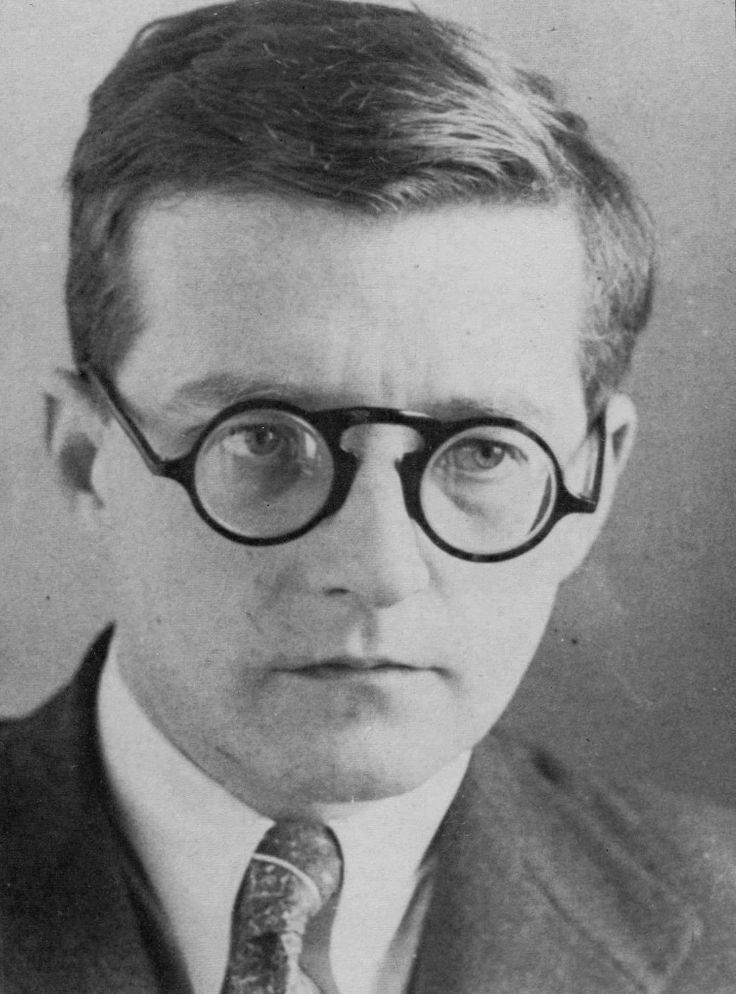

ドミートリイ・ショスタコーヴィチ

Dmitri Shostakovich, 1906-1975

Shostakovich

in 1950

☆ ドミトリー・ドミトリエヴィチ・ショスタコーヴィチ(1906年9月25日 - 1975年8月9日)は、ソ連時代のロシアの作曲家、ピアニスト.

| Dmitri

Dmitriyevich Shostakovich[n 1] (25 September [O.S. 12 September]

1906 –

9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist[1] who

became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony

in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer. Shostakovich achieved early fame in the Soviet Union, but had a complex relationship with its government. His 1934 opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was initially a success, but eventually was condemned by the Soviet government, putting his career at risk. In 1948 his work was denounced under the Zhdanov Doctrine, with professional consequences lasting several years. Even after his censure was rescinded in 1956, performances of his music were occasionally subject to state interventions, as with his Thirteenth Symphony (1962). Shostakovich was a member of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR (1947) and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union (from 1962 until his death), as well as chairman of the RSFSR Union of Composers (1960–1968). Over the course of his career, he earned several important awards, including the Order of Lenin, from the Soviet government. Shostakovich combined a variety of different musical techniques in his works. His music is characterized by sharp contrasts, elements of the grotesque, and ambivalent tonality; he was also heavily influenced by neoclassicism and by the late Romanticism of Gustav Mahler. His orchestral works include 15 symphonies and six concerti (two each for piano, violin, and cello). His chamber works include 15 string quartets, a piano quintet, and two piano trios. His solo piano works include two sonatas, an early set of 24 preludes, and a later set of 24 preludes and fugues. Stage works include three completed operas and three ballets. Shostakovich also wrote several song cycles, and a substantial quantity of music for theatre and film. Shostakovich's reputation has continued to grow after his death. Scholarly interest has increased significantly since the late 20th century, including considerable debate about the relationship between his music and his attitudes toward the Soviet government. |

ドミトリー・ドミトリエヴィチ・ショスタコーヴィチ[n

1](1906年9月25日 - 1975年8月9日)は、ソ連時代のロシアの作曲家、ピアニスト[1]。 1926年に交響曲第1番を初演して国際的に知られるようになり、以後大作曲家として知られるようになった。ショスタコーヴィチはソ連で早くから名声を得 たが、ソ連政府とは複雑な関係にあった。1934年に作曲したオペラ《ムツェンスクのマクベス夫人》は当初成功を収めたが、やがてソ連政府から非難を浴 び、彼のキャリアは危機に瀕した。1948年、彼の作品はジュダーノフ・ドクトリンによって糾弾され、仕事上の影響は数年に及んだ。1956年に批難が取 り消された後も、交響曲第13番(1962年)のように、彼の音楽の演奏が国家の介入を受けることがあった。ショスタコーヴィチは、ソビエト連邦最高会議 (1947年)とソビエト連邦最高会議(1962年から亡くなるまで)のメンバーであり、ソビエト連邦作曲家連合(1960年から1968年)の議長でも あった。キャリアを通じて、ソ連政府からレーニン勲章を含むいくつかの重要な賞を受賞した。 ショスタコーヴィチの作品には、さまざまな音楽技法が用いられている。彼の音楽は、鋭いコントラスト、グロテスクな要素、両義的な調性が特徴で、新古典主 義やグスタフ・マーラーの後期ロマン派からも大きな影響を受けている。管弦楽作品には15曲の交響曲と6曲の協奏曲(ピアノ、ヴァイオリン、チェロのため の各2曲)がある。室内楽作品には15の弦楽四重奏曲、ピアノ五重奏曲、2つのピアノ三重奏曲がある。ピアノ独奏曲には、2曲のソナタ、初期の24曲の前 奏曲集、後期の24曲の前奏曲とフーガ集がある。舞台作品としては、3つのオペラと3つのバレエが完成している。ショスタコーヴィチはまた、歌曲集もいく つか書いており、演劇や映画のための音楽もかなり多い。 ショスタコーヴィチの名声は彼の死後も高まり続けている。彼の音楽とソビエト政府に対する態度との関係についてかなりの議論が交わされるなど、20世紀後 半から学者たちの関心は著しく高まっている。 |

| Biography Youth Born into a Russian family that lived on Podolskaya Street in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, Shostakovich was the second of three children of Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich and Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina. Shostakovich's immediate forebears came from Siberia,[2] but his paternal grandfather, Bolesław Szostakowicz, was of Polish Roman Catholic descent, tracing his family roots to the region of the town of Vileyka in today's Belarus. A Polish revolutionary in the January Uprising of 1863–64, Szostakowicz was exiled to Narym in 1866 in the crackdown that followed Dmitry Karakozov's assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II.[3] When his term of exile ended, Szostakowicz decided to remain in Siberia. He eventually became a successful banker in Irkutsk and raised a large family. His son Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer's father, was born in exile in Narym in 1875 and studied physics and mathematics at Saint Petersburg University, graduating in 1899. He then went to work as an engineer under Dmitri Mendeleev at the Bureau of Weights and Measures in Saint Petersburg. In 1903, he married another Siberian immigrant to the capital, Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina, one of six children born to a Siberian Russian.[3] Their son, Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, displayed musical talent after he began piano lessons with his mother at the age of nine. On several occasions, he displayed a remarkable ability to remember what his mother had played at the previous lesson, and would get "caught in the act" of playing the previous lesson's music while pretending to read different music placed in front of him.[4] In 1918, he wrote a funeral march in memory of two leaders of the Kadet party murdered by Bolshevik sailors.[5] In 1919, at age 13,[6] Shostakovich was admitted to the Petrograd Conservatory, then headed by Alexander Glazunov, who monitored his progress closely and promoted him.[7] Shostakovich studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and Elena Rozanova, composition with Maximilian Steinberg, and counterpoint and fugue with Nikolay Sokolov, who became his friend.[8] He also attended Alexander Ossovsky's music history classes.[9] In 1925, he enrolled in the conducting classes of Nikolai Malko,[10] where he conducted the conservatory orchestra in a private performance of Beethoven's First Symphony. According to the recollections of the composer's classmate, Valerian Bogdanov-Berezhovsky [ru]: Shostakovich stood at the podium, played with his hair and jacket cuffs, looked around at the hushed teenagers with instruments at the ready and raised the baton. ... He neither stopped the orchestra, nor made any remarks; he focused his entire attention on aspects of tempi and dynamics, which were very clearly displayed in his gestures. The contrasts between the "Adagio molto" of the introduction and "Allegro con brio" first theme were quite striking, as were those between the percussive accents of the chords (woodwinds, French horns, pizzicato strings) and the momentarily extended piano in the introduction following them. In the character given to the pattern of the first theme, I recall, there was both vigorous striving and lightness; in the bass part there was an emphasized pliancy of tenderly threaded articulation. ... Moments of these sorts ... were discoveries of an improvised order, born from an intuitively refined understanding of the character of a piece and the elements of musical imagery embedded in it. And the players enjoyed it.[11] On 20 March 1925, Shostakovich's music was played in Moscow for the first time, in a program which also included works by his friend Vissarion Shebalin. To the composer's disappointment, the critics and public there received his music coolly. During his visit to Moscow, Mikhail Kvadri introduced him to Mikhail Tukhachevsky,[12] who helped the composer find accommodation and work there, and sent a driver to take him to a concert in "a very stylish automobile".[13] Shostakovich's musical breakthrough was the First Symphony, written as his graduation piece at the age of 19. Initially, Shostakovich aspired only to perform it privately with the conservatory orchestra and prepared to conduct the scherzo himself. By late 1925, Malko agreed to conduct its premiere with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra after Steinberg and Shostakovich's friend Boleslav Yavorsky brought the symphony to his attention.[14] On 12 May 1926, Malko led the premiere of the symphony; the audience received it enthusiastically, demanding an encore of the scherzo. Thereafter, Shostakovich regularly celebrated the date of his symphonic debut.[15] Early career Shostakovich in 1925 After graduation, Shostakovich embarked on a dual career as concert pianist and composer, but his dry keyboard style was often criticized.[16] Shostakovich maintained a heavy performance schedule until 1930; after 1933, he performed only his own compositions.[17] Along with Yuri Bryushkov [ru], Grigory Ginzburg, Lev Oborin, and Josif Shvarts, he was among the Soviet contestants in the inaugural I International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1927. Bogdanov-Berezhovsky later remembered: The self-discipline with which the young Shostakovich prepared for the 1927 [Chopin] Competition was astonishing. For three weeks, he locked himself away at home, practicing for hours at a time, having postponed his composing, and given up trips to the theatre and visits with friends. Even more startling was the result of this seclusion. Of course, prior to this time, he had played superbly and occasioned Glazunov's now famous glowing reports. But during those days, his pianism, sharply idiosyncratic and rhythmically impulsive, multi-timbered yet graphically defined, emerged in its concentrated form.[18] Natan Perelman [ru], who heard Shostakovich play his Chopin programs before he went to Warsaw, said that his "anti-sentimental" playing, which eschewed rubato and extreme dynamic contrasts, was unlike anything he had ever heard. Arnold Alschwang [ru] called Shostakovich's playing "profound and lacking any salon-like mannerisms."[19] Shostakovich was stricken with appendicitis on the opening day of the competition, but his condition improved by the time of his first performance on 27 January 1927. (He had his appendix removed on 25 April.) According to Shostakovich, his playing found favor with the audience. He persisted into the final round of the competition but ultimately earned only a diploma, no prize; Oborin was declared the winner. Shostakovich was upset about the result but for a time resolved to continue a career as performer. While recovering from his appendectomy in April 1927, Shostakovich said he was beginning to reassess those plans: When I was well, I practiced the piano every day. I wanted to carry on like that until autumn and then decide. If I saw that I had not improved, I would quit the whole business. To be a pianist who is worse than Szpinalski, Etkin, Ginzburg, and Bryushkov (it is commonly thought that I am worse than them) is not worth it.[20] After the competition, Shostakovich and Oborin spent a week in Berlin. There he met the conductor Bruno Walter, who was so impressed by Shostakovich's First Symphony that he conducted its first performance outside Russia later that year. Leopold Stokowski led the American premiere the next year in Philadelphia and also made the work's first recording.[21][22] In 1927, Shostakovich wrote his Second Symphony (subtitled To October), a patriotic piece with a pro-Soviet choral finale. Owing to its modernism, it did not meet with the same enthusiasm as his First.[23] This year also marked the beginning of Shostakovich's close friendship with musicologist and theatre critic Ivan Sollertinsky, whom he had first met in 1921 through their mutual friends Lev Arnshtam and Lydia Zhukova.[24][25] Shostakovich later said that Sollertinsky "taught [him] to understand and love such great masters as Brahms, Mahler, and Bruckner" and that he instilled in him "an interest in music ... from Bach to Offenbach."[26] While writing the Second Symphony, Shostakovich also began work on his satirical opera The Nose, based on the story by Nikolai Gogol. In June 1929, against the composer's wishes, the opera was given a concert performance; it was ferociously attacked by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM).[27] Its stage premiere on 18 January 1930 opened to generally poor reviews and widespread incomprehension among musicians.[28] In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Shostakovich worked at TRAM, a proletarian youth theatre. Although he did little work in this post, it shielded him from ideological attack. Much of this period was spent writing his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which was first performed in 1934. It was initially immediately successful, on both popular and official levels. It was described as "the result of the general success of Socialist construction, of the correct policy of the Party", and as an opera that "could have been written only by a Soviet composer brought up in the best tradition of Soviet culture".[29] Shostakovich married his first wife, Nina Varzar, in 1932. Difficulties led to a divorce in 1935, but the couple soon remarried when Nina became pregnant with their first child, Galina.[30] |

バイオグラフィー 青年期 ロシア帝国サンクトペテルブルクのポドルスカヤ通りに住むロシア人家庭に生まれたショスタコーヴィチは、ドミトリー・ボレスラヴォヴィチ・ショスタコー ヴィチとソフィヤ・ワシリエヴナ・コクリナの3人兄弟の2番目だった。ショスタコーヴィチの直系の祖先はシベリア出身だが[2]、父方の祖父であるボレス ワフ・ソスタコヴィッチはポーランドのローマ・カトリックの血を引いており、その家系は現在のベラルーシにあるヴィリーカという町にまで遡る。1863年 から64年にかけての1月蜂起のポーランド人革命家であったソスタコヴィッチは、1866年、ドミトリー・カラコゾフによるアレクサンドル2世の暗殺未遂 事件後の弾圧により、ナリムへ追放された[3]。やがてイルクーツクで銀行家として成功し、大家族を築いた。作曲家の父である息子のドミトリー・ボレスラ ヴォヴィチ・ショスタコーヴィチは、亡命先のナリムで1875年に生まれ、サンクトペテルブルク大学で物理学と数学を学び、1899年に卒業した。その 後、サンクトペテルブルクの度量衡局でドミトリー・メンデレーエフの下でエンジニアとして働く。1903年、同じくシベリアからサンクトペテルブルクに移 住してきたソフィア・ヴァシリエヴナ・コクリナと結婚。 その息子ドミトリー・ドミトリエヴィチ・ショスタコーヴィチは、9歳の時に母親のもとでピアノを習い始め、音楽の才能を発揮した。1918年には、ボリ シェヴィキの船員によって殺害されたカデット党の2人の指導者を偲んで、葬送行進曲を作曲した[5]。 1919年、13歳のショスタコーヴィチは、当時アレクサンドル・グラズノフが校長を務めていたペトログラード音楽院に入学し、グラズノフはショスタコー ヴィチの成長を厳しく監視し、昇進させた[7]。ショスタコーヴィチは、ピアノをレオニード・ニコライエフとエレナ・ロザノヴァに、作曲をマクシミリア ン・スタインベルクに、対位法とフーガを友人となったニコライ・ソコロフに師事した[8]。 [1925年、ニコライ・マルコの指揮クラスに入学し[10]、ベートーヴェンの交響曲第1番を個人的に演奏した際、音楽院のオーケストラを指揮した。作 曲者の同級生であるヴァレリアン・ボグダノフ=ベレショフスキー[ru]の回想によると、ショスタコーヴィチは、ベートーヴェンの交響曲第1番を個人的に 指揮した: ショスタコーヴィチは指揮台に立ち、髪と上着の袖口で演奏し、楽器を構えた10代の若者たちを見回し、タクトを振った。... ショスタコーヴィチはオーケストラの演奏を止めることもなく、発言することもなく、テンポとダイナミクスに全神経を集中させた。序奏の "アダージョ・モルト "と第1主題の "アレグロ・コン・ブリオ "の対比は、和音(木管楽器、フレンチ・ホルン、ピチカート弦楽器)のパーカッシブなアクセントと、それに続く序奏の一瞬伸びるピアノの対比と同様、非常 に印象的だった。第1主題のパターンに与えられた特徴には、力強い努力と軽やかさの両方があったと記憶している。... このような瞬間は......即興的な秩序の発見であり、曲の性格とそこに込められた音楽的イメージの要素に対する直感的に洗練された理解から生まれたも のだった。そして奏者たちはそれを楽しんでいた[11]。 1925年3月20日、ショスタコーヴィチの音楽は、彼の友人であるヴィサリオン・シェバリンの作品を含むプログラムで、モスクワで初めて演奏された。作 曲者の失望をよそに、モスクワの批評家や聴衆はショスタコーヴィチの音楽を冷淡に受け止めた。モスクワを訪れた際、ミハイル・クヴァドリは彼をミハイル・ トゥハチェフスキーに紹介し[12]、トゥハチェフスキーは作曲家がモスクワで宿と仕事を見つけるのを助け、「とてもスタイリッシュな自動車」でコンサー トに連れて行くために運転手を派遣した[13]。 ショスタコーヴィチの音楽的飛躍のきっかけとなったのは、19歳の時に卒業作品として書かれた交響曲第1番であった。 当初ショスタコーヴィチは、この曲を音楽院のオーケストラと個人的に演奏することだけを望み、スケルツォを自ら指揮する準備をしていた。1926年5月 12日、マルコはこの交響曲の初演を指揮し、聴衆は熱狂的に受け止め、スケルツォのアンコールを要求した[14]。その後、ショスタコーヴィチは定期的に 交響曲デビューの日を祝うようになった[15]。 初期のキャリア 1925年のショスタコーヴィチ 卒業後、ショスタコーヴィチはコンサート・ピアニストと作曲家の二足のわらじを履いたが、その乾いた鍵盤スタイルはしばしば批判された[16]。1930 年までショスタコーヴィチは多忙な演奏スケジュールをこなし、1933年以降は自作曲のみを演奏した[17]。ボグダノフ=ベレショフスキーは後にこう回 想している: 若いショスタコーヴィチが1927年の(ショパン)コンクールのために準備した自己鍛錬は驚くべきものだった。3週間の間、彼は家に閉じこもり、一度に何 時間も練習し、作曲は延期し、劇場への旅行や友人との訪問もあきらめた。さらに驚かされたのは、この隠遁生活の結果だった。もちろん、それ以前にも彼は素 晴らしい演奏を披露し、今では有名なグラズノフの熱烈な賞賛を浴びていた。しかし、この頃、彼のピアニズムは、鋭く特異で、リズムが衝動的で、多層的であ りながらグラフィカルに定義され、凝縮された形で出現したのである[18]。 ワルシャワに行く前にショスタコーヴィチのショパン・プログラムを聴いたナタン・ペレルマン[ru]は、ルバートや極端なダイナミック・コントラストを排 した彼の「反感傷的」な演奏は、これまで聴いたことのないものだったと述べている。アーノルド・アルシュヴァング [ru]は、ショスタコーヴィチの演奏を「深遠で、サロンのような作法がない」と評した[19]。 ショスタコーヴィチはコンクールの初日に虫垂炎にかかったが、1927年1月27日の初演までには病状が回復した。(ショスタコーヴィチによれば、彼の演 奏は聴衆の好感を得たという。ショスタコーヴィチによると、彼の演奏は聴衆の好感を得たという。彼はコンクールの最終ラウンドまで粘ったが、最終的に獲得 したのはディプロマだけで、賞はなく、オボーリンが優勝したと発表された。ショスタコーヴィチはこの結果に動揺したが、一時は演奏家としてのキャリアを続 ける決意を固めた。1927年4月、盲腸の手術から回復したショスタコーヴィチは、その計画を見直し始めたという: 元気なときは毎日ピアノの練習をしていた。元気なときは毎日ピアノの練習をした。もし上達していないことがわかったら、この仕事をやめるつもりだった。ス ピニャルスキ、エトキン、ギンズブルグ、ブリュシコフ(一般には、私は彼らよりも下手だと思われている)よりも下手なピアニストになることは、割に合わな い[20]。 コンクールの後、ショスタコーヴィチとオボーリンはベルリンで1週間を過ごした。そこで出会った指揮者のブルーノ・ワルターは、ショスタコーヴィチの交響 曲第1番に感銘を受け、その年の暮れにロシア国外での初演を指揮した。翌年、レオポルド・ストコフスキーがフィラデルフィアでアメリカ初演を指揮し、この 作品の初録音も行った[21][22]。 1927年、ショスタコーヴィチは交響曲第2番(副題:十月へ)を作曲。この年、ショスタコーヴィチは、1921年に共通の友人であるレフ・アルンシータ ムとリディア・ジューコワを通じて初めて出会った音楽学者で演劇評論家のイヴァン・ソラーチンスキーとの親密な交友を始める。 [後にショスタコーヴィチは、ソレルティンスキーが「ブラームス、マーラー、ブルックナーといった偉大な巨匠を理解し、愛することを教えてくれた」と語 り、「バッハからオッフェンバックに至るまで、音楽への興味」を植え付けたと語っている[26]。 交響曲第2番を作曲する一方で、ショスタコーヴィチはニコライ・ゴーゴリの物語に基づく風刺的なオペラ『鼻』の作曲にも着手した。1929年6月、作曲者 の意向に反して、このオペラは演奏会で上演されたが、ロシア・プロレタリア音楽家協会(RAPM)によって猛烈に攻撃された[27]。 1930年1月18日に初演された舞台は、全般的に評判が悪く、音楽家たちの間に無理解が広まった[28]。 1920年代後半から1930年代前半にかけて、ショスタコーヴィチはプロレタリア青少年劇場のトラムで働いていた。この職場ではほとんど仕事をしなかっ たが、イデオロギー的な攻撃から彼を守ることができた。この時期の多くは、1934年に初演されたオペラ《ムツェンスクのマクベス夫人》の作曲に費やされ た。このオペラは1934年に初演された。社会主義建設の全般的な成功、党の正しい政策の結果」であり、「ソヴィエト文化の最良の伝統に育まれたソヴィエ トの作曲家によってのみ書かれ得た」オペラであると評された[29]。 ショスタコーヴィチは1932年に最初の妻ニーナ・ヴァルツァールと結婚した。1935年に離婚したが、ニーナが第一子ガリーナを妊娠したため、すぐに再 婚した[30]。 |

| First denunciation On 17 January 1936, Joseph Stalin paid a rare visit to the opera for a performance of a new work, Quiet Flows the Don, based on the novel by Mikhail Sholokhov, by the little-known composer Ivan Dzerzhinsky, who was called to Stalin's box at the end of the performance and told that his work had "considerable ideological-political value".[31] On 26 January, Stalin revisited the opera, accompanied by Vyacheslav Molotov, Andrei Zhdanov and Anastas Mikoyan, to hear Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. He and his entourage left without speaking to anyone. Shostakovich had been forewarned by a friend that he should postpone a planned concert tour in Arkhangelsk in order to be present at that particular performance.[32] Eyewitness accounts testify that Shostakovich was "white as a sheet" when he went to take his bow after the third act.[33] The next day, Shostakovich left for Arkhangelsk, where he heard on 28 January that Pravda had published an editorial titled "Muddle Instead of Music", complaining that the opera was a "deliberately dissonant, muddled stream of sounds ...[that] quacks, hoots, pants and gasps."[34] Shostakovich continued his performance tour as scheduled, with no disruptions. From Arkhangelsk, he instructed Isaac Glikman to subscribe to a clipping service.[35] The editorial was the signal for a nationwide campaign, during which even Soviet music critics who had praised the opera were forced to recant in print, saying they "failed to detect the shortcomings of Lady Macbeth as pointed out by Pravda".[36] There was resistance from those who admired Shostakovich, including Sollertinsky, who turned up at a composers' meeting in Leningrad called to denounce the opera and praised it instead. Two other speakers supported him. When Shostakovich returned to Leningrad, he had a telephone call from the commander of the Leningrad Military District, who had been asked by Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky to make sure that he was all right. When the writer Isaac Babel was under arrest four years later, he told his interrogators that "it was common ground for us to proclaim the genius of the slighted Shostakovich."[37] On 6 February, Shostakovich was again attacked in Pravda, this time for his light comic ballet The Limpid Stream, which was denounced because "it jangles and expresses nothing" and did not give an accurate picture of peasant life on a collective farm.[38] Fearful that he was about to be arrested, Shostakovich secured an appointment with the Chairman of the USSR State Committee on Culture, Platon Kerzhentsev, who reported to Stalin and Molotov that he had instructed the composer to "reject formalist errors and in his art attain something that could be understood by the broad masses", and that Shostakovich had admitted being in the wrong and had asked for a meeting with Stalin, which was not granted.[39] The Pravda campaign against Shostakovich caused his commissions and concert appearances, and performances of his music, to decline markedly. His monthly earnings dropped from an average of as much as 12,000 rubles to as little as 2,000.[40] 1936 marked the beginning of the Great Terror, in which many of Shostakovich's friends and relatives were imprisoned or killed. These included Tukhachevsky, executed 12 June 1937; his brother-in-law Vsevolod Frederiks, who was eventually released but died before he returned home; his close friend Nikolai Zhilyayev, a musicologist who had taught Tukhachevsky, was executed; his mother-in-law, the astronomer Sofiya Mikhaylovna Varzar,[41] who was sent to a camp in Karaganda and later released; his friend the Marxist writer Galina Serebryakova, who spent 20 years in the gulag; his uncle Maxim Kostrykin (died); and his colleagues Boris Kornilov (executed) and Adrian Piotrovsky (executed).[42] Shostakovich's daughter Galina was born during this period in 1936;[43] his son Maxim was born two years later.[44] Withdrawal of the Fourth Symphony  Shostakovich before 1941 The publication of the Pravda editorials coincided with the composition of Shostakovich's Fourth Symphony. The work continued a shift in his style, influenced by the music of Mahler, and gave him problems as he attempted to reform his style. Despite the Pravda articles, he continued to compose the symphony and planned a premiere at the end of 1936. Rehearsals began that December, but according to Isaac Glikman, who had attended the rehearsals with the composer, the manager of the Leningrad Philharmonic persuaded Shostakovich to withdraw the symphony.[45] Shostakovich did not repudiate the work and retained its designation as his Fourth Symphony. (A reduction for two pianos was performed and published in 1946,[46] and the work was finally premiered in 1961.)[47] In the months between the withdrawal of the Fourth Symphony and the completion of the Fifth on 20 July 1937, the only concert work Shostakovich composed was the Four Romances on Texts by Pushkin.[48] Fifth Symphony and return to favor The composer's response to his denunciation was the Fifth Symphony of 1937, which was musically more conservative than his recent works. Premiered on 21 November 1937 in Leningrad, it was a phenomenal success. The Fifth brought many to tears and welling emotions.[49] Later, Shostakovich's purported memoir, Testimony, stated: "I'll never believe that a man who understood nothing could feel the Fifth Symphony. Of course they understood, they understood what was happening around them and they understood what the Fifth was about."[50] The success put Shostakovich in good standing once again. Music critics and the authorities alike, including those who had earlier accused him of formalism, claimed that he had learned from his mistakes and become a true Soviet artist. In a newspaper article published under Shostakovich's name, the Fifth was characterized as "A Soviet artist's creative response to just criticism."[51] The composer Dmitry Kabalevsky, who had been among those who disassociated themselves from Shostakovich when the Pravda article was published, praised the Fifth and congratulated Shostakovich for "not having given in to the seductive temptations of his previous 'erroneous' ways."[52] It was also at this time that Shostakovich composed the first of his string quartets. In September 1937, he began to teach composition at the Leningrad Conservatory, which provided some financial security.[53] |

最初の糾弾 1936年1月17日、ヨシフ・スターリンは、ミハイル・ショーロホフの小説を原作とする、あまり知られていない作曲家イワン・ドゼルジンスキーの新作 『ドンは静かに流れる』の上演のためにオペラを珍しく訪問し、上演の終わりにスターリンの席に呼ばれ、彼の作品には「かなりのイデオロギー的・政治的価値 がある」と告げられた[31]。 [31] 1月26日、スターリンはヴャチェスラフ・モロトフ、アンドレイ・ジュダーノフ、アナスタス・ミコヤンを伴い、『ムツェンスク郡のマクベス夫人』を聴くた めにオペラを再訪した。ショスタコーヴィチとその一行は、誰とも話すことなくその場を去った。ショスタコーヴィチは友人から、この公演に出席するために予 定されていたアルハンゲリスクでのコンサートツアーを延期すべきだと予告されていた[32]。目撃者の証言によると、ショスタコーヴィチは第3幕の後に一 礼しようとしたとき、「シーツのように真っ白」になっていた[33]。 翌日、ショスタコーヴィチはアルハンゲリスクに向かったが、1月28日、プラウダがこのオペラが「意図的に不協和音を発生させ、音の流れが混濁 し......クワッ、フーッ、パンツ、あえぎ声」[34]であると訴える社説を掲載したことを知った。アルハンゲリスクから、彼はアイザック・グリクマ ンにクリッピング・サービスに加入するよう指示した[35]。この社説は全国的なキャンペーンの合図となり、オペラを賞賛していたソ連の音楽評論家たちで さえ、「プラウダが指摘した『マクベス夫人』の欠点を見抜けなかった」と印刷物で撤回を余儀なくされた[36]。 [36]ソレルチンスキーを含むショスタコーヴィチを賞賛する人々からの抵抗があり、彼はオペラを非難するために招集されたレニングラードの作曲家会議に 現れ、代わりにこのオペラを賞賛した。他の2人の演説者も彼を支持した。ショスタコーヴィチがレニングラードに戻ると、ミハイル・トゥハチェフスキー元帥 からレニングラード軍管区の司令官から電話があった。4年後、作家のアイザック・バベルが逮捕されたとき、彼は取調官に「軽んじられたショスタコーヴィチ の天才ぶりを喧伝することは、われわれの共通認識だった」と語っている[37]。 2月6日、ショスタコーヴィチはプラウダ紙で再び攻撃された。今度は、軽妙な喜劇的バレエ『清流』についてである。 [逮捕されることを恐れたショスタコーヴィチは、ソ連国家文化委員会のプラトン・ケルジェンツェフ委員長とのアポを取り、同委員長はスターリンとモロトフ に、「形式主義的な誤りを拒絶し、芸術において広範な大衆に理解されうるものを獲得する」よう作曲家に指示したこと、ショスタコーヴィチが非を認め、ス ターリンとの面会を求めたが認められなかったことを報告した[39]。 ショスタコーヴィチに対するプラウダのキャンペーンによって、彼の依頼やコンサートへの出演、彼の音楽の演奏は著しく減少した。月収は平均12,000 ルーブルから2,000ルーブルにまで落ち込んだ[40]。 1936年には大テロが始まり、ショスタコーヴィチの友人や親戚の多くが投獄されたり殺されたりした。その中には、1937年6月12日に処刑されたトゥ ハチェフスキー、義弟のヴシェヴォロド・フレデリクス、最終的には釈放されたが帰国する前に亡くなったヴシェヴォロド・フレデリクス、親友でトゥハチェフ スキーを指導していた音楽学者のニコライ・ジリャーエフなどが含まれる; カラガンダの収容所に送られ、後に釈放された義母の天文学者ソフィア・ミハイロヴナ・ヴァルザル[41]、収容所で20年を過ごした友人のマルクス主義作 家ガリーナ・セレブリャコワ、叔父のマキシム・コストリキン(死亡)、同僚のボリス・コルニロフ(処刑)、アドリアン・ピオトロフスキー(処刑)。 [42] ショスタコーヴィチの娘ガリーナは1936年にこの時期に生まれ[43]、息子のマキシムはその2年後に生まれた[44]。 交響曲第4番の撤回  1941年以前のショスタコーヴィチ プラウダの社説が発表されたのは、ショスタコーヴィチの交響曲第4番が作曲された時期と重なる。この作品は、マーラーの音楽の影響を受けた彼の作風の転換 を続けており、作風を改めようとする彼に問題を与えた。プラウダの記事にもかかわらず、彼は交響曲の作曲を続け、1936年末の初演を計画した。リハーサ ルはその年の12月に始まったが、作曲者とともにリハーサルに参加したアイザック・グリクマンによると、レニングラード・フィルのマネージャーがショスタ コーヴィチに交響曲を取り下げるよう説得したという。(1946年に2台ピアノのための縮小版が演奏・出版され[46]、1961年にようやく初演された [47]。 交響曲第4番が取り下げられ、1937年7月20日に第5番が完成するまでの数ヶ月の間にショスタコーヴィチが作曲した唯一の演奏会用作品は、プーシキン のテクストによる4つの歌曲であった[48]。 交響曲第5番と復帰 1937年、ショスタコーヴィチは、最近の作品よりも音楽的に保守的な交響曲第5番を作曲した。1937年11月21日にレニングラードで初演され、驚異 的な成功を収めた。後にショスタコーヴィチの回顧録とされる『証言』にはこう記されている: 「何も理解していない人間が交響曲第5番を感じることができたとは、私は決して信じないだろう。もちろん、彼らは理解していたし、周囲で起きていることも 理解していたし、第5番が何について書かれた曲かも理解していた」[50]。 この成功により、ショスタコーヴィチの地位は再び向上した。音楽批評家も当局も、それ以前に彼を形式主義だと非難していた人々も含めて、彼は自分の過ちか ら学び、真のソビエトの芸術家になったと主張した。ショスタコーヴィチの名で発表された新聞記事では、第5番は「ソビエトの芸術家の、正当な批判に対する 創造的な反応」[51]と評され、プラウダの記事が発表されたときにショスタコーヴィチと縁を切った人々の一人であった作曲家のドミトリー・カバレフス キーは、第5番を賞賛し、「以前の『誤った』方法の魅惑的な誘惑に屈しなかった」ショスタコーヴィチを祝福した[52]。 ショスタコーヴィチが弦楽四重奏曲の第1番を作曲したのもこの時期である。1937年9月、彼はレニングラード音楽院で作曲を教え始め、経済的な安定を得 た[53]。 |

| Second World War In 1939, before Soviet forces attempted to invade Finland, the Party Secretary of Leningrad Andrei Zhdanov commissioned a celebratory piece from Shostakovich, the Suite on Finnish Themes, to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army paraded through Helsinki. The Winter War was a bitter experience for the Red Army, the parade never happened, and Shostakovich never laid claim to the authorship of this work.[54] It was not performed until 2001.[55] After the outbreak of war between the Soviet Union and Germany in 1941, Shostakovich initially remained in Leningrad. He tried to enlist in the military but was turned away because of his poor eyesight. To compensate, he became a volunteer for the Leningrad Conservatory's firefighter brigade and delivered a radio broadcast to the Soviet people. listenⓘ The photograph for which he posed was published in newspapers throughout the country.[56] Shostakovich's most famous wartime contribution was the Seventh Symphony. The composer wrote the first three movements in Leningrad while it was under siege; he completed the work in Kuybyshev (now Samara), where he and his family had been evacuated.[57] According to a radio address he made on 17 September 1941, he continued work on the symphony in order to show his fellow citizens that everyone had a "soldier's duty" to ensure life went on. In another article written on 8 October, he wrote that the Seventh was a "symphony about our age, our people, our sacred war, and our victory."[58] Shostakovich finished his Seventh Symphony on 27 December.[59] The symphony was premiered by the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra in Kuibyshev on 29 March and soon performed in London and the United States,[60] where several conductors vied to conduct its first American performance.[61] It was subsequently performed in Leningrad while the city was still under siege. The city's remaining orchestra only had 14 musicians left, which led conductor Karl Eliasberg to reinforce it by recruiting anyone who could play an instrument.[62] The Shostakovich family moved to Moscow in spring 1943, by which time the Red Army was on the offensive. As a result, Soviet authorities and the international public were puzzled by the tragic tone of the Eighth Symphony, which in the Western press had briefly acquired the nickname "Stalingrad Symphony". The symphony was received tepidly in the Soviet Union and the West. Olin Downes expressed his disappointment in the piece, but Carlos Chávez, who had conducted the symphony's Mexican premiere, praised it highly.[63] Shostakovich had expressed as early as 1943 his intention to cap his wartime trilogy of symphonies with a grandiose Ninth. On 16 January 1945, he announced to his students that he had begun work on its first movement the day before. In April, his friend Isaac Glikman heard an extensive portion of the first movement, noting that it was "majestic in scale, in pathos, in its breathtaking motion".[64] Shortly thereafter, Shostakovich ceased work on this version of the Ninth, which remained lost until musicologist Olga Digonskaya rediscovered it in December 2003.[65] Shostakovich began to compose his actual, unrelated Ninth Symphony in late July 1945; he completed it on 30 August. It was shorter and lighter in texture than its predecessors. Gavriil Popov wrote that it was "splendid in its joie de vivre, gaiety, brilliance, and pungency!"[66] By 1946 it was the subject of official criticism. Israel Nestyev asked whether it was the right time for "a light and amusing interlude between Shostakovich's significant creations, a temporary rejection of great, serious problems for the sake of playful, filigree-trimmed trifles."[67] The New York World-Telegram of 27 July 1946 was similarly dismissive: "The Russian composer should not have expressed his feelings about the defeat of Nazism in such a childish manner". Shostakovich continued to compose chamber music, notably his Second Piano Trio, dedicated to the memory of Sollertinsky, with a Jewish-inspired finale. In 1947, Shostakovich was made a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR.[68] Second denunciation In 1948, Shostakovich, along with many other composers, was again denounced for formalism in the Zhdanov decree. Andrei Zhdanov, Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, accused the composers (including Sergei Prokofiev and Aram Khachaturian) of writing inappropriate and formalist music. This was part of an ongoing anti-formalism campaign intended to root out all Western compositional influence as well as any perceived "non-Russian" output. The conference resulted in the publication of the Central Committee's Decree "On V. Muradeli's opera The Great Friendship", which targeted all Soviet composers and demanded that they write only "proletarian" music, or music for the masses. The accused composers, including Shostakovich, were summoned to make public apologies in front of the committee.[69] Most of Shostakovich's works were banned, and his family had privileges withdrawn. Yuri Lyubimov says that at this time "he waited for his arrest at night out on the landing by the lift, so that at least his family wouldn't be disturbed."[70] The decree's consequences for composers were harsh. Shostakovich was among those dismissed from the Conservatory altogether. For him, the loss of money was perhaps the heaviest blow. Others still in the Conservatory experienced an atmosphere thick with suspicion. No one wanted his work to be understood as formalist, so many resorted to accusing their colleagues of writing or performing anti-proletarian music.[71] During the next few years, Shostakovich composed three categories of work: film music to pay the rent, official works aimed at securing official rehabilitation, and serious works "for the desk drawer". The last included the Violin Concerto No. 1 and the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. The cycle was written at a time when the postwar anti-Semitic campaign was already under way, with widespread arrests, including that of Dobrushin and Yiditsky, the compilers of the book from which Shostakovich took his texts.[72] The restrictions on Shostakovich's music and living arrangements were eased in 1949, when Stalin decided that the Soviets needed to send artistic representatives to the Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace in New York City, and that Shostakovich should be among them. For Shostakovich, it was a humiliating experience, culminating in a New York press conference where he was expected to read a prepared speech. Nicolas Nabokov, who was present in the audience, witnessed Shostakovich starting to read "in a nervous and shaky voice" before he had to break off "and the speech was continued in English by a suave radio baritone".[73] Fully aware that Shostakovich was not free to speak his mind, Nabokov publicly asked him whether he supported the then recent denunciation of Stravinsky's music in the Soviet Union. A great admirer of Stravinsky who had been influenced by his music, Shostakovich had no alternative but to answer in the affirmative. Nabokov did not hesitate to write that this demonstrated that Shostakovich was "not a free man, but an obedient tool of his government."[74] Shostakovich never forgave Nabokov for this public humiliation.[75] That same year, he was obliged to compose the cantata Song of the Forests, which praised Stalin as the "great gardener".[76] Stalin's death in 1953 was the biggest step toward Shostakovich's rehabilitation as a creative artist, which was marked by his Tenth Symphony. It features a number of musical quotations and codes (notably the DSCH and Elmira motifs, Elmira Nazirova being a pianist and composer who had studied under Shostakovich in the year before his dismissal from the Moscow Conservatory),[77] the meaning of which is still debated, while the savage second movement, according to Testimony, is intended as a musical portrait of Stalin. The Tenth ranks alongside the Fifth and Seventh as one of Shostakovich's most popular works. 1953 also saw a stream of premieres of the "desk drawer" works. During the 1940s and 1950s, Shostakovich had close relationships with two of his pupils, Galina Ustvolskaya and Elmira Nazirova. In the background to all this remained Shostakovich's first, open marriage to Nina Varzar until her death in 1954. He taught Ustvolskaya from 1939 to 1941 and then from 1947 to 1948. The nature of their relationship is far from clear: Mstislav Rostropovich described it as "tender". Ustvolskaya rejected a proposal of marriage from him after Nina's death.[78] Shostakovich's daughter, Galina, recalled her father consulting her and Maxim about the possibility of Ustvolskaya becoming their stepmother.[78][79] Ustvolskaya's friend Viktor Suslin said that she had been "deeply disappointed by [Shostakovich's] conspicuous silence" when her music faced criticism after her graduation from the Leningrad Conservatory.[80] The relationship with Nazirova seems to have been one-sided, expressed largely in his letters to her, and can be dated to around 1953 to 1956. He married his second wife, Komsomol activist Margarita Kainova, in 1956; the couple proved ill-matched, and divorced five years later.[81] In 1954, Shostakovich wrote the Festive Overture, opus 96; it was used as the theme music for the 1980 Summer Olympics.[82] (His '"Theme from the film Pirogov, Opus 76a: Finale" was played as the cauldron was lit at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece.)[83][84] In 1959, Shostakovich appeared on stage in Moscow at the end of a concert performance of his Fifth Symphony, congratulating Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for their performance (part of a concert tour of the Soviet Union). Later that year, Bernstein and the Philharmonic recorded the symphony in Boston for Columbia Records.[85][86] |

第二次世界大戦 1939年、ソ連軍がフィンランドに侵攻する前、レニングラードのアンドレイ・ジュダーノフ党書記は、赤軍のマーチングバンドがヘルシンキをパレードする 際に演奏する祝典曲として、ショスタコーヴィチに「フィンランドの主題による組曲」を委嘱した。冬戦争は赤軍にとって苦い経験となり、パレードは実現せ ず、ショスタコーヴィチがこの作品の作曲者であることを主張することはなかった[54]。彼は軍隊に入隊しようとしたが、視力が悪かったために追い返され た。それを補うために、彼はレニングラード音楽院の消防隊のボランティアとなり、ソビエト国民に向けてラジオ放送を行った。 ショスタコーヴィチの戦時中の貢献で最も有名なのは交響曲第7番である。1941年9月17日に行ったラジオ演説によると、ショスタコーヴィチが交響曲の 作曲を続けたのは、生活が続けられるようにするために、誰もが「兵士の義務」を負っていることを同胞に示すためだったという。10月8日に書かれた別の記 事では、第7番は「我々の時代、我々の人々、我々の神聖な戦争、そして我々の勝利についての交響曲」であると書いている[58]。ショスタコーヴィチは 12月27日に交響曲第7番を完成させた[59]。交響曲は3月29日にクイビシェフでボリショイ劇場管弦楽団によって初演され、すぐにロンドンとアメリ カで演奏された[60]。そのため指揮者のカール・エリアスベルクは、楽器を演奏できる者なら誰でも採用することでオーケストラを補強した[62]。 ショスタコーヴィチ一家がモスクワに移ったのは1943年の春で、その頃には赤軍は攻勢に出ていた。その結果、ソ連当局と国際世論は交響曲第8番の悲劇的 な曲調に困惑し、西側の新聞では一時「スターリングラード交響曲」というニックネームが付けられた。この交響曲は、ソ連でも西側諸国でも冷淡に受け止めら れた。オリン・ダウネスはこの作品に失望を表明したが、この交響曲のメキシコ初演を指揮したカルロス・チャベスは高く評価した[63]。 ショスタコーヴィチは1943年の時点で、戦時中の交響曲三部作の最後を壮大な第九で締めくくる意向を示していた。1945年1月16日、彼はその前日に 第1楽章の作曲に着手したことを学生たちに発表した。その後まもなく、ショスタコーヴィチはこの「第九」の作曲を中止し、2003年12月に音楽学者のオ ルガ・ディゴンスカヤが再発見するまで、この「第九」は失われたままであった[65]。8月30日に完成したこの交響曲は、前作よりも短く、軽いテクス チュアであった。ガヴリール・ポポフはこの交響曲について、「生きる喜び、陽気さ、輝き、辛辣さにおいて素晴らしい!」[66]と書いている。1946年 7月27日付のニューヨーク・ワールド・テレグラム紙も同様に、「ロシアの作曲家は、ナチズムの敗北に対する彼の感情を、このような子供じみた方法で表現 すべきではなかった」と酷評している[67]。ショスタコーヴィチは室内楽の作曲を続け、特にソレルチンスキーの思い出に捧げたピアノ三重奏曲第2番は、 ユダヤ人にインスパイアされたフィナーレを持つ。 1947年、ショスタコーヴィチはソビエト連邦最高会議副議長に就任した[68]。 第二次糾弾 1948年、ショスタコーヴィチは、他の多くの作曲家とともに、ジュダーノフ法令において、形式主義を理由に再び糾弾された。ソビエト連邦最高会議議長の アンドレイ・ジュダーノフは、作曲家たち(セルゲイ・プロコフィエフやアラム・ハチャトゥリアンを含む)が不適切で形式主義的な音楽を書いていると非難し た。これは、あらゆる西洋の作曲の影響や、「非ロシア的」と思われる作品を根絶することを目的とした、進行中の反形式主義キャンペーンの一環であった。こ の会議の結果、中央委員会の法令「V.ムラデリのオペラ『偉大なる友情』について」が発表され、すべてのソビエトの作曲家を標的にし、「プロレタリア」音 楽、つまり大衆のための音楽だけを書くよう要求した。ショスタコーヴィチを含む告発された作曲家たちは、委員会の面前で公開謝罪をするよう召喚された [69]。ショスタコーヴィチの作品のほとんどは禁止され、彼の家族は特権を剥奪された。ユーリ・リュビモフはこの時、「彼は夜、エレベーターのそばの踊 り場で逮捕を待った。 この勅令が作曲家にもたらした結果は過酷なものだった。ショスタコーヴィチは音楽院から完全に解雇された。彼にとっては、おそらく金銭を失うことが最も大 きな打撃であった。音楽院に残っていた他の作曲家たちは、疑惑に満ちた雰囲気を味わった。誰も彼の作品が形式主義的だと理解されることを望まなかったた め、多くの人が、同僚が反プロレタリア的な音楽を書いたり演奏したりしていると非難することに頼った[71]。 その後数年間、ショスタコーヴィチは、家賃を払うための映画音楽、公的な更生を目的とした公的な作品、そして「机の引き出しのための」シリアスな作品とい う3つのカテゴリーの作品を作曲した。最後の作品には、ヴァイオリン協奏曲第1番と歌曲集『ユダヤの民衆詩より』が含まれる。この曲集は、戦後の反ユダヤ 主義運動がすでに進行していた時期に書かれたもので、ショスタコーヴィチがテクストを引用した本の編者であるドブルーシンとイディツキーの逮捕をはじめ、 広く逮捕者が出た[72]。 1949年、スターリンは、ソビエトがニューヨークで開催される世界平和のための文化科学会議に芸術家代表を派遣する必要があり、ショスタコーヴィチもそ のうちの一人であるべきだと決定し、ショスタコーヴィチの音楽と生活に対する制限は緩和された。ショスタコーヴィチにとっては屈辱的な経験であり、ニュー ヨークの記者会見では、用意されたスピーチを読むことを期待された。聴衆として出席していたニコラス・ナボコフは、ショスタコーヴィチが「緊張して震えた 声で」読み始めるのを目撃している。ストラヴィンスキーを敬愛し、彼の音楽に影響を受けてきたショスタコーヴィチには、肯定的に答える以外に選択肢はな かった。ナボコフは、このことがショスタコーヴィチが「自由人ではなく、政府の従順な道具」であることを証明していると書くことをためらわなかった [74]。 ショスタコーヴィチは、この公然の屈辱をナボコフに許すことはなかった[75]。 同じ年、彼はスターリンを「偉大な庭師」と讃えるカンタータ『森の歌』を作曲することを余儀なくされた[76]。 1953年のスターリンの死は、ショスタコーヴィチが創造的な芸術家として更生するための最大の一歩であり、それは交響曲第10番によって示された。この 交響曲第10番は、多くの音楽的引用やコード(特にDSCHとエルミラのモチーフ、エルミラ・ナジロワは、ショスタコーヴィチがモスクワ音楽院を解雇され る前年に師事したピアニスト兼作曲家である)を特徴としており[77]、その意味についてはいまだに議論されているところであるが、『証言』によれば、野 蛮な第2楽章はスターリンの音楽的肖像として意図されたものであるという。第10番は、第5番、第7番と並んで、ショスタコーヴィチの最も人気のある作品 のひとつである。また、1953年には「机の引き出し」作品の初演が相次いだ。 1940年代から50年代にかけて、ショスタコーヴィチは2人の弟子、ガリーナ・ウストヴォルスカヤとエルミラ・ナジロワと親密な関係にあった。この背景 には、1954年に彼女が亡くなるまで、ショスタコーヴィチがニーナ・ヴァルザールと初めて公然と結婚したことがあった。彼は1939年から1941年ま でウストヴォリスカヤを教え、1947年から1948年までウストヴォリスカヤを教えた。ムスティスラフ・ロストロポーヴィチはそれを「優しい」と表現し た。ウストヴォルスカヤは、ニーナの死後、彼からの求婚を断った[78]。ショスタコーヴィチの娘ガリーナは、ウストヴォルスカヤが継母になる可能性につ いて、父親が彼女とマキシムに相談したことを回想している[78][79]。 [78][79]ウストヴォルスカヤの友人ヴィクトル・サスリンは、彼女がレニングラード音楽院を卒業した後、彼女の音楽が批評に直面したとき、「(ショ スタコーヴィチの)際立った沈黙に深く失望した」と語っている[80]。ナジロワとの関係は一方的なものであったようで、主に彼女への手紙に表現されてお り、1953年から1956年頃までとされる。彼は1956年に2番目の妻であるコムソモール活動家のマルガリータ・カイノワと結婚したが、この夫婦は不 釣り合いであることが判明し、5年後に離婚した[81]。 1954年、ショスタコーヴィチは『祝典序曲』作品96を作曲し、1980年の夏季オリンピックのテーマ曲として使用された[82]: 2004年、ギリシャのアテネで開催された夏季オリンピックでは、「映画『ピロゴフ』のテーマ、作品76a:フィナーレ」が釜に点火される際に演奏された [83][84]。 1959年、ショスタコーヴィチは交響曲第5番の演奏会の終わりにモスクワのステージに登場し、レナード・バーンスタインとニューヨーク・フィルハーモ ニー管弦楽団の演奏(ソビエト連邦演奏旅行の一環)を祝福した。その年の暮れ、バーンスタインとフィルハーモニー管弦楽団はボストンでこの交響曲をコロン ビア・レコードに録音した[85][86]。 |

| Joining the Party The year 1960 marked another turning point in Shostakovich's life: he joined the Communist Party. The government wanted to appoint him Chairman of the RSFSR Union of Composers, but to hold that position he was required to obtain Party membership. It was understood that Nikita Khrushchev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party from 1953 to 1964, was looking for support from the intelligentsia's leading ranks in an effort to create a better relationship with the Soviet Union's artists.[87] This event has variously been interpreted as a show of commitment, a mark of cowardice, the result of political pressure, and his free decision. On the one hand, the apparat was less repressive than it had been before Stalin's death. On the other, his son recalled that the event reduced Shostakovich to tears,[88] and that he later told his wife Irina that he had been blackmailed.[89] Lev Lebedinsky has said that the composer was suicidal.[90] In 1960, he was appointed Chairman of the RSFSR Union of Composers;[91][92] from 1962 until his death, he also served as a delegate in the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.[93] By joining the party, Shostakovich also committed himself to finally writing the homage to Lenin that he had promised before. His Twelfth Symphony, which portrays the Bolshevik Revolution and was completed in 1961, was dedicated to Lenin and called "The Year 1917".  Shostakovich in 1950 Shostakovich's musical response to these personal crises was the Eighth String Quartet, composed in only three days. He subtitled the piece "To the victims of fascism and war",[94] ostensibly in memory of the Dresden fire bombing that took place in 1945. Yet like the Tenth Symphony, the quartet incorporates quotations from several of his past works and his musical monogram. Shostakovich confessed to his friend Isaac Glikman, "I started thinking that if some day I die, nobody is likely to write a work in memory of me, so I had better write one myself."[95] Several of Shostakovich's colleagues, including Natalya Vovsi-Mikhoels[96] and the cellist Valentin Berlinsky,[97] were also aware of the Eighth Quartet's biographical intent. Peter J. Rabinowitz has also pointed to covert references to Richard Strauss's Metamorphosen in it.[98] In 1962, Shostakovich married for the third time, to Irina Supinskaya. In a letter to Glikman, he wrote, "her only defect is that she is 27 years old. In all other respects she is splendid: clever, cheerful, straightforward and very likeable."[99] According to Galina Vishnevskaya, who knew the Shostakoviches well, this marriage was a very happy one: "It was with her that Dmitri Dmitriyevich finally came to know domestic peace... Surely, she prolonged his life by several years."[100] In November, he conducted publicly for the only time in his life, leading a couple of his own works in Gorky;[101] otherwise he declined to conduct, citing nerves and ill health.[citation needed] That year saw Shostakovich again turn to the subject of anti-Semitism in his Thirteenth Symphony (subtitled Babi Yar). The symphony sets a number of poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, the first of which commemorates a massacre of Ukrainian Jews during the Second World War. Opinions are divided as to how great a risk this was: the poem had been published in Soviet media and was not banned, but it remained controversial. After the symphony's premiere, Yevtushenko was forced to add a stanza to his poem that said that Russians and Ukrainians had died alongside the Jews at Babi Yar.[102] In 1965, Shostakovich raised his voice in defence of poet Joseph Brodsky, who was sentenced to five years of exile and hard labor. Shostakovich co-signed protests with Yevtushenko, fellow Soviet artists Kornei Chukovsky, Anna Akhmatova, Samuil Marshak, and the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. After the protests, the sentence was commuted, and Brodsky returned to Leningrad.[103] Later life In 1964, Shostakovich composed the music for the Russian film Hamlet, which was favorably reviewed by The New York Times: "But the lack of this aural stimulation—of Shakespeare's eloquent words—is recompensed in some measure by a splendid and stirring musical score by Dmitri Shostakovich. This has great dignity and depth, and at times an appropriate wildness or becoming levity".[104] In later life, Shostakovich suffered from chronic ill health, but he resisted giving up cigarettes and vodka.[105] Beginning in 1958, he suffered from a debilitating condition that particularly affected his right hand, eventually forcing him to give up piano playing; in 1965, it was diagnosed as poliomyelitis, but consensus on his diagnosis is unclear.[105] He also suffered heart attacks in 1966,[106]1970,[105] and 1971,[105] as well as several falls in which he broke both his legs;[105] in 1967, he wrote in a letter: "Target achieved so far: 75% (right leg broken, left leg broken, right hand defective). All I need to do now is wreck the left hand and then 100% of my extremities will be out of order."[107] A preoccupation with his own mortality permeates Shostakovich's later works, such as the later quartets and the Fourteenth Symphony of 1969 (a song cycle based on a number of poems on the theme of death). This piece also finds Shostakovich at his most extreme with musical language, with 12-tone themes and dense polyphony throughout. He dedicated the Fourteenth to his close friend Benjamin Britten, who conducted its Western premiere at the 1970 Aldeburgh Festival. The Fifteenth Symphony of 1971 is, by contrast, melodic and retrospective in nature, quoting Wagner, Rossini and the composer's own Fourth Symphony.[108] Death  Shostakovich voting in the election of the Council of Administration of Soviet Musicians in Moscow in 1974 (photograph by Yuri Shcherbinin) Despite suffering from motor neurone disease (ALS) or some other neurological ailment from as early as the 1950s,[105] Shostakovich insisted upon writing all his own correspondence and music himself, even when his right hand became virtually unusable. His last work was his Viola Sonata, which was first performed officially on 1 October 1975.[109][page needed] Shostakovich suffered from lung cancer (he was a heavy smoker). His death is variously attributed to lung cancer or heart failure, both diseases associated with smoking.[110][111][105] Shostakovich died on 9 August 1975 at the Central Clinical Hospital in Moscow. A civic funeral was held; he was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow. According to the New York Times, "He was known to have suffered from heart ailments that dated to his hospitalization for a heart attack in 1964".[112] Legacy Shostakovich left behind several recordings of his own piano works; other noted interpreters of his music include Mstislav Rostropovich,[113] Tatiana Nikolayeva,[114] Maria Yudina,[115] David Oistrakh,[116] and members of the Beethoven Quartet.[117][118] Shostakovich's influence on later composers outside the former Soviet Union has been relatively slight. His influence can be seen in some Nordic composers, such as Lars-Erik Larsson.[119] Many of his Russian contemporaries, and his pupils at the Leningrad Conservatory, were strongly influenced by his style (including German Okunev, Sergei Slonimsky, and Boris Tishchenko, whose Fifth Symphony of 1978 is dedicated to Shostakovich's memory). Shostakovich's conservative idiom has grown increasingly popular with audiences as the avant-garde has declined in influence and debate about his political views has developed.[citation needed] The Shostakovich Peninsula on Alexander Island, Antarctica, is named for him.[120] |

入党 1960年、ショスタコーヴィチは共産党に入党する。政府はショスタコーヴィチをロシア連邦作曲家連盟の会長に任命しようとしたが、その地位に就くには党 員資格を得る必要があった。1953年から1964年まで共産党第一書記を務めたニキータ・フルシチョフは、ソ連の芸術家たちとのより良い関係を築くため に、知識階級の有力者たちからの支持を求めていたことが理解されていた[87]。この出来事は、決意の表れ、臆病者の証、政治的圧力の結果、そして彼の自 由な決断と、さまざまに解釈されてきた。一方では、スターリンの死後、ソビエト政府は、スターリンの死以前よりも抑圧的ではなくなっていた。一方、彼の息 子は、この出来事によってショスタコーヴィチは涙を流し[88]、後に妻イリーナに脅迫されたと語ったと回想している[89]。 [1962年から亡くなるまで、ソビエト連邦最高会議代表も務めた[93]。党に入党することで、ショスタコーヴィチは以前から約束していたレーニンへの オマージュをついに書くことを約束した。1961年に完成したボリシェヴィキ革命を描いた交響曲第12番は、レーニンに捧げられ、「1917年」と名付け られた。  1950年のショスタコーヴィチ こうした個人的危機に対するショスタコーヴィチの音楽的応答が、わずか3日間で作曲された弦楽四重奏曲第8番である。彼はこの曲に「ファシズムと戦争の犠 牲者に捧ぐ」という副題をつけ[94]、表向きは1945年に起こったドレスデン大空襲を偲んでいる。しかし、交響曲第10番と同様に、この四重奏曲には 彼の過去の作品からの引用と、彼の音楽的モノグラムが組み込まれている。ショスタコーヴィチは友人のアイザック・グリクマンに、「いつか私が死んだら、誰 も私を偲ぶ作品を書いてくれそうにないから、自分で書いた方がいいと思い始めた」と告白している[95]。ナターリヤ・ヴォフシ=ミホエルス[96]や チェリストのヴァレンティン・ベルリンスキー[97]など、ショスタコーヴィチの同僚の何人かも、第8四重奏曲の伝記的意図に気づいていた。ピーター・ J・ラビノヴィッツは、この曲の中にリヒャルト・シュトラウスの『メタモルフォーゼン』への密かな言及があることも指摘している[98]。 1962年、ショスタコーヴィチはイリーナ・スピンスカヤと3度目の結婚をした。グリックマンに宛てた手紙の中で、「彼女の唯一の欠点は27歳ということ です。他のすべての点で、彼女は素晴らしく、賢く、陽気で、素直で、とても好感が持てる」[99] ショスタコーヴィチ夫妻をよく知るガリーナ・ヴィシュネフスカヤによれば、この結婚はとても幸せなものだったという: 「ドミートリ・ドミートリエヴィチがようやく家庭の平和を知るようになったのは、彼女のおかげだった。確かに、彼女は彼の人生を数年延ばした」 [100]。11月には、ゴーリキーで自作を数曲指揮し、生涯で唯一公の場で指揮をした[101]が、それ以外は緊張と体調不良を理由に指揮を辞退した [要出典]。 この年、ショスタコーヴィチは交響曲第13番(副題:バビ・ヤール)で再び反ユダヤ主義をテーマにした。この交響曲は、エフゲニー・エフトゥシェンコの詩 の数々を取り上げたもので、その最初の詩は、第二次世界大戦中のウクライナのユダヤ人虐殺を記念したものである。この詩はソ連のメディアに掲載されたこと があり、禁止はされなかったが、物議を醸した。交響曲の初演後、エフトゥシェンコは、ロシア人とウクライナ人がバビ・ヤールでユダヤ人とともに死んだとい う詩の一節を付け加えざるを得なくなった[102]。 1965年、ショスタコーヴィチは、5年間の国外追放と重労働を言い渡された詩人ヨゼフ・ブロツキーを擁護するために声を上げた。ショスタコーヴィチは、 エフトゥシェンコ、ソ連の芸術家仲間であるコルネイ・チュコフスキー、アンナ・アフマートワ、サムイル・マーシャク、フランスの哲学者ジャン=ポール・サ ルトルらと共同で抗議に署名した。抗議の後、刑は減刑され、ブロツキーはレニングラードに戻った[103]。 その後の人生 1964年、ショスタコーヴィチはロシア映画『ハムレット』の音楽を担当: 「しかし、シェイクスピアの雄弁な言葉という聴覚的な刺激の欠如は、ドミトリ・ショスタコーヴィチによる見事で感動的な音楽によって、いくらかは補われて いる。この楽譜は偉大な威厳と深みを持ち、時には適切な野性味や平静さを感じさせる」[104]。 1958年からは、特に右手が衰弱する症状に悩まされ、最終的にはピアノ演奏を断念せざるを得なくなった[105]。 [また、1966年、[106]1970年、[105]1971年に心臓発作に見舞われ、[105]また、何度か転倒して両足を骨折した[105]: 「これまでの目標達成率: これまでの目標達成率:75%(右足骨折、左足骨折、右手欠損)。あとは左手を壊すだけで、私の四肢は100%機能しなくなる」[107]。 ショスタコーヴィチの後期の作品、例えば後期の四重奏曲や1969年の交響曲第14番(死をテーマにした多くの詩に基づく歌曲集)には、彼自身の死に対す るこだわりが浸透している。この曲はまた、ショスタコーヴィチが最も極端な音楽表現を駆使した作品であり、12音からなる主題と濃密なポリフォニーを全編 に用いている。彼はこの第14番を親友のベンジャミン・ブリテンに捧げ、ブリテンは1970年のアルデバーグ音楽祭でこの曲の西初演を指揮した。1971 年の交響曲第15番は、対照的にメロディアスで回顧的な性格を持ち、ワーグナー、ロッシーニ、そして作曲者自身の交響曲第4番を引用している[108]。 死  1974年、モスクワで行われたソビエト音楽家管理評議会の選挙で投票するショスタコーヴィチ(写真:Yuri Shcherbinin) 1950年代から運動ニューロン疾患(ALS)やその他の神経疾患を患っていたにもかかわらず[105]、ショスタコーヴィチは、右手が事実上不自由に なっても、すべての手紙や楽譜を自分で書くことにこだわった。彼の最後の作品は、1975年10月1日に公式に初演されたヴィオラ・ソナタであった [109][要出典]。 ショスタコーヴィチは肺がんを患った(彼はヘビースモーカーだった)。彼の死因は肺がんや心不全など様々であるが、どちらも喫煙に関連する病気であった [110][111][105]。 1975年8月9日、モスクワの中央臨床病院で死去。市民葬が執り行われ、モスクワのノヴォデヴィチ墓地に埋葬された。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙による と、「彼は1964年に心臓発作で入院して以来、心臓の病気に苦しんでいたことで知られていた」[112]。 遺産 ショスタコーヴィチは自身のピアノ作品のいくつかの録音を残している。彼の音楽の他の著名な解釈者には、ムスティスラフ・ロストロポーヴィチ、[113] タチアナ・ニコラエヴァ、[114] マリア・ユディナ、[115] ダヴィッド・オイストラフ、[116] ベートーヴェン四重奏団のメンバーなどがいる[117][118]。 ショスタコーヴィチが旧ソ連以外の後進の作曲家に与えた影響は比較的軽微である。彼の影響はラース=エーリク・ラーションなど北欧の作曲家に見られる [119]。同時代のロシアの作曲家の多くやレニングラード音楽院での彼の弟子たちは、彼の作風から強い影響を受けている(ジャーマン・オクネフ、セルゲ イ・スロニムスキー、ボリス・ティシェンコなど。) ショスタコーヴィチの保守的なイディオムは、アヴァンギャルドの影響力が低下し、彼の政治的見解に関する議論が展開されるにつれ、聴衆の間でますます人気 が高まっている[要出典]。 南極のアレクサンダー島にあるショスタコーヴィチ半島は、彼にちなんで名付けられた[120]。 |

| Overview Shostakovich's works are broadly tonal[121] but with elements of atonality and chromaticism. In some of his later works (e.g., the Twelfth Quartet), he made use of tone rows. His output is dominated by his cycles of symphonies and string quartets, each totaling 15. The symphonies are distributed fairly evenly throughout his career, while the quartets are concentrated towards the latter part. Among the most popular are the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies and the Eighth and Fifteenth Quartets. Other works include the operas Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, The Nose and the unfinished The Gamblers, based on the comedy by Gogol; six concertos (two each for piano, violin and cello); two piano trios; and a large quantity of film music.[citation needed] Shostakovich's music shows the influence of many of the composers he most admired: Bach in his fugues and passacaglias; Beethoven in the late quartets; Mahler in the symphonies; and Berg in his use of musical codes and quotations. Among Russian composers, he particularly admired Modest Mussorgsky, whose operas Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina he reorchestrated; Mussorgsky's influence is most prominent in the wintry scenes of Lady Macbeth and the Eleventh Symphony, as well as in satirical works such as "Rayok".[122] Prokofiev's influence is most apparent in the earlier piano works, such as the first sonata and first concerto.[123] The influence of Russian church and folk music is evident in his works for unaccompanied choir of the 1950s.[124] Shostakovich's relationship with Stravinsky was profoundly ambivalent; as he wrote to Glikman, "Stravinsky the composer I worship. Stravinsky the thinker I despise."[125] He was particularly enamoured of the Symphony of Psalms, presenting a copy of his own piano version of it to Stravinsky when the latter visited the USSR in 1962. (The meeting of the two composers was not very successful; observers commented on Shostakovich's extreme nervousness and Stravinsky's "cruelty" to him.)[126] Many commentators have noted the disjunction between the experimental works before the 1936 denunciation and the more conservative ones that followed; the composer told Flora Litvinova, "without 'Party guidance' ... I would have displayed more brilliance, used more sarcasm, I could have revealed my ideas openly instead of having to resort to camouflage."[127] Articles Shostakovich published in 1934 and 1935 cited Berg, Schoenberg, Krenek, Hindemith, "and especially Stravinsky" among his influences.[128] Key works of the earlier period are the First Symphony, which combined the academicism of the conservatory with his progressive inclinations; The Nose ("The most uncompromisingly modernist of all his stage-works"[129]); Lady Macbeth, which precipitated the denunciation; and the Fourth Symphony, described in Grove's Dictionary as "a colossal synthesis of Shostakovich's musical development to date".[130] The Fourth was also the first piece in which Mahler's influence came to the fore, prefiguring the route Shostakovich took to secure his rehabilitation, while he himself admitted that the preceding two were his least successful.[131] After 1936, Shostakovich's music became more conservative. During this time he also composed more chamber music.[132] While his chamber works were largely tonal, the late chamber works, which Grove's Dictionary calls a "world of purgatorial numbness",[133] included tone rows, although he treated these thematically rather than serially. Vocal works are also a prominent feature of his late output.[134] Jewish themes In the 1940s, Shostakovich began to show an interest in Jewish themes. He was intrigued by Jewish music's "ability to build a jolly melody on sad intonations".[135] Examples of works that included Jewish themes are the Fourth String Quartet (1949), the First Violin Concerto (1948), and the Four Monologues on Pushkin Poems (1952), as well as the Piano Trio in E minor (1944). He was further inspired to write with Jewish themes when he examined Moisei Beregovski's 1944 thesis on Jewish folk music.[136] In 1948, Shostakovich acquired a book of Jewish folk songs, from which he composed the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. He initially wrote eight songs meant to represent the hardships of being Jewish in the Soviet Union. To disguise this, he added three more meant to demonstrate the great life Jews had under the Soviet regime. Despite his efforts to hide the real meaning in the work, the Union of Composers refused to approve his music in 1949 under the pressure of the anti-Semitism that gripped the country. From Jewish Folk Poetry could not be performed until after Stalin's death in March 1953, along with all the other works that were forbidden.[137] Self-quotations Throughout his compositions, Shostakovich demonstrated a controlled use of musical quotation. This stylistic choice had been common among earlier composers, but Shostakovich developed it into a defining characteristic of his music. Rather than quoting other composers, Shostakovich preferred to quote himself. Musicologists such as Sofia Moshevich, Ian McDonald, and Stephen Harris have connected his works through their quotations.[clarification needed][138] One example is the main theme of Katerina's aria, Seryozha, khoroshiy moy, from the fourth act of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. The aria's beauty comes as a breath of fresh air in the intense, overbearing tone of the scene, in which Katerina visits her lover Sergei in prison. The theme is made tragic when Sergei betrays her and finds a new lover upon blaming Katerina for his incarceration.[139] More than 25 years later, Shostakovich quoted this theme in his Eighth String Quartet. In the midst of this quartet's oppressive and somber themes, the cello introduces the Seryozha theme "in the 'bright' key of F-sharp major" about three minutes into the fourth movement.[140] This theme emerges once again in his Fourteenth String Quartet. As in the Eighth Quartet, the cello introduces the theme, which here serves as a dedication to the cellist of the Beethoven String Quartet, Sergei Shirinsky.[141] Posthumous publications In 2004, the musicologist Olga Digonskaya discovered a trove of Shostakovich manuscripts at the Glinka State Central Museum of Musical Culture in Moscow. In a cardboard file were some "300 pages of musical sketches, pieces and scores" in Shostakovich's hand. A composer friend bribed Shostakovich's housemaid to regularly deliver the contents of Shostakovich's office waste bin to him, instead of taking it to the garbage. Some of those cast-offs eventually found their way into the Glinka. ... The Glinka archive "contained a huge number of pieces and compositions which were completely unknown or could be traced quite indirectly," Digonskaya said.[142] Among these were Shostakovich's piano and vocal sketches for a prologue to an opera, Orango (1932). They were orchestrated by the British composer Gerard McBurney and premiered in December 2011 by the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen.[142] Reputation According to McBurney, opinion is divided on whether Shostakovich's music is "of visionary power and originality, as some maintain, or, as others think, derivative, trashy, empty and second-hand".[143] William Walton, his British contemporary, described him as "the greatest composer of the 20th century".[144] Musicologist David Fanning concludes in Grove's Dictionary that "Amid the conflicting pressures of official requirements, the mass suffering of his fellow countrymen, and his personal ideals of humanitarian and public service, he succeeded in forging a musical language of colossal emotional power."[145] Some modern composers have been critical. Pierre Boulez dismissed Shostakovich's music as "the second, or even third pressing of Mahler".[146] The Romanian composer and Webern disciple Philip Gershkovich called Shostakovich "a hack in a trance".[147] A related complaint is that Shostakovich's style is vulgar and strident: Stravinsky wrote of Lady Macbeth: "brutally hammering ... and monotonous".[148] English composer and musicologist Robin Holloway described his music as "battleship-grey in melody and harmony, factory-functional in structure; in content all rhetoric and coercion".[149] In the 1980s, the Finnish conductor and composer Esa-Pekka Salonen was critical of Shostakovich and refused to conduct his music. For instance, he said in 1987: Shostakovich is in many ways a polar counter-force for Stravinsky. ... When I have said that the 7th symphony of Shostakovich is a dull and unpleasant composition, people have responded: "Yes, yes, but think of the background of that symphony." Such an attitude does no good to anyone.[150] Salonen has since performed and recorded several of Shostakovich's works,[151] including leading the world premiere of Orango,[152] but has dismissed the Fifth Symphony as "overrated", adding that he was "very suspicious of heroic things in general".[153] Shostakovich borrows extensively from the material and styles both of earlier composers and of popular music; the vulgarity of "low" music is a notable influence on this "greatest of eclectics".[154] McBurney traces this to the avant-garde artistic circles of the early Soviet period in which Shostakovich moved early in his career, and argues that these borrowings were a deliberate technique to allow him to create "patterns of contrast, repetition, exaggeration" that gave his music large-scale structure.[155] |

概要 ショスタコーヴィチの作品は広範な調性[121]を持つが、無調や半音階の要素もある。晩年のいくつかの作品(例えば第12四重奏曲)では、トーン・ロー を用いた。彼の作品は、交響曲と弦楽四重奏曲のサイクルで占められており、それぞれ15曲からなる。交響曲は彼のキャリアを通じてほぼ均等に分布している が、弦楽四重奏曲は後半に集中している。最も人気があるのは、交響曲第5番と第7番、四重奏曲第8番と第15番である。その他の作品には、オペラ『ムツェ ンスクのマクベス夫人』、『鼻』、ゴーゴリの喜劇に基づく未完の『賭博者たち』、6曲の協奏曲(ピアノ、ヴァイオリン、チェロのための各2曲)、2曲のピ アノ三重奏曲、大量の映画音楽などがある[要出典]。 ショスタコーヴィチの音楽には、彼が最も敬愛した多くの作曲家の影響が見られる: フーガやパッサカリアではバッハ、後期四重奏曲ではベートーヴェン、交響曲ではマーラー、音楽コードや引用の使い方ではベルクなどである。ロシアの作曲家 の中では、モデスト・ムソルグスキーを特に尊敬しており、そのオペラ『ボリス・ゴドゥノフ』と『ホヴァンシチナ』を再オーケストラ化した。ムソルグスキー の影響は、『マクベス夫人』の冬の情景や交響曲第11番、『ラヨク』などの風刺的な作品に顕著に表れている。 [プロコフィエフの影響は、ソナタ第1番や協奏曲第1番などの初期のピアノ作品に最も顕著に見られる[122]。ロシアの教会音楽と民俗音楽の影響は、 1950年代の無伴奏合唱のための作品に顕著に見られる[124]。 ショスタコーヴィチとストラヴィンスキーの関係は、深いアンビバレントなものであった。1962年にストラヴィンスキーがソ連を訪問した際には、自作のピ アノ版のコピーを贈った。(2人の作曲家の会談はあまり成功しなかった。オブザーバーは、ショスタコーヴィチの極度の緊張とストラヴィンスキーの彼に対す る「残酷さ」についてコメントしている[126]。 多くの論者は、1936年の糾弾以前の実験的な作品と、その後の保守的な作品との間の断絶を指摘している。作曲家はフローラ・リトヴィノヴァに、「『党の 指導』がなければ......。1934年と1935年に発表されたショスタコーヴィチの記事には、影響を受けた作曲家として、ベルク、シェーンベルク、 クレネク、ヒンデミット、そして「特にストラヴィンスキー」が挙げられている[128]。 [この時期の主要な作品は、音楽院のアカデミズムと彼の進歩的な傾向を組み合わせた交響曲第1番、「鼻」(「彼の舞台作品の中で最も妥協のないモダニズ ム」[129])、糾弾のきっかけとなった「マクベス夫人」、そしてグローヴの辞典で「ショスタコーヴィチのこれまでの音楽的発展の巨大な総合」と評され た交響曲第4番である。 [130]。第4番はまた、マーラーの影響が前面に出た最初の作品であり、ショスタコーヴィチが更生を果たすために取った道を予見させるものであった。 1936年以降、ショスタコーヴィチの音楽はより保守的になる。1936年以降、ショスタコーヴィチの音楽はより保守的になり、室内楽作品も多く作曲され るようになった[132]。彼の室内楽作品の大部分は調性であったが、グローヴの辞典が「煉獄のような無感覚の世界」と呼ぶ後期の室内楽作品[133]に は、トーン・ローが含まれている。声楽作品もまた、晩年の作品の顕著な特徴である[134]。 ユダヤのテーマ 1940年代、ショスタコーヴィチはユダヤ人のテーマに興味を示し始めた。ユダヤ音楽の「悲しいイントネーションの上に陽気なメロディーを構築する能力」 に興味を持ったのである[135]。ユダヤ的なテーマを含む作品の例としては、弦楽四重奏曲第4番(1949年)、ヴァイオリン協奏曲第1番(1948 年)、プーシキンの詩による4つのモノローグ(1952年)、ピアノ三重奏曲ホ短調(1944年)などがある。1944年に発表されたモイセイ・ベレゴフ スキーのユダヤの民俗音楽に関する論文を検討した際、彼はユダヤをテーマにした作品を書くようさらに促された[136]。 1948年、ショスタコーヴィチはユダヤ民謡の本を手に入れ、そこから歌曲集『ユダヤの民謡より』を作曲した。彼は当初、ソビエト連邦におけるユダヤ人と しての苦難を表現することを意図して8曲を書いた。それを誤魔化すために、ソビエト政権下でユダヤ人が素晴らしい生活を送っていたことを示す3曲を追加し た。作品に込められた本当の意味を隠すための彼の努力にもかかわらず、1949年、作曲家連盟は、ソ連を襲った反ユダヤ主義の圧力の下で、彼の音楽を承認 することを拒否した。1953年3月にスターリンが死去するまで、『ユダヤの民衆詩』は、禁止された他の作品とともに演奏されることはなかった [137]。 自己引用 ショスタコーヴィチは、作曲を通して、音楽的引用の抑制された使用を示した。この様式的な選択は、それ以前の作曲家の間では一般的なものであったが、ショ スタコーヴィチはそれを彼の音楽の特徴として発展させた。他の作曲家の言葉を引用するよりも、ショスタコーヴィチは自分自身の言葉を引用することを好ん だ。ソフィア・モシェヴィチ、イアン・マクドナルド、スティーヴン・ハリスなどの音楽学者は、引用を通じて彼の作品を結びつけている[要解説] [138]。 その一例が、『ムツェンスク郡のマクベス夫人』第4幕のカテリーナのアリア「Seryozha, khoroshiy moy」のメインテーマである。このアリアの美しさは、カテリーナが恋人のセルゲイを牢獄に訪ねる場面の激しく威圧的な調子の中で、新鮮な息吹を与えてく れる。セルゲイが彼女を裏切り、投獄されたことをカテリーナのせいにして新しい恋人を見つけると、この主題は悲劇的なものとなる[139]。 その25年以上後、ショスタコーヴィチは第8番弦楽四重奏曲でこのテーマを引用している。この四重奏曲の抑圧的で陰鬱な主題の中で、チェロは第4楽章の約 3分後に「嬰ヘ長調の『明るい』調で」セリョーシャの主題を導入する[140]。この主題は彼の第14弦楽四重奏曲で再び登場する。ベートーヴェン弦楽四 重奏団のチェリスト、セルゲイ・シリンスキーへの献呈曲となっている[141]。 死後の出版物 2004年、音楽学者のオルガ・ディゴンスカヤは、モスクワのグリンカ国立音楽文化中央博物館でショスタコーヴィチの手稿の山を発見した。厚紙のファイル の中には、ショスタコーヴィチの手による「300ページほどの音楽のスケッチ、小品、楽譜」が入っていた。 ある作曲家の友人は、ショスタコーヴィチの家政婦に賄賂を渡し、ショスタコーヴィチのオフィスのゴミ箱の中身をゴミに出さず、定期的にショスタコーヴィチ に届けてもらった。これらの廃棄物の一部は、最終的にグリンカに持ち込まれた。... グリンカ・アーカイヴには、「まったく知られていなかったり、かなり間接的にたどることのできる膨大な数の作品や作曲が含まれていた」とディゴンスカヤは 言う[142]。 その中には、オペラ『オランゴ』(1932年)のプロローグのためのショスタコーヴィチのピアノと声楽のスケッチがあった。これらはイギリスの作曲家ジェ ラード・マクバーニーによってオーケストレーションされ、2011年12月にエサ=ペッカ・サロネン指揮ロサンジェルス・フィルハーモニックによって初演 された[142]。 評判 マクバーニーによれば、ショスタコーヴィチの音楽が「ある者が主張するように先見的な力と独創性を持つものなのか、他の者が考えるように、派生的で、ゴミ のようで、空虚で、二番煎じ」なのかについては意見が分かれている[143]。 [144]音楽学者のデイヴィッド・ファニングは、グローヴの辞典の中で、「公的な要求、同胞の多くの苦しみ、人道主義的で公共的な奉仕という個人的な理 想という相反する圧力の中で、彼は巨大な感情的パワーを持つ音楽言語を作り上げることに成功した」と結論付けている[145]。 現代の作曲家の中には批判的な者もいる。ルーマニアの作曲家でヴェーベルンの弟子であるフィリップ・ゲルシュコーヴィチは、ショスタコーヴィチを「トラン ス状態のハッカー」と呼んだ[147]: ストラヴィンスキーは『マクベス夫人』についてこう書いている: ストラヴィンスキーは『マクベス夫人』について「残酷なまでに打ちのめされ......そして単調だ」と書いている[148]。イギリスの作曲家で音楽学 者のロビン・ホロウェイは、彼の音楽を「メロディとハーモニーは戦艦のような灰色で、構造は工場のような機能的なもの。 1980年代、フィンランドの指揮者で作曲家のエサ=ペッカ・サロネンはショスタコーヴィチに批判的で、彼の音楽を指揮することを拒否していた。例えば、 彼は1987年にこう語っている: ショスタコーヴィチは、多くの点でストラヴィンスキーの対極にある存在だ。... 私がショスタコーヴィチの交響曲第7番は退屈で不快な作品だと言うと、人々はこう答えた: 「そうそう、でもあの交響曲の背景を考えてみてよ」。そのような態度は誰にとっても良いことはない[150]。 サロネンはその後、『オランゴ』の世界初演を指揮するなど、ショスタコーヴィチのいくつかの作品を演奏・録音している[151]が、交響曲第5番を「過大 評価」と断じ、「英雄的なもの全般を非常に疑っている」と付け加えている[153]。 ショスタコーヴィチは初期の作曲家やポピュラー音楽の素材や様式を広範囲に借用しており、「低俗」な音楽はこの「最大の折衷主義者」に顕著な影響を及ぼし ている[154]。マクバーニーはこれを、ショスタコーヴィチがキャリアの初期に活動したソ連初期の前衛芸術界にまで遡り、これらの借用は、彼の音楽に大 規模な構造を与える「コントラスト、反復、誇張のパターン」を作り出すことを可能にするための意図的な技法であったと論じている[155]。 |

| Personality Shostakovich was in many ways an obsessive man: according to his daughter he was "obsessed with cleanliness".[156] He synchronised the clocks in his apartment and regularly sent himself cards to test how well the postal service was working. Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered indexes 26 references to his nervousness. Mikhail Druskin remembers that even as a young man the composer was "fragile and nervously agile".[157] Yuri Lyubimov comments, "The fact that he was more vulnerable and receptive than other people was no doubt an important feature of his genius."[70] In later life, Krzysztof Meyer recalled, "his face was a bag of tics and grimaces."[158] In Shostakovich's lighter moods, sport was one of his main recreations, although he preferred spectating or umpiring to participating (he was a qualified football referee). His favorite football club was Zenit Leningrad (now Zenit Saint Petersburg), which he would watch regularly.[159] He also enjoyed card games, particularly patience.[109][page needed] Shostakovich was fond of satirical writers such as Gogol, Chekhov and Mikhail Zoshchenko. Zoshchenko's influence in particular is evident in his letters, which include wry parodies of Soviet officialese. Zoshchenko noted the contradictions in the composer's character: "he is ... frail, fragile, withdrawn, an infinitely direct, pure child ... [but also] hard, acid, extremely intelligent, strong perhaps, despotic and not altogether good-natured (although cerebrally good-natured)."[160] Shostakovich was diffident by nature: Flora Litvinova has said he was "completely incapable of saying 'No' to anybody."[161] This meant he was easily persuaded to sign official statements, including a denunciation of Andrei Sakharov in 1973.[162] His widow later told Helsingin Sanomat that his name was included without his permission.[163] But he was willing to try to help constituents in his capacities as chairman of the Composers' Union and Deputy to the Supreme Soviet. Oleg Prokofiev said, "he tried to help so many people that ... less and less attention was paid to his pleas."[164][162] When asked if he believed in God, Shostakovich said "No, and I am very sorry about it."[162] |

パーソナリティ 娘によれば、彼は「清潔さに執着していた」[156]。 彼はアパートの時計を同期させ、郵便サービスがどれだけ機能しているかをテストするために定期的に自分自身にカードを送っていた。エリザベス・ウィルソン の『Shostakovich: A Life Remembered(ショスタコーヴィチ:追憶の生涯)』では、彼の神経質さについて26の言及がある。ミハイル・ドルースキンは、作曲家が若い頃でさ え「傷つきやすく、神経質なほど機敏」であったと回想している[157]。 ユーリー・リュビモフは、「彼が他の人々よりも傷つきやすく、受容的であったという事実は、間違いなく彼の天才の重要な特徴であった」とコメントしている [70]。 ショスタコーヴィチの軽い気分では、スポーツは彼の主な娯楽の一つであったが、彼は参加するよりも観戦や審判を好んだ(彼はサッカーの審判の資格を持って いた)。また、カードゲーム、特に忍耐を楽しんだ[109][要出典]。 ショスタコーヴィチはゴーゴリ、チェーホフ、ミハイル・ゾシチェンコなどの風刺作家が好きだった。特にゾシチェンコの影響は、ソビエトの役人言葉の軽妙な パロディを含む彼の手紙に顕著に表れている。ゾシチェンコは作曲家の性格の矛盾を指摘した: 「彼は......か弱く、壊れやすく、引っ込み思案で、限りなく率直で純粋な子供だ......。[しかしまた、)硬く、酸っぱく、非常に知的で、おそ らく強く、専制的で、まったくお人好しではない(頭脳的にはお人好しだが)」[160]。 ショスタコーヴィチは生まれつき内向的だった: フローラ・リトヴィーノワは、彼は「誰に対しても "ノー "と言うことがまったくできなかった」と語っている[161]。そのため、1973年のアンドレイ・サハロフ非難を含む公式声明に署名するよう簡単に説得 された[162]。後に未亡人がヘルシンギン・サノマートに語ったところによれば、彼の名前は彼の許可なく記載されたものであった[163]。しかし、彼 は作曲家連盟の会長や最高ソビエト副議長としての立場において、有権者を助けようとする姿勢は厭わなかった。オレグ・プロコフィエフは、「彼はあまりにも 多くの人々を助けようとしたので、......彼の嘆願に関心が払われることは少なくなっていった」と述べている[164][162]。神を信じるかと問 われたショスタコーヴィチは、「いいえ、そしてそれについてはとても残念に思います」と答えた[162]。 |

| Orthodoxy and revisionism Shostakovich represented himself in some works with the DSCH motif, consisting of D-E♭-C-B. Shostakovich's response to official criticism and whether he used music as a kind of covert dissidence is a matter of dispute. He outwardly conformed to government policies and positions, reading speeches and putting his name to articles expressing the government line.[165] But it is evident he disliked many aspects of the regime, as confirmed by his family, his letters to Isaac Glikman, and the satirical cantata "Rayok", which ridiculed the "anti-formalist" campaign and was kept hidden until after his death.[166] He was a close friend of Marshal of the Soviet Union Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who was executed in 1937 during the Great Purge.[167] It is also uncertain to what extent Shostakovich expressed his opposition to the state in his music. The revisionist view was put forth by Solomon Volkov in the 1979 book Testimony, which claimed to be Shostakovich's memoirs dictated to Volkov. The book alleged that many of the composer's works contained coded anti-government messages, placing Shostakovich in a tradition of Russian artists outwitting censorship that goes back at least to Alexander Pushkin. He incorporated many quotations and motifs in his work, most notably his musical signature DSCH.[168] His longtime musical collaborator Yevgeny Mravinsky said, "Shostakovich very often explained his intentions with very specific images and connotations."[169] The revisionist perspective has subsequently been supported by his children, Maxim and Galina, although Maxim said in 1981 that Volkov's book was not his father's work.[170] Volkov has further argued, both in Testimony and in Shostakovich and Stalin, that Shostakovich adopted the role of the yurodivy or holy fool in his relations with the government. Maxim Shostakovich has also commented on Testimony and Volkov more favorably since 1991, when the Soviet regime fell. To Allan B. Ho and Dmitry Feofanov, he confirmed that his father had told him about "meeting a young man from Leningrad who knows his music extremely well" and that "Volkov did meet with Shostakovich to work on his reminiscences". Maxim has repeatedly said he is "a supporter both of Testimony and of Volkov."[171] Other prominent revisionists are Ian MacDonald, whose book The New Shostakovich put forward further revisionist interpretations of his music, and Elizabeth Wilson, whose Shostakovich: A Life Remembered provides testimony from many of the composer's acquaintances.[172] Musicians and scholars including Laurel Fay[173] and Richard Taruskin contested the authenticity and debate the significance of Testimony, alleging that Volkov compiled it from a combination of recycled articles, gossip, and possibly some information directly from the composer. Fay documents these allegations in her 2002 article "Volkov's Testimony reconsidered",[174] showing that the only pages of the original Testimony manuscript that Shostakovich had signed and verified are word-for-word reproductions of earlier interviews he gave, none of which are controversial. Ho and Feofanov have countered that at least two of the signed pages contain controversial material: for instance, "on the first page of chapter 3, where [Shostakovich] notes that the plaque that reads 'In this house lived [Vsevolod] Meyerhold' should also say 'And in this house his wife was brutally murdered'."[175] |

正統主義と修正主義 ショスタコーヴィチは、D-E♭-C-BからなるDSCHモチーフでいくつかの作品を表現している。 公的な批判に対するショスタコーヴィチの反応や、彼が音楽を一種の隠然たる反体制活動として用いたかどうかについては、議論が分かれるところである。ショ スタコーヴィチは表向きは政府の政策や立場に従順で、演説を読んだり、政府の方針を表明する記事に自分の名前を載せたりしていた[165]。 [しかし、彼が政権の多くの側面を嫌っていたことは、彼の家族、アイザック・グリクマンへの手紙、「反体制主義」キャンペーンを嘲笑し、死後まで隠されて いた風刺的カンタータ『ラヨク』によって確認されている[166]。 彼は、1937年の大粛清で処刑されたソ連元帥ミハイル・トゥハチェフスキーと親しかった[167]。 また、ショスタコーヴィチがどの程度まで国家への反発を音楽で表現していたかは定かではない。修正主義的な見解は、ソロモン・ヴォルコフによって1979 年に出版された『証言』という本の中で提示された。この本では、ショスタコーヴィチの作品の多くに暗号化された反政府的なメッセージが含まれていると主張 し、少なくともアレクサンドル・プーシキンまで遡るロシアの芸術家が検閲をかいくぐってきた伝統の中にショスタコーヴィチを位置づけている。彼の長年の音 楽的共同研究者であったエフゲニー・ムラヴィンスキーは、「ショスタコーヴィチは非常にしばしば、非常に具体的なイメージや含蓄をもって自分の意図を説明 していた」と述べている[169]。 マキシムは1981年に、ヴォルコフの著書は父の作品ではないと述べているが[170]、ヴォルコフはさらに、『証言』と『ショスタコーヴィチとスターリ ン』の両方で、ショスタコーヴィチは政府との関係においてユロディヴィや聖なる愚か者の役割を採用したと主張している。 マキシム・ショスタコーヴィチも、ソビエト政権が崩壊した1991年以降、『証言』やヴォルコフについて好意的なコメントを寄せている。アラン・B・ホー とドミトリー・フェオファーノフに対して、「レニングラードから来た、彼の音楽を非常によく知っている青年に会った」と父から聞いていたこと、そして 「ヴォルコフは回想録に取り組むためにショスタコーヴィチと会った」ことを確認した。マキシムは「証言とヴォルコフの両方の支持者」であると繰り返し述べ ている[171]。他の著名な修正主義者は、著書『The New Shostakovich』で彼の音楽の更なる修正主義的解釈を提唱したイアン・マクドナルドと、著書『Shostakovich: A Life Remembered』で作曲家の多くの知人からの証言を提供したエリザベス・ウィルソンである[172]。 ローレル・フェイ[173]やリチャード・タルスキンを含む音楽家や学者は、ヴォルコフがリサイクル記事やゴシップ、そしておそらくは作曲家から直接得た 情報を組み合わせて『証言』を編纂したと主張し、その信憑性に異議を唱え、『証言』の意義について議論している。フェイは、2002年の論文「ヴォルコフ の『証言』再考」[174]で、これらの疑惑を記録し、『証言』の原稿のうち、ショスタコーヴィチが署名し検証した唯一のページが、彼が以前に受けたイン タビューの一字一句再現したものであり、そのどれもが議論の余地のないものであることを示している。ホーとフェオファーノフは、署名されたページのうち少 なくとも2ページには論争を呼ぶような内容が含まれていると反論している。例えば、「第3章の最初のページで、『この家には(ヴシェヴォロド)マイヤー ホールドが住んでいた』と書かれたプレートには、『そしてこの家で彼の妻は残酷に殺された』と書かれるべきであると(ショスタコーヴィチが)記している」 [175]。 |

| In May 1958, during a visit to

Paris, Shostakovich recorded his two piano concertos with André

Cluytens, as well as some short piano works. These were issued on LP by

EMI and later reissued on CD. Shostakovich recorded the two concertos

in stereo in Moscow for Melodiya. Shostakovich also played the piano

solos in recordings of the Cello Sonata, Op. 40 with cellist Daniil

Shafran and also with Mstislav Rostropovich; the Violin Sonata, Op.

134, in a private recording made with violinist David Oistrakh; and the

Piano Trio, Op. 67 with violinist David Oistrakh and cellist Miloš

Sádlo. There is also a short newsreel of Shostakovich as soloist in a

1930s concert performance of the closing moments of his first piano

concerto. A color film of Shostakovich supervising the Soviet revival

of The Nose in 1974 was also made.[176] |

1958年5月、パリを訪れたショスタコーヴィチは、アンドレ・クリュ

イタンスと2曲のピアノ協奏曲といくつかの短いピアノ作品を録音した。これらはEMIからLPで発売され、後にCDで再発された。ショスタコーヴィチは、

2つの協奏曲をモスクワのメロディヤでステレオ録音した。また、チェロ・ソナタ作品40をチェリストのダニール・シャフランと、またムスティスラフ・ロス

トロポーヴィチと、ヴァイオリン・ソナタ作品134をヴァイオリニストのダヴィッド・オイストラフと、ピアノ三重奏曲作品67をヴァイオリニストのダ

ヴィッド・オイストラフとチェリストのミロシュ・サードロとそれぞれ録音している。また、1930年代のコンサートで、ショスタコーヴィチのピアノ協奏曲

第1番の終結の瞬間をソリストとして演奏するショスタコーヴィチの短いニュースフィルムもある。1974年にソビエトで上演された《鼻》を監督するショス

タコーヴィチのカラーフィルムもある[176]。 |

| Awards Soviet Union Hero of Socialist Labour (1966)[177] Order of Lenin (1946, 1956, 1966)[178] Order of the October Revolution (1971)[179] Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1940)[180] People's Artist of the RSFSR (1948)[68] People's Artist of the USSR (1954)[181] International Peace Prize (1954)[181] Lenin Prize (1958 – for the Symphony No. 11 "The Year 1905")[182] Stalin Prize (1941 – for Piano Quintet; 1942 – for the Symphony No. 7; 1946 – for Piano Trio No. 2; 1950 – for Song of the Forests and the score for the film The Fall of Berlin; 1952 – for Ten Poems on Texts by Revolutionary Poets)[183] USSR State Prize (1968 – for the cantata The Execution of Stepan Razin for bass, chorus and orchestra)[184] Glinka State Prize of the RSFSR (1974 – for the String Quartet No. 14 and choral cycle Loyalty)[179] Shevchenko National Prize (1976, posthumous – for the opera Katerina Izmailova) Academic titles Member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium (1960)[185] Other awards Léonie Sonning Music Prize (1973)[186] Wihuri Sibelius Prize (1958)[182] Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society (1966)[187] In 1962, he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Scoring of a Musical Picture for Khovanshchina (1959).[188] |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dmitri_Shostakovich |

|

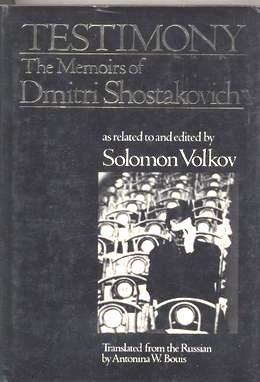

Testimony (Russian:

Свидетельство) is a book that was published in October 1979 by the

Russian musicologist Solomon Volkov. He claimed that it was the memoirs

of the composer Dmitri Shostakovich. From its publication, its

portrayal of the composer and his views was controversial: the

Shostakovich of the book was sometimes critical of fellow composers and

most notably was strongly anti-Soviet in his views. The book also

contained comments on his own music by indicating that it was intended

as veiled criticism of the Soviet authorities and support for the

dissident movement. The authenticity of the book is still disputed. Testimony (Russian:

Свидетельство) is a book that was published in October 1979 by the

Russian musicologist Solomon Volkov. He claimed that it was the memoirs

of the composer Dmitri Shostakovich. From its publication, its

portrayal of the composer and his views was controversial: the

Shostakovich of the book was sometimes critical of fellow composers and

most notably was strongly anti-Soviet in his views. The book also

contained comments on his own music by indicating that it was intended

as veiled criticism of the Soviet authorities and support for the

dissident movement. The authenticity of the book is still disputed.Volkov's claim Volkov said that Shostakovich dictated the material in the book at a series of meetings with him between 1971 and 1974. Volkov took notes at each meeting, transcribed and edited the material, and presented it to the composer at their next meeting. Shostakovich then signed the first page of each chapter. Unfortunately it is difficult without access to Volkov's original notes (claimed to be lost) to ascertain where Shostakovich possibly ends and Volkov possibly begins. Original manuscript The original typescript of Testimony has never been made available for scholarly investigation. After it was photocopied by Harper and Row, it was returned to Volkov who kept it in a Swiss bank until it was "sold to an anonymous private collector" in the late 1990s. Harper and Row made several changes to the published version, and illicitly circulating typescripts reflect various intermediate stages of the editorial process. Despite translation into 30 different languages, the Russian original has never been published. Dmitry Feofanov stated at the local meeting of the American Musicological Society in 1997 how publishing contracts customarily vest copyright and publication rights in a publisher, and not an author. Assuming Volkov signed a standard contract, he would have no say whatsoever in whether an edition in this or that language appears; such decisions would be made by his publisher.[1] That was why a group of anonymous Russian translators had translated the book from English into Russian and published it in network in 2009.[2] In their foreword they wrote: The purpose of opening this resource is not to participate in the debate... Moreover, we never discussed this question and it is quite possible that different translators have different opinions. This book itself is a fact of world culture and, above all, of course, Russian culture. But people of different countries have a possibility to read it in their own languages and to have their own opinion. And only in Russia it can do only those who not only know English language, but also has the ability to get the «Testimony»: this book is in the "Lenin Library", probably exists in other major libraries. At the same time the number of interested in the question is incomparably greater than those who have access to these centers of culture... We've seen our task in the opportunity to make up their minds about Volkov's book to everyone who speak the same language with us, nothing more.[citation needed] |

『証言』(ロシア語:Свидетельство)は、ロ

シアの音楽学者ソロモン・ヴォルコフが1979年10月に出版した本である。彼はこれを作曲家ドミトリー・ショスタコーヴィチの回想録だと主張した。この

本のショスタコーヴィチは、時に作曲家仲間に批判的であり、特に反ソ連的な考えを強く持っていた。この本には、ソ連当局への批判と反体制運動への支援を意

図したものであることを示す、彼自身の音楽についてのコメントも含まれていた。この本の真偽については、いまだに論争が続いている。 『証言』(ロシア語:Свидетельство)は、ロ

シアの音楽学者ソロモン・ヴォルコフが1979年10月に出版した本である。彼はこれを作曲家ドミトリー・ショスタコーヴィチの回想録だと主張した。この

本のショスタコーヴィチは、時に作曲家仲間に批判的であり、特に反ソ連的な考えを強く持っていた。この本には、ソ連当局への批判と反体制運動への支援を意