開発主義

Developmentalism

☆開発主義[Developmentalism]と は、発展途上経済が成長する最善の方法は、強固で多様な国内市場を育成し、輸入品に高い関税を課すことだと主張する経済理論である。 開発主義は学際的な思想潮流[1]であり、経済的繁栄への主要戦略として「開発」というイデオロギーを生み出した。この思想は、一部において、米国がアジ アやアフリカ全域で展開した民族独立運動への反対姿勢に対する反発として生まれた。米国はこうした運動を共産主義と位置づけていた[1]。国際経済の文脈 における開発主義は、経済発展を政治的取り組みや制度の中心に据える一連の思想として理解できる。また、政治領域における正当性を確立する手段としても機 能する。開発主義理論の支持者は、持続的な経済的進歩が政治指導者に正当な権威を与えると主張する。特にラテンアメリカや東アジアなどの発展途上国では、 そうでなければ指導者への社会的合意や先進国に対する国際政策の正当性を得られないと考える。開発主義者は、『第三世界』諸国が資本主義システムにおいて 外部資源を活用することで、国家の自律性を達成・維持できると信じる。こうした公言された目的のために、開発主義は1950~60年代に国際経済が発展途 上国に与えていた悪影響を逆転させようとする試みにおいて用いられたパラダイムであった。当時、ラテンアメリカ諸国は輸入代替戦略の実施を開始していた。 この理論を用いることで、経済発展は現代的な西洋基準によって枠組みづけられた。つまり、経済的成功は、国が発展し、自律的かつ正当な存在となることを意 味する資本主義的概念によって測定されるのである。[2] この理論は、全ての国に共通の発展段階が存在すること、そして伝統的あるいは原始的な段階から近代的あるいは工業化された段階へと直線的に移行するという 前提に基づいている。[3] 当初、アジア太平洋地域、ラテンアメリカ、アフリカの新興経済国に限定されていた開発主義の概念は、最近では先進国、特に米国のドナルド・トランプやバー ニー・サンダースといった「非正統派」の政策立案者たちの経済政策に再び登場している。[4]

| Developmentalism is

an economic theory which states that the best way for less developed

economies to develop is through fostering a strong and varied internal

market and imposing high tariffs on imported goods. Developmentalism is a cross-disciplinary school of thought[1] that gave way to an ideology of development as the key strategy towards economic prosperity. The school of thought was, in part, a reaction to the United States’ efforts to oppose national independence movements throughout Asia and Africa, which it framed as communist.[1] Developmentalism in the international economic context can be understood as consisting of a set of ideas which converge to place economic development at the center of political endeavors and institutions and also as a means through which to establish legitimacy in the political sphere. Adherents to the theory of developmentalism hold that the sustained economic progress grants legitimate leadership to political figures, especially in developing nations (in Latin America and East Asia) who would otherwise not have the benefit of a unanimous social consensus for their leadership or their international policy with regard to industrialized countries. Developmentalists believe that national autonomy for 'Third World' countries can be achieved and maintained through the utilization of external resources by those countries in a capitalist system. To those professed ends, developmentalism was the paradigm used in an attempt to reverse the negative impact that the international economy was having on developing countries in the 1950s–60s, at the time during which Latin American countries had begun to implement import substitution strategies. Using this theory, economic development was framed by modern-day Western criteria: economic success is gauged in terms of capitalistic notions of what it means for a country to become developed, autonomous, and legitimate.[2] The theory is based on the assumption that not only are there similar stages to development for all countries but also that there is a linear movement from one stage to another that goes from traditional or primitive to modern or industrialized.[3] Though initially the preserve of emerging economies in the Asia Pacific area, Latin America and Africa, the notion of developmentalism has resurfaced more recently in the developed world – notably in the economic planks of 'unorthodox' policy makers such as Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders in the United States.[4] |

開発主義[Developmentalism]とは、発展途上経済が成長する最善の方法は、強固で多様な国内

市場を育成し、輸入品に高い関税を課すことだと主張する経済理論である。 開発主義は学際的な思想潮流[1]であり、経済的繁栄への主要戦略として「開発」というイデオロギーを生み出した。この思想は、一部において、米国がアジ アやアフリカ全域で展開した民族独立運動への反対姿勢に対する反発として生まれた。米国はこうした運動を共産主義と位置づけていた[1]。国際経済の文脈 における開発主義は、経済発展を政治的取り組みや制度の中心に据える一連の思想として理解できる。また、政治領域における正当性を確立する手段としても機 能する。開発主義理論の支持者は、持続的な経済的進歩が政治指導者に正当な権威を与えると主張する。特にラテンアメリカや東アジアなどの発展途上国では、 そうでなければ指導者への社会的合意や先進国に対する国際政策の正当性を得られないと考える。開発主義者は、『第三世界』諸国が資本主義システムにおいて 外部資源を活用することで、国家の自律性を達成・維持できると信じる。こうした公言された目的のために、開発主義は1950~60年代に国際経済が発展途 上国に与えていた悪影響を逆転させようとする試みにおいて用いられたパラダイムであった。当時、ラテンアメリカ諸国は輸入代替戦略の実施を開始していた。 この理論を用いることで、経済発展は現代的な西洋基準によって枠組みづけられた。つまり、経済的成功は、国が発展し、自律的かつ正当な存在となることを意 味する資本主義的概念によって測定されるのである。[2] この理論は、全ての国に共通の発展段階が存在すること、そして伝統的あるいは原始的な段階から近代的あるいは工業化された段階へと直線的に移行するという 前提に基づいている。[3] 当初、アジア太平洋地域、ラテンアメリカ、アフリカの新興経済国に限定されていた開発主義の概念は、最近では先進国、特に米国のドナルド・トランプやバー ニー・サンダースといった「非正統派」の政策立案者たちの経済政策に再び登場している。[4] |

| Ideology and basic tenets There are four main ideas that are integrated behind the theory of developmentalism: First, there is the notion that the performance of a nation's economy is the central source of legitimacy that a regime may claim. Rather than subscribing to the notion, for example, that the ability to make and enforce laws gives a state power, developmentalists argue that the sustenance of economic growth and the subsequent promotion of citizens' welfare gives the general population incentive to support the regime in power, granting it both de facto and de jure legitimacy. The second tenet of developmentalism asserts that it is the role of regimes to use their governmental authority to spread out the risks associated with capitalist development, as well as to combine governmental and entrepreneurial wills in order to maximize the advancement of national interest.[5] Thirdly, developmentalism asserts that state bureaucrats become separated from politicians, which allows for the independent and successful redevelopments of leadership structures and administrative and bureaucratic procedures (when such changes become necessary). This separation is key to balancing the needs of the state and the importance of forming and maintaining strong international economic ties. The government, then, has the autonomy to deal with certain issues on a national level, while helping state bureaucrats maintain the internationalism necessary to develop the nation's economy. The final aspect of developmentalism's ideology deals with the idea that it is necessary for nations to utilize the capitalist system as a means of advancement in the international economy. Privileged positions in capitalist systems arise from active responses to external affairs in order to obtain the external resources with which to gain larger amounts of economic autonomy. The resources gained from active participation in international economic affairs help propel countries out of being exploited by capitalism to positions from which they can exploit the international economy for its own national gain.[6] |

イデオロギーと基本理念 開発主義理論の背景には、四つの主要な思想が統合されている: 第一に、国家の経済パフォーマンスこそが政権が主張し得る正当性の中心的な源泉であるという考え方がある。例えば、法律を制定し執行する能力が国家に権力 を与えるという見解に賛同するのではなく、開発主義者は、経済成長の維持とそれに伴う国民の福祉の促進こそが、一般大衆に現政権を支持する動機を与え、事 実上および法的な正当性の両方を政権に与えると主張する。 第二に、開発主義は、資本主義的発展に伴うリスクを分散させること、そして国家利益の最大化のために政府と企業の意思を統合することが体制の役割だと主張する。[5] 第三に、開発主義は国家官僚が政治家から分離されることで、指導体制や行政・官僚手続きの独立した再構築が可能になると主張する(そのような変更が必要と なった場合)。この分離こそが、国家の必要性と強固な国際経済関係の形成・維持の重要性とのバランスを取る鍵である。こうして政府は国家レベルで特定の問 題に対処する自律性を持ちつつ、国家官僚が国家経済を発展させるために必要なナショナリズムを維持するのを助けるのである。 開発主義のイデオロギーにおける最終的な側面は、国家が国際経済における発展の手段として資本主義システムを利用する必要性に関する考え方である。資本主 義システムにおける優位な立場は、より大きな経済的自律性を得るための外部資源を獲得するべく、対外関係に積極的に対応することで生まれる。国際経済活動 への積極的参加から得られる資源は、資本主義による搾取を受ける立場から脱却し、自国の利益のために国際経済を搾取できる立場へと国を押し上げる助けとな るのだ。[6] |

| History Tony Smith writes in his article Requiem or New Agenda for Third World Studies? about how developmentalism gained its footing in international affairs in the years immediately following World War II, during which the United States assumed leadership of a world that had been devastated by the war, while the United States was all but physically unscathed.[7] The end of Second World War catalyzed massive national liberation movements throughout Africa and Asia: these movements were a threat to the United States, in its fear that communism would take root in newly established independent nations. Therefore, these movements towards liberation became a top priority of the United States: developmentalism fit what the United States wanted very well, because its tenets create an environment of both national autonomy and widespread participation in the international economy. This participation would be in the capitalist form, so in promoting developmentalism, the United States was also promoting capitalism in newly independent nations. The school of developmentalist thought thrived on this sudden spike in support from the United States. Further, the school came to unite scholars from different social scientific disciplines under the umbrella of social ties and perceived common interest in the suppression of communism and gaining increasing influence on the politico-economic stage of the world. The ensuing 'Golden Age' of the developmentalist school began after 1945 and extended into the late 1960s. During the 1970s, however, the popularity and prevalence of developmentalism flickered and decreased. During the 1950s and 1960s, developmentalism in practice did much to promote prosperity in the Southern Cone (comprising parts of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay) and the Andean country of Chile. As noted by Naomi Klein, “[d]uring this dizzying period of expansion, the Southern Cone began to look more like Europe and North America than the rest of Latin America or other parts of the Third World.” Workers in new factories formed strong unions that negotiated middle-class salaries, and their children were sent off to study at newly constructed public universities. By the Fifties, Argentina had the largest middle class in South America, while Uruguay had a literacy rate of 95% and provided free health care to all its citizens.[8] |

歴史 トニー・スミスは論文『第三世界研究のレクイエムか、新たな課題か?』で、第二次世界大戦直後の国際情勢において開発主義が足場を固めた経緯を記してい る。この時代、米国は戦争で壊滅的な打撃を受けた世界の主導権を握ったが、自国は物理的にほとんど無傷だった。[7] 第二次世界大戦の終結は、アフリカとアジア全域で大規模な民族解放運動を触発した。これらの運動は、新たに独立した国々に共産主義が根付くことを恐れる米 国にとって脅威であった。したがって、解放に向けたこれらの運動は米国の最優先課題となった。開発主義はその理念が国家の自律性と国際経済への広範な参加 という環境を創出するため、米国の求めるものに非常に合致していた。この参加は資本主義の形態によるものだった。つまり開発主義を推進することで、米国は 新たに独立した国々への資本主義導入も同時に推進していたのである。開発主義思想の学派は、米国からのこの急激な支援拡大によって繁栄した。さらにこの学 派は、社会関係という共通の枠組みと、共産主義の抑圧および世界の政治経済舞台における影響力拡大という認識された共通利益の下で、異なる社会科学分野の 学者たちを結束させるに至った。 開発主義学派の「黄金時代」は1945年以降に始まり、1960年代後半まで続いた。しかし1970年代に入ると、開発主義の人気と普及は揺らぎ、衰退していった。 1950年代から1960年代にかけて、実践における開発主義は南米南部(ブラジル、アルゼンチン、ウルグアイの一部)とアンデス地域のチリにおいて繁栄 を促進する上で大きな役割を果たした。ナオミ・クラインが指摘するように、「この目まぐるしい拡大期に、南米南部は他のラテンアメリカ諸国や第三世界の地 域よりも、むしろヨーロッパや北米に似てきた」のである。新設工場の労働者は強力な労働組合を結成し、中産階級並みの賃金を交渉で勝ち取った。彼らの子供 たちは新設の公立大学へ進学した。1950年代までに、アルゼンチンは南米最大の中産階級を擁し、ウルグアイは識字率95%を達成し、国民全員に無料医療 を提供していた[8]。 |

| Goals Developmentalism attempts to codify the ways in which development is discussed on an international level. Through developmentalism, it is thought by its advocates that discussions about the economic development of the 'Third World' can be redesigned in such a way that everyone will use the same vocabulary to discuss the various phenomena of development. This way, societies can be discussed comparatively without the impediments associated with placing developmental disparities across nations in completely different categories of speech and thought. This increased uniformity of language would increase understanding and appreciation for the studies about development from different fields in the social sciences and allow freer and more productive communication about these studies. Before its decline in the 1970s, scholars had been optimistic that developmentalism could break down the barriers between the disciplines of social sciences when discussing the complexities of development. This school of thought produced such works as Talcott Parsons and Edward Shils's Toward A General Theory of Action; Clifford Geertz's Old Societies and New States; and Donald L.M. Blackmer and Max F. Millikan's The Emerging Nations.[9] |

目標 開発主義は、国際レベルで開発が議論される方法を体系化しようとする試みである。開発主義の支持者たちは、この手法を通じて「第三世界」の経済開発に関す る議論を再構築できると考えている。つまり、あらゆる人が開発の様々な現象を議論する際に同じ語彙を使用できるようにするのだ。こうすることで、国家間の 開発格差を全く異なる言語的・思考的カテゴリーに分類することに伴う障害なく、社会を比較検討できるようになる。この言語の統一性の向上は、社会科学の異 なる分野における開発研究への理解と評価を高め、これらの研究に関するより自由で生産的なコミュニケーションを可能にするだろう。1970年代に衰退する 前、学者たちは開発主義が開発の複雑性を議論する際に社会科学の学問分野間の障壁を打ち破れると楽観視していた。この学派はタルコット・パーソンズとエド ワード・シルズの『行動の一般理論に向けて』、クリフォード・ギアーツの『古い社会と新しい国家』、ドナルド・L・M・ブラックマーとマックス・F・ミリ カンの『新興諸国』といった著作を生み出した。[9] |

| Decline The model of developmentalism proved to have two major reasons for decline within the school: The model created a system that was too formal and structured, providing an ethnocentric and unilateral method for changing the third world. In this, developmentalists created plans for development that were mostly inflexible, as they relied heavily on the Western model of development as their primus modus. Western development, supposedly, held the keys to unlocking the door to the Global South’s development, and as such, could shed light on the changes that were occurring there. In doing so, however, the histories of the South were reduced into terms that could be applied to a model of development. This resulted in extremely rigid models in which labeled deviations from the conventional "traditional" (undeveloped) or "modern" (developed) society as dysfunctional, and to draw clear empirical distinctions between traditional and modern societies[10] A lack of cohesion within the models and the academic community itself. Developmentalist models attempted to create a universal system of development, and as such, resulted in methods that were too loose and incoherent to provide an accurate picture of the circumstances under which development could work in the Third World. Because of the vast amounts of difference in the cultures of the Global South, creating generalizations in which one theory of development was applicable to all settings became extremely difficult. Additionally, disagreement within the academic community itself and the lack of an obvious leader did not allow for internal cooperation. Many developmentalist scholars became disenchanted with the way in which the United States foreign policy was being implemented, especially during the Vietnam War and the Alliance for Progress. Intentions, as well, were not always non-partisan; many scholars had intended their writing to be policy-relevant in the spread of capitalism and an elite brand of democracy in the South, as well as in the struggle to block the spread of communism.[11] These problems eventually marked the decline of school of developmentalist theory in the late 1970s. Some scholars (such as Samuel Huntington and Jorge Domínguez) contend that this rise and fall is a predictable phenomenon that typifies the introduction of any theoretical paradigm to the trial phase: a surge in popularity is likely with such theories, followed by various stages of pausing and surging in their prevalence in international economies and politics. It is also a possibility that the failures of developmentalism in the 1970s resulted from a realization that, after twenty-five years, 'Third World' countries were still in the 'Third World,' despite efforts towards economic gain characterized by developmentalism. This view is elaborated on by Gabriel Almond, who asserts that the increasing number of developing countries that had turned to authoritarian regimes negated the optimism with which developmentalism had been embraced. The US policies, which incorporated the tenets of developmentalism, were, in the 1970s, increasingly being seen as harmful to the Third World in imperialistic ways, and thus the school entered into crisis.[12] |

衰退 開発主義のモデルは、学派内で衰退した二つの主要な理由を証明した。 このモデルは、第三世界を変えるための自民族中心的で一方的な手法を提供する、過度に形式的で構造化されたシステムを生み出した。 このため、開発主義者たちは主に柔軟性に欠ける開発計画を立案した。彼らは西欧型開発モデルを第一の規範として過度に依存したのである。西欧型開発は、グ ローバル・サウス(南半球諸国)の発展への扉を開く鍵を握っているとされ、それゆえ同地域で起きている変化を解明できるとされた。しかしその過程で、南半 球の歴史は開発モデルに適用可能な概念へと還元されてしまった。その結果、極めて硬直したモデルが生まれた。そこでは、従来の「伝統的」(未開発)または 「近代的」(開発済み)社会からの逸脱は機能不全とレッテルを貼られ、伝統社会と近代社会の間には明確な実証的区別が引かれた[10] モデル内部および学術コミュニティ自体における結束力の欠如。 開発主義モデルは普遍的な発展体系の構築を試みたが、その結果として生まれた手法は緩すぎて一貫性に欠け、第三世界における発展が機能し得る状況を正確に 描けなかった。グローバル・サウス諸国の文化には膨大な差異が存在したため、一つの発展理論があらゆる状況に適用可能とする一般化は極めて困難であった。 加えて、学術コミュニティ内部での意見の相違と明確な指導者の不在が、内部協力の妨げとなった。多くの開発主義学者は、特にベトナム戦争と進歩のための同 盟(Alliance for Progress)の時期に、米国外交政策の実施方法に幻滅した。意図もまた常に超党派的ではなかった。多くの学者は自らの著作が、南半球における資本主 義とエリート主義的民主主義の普及、そして共産主義拡大阻止の闘いにおいて政策関連性を持つことを意図していた。[11] こうした問題が最終的に1970年代後半の発展主義理論学派の衰退を決定づけた。一部の学者(サミュエル・ハンティントンやホルヘ・ドミンゲスなど)は、 この興隆と衰退は理論的パラダイムが試行段階に入る際の典型的な予測可能な現象だと主張する。つまり、こうした理論は一時的な人気急上昇を経て、国際経 済・政治における普及度において停滞と再浮上を繰り返す段階を経る可能性が高いというのだ。また、1970年代における開発主義の失敗は、25年を経ても 「第三世界」諸国が依然として「第三世界」に留まっているという現実認識に起因する可能性もある。開発主義的経済成長の努力にもかかわらず、である。この 見解はガブリエル・アーモンドによって展開され、開発主義が抱いた楽観主義を否定する形で、権威主義体制へ移行した途上国の増加が指摘されている。開発主 義の理念を取り入れた米国の政策は、1970年代において帝国主義的な方法で第三世界に有害であるとますます見なされるようになり、こうしてこの学派は危 機に陥ったのである。[12] |

| Partial revival in the developed world In the wake of the 2008–2012 Great Recession, the notion of developmentalism has somehow started to resurface, this time amongst "populist" politicians in the developed world, in association with some degree of mercantilism. In that perspective, the 'under-developed' jurisdictions that need to be protected and stimulated are no longer in the Southern Hemisphere but in the developed world itself, where pauperized states/regions such as Pennsylvania and the Great Lakes in the United States or parts of Northern France and Northern England are now suffering from the same kind of socioeconomic difficulties once found mostly in the Third World.[13] This unconventional use of the term is used to justify some degree of protectionism and industrial dirigisme e.g. in the context of Trumponomics in the United States:[13] "That [ideological] bravado endeared Donald Trump to millions of disenfranchised lower-middle-class voters across the Rust Belt and proved instrumental to his electoral victory in the fall [...] [He promised] to create 'millions of jobs' in America in the coming quarters. Not coincidentally, when it comes to investment destination, the president seems to have a preference for Pennsylvania, Upstate New York, Michigan, Wisconsin and Indiana: a new kind of capital stewardship for the era of self-seeking capitalism..." [14] |

先進国における部分的な復興 2008年から2012年にかけての大不況の後、開発主義という概念が再び浮上し始めた。今回は先進国の「ポピュリスト」政治家たちによって、ある程度の 重商主義と結びついて提唱されている。この観点では、保護と刺激を必要とする「未発達」地域はもはや南半球ではなく、先進国そのものにある。米国ペンシル ベニア州や五大湖地域、フランス北部やイングランド北部など貧困化した州・地域が、かつて主に第三世界でみられたのと同じ種類の社会経済的困難に苦悩して いるのだ。[13] この型破りな用語の使用は、ある程度の保護主義や産業統制主義を正当化するために用いられている。例えば、米国のトランプノミクスという文脈では、次のように述べられている。 「その(イデオロギー的な)虚勢が、ラストベルト地域に住む何百万人も の権利を剥奪された中流以下の有権者にドナルド・トランプを親しみやすい人物として受け入れさせ、秋の選挙での彼の勝利に大きく貢献した [...] [彼は] 今後数四半期でアメリカに「何百万もの雇用」を創出すると約束した。偶然ではないが、投資先に関しては、大統領はペンシルベニア州、ニューヨーク州北部、 ミシガン州、ウィスコンシン州、インディアナ州を好んでいるようだ。これは、自己利益追求型の資本主義の時代における、新しいタイプの資本管理であ る...」[14] |

| Examples Bretton-Woods (1944) International Development Association (1960) Truman’s Point Four (1949) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of OECD (1961) SUNFED (1958) UNDP (1965) These policies shifted focus from reconstruction to development to poverty reduction, created a demand for global development intervention and shift from exploitation to development U.S. aid programme, and created norms and statistics for international donors. |

例 ブレトン・ウッズ体制(1944年) 国際開発協会(1960年) トルーマンの四原則(1949年) OECD開発援助委員会(DAC) (1961) SUNFED (1958) UNDP (1965) これらの政策は、焦点を復興から開発、そして貧困削減へと移し、世界的な開発介入への需要を生み出した。また、米国の援助プログラムを搾取から開発へと転換させ、国際的な援助国向けの規範と統計を作成した。 |

| Criticism The implementation of developmentalist ideologies has been critiqued in multiple lights, both by the right and by the left. Developmentalism is often accused by the left (though not only by the left) of having an ideology of neocolonialism at its root. Developmentalist strategies use a Eurocentric viewpoint of development, a viewpoint that often goes hand in hand with the implication that non-European societies are underdeveloped. As such, it gives way for the perpetuation of Western dominance over such underdeveloped nations, in a neocolonialist fashion.[15] Developed nations such as the United States have been accused of seizing opportunities of disaster for their own benefit in what is known as disaster capitalism. Disaster capitalism, a term used by Naomi Klein, describes the process in which situations of financial crisis are used in order to force an emergency opening of the free market in order to regain economic stability. This happened in the examples of Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, and post-Katrina New Orleans, among others.[8] Developmentalist ideas also portray the Western ideal of development and democracy as an evolutionary course of history. In Eric Wolf’s book, Europe and the People without History, Wolf shows, through a long history of examples, that the Western world is only one of many visions of the world, and to view it as the pinnacle of a linear world evolutionary chain would be inaccurate.[16] Developmentalist strategies often implicate that history is on a unilateral path of evolution towards development, and that cultural derivations have little implication in the final product. From the right, critics say that developmentalist strategies deny the free market its autonomy. By creating a state controlled market economy, it takes away the organic nature in which a market is meant to be created. They argue that developmentalist strategies have not generally worked in the past, leaving many countries, in fact, worse off than they were before they began state-controlled development. This is due to a lack of freedom in the free market and its constrictive nature. In turn, it is argued, reactive totalitarian forces take hold of the government in response to Western intervention, such as Chávez's Venezuela and Ortega’s Nicaragua, creating even more complex problems for the Western vision of development.[17] Socio-anthropologists criticize the developmentalism as a form of social change implemented by an exogenous party. This creates what is called the developmentalist configuration.[18] |

批判 開発主義イデオロギーの実践は、右派からも左派からも様々な観点から批判されてきた。 開発主義は左派(左派だけではないが)から、その根底に新植民地主義のイデオロギーがあると非難されることが多い。開発主義的戦略は、非ヨーロッパ社会が 未発達であるという含意と密接に結びついた、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な開発観を用いる。したがって、それは新植民地主義的な手法で、こうした未発達諸国に対 する西洋の支配を永続させる余地を与えるのである[15]。アメリカ合衆国などの先進国は、いわゆる災害資本主義において、自らの利益のために災害の機会 を強奪していると非難されてきた。ナオミ・クラインが提唱した「災害資本主義」とは、金融危機の状況を悪用し、自由市場の緊急開放を強要することで経済安 定を回復するプロセスを指す。アルゼンチン、チリ、ボリビア、ハリケーン・カトリーナ後のニューオーリンズなどがその実例である[8]。開発主義思想はま た、西洋的な発展と民主主義の理想を、歴史の進化的な過程として描く。エリック・ウルフの著書『ヨーロッパと歴史なき民』では、長きにわたる事例を通じ て、西洋世界は数ある世界観の一つに過ぎず、それを直線的な世界進化の頂点と見なすのは誤りだと示されている[16]。開発主義的戦略は往々にして、歴史 が開発へ向けた一方的な進化の道を辿り、文化的差異は最終成果にほとんど影響を与えないと暗示する。 右派の批判によれば、開発主義戦略は自由市場の自律性を否定する。国家統制市場経済を創出することで、市場が本来持つ有機的性質を奪うのだ。彼らは、開発 主義戦略は過去において概して機能せず、多くの国々が国家統制開発を開始する前よりもむしろ悪化したと主張する。これは自由市場における自由の欠如と、そ の制約的な性質に起因する。これに対し、西側諸国の介入への反動として、チャベスのベネズエラやオルテガのニカラグアのように、反応的な全体主義勢力が政 府を掌握し、西側の発展構想にとってさらに複雑な問題を生み出すと反論される。[17] 社会人類学者は、開発主義を外部勢力によって実施される社会変革の一形態として批判する。これにより、いわゆる「開発主義的構成」が生み出される。[18] |

| Arthur Lewis Beijing Consensus Development economics Market intervention Neomercantilism Protectionism Structuralist economics |

アーサー・ルイス 北京コンセンサス 開発経済学 市場介入 新重商主義 保護主義 構造主義経済学 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Developmentalism |

★Development economics (開発経済学)

開発経済学[Development economics]は、低・中所得国における開発プロセスの経済的側面を扱う経済学の一分野である。その焦点は、経済開発・経済成長・構造転換を促進する方法だけでなく、公的・私的経路を問わず、健康・教育・職場環境などを通じて、大衆の潜在能力を向上させることにも置かれている。[1]開発経済学は、政策や実践の決定を支援し、国内レベルでも国際レベルでも実施可能な理論や方法の構築を伴う。[2] これには、市場インセンティブの再構築や、プロジェクト分析のための時間超越最適化といった数学的手法の活用、あるいは定量的・定性的手法の混合が含まれ る場合がある。[3] 一般的なテーマには、成長理論、貧困と不平等、人的資本、制度などが挙げられる。[4]他の多くの経済学分野とは異なり、開発経済学のアプローチでは特定の計画立案に社会的・政治的要因を取り入れることがある。[5] また他の分野と同様に、学生が習得すべき内容について共通認識は存在しない。[6] 異なるアプローチでは、世帯・地域・国家間の経済収斂または非収斂に寄与する要因を検討する。[7]

| Development economics

is a branch of economics that deals with economic aspects of the

development process in low- and middle- income countries. Its focus is

not only on methods of promoting economic development, economic growth

and structural change but also on improving the potential for the mass

of the population, for example, through health, education and workplace

conditions, whether through public or private channels.[1] Development economics involves the creation of theories and methods that aid in the determination of policies and practices and can be implemented at either the domestic or international level.[2] This may involve restructuring market incentives or using mathematical methods such as intertemporal optimization for project analysis, or it may involve a mixture of quantitative and qualitative methods.[3] Common topics include growth theory, poverty and inequality, human capital, and institutions.[4] Unlike in many other fields of economics, approaches in development economics may incorporate social and political factors to devise particular plans.[5] Also unlike many other fields of economics, there is no consensus on what students should know.[6] Different approaches may consider the factors that contribute to economic convergence or non-convergence across households, regions, and countries.[7] |

開発経済学[Development economics]は、低・中所得国における開発プロセスの経済的側面を扱う経済学の一分野である。その焦点は、経済開発・経済成長・構造転換を促進する方法だけでなく、公的・私的経路を問わず、健康・教育・職場環境などを通じて、大衆の潜在能力を向上させることにも置かれている。[1] 開発経済学は、政策や実践の決定を支援し、国内レベルでも国際レベルでも実施可能な理論や方法の構築を伴う。[2] これには、市場インセンティブの再構築や、プロジェクト分析のための時間超越最適化といった数学的手法の活用、あるいは定量的・定性的手法の混合が含まれ る場合がある。[3] 一般的なテーマには、成長理論、貧困と不平等、人的資本、制度などが挙げられる。[4] 他の多くの経済学分野とは異なり、開発経済学のアプローチでは特定の計画立案に社会的・政治的要因を取り入れることがある。[5] また他の分野と同様に、学生が習得すべき内容について共通認識は存在しない。[6] 異なるアプローチでは、世帯・地域・国家間の経済収斂または非収斂に寄与する要因を検討する。[7] |

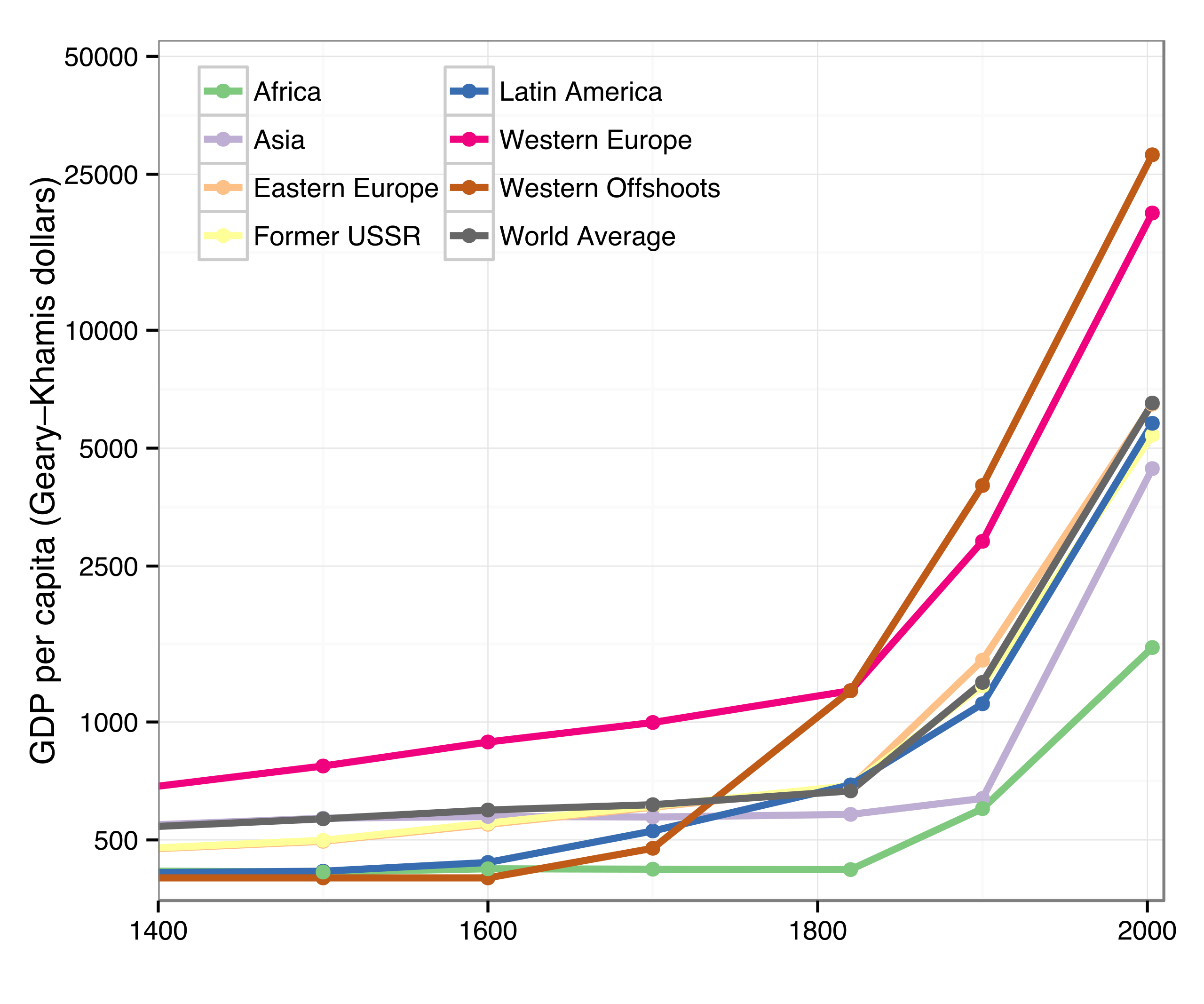

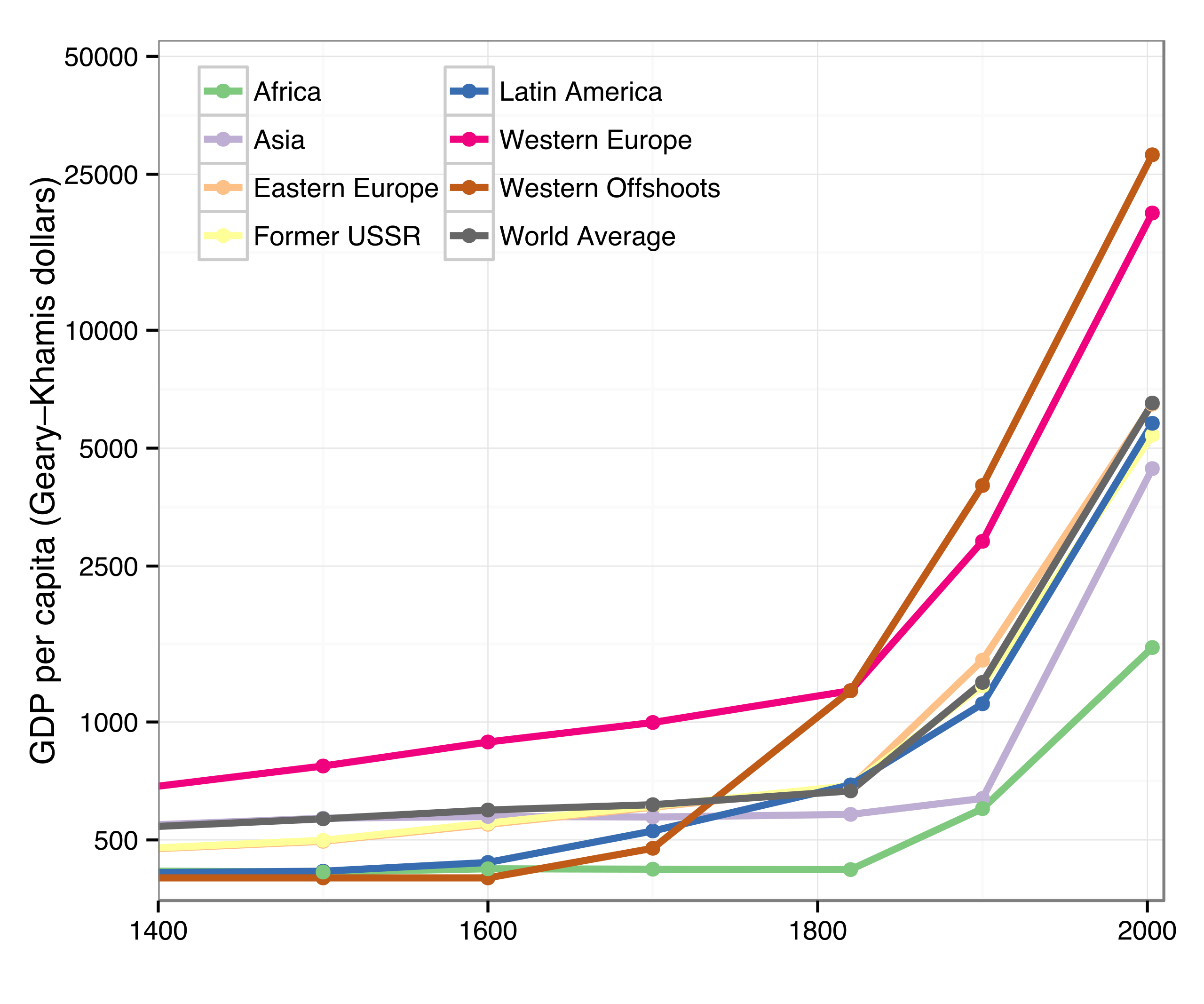

| Theories of development economics Mercantilism and physiocracy  World GDP per capita, from 1400 to 2003 CE Main article: Mercantilism The earliest Western theory of development economics was mercantilism, which developed in the 17th century, paralleling the rise of the nation state. Earlier theories had given little attention to development. For example, scholasticism, the dominant school of thought during medieval feudalism, emphasized reconciliation with Christian theology and ethics, rather than development. The 16th- and 17th-century School of Salamanca, credited as the earliest modern school of economics, likewise did not address development specifically. Major European nations in the 17th and 18th centuries all adopted mercantilist ideals to varying degrees, the influence only ebbing with the 18th-century development of physiocrats in France and classical economics in Britain. Mercantilism held that a nation's prosperity depended on its supply of capital, represented by bullion (gold, silver, and trade value) held by the state. It emphasised the maintenance of a high positive trade balance (maximising exports and minimising imports) as a means of accumulating this bullion. To achieve a positive trade balance, protectionist measures such as tariffs and subsidies to home industries were advocated. Mercantilist development theory also advocated colonialism. Theorists most associated with mercantilism include Philipp von Hörnigk, who in his Austria Over All, If She Only Will of 1684 gave the only comprehensive statement of mercantilist theory, emphasizing production and an export-led economy.[8] In France, mercantilist policy is most associated with 17th-century finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, whose policies proved influential in later American development. Mercantilist ideas continue in the theories of economic nationalism and neomercantilism. |

開発経済学の理論 重商主義と重農主義  世界一人当たりGDP(西暦1400年から2003年) 主な記事:重商主義 西洋における最も初期の開発経済学理論は重商主義であり、17世紀に国家の台頭と並行して発展した。それ以前の理論は開発にほとんど注目していなかった。 例えば中世封建制下で主流だったスコラ哲学は、発展よりもキリスト教神学や倫理との調和を重視した。16~17世紀のサラマンカ学派は近代経済学の始祖と されるが、同様に発展を特に対象としなかった。 17世紀から18世紀にかけての主要なヨーロッパ諸国は、程度の差こそあれ皆重商主義の理念を採用した。その影響力は、18世紀にフランスで重農主義が、 イギリスで古典派経済学が発展するにつれてようやく衰え始めた。重商主義は、国家の繁栄は国家が保有する貴金属(金、銀、貿易価値)に代表される資本の供 給量に依存すると主張した。この貴金属を蓄積する手段として、高い貿易黒字(輸出の最大化と輸入の最小化)の維持を重視した。貿易黒字を達成するため、関 税や国内産業への補助金といった保護主義的措置が提唱された。重商主義の発展理論は植民地主義も支持した。 重商主義と最も関連が深い理論家には、フィリップ・フォン・ヘルニヒクがいる。彼は1684年の『オーストリアが望むならば、オーストリアがすべてを支配 する』において、重商主義理論の唯一の包括的な声明を発表し、生産と輸出主導型経済を強調した[8]。フランスでは、重商主義政策は17世紀の財務大臣 ジャン=バティスト・コルベールと最も関連が深く、彼の政策は後のアメリカの発展に大きな影響を与えた。 重商主義的思想は、経済ナショナリズムや新重商主義の理論において継続している。 |

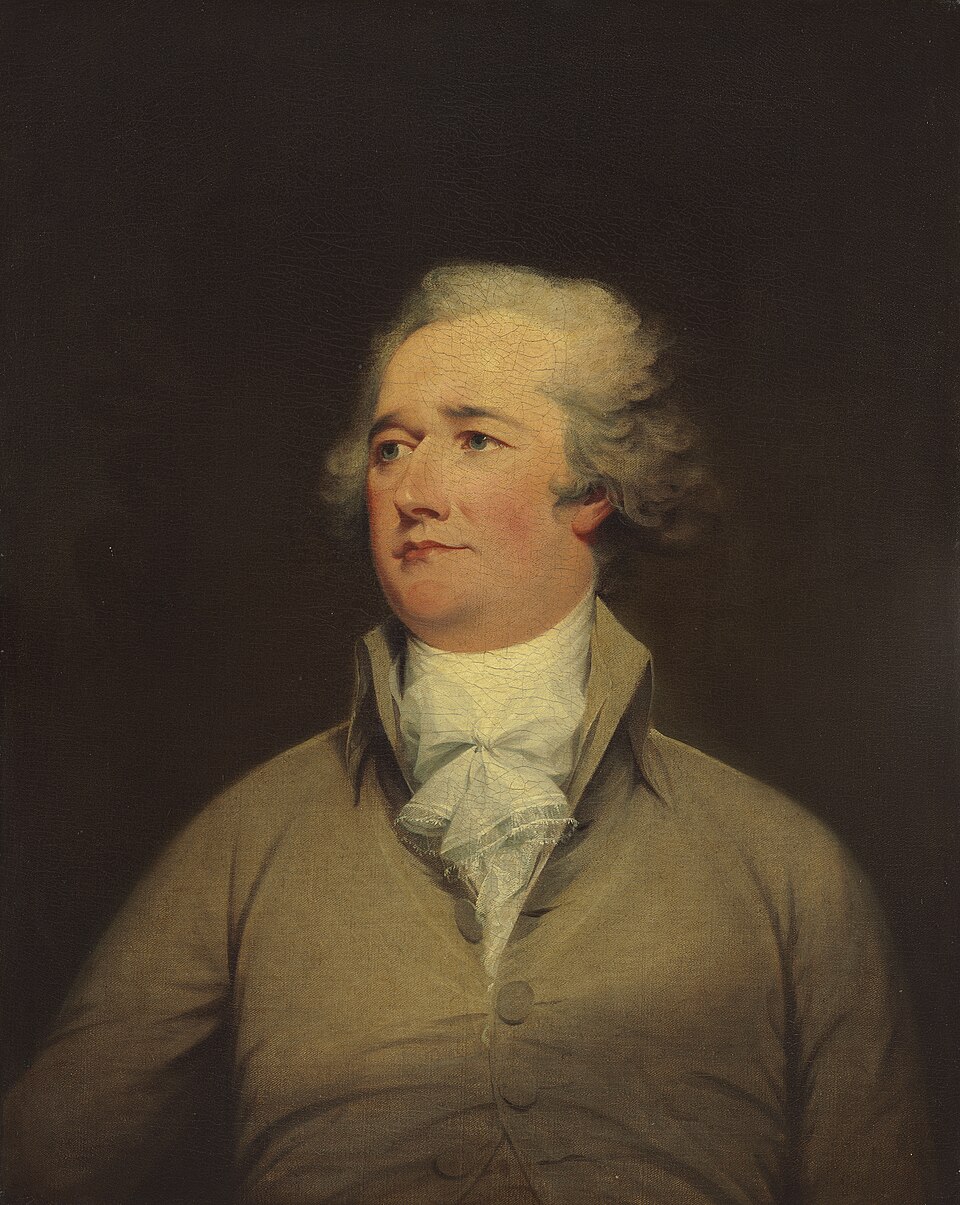

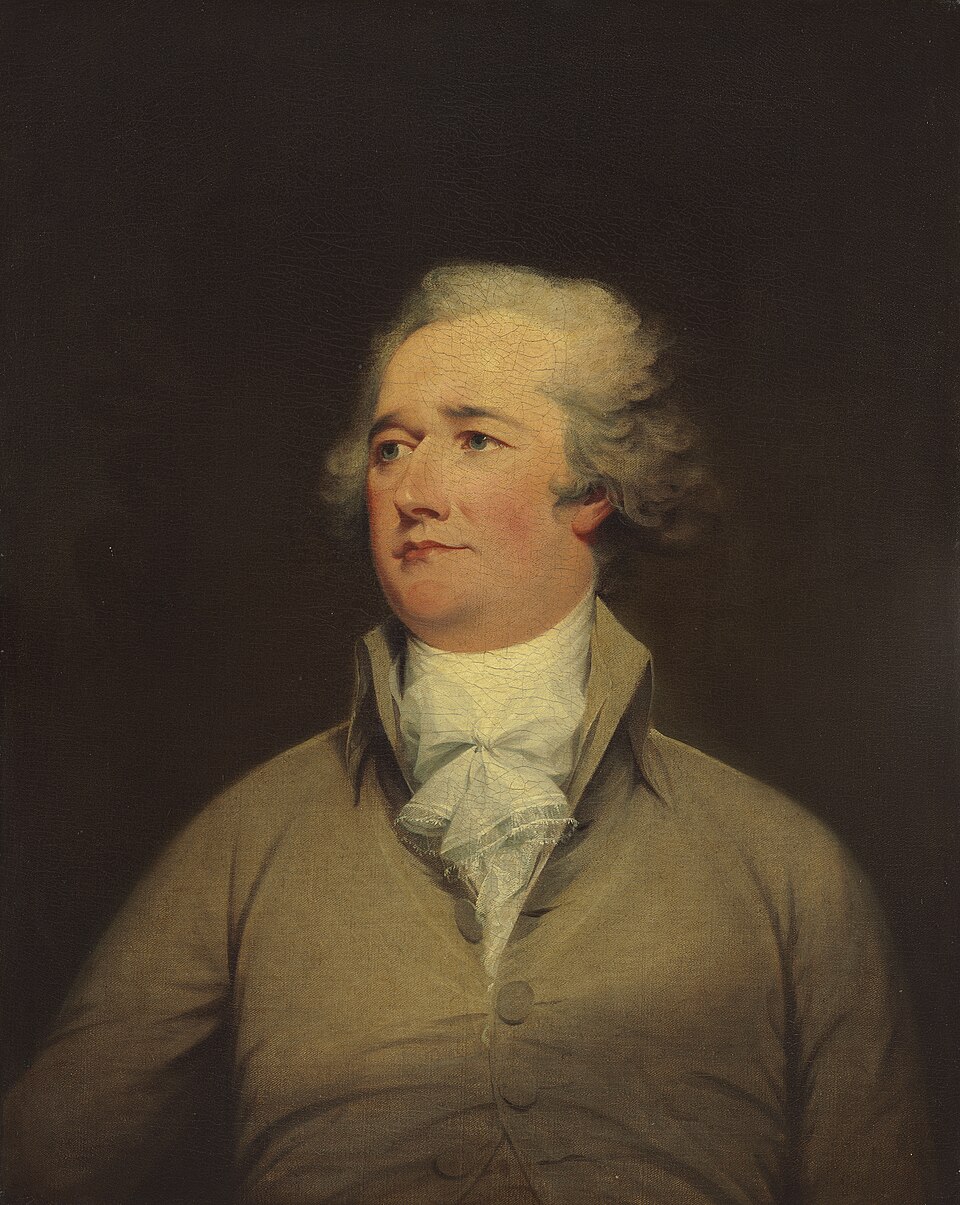

Economic nationalism Alexander Hamilton, credited as Father of the National System Main article: Economic nationalism Following mercantilism was the related theory of economic nationalism, promulgated in the 19th century related to the development and industrialization of the United States and Germany, notably in the policies of the American System in America and the Zollverein (customs union) in Germany. A significant difference from mercantilism was the de-emphasis on colonies, in favor of a focus on domestic production. The names most associated with 19th-century economic nationalism are the first United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, the German-American Friedrich List, and the American politician Henry Clay. Hamilton's 1791 Report on Manufactures, his magnum opus, is the founding text of the American System, and drew from the mercantilist economies of Britain under Elizabeth I and France under Colbert. List's 1841 Das Nationale System der Politischen Ökonomie (translated into English as The National System of Political Economy), which emphasized stages of growth. Hamilton professed that developing an industrialized economy was impossible without protectionism because import duties are necessary to shelter domestic "infant industries" until they could achieve economies of scale.[9] Such theories proved influential in the United States, with much higher American average tariff rates on manufactured products between 1824 and the WWII period than most other countries,[10] Nationalist policies, including protectionism, were pursued by Clay, and later by Abraham Lincoln, under the influence of economist Henry Charles Carey. Forms of economic nationalism and neomercantilism have also been key in Japan's development in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the more recent development of the Four Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore), and, most significantly, China. Following Brexit and the 2016 United States presidential election, some experts have argued a new kind of "self-seeking capitalism" popularly known as Trumponomics could have a considerable impact on cross-border investment flows and long-term capital allocation[11][12] |

経済ナショナリズム アレクサンダー・ハミルトン、国家システムの父として知られる 主な記事:経済ナショナリズム 重商主義に続いて、19 世紀に米国とドイツの成長と工業化に関連して、特に米国のアメリカン・システムとドイツの関税同盟(Zollverein)の政策において、経済ナショナ リズムという関連理論が公布された。重商主義との大きな違いは、植民地よりも国内生産に重点を置いた点である。 19世紀の経済ナショナリズムに最も関連のある人物は、初代米国財務長官アレクサンダー・ハミルトン、ドイツ系アメリカ人のフリードリヒ・リスト、そして アメリカの政治家ヘンリー・クレイである。ハミルトンの1791年の『製造業に関する報告書』は、彼の代表作であり、アメリカシステムの基礎となる文書で あり、エリザベス1世下のイギリスとコルベール下のフランスの重商主義経済から着想を得たものである。リストの1841年の『政治経済学の国家システム』 (英語に翻訳され『The National System of Political Economy』)は、成長の段階を強調した。ハミルトンは、保護主義なしでは工業化経済の発展は不可能だと主張した。なぜなら、国内の「乳児産業」が規 模の経済を達成するまでは、輸入関税によって保護する必要があるからだ。こうした理論は米国で影響力があり、1824年から第二次世界大戦までの間、米国 の製造品に対する平均関税率は他のほとんどの国よりもはるかに高かった。保護主義を含むナショナリスト政策は、経済学者ヘンリー・チャールズ・ケアリーの 影響を受けて、クレイ、そして後にエイブラハム・リンカーンによって追求された。 経済ナショナリズムと新重商主義の形態は、19 世紀から 20 世紀にかけての日本の発展、そしてより最近ではアジアの 4 つの虎(香港、韓国、台湾、シンガポール)、そして最も重要な中国の発展においても重要な役割を果たしてきた。 ブレグジットと2016年アメリカ大統領選挙後、一部の専門家は「自己利益追求型資本主義」として知られるトランプノミクスが、国境を越えた投資の流れと長期的な資本配分に大きな影響を与える可能性があると主張している[11][12] |

| Post-WWII theories See also: Industrial development and Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory The origins of modern development economics are often traced to the need for, and likely problems with the industrialization of eastern Europe in the aftermath of World War II.[13] The key authors are Paul Rosenstein-Rodan,[14] Kurt Mandelbaum,[15] Ragnar Nurkse,[16] and Sir Hans Wolfgang Singer. Only after the war did economists turn their concerns towards Asia, Africa, and Latin America. At the heart of these studies, by authors such as Simon Kuznets and W. Arthur Lewis[17] was an analysis of not only economic growth but also structural transformation.[18] Linear-stages-of-growth model See also: Rostow's stages of growth An early theory of development economics, the linear-stages-of-growth model was first formulated in the 1950s by W. W. Rostow in The Stages of Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto, following work of Marx and List. This theory modifies Marx's stages theory of development and focuses on the accelerated accumulation of capital, through the utilization of both domestic and international savings as a means of spurring investment, as the primary means of promoting economic growth and, thus, development.[5] The linear-stages-of-growth model posits that there are a series of five consecutive stages of development that all countries must go through during the process of development. These stages are "the traditional society, the pre-conditions for take-off, the take-off, the drive to maturity, and the age of high mass-consumption"[19] Simple versions of the Harrod–Domar model provide a mathematical illustration of the argument that improved capital investment leads to greater economic growth.[5] Such theories have been criticized for not recognizing that, while necessary, capital accumulation is not a sufficient condition for development. That is to say that this early and simplistic theory failed to account for political, social, and institutional obstacles to development. Furthermore, this theory was developed in the early years of the Cold War and was largely derived from the successes of the Marshall Plan. This has led to the major criticism that the theory assumes that the conditions found in developing countries are the same as those found in post-WWII Europe.[5] |

第二次世界大戦後の理論 関連項目:産業発展とラグナー・ヌルクセの均衡成長理論 現代の開発経済学の起源は、第二次世界大戦後の東欧における工業化の必要性と、おそらく生じた問題に求められることが多い。[13] 主な著者はポール・ローゼンシュタイン=ロダン[14]、クルト・マンデルバウム[15]、ラグナー・ヌルクセ[16]、サー・ハンス・ヴォルフガング・ シンガーである。経済学者がアジア、アフリカ、ラテンアメリカに関心を向けるようになったのは戦後になってからだった。サイモン・クズネッツやW・アー サー・ルイス[17]らによるこれらの研究の中核には、経済成長だけでなく構造転換の分析があった。[18] 線形成長段階モデル 関連項目: ロストウの成長段階論 開発経済学の初期理論である線形成長段階モデルは、マルクスやリストの研究を踏まえ、1950年代にW・W・ロストウが『成長の段階:非共産主義宣言』で 初めて提唱した。この理論はマルクスの発展段階論を修正し、経済成長および発展を促進する主要な手段として、投資を刺激する手段としての国内外の貯蓄の活 用を通じた資本の加速的蓄積に焦点を当てる[5]。直線的成長段階モデルは、発展過程において全ての国が通過しなければならない連続した五つの発展段階が 存在すると仮定する。これらの段階は「伝統社会、離陸の前提条件、離陸、成熟への推進、大量消費の時代」である[19]。ハロッド=ドマーモデルの簡略版 は、資本投資の改善がより大きな経済成長をもたらすという主張を数学的に示すものである[5]。 こうした理論は、資本蓄積が発展にとって必要ではあるが十分条件ではないという点を認識していないとして批判されてきた。つまり、この初期の単純化された 理論は、発展に対する政治的・社会的・制度的障害を考慮していなかった。さらに、この理論は冷戦の初期に構築され、主にマーシャルプランの成功から導かれ たものである。このため、発展途上国における条件が第二次世界大戦後のヨーロッパと同じであると仮定しているという重大な批判が寄せられている[5]。 |

| Structural change theory Structural change theory, or what is commonly known today as structural transformation was proposed by economist Sir Arthur Lewis in his seminal 1954 work, Economic Development with Unlimited Supply of Labor. Structural transformation is the process by which developing countries, composed primarily of subsistence agriculture labor, will shift towards more modern, urban and productive industrial work in both manufacturing and services. Over time this shift should bring substantial gains in the form of economic growth. After traveling to the Caribbean, Lewis proposed a two-sector model, in which surplus labor moves out of agriculture and into industry as a country's population continues to grow.[20] The purpose of this model is to show that economic growth comes at a time in a country's development trajectory when subsistence farmers move into the industrial sector in which capital is deployed and productivity is improved. Later on Hollis Chenery's Patterns of Development approach, which holds that different countries become wealthy via different trajectories. The pattern that a particular country will follow, in this framework, depends on its size and resources, and potentially other factors including its current income level and comparative advantages relative to other nations.[21][22] Empirical analysis in this framework studies the "sequential process through which the economic, industrial, and institutional structure of an underdeveloped economy is transformed over time to permit new industries to replace traditional agriculture as the engine of economic growth."[5] Structural change approaches to development economics have faced criticism for their emphasis on urban development at the expense of rural development which can lead to a substantial rise in inequality between internal regions of a country. The two-sector surplus model, which was developed in the 1950s, has been further criticized for its underlying assumption that predominantly agrarian societies suffer from a surplus of labor. Actual empirical studies have shown that such labor surpluses are only seasonal and drawing such labor to urban areas can result in a collapse of the agricultural sector. The patterns of development approach has been criticized for lacking a theoretical framework.[5][citation needed] |

構造転換理論 構造転換理論、すなわち今日一般的に構造転換として知られる概念は、経済学者サー・アーサー・ルイスが1954年の画期的な著作『労働力無制限の経済発 展』で提唱したものである。構造転換とは、主に自給農業労働で構成される発展途上国が、製造業とサービス業の両分野において、より近代的で都市的かつ生産 性の高い産業労働へと移行する過程を指す。この移行は時間の経過とともに、経済成長という形で大きな利益をもたらすはずである。 カリブ海地域を視察した後、ルイスは二部門モデルを提唱した。このモデルでは、人口が増加し続けるにつれて余剰労働力が農業から産業へ移行する[20]。 このモデルの目的は、経済成長が、自給自足農民が資本が投入され生産性が向上する産業部門へ移行する、国の発展軌道の特定の時期に訪れることを示すことに ある。 その後、ホリス・チェナリーの「発展のパターン」アプローチが登場した。これは、異なる国々が異なる軌跡を経て豊かになるという考え方である。この枠組み では、特定の国がたどるパターンはその規模や資源、さらに現在の所得水準や他国との比較優位性など、他の要因にも依存する。[21][22] この枠組みにおける実証分析は、 「未発達経済の経済的・産業的・制度的構造が、時間をかけて変容し、新たな産業が伝統的農業に取って代わり経済成長の原動力となる過程」を分析対象とする。[5] 開発経済学における構造転換アプローチは、農村開発を犠牲にして都市開発を重視する点で批判に直面してきた。これは国内地域間の格差を著しく拡大させる恐 れがある。1950年代に構築された二部門剰余モデルは、主に農業社会が労働力過剰によって苦悩しているという前提を暗に含んでいる点でさらに批判されて いる。実際の実証研究では、こうした労働力過剰は季節的なものに過ぎず、都市部へ労働力を引き込むことは農業部門の崩壊を招きうることを示している。発展 のパターン論は理論的枠組みを欠いていると批判されている。[5][出典が必要] |

| International dependence theory International dependence theories gained prominence in the 1970s as a reaction to the failure of earlier theories to lead to widespread successes in international development. Unlike earlier theories, international dependence theories have their origins in developing countries and view obstacles to development as being primarily external in nature, rather than internal. These theories view developing countries as being economically and politically dependent on more powerful, developed countries that have an interest in maintaining their dominant position. There are three different, major formulations of international dependence theory: neocolonial dependence theory, the false-paradigm model, and the dualistic-dependence model. The first formulation of international dependence theory, neocolonial dependence theory, has its origins in Marxism and views the failure of many developing nations to undergo successful development as being the result of the historical development of the international capitalist system.[5] |

従属理論 従属理論は、1970年代に台頭した。これは、それまでの理論が国際開発において広範な成功をもたらさなかったことへの反動として生まれた。従来の理論と は異なり、従属理論は発展途上国に起源を持ち、開発の障害を主に内部的ではなく外部的なものと見なす。これらの理論は、発展途上国が経済的・政治的に、自 らの優位な立場を維持する利害を持つより強力な先進国に依存していると考える。従属理論には主に三つの異なる枠組みがある:新植民地依存理論、誤ったパラ ダイムモデル、二元的依存モデルである。最初の枠組みである新植民地依存理論はマルクス主義に起源を持ち、多くの発展途上国が成功した発展を遂げられな かったのは、国際資本主義システムの歴史的発展の結果であると見なしている。[5] |

| Neoclassical theory First gaining prominence with the rise of several conservative governments in the developed world during the 1980s, neoclassical theories represent a radical shift away from International Dependence Theories. Neoclassical theories argue that governments should not intervene in the economy; in other words, these theories are claiming that an unobstructed free market is the best means of inducing rapid and successful development. Competitive free markets unrestrained by excessive government regulation are seen as being able to naturally ensure that the allocation of resources occurs with the greatest efficiency possible and that economic growth is raised and stabilized.[5][citation needed] There are several different approaches within the realm of neoclassical theory, each with subtle, but important, differences in their views regarding the extent to which the market should be left unregulated. These different takes on neoclassical theory are the free market approach, public-choice theory, and the market-friendly approach. Of the three, both the free-market approach and public-choice theory contend that the market should be totally free, meaning that any intervention by the government is necessarily bad. Public-choice theory is arguably the more radical of the two with its view, closely associated with libertarianism, that governments themselves are rarely good and therefore should be as minimal as possible.[5] Academic economists have given varied policy advice to governments of developing countries. See for example, Economy of Chile (Arnold Harberger), Economic history of Taiwan (Sho-Chieh Tsiang). Anne Krueger noted in 1996 that success and failure of policy recommendations worldwide had not consistently been incorporated into prevailing academic writings on trade and development.[5] The market-friendly approach, unlike the other two, is a more recent development and is often associated with the World Bank. This approach still advocates free markets but recognizes that there are many imperfections in the markets of many developing nations and thus argues that some government intervention is an effective means of fixing such imperfections.[5] |

新古典派理論 1980年代に先進国で保守政権が台頭したことで注目を集めた新古典派理論は、従属理論からの根本的な転換を表している。新古典派理論は、政府が経済に介 入すべきではないと主張する。言い換えれば、これらの理論は、妨げられない自由市場こそが迅速かつ成功した発展を促す最良の手段だと主張しているのだ。過 剰な政府規制に縛られない競争的な自由市場は、資源配分が可能な限り効率的に行われ、経済成長が促進・安定化することを自然に保証できると見なされてい る。[5][出典が必要] 新古典派理論の領域内にはいくつかの異なるアプローチが存在し、市場をどの程度規制せずに放置すべきかについての見解に、微妙だが重要な差異がある。新古 典派理論の異なる解釈として、自由市場アプローチ、公共選択理論、市場友好型アプローチが挙げられる。このうち自由市場アプローチと公共選択理論は、市場 は完全に自由であるべきだと主張する。つまり政府による介入はいかなる形でも悪影響を及ぼすという立場だ。公共選択理論はリバタリアニズムと密接に関連 し、政府自体が善であることは稀であるため、可能な限り最小限にすべきだという見解から、両者の中でより急進的だと言える。[5] 学術経済学者は発展途上国の政府に対し様々な政策提言を行ってきた。例えばチリの経済(アーノルド・ハーバーガー)、台湾の経済史(シャン・ショウチェ) を参照のこと。アン・クルーガーは1996年に、世界的な政策提言の成否が一貫して貿易と開発に関する主流の学術文献に反映されていないと指摘している。 [5] 市場重視のアプローチは、他の二つとは異なり比較的新しい発展であり、しばしば世界銀行と結びつけられる。このアプローチは依然として自由市場を提唱する が、多くの発展途上国の市場には多くの欠陥があることを認め、したがって政府による一定の介入がそうした欠陥を修正する効果的な手段であると主張する。 [5] |

| National development continuum theory This approach recognizes patterns across time and geographies to achieve certain standards of living across different sectors of the economy on a continuum, using wealth as a means to solve problems rather than an end in itself, recognizing that many high-income countries simultaneously experience a level of poverty elsewhere in the economy, while some lesser “developed” ones seem to achieve better outcomes on other measures. It also highlights that much like human development, real experiences are usually non-linear and use multiple trajectories. Author Joy D’Angelo describes it this way: “Our goals as humans may remain largely unchanged, even if periods of violence, conflict, poverty and change punctuate the journey. Also like we judge humans based on certain “achievements” like marriage, reproduction, knowledge accumulation or wisdom, the theory posits a framework to locate where a country might be on a “map”, and inspire leaders on where to make changes to unlock economic potential.” One of the first developed by a practitioner, the theory came from designing a tool[23] that external consultants could use for their own work, and to empower their national partners to identify and own their next steps. |

国家発展連続体理論 このアプローチは、経済の異なる分野において一定の生活水準を達成するための時間と地理を超えたパターンを認識する。富を目的そのものではなく問題解決の 手段として用い、多くの高所得国が経済の他の分野で貧困レベルを同時に経験している一方で、より「発展途上」とされる国々が他の指標ではより良い成果を上 げていることを認める。また、人間開発と同様に、実際の経験は通常非線形で複数の軌跡をたどることを強調する。 著者ジョイ・ダンジェロはこう説明する:「暴力や紛争、貧困、変革の時期が旅路を彩っても、人間の目標は概ね変わらない。結婚や子孫繁栄、知識蓄積、知恵 といった『達成』で人間を評価するように、この理論は国家が『地図』上のどこに位置するかを特定し、経済的可能性を解き放つための変革方向を指導者に示唆 する枠組みを提供する」 実務家によって最初に開発された理論の一つであり、外部コンサルタントが自らの業務に活用し、また国内のパートナーが自らの次のステップを特定し主体的に進める力を与えるためのツール[23]を設計する過程から生まれた。 |

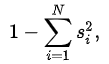

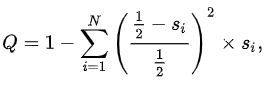

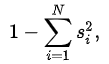

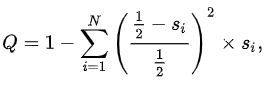

| Topics of research Development economics also includes topics such as third world debt, and the functions of such organisations as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. In fact, the majority of development economists are employed by, do consulting with, or receive funding from institutions like the IMF and the World Bank.[24] Many such economists are interested in ways of promoting stable and sustainable growth in poor countries and areas, by promoting domestic self-reliance and education in some of the lowest income countries in the world. Where economic issues merge with social and political ones, it is referred to as development studies. Geography and development Economists Jeffrey D. Sachs, Andrew Mellinger, and John Gallup argue that a nation's geographical location and topography are key determinants and predictors of its economic prosperity.[25] Areas developed along the coast and near "navigable waterways" are far wealthier and more densely populated than those further inland. Furthermore, countries outside the tropic zones, which have more temperate climates, have also developed considerably more than those located within the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. These climates outside the tropic zones, described as "temperate-near," hold roughly a quarter of the world's population and produce more than half of the world's GNP, yet account for only 8.4% of the world's inhabited area.[25] Understanding of these different geographies and climates is imperative, they argue, because future aid programs and policies to facilitate economic development must account for these differences. Economic development and ethnicity A growing body of research has been emerging among development economists since the very late 20th century focusing on interactions between ethnic diversity and economic development, particularly at the level of the nation-state. While most research looks at empirical economics at both the macro and the micro level, this field of study has a particularly heavy sociological approach. The more conservative branch of research focuses on tests for causality in the relationship between different levels of ethnic diversity and economic performance, while a smaller and more radical branch argues for the role of neoliberal economics in enhancing or causing ethnic conflict. Moreover, comparing these two theoretical approaches brings the issue of endogeneity (endogenicity) into questions. This remains a highly contested and uncertain field of research, as well as politically sensitive, largely due to its possible policy implications. The role of ethnicity in economic development Much discussion among researchers centers around defining and measuring two key but related variables: ethnicity and diversity. It is debated whether ethnicity should be defined by culture, language, or religion. While conflicts in Rwanda were largely along tribal lines, Nigeria's string of conflicts is thought to be – at least to some degree – religiously based.[26] Some have proposed that, as the saliency of these different ethnic variables tends to vary over time and across geography, research methodologies should vary according to the context.[27] Somalia provides an interesting example. Due to the fact that about 85% of its population defined themselves as Somali, Somalia was considered to be a rather ethnically homogeneous nation.[27] However, civil war caused ethnicity (or ethnic affiliation) to be redefined according to clan groups.[27] There is also much discussion in academia concerning the creation of an index for "ethnic heterogeneity". Several indices have been proposed in order to model ethnic diversity (with regards to conflict). Easterly and Levine have proposed an ethno-linguistic fractionalization index defined as FRAC or ELF defined by:  where si is size of group i as a percentage of total population.[27] The ELF index is a measure of the probability that two randomly chosen individuals belong to different ethno-linguistic groups.[27] Other researchers have also applied this index to religious rather than ethno-linguistic groups.[28] Though commonly used, Alesina and La Ferrara point out that the ELF index fails to account for the possibility that fewer large ethnic groups may result in greater inter-ethnic conflict than many small ethnic groups.[27] More recently, researchers such as Montalvo and Reynal-Querol, have put forward the Q polarization index as a more appropriate measure of ethnic division.[29] Based on a simplified adaptation of a polarization index developed by Esteban and Ray, the Q index is defined as  where si once again represents the size of group i as a percentage of total population, and is intended to capture the social distance between existing ethnic groups within an area.[29] Early researchers, such as Jonathan Pool, considered a concept dating back to the account of the Tower of Babel: that linguistic unity may allow for higher levels of development.[30] While pointing out obvious oversimplifications and the subjectivity of definitions and data collection, Pool suggested that we had yet to see a robust economy emerge from a nation with a high degree of linguistic diversity.[30] In his research Pool used the "size of the largest native-language community as a percentage of the population" as his measure of linguistic diversity.[30] Not much later, however, Horowitz pointed out that both highly diverse and highly homogeneous societies exhibit less conflict than those in between.[31] Similarly, Collier and Hoeffler provided evidence that both highly homogenous and highly heterogeneous societies exhibit lower risk of civil war, while societies that are more polarized are at greater risk.[32] As a matter of fact, their research suggests that a society with only two ethnic groups is about 50% more likely to experience civil war than either of the two extremes.[32] Nonetheless, Mauro points out that ethno-linguistic fractionalization is positively correlated with corruption, which in turn is negatively correlated with economic growth.[33] Moreover, in a study on economic growth in African countries, Easterly and Levine find that linguistic fractionalization plays a significant role in reducing national income growth and in explaining poor policies.[34][35] In addition, empirical research in the U.S., at the municipal level, has revealed that ethnic fractionalization (based on race) may be correlated with poor fiscal management and lower investments in public goods.[36] Finally, more recent research would propose that ethno-linguistic fractionalization is indeed negatively correlated with economic growth while more polarized societies exhibit greater public consumption, lower levels of investment and more frequent civil wars.[34] Economic development and its impact on ethnic conflict Increasingly, attention is being drawn to the role of economics in spawning or cultivating ethnic conflict. Critics of earlier development theories, mentioned above, point out that "ethnicity" and ethnic conflict cannot be treated as exogenous variables.[37] There is a body of literature that discusses how economic growth and development, particularly in the context of a globalizing world characterized by free trade, appears to be leading to the extinction and homogenization of languages.[38] Manuel Castells asserts that the "widespread destructuring of organizations, delegitimation of institutions, fading away of major social movements, and ephemeral cultural expressions" which characterize globalization lead to a renewed search for meaning; one that is based on identity rather than on practices.[39] Barber and Lewis argue that culturally-based movements of resistance have emerged as a reaction to the threat of modernization (perceived or actual) and neoliberal development.[40][41] On a different note, Chua suggests that ethnic conflict often results from the envy of the majority toward a wealthy minority which has benefited from trade in a neoliberal world.[37] She argues that conflict is likely to erupt through political manipulation and the vilification of the minority.[37] Prasch points out that, as economic growth often occurs in tandem with increased inequality, ethnic or religious organizations may be seen as both assistance and an outlet for the disadvantaged.[37] However, empirical research by Piazza argues that economics and unequal development have little to do with social unrest in the form of terrorism.[42] Rather, "more diverse societies, in terms of ethnic and religious demography, and political systems with large, complex, multiparty systems were more likely to experience terrorism than were more homogeneous states with few or no parties at the national level".[42] Recovery from conflict (civil war) Violent conflict and economic development are deeply intertwined. Paul Collier[43] describes how poor countries are more prone to civil conflict. The conflict lowers incomes catching countries in a "conflict trap." Violent conflict destroys physical capital (equipment and infrastructure), diverts valuable resources to military spending, discourages investment and disrupts exchange.[44] Recovery from civil conflict is very uncertain. Countries that maintain stability can experience a "peace dividend," through the rapid re-accumulation of physical capital (investment flows back to the recovering country because of the high return).[45] However, successful recovery depends on the quality of legal system and the protection of private property.[46] Investment is more productive in countries with higher quality institutions. Firms that experienced a civil war were more sensitive to the quality of the legal system than similar firms that had never been exposed to conflict.[47] |

研究テーマ 開発経済学には、第三世界の債務問題や、国際通貨基金(IMF)や世界銀行といった機関の機能といったテーマも含まれる。実際、開発経済学者たちの多く は、IMF や世界銀行などの機関に雇用されたり、コンサルティングを行ったり、資金援助を受けたりしている。こうした経済学者たちの多くは、世界でも最も低所得の国 々において、国内の自立と教育を促進することで、貧しい国や地域における安定的かつ持続的な成長を促進する方法に関心を持っている。経済問題が社会問題や 政治問題と融合する場合、それは開発研究と呼ばれる。 地理と開発 経済学者ジェフリー・D・サックス、アンドルー・メリンジャー、ジョン・ギャラップは、国民の地理的位置と地形がその経済的繁栄の重要な決定要因および予 測因子であると主張している[25]。海岸沿いや「航行可能な水路」の近くで発展した地域は、内陸部よりもはるかに豊かで人口密度が高い。さらに、熱帯地 域以外の、より温暖な気候の地域は、北回帰線や南回帰線にある地域よりもかなり発展している。熱帯地域以外の、いわゆる「温帯に近い」気候の地域は、世界 人口の約 4 分の 1 を擁し、世界の GNP の半分以上を生み出しているが、世界の居住地域の 8.4% にしか当たらない。[25] 彼らは、経済発展を促進する将来の援助プログラムや政策はこれらの差異を考慮しなければならないため、こうした異なる地理的・気候的条件を理解することが 不可欠だと主張する。 経済発展と民族性 20世紀末以降、開発経済学者の間で民族多様性と経済発展の相互作用、特に国家レベルでの関係に焦点を当てた研究が増えている。大半の研究はマクロ・ミク ロ両レベルの実証経済学を扱うが、この研究分野では特に社会学的アプローチが重視される。より保守的な研究分野は、民族多様性の異なるレベルと経済パ フォーマンスの関係における因果関係の検証に焦点を当てている。一方、より小規模で急進的な分野は、新自由主義経済学が民族紛争を増幅または引き起こす役 割を主張している。さらに、これら二つの理論的アプローチを比較すると、内生性(エンドジェニシティ)の問題が疑問視される。これは、主に政策への影響の 可能性から、依然として非常に議論の分かれる不確実な研究分野であり、政治的にも敏感な領域である。 経済発展における民族性の役割 研究者間の議論の多くは、二つの重要かつ関連する変数——民族性と多様性——の定義と測定に集中している。民族性を文化、言語、宗教のどれで定義すべきか については議論がある。ルワンダの紛争は主に部族間のものであった一方、ナイジェリアの連続した紛争は——少なくともある程度——宗教的基盤を持つと考え られている。[26] これらの異なる民族変数の重要性は時間や地域によって変動する傾向があるため、研究方法論も文脈に応じて変化させるべきだと提案する者もいる。[27] ソマリアは興味深い事例だ。人口の約85%が自らをソマリ人と定義していたため、ソマリアは民族的にかなり均質な国家と見なされていた。[27] しかし内戦により、部族集団に基づいて民族性(あるいは民族的帰属)が再定義されることとなった。[27] 学界では「民族的異質性」の指標作成についても多くの議論がある。民族的多様性(紛争との関連性において)をモデル化するため、いくつかの指標が提案され てきた。イースターリーとレバインは、FRAC(ethno-linguistic fractionalization index)またはELF(ethno-linguistic fractionalization)と定義される指標を提案している:  siは集団iの規模が総人口に占める割合である。[27] ELF指数とは、無作為に選ばれた2人の個人が異なる民族言語集団に属する確率を測る指標である。[27] 他の研究者らはこの指標を民族言語集団ではなく宗教集団に適用した例もある。[28] 広く用いられているものの、アレシナとラ・フェッラーラは、ELF指数では大規模な少数民族集団が多数の小規模民族集団よりも民族間紛争を引き起こす可能 性を考慮していないと指摘している。[27] 近年では、モンタルボやレイナル=ケロールら研究者が、民族分断のより適切な指標としてQ分極化指数を提唱している。[29] エステバンとレイが開発した分極化指数の簡略化版に基づくQ指数は、以下のように定義される。  ここでsiは再び、集団iの規模を総人口に対する割合として表し、ある地域内の既存民族集団間の社会的距離を捉えることを意図している。[29] ジョナサン・プールなどの初期の研究者は、バベルの塔の記述にまで遡る概念、すなわち言語的統一がより高い発展レベルを可能にするかもしれないという考え を検討した。[30] プールは、定義やデータ収集における明らかな単純化や主体性を指摘しつつも、高い言語多様性を持つ国家から強固な経済が出現した例はまだ見られないと示唆 した。[30] プールの研究では、言語多様性の尺度として「最大母語コミュニティの規模を人口に占める割合」を用いた。[30] しかし間もなく、ホロウィッツは高度に多様化した社会も高度に均質な社会も、その中間よりも紛争が少ないと指摘した[31]。同様にコリアーとヘフラー は、高度に均質な社会も高度に異質な社会も内戦リスクが低い一方、分極化した社会ほどリスクが高いという証拠を示した。[32] 実際、彼らの研究によれば、二つの民族グループしか存在しない社会は、両極端のいずれよりも内戦発生確率が約50%高いという。[32] とはいえ、マウロは民族言語的分断が汚職と正の相関関係にあり、汚職は経済成長と負の相関関係にあると指摘している。[33] さらに、アフリカ諸国の経済成長に関する研究において、イースターリーとレバインは、言語的分断が国民所得成長の抑制や不適切な政策の要因として重要な役 割を果たすことを明らかにしている。[34][35] 加えて、米国における自治体レベルの実証研究では、人種に基づく民族的分断が、財政管理の不備や公共財への投資減少と相関する可能性が示されている。 [36] 最後に、より新しい研究では、民族言語的分断が実際に経済成長と負の相関関係にあると示唆されている。一方で、分断が深刻な社会では公共消費が増大し、投 資水準が低下し、内戦が頻発する傾向がある。[34] 経済発展と民族紛争への影響 経済的要因が民族紛争を発生・助長する役割について、注目が集まっている。前述の従来の開発理論に対する批判は、「民族性」と民族紛争を外部変数として扱 うことはできないと指摘している。[37] 経済成長と開発、特に自由貿易を特徴とするグローバル化の世界において、言語の消滅と均質化が進行しているように見えることを論じる文献群が存在する。 [38] マヌエル・カステルスは、グローバル化の特徴である「組織の広範な解体、制度の正当性の喪失、主要な社会運動の衰退、そして儚い文化的表現」が、実践では なくアイデンティティに基づく意味の再探求を促すと主張する。[39] バーバーとルイスは、近代化(実態か認識か)と新自由主義的発展の脅威への反動として、文化に基づく抵抗運動が出現したと論じている。[40][41] 異なる観点から、チュアは、新自由主義的世界における貿易の恩恵を受けた富裕な少数派に対する多数派の羨望が、しばしば民族紛争を引き起こすと示唆してい る。[37] 彼女は、政治的操作と少数派の誹謗中傷を通じて紛争が発生する可能性が高いと論じている。[37] プラッシュは、経済成長がしばしば不平等拡大と並行して起こるため、民族的・宗教的組織が弱者にとって支援手段であると同時に発散の場とも見なされ得ると 指摘する。[37] しかしピアッツァの実証研究によれば、経済状況や不均衡な発展はテロリズムという形態の社会不安とはほとんど関係がないという。[42] むしろ「民族・宗教構成の多様性が高く、大規模で複雑な多党制を有する政治システムは、国家レベルで政党がほとんど存在しない均質な国家よりもテロリズム を経験する可能性が高い」と結論づけている。[42] 紛争(内戦)からの復興 暴力紛争と経済発展は深く絡み合っている。ポール・コリアー[43]は、貧しい国ほど内戦に陥りやすいと説明する。紛争は所得を低下させ、国を「紛争の 罠」に陥れる。暴力紛争は物的資本(設備やインフラ)を破壊し、貴重な資源を軍事支出に振り向け、投資意欲を削ぎ、取引を混乱させる。[44] 内戦からの復興は極めて不確実である。安定を維持した国々は、物的資本の急速な再蓄積(高収益を背景に投資が復興国へ回帰する)を通じて「平和の配当」を 得られる[45]。しかし、復興の成否は法制度の質と私有財産の保護に依存する[46]。制度の質が高い国ほど投資は生産的である。内戦を経験した企業 は、紛争に晒されたことのない類似企業よりも、法制度の質に敏感であった。[47] |

| Growth indicator controversy Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, real income, median income and disposable income are used by many developmental economists as an approximation of general national well-being. However, these measures are criticized as not measuring economic growth well enough, especially in countries where there is much economic activity that is not part of measured financial transactions (such as housekeeping and self-homebuilding), or where funding is not available for accurate measurements to be made publicly available for other economists to use in their studies (including private and institutional fraud, in some countries). Even though per-capita GDP as measured can make economic well-being appear smaller than it really is in some developing countries, the discrepancy could be still bigger in a developed country where people may perform outside of financial transactions an even higher-value service than housekeeping or homebuilding as gifts or in their own households, such as counseling, lifestyle coaching, a more valuable home décor service, and time management. Even free choice can be considered to add value to lifestyles without necessarily increasing the financial transaction amounts. More recent theories of Human Development have begun to see beyond purely financial measures of development, for example with measures such as medical care available, education, equality, and political freedom. One measure used is the Genuine Progress Indicator, which relates strongly to theories of distributive justice. Actual knowledge about what creates growth is largely unproven; however recent advances in econometrics and more accurate measurements in many countries are creating new knowledge by compensating for the effects of variables to determine probable causes out of merely correlational statistics. |

成長指標をめぐる論争 多くの開発経済学者は、国民総生産(GDP)一人当たり、実質所得、中位所得、可処分所得を、国家の一般的な福祉の近似値として用いている。しかし、これ らの指標は経済成長を十分に測れていないと批判されている。特に、測定対象外の経済活動(家事労働や自己住宅建設など)が多い国や、正確な測定データを他 の経済学者が研究に利用できるよう公開するための資金が不足している国(一部の国では民間・機関による不正も含まれる)では顕著だ。 測定された一人当たりGDPは、一部の発展途上国において実際の経済的幸福度を過小評価する可能性があるが、先進国ではこの乖離がさらに大きくなる恐れが ある。なぜなら先進国では、家計管理や住宅建設よりも高価値なサービスを、贈与や自家消費の形で金融取引外で提供している可能性があるからだ。例えばカウ ンセリング、ライフスタイル指導、より高付加価値な住宅装飾サービス、時間管理などが該当する。自由な選択さえも、金融取引額を必ずしも増やさずに生活様 式に付加価値をもたらすと考えられる。 より最近の人間開発理論は、医療の普及度、教育、平等性、政治的自由といった指標を用いることで、純粋に金融的な開発測定を超えた視点を持ち始めている。 真の進歩指標(GPI)はその一例であり、分配的公正の理論と強く関連している。成長を生み出す要因に関する実際の知見はほとんど実証されていない。しか し、計量経済学の進歩と多くの国における測定精度向上により、単なる相関統計から因果関係を特定する新たな知見が生まれている。 |

| Recent developments See also: Fair trade movement Recent theories revolve around questions about what variables or inputs correlate or affect economic growth the most: elementary, secondary, or higher education, government policy stability, tariffs and subsidies, fair court systems, available infrastructure, availability of medical care, prenatal care and clean water, ease of entry and exit into trade, and equality of income distribution (for example, as indicated by the Gini coefficient), and how to advise governments about macroeconomic policies, which include all policies that affect the economy. Education enables countries to adapt the latest technology and creates an environment for new innovations. The cause of limited growth and divergence in economic growth lies in the high rate of acceleration of technological change by a small number of developed countries.[citation needed] These countries' acceleration of technology was due to increased incentive structures for mass education which in turn created a framework for the population to create and adapt new innovations and methods. Furthermore, the content of their education was composed of secular schooling that resulted in higher productivity levels and modern economic growth. Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute also highlight the importance of using economic growth to improve the human condition, raising people out of poverty and achieving the Millennium Development Goals.[48] Despite research showing almost no relation between growth and the achievement of the goals 2 to 7 and statistics showing that during periods of growth poverty levels in some cases have actually risen (e.g. Uganda grew by 2.5% annually between 2000 and 2003, yet poverty levels rose by 3.8%), researchers at the ODI suggest growth is necessary, but that it must be equitable.[48] This concept of inclusive growth is shared even by key world leaders such as former Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, who emphasises that: "Sustained and equitable growth based on dynamic structural economic change is necessary for making substantial progress in reducing poverty. It also enables faster progress towards the other Millennium Development Goals. While economic growth is necessary, it is not sufficient for progress on reducing poverty."[48] Researchers at the ODI thus emphasise the need to ensure social protection is extended to allow universal access and that active policy measures are introduced to encourage the private sector to create new jobs as the economy grows (as opposed to jobless growth) and seek to employ people from disadvantaged groups.[48] |

最近の動向 関連項目:フェアトレード運動 最近の理論は、経済成長に最も相関または影響を与える変数や要素は何かという疑問を中心に展開している。具体的には、初等教育・中等教育・高等教育、政府 政策の安定性、関税と補助金、公正な司法制度、整備されたインフラ、医療・妊婦健診・清潔な水の確保、貿易参入・離脱の容易さ、所得分配の平等性(例えば ジニ係数で示される)などが挙げられる。さらに、経済に影響を与える全ての政策を含むマクロ経済政策について、政府にどう助言すべきかも議論の対象だ。教 育は国々が最新技術を取り入れることを可能にし、新たなイノベーションを生み出す環境を整える。 経済成長の停滞と格差の根源は、少数の先進国による技術革新の急速な加速にある。[出典必要] これらの国々の技術加速は、大衆教育へのインセンティブ構造強化によるもので、それが国民が新たなイノベーションや手法を創造・適応させる枠組みを構築し た。さらに、彼らの教育内容は世俗的な学校教育で構成され、それが高い生産性水準と近代的な経済成長をもたらしたのである。 海外開発研究所の研究者らはまた、経済成長を利用して人間の状態を改善し、人々を貧困から脱却させ、ミレニアム開発目標を達成することの重要性を強調して いる。[48] 成長と目標2~7の達成にはほとんど関連性がないことを示す研究や、成長期に貧困率が実際に上昇した事例(例:ウガンダは2000年から2003年にかけ て年率2.5%成長したが、貧困率は3.8%上昇)があるにもかかわらず、ODIの研究者らは成長は必要だが、それは公平でなければならないと示唆してい る。[48] この包摂的成長の概念は、潘基文(パン・ギムン)前国連事務総長のような世界の主要指導者にも共有されている。彼は次のように強調している: 「貧困削減において実質的な進展を図るには、ダイナミックな構造的経済変化に基づく持続的かつ公平な成長が必要である。それは他のミレニアム開発目標への進展も加速させる。経済成長は必要だが、貧困削減の進展には十分ではない。」[48] したがってODIの研究者らは、経済成長に伴い(雇用なき成長ではなく)民間部門が新たな雇用を創出し、不利な立場にある人々の雇用を図るよう促す積極的な政策措置を導入するとともに、普遍的アクセスを可能とするよう社会保護を拡大する必要性を強調している。[48] |

| Notable development economists Mahbub ul Haq, Minister of Finance for Islamic Republic of Pakistan, special advisor at UNDP. Muhammad Yunus, Founder of Grameen Bank, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate by Norwegian Nobel Committee. Daron Acemoglu, professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Nobel Prize and Clark Medal winner. Philippe Aghion, professor of economics at the London School of Economics and Collège de France, co-authored textbook in economic growth, forwarded Schumpeterian growth, and established creative destruction theories mathematically with Peter Howitt. Nava Ashraf, professor of economics at the London School of Economics. Oriana Bandiera, professor of economics at the London School of Economics and Director of the International Growth Centre. Abhijit Banerjee, professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Director of Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, co-recipient of the 2019 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Pranab Bardhan, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, author of texts in both trade and development economics, and editor of the Journal of Development Economics from 1985 to 2003. Kaushik Basu, professor of economics at Cornell University and author of Analytical Development Economics. Peter Thomas Bauer, former professor of economics at the London School of Economics, author of Dissent on Development. Tim Besley, professor of economics at the London School of Economics, and commissioner of the UK National Infrastructure Commission. Jagdish Bhagwati, professor of economics and law at Columbia University Nancy Birdsall is the founding president of the Center for Global Development (CGD) in Washington, DC, USA, and former executive vice-president of the Inter-American Development Bank. David E. Bloom, professor of economics and demography at the Harvard School of Public Health. François Bourguignon, professor of economics and Director of the Paris School of Economics. Robin Burgess, professor of economics at the London School of Economics and Director of the International Growth Centre. Francesco Caselli, professor of economics at the London School of Economics. Paul Collier, author of The Bottom Billion which attempts to tie together a series of traps to explain the self-fulfilling nature of poverty at the lower end of the development scale. Michael B. Connolly, development economist and a university professor Partha Dasgupta, professor of economics at the University of Cambridge. Dave Donaldson, professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Clark Medal winner. Angus Deaton, professor of economics at Princeton University and winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics. Melissa Dell, professor of economics at Harvard University and Clark Medal winner. Simeon Djankov, research fellow at the Financial Markets Group of the London School of Economics. Esther Duflo, Director of Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2009 MacArthur Fellow, 2010 Clark Medal winner, advocate for field experiment, co-recipient of the 2019 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. William Easterly, author of The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics[49][50] and White Man's Burden: How the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good.[51] Oded Galor, Israeli-American economist at Brown University; editor-in-chief of the Journal of Economic Growth, the principal journal in economic growth. Developer of the unified growth theory, the newest alternative to theories of endogenous growth. Maitreesh Ghatak, professor of economics at the London School of Economics. Peter Howitt, Canadian economist at Brown University; past president of the Canadian Economics Association, introduced the concept of Schumpeterian growth and established creative destruction theory mathematically with Philippe Aghion. Seema Jayachandran, professor of economics at Northwestern University. Dean Karlan, American economist at Northwestern University; co-director of the Global Poverty Research Lab at the Buffett Institute for Global Studies; founded Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA), a New Haven, Connecticut, based research outfit dedicated to creating and evaluating solutions to social and international development problems. Michael Kremer, University Professor at the University of Chicago, co-recipient of the 2019 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Eliana La Ferrara, professor at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government. W. Arthur Lewis, winner of the 1979 Nobel Prize in Economics for work in development economics. Justin Yifu Lin, Chinese economist at Peking University; former chief economist of World Bank, one of the most prominent Chinese economists. Sendhil Mullainathan, professor of computation and behavioural science at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Nathan Nunn, professor of economics at Harvard University. Benjamin Olken, professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Rohini Pande, professor of economics at Yale University. Lant Pritchett, professor at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government, and has held several prominent research positions at the World Bank. Nancy Qian, professor of economics at Northwestern University. Kate Raworth, Senior Research Associate at the Environmental Change Institute of the University of Oxford, author of Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, formerly economist for the United Nations Development Programme's Human Development Report and Senior Researcher at Oxfam. James Robinson, professor of economics at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy Studies. Dani Rodrik, professor at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government, has written extensively on globalization. Mark Rosenzweig, a professor at Yale University and director of Economic Growth Center at Yale Jeffrey Sachs, professor at Columbia University, author of The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities of Our Time (preview) and Common Wealth: Economics for a Crowded Planet. Amartya Sen, Indian economist, first Asian Nobel Prize winner for economics, author of Development as Freedom, known for incorporating philosophical components into economic models.[52] Nicholas Stern, professor of economics at the London School of Economics, former President of the British Academy and former World Bank Chief Economist. Joseph Stiglitz, professor at Columbia University and Nobel Prize winner and former chief economist at the World Bank. John Sutton, emeritus professor of economics at the London School of Economics. Erik Thorbecke, a co-originator of Foster–Greer–Thorbecke poverty measure who also played a significant role in the development and popularization of social accounting matrix. Michael Todaro, known for the Todaro and Harris–Todaro models of migration and urbanization; Economic Development. Robert M. Townsend, professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology known for his Thai Project, a model for many other applied and theoretical projects in economic development. Anthony Venables, professor of economics at the University of Oxford. Hernando de Soto, author of The Other Path: The Economic Answer to Terrorism and The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. Steven Radelet, professor at Georgetown University and author of The Great Surge-The Ascent of the Developing World. |

著名な開発経済学者 マフブブ・ウル・ハク:パキスタン・イスラム共和国財務大臣、国連開発計画(UNDP)特別顧問。 ムハマド・ユヌス:グラミン銀行創設者、ノルウェー・ノーベル委員会よりノーベル平和賞受賞者。 ダロン・アセモグル:マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)経済学教授、ノーベル賞及びクラーク賞受賞者。 フィリップ・アギオンはロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス及びコレージュ・ド・フランス経済学教授である。経済成長に関する教科書を共著し、シュンペーター的成長を推進した。ピーター・ハウイトと共に創造的破壊理論を数学的に確立した。 ナヴァ・アシュラフはロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス経済学教授である。 オリアナ・バンディエラはロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス経済学教授であり、国際成長センター所長である。 アビジット・バナジー。マサチューセッツ工科大学経済学部教授、アブドゥル・ラティフ・ジャミール貧困対策研究所所長。2019年ノーベル経済学賞共同受賞者。 プラナブ・バルダン。カリフォルニア大学バークレー校経済学部教授。貿易経済学と開発経済学の教科書著者。1985年から2003年まで『開発経済学ジャーナル』編集長を務めた。 コーネル大学経済学教授で『分析的開発経済学』の著者であるカウシク・バスー。 ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス元経済学教授で『開発論への異論』の著者であるピーター・トーマス・バウアー。 ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス経済学教授で英国国家インフラ委員会の委員であるティム・ベズリー。 ジャグディシュ・バグワティ:コロンビア大学経済学・法学教授 ナンシー・バーズオール:米国ワシントンD.C.にあるグローバル開発センター(CGD)の創設所長。米州開発銀行元副総裁。 デイビッド・E・ブルーム:ハーバード大学公衆衛生大学院経済学・人口統計学教授。 フランソワ・ブルギニョン。パリ経済高等学院の経済学教授かつ所長。 ロビン・バージェス。ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスの経済学教授かつ国際成長センター所長。 フランチェスコ・カゼッリ。ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスの経済学教授。 ポール・コリアー。『最貧の10億人』の著者。開発段階の最下層における貧困の自己実現的性質を説明するため、一連の罠を結びつける試みを行っている。 マイケル・B・コノリー。開発経済学者で大学教授。 パルタ・ダスグプタ。ケンブリッジ大学経済学教授。 デイブ・ドナルドソン。マサチューセッツ工科大学経済学教授でクラーク賞受賞者。 アンガス・ディートン。プリンストン大学経済学教授でノーベル経済学賞受賞者。 メリッサ・デル。ハーバード大学経済学教授でクラーク賞受賞者。 シメオン・ジャンコフ、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス金融市場グループ研究員。 エステル・デュフロ、アブドゥル・ラティフ・ジャミール貧困対策研究所所長、マサチューセッツ工科大学経済学教授、2009年マッカーサー・フェロー、2010年クラーク賞受賞者、フィールド実験の提唱者、2019年ノーベル経済学賞共同受賞者。 ウィリアム・イースタリー。『成長への逃れがたい探求:熱帯における経済学者の冒険と失敗』[49][50]、『白人の負担:西側が他者を支援しようとした努力が、いかに多くの害とわずかな益をもたらしたか』の著者。[51] オデッド・ガロール。ブラウン大学のイスラエル系アメリカ人経済学者。『経済成長ジャーナル』編集長。経済成長研究の主要学術誌である。内生的成長理論に代わる最新の理論「統一成長理論」の提唱者。 マイトリーシュ・ガタック、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス経済学教授。 ピーター・ハウイット、ブラウン大学カナダ人経済学者。カナダ経済学会元会長。シュンペーター的成長概念を導入し、フィリップ・アギオンと共に創造的破壊理論を数学的に確立した。 シーマ・ジャヤチャンドラン、ノースウェスタン大学経済学教授。 ディーン・カーラン、ノースウェスタン大学アメリカ人経済学者。バフェット国際研究センター内グローバル貧困研究ラボ共同ディレクター。コネチカット州 ニューヘブンに拠点を置く研究機関「貧困対策のためのイノベーション(IPA)」を設立。社会・国際開発問題の解決策創出と評価を専門とする。 マイケル・クレマー、シカゴ大学大学教授。2019年ノーベル経済学賞共同受賞者。 エリアナ・ラ・フェラーラ、ハーバード大学ケネディ行政大学院教授。 W・アーサー・ルイス、開発経済学の研究で1979年ノーベル経済学賞受賞者。 林毅夫、北京大学中国経済学者。世界銀行元チーフエコノミスト。中国を代表する経済学者の一人。 センディル・ムライナタン、シカゴ大学ブース経営大学院計算行動科学教授。 ネイサン・ナン、ハーバード大学経済学教授。 ベンジャミン・オルケン、マサチューセッツ工科大学経済学教授。 ロヒニ・パンデ、イェール大学経済学教授。 ラント・プリチェット、ハーバード大学ケネディ行政大学院教授。世界銀行で複数の主要研究職を歴任。 ナンシー・チェン、ノースウェスタン大学経済学教授。 ケイト・ラワース。オックスフォード大学環境変化研究所上級研究員。『ドーナツ経済学:21世紀の経済学者の考え方』著者。国連開発計画人間開発報告書元エコノミスト、オックスファム上級研究員。 ジェームズ・ロビンソン。シカゴ大学ハリス公共政策大学院経済学教授。 ダニ・ロドリック、ハーバード大学ケネディ行政大学院教授。グローバリゼーションに関する著作が多数ある。 マーク・ローゼンツワイグ、イェール大学教授、イェール経済成長センター所長。 ジェフリー・サックス、コロンビア大学教授。『貧困の終焉:現代における経済的可能性』(プレビュー)および『コモン・ウェルス:過密化した惑星のための経済学』の著者。 アマールヤ・セン。インドの経済学者。アジア人初のノーベル経済学賞受賞者。『開発とは自由である』の著者。経済モデルに哲学的要素を取り入れたことで知られる。 ニコラス・スターン。ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス経済学教授。英国学士院元会長、世界銀行元チーフエコノミスト。 ジョセフ・スティグリッツ、コロンビア大学教授、ノーベル賞受賞者、元世界銀行チーフエコノミスト。 ジョン・サットン、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス名誉教授。 エリック・トルベッケは、フォスター・グリア・トルベッケ貧困指標の共同開発者であり、社会会計マトリックスの開発と普及にも大きな役割を果たした。 マイケル・トダロは、移住と都市化のトダロ・ハリス・トダロモデルで知られる。経済開発。 ロバート・M・タウンゼントは、マサチューセッツ工科大学の教授であり、経済開発における他の多くの応用および理論的プロジェクトのモデルとなったタイ・プロジェクトで知られる。 オックスフォード大学の経済学教授であるアンソニー・ベナブルズ。 『もうひとつの道:テロリズムへの経済的解答』および『資本の謎:なぜ資本主義は西洋では成功し、他の地域では失敗するのか』の著者であるエルナンド・デ・ソト。 ジョージタウン大学の教授であり、『大躍進―発展途上世界の台頭』の著者であるスティーブン・ラデレット。 |

| Reform and opening up Democracy and economic growth Demographic economics Dependency theory Development Cooperation Issues Wikibooks Development Cooperation Stories Wikibooks Development Cooperation Testimonials Wikibooks Development studies Development theory Development wave Environmental determinism Human Development and Capability Association International Association for Feminist Economics International Monetary Fund International development Important publications in development economics Economic development International development UN Human Development Index Gini coefficient Lorenz curve Harrod–Domar model Debt relief Human security Kaldor's growth laws The Poverty of "Development Economics" Social development Sustainable development Women's education and development |

改革と開放 民主主義と経済成長 人口経済学 従属理論 開発協力の問題 ウィキブックス 開発協力の物語 ウィキブックス 開発協力の体験談 ウィキブックス 開発学 開発理論 開発の波 環境決定論 人間開発と能力協会 国際フェミニスト経済学会 国際通貨基金 国際開発 開発経済学における重要な出版物 経済発展 国際開発 国連人間開発指数 ジニ係数 ローレンツ曲線 ハロッド・ドマーモデル 債務救済 人間の安全保障 カルドールの成長法則 「開発経済学」の貧困 社会開発 持続可能な開発 女性の教育と開発 |