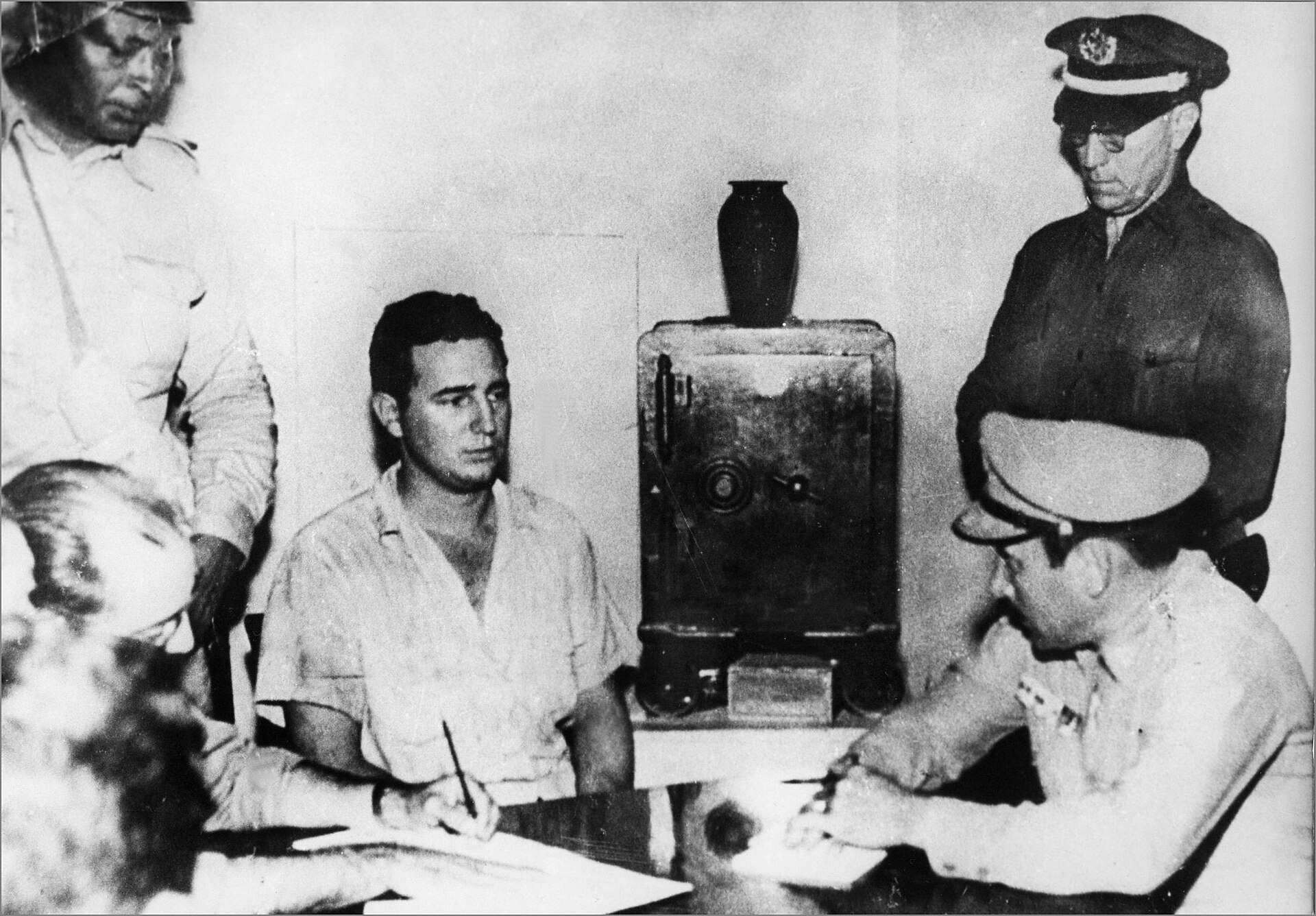

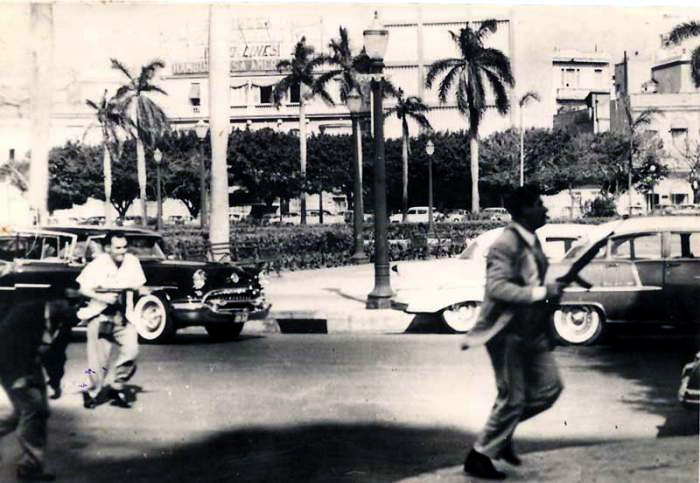

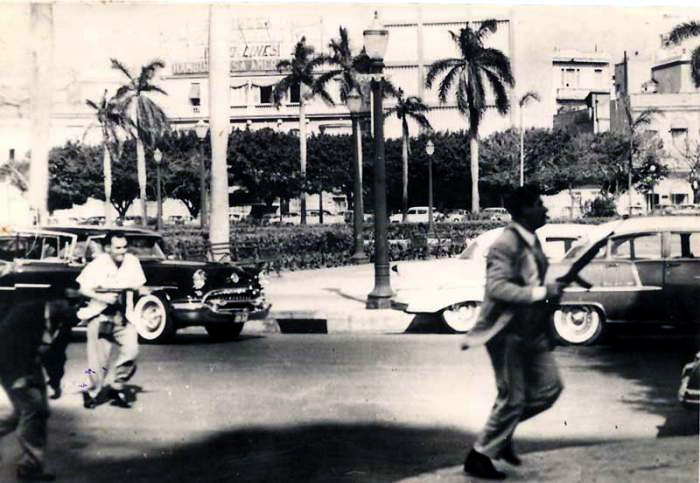

| Early stages: 1953–1955 Further information: Fidel Castro in the Cuban Revolution Attack on the Moncada Barracks Main article: Attack on the Moncada Barracks  Fidel Castro under arrest after the July 1953 attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba Striking their first blow against the Batista government, Fidel and Raúl Castro gathered 70 fighters and planned a multi-pronged attack on several military installations.[48] On 26 July 1953, the rebels attacked the Moncada Barracks in Santiago and the barracks in Bayamo, only to be decisively defeated by the far more numerous government soldiers.[49] It was hoped that the staged attack would spark a nationwide revolt against Batista's government. After an hour of fighting most of the rebels and their leader fled to the mountains.[50] The exact number of rebels killed in the battle is debatable; however, in his autobiography, Fidel Castro claimed that nine were killed in the fighting, and an additional 56 were executed after being captured by the Batista government.[51] Due to the government's large number of men, Hunt revised the number to be around 60 members taking the opportunity to flee to the mountains along with Castro.[29] Among the dead was Abel Santamaría, Castro's second-in-command, who was imprisoned, tortured, and executed on the same day as the attack.[52] Imprisonment and immigration Numerous key Movement revolutionaries, including the Castro brothers, were captured shortly afterwards. In a highly political trial, Fidel spoke for nearly four hours in his defense, ending with the words "Condemn me, it does not matter. History will absolve me." Castro's defense was based on nationalism, the representation and beneficial programs for the non-elite Cubans, and his patriotism and justice for the Cuban community.[53] Fidel was sentenced to 15 years in the Presidio Modelo prison, located on Isla de Pinos, while Raúl was sentenced to 13 years.[54] However, in 1955, under broad political pressure, the Batista government freed all political prisoners in Cuba, including the Moncada attackers. Fidel's Jesuit childhood teachers succeeded in persuading Batista to include Fidel and Raúl in the release.[55] Soon, the Castro brothers joined with other exiles in Mexico to prepare for the overthrow of Batista, receiving training from Alberto Bayo, a leader of Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War. In June 1955, Fidel met the Argentine revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara, who joined his cause.[55] Raúl and Fidel's chief advisor Ernesto aided the initiation of Batista's amnesty.[53] The revolutionaries named themselves the "26th of July Movement", in reference to the date of their attack on the Moncada Barracks in 1953.[49]  Student protests in Havana, 1956 Student demonstrations By late 1955, student riots and demonstrations became more common, and unemployment became problematic as new graduates could not find jobs.[56][57] These protests were dealt with increasing repression. All young people were seen as possible revolutionaries.[58] Due to its continued opposition to the Cuban government and much protest activity taking place on its campus, the University of Havana was temporarily closed on 30 November 1956 (it did not reopen until 1959 under the first revolutionary government).[59] Attack on the Domingo Goicuria Barracks While the Castro brothers and the other 26 July Movement guerrillas were training in Mexico and preparing for their amphibious deployment to Cuba, another revolutionary group followed the example of the Moncada Barracks assault. On 29 April 1956 at 12:50 pm during Sunday mass, an independent guerrilla group of around 100 rebels led by Reynol García attacked the Domingo Goicuria army barracks in Matanzas province. The attack was repelled with ten rebels and three soldiers killed in the fighting, and one rebel summarily executed by the garrison commander, Pilar García.[60] Florida International University historian Miguel A. Brito was in the nearby cathedral when the firefight began. He writes, "That day, the Cuban Revolution began for me and Matanzas."[61][62] |

初期段階 1953-1955 さらなる情報 キューバ革命におけるフィデル・カストロ モンカダ兵営襲撃事件 主な記事 モンカダ兵営襲撃事件  1953年7月、サンティアゴ・デ・クーバのモンカダ兵営襲撃事件後、逮捕されたフィデル・カストロ 1953年7月26日、反乱軍はサンティアゴのモンカダ兵舎とバヤモの兵舎を攻撃したが、はるかに多数の政府軍兵士によって決定的な敗北を喫した。しか し、フィデル・カストロは自伝の中で、戦闘で9人が死亡し、さらに56人がバティスタ政府に捕らえられた後に処刑されたと主張している[51]。 [51]政府の人数が多かったため、ハントはその数を約60名と修正し、この機会にカストロとともに山へ逃亡した。[29]死者の中には、カストロの副官 であったアベル・サンタマリアがおり、彼は投獄され、拷問を受け、攻撃と同じ日に処刑された[52]。 投獄と移民 カストロ兄弟を含む数多くの主要な革命家が、その直後に捕らえられた。高度に政治的な裁判で、フィデルは弁護のために4時間近く話し、最後に「私を非難し ても、それは問題ではない。歴史は私を赦すだろう" カストロの弁護は、ナショナリズム、非エリートのキューバ人のための代表と有益なプログラム、キューバ社会のための彼の愛国心と正義に基づいていた [53] フィデルは、イスラ・デ・ピノスに位置するプレシディオ・モデロ刑務所で15年の刑を宣告され、ラウルは13年の刑を宣告された[54] しかし、1955年に、広範な政治的圧力の下で、バティスタ政府は、モンカダ襲撃犯を含むキューバのすべての政治犯を解放した。フィデルの幼少期のイエズ ス会の教師は、フィデルとラウルを釈放に含めるようバティスタを説得することに成功した[55]。 間もなく、カストロ兄弟はメキシコで他の亡命者とともにバティスタ打倒の準備を進め、スペイン内戦における共和国軍の指導者アルベルト・バヨから訓練を受 けた。1955年6月、フィデルはアルゼンチンの革命家エルネスト・"チェ"・ゲバラと出会い、彼の大義に加わった[55]。ラウルとフィデルの最高顧問 エルネストは、バティスタの恩赦の開始を支援した[53]。  1956年、ハバナでの学生デモ 学生デモ 1955年後半になると、学生の暴動やデモが頻発するようになり、新卒者の就職難から失業が問題となった[56][57]。キューバ政府への継続的な反対 とそのキャンパスで行われていた多くの抗議活動のため、ハバナ大学は1956年11月30日に一時閉鎖された(再開は第一革命政府の下での1959年) [59]。 ドミンゴ・ゴイクリア兵舎襲撃事件 カストロ兄弟と他の7月26日運動ゲリラがメキシコで訓練し、キューバへの水陸両用配備の準備をしている間に、別の革命グループがモンカダ兵営襲撃の例に 倣った。1956年4月29日、日曜日のミサ中の午後12時50分、レイノル・ガルシア率いる約100人の反乱軍からなる独立ゲリラ集団が、マタンサス州 のドミンゴ・ゴイクリア陸軍兵舎を襲撃した。この攻撃は撃退され、10人の反乱軍と3人の兵士が戦死し、1人の反乱軍が守備隊長のピラール・ガルシアに よって即刻処刑された[60]。彼は「その日、私とマタンサスにとってキューバ革命が始まった」と書いている[61][62]。 |

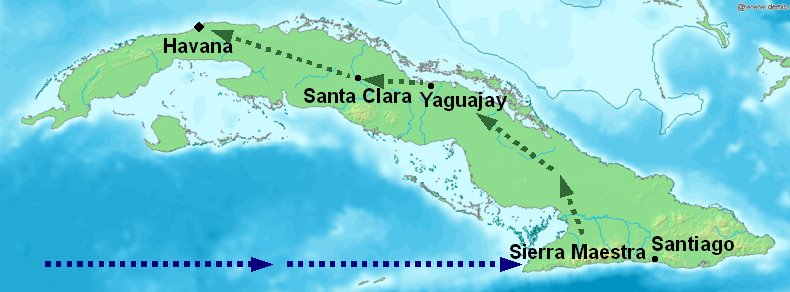

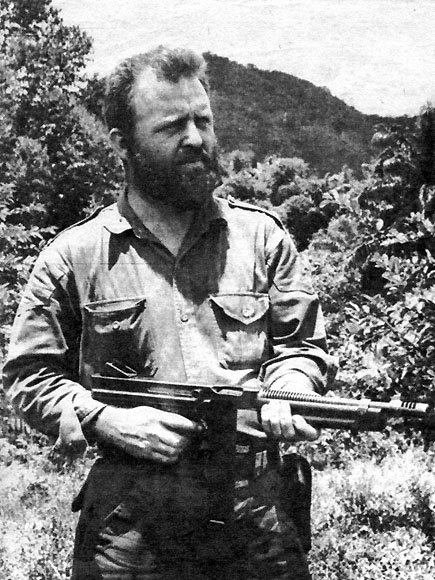

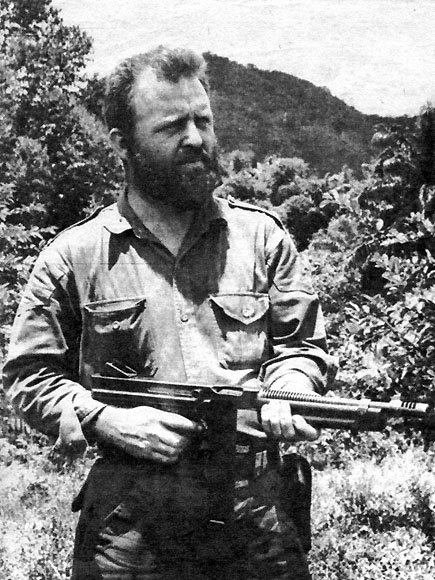

Insurgency: 1956–1957 Map of Cuba showing the location of the arrival of the rebels on the Granma in late 1956, the rebels' stronghold in the Sierra Maestra, and Guevara and Cienfuegos' route towards Havana via Las Villas Province in December 1958 Granma landing Main article: Granma (yacht) The yacht Granma departed from Tuxpan, Veracruz, Mexico, on 25 November 1956, carrying the Castro brothers and 80 others including Ernesto "Che" Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos, even though the yacht was only designed to accommodate 12 people with a maximum of 25. On 2 December,[63] it landed in Playa Las Coloradas, in the municipality of Niquero, arriving two days later than planned because the boat was heavily loaded, unlike during the practice sailing runs.[64] This dashed any hopes for a coordinated attack with the llano wing of the Movement. After arriving and exiting the ship, the band of rebels began to make their way into the Sierra Maestra mountains, a range in southeastern Cuba. Three days after the trek began, Batista's army attacked and killed most of the Granma participants – while the exact number is disputed, no more than twenty of the original eighty-two men survived the initial encounters with the Cuban army and escaped into the Sierra Maestra mountains.[65] The group of survivors included Fidel and Raúl Castro, Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos. The dispersed survivors, alone or in small groups, wandered through the mountains, looking for each other. Eventually, the men would link up again – with the help of peasant sympathizers – and would form the core leadership of the guerrilla army. A number of female revolutionaries, including Celia Sánchez and Haydée Santamaría (the sister of Abel Santamaría), also assisted Fidel Castro's operations in the mountains.[66] Presidential palace attack Main article: Havana Presidential Palace attack (1957)  Havana Presidential Palace attack, 13 March 1957 On 13 March 1957, a separate group of revolutionaries – including the student opposition group Directorio Revolucionario 13 de Marzo – stormed the Presidential Palace in Havana, attempting to assassinate Batista and overthrow the government. The attack ended in utter failure. The RD's leader, student José Antonio Echeverría, died in a shootout with Batista's forces at the Havana radio station he had seized to spread the news of Batista's anticipated death. The handful of survivors included Dr. Humberto Castello (who later became the Inspector General in the Escambray), Rolando Cubela and Faure Chomon (both later Comandantes of the 13 March Movement, centered in the Escambray Mountains of Las Villas Province).[67] The plan, as explained by Faure Chaumón Mediavilla, was to attack the Presidential Palace and occupy the radio station Radio Reloj at the Radiocentro CMQ Building in order to announce the death of Batista and call for a general strike. The Presidential Palace was to be captured by fifty men under the direction of Carlos Gutiérrez Menoyo and Faure Chomón, with support from a group of 100 armed men occupying the tallest buildings in the surrounding area of the Presidential Palace (La Tabacalera, the Sevilla Hotel, the Palace of Fine Arts). However this secondary support operation was not carried out, as the men failed to arrive at the scene due to last-minute hesitation. Although the attackers reached the third floor of the palace, they did not locate or execute Batista. Humboldt 7 massacre Main article: Humboldt 7 massacre  Havana police at the entrance door of apartment 201, 20 April 1957 The Humboldt 7 massacre occurred on 20 April 1957 at apartment 201 of the Humboldt 7 residential building when the National Police led by Lt. Colonel Esteban Ventura Novo assassinated four participants who had survived the assault on the Presidential Palace and in the seizure of the Radio Reloj station at the Radiocentro CMQ Building. Juan Pedro Carbó was sought by police for the assassination of Col. Antonio Blanco Rico, Chief of Batista's secret service.[68] Marcos Rodríguez Alfonso (also known as "Marquitos") began arguing with Fructuoso, Carbó and Machadito; Joe Westbrook had not yet arrived. Marquitos, who gave the airs to be a revolutionary, was strongly against the revolution and was thus resented by the others. On the morning of 20 April 1957, Marquitos met with Lt. Colonel Esteban Ventura and revealed the location of where the young revolutionaries were, Humboldt 7.[69][70] After 5:00 pm on 20 April, a large contingent of police officers arrived and assaulted apartment 201, where the four men were staying. The men were not aware that the police were outside. The police rounded up and executed the rebels, who were unarmed.[71] The incident was covered up until a post-revolution investigation in 1959. Marquitos was arrested and, after a double trial, was sentenced by the Supreme Court to the penalty of death by firing squad in March 1964.[72] Frank País Main article: Frank País Frank País was a revolutionary organizer who had built an extensive urban network, who had been tried and acquitted for his role in organizing an unsuccessful uprising in Santiago de Cuba in support of Castro's landing. On 30 June 1957, Frank's younger brother, Josué País, was killed by the Santiago police. During the latter part of July 1957, a wave of systematic police searches forced Frank País into hiding in Santiago de Cuba. On 30 July he was in a safe house with Raúl Pujol, despite warnings from other members of the Movement that it was not secure. The Santiago police under Colonel José Salas Cañizares surrounded the building. Frank and Raúl attempted to escape. However, an informant betrayed them as they tried to walk to a waiting getaway car. The police officers drove the two men to the Callejón del Muro (Rampart Lane) and shot them in the back of the head. In defiance of Batista's regime, País was buried in the Santa Ifigenia Cemetery in the olive green uniform and red and black armband of 26 July Movement. In response to the death of País, the workers of Santiago declared a spontaneous general strike. This strike was the largest popular demonstration in the city up to that point. The mobilization of 30 July 1957 is considered one of the most decisive dates in both the Cuban Revolution and the fall of Batista's dictatorship. This day has been instituted in Cuba as the Day of the Martyrs of the Revolution. The Frank País Second Front, the guerrilla unit led by Raúl Castro in the Sierra Maestra was named for the fallen revolutionary. His childhood home at 226 San Bartolomé Street was turned into The Santiago Frank País García House Museum and designated as a national monument. The international airport in Holguín, Cuba also bears his name.[73] Naval mutiny at Cienfuegos On 6 September 1957 elements of the Cuban navy in the Cienfuegos Naval Base staged a rising against the Batista regime. Led by junior officers in sympathy with the 26th of July Movement, this was originally intended to coincide with the seizure of warships in Havana harbour. Reportedly individual officials within the U.S. Embassy were aware of the plot and had promised U.S. recognition if it were successful.[74] By 5:30am the base was in the hands of the mutineers. Most of the 150 naval personnel sleeping at the base joined with the twenty-eight original conspirators, while eighteen officers were arrested. About two hundred 26th of July Movement members and other rebel supporters entered the base from the town and were given weapons. Cienfuegos was in rebel hands for several hours.[75] By the afternoon Government motorised infantry had arrived from Santa Clara, supported by B-26 bombers. Armoured units followed from Havana. After street fighting throughout the afternoon and night the last of the rebels, holding out in the police headquarters, were overwhelmed. Approximately 70 mutineers and rebel supporters were executed and reprisals against civilians added to the estimated total death toll of 300 men.[76] The use of bombers and tanks recently provided under a US-Cuban arms agreement specifically for use in hemisphere defence, now raised tensions between the two governments.[77] Escalation and US involvement The United States supplied Cuba with planes, ships, tanks, and other technology such as napalm, which was used against the rebels. This would eventually come to an end due to a later arms embargo in 1958.[78] According to Tad Szulc, the United States began funding the 26th of July Movement around October or November 1957 and ending around middle 1958. "No less than $50,000" would be delivered to key leaders of the 26th of July Movement,[79] the purpose being to instill sympathies to the United States amongst the rebels in case the movement succeeded.[80]  Comandante William Alexander Morgan of the Second National Front of the Escambray While Batista increased troop deployments to the Sierra Maestra region to crush the 26 July guerrillas, the Second National Front of the Escambray kept battalions of the Constitutional Army tied up in the Escambray Mountains region. The Second National Front was led by former Revolutionary Directorate member Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo and the "Comandante Yanqui" William Alexander Morgan. Gutiérrez Menoyo formed and headed the guerrilla band after news had broken out about Castro's landing in the Sierra Maestra, and José Antonio Echeverría had stormed the Havana Radio station. Though Morgan was dishonorably discharged from the U.S. Army, his recreating features from Army basic training made a critical difference in the Second National Front troops battle readiness.[81] Thereafter, the United States imposed an economic embargo on the Cuban government and recalled its ambassador, weakening the government's mandate further.[82] Batista's support among Cubans began to fade, with former supporters either joining the revolutionaries or distancing themselves from Batista. Once Batista started making drastic decisions concerning Cuba's economy, he began to nationalize U.S. oil refineries and other U.S. properties.[83] Batista's government often resorted to brutal methods to keep Cuba's cities under control. However, in the Sierra Maestra mountains, Castro, aided by Frank País, Ramos Latour, Huber Matos, and many others, staged successful attacks on small garrisons of Batista's troops. Castro was joined by CIA connected Frank Sturgis who offered to train Castro's troops in guerrilla warfare. Castro accepted the offer, but he also had an immediate need for guns and ammunition, so Sturgis became a gunrunner. Sturgis purchased boatloads of weapons and ammunition from CIA weapons expert Samuel Cummings' International Armament Corporation in Alexandria, Virginia. Sturgis opened a training camp in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where he taught Che Guevara and other 26 July Movement rebel soldiers guerrilla warfare. In addition, poorly armed irregulars known as escopeteros harassed Batista's forces in the forests and mountains of Oriente Province. The escopeteros also provided direct military support to Castro's main forces by protecting supply lines and by sharing intelligence.[84] Ultimately, the mountains came under Castro's control.[85] In addition to armed resistance, the rebels sought to use propaganda to their advantage. A pirate radio station called Radio Rebelde ("Rebel Radio") was set up in February 1958, allowing Castro and his forces to broadcast their message nationwide within enemy territory.[86] Castro's affiliation with the New York Times journalist Herbert Matthews created a front page-worthy report on anti-communist propaganda.[87] The radio broadcasts were made possible by Carlos Franqui, a previous acquaintance of Castro who subsequently became a Cuban exile in Puerto Rico.[88] During this time, Castro's forces remained quite small in numbers, sometimes fewer than 200 men, while the Cuban army and police force had a manpower of around 37,000.[89] Even so, nearly every time the Cuban military fought against the revolutionaries, the army was forced to retreat. An arms embargo – imposed on the Cuban government by the United States on 14 March 1958 – contributed significantly to the weakness of Batista's forces. The Cuban air force rapidly deteriorated: it could not repair its airplanes without importing parts from the United States.[90] |

反乱:1956-1957年 1956年末のグランマ号での反乱軍到着地点、シエラ・マエストラでの反乱軍の拠点、1958年12月のゲバラとシエンフエゴスのラス・ビジャ州経由ハバ ナへのルートを示すキューバ地図 グランマ号上陸 主な記事 グランマ号(ヨット) 1956年11月25日、カストロ兄弟とエルネスト・"チェ"・ゲバラ、カミロ・シエンフエゴスら80人を乗せたヨット「グランマ号」がメキシコのベラク ルス州トゥクスパンを出発。12月2日、船はニケロのプラヤ・ラス・コロラダスに上陸したが[63]、その到着は予定より2日遅れた。到着して船を降りた 反乱軍の一団は、キューバ南東部の山脈であるシエラ・マエストラ山脈への道を進み始めた。正確な数については議論があるが、当初の82人のうち20人以上 がキューバ軍との最初の遭遇を生き延び、シエラ・マエストラ山脈に逃げ込んだ。 生存者のグループには、フィデルとラウル・カストロ、チェ・ゲバラ、カミロ・シエンフエゴスが含まれていた。散り散りになった生存者たちは、単独で、ある いは小グループで、お互いを探しながら山中をさまよった。やがて男たちは、農民のシンパの助けを借りて再び手を組み、ゲリラ軍の中核的指導部を形成する。 セリア・サンチェスやヘイデ・サンタマリア(アベル・サンタマリアの妹)を含む多くの女性革命家も、山間部でのフィデル・カストロの活動を支援した [66]。 大統領官邸襲撃 主な記事 ハバナ大統領官邸襲撃事件(1957年)  ハバナ大統領官邸襲撃事件(1957年3月13日 1957年3月13日、学生反体制派を含む革命派の別働隊がハバナの大統領官邸を襲撃し、バティスタの暗殺と政府転覆を企てた。この攻撃は完全に失敗に終 わった。革命軍のリーダーである学生ホセ・アントニオ・エチェベリアは、バティスタの死が予想されるというニュースを広めるために占拠したハバナのラジオ 局で、バティスタ軍との銃撃戦の末に死亡した。一握りの生き残りには、ウンベルト・カステロ博士(後にエスカンブレーの監察総監となる)、ロランド・クベ ラ、フォウレ・チョモン(ともに後にラス・ビジャス州のエスカンブレー山脈を中心とする「13の3月運動」の司令官)らがいた[67]。 ファウレ・チョモン・メディアビージャの説明によれば、計画は、大統領官邸を攻撃し、ラジオセントロCMQビルのラジオ局Radio Relojを占拠して、バティスタの死を発表し、ゼネストを呼びかけるというものであった。大統領官邸は、カルロス・グティエレス・メノヨとフォーレ・ チョモンの指揮の下、50人の男たちによって占拠され、大統領官邸周辺の最も高い建物(ラ・タバカレラ、セビージャ・ホテル、美術宮殿)を占拠する100 人の武装集団の支援を受けることになっていた。しかし、この二次支援作戦は、土壇場で躊躇したために現場に到着できず、実行されなかった。襲撃者たちは宮 殿の3階まで到達したものの、バティスタの居場所を突き止めることも処刑することもできなかった。 フンボルト7世の虐殺 主な記事 フンボルト7世の虐殺  1957年4月20日、201号室の入り口のドアにいるハバナ警察 フンボルト7号事件とは、1957年4月20日、フンボルト7号住宅の201号室で、エステバン・ヴェントゥーラ・ノボ中佐率いる国家警察が、大統領官邸 襲撃事件とラジオセントロCMQビルでのラジオ・レロジ放送局占拠事件で生き残った4人の参加者を暗殺した事件である。 フアン・ペドロ・カルボは、バティスタのシークレットサービスのチーフであったアントニオ・ブランコ・リコ大佐の暗殺容疑で警察に追われていた[68]。 マルコス・ロドリゲス・アルフォンソ(「マルキトス」とも呼ばれた)は、フルクトゥオソ、カルボ、マチャディートと口論を始めたが、ジョー・ウェストブ ルックはまだ到着していなかった。マルキトスは革命家気取りだったが、革命に強く反対していたため、他のメンバーから反感を買っていた。1957年4月 20日の朝、マルキトスはエステバン・ヴェントゥーラ中佐に会い、若い革命家たちの居場所であるフンボルト7の場所を明かした[69][70]。4月20 日午後5時過ぎ、大勢の警察官が到着し、4人が滞在していたアパート201号室を襲撃した。男たちは警察が外にいることに気づいていなかった。警察は丸腰 だった反乱軍を一網打尽にし、処刑した[71]。 この事件は1959年の革命後の調査まで隠蔽された。マルキトスは逮捕され、二重裁判の後、1964年3月に最高裁判所から銃殺刑の判決を受けた [72]。 フランク・パイス 主な記事 フランク・パイス フランク・パイスは、広範な都市ネットワークを構築した革命的組織者で、カストロの上陸を支持するためにサンティアゴ・デ・クーバで蜂起を組織して失敗し た役割のために裁判にかけられ、無罪となった。1957年6月30日、フランクの弟ホスエ・パイスがサンティアゴ警察に殺された。1957年7月後半、警 察による組織的な捜査が相次ぎ、フランク・パイスはサンティアゴ・デ・クーバに身を隠さざるを得なくなった。7月30日、フランク・パイスはラウル・プ ジョルとともに隠れ家にいた。ホセ・サラス・カニサレス大佐率いるサンティアゴ警察が建物を包囲した。フランクとラウルは逃げようとした。しかし、待ち構 える逃走車まで歩こうとしたところを、情報提供者に裏切られた。警察官は二人をカジェホン・デル・ムロ(ランパート通り)まで追いやり、後頭部を撃ち抜い た。バチスタ政権に反抗して、パイスは7月26日運動のオリーブグリーンの制服と赤と黒の腕章をつけてサンタ・イフィゲニア墓地に埋葬された。 パイスの死を受け、サンティアゴの労働者たちは自然発生的なゼネストを宣言した。このストライキは、それまでのサンティアゴ最大の民衆デモであった。 1957年7月30日の動員は、キューバ革命とバティスタ独裁政権の崩壊の両方において、最も決定的な日付のひとつと考えられている。この日はキューバで 「革命の殉教者の日」として制定されている。ラウル・カストロがシエラ・マエストラで率いたゲリラ部隊「フランク・パイス第二戦線」は、殉職した革命家に ちなんで命名された。サン・バルトロメ通り226番地にある幼少期の家は、サンティアゴ・フランク・パイス・ガルシア家博物館となり、国の記念碑に指定さ れた。キューバのホルギンにある国際空港にも彼の名が冠されている[73]。 シエンフエゴスでの海軍反乱 1957年9月6日、シエンフエゴス海軍基地のキューバ海軍がバティスタ政権に反旗を翻した。7月26日運動に共鳴した下級将校が率いたこの蜂起は、当 初、ハバナ港での軍艦掌握と同時に行われる予定だった。伝えられるところによれば、アメリカ大使館内の個々の高官はこの計画を知っており、それが成功すれ ばアメリカの承認を得ることを約束していた[74]。 午前5時30分までに、基地は暴徒たちの手に落ちた。基地に寝泊まりしていた150人の海軍関係者のほとんどが28人の最初の陰謀者と合流し、18人の将 校が逮捕された。約200人の7月26日運動メンバーとその他の反乱軍支持者が町から基地に入り、武器を与えられた。シエンフエゴスは数時間、反乱軍の手 にあった[75]。午後には、B-26爆撃機の支援を受けた政府軍の歩兵部隊がサンタ・クララから到着した。ハバナからは機甲部隊が続いた。午後から夜に かけての街頭戦の後、警察本部で持ちこたえていた最後の反乱軍は制圧された。約70人の反乱軍と反乱軍支持者が処刑され、民間人に対する報復が300人の 推定死者数に加わった[76]。 半球防衛に使用するために特別に米国とキューバの武器協定に基づいて最近提供された爆撃機と戦車の使用は、今や両政府間の緊張を高めた[77]。 エスカレーションと米国の関与 米国はキューバに飛行機、船舶、戦車、ナパームなどの技術を提供し、反乱軍に対して使用された。これは1958年の後の武器禁輸措置により、最終的に終了 することになる[78]。 タッド・シュルクによれば、米国は1957年10月か11月頃に7月26日運動に資金を提供し始め、1958年半ば頃に終了した。7月26日運動の主要な 指導者たちに「5万ドルを下らない」資金が提供され[79]、その目的は運動が成功した場合に備えて反政府勢力の間にアメリカへのシンパシーを植え付ける ことであった[80]。  エスカンブレイ第二民族戦線のコマンダンテ、ウィリアム・アレクサンダー・モーガン バティスタが7月26日のゲリラ鎮圧のためにシエラ・マエストラ地方への派兵を強化する一方で、エスカンブレイ第二民族戦線はエスカンブレイ山脈地方に憲 政軍の大隊を拘束し続けた。第二民族戦線は、元革命局長エロイ・グティエレス・メノヨと「コマンダンテ・ヤンキ」ウィリアム・アレクサンダー・モルガンが 率いていた。グティエレス・メノヨは、カストロがシエラ・マエストラに上陸し、ホセ・アントニオ・エチェベリアがハバナラジオ局を襲撃したというニュース が流れた後、ゲリラバンドを結成し率いた。モーガンはアメリカ陸軍から不名誉除隊となったが、陸軍の基礎訓練での特徴を再現したことは、第二次国民戦線部 隊の戦闘態勢に決定的な違いをもたらした[81]。 その後、アメリカはキューバ政府に経済禁輸を課し、大使を召還して政府の権限をさらに弱めた[82]。キューバ人の間でバティスタの支持は衰え始め、かつ ての支持者は革命派に加わったり、バティスタから距離を置いたりした。バティスタはキューバの経済に関して思い切った決断を下し始めると、アメリカの石油 精製所やその他のアメリカの資産を国有化し始めた[83]。 バティスタの政府はキューバの都市を支配下に置くためにしばしば残忍な方法に訴えた。しかし、シエラ・マエストラ山脈では、カストロはフランク・パイス、 ラモス・ラトゥール、フーベル・マトス、その他多くの人々に助けられ、バティスタ軍の小さな守備隊への攻撃を成功させた。カストロにはCIAとつながりの あったフランク・スタージスが加わり、ゲリラ戦の訓練を申し出た。カストロはこの申し出を受け入れたが、銃と弾薬がすぐに必要だったため、スタージスは銃 の運び屋となった。スタージスはCIAの武器専門家であるサミュエル・カミングスのバージニア州アレクサンドリアにあるインターナショナル・アーマメン ト・コーポレーションから大量の武器と弾薬を購入した。スタージスはシエラ・マエストラ山脈に訓練キャンプを開設し、そこでチェ・ゲバラや7月26日運動 の反乱軍兵士たちにゲリラ戦を教えた。 さらに、オリエンテ州の森林や山岳地帯では、エスコペテロと呼ばれる低武装の非正規兵がバティスタ軍に嫌がらせをした。エスコペテーロはまた、補給線を保 護し、情報を共有することによって、カストロの主力部隊に直接的な軍事支援を提供した[84]。最終的に、山岳地帯はカストロの支配下に入った[85]。 武力抵抗に加えて、反乱軍はプロパガンダを利用しようとした。1958年2月にRadio Rebelde(「反乱軍ラジオ」)と呼ばれる海賊ラジオ局が設立され、カストロとその勢力は敵地内で自分たちのメッセージを全国に放送することができる ようになった[86]。 カストロがニューヨーク・タイムズのジャーナリストであるハーバート・マシューズと提携したことで、反共プロパガンダに関する一面を飾るに値する報道がな された[87]。 ラジオ放送は、カストロの以前の知人であり、その後プエルトリコのキューバ亡命者となったカルロス・フランキによって実現された[88]。 この間、カストロの軍隊は極めて少数にとどまり、時には200人に満たないこともあったが、キューバ陸軍と警察の兵力はおよそ37,000人であった [89]。それでも、キューバ軍が革命派と戦うたびに、軍は撤退を余儀なくされた。1958年3月14日に米国がキューバ政府に課した武器禁輸は、バティ スタ軍の弱体化に大きく貢献した。キューバ空軍は急速に悪化し、アメリカから部品を輸入しなければ飛行機を修理することができなかった[90]。 |

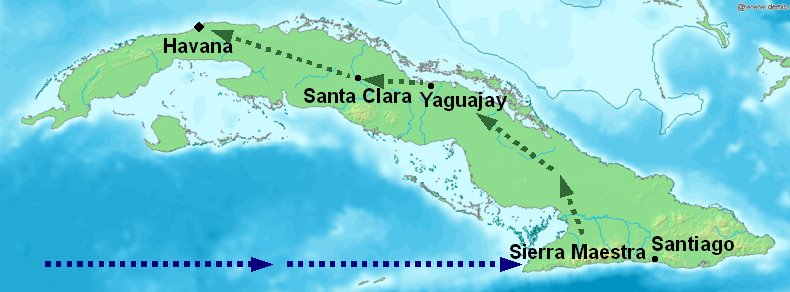

| Final offensives: 1958–1959 Operation Verano Main article: Operation Verano Batista finally responded to Castro's efforts with an attack on the mountains called Operation Verano (Summer), known to the rebels as la Ofensiva. The army sent some 12,000 soldiers, half of them untrained recruits, into the mountains. In a series of small skirmishes, Castro's determined guerrillas defeated the Cuban army.[90] In the Battle of La Plata, which lasted from 11 to 21 July 1958, Castro's forces defeated a 500-man battalion, capturing 240 men while losing just three of their own.[91] However, the tide nearly turned on 29 July 1958, when Batista's troops almost destroyed Castro's small army of some 300 men at the Battle of Las Mercedes. With his forces pinned down by superior numbers, Castro asked for, and received, a temporary cease-fire on 1 August. Over the next seven days, while fruitless negotiations took place, Castro's forces gradually escaped from the trap. By 8 August, Castro's entire army had escaped back into the mountains, and Operation Verano had effectively ended in failure for the Batista government.[90] Battle of Las Mercedes Main article: Battle of Las Mercedes The Battle of Las Mercedes (29 July–8 August 1958) was the last battle of Operation Verano.[citation needed] The battle was a trap, designed by Cuban General Eulogio Cantillo to lure Fidel Castro's guerrillas into a place where they could be surrounded and destroyed. The battle ended with a cease-fire which Castro proposed and which Cantillo accepted. During the cease-fire, Castro's forces escaped back into the mountains. The battle, though technically a victory for the Cuban army, left the army dispirited and demoralized. Castro viewed the result as a victory and soon launched his own offensive.  Map showing key locations of the Cuban Revolution Battalion 17 began its pull back on 29 July 1958. Castro sent a column of men under René Ramos Latour to ambush the retreating soldiers. They attacked the advance guard and killed some 30 soldiers but then came under attack from previously undetected Cuban forces. Latour called for help and Castro came to the battle scene with his own column of men. Castro's column also came under fire from another group of Cuban soldiers that had secretly advanced up the road from the Estrada Palma Sugar Mill. As the battle heated up, General Cantillo called up more forces from nearby towns and some 1,500 troops started heading towards the fighting. However, this force was halted by a column under Che Guevara's command. While some critics accuse Che for not coming to the aid of Latour, Major Bockman argues that Che's move here was the correct thing to do. Indeed, he called Che's tactical appreciation of the battle "brilliant". By the end of July, Castro's troops were fully engaged and in danger of being wiped out by the vastly superior numbers of the Cuban army. He had lost 70 men, including René Latour, and both he and the remains of Latour's column were surrounded. The next day, Castro requested a cease-fire with General Cantillo, even offering to negotiate an end to the war. This offer was accepted by General Cantillo for reasons that remain unclear. Batista sent a personal representative to negotiate with Castro on 2 August. The negotiations yielded no result but during the next six nights, Castro's troops managed to slip away unnoticed. On 8 August when the Cuban army resumed its attack, they found no one to fight. Castro's remaining forces had escaped back into the mountains, and Operation Verano had effectively ended in failure for the Batista government.[90] Battle of Yaguajay Main article: Battle of Yaguajay  Central part of the battle's monument and plaza with the statue of Camilo Cienfuegos In December 1958, Fidel Castro ordered his revolutionary army to go on the offensive against Batista's army. While Castro led one force against Guisa, Masó and other towns, another major offensive was directed at the capture of the city of Santa Clara, the capital of what was then Las Villas Province. Three columns were sent against Santa Clara under the command of Che Guevara, Jaime Vega, and Camilo Cienfuegos. Vega's column was caught in an ambush and completely destroyed. Guevara's column took up positions around Santa Clara (near Fomento). Cienfuegos's column directly attacked a local army garrison at Yaguajay. Initially numbering just 60 men out of Castro's hardened core of 230, Cienfuegos's group had gained many recruits as it crossed the countryside towards Santa Clara, eventually reaching an estimated strength of 450 to 500 fighters. The garrison consisted of some 250 men under the command of a Cuban captain of Chinese ancestry, Alfredo Abon Lee.[92][93] The attack seems to have started around 19 December. Convinced that reinforcements would be sent from Santa Clara, Lee put up a determined defense of his post. The guerrillas repeatedly attempted to overpower Lee and his men, but failed each time. By 26 December Camilo Cienfuegos had become quite frustrated; it seemed that Lee could not be overpowered, nor could he be convinced to surrender. In desperation, Cienfuegos tried using a homemade tank against Lee's position. The "tank" was actually a large tractor encased in iron plates with attached makeshift flamethrowers on top. It, too, proved unsuccessful. Finally, on 30 December Lee ran out of ammunition and was forced to surrender his force to the guerrillas.[citation needed] The surrender of the garrison was a major blow to the defenders of the provincial capital of Santa Clara. The next day, the combined forces of Cienfuegos, Guevara, and local revolutionaries under William Alexander Morgan captured the city in a fight of vast confusion. Battle of Guisa Main article: Battle of Guisa On the morning of 20 November 1958, a convoy of the Batista soldiers began its usual journey from Guisa. Shortly after leaving that town, located in the mountains of the Sierra Maestra, the rebels attacked the caravan.[94] Guisa was 12 kilometers from the Command Post of the Zone of Operations, located on the outskirts of the city of Bayamo. Nine days earlier, Fidel Castro had left the La Plata Command, beginning an unstoppable march east with his escort and a small group of combatants.[a] On 19 November, the rebels arrived in Santa Barbara. By that time, there were approximately 230 combatants. Fidel gathered his officers to organize the siege of Guisa, and ordered the placement of a mine on the Monjarás bridge, over the Cupeinicú river. That night the combatants made a camp in Hoyo de Pipa. In the early morning, they took the path that runs between the Heliografo hill and the Mateo Roblejo hill, where they occupied strategic positions. In the meeting on the 20th, the army lost a truck, a bus, and a jeep. Six were killed and 17 prisoners were taken, three of them wounded. At around 10:30 am, the military Command Post located in the Zone of Operations in Bayamo sent a reinforcement made up of Co. 32, plus a platoon from Co. L and another platoon from Co. 22. This force was unable to advance for the resistance of the rebels. Fidel ordered the mining of another bridge over a tributary of the Cupeinicú River. Hours later the army sent a platoon from Co. 82 and another platoon from Co. 93, supported by a T-17 tank.[95][b][96] 1958 Cuban general election Main article: 1958 Cuban general election    Andrés Rivero Agüero, 1958 president elect General elections were held in Cuba on 3 November 1958.[97] The three major presidential candidates were Carlos Márquez Sterling of the Partido del Pueblo Libre, Ramón Grau of the Partido Auténtico and Andrés Rivero Agüero of the Coalición Progresista Nacional. There was also a minor party candidate on the ballot, Alberto Salas Amaro for the Union Cubana party. Voter turnout was estimated at 50% of eligible voters.[98] Although Andrés Rivero Agüero won the presidential election with 70% of the vote, he was unable to take office due to the Cuban Revolution.[99] Rivero Agüero was due to be sworn in on 24 February 1959. In a conversation between him and the American ambassador Earl E. T. Smith on 15 November 1958, he called Castro a "sick man" and stated it would be impossible to reach a settlement with him. Rivero Agüero also said that he planned to restore constitutional government and would convene a Constitutional Assembly after taking office.[100] This was the last competitive election in Cuba, the 1940 Constitution of Cuba, the Congress and the Senate of the Cuban Republic, were quickly dismantled shortly thereafter. The rebels had publicly called for an election boycott, issuing its Total War Manifesto on 12 March 1958, threatening to kill anyone that voted.[citation needed] Battle of Santa Clara and Batista's flight  Fidel Castro and Camilo Cienfuegos entering Havana after the rebel victory, 8 January 1959 On 31 December 1958, the Battle of Santa Clara took place in a scene of great confusion. The city of Santa Clara fell to the combined forces of Che Guevara, Cienfuegos, and Revolutionary Directorate (RD) rebels led by Comandantes Rolando Cubela, Juan ("El Mejicano") Abrahantes, and William Alexander Morgan. News of these defeats caused Batista to panic. He fled Cuba by air for the Dominican Republic just hours later on 1 January 1959. Comandante William Alexander Morgan, leading RD rebel forces, continued fighting as Batista departed, and had captured the city of Cienfuegos by 2 January.[101] Cuban General Eulogio Cantillo entered Havana's Presidential Palace, proclaimed the Supreme Court judge Carlos Piedra as the new president, and began appointing new members to Batista's old government.[102] Castro learned of Batista's flight in the morning and immediately started negotiations to take over Santiago de Cuba. On 2 January, the military commander in the city, Colonel Rubido, ordered his soldiers not to fight, and Castro's forces took over the city. The forces of Guevara and Cienfuegos entered Havana at about the same time. They had met no opposition on their journey from Santa Clara to Cuba's capital. Castro himself arrived in Havana on 8 January after a long victory march. His initial choice of president, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, took office on 3 January.[103] |

最終攻勢 1958-1959 ヴェラーノ作戦 主な記事 ベラノ作戦 バティスタはついにカストロの努力に応え、ベラノ(夏)作戦と呼ばれる山岳地帯への攻撃を開始した。軍は約12,000人の兵士を送り込んだが、その半数 は訓練を受けていない新兵だった。1958年7月11日から21日まで続いたラ・プラタの戦いでは、カストロ軍は500人の大隊を破り、240人を捕虜に する一方、わずか3人しか失わなかった[91]。 しかし、1958年7月29日、ラス・メルセデスの戦いでバティスタ軍がカストロの300人ほどの小軍をほぼ壊滅させ、流れはほぼ変わった。優勢な兵力に よって身動きがとれなくなったカストロは、8月1日に一時停戦を求め、それを受け入れた。その後7日間、実りのない交渉が行われる中、カストロ軍は徐々に 罠から逃れていった。8月8日までにカストロの全軍は山中に逃げ帰り、ベラーノ作戦はバティスタ政権にとって事実上失敗に終わった[90]。 ラス・メルセデスの戦い 主な記事 ラス・メルセデスの戦い ラス・メルセデスの戦い(1958年7月29日-8月8日)は、ヴェラーノ作戦の最後の戦いであった[要出典]。この戦いは、キューバのエウロヒオ・カン ティージョ将軍が、フィデル・カストロのゲリラを包囲して破壊できる場所におびき寄せるために計画した罠であった。戦いは、カストロが提案し、カンティー ジョが受け入れた停戦で終わった。停戦中、カストロの部隊は山中に逃げ帰った。この戦闘は、技術的にはキューバ軍の勝利であったが、キューバ軍は意気消沈 し、戦意を喪失した。カストロはこの結果を勝利とみなし、すぐに独自の攻勢を開始した。  キューバ革命の主要拠点を示す地図 第17大隊は1958年7月29日に撤退を開始した。カストロはルネ・ラモス・ラトゥール率いる隊列を送り込み、撤退する兵士を待ち伏せた。彼らは先遣隊 を攻撃し、30人ほどの兵士を殺害したが、その後、それまで発見されていなかったキューバ軍の攻撃を受けた。ラトゥールは救援を要請し、カストロも自軍の 隊列を率いて戦場に駆けつけた。カストロの隊列は、エストラーダ・パルマ製糖工場から密かに道を進んできた別のキューバ兵の一団からも銃撃を受けた。 戦闘がヒートアップするにつれ、カンティージョ将軍は近隣の町から増援部隊を招集し、約1,500人の部隊が戦闘に向かい始めた。しかし、この部隊は チェ・ゲバラ指揮下の隊列によって阻止された。チェがラトゥールを助けに来なかったことを非難する批評家もいるが、ボックマン少佐はチェのこの行動は正し かったと主張する。実際、彼はチェのこの戦いに対する戦術的評価を「見事」と呼んだ。 7月末までに、カストロの部隊は完全に交戦状態となり、圧倒的に優勢なキューバ軍によって全滅の危機に瀕した。カストロはルネ・ラトゥールを含む70人の 兵士を失い、カストロとラトゥールの部隊は包囲された。翌日、カストロはカンティージョ将軍に停戦を要請し、終戦交渉を持ちかけた。この申し出は、理由は 不明だがカンティージョ将軍に受け入れられた。 バチスタは8月2日、カストロとの交渉のために個人代表を派遣した。交渉は不調に終わったが、その後6日間、カストロ軍は気づかれることなく逃げ切った。 8月8日、キューバ軍が攻撃を再開したとき、戦う相手は誰もいなかった。 カストロの残存兵力は山に逃げ帰り、ベラーノ作戦はバティスタ政権にとって事実上失敗に終わった[90]。 ヤグアヘイの戦い 主な記事 ヤグアヘイの戦い  戦いの記念碑とカミーロ・シエンフエゴス像のある広場の中央部分 1958年12月、フィデル・カストロはバティスタ軍に対して攻勢に出るよう革命軍に命じた。カストロはグイサ、マソ、その他の町に対する一軍を率いた が、もう一つの大攻勢は、当時のラス・ビジャス州の州都であったサンタ・クララ市の占領に向けられた。 チェ・ゲバラ、ハイメ・ベガ、カミロ・シエンフエゴスの指揮の下、3隊がサンタ・クララに向かった。ベガの隊列は待ち伏せに遭い、完全に破壊された。ゲバ ラの隊はサンタ・クララ周辺(フォメント付近)に陣取った。シエンフエゴスの隊は、ヤグアヘイの地元軍の守備隊を直接攻撃した。シエンフエゴス隊は、カス トロの230人の中核部隊のうち、当初はわずか60人であったが、サンタ・クララに向かって田園地帯を横断する間に多くの新兵を獲得し、最終的には450 人から500人の戦闘員に達したと推定された。 守備隊は、中国人の血を引くキューバ人隊長アルフレド・アボン・リーの指揮の下、約250人で構成されていた[92][93]。 サンタ・クララから援軍が送られると確信していたリーは、持ち場を断固として守り抜いた。ゲリラたちは何度もリーとその部下たちを制圧しようとしたが、そ のたびに失敗した。12月26日までに、カミロ・シエンフエゴスはかなり不満を募らせていた。リーを制圧することも、降伏させることもできないようだっ た。自暴自棄になったシエンフエゴスは、リーの陣地に対して自家製の戦車を使おうとした。その "戦車 "は、鉄板に包まれた大型トラクターの上に、その場しのぎの火炎放射器を取り付けたものだった。これも失敗に終わった。 ついに12月30日、リーは弾薬を使い果たし、ゲリラに兵力を明け渡すことを余儀なくされた。翌日、シエンフエゴス、ゲバラ、そしてウィリアム・アレクサ ンダー・モーガン率いる地元の革命家の連合軍は、大混乱の戦いの中でサンタクララを占領した。 ギサの戦い 主な記事 ギサの戦い 1958年11月20日の朝、バチスタ軍の車列がグイサから出発した。シエラ・マエストラ(Sierra Maestra)の山中に位置するその町を出発した直後、反乱軍がキャラバンを攻撃した[94]。 グイサは、バヤモ市の郊外にある作戦地域司令部から12キロメートルのところにあった。その9日前、フィデル・カストロはラプラタ司令部を出発し、護衛と 少数の戦闘員とともに東への止むに止まれぬ行軍を開始していた[a]。 11月19日、反乱軍はサンタバーバラに到着した。その時点で、戦闘員は約230名であった。フィデルはギサの包囲を組織するために将校を集め、キュペイ ニクー川にかかるモンジャラス橋に地雷を設置するよう命じた。その夜、戦闘員たちはホヨ・デ・ピパに宿営した。早朝、彼らはヘリオグラフォの丘とマテオ・ ロブレホの丘の間を通る道を行き、そこで戦略的な位置を占めた。20日の会合で、軍はトラック、バス、ジープを失った。6人が死亡、17人が捕虜となり、 うち3人が負傷した。午前10時30分ごろ、バヤモの作戦区域にある軍司令部は、32小隊とL小隊、L小隊の別の小隊からなる増援部隊を派遣した。Lの小 隊と22の小隊で構成されていた。この部隊は、反乱軍の抵抗のために前進することができなかった。フィデルは、キュペイニクー川の支流に架かる別の橋の採 掘を命じた。数時間後、軍はT-17戦車によってサポートされた82から小隊と93から別の小隊を送った[95][b][96]。 1958年キューバ総選挙 主な記事 1958年キューバ総選挙  アンドレス・リベロ・アグエロ、1958年大統領当選者 1958年11月3日、キューバで総選挙が行われた[97]。3人の主要な大統領候補は、パルティード・デル・プエブロ・リブレのカルロス・マルケス・ス ターリング、パルティード・アウテンティコのラモン・グラウ、コーリシオン・プログレシスタ・ナシオナルのアンドレス・リベロ・アグエロであった。また、 マイナー政党であるウニオン・クバーナ党のアルベルト・サラス・アマロ候補も投票に参加した。投票率は有権者の50%と推定された[98]。アンドレス・ リベロ・アグエロは70%の得票率で大統領選挙に勝利したものの、キューバ革命のために大統領に就任することはできなかった[99]。 リベロ・アグエロは1959年2月24日に就任する予定であった。1958年11月15日、彼とアメリカ大使アール・E・T・スミスとの会話の中で、彼は カストロを「病人」と呼び、カストロとの和解は不可能であると述べた。リベロ・アグエロはまた、立憲政治を復活させるつもりであり、就任後に憲法制定議会 を招集すると述べた[100]。 これがキューバにおける最後の競争選挙となり、キューバ共和国の1940年憲法、議会、上院はその後すぐに解体された。反乱軍は選挙ボイコットを公に呼び かけ、1958年3月12日に総力戦宣言を発表し、投票した者を殺すと脅迫した[要出典]。 サンタ・クララの戦いとバティスタの逃亡  反乱軍勝利後、ハバナに入るフィデル・カストロとカミーロ・シエンフエゴス(1959年1月8日) 1958年12月31日、サンタ・クララの戦いは大混乱の中で行われた。サンタ・クララ市は、チェ・ゲバラ、シエンフエゴス、そしてロランド・クベラ、フ アン(「エル・メヒカーノ」)・アブラハンテス、ウィリアム・アレクサンダー・モルガン司令官率いる革命評議会(RD)の反乱軍の連合軍によって陥落し た。これらの敗北のニュースはバティスタをパニックに陥れた。彼はわずか数時間後の1959年1月1日、ドミニカ共和国に向けてキューバから飛行機で逃亡 した。反乱軍を率いるコマンダンテ・ウィリアム・アレクサンダー・モルガンは、バティスタが去った後も戦闘を続け、1月2日までにシエンフエゴス市を占領 した[101]。 キューバのエウロヒオ・カンティージョ将軍はハバナの大統領官邸に入り、最高裁判所判事のカルロス・ピエドラを新大統領として宣言し、バティスタの旧政権 に新たなメンバーを任命し始めた[102]。 カストロは午前中にバティスタの逃亡を知り、直ちにサンティアゴ・デ・クーバを占領するための交渉を開始した。1月2日、サンティアゴ・デ・クーバの軍司 令官であったルビド大佐は兵士たちに戦わないよう命じ、カストロ軍がサンティアゴ・デ・クーバを占領した。ゲバラとシエンフエゴスの軍もほぼ同時にハバナ に入った。サンタ・クララからキューバの首都への旅路で、彼らは何の反対も受けなかった。カストロ自身は、長い戦勝行軍の後、1月8日にハバナに到着し た。彼が最初に選んだ大統領マヌエル・ウルティア・リョは1月3日に就任した[103]。 |

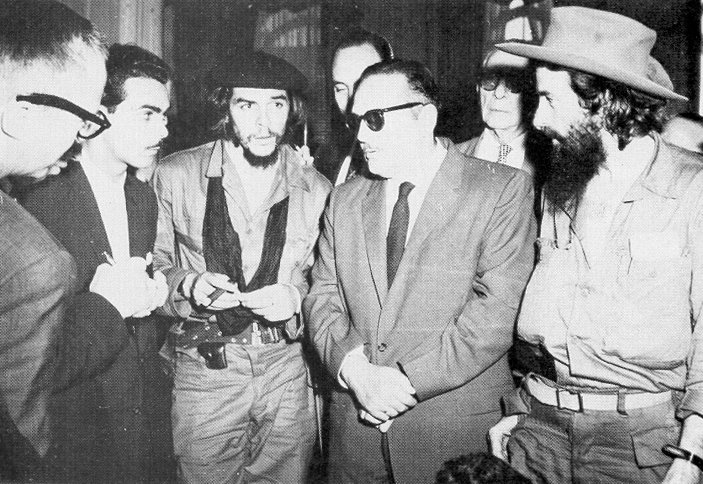

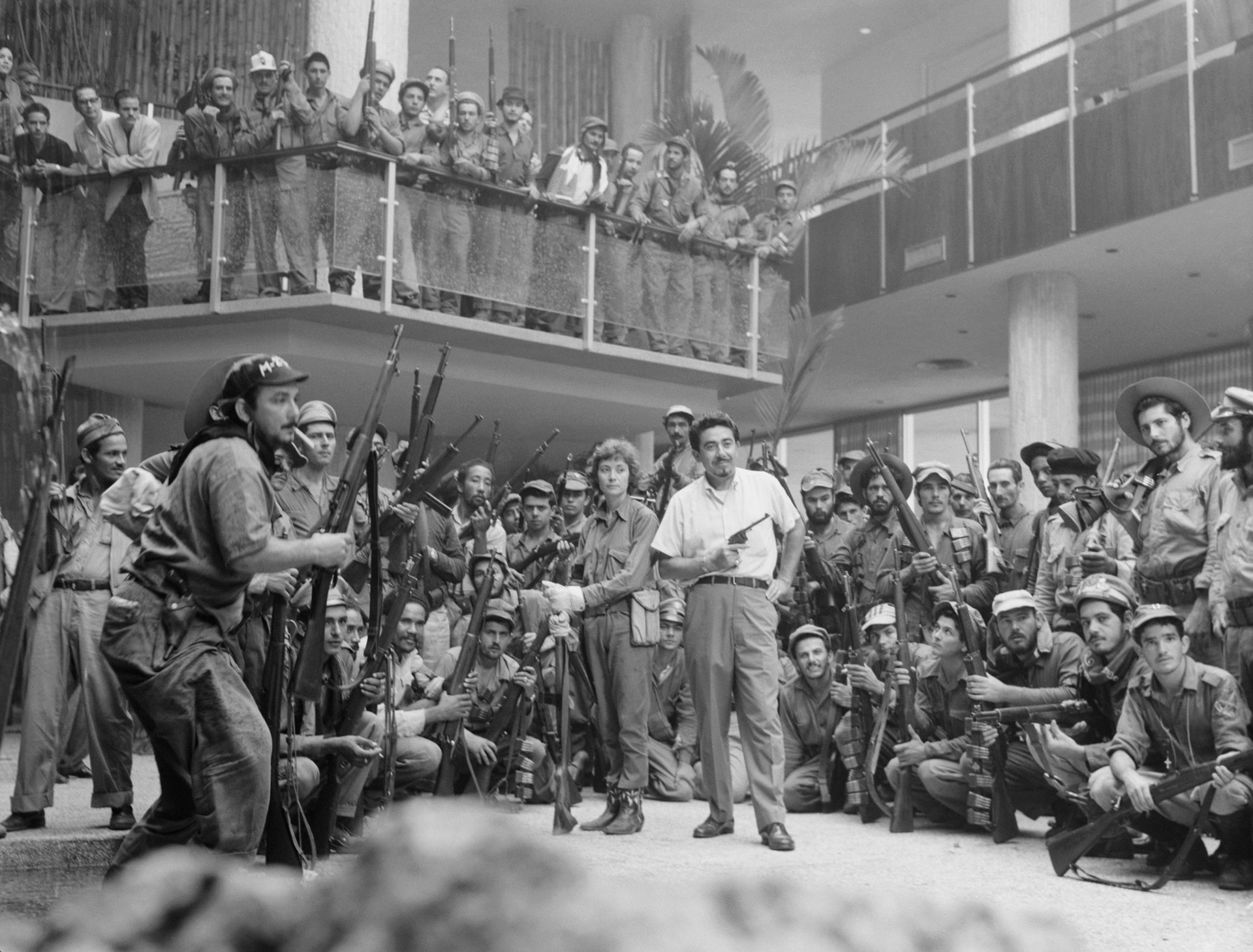

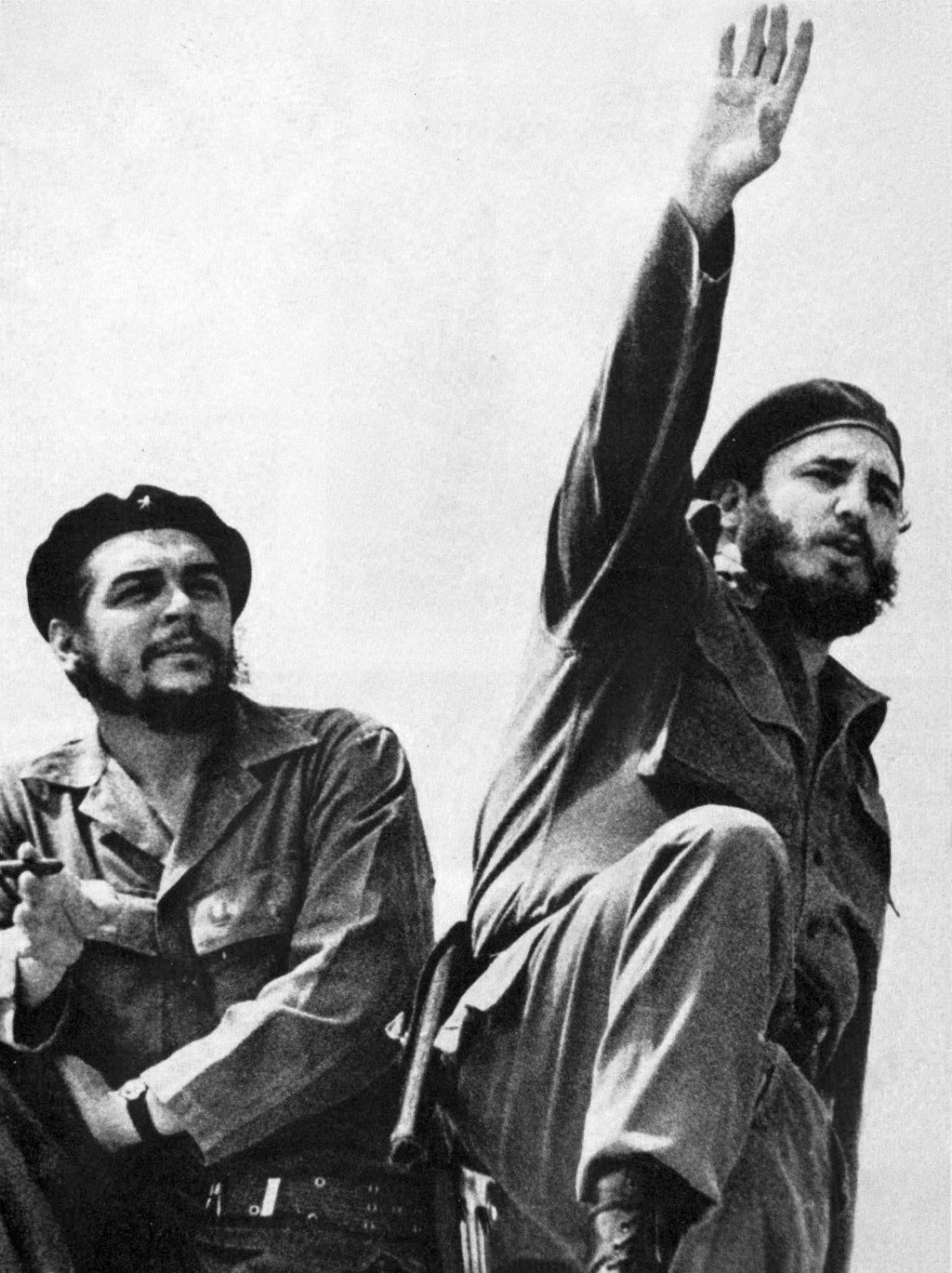

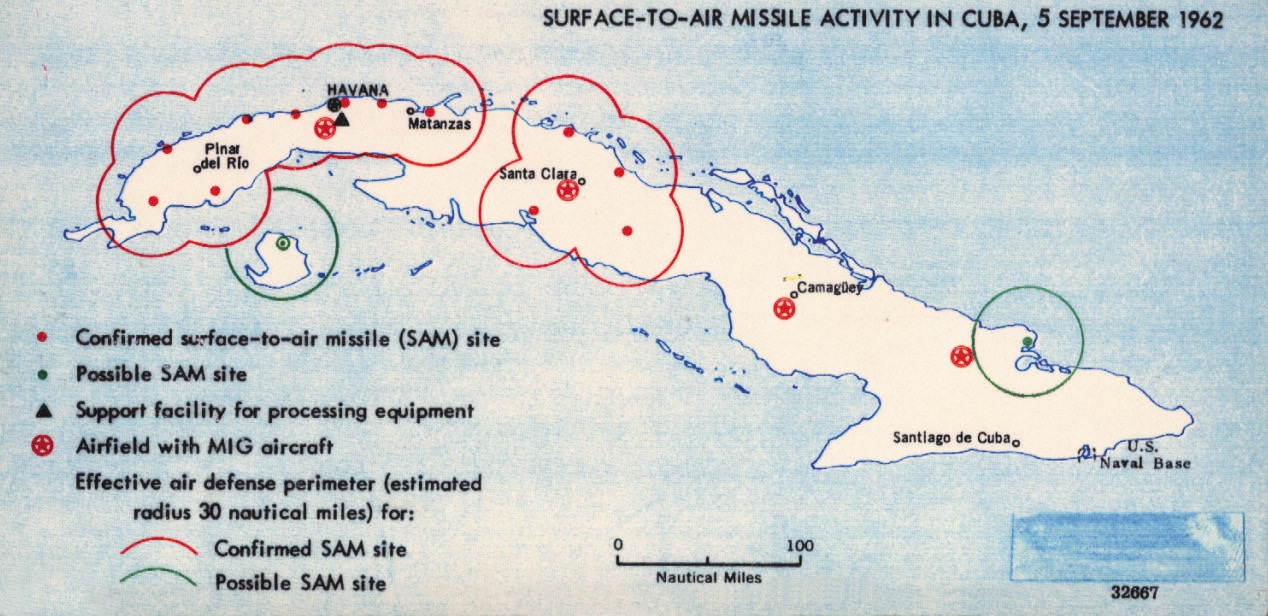

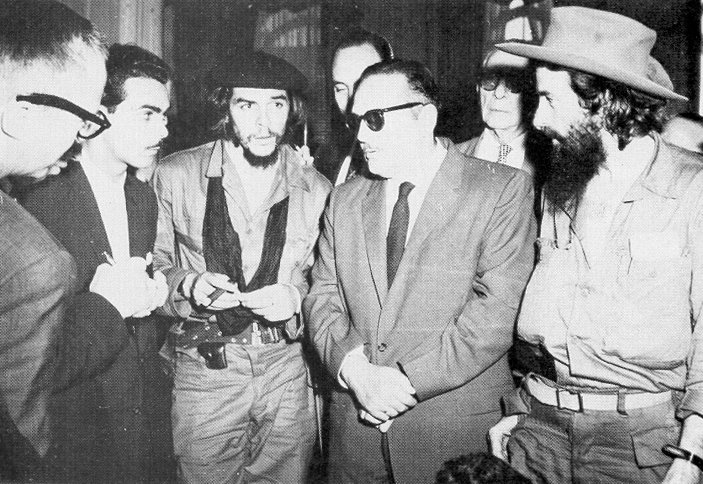

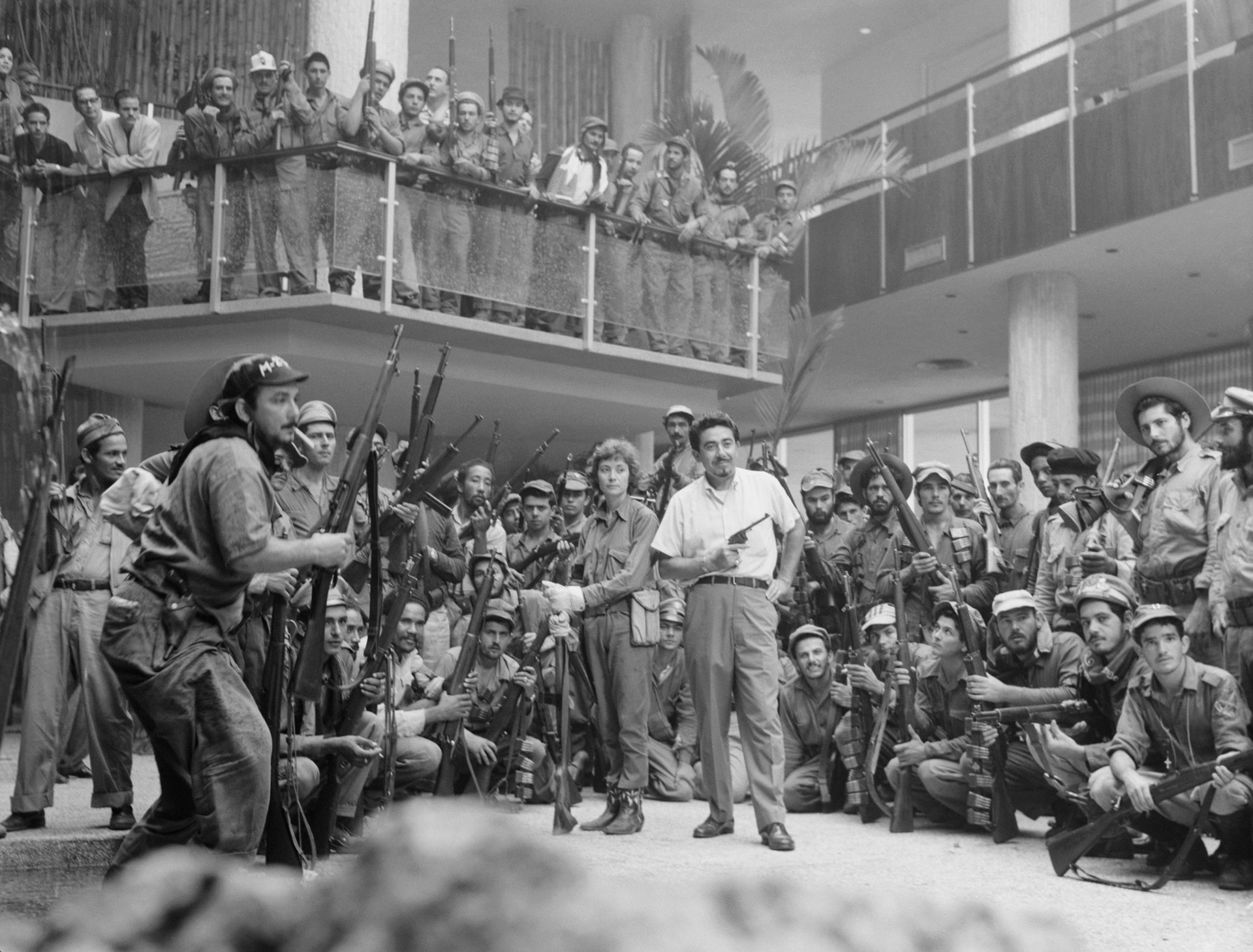

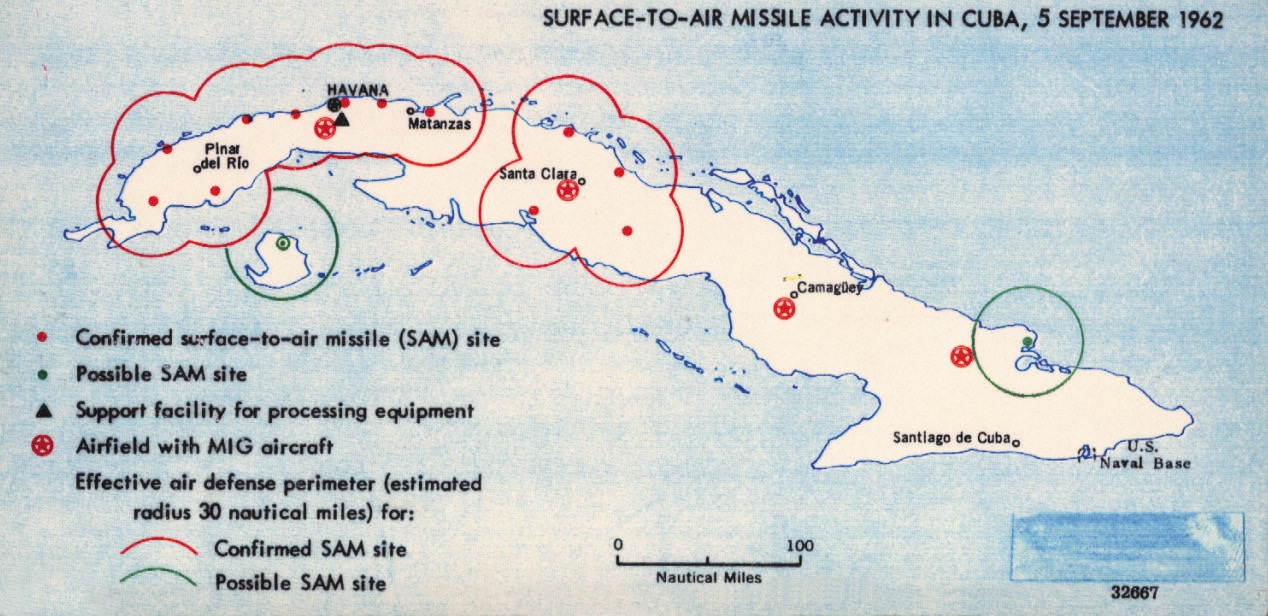

| Aftermath Further information: Consolidation of the Cuban Revolution Presidency of Manuel Urrutia Lleó Main article: Manuel Urrutia Lleó  Manuel Urrutia Lleó, in the presidential palace, president of Cuba, 1959  Che Guevara with Manuel Urrutia in 1959, who was president at the beginning of the revolution, after being appointed by the rebels Manuel Urrutia Lleó (8 December 1901 – 5 July 1981) was a liberal Cuban lawyer and politician. He campaigned against the Gerardo Machado government and the second presidency of Fulgencio Batista during the 1950s, before serving as president in the first revolutionary government of 1959. Urrutia resigned his position after seven months, owing to a series of disputes with revolutionary leader Fidel Castro, and emigrated to the United States shortly afterward. The Cuban Revolution gained victory on 1 January 1959, and Urrutia returned from exile in Venezuela to take up residence in the presidential palace. His new revolutionary government consisted largely of Cuban political veterans and pro-business liberals including José Miró, who was appointed as prime minister.[104] Once in power, Urrutia swiftly began a program of closing all brothels, gambling outlets and the national lottery, arguing that these had long been a corrupting influence on the state. The measures drew immediate resistance from the large associated workforce. The disapproving Castro, then commander of Cuba's new armed forces, intervened to request a stay of execution until alternative employment could be found.[105] Disagreements also arose in the new government concerning pay cuts, which were imposed on all public officials on Castro's demand. The disputed cuts included a reduction of the $100,000 a year presidential salary Urrutia had inherited from Batista.[106] By February, following the surprise resignation of Miró, Castro had assumed the role of prime minister; this strengthened his power and rendered Urrutia increasingly a figurehead president.[104] As Urrutia's participation in the legislative process declined, other unresolved disputes between the two leaders continued to fester. His belief in the restoration of elections was rejected by Castro, who felt that they would usher in a return to the old discredited system of corrupt parties and fraudulent balloting that had marked the Batista era.[107] Urrutia was then accused by the Avance newspaper of buying a luxury villa, which was portrayed as a frivolous betrayal of the revolution and led to an outcry from the general public. He denied the allegation issuing a writ against the newspaper in response. The story further increased tensions between the various factions in the government, though Urrutia asserted publicly that he had "absolutely no disagreements" with Fidel Castro. Urrutia attempted to distance the Cuban government (including Castro) from the growing influence of the communists within the administration, making a series of critical public comments against the latter group. Whilst Castro had not openly declared any affiliation with the Cuban communists, Urrutia had been a declared anti-communist since they had refused to support the insurrection against Batista,[108] stating in an interview, "If the Cuban people had heeded those words, we would still have Batista with us ... and all those other war criminals who are now running away".[107] Relations with the United States Main article: Cuba–United States relations  Victorious rebels in the Havana Hilton, January 1959  Fidel Castro and Che Guevara in 1962 The Cuban Revolution was a crucial turning point in U.S.-Cuban relations. Although the United States government was initially willing to recognize Castro's new government,[109] it soon came to fear that Communist insurgencies would spread through the nations of Latin America, as they had in Southeast Asia.[110] Meanwhile, Castro's government resented the Americans for providing aid to Batista's government during the revolution.[109] After the revolutionary government nationalized all U.S. property in Cuba in August 1960, the American Eisenhower administration froze all Cuban assets on American soil, severed diplomatic ties and tightened its embargo of Cuba.[9][14][111] The Key West–Havana ferry shut down. In 1961, the U.S. government launched the Bay of Pigs Invasion, in which Brigade 2506 (a CIA-trained force of 1,500 soldiers, mostly Cuban exiles) landed on a mission to oust Castro; the attempt to overthrow Castro failed, with the invasion being repulsed by the Cuban military.[110][112] The U.S. embargo against Cuba is still in force as of 2020, although it underwent a partial loosening during the Obama administration, only to be strengthened in 2017 under Trump.[9] The U.S. began efforts to normalize relations with Cuba in the mid-2010s,[11][113] and formally reopened its embassy in Havana after over half a century in August 2015.[12] The Trump administration reversed much of the Cuban Thaw by severely restricting travel by US citizens to Cuba and tightening the US government's embargo against the country.[114][115] I believe that there is no country in the world, including the African regions, including any and all the countries under colonial domination, where economic colonization, humiliation and exploitation were worse than in Cuba, in part owing to my country's policies during the Batista regime. I believe that we created, built and manufactured the Castro movement out of whole cloth and without realizing it. I believe that the accumulation of these mistakes has jeopardized all of Latin America. The great aim of the Alliance for Progress is to reverse this unfortunate policy. This is one of the most, if not the most, important problems in America foreign policy. I can assure you that I have understood the Cubans. I approved the proclamation which Fidel Castro made in the Sierra Maestra, when he justifiably called for justice and especially yearned to rid Cuba of corruption. I will go even further: to some extent it is as though Batista was the incarnation of a number of sins on the part of the United States. Now we shall have to pay for those sins. In the matter of the Batista regime, I am in agreement with the first Cuban revolutionaries. — U.S. President John F. Kennedy, interview with Jean Daniel, 24 October 1963[116] Relations with the Soviet Union Main article: Cuba–Soviet Union relations Following the American embargo, the Soviet Union became Cuba's main ally.[14] The Soviet Union did not initially want anything to do with Cuba or Latin America until the United States had taken an interest in dismantling Castro's communist government.[38] At first, many people in the Soviet Union did not know anything about Cuba, and those that did saw Castro as a "troublemaker" and the Cuba Revolution as "one big heresy".[38] There were three big reasons why the Soviet Union changed their attitudes and finally took interest in the island country. First was the success of the Cuban Revolution, to which Moscow responded with great interest as they understood that if a communist revolution was successful for Cuba, it could be successful elsewhere in Latin America. So from then on the Soviets began looking into foreign affairs in Latin America. Second, after learning about the United States' aggressive plan to deploy another Guatemala scenario in Cuba, the Soviet opinion quickly changed feet.[38] Third, Soviet leaders saw the Cuban Revolution as first and foremost an anti–North American revolution which of course whet their appetite as this was during the height of the cold war and the Soviet, US battle for global dominance was at its apex.[117]  Map created by American intelligence showing Surface-to-Air Missile Activity in Cuba, 5 September 1962, a month before the beginning of the Cuban Missile Crisis The Soviets' attitude of optimism changed to one of concern for the safety of Cuba after it was excluded from the inter-American system at the conference held at Punta del Este in January 1962 by the Organization of American States.[117] This coupled with the threat of a United States invasion of the island was really the turning point for Soviet Concern, the idea was that should Cuba be defeated by the United States it would mean defeat for the Soviet Union and for Marxism–Leninism. If Cuba were to fall, "other Latin American countries would reject us, claiming that for all our might the Soviet Union had not been able to do anything for Cuba except to make empty protests to the United Nations" wrote Khrushchev.[117] The Soviet attitude towards Cuba changed to concern for the safety of the island nation because of increased US tensions and threats of invasion making the Soviet–Cuban relationship superficial insofar as it only cared about denying the US power in the region and maintaining Soviet supremacy.[117] All of these events led to the two countries quickly developing close military and intelligence ties, which culminated in the stationing of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba in 1962, an act which triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. The aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis saw embarrassment for the Soviet Union,[citation needed] and many countries including Soviet countries were quick to criticize Moscow's handling of the situation. In a letter that Khrushchev writes to Castro in January of the following year (1963), after the end of conflict, he talks about wanting to discuss the issues in the two countries' relations. He writes attacking voices from other countries, including socialist ones, blaming the USSR of being opportunistic and self-serving. He explained the decision to withdraw missiles from Cuba, stressing the possibility of advancing Communism through peaceful means. Khrushchev underlined the importance of guaranteeing against an American attack on Cuba and urged Havana to focus on economic, cultural, and technological development to become a shining beacon of socialism in Latin America. In closing he invites Fidel Castro to visit Moscow and discuss the preparations for such a trip.[118] The following two decades in the 1970s and 1980s were somewhat of an enigma in the sense that the 1970s and 1980s were filled with the most prosperity in Cuba's history, yet the revolutionary government hit full stride in achieving its most organized form, and it adopted and enacted several brutal features of socialist regimes from the Eastern Bloc.[citation needed] Despite this it seems to be a time of prosperity.[citation needed] In 1972 Cuba joined COMECON, officially joining their trade with the Soviet Union's socialist trade bloc. That along with increased Soviet subsidies, better trade terms, and better, more practical domestic policy led to several years of prosperous growth. This period also sees Cuba strengthening its foreign policy with other communistic anti-US imperial countries like Nicaragua. This period is marked as the Sovietization of the 1970s and 1980s.[119] Cuba maintained close links to the Soviets until the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991. The end of Soviet economic aid and the loss of its trade partners in the Eastern Bloc led to an economic crisis and period of shortages known as the Special Period in Cuba.[120] Current day relations with Russia, formerly the Soviet Union, ended in 2002 after the Russian Federation closed an intelligence base in Cuba over budgetary concerns. However, in the last decade, relations have increased in recent years after Russia faced international backlash from the West over the situation in Ukraine in 2014. In retaliation for NATO expansion towards the east, Russia has sought to create these same agreements in Latin America. Russia has specifically sought greater ties with Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Brazil, and Mexico. Currently, these countries maintain close economic ties with the United States. In 2012, Putin decided that Russia focus its military power in Cuba like it had in the past. Putin is quoted saying "Our goal is to expand Russia's presence on the global arms and military equipment market. This means expanding the number of countries we sell to and expanding the range of goods and services we offer."[121] Global influence The greatest threat presented by Castro's Cuba is as an example to other Latin American states which are beset by poverty, corruption, feudalism, and plutocratic exploitation ... his influence in Latin America might be overwhelming and irresistible if, with Soviet help, he could establish in Cuba a Communist utopia. — Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, 27 April 1964[122] Castro's victory and post-revolutionary foreign policy had global repercussions as influenced by the expansion of the Soviet Union into Eastern Europe after the 1917 October Revolution. In line with his call for revolution in Latin America and beyond against imperial powers, laid out in his Declarations of Havana, Castro immediately sought to "export" his revolution to other countries in the Caribbean and beyond, sending weapons to Algerian rebels as early as 1960.[18] In the following decades, Cuba became heavily involved in supporting Communist insurgencies and independence movements in many developing countries, sending military aid to insurgents in Ghana, Nicaragua, Yemen, and Angola, among others.[18] Castro's intervention in the Angolan Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s was particularly significant, involving as many as 60,000 Cuban soldiers.[18][123] |