慣習法

Customary law

A

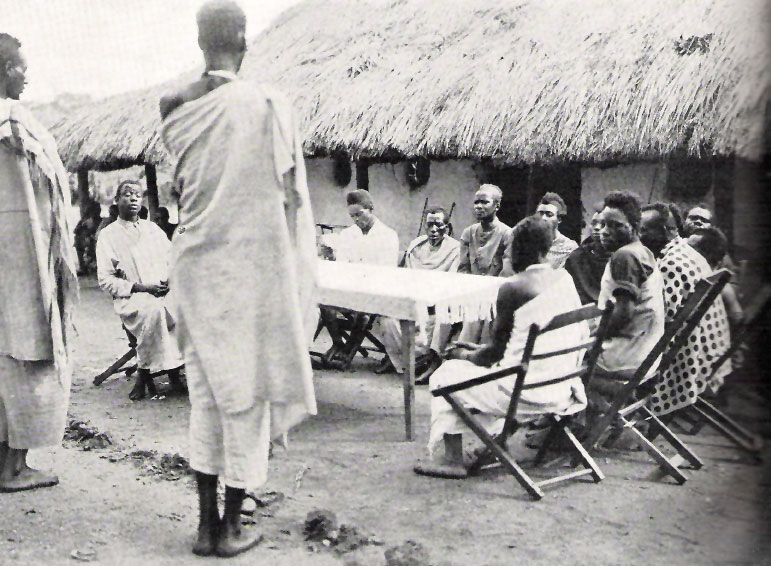

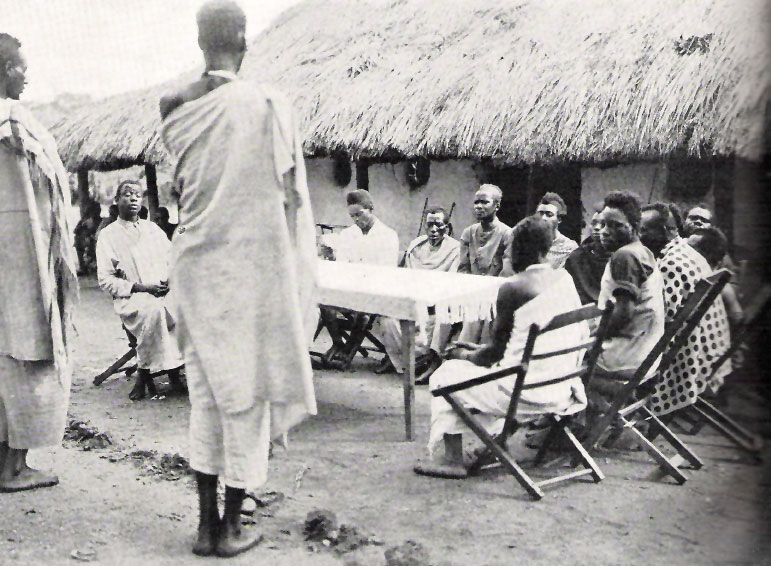

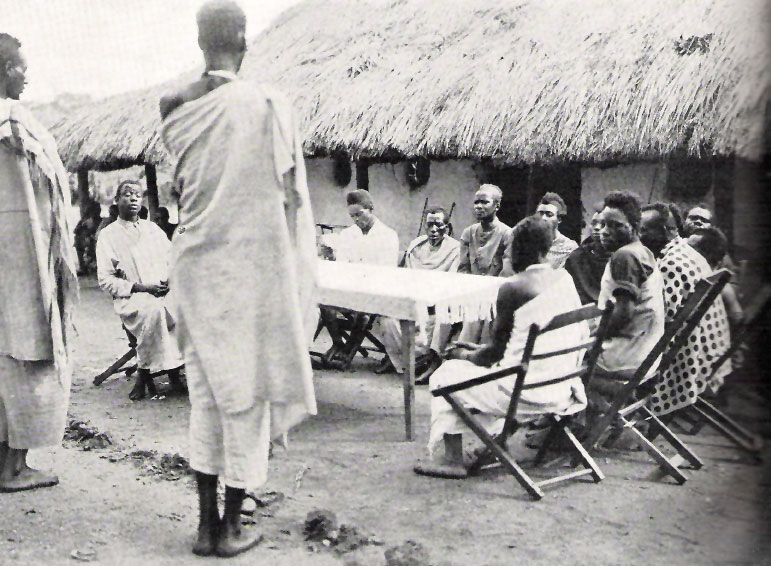

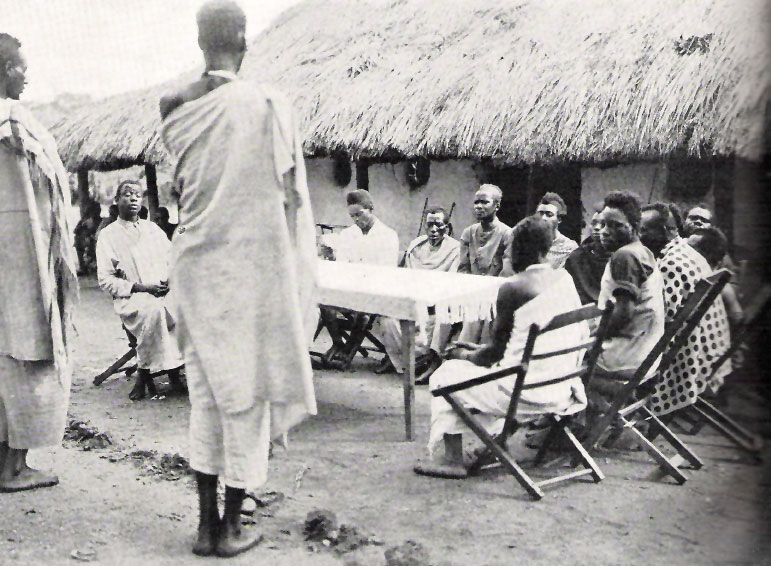

court presided over by a customary chief in the Belgian Congo, c.1942

☆ 慣習法(Customary law) とは、特定の社会環境における確立された行動様式である。主張は、「常に法律によって認められ、行われてきたこと」を擁護するために行うことができる。 慣習法(また、不文法または非公式法)は、 特定の法的慣行が遵守され、 関係者がそれを法または必要性の見解(オピニオ・ジュリス)であるとみなす。 ほとんどの慣習法は、特定の地域で長年にわたって確立されてきたコミュニティの基準を扱うものである。しかし、この用語は、ある基準が正しい行動の基礎と してほぼ世界的に受け入れられている国際法の分野にも適用される。例えば、著作権侵害や奴隷制度に対する法律(hostis humani generisを参照)などである。多くの場合、すべてではないが、慣習法には、その法則を法律としてさらに重みづけし、また関連裁判所によるその法の解 釈の進化の軌跡(もしあれば)を示す、時間をかけて発展してきた支持的な判決や判例がある。

| A legal custom is

the established pattern of behavior within a particular social setting.

A claim can be carried out in defense of "what has always been done and

accepted by law". Customary law (also, consuetudinary or unofficial law) exists where: 1. a certain legal practice is observed and t2. he relevant actors consider it to be an opinion of law or necessity (opinio juris). Most customary laws deal with standards of the community that have been long-established in a given locale. However, the term can also apply to areas of international law where certain standards have been nearly universal in their acceptance as correct bases of action – for example, laws against piracy or slavery (see hostis humani generis). In many, though not all instances, customary laws will have supportive court rulings and case law that have evolved over time to give additional weight to their rule as law and also to demonstrate the trajectory of evolution (if any) in the interpretation of such law by relevant courts. |

慣習法とは、特定の社会環境における確立された行動様式である。主張

は、「常に法律によって認められ、行われてきたこと」を擁護するために行うことができる。 慣習法(また、不文法または非公式法)は、 1. 特定の法的慣行が遵守され、 2. 関係者がそれを法または必要性の見解(オピニオ・ジュリス)であるとみなす。 ほとんどの慣習法は、特定の地域で長年にわたって確立されてきたコミュニティの基準を扱うものである。しかし、この用語は、ある基準が正しい行動の基礎と してほぼ世界的に受け入れられている国際法の分野にも適用される。例えば、著作権侵害や奴隷制度に対する法律(hostis humani generisを参照)などである。多くの場合、すべてではないが、慣習法には、その法則を法律としてさらに重みづけし、また関連裁判所によるその法の解 釈の進化の軌跡(もしあれば)を示す、時間をかけて発展してきた支持的な判決や判例がある。 |

| Nature, definition and sources A central issue regarding the recognition of custom is determining the appropriate methodology to know what practices and norms actually constitute customary law. It is not immediately clear that classic Western theories of jurisprudence can be reconciled in any useful way with conceptual analyses of customary law, and thus some scholars (like John Comaroff and Simon Roberts)[1] have characterized customary law norms in their own terms. Yet, there clearly remains some disagreement, which is seen in John Hund's critique of Comaroff and Roberts' theory, and preference for the contributions of H. L. A. Hart. Hund argues that Hart's The Concept of Law solves the conceptual problem with which scholars who have attempted to articulate how customary law principles may be identified, defined, and how they operate in regulating social behavior and resolving disputes.[2] Customary law is the set of customs, practices and beliefs that are accepted as obligatory rules of conduct by a community. As an indefinite repertoire of norms  A court presided over by a customary chief in the Belgian Congo, c.1942 Comaroff and Roberts' famous work, "Rules and Processes",[1] attempted to detail the body of norms that constitute Tswana law in a way that was less legalistic (or rule-oriented) than had Isaac Schapera. They defined "mekgwa le melao ya Setswana" in terms of Casalis and Ellenberger's definition: melao therefore being rules pronounced by a chief and mekgwa as norms that become customary law through traditional usage.[3] Importantly, however, they noted that the Tswana seldom attempt to classify the vast array of existing norms into categories[3] and they thus termed this the 'undifferentiated nature of the normative repertoire'. Moreover, they observe the co-existence of overtly incompatible norms that may breed conflict, either due to circumstances in a particular situation or inherently due to their incongruous content.[4] This lack of rule classification and failure to eradicate internal inconsistencies between potentially conflicting norms allows for much flexibility in dispute settlement and is also viewed as a 'strategic resource' for disputants who seek to advance their own success in a case. The latter incongruities (especially inconsistencies of norm content) are typically solved by elevating one of the norms (tacitly) from 'the literal to the symbolic.[5] This allows for the accommodation of both as they now theoretically exist in different realms of reality. This is highly contextual, which further illustrates that norms cannot be viewed in isolation and are open to negotiation. Thus, although there are a small number of so-called non-negotiable norms, the vast majority are viewed and given substance contextually, which is seen as fundamental to the Tswana. Comaroff and Roberts describe how outcomes of specific cases have the ability to change the normative repertoire, as the repertoire of norms is seen to be both in a state of formation and transformation at all times.[6] These changes are justified on the grounds that they are merely giving recognition to de facto observations of transformation [219]. Furthermore, the legitimacy of a chief is a direct determinant of the legitimacy of his decisions.[7] In the formulation of legislative pronouncements, as opposed to decisions made in dispute resolution,[8] the chief first speaks of the proposed norm with his advisors, then council of headmen, then the public assembly debate the proposed law and may accept or reject it. A chief can proclaim the law even if the public assembly rejects it, but this is not often done; and, if the chief proclaims the legislation against the will of the public assembly, the legislation will become melao, however, it is unlikely that it will be executed because its effectiveness depends on the chief's legitimacy and the norm's consistency with the practices (and changes in social relations) and will of the people under that chief.[8] Regarding the invocation of norms in disputes, Comaroff and Roberts used the term, "paradigm of argument", to refer to the linguistic and conceptual frame used by a disputant, whereby 'a coherent picture of relevant events and actions in terms of one or more implicit or explicit normative referents' is created.[9] In their explanation, the complainant (who always speaks first) thus establishes a paradigm the defendant can either accept and therefore argue within that specific paradigm or reject and therefore introduce his or her own paradigm (usually, the facts are not contested here). If the defendant means to change the paradigm, they will refer to norms as such, where actually norms are not ordinarily explicitly referenced in Tswana dispute resolution as the audience would typically already know them and just the way one presents one's case and constructs the facts will establish one's paradigm. The headman or chief adjudicating may also do same: accept the normative basis implied by the parties (or one of them), and thus not refer to norms using explicit language but rather isolate a factual issue in the dispute and then make a decision on it without expressly referring to any norms, or impose a new or different paradigm onto the parties.[9] Law as necessarily rule-governed Hund finds Comaroff and Roberts' flexibility thesis of a 'repertoire of norms' from which litigants and adjudicator choose in the process of negotiating solutions between them uncompelling.[2] He is therefore concerned with disproving what he calls "rule scepticism" on their part. He notes that the concept of custom generally denotes convergent behaviour, but not all customs have the force of law. Hund therefore draws from Hart's analysis distinguishing social rules, which have internal and external aspects, from habits, which have only external aspects. Internal aspects are the reflective attitude on the part of adherents toward certain behaviours perceived to be obligatory, according to a common standard. External aspects manifest in regular, observable behaviour, but is not obligatory. In Hart's analysis, then, social rules amount to custom that has legal force. Hart identifies three further differences between habits and binding social rules.[2] First, a social rule exists where society frowns on deviation from the habit and attempts to prevent departures by criticising such behaviour. Second, when this criticism is seen socially as a good reason for adhering to the habit, and it is welcomed. And, third, when members of a group behave in a common way not only out of habit or because everyone else is doing it, but because it is seen to be a common standard that should be followed, at least by some members. Hund, however, acknowledges the difficulty of an outsider knowing the dimensions of these criteria that depend on an internal point of view. For Hund, the first form of rule scepticism concerns the widely held opinion that, because the content of customary law derives from practice, there are actually no objective rules, since it is only behaviour that informs their construction. On this view, it is impossible to distinguish between behaviour that is rule bound and behaviour that is not—i.e., which behaviour is motivated by adherence to law (or at least done in recognition of the law) and is merely a response to other factors. Hund sees this as problematic because it makes quantifying the law almost impossible, since behaviour is obviously inconsistent. Hund argues that this is a misconception based on a failure to acknowledge the importance of the internal element. In his view, by using the criteria described above, there is not this problem in deciphering what constitutes "law" in a particular community.[2] According to Hund, the second form of rule scepticism says that, though a community may have rules, those rules are not arrived at 'deductively', i.e. they are not created through legal/moral reasoning only but are instead driven by the personal/political motives of those who create them. The scope for such influence is created by the loose and undefined nature of customary law, which, Hund argues, grants customary-lawmakers (often through traditional 'judicial processes') a wide discretion in its application. Yet, Hund contends that the fact that rules might sometimes be arrived at in the more ad hoc way, does not mean that this defines the system. If one requires a perfect system, where laws are created only deductively, then one is left with a system with no rules. For Hund, this cannot be so and an explanation for these kinds of law-making processes is found in Hart's conception of "secondary rules" (rules in terms of which the main body of norms are recognised). Hund therefore says that for some cultures, for instance in some sections of Tswana society, the secondary rules have developed only to the point where laws are determined with reference to politics and personal preference. This does not mean that they are not "rules". Hund argues that if we acknowledge a developmental pattern in societies' constructions of these secondary rules then we can understand how this society constructs its laws and how it differs from societies that have come to rely on an objective, stand-alone body of rules.[2] |

自然、定義、および情報源 慣習の認定に関する主要な問題は、どのような慣行や規範が実際に慣習法を構成するのかを知るための適切な方法論を決定することである。古典的な西洋の法理 論が慣習法の概念分析と有益な形で調和しうるかどうかは、すぐには明らかではない。そのため、一部の学者(ジョン・コマロフやサイモン・ロバーツなど) は、独自の観点から慣習法の規範を特徴づけている。しかし、ジョン・ハントによるコマロフとロバーツの理論に対する批判や、H. L. A. ハートの貢献に対する好みなど、いくつかの意見の相違が依然として存在していることは明らかである。ハントは、ハートの著書『法の概念』が、慣習法の原則 を特定し、定義し、社会行動の規制や紛争解決においてどのように機能するかを明確にしようとした学者たちが抱えていた概念上の問題を解決したと主張してい る。 慣習法とは、ある社会集団によって義務的な行動規範として受け入れられている慣習、慣行、信念の集合である。 無限の規範のレパートリーとして  1942年頃のベルギー領コンゴにおける慣習の長が主宰する裁判所 ComaroffとRobertsの有名な著作『規則とプロセス』[1]は、ツワナ法を構成する規範体系を、アイザック・シャペラよりも法学的(あるいは 規則中心)でない方法で詳細に説明しようとした。彼らは「ツワナ人の法」をカサリスとエレンバーガーの定義に従って「mekgwa le melao ya Setswana」と定義した。すなわち、melaoは首長によって公布された規則であり、mekgwaは伝統的な慣習法となる規範である。[3] しかし重要なのは、ツワナ人は既存の膨大な数の規範をカテゴリーに分類しようとすることはほとんどない[3]と彼らが指摘している点であり、彼らはこれを 「規範レパートリーの未分化な性質」と呼んでいる。さらに、彼らは、特定の状況における状況や、本質的に内容が不調和であることによる、対立を生み出す可 能性のある、明白に相容れない規範の共存を観察している。[4] 規範の分類の欠如と、潜在的に対立する規範間の内部矛盾を排除できないことは、紛争解決に多くの柔軟性を許容し、また、訴訟で自身の成功を収めようとする 当事者にとっては「戦略的資源」ともみなされる。後者の不整合(特に規範内容の矛盾)は、通常、規範の1つを(暗黙のうちに)「文字から象徴へ」と昇華さ せることで解決される。[5] これにより、両者は理論上、現実の異なる領域に存在することになるため、両立が可能となる。これは文脈に大きく依存しており、規範は孤立して捉えられるも のではなく、交渉の余地があることをさらに示している。したがって、いわゆる譲歩できない規範は少数であるが、大半は文脈に応じて捉えられ、実質が与えら れる。これはツワナ族にとって根本的なものである。 コマロフとロバーツは、特定の事例の結果が規範レパートリーを変える能力を持つことを説明している。規範レパートリーは常に形成と変容の過程にあると見な されているためである。[6] これらの変化は、単に変容の事実上の観察結果を認識しているに過ぎないという理由で正当化される。[219] さらに、首長の正当性は、その首長の決定の正当性を直接決定づけるものである。[7] 立法による布告の策定においては、紛争解決における決定とは対照的に、[8] 首長はまず顧問たちと提案された規範について話し合い、次に首長会議で話し合い、その後、一般集会で提案された法律について討論し、それを承認または拒否 する。首長は、公の集会が法律を否決した場合でも、その法律を公布することができるが、これはあまり行われない。また、首長が公の集会の意思に反して法律 を公布した場合、その法律はメラオとなるが、首長の正当性や、その首長の下で暮らす人々の慣習(および社会関係の変化)と法律の整合性によってその有効性 が左右されるため、実際に施行されることはほとんどない。 論争における規範の適用について、コマロフとロバーツは「議論のパラダイム」という用語を使用し、論争当事者が使用する言語的・概念的枠組みを指し示して いる。これにより、「1つまたは複数の暗黙的または明示的な規範的参照対象に関する、関連する出来事や行動の一貫した全体像」が作成される。参照先」が作 成される。[9] 彼らの説明では、原告(常に最初に発言する)は、被告がそのパラダイムを受け入れ、その特定のパラダイム内で議論するか、あるいは拒否して独自のパラダイ ムを導入する(通常、この段階では事実の争いは行われない)ことができるように、パラダイムを確立する。被告がパラダイムの変更を意図している場合、彼ら は「規範」という言葉を使うが、実際にはツワナ族の紛争解決では、通常、規範は明示的に参照されることはない。なぜなら、聴衆は通常すでに規範を知ってお り、自分の主張の提示方法と事実の構成によって、自分のパラダイムが確立されるからである。また、裁定を行う首長や長も同様である。当事者(または当事者 の一方)が暗示する規範的根拠を受け入れ、明示的な言語を使用して規範を参照することなく、紛争における事実上の問題を特定し、規範を明示的に参照するこ となく、その問題について決定を下すか、または当事者に新たな、または異なるパラダイムを押し付ける。[9] 法は必然的に規則に支配される ハントは、コマロフとロバーツの「規範のレパートリー」という柔軟性に関する論文を、訴訟当事者と裁定者が解決策を交渉する過程で選択する説得力に欠ける ものだと考えている。[2] そのため、彼は彼らの「規則懐疑論」を否定することに関心を抱いている。彼は、慣習という概念は一般的に収束的な行動を示すが、すべての慣習が法的な強制 力を持つわけではないと指摘している。そのため、ハートによる分析から、内部的側面と外部的側面を持つ社会的ルールと、外部的側面のみを持つ習慣とを区別 する考え方を引き出している。内部的側面とは、共通の基準に従って義務的であると認識される特定の行動に対する支持者の内省的な態度である。外部的側面 は、規則正しい、観察可能な行動に現れるが、義務的ではない。ハートの分析では、社会的ルールは法的効力を持つ習慣に相当する。 ハートは、習慣と拘束力のある社会規範の間のさらなる3つの相違点を特定している。[2] まず、社会が習慣からの逸脱を嫌悪し、そのような行動を批判することで逸脱を防止しようとする場合に、社会規範が存在する。次に、この批判が社会的に習慣 に従う正当な理由とみなされ、歓迎される場合。そして3つ目に、グループのメンバーが共通の方法で行動するとき、それは単に習慣や他のメンバーがそうして いるからという理由だけではなく、少なくとも一部のメンバーにとっては、そうすることが共通の基準であると見なされるからである。しかし、ハントは、内部 の視点に依存するこれらの基準の次元を外部の人間が知ることは難しいと認めている。 フントにとって、規則懐疑論の第一の形態は、慣習法の内容は実践から派生するものであるため、その構築を伝えるのは行動のみであることから、実際には客観 的な規則は存在しないという広く受け入れられている意見に関するものである。この見解では、規則に縛られた行動とそうでない行動を区別することは不可能で ある。つまり、どの行動が法の遵守(または少なくとも法を認識した上で行われる)に動機づけられ、単に他の要因への反応であるかを区別することは不可能で ある。フントは、行動には明らかに矛盾があるため、これは問題であると考える。フントは、これは内部要素の重要性を認識していないことによる誤解であると 主張する。彼の考えでは、上述の基準を用いれば、特定のコミュニティにおける「法」を構成するものを解読する際に、このような問題は生じない。 ハントによると、規則懐疑論の第二の形は、共同体が規則を有していても、それらの規則は「演繹的」に導き出されたものではない、すなわち、法的な/道徳的 な推論のみによって作られたものではなく、それらを作った人々の個人的な/政治的な動機によって作られたものである、と主張する。このような影響力の余地 は、慣習法の定義が曖昧で不明確であることから生じるものであり、ハントは、慣習法制定者(伝統的な「司法手続き」を通じて)がその適用において幅広い裁 量権を有していると主張している。しかし、ハントは、規則が時としてより即興的な方法で決定されることがあるからといって、それがそのシステムを定義づけ るわけではないと主張している。もし完璧なシステムを求めるのであれば、法は演繹法のみによって作成されるべきであり、そうなると規則のないシステムが残 されることになる。ハントは、そうはならないと主張し、このような法制定プロセスの説明はハートの「二次規則」(規範の本体が認識される規則)の概念に見 られると述べている。したがって、ハントは、ツワナ社会の一部など、一部の文化では、二次規則が発展し、政治や個人的な好みを参照して法が決定される程度 にまで達していると述べている。これは、それらが「規則」ではないということを意味するものではない。フントは、社会がこれらの二次規則を構築する際に発 展パターンを認めるのであれば、その社会が法律をどのように構築し、客観的で独立した規則体系に依存するようになった社会とどのように異なるかを理解でき ると主張している。[2] |

| Codification Main article: Codification (law) The modern codification of civil law developed from the tradition of medieval custumals, collections of local customary law that developed in a specific manorial or borough jurisdiction, and which were slowly pieced together mainly from case law and later written down by local jurists. Custumals acquired the force of law when they became the undisputed rule by which certain rights, entitlements, and obligations were regulated between members of a community.[10] Some examples include Bracton's De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae for England, the Coutume de Paris for the city of Paris, the Sachsenspiegel for northern Germany, and the many fueros of Spain. |

成文化 詳細は「成文化 (法律)」を参照 中世のカスタムール(custumals)の伝統から発展した近代的な民法の成文化は、特定の荘園や自治体の管轄内で発展した地域慣習法の集成であり、主 に判例法から徐々にまとめられ、後に地域の法律家によって書き留められたものである。ある特定の権利、資格、義務がコミュニティのメンバー間で規制される 際の議論の余地のない規則となった時点で、カスタムールは法としての効力を得た。[10] その例としては、イングランドのブラクトンの『イングランドの法と慣習について』、パリのパリの慣習法、北ドイツのザクセン法、スペインの多くのフエロス などがある。 |

| International law Main article: Customary international law In international law, customary law refers to the Law of Nations or the legal norms that have developed through the customary exchanges between states over time, whether based on diplomacy or aggression. Essentially, legal obligations are believed to arise between states to carry out their affairs consistently with past accepted conduct. These customs can also change based on the acceptance or rejection by states of particular acts. Some principles of customary law have achieved the force of peremptory norms, which cannot be violated or altered except by a norm of comparable strength. These norms are said to gain their strength from universal acceptance, such as the prohibitions against genocide and slavery. Customary international law can be distinguished from treaty law, which consists of explicit agreements between nations to assume obligations. However, many treaties are attempts to codify pre-existing customary law. |

国際法 詳細は「慣習国際法」を参照 国際法において、慣習法とは、外交または侵略に基づくかどうかに関わらず、国家間の長年にわたる慣習的な交流を通じて発展してきた法の支配、または法規範 を指す。本質的には、国家間の法的義務は、過去の受け入れられた行動と一貫性のある形で遂行されるべきであると考えられている。これらの慣習は、特定の行 為に対する国家の受容または拒絶に基づいて変化することもある。慣習法のいくつかの原則は、強行規範としての効力を獲得しており、同等の強さの規範によっ てのみ、これを侵害または変更することができる。これらの規範は、大量虐殺や奴隷制度の禁止など、普遍的な受容によってその効力を得ている。慣習国際法 は、義務を負うことを目的とした国家間の明示的な合意である条約法とは区別される。しかし、多くの条約は、既存の慣習法を成文化しようとする試みである。 |

| Within contemporary legal systems Customary law is a recognized source of law within jurisdictions of the civil law tradition, where it may be subordinate to both statutes and regulations. In addressing custom as a source of law within the civil law tradition, John Henry Merryman notes that, though the attention it is given in scholarly works is great, its importance is "slight and decreasing".[11] On the other hand, in many countries around the world, one or more types of customary law continue to exist side by side with official law, a condition referred to as legal pluralism (see also List of national legal systems). In the canon law of the Catholic Church, custom is a source of law. Canonical jurisprudence, however, differs from civil law jurisprudence in requiring the express or implied consent of the legislator for a custom to obtain the force of law.[citation needed] In the English common law, "long usage" must be established.[citation needed] It is a broad principle of property law that, if something has gone on for a long time without objection, whether it be using a right of way or occupying land to which one has no title, the law will eventually recognise the fact and give the person doing it the legal right to continue.[citation needed] It is known in case law as "customary rights". Something which has been practised since time immemorial by reference to a particular locality may acquire the legal status of a custom, which is a form of local law. The legal criteria defining a custom are precise. The most common claim in recent times, is for customary rights to moor a vessel.[citation needed] The mooring must have been in continuous use for "time immemorial" which is defined by legal precedent as 12 years (or 20 years for Crown land) for the same purpose by people using them for that purpose. To give two examples: a custom of mooring which might have been established in past times for over two hundred years by the fishing fleet of local inhabitants of a coastal community will not simply transfer so as to benefit present day recreational boat owners who may hail from much further afield. Whereas a group of houseboats on a mooring that has been in continuous use for the last 25 years with a mixture of owner occupiers and rented houseboats, may clearly continue to be used by houseboats, where the owners live in the same town or city. Both the purpose of the moorings and the class of persons benefited by the custom must have been clear and consistent.[12] In Canada, customary aboriginal law has a constitutional foundation[13] and for this reason has increasing influence.[14] In the Scandinavian countries customary law continues to exist and has great influence.[citation needed] Customary law is also used in some developing countries, usually used alongside common or civil law.[15] For example, in Ethiopia, despite the adoption of legal codes based on civil law in the 1950s according to Dolores Donovan and Getachew Assefa there are more than 60 systems of customary law currently in force, "some of them operating quite independently of the formal state legal system". They offer two reasons for the relative autonomy of these customary law systems: one is that the Ethiopian government lacks sufficient resources to enforce its legal system to every corner of Ethiopia; the other is that the Ethiopian government has made a commitment to preserve these customary systems within its boundaries.[16] In 1995, President of Kyrgyzstan Askar Akaev announced a decree to revitalize the aqsaqal courts of village elders. The courts would have jurisdiction over property, torts and family law.[17] The aqsaqal courts were eventually included under Article 92 of the Kyrgyz constitution. As of 2006, there were approximately 1,000 aqsaqal courts throughout Kyrgyzstan, including in the capital of Bishkek.[17] Akaev linked the development of these courts to the rekindling of Kyrgyz national identity. In a 2005 speech, he connected the courts back to the country's nomadic past and extolled how the courts expressed the Kyrgyz ability of self-governance.[18] Similar aqsaqal courts exist, with varying levels of legal formality, in other countries of Central Asia. The Somali people in the Horn of Africa follow a customary law system referred to as xeer. It survives to a significant degree everywhere in Somalia[19] and in the Somali communities in the Ogaden.[20] Economist Peter Leeson attributes the increase in economic activity since the fall of the Siad Barre administration to the security in life, liberty and property provided by Xeer in large parts of Somalia.[21] The Dutch attorney Michael van Notten also draws upon his experience as a legal expert in his comprehensive study on Xeer, The Law of the Somalis: A Stable Foundation for Economic Development in the Horn of Africa (2005).[22] In India many customs are accepted by law. For example, Hindu marriage ceremonies are recognized by the Hindu Marriage Act. In Indonesia, customary adat laws of the country's various indigenous ethnicities are recognized, and customary dispute resolution is recognized in Papua. Indonesian adat law are mainly divided into 19 circles, namely Aceh, Gayo, Alas, and Batak, Minangkabau, South Sumatra, the Malay regions, Bangka and Belitung, Kalimantan, Minahasa, Gorontalo, Toraja, South Sulawesi, Ternate, the Molluccas, Papua, Timor, Bali and Lombok, Central and East Java including the island of Madura, Sunda, and the Javanese monarchies, including the Yogyakarta Sultanate, Surakarta Sunanate, and the Pakualaman and Mangkunegaran princely states. |

現代の法制度においては 慣習法は、民法の伝統を持つ管轄区域における法の源として認められているが、制定法や規則に従属する可能性もある。ジョン・ヘンリー・メリーマンは、民法 の伝統における慣習法を法源として論じる中で、学術的な研究における関心は高いものの、その重要性は「わずかであり、減少している」と指摘している。 [11] 一方、世界の多くの国々では、1つまたは複数の種類の慣習法が公式の法と並存し続けている。この状態は法の多元主義(legal pluralism)と呼ばれている(各国の法体系の一覧も参照)。 カトリック教会の教会法では、慣習は法の源である。しかし、教会法の法解釈は、慣習が法としての効力を得るために立法者の明示的または黙示的な同意を必要とする点で、民法の法解釈とは異なる。 英米法では、「長年の慣習」が確立されていなければならない。 これは財産法の広範な原則であり、何らかの権利の行使や、所有権のない土地の占有など、異議なく長期間にわたって継続している場合、法律は最終的にその事実を認め、それを継続する法的権利をその者に与えることになる。 判例法では「慣習権」として知られている。特定の地域において太古の昔から行われてきた慣習は、地域法の一形態である慣習の法的地位を獲得することがある。慣習を定義する法的基準は明確である。最近最も多い主張は、船舶係留の慣習権である。 係留は「太古の昔」から継続的に使用されていなければならず、判例法では、同じ目的で使用する人々によって、同じ目的で12年間(または王領地の場合は 20年間)使用されていると定義されている。例えば、沿岸地域の住民の漁船団が過去に確立した係留の慣習が200年以上続いている場合、遠方から来たレ ジャー用ボートの現在の所有者の利益のために、その慣習が簡単に移行されることはない。一方で、過去25年間継続して使用されている係留地にある屋形船の グループは、所有者居住者と貸し屋形船が混在しているが、同じ町や市に住む所有者によって、明らかに引き続き使用されている。係留の目的と、その慣習から 利益を得る人々の種類は、明確かつ一貫していなければならない。[12] カナダでは、先住民の慣習法は憲法上の基盤を有しており[13]、この理由により影響力が増大している[14]。 スカンディナヴィア諸国では慣習法が依然として存在し、大きな影響力を持っている[要出典]。 慣習法は一部の発展途上国でも用いられており、通常は普通法や民法と並行して用いられている。[15] 例えば、エチオピアでは、ドロレス・ドノバンとゲタチュ・アセファによると、1950年代に民法に基づく法体系が採用されたにもかかわらず、現在も60以 上の慣習法が施行されており、「そのうちのいくつかは、公式な国家の法体系とは全く独立して運用されている」という。彼らは、これらの慣習法システムが相 対的に自律性を保っている理由として2つの理由を挙げている。1つは、エチオピア政府が自国の隅々まで法制度を施行するだけの十分なリソースを欠いている こと、もう1つは、エチオピア政府が自国の領域内でこれらの慣習システムを維持する義務を負っていることである。[16] 1995年、キルギス大統領のアスカール・アカエフは、村の長老によるアクサカル裁判所の活性化を命じる法令を発表した。この裁判所は、財産、不法行為、 家族法に関する管轄権を持つこととなった。[17] 最終的に、アクサカル裁判所はキルギス憲法第92条に盛り込まれた。2006年現在、首都ビシュケクを含むキルギス全土に約1,000のアクサカル裁判所 が存在している。[17] アカエフ大統領は、この裁判所の発展をキルギス国民のアイデンティティの再燃と関連付けた。2005年の演説で、彼はこの裁判所を国の遊牧の過去に結びつ け、この裁判所がキルギスの自治能力をいかに表現しているかを賞賛した。[18] 同様のアクサカル裁判所は、中央アジアの他の国々にも、法的形式の度合いは様々ではあるが存在している。 アフリカの角」と呼ばれるアフリカ東部のソマリアでは、シーアと呼ばれる慣習法制度が採用されている。それはソマリアの至る所でかなりの程度まで生き残っ ており[19]、オガデン地方のソマリア人社会でも同様である[20]。経済学者ピーター・リースンは、シアド・バーレ政権崩壊後の経済活動の活発化は、 ソマリアの大部分でシーアが保障する生命、自由、財産の安全に起因するものと見ている[21]。オランダ人弁護士マイケル・ヴァン・ノッテンも、法律の専 門家としての経験を活かし、シーアに関する包括的な研究『ソマリア人の法: アフリカの角における経済発展の安定した基盤(2005年)』を著している。[22] インドでは、多くの慣習が法律によって認められている。例えば、ヒンドゥー教の婚姻儀式はヒンドゥー婚姻法によって認められている。 インドネシアでは、同国のさまざまな先住民族の慣習法であるアダット法が認められており、パプアでは慣習的な紛争解決が認められている。インドネシアのア ダット法は主に19の地域、すなわちアチェ、ガヨ、アラス、バタック、ミナンカバウ、南スマトラ、マレー地域、バンカ・ビリトン、カリマンタン、ミナハ サ、ゴロンタロ、トラジャ、南スラウェシ、テルナテ、 モルッカ諸島、パプア、ティモール、バリおよびロンボク、マドゥラ島を含む中部および東部ジャワ、スンダ、そしてジョグジャカルタのスルタン国、スラカル タのスナン国、パクアラマンおよびマンクネガランの諸侯国を含むジャワ諸侯国である。 |

| Custom in torts This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. Please help clarify the section. There might be a discussion about this on the talk page. (November 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Custom is used in tort law to help determine negligence. Following or disregarding a custom is not determinative of negligence, but instead is an indication of possible best practices or alternatives to a particular action. |

不法行為における慣習 この節は読者にとって混乱を招く恐れがある内容です。 節の明確化にご協力ください。 これについて議論するページがトークページにあるかもしれません。 (2008年11月) (このメッセージの削除方法およびタイミングについては、こちらをご覧ください) 不法行為法では、過失の認定に慣習が用いられる。慣習に従うことや無視することは過失の認定には決定的なものではなく、むしろ特定の行為に対する最善の慣習や代替案の可能性を示すものである。 |

| Customary legal systems See also: List of national legal systems Adat (Malays of Nusantara) Anglo-Saxon law (England) Aqsaqal (Central Asia) Australian Aboriginal customary law Basque and Pyrenean law Coutume (France) Custom (Catholic canon law) Early Germanic law Early Irish law (Ireland) Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Kanun of Leke Dukagjini (Albania) Laws of the Brets and Scots (Scotland) Medieval Scandinavian laws Pashtunwali and Jirga (Pashtuns of Pakistan and Afghanistan) Smriti and Ācāra (India) Customary law (South Africa) Urf (Arab world/Islamic law) Cyfraith Hywel (Wales) Xeer (Somalia) Usos y costumbres (various regions of Latin America) Wahkohtowin (Cree Territories, Canada) |

慣習法 参照:各国の法体系の一覧 アダト(ヌサンタラのマレー人) アングロ・サクソン法(イングランド) アクサカル(中央アジア) オーストラリアのアボリジニの慣習法 バスクおよびピレネー法 クチューム(フランス) 慣習(カトリック教会法) 初期ゲルマン法 初期アイルランド法(アイルランド) イヌイット・カウジマタカタンギット レケの法典(アルバニア) ブレツとスコッツの法(スコットランド) 中世スカンディナヴィアの法 パシュトゥーン暦とジルガ(パキスタンとアフガニスタンのパシュトゥーン族) スミティとアーカーラ(インド) 慣習法(南アフリカ) ウルフ(アラブ世界/イスラム法) サイフラ・ヒウェル(ウェールズ) シーア(ソマリア) 慣習法(ラテンアメリカ各地域) ワホトウィン(カナダ、クリー族の領土) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Customary_law |

|

| Usos y costumbres

("customs and traditions"; literally, "uses and customs") is the

indigenous customary law in Hispanic America. Since the era of Spanish

colonialism, authorities have recognized local forms of rulership, self

governance, and juridical practice, with varying degrees of acceptance

and formality. The term is often used in English without translation. Usos y costumbres political mechanisms are used by numerous indigenous peoples in Mexico, Guatemala, Bolivia, and other countries to govern water rights, in criminal and civil conflicts, and to elect their representatives to regional and national bodies. |

ウ

ソス・イ・コストゥンブレス(「慣習と伝統」、文字通りには「用法と慣習」)は、ラテンアメリカにおける先住民の慣習法である。スペインの植民地主義の時

代から、当局は、程度の差こそあれ、受け入れられ、形式化された、地方の支配形態、自治、司法慣行を認めてきた。この用語は、英語では翻訳なしでしばしば

使用される。 ウソス・イ・コストゥンブレス(Usos y costumbres)という政治的メカニズムは、メキシコ、グアテマラ、ボリビア、その他の国々における多数の先住民によって、水資源の権利、刑事およ び民事の紛争、地域および国家機関への代表者の選出などに用いられている。 |

| Under Spanish colonial rule Spanish colonial authorities in the Americas were ordered to investigate the traditions and customs of indigenous communities, and to apply these traditions to disputes among Indian subjects.[1] Scholar José Rabasa traces the term usos y costumbres to the New Laws of 1542, which ordered traditional procedures be used in dealings with Indians rather than "ordinary" Spanish legal proceedings. The division of legal authority is associated with notion of a Republic of Indians (Spanish: República de Indios) subject to distinct legal norms under Spanish colonial rule.[2] According to Rabasa, this division "at once protects Indian communities from Spaniards, criollos, and mestizos, and alienates Indians in a separate republic, in a structure not unlike apartheid."[2] |

スペインの植民地支配下において アメリカ大陸のスペイン植民地当局は、先住民社会の伝統や慣習を調査し、これらの伝統をインディオの被支配者間の紛争に適用するよう命じられた。[1] 学者ホセ・ラバサは、1542年の新法に「ウソス・イ・コストゥンブレス」という用語の起源をたどり、この法律では、インディオとの取引には「通常の」ス ペインの法的手続きではなく、伝統的な手続きを用いるよう命じている。法的な権限の分割は、スペイン植民地支配下における独自の法規に従うインディオ共和 国(スペイン語:República de Indios)という概念と関連している。[2] ラバサによると、この分割は「スペイン人、クリオーリョ、メスティーソからインディオのコミュニティを即座に保護し、アパルトヘイトと似た構造の中で、イ ンディオを別の共和国から疎外する」ものである。[2] |

| North America Mexico In Mexico, usos y costumbres practices are widely used by indigenous communities and are officially recognized in the states of Oaxaca (for 417 of 570 municipalities), Sonora, and Chiapas.[3] Central America Guatemala In Guatemala, Maya communities have used a variety of community-oriented or informal mechanisms for conflict resolution. That is commonly referred to as Maya justice, or usos y costumbres.[4] South America Bolivia In Bolivia, indigenous norms for self-governance, justice, and administration of territory are extensively recognized by the 2009 Constitution, which defines the country as plurinational. This recognition builds on earlier incorporation of indigenous customary law into the Bolivian legal system. In eight of the country's nine departments, minority indigenous peoples (and in La Paz, Afro-Bolivians) elect representatives to the Departmental Assembly through customary procedures.[5] Native Community Lands (Spanish: Tierras Comunitarias de Origen; TCOs), as recognized by the 1994 Constitutional reform, are indigenous territories whose governance is determined by usos y costumbres.[6] As of 2011, TCOs are being included under the Indigenous-Origin Campesino Autonomy regime. The eleven municipalities also under this regime may choose to use usos y costumbres for their internal governance.[7] Indigenous water rights, governed by usos y costumbres, were recognized by amendments to Bolivia's Law 2029 following the 2000 Cochabamba Water War.[8] Colombia In Colombia, the 1991 Constitution recognizes locally elected cabildos, chosen by usos y costumbres, as the governing authorities of indigenous reserves (resguardos) and the validity of customary law in these territories.[9] |

北米 メキシコ メキシコでは、ウソス・イ・コストゥンブレスの慣習が先住民コミュニティによって広く用いられており、オアハカ州(570の自治体のうち417)、ソノラ州、チアパス州で公式に認められている。[3] 中米 グアテマラ グアテマラでは、マヤ族のコミュニティが紛争解決のために、さまざまなコミュニティ志向または非公式のメカニズムを用いている。これは一般的にマヤの正義、またはウソス・イ・コストゥンブレスと呼ばれている。[4] 南アメリカ ボリビア ボリビアでは、2009年の憲法で、自治、司法、領土管理に関する先住民の規範が広く認められている。この憲法は、同国を多民族国家と定義している。この 認識は、先住民の慣習法がボリビアの法制度に組み込まれたことに基づいている。同国の9つの県のうち8つの県では、少数派の先住民(ラパスではアフリカ系 ボリビア人も)が慣習的な手続きにより、県議会代表を選出している。 先住民コミュニティの土地(スペイン語:Tierras Comunitarias de Origen、TCO)は、1994年の憲法改正で認められたもので、慣習法(usos y costumbres)によって統治が決定される先住民の領土である。2011年現在、TCOは先住民起源の農民自治体制に組み込まれている。この体制下 にある11の自治体は、内部統治に「ウソス・イ・コストゥンブレス」を採用する選択肢もある。[7] ウソス・イ・コストゥンブレスによって統治される先住民の水利権は、2000年のコチャバンバ水戦争を受けてボリビアの法律2029が改正され、認められ ることとなった。[8] コロンビア コロンビアでは、1991年の憲法が、ウソス・イ・コストゥンブレスによって選出された地元選出のカビルドを先住民保護区(レスガード)の統治当局として認め、これらの地域における慣習法の有効性を認めている。[9] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Usos_y_costumbres |

|

| Los pueblos indígenas del país

concluyen el proceso de elección de sus asambleístas mediante el método

de usos y costumbres indígenas o por procedimientos propios. Los pueblos indígenas de Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, Beni, Pando, Chuquisaca y Tarija ya eligieron a sus asambleístas. Sólo faltaría el representante de los uru-chipaya de Oruro, y cuatro asambleístas que representarán a los pueblos afroboliviano, mosetén, leco, kallawaya y araona de La Paz. Potosí no presenta escaños indígenas. Ayer, en Cobija, Pando, los indígenas de la Amazonia eligieron a Manuel Rodríguez como representante indígena en la Asamblea Departamental pandina. También, el fin de semana el pueblo guarayo de Santa Cruz eligió a sus dos representantes: Wilson Áñez Yamba y Celinda Agei. En La Paz, los tacanas ya eligieron a su asambleísta y en Cochabamba se promovió a dos representantes de las etnias yuqui y yuracaré. La Corte Nacional Electoral (CNE) anunció que 23 asambleístas indígenas deben ser elegidos por usos y costumbres o por procedimientos propios. Uru-chipayas no logran elegir a su representante Los indígenas uru-chipaya del departamento de Oruro no lograron establecer el modo de elección de su representante ante la Asamblea Departamental y, según la radio Pío XII, elegirán a su asambleísta el 4 de abril por sufragio. Según un reporte de Erbol, los indígenas no lograron ponerse de acuerdo si elegirían a su representante por aclamación o no. La vocal de la Corte Nacional Electoral (CNE), Roxana Ibarnegaray, anunció que esta etnia tiene hasta el 4 de abril para elegir a su representante. El organismo electoral supervisa estos procedimientos. [Fuente: La Razón, La Paz, 31mar10] |

同国の先住民族は、先住民族の習慣や伝統に従った方法、あるいは独自の手続きによって、議会議員を選出するプロセスを終えている。 コチャバンバ、サンタクルス、ベニ、パンド、チュキサカ、タリハの先住民族はすでに議員を選出した。オルーロのウル=チパヤ族代表と、ラパスのアフロ=ボ リビア族、モセテン族、レコ族、カラワヤ族、アラオナ族を代表する4人の議員だけがまだ選出されていない。ポトシには先住民の議席はない。 昨日、パンド県コビジャでは、アマゾンの先住民がパンド県議会先住民代表にマヌエル・ロドリゲスを選出した。 また、週末にはサンタ・クルスのグアラヨ族が2人の代表を選出した: ウィルソン・アニェス・ヤンバ氏とセリンダ・アゲイ氏である。 ラパスでは、タカナス族がすでに議員を選出し、コチャバンバでは、ユキ族とユラカレ族の2人の代表が昇格した。 国家選挙裁判所(CNE)は、23人の先住民族議会議員をusos y costumbresまたは独自の手続きによって選出しなければならないと発表した。 ウル=チパヤ族、代表選出に失敗 オルーロ県の先住民ウル=チパヤ族は、県議会代表の選出方法を確立できていない。 ラジオ・ピオXIIによると、彼らは4月4日に参政権によって代表を選出する予定である。 Erbolの報道によると、先住民族は代表を拍手で選ぶかどうかで合意できなかったという。 全国選挙裁判所(CNE)のロクサナ・イバルネガライ委員は、先住民族は4月4日までに代表を選出すると発表した。同選挙機関はこれらの手続きを監督している。 [Source: La Razón, La Paz, 31 Mar10.] |

★ポリセントリック・ロー(多極的=多中心法[概念])

| Polycentric law

is a theoretical legal structure in which "providers" of legal systems

compete or overlap in a given jurisdiction, as opposed to monopolistic

statutory law according to which there is a sole provider of law for

each jurisdiction. Devolution of this monopoly occurs by the principle

of jurisprudence in which they rule according to higher law. |

多中心法とは、特定の管轄区域において法体系の「提供者」が競合または重複する理論的法構造である。これは、各管轄区域に唯一の法提供者が存在する独占的成文法とは対照的だ。この独占の委譲は、上位法に従って裁定する法解釈の原則によって生じる。 |

| Overview Tom W. Bell, former director of telecommunications and technology studies at Cato Institute,[1] now a professor of law at Chapman University School of Law in California,[2] wrote "Polycentric Law", published by the Institute for Humane Studies, when he was a law student at the University of Chicago. In it he notes that others use phrases such as "non-monopolistic law" to describe these polycentric alternatives.[3] He outlines traditional customary law (also known as consuetudinary law) before the creation of states, including as described by Friedrich A. Hayek, Bruce L. Benson, and David D. Friedman. He mentions specifically the Anglo-Saxon customary law, but also church law, guild law, and merchant law as examples of what he believes is polycentric law. He states that customary and statutory law have co-existed through history, as when Roman law applied to Romans throughout the Roman Empire, but indigenous legal systems were permitted for non-Romans.[3] In "Polycentric Law in the New Millennium," which won first place in the Mont Pelerin Society's 1998 Friedrich A. Hayek Fellowship competition, Bell predicts three areas where polycentric law might develop: alternative dispute resolution, private communities, and the Internet. The University of Helsinki (Finland) funded a "Polycentric Law" research project from 1992 to 1995, led by professor Lars D. Eriksson. Its goal was to demonstrate "the inadequacy of current legal paradigms by mapping the indeterminacies of both the modern law and the modern legal theory. It also addressed the possibility of legal and ethical alternativies to the modern legal theories" and "provided openings to polycentric legal theories both by deconstructing the idea of unity in law and re-constructing legal and ethical differences". The project hosted two international conferences. In 1998 the book Polycentricity: The Multiple Scenes of Law, edited by Ari Hirvonen, collected essays written by scholars involved with the project.[4] Professor Randy Barnett, who originally wrote about "non-monopolistic" law, later used the phrase "polycentric legal order". He explains what he sees as advantages of such a system in his book The Structure of Liberty: Justice and the Rule of Law.[5] Bruce L. Benson also uses the phrase, writing in a Cato Institute publication in 2007: "A customary system of polycentric law would appear to be much more likely to generate efficient sized jurisdictions for the various communities involved—perhaps many smaller than most nations, with others encompassing many of today’s political jurisdictions (e.g., as international commercial law does today)."[6] John K. Palchak and Stanley T. Leung in "No State Required? A Critical Review of the Polycentric Legal Order," criticize the concept of polycentric law.[7] Legal scholar Gary Chartier in "Anarchy and Legal Order" elaborates and defends the idea of law without the state.[8] It proposes an understanding of how law enforcement in a stateless society could be legitimate and what the optimal substance of law without the state might be, he suggests ways in which a stateless legal order could foster the growth of a culture of freedom, and situates the project it elaborates in relation to leftist, anti-capitalist, and socialist traditions. |

概要 トム・W・ベルは、カト研究所の電気通信・技術研究部門の元所長[1]であり、現在はカリフォルニア州チャップマン大学ロースクールの法学教授[2]であ る。シカゴ大学の法学部の学生だった頃、ヒューマン・スタディーズ研究所から出版された『多中心的な法』を執筆した。この本の中で、彼は、他の人々が「非 独占的な法」などの表現を使って、こうした多中心的な代替案を説明していると述べている。彼は、フリードリヒ・A・ハイエク、ブルース・L・ベンソン、デ ビッド・D・フリードマンらが述べたように、国家が成立する前の伝統的な慣習法(慣習法とも呼ばれる)の概要を説明している。特にアングロサクソン慣習法 を挙げつつ、教会法・ギルド法・商人法も多中心法の例として言及している。ローマ法が帝国全域のローマ人に適用される一方で非ローマ人への土着法体系が容 認されたように、慣習法と成文法は歴史的に共存してきたと述べている。[3] モンペレラン・ソサエティ主催の1998年フリードリヒ・A・ハイエク研究助成金コンペティションで最優秀賞を受賞した論文「新千年紀における多中心法」 において、ベルは多中心法が発展する可能性のある三つの領域を予測している。それは代替的紛争解決、私的共同体、そしてインターネットである。 ヘルシンキ大学(フィンランド)は1992年から1995年にかけ、ラース・D・エリクソン教授主導の「多中心法」研究プロジェクトを資金援助した。その 目的は「現代法と現代法理論の双方の不確定性を明らかにすることで、現行の法的パラダイムの不十分さを示すこと」であった。また「現代法理論に対する法 的・倫理的代替案の可能性」を検討し、「法の統一性という概念を解体し、法的・倫理的差異を再構築することで、多中心的法理論への道を開いた」とされた。 このプロジェクトでは二回の国際会議が開催された。1998年にはアリ・ヒルヴォネン編による書籍『多中心性:法の複数の舞台』が刊行され、プロジェクト に関わった学者たちの論文が収録された。[4] ランディ・バーネット教授は当初「非独占的」法について論じたが、後に「多中心的法秩序」という表現を用いた。彼は著書『自由の構造:正義と法の支配』において、このシステムの利点と見なす点を説明している。[5] ブルース・L・ベンソンもこの表現を用い、2007年のカトー研究所刊行物で次のように記している:「慣習的な多中心的法体系は、関係する様々な共同体に とって効率的な規模の管轄区域を生み出す可能性がはるかに高いと思われる。おそらく多くの国民よりも小規模なものもあれば、今日の多くの政治的管轄区域を 包含するものもあるだろう(例えば、今日の国際商法がそうであるように)。」[6] ジョン・K・パルチャックとスタンリー・T・レオンは「国家は不要か? 多中心的法秩序の批判的検討」において、多中心法という概念を批判している。[7] 法学者ゲイリー・チャティエは「無政府状態と法秩序」において、国家なき法の概念を詳述し擁護している。[8] それは、国家のない社会における法執行が如何にして正当性を得るか、そして国家なき法の最適な本質が如何なるものであるかについての理解を提案する。彼 は、国家なき法的秩序が自由の文化の成長を如何に促進し得るかを示唆し、そのプロジェクトを左翼的、反資本主義的、社会主義的伝統との関係に位置づけてい る。 |

| Anarcho-capitalism Autonomism Consociationalism Corporative federalism Governance without government Heterarchy Horizontalidad Legal pluralism Libertarian municipalism Ophelimity Panarchy Personal jurisdiction Pillarisation Voluntary association Voluntaryism |

アナキスト資本主義 オートノミズム コンソシエーション主義 コーポラティスト連邦主義 政府なき統治 ヘテロアーキー 水平性 法的多元主義 リバタリアン・ミュニシパリズム オフェリミティ パナークシー 人的管轄権 柱化 自発的連合 自発主義 |

| 1. Bell, Tom (Autumn 1999).

"Polycentric Law in the New Century" (PDF). Policy Magazine. Centre for

Independent Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-01.

Retrieved 2018-10-20. An earlier version was published by the Cato

Institute. 2. "Faculty Profile". www.chapman.edu. 3. Tom W. Bell, Polycentric Law, Institute for Humane Studies Review, Volume 7, Number 1 Winter 1991/92. 4. Research project on polycentric law. 5. Randy E. Barnett, E/TOC.htm The Structure of Liberty: Justice and the Rule of Law, Chapters 12, 14, Oxford University Press, 2000. 6. Bruce L. Benson, "Polycentric Governance", Cato Unbound, August 16th, 2007. 7. John K. Palchak and Stanley T. Leung, "No State Required? A Critical Review of the Polycentric Legal Order," 38 Gonzaga Law Review, 289, (2002). 8. "Is Anarchism Socialist or Capitalist?". 22 March 2013. |

1. ベル、トム(1999年秋)。「新世紀における多中心法」(PDF)。政策雑誌。独立研究センター。2014年2月1日にオリジナルからアーカイブ(PDF)。2018年10月20日に取得。初期版はカトー研究所により出版された。 2. 「教員プロフィール」. www.chapman.edu. 3. トム・W・ベル, 『多中心法』, 人間研究協会レビュー, 第7巻第1号, 1991/92年冬号. 4. 多中心法に関する研究プロジェクト。 5. ランディ・E・バーネット『自由の構造:正義と法の支配』第12章、第14章、オックスフォード大学出版局、2000年。 6. ブルース・L・ベンソン「多中心的ガバナンス」『カトー・アンバウンド』2007年8月16日。 7. ジョン・K・パルチャックとスタンリー・T・レオン、「国家は不要か? 多中心的法秩序の批判的検討」、38 ゴンザガ・ロー・レビュー、289頁、(2002年)。 8. 「アナキズムは社会主義か資本主義か?」、2013年3月22日。 |

| Adam Chacksfield, "Polycentric

Law and the Minimal State: The Case of Air Pollution", Libertarian

Alliance, Political Notes 76, 1993. Roderick T. Long, "The Nature of Law", Formulations, published by Free Nation Foundation, Spring 1994. |

アダム・チャックスフィールド「多中心的な法と最小国家:大気汚染の事例」、『リバタリアン・アライアンス』政治ノート76号、1993年。 ロデリック・T・ロング「法の本質」、『フォーミュレーションズ』、フリー・ネイション国民刊、1994年春号。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polycentric_law |

★

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆