民主化

Democratization

Diretas

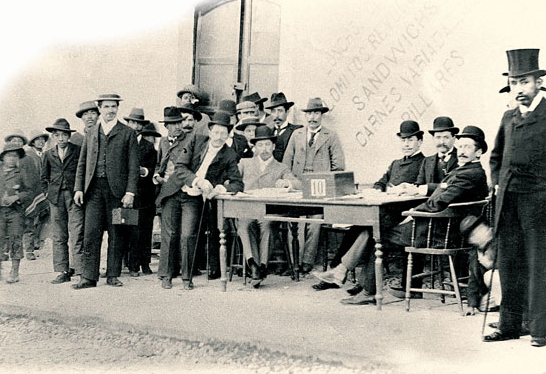

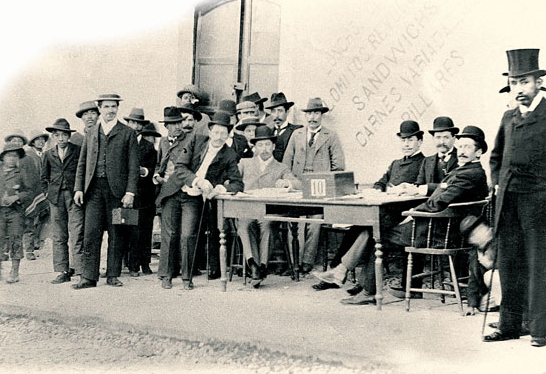

Já demonstration in Brasília for open elections

☆

民主化(Democratization,

or

democratisation)

とは、権威主義的な政府からより民主的な政治体制への構造的な移行を指す。これには民主的な方向へ向かう実質的な政治的変化も含まれる。[1][2]

民主化が起きるかどうか、またその程度は、経済発展、歴史的遺産、市民社会、国際的なプロセスなど様々な要因によって影響を受ける。民主化に関する説明の

中には、エリート層が民主化を推進した点を強調するものもあれば、草の根のボトムアップ的プロセスを重視するものもある。[3]

民主化の進行様式は、国家が戦争に突入するか、経済が成長するかといった他の政治現象を説明する上でも用いられてきた。[4]

これと反対の過程は、民主主義の後退または独裁化として知られる。

| Democratization,

or

democratisation, is the structural government transition from an

authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime,

including substantive political changes moving in a democratic

direction.[1][2] Whether and to what extent democratization occurs can be influenced by various factors, including economic development, historical legacies, civil society, and international processes. Some accounts of democratization emphasize how elites drove democratization, whereas other accounts emphasize grassroots bottom-up processes.[3] How democratization occurs has also been used to explain other political phenomena, such as whether a country goes to a war or whether its economy grows.[4] The opposite process is known as democratic backsliding or autocratization. |

民主化とは、権威主義的な政府からより民主的な政治体制への構造的な移

行を指す。これには民主的な方向へ向かう実質的な政治的変化も含まれる。[1][2] 民主化が起きるかどうか、またその程度は、経済発展、歴史的遺産、市民社会、国際的なプロセスなど様々な要因によって影響を受ける。民主化に関する説明の 中には、エリート層が民主化を推進した点を強調するものもあれば、草の根のボトムアップ的プロセスを重視するものもある。[3] 民主化の進行様式は、国家が戦争に突入するか、経済が成長するかといった他の政治現象を説明する上でも用いられてきた。[4] これと反対の過程は、民主主義の後退または独裁化として知られる。 |

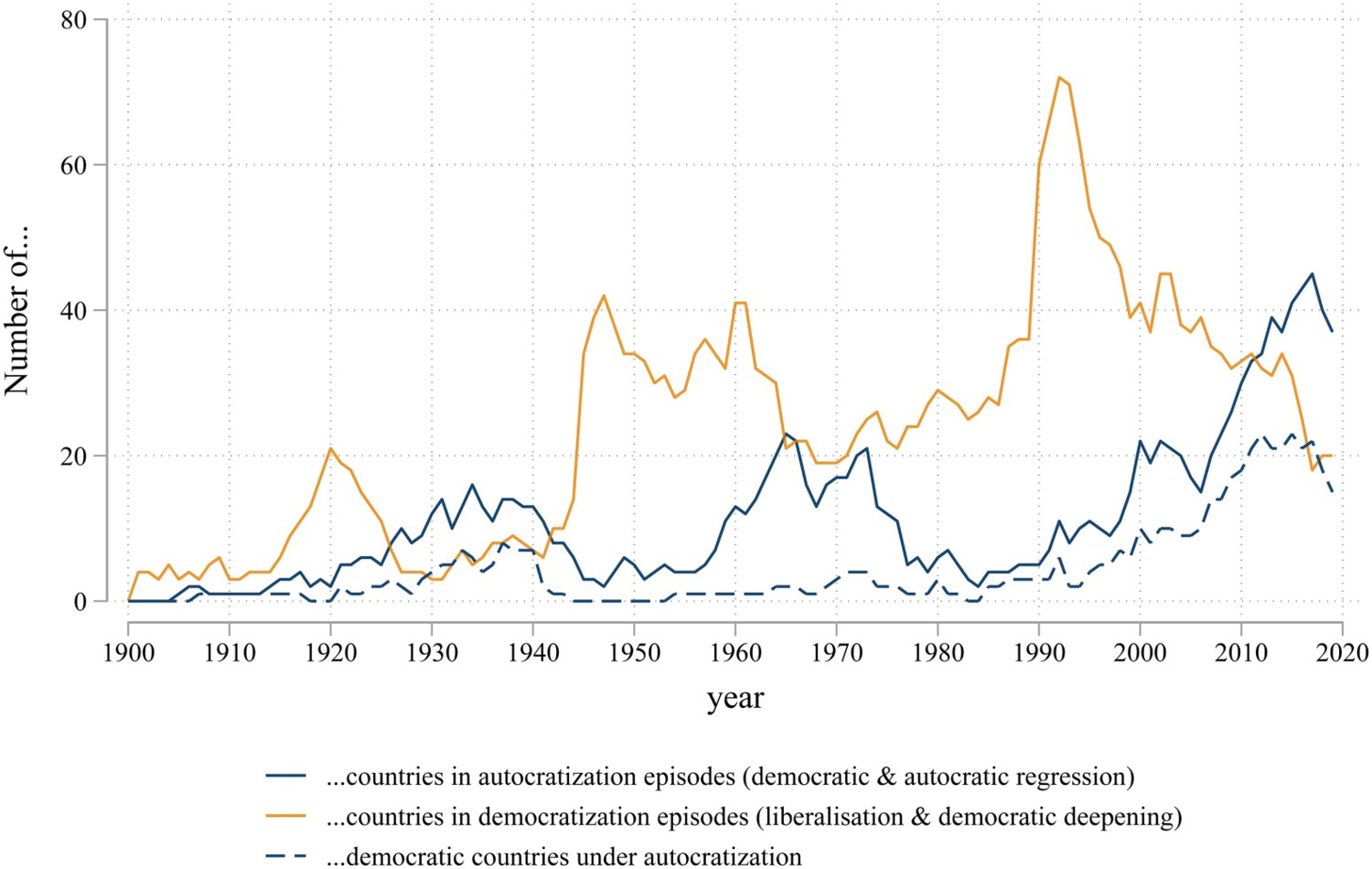

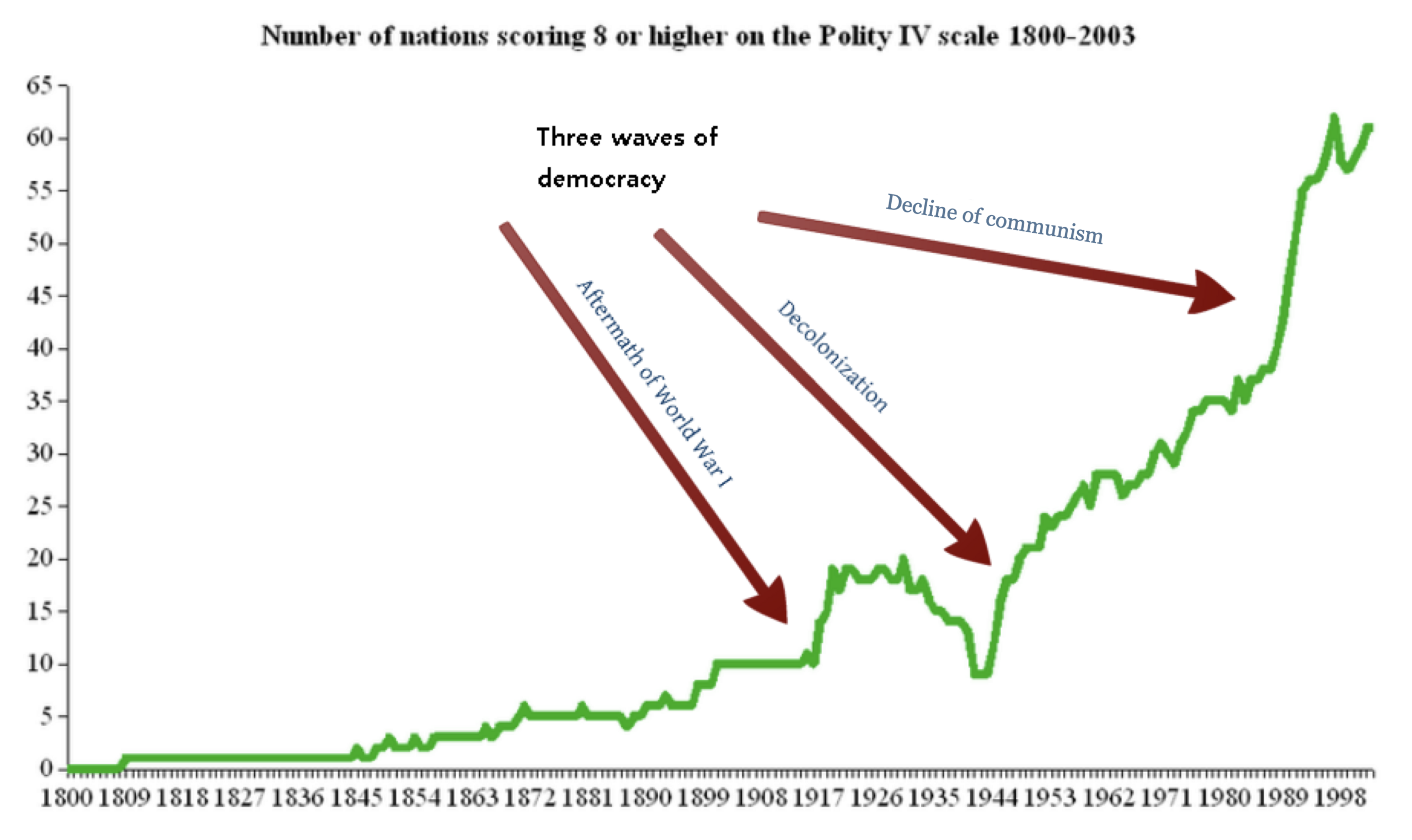

Since 1900, the number of

countries democratizing (yellow) has been higher than those

autocratizing (blue), except in the late 1920s through 1940s and since

2010. |

1900年以降、民主化が進む国(黄色)の数は、1920年代後半から

1940年代にかけてと2010年以降を除き、独裁化が進む国(青色)の数を上回っている。 |

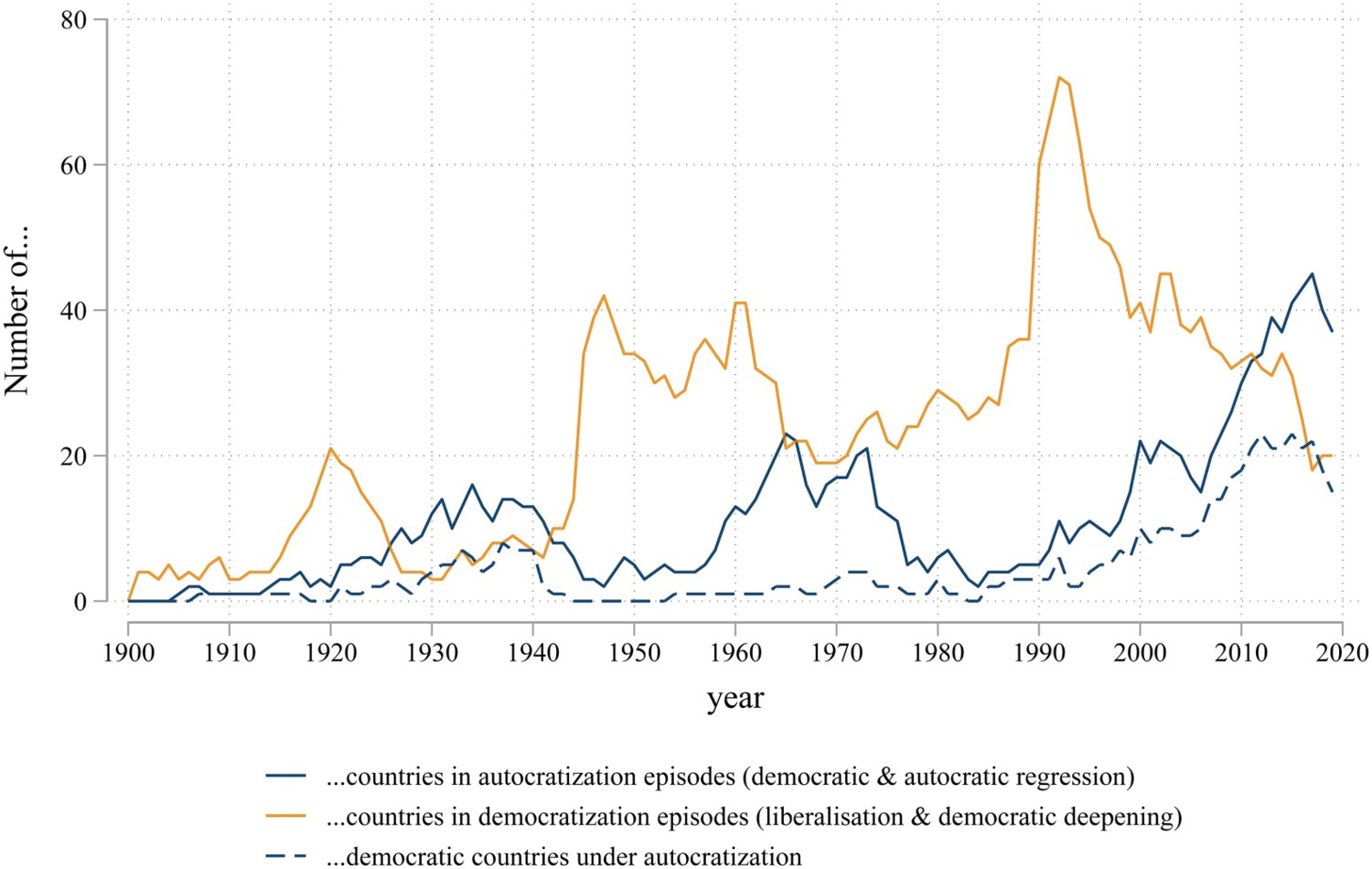

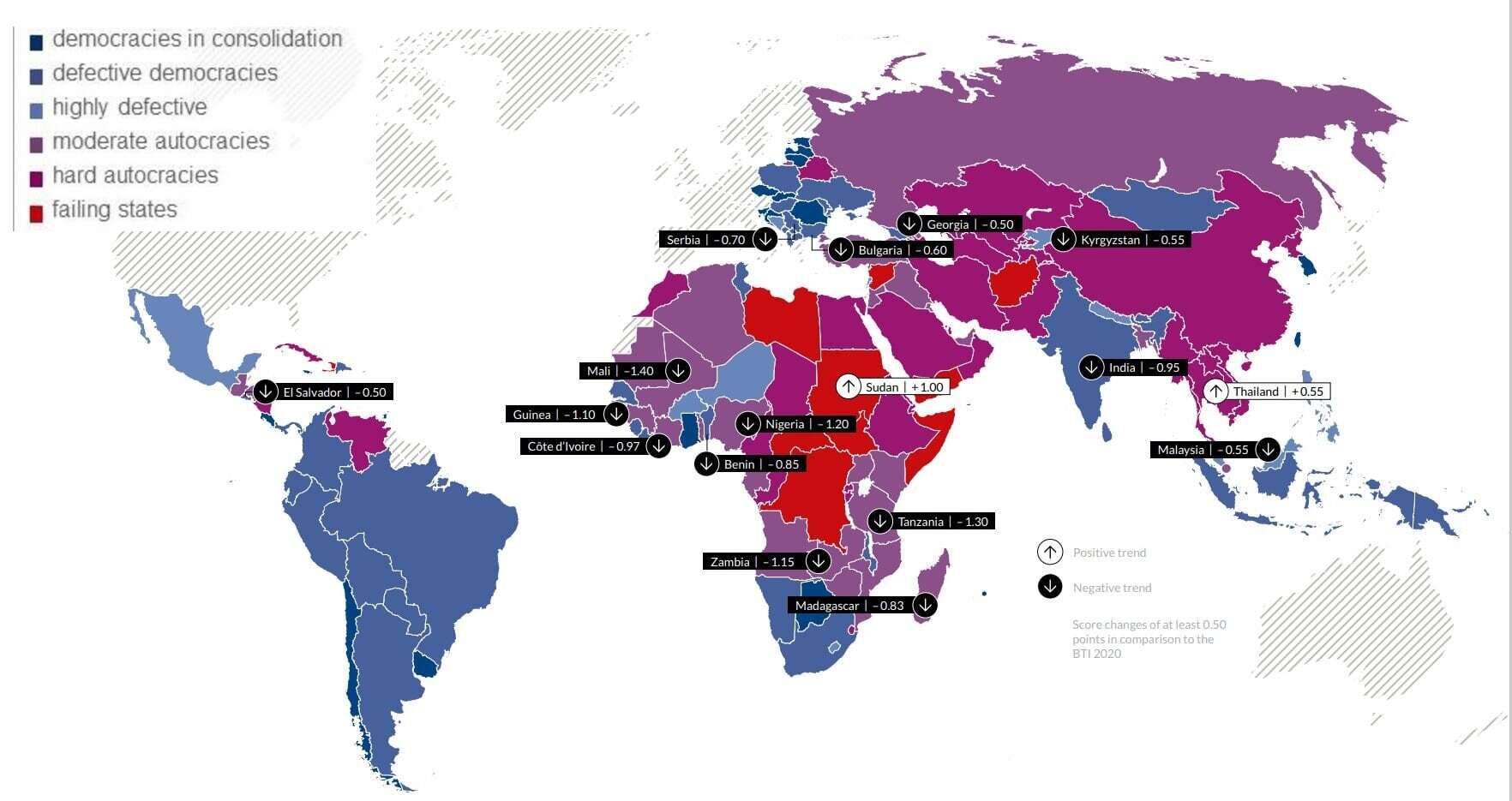

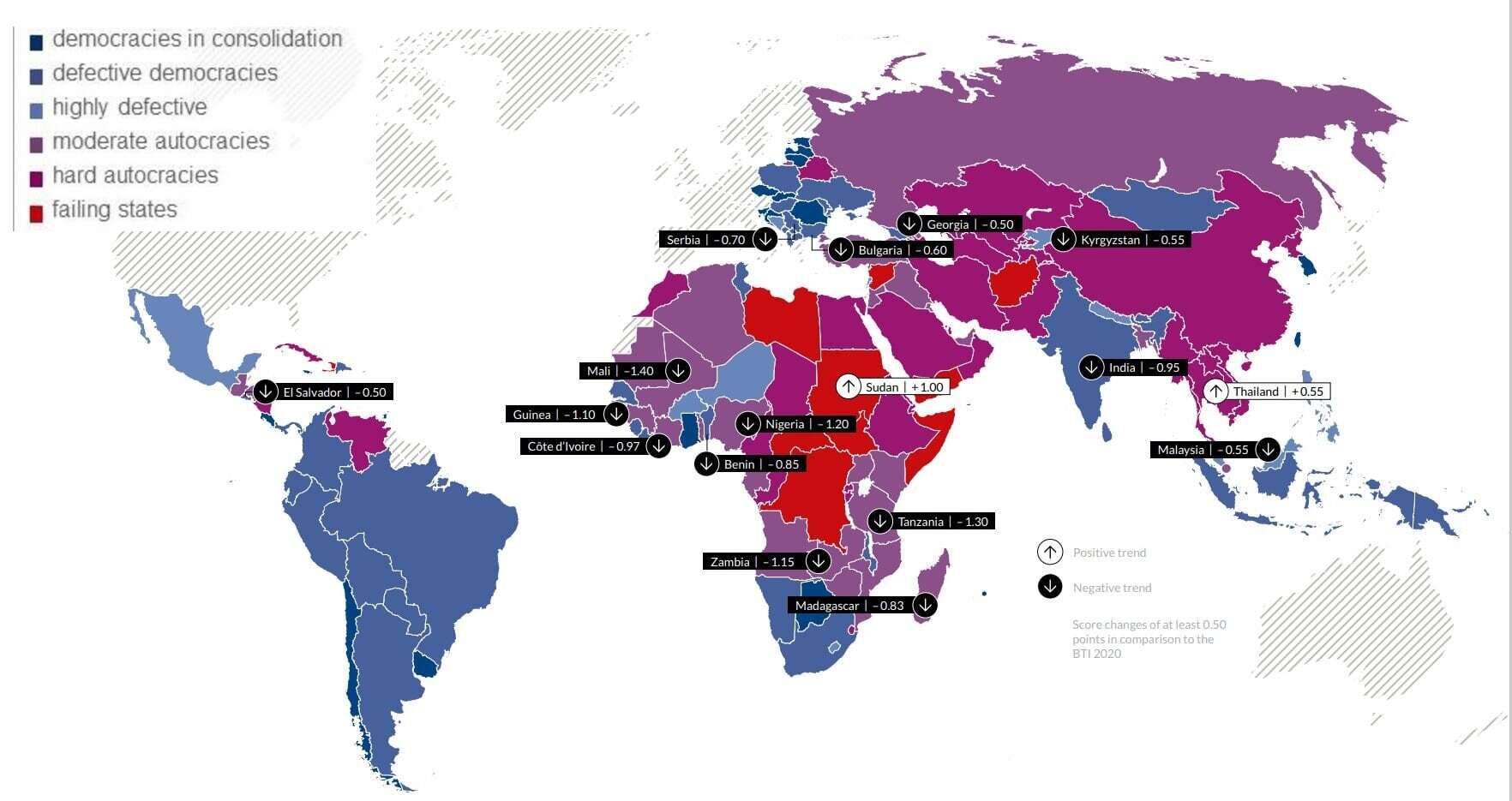

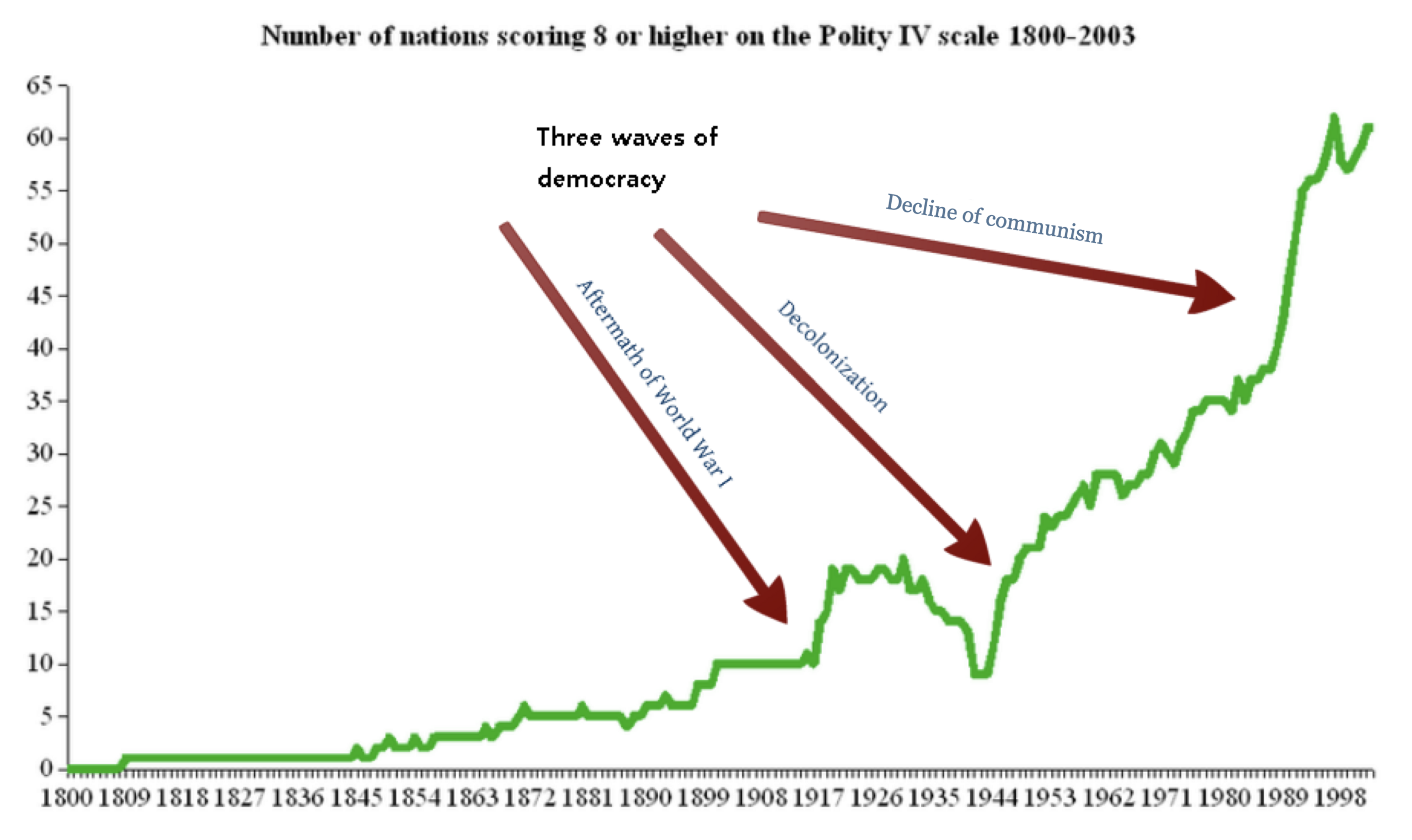

| Description Further information: Hybrid regime  Global trend report Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2022[5] Theories of democratization seek to explain a large macro-level change of a political regime from authoritarianism to democracy. Symptoms of democratization include reform of the electoral system, increased suffrage and reduced political apathy. Measures of democratization Democracy indices enable the quantitative assessment of democratization. Some common democracy indices are Freedom House, Polity data series, V-Dem Democracy indices and Democracy Index. Democracy indices can be quantitative or categorical. Some disagreements among scholars concern the concept of democracy and how to measure democracy – and what democracy indices should be used. Waves of democratization One way to summarize the outcome theories of democratization seek to account is with the idea of waves of democratization.  The three waves of democracy identified by Samuel P. Huntington A wave of democratization refers to a major surge of democracy in history. Samuel P. Huntington identified three waves of democratization that have taken place in history.[6] The first one brought democracy to Western Europe and North America in the 19th century. It was followed by a rise of dictatorships during the Interwar period. The second wave began after World War II, but lost steam between 1962 and the mid-1970s. The latest wave began in 1974 and is still ongoing. Democratization of Latin America and the former Eastern Bloc is part of this third wave. Waves of democratization can be followed by waves of de-democratization. Thus, Huntington, in 1991, offered the following depiction. • First wave of democratization, 1828–1926 • First wave of de-democratization, 1922–42 • Second wave of democratization, 1943–62 • Second wave of de-democratization, 1958–75 • Third wave of democratization, 1974– The idea of waves of democratization has also been used and scrutinized by many other authors, including Renske Doorenspleet,[7] John Markoff,[8] Seva Gunitsky,[9] and Svend-Erik Skaaning.[10] According to Seva Gunitsky, from the 18th century to the Arab Spring (2011–2012), 13 democratic waves can be identified.[9] The V-Dem Democracy Report identified for the year 2023 9 cases of stand-alone democratization in East Timor, The Gambia, Honduras, Fiji, Dominican Republic, Solomon Islands, Montenegro, Seychelles, and Kosovo and 9 cases of U-Turn Democratization in Thailand, Maldives, Tunisia, Bolivia, Zambia, Benin, North Macedonia, Lesotho, and Brazil.[11] |

説明 補足情報:ハイブリッド体制  グローバルトレンドレポート ベルテルスマン変革指数2022[5] 民主化理論は、政治体制が権威主義から民主主義へ移行する大規模なマクロレベルの変化を説明しようとするものである。民主化の兆候には、選挙制度の改革、 選挙権の拡大、政治的無関心の減少などが含まれる。 民主化の測定 民主主義指標は民主化の定量的評価を可能にする。代表的な指標としてフリーダムハウス、ポリティデータシリーズ、V-Dem民主主義指標、民主主義指数が ある。民主主義指標は定量的または分類的である。学者の間では民主主義の概念や測定方法、使用する指標の選択について意見の相違がある。 民主化の波 民主化の結果理論を要約する一つの方法は、民主化の波という概念を用いることである。  サミュエル・P・ハンティントンが特定した三つの民主化の波 民主化の波とは、歴史上における民主主義の大きな高まりを指す。サミュエル・P・ハンティントンは、歴史上起こった三つの民主化の波を特定した。[6] 第一の波は19世紀に西ヨーロッパと北米に民主主義をもたらした。その後、戦間期に独裁政権が台頭した。第二の波は第二次世界大戦後に始まったが、 1962年から1970年代半ばにかけて勢いを失った。最新の第三の波は1974年に始まり、現在も継続中である。ラテンアメリカと旧東側諸国の民主化は この第三の波の一部である。 民主化の波には、非民主化の波が続くこともある。そこでハンティントンは1991年、次のように描いた。 • 民主化の第一波:1828年~1926年 • 非民主化の第一波:1922年~1942年 • 民主化の第二波:1943年~1962年 • 第二波脱民主化、1958–75年 • 第三波民主化、1974年– 民主化の波という概念は、レンスケ・ドゥーレンスプリーテ[7]、ジョン・マーコフ[8]、セヴァ・グニツキー[9]、スヴェンド=エリック・スカーニン グなど、他の多くの著者によっても用いられ、検証されてきた。[10] セヴァ・グニツキーによれば、18世紀からアラブの春(2011–2012年)までに、13の民主化の波が確認できる。[9] V-Dem民主主義報告書は、2023年において、東ティモール、ガンビア、ホンジュラス、フィジー、ドミニカ共和国、ソロモン諸島、モンテネグロ、セイ シェル、コソボにおける9件の単独民主化事例と、タイ、モルディブ、チュニジア、ボリビア、ザンビア、ベナン、北マケドニア、レソト、ブラジルにおける9 件のUターン民主化事例を特定した。[11] |

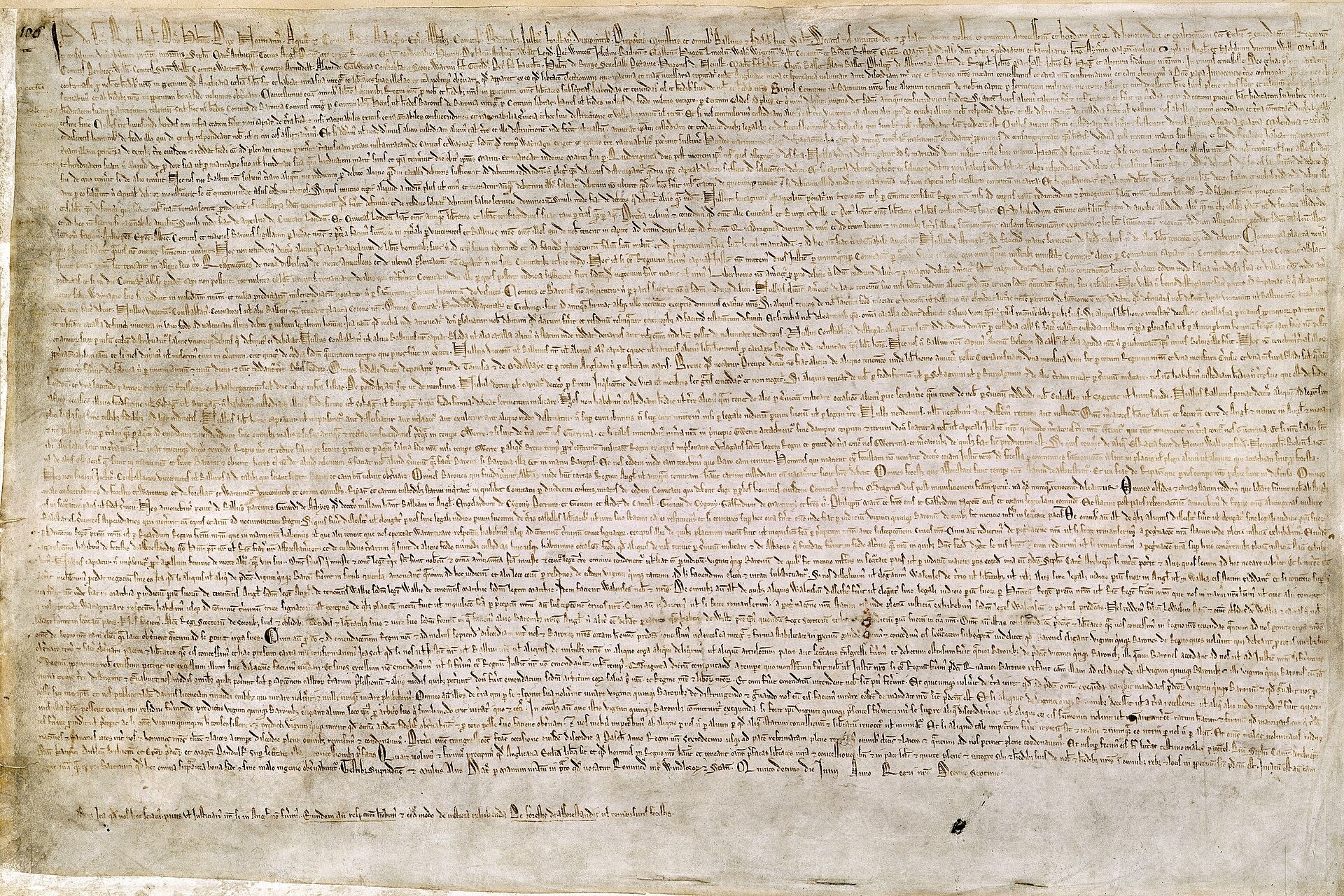

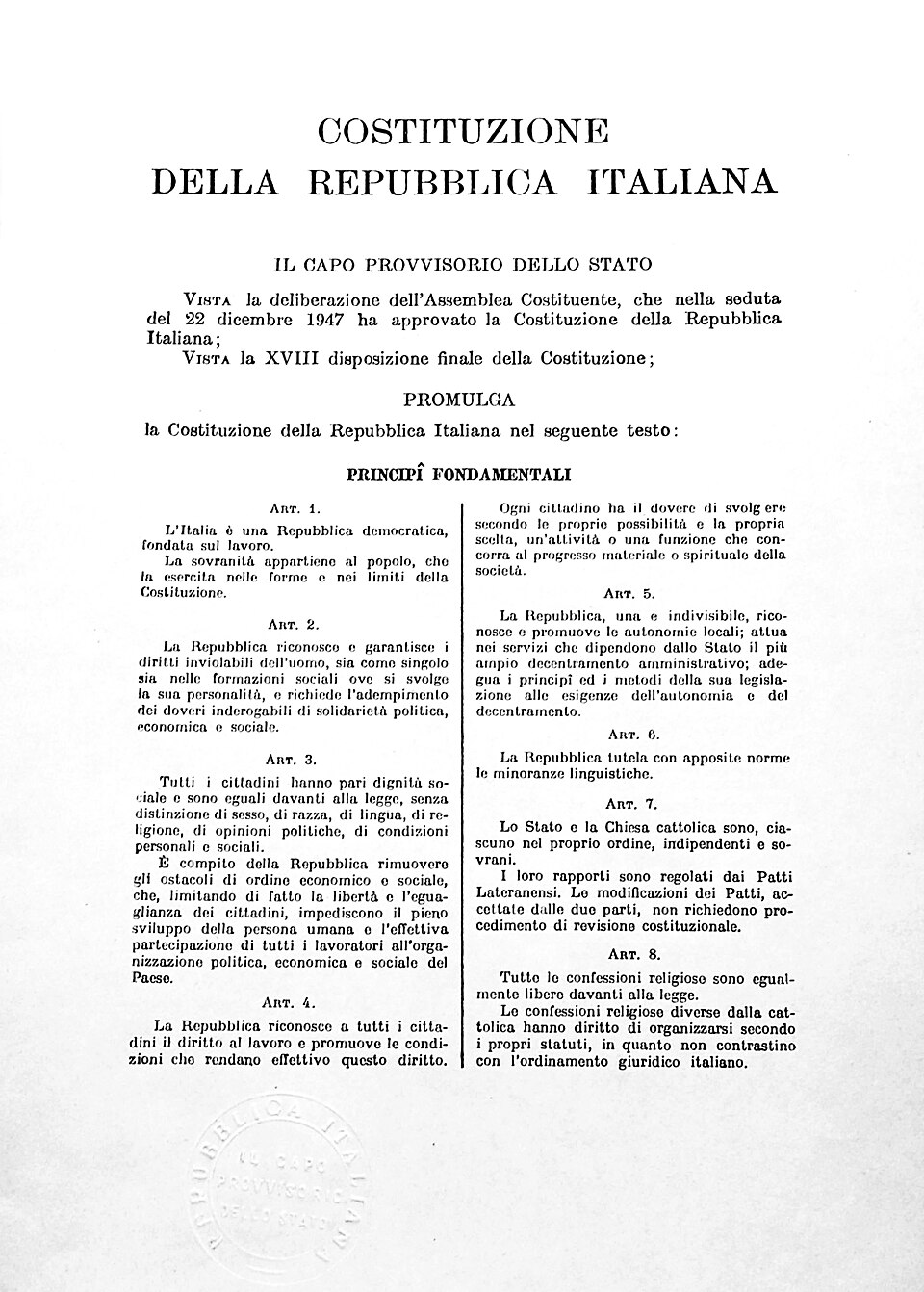

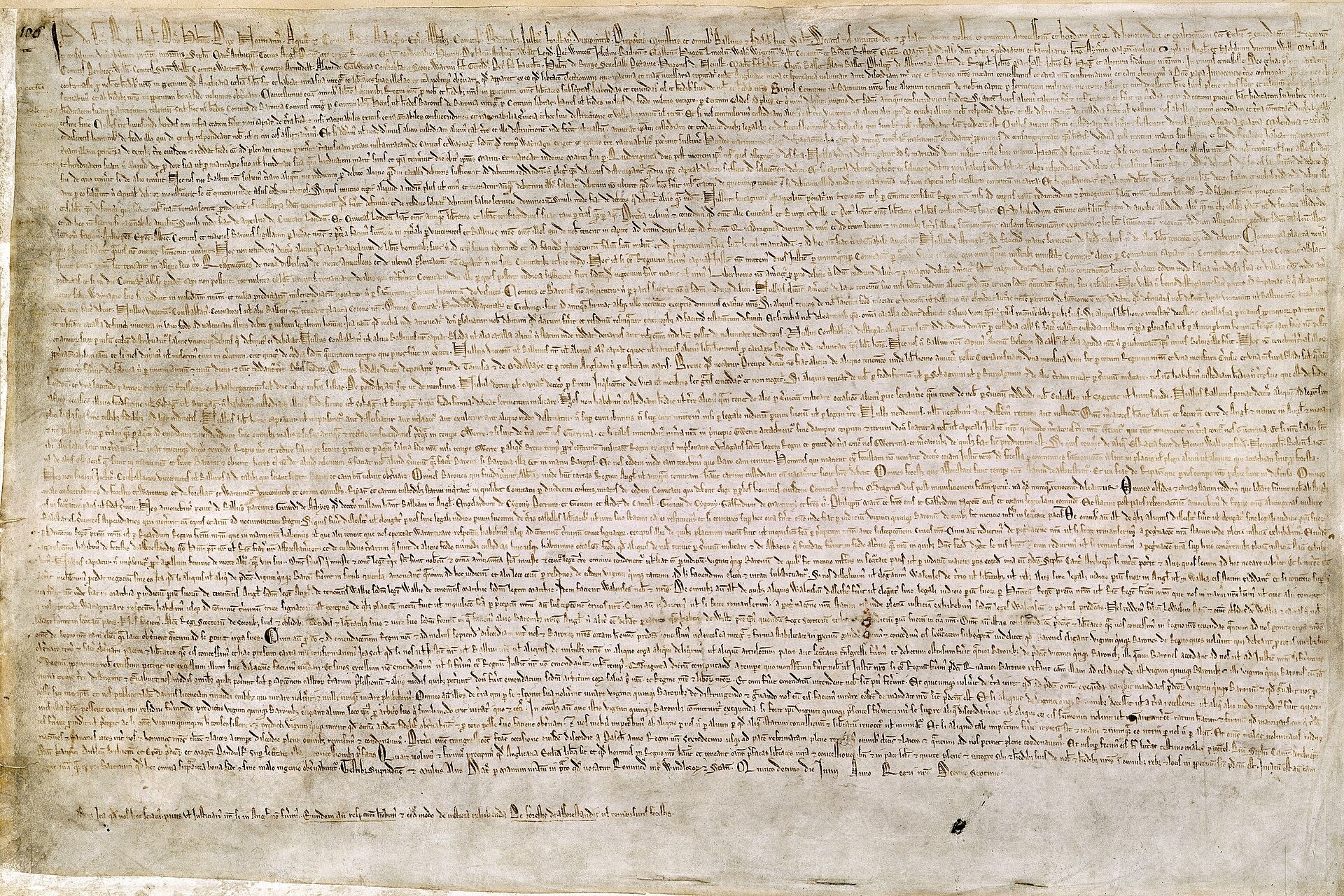

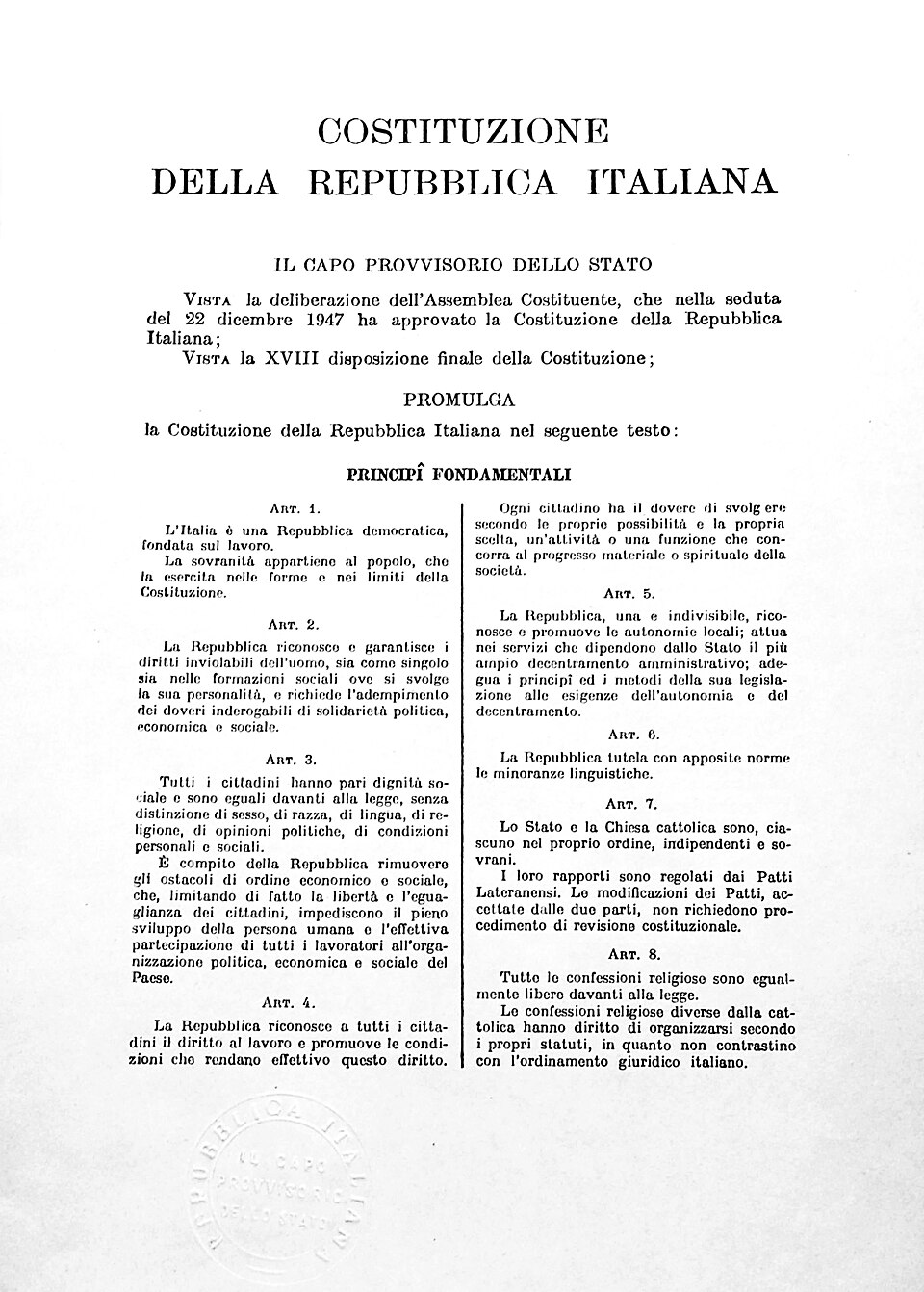

| Throughout

the history of democracy, enduring democracy advocates succeed almost

always through peaceful means when there is a window of opportunity.

One major type of opportunity include governments weakened after a

violent shock.[12] The other main avenue occurs when autocrats are not

threatened by elections, and democratize while retaining power.[13] The

path to democracy can be long with setbacks along the way.[14][15][16] Athens This section is an excerpt from Athenian Revolution.[edit] The Athenian Revolution (508–507 BCE) was a revolt by the people of Athens that overthrew the ruling aristocratic oligarchy, establishing the almost century-long self-governance of Athens in the form of a participatory democracy – open to all free male citizens. It was a reaction to a broader trend of tyranny that had swept through Athens and the rest of Greece.[17] Benin This section is an excerpt from 1989–1990 unrest in Benin.[edit] The 1989–1990 unrest in Benin was a wave of protests, demonstrations, nonviolent boycotts, grassroots rallies, opposition campaigns and strikes in Benin against the government of Mathieu Kérékou, unpaid salaries, and new budget laws.[18] Brazil This section is an excerpt from Redemocratization in Brazil.[edit]  Diretas Já demonstration in Brasília for open elections The redemocratization of Brazil (Portuguese: abertura política, lit. 'political opening') was the 1974–1988 period of liberalization under the country's military dictatorship, ending with the decline of the regime, the signing of the country's new constitution, and the transition to democracy.[19] Then-president Ernesto Geisel began the process of liberalization (nicknamed Portuguese: distensão) in 1974, by allowing for the Brazilian Democratic Movement opposition party's participation in congressional elections. He worked to address human rights violations and began to undo the military dictatorship's founding legislation, the Institutional Acts, in 1978. General João Figueiredo, elected the next year, continued the transition to democracy, freeing the last political prisoners in 1980 and instituting direct elections in 1982. The 1985 election of a ruling opposition party marked the military dictatorship's end. The process of liberalization ultimately was successful, culminating with the promulgation of the 1988 Brazilian Constitution.[20] Chile This section is an excerpt from Chilean transition to democracy.[edit] The military dictatorship of Chile led by General Augusto Pinochet ended on 11 March 1990 and was replaced by a democratically elected government.[21] The transition period lasted roughly two years,[22] although some aspects of the process lasted significantly longer. Unlike most democratic transitions, led by either the elite or the people, Chile's democratic transition process is known as an intermediate transition[21] – a transition involving both the regime and the civil society.[23] Throughout the transition, though the regime increased repressive violence, it simultaneously supported liberalization – progressively strengthening democratic institutions[24] and gradually weakening those of the military.[25] France The French Revolution (1789) briefly allowed a wide franchise. The French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars lasted for more than twenty years. The French Directory was more oligarchic. The First French Empire and the Bourbon Restoration restored more autocratic rule. The French Second Republic had universal male suffrage but was followed by the Second French Empire. The Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) resulted in the French Third Republic. Germany Germany established its first democracy in 1919 with the creation of the Weimar Republic, a parliamentary republic created following the German Empire's defeat in World War I. The Weimar Republic lasted only 14 years before it collapsed and was replaced by Nazi dictatorship.[26] Historians continue to debate the reasons why the Weimar Republic's attempt at democratization failed.[26] After Germany was militarily defeated in World War II, democracy was reestablished in West Germany during the U.S.-led occupation which undertook the denazification of society.[27] United Kingdom  Magna Carta in the British Library. The document was described as "the chief cause of Democracy in England". In Great Britain, there was renewed interest in Magna Carta in the 17th century.[28] The Parliament of England enacted the Petition of Right in 1628 which established certain liberties for subjects. The English Civil War (1642–1651) was fought between the King and an oligarchic but elected Parliament,[29] during which the idea of a political party took form with groups debating rights to political representation during the Putney Debates of 1647.[30] Subsequently, the Protectorate (1653–59) and the English Restoration (1660) restored more autocratic rule although Parliament passed the Habeas Corpus Act in 1679, which strengthened the convention that forbade detention lacking sufficient cause or evidence. The Glorious Revolution in 1688 established a strong Parliament that passed the Bill of Rights 1689, which codified certain rights and liberties for individuals.[31] It set out the requirement for regular parliaments, free elections, rules for freedom of speech in Parliament and limited the power of the monarch, ensuring that, unlike much of the rest of Europe, royal absolutism would not prevail.[32][33] Only with the Representation of the People Act 1884 did a majority of the males get the vote. Greece This section is an excerpt from Metapolitefsi.[edit] The Metapolitefsi (Greek: Μεταπολίτευση, romanized: Metapolítefsi, IPA: [metapoˈlitefsi], "regime change") was a period in modern Greek history from the fall of the Ioannides military junta of 1973–74 to the transition period shortly after the 1974 legislative elections. Indonesia Further information: Liberal democracy period in Indonesia and Post-Suharto era in Indonesia Italy  King Charles Albert of Sardinia signs the Albertine Statute, 4 March 1848.  Constitution of the Italian Republic, came into force on 1 January 1948 after the 1946 Italian institutional referendum. In September 1847, violent riots inspired by Liberals broke out in Reggio Calabria and in Messina in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which were put down by the military. On 12 January 1848 a rising in Palermo spread throughout the island and served as a spark for the Revolutions of 1848 all over Europe. After similar revolutionary outbursts in Salerno, south of Naples, and in the Cilento region which were backed by the majority of the intelligentsia of the Kingdom, on 29 January 1848 King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies was forced to grant a constitution, using for a pattern the French Charter of 1830. This constitution was quite advanced for its time in liberal democratic terms, as was the proposal of a unified Italian confederation of states.[34] On 11 February 1848, Leopold II of Tuscany, first cousin of Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria, granted the Constitution, with the general approval of his subjects. The Habsburg example was followed by Charles Albert of Sardinia (Albertine Statute; later became the constitution of the unified Kingdom of Italy and remained in force, with changes, until 1948[35]) and by Pope Pius IX (Fundamental Statute). However, only King Charles Albert maintained the statute even after the end of the riots. The Kingdom of Italy, after the unification of Italy in 1861, was a constitutional monarchy. The new kingdom was governed by a parliamentary constitutional monarchy dominated by liberals.[a] The Italian Socialist Party increased in strength, challenging the traditional liberal and conservative establishment. From 1915 to 1918, the Kingdom of Italy took part in World War I on the side of the Entente and against the Central Powers. In 1922, following a period of crisis and turmoil, the Italian fascist dictatorship was established. During World War II, Italy was first part of the Axis until it surrendered to the Allied powers (1940–1943) and then, as part of its territory was occupied by Nazi Germany with fascist collaboration, a co-belligerent of the Allies during the Italian resistance and the subsequent Italian Civil War, and the liberation of Italy (1943–1945). The aftermath of World War II left Italy also with an anger against the monarchy for its endorsement of the Fascist regime for the previous twenty years. These frustrations contributed to a revival of the Italian republican movement.[36] Italy became a republic after the 1946 Italian institutional referendum[37] held on 2 June, a day celebrated since as Festa della Repubblica. Italy has a written democratic constitution, resulting from the work of a Constituent Assembly formed by the representatives of all the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the liberation of Italy and the Italian Civil War,[38] and coming into force on 1 January 1948. Japan In Japan, limited democratic reforms were introduced during the Meiji period (when the industrial modernization of Japan began), the Taishō period (1912–1926), and the early Shōwa period.[39] Despite pro-democracy movements such as the Freedom and People's Rights Movement (1870s and 1880s) and some proto-democratic institutions, Japanese society remained constrained by a highly conservative society and bureaucracy.[39] Historian Kent E. Calder notes that writers that "Meiji leadership embraced constitutional government with some pluralist features for essentially tactical reasons" and that pre-World war II Japanese society was dominated by a "loose coalition" of "landed rural elites, big business, and the military" that was averse to pluralism and reformism.[39] While the Imperial Diet survived the impacts of Japanese militarism, the Great Depression, and the Pacific War, other pluralistic institutions, such as political parties, did not. After World War II, during the Allied occupation, Japan adopted a much more vigorous, pluralistic democracy.[39]  Voting in Valparaíso, Chile, in 1888 Madagascar This section is an excerpt from 1990–1992 movement in Madagascar.[edit] The 1990–1992 movement in Madagascar (Malagasy: Fihetsiketsehana 1990-1992 teto Madagasikara) was a period of widespread popular unrest in Madagascar between March 1990 and August 1992. It began as a wave of strike action against the autocratic regime of President Didier Ratsiraka and culminated in the promulgation of a new constitution and a period of democratic transition leading to Ratsiraka handing the Presidency to opposition leader Albert Zafy in March 1993.[40] |

民

主主義の歴史を通じて、永続的な民主主義の擁護者たちは、機会が訪れた際にはほぼ常に平和的手段によって成功を収めてきた。主要な機会の類型の一つは、暴

力的な衝撃後に弱体化した政府である[12]。もう一つの主な道筋は、独裁者が選挙によって脅威を感じず、権力を保持したまま民主化を進める場合である

[13]。民主主義への道は長く、途中で挫折を伴うこともある[14][15]。[16] アテネ この節はアテナイ革命からの抜粋である。[編集] アテナイ革命(紀元前508年~507年)は、アテナイ市民による反乱であり、支配的な貴族寡頭政治を打倒し、自由な男性市民全員に開かれた参加型民主主 義という形で、ほぼ1世紀にわたるアテナイの自治を確立した。これはアテネ及びギリシャ全土を席巻した専制政治の広範な潮流に対する反動であった。 [17] ベナン この節は「1989-1990年ベナン騒乱」からの抜粋である。[編集] 1989年から1990年にかけてのベナンにおける騒乱は、マチュー・ケレクー政権、未払いの給与、新たな予算法に対する抗議、デモ、非暴力ボイコット、 草の根集会、反対運動、ストライキの波であった。[18] ブラジル この節はブラジルにおける再民主化からの抜粋である。[編集]  ブラジリアでの直接選挙要求デモ「ディレタス・ジャ」 ブラジルの再民主化(ポルトガル語: abertura política、直訳「政治的開放」)とは、1974年から1988年にかけて軍事独裁政権下で進められた自由化政策を指す。この政策は政権の衰退、新 憲法の制定、民主主義への移行をもって終結した。[19] 当時のエルネスト・ゲイゼル大統領は1974年、野党ブラジル民主運動党の議会選挙参加を認めることで自由化プロセス(ポルトガル語で「ディステンサ」と 呼ばれる)を開始した。彼は人権侵害への対応に取り組み、1978年には軍事独裁政権の基盤となる法律である「制度的法令」の撤廃を始めた。翌年に選出さ れたジョアン・フィゲイレド将軍は民主化への移行を継続し、1980年に最後の政治犯を解放、1982年には直接選挙を導入した。1985年の与党野党の 選挙勝利は軍事独裁政権の終焉を意味した。自由化プロセスは最終的に成功し、1988年ブラジル憲法の公布をもって頂点を迎えた。[20] チリ この節はチリの民主化移行期からの抜粋である。[編集] アウグスト・ピノチェト将軍率いるチリの軍事独裁政権は1990年3月11日に終結し、民主的に選出された政府に取って代わられた。[21] 移行期間はおよそ2年間続いたが、[22] プロセスの一部はさらに長く続いた。エリート層か民衆のいずれかが主導する大半の民主化移行とは異なり、チリの民主化移行プロセスは中間的移行[21]と して知られる。これは政権と市民社会双方が関与する移行である[23]。移行期間中、政権は抑圧的暴力を行使しつつも、同時に自由化を支持した。民主的機 関を段階的に強化[24]し、軍事的機関を徐々に弱体化させたのである[25]。 フランス フランス革命(1789年)は一時的に広範な選挙権を認めた。フランス革命戦争とナポレオン戦争は20年以上続いた。フランス・ディレクトワールはより寡 頭制的であった。第一帝政とブルボン復古はより専制的な統治を復活させた。第二共和政は男性普通選挙権を有したが、第二帝政に取って代わられた。普仏戦争 (1870-71年)の結果、第三共和政が成立した。 ドイツ ドイツは1919年、第一次世界大戦におけるドイツ帝国の敗戦後に設立された議会制共和国であるワイマール共和国により、初の民主主義を確立した。ワイ マール共和国はわずか14年で崩壊し、ナチス独裁政権に取って代わられた。[26] ワイマール共和国の民主化試みが失敗した理由については、歴史家たちの間で議論が続いている。[26] 第二次世界大戦での軍事的敗北後、西ドイツではアメリカ主導の占領下で民主主義が再建され、社会の脱ナチ化が実施された。[27] イギリス  大英図書館所蔵のマグナ・カルタ。この文書は「イングランド民主主義の主因」と評された。 イギリスでは17世紀にマグナ・カルタへの関心が再燃した。[28] イングランド議会は1628年に権利請願を制定し、臣民に一定の自由を保障した。イングランド内戦(1642-1651)は国王と寡頭制ながら選出された 議会との間で戦われ[29]、1647年のパトニー討論では政治的代表権を巡る議論が交わされ、政党の概念が形作られていった。[30] その後、護国卿時代(1653-59年)とイングランド王政復古(1660年)によりより専制的な統治が復活したが、議会は1679年に人身保護令状法を 可決し、十分な理由や証拠のない拘留を禁じる慣習を強化した。1688年の名誉革命により強力な議会が確立され、1689年権利章典が制定された。これは 個人の権利と自由を法典化したものである[31]。定期議会、自由選挙、議会における言論の自由の規則を定め、君主の権力を制限した。これにより、ヨー ロッパの他の多くの地域とは異なり、王権絶対主義が優勢になることはなかった。[32][33] 1884年の人民代表法によって初めて、男性の過半数が選挙権を得たのである。 ギリシャ この節はメタポリテフシからの抜粋である。[編集] メタポリテフシ(ギリシャ語: Μεταπολίτευση、ローマ字表記: Metapolítefsi、IPA: [metapoˈlitefsi]、「政権交代」の意)とは、1973年から1974年にかけてのイオアニデス軍事政権の崩壊から、1974年総選挙直後 の移行期に至る、近代ギリシャ史における一時期を指す。 インドネシア 詳細情報:インドネシアの自由民主主義期およびインドネシアのスハルト政権終焉後の時代 イタリア  サルデーニャ王カルロ・アルベルトがアルベルティーノ憲法に署名、1848年3月4日。  イタリア共和国憲法は、1946年のイタリア憲法国民投票を経て、1948年1月1日に発効した。 1847年9月、両シチリア王国においてリベラル派に煽られた暴動がレッジョ・ディ・カラブリアとメッシーナで発生し、軍によって鎮圧された。1848年 1月12日、パレルモで勃発した反乱は島全体に広がり、ヨーロッパ全域における1848年革命の火種となった。ナポリ南部のサレルノやチレント地方でも同 様の革命的暴動が発生し、両シチリア王国の知識人層の大半がこれを支持した。1848年1月29日、両シチリア王フェルディナンド2世は、1830年フラ ンス憲章をモデルとした憲法の公布を余儀なくされた。この憲法は自由民主主義の観点から当時としてはかなり先進的であり、統一されたイタリア諸州連合の提 案も同様であった[34]。1848年2月11日、オーストリア皇帝フェルディナント1世の従兄弟であるトスカーナ大公レオポルド2世は、臣民の概ねの賛 同を得て憲法を公布した。ハプスブルク家の例に倣い、サルデーニャのカルロ・アルベルト(アルベルティーノ憲法;後に統一イタリア王国の憲法となり、改正 を経て1948年まで効力を維持した[35])と教皇ピウス9世(基本法令)も憲法を公布した。しかし、騒乱終結後も憲法を維持したのはカルロ・アルベル ト王のみであった。 1861年のイタリア統一後、イタリア王国は立憲君主国となった。新王国は自由主義者が支配する議会制立憲君主制で統治された。イタリア社会党は勢力を拡 大し、伝統的な自由主義・保守主義体制に挑戦した。1915年から1918年にかけて、イタリア王国は第一次世界大戦に連合国側として参戦し、中央同盟国 と戦った。1922年、危機と混乱の時期を経て、イタリアのファシスト独裁政権が樹立された。第二次世界大戦中、イタリアは当初枢軸国の一員であったが、 連合国に降伏した(1940年~1943年)。その後、領土の一部がナチス・ドイツに占領されファシスト政権が協力したため、イタリア抵抗運動と続くイタ リア内戦、そしてイタリア解放(1943年~1945年)の期間中は連合国の共戦国となった。第二次世界大戦後のイタリアでは、過去20年にわたりファシ スト政権を支持した君主制への怒りも残った。こうした不満がイタリア共和主義運動の復活に寄与した[36]。1946年6月2日に行われたイタリア憲法国 民投票[37]を経て、イタリアは共和国となった。この日は現在「共和国記念日」として祝われている。イタリアには成文民主憲法がある。これはイタリア解 放と内戦においてナチス・ファシスト勢力の打倒に貢献した反ファシスト勢力の代表者で構成された制憲議会による作業の結果として制定され、1948年1月 1日に発効したものである。 日本 日本では、明治時代(日本の産業近代化が始まった時期)、大正時代(1912年~1926年)、そして昭和初期に、限定的な民主化改革が導入された。 [39] 自由民権運動(1870年代~1880年代)などの民主化運動や、いくつかの民主主義の原型となる制度が存在したにもかかわらず、日本社会は極めて保守的 な社会と官僚機構によって制約され続けた。[39] 歴史家ケント・E・カルダーは、明治政府が「本質的に戦術的な理由から多元主義的特徴を伴う立憲政治を採用した」と指摘し、第二次世界大戦前の日本社会は 多元主義と改革主義を嫌う「土地所有農村エリート、大企業、軍部」による「緩やかな連合」が支配していたと述べている。[39] 帝国議会は日本ミリタリズム、世界恐慌、太平洋戦争の衝撃を乗り切ったが、政党などの他の多元的制度はそうではなかった。第二次世界大戦後、連合国占領下 で日本はより活発な多元的民主主義を採用した。[39]  1888年チリ・バルパライソでの投票 マダガスカル この節はマダガスカルにおける1990-1992年の運動からの抜粋である。[編集] マダガスカルにおける1990-1992年の運動(マダガスカル語: Fihetsiketsehana 1990-1992 teto Madagasikara)は、1990年3月から1992年8月にかけてマダガスカルで広範な民衆の動乱が起きた時期を指す。ディディエ・ラツィラカ大 統領の独裁政権に対するストライキの波として始まり、新憲法の公布と民主化移行期を経て、1993年3月にラツィラカが野党指導者アルベール・ザフィに大 統領職を譲る結果に至った。[40] |

| Malawi Banda agreed to hold the referendum in response to international pressure and growing domestic unrest. Opposition groups had initially doubted the legitimacy of the process, but eventually participated once they were allowed to register as “special interest groups” and after a series of discussions led to an agreed legal framework. Major opposition participants included the Catholic and Presbyterian Churches, the United Democratic Front (representing internal opponents and dissident government officials), and the Alliance for Democracy (linked to trade unions and opposition groups in exile).[41] Latin America Countries in Latin America became independent between 1810 and 1825, and soon had some early experiences with representative government and elections. All Latin American countries established representative institutions soon after independence, the early cases being those of Colombia in 1810, Paraguay and Venezuela in 1811, and Chile in 1818.[42] Adam Przeworski shows that some experiments with representative institutions in Latin America occurred earlier than in most European countries.[43] Mass democracy, in which the working class had the right to vote, become common only in the 1930s and 1940s.[44] Portugal This section is an excerpt from Portuguese transition to democracy.[edit] Portugal's redemocratization process started with the Carnation Revolution of 1974. It ended with the enactment of the Constitution of Portugal in 1976. Philippines  A picture of Corazon Aquino campaigning under the UNIDO banner during the 1986 snap elections. In 1986, democratic institutions throughout the Philippines were reinstated during the deposition of the 20-year long Marcos regime through the People Power Revolution. Barred constitutionally from running a third term by 1973, Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his administration announced Proclamation No. 1081 on September 23, 1972, a declaration of martial law that deliberately decreed emergency powers over every democratic functions in the country, ostensibly under the pretext of a communist overthrow. Throughout the 20-year long martial law, most civil liberties of the once democratic Philippines were suppressed, criminalized, or just plainly abolished. By 1981, the loan-reliant economy of the Marcos regime experienced unforecasted contractions when the Reagan administration announced the lowering of American interest rates during the global recession at that time, further plunging the Philippine economy into debt. In 1983, Benigno Aquino Jr., a renowned dissident of the Marcos regime, returned to the Philippines after his self-exile in the United States. After disembarking China Airlines Flight 811 on Gate 8 at Manila International Airport, Aquino, on the service steps of his van guarded by the Aviation Security Command (AVESCOM), was shot multiple times by assailants outside the van at point blank. He died from his wounds on the way to Fort Bonifacio Hospital. In response to the assassination of Aquino, public outrage revitalized in the form of Jose W. Diokno's nationalist liberal democrat umbrella organization, the Kilusan sa Kapangyarihan at Karapatan ng Bayan or KAAKBAY, then leading the Justice for Aquino Justice for All or JAJA movement. JAJA consisted of the social democrat-dominant August Twenty One Movement or the ATOM, led by Butz Aquino. These political movements and organizations coalesced into the Kongreso ng Mamamayang Pilipino or KOMPIL, a call for parliamentarianism and democratization during this period. In the middle of 1984, JAJA was replaced by the Coalition for the Restoration of Democracy (CORD), with largely the same principles. In November of 1985, the rapid development of opposition organizations swayed the Marcos administration, with some American intervention, to announce the Batas Pambansa Blg. 883 (National Law No. 883), a 1986 snap election, by the unicameral body, the Regular Batasang Pambansa. Immediately after the decree, the United Nationalist Democratic Organization (UNIDO), the main opposition multi-party electoral alliance, rallied even more public support, headed by assigned party leader Corazon "Cory" Cojuangco Aquino, Benigno Aquino's wife, and Salvador "Doy" Ramon Hidalgo Laurel. The 1986 snap election was marred with electoral fraud, as discrepant figures from both the government-sponsored election canvasser, Commission on Elections (COMELEC), and the publicly-accredited poll watcher, National Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL), finalized different tally figures. COMELEC announced a Marcos victory of 10,810,000 votes against Aquino's 9,300,000, while NAMFREL announced an Aquino victory of 7,840,000 votes against Marcos' 7,050,000. The apparent tampered snap election stirred public unrest, even prompting COMELEC technicians to proceed with a walkout mid-voting, an event cited to be the first act of civil disobedience during the People Power Revolution. Occurring afterwards were a series of popular demonstrations against the regime occurring from February 22 to 26, referred to as the People Power Revolution, then culminating into the departure of Marcos and the non-violent transition of power, restoring democracy under Aquino's UNIDO. Immediately after Aquino's ascension, she ratified Proclamation No. 3, a law declaring a provisional constitution and government. The promulgation of the 1986 Freedom Constitution superseded many of the autocratic provisions of the 1973 Constitution, abolishing the Regular Batasang Pambansa, along with plebiscitarian dependence for the creation of a new Congress. The official adoption of the 1987 Constitution signalled the completion of Philippine democratization. Senegal This section is an excerpt from Democracy in Senegal.[edit] The Democracy in Senegal was touted as one of the more stable democracies in Africa, with a long tradition of peaceful democratic discourse. Democratization proceeded gradually from 1970s to 1990s. Spain This section is an excerpt from Spanish transition to democracy.[edit] The Spanish transition to democracy, known in Spain as la Transición (IPA: [la tɾansiˈθjon]; 'the Transition') or la Transición española ('the Spanish Transition'), was a period of modern Spanish history encompassing the regime change that moved from the Francoist dictatorship to the consolidation of a parliamentary system, in the form of constitutional monarchy under Juan Carlos I. The democratic transition began two days after the death of Francisco Franco, in November 1975.[45] Initially, "the political elites left over from Francoism" attempted "reform of the institutions of dictatorship" through existing legal means,[46] but social and political pressure saw the formation of a democratic parliament in the 1977 general election, which had the imprimatur to write a new constitution that was then approved by referendum in December 1978. The following years saw the beginning of the development of the rule of law and establishment of regional government, amidst ongoing terrorism, an attempted coup d'état and global economic problems.[46] The Transition is said to have concluded after the landslide victory of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the 1982 general election and the first peaceful transfer of executive power.[46][b] |

マラウイ バンダは国際的な圧力と国内の不安の高まりを受けて、国民投票の実施に同意した。野党勢力は当初、このプロセスの正当性を疑っていたが、「特別利益団体」 として登録が認められ、一連の協議を経て合意された法的枠組みが整った後、最終的に参加した。主要な野党参加団体には、カトリック教会と長老派教会、国内 の反対勢力と反体制派政府高官を代表する統一民主戦線、そして労働組合や亡命野党団体と結びついた民主主義同盟が含まれていた。[41] ラテンアメリカ ラテンアメリカの諸国は1810年から1825年の間に独立を果たし、間もなく代議制政府と選挙の初期段階を経験した。全てのラテンアメリカ諸国は独立後 すぐに代表制機関を設立した。初期の事例としては、1810年のコロンビア、1811年のパラグアイとベネズエラ、1818年のチリが挙げられる。 [42] アダム・プシェヴォルスキは、ラテンアメリカにおける代表制機関の実験が、ほとんどのヨーロッパ諸国よりも早く行われたことを示している。[43] 労働者階級に投票権が与えられた大衆民主主義が一般的になったのは、1930年代から1940年代になってからだ。[44] ポルトガル この節は「ポルトガルの民主化への移行」からの抜粋である。[編集] ポルトガルの再民主化プロセスは1974年のカーネーション革命で始まり、1976年のポルトガル憲法制定で終結した。 フィリピン  1986年の緊急総選挙で国連工業開発機関(UNIDO)の旗の下で選挙運動を行うコラソン・アキノの写真。 1986年、20年に及んだマルコス政権が人民力革命によって打倒され、フィリピン全土で民主的制度が復活した。 1973年までに憲法上3期目の出馬が禁止されたフェルディナンド・マルコス・シニアとその政権は、1972年9月23日に大統領令第1081号を発表し た。これは戒厳令宣言であり、共産主義者による政権転覆を口実に、国内のあらゆる民主的機能を意図的に緊急権限下に置くことを定めた。20年に及ぶ戒厳令 下で、かつて民主主義国家であったフィリピンの市民的自由の大半は抑圧され、犯罪化され、あるいは単純に廃止された。1981年、世界的な不況下でレーガ ン政権が米国金利の引き下げを発表した際、マルコス政権の融資依存型経済は予測外の縮小を経験し、フィリピン経済はさらに債務の深淵へと沈んだ。 1983年、マルコス政権の著名な反体制派ベニグノ・アキノ・ジュニアが米国での亡命生活からフィリピンに帰国した。マニラ国際空港8番ゲートでチャイナ エアライン811便から降りたアキノは、航空保安司令部(AVESCOM)に護衛されたバンから降りた直後、車外にいた襲撃者らに至近距離から複数発の銃 弾を浴びせられた。彼はボニファシオ要塞病院への搬送中に死亡した。 アキノ暗殺を受けて、民衆の怒りはホセ・W・ディオクノ率いるナショナリスト自由民主主義連合組織「国民権力・権利運動(KAAKBAY)」を通じて再燃 した。同組織は当時「アキノに正義を、すべての人に正義を(JAJA)」運動を主導していた。JAJAは社会民主主義が主流の「8月21日運動 (ATOM)」を包含し、同運動はブッツ・アキノが率いていた。これらの政治運動・組織は「フィリピン国民議会(KOMPIL)」へと統合され、この期間 における議会制民主主義と民主化を訴えた。1984年半ば、JAJAはほぼ同原則を掲げる「民主主義回復連合(CORD)」に取って代わられた。 1985年11月、野党組織の急速な発展と米国の介入もあり、マルコス政権は単院制議会である通常バタサン・パンバンサによる1986年総選挙実施を定め た「バタス・パンバンサ第883号法(国家法第883号)」を発表した。この法令発布直後、主要野党連合である統一ナショナリスト民主機構(UNIDO) は、指名党首のコラソン・コジュアンコ・アキノ(ベニグノ・アキノの妻)とサルバドール・ラモン・イダルゴ・ローレルを中心に、さらに多くの国民的支持を 集めた。 1986年の急遽実施された選挙は不正選挙にまみれていた。政府が支援する選挙開票機関である選挙管理委員会(COMELEC)と、公的に認可された選挙 監視団体である自由選挙のための国民運動(NAMFREL)が、それぞれ異なる集計結果を確定させたためである。COMELECはマルコスが1081万 票、アキノが930万票でマルコス勝利と発表したが、NAMFRELはアキノが784万票、マルコスが705万票でアキノ勝利と発表した。明らかに不正が 働いたこの選挙は民衆の不安を煽り、投票途中での選挙管理委員会の技術者によるストライキを引き起こした。この出来事は「ピープル・パワー革命」における 最初の市民的不服従の行為とされている。 その後2月22日から26日にかけて、政権に対する一連の民衆デモが発生した。これは「ピープル・パワー革命」と呼ばれ、マルコス大統領の退陣と非暴力に よる政権移行へと発展。アキノ率いるUNIDO(国家統一民主改革評議会)のもと民主主義が回復した。アキノ政権発足直後、暫定憲法と政府を宣言する法令 「第3号宣言」が公布された。1986年自由憲法の公布により、1973年憲法の独裁的規定の多くが廃止され、常設国民議会(バタサン・パンバンサ)が廃 止されるとともに、新議会の設置における国民投票依存制も撤廃された。1987年憲法の正式採択は、フィリピン民主化の完成を告げるものだった。 セネガル この節は「セネガルの民主主義」からの抜粋である。[編集] セネガルの民主主義は、平和的な民主的言説の長い伝統を持つ、アフリカで最も安定した民主主義の一つとして称賛された。民主化は1970年代から1990 年代にかけて徐々に進んだ。 スペイン このセクションは、スペインの民主化への移行からの抜粋である。[編集] スペインの民主化への移行は、スペインではラ・トランシシオン(IPA: [la tɾansiˈθjon]; 「移行」)、あるいはラ・トランシシオン・エスパニョーラ(「スペインの移行」)として知られる、フランコ独裁政権からフアン・カルロス1世による立憲君 主制という形の議会制の確立へと移行した政権交代を含む、現代スペイン史の一時期である。 民主化への移行は、1975年11月のフランシスコ・フランコ死の2日後に始まった。[45] 当初、「フランコ主義から残った政治エリート」は、既存の法的手段を通じて「独裁体制の制度改革」を試みた[46]が、社会的・政治的圧力により、 1977年の総選挙で民主的な議会が結成され、新憲法を起草する権限が与えられた。この新憲法は、1978年12月の国民投票で承認された。その後数年間 は、テロリズムの継続、クーデター未遂、世界的な経済問題などの中で、法の支配の発展と地方政府の設立が始まった[46]。1982年の総選挙でスペイン 社会労働党(PSOE)が圧勝し、初めて平和的な行政権の移譲が行われたことで、移行期は終了したとされる[46][b]。 |

| South Africa The apartheid system in South Africa was ended through a series of bilateral and multi-party negotiations between 1990 and 1993. The negotiations culminated in the passage of a new interim Constitution in 1993, a precursor to the Constitution of 1996; and in South Africa's first non-racial elections in 1994, won by the African National Congress (ANC) liberation movement. South Korea This section is an excerpt from June Democratic Struggle.[edit]  Crowds gather at the state funeral of Lee Han-yeol in Seoul, July 9, 1987. The June Democratic Struggle (Korean: 6월 민주 항쟁), also known as the June Democracy Movement and the June Uprising,[50] was a nationwide pro-democracy movement in South Korea that generated mass protests from June 10 to 29, 1987. The demonstrations forced the ruling authoritarian government to hold direct presidential elections and institute other democratic reforms, which led to the establishment of the Sixth Republic, the present-day government of the Republic of Korea (South Korea). Soviet Union This section is an excerpt from Demokratizatsiya (Soviet Union).[edit] Demokratizatsiya (Russian: демократизация, IPA: [dʲɪməkrətʲɪˈzatsɨjə], democratization) was a slogan introduced by CPSU General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in January 1987 calling for the infusion of "democratic" elements into the Soviet Union's single-party government. Gorbachev's Demokratizatsiya meant the introduction of multi-candidate—though not multi-party—elections for local Communist Party (CPSU) officials and Soviets. In this way, he hoped to rejuvenate the party with reform-minded personnel who would carry out his institutional and policy reforms. The CPSU would retain sole custody of the ballot box.[51] Switzerland These paragraphs are an excerpt from Switzerland as a federal state.[edit] The rise of Switzerland as a federal state began on 12 September 1848, with the creation of a federal constitution in response to a 27-day civil war, the Sonderbundskrieg. Roman Republic This section is an excerpt from Overthrow of the Roman monarchy.[edit] The overthrow of the Roman monarchy was an event in ancient Rome that took place between the 6th and 5th centuries BC where a political revolution replaced the then-existing Roman monarchy under Lucius Tarquinius Superbus with a republic. The details of the event were largely forgotten by the Romans a few centuries later; later Roman historians presented a narrative of the events, traditionally dated to c. 509 BC, but it is largely believed by modern scholars to be fictitious. Tunisia This section is an excerpt from Tunisian revolution.[edit] [[File: |thumb|]] The Tunisian revolution (Arabic: الثورة التونسية), also called the Jasmine Revolution and Tunisian Revolution of Dignity,[52][53][54] was an intensive 28-day campaign of civil resistance. It included a series of street demonstrations which took place in Tunisia, and led to the ousting of longtime dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in January 2011.[55] It eventually led to a thorough democratization of the country and to free and democratic elections, which had led to people believing it was the only successful movement in the Arab Spring.[56] Ukraine These paragraphs are an excerpt from 1989–1991 Ukrainian revolution.[edit] From the formal establishment of the People's Movement of Ukraine on 1 July 1989 to the formalisation of the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine via referendum on 1 December 1991, a non-violent protest movement worked to achieve Ukrainian independence from the Soviet Union.[57] Led by Soviet dissident Viacheslav Chornovil, the protests began as a series of strikes in the Donbas that led to the removal of longtime communist leader Volodymyr Shcherbytsky. Later, the protests grew in size and scope, leading to a human chain across the country and widespread student protests against the falsification of the 1990 Ukrainian Supreme Soviet election. The protests were ultimately successful, leading to the independence of Ukraine amidst the broader dissolution of the Soviet Union. United States The American Revolution (1765–1783) created the United States. The new Constitution established a relatively strong federal national government that included an executive, a national judiciary, and a bicameral Congress that represented states in the Senate and the population in the House of Representatives.[58][59] In many fields, it was a success ideologically in the sense that a true republic was established that never had a single dictator, but voting rights were initially restricted to white male property owners (about 6% of the population).[60] Slavery was not abolished in the Southern states until the constitutional Amendments of the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War (1861–1865). The provision of Civil Rights for African-Americans to overcome post-Reconstruction Jim Crow segregation in the South was achieved in the 1960s. |

南アフリカ 南アフリカのアパルトヘイト制度は、1990年から1993年にかけての二国間および多党間交渉を経て終結した。交渉は1993年の新暫定憲法制定 (1996年憲法の前身)と、1994年に実施された南アフリカ初の非人種差別選挙(アフリカ民族会議(ANC)解放運動が勝利)で頂点を迎えた。 韓国 この節は「6月民主抗争」からの抜粋である。[編集]  1987年7月9日、ソウルで行われた李漢燁の葬儀に群衆が集まる(→六・民主蜂起と) 六・民主抗争(韓国語: 6월 민주 항쟁)は、六・民主化運動または六・民主蜂起とも呼ばれ、1987年6月10日から29日にかけて韓国全土で起きた民主化運動である。この抗議活動は、当 時の権威主義政権に直接大統領選挙の実施やその他の民主化改革を迫り、現在の大韓民国政府である第六共和制の樹立につながった。 ソビエト連邦 この節は「デモクラティザツィヤ(ソビエト連邦)」からの抜粋である。[編集] デモクラティザツィヤ(ロシア語: демократизация、IPA: [dʲɪməkrətʲɪˈzatsɨjə]、民主化)は、1987年1月にソ連共産党書記長ミハイル・ゴルバチョフが打ち出したスローガンであり、ソ連 の一党独裁体制に「民主的」要素を導入することを求めた。ゴルバチョフの民主化とは、地方の共産党(CPSU)幹部やソビエト(人民議会)の選挙におい て、複数候補制(ただし複数政党制ではない)を導入することを意味した。これにより、彼は自らの制度・政策改革を推進する改革志向の人材で党を刷新するこ とを望んだ。CPSUは投票箱の管理権を独占し続ける。[51] スイス これらの段落は「連邦国家としてのスイス」からの抜粋である。[編集] 連邦国家としてのスイスの台頭は、27日間の内戦であるゾンダーブント戦争への対応として連邦憲法が制定された1848年9月12日に始まった。 ローマ共和国 この節は「ローマ王政の打倒」からの抜粋である。[編集] ローマ王政の打倒は、紀元前6世紀から5世紀にかけて古代ローマで起きた事件である。政治革命により、ルキウス・タルクィニウス・スペルブス率いる当時の ローマ王政が共和政に取って代わられた。この出来事の詳細は、数世紀後にはローマ人によってほとんど忘れ去られていた。後のローマの歴史家たちは、伝統的 に紀元前509年頃とされている出来事の物語を提示したが、現代の学者たちはそのほとんどが虚構であると信じている。 チュニジア この節はチュニジア革命からの抜粋である。[編集] [[File: |thumb|]] チュニジア革命(アラビア語: الثورة التونسية)は、ジャスミン革命または尊厳のチュニジア革命とも呼ばれ[52]、 [53][54]は、28日間にわたる激しい市民抵抗運動であった。チュニジア国内で行われた一連の街頭デモを含み、2011年1月に長期独裁者ジネ・エ ル・アビディン・ベン・アリの追放につながった[55]。最終的には国の徹底的な民主化と自由で民主的な選挙をもたらし、アラブの春で唯一成功した運動だ と人々に信じさせるに至った。[56] ウクライナ これらの段落は1989–1991年ウクライナ革命からの抜粋である。[編集] 1989年7月1日のウクライナ人民運動の正式発足から、1991年12月1日の国民投票によるウクライナ独立宣言の正式化に至るまで、非暴力抗議運動が ソビエト連邦からのウクライナ独立達成に向けて活動した。[57] ソ連の反体制派ヴィアチェスラフ・チョルノヴィルが主導した抗議活動は、ドンバス地方での一連のストライキとして始まり、長年の共産党指導者ヴォロディミ ル・シェルビツキーの解任につながった。その後、抗議活動は規模と範囲を拡大し、全国を横断する人間の鎖や、1990年のウクライナ最高会議選挙の不正に 対する広範な学生抗議へと発展した。抗議運動は最終的に成功し、ソビエト連邦の解体という大きな流れの中でウクライナの独立をもたらした。 アメリカ合衆国 アメリカ独立戦争(1765年~1783年)によってアメリカ合衆国が誕生した。新たな憲法は、行政府、国家司法府、そして上院で州を、下院で国民を代表 する二院制議会を含む、比較的強力な連邦政府を確立した。[58] 多くの分野において、独裁者が一人も現れなかった真の共和制が確立されたという意味で、イデオロギー的には成功だったと言える。しかし当初、投票権は白人 男性財産所有者(人口の約6%)に限定されていた。奴隷制は、南北戦争(1861–1865)後の復興期における憲法修正条項によって、南部諸州でようや く廃止された。南部における再建後のジム・クロウ法による人種隔離を克服するためのアフリカ系アメリカ人の公民権保障は、1960年代に達成された。 |

| Causes and factors There is considerable debate about the factors which affect (e.g., promote or limit) democratization.[61] Factors discussed include economic, political, cultural, individual agents and their choices, international and historical. Economic factors Economic development and modernization theory Industrialization was seen by many theorists as a driver of democratization. Scholars such as Seymour Martin Lipset;[62] Carles Boix, Susan Stokes,[63]Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Evelyne Stephens, and John Stephens[64] argue that economic development increases the likelihood of democratization. Initially argued by Lipset in 1959, this has subsequently been referred to as modernization theory.[65][66] According to Daniel Treisman, there is "a strong and consistent relationship between higher income and both democratization and democratic survival in the medium term (10–20 years), but not necessarily in shorter time windows."[67] Robert Dahl argued that market economies provided favorable conditions for democratic institutions.[68] A higher GDP/capita correlates with democracy. Some Who? claim the wealthiest democracies have never been observed to fall into authoritarianism.[69] The rise of Hitler and of the Nazis in Weimar Germany can be seen as an obvious counter-example. Although, in early 1930s, Germany was already an advanced economy. By that time, the country was also living in a state of economic crisis virtually since the first World War (in the 1910s). A crisis that was eventually worsened by the effects of the Great Depression. There is also the general observation that democracy was very rare before the industrial revolution. Empirical research thus led many to believe that economic development either increases chances for a transition to democracy, or helps newly established democracies consolidate.[69][70] One study finds that economic development prompts democratization but only in the medium run (10–20 years). This is because development may entrench the incumbent leader while making it more difficult for him deliver the state to a son or trusted aide when he exits.[71] However, the debate about whether democracy is a consequence of wealth is far from conclusive.[72] Another study suggests that economic development depends on the political stability of a country to promote democracy.[73] Clark, Robert and Golder, in their reformulation of Albert Hirschman's model of Exit, Voice and Loyalty, explain how it is not the increase of wealth in a country per se which influences a democratization process, but rather the changes in the socio-economic structures that come together with the increase of wealth. They explain how these structural changes have been called out to be one of the main reasons several European countries became democratic. When their socioeconomic structures shifted because modernization made the agriculture sector more efficient, bigger investments of time and resources were used for the manufacture and service sectors. In England, for example, members of the gentry began investing more in commercial activities that allowed them to become economically more important for the state. These new kinds of productive activities came with new economic power. Their assets became more difficult for the state to count and hence, more difficult to tax. Because of this, predation was no longer possible and the state had to negotiate with the new economic elites to extract revenue. A sustainable bargain had to be reached because the state became more dependent on its citizens remaining loyal, and with this, citizens now had the leverage to be taken into account in the decision making process for the country.[74][unreliable source?][75] Adam Przeworski and Fernando Limongi argue that while economic development makes democracies less likely to turn authoritarian, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that development causes democratization (turning an authoritarian state into a democracy).[76] Economic development can boost public support for authoritarian regimes in the short-to-medium term.[77] Andrew J. Nathan argues that China is a problematic case for the thesis that economic development causes democratization.[78] Michael Miller finds that development increases the likelihood of "democratization in regimes that are fragile and unstable, but makes this fragility less likely to begin with."[79] There is research to suggest that greater urbanization, through various pathways, contributes to democratization.[80][81] Numerous scholars and political thinkers have linked a large middle class to the emergence and sustenance of democracy,[68][82] whereas others have challenged this relationship.[83] In "Non-Modernization" (2022), Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argue that modernization theory cannot account for various paths of political development "because it posits a link between economics and politics that is not conditional on institutions and culture and that presumes a definite endpoint—for example, an 'end of history'."[84] A meta-analysis by Gerardo L. Munck of research on Lipset's argument shows that a majority of studies do not support the thesis that higher levels of economic development leads to more democracy.[85] A 2024 study linked industrialization to democratization, arguing that large-scale employment in manufacturing made mass mobilization easier to occur and harder to repress.[86] Capital mobility Theories on causes to democratization such as economic development focuses on the aspect of gaining capital. Capital mobility focuses on the movement of money across borders of countries, different financial instruments, and the corresponding restrictions. In the past, there have been multiple theories as to what the relationship is between capital mobility and democratization.[87] The "doomsway view" is that capital mobility is an inherent threat to underdeveloped democracies by the worsening of economic inequalities, favoring the interests of powerful elites and external actors over the rest of society. This might lead to depending on money from outside, therefore affecting the economic situation in other countries. Sylvia Maxfield argues that a bigger demand for transparency in both the private and public sectors by some investors can contribute to a strengthening of democratic institutions and can encourage democratic consolidation.[88] A 2016 study found that preferential trade agreements can increase democratization of a country, especially trading with other democracies.[89] A 2020 study found increased trade between democracies reduces democratic backsliding, while trade between democracies and autocracies reduces democratization of the autocracies.[90] Trade and capital mobility often involve international organizations, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and World Trade Organization (WTO), which can condition financial assistance or trade agreements on democratic reforms.[91] |

原因と要因 民主化に影響を与える(例えば、促進または制限する)要因については、かなりの議論がある。議論されている要因には、経済的、政治的、文化的、個人の主体 とその選択、国際的、歴史的要因などがある。 経済的要因 経済発展と近代化理論 多くの理論家は、工業化を民主化の推進力と見なしていた。 シーモア・マーティン・リップセット[62]、カレス・ボイクス、スーザン・ストークス[63]、ディートリッヒ・ルーシェマイヤー、エヴェリン・ス ティーブンス、ジョン・スティーブンス[64] などの学者は、経済発展は民主化の可能性を高める、と主張している。1959年にリップセットが最初に主張したこの理論は、その後、近代化理論と呼ばれる ようになった[65][66]。ダニエル・トレイスマンによれば、「中期的(10~20年)には、高所得と民主化および民主主義の存続との間には強固かつ 一貫した関係があるものの、より短期間では必ずしもそうとは限らない」[67]。ロバート・ダールは、市場経済は民主主義制度にとって好ましい条件を提供 すると主張した。[68] 一人当たりGDPが高いほど民主主義と相関する。一部の「誰?」は、最も豊かな民主主義国が権威主義に陥った例は一度もないと主張する。[69] ワイマール共和国におけるヒトラーとナチスの台頭は明らかな反例と見なせる。とはいえ、1930年代初頭のドイツは既に先進経済国であった。当時、同国は 第一次世界大戦(1910年代)以来、実質的に経済危機状態にあった。この危機は大恐慌の影響でさらに悪化した。また産業革命以前には民主主義が極めて稀 だったという一般的な観察もある。こうした実証研究から、経済発展は民主主義への移行可能性を高めるか、新たに確立された民主主義の定着を助けるという見 解が広く支持された。[69] [70] ある研究によれば、経済発展は民主化を促すが、その効果は中期的(10~20年)に現れるという。これは、発展が既存の指導者の地位を固めつつ、その指導 者が退任時に国家を息子や信頼できる側近に引き継ぐことを困難にするためである。[71] しかし、民主主義が富の結果であるか否かについての議論は、結論から程遠い。[72] 別の研究では、経済発展が民主主義を促進するには、その国の政治的安定が不可欠だと示唆している。[73] クラークとゴルダーは、アルバート・ハーシュマンの「退出・発言・忠誠」モデルを再構築し、民主化プロセスに影響を与えるのは国の富の増加そのものではな く、富の増加に伴って生じる社会経済構造の変化だと説明している。彼らは、こうした構造的変化こそが、いくつかのヨーロッパ諸国が民主化した主因の一つと して指摘されてきたと説明する。近代化によって農業部門の効率が向上し、社会経済構造が変化すると、時間と資源のより大きな投資が製造業やサービス業に向 けられた。例えばイングランドでは、紳士階級が商業活動への投資を増やし、国家にとって経済的に重要な存在となった。こうした新たな生産活動は新たな経済 的権力を伴った。彼らの資産は国家が把握しづらくなり、したがって課税も困難になった。このため搾取は不可能となり、国家は新たな経済エリートと交渉して 歳入を確保せざるを得なくなった。国家は国民の忠誠維持への依存度が高まったため、持続可能な取引が成立せねばならず、これに伴い国民は国家の意思決定プ ロセスに参画する影響力を得たのである。[74][信頼性の低い出典?] [75] アダム・プシェヴォルスキとフェルナンド・リモンギは、経済発展は民主主義が権威主義に転換する可能性を低くするが、発展が民主化(権威主義国家の民主主 義化)をもたらすという結論を導くには証拠が不十分であると主張している。[76] 経済発展は、短期的から中期的には権威主義体制に対する国民の支持を高める可能性がある。[77] アンドルー・J・ネイサンは、経済発展が民主化をもたらすという説にとって、中国は問題のある事例であると主張している。[78] マイケル・ミラーは、開発は「脆弱で不安定な体制における民主化の可能性を高めるが、そもそもその脆弱性を生じにくくする」と結論づけている。[79] 様々な経路を通じて、都市化の進展が民主化に貢献することを示唆する研究がある。[80][81] 多くの学者や政治思想家は、大規模な中産階級と民主主義の出現および維持を関連付けている。[68][82] 一方、この関係を疑問視する学者もいる。[83] ダロン・アセモグルとジェームズ・A・ロビンソンは『非近代化』(2022年)において、近代化理論は政治発展の多様な経路を説明できないと論じている。 「なぜなら、この理論は経済と政治の間に、制度や文化に依存しない因果関係を仮定し、明確な終着点——例えば『歴史の終わり』——を前提としているから だ」 リプセットの主張に関する研究をメタ分析したゲラルド・L・マンクは、大多数の研究が「経済発展の高度化が民主主義の進展をもたらす」という命題を支持し ていないことを示している。[85] 2024年の研究は工業化と民主化を結びつけ、製造業における大規模雇用が民衆動員を発生させやすく、抑圧を困難にすると論じた。[86] 資本移動 経済発展など民主化要因に関する理論は資本獲得の側面に焦点を当てる。資本移動は国境を越えた資金の移動、異なる金融商品、それに伴う規制に焦点を当て る。過去には資本移動と民主化の関係性について複数の理論が存在した。[87] 「破滅的見解」によれば、資本移動は経済格差の拡大を通じて未成熟な民主主義にとって本質的な脅威であり、有力なエリート層や外部勢力の利益を社会全体の 利益より優先させる。これにより外部資金への依存が生じ、他国の経済状況に影響を及ぼす可能性がある。シルビア・マックスフィールドは、一部の投資家が民 間・公共部門双方に求める透明性の高まりが、民主的制度の強化や民主主義の定着を促進し得ると主張する。[88] 2016年の研究によれば、特恵貿易協定は、特に他の民主主義国との貿易を通じて、国家の民主化を促進しうる。[89] 2020年の研究によれば、民主主義国家間の貿易増加は民主主義の後退を抑制するが、民主主義国家と独裁国家間の貿易は独裁国家の民主化を阻害する。 [90] 貿易と資本移動には国際通貨基金(IMF)、世界銀行、世界貿易機関(WTO)などの国際機関が関与することが多く、これらの機関は財政支援や貿易協定を 民主化改革の条件とすることがある。[91] |

| Classes, cleavages and alliances Theorists such as Barrington Moore Jr. argued that the roots of democratization could be found in the relationship between lords and peasants in agrarian societies. Sociologist Barrington Moore Jr., in his influential Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (1966), argues that the distribution of power among classes – the peasantry, the bourgeoise and the landed aristocracy – and the nature of alliances between classes determined whether democratic, authoritarian or communist revolutions occurred.[92] Moore also argued there were at least "three routes to the modern world" – the liberal democratic, the fascist, and the communist – each deriving from the timing of industrialization and the social structure at the time of transition. Thus, Moore challenged modernization theory, by stressing that there was not one path to the modern world and that economic development did not always bring about democracy.[93] Many authors have questioned parts of Moore's arguments. Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Evelyne Stephens, and John D. Stephens, in Capitalist Development and Democracy (1992), raise questions about Moore's analysis of the role of the bourgeoisie in democratization.[94] Eva Bellin argues that under certain circumstances, the bourgeoise and labor are more likely to favor democratization, but less so under other circumstances.[95] Samuel Valenzuela argues that, counter to Moore's view, the landed elite supported democratization in Chile.[96] A comprehensive assessment conducted by James Mahoney concludes that "Moore's specific hypotheses about democracy and authoritarianism receive only limited and highly conditional support."[97] A 2020 study linked democratization to the mechanization of agriculture: as landed elites became less reliant on the repression of agricultural workers, they became less hostile to democracy.[98] According to political scientist David Stasavage, representative government is "more likely to occur when a society is divided across multiple political cleavages."[99] A 2021 study found that constitutions that emerge through pluralism (reflecting distinct segments of society) are more likely to induce liberal democracy (at least, in the short term).[100] Political-economic factors Rulers' need for taxation Robert Bates and Donald Lien, as well as David Stasavage, have argued that rulers' need for taxes gave asset-owning elites the bargaining power to demand a say on public policy, thus giving rise to democratic institutions.[101][102][103] Montesquieu argued that the mobility of commerce meant that rulers had to bargain with merchants in order to tax them, otherwise they would leave the country or hide their commercial activities.[104][101] Stasavage argues that the small size and backwardness of European states, as well as the weakness of European rulers, after the fall of the Roman Empire meant that European rulers had to obtain consent from their population to govern effectively.[103][102] According to Clark, Golder, and Golder, an application of Albert O. Hirschman's exit, voice, and loyalty model is that if individuals have plausible exit options, then a government may be more likely to democratize. James C. Scott argues that governments may find it difficult to claim a sovereignty over a population when that population is in motion.[105] Scott additionally asserts that exit may not solely include physical exit from the territory of a coercive state, but can include a number of adaptive responses to coercion that make it more difficult for states to claim sovereignty over a population. These responses can include planting crops that are more difficult for states to count, or tending livestock that are more mobile. In fact, the entire political arrangement of a state is a result of individuals adapting to the environment, and making a choice as to whether or not to stay in a territory.[105] If people are free to move, then the exit, voice, and loyalty model predicts that a state will have to be of that population representative, and appease the populace in order to prevent them from leaving.[106] If individuals have plausible exit options then they are better able to constrain a government's arbitrary behaviour through threat of exit.[106] Inequality and democracy Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argued that the relationship between social equality and democratic transition is complicated: People have less incentive to revolt in an egalitarian society (for example, Singapore), so the likelihood of democratization is lower. In a highly unequal society (for example, South Africa under Apartheid), the redistribution of wealth and power in a democracy would be so harmful to elites that these would do everything to prevent democratization. Democratization is more likely to emerge somewhere in the middle, in the countries, whose elites offer concessions because (1) they consider the threat of a revolution credible and (2) the cost of the concessions is not too high.[107] This expectation is in line with the empirical research showing that democracy is more stable in egalitarian societies.[69] Other approaches to the relationship between inequality and democracy have been presented by Carles Boix, Stephan Haggard Robert Kaufman,Ben Ansell, and David Samuels.[108][109] In their 2019 book The Narrow Corridor and a 2022 study in the American Political Science Review, Acemoglu and Robinson argue that the nature of the relationship between elites and society determine whether stable democracy emerges. When elites are overly dominant, despotic states emerge. When society is overly dominant, weak states emerge. When elites and society are evenly balance, inclusive states emerge.[110][111] Natural resources The abundance of oil is sometimes seen as a curse. Research shows that oil wealth lowers levels of democracy and strengthens autocratic rule.[112][113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121] According to Michael Ross, petroleum is the sole resource that has "been consistently correlated with less democracy and worse institutions" and is the "key variable in the vast majority of the studies" identifying some type of resource curse effect.[122] A 2014 meta-analysis confirms the negative impact of oil wealth on democratization.[123] Thad Dunning proposes a plausible explanation for Ecuador's return to democracy that contradicts the conventional wisdom that natural resource rents encourage authoritarian governments. Dunning proposes that there are situations where natural resource rents, such as those acquired through oil, reduce the risk of distributive or social policies to the elite because the state has other sources of revenue to finance this kind of policies that is not the elite wealth or income.[124] And in countries plagued with high inequality, which was the case of Ecuador in the 1970s, the result would be a higher likelihood of democratization.[125] In 1972, the military coup had overthrown the government in large part because of the fears of elites that redistribution would take place.[126] That same year oil became an increasing financial source for the country.[126] Although the rents were used to finance the military, the eventual second oil boom of 1979 ran parallel to the country's re-democratization.[126] Ecuador's re-democratization can then be attributed, as argued by Dunning, to the large increase of oil rents, which enabled not only a surge in public spending but placated the fears of redistribution that had grappled the elite circles.[126] The exploitation of Ecuador's resource rent enabled the government to implement price and wage policies that benefited citizens at no cost to the elite and allowed for a smooth transition and growth of democratic institutions.[126] The thesis that oil and other natural resources have a negative impact on democracy has been challenged by historian Stephen Haber and political scientist Victor Menaldo in a widely cited article in the American Political Science Review (2011). Haber and Menaldo argue that "natural resource reliance is not an exogenous variable" and find that when tests of the relationship between natural resources and democracy take this point into account "increases in resource reliance are not associated with authoritarianism."[127] Cultural factors Values and religion It is claimed by some that certain cultures are simply more conducive to democratic values than others. This view is likely to be ethnocentric. Typically, it is Western culture which is cited as "best suited" to democracy, with other cultures portrayed as containing values which make democracy difficult or undesirable. This argument is sometimes used by undemocratic regimes to justify their failure to implement democratic reforms. Today, however, there are many non-Western democracies. Examples include India, Japan, Indonesia, Namibia, Botswana, Taiwan, and South Korea. Research finds that "Western-educated leaders significantly and substantively improve a country's democratization prospects".[128] Huntington presented an influential, but also controversial arguments about Confucianism and Islam. Huntington held that "In practice Confucian or Confucian-influenced societies have been inhospitable to democracy."[129] He also held that "Islamic doctrine ... contains elements that may be both congenial and uncongenial to democracy," but generally thought that Islam was an obstacle to democratization.[130] In contrast, Alfred Stepan was more optimistic about the compatibility of different religions and democracy.[131] The compatibility of Islam and democracy continues to be a focus of discussion; the image depicts a mosque in Medina, Saudi Arabia. Steven Fish and Robert Barro have linked Islam to undemocratic outcomes.[132][133] However, Michael Ross argues that the lack of democracies in some parts of the Muslim world has more to do with the adverse effects of the resource curse than Islam.[134] Lisa Blaydes and Eric Chaney have linked the democratic divergence between the West and the Middle-East to the reliance on mamluks (slave soldiers) by Muslim rulers whereas European rulers had to rely on local elites for military forces, thus giving those elites bargaining power to push for representative government.[135] Robert Dahl argued, in On Democracy, that countries with a "democratic political culture" were more prone for democratization and democratic survival.[68] He also argued that cultural homogeneity and smallness contribute to democratic survival.[68][136] Other scholars have however challenged the notion that small states and homogeneity strengthen democracy.[137] A 2012 study found that areas in Africa with Protestant missionaries were more likely to become stable democracies.[138] A 2020 study failed to replicate those findings.[139] Sirianne Dahlum and Carl Henrik Knutsen offer a test of the Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel revised version of modernization theory, which focuses on cultural traits triggered by economic development that are presumed to be conducive to democratization.[140] They find "no empirical support" for the Inglehart and Welzel thesis and conclude that "self-expression values do not enhance democracy levels or democratization chances, and neither do they stabilize existing democracies."[141] Education It has long been theorized that education promotes stable and democratic societies.[142] Research shows that education leads to greater political tolerance, increases the likelihood of political participation and reduces inequality.[143] One study finds "that increases in levels of education improve levels of democracy and that the democratizing effect of education is more intense in poor countries".[143] It is commonly claimed that democracy and democratization were important drivers of the expansion of primary education around the world. However, new evidence from historical education trends challenges this assertion. An analysis of historical student enrollment rates for 109 countries from 1820 to 2010 finds no support for the claim that democratization increased access to primary education around the world. It is true that transitions to democracy often coincided with an acceleration in the expansion of primary education, but the same acceleration was observed in countries that remained non-democratic.[144] Wider adoption of voting advice applications can lead to increased education on politics and increased voter turnout.[145] Social capital and civil society Civic engagement, including volunteering, is conducive to democratization. These volunteers are cleaning up after the 2012 Hurricane Sandy. Civil society refers to a collection of non-governmental organizations and institutions that advance the interests, priorities and will of citizens. Social capital refers to features of social life—networks, norms, and trust—that allow individuals to act together to pursue shared objectives.[8] Robert Putnam argues that certain characteristics make societies more likely to have cultures of civic engagement that lead to more participatory democracies. According to Putnam, communities with denser horizontal networks of civic association are able to better build the "norms of trust, reciprocity, and civic engagement" that lead to democratization and well-functioning participatory democracies. By contrasting communities in Northern Italy, which had dense horizontal networks, to communities in Southern Italy, which had more vertical networks and patron-client relations, Putnam asserts that the latter never built the culture of civic engagement that some deem as necessary for successful democratization.[146] Sheri Berman has rebutted Putnam's theory that civil society contributes to democratization, writing that in the case of the Weimar Republic, civil society facilitated the rise of the Nazi Party.[147] According to Berman, Germany's democratization after World War I allowed for a renewed development in the country's civil society; however, Berman argues that this vibrant civil society eventually weakened democracy within Germany as it exacerbated existing social divisions due to the creation of exclusionary community organizations.[147] Subsequent empirical research and theoretical analysis has lent support for Berman's argument.[148] Yale University political scientist Daniel Mattingly argues civil society in China helps the authoritarian regime in China to cement control.[149] Clark, M. Golder, and S. Golder also argue that despite many believing democratization requires a civic culture, empirical evidence produced by several reanalyses of past studies suggest this claim is only partially supported.[14] Philippe C. Schmitter also asserts that the existence of civil society is not a prerequisite for the transition to democracy, but rather democratization is usually followed by the resurrection of civil society (even if it did not exist previously).[16] Research indicates that democracy protests are associated with democratization. According to a study by Freedom House, in 67 countries where dictatorships have fallen since 1972, nonviolent civic resistance was a strong influence over 70 percent of the time. In these transitions, changes were catalyzed not through foreign invasion, and only rarely through armed revolt or voluntary elite-driven reforms, but overwhelmingly by democratic civil society organizations utilizing nonviolent action and other forms of civil resistance, such as strikes, boycotts, civil disobedience, and mass protests.[150] A 2016 study found that about a quarter of all cases of democracy protests between 1989 and 2011 lead to democratization.[151] Theories based on political agents and choices Elite-opposition negotiations and contingency Scholars such as Dankwart A. Rustow,[152][153] Guillermo O'Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter in their classic Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies (1986),[154] argued against the notion that there are structural "big" causes of democratization. These scholars instead emphasize how the democratization process occurs in a more contingent manner that depends on the characteristics and circumstances of the elites who ultimately oversee the shift from authoritarianism to democracy. O'Donnell and Schmitter proposed a strategic choice approach to transitions to democracy that highlighted how they were driven by the decisions of different actors in response to a core set of dilemmas. The analysis centered on the interaction among four actors: the hard-liners and soft-liners who belonged to the incumbent authoritarian regime, and the moderate and radical oppositions against the regime. This book not only became the point of reference for a burgeoning academic literature on democratic transitions, it was also read widely by political activists engaged in actual struggles to achieve democracy.[155] Adam Przeworski, in Democracy and the Market (1991), offered the first analysis of the interaction between rulers and opposition in transitions to democracy using rudimentary game theory. and he emphasizes the interdependence of political and economic transformations.[156] Elite-driven democratization Scholars have argued that processes of democratization may be elite-driven or driven by the authoritarian incumbents as a way for those elites to retain power amid popular demands for representative government.[157][158][159][160] If the costs of repression are higher than the costs of giving away power, authoritarians may opt for democratization and inclusive institutions.[161][162][163] According to a 2020 study, authoritarian-led democratization is more likely to lead to lasting democracy in cases when the party strength of the authoritarian incumbent is high.[164] However, Michael Albertus and Victor Menaldo argue that democratizing rules implemented by outgoing authoritarians may distort democracy in favor of the outgoing authoritarian regime and its supporters, resulting in "bad" institutions that are hard to get rid of.[165] According to Michael K. Miller, elite-driven democratization is particularly likely in the wake of major violent shocks (either domestic or international) which provide openings to opposition actors to the authoritarian regime.[163] Dan Slater and Joseph Wong argue that dictators in Asia chose to implement democratic reforms when they were in positions of strength in order to retain and revitalize their power.[160] According to a study by political scientist Daniel Treisman, influential theories of democratization posit that autocrats "deliberately choose to share or surrender power. They do so to prevent revolution, motivate citizens to fight wars, incentivize governments to provide public goods, outbid elite rivals, or limit factional violence." His study shows that in many cases, "democratization occurred not because incumbent elites chose it but because, in trying to prevent it, they made mistakes that weakened their hold on power. Common mistakes include: calling elections or starting military conflicts, only to lose them; ignoring popular unrest and being overthrown; initiating limited reforms that get out of hand; and selecting a covert democrat as leader. These mistakes reflect well-known cognitive biases such as overconfidence and the illusion of control."[166] Sharun Mukand and Dani Rodrik dispute that elite-driven democratization produce liberal democracy. They argue that low levels of inequality and weak identity cleavages are necessary for liberal democracy to emerge.[167] A 2020 study by several political scientists from German universities found that democratization through bottom-up peaceful protests led to higher levels of democracy and democratic stability than democratization prompted by elites.[168] The three dictatorship types, monarchy, civilian and military have different approaches to democratization as a result of their individual goals. Monarchic and civilian dictatorships seek to remain in power indefinitely through hereditary rule in the case of monarchs or through oppression in the case of civilian dictators. A military dictatorship seizes power to act as a caretaker government to replace what they consider a flawed civilian government. Military dictatorships are more likely to transition to democracy because at the onset, they are meant to be stop-gap solutions while a new acceptable government forms.[169][170][171] Research suggests that the threat of civil conflict encourages regimes to make democratic concessions. A 2016 study found that drought-induced riots in Sub-Saharan Africa lead regimes, fearing conflict, to make democratic concessions.[172] Scrambled constituencies Mancur Olson theorizes that the process of democratization occurs when elites are unable to reconstitute an autocracy. Olson suggests that this occurs when constituencies or identity groups are mixed within a geographic region. He asserts that this mixed geographic constituencies requires elites to for democratic and representative institutions to control the region, and to limit the power of competing elite groups.[173] Death or ouster of dictator One analysis found that "Compared with other forms of leadership turnover in autocracies—such as coups, elections, or term limits—which lead to regime collapse about half of the time, the death of a dictator is remarkably inconsequential. ... of the 79 dictators who have died in office (1946–2014)... in the vast majority (92%) of cases, the regime persists after the autocrat's death."[174] Women's suffrage One of the critiques of Huntington's periodization is that it doesn't give enough weight to universal suffrage.[175][176] Pamela Paxton argues that once women's suffrage is taken into account, the data reveal "a long, continuous democratization period from 1893–1958, with only war-related reversals."[177] International factors War and national security Jeffrey Herbst, in his paper "War and the State in Africa" (1990), explains how democratization in European states was achieved through political development fostered by war-making and these "lessons from the case of Europe show that war is an important cause of state formation that is missing in Africa today."[178] Herbst writes that war and the threat of invasion by neighbors caused European state to more efficiently collect revenue, forced leaders to improve administrative capabilities, and fostered state unification and a sense of national identity (a common, powerful association between the state and its citizens).[178] Herbst writes that in Africa and elsewhere in the non-European world "states are developing in a fundamentally new environment" because they mostly "gained Independence without having to resort to combat and have not faced a security threat since independence."[178] Herbst notes that the strongest non-European states, South Korea and Taiwan, are "largely 'warfare' states that have been molded, in part, by the near constant threat of external aggression."[178] Elizabeth Kier has challenged claims that total war prompts democratization, showing in the cases of the UK and Italy during World War I that the policies adopted by the Italian government prompted a fascist backlash whereas UK government policies towards labor undermined broader democratization.[179] War and peace Main article: Territorial peace theory Two British Marine Commandos take protection behind debris during the capture of Walcheren Island during World War II. The link between war and democratization has been a focus of some theories. Wars may contribute to the state-building that precedes a transition to democracy, but war is mainly a serious obstacle to democratization. While adherents of the democratic peace theory believe that democracy causes peace, the territorial peace theory makes the opposite claim that peace causes democracy. In fact, war and territorial threats to a country are likely to increase authoritarianism and lead to autocracy. This is supported by historical evidence showing that in almost all cases, peace has come before democracy. A number of scholars have argued that there is little support for the hypothesis that democracy causes peace, but strong evidence for the opposite hypothesis that peace leads to democracy.[180][181][182] Christian Welzel's human empowerment theory posits that existential security leads to emancipative cultural values and support for a democratic political organization.[183] This is in agreement with theories based on evolutionary psychology. The so-called regality theory finds that people develop a psychological preference for a strong leader and an authoritarian form of government in situations of war or perceived collective danger. On the other hand, people will support egalitarian values and a preference for democracy in situations of peace and safety. The consequence of this is that a society will develop in the direction of autocracy and an authoritarian government when people perceive collective danger, while the development in the democratic direction requires collective safety.[184] International institutions A number of studies have found that international institutions have helped facilitate democratization.[185][186][187] Thomas Risse wrote in 2009, "there is a consensus in the literature on Eastern Europe that the EU membership perspective had a huge anchoring effects for the new democracies."[188] Scholars have also linked NATO expansion with playing a role in democratization.[189] international forces can significantly affect democratization. Global forces like the diffusion of democratic ideas and pressure from international financial institutions to democratize have led to democratization.[190] Promotion, foreign influence, and intervention Main article: Democracy promotion The European Union has contributed to the spread of democracy, in particular by encouraging democratic reforms in aspiring member states. Thomas Risse wrote in 2009, "there is a consensus in the literature on Eastern Europe that the EU membership perspective had a huge anchoring effects for the new democracies."[188] Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way have argued that close ties to the West increased the likelihood of democratization after the end of the Cold War, whereas states with weak ties to the West adopted competitive authoritarian regimes.[191][192] A 2002 study found that membership in regional organizations "is correlated with transitions to democracy during the period from 1950 to 1992."[193] A 2004 study found no evidence that foreign aid led to democratization.[194] Democracies have often been imposed by military intervention, for example in Japan and Germany after World War II.[195][196] In other cases, decolonization sometimes facilitated the establishment of democracies that were soon replaced by authoritarian regimes. For example, Syria, after gaining independence from French mandatory control at the beginning of the Cold War, failed to consolidate its democracy, so it eventually collapsed and was replaced by a Ba'athist dictatorship.[197] Robert Dahl argued in On Democracy that foreign interventions contributed to democratic failures, citing Soviet interventions in Central and Eastern Europe and U.S. interventions in Latin America.[68] However, the delegitimization of empires contributed to the emergence of democracy as former colonies gained independence and implemented democracy.[68] Geographic factors Some scholars link the emergence and sustenance of democracies to areas with access to the sea, which tends to increase the mobility of people, goods, capital, and ideas.[198][199] Historical factors Historical legacies In seeking to explain why North America developed stable democracies and Latin America did not, Seymour Martin Lipset, in The Democratic Century (2004), holds that the reason is that the initial patterns of colonization, the subsequent process of economic incorporation of the new colonies, and the wars of independence differ. The divergent histories of Britain and Iberia are seen as creating different cultural legacies that affected the prospects of democracy.[200] A related argument is presented by James A. Robinson in "Critical Junctures and Developmental Paths" (2022).[201] Sequencing and causality Scholars have discussed whether the order in which things happen helps or hinders the process of democratization. An early discussion occurred in the 1960s and 1970s. Dankwart Rustow argued that "'the most effective sequence' is the pursuit of national unity, government authority, and political equality, in that order."[202] Eric Nordlinger and Samuel Huntington stressed "the importance of developing effective governmental institutions before the emergence of mass participation in politics."[202] Robert Dahl, in Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (1971), held that the "commonest sequence among the older and more stable polyarchies has been some approximation of the ... path [in which] competitive politics preceded expansion in participation."[203] In the 2010s, the discussion focused on the impact of the sequencing between state building and democratization. Francis Fukuyama, in Political Order and Political Decay (2014), echoes Huntington's "state-first" argument and holds that those "countries in which democracy preceded modern state-building have had much greater problems achieving high-quality governance."[204] This view has been supported by Sheri Berman, who offers a sweeping overview of European history and concludes that "sequencing matters" and that "without strong states...liberal democracy is difficult if not impossible to achieve." [205] However, this state-first thesis has been challenged. Relying on a comparison of Denmark and Greece, and quantitative research on 180 countries across 1789–2019, Haakon Gjerløw, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Tore Wig, and Matthew C. Wilson, in One Road to Riches? (2022), "find little evidence to support the stateness-first argument."[206] Based on a comparison of European and Latin American countries, Sebastián Mazzuca and Gerardo Munck, in A Middle-Quality Institutional Trap (2021), argue that counter to the state-first thesis, the "starting point of political developments is less important than whether the State–democracy relationship is a virtuous cycle, triggering causal mechanisms that reinforce each."[207] In sequences of democratization for many countries, Morrison et al. found elections as the most frequent first element of the sequence of democratization but found this ordering does not necessarily predict successful democratization.[208] The democratic peace theory claims that democracy causes peace, while the territorial peace theory claims that peace causes democracy.[209] |