方法序説

Discourse on the Method, Discours de la Méthode pour

bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les sciences

池田光穂

★『方法序説(Discourse on the Method )』(原題:Discours de la Méthode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les sciences)は、ルネ・デカルトが1637年に発表した哲学的・自伝的論文である。この著作は、第4部にある有名な引用句「Je pense, donc je suis」(「我思う、故に我あり」、あるいは「我は思考する、故に我は存在する」)の出典として最もよく知られている。この正確な表現ではないが、同様 の議論は『第一哲学の省察』(1641年)にも見られ、同じ主張のラテン語版「Cogito, ergo sum」は『哲学の原理』(1644年)に記されている。 『方法序説』は近代哲学史上最も影響力のある著作の一つであり、自然科学の発展にとって重要である。[2] この著作でデカルトは、他の哲学者たちが既に研究していた懐疑主義の問題に取り組んだ。先人や同時代人への言及を交えつつ、デカルトは自らの確信する不可 争の真理を説明するため彼らの手法を修正した。あらゆるものを疑うことから推論を始め、先入観のない新たな視点から世界を評価しようとしたのである。 本書は当初オランダのライデンで出版された。後にラテン語に翻訳され、1656年にアムステルダムで刊行された。本書は三つの著作——『屈折論』『気象 論』『幾何学』——への序章として意図されていた。『幾何学』には、後にデカルト座標系へと発展するデカルトの初期概念が含まれている。このテキストは、 当時の哲学・科学文献の主流言語であったラテン語よりも広い読者層に届くよう、フランス語で執筆・出版された[3]。デカルトの他の著作の大半はラテン語 で書かれている。 『第一哲学の省察』『哲学の原理』『心の指導に関する規則』と合わせて、デカルト主義として知られる認識論の基盤を成す。

| Discourse

on the

Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the

Sciences (French: Discours de la Méthode pour bien conduire sa

raison,

et chercher la vérité dans les sciences) is a philosophical and

autobiographical treatise published by René Descartes in 1637. It is

best known as the source of the famous quotation "Je pense, donc je

suis" ("I think, therefore I am", or "I am thinking, therefore I

exist"),[1] which occurs in Part IV of the work. A similar argument

without this precise wording is found in Meditations on First

Philosophy (1641), and a Latin version of the same statement, "Cogito,

ergo sum", is found in Principles of Philosophy (1644). Discourse on the Method is one of the most influential works in the history of modern philosophy, and important to the development of natural sciences.[2] In this work, Descartes tackles the problem of skepticism, which had previously been studied by other philosophers. While addressing some of his predecessors and contemporaries, Descartes modified their approach to account for a truth he found to be incontrovertible; he started his line of reasoning by doubting everything, so as to assess the world from a fresh perspective, clear of any preconceived notions. The book was originally published in Leiden, in the Netherlands. Later, it was translated into Latin and published in 1656 in Amsterdam. The book was intended as an introduction to three works: Dioptrique, Météores [fr], and Géométrie. Géométrie contains Descartes's initial concepts that later developed into the Cartesian coordinate system. The text was written and published in French so as to reach a wider audience than Latin, the language in which most philosophical and scientific texts were written and published at that time, would have allowed.[3] Most of Descartes' other works were written in Latin. Together with Meditations on First Philosophy, Principles of Philosophy and Rules for the Direction of the Mind, it forms the base of the epistemology known as Cartesianism. |

『方法序説』(原題:Discours de la Méthode

pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les

sciences)は、ルネ・デカルトが1637年に発表した哲学的・自伝的論文である。この著作は、第4部にある有名な引用句「Je pense,

donc je

suis」(「我思う、故に我あり」、あるいは「我は思考する、故に我は存在する」)の出典として最もよく知られている。この正確な表現ではないが、同様

の議論は『第一哲学の省察』(1641年)にも見られ、同じ主張のラテン語版「Cogito, ergo

sum」は『哲学の原理』(1644年)に記されている。 『方法序説』は近代哲学史上最も影響力のある著作の一つであり、自然科学の発展にとって重要である。[2] この著作でデカルトは、他の哲学者たちが既に研究していた懐疑主義の問題に取り組んだ。先人や同時代人への言及を交えつつ、デカルトは自らの確信する不可 争の真理を説明するため彼らの手法を修正した。あらゆるものを疑うことから推論を始め、先入観のない新たな視点から世界を評価しようとしたのである。 本書は当初オランダのライデンで出版された。後にラテン語に翻訳され、1656年にアムステルダムで刊行された。本書は三つの著作——『屈折論』『気象 論』『幾何学』——への序章として意図されていた。『幾何学』には、後にデカルト座標系へと発展するデカルトの初期概念が含まれている。このテキストは、 当時の哲学・科学文献の主流言語であったラテン語よりも広い読者層に届くよう、フランス語で執筆・出版された[3]。デカルトの他の著作の大半はラテン語 で書かれている。 『第一哲学の省察』『哲学の原理』『心の指導に関する規則』と合わせて、デカルト主義として知られる認識論の基盤を成す。 |

| Organization The book is divided into six parts, described in the author's preface as: 1. Various considerations touching the Sciences 2. The principal rules of the Method which the Author has discovered 3. Certain of the rules of Morals which he has deduced from this Method 4. The reasonings by which he establishes the existence of God and of the Human Soul 5. The order of the Physical questions which he has investigated, and, in particular, the explication of the motion of the heart and of some other difficulties pertaining to Medicine, as also the difference between the soul of man and that of the brutes 6. What the Author believes to be required in order to greater advancement in the investigation of Nature than has yet been made, with the reasons that have induced him to write |

構成 本書は六つの部分に分かれており、著者の序文では次のように説明されている: 1. 諸科学に関する諸考察 2. 著者が発見した方法の主要な規則 3. この方法から導き出された道徳の諸規則 4. 神と人間の魂の存在を立証する論証 5. 著者が調査した物理的問題の順序、特に心臓の運動や医学に関連するその他の難題の解説、ならびに人間と獣の魂の違い 6. 自然研究においてこれまで以上に大きな進歩を遂げるために必要と著者が考える事項、および本書執筆に至った理由 |

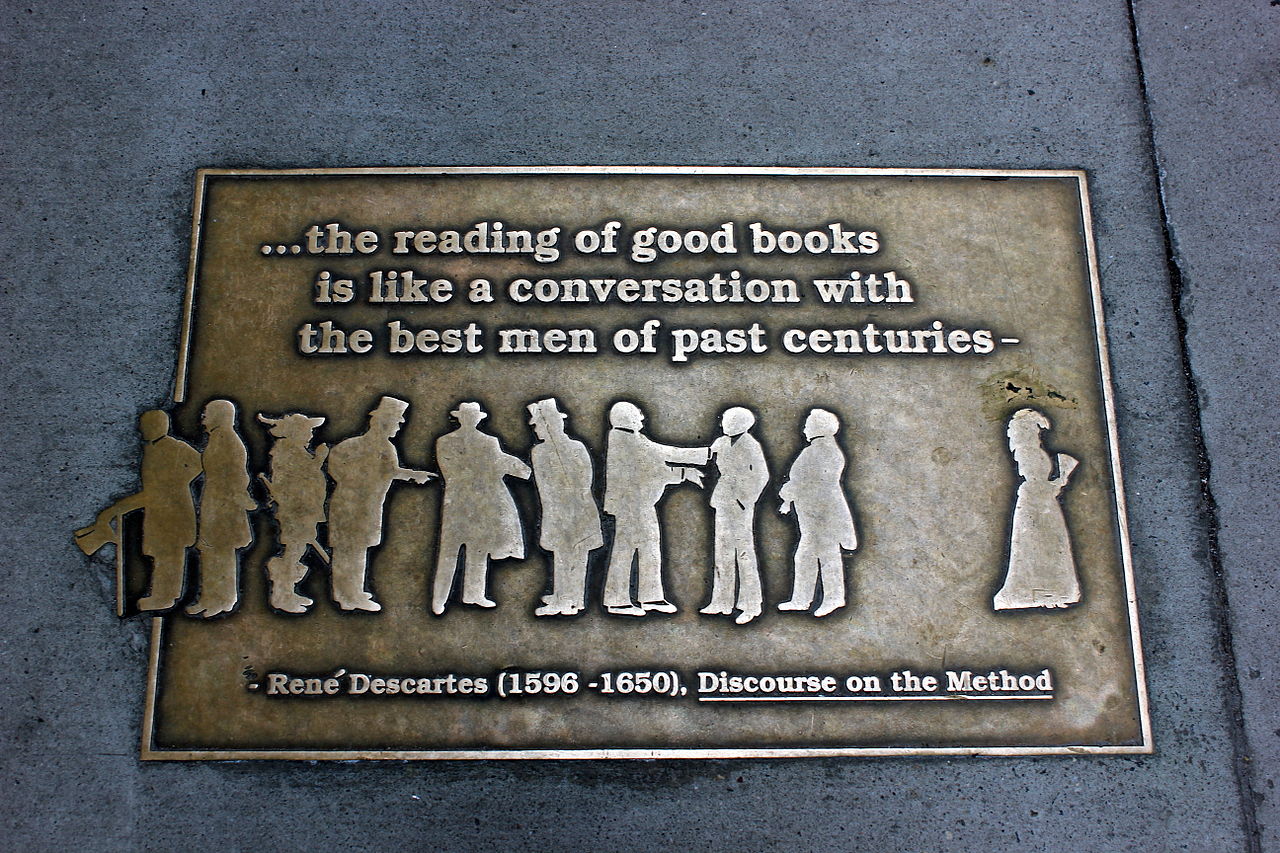

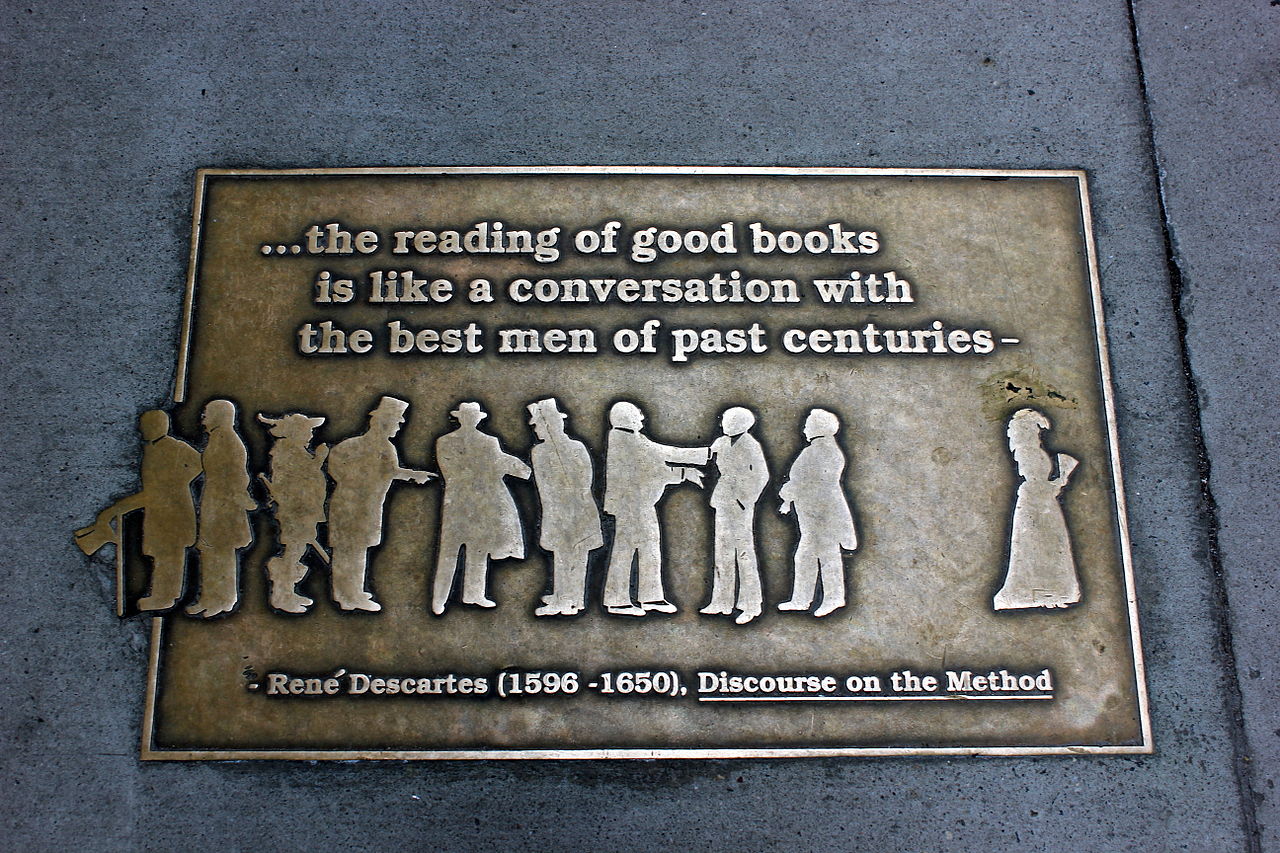

| Part I: Various scientific

considerations Descartes begins by allowing himself some wit: Good sense is, of all things among men, the most equally distributed; for every one thinks himself so abundantly provided with it, that those even who are the most difficult to satisfy in everything else, do not usually desire a larger measure of this quality than they already possess.  "...the reading of good books is like a conversation with the best men of past centuries–" (Discourse part I, AT p. 5) A similar observation can be found in Hobbes, when he writes about human abilities, specifically wisdom and "their own wit": "But this proveth rather that men are in that point equal, than unequal. For there is not ordinarily a greater sign of the equal distribution of anything than that every man is contented with his share,"[4] but also in Montaigne, whose formulation indicates that it was a commonplace at the time: "Tis commonly said that the justest portion Nature has given us of her favors is that of sense; for there is no one who is not contented with his share."[5][6] Descartes continues with a warning:[7] For to be possessed of a vigorous mind is not enough; the prime requisite is rightly to apply it. The greatest minds, as they are capable of the highest excellences, are open likewise to the greatest aberrations; and those who travel very slowly may yet make far greater progress, provided they keep always to the straight road, than those who, while they run, forsake it. Descartes describes his disappointment with his education: "[A]s soon as I had finished the entire course of study…I found myself involved in so many doubts and errors, that I was convinced I had advanced no farther…than the discovery at every turn of my own ignorance." He notes his special delight with mathematics, and contrasts its strong foundations to "the disquisitions of the ancient moralists [which are] towering and magnificent palaces with no better foundation than sand and mud." |

第一部:様々な科学的考察 デカルトはまず、ある種の機知を交えてこう述べる: 良識は、人間にあって最も均等に分配されているものだ。なぜなら誰もが、自分は十分に良識を備えていると考えるからだ。他のあらゆる点で満足しがたい者で さえ、通常は既に持っている以上の良識を望まない。  「良書を読むことは、過去の偉人たちとの対話のようなものだ」 (『言説』第一部、AT p. 5) 同様の観察はホッブズにも見られる。彼は人間の能力、特に知恵と「自らの機知」についてこう記している。「しかしこれは、人間がその点において不平等であ るというより、むしろ平等であることを証明している。なぜなら、あらゆるものの平等な分配を示す最も明らかな徴候は、各人が自らの分け前に満足しているこ とにあるからだ」[4]。モンテーニュも同様の表現を用いているが、その言い回しは当時すでに常識であったことを示している:「自然が与えた恩恵の中で最 も公平な分配は感覚の配分だと言われる。なぜなら、自らの分け前に満足しない者はいないからだ」[5][6]。デカルトはさらに警告を続ける: [7] なぜなら、鋭い知性を備えているだけでは不十分だからだ。最も重要なのは、それを正しく用いることである。最も優れた知性は、最高の卓越性を発揮できると 同時に、最大の誤謬にも陥りやすい。ゆっくりと進む者でも、常に正しい道を歩み続ければ、走りながら道を外れる者よりもはるかに大きな進歩を遂げられるの だ。 デカルトは自身の教育への失望をこう述べる: 「学問の全課程を終えた途端…私は数多の疑念と誤りに巻き込まれ、自らの無知を至る所で発見する以外に…何ら前進していないと確信した」と記す。彼は数学 への特別な喜びを述べ、その強固な基盤を「古代の道徳家たちの論考は、砂や泥に過ぎない土台の上に聳え立つ壮麗な宮殿のようなものだ」と対比する。 |

| Part II: Principal rules of the

Method Descartes was in Germany, attracted thither by the wars in that country, and describes his intent by a "building metaphor" (see also: Neurath's boat). He observes that buildings, cities or nations that have been planned by a single hand are more elegant and commodious than those that have grown organically. He resolves not to build on old foundations, nor to lean upon principles which he had taken on faith in his youth. Descartes seeks to ascertain the true method by which to arrive at the knowledge of whatever lies within the compass of his powers. He presents four precepts:[8] The first was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgment than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all ground of doubt. The second, to divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and as might be necessary for its adequate solution. The third, to conduct my thoughts in such order that, by commencing with objects the simplest and easiest to know, I might ascend by little and little, and, as it were, step by step, to the knowledge of the more complex; assigning in thought a certain order even to those objects which in their own nature do not stand in a relation of antecedence and sequence. And the last, in every case to make enumerations so complete, and reviews so general, that I might be assured that nothing was omitted. |

第二部:方法の主要な規則 デカルトはドイツにいた。同国での戦争に惹かれて渡ったのだ。彼は自らの意図を「建築の隠喩」で説明している(参照:ノイラートの船)。彼は、単一の設計 者によって計画された建物や都市、国家は、有機的に成長したものよりも優雅で便利だと指摘する。彼は古い基礎の上に築くことも、若き日に盲信した原理に依 存することも拒んだ。デカルトは自らの能力の範囲内にあるあらゆる事物の知識に到達する真の方法を見出そうとした。彼は四つの戒律を提示する: [8] 第一に、明らかに真であると知らぬものは決して真実として受け入れないこと。すなわち、軽率さや先入観を慎重に避け、疑いの余地を一切排除するほど明瞭か つ鮮明に心に提示されたもののみを判断に含めること。 第二に、検討中の困難を可能な限り多くの部分へ分割し、その適切な解決に必要なだけ細分化すること。 第三に、思考を秩序立てて進めること。すなわち、最も単純で容易に知ることのできる対象から始め、次第に、いわば一歩一歩、より複雑な対象の知識へと昇華 していく。その際、本質的に先行・後続の関係にない対象に対しても、思考の中で一定の順序を割り当てる。 そして最後に、あらゆる場合において、列挙を完全にし、検討を総括的に行うこと。そうすれば、何も見落とすことがないという確信が持てる。 |

| Part III: Morals and Maxims of

conducting the Method Descartes uses the analogy of rebuilding a house from secure foundations, and extends the analogy to the idea of needing a temporary abode while his own house is being rebuilt. Descartes adopts the following "three or four" maxims in order to remain effective in the "real world" while experimenting with his method of radical doubt. They form a rudimentary belief system from which to act before his new system is fully developed: 1. The first was to obey the laws and customs of my country, adhering firmly to the faith in which, by the grace of God, I had been educated from my childhood; and regulating my conduct in every other matter according to the most moderate opinions, and the farthest removed from extremes, which should happen to be adopted in practice with general consent of the most judicious of those among whom I might be living. 2. Be as firm and resolute in my actions as I was able. 3. Endeavor always to conquer myself rather than fortune, and change my desires rather than the order of the world, and in general, accustom myself to the persuasion that, except our own thoughts, there is nothing absolutely in our power; so that when we have done our best in things external to us, our ill-success cannot possibly be failure on our part. Finally, Descartes states his resolute belief that there is no better use of his time than to cultivate his reason and to advance his knowledge of the truth according to his method. |

第三部:方法の運用に関する道徳と格律 デカルトは、確固たる基礎から家を再建するという比喩を用い、その家を再建している間は仮の住まいが必要だという考えへと比喩を拡張する。デカルトは、根 本的懐疑という自身の方法を試行しながら「現実世界」で効果的に行動し続けるために、以下の「三つか四つ」の格律を採用する。これらは、彼の新しい体系が 完全に確立される前に、行動の基盤となる初歩的な信念体系を形成するものである: 1. 第一に、我が国の法律と慣習に従い、幼少期から神の恩寵により育まれた信仰を堅く守り、その他のあらゆる事柄においては、最も穏健な意見、すなわち極端か ら最も遠く離れた意見に従って行動すること。その意見は、私が暮らす人々のうち最も賢明な者たちの一般的な合意によって実践されているものでなければなら ない。 2. 行動においては可能な限り堅固かつ断固たる態度を保つこと。 3. 常に運命よりも己を征服し、世界の秩序よりも己の欲望を変えるよう努め、概して「己の思考を除けば、絶対的に我が力の及ぶものは何もない」という確信を己 に植え付けること。そうすれば、外的な事柄において最善を尽くしたならば、たとえ不成功に終わっても、それは決して己の失敗とは言えないのである。 最後にデカルトは、自らの理性を磨き、自らの方法に従って真理の知識を深めることに時間を費やす以上に優れた使い道はないと断固として信じていると述べて いる。 |

| Part IV: Proof of God and the

Soul Applying the method to itself, Descartes challenges his own reasoning and reason itself. But Descartes believes three things are not susceptible to doubt and the three support each other to form a stable foundation for the method. He cannot doubt that something has to be there to do the doubting: I think, therefore I am. The method of doubt cannot doubt reason as it is based on reason itself. By reason there exists a God, and God is the guarantor that reason is not misguided. Descartes supplies three different proofs for the existence of God, including what is now referred to as the ontological proof of the existence of God. |

第四部:神と魂の証明 デカルトは自らの方法論をその方法論自体に適用し、自らの推論と理性そのものに疑問を投げかける。しかしデカルトは、三つの事柄が疑いの余地がないと信じ ている。この三つは互いに支え合い、方法論の安定した基盤を形成する。疑う行為を行う主体が存在しなければならないことは疑えない。「我思う、故に我あ り」。疑いの方法は、それ自体が理性に基づいているため、理性そのものを疑うことはできない。理性によって神は存在し、神は理性が誤った方向へ導かれない ことを保証する。デカルトは神の存在について三つの異なる証明を提示し、その中には現在「存在論的証明」と呼ばれるものも含まれている。 |

| Part V: Physics, the heart, and

the soul of man and animals Descartes briefly sketches how in an unpublished treatise (published posthumously as Le Monde) he had laid out his ideas regarding the laws of nature, the sun and stars, the moon as the cause of "ebb and flow" (meaning the tides), gravitation, light, and heat. Describing his work on light, he states: [I] expounded at considerable length what the nature of that light must be which is found in the sun and the stars, and how thence in an instant of time it traverses the immense spaces of the heavens. His work on such physico-mechanical laws is, however, framed as applying not to our world but to a theoretical "new world" created by God somewhere in the imaginary spaces [with] matter sufficient to compose ... [a "new world" in which He] ... agitate[d] variously and confusedly the different parts of this matter, so that there resulted a chaos as disordered as the poets ever feigned, and after that did nothing more than lend his ordinary concurrence to nature, and allow her to act in accordance with the laws which he had established. Descartes does this "to express my judgment regarding ... [his subjects] with greater freedom, without being necessitated to adopt or refute the opinions of the learned." (Descartes' hypothetical world would be a deistic universe.) He goes on to say that he "was not, however, disposed, from these circumstances, to conclude that this world had been created in the manner I described; for it is much more likely that God made it at the first such as it was to be." Despite this admission, it seems that Descartes' project for understanding the world was that of re-creating creation—a cosmological project which aimed, through Descartes' particular brand of experimental method, to show not merely the possibility of such a system, but to suggest that this way of looking at the world—one with (as Descartes saw it) no assumptions about God or nature—provided the only basis upon which he could see knowledge progressing (as he states in Book II). Thus, in Descartes' work, we can see some of the fundamental assumptions of modern cosmology in evidence—the project of examining the historical construction of the universe through a set of quantitative laws describing interactions which would allow the ordered present to be constructed from a chaotic past. He goes on to the motion of the blood in the heart and arteries, endorsing the findings of "a physician of England" about the circulation of blood, referring to William Harvey and his work De motu cordis in a marginal note.[9]: 51 But then he disagrees strongly about the function of the heart as a pump, ascribing the motive power of the circulation to heat rather than muscular contraction.[10] He describes that these motions seem to be totally independent of what we think, and concludes that our bodies are separate from our souls. He does not seem to distinguish between mind, spirit, and soul, all of which he identifies with our faculty for rational thinking. Hence the term "I think, therefore I am." All three of these words (particularly "mind" and "soul") can be signified by the single French term âme. |

第五部:物理学、心臓、そして人間と動物の魂 デカルトは未発表の論文(死後『世界論』として出版)において、自然の法則、太陽と星々、月の「満ち引き」(潮汐を指す)の原因、重力、光、熱に関する自 身の考えを概説したことを簡潔に記している。光に関する研究について彼は次のように述べている: [私は]太陽や星々に存在する光の性質が如何なるものであるか、またそれが如何にして瞬時に天界の広大な空間を横断するのかについて、かなり詳細に論じ た。 しかし、こうした物理機械的法則に関する彼の研究は、我々の世界ではなく、神が創造した理論上の「新たな世界」に適用されるものとして構築されている。 想像上の空間のどこかに存在する「新たな世界」に適用されるものとして構築されている。そこには…(「新たな世界」を構成するのに十分な)物質が存在し、 神はこの物質の異なる部分を…異様に、そして無秩序に攪拌した。その結果、詩人たちがかつて想像したような混沌が生じた。その後、神は何もせず、単に自然 に対して通常の同意を与え、自身が定めた法則に従って自然が作用することを許したに過ぎない。 デカルトはこう述べる。「学識者の見解を採用したり反駁したりする必要なく、より自由に…[彼の主題]に関する私の判断を表明するためである。」(デカル トの仮説的世界は、神を信じる宇宙観となるだろう。) 彼はさらに「しかし、こうした事情から、この世界が私が述べた方法で創造されたと結論づける気にはならなかった。なぜなら、神が最初からこの世界をあるべ き姿のままに創造した可能性の方がはるかに高いからだ」と述べている。この認めに反して、デカルトの世界理解の企ては創造の再創造であったようだ。これは デカルト独自の実験的手法を通じて、単にそのような体系の可能性を示すだけでなく、神や自然に関する仮定を一切伴わない(デカルトの見解では)この世界観 こそが、知識の進展を可能とする唯一の基盤であると示唆する宇宙論的企てであった(第二巻で述べられている通り)。 したがってデカルトの著作には、現代宇宙論の根本的前提がすでに現れている。すなわち、定量的な法則によって相互作用を記述し、混沌とした過去から秩序あ る現在を構築するという宇宙の歴史的構築を検証する試みである。 彼はさらに心臓と動脈における血液の運動について論じ、『イングランドの医師』による血液循環の発見を支持する。これはウィリアム・ハーヴェイとその著作 『心臓の運動について』を指す注釈である[9]: 51 。しかし心臓のポンプ機能については強く異論を唱え、循環の原動力は筋肉収縮ではなく熱にあると 主張する[10]。彼はこれらの動きが我々の思考とは全く無関係に存在すると述べ、身体は魂から分離していると結論づける。 彼は精神、霊魂、魂を区別せず、これら全てを理性的な思考能力と同一視している。故に「我思う、故に我あり」という表現が生まれる。これら三つの概念(特 に「精神」と「魂」)は、単一のフランス語「âme」で表される。 |

| Part VI: Prerequisites for

advancing the investigation of Nature Descartes begins by obliquely referring to the recent trial of Galileo for heresy and the Church's condemnation of heliocentrism; he explains that for these reasons he has held back his own treatise from publication.[11] However, he says, because people have begun to hear of his work, he is compelled to publish these small parts of it (that is, the Discourse, Dioptrique, Météores [fr], and Géométrie) in order that people not wonder why he doesn't publish. The discourse ends with some discussion of scientific experimentation: Descartes believes that experimentation is indispensable, time-consuming, and yet not easily delegated to others. He exhorts the reader to investigate the claims laid out in Dioptrique, Météores, and Géométrie and communicate their findings or criticisms to his publisher; he commits to publishing any such queries he receives along with his answers. |

第六部:自然研究を進めるための前提条件 デカルトはまず、ガリレオの異端審問と教会による地動説の非難に間接的に言及する。彼はこれらの事情から自身の論文の出版を控えてきたと説明する。 [11] しかし、人々が彼の著作について耳にするようになったため、出版しない理由を人々が不思議に思わないように、これらの小部分(すなわち『言説』『屈折論』 『流星論』『幾何学』)を出版せざるを得なくなったと述べる。 この言説は科学実験に関する議論で締めくくられている。デカルトは実験が不可欠であり、時間を要する作業でありながら、他人に委ねるのが容易ではないと考 える。彼は読者に『屈折論』『流星論』『幾何学』に記された主張を検証し、その結果や批判を自身の出版社に伝えるよう促す。そして受け取った質問とそれに 対する自身の回答を全て出版することを約束する。 |

| Influencing future science Skepticism had previously been discussed by philosophers such as Sextus Empiricus, Al-Kindi,[12] Al-Ghazali,[13] Francisco Sánchez and Michel de Montaigne. Descartes started his line of reasoning by doubting everything, so as to assess the world from a fresh perspective, clear of any preconceived notions or influences. This is summarized in the book's first precept to "never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such". This method of pro-foundational skepticism is considered to be the start of modern philosophy.[14][15] |

将来の科学に影響を与える 懐疑主義は、セクストゥス・エンピリクス、アル・キンディ[12]、アル・ガザーリー[13]、フランシスコ・サンチェス、ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュな どの哲学者たちによって、以前から議論されていた。デカルトは、あらゆる先入観や影響から解放された、新たな視点から世界を見直そうと、あらゆるものを疑 うことからその論理を展開した。これは、この本の最初の教訓「自分が明らかに真実であると認識していないものは、決して真実として受け入れてはならない」 に要約されている。この基礎を揺るがす懐疑主義の手法は、近代哲学の始まりと考えられている。 |

| Quotations This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. Please help summarise the quotations. Consider transferring direct quotations to Wikiquote or excerpts to Wikisource. (October 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) "The most widely shared thing in the world is good sense, for everyone thinks he is so well provided with it that even those who are the most difficult to satisfy in everything else do not usually desire to have more good sense than they have. It is not likely that everyone is mistaken in this…" (part I, AT p. 1 sq.) "I know how very liable we are to delusion in what relates to ourselves; and also how much the judgments of our friends are to be suspected when given in our favor." (part I, AT p. 3) "… I believed that I had already given sufficient time to languages, and likewise to the reading of the writings of the ancients, to their histories and fables. For to hold converse with those of other ages and to travel, are almost the same thing." (part I, AT p. 6) "Of philosophy I will say nothing, except that when I saw that it had been cultivated for so many ages by the most distinguished men; and that yet there is not a single matter within its sphere which is still not in dispute and nothing, therefore, which is above doubt, I did not presume to anticipate that my success would be greater in it than that of others." (part I, AT p. 8) "… I entirely abandoned the study of letters, and resolved no longer to seek any other science than the knowledge of myself, or of the great book of the world.…" (part I, AT p. 9) "The first was to include nothing in my judgments than what presented itself to my mind so clearly and distinctly that I had no occasion to doubt it." (part II, AT p. 18) "… In what regards manners, everyone is so full of his own wisdom, that there might be as many reformers as heads.…" (part VI, AT p. 61) "… And although my speculations greatly please myself, I believe that others have theirs, which perhaps please them still more." (part VI, AT p. 61) |

引用 この記事には引用が多すぎるか、あるいは引用が長すぎる。引用を要約する手助けをしてほしい。直接引用はWikiquoteへ、抜粋は Wikisourceへ移すことを検討してほしい。(2023年10月) (このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 「世界で最も広く共有されているものは良識である。なぜなら誰もが自分は十分に良識を備えていると考えているからだ。他のあらゆる点で最も満足しにくい人 々でさえ、通常は自分が持っている以上の良識を望まない。誰もがこの点で間違っているとは考えにくい…」 (第1部, AT p. 1 sq.) 「我々は自分自身に関わる事柄においていかに錯覚に陥りやすいか、また我々を称賛する友人たちの判断がいかに疑わしいものであるかを、私は知っている。」 (第1部、AT p. 3) 「…私は既に言語学習に十分な時間を費やしたと考えていた。同様に、古代の著作や歴史、神話を読むことにも時間を割いた。なぜなら、過去の時代の人々と対 話することは、旅をすることとほぼ同じことだからだ。」(第1部、AT p. 6) 「哲学については何も言わない。ただ、これほど多くの時代を通じて最も優れた人々が研究してきたにもかかわらず、その領域内のいかなる事柄も未だに議論の 余地がなく、したがって疑いの余地がないものなど一つもないと知った時、私はこの分野で他者より優れた成果を上げられるとは思いもしなかった。」(第1 部、AT p.8) 「…私は文学の研究を完全に放棄し、もはや自己の知識、あるいは世界の偉大な書物以外のいかなる学問も求めないと決意した。」(第一部、AT p.9) 「第一の方法は、私の心に明瞭かつ鮮明に現れ、疑う余地のないものだけを判断に含めることだった。」(第二部、AT p.18) 「… 習慣に関しては、誰もが自らの知恵に満ちているため、頭の数だけ改革者が存在するかもしれない。」(第6部、AT p.61) 「… そして、私の思索は私自身を大いに喜ばせるが、他者にも彼ら自身の思索があり、おそらくそれは彼らをさらに喜ばせているのだろう。」(第6部、AT p.61) |

| Mathesis universalis Great Conversation |

普遍数学 偉大なる対話 |

| 1. Garber, Daniel. [1998] 2003.

"The Cogito Argument | Descartes, René Archived 2021-09-15 at the

Wayback Machine." In Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E.

Craig. London: Routledge. Retrieved 2017-11-12. 2. Davis, Philip J., and Reuben Hersh. 1986. Descartes' Dream: The World According to Mathematics. Cambridge, MA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 3. Burns, William E. (2001). The scientific revolution: an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-87436-875-8. 4. "Oregon State University". oregonstate.edu. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. 5. "Essays of Montaigne, vol. 6 - Online Library of Liberty". libertyfund.org. 6. "Essays of Montaigne, vol. 6 - Online Library of Liberty". libertyfund.org. 7. Descartes, Rene (1960). Discourse on Method and Meditations. Laurence J. Lafleur (trans). New York: The Liberal Arts Press. ISBN 978-0-672-60278-8. 8. Descartes, René (2004) [1637]. A Discourse on Method: Meditations and Principles. Translated by Veitch, John. London: Orion Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 9780460874113. 9. Descartes (1637). 10. W. Bruce Fye: Profiles in Cardiology – René Descartes, Clin. Cardiol. 26, 49–51 (2003), Pdf 58,2 kB. 11. "Three years have now elapsed since I finished the treatise containing all these matters; and I was beginning to revise it, with the view to put it into the hands of a printer, when I learned that persons to whom I greatly defer, and whose authority over my actions is hardly less influential than is my own reason over my thoughts, had condemned a certain doctrine in physics, published a short time previously by another individual to which I will not say that I adhered, but only that, previously to their censure I had observed in it nothing which I could imagine to be prejudicial either to religion or to the state, and nothing therefore which would have prevented me from giving expression to it in writing, if reason had persuaded me of its truth; and this led me to fear lest among my own doctrines likewise some one might be found in which I had departed from the truth, notwithstanding the great care I have always taken not to accord belief to new opinions of which I had not the most certain demonstrations, and not to give expression to aught that might tend to the hurt of any one. This has been sufficient to make me alter my purpose of publishing them; for although the reasons by which I had been induced to take this resolution were very strong, yet my inclination, which has always been hostile to writing books, enabled me immediately to discover other considerations sufficient to excuse me for not undertaking the task." 12. Prioreschi, Plinio (2002). "Al-Kindi, A Precursor of the Scientific Revolution" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine (2): 17–20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021. 13. Najm, Sami M. (July–October 1966). "The Place and Function of Doubt in the Philosophies of Descartes and Al-Ghazali". Philosophy East and West. 16 (3–4): 133–141. doi:10.2307/1397536. JSTOR 1397536. 15. Descartes' Life and Works by Kurt Smith, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2017-11-20 16. Descartes, Rene by Justin Skirry (Nebraska-Wesleyan University), The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ISSN 2161-0002. Retrieved 2017-11-20 |

1. ガーバー、ダニエル。[1998] 2003.

「コギトの議論 | デカルト、ルネ 2021-09-15 ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ」 『ラウトレッジ哲学百科事典』 E.

クレイグ編。ロンドン:ラウトレッジ。2017-11-12 取得。 2. デイヴィス、フィリップ J.、ルーベン・ハーシュ。1986年。『デカルトの夢:数学による世界』 マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:Harcourt Brace Jovanovich。 3. バーンズ、ウィリアム E. (2001)。『科学革命:百科事典』 カリフォルニア州サンタバーバラ:ABC-CLIO。ISBN 978-0-87436-875-8。 4. 「オレゴン州立大学」。oregonstate.edu。2010年5月28日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。 5. 「モンテーニュの随筆、第6巻 - オンライン自由図書館」。libertyfund.org。 6. 「モンテーニュの随筆、第6巻 - オンライン自由図書館」。libertyfund.org。 7. デカルト、ルネ (1960). 『方法序説と省察』. ローレンス・J・ラフルール (訳). ニューヨーク: リベラルアーツプレス. ISBN 978-0-672-60278-8. 8. デカルト、ルネ (2004) [1637]. 『方法序説:省察と原理』. ジョン・ヴィーチ (訳). ロンドン:オリオン出版グループ。p. 15。ISBN 9780460874113。 9. デカルト (1637)。 10. W. ブルース・ファイ:心臓病学における人物像 – ルネ・デカルト、『臨床心臓病学』26巻、49–51頁 (2003年)、PDF 58.2 kB。 11. 「これら全ての事柄を含む論文を完成させてから三年が経過した。印刷所に渡すべく校閲を始めようとした矢先、私が深く敬意を抱き、その行動への影響力が私 の思考に対する理性と同等とも言える人格たちが、物理学におけるある教義を非難したことを知った。その学説は、私が支持していたとは言わないが、彼らが非 難する前には、宗教や国家にとって有害と思われる点も、したがって私がその真実性を理性によって確信した場合に書面で表明することを妨げるような点も、私 は見出せなかった。このことから、私自身の教説の中にも、たとえ真実から逸脱したものが一つでも見つかればと恐れるようになった。私は常に、最も確かな証 明のない新しい意見には決して同意せず、誰かを傷つける恐れのあることは決して口にしないよう細心の注意を払ってきたにもかかわらずである。このため、私 はそれらを出版する決意を翻すに至った。この決断に至った理由は非常に強固であったが、もともと書物を著すことに消極的であった私の性向が、この任務を引 き受けないことを正当化する他の十分な理由を即座に見出させたのである。」 12. プリオーレスキ、プリニオ (2002). 「アル=キンディ、科学革命の先駆者」 (PDF). イスラム医学史国際学会誌 (2): 17–20. 2021年6月30日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。2021年7月19日に閲覧。 13. ナジム、サミ・M.(1966年7月~10月)。「デカルトとアル=ガザーリーの哲学における疑いの位置と機能」。『東洋と西洋の哲学』。16巻3~4 号:133–141頁。doi:10.2307/1397536。JSTOR 1397536。 15. カート・スミス著『デカルトの生涯と著作』スタンフォード哲学百科事典。2017年11月20日取得。 16. ジャスティン・スキリー(ネブラスカ・ウェスリアン大学)著『ルネ・デカルト』インターネット哲学百科事典、ISSN 2161-0002。2017年11月20日取得。 |

| Descartes, René (1637). Discours

de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison et chercher la vérité dans

les sciences, plus la dioptrique, les météores et la géométrie (in

French), BnF Gallica Discourse on the Method at Project Gutenberg Discours de la Méthode at Project Gutenberg (édition Victor Cousin, Paris 1824) Discours de la méthode, par Adam et Tannery, Paris 1902. (academic standard edition of the original text, 1637), Pdf, 80 pages, 362 kB.(リンク 切れ) Contains Discourse on the Method, slightly modified for easier reading(リンク切れ) Free audiobook at librivox.org or at audioofclassics |

デカルト、ルネ(1637)。『方法序説、すなわち、理性を正しく導

き、科学、さらに屈折光学、流星学、幾何学において真理を探求する方法について』(フランス語)、BnF Gallica プロジェクト・グーテンベルク『方法序説』 プロジェクト・グーテンベルク『方法序説』(ヴィクトル・クザン版、パリ 1824年) 方法に関する談話、アダムとタナリー著、パリ 1902年。(1637年の原文の学術標準版)、PDF、80ページ、362 kB。 読解を容易にするため若干修正を加えた『方法に関する談話』を含む。 librivox.org または audioofclassics で無料のオーディオブックを入手できる。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discourse_on_the_Method |

☆「『方法序説』(ほ うほうじょせつ、方法叙説とも、仏: Discours de la méthode)とは、1637年に公刊されたフランスの哲学者、ルネ・デカルトの著書である。 刊行当時の正式名称は、『理性を正しく導き、学問において真理を探究するための方法の話。加えて、その試みである屈折光学、気象学、幾何学。』(りせいを ただしくみちびき、がくもんにおいてしんりをたんきゅうするためのほうほうのはなし。くわえて、そのこころみであるくっせつこうがく、きしょうがく、きか がく、仏: Discours de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les sciences. Plus la Dioptrique, les Météores et la Géométrie, qui sont des essais de cette méthode.)であり、元来は3つの科学論文集を収めた500ページを超える大著だった。今日の『方法序説』として扱われているテキストは、その書籍 中の最初の78ページの「序文」部分であり[1]、自身の方法論の発見・確立や刊行に至るまでの経緯を述べている。 序説と訳されるDiscoursは、Traitéが教科書のように体系的に書かれた論説であるのに対して、形式ばらない論考の意であり、デカルト自身がメ ルセンヌへの書簡で「方法の試み」であると呼んでいる。哲学的な内容はその後に出版された『省察 Meditationes de prima philosophia』とほぼ重なっているが、『方法序説』は自伝の記述をふくみ、思索の順序を追ってわかりやすく書かれているため、この一冊でデカル ト哲学の核心を知ることができる。当時、多くの本がラテン語で書かれることが多い中、ラテン語の教育を受ける可能性が低かった当時の女性や子供たちでも読 めるように、フランス語で書かれ、6つの部分に分かれている。 オランダのライデンで出版され、その後ラテン語に翻訳されて、1656年にアムステルダムで出版された。初版は、宗教裁判によって異端とされることを恐れ て、偽名で発行された。」

第1部は「良識(bon sens)はこの世でもっとも公平に配分されているものである」という書き出しで始まる。ここでの良識は理性と同一視できるものとされる。健全な精神を 持っているだけでは十分ではない。この序説の目的は、理性を正しく導くためにしたがうべき方法を教えるというより、デカルト自身が種々の心得や考察に至る までにどのような道筋をたどったかを示すことである、と宣言する。学校での全課程を修了し「珍奇な学問 Sciences occulte」まで渉猟しつくしたにもかかわらず、多くの疑惑にとらわれている自分を発見したデカルトは、語学・歴史・雄弁・詩歌・数学・神学・スコラ 学・法学・医学は、有益な学問ではあるがどれも不確実で堅固な基盤を持っていないことが分かり、文字の学問をすっかり投げ打つことにした、と語る。

第2部は、三十年戦争に従軍してドイツにいたときの思索について述べる。有名な「暖炉」に一

日中こもって、最初に考えたことは一人の者が仕上げた仕事はたくさんの人の手を経た仕事に比べて完全であり、一人の常識ある人間が自分の目の前の事柄に単

純に下す推論は多くの異なった人々によって形成された学問より優れている、ということだった。賛成者が多いということは、発見しがたい真理に対しては何の

価値もない証明である。したがってデカルトはその時まで信頼して受け容れてきた意見から脱却することを志した。その際に精神を導く4つの準則として

1. 私が明証的に真理であると認めるものでなければ、いかなる事柄でもこれを真なりとして認めないこと

2. 検討しようとする難問をよりよく理解するために、多数の小部分に分割すること

3. もっとも単純なものからもっとも複雑なものの認識へと至り、先後のない事物の間に秩序 を仮定すること

4. 最後に完全な列挙と、広範な再検討をすること

を定めた。これによりデカルトは代数学や他の諸科学を検討して、理性を有効に活用し得たと感

じたが、それらの諸科学の基本となるべき哲学の原理を見いだしていないことに気づく。このとき彼は23歳であったが、もっと経験を積み円熟した年齢になる

まで、悪い見解や誤謬を自分から根絶するために多くの時間を費やすことを決意する。

第3部は、理性が不決断である間でも自分の行為を律し幸福な生活を送るためにデカルトが設け

た3つの道徳律を紹介する。

1. 自分の国の法律と習慣に従うこと。

2. 一度決心したことは断固かつ毅然として行うこと。

3. つねに運命よりも自分に克つことにつとめ、世界の秩序よりも自分の欲望を変えるように 努力すること。

デカルトは理性を教化し自分が自分で決めた方法に従って真理の認識に近づくことを、自分に とって最善の職業と考えた。暖炉部屋を出て、9年間は世間を見て歩き、疑わしいもの・誤謬を観察反省し、1628年いよいよ哲学の基礎を定めるため、オラ ンダに隠遁することにした。

第4部でデカルトは、少しでも疑問を差し挟む余地あるものは疑い、感覚・論証・精神に入りこ んでいた全てを真実でないと仮定しても、一切を虚偽と考えようとする「私」はどうしても何者かでなければならないことに気づく。フランス語で書かれた『方 法序説』の「Je pense, donc je suis」私は考えるので私はあるを、デカルトと親交のあったメルセンヌがラテン語訳し「Cogito ergo sum」「我思う、ゆえに我あり」コギト・エルゴ・スムとした。この命題は、我々が明瞭かつ判然と了解するものはすべて真実であることを一般規則として導 く。その規則からデカルトは、さらに神の存在と本性・霊魂について演繹している。

第5部で、公表を控えていた論文『世界論』(『宇宙論』)の内容を略述する。

第6部では、ガリレイの審問と地動説の否認という事件が、デカルトに自分の物理学上の意見の

公表を躊躇させたと述べる。人間を自然の主人とするための生活にとって有用な知識に到達することは可能であり、それを隠すことはデカルトにも大罪と思われ

た。実験や観察は重要であり、公衆がそれから得る利益を互いに公開することが今後大切になるはずだと。しかし、ガリレオ事件で教訓を得たデカルトは、まだ

発見されていない若干の真理を探究する時間を失わないために、反駁や論議を招くような自分の著書は生前に出版することを断念することにした。しかし自分が

著作を用意していたことを知る人々に意図を誤解されないよう、1634年になって書かれた論考から慎重に選ばれた『屈折光学』『気象学』『幾何学』に『方

法序説』を附して公表することに同意した、と述べる。

| 1. Je ne sais si je dois vous entretenir des premières méditations que j'y ai faites; car elles sont si métaphysiques et si peu communes, qu'elles ne seront peut-être pas au goût de tout le monde. Et toutefois, afin qu'on puisse juger si les fondements que j'ai pris sont assez fermes, je me trouve en quelque façon contraint d'en parler. J'avais dès longtemps remarqué que, pour les mœurs, il est besoin quelquefois de suivre des opinions qu'on sait fort incertaines, tout de même que si elles étaient indubitables, ainsi qu'il a été dit ci-dessus; mais, parce qu'alors je désirais vaquer seulement à la recherche de la vérité, je pensai qu'il fallait que je fisse tout le contraire, et que je rejetasse, comme absolument faux, tout ce en quoi je pourrais imaginer le moindre doute afin de voir s'il ne resterait point, après cela, quelque chose en ma créance, qui fût entièrement indubitable. Ainsi, à cause que nos sens nous trompent quelquefois, je voulus supposer qu'il n'y avait aucune chose qui fût telle qu'ils nous la font imaginer. Et parce qu'il y a des hommes qui se méprennent en raisonnant, même touchant les plus simples matières de géométrie, et y font des paralogismes, jugeant que j'étais sujet à faillir, autant qu'aucun autre, je rejetai comme fausses toutes les raisons que j'avais prises auparavant pour démonstrations. Et enfin, considérant que toutes les mêmes pensées, que nous avons étant éveillés, nous peuvent aussi venir, quand nous dormons, sans qu'il y en ait aucune, pour lors, qui soit vraie, je me résolus de feindre que toutes les choses qui m'étaient jamais entrées en l'esprit n'étaient non plus vraies que les illusions de mes songes. Mais, aussitôt après, je pris garde que, pendant que je voulais ainsi penser que tout était faux, il fallait nécessairement que moi, qui le pensais, fusse quelque chose. Et remarquant que cette vérité :je pense, donc je suis, était si ferme et si assurée, que toutes les plus extravagantes suppositions des sceptiques n'étaient pas capables de l'ébranler, je jugeai que je pouvais la recevoir, sans scrupule, pour le premier principe de la philosophie que je cherchais. |

【1】 その地でおこなった最初の省察をお話しすべきかどうかはわかりません。というのもこの省察は〈形而上学〉で扱うようなひどく現実ばなれのした、ありふれて いない必のなので、おそらくみなさんの好みにあわないでしょうから。ところが、私の選んだ基礎がじゅうぶんしっかりしているかどうかを判断していただける ためには、どうしてもそれをお話ししなければならない、いわばそういうはめに陥っているのに気がついたのです。だいぶまえから私は、生き方については、ひ どく不確かだとわかっている意見でも、疑う余地のないものだったばあいとまったく同じように、それに従う必要がときにはあると気づいていました。これはま えにも申しあげたとおりです。しかし、そのころはただひたすら真理の探求に打ち込みたいと願っていましたので、その正反対のことをやり、ほんの少しでも疑 いをふくむと想像されるおそれのあるものはみな、ぜったいにまちがっているとしてしりぞけるのが必要だと考えました。どこにも疑いをさしはさむ余地のない ものが、そのあとで、何か私の信念に残りはしないかを見ようとして、そう考えたのです。たとえば私たちの感覚はときどき私たちを欺くので、どんなものでも 感覚が私たちに想像させるとおりのものはないと私は想定しようと思ったのです。そして〈幾何学〉のどんなに単純な素材を扱うときにも、推論をするうちに勘 ちがいをし、〈誤謬推理〉をする人がいるのですから、私もほかのどんな人とも同じだけまちがいを犯しやすいのだと判断して、それ以前に〈論証〉とみなして いた論拠をどれもこれもまちがったものとしてしりぞけました。そして最後に、私たちが目を覚ましていていだく同じ考えがどれもみな眠っているときにやって くることもありうるが、そのときには何ひとつほんとうのものはないということを考えめぐらして、私は、それまでに自分の精神にはいりこんでいたものはみ な、私の夢のまぼろし以上にほんとうではないと仮想することに決めまじた。しかし、すぐあとで、そんなふうにどれもまちがいだと考えたいと思っているあい だにも、そう考えている自分は何かであることがどうしても必要だということに気づきました。そしてこの「私は考える、だから私は有る」という真理はいかに もしっかりしていて、保証つきであるため、〈懐疑論者たち〉のどんなに並みはずれた想定を残らず使ってもこれをゆるがすことができないのを見てとって、私 はこの真理を、求めていた〈哲学〉の第一の原理として、疑惑なしに受け入れることができると判断しました。 |

| 2. Puis, examinant avec attention ce que j'étais, et voyant que je pouvais feindre que je n'avais aucun corps, et qu'il n'y avait aucun monde, ni aucun lieu où je fusse; mais que je ne pouvais pas feindre, pour cela, que je n'étais point; et qu'au contraire, de cela même que je pensais à douter de la vérité des autres choses, il suivait très évidemment et très certainement que j'étais; au lieu que, si j'eusse seulement cessé de penser, encore que tout le reste de ce que j'avais jamais imaginé eût été vrai, je n'avais aucune raison de croire que j'eusse été : je connus de là que j'étais une substance dont toute l'essence ou la nature n'est que de penser, et qui, pour être, n'a besoin d'au¬cun lieu, ni ne dépend d'aucune chose matérielle. En sorte que ce moi, c'est-à-dire l'âme par laquelle je suis ce que je suis, est entièrement distincte du corps, et même qu'elle est plus aisée à connaître que lui, et qu'encore qu'il ne fût point, elle ne laisse¬rait pas d'être tout ce qu'elle est. |

【2】 それから、自分が何であるかを注意ぶかく検討し、そして自分にはどんな体もなく、またどんな世界も、自分がいるどんな揚所もないと仮想することはできて も、だからといって自分が無いと仮想することはできないし、それどころか、ほかのいろいろなものがほんとうであるかどうかを疑おうと考えていること自体か ら、私が有るということがきわめて明白確実に出てくるのにたいして、一方では、ただ私が考えることをやめさえしたら、たとえ私がかつて想像したものの残り ぜんぶがほんとうであったとしても、私には自分が有ったと信じるどんな理由もなくなるだろうということを見て、私はそこから、自分がひとつの実体であり、 その実体の本質なり本性なりは考えることだけにつきるし、またその実体は有るためにどんな揚所も必要としなければ、どんな物質的なものにも依存しないこと を認識したのです。ですからこの〈私〉、つまり私を現在あるものにしている〈魂〉は、体とはまるきりべつなものであり、しかも体よりも認識しやすく、たと え体が無かったとしてもそっくり今あるままであることに変わりはないでしょう。 |

| 3. Après cela, je considérai en général ce qui est requis à une proposition pour être vraie et certaine; car, puisque je venais d'en trouver une que je savais être telle, je pensai que je devais aussi savoir en quoi consiste cette certitude. Et ayant remarqué qu'il n'y a rien du tout en ceci : je pense, donc je suis, qui m'assure que je dis la vérité, sinon que je vois très clairement que, pour penser, il faut être : je jugeai que je pouvais prendre pour règle générale, que les choses que nous concevons fort claire¬ment et fort distinctement sont toutes vraies; mais qu'il y a seulement quelque difficulté à bien remarquer quelles sont celles que nous concevons distinctement. |

【3】 そのあとで、私は、ひとつの命題にとってほんとうで確かであるためには何が要求されるかを、全般にわたって考えめぐらしました。というのも、私がほんとう で確かであることを知っているひとつの命題をいま見つけたところでしたから、その確実さがどういう点から成り立つのかも私は知っているはずだと考えたから です。そしてこの「私は考える、だから私は有る」ということのなかには、私の言っていることがほんとうだと保証してくれるものは、考えるためには有ること が必要だとひじようにはっきりわかっていること以外には何もないの.を見てとって、私はつぎのように判断しました。私たちがきわめてはっきりとまぎれなく つかむものはどれもみなほんとうだということを一般的な規則とみなしていい、しかし私たちがまぎれなくつかむものはどんなものであるかをよく見分けるの に、ただむずかしい点がいくらかあると。 |

| 4. En suite de quoi, faisant réflexion sur ce que je doutais, et que, par conséquent, mon être n'était pas tout parfait, car je voyais clairement que c'était une plus grande perfection de connaître que de douter, je m'avisai de chercher d'où j'avais appris à penser à quelque chose de plus parfait que je n'étais; et je connus évidemment que ce devait être de quelque nature qui fût en effet plus parfaite. Pour ce qui est des pensées que j'avais de plu¬sieurs autres choses hors de moi, comme du ciel, de la terre, de la lumière, de la chaleur, et de mille autres, je n'étais point tant en peine de savoir d'où elles venaient, à cause que, ne remarquant rien en elles qui me semblât les rendre supérieures à moi, je pouvais croire que, si elles étaient vraies, c'étaient des dépendan¬ces de ma nature, en tant qu'elle avait quelque perfection; et si elles ne l'étaient pas, que je les tenais du néant, c'est-à-dire qu'elles étaient en moi, parce que j'avais du défaut. Mais ce ne pouvait être le même de l'idée d'un être plus parfait que le mien : car, de la tenir du néant, c'était chose manifestement impossible; et parce qu'il n'y a pas moins de répugnance que le plus parfait soit une suite et une dépendance du moins parfait, qu'il y en a que de rien procède quelque chose, je ne la pouvais tenir non plus de moi-même. De façon qu'il restait qu'elle eût été mise en moi par une nature qui fût véritablement plus parfaite que je n'étais, et même qui eût en soi toutes les perfections dont je pouvais avoir quelque idée, c'est-à-dire, pour m'expliquer en un mot, qui fût Dieu. A quoi j'ajoutai que, puisque je connaissais quelques perfections que je n'avais point, je n'étais pas le seul être qui existât (j'userai, s'il vous plaît, ici librement des mots de l'École), mais qu'il fallait, de nécessité, qu'il y en eût quelque autre plus parfait, duquel je dépendisse, et duquel j'eusse acquis tout ce que j'avais. Car, si j'eus¬se été seul et indépendant de tout autre, en sorte que j'eusse eu, de moi-même, tout ce peu que je participais de l'être parfait, j'eusse pu avoir de moi, par même raison, tout le surplus que je connaissais me manquer, et ainsi être moi-même infini, éternel, immuable, tout connaissant, tout-puissant, et enfin avoir toutes les per¬fec¬tions que je pouvais remarquer être en Dieu. Car, suivant les raisonnements que je viens de faire, pour connaître la nature de Dieu, autant que la mienne en était capable, je n'avais qu'à considérer de toutes les choses dont je trouvais en moi quelque idée, si c'était perfection, ou non, de les posséder, et j'étais assuré qu'aucune de celles qui marquaient quelque imperfection n'était en lui, mais que toutes les autres y étaient. Comme je voyais que le doute, l'inconstance, la tristesse, et choses semblables, n'y pouvaient être, vu que j'eusse été moi-même bien aise d'en être exempt. Puis, outre cela, j'avais des idées de plusieurs choses sensibles et corpo¬rel¬les : car, quoique je supposasse que je rêvais, et que tout ce que je voyais ou imagi¬nais était faux, je ne pouvais nier toutefois que les idées n'en fussent véritablement en ma pensée; mais parce que j'avais déjà connu en moi très clairement que la nature intelligente est dis¬tincte de la corporelle, considérant que toute composition témoigne de la dépen¬dance, et que la dépendance est manifestement un défaut, je jugeais de là, que ce ne pouvait être une perfection en Dieu d'être composé de ces deux natures, et que, par consé¬quent, il ne l'était pas; mais que, s'il y avait quelques corps dans le monde, ou bien quelques intelligences, ou autres natures, qui ne fussent point toutes parfaites, leur être devait dépendre de sa puissance, en telle sorte qu'elles ne pou¬vaient subsister sans lui un seul moment. |

【4】 それにつづいて、私が疑っているということ、したがって私の有が完全無欠ではないことについて、というのも疑うよりは認識するほうが完全度の高いものだと はっきりわかっていたからですが、そうしたことに反省を加えながら、私は自分よりも完全なものを何か考えることをどこから学んだのか探そうと思いつきまし た。そしてそれは現実にいっそう完全な本性をそなえたあるものからにちがいないと明白に認識しました。私の外にあるほかのかずかずのもの、たとえば天空や 大地や光や熱やそのほかの数えきれないものについて私がいだいていた考えはどうかといえば、そうした考えがどこから来たのかそれほど苦労して知ろうとも思 いませんでした。そうした考えを私よりもすぐれたものにしていると思われる点がそれらの考えのなかに何込見あたりませんでしたので、私はつぎのように信じ ることができたからです。もしそうした考えがほんとうならば、私の本性に何か完全さがあるかぎり、私の本性に依存するものであるし、またもしそうした考え がほんとうでないとしたら、私はそれを無から得ている、つまり私に欠陥があるから私のなかにあるのだと。しかし私の有よりも完全な有の観念については同じ であるわけにはいきませんでした。というのもその観念を無かち得ることは、明らかに不可能なことだったからです。そして完全度の高いもののほうが完全度の 低いものの結果でありそれに依存するものであるなどというのは、何もないものから何かが出てくるというのに劣らず矛盾していますから、私はその観念を自分 自身からも得ることはできませんでした。こういうふうにして残るところは、その観念が私よりもほんとうに完全なある本性によって私のなかに置かれたという ことでした。その本性は、しかもどんな完全さであろうと私がそれについて何かしら観念をいだくことのできるかぎりのあらゆる完全さをそれ自体のうちにそな えている、つまりひとことで言いあらわせば、神であるようなものです。これに私はつぎのことを加えました。つまり私は自分の持っていない完全さをいくつか 認識している以上、私だけが存在する唯一の有ではなく(よろしければ、ここで自由に〈学校〉の用語を使うことにします〉、かならず、何かほかのもっと完全 なものがあって、私はそれに依存し、いま持っているものはすべてそこかち得たのにちがいないと。もし私がたつたひとりでほかのどんなものにも依存せずに独 立していて、したがって完全な有から分有しているこのわずかばかりのものをすべて私自身から得たとすれば、私が自分に欠けているのを認識しているあとのも のぜんぷを、同じ理由によって、自分から得ることができ、したがって私自身、無限で永遠で不変で全知で全能になり、そして最後に、どんな完全さでも神のな かにあると私が認めることのできるかぎり残らず身につけることができたはずだからです。というのもいま試みてきた推論に従えば、私の本性にその力のあるか ぎり、神の本性を認識するためには、どんなものでも自分のなかにその観念が何か見つかるものについて、私はただ、それを所有することが完全さであるかない かを考えめぐらしさえすればよかったのですし、またどこかに不完全さが認められるようなものは神のなかに何ひとつなく、そうでないものは何でもあるという 確信をいだいていたからです。たとえば疑いとか、変わりゃすい心とか、悲しみとか、またそれに似たものは、私自身もそんなものから免れたらどんなにうれし いだろうと思っているのですから、神のなかにありえないといおっこともわかりました。それから、そのほかにも、感覚でとらえることができ物体に属するかず かずのものについて私はいろいろな観念を持っていました。というのも、私は夢を見ていて、見るなり想像するなりしているものはどんなものでもみなまちがい だと想定してみても、そういうものの観念がほんとうに私の考えのなかにあることはやはり否定できなかったからです。しかし私は知的な本性が物体的な本性と はま、ぎれもない別なものであることを、すでに私のうちにひじようにはっきり認識していたのですから、合成はどんなばあいでも依存の証拠であり、依存は明 らかに欠陥だということを考えめぐらして、私は以上のことからつぎのように判断しました。この二つの本性から合成されているということは、神のうちにあっ ても完全さではありえないし、したがって神はそうしたものではない、しかしこの世にいろいろな物体や、あるいはまた知性とかその他の本性で、完全無欠とは いえないものが何かあるとしたら、そういうものの有は神の力に依存しているにちがいなく、したがってそういうものは神がなくては一瞬も存続することはでき ないと。 |

| 5. Je voulus chercher, après cela, d'autres vérités, et m'étant proposé l'objet des géo-mè¬tres, que je concevais comme un corps continu, ou un espace indéfiniment étendu en longueur, largeur et hauteur ou profondeur, divisible en diverses parties, qui pouvaient avoir diverses figures et grandeurs, et être mues ou transposées en toutes sortes, car les géomètres supposent tout cela du leur objet, je parcourus quelques-unes de leurs plus simples démonstrations. Et ayant pris garde que cette grande certitude, que tout le monde leur attribue, n'est fondée que sur ce qu'on les conçoit évidemment, suivant la règle que j'ai tantôt dite, je pris garde aussi qu'il n'y avait rien du tout en elles qui m'assurât de l'existence de leur objet. Car, par exemple, je voyais bien que, supposant un triangle, il fallait que ses trois angles fussent égaux à deux droits; mais je ne voyais rien pour cela qui m'assurât qu'il y eût au monde aucun triangle. Au lieu que, revenant à examiner l'idée que j'avais d'un Être parfait, je trouvais que l'existence y était comprise, en même façon qu'il est compris en celles d'un triangle que ses trois angles sont égaux à deux droits, ou en celle d'une sphère que toutes ses parties sont également distantes de son centre, ou même encore plus évidemment; et que, par conséquent, il est pour le moins aussi certain, que Dieu, qui est cet Être parfait, est ou existe, qu'aucune démonstration de géométrie le saurait être. |

【5】 そのあとで、私はほかの真理を求めたいと思いました。そして〈幾何学者〉の扱う対象をとりあげましたが、私はそれを連続休として、つまり長さ、幅、高さま たは深さにおいて果てしなくひろがり、いろいろな部分に分割できる空間としてつかんでいました。分割された部分は形と大きさをいろいろに変えることもでき れば、どんなやり方で動かしたり移したりすることもできます。というのも〈幾何学者〉が自分たちの対象にそういうことをすべて想定しているからです。私は 幾何学者のそういう対象をとりあげて、彼らのいちばん簡単な論証にいくつか目を通してみました。するとそうした論証に世間の人がみんな高い確実性を与えて いるとしても、それは私が先ほど申し述べた規則に従って、論証を明白につかんでいるということだけにもとづいているのに気がついたうえ、そうした論証のな かには、論証の対象の存在を保証してくれるようなものは皆無だということにも気づきました。たとえば、ひとつの三角形を想定してみると、その三つの角の和 が二直角に等しくなければならないのはよくわかりましたが、だからといってこの世にひとつでも三角形があると保証してくれるようなものは何も見あたらな かったからです。一方、ある完全な〈有〉についていだいていた観念にたちかえって検討してみると、その観念に存在がふくまれているのがわかりました。それ はちょうど三角形の観念にその三つの角の和は二直角に等しいとか、球面の観念にその部分はどこも中心から距離が等しいということがふくまれているのと同じ ぐあいか、それどころかもっと明白になのです。またしたがって、少なくとも、神、すなわちこの完全な〈有〉であるものが有るもしくは存在することは、〈幾 何学〉のどんな論証とも同じくらい確かだということもわかったのです。 |

| 6. Mais ce qui fait qu'il y en a plusieurs qui se persuadent qu'il y a de la difficulté à le connaître, et même aussi à connaître ce que c'est que leur âme, c'est qu'ils n'élèvent jamais leur esprit au delà des choses sensibles, et qu'ils sont tellement accoutumés à ne rien considérer qu'en l'imaginant, qui est une façon de penser particulière pour les choses matérielles, que tout ce qui n'est pas imaginable leur semble n'être pas intelli¬gible. Ce qui est assez manifeste de ce que même les philosophes tiennent pour maxi¬me, dans les écoles, qu'il n'y a rien dans l'entendement qui n'ait premièrement été dans le sens, où toutefois il est certain que les idées de Dieu et de l'âme n'ont jamais été. Et il me semble que ceux qui veulent user de leur imagination, pour les compren¬dre, font tout de même que si, pour ouïr les sons, ou sentir les odeurs, ils se voulaient servir de leurs yeux : sinon qu'il y a encore cette différence, que le sens de la vue ne nous assure pas moins de la vérité de ses objets, que font ceux de l'odorat ou de l'ouïe; au lieu que ni notre imagination ni nos sens ne nous sauraient jamais assurer d'aucune chose, si notre entendement n'y intervient. |

【6】 しかし神を認識するのには、そればかりでなく自分の魂とは何であるかを認識するのにも困難があると思いこむ人は大勢いますが、どうしてそういうことが起こ るかといえば、それはそういう人たちが感覚でとらえることのできるもの以上に自分の精神をけっして高めないからですし、またイメージを浮かべて想像しなけ れば——これは物質的なものにたいする特殊な考え方なのですが——何も考えめぐらさない習慣がすっかりついてしまって、イメージの浮かばないものはどんな ものでもそういう人たちには理解できないように思われるからなのです。〈哲学者たち〉でさえも、理解力のなかにあってまずはじめに感覚のなかになかったも のは何もないというのを、〈学校〉で、格率とみなしていることから——しかも感覚のなかに神の観念と魂の観念がけっしてなかったことは確かですし——以上 のことはじゅうぶん明らかです。そしてそうした観念をとらえるために、自分の想像力を使いたいと思う人たちは、音を聞いたり匂いをかいだりするために、目 を使いたいと思ったばあいとまったく同じようなことをしているように私には思われます。ただしそれでもなおつぎのような相違はあるのです。つまり視覚は、 嘆覚や聴覚に劣らずその対象の真実を私たちに保証してくれるのですが、一方私たちの想像力も感覚も、理解力がそこにはいってこなければ、私たちにどんなも のもけっして保証するすべはないだろうということです。 |

| 7. Enfin, s'il y a encore des hommes qui ne soient pas assez persuadés de l'existence de Dieu et de leur âme, par les raisons que j'ai apportées, je veux bien -qu'ils sachent que toutes les autres choses, dont ils se pensent peut-être plus assurés, comme d'avoir un corps, et qu'il y a des astres et une terre, et choses semblables, sont moins certai¬nes. Car encore qu'on ait une assurance morale de ces choses, qui est telle, qu'il semble qu'à moins que d'être extravagant, on n'en peut douter, toutefois aussi, à moins que d'être déraisonnable, lorsqu'il est question d'une certitude métaphysique, on ne peut nier que ce ne soit assez de sujet, pour n'en être pas entièrement assuré, que d'avoir pris garde qu'on peut, en même façon, s'imaginer, étant endormi, qu'on a un autre corps, et qu'on voit d'autres astres, et une autre terre, sans qu'il en soit rien. Car d'où sait-on que les pensées qui viennent en songe sont plutôt fausses que les autres, vu que souvent elles ne sont pas moins vives et expresses ? Et que les meilleurs esprits y étudient tant qu'il leur plaira, je ne crois pas qu'ils puissent donner aucune raison qui soit suffisante pour ôter ce doute, s'ils ne présupposent l'existence de Dieu. Car, pre¬mièrement, cela même que j'ai tantôt pris pour une règle, à savoir que les choses que nous concevons très clairement et très distinctement sont toutes vraies, n'est assuré qu'à cause que Dieu est ou existe, et qu'il est un être parfait, et que tout ce qui est en nous vient de lui. D'où il suit que nos idées ou notions, étant des choses réelles, et qui viennent de Dieu, en tout ce en quoi elles sont claires et distinctes, ne peuvent en cela être que vraies. En sorte que, si nous en avons assez souvent qui contiennent de la fausseté, ce ne peut être que de celles qui ont quelque chose de confus et obscur, à cause qu'en cela elles participent du néant, c'est-à-dire, qu'elles ne sont en nous ainsi confuses, qu'à cause que nous ne sommes pas tout parfaits. Et il est évident qu'il n'y a pas moins de répugnance que la fausseté ou l'imperfection procède de Dieu, en tant que telle, qu'il y en a que la vérité ou la perfection procède du néant. Mais si nous ne savions point que tout ce qui est en nous de réel et de vrai vient d'un être parfait et infini, pour claires et distinctes que fussent nos idées, nous n'aurions aucune raison qui nous assurât qu'elles eussent la perfection d'être vraies. |

【7】 最後に、私が持ち出した論拠によっても、神の存在と自分の魂の存在にじゅうぶん納得のいかない人たちがまだいるならば、そういう人たちがおそらくいっそう 強く確信しているほかのどんなことでも、たとえば体を持っているとか、いろいろな天体とひとつの地球とがあるとか、またそれと似たことでも、それほど確か でないということを知ってほしいと思います。というのも、それらのことについては実際生活のうえでの安心感を持っていて、常軌を逸している人でなければ、 疑うこともできないように思われるほどですが、しかしまた、形而上学的な確実さが問題になるときには、理性に欠けている人でないかぎり、つぎのことに気づ いただけでもじゅうぶん、そのことについて全面的には確信がいだけない根拠になるのを否定できないからです。づまり眠っていながら、べつな体を持っている とか、またほかの天体や、もうひとつの地球を見ていると、そんなことはないのに、想像することも、同じように、ありうるということです。というのも、夢に 浮かぶ考えは、目覚めているときの考えに劣らず生き生きしてあざやかなことがよくあるのを見ると、そのほうがむしろまちがっているというととがどこからわ かるのでしょう。そしてどんなにすぐれた精神の持ち主が好きなだけそういうことを勉強しても、神の存在を前提しておかなければ、こうした疑いを取り除くの にじゅうぶんな論拠は何ひとつ示すことができようとは思えません。というのも、まず第一に、先ほど規則とみなしたこと、づまり私たちがひじようにはっきり とま、ぎれなくつかむものはどれもみなほんとうだということ自体が保証されるのはただ、神が有りまたは存在し、そして神は完全な有であり、私たちのうちに 有るものはみな神に由来するという理由によるだけだからです。そのけっか私たちの観念なり知見なりは、どんなもののなかでもはっきりしてまぎれのないもの であるかぎり、実在の、神に由来するものであって、その点でほんとうでしかありえません。したがって私たちがまちがいをふくむ観念をずいぶんたびたび持つ としても、それは何かまぎらわしくてぼんやりしたところのある観念から来るほかはありえません。こうした点でそれらの観念が無の性質を帯びているからで す。つまりそうした観念が私たちのなかでそのようにまぎらわしいのは、私たちが完全無欠ではないからにほかなりません。そしてまちがいなり不完全さなり が、そうしたものであるかぎり、神から出てくるということには、真理なり完全さなりが無から出てくるのに劣らず矛盾があるのは明白です。しかし私たちのう ちにある実在の、ほんとうのものがみな、完全で無限な有から来ていることを知らなかったら、私たちの観念がどんなにはっきりしてまぎれがなくても、それら の観念がほんとうであるという完全さを持つことを保証してくれるような理由を私たちは何ひとつ持たなくなるでしょう。 |

| 8. Or, après que la connaissance de Dieu et de l'âme nous a ainsi rendus certains de cette règle, il est bien aisé à connaître que les rêveries que nous imaginons étant endormis ne doivent aucunement nous faire douter de la vérité des pensées que nous avons étant éveillés. Car, s'il arrivait, même en dormant, qu'on eût quelque idée fort dis¬tinc¬te, comme, par exemple, qu'un géomètre inventât quelque nouvelle dé¬mons-tration, son sommeil ne l'empêcherait pas d'être vraie. Et pour l'erreur la plus ordi-naire de nos songes, qui consiste en ce qu'ils nous représentent divers objets en même façon que font nos sens extérieurs, n'importe pas qu'elle nous donne occasion de nous défier de la vérité de telles idées, à cause qu'elles peuvent aussi nous tromper assez souvent, sans que nous dormions : comme lorsque ceux qui ont la jaunisse voient tout de couleur jaune, ou que les astres ou autres corps fort éloignes nous paraissent beaucoup plus petits qu'ils ne sont. Car enfin, soit que nous veillions, soit que nous dormions, nous ne nous devons jamais laisser persuader qu'à. l'évidence de notre raison. Et il est à remarquer que je dis, de notre raison, et non point, de notre imagina¬tion ni de nos sens. Comme, encore que nous voyons le soleil très clairement, nous ne devons pas juger pour cela qu'il ne soit que de la grandeur que nous le voyons; et nous pouvons bien imaginer distinctement une tête de lion entée sur le corps d'une chèvre, sans qu'il faille conclure, pour cela, qu'il y ait au monde une chimère : car la raison ne nous dicte point que ce que nous voyons ou imaginons ainsi soit véritable. Mais elle nous dicte bien que toutes nos idées ou notions doivent avoir quelque fondement de vérité; car il ne serait pas possible que Dieu, qui est tout parfait et tout véritable, les eût mises en nous sans cela. Et parce que nos raisonnements ne sont jamais si évidents ni si entiers pendant le sommeil que pendant la veille, bien que quelquefois nos imaginations soient alors autant ou plus vives et expresses, elle nous dicte aussi que nos pensées ne pouvant être toutes vraies, à cause que nous ne sommes pas tout parfaits, ce qu'elles ont de vérité doit infailliblement se rencontrer en celles que nous avons étant éveillés, plutôt qu'en nos songes. |

【8】 ところで、神と魂とを認識したけっか私たちがこの規則をこうして確かだとみなすようになったあとでは、眠っていながら妄想を思い描くからといって、目覚め ていながらいだく考えがほんとうかどうかを疑う理由になるはずは少しもないということはわけなく認識できるのです。というのも、眠っているのにひじように まぎれのない考えが何か思い浮かんだとしても、たとえば〈幾何学者〉が何か新しい論証を考え出すというようなことが起こっても、眠っていたからといってそ の論証がほんとうでなくなるということはありますまい。また私たちの夢のいちばんふつうの迷いは、夢が外部感覚と同じ仕方でいろいろな対象を再現してくれ る点にありますが、その迷いがきっかけとなってそうした観念がほんとうかどうかについて私たちが不審をいだくようになってもかまいません。そうした観念は また、私たちが限ってもいないのに、私たちをたびたび欺くおそれがあるからです。黄疸にかかった人たちに何でも黄色く見えたり、天体やはるか遠くにある物 体が実際よりずっと小さく見えたりするばあいのようにです。というのも、けっきょく、目を覚ましていようと眠っていようと、私たちはけっして私たちの理性 の明白さだけにしか自分を説得させてはならないからです。しかも注意すべきことは、私たちの理性の、と私は言っているのであって、私たちの想像力の、とも 感覚の、とも言っているのではないことです。たとえば、私たちには太陽がひじょうにはっきり見えますけれども、だからといって見えるとおりの大きさしかな いと判断してはなりませんし、山羊の胴体にライオンの頭をつ、ぎたしたのをまぎれもなく想像することはできるにしても、だからといってこの世にそういうキ マイラという怪獣がいると結論してはなりません。というのも理性は、そんなふうに私たちが見たり想像したりするものがほんものだとは告げていないからで す。そうではなくて理性は、私たちの観念なり知見なりがいくらか真理の基礎を持っているはずだとはっきり告げているのです。というのも完全無欠で真正無比 の神が、そういうこともなしに観念なり知見なりを私たちのうちに置いたということはありえないでしょうから。そして私たちの想像力は眠っているあいだも目 を覚ましているあいだと同じくらいかあるいはいっそう生き生きしてあざやかなばあいがときどきあるとはいえ、私たちの推論は眠っているあいだには目を覚ま しているあいだほど明白でもなければ、すきのないものでもないために、理性はまたこう告げるのです。つまり私たちは完全無欠ではないから、私たちの考えも ぜんぶがぜんぶほんとうとはかぎらず、私たちの考えが帯びている真実さは、夢のなかよりもむしろ、目を覚ましていながらいだく考えのなかにまちがいなく見 あたるはずだと。 |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Do not copy and paste, but you might [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099