文化的表現の多様性の保護及び促進に関する条約

Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions

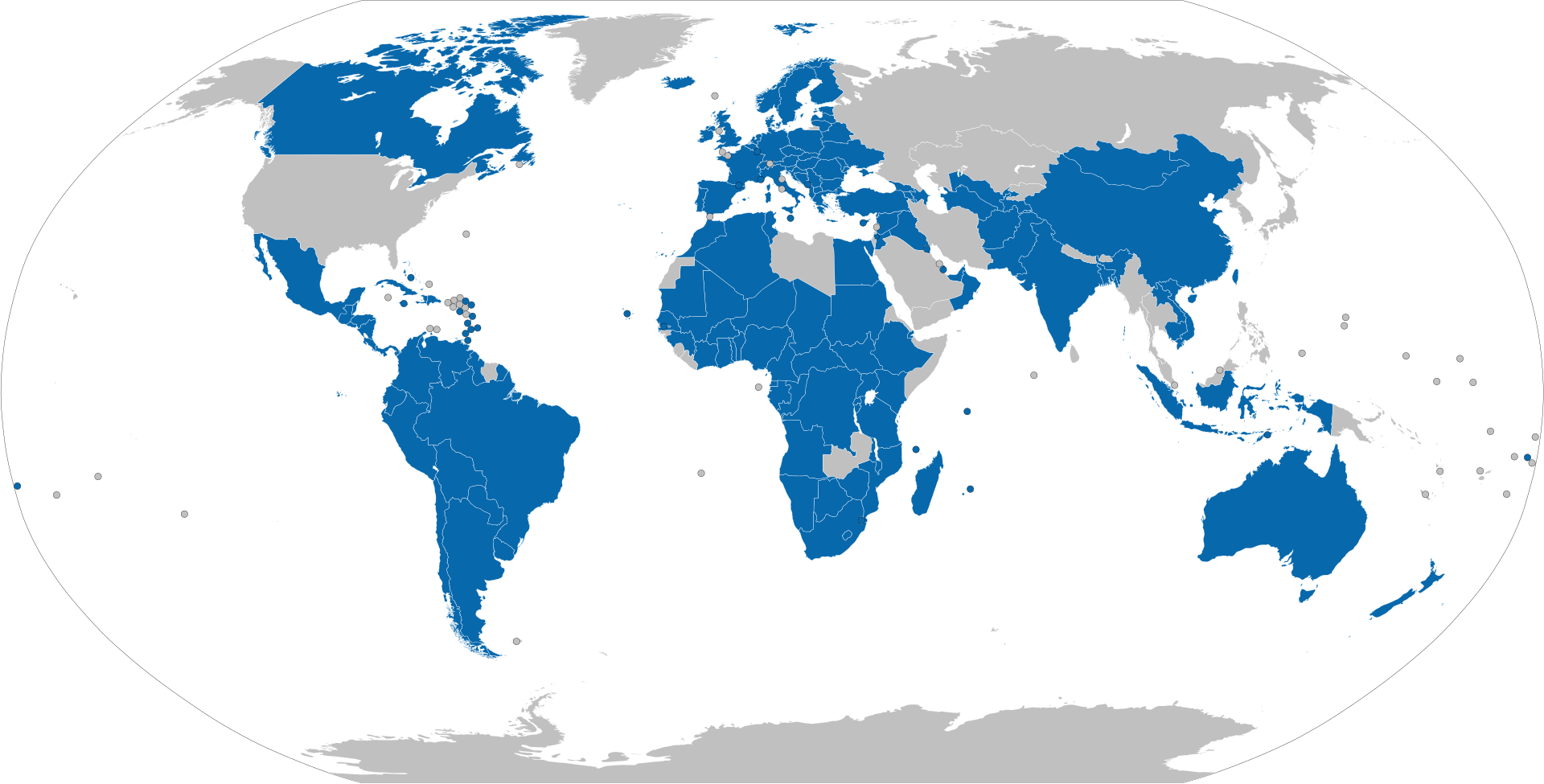

Parties

that have ratified (or approved with a legally equivalent process) the

Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural

Expressions, an international treaty adopted in October 2005 during the

33rd session of the General Conference of the United Nations

Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

☆

「文化的表現の多様性の保護及び促進に関する条約」は、2005年10月にパリで開催されたユネスコ(UNESCO)の第33回総会で採択された国際条約

である。グローバル化により世界文化が一層画一化されるという懸念に応えるため、各国が自国の文化産業を振興・保護することで文化の多様性を守ることが可

能となる。また、発展途上国の文化産業保護を支援するための国際協力も確立され、 国際文化多様性基金の創設を含む。

2001年のユネスコ文化多様性世界宣言の原則の多くを再確認しているが、その宣言とは異なり、法的拘束力があり、加盟国の法的批准を必要とする。この条

約は、文化財に特別な地位を与える初めての国際条約であり、文化的な価値だけでなく経済的な価値も認めている。

この条約は、さまざまな対象者に向けており、3つの主要なレベルで機能している。まず、国家間の協力関係を規定する国際条約である。次に、国家および国際

政府に対し、自国または自国地域内の文化多様性を保護するために採ることができる立法やその他の行動について指針を示している。第3に、地方および国家レ

ベルでの公的機関や市民団体による、多様な文化表現の支援を求めるものである。この条約には強制執行機関がなく、加盟国による執行に委ねられているが、加

盟国間の紛争が発生した場合の手続きが定められている。

148

148カ国が条約を承認し、5カ国が棄権、米国とイスラエルは反対した。この協定は2007年3月に発効し、現在までに151カ国および欧州連合が批准し

ている。

| The Convention on

the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions is an international treaty adopted in October 2005 in Paris during the 33rd session of the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In response to the fears that globalization would lead to an increasingly uniform global culture, it allows states to protect cultural diversity by promoting and defending their own cultural industries.[1] It also establishes international co-operation to help protect the cultural industries of developing countries, including the creation of the International Fund for Cultural Diversity.[2] It reaffirms many of the principles of the 2001 UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity but, unlike that declaration, it is legally binding and requires legal ratification by member states. The convention is the first international treaty to give cultural goods a special status, having cultural as well as economic value.[3] The convention addresses many audiences and operates at three main levels. First, it is an international treaty governing co-operation between states. Second, it guides national and international governments in the legislation and other actions they can take to preserve cultural diversity within their states or regions. Third, it calls for action by public and civil bodies at local and national levels to support diverse cultural expressions.[4] The convention has no enforcing body; it leaves enforcement to the member states but sets out procedures in case of disputes between them.[5] One hundred and forty-eight countries voted to approve the treaty, with five abstaining and the United States and Israel opposing.[6] The agreement came into effect in March 2007 and has been ratified by 151 states, as well as by the European Union. |

「文化的表現の多様性の保護及び促進に関する条約」 「文化的表現の多様性の保護及び促進に関する条約」は、2005年10 月にパリで開催されたユネスコ(UNESCO)の第33回総会で採択された国際条約である。グローバル化により世界文化が一層画一化されるという懸念に応 えるため、各国が自国の文化産業を振興・保護することで文化の多様性を守ることが可能となる[1]。また、発展途上国の文化産業保護を支援するための国際 協力も確立され、 国際文化多様性基金の創設を含む。[2] 2001年のユネスコ文化多様性世界宣言の原則の多くを再確認しているが、その宣言とは異なり、法的拘束力があり、加盟国の法的批准を必要とする。この条 約は、文化財に特別な地位を与える初めての国際条約であり、文化的な価値だけでなく経済的な価値も認めている[3]。 この条約は、さまざまな対象者に向けており、3つの主要なレベルで機能している。まず、国家間の協力関係を規定する国際条約である。次に、国家および国際 政府に対し、自国または自国地域内の文化多様性を保護するために採ることができる立法やその他の行動について指針を示している。第3に、地方および国家レ ベルでの公的機関や市民団体による、多様な文化表現の支援を求めるものである[4]。この条約には強制執行機関がなく、加盟国による執行に委ねられている が、加盟国間の紛争が発生した場合の手続きが定められている[5]。 148 148カ国が条約を承認し、5カ国が棄権、米国とイスラエルは反対した[6]。この協定は2007年3月に発効し、現在までに151カ国および欧州連合が 批准している。 |

| Background and negotiations The convention was a response to treaties and other international measures promoting trade liberalization in cultural goods, especially the actions of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). These were seen as undermining the sovereign right of states to use cultural policies to support their own cultural industries.[6] The convention aimed to provide a legally binding international agreement that reaffirms that right.[7][2] It enshrined the view that goods and services created as cultural expressions have both an economic and cultural nature and so cannot be seen purely as economic goods.[8] The convention also defines cultural industry and interculturality[9] and calls for international co-operation, especially to support the cultural industries of developing countries.[10] The impact of trade liberalization on cultural policy The concept of diversity of cultural expressions is the result of a paradigm shift in the way that culture is considered in international relations, particularly in the context of agreements aimed at liberalizing trade. It succeeds the concepts of cultural exception or cultural exemption that appeared during the 1980s. The awareness on the part of certain states of the impacts of the liberalization of economic exchanges on their cultural policies is the trigger for the emergence of the concept of cultural diversity[11] and the need to protect the diversity of cultural expressions, particularly because of the strength of the Hollywood film market.[12] The convention was born out of a desire to reconcile cultural diversity with increasingly liberal trade agreements.[12] The international community was progressively lowering barriers to free trade, easing the movement of goods, services and capital between states. In several free trade agreements, states were able to establish exceptions to their commitments, either to protect specific sectors or to protect their policies such as environmental, social or culture. The 1947 the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade already recognized the cultural specificity of the film sector by allowing states to maintain certain types of screen quotas to ensure the broadcasting of national films.[13] When the trade system was being reformed in the 1980s and 1990s, Canada and France asked that special treatment be given to audiovisual services in the new General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)[13] then under negotiation. The United States firmly opposed this, which led to the "failure of the cultural exception", an expression that reflects the impossibility of excluding the cultural sector from the reformed multilateral trade system.[13] The vulnerability of state cultural policies is also apparent in some trade disputes, most notably in Canada - Certain Measures Concerning Periodicals.[14] In that case, the panel rejected one of Canada's arguments that, because the content of Canadian and U.S. periodicals differ, the products are not similar and, therefore, may be treated differently by Canada.[15] In the end, certain measures to protect the Canadian periodical industry were not adopted.[16] One topic of negotiation is whether products with cultural value be treated like any other commodity.[17] Some states answer in the affirmative, arguing that it is necessary to adopt a legal instrument that is independent of the WTO's multilateral trade system[18] in order to recognize the dual nature, economic and cultural, of cultural goods and services. The recognition of this dual nature is reflected in certain bilateral or regional trade agreements that include cultural exemption clauses. The first agreement to contain a cultural exemption clause was the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement of 1988. The application of trade rules to cultural products raises a particular problem. By making commitments in economic agreements, states agree to eliminate all forms of discrimination between domestic and imported cultural products. In doing so, they are gradually relinquishing their cultural sovereignty, that is, their ability to develop cultural policies and provide support for their own cultural industries, which reflect their identity. In this sense, the very foundations of free trade make it difficult to recognize the specific nature of cultural products, which are bearers of identity, value and meaning,[19] hence the need to incorporate cultural exception and cultural exemption clauses (cultural clauses) into economic agreements. Although these clauses are multiplying,[20] concern remains in cultural circles about the progressive liberalization of the cultural sector and the repeated characterization of cultural products as mere "merchandise".[21] In fact, cultural clauses receive a mixed reception during trade negotiations. Some states consider them to be protectionist and therefore antithetical to the ideology of free trade, which favours open markets. The United States generally refuses to incorporate such clauses into the free trade agreements it negotiates. The concept of cultural diversity allows for a more positive perspective and a more positive approach to free trade. It allows for a balance to be struck between the economic benefits of opening up economies and taking into account the specificity of cultural products.[22] The role of UNESCO The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions is one of seven UNESCO conventions that deal with the four core areas of creative diversity; cultural and natural heritage, movable cultural property, intangible cultural heritage and contemporary creativity.[8] The others are the Universal Copyright Convention (1952, followed by a revision in 1971), the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (1954/1999), the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970), the Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972), the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (2001), and the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003).[8] Faced with the fact that the commitments made within the WTO did not allow for the recognition of the dual nature of cultural goods and services,[23] some states decided at the end of the 1990s to move the debate to UNESCO. On the one hand, UNESCO's constitution, and particularly Articles 1 and 2, make it the appropriate international forum for this debate.[24] On the other hand, the United States was not a member of this organization at the time (it rejoined UNESCO in 2003 when the negotiation of the convention was launched), which created a favourable context for the development of a multilateral instrument aimed at protecting cultural diversity.[25] In 1998, the Action Plan on Cultural Policies for Development drawn up at the Stockholm Conference[26] recommended that cultural goods and services should be treated differently from other merchandise.[27] This action plan sets the stage for developments in cultural diversity from the early 2000s onwards. UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity was adopted unanimously by 188 member states on 2 November 2001, in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks.[28] It affirms "that respect for the diversity of cultures, tolerance, dialogue and cooperation, in a climate of mutual trust and understanding, are among the best guarantees of international peace and security". It represents an opportunity to "categorically reject the thesis of inescapable conflicts of cultures and civilizations".[29] In Article 8 of the declaration, UNESCO members affirm that "cultural goods and services [...], because they convey identity, values and meaning, should not be treated as commodities or consumer goods like any other." In Article 9, the role of cultural policies is defined as a tool to "create conditions conducive to the production and dissemination of diversified cultural goods and services". This declaration is not legally binding.[30] The desirability of negotiating a binding international legal instrument is set out in Annex II of the declaration. Several articles of the declaration are included in the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. Negotiations Work towards the convention began in the fall of 2003, with a decision of the UNESCO General Conference.[31][32] Fifteen independent experts participated in a series of three meetings to create a preliminary draft. This draft was distributed to member states in July 2004. It formed the basis for the intergovernmental negotiations from the fall of 2004 onwards to prepare the draft convention to be presented to the General Conference in 2005.[33][34][35][36] The first intergovernmental meeting, held from 20 to 24 September 2004, set up the negotiating structure and expressed the respective views on the type of convention to come. Differences of opinion persisted regarding the purpose of the convention, its relationship with other international agreements and the level of commitment required.[34] At the second intergovernmental meeting, the Plenary Assembly considered almost all of the provisions of the preliminary draft. Definitions of key terms were discussed, as was the dispute settlement mechanism.[35] One of the significant difficulties encountered in the negotiations was the question of whether the convention would prevail over, or be subordinate to, other existing or future international agreements negotiated by the parties.[37] Initially, the positions of the states were polarized on whether there would be an explicit clause setting out the relations between the convention and other international commitments.[38][39] Some states, including the United States, Japan, New Zealand, Tunisia and India, questioned the need for such a clause.[35] A majority of states, on the other hand, wanted the convention placed on an equal footing with other instruments.[40] They argued that the dual nature of cultural goods and services mean that they should be treated by both the WTO and UNESCO texts.[41] The need to incorporate such a clause was finally agreed upon. It would confirm complementarity and non-hierarchy between the convention and other international legal instruments. This would become Article 20 of the convention.[42][35] At the third intergovernmental meeting, a working group was charged with finding a compromise between the positions expressed to date on the relationship of the convention to other treaties. A stormy vote on the text of Article 20 led the United States to request registration of its formal opposition to the adopted text. Between the end of the negotiations and the 33rd General Conference of UNESCO, the United States led a campaign to reopen the negotiations.[43] Canada responded by proposing that the preliminary draft be considered a draft convention to be voted on for adoption at the 33rd session of the General Conference, which it was.[33] In advance of the General Conference, Condoleezza Rice, the United States Secretary of State, wrote to attendees, asking them not to sign the convention, which she said "invites abuse by forces opposed to freedom of expression and free trade".[44] |

背景と交渉 この条約は、文化商品の貿易自由化を進める条約やその他の国際的な措置、特に世界貿易機関(WTO)の行動に対する対応であった。これらは、自国の文化産 業を支援するために文化政策を用いる主権的権利を損なうものと見なされていた[6]。この条約は、その権利を再確認する法的拘束力のある国際協定を提供す ることを目的としていた[7][2]。文化表現として生み出された商品やサービスは、経済性と文化性の両方を兼ね備えているため、純粋に経済的な商品とし てのみ捉えることはできないという見解が盛り込まれた[8]。また、文化産業と異文化性についても定義し[9]、特に発展途上国の文化産業を支援するため に国際協力を求めている[10]。 貿易自由化による文化政策への影響 文化表現の多様性という概念は、国際関係における文化の捉え方のパラダイムシフト、特に貿易自由化を目指す協定の文脈において生まれたものである。これ は、1980年代に登場した「文化の例外」や「文化の免除」という概念を継承するものである。一部の国家が、経済交流の自由化が自国の文化政策に与える影 響に気づいたことが、文化の多様性という概念[11]の登場と、特にハリウッド映画市場の力強さ[12]を理由に、文化表現の多様性を保護する必要性の きっかけとなった。ハリウッド映画市場の力強さがその理由である[12]。 この条約は、自由貿易協定の進展と文化の多様性を両立させるという願いから生まれた[12]。国際社会は、自由貿易の障壁を徐々に低くし、国家間の商品、 サービス、資本の移動を容易にしていった。いくつかの自由貿易協定では、特定の分野を保護するため、あるいは環境、社会、文化などの政策を保護するため に、加盟国は義務の例外を設けることができた。 1947年の関税貿易一般協定(GATT)は、すでに映画産業の文化的特殊性を認識しており、各国が自国の映画を放送するために一定のスクリーン・クォー タを維持することを認めていた[13]。1980年代から1990年代にかけて貿易システムが改革される際、カナダとフランスは、交渉中であった新しい サービス貿易一般協定(GATS)において、視聴覚サービスに特別な待遇を与えるよう求めた[13]。米国はこれに強く反対し、その結果、文化部門を多国 間貿易体制の改革から除外できないことを反映した「文化例外の失敗」という表現が生まれた[13]。 国家の文化政策の脆弱性は、いくつかの貿易紛争、特にカナダ - 定期刊行物に関する特定の措置[14]でも明らかである。このケースでは、パネルは、カナダと米国の定期刊行物の内容が異なるため、両者は類似しておら ず、カナダは両者を別個に扱うことができるというカナダの主張を退けた[15]。結局、カナダの定期刊行物産業を保護するための措置は採用されなかった [16]。 交渉の 交渉の議題のひとつは、文化的な価値を持つ商品が他の商品と同じように扱われるかどうかである[17]。いくつかの国は肯定的に答え、文化的な商品やサー ビスの経済的および文化的という二重の性質を確認するためには、WTOの多角的貿易システムから独立した法的手段を採用する必要がある[18]と主張して いる。この二重の性質は、文化的な免除条項を含む一部の二国間または地域貿易協定に反映されている。文化的な免除条項を含む最初の協定は、1988年のカ ナダ・米国自由貿易協定であった。 文化製品に対する貿易ルールの適用は、特別な問題を引き起こす。経済協定で約束を交わすことで、各国は国内と輸入文化製品間のあらゆる形態の差別を撤廃す ることに同意する。そうすることで、国家は徐々に文化主権を放棄することになる。つまり、国家のアイデンティティを反映した文化政策を策定し、自国の文化 産業を支援する能力を自ら放棄することになる。この意味で、自由貿易の基盤そのものが、アイデンティティ、価値、意味の担い手である文化製品の特殊性を認 識することを困難にしている[19]。そのため、経済協定に文化例外条項および文化免除条項(文化条項)を盛り込む必要がある。 このような条項は増えているが[20]、文化界では文化セクターの段階的な自由化や、文化商品が単なる「商品」として扱われることの繰り返しに対する懸念 が残っている[21]。実際、貿易交渉において文化条項は賛否両論である。一部の国家は、文化条項を保護主義的であり、自由貿易の理念に反するものと考え ている。米国は、交渉する自由貿易協定にこのような条項を盛り込むことを一般的に拒否している。 文化の多様性という概念は、自由貿易に対してより前向きな視点とアプローチを可能にする。経済開放がもたらす経済的利益と文化製品の特殊性を考慮することのバランスを取ることができる[22]。 ユネスコの役割 文化の多様性の保護と促進に関する条約は、創造的多様性の4つの主要分野、すなわち文化遺産と自然遺産、移動可能な文化財、無形文化遺産、現代における創 造性に関する7つのユネスコ条約のひとつである[8]。 1952年、1971年に改訂)、武力紛争における文化遺産の保護に関するハーグ条約(1954年/1999年)、文化遺産の不法な輸入、輸出及び所有権 の移転の禁止及び防止に関する条約(1970年)、世界文化遺産及び自然遺産の保護に関する条約(1972年)、 2001年の「水中文化遺産の保護に関する条約」、2003年の「無形文化遺産の保護に関する条約」である[8]。 WTOにおける約束では、文化財や文化サービスの二重性を認めることができないという事実を前にして、[23] 1990年代末に、一部の国家は議論の場をユネスコに移すことを決定した。一方、ユネスコの規約、特に第1条と第2条は、この議論を行うのにふさわしい国 際フォーラムである[24]。他方、当時米国はユネスコに加盟していなかった(条約交渉が開始された2003年にユネスコに再加盟)。文化の多様性を保護 することを目的とした多国間協定の発展に有利な状況を作り出した[25]。 1998年、ストックホルム会議で策定された「開発のための文化政策に関する行動計画」[26]では、文化財や文化サービスは他の商品とは区別して扱うべきであると勧告された[27]。この行動計画は、2000年代初頭からの文化の多様性に関する発展の基盤となった。 ユネスコ文化多様性世界宣言 ユネスコ文化多様性世界宣言は、2001年9月11日の同時多発テロ事件を受けて、同年11月2日に188加盟国によって全会一致で採択された[28]。 この宣言は、「相互の信頼と理解の雰囲気の中で、文化の多様性に対する尊重、寛容、対話、協力は、国際的な平和と安全の最も優れた保証の一つである」と断 言している。この宣言は、「文化や文明の避けられない対立という説を明確に否定する」機会を提供するものである[29]。 宣言の第8条では、ユネスコ加盟国が「文化財や文化サービスは、アイデンティティ、価値観、意味を伝えるものであるため、他の商品や消費財と同様に扱われ るべきではない」と主張している。第9条では、文化政策の役割は、「多様な文化財や文化サービスの生産と普及を促進する条件を整える」ためのツールである と定義されている。 この宣言は法的拘束力を持たない[30]。拘束力のある国際法的文書を交渉することの是非については、宣言の付属文書 II に記載されている。宣言のいくつかの条文は、「文化の多様性の保護及び促進に関する条約」に盛り込まれている。 交渉 この条約に向けた作業は、2003年秋にユネスコ総会で決定されたことにより始まった[31][32]。15人の独立した専門家が3回の会議に参加し、草 案を作成した。この草案は2004年7月に加盟国に配布された。これは、2005年の総会に提出する条約草案の準備を目的とした、2004年秋以降の政府 間交渉の基礎となった[33][34][35][36]。 2004年9月20日から24日にかけて開催された第1回政府間会合では、交渉体制が確立され、今後の条約の種類についてそれぞれの見解が表明された。条 約の目的、他の国際協定との関係、求められるコミットメントのレベルについて意見の相違が続いた[34]。第2回政府間会合では、総会が予備草案のほぼす べての条項について審議した。重要な用語の定義や紛争解決メカニズムについても議論された[35]。 交渉で直面した大きな難問のひとつは、この条約が、締約国が交渉した既存の国際協定や将来締結される国際協定よりも優先されるのか、それとも従属するのか という問題であった[37]。当初、条約と他の国際的義務との関係について明記した条項を設けるかどうかで、各国の立場は二分されていた[38] [39]。米国、日本、ニュージーランド、チュニジア、インドを含む一部の国は、そのような条項を設ける必要性に疑問を呈した[35]。一方、大多数の国 は、条約を他の文書と同等の地位に置くことを望んだ[40]。彼らは、文化財と文化サービスの二重の性質から、これらはWTOとユネスコの双方の文書に よって扱われるべきであると主張した[41]。このような条項を盛り込む必要性は最終的に合意された。これにより、条約と他の国際法文書との補完性と非優 位性が確認されることになる。これは条約の第20条となる予定である[42][35]。 第3回政府間会合では、条約と他の条約との関係についてこれまでに表明された見解の妥協点を見出すことを作業部会に委ねた。第20条本文の激しい投票の結 果、米国は採択された本文に対する正式な反対の登録を要請することとなった。交渉の終了から第33回ユネスコ総会までの間、米国は交渉再開を求めるキャン ペーンを主導した[43]。これに対し、カナダは予備草案を第33回総会で採択投票を行う条約草案とみなすよう提案した。そして、実際にそうされた [33]。国連総会に先立ち、コンドリーザ・ライス米国務長官は、出席者宛てに「表現の自由と自由貿易に反対する勢力の濫用を招く」という理由で、条約に 署名しないよう求める書簡を送った[44]。 |

| Purpose The main objective for the convention is to protect and promote the diversity of cultural expressions.[45] The convention highlights the fact that cultural creativity has been placed upon all of humanity and that aside from economical gains, creative diversity reaps plenty of cultural and social advantages.[8] States must also promote "openness to other cultures of the world". Protective measures are also included in the convention and international co-operation is encouraged in times of need. Additional objectives are as follows: To reaffirm the sovereign rights of states to adopt cultural policies while ensuring the free movement of ideas and works. To recognise the distinct nature of cultural goods and services as vehicles of values, identity and meaning. To define a new framework for international cultural co-operation, the keystone of the convention. To create the conditions for cultures to flourish and freely interact in a mutually beneficial manner. To endeavour to support co-operation for sustainable development and poverty reduction, via assistance from the International Fund for Cultural Diversity. To ensure that civil society plays a major role in the implementation of the convention. To "strengthen international cooperation and solidarity with a view to favouring the cultural expressions of all countries, in particular those whose cultural goods and services suffer from lack of access to the means of creation, production and dissemination at the national and international level."[45] The convention also affirms that "Cultural diversity can be protected and promoted only if human rights and fundamental freedoms, such as freedom of expression, information and communication, as well as the ability of individuals to choose cultural expressions, are guaranteed"[46] in a manner against a cultural relativism that may undermine universality of human rights. The intended beneficiaries to the convention include all individuals and societies. The convention lists several groups such as women, indigenous peoples, minorities, and artists and practitioners of developing nations as specifically intended to benefit.[8] |

目的 この条約の主な目的は、文化表現の多様性を保護し、促進することである[45]。この条約は、文化的な創造性が人類全体に課せられたものであり、経済的利 益とは別に、創造的な多様性は文化面や社会面で多くの利点をもたらすという事実を強調している[8]。各国は「世界の他の文化に対する開放性」も促進しな ければならない。条約には保護措置も含まれており、必要な場合には国際協力が奨励されている。 その他の目的は以下のとおりである。 思想や作品の自由な移動を確保しながら、文化政策を採択する国家の主権的権利を再確認すること。 文化財や文化サービスの価値、アイデンティティ、意味を伝える媒体としての独自性を認識すること。 国際文化協力の新たな枠組みを定義し、条約の要とすること。 文化が繁栄し、相互に有益な形で自由に交流できる条件を整えること。 文化の多様性に関する国際基金からの支援を通じて、持続可能な開発と貧困削減のための協力を支援するよう努める。 市民社会が条約の実施において重要な役割を果たすことを確保する。 「すべての国の文化的表現、特に、国内および国際レベルでの創作、生産、普及の手段へのアクセスが欠如しているために文化的財やサービスの提供に支障が生じている国の文化的表現を奨励することを目的として、国際協力と連帯を強化する」[45]。 また、この条約は、「文化の多様性は、表現、情報、コミュニケーションの自由、および個人が文化表現を選択できる能力といった人権と基本的自由が保障され ている場合にのみ、保護および促進することができる」[46]と断言している。これは、人権の普遍性を損なう恐れのある文化相対主義に対するものである。 この条約の受益者は、個人および社会全体である。この条約では、女性、先住民、少数民族、発展途上国の芸術家や芸術家志望者など、特に恩恵を受けるべき対象としていくつかのグループが挙げられている[8]。 |

| Content Preamble The preamble affirms the importance and benefits of cultural diversity and of the "framework of democracy, tolerance, social justice and mutual respect" needed for it to flourish. It refers to many issues on the periphery of the scope of the convention, yet intimately linked to the diversity of cultural expressions, including intellectual property rights, the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms, linguistic diversity, and traditional knowledge.[47] Section I: Objectives and guiding principles Article 1 of the convention sets out the convention's nine purposes discussed above. Article 2 lists eight principles that guide the interpretation of commitments made by the parties: Principle of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms Principle of sovereignty Principle of equal dignity and respect for all cultures Principle of international solidarity and cooperation Principle of the complementarity of economic and cultural aspects of development Principle of sustainable development Principle of equitable access Principle of openness and balance Section II: Scope of application Article 3 sets out the scope of application: "This Convention shall apply to the policies and measures adopted by the Parties relating to the protection and promotion of the diversity of cultural expressions." Section III: Definitions The convention defines the following terms to explain their specific legal meaning: "cultural diversity", "cultural content", "cultural expressions", "cultural activities, goods and services", "cultural industries", "cultural policies and measures", "protection" and "interculturality".[48] The convention creates several new concepts and uses similar expressions to some already known.[49] As interpreted in the convention, cultural activities, goods, or services must result from creativity and have cultural content: symbolic meaning, artistic dimension or values related to cultural identity. "Cultural diversity" is interpreted both in terms of cultural heritage that is preserved, and in terms of diverse ways of creating, sharing, and enjoying art. This definition creates the link with the Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity.[50] Section IV: Rights and obligations of the parties The section on rights and obligations is central to the convention. It focuses on rights, especially the rights of states to take action to protect their cultural diversity. Most of these rights are expressed as options ("Parties may...") rather than requirements ("Parties shall...").[51] In article 5, the convention reaffirms the sovereign right of states to use legislation to promote and protect the diversity of cultural expressions.[41] Article 6 goes into more detail, listing examples of what states may do. It suggests regulation; the use of quotas on cultural content;[52] subsidies and other support for cultural institutions or for individual artists; and giving domestic cultural industries ways to produce, promote, and publicise their output.[51] The obligation to promote cultural expressions is set out in article 7. Parties to the convention have an obligation to promote cultural expressions within their territory, giving individuals and society access to a diverse set of cultural influences from their own country and from around the world. Article 8 sets out the powers of a state to identify a situation where a cultural expression is in need of "urgent safeguarding"[53] and to take "all appropriate measures". It requires the parties to notify the Intergovernmental Committee (created by article 23) of any such measure. The committee may then make appropriate recommendations.[54] Articles 9 to 11 commit the states to sharing information transparently, to promoting cultural diversity through education and public awareness programs, and to working with civil society to achieve the convention's goals. Article 12 sets out the five objectives of states in relation to international cooperation. Article 13 sets out the obligation of the parties to integrate culture into their sustainable development policies at all levels. This echoes article 11 of the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, which describes cultural diversity as "a guarantee of sustainable human development". Article 14 provides a list of suggested forms of international cultural cooperation. These relate to the strengthening of cultural industries, capacity building, transfer of technology and know-how, and financial support.[55] Article 15 is the most explicit provision for partnerships between public authorities and civil society, especially to respond to the needs of developing countries.[56] Article 16 contains one of the most binding commitments of the convention. It states that "[d]eveloped countries shall facilitate cultural exchanges with developing countries by granting, through appropriate institutional and legal frameworks, preferential treatment to their artists and other cultural professionals and practitioners, as well as to their cultural goods and services." The obligation to "facilitate cultural exchanges" rests with developed countries and must benefit developing countries.[57] This is the first time that a binding agreement in the cultural field has explicitly referred to "preferential treatment".[citation needed] Preferential treatment measures can be cultural in nature (e.g., hosting artists from developing countries in artists' residencies in developed countries), commercial in nature (e.g., easing the demands of artists in developed countries), or commercial in nature (e.g., facilitating the movement of cultural goods and services) or mixed, i.e., both cultural and commercial (e.g., entering into a film co-production agreement that includes measures that facilitate access to the developed country market for the co-produced work). Article 17 commits parties to cooperate in situations of serious threat to cultural expressions of the kind mentioned in article 8. The International Fund for Cultural Diversity (IFCD) was created as a result of the demands of developing countries[58] and is established under article 18 of the convention.[59][60] It is funded by voluntary contributions from member states. This creates some uncertainty as to the sustainability of the funding and ensures that the establishment of the fund is based on the principle of "hierarchical solidarity" rather than "reciprocity".[61] Developing countries that are parties to the convention can apply to the IFCD for funding for specific activities that develop their cultural policies and cultural industries. As of April 2023, UNESCO reports that 140 projects in 69 developing countries have been carried out with funding from the IFCD.[59] In article 19, the parties commit to sharing data, expertise, and best practice for the protection and promotion of culture, creating a data bank maintained by UNESCO. Section V: Relationship with other instruments Article 20 explains that the convention is to be interpreted as complementary to other existing treaties, not overruling or modifying them. In article 21, the parties "undertake to promote the objectives and principles of this Convention in other international forums." The term "other international forums" refers in particular to the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), but also to more informal bilateral or regional fora or negotiating groups.[citation needed] Section VI: Organs of the convention Article 22 establishes the Conference of the Parties, the governing body of the convention. This is composed of all the countries that have ratified the convention and meets every two years. Article 23 creates an Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. This is composed of 24 parties elected by the Conference of the Parties from all regions of the world. Members are given a four-year term and meet annually.[62] These two bodies together act as a "political forum on the future of cultural policy and international cooperation".[63] Article 24 requires the UNESCO Secretariat to assist both of them.[64] |

内容 前文 前文では、文化の多様性の重要性とその利益、そしてそれを発展させるために必要な「民主主義、寛容、社会正義、相互尊重の枠組み」が強調されている。この 前文では、文化表現の多様性と密接に関連しているものの、条約の適用範囲外の問題として扱われている多くの問題について言及されている。その問題には、知 的財産権、基本的人権と自由の保護、言語の多様性、伝統的知識などが含まれる[47]。 第1条: 目的と指針となる原則 条約の第1条では、前述の条約の9つの目的が定められている。第2条では、締約国による義務の解釈を導く8つの原則が列挙されている。 人権と基本的自由の尊重の原則 主権尊重の原則 すべての文化の尊厳と平等な尊重の原則 国際連帯と協力の原則 開発における経済的、文化的側面を補完し合う原則 持続可能な開発の原則 衡平なアクセスの原則 開放性と均衡の原則 第2条:適用範囲 第3条では、本条約の適用範囲を次のように定めている。「この条約は、締約国が文化の多様性の保護と促進に関して採択する政策および措置に適用されるものとする」。 第3章:定義 この条約では、以下の用語を定義し、その法的意味を具体的に説明している。「文化の多様性」、「文化的内容」、「文化表現」、「文化活動、商品およびサー ビス」、「文化産業」、「文化政策および措置」、「保護」、「異文化性」などである[48]。同条約はいくつかの新しい概念を生み出し、既知の概念と類似 した表現を用いている[49]。同条約の解釈では、文化活動、商品、またはサービスは創造性から生み出され、文化的内容(文化的アイデンティティに関連す る象徴的な意味、芸術的側面、または価値観)を持つ必要がある。「文化の多様性」は、保存されている文化遺産と、芸術の創造、共有、享受の多様な方法の両 方の観点から解釈される。この定義は、「文化の多様性に関する世界宣言」との関連性を生み出している[50]。 第4条:締約国の権利と義務 権利と義務に関する条項は、この条約の中心をなすものである。この条項は、特に締約国が文化の多様性を保護するためにとる措置に関する権利に焦点を当てて いる。これらの権利のほとんどは、義務(「締約国は...しなければならない」)ではなく、選択肢(「締約国は...してもよい」)として表現されている [51]。第5条では、文化表現の多様性を促進し保護するために立法措置を講じる主権的権利を、条約は改めて確認している[41]。第6条では、さらに詳 しく、各国が講じることができる措置の例を挙げている。同条では、規制、文化コンテンツに対するクォータ制の導入[52]、文化機関や個人アーティストに 対する補助金やその他の支援、国内文化産業が自らの作品を制作、宣伝、公開する方法の提供などが提案されている[51]。 文化表現の促進義務は、第7条に規定されている。同条約の締約国は、自国の領域内で文化表現を促進し、個人や社会が自国および世界中から多様な文化の影響を受けられるようにする義務を負う。 第 8 条は、文化表現が「緊急の保護」[53] を必要とする状況を特定し、「あらゆる適切な措置」を講じる国家の権限を規定している。締約国は、このような措置を政府間委員会(第 23 条により設置)に通知することが義務付けられている。委員会は、適切な勧告を行うことができる[54]。 第9条から第11条では、各国が情報を透明性をもって共有すること、教育や啓発プログラムを通じて文化の多様性を促進すること、そして市民社会と協力し、この条約の目標を達成することを義務付けている。 第12条では、国際協力に関する各国の5つの目標が定められている。第13条では、あらゆるレベルにおいて持続可能な開発政策に文化を組み込むことを締約 国に義務付けている。これは、文化の多様性を「持続可能な人間開発を保証するもの」と表現するユネスコの世界文化多様性宣言の第11条を反映したものであ る。第14条は、国際文化協力の推奨形態を列挙している。これらは、文化産業の強化、能力開発、技術とノウハウの移転、財政支援に関するものである [55]。 第15条は、公的機関と市民社会間のパートナーシップに関する最も明確な規定であり、特に発展途上国のニーズに応えることを目的としている[56]。 第16条は、この条約の中で最も拘束力のある義務の一つを定めている。「先進国は、適切な制度的・法的枠組みを通じて、発展途上国の芸術家やその他の文化 専門家や実務者、そして文化的な商品やサービスに優遇措置を与えることにより、発展途上国との文化交流を促進しなければならない」と規定されている。「文 化交流を促進する」義務は先進国に課せられており、発展途上国に利益をもたらすものでなければならない[57]。文化分野における拘束力のある協定で「優 遇措置」が明示的に言及されたのはこれが初めてである[出典が必要]。優遇措置には、文化的なもの(例えば、先進国のアーティスト・イン・レジデンスに発 展途上国のアーティストを招待する)、 商業的性質のもの(例えば、先進国における芸術家の要求を緩和すること)、または商業的性質のもの(例えば、文化的な商品やサービスの移動を容易にす る)、または混合したもの、すなわち、文化的なものと商業的なものの両方(例えば、共同制作された作品が先進国市場にアクセスしやすくなるような措置を含 む映画共同制作契約を締結すること)などである。 第17条では、締約国が、第8条に挙げたような文化表現に深刻な脅威が及ぶ状況において協力することを義務付けている。 国際文化多様性基金(IFCD)は、発展途上国の要求[58]を受けて創設され、条約の第18条に基づいて設立された[59][60]。これにより、資金 調達の持続可能性に若干の不確実性が生じることになるが、基金の設立は「互恵」ではなく「階層的連帯」の原則に基づいていることが保証される[61]。条 約の締約国である発展途上国は、自国の文化政策や文化産業を発展させるための特定の活動に対する資金援助をIFCDに申請することができる。2023年4 月現在、ユネスコはIFCDからの資金提供により、69か国の開発途上国で140のプロジェクトが実施されたと報告している[59]。 第19条では、締約国は文化の保護と振興のためのデータ、専門知識、ベストプラクティスの共有を約束し、ユネスコが管理するデータベースが作成される。 第V章:他の条約との関係 第20条では、この条約は他の既存の条約を補完するものとして解釈され、それらに優先したり変更したりするものではないと説明されている。第21条では、 締約国は「他の国際フォーラムでこの条約の目的と原則を促進することを約束する」とされている。「その他の国際フォーラム」とは、特に世界貿易機関 (WTO)、世界知的所有権機関(WIPO)、経済協力開発機構(OECD)を指すが、より非公式な二国間または地域フォーラムや交渉グループも含まれる [要出典]。 第6条:条約の機関 第22条は、条約の統治機関である締約国会議を設置する。これは条約を批准したすべての国で構成され、2年ごとに開催される。第23条は、文化表現の多様 性の保護と促進のための政府間委員会を設置する。これは、世界のあらゆる地域から締約国会議によって選出された24の締約国で構成される。委員の任期は4 年で、毎年会合を開く[62]。この2つの機関は、合わせて「文化政策と国際協力の将来に関する政治フォーラム」として機能する[63]。第24条は、ユ ネスコ事務局に両機関を支援することを義務付けている[64]。 |

| Ratification and implementation Ratification and non-ratification To date, 151 signatory states, as well as the European Union, have registered their ratification of the convention, or a legally equivalent process. Canada was the first party to ratify the treaty on 28 November 2005.[65] Many more ratifications took place until 2007, after which the rate slowed down.[66] The most recent ratifications are from Cape Verde (26 May 2021) and Pakistan (4 March 2022).[65] A November 2007 meeting of delegates from 59 member states of the Commonwealth produced the Kampala Civil Society Statement, which made recommendations to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting. One recommendation was that Commonwealth states should ratify the convention and work with civil society to implement it.[67] Some Arab states, states in the Asia-Pacific region, Russia and Japan have not ratified or implemented the convention.[68] The United States refused to ratify despite actively participating in the negotiations and drafting.[69] The main argument of their opposition is that cultural products are commodities in the same way as other goods and services. They argue that the benefits of free trade extend to cultural goods and services.[70] The United States left UNESCO at the end of 2018[71] but officially rejoined in July 2023.[72][73] Implementation monitoring The monitoring framework is structured by four overarching objectives from the convention, as well as by the desired outcomes, core indicators and means of verification.[74] The four objectives are: (1) supporting sustainable cultural governance systems, (2) achieving a balanced exchange of cultural goods and services and increasing the mobility of artists and cultural professionals, (3) including culture in sustainable development frameworks and (4) promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms.[75] The monitoring framework is based on Article 9 of the convention. It is specified by the Operational Guidelines[76] for information sharing and transparency. In order to respect this commitment, the parties designate a point of contact[77] and must produce periodic reports every four years, starting from the date of deposit of its instrument of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession.[78][79] These reports are examined by the Conference of the Parties in order to plan international cooperation by identifying innovative measures and targeting the needs of countries that could benefit.[80] As of 2021, it was reported that just half the ratifying states have complied with their reporting duties; there are no penalties for failing to comply.[81] The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) has worked to support the convention by creating a Framework for Cultural Statistics and establishing an Expert Group on Measuring the Diversity of Cultural Expressions.[82] Effect on subsequent international agreements UNESCO reports that "at least eight bilateral and regional free trade agreements concluded between 2015 and 2017 have introduced cultural clauses or list [sic] of commitments that promote the objectives and principles of the 2005 Convention."[83] Implementation in the online environment The convention was negotiated at a time when music and films were mainly sold on CD and DVD formats. The subsequent years saw the rise of online streaming media, meaning that cultural works could be exported from one country to another without a physical medium. This increased the risk that cultural diversity would be threatened as more people had immediate access to the cultural productions of particular countries.[84] The convention was intended to be technologically neutral so that future advancements would not leave it outdated. The definitions in section III allow states to develop cultural policies for digital cultural products.[85] However, this rapid technological change raised the question of how to interpret the convention's rights and obligations relating to online cultural works. The community responded in 2017 by creating and adopting the Operational Guidelines on the Implementation of the Convention in the Digital Environment.[86] The role of civil society The convention repeatedly mentions civil society — including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), cultural professionals and cultural groups — as necessary for implementation of its desired changes.[87] Civil society organizations are involved at several levels in the implementation and promotion of the convention.[notes 1] Although they cannot attend the Conferences of the Parties,[88] they can attend, by invitation, the meetings of the Intergovernmental Committee; participate in funding; contribute their expertise; or receive grants from the International Fund for Cultural Diversity.[89] A 2015 study found that many activities arising from the convention involved civil society, or partnerships between civil society and government, although fewer than half of the national reports mentioned involving civil society. It also found that the NGOs most involved in these activities were usually already well-established and used to working with government, which tend to be organizations in the Global North. The authors conclude that there are successful cases of involving civil society in the convention's implementation but that the participating organisations were not yet truly diverse.[90] In 2009, the Intergovernmental Committee identified three general reasons why, in some countries, civil society participation was less than expected: 1) an organisationally weak cultural sector; 2) an excessively top-down approach by government and public bodies; and 3) poor communication between public bodies, civil society, and the cultural sector.[91] Civil society includes UNESCO Chairs: professors whose research objectives are linked to those of the 2005 convention. The UNESCO Chair on the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, launched in November 2016, participates in the implementation of the convention and in the development of knowledge.[92] |

批准と実施 批准と不批准 現在までに、151の署名国および欧州連合が、この条約の批准、または法的に同等の手続きを登録している。カナダが2005年11月28日に批准したのを 皮切りに、2007年までに多くの国が批准した。その後、批准のペースは鈍化した[66]。最新の批准は、カーボベルデ(2021年5月26日 2021年5月26日)とパキスタン(2022年3月4日)である[65]。 2007年11月、英連邦加盟59カ国の代表による会議で「カンパラ市民社会声明」が作成され、英連邦首脳会議に提言が行われた。その一つは、英連邦諸国が条約を批准し、市民社会と協力して条約を実施すべきであるという提言であった[67]。 一部のアラブ諸国、アジア太平洋地域の国々、ロシア、日本は条約を批准も実施もしていない[68]。米国は、交渉や草案作成に積極的に参加していたにもか かわらず、批准を拒否した[69]。反対の主な論点は、文化製品は他の商品やサービスと同様に商品であるということである。彼らは、自由貿易の恩恵は文化 的な商品やサービスにも及ぶと主張している[70]。米国は2018年末にユネスコを脱退したが[71]、2023年7月に正式に再加盟した[72] [73]。 実施状況のモニタリング モニタリングの枠組みは、条約の4つの包括的な目標、望ましい成果、中核となる指標、検証手段によって構成されている[74]。4つの目標とは、 (1) 持続可能な文化ガバナンスシステムの支援、(2) 文化財・サービスのバランスの取れた交流の実現と芸術家・文化関係者の移動性の向上、(3) 文化を持続可能な開発枠組みに組み込むこと、(4) 人権と基本的自由の促進[75]。 モニタリングの枠組みは、条約第9条に基づいており、情報共有と透明性に関する「運用指針」[76]で規定されている。この約束を尊重するために、締約国 は連絡窓口[77] を指定し、批准、受諾、承認、加盟の文書を寄託した日から4年ごとに定期報告書を提出しなければならない[78][79]。これらの報告書は、革新的な施 策を特定し、恩恵を受ける可能性のある国のニーズを明確化することで国際協力を計画するために、締約国会議で審査される[8 2021年現在、批准国のうち報告義務を果たしているのは半数にとどまっていると報告されている。報告義務を果たさなかった場合の罰則はない[81]。 ユネスコ統計研究所(UIS)は、文化統計の枠組みを作成したり、文化表現の多様性を測定するための専門家グループを設立したりするなど、この条約を支援する取り組みを行ってきた[82]。 その後の国際協定への影響 その後の国際協定への影響 ユネスコは、「2015年から2017年の間に締結された少なくとも8つの二国間および地域自由貿易協定は、2005年の条約の目的と原則を促進する文化条項または約束事項リスト(原文ママ)を導入している」と報告している[83]。 オンライン環境での実施 この条約は、音楽や映画が主にCDやDVD形式で販売されていた時代に交渉された。その後、オンラインストリーミングメディアが台頭し、物理的な媒体を介 さずに文化作品を他国へ輸出することが可能となった。これにより、特定の国の文化作品を多くの人がすぐにアクセスできるようになったため、文化の多様性が 脅かされるリスクが高まった[84]。この条約は、将来的な技術進歩によって時代遅れにならないよう、技術的に中立的なものとなるよう意図されていた。第 III 章の定義により、各国はデジタル文化製品に関する文化政策を策定することができる[85]。しかし、この急速な技術的変化により、オンライン文化作品に関 する条約上の権利と義務をどのように解釈するかという問題が生じた。2017年、コミュニティは「デジタル環境における条約の実施に関する運用ガイドライ ン」を作成・採択することで対応した[86]。 市民社会の役割 この条約では、望ましい変化を実現するために必要なものとして、非政府組織(NGO)、文化専門家、文化団体などの市民社会が繰り返し言及されている [87]。市民社会組織は、条約の実施と推進にいくつかのレベルで関与している[注釈1]。締約国会議には出席できないが[88]、政府間委員会の会議に は招待により出席でき、資金提供に参加したり、専門知識を貢献したり、国際文化多様性基金からの助成金を受け取ったりすることができる[89]。 2015年の研究では、条約から生まれた多くの活動には市民社会が関与していたり、市民社会と政府間のパートナーシップが存在していることがわかったが、 市民社会の関与について言及している国家報告書の数は半数に満たなかった。また、これらの活動で最も関与している NGO は、通常すでに確立されており、政府との協力に慣れていることがわかった。著者は、条約の実施に市民社会を関与させることに成功した事例はあるが、参加組 織は真に多様ではないと結論付けている[90]。2009年、政府間委員会は、一部の国々で市民社会の参加が期待されたほど進まなかった理由として、次の 3つの一般的な理由を特定した。1)組織的に脆弱な文化部門、2)政府および公共機関による過剰なトップダウンアプローチ、3)公共機関、市民社会、文化 部門間のコミュニケーション不足である[91]。 市民社会には、ユネスコ・チェアも含まれる。ユネスコ・チェアとは、2005年の条約の研究目的と関連のある研究を行う教授職のことである。2016年11月に発足した「文化表現の多様性に関するユネスコ・チェア」は、条約の実施と知識の発展に参加している[92]。 |

Global reports Cover of the 2018 global report, Re-shaping cultural policies: advancing creativity for development UNESCO has published a series of reports that monitor the outcomes of the 2005 Convention and the progress being made within signatory states.[93] UNESCO (2015). Re|shaping cultural policies: a decade promoting the diversity of cultural expressions for development. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100136-9. (foreword by Irina Bokova) UNESCO (2017). Re|shaping cultural policies: advancing creativity for development. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100256-4. (foreword by Audrey Azoulay) Cuny, Lawrence (2020). Freedom & Creativity: Defending art, defending diversity. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100379-0. (foreword by Ernesto Ottone) Conor, Bridget (2021). Gender & creativity: progress on the precipice. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100444-5. (foreword by Ernesto Ottone) UNESCO (2022). Re|shaping policies for creativity: addressing culture as a global public good. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100503-9. (foreword by Audrey Azoulay) |

グローバルレポート 2018年グローバルレポート『文化政策の再構築:開発のための創造性の促進』の表紙 ユネスコは、2005年の条約の成果と署名国における進捗状況を監視する一連のレポートを発行している[93]。 UNESCO (2015). Re|shaping cultural policies: a decade promoting the diversity of cultural expressions for development. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100136-9。 UNESCO (2017). Re|shaping cultural policies: advancing creativity for development. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100256-4。 Cuny, Lawrence (2020). Freedom & Creativity: Defending art, defending diversity. ユネスコ。ISBN 978-92-3-100379-0。 コナー、ブリジット(2021年)。『ジェンダーと創造性:崖っぷちの進歩』。ユネスコ。ISBN 978-92-3-100444-5。 ユネスコ(2022年)。創造性に関する政策の再構築:グローバルな公共財としての文化への対応。ユネスコ。ISBN 978-92-3-100503-9。序文:オードリー・アズレイ |

| Scholarly reception The convention has received both praise and criticism from academic sources.[94] According to Lilian Richieri Hanania of the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, the convention was significantly watered-down by the negotiation process and so "it has been strongly questioned" whether it can provide a counterbalance to trade agreements. Despite this, she argued in 2014, the core elements of the convention are still relevant and should inform the co-ordination of policy and regulation.[95] The Australian economist David Throsby argued in 2016 that the convention, as a legally binding treaty with many signatories, has achieved much more than the Sustainable Development Goals to advance cultural and economic development in a sustainable context. Reading the national reports on the implementation of the convention, he found that many countries have benefited by making the required policy changes.[94] Evaluating the convention ten years after its creation, Christiaan De Beukelaer and Miikka Pyykkönen described it as "a useful and important instrument in the debate on cultural diversity" but warn that it is "not broad and sufficient enough to confront cultural diversity as a whole, including challenges concerning human rights and sustainability."[4] Sociologist John Clammer praised the convention for highlighting the role of culture but said it "lacks a hard-edged analysis or concrete policy proposals of how to address the very issues that it itself raises".[96] Cultural policy scholar Johnathan Vickery warned that the democratic, pluralist values motivating the convention could lead to practices undermining those same values: that the document "can be used to legitimise and bolster current patriarchal, traditional, customary, superstitious or religious 'culture'". He described it as setting out a desirable democratic system of cultural governance without specifying how this could be achieved: "it is hard to see how many of the non-democratic members of the UN Assembly could ever implement many of its Articles".[97] In 2018, the Polish sociologist Dobrosława Wiktor-Mach described the political support for the convention, leading to its rapid ratification by many states, as impressive. She said that the convention "has had a direct impact on current debates on culture and sustainability" but that the interpretation of cultural diversity that has been implemented is narrow – focused on the market for creative goods – compared to the broad language of the declaration. She observed that the International Fund for Cultural Diversity, being reliant on donations, "has difficulties making real change."[98] According to Nancy Duxbury and co-authors, although the convention mentions sustainability, it does not truly integrate sustainability requirements into its account of development. They drew a contrast with the 1996 Our Creative Diversity report by the World Commission on Culture and Development which considered culture not as a sector of the economy but in terms of the values and practices that define desirable futures.[99] Reviewing the second global report in 2018, Barbara Lovrinić of the Institute for Development and International Relations observed that the reports show that countries have made progress and have come up with new ways to address the strategic issues of promoting cultural diversity, but that the stated long-term goal of reshaping cultural policy was not yet being achieved. She criticised UNESCO for not promoting more public awareness of the 2005 Convention and the Sustainable Development Goals.[100] |

学術界の評価 この条約は、学術界から賞賛と批判の両方を受けている[94]。パリ第1大学パンテオン・ソルボンヌのリリアン・リシェリ・ハナニア教授によると、この条 約は交渉の過程で大幅に骨抜きにされたため、貿易協定の対抗策となりうるかどうかについて「強い疑問が呈されている」という。それにもかかわらず、彼女は 2014年に、条約の核心となる要素は依然として適切であり、政策と規制の調整に役立つべきだと主張した[95]。オーストラリアの経済学者デビッド・ス ロスビーは2016年に、多くの署名国を持つ法的拘束力のある条約であるこの条約は、持続可能な文脈における文化と経済の発展を促進するという点で、持続 可能な開発目標をはるかに上回る成果を上げていると主張した。同条約の実施に関する各国報告書を読み、多くの国が必要な政策変更を行うことによって利益を 得ていることを発見した[94]。 条約制定から10年後の同条約の評価について、クリスティアン・デ・ベウケラールとミッカ・ピヨッコーネンは、同条約を「文化多様性に関する議論において 有用かつ重要な手段」と表現したが、 多様性」に関する議論において「有用かつ重要な手段」であるとしながらも、「人権や持続可能性に関する課題を含め、文化の多様性全体と向き合うには、広範 かつ十分ではない」と警告している[4]。社会学者ジョン・クラマーは、文化の役割を強調した同条約を称賛する一方で、「同条約自体が提起している非常に 重要な問題に対処する方法について、鋭い分析や具体的な政策提言が欠けている」と指摘している[96]。同条約自身が提起している問題に対処する方法につ いて、鋭い分析や具体的な政策提言が欠けている」と述べた[96]。文化政策学者のジョナサン・ヴィッカリーは、同条約を動機付けている民主的かつ多元的 な価値観が、同じ価値観を損なう行為につながる可能性があると警告した。すなわち、同文書は「現在の家父長制、伝統、慣習、迷信、宗教に基づく『文化』を 正当化し、強化するために利用される可能性がある」というのだ。彼は、これを望ましい文化ガバナンスの民主的システムの概要と表現したが、これをどのよう に実現するかについては言及していない。「国連総会における非民主的な加盟国のうち、その多くの条文を実際に実施できる国があるとは考えにくい」 [97]。 2018年、ポーランドの社会学者ドブロスワヴァ・ヴィクトル=マッハは、この条約に対する政治的支援が多くの国々による迅速な批准につながったことは素 晴らしいと述べた。同氏は、この条約は「文化と持続可能性に関する現在の議論に直接的な影響を与えた」が、実施されている文化多様性の解釈は、宣言の幅広 い表現に比べ、創造財の市場に焦点を当てた狭いものである、と述べた。彼女は、寄付金に頼っている国際文化多様性基金は「実質的な変化をもたらすのが難し い」と指摘している[98]。ナンシー・ダクスベリーと共同執筆者によると、同条約では持続可能性について言及されているが、開発に関する説明に持続可能 性の要件を真に統合していないという。彼らは、文化を経済の一部門としてではなく、望ましい未来を定義する価値観や慣習の観点から捉えた、1996年の世 界文化開発委員会による「Our Creative Diversity」報告書との対比を指摘した[99]。 2018年に発表された第2回世界報告書をレビューした 開発と国際関係研究所のバーバラ・ロヴリニッチは、2018年に発表された第2回世界報告書をレビューし、報告書は各国が文化多様性の促進という戦略的課 題に取り組む上で進歩を遂げ、新たな方法を編み出してきたことを示すが、文化政策の再構築という長期目標はまだ達成されていないと指摘した。彼女は、 2005年の条約と持続可能な開発目標について、ユネスコが国民の認知度を高めるための取り組みを怠っていると批判した[100]。 |

| For

example, Coalitions for the Diversity of Cultural Expressions are

active around the world: Canada, Australia, Belgium, Benin, Chad,

Chile, France, Gabon, Germany, Mali, Nigeria, Paraguay, Portugal,

Slovakia, Switzerland, Togo and Turkey. There is also the International

Network of Jurists for the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, the World

Organization of the Francophonie. |

例

えば、文化表現の多様性に関する連合は、カナダ、オーストラリア、ベルギー、ベナン、チャド、チリ、フランス、ガボン、ドイツ、マリ、ナイジェリア、パラ

グアイ、ポルトガル、スロバキア、スイス、トーゴ、トルコなど、世界中で活動している。また、文化表現の多様性に関する国際法律家ネットワークや、フラン

ス語圏諸国機構もある。 |

| Sources Bernier, Ivan (May 2008). "The UNESCO Convention on the Diversity of Cultural Expressions: A Cultural Instrument at the Crossroads of Law and Policy" (PDF). Québec: Chronique, Ministère de la Culture et des Communications. Beukelaer, Christiaan; Pyykkönen, Miikka; Singh, J. P., eds. (2015). Globalization, culture and development : the UNESCO Convention on Cultural Diversity. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-39763-8. Anheier, Helmut K.; Hoelsche, Michael. "The 2005 UNESCO Convention and Civil Society: An Initial Assessment". In Beukelaer, Pyykkönen & Singh (2015). De Beukelaer, Christiaan; Pyykkönen, Miikka. "Introduction: UNESCO's "Diversity Convention" – Ten Years on". In Beukelaer, Pyykkönen & Singh (2015). Guèvremont, Véronique. "The 2005 Convention in the Digital Age". In Beukelaer, Pyykkönen & Singh (2015). Singh, J. P. "Cultural Globalization and the Convention". In Beukelaer, Pyykkönen & Singh (2015). Clammer, John. "Cultural Diversity, Global Change, and Social Justice: Contextualizing the 2005 Convention in a World in Flux". In Beukelaer, Pyykkönen & Singh (2015). Hahn, Michael (2007). "The Convention on Cultural Diversity and International Economic Law". Asian Journal of WTO & International Health Law and Policy. 2 (2). SSRN 1019387. Neil, Garry (2006). "Policy Review: Assessing the effectiveness of UNESCO's new Convention on cultural diversity". Global Media and Communication. 2 (2): 257–262. doi:10.1177/1742766506066278. ISSN 1742-7665. S2CID 146884655. Turp, Daniel (2013). "La Contribution Du Droit International Au Maintien de La Diversité Culturelle". Collected Courses of the Hague Academy of International Law (in French). Vol. 363. Brill Reference Online. Hanania, Lilian Richieri; Norodom, Anne-Thida, eds. (2016). Diversité des expressions culturelles à l'ère du numérique (in French). Buenos Aires: Teseopress. doi:10.55778/ts096909001. ISBN 979-10-96909-00-1. S2CID 252803309. Théorêt, Yves, ed. (2008). David contre Goliath: la Convention sur la protection et la promotion de la diversité des expressions culturelles de l'UNESCO (in French). Montréal: Hurtubise HMH. OCLC 1319339094. Théorêt, Yves (2008a). "Petite histoire de la reconnaissance de la diversité des expressions culturelles". In Théorêt (2008). George, Éric. "La politique de "contenu canadien" à l'ère de la "diversité culturelle" dans le contexte de la mondialisation". In Théorêt (2008). Vlassis, Antonios (5 January 2012). "La mise en oeuvre de la Convention sur la diversité des expressions culturelles: Portée et enjeux de l'interface entre le commerce et la culture". Études internationales (in French). 42 (4): 493–510. doi:10.7202/1007552ar. Further reading Barreiro Carril, Beatriz; Jakubowski, Andrzej; Lixinski, Lucas, eds. (2023). 15 Years of the UNESCO Diversity of Cultural Expressions Convention: Actors, Processes and Impact. Hart Publishing. doi:10.5040/9781509961474. ISBN 978-1-50996-147-4. S2CID 257242641. Garner, B; O'Connor, J (23 December 2019). "Rip it up and start again? The contemporary relevance of the 2005 UNESCO Convention on Cultural Diversity". The Journal of Law, Social Justice and Global Development (24): 8–23. doi:10.31273/LGD.2019.2401. S2CID 213154050. Schorlemer, Sabine; Stoll, Peter-Tobias, eds. (2012). The UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions : explanatory notes. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-25995-1. External links Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions: full text, list of parties, and documents from the Conference of Parties and the Intergovernmental Committee Texts in all official languages, plus Operational Guidelines Procedural history and related documents on the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions in the Historic Archives of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law |

情報源 Bernier, Ivan (2008年5月). 「The UNESCO Convention on the Diversity of Cultural Expressions: A Cultural Instrument at the Crossroads of Law and Policy」 (PDF). Québec: Chronique, Ministère de la Culture et des Communications. Beukelaer, Christiaan; Pyykkönen, Miikka; Singh, J. P., eds. (2015). Globalization, culture and development : the UNESCO Convention on Cultural Diversity. ハウンズミルズ、ベイジングストーク、ハンプシャー:Palgrave Macmillan。ISBN 978-1-137-39763-8。 Anheier, Helmut K.; Hoelsche, Michael. 「The 2005 UNESCO Convention and Civil Society: An Initial Assessment」. In Beukelaer, Pyykkönen & Singh (2015). デ・ブケラール、クリスティアーン、ピユッコネン、ミッカ。 「序文:ユネスコの「多様性条約」 - 10 年後の今」。 ブケラール、ピユッコネン、シン著(2015 年)所収。 ゲヴレモン、ヴェロニク。 「デジタル時代の 2005 年条約」。 ブケラール、ピユッコネン、シン著(2015 年)所収。 Singh, J. P. 「Cultural Globalization and the Convention」. In Beukelaer, Pyykkönen & Singh (2015). Clammer, John. 「Cultural Diversity, Global Change, and Social Justice: Contextualizing the 2005 Convention in a World in Flux」. In Beukelaer, Pyykkönen & Singh (2015). Hahn, Michael (2007). 「文化多様性条約と国際経済法」『アジアWTOジャーナル & 国際保健法・政策』2 (2). SSRN 1019387. ニール、ギャリー (2006). 「政策レビュー:ユネスコの文化多様性条約の有効性評価」『グローバルメディア・コミュニケーション』2 (2): 257–262. 2 (2): 257–262. doi:10.1177/1742766506066278. ISSN 1742-7665. S2CID 146884655. Turp, Daniel (2013). 「La Contribution Du Droit International Au Maintien de La Diversité Culturelle」. ハーグ国際法アカデミー講義集(フランス語)。第363巻。ブリル・リファレンス・オンライン。 Hanania, Lilian Richieri; Norodom, Anne-Thida, eds. (2016). Diversité des expressions culturelles à l'ère du numérique (in French). Buenos Aires: Teseopress. doi:10.55778/ts096909001. ISBN 979-10-96909-00-1。 Théorêt, Yves, ed. (2008). David contre Goliath: la Convention sur la protection et la promotion de la diversité des expressions culturelles de l'UNESCO (in French). Montréal: Hurtubise HMH. OCLC 1319339094. Théorêt, Yves (2008a). 「Petite histoire de la reconnaissance de la diversité des expressions culturelles」. In Théorêt (2008). George, Éric. 「La politique de 」contenu canadien「 à l'ère de la 」diversité culturelle「 dans le contexte de la mondialisation」. In Théorêt (2008). Vlassis, Antonios (5 January 2012). 「文化の多様性に関する条約の実施:商業と文化の接点における影響と課題」。Études internationales(フランス語)。42(4):493–510。doi:10.7202/1007552ar。 さらに読む Barreiro Carril, Beatriz; Jakubowski, Andrzej; Lixinski, Lucas, eds. (2023). 15 Years of the UNESCO Diversity of Cultural Expressions Convention: Actors, Processes and Impact. Hart Publishing. doi:10.5040/9781509961474. ISBN 978-1-50996-147-4. S2CID 257242641. ガーナー、B; オコナー、J (2019年12月23日). 「Rip it up and start again? The contemporary relevance of the 2005 UNESCO Convention on Cultural Diversity」. The Journal of Law, Social Justice and Global Development (24): 8–23. doi:10.31273/LGD.2019.2401. S2CID 213154050。 Schorlemer, Sabine; Stoll, Peter-Tobias, eds. (2012). The UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions : explanatory notes. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-25995-1. 外部リンク 文化の多様性の保護及び振興に関する条約:全文、締約国リスト、締約国会議および政府間委員会の文書 すべての公用語による本文、および運用ガイドライン 国際連合視聴覚図書館国際法オーディオビジュアルライブラリーにおける文化の多様性の保護及び振興に関する条約の手続きの経緯および関連文書 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convention_on_the_Protection_and_Promotion_of_the_Diversity_of_Cultural_Expressions |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099