ダイアモンド・ジェネス

Diamond Jenness,

1886-1969

☆ダイアモンド・ジェネス(Diamond

Jenness, CC FRCGS(1886年2月10日、ニュージーランド・ウェリントン -

1969年11月29日、カナダ・ケベック州チェルシー)は、カナダで最も偉大な初期の科学者の一人であり、カナダ人類学の先駆者である。

| Diamond Jenness, CC

FRCGS (February 10, 1886, Wellington, New Zealand – November 29, 1969,

Chelsea, Quebec, Canada) was one of Canada's greatest early

scientists[1][2] and a pioneer of Canadian anthropology. |

Diamond Jenness, CC

FRCGS(1886年2月10日、ニュージーランド・ウェリントン -

1969年11月29日、カナダ・ケベック州チェルシー)は、カナダで最も偉大な初期の科学者の一人[1][2]であり、カナダ人類学の先駆者である。 |

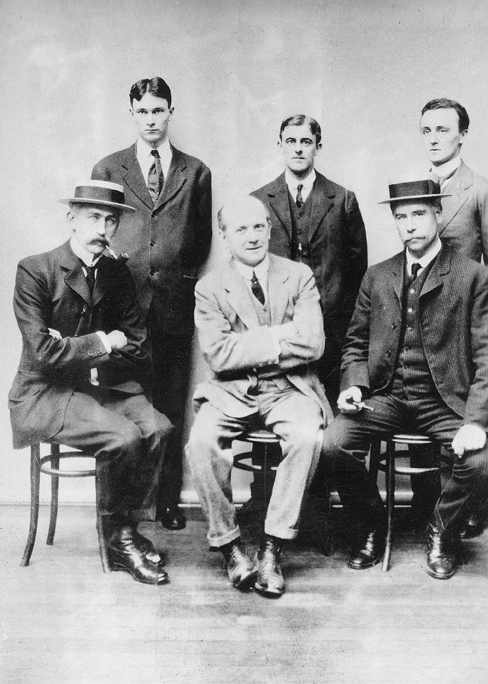

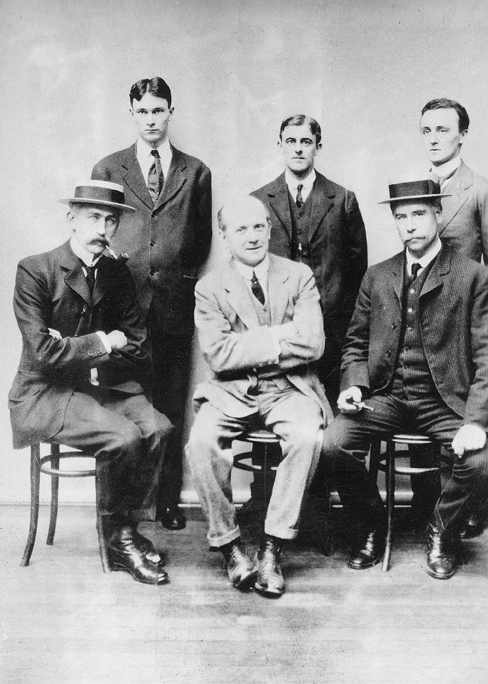

Early life (1886–1910) University of Oxford Anthropology Diploma class of 1910–11. Jenness is in the center of the back row. Family and childhood Diamond Jenness was the second youngest son in a middle-class family of ten children. His father's profession was that of a watchmaker/jeweler, though he also installed several clocks in municipal building towers in New Zealand. The family was encouraged to read, learn music, and engage in sports. Richling, in his biography “In Twilight and in Dawn,” writes that the young Jenness “was a proficient outdoorsman and an accomplished sharpshooter,” skills that helped prepare him for his experience in the arctic years later.[3] Education At an early age, Jenness showed proficiency for learning. He earned his first scholarship at the age of twelve by entering a composition competition for children under fourteen. In those days, in New Zealand, secondary education was only available to the wealthier families, so this scholarship enabled Jenness to complete high school and three years of college. He finished his final year of secondary education with six prizes: mathematics, science, Latin, French and English, and was named top student. He attended Lower Hutt School, then Wellington College.[4][5][6] He and sister May were the only two siblings to proceed on to college.[3] Jenness graduated from the University of New Zealand (from the constituent college then called Victoria University College) (B.A. 1907; M.A. 1908), receiving first class honors for both degrees. Then, when 22 years old, he received a scholarship that allowed him to pursue further education at Balliol College, University of Oxford (Diploma in Anthropology, 1910; M.A. 1916). |

生い立ち(1886-1910) 1910-11年のオックスフォード大学人類学卒業証書クラス。後列中央がジェネス。 家族と子供時代 ダイヤモンド・ジェネスは10人家族の中流家庭の次男として生まれた。父親の職業は時計職人であったが、ニュージーランドでは市庁舎の塔に時計をいくつか 取り付けていた。一家は読書、音楽、スポーツを奨励されていた。リッチリングは伝記『In Twilight and in Dawn(黄昏と夜明けの中で)』の中で、若き日のジェネスは「アウトドアに精通し、射撃の名手であった」と書いている。 教育 ジェネスは幼い頃から学問に長けていた。12歳のとき、14歳以下を対象とした作曲コンクールに応募し、初めて奨学金を得た。当時のニュージーランドで は、中等教育は裕福な家庭でしか受けられなかったため、この奨学金によってジェンネスは高校と3年間の大学を卒業することができた。彼は中等教育の最終学 年を数学、科学、ラテン語、フランス語、英語の6つの賞で終え、成績優秀者に選ばれた。ローワー・ハット・スクールを経て、ウェリントン・カレッジに通っ た[4][5][6]。大学へ進学したのは姉のメイと2人だけだった[3]。 ジェネスはニュージーランド大学(当時はヴィクトリア・ユニバーシティ・カレッジと呼ばれていた)を卒業し(学士号1907年、修士号1908年)、両学 位とも一等賞を受賞した。その後、22歳のときに奨学金を得て、オックスフォード大学バリオール・カレッジでさらに教育を受けた(人類学のディプロマ、 1910年、修士号、1916年)。 |

| Career (1911–1948) Field work – Northern D’Entrecasteaux From 1911 to 1912, as an Oxford Scholar, he studied a little-known group of people on the D'Entrecasteaux Islands in eastern Papua New Guinea.[3] Jenness comments: "They peered at me from out-of-the-way corners, or through the doors of their huts, always at a safe distance. Recalling a children's [game] I had learned in one of the coast villages, I stooped down, tapped the ground with my fingers and chanted the refrain. The children drew nearer and nearer, and one or two with broad smiles began to imitate me. Then with a piece of string, I made some of their own cat's cradle figures and held them out for their inspection. This turned the scale. Five minutes later a laughing crowd surrounded me…The natives could hardly believe that I was a white man, and kept asking my [guides] who I was, how I came to speak their language and where I had learned their game.”[7] Canadian Arctic Expedition In 1913, Jenness was invited to join the government-funded Canadian Arctic Expedition (CAE) that was led by two Arctic explorers - Vilhjalmur Stefansson and R.M. Anderson.[8] He would be one of the two anthropologists on board; the other was Henri Beuchat.[9] In June of that year, having barely recuperated from yellow fever contracted while in New Guinea, Jenness boarded the whaling vessel Karluk along with 12 other scientists. The ship steamed up the British Columbia coastline towards Nome, Alaska, where they met up with Stefansson who had purchased two 60-foot schooners to assist in the expedition work. The three vessels then proceeded towards their rendezvous point, Herschel Island, just east of the mouth of the Mackenzie River, Northwest Territories.[8] The rendezvous never took place. On 12 August, the Karluk became locked in the sea ice. Stefansson, with his secretary McConnell, Jenness, Wilkins (later Sir Hubert Wilkins), and two Eskimos, set out to procure meat for the crew. While they were ashore, the Karluk drifted westward to the East Siberian Sea, where it was eventually crushed in the ice off Wrangel Island.[8][9] Thirteen of the crew perished on board, including Henri Beuchat.[10] With the ship gone, the hunting party set off on foot towards Barrow, Alaska (Utqiaġvik), 150 miles away, hoping to meet the two other vessels involved in the expedition: the Mary Sachs and Alaska.[9] In Barrow, they learned that the two ships had anchored in Camden Bay, making it their winter base.[8] Jenness remained behind and spent the first winter at Harrison Bay, Alaska, where he learned how to speak the Northern Eskimo language, and compiled information about their customs and folklore. The next year, in 1914, assisted by interpreter Patsy Klengenberg (son of an Inuit woman and the trader Christian Klengenberg), Jenness commenced studying the Copper Inuit, sometimes called the Blond Eskimos, in the Coronation Gulf area.[11] This group of people had had very little contact with Europeans, and Jenness, now the only anthropologist, was solely in charge of recording the aboriginal way of life in this area.[8][9][10]  Hubert Wilkins photograph of Ikpukhuak and his shaman wife Higalik Jenness spent two years with the Copper Inuit and lived as an adopted son of a hunter named Ikpukhuak and his shaman wife Higalik (name meaning Ice House).[8][9] During that time he hunted and travelled with his "family," sharing both their festivities and their famine.[9] By living with this Inuit family and partaking in their everyday experiences, Jenness did something that was "not often employed by other ethnologists" at the time: he lived with the people who were the subjects of his fieldwork.[8] As Morrison in his “Arctic Hunters: The Inuit and Diamond Jenness” states: “His goal was to understand the Copper Inuit on their own terms, not in relation to some preconceived ‘ladder of creation’ with Europeans perched firmly at the top.”[12] Summarizing his first year with the Copper Inuit, Jenness wrote: "By Isolating myself among the Eskimos ... I had followed their wanderings day by day from autumn round to autumn. I had observed their reactions to every season, the disbanding of the tribes and their reassembling, the migrations from sea to land and from land to sea, the diversion from sealing to hunting, hunting to fishing, fishing to hunting, and then to sealing again. All these changes caused by their economic environment I had seen and studied; now, with a greater knowledge of the language, I could concentrate on other phases of their life and history."[13] As anthropologist de Laguna noted years later, his “accomplishments are the more remarkable when it is remembered that Jenness had to perform not only his own duties but [also] those of his unfortunate colleague, Beauchat.”[14] Furthermore, Jenness's camera, anthropometric instruments, books, papers and even heavy winter clothing had all remained on board the ill-fated Karlak.[15] The CAE scientists kept daily diary logs, took extensive research notes, and collected samples which were shipped or brought back to Ottawa. Jenness collected a variety of ethnological materials from clothing and hunting tools to stories and games, and 137 wax phonographic cylinder song recordings he had made.[11][8] (The latter's musical transcription and analysis by Columbia University's Hellen H. Roberts with Jenness's word translations can be found in the monograph “Songs of the Copper Eskimos” (1925).[16] Eight of Jenness's Copper Inuit recordings can be heard on CKUG's website. Archived 2021-12-01 at the Wayback Machine The radio station is located in Kugluktuk, Nunavut, Canada. The website also features a short video demonstrating how Jenness recorded these songs with the technology available in 1913.) Copper Inuit subgroups studied by Jenness Several subgroups were reported on by Jenness and they include:[17] Akuliakattagmiut Haneragmiut Kogluktogmiut Pallirmiut Puiplirmiut Uallirgmiut (Kanianermiut) Origin of the Copper Eskimos and their copper culture In his article in Geographical Review, Jenness described how the Copper Inuit are more closely related to tribes of the east and southeast in comparison to western cultural groups, basing his conclusion on archaeological remains, materials used for housing, weapons, utensils, art, tattoos, customs, traditions, religion, and also linguistic patterns. He also considered how the dead are handled: whether they are covered by stone or wood, without any artifacts, as in the west, or “as in the east, laid out on the surface of the ground, unprotected but with replicas of their clothing and miniature implements placed beside them.”.[18] Jenness characterized the "Copper Eskimos" as being in a pseudo-metal stage, in between the Stone and Iron Ages, because this cultural group treated copper as simply a malleable stone which is hammered into tools and weapons. He discussed whether the use of copper arose independently with different cultural groups or in one group and was then "borrowed" by others. Jenness goes on to explain that indigenous communities began to use copper first and following this, the Inuit adopted it. He cited the fact that slate was previously used among Inuit and was replaced by copper at a later time after the indigenous communities had begun to use it.[18] The work of Diamond Jenness contributed significantly to the understanding of how migration patterns influence cultural practices and the transitions from one culture into another.[citation needed] First World War The scientific members of the Canadian Arctic Expedition completed their mission and left the north in 1916. Jenness was assigned an office in the Victoria Museum of Ottawa and instructed to write up his expedition findings. After six months of feverishly working on his collections, notes, and initial reports for the government, Jenness, concerned about the events in Europe, enlisted in the World War 1 and served in France and Belgium. Being of slight build and short of stature, he was assigned to duties other than direct combat.[19] Field work and writing In December, 1918, Jenness applied and received military leave to finish writing his Papua studies report in Oxford, (delayed due his having joined the CAE and then the war). While in Oxford, he received word that his unit was one of the first to be sent home from the war. Jenness returned to Ottawa in March, 1919, and the next month married his fiancé, Eileen Bleakney. After their honeymoon in New Zealand, Jenness set about writing up his Arctic reports, and produced eight government reports in five volumes, totaling 1,368 pages.[20] Richling states: “The scientific results of the Canadian Arctic Expedition filled fifteen volumes. One-third of them contained the product of Jenness's investigations.”[21] Canadian First Nations A year and a half after his return from the war, the Canadian Government made his employment at the Victoria Memorial Museum permanent, and he was assigned to study many of the Indian tribes of Canada. (Jenness's employment had previously been on a yearly contract basis.)[22] The Sarcee, on a reserve in Calgary, Alberta, were the first of many First Nation tribes in Jenness's fieldwork. That experience also provided his first encounter with the deplorable conditions Canada's indigenous peoples experienced on reserves.[23] After the Sarcee, Jenness undertook fieldwork study of the Sekani. Beothuk (extinct), Ojibwa, and Salish. Collins and Taylor refer to Jenness's Indians of Canada (1931c) as "the definitive work on the Canadian aborigines, dealing comprehensively with the ethnology and history of the Canadian Indians and Eskimos".[8] Archaeological discoveries Although most of Jenness's time was devoted to Indian studies and administrative duties, he also identified two very important prehistoric Eskimo cultures: the Dorset culture in Canada (in 1925)[24] and the Old Bering Sea culture in Alaska (in 1926),[25] for which he later was named "Father of Eskimo Archaeology."[26] These archaeological findings were fundamental in explaining migration patterns, and Jenness's views were thought to be "radical" at that time. Helmer states: “These theories are now widely accepted, having been vindicated by carbon-14 dating and subsequent field research.”[9] Administrative duties In 1926, Jenness succeeded Canada's first Chief Anthropologist, Dr. Edward Sapir, as Chief of Anthropology at the National Museum of Canada, a position he retained until his retirement in 1948. During the intervening years, although hampered by the Great Depression and World War II, he “strove passionately, but with mixed success, to improve the knowledge and welfare of Canada's aboriginal peoples and to enhance the international reputation of the National Museum.”[27] Other administrative duties during this time include representing Canada at the Fourth Pacific Science Congress in 1929, and chairing the Anthropological Section of the First Pacific Science Congress in 1933. Jenness also served as Canada's official delegate to the International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences in Copenhagen, 1938. Second World War and its aftermath In 1941, eager to contribute to the war effort, he was seconded to the Royal Canadian Air Force, where he served until 1944 as civilian deputy director of Special Intelligence. In 1944, he was made chief of the newly established Inter-Services Topographic Section (ISTS), the non-military section of the Canadian Department of National Defence (patterned after a similar Great Britain military intelligence organization, Inter-Services Topographic Department.) Jenness retained this position when, in 1947, the Canadian ISTS unit changed name (became the Geographic Bureau) and was placed under the Department of Mines and Resources.[28] Retirement years (1948–1969) During his retirement, Jenness continued to travel, research, and publish. (See Through Darkening Spectacles, Table 2, p. 364 for a complete table of locations visited.) He also taught courses at universities, such as the University of British Columbia (1951) and McGill (1955), on arctic ethnology and archaeology.[29] From 1949 until his death in 1969, Jenness published more than two dozen writings, including the monographs: The Corn Goddess and other tales from Indian Canada (1956), Dawn in Arctic Alaska (1957) a popular account of the one year (1913 to 1914) he spent among the Inupiat of Northern Alaska, The Economics of Cypress (1962), and four scholarly reports on Eskimo Administration in Alaska, Canada, Labrador, and Greenland, plus a fifth report providing an analysis and overview of the four government systems (published between 1962 and 1968 by the Arctic Institute of North America).[7] He was able to complete these writings due to an award from the Guggenheim Foundation to further “whatever scholarly purposes he deemed fit,” an award that amounted to more than two and half times his annual pension from the Canadian government. When health prevented him from escaping Canada's bitter winters, he commenced writing his memoir, a project which his son, Stuart Edward Jenness, “completed” and published in 2008 under the title Through Darkening Spectacles.[30] |

経歴(1911年~1948年) フィールドワーク - ダントルカストー北部 1911年から1912年にかけて、彼はオックスフォード大学の奨学生として、パプアニューギニア東部のダントルカストー諸島に住む、あまり知られていない人々を研究した[3]: 「彼らは人目につかない隅から、あるいは小屋の扉から、いつも安全な距離を保って私を覗き込んだ。海岸沿いの村で覚えた子供の遊びを思い出し、私は身をか がめて指で地面をたたき、リフレインを唱えた。子どもたちはどんどん近づいてきて、1人か2人は満面の笑みを浮かべて私の真似をし始めた。それから私は、 紐で猫のゆりかごの形を作り、子どもたちに見せた。これには度肝を抜かれた。5分後、笑いに包まれた群衆が私を取り囲んだ......原住民たちは私が白 人だとはとても信じられず、私が誰なのか、どうやって彼らの言葉を話すようになったのか、どこで彼らの遊びを覚えたのか、と私の(ガイドに)尋ね続けた」 [7]。 カナダ北極探検 1913年、ジェネスは、ヴィルヤルムール・ステファンソンとR.M.アンダーソンという2人の北極探検家が率いるカナダ北極探検隊(CAE)に政府資金 で参加するよう招かれた[8]。船はブリティッシュ・コロンビアの海岸線を遡り、アラスカのノームへと向かった。そこで彼らは、遠征作業を支援するために 60フィートのスクーナー2隻を購入したステファンソンと合流した。3隻の船はその後、ノースウェスト準州のマッケンジー川河口のすぐ東に位置するハー シェル島をランデブー地点として進んだ[8]。 ランデブーは実現しなかった。8月12日、カールーク号は海氷にロックされた。ステファンソンは、秘書のマコーネル、ジェネス、ウィルキンス(後のヒュー バート・ウィルキンス卿)、2人のエスキモーとともに、乗組員のために肉を調達しに出かけた。彼らが上陸している間に、カルルク号は東シベリア海へと西に 漂流し、最終的にランゲル島沖の氷に砕かれた。[8][9] 乗組員のうち、アンリ・ボーシャを含む13名が船内で死亡した[10]。 船を失った狩猟隊は、150マイル離れたアラスカのバロー(Utqiaġvik)に向かって徒歩で出発し、遠征に参加していた他の2隻の船、メアリー・ サックス号とアラスカ号に会うことを望んだ[9]。バローでは、2隻の船がカムデン湾に停泊していることを知り、そこを冬の基地とした[8]。ジェネスは アラスカのハリソン湾に残り、最初の冬を過ごした。翌1914年、ジェネスは通訳のパッツィ・クレンゲンバーグ(イヌイット女性と貿易商クリスチャン・ク レンゲンバーグの息子)に助けられ、コロネーション湾地域のコッパー・イヌイット(ブロンド・エスキモーと呼ばれることもある)の調査を開始した [11]。このグループはヨーロッパ人とほとんど接触しておらず、唯一の人類学者となったジェネスは、この地域の原住民の生活様式を記録することだけを担 当した[8][9][10]。  イクプクワクとシャーマンの妻ヒガリクを写したヒューバート・ウィルキンスの写真 ジェネスはコッパー・イヌイットとともに2年間を過ごし、イクプクワクという名の猟師とそのシャーマンの妻ヒガリク(名前は氷の家を意味する)の養子とし て暮らした[8][9]。その間、彼は「家族」とともに狩りをし、旅をし、彼らの祝祭と飢えを分かち合った。 [このイヌイットの家族と暮らし、彼らの日常的な体験に参加することで、ジェネスは当時「他の民族学者にはあまり採用されなかった」ことを行った: イヌイットとダイヤモンド・ジェネス』の中でモリソンはこう述べている: 彼の目標は、ヨーロッパ人が頂点にしっかりと腰を据えた、先入観にとらわれない 「創造の梯子 」のようなものとの関係ではなく、銅のイヌイットを彼ら自身の言葉で理解することだった」[12]。 コッパー・イヌイットとの最初の1年を総括して、ジェネスはこう書いている: 「エスキモーの中に孤立することで、私は彼らの放浪の日々を追った。私は秋から秋にかけて、彼らの放浪の日々を追った。 季節ごとの彼らの反応、部族の解散と再集合、海から陸へ、陸から海へと移動する様子を観察した。 海から陸へ、陸から海への移動、封印から狩猟へ、狩猟から漁業へ、漁業から狩猟へ、 そしてまた封印に戻る。このような経済的環境による変化はすべて、私が見てきたものであり、研究してきたものである、 言語の知識が深まったことで、彼らの生活と歴史の他の局面に集中できるようになった」[13]。 人類学者のデ・ラグーナが数年後に述べているように、「ジェネスは自分自身の任務だけでなく、不運な同僚のボーシャットの任務も果たさなければならなかっ たことを思い起こせば、彼の業績はより注目に値する」[14]。さらに、ジェネスのカメラ、人体測定機器、書籍、書類、そして冬の厚着までもが、不運な カーラック号の船内に残されていた[15]。 CAEの科学者たちは毎日日誌をつけ、膨大な調査メモをとり、サンプルを採取してオタワに発送したり持ち帰ったりした。ジェネスは衣服や狩猟用具から物語 やゲームに至るまで、さまざまな民族学的資料を収集し、彼が録音した137曲の蝋の蓄音機シリンダーによる歌の録音も収集した[11][8](後者の譜刻 とコロンビア大学のヘレン・H・ロバーツによる分析、およびジェネスの語訳は、単行本『銅エスキモーの歌』(1925年)に収録されている[16]。 Archived 2021-12-01 at the Wayback Machine このラジオ局はカナダのヌナブト州クグルクトゥクにある。ウェブサイトには、ジェネスが1913年当時の技術でどのようにこれらの曲を録音したかを示す短 いビデオもある(英語)。 ジェネスが調査した銅イヌイットのサブグループ ジェネスはいくつかのサブグループについて報告しており、それらは以下の通りである[17]。 Akuliakattagmiut Haneragmiut コグルクトグミウト パリルミウト Puiplirmiut ウアリルグミウト(カニアルミウト) 銅エスキモーの起源と銅文化 ジェネスはGeographical Review誌の論文の中で、銅イヌイットが西部の文化グループと比較して、東部や南東部の部族とより密接な関係にあることを、考古学的遺物、住居に使わ れた材料、武器、道具、芸術、刺青、習慣、伝統、宗教、そして言語的パターンに基づいて説明した。彼はまた、死者がどのように扱われるかを検討した。西側 のように石や木で覆われ、何の工芸品もない状態なのか、それとも「東側のように、無防備なまま地表に横たえられ、衣服のレプリカやミニチュアの道具が傍ら に置かれている」状態なのか、である[18]。 ジェネスは「銅のエスキモー」を、石器時代と鉄器時代の中間に位置する擬似金属段階であるとした。彼は、銅の使用が異なる文化集団で独自に発生したのか、 それともある集団で発生し、他の集団に「借用」されたのかについて議論した。ジェネスは、先住民のコミュニティが最初に銅を使い始め、それに続いてイヌ イットが銅を採用したと説明する。彼は、イヌイットの間では以前は粘板岩が使われていたが、先住民のコミュニティが銅を使い始めた後、銅に取って代わられ たという事実を挙げている[18]。 ダイヤモンド・ジェネスの研究は、移住のパターンがどのように文化的慣習に影響を与えるか、またある文化から別の文化への移行を理解する上で大きく貢献した[要出典]。 第一次世界大戦 カナダ北極探検隊の科学者たちは任務を終え、1916年に北極を離れた。ジェネスはオタワのヴィクトリア博物館にオフィスを与えられ、探検の成果を書き上 げるよう指示された。6ヵ月間、収集物やメモ、政府への初期報告書の作成に熱中した後、ジェネスはヨーロッパでの出来事を懸念し、第一次世界大戦に入隊し てフランスとベルギーで従軍した。小柄で背が低かったため、直接戦闘以外の任務に就いた[19]。 フィールドワークと執筆 1918年12月、ジェネスはオックスフォードでパプア調査報告書の執筆を終えるため、兵役休暇を申請し、許可を得た(CAEに入隊したことと、その後の 戦争で遅れたため)。オックスフォード滞在中に、彼の部隊が戦争から帰還させられる最初の部隊の1つになったという知らせを受けた。ジェネスは1919年 3月にオタワに戻り、翌月、婚約者のアイリーン・ブリークニーと結婚した。ニュージーランドでの新婚旅行の後、ジェネスは北極圏報告書の執筆に取りかか り、5巻8冊、合計1,368ページの政府報告書を作成した[20]: 「カナダ北極探検隊の科学的成果は15巻に及んだ。その3分の1がジェネスの調査の成果である」[21]。 カナダの先住民 戦争から帰還して1年半後、カナダ政府は彼のヴィクトリア記念博物館での雇用を恒久的なものとし、彼はカナダの多くのインディアン部族を研究することになった。(それまでジェネスの雇用は1年ごとの契約ベースだった)[22]。 アルバータ州カルガリーの保護区に住むサーシー族は、ジェネスのフィールドワークにおける多くの先住民族の最初の部族であった。この経験はまた、カナダの 先住民族が保護区で経験する悲惨な状況に彼が初めて遭遇するきっかけともなった[23]。 サルシー族の後、ジェネスはセカニ族のフィールドワーク研究を行った。ベオトゥク族(絶滅)、オジブワ族、セイリッシュ族である。コリンズとテイラーは、 ジェネスの『Indians of Canada』(1931c)を「カナダの原住民に関する決定的な著作であり、カナダのインディアンとエスキモーの民族学と歴史を包括的に扱っている」と 紹介している[8]。 考古学的発見 ジェネスのほとんどの時間はインディアン研究と行政業務に費やされていたが、彼はまた、カナダのドーセット文化(1925年)[24]とアラスカの旧ベー リング海文化(1926年)[25]という2つの非常に重要な先史時代のエスキモー文化を特定し、後に「エスキモー考古学の父」と称された[26]。ヘル マーは次のように述べている: 「これらの理論は、炭素14年代測定やその後の現地調査によって正当性が証明され、今では広く受け入れられている」[9]。 行政業務 1926年、ジェネスはカナダ初の人類学者エドワード・サピア博士の後任として、カナダ国立博物館の人類学主任となった。その間、世界大恐慌と第二次世界 大戦に阻まれながらも、「カナダの原住民の知識と福祉を向上させ、国立博物館の国際的な評判を高めるために、情熱的に、しかしさまざまな成功を収めながら 奮闘した」[27]。 1929年の第4回太平洋科学会議ではカナダ代表として、1933年の第1回太平洋科学会議では人類学部門の議長を務めた。ジェネスはまた、1938年にコペンハーゲンで開催された国際人類学民族学科学会議のカナダ公式代表も務めた。 第二次世界大戦とその余波 1941年、戦争への貢献を熱望してカナダ空軍に出向し、1944年まで特殊情報部の文民副部長を務めた。1944年には、カナダ国防省の非軍事部門とし て新設された軍間トポグラフィ部門(ISTS)のチーフに任命された(同様の英国軍情報組織である軍間トポグラフィ部門に倣った)。1947年にカナダの ISTSが名称変更(地理局となる)し、鉱山資源省の管轄となった際も、ジェネスはこの役職を維持した[28]。 引退後(1948年-1969年) 引退後もジェネスは旅行、研究、出版を続けた。(訪問地の全表は、『Through Darkening Spectacles』の表2、p.364を参照のこと)。また、ブリティッシュ・コロンビア大学(1951年)やマギル大学(1955年)などの大学 で、北極圏の民族学や考古学に関する講義を行った[29]。 1949年から1969年に亡くなるまで、ジェネスは単行本を含む20冊以上の著作を出版した: トウモロコシの女神』(The Corn Goddess and other tales from Indian Canada、1956年)、『北極圏アラスカの夜明け』(Dawn in Arctic Alaska、1957年)、『サイプレスの経済学』(The Economics of Cypress、1962年)、アラスカ、カナダ、ラブラドール、グリーンランドのエスキモー行政に関する4つの学術報告書、および4つの行政制度の分析 と概要をまとめた5つ目の報告書(Arctic Institute of North America、1962年から1968年にかけて出版)などである。 [7] 彼がこれらの著作を完成させることができたのは、グッゲンハイム財団から「彼が適当と考えるあらゆる学術的目的」のために授与された賞のおかげであり、こ の賞はカナダ政府からの年金の2.5倍以上に相当した。健康上の理由でカナダの厳しい冬を逃れることができなくなったとき、彼は回顧録の執筆を開始した。 このプロジェクトは息子のスチュアート・エドワード・ジェネスが「完成」させ、『Through Darkening Spectacles』というタイトルで2008年に出版した[30]。 |

| Role in applied anthropology Jenness entered the field of anthropology at its outset and was able to study cultures that had experienced little or no previous interaction with “white” people. He began his career engaging in the early traditional fields: ethnology, linguistics, physical (biological), and archaeology. But as he noticed the decline in the morale, economics and health of Canada's indigenous peoples, he shifted his attention towards applied anthropology. Richling, who spent over two decades studying the professional life of Jenness, writes, “Jenness's interest in Indian affairs deepened in the thirties out of concern for the worsening crisis among Native peoples wrought by the Depression and the effects of a long-outmoded government policy of ‘Bible and Plough’.”[31] Recommendations to deputy minister (1936) In his biography “In Twilight and in Dawn,” Richling writes that in 1936 Jenness sent a memo to Deputy Minister Charles Camsell stating the reserves “had denigrated into a ‘system of permanent segregation,’ one whose inhabitants have been stripped of all but a token remnant of control over their own material and spiritual well-being. Rather than bringing opportunity, choice, and self-sufficiency, reserves brought hardship, hopelessness, and dependency, ‘destroy[ing] their morale and their health’ making them outcasts in the wider society.”[32] Jenness recommended: 1) closing of separate schools; 2) creation of scholarships for attending high school, technical schools, and in special cases universities; 3) establishing follow-up after completion of school to help ensure they had steady employment; 4) not enforcing the Potash Law; 5) improving Indian health services; 6) protecting native hunting and trapping grounds.[33] His suggestions appear to have had little influence.[33] The government shifted attention away from domestic problems when World War II broke out, and Jenness (being too old for combat) was assigned temporary duties to assist in war efforts at home.[34] Shortly after the war, he is recorded as having said: “Unhappily nearly all our Indians today—not only the northern ones, but those in the south, too, who live on reserves, whether here in the east or on the prairies or in British Columbia—have lost their dignity, their self-reliance and self-respect.”[35] Joint parliamentary committee meeting (1947) In 1947, Jenness – officially billed as “Dominion Anthropologist” – was called before a joint parliamentary committee to share his views and answer questions.[36] He presented a plan to address what he referred to as the “immorally indefensible” state of Indian social and economic conditions. His plan was based upon New Zealand's management of its native affairs since the early 1860s, which, in his view, was being administered successfully at that time. “Because they are ‘free citizens,’ ” Jenness stated, “Maori are neither segregated on reserves, nor subject to state-sanctioned institutional barriers limiting their participation in national life.”[35] He pointed out that Maoris were treated as full and equal citizens but also encouraged to maintain their distinct cultural identity, values, and traditions. They were allowed to attend public schools and hold government office. Their local communities were becoming largely self-governing - operating in accord with customary tribal authority yet with access to courts to settle land disputes.[37] Some modern viewpoints Some anthropologists are critical of the role played by Diamond Jenness in Canadian state policies. Stevenson, one of Jenness's modern critics who references Kulchyski's views in her book, concludes that his solution for Inuit groups was to "ensure that in a 'definite and not too remote' future there will be 'no such thing' as an Indian or an Eskimo."[38] These critics say that a focus on assimilation destroys the cultural identity of the indigenous peoples. Richling points out that fifteen years before he presented his plan, Jenness had “pessimistically predicted in The Indians of Canada that social and economic forces had already foreclosed on the cultural (and for some, even physical) survival of nearly all Canada's Aboriginal peoples.”[31] At the meeting in 1947, Jenness, as before in his memo to the Deputy Minister Camden, emphasized the importance of education and vocational training to assist these already displaced peoples in becoming more self-sufficient.[39] Using the example of Eskimos in Greenland and Siberia, he suggested teaching the migratory northern Indians skills for trades such as airplane pilot and mechanic, mineral prospecting, wireless operation, game and forest protection, and fur farming.[40] Jenness also pointed out that Japanese children were attending schools with white children in British Columbia while half a mile away Indian children attended segregated schools.[39] In response to his comment, one of the committee members said that this was his district and he'd personally observed Japanese students in classrooms with white children. He added that the Japanese and [west coast] Indians are both members of Oriental races, a fact that had been overlooked, and to put the Indian children in separate schooling, in his opinion, was wrong.[41] Another criticism of Jenness is that he “cared about the Inuit: he didn't want them to become dependent on welfare and thus demoralized, and he wanted them to be as resourceful as their ancestors. However, his way of caring ignored who they were or wanted to become."[38] In the same 1947 parliamentary proceedings the critic refers to, Jenness told the committee there certainly were other approaches to be weighed [than the ones he suggested], especially those originating with the peoples whose future hung in the balance. The committee then questioned him whether he felt the Indians themselves should be asked what they think? Jenness responded “Yes.” He continued to say he felt a proposed plan should be shared with them, and their views should be considered. “I think you would get some very constructive ideas from some of the Indians,” he said.[42] “A truth we often overlook,” Jenness wrote before the war, “[is] that the strongest forces for the regeneration or upbuilding of peoples comes from within their own ranks, not from without.”[43] Outcome of the 1947 meeting “In the end,” Richling writes, “little of a practical nature came of Jenness's proposals on policy reform in the early post-war period.”[31] During the next decade, the government reorganized its bureaucratic departments, replaced mission-run residential schools with state-run (but not integrated) day schools, and offered social benefits such as unemployment insurance, child allowances, and universal health care.[43] In 1968, in the appendix of Eskimo Administration V5: Reflections and Recommendations, Jenness included his proposed plan to help the indigenous peoples of Canada's north become more self-sufficient. He again emphasized the importance of vocational training, giving several specific suggestions such as establishing a small Seaman's School (Navigation School) to train Eskimo youth. Denmark, Jenness wrote, was helping her indigenous by training fishermen to work offshore in well-equipped vessels, and training seaman in a seaman's school at Kogtved, Denmark—a school with an international reputation—then enlisting them among crew for arctic and Antarctic navigation.[44] 21st-century reflections Richling not only provides biographical information on the professional life of Jenness in In Twilight and in Dawn, he objectively reviews many opposing viewpoints of Jenness's role in applied anthropology — including his own. He shares that critics’ arguments range from his being “a well-intentioned … supporter of assimilation, … [to] an ardent imperialist idealogue”[45] then concludes with the following quotes in his last chapter: “ 'Today, makes yesterday mean.’ ~Emily Dickinson "There is an ‘undoubted truth’ in Dickinson's lovely double entendre. “It is that ‘perspectives of the present invariably colour the meanings we ascribe to the past.’ ” ~Richling (who includes quote from Wilson, Douglas.)[46] |

応用人類学における役割 ジェネスは人類学の黎明期に参入し、それまで「白人」とほとんど、あるいはまったく交流のなかった文化を研究することができた。彼は初期の伝統的な分野で ある民族学、言語学、物理学(生物学)、考古学に従事してキャリアをスタートさせた。しかし、カナダの先住民の士気、経済、健康が低下していることに気づ き、応用人類学へと関心を移した。ジェネスの専門家としての生涯を20年以上かけて研究したリッチリングは、「ジェネスのインディアン問題への関心は、大 恐慌がもたらした先住民の危機の悪化と、『聖書と耕作』という長らく時代遅れだった政府の政策の影響への懸念から、30年代に深まった」と書いている [31]。 副大臣への推薦(1936年) リッチリングの伝記「黄昏と夜明けの中で」の中で、ジェネスは1936年にチャールズ・カムセル副大臣にメモを送り、保護区は「『永続的な隔離のシステ ム』へと堕落し、その住民は自分たちの物質的、精神的な幸福をコントロールするための形ばかりの名残を除いて、すべてを剥奪された」と述べたと書いてい る。予備軍は、機会、選択、自給自足をもたらすどころか、苦難、絶望、依存をもたらし、『彼らの士気と健康を破壊し』、より広い社会からのけ者にした」 [32]: 1)別学校の閉鎖、2)高校、専門学校、特別な場合には大学への進学のための奨学金の創設、3)安定した雇用を確保するための学校卒業後のフォローアップ の確立、4)ポタシュ法の不施行、5)インディアンの保健サービスの改善、6)先住民の狩猟・捕獲場の保護[33]。 彼の提案はほとんど影響力を持たなかったようである[33]。 第二次世界大戦が勃発すると、政府は国内問題から注意をそらし、ジェネスは(戦闘には年を取りすぎていたため)国内での戦争活動を支援するために臨時の任 務を割り当てられた[34]: 「不幸なことに、今日のほとんどすべてのインディアンは、北部のインディアンだけでなく、南部のインディアンも、ここ東部であれ、草原地帯であれ、ブリ ティッシュ・コロンビア州であれ、保護区に住んでいるインディアンも、尊厳と自立と自尊心を失っている」[35]。 合同議会委員会(1947年) 1947年、ジェネスは公式に「ドミニオン人類学者」と称され、議会合同委員会に呼ばれ、自身の見解を述べ、質問に答えた[36]。彼の計画は、1860 年代初頭からのニュージーランドの先住民問題管理に基づいており、彼の見解では、当時はうまく運営されていた。「マオリは 「自由市民 」であるため、保護区に隔離されることもなく、国家公認の制度的障壁によって国民生活への参加が制限されることもない。彼らは公立学校に通い、政府の役職 に就くことが許されていた。彼らの地域コミュニティは、慣習的な部族の権限に則って運営されつつも、土地紛争を解決するための裁判所へのアクセス権を持 ち、ほぼ自治されるようになっていた[37]。 現代の視点 カナダの国家政策においてダイヤモンド・ジェネスが果たした役割に批判的な人類学者もいる。ジェネスの現代的な批評家の一人であるスティーヴンソンは、そ の著書の中でクルヒスキーの見解に言及しているが、イヌイット集団に対する彼の解決策は「『明確であまり遠くない』未来に、インディアンやエスキモーと いった『存在しないもの』が存在するようにする」ことであったと結論付けている[38]。これらの批評家は、同化に焦点を当てることは先住民の文化的アイ デンティティを破壊すると述べている。 リッチリングは、彼が計画を発表する15年前に、ジェネスは『カナダのインディアン』(The Indians of Canada)のなかで、「社会的・経済的な力によって、カナダのほぼすべての先住民の文化的(そして一部の人々にとっては物理的な)生存がすでに絶たれ ていると悲観的に予測していた」と指摘している[31]。 1947年の会議でジェネスは、カムデン副大臣に宛てたメモの中で以前と同様に、すでに離散しているこれらの民族の自立を支援するための教育と職業訓練の 重要性を強調した[39]。 グリーンランドやシベリアのエスキモーの例を用いて、彼は移住してくる北部インディアンに飛行機のパイロットや整備士、鉱物の試掘、無線操作、狩猟や森林 保護、毛皮の栽培といった職業の技術を教えることを提案した[40]。 ジェネスはまた、ブリティッシュコロンビア州では日本人の子供たちが白人の子供たちと一緒に学校に通っている一方で、半マイル離れたインディアンの子供た ちは隔離された学校に通っていることを指摘した[39]。彼のコメントに対して、委員会のメンバーの一人は、ここは彼の選挙区であり、日本人の生徒が白人 の子供たちと一緒に教室にいるのを個人的に観察したことがあると述べた。さらに彼は、日本人と[西海岸の]インディアンは同じ東洋人種であり、この事実は 見落とされており、インディアンの子どもたちを別々の学校に入れることは間違っている、と述べた[41]。 ジェネスに対するもうひとつの批判は、彼が「イヌイットを気にかけていた」ということである。彼は彼らが福祉に依存するようになり、その結果士気が低下す ることを望まなかったし、彼らが彼らの祖先のように機知に富んだ人間になることを望んだ。しかし、彼の気遣いの仕方は、彼らが何者であるか、あるいは何者 でありたいかを無視していた」[38]。 批評家が言及した1947年の議会議事録の中で、ジェネスは委員会に対し、[彼が提案したもの以外にも]重きを置くべきアプローチがあったことは確かであ り、特に、その将来が天秤にかかっている民族に由来するアプローチは重要であると述べた。そして委員会は、インディアン自身に意見を聞くべきだと思うか、 と彼に質問した。ジェネスは「はい」と答えた。彼は、計画案は彼らと共有されるべきであり、彼らの意見を考慮すべきだと続けた。「インディアンの一部から 非常に建設的なアイデアが得られると思います」と彼は言った[42]。 「私たちがしばしば見落としている真実がある」とジェネスは戦前に書いている、 「民族の再生や再建のための最も強力な力は、その民族の内部から生まれるということである。 は、外部からではなく、自分たちの内部からやってくるということである」[43]。 1947年の会議の結果 「リッチリングは、「結局のところ、戦後初期の政策改革に関するジェネスの提案からは、ほとんど実用的なものは生まれなかった」と書いている[31]。 1968年、ジェネスは『エスキモー行政V5:反省と提言』の付録として、カナダ北部の先住民の自立を支援するための計画案を掲載した。彼は再び職業訓練 の重要性を強調し、エスキモーの若者を訓練するための小規模な船員学校(航海学校)の設立など、いくつかの具体的な提案を行った。デンマークは、設備の 整った船で沖合で働く漁師を訓練し、国際的に評判の高いデンマークのコグトヴェドにある船員学校で船員を訓練し、彼らを北極や南極の航海の乗組員に加える ことで、先住民を助けているとジェネスは書いている[44]。 21世紀の考察 リッチリングは『黄昏と夜明け』の中で、ジェネスの職業人生に関する伝記的情報を提供するだけでなく、応用人類学におけるジェネスの役割について、彼自身 を含め、多くの反対意見を客観的に検証している。批評家たちの主張は、彼が「善意の......同化の支持者、......熱烈な帝国主義的理想主義者」 [45]であったというものから、次のようなものまで多岐にわたっていることを紹介し、最終章では次のような引用で締めくくっている: 「今日は、昨日を意味あるものにする"。~エミリー・ディキンソン ディキンソンの素敵な二重表現には「疑いようのない真実」がある。 それは、「現在の視点は、私たちが過去に当てはめる意味に必ず色をつける 」ということである。」 ~リッチリング(ウィルソン、ダグラスからの引用を含む)[46]。 |

| Recognition Awards and honors Diamond Jenness received many distinguished awards and honors in recognition of his contributions to his profession. In 1953 Jenness was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.[47] In 1962, he was awarded the Massey Medal by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, and in 1968 he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada, Canada's highest honor. Between 1935 and 1968, he was awarded honorary doctorate degrees from the University of New Zealand, Waterloo University, University of Saskatchewan, Carleton University, and McGill University.[14] In 1973, the Canadian government designated him a Person of National Historic Significance[48] and in the same year the Diamond Jenness Secondary School in Hay River was named after him.[49] In 1978, the Canadian Government named the middle peninsula on the west coast of Victoria Island for him, and in 1998 Maclean's magazine listed him as one of the 100 most important Canadians in history as well as third among the ten foremost Canadian scientists.[50] In 2004, his name was used for a rock examined by the Mars exploration rover Opportunity.[51] Appointments Moreau writes that Jenness held many high posts in professional societies, demonstrating the high regard he was held in by his colleagues. For example, Jenness was vice-president and later President of the American Anthropological Association,(1937-1940), President of the Society for American Archaeology (1937),[52] and vice-president of Section H (Anthropology) of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1938).[53] Publications During his lifetime, Jenness authored more than 100 works on Canada's Inuit and First Nations people. Chief among these are his scholarly government report, Life of the Copper Eskimos (published 1922), his ever-popular account of two years with the Copper Inuit, The People of the Twilight (published 1928), his definitive and durable The Indians of Canada (published 1932 and now in its seventh edition), and four scholarly reports on Eskimo Administration in Alaska, Canada, Labrador, and Greenland, plus a fifth report providing an analysis and overview of the four government systems (published between 1962 and 1968 by the Arctic Institute of North America). He also published a popular account of the one year (1913 to 1914) he spent among the Inupiat of Northern Alaska, Dawn in Arctic Alaska (published 1957 and 1985).[14] For a complete list of Jenness's 138 articles and publications, please refer to Appendix 2 in Through Darkening Spectacles: Memoirs of Diamond Jenness by Diamond Jenness and Stuart E. Jenness, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Mercury Series, (2008). Dr. de Laguna's obituary of Jenness in the American Anthropologist [14] lists 109 publications, and the University of Calgary's: Arctic 23-2-71 obituary of Jenness by Collins, Henry B. & Taylor, William E. Jr. lists 98.[8] Biographies Nansi Swayze published a brief popular account about Jenness' life in The Man Hunters (1960). The Canadian Museum of Civilization published Through Darkening Spectacles: Memoirs of Diamond Jenness (2008). The story is told primarily by Diamond himself with additional sections by his son Stuart Jenness. This biography covers Diamond's professional and personal life. Barnett Richling has, since 1989, published several articles on various aspects of Jenness' life, and a complete, scholarly biography of Jenness's professional life: In Twilight and in Dawn: A Biography of Diamond Jenness published in 2012 by McGill-Queen's University Press. |

表彰 受賞と栄誉 ダイヤモンド・ジェネスは、その専門分野での貢献が認められ、多くの著名な賞を受賞した[47]。1962年には王立カナダ地理学会からマッセイメダルを 授与され、1968年にはカナダ最高の栄誉であるカナダ勲章コンパニオンの称号を授与された[47]。1935年から1968年の間に、ニュージーランド 大学、ウォータールー大学、サスカチュワン大学、カールトン大学、マギル大学から名誉博士号を授与された[14]。1973年、カナダ政府は彼を歴史的に 重要な人物に指定し[48]、同年、ヘイ・リバーのダイヤモンド・ジェネス・セカンダリー・スクールに彼の名前が付けられた。 [49]1978年、カナダ政府はビクトリア島の西海岸にある半島の中央部を彼の名前にちなんで命名し、1998年、Maclean's誌は彼を歴史上最 も重要なカナダ人100人のうちの1人、またカナダを代表する科学者10人のうちの3番目に挙げた[50]。 2004年、火星探査機オポチュニティが調査した岩石に彼の名前が使われた[51]。 任命 モローによれば、ジェネスは専門家集団で多くの要職を歴任し、同僚たちから高く評価されていた。例えば、ジェネスはアメリカ人類学会の副会長、後に会長 (1937-1940年)、アメリカ考古学協会の会長(1937年)[52]、アメリカ科学振興協会のセクションH(人類学)の副会長(1938年)を務 めている[53]。 出版物 ジェネスは生前、カナダのイヌイットおよびファースト・ネーションズに関する100以上の著作を残した。その主なものは、学術的な政府報告書である 『Life of the Copper Eskimos』(1922年出版)、コッパー・イヌイットとの2年間を綴った人気の高い『The People of the Twilight』(1928年出版)、決定的で耐久性のある『The Indians of Canada』(1932年出版、現在は第7版)である、 アラスカ、カナダ、ラブラドール、グリーンランドのエスキモー行政に関する4つの学術報告書と、4つの行政制度の分析と概観を示した5つ目の報告書 (1962年から1968年にかけて北米北極研究所から出版)を出版した。また、彼がアラスカ北部のイヌピアトの間で過ごした1年間(1913年から 1914年)の記録『Dawn in Arctic Alaska』(1957年と1985年に出版)も好評を博した[14]。 ジェネスの138の記事と出版物の完全なリストについては、『Through Darkening Spectacles』の付録2を参照のこと: Diamond Jenness and Stuart E. Jenness, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Mercury Series, (2008)の付録2を参照のこと。American Anthropologist』誌に掲載されたデ・ラグナ博士の追悼記事[14]には109の著書が挙げられており、カルガリー大学のものもある: Arctic 23-2-71 obituary of Jenness by Collins, Henry B. & Taylor, William E. Jr.では98件となっている[8]。 伝記 ナンシー・スウェイジは『The Man Hunters』(1960年)の中でジェネスの生涯を簡単に紹介している。 カナダ文明博物館は『Through Darkening Spectacles』を出版した: Memoirs of Diamond Jenness』(2008年)を出版した。この伝記は主にダイヤモンド自身によって語られ、息子のスチュアート・ジェネスによる追加部分もある。この伝 記はダイヤモンドの仕事と私生活を網羅している。 バーネット・リッチリングは1989年以来、ジェネスの人生のさまざまな側面に関するいくつかの記事を発表しており、2012年にはジェネスの職業生活に 関する完全で学術的な伝記『In Twilight and in Dawn: A Biography of Diamond Jenness』がマギル・クイーンズ大学出版局から出版された。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diamond_Jenness |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099