ダダ・ダダイズム

Dada or Dadaism

★ダダまたはダダイズムは、20世紀初頭のヨーロッパの前衛芸術運動であり、初期の中心はス イスのチューリッヒ、キャバレーヴォルテール (1916年)であった。ニューヨークのダダは1915年頃に始まり[2][3]、1920年以降はパリで盛んになった。ダダの活動は1920年代半ばま で続いた。

| Dada

(/ˈdɑːdɑː/) or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde

in the early 20th century, with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland,

at the Cabaret Voltaire (in 1916). New York Dada began c. 1915,[2][3]

and after 1920 Dada flourished in Paris. Dadaist activities lasted

until the mid 1920s. Developed in reaction to World War I, the Dada movement consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works.[4][5][6] The art of the movement spanned visual, literary, and sound media, including collage, sound poetry, cut-up writing, and sculpture. Dadaist artists expressed their discontent toward violence, war, and nationalism, and maintained political affinities with radical left-wing and far-left politics.[7][8][9][10] There is no consensus on the origin of the movement's name; a common story is that the German artist Richard Huelsenbeck slid a paper knife (letter-opener) at random into a dictionary, where it landed on "dada", a colloquial French term for a hobby horse. Jean Arp wrote that Tristan Tzara invented the word at 6 p.m. on 6 February 1916, in the Café de la Terrasse in Zürich.[11] Others note that it suggests the first words of a child, evoking a childishness and absurdity that appealed to the group. Still others speculate that the word might have been chosen to evoke a similar meaning (or no meaning at all) in any language, reflecting the movement's internationalism.[12] The roots of Dada lie in pre-war avant-garde. The term anti-art, a precursor to Dada, was coined by Marcel Duchamp around 1913 to characterize works that challenge accepted definitions of art.[13] Cubism and the development of collage and abstract art would inform the movement's detachment from the constraints of reality and convention. The work of French poets, Italian Futurists and the German Expressionists would influence Dada's rejection of the tight correlation between words and meaning.[14] Works such as Ubu Roi (1896) by Alfred Jarry and the ballet Parade (1916–17) by Erik Satie would also be characterized as proto-Dadaist works.[15] The Dada movement's principles were first collected in Hugo Ball's Dada Manifesto in 1916. The Dadaist movement included public gatherings, demonstrations, and publication of art/literary journals; passionate coverage of art, politics, and culture were topics often discussed in a variety of media. Key figures in the movement included Jean Arp, Johannes Baader, Hugo Ball, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield, Emmy Hennings, Hannah Höch, Richard Huelsenbeck, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Hans Richter, Kurt Schwitters, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Tristan Tzara, and Beatrice Wood, among others. The movement influenced later styles like the avant-garde and downtown music movements, and groups including Surrealism, nouveau réalisme, pop art and Fluxus.[16] |

ダ

ダ(/ˈdɑ)またはダダイズムは、20世紀初頭のヨーロッパの前衛芸術運動であり、初期の中心はスイスのチューリッヒ、キャバレーヴォルテール

(1916年)であった。ニューヨークのダダは1915年頃に始まり[2][3]、1920年以降はパリで盛んになった。ダダの活動は1920年代半ばま

で続いた。 第一次世界大戦の反動から、現代資本主義社会の論理、理性、美学を否定し、ナンセンス、不合理、反ブルジョア的な抗議を作品に表現した芸術家たちからなる [4][5][6] ダダの芸術活動は、コラージュ、音詩、切り文字、彫刻など視覚、文学、音響メディアにわたっている。ダダイストの芸術家は暴力、戦争、ナショナリズムに対 する不満を表明し、急進的な左翼や極左の政治と政治的な親和性を維持した[7][8][9][10]。 この運動の名前の起源についてはコンセンサスが得られていない。よくある話は、ドイツのアーティストであるリチャード・ヒュルゼンベックがペーパーナイフ (レターオープナー)をランダムに辞書にスライドさせ、それが趣味の馬の口語的フランス語である「ダダ」に着地したというものである。ジャン・アルプは、 トリスタン・ツァラが1916年2月6日の午後6時にチューリッヒのカフェ・デ・ラ・テラスでこの言葉を発明したと書いている[11]。また、この言葉が 子供の最初の言葉を示唆しており、グループにとって魅力的だった子供っぽさと不条理を連想させると指摘する者もいる。さらに他の人々は、この言葉は運動の 国際性を反映して、どの言語でも似たような意味(または全く意味なし)を喚起するために選ばれたかもしれないと推測している[12]。 ダダのルーツは戦前のアヴァンギャルドにある。ダダの前身である反芸術という言葉は、1913年頃にマルセル・デュシャンによって、受け入れられている芸 術の定義に挑戦する作品を特徴づけるために作られた[13]。フランスの詩人、イタリアの未来派、ドイツの表現主義の作品は、言葉と意味の間の緊密な相関 関係のダダの拒絶に影響を与えた[14]。アルフレッド・ジャリーの『ユビュ・ロワ』(1896)やエリック・サティのバレー『パレード』(1916- 17)などの作品は、ダダの原型作品として特徴付けられる[15]。 ダダイズム運動は、公共の集会、デモ、芸術/文学雑誌の出版を含み、芸術、政治、文化に対する情熱的な報道は、様々なメディアでしばしば議論されるトピッ クであった。ジャン・アルプ、ヨハネス・バーダー、ヒューゴ・ボール、マルセル・デュシャン、マックス・エルンスト、エルザ・フォン・フライターク=ロー リングホーベン、ジョージ・グロッシュ、ラウル・ハウスマン、ジョン・ハートフィールド、エミー・ヘニング、ハンナ・ヘッホ、リチャード・ヒュンゼルベッ ク、フランシス・ピカビア、マン・レイ、ハンス・リヒター、クルト・シュビッター、ソフィ・テーバー・アルプ、トリスタン・ツァラ、ビアトリース・ウッド など、さまざまな人物がこの運動の主要人物である。この運動は、アヴァンギャルドやダウンタウン音楽運動といった後のスタイルや、シュルレアリスム、ヌー ヴォー・レアリスム、ポップアート、フルクサスなどのグループに影響を与えた[16]。 |

| Dada

was an informal international movement, with participants in Europe and

North America. The beginnings of Dada correspond with the outbreak of

World War I. For many participants, the movement was a protest against

the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests, which many

Dadaists believed were the root cause of the war, and against the

cultural and intellectual conformity—in art and more broadly in

society—that corresponded to the war.[17] Avant-garde circles outside France knew of pre-war Parisian developments. They had seen (or participated in) Cubist exhibitions held at Galeries Dalmau, Barcelona (1912), Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin (1912), the Armory Show in New York (1913), SVU Mánes in Prague (1914), several Jack of Diamonds exhibitions in Moscow and at Moderne Kunstkring, Amsterdam (between 1911 and 1915). Futurism developed in response to the work of various artists. Dada subsequently combined these approaches.[14][18] Many Dadaists believed that the 'reason' and 'logic' of bourgeois capitalist society had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in artistic expression that appeared to reject logic and embrace chaos and irrationality.[5][6] For example, George Grosz later recalled that his Dadaist art was intended as a protest "against this world of mutual destruction".[5] According to Hans Richter Dada was not art: it was "anti-art".[17] Dada represented the opposite of everything which art stood for. Where art was concerned with traditional aesthetics, Dada ignored aesthetics. If art was to appeal to sensibilities, Dada was intended to offend. Additionally, Dada attempted to reflect onto human perception and the chaotic nature of society. Tristan Tzara proclaimed, "Everything is Dada, too. Beware of Dada. Anti-dadaism is a disease: selfkleptomania, man's normal condition, is Dada. But the real Dadas are against Dada".[19] As Hugo Ball expressed it, "For us, art is not an end in itself ... but it is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in."[20] A reviewer from the American Art News stated at the time that "Dada philosophy is the sickest, most paralyzing and most destructive thing that has ever originated from the brain of man." Art historians have described Dada as being, in large part, a "reaction to what many of these artists saw as nothing more than an insane spectacle of collective homicide".[21] Years later, Dada artists described the movement as "a phenomenon bursting forth in the midst of the postwar economic and moral crisis, a savior, a monster, which would lay waste to everything in its path... [It was] a systematic work of destruction and demoralization... In the end it became nothing but an act of sacrilege."[21] To quote Dona Budd's The Language of Art Knowledge, Dada was born out of negative reaction to the horrors of the First World War. This international movement was begun by a group of artists and poets associated with the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich. Dada rejected reason and logic, prizing nonsense, irrationality and intuition. The origin of the name Dada is unclear; some believe that it is a nonsensical word. Others maintain that it originates from the Romanian artists Tristan Tzara's and Marcel Janco's frequent use of the words "da, da," meaning "yes, yes" in the Romanian language. Another theory says that the name "Dada" came during a meeting of the group when a paper knife stuck into a French–German dictionary happened to point to 'dada', a French word for 'hobbyhorse'.[6] The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature, poetry, art manifestos, art theory, theatre, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti-war politics through a rejection of the prevailing standards in art through anti-art cultural works. The creations of Duchamp, Picabia, Man Ray, and others between 1915 and 1917 eluded the term Dada at the time, and "New York Dada" came to be seen as a post facto invention of Duchamp. At the outset of the 1920s the term Dada flourished in Europe with the help of Duchamp and Picabia, who had both returned from New York. Notwithstanding, Dadaists such as Tzara and Richter claimed European precedence. Art historian David Hopkins notes: Ironically, though, Duchamp's late activities in New York, along with the machinations of Picabia, re-cast Dada's history. Dada's European chroniclers—primarily Richter, Tzara, and Huelsenbeck—would eventually become preoccupied with establishing the pre-eminence of Zurich and Berlin at the foundations of Dada, but it proved to be Duchamp who was most strategically brilliant in manipulating the genealogy of this avant-garde formation, deftly turning New York Dada from a late-comer into an originating force.[22] |

ダ

ダは、ヨーロッパと北米の参加者による非公式な国際運動であった。ダダの始まりは第一次世界大戦の勃発に対応している。多くの参加者にとって、この運動

は、多くのダダイストが戦争の根本原因であると信じていたブルジョアの民族主義と植民地主義の利益に対する抗議であり、戦争に対応した芸術とより広い社会

における文化と知的適合に対する抗議であった[17]。 フランス国外のアヴァンギャルド界は戦前のパリの動向を知っていた。彼らはバルセロナのダルマウ画廊(1912)、ベルリンのシュトゥルム画廊 (1912)、ニューヨークのアーモリーショー(1913)、プラハのSVUマーネス(1914)、モスクワのダイヤモンドのジャック展、アムステルダム の近代美術館(1911-1915)で開かれたキュビスムの展覧会を見た(あるいは参加した)のであった。未来派は、さまざまな芸術家の作品に呼応して発 展した。その後、ダダはこれらのアプローチを組み合わせた[14][18]。 多くのダダイストは、ブルジョア資本主義社会の「理性」と「論理」が人々を戦争に導いたと信じていた。彼らは論理を拒絶し、カオスや非合理性を受け入れる ように見える芸術表現でそのイデオロギーの拒絶を表現した[5][6]。 例えば、ジョージ・グロッシュは後に彼のダダイストの芸術が「この相互破壊の世界に対する」抗議として意図されていたと回想している[5]。 ハンス・リヒターによれば、ダダは芸術ではなく、「反芸術」であった[17]。ダダは芸術が象徴するすべてのものの反対を代表することができたのである。 芸術が伝統的な美学に関係していたのに対して、ダダは美学を無視した。芸術が感性に訴えかけるものであるならば、ダダは不快にさせることを意図していた。 さらに、ダダは人間の認識や社会の無秩序な本質を反映しようとした。トリスタン・ツァラは「すべてもダダである」と宣言した。ダダには気をつけろ。反ダダ イズムは病気だ。自己陶酔、人間の正常な状態、それがダダなのだ。しかし、本当のダダはダダに反対している」[19]。 ヒューゴ・ボールが表現したように、「私たちにとって芸術はそれ自体が目的ではなく、...私たちが生きている時代の真の認識と批判のための機会である」 [20]。 アメリカン・アート・ニュースの批評家は当時、"ダダの哲学は人間の脳から生まれた最も病的で、最も麻痺させ、最も破壊的なものだ "と述べている[20]。美術史家はダダを、大部分は「これらの芸術家の多くが集団的殺人の狂気の光景に過ぎないと見ていたものへの反応」であると説明し ている[21]。 数年後、ダダのアーティストたちはこの運動を「戦後の経済的・道徳的危機の中で炸裂した現象、救世主、怪物、それはその行く手にあるすべてのものを蹂躙す るだろう...」と表現していた。[それは破壊と戦意喪失の組織的な仕事だった......。結局、それは冒涜的行為以外の何ものでもなかった」 [21]。 ドナ・バッドの『芸術の知識の言語』を引用する。 ダダは、第一次世界大戦の惨禍に対する否定的な反応から生まれた。この国際的な運動は、チューリッヒのキャバレー・ボルテールに関連する芸術家と詩人のグ ループによって始められた。ダダは理性や論理を否定し、ナンセンスや非合理性、直感を重んじた。ダダという名前の由来は不明で、無意味な言葉という説もあ る。また、ルーマニアの芸術家トリスタン・ツァラとマルセル・ヤンコが、ルーマニア語で「イエス、イエス」を意味する「ダ、ダ」という言葉を頻繁に使った ことに由来するとする説もある。また、「ダダ」という名称は、グループの会合の際に、仏独辞典に刺さったペーパーナイフがたまたま「ダダ」(フランス語で 「趣味の馬」の意)を指していたことに由来するという説もある[6]。 この運動は主に視覚芸術、文学、詩、芸術宣言、芸術理論、演劇、グラフィックデザインに関わり、反芸術文化作品を通じて芸術における一般的な基準を拒否す ることによって反戦政治を集中させた。 1915年から1917年にかけてのデュシャン、ピカビア、マン・レイらの創作は、当時のダダの呼称からは外れており、「ニューヨーク・ダダ」はデュシャ ンの事後的な発明と見なされるようになる。1920年代初頭、ダダという言葉は、ニューヨークから帰国したデュシャンとピカビアによって、ヨーロッパで盛 んになった。しかし、ツァラやリヒターといったダダイストたちは、ヨーロッパで先行することを主張している。美術史家のデイヴィッド・ホプキンスはこう指 摘する。 しかし皮肉なことに、デュシャンのニューヨークでの後期の活動は、ピカビアの策略とともに、ダダの歴史を塗り替えた。ダダのヨーロッパの記録者たち、主に リヒター、ツァラ、ヒュールセンベックは、やがてダダの基礎となったチューリッヒとベルリンの優位性を確立することに夢中になったが、この前衛の形成の系 譜を操る上で最も戦略的に優れていたのはデュシャンであることが証明され、ニューヨーク・ダダを後発から発進へと巧みに変えている[22]」。 |

| History Dada emerged from a period of artistic and literary movements like Futurism, Cubism and Expressionism; centered mainly in Italy, France and Germany respectively, in those years. However, unlike the earlier movements Dada was able to establish a broad base of support, giving rise to a movement that was international in scope. Its adherents were based in cities all over the world including New York, Zürich, Berlin, Paris and others. There were regional differences like an emphasis on literature in Zürich and political protest in Berlin.[23] Prominent Dadaists published manifestos, but the movement was loosely organized and there was no central hierarchy. On 14 July 1916, Ball originated the seminal Dada Manifesto. Tzara wrote a second Dada manifesto,[24][25] considered important Dada reading, which was published in 1918.[26] Tzara's manifesto articulated the concept of "Dadaist disgust"—the contradiction implicit in avant-garde works between the criticism and affirmation of modernist reality. In the Dadaist perspective modern art and culture are considered a type of fetishization where the objects of consumption (including organized systems of thought like philosophy and morality) are chosen, much like a preference for cake or cherries, to fill a void.[27] The shock and scandal the movement inflamed was deliberate; Dadist magazines were banned and their exhibits closed. Some of the artists even faced imprisonment. These provocations were part of the entertainment but, over time, audiences' expectations eventually outpaced the movement's capacity to deliver. As the artists' well-known "sarcastic laugh" started to come from the audience, the provocations of Dadaists began to lose their impact. Dada was an active movement during years of political turmoil from 1916 when European countries were actively engaged in World War I, the conclusion of which, in 1918, set the stage for a new political order.[28] |

歴史 ダダは、未来派、キュビズム、表現主義など、イタリア、フランス、ドイツを中心とした芸術・文学運動の中で生まれました。しかし、これらの運動とは異な り、ダダは幅広い支持層を獲得し、国際的な運動となった。ニューヨーク、チューリッヒ、ベルリン、パリなど、世界各地の都市を拠点に活動していた。チュー リッヒでは文学に重点を置き、ベルリンでは政治的な抗議に重点を置くなど、地域的な違いもあった[23]。 著名なダダイストたちはマニフェストを発表したが、運動は緩やかに組織され、中央のヒエラルキーは存在しなかった。1916年7月14日、ボールはダダ宣 言の原型となるものを発表した。ツァラは「ダダイ主義的嫌悪感」-前衛的な作品における近代主義的現実の批判と肯定との間の暗黙の矛盾-の概念を明示した [26]。ダダイストの観点では、現代の芸術と文化は、ケーキやサクランボを好むように、消費の対象(哲学や道徳のような組織的な思考体系を含む)が空白 を埋めるために選ばれる一種のフェティッシュ化であると考えられている[27]。 この運動が引き起こした衝撃とスキャンダルは意図的なものであり、ダディストの雑誌は禁止され、展示は閉鎖された。何人かのアーティストは投獄の危機に直 面した。これらの挑発はエンターテインメントの一部であったが、時が経つにつれ、観客の期待は結局運動の提供能力を超えてしまった。芸術家たちのよく知ら れた「皮肉な笑い」が観客から出るようになると、ダダイストの挑発はそのインパクトを失い始めたのです。ダダは、ヨーロッパ諸国が第一次世界大戦に活発に 関与していた1916年からの政治的混乱の時代に活発な運動であり、1918年にその終結によって新しい政治秩序のための舞台が設定された[28]。 |

| Zürich There is some disagreement about where Dada originated. The movement is commonly accepted by most art historians and those who lived during this period to have identified with the Cabaret Voltaire (housed inside the Holländische Meierei bar in Zürich) co-founded by poet and cabaret singer Emmy Hennings and Hugo Ball.[29] Some sources propose a Romanian origin, arguing that Dada was an offshoot of a vibrant artistic tradition that transposed to Switzerland when a group of Jewish modernist artists, including Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, and Arthur Segal settled in Zürich. Before World War I, similar art had already existed in Bucharest and other Eastern European cities; it is likely that Dada's catalyst was the arrival in Zürich of artists like Tzara and Janco.[30] The name Cabaret Voltaire was a reference to the French philosopher Voltaire, whose novel Candide mocked the religious and philosophical dogmas of the day. Opening night was attended by Ball, Tzara, Jean Arp, and Janco. These artists along with others like Sophie Taeuber, Richard Huelsenbeck and Hans Richter started putting on performances at the Cabaret Voltaire and using art to express their disgust with the war and the interests that inspired it. Having left Germany and Romania during World War I, the artists arrived in politically neutral Switzerland. They used abstraction to fight against the social, political, and cultural ideas of that time. They used shock art, provocation, and "vaudevilleian excess" to subvert the conventions they believed had caused the Great War.[31] The Dadaists believed those ideas to be a byproduct of bourgeois society that was so apathetic it would wage war against itself rather than challenge the status quo:[32] We had lost confidence in our culture. Everything had to be demolished. We would begin again after the tabula rasa. At the Cabaret Voltaire we began by shocking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order." — Marcel Janco[33] Ball said that Janco's mask and costume designs, inspired by Romanian folk art, made "the horror of our time, the paralyzing background of events" visible.[31] According to Ball, performances were accompanied by a "balalaika orchestra playing delightful folk-songs". Influenced by African music, arrhythmic drumming and jazz were common at Dada gatherings.[34][35] After the cabaret closed down, Dada activities moved on to a new gallery, and Hugo Ball left for Bern. Tzara began a relentless campaign to spread Dada ideas. He bombarded French and Italian artists and writers with letters, and soon emerged as the Dada leader and master strategist. The Cabaret Voltaire re-opened, and is still in the same place at the Spiegelgasse 1 in the Niederdorf. Zürich Dada, with Tzara at the helm, published the art and literature review Dada beginning in July 1917, with five editions from Zürich and the final two from Paris. Other artists, such as André Breton and Philippe Soupault, created "literature groups to help extend the influence of Dada".[36] After the fighting of the First World War had ended in the armistice of November 1918, most of the Zürich Dadaists returned to their home countries, and some began Dada activities in other cities. Others, such as the Swiss native Sophie Taeuber, would remain in Zürich into the 1920s. |

チューリッヒ ダダがどこで生まれたかについては意見が分かれるところである。多くの美術史家やこの時代に生きた人々は、詩人でキャバレー歌手のエミー・ヘニングスと フーゴ・ボールが共同で設立したキャバレー・ヴォルテール(チューリッヒのバー「ホレンディッシェ・マイエーレ」内にある)を起源とする運動と受け止めて いる[29]。ルーマニア起源とする資料もあり、ダダは、ユダヤ系近代主義芸術家のトリスタン・ツァラやマルセル・ジャンコ、アーサー・セガールがチュー リッヒに移住し、活発な芸術伝統からスイスに転化したと主張する。第一次世界大戦前、ブカレストや他の東欧の都市でも同様の芸術が既に存在していた。ダダ のきっかけは、ツァラやヤンコのような芸術家がチューリッヒに到着したことだったと思われる[30]。 キャバレー・ボルテールという名前はフランスの哲学者であるヴォルテールにちなんでおり、彼の小説『キャンディード』は当時の宗教的、哲学的な教義を嘲っ ていた。オープニング・ナイトには、ボール、ツァラ、ジャン・アルプ、ジャンコが参加した。これらのアーティストやソフィー・タウバー、リヒャルト・ヒュ ルゼンベック、ハンス・リヒターらは、キャバレー・ボルテールでパフォーマンスを行い、戦争とそれに影響を与えた利益に対する嫌悪感を芸術で表現し始め る。第一次世界大戦中にドイツとルーマニアを離れた芸術家たちは、政治的に中立なスイスに到着した。彼らは、当時の社会的、政治的、文化的な考え方に対抗 するために、抽象的な表現を用いました。彼らはショックアート、挑発、そして「ボードヴィルの過剰」を用いて、第一次世界大戦を引き起こしたと信じる慣習 を覆した[31]。ダダイストはそれらの思想が、現状に挑戦するよりもむしろそれ自身に対して戦争を行うほど無気力であるブルジョア社会の副産物であると 信じていた[32]。 私たちは自分たちの文化に対する自信を失っていた。すべては解体されなければならなかった。私たちはタブラ・ラサの後に再び始めることになるのだ。キャバ レー・ヴォルテールでは,常識,世論,教育,制度,美術館,趣味,要するに,一般的な秩序全体に衝撃を与えることから始めたのだ」。 - マルセル・ヤンコ[33]。 ボールは、ルーマニアの民芸品に触発されたヤンコのマスクと衣装のデザインは「我々の時代の恐怖、出来事の麻痺した背景」を可視化したと述べている [31]。 ボールによれば、パフォーマンスは「楽しい民謡を演奏するバラライカ・オーケストラ」と共に行われた。アフリカ音楽の影響を受け、ダダの集会では、不整脈 の太鼓やジャズがよく使われた[34][35]。 キャバレーが閉鎖された後、ダダの活動は新しいギャラリーに移り、フーゴ・ボールはベルンに向かった。ツァラはダダの思想を広めるために執拗なキャンペー ンを始めた。彼はフランスやイタリアの芸術家や作家たちに手紙を送り続け、やがてダダの指導者、名参謀として頭角を現していく。キャバレー「ヴォルテー ル」が再開され、現在もニーデルドルフのシュピーゲルガッセ1番地の同じ場所にある。 ツァラを中心とするチューリッヒ・ダダは、1917年7月から『芸術と文学の批評 ダダ』を発行し、チューリッヒから5版、パリから最終2版を刊行した。 アンドレ・ブルトンやフィリップ・スポーのような他の芸術家は、「ダダの影響力を拡大するための文学グループ」を作った[36]。 第一次世界大戦の戦闘が1918年11月の休戦で終わると、チューリッヒのダダイストのほとんどは母国に戻り、何人かは他の都市でダダの活動を始める。ま た、スイス出身のソフィー・タウバーのように、1920年代までチューリッヒに留まる者もいた[36]。 |

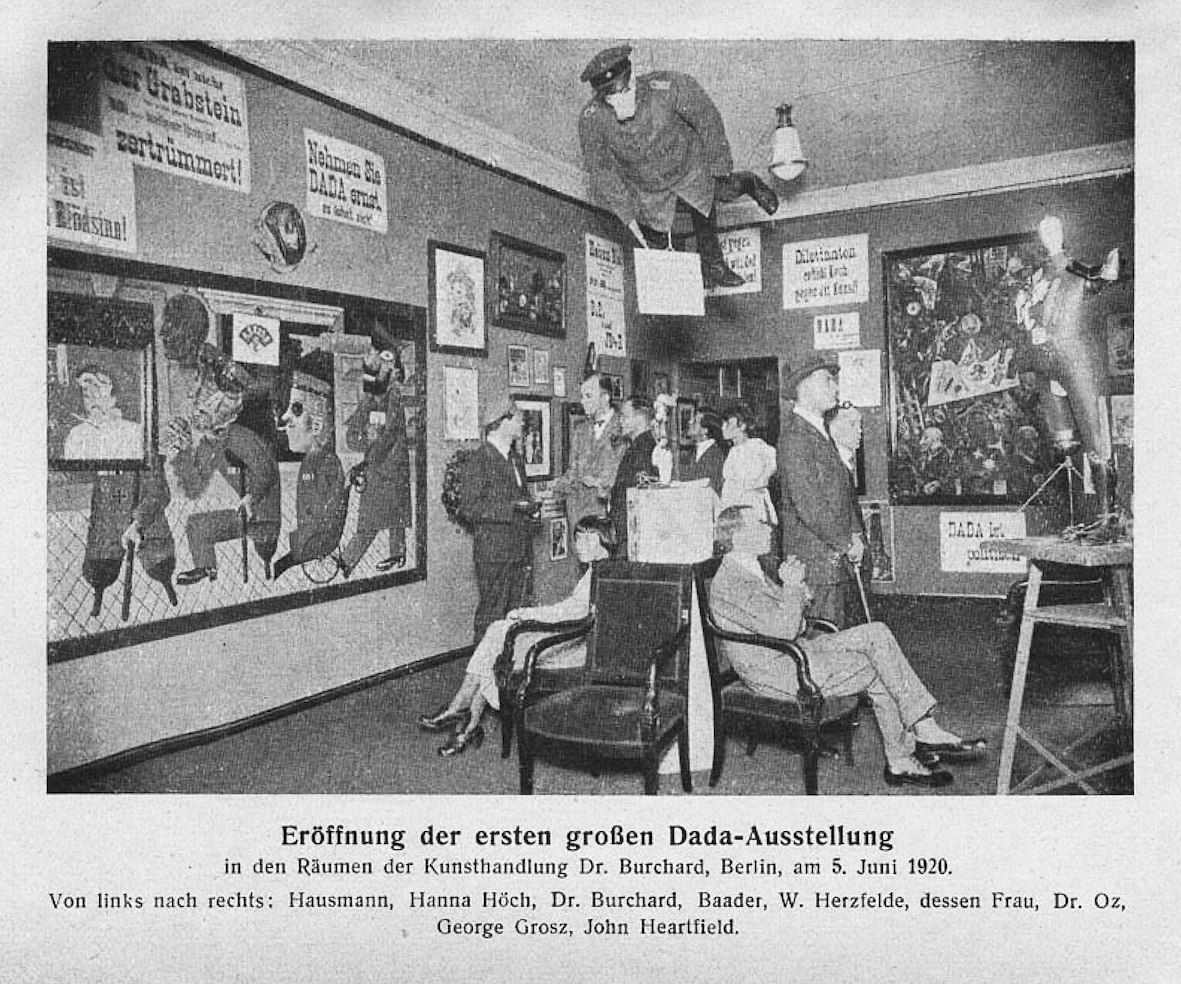

Grand opening of the

first Dada exhibition: International Dada Fair, Berlin, 5 June 1920.

The central figure hanging from the ceiling was an effigy of a German

officer with a pig's head. From left to right: Raoul Hausmann, Hannah

Höch (sitting), Otto Burchard, Johannes Baader, Wieland Herzfelde,

Margarete Herzfelde, Dr. Oz (Otto Schmalhausen), George Grosz and John

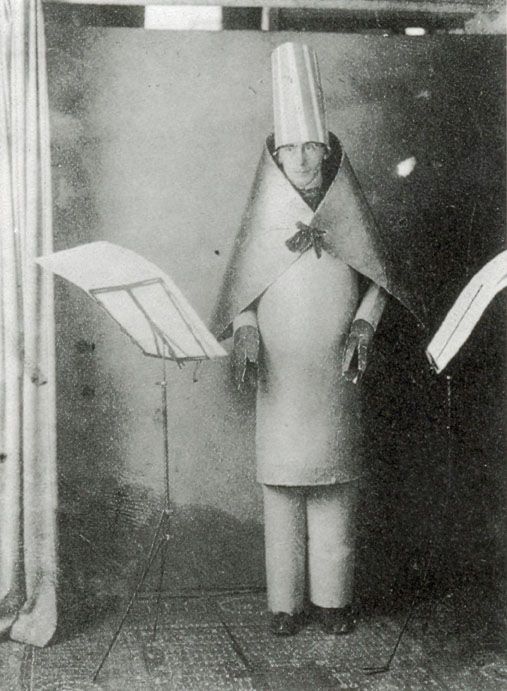

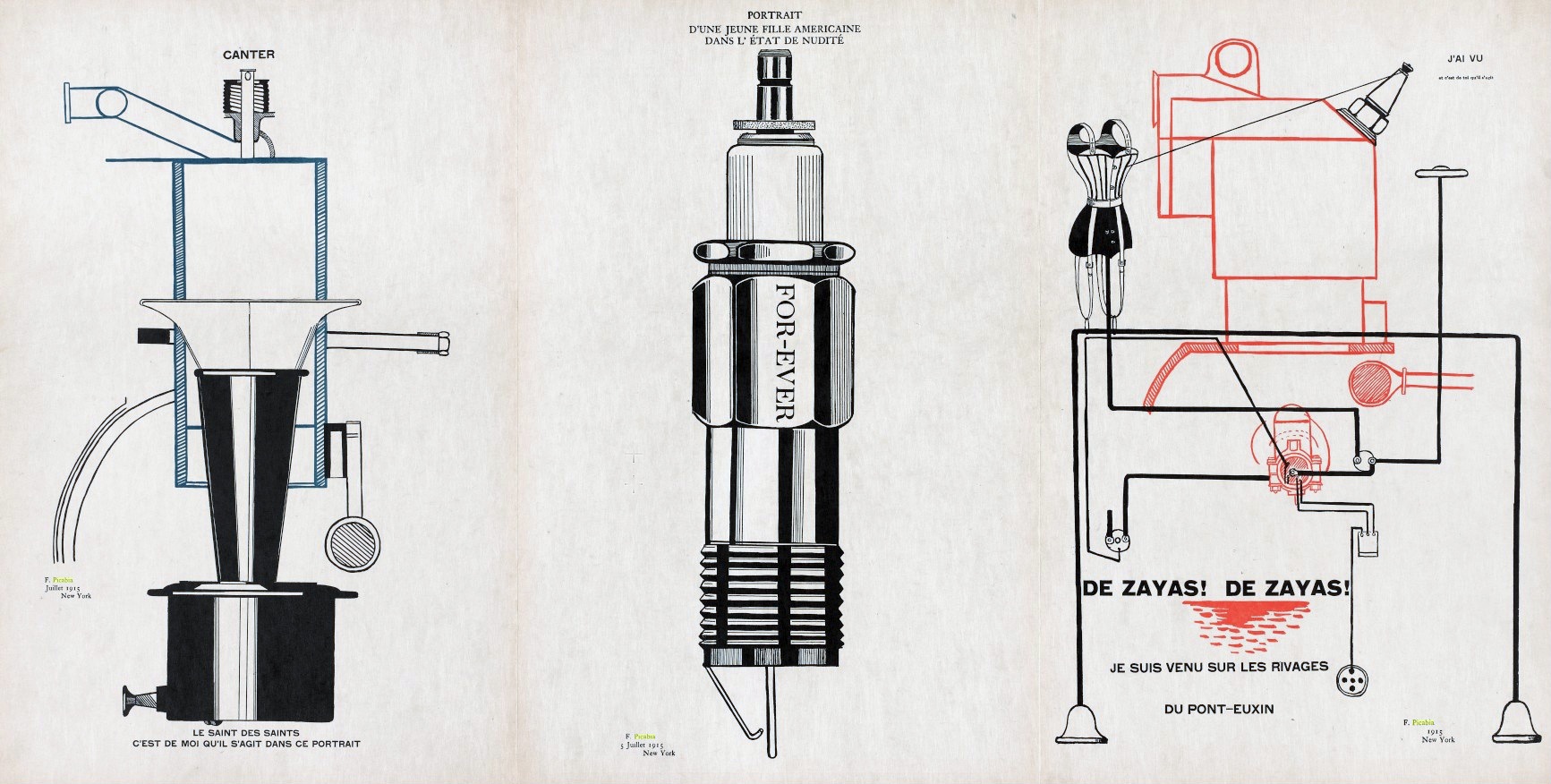

Heartfield.[1]/ キャバレー・ヴォルテールでキュビスム風の格好をしたフーゴ・バル(1916年)/ Francis

Picabia: left, Le saint des saints c'est de moi qu'il s'agit dans ce

portrait, 1 July 1915; center, Portrait d'une jeune fille americaine

dans l'état de nudité, 5 July 1915; right, J'ai vu et c'est de toi

qu'il s'agit, De Zayas! De Zayas! Je suis venu sur les rivages du

Pont-Euxin, New York, 1915./ Dada artists, group photograph, 1920,

Paris. From left to right, Back row: Louis Aragon, Theodore Fraenkel,

Paul Eluard, Clément Pansaers, Emmanuel Fay (cut off). Second row: Paul

Dermée, Philippe Soupault, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes. Front row:

Tristan Tzara (with monocle), Celine Arnauld, Francis Picabia, André

Breton.

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆