E. T. A. ホフマン

E. T. A. Hoffmann, 1776-1822

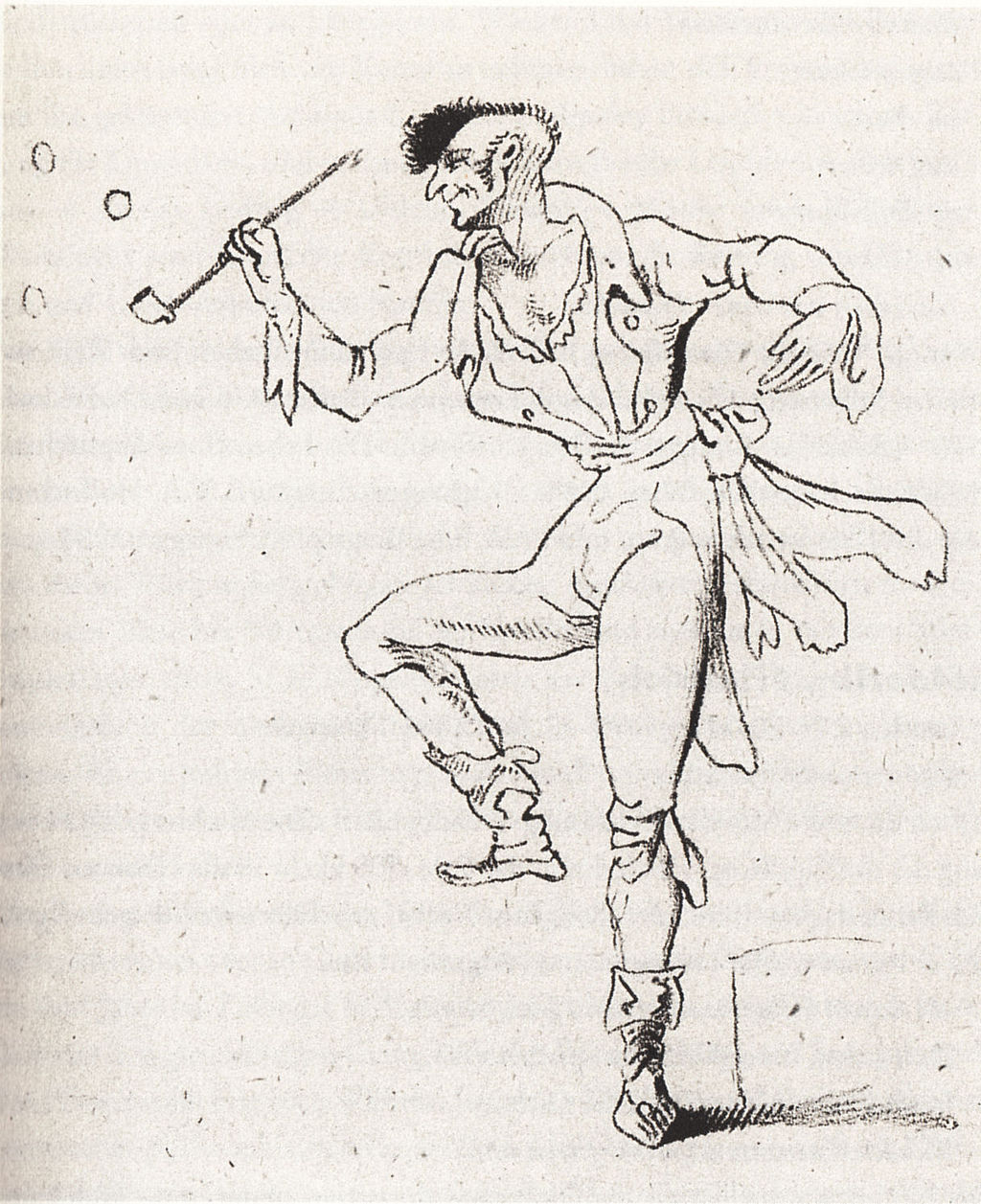

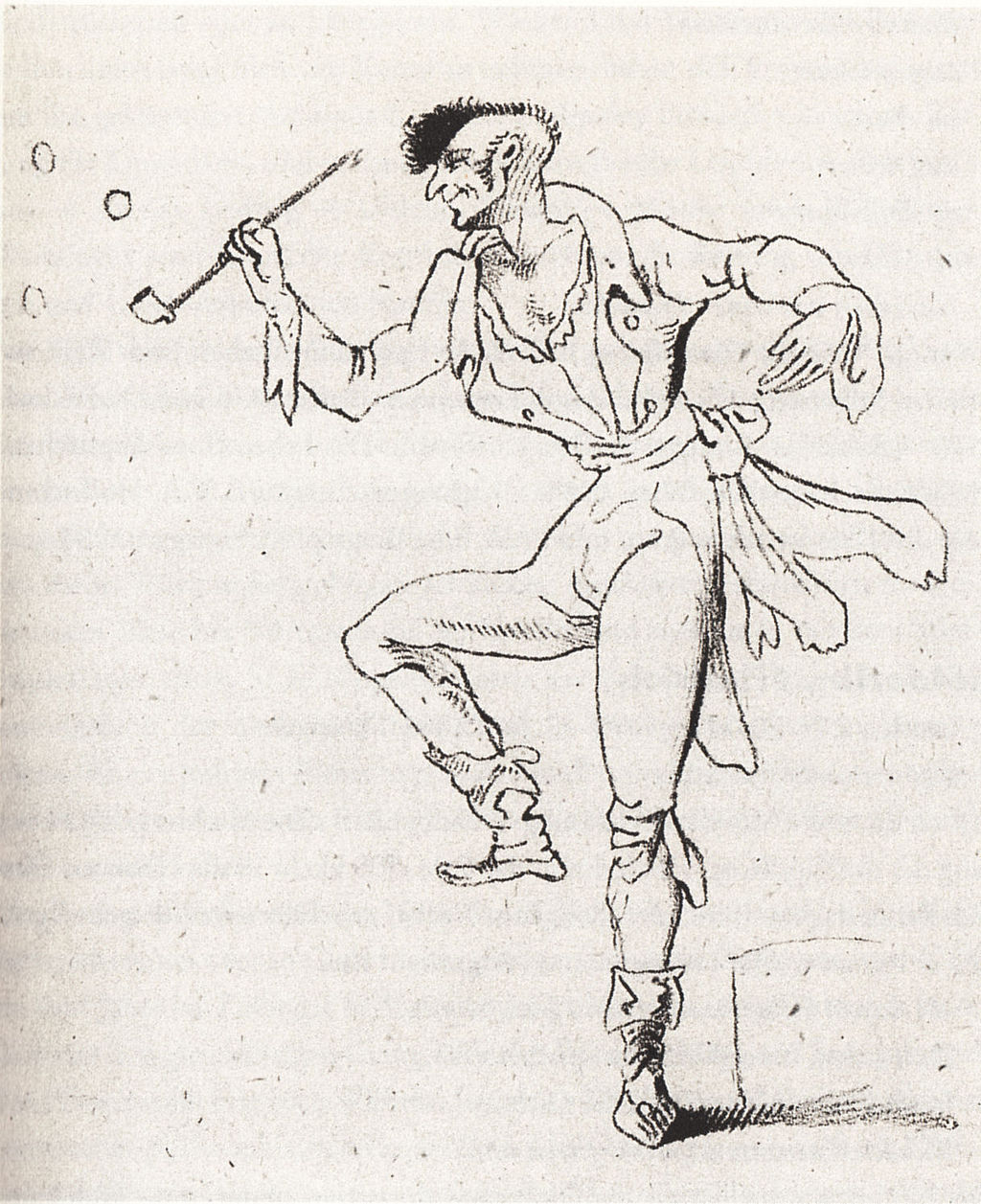

Self-portrait,

by E. T. A. Hoffmann

☆

エルンスト・テオドール・アマデウス・ホフマン(Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann、本名:Ernst Theodor

Wilhelm Hoffmann、1776年1月24日 -

1822年6月25日)は、ドイツ・ロマン派のファンタジーとゴシック・ホラーの作家であり、法学者、作曲家、音楽評論家、芸術家でもある。また、ピョー

トル・イリイチ・チャイコフスキーのバレエ『くるみ割り人形』の原作となった小説『くるみ割り人形とねずみの王様』の作者でもある。バレエ『コッペリア』

はホフマンが書いた他の2つの物語に基づいており、シューマンの『クライスレリアーナ』[4]はホフマンの登場人物ヨハネス・クライスラーに基づいてい

る。

ホフマンの物語は19世紀の文学に大きな影響を与え、ロマン主義運動の主要な作家の一人である。

| Ernst Theodor

Amadeus Hoffmann (born Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann; 24 January 1776

– 25 June 1822) was a German Romantic author of fantasy and Gothic

horror, a jurist, composer, music critic and artist.[1][2][3] His

stories form the basis of Jacques Offenbach's opera The Tales of

Hoffmann, in which Hoffmann appears (heavily fictionalized) as the

hero. He is also the author of the novella The Nutcracker and the Mouse

King, on which Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker is

based. The ballet Coppélia is based on two other stories that Hoffmann

wrote, while Schumann's Kreisleriana[4] is based on Hoffmann's

character Johannes Kreisler. Hoffmann's stories highly influenced 19th-century literature, and he is one of the major authors of the Romantic movement. |

エルンスト・テオドール・アマデウス・ホフマン(Ernst

Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann、本名:Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann、1776年1月24日 -

1822年6月25日)は、ドイツ・ロマン派のファンタジーとゴシック・ホラーの作家であり、法学者、作曲家、音楽評論家、芸術家でもある。また、ピョー

トル・イリイチ・チャイコフスキーのバレエ『くるみ割り人形』の原作となった小説『くるみ割り人形とねずみの王様』の作者でもある。バレエ『コッペリア』

はホフマンが書いた他の2つの物語に基づいており、シューマンの『クライスレリアーナ』[4]はホフマンの登場人物ヨハネス・クライスラーに基づいてい

る。 ホフマンの物語は19世紀の文学に大きな影響を与え、ロマン主義運動の主要な作家の一人である。 |

| Life Youth Hoffmann's ancestors, both maternal and paternal, were jurists.[5] His father, Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann (1736–97), was a barrister in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), as well as a poet and amateur musician who played the viola da gamba. In 1767 he married his cousin, Lovisa Albertina Doerffer (1748–96). Ernst Theodor Wilhelm, born on 24 January 1776, was the youngest of three children, of whom the second died in infancy. When his parents separated in 1778, his father went to Insterburg (now Chernyakhovsk) with his elder son, Johann Ludwig Hoffmann (1768–1822), while Hoffmann's mother stayed in Königsberg with her relatives: two aunts, Johanna Sophie Doerffer (1745–1803) and Charlotte Wilhelmine Doerffer (c. 1754–79) and their brother, Otto Wilhelm Doerffer (1741–1811), who were all unmarried. The trio raised the youngster. The household, dominated by the uncle (whom Ernst nicknamed O Weh—"Oh dear!"—in a play on his initials "O.W."), was pietistic and uncongenial. Hoffmann was to regret his estrangement from his father. Nevertheless, he remembered his aunts with great affection, especially the younger, Charlotte, whom he nicknamed Tante Füßchen ("Aunt Littlefeet"). Although she died when he was only three years old, he treasured her memory (a character in Hoffmann's Lebensansichten des Katers Murr is named after her) and embroidered stories about her to such an extent that later biographers sometimes assumed her to be imaginary, until proof of her existence was found after World War II.[6] Between 1781 and 1792 he attended the Lutheran school or Burgschule, where he made good progress in classics. Ernst showed great talent for piano-playing, and busied himself with writing and drawing. The provincial setting was not, however, conducive to technical progress, and despite his many-sided talents he remained rather ignorant of both classical forms and of the new artistic ideas that were developing in Germany. He had, however, read Schiller, Goethe, Swift, Sterne, Rousseau and Jean Paul, and wrote part of a novel titled Der Geheimnisvolle. Around 1787 he became friends with Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Younger (1775–1843), the son of a pastor, and nephew of Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Elder, the well-known writer friend of Immanuel Kant. During the year 1792, both attended some of Kant's lectures at the University of Königsberg. Their friendship, although often tested by an increasing social difference, was to be lifelong. In 1794, Hoffmann became enamored of Dora Hatt, a married woman to whom he had given music lessons. She was ten years older, and gave birth to her sixth child in 1795.[7] In February 1796, her family protested against his attentions and, with his hesitant consent, asked another of his uncles to arrange employment for him in Glogau (Głogów), Prussian Silesia.[8] The provinces From 1796, Hoffmann obtained employment as a clerk for his uncle, Johann Ludwig Doerffer, who lived in Glogau with his daughter Minna. After passing further examinations he visited Dresden, where he was amazed by the paintings in the gallery, particularly those of Correggio and Raphael. During the summer of 1798, his uncle was promoted to a court in Berlin, and the three of them moved there in August—Hoffmann's first residence in a large city. It was there that Hoffmann first attempted to promote himself as a composer, writing an operetta called Die Maske and sending a copy to Queen Luise of Prussia. The official reply advised to him to write to the director of the Royal Theatre, a man named Iffland. By the time the latter responded, Hoffmann had passed his third round of examinations and had already left for Posen (Poznań) in South Prussia in the company of his old friend Hippel, with a brief stop in Dresden to show him the gallery. From June 1800 to 1803, he worked in Prussian provinces in the area of Greater Poland and Masovia. This was the first time he had lived without supervision by members of his family, and he started to become "what school principals, parsons, uncles, and aunts call dissolute."[9] His first job, at Posen, was endangered after Carnival on Shrove Tuesday 1802, when caricatures of military officers were distributed at a ball. It was immediately deduced who had drawn them, and complaints were made to authorities in Berlin, who were reluctant to punish the promising young official. The problem was solved by "promoting" Hoffmann to Płock in New East Prussia, the former capital of Poland (1079–1138), where administrative offices were relocated from Thorn (Toruń). He visited the place to arrange lodging, before returning to Posen where he married Mischa (Maria or Marianna Thekla Michalina Rorer, whose Polish surname was Trzcińska). They moved to Płock in August 1802. Hoffmann despaired because of his exile, and drew caricatures of himself drowning in mud alongside ragged villagers. He did make use, however, of his isolation, by writing and composing. He started a diary on 1 October 1803. An essay on the theatre was published in Kotzebue's periodical, Die Freimüthige, and he entered a competition in the same magazine to write a play. Hoffmann's was called Der Preis ("The Prize"), and was itself about a competition to write a play. There were fourteen entries, but none was judged worthy of the award: 100 Friedrichs d'or. Nevertheless, his entry was singled out for praise.[10] This was one of the few good times of a sad period of his life, which saw the deaths of his uncle J. L. Hoffmann in Berlin, his Aunt Sophie, and Dora Hatt in Königsberg. At the beginning of 1804, he obtained a post at Warsaw.[11] On his way there, he passed through his hometown and met one of Dora Hatt's daughters. He was never to return to Königsberg. Warsaw Hoffmann assimilated well with Polish society; the years spent in Prussian Poland he recognized as the happiest of his life. In Warsaw he found the same atmosphere he had enjoyed in Berlin, renewing his friendship with Zacharias Werner, and meeting his future biographer, a neighbour and fellow jurist called Julius Eduard Itzig (who changed his name to Hitzig after his baptism). Itzig had been a member of the Berlin literary group called the Nordstern, or "North Star", and he gave Hoffmann the works of Novalis, Ludwig Tieck, Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano, Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, Carlo Gozzi and Calderón. These relatively late introductions marked his work profoundly. He moved in the circles of August Wilhelm Schlegel, Adelbert von Chamisso, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Rahel Levin and David Ferdinand Koreff. But Hoffmann's fortunate position was not to last: on 28 November 1806, during the War of the Fourth Coalition, Napoleon Bonaparte's troops captured Warsaw, and the Prussian bureaucrats lost their jobs. They divided the contents of the treasury between them and fled. In January 1807, Hoffmann's wife and two-year-old daughter Cäcilia returned to Posen, while he pondered whether to move to Vienna or go back to Berlin. A delay of six months was caused by severe illness. Eventually the French authorities demanded that all former officials swear allegiance or leave the country. As they refused to grant Hoffmann a passport to Vienna, he was forced to return to Berlin. He visited his family in Posen before arriving in Berlin on 18 June 1807, hoping to further his career there as an artist and writer. Berlin and Bamberg The next fifteen months were some of the worst in Hoffmann's life. The city of Berlin was also occupied by Napoleon's troops. Obtaining only meagre allowances, he had frequent recourse to his friends, constantly borrowing money and still going hungry for days at a time; he learned that his daughter had died. Nevertheless, he managed to compose his Six Canticles for a cappella choir: one of his best compositions, which he would later attribute to Kreisler in Lebensansichten des Katers Murr.  Hoffmann's portrait of Kapellmeister Kreisler On 1 September 1808 he arrived with his wife in Bamberg, where he began a job as theatre manager. The director, Count Soden, left almost immediately for Würzburg, leaving a man named Heinrich Cuno in charge. Hoffmann was unable to improve standards of performance, and his efforts caused intrigues against him which resulted in him losing his job to Cuno. He began work as music critic for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, a newspaper in Leipzig, and his articles on Beethoven were especially well received, and highly regarded by the composer himself. It was in its pages that the "Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler" character made his first appearance. Hoffmann's breakthrough came in 1809, with the publication of Ritter Gluck, a story about a man who meets, or believes he has met, the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–87) more than twenty years after the latter's death. The theme alludes to the work of Jean Paul, who invented the term Doppelgänger the previous decade, and continued to exact a powerful influence over Hoffmann, becoming one of his earliest admirers. With this publication, Hoffmann began to use the pseudonym E. T. A. Hoffmann, telling people that the "A" stood for Amadeus, in homage to the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91). However, he continued to use Wilhelm in official documents throughout his life, and the initials E. T. W. also appear on his gravestone. The next year, he was employed at the Bamberg Theatre as stagehand, decorator, and playwright, while also giving private music lessons. He became so enamored of a young singing student, Julia Marc, that his feelings were obvious whenever they were together, and Julia's mother quickly found her a more suitable match. When Joseph Seconda offered Hoffmann a position as musical director for his opera company (then performing in Dresden), he accepted, leaving on 21 April 1813. Dresden and Leipzig Prussia had declared war against France on 16 March during the War of the Sixth Coalition, and their journey was fraught with difficulties. They arrived on the 25th, only to find that Seconda was in Leipzig; on the 26th, they sent a letter pleading for temporary funds. That same day Hoffmann was surprised to meet Hippel, whom he had not seen for nine years. The situation deteriorated, and in early May Hoffmann tried in vain to find transport to Leipzig. On 8 May, the bridges were destroyed, and his family were marooned in the city. During the day, Hoffmann would roam, watching the fighting with curiosity. Finally, on 20 May, they left for Leipzig, only to be involved in an accident which killed one of the passengers in their coach and injured his wife. They arrived on 23 May, and Hoffmann started work with Seconda's orchestra, which he found to be of the best quality. On 4 June an armistice began, which allowed the company to return to Dresden. But on 22 August, after the end of the armistice, the family was forced to relocate from their pleasant house in the suburbs into the town, and during the next few days the Battle of Dresden raged. The city was bombarded; many people were killed by bombs directly in front of him. After the main battle was over, he visited the gory battlefield. His account can be found in Vision auf dem Schlachtfeld bei Dresden. After a long period of continued disturbance, the town surrendered on 11 November, and on 9 December the company travelled to Leipzig. On 25 February, Hoffmann quarrelled with Seconda, and the next day he was given notice of twelve weeks. When asked to accompany them on their journey to Dresden in April, he refused, and they left without him. But during July his friend Hippel visited, and soon he found himself being guided back into his old career as a jurist. Berlin  Grave of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated, the inscription reads: E. T. W. Hoffmann, born on 24 January 1776, in Königsberg, died on 25 June 1822, in Berlin, Councillor of the Court of Justice, excellent in his office, as a poet, as a musician, as a painter, dedicated by his friends. At the end of September 1814, in the wake of Napoleon's defeat, Hoffmann returned to Berlin and succeeded in regaining a job at the Kammergericht, the chamber court. His opera Undine was performed by the Berlin Theatre. Its successful run came to an end only after a fire on the night of the 25th performance. Magazines clamoured for his contributions, and after a while his standards started to decline. Nevertheless, many masterpieces date from this time. During the period from 1819, Hoffmann was involved with legal disputes, while fighting ill health. Alcohol abuse and syphilis eventually caused weakening of his limbs during 1821, and paralysis from the beginning of 1822. His last works were dictated to his wife or to a secretary. Prince Metternich's anti-liberal programs began to put Hoffmann in situations that tested his conscience. Thousands of people were accused of treason for having certain political opinions, and university professors were monitored during their lectures. King Frederick William III of Prussia appointed an Immediate Commission for the investigation of political dissidence; when he found its observance of the rule of law too frustrating, he established a Ministerial Commission to interfere with its processes. The latter was greatly influenced by Commissioner Kamptz. During the trial of "Turnvater" Jahn, the founder of the gymnastics association movement, Hoffmann found himself annoying Kamptz, and became a political target. When Hoffmann caricatured Kamptz in a story (Meister Floh), Kamptz began legal proceedings. These ended when Hoffmann's illness was found to be life-threatening. The King asked for a reprimand only, but no action was ever taken. Eventually Meister Floh was published with the offending passages removed. Hoffmann died of syphilis in Berlin on 25 June 1822 at the age of 46. His grave is preserved in the Protestant Friedhof III der Jerusalems- und Neuen Kirchengemeinde (Cemetery No. III of the congregations of Jerusalem Church and New Church) in Berlin-Kreuzberg, south of Hallesches Tor at the underground station Mehringdamm. |

人生 青年期 父クリストフ・ルートヴィヒ・ホフマン(1736-97)は、プロイセンのケーニヒスベルク(現ロシアのカリーニングラード)の法廷弁護士であり、詩人で もあり、ヴィオラ・ダ・ガンバを演奏するアマチュア音楽家でもあった。1767年に従姉妹のロヴィーサ・アルベルティーナ・ドールファー(1748- 96)と結婚した。エルンスト・テオドール・ヴィルヘルムは、1776年1月24日に3人兄弟の末っ子として生まれた。 1778年に両親が別居すると、父親は長男のヨハン・ルートヴィッヒ・ホフマン(1768-1822)と共にインスターブルク(現在のチェルニャホフス ク)へ行き、ホフマンの母親はケーニヒスベルクに残り、親戚のヨハンナ・ゾフィー・ドアッファー(1745-1803)とシャルロッテ・ヴィルヘルミネ・ ドアッファー(1754-79)、そしてその弟のオットー・ヴィルヘルム・ドアッファー(1741-1811)と共にケーニヒスベルクに残った。この3人 が若者を育てた。 叔父(エルンストは自分のイニシャル "O.W. "をもじって "O.W. "とあだ名した)が支配する家庭は、敬虔で和やかではなかった。ホフマンは父と疎遠になったことを後悔することになる。それでもホフマンは、叔母たちのこ とをとても可愛がっており、特に年下のシャルロッテのことは、"Tante Füßchen"("Aunt Littlefeet")と愛称で呼んでいた。叔母はホフマンがわずか3歳のときに亡くなったが、ホフマンは叔母の思い出を大切にし(ホフマンの『ミュー ルの伯母さん』の登場人物は叔母にちなんで命名されている)、叔母にまつわる物語を刺繍した。 1781年から1792年にかけて、エルンストはルター派の学校(ブルグシューレ)に通い、古典の成績は上々であった。エルンストはピアノ演奏に優れた才 能を発揮し、執筆やデッサンにも精を出した。しかし、地方の環境は技術的な進歩を促すものではなく、多方面で才能を発揮していたにもかかわらず、エルンス トは古典的な形式にも、ドイツで発展しつつあった新しい芸術思想にも無知なままだった。しかし、シラー、ゲーテ、スウィフト、シュテルン、ルソー、ジャ ン・パウルは読んでおり、『Der Geheimnisvolle』という小説の一部を書いた。 1787年頃、彼は牧師の息子で、イマヌエル・カントの友人として有名な作家テオドール・ゴットリープ・フォン・ヒッペルの甥であるテオドール・ゴット リープ・フォン・ヒッペル・ザ・ヤンガー(1775-1843)と親しくなった。1792年、二人はケーニヒスベルク大学でのカントの講義に出席した。二 人の友情は、社会的な違いによって試されることも多かったが、生涯続くものとなった。 1794年、ホフマンは音楽のレッスンをしていた人妻ドラ・ハットに夢中になる。彼女は10歳年上で、1795年に6人目の子供を出産した[7]。 1796年2月、彼女の家族はホフマンの誘惑に抗議し、ホフマンはためらいながらも別の叔父に頼んで、プロイセンのシレジア地方グロガウ(Głogów) での就職を斡旋してもらった[8]。 地方 1796年、ホフマンは叔父のヨハン・ルートヴィヒ・ドーアファーのもとで事務員として働き、娘のミンナとともにグロガウに住んだ。試験に合格した後、ド レスデンを訪れ、ギャラリーの絵画、特にコレッジョとラファエロの絵画に感銘を受ける。1798年の夏、叔父がベルリンの宮廷に昇進し、3人は8月にベル リンに移り住んだ。そこでホフマンは初めて作曲家としての昇進を試み、『仮面』というオペレッタを書き、そのコピーをプロイセン王妃ルイーゼに送った。王 立劇場の館長イフランドに手紙を書くようにとの公式回答があった。イフランドから返事が来た時には、ホフマンはすでに3次試験に合格しており、旧友ヒッペ ルと共に南プロイセンのポゼン(ポズナン)に向かっていた。 1800年6月から1803年まで、彼はプロイセンの大ポーランドとマゾヴィア地方で仕事をした。家族の監視なしに生活したのはこれが初めてで、「校長、 牧師、叔父、叔母の言う放蕩者」[9]になり始めた。 1802年、ポーゼンでの最初の仕事は、カーニバルの後に危険にさらされた。この風刺画を描いたのが誰であるかはすぐに判明し、ベルリンの当局に苦情が寄 せられたが、当局はこの有望な若手官吏を罰することには消極的であった。問題はホフマンを新東プロイセンのプウォックに「昇進」させることで解決した。プ ウォックはポーランドの旧首都(1079~1138年)で、行政官庁はソーン(トルン)から移転していた。彼は宿を手配するためにその地を訪れ、その後 ポーゼンへ戻り、ミッシャ(マリアまたはマリアナ・テクラ・ミハリナ・ローラー、ポーランド姓はトルシンスカ)と結婚した。二人は1802年8月にプ ウォックに移った。 ホフマンは追放されたことで絶望し、ボロボロの村人と一緒に泥の中で溺れている風刺画を描いた。しかし、ホフマンは孤独を利用して、執筆や作曲に励んだ。 1803年10月1日には日記を書き始めた。演劇についてのエッセイがコツェブーの定期刊行物『Die Freimüthige』に掲載され、同誌の戯曲コンクールに応募した。ホフマンの作品は『賞』(Der Preis)と呼ばれ、戯曲を書くコンクールそのものだった。14本の応募があったが、100本のフリードリヒ・ドール賞に値するものはなかった。ベルリ ンの叔父J.L.ホフマン、叔母ゾフィー、ケーニヒスベルクのドーラ・ハットの死を経験した悲しい人生の中で、これは数少ない良い時だった[10]。 1804年の初め、彼はワルシャワに赴任した[11]。その途中、故郷を通りかかった彼は、ドラ・ハットの娘のひとりに出会った。ケーニヒスベルクに戻る ことはなかった。 ワルシャワ プロイセン領ポーランドで過ごした数年間は、ホフマンにとって人生で最も幸福なものであった。ワルシャワではベルリンで味わったのと同じ雰囲気を味わい、 ザカリアス・ヴェルナーとの友情を新たにし、後に伝記作家となるユリウス・エドゥアルド・イツィヒ(洗礼を受けた後にヒツィヒと改名)と呼ばれる隣人で法 学者仲間に出会った。イツィヒはベルリンのノルトシュテルン(北極星)と呼ばれる文学グループのメンバーで、ノヴァーリス、ルートヴィヒ・ティーク、アヒ ム・フォン・アルニム、クレメンス・ブレンターノ、ゴッティルフ・ハインリヒ・フォン・シューベルト、カルロ・ゴッツィ、カルデロンの作品をホフマンに与 えた。これらの比較的後期の紹介は、彼の作品に大きな影響を与えた。 彼は、アウグスト・ヴィルヘルム・シュレーゲル、アデルベルト・フォン・シャミッソ、フリードリヒ・ド・ラ・モット・フーケ、ラヘル・レヴィン、ダヴィッ ド・フェルディナンド・コレフのサークルで活動した。 1806年11月28日、第四次連合戦争の最中、ナポレオン・ボナパルト軍がワルシャワを占領し、プロイセンの官僚たちは職を失った。プロイセンの官僚た ちは職を失い、国庫の財産を山分けして逃亡した。1807年1月、ホフマンの妻と2歳の娘チェチーリアはポーゼンへ戻り、ホフマンはウィーンに移るかベル リンに戻るか思案した。重病のために6ヶ月の遅れが生じた。やがてフランス当局は、すべての元官吏に忠誠を誓うか国外退去を要求した。彼らはホフマンに ウィーンへのパスポートを与えることを拒否したため、彼はベルリンに戻ることを余儀なくされた。1807年6月18日にベルリンに到着する前に、ホフマン はポーゼンの家族を訪ねた。 ベルリンとバンベルク それからの15ヶ月は、ホフマンの人生の中でも最悪の時期であった。ベルリンはナポレオン軍に占領されていた。わずかな手当しかもらえず、友人たちにたび たび頼っては金を借り、それでも何日も空腹に耐えなければならなかった。それにもかかわらず、彼はアカペラ合唱のための「6つのカンティクル」を作曲する ことができた。これは彼の最高傑作のひとつであり、後に彼は『ミュラーの生涯』の中でクライスラーの作品であるとしている。  ホフマンが描いたクライスラーの肖像画 1808年9月1日、彼は妻と共にバンベルクに到着し、劇場支配人の仕事を始めた。演出家のゾーデン伯爵はすぐにヴュルツブルクへ去り、ハインリヒ・クー ノという男が責任者となった。ホフマンは公演の水準を向上させることができず、彼の努力は彼の陰謀を招き、結果的にクーノに職を奪われることになった。彼 はライプツィヒの新聞『Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung』の音楽評論家として仕事を始め、ベートーヴェンに関する彼の記事は特に評判が高く、作曲家本人からも高く評価された。カペルマイスター・ ヨハネス・クライスラー」というキャラクターが初めて登場したのも、この紙面だった。 リッター・グルック』は、作曲家クリストフ・ウィリバルト・グルック(1714-87)の死後20年以上経ってから、その人物に出会う、あるいは出会った と信じる男の物語である。このテーマは、その前の10年間にドッペルゲンガーという言葉を発明し、ホフマンに強い影響を与え続けたジャン・パウルの仕事を 暗示しており、彼の最も初期の崇拝者の一人となった。この出版を機に、ホフマンはE.T.A.ホフマンというペンネームを使い始め、作曲家ヴォルフガン グ・アマデウス・モーツァルト(1756-91)へのオマージュとして、「A」はアマデウスの略だと人々に語った。しかし、彼は生涯を通じて公式文書では ヴィルヘルムを使い続け、墓碑銘にもイニシャルE.T.W.が記されている。 翌年、彼はバンベルク劇場で舞台係、装飾係、劇作家として雇われ、同時に音楽の個人レッスンも行った。彼は若い歌の生徒ユリア・マルクに夢中になり、一緒 にいるときはいつも彼の気持ちが明らかであった。ヨーゼフ・セコンダがホフマンに、当時ドレスデンで上演していた自分の歌劇団の音楽監督としての地位をオ ファーすると、ホフマンはこれを受け入れ、1813年4月21日に退団した。 ドレスデンとライプツィヒ プロイセンは第6次連合戦争中の3月16日にフランスに宣戦布告しており、彼らの旅は困難を極めた。25日に到着した彼らは、セコンダがライプツィヒにい ることを知り、26日に一時的な資金を求める手紙を送った。同じ日、ホフマンは9年間会っていなかったヒッペルに会って驚いた。 状況は悪化し、5月初旬、ホフマンはライプツィヒへの輸送手段を見つけようとしたが無駄だった。5月8日、橋は破壊され、彼の家族は市内に取り残された。 日中、ホフマンは歩き回り、好奇心を持って戦闘を見守った。5月20日、彼らはライプツィヒに向かったが、馬車で乗客の一人が死亡し、妻が負傷する事故に 巻き込まれた。 5月23日に到着し、ホフマンはセコンダのオーケストラと仕事を始めた。6月4日、休戦協定が始まり、ホフマンはドレスデンに戻ることができた。しかし8 月22日、休戦協定終了後、一家は郊外の快適な家から街への移転を余儀なくされ、その後の数日間、ドレスデンの戦いは激しさを増した。街は砲撃され、多く の人々が彼の目の前で爆弾で殺された。主戦が終わった後、彼は悲惨な戦場を訪れた。彼の記録は『Vision auf dem Schlachtfeld bei Dresden』に掲載されている。長い騒乱が続いた後、11月11日に町は降伏し、12月9日に中隊はライプツィヒに向かった。 2月25日、ホフマンはセコンダと口論になり、翌日、12週間の解雇通告を受けた。4月にドレスデンへの旅に同行するよう求められたが、ホフマンはこれを 拒否し、一行はホフマンを置いて出発した。しかし、7月に友人のヒッペルが訪れ、ホフマンはすぐに、かつての法学者としてのキャリアに戻るよう導かれた。 ベルリン  E・T・A・ホフマンの墓。碑文を翻訳するとこうなる: E.T.W.ホフマン、1776年1月24日ケーニヒスベルク生まれ、1822年6月25日ベルリンにて死去、司法裁判所参事官、詩人として、音楽家とし て、画家として、その職務に秀でた、友人たちによって捧げられた。 1814年9月末、ナポレオンの敗戦を受け、ホフマンはベルリンに戻り、室内裁判所であるカンマーゲリヒトでの職を取り戻すことに成功した。彼のオペラ 『ウンディーネ』はベルリン劇場で上演された。その成功は、第25回公演の夜に起きた火災の後、幕を閉じた。雑誌は彼の寄稿を求め、しばらくして彼の水準 は下がり始めた。それでも、多くの傑作がこの時代に生まれた。 1819年からの間、ホフマンは体調不良と闘いながら、法的紛争に巻き込まれた。アルコールの濫用と梅毒のために、1821年には手足が弱り、1822年 の初めには麻痺を起こした。彼の最後の作品は、妻か秘書に口述筆記された。 メッテルニヒ公の反自由主義政策は、ホフマンを良心が試されるような状況に追い込み始めた。何千人もの人々が、特定の政治的意見を持ったという理由で反逆 罪に問われ、大学教授たちは講義中に監視された。 プロイセン国王フリードリヒ・ウィリアム3世は、政治的反体制を調査するための即時委員会を任命したが、その委員会が法の支配を遵守することがあまりにも 不満であると判断すると、そのプロセスに干渉するための大臣委員会を設置した。後者はカンプツ委員に大きな影響を受けた。体操協会運動の創始者である "ターンヴァーター "ヤーンの裁判の際、ホフマンはカンプツを困らせ、政治的標的となった。ホフマンが『マイスター・フロー』の中でカンプツを風刺すると、カンプツは法的手 続きを開始した。ホフマンの病気が命にかかわるものであることが判明し、訴訟は終結した。国王は譴責処分のみを求めたが、処分は下されなかった。結局、 『マイスター・フロー』は問題の箇所を削除して出版された。 ホフマンは1822年6月25日、梅毒のためベルリンで46歳の生涯を閉じた。彼の墓は、ベルリンのクロイツベルクにあるプロテスタント墓地 Friedhof III der Jerusalems- und Neuen Kirchengemeinde(エルサレム教会と新教会の信徒の墓地No.III)にある。 |

| Works For a more comprehensive list, see E. T. A. Hoffmann bibliography. Literary Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier (collection of previously published stories, 1814)[12] "Ritter Gluck", "Kreisleriana", "Don Juan", "Nachricht von den neuesten Schicksalen des Hundes Berganza" "Der Magnetiseur", "Der goldne Topf" (revised in 1819), "Die Abenteuer der Silvesternacht" Die Elixiere des Teufels (1815) Nachtstücke (1817) "Der Sandmann", "Das Gelübde", "Ignaz Denner", "Die Jesuiterkirche in G." "Das Majorat", "Das öde Haus", "Das Sanctus", "Das steinerne Herz" Seltsame Leiden eines Theater-Direktors (1819) Little Zaches (1819) Die Serapionsbrüder (1819) "Der Einsiedler Serapion", "Rat Krespel", "Die Fermate", "Der Dichter und der Komponist" "Ein Fragment aus dem Leben dreier Freunde", "Der Artushof", "Die Bergwerke zu Falun", "Nußknacker und Mausekönig" (1816) "Der Kampf der Sänger", "Eine Spukgeschichte", "Die Automate", "Doge und Dogaresse" "Alte und neue Kirchenmusik", "Meister Martin der Küfner und seine Gesellen", "Das fremde Kind" "Nachricht aus dem Leben eines bekannten Mannes", "Die Brautwahl", "Der unheimliche Gast" "Das Fräulein von Scuderi", "Spielerglück" (1819), "Der Baron von B." "Signor Formica", "Zacharias Werner", "Erscheinungen" "Der Zusammenhang der Dinge", "Vampirismus", "Die ästhetische Teegesellschaft", "Die Königsbraut" Prinzessin Brambilla (1820) Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (1820) "Die Irrungen" (1820) "Die Geheimnisse" (1821) "Die Doppeltgänger" (1821) Meister Floh (1822) "Des Vetters Eckfenster" (1822) Letzte Erzählungen (1825) Musical Vocal music Messa d-moll (1805) Trois Canzonettes à 2 et à 3 voix (1807) 6 Canzoni per 4 voci alla capella (1808) Miserere b-moll (1809) In des Irtisch weiße Fluten (Kotzebue), Lied (1811) Recitativo ed Aria „Prendi l'acciar ti rendo" (1812) Tre Canzonette italiane (1812); 6 Duettini italiani (1812) Nachtgesang, Türkische Musik, Jägerlied, Katzburschenlied für Männerchor (1819–21) Works for stage Die Maske (libretto by Hoffmann), Singspiel (1799) Die lustigen Musikanten (libretto: Clemens Brentano), Singspiel (1804) Incidental music to Zacharias Werner's tragedy Das Kreuz an der Ostsee (1805) Liebe und Eifersucht (libretto by Hoffmann after Calderón, translated by August Wilhelm Schlegel) (1807) Arlequin, ballet (1808) Der Trank der Unsterblichkeit (libretto: Julius von Soden), romantic opera (1808) Wiedersehn! (libretto by Hoffmann), prologue (1809) Dirna (libretto: Julius von Soden), melodrama (1809) Incidental music to Julius von Soden's drama Julius Sabinus (1810) Saul, König von Israel (libretto: Joseph von Seyfried), melodrama (1811) Aurora (libretto: Franz von Holbein), heroic opera (1812) Undine (libretto: Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué), Zauberoper (1816) Der Liebhaber nach dem Tode (unfinished) Instrumental Rondo für Klavier (1794/95) Ouvertura. Musica per la chiesa d-moll (1801) Klaviersonaten: A-Dur, f-moll, F-Dur, f-moll, cis-moll (1805–1808) Große Fantasie für Klavier (1806) Sinfonie Es-Dur (1806) Harfenquintett c-moll (1807) Grand Trio E-Dur (1809) Walzer zum Karolinentag (1812) Teutschlands Triumph in der Schlacht bei Leipzig, (by "Arnulph Vollweiler", 1814; lost) Serapions-Walzer (1818–1821) |

"Don Juan"は、1813年に新聞に発表される。 |

Assessment Statue of "E. T. A. Hoffmann and his cat" in Bamberg Hoffmann is one of the best-known representatives of German Romanticism, and a pioneer of the fantasy genre, with a taste for the macabre combined with realism that influenced such authors as Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), Nikolai Gogol[13][14] (1809–1852), Charles Dickens (1812–1870), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), George MacDonald (1824–1905),[15] Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), Vernon Lee (1856–1935),[16] Franz Kafka (1883–1924) and Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980). Hoffmann's story Das Fräulein von Scuderi is sometimes cited as the first detective story and a direct influence on Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue";[17] Characters from it also appear in the opera Cardillac by Paul Hindemith. The twentieth-century Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin characterised Hoffmann's works as Menippea, essentially satirical and self-parodying in form, thus including him in a tradition that includes Cervantes, Diderot and Voltaire. Robert Schumann's piano suite Kreisleriana (1838) takes its title from one of Hoffmann's books (and according to Charles Rosen's The Romantic Generation, is possibly also inspired by "The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr", in which Kreisler appears).[4] Jacques Offenbach's masterwork, the opera Les contes d'Hoffmann ("The Tales of Hoffmann", 1881), is based on the stories, principally "Der Sandmann" ("The Sandman", 1816), "Rat Krespel" ("Councillor Krespel", 1818), and "Das verlorene Spiegelbild" ("The Lost Reflection") from Die Abenteuer der Silvester-Nacht (The Adventures of New Year's Eve, 1814). Klein Zaches genannt Zinnober (Little Zaches called Cinnabar, 1819) inspired an aria as well as the operetta Le Roi Carotte, 1872). Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker (1892) is based on "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King", and the ballet Coppélia, with music by Delibes, is based on two eerie Hoffmann stories. Hoffmann also influenced 19th-century musical opinion directly through his music criticism. His reviews of Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808) and other important works set new literary standards for writing about music, and encouraged later writers to consider music as "the most Romantic of all the arts."[18] Hoffmann's reviews were first collected for modern readers by Friedrich Schnapp, ed., in E.T.A. Hoffmann: Schriften zur Musik; Nachlese (1963) and have been made available in an English translation in E.T.A. Hoffmann's Writings on Music, Collected in a Single Volume (2004).  Hoffmann's drawing of himself, riding on Tomcat Murr and fighting "Prussian bureaucracy" Hoffmann strove for artistic polymathy. He created far more in his works than mere political commentary achieved through satire. His masterpiece novel Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr, 1819–1821) deals with such issues as the aesthetic status of true artistry and the modes of self-transcendence that accompany any genuine endeavour to create. Hoffmann's portrayal of the character Kreisler (a genius musician) is wittily counterpointed with the character of the tomcat Murr – a virtuoso illustration of artistic pretentiousness that many of Hoffmann's contemporaries found offensive and subversive of Romantic ideals. Hoffmann's literature indicates the failings of many so-called artists to differentiate between the superficial and the authentic aspects of such Romantic ideals. The self-conscious effort to impress must, according to Hoffmann, be divorced from the self-aware effort to create. This essential duality in Kater Murr is conveyed structurally through a discursive 'splicing together' of two biographical narratives. Science fiction While disagreeing with E. F. Bleiler's claim that Hoffmann was "one of the two or three greatest writers of fantasy", Algis Budrys of Galaxy Science Fiction said that he "did lay down the groundwork for some of our most enduring themes".[19] Historian Martin Willis argues that Hoffmann's impact on science fiction has been overlooked, saying "his work reveals a writer dynamically involved in the important scientific debates of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries." Willis points out that Hoffmann's work is contemporary with Frankenstein (1818) and with "the heated debates and the relationship between the new empirical science and the older forms of natural philosophy that held sway throughout the eighteenth century." His "interest in the machine culture of his time is well represented in his short stories, of which the critically renowned The Sandman (1816) and Automata (1814) are the best examples. ...Hoffmann's work makes a considerable contribution to our understanding of the emergence of scientific knowledge in the early years of the nineteenth century and to the conflict between science and magic, centred mainly on the 'truths' available to the advocates of either practice. ...Hoffmann's balancing of mesmerism, mechanics, and magic reflects the difficulty in categorizing scientific knowledge in the early nineteenth century."[20] |

評価 バンベルクの「E・T・A・ホフマンと猫」像 エドガー・アラン・ポー(1809-1849)、ニコライ・ゴーゴリ[13][14](1809-1852)、チャールズ・ディケンズ(1812- 1870)、シャルル・ボードレール(1821-1867)、ジョージ・マクデレール(1821-1867)などに影響を与えた、 チャールズ・ディケンズ(1812-1870)、シャルル・ボードレール(1821-1867)、ジョージ・マクドナルド(1824-1905)、フョー ドル・ドストエフスキー(1821-1881)、ヴァーノン・リー(1856-1935)、フランツ・カフカ(1883-1924)[16]、アルフレッ ド・ヒッチコック(1899-1980)らに影響を与えた。ホフマンの『スクデリ嬢の物語』は、最初の探偵小説として、またポーの『モルグ街の殺人』に直 接影響を与えた作品として挙げられることもある[17]。 20世紀ロシアの文学理論家ミハイル・バフチンは、ホフマンの作品をメニッペアと呼び、本質的に風刺的でセルフ・パロディ的な形式をとっているとし、セルバンテス、ディドロ、ヴォルテールを含む伝統に彼を含めている。 ロベルト・シューマンのピアノ組曲『クライスレリアーナ』(1838年)のタイトルは、ホフマンの著書の1冊から取られている(チャールズ・ローゼンの 『ロマン派世代』によれば、クライスラーが登場する『トムキャット・ムールの人生と意見』からも着想を得ている可能性がある)。 [ジャック・オッフェンバックの代表作であるオペラ『ホフマン物語』(Les contes d'Hoffmann、1881年)は、主に『サンドマン』(Der Sandmann、1816年)、『ラト・クレスペル』(Rat Krespel、1818年)、『ジルヴェスター・ナハトの冒険』(Die Abenteuer der Silvester-Nacht、1814年)の『失われたシュピーゲルビルト』(Das verlorene Spiegelbild、1814年)の物語に基づいている。) クライン・ザッヘス・ジェナント・ジンノーバー(辰砂と呼ばれる小さなザッヘス、1819年)は、オペレッタ『ル・ロワ・カロット』(1872年)と同様 に、アリアを作曲した。ピョートル・イリイチ・チャイコフスキーのバレエ『くるみ割り人形』(1892年)は『くるみ割り人形とねずみの王様』に基づいて おり、デリーベが音楽を担当したバレエ『コッペリア』は不気味なホフマンの2つの物語に基づいている。 ホフマンはまた、その音楽批評を通して19世紀の音楽論にも直接影響を与えた。ベートーヴェンの交響曲第5番ハ短調作品67(1808年)やその他の重要 な作品に対する彼の批評は、音楽について書くための新しい文学的基準を打ち立て、後世の作家たちに音楽を「あらゆる芸術の中で最もロマンティックなもの」 と考えるよう促した[18]。  トムキャット・ムールに乗り、"プロイセン官僚主義 "と戦うホフマンのデッサン。 ホフマンは芸術的多義性を追求した。彼の作品には、風刺によって達成される単なる政治的コメント以上のものがある。彼の代表作『トムキャット・ムールの人 生と意見』(Lebensansichten des Katers Murr, 1819-1821)は、真の芸術の美的地位や、真の創造的努力に伴う自己超越の様式といった問題を扱っている。ホフマンが描くクライスラー(天才音楽 家)のキャラクターは、猫のムルというキャラクターと軽妙に対比されている。 ホフマンの文学は、芸術家と呼ばれる人たちの多くが、ロマン派の理想の表面的な面と本物の面を区別することに失敗していることを示している。ホフマンによ れば、印象づけようとする自己意識的な努力は、創造しようとする自己意識的な努力から切り離されなければならない。ケーター・ムール』におけるこの本質的 な二面性は、2つの伝記的な物語を「つなぎ合わせる」という言説によって構造的に表現されている。 サイエンス・フィクション ホフマンは「ファンタジーの二、三大作家の一人」であるというE・F・ブレイラーの主張には同意できないが、『ギャラクシー・サイエンス・フィクション』のアルジス・バドリスは、彼は「われわれの最も永続的なテーマのいくつかの基礎を築いた」と述べている[19]。 歴史家のマーティン・ウィリスは、ホフマンがSFに与えた影響は見過ごされてきたと主張し、「彼の作品は、18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけての重要な 科学論争にダイナミックに関与した作家であることを明らかにしている」と述べている。ウィリスは、ホフマンの作品が『フランケンシュタイン』(1818 年)と同時代であり、"18世紀を通じて支配的であった、新しい経験科学と古い自然哲学の間の熱い議論と関係 "と指摘している。彼の「当時の機械文化への関心は短編小説によく表れており、中でも批評的に有名な『サンドマン』(1816年)と『オートマタ』 (1814年)はその最たるものである。...ホフマンの作品は、19世紀初頭における科学的知識の出現と、科学と魔術の対立を理解する上で、多大な貢献 を果たしている。...ホフマンのメスメリズム、機械学、魔術のバランス感覚は、19世紀初頭における科学知識の分類の難しさを反映している」[20]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._T._A._Hoffmann |

|

| The genre of Menippean satire

is a form of satire, usually in prose, that is characterized by

attacking mental attitudes rather than specific individuals or

entities.[1] It has been broadly described as a mixture of allegory,

picaresque narrative, and satirical commentary.[2] Other features found

in Menippean satire are different forms of parody and mythological

burlesque,[3] a critique of the myths inherited from traditional

culture,[3] a rhapsodic nature, a fragmented narrative, the combination

of many different targets, and the rapid moving between styles and

points of view.[4] The term is used by classical grammarians and by philologists mostly to refer to satires in prose (cf. the verse Satires of Juvenal and his imitators). Social types attacked and ridiculed by Menippean satires include "pedants, bigots, cranks, parvenus, virtuosi, enthusiasts, rapacious and incompetent professional men of all kinds," although they are addressed in terms of "their occupational approach to life as distinct from their social behavior ... as mouthpieces of the idea they represent".[1][5] Characterization in Menippean satire is more stylized than naturalistic, and presents people as an embodiment of the ideas they represent.[1] The term Menippean satire distinguishes it from the earlier satire pioneered by Aristophanes, which was based on personal attacks.[6] Origins The form is named after the third-century-BC Greek cynic parodist and polemicist Menippus.[7] His works, now lost, influenced the works of Lucian (2nd century AD) and Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC), the latter being the first to identify the genre by referring to his own satires as saturae menippeae; such satires are sometimes also termed Varronian satire. According to Mikhail Bakhtin, the genre itself was in existence prior to Menippus, with authors such as Antisthenes (c. 446 – c. 366 BC), Heraclides Ponticus (c. 390 BC – c. 310 BC)) and Bion of Borysthenes (c. 325 – c. 250 BC).[8] Classical tradition Varro's own 150 books of Menippean satires survive only through quotations. The genre continued with Seneca the Younger, whose Apocolocyntosis, or "Pumpkinification", is the only near-complete classical Menippean satire to survive. It consisted in an irreverent parody of the deification of Emperor Claudius.[7] The Menippean tradition is also evident in Petronius' Satyricon, especially in the banquet scene "Cena Trimalchionis", which combines epic form, tragedy, and philosophy with verse and prose. Both Satyricon and Apuleius' Metamorphoses (The Golden Ass), are Menippea "extended to the limits of the novel".[9] The most complete picture of the genre in ancient times is to be found in the satires of Lucian.[10] The influence of Menippean satire can be found in ancient Greek novels, in the Roman satires of Gaius Lucilius and Horace, and in early Christian literature, including the Gospels.[11][12] Later examples include The Consolation of Philosophy of Boethius[13] and The Caesars of Julian the apostate.[14] Characteristics Bakhtin identifies a number of basic characteristics that distinguish Menippean satire from comparable genres in antiquity:[15] There is a significantly heightened comic element, although there are exceptions (for example in Boethius). There is an extraordinary freedom of plot and philosophical invention. It is not bound by the orthodoxies of legend, or by the need for historical or everyday realism, even when its central characters are based on legendary or historical figures. It freely operates in the realm of "the fantastic". The unrestrained use of the fantastic is internally motivated by a philosophical objective: a philosophical idea, embodied in a seeker of truth, is tested in extraordinary situations. Fantastic and mystical elements are combined with a crude slum naturalism: the 'testing of the idea' never avoids the degenerate or grotesque side of earthly existence. The man of the idea encounters "worldly evil, depravity, baseness and vulgarity in their most extreme expression". The ideas being tested are always of an "ultimate" nature. Merely intellectual or academic problems or arguments had no place: the whole man and his whole life are at stake in the process of the testing of his idea. Everywhere there is the "stripped down pro et contra of life's ultimate questions". A three-planed construction—Earth, Olympus and the nether-world—is apparent. Action and dialogue frequently take place on the "threshold" between the planes. An experimental fantasticality in narrative point of view appears, for example the "view from above" (kataskopia). An experimentation with psychopathological states of mind – madness, split personality, unrestrained daydreaming, weird dreams, extreme passions, suicides etc. Such phenomena function in the Menippea to destabilize the unity of an individual and his fate – a unity that is always assumed in other genres such as the epic. The person discovers other possibilities than those apparently preordained in himself and his life: "he loses his finalized quality and ceases to mean only one thing; he ceases to coincide with himself". This non-finalization and non-coincidence is facilitated by a rudimentary form of "dialogic relationship to one's own self". Breaches of conventional behaviour and disruptions to the customary course of events are characteristic of the Menippea. Scandals and eccentricities have the same function in 'the world' that mental disorders have in 'the individual' – they shatter the fragile unity and stability of the established order and the 'normal', expected course of events. The inappropriate, cynical word that unmasks a false idol or an empty social convention is similarly characteristic. Sharp contrasts, abrupt transitions, oxymoronic combinations, counterintuitive comparisons and unexpected meetings between unrelated things are essential to the Menippea. Opposites are brought together, or united in a single character – the noble criminal, the virtuous courtesan, the emperor who becomes a slave. There is often an element of social utopia, usually in the form of a dream or journey to an unknown land. Widespread use of inserted genres such as novellas, letters, speeches, diatribes, soliloquys, symposia, and poetry, frequently of a parodic nature. A sharp satirical focus on a wide variety of contemporary ideas and issues. Despite the apparent heterogeneity of these characteristics, Bakhtin emphasizes the "organic unity" and the "internal integrity" of the genre. He argues that Menippean satire is the best expression and the truest reflection of the social-philosophical tendencies of the epoch in which it flowered. This was the epoch of the decline of national legend, the disintegration of associated ethical norms, and the concomitant explosion of new religious and philosophical schools vying with each other over "ultimate questions". The "epic and tragic wholeness of a man and his fate" lost its power as a social and literary ideal, and consequently social 'positions' became devalued, transformed into 'roles' played out in a theatre of the absurd. Bakhtin argues that the generic integrity of Menippean satire in its expression of a decentred reality is a quality that has enabled it to exercise an immense influence over the development of European novelistic prose.[16] According to Bakhtin, the cultural force that underpins the integrity and unity of Menippean satire as a genre, despite its extreme variability and the heterogeneity of its elements, is carnival. The genre epitomises the transposition of the "carnival sense of the world" into the language and forms of literature, a process Bakhtin refers to as Carnivalisation. Carnival as a social event is "syncretic pageantry of a ritualistic sort": its essential elements were common to a great diversity of times and places, and over time became deeply rooted in the individual and collective psyche. These elements revolved around the suspension of the laws, prohibitions and restrictions that governed the structure of ordinary life, and the acceptance and even celebration of everything that was hidden or repressed by that structure.[17] The apparently heterogeneous characteristics of Menippean satire can, in essence, be traced back to the "concretely sensuous forms" worked out in the carnival tradition and the unified "carnival sense of the world" that grew out of them.[18] Later examples In a series of articles, Edward Milowicki and Robert Rawdon Wilson, building upon Bakhtin's theory, have argued that Menippean is not a period-specific term, as many Classicists have claimed, but a term for discursive analysis that instructively applies to many kinds of writing from many historical periods including the modern. As a type of discourse, “Menippean” signifies a mixed, often discontinuous way of writing that draws upon distinct, multiple traditions. It is normally highly intellectual and typically embodies an idea, an ideology or a mind-set in the figure of a grotesque, even disgusting, comic character. The form was revived during the Renaissance by Erasmus, Burton, and Laurence Sterne,[19] while 19th-century examples include the John Buncle of Thomas Amory and The Doctor of Robert Southey.[19] The 20th century saw renewed critical interest in the form, with Menippean satire significantly influencing postmodern literature.[3] Among the works that contemporary scholars have identified as growing out of the Menippean tradition are: Erasmus, In Praise of Folly (1509)[20] François Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel (1564)[21] John Barclay, Euphormionis Satyricon (1605)[2] Joseph Hall, Mundus Alter et Idem (1605)[2] Miguel Cervantes, Novelas ejemplares (1612)[22] Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621)[21][23] Jonathan Swift, A Tale of a Tub and Gulliver's Travels (1726)[24] Voltaire, Candide (1759)[21] William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1794)[25] Thomas Love Peacock, Nightmare Abbey (1818)[21] Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus (1836)[26] Nikolai Gogol, "Dead Souls" (1842)[27] Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland (1865)[23] Fyodor Dostoevsky, Bobok (1873)[28] Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (1877)[29] Aldous Huxley, Point Counter Point (1928)[21] James Joyce, Finnegans Wake (1939)[30] Flann O'Brien, The Third Policeman (1939)[31] Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita (1967)[32] Martin Amis, Dead Babies (novel) (1975)[33] Terry Gilliam, Brazil (1985)[34] Dave Eggers, The Circle (2013)[35] According to P. Adams Sitney in "Visionary Film", Mennipea became the dominant new genre in avant-garde cinema at the turn of the century. Filmmakers he cited include Yvonne Rainer, Sidney Peterson, Michael Snow, and Hollis Frampton.[36] For Bakhtin, Menippean satire as a genre reached its summit in the modern era in the novels and short stories of Dostoevsky. He argues that all the characteristics of the ancient Menippea are present in Dostoevsky but in a highly developed and more complex form. This was not because Dostoevsky intentionally adopted and expanded it as a form: his writing was not in any sense a stylization of the ancient genre. Rather it was a creative renewal based in an instinctive recognition of its potential as a form through which to express the philosophical, spiritual and ideological ferment of his time. It could be said that "it was not Dostoevsky's subjective memory, but the objective memory of the very genre in which he worked, that preserved the peculiar features of the ancient menippea." The generic features of Menippean satire were the ground on which Dostoevsky was able to build a new literary genre, which Bakhtin calls Polyphony.[37] Frye's definition Critic Northrop Frye said that Menippean satire moves rapidly between styles and points of view.[citation needed] Such satires deal less with human characters than with the single-minded mental attitudes, or "humours", that they represent: the pedant, the braggart, the bigot, the miser, the quack, the seducer, etc. Frye observed, The novelist sees evil and folly as social diseases, but the Menippean satirist sees them as diseases of the intellect […][23] He illustrated this distinction by positing Squire Western (from Tom Jones) as a character rooted in novelistic realism, but the tutors Thwackum and Square as figures of Menippean satire. Frye found the term 'Menippean satire' to be "cumbersome and in modern terms rather misleading", and proposed as replacement the term 'anatomy' (taken from Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy). In his theory of prose fiction it occupies the fourth place with the novel, romance and confession.[23] |

メニッペ風刺のジャンルは、通常は

散文による風刺の一形態であり、特定の個人や団体を攻撃するのではなく、精神的態度を攻撃することを特徴とする[1]。

[2]メニッペ風刺に見られる他の特徴としては、様々な形式のパロディや神話的バーレスク、[3]伝統文化から受け継いだ神話への批判、[3]狂言的な性

質、断片的な物語、多くの異なる対象の組み合わせ、様式や視点間の急速な移動などが挙げられる[4]。 この用語は、古典的な文法学者や言語学者によって、主に散文による風刺(ユヴェナールとその模倣者の詩による風刺を参照)を指すために使用されている。メ ニッペ風刺によって攻撃され、嘲笑される社会的タイプには、「女衒、偏屈者、変人、パルヴェヌス、ヴィルトゥオーゾ、マニア、強欲で無能なあらゆる種類の 職業人」が含まれる。1][5]メニッペ風刺における人物描写は、自然主義的というよりは様式化されたものであり、人々を、彼らが代表する思想の体現とし て提示する。 メニッペ風刺という用語は、個人的な攻撃に基づいていたアリストファネスによって開拓された以前の風刺と区別するものである[6]。 起源 メニッペ風刺は、紀元前3世紀のギリシアのパロディストでありポレミストであったメニッポスにちなんで命名された[7]。現在では失われている彼の作品 は、ルキアヌス(紀元後2世紀)やマルクス・テレンティウス・ヴァッロ(紀元前116-27年)の作品に影響を与え、ヴァッロは自身の風刺を saturae menippeaeと呼ぶことで初めてこのジャンルを特定した。ミハイル・バフチンによれば、このジャンル自体はメニッポス以前から存在しており、アン ティステネス(紀元前446年頃~紀元前366年頃)、ヘラクリデス・ポンティコス(紀元前390年頃~紀元前310年頃)、ボリステネスのビオン(紀元 前325年頃~紀元前250年頃)といった作家がいた[8]。 古典の伝統 ヴァッロ自身の150冊のメニッペ風刺は、引用によってのみ残っている。このジャンルは若きセネカにも受け継がれ、セネカの Apocolocyntosis(「パンプキン化」)は、現存する古典的メニッペ風刺の中で唯一ほぼ完全なものである。メニッペの伝統はペトロニウスの 『サテュリコン』にも見られ、特に宴会の場面「ケーナ・トリマルキオニス」は叙事詩と散文に叙事詩、悲劇、哲学を組み合わせたものである。サテュリコン』 とアプレイウスの『変身物語』(『黄金の驢馬』)はともに、メニッペアを「小説の限界まで拡張」したものである。 [10]メニッペ風刺の影響は古代ギリシアの小説、ガイウス・ルシリウスやホラーチェのローマ風刺、福音書を含む初期キリスト教文学にも見られる[11] [12]。後世の例としてはボエティウスの『哲学の慰め』[13]や背教者ユリアヌスの『シーザー』などがある[14]。 特徴 バフチンはメニッペ風刺を古代における類似のジャンルと区別するいくつかの基本的な特徴を挙げている[15]。 例外もあるが(例えばボエティウス)、コミカルな要素が著しく強調されている。 プロットと哲学的発明の自由度が並外れて高い。中心人物が伝説上の人物や歴史上の人物に基づいている場合でも、伝説の正統性や歴史的・日常的リアリズムの必要性に縛られることはない。ファンタジー」の領域で自由に活動するのだ。 ファンタジーの自由奔放な使用は、内面的には哲学的な目的に突き動かされている。真理の探求者の中に具現化された哲学的思想が、非日常的な状況の中で試されるのだ。 幻想的で神秘的な要素は、粗野なスラムの自然主義と組み合わされる。「思想のテスト」は、地上存在の退廃的でグロテスクな側面を決して避けることはない。アイデアの持ち主は、「世俗の悪、堕落、卑しさ、下品さを極限まで表現したもの」に遭遇する。 試される思想は常に「究極」の性質を持つ。単に知的な、あるいは学問的な問題や議論は、その場には存在しない。自分の思想が試される過程では、人間全体と その人生全体がかかっているのだ。いたるところに、「人生の究極的な問いに対するプロとコントラが剥き出しになっている」のである。 地球、オリンポス、冥界という3つの平面構造が明白である。アクションと対話は、各プレーンの間の「境界線」で頻繁に行われる。 例えば「上からの眺め」(カタスコピア)のように、物語の視点に実験的な幻想性が現れる。 精神病理学的精神状態の実験-狂気、分裂人格、自由奔放な白昼夢、奇妙な夢、極度の激情、自殺など。このような現象は、『メニッペア』において、個人とそ の運命の一体性--叙事詩のような他のジャンルでは常に想定されている一体性--を不安定にするために機能している。その人物は、自分自身とその人生にお いて、明らかにあらかじめ定められた可能性とは別の可能性を発見するのである。この非最終化と非同一化は、初歩的な形の「自己との対話的関係」によって促 進される。 メニッペアの特徴として、慣習にとらわれない行動や慣習的な出来事への混乱がある。スキャンダルや奇行は、精神障害が「個人」において持っているのと同じ 機能を「世界」において持っている。つまり、既成の秩序や「正常な」期待された出来事の流れの脆弱な統一性や安定性を打ち砕くのである。偽りの偶像や空虚 な社会通念の正体を暴く不適切で皮肉な言葉も、同様に特徴的である。 鋭い対比、突然の転換、矛盾した組み合わせ、直感に反する比較、無関係なもの同士の予期せぬ出会いは、メニッペアに欠かせない。高貴な犯罪者、高潔な宮廷女官、奴隷となった皇帝など、相反するものが一体となったり、ひとつの人物の中で結びついたりする。 しばしば社会的ユートピアの要素が、夢や未知の土地への旅という形で登場する。 小説、書簡、演説、放言、独り言、シンポジウム、詩などの挿入されたジャンルが広く使われ、しばしばパロディ的な性質を持つ。 現代のさまざまな思想や問題を鋭く風刺している。 これらの特徴が明らかに異質であるにもかかわらず、バフチンはこのジャンルの「有機的統一性」と「内的完全性」を強調している。彼は、メニッペ風刺は、そ れが花開いた時代の社会哲学的傾向を最もよく表現し、最も忠実に反映していると主張する。この時代は、国家伝説の衰退、関連する倫理規範の崩壊、それに伴 う新しい宗教的・哲学的学派の爆発的な増加の時代であり、「究極の問題」をめぐって互いに争っていた。人間とその運命の叙事詩的で悲劇的な全体性」は、社 会的・文学的理想としての力を失い、その結果、社会的な「立場」は軽んじられ、不条理劇場で演じられる「役割」へと変化した。バフチンは、メニッペ風刺が まっとうな現実を表現しているという一般的な完全性が、ヨーロッパの小説的散文の発展に絶大な影響を及ぼすことを可能にした質であると論じている [16]。 バフチンによれば、その極端な多様性と要素の異質性にもかかわらず、ジャンルとしてのメニッペ風刺の完全性と統一性を支えている文化的な力はカーニバルで ある。このジャンルは、「カーニバルの世界観」を文学の言語と形式に移し替えた典型であり、バフチンはこのプロセスを「カーニバル化」と呼んでいる。社会 的なイベントとしてのカーニバルは、「儀式的な一種のシンクレティックなページェントリー」である。その本質的な要素は、時代や場所の多様性に共通するも のであり、時間の経過とともに、個人や集団の精神に深く根付いていった。これらの要素は、日常生活の構造を支配している法律、禁止事項、制限の停止、そし てその構造によって隠されたり抑圧されたりしているすべてのものの受容と祝福を中心に展開されていた[17]。メニッペ風刺の一見異質な特徴は、要する に、カーニバルの伝統の中で作り上げられた「具体的に感覚的な形式」と、そこから芽生えた統一された「カーニバルの世界観」にまで遡ることができる [18]。 後の例 エドワード・ミロウィッキーとロバート・ロードン・ウィルソンは一連の論文において、バフチンの理論に基づき、メニッペは多くの古典主義者が主張するよう な時代特有の用語ではなく、近代を含む多くの歴史的時代の多くの種類の文章に有益に適用される言説分析のための用語であると主張している。言説の一種とし て、「メニッペ」は、異なる複数の伝統に依拠した、混在した、しばしば不連続な書き方を意味する。通常、メニッペは非常に知的であり、グロテスクな、さら には嫌悪感を抱かせるような滑稽な人物の姿に、思想やイデオロギー、あるいは心構えを具現化するのが一般的である。 この形式はルネサンス期にエラスムス、バートン、ローレンス・スターンによって復活し[19]、19世紀の例としてはトマス・エイモリーの『ジョン・バン クル』やロバート・サウシーの『博士』などがある[19]。20世紀にはこの形式に対する批評家の関心が再び高まり、メニッペ風刺はポストモダン文学に大 きな影響を与えた[3]。現代の研究者がメニッペの伝統から発展したと認定している作品には以下のようなものがある: エラスムス『愚行礼賛』(1509年)[20]。 フランソワ・ラブレー『ガルガンチュアとパンタグリュエル』(1564年)[21]。 ジョン・バークレイ『ユーフォミオーニス・サテュリコン』(1605年)[2]。 ジョセフ・ホール『ムンドゥス・アルター・エ・アイデム』(1605年)[2] ミゲル・セルバンテス『小説の模範』(1612年)[22]。 ロバート・バートン『憂鬱の解剖学』(1621年)[21][23]。 ジョナサン・スウィフト『桶物語』と『ガリバー旅行記』(1726年)[24]。 ヴォルテール『キャンディード』(1759年)[21]。 ウィリアム・ブレイク『天国と地獄の結婚』(1794年)[25]。 トマス・ラヴ・ピーコック『悪夢の修道院』(1818年)[21] トマス・カーライル『サルトル・レザルトゥス』(1836年)[26]。 ニコライ・ゴーゴリ『死霊』(1842年)[27]。 ルイス・キャロル『不思議の国のアリス』(1865年)[23]。 フョードル・ドストエフスキー『ボーボック』(1873年)[28] フョードル・ドストエフスキー『滑稽な男の夢』(1877年)[29]。 オルダス・ハクスリー『ポイント・カウンター・ポイント』(1928年)[21] ジェイムズ・ジョイス『フィネガンズ・ウェイク』(1939年)[30]。 フラン・オブライエン『第三の警官』(1939年)[31]。 ミハイル・ブルガーコフ『巨匠とマルガリータ』(1967年)[32] マーティン・エイミス『デッド・ベイビーズ』(小説)(1975年)[33]。 テリー・ギリアム『ブラジル』(1985年)[34] デイヴ・エガーズ『ザ・サークル』(2013年)[35]。 P.アダムス・シットニーの『ビジョナリー・フィルム』によれば、メニペアは世紀末の前衛映画において支配的な新ジャンルとなった。彼が挙げた映画作家には、イヴォンヌ・ライナー、シドニー・ピーターソン、マイケル・スノウ、ホリス・フランプトンがいる[36]。 バフチンにとって、ジャンルとしてのメニッペ風刺は、ドストエフスキーの小説と短編において、近代において頂点に達した。彼は、古代のメニッペアの特徴は すべてドストエフスキーの中に存在するが、高度に発達し、より複雑な形になっていると主張する。これは、ドストエフスキーが意図的にメニッペアを形式とし て採用し、拡大したからではない。彼の文章は、ある意味で古代のジャンルの様式化ではなかった。むしろそれは、彼の時代の哲学的、精神的、イデオロギー的 発酵を表現する形式としての可能性を本能的に認識した上での創造的刷新であった。ドストエフスキーの主観的な記憶ではなく、彼が仕事をしたジャンルそのも のの客観的な記憶が、古代のメニッペアの独特な特徴を保存していたのだ」と言える。メニッペ風刺の一般的な特徴は、ドストエフスキーがバフチンがポリフォ ニーと呼ぶ新しい文学ジャンルを構築することができた根拠であった[37]。 フライの定義 批評家ノースロップ・フライは、メニッペ風刺は様式と視点の間を素早く移動すると述べている。このような風刺は、人間の登場人物というよりも、それらが表現する一途な精神的態度、すなわち「ユーモア」を扱っている。フライはこう述べている、 小説家は悪や愚かさを社会的な病気として見るが、メニッペ風刺作家はそれらを知性の病気として見る[...][23]。 彼はこの区別を、(『トム・ジョーンズ』の)従者ウェスタンを小説的リアリズムに根ざした人物とし、家庭教師のトゥワッカムとスクエアをメニッペ風刺の人物とすることで説明した。 フライは、「メニッペ風刺」という用語は「煩雑であり、現代的な用語としてはむしろ誤解を招きやすい」と考え、それに代わる用語として「解剖学」(バート ンの『憂鬱の解剖学』から引用)を提案した。彼の散文小説論において、それは小説、ロマンス、告白と並ぶ第4の地位を占めている[23]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menippean_satire |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆