北米先住民に対する文化的同化政策

Cultural assimilation of Native Americans

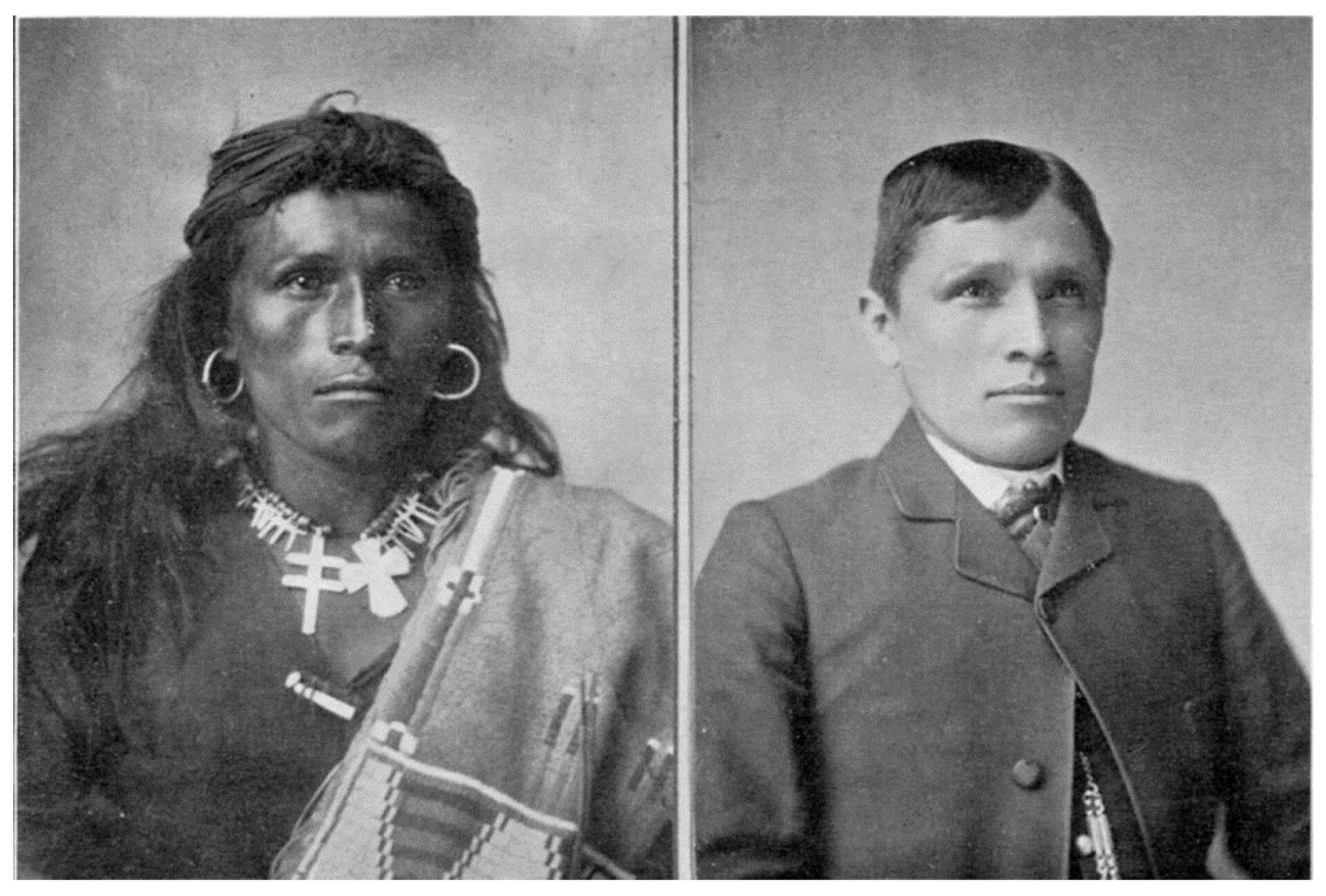

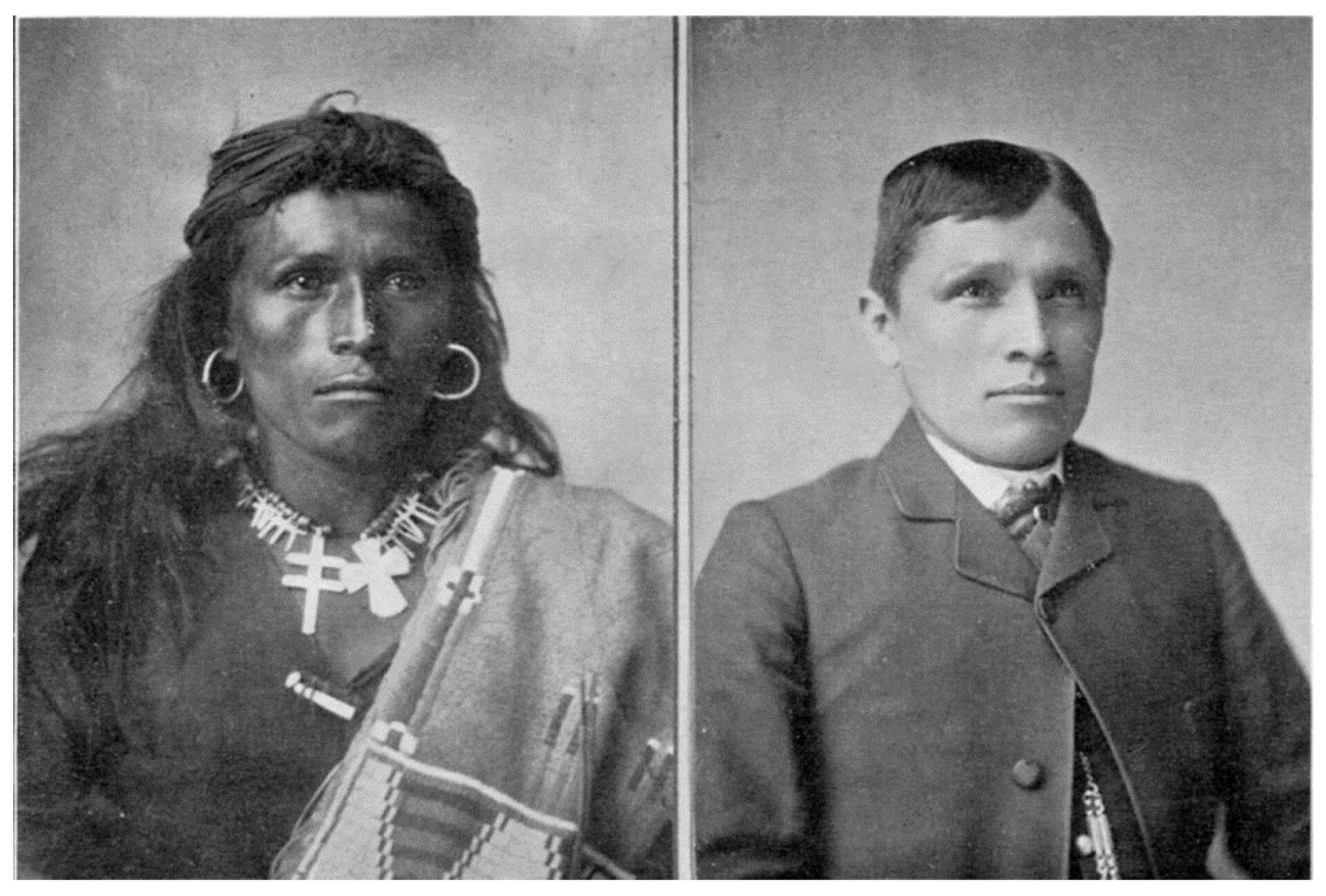

Tom Torlino entered Carlisle School on October 21, 1882 at the age of 22 and departed on August 28, 1886.

☆ アメリカでは1790年から1920年にかけて、ネイティブ・アメリカンをヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の主流文化に同化させるための一連の取り組みが行われ た。 ジョージ・ワシントンとヘンリー・ノックスは、アメリカの文脈でネイティブ・アメリカンの文化的同化を最初に提唱した。 彼らはいわゆる「文明化プロセス」を奨励する政策を策定した。ヨーロッパからの移民の波が増加するにつれて、市民の大多数が共通に持つべき文化的価値観や 慣習の標準セットを奨励するための教育に対する社会的支持が高まった。教育は、マイノリティの社会化プロセスにおける主要な方法と見なされた。 アメリカ化政策は、先住民がアメリカの習慣や価値観を学べば、部族の伝統をアメリカ文化と融合させ、平和的に社会の多数派に加わることができるという考え に基づいていた。インディアン戦争終結後、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、連邦政府は伝統的な宗教儀式の実践を違法とした。連邦政府はネイティ ブ・アメリカンの寄宿学校を設立し、子供たちはそこに通うことを義務付けられた。これらの学校では、英語を話し、標準的な科目を勉強し、教会に通い、部族 の伝統から離れることを強制された。 1887年のドーズ法(Dawes Act)は、部族の土地を個人に数個ずつ割り当てたもので、ネイティブ・アメリカンのために個々のホームステッドを作る方法と見なされた。土地の割当て は、ネイティブ・アメリカンが米国市民となり、部族の自治と制度の一部を放棄することと引き換えに行われた。その結果、推定で合計9,300万エーカー (380,000 km2)がネイティブ・アメリカンの支配から移された。そのほとんどは、個人に売却されるか、ホームステッド法を通じて無償で譲渡されるか、インディアン 個人に直接譲渡された。1924年のインディアン市民権法もアメリカ化政策の一環であり、居留地に住むインディアン全員に完全な市民権を与えた。強制的な 同化に反対した代表的な人物は、1933年から1945年まで連邦インディアン問題局を指揮したジョン・コリアーであり、既成の政策の多くを覆そうとし た。

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_assimilation_of_Native_Americans

| A series of efforts

were made by the United States to assimilate Native Americans into

mainstream European–American culture between the years of 1790 and

1920.[1][2] George Washington and Henry Knox were first to propose, in

the American context, the cultural assimilation of Native Americans.[3]

They formulated a policy to encourage the so-called "civilizing

process".[2] With increased waves of immigration from Europe, there was

growing public support for education to encourage a standard set of

cultural values and practices to be held in common by the majority of

citizens. Education was viewed as the primary method in the

acculturation process for minorities. Americanization policies were based on the idea that when Indigenous people learned customs and values of the United States, they would be able to merge tribal traditions with American culture and peacefully join the majority of the society. After the end of the Indian Wars, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the federal government outlawed the practice of traditional religious ceremonies. It established Native American boarding schools which children were required to attend. In these schools they were forced to speak English, study standard subjects, attend church, and leave tribal traditions behind. The Dawes Act of 1887, which allotted tribal lands in severalty to individuals, was seen as a way to create individual homesteads for Native Americans. Land allotments were made in exchange for Native Americans becoming US citizens and giving up some forms of tribal self-government and institutions. It resulted in the transfer of an estimated total of 93 million acres (380,000 km2) from Native American control. Most was sold to individuals or given out free through the Homestead law, or given directly to Indians as individuals. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 was also part of Americanization policy; it gave full citizenship to all Indians living on reservations. The leading opponent of forced assimilation was John Collier, who directed the federal Office of Indian Affairs from 1933 to 1945, and tried to reverse many of the established policies. |

アメリカでは1790年から1920年にかけて、ネイティブ・アメリカ

ンをヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の主流文化に同化させるための一連の取り組みが行われた[1][2]。

ジョージ・ワシントンとヘンリー・ノックスは、アメリカの文脈でネイティブ・アメリカンの文化的同化を最初に提唱した[3]。

彼らはいわゆる「文明化プロセス」を奨励する政策を策定した[2]。ヨーロッパからの移民の波が増加するにつれて、市民の大多数が共通に持つべき文化的価

値観や慣習の標準セットを奨励するための教育に対する社会的支持が高まった。教育は、マイノリティの社会化プロセスにおける主要な方法と見なされた。 アメリカ化政策は、先住民がアメリカの習慣や価値観を学べば、部族の伝統をアメリカ文化と融合させ、平和的に社会の多数派に加わることができるという考え に基づいていた。インディアン戦争終結後、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、連邦政府は伝統的な宗教儀式の実践を違法とした。連邦政府はネイティ ブ・アメリカンの寄宿学校を設立し、子供たちはそこに通うことを義務付けられた。これらの学校では、英語を話し、標準的な科目を勉強し、教会に通い、部族 の伝統から離れることを強制された。 1887年のドーズ法(Dawes Act)は、部族の土地を個人に数個ずつ割り当てたもので、ネイティブ・アメリカンのために個々のホームステッドを作る方法と見なされた。土地の割当て は、ネイティブ・アメリカンが米国市民となり、部族の自治と制度の一部を放棄することと引き換えに行われた。その結果、推定で合計9,300万エーカー (380,000 km2)がネイティブ・アメリカンの支配から移された。そのほとんどは、個人に売却されるか、ホームステッド法を通じて無償で譲渡されるか、インディアン 個人に直接譲渡された。1924年のインディアン市民権法もアメリカ化政策の一環であり、居留地に住むインディアン全員に完全な市民権を与えた。強制的な 同化に反対した代表的な人物は、1933年から1945年まで連邦インディアン問題局を指揮したジョン・コリアーであり、既成の政策の多くを覆そうとし た。 |

Europeans and Native Americans in North America, 1601–1776 Eastern North America; the 1763 "Proclamation line" is the border between the red and the pink areas. Epidemiological and archeological work has established the effects of increased immigration of children accompanying families from Central Africa to North America between 1634 and 1640. They came from areas where smallpox was endemic in Europea, and passed on the disease to indigenous people. Tribes such as the Huron-Wendat and others in the Northeast particularly suffered devastating epidemics after 1634.[4] During this period European powers fought to acquire cultural and economic control of North America, just as they were doing in Europe. At the same time, indigenous peoples competed for dominance in the European fur trade and hunting areas. The European colonial powers sought to hire Native American tribes as auxiliary forces in their North American armies, otherwise composed mostly of colonial militia in the early conflicts. In many cases indigenous warriors formed the great majority of fighting forces, which deepened some of their rivalries. To secure the help of the tribes, the Europeans offered goods and signed treaties. The treaties usually promised that the European power would honor the tribe's traditional lands and independence. In addition, the indigenous peoples formed alliances for their own reasons, wanting to keep allies in the fur and gun trades, positioning European allies against their traditional enemies among other tribes, etc. Many Native American tribes took part in King William's War (1689–1697), Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) (War of the Spanish Succession), Dummer's War (c. 1721–1725), and the French and Indian War (1754–1763) (Seven Years' War). As the dominant power after the Seven Years' War, Great Britain instituted the Royal Proclamation of 1763, to try to protect indigenous peoples' territory from colonial encroachment of peoples from east of the Appalachian Mountains. The document defined a boundary to demarcate Native American territory from that of the European-American settlers. Despite the intentions of the Crown, the proclamation did not effectively prevent colonists from continuing to migrate westward. The British did not have sufficient forces to patrol the border and keep out migrating colonists. From the perspective of the colonists, the proclamation served as one of the Intolerable Acts and one of the 27 colonial grievances that would lead to the American Revolution and eventual independence from Britain.[5] |

北米におけるヨーロッパ人とアメリカ先住民、1601-1776年 北米東部。1763年の「布告ライン」が赤とピンクの地域の境界である。 1634年から1640年にかけて、中央アフリカから北アメリカへの家族連れの子供の移民が増加した影響が、疫学的および考古学的調査によって立証され た。彼らはヨーロッパで天然痘が流行していた地域からやってきて、先住民に伝染させたのである。ヒューロン・ウェンダット族などの北東部の部族は、特に 1634年以降、壊滅的な伝染病に見舞われた[4]。 この時期、ヨーロッパ列強はヨーロッパと同じように北アメリカの文化的・経済的支配権を獲得しようと争った。同時に、先住民はヨーロッパの毛皮貿易と狩猟 地域における覇権を争った。ヨーロッパの植民地勢力は、植民地民兵で構成されていた北米軍隊の補助部隊として、先住民族を雇用しようとした。多くの場合、 先住民の戦士が戦闘部隊の大部分を占め、それが対立を深めていった。部族の協力を得るため、ヨーロッパ人は物資を提供し、条約を結んだ。条約は通常、ヨー ロッパ勢力が部族の伝統的な土地と独立を尊重することを約束するものであった。加えて、先住民族は毛皮や銃の取引で同盟者を維持したい、他の部族の伝統的 な敵に対してヨーロッパ人の同盟者を位置づけたいなど、それぞれの理由で同盟を結んだ。多くのアメリカ先住民部族がウィリアム王戦争(1689年〜 1697年)、アン女王戦争(1702年〜1713年)(スペイン継承戦争)、ダマー戦争(1721年頃〜1725年)、フレンチ・インディアン戦争 (1754年〜1763年)(七年戦争)に参加した。 七年戦争後、支配国であったイギリスは、アパラチア山脈以東からの植民地侵攻から先住民族の領土を守ろうと、1763年の王室布告を制定した。この公布 は、アメリカ先住民の領土とヨーロッパ系アメリカ人入植者の領土との境界を定めるものであった。王室の意図とは裏腹に、この布告は植民者たちが西へ移動を 続けるのを効果的に防ぐことはできなかった。イギリスは、国境をパトロールし、移住してくる入植者を排除するだけの十分な戦力を有していなかったのであ る。植民者たちから見れば、この布告は耐え難い行為のひとつであり、アメリカ独立と最終的なイギリスからの独立につながる27の植民者の不満のひとつで あった[5]。 |

| The United States and Native Americans, 1776–1860 See also: Native American genocide in the United States  Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins demonstrating European methods of farming to Creek (Muscogee) on his Georgia plantation situated along the Flint River, 1805 The most important facet of the foreign policy of the newly independent United States was primarily concerned with devising a policy to deal with the various Native American tribes it bordered. To this end, they largely continued the practises that had been adopted since colonial times by settlers and European governments.[6] They realized that good relations with bordering tribes were important for political and trading reasons, but they also reserved the right to abandon these good relations to conquer and absorb the lands of their enemies and allies alike as the American frontier moved west. The United States continued the use of Native Americans as allies, including during the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. As relations with Britain and Spain normalized during the early 19th century, the need for such friendly relations ended. It was no longer necessary to "woo" the tribes to prevent the other powers from allying with them against the United States. Now, instead of a buffer against European powers, the tribes often became viewed as an obstacle in the expansion of the United States.[5] George Washington formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process.[2] He had a six-point plan for civilization which included: impartial justice toward Native Americans regulated buying of Native American lands promotion of commerce promotion of experiments to civilize or improve Native American society presidential authority to give presents punishing those who violated Native American rights.[7] Robert Remini, a historian, wrote that "once the Indians adopted the practice of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans".[8] The United States appointed agents, like Benjamin Hawkins, to live among the Native Americans and to teach them how to live like whites.[3] How different would be the sensation of a philosophic mind to reflect that instead of exterminating a part of the human race by our modes of population that we had persevered through all difficulties and at last had imparted our Knowledge of cultivating and the arts, to the Aboriginals of the Country by which the source of future life and happiness had been preserved and extended. But it has been conceived to be impracticable to civilize the Indians of North America – This opinion is probably more convenient than just. — Henry Knox to George Washington, 1790s.[7] Indian removal The Indian Removal Act of 1830 characterized the U.S. government policy of Indian removal, which called for the forced relocation of Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river. While it did not authorize the forced removal of the indigenous tribes, it authorized the President to negotiate land exchange treaties with tribes located in lands of the United States. The Intercourse Law of 1834 prohibited United States citizens from entering tribal lands granted by such treaties without permission, though it was often ignored. On September 27, 1830, the Choctaws signed Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek and the first Native American tribe was to be voluntarily removed. The agreement represented one of the largest transfers of land that was signed between the U.S. Government and Native Americans without being instigated by warfare. By the treaty, the Choctaws signed away their remaining traditional homelands, opening them up for American settlement in Mississippi Territory. While the Indian Removal Act made the relocation of the tribes voluntary, it was often abused by government officials. The best-known example is the Treaty of New Echota. It was negotiated and signed by a small fraction of Cherokee tribal members, not the tribal leadership, on December 29, 1835. While tribal leaders objected to Washington, DC and the treaty was revised in 1836, the state of Georgia proceeded to act against the Cherokee tribe. The tribe was forced to relocate in 1838.[1] An estimated 4,000 Cherokees died in the march, now known as the Trail of Tears. In the decades that followed, white settlers encroached even into the western lands set aside for Native Americans. American settlers eventually made homesteads from coast to coast, just as the Native Americans had before them. No tribe was untouched by the influence of white traders, farmers, and soldiers. Office of Indian Affairs The Office of Indian Affairs (Bureau of Indian Affairs as of 1947) was established on March 11, 1824, as an office of the United States Department of War, an indication of the state of relations with the Indians. It became responsible for negotiating treaties and enforcing conditions, at least for Native Americans. In 1849 the bureau was transferred to the Department of the Interior as so many of its responsibilities were related to the holding and disposition of large land assets. In 1854 Commissioner George W. Manypenny called for a new code of regulations. He noted that there was no place in the West where the Indians could be placed with a reasonable hope that they might escape conflict with white settlers. He also called for the Intercourse Law of 1834 to be revised, as its provisions had been aimed at individual intruders on Indian territory rather than at organized expeditions. In 1858 the succeeding Commissioner, Charles Mix, noted that the repeated removal of tribes had prevented them from acquiring a taste for European way of life. In 1862 Secretary of the Interior Caleb B. Smith questioned the wisdom of treating tribes as quasi-independent nations.[6] Given the difficulties of the government in what it considered good efforts to support separate status for Native Americans, appointees and officials began to consider a policy of Americanization instead. |

アメリカ合衆国とネイティブ・アメリカン、1776年-1860年 以下も参照のこと: アメリカにおけるアメリカ先住民虐殺  1805年、フリント川沿いにあるジョージア州の農園で、クリーク族(マスコギー族)にヨーロッパの農法を教えるインディアン要員ベンジャミン・ホーキンス。 独立したばかりのアメリカ合衆国の外交政策で最も重要なのは、国境を接するさまざまなアメリカ先住民族に対処する政策を考案することであった。この目的の ために、彼らは植民地時代から入植者やヨーロッパ政府によって採用されてきた慣行をほぼ継続した[6]。彼らは、国境を接する部族との良好な関係が政治 的・交易的な理由から重要であることを理解していたが、アメリカのフロンティアが西に移動するにつれて、敵や味方の土地を征服・吸収するためにこれらの良 好な関係を放棄する権利も留保していた。アメリカは、アメリカ独立戦争や1812年戦争でも、ネイティブ・アメリカンを同盟国として利用し続けた。19世 紀初頭にイギリスやスペインとの関係が正常化すると、そのような友好関係の必要性はなくなった。他の列強がアメリカと同盟を結ぶのを防ぐために、部族を 「口説く」必要はなくなったのだ。今や部族はヨーロッパ列強に対する緩衝材ではなく、しばしばアメリカ合衆国の拡大の障害と見なされるようになった [5]。 ジョージ・ワシントンは「文明化」プロセスを促進するための政策を策定した[2]。 彼は文明化のための6項目の計画を持っていた: ネイティブ・アメリカンに対する公平な正義 アメリカ先住民の土地の購入を規制する 商業の促進 ネイティブ・アメリカン社会を文明化または改善するための実験の促進 大統領によるプレゼントの権限 ネイティブ・アメリカンの権利を侵害した人々を罰すること[7]。 歴史家のロバート・レミニは、「ひとたびインディアンが私有財産の習慣を取り入れ、家を建て、農業を営み、子供たちに教育を施し、キリスト教を受け入れる ようになれば、これらのネイティブ・アメリカンは白人アメリカンから受け入れられるようになるだろう」と書いている[8]。 アメリカはベンジャミン・ホーキンスのようなエージェントを任命し、ネイティブ・アメリカンの間で生活させ、白人のように生活する方法を教えた[3]。 われわれの人口形態によって人類の一部を絶滅させる代わりに、われわれはあらゆる困難を乗り越えて忍耐し、ついには耕作と芸術に関するわれわれの知識をそ の国の原住民に伝授し、それによって将来の生命と幸福の源泉が維持され、拡大されたのだと考えたら、哲学的精神の感覚はどれほど違ったものになるだろう。 しかし、北アメリカのインディアンを文明化することは現実的ではないと考えられてきた。 - ヘンリー・ノックスからジョージ・ワシントンへ、1790年代[7]。 インディアンの除去 1830年のインディアン除去法は、アメリカ政府のインディアン除去政策を特徴づけるもので、ミシシッピ川以東に住むネイティブ・アメリカン部族を川以西 の土地に強制移住させることを求めた。この法律は先住民部族の強制移住を許可するものではなかったが、大統領がアメリカ合衆国の土地に位置する部族と土地 交換条約を交渉することを許可した。1834年の交流法は、合衆国市民がそのような条約によって与えられた部族の土地に許可なく立ち入ることを禁止した が、しばしば無視された。 1830年9月27日、チョクトー族はダンシング・ラビット・クリーク条約に調印し、最初のネイティブ・アメリカン部族が自主的に追放されることになっ た。この協定は、アメリカ政府とネイティブ・アメリカンの間で、戦争によって扇動されることなく調印された、最大規模の土地譲渡のひとつであった。この条 約により、チョクトー族は残された伝統的な故郷を手放し、ミシシッピ準州へのアメリカ人入植のために開放された。 インディアン移動法は部族の移転を自発的なものとしたが、政府高官によって悪用されることもしばしばあった。最もよく知られている例は、ニューエコタ条約 である。この条約は、1835年12月29日に、部族の指導者ではなく、チェロキーインディアンのごく一部の部族によって交渉され、署名された。部族の指 導者たちがワシントンDCに異議を申し立て、1836年に条約が改訂されたが、ジョージア州はチェロキー族に対して行動を起こした。現在「涙の道 (Trail of Tears)」として知られているこの行進で、推定4,000人のチェロキーインディアンが死んだ。 その後数十年間、白人入植者たちは、アメリカ先住民のために確保された西部の土地にまで侵入した。アメリカ人入植者たちは、ネイティブ・アメリカンがそう であったように、海岸から海岸までホームステッドを作った。どの部族も白人商人、農民、兵士の影響を受けなかったわけではない。 インディアン事務局 インディアン問題局(1947年現在ではインディアン問題局)は、1824年3月11日にアメリカ合衆国陸軍省の一部門として設立された。少なくともアメ リカ先住民に対しては、条約の交渉と条件の執行を担当するようになった。1849年、その責務の多くが大規模な土地資産の保有と処分に関連していたため、 内務省に移管された。 1854年、コミッショナーのジョージ・W・メニーペニー(George W. Manypenny)は、新しい規則規定を求めた。彼は、西部にはインディアンが白人入植者との衝突を避けられるような、合理的な希望を持てる場所がない と指摘した。彼はまた、1834年に制定された交易法を改正するよう求めた。その規定は、組織的な遠征ではなく、インディアン領土への個人的な侵入者を対 象としていたからである。 1858年、後任のチャールズ・ミックス(Charles Mix)長官は、部族の度重なる移動がヨーロッパ的な生活様式を身につけることを妨げてきたと指摘した。1862年、内務長官ケイレブ・B・スミスは、部 族を準独立国家として扱うことの賢明さに疑問を呈した[6]。 政府がネイティブ・アメリカンの独立した地位を支持するための最善の努力と考えることが困難であったことから、任命者や役人は代わりにアメリカ人化政策を 検討し始めた。 |

| Americanization and assimilation (1857–1920) See also: Federal Indian Policy § Allotment and assimilation era (1887–1943)  Portrait of Marsdin, non-native man, and group of students from the Alaska region The movement to reform Indian administration and assimilate Indians as citizens originated in the pleas of people who lived in close association with the natives and were shocked by the fraudulent and indifferent management of their affairs. They called themselves "Friends of the Indian" and lobbied officials on their behalf. Gradually the call for change was taken up by Eastern reformers.[6] Typically the reformers were Protestants from well organized denominations who considered assimilation necessary to the Christianizing of the Indians; Catholics were also involved. The 19th century was a time of major efforts in evangelizing missionary expeditions to all non-Christian people. In 1865 the government began to make contracts with various missionary societies to operate Indian schools for teaching citizenship, English, and agricultural and mechanical arts,[9] and decades later was continued by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[10] Grant's "Peace Policy" Main article: Native American policy of the Ulysses S. Grant administration Further information: Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant In his State of the Union Address on December 4, 1871, Ulysses Grant stated that "the policy pursued toward the Indians has resulted favorably ... many tribes of Indians have been induced to settle upon reservations, to cultivate the soil, to perform productive labor of various kinds, and to partially accept civilization. They are being cared for in such a way, it is hoped, as to induce those still pursuing their old habits of life to embrace the only opportunity which is left them to avoid extermination."[11] The emphasis became using civilian workers (not soldiers) to deal with reservation life, especially Protestant and Catholic organizations. The Quakers had promoted the peace policy in the expectation that applying Christian principles to Indian affairs would eliminate corruption and speed assimilation. Most Indians joined churches, but there were unexpected problems, such as rivalry between Protestants and Catholics for control of specific reservations in order to maximize the number of souls converted.[12] The Quakers were motivated by high ideals, played down the role of conversion, and worked well with the Indians. They had been highly organized and motivated by the anti-slavery crusade, and after the Civil War expanded their energies to include both ex-slaves and the western tribes. They had Grant's ear and became the principal instruments for his peace policy. During 1869–1885, they served as appointed agents on numerous reservations and superintendencies in a mission centered on moral uplift and manual training. Their ultimate goal of acculturating the Indians to American culture was not reached because of frontier land hunger and Congressional patronage politics.[13] Many other denominations volunteered to help. In 1871, John H. Stout, sponsored by the Dutch Reformed Church, was sent to the Pima reservation in Arizona to implement the policy. However Congress, the church, and private charities spent less money than was needed; the local whites strongly disliked the Indians; the Pima balked at removal; and Stout was frustrated at every turn.[14] In Arizona and New Mexico, the Navajo were resettled on reservations and grew rapidly in numbers. The Peace Policy began in 1870 when the Presbyterians took over the reservations. They were frustrated because they did not understand the Navajo. However, the Navajo not only gave up raiding but soon became successful at sheep ranching.[15] The peace policy did not fully apply to the Indian tribes that had supported the Confederacy. They lost much of their land as the United States began to confiscate the western portions of the Indian Territory and began to resettle the Indians there on smaller reservations.[16] Reaction to the massacre of Lt. Col. George Custer's unit at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876 was shock and dismay at the failure of the Peace Policy. The Indian appropriations measure of August 1876 marked the end of Grant's Peace Policy. The Sioux were given the choice of either selling their lands in the Black Hills for cash or not receiving government gifts of food and other supplies.[17] Code of Indian Offenses In 1882, Interior Secretary Henry M. Teller called attention to the "great hindrance" of Indian customs to the progress of assimilation. The resultant "Code of Indian Offenses" in 1883 outlined the procedure for suppressing "evil practice." A Court of Indian Offenses, consisting of three Indians appointed by the Indian Agent, was to be established at each Indian agency. The Court would serve as judges to punish offenders. Outlawed behavior included participation in traditional dances and feasts, polygamy, reciprocal gift giving and funeral practices, and intoxication or sale of liquor. Also prohibited were "medicine men" who "use any of the arts of the conjurer to prevent the Indians from abandoning their heathenish rites and customs." The penalties prescribed for violations ranged from 10 to 90 days imprisonment and loss of government-provided rations for up to 30 days.[18] The Five Civilized Tribes were exempt from the Code which remained in effect until 1933.[19] In implementation on reservations by Indian judges, the Court of Indian Offenses became mostly an institution to punish minor crimes. The 1890 report of the Secretary of the Interior lists the activities of the Court on several reservations and apparently no Indian was prosecuted for dances or "heathenish ceremonies."[20] Significantly, 1890 was the year of the Ghost Dance, ending with the Wounded Knee Massacre. The role of the Supreme Court in assimilation  Portrait of an assimilated Indigenous Californian in Sacramento, 1867. In 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney expressed that since Native Americans were "free and independent people" that they could become U.S. citizens.[21] Taney asserted that Native Americans could be naturalized and join the "political community" of the United States.[21] [Native Americans], without doubt, like the subjects of any other foreign Government, be naturalized by the authority of Congress, and become citizens of a State, and of the United States; and if an individual should leave his nation or tribe, and take up his abode among the white population, he would be entitled to all the rights and privileges which would belong to an emigrant from any other foreign people. The political ideas during the time of assimilation policy are known by many Indians as the progressive era, but more commonly known as the assimilation era.[22] The progressive era was characterized by a resolve to emphasize the importance of dignity and independence in the modern industrialized world.[23] This idea is applied to Native Americans in a quote from Indian Affairs Commissioner John Oberly: "[The Native American] must be imbued with the exalting egotism of American civilization so that he will say ‘I’ instead of ‘We’, and ‘This is mine’ instead of ‘This is ours’."[24] Progressives also had faith in the knowledge of experts.[23] This was a dangerous idea to have when an emerging science was concerned with ranking races based on moral capabilities and intelligence.[25] Indeed, the idea of an inferior Indian race made it into the courts. The progressive era thinkers also wanted to look beyond legal definitions of equality to create a realistic concept of fairness. Such a concept was thought to include a reasonable income, decent working conditions, as well as health and leisure for every American.[23] These ideas can be seen in the decisions of the Supreme Court during the assimilation era. Cases such as Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, Talton v. Mayes, Winters v. United States, United States v. Winans, United States v. Nice, and United States v. Sandoval provide excellent examples of the implementation of the paternal view of Native Americans as they refer back to the idea of Indians as "wards of the nation".[26] Some other issues that came into play were the hunting and fishing rights of the natives, especially when land beyond theirs affected their own practices, whether or not Constitutional rights necessarily applied to Indians, and whether tribal governments had the power to establish their own laws. As new legislation tried to force the American Indians into becoming just Americans, the Supreme Court provided these critical decisions. Native American nations were labeled "domestic dependent nations" by Marshall in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, one of the first landmark cases involving Indians.[27] Some decisions focused more on the dependency of the tribes, while others preserved tribal sovereignty, while still others sometimes managed to do both. |

アメリカ化と同化 (1857-1920) 以下も参照のこと: 連邦インディアン政策§割当てと同化の時代 (1887-1943)  マースディン、非ネイティブ男性、アラスカ地域の学生グループの肖像画 インディアン行政を改革し、インディアンを市民として同化させようとする運動は、原住民と密接に関わりながら生活し、その不正で無関心な管理に衝撃を受け た人々の嘆願に端を発する。彼らは自らを「インディアンの友」と呼び、彼らのために役人に働きかけた。改革を求める声は次第に東方の改革者たちによって取 り上げられるようになった[6]。一般的に改革者たちは、よく組織された教派のプロテスタントであり、インディアンをキリスト教化するためには同化が必要 だと考えていた。19世紀は、すべての非キリスト教徒を対象とした布教活動が盛んに行われた時代であった。1865年、政府は様々な宣教師協会と契約を結 び、市民権、英語、農業や機械技術を教えるインディアン学校を運営し始め[9]、数十年後にはインディアン問題局によって継続された[10]。 グラントの「平和政策」 主な記事 ユリシーズ・グラント政権のアメリカ先住民政策 さらに詳しい情報 ユリシーズ・S・グラント大統領時代 1871年12月4日の一般教書演説で、ユリシーズ・グラントは「インディアンに対する政策は好ましい結果をもたらした......インディアンの多くの 部族は保留地に定住するように誘導され、土壌を耕し、さまざまな種類の生産的労働を行い、部分的に文明を受け入れるようになった。彼らは、まだ古い生活習 慣を続けている部族が、絶滅を避けるために残された唯一の機会を受け入れるように誘導するような方法で世話されている。クエーカー教徒は、インディアンの 問題にキリスト教の原則を適用することで、腐敗をなくし、同化を早めることができると期待し、平和政策を推進していた。ほとんどのインディアンは教会に入 信したが、改宗者の数を最大化するために、特定の居留地の支配権をめぐってプロテスタントとカトリックが対立するなど、予期せぬ問題も起こった[12]。 クエーカー教徒は、高い理想に突き動かされ、改宗の役割を軽視し、インディアンたちとうまくやっていた。彼らは反奴隷運動によって高度に組織化され、意欲 を高めていたが、南北戦争後は元奴隷と西部の部族の両方にその勢力を拡大した。彼らはグラントの耳目を集め、彼の和平政策の主要な道具となった。1869 年から1885年にかけて、彼らは多くの居留地や管理区で任命代理人として、道徳の向上と手先の訓練を中心とした使命を果たした。インディアンをアメリカ 文化に馴化させるという彼らの最終目標は、開拓地の土地の飢えと議会の後援政治のために達成されなかった[13]。 他の多くの教派がボランティアとして協力した。1871年には、オランダ改革派教会がスポンサーとなったジョン・H・スタウトがアリゾナのピマ保留地に派 遣され、この政策を実施した。しかし、議会、教会、民間の慈善団体は必要な資金よりも少ない資金しか使わず、地元の白人はインディアンを強く嫌い、ピマ族 は移住に難色を示し、スタウトはことごとく挫折した[14]。 アリゾナとニューメキシコでは、ナバホ族は保留地に再定住され、急速に数を増やした。平和政策は1870年に長老派が居留地を引き継いだときに始まった。 彼らはナバホ族を理解できず、不満を募らせた。しかし、ナバホ族は略奪をやめただけでなく、すぐに牧羊で成功するようになった[15]。 和平政策は南部連合を支持していたインディアン部族には完全には適用されなかった。アメリカはインディアン準州の西部を没収し始め、そこのインディアンを小さな保留地に再定住させ始めたので、彼らは多くの土地を失った[16]。 1876年のリトル・ビッグ・ホーンの戦いでのジョージ・カスター中佐の部隊の虐殺に対する反応は、平和政策の失敗に対する衝撃と落胆であった。1876 年8月のインディアン予算措置は、グラントの平和政策の終焉を意味した。スー族はブラックヒルズの土地を現金で売却するか、政府からの食糧やその他の物資 の贈与を受けないかの選択を迫られた[17]。 インディアン犯罪規定 1882年、内務長官ヘンリー・M・テラーは、同化の進展に対するインディアンの習慣の「大きな障害」に注意を喚起した。その結果、1883年に 「Code of Indian Offenses 」が制定され、「悪習 」を取り締まるための手続きが概説された。 インディアン諜報員によって任命された3人のインディアンからなるインディアン犯罪裁判所は、各インディアン機関に設置されることになっていた。裁判所は 犯罪者を罰する裁判官の役割を果たす。禁止された行為には、伝統的なダンスや祝宴への参加、一夫多妻制、贈り物の相互贈与や葬儀の慣習、酩酊や酒の販売な どが含まれた。また、「インディアンが異教的な儀式や習慣を捨てないように、呪術師の術を使う」「メディスンマン」も禁止された。違反した場合の罰則は、 10日から90日の禁固刑と、政府から支給される配給を最大30日間失うというものであった[18]。 5文明部族は、1933年まで有効であったこの法典から除外されていた[19]。 インディアン裁判官による居留地での実施において、インディアン犯罪裁判所は主に軽犯罪を罰する機関となった。1890年の内務省長官の報告書には、いく つかの居留地における裁判所の活動が記載されており、ダンスや「異教徒の儀式」で起訴されたインディアンはいなかったようである[20]。重要なことに、 1890年はゴーストダンスの年であり、ウーンデッド・ニーの虐殺で幕を閉じた。 同化における最高裁判所の役割  1867年、サクラメントで同化したカリフォルニア先住民の肖像 1857年、ロジャー・B・タニー最高裁長官は、ネイティブ・アメリカンは「自由で独立した人々」であり、アメリカ市民になることができると表明した[21]。 [アメリカ先住民は)間違いなく、他の外国政府の臣民と同様に、議会の権限によって帰化し、州の市民となり、合衆国の市民となることができる。 同化政策の時代の政治思想は、多くのインディアンによって進歩的な時代として知られているが、より一般的には同化の時代として知られている[22]。進歩 的な時代は、現代の工業化された世界における尊厳と独立の重要性を強調する決意によって特徴づけられていた[23]。この思想は、インディアン問題コミッ ショナーJohn Oberlyの引用の中でネイティブ・アメリカンに適用されている: ネイティブ・アメリカンは)アメリカ文明の高揚したエゴイズムを植え付けられなければならない。そうすれば、彼は 「We 」ではなく 「I 」と言い、「This is ours 」ではなく 「This is mine 」と言うようになる」[24]。進歩主義者たちはまた、専門家の知識を信頼していた[23]。新興の科学が道徳的能力や知性に基づいて人種をランク付けす ることに関心を持っていたときには、これは危険な考えであった。進歩的な時代の思想家たちはまた、平等の法的な定義を超えて、現実的な公平の概念を作り出 そうとした。そのような概念には、すべてのアメリカ人のための健康や余暇だけでなく、妥当な収入、適切な労働条件が含まれると考えられていた[23]。こ のような考えは、同化時代の最高裁判所の判決に見ることができる。 ローンウルフ対ヒッチコック事件、タルトン対メイズ事件、ウィンターズ対アメリカ合衆国事件、アメリカ合衆国対ウィナンズ事件、アメリカ合衆国対ニース事 件、アメリカ合衆国対サンドヴァル事件などは、「国家の被保護者」としてのインディアンの考え方に言及しており、ネイティブ・アメリカンに対する父性的見 解の実践の優れた例を示している。 [26]その他にも、先住民の狩猟権や漁業権、特に彼らの土地以外の土地が彼らの慣習に影響を及ぼす場合、憲法上の権利が必ずしもインディアンに適用され るのかどうか、部族政府に独自の法律を制定する権限があるのかどうかなどが問題となった。新たな法律がアメリカ・インディアンを単なるアメリカ人に強制し ようとする中、最高裁判所はこれらの重要な決定を下した。インディアンに関わる最初の画期的な裁判のひとつであるチェロキー族対ジョージア州の裁判では、 マーシャルによってアメリカ先住民の国々は「国内従属国」とレッテルを貼られた[27]。部族の従属性に重点を置いた判決もあれば、部族の主権を維持した 判決もあり、またその両方を実現した判決もあった。 |

| Decisions focusing on dependence United States vs. Kagama The United States Supreme Court case United States v. Kagama (1886) set the stage for the court to make even more powerful decisions based on plenary power. To summarize congressional plenary power, the court stated: The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful, now weak and diminished in numbers, is necessary to their protection, as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell. It must exist in that government, because it never has existed anywhere else; because the theater of its exercise is within the geographical limits of the United [118 U.S. 375, 385] States; because it has never been denied; and because it alone can enforce its laws on all the tribes.[28] The decision in United States v. Kagama led to the new idea that "protection" of Native Americans could justify intrusion into intratribal affairs. The Supreme Court and Congress were given unlimited authority with which to force assimilation and acculturation of Native Americans into American society.[24] United States v. Nice During the years leading up to passage of the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act, United States v. Nice (1916), was a result of the idea of barring American Indians from the sale of liquor. The United States Supreme Court case overruled a decision made eleven years before, Matter of Heff, 197 U.S. 48 (1905), which allowed American Indian U.S. citizens to drink liquor.[29] The quick reversal shows how law concerning American Indians often shifted with the changing governmental and popular views of American Indian tribes.[30] The US Congress continued to prohibit the sale of liquor to American Indians. While many tribal governments had long prohibited the sale of alcohol on their reservations, the ruling implied that American Indian nations could not be entirely independent, and needed a guardian for protection. United States v. Sandoval Like United States v. Nice, the United States Supreme Court case of United States v. Sandoval (1913) rose from efforts to bar American Indians from the sale of liquor. As American Indians were granted citizenship, there was an effort to retain the ability to protect them as a group which was distinct from regular citizens. The Sandoval Act reversed the U.S. v. Joseph decision of 1876, which claimed that the Pueblo were not considered federal Indians. The 1913 ruling claimed that the Pueblo were "not beyond the range of congressional power under the Constitution".[31] This case resulted in Congress continuing to prohibit the sale of liquor to American Indians. The ruling continued to suggest that American Indians needed protection. Decisions focusing on sovereignty There were several United States Supreme Court cases during the assimilation era that focused on the sovereignty of American Indian nations. These cases were extremely important in setting precedents for later cases and for legislation dealing with the sovereignty of American Indian nations. Ex parte Crow Dog (1883) Ex parte Crow Dog was a US Supreme Court appeal by an Indian who had been found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. The defendant was an American Indian who had been found guilty of the murder of another American Indian. Crow Dog argued that the district court did not have the jurisdiction to try him for a crime committed between two American Indians that happened on an American Indian reservation. The court found that although the reservation was located within the territory covered by the district court's jurisdiction, Rev. Stat. § 2146 precluded the inmate's indictment in the district court. Section 2146 stated that Rev. Stat. § 2145, which made the criminal laws of the United States applicable to Indian country, did not apply to crimes committed by one Indian against another, or to crimes for which an Indian was already punished by the law of his tribe. The Court issued the writs of habeas corpus and certiorari to the Indian.[32] Talton v. Mayes (1896) The United States Supreme Court case of Talton v. Mayes was a decision respecting the authority of tribal governments. This case decided that the individual rights protections, specifically the Fifth Amendment, which limit federal, and later, state governments, do not apply to tribal government. It reaffirmed earlier decisions, such as the 1831 Cherokee Nation v. Georgia case, that gave Indian tribes the status of "domestic dependent nations", the sovereignty of which is independent of the federal government.[33] Talton v. Mayes is also a case dealing with Native American dependence, as it deliberated over and upheld the concept of congressional plenary authority. This part of the decision led to some important pieces of legislation concerning Native Americans, the most important of which is the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968. Good Shot v. United States (1900) This United States Supreme Court case occurred when an American Indian shot and killed a non-Indian. The question arose of whether or not the United States Supreme Court had jurisdiction over this issue. In an effort to argue against the Supreme Court having jurisdiction over the proceedings, the defendant filed a petition seeking a writ of certiorari. This request for judicial review, upon writ of error, was denied. The court held that a conviction for murder, punishable with death, was no less a conviction for a capital crime by reason even taking into account the fact that the jury qualified the punishment. The American Indian defendant was sentenced to life in prison.[34] Montoya v. United States (1901) This United States Supreme court case came about when the surviving partner of the firm of E. Montoya & Sons petitioned against the United States and the Mescalero Apache Indians for the value their livestock which was taken in March 1880. It was believed that the livestock was taken by "Victorio's Band" which was a group of these American Indians. It was argued that the group of American Indians who had taken the livestock were distinct from any other American Indian tribal group, and therefore the Mescalero Apache American Indian tribe should not be held responsible for what had occurred. After the hearing, the Supreme Court held that the judgment made previously in the Court of Claims would not be changed. This is to say that the Mescalero Apache American Indian tribe would not be held accountable for the actions of Victorio's Band. This outcome demonstrates not only the sovereignty of American Indian tribes from the United States, but also their sovereignty from one another. One group of American Indians cannot be held accountable for the actions of another group of American Indians, even though they are all part of the American Indian nation.[35] US v. Winans (1905) In this case, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Yakama tribe, reaffirming their prerogative to fish and hunt on off-reservation land. Further, the case established two important principles regarding the interpretation of treaties. First, treaties would be interpreted in the way Indians would have understood them and "as justice and reason demand".[36] Second, the Reserved Rights Doctrine was established which states that treaties are not rights granted to the Indians, but rather "a reservation by the Indians of rights already possessed and not granted away by them".[37] These "reserved" rights, meaning never having been transferred to the United States or any other sovereign, include property rights, which include the rights to fish, hunt and gather, and political rights. Political rights reserved to the Indian nations include the power to regulate domestic relations, tax, administer justice, or exercise civil and criminal jurisdiction.[38] Winters v. United States (1908) The United States Supreme Court case Winters v. United States was a case primarily dealing with water rights of American Indian reservations. This case clarified what water sources American Indian tribes had "implied" rights to put to use.[39] This case dealt with the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation and their right to utilize the water source of the Milk River in Montana. The reservation had been created without clearly stating the explicit water rights that the Fort Belknap American Indian reservation had. This became a problem once non-Indian settlers began moving into the area and using the Milk River as a water source for their settlements.[40] As water sources are extremely sparse and limited in Montana, this argument of who had the legal rights to use the water was presented. After the case was tried, the Supreme Court came to the decision that the Fort Belknap reservation had reserved water rights through the 1888 agreement which had created the American Indian Reservation in the first place. This case was very important in setting a precedent for cases after the assimilation era. It was used as a precedent for the cases Arizona v. California, Tulee v. Washington, Washington v. McCoy, Nevada v. United States, Cappaert v. United States, Colorado River Water Conservation Dist. v. United States, United States v. New Mexico, and Arizona v. San Carlos Apache Tribe of Arizona which all focused on the sovereignty of American Indian tribes. Choate v. Trapp (1912) As more Native Americans received allotments through the Dawes Act, there was a great deal of public and state pressure to tax allottees. However, in the United States Supreme court case Choate v. Trapp, 224 U.S. 665 (1912), the court ruled for Indian allottees to be exempt from state taxation.[29] Clairmont v. United States (1912) This United States Supreme Court case resulted when a defendant appealed the decision on his case. The defendant filed a writ of error to obtain review of his conviction after being convicted of unlawfully introducing intoxicating liquor into an American Indian reservation. This act was found a violation of the Act of Congress of January 30, 1897, ch. 109, 29 Stat. 506. The defendant's appeal stated that the district court lacked jurisdiction because the offense for which he was convicted did not occur in American Indian country. The defendant had been arrested while traveling on a train that had just crossed over from American Indian country. The defendant's argument held and the Supreme Court reversed the defendant's conviction remanding the cause to the district court with directions to quash the indictment and discharge the defendant.[41] United States v. Quiver (1916) This case was sent to the United States Supreme Court after first appearing in a district court in South Dakota. The case dealt with adultery committed on a Sioux Indian reservation. The district court had held that adultery committed by an Indian with another Indian on an Indian reservation was not punishable under the act of March 3, 1887, c. 397, 24 Stat. 635, now § 316 of the Penal Code. This decision was made because the offense occurred on a Sioux Indian reservation which is not said to be under jurisdiction of the district court. The United States Supreme Court affirmed the judgment of the district court saying that the adultery was not punishable as it had occurred between two American Indians on an American Indian reservation.[42] |

依存性に焦点を当てた判決 アメリカ合衆国対カガマ事件 合衆国最高裁判所のUnited States v. Kagama事件(1886年)は、裁判所が全権委任に基づき、さらに強力な決定を下す舞台となった。連邦議会の全権を要約すると、裁判所は次のように述べた: かつては強大であったが、現在は弱体化し、数も減少している民族の残党に対する一般政府の権限は、彼らの保護と、彼らが居住する人々の安全のために必要で ある。なぜなら、それは他のどこにも存在したことがないからであり、その行使の場が合衆国[118 U.S. 375, 385]の地理的範囲内にあるからであり、否定されたことがないからであり、すべての部族に対してその法律を執行できるのはその政府だけだからである [28]。 合衆国対カガマ裁判の判決によって、アメリカ先住民の「保護」は部族内の問題への介入を正当化できるという新しい考え方が生まれた。最高裁判所と連邦議会は、アメリカ社会へのアメリカ先住民の同化と馴化を強制する無制限の権限を与えられた[24]。 アメリカ合衆国対ニース事件 修正第18条とボルステッド法が成立するまでの数年間、アメリカ・インディアンに酒類販売を禁止するという考えから生まれたのが、アメリカ合衆国対ニース 事件(1916年)であった。この合衆国最高裁判所の判例は、その11年前に下された判決、Matter of Heff, 197 U.S. 48 (1905)を覆し、アメリカ・インディアンの合衆国市民が酒を飲むことを認めた[29]。この迅速な逆転は、アメリカ・インディアンに関する法律が、ア メリカ・インディアンの部族に対する政府や民衆の見解の変化によって、しばしば変化したことを示している[30]。多くの部族政府は長い間居留地での酒類 販売を禁止していたが、この判決はアメリカン・インディアン諸国が完全に独立することはできず、保護のための保護者が必要であることを暗示していた。 合衆国対サンドバル事件 合衆国対ニース事件と同様に、合衆国対サンドバル事件(1913年)も、アメリカン・インディアンの酒類販売を禁じようとする努力から生まれたものであ る。アメリカン・インディアンに市民権が与えられたため、彼らを一般市民とは異なるグループとして保護する能力を保持しようとする努力があった。サンドバ ル法は、プエブロ族は連邦インディアンとはみなされないと主張した1876年のU.S. v. Joseph判決を覆した。1913年の判決では、プエブロは「憲法の下での議会の権限の範囲を超えていない」と主張した[31]。この判決は、アメリカ ン・インディアンには保護が必要であることを示唆し続けた。 主権に焦点を当てた判決 同化時代には、アメリカ・インディアン国家の主権に焦点を当てた合衆国最高裁判所の判例がいくつかあった。これらの判例は、後の判例やアメリカ・インディアン国家の主権を扱う法律の前例となる非常に重要なものであった。 一方的クロウ・ドッグ事件 (1883) Ex parte Crow Dogは、殺人罪で有罪となり死刑を宣告されたインディアンによる連邦最高裁判所への上訴であった。被告はアメリカ・インディアンであり、他のアメリカ・ インディアンを殺害した罪で有罪判決を受けた。クロウ・ドッグ被告は、アメリカ・インディアン居留地で起きたアメリカ・インディアン同士の犯罪を裁く管轄 権が連邦地裁にはないと主張した。裁判所は、保留地は地方裁判所の管轄区域内にあるが、Rev. Stat. § 2146条は、受刑者が連邦地裁で起訴されることを妨げるものであった。第2146条は、州法第2145条を規定している。§ 2146条は、合衆国刑法がインディアン居住地に適用されることを定めた連邦法第2145条は、あるインディアンが他のインディアンに対して犯した犯罪 や、インディアンがその部族の法律によってすでに処罰されている犯罪には適用されないと述べている。裁判所はインディアンに対して人身保護令状と訴訟令状 を発行した[32]。 タルトン対メイズ事件(1896年) タルトン対メイズ事件(Talton v. Mayes)は、部族政府の権限に関する判決である。この判例は、連邦政府、後に州政府を制限する個人の権利保護、特に修正第5条は部族政府には適用され ないと決定した。1831年のチェロキー族対ジョージア州事件など、インディアン部族に連邦政府から独立した主権を持つ「国内従属国」の地位を与えた以前 の判決を再確認したものである[33]。タルトン対メイズ事件もネイティブ・アメリカンの従属性を扱った事件であり、議会の全権委任の概念を審議し支持し たものである。この判決により、アメリカ先住民に関するいくつかの重要な法律が制定されたが、その中で最も重要なものは1968年のインディアン公民権法 である。 グッドショット対合衆国(1900年) この合衆国最高裁判所の事件は、アメリカ・インディアンが非インディアンを射殺したときに起こった。合衆国最高裁判所にこの問題の管轄権があるかどうかが 問題となった。最高裁に裁判権がないことを主張するために、被告は、再審理令状を求める嘆願書を提出した。この司法審査請求は、誤判状により却下された。 裁判所は、死刑に値する殺人罪の有罪判決は、陪審員が刑罰を適格とした事実を考慮しても、死刑犯罪の有罪判決であることに変わりはないとした。アメリカ・ インディアン被告は終身刑を言い渡された[34]。 モントーヤ対合衆国(1901年) この合衆国最高裁判所の裁判は、E.モントヤ&サンズ社の存続する共同経営者が、1880年3月に奪われた家畜の価値を求めて、合衆国とメスカレロ・ア パッチ・インディアンに対して申し立てたことから起こった。この家畜は、アメリカ・インディアンのグループである「ビクトリオ・バンド」によって奪われた と考えられていた。家畜を奪ったアメリカ・インディアンの集団は、他のどのアメリカ・インディアンの部族集団とも異なっており、したがってメスカレロ・ア パッチ・アメリカン・インディアン部族は、起こったことに対して責任を負うべきでないと主張した。審理の結果、最高裁判所は、先に請求裁判所で下された判 断は変更されないとした。つまり、メスカレロ・アパッチ・アメリカン・インディアン部族は、ビクトリオ・バンドの行為に対して責任を問われないということ である。この結果は、アメリカン・インディアン部族のアメリカに対する主権だけでなく、互いの主権をも示している。アメリカ・インディアンのある集団は、 たとえそれらがすべてアメリカ・インディアン国家の一部であったとしても、アメリカ・インディアンの別の集団の行為に対して責任を問われることはない [35]。 US対ワイナンズ事件(1905年) この事件で最高裁判所はヤカマ族に有利な判決を下し、居留地外の土地で漁猟をする彼らの特権を再確認した。さらにこの事件は、条約の解釈に関する2つの重 要な原則を確立した。第一に、条約はインディアンが理解したであろう方法で解釈され、「正義と理性が要求するように」解釈される[36]。第二に、条約は インディアンに付与された権利ではなく、「インディアンがすでに所有し、付与されていない権利を留保したものである」とする留保権教義が確立された [37]。これらの「留保された」権利とは、アメリカ合衆国や他の主権者に譲渡されたことがないという意味であり、漁業権、狩猟権、採集権などの財産権と 政治権が含まれる。インディアン諸国に留保された政治的権利には、内政関係の規制、課税、司法の管理、民事および刑事裁判権の行使の権限が含まれる [38]。 ウィンターズ対アメリカ合衆国事件(1908年) 合衆国最高裁のWinters対合衆国裁判は、主にアメリカン・インディアン居留地の水利権を扱った裁判である。この事件は、アメリカ・インディアン部族 がどのような水源を利用する「黙示の」権利を有しているかを明らかにした[39]。この事件は、フォート・ベルナップ・インディアン居留地と、モンタナ州 のミルク川の水源を利用する権利を扱ったものである。この保留地は、フォート・ベルクナップ・アメリカン・インディアン保留地が有する明確な水利権を明示 することなく創設された。このことは、インディアン以外の入植者がこの地域に移り住み始め、ミルク川を彼らの入植地の水源として利用し始めると問題となっ た[40]。モンタナ州では水源が極めてまばらで限られているため、誰が水を利用する法的権利を持っているのかというこの議論が提示された。裁判の結果、 最高裁判所は、フォート・ベルナップ保留地は、そもそもアメリカン・インディアン保留地を創設した1888年の協定によって水利権を留保しているという判 決を下した。この裁判は、同化時代以降の裁判の先例を作る上で非常に重要であった。アリゾナ対カリフォルニア、チュリー対ワシントン、ワシントン対マッコ イ、ネバダ対アメリカ合衆国、カッパート対アメリカ合衆国、コロラド川水利保全地区対アメリカ合衆国、アメリカ合衆国対ニューメキシコ、アリゾナ対アリゾ ナ州サンカルロス・アパッチ部族など、アメリカインディアン部族の主権に焦点を当てた裁判の先例として用いられた。 チョート対トラップ事件(1912年) ドーズ法によってより多くのネイティブ・アメリカンが割当てを受けるようになると、割当てを受けた人々に課税するよう世論と州から大きな圧力がかかった。 しかし、合衆国最高裁判所のChoate v. Trapp事件(224 U.S. 665 (1912))において、裁判所はインディアンの割当地は州の課税から免除されるとの判決を下した[29]。 クレアモント対アメリカ合衆国(1912年) この連邦最高裁判例は、被告が自分の裁判の判決を不服として上告したことから生じた。被告は、アメリカン・インディアン居留地に酩酊させる酒類を不法に持 ち込んだ罪で有罪判決を受けた後、その判決の再審理を得るために誤判状を提出した。この行為は、1897年1月30日の連邦議会法109条(29 Stat. 被告人の控訴は、有罪判決を受けた犯罪がアメリカ・インディアンの居住地で発生したものではないため、連邦地裁には管轄権がないと述べている。被告が逮捕 されたのは、アメリカン・インディアン居住地を通過したばかりの列車に乗車中であった。被告の主張が支持され、最高裁は被告の有罪判決を破棄し、起訴を破 棄して被告を釈放するよう指示して連邦地裁に差し戻した[41]。 合衆国対クイヴァー事件(1916年) この事件は、サウスダコタ州の地方裁判所に最初に出廷した後、合衆国最高裁判所に送られた。この事件はスー族のインディアン居留地で行われた姦通を扱った ものであった。連邦地裁は、インディアン居留地においてインディアンが他のインディアンと犯した姦通は、1887年3月3日制定397号、24 Stat. この決定は、この犯罪が、地方裁判所の管轄下にあるとは言われないスー・インディアン居留地で発生したために下されたものである。合衆国最高裁判所は、姦 通はアメリカ・インディアン居留地において2人のアメリカ・インディアンの間で起こったものであるため、処罰の対象にはならないとし、連邦地方裁判所の判 決を支持した[42]。 |

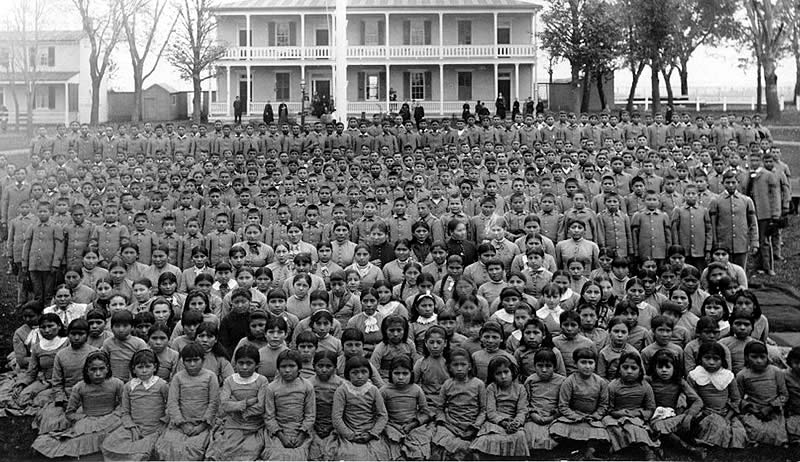

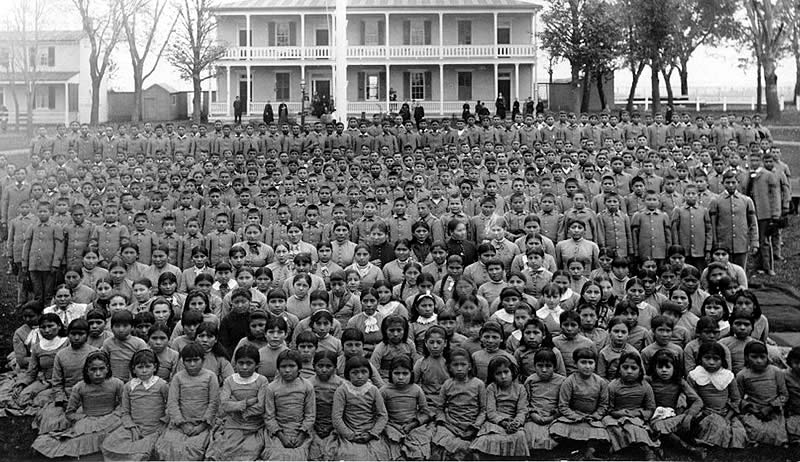

| Native American education and boarding schools Main article: Native American boarding schools See also: Boarding school Non-reservation boarding schools  The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was a major institution for the assimilation of Native Americans. From 1879 until 1918, over 10,000 children from 140 tribes attended Carlisle.[43] In 1634, Fr. Andrew White of the Jesuits established a mission in what is now the state of Maryland, and the purpose of the mission, stated through an interpreter to the chief of an Indian tribe there, was "to extend civilization and instruction to his ignorant race, and show them the way to heaven".[44] The mission's annual records report that by 1640, a community had been founded which they named St. Mary's, and the Indians were sending their children there to be educated.[45] This included the daughter of the Pascatoe Indian chief Tayac, which suggests not only a school for Indians, but either a school for girls, or an early co-ed school. The same records report that in 1677, "a school for humanities was opened by our Society in the centre of [Maryland], directed by two of the Fathers; and the native youth, applying themselves assiduously to study, made good progress. Maryland and the recently established school sent two boys to St. Omer who yielded in abilities to few Europeans, when competing for the honour of being first in their class. So that not gold, nor silver, nor the other products of the earth alone, but men also are gathered from thence to bring those regions, which foreigners have unjustly called ferocious, to a higher state of virtue and cultivation."[46] In 1727, the Sisters of the Order of Saint Ursula founded Ursuline Academy in New Orleans, which is currently the oldest, continuously operating school for girls and the oldest Catholic school in the United States. From the time of its foundation it offered the first classes for Native American girls, and would later offer classes for female African-American slaves and free women of color.  Male Carlisle School students (1879) The Carlisle Indian Industrial School founded by Richard Henry Pratt in 1879 was the first Indian boarding school established. Pratt was encouraged by the progress of Native Americans whom he had supervised as prisoners in Florida, where they had received basic education. When released, several were sponsored by American church groups to attend institutions such as Hampton Institute. He believed education was the means to bring American Indians into society. Pratt professed "assimilation through total immersion". Because he had seen men educated at schools like Hampton Institute become educated and assimilated, he believed the principles could be extended to Indian children. Immersing them in the larger culture would help them adapt. In addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic, the Carlisle curriculum was modeled on the many industrial schools: it constituted vocational training for boys and domestic science for girls, in expectation of their opportunities on the reservations, including chores around the school and producing goods for market. In the summer, students were assigned to local farms and townspeople for boarding and to continue their immersion. They also provided labor at low cost, at a time when many children earned pay for their families. Carlisle and its curriculum became the model for schools sponsored by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. By 1902 there were twenty-five federally funded non-reservation schools across fifteen states and territories with a total enrollment of over 6,000. Although federal legislation made education compulsory for Native Americans, removing students from reservations required parental authorization. Officials coerced parents into releasing a quota of students from any given reservation. Once the new students arrived at the boarding schools, their lives altered drastically. They were usually given new haircuts, uniforms of European-American style clothes, and even new English names, sometimes based on their own, other times assigned at random. They could no longer speak their own languages, even with each other. They were expected to attend Christian churches. Their lives were run by the strict orders of their teachers, and it often included grueling chores and stiff punishments. Additionally, infectious disease was widespread in society, and often swept through the schools. This was due to lack of information about causes and prevention, inadequate sanitation, insufficient funding for meals, overcrowded conditions, and students whose resistance was low.  Native American group of Carlisle Indian Industrial School male and female students; brick dormitories and bandstand in background (1879) An Indian boarding school was one of many schools that were established in the United States during the late 19th century to educate Native American youths according to American standards. In some areas, these schools were primarily run by missionaries. Especially given the young age of some of the children sent to the schools, they have been documented as traumatic experiences for many of the children who attended them. They were generally forbidden to speak their native languages, taught Christianity instead of their native religions, and in numerous other ways forced to abandon their Indian identity and adopt American culture. Many cases of mental and sexual abuse have been documented, as in North Dakota.[citation needed] Little recognition to the drastic change in life of the younger children was evident in the forced federal rulings for compulsory schooling and sometimes harsh interpretation in methods of gathering, even to intruding in the Indian homes. This proved extremely stressful to those who lived in the remote desert of Arizona on the Hopi Mesas well isolated from the American culture. Separation and boarding school living would last several years. It remains today, a topic in traditional Hopi Indian recitations of their history—the traumatic situation and resistance to government edicts for forced schooling. Conservatives in the village of Oraibi opposed sending their young children to the Government school located in Keams Canyon. It was far enough away to require full time boarding for at least each school year. At the closing of the nineteenth century, the Hopi were for the most part a walking society. Unfortunately, visits between family and the schooled children were impossible. As a result, children were hidden to prevent forced collection by the U.S. military. Wisely, the Indian Agent, Leo Crane [47] requested the military troop to remain in the background while he and his helpers searched and gathered the youngsters for their multi-day travel by military wagon and year-long separation from their family.[48] By 1923 in the Northwest, most Indian schools had closed and Indian students were attending public schools. States took on increasing responsibility for their education.[49] Other studies suggest attendance in some Indian boarding schools grew in areas of the United States throughout the first half of the 20th century, doubling from 1900 to the 1960s.[50] Enrollment reached its highest point in the 1970s. In 1973, 60,000 American Indian children were estimated to have been enrolled in an Indian boarding school.[50][51] In 1976, the Tobeluk vs Lind case was brought by teenage Native Alaskan plaintiffs against the State of Alaska alleging that the public school situation was still an unequal one. The Meriam Report of 1928 The Meriam Report, officially titled "The Problem of Indian Administration", was prepared for the Department of Interior. Assessments found the schools to be underfunded and understaffed, too heavily institutionalized, and run too rigidly. What had started as an idealistic program about education had gotten subverted.[52] It recommended: abolishing the "Uniform Course of Study", which taught only majority American cultural values; having younger children attend community schools near home, though older children should be able to attend non-reservation schools; and ensuring that the Indian Service provided Native Americans with the skills and education to adapt both in their own traditional communities (which tended to be more rural) and the larger American society. Indian New Deal John Collier, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1933–1945, set the priorities of the New Deal policies toward Native Americans, with an emphasis on reversing as much of the assimilationist policy as he could. Collier was instrumental in ending the loss of reservations lands held by Indians, and in enabling many tribal nations to re-institute self-government and preserve their traditional culture. Some Indian tribes rejected the unwarranted outside interference with their own political systems the new approach had brought them. Collier's 1920–1922 visit to Taos Pueblo had a lasting impression on Collier. He now saw the Indian world as morally superior to American society, which he considered to be "physically, religiously, socially, and aesthetically shattered, dismembered, directionless".[53] Collier came under attack for his romantic views about the moral superiority of traditional society as opposed to modernity.[54] Philp says after his experience at the Taos Pueblo, Collier "made a lifelong commitment to preserve tribal community life because it offered a cultural alternative to modernity. ... His romantic stereotyping of Indians often did not fit the reality of contemporary tribal life."[55] Collier carried through the Indian New Deal with Congress' passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. It was one of the most influential and lasting pieces of legislation relating to federal Indian policy. Also known as the Wheeler–Howard Act, this legislation reversed fifty years of assimilation policies by emphasizing Indian self-determination and a return of communal Indian land, which was in direct contrast with the objectives of the Indian General Allotment Act of 1887. Collier was also responsible for getting the Johnson–O'Malley Act passed in 1934, which allowed the Secretary of the Interior to sign contracts with state governments to subsidize public schooling, medical care, and other services for Indians who did not live on reservations. The act was effective only in Minnesota.[56] Collier's support of the Navajo Livestock Reduction program resulted in Navajo opposition to the Indian New Deal.[57][58] The Indian Rights Association denounced Collier as a "dictator" and accused him of a "near reign of terror" on the Navajo reservation.[59] According to historian Brian Dippie, "(Collier) became an object of 'burning hatred' among the very people whose problems so preoccupied him."[59] Change to community schools Several interesting events in the late 1960s and mid-1970s (Kennedy Report, National Study of American Indian Education, Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975) led to renewed emphasis on community schools. Many large Indian boarding schools closed in the 1980s and early 1990s. In 2007, 9,500 American Indian children lived in an Indian boarding school dormitory.[citation needed] From 1879 when the Carlisle Indian School was founded to the present day, more than 100,000 American Indians are estimated to have attended an Indian boarding school. A similar system in Canada was known as the Canadian residential school system.[60] |

ネイティブ・アメリカンの教育と寄宿学校 主な記事 ネイティブアメリカンの寄宿学校 も参照のこと: 寄宿学校 居留地以外の寄宿学校  カーライル・インディアン・インダストリアルスクールは、ネイティブ・アメリカンの同化のための主要な施設であった。1879年から1918年まで、140部族から10,000人以上の子供たちがカーライルに通った[43]。 1634年、イエズス会のアンドリュー・ホワイト師は、現在のメリーランド州に伝道所を設立した。この伝道所の目的は、そこのインディアン部族の酋長に通 訳を通して述べられたもので、「彼の無知な種族に文明と教育を広め、天国への道を示すこと」であった。 [44] ミッションの年次記録によれば、1640年までにセント・メアリーズと名付けられたコミュニティが設立され、インディアンたちは教育を受けるために子供た ちをそこに送っていた[45]。この中にはパスカトー・インディアンの酋長テイヤックの娘も含まれており、インディアンのための学校であるだけでなく、女 子校、あるいは初期の男女共学校であったことを示唆している。同記録によれば、1677年、「メリーランド州の中心部に私たちの協会によって人文学校が開 校され、2人の神父が指導した。メリーランド州と最近設立された学校は、2人の少年を聖オメールに送り込んだが、彼らは、クラスで1番の栄誉を競い合った とき、その能力において、ほとんどヨーロッパ人に引けを取らなかった。外国人が不当に獰猛と呼んだこれらの地域を、より高い徳と耕作の状態にするために、 金や銀や大地の産物だけでなく、人間もまたそこから集められたのである」[46]。 1727年、聖ウルスラ修道会のシスターたちはニューオーリンズにウルスライン・アカデミーを設立した。創立当初から、ネイティブ・アメリカンの少女たち のための最初のクラスを提供し、後にアフリカ系アメリカ人の奴隷や自由な有色人種の女性たちのためのクラスを提供することになる。  カーライル・スクールの男子生徒(1879年) 1879年にリチャード・ヘンリー・プラットによって設立されたカーライル・インディアン・インダストリアルスクールは、インディアンの寄宿学校として最 初に設立された。プラットは、フロリダで囚人として監督していたネイティブ・アメリカンの進歩に励まされ、そこで基本的な教育を受けた。釈放されると、何 人かはアメリカの教会グループのスポンサーとなり、ハンプトン・インスティテュートのような教育機関に通うようになった。彼は、教育こそがアメリカ・イン ディアンを社会に引き入れる手段だと信じていた。 プラットは「完全な没入による同化」を公言した。ハンプトン・インスティテュートのような学校で教育を受けた人々が教養を身につけ、同化していくのを目の 当たりにした彼は、その原理をインディアンの子供たちにも適用できると考えた。インディアンの子供たちを大きな文化に没頭させることが、彼らの適応に役立 つと考えたのである。読み、書き、算数に加え、カーライルのカリキュラムは多くの工業学校をモデルにしていた。男子生徒には職業訓練、女子生徒には家政学 を教え、学校周辺の雑用や市場向けの商品の生産など、居留地での機会を想定していた。夏には、生徒たちは地元の農場や町民のもとで寄宿生活を送りながら、 学校漬けの生活を続けた。多くの子供たちが家族のために給料を稼いでいた時代に、彼らはまた安価な労働力を提供した。 カーライルとそのカリキュラムは、インディアン局が後援する学校のモデルとなった。1902年までに、15の州と準州に連邦政府が資金援助する非保護地学 校が25校設立され、総生徒数は6,000人を超えた。連邦法はアメリカ先住民に義務教育を課したが、居留地から生徒を連れ出すには親の許可が必要であっ た。役人は保護者に対し、指定された居留地から割り当てられた生徒を解放するよう強要した。 新入生が寄宿学校に到着すると、彼らの生活は一変した。彼らは通常、新しい髪型にされ、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人風の服の制服を着せられ、新しい英語の名前 さえつけられた。彼らはもはや自国語を話すことはできなかった。キリスト教の教会に通うことが求められた。彼らの生活は教師の厳格な命令によって運営さ れ、しばしば過酷な雑用や厳しい罰が課せられた。 さらに、社会には感染症が蔓延し、しばしば学校にも押し寄せた。原因や予防法についての情報不足、不十分な衛生環境、給食費の不足、過密な環境、抵抗力の弱い生徒たちなどが原因だった。  カーライル・インディアン・インダストリアル・スクールの男女生徒からなるネイティブ・アメリカンのグループ、背景はレンガ造りの寮とバンドスタンド(1879年) インディアン寄宿学校は、19世紀後半にアメリカでアメリカ人の基準に従ってネイティブ・アメリカンの青少年を教育するために設立された多くの学校の一つ である。地域によっては、これらの学校は主に宣教師によって運営されていた。特に、この学校に送られた子供たちの年齢が若かったことから、この学校に通っ た子供たちの多くにとってトラウマ的な体験であったことが記録されている。彼らは一般的に、母国語を話すことを禁じられ、母国宗教の代わりにキリスト教を 教えられ、その他多くの方法で、インディアンとしてのアイデンティティを捨て、アメリカ文化を取り入れることを強要された。ノースダコタ州のように、精神 的・性的虐待の事例も数多く記録されている[要出典]。 義務教育を強制する連邦政府の裁定や、時にはインディアンの家に侵入してまで採集方法を厳しく解釈することで、幼い子供たちの生活の劇的な変化に対する認 識はほとんどなかった。このことは、アリゾナ州の人里離れた砂漠地帯、アメリカ文化から隔絶されたホピ・メサで暮らす彼らにとって、非常に大きなストレス となった。別居と寄宿学校生活は数年間続いた。このトラウマ的な状況と、強制的な学校教育を求める政府の勅令に対する抵抗は、今日でもホピ・インディアン の伝統的な歴史を語る際のトピックとなっている。オライビ村の保守派は、キームズ・キャニオンにある政府立学校に幼い子供たちを通わせることに反対した。 少なくとも各学年は全寮制にしなければならないほど遠かったからだ。19世紀末、ホピ族はほとんど徒歩社会だった。残念ながら、家族と学校に通う子供たち の面会は不可能だった。その結果、子供たちは米軍による強制徴収を防ぐために隠された。賢明なことに、インディアン諜報員のレオ・クレーン[47]は、彼 と彼の助っ人たちが軍用ワゴン車で数日間移動し、家族から1年間引き離されるために若者たちを捜索し集めている間、軍の部隊は背後に控えているよう要請し た[48]。 1923年までに、北西部ではほとんどのインディアン学校が閉鎖され、インディアンの生徒は公立学校に通うようになった。他の研究によると、20世紀前半 を通して、アメリカのいくつかの地域ではインディアン寄宿学校の出席者が増加し、1900年から1960年代にかけて倍増した[50]。1973年には、 6万人のアメリカ・インディアンの子供たちがインディアンの寄宿学校に在籍していたと推定されている[50][51]。 1976年には、10代のアラスカ先住民の原告によって、公立学校の状況は依然として不平等であると主張するアラスカ州を相手取ったTobeluk vs Lind裁判が起こされた。 1928 年のメリアム報告 メリアム報告は、正式には「インディアン行政の問題」と題され、内務省のために作成された。調査の結果、学校は資金不足、人員不足、制度化されすぎ、厳格 に運営されていることがわかった。教育についての理想主義的なプログラムとして始まったものが、破壊されてしまったのである[52]。 それはこう提言した: 多数派のアメリカ文化的価値観のみを教える「統一学習指導要領」を廃止する; 年少の子供たちは自宅近くのコミュニティ・スクールに通わせるが、年長の子供たちは居留地以外の学校に通わせる。 インディアン・サービスは、ネイティブ・アメリカンが自分たちの伝統的なコミュニティ(農村に多い)と、より大きなアメリカ社会の両方に適応するためのスキルと教育を提供することを保証した。 インディアン・ニューディール 1933年から1945年までインディアン問題担当長官を務めたジョン・コリアーは、アメリカ先住民に対するニューディール政策の優先順位を決め、同化主 義的な政策をできるだけ撤回することに重点を置いた。コリアーは、インディアンが所有していた保留地の喪失を終わらせ、多くの部族国家が自治を再開し、伝 統文化を維持できるようにすることに尽力した。一部のインディアン部族は、新しいアプローチがもたらした彼ら自身の政治制度への不当な外部からの干渉を拒 絶した。 1920年から1922年にかけてのタオス・プエブロ訪問は、コリアーに永続的な印象を与えた。彼はいまやインディアンの世界を、「物理的にも、宗教的に も、社会的にも、美学的にも、粉々に砕け散り、バラバラになり、方向性を失った」[53]アメリカ社会よりも道徳的に優れたものと見なしていた。 コリアーは、近代とは対照的な伝統的社会の道徳的優越性に関する彼のロマンティックな見解のために攻撃を受けるようになった[54]。 フィルプは、タオス・プエブロでの体験後、コリアーは「近代に代わる文化的な選択肢を提供するものであるからこそ、部族共同体の生活を保護することに生涯 を賭けるようになった。... 彼のインディアンに対するロマンチックなステレオタイプは、しばしば現代の部族生活の現実にそぐわなかった」[55]。 コリアーは、議会が1934年にインディアン再編法を可決したことで、インディアン・ニューディールを貫徹した。この法律は、連邦インディアン政策に関す る最も影響力のある永続的な法律のひとつであった。ウィーラー=ハワード法としても知られるこの法律は、インディアンの自決とインディアン共有地の返還を 強調し、50年にわたる同化政策を覆すもので、1887年のインディアン一般割当法の目的とは正反対のものであった。 コリアーはまた、1934年にジョンソン・オマリー法を成立させた責任者でもあった。この法律は、保留地に住んでいないインディアンに対して、公立学校教 育、医療、その他のサービスを補助する契約を州政府と結ぶことを内務長官に許可するものであった。この法律はミネソタ州でのみ有効であった[56]。 コリアーのナバホ家畜削減プログラムへの支援は、インディアン・ニューディールに対するナバホの反発を招く結果となった[57][58]。 インディアン・ライツ協会はコリアーを「独裁者」と非難し、ナバホ居留地における「恐怖支配に近い」と非難した[59]。 歴史家のブライアン・ディッピーによれば、「(コリアーは)彼の問題に夢中になっていたまさにその人々の間で『燃えるような憎しみ』の対象となった」 [59]。 コミュニティ・スクールへの変更 1960年代後半から1970年代半ばにかけてのいくつかの興味深い出来事(ケネディ報告、アメリカ・インディアン教育全国調査、1975年インディアン 自決・教育支援法)によって、コミュニティ・スクールが再び重視されるようになった。1980年代から1990年代初頭にかけて、多くの大規模なインディ アン寄宿学校が閉鎖された。2007年には、9,500人のアメリカ・インディアンの子供たちがインディアン寄宿学校の寮に住んでいた[要出典]。カーラ イル・インディアン・スクールが設立された1879年から現在に至るまで、10万人以上のアメリカ・インディアンがインディアン寄宿学校に通っていたと推 定されている。 カナダにおける同様の制度は、カナダ・レジデンシャル・スクール制度として知られていた[60]。 |

| Lasting effects of the Americanization policy While the concerted effort to assimilate Native Americans into American culture was abandoned officially, integration of Native American tribes and individuals continues to the present day. Often Native Americans are perceived as having been assimilated. However, some Native Americans feel a particular sense of being from another society or do not belong in a primarily "white" European majority society, despite efforts to socially integrate them.[citation needed] In the mid-20th century, as efforts were still under way for assimilation, some studies treated American Indians simply as another ethnic minority, rather than citizens of semi-sovereign entities which they are entitled to by treaty. The following quote from the May 1957 issue of Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, shows this: The place of Indians in American society may be seen as one aspect of the question of the integration of minority groups into the social system.[61] Since the 1960s, however, there have been major changes in society. Included is a broader appreciation for the pluralistic nature of United States society and its many ethnic groups, as well as for the special status of Native American nations. More recent legislation to protect Native American religious practices, for instance, points to major changes in government policy. Similarly the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 was another recognition of the special nature of Native American culture and federal responsibility to protect it. As of 2013, "Montana is the only state in the U.S. with a constitutional mandate to teach American Indian history, culture, and heritage to preschool through higher education students via the Indian Education for All Act."[62] The "Indian Education for All" curriculum, created by the Montana Office of Public Instruction, is distributed online for primary and secondary schools.[63] |

アメリカ化政策の永続的効果 ネイティブ・アメリカンをアメリカ文化に同化させるという協調的な努力は公式には放棄されたが、ネイティブ・アメリカンの部族や個人の統合は現在まで続い ている。多くの場合、ネイティブ・アメリカンは同化されたと認識されている。しかし、ネイティブ・アメリカンの中には、彼らを社会的に統合しようとする努 力にもかかわらず、別の社会から来たという特別な感覚や、主に「白人」であるヨーロッパ人が大多数を占める社会に属していないという感覚を抱いている者も いる[要出典]。 20世紀半ば、まだ同化の努力が進められていた頃、アメリカン・インディアンを条約によって権利を与えられている半主権国家の市民としてではなく、単にも うひとつの少数民族として扱う研究もあった。1957年5月発行の『Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science』からの引用がそれを示している: アメリカ社会におけるインディアンの地位は、マイノリティ・グループの社会システムへの統合という問題の一側面とみなすことができる[61]。 しかし1960年代以降、社会には大きな変化が起きている。その中には、アメリカ社会の多元的な性質と多くのエスニック・グループ、そしてアメリカ先住民 の特別な地位に対する、より広範な理解が含まれている。例えば、ネイティブ・アメリカンの宗教的慣習を保護するための最近の法律は、政府の政策に大きな変 化をもたらしている。同様に、1990年に制定された「アメリカ先住民の墓の保護と送還に関する法律」も、アメリカ先住民の文化の特別な性質と、それを保 護する連邦政府の責任が認められたものである。 2013年現在、「モンタナ州は、インディアン教育法(Indian Education for All Act)を通じて、アメリカン・インディアンの歴史、文化、遺産を就学前の学生から高等教育の学生まで教えることを憲法で義務づけられている全米唯一の州 である」[62]。モンタナ州公教育局が作成した「インディアン教育法(Indian Education for All)」のカリキュラムは、初等・中等教育向けにオンラインで配布されている[63]。 |

| Modern cultural and linguistic preservation Further information: Language shift and Language revitalization To evade a shift to English, some Native American tribes have initiated language immersion schools for children, where a native Indian language is the medium of instruction. For example, the Cherokee Nation instigated a 10-year language preservation plan that involved growing new fluent speakers of the Cherokee language from childhood on up through school immersion programs as well as a collaborative community effort to continue to use the language at home.[64] This plan was part of an ambitious goal that in 50 years, 80% or more of the Cherokee people will be fluent in the language.[65] The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested $3 million into opening schools, training teachers, and developing curricula for language education, as well as initiating community gatherings where the language can be actively used.[65] Formed in 2006, the Kituwah Preservation & Education Program (KPEP) on the Qualla Boundary focuses on language immersion programs for children from birth to fifth grade, developing cultural resources for the general public and community language programs to foster the Cherokee language among adults.[66] There is also a Cherokee language immersion school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma that educates students from pre-school through eighth grade.[67] Because Oklahoma's official language is English, Cherokee immersion students are hindered when taking state-mandated tests because they have little competence in English.[68] The Department of Education of Oklahoma said that in 2012 state tests: 11% of the school's sixth-graders showed proficiency in math, and 25% showed proficiency in reading; 31% of the seventh-graders showed proficiency in math, and 87% showed proficiency in reading; 50% of the eighth-graders showed proficiency in math, and 78% showed proficiency in reading.[68] The Oklahoma Department of Education listed the charter school as a Targeted Intervention school, meaning the school was identified as a low-performing school but has not so that it was a Priority School.[68] Ultimately, the school made a C, or a 2.33 grade point average on the state's A–F report card system.[68] The report card shows the school getting an F in mathematics achievement and mathematics growth, a C in social studies achievement, a D in reading achievement, and an A in reading growth and student attendance.[68] "The C we made is tremendous," said school principal Holly Davis, "[t]here is no English instruction in our school's younger grades, and we gave them this test in English."[68] She said she had anticipated the low grade because it was the school's first year as a state-funded charter school, and many students had difficulty with English.[68] Eighth graders who graduate from the Tahlequah immersion school are fluent speakers of the language, and they usually go on to attend Sequoyah High School where classes are taught in both English and Cherokee. |

現代の文化・言語保護 さらに詳しい情報 言語移行と言語再生 英語への移行を回避するために、ネイティブ・アメリカンの部族の中には、インディアンの母国語を教育媒体とする、子供のための言語イマージョン・スクール を始めたところもある。この計画は、50年後にはチェロキーインディアンの80%以上の人々がチェロキーインディアンの言語を流暢に話せるようになるとい う野心的な目標の一部であった[64]。 [65]チェロキー保存財団は、300万ドルを投じて、学校を開き、教師を訓練し、言語教育のためのカリキュラムを開発し、また、言語が活発に使われるよ うなコミュニティーの集まりを始めた[65]。2006年に結成されたクアラ・バウンダリーのキトゥワー保存教育プログラム(KPEP)は、生まれてから 5年生までの子供たちのための言語イマージョン・プログラム、一般の人々のための文化資源の開発、そして、大人の間でチェロキー語を育てるためのコミュニ ティー言語プログラムに力を入れている[66]。 また、オクラホマ州タールクアには、未就学児から中学2年生までの生徒を教育するチェロキー・インマージョン・スクールもある[67]。オクラホマ州の公 用語は英語であるため、チェロキー・インマージョンの生徒は、英語の能力がほとんどないため、州が定めたテストを受ける時に支障がある[68]: 同校の6年生の11%が数学に習熟し、25%が読解に習熟していた。7年生の31%が数学に習熟し、87%が読解に習熟していた。8年生の50%が数学に 習熟し、78%が読解に習熟していた。 [68]オクラホマ州教育省は、このチャータースクールをTargeted Intervention School、つまり低業績校として認定したが、Priority Schoolとまでは認定していない。 [68]この成績表では、数学の成績と数学の成績がF、社会科の成績がC、読解の成績がD、読解の成績と生徒の出席率がAとなっている[68]。ホリー・ デイビス校長は、「私たちの学校の低学年には英語の授業がなく、英語のテストを行った。 「タールカ・イマージョン・スクールを卒業した8年生は、チェロキー語を流暢に話し、英語とチェロキー語の両方で授業が行われるセコイヤ高校に進学する。 |

| Acculturation American Indian boarding schools Bureau of Indian Affairs Canadian Indian residential school system Contemporary Native American issues in the United States Cultural appropriation Detraditionalization Detribalization European colonization of the Americas Gradual Civilization Act Indian Relocation Act of 1956 Indian Placement Program Indian removal Indian termination policy Modern social statistics of Native Americans Native American identity in the United States Native American reservation politics Native American self-determination Native Americans and reservation inequality Russification St. Joseph's Indian School Stolen Generations Tribal disenrollment Tribal knowledge Our Fires Still Burn American Indian outing programs |

文化的適応 アメリカン・インディアン寄宿学校 インディアン局 カナダ・インディアン寄宿学校制度 アメリカにおける現代のネイティブ・アメリカン問題 文化的流用 非伝統化 脱部族化 ヨーロッパ人のアメリカ大陸植民地化 段階的文明化法 1956年インディアン移転法 インディアン配置プログラム インディアン除去 インディアン解雇政策 インディアンの現代社会統計 アメリカにおけるアメリカ先住民のアイデンティティ アメリカ先住民の保留地政治 アメリカ先住民の自決 ネイティブ・アメリカンと保留地の不平等 ラシフィケーション セント・ジョセフ・インディアン・スクール 盗まれた世代 部族離脱 部族の知識 私たちの火はまだ燃えている アメリカン・インディアンの遠足プログラム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_assimilation_of_Native_Americans |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆