笑うデモクリトス

Laughing Democritus

Democritus (c. 1630) by Johannes Paulus Moreelse.

☆デ

モクリトス(Democritus、紀元前460年頃-紀元前370年頃)は、トラキア地方のアブデラ(Abdera)の人。レウキッポスを師として原子

論を大成した。アナクサゴラスの弟子でもあり、ペルシアの僧侶やエジプトの神官に学び、エチオピアやインドにも旅行したと伝えられる。財産を使いはたして

故郷の兄弟に扶養されたが、その著作の公開朗読により100タレントの贈与を受け、国葬されたという。哲学のほか数学・天文学・音楽・詩学・倫理学・生物

学などに通じ、その博識のために「知恵(Sophia)」と呼ばれた。またおそらくはその快活な気性のために、「笑う人(Gelasinos)」とも称さ

れた。

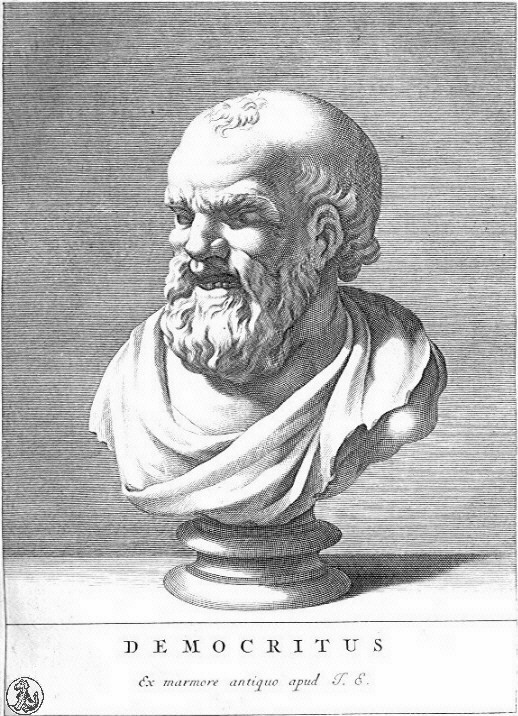

| Democritus

(/dɪˈmɒkrɪtəs/, dim-OCK-rit-əs; Greek: Δημόκριτος, Dēmókritos, meaning

"chosen of the people"; c. 460 – c. 370 BC) was an Ancient Greek

pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for

his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe.[2] Democritus

wrote extensively on a wide variety of topics.[3] None of Democritus' original work has survived, except through second-hand references. Many of these references come from Aristotle, who viewed him as an important rival in the field of natural philosophy.[4] He was known in antiquity as the ‘laughing philosopher’ because of his emphasis on the value of cheerfulness.[5] |

デモクリトス(/dɪˈmɒkrɪtəs/、dim-OCK-rit-

əs; ギリシア語: Δημόκριτος、Dēmókritos、「民衆によって選ばれた」の意; c. 紀元前460年頃 -

紀元前370年頃)は、古代ギリシャのアベーダ出身のプレソクラテス派の哲学者であり、今日では主に彼が唱えた原子論で知られている。[2]

デモクリトスは、幅広いトピックについて広範囲にわたって著作を残している。[3] デモクリトスの原著作は、伝聞による参照を除いて、どれも現存していない。これらの参照文献の多くは、自然哲学の分野における重要なライバルとして彼を捉 えていたアリストテレスによるものである。[4] 彼は陽気さの価値を強調していたため、古代では「笑う哲学者」として知られていた。[5] |

| Life Democritus was born in Abdera, on the coast of Thrace.[b][6] He was a polymath and prolific writer, producing nearly eighty treatises on subjects such as poetry, harmony, military tactics, and Babylonian theology. He traveled extensively, visiting Egypt and Persia, but wasn't particularly impressed by these countries. He once remarked that he would rather uncover a single scientific explanation than become the king of Persia.[3] Although many anecdotes about Democritus' life survive, their authenticity cannot be verified and modern scholars doubt their accuracy.[6] Ancient accounts of his life have claimed that he lived to a very old age, with some writers[c][d] claiming that he was over a hundred years old at the time of his death.[6] |

生涯 デモクリトスはトラキアの海岸沿いにあるアブデラで生まれた。[b][6] 彼は博識で多作な作家であり、詩、調和、軍事戦略、バビロニア神学などのテーマについて80編近い論文を著した。彼はエジプトやペルシアなど広範囲にわ たって旅したが、これらの国々に対して特に感銘を受けたわけではなかった。彼はかつて、ペルシャ王になるくらいなら、科学的な説明をひとつでも多く見つけ たいと述べたことがある。[3] デモクリトスの生涯に関する逸話は数多く残されているが、その信憑性は証明できず、現代の学者はその正確性を疑っている。[6] 古代の記録では、彼は非常に長生きしたとされており、一部の作家は[c][d]、彼の死の時には100歳を超えていたと主張している。[6] |

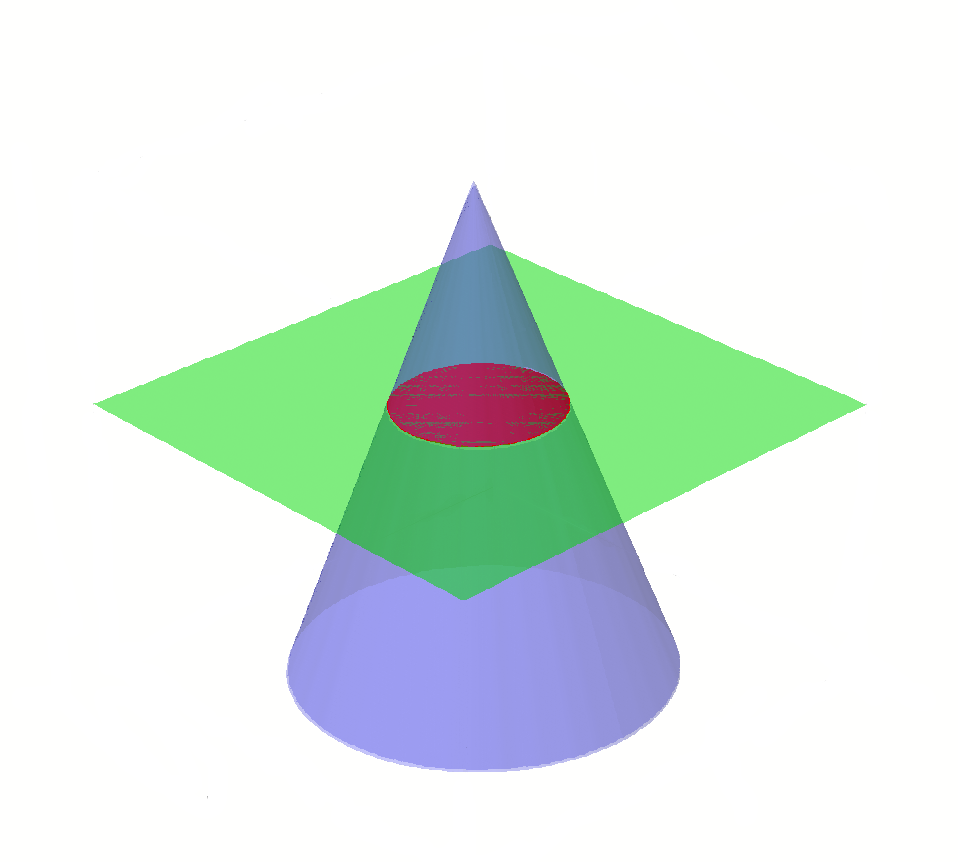

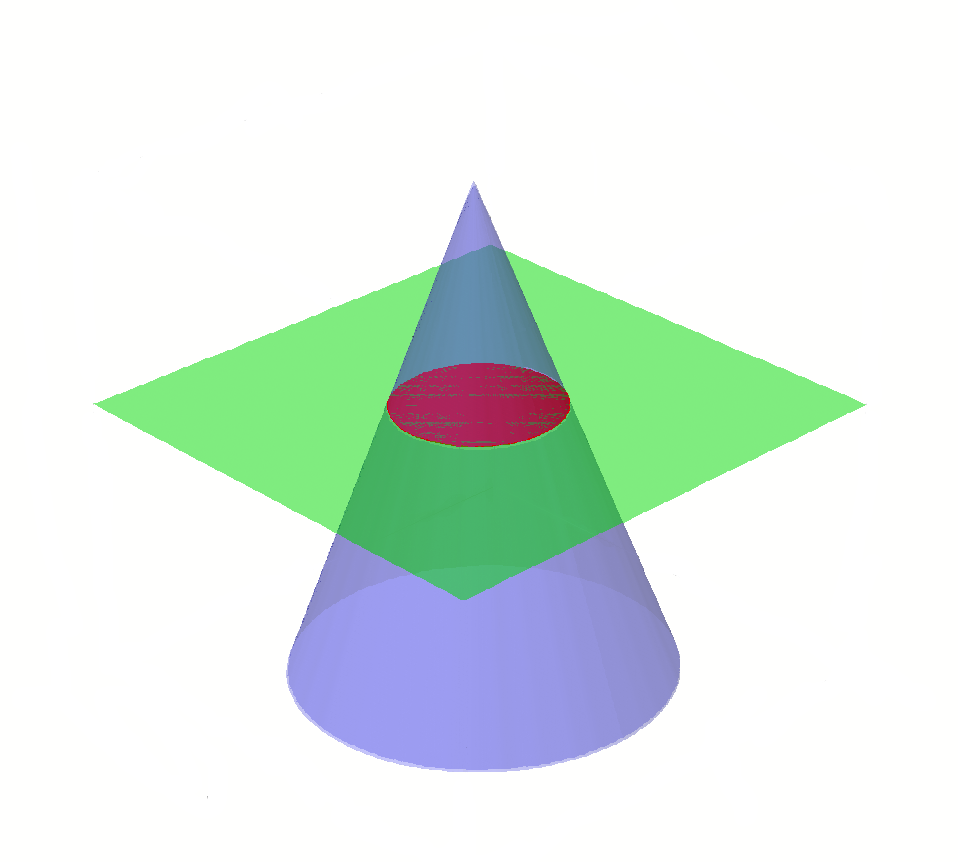

| Philosophy and science Democritus wrote on ethics as well as physics.[7] Democritus was a student of Leucippus. Early sources such as Aristotle and Theophrastus credit Leucippus with creating atomism and sharing its ideas with Democritus, but later sources credit only Democritus, making it hard to distinguish their individual contributions.[6] Atomic hypothesis See also: Atomism We have various quotes from Democritus on atoms, one of them being: δοκεῖ δὲ αὐτῶι τάδε· ἀρχὰς εἶναι τῶν ὅλων ἀτόμους καὶ κενόν, τὰ δ'ἀλλα πάντα νενομίσθαι [δοξάζεσθαι]. (Diogenes Laërtius, Democritus, Vol. IX, 44) Now his principal doctrines were these. That atoms and the vacuum were the beginning of the universe; and that everything else existed only in opinion. (trans. Yonge 1853) He concluded that divisibility of matter comes to an end, and the smallest possible fragments must be bodies with sizes and shapes, although the exact argument for this conclusion of his is not known. The smallest and indivisible bodies he called "atoms."[3] Atoms, Democritus believed, are too small to be detected by the senses; they are infinite in numbers and come in infinitely many varieties, and they have existed forever and that these atoms are in constant motion in the void or vacuum. The middle-sized objects of everyday life are complexes of atoms that are brought together by random collisions, differing in kind based on the variations among their constituent atoms.[3] For Democritus, the only true realities are atoms and the void. What we perceive as water, fire, plants, or humans are merely combinations of atoms in the void. The sensory qualities we experience are not real; they exist only by convention.[7] Of the mass of atoms, Democritus said, "The more any indivisible exceeds, the heavier it is." However, his exact position on atomic weight is disputed.[8] His exact contributions are difficult to disentangle from those of his mentor Leucippus, as they are often mentioned together in texts. Their speculation on atoms, taken from Leucippus, bears a passing and partial resemblance to the 19th-century understanding of atomic structure that has led some to regard Democritus as more of a scientist than other Greek philosophers; however, their ideas rested on very different bases.[4] Democritus, along with Leucippus and Epicurus, proposed the earliest views on the shapes and connectivity of atoms. They reasoned that the solidness of the material corresponded to the shape of the atoms involved.[4] Using analogies from humans' sense experiences, he gave a picture or an image of an atom that distinguished them from each other by their shape, their size, and the arrangement of their parts. Moreover, connections were explained by material links in which single atoms were supplied with attachments: some with hooks and eyes, others with balls and sockets.[e] The Democritean atom is an inert solid that excludes other bodies from its volume and interacts with other atoms mechanically. Quantum-mechanical atoms are similar in that their motion can be described by mechanics in addition to their electric, magnetic and quantum interactions. They are different in that they can be split into protons, neutrons, and electrons. The elementary particles are similar to Democritean atoms in that they are indivisible but their collisions are governed purely by quantum physics. Fermions observe the Pauli exclusion principle, which is similar to the Democritean principle that atoms exclude other bodies from their volume. However, bosons do not, with the prime example being the elementary particle photon. Correlation with modern science The theory of the atomists appears to be more nearly aligned with that of modern science than any other theory of antiquity. However, the similarity with modern concepts of science can be confusing when trying to understand where the hypothesis came from. Classical atomists could not have had an empirical basis for modern concepts of atoms and molecules. The atomistic void hypothesis was a response to the paradoxes of Parmenides and Zeno, the founders of metaphysical logic, who put forth difficult-to-answer arguments in favor of the idea that there can be no movement. They held that any movement would require a void—which is nothing—but a nothing cannot exist. The Parmenidean position was "You say there is a void; therefore the void is not nothing; therefore there is not the void."[9][f] The position of Parmenides appeared validated by the observation that where there seems to be nothing there is air, and indeed even where there is not matter there is something, for instance light waves. The atomists agreed that motion required a void, but simply rejected the argument of Parmenides on the grounds that motion was an observable fact. Therefore, they asserted, there must be a void. Democritus held that originally the universe was composed of nothing but tiny atoms churning in chaos, until they collided together to form larger units—including the earth and everything on it.[2] He surmised that there are many worlds, some growing, some decaying; some with no sun or moon, some with several. He held that every world has a beginning and an end and that a world could be destroyed by collision with another world.[g] Mathematics  Democritus argued that the circular cross-section of a cone would need step-like sides,[4] rather than being shaped like a cylinder. Democritus was also a pioneer of mathematics and geometry in particular. According to Archimedes,[h] Democritus was among the first to observe that a cone and pyramid with the same base area and height has one-third the volume of a cylinder or prism respectively, a result which Archimedes states was later proved by Eudoxus of Cnidus.[i][11] Plutarch[j] also reports that Democritus worked on a problem involving the cross-section of a cone that Thomas Heath suggests may be an early version of infinitesimal calculus.[11] Anthropology Democritus thought that the first humans lived an anarchic and animal sort of life, foraging individually and living off the most palatable herbs and the fruit which grew wild on the trees, until fear of wild animals drove them together into societies. He believed that these early people had no language, but that they gradually began to articulate their expressions, establishing symbols for every sort of object, and in this manner came to understand each other. He says that the earliest men lived laboriously, having none of the utilities of life; clothing, houses, fire, domestication, and farming were unknown to them. Democritus presents the early period of mankind as one of learning by trial and error, and says that each step slowly led to more discoveries; they took refuge in the caves in winter, stored fruits that could be preserved, and through reason and keenness of mind came to build upon each new idea.[2][k] Ethics Democritus was eloquent on ethical topics. Some sixty pages of his fragments, as recorded in Diels–Kranz, are devoted to moral counsel. The ethics and politics of Democritus come to us mostly in the form of maxims. In placing the quest for happiness at the center of moral philosophy, he was followed by almost every moralist of antiquity. The most common maxims associated with him are "Accept favours only if you plan to do greater favours in return", and he is also believed to impart some controversial advice such as "It is better not to have any children, for to bring them up well takes great trouble and care, and seeing them grow up badly is the cruellest of all pains".[12] He also wrote a treatise on the purpose of life and the nature of happiness. He held that "happiness was not to be found in riches but in the goods of the soul and one should not take pleasure in mortal things". Another saying that is often attributed to him is "The hopes of the educated were better than the riches of the ignorant". He also stated that "the cause of sin is ignorance of what is better" which become a central notion later in the Socratic moral thought. Another idea he propounded which was later echoed in the Socratic moral thought was the maxim that "you are better off being wronged than doing wrong".[12] His other moral notions went contrary to the then prevalent views such as his idea that "A good person not only refrains from wrongdoing but does not even want to do wrong." for the generally held notion back then was that virtue reaches it apex when it triumphs over conflicting human passions.[13] Aesthetics Later Greek historians consider Democritus to have established aesthetics as a subject of investigation and study,[14] as he wrote theoretically on poetry and fine art long before authors such as Aristotle. Specifically, Thrasyllus identified six works in the philosopher's oeuvre which had belonged to aesthetics as a discipline, but only fragments of the relevant works are extant; hence of all Democritus writings on these matters, only a small percentage of his thoughts and ideas can be known. |

哲学と科学 デモクリトスは倫理学だけでなく物理学についても著述している。[7] デモクリトスはレウキッポスの弟子であった。初期の資料では、アリストテレスやテオフラストスはレウキッポスが原子論を創始し、その考えをデモクリトスに 伝えたとしているが、後の資料ではデモクリトスだけが功績を認められており、両者の貢献を区別することが難しくなっている。[6] 原子仮説 参照:原子論 デモクリトスの原子に関するさまざまな引用があるが、そのうちの1つは次の通りである。 δοκεῖ δὲ αὐτῶι τάδε· ἀρχὰς εἶναι τῶν ὅλων ἀτ そして、それ以外のものはすべて、そう考えられている(そう考えられている)。(ディオゲネス・ラエルティオス著『デモクリトス』第9巻、44ページ) さて、彼の主な教説は次の通りであった。 原子と真空が宇宙の始まりであり、その他のすべてのものは単に人々の意見として存在しているに過ぎない、と主張した。(訳:Yonge 1853) 彼は、物質の分割はどこかで終わりを迎え、最小の断片はサイズと形状を持つ物体でなければならないと結論付けた。ただし、この結論の正確な論拠は不明であ る。 彼が「原子」と呼んだ最小かつ不可分の物体は、[3] 感覚では感知できないほど小さいとデモクリトスは考えた。原子は無限の数で存在し、無限の多様性があり、永遠に存在し、これらの原子は空虚または真空の中 で絶え間なく運動している。 日常生活で目にする中程度の物体は、ランダムな衝突によって集まった原子の複合体であり、構成原子のバリエーションの違いによって種類が異なる。[3] デモクリトスにとって、真実なのは原子と空虚のみである。我々が水、火、植物、人間として知覚しているものは、空虚における原子の組み合わせにすぎない。 我々が経験する感覚的な性質は現実のものではなく、慣習によってのみ存在している。[7] 原子の塊について、デモクリトスは「分割できないものがより多く存在すればするほど、より重くなる」と述べた。しかし、原子の重量に関する彼の正確な見解 については異論がある。[8] 彼の正確な貢献は、師であるレウキッポスのものと区別するのが難しい。なぜなら、それらはしばしばテキストで一緒に言及されているからだ。 彼らの原子に関する推測は、レウキッポスから引き継いだもので、19世紀の原子構造の理解と表面的で部分的な類似性がある。そのため、デモクリトスを他の ギリシャの哲学者よりも科学者として捉える人もいる。しかし、彼らの考えは全く異なる基盤の上に成り立っている。[4] デモクリトスは、レウキッポスやエピクロスとともに、原子の形状と結合に関する最も初期の見解を提唱した。彼らは 彼らは、物質の固体性は関与する原子の形状に対応すると論じた。[4] 人間の感覚経験からの類推を用いて、彼は、形状、大きさ、および各部分の配置によって互いに区別される原子の絵やイメージを示した。さらに、接続は、単一 の原子が接続部分を備える物質のリンクによって説明された。フックとアイで接続されるものもあれば、ボールとソケットで接続されるものもある。[e] デモクリトスの原子は不活性な固体であり、その体積から他の物体を排除し、他の原子と機械的に相互作用する。量子力学的な原子は、その運動が電気、磁気、 量子力学的相互作用に加えて力学によって記述できるという点で類似している。それらは陽子、中性子、電子に分割できるという点で異なる。素粒子は分割でき ないという点でデモクリトスの原子に類似しているが、その衝突は純粋に量子物理学によって支配される。フェルミ粒子はパウリの排他原理に従うが、これはデ モクリテス学派の原子がその体積から他の物体を排除するという原理に似ている。しかし、ボソン粒子はそうではなく、その典型的な例は素粒子の光子である。 現代科学との相関 原子論の理論は、古代の他のどの理論よりも現代科学の理論により近いように見える。しかし、その仮説がどこから来たのかを理解しようとする際に、現代の科 学概念との類似性は混乱を招く可能性がある。古典的な原子論者たちは、現代の原子や分子の概念の実証的根拠を持っていなかったはずである。 原子論的真空説は、形而上学的論理学の創始者であるパルメニデスとゼノンのパラドックスに対する回答であった。彼らは、動きはあり得ないという考えを支持 する答えにくい議論を展開した。彼らは、あらゆる運動には「無」すなわち「何もないもの」が必要であると主張したが、「何もないもの」は存在しえない。 パルメニデスの立場は、「あなたは無があると言う。したがって、無は無ではない。したがって、無はない」というものだった。[9][f] パルメニデスの立場は、何もないように見える場所には空気があり、実際には物質が存在しない場所にも何かしらのものがある、例えば光波がある、という観察 によって裏付けられているように見えた。 原子論者たちは、運動には空虚が必要であるという点では同意していたが、運動は観察可能な事実であるという理由で、パルメニデスの主張を単純に否定した。したがって、彼らは主張した。空虚がなければならないと。 デモクリトスは、宇宙はもともと、混沌の中で回転する小さな原子だけで構成されていたが、それらが衝突してより大きな単位を形成し、地球や地球上のあらゆ るものを含むようになったと主張した。[2] 彼は、多くの世界があり、成長する世界もあれば、衰退する世界もあると推測した。太陽や月がない世界もあれば、いくつかある世界もある。彼は、すべての世 界には始まりと終わりがあり、ある世界は別の世界との衝突によって破壊される可能性があると主張した。[g] 数学  デ モクリトスは、円錐の断面は円柱状ではなく階段状であるべきだと主張した。 デモクリトスは デモクリトスは数学、特に幾何学のパイオニアでもあった。アルキメデスによると、[h] デモクリトスは、底面積と高さが同じ円錐と角錐の体積はそれぞれ円柱と角柱の3分の1であることを最初に観察した人物の一人であった。アルキメデスは、こ の結果は後にキュノドスのエウドクソスによって証明されたと述べている 。プルタルコス[j]は、デモクリトスが円錐の断面に関する問題に取り組んでいたと報告しているが、トマス・ヒースは、これは微積分学の初期のバージョン である可能性があると示唆している。 人類学 人類学 デモクリトスは、最初の人間は無秩序で動物的な生活を送り、それぞれが単独で食物を探し、最もおいしいハーブや木に自生する果実を食べていたが、野生動物 の恐怖から社会生活を営むようになったと考えた。彼は、初期の人類には言語がなく、徐々に表現を明確にし、あらゆる種類の物体のシンボルを確立し、この方 法で互いを理解するようになったと考えた。初期の人類は、衣服、家屋、火、家畜、農業といった生活必需品を持たず、苦労して暮らしていたと彼は言う。デモ クリトスは、人類の初期を試行錯誤の学習期間として描き、それぞれの段階が徐々にさらなる発見につながっていったと述べている。人類は冬には洞窟に避難 し、保存可能な果物を蓄え、理性と鋭い洞察力によって新たなアイデアを積み重ねていった。[2][k] エト 倫理 デモクリトスは倫理的なテーマについて雄弁であった。ディエルス・クランツに収録されている彼の断片の約60ページは、道徳的な助言に割かれている。デモ クリトスの倫理と政治は、ほとんどが格言の形で我々の手元に残されている。幸福の探求を道徳哲学の中心に据えた彼は、古代のほとんどすべての道徳家たちに 影響を与えた。 彼にまつわる格言で最もよく知られているのは「恩を受け入れるのは、それ以上の恩を返すつもりがある場合のみ」というものであり、また「子供は持たない方 が良い。子供を立派に育てるには多大な苦労と配慮が必要であり、子供が悪い方向に成長するのを見るのは、あらゆる苦しみの中で最も残酷なことである」とい うような物議を醸す助言をしたとも言われている。[12] また、人生の目的と幸福の本質に関する論文も著している。「幸福は富にあるのではなく、魂の善にある。そして、人は死すべきものに喜びを見出すべきではな い」と主張した。また、彼にしばしば帰される言葉に「教養ある者の希望は、無知な者の富よりも優れている」というものがある。また、「罪の原因は、より善 きものを知らぬことにある」とも述べ、これはソクラテス道徳思想の後の中心的な概念となった。 また、後にソクラテス道徳思想の中で繰り返し唱えられた彼の考えに、「悪事を働くよりも悪事に遭う方がましである」という格言がある。[12] 彼の他の道徳観は、当時一般的であった考えとは対照的であった。例えば、「善良な人間は悪事を慎むだけでなく、悪事を働きたいとも思わない」という考えで ある。当時、一般的に信じられていた考えでは、美徳は相反する人間の情念に打ち勝ったときに頂点に達する、とされていた。[13] 美学 後世のギリシアの歴史家たちは、デモクリトスが美学を研究・学習の対象として確立したと考えている。[14] 彼は、アリストテレスなどの作家よりもずっと以前から、詩や芸術について理論的に記述していた。具体的には、トラュッロスは哲学者の作品のうち、学問分野 としての美学に属する6つの作品を特定したが、現存するのはその断片のみである。したがって、デモクリトスのこれらの問題に関する著作のすべての中で、彼 の思想やアイデアのほんの一部しか知ることができない。 |

| Works Diogenes Laertius attributes several works to Democritus, but none of them have survived in a complete form.[4] Ethics Pythagoras, On the Disposition of the Wise Man, On the Things in Hades, Tritogenia, On Manliness or On Virtue, The Horn of Amaltheia, On Contentment, Ethical Commentaries Natural science The Great World-System,[l] Cosmography, On the Planets, On Nature, On the Nature of Man or On Flesh (two books), On the Mind, On the Senses, On Flavours, On Colours, On Different Shapes, On Changing Shape, Buttresses, On Images, On Logic (three books) Nature Heavenly Causes, Atmospheric Causes, Terrestrial Causes, Causes Concerned with Fire and Things in Fire, Causes Concerned with Sounds, Causes Concerned with Seeds and Plants and Fruits, Causes Concerned with Animals (three books), Miscellaneous Causes, On Magnets Mathematics On Different Angles or On contact of Circles and Spheres, On Geometry, Geometry, Numbers, On Irrational Lines and Solids (two books), Planispheres, On the Great Year or Astronomy (a calendar) Contest of the Waterclock, Description of the Heavens, Geography, Description of the Poles, Description of Rays of Light, Literature On the Rhythms and Harmony, On Poetry, On the Beauty of Verses, On Euphonious and Harsh-sounding Letters, On Homer, On Song, On Verbs, Names Technical works Prognosis, On Diet, Medical Judgment, Causes Concerning Appropriate and Inappropriate Occasions, On Farming, On Painting, Tactics, Fighting in Armor Commentaries On the Sacred Writings of Babylon, On Those in Meroe, Circumnavigation of the Ocean, On History, Chaldaean Account, Phrygian Account, On Fever and Coughing Sicknesses, Legal Causes, Problems[15] A collections of sayings credited to Democritus have been preserved by Stobaeus, as well as a collection of sayings ascribed to Democrates which some scholars including Diels and Kranz have also ascribed to Democritus.[4] |

著作 ディオゲネス・ラエルティオスは、いくつかの著作をデモクリトスのものとみなしているが、そのどれもが完全な形で現存していない。[4] 倫理学 ピタゴラス、『賢者の性向について』、『黄泉の国の事物について』、『トリトゲニア』、『男らしさについて、あるいは徳について』、『アマルテイアの角』、『満足について』、『倫理論』 自然科学 大世界体系[l]、宇宙誌、惑星について、自然について、人間の性質についてまたは肉について(2冊)、心について、感覚について、味について、色について、さまざまな形について、形が変わることについて、支柱について、像について、論理学について(3冊) 自然 天上の原因、大気中の原因、地上の原因、火および火の中の物に関する原因、音に関する原因、種子、植物、果実に関する原因、動物に関する原因(3冊)、その他の原因、磁石について 数学 異なる角度について、または円と球の接触について、幾何学について、幾何学、数について、非合理な線と立体について(2冊)、天球儀、グレートイヤーについてまたは天文学(暦)水時計のコンテスト、天体の記述、地理、極の記述、光線の記述、 文学 リズムとハーモニーについて、詩について、詩の美について、耳触りの良い音と耳障りな音について、ホメーロスについて、歌について、動詞について、名前について 専門書 予言、食事について、医学的判断、適切な場合と不適切な場合の原因、農業について、絵画について、戦術、鎧を着ての戦い 論評 バビロニアの聖典について、メロエの人々について、海洋の周航、歴史について、カルデア人の記録、フリギア人の記録、熱と咳の病気について、法的問題、問題[15] デモクリトスに帰せられる格言集は、ストバエウスによって保存されている。また、ディエルスやクランツを含む一部の学者がデモクラテスに帰した格言集も、デモクリトスに帰せられている。[4] |

| Legacy Diogenes Laertius claims that Plato disliked Democritus so much that he wished to have all of his books burned.[m] He was nevertheless well known to his fellow northern-born philosopher Aristotle, and was the teacher of Protagoras.[n] Democritus is evoked by English writer Samuel Johnson in his poem, The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749), ll. 49–68, and summoned to "arise on earth, /With chearful wisdom and instructive mirth, /See motley life in modern trappings dress'd, /And feed with varied fools th'eternal jest." |

レガシー ディオゲネス・ラエルティオスは、プラトンがデモクリトスを非常に嫌っていたため、彼の著書をすべて焼却することを望んでいたと主張している。[m] しかし、彼は同じく北方出身の哲学者アリストテレスにはよく知られており、プロタゴラスの師でもあった。[n] デモクリトスは、イギリスの作家サミュエル・ジョンソンの詩『人間の望みの虚栄』(1749年)の49-68行で言及されており、「地上に現れよ。/陽気 な知恵と教訓的な笑いを携えて。/現代的な装いで着飾った多彩な人生を見よ。/そして、さまざまな愚か者たちに永遠の冗談を聞かせよ。」と召喚されてい る。 |

| Atom John Dalton Democritus University of Thrace Kaṇāda Mochus National Centre of Scientific Research "DEMOKRITOS" Pseudo-Democritus Vaisheshika |

アトム ジョン・ダルトン デモクリトス・トラキア大学 カナダ モカス 国立科学研究所「デモクリトス」 偽デモクリトス ヴァイシェーシカ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Democritus |

|

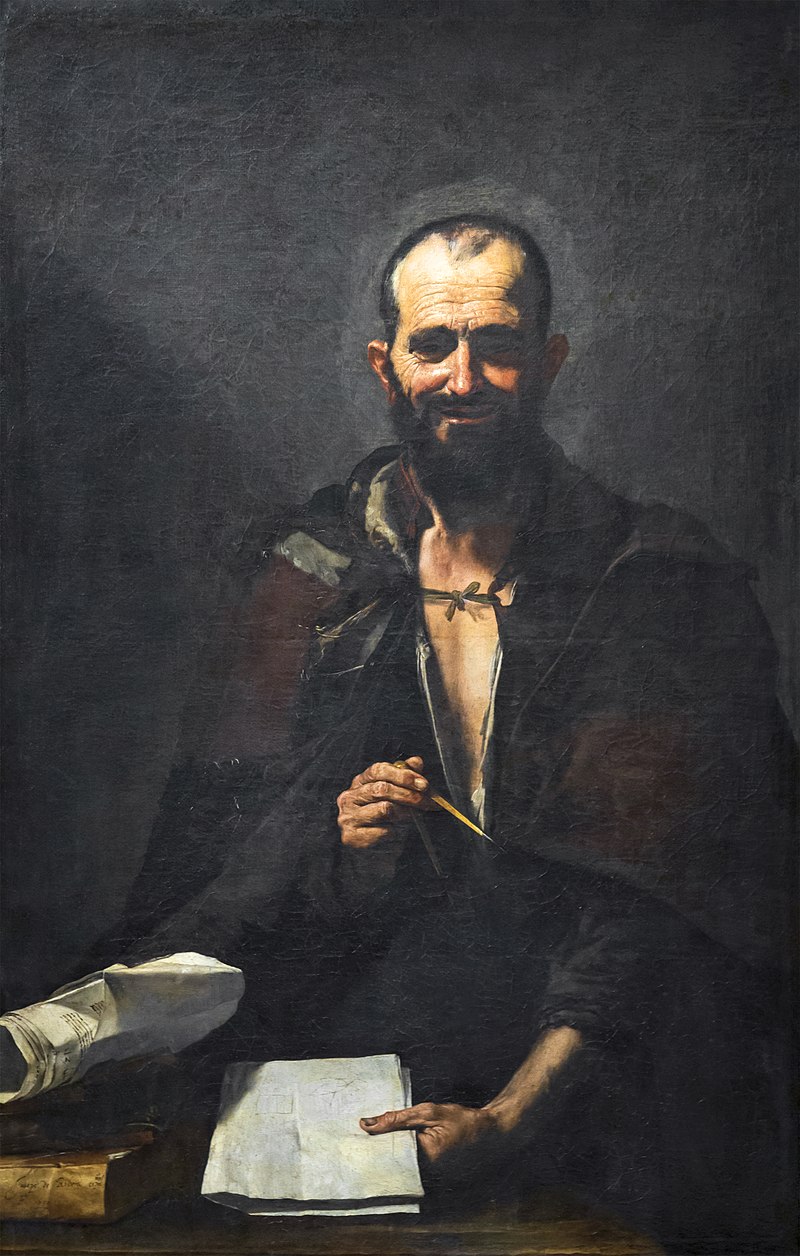

A Renaissance imagined representation of Democritus, the laughing philosopher, by Agostino Carracci |

アゴスティーノ・カラッチによる、笑う哲学者デモクリトスのルネサンス風の想像図 |

|

ホセ・デ・リベーラ『デモクリトス』プラド美術館、マドリード |

Charles-Antoine Coypel, Cheerful Democritus, 1746. |

|

|

|

| デモクリトスの学説 「原子(アトム)」は不生・不滅・無性質・分割不可能な自然の最小単位であって、たえず運動し、その存在と運動の場所として「空虚(ケノン)」の存在が前 提される。無限の空虚の中では上も下もない。形・大きさ・配列・姿勢の違うこれら無数の原子の結合や分離の仕方によって、すべての感覚でとらえられる対象 や生滅の現象が生じる。また魂と火(熱)とを同一視し、原子は無数あるが、あらゆるものに浸透して他を動かす「球形のものが火であり、魂である」とした [2]。デモクリトスは世界の起源については語らなかったが、「いかなることも偶然によって起こりえない」と述べた。 デモクリトスの倫理学においては、政治の騒がしさや神々への恐怖から解放された「魂の快活さ/晴れやかさ(エウテュミア, εὐθυμία)」が理想の境地・究極目的とされ、それは「幸福(エウエストー, εὐεστὼ)」であるとも表現されている[3]。また詩学においては霊感の力が説かれている。原子論を中心とする彼の学説は、古代ギリシアにおける唯物 論の完成であると同時に、後代のエピクロス及び近代の自然科学に決定的な影響を与えた。 しかし、プラトンやアリストテレスの学説に比べてデモクリトスの学説は当時あまり支持されず、彼の著作は断片しか残されていない。プラトンが手に入る限り のデモクリトスの著作を集めて、すべて焼却したという伝説もある[4]。プラトンの対話篇には同時代の哲学者が多数登場するが、デモクリトスに関しては一 度も言及されていない。それに対して、セネカやキケロなどの古代ローマの知識人にはその鋭敏な知性と魂の偉大さを高く評価されている[5]。 また、自然の根源についての学説は、アリストテレスが完成させた四大元素説が優勢であり、原子論は長らく顧みられる事は無かった。18世紀以降、化学者の ジョン・ドルトンやアントワーヌ・ラヴォアジエによって原子論が優勢となり四大元素説は放棄された。もっともドルトンやラヴォアジエ以降の近代的な原子論 は、デモクリトスの古代原子論と全く同一という訳ではない。ただし「原子」と「空虚」が存在するという意味において、デモクリトスの原子論は現代の原子論 とも共通するとされる[6]。 著作 上述した通り、デモクリトスの著作は中世以降の歴史の過程で散逸してしまったが、その膨大な量の著作は、少なくとも古代ローマには継承されていたこと、そ して『プラトン全集』と同じく、トラシュロスによって、それらが四部作集にまとめられていたことが、『ギリシア哲学者列伝』第9巻 第7章で述べられている。(そして、セネカの『心の平静について』第2章3節などで、デモクリトスの著作・思想について好意的に言及されていることが、 ローマにおけるデモクリトスの著作の継承・普及を傍証している。) 『列伝』に列挙されているデモクリトスの著作は、以下の通り。 倫理学 1 ピュタゴラス 賢者のあり方について ハデス(冥界)にいる者たちについて アテネ女神(トリートゲネイア) 2 男の卓越性について、あるいは徳(勇気)について アマルテイア(山羊神)の角 快活さ(エウテュミア)について 倫理学覚書 自然学 3 大宇宙体系(※ペリパトス派ではレウキッポスの作とも) 小宇宙体系 世界形状論 諸惑星について 4 自然について(第1) 人間の本性について(あるいは、肉体について) - 自然について(第2) 知性について 感覚について 5 味について 色について 種々の形態(アトム)について 形態(アトム)の変換について 6 学説の補強 映像(エイドーロン)について、あるいは(未来の)予知について 論理学上の規準について、3巻 問題集 その他 天体現象の諸原因 空中の現象の諸原因 地上の現象の諸原因 火および火の中にあるものについての諸原因 音に関する諸原因 種子、植物、および果実に関する諸原因 動物に関する諸原因、3巻 原因雑纂 磁石について 数学 7 意見の相違について、あるいは円と球の接触について 幾何学について 幾何学の諸問題 数 8 通約不可能な線分と立体について、2巻 (渾天儀の) 投影図 大年、あるいは天文学、暦 水時計 (と天(の時間)と) の争い 9 天界の記述 大地の記述(地理学) 極地の記述 光線論 文芸・音楽 10 韻律と調和について 詩作について 詩句の美しさについて 発音しやすい文字と発音しにくい文字について 11 ホメロス論、あるいは正しい措辞と稀語について 歌について 語句論 語彙集 技術 12 予後 養生について、あるいは養生論 医療の心得 時期外れのものと季節にかなったものに関する諸原因 13 農業について、あるいは土地測定論 絵画について 戦術論 重武装戦闘論 覚書からの抜粋 バビュロンの神聖な文書について メロエーの神聖な文書について オケアノス(大洋)の周航 歴史研究について カルダイオス人の言説 プリュギア人の言説 発熱および病気のために咳をしている人たちについて 法律の原因(起源) 手製の防具 参考資料 F.A.ランゲ『唯物論史 Geschichte des Materialismus und Kritik seiner Bedeutung in der Gegenwart』1866年 H.Ritter, L.Preller共著『ギリシア哲学史 Historia Philosophiae Graecae』1934年 H.Diels『ソクラテス以前哲学者断片集 Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker』第2巻 1935年 ディオゲネス・ラエルティオス, 加来彰俊『ギリシア哲学者列伝 上 中 下』岩波書店〈岩波文庫 青(33)-663-1,2,3〉、1984年。ISBN 4003366336。 NCID BN01500219。 下巻より https://x.gd/4eUTj |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099