ダーウィニズム

Darwinism

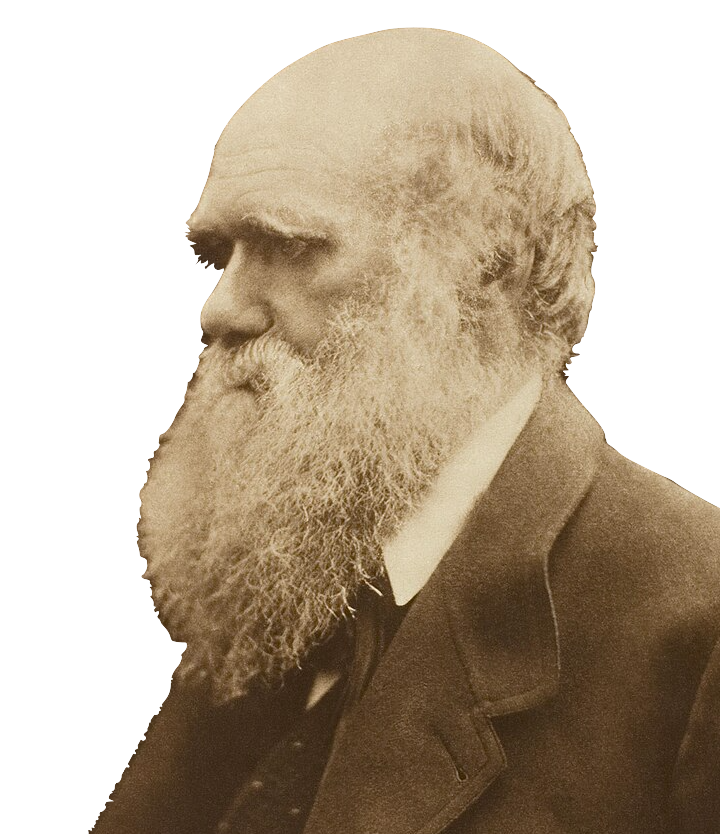

1871年のチャールズ・ダーウィン

☆ ダーウィニズム(Darwinism) とは、イギリスの博物学者チャールズ・ダーウィン(Charles Darwin, 1809-1882)らによって提唱された生物進化論であり、すべての生物種は、個体の競争力、生存力、繁殖力を高める小さな遺伝的変異の自然淘汰によっ て発生し、発展するとする。ダーウィン理論とも呼ばれ、もともとは、ダーウィンが1859年に『種の起源』を発表した後に一般的な科学的受容を得た、種の 転変や進化の広範な概念を含むもので、ダーウィンの理論以前の概念も含まれる。イギリスの生物学者トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーは1860年4月にダー ウィニズムという言葉を作った。ダーウィニズム(Darwinism)は、単純にダーウィン主義、とかダーウィン論とも翻訳できるが、現代の日本語では、ダーウィニズムは「ダーウィン理論(Darwinian theory; Theory of Charles Darwin)」という意味で使われる。

| Darwinism

is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist

Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of

organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small,

inherited variations that increase the individual's ability to compete,

survive, and reproduce. Also called Darwinian theory, it originally

included the broad concepts of transmutation of species or of evolution

which gained general scientific acceptance after Darwin published On

the Origin of Species in 1859, including concepts which predated

Darwin's theories. English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley coined the

term Darwinism in April 1860.[1] |

ダー

ウィニズム(Darwinism)とは、イギリスの博物学者チャールズ・ダーウィン(Charles Darwin,

1809-1882)らによって提唱された生物進化論であり、すべての生物種は、個体の競争力、生存力、繁殖力を高める小さな遺伝的変異の自然淘汰によっ

て発生し、発展するとする。ダーウィン理論とも呼ばれ、もともとは、ダーウィンが1859年に『種の起源』を発表した後に一般的な科学的受容を得た、種の

転変や進化の広範な概念を含むもので、ダーウィンの理論以前の概念も含まれる。イギリスの生物学者トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーは1860年4月にダー

ウィニズムという言葉を作った[1]。 |

| Terminology Darwinism subsequently referred to the specific concepts of natural selection, the Weismann barrier, or the central dogma of molecular biology.[2] Though the term usually refers strictly to biological evolution, creationists have appropriated it to refer to the origin of life or to cosmic evolution, that are distinct to biological evolution.[3] It is therefore considered the belief and acceptance of Darwin's and of his predecessors' work, in place of other concepts, including divine design and extraterrestrial origins.[4][5] English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley coined the term Darwinism in April 1860.[6] It was used to describe evolutionary concepts in general, including earlier concepts published by English philosopher Herbert Spencer. Many of the proponents of Darwinism at that time, including Huxley, had reservations about the significance of natural selection, and Darwin himself gave credence to what was later called Lamarckism. The strict neo-Darwinism of German evolutionary biologist August Weismann gained few supporters in the late 19th century. During the approximate period of the 1880s to about 1920, sometimes called "the eclipse of Darwinism", scientists proposed various alternative evolutionary mechanisms which eventually proved untenable. The development of the modern synthesis in the early 20th century, incorporating natural selection with population genetics and Mendelian genetics, revived Darwinism in an updated form.[7] While the term Darwinism has remained in use amongst the public when referring to modern evolutionary theory, it has increasingly been argued by science writers such as Olivia Judson, Eugenie Scott, and Carl Safina that it is an inappropriate term for modern evolutionary theory.[8][9][10] For example, Darwin was unfamiliar with the work of the Moravian scientist and Augustinian friar Gregor Mendel,[11] and as a result had only a vague and inaccurate understanding of heredity. He naturally had no inkling of later theoretical developments and, like Mendel himself, knew nothing of genetic drift, for example.[12][13] In the United States, creationists often use the term "Darwinism" as a pejorative term in reference to beliefs such as scientific materialism. This is now also the case even in the United Kingdom.[8] |

用語解説 ダーウィニズムはその後、自然淘汰、ワイスマンの壁、または分子生物学のセントラル・ドグマの特定の概念を指すようになった[2]。通常、この用語は厳密 に生物学的進化を指すが、創造論者は生物学的進化とは異なる生命の起源や宇宙進化を指すためにこの用語を使用している[3]。 イギリスの生物学者トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーは、1860年4月にダーウィニズムという言葉を作り出した[6]。この言葉は、イギリスの哲学者ハー バート・スペンサーによって発表された以前の概念も含め、進化論的概念全般を表すのに使われた。ハクスリーを含む当時のダーウィニズム支持者の多くは、自 然淘汰の意義に疑問を持っており、ダーウィン自身は後にラマルク主義と呼ばれるものを信奉していた。ドイツの進化生物学者アウグスト・ヴァイスマンの厳格 な新ダーウィニズムは、19世紀後半にはほとんど支持者を得なかった。ダーウィニズムの蝕み」とも呼ばれる1880年代から1920年頃までの間、科学者 たちは様々な代替進化メカニズムを提案したが、結局は支持されなかった。20世紀初頭に自然淘汰を集団遺伝学とメンデル遺伝学に取り入れた現代的統合が発 展し、ダーウィニズムが更新された形で復活した[7]。 例えば、ダーウィンはモラヴィア派の科学者でありアウグスティヌス派の修道士であったグレゴール・メンデル[11]の研究をよく知らず、その結果遺伝につ いて曖昧で不正確な理解しかしていなかった。当然のことながら、メンデルはその後の理論的発展について何も知らず、メンデル自身と同様に、例えば遺伝的ド リフトについては何も知らなかった[12][13]。 アメリカでは、創造論者が科学的唯物論のような信念を指して「ダーウィニズム」という言葉を蔑称として使うことが多い。これは現在、イギリスでも同様である[8]。 |

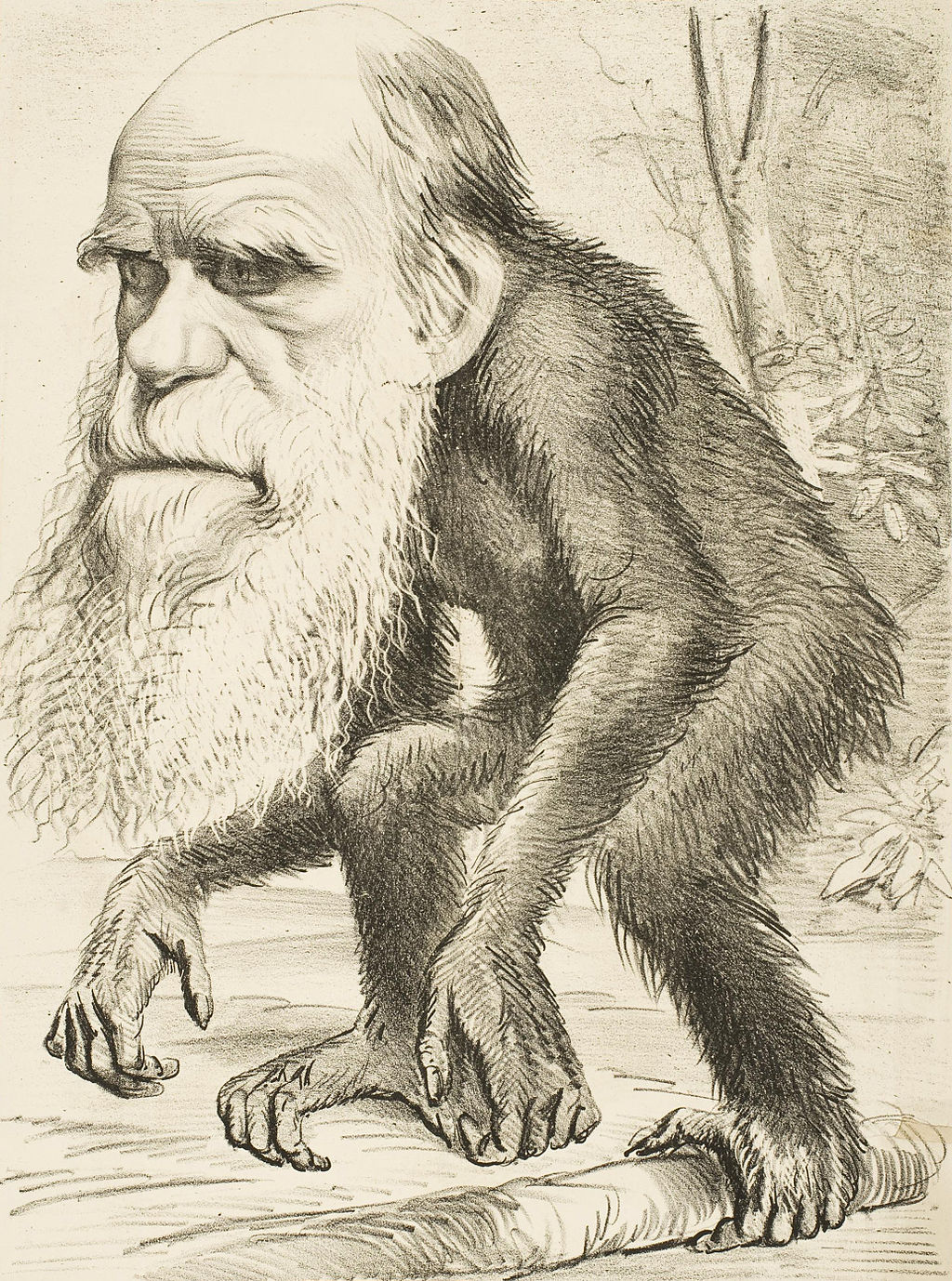

Huxley and Kropotkin As evolution became widely accepted in the 1870s, caricatures of Charles Darwin with the body of an ape or monkey symbolised evolution.[14] Huxley, upon first reading Darwin's theory in 1858, responded, "How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!"[15] While the term Darwinism had been used previously to refer to the work of Erasmus Darwin in the late 18th century, the term as understood today was introduced when Charles Darwin's 1859 book On the Origin of Species was reviewed by Thomas Henry Huxley in the April 1860 issue of the Westminster Review.[16] Having hailed the book as "a veritable Whitworth gun in the armoury of liberalism" promoting scientific naturalism over theology, and praising the usefulness of Darwin's ideas while expressing professional reservations about Darwin's gradualism and doubting if it could be proved that natural selection could form new species,[17] Huxley compared Darwin's achievement to that of Nicolaus Copernicus in explaining planetary motion: What if the orbit of Darwinism should be a little too circular? What if species should offer residual phenomena, here and there, not explicable by natural selection? Twenty years hence naturalists may be in a position to say whether this is, or is not, the case; but in either event they will owe the author of "The Origin of Species" an immense debt of gratitude.... And viewed as a whole, we do not believe that, since the publication of Von Baer's "Researches on Development," thirty years ago, any work has appeared calculated to exert so large an influence, not only on the future of Biology, but in extending the domination of Science over regions of thought into which she has, as yet, hardly penetrated.[6] These are the basic tenets of evolution by natural selection as defined by Darwin: More individuals are produced each generation than can survive. Phenotypic variation exists among individuals and the variation is heritable. Those individuals with heritable traits better suited to the environment will survive. When reproductive isolation occurs new species will form. Another important evolutionary theorist of the same period was the Russian geographer and prominent anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin who, in his book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902), advocated a conception of Darwinism counter to that of Huxley. His conception was centred around what he saw as the widespread use of co-operation as a survival mechanism in human societies and animals. He used biological and sociological arguments in an attempt to show that the main factor in facilitating evolution is cooperation between individuals in free-associated societies and groups. This was in order to counteract the conception of fierce competition as the core of evolution, which provided a rationalization for the dominant political, economic and social theories of the time; and the prevalent interpretations of Darwinism, such as those by Huxley, who is targeted as an opponent by Kropotkin. Kropotkin's conception of Darwinism could be summed up by the following quote: In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense—not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species. The animal species, in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits, and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development, are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.[18] — Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902), Conclusion |

ハクスリーとクロポトキン 1870年代に進化論が広く受け入れられるようになると、猿の体をしたチャールズ・ダーウィンの風刺画が進化論を象徴するようになった[14]。 ハクスリーは、1858年にダーウィンの理論を初めて読んだとき、「それを考えつかなかったとは、なんと愚かなことか!」と答えた[15]。 ダーウィニズムという用語は、18世紀後半のエラスマス・ダーウィンの仕事を指すために以前から使用されていたが、今日理解されている用語は、チャール ズ・ダーウィンの1859年の著書『種の起源』が、1860年4月号の『ウェストミンスター・レビュー』でトマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーによって書評され たときに導入された。 [神学よりも科学的自然主義を推進する「リベラリズムの武器庫における正真正銘のウィットワース銃」としてこの本を称賛し、ダーウィンのアイデアの有用性 を賞賛する一方で、ダーウィンの漸進主義に対する専門的な留保を表明し、自然淘汰によって新しい種が形成されることが証明されるかどうか疑っていたハクス リーは、ダーウィンの業績を、惑星の運動を説明したニコラウス・コペルニクスの業績になぞらえた[17]: ダーウィニズムの軌道が少し円形すぎるとしたらどうだろう。もしダーウィニズムの軌道が少し円形過ぎるとしたらどうだろう。もし種が自然淘汰では説明でき ないような現象をあちこちに残しているとしたらどうだろう。いずれにせよ、彼らは『種の起源』の著者に莫大な恩義を感じていることだろう......。そ して全体として見れば、30年前にフォン・ベールの『発生に関する研究』が出版されて以来、生物学の将来にこれほど大きな影響を及ぼすだけでなく、科学が まだほとんど入り込んでいない思想の領域にまで科学の支配を拡大するような著作が現れたとは考えられない[6]。 これらは、ダーウィンが定義した自然淘汰による進化の基本的な考え方である: 各世代で、生存できる個体よりも多くの個体が生まれる。 個体間には表現型の変異が存在し、その変異は遺伝可能である。 環境に適した遺伝形質を持つ個体が生き残る。 生殖隔離が起こると、新しい種が形成される。 同時代のもう一人の重要な進化論者は、ロシアの地理学者で著名な無政府主義者であったピョートル・クロポトキンである: 彼は著書『相互扶助:進化の要因』(1902年)の中で、ハクスリーとは逆のダーウィニズムの概念を提唱した。クロポトキンの概念は、人間社会と動物にお いて生存のメカニズムとして協力が広く用いられていることを中心に据えたものであった。彼は生物学的、社会学的な議論を用いて、進化を促進する主な要因 は、自由な社会と集団における個人間の協力であることを示そうとした。これは、当時支配的だった政治的、経済的、社会的理論に合理性を与えた進化の核心と しての熾烈な競争という概念や、クロポトキンが敵対視していたハクスリーのようなダーウィニズムの一般的な解釈に対抗するためであった。クロポトキンの ダーウィニズムに対する考え方は、次の引用に要約される: 動物の世界では、大多数の種が社会で生活しており、彼らは生命のための闘争のための最良の武器を団結の中に見出している。個体間の闘争が極限まで抑えら れ、相互扶助が最も発達した動物種は、常に最も数が多く、最も繁栄し、更なる進歩の可能性がある。この場合に得られる相互扶助、老齢に達して経験を蓄積す る可能性、より高い知的発達、社交的な習慣のさらなる成長は、種の維持、種の拡大、種のさらなる進化を保証する。反対に、非社交的な種は衰退する運命にあ る。 - ピーター・クロポトキン『相互扶助: 進化の要因』(1902年)、結論 |

| Other 19th-century usage "Darwinism" soon came to stand for an entire range of evolutionary (and often revolutionary) philosophies about both biology and society. One of the more prominent approaches, summed in the 1864 phrase "survival of the fittest" by Herbert Spencer, later became emblematic of Darwinism even though Spencer's own understanding of evolution (as expressed in 1857) was more similar to that of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck than to that of Darwin, and predated the publication of Darwin's theory in 1859. What is now called "Social Darwinism" was, in its day, synonymous with "Darwinism"—the application of Darwinian principles of "struggle" to society, usually in support of anti-philanthropic political agenda. Another interpretation, one notably favoured by Darwin's half-cousin Francis Galton, was that "Darwinism" implied that because natural selection was apparently no longer working on "civilized" people, it was possible for "inferior" strains of people (who would normally be filtered out of the gene pool) to overwhelm the "superior" strains, and voluntary corrective measures would be desirable—the foundation of eugenics. In Darwin's day there was no rigid definition of the term "Darwinism", and it was used by opponents and proponents of Darwin's biological theory alike to mean whatever they wanted it to in a larger context. The ideas had international influence, and Ernst Haeckel developed what was known as Darwinismus in Germany, although, like Spencer's "evolution", Haeckel's "Darwinism" had only a rough resemblance to the theory of Charles Darwin, and was not centred on natural selection.[19] In 1886, Alfred Russel Wallace went on a lecture tour across the United States, starting in New York and going via Boston, Washington, Kansas, Iowa and Nebraska to California, lecturing on what he called "Darwinism" without any problems.[20] In his book Darwinism (1889), Wallace had used the term pure-Darwinism which proposed a "greater efficacy" for natural selection.[21][22] George Romanes dubbed this view as "Wallaceism", noting that in contrast to Darwin, this position was advocating a "pure theory of natural selection to the exclusion of any supplementary theory."[23][24] Taking influence from Darwin, Romanes was a proponent of both natural selection and the inheritance of acquired characteristics. The latter was denied by Wallace who was a strict selectionist.[25] Romanes' definition of Darwinism conformed directly with Darwin's views and was contrasted with Wallace's definition of the term.[26] |

その他の19世紀の用法 「ダーウィニズム」はやがて、生物学と社会の両方に関する進化論的な(そしてしばしば革命的な)哲学全体を表すようになった。ハーバート・スペンサーによ る1864年の「適者生存」という言葉に集約される、より顕著なアプローチのひとつは、後にダーウィニズムを象徴するものとなったが、スペンサー自身の進 化に対する理解(1857年に表明)は、ダーウィンのそれよりもジャン=バティスト・ラマルクのそれに近いものであり、1859年にダーウィンの理論が発 表されるよりも前のものであった。現在「社会ダーウィニズム」と呼ばれているものは、当時は「ダーウィニズム」と同義であり、ダーウィンの「闘争」の原理 を社会に適用し、通常は反人道的な政治的アジェンダを支持するものであった。もうひとつの解釈は、ダーウィンの異母兄弟であるフランシス・ガルトンが好ん だもので、「ダーウィニズム」は、自然淘汰がもはや「文明人」には働かないらしいので、「劣った」系統の人々(通常は遺伝子プールから濾過される)が「優 れた」系統の人々を圧倒する可能性があり、自発的な是正措置が望ましい、つまり優生学の基礎をなすものだ、というものだった。 ダーウィンの時代には、「ダーウィニズム」という言葉に厳密な定義はなく、ダーウィンの生物学理論に反対する人々も支持する人々も、大きな文脈の中で、ど んな意味にも使われた。しかし、スペンサーの「進化論」のように、ヘッケルの「ダーウィニズム」はチャールズ・ダーウィンの理論に大まかに似ているだけ で、自然淘汰を中心としたものではなかった。 [1886年、アルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスは、ニューヨークを皮切りに、ボストン、ワシントン、カンザス、アイオワ、ネブラスカを経てカリフォルニ アまで、アメリカ全土を講演旅行し、「ダーウィニズム」と呼ばれるものを問題なく講演した[20]。 ウォレスは著書『ダーウィニズム』(1889年)の中で、自然淘汰の「より大きな効力」を提唱する純粋ダーウィニズムという言葉を用いていた[21] [22]。ジョージ・ロマネズはこの見解を「ウォレス主義」と呼び、ダーウィンとは対照的に、この立場は「いかなる補足理論も排除した純粋な自然淘汰理 論」を提唱していると指摘した[23][24]。後者は厳格な淘汰主義者であったウォレスによって否定された[25]。ロマネスのダーウィニズムの定義は ダーウィンの見解にそのまま合致し、ウォレスの定義とは対照的であった[26]。 |

| Contemporary usage The term Darwinism is often used in the United States by promoters of creationism, notably by leading members of the intelligent design movement, as an epithet to attack evolution as though it were an ideology (an "ism") based on philosophical naturalism, atheism, or both.[27] For example, in 1993, UC Berkeley law professor and author Phillip E. Johnson made this accusation of atheism with reference to Charles Hodge's 1874 book What Is Darwinism?.[28] However, unlike Johnson, Hodge confined the term to exclude those like American botanist Asa Gray who combined Christian faith with support for Darwin's natural selection theory, before answering the question posed in the book's title by concluding: "It is Atheism."[29][30] Creationists use pejoratively the term Darwinism to imply that the theory has been held as true only by Darwin and a core group of his followers, whom they cast as dogmatic and inflexible in their belief.[31] In the 2008 documentary film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed, which promotes intelligent design (ID), American writer and actor Ben Stein refers to scientists as Darwinists. Reviewing the film for Scientific American, John Rennie says "The term is a curious throwback, because in modern biology almost no one relies solely on Darwin's original ideas... Yet the choice of terminology isn't random: Ben Stein wants you to stop thinking of evolution as an actual science supported by verifiable facts and logical arguments and to start thinking of it as a dogmatic, atheistic ideology akin to Marxism."[32] However, Darwinism is also used neutrally within the scientific community to distinguish the modern evolutionary synthesis, which is sometimes called "neo-Darwinism", from those first proposed by Darwin. Darwinism also is used neutrally by historians to differentiate his theory from other evolutionary theories current around the same period. For example, Darwinism may refer to Darwin's proposed mechanism of natural selection, in comparison to more recent mechanisms such as genetic drift and gene flow. It may also refer specifically to the role of Charles Darwin as opposed to others in the history of evolutionary thought—particularly contrasting Darwin's results with those of earlier theories such as Lamarckism or later ones such as the modern evolutionary synthesis. In political discussions in the United States, the term is mostly used by its enemies.[33] "It's a rhetorical device to make evolution seem like a kind of faith, like 'Maoism,'" says Harvard University biologist E. O. Wilson. He adds, "Scientists don't call it 'Darwinism'."[34] In the United Kingdom, the term often retains its positive sense as a reference to natural selection, and for example British ethologist and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins wrote in his collection of essays A Devil's Chaplain, published in 2003, that as a scientist he is a Darwinist.[35] In his 1995 book Darwinian Fairytales, Australian philosopher David Stove[36] used the term "Darwinism" in a different sense than the above examples. Describing himself as non-religious and as accepting the concept of natural selection as a well-established fact, Stove nonetheless attacked what he described as flawed concepts proposed by some "Ultra-Darwinists." Stove alleged that by using weak or false ad hoc reasoning, these Ultra-Darwinists used evolutionary concepts to offer explanations that were not valid: for example, Stove suggested that the sociobiological explanation of altruism as an evolutionary feature was presented in such a way that the argument was effectively immune to any criticism. English philosopher Simon Blackburn wrote a rejoinder to Stove,[37] though a subsequent essay by Stove's protégé James Franklin[38] suggested that Blackburn's response actually "confirms Stove's central thesis that Darwinism can 'explain' anything." In more recent times, the Australian moral philosopher and professor Peter Singer, who serves as the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University, has proposed the development of a "Darwinian left" based on the contemporary scientific understanding of biological anthropology, human evolution, and applied ethics in order to achieve the establishment of a more equal and cooperative human society in accordance with the sociobiological explanation of altruism.[39] |

現代の用法 ダーウィニズムという用語は、米国では創造論の推進者、特にインテリジェントデザイン運動の主要メンバーによって、進化論が哲学的自然主義、無神論、また はその両方に基づくイデオロギー(「イズム」)であるかのように攻撃するための蔑称としてしばしば使用されている[27]。しかし、ジョンソンとは異な り、ホッジはこの言葉を、キリスト教信仰とダーウィンの自然淘汰理論への支持を結びつけたアメリカの植物学者アサ・グレイのような人たちを除外するために 限定し、本のタイトルで提起された問いに答える前に、こう結論づけた: 「それは無神論である」[29][30]。 創造論者はダーウィニズムという用語を侮蔑的に使用し、ダーウィンとその信奉者の中核グループによってのみ理論が真実であるとされてきたことを暗示する: インテリジェント・デザイン(ID)を推進する2008年のドキュメンタリー映画『Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed』では、アメリカの作家で俳優のベン・スタインが科学者をダーウィニストと呼んでいる。この映画を『サイエンティフィック・アメリカン』誌 で評論したジョン・レニーは、「現代生物学において、ダーウィンのオリジナルな考えだけに依拠している人はほとんどいないから、この用語は不思議な投げや りさだ...」と述べている。しかし、この用語の選択は無作為ではない: ベン・スタインは、進化論を検証可能な事実と論理的論拠に支えられた実際の科学として考えるのをやめ、マルクス主義に似た独断的で無神論的なイデオロギー として考え始めることを望んでいる」[32]。 しかし、ダーウィニズムは、科学界では、ダーウィンが最初に提唱したものから「ネオ・ダーウィニズム」と呼ばれることもある現代の進化論的統合を区別する ために中立的に使用されることもある。ダーウィニズムはまた、歴史家たちがダーウィンの理論を同時代の他の進化論と区別するためにも中立的に使われる。例 えば、ダーウィニズムとは、ダーウィンが提唱した自然淘汰のメカニズムを指す場合もあれば、遺伝的ドリフトや遺伝子フローといった最近のメカニズムと比較 する場合もある。また、進化思想の歴史におけるチャールズ・ダーウィンの役割、特にダーウィンの結果とラマルク説などの初期の理論や現代進化論的統合など の後期の理論との対比を指すこともある。 ハーバード大学の生物学者E.O.ウィルソンは、「進化論を『毛沢東主義』のような一種の信仰のように見せるための修辞法だ」と言う。イギリスでは、この 用語は自然淘汰への言及として肯定的な意味を保っていることが多く、例えばイギリスの倫理学者であり進化生物学者であるリチャード・ドーキンスは、 2003年に出版したエッセイ集『A Devil's Chaplain』の中で、科学者として自分はダーウィニストであると書いている[35]。 オーストラリアの哲学者デイヴィッド・ストーブ[36]は、1995年の著書『ダーウィンのおとぎ話』の中で、上記の例とは異なる意味で「ダーウィニズ ム」という言葉を用いている。ストーブは自らを非宗教的であり、自然淘汰の概念を確立された事実として受け入れているとしながらも、一部の "ウルトラ・ダーウィニスト "によって提案された欠陥のある概念であると攻撃した。例えば、ストーブは、利他主義を進化論的特徴として社会生物学的に説明することは、事実上批判を免 れるような方法で提示されていると指摘した。イギリスの哲学者サイモン・ブラックバーンはストーブに反論を書いたが[37]、ストーブの弟子であるジェー ムズ・フランクリン[38]は、ブラックバーンの反論は実際には「ダーウィニズムは何でも "説明 "できるというストーブの中心的なテーゼを裏付けるもの」だと示唆した。 最近では、プリンストン大学のアイラ・W・デキャンプ教授(生命倫理学)を務めるオーストラリアの道徳哲学者であり教授であるピーター・シンガーが、利他 主義の社会生物学的説明に従って、より平等で協力的な人間社会の確立を達成するために、生物人類学、人類進化学、応用倫理学の現代科学的理解に基づく 「ダーウィン左派」の発展を提案している[39]。 |

| Esoteric usage In evolutionary aesthetics theory, there is evidence that perceptions of beauty are determined by natural selection and therefore Darwinian; that things, aspects of people and landscapes considered beautiful are typically found in situations likely to give enhanced survival of the perceiving human's genes.[40][41] |

秘教的用法 進化論的美学理論では、美の知覚は自然淘汰によって決定され、したがってダーウィン的であるという証拠があり、美とみなされる物、人の側面、風景は、知覚する人間の遺伝子の生存を高める可能性が高い状況に一般的に見られるという[40][41]。 |

| Darwin Awards Evidence of common descent History of evolutionary thought Modern evolutionary synthesis Neural Darwinism Pangenesis—Charles Darwin's hypothetical mechanism for heredity Speciation Universal Darwinism |

ダーウィン賞 進化論の歴史 進化論の歴史 現代の進化論的統合 神経ダーウィニズム パンゲネシス-チャールズ・ダーウィンの仮説的遺伝メカニズム 種分化 普遍的ダーウィニズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darwinism |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆