人類(マン)の起源と性に関連する選択(=性淘汰)

The Descent of Man, and Selection in

Relation to Sex

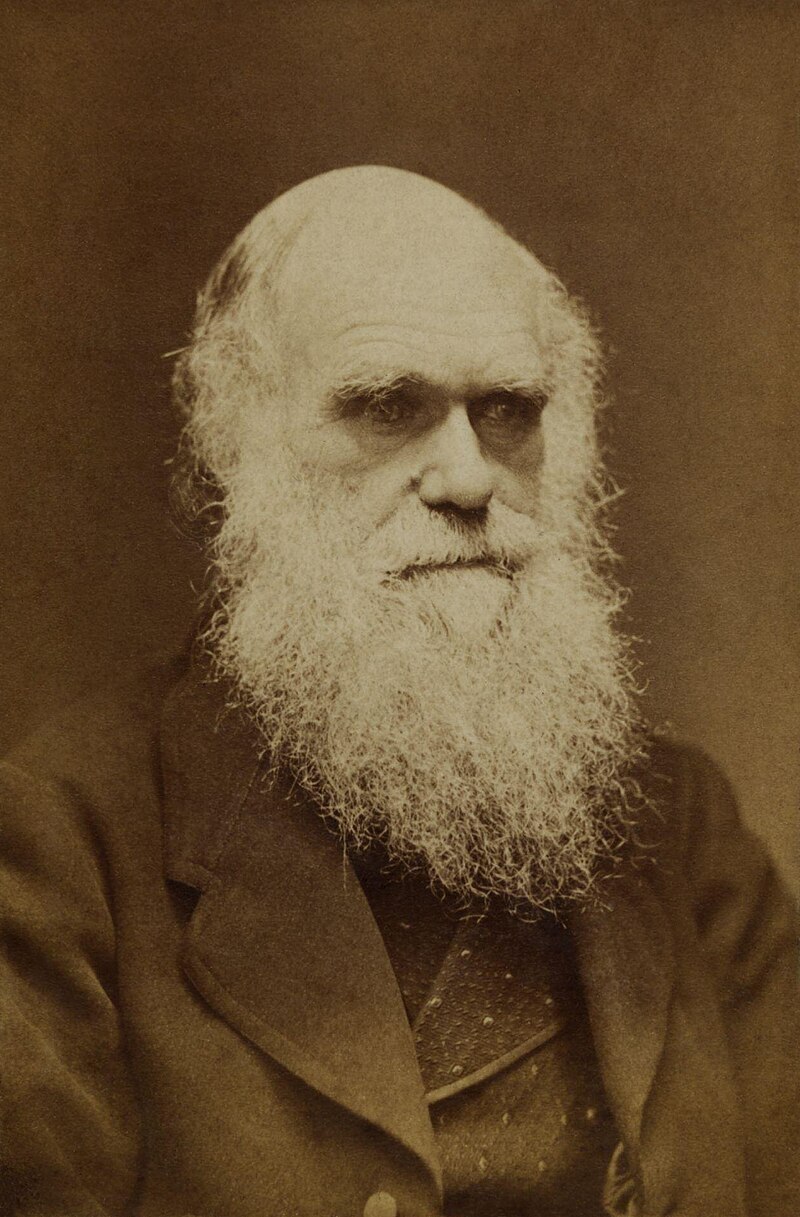

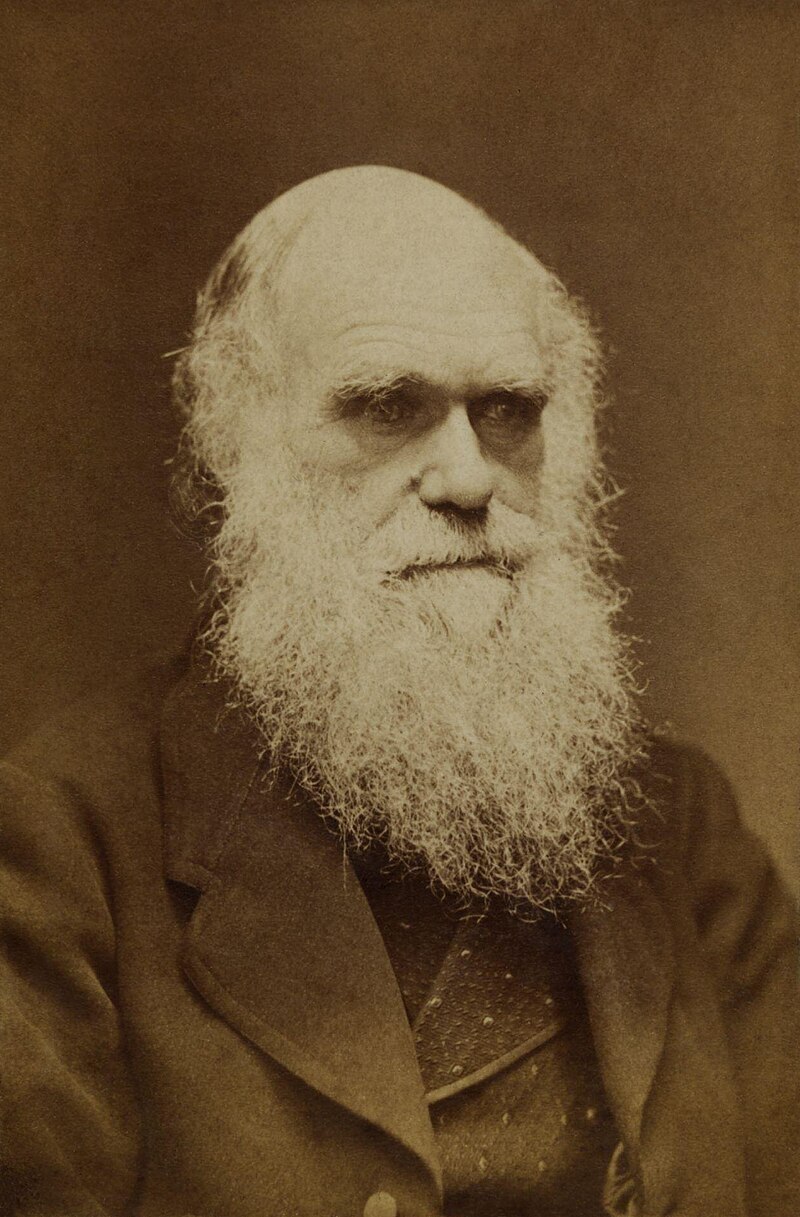

☆ 『人類の起源と性に関連する選択(=性淘汰)』=The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sexは1871 年に出版されたイギリスの博物学者チャールズ・ダーウィンによる著書で、進化論を人間の進化に応用し、自然淘汰とは異なるが相互に関連する生物学的適応の 一形態である性淘汰の理論を詳述したものである。本書では、進化心理学、進化倫理学、進化音楽学、人種間の違い、男女間の違い、配偶者選択における女性の 支配的役割、進化論と社会との関連性など、多くの関連問題を論じている。

| The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex

is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in

1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details

his theory of sexual selection, a form of biological adaptation

distinct from, yet interconnected with, natural selection. The book

discusses many related issues, including evolutionary psychology,

evolutionary ethics, evolutionary musicology, differences between human

races, differences between sexes, the dominant role of women in mate

choice, and the relevance of the evolutionary theory to society. |

『人類の起源と性に関連する選択(=性淘汰)』=The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sexは1871

年に出版されたイギリスの博物学者チャールズ・ダーウィンによる著書で、進化論を人間の進化に応用し、自然淘汰とは異なるが相互に関連する生物学的適応の

一形態である性淘汰の理論を詳述したものである。本書では、進化心理学、進化倫理学、進化音楽学、人種間の違い、男女間の違い、配偶者選択における女性の

支配的役割、進化論と社会との関連性など、多くの関連問題を論じている。 |

| Publication As Darwin wrote, he sent chapters to his daughter Henrietta for editing to ensure that damaging inferences could not be drawn, and also took advice from his wife Emma. The zoological illustrator T. W. Wood, (who had also illustrated Wallace's The Malay Archipelago (1869)), drew many of the figures in this book. The corrected proofs were sent off on 15 January 1871 to the publisher John Murray and published on 24 February 1871 as two 450-page volumes, which Darwin insisted was one complete, coherent work, and were priced at £14 shillings.[1] Within three weeks of publication a reprint had been ordered, and 4,500 copies were in print by the end of March 1871, netting Darwin almost £1,500.[2] Darwin's name created demand for the book, but the ideas were old news. "Everybody is talking about it without being shocked," which he found "proof of the increasing liberality of England".[note 1] Editions and reprints Darwin and some of his children edited many of the large number of revised editions, some extensively. In late 1873, Darwin tackled a new edition of the Descent of Man. Initially, he offered Wallace the work of assisting him, but, when Emma found out, she had the task given to their son George, so Darwin had to write apologetically to Wallace. Huxley assisted with an update on ape-brain inheritance, which Huxley thought "pounds the enemy into a jelly... though none but anatomists" would know it. The manuscript was completed in April 1874 and published on 13 November that year. This has been the edition most commonly reprinted after Darwin's death and to the present day. |

出版 ダーウィンは執筆中、有害な推論が導き出されないように、娘のヘンリエッタに各章を送り編集を依頼し、妻のエマからも助言を受けた。動物学イラストレー ターのT.W.ウッド(ウォレスの『マレー諸島』(1869年)のイラストも担当)が、本書の多くの図を描いた。校正刷りは1871年1月15日に出版社 ジョン・マレーに送られ、1871年2月24日に450ページの2冊として出版された。 出版から3週間以内に再版の注文が入り、1871年3月末までに4,500部が印刷され、ダーウィンは1,500ポンド近い利益を得た[2]。ダーウィン の名前はこの本の需要を生み出したが、アイデアは古いニュースだった。ダーウィンは、「誰もがショックを受けることなくこの本について話している」こと を、「イギリスがますます寛大になっている証拠」だと感じた[注釈 1]。 編集と再版 ダーウィンとダーウィンの子供たちの何人かは、多数の改訂版の多くを編集した。1873年末、ダーウィンは『人間の下降』の新版に取り組んだ。当初、ダー ウィンはウォーレスに助手の仕事を依頼したが、それを知ったエマが息子のジョージにその仕事を任せたため、ダーウィンはウォーレスに謝罪の手紙を書かなけ ればならなかった。ハクスリーは猿の脳の遺伝に関する最新情報を提供し、「敵をゼリー状に打ちのめす...解剖学者以外にはわからないだろうが」と考え た。原稿は1874年4月に完成し、同年11月13日に出版された。これはダーウィンの死後、今日に至るまで最も多く再版されている版である。 |

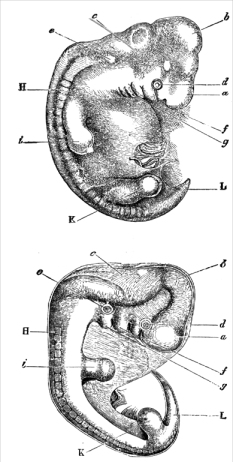

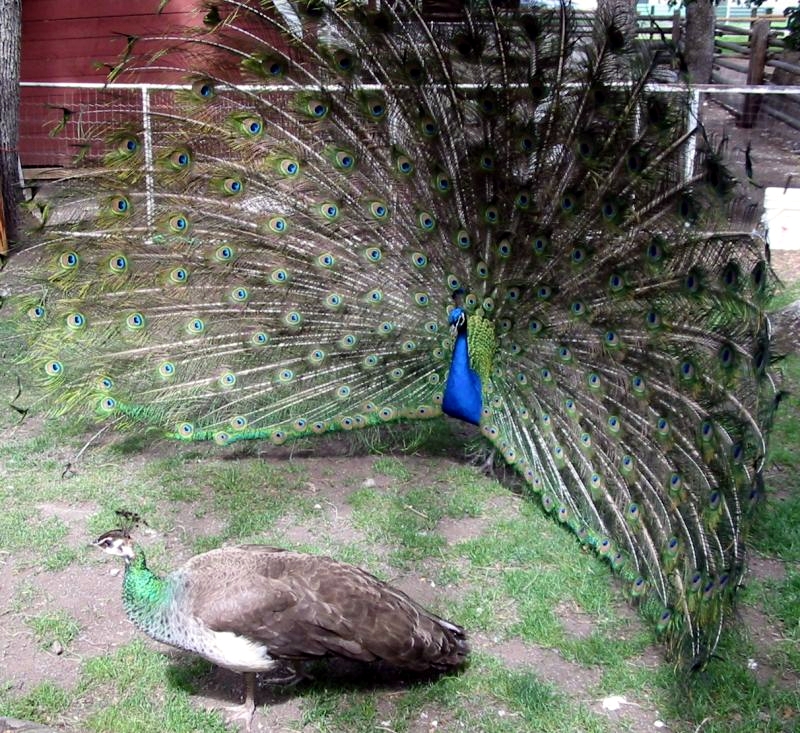

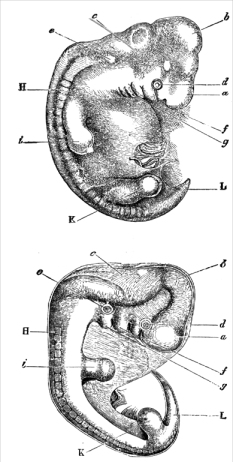

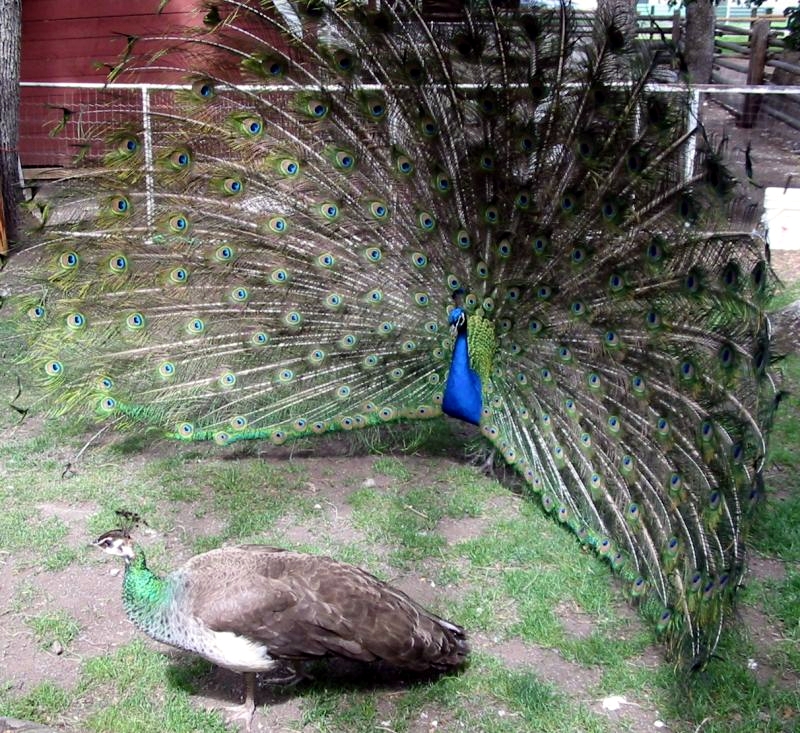

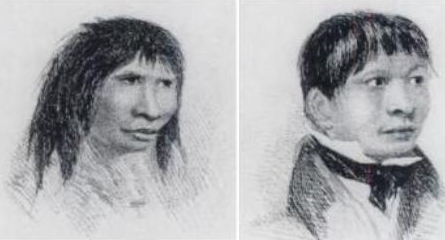

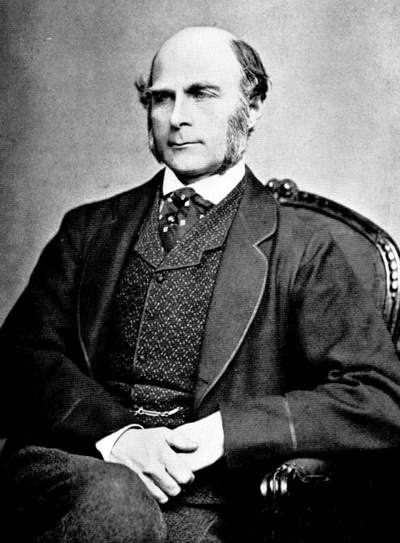

| Content "It has often and confidently been asserted, that man's origin can never be known: but ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge: it is those who know little, and not those who know much, who so positively assert that this or that problem will never be solved by science." – Charles Darwin[3] Part I: The evolution of man Evolution of physical traits  Embryology (here comparing a human and dog) provided one mode of evidence[4] In the introduction to Descent, Darwin lays out the purpose of his text: "The sole object of this work is to consider, firstly, whether man, like every other species, is descended from some pre-existing form; secondly, the manner of his development; and thirdly, the value of the differences between the so-called races of man." Darwin's approach to arguing for the evolution of human beings is to outline how similar human beings are to other animals. He begins by using anatomical similarities, focusing on body structure, embryology, and "rudimentary organs" that presumably were useful in one of man's "pre-existing" forms. He then moves on to argue for the similarity of mental characteristics. Evolution of mental traits Based on the work of his cousin, Francis Galton, Darwin asserts that human character traits and mental characteristics are inherited in the same way as physical characteristics, and argues against the mind/body distinction for the purposes of evolutionary theory. From this Darwin then provides evidence for similar mental powers and characteristics in certain animals, focusing especially on apes, monkeys, and dogs for his analogies for love, cleverness, religion, kindness, and altruism. He concludes on this point that "Nevertheless the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind."[5] He additionally turns to the behaviour of "savages" to show how many aspects of Victorian England's society can be seen in more primitive forms. In particular, Darwin argues that even moral and social instincts are evolved, comparing religion in man to fetishism in "savages" and his dog's inability to tell whether a wind-blown parasol was alive or not. Darwin also argues that all civilisations had risen out of barbarism, and that he did not think that barbarism is a "fall from grace" as many commentators of his time had asserted.  Darwin's primary rhetorical strategy was to argue by analogy. Baboons, dogs, and "savages" provided his chief evidence for human evolution. Natural selection and civilised society In this section of the book, Darwin also turns to the questions of what after his death would be known as social Darwinism and eugenics. Darwin notes that, as had been discussed by Alfred Russel Wallace and Galton, natural selection seemed to no longer act upon civilised communities in the way it did upon other animals: With savages, the weak in body or mind are soon eliminated; and those that survive commonly exhibit a vigorous state of health. We civilised men, on the other hand, do our utmost to check the process of elimination; we build asylums for the imbecile, the maimed, and the sick; we institute poor-laws; and our medical men exert their utmost skill to save the life of every one to the last moment. There is reason to believe that vaccination has preserved thousands, who from a weak constitution would formerly have succumbed to small-pox. Thus the weak members of civilised societies propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race of man. It is surprising how soon a want of care, or care wrongly directed, leads to the degeneration of a domestic race; but excepting in the case of man himself, hardly any one is so ignorant as to allow his worst animals to breed. The aid we feel impelled to give to the helpless is mainly an incidental result of the instinct of sympathy, which was originally acquired as part of the social instincts, but subsequently rendered, in the manner previously indicated, more tender and more widely diffused. Nor could we check our sympathy, even at the urging of hard reason, without deterioration in the noblest part of our nature. The surgeon may harden himself whilst performing an operation, for he knows that he is acting for the good of his patient; but if we were intentionally to neglect the weak and helpless, it could only be for a contingent benefit, with an overwhelming present evil. We must therefore bear the undoubtedly bad effects of the weak surviving and propagating their kind; but there appears to be at least one check in steady action, namely that the weaker and inferior members of society do not marry so freely as the sound; and this check might be indefinitely increased by the weak in body or mind refraining from marriage, though this is more to be hoped for than expected. (Chapter 5)[6] Darwin felt that these urges towards helping the "weak members" was part of our evolved instinct of sympathy, and concluded that "nor could we check our sympathy, even at the urging of hard reason, without deterioration in the noblest part of our nature". As such, '"we must therefore bear the undoubtedly bad effects of the weak surviving and propagating their kind". Darwin did feel that the "savage races" of man would be subverted by the "civilised races" at some point in the near future, as stated in the human races section below.[7] He did show a certain disdain for "savages", professing that he felt more akin to certain altruistic tendencies in monkeys than he did to "a savage who delights to torture his enemies". However, Darwin is not advocating genocide, but clinically predicting, by analogy to the ways that "more fit" varieties in a species displace other varieties, the likelihood that indigenous peoples will eventually die out from their contact with "civilization", or become absorbed into it completely.[8][9] His political opinions (and Galton's as well) were strongly inclined against the coercive, authoritarian forms of eugenics that became so prominent in the 20th century.[9] Note that even Galton's ideas about eugenics were not the compulsory sterilisation which became part of eugenics in the United States, or the later genocidal programs of Nazi Germany, but rather further education on the genetic aspects of reproduction, encouraging couples to make better choices for their wellbeing. For each tendency of society to produce negative selections, Darwin also saw the possibility of society to itself check these problems, but also noted that with his theory "progress is no invariable rule." Towards the end of Descent of Man, Darwin said that he believed man would "sink into indolence" if severe struggle was not continuous, and thought that "there should be open competition for all men; and the most able should not be prevented by laws or customs from succeeding best and rearing the largest number of offspring", but also noted that he thought that the moral qualities of man were advanced much more by habit, reason, learning, and religion than by natural selection. The question plagued him until the end of his life, and he never concluded fully one way or the other about it. On the Races of Man In the first chapters of the book, Darwin argued that there is no fundamental gap between humans and other animals in intellectual and moral faculties as well as anatomy. Retreating from his egalitarian ideas of the 1830s, he ranked life on a hierarchic scale which he extended to human races on the basis of anthropology published since 1860: human prehistory outlined by John Lubbock and Edward Burnett Tylor combined archaeology and studies of modern indigenous peoples to show progressive evolution from Stone Age to steam age; the human mind as the same in all cultures but with modern "primitive" peoples giving insight into prehistoric ways of life. Darwin did not support their view that progress was inevitable, but he shared their belief in human unity and held the common attitude that male European liberalism and civilisation had progressed further in morality and intellect than "savage" peoples.[10][11] He attributed the "great break in the organic chain between man and his nearest allies" to extinction, and as spreading civilisation wiped out wildlife and native human cultures, the gap would widen to somewhere "between man in a more civilised state, as we may hope, than the Caucasian, and some ape as low as a baboon, instead of as at present between the negro or Australian and the gorilla." While there "can be no doubt that the difference between the mind of the lowest man and that of the highest animal is immense", the "difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, is certainly one of degree and not of kind."[12][13] At the same time, all human races had many mental similarities, and early artefacts showing shared culture were evidence of evolution through common descent from an ancestral species which was likely to have been fully human.[14][15] Introducing chapter seven ("On the Races of Man"), Darwin wrote: "It is not my intention here to describe the several so-called races of men; but to inquire what is the value of the differences between them under a classificatory point of view, and how they have originated."[16] In answering the question of whether the races should rank as varieties of the same species or count as different species, Darwin discussed arguments which could support the idea that human races were distinct species.[17][18] This included the geographical distribution of mammal groups which was correlated with the distribution of human races,[19] and the finding of Henry Denny that different species of lice affected different races differently.[20] Darwin then presented the stronger evidence that human races are all the same species, noting that when races mixed together, they intercrossed beyond the "usual test of specific distinctness"[21] and that characteristics identifying races were highly variable.[22] He put great weight on the point that races graduate into each other, writing "But the most weighty of all the arguments against treating the races of man as distinct species, is that they graduate into each other, independently in many cases, as far as we can judge, of their having intercrossed",[23] and concluded that the stronger evidence was that they were not different species.[24] This conclusion on human unity was supported by monogenism, including John Bachman's evidence that intercrossed human races were fully fertile. Proponents of polygenism opposed unity, but the gradual transition from one race to another confused them when they tried to decide how many human races should count as species: Louis Agassiz said eight, but Morton said twenty-two.[25][23] Darwin commented that the "question whether mankind consists of one or several species has of late years been much agitated by anthropologists, who are divided into two schools of monogenists and polygenists." The latter had to "look at species either as separate creations or as in some manner distinct entities" but those accepting evolution "will feel no doubt that all the races of man are descended from a single primitive stock". Although races differed considerably, they also shared so many features "that it is extremely improbable that they should have been independently acquired by aboriginally distinct species or races." He drew on his memories of Jemmy Button and John Edmonstone to emphasise "the numerous points of mental similarity between the most distinct races of man. The American aborigines, Negroes and Europeans differ as much from each other in mind as any three races that can be named; yet I was incessantly struck, whilst living with the Fuegians on board the Beagle, with the many little traits of character, shewing how similar their minds were to ours; and so it was with a full-blooded negro with whom I happened once to be intimate."[26][27] Darwin concluded that "when the principles of evolution are generally accepted, as they surely will be before long, the dispute between the monogenists and the polygenists will die a silent and unobserved death."[28][29] Darwin rejected both the idea that races had been separately created, and the concept that races had evolved in parallel from separate ancestral species of apes.[30] He reviewed possible explanations of divergence into racial differences such as adaptations to different climates and habitats, but found inadequate evidence to support them, and proposed that the most likely cause was sexual selection,[31] a subject to which he devoted the greater part of the book, as described in the following section. Part II and III: Sexual selection See also: Sexual selection in human evolution and Sexual selection  Darwin argued that the female peahen chose to mate with the male peacock who she believed had the most beautiful plumage. Part II of the book begins with a chapter outlining the basic principles of sexual selection, followed by a detailed review of many different taxa of the kingdom Animalia which surveys various classes such as molluscs and crustaceans. The tenth and eleventh chapters are both devoted to insects, the latter specifically focusing on the order Lepidoptera, the butterflies and moths. The remainder of the book shifts to the vertebrates, beginning with cold blooded vertebrates (fishes, amphibians and reptiles) followed by four chapters on birds. Two chapters on mammals precede those on humans. Darwin explained sexual selection as a combination of "female choosiness" and "direct competition between males".[32]  Antoinette Blackwell, one of the first women to write a critique of Darwin Darwin's theories of evolution by natural selection were used to try to show women's place in society was the result of nature.[33] One of the first women to critique Darwin, Antoinette Brown Blackwell published The Sexes Throughout Nature in 1875.[34] She was aware she would be considered presumptuous for criticising evolutionary theory but wrote that "disadvantages under which we [women] are placed...will never be lessened by waiting".[35] Blackwell's book answered Darwin and Herbert Spencer, who she thought were the two most influential living men.[36] She wrote of "defrauded womanhood" and her fears that "the human race, forever retarding its own advancement...could not recognize and promote a genuine, broad, and healthful equilibrium of the sexes".[37] In the Descent of Man, Darwin wrote that by choosing tools and weapons over the years, "man has ultimately become superior to woman",[38] but Blackwell's argument for women's equality went largely ignored until the 1970s when feminist scientists and historians began to explore Darwin.[39] As recently as 2004, Griet Vandermassen, aligned with other Darwinian feminists of the 1990s and early 2000s (decade), wrote that a unifying theory of human nature should include sexual selection.[34] But then the "opposite ongoing integration" was promoted by another faction as an alternative in 2007.[40] Nonetheless, Darwin's explanation of sexual selection continues to receive support from both social and biological scientists as "the best explanation to date".[41] Apparently non-adaptive features In Darwin's view, anything that could be expected to have some adaptive feature could be explained easily with his theory of natural selection. In On the Origin of Species, Darwin wrote that to use natural selection to explain something as complicated as a human eye, "with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration" might at first appear "absurd in the highest possible degree," but nevertheless, if "numerous gradations from a perfect and complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade being useful to its possessor, can be shown to exist", then it seemed quite possible to account for within his theory.  "The sight of a feather in a peacock's tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!" More difficult for Darwin were highly evolved and complicated features that conveyed apparently no adaptive advantage to the organism. Writing to colleague Asa Gray in 1860, Darwin commented that he remembered well a "time when the thought of the eye made me cold all over, but I have got over this stage of the complaint, & now small trifling particulars of structure often make me very uncomfortable. The sight of a feather in a peacock's tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!"[42] Why should a bird like the peacock develop such an elaborate tail, which seemed at best to be a hindrance in its "struggle for existence"? To answer the question, Darwin had introduced in the Origin the theory of sexual selection, which outlined how different characteristics could be selected for if they conveyed a reproductive advantage to the individual. In this theory, male animals in particular showed heritable features acquired by sexual selection, such as "weapons" with which to fight over females with other males, or beautiful plumage with which to woo the female animals. Much of Descent is devoted to providing evidence for sexual selection in nature, which he also ties into the development of aesthetic instincts in human beings, as well as the differences in coloration between the human races.[43] Darwin had developed his ideas about sexual selection for this reason since at least the 1850s, and had originally intended to include a long section on the theory in his large, unpublished book on species. When it came to writing Origin (his "abstract" of the larger book), though, he did not feel he had sufficient space to engage in sexual selection to any strong degree, and included only three paragraphs devoted to the subject. Darwin considered sexual selection to be as much of a theoretical contribution of his as was his natural selection, and a substantial amount of Descent is devoted exclusively to this topic. |

内容 「人間の起源は決して知ることができないと、しばしば自信たっぷりに主張されてきたが、無知が自信を生むことは知識よりも多い。この問題やあの問題は、科 学では決して解決できないと断言するのは、多くを知る者ではなく、ほとんど何も知らない者である」——チャールズ・ダーウィン[3] 第一部:人間の進化 身体的特徴の進化  発生学(ここではヒトとイヌの比較)が証拠の1つの方法を提供した[4]。 ダーウィンは『下降』の序文で、この著作の目的を述べている: 「この著作の唯一の目的は、第一に、人間が他のあらゆる種と同様に、何らかの既存の形態の子孫であるかどうか、第二に、その発生の仕方、第三に、いわゆる人間の種族間の違いの価値について考察することである」。 人間の進化を論証するダーウィンのアプローチは、人間が他の動物といかに似ているかを概説することである。彼はまず、解剖学的類似性を用いて、身体の構 造、発生学、そしておそらく人間の "既存の "形態の一つで有用であったと思われる "初歩的器官 "に焦点を当てる。次に、精神的特徴の類似性を論じる。 精神的特徴の進化 従兄弟のフランシス・ガルトンの研究に基づき、ダーウィンは人間の性格的特徴や精神的特徴は身体的特徴と同じように遺伝すると主張し、進化論の目的上、心 と体の区別に反対する。そこからダーウィンは、ある種の動物に似たような精神力や特性があることを示す証拠を示し、特に類人猿、サル、イヌに焦点を当て、 愛、賢さ、宗教、優しさ、利他主義を類推する。彼はこの点について、「それにもかかわらず、人間と高等動物との間の心の違いは、それが大きいとしても、種 類の違いではなく、程度の違いであることは確かである」と結論づけている[5]。さらに彼は、ヴィクトリア朝イングランドの社会の多くの側面が、より原始 的な形態に見られることを示すために、「未開人」の行動に目を向ける。 特にダーウィンは、人間の宗教と「未開人」のフェティシズムを比較したり、彼の犬が風に飛ばされた日傘が生きているかどうかを見分けることができなかった りすることで、道徳的・社会的本能さえも進化したものであると主張する。ダーウィンはまた、すべての文明は野蛮から勃興したものであり、当時の多くの論者 が主張していたように、野蛮が「恩寵からの転落」だとは考えていないと主張する。  ダーウィンの主な修辞的戦略は、類推によって論じることであった。ヒヒ、イヌ、そして "野蛮人 "が、人類の進化を証明するダーウィンの主な証拠となった。 自然淘汰と文明社会 本書のこのセクションでは、ダーウィンは、彼の死後、社会ダーウィニズムと優生学として知られることになる問題にも目を向けている。ダーウィンは、アルフ レッド・ラッセル・ウォレスやガルトンが論じていたように、自然淘汰はもはや文明社会では他の動物に作用するようには作用しないようだと述べている: 未開人の場合、肉体的にも精神的にも弱い者はすぐに淘汰される。一方、われわれ文明人は、淘汰のプロセスを阻止するために最大限の努力を払っている。身体 障害者、身体障害者、病人のために療養所を建設し、貧民法を制定し、医療従事者は最後の瞬間まですべての人の命を救うために最大限の技術を発揮する。予防 接種によって、体質が弱ければ天然痘で倒れるはずだった何千人もの人々が助かったと信じるに足る理由がある。このように、文明社会の弱者たちは自分たちの 種を繁殖させている。家畜の繁殖に携わったことのある人なら、家畜の繁殖が人間の種族にとって非常に有害であることを疑う者はいないだろう。しかし、人間 自身の場合を除けば、最悪の家畜の繁殖を許すほど無知な人はほとんどいない。私たちが無力な者に与えざるを得ないと感じる援助は、主として同情という本能 の付随的な結果である。この本能はもともと社会的本能の一部として獲得されたものだが、その後、先に述べたような方法で、より優しく、より広く普及するよ うになった。たとえ厳しい理性に促されても、人間の本性の最も崇高な部分を損なうことなく、同情を抑えることはできない。外科医が手術をするときに身を固 くするのは、自分が患者のために行動していることを知っているからである。しかし、もし私たちが意図的に弱く無力な人々をないがしろにするとしたら、それ は偶発的な利益のためであり、圧倒的な現在の弊害のためでしかない。したがって我々は、弱者が生き残り、その種を繁殖させることによる間違いなく悪い影響 に耐えなければならない。しかし、着実な行動には少なくとも1つの歯止めがあるように思われる。すなわち、社会の弱者や劣等生は健全な者ほど自由に結婚し ないということである。(第5章)[6]。 ダーウィンは、このような「弱い者」を助けようとする衝動は、私たちが進化させた同情の本能の一部であると考え、「たとえ厳しい理性に促されても、私たち の本性の最も高貴な部分を劣化させることなく、同情を抑制することはできない」と結論づけた。そのため、「弱者が生き残り、その種族を繁殖させるという間 違いなく悪い影響を、我々は負わなければならない」。ダーウィンは「野蛮な種族」が近い将来「文明化された種族」によって破壊されるだろうと感じていた。 しかし、ダーウィンは大量虐殺を提唱しているわけではなく、ある種の中で「より適した」品種が他の品種を駆逐していく様子になぞらえて、原住民が「文明」 との接触によっていずれ絶滅するか、あるいは完全に文明に吸収されてしまう可能性を臨床的に予測しているのである[8][9]。 彼の政治的意見(そしてガルトンも同様)は、20世紀に顕著になった強制的で権威主義的な形態の優生学に反対する傾向が強かった[9]。ガルトンの優生学 に関する考えも、アメリカにおける優生学の一部となった強制不妊手術や、後にナチス・ドイツが行った大量虐殺プログラムではなく、むしろ生殖の遺伝的側面 に関するさらなる教育であり、夫婦が自分たちの幸福のためにより良い選択をすることを奨励するものであったことに留意されたい。 ダーウィンは、社会が否定的な淘汰を生み出す傾向のそれぞれについて、社会が自らこれらの問題をチェックする可能性も見出していたが、彼の理論では "進歩は不変のルールではない "とも述べている。ダーウィンは『人間下降論』の終盤で、厳しい闘争が続かなければ人間は「怠惰に沈む」と考え、「すべての人間に対して開かれた競争があ るべきであり、最も能力のある者が最もよく成功し、最も多くの子孫を残すことを法律や習慣によって妨げるべきではない」と述べた。この疑問は晩年まで彼を 悩ませ、どちらか一方に完全な結論を出すことはなかった。 人間の人種について この本の最初の章では、ダーウィンは、人間と他の動物との間には、知的能力や道徳的能力だけでなく、解剖学的にも根本的な隔たりはないと主張した。ジョ ン・ラボックとエドワード・バーネット・タイラーによって概説された人類の先史時代は、考古学と現代の先住民の研究を組み合わせて、石器時代から蒸気時代 への漸進的進化を示した。ダーウィンは、進歩は必然的なものであるという彼らの見解を支持することはなかったが、人間の一体性に対する彼らの信念を共有 し、ヨーロッパの男性の自由主義と文明は「未開の」民族よりも道徳と知性においてさらに進歩しているという共通の態度を持っていた[10][11]。 彼は「人間とその最も近い盟友との間の有機的な連鎖の大きな断絶」を絶滅に帰結させ、文明の拡散が野生動物や先住民の文化を一掃するにつれて、その差は 「現在のように黒人やオーストラリア人とゴリラの間ではなく、我々が望むように、コーカサス人よりも文明化した状態の人間と、ヒヒのように低い猿との間」 にまで広がるだろうとした。最も低い人間の心と最も高い動物の心の差が計り知れないものであることは疑いようがない」が、「人間と高等動物の心の差は、そ れが大きいとしても、種類の差ではなく程度の差であることは間違いない」[12][13]。 第7章(「人間の種族について」)の冒頭で、ダーウィンは次のように書いている。「ここで私が意図しているのは、いわゆる人間のいくつかの種族について説 明することではなく、分類学的な観点から見て、それらの違いがどのような価値を持つのか、そしてそれらはどのようにして生まれたのかを問うことである。 「16]人種が同じ種の変種として位置づけられるべきか、それとも異なる種として数えられるべきかという問いに答えるために、ダーウィンは人間の人種が別 個の種であるという考えを支持しうる論拠について論じた。 [20]その後ダーウィンは、人間の人種がすべて同じ種であるという、より強力な証拠を提示し、人種が混ざり合うと、「特定の区別の通常のテスト」 [21]を超えて交雑し、人種を識別する特徴が非常に変化することを指摘した。 [しかし、人間の種族を別個の種として扱うことに反対するすべての議論の中で最も重要なことは、多くの場合、我々が判断できる限りにおいて、それらが交雑 したこととは無関係に、それらが互いに卒業することである」[23]と書き、人種が互いに卒業するという点に大きな重きを置き、より強力な証拠は、それら が別個の種ではないということであると結論づけた[24]。 ヒトの単一性に関するこの結論は、交配されたヒトの種族が完全に受胎可能であったというジョン・バックマンの証拠を含む一遺伝子主義によって支持されてい た。多遺伝子主義の支持者たちは単一性に反対していたが、ある種族から別の種族への漸進的な移行は、人間の種族をいくつと数えるべきかを決めようとしたと きに彼らを混乱させた: ルイ・アガシは8種と言ったが、モートンは22種と言った。[25][23] ダーウィンは、「人類が1つの種から成っているのか、それともいくつかの種から成っているのかという問題は、近年、人類学者によって大いに議論されてい る。後者は「種を別個の創造物として、あるいは何らかの形で別個の存在として」見なければならなかったが、進化論を受け入れる人々は「人間のすべての種族 が単一の原始的な家系の子孫であることに疑いを抱くことはないだろう」と述べている。種族はかなり異なるが、多くの特徴を共有している。彼は、ジェミー・ バトンとジョン・エドモンストンの思い出を引き合いに出し、「人間の最も異なる種族の間には、精神的な類似点が数多くある」ことを強調した。しかし、ビー グル号でフエジア人と生活していたとき、彼らの心がわれわれといかに似ているかを示す性格の多くの小さな特徴に、私は絶え間なく心を打たれた。 「ダーウィンは、「進化の原理が一般的に受け入れられるようになれば、やがてそうなるに違いないが、単遺伝子論者と多遺伝子論者の論争は、静かで観察され ることのない死を迎えるだろう」と結論づけた[28][29]。 ダーウィンは、人種が別々に創造されたという考え方と、人種が猿の別々の祖先種から並行して進化したという考え方の両方を否定した[30]。彼は、異なる 気候や生息地への適応など、人種の違いに分岐する可能性のある説明を検討したが、それらを支持する証拠が不十分であることを発見し、最も可能性の高い原因 は性淘汰であると提唱した[31]。 第II部と第III部:性淘汰 以下も参照: 人類進化における性淘汰と性淘汰  ダーウィンは、メスのクジャクは、最も美しい羽毛を持つと思われるオスのクジャクとの交尾を選ぶと主張した。 本書の第II部は、性淘汰の基本原理を概説する章から始まり、軟体動物や甲殻類などの様々な分類を調査した動物界(Animalia)の様々な分類群につ いての詳細なレビューが続く。第10章と第11章はともに昆虫に割かれており、後者は特に鱗翅目、チョウやガに焦点を当てている。本書の残りは脊椎動物に 移り、冷血動物(魚類、両生類、爬虫類)から始まり、鳥類に関する4つの章が続く。哺乳類に関する2章が人間に関する章の前にある。ダーウィンは性淘汰を 「メスの選択性」と「オス同士の直接的な競争」の組み合わせとして説明した[32]。  アントワネット・ブラックウェルは、ダーウィンの進化論に対する批評を書いた最初の女性の一人である。 ダーウィンの自然淘汰による進化論は、社会における女性の地位が自然の結果であることを示そうとするために使用された[33]。 ブラックウェルの著書は、ダーウィンとハーバート・スペンサーに答えたものであり、ダーウィンは現存する最も影響力のある2人の男性だと考えていた [36]。 ダーウィンは『人間の下降』の中で、長い年月をかけて道具や武器を選択することで、「人間は最終的に女性よりも優れた存在になった」と書いている[38] が、女性の平等を求めるブラックウェルの主張は、フェミニストの科学者や歴史家がダーウィンを探求し始めた1970年代まで、ほとんど無視されていた。 [39]最近では、2004年にグリエット・ヴァンダーマッセンが1990年代から2000年代初頭(10年間)の他のダーウィンのフェミニストと並ん で、人間の本性に関する統一的な理論は性淘汰を含むべきだと書いている[34]。 しかしその後、2007年に別の派閥によって「反対の進行中の統合」が代替案として推進された[40]。 それにもかかわらず、性淘汰に関するダーウィンの説明は、「現在までの最良の説明」として社会科学者と生物科学者の両方から支持を受け続けている [41]。 明らかに非適応的な特徴 ダーウィンの考えでは、何らかの適応的特徴を持つと予想されるものはすべて、彼の自然淘汰の理論で簡単に説明することができる。ダーウィンは『種の起源』 の中で、人間の目のような複雑なものを自然淘汰で説明することは、「異なる距離にピントを合わせたり、異なる量の光を取り入れたりするための、他にはない あらゆる工夫がある、 しかし、「完全で複雑な目から、非常に不完全で単純な目までの数多くの段階が存在し、それぞれの段階がその所有者にとって有用であることが示される」ので あれば、彼の理論で説明することは十分に可能である。  「孔雀の尾の羽を見ると、それを眺めるたびに気分が悪くなる ダーウィンにとってより困難だったのは、高度に進化した複雑な特徴であり、その生物にとって明らかに適応的な利点はない。1860年に同僚のエイサ・グレ イに宛てた手紙の中で、ダーウィンは「目のことを考えると全身が寒くなるような時期があった。孔雀の尾の羽毛を見ると、それを眺めるたびに気分が悪くな る!」[42] なぜ孔雀のような鳥が、せいぜい「生存のための闘争」の邪魔にしかならないような、あのような精巧な尾を発達させなければならないのだろうか?その疑問に 答えるため、ダーウィンは『起源』の中で性淘汰の理論を導入した。この理論では、特にオスの動物は、他のオスとメスを奪い合うための "武器 "や、メスに言い寄るための美しい羽など、性淘汰によって獲得された遺伝的特徴を示す。天孫降臨』の大部分は、自然界における性淘汰の証拠を提供すること に費やされており、彼はそれを人間の美的本能の発達や人種間の色彩の違いにも結びつけている[43]。 ダーウィンは少なくとも1850年代から、このような理由から性淘汰についての考えを発展させており、当初は未発表の種に関する大著の中に、この理論に関 する長い章を含めるつもりでいた。しかし、『起源』(大著の "抄録")を執筆することになったとき、彼は性淘汰について深く考察するのに十分なスペースがあるとは思えず、性淘汰をテーマにしたのはわずか3段落にと どまった。ダーウィンは性淘汰を自然淘汰と同じくらい理論的な貢献と考えており、『下降』のかなりの部分はこのテーマだけに費やされている。 |

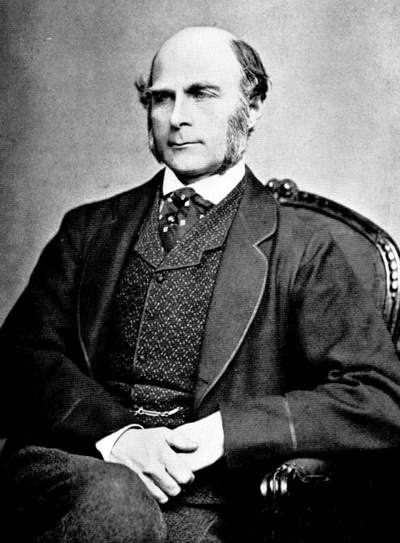

| Darwin's background issues and concerns Further information: Darwin from Descent of Man to Emotions  Charles Darwin's second book of theory involved many questions of Darwin's time. It was Darwin's second book on evolutionary theory, following his 1859 work, On the Origin of Species, in which he explored the concept of natural selection and which had been met with a firestorm of controversy in reaction to Darwin's theory. A single line in this first work hinted at such a conclusion: "light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history". When writing The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication in 1866, Darwin intended to include a chapter including man in his theory, but the book became too big and he decided to write a separate "short essay" on ape ancestry, sexual selection and human expression, which became The Descent of Man. The book is a response to various debates of Darwin's time far more wide-ranging than the questions he raised in Origin. It is often erroneously assumed that the book was controversial because it was the first to outline the idea of human evolution and common descent. Coming out so late into that particular debate, while it was clearly Darwin's intent to weigh in on this question, his goal was to approach it through a specific theoretical lens (sexual selection), which other commentators at the period had not discussed, and consider the evolution of morality and religion. The theory of sexual selection was also needed to counter the argument that beauty with no obvious utility, such as exotic birds' plumage, proved divine design, which had been put strongly by the Duke of Argyll in his book The Reign of Law (1868).[44] Human faculties The major sticking point for many in the question of human evolution was whether human mental faculties could have possibly been evolved. The gap between humans and even the smartest ape seemed too large, even for those who were sympathetic to Darwin's basic theory. Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection, believed that the human mind was too complex to have evolved gradually, and began over time to subscribe to a theory of evolution that took more from spiritualism than it did the natural world. Darwin was deeply distressed by Wallace's change of heart, and much of the Descent of Man is in response to opinions put forth by Wallace. Darwin focuses less on the question of whether humans evolved than he does on showing that each of the human faculties considered to be so far beyond those of beasts—such as moral reasoning, sympathy for others, beauty, and music—can be seen in kind (if not degree) in other animal species (usually apes and dogs). Human races  On the Beagle voyage, Darwin met Fuegians including Jemmy Button who had been briefly educated in England.  He was shocked to encounter their relatives in Tierra del Fuego, who appeared to him to be primitive savages. Darwin was a long-time abolitionist who had been horrified by slavery when he first came into contact with it in Brazil while touring the world on the Beagle voyage many years before (slavery had been illegal in the British Empire since 1833).[45][page needed][46] Darwin also was perplexed by the "savage races" he saw in South America at Tierra del Fuego, which he saw as evidence of man's more primitive state of civilisation. During his years in London, his private notebooks were riddled with speculations and thoughts on the nature of the human races, many decades before he published Origin and Descent. When making his case that human races were all closely related and that the apparent gap between humans and other animals was due to closely related forms being extinct, Darwin drew on his experiences on the voyage showing that "savages" were being wiped out by "civilized" peoples.[8] When Darwin referred to "civilised races" he was almost always describing European cultures, and apparently drew no clear distinction between biological races and cultural races in humans. Few made that distinction at the time, an exception being Alfred Russel Wallace.[8] Social implications of Darwinism  Darwin's cousin, Francis Galton, proposed that an interpretation of Darwin's theory was the need for eugenics to save society from "inferior" minds. Since the publication of Origin, a wide variety of opinions had been put forward on whether the theory had implications towards human society. One of these, later known as Social Darwinism, has been attributed to Herbert Spencer's writings before publication of Origin, and argued that society would naturally sort itself out, and that the more "fit" individuals would rise to positions of higher prominence, while the less "fit" would succumb to poverty and disease. On this interpretation, Spencer alleged that government-run social programmes and charity hinder the "natural" stratification of the populace. But while Spencer did first introduce the phrase "survival of the fittest" in 1864, he always vigorously denied this interpretation of his works, arguing that the natural course of social evolution is toward greater altruism, and that the good done by charity and giving aid to the less fortunate, so long as done without coercion and in such a way as to foster independence rather than dependence, outweighs any harm done by saving the less fit. In any case, Spencer was primarily a Lamarckian evolutionist; hence, fitness could be acquired in a single generation and thus in no way did "survival of the fittest" as a tenet of Darwinian evolution predate it. Another of these interpretations, later known as eugenics, was put forth by Darwin's cousin, Francis Galton, in 1865 and 1869. Galton argued that just as physical traits were clearly inherited among generations of people, so could be said for mental qualities (genius and talent). Galton argued that social mores needed to change so that heredity was a conscious decision, to avoid over-breeding by "less fit" members of society and the under-breeding of the "more fit" ones. In Galton's view, social institutions such as welfare and insane asylums were allowing "inferior" humans to survive and reproduce at levels faster than the more "superior" humans in respectable society, and if corrections were not soon taken, society would be awash with "inferiors." Darwin read his cousin's work with interest, and devoted sections of Descent of Man to discussion of Galton's theories. Neither Galton nor Darwin, though, advocated any eugenic policies such as those undertaken in the early 20th century, as government coercion of any form was very much against their political opinions. |

ダーウィンの背景にある問題と懸念 さらに詳しい情報 ダーウィン 人間の下降から感情まで  チャールズ・ダーウィンの2冊目の理論書は、ダーウィンの時代の多くの問題を含んでいた。 自然淘汰の概念を探求した1859年の著作『種の起源』に続く、ダーウィンの進化論に関する2冊目の著書であり、ダーウィンの理論に対する反発から大論争 が巻き起こった。この最初の著作の中の一行が、そのような結論を暗示していた: 「人間の起源とその歴史に光が当てられるだろう」。1866年に『家畜化下の動植物の変異』を執筆する際、ダーウィンは人間を含む章を自説に含めるつもり だったが、本が大きくなりすぎたため、類人猿の祖先、性淘汰、人間の表現に関する「短いエッセイ」を別に書くことにし、それが『人間の下降』となった。 この本は、ダーウィンが『起源』で提起した問題よりもはるかに広範な、ダーウィン当時のさまざまな議論への応答である。この本が物議を醸したのは、人類の 進化と共通の子孫という考え方を最初に概説したからだと、しばしば誤って考えられている。ダーウィンの目的は、当時他の論者が論じていなかった特定の理論 的レンズ(性淘汰)を通してこの問題にアプローチし、道徳と宗教の進化を考察することであった。性淘汰の理論はまた、異国の鳥の羽毛のような明らかな有用 性のない美しさは神の設計を証明するという議論に対抗するためにも必要であった。 人間の能力 人類の進化の問題で多くの人にとっての大きな論点は、人間の精神的能力が進化した可能性があるかどうかということであった。ダーウィンの基本理論に共感す る人々にとっても、ヒトと最も賢い類人猿との間のギャップは大きすぎると思われた。自然淘汰による進化の共同発見者であるアルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレ スは、人間の精神は徐々に進化するには複雑すぎると考え、自然界よりも精神主義から多くのものを取り入れた進化論を支持し始めた。ダーウィンはウォーレス の心変わりに深く心を痛め、『人間下降論』の大部分はウォーレスが提示した意見に対するものである。ダーウィンは、人間が進化したかどうかという問題より も、道徳的な理性、他者への共感、美、音楽など、獣類をはるかに凌ぐと考えられている人間の能力のそれぞれが、他の動物種(通常は類人猿や犬)にも(程度 はともかく)一応見られることを示すことに重点を置いている。 人間の種族  ビーグル号の航海中、ダーウィンはイギリスで短期間教育を受けたジェミー・バトンを含むフエジア人に出会った。  ダーウィンはティエラ・デル・フエゴで、原始的な野蛮人にしか見えない彼らの親類に出会い、衝撃を受けた。 ダーウィンは長年の奴隷制度廃止論者であり、何年も前にビーグル号の航海で世界を巡っていたときにブラジルで初めて奴隷制度に接し、恐怖を覚えた(奴隷制 度は1833年以降、大英帝国では違法となっていた)。ロンドンにいた数年間、彼の私的なノートには、『起源と子孫』を出版する何十年も前から、人類の種 族の性質に関する推測や考えが書き連ねられていた。 ダーウィンは、人類の種族はすべて近縁であり、人類と他の動物との間にある明らかな隔たりは、近縁の種族が絶滅したためであると主張する際、「未開人」が 「文明化された」人々によって一掃されていることを示す航海での経験を利用した[8]。ダーウィンが「文明化された種族」に言及するとき、彼はほとんど常 にヨーロッパの文化について述べており、人間における生物学的種族と文化的種族との明確な区別はしていなかったようである。当時、そのような区別をする者 はほとんどいなかったが、アルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスは例外であった[8]。 ダーウィニズムの社会的意味合い  ダーウィンの従兄弟であるフランシス・ガルトンは、ダーウィンの理論の解釈として、「劣った」精神から社会を救うための優生学の必要性を提唱した。 Origin』の出版以来、ダーウィンの理論が人間社会にどのような影響を与えるかについて、さまざまな意見が出された。そのうちのひとつは、後に社会 ダーウィニズムとして知られるようになったもので、『起源』出版以前のハーバート・スペンサーの著作に起因するとされ、社会は自然に整理され、より「適合 した」個人はより高い地位に上り詰め、「適合していない」個人は貧困や病気に苦しむことになると主張した。この解釈に基づき、スペンサーは政府が運営する 社会プログラムや慈善事業が、民衆の「自然な」階層化を妨げると主張した。しかし、スペンサーは1864年に「適者生存」という言葉を初めて紹介したが、 彼は自分の著作のこの解釈を常に激しく否定し、社会進化の自然な流れはより大きな利他主義に向かうものであり、慈善事業や恵まれない人々への援助によって もたらされる善は、強制されることなく、依存ではなく自立を促すような方法で行われる限り、適性の低い人々を救うことによってもたらされるいかなる害をも 上回ると主張した。いずれにせよ、スペンサーは主としてラマルク派の進化論者であった。それゆえ、適性は一世代で獲得される可能性があり、ダーウィン進化 論の信条としての「適者生存」は、それ以前のものでは決してなかったのである。 ダーウィンの従兄弟であるフランシス・ガルトンが1865年と1869年に提唱したのが、後に優生学として知られることになる別の解釈である。ガルトン は、身体的形質が何世代にもわたって明らかに遺伝するように、精神的な資質(天才や才能)についても同じことが言えると主張した。ガルトンは、遺伝が意識 的な意思決定となるように、社会的風潮を変える必要があると主張した。社会的に「適性の低い」人々による過剰繁殖と、「適性の高い」人々による過小繁殖を 避けるためである。ガルトンの考えでは、福祉施設や精神病院といった社会制度が、「劣った」人間が立派な社会の「優れた」人間よりも早く生存し、繁殖する ことを許しており、すぐに是正しなければ、社会は「劣った」人間で溢れかえってしまうということだった。ダーウィンは従兄弟の研究を興味深く読み、『人間 の下降』の一部をガルトンの理論の議論に割いた。しかし、ガルトンもダーウィンも、20世紀初頭に行われたような優生政策を提唱することはなかった。政府 によるいかなる強制も、彼らの政治的意見には大反対だったからである。 |

| Sexual selection Darwin's views on sexual selection were opposed strongly by his co-discoverer of natural selection, Alfred Russel Wallace, though much of his "debate" with Darwin took place after Darwin's death. Wallace argued against sexual selection, saying that the male-male competition aspects were simply forms of natural selection, and that the notion of female mate choice was attributing the ability to judge standards of beauty to animals far too cognitively undeveloped to be capable of aesthetic feeling (such as beetles).[43] Wallace also argued that Darwin too much favoured the bright colours of the male peacock as adaptive without realising that the "drab" peahen's coloration is itself adaptive, as camouflage. Wallace more speculatively argued that the bright colours and long tails of the peacock were not adaptive in any way, and that bright coloration could result from non-adaptive physiological development (for example, the internal organs of animals, not being subject to a visual form of natural selection, come in a wide variety of bright colours). This has been questioned by later scholars as quite a stretch for Wallace, who in this particular instance abandoned his normally strict "adaptationist" agenda in asserting that the highly intricate and developed forms such as a peacock's tail resulted by sheer "physiological processes" that were somehow not at all subjected to adaptation. Apart from Wallace, a number of scholars considered the role of sexual selection in human evolution controversial. Darwin was accused of looking at the evolution of early human ancestors through the moral lens of the 19th century Victorian society. Joan Roughgarden, citing many elements of sexual behaviour in animals and humans that cannot be explained by the sexual selection model, suggested that the function of sex in human evolution was primarily social.[47] Joseph Jordania suggested that in explaining such human morphological and behavioural characteristics as singing, dancing, body painting, wearing of clothes, Darwin (and proponents of sexual selection) neglected another important evolutionary force, intimidation of predators and competitors with the ritualised forms of warning display. Warning display uses virtually the same arsenal of visual, audio, olfactory and behavioural features as sexual selection. According to the principle of aposematism (warning display), to avoid costly physical violence and to replace violence with the ritualised forms of display, many animal species (including humans) use different forms of warning display: visual signals (contrastive body colours, eyespots, body ornaments, threat display and various postures to look bigger), audio signals (hissing, growling, group vocalisations, drumming on external objects), olfactory signals (producing strong body odors, particularly when excited or scared), behavioural signals (demonstratively slow walking, aggregation in large groups, aggressive display behaviour against predators and conspecific competitors). According to Jordania, most of these warning displays were incorrectly attributed to the forces of sexual selection.[48] While debates on the subject continued, in January 1871 Darwin started on another book, using leftover material on emotional expressions, which became The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. In recent years controversy also involved the peacock tail, the most famous symbol of the principle of sexual selection. A seven-year Japanese study of free-ranging peafowl came to the conclusion that female peafowl do not select mates merely on the basis of their trains. Mariko Takahashi found no evidence that peahens expressed any preference for peacocks with more elaborate trains, such as trains having more ocelli, a more symmetrical arrangement or a greater length.[49] Takahashi determined that the peacock's train was not the universal target of female mate choice, showed little variance across male populations, and, based on physiological data collected from this group of peafowl, do not correlate to male physical conditions. Adeline Loyau and her colleagues responded to Takahashi's study by voicing concern that alternative explanations for these results had been overlooked and that these might be essential for the understanding of the complexity of mate choice.[50] They concluded that female choice might indeed vary in different ecological conditions. Jordania suggested that peacock's display of colourful and oversize train with plenty of eyespots, together with their extremely loud call and fearless behaviour has been formed by the forces of natural selection (not sexual selection), and served as a warning (aposematic) display to intimidate predators and rivals.[51] Effect on society In January 1871, Thomas Huxley's former disciple, the anatomist St. George Mivart, had published On the Genesis of Species as a critique of natural selection. In an anonymous Quarterly Review article, he claimed that the Descent of Man would unsettle "our half educated classes" and talked of people doing as they pleased, breaking laws and customs.[52] An infuriated Darwin guessed that Mivart was the author and, thinking "I shall soon be viewed as the most despicable of men", looked for an ally. In September, Huxley wrote a cutting review of Mivart's book and article and a relieved Darwin told him "How you do smash Mivart's theology... He may write his worst & he will never mortify me again". As 1872 began, Mivart politely inflamed the argument again, writing "wishing you very sincerely a happy new year" while wanting a disclaimer of the "fundamental intellectual errors" in the Descent of Man. This time, Darwin ended the correspondence. |

性淘汰 性淘汰に関するダーウィンの見解は、自然淘汰の共同発見者であるアルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスによって強く反対されたが、ダーウィンとの「論争」の多 くはダーウィンの死後に行われた。ウォレスは、オスとオスの競争という側面は単なる自然淘汰の一形態であり、メスの交尾相手の選択という概念は、美的感覚 を持つにはあまりにも認知的に未発達な動物(カブトムシなど)に美の基準を判断する能力を帰するものであるとして、性淘汰に反対を主張した[43]。 ウォレスはまた、ダーウィンがクジャクのオスの鮮やかな色を適応的なものとして優遇しすぎており、「無味乾燥な」クジャクの色彩自体がカモフラージュとし て適応的であることに気づいていないと主張した。ウォレスはさらに思索的に、クジャクの鮮やかな色と長い尾は何ら適応的ではなく、鮮やかな色彩は非適応的 な生理学的発達の結果であると主張した(例えば、動物の内臓は視覚的な自然淘汰を受けないため、多種多様な鮮やかな色がある)。後世の学者たちからは、 ウォーレスにはかなり無理があるとして疑問視されている。ウォーレスはこの特別な例において、普段は厳格な「適応主義者」であるはずの自分の主張を放棄 し、クジャクの尾のような非常に複雑で発達した形態は、どういうわけか適応にまったく左右されない、単なる「生理学的プロセス」によって生じたと主張した のである。 ウォレス以外にも、人類の進化における性淘汰の役割について、多くの学者が論争を巻き起こした。ダーウィンは、初期の人類の祖先の進化を、19世紀のヴィ クトリア朝社会の道徳的なレンズを通して見ていると非難された。ジョーン・ラフガーデンは、性淘汰モデルでは説明できない動物やヒトの性行動の多くの要素 を挙げ、ヒトの進化における性の機能は主に社会的なものであったと示唆した[47]。ジョセフ・ジョルダニアは、歌、ダンス、ボディペインティング、衣服 の着用といったヒトの形態学的・行動学的特徴を説明する際に、ダーウィン(および性淘汰の支持者)はもう一つの重要な進化的力である、警告表示の儀式化さ れた形式による捕食者や競争相手への威嚇を軽視していると示唆した。警告表示は、視覚的、聴覚的、嗅覚的、行動的特徴など、事実上、性淘汰と同じ武器を 使っている。アポセマティズム(警告表示)の原則に従い、コストのかかる肉体的暴力を避け、暴力を儀式化された表示形態に置き換えるため、多くの動物種 (ヒトを含む)はさまざまな形態の警告表示を用いる: 視覚的シグナル(対照的な体の色、目玉、体の装飾品、威嚇表示、大きく見せるためのさまざまな姿勢)、音声的シグナル(ヒスノイズ、うなり声、集団での発 声、外部物体の上で太鼓をたたく)、嗅覚的シグナル(特に興奮時や恐怖時に強い体臭を発する)、行動的シグナル(誇示的にゆっくり歩く、大集団になる、捕 食者や同種の競争相手に対する攻撃的表示行動)。ジョルダニアによれば、これらの警告的ディスプレイのほとんどは、性淘汰の力によるものと誤って考えられ ていた[48]。 このテーマに関する論争が続く一方で、1871年1月、ダーウィンは感情表現に関する余った資料を使って別の本の執筆に着手し、『人間と動物における感情の表現』となった。 近年では、性淘汰の原理の最も有名なシンボルである孔雀の尾にも論争が巻き起こった。放し飼いにされたクジャクを対象に7年間行われた日本の研究では、ク ジャクのメスは単に電車を基準に相手を選ぶわけではないという結論に達した。高橋真理子は、クジャクがより精巧な電車、例えば、より多くの眼球、より対称 的な配置、より長い電車を持つクジャクに好意を示したという証拠を発見しなかった[49]。高橋は、クジャクの電車はメスの配偶者選択の普遍的な対象では なく、オスの個体群間でほとんど差異がなく、このクジャクのグループから収集された生理学的データに基づくと、オスの身体的条件とは相関しないと断定し た。アデリーヌ・ロワイヨとその同僚は、高橋の研究に対して、これらの結果に対する別の説明が見落とされていることに懸念を示し、これらの説明が交尾選択 の複雑さを理解するために不可欠であるかもしれないと述べた[50]。ジョルダニアは、クジャクのカラフルで特大の目玉がたくさんある電車のディスプレイ は、非常に大きな鳴き声と大胆不敵な行動とともに、(性淘汰ではなく)自然淘汰の力によって形成され、捕食者やライバルを威嚇するための警告(アポセマ ティック)ディスプレイとして機能したことを示唆した[51]。 社会への影響 1871年1月、トマス・ハクスリーのかつての弟子である解剖学者セント・ジョージ・ミヴァートは、自然淘汰に対する批判として『種の起源』を発表した。 匿名の季刊誌『クォータリー・レビュー』の記事の中で、彼は『人間の下降』が「我々の半端な教養階級」を動揺させると主張し、人々が法律や慣習を破って好 きなように行動していると語った[52]。激怒したダーウィンは、ミヴァートが著者であると推測し、「私はすぐに最も卑劣な人間として見られるだろう」と 考え、味方を探した。9月、ハクスリーはミヴァートの著書と論文について斬新な批評を書き、ほっとしたダーウィンは彼に「ミヴァートの神学を叩き潰すと は......。ミヴァートの神学を叩き潰すとは......彼は最悪のことを書くかもしれないが、二度と私を苛立たせることはないだろう」。1872年 が始まると、ミヴァートは「心から新年のご挨拶を申し上げます」と書きながら、『人間下降論』の「根本的な知的誤り」についての免責を求め、再び丁重に論 争を煽った。この時、ダーウィンは文通を打ち切った。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Descent_of_Man,_and_Selection_in_Relation_to_Sex |

|

| 本文から |

|

| When we treat of sexual selection we shall see that primeval man, or rather some early progenitor of man, probably first used his voice in producing true musical cadences, that is in singing, as do some of the gibbon-apes at the present day; and we may conclude from a widely-spread analogy, that this power would have been especially exerted during the courtship of the sexes,—would have expressed various emotions, such as love, jealousy, triumph,—and would have served as a challenge to rivals. It is, therefore, probable that the imitation of musical cries by articulate sounds may have given rise to words expressive of various complex emotions. | 性淘汰について論じるとき、原始人、いやむしろ人間の初期の祖先が、おそらく最初に自分の声を使ったのは、現在のテナガザルの一部のように、真の音楽的カ デンツ、つまり歌うことであったことがわかるだろう。広く普及している類推から結論づけると、この力は男女の求愛の際に特に発揮され、愛、嫉妬、勝利など さまざまな感情を表現し、ライバルへの挑戦の役割を果たしたであろう。したがって、音楽的な叫び声を明瞭な音で模倣することで、さまざまな複雑な感情を表 す言葉が生まれた可能性がある |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆