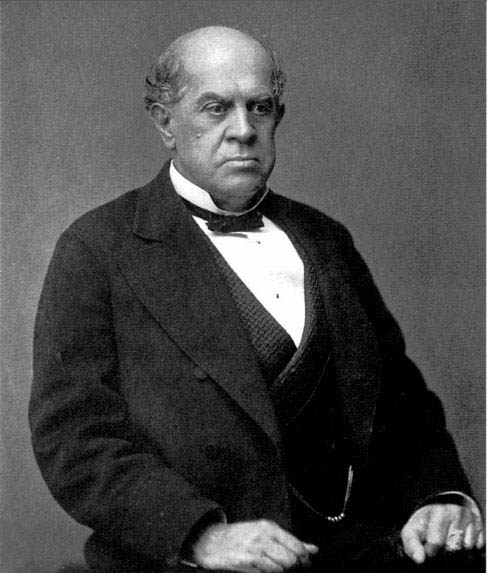

ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント

Domingo Faustino

Sarmiento, 1811-1888

☆

ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント[c](1811年2月15日 -

1888年9月11日)は、1868年から1874年までアルゼンチンの大統領を務めた。彼は「1837年世代」として知られる知識人グループのメンバー

であり、19世紀のアルゼンチンに大きな影響を与えた。彼は特に教育問題に関心を寄せ、地域の文学にも重要な影響を与えた。その著作はジャーナリズムから

自伝、政治哲学、歴史に至るまで、幅広いジャンルと主題を扱っている。

サルミエントは貧しいが政治的に活発な家庭で育ち、これが彼の将来の多くの業績の礎となった。1843年から1850年にかけては頻繁に亡命生活を送り、

チリとアルゼンチンの両方で執筆活動を行った。彼の最も有名な作品は『ファクンド』で、チリ亡命中に新聞『エル・プログレソ』で働きながら執筆したフア

ン・マヌエル・デ・ロサス批判の書である。この著作は彼に文学的評価以上のものをもたらした。彼は独裁政権、特にロサス政権との戦いに尽力し、民主主義・

社会福祉・知的な思考が尊重される啓蒙されたヨーロッパと、ガウチョ、とりわけ19世紀アルゼンチンの冷酷な強権者であるカウディージョの野蛮さを対比さ

せた。

大統領としてサルミエントは、ラテンアメリカにおける知性ある思想(児童・女性教育を含む)と民主主義を推進した。鉄道網、郵便制度、総合的な教育制度の

近代化と整備も行った。連邦・州レベルで長年にわたり大臣職を務め、海外視察で他国の教育制度を研究した。

サルミエントは77歳で心臓発作によりパラグアイのアスンシオンで死去した。遺体はブエノスアイレスに埋葬された。今日では政治的革新者かつ作家として尊

敬されている。ミゲル・デ・ウナムーノは彼をカスティーリャ語散文の最高峰の作家の一人と評した。

| Domingo Faustino

Sarmiento[c] (15 February 1811 – 11 September 1888) was President of

Argentina from 1868 to 1874. He was a member of a group of

intellectuals, known as the Generation of 1837, who had a great

influence on 19th-century Argentina. He was particularly concerned with

educational issues and was also an important influence on the region's

literature. His works spanned a wide range of genres and topics, from

journalism to autobiography, to political philosophy and history. Sarmiento grew up in a poor but politically active family that paved the way for many of his future accomplishments. Between 1843 and 1850, he was frequently in exile, and wrote in both Chile and in Argentina. His most famous work was Facundo, a critique of Juan Manuel de Rosas, that Sarmiento wrote while working for the newspaper El Progreso during his exile in Chile. The book brought him far more than just literary recognition; he expended his efforts and energy on the war against dictatorships, specifically that of Rosas, and contrasted enlightened Europe—a world where, in his eyes, democracy, social services, and intelligent thought were valued—with the barbarism of the gaucho and especially the caudillo, the ruthless strongmen of 19th-century Argentina. As president, Sarmiento championed intelligent thought—including education for children and women—and democracy for Latin America. He also modernized and developed train systems, a postal system, and a comprehensive education system. He spent many years in ministerial roles on the federal and state levels where he travelled abroad and examined other education systems. Sarmiento died in Asunción, Paraguay, at the age of 77 from a heart attack. He was buried in Buenos Aires. Today, he is respected as a political innovator and writer. Miguel de Unamuno considered him among the greatest writers of Castilian prose.[1] |

ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント[c](1811年2月15

日 -

1888年9月11日)は、1868年から1874年までアルゼンチンの大統領を務めた。彼は「1837年世代」として知られる知識人グループのメンバー

であり、19世紀のアルゼンチンに大きな影響を与えた。彼は特に教育問題に関心を寄せ、地域の文学にも重要な影響を与えた。その著作はジャーナリズムから

自伝、政治哲学、歴史に至るまで、幅広いジャンルと主題を扱っている。 サルミエントは貧しいが政治的に活発な家庭で育ち、これが彼の将来の多くの業績の礎となった。1843年から1850年にかけては頻繁に亡命生活を送り、 チリとアルゼンチンの両方で執筆活動を行った。彼の最も有名な作品は『ファクンド』で、チリ亡命中に新聞『エル・プログレソ』で働きながら執筆したフア ン・マヌエル・デ・ロサス批判の書である。この著作は彼に文学的評価以上のものをもたらした。彼は独裁政権、特にロサス政権との戦いに尽力し、民主主義・ 社会福祉・知的な思考が尊重される啓蒙されたヨーロッパと、ガウチョ、とりわけ19世紀アルゼンチンの冷酷な強権者であるカウディージョの野蛮さを対比さ せた。 大統領としてサルミエントは、ラテンアメリカにおける知性ある思想(児童・女性教育を含む)と民主主義を推進した。鉄道網、郵便制度、総合的な教育制度の 近代化と整備も行った。連邦・州レベルで長年にわたり大臣職を務め、海外視察で他国の教育制度を研究した。 サルミエントは77歳で心臓発作によりパラグアイのアスンシオンで死去した。遺体はブエノスアイレスに埋葬された。今日では政治的革新者かつ作家として尊 敬されている。ミゲル・デ・ウナムーノは彼をカスティーリャ語散文の最高峰の作家の一人と評した。 |

Youth and influences Facade of Sarmiento's childhood home in San Juan, Argentina. Sarmiento was born in Carrascal, a poor suburb of San Juan, Argentina, on 15 February 1811.[2] His father, José Clemente Quiroga Sarmiento y Funes, had served in the military during the wars of independence, returning prisoners of war to San Juan.[3] His mother, Doña Paula Zoila de Albarracín e Irrazábal, was a very pious woman,[4] who lost her father at a young age and was left with very little to support herself.[4] As a result, she took to selling her weaving in order to afford to build a house of her own. On 21 September 1801, José and Paula were married. They had 15 children, 9 of whom died young; Domingo was the only son to survive to adulthood.[4] Sarmiento was greatly influenced by his parents, his mother who was always working hard, and his father who told stories of being a patriot and serving his country, something Sarmiento strongly believed in.[3] In Sarmiento's own words: I was born in a family that lived long years in mediocrity bordering on destitution, and which is to this day poor in every sense of the word. My father is a good man whose life has nothing remarkable except [for his] having served in subordinate positions in the War of Independence... My mother is the true figure of Christianity in its purest sense; with her, trust in Providence was always the solution to all difficulties in life."[5] At the age of four, Sarmiento was taught to read by his father and his uncle, José Eufrasio Quiroga Sarmiento, who later became Bishop of Cuyo.[6] Another uncle who influenced him in his youth was Domingo de Oro, a notable figure in the young Argentine Republic who was influential in bringing Juan Manuel de Rosas to power.[7] Though Sarmiento did not follow de Oro's political and religious leanings, he learned the value of intellectual integrity and honesty.[7] He developed scholarly and oratorical skills, qualities which de Oro was famous for.[7][8] In 1816, at the age of five, Sarmiento began attending the primary school La Escuela de la Patria. He was a good student, and earned the title of First Citizen (Primer Ciudadano) of the school.[9] After completing primary school, his mother wanted him to go to Córdoba to become a priest. He had spent a year reading the Bible and often spent time as a child helping his uncle with church services,[10] but Sarmiento soon became bored with religion and school, and got involved with a group of aggressive children.[11] Sarmiento's father took him to the Loreto Seminary in 1821, but for reasons unknown, Sarmiento did not enter the seminary, returning instead to San Juan with his father.[12] In 1823, the Minister of State, Bernardino Rivadavia, announced that the six top pupils of each state would be selected to receive higher education in Buenos Aires. Sarmiento was at the top of the list in San Juan, but it was then announced that only ten pupils would receive the scholarship. The selection was made by lot, and Sarmiento was not one of the scholars whose name was drawn.[13] Like many other nineteenth century Argentines prominent in public life, he was a freemason.[d] |

青年期と影響 アルゼンチン、サンフアンにあるサルミエントの生家の外観。 サルミエントは1811年2月15日、アルゼンチン・サンフアンの貧しい郊外カルラスカルで生まれた。[2] 父ホセ・クレメンテ・キロガ・サルミエント・イ・フネスは独立戦争中に軍務に就き、捕虜をサンフアンへ送還した人物である。[3] 母ドニャ・パウラ・ソイラ・デ・アルバラシン・イ・イラサバルは極めて信心深い女性だった[4]。彼女は幼くして父を亡くし、生計を立てる手段がほとんど なかった[4]。そのため、自らの家を建てる資金を工面するため、織物の販売を始めた。1801年9月21日、ホセとパウラは結婚した。二人は15人の子 をもうけたが、そのうち9人は幼くして亡くなった。成人まで生き延びた息子はドミンゴただ一人であった。[4] サルミエントは両親から大きな影響を受けた。常に懸命に働く母と、愛国者として祖国に奉仕した物語を語る父である。サルミエントはこの信念を強く抱いた。 [3] サルミエント自身の言葉を借りれば: 「私は、貧困に限りなく近い平凡な生活を送ってきた家庭に生まれた。その家庭は今日に至るまで、あらゆる意味で貧しいままである。父は善良な人間だが、独 立戦争で下級将校を務めたこと以外、特筆すべき経歴はない…母は純粋なキリスト教精神の体現者であり、彼女にとって、人生のあらゆる困難に対する解決策は 常に神の摂理への信頼であった」[5] 四歳の時、サルミエントは父と叔父のホセ・エウフラシオ・キロガ・サルミエント(後にクヨ司教となる)から読み書きを教わった[6]。青年期に影響を与え たもう一人の叔父はドミンゴ・デ・オロで、若きアルゼンチン共和国においてフアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスを権力の座に就かせるのに影響力を持った著名な人 物であった。[7] サルミエントはデ・オロの政治的・宗教的傾向には従わなかったが、知的な誠実さと正直さの価値を学んだ。[7] 彼は学識と弁論の技量を身につけた。これらはデ・オロが有名だった資質である。[7][8] 1816年、5歳の時にサルミエントは小学校「ラ・エスクエラ・デ・ラ・パトリア」に通い始めた。彼は優秀な生徒で、学校の「第一市民(プリメーロ・シウ ダダノ)」の称号を得た。[9] 初等教育を終えた後、母親は彼をコルドバに送って司祭になることを望んだ。彼は1年間聖書を読み、子供の頃によく叔父の教会奉仕を手伝っていたが、 [10] サルミエントはすぐに宗教と学校に飽きてしまい、攻撃的な子供たちのグループと関わるようになった。[11] 1821年、父は彼をロレート神学校へ連れて行ったが、理由は不明ながらサミルエントは入学せず、父と共にサンフアンへ戻った。[12] 1823年、国務大臣ベルナルディーノ・リバダビアは、各州の上位6名の生徒を選抜しブエノスアイレスで高等教育を受けさせることを発表した。サルミエン トはサンフアン州のトップに選ばれたが、その後奨学金の対象は10名のみと発表された。抽選で選ばれた奨学生の中に、サルミエントの名前はなかった。 [13] 19世紀のアルゼンチンで公的生活で活躍した多くの著名人と同様に、彼はフリーメイソンであった。[d] |

Political background and exiles 1845 portrait of Sarmiento during his exile in Chile, by Franklin Rawson.  Sarmiento portrayed by Ignacio Baz. In 1826, an assembly elected Bernardino Rivadavia as president of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. This action roused the ire of the provinces, and civil war was the result. Support for a strong, centralized Argentine government was based in Buenos Aires, and gave rise to two opposing groups. The wealthy and educated of the Unitarian Party, such as Sarmiento, favored centralized government. In opposition to them were the Federalists, who were mainly based in rural areas and tended to reject European mores. Numbering figures such as Manuel Dorrego and Juan Facundo Quiroga among their ranks, they were in favor of a loose federation with more autonomy for the individual provinces.[14] Opinion of the Rivadavia administration was divided between the two ideologies. For Unitarians like Sarmiento, Rivadavia's presidency was a positive experience. He set up a European-staffed university and supported a public education program for rural male children. He also supported theater and opera groups, publishing houses and a museum. These contributions were considered as civilizing influences by the Unitarians, but they upset the Federalist constituency. Common laborers had their salaries subjected to a government cap, and the gauchos were arrested by Rivadavia for vagrancy and forced to work on public projects, usually without pay.[15] In 1827, the Unitarians were challenged by Federalist forces. After the resignation of Rivadavia, Manuel Dorrego was installed as governor of Buenos Aires province. He quickly made peace with Brazil but, on returning to Argentina, was overthrown and executed by the Unitarian general Juan Lavalle, who took Dorrego's place.[16] However, Lavalle did not spend long as governor either: he was soon overthrown by militias composed largely of gauchos led by Rosas and Estanislao López. By the end of 1829 the old legislature that Lavalle had disbanded was back in place and had appointed Rosas as governor of Buenos Aires.[16] The first time Sarmiento was forced to leave home was with his uncle, José de Oro, in 1827, because of his military activities.[17] José de Oro was a priest who had fought in the Battle of Chacabuco under General San Martín.[18] Together, Sarmiento and de Oro went to San Francisco del Monte de Oro, in the neighbour province of San Luis. He spent much of his time with his uncle learning and began to teach at the only school in town. Later that year, his mother wrote to him asking him to come home. Sarmiento refused, only to receive a response from his father that he was coming to collect him.[19] His father had persuaded the governor of San Juan to send Sarmiento to Buenos Aires to study at the College of Moral Sciences (Colegio de Ciencias Morales).[19] Soon after Sarmiento's return, the province of San Juan broke out into civil war and Facundo Quiroga invaded Sarmiento's town.[20] As historian William Katra describes this "traumatic experience": At sixteen years of age, he stood in front of the shop he tended and viewed the entrance into San Juan of Facundo Quiroga and some six hundred mounted montonera horsemen. They constituted an unsettling presence [. . . ]. That sight, with its overwhelmingly negative associations, left an indelible impression on his budding consciousness. For the impressionable youth Quiroga's ascent to protagonist status in the province's affairs was akin to the rape of civilized society by incarnated evil.[21] Unable to attend school in Buenos Aires due to the political turmoil, Sarmiento chose to fight against Quiroga.[22] He joined and fought in the unitarian army, only to be placed under house arrest when San Juan was eventually taken over by Quiroga[22] after the battle of Pilar.[23] He was later released, only to join the forces of General Paz, a key unitarian figure.[24] First exile in Chile Fighting and war soon resumed, but, one by one, Quiroga vanquished the main allies of General Paz, including the Governor of San Juan, and in 1831 Sarmiento fled to Chile.[24] He did not return to Argentina for five years.[25] At the time, Chile was noted for its good public administration, its constitutional organization, and the rare freedom to criticize the regime. In Sarmiento's view, Chile had "Security of property, the continuation of order, and with both of these, the love of work and the spirit of enterprise that causes the development of wealth and prosperity."[26] As a form of freedom of expression, Sarmiento began to write political commentary. In addition to writing, he also began teaching in Los Andes. Due to his innovative style of teaching, he found himself in conflict with the governor of the province. He founded his own school in Pocuro as a response to the governor. During this time, Sarmiento fell in love and had an illegitimate daughter named Ana Faustina, who Sarmiento did not acknowledge until she married.[27] |

政治的背景と亡命 1845年、チリ亡命中のサルミエントの肖像画。フランクリン・ローソン作。  イグナシオ・バズが描いたサルミエント。 1826年、議会はベルナルディーノ・リバダビアをリオ・デ・ラ・プラタ連合州の大統領に選出した。この決定は各州の怒りを買い、内戦が勃発した。強固で 中央集権的なアルゼンチン政府を支持する勢力はブエノスアイレスに拠点を置き、2つの対立するグループを生み出した。サルミエントのような、ユニタリアン 党の富裕層や知識層は、中央集権的な政府を支持した。彼らに対抗したのは、主に農村地域を拠点とし、ヨーロッパの慣習を拒絶する傾向があった連邦主義者た ちであった。マヌエル・ドレゴやフアン・ファクンド・キロガらを擁する連邦派は、各州の自治権を拡大した緩やかな連邦制を支持した[14]。 リバダビア政権に対する評価は、この二つのイデオロギーによって分かれた。サルミエントのような統一派にとって、リバダビアの政権運営は肯定的な経験で あった。彼は欧州人教員による大学を設立し、農村部の男子児童向け公教育プログラムを支援した。さらに劇場やオペラ団、出版社、博物館も後援した。こうし た貢献は統一派によって文明化の推進と評価されたが、連邦派支持層の反発を招いた。一般労働者の賃金は政府による上限規制の対象となり、ガウチョたちは浮 浪罪でリバダビアに逮捕され、通常は無給の公共事業に従事させられた。[15] 1827年、ユニタリア派はフェデラリスト勢力に挑まれた。リバダビアの辞任後、マヌエル・ドレゴがブエノスアイレス州知事に就任した。彼はすぐにブラジ ルと和平を結んだが、アルゼンチンに戻ると、ユニタリア派の将軍フアン・ラバジェに打倒され処刑された。ラバジェはドレゴの後任となった。[16] しかしラバジェも長く知事を務められなかった。間もなくロサスとエスタニスラオ・ロペスが率いるガウチョ主体の民兵に打倒されたのである。1829年末ま でに、ラバジェが解散させた旧議会が復活し、ロサスをブエノスアイレス知事に任命した。[16] サルミエントが初めて家を離れることを余儀なくされたのは、1827年に叔父のホセ・デ・オロと共に、軍事活動のためであった。[17] ホセ・デ・オロは司祭であり、サン・マルティン将軍の下でチャカブコの戦いに参戦した人物であった。[18] サルミエントとデ・オロは共に、隣接するサン・ルイス州のサン・フランシスコ・デル・モンテ・デ・オロへ向かった。彼は叔父のもとで多くの時間を学びに費 やし、町唯一の学校で教え始めた。その年の後半、母が帰郷を促す手紙を送ったが、サルミエントは拒否。すると父から「迎えに行く」との返答が届いた [19]。父はサンフアン州知事を説得し、サルミエントをブエノスアイレスの道徳科学学院(Colegio de Ciencias Morales)へ留学させることに成功したのである。[19] サルミエントが帰郷して間もなく、サンフアン州で内戦が勃発し、ファクンド・キロガが彼の町を襲撃した[20]。歴史家ウィリアム・カトラはこの「トラウマ的な体験」をこう描写している: 16歳の彼は、自分が店番をしていた店の前に立ち、ファクンド・キロガと約600人のモンテロラ騎兵隊がサンフアンの入口に現れるのを見た。彼らは不穏な 存在感を放っていた[……]。その光景は圧倒的な悪意を伴い、彼の芽生えつつある意識に消えない刻印を残した。感受性の強い青年にとって、キローガが州政 の主役へと台頭する様は、文明社会が具現化した悪に蹂躙されることに等しかった。[21] 政治的混乱のためブエノスアイレスの学校に通えなかったサルミエントは、キローガと戦う道を選んだ[22]。彼は統一派軍に加わり戦ったが、ピラールの戦 いの後[23]、サンフアンがキローガに占領されると[22]、自宅軟禁状態に置かれた。後に解放された彼は、統一派の重要人物であるパズ将軍の軍に加 わった。[24] チリへの最初の亡命 戦乱はすぐに再燃したが、キローガはサンフアン州知事を含むパズ将軍の主要な同盟者を次々と打ち破り、1831年にサルミエントはチリへ逃れた。[24] 彼はその後5年間、アルゼンチンへ戻らなかった。[25] 当時チリは、優れた行政、憲法に基づく組織、そして政権批判が許される稀有な自由で知られていた。サルミエントの見解では、チリには「財産の安全、秩序の 継続、そしてこれら二つの基盤の上に、労働への愛と企業精神が育まれ、富と繁栄の発展をもたらしている」[26]。 表現の自由の一形態として、サルミエントは政治評論の執筆を始めた。執筆活動に加え、ロスアンデスで教鞭も執り始めた。革新的な教授法のため、州知事と対 立する事態となった。これに対しポクロに自らの学校を設立した。この時期、サルミエントは恋に落ち、アナ・ファウスティナという非嫡出子をもうけた。娘が 結婚するまで、サルミエントは彼女を認知しなかった。[27] |

San Juan and second and third exiles in Chile Daguerreotype of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento after the Battle of Caseros. He is wearing the Brazilian Imperial Order of the Southern Cross given to him by Emperor Pedro II of Brazil during his exile in Petrópolis in 1852[28] Monument in homage to Domingo F. Sarmiento in Boston, Massachusetts Domingo Faustino Sarmiento in Boston, Massachusetts In 1836, Sarmiento returned to San Juan, seriously ill with typhoid fever; his family and friends thought he would die upon his return, but he recovered and established an anti-federalist journal called El Zonda.[29] The government of San Juan did not like Sarmiento's criticisms and censored the magazine by imposing an unaffordable tax upon each purchase. Sarmiento was forced to cease publication of the magazine in 1840. He also founded a school for girls during this time called the Santa Rosa High School, which was a preparatory school.[29] In addition to the school, he founded a Literary Society.[29] It is around this time that Sarmiento became associated with the so-called "Generation of 1837". This was a group of activists, who included Esteban Echeverría, Juan Bautista Alberdi, and Bartolomé Mitre, who spent much of the 1830s to 1880s first agitating for and then bringing about social change, advocating republicanism, free trade, freedom of speech, and material progress.[30] Though, based in San Juan, Sarmiento was absent from the initial creation of this group, in 1838 he wrote to Alberdi seeking the latter's advice;[31] and in time he would become the group's most fervent supporter.[32] In 1840, after being arrested and accused of conspiracy, Sarmiento was forced into exile in Chile again.[33] It was en route to Chile that, in the baths of Zonda, he wrote the graffiti "On ne tue point les idées,"[33] an incident that would later serve as the preface to his book Facundo. Once on the other side of the Andes, in 1841 Samiento started writing for the Valparaíso newspaper El Mercurio, as well working as a publisher of the Crónica Contemporánea de Latino América ("Contemporary Latin American Chronicle").[34] In 1842, Sarmiento was appointed the Director of the first Normal School in South America; the same year he also founded the newspaper El Progreso.[34] During this time he sent for his family from San Juan to Chile. In 1843, Sarmiento published Mi Defensa ("My Defence"), while continuing to teach.[25] And in May 1845, El Progreso started the serial publication of the first edition of his best-known work, Facundo; in July, Facundo appeared in book form.[35] Between the years 1845 and 1847, Sarmiento travelled on behalf of the Chilean government across parts of South America to Uruguay, Brazil, to Europe, France, Spain, Algeria, Italy, Armenia, Switzerland, England, to Cuba, and to North America, the United States and Canada in order to examine different education systems and the levels of education and communication. Sarmiento began his visit to the United States with a mere six hundred dollars from the Chilean government, much of the former allowance being expended on preceding journeys to Africa and Europe. As a result, he planned to visit as much of the country as financially possible and end his journey in Havana, where he would take the role of a teacher and journalist to earn more funds to finance future journeys across the American continents. However, Sarmiento discarded this plan upon meeting Santiago Arcos, a Chilean journalist who agreed to defraying the expenses of subsequent journeys. Sarmiento initially could not locate or find any information about the whereabouts of Arcos, but the two eventually met in Philadelphia. During his visit to the United States, Sarmiento visited major locations such as Boston, Washington, D.C., and New Orleans. Sarmiento would again travel to the United States from the years 1865 to 1868 when serving as Argentina's minister plenipotentiary to the country.[36] Based on his travels, he wrote the book Viajes por Europa, África, y América which was published in 1849.[25] In 1848, Sarmiento voluntarily left to Chile once again. During the same year, he met widow Benita Martínez Pastoriza, married her, and adopted her son, Domingo Fidel, or Dominguito,[25] who would be killed in action during the War of the Triple Alliance at Curupaytí in 1866.[37] Sarmiento continued to exercise the idea of freedom of the press and began two new periodicals entitled La Tribuna and La Crónica respectively, which strongly attacked Juan Manuel de Rosas. During this stay in Chile, Sarmiento's essays became more strongly opposed to Juan Manuel de Rosas. The Argentine government tried to have Sarmiento extradited from Chile to Argentina, but the Chilean government refused to hand him over.[27] In 1850, he published both Argirópolis and Recuerdos de Provincia (Recollections of a Provincial Past). In 1852, Rosas's regime was finally brought down. Sarmiento became involved in debates about the country's new constitution.[38] |

サンフアンとチリでの二度目、三度目の亡命 カセロスの戦い後のドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエントのダゲレオタイプ。彼は1852年にペトロポリスで亡命中、ブラジル皇帝ペドロ2世から授与されたブラジル帝国南十字星勲章を身につけている[28] マサチューセッツ州ボストンにあるドミンゴ・F・サルミエントへの賛辞の記念碑 マサチューセッツ州ボストンにおけるドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント 1836年、サルミエントは腸チフスで重病となりサンフアンに戻った。家族や友人は帰国時に死ぬだろうと思ったが、彼は回復し、反連邦主義の雑誌『エル・ ゾンダ』を創刊した[29]。サンフアン政府はサルミエントの批判を快く思わず、雑誌購入ごとに支払えないほどの税金を課すことで検閲した。サルミエント は1840年に雑誌の発行を中止せざるを得なかった。この頃、彼は女子校「サンタ・ロサ高等学校」を設立した。これは予備校であった[29]。学校に加 え、彼は文学協会も設立した[29]。 サルミエントが所謂「1837年世代」と関わりを持つようになったのは、この頃である。これはエステバン・エチェベリア、フアン・バウティスタ・アルベル ディ、バルトロメ・ミトレら活動家から成る集団で、1830年代から1880年代にかけて共和主義、自由貿易、言論の自由、物質的進歩を主張し、社会変革 をまず扇動し、やがて実現させた。[30] サンフアンを拠点としていたサルミエントは、このグループの初期形成には関与していなかったが、1838年にはアルベルディに助言を求める書簡を送ってい る[31]。やがて彼はこのグループで最も熱心な支持者となる。[32] 1840年、陰謀罪で逮捕されたサルミエントは再びチリへの亡命を余儀なくされた[33]。チリへ向かう途中、ゾンダの温泉で彼は「思想は殺せない(On ne tue point les idées)」という落書きを残した[33]。この出来事は後に彼の著作『ファクンド』の序文として用いられることになる。アンデス山脈を越えた1841 年、サルミエントはバルパライソの新聞『エル・メルクーリオ』への寄稿を開始すると同時に、『ラテンアメリカ現代クロニカ』の出版者としても活動した。 [34] 1842年には南米初の師範学校の校長に任命され、同年『エル・プログレソ』新聞を創刊した。[34] この時期、サンフアンから家族をチリへ呼び寄せた。1843年には教職を続けながら『我が弁明』を出版した。[25] そして1845年5月、『エル・プログレソ』紙は彼の代表作『ファクンド』初版の連載を開始。同年7月には単行本として刊行された。[35] 1845年から1847年にかけて、サルミエントはチリ政府の使節として南米各地、ウルグアイ、ブラジル、ヨーロッパ(フランス、スペイン、アルジェリ ア、イタリア、アルメニア)、スイス、イギリス、キューバ、そして北米(アメリカ合衆国とカナダ)を巡り、異なる教育制度や教育水準、通信手段を調査し た。サルミエントはチリ政府からわずか600ドルの資金でアメリカ合衆国訪問を開始した。以前のアフリカ・ヨーロッパ旅行で前任者の手当の大半が消費され ていたためである。結果として、彼は財政的に可能な限り多くの地域を訪問し、ハバナで旅程を終える計画を立てた。そこで教師とジャーナリストとして働き、 将来のアメリカ大陸横断旅行の資金を稼ぐつもりだった。しかしサルミエントはこの計画を放棄した。チリ人ジャーナリストのサンティアゴ・アルコスと出会 い、彼が今後の旅費を負担することに同意したからだ。当初サルミエントはアルコスの居場所を全く把握できなかったが、二人は最終的にフィラデルフィアで再 会した。アメリカ滞在中、サルミエントはボストン、ワシントンD.C.、ニューオーリンズなどの主要都市を訪れた。サルミエントは1865年から1868 年にかけて、アルゼンチン全権公使として再びアメリカ合衆国を訪れた[36]。これらの旅を基に、1849年に『ヨーロッパ、アフリカ、アメリカ大陸の 旅』(Viajes por Europa, África, y América)を著した。[25] 1848年、サルミエントは再び自発的にチリへ渡った。同年、未亡人ベニータ・マルティネス・パストリサと出会い、彼女と結婚し、その息子ドミンゴ・フィ デル(通称ドミンギート)を養子にした[25]。このドミンギートは1866年、三国同盟戦争のクルパイトイの戦いで戦死した。[37] サルミエントは言論の自由の理念を貫き、新たに『ラ・トリブナ』と『ラ・クロニカ』という二つの定期刊行物を創刊した。これらはフアン・マヌエル・デ・ロ サスを激しく攻撃した。チリ滞在中、サルミエントの論説はロサスに対する反対姿勢を強めた。アルゼンチン政府はサルミエントのチリからの引き渡しを要求し たが、チリ政府はこれを拒否した。[27] 1850年、彼は『アルジロポリス』と『地方の回想』の両方を出版した。1852年、ロサスの政権はついに倒れた。サルミエントは国の新憲法に関する議論に関与した。[38] |

Return to Argentina Sarmiento in 1864. Photograph by Eugenio Courret. In 1854, Sarmiento briefly visited Mendoza, just across the border from Chile in Western Argentina, but he was arrested and imprisoned. Upon his release, he went back to Chile.[25] But in 1855 he put an end to what was now his "self-imposed" exile in Chile:[39] he arrived in Buenos Aires, soon to become editor-in-chief of the newspaper El Nacional.[40] He was also appointed town councillor in 1856, and 1857 he joined the provincial Senate, a position he held until 1861.[41] It was in 1861, shortly after Mitre became Argentine president, that Sarmiento left Buenos Aires and returned to San Juan, where he was elected governor, a post he took up in 1862.[42] It was then that he passed the Statutory Law of Public Education, making it mandatory for children to attend primary school. It allowed for a number of institutions to be opened including secondary schools, military schools and an all-girls school.[43] While governor, he developed roads and infrastructure, built public buildings and hospitals, encouraged agriculture and allowed for mineral mining.[27] He resumed his post as editor of El Zonda. In 1863, Sarmiento fought against the power of the caudillo of La Rioja and found himself in conflict with the Interior Minister of General Mitre's government, Guillermo Rawson. Sarmiento stepped down as governor of San Juan to become the Plenipotentiary Minister to the United States, where he was sent in 1865, soon after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Moved by the story of Lincoln, Sarmiento ended up writing his book Vida de Lincoln.[27] It was on this trip that Sarmiento received an honorary degree from the University of Michigan. A bust of him stood in the Modern Languages Building at the University of Michigan until multiple student protests prompted its removal. Students installed plaques and painted the bust red to represent the controversies surrounding his policies towards the indigenous people in Argentina. There still stands a statue of Sarmiento at Brown University. While on this trip, he was asked to run for President again. He won, taking office on 12 October 1868.[27] |

アルゼンチンへの帰還 1864年のサルミエント。撮影:エウヘニオ・クーレ。 1854年、サルミエントはアルゼンチン西部のチリ国境に接するメンドーサを短期間訪れたが、逮捕され投獄された。釈放後、彼はチリに戻った。[25] しかし1855年、彼は自ら選んだチリ亡命生活に終止符を打った[39]。ブエノスアイレスに到着すると、間もなく新聞『エル・ナシオナル』の編集長に就 任した[40]。1856年には市議会議員に任命され、1857年には州上院議員となり、この職を1861年まで務めた。[41] ミトレがアルゼンチン大統領に就任した直後の1861年、サルミエントはブエノスアイレスを離れサンフアンに戻った。そこで州知事に選出され、1862年 にその職に就いた。[42] この時、彼は初等教育の義務化を定めた公教育基本法を成立させた。これにより中等学校、軍事学校、女子校を含む複数の教育機関の開設が可能となった。 [43] 知事在任中、彼は道路やインフラ整備を進め、公共施設や病院を建設し、農業を奨励し、鉱物採掘を許可した。[27] 彼は『エル・ゾンダ』紙の編集長職に復帰した。1863年、サルミエントはラ・リオハの軍閥指導者の権力に抗い、ミトレ将軍政権の内務大臣ギジェルモ・ラ ウソンと対立した。サンフアン州知事職を辞任し、1865年にアメリカ合衆国全権公使に任命された。これはエイブラハム・リンカーン大統領暗殺直後のこと だった。リンカーンの物語に感銘を受けたサルミエントは、結局『リンカーン伝』を執筆した[27]。この渡米中に、彼はミシガン大学から名誉学位を授与さ れた。彼の胸像はミシガン大学現代言語学棟に設置されていたが、学生による抗議活動が相次いだため撤去された。学生たちはプレートを設置し、胸像を赤く 塗った。これはアルゼンチン先住民に対する彼の政策をめぐる論争を象徴するものだった。ブラウン大学には今もサルミエントの像が立っている。この旅行中、 彼は再び大統領選への出馬を要請された。彼は当選し、1868年10月12日に大統領職に就いた[27]。 |

Presidency (1868–1874)  Portrait, 1873 Sarmiento served as President of Argentina from 1868 to 1874, becoming president despite the maneuverings of his predecessor Bartolomé Mitre.[44] According to biographer Allison Bunkley, his presidency "marks the advent of the middle, or land-owning classes as the pivot power of the nation. The age of the gaucho had ended, and the age of the merchant and cattleman had begun."[45] Sarmiento sought to create basic freedoms, and wanted to ensure civil safety and progress for everyone, not just the few. Sarmiento's tour of the United States had given him many new ideas about politics, democracy, and the structure of society, especially when he was the Argentine ambassador to the country from 1865 to 1868. He found New England, specifically the Boston-Cambridge area to be the source of much of his influence, writing in an Argentine newspaper that New England was "the cradle of the modern republic, the school for all of America." He described Boston as "The pioneer city of the modern world, the Zion of the ancient Puritans ... Europe contemplates in New England the power which in the future will supplant her."[46] Not only did Sarmiento evolve political ideas, but also structural ones by transitioning Argentina from a primarily agricultural economy to one focused on cities and industry.[47] Historian David Rock notes that, beyond putting an end to caudillismo, Sarmiento's main achievements in government concerned his promotion of education. Sarmiento's focus on education became a divisive tool of his nation-building strategy. With this focus, he was able to build the foundation to promote the intellect of future generations and securing their prosperity. There was an emphasis on constructing educational buildings, and training prospective teachers. His emphasis on constructing these schools and promoting education served as an example for future administrations to build upon. As stated by Garrard, Henderson, and McCann, this foundation would eventually make "the Argentine people among the most literate in the hemisphere."[48] As Rock reports, "between 1868 and 1874 educational subsidies from the central government to the provinces quadrupled."[44] He established 800 educational and military institutions, and his improvements to the educational system enabled 100,000 children to attend school. He also pushed forward modernization more generally, building infrastructure including 5,000 kilometres (3,100 mi) of telegraph line across the country for improved communications, making it easier for the government in Buenos Aires and the provinces to communicate; modernizing the postal and train systems which he believed to be integral for interregional and national economies, as well as building the Red Line, a train line that would bring goods to Buenos Aires in order to better facilitate trade with Great Britain. By the end of his presidency, the Red Line extended 1,331 kilometres (827 mi). In 1869, he conducted Argentina's first national census.[27] Although the rapid expansion of the railroad promoted trade, Latin America saw a rise in inequality and an intensified pressure to drive indigenous people from their land in order to expand the economy. With the expansion of the railroad itself came an expansion of exploration, stimulated by the access to previously inaccessible lands. Sarmiento's successor, Nicolas Avellaneda, further promoted this policy. In the late 1870s Julio Roca, his minister of war, carried out the Conquest of the Desert.[48] This war, stimulated by the expansion of Latin American railroads, was waged against the indigenous people of Southern Argentina. In addition to the expansion and driving out that was done by the people, the government had now officially declared its intentions. Following the model of displacement that had been outlined by North America, the Conquest of the Desert established the dominance of Argentina as a nation-state, and set a dangerous precedent. With this precedent, Argentine dominance cost the killing and displacement of the Mapuche people in the Patagonia providence.[48] Though Sarmiento promoted modernization and growth that made Argentina stronger, the idea of expansion meant the expulsion and killings of indigenous peoples. Though Sarmiento is well known historically, he was not a popular president.[49] Indeed, Rock judges that "by and large his administration was a disappointment".[44] During his presidency, Argentina conducted an unpopular war against Paraguay; at the same time, people were displeased with him for not fighting for the Straits of Magellan from Chile.[49] Although he increased productivity, he increased expenditures, which also negatively affected his popularity.[50] In addition, the arrival of a large influx of European immigrants was blamed for the outbreak of Yellow Fever in Buenos Aires and the risk of civil war.[50] Moreover, Sarmiento's presidency was further marked by ongoing rivalry between Buenos Aires and the provinces. In the war against Paraguay, Sarmiento's adopted son was killed.[27] Sarmiento suffered from immense grief and was thought to never have been the same again. On 22 August 1873, Sarmiento was the target of an unsuccessful assassination attempt, when two Italian anarchist brothers shot at his coach. They had been hired by federal caudillo Ricardo López Jordán.[27] A year later in 1874, he completed his term as President and stepped down, handing his presidency over to Nicolás Avellaneda, his former Minister of Education.[51] |

大統領職(1868年–1874年) 肖像画、1873年 サルミエントは1868年から1874年までアルゼンチン大統領を務めた。前任者バルトロメ・ミトレの策略にもかかわらず大統領に就任したのである。 [44] 伝記作家アリソン・バンクリーによれば、彼の政権は「中産階級、すなわち土地所有階級が国民の要となる力の台頭を象徴する。ガウチョの時代は終わり、商人 と牧畜業者の時代が始まったのである」[45]。サルミエントは基本的な自由の確立を目指し、少数者だけでなく全ての人々の市民的安全と進歩を保障しよう とした。サルミエントの米国訪問は、特に1865年から1868年にかけての駐米アルゼンチン大使時代、政治・民主主義・社会構造に関する多くの新思想を もたらした。ニューイングランド、特にボストン・ケンブリッジ地域が彼の影響源であり、アルゼンチン紙に「ニューイングランドは近代共和国の揺籃であり、 全米の学校である」と記している。彼はボストンを「現代世界の開拓都市、古きピューリタンのシオン……ヨーロッパはニューイングランドに、将来自国に取っ て代わる力を窺う」と描写した[46]。サルミエントは政治思想を進化させただけでなく、アルゼンチンを農業中心経済から都市と産業に焦点を当てた経済へ と移行させることで、構造的な変革も推進した。[47] 歴史家デイヴィッド・ロックは、サルミエントの政府における主な功績は、カウディージモ(独裁的指導者政治)の終焉をもたらしたことに加え、教育の推進に あったと指摘している。サルミエントの教育重視は、国民建設戦略における分断の道具となった。この重点政策により、彼は将来の世代の知性を育み、その繁栄 を保障する基盤を築くことができた。教育施設の建設と教員候補者の育成が特に重視された。こうした学校建設と教育振興への彼の重点的取り組みは、後続政権 が発展させるべき模範となった。ギャラード、ヘンダーソン、マッキャンの指摘通り、この基盤は最終的に「アルゼンチン国民を半球で最も識字率の高い国民の 一つ」に押し上げた[48]。ロックが報告する通り、「1868年から1874年の間に、中央政府から州への教育補助金は4倍に増加した」。[44] 彼は800の教育機関と軍事機関を設立し、教育制度の改善により10万人の児童が就学できるようになった。 さらに彼はより広範な近代化を推進し、通信改善のため全国に5,000キロメートル(3,100マイル)の電信線を敷設し、ブエノスアイレス政府と各州の 連絡を容易にした。地域間・国民経済に不可欠と考えた郵便・鉄道システムの近代化、英国との貿易促進を目的とした貨物輸送路線「レッドライン」の建設も推 進した。大統領任期終了時までにレッドラインは1,331キロメートル(827マイル)に延伸された。1869年にはアルゼンチン初の全国人口調査を実施 した。[27] 鉄道の急速な拡張は貿易を促進したが、ラテンアメリカでは不平等が拡大し、経済拡大のために先住民を土地から追い出す圧力が強まった。鉄道拡張そのものが 探検活動の拡大をもたらし、これまでアクセスできなかった土地への到達がこれを刺激した。サルミエントの後継者ニコラス・アベジャネダはこの政策をさらに 推進した。1870年代後半、フリオ・ロカ政権下の陸軍大臣が「砂漠征服」を実行した[48]。ラテンアメリカ鉄道拡張に刺激されたこの戦争は、アルゼン チン南部の先住民を標的とした。民間による拡張と追放に加え、政府が公式にその意図を宣言したのである。北米が示した移住モデルを踏襲した「砂漠征服」 は、アルゼンチンという国民国家の支配を確立し、危険な前例を作った。この前例により、アルゼンチンの支配はパタゴニア州におけるマプチェ族の虐殺と追放 を招いた[48]。サルミエントが推進した近代化と成長はアルゼンチンを強大にしたが、拡張という思想は先住民の追放と殺戮を意味していた。 サルミエントは歴史上よく知られているが、人気のある大統領ではなかった[49]。実際、ロックは「概して彼の政権は失望だった」と評している[44]。 大統領在任中、アルゼンチンはパラグアイとの不人気な戦争を遂行した。同時に、チリからマゼラン海峡を奪還しなかったことでも国民の不信を買った [49]。生産性は向上させたものの、支出も増加させ、これもまた彼の人気に悪影響を及ぼした。[50] さらに、ヨーロッパからの移民の大規模な流入がブエノスアイレスでの黄熱病の発生や内戦の危険性の原因とされた。[50] 加えて、サルミエントの政権はブエノスアイレスと各州の間の継続的な対立によってさらに特徴づけられた。パラグアイとの戦争では、サルミエントの養子が戦 死した。[27] サルミエントは計り知れない悲しみに苦悩し、その後も以前と同じようにはならなかったと考えられている。 1873年8月22日、サルミエントは暗殺未遂事件の標的となった。イタリア人無政府主義者の兄弟が彼の馬車を銃撃したのだ。彼らは連邦派の指導者リカル ド・ロペス・ホルダンに雇われていた。[27] 1年後の1874年、彼は大統領任期を終え退任し、元教育大臣のニコラス・アベジャネダに大統領職を引き継いだ。[51] |

| Final years (Left): post mortem portrait of Sarmiento in Asunción, Paraguay, 11 September 1888; (right): The coffin with Sarmiento's body, arriving in Buenos Aires ten days after his death In 1875, following his term as President, Sarmiento became the General Director of Schools for the Province of Buenos Aires. That same year, he became the Senator for San Juan, a post that he held until 1879, when he became Interior Minister.[52] But he soon resigned, following conflict with the Governor of Buenos Aires, Carlos Tejedor. He then assumed the post of Superintendent General of Schools for the National Education Ministry under President Roca and published El Monitor de la Educación Común, which is a fundamental reference for Argentine education.[53] In 1882, Sarmiento was successful in passing the sanction of Free Education allowing schools to be free, mandatory, and separate from that of religion.[27] In May 1888, Sarmiento left Argentina for Paraguay.[52] He was accompanied by his daughter, Ana, and his companion Aurelia Vélez. He died in Asunción on 11 September 1888, from a heart attack, and was buried in Buenos Aires,[25] after a ten-day trip.[54] His tomb at La Recoleta Cemetery lies under a sculpture, a condor upon a pylon, designed by himself and executed by Victor de Pol. Pedro II, the Emperor of Brazil and a great admirer of Sarmiento, sent to his funeral procession a green and gold crown of flowers with a message written in Spanish remembering the highlights of his life: "Civilization and Barbarism, Tonelero, Monte Caseros, Petrópolis, Public Education. Remembrance and Homage from Pedro de Alcântara."[55] |

晩年 (左):1888年9月11日、パラグアイのアスンシオンで描かれたサルミエントの死後肖像画;(右):死後10日を経てブエノスアイレスに到着したサルミエントの遺体を収めた棺 1875年、大統領任期終了後、サルミエントはブエノスアイレス州の学校総監督に就任した。同年、サンフアン州の上院議員となり、1879年に内務大臣に 就任するまでその職を務めた[52]。しかし間もなく、ブエノスアイレス州知事カルロス・テヘドールとの対立により辞任した。その後、ロカ大統領の下で国 家教育省の学校総監に就任し、アルゼンチン教育の基礎的指針となる『一般教育モニター』を刊行した[53]。1882年には、学校を無償・義務教育とし、 宗教から分離させる「無償教育法」の成立に成功した[27]。 1888年5月、サルミエントはアルゼンチンを離れパラグアイへ向かった。[52] 同行したのは娘のアナと愛人のアウレリア・ベレスであった。10日間の旅の末、1888年9月11日にアスンシオンで心臓発作により死去し、ブエノスアイ レスに埋葬された[25]。[54] レコレタ墓地の彼の墓は、自身で設計しビクトル・デ・ポルが制作した、ピラミッド状の台座に立つコンドルの彫刻の下にある。ブラジル皇帝ペドロ2世は、サ ルミエントの熱烈な崇拝者であり、葬儀の行列に緑と金の花冠を贈った。スペイン語で記されたメッセージには、彼の生涯の功績が列挙されていた:「文明と野 蛮、トネレロ、モンテ・カセロス、ペトロポリス、公教育。ペドロ・デ・アルカンタラより追悼と敬意を込めて。」 |

Philosophy The statue of Sarmiento made by Auguste Rodin, when being unveiled in 1900 Sarmiento was well known for his modernization of the country, and for his improvements to the educational system. He firmly believed in democracy and European liberalism, but was most often seen as a romantic. Sarmiento was well versed in Western philosophy including the works of Karl Marx and John Stuart Mill.[56] He was particularly fascinated with the liberty given to those living in the United States, which he witnessed as a representative of the Peruvian government. He did, however, see pitfalls to liberty, pointing for example to the aftermath of the French Revolution, which he compared to Argentina's own May Revolution.[57] He believed that liberty could turn into anarchy and thus civil war, which is what happened in France and in Argentina. Therefore, his use of the term "liberty" was more in reference to a laissez-faire approach to the economy, and religious liberty.[57] Though a Catholic himself, he began to adopt the ideas of separation of church and state modeled after the US.[58] He believed that there should be more religious freedom, and less religious affiliation in schools.[59] This was one of many ways in which Sarmiento tried to connect South America to North America.[60] Statue of Sarmiento photographed in 2009 Sarmiento believed that the material and social needs of people had to be satisfied but not at the cost of order and decorum. He put great importance on law and citizen participation. These ideas he most equated to Rome and to the United States, a society which he viewed as exhibiting similar qualities. In order to civilize the Argentine society and make it equal to that of Rome or the United States, Sarmiento believed in eliminating the caudillos, or the larger landholdings and establishing multiple agricultural colonies run by European immigrants.[61] Coming from a family of writers, orators, and clerics, Domingo Sarmiento placed a great value on education and learning. He opened a number of schools including the first school in Latin America for teachers in Santiago in 1842: La Escuela Normal Preceptores de Chile.[43] He proceeded to open 18 more schools and had mostly female teachers from the United States come to Argentina to instruct graduates how to be effective when teaching.[43] Sarmiento's belief was that education was the key to happiness and success, and that a nation could not be democratic if it was not educated.[62] "We must educate our rulers," he said. "An ignorant people will always choose Rosas.".[63] His views on the South American Indians have been more controversial, with some scholars arguing Sarmiento's views reflected the racism of his day.[64][65] For example, in the periodical El Nacional, dated November 25, 1857, Sarmiento wrote: “Will we be able to exterminate the Indians? For the savages of America, I feel an invincible repugnance that I cannot cure. Those scoundrels are not anything more than disgusting Indians that I would hang if they reappeared. Lautaro and Caupolicán are dirty Indians, because that's how they are all. Incapable of progress, their extermination is providential and useful, sublime and great. They must be exterminated without even sparing the little one, who already has the instinctive hatred for the civilized man.” |

哲学 1900年に除幕された、オーギュスト・ロダン制作のサルミエントの像 サルミエントは、国の近代化と教育制度の改善でよく知られていた。彼は民主主義とヨーロッパの自由主義を固く信じていたが、ほとんどの場合、ロマンチスト と見なされていた。サルミエントは、カール・マルクスやジョン・スチュワート・ミルの著作を含む西洋哲学に精通していた。[56] 彼は、ペルー政府の代表として目にした、米国に住む人々に与えられた自由に特に魅了された。しかし、彼は自由の落とし穴も認識しており、例えば、アルゼン チンの5月革命と比較したフランス革命の余波を例に挙げた。[57] 彼は、自由は無政府状態、ひいては内戦に陥る可能性があると信じており、それはフランスとアルゼンチンで実際に起こったことである。したがって、彼が「自 由」という用語を使用したのは、経済に対する自由放任主義と宗教の自由を指す場合が多かった。[57] 彼自身はカトリック教徒であったが、米国をモデルとした政教分離の考え方を採用し始めた。[58] 彼は、宗教の自由はもっとあるべきであり、学校における宗教的所属は少なくあるべきだと考えていた。[59] これはサルミエントが南米と北米を結びつけようとした数多くの試みの一つであった。[60] 2009年に撮影されたサルミエントの像 サルミエントは、人々の物質的・社会的ニーズは満たされるべきだが、秩序と礼節を犠牲にしてはならないと考えていた。彼は法と市民参加を極めて重要視し た。これらの思想はローマとアメリカ合衆国に最も近似すると考え、両社会は類似の特質を備えていると見ていた。アルゼンチン社会を文明化し、ローマやアメ リカと同等にするため、サルミエントはカウディージョ(地方支配者)や大規模土地所有を消去法により排除し、欧州移民による複数の農業コロニーを設立すべ きだと主張した。[61] 作家、演説家、聖職者の家系に生まれたドミンゴ・サルミエントは、教育と学問を非常に重視した。彼は1842年にサンティアゴにラテンアメリカ初の教員養 成学校「チリ師範学校」を含む数多くの学校を開設した[43]。その後さらに18校を開校し、主にアメリカ合衆国から女性教師を招き、卒業生に効果的な教 授法を指導させた。[43] サルミエントは教育こそが幸福と成功の鍵であり、国民が教育を受けていない限り、民主主義はありえないと信じていた。[62] 「我々は統治者を教育せねばならない」と彼は述べた。「無知な民衆は常にロサスを選ぶだろう」。[63] 南米先住民に対する彼の見解はより議論を呼んでおり、当時の人種主義を反映していると指摘する学者もいる。[64][65] 例えば1857年11月25日付の週刊誌『エル・ナシオナル』で、サルミエントはこう記している。「我々はインディオを根絶できるだろうか? アメリカの野蛮人に対して、私は治癒不能な圧倒的な嫌悪感を抱いている。あの卑劣な連中は、再出現したら吊るし首にするような、ただただ嫌悪すべきイン ディオに過ぎない。ラウタロもカウポリカンも汚らわしいインディオだ。なぜなら彼らは皆そうだからだ。進歩する能力もなく、彼らの絶滅は天の恵みであり有 益であり、崇高で偉大である。幼い者さえも容赦せず絶滅させねばならない。幼い者でさえ、文明人に対する本能的な憎悪を既に持っているのだから。」 |

| Publications Major works Facundo – Civilización y Barbarie – Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga, 1845. Written during his long exile in Chile. Originally published in 1845 in Chile in installments in El Progreso newspaper, Facundo is Sarmiento's most famous work. It was first published in book form in 1851, and the first English translation, by Mary Mann, appeared in 1868.[66] A recent modern edition in English was translated by Kathleen Ross. Facundo promotes further civilization and European influence on Argentine culture through the use of anecdotes and references to Juan Facundo Quiroga, Argentine caudillo general. As well as being a call to progress, Sarmiento discusses the nature of Argentine peoples as well as including his thoughts and objections to Juan Manuel de Rosas, governor of Buenos Aires from 1829 to 1832 and again from 1835, due to the turmoil generated by Facundo's death, to 1852. As literary critic Sylvia Molloy observes, Sarmiento claimed that this book helped explain Argentine struggles to European readers, and was cited in European publications.[67] Written with extensive assistance from others, Sarmiento adds to his own memory the quotes, accounts, and dossiers from other historians and companions of Facundo Quiroga. Facundo maintains its relevance in modern-day as well, bringing attention to the contrast of lifestyles in Latin America, the conflict and struggle for progress while maintaining tradition, as well as the moral and ethical treatment of the public by government officials and regimes.[68] Let us move onto more precise reasons why the book was created. Sarmiento sought to understand why the two sides in Argentina fought ongoing civil wars. The book contrasts the rural world, where the Indian and gaucho were central, with the urban world of Buenos Aires, seen as an enlightened cultural model. Sarmiento explored the tensions between these two worlds in shaping the nation. He argued that Argentina’s scientific and industrial backwardness mirrored Spain’s, both due to a lingering attachment to medievalism. At the core of this backwardness was the dominance of Catholic dogmas. Sarmiento’s analysis examined how these factors contributed to the social and political crises of his time.[69] Recuerdos de Provincia (Recollections of a Provincial Past), 1850. In this second autobiography, Sarmiento displays a stronger effort to include familial links and ties to his past, in contrast to Mi defensa, choosing to relate himself to San Juan and his Argentine heritage. Sarmiento discusses growing up in rural Argentina with basic ideologies and simple livings. Similar to Facundo, Sarmiento uses previous dossiers filed against himself by enemies to assist in writing Recuerdos and therefore fabricating an autobiography based on these files and from his own memory. Sarmiento's persuasion in this book is substantial. The accounts, whether all true or false against him, are a source of information to write Recuerdos as he is then able to object and rectify into what he creates as a 'true account' of autobiography.[70] Other works Sarmiento was a prolific author. The following is a selection of his other works: Mi defensa, 1843. This was Sarmiento's first autobiography in a pamphlet form, which omits any substantial information or recognition of his illegitimate daughter Ana. This would have discredited Sarmiento as a respected father of Argentina, as Sarmiento portrays himself as a sole individual, disregarding or denouncing important ties to other people and groups in his life.[71] Viajes por Europa, África, y América 1849. A description and observations while travelling as a representative of the Chilean government to learn more about educational systems around the world.[71] Argirópolis 1850. A description of a future utopian city in the River Plate States.[72] Comentarios sobre la constitución 1852. This is Sarmiento's official account of his ideologies promoting civilization and the "Europeanization" and "Americanization" of Argentina. This account includes dossiers, articles, speeches and information regarding the pending constitution.[73] Informes sobre educación, 1856. This report was the first official statistic report on education in Latin America includes information on gender and location distribution of pupils, salaries and wages, and comparative achievement. Informes sobre educación proposes new theories, plans, and methods of education as well as quality controls on schools and learning systems.[72] Las Escuelas, base de la prosperidad y de la republica en los Estados Unidos 1864. This work, along with the previous two, were intended to persuade Latin America and Argentines of the benefits of the educational, economic and political systems of the United States, which Sarmiento supported.[71] Conflicto y armonías de las razas en América 1883, deals with race issues in Latin America in the late 1800s. While situations in the book remain particular to the time period and location, race issues and conflicts of races are still prevalent and enable the book to be relevant in the present day.[74] Vida de Dominguito, 1886. A memoir of Dominguito, Sarmiento's adopted son who was the only child Sarmiento had always accepted. Many of the notes used to compile Vida de Dominguito had been written 20 years prior during one of Sarmiento's stays in Washington.[74] Educar al soberano, a compilation of letters written from 1870 to 1886 on the topic of improved education, promoting and suggesting new reforms such as secondary schools, parks, sporting fields and specialty schools. This compilation was met with far greater success than Ortografía, Instrucción Publica and received greater public support.[72] El camino de Lacio, which impacted Argentina by influencing many Italians to immigrate by relating Argentinas history to that of Latium of the Roman empire.[73] Inmigración y colonización, a publication which led to mass immigration of Europeans to mostly urban Argentina, which Sarmiento believed would assist in 'civilizing' the country over the more barbaric gauchos and rural provinces. This had a large impact on Argentine politics, especially as much of the civil tension in the country was divided between the rural provinces and the cities. In addition to increased urban population, these European immigrants had a cultural effect upon Argentina, providing what Sarmiento believed to be more civilized culture similar to North America's.[71] On the Condition of Foreigners, which helped to assist political changes for immigrants in 1860.[73] Ortografía, Instrucción Publica, an example of Sarmiento's passion for improved education. Sarmiento focused on illiteracy of the youth, and suggested simplifying reading and spelling for the public education system, a method which was never implemented.[73] Práctica Constitucional, a three volume work, describing current political methods as well as propositions for new methodologies.[73] Presidential Papers, a history of his presidency, formed of many personal and external documents.[73] Travels in the United States in 1847, (Edited and translated into English by Michael Aaron Rockland.)[75] |

著作 主要作品 ファクンド ― 文明と野蛮 ― フアン・ファクンド・キロガの生涯、1845年。チリでの長期亡命中に執筆された。1845年にチリの新聞エル・プログレソで連載され、サルミエントの最 も有名な作品である。1851年に初めて単行本として出版され、メアリー・マンによる最初の英訳は1868年に現れた[66]。最近の現代英語版はキャス リーン・ロスが翻訳した。ファクンドは、アルゼンチンの軍閥指導者フアン・ファクンド・キロガに関する逸話や言及を通じて、アルゼンチン文化へのさらなる 文明化とヨーロッパの影響を促進する。進歩への呼びかけであると同時に、サルミエントはアルゼンチン人の本質について論じ、1829年から1832年、そ してファクンドの死による混乱を契機に1835年から1852年までブエノスアイレス総督を務めたフアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスに対する自身の考えや異議 も述べている。文学評論家シルビア・モロイが指摘するように、サルミエントはこの著作がヨーロッパ読者にアルゼンチンの葛藤を理解させる助けとなり、欧州 の出版物で引用されたと主張している[67]。他者の多大な協力を得て執筆された本書には、サルミエント自身の記憶に加え、ファクンド・キロガの史家や仲 間たちによる引用、記録、資料が加えられている。『ファクンド』は現代においてもその意義を失っておらず、ラテンアメリカの生活様式の対比、伝統維持と進 歩の葛藤、そして政府高官や体制による公衆への道徳的・倫理的扱いといった問題に注目を集めている[68]。本書が書かれたより具体的な理由に移ろう。サ ルミエントは、アルゼンチンで両陣営が継続的な内戦を繰り広げた理由を理解しようとしたのである。本書は、インディオとガウチョが中心となる農村世界と、 啓蒙された文化的モデルと見なされたブエノスアイレスの都市世界を対比させる。サルミエントは国民形成におけるこの二つの世界の緊張関係を探求した。彼 は、アルゼンチンの科学的・産業的遅滞はスペインのそれと鏡像関係にあり、どちらも中世主義への未練が原因だと主張した。この遅れの核心にはカトリック教 義の支配があった。サルミエントの分析は、これらの要因が当時の社会的・政治的危機にどう寄与したかを検証した。[69] 『地方の回想』(Recuerdos de Provincia)、1850年。この第二の自伝において、サルミエントは『我が弁護』とは対照的に、家族的絆や過去との繋がりをより強く取り入れよう とする姿勢を示している。サン・フアン州やアルゼンチンの遺産との関連性を自ら選択して語るのである。サルミエントは、基本的なイデオロギーと質素な生活 の中でアルゼンチンの田舎で育った経験を論じている。『ファクンド』と同様に、サルミエントは敵対者によって過去に提出された自身の告発書類を『回想録』 執筆の補助として利用し、これらの書類と自身の記憶に基づいて自伝を構築している。本書におけるサルミエントの説得力は大きい。彼に対する記述が真実であ れ虚偽であれ、それらは『回想録』執筆の情報源となり、彼はそれらに反論し修正を加えることで、自伝としての「真実の記録」を創り上げているのだ。 [70] その他の著作 サルミエントは多作な著者であった。以下は彼のその他の著作の一部である: 『我が弁護』(1843年)。これはパンフレット形式のサルミエント初の自伝であり、非嫡出子アナに関する実質的な情報や言及を一切省いている。この記述 はサルミエントをアルゼンチンの尊敬される父として信用を損なうものだった。なぜならサルミエントは自らを孤高の人物として描き、人生における他の人々や 集団との重要な絆を無視し、あるいは否定しているからである。[71] 『ヨーロッパ、アフリカ、アメリカ旅行記』1849年。チリ政府の代表として世界各国の教育制度を視察した際の記録と所見である。[71] 『アルギリポリス』1850年。ラプラタ諸州における未来のユートピア都市構想を記述したものである。[72] 『憲法に関する論評』1852年。これはサルミエントがアルゼンチンの文明化と「ヨーロッパ化」「アメリカ化」を推進するイデオロギーを公式に記した文書である。この文書には、憲法制定に関する資料、記事、演説、情報などが含まれている。[73] 教育に関する報告書、1856年。この報告書はラテンアメリカ初の公式教育統計報告書であり、生徒の性別・地域分布、給与・賃金、学力比較などの情報を含 む。『教育に関する報告書』は、新たな教育理論・計画・方法論に加え、学校及び学習システムに対する品質管理を提唱している。[72] 『学校は米国における繁栄と共和国の基盤である』1864年。本著作は前述の二作品と共に、サルミエントが支持した米国の教育・経済・政治システムの利点をラテンアメリカ及びアルゼンチン人に説得する目的で執筆された。[71] 『アメリカ大陸における人種の対立と調和』(1883年)は、19世紀末ラテンアメリカの人種問題を扱っている。本書の状況は時代と地域に特有のものだが、人種問題と人種間の対立は今も普遍的であり、本書を現代においても関連性のあるものにしている。[74] 『ドミンギート伝』(1886年)。サルミエントが養子として唯一認めた息子ドミンギートの回想録である。本書の編纂に用いられた多くの記録は、サルミエントがワシントンに滞在した20年前の時期に書かれたものだ。[74] 『国民を教育せよ』は、1870年から1886年にかけて書かれた書簡集である。教育の改善をテーマとし、中等学校、公園、運動場、専門学校といった新た な改革を提唱している。この書簡集は『正書法』『公教育』よりもはるかに成功を収め、より大きな公的支援を得た。[72] 『ラツィオへの道』は、アルゼンチンの歴史をローマ帝国のラツィオ地方の歴史と結びつけることで多くのイタリア人移民を促し、アルゼンチンに影響を与えた。[73] 『移民と植民』は、主に都市部へのヨーロッパ人移民を大量に呼び込んだ出版物である。サルミエントは、この移民がより野蛮なガウチョや地方州を「文明化」 する助けになると信じていた。これはアルゼンチン政治に大きな影響を与えた。特に国内の市民的緊張は地方と都市の間で分断されていたからだ。都市人口の増 加に加え、これらの欧州移民はアルゼンチンに文化的影響をもたらした。サルミエントが北米に似たより文明化された文化と見なしたものを提供したのである。 [71] 『外国人に関する条件』は、1860年の移民に関する政治的変化を支援するのに役立った。[73] 『正書法と公教育』は、サルミエントの教育改善への情熱を示す一例だ。彼は若者の非識字問題に注目し、公教育制度における読解と綴りの簡素化を提案したが、この方法は結局実施されなかった。[73] 『憲法実践』は全3巻からなる著作で、当時の政治手法を解説するとともに新たな方法論を提唱している。[73] 大統領文書集。大統領在任中の記録であり、多数の個人的文書及び外部文書で構成されている。[73] 1847年アメリカ旅行記(マイケル・アーロン・ロックランドによる編集・英訳)。[75] |

| Legacy Sarmiento's house on the Parana delta The impact of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento is most obviously seen in the establishment of September 11 as Panamerican Teacher's Day which was done in his honor at the 1943 Interamerican Conference on Education, held in Panama. Today, he is still considered to be Latin America's teacher.[76] In his time, he opened countless schools, created free public libraries, opened immigration, and worked towards a Union of Plate States.[77] His impact was not only on the world of education, but also on Argentine political and social structure. His ideas are now revered as innovative, though at the time they were not widely accepted.[78] He was a self-made man and believed in sociological and economic growth for Latin America, something that the Argentine people could not recognize at the time with the soaring standard of living which came with high prices, high wages, and an increased national debt.[78] There is a building named in his honor at the Argentine embassy in Washington D.C. Today, there is a statue in honor of Sarmiento in Boston on the Commonwealth Avenue Mall, between Gloucester and Hereford streets, erected in 1973.[79] There is a square, Plaza Sarmiento in Rosario, Argentina.[80] One of Rodin's last sculptures was that of Sarmiento which is now in Buenos Aires.[81] |

遺産 パラナ川デルタにあるサルミエントの家 ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエントの影響は、1943年にパナマで開催された米州教育会議で彼を称えて9月11日を「米州教師の日」と定めたこと に最も顕著に表れている。今日でも彼はラテンアメリカの教師と見なされている[76]。当時、彼は無数の学校を開設し、無料の公共図書館を創設し、移民政 策を推進し、プラテ諸州連合の実現に向けて尽力した[77]。 彼の影響は教育界だけでなく、アルゼンチンの政治・社会構造にも及んだ。彼の思想は当時広く受け入れられなかったものの、今では革新的として称賛されてい る。[78] 彼は独力で成功を収めた人物であり、ラテンアメリカの社会学的・経済的成長を信じていた。しかし当時のアルゼンチン国民は、物価高・賃金高・国家債務増加 に伴う生活水準の急上昇の中で、その価値を認識できなかったのである。[78] ワシントンD.C.のアルゼンチン大使館には、彼の名を冠した建物がある。 現在、ボストンのコモンウェルス・アベニュー・モール(グロスター通りとヘレフォード通りの間)には、1973年に建立されたサルミエントの像が立ってい る。[79] アルゼンチンのロサリオには「サルミエント広場」がある。[80] ロダンの最後の彫刻作品の一つであるサルミエント像は、現在ブエノスアイレスに所在する。[81] |

| Notes & Footnotes |

|

| References Bunkley, Allison Williams (1969) [1952], The Life of Sarmiento, New York: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-8371-2392-5. Calmon, Pedro (1975), História de D. Pedro II (in Portuguese), vol. 1, Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio Crowley, Francis G. (1972), Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, New York: Twayne. Galvani, Victoria, ed. (1990), Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (in Spanish), Madrid: Institución de Cooperación Iberoamericana, ISBN 84-7232-577-6. Halperín Donghi, Tulio (1994), "Sarmiento's Place in Postrevolutionary Argentina", in Halperin Donghi, Tulio; Jaksic, Ivan; Kirkpatrick, Gwen; et al. (eds.), Sarmiento: Author of a Nation, ??: University of California Press, pp. 19–30. Katra, William H. (1993), Sarmiento de frente y perfil (in Spanish), New York: Peter Lang, ISBN 0-8204-2044-1. Katra, William H. (1994), "Reading Viajes", in Halperin Donghi, Tulio; Jaksic, Ivan; Kirkpatrick, Gwen; et al. (eds.), Sarmiento: Author of a Nation, ??: University of California Press, pp. 73–100. Katra, William H. (1996), The Argentine Generation of 1837: Echeverría, Alberti, Sarmiento, Mitre, London: Associated University Presses, ISBN 0-8386-3599-7. Kirkpatrick, Gwen; Masiello, Francine (1994), "Introduction: Sarmiento between History and Fiction", in Halperin Donghi, Tulio; Jaksic, Ivan; Kirkpatrick, Gwen; et al. (eds.), Sarmiento: Author of a Nation, ??: University of California Press, pp. 1–18. Mann, Mary Tyler Peabody (2001), "My Dear Sir": Mary Mann's Letters to Sarmiento, 1865–1881, Buenos Aires: Instituto Cultural Argentino Norteamericano, ISBN 987-98659-0-1. Edited by Barry L. Velleman. There is a Spanish translation of these letters, "Mi estimado señor": Cartas de Mary Mann a Sarmiento (1865–1881). Buenos Aires: Icana y Victoria Ocampo, 2005. Edited by Barry L. Velleman. Translated by Marcela Solá. ISBN 987-1198-03-5. Molloy, Sylvia (1991), At Face Value: Autobiographical Writing in Spanish America, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-33195-1 Moss, Joyce; Valestuk, Lorraine (1999), "Facundo: Domingo F. Sarmiento", Latin American Literature and Its Times, vol. 1, World Literature and Its Times: Profiles of Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events That Influenced Them, Detroit: Gale Group, pp. 171–180, ISBN 0-7876-3726-2 Patton, Elda Clayon (1976), Sarmiento in the United States, Evansville Indiana: The University of Evansville Press. Penn, Dorothy (August 1946), "Sarmiento--"School Master President" of Argentina", Hispania, 29 (3), American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese: 386–389, doi:10.2307/333368, JSTOR 333368. Rock, David (1985), Argentina, 1516–1982: From Spanish Colonization to the Falklands War, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05189-0. Ross, Kathleen (2003), "Translator's Introduction", in Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (ed.), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, trans. Kathleen Ross, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 17–26. Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino (2005), Recollections of a Provincial Past, ??: Library of Latin America, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-511369-1. Trans. by Elizabeth Garrels and Asa Zatz. Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino (2003), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, translated by Kathleen Ross, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (published 1845), ISBN 0-520-23980-6 The first complete English translation. |

参考文献 Bunkley, Allison Williams (1969) [1952], The Life of Sarmiento, New York: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-8371-2392-5. Calmon, Pedro (1975), História de D. Pedro II (in Portuguese), vol. 1, Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio Crowley, Francis G. (1972), Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, New York: Twayne. Galvani, Victoria, ed. (1990), Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (in Spanish), Madrid: Institución de Cooperación Iberoamericana, ISBN 84-7232-577-6. ハルペリン・ドンギ、トゥリオ(1994)、『革命後のアルゼンチンにおけるサルミエントの立場』、ハルペリン・ドンギ、トゥリオ、ジャクシック、イヴァ ン、カークパトリック、グウェン、他(編)、『サルミエント:国民の創作者』、??:カリフォルニア大学出版、19-30 ページ。 カトラ、ウィリアム・H.(1993)、『サルミエント:正面と横顔』(スペイン語)、ニューヨーク:ピーター・ラング、ISBN 0-8204-2044-1。 カトラ、ウィリアム・H.(1994)、「『旅』を読む」、『サルミエント:国民の作者』所収、ハルペリン・ドンギ、トゥリオ;ヤクシッチ、イヴァン;カークパトリック、グウェン;他(編)、??:カリフォルニア大学出版局、73–100頁。 カトラ、ウィリアム・H.(1996)『アルゼンチン1837年世代:エチェベリア、アルベルティ、サルミエント、ミトレ』ロンドン:アソシエイテッド・ユニバーシティ・プレス、ISBN 0-8386-3599-7。 カトラ、ウィリアム・H.(1996)、「序論:歴史と虚構の狭間にあるサルミエント」、ハルペリン・ドンギ、トゥリオ;ヤクシッチ、イヴァン;カトラー、グウェン;他(編)、『サルミエント:国民の作者』、??:カリフォルニア大学出版局、pp. 1–18。 マン、メアリー・タイラー・ピーボディ(2001)、「親愛なる殿下へ」:メアリー・マンのサルミエント宛て書簡集、1865–1881年、ブエノスアイ レス:アルゼンチン・北米文化研究所、ISBN 987-98659-0-1。バリー・L・ヴェレマン編。これらの書簡のスペイン語訳がある。「親愛なる殿下へ」:メアリー・マンからサルミエントへの書 簡(1865–1881)。ブエノスアイレス:イカナ・イ・ビクトリア・オカンポ、2005年。バリー・L・ヴェレマン編。マルセラ・ソラ訳。ISBN 987-1198-03-5。 モロイ、シルビア(1991年)『表面的な価値:スペイン語圏アメリカにおける自伝的著作』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、ISBN 0-521-33195-1 モス、ジョイス、ヴァレストゥク、ロレイン(1999)、『ファクンド:ドミンゴ・F・サルミエント』、ラテンアメリカ文学とその時代、第 1 巻、世界文学とその時代:著名な文学作品とそれに影響を与えた歴史的出来事のプロフィール、デトロイト:ゲイル・グループ、171-180 ページ、ISBN 0-7876-3726-2 パットン、エルダ・クレイヨン (1976)、『米国におけるサルミエント』、インディアナ州エヴァンズビル:エヴァンズビル大学出版局。 ペン、ドロシー (1946年8月)、『サルミエント - アルゼンチンの「学校長大統領」』、Hispania、29 (3)、米国スペイン語・ポルトガル語教師協会:386–389、 doi:10.2307/333368, JSTOR 333368. ロック、デイヴィッド (1985)、『アルゼンチン、1516-1982:スペイン植民地時代からフォークランド紛争まで』、バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版、ISBN 0-520-05189-0。 ロス、キャスリーン(2003)、「訳者序文」、ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サルミエント(編)、『ファクンド:文明と野蛮』、訳キャスリーン・ロス、カリフォルニア州バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局、17–26頁。 サルミエント、ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ(2005)『地方の過去を回想して』??:ラテンアメリカ図書館、オックスフォード大学出版局、ISBN 0-19-511369-1。エリザベス・ギャレルズとアサ・ザッツ訳。 サルミエント、ドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ(2003)『ファクンド:文明と野蛮』キャスリーン・ロス訳、カリフォルニア州バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版局(1845年刊行)、ISBN 0-520-23980-6。初の完全英訳版。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domingo_Faustino_Sarmiento |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099