南北アメリカ大陸の脱植民地化

Decolonization of the Americas

1818年2月18日のチリの独立宣言(→「脱植民地化」)

☆ アメリカ大陸の脱植民地化は、数世紀にわたって行われ、アメリカ大陸のほとんどの国がヨーロッパの支配から独立を勝ち取った。アメリカ大陸で最初に行われ たのはアメリカ独立革命であり、アメリカ独立革命戦争(1775年~1783年)におけるイギリスの敗北は、イギリスの敵国であったフランスとスペインの 支援を受けた大国に対する勝利であった。その後、ヨーロッパではフランス革命が起こり、これらの出来事はアメリカ大陸のスペイン、ポルトガル、フランスの 植民地に大きな影響を与えた。革命の波は続き、ラテンアメリカではいくつかの独立国が誕生した。ハイチ革命は1791年から1804年まで続き、フランス 領の奴隷植民地が独立した。ナポレオンによるスペイン占領に端を発したフランスとの半島戦争により、スペイン領アメリカにおけるスペイン系クリオール人た ちはスペインへの忠誠を疑うようになり、独立運動が活発化し、最終的にスペイン領アメリカ独立戦争(1808年~1833年)へと発展した。この戦争は主 に植民地出身者たちの対立グループ間で戦われ、スペイン軍との戦いは二次的なものに過ぎなかった。同時に、ポルトガル王政はフランスによるポルトガル侵攻 の際にブラジルに逃亡した。王宮がリスボンに戻った後、摂政ペドロ王子はブラジルに残り、1822年にブラジル帝国の皇帝として即位した。 スペインは1800年代の終わりまでに、カリブ海に残っていた3つの植民地をすべて失うことになる。サント・ドミンゴは1821年にスペイン領ハイチ共和 国として独立を宣言した。旧フランス領ハイチとの統合と分裂を経て、ドミニカ共和国の大統領は1861年にスペインの植民地に戻す協定に署名した。これが ドミニカ回復戦争の引き金となり、1865年にドミニカ共和国はスペインから2度目の独立を果たした。キューバは10年戦争(1868年~1878年)、 小戦争(1879年~1880年)、そして最終的にキューバ独立戦争(1895年~1898年)でスペインからの独立を求めて戦った。1898年のアメリ カの介入は米西戦争となり、アメリカはプエルトリコ、グアム(現在もアメリカの領土)、太平洋上のフィリピン諸島を獲得した。軍事占領下にあったキューバ は、1902年に独立するまでアメリカの保護領となった。 植民地大国の自主的な撤退による平和的な独立は、20世紀後半には一般的となった。しかし、北米には現在でもイギリスとオランダの植民地(ほとんどがカリ ブ海諸島)が存在する。フランスは、かつての植民地の大半(フランス領ギアナ、グアドループ島、マルティニーク)を、フランスの完全な構成省として完全に 統合している。

| The decolonization

of the Americas occurred over several centuries as most of the

countries in the Americas gained their independence from European rule.

The American Revolution was the first in the Americas, and the British

defeat in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) was a victory

against a great power, aided by France and Spain, Britain's enemies.

The French Revolution in Europe followed, and collectively these events

had profound effects on the Spanish, Portuguese, and French colonies in

the Americas. A revolutionary wave followed, resulting in the creation

of several independent countries in Latin America. The Haitian

Revolution lasted from 1791 to 1804 and resulted in the independence of

the French slave colony. The Peninsular War with France, which resulted

from the Napoleonic occupation of Spain, caused Spanish Creoles in

Spanish America to question their allegiance to Spain, stoking

independence movements that culminated in various Spanish American wars

of independence (1808–33), which were primarily fought between opposing

groups of colonists and only secondarily against Spanish forces. At the

same time, the Portuguese monarchy fled to Brazil during the French

invasion of Portugal. After the royal court returned to Lisbon, the

prince regent, Pedro, remained in Brazil and in 1822 successfully

declared himself emperor of a newly independent Brazilian Empire.[1] Spain would lose all three of its remaining Caribbean colonies by the end of the 1800s. Santo Domingo declared independence in 1821 as the Republic of Spanish Haiti. After unification and then split from the former French colony of Haiti, the President of the Dominican Republic signed an agreement that reverted the country to a Spanish colony in 1861. This triggered the Dominican Restoration War, which resulted in the Dominican Republic's second independence from Spain in 1865. Cuba fought for independence from Spain in the Ten Years' War (1868–78) and Little War (1879-80) and finally the Cuban War of Independence (1895–98). American intervention in 1898 became the Spanish–American War and resulted in the United States gaining Puerto Rico, Guam (which are still U.S. territories), and the Philippine Islands in the Pacific Ocean. Under military occupation, Cuba became a U.S. protectorate until its independence in 1902. Peaceful independence by the voluntary withdrawal of colonial powers then became the norm in the second half of the 20th century. However, there are still British and Dutch colonies in North America (mostly Caribbean islands). France has fully integrated most of its former colonies in the Americas (French Guiana, Guadeloupe, and Martinique) as fully constituent Departments of France. |

アメリカ大陸の脱植民地化(decolonization

of the Americas)は、数世紀にわたって行われ、アメリカ大陸の

ほとんどの国がヨーロッパの支配から独立を勝ち取った。アメリカ大陸で最初に行われたのはアメリカ独立革命であり、アメリカ独立革命戦争(1775年

~1783年)におけるイギリスの敗北は、イギリスの敵国であったフランスとスペインの支援を受けた大国に対する勝利であった。その後、ヨーロッパではフ

ランス革命が起こり、これらの出来事はアメリカ大陸のスペイン、ポルトガル、フランスの植民地に大きな影響を与えた。革命の波は続き、ラテンアメリカでは

いくつかの独立国が誕生した。ハイチ革命は1791年から1804年まで続き、フランス領の奴隷植民地が独立した。ナポレオンによるスペイン占領に端を発

したフランスとの半島戦争により、スペイン領アメリカにおけるスペイン系クリオール人たちはスペインへの忠誠を疑うようになり、独立運動が活発化し、最終

的にスペイン領アメリカ独立戦争(1808年~1833年)へと発展した。この戦争は主に植民地出身者たちの対立グループ間で戦われ、スペイン軍との戦い

は二次的なものに過ぎなかった。同時に、ポルトガル王政はフランスによるポルトガル侵攻の際にブラジルに逃亡した。王宮がリスボンに戻った後、摂政ペドロ

王子はブラジルに残り、1822年にブラジル帝国の皇帝として即位した。 スペインは1800年代の終わりまでに、カリブ海に残っていた3つの植民地をすべて失うことになる。サント・ドミンゴは1821年にスペイン領ハイチ共和 国として独立を宣言した。旧フランス領ハイチとの統合と分裂を経て、ドミニカ共和国の大統領は1861年にスペインの植民地に戻す協定に署名した。これが ドミニカ回復戦争の引き金となり、1865年にドミニカ共和国はスペインから2度目の独立を果たした。キューバは10年戦争(1868年~1878年)、 小戦争(1879年~1880年)、そして最終的にキューバ独立戦争(1895年~1898年)でスペインからの独立を求めて戦った。1898年のアメリ カの介入は米西戦争となり、アメリカはプエルトリコ、グアム(現在もアメリカの領土)、太平洋上のフィリピン諸島を獲得した。軍事占領下にあったキューバ は、1902年に独立するまでアメリカの保護領となった。 植民地大国の自主的な撤退による平和的な独立は、20世紀後半には一般的となった。しかし、北米には現在でもイギリスとオランダの植民地(ほとんどがカリ ブ海諸島)が存在する。フランスは、かつての植民地の大半(フランス領ギアナ、グアドループ島、マルティニーク)を、フランスの完全な構成省として完全に 統合している。 |

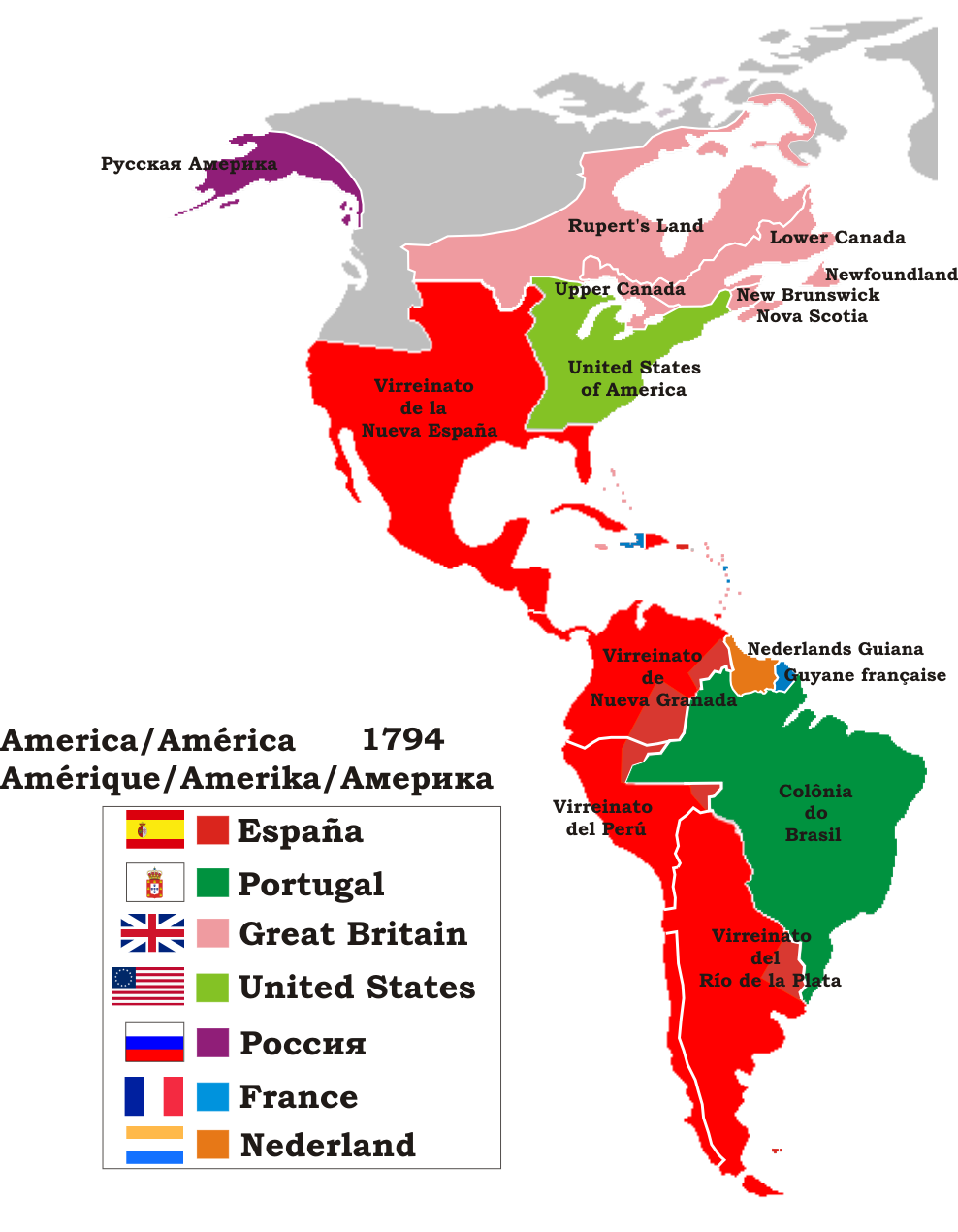

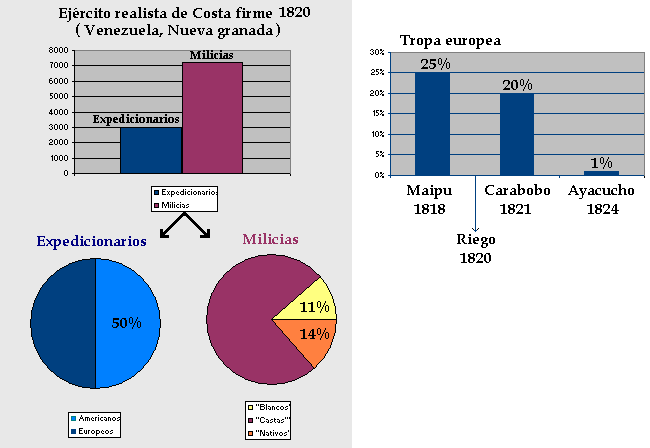

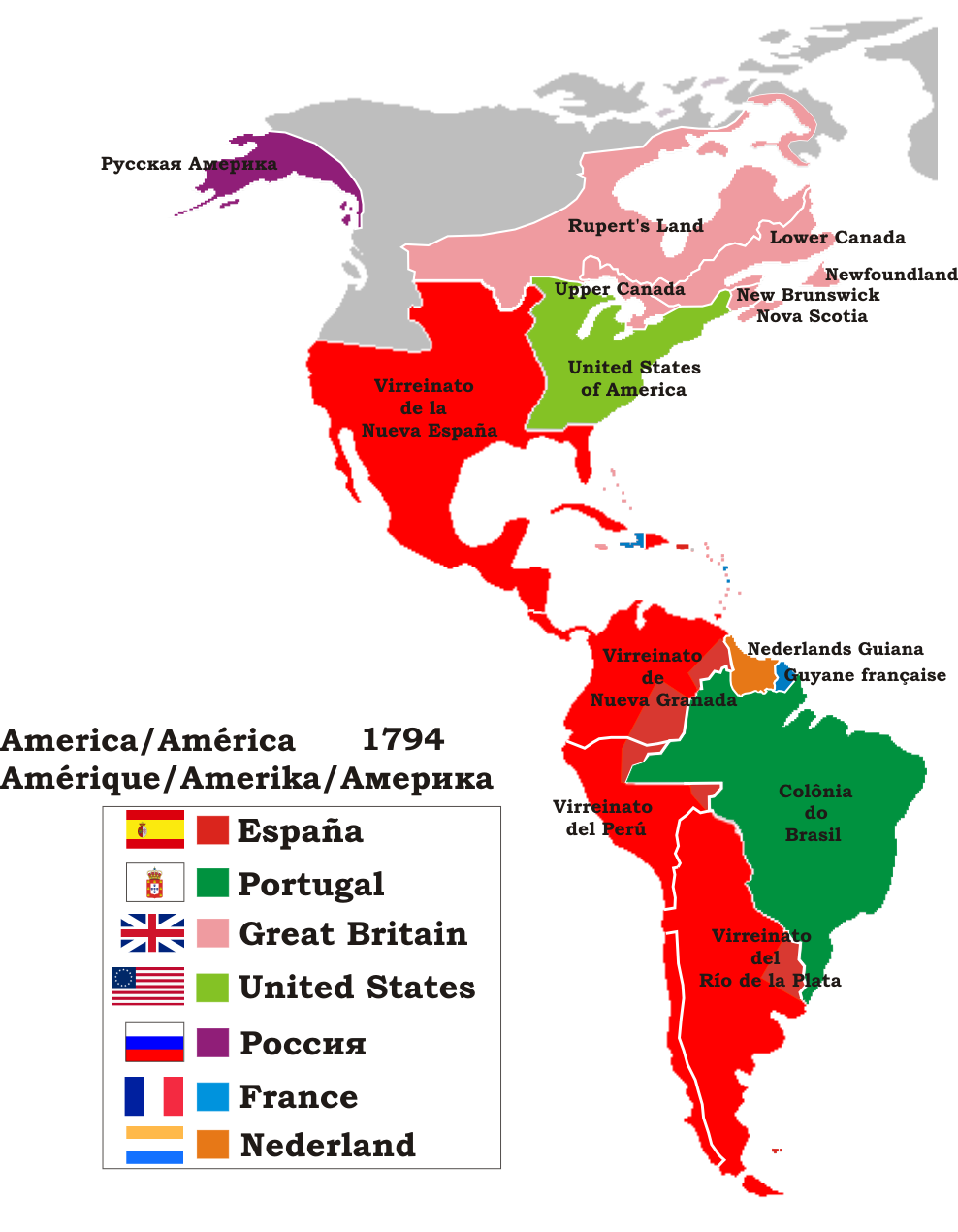

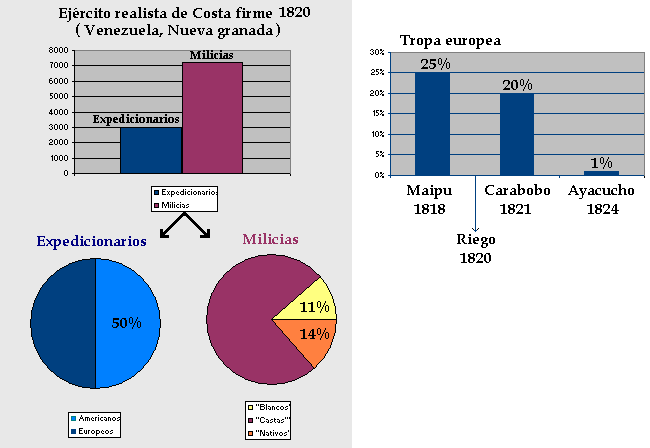

| Conditions before revolution Undermining of metropolitan authority  Political map of the Americas in 1794 During the 18th century, Spain recovered much of the strength it had lost in the 17th century but the country's resources were under strain because of the incessant warfare in Europe from 1793. This led to increased local participation in the financing of defense and increased participation in militias by the locally born. Such development was at odds with the ideals of the centralized absolute monarchy. The Spanish also made formal concessions to strengthen defense; In Chiloé, Spanish authorities promised freedom from the Encomienda for indigenous locals who settled near the new stronghold of Ancud (founded in 1768) and contributed to its defense. The increased local organization of the defenses would ultimately undermine the metropolitan authority and bolster the independence movement.[2] Napoleonic Wars Main articles: Napoleonic Wars and Peninsular War The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars fought between France (led by Napoleon Bonaparte) and alliances involving Britain, Prussia, Spain, Portugal, Russia, and Austria at different times, from 1799 to 1815. In the case of Spain and its colonies, in May 1808, Napoleon captured Carlos IV and King Fernando VII and installed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as Spanish monarch. This event disrupted the political stability of Spain and broke the link with some of the colonies which were loyal to the Bourbon Dynasty. The local elites, the creoles, took matters into their own hands organizing themselves into juntas to take "in absence of the king, Fernando VII, their sovereignty devolved temporarily back to the community". The juntas swore loyalty to the captive Fernando VII and each ruled different and diverse parts of the colony. Most of Fernando's subjects were loyal to him in 1808, but after he was restored to the Spanish crown in 1814, his policy of restoring absolute power alienated both the juntas and his subjects. He abrogated the Cádiz Constitution of 1812 and punished those who had supported it. The violence used by royalist forces and the prospect of being ruled by Fernando shifted the majority of the colonist population in favor of separation from Spain.[3] The local elites reacted to absolutism in much the same way that the British colonial elites, Tory and Whig alike, had reacted to London's interference before 1775. Spanish military presence in its colonies  Graphs showing the make-up of the royalist army at the time of the revolution. The colonial army of the Spanish Empire in the Americas was made up of local American and European supporters of King Ferdinand. The Royalists were made up of a cross-section of society loyal to the crown with Americans composing the majority of the royalist forces on all fronts. There were two types of military units: from the regular Spanish army which were sent out or formed with local Europeans and called Expidicionarios and units called veterans or militias created in the Americas. The militias included some veteran units and were called the disciplined militia. Only 11% of the personnel in the militias were European or American whites. After Rafael del Riego's revolution in 1820, no more Spanish soldiers were sent to the wars in the Americas. In 1820 there were only 10,000 soldiers in Royal Army in Colombia and Venezuela, and Spaniards formed only 10% of all the royalist armies, and only half of the soldiers of the expeditionary units were European. By the Battle of Ayacucho in 1824, less than 1% of the soldiers were European.[citation needed] Other factors Main articles: Enlightenment Spain and Bourbon Reforms The Enlightenment spurred the desire for social and economic reform to spread throughout the Americas and the Iberian Peninsula. Ideas about free trade and physiocratic economics were raised by the Enlightenment. Independence movements in South America can be traced back to slave revolts in plantations in the northernmost part of the continent and the Caribbean. In 1791, a massive slave revolt sparked a general insurrection against the plantation system and French colonial power.[4] These events were followed by a violent uprising led by José Leonardo Chirino and José Caridad González that sprung up in 1795 Venezuela, allegedly inspired by the revolution in Haiti. Toussaint L'Ouverture was born a slave in Saint-Domingue where he developed labor skills that would give him higher privileges than other slaves. He intellectually and physically advanced resulting in promotion, land of his own, and owning slaves. In 1791, slaves in Haiti formed a revolution to seek independence from their French owners. L'Ouverture joined the rebellion as a top military official to abolish slavery without complete independence. However, through a series of letters written by Toussaint, it became clear that he grew open to equal human rights for all that live in Haiti. Similar to how the United States Constitution was ratified, the enlightenment ideas of equality and representation of the people created an impact of change against the status quo that sparked the revolution. The letter details the great concerns he felt due to a conservative shift in France's legislature after the revolution in 1797. The greatest fear was that these conservative values could give ideas to the French Government to bring back slavery. The enlightenment has proven to forever change the way a captive society thinks after L'Ouverture refuses to let the French send him and his people back into slavery. "[W]hen finally the rule of law took the place of anarchy under which the unfortunate colony had too long suffered, what fatality can have led the greatest enemy of its prosperity and our happiness still to dare to threaten us with the return of slavery?" Ultimately, slavery was abolished from French colonies in 1794 and Haiti declared Independence from France in 1804.[5] |

革命前の状況 首都権力の弱体化  1794年の南北アメリカ大陸の政治地図 18世紀、スペインは17世紀に失った力を取り戻したが、1793年からのヨーロッパでの絶え間ない戦争により、国の資源はひっ迫していた。このため、防 衛費用の調達に地元民が参加するようになり、地元生まれの人々の民兵への参加も増加した。このような発展は、中央集権的な絶対王政の理想とは相容れないも のであった。スペインはまた、防衛を強化するために正式な譲歩を行った。チロエでは、スペイン当局は、アンクード(1768年に建設)の新しい要塞の近く に定住し、その防衛に貢献した先住民に対して、エンコミエンダからの解放を約束した。防衛のための地域組織の増加は、最終的に首都の権威を弱体化させ、独 立運動を強化することとなった。 ナポレオン戦争 詳細は「ナポレオン戦争」および「半島戦争」を参照 ナポレオン戦争は、1799年から1815年にかけて、フランス(指導者はナポレオン・ボナパルト)と、イギリス、プロイセン、スペイン、ポルトガル、ロ シア、オーストリアが同盟を組んだ時期もあったが、フランスとそれらの国々との間で戦われた一連の戦争である。 スペインとその植民地の場合、1808年5月にナポレオンはカルロス4世とフェルナンド7世を捕らえ、兄のジョゼフ・ボナパルトをスペインの君主として据 えた。この出来事はスペインの政治的安定を乱し、ブルボン朝に忠誠を誓っていた植民地のいくつかとのつながりを断ち切った。現地のエリート層であるクリ オールたちは、自らを統治する組織として軍事会議を組織し、「フェルナンド7世という王が不在である間、彼らの主権は一時的に地域社会に戻された」のであ る。軍事会議は捕虜となっていたフェルナンド7世に忠誠を誓い、それぞれが植民地の異なる地域を統治した。1808年にはフェルナンド王の臣民のほとんど が王に忠誠を誓っていたが、1814年にスペイン王位に復帰した後、王が絶対権力を回復する政策を打ち出したため、各ジュンタや臣民の間に不満が広がっ た。王は1812年のカディス憲法を廃止し、憲法を支持した人々を処罰した。王党派の軍勢による暴力とフェルナンドによる支配の可能性により、入植者の大 半がスペインからの分離を支持するようになった。[3] 地元のエリート層は、1775年以前にロンドンの干渉に対して保守党とホイッグ党のエリート層がとったのと同じような反応を、絶対王政に対して示した。 スペインの植民地における軍事的存在  革命当時の王党派軍の構成を示すグラフ。 スペイン帝国のアメリカ植民地軍は、フェルディナンド国王を支持するアメリカ大陸のヨーロッパ系住民とアメリカ人によって構成されていた。王党派は、王政 に忠誠を誓う社会のあらゆる階層の人々で構成されていたが、王党派軍の大多数はアメリカ人であった。軍事部隊には2つのタイプがあった。スペイン正規軍か ら派遣された、または現地のヨーロッパ人とともに編成された遠征軍と、アメリカ大陸で結成された退役軍人部隊や民兵部隊である。民兵部隊には退役軍人部隊 も含まれ、規律ある民兵と呼ばれた。民兵部隊の隊員のわずか11%がヨーロッパ人またはアメリカ大陸の白人であった。1820年のラファエル・デル・リエ ゴの革命の後、スペイン兵士がアメリカ大陸の戦争に派遣されることはなくなった。1820年には、コロンビアとベネズエラの王立軍には1万人の兵士しかお らず、王党派軍のスペイン人は全体の10%しかおらず、遠征部隊の兵士の半分しかヨーロッパ人ではなかった。1824年のアヤクチョの戦いまでに、ヨー ロッパ人の兵士は1%以下となった。 その他の要因 詳細は「啓蒙思想」および「ブルボン家の改革」を参照 啓蒙思想は、南北アメリカ大陸とイベリア半島全体に広がる社会・経済改革への願望を刺激した。自由貿易と重農主義経済に関する考え方は、啓蒙思想によって 提起された。 南米における独立運動は、大陸最北端およびカリブ海のプランテーションにおける奴隷の反乱にまで遡ることができる。1791年、大規模な奴隷反乱が引き金 となり、プランテーション制度とフランス植民地権力に対する反乱が勃発した。[4] これらの出来事に続いて、1795年のベネズエラで、ハイチの革命に触発されたとされるホセ・レオナルド・チリーノとホセ・カリダ・ゴンサレスが率いる暴 動が勃発した。 トゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールは、サン・ドマングで奴隷として生まれ、他の奴隷よりも高い特権を得るための労働技術を身につけた。彼は知力と体力を向上 させ、昇進し、自分の土地を持ち、奴隷を所有するようになった。1791年、ハイチの奴隷たちはフランス人所有者からの独立を求めて革命を起こした。ルー ヴェルチュールは、完全な独立を求めず、奴隷制度の廃止を目的として、反乱軍の最高軍事責任者として参加した。しかし、トゥーサンが書いた一連の手紙によ り、ハイチに住むすべての人々の平等な人権を認めるようになったことが明らかになった。米国憲法が批准されたのと同様に、平等と人民の代表という啓蒙思想 が現状に対する変化のきっかけとなり、革命が引き起こされた。その手紙には、1797年の革命後にフランス議会で保守派が台頭したことに対する彼の大きな 懸念が詳細に述べられている。最も恐れていたのは、こうした保守的な価値観がフランス政府に奴隷制復活のアイデアを与えるのではないかということだった。 啓蒙思想は、フランスが彼と自国民を再び奴隷として送り返そうとするのを拒否したルヴェルチュール以降、囚われの身となった社会の考え方を永遠に変えるこ とが証明された。「不幸な植民地が長きにわたって苦しんできた無政府状態に、ついに法の支配が取って代わったとき、繁栄と私たちの幸福の最大の敵が、なぜ 今なお奴隷制復活の脅威を私たちに突きつけるのか?」 最終的に、奴隷制は1794年にフランス植民地から廃止され、ハイチは1804年にフランスからの独立を宣言した。[5] |

| United States Main articles: American Revolution and History of United States continental expansion The United States of America declared independence from Great Britain on July 4, 1776, thus becoming the first independent, foreign-recognized nation in the Americas and the first European colonial entity to break from its mother country. Britain formally acknowledged American independence in 1783 after its defeat in the American Revolutionary War. The U.S. victory encouraged independence movements in other parts of the Americas. Although initially occupying only the land east of the Mississippi between Canada and Florida, the United States would later eventually acquire various other North American territories from the British, French, Spanish, and Russians in succeeding years under the mantle of Manifest Destiny. While ending European control over the region, these events resulted in the expansion of settler colonialism against Native nations, especially following the discovery of gold in regions such as the Dakotas and California, as well as opportunities for American settlers to claim farmland in the Great Plains. Land speculators and individual settlers both played a significant role in the expansion of America into what was then termed Indian Territory. American encroachment on indigenous nations prompted the creation of several federations opposed to Manifest Destiny such as the Northwestern confederacy and Tecumseh's Confederacy. |

アメリカ合衆国 詳細は「アメリカ独立革命」および「アメリカ合衆国の歴史」を参照 アメリカ合衆国は1776年7月4日にイギリスからの独立を宣言し、アメリカ州で最初に独立を達成した国家となり、またヨーロッパの植民地国家が宗主国か ら独立した最初の国家となった。イギリスはアメリカ独立戦争での敗北の後、1783年にアメリカ独立を正式に承認した。アメリカの勝利は、アメリカ州の他 の地域での独立運動を促した。 当初はカナダとフロリダの間にあるミシシッピ川の東側の土地のみを占領していたが、アメリカ合衆国はその後、マニフェスト・デスティニー(明白なる運命) という大義名分の下、イギリス、フランス、スペイン、ロシアから北米のさまざまな領土を獲得していった。これらの出来事は、ヨーロッパによる同地域の支配 を終わらせた一方で、特にダコタやカリフォルニアなどの地域で金が発見されたことや、アメリカ開拓民がグレートプレーンズの農地を要求する機会を得たこと などにより、ネイティブアメリカン諸国に対する入植者植民地主義の拡大につながった。土地投機家と個人入植者たちは、当時インディアン居留地と呼ばれてい た地域へのアメリカの進出において、ともに重要な役割を果たした。アメリカの先住民に対する侵攻は、北西部連合やテカムセ連合など、明白な使命に反対する いくつかの連合の結成を促した。 |

| Haiti and the French Antilles Main article: Haitian Revolution The American and French Revolutions had profound effects on Spanish, Portuguese and French colonies in the Americas. Haiti, a French slave colony, was the first to follow the United States to independence, during the Haitian Revolution, which lasted from 1791 to 1804. Thwarted in his attempt to rebuild a French empire in North America, Napoleon Bonaparte sold Louisiana to the United States and from then on focused on the European theater, marking the end of France's ambitions of building a colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere. |

ハイチとフランス領アンティル 詳細は「ハイチ革命」を参照 アメリカ独立革命とフランス革命は、アメリカ大陸のスペイン、ポルトガル、フランスの植民地に大きな影響を与えた。フランス領の奴隷植民地であったハイチ は、1791年から1804年まで続いたハイチ革命の間に、アメリカ合衆国に続いて独立を果たした最初の国となった。北アメリカにおけるフランス帝国の再 建を試みたナポレオン・ボナパルトは、ルイジアナをアメリカ合衆国に売却し、それ以降はヨーロッパに焦点を絞った。これにより、西半球におけるフランスに よる植民地帝国建設の野望は終焉を迎えた。 |

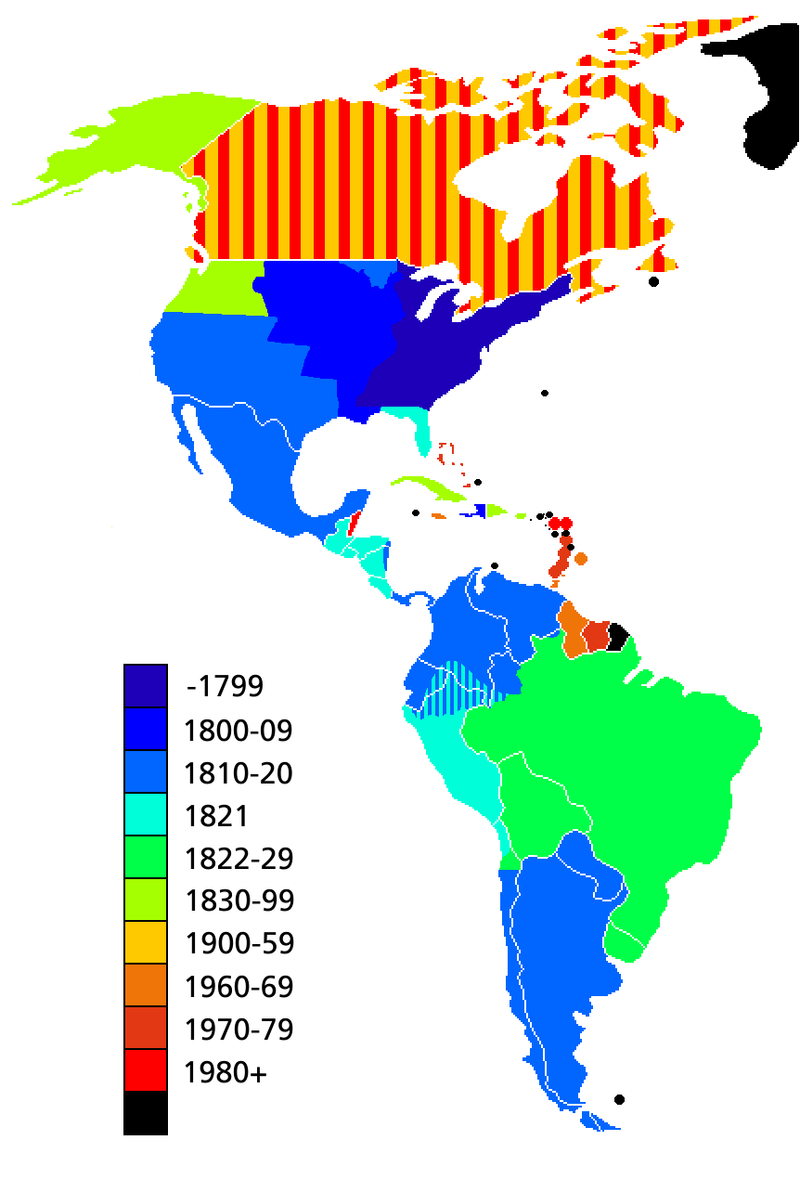

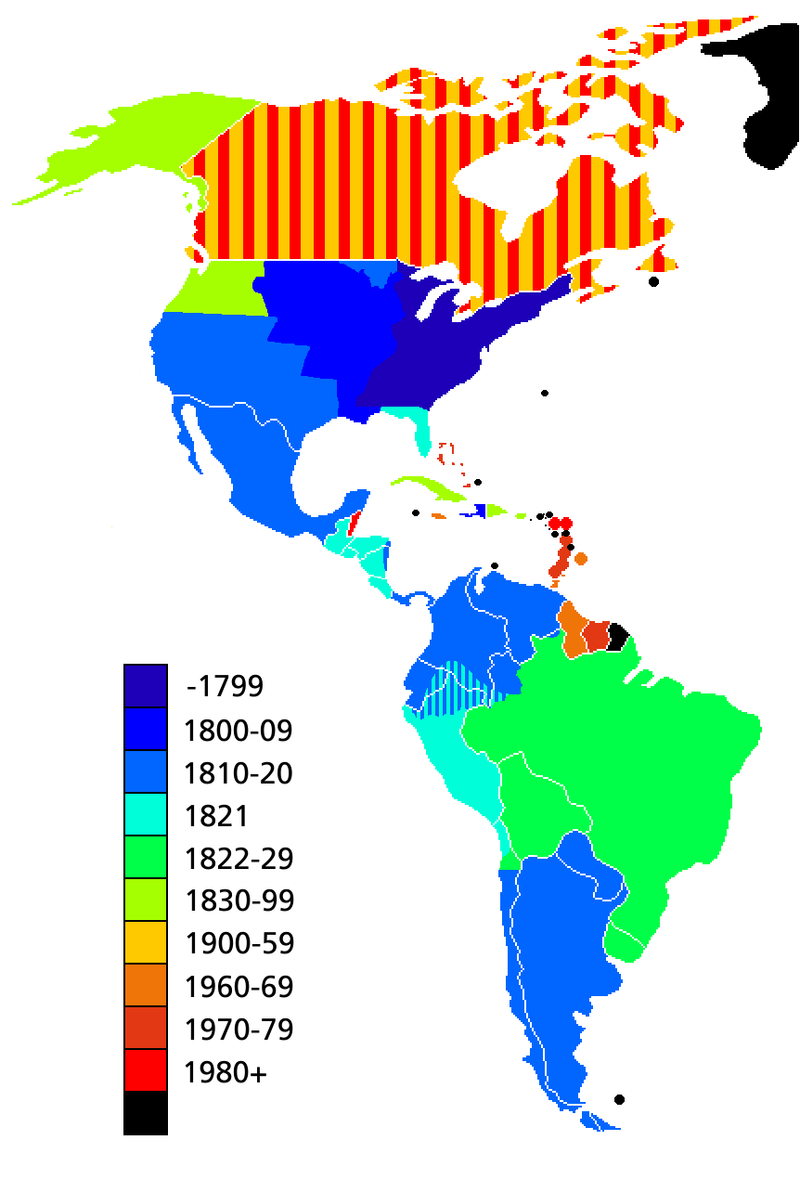

| Spanish America Main article: Spanish American wars of independence Further information: Libertadores  Places in the Americas by date of independence.[contradictory] Note that the United States did not complete its continental territorial expansion until 1867; Canada did not complete sovereignty as an independent country until 1982.  Intendecies (provinces) of the South American viceroyalties. Except for Cuba and Puerto Rico, the Spanish colonies in the Americas won their independence during the first quarter of the 19th century. During the Peninsular War, Napoleon installed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, on the Spanish throne and captured the King Fernando VII. The crisis of political legitimacy sparked a reaction in Spain's overseas empire. Several assemblies were established after 1810 by the Criollos (Latin Americans who are of full or near full Spanish descent) to recover sovereignty and self-government based on the Castilian law and to rule American lands in the name of Ferdinand VII of Spain. This experience of self-government, along with the influence of Liberalism and the ideas of the French and American Revolutions, brought about a struggle for independence, led by the Libertadores. The territories freed themselves, often with help from foreign mercenaries and privateers. The United States and Europe were neutral, yet aimed to achieve political influence and trade without the Spanish monopoly. In South America, Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín led the final phase of the independence struggle. Although Bolívar attempted to keep the Spanish-speaking parts of the continent politically unified, they rapidly became independent of one another as well, and several further wars were fought, such as the Paraguayan War and the War of the Pacific. A related process took place in what is now Mexico, Central America, and parts of North America between 1810 and 1821 with the Mexican War of Independence. Independence was achieved in 1821 by a coalition uniting under Agustín de Iturbide and the Army of the Three Guarantees. Unity was maintained for a short period under the First Mexican Empire, but within a decade the region fought against the United States over the borderlands (losing the bordering lands of California and Texas). Most of the heat was during the official Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1848.[6] In 1898, in the Greater Antilles, the United States won the Spanish–American War and occupied Cuba and Puerto Rico, ending Spanish territorial control in the Americas. Argentina Main article: Argentine War of Independence After the defeat of Spain in the Peninsular War and the abdication of King Ferdinand VII, the Spanish colonial government of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, present-day Argentina, majority of Bolivia, parts of Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay, became greatly weakened. Without a recognized king on the Spanish throne to render the office of the Viceroy legitimate, the right of Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros to govern came under fire. The local elites, tired of the Spanish trade restrictions and taxes, seized the opportunity and during the May Revolution of 1810, removed Cisneros and created the first local government, the Primera Junta.  José de San Martín Following half a decade of battles and skirmishes with provincial royalist forces within the former Vice-royalty along with military expeditions across the Andes to Chile, Peru and Bolivia led by General José de San Martín to finally end Spanish rule in America, a formal declaration was signed on 9 July 1816, by an assembly in San Miguel de Tucumán, declaring full independence with provisions for a national constitution. The Argentine Constitution was signed in 1853, declaring the creation of the Argentine Republic. Bolivia Main article: Bolivian War of Independence Following upheaval caused by the May Revolution, along with the independence movements in Chile and Venezuela, a local struggle for independence kicked off with two failed revolutions. Over sixteen years of struggle followed before the first steps toward the establishment of a republic were taken. Formally, it is considered that the fight for independence culminated in the Battle of Ayacucho, on 9 December 1824.[citation needed]  Retreat of European colonialism and change of political borders in South America, 1700–present Colombia  The Battle of Boyacá sealed Colombia's independence Main articles: Patria Boba, Spanish reconquest of New Granada, and Bolívar's campaign to liberate New Granada [icon] This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (August 2020) Chile Main article: Chilean War of Independence The Chilean Independence campaign was led by Liberator General Jose de San Martin with the support of Chilean exiles such as Bernardo O'Higgins. The local independence movement was composed of Chilean-born criollos, who sought political and economic independence from Spain. The independence movement was far from gaining unanimous support among Chileans, who became divided between independentists and royalists. What started as an elitist political movement against their colonial master, finally ended as a full-fledged civil war. Traditionally, the process is divided into three stages: Patria Vieja, Reconquista, and Patria Nueva. Ecuador Main article: Ecuadorian War of Independence The first uprising against Spanish rule took place in 1809, and criollos in Ecuador set up a junta on 22 September 1810, to rule in the name of the Bourbon monarch; but as elsewhere, it allowed assertion of their power.[7] Only in 1822 did Ecuador fully gain independence and became part of Gran Colombia, from which it withdrew in 1830.[8] At the Battle of Pichincha, near present-day Quito, Ecuador on 24 May 1822, General Antonio José de Sucre's forces defeated a Spanish force defending Quito. The Spanish defeat guaranteed the liberation of Ecuador. Guatemala In 1821, the entire Kingdom of Guatemala was peacefully subject to Spanish rule. With the innovations produced by the constitutional system, the freedom of the press and the exaltation of the parties, which were born in the popular elections, opinion in favor of independence spread. Those in favor of independence held meetings in Guatemala, but they did not have the resources to rise up against the government; They expected everything from the progress made in Mexico by the Plan of Iguala or Plan of Independence. Likewise, not all the independentists were in agreement with the system of government proclaimed by Iturbide, much less by the dynasty called to the Mexican throne, but then it was only about independence, each one reserving their opinion regarding the forms of government. On September 13, the minutes of Ciudad Real de Chiapas and other towns of that State adhering to the Plan of Iguala were received in Guatemala; the advances that the army was making gave all their strength to the pronouncements of Chiapas, which by itself never had any political importance in that kingdom. The trustee of the Guatemala City Council, Mr. Mariano Aycinena, requested an extraordinary session to present a petition in order to proclaim independence. pp. 85–90.</ref>[9] Mexico Main article: Mexican War of Independence Independence in Mexico was a protracted struggle from 1808 until the fall of the royal government in 1821 and the establishment of independent Mexico. In the Viceroyalty of New Spain, as elsewhere in Spanish America in 1808, people reacted to the unexpected French invasion of the Iberian peninsula and the ouster of the Bourbon king, replaced by Joseph Bonaparte. Local American-born Spaniards saw the opportunity to seize control from Viceroy José de Iturrigaray who may well have been sympathetic to creoles' aspirations. Iturrigaray was ousted by pro-royalists. A few from among the creole elites sought independence, including Juan Aldama, Ignacio Allende, and the secular parish priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. Hidalgo made a proclamation in his home parish of Dolores, which was not recorded in writing at the time, but denounced the bad government and gachupines (pejorative for peninsular-born Spaniards), and declared independence. The unorganized hordes following Hidalgo wrought destruction on the property and the lives of whites in the region of the Bajío. Hidalgo was caught, defrocked, and executed in 1811, along with Allende. Their heads remained on display until 1821. His former student José María Morelos continued the rebellion and was himself caught and killed in 1815. The struggle of Mexican insurgents continued under the leadership of Vicente Guerrero and Guadalupe Victoria. From 1815 to 1820 there was a stalemate in New Spain, with royalist forces unable to defeat the insurgents and the insurgents unable to expand beyond their narrow territory in the southern region. Again, events in Spain intervened, with an uprising of military men against Ferdinand VII and the restoration of the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812, which mandated a constitutional monarchy and curtailed the power of the Roman Catholic Church. The monarch repudiated the constitution once the Spanish monarchy was restored in 1814. For conservatives in New Spain, these changed political circumstances threatened the institutions of church and state. Royal military officer Agustín de Iturbide seized the opportunity to lead, allying with his former enemy Guerrero. Iturbide proclaimed the Plan de Iguala, which called for independence, equality of peninsular and American-born Spaniards, a monarchy with a prince from Spain as king, and secured Catholicism as the proclaimed state religion. [10]He persuaded the insurgent Guerrero to ally with him and create the Army of the Three Guarantees. Juan O'Donojú,the final Viceroy of New Spain, and Iturbide settled a treaty in Córdoba which recognized Mexico as independent from the Spanish Empire. Iturbide and O'Donojú entered Mexico City with the Army of the Three Guarantees on September 27, 1821, where the remaining Spanish forces surrendered.[11] With no European monarch presenting himself for the Crown of Mexico, Iturbide himself was proclaimed emperor Agustín I in 1822. He was overthrown in 1823 and Mexico was established as a republic. Decades of political and economic instability ensued which resulted in a population decline. Paraguay Paraguay gained its independence on the night of May 14 and the morning of May 15, 1811, after a plan organized by various pro-independence nationalists including Fulgencio Yegros and José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia. Peru Main article: Peruvian War of Independence  Painting of José de San Martín's proclamation of the independence of Peru on 28 July 1821 in Lima Spain initially had the support of the Lima oligarchs because of their opposition to the commercial interests of Buenos Aires and Chile. Therefore, the Viceroyalty of Peru became the last redoubt of the Spanish Monarchy in South America. Nevertheless, a Creole rebellion arose in 1812 in Huánuco and another in Cusco between 1814 and 1816. Both were suppressed. These rebellions were supported by the armies of Buenos Aires. Peru finally succumbed after the decisive continental campaigns of José de San Martín (1820–1823) and Simón Bolívar (1824). While San Martín was in charge of the land campaign, a newly-built Chilean Navy led by Lord Cochrane transported the fighting troops and launched a sea campaign against the Spanish fleet in the Pacific. San Martín, who had displaced the royalists of Chile after the Battle of Maipú, and who had disembarked in Paracas in 1820, proclaimed the independence of Peru in Lima on 28 July 1821. Four years later, the Spanish Monarchy was defeated definitively at the Battle of Ayacucho in late 1824. After independence, the conflicts of interests that faced different sectors of Creole Peruvian society and the particular ambitions of the caudillos, made the organization of the country excessively difficult. Only three civilians — Manuel Pardo, Nicolás de Piérola, and Francisco García Calderón — acceded to the presidency in the first seventy-five years of Peru's independence. The Republic of Bolivia was created in Upper Peru. In 1837, a Peru-Bolivian Confederation was also created, but was dissolved two years later due to Chilean military intervention. Uruguay Following the events of the May Revolution, in 1811 José Gervasio Artigasled a successful revolt against the Spanish forces in the Provincia Oriental, now Uruguay, joining the independentist movement that was taking place in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata at the time. In 1821, the Provincia Oriental was invaded by Portugal, trying to annex it into Brazil under the name of Província Cisplatina. The former Vice-royalty of the Río de la Plata, United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, fought back against Brazil in a war that lasted over 2 years, eventually turning into a stalemate. The Brazilian forces withdrew with the United Provinces keeping them at bay but failing to win any decisive victory. With neither side gaining the upper hand and the economic burden of the war crippling the United Provinces economy, the Treaty of Montevideo was signed in 1828, fostered by Britain, declaring Uruguay as an independent state.[12] Venezuela Main articles: Venezuelan War of Independence, First Republic of Venezuela, and Second Republic of Venezuela According to the Encyclopedia Americana of 1865, General Francisco de Miranda, already a hero to the French, Prussians, English, and Americans had garnered a series of successes against the Spanish between 1808 and 1812. He had effectively negated their access to all the ports in the Caribbean, thus preventing them from receiving reinforcements and supplies, and was essentially conducting mopping-up operations throughout the country. At that point, he convinced Simon Bolívar to join the struggle and put him in charge of the fort at Puerto Cabello. This was all at once a supply and arms depot, a strategic port, and the central holding facility for Spanish prisoners. Through what amounts to a gross dereliction of duty, Simon Bolívar neglected to enforce the customary security dispositions before departing to a social event. During the night there was an uprising of the Spanish prisoners and they managed to subdue the Independentist garrison and gain control of the supplies, arms and ammunition, and the port. The Loyalist forces progressively regained control of the country and eventually, Monteverde's successes forced the newly formed congress of the republic to ask Miranda that he sign a capitulation at La Victoria in Aragua, on July 12, 1812, thus ending the first phase of the revolutionary war. After the capitulation of 1812, Simón Bolívar turned over Francisco de Miranda to the Spanish authorities, secured a safe passage for himself and his closest officers, and fled to New Granada. He later returned with a new army, while the war had entered a tremendously violent phase. After much of the local aristocracy had abandoned the cause of independence, blacks and mulattoes carried on the struggle. Elites reacted with open distrust and opposition to the efforts of these common people. Bolívar's forces invaded Venezuela from New Granada in 1813, waging a campaign with a ferocity captured perfectly by their motto of "war to the death". Bolívar's forces defeated Domingo Monteverde's Spanish army in a series of battles, taking Caracas on August 6, 1813, and besieging Monteverde at Puerto Cabello in September 1813.  Battle of Carabobo With loyalists displaying the same passion and violence, the rebels achieved only short-lived victories. The army led by the loyalist José Tomás Boves demonstrated the key military role that the Llaneros came to play in the region's struggle. Turning the tide against independence, these highly mobile, ferocious fighters made up a formidable military force that pushed Bolívar out of his home country once more. In 1814, heavily reinforced Spanish forces in Venezuela lost a series of battles to Bolívar's forces but then decisively defeated Bolivar at La Puerta on June 15, took Caracas on July 16, and again defeated his army at Aragua on August 18, for 2,000 Spanish casualties out of 10,000 soldiers as well as most of the 3,000 in the rebel army. Bolívar and other leaders then returned to New Granada. Later that year the largest expeditionary force ever sent by Spain to America arrived under the command of Pablo Morillo. This force effectively replaced the improvised llanero units, who were disbanded by Morillo. Bolívar and other republican leaders returned to Venezuela in December 1816, leading a largely unsuccessful insurrection against Spain from 1816 to 1818 from bases in the Llanos and Ciudad Bolívar in the Orinoco River area. In 1819 Bolívar successfully invaded New Granada, and returned to Venezuela in April 1821, leading an army of 7,000. At Carabobo on June 24, his forces decisively defeated Spanish and colonial forces, winning Venezuelan independence, although hostilities continued. |

スペイン領アメリカ 詳細は「スペイン語圏諸国の独立戦争」を参照 詳細は「解放者たち」を参照  南北アメリカ大陸の独立年順の場所[矛盾] アメリカ合衆国は1867年まで大陸の領土拡大を完了せず、カナダは1982年まで独立国としての主権を確立しなかったことに留意されたい。  南米副王領のインテンデンシア(州)。 キューバとプエルトリコを除き、アメリカ大陸のスペイン植民地は19世紀の最初の4分の1の間に独立を達成した。 半島戦争中、ナポレオンは弟のジョセフ・ボナパルトをスペイン王位に就かせ、フェルナンド7世を捕虜にした。政治的正当性に対する危機は、スペインの海外 帝国に反発を引き起こした。1810年以降、クリオーリョ(スペイン人の血を引くラテンアメリカ人)によって複数の議会が設立され、カスティーリャ法に基 づく主権と自治を回復し、スペインのフェルナンド7世の名のもとにアメリカ大陸の土地を統治しようとした。 この自治の経験と、自由主義の影響、そしてフランス革命とアメリカ独立革命の理念が相まって、リベルタドーレスが主導する独立のための闘争がもたらされ た。 多くの場合、外国の傭兵や私掠船の支援を受けながら、各領土は独立を果たした。 アメリカ合衆国とヨーロッパは中立の立場を保っていたが、スペインの独占を排除して政治的影響力と貿易の獲得を目指していた。 南アメリカでは、シモン・ボリバルとホセ・デ・サン・マルティンが独立闘争の最終局面を主導した。ボリバルはスペイン語圏の大陸を政治的に統一しようとし たが、スペイン語圏の地域は急速に互いに独立し、パラグアイ戦争や太平洋戦争など、さらにいくつかの戦争が勃発した。 メキシコ独立戦争では、1810年から1821年にかけて、現在のメキシコ、中央アメリカ、北米の一部で同様の動きが起こった。1821年、アグスティ ン・デ・イトゥルビデと三権保証軍の連合により独立が達成された。第一メキシコ帝国のもとで短期間統一が維持されたが、10年以内にこの地域は国境地域を 巡ってアメリカ合衆国と戦い(カリフォルニア州とテキサス州の国境地帯を失った)。 最も激しい戦闘は、1846年から1848年にかけての公式な米墨戦争の期間中であった。 1898年、大アンティル諸島では、アメリカが米西戦争に勝利し、キューバとプエルトリコを占領し、アメリカ大陸におけるスペインの領土支配に終止符を 打った。 アルゼンチン 詳細は「アルゼンチンの独立戦争」を参照 半島戦争におけるスペインの敗北とフェルディナンド7世の退位により、現在のアルゼンチン、ボリビアの大部分、チリの一部、パラグアイ、ウルグアイを領有 していたリオ・デ・ラ・プラタ副王領のスペイン植民地政府は大幅に弱体化した。スペイン王位継承者が不在となり、副王の地位が正当性を失ったため、バルタ サル・イダルゴ・デ・シスネロス副王の統治権は批判にさらされることとなった。スペインの貿易制限や課税に嫌気がさしていた地元のエリート層は、1810 年の5月革命の機に乗じてシスネロスを追放し、初の地方自治政府であるプリメーラ・フンタを樹立した。  ホセ・デ・サン・マルティン アルゼンチン憲法は1853年に署名され、アルゼンチン共和国の建国が宣言された。 旧副王領内の王党派軍との5年にわたる戦闘や小競り合い、そしてホセ・デ・サン・マルティン将軍率いるアンデス山脈を越えたチリ、ペルー、ボリビアへの遠 征を経て、ついにスペインによるアメリカ支配に終止符が打たれた。1816年7月9日、サン・ミゲル・デ・トゥクマンでの会議により、正式な宣言書が署名 され、国家憲法の規定とともに完全な独立が宣言された。アルゼンチン共和国の建国を宣言するアルゼンチン憲法は1853年に署名された。 ボリビア 詳細は「ボリビア独立戦争」を参照 5月革命による動乱の後、チリとベネズエラにおける独立運動とともに、2度の革命の失敗を経て、ボリビアの独立を求める戦いが始まった。共和国樹立への第 一歩が踏み出されるまで、16年以上の戦いが続いた。 公式には、1824年12月9日のアヤクーチョの戦いで独立戦争が頂点に達したとされている。  ヨーロッパの植民地主義の衰退と南アメリカの政治的境界の変化、1700年~現在 コロンビア  ボヤカの戦いでコロンビアの独立が確定した 詳細は「パトリオ・ボバ」、「スペインによる新グラナダ再征服」、「ボリバルによる新グラナダ解放戦争」を参照 [icon] このセクションは空欄である。 追加して編集していただくと助かります。 (2020年8月) チリ 詳細は「チリの独立戦争」を参照 チリの独立運動は、ベルナルド・オヒギンズなどのチリ亡命者の支援を受けた解放将軍ホセ・デ・サン・マルティンが主導した。 地元の独立運動は、スペインからの政治的・経済的独立を求めたチリ生まれのクリオーリョたちによって構成されていた。独立運動はチリ人の間で満場一致の支 持を得るには程遠く、独立派と王党派に分裂した。植民地支配者に対するエリート主義的な政治運動として始まったものが、最終的には本格的な内戦として終結 した。伝統的に、この過程は3つの段階に分けられる。パトリア・ビエハ、レコンキスタ、パトリア・ヌエバである。 エクアドル 詳細は「エクアドル独立戦争」を参照 スペイン支配に対する最初の蜂起は1809年に起こり、1810年9月22日、エクアドルのクリオーリョたちはブルボン朝君主の名のもとに統治を行うこと を目的として軍事政権を樹立した。しかし、他の地域と同様に、それは彼らの権力の主張を許すこととなった。エクアドルは完全に独立を達成し、1830年に 脱退するまではグラン・コロンビアの一部となった。[8] 1822年5月24日、現在のエクアドル・キト近郊のピチンチャの戦いにおいて、アントニオ・ホセ・デ・スクレ将軍の軍勢がキトを守るスペイン軍を破っ た。スペインの敗北により、エクアドルの解放が確実となった。 グアテマラ 1821年、グアテマラ王国全体が平和的にスペインの支配下に入った。憲法制度による改革、報道の自由、そして国民選挙で誕生した政党の隆盛により、独立 支持の意見が広がった。 独立派の人々はグアテマラで会議を開いたが、政府に立ち向かうだけの資源は持っていなかった。彼らはイグアラの計画または独立の計画によってメキシコで達 成された進歩にすべてを託していた。同様に、独立派の人々はすべてがイトゥルビデが宣言した政府体制に賛成していたわけではなく、ましてやメキシコの王位 に就いた王朝に賛成していたわけではなかったが、当時は独立についてのみであり、各々が政府の形態について意見を保留していた。 9月13日、イグアラの計画を支持するチアパス州シウダー・レアル市および同州の他の町からの書簡がグアテマラに届いた。軍の進撃により、それまで王国で は政治的に重要視されていなかったチアパス州の宣言に勢いがついた。 グアテマラシティ評議会の受託者、マリアーノ・アシンネナ氏は、独立宣言を行うための請願を提出するために臨時会議の開催を要請した。 pp. 85–90.</ref>[9] メキシコ 詳細は「メキシコ独立戦争」を参照 メキシコの独立は、1808年から1821年の王政崩壊とメキシコ独立の確立までの長期にわたる闘争であった。 1808年、スペイン領ニュー・スペインでは、他のスペイン領アメリカと同様に、人々は予想外のフランスによるイベリア半島侵攻とブルボン朝王の追放に反 応し、ジョゼフ・ボナパルトが王位についた。アメリカ生まれのスペイン系住民たちは、おそらくはクレオールたちの希望に共感していたであろう副王ホセ・ デ・イトゥリガライから権力を奪取する好機と捉えた。イトゥリガライは王党派によって追放された。クレオールエリートの中には、フアン・アルダマ、イグナ シオ・アジェンデ、世俗派の教区司祭ミゲル・イダルゴ・イ・コスティージャなど、独立を求める者もいた。ヒダルゴは、当時文書には記録されなかったが、自 身の出身教区であるドロレスで宣言を行い、悪政とガチュピネス(スペイン本土生まれのスペイン人に対する蔑称)を非難し、独立を宣言した。ヒダルゴに従う 未組織の暴徒たちは、バヒオ地方の白人の財産と生活を破壊した。ヒダルゴは1811年に逮捕され、聖職を剥奪され、アジェンデとともに処刑された。彼らの 首は1821年まで展示されていた。彼の元生徒ホセ・マリア・モレロスは反乱を継続し、1815年に捕らえられ殺された。メキシコの反乱軍の闘争は、ビセ ンテ・ゲレロとグアダルーペ・ビクトリアの指導の下で継続した。1815年から1820年にかけて、ヌエバ・エスパーニャでは膠着状態が続き、王党派軍は 反乱軍を打ち負かすことができず、反乱軍は南部の狭い地域を越えて拡大することができなかった。再びスペインでの出来事が介入し、フェルディナンド7世に 対する軍人の反乱が起こり、1812年の自由主義スペイン憲法が復活した。この憲法は立憲君主制を義務付け、ローマ・カトリック教会の権力を制限するもの であった。1814年にスペイン王政が復活すると、君主は憲法を否定した。新スペインの保守派にとって、これらの政治情勢の変化は教会と国家の制度を脅か すものだった。王立軍将校のアグスティン・デ・イトゥルビデは、この機に乗じて、かつての敵であったゲレロと手を組み、指導者となった。イトゥルビデは、 独立、スペイン本土とアメリカ生まれのスペイン人の平等、スペイン出身の王子を国王とする君主制、国教としてのカトリックの擁護を掲げた「イグアラ計画」 を宣言した。[10]彼は、反乱軍のゲレロを説得して手を組み、三権保障軍を結成した。新スペインの最後の副王フアン・オドノヒューとイトゥルビデは、コ ルドバで条約を締結し、スペイン帝国からのメキシコの独立を承認した。1821年9月27日、イトゥルビデとオドノヒューは「3つの保証」軍とともにメキ シコシティに入城し、残存するスペイン軍は降伏した。[11] メキシコ王位に就くヨーロッパの君主が現れなかったため、イトゥルビデは1822年に自ら皇帝アグスティン1世を宣言した。彼は1823年に失脚し、メキ シコは共和国として樹立された。その後数十年にわたって政治と経済の不安定が続き、人口減少を招いた。 パラグアイ パラグアイは、フルヘンシオ・イェグロスやホセ・ガスパール・ロドリゲス・デ・フランシアを含む独立派の愛国者たちによる計画を経て、1811年5月14 日の夜から翌朝にかけて独立を達成した。 ペルー 詳細は「ペルー独立戦争」を参照  1821年7月28日、リマでペルーの独立を宣言するホセ・デ・サン・マルティンの絵画 スペインは当初、ブエノスアイレスとチリの商業的利益に反対する立場から、リマの寡頭制勢力の支援を受けていた。そのため、ペルー副王領は南アメリカにお けるスペイン王政の最後の砦となった。しかし、1812年にワヌコで、1814年から1816年にかけてクスコで、それぞれクレオール人の反乱が起こっ た。いずれも鎮圧された。これらの反乱はブエノスアイレスの軍隊に支援されていた。 ペルーは、ホセ・デ・サン・マルティン(1820年~1823年)とシモン・ボリバル(1824年)による大陸での決戦キャンペーンの後に、ついに降伏し た。サン・マルティンが陸上でのキャンペーンを指揮している間、コクラン卿が率いる新設のチリ海軍が戦闘部隊を輸送し、太平洋のスペイン艦隊に対して海上 キャンペーンを開始した。マイプの戦いの後チリの王党派を追放し、1820年にパラカスに上陸したサン・マルティンは、1821年7月28日にリマでペ ルーの独立を宣言した。それから4年後の1824年末、スペイン王政はアヤクーチョの戦いで決定的に敗北した。 独立後、ペルーのクリオール社会のさまざまなセクターが直面した利害の対立や、カウディージョたちの野望により、国の組織化は非常に困難なものとなった。 ペルー独立後の75年間で、マヌエル・パルド、ニコラス・デ・ピエローラ、フランシスコ・ガルシア・カルデロンの3人の文民のみが大統領に就任した。ボリ ビア共和国は、ペルーの上ペルー地域に誕生した。1837年にはペルー・ボリビア連合が誕生したが、チリの軍事介入により2年後に解散した。 ウルグアイ 1811年、5月革命の余波を受け、ホセ・ヘルバシオ・アーティガスが東方州(現在のウルグアイ)でスペイン軍に対する反乱を成功させ、当時リオ・デ・ ラ・プラタ副王領で起こっていた独立運動に加わった。1821年、東方州はプロビンシア・シスプラティーナの名のもとにブラジルに併合しようとしたポルト ガルに侵略された。 リオ・デ・ラ・プラタ副王領であったリオ・デ・ラ・プラタ連合州は、ブラジルに対して2年以上にわたって抵抗したが、結局は膠着状態に陥った。ブラジル軍 は連合州に撃退されながらも撤退し、決定的な勝利を収めることはできなかった。どちらの側も優勢に立つことができず、戦争による経済的負担が連合州の経済 を疲弊させたため、1828年にイギリスの仲介によりモンテビデオ条約が締結され、ウルグアイが独立国として宣言された。 ベネズエラ 詳細は「ベネズエラ独立戦争」、「ベネズエラ第一共和政」、および「ベネズエラ第二共和政」を参照 1865年の『エンサイクロペディア・アメリカーナ』によると、すでにフランス、プロイセン、イギリス、アメリカ合衆国の英雄となっていたフランシスコ・ デ・ミランダ将軍は、1808年から1812年の間、スペインに対して一連の成功を収めていた。彼はスペインがカリブ海のすべての港にアクセスするのを効 果的に阻止し、スペインが援軍や物資を受け取れないようにし、事実上、国内の掃討作戦を指揮していた。その時点で、彼はシモン・ボリバルを説得して戦いに 参加させ、プエルト・カベヨの要塞の指揮を任せることにした。ここは物資と武器の貯蔵庫であり、戦略的な港であり、スペイン人捕虜の中央収容施設でもあっ た。重大な職務怠慢ともいえる行為により、シモン・ボリーバルは社交の場に出かける前に、通常の安全対策を怠った。夜の間、スペイン人捕虜が蜂起し、彼ら は独立派の守備隊を制圧し、物資、武器、弾薬、港を掌握した。王党派軍は徐々に国の支配権を取り戻し、最終的にモンテベルデの成功により、新しく結成され た共和国議会はミランダに降伏を求め、1812年7月12日にアラグアのラ・ビクトリアで降伏調印が行われ、革命戦争の第一段階が終了した。 1812年の降伏後、シモン・ボリバルはフランシスコ・デ・ミランダをスペイン当局に引き渡し、自身と最も親しい士官たちの安全な通行を確保し、新グラナ ダに逃亡した。その後、彼は新たな軍隊とともに戻ってきたが、その頃には戦争はすさまじい暴力の段階に入っていた。地元の貴族階級の多くが独立運動から離 脱した後、黒人と混血の人々が闘争を続けた。エリート層は、こうした庶民の努力に対して公然と不信感と反対を示した。1813年、ボリバル軍は「死を賭け た戦い」というモットーに完璧に表されたような激しさで、ニューグラナダからベネズエラに侵攻した。ボリバル軍は一連の戦いでドミンゴ・モンテベルデ率い るスペイン軍を破り、1813年8月6日にはカラカスを占領し、1813年9月にはプエルト・カベヨでモンテベルデを包囲した。  カラボボの戦い 忠誠派も同様に情熱と暴力をむき出しにしたため、反乱軍は短命の勝利しか収めることができなかった。 忠誠派のホセ・トマス・ボーベスが率いる軍隊は、この地域の闘争において、リャネロスが果たすことになる重要な軍事的役割を示した。 独立派に逆風が吹き荒れる中、機動力に優れ、獰猛な戦士たちで構成されたこの軍隊は、ボリーバルを再び祖国から追い出す強大な軍事力を形成した。1814 年、ベネズエラで大幅に増強されたスペイン軍は、ボリバル軍に一連の戦いで敗北を喫したが、6月15日にラ・プエルタでボリバルを打ち負かし、7月16日 にはカラカスを占領、8月18日にはアラグアで再びボリバル軍を打ち負かした。スペイン軍の死傷者は1万人中2,000人、反乱軍の死傷者は3,000人 中ほとんどであった。その後、ボリーバルと他の指導者たちは、ニューグラナダに戻った。その年の後半、スペインがアメリカ大陸に派遣した史上最大の遠征軍 が、パブロ・モリージョの指揮下に到着した。この軍勢は、モリージョによって解散させられた即席のチャノ族部隊に取って代わるものとなった。 ボリーバルとその他の共和制指導者たちは1816年12月にベネズエラに戻り、1816年から1818年にかけてオリノコ川流域のラノスとシウダー・ボリ バルを拠点に、スペインに対するほとんど成功しなかった反乱を主導した。 1819年、ボリバルはニューグラナダへの侵攻に成功し、1821年4月には7,000人の軍勢を率いてベネズエラに戻った。カラボボの戦い(6月24 日)で、彼の軍勢はスペイン軍と植民地軍を打ち破り、ベネズエラの独立を勝ち取ったが、戦闘はその後も続いた。 |

| Brazil Main article: Independence of Brazil Prince Pedro in São Paulo after giving the news of the Brazilian independence on 7 September 1822 Unlike the Spanish, the Portuguese did not divide their colonial territory in the Americas. The captaincies they created were subdued to a centralized administration in Salvador which reported directly to the Crown in Lisbon. Therefore, it is not common to refer to "Portuguese America" (like Spanish America, Dutch America, etc.), but rather to Brazil, as a unified colony since its very beginnings. As a result, Brazil did not split into several states by the time of independence (1822), as happened to its Spanish-speaking neighbors. The adoption of a monarchy instead of a federal republic in the first six decades of Brazilian political sovereignty also contributed to the nation's unity. [citation needed] After several failed revolts in the Portuguese colony, Dom Pedro I (also Pedro IV of Portugal), son of the Portuguese king Dom João VI, proclaimed the country's independence in 1822 and became Brazil's first Emperor. This began when Napoleon Bonaparte forced the Portuguese court out of their capital city of Lisbon and into exile in Brazil. Over the next eight years, the capital of the Portuguese empire would be located in Rio de Janeiro. In 1815, after Lisbon was reclaimed from the French by the Portuguese, King Dom João VI declared that Rio and Lisbon would become equal centers of the empire. King João VI was forced back to Lisbon in 1821 by the Portuguese Cortes but left his son Dom Pedro behind to run Rio. A year later, Dom Pedro declared independence for Brazil and officially became emperor Pedro I. Although Brazil's independence was met with little resistance from Portugal, several small-scale battles were fought against Portuguese loyalist forces until 1824 to bring the rest of the Brazilian territories under the control of the new Brazilian government, and they were officially recognized by their former colonial overlords in 1825. [13] Canada Main article: Canadian Confederation Canada's transition from colonial rule to independence occurred gradually over many decades and was achieved mostly through political means, as opposed to the violent revolutions that marked the end of colonialism in other North and South American countries. Attempts at revolting against the British, such as the Rebellions of 1837–1838, were brief and quickly put down. Canada was declared a dominion within the British Empire in 1867. Originally, the Canadian Confederation included just a few of what are now Canada's eastern provinces; other British colonies in modern-day Canada, such as British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland, would join later (the last only in 1949). Additionally, Britain's and Norway's claims to Arctic lands were ceded to Canada in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By 1931, the United Kingdom had relinquished its control over Canada's foreign policy. What few political links that remained between Canada and the UK were formally severed in 1982 with the Canada Act. |

ブラジル 詳細は「ブラジルの独立」を参照 1822年9月7日、サンパウロのペドロ王子がブラジル独立の知らせを伝えた スペイン人とは異なり、ポルトガル人はアメリカ大陸の植民地を分割統治することはなかった。彼らが作った総督領は、リスボン王家に直接報告するサルバドー ルに置かれた中央政府に従属した。そのため、「ポルトガル領アメリカ」(スペイン領アメリカ、オランダ領アメリカなど)という表現は一般的ではなく、むし ろ当初から統一された植民地としてブラジルと呼ばれている。 その結果、ブラジルは独立(1822年)の時点で、スペイン語圏の近隣諸国のようにいくつかの国家に分裂することはなかった。ブラジルの政治的主権の最初 の60年間において、連邦共和国ではなく君主制が採用されたことも、国家の統一に貢献した。[要出典] ポルトガル植民地で何度か反乱が失敗した後、ポルトガル王ドン・ジョアン6世の息子ドン・ペドロ1世(ポルトガル王ペドロ4世)が1822年にブラジルの 独立を宣言し、ブラジル初代皇帝となった。これは、ナポレオン・ボナパルトがポルトガル王室を首都リスボンから追放し、ブラジルに亡命させたことから始 まった。その後8年間、ポルトガル帝国の首都はリオ・デ・ジャネイロに置かれることとなった。1815年、ポルトガルがフランスからリスボンを奪還した 後、ドン・ジョアン6世はリオとリスボンを帝国の対等な中心地とすると宣言した。ジョアン6世は1821年にポルトガル議会によってリスボンへの帰還を余 儀なくされたが、リオの統治を息子ドン・ペドロに委ねた。1年後、ドン・ペドロはブラジルの独立を宣言し、正式にペドロ1世として即位した。ブラジルの独 立はポルトガルからの抵抗はほとんどなかったが、1824年までポルトガル王党派軍との小規模な戦闘がいくつか起こり、ブラジル政府が残りのブラジル領土 を支配下に置くまで続いた。そして、1825年に旧宗主国によって正式に承認された。[13] カナダ 詳細は「カナダ連邦」を参照 カナダの植民地支配から独立への移行は、数十年にわたって徐々に起こり、他の北米や南米諸国における植民地主義の終焉を告げた暴力的な革命とは対照的に、 主に政治的な手段によって達成された。1837年から1838年にかけての反乱など、イギリスに対する反乱の試みは短期間で鎮圧された。1867年、カナ ダは大英帝国内の自治領(ドミニオン)として宣言された。当初、カナダ連邦には現在のカナダ東部の州の一部のみが含まれていた。現在のカナダにある他のイ ギリス植民地、ブリティッシュコロンビア州、プリンスエドワードアイランド州、ニューファンドランド州などは、後に加わった(ニューファンドランド州は 1949年のみ)。さらに、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、イギリスとノルウェーが主張していた北極圏の土地がカナダに割譲された。1931年ま でに、イギリスはカナダの外交政策に対する支配権を放棄した。カナダとイギリスとの間にわずかに残っていた政治的なつながりは、1982年のカナダ法に よって正式に断絶された。 |

| 20th century |

20世紀(省略) |

|

|

| World reaction [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) United States and Great Britain Great Britain and the United States were rivals for influence in the newly independent sovereign nations.[26] As a result of the successful revolutions which established so many newly independent nations, United States President James Monroe and the Secretary of State John Quincy Adams drafted the Monroe Doctrine.[citation needed] It stated that the United States would not tolerate any European interference in the Western Hemisphere. This measure ostensibly was taken to safeguard the newfound liberties of these new countries, but it was also taken as a precautionary measure against the intrusion of European states.[citation needed] Since the United States was a newly founded nation, it could not prevent other European powers from interfering, for that the United States looked for Britain's help and support to execute the Monroe Doctrine into action. Great Britain's trade with Latin America greatly expanded during the revolutionary period, which until then was restricted due to Spanish mercantilist trade policies. British pressure was sufficient to prevent Spain from attempting any serious reassertion of its control over its lost colonies. Attempts at hemispheric unity Main article: Latin American integration The notion of closer Spanish American cooperation and unity was first put forward by the Liberator Simón Bolívar who, in 1826 Congress of Panama, proposed the creation of a league of American republics, with a common military, a mutual defense pact, and a supranational parliamentary assembly. This meeting was attended by representatives of Gran Colombia (comprising the modern-day nations of Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela), Peru, the United Provinces of Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica), and Mexico. Nevertheless, the great distances and geographical barriers, not to mention the different national and regional interests, made union impossible. Sixty-three years later the Commercial Bureau of the American Republics was established. It was renamed the International Commercial Bureau at the Second International Conference of 1901–1902. These two bodies, in existence as of 14 April 1890, represent the point of inception of today's Organization of American States. |

世界の反応 [icon] この節は拡大が必要である。 あなたも追加して手伝える。 (June 2008) アメリカ合衆国とイギリス イギリスとアメリカ合衆国は、新たに独立した主権国家における影響力を巡ってライバル関係にあった。[26] 多くの新たな独立国家を樹立した革命の成功の結果、アメリカ合衆国大統領ジェームズ・モンローと国務長官ジョン・クィンシー・アダムズはモンロー主義を起 草した。[要出典] それには、アメリカ合衆国は西半球におけるヨーロッパの干渉を一切容認しないことが明記されていた。この措置は、表向きにはこれらの新興国の新しく獲得し た自由を守るために取られたが、ヨーロッパ諸国の侵入に対する予防措置としても取られた。[要出典] アメリカ合衆国は新興国であったため、他のヨーロッパ諸国の干渉を防ぐことはできず、そのためアメリカ合衆国はモンロー主義を実行に移すためにイギリスの 支援と支持を求めた。 スペインの重商主義的な貿易政策により制限されていたラテンアメリカとの貿易は、革命期に大きく拡大した。英国の圧力は、スペインが失った植民地に対する 支配を再び主張するのを防ぐのに十分であった。 南北アメリカ大陸の統一への試み 詳細は「ラテンアメリカ統合」を参照 スペイン語圏アメリカ諸国の緊密な協力と統一という概念は、解放者シモン・ボリバルが1826年のパナマ会議で、共通の軍隊、相互防衛条約、超国家的な議 会を持つアメリカ共和国連合の創設を提案したときに初めて提唱された。この会議には、グラン・コロンビア(現在のコロンビア、エクアドル、パナマ、ベネズ エラ)、ペルー、中央アメリカ連合(グアテマラ、エルサルバドル、ホンジュラス、ニカラグア、コスタリカ)、メキシコの代表が参加した。しかし、大きな距 離と地理的な障壁、そして言うまでもなく国家や地域ごとの利害の相違により、連合は不可能であった。 それから63年後、米州商業会議所が設立された。1901年から1902年にかけて開催された第2回国際会議で、国際商業会議所に改称された。1890年 4月14日に設立されたこれら2つの機関が、現在の米州機構の始まりである。 |

| Colonialism Decolonization Wars of national liberation Predecessors of sovereign states in South America Creole nationalism Spanish Empire Libertadores Spanish reconquest of Mexico Spanish American Royalists Wars of national liberation History of Central America History of South America History of Cuba History of the Dominican Republic History of Puerto Rico Age of Revolution Territorial evolution of the Caribbean Spanish American wars of independence |

植民地主義 脱植民地化 民族解放戦争 南米における主権国家の先駆者 クレオール民族主義 スペイン帝国 リベルタドール スペインによるメキシコ再征服 スペイン系アメリカ人の王党派 民族解放戦争 中米の歴史 南米の歴史 キューバの歴史 ドミニカ共和国の歴史 プエルトリコの歴史 革命の時代 カリブ海地域の領土変遷 スペイン系アメリカ独立戦争 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decolonization_of_the_Americas |

Juan Manuel Blanes, The Paraguayan Woman, 1879, National Museum of Visual Arts of Uruguay, Montevideo.

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆