キューバン・ルンバ

Cuban rumba

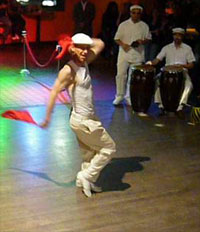

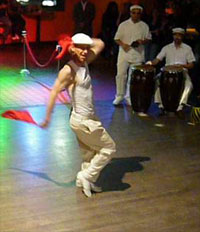

Cuban

rumba dancers at the workers square in Camagüey, Cuba.

☆ ルンバは、ダンス、パーカッション、歌を含むキューバ音楽の世俗的なジャンルである。19世紀後半にキューバ北部、主にハバナやマタンサスの都市部で生ま れた。アバクアやユカといったアフリカの音楽・舞踊の伝統や、スペインをベースとしたコロス・デ・クラーベがベースとなっている。アルゲリエ・レオンによ れば、ルンバはキューバ音楽の主要な「ジャンル・コンプレックス」のひとつであり、ルンバ・コンプレックスという用語は現在、音楽学者によって一般的に使 用されている。このコンプレックスは、ルンバの3つの伝統的な形式(ヤンブー、グアグアンコー、 コロンビア)と、それらの現代的な派生形式やその他のマイナーなスタイルを包含している。 伝統的にアフリカ系の貧しい労働者たちが路上やソラーレ(中庭)で演奏してきたルンバは、現在でもキューバで最も特徴的な音楽とダンスの形態のひとつであ る。ボーカルの即興、手の込んだダンス、ポリリズムのドラムが、すべてのルンバ・スタイルの重要な要素である。20世紀初頭までカホン(木製の箱)が太鼓 として使われていたが、トゥンバドーラ(コンガ・ドラム)に取って代わられた。1940年代に始まったこのジャンルの記録された歴史の中で、ロス・パピネ ス、ロス・ムニエキトス・デ・マタンサス、クラーベ・イ・グアグアンコー、アフロ・クーバ・デ・マタンサス、ヨルバ・アンダボなど、数多くのルンバ・バン ドが成功を収めてきた。 初期の頃から、このジャンルの人気はキューバ国内に限られていたが、その遺産はキューバ国外にも及んでいる。アメリカでは、いわゆる 「ボールルーム・ルンバ」、またはルンバと呼ばれ、アフリカでは、スークスは一般的に 「コンゴ・ルンバ 」と呼ばれている(実際にはソン・クバーノが元になっているにもかかわらず)。スペインにおけるスークスの影響は、ルンバ・フラメンカやカタルーニャ・ル ンバなどの派生曲が物語っている。

| Rumba is a secular

genre of Cuban music involving dance, percussion, and song. It

originated in the northern regions of Cuba, mainly in urban Havana and

Matanzas, during the late 19th century. It is based on African music

and dance traditions, namely Abakuá and yuka, as well as the

Spanish-based coros de clave. According to Argeliers León, rumba is one

of the major "genre complexes" of Cuban music,[1] and the term rumba

complex is now commonly used by musicologists.[2][3] This complex

encompasses the three traditional forms of rumba (yambú, guaguancó and

columbia), as well as their contemporary derivatives and other minor

styles. Traditionally performed by poor workers of African descent in streets and solares (courtyards), rumba remains one of Cuba's most characteristic forms of music and dance. Vocal improvisation, elaborate dancing and polyrhythmic drumming are the key components of all rumba styles. Cajones (wooden boxes) were used as drums until the early 20th century, when they were replaced by tumbadoras (conga drums). During the genre's recorded history, which began in the 1940s, there have been numerous successful rumba bands such as Los Papines, Los Muñequitos de Matanzas, Clave y Guaguancó, AfroCuba de Matanzas and Yoruba Andabo. Since its early days, the genre's popularity has been largely confined to Cuba, although its legacy has reached well beyond the island. In the United States, it gave its name to the so-called "ballroom rumba", or rhumba, and in Africa, soukous is commonly referred to as "Congolese rumba" (despite being actually based on son cubano). Its influence in Spain is testified by rumba flamenca and derivatives such as Catalan rumba. |

ルンバは、ダンス、パーカッション、歌を含むキューバ音楽の世俗的な

ジャンルである。19世紀後半にキューバ北部、主にハバナやマタンサスの都市部で生まれた。アバクアやユカといったアフリカの音楽・舞踊の伝統や、スペイ

ンをベースとしたコロス・デ・クラーベがベースとなっている。アルゲリエ・レオンによれば、ルンバはキューバ音楽の主要な「ジャンル・コンプレックス」の

ひとつであり[1]、ルンバ・コンプレックスという用語は現在、音楽学者によって一般的に使用されている[2][3]。このコンプレックスは、ルンバの3

つの伝統的な形式(ヤンブー、グアグアンコー、コロンビア)と、それらの現代的な派生形式やその他のマイナーなスタイルを包含している。 伝統的にアフリカ系の貧しい労働者たちが路上やソラーレ(中庭)で演奏してきたルンバは、現在でもキューバで最も特徴的な音楽とダンスの形態のひとつであ る。ボーカルの即興、手の込んだダンス、ポリリズムのドラムが、すべてのルンバ・スタイルの重要な要素である。20世紀初頭までカホン(木製の箱)が太鼓 として使われていたが、トゥンバドーラ(コンガ・ドラム)に取って代わられた。1940年代に始まったこのジャンルの記録された歴史の中で、ロス・パピネ ス、ロス・ムニエキトス・デ・マタンサス、クラーベ・イ・グアグアンコー、アフロ・クーバ・デ・マタンサス、ヨルバ・アンダボなど、数多くのルンバ・バン ドが成功を収めてきた。 初期の頃から、このジャンルの人気はキューバ国内に限られていたが、その遺産はキューバ国外にも及んでいる。アメリカでは、いわゆる 「ボールルーム・ルンバ」、またはルンバと呼ばれ、アフリカでは、スークスは一般的に 「コンゴ・ルンバ(Congolese rumba) 」と呼ばれている(実際にはソン・クバーノが元になっているにもかかわらず)。スペインにおけるスークスの影響は、ルンバ・フラメンカやカタルーニャ・ル ンバなどの派生曲が物語っている。 |

| Etymology According to Joan Corominas, the word derives from "rumbo", meaning "uproar" (and previously "pomp") and also "the course of a ship", which itself may derive from the word "rombo" ("rhombus"), a symbol used in compasses.[4] In the 1978 documentary La rumba, directed by Óscar Valdés, it is stated that the term rumba originated in Spain to denote "all that is held as frivolous", deriving from the term "mujeres de rumbo".[5] Alternatively, in Cuba the term might have originated from a West African or Bantu language, due to its similarity to other Afro-Caribbean words such as tumba, macumba, mambo and tambó.[2] During the 19th century in Cuba, specifically in urban Havana and Matanzas, people of African descent originally used the word rumba as a synonym for party. According to Olavo Alén, in these areas "[over time] rumba ceased to be simply another word for party and took on the meaning both of a defined Cuban musical genre and also of a very specific form of dance."[6] The terms rumbón and rumbantela (the latter of Galician or Portuguese origin[4]) are frequently used to denote rumba performances in the streets.[7][8] According to non-etymological sources, rumba could be related to "nkumba" meaning "navel" in Kikongo, which refers to a dance characterized by the joining and rubbing of navels. This dance was integral to the celebrations of the Kingdom of Kongo, a historical region that spanned present-day Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola.[9] Due to its broad etymology, the term rumba historically retained a certain degree of polysemy. By the end of the 19th century, Cuban peasants (guajiros) began to perform rumbitas during their parties (guateques, changüís, parrandas and fiestas patronales). These songs were actually in the form of urban guarachas (not proper rumbas), which had a binary meter in contrast to the ternary meter of traditional rural genres such as tonada and zapateo.[10][11] Similarly, in Cuban bufo theatre at the beginning of the 20th century, the guarachas that were sung at the end of the show were referred to as rumba final despite not sharing any musical similarities with actual rumba.[12][13] |

語源 ジョアン・コロミナスによると、ルンバの語源は「騒動」(以前は「華やかさ」)を意味する「rumbo(ルンボ)」であり、「船の進路」をも意味する。 [4]オスカル・バルデス監督の1978年のドキュメンタリー映画『La rumba』では、ルンバという言葉はスペインで「軽薄なものすべて」を意味する言葉として生まれ、「mujeres de rumbo」という言葉に由来すると述べられている[5]。 あるいは、キューバでは、tumba(トゥンバ)、macumba(マクンバ)、mambo(マンボ)、tambó(タンボ)といった他のアフロカリビア ン語と類似していることから、西アフリカ語やバントゥー語が語源である可能性もある[2]。 19世紀のキューバ、特にハバナやマタンサスの都市部では、もともとアフリカ系の人々がパーティーの代名詞としてルンバという言葉を使用していた。 Olavo Alénによれば、これらの地域では「(時間の経過とともに)ルンバは単にパーティーを意味する別の言葉ではなくなり、定義されたキューバの音楽ジャンル と非常に特殊なダンス形式の両方の意味を持つようになった」[6]。 語源説に基づかない資料によれば、ルンバはキコンゴ語で「へそ」を意味する「ンクンバ」に関連している可能性があり、これはへそを合わせたりこすったりす ることを特徴とするダンスを指す。このダンスは、現在のコンゴ共和国、コンゴ民主共和国、アンゴラにまたがる歴史的地域であるコンゴ王国の祝祭に欠かせな いものであった[9]。 その幅広い語源のため、ルンバという言葉は歴史的にある程度の多義性を保っていた。19世紀末になると、キューバの農民(guajiros)は、宴会 (guateques、changüís、parrandas、fiestas patronales)の際にルンビタを演奏し始めた。これらの歌は実際には都市部のグアラチャス(正式なルンバではない)の形式をとっており、トナダや サパテオといった伝統的な農村部のジャンルの3分音符とは対照的に2分音符であった[10][11]。同様に、20世紀初頭のキューバのブフォ劇場では、 ショーの最後に歌われるグアラチャスは、実際のルンバとは音楽的な類似性がないにもかかわらず、ルンバ・ファイナルと呼ばれていた[12][13]。 |

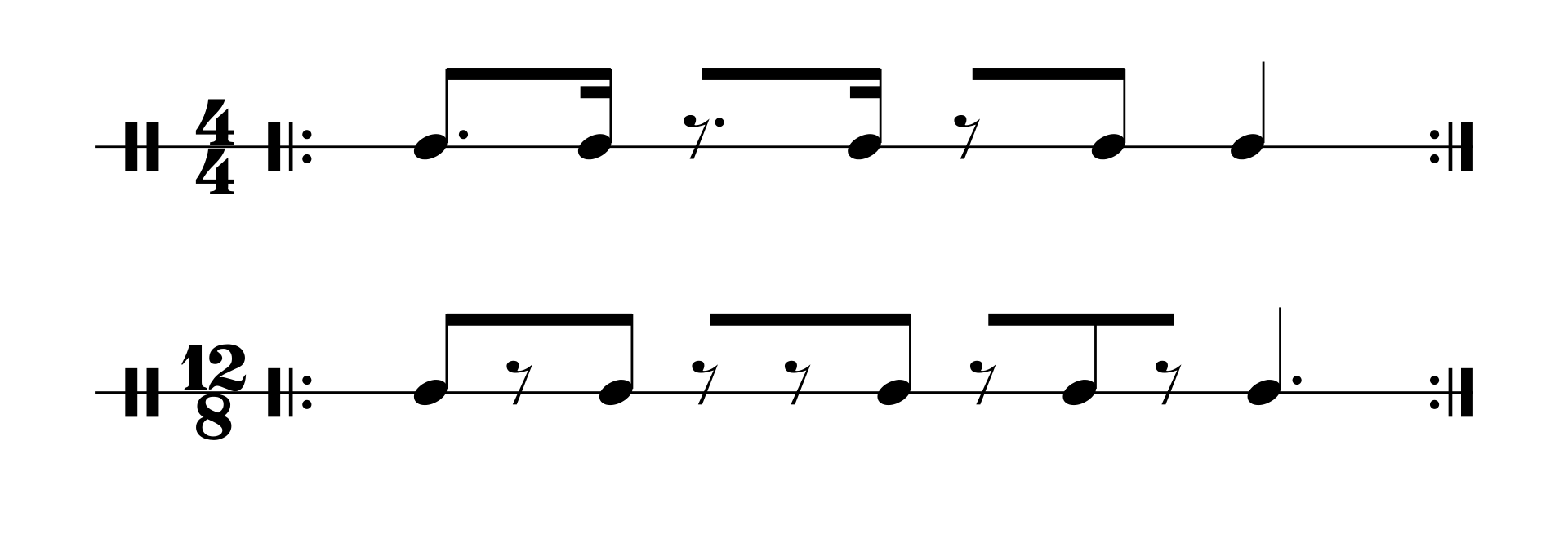

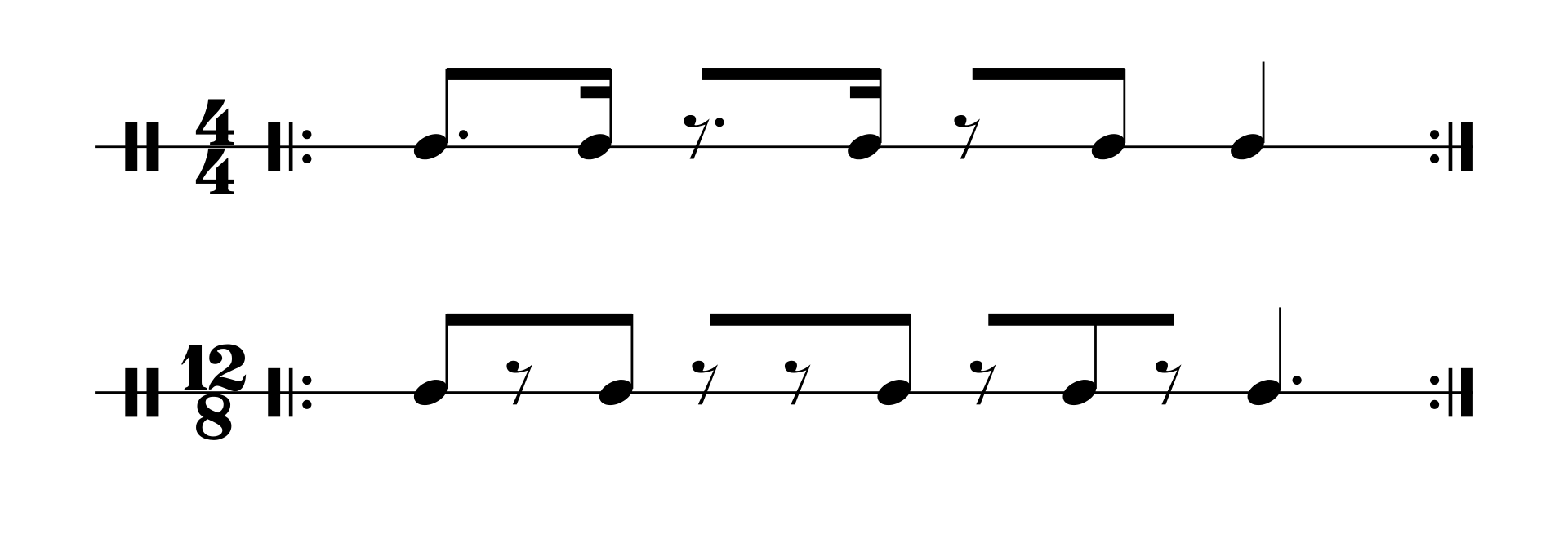

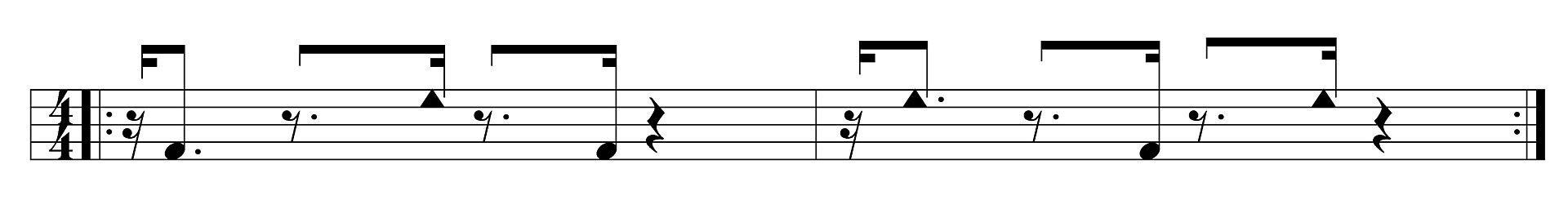

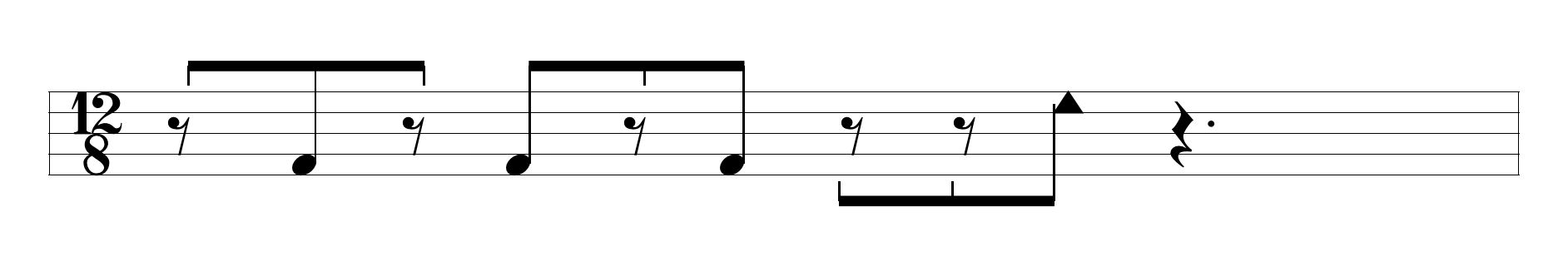

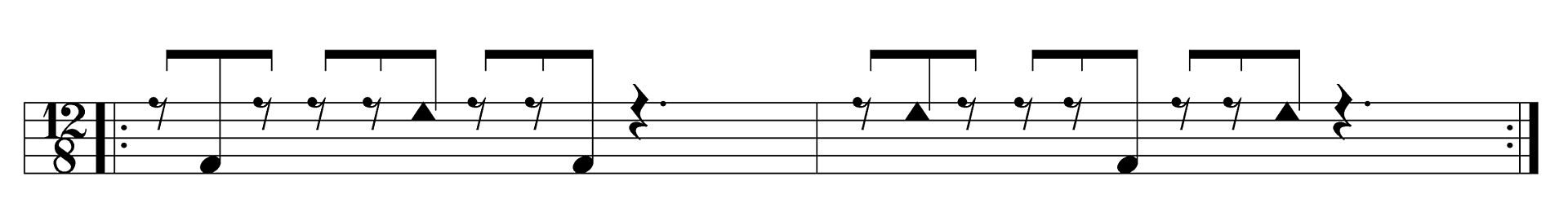

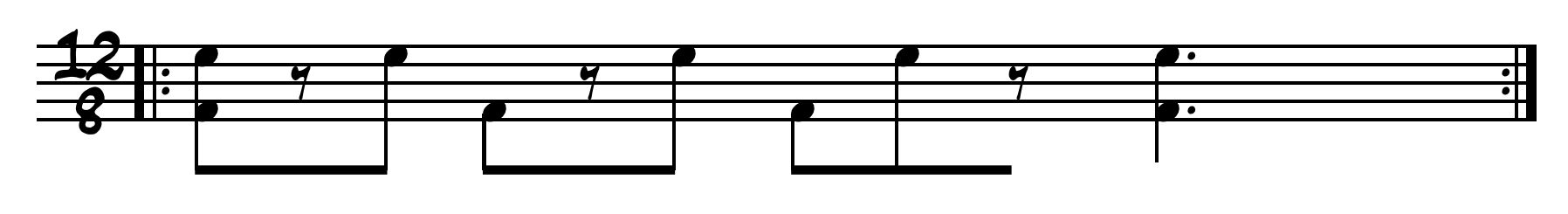

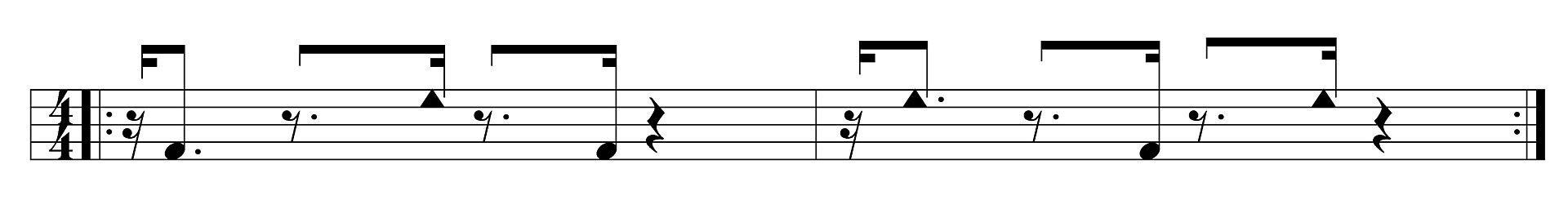

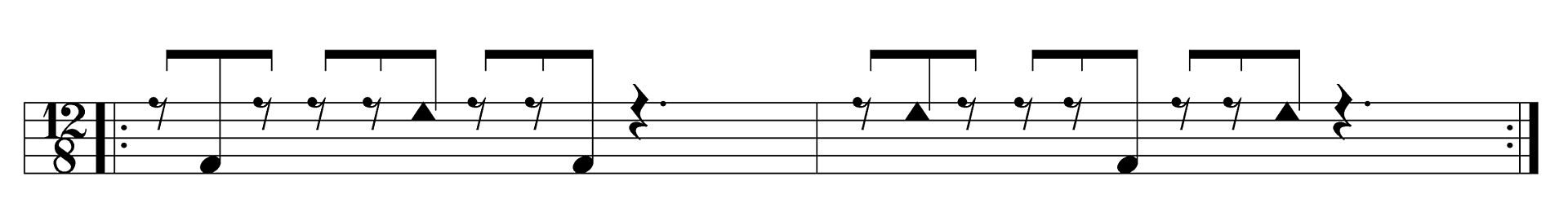

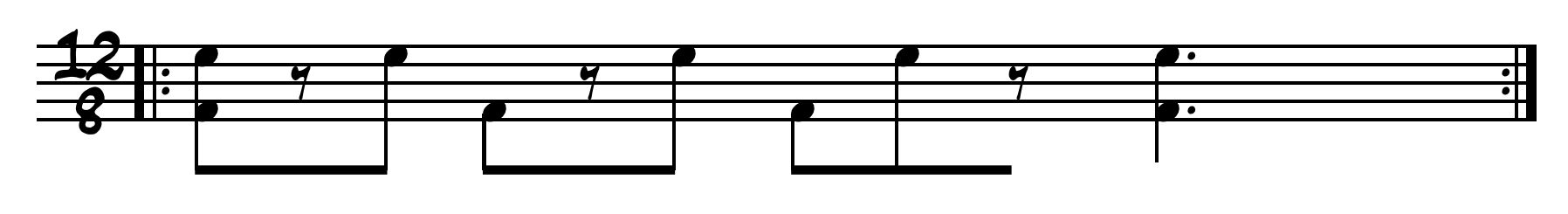

| Characteristics Instrumentation Rumba instrumentation has varied historically depending on the style and the availability of the instruments. The core instruments of any rumba ensemble are the claves, two hard wooden sticks that are struck against each other, and the conga drums: quinto (lead drum, highest-pitched), tres dos (middle-pitched), and tumba or salidor (lowest-pitched). Other common instruments include the catá or guagua, a wooden cylinder; the palitos, wooden sticks to strike the catá; shakers such as the chekeré and the maracas; scraper percussion instruments such as the güiro; bells, and cajones, wooden boxes that preceded the congas.[2][14][15][16] During the 1940s, the genre experienced a mutual influence with son cubano, especially by Ignacio Piñeiro's Septeto Nacional and Arsenio Rodríguez's conjunto, which led to the incorporation of instruments such as the tres, the double bass, the trumpet and the piano, and the removal of idiophone instruments.[17] At the same time, Cuban big bands, in collaboration with musical artists such as Chano Pozo, began to include authentic rumbas among their dance pieces. The group AfroCuba de Matanzas, founded in 1957, added batá drums to the traditional rumba ensemble in their style, known as batá-rumba. More recently, a cappella (vocals-only, without instruments) rumba has been performed by the Cuban ensemble Vocal Sampling, as heard in their song "Conga Yambumba". Rhythm  Rumba clave in duple-pulse and triple-pulse structures See also: Clave (rhythm) § Rumba clave Although rumba is played predominantly in binary meter (duple pulse: 2 4, 4 4), triple meter (triple pulse: 9 8, 3 4) is also present. In most rumba styles, such as yambú and guaguancó, duple pulse is primary and triple-pulse is secondary.[18] In contrast, in the rural style columbia, triple pulse is the primary structure and duple pulse is secondary. This can be explained due to the "binarization" of African-based ternary rhythms.[19] Both the claves and the quinto (lead drum) are responsible for establishing the rhythm. Subsequently, the other instruments play their parts supporting the lead drum. Rhythmically, rumba is based on the five-stroke guide pattern called clave and the inherent structure it conveys.[20] Song structure Yambú and guaguancó songs often begin with the soloist singing a melody with meaningless syllables, rather than with word-based lyrics. This introductory part is called the diana. According to Larry Crook, the diana is important because it "also contains the first choral refrain". The lead singer provides a melodic phrase or musical motive/theme for the choral sections, or they may present new but related material. Parallel harmonies are usually built above or below a melodic line, with "thirds, sixths, and octaves most common."[21] Therefore, the singer who is singing the diana initiates the beginning of the rumba experience for the audience. The singer then improvises lyrics stating the reason for holding and performing the present rumba. This kind of improvisation is called decimar, since it is done in décimas, ten-line stanzas. Alternatively, the singer might sing an established song. Some of the most common and recognizable rumba standards are "Ave Maria Morena" (yambú), "Llora como lloré" (guaguancó), "Cuba linda, Cuba hermosa" (guaguancó), "China de oro (Laye Laye)" (columbia), and "A Malanga" (columbia). Rumba songs consist of two main sections. The first, the canto, features the lead vocalist, performing an extended text of verses that are sometimes partially improvised. The lead singer usually plays claves.[22] The first section may last a few minutes, until the lead vocalist signals for the other singers to repeat the short refrain of the chorus, in call and response. This second section of the song is sometimes referred to as the montuno. |

特徴 楽器編成 ルンバの楽器編成は、スタイルや楽器の入手状況によって歴史的に変化してきた。ルンバ・アンサンブルの核となる楽器は、クラベス(互いに打ち合う2本の硬 い木製スティック)とコンガ・ドラム(キント(リード・ドラム、最高音)、トレス・ドス(中音)、トゥンバまたはサリドール(最低音))である。その他の 一般的な楽器としては、木製の円筒であるカタまたはグアグア、カタを叩くための木製のスティックであるパリトス、チェケレやマラカスなどのシェイカー、グ イロなどのスクレーパー打楽器、鐘、コンガに先立つ木製の箱であるカホンなどがある。 [2][14][15][16]1940年代には、特にイグナシオ・ピニェイロのセプテート・ナシオナルとアルセニオ・ロドリゲスのコンジュントによっ て、このジャンルはソン・クバーノと相互の影響を受け、トレス、コントラバス、トランペット、ピアノなどの楽器が取り入れられ、イディオフォン楽器が取り 除かれた。 [17]同じ頃、キューバのビッグバンドは、チャノ・ポゾなどの音楽アーティストと共同で、ダンス曲の中に本格的なルンバを取り入れるようになった。 1957年に結成されたアフロキューバ・デ・マタンサス(AfroCuba de Matanzas)は、バタ・ルンバとして知られる彼らのスタイルで、伝統的なルンバのアンサンブルにバタ・ドラムを加えた。最近では、キューバのアンサ ンブル、ヴォーカル・サンプリングがアカペラ(楽器を使わずヴォーカルのみ)でルンバを演奏している。 リズム  ルンバのクラーベは2重パルスと3重パルス構造になっている。 こちらも参照のこと: クラーベ(リズム)§ルンバ・クラーベ ルンバは主に二進法で演奏されるが(二拍子:2 4, 4 4)、三拍子(三拍子:9 8, 3 4)も存在する。ヤンブーやグアグアンコーなどほとんどのルンバ・スタイルでは、二拍子が主で三拍子が従である[18]。対照的に、田舎風のコロンピアでは 三拍子が主で二拍子が従である。これはアフリカン・ベースの3拍子リズムの「2値化」によって説明できる[19]。クラーベとキント(リード・ドラム)の 両方がリズムを確立する役割を担う。その後、他の楽器がリード・ドラムをサポートする役割を果たす。リズム的には、ルンバはクラーベと呼ばれる5連のガイ ドパターンと、それが伝える固有の構造に基づいている[20]。 曲の構成 ヤンブーとグアグアンコー(guaguancó)の歌は、言葉による歌詞ではなく、意味のない音節でメロディーを歌うソロから始まることが多い。この導入部はディアナと呼ばれる。 ラリー・クルックによれば、ディアナは「最初の合唱のリフレインも含まれている」ので重要である。リード・シンガーは、合唱パートにメロディ・フレーズや 音楽的動機/テーマを提供したり、新しいが関連した素材を提示したりする。平行和声は通常、旋律線の上または下に構築され、「3分の3、6分の6、オク ターブが最も一般的」[21]である。したがって、ディアナを歌っている歌手が、観客にとってのルンバ体験の始まりを告げる。その後、歌い手は現在のルン バを持ち、演奏する理由を即興で歌詞にする。このような即興は、10行のスタンザであるデシマ(décimas)で行われるため、デシマ (decimar)と呼ばれる。また、既成の曲を歌うこともある。ルンバのスタンダード曲としてよく知られているのは、「Ave Maria Morena」(ヤンブー)、「Llora como lloré」(グアガンコー)、「Cuba linda, Cuba hermosa」(グアガンコー)、「China de oro (Laye Laye)」(コロンビア)、「A Malanga」(コロンビア)などである。 ルンバの曲は、主に2つのセクションから構成されている。1つ目のカントは、リード・ヴォーカルをフィーチャーしたもので、部分的に即興で歌われることも ある。リード・ヴォーカルは通常クラベを演奏する[22]。最初のセクションは、リード・ヴォーカルが他のヴォーカリストにコール・アンド・レスポンスで サビの短いリフレインを繰り返すように合図するまで、数分間続くことがある。この第2セクションはモントゥーノと呼ばれることもある。 |

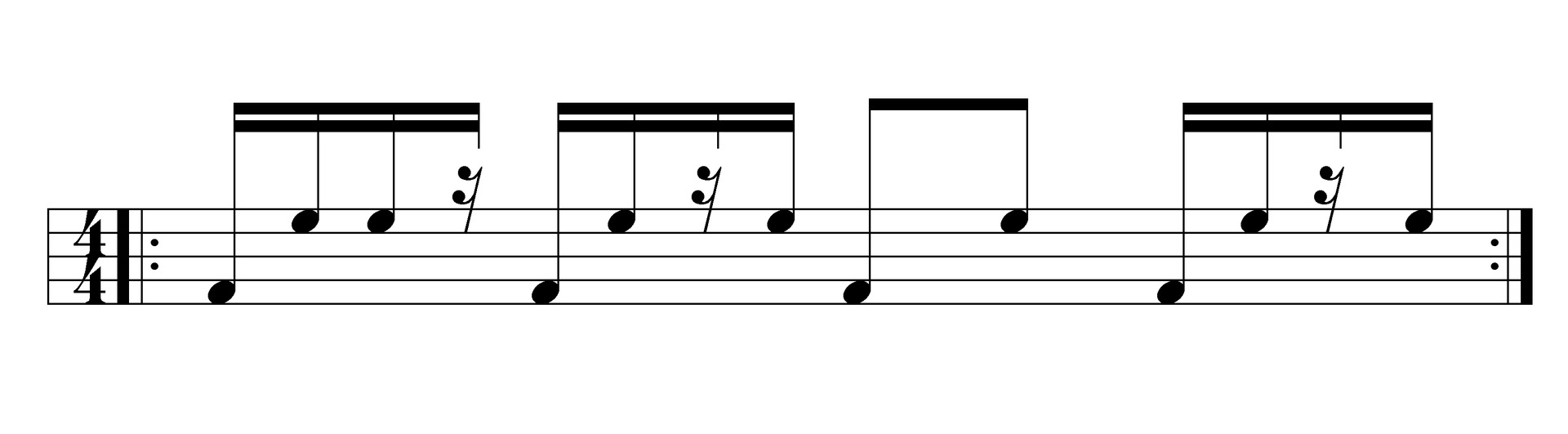

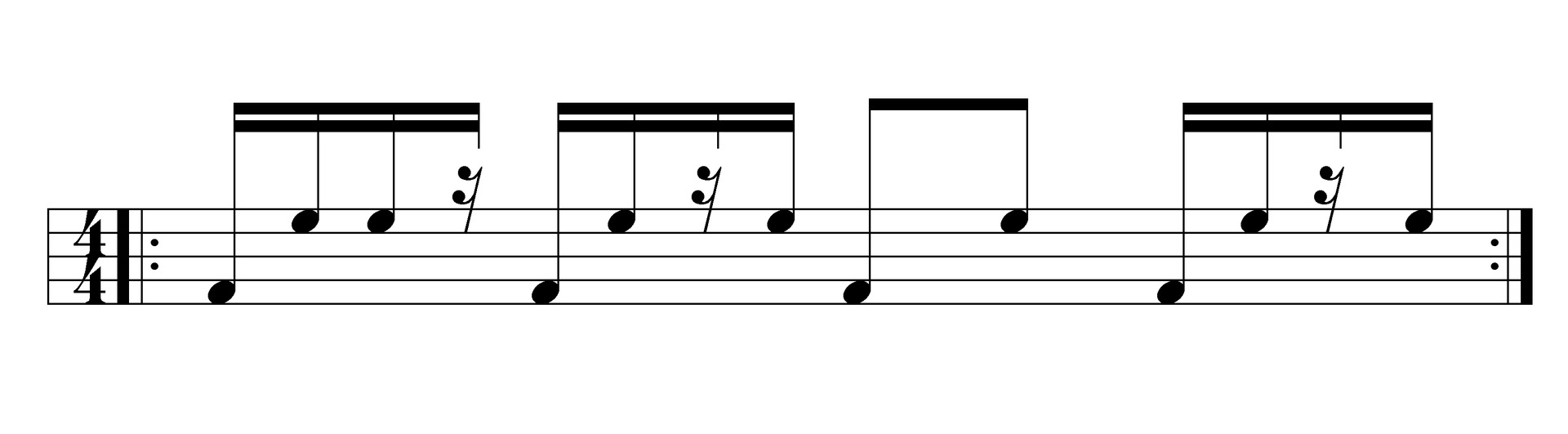

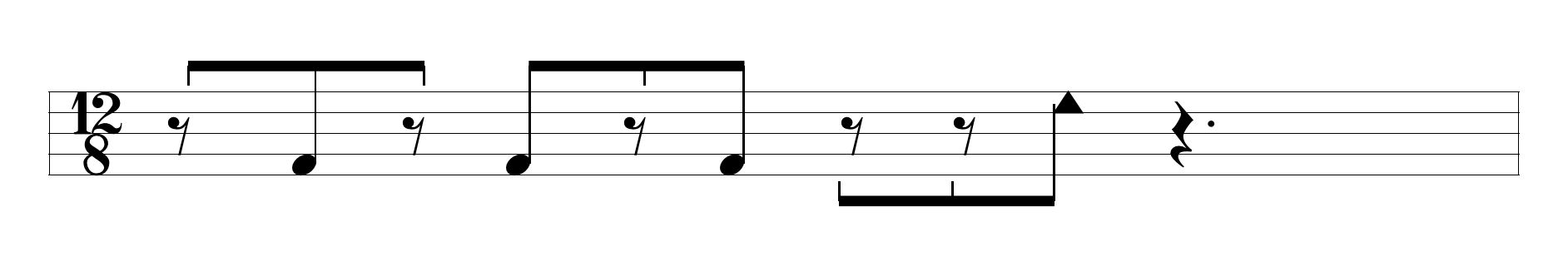

| History Syncretic origins It should be mentioned at the outset that the history of rumba is filled with so many unknowns, contradictions, conjectures and myths which have, over time been taken as fact, that any definitive history of the genre is probably impossible to reconstruct. Even elders who were present at historic junctures in rumba’s development will often disagree over the critical details of its history.-- David Peñalosa[23] Enslaved Africans were first brought to Cuba in the 16th century by the early Spanish settlers. Due to the significance of sugar as an export during the late 18th and early 19th century, even greater numbers of people from Africa were enslaved, brought to Cuba, and forced to work on the sugar plantations. Where large populations of enslaved Africans lived, African religion, dance, and drumming were clandestinely preserved through the generations. Cultural retention among the Bantu, Yoruba, Fon (Arará), and Efik (Abakuá) had the most significant impact in western Cuba, where rumba was born. The consistent interaction of Africans and Europeans on the island brought about what today is known as Afro-Cuban culture. This is a process known as transculturation, an idea that Cuban scholar Fernando Ortiz brought to the forefront in cultural studies like Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar. Cuban transculturation melds Spanish culture with African cultures, as with the seamless merging found in rumba. Ortiz saw transculturation as a positive social force: "consecrating the need for mutual understanding on an objective grounding of truth to move toward achieving the definitive integrity of the nation."[24] Most ethnomusicologists agree that the roots of rumba can be found in the solares of Havana and Matanzas during the 1880s.[25] The solares, also known as cuarterías, were large houses in the poor dock neighborhoods of Havana and Matanzas. Many of the important figures in the history of rumba, from Malanga to Mongo Santamaría were raised in solares.[26] Slavery was abolished in 1886 in Cuba and first-generation of free black citizens were often called negros de nación, a term commonly found in the lyrics of rumba songs.[26] The earliest progenitors of the urban styles of rumba (yambú and guaguancó) might have developed during the early 19th century in slave barracks (barracones) long before the use of the term rumba as a genre became established.[25] Such proto-rumba styles were probably instrumented with household items such as boxes and drawers instead of the congas, and frying pans, spoons and sticks instead of guaguas, palitos and claves.[25] While these early precursors of rumba have been barely documented, the direct precursors towards the mid- and late-19th century have been widely studied. Urban rumba styles are rooted in the so-called coros de clave and coros de guaguancó, street choirs that derived from the Spanish orfeones. In addition, the widespread yuka dance and music of Congolese origin became integrated into such choirs, lending its percussion instruments and dance moves. In addition, the secret Abakuá traditions rooted in the Calabar region of West Africa that prevailed in both Havana and Matanzas also influenced the development of rumba as a syncretic genre. Coros de clave Main article: Coros de clave Coros de clave were introduced by Catalan composer Josep Anselm Clavé and became popular between the 1880s and the 1910s.[27] They comprised as many as 150 men and women who sang in 6 8 time with European harmonies and instruments. Songs began with a female solo singer followed by call-and-response choral singing. As many as 60 coros de clave might have existed by 1902, some of which denied any African influence on their music.[28] Examples of popular coros de clave include El Arpa de Oro and La Juventud. From the coros the clave evolved the coros de guaguancó, which comprised mostly men, had a 2 4 time, and incorporated drums.[28] Famous coros de guaguancó include El Timbre de Oro, Los Roncos (both featuring Ignacio Piñeiro, the latter as director), and Paso Franco.[29] These ensembles gave rise to the first authentic rumba groups, and with them several types of rumba emerged, including the now popular guaguancó and yambú. However, others have been lost to time or are extremely rare today, such as the tahona,[30] papalote,[27] tonada,[31] and the jiribilla and resedá.[6] Early recognition and recordings Rumba served as an expression to those who were oppressed, thus beginning a social and racial identity with rumba. The synthesis of cultures can be seen in rumba because it "exhibits both continuity with older traditions and development of new ones. The rumba itself is a combination of music, dance, and poetry."[21] During slavery, and after it was abolished, rumba served as a social outlet for oppressed slaves and the underclass which was typically danced in the streets or backyards in urban areas. Rumba is believed to have grown out of the social circumstances of Havana because it "was the center for large numbers of enslaved Africans by the end of the eighteenth century. Rebellion was difficult and dangerous, but protest in a disguised form was often expressed in recreational music and dance."[32] Even after slavery was abolished in Cuba, there still remained social and racial inequality, which Afro-Cubans dealt with by using rumba's music and dancing as an outlet of frustration. Because Afro-Cubans had fewer economic opportunities and the majority lived in poverty, the style of dance and music did not gain national popularity and recognition until the 1950s, and especially after the effects of the 1959 Cuban Revolution, which institutionalized it. The first commercial studio recordings of Cuban rumba were made in 1947 in New York by Carlos Vidal Bolado and Chano Pozo for SMC Pro-Arte, and in 1948 in Havana by Filiberto Sánchez for Panart. The first commercial ensemble recordings of rumba were made in the mid 1950s by Alberto Zayas and his Conjunto Afrocubano Lulú Yonkori, yielding the 1956 hit "El vive bien". The success of this song prompted the promotion of another rumba group, Los Muñequitos de Matanzas, which became extremely popular.[33] Together with Los Muñequitos, Los Papines were the first band to popularize rumba in Cuba and abroad. Their very stylized version of the genre has been considered a "unique" and "innovative" approach.[34] Post-revolutionary institutionalization After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, there were many efforts by the government to institutionalize rumba, which has resulted in two different types of performances. The first was the more traditional rumba performed in a backyard with a group of friends and family without any type of governmental involvement. The second was a style dedicated to tourists while performed in a theater setting. Two institutions that promoted rumba as part of Cuban culture –thus creating the tourist performance– are the Ministry of Culture and the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional de Cuba ('Cuban Nacional Folkloric Company'). As Folklórico Nacional became more prevalent in the promotion of rumba, the dance "shifted from its original locus, street corners, where it often shared attention with parallel activities of traffic, business, and socializing, to its secondary quarters, the professional stage, to another home, the theatrical patio."[35] Although Folklórico Nacional aided in the tourist promotion of rumba, the Ministry of Culture helped successfully and safely organize rumba in the streets. In early post-revolutionary times, spontaneous rumba might have been considered problematic due to its attraction of large groups at unpredictable and spontaneous times, which caused traffic congestion in certain areas and was linked with fights and drinking. The post-revolutionary government aimed to control this "by organizing where rumba could take place agreeable and successfully, the government, through the Ministry of Culture, moved to structurally safeguard one of its major dance/music complexes and incorporate it and Cuban artists nearer the core of official Cuban culture."[36] This change in administering rumba not only helped organize the dances but also helped it move away from the negative connotation of being a disruptive past time event. Although this organization helped the style of rumba develop as an aspect of national culture, it also had some negative effects. For example, one of the main differences between pre- and post-revolutionary is that after the revolution rumba became more structured and less spontaneous. For instance, musicians dancers and singers gathered together to become inspired through rumba. In other words, rumba was a form of the moment where spontaneity was essentially the sole objective. However, post-revolutionary Cuba "led to manipulation of rumba form. It condensed the time of a rumba event to fit theater time and audience concentration tie. It also crystallized specific visual images through... [a] framed and packaged... dance form on stages and special performance patios."[37] Yvonne Daniel states: “Folklórico Nacional dancers . . . must execute each dance as a separate historical entity in order to guard and protect the established representations of Cuban folkloric traditions . . . by virtue of their membership in the national company, the license to elaborate or create stylization . . . is not available to them.”[38] As official caretakers of the national folkloric treasure, the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional has successfully preserved the sound of the mid-twentieth century Havana-style rumba.[39] True traditional or folkloric rumba is not as stylized as the theatrical presentations performed by professional rumba groups; rather, "[i]t is more of an atmosphere than a genre. It goes without saying that in Cuba there is not one rumba, but many rumbas."[40] Despite the structure enforced in rumba through the Folklórico Nacional and the Ministry of Culture, traditional forms of rumba danced at informal social gatherings remain pervasive. Modernization In the 1980s, Los Muñequitos de Matanzas greatly expanded the melodic parameters of the drums, inspiring a wave of creativity that ultimately led to the modernization of rumba drumming. Freed from the confines of the traditional drum melodies, rumba became more an aesthetic, rather than a specific combination of individual parts. The most significant innovation of the late 1980s was the rumba known as guarapachangueo, created by Los Chinitos of Havana, and batá-rumba, created by AfroCuba de Matanzas. Batá-rumba initially was just a matter of combining guaguancó and chachalokuafún, but it has since expanded to include a variety of batá rhythms. A review of the 2008 CD by Pedro Martínez and Román Díaz, The Routes of Rumba, describes guarapachangueo as follows:[41] Guarapachangueo, invented by the group Los Chinitos in Havana in the 1970s, is based on "the interplay of beats and rests", and is highly conversational (Jottar, 2008[42]). Far from the standardized regularity of the drum rhythms of recordings such as Alberto Zayas's "El vive bien", guarapachangueo often sounds slightly random or unorganized to the untrained ear, yet presents a plethora of percussive synchronicities for those who understand the clave. Using both cajones (wooden boxes) and tumbadoras (congas), Martinez and Diaz reflect the tendencies of their generation of rumberos in combining these instruments, which widens the sonic plane to include more bass and treble sounds. In their video about the history of guarapachangueo, Los Chinitos say that initially the word "guarapachangueo" was used by their colleague musician in a disparaging way: "What kind of guarapachangueo are you playing?".[43] Pancho Quinto and his group Yoruba Andabo also played a vital role in the development of the genre.[44] The word derives from "guarapachanga", itself a portmanteau of "guarapo" and "pachanga" coined by composer Juan Rivera Prevot in 1961.[45][nb 1] Legacy and influence Rumba is considered "the quintessential genre of Cuban secular music and dance".[16] In 1985 the Cuban Minister of Culture stated that "rumba without Cuba is not rumba, and Cuba without rumba is not Cuba."[47] For many Cubans, rumba represents "a whole way of life",[48] and professional rumberos have called it "a national sport, as important as baseball".[49] The genre has permeated not only the culture of Cuba but also that of the whole of Latin America, including the United States, through its influence on genres such as ballroom rumba ("rhumba"), Afro-Cuban jazz and salsa. Even though rumba is technically complicated and usually performed by a certain social class and one "racial group", Cubans consider it one of the most important facets of their cultural identity. In fact, it is acknowledged as intimately and fundamentally "Cuban" by most Cubans because it rose from Cuban social dance. After its institutionalization following the Revolution, rumba has adopted a position as a symbol of what Cuba stands for and of how Cubans want the international community to envision their country and its culture and society: vibrant, full of joy and authentic.[50] Influence on other Afro-Cuban traditions Rumba has influenced both the transplanted African drumming traditions and the popular dance music created on the island. In 1950, Fernando Ortíz observed the influence of rumba upon ceremonial batá drumming: "“The drummers are alarmed at the disorder that is spreading in the temples regarding the liturgical toques ['batá rhythms']. The people wish to have fun and ask for arrumbados, which are toques similar to rumbas and are not orthodox according to rites; the drummers who do not gratify the faithful, who are the ones that pay, are not called to play and if they do not play, they do not collect.”[51] The batá rhythms chachalokuafun and ñongo in particular have absorbed rumba aesthetics. Michael Spiro states: “When I hear ñongo played by young drummers today, I hear rumba."[52] In chachalokuafun the high-pitched okónkolo drum, usually the most basic and repetitive batá, improvises independently of the conversations carried on between the other two drums (iyá and itótele), in a manner suggestive of rumba. The contemporary style of lead drum accompaniment for the chekeré ensemble known as agbe or guiro, is played on the high-pitched quinto, instead of the lower-pitched tumba as was done in earlier times. The part has evolved away from the bembé caja (lead drum) vocabulary towards quinto-like phrases.[53] Rumba has had a notable influence on cajón pa’ los muertos ceremonies. In a rare turn of events, the secular yambú was adopted into this Afro-Cuban religion.[54] Influence on contemporary music Many of the rhythmic innovations in Cuban popular music, from the early twentieth century, until present, have been a matter of incorporating rumba elements into the son-based template. For example, bongos incorporating quinto phrases are heard on 1920s recordings of son. Several of the timbales cowbell parts introduced during the mambo era of the 1940s are Havana-style guaguancó guagua patterns:  Four different timbales bell parts adapted from guaguancó guagua patterns. Play 1ⓘ、2ⓘ、3ⓘ、4ⓘ Descargas (mostly instrumental jams sessions) where jazz-influenced improvisation was developed, were first known as rumbitas in the early 1940s.[55] The musicians improvised with a rumba sensibility. By the 1950s the rhythmic vocabulary of the rumba quinto was the source of a great deal of rhythmically dynamic phrases and passages heard in Cuban popular music and Latin jazz. Even with today’s flashy percussion solos, where snare rudiments and other highly developed techniques are used, analysis of the prevailing accents will often reveal an underlying quinto structure.[citation needed] In the late 1970s guaguancó was incorporated into Cuban popular music in the style known as songo. Songo congas play a hybrid of the salidor and quinto, while the timbales or drum kit play an embellishment of the Matanzas-style guagua.  Matanzas-style guaguancó guagua.  Basic songo stick pattern. Contemporary timba musicians cite rumba as a primary source of inspiration in composing and arranging. Timba composer Alain Pérez states: "In order to get this spontaneous and natural feel, you should know la rumba . . . all the percussion, quinto improvising."[56] |

歴史 シンクレティックな起源 ルンバの歴史は、多くの不明な点、矛盾、憶測、神話で埋め尽くされており、それが時間の経過とともに事実のように受け取られ、このジャンルの決定的な歴史 を再構築することはおそらく不可能である。ルンバが発展する歴史的な節目に立ち会った長老でさえ、その歴史の重要な詳細については意見が分かれることが多 い。——デヴィッド・ペニャローサ[23]。 奴隷にされたアフリカ人は、初期のスペイン人入植者によって16世紀に初めてキューバに連れてこられた。18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけて、輸出品と しての砂糖の重要性が高まったため、さらに多くのアフリカ人が奴隷としてキューバに連れてこられ、砂糖プランテーションで働かされた。奴隷にされたアフリ カ人が大勢住んでいた場所では、アフリカの宗教、ダンス、太鼓が何世代にもわたって密かに保存されていた。バンツー族、ヨルバ族、フォン族(アララ族)、 エフィク族(アバクア族)の間での文化保持は、ルンバが生まれたキューバ西部で最も大きな影響を与えた。島におけるアフリカ人とヨーロッパ人の一貫した交 流は、今日アフロ・キューバ文化として知られるものをもたらした。これはトランスカルチュレーションとして知られるプロセスであり、キューバの学者フェル ナンド・オルティスが『キューバの対位法』のような文化研究において前面に押し出した考え方である: タバコと砂糖』だ。キューバのトランスカルチュレーションは、ルンバに見られるシームレスな融合のように、スペイン文化とアフリカ文化を融合させる。オル ティスはトランスカルチュレーションを肯定的な社会的力としてとらえた: 「国家の決定的な完全性を達成するために、真実という客観的な根拠に基づいて相互理解の必要性を聖別する」[24]。 ほとんどの民族音楽学者は、ルンバのルーツは1880年代のハバナやマタンサスのソラーレにあると認めている[25]。ソラーレはクアルテリアとも呼ば れ、ハバナやマタンサスの貧しいドック地区にある大きな家だった。マランガからモンゴ・サンタマリアまで、ルンバの歴史における重要人物の多くはソラーレ スで育った[26]。1886年にキューバでは奴隷制度が廃止され、第一世代の自由黒人市民はしばしばnegros de naciónと呼ばれた。 ルンバの都会的なスタイル(ヤンブーとグアグアンコー)の最も古い祖先は、ジャンルとしてのルンバという言葉が確立されるずっと前の19世紀初頭に奴隷の バラック(barracones)で発展したのかもしれない。 [25]このようなルンバの原型となるスタイルは、コンガの代わりに箱や引き出し、グアグア、パリトー、クラーベの代わりにフライパン、スプーン、棒など の家庭用品を使って演奏されていたと思われる[25]。これらのルンバの初期の前身はほとんど記録されていないが、19世紀半ばから後半にかけての直接的 な前身は広く研究されている。都市のルンバのスタイルは、スペインのオルフェオネスから派生したストリート合唱団、いわゆるコロス・デ・クラーベやコロ ス・デ・グアグアンコーに根ざしている。加えて、コンゴ発祥のユカ・ダンスと音楽が広まり、打楽器やダンスの動きもこうした合唱団に組み込まれるように なった。さらに、ハバナとマタンサスの両地域で広まっていた西アフリカのカラバル地方に根ざした秘密のアバクアの伝統も、シンクレティックなジャンルとし てのルンバの発展に影響を与えた。 コロス・デ・クラベ 主な記事 コロ・デ・クラーベ カタルーニャの作曲家ジョセップ・アンセルム・クラヴェによって導入されたコロス・デ・クラヴェは、1880年代から1910年代にかけて流行した[27]。 8拍子をヨーロッパのハーモニーと楽器で歌う。歌は女性の独唱から始まり、コール・アンド・レスポンスの合唱が続く。1902年までに60ものコーロ・ デ・クラーベが存在したと思われるが、その中にはアフリカの影響を否定するものもあった[28]。人気のあるコーロ・デ・クラーベの例としては、エル・ア ルパ・デ・オロ(El Arpa de Oro)やラ・フベントゥ(La Juventud)などがある。 クラーベのコロスから発展したグアグアンコのコロスは、ほとんどが男性で構成され、2拍子、4拍子、太鼓を取り入れたものであった。 28]有名なグアグアンコ・コロには、エル・ティンブレ・デ・オロ、ロス・ロンコス(いずれもイグナシオ・ピニェイロをディレクターとして起用)、パソ・ フランコなどがある[29]。これらのアンサンブルは最初の本格的なルンバ・グループを生み出し、現在人気のグアグアンコやヤンブーなど、いくつかのタイ プのルンバが生まれた。しかし、タホナ、[30]パパロテ、[27]トナダ、[31]ジリビージャやレセダなど、時間の経過とともに失われてしまったもの や、今日では非常に珍しいものもある[6]。 初期の認識と録音 ルンバは抑圧された人々への表現として機能し、ルンバによる社会的、人種的アイデンティティが始まった。ルンバは「古い伝統との連続性と新しい伝統の発展 の両方を示している」ため、文化の統合をルンバに見ることができる。ルンバそのものが、音楽、ダンス、詩の組み合わせである」[21]。奴隷制の時代、そ してそれが廃止された後、ルンバは抑圧された奴隷や下層階級の社会的なはけ口として機能し、都市部の路上や裏庭で踊られるのが一般的だった。ルンバはハバ ナの社会情勢から発展したと考えられているが、その理由は「18世紀末には、奴隷にされたアフリカ人が大勢集まる中心地だったから」である。反乱は困難で 危険なものだったが、偽装された形での抗議は、娯楽的な音楽やダンスで表現されることが多かった」[32]。 キューバで奴隷制度が廃止された後も、社会的・人種的不平等が残っており、アフロ・キューバ人はルンバの音楽と踊りをフラストレーションのはけ口として使 うことでそれに対処していた。アフロ・キューバ人は経済的な機会が少なく、大多数が貧困の中で暮らしていたため、ダンスと音楽のスタイルが全国的な人気と 認知を得るのは1950年代になってからで、特に1959年のキューバ革命の影響で制度化された後だった。キューバ・ルンバの最初の商業用スタジオ録音 は、1947年にカルロス・ビダル・ボラドとチャノ・ポゾがSMCプロアルテのためにニューヨークで行ったもので、1948年にはフィリベルト・サンチェ スがパナートのためにハバナで行った。1950年代半ば、アルベルト・サヤスと彼のコンジュント・アフロクバーノ・ルル・ヨンコリによって、ルンバの最初 の商業的アンサンブル録音が行われ、1956年に 「El vive bien 」がヒットした。この曲の成功により、別のルンバグループ、ロス・ムニェキトス・デ・マタンサスがプロモートされ、大人気となった[33]。ロス・ムニェ キトスと共に、ロス・パピネスはキューバ国内外にルンバを広めた最初のバンドである。彼らの非常に様式化されたジャンルのバージョンは、「ユニーク」で 「革新的」なアプローチとみなされている[34]。 革命後の制度化 1959年のキューバ革命後、ルンバを制度化するために政府による多くの努力がなされ、その結果、2つの異なるタイプのパフォーマンスが生まれた。1つ目 は、裏庭で友人や家族と行う伝統的なルンバで、政府は一切関与していない。もうひとつは、劇場で上演される観光客向けのスタイルである。 ルンバをキューバ文化の一部として普及させ、観光客向けのパフォーマンスを生み出した2つの機関は、文化省とコンジュント・フォルクローリコ・ナシオナ ル・デ・クーバ(「キューバ民族民俗劇団」)である。フォルクローリコ・ナシオナルがルンバの普及に力を入れるにつれて、ダンスは「本来の場所である街角 から、しばしば交通、ビジネス、社交といった並行した活動と注目を共有するようになり、二次的な場所であるプロの舞台から、もうひとつの家である劇場のパ ティオへと移行した」[35]。フォルクローリコ・ナシオナルはルンバの観光振興に貢献したが、文化省は街頭でのルンバの組織化を成功させ、安全に支援し た。 革命後の初期には、自然発生的なルンバは、予測不可能で突発的な時間帯に大集団を惹きつけ、特定の地域で交通渋滞を引き起こしたり、喧嘩や飲酒に結びつい たりしたため、問題視されたかもしれない。革命後の政府は、「ルンバが合意され、成功裏に行われる場所を組織することで、政府は文化省を通じて、主要なダ ンス/音楽の複合体のひとつを構造的に保護し、ルンバとキューバ人アーティストをキューバの公式文化の核心に近づけるよう動いた。 この組織化はルンバのスタイルを国民文化の一側面として発展させるのに役立ったが、いくつかの悪影響ももたらした。例えば、革命前と革命後の主な違いのひ とつは、革命後のルンバはより構造化され、自然発生的ではなくなったことだ。例えば、ミュージシャンやダンサー、歌手はルンバを通してインスピレーション を得るために集まった。言い換えれば、ルンバは本質的に自発性が唯一の目的であった瞬間の形式であった。しかし、革命後のキューバは「ルンバの形式を操作 するようになった。劇場の時間と観客の集中力のタイに合わせて、ルンバのイベントの時間を凝縮した。また、...を通じて特定の視覚的イメージを結晶化さ せた。[舞台や特別なパフォーマンス・パティオでの...額縁に入れられ、包装された...ダンス・フォームを通して...特定の視覚的イメージを結晶化 させた」[37]とイヴォンヌ・ダニエルは述べる: 「フォルクローリコ・ナシオナルのダンサーたちは......キューバの民俗的伝統の確立された表象を守り、保護するために、それぞれの踊りを独立した歴 史的実体として実行しなければならない。ナショナル・カンパニーの一員であることを理由に、精巧に作ったり様式化したりするライセンスは......彼ら にはない」[38]。国家的なフォークロアの宝の公式な管理人として、コンジュント・フォルクローリコ・ナシオナルは20世紀半ばのハバナ・スタイルのル ンバの響きを見事に守ってきた[39]。 真の伝統的な、あるいは民俗的なルンバは、プロのルンバ・グループが演じる演劇的なプレゼンテーションのように様式化されたものではなく、むしろ「ジャン ルというよりも雰囲気のようなもの」である。フォルクローリコ・ナシオナルや文化省を通じてルンバの構造が強制されているにもかかわらず、非公式な社交の 場で踊られる伝統的なルンバの形式は依然として広く残っている。 近代化 1980年代、ロス・ムニェキトス・デ・マタンサスは、ドラムのメロディーのパラメーターを大幅に拡大し、ルンバ・ドラムの近代化につながる創造性の波を 刺激した。伝統的なドラムのメロディーの枠から解き放たれたルンバは、個々のパートの特定の組み合わせというより、むしろ美学となった。1980年代後半 の最も重要な革新は、ハバナのロス・チニトスが生み出したグアラパチャングエオとして知られるルンバと、アフロキューバ・デ・マタンサスが生み出したバ タ・ルンバだった。バタ・ルンバは当初、グアグアンコーとチャチャロクアフンを組み合わせただけのものだったが、その後、さまざまなバタのリズムを含むよ うになった。 ペドロ・マルティネスとロマン・ディアスによる2008年のCD『The Routes of Rumba』のレビューでは、グアラパチャングエオについて以下のように説明している[41]。 グアラパチャングエオは、1970年代にハバナのグループ、ロス・チニートスによって考案されたもので、「拍子と休符の相互作用」に基づいており、非常に 会話的である(Jottar, 2008[42])。アルベルト・サヤスの 「El vive bien 」のような録音に見られるドラムのリズムの標準化された規則性からかけ離れたグアラパチャングエオは、訓練されていない耳にはやや不規則で整理されていな いように聞こえることが多いが、クラーベを理解する者にとってはパーカッシブな共時性の宝庫である。マルティネスとディアスは、カホン(木の箱)とトゥン バドーラ(コンガ)の両方を使い、彼らの世代のルンベロの傾向を反映してこれらの楽器を組み合わせている。 ロス・チニートスは、グアラパチャングエオの歴史についてのビデオの中で、当初「グアラパチャングエオ」という言葉は同僚のミュージシャンによって蔑称と して使われていたと語っている: 「また、パンチョ・キントと彼のグループであるヨルバ・アンダボも、このジャンルの発展において重要な役割を果たした[44]。 グアラパチャングエオという言葉は、1961年に作曲家のフアン・リベラ・プレボが作った「グアラポ」と「パチャンガ」の合成語である「グアラパチャング エオ」に由来する[45][nb 1]。 遺産と影響 1985年、キューバの文化大臣は「キューバ抜きのルンバはルンバではなく、ルンバ抜きのキューバはキューバではない」と述べている[47]。多くの キューバ人にとってルンバは「生活様式そのもの」であり[48]、プロのルンベロたちはルンバを「野球と同じくらい重要な国技」と呼んでいる[49]。 [49]このジャンルは、社交ルンバ(「ルンバ」)、アフロ・キューバン・ジャズ、サルサなどのジャンルへの影響を通じて、キューバだけでなく、アメリカ を含むラテンアメリカ全体の文化に浸透している。 ルンバは技術的に複雑で、通常は特定の社会階級やある「人種グループ」によって演奏されるものだが、キューバ人はこれを自分たちの文化的アイデンティティ の最も重要な側面のひとつと考えている。実際、ルンバはキューバの社交ダンスから発展したものであるため、ほとんどのキューバ人はルンバを密接かつ根本的 に 「キューバ的 」なものとして認めている。革命後に制度化された後、ルンバはキューバが象徴するもの、キューバ人が国際社会にキューバとその文化や社会をどのようにイ メージしてほしいかを示す象徴としての地位を獲得した。 他のアフロ・キューバの伝統への影響 ルンバは、移植されたアフリカの太鼓の伝統と、この島で創作された大衆的なダンス音楽の両方に影響を与えた。1950年、フェルナンド・オルティスはルン バが儀式用のバタ・ドラムに与える影響を観察した: 「太鼓奏者たちは、典礼のトーケ(「バタのリズム」)に関して寺院に広がっている無秩序に警鐘を鳴らしている。人々は楽しみを求め、ルンバに似たトックで あり、儀式に従った正統的なものではないアルムバドスを要求する。お金を払う者である信者を喜ばせない太鼓奏者は演奏に呼ばれず、演奏しなければ徴収もさ れない」[51]。 特にバタのリズムであるチャチャロクアフンとニョンゴはルンバの美学を吸収している。マイケル・スピロはこう述べている: 「チャチャロクアフンでは、通常最も基本的で反復的なバタである高音のオコンコロ・ドラムが、他の2つのドラム(イヤーとイトテレ)の間で交わされる会話 とは別に、ルンバを思わせる方法で即興演奏を行う。 アッベまたはギロとして知られるチェケレ・アンサンブルのリード・ドラム伴奏の現代的なスタイルは、以前のように低音のトゥンバではなく、高音のキントで 演奏される。このパートは、ベンベ・カハ(リード・ドラム)のボキャブラリーからキントに似たフレーズへと進化している[53]。 ルンバはカホン・パ・ロス・ムエルトスの儀式に顕著な影響を与えている。珍しいことに、世俗的なヤンブーがこのアフロ・キューバの宗教に採用された[54]。 現代音楽への影響 20世紀初頭から現在に至るまで、キューバのポピュラー音楽におけるリズムの革新の多くは、ルンバの要素をソンをベースとしたテンプレートに取り入れたも のである。例えば、キントのフレーズを取り入れたボンゴは、1920年代のソンの録音で聴くことができる。1940年代のマンボ時代に導入されたティンバ レスのカウベルパートのいくつかは、ハバナ風のグアグアンコ・グアグアのパターンである:  グアグアンコ・グアグア・パターンをアレンジした4種類のティンバレスのベル・パート。1ⓘ、2ⓘ、3ⓘ、4ⓘを演奏する。 ジャズの影響を受けた即興演奏が展開されたデスカルガス(主にインストゥルメンタル・ジャム・セッション)は、1940年代初頭にルンビタスとして知られ るようになった[55]。1950年代までに、ルンバ・キントのリズム・ボキャブラリーは、キューバのポピュラー音楽やラテン・ジャズで聴かれる、リズミ カルでダイナミックなフレーズやパッセージの多くの源となった。今日の派手なパーカッション・ソロでも、スネア・ルーディメンツや他の高度に発達したテク ニックが使われているが、そのアクセントを分析すると、根底にキントの構造があることがよくわかる[要出典]。 1970年代後半、グアガンコーはソンゴとして知られるスタイルでキューバのポピュラー音楽に取り入れられた。ソンゴのコンガはサリドールとキントのハイブリッドを演奏し、ティンバレスやドラムキットはマタンサススタイルのグアグアの装飾を演奏する。  マタンサス風グアグアンコ・グアグア  基本的なソンゴのスティックパターン。 現代のティンバ・ミュージシャンたちは、ルンバを作曲やアレンジのインスピレーションの源としている。ティンバの作曲家アラン・ペレスはこう語る: 「こののびのびとした自然な感じを得るためには、ラ・ルンバを知っている必要がある......すべてのパーカッション、キントの即興演奏」[56]。 |

| Styles Traditionally rumba has been classified into three main subgenres: yambú, guaguancó and columbia. Both yambú and guaguancó originated in the solares, large houses in the poorest districts of Havana and Matanzas mostly inhabited by the descendants of enslaved Africans.[35] Both styles are thus predominantly urban, danced by men and women alike, and exhibit a historical "binarization" of their meter, as described by Cuban musicologist Rolando Antonio Pérez Fernández.[19] In contrast, columbia has a primarily rural origin, also in the central regions of Cuba, being almost exclusively danced by men, and remaining much more grounded in West African (specifically Abakuá) traditions, which is exemplified by its triple meter. During the 20th century, these styles have evolved, and other subgenres have appeared such as guarapachangueo and batá-rumba. In all rumba styles, there is a gradual heightening of tension and dynamics, not simply between dancers but also between dancers and musicians and dancers and spectator/participants.” [57] Yambú Yambú is considered the oldest style of rumba, originating in colonial times. Hence, it is often called "yambú de tiempo España" (yambú of Spanish times). It has the slowest tempo of all rumba styles and its dance incorporates movements feigning frailty. It can be danced alone (usually by women) or by men and women together. Although male dancers may flirt with female dancers during the dance, they do not use the vacunao of guaguancó. In Matanzas the basic quinto part for yambú and guaguancó alternates the tone-slap melody. The following example shows the sparsest form of the basic Matanzas-style quinto for yambú and guaguancó. The first measure is tone-slap-tone, and the second measure is the opposite: slap-tone-slap.[58] Regular note-heads indicate open tones and triangle note-heads indicate slaps.  Basic Matanzas-style quinto part for yambú and guaguancó. Guaguancó Main article: Guaguancó Guaguancó is the most popular and influential rumba style. It is similar to yambú in most aspects, having derived from it,[59] but it has a faster tempo. The term "guaguancó" originally referred to a narrative song style (coros de guaguancó) which emerged from the coros de clave of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Rogelio Martínez Furé states: “[The] old folks contend that strictly speaking, the guaguancó is the narrative."[60] The term guaguancó itself may derive etimologically from the guagua instrument.[59] Guaguancó is a couple dance of sexual competition between the male and female. The male periodically attempts to “catch” his partner with a single thrust of his pelvis. This erotic movement is called the vacunao (‘vaccination’ or more specifically ‘injection’), a gesture derived from yuka and makuta, symbolizing sexual penetration. The vacunao can also be expressed with a sudden gesture made by the hand or foot. The quinto often accents the vacunao, usually as the resolution to a phrase spanning more than one cycle of clave. Holding onto the ends of her skirt while seductively moving her upper and lower body in contrary motion, the female “opens” and “closes” her skirt in rhythmic cadence with the music. The male attempts to distract the female with fancy (often counter-metric) steps, accented by the quinto, until he is in position to “inject” her. The female reacts by quickly turning away, bringing the ends of her skirts together, or covering her groin area with her hand (botao), symbolically blocking the “injection.” Most of the time the male dancer does not succeed in “catching” his partner. The dance is performed with good-natured humor.[25] Vernon Boggs states that the woman's "dancing expertise resides in her ability to entice the male while skillfully avoiding being touched by his vacunao."[61] Columbia  Rumba columbia performance in Washington, DC (2008). Columbia is a fast and energetic rumba, in a triple-pulse (6 8, 12 8) structure, and often accompanied the standard bell pattern struck on a guataca ('hoe blade') or a metal bell. Columbia originated in the hamlets, plantations, and docks where men of African descent worked together. Unlike other rumba styles, columbia is traditionally meant to be a solo male dance.[14] According to Cuban rumba master and historian Gregorio "El Goyo" Hernández, columbia originated from the drum patterns and chants of religious Cuban Abakuá traditions. The drum patterns of the lowest conga drum is essentially the same in both columbia and Abakuá. The rhythmic phrasing of the Abakuá lead drum bonkó enchemiyá is similar, and in some instances, identical to columbia quinto phrases.[62]  Abakuá bonkó phrase which is also played by the quinto in Columbia. In Matanzas, the melody of the basic columbia quinto part alternates with every clave. As seen in the example below, the first measure is tone-slap-tone, while the second measure is the inverse: slap-tone-slap.[63]  Basic Matanzas-style columbia quinto part. The guagua (cáscara or palito) rhythm of columbia, beaten either with two sticks on a guagua (hollowed piece of bamboo) or on the rim of the congas, is the same as the pattern used in abakuá music, played by two small plaited rattles (erikundi) filled with beans or similar objects. One hand plays the triple-pulse rumba clave pattern, while the other plays the four main beats.  Abakuá erikundi and Columbia guagua pattern. The fundamental salidor and segundo drum melody of the Havana-style columbia, is an embellishment of six cross-beats.[64] The combined open tones of these drums generate the melodic foundation. Each cross-beat is "doubled", that is, the very next pulse is also sounded.  Havana-style Columbia salidor and segundo composite melody Columbia quinto phrases correspond directly to accompanying dance steps. The pattern of quinto strokes and the pattern of dance steps are at times identical, and at other times, imaginatively matched. The quinto player must be able to switch phrases immediately in response to the dancer's ever-changing steps. The quinto vocabulary is used to accompany, inspire and in some ways, compete with the dancers' spontaneous choreography. According to Yvonne Daniel, "the columbia dancer kinesthetically relates to the drums, especially the quinto (...) and tries to initiate rhythms or answer the riffs as if he were dancing with the drum as a partner."[65] Men may also compete with other men to display their agility, strength, confidence and even sense of humor. Some of these aforementioned aspects of rumba columbia are derived from a colonial Cuban martial art/dance called juego de maní which shares similarities to Brazilian capoeira. Columbia incorporates many movements derived from Abakuá and yuka dances, as well as Spanish flamenco, and contemporary expressions of the dance often incorporate breakdancing and hip hop moves. In recent decades, women are also beginning to dance columbia.[citation needed] |

スタイル 伝統的にルンバは、ヤンブー、グアグアンコー、コロンビアの3つのサブジャンルに分類されている。ヤンブーとグアグアンコはともにソラーレ(ハバナやマタ ンサスの貧しい地区にある、奴隷にされたアフリカ人の子孫が住む大きな家)に起源を持つ[35]。 [19]対照的に、コロンビアの起源は主にキューバ中央部の農村地帯であり、ほとんど男性によってのみ踊られ、西アフリカ(特にアバクア)の伝統により深 く根ざしている。20世紀には、これらのスタイルが進化し、グアラパチャングエオやバタ・ルンバなどのサブジャンルが登場した。どのルンバ・スタイルにお いても、ダンサー間だけでなく、ダンサーとミュージシャン、ダンサーと観客・参加者間の緊張とダイナミクスが徐々に高まっていく。[57] ヤンブー ヤンブーは植民地時代に生まれた最も古いルンバのスタイルと考えられている。そのため、しばしば「ヤンブー・デ・ティエンポ・エスパーニャ(スペイン時代 のヤンブー)」と呼ばれる。ルンバの中で最もテンポが遅く、虚弱を装う動きを取り入れた踊りである。一人で踊ることもあれば(通常は女性が踊る)、男女が 一緒に踊ることもある。男性ダンサーは踊りの最中に女性ダンサーといちゃつくことがあるが、グアグアンコのヴァクナオは使わない。マタンサスでは、ヤン ブーとグアグアンコのための基本的なキントパートは、トーンとスラップのメロディーを交互に繰り返す。次の例は、ヤンブーとグアガンコのためのマタンサス 式キントの最も基本的な形である。第1小節はトーン-スラップ-トーン、第2小節はその逆のスラップ-トーン-スラップである[58]。通常の音符の頭は オープントーンを、三角形の音符の頭はスラップを示す。  ヤンブーとグアングアンコーのための基本的なマタンサス様式のキントパート。 グアガンコー 主な記事 グアグアンコー グアグアンコーは最もポピュラーで影響力のあるルンバ・スタイルである。ほとんどの面でヤンブーと似ており、ヤンブーから派生したものであるが[59]、 テンポが速い。グアグアンコー」という用語は、元々は19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてのコロス・デ・クラーベから生まれた物語的な歌のスタイル(コ ロス・デ・グアグアンコー)を指していた。ロジェリオ・マルティネス・フーレはこう述べている: 「厳密に言えば、グアグアンコこそが物語なのだと、昔の人々は主張している」[60] グアグアンコという言葉自体は、エチモロジー的にはグアグアという楽器に由来するのかもしれない[59]。 グアグアンコーは男女の性的競争のカップルダンスである。男性は定期的に骨盤を一突きしてパートナーを「捕まえ」ようとする。このエロティックな動きは ヴァクナオ(「ワクチン接種」、より具体的には「注射」)と呼ばれ、性的な挿入を象徴するユカとマクタに由来するジェスチャーである。ヴァクナオは、手や 足の突然のジェスチャーで表現することもできる。クイントはしばしばヴァクナオにアクセントをつけ、通常はクラーベの1サイクル以上にまたがるフレーズの 解決として使われる。スカートの端を掴みながら、上半身と下半身を相反する動きで魅惑的に動かし、女性は音楽に合わせてリズミカルにスカートを「開いた り」「閉じたり」する。男性は、キントでアクセントをつけながら、派手な(しばしば反計量の)ステップで女性の気をそらそうとし、「注入」できる位置まで 行く。女性は素早く背を向け、スカートの端を合わせ、あるいは手で股間を覆い(ボタオ)、象徴的に 「注射 」を阻止する。ほとんどの場合、男性ダンサーはパートナーを「捕まえる」ことに成功しない。このダンスは気さくなユーモアをもって演じられる[25]。 ヴァーノン・ボッグスは、女性の「踊りの専門知識は、男性のヴァクナオに触られるのを巧みに避けながら男性を誘惑する能力にある」と述べている[61]。 コロンビア  ワシントンDCでのルンバ・コロンビア公演(2008年)。 コロンビアは高速でエネルギッシュなルンバで、トリプル・パルス(6 8, 12 8)構成で、しばしばグアタカ(「鍬の刃」)や金属製の鈴で叩く標準的な鈴のパターンを伴う。コロンビアは、アフリカ系の男たちが一緒に働いていた集落、 プランテーション、波止場で生まれた。他のルンバスタイルとは異なり、コロンビアは伝統的に男性のソロダンスであることを意味している[14]。 キューバのルンバマスターであり歴史家でもあるグレゴリオ・「エル・ゴヨ」・エルナンデスによれば、コロンビアの起源はキューバの宗教的なアバクアの伝統 のドラムパターンとチャントであるという。最も低いコンガ・ドラムのドラム・パターンは、コロンビアでもアバクアでも基本的に同じである。アバクアのリー ド・ドラムであるボンコ・エンセミヤのリズム・フレーズは、コロンビア・キントのフレーズに似ており、場合によっては同一であることもある[62]。  コロンビアのキントでも演奏されるアバクアのボンコー・フレーズ。 マタンサスでは、基本的なコロンビアのキントパートのメロディーはクラーベごとに交互に演奏される。下の例に見られるように、第1小節はトーン-スラップ-トーンであり、第2小節はその逆、スラップ-トーン-スラップである[63]。  基本的なマタンサス式コロンビア・キントのパート。 コロンビアのグアグア(cáscaraまたはpalito)のリズムは、グアグア(竹をくりぬいたもの)の上に2本の棒を置いたり、コンガの縁で叩いたり するもので、アバクア音楽で使われるパターンと同じである。片方の手で三拍子のルンバ・クラーベ・パターンを演奏し、もう片方の手で主要な4拍子を演奏す る。  アバクアのエリクンディとコロンビアのグアグア・パターン。 ハバナ・スタイルのコロンビアの基本的なサリドールとセグンド・ドラムの旋律は、6つのクロス・ビートの装飾である[64]。それぞれのクロス・ビートは「倍増」され、つまり次のパルスも鳴らされる。  ハバナ風のコロンビアのサリドールとセグンドの複合旋律 コロンビアのキント・フレーズは、伴奏のダンス・ステップに直接対応している。キントのストロークパターンとダンスステップのパターンは、ある時は同一で あり、またある時はイメージ的に一致する。キント奏者は、刻々と変化するダンサーのステップに合わせて、即座にフレーズを切り替えることができなければな らない。キントのボキャブラリーは、ダンサーの自発的な振付に寄り添い、インスピレーションを与え、ある意味では競い合うために使われる。イヴォンヌ・ダ ニエルによれば、「コロンビアのダンサーは運動学的にドラム、特にキントに関わり(...)、まるでドラムをパートナーとして踊っているかのようにリズム を始めたり、リフに答えようとする」[65]。 男性はまた、敏捷性、強さ、自信、さらにはユーモアのセンスを示すために、他の男性と競い合うこともある。ルンバ・コロンビアの前述の側面のいくつかは、 ブラジルのカポエイラと類似点を共有するジュエゴ・デ・マニ(juego de maní)と呼ばれる植民地時代のキューバの武術/ダンスに由来する。コロンビアはアバクアやユカ、スペインのフラメンコから派生した動きを多く取り入れ ており、現代的な表現ではブレイクダンスやヒップホップの動きを取り入れることも多い。ここ数十年、女性もコロンビアを踊り始めている[要出典]。 |

| Clave (rhythm) Rumba (disambiguation) Rumberas film |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuban_rumba |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆