プロレタリア文化大革命

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

PLA officers and soldiers

reading books for the "Three Supports and Two Militaries", 1968

☆ 文化大革命は、正式にはプロレタリア文化大革命といい、中華人民共和国 の社会政治運動である。1966年に毛沢東によって開始され、1976年に死去する まで続いた。その目的は、中国社会から資本主義的・伝統的要素の残滓を 一掃し、中国共産主義を維持することであった。その主な目標を達成することはできなかったが、文化大革命は毛沢東が権力の中枢に実質的に復帰したことを意味し た。これは、毛沢東がまだ中国共産党主席であったときに起こった大躍 進とそれに続く中国大飢饉の余波で、より穏健な七千人会議によって傍観されていた毛沢 東が、相対的に不在の期間を過ごした後のことであった。

★文化大革命は、その後に資本主義が勃興する条件を生み出す「ショック」だったのではないか?——ジジェク(2010:220)

| The Cultural

Revolution (CR), formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural

Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of

China (PRC). It was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasted until

his death in 1976. Its stated goal was to preserve Chinese communism by

purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese

society. Though it failed to achieve its main goals, CR marked the

effective return of Mao to the center of power. This came after a

period of relative absence for Mao, who had been sidelined by the more

moderate Seven Thousand Cadres Conference in the aftermath of the Great

Leap Forward and the following Great Chinese Famine, which occurred

while he was still chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In May 1966, with the help of the Cultural Revolution Group, Mao claimed that bourgeois elements had infiltrated the government and society with the aim of restoring capitalism. Mao called on young people to "bombard the headquarters", and proclaimed that "to rebel is justified". Many young people, mainly students, responded by forming cadres of Red Guards throughout the country. A selection of Mao's sayings were compiled into the Little Red Book, which became revered within his cult of personality. Public "struggle sessions" were regularly organized, targeting those deemed to be capitalists, reactionaries, or revisionists. In 1967, emboldened radicals began seizing power from local governments and party branches, establishing new "revolutionary committees" in their stead. These committees often split into rival factions, precipitating armed clashes among the radicals. The violence came to an end only when the People's Liberation Army (PLA) was ordered to intervene. Lin Biao, a PLA marshal, ascended to become Mao's heir apparent after the PLA intervention, only to be accused of planning and executing a botched coup against Mao. Lin fled the country, but died when his plane crashed. The Gang of Four became influential in 1972, and the Revolution continued until Mao's death in 1976, rapidly followed by the arrest of the Gang of Four. The Cultural Revolution was characterized by violence and chaos across Chinese society. Estimates of the death toll vary widely, typically ranging from 500,000 to 2,000,000.[1][2] Mass upheaval began in Beijing with Red August in 1966. This period saw numerous atrocities, including a massacre in Guangxi that included acts of cannibalism,[3][4] as well as incidents in Inner Mongolia, Guangdong, Yunnan, and Hunan. Red Guards, primarily consisting of university students, endeavored to destroy the "Four Olds": old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits. This often took the form of destroying historical artifacts, ransacking cultural and religious sites, and targeting other citizens deemed to be representative of the Four Olds. Tens of millions were persecuted, including senior officials: most notably, president Liu Shaoqi, as well as Deng Xiaoping, Peng Dehuai, and He Long, were purged or exiled. Millions were formally accused of being members of the Five Black Categories, and suffered public humiliation, imprisonment, torture, hard labor, seizure of property, and sometimes execution or harassment into suicide. Intellectuals were considered to be the "Stinking Old Ninth", and became widely persecuted, with scholars and scientists such as Lao She, Fu Lei, Yao Tongbin, and Zhao Jiuzhang killed or forced to commit suicide. The country's schools and universities were closed, and the National College Entrance Examination were cancelled. Over 10 million youth from urban areas were relocated under the Down to the Countryside Movement policy. In December 1978, Deng Xiaoping became the new paramount leader of China, replacing Mao's successor Hua Guofeng. He and his allies introduced the Boluan Fanzheng program, which gradually dismantled the Cultural Revolution.[5][6] In 1981, the Party publicly acknowledged numerous failures of the Cultural Revolution, and moreover declared that it was wrong, and "responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the people, the country, and the party since the founding of the People's Republic."[7][8][9] In contemporary China, after CR directly affected so many individuals across society, memories and perspectives are varied and complex. It is often referred to in retrospect as the "ten years of chaos" (十年动乱; shí nián dòngluàn or 十年浩劫; shí nián hàojié).[10] |

文化大革命は、正式にはプロレタリア文化大革命といい、中華人民共和国

の社会政治運動である。1966年に毛沢東によって開始され、1976年に死去するまで続いた。その目的は、中国社会から資本主義的・伝統的要素の残滓を

一掃し、中国共産主義を維持することであった。その主な目標を達成することはできなかったが、文化大革命は毛沢東が権力の中枢に実質的に復帰したことを意

味し

た。これは、毛沢東がまだ中国共産党主席であったときに起こった大躍進とそれに続く中国大飢饉の余波で、より穏健な七千人会議によって傍観されていた毛沢

東が、相対的に不在の期間を過ごした後のことであった。 1966年5月、毛沢東は文化大革命グループの協力を得て、資本主義の復活を目的としてブルジョア的要素が政府と社会に浸透していると主張した。毛沢東は 若者たちに「司令部を砲撃せよ」と呼びかけ、「反抗することは正当化される」と宣言した。 学生を中心とする多くの若者が、紅衛兵の幹部を全国に結成してこれに応じた。毛沢東の言葉は「小紅書」にまとめられ、毛沢東カルトの中で崇拝されるように なった。 資本主義者、反動主義者、修正主義者とみなされた人々を標的に、公開の「闘争会議」が定期的に組織された。1967年、勢いづいた急進派は、地方政府や党 支部から権力を掌握し始め、その代わりに新しい「革命委員会」を設立した。これらの委員会はしばしば対立する派閥に分裂し、急進派同士の武力衝突を引き起 こした。 暴力が終息したのは、人民解放軍が介入を命じられたときだった。PLAの元帥であった林彪は、PLAの介入後、毛沢東の後継者となったが、毛沢東に対する 不手際なクーデターを計画し、実行したとして告発された。林は国外に逃亡したが、飛行機が墜落して死亡した。 四人組は1972年に影響力を持つようになり、革命は1976年に毛沢東が死去するまで続いた。 文化大革命は、中国社会全体の暴力と混乱を特徴とした。死者数の見積もりは大きく異なり、通常50万人から200万人である[1][2]。大規模な動乱は 1966年の「赤い八月」から北京で始まった。この時期には、内モンゴル、広東、雲南、湖南での事件だけでなく、食人行為を含む広西チワン族自治区での大 虐殺[3][4]を含む数多くの残虐行為が見られた。紅衛兵は主に大学生で構成され、「四大老」(古い思想、古い文化、古い習慣、古い習慣)を破壊しよう と努めた。これはしばしば、歴史的な芸術品を破壊し、文化的・宗教的な場所を略奪し、四大老の代表とみなされる市民を標的にするという形をとった。劉少奇 国家主席をはじめ、鄧小平、彭徳懐、何龍といった高官が粛清されたり、追放された。数百万人が正式に「五黒」のメンバーとして告発され、公衆の面前で屈辱 を受け、投獄、拷問、重労働、財産の差し押さえ、時には処刑や自殺への嫌がらせを受けた。知識人は「胡散臭い老九」とみなされ、広く迫害されるようにな り、老女、傅磊、姚同斌、趙九章などの学者や科学者が殺されたり、自殺に追い込まれたりした。全国の学校と大学は閉鎖され、大学入学資格試験は中止され た。都市部の1000万人以上の若者が、「下野運動」政策によって移住させられた。 1978年12月、毛沢東の後継者である華国鋒に代わり、鄧小平が中国の新しい最高指導者に就任した。1981年、党は文化大革命の数々の失敗を公に認 め、さらにそれが誤りであり、「人民共和国建国以来、人民、国、党が被った最も深刻な後退と最も大きな損失の責任がある」と宣言した[7][8][9]。 現代の中国では、CRが社会全体の多くの個人に直接影響を与えた後、記憶や見方は多様で複雑である。それはしばしば「混沌の10年」(十年动乱;shí nián dòngluànまたは十年浩劫;shí nián hàojié)と回顧される[10]。 |

| Great Leap Forward See also: Seven Thousand Cadres Conference This section is an excerpt from Great Leap Forward.[edit]  Rural workers smelting iron during the nighttime in 1958 The major changes which occurred in the lives of rural Chinese people included the incremental introduction of mandatory agricultural collectivization. Private farming was prohibited, and those people who engaged in it were persecuted and labeled counter-revolutionaries. Restrictions on rural people were enforced with public struggle sessions and social pressure, and forced labor was also exacted from people.[11] Rural industrialization, while officially a priority of the campaign, saw "its development ... aborted by the mistakes of the Great Leap Forward".[12] The Great Leap was one of two periods between 1953 and 1976 in which China's economy shrank.[13] Economist Dwight Perkins argues that "enormous amounts of investment only produced modest increases in production or none at all. ... In short, the Great Leap was a very expensive disaster".[14] Rural workers producing steel at night during the Great Leap Forward, 1958 Impact of international tensions and anti-revisionism Main article: Sino-Soviet split In the early 1950s, the PRC and the Soviet Union (USSR) were the world's two largest communist states. Although initially they were mutually supportive, disagreements arose after Nikita Khrushchev took power in the USSR. In 1956, Khrushchev denounced his predecessor Josef Stalin and his policies, and began implementing economic reforms. Mao and many other CCP members opposed these changes, believing that they would damage the worldwide communist movement.[15]: 4–7 Mao believed that Khrushchev was a revisionist, altering Marxist–Leninist concepts, which Mao claimed would give capitalists control of the USSR. Relations soured. The USSR refused to support China's case for joining the United Nations and reneged on its pledge to supply China with a nuclear weapon.[15]: 4–7 Mao publicly denounced revisionism in April 1960. Without pointing at the USSR, Mao criticized its Balkan ally, the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. In turn, the USSR criticized China's Balkan ally, the Party of Labour of Albania.[15]: 7 In 1963, CCP began to denounce the USSR, publishing nine polemics. One was titled On Khrushchev's Phoney Communism and Historical Lessons for the World, in which Mao charged that Khrushchev was a revisionist and risked capitalist restoration.[15]: 7 Khrushchev's defeat by an internal coup d'état in 1964 contributed to Mao's fears, mainly because of his declining prestige after the Great Leap Forward.[15]: 7 Other Soviet actions increased concerns about potential fifth columnists in China.[16]: 141 As a result of the tensions following the Sino-Soviet split, Soviet leaders authorized radio broadcasts into China stating that the Soviet Union would assist "genuine communists" who overthrew Mao and his "erroneous course".[16]: 141 Chinese leadership also feared the increasing military conflict between the United States and North Vietnam, concerned that China's support would lead to the United States to seek out potential Chinese assets.[16]: 141 Precursor See also: Socialist Education Movement and Hai Rui Dismissed from Office  The purge of General Luo Ruiqing solidified the PLA's loyalty to Mao In 1963, Mao launched the Socialist Education Movement, the CR's precursor.[17] Mao set the scene by "cleansing" powerful Beijing officials of questionable loyalty. His approach was not transparent, executed via newspaper articles, internal meetings, and by his network of political allies.[17] In late 1959, historian and deputy mayor of Beijing Wu Han published a historical drama entitled Hai Rui Dismissed from Office. In the play, an honest civil servant, Hai Rui, is dismissed by a corrupt emperor. While Mao initially praised the play, in February 1965, he secretly commissioned his wife Jiang Qing and Shanghai propagandist Yao Wenyuan to publish an article criticizing it.[15]: 15–18 Yao described the play as an allegory attacking Mao; flagging, Mao as the emperor, and Peng Dehuai as the honest civil servant.[15]: 16 Yao's article put Beijing mayor Peng Zhen[note 1] on the defensive. Peng, Wu Han's direct superior, was the head of the "Five Man Group", a committee commissioned by Mao to study the potential for a cultural revolution. Peng Zhen, aware that he would be implicated if Wu indeed wrote an "anti-Mao" play, wished to contain Yao's influence. Yao's article was initially published only in select local newspapers. Peng forbade its publication in the nationally distributed People's Daily and other major newspapers under his control, instructing them to write exclusively about "academic discussion," and not pay heed to Yao's petty politics.[15]: 14–19 While the "literary battle" against Peng raged, Mao fired Yang Shangkun—director of the party's General Office, an organ that controlled internal communications—making unsubstantiated charges. He installed loyalist Wang Dongxing, head of Mao's security detail. Yang's dismissal likely emboldened Mao's allies to move against their factional rivals.[15]: 14–19 On 12 February 1966, the "Five Man Group" issued a report known as the February Outline. The Outline as sanctioned by the party center defined Hai Rui as a constructive academic discussion and aimed to distance Peng Zhen formally from any political implications. However, Jiang Qing and Yao Wenyuan continued their denunciations. Meanwhile, Mao sacked Propaganda Department director Lu Dingyi, a Peng ally.[15]: 20–27 Lu's removal gave Maoists unrestricted access to the press. Mao delivered his final blow to Peng at a high-profile Politburo meeting through loyalists Kang Sheng and Chen Boda. They accused Peng of opposing Mao, labeled the February Outline "evidence of Peng Zhen's revisionism", and grouped him with three other disgraced officials as part of the "Peng-Luo-Lu-Yang Anti-Party Clique."[15]: 20–27 On 16 May, the Politburo formalized the decisions by releasing an official document condemning Peng and his "anti-party allies" in the strongest terms, disbanding his "Five Man Group", and replacing it with the Maoist Cultural Revolution Group (CRG).[15]: 27–35 |

大躍進 こちらもご覧ください: 七千人幹部会議 このセクションは『大躍進』からの抜粋である[編集]。  1958年、夜間に鉄を製錬する農村労働者たち 中国の農村の人々の生活に起こった大きな変化には、強制的な農業集団化の段階的導入が含まれる。私営農業は禁止され、農業に従事する人々は迫害され、反革 命分子のレッテルを貼られた。農村の人々に対する規制は、公開闘争や社会的圧力によって強制され、強制労働もまた人々から強要された[11]。農村の工業 化は、公式にはキャンペーンの優先事項であったが、「その発展は......大躍進の過ちによって頓挫した」[12]。... 要するに、大躍進は非常に高くついた災難だった」[14]。 大躍進期、夜間に鉄鋼を生産する農村労働者(1958年 国際緊張と反改革主義の影響 主な記事 中ソ分裂 1950年代初頭、中国とソ連は世界の2大共産主義国家であった。当初は互いに協力し合っていたが、ニキータ・フルシチョフがソ連で権力を握った後、意見 の相違が生じた。1956年、フルシチョフは前任者ヨシフ・スターリンとその政策を非難し、経済改革を実施し始めた。毛沢東をはじめとする多くの中国共産 党員は、これらの改革が世界の共産主義運動にダメージを与えると考え、反対した[15]: 4-7 毛沢東は、フルシチョフが修正主義者であり、マルクス・レーニン主義の概念を変え、資本家がソ連を支配するようになると考えていた。関係は悪化した。ソ連 は中国の国連加盟を支持することを拒否し、中国に核兵器を供給するという約束を反故にした[15]: 4-7 毛沢東は1960年4月、修正主義を公に非難した。毛沢東はソ連を非難することなく、バルカン半島の同盟国であるユーゴスラビア共産主義者同盟を批判し た。1963年、中国共産党はソ連を糾弾し始め、9つの極論を発表した。そのうちの1冊は、『フルシチョフのインチキ共産主義と世界への歴史的教訓につい て』と題されたもので、毛沢東はフルシチョフが修正主義者であり、資本主義復活の危険性があると告発した[15]: 7 1964年にフルシチョフが内部クーデターによって敗北したことが、毛沢東の恐怖心を煽った。 その他のソ連の行動は、中国における潜在的な第五列主義者に対する懸念を増大させた[16]: 141 中ソ分裂後の緊張の結果、ソ連の指導者たちは、毛沢東と彼の「誤った路線」を打倒する「本物の共産主義者」をソ連が支援するという内容の中国向けラジオ放 送を許可した[16]: 141 中国の指導部もまた、アメリカと北ベトナムとの軍事衝突の激化を恐れており、中国の支援によってアメリカが中国の潜在的な資産を探し出すことを懸念してい た[16]: 141 前兆 以下も参照: 社会主義教育運動と解任された海瑞  羅瑞慶将軍の粛清はPLA(人民解放軍)の毛沢東への忠誠を強固にした 1963年、毛沢東はCRの前身である社会主義教育運動を開始した。彼のやり方は透明性がなく、新聞記事や内部会議、政治的同盟者のネットワークを通じて 実行された[17]。 1959年末、歴史家で北京副市長の呉翰は、『海瑞罷免』というタイトルの歴史劇を発表した。この戯曲では、誠実な公務員である海瑞が腐敗した皇帝によっ て罷免される。毛沢東は当初この戯曲を賞賛していたが、1965年2月、密かに妻の江青と上海の宣伝家姚文源に依頼し、戯曲を批判する論文を発表させた [15]: 15-18姚はこの戯曲を毛沢東を攻撃する寓話であるとし、毛沢東を皇帝に、彭徳懐を誠実な公務員に見立てた[15]: 16 姚の記事は北京市長の彭真[注釈 1]を守勢に立たせた。呉涵の直属の上司である彭は、毛沢東が文化大革命の可能性を調査するために委嘱した委員会「五人組」の長であった。彭真は、呉が本 当に「反毛沢東」の戯曲を書いた場合、自分が巻き込まれることを認識しており、姚の影響力を封じ込めようとした。姚の論文は当初、一部の地方紙にのみ掲載 された。彭は、全国に配布される『人民日報』や彼の支配下にある他の主要な新聞に掲載することを禁じ、「学術的な議論」だけを書くように指示し、姚の小政 治には関心を払わないようにした[15]: 14-19 毛沢東は、彭に対する「文戦」が激化している間に、党内広報を管理する機関である党総署の楊尚昆処長を、根拠のない告発をして解雇した。毛沢東は、毛沢東 に忠誠を誓う王東興を毛沢東の警備隊長に据えた。楊が解任されたことで、毛沢東の盟友たちは派閥のライバルたちに対抗する動きを強めたと思われる [15]: 14-19 1966年2月12日、「五人組」は「二月綱要」として知られる報告書を発表した。党中央が承認した「綱要」は、海瑞を建設的な学術的議論と定義し、彭真 を政治的な意味合いから形式的に遠ざけることを目的としていた。しかし、江青と姚文元は糾弾を続けた。一方、毛沢東は彭の盟友であった宣伝部長の陸鼎儀を 解任した。 呂の解任により、毛沢東は報道機関へのアクセスを無制限にした。毛沢東は、注目された政治局会議で、忠実な政治家である康生と陳保大を通じて、彭に最後の 一撃を加えた。彼らは彭を毛沢東に反対していると非難し、「二月綱要」に「彭真の修正主義の証拠」というレッテルを貼り、失脚した他の3人の幹部とともに 「彭・羅・魯・陽反党閥」の一員としてグループ化した。 「15]: 20-27 5月16日、政治局は、彭とその「反党の盟友」を最も強い言葉で非難し、彼の「五人組」を解散させ、毛沢東文化大革命グループ(CRG)と置き換える公式 文書を発表し、この決定を正式に決定した[15]: 27-35 |

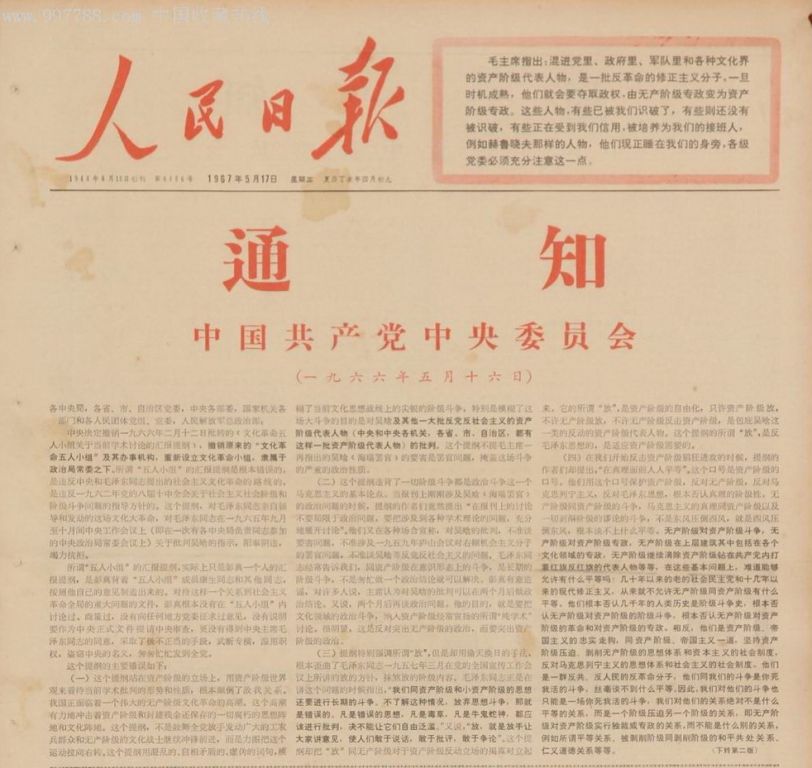

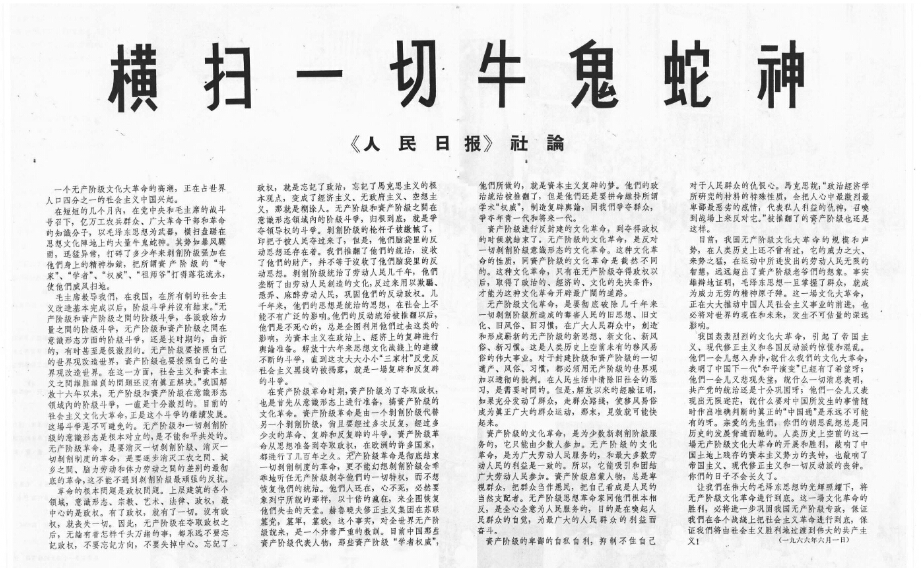

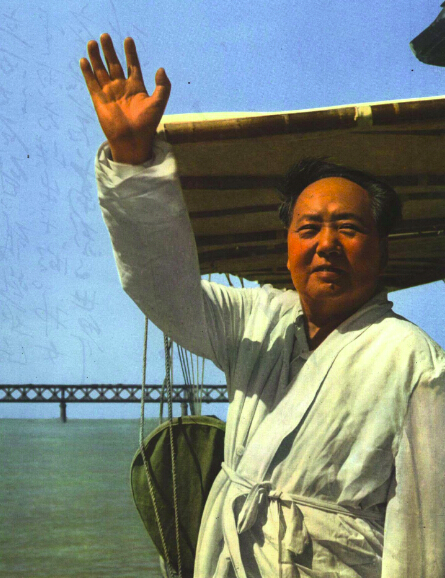

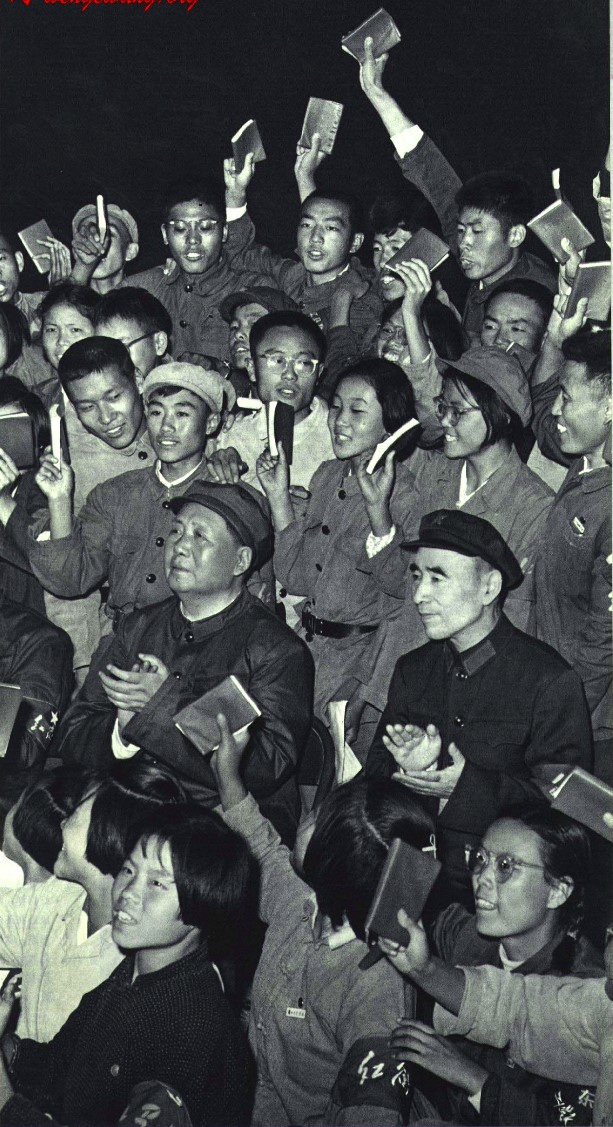

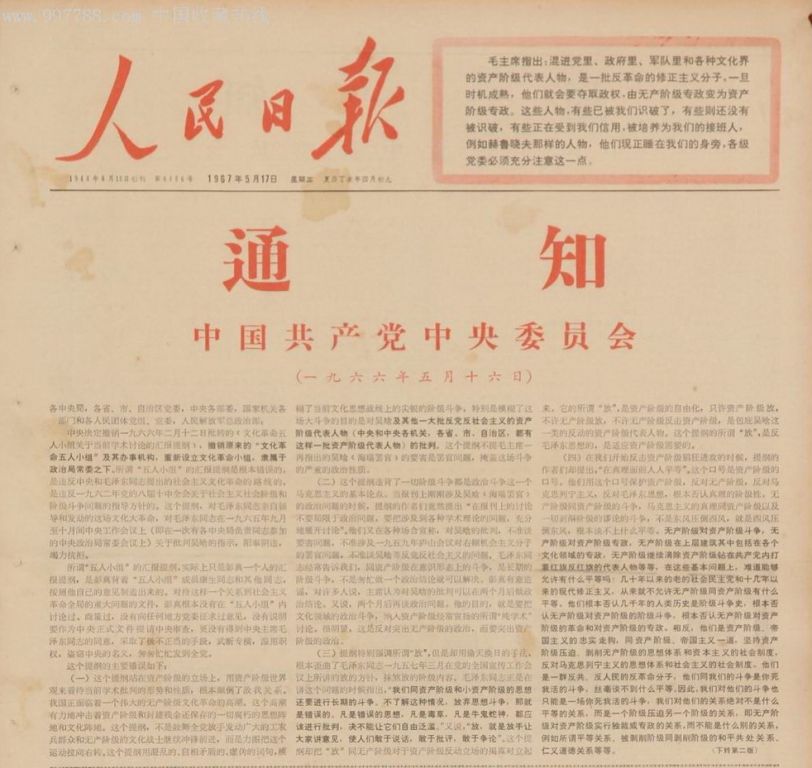

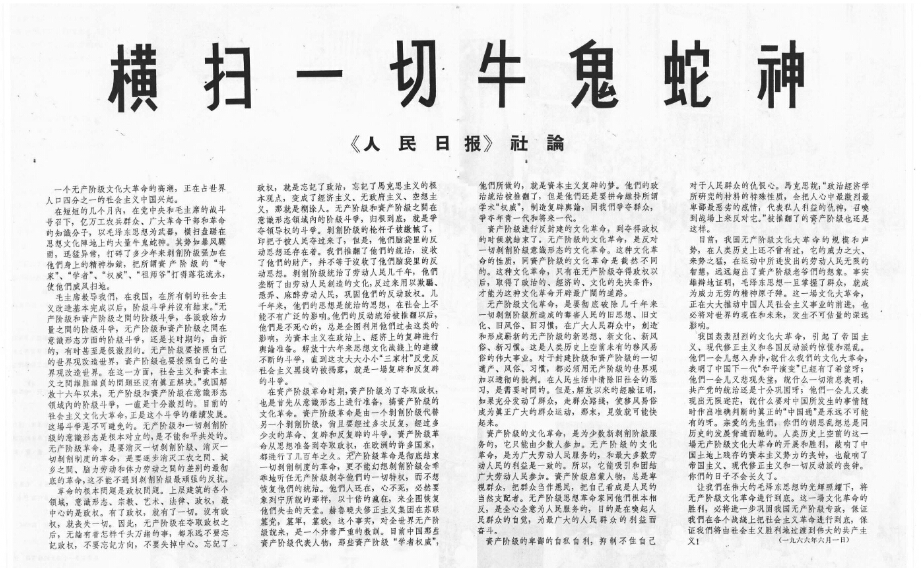

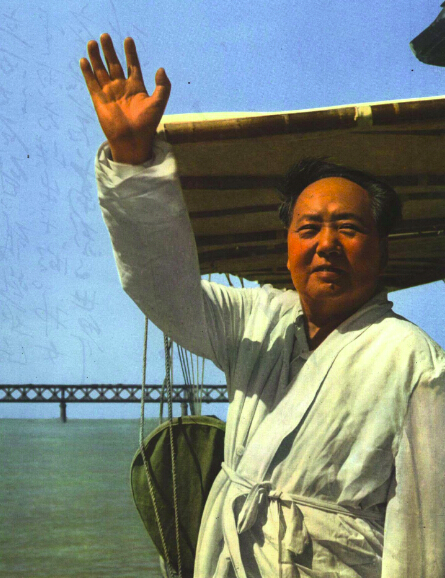

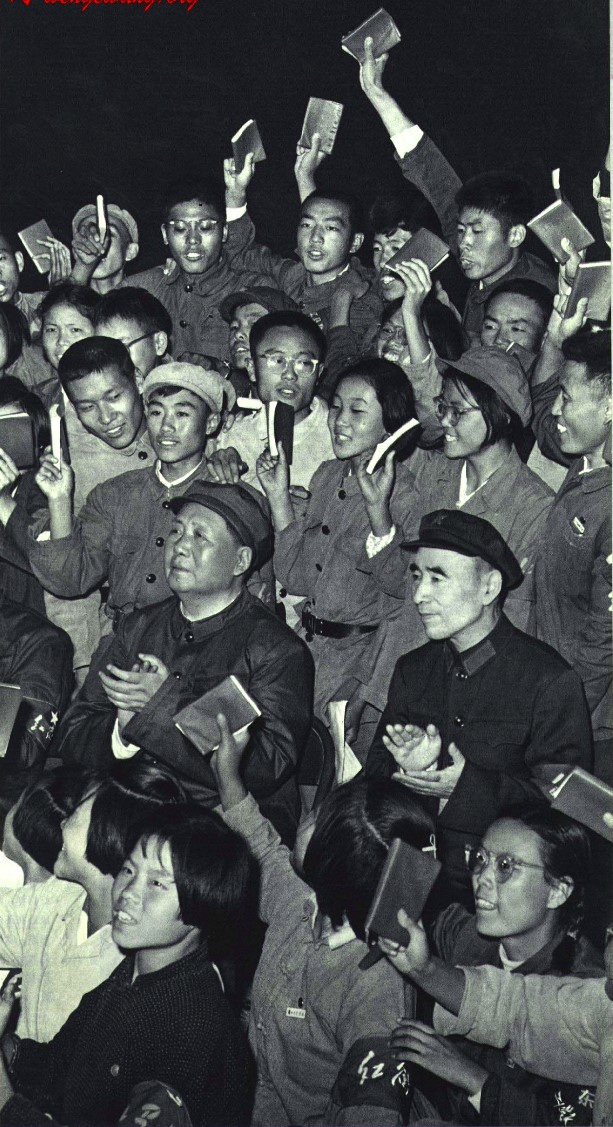

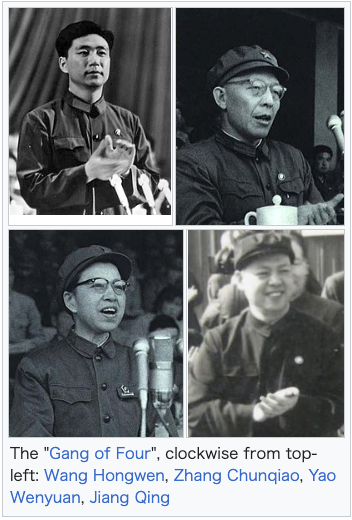

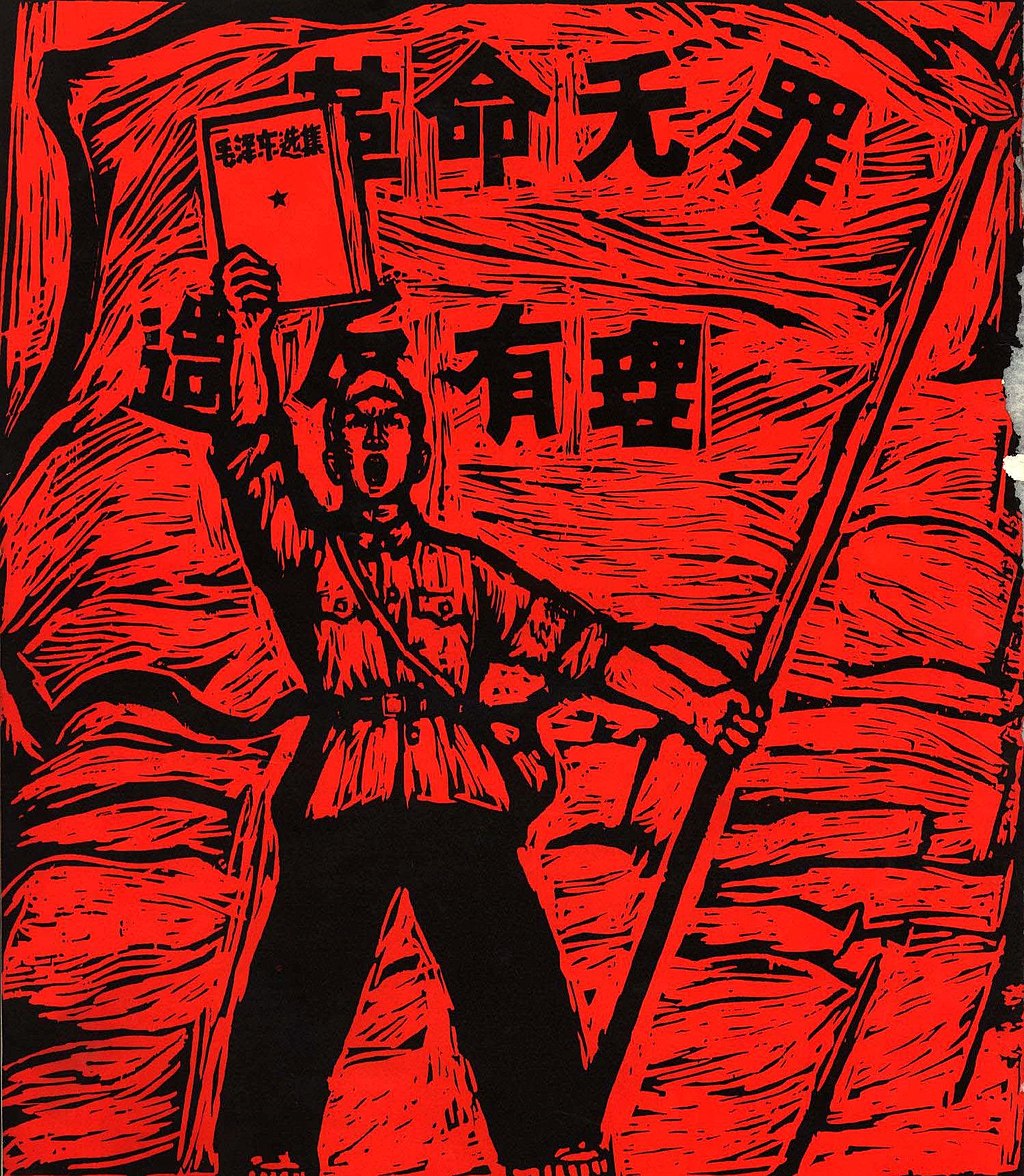

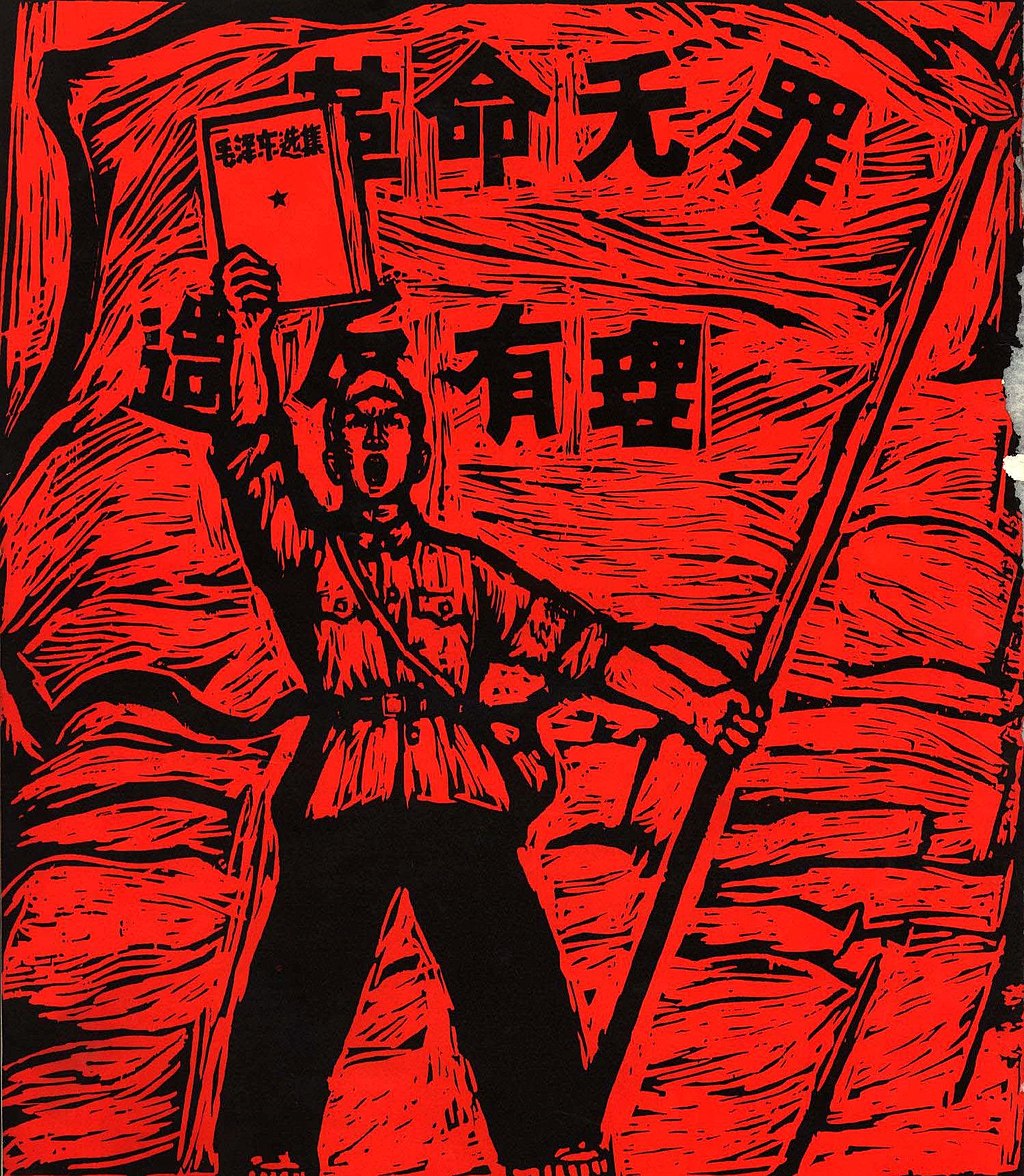

| 1966: Outbreak The Cultural Revolution can be divided into two main periods: spring 1966 to summer 1968 (when most of the key events took place) a tailing period that lasted until fall 1976.[18] The early phase was characterized by mass movement and political pluralization.[18] Virtually anyone could create a political organization, even without party approval.[18] Known as Red Guards, these organizations originally arose in schools and universities and later in factories and other institutions.[18] After 1968, most of these organizations ceased to exist, although their legacies were a topic of controversy later.[18] Notification Main article: 16 May Notification  The 16 May Notification In May 1966, an expanded session of the Politburo was called in Beijing. The conference was laden with Maoist political rhetoric on class struggle and filled with meticulously prepared 'indictments' of recently ousted leaders such as Peng Zhen and Luo Ruiqing. One of these documents, distributed on 16 May, was prepared with Mao's personal supervision and was particularly damning:[15]: 39-40 Those representatives of the bourgeoisie who have sneaked into the Party, the government, the army, and various spheres of culture are a bunch of counter-revolutionary revisionists. Once conditions are ripe, they will seize political power and turn the dictatorship of the proletariat into a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. Some of them we have already seen through; others we have not. Some are still trusted by us and are being trained as our successors, persons like Khrushchev for example, who are still nestling beside us.[15]: 47 Later known as the "16 May Notification", this document summarized Mao's ideological justification for CR.[15]: 40 Initially kept secret, distributed only among high-ranking party members, it was later declassified and published in People's Daily on 17 May 1967.[15]: 41 Effectively it implied that enemies of the Communist cause could be found within the Party: class enemies who "wave the red flag to oppose the red flag." The only way to identify these people was through "the telescope and microscope of Mao Zedong Thought."[15]: 46 While the party leadership was relatively united in approving Mao's agenda, many Politburo members were not enthusiastic, or simply confused about the direction.[19]: 13 The charges against party leaders such as Peng disturbed China's intellectual community and the eight non-Communist parties.[15]: 41 Mass rallies (May–June)  "Sweep Away All Cow Demons and Snake Spirits", an editorial published on the front page of People's Daily on 1 June 1966, calling for the proletariat to "completely eradicate" the "Four Olds [...] that have poisoned the people of China for thousands of years, fostered by the exploiting classes".[20]: 50- After the purge of Peng Zhen, the Beijing Party Committee effectively ceased to function, paving the way for disorder in the capital. On 25 May, under the guidance of Cao Yi'ou [zh]—wife of Mao loyalist Kang Sheng—Nie Yuanzi, a philosophy lecturer at Peking University, authored a big-character poster along with other leftists and posted it to a public bulletin. Nie attacked the university's party administration and its leader Lu Ping.[15]: 56–58 Nie insinuated that the university leadership, much like Peng, were trying to contain revolutionary fervor in a "sinister" attempt to oppose the party and advance revisionism.[15]: 56–58 Mao promptly endorsed Nie's poster as "the first Marxist big-character poster in China". Approved by Mao, the poster rippled across educational institutions. Students began to revolt against their school's party establishments. Classes were cancelled in Beijing primary and secondary schools, followed by a decision on 13 June to expand the class suspension nationwide.[15]: 59–61 By early June, throngs of young demonstrators lined the capital's major thoroughfares holding giant portraits of Mao, beating drums, and shouting slogans.[15]: 59–61 When the dismissal of Peng and the municipal party leadership became public in early June, confusion was widespread. The public and foreign missions were kept in the dark on the reason for Peng's ousting.[15]: 62–64 Top Party leadership was caught off guard by the sudden protest wave and struggled with how to respond.[15]: 62–64 After seeking Mao's guidance in Hangzhou, Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping decided to send in 'work teams'—effectively 'ideological guidance' squads of cadres—to the city's schools and People's Daily to restore some semblance of order and re-establish party control.[15]: 62–64 The work teams had a poor understanding of student sentiment. Unlike the political movement of the 1950s that squarely targeted intellectuals, the new movement was focused on established party cadres, many of whom were part of the work teams. As a result, the work teams came under increasing suspicion as thwarting revolutionary fervor.[15]: 71 Party leadership subsequently became divided over whether or not work teams should continue. Liu Shaoqi insisted on continuing work-team involvement and suppressing the movement's most radical elements, fearing that the movement would spin out of control.[15]: 75  Bombard the Headquarters (July) Mao–Liu conflict Mao Zedong, Chairman Liu Shaoqi, President In 1966, Mao broke with Liu Shaoqi (right), then serving as President, over the work-teams issue. Mao's polemic Bombard the Headquarters was widely recognized as targeting Liu, the purported "bourgeois" party headquarters ++++++++++++++ Bombard The Headquarters – My Big-Character Poster (Chinese: 炮打司令部——我的一张大字报; pinyin: Pào dǎ sīlìng bù——wǒ de yī zhāng dàzì bào) was a short document written by Chairman Mao Zedong on August 5, 1966, during the 11th Plenary Session of the 8th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, and published in the Communist Party's official newspaper People's Daily a year later, on August 5, 1967. It is commonly believed that this "big-character poster" directly targeted Chinese President Liu Shaoqi and senior leader Deng Xiaoping, who were then in charge of the Chinese government's daily affairs and who tried to cool down the mass movement which had been coming into shape in several universities in Beijing since the May 16 Notice, through which Mao officially launched the Cultural Revolution, was issued. Many larger-scale mass persecutions followed the publication of this big-character poster, resulting in turmoil throughout the country and the death of thousands of "class enemies", including President Liu Shaoqi. English translation: China's first Marxist-Leninist big-character poster and Commentator's article on it in People's Daily are indeed superbly written! Comrades, please read them again. But in the last fifty days or so some leading comrades from the central down to the local levels have acted in a diametrically opposite way. Adopting the reactionary stand of the bourgeoisie, they have enforced a bourgeois dictatorship and struck down the surging movement of the Great Cultural Revolution of the proletariat. They have stood facts on their head and juggled black and white, encircled and suppressed revolutionaries, stifled opinions differing from their own, imposed a white terror, and felt very pleased with themselves. They have puffed up the arrogance of the bourgeoisie and deflated the morale of the proletariat. How poisonous! Viewed in connection with the Right deviation in 1962 and the wrong tendency of 1964 which was 'Left' in form but Right in essence, shouldn't this make one wide awake? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombard_the_Headquarters ++++++++++++++++++  Mao waves to the crowd on the banks of the Yangtze before his swim across, July 1966 In Beijing Mao criticized party leadership for its handling of the work-teams issue. Mao accused the work teams of undermining the student movement, calling for their full withdrawal on July 24. Several days later a rally was held at the Great Hall of the People to announce the decision and reveal the tone of the movement to teachers and students. At the rally, Party leaders told the masses assembled to 'not be afraid' and bravely take charge of the movement, free of Party interference.[15]: 84 The work-teams issue marked a decisive defeat for Liu politically; it also signaled that disagreement over how to handle the CR's unfolding events would irreversibly split Mao from the party leadership. On 1 August, the Eleventh Plenum of the 8th Central Committee was convened to advance Mao's radical agenda. At the plenum, Mao showed outright disdain for Liu, repeatedly interrupting him as he delivered his opening day speech.[15]: 94 For several days, Mao repeatedly insinuated that the party's leadership had contravened his revolutionary vision. Mao's line of thinking received a lukewarm reception from conference attendees. Sensing that the largely obstructive party elite was unwilling to embrace his revolutionary ideology on a full scale, Mao went on the offensive.[citation needed] Red Guards in Beijing From left: (1) Students at Beijing Normal University making big-character posters denouncing Liu Shaoqi; (2) Big-characters posted at Peking University; (3) Students at No. 23 Middle School in Beijing reading People's Daily during the "Resume Classes" campaign On July 28, Red Guard representatives wrote to Mao, calling for rebellion and upheaval to safeguard the revolution. Mao then responded to the letters by writing his own big-character poster entitled Bombard the Headquarters, rallying people to target the "command centre (i.e., Headquarters) of counterrevolution." Mao wrote that despite having undergone a communist revolution, a "bourgeois" elite was still thriving in "positions of authority" in the government and Communist Party.[21] Although no names were mentioned, this provocative statement by Mao has been interpreted as a direct indictment of the party establishment under Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping—the purported "bourgeois headquarters" of China. The personnel changes at the Plenum reflected a radical re-design of the party's hierarchy to suit this new ideological landscape. Liu and Deng kept their seats on the Politburo Standing Committee but were in fact sidelined from day-to-day party affairs. Lin Biao was elevated to become the CCP's number-two figure; Liu Shaoqi's rank went from second to eighth and was no longer Mao's heir apparent.[21]  A struggle session targeting Liu Shaoqi's wife Wang Guangmei Coinciding with the top leadership being thrown out of positions of power was the thorough undoing of the entire national bureaucracy of the Communist Party. The extensive Organization Department, in charge of party personnel, virtually ceased to exist. The Cultural Revolution Group (CRG), Mao's ideological 'Praetorian Guard', was catapulted to prominence to propagate his ideology and rally popular support. The top officials in the Propaganda Department were sacked, with many of its functions folding into the CRG.[15]: 96 Red August and the Sixteen Points Main article: Red August  Mao and Lin Biao surrounded by rallying Red Guards in Beijing, December 1966 The Little Red Book was the mechanism that led the Red Guards to commit to their objective as the future for China. These quotes directly from Mao led to other actions by the Red Guards in the views of other Maoist leaders,[15]: 107 and by December 1967, 350 million copies of the book had been printed.[22]: 61–64 Quotations in the Little Red Book that the Red Guards would later follow as a guide, provided by Mao, included the famous "Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun." The passage goes on: Revolutionary war is an antitoxin which not only eliminates the enemy's poison but also purges us of our filth. Every just, revolutionary war is endowed with tremendous power and can transform many things or clear the way for their transformation. The Sino-Japanese war will transform both China and Japan; Provided China perseveres in the War of Resistance and in the united front, the old Japan will surely be transformed into a new Japan and the old China into a new China, and people and everything else in both China and Japan will be transformed during and after the war. The world is yours, as well as ours, but in the last analysis, it is yours. You young people, full of vigor and vitality, are in the bloom of life, like the sun at eight or nine in the morning. Our hope is placed on you ... The world belongs to you. China's future belongs to you. During the Red August of Beijing, on August 8, 1966, the party's General Committee passed its "Decision Concerning the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution," later to be known as the "Sixteen Points."[23] This decision defined the Cultural Revolution as "a great revolution that touches people to their very souls and constitutes a deeper and more extensive stage in the development of the socialist revolution in our country:"[24] Although the bourgeoisie has been overthrown, it is still trying to use the old ideas, culture, customs, and habits of the exploiting classes to corrupt the masses, capture their minds, and stage a comeback. The proletariat must do just the opposite: It must meet head-on every challenge of the bourgeoisie ... to change the outlook of society. Currently, our objective is to struggle against and crush those people in authority who are taking the capitalist road, to criticize and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic "authorities" and the ideology of the bourgeoisie and all other exploiting classes and to transform education, literature and art, and all other parts of the superstructure that do not correspond to the socialist economic base, so as to facilitate the consolidation and development of the socialist system. The implications of the Sixteen Points were far-reaching. It elevated what was previously a student movement to a nationwide mass campaign that would galvanize workers, farmers, soldiers and lower-level party functionaries to rise, challenge authority, and re-shape the "superstructure" of society. Tiananmen Square on 15 September 1966, the occasion of Chairman Mao's third of eight mass rallies with Red Guards in 1966.[25] On 18 August in Beijing, over a million Red Guards from all over the country gathered in and around Tiananmen Square for a personal audience with the chairman.[15]: 106–07 Mao personally mingled with Red Guards and encouraged their motivation, donning a Red Guard armband himself.[19]: 66 Lin Biao also took centre stage at the August 18 rally, vociferously denouncing all manner of perceived enemies in Chinese society that were impeding the "progress of the revolution."[19]: 66 Subsequently, violence significantly escalated in Beijing and quickly spread to other areas of China.[26][27] On 22 August, a central directive was issued to stop police intervention in Red Guard activities, and those in the police force who defied this notice were labeled counter-revolutionaries.[15]: 124 Mao's praise for rebellion encouraged actions of the Red Guards.[15]: 515 Central officials lifted restraints on violent behavior in support of the revolution.[15]: 126 Xie Fuzhi, the national police chief, often pardoned Red Guards for their "crimes."[15]: 125 In about two weeks, the violence left some 100 officials of the ruling and middle class dead in Beijing's western district alone. The number injured exceeded that.[15]: 126 The most violent aspects of the campaign included incidents of torture, murder, and public humiliation. Many people who were indicted as counter-revolutionaries died by suicide. During the Red August 1966, in Beijing alone 1,772 people were murdered; many of the victims were teachers who were attacked and even killed by their own students.[28] In Shanghai, there were 704 suicides and 534 deaths related to the Cultural Revolution in September. In Wuhan, there were 62 suicides and 32 murders during the same period.[15]: 124 Peng Dehuai was brought to Beijing to be publicly ridiculed. Destruction of the Four Olds (August–November) Main article: Four Olds  The remains of Wanli Emperor at the Ming tombs. Red Guards dragged the remains of the Wanli Emperor and Empresses to the front of the tomb, where they were posthumously "denounced" and burned[29] Between August and November 1966, eight mass rallies were held in which over 12 million people from all over the country, most of whom were Red Guards, participated.[15]: 106 The government bore the expenses of Red Guards traveling around the country exchanging "revolutionary experiences".[15]: 110 At the Red Guard rallies, Lin Biao also called for the destruction of the "Four Olds"; namely, old customs, culture, habits, and ideas.[19]: 66 A revolutionary fever swept the country by storm, with Red Guards acting as its most prominent warriors. Some changes associated with the "Four Olds" campaign were mainly benign, such as assigning new names to city streets, places, and even people; millions of babies were born with "revolutionary"-sounding names during this period.[30] Other aspects of Red Guard activities were more destructive, particularly in the realms of culture and religion. Various historical sites throughout the country were destroyed. The damage was particularly pronounced in the capital, Beijing. Red Guards also laid siege to the Temple of Confucius in Qufu,[15]: 119 and numerous other historically significant tombs and artifacts.[31] Libraries full of historical and foreign texts were destroyed; books were burned. Temples, churches, mosques, monasteries, and cemeteries were closed down and sometimes converted to other uses, looted, and destroyed.[32] Marxist propaganda depicted Buddhism as superstition, and religion was looked upon as a means of hostile foreign infiltration, as well as an instrument of the ruling class.[33] Clergy were arrested and sent to camps; many Tibetan Buddhists were forced to participate in the destruction of their monasteries at gunpoint.[33] The cemetery of Confucius was attacked by Red Guards in November 1966.[31][34] The cemetery of Confucius was attacked by Red Guards in November 1966.[31][34] This statue of the Yongle Emperor was originally carved in stone, and was destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. A metal replica is in its place. This statue of the Yongle Emperor was originally carved in stone, and was destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. A metal replica is in its place. The remains of the 8th century Buddhist monk Huineng were attacked during the Cultural Revolution. The remains of the 8th century Buddhist monk Huineng were attacked during the Cultural Revolution. A frieze damaged during the Cultural Revolution, originally from a garden house of a rich imperial official in Suzhou. A frieze damaged during the Cultural Revolution, originally from a garden house of a rich imperial official in Suzhou. Central Work Conference (October) In October 1966, Mao convened a "Central Work Conference", mostly to convince those in the party leadership who had not yet adopted revolutionary ideology. Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping were prosecuted as part of a bourgeois reactionary line and begrudgingly gave self-criticisms.[15]: 137 After the conference, Liu, once a powerful moderate pundit of the ruling class, was placed under house arrest in Beijing, then sent to a detention camp, where he was denied medical treatment and died in 1969. Deng Xiaoping was sent away for a period of re-education three times and was eventually sent to work in an engine factory in Jiangxi. Rebellion by party cadres accelerated after the conference.[35] End of the year In Macau, rioting broke out during the 12-3 incident.[36]: 84 The event was prompted by the colonial government's delays in approving a new wing for a Communist Party elementary school in Taipa.[36]: 84 The school board illegally began construction and the colonial government sent police to stop the workers; several people were injured in the resulting conflict.[36]: 84 On December 3, 1966, two days of rioting occurred in which hundreds were injured and six[36]: 84 to eight people were killed, leading also to a total backing down by the Portuguese government.[37] The event set in motion Portugal's de facto abdication of control over Macau, putting Macau on the path to eventual decolonization.[36]: 84–85 1967: Seizure of power See also: Seizure of power (Cultural Revolution), Violent struggle, and Rebel faction (Cultural Revolution)  PLA officers and soldiers reading books for the "Three Supports and Two Militaries", 1968 Mass organizations in China roughly coalesced into two hostile factions, the radicals who backed Mao's purge of the Communist party, and the conservatives who backed the moderate party establishment. The "support the left" policy was established in late January 1967.[38] As conceived by Mao, the policy was intended to support the rebels in seizing power; it required the People's Liberation Army (PLA) to support "the broad masses of the revolutionary leftists in their struggle to seize power."[38] In March 1967, the policy was adapted into the "Three Supports and Two Militaries" initiative, in which PLA troops were sent to schools and work units across the country in an effort to stabilize political tumult and end factional warfare.[39]: 345 The three "Supports" were to "support the left", "support the interior", "support industry". The "two Militaries" referred to "military management" and "military training".[39]: 345 The policy of supporting the left was flawed from inception by its failure to define "leftists" at a time when almost all mass organizations claimed to be "leftist" or "revolutionary".[38] The PLA commanders had developed close working relations with the party establishment, many military units worked to repress radicals.[40] Spurred by the events in Beijing, "power seizure groups" formed across the country and began expanding into factories and the countryside. In Shanghai, a young factory worker named Wang Hongwen organized a far-reaching revolutionary coalition, one that galvanized and displaced existing Red Guard groups. On January 3, 1967, with support from CRG heavyweights Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan, the group of firebrand activists overthrew the Shanghai municipal government under Chen Pixian in what became known as the "January Storm," and formed in its place the Shanghai People's Commune.[41][22]: 115  Rebel factions of Red Guards marching in Shanghai, 1967 Shanghai's was the first provincial level government overthrown.[42] Within days, Mao expressed his approval.[42] Provincial governments and many parts of the state and party bureaucracy were affected, with power seizures taking place in a remarkably different fashion. In the next three weeks, 24 more province-level governments were overthrown.[42] "Revolutionary committees" were subsequently established, in place of local governments and branches of the Communist Party.[43] For example, in Beijing, three separate revolutionary groups declared power seizures on the same day, while in Heilongjiang, the local party secretary Pan Fusheng seized power from the party organization under his own leadership. Some leaders even wrote the CRG asking to be overthrown.[15]: 170–72 In Beijing, Jiang Qing and Zhang Chunqiao made a target out of Vice-Premier Tao Zhu. The power-seizure movement was rearing its head in the military as well. In February, prominent generals Ye Jianying and Chen Yi, as well as Vice-Premier Tan Zhenlin, vocally asserted their opposition to the more extreme aspects of the movement, with some party elders insinuating that the CRG's real motives were to remove the revolutionary old guard. Mao, initially ambivalent, took to the Politburo floor on February 18 to denounce the opposition directly, giving a full-throated endorsement to the radicals' activities. This short-lived resistance was branded the "February Countercurrent"[15]: 195–96 —effectively silencing critics of the movement within the party in the years to come.[19]: 207–09 Red Guards marching in Guizhou, 1967. The banner in the center reads: "The People's Liberation Army firmly supports the proletarian revolutionary faction." Although in early 1967 popular insurgencies were still limited outside of the biggest cities, local governments nonetheless began collapsing all across China.[44]: 21 While revolutionaries dismantled ruling government and party organizations all over the country, because power seizures lacked centralized leadership, it was no longer clear who truly believed in Mao's revolutionary vision and who was opportunistically exploiting the chaos for their own gain. The formation of rival revolutionary groups, some manifestations of long-established local feuds, led to violent struggles between factions emerging across the country. Tension grew between mass organizations and the military as well. In response, Lin Biao issued a directive for the army to aid the radicals. At the same time, the army took control of some provinces and locales that were deemed incapable of sorting out their own power transitions.[19]: 219–21 In the central city of Wuhan, like in many other cities, two major revolutionary organizations emerged, one supporting the conservative establishment and the other opposed to it. The groups fought over the control of the city. Chen Zaidao, the Army general in charge of the area, forcibly repressed the anti-establishment demonstrators who were backed by Mao. However, during the commotion, Mao himself flew to Wuhan with a large entourage of central officials in an attempt to secure military loyalty in the area. On July 20, 1967, local agitators in response kidnapped Mao's emissary Wang Li, in what became known as the Wuhan Incident. Subsequently, Gen. Chen Zaidao was sent to Beijing and tried by Jiang Qing and the rest of the Cultural Revolution Group. Chen's resistance was the last major open display of opposition to the movement within the PLA.[15]: 214 The Gang of Four's Zhang Chunqiao, admitted that the most crucial factor in the Cultural Revolution was not the Red Guards or the Cultural Revolution Group or the "rebel worker" organisations, but the side on which the PLA stood. When the PLA local garrison supported Mao's radicals, they were able to take over the local government successfully, but if they were not cooperative, the seizures of power were unsuccessful.[15]: 175 Violent clashes virtually occurred in all cities, according to one historian.[citation needed] In response to the Wuhan Incident, Mao and Jiang Qing began establishing a "workers' armed self-defense force", a "revolutionary armed force of mass character" to counter what he estimated as rightism in "75% of the PLA officer corps." Chongqing city, a center of arms manufacturing, was the site of ferocious armed clashes between the two factions, with one construction site in the city estimated to involve 10,000 combatants with tanks, mobile artillery, anti-aircraft guns and "virtually every kind of conventional weapon." Ten thousand artillery shells were fired in Chongqing during August 1967.[15]: 214–15 Nationwide, a total of 18.77 million firearms, 14,828 artillery pieces, 2,719,545 grenades ended up in civilian hands. They were used in the course of violent struggles ,which mostly took place from 1967 to 1968. In the cities of Chongqing, Xiamen, and Changchun, tanks, armored vehicles and even warships were deployed in combat.[40] |

1966: 勃発 文化大革命は大きく2つの時期に分けられる: 1966年春から1968年夏(重要な出来事のほとんどが起こった時期) 1976年秋まで続いた尾を引く時期[18]。 初期段階は大衆運動と政治的多元化が特徴であった[18]。 党の承認がなくても、事実上誰でも政治組織を創設することができた[18]。紅衛兵として知られるこれらの組織は、当初は学校や大学で、後には工場やその 他の施設で生まれた[18]。1968年以降、これらの組織のほとんどは消滅したが、その遺産は後に論争の的となった[18]。 通知 主な記事 5月16日通達  5月16日通達 1966年5月、政治局の拡大会議が北京で招集された。この会議には、階級闘争に関する毛沢東主義的な政治的レトリックがふんだんに盛り込まれ、彭真や羅 瑞慶といった最近失脚した指導者たちに対する、綿密に準備された「告発状」で埋め尽くされた。5月16日に配布されたこれらの文書のひとつは、毛沢東の個 人的な監督下で作成されたもので、特に非難されるべきものであった[15]: 39-40 党、政府、軍隊、文化の諸領域に潜り込んでいるブルジョアジーの代表者 たちは、反革命修正主義者の集団である。ひとたび条件が整えば、彼らは政治権力を掌 握し、プロレタリアートの独裁をブルジョアジーの独裁に変えるであろう。われわれがすでに見破っている者もいれば、見破っていない者もいる。例えば、フル シチョフのような人物は、まだわれわれのそばに寄り添っている: 47 後に「5月16日通達」として知られるこの文書は、毛沢東の文化大革命に対するイデオロギー的正当性を要約したものである[15]: 40 初めは秘密にされ、高位の党員にのみ配布されたが、後に機密扱いが解除され、1967年5月17日に人民日報に掲載された[15]: 41 それは事実上、共産主義の大義に対する敵が党内にいることを暗示していた。「赤い旗に反対するために赤い旗を振る」階級の敵である。これらの人々を識別す る唯一の方法は、「毛沢東思想の望遠鏡と顕微鏡」[15]を通すことであった: 46 党指導部は毛沢東のアジェンダを承認することで比較的一致していたが、多くの政治局員は熱心ではなく、あるいは単に方向性に戸惑っていた[19]: 13 彭のような党指導者に対する告発は、中国の知識人社会と非共産党8党を不安にさせた[15]: 41 大規模集会(5月~6月)  1966年6月1日、人民日報の一面に掲載された社説「すべての牛鬼と蛇霊を一掃せよ」は、プロレタリアートに対し、搾取階級によって育まれ、何千年もの 間、中国人民を毒してきた「四老[...]」を「完全に根絶」するよう呼びかけた[20]: 50- 彭真の粛清後、北京市党委員会は事実上機能しなくなり、首都の無秩序に道を開いた。5月25日、毛沢東に忠誠を誓う姜尚中の妻である曹義応の指導のもと、 北京大学の哲学講師であった聶元子は、他の左翼とともに大文字のポスターを作成し、公共の掲示板に掲載した。聶は大学の党政権とその指導者である呂平を攻 撃した[15]: 56-58 謝は、大学指導部は彭と同じように、党に反対し修正主義を前進させようとする「不吉な」試みで革命熱を封じ込めようとしているとほのめかした[15]: 56-58 毛沢東は、聶のポスターを「中国初のマルクス主義大文字ポスター」として即座に承認した。毛沢東によって承認されたこのポスターは、教育機関全体に波及し た。学生たちは学校の党組織に反旗を翻し始めた。北京の小中学校では授業が中止され、6月13日には授業停止を全国に拡大することが決定された[15]: 59-61 6月初旬までに、若いデモ隊の群れが毛沢東の巨大な肖像画を掲げ、太鼓を打ち鳴らし、スローガンを叫びながら首都の大通りに並んだ[15]: 59-61 6月上旬に彭と市党指導部の解任が公になると、混乱が広がった。一般市民と外国公館は、彭の更迭の理由を知らされていなかった[15]: 62-64 党指導部は突然の抗議の波に不意を突かれ、どう対応すべきか苦慮した。 [15]: 62-64 劉少奇と鄧小平は、杭州で毛沢東の指導を仰いだ後、「作業チーム」(事実上「思想指導」部隊)を市内の学校と人民日報社に派遣し、秩序を取り戻し、党の統 制を再確立することを決定した。 作業チームは学生の感情をよく理解していなかった。知識人を正面から標的にした1950年代の政治運動とは異なり、新しい運動は既成の党幹部に焦点を当て たものであり、その多くは作業チームの一員であった。その結果、工作チームは革命の熱狂を妨げているのではないかという疑惑の目を向けられるようになった [15]。劉少奇は、運動が制御不能になることを恐れ、作業チームの関与を継続し、運動の最も急進的な要素を弾圧することを主張した[15]: 75。  本部を砲撃せよ(7月) 毛沢東衝突 毛沢東(主席 劉少奇(主席 1966年、毛沢東は作業チーム問題をめぐり、当時主席を務めていた劉少奇(右)と対立。毛沢東の「党本部を砲撃せよ」という極論は、「ブルジョア」とさ れる党本部の劉を標的にしたものとして広く認識された。 ++++++++++++++ 『大本営砲撃-私の大文字ポスター』(中国語:炮打司令部--我的一张大字报;ピンイン: Pào dǎ sīlìng bù--wǒ de yī zhāng dàzì bào)は、毛沢東主席が1966年8月5日、中国共産党第8期中央委員会第11回全体会議で書き、1年後の1967年8月5日に共産党機関紙『人民日 報』に発表した短い文書である。 この「大文字ポスター」は、毛沢東が文化大革命を正式に開始した「5・16通達」以降、北京のいくつかの大学で具体化しつつあった大衆運動を沈静化させよ うとした、当時の中国政府の日常業務を担当していた劉少奇国家主席と鄧小平先輩を直接の標的としたものだと一般に考えられている。 この大書ポスターの発表後、多くの大規模な集団迫害が行われ、その結果、中国全土が混乱し、劉少奇国家主席を含む数千人の「階級の敵」が死亡した。 原文: 全国第一张马列主义的大字报和人民日报评论员的评论,写得何等好呵!请同志们重读这一张大字报和这个评论。可是在50多天里,从中央到地方的某些领导同 志,却反其道而行之,站在反动的资产阶级立场上,实行资产阶级专政,将无产阶级轰轰烈烈的文化大革命运动打下去,颠倒是非,混淆黑白,围剿革命派,压制不 同意见,实行白色恐怖,自以为得意,长资产阶级的威风,灭无产阶级的志气,又何其毒也!联想到1962年的右倾和1964年形“左”实右的错误倾向,岂不 是可以发人深醒的吗?[1] 英訳: 中国初のマルクス・レーニン主義的大文字ポスターと、それに関する人民日報の解説記事は、実に見事な文章である!同志諸君、もう一度読んでほしい。しか し、ここ50日ほどの間に、中央から地方に至るまで、一部の指導的な同志たちが正反対の行動をとった。彼らは、ブルジョアジーの反動的立場を採用し、ブル ジョア独裁を強行し、プロレタリアートの文化大革命の高揚する運動を打ちのめした。彼らは、事実を逆立ちさせ、黒と白を錯綜させ、革命家を包囲し、弾圧 し、自分たちと異なる意見を封じ込め、白い恐怖を押しつけ、自分たちに大満足している。彼らは、ブルジョアジーの傲慢さを膨れ上がらせ、プロレタリアート の士気を萎えさせた。なんと毒々しいことか!1962年の右派の逸脱や、形式的には「左派」だが本質的には右派であった1964年の誤った傾向との関連で 見れば、このことは人を大きく覚醒させるべきではないだろうか。 英訳: 中国初のマルクス・レーニン主義的大文字ポスターと、それに関する人民 日報の解説記事は、実に見事な文章である!同志諸君、もう一度読んでほしい。しかし、ここ50日ほどの間に、中央から地方に至るまで、一部の指導的な同志 たちが正反対の行動をとった。彼らは、ブルジョアジーの反動的立場を採用し、ブルジョア独裁を強行し、プロレタリアートの文化大革命の高揚する運動を打ち のめした。彼らは、事実を逆立ちさせ、黒と白を錯綜させ、革命家を包囲し、弾圧し、自分たちと異なる意見を封じ込め、白い恐怖を押しつけ、自分たちに大満 足している。彼らは、ブルジョアジーの傲慢さを膨れ上がらせ、プロレタリアートの士気を萎えさせた。なんと毒々しいことか!1962年の右派の逸脱や、形 式的には「左派」だが本質的には右派であった1964年の誤った傾向との関連で見れば、このことは人を大きく覚醒させるべきではないだろうか。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombard_the_Headquarters ++++++++++++++++  泳いで渡る前に長江のほとりで群衆に手を振る毛沢東(1966年7月) 北京で毛沢東は、党指導部の作業チーム問題への対応を批判した。毛沢東は、作業班が学生運動を弱体化させていると非難し、7月24日に作業班の完全撤退を 呼びかけた。数日後、人民大会堂で集会が開かれ、この決定を発表し、教師と学生に運動の基調を明らかにした。この集会で党幹部は、集まった大衆に「恐れ ず」、党の干渉を受けずに勇敢に運動の主導権を握るよう呼びかけた[15]: 84。 作業チーム問題は、劉にとって政治的に決定的な敗北となった。それはまた、CRの展開にどう対処すべきかをめぐる意見の相違が、毛沢東を党指導部から不可 逆的に分裂させることを示すものでもあった。8月1日、毛沢東の急進的なアジェンダを推進するために、第8期中央委員会第11回全体会議が招集された。全 体会議で毛沢東は、劉が初日の演説をするのを何度も遮り、劉を軽蔑していた[15]: 94。 数日間、毛沢東は、党の指導部が自分の革命的ビジョンに反していると繰り返しほのめかした。毛沢東の考え方は、会議の出席者たちから生ぬるい歓迎を受け た。妨害的な党のエリートたちが、彼の革命思想を全面的に受け入れようとしないことを察知した毛沢東は、攻勢に転じた[要出典]。 北京の紅衛兵 左から:(1)劉少奇を糾弾する大文字のポスターを作る北京師範大学の学生、(2)北京大学に貼られた大文字、(3)「授業再開」キャンペーンで人民日報 を読む北京市23中学の学生。 7月28日、紅衛兵の代表が毛沢東に書簡を送り、革命を守るための反乱と動乱を呼びかけた。毛沢東はこの手紙に応え、「反革命の司令部(=本部)」を標的 にするよう民衆に呼びかけるため、「本部を爆撃せよ」と題した自身の大書ポスターを書いた。毛沢東は、共産主義革命を経たにもかかわらず、「ブルジョア」 のエリートが政府と共産党の「権威ある地位」で依然として繁栄していると書いた[21]。 名前は挙げられていないが、毛沢東のこの挑発的な発言は、劉少奇と鄧小平のもとでの党の体制、つまり中国の「ブルジョア本部」と称されるものを直接非難し たものと解釈されている。全人代での人事異動は、この新しいイデオロギーの風景に合うよう、党のヒエラルキーの根本的な再設計を反映したものだった。劉と 鄧は政治局常務委員会の議席を維持したが、実際には日常の党務からは遠ざけられた。林彪は中国共産党のナンバー2に昇格し、劉少奇の地位は2位から8位に 下がり、もはや毛沢東の後継者ではなかった[21]。  劉少奇の妻・王光梅をターゲットにした闘争会議 最高指導部が権力の座を追われたのと同時に、共産党の全国官僚機構全体が徹底的に解体された。党人事を担当する広範な組織部は事実上消滅した。毛沢東のイ デオロギー的な「親衛隊」である文化大革命グループ(CRG)は、毛沢東のイデオロギーを宣伝し、民衆の支持を集めるために、一躍脚光を浴びた。宣伝部の 幹部はクビになり、宣伝部の機能の多くが文化大革命グループに組み込まれた[15]: 96。 赤い八月と十六箇条 主な記事 赤い八月  1966年12月、北京で紅衛兵に囲まれる毛沢東と林彪。 小紅書』は、紅衛兵に中国の未来としての目標を約束させるメカニズムであった。毛沢東から直接引用されたこれらの言葉は、他の毛沢東指導者の見解に基づく 紅衛兵の他の行動につながった[15]: 107 そして、1967年12月までに3億5千万部の本が印刷された。[22]: 61-64 後に紅衛兵が指針として従うことになる、毛沢東が提供した『小赤書』の引用には、有名な "政治権力は銃口から成長する "が含まれていた。その一節はこう続く: 革命戦争は抗毒素であり、敵の毒を除去するだけでなく、われわれの汚物を浄化する。すべての正義と革命の戦争には、とてつもない力が備わっており、多くの ものを変革し、あるいは変革の道を開くことができる。中国が抵抗戦争と統一戦線に耐え抜けば、旧日本は必ず新日本に、旧中国は必ず新中国に変貌し、中日両 国の人々やあらゆるものは、戦時中も戦後も変貌する。世界はあなたのものであり、私たちのものでもあるが、最終的にはあなたのものなのだ。活力と生命力に 満ち溢れ、朝8時か9時の太陽のように、人生の花盛りを迎えている若者たちよ。私たちの希望は君たちに託されている.世界は君たちのものだ。中国の未来は 君たちのものだ 北京の「赤い8月」の最中、1966年8月8日、党の総委員会は、後に「十六箇条」として知られることになる「プロレタリア文化大革命に関する決定」を可 決した[23]。この決定は、文化大革命を「人々の魂に触れる偉大な革命であり、わが国の社会主義革命の発展において、より深く、より広範な段階を構成す る」と定義した[24]。 ブルジョアジーは打倒されたとはいえ、搾取階級の古い思想、文化、風習、習慣を利用して、大衆を堕落させ、彼らの心をとらえ、カムバックを果たそうとして いる。プロレタリアートは、正反対のことをしなければならない: 社会の展望を変えるために、ブルジョアジーのあらゆる挑戦に真っ向から立ち向かわなければならない。現在、われわれの目標は、資本主義の道を歩んでいる権 力者たちと闘争し、彼らを粉砕すること、反動的なブルジョア学問的「権威」とブルジョアジーおよび他のすべての搾取階級のイデオロギーを批判し、否認する こと、そして、社会主義体制の強化と発展を促進するように、教育、文学、芸術、その他社会主義経済基盤に対応しない上部構造のすべての部分を変革すること である。 十六カ条の意味は広範囲に及んだ。それまで学生運動であったものを、労働者、農民、兵士、党の下級幹部が立ち上がり、権力に挑戦し、社会の「上部構造」を 再構築するための全国的な大衆運動へと高めたのである。 1966年9月15日、天安門広場。毛沢東主席が1966年に紅衛兵を率いて行った8回の大規模集会のうち、3回目の集会の場となった[25]。 8月18日、北京では、全国から100万人以上の紅衛兵が、主席との個人的な謁見のために天安門広場とその周辺に集まった[15]: 106-07 毛沢東は自ら紅衛兵と交流し、自ら紅衛兵の腕章をつけて彼らのやる気を鼓舞した[19]: 66 林彪もまた8月18日の集会の中心的な役割を担い、「革命の前進」を妨げている中国社会のあらゆる敵を激しく非難した[19]: 66 その後、北京では暴力が著しくエスカレートし、瞬く間に中国の他の地域にも広がった[26][27]。 8月22日、紅衛兵の活動への警察の介入を停止するよう中央から通達が出され、この通達に背いた警察関係者は反革命分子のレッテルを貼られた[15]: 124 毛沢東の反乱への賛美が紅衛兵の行動を後押しした[15]: 515 中央当局は、革命を支持するための暴力行為の抑制を解除した[15]: 126 国家警察長官であった謝福子は、しばしば紅衛兵の「罪」を赦免した[15]: 125 約2週間で、北京の西部地区だけで支配階級と中産階級の幹部約100人が死亡した。負傷者の数はそれを上回った[15]: 126 キャンペーンの最も暴力的な側面には、拷問、殺人、公衆への辱めの事件が含まれていた。反革命分子として起訴された多くの人々が自殺した。犠牲者の多くは 教師で、生徒たちに襲われ、殺された。上海では9月に704人が自殺し、534人が文化大革命に関連して死亡した[28]。武漢では同時期に62人が自殺 し、32人が殺害された[15]: 124 彭徳懐が北京に連行され、公衆の面前で嘲笑される。 四老の破壊(8月~11月) 主な記事 四老  明の陵墓にある万里帝の遺骨。紅衛兵が万里帝と皇后の遺骨を陵墓の前に引きずり出し、死後に「糾弾」して焼却した[29]。 1966年8月から11月にかけて、8回の大規模集会が開催され、全国から1200万人以上が参加し、そのほとんどが紅衛兵であった[15]: 106 赤衛兵が「革命経験」を交換するために全国を旅行する費用は政府が負担した[15]: 110 紅衛兵の集会で、林彪は「四老」、すなわち古い習慣、文化、習慣、思想の破壊も呼びかけた[19]: 66 革命熱は国中を席巻し、紅衛兵はその最も著名な戦士として活動した。四大老」キャンペーンに関連したいくつかの変化は、街の通りや地名、さらには人に新し い名前をつけるなど、主に穏やかなものであった。この時期、何百万人もの赤ん坊が「革命的」な響きのある名前で生まれた[30]。 紅衛兵の活動の他の側面は、特に文化や宗教の領域において、より破壊的であった。全国各地のさまざまな史跡が破壊された。被害は特に首都北京で顕著だっ た。紅衛兵は曲阜の孔子廟も包囲した[15]: 119のほか、歴史的に重要な墳墓や工芸品が多数破壊された[31]。 歴史的な書物や外国の書物でいっぱいの図書館は破壊され、書物は燃やされた。寺院、教会、モスク、修道院、墓地は閉鎖され、時には他の用途に転用され、略 奪され、破壊された[32]。マルクス主義のプロパガンダは仏教を迷信として描き、宗教は敵対的な外国人の侵入の手段であり、支配階級の道具であるとみな された[33]。聖職者は逮捕され、収容所に送られた。多くのチベット仏教徒は銃を突きつけられ、修道院の破壊に参加させられた[33]。 孔子の墓地は1966年11月に紅衛兵によって襲撃された[31][34]。 孔子の墓地は1966年11月に紅衛兵に襲撃された[31][34]。 この永楽帝の像は元々石で彫られていたが、文化大革命で破壊された。代わりに金属製のレプリカが置かれている。 この永楽帝の像は元々石で彫られており、文化大革命で破壊された。代わりに金属製のレプリカが置かれている。 8世紀の仏教僧、慧能の遺骨は文化大革命で破壊された。 8世紀の仏教僧慧能の遺骨は文化大革命で攻撃された。 文化大革命の際に破損したフリーズ、もともとは蘇州の裕福な皇室の役人の庭園の家にあったもの。 文化大革命で破損したフリーズ、元は蘇州の裕福な皇室の役人の庭園の家だった。 中央工作会議(10月) 1966年10月、毛沢東は「中央工作会議」を開き、革命思想を採用していない党指導部を説得した。劉少奇と鄧小平はブルジョア反動路線の一員として告発 され、嫌々ながら自己批判を行った[15]: 137 会議後、かつて支配階級の強力な穏健派論客であった劉は北京で軟禁され、その後収容所に送られ、そこで治療を拒否され、1969年に死亡した。鄧小平は3 度にわたって再教育のために国外に送られ、最終的には江西省のエンジン工場で働くことになった。会議後、党幹部による反乱が加速した[35]。 年末 マカオでは、12・3事件で暴動が発生した[36]: 84 この事件は、タイパにある共産党小学校の新校舎の認可を植民地政府が遅らせたことに端を発していた[36]: 84 教育委員会が違法に工事を開始したため、植民地政府は労働者を阻止するために警察を派遣した。 [1966年12月3日、2日間に渡って暴動が発生し、数百人が負傷、6[36]: 84~8人が死亡し、ポルトガル政府も全面的に引き下がることになった[37]。この出来事により、ポルトガルはマカオに対する支配権を事実上放棄し、マ カオは最終的に脱植民地化への道を歩むことになった[36]: 84-85 1967: 権力の掌握 以下も参照: 権力の掌握(文化大革命)、暴力闘争、反乱派閥(文化大革命) 「三援二軍」の本を読むPLAの将校と兵士(1968年 中国の大衆組織は、毛沢東の共産党粛清を支持する急進派と、穏健な党内体制を支持する保守派の2つの敵対派閥に大別された。左派を支援する」政策は 1967年1月下旬に確立された[38]。毛沢東が構想したように、この政策は政権奪取において反政府勢力を支援することを意図したものであり、人民解放 軍(PLA)に「政権奪取の闘争において革命的左派の広範な大衆」を支援することを要求した[38]。 1967年3月、この政策は「3つの支援と2つの軍隊」構想へと変更され、PLA部隊は政変を安定させ派閥抗争を終わらせるために全国の学校や労働部隊に 派遣された[39]: 345 3つの「支援」とは、「左派を支援」、「内政を支援」、「産業を支援」することであった。二つの軍隊」とは、「軍事管理」と「軍事訓練」のことであった [39]: 345 左翼を支援するという政策は、ほとんどすべての大衆組織が「左翼」あるいは「革命的」であると主張していた時代に「左翼」を定義することができなかったこ とによって、当初から欠陥があった[38]。PLAの司令官たちは党の体制と緊密な協力関係を築いており、多くの軍部隊は急進派を弾圧するために活動して いた[40]。 北京での出来事に刺激され、「権力奪取グループ」が全国で結成され、工場や地方に拡大し始めた。上海では、王洪文という若い工場労働者が、既存の紅衛兵グ ループを結集し追い出すような、広範囲に及ぶ革命連合を組織した。1967年1月3日、紅衛兵の重鎮であった張春橋と姚文源の支援を受けたこの熱烈な活動 家グループは、「1月の嵐」として知られるようになった陳丕賢率いる上海市政府を打倒し、その代わりに上海人民公社を結成した[41][22]: 115  上海で行進する紅衛兵の反乱派(1967年) 上海は最初の省レベルの政府打倒であった[42]。数日以内に毛沢東は承認を表明した[42]。省政府、国家および党官僚機構の多くの部分が影響を受け、 権力の掌握は著しく異なる方法で行われた。その後3週間で、さらに24の省レベルの政府が打倒された[42]。その後、地方政府と共産党支部に代わって 「革命委員会」が設立された[43]。例えば、北京では、3つの別々の革命グループが同じ日に権力の掌握を宣言し、黒竜江では、地方の党書記である潘福生 が自らの指導のもとで党組織から権力を掌握した。一部の指導者はCRGに打倒を求める手紙を出したほどであった[15]: 170-72 北京では、江青と張春橋が濤朱副総理をターゲットにした。権力掌握の動きは軍部でも頭をもたげていた。2月、葉剣英、陳儀の両将軍と譚振林副総理は、この 運動の過激な側面への反対を声高に主張した。毛沢東は当初は曖昧な態度をとっていたが、2月18日の政治局議場で反対派を直接糾弾し、急進派の活動を全面 的に支持した。この短期間の抵抗は「二月の逆流」と烙印を押された[15]: 195-96年、この運動に対する党内の批判者を効果的に黙らせることに なった[19]: 207-09  1967年、貴州で行進する紅衛兵。中央の旗にはこう書かれている: 「人民解放軍はプロレタリア革命派を断固支持する」。 1967年初頭には、民衆の反乱は大都市以外ではまだ限られていたが、それでも地方政府は中国全土で崩壊し始めた[44]: 21 革命家たちが全国で与党政府と党組織を解体する一方で、権力の掌握には中央集権的な指導力が欠けていたため、誰が本当に毛沢東の革命的ビジョンを信じてい るのか、誰が日和見主義的に自分たちの利益のために混乱を利用しているのか、もはや明確ではなかった。対立する革命グループが形成され、その一部は長年に 渡る地元の確執の表れであり、全国で発生した派閥間の暴力的な闘争につながった。大衆組織と軍の間でも緊張が高まった。これに対し、林彪は軍隊に急進派を 援助するよう指令を出した。同時に、軍隊は自分たちの権力移行を整理することができないとみなされたいくつかの省や地方を掌握した[19]: 219-21 武漢の中心都市では、他の多くの都市と同様に、2つの主要な革命組織が出現し、一方は保守的な体制を支持し、もう一方はそれに反対した。両組織は都市の支 配権をめぐって争った。陸軍大将の陳才高は、毛沢東の支援を受けた反体制派のデモ隊を強制的に弾圧した。しかし、この騒動の最中、毛沢東自身が中央の大幹 部を引き連れて武漢に飛び、この地域の軍事的忠誠を確保しようとした。1967年7月20日、地元の扇動家たちが毛沢東の使者である王立を誘拐し、武漢事 件として知られるようになった。その後、陳宰大将は北京に送られ、江青ら文化大革命グループによって裁かれた。陳の抵抗は、PLA内部で運動に対する反対 を公然と表明した最後の大規模なものであった[15]: 214。 四人組の張春橋は、文化大革命の最も重要な要因は、紅衛兵でも文化大革命グループでも「反逆の労働者」組織でもなく、PLAがどの側に立つかであったと認 めている。PLAの地方守備隊が毛沢東の急進派を支持した場合、彼らは地方政府をうまく乗っ取ることができたが、協力的でなかった場合、権力の掌握は失敗 に終わった[15]: 175 ある歴史家によれば、暴力的な衝突は事実上すべての都市で発生した[要出典]。 武漢事件を受けて、毛沢東と江青は「労働者武装自衛軍」の創設を開始した。"PLA将校団の75%"に見られる右派主義に対抗するための「大衆的性格を持 つ革命的武装勢力」であった。重慶市は武器製造の中心地であり、両派の激しい武力衝突の場となった。市内のある建設現場では、戦車、機動砲、高射砲、「事 実上あらゆる種類の通常兵器」を携えた1万人の戦闘員が参加したと推定されている。重慶では1967年8月に1万発の砲弾が発射された[15]: 214-15 全国で合計1,877万丁の銃器、14,828丁の砲弾、2,719,545個の手榴弾が民間人の手に渡った。これらは、主に1967年から1968年に かけて起こった暴力闘争の過程で使用された。重慶、アモイ、長春の都市では、戦車、装甲車、軍艦までもが戦闘に投入された[40]。 |

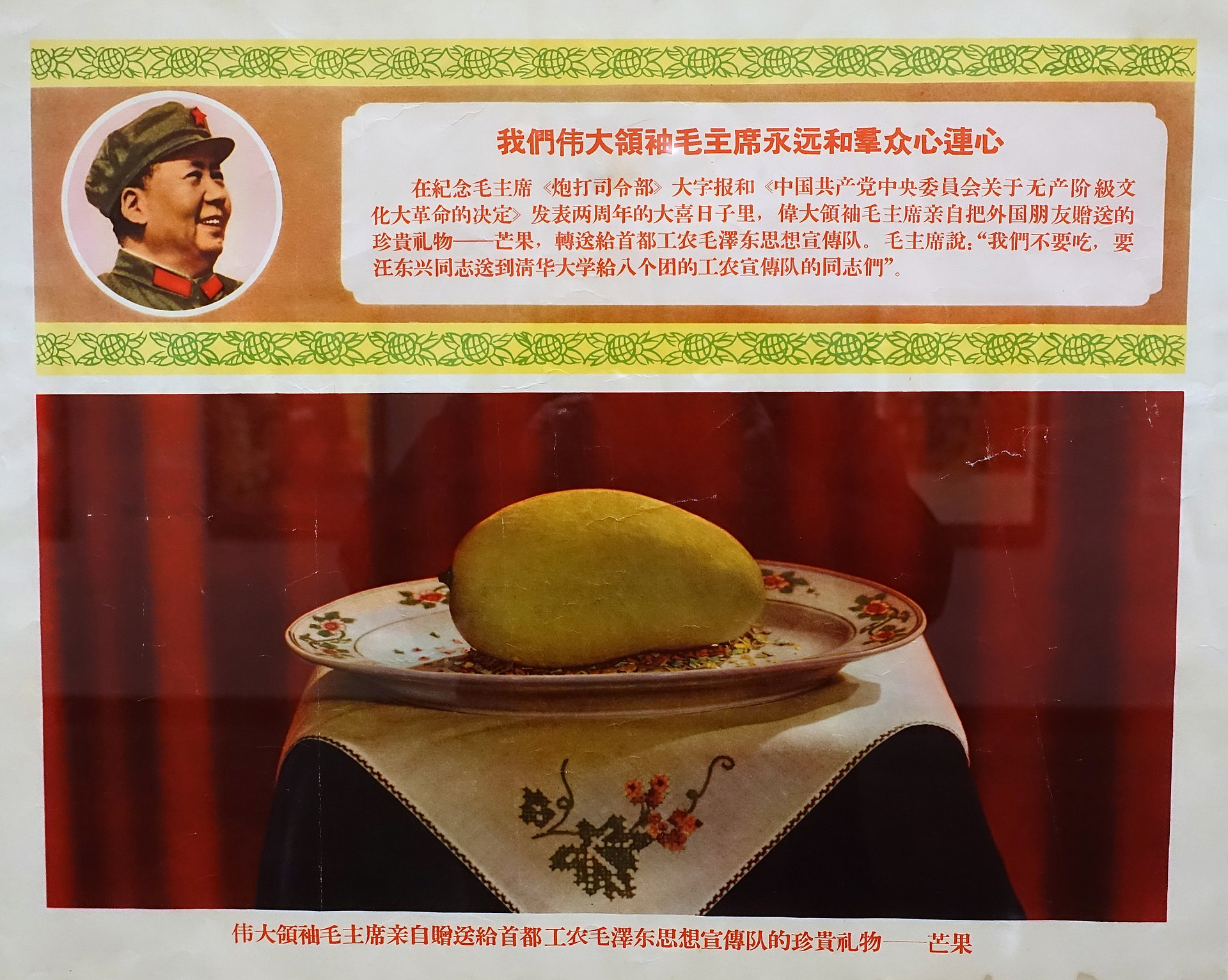

| 1968: Purges See also: Cleansing the Class Ranks  A rally in opposition to Liu Shaoqi In May 1968, Mao launched a massive political purge. Many people were sent to the countryside to work in reeducation camps. Generally, the campaign targeted rebels from the earlier, more populist, phase of the Cultural Revolution.[39]: 239 On 27 July, the Red Guards' power over the PLA was officially ended, and the establishment government sent in units to besiege areas that remained untouched by the Guards. A year later, the Red Guard factions were dismantled entirely; Mao predicted that the chaos might begin running its own agenda and be tempted to turn against revolutionary ideology. Their purpose had been largely fulfilled; Mao and his radical colleagues had largely overturned establishment power.[citation needed] Liu was expelled from the CCP at the 12th Plenum of the 8th Central Committee in September, and labelled the "headquarters of the bourgeoisie".[45] Mao meets with Red Guard leaders (July) As the Red Guard movement had waned over the course of the preceding year, violence by the remaining militant Red Guards increased on some Beijing campuses.[46] Violence was particularly pronounced at Qinghua University, where a few thousand hardliners of two different factions continued to fight.[47] At Mao's initiative, on 27 July 1968, tens of thousands of workers entered the Qinghua campus shouting slogans in opposition to the violence.[47] Red Guards attacked the workers, who continued to remain peaceful.[47] Ultimately, the workers disarmed the students and occupied the campus.[47] On July 28, 1968, Mao and the Central Group met with the five most important remaining Beijing Red Guard leaders to address the movement's excessive violence and political exhaustion.[46] It was the only time during the Cultural Revolution that Mao met and addressed the student leaders directly. In response to a Red Guard leader's telegram sent prior to the meeting, which claimed that some "Black Hand" had maneuvered the workers against the Red Guards to suppress the Cultural Revolution, Mao told the student leaders, "The Black Hand is nobody else but me! ... I asked [the workers] how to solve the armed fighting in the universities, and told them to go there to have a look."[48] During the meeting, Mao and the Central Group for the Cultural Revolution stated, "[W]e want cultural struggle, we do not want armed struggle" and "The masses do not want civil war."[49] Mao told the student leaders:[50] You have been involved in the Cultural Revolution for two years: struggle-criticism-transformation. Now, first, you're not struggling; second, you're not criticizing; and third, you're not transforming. Or rather, you are struggling, but it's an armed struggle. The people are not happy, the workers are not happy, city residents are not happy, most people in schools are not happy, most of the students even in your schools are not happy. Even within the faction that supports you, there are unhappy people. Is this the way to unify the world? Mao's cult of personality and "mango fever" (August) Main article: Mango cult See also: Mao Zedong's cult of personality A propaganda oil painting of Mao during the Cultural Revolution (1967) In the spring of 1968, a massive campaign that aimed at enhancing Mao's reputation began. A notable example was the "mango fever". On 4 August 1968, Mao was presented with about 40 mangoes by the Pakistani foreign minister Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada, in an apparent diplomatic gesture.[51] Mao had his aide send the box of mangoes to his propaganda team at Tsinghua University on 5 August, the team stationed there to quiet strife among Red Guard factions.[52][51] On 7 August, an article was published in People's Daily, saying: In the afternoon of the fifth, when the great happy news of Chairman Mao giving mangoes to the Capital Worker and Peasant Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Team reached the Tsinghua University campus, people immediately gathered around the gift given by the Great Leader Chairman Mao. They cried out enthusiastically and sang with wild abandonment. Tears swelled up in their eyes, and they again and again sincerely wished that our most beloved Great Leader lived ten thousand years without bounds ... They all made phone calls to their own work units to spread this happy news; and they also organised all kinds of celebratory activities all night long, and arrived at [the national leadership compound] Zhongnanhai despite the rain to report the good news, and to express their loyalty to the Great Leader Chairman Mao.[52]  Poster featuring mangoes, 1968 Subsequent articles were also written by government officials propagandizing the reception of the mangoes,[53] and another poem in the People's Daily said: "Seeing that golden mango/Was as if seeing the great leader Chairman Mao ... Again and again touching that golden mango/the golden mango was so warm."[54] Few people at this time in China had ever seen a mango before, and a mango was seen as "a fruit of extreme rarity, like Mushrooms of Immortality."[54] One of the mangoes was sent to the Beijing Textile Factory,[52] whose revolutionary committee organized a rally in the mangoes' honor.[53] Workers read out quotations from Mao and celebrated the gift. Altars were erected to display the fruit prominently. When the mango peel began to rot after a few days, the fruit was peeled and boiled in a pot of water. Workers then filed by and each was given a spoonful of mango water. The revolutionary committee also made a wax replica of the mango and displayed this as a centerpiece in the factory.[52] There followed several months of "mango fever", as the fruit became a focus of a "boundless loyalty" campaign for Chairman Mao. More replica mangoes were created, and the replicas were sent on tour around Beijing and elsewhere in China. Many revolutionary committees visited the mangoes in Beijing from outlying provinces. Approximately half a million people greeted the replicas when they arrived in Chengdu. Badges and wall posters featuring the mangoes and Mao were produced in the millions.[52] The fruit was shared among all institutions that had been a part of the propaganda team, and large processions were organized in support of the "precious gift", as the mangoes were known.[55] A dentist in a small town, Dr. Han, saw the mango and said it was nothing special and looked just like a sweet potato. He was put on trial for "malicious slander", found guilty, paraded publicly throughout the town, and then executed with a gunshot to the head.[54][56] It has been claimed that Mao used the mangoes to express support for the workers who would go to whatever lengths necessary to end the factional fighting among students, and a "prime example of Mao's strategy of symbolic support."[53] Even up until early 1969, participants of Mao Zedong Thought study classes in Beijing would return with mass-produced mango facsimiles, gaining media attention in the provinces.[55] Down to the Countryside Movement (December) Main article: Down to the Countryside Movement In December 1968, Mao began the "Down to the Countryside Movement." During this movement, which lasted for the next decade, young bourgeoisie living in cities were ordered to go to the countryside to experience working life. The term "young intellectuals" was used to refer to recently graduated college students. In the late 1970s, these students returned to their home cities. Many students who were previously Red Guard members supported the movement and Mao's vision. This movement was thus in part a means of moving Red Guards from the cities to the countryside, where they would cause less social disruption. It also served to spread revolutionary ideology across China geographically.[57] |

1968: 粛清 以下も参照: 階級浄化  劉少奇に反対する集会 1968年5月、毛沢東は大規模な政治的粛清を開始した。多くの人々が地方に送られ、再教育キャンプで働かされた。一般に、このキャンペーンは、文化大革 命の初期の、より大衆的な段階からの反逆者を標的にしていた[39]:239。 7月27日、紅衛兵のPLAに対する権力は正式に終了し、建国政府は紅衛兵の手つかずの地域を包囲する部隊を派遣した。1年後、紅衛兵の派閥は完全に解体 された。毛沢東は、混乱が独自の思惑で動き始め、革命イデオロギーに背を向ける誘惑に駆られるかもしれないと予測していた。毛沢東と彼の急進的な仲間たち は、既成の権力をほぼ覆したのである[要出典]。 劉は9月の第8期中央委員会第12回全体会議で中国共産党から除名され、「ブルジョアジーの本部」のレッテルを貼られた[45]。 毛沢東、紅衛兵指導者と会談(7月) 紅衛兵運動が前年のうちに衰退するにつれて、北京のいくつかのキャンパスでは、残存する過激派紅衛兵による暴力が増加した[46]。 [毛沢東の主導で、1968年7月27日、数万人の労働者が暴力に反対するスローガンを叫びながら清華大学のキャンパスに入った[47]。紅衛兵は、平和 的な態度をとり続けた労働者を攻撃した[47]。最終的に、労働者は学生を武装解除し、キャンパスを占拠した[47]。 1968年7月28日、毛沢東と中央グループは、北京紅衛兵の最も重要な5人の指導者と会談し、運動の行き過ぎた暴力と政治的疲弊に対処した[46]。 それは、文化大革命の間、毛沢東が学生指導者と直接会い、演説した唯一の機会であった。紅衛兵の指導者が会議に先立って送った電報で、文化大革命を弾圧す るために「黒い手」が紅衛兵に対して労働者を操ったと主張したことに対して、毛沢東は学生指導者たちに「黒い手とは私以外の誰のことでもない!... 私は(労働者たちに)大学での武力闘争をどう解決するか尋ね、そこに行って見るように言った」[48]。 会議の中で、毛沢東と文化大革命中央グループは、「われわれは文化闘争を望んでおり、武装闘争は望んでいない」、「大衆は内戦を望んでいない」と述べた [49]。毛沢東は学生指導者たちに次のように言った[50]。 君たちは2年間、闘争-批判-変革という文化大革命に携わってきた。今、第一に、君たちは闘っていない。第二に、君たちは批判していない。第三に、君たち は変革していない。というより、闘争はしているが、それは武装闘争だ。国民も、労働者も、都市住民も、学校にいるほとんどの人も、学校にいるほとんどの生 徒も、幸せではない。あなたを支持する派閥の中にさえ、不幸な人々がいる。これが世界を統一する方法なのか? 毛沢東のカルト・オブ・パーソナリティと「マンゴー・フィーバー」(8月) 主な記事 マンゴーカルト こちらも参照: 毛沢東のカルト・オブ・パーソナリティ 文化大革命時の毛沢東のプロパガンダ油絵(1967年) 1968年春、毛沢東の評判を高めることを目的とした大規模なキャンペーンが始まった。特筆すべきは「マンゴー・フィーバー」である。1968年8月4 日、毛沢東はパキスタンの外相Syed Sharifuddin Pirzadaから約40個のマンゴーを贈られたが、これは明らかに外交的なジェスチャーであった[51]。毛沢東は8月5日、側近にマンゴーの箱を清華 大学の宣伝チームに送らせた: 5日の午後、毛沢東主席が資本労働者農民毛沢東思想宣伝チームにマンゴーを贈ったという喜ばしいニュースが清華大学のキャンパスに届くと、人々はすぐさま 偉大なる指導者毛沢東主席からの贈り物の周りに集まった。彼らは熱狂的に叫び、奔放に歌った。彼らの目には涙が溢れ、彼らは何度も何度も、最も敬愛する偉 大な指導者が限りなく一万年生きることを心から願った.彼らは皆、この嬉しい知らせを広めるために自分の仕事場に電話をかけ、また、一晩中あらゆる種類の 祝賀活動を組織し、雨にもかかわらず[国家指導部の敷地]中南海に到着し、良い知らせを報告し、偉大な指導者である毛主席への忠誠を表明した[52]。  マンゴーのポスター、1968年 その後、政府高官によってマンゴーの受け入れを宣伝する記事も書かれ[53]、『人民日報』には別の詩も掲載された: 「あの黄金のマンゴーを見ていると、偉大な指導者毛主席を見るようだ。何度も何度もその黄金のマンゴーに触れ/黄金のマンゴーはとても温かかった」 [54]。この頃の中国では、マンゴーを見たことがある人はほとんどおらず、マンゴーは「不老不死のキノコのような、極めて珍しい果物」と見られていた [54]。 マンゴーの一つは北京繊維工場に送られ[52]、その革命委員会はマンゴーの栄誉を称える集会を組織した[53]。マンゴーの果実が目立つように祭壇が設 けられた。数日後、マンゴーの皮が腐り始めると、果実は皮を剥かれ、鍋の水で煮られた。マンゴーの皮は数日後に腐り始めると、皮をむいて鍋の湯で煮た。革 命委員会はまた、マンゴーの蝋のレプリカを作り、これを工場の目玉として飾った[52]。 その後数ヶ月間「マンゴーフィーバー」が続き、マンゴーは毛主席への「限りない忠誠」キャンペーンの焦点となった。さらに多くのマンゴーのレプリカが作ら れ、そのレプリカは北京や中国各地を巡回した。多くの革命委員会が地方から北京のマンゴーを訪れた。レプリカが成都に到着すると、約50万人が出迎えた。 マンゴーと毛沢東をモチーフにしたバッジや壁のポスターは数百万枚も作られた[52]。 この果実は宣伝隊の一員であったすべての機関の間で共有され、マンゴーは「貴重な贈り物」として知られていたため、大行列が組まれた[55]。小さな町の 歯科医、ハン医師はマンゴーを見て、特別なものではなく、サツマイモにそっくりだと言った。彼は「悪意のある誹謗中傷」で裁判にかけられ、有罪となり、町 中を公開パレードした後、頭を銃で撃たれて処刑された[54][56]。 毛沢東がマンゴーを使ったのは、学生間の派閥争いを終わらせるためなら手段を選ばない労働者への支持を表明するためであり、「毛沢東の象徴的支持戦略の代 表例」であったと主張されている[53]。1969年初頭まで、北京で行われた毛沢東思想の学習クラスの参加者は、大量生産されたマンゴーの複製を持って 帰ってきて、地方でメディアの注目を集めた[55]。 下放運動(12月) 主な記事 下放運動 1968年12月、毛沢東は「下野運動」を開始した。その後10年間続いたこの運動の間、都市に住む若いブルジョワジーは、労働生活を体験するために田舎 に行くよう命じられた。若い知識人」という言葉は、大学を卒業したばかりの学生を指す言葉として使われた。1970年代後半、これらの学生たちは故郷の都 市に戻った。紅衛兵だった学生の多くは、この運動と毛沢東の構想を支持した。この運動は、紅衛兵を都市から地方に移動させ、社会的混乱を引き起こさないよ うにする手段でもあった。また、革命イデオロギーを地理的に中国全土に広める役割も果たした[57]。 |

| 1969–71: Rise and fall of Lin

Biao The 9th National Congress held in April 1969 served as a means to "revitalize" the party with fresh thinking—as well as new cadres, after much of the old guard had been destroyed in the struggles of the preceding years.[15]: 285 The party framework of established two decades previously had now broken down almost entirely: rather than through an election by party members, delegates for this Congress were effectively selected by Revolutionary Committees.[15]: 288 Representation of the military increased by a large margin from the previous Congress, reflected in the election of more PLA members to the new Central Committee—with over 28% of delegates being PLA members.[15]: 292 Many officers now elevated to senior positions were loyal to PLA Marshal Lin Biao, which would open a new rift between the military and civilian leadership.[15]: 292 We do not only feel boundless joy because we have as our great leader the greatest Marxist–Leninist of our era, Chairman Mao, but also great joy because we have Vice Chairman Lin as Chairman Mao's universally recognized successor. — Premier Zhou Enlai at the 9th Party Congress[58] Reflecting this, Lin Biao was officially elevated to become the Party's preeminent figure outside of Mao, with his name written into the party constitution as his "closest comrade-in-arms" and "universally recognized successor."[15]: 291 At the time, no other Communist parties or governments anywhere in the world had adopted the practice of enshrining a successor to the current leader into their constitutions; this practice was unique to China. Lin delivered the keynote address at the Congress: a document drafted by hardliner leftists Yao Wenyuan and Zhang Chunqiao under Mao's guidance.[15]: 289 The report was heavily critical of Liu Shaoqi and other "counter-revolutionaries" and drew extensively from quotations in the Little Red Book. The Congress solidified the central role of Maoism within the party psyche, re-introducing Maoism as an official guiding ideology of the party in the party constitution. Lastly, the Congress elected a new Politburo with Mao Zedong, Lin Biao, Chen Boda, Zhou Enlai and Kang Sheng as the members of the new Politburo Standing Committee.[15]: 290 Lin, Chen and Kang were all beneficiaries of the Cultural Revolution. Zhou, who was demoted in rank, voiced his unequivocal support for Lin at the Congress.[15]: 290 Mao also restored the function of some formal party institutions, such as the operations of the party's Politburo, which ceased functioning between 1966 and 1968 because the Central Cultural Revolution Group held de facto control of the country.[15]: 296 PLA encroachment  Mao (left) and Lin (right) in 1967, riding in the back of a vehicle during an International Workers' Day parade Mao's efforts at re-organizing party and state institutions generated mixed results. The situation in some of the provinces remained volatile, even as the political situation in Beijing stabilized. Factional struggles, many violent, continued at a local level despite the declaration that the 9th National Congress marked a temporary "victory" for the Cultural Revolution.[15]: 316 Furthermore, despite Mao's efforts to put on a show of unity at the Congress, the factional divide between Lin Biao's PLA camp and the Jiang Qing-led radical camp was intensifying. Indeed, a personal dislike of Jiang Qing drew many civilian leaders, including prominent theoretician Chen Boda, closer to Lin Biao.[59]: 115 Between 1966 and 1968, China was isolated internationally, having declared its enmity towards both the Soviet Union and the United States. The friction with the Soviet Union intensified after border clashes on the Ussuri River in March 1969 as the Chinese leadership prepared for all-out war.[15]: 317 In June 1969, the PLA's enforcement of political discipline and suppression of the factions that had emerged during the Cultural Revolution became intertwined with the central Party's efforts to accelerate Third Front work.[16]: 150 Those who did not return to work would be viewed as engaging in 'schismatic activity' which risked undermining preparations to defend China from potential invasion.[16]: 150–51 In October 1969, the Party attempted to focus more on war preparedness and less on suppression of the factions that had emerged during the mass movement phase of the Cultural Revolution.[16]: 151 That month, senior leaders were evacuated from Beijing.[15]: 317 Amidst the tension, Lin Biao issued what appeared to be an executive order to prepare for war to the PLA's eleven military regions on October 18 without going through Mao. This drew the ire of the chairman, who saw it as evidence that his authority was prematurely usurped by his declared successor.[15]: 317 The prospect of war elevated the PLA to greater prominence in domestic politics, increasing the stature of Lin Biao at the expense of Mao.[15]: 321 There is some evidence to suggest that Mao was pushed to seek closer relations with the United States as a means to avoid PLA dominance in domestic affairs that would result from a military confrontation with the Soviet Union.[15]: 321 During his later meeting with Richard Nixon in 1972, Mao hinted that Lin had opposed seeking better relations with the U.S.[15]: 322 Restoration of State Chairman position Liu Shaoqi on his deathbed in 1969 After Lin was confirmed as Mao's successor, his supporters focused on the restoration of the position of State Chairman,[note 2] which had been abolished by Mao after the purge of Liu Shaoqi. They hoped that by allowing Lin to ease into a constitutionally sanctioned role, whether Chairman or vice-chairman, Lin's succession would be institutionalized. The consensus within the Politburo was that Mao should assume the office with Lin becoming vice-chairman; but perhaps wary of Lin's ambitions or for other unknown reasons, Mao had voiced his explicit opposition to the recreation of the position and his assuming it.[15]: 327 Factional rivalries intensified at the Second Plenum of the Ninth Congress in Lushan held in late August 1970. Chen Boda, now aligned with the PLA faction loyal to Lin, galvanized support for the restoration of the office of President of China, despite Mao's wishes to the contrary.[15]: 331 Moreover, Chen launched an assault on Zhang Chunqiao, a staunch Maoist who embodied the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, over the evaluation of Mao's legacy.[15]: 328 The attacks on Zhang found favour with many attendees at the Plenum and may have been construed by Mao as an indirect attack on the Cultural Revolution itself. Mao confronted Chen openly, denouncing him as a "false Marxist,"[15]: 332 and removed him from the Politburo Standing Committee. In addition to the purge of Chen, Mao asked Lin's principal generals to write self-criticisms on their political positions as a warning to Lin. Mao also inducted several of his supporters to the Central Military Commission and placed his loyalists in leadership roles of the Beijing Military Region.[15]: 332 Project 571 Main article: Project 571 By 1971, diverging interests between the civilian and military wings of the leadership were apparent. Mao was troubled by the PLA's newfound prominence, and the purge of Chen Boda marked the beginning of a gradual scaling-down of the PLA's political involvement.[15]: 353 According to official sources, sensing the reduction of Lin's power base and his declining health, Lin's supporters plotted to use the military power still at their disposal to oust Mao in a coup.[59] Lin's son Lin Liguo, along with other high-ranking military conspirators, formed a coup apparatus in Shanghai and dubbed the plan to oust Mao Outline for Project 571—in the original Mandarin, the phrase sounds similar to the term for 'military uprising'. It is disputed whether Lin Biao was directly involved in this process. While official sources maintain that Lin did plan and execute the coup attempt, scholars such as Jin Qiu portray Lin as passive, cajoled by elements among his family and supporters.[59] Qiu contests that Lin Biao was never personally involved in drafting the Outline, with evidence suggesting that Lin Liguo was directly responsible for the draft.[59] The Outline allegedly consisted mainly of plans for aerial bombardments through use of the Air Force. It initially targeted Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan, but would later involve Mao himself. If the plan succeeded, Lin would arrest his political rivals and assume power. Assassination attempts were alleged to have been made against Mao in Shanghai, from September 8 to 10, 1971. Perceived risks to Mao's safety were allegedly relayed to the chairman. One internal report alleged that Lin had planned to bomb a bridge that Mao was to cross to reach Beijing; Mao reportedly avoided this bridge after receiving intelligence reports.[citation needed] Lin's flight and plane crash Main article: Lin Biao incident Graffiti of Lin Biao's foreword to the Little Red Book, with his name (lower right) later scratched out According to the official narrative, on 13 September Lin Biao, his wife Ye Qun, Lin Liguo, and members of his staff attempted to flee to the Soviet Union ostensibly to seek political asylum. En route, Lin's plane crashed in Mongolia, killing all on board. The plane apparently ran out of fuel en route to the Soviet Union. A Soviet team investigating the incident was not able to determine the cause of the crash but hypothesized that the pilot was flying low to evade radar and misjudged the plane's altitude. The official account has been put to question by foreign scholars, who have raised doubts over Lin's choice of the Soviet Union as a destination, the plane's route, the identity of the passengers, and whether or not a coup was actually taking place.[59][60] On 13 September, the Politburo met in an emergency session to discuss Lin Biao. His death was only confirmed in Beijing on 30 September, which led to the cancellation of the National Day celebration events the following day. The Central Committee kept information under wraps, and news of Lin's death was not released to the public until two months following the incident.[59] Many of Lin's supporters sought refuge in Hong Kong. Those who remained on the mainland were purged.[59] The event caught the party leadership off guard: the concept that Lin could betray Mao de-legitimized a vast body of Cultural Revolution political rhetoric and by extension, Mao's absolute authority, as Lin was already enshrined into the Party Constitution as Mao's "closest comrade-in-arms" and "successor." For several months following the incident, the party information apparatus struggled to find a "correct way" to frame the incident for public consumption, but as the details came to light, the majority of the Chinese public felt disillusioned and realised they had been manipulated for political purposes.[59] |

1969-71: 林彪の興亡 1969年4月に開催された第9回全国代表大会は、新鮮な考え方と新しい幹部によって党を「活性化」する手段として機能した。 [15]: 288 軍部の代表は前大会から大幅に増加し、新しい中央委員会に多くのPLA党員が選出されたことに反映され、代表の28%以上がPLA党員であった。 [15]: 292 現在、上級職に昇格した将校の多くはPLA元帥の林彪に忠誠を誓っていたが、これは軍部と文民指導部の間に新たな亀裂を生むことになった。 われわれの偉大な指導者として、われわれの時代の最も偉大なマルクス・レーニン主義者である毛主席がいるため、われわれは限りない喜びを感じているだけで なく、毛主席の後継者として誰もが認める林副主席がいるため、われわれは大きな喜びを感じている。 - 第9回党大会での周恩来総理[58]。 これを反映して、林彪は正式に毛沢東以外の党の傑出した人物に昇格し、「最も親しい戦友」「誰もが認める後継者」として党憲法にその名が記された [15]: 291。当時、現指導者の後継者を憲法に明記する慣行を採用した共産党や政府は世界のどこにもなく、この慣行は中国独自のものだった。林は大会で基調演説 を行った。この文書は、毛沢東の指導の下、強硬左派の姚文元と張春橋によって起草された[15]: 289。 この報告書は、劉少奇をはじめとする「反革命分子」を激しく批判し、『小赤書』の引用を多用したものであった。党大会は、党憲法の中で毛沢東主義を党の公 式指導思想として再導入し、党精神における毛沢東主義の中心的役割を確固たるものにした。最後に、大会は新しい政治局を選出し、毛沢東、林彪、陳保大、周 恩来、康生が新しい政治局常務委員会のメンバーとなった[15]。 林、陳、康はいずれも文化大革命の受益者であった。また毛沢東は、中央文化大革命グループが国内を事実上掌握していたため、1966年から1968年にか けて機能停止していた党政治局の運営など、いくつかの正式な党機関の機能を回復させた[15]: 296。 PLAの侵食  1967年、国際労働者デーのパレードで車の後ろに乗る毛沢東(左)と林(右)。 毛沢東による党と国家機関の再編成の努力は、さまざまな結果をもたらした。北京の政治情勢が安定しても、一部の地方の情勢は不安定なままだった。第9回全 国代表大会が文化大革命の一時的な「勝利」を意味するという宣言にもかかわらず、地方レベルでは派閥闘争が続き、その多くは暴力的であった[15]: 316 さらに、毛沢東が大会で団結を見せようと努力したにもかかわらず、林彪のPLA陣営と江青率いる急進陣営との間の派閥対立は激化していた。実際、江青に対 する個人的な嫌悪感から、著名な理論家である陳保大を含む多くの民間指導者が林彪に接近した[59]: 115 1966年から1968年にかけて、中国は国際的に孤立し、ソ連とアメリカの両方に対して敵意を表明した。1969年3月にウスリー川で国境衝突が起こ り、中国指導部は全面戦争に備えたため、ソ連との摩擦は激化した[15]: 317 1969年6月、PLAによる政治規律の強制と文化大革命中に生まれた派閥の弾圧は、第三戦線活動を加速させようとする党中央の努力と絡み合うようになっ た[16]: 150 仕事に復帰しない者は、潜在的な侵略から中国を防衛する準備を損なう危険性のある「分裂活動」に従事しているとみなされた[16]: 150-51 1969年10月、党は戦争準備により重点を置き、文化大革命の大衆運動の段階で出現した派閥の弾圧にはあまり重点を置かなかった[16]: 151 その月、上級指導者たちは北京から避難した[15]: 317 緊張が高まる中、林彪は10月18日、毛沢東を通さずにPLAの11の軍区に戦争準備のための行政命令らしきものを出した。林彪はこれを、自分の権威が早 々に後継者に簒奪された証拠とみなし、主席の怒りを買った[15]: 317 戦争の予感は、PLAを国内政治においてより重要な地位に押し上げ、毛沢東を犠牲にして林彪の地位を高めた[15]: 321 毛沢東は、ソ連との軍事的対立から生じるPLAの内政における支配を回避する手段として、アメリカとの関係の緊密化を求めるようになったことを示唆するい くつかの証拠がある[15]: 321 毛沢東は後に1972年にリチャード・ニクソンと会談した際、林がアメリカとの関係改善に反対していたことをほのめかしている[15]: 322 国家主席の地位回復 1969年、死に際の劉少奇 林が毛沢東の後継者に決まった後、彼の支持者たちは、毛沢東が劉少奇を粛清した後に廃止した国家主席[注釈 2]の地位の回復に焦点を当てた。彼らは、林が主席であれ副主席であれ、憲法で認められた役割に安住することで、林の後継が制度化されることを期待した。 政治局内のコンセンサスは、毛沢東が主席に就任し、林が副主席になることであったが、林の野心を警戒してか、その他の理由は不明だが、毛沢東は主席の再登 板と林の副主席就任に明確な反対を表明していた[15]: 327 1970年8月下旬に廬山で開催された第九回大会第二回全体会議では、派閥対立が激化した。陳保大は、林に忠誠を誓うPLA派に属し、毛沢東の反対にもか かわらず、国家主席の地位回復を支持した[15]: 331 さらに陳は、毛沢東の遺産の評価をめぐって、文化大革命の混乱を体現していた強固な毛沢東主義者である張春橋への攻撃を開始した[15]: 328 張への攻撃は全人代の多くの出席者に好意的に受け止められ、毛沢東は文化大革命そのものへの間接的な攻撃と解釈したのかもしれない。毛沢東は陳と公然と対 立し、彼を「偽のマルクス主義者」と非難した[15]: 332し、政治局常務委員会から解任した。陳の粛清に加えて、毛沢東は林に対する警告として、林 の主要な将軍たちに自らの政治的立場について自己批判を書くよう求めた。毛沢東はまた、彼の支持者数名を中央軍事委員会に入会させ、彼の忠実な支持者を北 京軍区の指導的役割に就かせた[15]: 332 プロジェクト571 主な記事 プロジェクト571 1971年になると、指導部の文民部門と軍事部門の間で利害の相違が明らかになった。毛沢東はPLAが新たに台頭してきたことに頭を悩ませており、陳保大 の粛清はPLAの政治的関与の段階的縮小の始まりとなった[15]: 353 政府筋によると、林の権力基盤の縮小と健康状態の悪化を察知した林の支持者は、まだ自由に使える軍事力を使ってクーデターで毛沢東を追い落とそうと画策し た[59]。 林の息子である林立国は、他の軍の高官たちとともに上海でクーデター組織を結成し、毛沢東追放計画を「571計画要綱」と名付けた。林彪がこのプロセスに 直接関与していたかどうかについては議論がある。邱は、林彪が要綱の起草に個人的に関与したことはなく、林立国が起草に直接関与したことを示唆する証拠が あると論じている[59]。 要綱は主に空軍を使った空爆の計画で構成されていたとされる。当初は張春橋と姚文源をターゲットにしていたが、後に毛沢東自身も巻き込むことになる。計画 が成功すれば、林は政敵を逮捕し、権力を握ることになる。1971年9月8日から10日にかけて、上海で毛沢東に対する暗殺未遂事件が起きたとされてい る。毛沢東の安全が脅かされると思われる事態は、主席に伝えられたとされる。ある内部報告によると、林は毛沢東が北京に行くために渡る橋を爆破する計画を 立てていたとされ、毛沢東は情報報告を受けてこの橋を避けたとされる[要出典]。 林の飛行と飛行機事故 主な記事 林彪事件 林彪の『小紅書』序文の落書き、林彪の名前(右下)は後にかき消された。 公式発表によると、9月13日、林彪、妻の葉群、林立国、林彪のスタッフは、表向きは政治亡命を求めてソ連に逃亡しようとした。その途中、林の飛行機はモ ンゴルで墜落し、乗員全員が死亡した。飛行機はソ連に向かう途中で燃料が尽きたらしい。ソ連の調査チームは墜落の原因を特定できなかったが、パイロットが レーダーを避けるために低空飛行をし、飛行機の高度を見誤ったという仮説を立てた。 林が目的地としてソ連を選んだこと、飛行機のルート、乗客の身元、実際にクーデターが起きていたかどうかについて疑問を呈しており、海外の学者によって公 式の説明は疑問視されている[59][60]。 9月13日、政治局は緊急会議を開き、林彪について話し合った。林彪の死が北京で確認されたのは9月30日のことで、翌日の国慶節行事は中止された。中央 委員会は情報を隠蔽し、林彪の訃報が一般に公表されたのは事件から2ヵ月後のことだった[59]。本土に残った者は粛清された[59]。 林が毛沢東を裏切る可能性があるという概念は、文化大革命の膨大な政治的レトリックの正当性を否定するものであり、ひいては毛沢東の絶対的権威を否定する ものであった。事件後数カ月間、党の情報機構は事件を大衆の消費に乗せるための「正しい方法」を見つけるのに苦労したが、詳細が明らかになるにつれ、中国 国民の大多数は幻滅を感じ、自分たちが政治的目的のために操られていたことに気づいた[59]。 |