ヘルダーリン「イスター」

Der Ister, Hölderlin

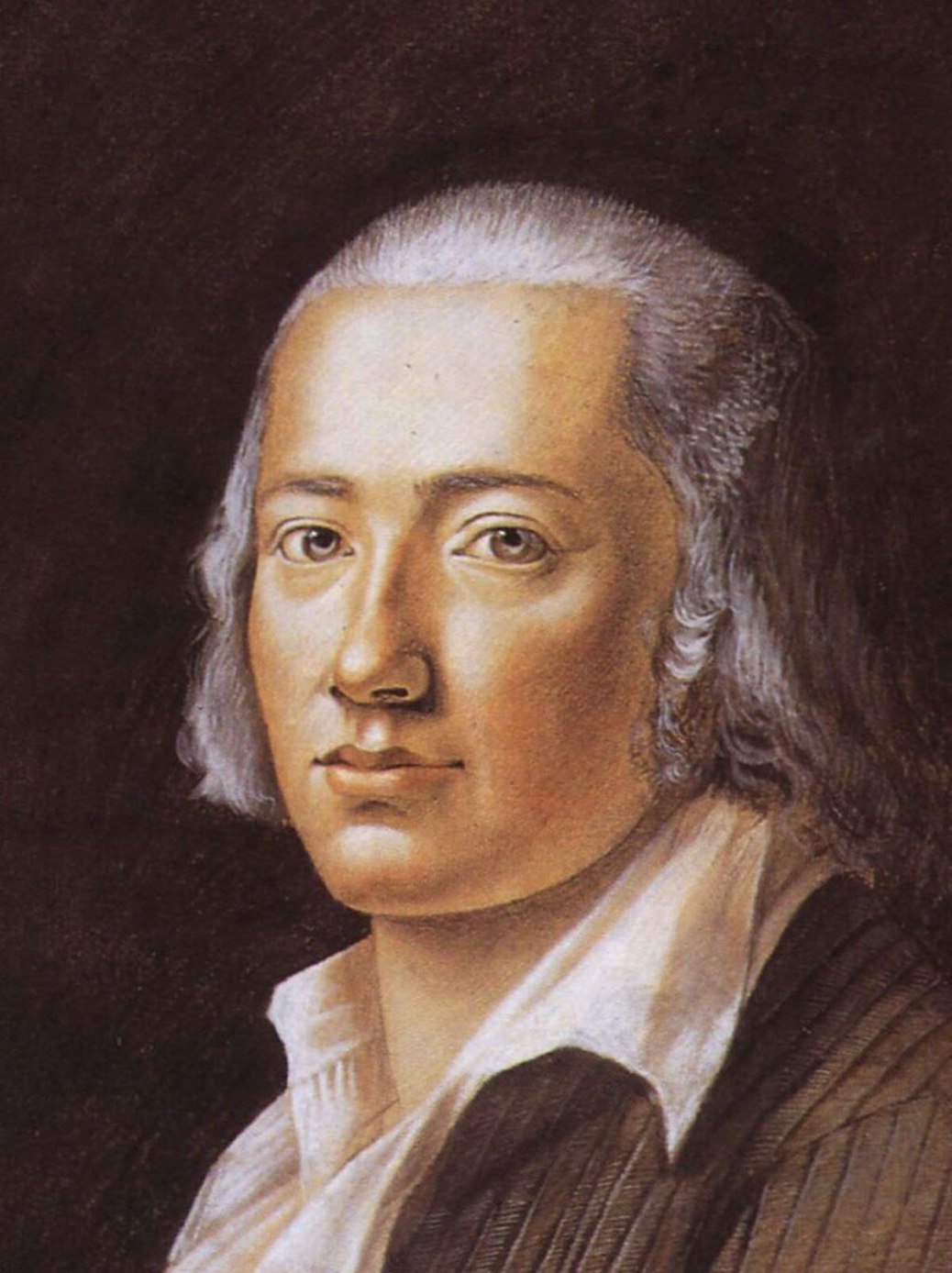

☆ヨハン・クリスティアン・フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン(Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin、1770年3月20日 - 1843年6月7日)は、ドイツの詩人、哲学者である。ノルベルト・フォン・ヘリングラートは彼を「ドイツ人の中で最もドイツ人らしい人物」と評したが、 ホルデルリンはドイツロマン主義の重要な人物であった。特に、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルやフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ヨゼ フ・シェリングと早くから交流があり、哲学的な影響を与えたことから、ドイツ観念論の発展において重要な思想家でもあった

| ヘルダーリン『イスター』浅井真男訳 |

Der Ister. Friedrich Hölderlin | The Ister, Friedrich Hölderlin |

| いまこそ来たれ、火よ! われらこがれる思いで 日を見るのを待っている、 まことに、試練が ひざまづく者にとって過ぎれば、 彼は森の叫びに気づくであろう。 けれどもわれらは、インダス河から、 アルプェイオスを通ってはるばると やって来たものを歌う。長いあいだ われらはふさわしいものを探し求めたのだ、 いささかの飛躍をもって 身近なものにまっすぐに 手をのばし、反対がわにおもむく者もあろう。 しかしわれらはここで土をたがやそう。 あまたの川が土地を耕地に してくれるからだ。なぜなら、雑草がはびこり、 夏に水を飲もうとして、けものが 川のほとりにゆくならば、 人間もまた仕事をはじめるのだから。 だがこの川をひとはイスターと呼ぶ。 この川はうるわしく土地になじんでいる。円柱をなす樹々の葉は熟し、 ざわめいている。樹々は野生のままに 入り乱れて立っている。その上には 樹々とはちがう高度を保って、岩々の 屋根がそびえている。これを見れば、 この川がヘラクレスを客として 迎えたことも、わたしを驚かさない。 遠くまで輝きをとどかせて、この川は 彼が炎暑のイストモスから影を求めて来たときに、 あの南方のオリュンポス山のほとりで、彼をさそったのだ。 なぜならば、そこでもひとびとは活気に満ちていたのだが、 死者たちの霊のためにはやはり 冷気が必要だったのだ。だからこそ彼は好んで ここの泉と黄色い岸辺まで足をのばしたのだ。 ここでは高いところでは強い香りがただよい、 猟人が好んでさすらう谷間は 真昼にも唐檜の森におおわれて暗く、 イスターの樹脂の多い樹々からは その成長の音が聞き取れるのだ。 ところがイスターは引っ返してゆくように見え、 わたしには、この川が 東方から来たとしてか思えない。 これについては あまたのことが言えるだろう。そしてこの川は、なぜ 山々にまといついているのだろう、もうひとつの川、 ラインはわきによけて 流れ去っていったのに。あまたの川が 乾燥地帯を流れるのもあだではない。だが、どうしてか?太陽と月とを、 また日と夜とを、心情のなかに 分かちがたく保持して、運び、 天上的なものたちが温くたがいを感じあうための しるしこそは、ぜひとも必要だからなのだ。 だからこそ、あのあまたの川はまた 最高者の喜びなのだ。 どうして最高者は 地上におりてこられよう?そしてヘルタが緑であるように、 川はみな天空の子らなのだ。だがイスターはわたしには あまりに忍耐づよく、 殆ど見る者をあざけるほどに、自由でないように見える。すなわち、 日は、生長しはじめる 青春のときに昇らなくてはならず、 もうひとつの川は青春のおりに 早くも高々と壮麗な活動を示し、若駒にひとしく、 埒のなかで荒れ狂い、遙か遠くの風も その狂乱を聞くのに、 イスターは満足しているのだ。 けれども岩には通路が 大地には鋤溝が必要なので、 もし停滞がなかったら、川は荒廖たるものになるだろう。 だが、あの川のなすことは、 だれも知らない。 |

Jezt komme, Feuer! Begierig sind wir Zu schauen den Tag, Und wenn die Prüfung Ist durch die Knie gegangen, Mag einer spüren das Waldgeschrei. Wir singen aber vom Indus her Fernangekommen und Vom Alpheus, lange haben Das Schikliche wir gesucht, Nicht ohne Schwingen mag Zum nächsten einer greifen Geradezu Und kommen auf die andere Seite. Hier aber wollen wir bauen. Denn Ströme machen urbar Das Land. Wenn nemlich Kräuter wachsen Und an denselben gehn Im Sommer zu trinken die Thiere, So gehn auch Menschen daran. Man nennet aber diesen den Ister. Schön wohnt er. Es brennet der Säulen Laub, Und reget sich. Wild stehn Sie aufgerichtet, untereinander; darob Ein zweites Maas, springt vor Von Felsen das Dach. So wundert Mich nicht, dass er Den Herkules zu Gaste geladen, Fernglänzend, am Olympos drunten, Da der, sich Schatten zu suchen Vom heissen Isthmos kam, Denn voll des Muthes waren Daselbst sie, es bedarf aber, der Geister wegen, Der Kühlung auch. Darum zog jener lieber An die Wasserquellen hieher und gelben Ufer, Hoch duftend oben, und schwarz Vom Fichtenwald, wo in den Tiefen Ein Jäger gern lustwandelt Mittags, und Wachstum hörbar ist An harzigen Bäumen des Isters, Der scheinet aber fast Rückwärts zu gehen und Ich mein, er müsse kommen Von Osten. Vieles wäre Zu sagen davon. Und warum hängt er An den Bergen gerad? Der andre Der Rhein ist seitwärts Hinweggegangen. Umsonst nicht gehn Im Troknen die Ströme. Aber wie? Sie sollen nemlich Zur Sprache seyn. Ein Zeichen braucht es, Nichts anderes, schlecht und recht, damit es Sonn' Und Mond trag' im Gemüth', untrennbar, Und fortgeh, Tag und Nacht auch, und Die Himmlischen warm sich fühlen aneinander. Darum sind jene auch Die Freude des Höchsten. Denn wie käm er sonst Herunter? Und wie Hertha grün, Sind sie die Kinder des Himmels. Aber allzugedultig Scheint der mir, nicht Freier, und fast zu spotten. Nemlich wenn Angehen soll der Tag In der Jugend, wo er zu wachsen Anfängt, es treibet ein anderer da Hoch schon die Pracht, und Füllen gleich In den Zaum knirscht er, und weithin hören Das Treiben die Lüfte, Ist der betrübt; Es brauchet aber Stiche der Fels Und Furchen die Erd', Unwirthbar wär es, ohne Weile; Was aber jener thuet der Strom, Weis niemand. | Now is the time for fire! Impatient for the daylight, We're on our knees, Exhausted with waiting. It's then, in that silence, We hear the woods' strange call. Meanwhile, we sing from the Indus, Which comes from far away, and From the Alpheus, since we've Long desired decorum. It's not without dramatic flourish That one grasps Straight ahead What is closest To reach the other side. But here we want to build. Rivers make the land fertile And allow the foliage to grow. And if in the summer Animals gather at a watering place People will go there, too. This river is called the Ister. It lives in beauty. Columns of leaves burn And stir. They stand in the forest Supporting each other; above, A second dimension juts out From a dome of stones. So I'm Not surprised that the distantly gleaming river Made Hercules its guest, When in search of shadows He came down from Olympus And up from the heat of Isthmus. They were full of courage there, Which always comes in handy, like cool water And a path for the spirit to follow. That's why the hero preferred To come to the water's source, its fragrant yellow banks Black with fir trees, in whose depths The hunter likes to roam At noon and the resinous trees Moan as they grow. Yet the river almost seems To flow backwards, and I Think it must come From the East. Much could Be said further. But why does It hang so straight from the mountain? That other river, The Rhine, has gone away Sideways. Not for nothing rivers Flow in dryness. But how? We need a sign, Nothing more, something plain and simple, To remind us of sun and moon, so inseparable, Which go away — day and night also — And warm each other in heaven. They give joy to the highest god. For how Can he descend to them? And like earth's ancient greenness They are the children of heaven. But he seems Too indulgent to me, not freer, And almost scornful. For when Day begins in youth, Where it commences growing, Another is already there To further enhance the beauty, and chafes At the bit like foals. And if he is happy Distant breezes hear the commotion; But the rock needs engraving And the earth needs its furrows; If not, an endless desolation; But what a river will do, Nobody knows. |

| https://x.gd/rFLJi |

https://x.gd/rFLJi | https://x.gd/rFLJi |

Johann

Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (UK: /ˈhɜːldərliːn/, US: /ˈhʌl-/;[1]

German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈhœldɐliːn] ⓘ; 20 March 1770 – 7 June 1843) was a

German poet and philosopher. Described by Norbert von Hellingrath as

"the most German of Germans", Hölderlin was a key figure of German

Romanticism.[2] Particularly due to his early association with and

philosophical influence on Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich

Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, he was also an important thinker in the

development of German Idealism.[3][4][5][6] Johann

Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (UK: /ˈhɜːldərliːn/, US: /ˈhʌl-/;[1]

German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈhœldɐliːn] ⓘ; 20 March 1770 – 7 June 1843) was a

German poet and philosopher. Described by Norbert von Hellingrath as

"the most German of Germans", Hölderlin was a key figure of German

Romanticism.[2] Particularly due to his early association with and

philosophical influence on Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich

Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, he was also an important thinker in the

development of German Idealism.[3][4][5][6]Born in Lauffen am Neckar, Hölderlin had a childhood marked by bereavement. His mother intended for him to enter the Lutheran ministry, and he attended the Tübinger Stift, where he was friends with Hegel and Schelling. He graduated in 1793 but could not devote himself to the Christian faith, instead becoming a tutor. Two years later, he briefly attended the University of Jena, where he interacted with Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Novalis, before resuming his career as a tutor. He struggled to establish himself as a poet, and was plagued by mental illness. He was sent to a clinic in 1806 but deemed incurable and instead given lodging by a carpenter, Ernst Zimmer. He spent the final 36 years of his life in Zimmer's residence, and died in 1843 at the age of 73. Hölderlin followed the tradition of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller as an admirer of Greek mythology and Ancient Greek poets such as Pindar and Sophocles, and melded Christian and Hellenic themes in his works. Martin Heidegger, upon whom Hölderlin had a great influence, said: "Hölderlin is one of our greatest, that is, most impending thinkers because he is our greatest poet."[7] |

ヨ

ハン・クリスティアン・フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン(Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin、イギリス発音:

/ˈhɜːldərliːn/、アメリカ発音: /ˈhʌl-/、[1]ドイツ語発音: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈhœldɐliːn]

ⓘ、1770年3月20日 -

1843年6月7日)は、ドイツの詩人、哲学者である。ノルベルト・フォン・ヘリングラートは彼を「ドイツ人の中で最もドイツ人らしい人物」と評したが、

ホルデルリンはドイツロマン主義の重要な人物であった[2]。特に、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルやフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ヨゼ

フ・シェリングと早くから交流があり、哲学的な影響を与えたことから、ドイツ観念論の発展において重要な思想家でもあった[3][4][5][6]。 ヨ

ハン・クリスティアン・フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン(Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin、イギリス発音:

/ˈhɜːldərliːn/、アメリカ発音: /ˈhʌl-/、[1]ドイツ語発音: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈhœldɐliːn]

ⓘ、1770年3月20日 -

1843年6月7日)は、ドイツの詩人、哲学者である。ノルベルト・フォン・ヘリングラートは彼を「ドイツ人の中で最もドイツ人らしい人物」と評したが、

ホルデルリンはドイツロマン主義の重要な人物であった[2]。特に、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルやフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ヨゼ

フ・シェリングと早くから交流があり、哲学的な影響を与えたことから、ドイツ観念論の発展において重要な思想家でもあった[3][4][5][6]。ラウフェン・アム・ネッカーで生まれたホルデルリンは、幼少期に両親を亡くした。母親は息子をルター派の牧師にするつもりだったが、彼はテュービンゲン大 学に入学し、そこでヘーゲルやシェリングと友人になった。1793年に卒業したが、キリスト教に専念することはできず、家庭教師になった。2年後、イエナ 大学に短期間在籍し、ヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテやノヴァーリスと交流したが、その後家庭教師としてのキャリアを再開した。彼は詩人として成功しよう と苦心したが、精神疾患に悩まされていた。1806年に精神病院に入院したが、治療不可能と診断され、代わりに大工のエルンスト・ツィマーに宿を提供して もらった。彼は人生の最後の36年間をツィマーの家で過ごし、1843年に73歳で亡くなった。 ゲーテやシラーに倣い、ギリシャ神話やピンダロス、ソフォクレスといった古代ギリシャの詩人を愛したホレドルンは、キリスト教とギリシャ神話を融合させた 作品を執筆した。ホレドルンに大きな影響を受けたマルティン・ハイデッガーは、「ホレドルンは偉大な詩人であるからこそ、最も偉大な、つまり最も重要な思 想家の1人である」と語っている[7]。 |

| Biography Early life  Friedrich Hölderlin's birthplace, Lauffen am Neckar Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin was born on 20 March 1770 in Lauffen am Neckar, then a part of the Duchy of Württemberg. He was the first child of Johanna Christiana Heyn (1748—1828) and Heinrich Friedrich Hölderlin (1736—1772). His father, the manager of a church estate, died when he was two years old, and Friedrich and his sister, Heinrike, were brought up by their mother.[8] In 1774, his mother moved the family to Nürtingen when she married Johann Christoph Gok. Two years later, Johann Gok became the burgomaster of Nürtingen, and Hölderlin's half-brother, Karl Christoph Friedrich Gok, was born. In 1779, Johann Gok died at the age of 30. Hölderlin later expressed how his childhood was scarred by grief and sorrow, writing in a 1799 correspondence with his mother: When my second father died, whose love for me I shall never forget, when I felt, with an incomprehensible pain, my orphaned state and saw, each day, your grief and tears, it was then that my soul took on, for the first time, this heaviness that has never left and that could only grow more severe with the years.[9] Education Hölderlin began his education in 1776, and his mother planned for him to join the Lutheran church. In preparation for entrance exams into a monastery, he received additional instruction in Greek, Hebrew, Latin and rhetoric, starting in 1782. During this time, he struck a friendship with Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, who was five years Hölderlin's junior. On account of the age difference, Schelling was "subjected to universal teasing" and Hölderlin protected him from abuse by older students.[10] Also during this time, Hölderlin began playing the piano and developed an interest in travel literature through exposure to Georg Forster's A Voyage Round the World. In 1784, Hölderlin entered the Lower Monastery in Denkendorf and started his formal training for entry into the Lutheran ministry. At Denkendorf, he discovered the poetry of Friedrich Schiller and Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, and took tentative steps in composing his own verses.[11] The earliest known letter of Hölderlin's is dated 1784 and addressed to his former tutor Nathanael Köstlin. In the letter, Hölderlin hinted at his wavering faith in Christianity and anxiety about his mental state.[12] Hölderlin progressed to the Higher Monastery at Maulbronn in 1786. There he fell in love with Luise Nast, the daughter of the monastery's administrator, and began to doubt his desire to join the ministry; he composed Mein Vorsatz in 1787, in which he states his intention to attain "Pindar's light" and reach "Klopstock-heights". In 1788, he read Schiller's Don Carlos on Luise Nast's recommendation. Hölderlin later wrote a letter to Schiller regarding Don Carlos, stating: "It won't be easy to study Carlos in a rational way, since he was for so many years the magic cloud in which the good god of my youth enveloped me so that I would not see too soon the pettiness and barbarity of the world."[13]  Hölderlin attended the Tübinger Stift (pictured) from 1788 to 1793. In October 1788, Hölderlin began his theological studies at the Tübinger Stift, where his fellow students included Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Isaac von Sinclair and Schelling. It has been speculated that it was Hölderlin who, during their time in Tübingen, brought to Hegel's attention the ideas of Heraclitus regarding the unity of opposites, which Hegel would later develop into his concept of dialectics.[14] In 1789, Hölderlin broke off his engagement with Luise Nast, writing to her: "I wish you happiness if you choose one more worthy than me, and then surely you will understand that you could never have been happy with your morose, ill-humoured, and sickly friend," and expressed his desire to transfer out and study law but succumbed to pressure from his mother to remain in the Stift.[15] Along with Hegel and Schelling and his other peers during his time in the Stift, Hölderlin was an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution.[16] Although he rejected the violence of the Reign of Terror, his commitment to the principles of 1789 remained intense.[17] Hölderlin's republican sympathies influenced many of his most famous works such as Hyperion and The Death of Empedocles.[18] Career After he obtained his magister degree in 1793, his mother expected him to enter the ministry. However, Hölderlin found no satisfaction in the prevailing Protestant theology, and worked instead as a private tutor. In 1794, he met Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and began writing his epistolary novel Hyperion. In 1795 he enrolled for a while at the University of Jena where he attended Johann Gottlieb Fichte's classes and met Novalis. There is a seminal manuscript, dated 1797, now known as the Das älteste Systemprogramm des deutschen Idealismus ("The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism"). Although the document is in Hegel's handwriting, it is thought to have been written by Hegel, Schelling, Hölderlin, or an unknown fourth person.[19] As a tutor in Frankfurt am Main from 1796 to 1798, he fell in love with Susette Gontard, the wife of his employer, the banker Jakob Gontard. The feeling was mutual, and this relationship became the most important in Hölderlin's life. After a while, their affair was discovered, and Hölderlin was harshly dismissed. He then lived in Homburg from 1798 to 1800, meeting Susette in secret once a month and attempting to establish himself as a poet, but his life was plagued by financial worries and he had to accept a small allowance from his mother. His mandated separation from Susette Gontard also worsened Hölderlin's doubts about himself and his value as a poet; he wished to transform German culture but did not have the influence he needed. From 1797 to 1800, he produced three versions—all unfinished—of a tragedy in the Greek manner, The Death of Empedocles, and composed odes in the vein of the Ancient Greeks Alcaeus and Asclepiades of Samos. Mental breakdown In the late 1790s, Hölderlin was diagnosed with schizophrenia, then referred to as "hypochondrias", a condition that would worsen after his last meeting with Susette Gontard in 1800. After a sojourn in Stuttgart at the end of 1800, likely to work on his translations of Pindar, he found further employment as a tutor in Hauptwyl, Switzerland, and then at the household of the Hamburg consul in Bordeaux, in 1802. His stay in the French city is celebrated in Andenken ("Remembrance"), one of his greatest poems. In a few months, however, he returned home on foot via Paris (where he saw authentic Greek sculptures, as opposed to Roman or modern copies, for the only time in his life). He arrived at his home in Nürtingen both physically and mentally exhausted in late 1802, and learned that Gontard had died from influenza in Frankfurt at around the same time. At his home in Nürtingen with his mother, a devout Christian, Hölderlin melded his Hellenism with Christianity and sought to unite ancient values with modern life; in his elegy Brod und Wein ("Bread and Wine"), Christ is seen as sequential to the Greek gods, bringing bread from the earth and wine from Dionysus. After two years in Nürtingen, Hölderlin was taken to the court of Homburg by Isaac von Sinclair, who found a sinecure for him as court librarian, but in 1805 von Sinclair was denounced as a conspirator and tried for treason. Hölderlin was in danger of being tried too but was declared mentally unfit to stand trial. On 11 September 1806, he was delivered into the clinic at Tübingen run by Dr. Johann Heinrich Ferdinand von Autenrieth, the inventor of a mask for the prevention of screaming in the mentally ill.[20]  The first floor of the yellow tower (now known as the Hölderlinturm) was Hölderlin's place of residence from 1807 until his death in 1843. The clinic was attached to the University of Tübingen and the poet Justinus Kerner, then a student of medicine, was assigned to look after Hölderlin. The following year Hölderlin was discharged as incurable and given three years to live, but was taken in by the carpenter Ernst Zimmer (a cultured man, who had read Hyperion) and given a room in his house in Tübingen, which had been a tower in the old city wall with a view across the Neckar river. The tower would later be named the Hölderlinturm, after the poet's 36-year-long stay in the room. His residence in the building made up the second half of his life and is also referred to as the Turmzeit (or "Tower period"). Later life and death  Sketch of Hölderlin by Luise Keller, 1842 In the tower, Hölderlin continued to write poetry of a simplicity and formality quite unlike what he had been writing up to 1805. As time went on he became a minor tourist attraction and was visited by curious travelers and autograph-hunters. Often he would play the piano or spontaneously write short verses for such visitors, pure in versification but almost empty of affect—although a few of these (such as the famous Die Linien des Lebens ("The Lines of Life"), which he wrote out for his carer Zimmer on a piece of wood) have a piercing beauty and have been set to music by many composers.[21] Hölderlin's own family did not financially support him but petitioned successfully for his upkeep to be paid by the state. His mother and sister never visited him, and his stepbrother did so only once. His mother died in 1828: his sister and stepbrother quarreled over the inheritance, arguing that too large a share had been allotted to Hölderlin, and unsuccessfully tried to have the will overturned in court. Neither of them attended his funeral in 1843 nor did his childhood friends, Hegel (as he had died roughly a decade prior) and Schelling, who had long since ignored him; the Zimmer family were his only mourners. His inheritance, including the patrimony left to him by his father when he was two, had been kept from him by his mother and was untouched and continually accruing interest. He died a rich man, but did not know it.[22] |

経歴 生い立ち  フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリンの生家、ラウフェン・アム・ネッカー ヨハン・クリスティアン・フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリンは、1770年3月20日、当時ヴュルテンベルク公国の一部であったラウフェン・アム・ネッカーで生 まれた。彼はヨハンナ・クリスチアナ・ハイン(1748年~1828年)とハインリヒ・フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン(1736年~1772年)の最初の子 供であった。教会の不動産管理者を務めていた彼の父親は、彼が2歳のときに死去し、フリードリヒと姉のハインリケは母親の手で育てられた[8]。 1774年、母親はヨハン・クリストフ・ゴックと結婚し、ニュルティンゲンに一家を移した。2年後、ヨハン・ゴックはニュルティンゲンの町長に就任し、フ リードリヒの異母兄弟であるカール・クリストフ・フリードリヒ・ゴックが誕生した。1779年、ヨハン・ゴックは30歳で死去した。 ヘルダーリンは、後に母との1799年の書簡の中で、幼少期の悲しみと悲嘆に傷ついた日々について次のように述べている。 私にとって忘れられない愛情を注いでくれた第二の父が亡くなったとき、私は理解できないほどの痛みを感じ、孤児となったことを実感し、毎日、あなたの悲し みと涙を目にしたとき、私の魂は初めて、 それは、決して消えることなく、年を重ねるごとに深まるばかりの重苦しさを、初めて私の魂に与えたのだ。 教育 1776年に教育を開始したホーデルリンは、母親の計画によりルター派教会に入会することになっていた。修道院への入学試験に備えて、1782年からギリ シャ語、ヘブライ語、ラテン語、修辞学を学んだ。この時期に、5歳年下のフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ヨーゼフ・シェリングと友人になった。年齢の違いか ら、シェリングは「誰からもからかわれる」対象となり、ホルデルリンは年上の学生たちからのいじめから彼を守った[10]。また、この時期にホルデルリン はピアノを弾き始め、ゲオルク・フォスターの『世界一周』に触れて旅行文学に興味を持つようになった。 1784年、ホルデルリンはデンケンドルフの下部修道院に入り、ルター派聖職者になるための正式な訓練を開始した。デンケンドルフで、彼はフリードリヒ・ シラーとフリードリヒ・ゴットリープ・クロプストクの詩を発見し、自身の詩作の第一歩を踏み出した[11]。現在知られている中で最も古いヘルダーリンの 手紙は1784年に書かれたもので、かつての家庭教師ナタナエル・ケストリン宛てである。この手紙の中で、ヘルダーリンはキリスト教への揺らぎがちな信仰 と、自身の精神状態への不安を示唆している[12]。 ヘルダーリンは1786年にマウルブロン修道院高等学院に進学した。そこで修道院の管理人の娘であるルイゼ・ナストと恋に落ち、牧師になることに疑問を抱 き始めた。1787年に『Mein Vorsatz』を執筆し、ピンドールの光を手に入れ、クロプシュトックの頂点に達するという決意を表明した。1788年、ルイゼ・ナストの勧めでシラー の『ドン・カルロス』を読んだ。後に、ヘルダーリンはシラーにドン・カルロスについて手紙を書き、「カルロスを理性的に研究するのは容易ではない。なぜな ら、彼は長年にわたり、私の青春時代の善良な神が私を包み込む魔法の雲であり、私は世界の卑しさや野蛮さを早くには見ることができなかったからだ」と述べ た[13]。  ヘルダーリンは、1788年から1793年までテュービンゲン大学(写真)に通った。 1788年10月、ヘーゲル、アイザック・フォン・シンクレア、シェリングらを同級生に迎えたテュービンゲン大学にて、ヘーデルリンは神学の研究を始め た。チュービンゲン時代、ヘーゲルの注意をヘラクレイトスの「相反するものの統一」という思想に惹きつけたのは、ホルデルリンだったのではないかと推測さ れている。[14] 1789年、ホルデルリンはルイゼ・ナストとの婚約を解消し、彼女に宛てて次のように書いた。「もし私よりもふさわしい相手を選ぶのなら、幸せになってほ しい。そして、不機嫌で気難しく病弱な友人とは決して幸せになれなかったのだと、きっと理解するだろう」と書き、法学を勉強するために転校したいと望んだ が、シュティフトに残るよう母親からの圧力に屈した[15]。 シュティフト時代、ヘーゲルやシェリング、そして他の仲間たちとともに、ホルデルリンは フランス革命の熱心な支持者であった[16]。恐怖政治の暴力を否定したが、1789年の原則に対する彼の献身は強かった[17]。ホルデルリンの共和主 義的共感は、『ヒペリオン』や『エンペドクレスの死』などの彼の最も有名な作品の多くに影響を与えた[18]。 経歴 1793年に修士号を取得した後、母親は彼に聖職者になることを期待した。しかし、ホルデルリンは当時主流であったプロテスタント神学に満足できず、家庭 教師として働いた。1794年、フリードリヒ・シラーとヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテと出会い、書簡体小説『ハイペリオン』の執筆を開始した。 1795年、イエナ大学にしばらく在籍し、ヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテの講義を受講し、ノヴァーリスと出会った。 1797年付けの重要な草稿が現存しており、現在では「Das älteste Systemprogramm des deutschen Idealismus(ドイツ観念論の最も古い体系プログラム)」として知られている。この文書はヘーゲルの筆跡であるが、ヘーゲル、シェリング、ホレド ルン、あるいは不明の4人目の人物によって書かれたと考えられている[19]。 1796年から1798年にかけてフランクフルト・アム・マインで家庭教師をしていた彼は、雇い主である銀行家ヤコブ・ゴンタールの妻スゼッテ・ゴンタル ドと恋に落ちた。 2人の気持ちは通じ合い、この関係はホーデルリンの人生で最も重要なものとなった。しばらくして2人の関係が露見し、ホーデルリンは厳しく解雇された。そ の後、1798年から1800年にかけてホンブルクに住み、月に一度ひそかにスゼットと会い、詩人として自立しようとしたが、経済的な不安に悩まされ、母 親からのわずかな仕送りを頼りにしなければならなかった。 スゼット・ゴンタルドとの別居も、ヘルダーリンの詩人としての価値に対する疑念を深めることとなった。彼はドイツ文化を変革したいと願っていたが、必要な 影響力を持ち合わせていなかったのだ。1797年から1800年にかけて、彼はギリシャ悲劇のスタイルで、未完のまま3つのバージョンを制作した。その悲 劇は『エンペドクレスの死』と題され、古代ギリシャのアルカイオスやサモスのアスクレピアデスを題材にした頌歌も作曲した。 精神の崩壊 1790年代後半、ヘルダーリンは統合失調症と診断された。当時は「心気症」と呼ばれていたが、1800年にスゼッテ・ゴンタルドと最後に会った後、病状 は悪化した。1800年末にシュトゥットガルトに滞在し、ピンドルの翻訳に取り組んだ後、1802年にはスイスのハウプトヴィルで家庭教師として、またハ ンブルク領事のボルドーの家庭で家庭教師としてさらに職を得た。 フランスの都市での滞在は、彼の最高傑作のひとつである詩『Andenken(追憶)』で称えられている。しかし数か月後、彼はパリを経由して徒歩で故郷 に戻った(そこで彼は、ローマ時代や近代の模造品ではなく、本物のギリシャ彫刻を人生で初めて目にした)。1802年の終わり、心身ともに疲れ果てた状態 でニュルティンゲンの自宅に戻った彼は、同じ頃、ゴンタルがフランクフルトでインフルエンザにより亡くなったことを知った。 敬虔なキリスト教徒である母親とともにニュルティンゲンの自宅に戻ったヘルダーリンは、自らのヘレニズムとキリスト教を融合させ、古代の価値観と現代生活 を結びつけようとした。彼の哀歌『パンとワイン』では、キリストはギリシャ神話の神々の一員として描かれ、大地からパンを、ディオニュソスからワインをも たらす存在となっている。ニュルティンゲンでの2年間の滞在の後、ホーデルリンはアイザック・フォン・シンクレアによってホンブルク宮廷に連れて行かれ、 宮廷司書として無難な職に就くことができたが、1805年にシンクレアは陰謀の共謀者として告発され、反逆罪で裁判にかけられた。ホーデルリンも裁判にか けられる危険にさらされたが、精神的に裁判を受ける能力がないと宣言された。1806年9月11日、彼は精神障害者の叫び声を防ぐためのマスクを発明した ヨハン・ハインリヒ・フェルディナント・フォン・アウテンリート博士が運営するテュービンゲンのクリニックに収容された[20]。  黄色い塔(現在はヘルダーリン塔として知られている)の1階は、1807年から1843年にヘルダーリンが亡くなるまで、彼の住居であった。 この病院はテュービンゲン大学に付属しており、当時医学部の学生だった詩人ユスティヌス・ケルナーが、ヘルダーリンの世話をするよう任命された。翌年、ヘ ルダーリンは不治の病と診断され余命3年と宣告されたが、大工のエルンスト・ツィマー(教養のある人物で『ハイペリオン』を読んでいた)に引き取られ、 テュービンゲンの自宅の一室を与えられた。この塔は後に、詩人が36年間この部屋に滞在していたことにちなんで、ヘルダーリン塔と名付けられることにな る。この建物での生活は、彼の生涯の後半を占め、Turmzeit(塔の時代)とも呼ばれている。 晩年と死  1842年、ルイゼ・ケラーによるヘルダーリンのスケッチ 塔の中で、ヘルダーリンは1805年までの作品とは全く異なる、簡潔で形式的な詩を書き続けた。時が経つにつれ、彼はちょっとした観光名所となり、好奇心 旺盛な旅行者やサインを求める人々が訪れるようになった。彼はしばしばピアノを弾いたり、そのような訪問客のために即興で短い詩を作ったりした。詩は純粋 な韻律を持っていたが、感情はほとんど込められていなかった。しかし、そのうちのいくつかは(例えば、彼の介護人ツィマーのために木片に書き留めた有名な 『人生の線』など)心に突き刺さるような美しさを持ち、多くの作曲家によって音楽にされている。介護人のツィマーのために木片に書いた「人生の線」など) は、心に突き刺さるような美しさを持ち、多くの作曲家によって曲にされている。 [21] ホーデルリンの家族は彼に対して経済的な援助はしなかったが、彼の生活費を国が負担するよう求める嘆願は成功した。彼の母と妹は一度も彼を訪れることはな く、義理の兄も一度しか訪ねてこなかった。 1828年に彼の母が死去すると、妹と義理の兄は遺産相続をめぐって争い、ホルデルリンに割り当てられた遺産の割合が大きすぎると主張し、裁判所で遺言を 無効にしようと試みたが、失敗に終わった。1843年の彼の葬儀には、どちらも出席しなかった。また、ヘーゲル(およそ10年前に死去)やシェリングと いった幼なじみたちも出席しなかった。彼らは、ずっと前から彼を無視していたのだ。彼の葬儀に参列したのは、ツィマー家の人々だけだった。彼の遺産は、彼 が2歳のときに父親から受け継いだ遺産を含め、母親によって彼から隠され、そのまま利子をつけて増えていた。彼は裕福なまま亡くなったが、そのことに気づ かなかった[22]。 |

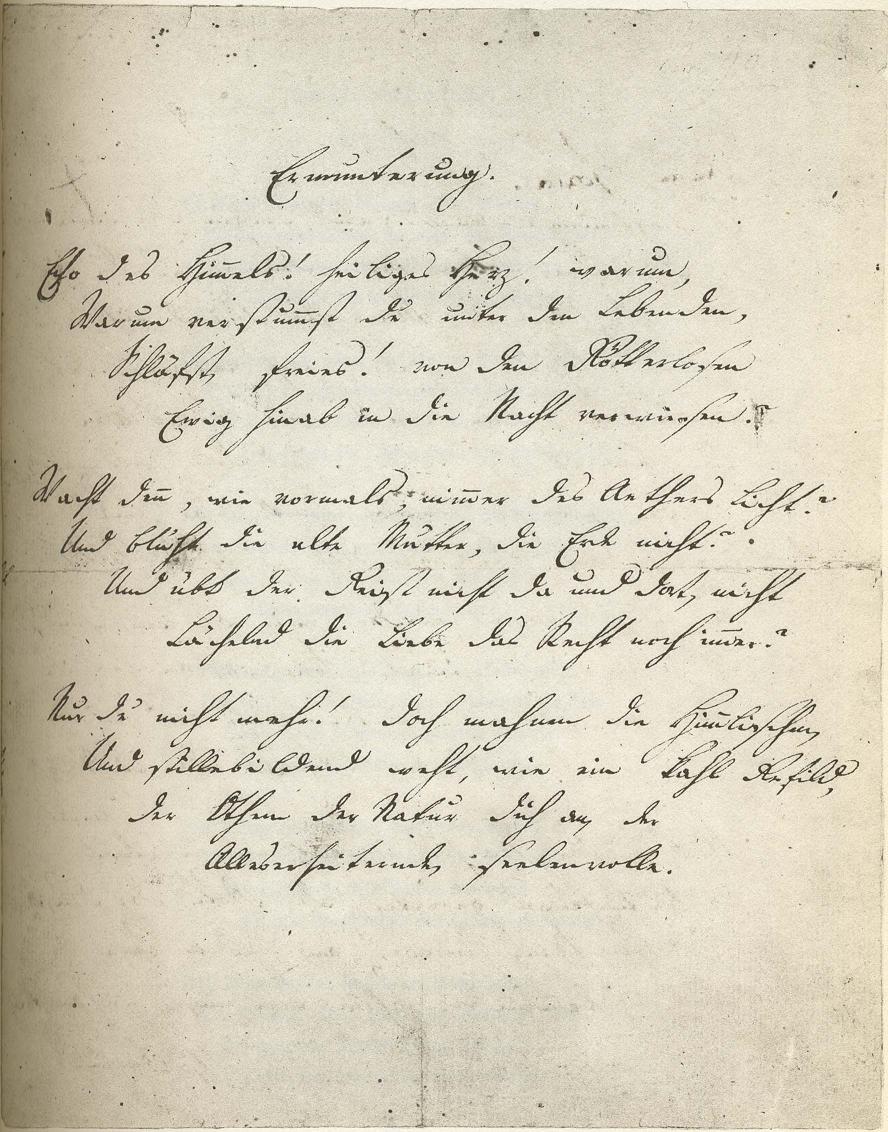

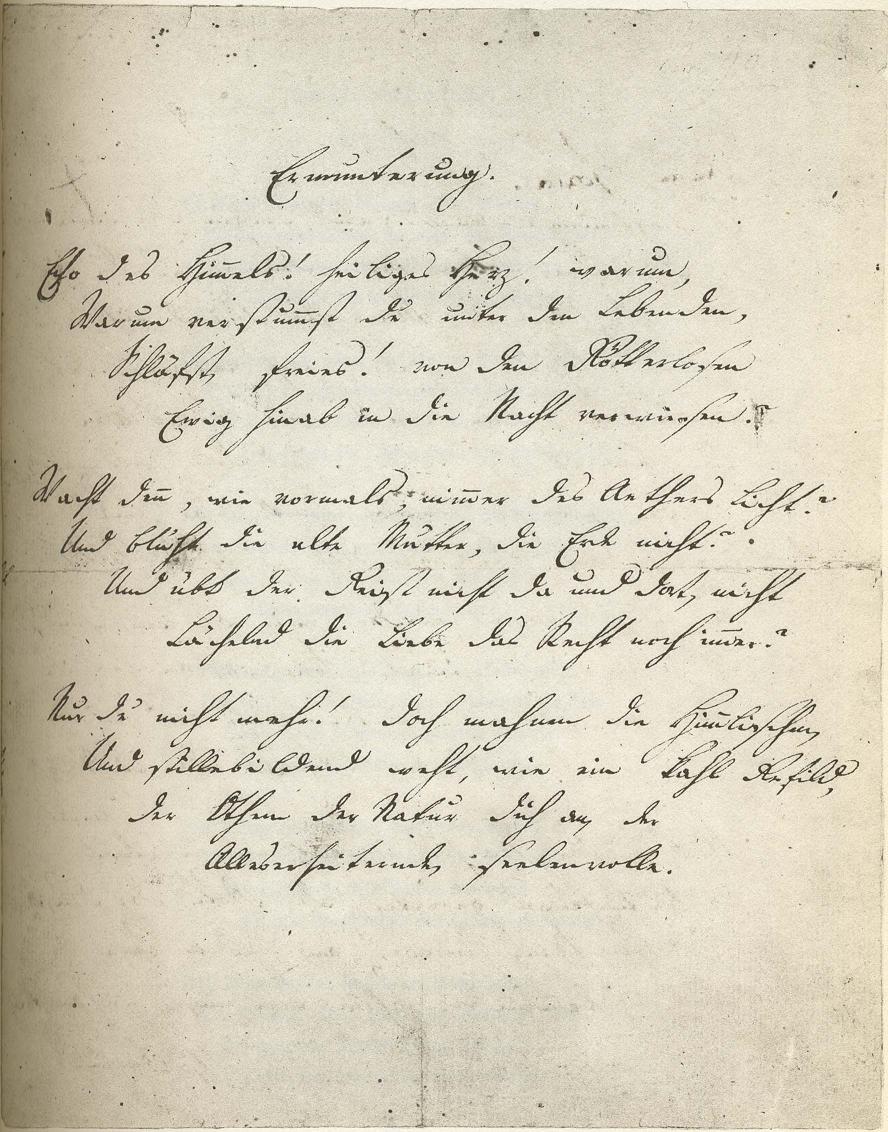

| Works The poetry of Hölderlin, widely recognized today as one of the highest points of German literature, was little known or understood during his lifetime, and slipped into obscurity shortly after his death; his illness and reclusion made him fade from his contemporaries' consciousness—and, even though selections of his work were published by his friends during his lifetime, it was largely ignored for the rest of the 19th century.  Hölderlin's autograph of the first three stanzas of his ode "Ermunterung" ("Exhortation") Like Goethe and Schiller, his older contemporaries, Hölderlin was a fervent admirer of ancient Greek culture, but for him the Greek gods were not the plaster figures of conventional classicism, but wonderfully life-giving actual presences, yet at the same time terrifying. Much later, Friedrich Nietzsche would recognize Hölderlin as the poet who first acknowledged the Orphic and Dionysian Greece of the mysteries, which he would fuse with the Pietism of his native Swabia in a highly original religious experience.[23] Hölderlin developed an early idea of cyclical history and therefore believed political radicalism and an aesthetic interest in antiquity, and, in parallel, Christianity and Paganism should be fused.[23] He understood and sympathised with the Greek idea of the tragic fall, which he expressed movingly in the last stanza of his "Hyperions Schicksalslied" ("Hyperion's Song of Destiny"). In the great poems of his maturity, Hölderlin would generally adopt a large-scale, expansive and unrhymed style. Together with these long hymns, odes and elegies—which included "Der Archipelagus" ("The Archipelago"), "Brod und Wein" ("Bread and Wine") and "Patmos"—he also cultivated a crisper, more concise manner in epigrams and couplets, and in short poems like the famous "Hälfte des Lebens" ("The Middle of Life"). In the years after his return from Bordeaux, he completed some of his greatest poems but also, once they were finished, returned to them repeatedly, creating new and stranger versions sometimes in several layers on the same manuscript, which makes the editing of his works troublesome. Some of these later versions (and some later poems) are fragmentary, but they have astonishing intensity. He seems sometimes also to have considered the fragments, even with unfinished lines and incomplete sentence-structure, to be poems in themselves. This obsessive revising and his stand-alone fragments were once considered evidence of his mental disorder, but they were to prove very influential on later poets such as Paul Celan. In his years of madness, Hölderlin would occasionally pencil ingenuous rhymed quatrains, sometimes of a childlike beauty, which he would sign with fantastic names (most often "Scardanelli") and give fictitious dates from previous or future centuries. |

作品 今日、ドイツ文学の最高峰のひとつとして広く認められているヘルダーリンの詩は、彼の存命中はほとんど知られておらず、理解もされていなかった。彼の死後 まもなく、その詩は忘れ去られてしまった。病と引きこもりにより、彼は同時代の人の記憶から消えていった。彼の友人たちが彼の生前に作品を出版していたに もかかわらず、19世紀の残りの期間、その作品はほとんど無視されていた。  「Ermunterung」(「Exhortation」、激励)という頌歌の最初の3節のホレドリンの自筆 ホレドリンは、同時代の先輩であるゲーテやシラーと同様、古代ギリシャ文化の熱烈な愛好家であったが、彼にとってギリシャの神々は、従来の古典主義の石膏 像ではなく、素晴らしく生命力に満ちた実在の存在であり、同時に恐ろしい存在でもあった。ずっと後の時代、フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、オルフェウスやディ オニュソスに代表される神秘的なギリシャを最初に認めた詩人としてヘルダーリンを認め、それを故郷シュヴァーベンの敬虔主義と融合させた。ヘルダーリンは 循環史観を早くから提唱しており、そのため政治的な 政治的な急進主義と古代への美的関心、そして並行してキリスト教と多神教を融合させるべきだと信じていた[23]。彼は、悲劇的な没落というギリシャの思 想を理解し、共感していた。彼は『ハイペリオン・シュケッカルズリート』(「ハイペリオンの運命の歌」)の最後の詩節で、その考えを感動的に表現してい る。 成熟期の偉大な詩では、ヘルダーリンは一般的に、大規模で広範囲にわたる韻を踏まないスタイルを採用した。これらの長い賛歌、頌歌、哀歌(「群島」や「パ ンとワイン」、「パトモス」など)とともに、彼はより簡潔で凝縮された手法を、銘文や対句、有名な「人生の半ば」のような短い詩でも用いた。 ボルドーから戻った後、彼はいくつかの最高傑作を完成させたが、完成後も何度も手直しし、時には同じ原稿に何層もの新しい、より奇抜なバージョンを書き加 えたため、彼の作品の編集は困難を極めた。これらの後期のバージョン(および後期の詩)の一部は断片的であるが、驚くべき強度を持っている。彼は、未完成 の行や不完全な文構造を持つ断片も、それ自体が詩であると考えていたようである。この執拗な推敲と、彼の単独で書かれた断片は、かつては彼の精神障害の証 拠と考えられていたが、後にポール・ツェランなどの詩人たちに多大な影響を与えた。 ホルデルリンは狂気の日々の中で、時に子供のような美しさを持つ素朴な韻文の四行詩を鉛筆で書き、空想上の名前(最も多かったのは「スカルダネッリ」)で 署名し、過去や未来の世紀に架空の日付を記していた。 |

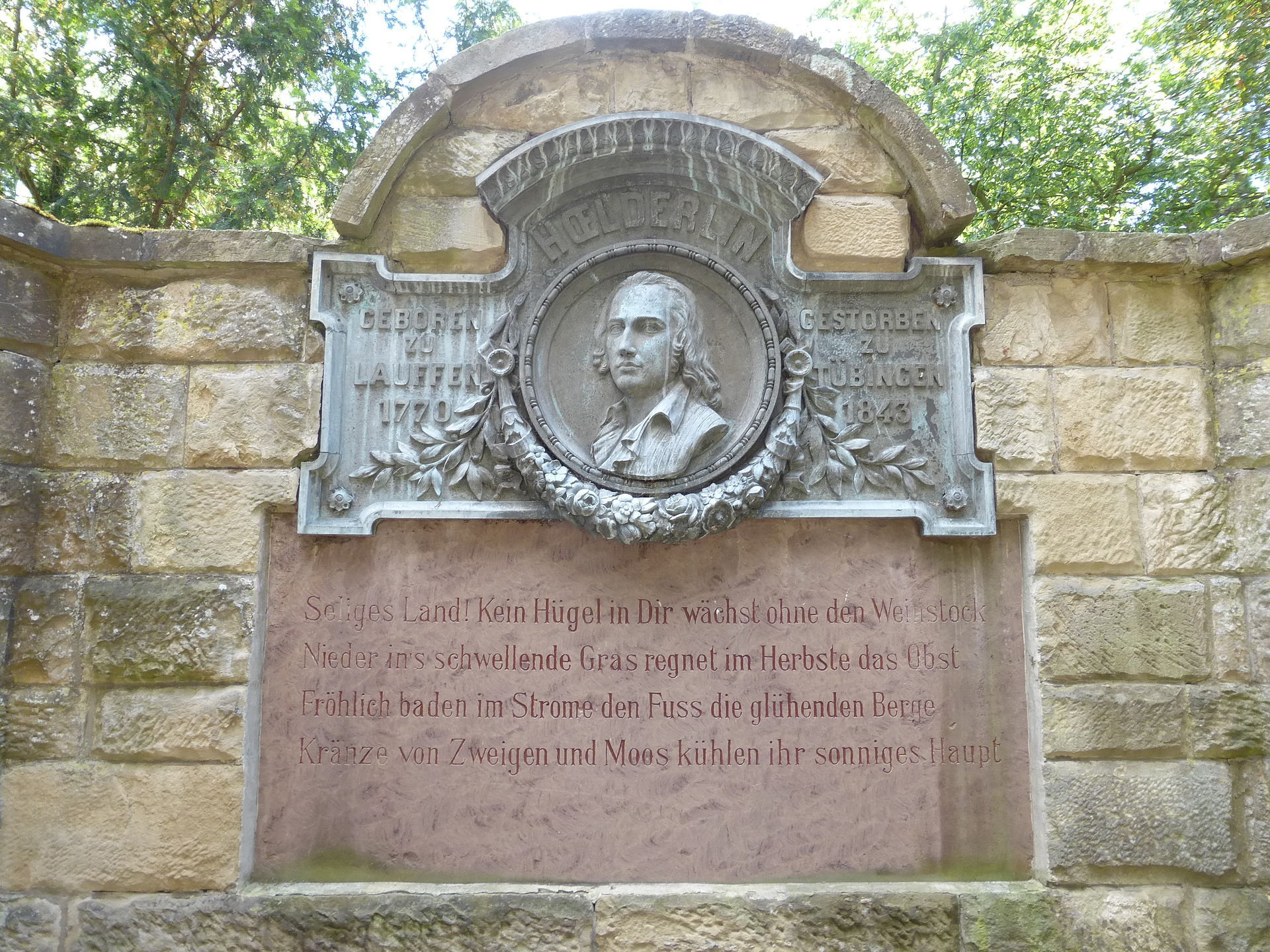

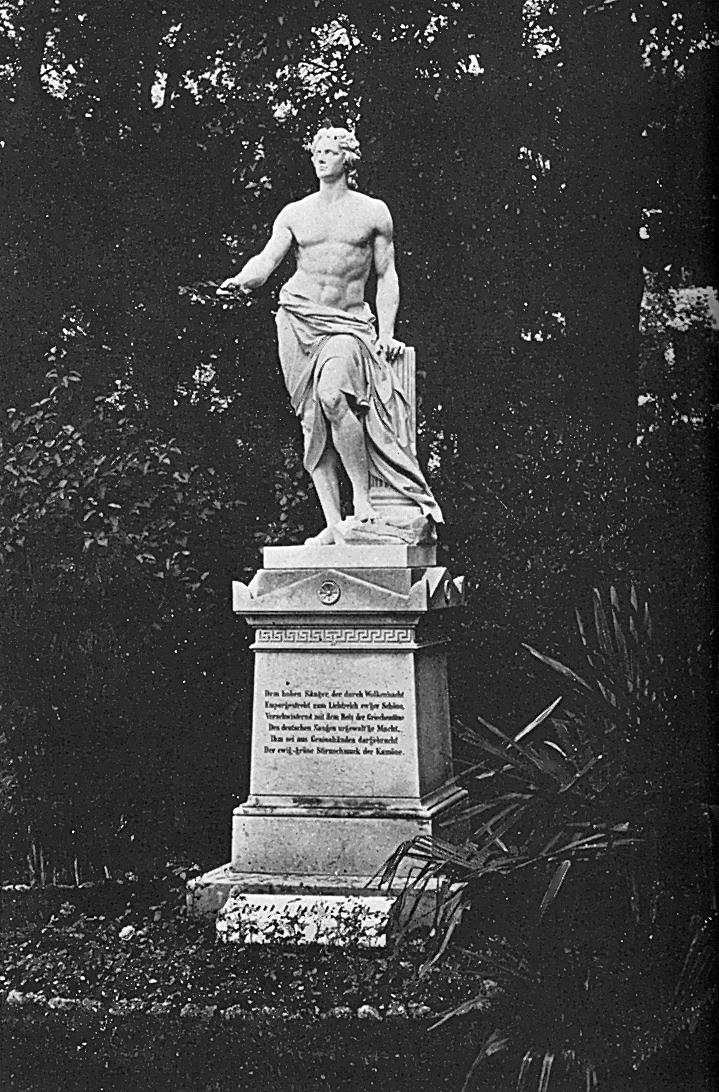

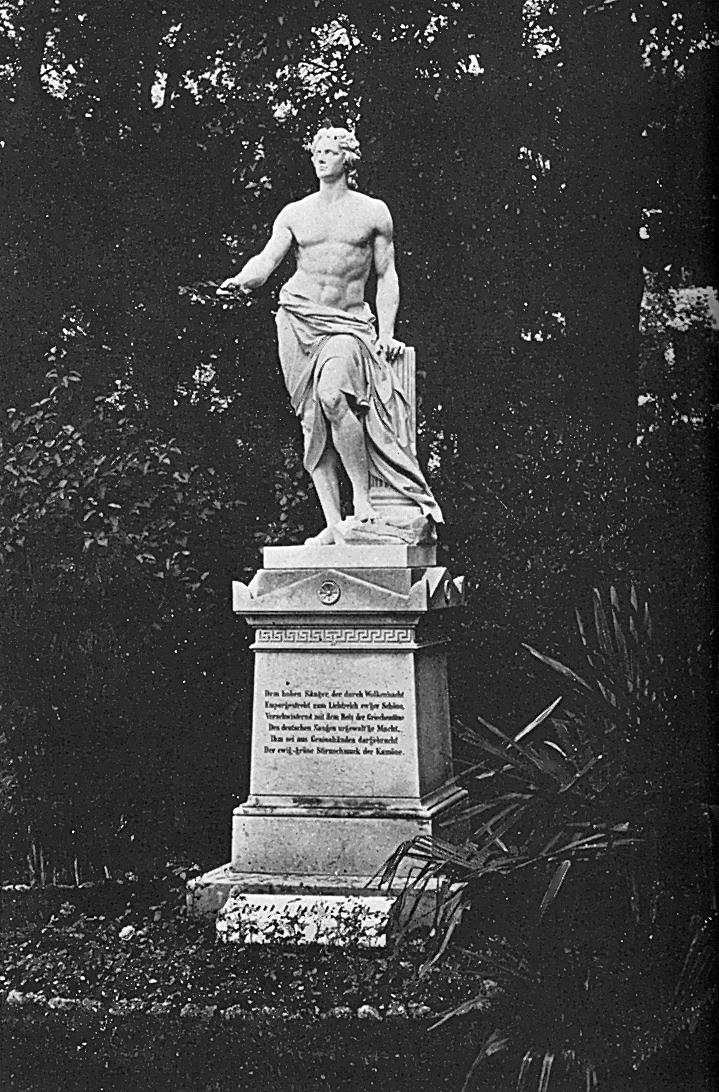

Dissemination and influence Friedrich Hölderlin Memorial in Lauffen am Neckar Hölderlin's major publication in his lifetime was his novel Hyperion, which was issued in two volumes (1797 and 1799). Various individual poems were published but attracted little attention. In 1799 he produced a periodical, Iduna. In 1804, his translations of the dramas of Sophocles were published but were generally met with derision over their apparent artificiality and difficulty, which according to his critics were caused by transposing Greek idioms into German. However, 20th-century theorists of translation such as Walter Benjamin have vindicated them, showing their importance as a new—and greatly influential—model of poetic translation. Der Rhein and Patmos, two of the longest and most densely charged of his hymns, appeared in a poetic calendar in 1808. Wilhelm Waiblinger, who visited Hölderlin in his tower repeatedly in 1822–23 and depicted him in the protagonist of his novel Phaëthon, stated the necessity of issuing an edition of his poems, and the first collection of his poetry was released by Ludwig Uhland and Christoph Theodor Schwab in 1826. However, Uhland and Schwab omitted anything they suspected might be "touched by insanity", which included much of Hölderlin's fragmented works. A copy of this collection was given to Hölderlin, but later was stolen by an autograph-hunter.[22] A second, enlarged edition with a biographical essay appeared in 1842, the year before Hölderlin's death. Only in 1913 did Norbert von Hellingrath, a member of the literary Circle led by the German Symbolist poet Stefan George, publish the first two volumes of what eventually became a six-volume edition of Hölderlin's poems, prose and letters (the "Berlin Edition", Berliner Ausgabe). For the first time, Hölderlin's hymnic drafts and fragments were published and it became possible to gain some overview of his work in the years between 1800 and 1807, which had been only sparsely covered in earlier editions. The Berlin edition and von Hellingrath's advocacy led to Hölderlin posthumously receiving the recognition that had always eluded him in life. As a result, Hölderlin has been recognized since 1913 as one of the greatest poets ever to write in the German language.  Norbert von Hellingrath during World War I Norbert von Hellingrath enlisted in the Imperial German Army at the outbreak of World War I and was killed in action at the Battle of Verdun in 1916. The fourth volume of the Berlin edition was published posthumously. The Berlin Edition was completed after the German Revolution of 1918 by Friedrich Seebass and Ludwig von Pigenot; the remaining volumes appeared in Berlin between 1922 and 1923. Already in 1912, before the Berlin Edition began to appear, Rainer Maria Rilke composed his first two Duino Elegies whose form and spirit draw strongly on the hymns and elegies of Hölderlin. Rilke had met von Hellingrath a few years earlier and had seen some of the hymn drafts, and the Duino Elegies heralded the beginning of a new appreciation of Hölderlin's late work. Although his hymns can hardly be imitated, they have become a powerful influence on modern poetry in German and other languages, and are sometimes cited as the very crown of German lyric poetry.  Hölderlin Monument in the Alter Botanischer Garten Tübingen, 1881 The Berlin Edition was to some extent superseded by the Stuttgart Edition (Grosse Stuttgarter Ausgabe), which began to be published in 1943 and eventually saw completion in 1986. This undertaking was much more rigorous in textual criticism than the Berlin Edition and solved many issues of interpretation raised by Hölderlin's unfinished and undated texts (sometimes several versions of the same poem with major differences). Meanwhile, a third complete edition, the Frankfurt Critical Edition (Frankfurter Historisch-kritische Ausgabe), began publication in 1975 under the editorship of Dietrich Sattler. Though Hölderlin's hymnic style—dependent as it is on a genuine belief in the divine—creates a deeply personal fusion of Greek mythic figures and romantic mysticism about nature, which can appear both strange and enticing, his shorter and sometimes more fragmentary poems have exerted wide influence too on later German poets, from Georg Trakl onwards. He also had an influence on the poetry of Hermann Hesse and Paul Celan. (Celan wrote a poem about Hölderlin, called "Tübingen, January" which ends with the word Pallaksch—according to Schwab, Hölderlin's favourite neologism "which sometimes meant Yes, sometimes No".) Hölderlin was also a thinker who wrote, fragmentarily, on poetic theory and philosophical matters. His theoretical works, such as the essays "Das Werden im Vergehen" ("Becoming in Dissolution") and "Urteil und Sein" ("Judgement and Being") are insightful and important if somewhat tortuous and difficult to parse. They raise many of the key problems also addressed by his Tübingen roommates Hegel and Schelling, and, though his poetry was never "theory-driven", the interpretation and exegesis of some of his more difficult poems have given rise to profound philosophical speculation by thinkers such as Martin Heidegger, Theodor Adorno, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault and Alain Badiou. Music Hölderlin's poetry has inspired many composers, generating vocal music and instrumental music. Vocal music One of the earliest settings of Hölderlin's poetry is Schicksalslied by Johannes Brahms, based on Hyperions Schicksalslied.[24] Other composers of Hölderlin settings include Ludwig van Beethoven (An die Hoffnung - Opus 32), Peter Cornelius, Hans Pfitzner, Richard Strauss (Drei Hymnen), Max Reger ("An die Hoffnung"), Alphons Diepenbrock (Die Nacht), Walter Braunfels ("Der Tod fürs Vaterland"), Richard Wetz (Hyperion), Josef Matthias Hauer, Denise Roger, Hermann Reutter, Margarete Schweikert, Stefan Wolpe, Paul Hindemith, Benjamin Britten (Sechs Hölderlin-Fragmente), Hans Werner Henze, Bruno Maderna (Hyperion, Stele an Diotima), Luigi Nono (Prometeo), Heinz Holliger (the Scardanelli-Zyklus), Hans Zender (Hölderlin lesen I-IV), György Kurtág (who planned an opera on Hölderlin), György Ligeti (Three Fantasies after Friedrich Hölderlin), Hanns Eisler (Hollywood Liederbuch), Viktor Ullmann, Wolfgang von Schweinitz, Walter Zimmermann (Hyperion, an epistolary opera) and Wolfgang Rihm. Siegfried Matthus composed the orchestral song cycle Hyperion-Fragmente. Carl Orff used Hölderlin's German translations of Sophocles in his operas Antigone and Oedipus der Tyrann. In 2020, for the 250th anniversary of Hölderlin's birth, the American composaer Chris Jarrett wrote "Sechs Hölderlin Lieder" for baritone and piano. They have been recorded on the DaVinci Classics label and are available in print as well. Wilhelm Killmayer based three song cycles, Hölderlin-Lieder, for tenor and orchestra on Hölderlin's late poems; Kaija Saariaho's Tag des Jahrs (2001) for mixed choir and electronics is based on four of these poems,[25] while more are set in her Überzeugung for choir (2001)[26] and Die Aussicht for soprano and four instruments (1996).[27] In 2003, Graham Waterhouse composed a song cycle, Sechs späteste Lieder, for voice and cello based on six of Hölderlin's late poems. Lucien Posman based a concerto-cantate for clarinet, choir, piano & percussion on 3 Hölderlin poems (Teil 1. Die Eichbäume, Teil 2. Mein Eigentum, Teil 3. Da ich ein Knabe war) (2015). He also set An die Parzen to music for choir & piano (2012) and Hälfte des Lebens for choir. Several works by Georg Friedrich Haas take their titles or text from Hölderlin's writing, including Hyperion, Nacht, and the solo ensemble "... Einklang freier Wesen ..." as well as its constituent solo pieces each named "... aus freier Lust ... verbunden ...". In 2020, as part of the German celebration of Hölderlin's 250th birthday, Chris Jarrett composed his "Sechs Hölderlin Lieder" for baritone and piano. Finnish melodic death metal band Insomnium set Hölderlin's verses to music in several of their songs, and many songs of Swedish alternative rock band ALPHA 60 also contain lyrical references to Hölderlin's poetry. Instrumental music Robert Schumann's late piano suite Gesänge der Frühe was inspired by Hölderlin, as was Luigi Nono's string quartet Fragmente-Stille, an Diotima and parts of his opera Prometeo. Josef Matthias Hauer wrote many piano pieces inspired by individual lines of Hölderlin's poems. Paul Hindemith's First Piano Sonata is influenced by Hölderlin's poem Der Main. Hans Werner Henze's Seventh Symphony is partly inspired by Hölderlin. Cinema A 1981–1982 television drama, Untertänigst Scardanelli (The Loyal Scardanelli), directed by Jonatan Briel in Berlin. The 1985 film Half of Life is named after a poem of Hölderlin and deals with the secret relationship between Hölderlin and Susette Gontard. In 1986 and 1988, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub shot two films, Der Tod des Empedokles and Schwarze Sünde, in Sicily, which were both based on the drama Empedokles (respectively for the two films they used the first and third version of the text). German director Harald Bergmann has dedicated several works to Hölderlin; these include the movies Lyrische Suite/Das untergehende Vaterland (1992), Hölderlin Comics (1994), Scardanelli (2000) and Passion Hölderlin (2003).[28] A 2004 film, The Ister, is based on Martin Heidegger's 1942 lecture course (published as Hölderlin's Hymn "The Ister"). |

普及と影響 ラウフェン・アム・ネッカーのフリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン記念館 ヘルダーリンが生前に発表した主な著作は、2巻本(1797年と1799年)で出版された小説『ハイペリオン』である。個々の詩はいくつか発表されているが、注目されることはほとんどなかった。1799年には、定期刊行誌『イドゥナ』を刊行した。 1804年には、ソフォクレスの戯曲を翻訳した作品が発表されたが、その人工的で難解な内容から、ギリシャの慣用句をドイツ語に置き換えたことが原因だと 批判され、一般的に嘲笑された。しかし、20世紀の翻訳理論家であるヴァルター・ベンヤミンなどは、これらの翻訳を正当化し、詩の翻訳における新しい、そ して非常に影響力の強いモデルとして、その重要性を示している。彼の賛美歌の中で最も長く、最も意味が凝縮された2つの作品『ライン』と『パトモス』は、 1808年に詩の暦に掲載された。 1822年から1823年にかけて、ホーデルリンの塔に何度も足を運び、小説『ファエトン』の主人公にホーデルリンを描写したヴィルヘルム・ヴァイブリン ガーは、ホーデルリンの詩集を出版する必要性を訴え、1826年にルートヴィヒ・ウーラントとクリストフ・テオドール・シュヴァブによってホーデルリンの 最初の詩集が発表された。しかし、ウーラントとシュヴァブは、ヘルダーリンの断片的な作品の多くを含む「狂気に触れた」可能性があると疑われるものはすべ て省略した。このコレクションのコピーはヘルダーリンに贈られたが、後にサイン泥棒に盗まれた[22]。伝記的エッセイを収録した第2版の増補版は、ヘル ダーリンの死の前年である1842年に出版された。 1913年になって初めて、ドイツ象徴派の詩人シュテファン・ゲオルゲが主宰する文学サークルの一員であったノルベルト・フォン・ヘリングラートが、最終 的に6巻本となったヘルダーリンの詩、散文、手紙の最初の2巻を出版した(「ベルリン版」、Berliner Ausgabe)。初めて、ヘルダーリンの賛歌の草稿や断片が発表され、それまでの版ではほとんど触れられていなかった1800年から1807年までの彼 の作品の概要を把握することが可能になった。ベルリン版とフォン・ヘリングラートの主張により、ヘルダーリンは生前得られなかった評価を死後に受けること になった。その結果、1913年以降、ヘルダーリンはドイツ語で書かれた詩人の中でも最も偉大な詩人の一人として認められている。  第一次世界大戦中のノルベルト・フォン・ヘリングラート ノルベルト・フォン・ヘリングラートは、第一次世界大戦勃発時にドイツ帝国軍に入隊し、1916年のヴェルダン会戦で戦死した。ベルリン版第4巻は、彼の 死後に出版された。ベルリン版は、1918年のドイツ革命後にフリードリヒ・ゼーバスとルートヴィヒ・フォン・ピゲノによって完成し、残りの巻は1922 年から1923年にかけてベルリンで出版された。 ベルリン版が出版される前の1912年、ライナー・マリア・リルケは最初の2編の『ドゥイノの哀歌』を作曲した。その形式と精神は、ヘルダーリンの賛美歌 と哀歌から強い影響を受けている。リルケは数年前、フォン・ヘリングラートと出会い、いくつかの賛美歌の草稿を目にしていた。デュイノの哀歌は、ヘルダー リンの晩年の作品に対する新たな評価の始まりを告げるものだった。彼の賛美歌は模倣することはほとんど不可能だが、ドイツ語やその他の言語の現代詩に多大 な影響を与え、ドイツ抒情詩の頂点として引用されることもある。  1881年、テュービンゲン植物園内のホーデルリン記念碑 ベルリン版は、1943年に出版が開始され、最終的に1986年に完成したシュトゥットガルト版(Grosse Stuttgarter Ausgabe)に取って代わられることになった。この事業は、ベルリン版よりもはるかに厳格な校訂作業が行われ、未完で日付の記載がない作品(時には同 じ詩でも大きな違いがある複数のバージョンがある)から生じる解釈上の多くの問題が解決された。一方、1975年には、ディートリヒ・ザトラーが編集を担 当する第三の完全版、フランクフルト校訂版(Frankfurter Historisch-kritische Ausgabe)の出版が開始された。 ホーデルリンの賛歌的なスタイルは、神への純粋な信仰に依拠しており、ギリシャ神話の登場人物と自然に関するロマン主義的な神秘主義を深く融合させた、奇 妙で魅力的な作品を生み出しているが、彼のより短く、時に断片的な詩も、ゲオルク・トラクル以降の後世のドイツ人詩人たちに広く影響を与えている。また、 ヘルマン・ヘッセやパウル・ツェランの詩にも影響を与えている。(ツェランは、ホーデルリンについて「チュービンゲン、1月」という詩を書いた。この詩は 「Pallaksch」という言葉で終わっている。シュヴァブによると、これはホーデルリンのお気に入りの新造語で、「時にはイエス、時にはノー」を意味 するという。) ホーデルリンは、詩的理論や哲学的事柄について断片的に執筆した思想家でもあった。彼の理論的作品、例えば「Das Werden im Vergehen」(「消滅における生成」)や「Urteil und Sein」(「判断と存在」)といったエッセイは、やや難解で解釈が難しいものの、洞察力に富み、重要なものである。それらは、チュービンゲン時代のルー ムメイトであったヘーゲルやシェリングが取り組んだ重要な問題の多くにも言及しており、彼の詩は決して「理論先行」のものではなかったが、彼の難解な詩の 解釈や注釈は、マルティン・ハイデッガー、テオドール・アドルノ、ジャック・デリダ、ミシェル・フーコー、アラン・バディウといった思想家たちによる深い 哲学的思索を生み出した。 音楽 ホーデルリンの詩は多くの作曲家にインスピレーションを与え、声楽や器楽の曲が生み出された。 声楽 ホーデルリンの詩を最も早く作曲した作曲家の一人が、ヨハネス・ブラームスである。彼の『運命の歌』は、ハイペリオンスの『運命の歌』に基づくものである [24]。ホーデルリンの詩を曲にした作曲家には、ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェン(『希望に捧ぐ』作品32)、ペーター・コルネリウス、ハンス・ プフィッツナー、リヒャルト・シュトラウス(『3つの賛歌』)、マックス・レーガー(『希望に捧ぐ』)、アルフォンス・ディペンブロック(『夜』)、 ウォルター・ブラウンフェルス(『祖国への死』)、リヒャルト・ヴェッツ(『ハイペリオン』)、ヨーゼフ・マティアス・ハウアー、デニス・ロジャー、ヘル マン・ロイター、マルガレーテ・シュヴァイカート、シュテファン・ヴォルペ、パウル・ヒンデミット、ベンジャミン・ブリテン(『6つのホルデルリンの断 章』)、ハンス・ヴェルナー・ヘンツェ、ブルーノ・マデルナ(『ハイペリオン』、『ディオティマへの碑』)、ルイジ・ノーノ(『プロメテオ』)、ハイン ツ・ホリガー(『スカルダネッリ・ツィクルス』)、ハンス・ツェンダー(『ホルデルリンを読む I-IV』)、ジェルジ・クルターク(ホルデルリンのオペラを企画)、ジェルジ・リゲティ(『フリードリヒ・ホルデルリンによる3つの幻想 Scardanelli-Zyklus)、ハンス・ツェンダー(Hölderlin lesen I-IV)、ジェルジ・クルターグ(クルターグは、ヘルダーリンのオペラを構想していた)、ジェルジ・リゲティ(Friedrich Hölderlinによる3つの幻想曲)、ハンス・アイスラー(Hollywood Liederbuch)、ヴィクトル・ウルマン、ヴォルフガング・フォン・シュヴァインツ、ヴァルター・ツィンマーマン(書簡オペラ『ハイペリオン』)、 ヴォルフガング・リーム。ジークフリート・マチューシュは、オーケストラのための歌曲集『ハイペリオン断章』を作曲した。カール・オルフは、オペラ『アン ティゴネ』と『オイディプス王』で、ヘルダーリンによるソフォクレスのドイツ語訳を使用している。2020年、ヘルダーリン生誕250周年を記念して、ア メリカの作曲家クリス・ジャレットがバリトンとピアノのための歌曲集『6つのヘルダーリン歌曲』を作曲した。これらはダヴィンチ・クラシックスレーベルで 録音され、CDでも発売されている。 ヴィルヘルム・キルマイヤーは、ホルデルリンの晩年の詩を題材に、テノールとオーケストラのための歌曲集『ホルデルリン歌曲』3曲を制作した。カイヤ・ サーリアホの混声合唱とエレクトロニクスのための『Tag des Jahrs』(2001)は、これらの詩のうちの4つを基に作曲された[25]。Überzeugung for choir (2001)[26] and Die Aussicht for soprano and four instruments (1996).[27] 2003年、グラハム・ウォーターハウスは、ホルデルリンの晩年の詩6編に基づく声楽とチェロのための歌曲集『Sechs späteste Lieder』を作曲した。ルシアン・ポスマンは、ホルダーリンの詩3編(第1部『菩提樹』、第2部『私の所有物』、第3部『少年時代』)を基に、クラリ ネット、合唱、ピアノ、打楽器のためのコンチェルト・カンタータを作曲した(2015年)。また、合唱とピアノのための『パルツェンに捧ぐ』(2012 年)や合唱のための『人生の半分』を作曲している。ゲオルク・フリードリヒ・ハースのいくつかの作品は、タイトルやテキストをヘルダーリンの作品から引用 している。その中には『ハイペリオン』、『夜』のほか、独唱とアンサンブルのための『... Einklang freier Wesen ...』とその構成曲である独唱曲『... aus freier Lust ... verbunden ...』などがある。2020年、ヘルダーリン生誕250年を記念するドイツでの催しの一環として、クリス・ジャレットがバリトンとピアノのための『6つ のヘルダーリンの歌』を作曲した。 フィンランドのメロディックデスメタルバンド、インソムニウムは、いくつかの曲でヘルダーリンの詩に曲をつけた。また、スウェーデンのオルタナティブロックバンド、アルファ60の多くの曲にも、ヘルダーリンの詩に言及した歌詞がある。 器楽 ロベルト・シューマンの晩年のピアノ組曲『早朝の歌』は、ルイジ・ノーノの弦楽四重奏曲『断片―静寂』やディオティマ、そして彼のオペラ『プロメテオ』の 一部に触発されて作曲された。ヨーゼフ・マティアス・ハウアーは、ヘルダーリンの詩の一節に触発されて多くのピアノ曲を書き上げた。パウル・ヒンデミット のピアノソナタ第1番は、ヘルダーリンの詩『マイン川』の影響を受けている。ハンス・ヴェルナー・ヘンツェの交響曲第7番は、部分的にヘルダーリンの影響 を受けている。 映画 1981年から1982年にかけてベルリンでジョナサン・ブリエル監督により制作されたテレビドラマ『Untertänigst Scardanelli(The Loyal Scardanelli)』。 1985年の映画『Half of Life』はヘルダーリンの詩にちなんで名づけられ、ヘルダーリンとスゼッテ・ゴンタールの秘密の関係を描いている。 1986年と1988年に、ダニエル・ユイレとジャン=マリー・ストローブはシチリアで2本の映画『エンペドクレスの死』と『黒い罪』を撮影したが、どちらも戯曲『エンペドクレス』が原作である(2本の映画では、それぞれ戯曲の第一版と第三版が使用された)。 ドイツの映画監督ハラルド・ベルクマンは、ヘルダーリンに捧げた作品をいくつか発表している。映画『リリッシェ・スイート/沈みゆく祖国』(1992 年)、『ヘルダーリン・コミック』(1994年)、『スカルダネッリ』(2000年)、『パッション (2003年)[28]。 2004年の映画『イスター』は、1942年にマルティン・ハイデガーが行った講義コース(『イスター』として出版された)を基に制作された。 |

English translations Hyperion Some Poems of Friedrich Holderlin. Trans. Frederic Prokosch. (Norfolk, CT: New Directions, 1943). Alcaic Poems. Trans. Elizabeth Henderson. (London: Wolf, 1962; New York: Unger, 1963). ISBN 978-0-85496-303-4 Friedrich Hölderlin: Poems & Fragments. Trans. Michael Hamburger. (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966; 4ed. London: Anvil Press, 2004). ISBN 978-0-85646-245-0 Friedrich Hölderlin, Eduard Mörike: Selected Poems. Trans. Christopher Middleton (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1972). ISBN 978-0-226-34934-3 Poems of Friedrich Holderlin: The Fire of the Gods Drives Us to Set Forth by Day and by Night. Trans. James Mitchell. (San Francisco: Hoddypodge, 1978; 2ed San Francisco: Ithuriel's Spear, 2004). ISBN 978-0-9749502-9-7 Hymns and Fragments. Trans. Richard Sieburth. (Princeton: Princeton University, 1984). ISBN 978-0-691-01412-8 Friedrich Hölderlin: Essays and Letters on Theory. Trans. Thomas Pfau. (Albany, NY: State University of New York, 1988). ISBN 978-0-88706-558-3 Hyperion and Selected Poems. The German Library vol.22. Ed. Eric L. Santner. Trans. C. Middleton, R. Sieburth, M. Hamburger. (New York: Continuum, 1990). ISBN 978-0-8264-0334-6 Friedrich Hölderlin: Selected Poems. Trans. David Constantine. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe, 1990; 2ed 1996; 3ed 2018) ISBN 9781780374017 Friedrich Hölderlin: Selected Poems and Fragments. Ed. Jeremy Adler. Trans. Michael Hamburger. (London: Penguin, 1996). ISBN 978-0-14-042416-4 What I Own: Versions of Hölderlin and Mandelshtam. Trans. John Riley and Tim Longville. (Manchester: Carcanet, 1998). ISBN 978-1-85754-175-5 Holderlin's Sophocles: Oedipus and Antigone. Trans. David Constantine. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe, 2001). ISBN 978-1-85224-543-6 Odes and Elegies. Trans. Nick Hoff. (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan Press, 2008). ISBN 978-0-8195-6890-8 Hyperion. Trans. Ross Benjamin. (Brooklyn, NY: Archipelago Books, 2008) ISBN 978-0-9793330-2-6 Selected Poems of Friedrich Hölderlin. Trans. Maxine Chernoff and Paul Hoover. (Richmond, CA: Omnidawn, 2008). ISBN 978-1-890650-35-3 Essays and Letters. Trans. Jeremy Adler and Charlie Louth. (London: Penguin, 2009). ISBN 978-0-14-044708-8 The Death of Empedocles: A Mourning-Play. Trans. David Farrell Krell. (Albany, NY: State University of New York, 2009). ISBN 978-0-7914-7648-2 Selected Poems. Trans. Emery George (Kylix Press, 2011) Poems at the Window / Poèmes à la Fenêtre, Hölderlin's late contemplative poems, English and French rhymed and metered translations by Claude Neuman, trilingual German-English-French edition, Editions www.ressouvenances.fr, 2017 Aeolic Odes / Odes éoliennes, English and French metered translations by Claude Neuman, trilingual German-English-French edition, Editions www.ressouvenances.fr, 2019 ; bilingual German-English edition : Edwin Mellen Press, 2022 The Elegies / Les Elegies, English and French metered translations by Claude Neuman, trilingual German-English-French edition, Editions www.ressouvenances.fr, 2020 ; bilingual German-English edition : Edwin Mellen Press, 2022 Bibliography Internationale Hölderlin-Bibliographie (IHB). Hrsg. vom Hölderlin-Archiv der Württembergischen Landesbibliothek Stuttgart. 1804–1983. Bearb. Von Maria Kohler. Stuttgart 1985. Internationale Hölderlin-Bibliographie (IHB). Hrsg. vom Hölderlin-Archiv der Württembergischen Landesbibliothek Stuttgart. Bearb. Von Werner Paul Sohnle und Marianne Schütz, online 1984 ff (after 1 January 2001: IHB online). Homepage of Hölderlin-Archiv https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_H%C3%B6lderlin |

英語訳 ハイペリオン フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリンの詩集。フレデリック・プロコシュ訳。 (コネチカット州ノーフォーク: ニュー・ディレクションズ、1943年)。 アルカイック詩集。エリザベス・ヘンダーソン訳。 (ロンドン: ウルフ、1962年; ニューヨーク: ウンガー、1963年)。 ISBN 978-0-85496-303-4 フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン:詩と断片。マイケル・ハンバーガー訳。(ロンドン:Routledge & Kegan Paul、1966年、第4版。ロンドン:Anvil Press、2004年)。ISBN 978-0-85646-245-0 フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン、エドゥアルト・メーリケ:詩選。クリストファー・ミドルトン訳(シカゴ:シカゴ大学、1972年)。ISBN 978-0-226-34934-3 フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリンの詩:神々の炎が昼も夜も私たちを駆り立てる。ジェームズ・ミッチェル訳。 (サンフランシスコ: Hoddypodge, 1978; 2nd edition San Francisco: Ithuriel's Spear, 2004). ISBN 978-0-9749502-9-7 Hymns and Fragments. Richard Sieburth 訳。 (Princeton: Princeton University, 1984). ISBN 978-0-691-01412-8 Friedrich Hölderlin: Essays and Letters on Theory. Thomas Pfau 訳。 (Albany, NY: State University of New York, 1988). ISBN 978-0-88706-558-3 ハイペリオンと詩選。The German Library vol.22。Eric L. Santner編。C. Middleton、R. Sieburth、M. Hamburger訳。 (ニューヨーク:コンティニュアム、1990年)。ISBN 978-0-8264-0334-6 フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン:詩選。デビッド・コンスタンティン著。 (ニューカッスル・アポン・タイン: Bloodaxe, 1990; 2nd ed 1996; 3rd ed 2018) ISBN 9781780374017 フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン: 詩と断片選。 ジェレミー・アドラー編。マイケル・ハンバーガー訳。 (ロンドン: ペンギン, 1996). ISBN 978-0-14-042416-4 What I Own: Versions of Hölderlin and Mandelshtam. Trans. John Riley and Tim Longville. (Manchester: Carcanet, 1998). ISBN 978-1-85754-175-5 Holderlin's Sophocles: Oedipus and Antigone. Trans. David Constantine. (ニューカッスル・アポン・タイン:ブラッドアクス、2001年)。ISBN 978-1-85224-543-6 Odes and Elegies. Trans. Nick Hoff. (コネチカット州ミドルタウン:ウェスリアン・プレス、2008年)。ISBN 978-0-8195-6890-8 Hyperion. Trans. Ross Benjamin. (ニューヨーク州ブルックリン:Archipelago Books、2008年) ISBN 978-0-9793330-2-6 フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン詩選。マックス・チェルノフ、ポール・フーヴァー訳。 (カリフォルニア州リッチモンド:Omnidawn、2008年) ISBN 978-1-890650-35-3 エッセイと書簡。ジェレミー・アドラー、チャーリー・ラウス訳。(ロンドン:ペンギン、2009年)。ISBN 978-0-14-044708-8 エンペドクレスの死:哀悼劇。デイヴィッド・ファレル・クレル訳。 (ニューヨーク州オールバニー:ニューヨーク州立大学、2009年)。ISBN 978-0-7914-7648-2 詩選。エメリー・ジョージ(Kylix Press、2011年) 窓辺の詩 / Poèmes à la Fenêtre、ホルダーリンの晩年の思索的な詩、クロード・ノイマンによる英語とフランス語の韻律と音節を踏まえた翻訳、ドイツ語・英語・フランス語の 3か国語版、Editions www.ressouvenances.fr、 2017 Aeolic Odes / Odes windiennes, 英語とフランス語の韻律翻訳:Claude Neuman、ドイツ語・英語・フランス語の3か国語版、Editions www.ressouvenances.fr、2019年;ドイツ語・英語の2か国語版:Edwin Mellen Press、2022年 The 哀歌 / Les Elegies, 英語とフランス語の計り訳版、Claude Neuman 著、ドイツ語・英語・フランス語の3か国語版、Editions www.ressouvenances.fr、2020年;ドイツ語・英語の2か国語版:Edwin Mellen Press、2022年 参考文献 IHB(Internationale Hölderlin-Bibliographie)国際ヘルダーリン書誌。シュトゥットガルト州立図書館のヘルダーリン・アーカイブ編。1804年~1983年。マリア・コーラー編。シュトゥットガルト、1985年。 国際ヘルダーリン・ビブリオグラフィー(IHB)。シュトゥットガルト州立図書館のヘルダーリン・アーカイブ編。ヴェルナー・ポール・ゾーンレとマリアンヌ・シュッツによる編集、1984年以降オンライン(2001年1月1日以降:IHBオンライン)。 ホーデルリン・アーカイブのホームページ |

| The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism "The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism" (German: Das älteste Systemprogramm des deutschen Idealismus) is a fragmentary 1796/97 essay of unknown authorship. The document was first published (in German) by Franz Rosenzweig in 1917.[1][2] An English translation was made by Diana I. Behler.[3][4] The German title is: Das Älteste Systemprogramm Des Deutschen Idealismus. This title was made up by Franz Rosenzweig in 1917, when he first published the manuscript. He found the manuscript in the Royal Library in Berlin in 1913. The manuscript suggested date is around 1796 and was done by handwriting research. However, the manuscript is not dated. The Prussian State Library auctioned in March 1913 from the auction of the house Liepmannssohn in Berlin a single sheet on the front and back with Hegel's cursive handwriting. The manuscript was lost during WWII. But Dieter Henrich found it again in 1979 in the “Biblioteka Jagiellonska” in Krakow (Poland), where it is today. Address: Jagiellonian Library, Jagiellonian University, al. Mickiewicza 22, 30-059 Cracow, Poland. Later research suggests that manuscript had come from the estate of Hegel's student Friedrich Christoph Förster (1791-1868). He was one of the editors of Hegel's posthumous works and most likely had access to a number of Hegel's manuscripts. This text actually being one of them. Hegel traveled around Bohemia with Marie and Friedrich Christoph Förster around the year 1820–21.[5] Authorship Although the document is in G. W. F. Hegel's handwriting, it is thought it has been written by either Hegel, F. W. J. Schelling, Friedrich Hölderlin, or an unknown fourth person.[6] Yves Bonnefoy writes that it was "certainly inspired by Hölderlin."[7] According to Glenn Magee, most Hegel scholars assume that Hegel is the author of the document.[8] In the book Martin Heidegger's Path of Thinking by Otto Pöggeler, page 265. Reports. “Heidegger owned the Rosenzweig’s edition of the “oldest systematic program” of 1917, but said he could “never reconcile himself with the notion”: “Text by Schelling, notes by Hegel”. At the time the manuscript was drafted, Hegel and Hölderlin were about 26 and Schelling was 21. Three years earlier, the three had been classmates and roommates together at Tübinger Stift, the seminary of the University of Tübingen, and were then collectively known as the "Tübingen Three". Hegel and Hölderlin were at the seminary from age 18 to 23, and Schelling from age 13 to 18. Scholars on the topic of authorship:[citation needed] Franz Rosenzweig (1917) – Schelling Wilhelm Böhm (1926) – Hölderlin[9] Johannes Hoffmeister (1931) - Schelling. Hans-Gero Boehm (1932) - Schelling. Johannes Hoffmeister (1932) - Schelling. Kurt Schilling (1934) - Schelling und Hölderlin. Emil Staiger (1935) - Schelling. Johannes Hoffmeister (1936) - Schelling. Theodor Ludwig Haering (1938) - Schelling/Hölderlin/Hegel? Johannes Jeremias (1938) - Hegel? Gertrud Jäger (1939) - Schelling. Kurt Hildebrandt (1939) - Schelling und Hölderlin. Johannes Hoffmeister (1939) - Schelling. Hermann Glockner (1940) - Schelling und Hölderlin. Wilhelm Michel (1940) - Schelling. Johannes Hoffmeister (1942) - Schelling. Boris Jakowenko (1943) - Hegel! Ernst Müller (1944) - Schelling. Georg Lukäcs (1948) - Schelling. Richard Geis (1950) - Schelling. Hermann Zeltner (1954) - Schelling. Karl Jaspers (1955) - Schelling. Walter Schulz (1955) - Schelling. Alexander Hollerbach (1957) - Schelling. Manfred Schröter (1960) - Schelling. Friedrich Beißner (1961) - Schelling. Heinz Otto Burger (1962) - Schelling. Horst Fuhrmans (1962) - Schelling. Jürgen Habermas (1963) - Schelling. Otto Pöggeler (1965) - Hegel. List from: Frank-Peter Hansen (see Bibliography). Martin Heidegger (1965) - not Schelling. But did not side with any other author. Martin Oesch (1995) - Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel Daniel Fidel Ferrer (2021) – Hegel (see Ferrer, page 25). Content Raffaele Milani writes that in the essay, "...the idea of Beauty unifies all others in a fusion of the self and nature."[10] Dieter Henrich called the document a "program for agitation." It called for a new mythology to mediate between the present state and the future envisioned poeticized state, in which poetry will function for the arts and sciences, including philosophy.[6] Jason Josephson-Storm has interpreted the essay as a source on Hegel's view of myth, especially Hegel's perception (in line with other eighteenth- and nineteenth-century German philosophers) that myth has disappeared and left a cultural vacuum, which Josephson-Storm argues anticipates the idea of disenchantment.[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Oldest_Systematic_Program_of_German_Idealism |

ドイツ観念論の最も古い体系的なプログラム 「ドイツ観念論の最も古い体系的なプログラム」(ドイツ語:Das älteste Systemprogramm des deutschen Idealismus)は、1796年または1797年に書かれた、作者不明の断片的な論文である。この文書は、1917年にフランツ・ローゼンツヴァイ クによって初めて(ドイツ語で)出版された[1][2]。英語訳はダイアナ・I・ベーラーによって行われた[3][4]。 ドイツ語のタイトルは「Das Älteste Systemprogramm Des Deutschen Idealismus」である。このタイトルは、フランツ・ローゼンツヴァイクが1917年に初めて原稿を出版した際に付けたものである。彼は1913年 にベルリン王立図書館でこの原稿を発見した。この原稿は1796年頃に書かれたと推測され、手書きの研究によって行われた。しかし、この原稿には日付がな い。1913年3月、プロイセン州立図書館は、ベルリンのリープマンソン家のオークションで、ヘーゲルの草書体で書かれた表裏1枚の紙を競売にかけた。こ の原稿は第二次世界大戦中に紛失したが、ディーター・ヘンリッヒが1979年にポーランドのクラクフにある「ジャギェウォ大学図書館」で再び発見した。現 在の保管場所は次のとおり。住所:Jagiellonian Library, Jagiellonian University, al. Mickiewicza 22, 30-059 Cracow, Poland. 後の研究により、この原稿はヘーゲルの弟子フリードリヒ・クリストフ・フェルスター(1791-1868)の遺産から出たものであることが判明した。 彼はヘーゲルの死後出版された著作の編集者の一人であり、おそらくヘーゲルの多くの原稿にアクセスしていた可能性が高い。このテキストも、そのうちの1つ である。ヘーゲルは1820年から1821年にかけて、マリーとフリードリヒ・クリストフ・フェルスターとともにボヘミアを旅行した[5]。 著者 この文書はG. W. F. ヘーゲルの筆跡であるが、ヘーゲル、F. W. J. シェリング、フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン、 または正体不明の4人目であると考えられている[6]。イヴ・ボヌフォイは、この文書は「確かにヘルダーリンからインスピレーションを得ている」と書いて いる[7]。グレン・マギーによると、ほとんどのヘーゲル研究者は、ヘーゲルがこの文書の著者であると仮定している[8]。オットー・ペッゲラー著 『Martin Heidegger's Path of Thinking』265ページ。「ハイデッガーは1917年に出版された『最も古い体系的なプログラム』のローゼンツヴァイク版を所有していたが、ハイ デッガーは「シェリングのテキスト、ヘーゲルの注釈」という概念に「決して折り合いをつけることはできない」と述べていた。 この草稿が書かれた当時、ヘーゲルとヘルダーリンは26歳、シェリングは21歳であった。3年前、この3人はテュービンゲン大学神学校であるテュービンゲ ン・シュティフトでクラスメートでありルームメイトでもあった。そして、彼らは「テュービンゲン3人組」として知られていた。ヘーゲルとヘルダーリンは 18歳から23歳まで、シェリングは13歳から18歳まで神学校に通っていた。 著作権のテーマに関する学者:[出典が必要] フランツ・ローゼンツヴァイク (1917) - シェリング ヴィルヘルム・ベーム (1926) - ヘルダーリン[9] ヨハネス・ホフマイスター (1931) - シェリング ハンス・ゲロ・ベーム (1932) - シェリング ヨハネス・ホフマイスター (1932) - シェリング クルト・シリング(1934年) - シェリングとヘルダーリン。 エミル・スタイガー(1935年) - シェリング。 ヨハネス・ホフマイスター(1936年) - シェリング。 テオドール・ルートヴィヒ・ヘーリング(1938年) - シェリング/ヘルダーリン/ヘーゲル? ヨハネス・イェレミアス(1938年) - ヘーゲル? ゲルトルート・イェーガー(1939年) - シェリング。 クルト・ヒルデブラント(1939年) - シェリングとヘルダーリン。 ヨハネス・ホフマイスター(1939年) - シェリング。 ヘルマン・グロクナー(1940年) - シェリングとヘルダーリン。 ヴィルヘルム・ミシェル(1940年) - シェリング。 ヨハネス・ホフマイスター(1942年) - シェリング。 ボリス・ヤコヴェンコ(1943年) - ヘーゲル! エルンスト・ミュラー(1944年) - シェリング。 ゲオルク・ルカーチ(1948年) - シェリング。 リヒャルト・ガイス(1950年) - シェリング。 ヘルマン・ツェルトナー(1954年) - シェリング。 カール・ヤスパース(1955年) - シェリング。 ヴァルター・シュルツ(1955年) - シェリング。 アレクサンダー・ホラーバッハ(1957年) - シェリング。 マンフレート・シュレーター(1960年) - シェリング。 フリードリヒ・バイスナー(1961年) - シェリング。 ハインツ・オットー・バーガー(1962年) - シェリング。 ホルスト・フュルマンス(1962年) - シェリング。 ユルゲン・ハーバーマス(1963年) - シェリング。 オットー・ペッゲラー(1965年) - ヘーゲル。 リストの出典:フランク=ペーター・ハンセン(参考文献参照)。 マーティン・ハイデガー(1965年) - シェリングではない。しかし、他の著者の側にも付かなかった。 マーティン・オッシュ(1995年) - ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・シュレーゲル ダニエル・フィデル・フェレール(2021年) - ヘーゲル(フェレール、25ページを参照)。 内容 ラファエレ・ミラニは、この論文について「美の概念は、自己と自然の融合において、他のすべての概念を統一する」[10]と書いている。ディーター・ヘン リッヒは、この文書を「扇動のためのプログラム」と呼んだ。それは、詩が哲学を含む芸術と科学に機能する、詩的に表現された未来の状態と現在の状態を仲介 する新しい神話を求めた。ジェイソン・ジョセフソン・ストームは、この論文をヘーゲルの神話観の資料として解釈している。特に、神話が消滅し、文化的空白 が生じたというヘーゲルの認識(18世紀および19世紀のドイツの哲学者たちの見解に沿ったもの)について、ジェイソン・ジョセフソン=ストームは、この 見解が「幻滅」の概念を先取りしていると主張している[11]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆