神・神格

Deity

☆神(deity or god)

とは、宇宙や生命の何らかの側面に対する権威を持つため、神聖であり崇拝に値すると考えられる超自然的な存在である。[1][2]

オックスフォード英語辞典は神を「神または女神、あるいは神聖と崇められるあらゆるもの」と定義する。[3]

C・スコット・リトルトンは神を「普通の人間よりも大きな力を持つ存在であり、人間と積極的にあるいは否定的に関わり、人間を日常の現実的な関心事を超え

た新たな意識の段階へと導く」と定義する。[4]

宗教は崇拝する神々の数によって分類できる。一神教は唯一の神(主に「神」と呼ばれる)のみを認める[5][6]。一方、多神教は複数の神々を認める

[7]。一神一神教は他の神々を否定せず、それらを同一の神聖な原理の側面と見なす最高神を認める。[8][9]

無神論的宗教は、至高の永遠の創造主神を否定するが、他の存在と同様に生と死を経験し、再生する可能性のある神々の集合体を認める場合がある。[10]:

35–37 [11]: 357–358

一神教の多くは伝統的に、その神を全能・遍在・全知・全善・永遠の存在と想定する[12][13]。しかしこれらの性質はいずれも「神」の定義に必須では

ない[14][15][16]。様々な文化圏で神々の概念は異なる。一神教は通常、神を男性的な表現で指すが、他の宗教では神々を様々な方法で表現する

——男性、女性、両性具有、あるいは性別を持たない形でだ。[21]

多くの文化——古代メソポタミア、エジプト、ギリシャ、ローマ、ゲルマン民族など——は自然現象を擬人化し、意図的な原因または結果として多様な形で表現

してきた。[22][23][24] アヴェスターやヴェーダの神々の中には倫理的概念と見なされたものもあった。[22][23]

インドの宗教では、神々はあらゆる生き物の身体という神殿の中に、感覚器官や心として顕現すると考えられてきた。[25][26][27]

神々は、倫理的な生活を通じて功徳を得た人間が転生後の存在形態(輪廻)として描かれる。彼らは守護神となり天国で幸福に暮らす一方、功徳を失えば死の運

命にも晒される。[10]: 35–38 [11]: 356–359

[10]: 35–38 [11]: 356–359

| A deity or god is a

supernatural being considered to be sacred and worthy of worship due to

having authority over some aspect of the universe and/or life.[1][2]

The Oxford Dictionary of English defines deity as a god or goddess, or

anything revered as divine.[3] C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a

being with powers greater than those of ordinary humans, but who

interacts with humans, positively or negatively, in ways that carry

humans to new levels of consciousness, beyond the grounded

preoccupations of ordinary life".[4] Religions can be categorized by how many deities they worship. Monotheistic religions accept only one deity (predominantly referred to as "God"),[5][6] whereas polytheistic religions accept multiple deities.[7] Henotheistic religions accept one supreme deity without denying other deities, considering them as aspects of the same divine principle.[8][9] Nontheistic religions deny any supreme eternal creator deity, but may accept a pantheon of deities which live, die and may be reborn like any other being.[10]: 35–37 [11]: 357–358 Although most monotheistic religions traditionally envision their god as omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, omnibenevolent, and eternal,[12][13] none of these qualities are essential to the definition of a "deity"[14][15][16] and various cultures have conceptualized their deities differently.[14][15] Monotheistic religions typically refer to their god in masculine terms,[17][18]: 96 while other religions refer to their deities in a variety of ways—male, female, hermaphroditic, or genderless.[19][20][21] Many cultures—including the ancient Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Germanic peoples—have personified natural phenomena, variously as either deliberate causes or effects.[22][23][24] Some Avestan and Vedic deities were viewed as ethical concepts.[22][23] In Indian religions, deities have been envisioned as manifesting within the temple of every living being's body, as sensory organs and mind.[25][26][27] Deities are envisioned as a form of existence (Saṃsāra) after rebirth, for human beings who gain merit through an ethical life, where they become guardian deities and live blissfully in heaven, but are also subject to death when their merit is lost.[10]: 35–38 [11]: 356–359 |

神とは、宇宙や生命の何らかの側面に対する権威を持つため、神聖であり

崇拝に値すると考えられる超自然的な存在である。[1][2]

オックスフォード英語辞典は神を「神または女神、あるいは神聖と崇められるあらゆるもの」と定義する。[3]

C・スコット・リトルトンは神を「普通の人間よりも大きな力を持つ存在であり、人間と積極的にあるいは否定的に関わり、人間を日常の現実的な関心事を超え

た新たな意識の段階へと導く」と定義する。[4] 宗教は崇拝する神々の数によって分類できる。一神教は唯一の神(主に「神」と呼ばれる)のみを認める[5][6]。一方、多神教は複数の神々を認める [7]。一神一神教は他の神々を否定せず、それらを同一の神聖な原理の側面と見なす最高神を認める。[8][9] 無神論的宗教は、至高の永遠の創造主神を否定するが、他の存在と同様に生と死を経験し、再生する可能性のある神々の集合体を認める場合がある。[10]: 35–37 [11]: 357–358 一神教の多くは伝統的に、その神を全能・遍在・全知・全善・永遠の存在と想定する[12][13]。しかしこれらの性質はいずれも「神」の定義に必須では ない[14][15][16]。様々な文化圏で神々の概念は異なる。一神教は通常、神を男性的な表現で指すが、他の宗教では神々を様々な方法で表現する ——男性、女性、両性具有、あるいは性別を持たない形でだ。[21] 多くの文化——古代メソポタミア、エジプト、ギリシャ、ローマ、ゲルマン民族など——は自然現象を擬人化し、意図的な原因または結果として多様な形で表現 してきた。[22][23][24] アヴェスターやヴェーダの神々の中には倫理的概念と見なされたものもあった。[22][23] インドの宗教では、神々はあらゆる生き物の身体という神殿の中に、感覚器官や心として顕現すると考えられてきた。[25][26][27] 神々は、倫理的な生活を通じて功徳を得た人間が転生後の存在形態(輪廻)として描かれる。彼らは守護神となり天国で幸福に暮らす一方、功徳を失えば死の運 命にも晒される。[10]: 35–38 [11]: 356–359 |

| Etymology Main articles: Dyeus, Deus, God (word), and Deva (Hinduism) The English language word deity derives from Old French deité,[28][page needed] the Latin deitatem (nominative deitas) or "divine nature", coined by Augustine of Hippo from deus ("god"). Deus is related through a common Proto-Indo-European (PIE) origin to *deiwos.[29] This root yields the ancient Indian word Deva meaning "to gleam, a shining one", from *div- "to shine", as well as Greek dios "divine" and Zeus; and Latin deus "god" (Old Latin deivos).[30][31][32]: 230–31 Deva is masculine, and the related feminine equivalent is devi.[33]: 496 Etymologically, the cognates of Devi are Latin dea and Greek thea.[34] In Old Persian, daiva- means "demon, evil god",[31] while in Sanskrit it means the opposite, referring to the "heavenly, divine, terrestrial things of high excellence, exalted, shining ones".[33]: 496 [35][36] The closely linked term "god" refers to "supreme being, deity", according to Douglas Harper,[37] and is derived from Proto-Germanic *guthan, from PIE *ghut-, which means "that which is invoked".[32]: 230–231 Guth in the Irish language means "voice". The term *ghut- is also the source of Old Church Slavonic zovo ("to call"), Sanskrit huta- ("invoked", an epithet of Indra), from the root *gheu(e)- ("to call, invoke."),[37] An alternate etymology for the term "god" comes from the Proto-Germanic Gaut, which traces it to the PIE root *ghu-to- ("poured"), derived from the root *gheu- ("to pour, pour a libation"). The term *gheu- is also the source of the Greek khein "to pour".[37] Originally the word "god" and its other Germanic cognates were neuter nouns but shifted to being generally masculine under the influence of Christianity in which the god is typically seen as male.[32]: 230–231 [37] In contrast, all ancient Indo-European cultures and mythologies recognized both masculine and feminine deities.[36] |

語源 主な記事:ダイウス、デウス、神(語)、デーヴァ(ヒンドゥー教) 英語の「deity」は古フランス語の「deité」[28][ページ必要]、ラテン語の「deitatem」(主格「deitas」)すなわち「神性」 に由来する。これはヒッポのアウグスティヌスが「deus」(神)から造語したものである。デウスは、共通のインド・ヨーロッパ祖語(PIE)起源である *deiwos[29]と関連している。この語根は、古代インドのデヴァ(「輝く、輝く者」を意味する)を生み出した。これは*div-(「輝く」)に由 来し、ギリシャ語のディオス(「神聖な」)やゼウス、ラテン語のデウス(「神」:古ラテン語ではdeivos)も派生語である。[30][31] [32]: 230–31 デーヴァは男性形であり、関連する女性形はデーヴィである。[33]: 496 語源的には、デーヴィの同根語はラテン語のデアとギリシャ語のテーアである。[34] 古代ペルシア語ではdaiva-は「悪魔、邪神」を意味する[31]が、サンスクリット語ではその反対を意味し、「天上の、神聖な、地上における卓越し た、崇高な、輝く存在」を指す[33]: 496 [35][36] 密接に関連する用語「神」は、ダグラス・ハーパーによれば「至高の存在、神格」を指す[37]。これは原ゲルマン語*guthanに由来し、さらに PIE*ghut-(呼び出されるもの)に遡る[32]:230–231。アイルランド語のguthは「声」を意味する。*ghut-という語源は、古教 会スラヴ語のzovo(「呼ぶ」)、サンスクリットのhuta-(「呼び出された」、インドラの称号)の源でもあり、これらは*gheu(e)-(「呼 ぶ、呼び出す」)という語根に由来する。[37] 「神」という語の別の語源説は、プロト・ゲルマン語のガウトに由来する。これはPIE語根*ghu-to-(「注がれた」)に遡り、語根*gheu- (「注ぐ、献酒を注ぐ」)から派生したものである。*gheu-はギリシャ語のkhein(「注ぐ」)の語源でもある。[37] もともと「神」という言葉と他のゲルマン語派の同根語は中性名詞だったが、神を男性と見る傾向が強いキリスト教の影響で、一般に男性名詞へと変化した。 [32]: 230–231 [37] これに対し、古代のインド・ヨーロッパ語族の文化や神話では、男性神と女性神の両方が認識されていた。[36] |

Definitions Pantheists believe that the universe itself and everything in it forms a single, all-encompassing deity.[38][39] There is no universally accepted consensus on what a deity is, and concepts of deities vary considerably across cultures.[18]: 69–74 [40] Huw Owen states that the term "deity or god or its equivalent in other languages" has a bewildering range of meanings and significance.[41]: vii–ix It has ranged from "infinite transcendent being who created and lords over the universe" (God), to a "finite entity or experience, with special significance or which evokes a special feeling" (god), to "a concept in religious or philosophical context that relates to nature or magnified beings or a supra-mundane realm", to "numerous other usages".[41]: vii–ix A deity is typically conceptualized as a supernatural or divine concept, manifesting in ideas and knowledge, in a form that combines excellence in some or all aspects, wrestling with weakness and questions in other aspects, heroic in outlook and actions, yet tied up with emotions and desires.[42][43] In other cases, the deity is a principle or reality such as the idea of "soul". The Upanishads of Hinduism, for example, characterize Atman (soul, self) as deva (deity), thereby asserting that the deva and eternal supreme principle (Brahman) is part of every living creature, that this soul is spiritual and divine, and that to realize self-knowledge is to know the supreme.[44][45][46] Theism is the belief in the existence of one or more deities.[47][48] Polytheism is the belief in and worship of multiple deities,[49] which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, with accompanying rituals.[49] In most polytheistic religions, the different gods and goddesses are representations of forces of nature or ancestral principles, and can be viewed either as autonomous or as aspects or emanations of a creator God or transcendental absolute principle (monistic theologies), which manifests immanently in nature.[49] Henotheism accepts the existence of more than one deity, but considers all deities as equivalent representations or aspects of the same divine principle, the highest.[9][50][8][51] Monolatry is the belief that many deities exist, but that only one of these deities may be validly worshipped.[52][53] Monotheism is the belief that only one deity exists.[54][55][56][57][58][59][60][excessive citations] A monotheistic deity, known as "God", is usually described as omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, omnibenevolent and eternal.[61] However, not all deities have been regarded this way[14][16][62][63] and an entity does not need to be almighty, omnipresent, omniscient, omnibenevolent or eternal to qualify as a deity.[14][16][62] Deism is the belief that only one deity exists, who created the universe, but does not usually intervene in the resulting world.[64][65][66][page needed] Deism was particularly popular among western intellectuals during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[67][68] Pantheism is the belief that the universe itself is God[38] or that everything composes an all-encompassing, immanent deity.[39] Pandeism is an intermediate position between these, proposing that the creator became a pantheistic universe.[69] Panentheism is the belief that divinity pervades the universe, but that it also transcends the universe.[70] Agnosticism is the position that it is impossible to know for certain whether a deity of any kind exists.[71][72][73] Atheism is the non-belief in the existence of any deity.[74] |

定義 汎神論者は、宇宙そのものとそこに存在する全てのものが、単一の包括的な神格を成すと信じる。[38][39] 神とは何かについて普遍的に受け入れられた合意はなく、神々の概念は文化によって大きく異なる。[18]: 69–74 [40] ヒュー・オーウェンは「神、あるいは他の言語における同等の概念」という用語が、驚くほど多様な意味と重要性を持つと述べている。[41]: vii–ix その範囲は「宇宙を創造し支配する無限の超越的存在」(神)から、「特別な意義を持つ、あるいは特別な感情を喚起する有限の存在や経験」(神)、「自然や 拡大された存在、あるいは超世俗的な領域に関連する宗教的・哲学的文脈における概念」、さらには「その他多数の使用法」にまで及ぶ。[41]: vii–ix 神は通常、超自然的あるいは神聖な概念として概念化される。それは思想や知識の中に現れ、ある側面あるいは全ての側面において卓越性を備えつつ、他の側面 では弱さや疑問と格闘し、英雄的な見解と行動を持ちながらも、感情や欲望と結びついている。[42][43] 他の場合、神は「魂」の概念のような原理や実体である。例えばヒンドゥー教のウパニシャッドは、アートマン(魂、自己)をデーヴァ(神)と特徴づけ、それ によってデーヴァと永遠の至高原理(ブラフマン)があらゆる生き物の一部であり、この魂が精神的かつ神聖であり、自己認識を実現することが至高を知ること に等しいと主張する。[44][45][46] 有神論とは、一つ以上の神々の存在を信じる思想である。[47][48] 多神教とは、複数の神々を信じ崇拝する思想であり、[49] それらは通常、神々と女神たちの神殿に集められ、それに伴う儀礼が行われる。[49] 多くの多神教では、異なる神々は自然の力や祖先の原理を表しており、自律的な存在として、あるいは創造主神や超越的絶対原理(一神論的神学)の側面・発現 として見なされる。この原理は自然の中に内在的に顕現する。一神教は唯一の神の存在を信じる。[52][53] 一神教の神は「神」として知られる。 一神教は唯一の神のみが存在するとする信仰である。[54][55][56][57][58][59][60][過剰な引用]「神」として知られる一神教 の神は、通常、全能・遍在・全知・全善・永遠の存在として描写される。[61] ただし、全ての神々がこのように見なされてきたわけではない [14][16][62][63] また、実体が全能・遍在・全知・全善・永遠である必要は、神格として認められる条件ではない。[14][16][62] 自然神論とは、唯一の神が宇宙を創造したが、通常はその結果として生まれた世界には介入しないという信念である。[64][65][66][ページ必要] デイズムは18世紀から19世紀にかけて西洋の知識人の間で特に流行した[67][68]。汎神論は宇宙そのものが神である[38]、あるいは万物が包括 的で内在的な神性を構成するという信念である[39]。汎神論と汎神論の中間的な立場である汎神論は、創造主が汎神論的な宇宙へと変化したと主張する。汎 神論は、神性が宇宙に遍在するが、同時に宇宙を超越しているという信念である[70]。不可知論は、いかなる神の存在も確実に知ることは不可能だという立 場である[71][72][73]。無神論は、いかなる神の存在も信じないことである[74]。 |

Prehistoric Statuette of a nude, corpulent, seated woman flanked by two felines from Çatalhöyük, dating to c. 6000 BCE, thought by most archaeologists to represent a goddess of some kind[75][76] Further information: Prehistoric religion Scholars infer the probable existence of deities in the prehistoric period from inscriptions and prehistoric arts such as cave drawings, but it is unclear what these sketches and paintings are and why they were made.[77] Some engravings or sketches show animals, hunters or rituals.[78] It was once common for archaeologists to interpret virtually every prehistoric female figurine as a representation of a single, primordial goddess, the ancestor of historically attested goddesses such as Inanna, Ishtar, Astarte, Cybele, and Aphrodite;[79] this approach has now generally been discredited.[79] Modern archaeologists now generally recognize that it is impossible to conclusively identify any prehistoric figurines as representations of any kind of deities, let alone goddesses.[79] Nonetheless, it is possible to evaluate ancient representations on a case-by-case basis and rate them on how likely they are to represent deities.[79] The Venus of Willendorf, a female figurine found in Europe and dated to about 25,000 BCE has been interpreted by some as an exemplar of a prehistoric female deity.[78] A number of probable representations of deities have been discovered at 'Ain Ghazal[79] and the works of art uncovered at Çatalhöyük reveal references to what is probably a complex mythology.[79] |

先史時代 カタールホイユク出土の裸体の肥満した座った女性の小像。両脇に二匹のネコ科動物が配置されている。紀元前6000年頃のものとされ、多くの考古学者によって何らかの女神を表すと考えられている[75] [76] 詳細情報:先史時代の宗教 学者たちは、洞窟壁画などの先史時代の芸術や碑文から、先史時代に神々が存在した可能性を推測している。しかし、これらの素描や絵画が何であり、なぜ制作 されたのかは不明である。[77] 動物や狩人、儀礼の描写を示す彫刻やスケッチも存在する。[78] かつて考古学者たちは、ほぼ全ての先史時代の女性像を単一の原始的な女神の表現と解釈するのが通例であった。その女神は、イナンナ、イシュタル、アスタル テ、キュベレー、アフロディーテといった歴史的に確認された女神たちの祖先とされる。[79] しかしこの解釈は現在では概ね否定されている。[79] 現代の考古学者は概ね、先史時代の置物をいかなる神々の表現とも断定的に特定することは不可能だと認識している。ましてや女神などなおさらだ。[79] とはいえ、古代の表現を個別に評価し、神々を表している可能性の度合いを評価することは可能である。[79] ヨーロッパで発見され紀元前25,000年頃と推定される女性像「ヴィレンドルフのヴィーナス」は、先史時代の女性神々の典型例と解釈する学者もいる。 [78] アイン・ガザルでは複数の神々の表現と推定される遺物が発見されており[79]、チャタル・ヒュユクで出土した芸術作品には、おそらく複雑な神話体系への 言及が示されている。[79] |

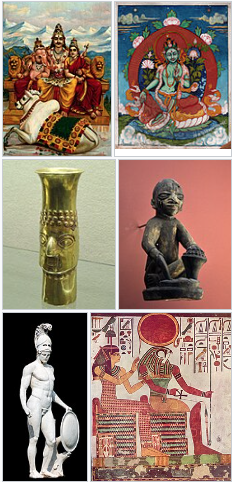

| Religions and cultures Sub-Saharan African Main articles: List of African mythological figures, Traditional African religion, Afro-American religion, and Orisha  Yoruba deity from Nigeria Diverse African cultures developed theology and concepts of deities over their history. In Nigeria and neighboring West African countries, for example, two prominent deities (locally called Òrìṣà)[80] are found in the Yoruba religion, namely the god Ogun and the goddess Osun.[80] Ogun is the primordial masculine deity as well as the archdivinity and guardian of occupations such as tools making and use, metal working, hunting, war, protection and ascertaining equity and justice.[81][82] Osun is an equally powerful primordial feminine deity and a multidimensional guardian of fertility, water, maternal, health, social relations, love and peace.[80] Ogun and Osun traditions were brought into the Americas on slave ships. They were preserved by the Africans in their plantation communities, and their festivals continue to be observed.[80][81] In Southern African cultures, a similar masculine-feminine deity combination has appeared in other forms, particularly as the Moon and Sun deities.[83] One Southern African cosmology consists of Hieseba or Xuba (deity, god), Gaune (evil spirits) and Khuene (people). The Hieseba includes Nladiba (male, creator sky god) and Nladisara (females, Nladiba's two wives). The Sun (female) and the Moon (male) deities are viewed as offspring of Nladiba and two Nladisara. The Sun and Moon are viewed as manifestations of the supreme deity, and worship is timed and directed to them.[84] In other African cultures the Sun is seen as male, while the Moon is female, both symbols of the godhead.[85]: 199–120 In Zimbabwe, the supreme deity is androgynous with male-female aspects, envisioned as the giver of rain, treated simultaneously as the god of darkness and light and is called Mwari Shona.[85]: 89 In the Lake Victoria region, the term for a deity is Lubaale, or alternatively Jok.[86] |

宗教と文化 サハラ以南のアフリカ 主な記事:アフリカの神話上の人物のリスト、伝統的なアフリカの宗教、アフリカ系アメリカ人の宗教、オリッシュ  ナイジェリアのヨルバ神 多様なアフリカの文化は、その歴史の中で神学と神々の概念を発展させてきた。例えばナイジェリアや近隣の西アフリカ諸国では、ヨルバ宗教において二つの顕 著な神々(現地ではオリシャと呼ばれる)が存在する。すなわち神オグンと女神オスンである。オグンは原初の男性神であると同時に、道具の製作・使用、金属 加工、狩猟、戦争、保護、公平と正義の確立といった職業の守護神であり、最高神でもある。[81][82] オスンは同様に強力な原始的な女性神であり、豊穣、水、母性、健康、社会関係、愛、平和の多面的な守護神である。[80] オグンとオスンの信仰は奴隷船によってアメリカ大陸に持ち込まれた。アフリカ系住民はプランテーション共同体でこれらの信仰を守り続け、祭りは現在も執り 行われている。[80][81] 南部アフリカの文化では、同様の男性的・女性的神格の組み合わせが他の形態、特に月と太陽の神々として現れている。[83] 南部アフリカの宇宙観の一つは、ヒエバまたはクスバ(神格、神)、ガウネ(悪霊)、クウェネ(人民)で構成される。ヒエバには、ンラディバ(男性、創造主 である天空神)とンラディサラ(女性、ンラディバの二人の妻)が含まれる。太陽(女性)と月(男性)の神々は、ンラディバと二人のンラディサラの子孫と見 なされる。太陽と月は至高神の実体化とされ、崇拝はそれらに向けられ、時期も定められる。[84] 他のアフリカ文化では、太陽は男性、月は女性とされ、どちらも神性の象徴である。[85]: 199–120 ジンバブエでは、最高神は男女両性の特徴を持つ両性具有であり、雨をもたらす存在として想像される。同時に闇と光の神として扱われ、ムワリ・ショナと呼ば れる。[85]: 89 ビクトリア湖地域では、神を指す用語はルバアレ、あるいは別の呼び名としてジョクである。[86] |

| Ancient Near Eastern Main article: Religions of the ancient Near East Egyptian Main articles: Ancient Egyptian deities, Egyptian mythology, and Ancient Egyptian religion  Egyptian tomb painting showing the gods Osiris, Anubis, and Horus, who are among the major deities in ancient Egyptian religion[87] Ancient Egyptian culture revered numerous deities. Egyptian records and inscriptions list the names of many whose nature is unknown and make vague references to other unnamed deities.[88]: 73 Egyptologist James P. Allen estimates that more than 1,400 deities are named in Egyptian texts,[89] whereas Christian Leitz offers an estimate of "thousands upon thousands" of Egyptian deities.[90]: 393–394 Their terms for deities were nṯr (god), and feminine nṯrt (goddess);[91]: 42 however, these terms may also have applied to any being – spirits and deceased human beings, but not demons – who in some way were outside the sphere of everyday life.[92]: 216 [91]: 62 Egyptian deities typically had an associated cult, role and mythologies.[92]: 7–8, 83 Around 200 deities are prominent in the Pyramid texts and ancient temples of Egypt, many zoomorphic. Among these, were Min (fertility god), Neith (creator goddess), Anubis, Atum, Bes, Horus, Isis, Ra, Meretseger, Nut, Osiris, Shu, Sia and Thoth.[87]: 11–12 Most Egyptian deities represented natural phenomenon, physical objects or social aspects of life, as hidden immanent forces within these phenomena.[93][94] The deity Shu, for example represented air; the goddess Meretseger represented parts of the earth, and the god Sia represented the abstract powers of perception.[95]: 91, 147 Deities such as Ra and Osiris were associated with the judgement of the dead and their care during the afterlife.[87]: 26–28 Major gods often had multiple roles and were involved in multiple phenomena.[95]: 85–86 The first written evidence of deities are from early 3rd millennium BCE, likely emerging from prehistoric beliefs.[96] However, deities became systematized and sophisticated after the formation of an Egyptian state under the Pharaohs and their treatment as sacred kings who had exclusive rights to interact with the gods, in the later part of the 3rd millennium BCE.[97][88]: 12–15 Through the early centuries of the common era, as Egyptians interacted and traded with neighboring cultures, foreign deities were adopted and venerated.[98][90]: |

古代近東 主な記事: 古代近東の宗教 エジプト 主な記事: 古代エジプトの神々、エジプト神話、古代エジプトの宗教  古代エジプトの宗教における主要な神々であるオシリス、アヌビス、ホルスを描いたエジプトの墓壁画[87] 古代エジプト文化は数多くの神々を崇拝した。エジプトの記録や碑文には、性質が不明な多くの神々の名が列挙され、他の無名の神々についても曖昧な言及がな されている[88]: 73 。エジプト学者ジェームズ・P・アレンは、エジプトの文献に1,400以上の神々が名指しされていると推定している [89]。一方、クリスチャン・ライツは「数えきれないほどの」エジプト神々を推定している。[90]: 393–394 彼らの神々の呼称は男性神を意味するnṯr(神)、女性神を意味するnṯrt(女神)であった。[91]: 42 ただし、これらの呼称は日常の領域の外にある存在―精霊や死んだ人間(悪魔を除く)―にも適用された可能性がある。[92]: 216 [91]: 62 エジプトの神々は通常、関連する信仰、役割、神話を持っていた。[92]: 7–8, 83 約200の神々が、エジプトのピラミッド文書や古代神殿において顕著な存在であり、その多くは動物を模した姿をしている。これらの中には、ミン(豊穣の 神)、ネイト(創造の女神)、アヌビス、アトゥム、ベス、ホルス、イシス、ラー、メレツェゲル、ヌト、オシリス、シュ、シア、トートなどが含まれる。 [87]: 11–12 ほとんどのエジプト神々は、自然現象や物理的対象、あるいは生活の社会的側面を、それらの現象に内在する隠れた力として体現していた。[93][94] 例えば神シュは空気を、女神メレツゲヘルは地の一部を、神シアは知覚の抽象的な力をそれぞれ象徴していた。[95]: 91, 147 ラーやオシリスと いった神々は、死者の審判と来世における守護と結びつけられていた。[87]: 26–28 主要な神々はしばしば複数の役割を持ち、様々な現象に関与し ていた。[95]: 85–86 神々の最初の文字記録は紀元前3千年紀初頭に遡り、おそらく先史時代の信仰から発展したものである。[96] しかし神々は、紀元前3千年紀後半にファラオによるエジプト国家が成立し、神々と交信する独占的権利を持つ神聖な王として扱われるようになってから、体系 化され洗練された。[97][88]: 12–15 紀元後数世紀にわたり、エジプト人が近隣文化と交流・交易する中で、外国の神々が取り入れられ崇拝されるようになった。[98][90]: |

Levantine The God on the Winged Wheel coin, a 4th-century BCE drachm (quarter shekel) coin from the Achaemenid Empire, possibly representing Yahweh seated on a winged and wheeled sun-throne Main articles: Ancient Canaanite religion, Origins of Judaism, Ancient Semitic religion, Yahweh, Second Temple Judaism, and History of ancient Israel and Judah The ancient Canaanites were polytheists who believed in a pantheon of deities,[99][100][101] the chief of whom was the god El, who ruled alongside his consort Asherah and their seventy sons.[99]: 22–24 [100][101] Baal was the god of storm, rain, vegetation and fertility,[99]: 68–127 while his consort Anat was the goddess of war[99]: 131, 137–139 and Astarte, the West Semitic equivalent to Ishtar, was the goddess of love.[99]: 146–149 The people of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah originally believed in these deities,[99][101][102] alongside their own national god Yahweh.[103][104] El later became syncretized with Yahweh, who took over El's role as the head of the pantheon,[99]: 13–17 with Asherah as his divine consort[105]: 45 [99]: 146 and the "sons of El" as his offspring.[99]: 22–24 During the later years of the Kingdom of Judah, a monolatristic faction rose to power insisting that only Yahweh was fit to be worshipped by the people of Judah.[99]: 229–233 Monolatry became enforced during the reforms of King Josiah in 621 BCE.[99]: 229 Finally, during the national crisis of the Babylonian captivity, some Judahites began to teach that deities aside from Yahweh were not just unfit to be worshipped, but did not exist.[106][41]: 4 The "sons of El" were demoted from deities to angels.[99]: 22 |

レバント 翼のある車輪の神の硬貨。アケメネス朝時代の紀元前4世紀のドラクマ(四分の一シェケル)硬貨で、翼と車輪を備えた太陽の玉座に座るヤハウェを表している可能性がある 主な項目:古代カナン宗教、ユダヤ教の起源、古代セム宗教、ヤハウェ、第二神殿期ユダヤ教、古代イスラエルとユダの歴史 古代カナン人は多神教徒であり、神々のパンテオンを信じていた[99][100][101]。その頂点に立つのは神エルであり、配偶神アシェラと70人の 息子たちと共に統治していた。[99]: 22–24 [100][101] バアルは嵐・雨・植物・豊穣の神であり[99]: 68–127 、その配偶神アナトは戦いの女神であった[99]: 131, 137–139。またア スタルテは西セム語圏におけるイシュタルに相当する愛の女神であった[99]: 146–149。イスラエル王国とユダ王国の人民は、自国の国民神ヤハ ウェと共に、これらの神々を信仰していた[99][101][102]。[103][104] 後にエルはヤハウェと融合し、ヤハウェがエルの役割である神々の頂点に立った[99]: 13–17 。アシェラはヤハウェの配偶神[105]: 45 [99]: 146 となり、「エルの子ら」はヤハウェの子孫とされた。[99]: 22–24 ユダ王国後期、一神崇拝派が勢力を伸ばし、ユダ民が崇拝すべきはヤハウェのみだと主張した。[99]: 229–233 紀元前621年のヨシヤ王の改革で一神崇拝が強制された。[99]:229 最終的にバビロン捕囚という国民的危機において、一部のユダ人はヤハウェ以外 の神々は崇拝に値しないばかりか存在すらしないと教え始めた。[106][41]:4 「エルの子ら」は神格から天使へと格下げされた。[99]:22 |

Mesopotamian Akkadian cylinder seal impression showing Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love, sex, and war  Wall relief of the Assyrian national god Aššur in a "winged male" hybrid iconography Main articles: List of Mesopotamian deities, Ancient Mesopotamian religion, and Sumerian religion Ancient Mesopotamian culture in southern Iraq had numerous dingir (deities, gods and goddesses).[18]: 69–74 [40] Mesopotamian deities were almost exclusively anthropomorphic.[107]: 93 [18]: 69–74 [108] They were thought to possess extraordinary powers[107]: 93 and were often envisioned as being of tremendous physical size.[107]: 93 They were generally immortal,[107]: 93 but a few of them, particularly Dumuzid, Geshtinanna, and Gugalanna were said to have either died or visited the underworld.[107]: 93 Both male and female deities were widely venerated.[107]: 93 In the Sumerian pantheon, deities had multiple functions, which included presiding over procreation, rains, irrigation, agriculture, destiny, and justice.[18]: 69–74 The gods were fed, clothed, entertained, and worshipped to prevent natural catastrophes as well as to prevent social chaos such as pillaging, rape, or atrocities.[18]: 69–74 [109]: 186 [107]: 93 Many of the Sumerian deities were patron guardians of city-states.[109] The most important deities in the Sumerian pantheon were known as the Anunnaki,[110] and included deities known as the "seven gods who decree": An, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu and Inanna.[110] After the conquest of Sumer by Sargon of Akkad, many Sumerian deities were syncretized with East Semitic ones.[109] The goddess Inanna, syncretized with the East Semitic Ishtar, became popular,[111][112]: xviii, xv [109]: 182 [107]: 106–09 with temples across Mesopotamia.[113][107]: 106–09 The Mesopotamian mythology of the first millennium BCE treated Anšar (later Aššur) and Kišar as primordial deities.[114] Marduk was a significant god among the Babylonians. He rose from an obscure deity of the third millennium BCE to become one of the most important deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon of the first millennium BCE. The Babylonians worshipped Marduk as creator of heaven, earth and humankind, and as their national god.[18]: 62, 73 [115] Marduk's iconography is zoomorphic and is most often found in Middle Eastern archaeological remains depicted as a "snake-dragon" or a "human-animal hybrid".[116][117][118] |

メソポタミア アッカドの円筒印章に刻まれたイナンナ。シュメールの愛と性、戦争の女神である  アッシリアの国民神アッシュルの壁面レリーフ。「翼のある男性」というハイブリッドな図像で表現されている 主な記事:メソポタミアの神々一覧、古代メソポタミアの宗教、シュメールの宗教 古代メソポタミア文化(イラク南部)には数多くのディンギル(神々、男神と女神)が存在した[18]: 69–74 [40]。メソポタミアの神々はほぼ 例外なく擬人化されていた[107]: 93 [18]: 69–74 [108]。彼らは非凡な力を有すると考えられていた[107]: 93 、しば しば巨大な身体的規模を持つ存在として描かれた[107]: 93 。一般に不死であったが[107]: 93 、特にドゥムジド、ゲシュティナンナ、グ ガランナなど一部の神々は死んだか、冥界を訪れたと伝えられている。[107]:93 男女の神々が広く崇拝されていた。[107]:93 シュメールの神々には複数の役割があり、生殖、降雨、灌漑、農業、運命、正義などを司っていた。[18]: 69–74 神々は、自然災害を防ぐため、また略奪や強姦、残虐行為といった社会混乱を防ぐために、食料を与えられ、衣服を着せられ、歓待され、崇拝された。 [18]: 69–74 [109]: 186 [107]: 93 シュメールの神々の多くは都市国家の守護神であった。[109] シュメール神話体系で最も重要な神々はアヌンナキとして知られ[110]、「七人の裁定神」と呼ばれるアン、エンリル、エンキ、ニンフルサグ、ナンナ、ウ トゥ、イナンナが含まれた。[110] アッカドのサルゴンによるシュメール征服後、多くのシュメール神々は東セム系神々と融合した。[109] 女神イナンナは東セム系のイシュタルと融合し、人気を博した。[111][112]: xviii, xv [109]: 182 [107]: 106–09 メソポタミア全域に神殿が建てられた。[113][107]: 106–09 紀元前1千年紀のメソポタミア神話では、アンシャル(後のアッシュール)とキシャルが原初の神々として扱われた。[114] マルドゥクはバビロニア人にとって重要な神であった。彼は紀元前3千年紀には無名の神であったが、紀元前1千年紀にはメソポタミア神話体系において最も重 要な神の一人へと昇格した。バビロニア人はマルドゥクを天地と人類の創造主として、また彼らの国民神として崇拝した。[18]: 62, 73 [115] マルドゥクの図像は動物的形態をとり、中東の考古学的遺物では「蛇竜」あるいは「人獣混合体」として描かれることが最も多い。[116][117] [118] |

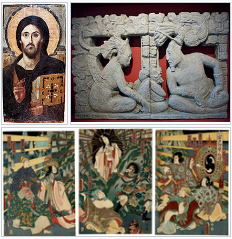

| ndo-European Main article: Proto-Indo-European religion Germanic The Kirkby Stephen Stone, discovered in Kirkby Stephen, England, depicts a bound figure, who some have theorized may be the Germanic god Loki. Main articles: List of Germanic deities, Germanic paganism, Germanic mythology, Common Germanic deities, Æsir, and Vanir In Germanic languages, the terms cognate with 'god' such as Old English: god and Old Norse: guð were originally neuter but became masculine, as in modern Germanic languages, after Christianisation due their use in referring to the Christian god.[119] In Norse mythology, Æsir (singular áss or ǫ́ss) are the principal group of gods,[120] while the term ásynjur (singular ásynja) refers specifically to the female Æsir.[121] These terms, states John Lindow, may be ultimately rooted in the Indo-European root for "breath" (as in "life giving force"), and are cognate with Old English: os (a heathen god) and Gothic: anses.[122]: 49–50 Another group of deities found in Norse mythology are termed as Vanir, and are associated with fertility. The Æsir and the Vanir went to war, according to the Nordic sources. The account in Ynglinga saga describes the Æsir–Vanir War ending in truce and ultimate reconciliation of the two into a single group of gods, after both sides chose peace, exchanged ambassadors (hostages),[123]: 181 and intermarried.[122]: 52–53 [124] The Norse mythology describes the cooperation after the war, as well as differences between the Æsir and the Vanir which were considered scandalous by the other side.[123]: 181 The goddess Freyja of the Vanir taught magic to the Æsir, while the two sides discover that while Æsir forbid mating between siblings, Vanir accepted such mating.[123]: 181 [125][126] Temples hosting images of Germanic gods (such as Thor, Odin and Freyr), as well as pagan worship rituals, continued in Scandinavia into the 12th century, according to historical records. It has been proposed that over time, Christian equivalents were substituted for the Germanic deities to help suppress paganism as part of the Christianisation of the Germanic peoples.[123]: 187–188 Worship of the Germanic gods has been revived in the modern period as part of the new religious movement of Heathenry.[127] |

インド・ヨーロッパ語族 主な記事: 原始インド・ヨーロッパ宗教 ゲルマン イングランドのカークビー・スティーブンで発見されたカークビー・スティーブン石には、縛られた人物が刻まれている。これはゲルマン神話の神ロキである可能性があると推測する学者もいる。 主な記事:ゲルマン神々のリスト、ゲルマン異教、ゲルマン神話、共通ゲルマン神々、アス神族、ヴァニル神族 ゲルマン語族において、「神」に相当する語(古英語 god、古ノルド語 guð など)は、もともと中性語であったが、キリスト教化後にキリスト教の神を指すために用いられるようになり、現代ゲルマン語では男性名詞となった[119]。 北欧神話において、エーシルの神々(単数形はアッスまたはオッス)は主要な神々の集団である[120]。一方、アスィンユル(単数形はアスィンヤ)という 用語は、特に女性のエーシルを指す。[121] ジョン・リンドウによれば、これらの用語は最終的に「息」(「生命を与える力」の意味)を表すインド・ヨーロッパ語族の語根に由来し、古英語の os(異教の神)やゴート語の anses と同源である。[122]: 49–50 北欧神話に登場する別の神々の集団はヴァニルと呼ばれ、豊穣と結びついている。北欧の資料によれば、アシールとヴァニルは戦争を起こした。『イングリング サガ』の記述によれば、両陣営が平和を選択し、使節(人質)を交換し[123]: 181、婚姻関係を結び[122]: 52–53 [124]、最終的 に休戦と和解に至り、両神族は一つの神々の集団へと統合された。 北欧神話では、戦後の協力関係と、アース神族とヴァーニル神族の間の、相手側にとって不名誉とみなされた差異についても記述されている[123]: 181。ヴァーニル神族の女神フレイヤはアース神族に呪術を教えたが、両神族は、アース神族が血縁者同士の交わりを禁じているのに対し、ヴァーニル神族は それを容認していることを発見した。[123]: 181 [125][126] 歴史記録によれば、ゲルマン神々(トール、オーディン、フレイなど)の像を祀る神殿や異教の儀礼は、12世紀までスカンディナヴィアで続いた。ゲルマン民 族のキリスト教化の一環として、異教を抑制するため、時間の経過とともにゲルマン神々にキリスト教の対応神が置き換えられたという説がある。[123]: 187–188 現代において、ゲルマン神々の崇拝は、新たな宗教運動であるヘイサニー(異教復興運動)の一部として復活している。[127] |

| Greek Zeus, the king of the gods in ancient Greek religion, shown on a gold stater from Lampsacus (c. 360–340 BCE) Corinthian black-figure plaque of Poseidon, the Greek god of the seas (c. 550–525 BCE) Attic white-ground red-figured kylix of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, riding a swan (c. 46–470 BCE) Bust of Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, copy after a votive statue of Kresilas in Athens (c. 425 BCE) Main articles: List of Greek deities, Greek mythology, Ancient Greek religion, and Twelve Olympians The ancient Greeks revered both gods and goddesses.[128] These continued to be revered through the early centuries of the common era, and many of the Greek deities inspired and were adopted as part of much larger pantheon of Roman deities.[129]: 91–97 The Greek religion was polytheistic, but had no centralized church, nor any sacred texts.[129]: 91–97 The deities were largely associated with myths and they represented natural phenomena or aspects of human behavior.[128][129]: 91–97 Several Greek deities probably trace back to more ancient Indo-European traditions, since the gods and goddesses found in distant cultures are mythologically comparable and are cognates.[32]: 230–231 [130]: 15–19 Eos, the Greek goddess of the dawn, for instance, is cognate to Indic Ushas, Roman Aurora and Latvian Auseklis.[32]: 230–232 Zeus, the Greek king of gods, is cognate to Latin Iūpiter, Old German Ziu, and Indic Dyaus, with whom he shares similar mythologies.[32]: 230–232 [131] Other deities, such as Aphrodite, originated from the Near East.[132][133][134][135] Greek deities varied locally, but many shared panhellenic themes, celebrated similar festivals, rites, and ritual grammar.[136] The most important deities in the Greek pantheon were the Twelve Olympians: Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Hermes, Demeter, Dionysus, Hephaestus, and Ares.[130]: 125–170 Other important Greek deities included Hestia, Hades and Heracles.[129]: 96–97 These deities later inspired the Dii Consentes galaxy of Roman deities.[129]: 96–97 Besides the Olympians, the Greeks also worshipped various local deities.[130]: 170–181 [137] Among these were the goat-legged god Pan (the guardian of shepherds and their flocks), Nymphs (nature spirits associated with particular landforms), Naiads (who dwelled in springs), Dryads (who were spirits of the trees), Nereids (who inhabited the sea), river gods, satyrs (a class of lustful male nature spirits), and others. The dark powers of the underworld were represented by the Erinyes (or Furies), said to pursue those guilty of crimes against blood-relatives.[137] The Greek deities, like those in many other Indo-European traditions, were anthropomorphic. Walter Burkert describes them as "persons, not abstractions, ideas or concepts".[130]: 182 They had fantastic abilities and powers; each had some unique expertise and, in some aspects, a specific and flawed personality.[138]: 52 They were not omnipotent and could be injured in some circumstances.[139] Greek deities led to cults, were used politically and inspired votive offerings for favors such as bountiful crops, healthy family, victory in war, or peace for a loved one recently deceased.[129]: 94–95 [140] |

ギリシャ 古代ギリシャ神話の神々の王ゼウス。ランプサコス産の金貨(紀元前360~340年頃)に描かれた姿 コリント式黒絵式ポセイドン像。ギリシャの海の神(紀元前550~525年頃) アッティカ白地赤絵式キリュクス。白鳥に乗るギリシャの愛の女神アフロディーテ(紀元前46~470年頃) アテナイのクレシラス作奉献像を模した、知恵の女神アテナの胸像(紀元前425年頃) 主な記事:ギリシャ神話の神々の一覧、ギリシャ神話、古代ギリシャの宗教、十二神 古代ギリシャ人は神々と女神の両方を崇拝した[128]。これらの崇拝は紀元後数世紀にわたり続き、多くのギリシャ神々はローマ神話の大規模な神々の体系 に採用され、影響を与えた。[129]: 91–97 ギリシャの宗教は多神教であったが、中央集権的な教会も聖典も存在しなかった。[129]: 91–97 神々は主に神話と結びつき、自然現象や人間の行動様式を象徴していた。[128][129]: 91–97 いくつかのギリシャ神々は、より古代のインド・ヨーロッパ語族の伝統に遡る可能性が高い。なぜなら、遠く離れた文化に見られる神々は神話的に類似してお り、語源的に同源だからだ。[32]: 230–231 [130]: 15–19 例えば、ギリシャの暁の女神エオスは、インドのウシャス、ローマのアウロラ、ラトビアのアウセクリスと同源である。[32]: 230–232 ギリシャの神々の王ゼウスは、ラテン語のユピテル、古ゲルマン語のジウ、インドのディヤウスと同源であり、これらと類似した神話体系を共有している。 [32]: 230–232 [131] アフロディーテのような他の神々は、近東に起源を持つ。[132][133][134][135] ギリシャの神々は地域によって異なるが、多くの神々が汎ギリシャ的な主題を共有し、類似した祭事、儀式、儀礼の文法を祝った。[136] ギリシャ神話において最も重要な神々は十二神(オリンポスの十二神)である:ゼウス、ヘラ、ポセイドン、アテナ、アポロン、アルテミス、アフロディーテ、 ヘルメス、デメテル、ディオニュソス、ヘファイストス、アレス。[130]: 125–170 その他の重要なギリシャ神には、ヘスティア、ハデス、ヘラクレスが含まれる。[129]: 96–97 これらの神々は後に、ローマ神話のディイ・コンセンテス(一致する神々)の群れに影響を与えた。[129]: 96–97 オリンポスの神々以外にも、ギリシャ人は様々な地方の神々を崇拝した。[130]: 170–181 [137] これらには、山羊の脚を持つ神パン(羊飼いとその群れの守護神)、ニンフ(特定の地形と結びついた自然精霊)、ナイアデス(泉に住む精霊)、ドライアデス (樹木の精霊)、ネレイデス(海に住む精霊)、川の神々、サテュロス(好色な男性自然精霊の一種)などが含まれた。冥界の闇の力は、血縁者に対する罪を犯 した者を追うと言われるエリュニエス(あるいはフュリーズ)によって象徴されていた。[137] ギリシャの神々は、他の多くのインド・ヨーロッパ系伝統の神々と同様に擬人化されていた。ヴァルター・ブルクハルトは彼らを「抽象概念や観念ではなく、実 体としての人格」と表現している[130]:182。彼らは驚異的な能力と力を持ち、それぞれが独自の専門性と、ある面では欠点のある個性を備えていた。 [138]: 52 全能ではなく、状況によっては傷つけられることもあった。[139] ギリシャの神々は信仰の対象となり、政治的に利用され、豊作、家族の健康、戦勝、あるいは最近亡くなった愛する者の安寧といった恩恵を得るための奉納物を 促した。[129]: 94–95 [140] |

| Roman Main articles: List of Roman deities, Roman mythology, Religion in ancient Rome, and Capitoline Triad 4th-century Roman sarcophagus depicting the creation of man by Prometheus, with major Roman deities Jupiter, Neptune, Mercury, Juno, Apollo, Vulcan watching The Roman pantheon had numerous deities, both Greek and non-Greek.[129]: 96–97 The more famed deities, found in the mythologies and the 2nd millennium CE European arts, have been the anthropomorphic deities syncretized with the Greek deities. These include the six gods and six goddesses: Venus, Apollo, Mars, Diana, Minerva, Ceres, Vulcan, Juno, Mercury, Vesta, Neptune, Jupiter (Jove, Zeus); as well Bacchus, Pluto and Hercules.[129]: 96–97 [141] The non-Greek major deities include Janus, Fortuna, Vesta, Quirinus and Tellus (mother goddess, probably most ancient).[129]: 96–97 [142] Some of the non-Greek deities had likely origins in more ancient European culture such as the ancient Germanic religion, while others may have been borrowed, for political reasons, from neighboring trade centers such as those in the Minoan or ancient Egyptian civilization.[143][144][145] The Roman deities, in a manner similar to the ancient Greeks, inspired community festivals, rituals and sacrifices led by flamines (priests, pontifs), but priestesses (Vestal Virgins) were also held in high esteem for maintaining sacred fire used in the votive rituals for deities.[129]: 100–101 Deities were also maintained in home shrines (lararium), such as Hestia honored in homes as the goddess of fire hearth.[129]: 100–101 [146] This Roman religion held reverence for sacred fire, and this is also found in Hebrew culture (Leviticus 6), Vedic culture's Homa, ancient Greeks and other cultures.[146] Ancient Roman scholars such as Varro and Cicero wrote treatises on the nature of gods of their times.[147] Varro stated, in his Antiquitates Rerum Divinarum, that it is the superstitious man who fears the gods, while the truly religious person venerates them as parents.[147] Cicero, in his Academica, praised Varro for this and other insights.[147] According to Varro, there have been three accounts of deities in the Roman society: the mythical account created by poets for theatre and entertainment, the civil account used by people for veneration as well as by the city, and the natural account created by the philosophers.[148] The best state is, adds Varro, where the civil theology combines the poetic mythical account with the philosopher's.[148] The Roman deities continued to be revered in Europe through the era of Constantine, and past 313 CE when he issued the Edict of Toleration.[138]: 118–120 |

ローマ 主な記事:ローマ神話の神々の一覧、ローマ神話、古代ローマの宗教、カピトリーヌの三神 4世紀のローマ製石棺。プロメテウスによる人間の創造を描き、主要なローマ神々であるユピテル、ネプトゥヌス、メルクリウス、ユノー、アポロン、ウルカヌスがそれを見守る様子が刻まれている ローマ神話にはギリシャ神話由来のものと非ギリシャ神話由来のものを含め、数多くの神々が存在した[129]: 96–97 。神話や紀元後2千年紀の ヨーロッパ芸術に描かれる著名な神々は、ギリシャ神話の神々と融合した擬人化された神々である。これには六神と六女神が含まれる:ヴィーナス、アポロン、 マルス、ディアナ、ミネルヴァ、ケレス、ウルカヌス、ユノー、メルクリウス、ヴェスタ、ネプチューヌス、ユピテル(ジュピター、ゼウス)。またバッカス、 プルートゥス、ヘラクレスも含まれる。[129]: 96–97 [141] 非ギリシャ系の主要神にはヤヌス、フォルチュナ、ウェスタ、クイリヌス、テルス(母なる女神、おそらく最も古い)が含まれる。[129]: 96–97 [142] 非ギリシャ神々の一部は、古代ゲルマン宗教などより古いヨーロッパ文化に起源を持つ可能性が高い。他方、ミノア文明や古代エジプト文明といった近隣交易中 心地から、政治的理由で借用されたものもある。[143][144][145] ローマの神々は、古代ギリシャと同様に、フラミネス(祭司、ポンティフクス)が主導する共同体の祭典、儀礼、犠牲を促した。しかし、女神への奉納儀式で用 いられる聖火を維持する巫女(ヴェスタルの処女)も高く評価されていた。[129]: 100–101 家庭の祭壇(ララリウム)でも神々が祀られていた。例えば家庭の火の神として崇められたヘスティアがそれに当たる。[129]: 100–101 [146] このローマ宗教は聖なる火を崇拝しており、これはヘブライ文化(レビ記6章)、ヴェーダ文化のホーマー、古代ギリシャ人、その他の文化にも見られる。 [146] ヴァロやキケロといった古代ローマの学者たちは、当時の神々の本質について論考を著した。[147] ヴァロは『神事の古事』において、神々を恐れるのは迷信深い人間であり、真に宗教的な人格は親のように神々を崇拝すると述べている。[147] キケロは『アカデミカ』で、この見解を含むヴァロの洞察を称賛した. [147] ヴァロによれば、ローマ社会における神々の説明は三種類あった。詩人たちが演劇や娯楽のために創作した神話的説明、人民や国家が崇敬のために用いた市民的 説明、そして哲学者たちが構築した自然的説明である。[148] ヴァロはさらに、最良の国家とは、市民的神学が詩的な神話的解釈と哲学者の解釈を融合させたものであると付け加えている。[148] ローマの神々は、コンスタンティヌス帝の時代を通じて、また彼が寛容令を発布した西暦313年以降も、ヨーロッパで崇敬され続けた。[138]: 118–120 [148] ヴァロはさらに、市民神学が詩的・神話的説明と哲学者の説明を融合させた国家こそが最良であると述べている。[148] |

| Native American Inca Inti Raymi, a winter solstice festival of the Inca people, reveres Inti, the sun deity—offerings include round bread and maize beer. Main articles: Inca mythology, Religion in the Inca Empire, and Inca religion in Cusco The Inca culture has believed in Viracocha (also called Pachacutec) as the creator deity.[149]: 27–30 [150]: 726–729 Viracocha has been an abstract deity to Inca culture, one who existed before he created space and time.[151] All other deities of the Inca people have corresponded to elements of nature.[149][150]: 726–729 Of these, the most important ones have been Inti (sun deity) responsible for agricultural prosperity and as the father of the first Inca king, and Mama Qucha the goddess of the sea, lakes, rivers and waters.[149] Inti in some mythologies is the son of Viracocha and Mama Qucha.[149][152] Inca Sun deity festival Oh creator and Sun and Thunder, be forever copious, do not make us old, let all things be at peace, multiply the people, and let there be food, and let all things be fruitful. —Inti Raymi prayers[153] Inca people have revered many male and female deities. Among the feminine deities have been Mama Kuka (goddess of joy), Mama Ch'aska (goddess of dawn), Mama Allpa (goddess of harvest and earth, sometimes called Mama Pacha or Pachamama), Mama Killa (moon goddess) and Mama Sara (goddess of grain).[152][149]: 31–32 During and after the imposition of Christianity during Spanish colonialism, the Inca people retained their original beliefs in deities through syncretism, where they overlay the Christian God and teachings over their original beliefs and practices.[154][155][156] The male deity Inti became accepted as the Christian God, but the Andean rituals centered around Inca deities have been retained and continued thereafter into the modern era by the Inca people.[156][157] |

ネイティブアメリカン インカ インカの冬至祭「インティ・ライミ」は太陽神インティを崇める祭りで、供物には丸いパンやトウモロコシのビールが含まれる。 主な記事:インカ神話、インカ帝国の宗教、クスコのインカ宗教 インカ文化は創造神としてビラコチャ(パチャクテクとも呼ばれる)を信仰してきた。[149]: 27–30 [150]: 726–729 ヴィラコチャはインカ文化において抽象的な神であり、空間と時間を創造する以前から存在していた。[151] インカ民族の他の全ての神々は自然の要素に対応していた。[149][150]: 726–729 その中でも最も重要なのは、農業の繁栄を担い初代インカ王の父とされる太陽神インティと、海・湖・川・水の女神ママ・クチャであった。[149] 一部の神話ではインティはビラコチャとママ・クチャの子とされる。[149] [152] インカの太陽神祭 おお創造主よ、太陽よ、雷よ、 永遠に豊穣あれ、 我らを老いさせず、 万物を平穏に保ち、 人民を増やし、 食糧を与え、 万物を実らせよ。 —インティ・ライミの祈り[153] インカの人民は多くの男女の神々を崇拝してきた。女性神にはママ・クカ(歓喜の女神)、ママ・チャスカ(夜明けの女神)、ママ・アルパ(収穫と大地の女 神、ママ・パチャまたはパチャママとも呼ばれる)、ママ・キッラ(月の女神)、ママ・サラ(穀物の女神)などがいる。[152][149]: 31–32 スペイン植民地時代におけるキリスト教の強制導入中およびその後も、インカの人民は神々への本来の信仰を、キリスト教の神と教えを自らの信仰や慣習に重ね 合わせるシンクレティズム(融合)によって維持した。[154][155][156] 男性神インティはキリスト教の神として受け入れられたが、インカの神々を中心としたアンデスの儀礼はその後も維持され、現代に至るまでインカの人民によっ て継承されている。[156][157] |

| Maya and Aztec Main articles: List of Maya gods and supernatural beings, Maya religion, List of Aztec gods and supernatural beings, and Aztec mythology In Maya culture, Kukulkan has been the supreme creator deity, also revered as the god of reincarnation, water, fertility and wind.[150]: 797–798 The Maya people built step pyramid temples to honor Kukulkan, aligning them to the Sun's position on the spring equinox.[150]: 843–844 Other deities found at Maya archaeological sites include Xib Chac—the benevolent male rain deity, and Ixchel—the benevolent female earth, weaving and pregnancy goddess.[150]: 843–844 The Maya calendar had 18 months, each with 20 days (and five unlucky days of Uayeb); each month had a presiding deity, who inspired social rituals, special trading markets and community festivals.[157] Quetzalcoatl in the Codex Borgia A deity with aspects similar to Kulkulkan in the Aztec culture has been called Quetzalcoatl.[150]: 797–798 However, states Timothy Insoll, the Aztec ideas of deity remain poorly understood. What has been assumed is based on what was constructed by Christian missionaries. The deity concept was likely more complex than these historical records.[158] In Aztec culture, there were hundred of deities, but many were henotheistic incarnations of one another (similar to the avatar concept of Hinduism). Unlike Hinduism and other cultures, Aztec deities were usually not anthropomorphic, and were instead zoomorphic or hybrid icons associated with spirits, natural phenomena or forces.[158][159] The Aztec deities were often represented through ceramic figurines, revered in home shrines.[158][160] |

マヤとアステカ 主な記事:マヤの神々と超自然的存在の一覧、マヤの宗教、アステカの神々と超自然的存在の一覧、アステカ神話 マヤ文化において、ククルカンは至高の創造神であり、転生の神、水の神、豊穣の神、風の神としても崇められてきた。[150]: 797–798 マヤの 人民はククルカンを称えるため階段ピラミッド寺院を建造し、春分点の太陽の位置に合わせて配置した。[150]: 843–844 マヤ遺跡で見つかる他 の神々には、慈悲深い男性雨神シブ・チャク、慈悲深い女性の大地・織物・妊娠の女神イクシェルがいる。[150]: 843–844 マヤ暦は18の月で構成され、各月は20日(不吉な5日間のウアイェブを含む)であった。各月には守護神がおり、社会的儀礼、特別な交易市場、共同体祭り を促した。[157] ボルジア写本に描かれたケツァルコアトル アステカ文化におけるクルクルカンと類似した側面を持つ神はケツァルコアトルと呼ばれてきた。[150]: 797–798 しかしティモシー・インソルは、アステカの神観念は依然として十分に理解されていないと述べる。既知の事実はキリスト教宣教師が構築した解釈に基づく。実 際の神概念は歴史記録よりも複雑だった可能性が高い。[158] アステカ文化には数百の神々が存在したが、多くは互いに単一神信仰的な化身関係にあった(ヒンドゥー教のアヴァター概念に類似)。ヒンドゥー教や他の文化 とは異なり、アステカの神々は通常、擬人化されておらず、代わりに精霊や自然現象、自然の力と結びついた動物的またはハイブリッドな象徴であった。 [158][159] アステカの神々はしばしば陶器の人形で表現され、家庭の聖堂で崇められていた。[158][160] |

| Polynesian Deities of Polynesia carved from wood (bottom two are demons) Main article: Polynesian narrative The Polynesian people developed a theology centered on numerous deities, with clusters of islands having different names for the same idea. There are great deities found across the Pacific Ocean. Some deities are found widely, and there are many local deities whose worship is limited to one or a few islands or sometimes to isolated villages on the same island.[161]: 5–6 The Māori people, of what is now New Zealand, called the supreme being as Io, who is also referred elsewhere as Iho-Iho, Io-Mataaho, Io Nui, Te Io Ora, Io Matua Te Kora among other names.[162]: 239 The Io deity has been revered as the original uncreated creator, with power of life, with nothing outside or beyond him.[162]: 239 Other deities in the Polynesian pantheon include Tangaloa (god who created men),[161]: 37–38 La'a Maomao (god of winds), Tu-Matauenga or Ku (god of war), Tu-Metua (mother goddess), Kane (god of procreation) and Rangi (sky god father).[162]: 261, 284, 399, 476 The Polynesian deities have been part of a sophisticated theology, addressing questions of creation, the nature of existence, guardians in daily lives as well as during wars, natural phenomena, good and evil spirits, priestly rituals, as well as linked to the journey of the souls of the dead.[161]: 6–14, 37–38, 113, 323 |

ポリネシア ポリネシアの神々を木彫りで表現したもの(下段の二体は悪魔である) メイン記事: ポリネシア神話 ポリネシアの人民は、多数の神々を中心とした神学を発展させた。同じ概念でも島々のグループによって異なる名称が用いられる。太平洋全域にまたがる偉大な 神々が存在する。広く崇拝される神々もいれば、特定の島々や、時には同じ島内の孤立した村々に限って崇拝される多くの地方神も存在する。[161]: 5–6 現在のニュージーランドに当たる地域のマオリ人民は、最高神をイオと呼んだ。この神は他の地域ではイホ・イホ、イオ・マタアホ、イオ・ヌイ、テ・イオ・オ ラ、イオ・マトゥア・テ・コラなど様々な名で呼ばれている。[162]: 239 イオ神は、創造されざる原初の創造主として崇められ、生命の力を持ち、その外にもその先にも何もない存在とされる。[162]: 239 ポリネシア神話 体系の他の神々には、タンガロア(人間を創造した神)、[161]: 37–38 ラア・マオマオ(風の神)、トゥ・マタウエンガまたはク(戦いの神)、トゥ・メトゥア(母なる女神)、カネ(生殖の神)、ランギ(天空の神である父)など がいる。[162]: 261, 284, 399, 476 ポリネシアの神々は洗練された神学の一部であり、創造、存在の本質、日常生活や戦争時の守護者、自然現象、善悪の精霊、祭司の儀礼、そして死者の魂の旅路といった問題に取り組んできた。[161]: 6–14, 37–38, 113, 323 |

| Abrahamic Christianity Holy Trinity (1756–1758) by Szymon Czechowicz, showing God the Father, God the Son, and the Holy Spirit, all of whom are revered in Christianity as a single deity Main articles: God in Christianity, Trinity, God the Father, God the Son, Jesus in Christianity, Holy Spirit in Christianity, Names of God in Christianity, and Christian theology Christianity is a monotheistic religion in which most mainstream congregations and denominations accept the concept of the Holy Trinity.[163]: 233–234 Modern orthodox Christians believe that the Trinity is composed of three equal, cosubstantial persons: God the Father, God the Son, and the Holy Spirit.[163]: 233–234 The first person to describe the persons of the Trinity as homooúsios (ὁμοούσιος; "of the same substance") was the Church Father Origen.[164] Although most early Christian theologians (including Origen) were Subordinationists,[165] who believed that the Father was superior to the Son and the Son superior to the Holy Spirit,[164][166][167] this belief was condemned as heretical by the First Council of Nicaea in the fourth century, which declared that all three persons of the Trinity are equal.[165] Christians regard the universe as an element in God's actualization[163]: 273 and the Holy Spirit is seen as the divine essence that is "the unity and relation of the Father and the Son".[163]: 273 According to George Hunsinger, the doctrine of the Trinity justifies worship in a Church, wherein Jesus Christ is deemed to be a full deity with the Christian cross as his icon.[163]: 296 The theological examination of Jesus Christ, of divine grace in incarnation, his non-transferability and completeness has been a historic topic. For example, the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE declared that in "one person Jesus Christ, fullness of deity and fullness of humanity are united, the union of the natures being such that they can neither be divided nor confused".[168] Jesus Christ, according to the New Testament, is the self-disclosure of the one, true God, both in his teaching and in his person; Christ, in Christian faith, is considered the incarnation of God.[41]: 4, 29 [169][170] |

アブラハムの宗教 キリスト教 シモン・チェホヴィチ作『聖三位一体』(1756–1758年)。キリスト教において単一の神として崇められる父なる神、子なる神、聖霊を描いた作品 主な項目:キリスト教における神、三位一体、父なる神、子なる神、キリスト教におけるイエス、キリスト教における聖霊、キリスト教における神の名、キリスト教神学 キリスト教は一神教であり、主流の教会や宗派のほとんどが聖三位一体の概念を受け入れている[163]: 233–234 。現代の正統派キリスト教徒 は、三位一体が三つの等しく、同質的な人格、すなわち父なる神、子なる神、聖霊から成ると信じている。[163]: 233–234 三位一体の人格をホ モウシオス(ὁμοούσιος;「同質」の意)と初めて表現したのは教父オリゲネスである。[164] 初期キリスト教神学者の大半(オリゲネスを含む)は従属論者であり[165]、父が子より優位、子が聖霊より優位と信じた[164][166] [167]。しかしこの教義は4世紀のニカイア第一公会議で異端と断じられ、三位一体の三位格は全て等しいと宣言された。[165] キリスト教徒は宇宙を神の実現の一要素と見なす[163]: 273 。聖霊は「父と子の統一と関係」である神の本質と見なされる。[163]: 273 ジョージ・ハンシンガーによれば、三位一体の教義は教会における礼拝を正当化する。そこではイエス・キリストは完全な神格とされ、キリスト教の十字架がそ の象徴とされる。[163]: 296 イエス・キリストの神学的考察、すなわち受肉における神の恵み、その非移転性および完全性は歴史的な主題である。例えば、451年のカルケドン公会議は 「一人の人格イエス・キリストにおいて、神性の充満と人性の充満が結合している。この二つの本性の結合は、分離も混同も不可能なものである」と宣言した。 [168] 新約聖書によれば、イエス・キリストは教えと人格の両面において唯一真の神の自己啓示である。キリスト教信仰において、キリストは神の受肉と見なされてい る。[41]: 4, 29 [169][170] |

| Islam Main articles: Allah, Ilah, God in Islam, and Names of God in Islam Ilah, ʾIlāh (Arabic: إله; plural: آلهة ʾālihah), is an Arabic word meaning "god".[171][172] It appears in the name of the monotheistic god of Islam as Allah (al-Lāh).[173][174][175] which literally means "the god" in Arabic.[171][172] Islam is strictly monotheistic[176] and the first statement of the shahada, or Muslim confession of faith, is that "there is no ʾilāh (deity) but Allah (God)",[177] who is perfectly unified and utterly indivisible.[176][177][178] The term Allah is used by Muslims for God. The Persian word Khuda (Persian: خدا) can be translated as god, lord or king, and is also used today to refer to God in Islam by Persian, Urdu, Tat and Kurdish speakers. The Turkic word for god is Tengri; it exists as Tanrı in Turkish. Judaism The tetragrammaton in Phoenician (12th century BCE to 150 BCE), Paleo-Hebrew (10th century BCE to 135 CE), and square Hebrew (3rd century BCE to present) scripts Main articles: God in Judaism, Yahweh, Tetragrammaton, Elohim, and Names of God in Judaism Judaism affirms the existence of one God (Yahweh, or YHWH), who is not abstract, but He who revealed himself throughout Jewish history particularly during the Exodus and the Exile.[41]: 4 Judaism reflects a monotheism that gradually arose, was affirmed with certainty in the sixth century "Second Isaiah", and has ever since been the axiomatic basis of its theology.[41]: 4 The classical presentation of Judaism has been as a monotheistic faith that rejected deities and related idolatry.[179] However, states Breslauer, modern scholarship suggests that idolatry was not absent in biblical faith, and it resurfaced multiple times in Jewish religious life.[179] The rabbinic texts and other secondary Jewish literature suggest worship of material objects and natural phenomena through the medieval era, while the core teachings of Judaism maintained monotheism.[179][180][page needed] According to Aryeh Kaplan, God is always referred to as "He" in Judaism, "not to imply that the concept of sex or gender applies to God", but because "there is no neuter in the Hebrew language, and the Hebrew word for God is a masculine noun" as he "is an active rather than a passive creative force".[181] Mandaeism Main article: Hayyi Rabbi Further information: Mandaeism In Mandaeism, Hayyi Rabbi (lit=The Great Life), or 'The Great Living God',[182] is the supreme God from which all things emanate. He is also known as 'The First Life', since during the creation of the material world, Yushamin emanated from Hayyi Rabbi as the "Second Life."[183] "The principles of the Mandaean doctrine: the belief of the only one great God, Hayyi Rabbi, to whom all absolute properties belong; He created all the worlds, formed the soul through his power, and placed it by means of angels into the human body. So He created Adam and Eve, the first man and woman."[184] Mandaeans recognize God to be the eternal, creator of all, the one and only in domination who has no partner.[185] |

イスラム教 主な記事:アッラー、イラー、イスラム教における神、イスラム教における神の名称 イラー(アラビア語: إله; 複数形: آلهة ʾālihah)は、アラビア語で「神」を意味する言葉である。[171][172] これはイスラム教の一神教の神の名においてアッラー(al-Lāh)として現れる。[173][174][175] アラビア語で文字通り「神」を意味する。[171][172] イスラム教は厳格な一神教である[176]。シャハーダ(信仰告白)の最初の宣言は「アッラー(神)以外に神(ʾilāh)は存在しない」[177]とい うもので、アッラーは完全に統一され、全く分割不可能な存在である[176][177][178]。 アッラーという語はムスリムが神を指すのに用いる。ペルシア語のクッダ(خدا)は神、主、王と訳され、今日でもペルシア語、ウルドゥー語、タト語、クル ド語話者によるイスラムの神を指すのに用いられる。テングリは神を表すテュルク語であり、トルコ語ではタンリとして存在する。 ユダヤ教 テトラグラマトン(四文字の神名)の表記:フェニキア文字(紀元前12世紀~紀元前150年)、古ヘブライ文字(紀元前10世紀~紀元135年)、正方ヘブライ文字(紀元前3世紀~現代) 関連項目:ユダヤ教における神、ヤハウェ、テトラグラマトン、エロヒム、ユダヤ教における神の名 ユダヤ教は唯一の神(ヤハウェ、またはYHWH)の存在を認める。この神は抽象的な存在ではなく、ユダヤの歴史、特に出エジプトとバビロン捕囚の時代に自 らを明らかにした存在である[41]:4。ユダヤ教の一神教観は徐々に形成され、紀元前6世紀の「第二イザヤ」によって確固たるものとなり、それ以来、そ の神学の公理的基盤となっている。[41]: 4 ユダヤ教の古典的表現は、神々や関連する偶像崇拝を拒絶する一神教的信仰であった。[179] しかしブレスラウアーは、現代の研究によれば聖書的信仰において偶像崇拝が存在しなかったわけではなく、ユダヤ教の宗教生活において幾度も再出現したと述 べている。[179] ラビ文学やその他の二次的ユダヤ文献は、中世期を通じて物質的対象や自然現象への崇拝を示唆しているが、ユダヤ教の中核的教義は一神教を維持していた。 [179][180][ページ指定が必要] アリエ・カプランによれば、ユダヤ教において神は常に「彼」と表現される。これは「性や性別という概念が神に適用されることを示唆するため」ではなく、 「ヘブライ語には中性形が存在せず、神のヘブライ語表現は男性名詞である」ためであり、神は「受動的ではなく能動的な創造力」だからである。[181] マンダ教 詳細記事: ハイイ・ラビ 関連項目: マンダ教 マンダ教において、ハイイ・ラビ(文字通り「偉大なる生命」)、あるいは「偉大なる生ける神」[182]は、万物を発する至高の神である。彼はまた「最初 の生命」としても知られている。物質世界の創造の際、ユシャミンがハイイ・ラビから「第二の生命」として発現したためである。[183] 「マンダ教の教義の原則:唯一の偉大なる神、ハイイ・ラビへの信仰。彼には全ての絶対的属性が属する。彼は全ての世界を創造し、その力によって魂を形成 し、天使たちを通じてそれを人間の身体に宿した。こうして彼は最初の男女であるアダムとイブを創造した。」 [184] マンダエ派は神を永遠なる存在、万物の創造主、支配において唯一無二の存在であり、いかなるパートナーも持たないと認めている。[185] |

| Asian Anitism Left: Bakunawa depicted in a Bisaya sword hilt; Right: Ifugao rice deity statues Further information: Indigenous Philippine folk religions, Philippine mythology, and List of Philippine mythological figures Anitism, composed of an array of indigenous religions from the Philippines, has multiple pantheons of deities. There are more than a hundred different ethnic groups in the Philippines, each having their own supreme deity or deities. Each supreme deity or deities normally rules over a pantheon of deities, contributing to the sheer diversity of deities in Anitism.[186]The supreme deity or deities of ethnic groups are almost always the most notable.[186] For example, Bathala is the Tagalog supreme deity,[187] Mangechay is the Kapampangan supreme deity,[188] Malayari is the Sambal supreme deity,[189] Melu is the Blaan supreme deity,[190] Kaptan is the Bisaya supreme deity,[191] and so on. Buddhism Left: Buddhist deity in Ssangbongsa in South Korea; Right: Chinese deity adopted into Buddhism Further information: Creator in Buddhism and Buddhist deities Although Buddhists do not believe in a creator deity,[192] deities are an essential part of Buddhist teachings about cosmology, rebirth, and saṃsāra.[192] Buddhist deities (such as devas and bodhisattvas) are believed to reside in a pleasant, heavenly realm within Buddhist cosmology, which is typically subdivided into twenty six sub-realms.[193][192][10]: 35 Devas are numerous, but they are still mortal;[193] they live in the heavenly realm, then die and are reborn like all other beings.[193] A rebirth in the heavenly realm is believed to be the result of leading an ethical life and accumulating very good karma.[193] A deva does not need to work, and is able to enjoy in the heavenly realm all pleasures found on Earth. However, the pleasures of this realm lead to attachment (upādāna), lack of spiritual pursuits, and therefore no nirvana.[10]: 37 Nonetheless, according to Kevin Trainor, the vast majority of Buddhist lay people in countries practicing Theravada have historically pursued Buddhist rituals and practices because they are motivated by their potential rebirth into the deva realm.[193][194][195] The deva realm in Buddhist practice in Southeast Asia and East Asia, states Keown, include gods found in Hindu traditions such as Indra and Brahma, and concepts in Hindu cosmology such as Mount Meru.[10]: 37–38 Mahayana Buddhism also includes different kinds of deities, such as numerous Buddhas, bodhisattvas and fierce deities. Hinduism Left: Ganesha god of new beginnings, remover of obstacle; Right: Saraswati, goddess of knowledge and music Main articles: Hindu deities, Deva (Hinduism), Devi, God in Hinduism, Ishvara, and Bhagavan The concept of God varies in Hinduism, it being a diverse system of thought with beliefs spanning henotheism, monotheism, polytheism, panentheism, pantheism and monism among others.[196][197] In the ancient Vedic texts of Hinduism, a deity is often referred to as Deva (god) or Devi (goddess).[33]: 496 [35] The root of these terms mean "heavenly, divine, anything of excellence".[33]: 492 [35] Deva is masculine, and the related feminine equivalent is devi. In the earliest Vedic literature, all supernatural beings are called Asuras.[198]: 5–11, 22, 99–102 [33]: 121 Over time, those with a benevolent nature become deities and are referred to as Sura, Deva or Devi.[198]: 2–6 [199] Devas or deities in Hindu texts differ from Greek or Roman theodicy, states Ray Billington, because many Hindu traditions believe that a human being has the potential to be reborn as a deva (or devi), by living an ethical life and building up saintly karma.[200] Such a deva enjoys heavenly bliss, till the merit runs out, and then the soul is reborn again into Saṃsāra. Thus deities are henotheistic manifestations, embodiments and consequence of the virtuous, the noble, the saint-like living in many Hindu traditions.[200] Shinto Main article: Shinto Shinto is polytheistic, involving the veneration of many deities known as kami,[201] or sometimes as jingi.[202] In Japanese, no distinction is made here between singular and plural, and hence the term kami refers both to individual kami and the collective group of kami.[203] Although lacking a direct English translation,[204] the term kami has sometimes been rendered as "god" or "spirit".[205] The historian of religion Joseph Kitagawa deemed these English translations "quite unsatisfactory and misleading",[206] and various scholars urge against translating kami into English.[207] In Japanese, it is often said that there are eight million kami, a term which connotes an infinite number,[208] and Shinto practitioners believe that they are present everywhere.[209] They are not regarded as omnipotent, omniscient, or necessarily immortal.[210] Taoism Main articles: Taoism, Chinese mythology, and Chinese gods and immortals Taoism is a polytheistic religion. The gods and immortals(神仙) believed in by Taoism can be roughly divided into two categories, namely "gods" and "xian" (immortals). Among them,"Gods" are also called deities and there are many kinds, that is, god of heaven(天神), god of ground(地祇), wuling(物灵: animism, the spirit of all things), god of netherworld(地府神灵), god of human body(人体之神), god of human ghost(人鬼之神)etc. Among these "gods" such as god of heaven(天神), god of ground(地祇), god of netherworld(阴府神灵), god of human body(人体之神) are innate beings.In China, "gods" are often referred to together with "xian". "Xian" (immortals) is acquired the cultivation of the Tao,persons with vast supernatural powers, unpredictable changes and immortality.[211] Jainism Padmavati, a Jain guardian deity Main articles: God in Jainism and Deva (Jainism) Jainism does not believe in a creator, omnipotent, omniscient, eternal God; however, the cosmology of Jainism incorporates a meaningful causality-driven reality, including four realms of existence (gati), one of them being deva (celestial beings, gods).[11]: 351–357 A human being can choose and live an ethical life, such as being non-violent (ahimsa) against all living beings, and thereby gain merit and be reborn as deva.[11]: 357–358 [212] Jain texts reject a trans-cosmic God, one who stands outside of the universe and lords over it, but they state that the world is full of devas who are in human-image with sensory organs, with the power of reason, conscious, compassionate and with finite life.[11]: 356–357 Jainism believes in the existence of the soul (Self, atman) and considers it to have "god-quality", whose knowledge and liberation is the ultimate spiritual goal in both religions. Jains also believe that the spiritual nobleness of perfected souls (Jina) and devas make them worship-worthy beings, with powers of guardianship and guidance to better karma. In Jain temples or festivals, the Jinas and Devas are revered.[11]: 356–357 [213] Zoroastrianism Investiture of Sassanid emperor Shapur II (center) with Mithra (left) and Ahura Mazda (right) at Taq-e Bostan, Iran Main article: Ahura Mazda Ahura Mazda (/əˌhʊrəˌmæzdə/);[214] is the Avestan name for the creator and sole God of Zoroastrianism.[215] The literal meaning of the word Ahura is "mighty" or "lord" and Mazda is wisdom.[215] Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism, taught that Ahura Mazda is the most powerful being in all of the existence[216] and the only deity who is worthy of the highest veneration.[216] Nonetheless, Ahura Mazda is not omnipotent because his evil twin brother Angra Mainyu is nearly as powerful as him.[216] Zoroaster taught that the daevas were evil spirits created by Angra Mainyu to sow evil in the world[216] and that all people must choose between the goodness of Ahura Mazda and the evil of Angra Mainyu.[216] According to Zoroaster, Ahura Mazda will eventually defeat Angra Mainyu and good will triumph over evil once and for all.[216] Ahura Mazda was the most important deity in the ancient Achaemenid Empire.[217] He was originally represented anthropomorphically,[215] but, by the end of the Sasanian Empire, Zoroastrianism had become fully aniconic.[215] |

アジア アニティズム 左:ビサヤの剣柄に描かれたバクナワ;右:イフガオの稲神像 詳細情報:フィリピンの土着民間宗教、フィリピン神話、フィリピン神話上の人物一覧 アニティズムは、フィリピンの様々な土着宗教から成り立ち、複数の神々の体系を持つ。フィリピンには百を超える異なる民族集団が存在し、それぞれが独自の 最高神を擁している。各最高神は通常、神々の体系を統べるため、アニティズムにおける神々の多様性が際立つのである[186]。民族集団の最高神は、ほぼ 例外なく最も顕著な存在である。[186] 例えば、バタラはタガログ族の最高神[187]、マンゲチャイはカパンパンガン族の最高神[188]、マラヤリはサンバル族の最高神[189]、メルはブラン族の最高神[190]、カプタンはビサヤ族の最高神[191]などである。 仏教 左:韓国・双峰寺の仏教神像;右:仏教に取り込まれた中国神話の神 詳細情報:仏教における創造主と仏教神々 仏教徒は創造主神を信じないが[192]、神々は仏教の宇宙論・輪廻・サンスカーラに関する教えにおいて不可欠な要素である。[192] 仏教の神々(天界や菩薩など)は、仏教宇宙論における快楽に満ちた天界に存在するとされる。この天界は通常、二十六天界に細分化される。[193] [192][10]: 35 天人は数多いが、それでも死すべき存在である[193]。彼らは天界に生き、やがて死んで他の全ての存在と同様に生まれ変わる[193]。天界への再生 は、倫理的な生活を送ることと非常に良い業を積む結果であると信じられている[193]。天人は働く必要がなく、天界において地上に見られるあらゆる快楽 を享受できる。しかし、この世界の快楽は執着(ウパーダーナ)を生み、精神的探求を阻むため、涅槃には至らない。[10]:37 とはいえ、ケヴィン・トレイナーによれば、上座部仏教を実践する国々の仏教徒の大多数は、歴史的にデヴァ界への転生を期待して仏教の儀礼や修行を追求して きた。[193][194] [195] キーンによれば、東南アジア及び東アジアにおける仏教実践の天界には、インドラやブラフマーといったヒンドゥー教の伝統に見られる神々、そして須弥山のよ うなヒンドゥー教宇宙論の概念が含まれる。[10]: 37–38 大乗仏教もまた、無数の仏、菩薩、毘沙門天などの異なる神々を含む。 ヒンドゥー教 左:新たな始まりと障害除去の神ガネーシャ;右:知識と音楽の女神サラスヴァティー 主な項目:ヒンドゥー教の神々、デヴァ(ヒンドゥー教)、デーヴィー、ヒンドゥー教における神、イシュヴァラ、バガヴァン ヒンドゥー教における神の概念は多様であり、一神教、多神教、汎神論、一元論など様々な思想体系が存在する。[196][197] 古代ヴェーダの文献では、神々はデヴァ(男神)またはデーヴィ(女神)と呼ばれることが多い。[33]: 496 [35] これらの語源は「天上の、神聖な、卓越したあらゆるもの」を意味する。[33]: 492 [35] デーヴァは男性形であり、関連する女性形はデーヴィである。最古のヴェーダ文献では、全ての超自然的存在はアスラと呼ばれる。[198]: 5–11, 22, 99–102 [33]: 121 時間の経過と共に、慈悲深い性質を持つ存在は神々となり、スラ、デーヴァ、またはデーヴィと呼ばれるようになる。[198]: 2–6 [199] ヒンドゥー教の文献におけるデーヴァ(神々)は、ギリシャやローマの神学とは異なる、とレイ・ビリングトンは述べる。多くのヒンドゥー教の伝統では、人間 は倫理的な生活を送って聖なるカルマを積み重ねることで、デーヴァ(またはデーヴィ)として生まれ変わる可能性を信じているからだ。[200] そのようなデーヴァは、功徳が尽きるまで天上の至福を享受し、その後魂は再びサンサーラ(輪廻)に生まれ変わる。したがって、多くのヒンドゥー教の伝統に おいて、神々は一神教的顕現であり、高潔で聖人のような生き方の具現化であり、結果なのである。[200] 神道 主な記事: 神道 神道は多神教であり、神(かみ)[201]、あるいは神霊(じんぎ)として知られる多くの神々の崇拝を伴う。日本語では単数形と複数形の区別がなく、 kamiという語は個々の神と神々の集合体の両方を指す。直接的な英語訳は存在しないが、kamiは「神」や「精霊」と訳されることがある。[205] 宗教学者ジョセフ・キタガワはこれらの英語訳を「全く不十分で誤解を招く」と評した[206]。多くの学者は神を英語に翻訳すべきでないと主張している [207]。日本語では「八百万の神々」という表現が用いられ、これは無限の数を暗示する[208]。神道信者は神々が遍在すると信じている[209]。 彼らは全能でも全知でもなく、必ずしも不死ではないと見なされている[210]。 道教 主な記事:道教、中国神話、中国の神々と仙人 道教は多神教である。道教が信じる神々と仙人(神仙)は、おおむね「神」と「仙」の二種類に分けられる。このうち「神」は神霊とも呼ばれ、種類は多い。す なわち天神、地祇、物霊(アニミズム、万物の精霊)、地府神霊、人体之神、人鬼之神などである。これらの「神々」のうち、天神、地祇、陰府神霊、人体之神 などは、生まれながらに存在する存在である。中国では、「神々」はしばしば「仙」と併せて言及される。「仙」とは、道(タオ)を修めて得た存在であり、広 大な超自然的力と予測不可能な変化、不死性を備えた人格である。[211] ジャイナ教 ジャイナ教の守護神パドマヴァティ 主な記事:ジャイナ教の神々、デヴァ(ジャイナ教) ジャイナ教は、創造主であり、全能、全知、永遠の神を信じない。しかし、ジャイナ教の宇宙論は、四つの存在界(ガティ)を含む、意味のある因果関係に基づ く現実を取り入れている。その一つがデヴァ(天界の存在、神々)である。[11]: 351–357 人間は、あらゆる生き物に対する非暴力(アヒンサー)など、倫理的な生活を選択し実践することで功徳を得て、デヴァとして生まれ変わる可能性がある。 [11]: 357–358 [212] ジャイナ教の経典は、宇宙の外に存在し支配する超越的な神を否定する。しかし世界には感覚器官を持ち、理性を備え、意識的で慈悲深く、有限の寿命を持つ人 間に似た姿のデヴァ(天人)が満ちていると説く。[11]: 356–357 ジャイナ教は魂(自己、アートマン)の存在を信じ、それが「神性」を持つと考える。その知識と解脱こそが、両宗教における究極の精神的目標である。ジャイ ナ教徒はまた、完成した魂(ジーナ)と神々の精神的貴さが、彼らを崇拝に値する存在とし、守護と導きによる善業への力を与えると信じる。ジャイナ教の寺院 や祭礼では、ジーナと神々が崇敬される。[11]: 356–357 [213] ゾロアスター教 イラン、タク・エ・ボスタンのササン朝皇帝シャプール2世(中央)の戴冠式。左はミトラ、右はアフラ・マズダ 詳細記事: アフラ・マズダ アフラ・マズダ(/əˌhʊrəˌmæzdə/)[214]は、ゾロアスター教の創造主かつ唯一神のアヴェスター語名である。[215] 「アフラ」は「強大な者」あるいは「主」を、「マズダ」は「知恵」を意味する。[215] ゾロアスター教の創始者ゾロアスターは、アフラ・マズダが全存在において最も強大な存在[216]であり、最高の崇拝に値する唯一の神であると教えた。 [216] しかしながら、アフラ・マズダは全能ではない。なぜなら、その邪悪な双子の兄弟アングラ・マインユが、ほぼ同等の力を持つからだ。[216] ゾロアスターは、デーヴァ(悪魔)はアングラ・マインユが世界に悪を撒くために創造した邪悪な精霊であると教えた。[216] そして、全ての人間はアフラ・マズダの善とアングラ・マインユの悪のどちらかを選ばねばならないと説いた。[216] ゾロアスターによれば、アフラ・マズダは最終的にアングラ・マインユを打ち倒し、善い意志は悪に永遠に勝利する[216]。アフラ・マズダは古代アケメネ ス朝において最も重要な神であった[217]。当初は擬人化されて表現されていたが[215]、ササン朝末期までにゾロアスター教は完全に偶像を排する宗 教となった[215]。 |

| Skeptical interpretations The Greek philosopher Democritus argued that belief in deities arose when humans observed natural phenomena such as lightning and attributed such phenomena to supernatural beings. See also: Evolutionary origin of religions, Evolutionary psychology of religion, and Neurotheology Attempts to rationally explain belief in deities extend all the way back to ancient Greece.[130]: 311–317 The Greek philosopher Democritus argued that the concept of deities arose when human beings observed natural phenomena such as lightning, solar eclipses, and the changing of the seasons.[130]: 311–317 Later, in the third century BCE, the scholar Euhemerus argued in his book Sacred History that the gods were originally flesh-and-blood mortal kings who were posthumously deified, and that religion was therefore the continuation of these kings' mortal reigns, a view now known as Euhemerism.[218] Sigmund Freud suggested that God concepts are a projection of one's father.[219] A tendency to believe in deities and other supernatural beings may be an integral part of the human consciousness.[220][221][222][223]: 2–11 Children are naturally inclined to believe in supernatural entities such as gods, spirits, and demons, even without being introduced into a particular religious tradition.[223]: 2–11 Humans have an overactive agency detection system,[220][224][223]: 25–27 which has a tendency to conclude that events are caused by intelligent entities, even if they really are not.[220][224] This is a system which may have evolved to cope with threats to the survival of human ancestors:[220] in the wild, a person who perceived intelligent and potentially dangerous beings everywhere was more likely to survive than a person who failed to perceive actual threats, such as wild animals or human enemies.[220][223]: 2–11 Humans are also inclined to think teleologically and ascribe meaning and significance to their surroundings, a trait which may lead people to believe in a creator-deity.[225] This may have developed as a side effect of human social intelligence, the ability to discern what other people are thinking.[225] Stories of encounters with supernatural beings are especially likely to be retold, passed on, and embellished due to their descriptions of standard ontological categories (person, artifact, animal, plant, natural object) with counterintuitive properties (humans that are invisible, houses that remember what happened in them, etc.).[226] As belief in deities spread, humans may have attributed anthropomorphic thought processes to them,[227] leading to the idea of leaving offerings to the gods and praying to them for assistance,[227] ideas which are seen in all cultures around the world.[220] Sociologists of religion have proposed that the personality and characteristics of deities may reflect a culture's sense of self-esteem and that a culture projects its revered values into deities and in spiritual terms. The cherished, desired or sought human personality is congruent with the personality it defines to be gods.[219] Lonely and fearful societies tend to invent wrathful, violent, submission-seeking deities, while happier and secure societies tend to invent loving, non-violent, compassionate deities.[219] Émile Durkheim states that gods represent an extension of human social life to include supernatural beings. According to Matt Rossano, God concepts may be a means of enforcing morality and building more cooperative community groups.[228] |

懐疑的な解釈 ギリシャの哲学者デモクリトスは、人間が稲妻などの自然現象を観察し、それらを超自然的な存在の仕業とみなした結果、神々の信仰が生まれたと主張した。 関連項目:宗教の進化的起源、宗教の進化心理学、神経神学 神への信仰を合理的に説明しようとする試みは、古代ギリシャにまで遡る。[130]: 311–317 ギリシャの哲学者デモクリトスは、神々の概念は、人間が稲妻、日食、季節の変化といった自然現象を観察したときに生まれたと主張した。[130]: 311–317 その後、紀元前3世紀に学者エウヘメロスは著書『神聖史』で、神々はもともと生身の人間である王であり、死後に神格化されたと主張した。したがって宗教は これらの王たちの生前の統治の継続であるという見解は、現在エウヘメリズムとして知られている。[218] ジークムント・フロイトは、神概念は父親の投影であると示唆した。[219] 神々やその他の超自然的存在を信じる傾向は、人間の意識に内在する部分かもしれない。[220][221][222][223]: 2–11 子供は特定 の宗教的伝統に触れられなくとも、神々、精霊、悪魔といった超自然的存在を信じる傾向を自然に持つ。[223]: 2–11 人間は過剰に働く主体性検出システムを持っている。[220][224][223]: 25–27 このシステムは、たとえ実際には知性を持つ存在が原因でなくても、事象が知性ある存在によって引き起こされたと結論づける傾向がある。[220] [224] このシステムは、人類の祖先の生存脅威に対処するために進化した可能性がある[220]。野生環境では、至る所に知性ある危険な存在を感知する人格は、野 生動物や敵対者といった実際の脅威を感知できない人格より生存確率が高かったのだ。[220][223]: 2–11 人間はまた目的論的に考え、周囲に意味や意義を帰する傾向がある。この特性は創造主神を信じることに繋がりうる。[225] これは人間の社会的知性、すなわち他者の思考を察知する能力の副産物として発達した可能性がある。[225] 超自然的存在との遭遇譚は特に、標準的な存在論的カテゴリー(人格、人工物、動物、植物、自然物)に直感に反する性質(見えない人間、記憶を持つ家など) を付与する描写ゆえに、繰り返し語られ、伝承され、誇張されやすい。[226] 神への信仰が広がるにつれ、人間は神々に擬人化された思考過程を帰属させた可能性がある[227]。これが神への供物や援助を求める祈りの概念につながり [227]、こうした考え方は世界中のあらゆる文化に見られる。[220] 宗教社会学者は、神々の人格や特性は文化の自尊心の感覚を反映し、文化が尊ぶ価値観を神々や精神的概念に投影すると提唱している。人間が大切にし、望み、 求める人格は、神と定義される人格と一致する。孤独で恐怖に満ちた社会は、怒りっぽく暴力的で服従を求める神々を創造する傾向がある。一方、幸福で安全な 社会は、慈愛に満ち、非暴力的で慈悲深い神々を創造する傾向がある。エミール・デュルケームは、神々は人間の社会生活を超自然的存在へと拡張したものだと 述べている。マット・ロッサーノによれば、神概念は道徳を強制し、より協力的な共同体を構築する手段となり得る。 |

| Aeon (Gnosticism) Apotheosis Deicide Existence of God Hero cult Imperial cult List of deities List of deities in fiction Third man factor |

エオン(グノーシス主義) 神格化 神殺し 神の存在 英雄崇拝 皇帝崇拝 神々のリスト フィクションにおける神々のリスト 第三者の要因 |

| Sources Bocking, Brian (1997). A Popular Dictionary of Shinto (revised ed.). Richmond: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1051-5. Boyd, James W.; Williams, Ron G. (2005). "Japanese Shinto: An Interpretation of a Priestly Perspective". Philosophy East and West. 55 (1): 33–63. doi:10.1353/pew.2004.0039. S2CID 144550475. Cali, Joseph; Dougill, John (2013). Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan's Ancient Religion. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3713-6. Earhart, H. Byron (2004). Japanese Religion: Unity and Diversity (fourth ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-534-17694-5. Hardacre, Helen (2017). Shinto: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-062171-1. Kitagawa, Joseph M. (1987). On Understanding Japanese Religion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-10229-0. Littleton, C. Scott (2002). Shinto: Origins, Rituals, Festivals, Spirits, Sacred Places. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-521886-2. OCLC 49664424. Nelson, John K. (1996). A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97500-9. Offner, Clark B. (1979). "Shinto". In Norman Anderson (ed.). The World's Religions (fourth ed.). Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press. pp. 191–218. |

出典 Bocking, Brian (1997). A Popular Dictionary of Shinto (改訂版). Richmond: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1051-5. Boyd, James W.; Williams, Ron G. (2005). 「Japanese Shinto: An Interpretation of a Priestly Perspective」. Philosophy East and West. 55 (1): 33–63. doi:10.1353/pew.2004.0039. S2CID 144550475. カリ, ジョセフ; ドギル, ジョン (2013). 『神道聖堂:日本の古代宗教の聖地ガイド』. ホノルル: ハワイ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-8248-3713-6。 アールハート、H・バイロン(2004)。『日本の宗教:統一性と多様性』(第4版)。カリフォルニア州ベルモント:ワズワース。ISBN 978-0-534-17694-5。 ハードエーカー、ヘレン(2017)。『神道:その歴史』。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-062171-1。 北川、ジョセフ・M.(1987)。『日本宗教の理解について』。ニュージャージー州プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-691-10229-0。 リトルトン、C. スコット (2002)。『神道:起源、儀礼、祭事、精霊、聖地』。ニューヨーク州オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-521886-2。OCLC 49664424。 ネルソン、ジョン K. (1996)。『神社の1年』。シアトルおよびロンドン:ワシントン大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-295-97500-9。 オフナー、クラーク B. (1979)。「神道」。ノーマン・アンダーソン (編) 『世界の宗教 (第 4 版)』所収。レスター:インターバーシティプレス。191–218 ページ。 |

| Further reading Baines, John (2001). Fecundity Figures: Egyptian Personification and the Iconology of a Genre (Reprint ed.). Oxford: Griffith Institute. ISBN 978-0-900416-78-1. |

さらに読む ベインズ、ジョン (2001)。『豊饒の象徴:エジプトの擬人化とジャンルの図像学』(再版)。オックスフォード:グリフィス研究所。ISBN 978-0-900416-78-1。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deity |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099