だって俺たち犬儒派なんだもん: Part 2

Because we are Cynicists, not dog-matic

Confucianists, Part II

☆ だって俺たち犬儒派なんだもんのパート1は こちらです。シニシズム(古代ギリシア語: κυνισμός)は、古代ギリシア哲学の一派で、古典期からヘレニズム時代、ローマ帝国時代に至る思想である。シニシズムによれば、人は理性的な動物で あり、人生の目的、幸福を得る方法は、社会的な束縛から解放されたシンプルで恥知らずな生き方によって、自然の理性に従って、徳の達成を目指すことであ る。キニックス(古代ギリシア語:Κυνικοί、ラテン語:Cynici)は、富、権力、栄光、社会的認知、順応性、世俗的所有物に対する従来のあらゆ る欲望を否定し、公の場で公然と嘲笑的にそのような慣習に背くことさえした。 これらのテーマを最初に概説した哲学者は、紀元前400年代後半にソクラテスの弟子であったアンティステネスである。彼はアテネの路上で陶器の壷の中で生 活していた。ディオゲネスは、その有名な公衆の面前での不適合のデモンストレーションによって、シニシズムを論理的に極限まで高め、典型的なシニシズムの 哲学者とみなされるようになった。テーベのクラテスは莫大な財産を手放し、アテネでシニシズム的な清貧生活を送るようになった。 紀元前3世紀以降、キニシズムの重要性は徐々に低下したが[3]、1世紀にローマ帝国が勃興すると復活を遂げた。シニシズムは帝国の各都市で物乞いや説教 をする姿が見られ、初期のキリスト教にも同様の禁欲的で修辞的な思想が登場した。19世紀までには、キニク哲学の否定的な側面が強調され、人間の動機や行 動の誠実さや善良さを信じない気質を意味するシニシズムの現代的理解につながった。

| Cynicism (Ancient Greek: κυνισμός) is

a school of thought in ancient Greek philosophy, originating in the

Classical period and extending into the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial

periods. According to Cynicism, people are reasoning animals and the

purpose of life and the way to gain happiness is to achieve virtue, in

agreement with nature, following one's natural sense of reason by

living simply and shamelessly free from social constraints. The Cynics

(Ancient Greek: Κυνικοί, Latin: Cynici) rejected all conventional

desires for wealth, power, glory, social recognition, conformity, and

worldly possessions and even flouted such conventions openly and

derisively in public. The first philosopher to outline these themes was Antisthenes, who had been a pupil of Socrates in the late 400s BC. He was followed by Diogenes, who lived in a ceramic jar on the streets of Athens.[2] Diogenes took Cynicism to its logical extremes with his famous public demonstrations of non-conformity, coming to be seen as the archetypal Cynic philosopher. He was followed by Crates of Thebes, who gave away a large fortune so he could live a life of Cynic poverty in Athens. Cynicism gradually declined in importance after the 3rd century BC,[3] but it experienced a revival with the rise of the Roman Empire in the 1st century. Cynics could be found begging and preaching throughout the cities of the empire, and similar ascetic and rhetorical ideas appeared in early Christianity. By the 19th century, emphasis on the negative aspects of Cynic philosophy led to the modern understanding of cynicism to mean a disposition of disbelief in the sincerity or goodness of human motives and actions. |

シニシズム(古代ギリシア語:

κυνισμός)は、古代ギリシア哲学の一派で、古典期からヘレニズム時代、ローマ帝国時代に至る思想である。シニシズムによれば、人は理性的な動物で

あり、人生の目的、幸福を得る方法は、社会的な束縛から解放されたシンプルで恥知らずな生き方によって、自然の理性に従って、徳の達成を目指すことであ

る。キニックス(古代ギリシア語:Κυνικοί、ラテン語:Cynici)は、富、権力、栄光、社会的認知、順応性、世俗的所有物に対する従来のあらゆ

る欲望を否定し、公の場で公然と嘲笑的にそのような慣習に背くことさえした。 これらのテーマを最初に概説した哲学者は、紀元前400年代後半にソクラテスの弟子であったアンティステネスである。彼はアテネの路上で陶器の壷の中で生 活していた。ディオゲネスは、その有名な公衆の面前での不適合のデモンストレーションによって、シニシズムを論理的に極限まで高め、典型的なシニシズムの 哲学者とみなされるようになった。テーベのクラテスは莫大な財産を手放し、アテネでシニシズム的な清貧生活を送るようになった。 紀元前3世紀以降、キニシズムの重要性は徐々に低下したが[3]、1世紀にローマ帝国が勃興すると復活を遂げた。シニシズムは帝国の各都市で物乞いや説教 をする姿が見られ、初期のキリスト教にも同様の禁欲的で修辞的な思想が登場した。19世紀までには、キニク哲学の否定的な側面が強調され、人間の動機や行 動の誠実さや善良さを信じない気質を意味するシニシズムの現代的理解につながった。 |

| Origin of the Cynic name The term cynic derives from Ancient Greek κυνικός (kynikos) 'dog-like', and κύων (kyôn) 'dog' (genitive: kynos).[4] One explanation offered in ancient times for why the Cynics were called "dogs" was because the first Cynic, Antisthenes, taught in the Cynosarges gymnasium at Athens.[5] The word cynosarges means the "place of the white dog". It seems certain, however, that the word dog was also thrown at the first Cynics as an insult for their shameless rejection of conventional manners, and their decision to live on the streets. Diogenes, in particular, was referred to as the "Dog",[6] a distinction he seems to have revelled in, stating that "other dogs bite their enemies, I bite my friends to save them."[7] Later Cynics also sought to turn the word to their advantage, as a later commentator explained: There are four reasons why the Cynics are so named. First because of the indifference of their way of life, for they make a cult of indifference and, like dogs, eat and make love in public, go barefoot, and sleep in tubs and at crossroads. The second reason is that the dog is a shameless animal, and they make a cult of shamelessness, not as being beneath modesty, but as superior to it. The third reason is that the dog is a good guard, and they guard the tenets of their philosophy. The fourth reason is that the dog is a discriminating animal which can distinguish between its friends and enemies. So do they recognize as friends those who are suited to philosophy, and receive them kindly, while those unfitted they drive away, like dogs, by barking at them.[8] |

シニックの名前の由来 シニックスという言葉は、古代ギリシャ語のκυνικός(kynikos)「犬のような」、κύων(kyôn)「犬」(主格:kynos)に由来する [4]。なぜシニックスが「犬」と呼ばれるようになったかについて、古代に提示された説明のひとつは、最初のシニックスであるアンティステネスがアテネの シノサルゲス体育館で教えていたからである[5]。しかし、犬という言葉が、従来の礼儀作法を恥ずかしげもなく否定し、路上で生活することを決めた最初の キニックスに対する侮辱として投げかけられたことも確かなようである。特にディオゲネスは「犬」と呼ばれ[6]、その区別を喜んでいたようで、「他の犬は 敵を噛むが、私は友人を噛んで助ける」と述べている[7]: キニクスの名がそう呼ばれる理由は4つある。彼らは無関心を崇拝し、犬のように公衆の面前で食事をし、愛し合い、裸足になり、浴槽や十字路で寝るからであ る。第二の理由は、犬は恥知らずな動物であり、彼らは恥知らずを崇拝する。第三の理由は、犬は良い番人であり、彼らは自分たちの哲学の信条を守るからであ る。第四の理由は、犬は敵味方の区別がつく動物だからである。だから彼らは、哲学にふさわしい者を友と認め、親切に迎え入れ、ふさわしくない者は犬のよう に吠えて追い払うのである[8]。 |

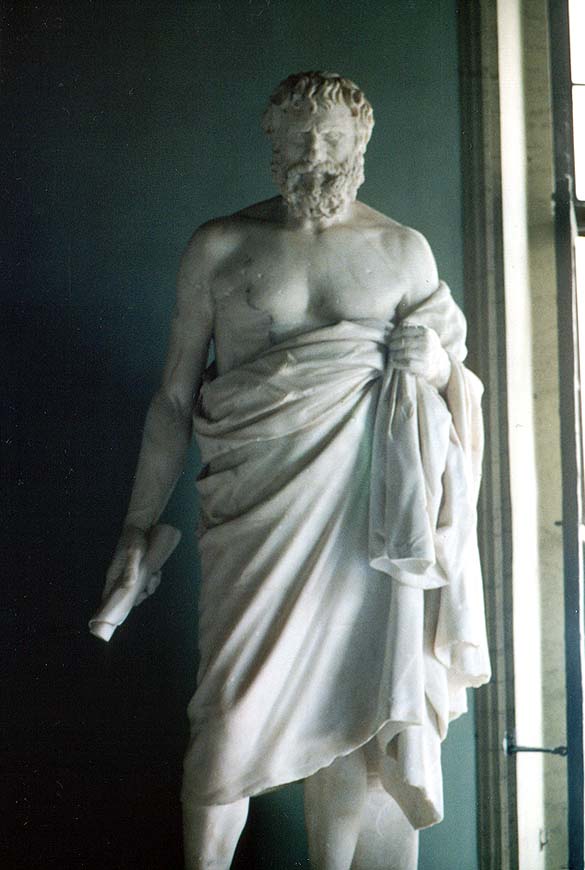

| Philosophy Cynicism is one of the most striking of all the Hellenistic philosophies.[9] It claimed to offer people the possibility of happiness and freedom from suffering in an age of uncertainty. Although there was never an official Cynic doctrine, the fundamental principles of Cynicism can be summarized as follows:[10][11][12] The goal of life is eudaimonia and mental clarity or lucidity (ἁτυφια)—literally "freedom from smoke (τύφος)" which signified false belief, mindlessness, folly, and conceit. Eudaimonia, or human flourishing, depends on self-sufficiency (αὐτάρκεια), equanimity, arete, love of humanity, parrhesia, and indifference to the vicissitudes of life (adiaphora ἁδιαφορία).[12] Eudaimonia is achieved by living in accord with Nature as understood by human reason. Arrogance (τύφος) is caused by false judgments of value, which cause negative emotions, unnatural desires, and a vicious character. One progresses towards flourishing and clarity through ascetic practices (ἄσκησις) which help one become free from influences such as wealth, fame, and power which have no value in Nature. Instead they promoted living a life of ponos. For the Cynics, this did not seem to mean actual physical work. Diogenes of Sinope, for example, lived by begging, not by doing manual labor. Rather, it means deliberately choosing a hard life—for instance, wearing only a thin cloak and going barefoot in winter.[13] A Cynic practices shamelessness or impudence (Αναιδεια) and defaces the nomos of society: the laws, customs, and social conventions that people take for granted.  The Cynics adopted Heracles, shown here in this gilded bronze statue from the second century CE, as their patron hero.[14][15] Thus a Cynic has no property and rejects all conventional values of money, fame, power and reputation.[10] A life lived according to nature requires only the bare necessities required for existence, and one can become free by unshackling oneself from any needs which are the result of convention.[16] The Cynics adopted Heracles as their hero, as epitomizing the ideal Cynic.[14] Heracles "was he who brought Cerberus, the hound of Hades, from the underworld, a point of special appeal to the dog-man, Diogenes."[15] According to Lucian, "Cerberus and Cynic are surely related through the dog."[17] The Cynic way of life required continuous training, not just in exercising judgments and mental impressions, but a physical training as well: [Diogenes] used to say, that there were two kinds of exercise: that, namely, of the mind and that of the body; and that the latter of these created in the mind such quick and agile impressions at the time of its performance, as very much facilitated the practice of virtue; but that one was imperfect without the other, since the health and vigour necessary for the practice of what is good, depend equally on both mind and body.[18] None of this meant that a Cynic would retreat from society. Cynics were in fact to live in the full glare of the public's gaze and be quite indifferent in the face of any insults which might result from their unconventional behaviour.[10] The Cynics are said to have invented the idea of cosmopolitanism: when he was asked where he came from, Diogenes replied that he was "a citizen of the world, (kosmopolitês)."[19] The ideal Cynic would evangelise; as the watchdog of humanity, they thought it was their duty to hound people about the error of their ways.[10] The example of the Cynic's life (and the use of the Cynic's biting satire) would dig up and expose the pretensions which lay at the root of everyday conventions.[10] Although Cynicism concentrated primarily on ethics, some Cynics, such as Monimus, addressed epistemology with regard to tuphos (τῦφος) expressing skeptical views. Cynic philosophy had a major impact on the Hellenistic world, ultimately becoming an important influence for Stoicism. The Stoic Apollodorus, writing in the 2nd century BC, stated that "Cynicism is the short path to virtue."[20] |

哲学 シニシズムはヘレニズム哲学の中でも最も印象的なもののひとつである[9]。 不確実な時代において、人々に幸福の可能性と苦しみからの解放を提供すると主張した。公式なシニシズムの教義は存在しなかったが、シニシズムの基本原理は 以下のように要約することができる[10][11][12]。 人生の目標はエウダイモニアであり、精神の明晰さまたは明晰さ(ἁτυφια)であり、文字通り「煙(τύφος)からの自由」である。 エウダイモニア、すなわち人間の繁栄は、自己充足(αŐτάρκεια)、平静、アレテー、人間愛、パーレシア、人生の波乱に対する無関心 (adiaphora āδιαφορία)によって決まる[12]。 エウダイモニアは、人間の理性によって理解される自然に従って生きることによって達成される。 傲慢(τύφος)は誤った価値判断によって引き起こされ、それが否定的な感情、不自然な欲望、悪質な性格を引き起こす。 人は、富、名声、権力など、自然界では何の価値もないものからの影響から自由になるための禁欲的な修行(ἄσκησις)を通して、繁栄と明晰さに向かっ て進歩します。その代わりに、彼らはポノスの生活を奨励した。キニクスの人々にとって、これは実際の肉体労働を意味するものではなかったようだ。例えば、 シノペのディオゲネスは、肉体労働ではなく、物乞いをして生きていた。むしろ、それは意図的に厳しい生活を選ぶことを意味する。例えば、薄い外套だけを着 て、冬には裸足になるなどである[13]。 キニク主義者は無恥や不遜(Αναιδεια)を実践し、社会のノモス(人々が当然と思っている法律、慣習、社会的慣習)を汚す。  キニク派はヘラクレスを守護英雄として採用した。 従って、キニク主義者は財産を持たず、金銭、名声、権力、評判といった従来の価値観をすべて否定する[10]。自然に従って生きる人生は、存在するために 必要な最低限のものだけを必要とし、慣習の結果であるあらゆる欲求から自らを解き放つことによって自由になることができる。 [ヘラクレスは「黄泉の猟犬ケルベロスを冥界から連れ出した人物であり、犬人間のディオゲネスにとっては特別なアピールポイントであった」[15]。 キニスの生き方は、判断力や精神的な印象の訓練だけでなく、肉体的な訓練も必要とした: [ディオゲネスは]運動には二種類ある、すなわち心の運動と身体の運動があり、後者の運動はその実行時に心に迅速で機敏な印象を与え、徳の実践を非常に容 易にするが、一方は他方がなければ不完全であり、善いことの実践に必要な健康と活力は心と身体の両方に等しく依存するからである[18]と言っていた。 このことはいずれも、シニシズムの持ち主が社会から退くことを意味するものではなかった。実際、キニク主義者は世間の視線を一身に浴びて生きており、その 型破りな行動から生じるかもしれない侮辱に対してまったく無関心であった[10]。キニク主義者はコスモポリタニズムという考え方を発明したと言われてい る。ディオゲネスは、どこから来たのかと尋ねられたときに、自分は「世界市民(コスモポリテス)」であると答えた[19]。 理想的なシニシズムは伝道するものであり、人類の番犬として、人々に自分たちのやり方の誤りを追い詰めることが自分たちの義務であると考えていた [10]。シニシズムの生き方の模範は(そしてシニシズムの痛烈な風刺の使用は)、日常的な慣習の根底にある虚勢を掘り起こし、暴露するものであった [10]。 シニシズムは主に倫理に集中していたが、モニムスのような一部のシニシズムは、懐疑的な見解を表明するトゥフォス(τῦφος)に関して認識論を扱った。 キニクスの哲学はヘレニズム世界に大きな影響を与え、最終的にはストア派に重要な影響を与えた。紀元前2世紀に書かれたストア派のアポロドロスは、「シニ シズムは徳への近道である」と述べている[20]。 |

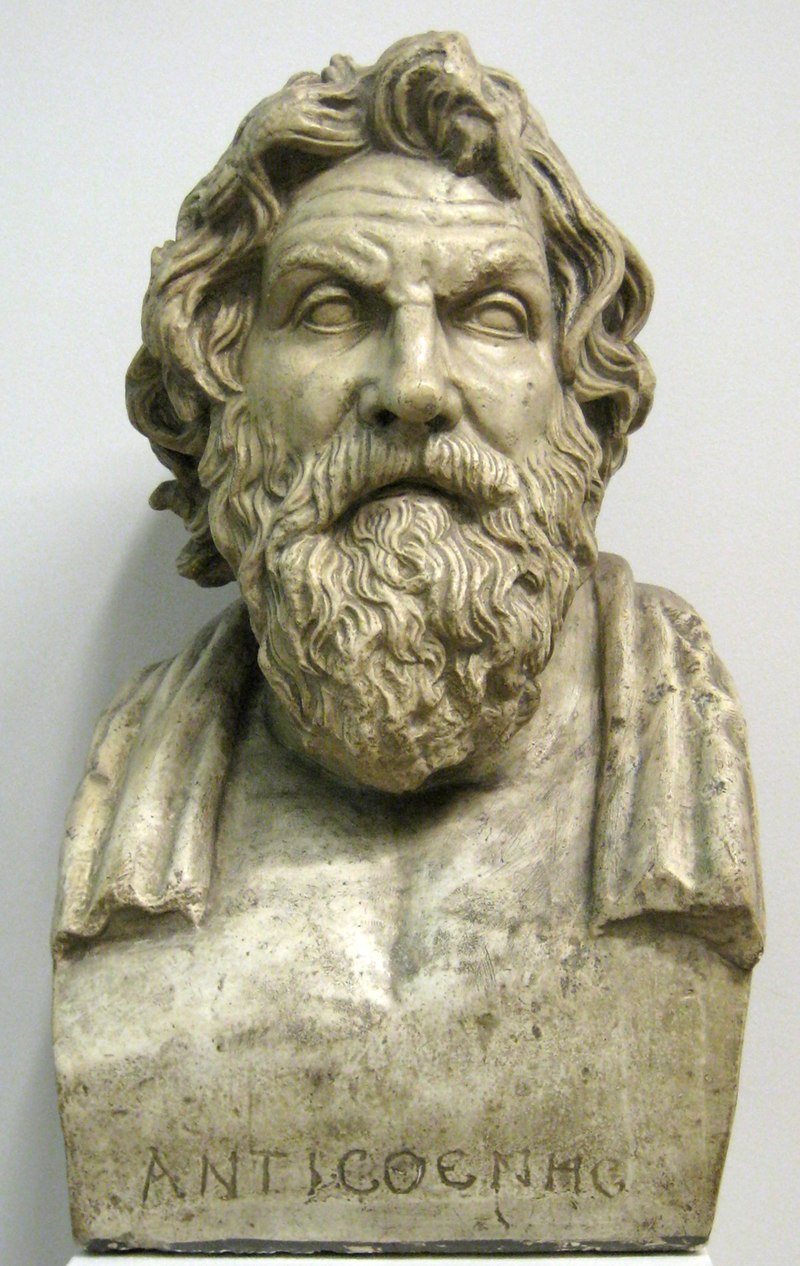

History of Cynicism Bust of Antisthenes The classical Greek and Roman Cynics regarded virtue as the only necessity for happiness, and saw virtue as entirely sufficient for attaining it. Classical Cynics followed this philosophy to the extent of neglecting everything not furthering their perfection of virtue and attainment of happiness, thus, the title of Cynic, derived from the Greek word κύων (meaning "dog") because they allegedly neglected society, hygiene, family, money, etc., in a manner reminiscent of dogs. They sought to free themselves from conventions; become self-sufficient; and live only in accordance with nature. They rejected any conventional notions of happiness involving money, power, and fame, to lead entirely virtuous, and thus happy, lives.[21] The ancient Cynics rejected conventional social values, and would criticise the types of behaviours, such as greed, which they viewed as causing suffering. Emphasis on this aspect of their teachings led, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries,[22] to the modern understanding of cynicism as "an attitude of scornful or jaded negativity, especially a general distrust of the integrity or professed motives of others."[23] This modern definition of cynicism is in marked contrast to the ancient philosophy, which emphasized "virtue and moral freedom in liberation from desire."[24] Influences Various philosophers, such as the Pythagoreans, had advocated simple living in the centuries preceding the Cynics. In the early 6th century BC, Anacharsis, a Scythian sage, had combined plain living together with criticisms of Greek customs in a manner which would become standard among the Cynics.[25] Perhaps of importance were tales of Indian philosophers, known as gymnosophists, who had adopted a strict asceticism. By the 5th century BC, the sophists had begun a process of questioning many aspects of Greek society such as religion, law and ethics. However, the most immediate influence for the Cynic school was Socrates. Although he was not an ascetic, he did profess a love of virtue and an indifference to wealth,[26] together with a disdain for general opinion.[27] These aspects of Socrates' thought, which formed only a minor part of Plato's philosophy, became the central inspiration for another of Socrates' pupils, Antisthenes.[citation needed] Symbolisms Cynics were often recognized in the ancient world by their apparel—an old cloak and a staff. The cloak was an allusion to Socrates and his manner of dress, the staff to the club of Heracles. These items became so symbolic of the Cynic vocation that ancient writers accosted those who thought that donning the Cynic garb would make them suited to the philosophy.[28] In the social evolution from the archaic age to the classical, the public ceased carrying weapons into the poleis. Originally it was expected that one carried a sword while in the city. However, a transition to spears and then to staffs occurred until wearing any weapon in the city became a foolish old custom.[29] Thus, the very act of carrying a staff was slightly taboo itself. According to modern theorists, the symbol of the staff was one which both functions as a tool to signal the user's dissociation from physical labour, that is, as a display of conspicuous leisure, and at the same time it also has an association with sport and typically plays a part in hunting and sports clothing. Thus, it displays active and warlike qualities, rather than being a symbol of a weak man's need to support himself.[30][31] The staff itself became a message of how the Cynic was free through its possible interpretation as an item of leisure, but, just as equivalent, was its message of strength—a virtue held in abundance by the Cynic philosopher.[citation needed] Antisthenes Main article: Antisthenes The story of Cynicism traditionally begins with Antisthenes (c. 445–365 BC),[32][33] who was an older contemporary of Plato and a pupil of Socrates. About 25 years his junior, Antisthenes was one of the most important of Socrates' disciples.[34] Although later classical authors had little doubt about labelling him as the founder of Cynicism,[35] his philosophical views seem to be more complex than the later simplicities of pure Cynicism. In the list of works ascribed to Antisthenes by Diogenes Laërtius,[36] writings on language, dialogue and literature far outnumber those on ethics or politics,[37] although they may reflect how his philosophical interests changed with time.[38] It is certainly true that Antisthenes preached a life of poverty: I have enough to eat till my hunger is stayed, to drink till my thirst is sated; to clothe myself as well; and out of doors not [even] Callias there, with all his riches, is more safe than I from shivering; and when I find myself indoors, what warmer shirting do I need than my bare walls?[39] Diogenes of Sinope  Diogenes Searching for an Honest Man (c. 1780) attributed to J. H. W. Tischbein Main article: Diogenes Diogenes (c. 412–323 BC) dominates the story of Cynicism like no other figure. He originally went to Athens, fleeing his home city, after he and his father, who was in charge of the mint at Sinope, got into trouble for falsifying the coinage.[40] (The phrase "defacing the currency" later became proverbial in describing Diogenes' rejection of conventional values.)[41] Later tradition claimed that Diogenes became the disciple of Antisthenes,[42] but it is by no means certain that they ever met.[43][44][45] Diogenes did however adopt Antisthenes' teachings and the ascetic way of life, pursuing a life of self-sufficiency (autarkeia), austerity (askēsis), and shamelessness (anaideia).[46] There are many anecdotes about his extreme asceticism (sleeping in a tub),[47] his shameless behaviour (eating raw meat),[48] and his criticism of conventional society ("bad people obey their lusts as servants obey their masters"),[49] and although it is impossible to tell which of these stories are true, they do illustrate the broad character of the man, including an ethical seriousness.[50] Crates of Thebes  Crates and Hipparchia, an antique fresco from Rome Crates of Thebes (c. 365–c. 285 BC) is the third figure who dominates Cynic history. He is notable because he renounced a large fortune to live a life of Cynic poverty in Athens.[51] He is said to have been a pupil of Diogenes,[52] but again this is uncertain.[53] Crates married Hipparchia of Maroneia after she had fallen in love with him and together they lived like beggars on the streets of Athens,[54] where Crates was treated with respect.[55] Crates' later fame (apart from his unconventional lifestyle) lies in the fact that he became the teacher of Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism.[56] The Cynic strain to be found in early Stoicism (such as Zeno's own radical views on sexual equality spelled out in his Republic) can be ascribed to Crates' influence.[57] Other Cynics There were many other Cynics in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, including Onesicritus (who sailed with Alexander the Great to India), the skeptic Monimus, the moral satirist Bion of Borysthenes, the legislator Cercidas of Megalopolis, the diatribist Teles and Menippus of Gadara. However, with the rise of Stoicism in the 3rd century BC, Cynicism as a serious philosophical activity underwent a decline,[3][58] and it is not until the Roman era that Cynicism underwent a revival in the first century AD.[59] |

シニシズムの歴史 アンティステネスの胸像 古典ギリシア・ローマのキニク派は、徳こそが幸福に必要な唯一のものであり、徳があれば幸福を得るのに十分であると考えた。古典的なキニク派は、徳の完成 と幸福の達成を促進しないものはすべて無視するという程度までこの哲学に従った。そのため、キニクという称号は、ギリシャ語のκύων(「犬」の意味)に 由来する。彼らは慣習から自らを解放し、自給自足し、自然に従ってのみ生きようとした。彼らは金銭、権力、名声を含む従来の幸福の概念を一切否定し、完全 に高潔な、したがって幸福な生活を送ることを目指した[21]。 古代のキニク派は従来の社会的価値観を否定し、苦しみを引き起こすとみなした貪欲などの行動を批判していた。彼らの教えのこの側面への強調は、18世紀後 半から19世紀初頭にかけて、シニシズムを「軽蔑的または色あせた否定的な態度、特に他者の誠実さや公言された動機に対する一般的な不信」[23]として 現代的に理解することにつながった。このシニシズムの現代的な定義は、「欲望からの解放における美徳と道徳的自由」[24]を強調した古代の哲学とは著し く対照的である。 影響 ピタゴラス派のような様々な哲学者は、シニックスに先立つ数世紀においてシンプルな生活を提唱していた。紀元前6世紀初頭、スキタイの賢者アナハルシス は、質素な生活とギリシアの風習に対する批判を組み合わせて、後にキニクスの標準となるような方法を提唱していた[25]。おそらく重要なのは、厳格な禁 欲主義を採用していたギムノソフィストとして知られるインドの哲学者の話であろう。紀元前5世紀までに、ソフィストたちは宗教、法律、倫理などギリシア社 会の多くの側面に疑問を投げかけるプロセスを始めていた。しかし、キニコス派に最も直接的な影響を与えたのはソクラテスだった。ソクラテスは無欲主義者で はなかったが、美徳を愛し、富に無関心であることを公言しており[26]、一般的な意見を軽んじていた[27]。プラトンの哲学のごく一部に過ぎなかった ソクラテスの思想のこれらの側面は、ソクラテスの弟子の一人であるアンティステネスの中心的なインスピレーションとなった[要出典]。 象徴 シニシズムは、古代の世界では古いマントと杖という服装でしばしば認識されていた。マントはソクラテスと彼の服装、杖はヘラクレスの棍棒を連想させる。こ れらのアイテムはキニコス派の職業を象徴するものとなり、古代の作家たちは、キニコス派の衣装を身につければ哲学に適するようになると考える人々を非難し た[28]。 古風な時代から古典的な時代への社会的進化において、一般市民は武器をポーリスに持ち込むことをやめた。元来、都市にいる間は剣を携帯することが期待され ていた。しかし、槍、そして杖への移行が起こり、街中で武器を身につけることは愚かな古い習慣となった[29]。現代の理論家によれば、杖のシンボルは、 使用者が肉体労働から解き放たれていることを示す道具として、つまり目立つ余暇を示す道具として機能すると同時に、スポーツとの関連も持ち、典型的には狩 猟やスポーツの服装の一翼を担っていた。したがって、杖は弱者が自らを支える必要性の象徴ではなく、活動的で戦争的な資質を示すものである[30] [31]。杖そのものは、余暇のアイテムとして解釈される可能性を通じて、いかにキニスが自由であったかを示すメッセージとなったが、それと同様に、キニ スの哲学者が豊富に持っていた美徳である強さを示すメッセージでもあった[要出典]。 アンティステネス 主な記事 アンティステネス キニシズムの物語は伝統的にアンティステネス(紀元前445-365年頃)から始まる[32][33]。アンティステネスはソクラテスの最も重要な弟子の 一人であり、25歳ほど年下であった[34]。後世の古典的著者はアンティステネスをシニシズムの創始者とすることにほとんど疑問を持たなかったが [35]、彼の哲学的見解は後の純粋なシニシズムの単純さよりも複雑であったようである。ディオゲネス・ラエルティウスによるアンティステネスの著作リス ト[36]では、言語、対話、文学に関する著作が倫理学や政治学に関する著作をはるかに上回っている[37]: 私は飢えが収まるまで食べるのに十分であり、喉の渇きが満たされるまで飲むのに十分であり、衣服も十分であり、戸外では、あらゆる富を持つカリアスでさえ も、震えから私より安全ではない。 シノープのディオゲネス  『誠実な男を探すディオゲネス』(1780年頃)J. H. W. ティッシュバインの作とされる。 主な記事 ディオゲネス ディオゲネス(紀元前412-323年頃)は、シニシズムを語る上で欠かせない人物である。彼はもともと、シノペの造幣局の責任者であった父とともに、貨 幣の偽造で問題を起こした後、故郷を逃れてアテネに向かった[40](「貨幣を汚す」という言葉は、後に、ディオゲネスの従来の価値観に対する拒絶を表す ことわざとなった)[41]。 [43][44][45]しかし、ディオゲネスはアンティステネスの教えと禁欲的な生き方を取り入れ、自給自足(autarkeia)、緊縮 (askēsis)、無恥(anaideia)の生活を追求した。 [彼の極端な禁欲主義(浴槽で寝る)[47]、彼の恥知らずな行動(生肉を食べる)[48]、彼の従来の社会に対する批判(「悪い人間は、召使いが主人に 従うように、自分の欲望に従う」)[49]に関する逸話は数多くあり、これらの話のどれが真実かはわからないが、倫理的な真面目さを含む彼の幅広い性格を 物語っている[50]。 テーベのクラテス  ローマ時代のフレスコ画『テーベのクレイツとヒッパルキア』 テーベのクラテス(前365-前285年)は、キニクスの歴史を支配する3人目の人物である。ディオゲネスの弟子であったとも言われているが[52]、こ れも定かではない。[53]クラテスはマロネイアのヒッパルキアと恋に落ちて結婚し、アテネの路上で乞食のような生活を共にしたが[54]、クラテスはそ こで敬意を持って扱われた。 [55]クラテスの後の名声は(その型破りなライフスタイルとは別に)、彼がストア派の創始者であるシティウムのゼノンの師となったという事実にある [56]。初期ストア派に見られるシニックの系統(ゼノン自身の『共和国』に綴られた性的平等に関する急進的な見解など)は、クラテスの影響に帰すること ができる[57]。 他のシニックス 紀元前4世紀から3世紀にかけては、オネシクリトス(アレクサンドロス大王とともにインドへ航海した)、懐疑論者モニムス、ボリステネスの道徳風刺主義者 ビオン、メガロポリスの立法者チェルシダス、放言主義者テレス、ガダラのメニッポスなど、他にも多くのキニク派がいた。しかし紀元前3世紀にストア派が台 頭すると、本格的な哲学活動としてのシニシズムは衰退し[3][58]、紀元1世紀にシニシズムが復活するのはローマ時代になってからである[59]。 |

Cynicism in the Roman world Diogenes Sitting in His Tub (1860) by Jean-Léon Gérôme There is little record of Cynicism in the 2nd or 1st centuries BC; Cicero (c. 50 BC), who was much interested in Greek philosophy, had little to say about Cynicism, except that "it is to be shunned; for it is opposed to modesty, without which there can be neither right nor honor."[60] However, by the 1st century CE, Cynicism reappeared with full force. The rise of Imperial Rome, like the Greek loss of independence under Philip and Alexander three centuries earlier, may have led to a sense of powerlessness and frustration among many people, which allowed a philosophy which emphasized self-sufficiency and inner-happiness to flourish once again.[61] Cynics could be found throughout the empire, standing on street corners, preaching about virtue.[62] Lucian complained that "every city is filled with such upstarts, particularly with those who enter the names of Diogenes, Antisthenes, and Crates as their patrons and enlist in the Army of the Dog,"[63] and Aelius Aristides observed that "they frequent the doorways, talking more to the doorkeepers than to the masters, making up for their lowly condition by using impudence."[64] The most notable representative of Cynicism in the 1st century CE was Demetrius, whom Seneca praised as "a man of consummate wisdom, though he himself denied it, constant to the principles which he professed, of an eloquence worthy to deal with the mightiest subjects."[65] Cynicism in Rome was both the butt of the satirist and the ideal of the thinker. In the 2nd century CE, Lucian, whilst pouring scorn on the Cynic philosopher Peregrinus Proteus,[66] nevertheless praised his own Cynic teacher, Demonax, in a dialogue.[67] Cynicism came to be seen as an idealised form of Stoicism, a view which led Epictetus to eulogise the ideal Cynic in a lengthy discourse.[68] According to Epictetus, the ideal Cynic "must know that he is sent as a messenger from Zeus to people concerning good and bad things, to show them that they have wandered."[69] Unfortunately for Epictetus, many Cynics of the era did not live up to the ideal: "consider the present Cynics who are dogs that wait at tables, and in no respect imitate the Cynics of old except perchance in breaking wind."[70] Unlike Stoicism, which declined as an independent philosophy after the 2nd century CE, Cynicism seems to have thrived into the 4th century.[71] The emperor Julian (ruled 361–363), like Epictetus, praised the ideal Cynic and complained about the actual practitioners of Cynicism.[72] The final Cynic noted in classical history is Sallustius of Emesa in the late 5th century.[73] A student of the Neoplatonic philosopher Isidore of Alexandria, he devoted himself to living a life of Cynic asceticism.[citation needed] |

ローマ世界のシニシズム 浴槽に座るディオゲネス(1860年)ジャン=レオン・ジェローム作 紀元前2世紀や1世紀にはシニシズムに関する記録はほとんどなく、ギリシア哲学に大きな関心を寄せていたキケロ(紀元前50年頃)は、シニシズムについて 「慎み深さに反するものであり、それなくしては正しいことも名誉もあり得ないから、慎み深さを避けるべきである」と述べた以外、ほとんど何も語っていない [60]。帝政ローマの台頭は、その3世紀前にフィリップとアレクサンダーのもとで独立を失ったギリシア人のように、多くの人々の無力感とフラストレー ションを引き起こし、それが自己充足と内なる幸福を強調する哲学を再び繁栄させることになったのだろう[61]。 [特にディオゲネス、アンティステネス、クラテスの名をパトロンとし、犬の軍団に入隊する者たちである。 「紀元1世紀におけるシニシズムの最も顕著な代表者はデメトリアスであり、セネカは「完璧な知恵の持ち主であったが、彼自身はそれを否定しており、公言し ている原則に忠実で、最も強大な主題を扱うにふさわしい雄弁の持ち主であった」と称賛している[65]。ローマにおけるシニシズムは、風刺の対象であると 同時に思想家の理想でもあった。紀元2世紀、ルキアヌスはキニシズムの哲学者ペレグリヌス・プロテウスを軽蔑しながらも[66]、対話の中で自身のキニシ ズムの師であるデモナクスを賞賛した[67]。 エピクテトスによれば、理想的なキニク主義者は「自分が善悪に関するゼウスからの使者として人々に遣わされ、彼らが迷い込んでいることを示すことを知らな ければならない」[68]。 「69]。エピクテトスにとって残念なことに、当時の多くのキニク派は理想通りには生きていなかった。「現在のキニク派はテーブルで待つ犬であり、風を切 ること以外には昔のキニク派を真似ていないことを考えよ」[70]。 ユリアヌス帝(在位361-363年)はエピクテトスと同様に、理想的なキニシズムを賞賛し、実際のキニシズムの実践者については苦言を呈した。 [新プラトン主義の哲学者であるアレクサンドリアのイシドールの弟子であったサルスティウスは、キニシズム的な禁欲生活を送ることに専念した[73]。 |

Cynicism and Christianity Coptic icon of Saint Anthony of the Desert, an early Christian ascetic. Early Christian asceticism may have been influenced by Cynicism.[74] Jesus as a Jewish Cynic Some historians have noted the similarities between the teachings of Jesus and those of the Cynics. Some scholars have argued that the Q document, a hypothetical common source for the gospels of Matthew and Luke, has strong similarities to the teachings of the Cynics.[75][76] Scholars on the quest for the historical Jesus, such as Burton L. Mack and John Dominic Crossan of the Jesus Seminar, have argued that 1st-century AD Galilee was a world in which Hellenistic ideas collided with Jewish thought and traditions. The city of Gadara, only a day's walk from Nazareth, was particularly notable as a centre of Cynic philosophy,[77] and Mack has described Jesus as a "rather normal Cynic-type figure."[78] For Crossan, Jesus was more like a Cynic sage from a Hellenistic Jewish tradition than either a Christ who would die as a substitute for sinners or a messiah who wanted to establish an independent Jewish state of Israel.[79] Other scholars doubt that Jesus was deeply influenced by the Cynics and see the Jewish prophetic tradition as of much greater importance.[80] Cynic influences on early Christianity Many of the ascetic practices of Cynicism may have been adopted by early Christians, and Christians often employed the same rhetorical methods as the Cynics.[81] Some Cynics were martyred for speaking out against the authorities.[82] One Cynic, Peregrinus Proteus, lived for a time as a Christian before converting to Cynicism,[83] whereas in the 4th century, Maximus of Alexandria, although a Christian, was also called a Cynic because of his ascetic lifestyle. Christian writers would often praise Cynic poverty,[84] although they scorned Cynic shamelessness, Augustine stating that they had, "in violation of the modest instincts of men, boastfully proclaimed their unclean and shameless opinion, worthy indeed of dogs."[85] The ascetic orders of Christianity (such as the Desert Fathers) also had direct connection with the Cynics, as can be seen in the wandering mendicant monks of the early church, who in outward appearance and in many of their practices differed little from the Cynics of an earlier age.[74] Emmanuel College scholar Leif E. Vaage compared the commonalities between the Q document and Cynic texts, such as the Cynic epistles.[75] The epistles contain the wisdom and (often polemical) ethics preached by Cynics along with their sense of purity and ascetic practices.[86] During the 2nd century, Justin Martyr clashed with Crescens the Cynic, who is recorded as claiming the Christians were atheotatous (“the most without a god”), in reference to their rejection of the pagan gods and their absence of temples, statues, or sacrifices. This was a popular criticism of the Christians and it continued on into the 4th century.[87] |

シニシズムとキリスト教 初期キリスト教の禁欲主義者、砂漠の聖アンソニーのコプト・イコン。初期キリスト教の禁欲主義はシニシズムの影響を受けていた可能性がある[74]。 ユダヤ人シニシズムとしてのイエス 何人かの歴史家はイエスの教えとキニシズムの教えの類似性を指摘している。何人かの学者はマタイとルカの福音書の仮説的共通源であるQ文書がキニシズムの 教えと強い類似性を持っていると主張している[75][76]。イエス・セミナーのバートンL.マックとジョン・ドミニク・クロッサンのような歴史的イエ スを探求する学者たちは、紀元1世紀のガリラヤはヘレニズム的思想がユダヤ人の思想と伝統と衝突する世界であったと主張している。ナザレから一日歩いたと ころにあるガダラという町は、キニコス哲学の中心地として特に注目されており[77]、マックはイエスを「むしろ普通のキニコス型の人物」と評している [78]。 「クロッサンによれば、イエスは罪人の身代わりとして死ぬキリストや、独立したユダヤ人のイスラエル国家を樹立しようとする救世主というよりは、ヘレニズ ム的なユダヤ教の伝統に基づくキニク派の賢者のような存在であった[79]。他の学者たちは、イエスがキニク派から深い影響を受けていたことを疑ってお り、ユダヤ教の予言的伝統の方がはるかに重要であると考えている[80]。 初期キリスト教におけるキニク派の影響 またキリスト教徒はしばしばキニク派と同じ修辞法を用いていた[81]。キニク派の中には当局に反対する発言をしたために殉教した者もいた[82]。キリ スト教の著述家たちはしばしばキニシズムの清貧を賞賛していたが[84]、彼らはキニシズムの恥知らずさを軽蔑しており、アウグスティヌスは「人間の慎み 深い本能に反して、犬にも値するような汚れた恥知らずな意見を誇らしげに宣言した」と述べている。 「キリスト教の禁欲的な修道会(砂漠の教父たちなど)もまた、初期教会の放浪する托鉢修道士たちに見られるように、キニックスと直接的なつながりがあっ た。 [74]エマニュエル・カレッジの学者レイフ・E・ヴァーゲは、Q文書とキニク書簡のようなキニク派のテキストとの共通点を比較している[75]。 2世紀、ユスティン殉教者は、異教の神々を拒絶し、神殿、彫像、生贄を持たないキリスト教徒を無神論者であると主張したと記録されているキニコス派のクレ スケンスと衝突した。これはキリスト教徒に対する一般的な批判であり、4世紀まで続いた[87]。 |

| Anticonformism Asceticism Cynic epistles Encratites Foolishness for Christ List of ancient Greek philosophers List of Cynic philosophers Natural law Stoicism Kotzker Rebbe (a chasidic "Cynic" in the ancient sense of the word) |

反体制主義 禁欲主義 キニク書簡 エンクラタイト キリストのための愚行 古代ギリシャの哲学者のリスト キニスの哲学者リスト 自然法 禁欲主義 コツカー・リベ(古代の意味でのチャシディックな「キニク主義者) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cynicism_(philosophy) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

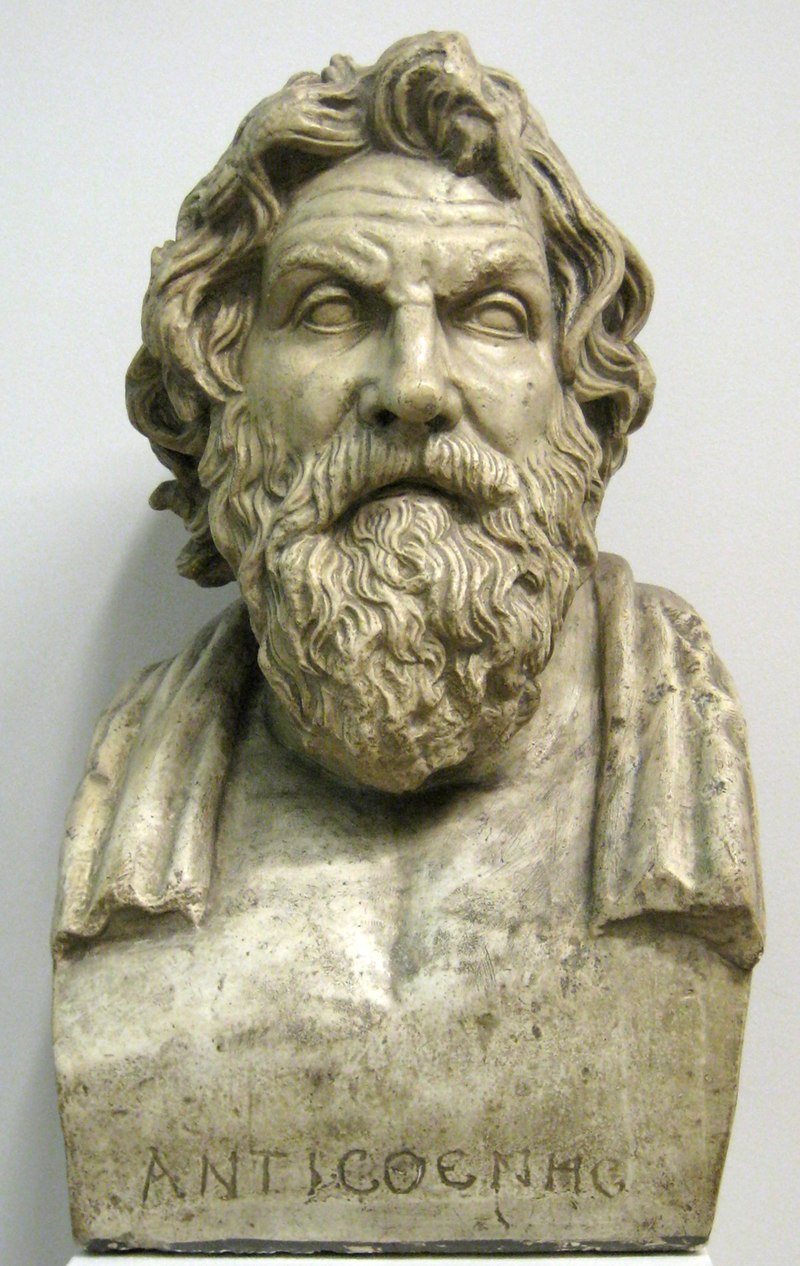

Statue

of an unknown Cynic philosopher from the Capitoline Museums in Rome.

This statue is a Roman-era copy of an earlier Greek statue from the

third century BC.[1] The scroll in his right hand is an 18th-century

restoration.

☆

☆

☆