エドワード・オズボーン・ウィルソン

Edward Osborne Wilson, 1929-2021

☆

エドワード・オズボーン・ウィルソン(Edward Osborne Wilson、1929年6月10日 -

2021年12月26日)は、社会生物学の分野を開拓したことで知られるアメリカの生物学者、自然主義者、生態学者、昆虫学者である。

アラバマ州で生まれたウィルソンは、幼い頃から自然に興味を持ち、アウトドアに親しんだ。7歳の時に釣り中の事故で視力を一部失明し、視力が低下したこと

でウィルソンは昆虫学を研究することを決意した。アラバマ大学を卒業後、ウィルソンはハーバード大学に編入し、複数の分野で頭角を現した。1956年に

は、性格転位理論を定義する論文を共同執筆した。1967年には、ロバート・マッカーサーとともに島嶼生物地理学説を展開した。

ウィルソンは、ハーバード大学有機体進化生物学部のペレグリン大学特別研究教授(名誉教授)であり、デューク大学の講師でもあった。また、懐疑的調査委員

会の研究員でもあった。スウェーデン王立科学アカデミーはウィルソンにクラフォード賞を授与した。彼は国際人文主義アカデミーの人文主義者賞受賞者であっ

た。[3][4]

彼はピューリッツァー賞一般ノンフィクション部門を2度受賞している(1979年の『人間の本性について』、1991年の『蟻』)。また、『地球の社会的

征服』、『若い科学者への手紙』、『人間の存在の意味』はニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のベストセラーとなった。

ウィルソンの作品は、存命中から賞賛と批判の両方を集めた。彼の著書『社会生物学』は特に論争の火種となり、社会生物学研究会から批判を受けた。[7]

[8] ウィルソンの進化論の解釈は、リチャード・ドーキンスとの論争として広く報道された。[9]

彼の死後、手紙の調査により、彼は心理学者のJ.フィリップ・ラシュトンを支持していたことが明らかになった。ラシュトンの人種と知能に関する研究は、科学界では広く欠陥が多く人種差別的であるとみなされている。[10][11]

| Edward

Osborne Wilson ForMemRS (June 10, 1929 – December 26, 2021) was an

American biologist, naturalist, ecologist, and entomologist known for

developing the field of sociobiology. Born in Alabama, Wilson found an early interest in nature and frequented the outdoors. At age seven, he was partially blinded in a fishing accident; due to his reduced sight, Wilson resolved to study entomology. After graduating from the University of Alabama, Wilson transferred to complete his dissertation at Harvard University, where he distinguished himself in multiple fields. In 1956, he co-authored a paper defining the theory of character displacement. In 1967, he developed the theory of island biogeography with Robert MacArthur. Wilson was the Pellegrino University Research Professor Emeritus in Entomology for the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, a lecturer at Duke University,[2] and a fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. The Royal Swedish Academy awarded Wilson the Crafoord Prize. He was a humanist laureate of the International Academy of Humanism.[3][4] He was a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction (for On Human Nature in 1979, and The Ants in 1991) and a New York Times bestselling author for The Social Conquest of Earth,[5] Letters to a Young Scientist,[5][6] and The Meaning of Human Existence. Wilson's work received both praise and criticism during his lifetime. His book Sociobiology was a particular flashpoint for controversy, and drew criticism from the Sociobiology Study Group.[7][8] Wilson's interpretation of the theory of evolution resulted in a widely reported dispute with Richard Dawkins.[9] Examinations of his letters after his death revealed that he had supported the psychologist J. Philippe Rushton, whose work on race and intelligence is widely regarded by the scientific community as deeply flawed and racist.[10][11] |

エドワード・オズボーン・ウィルソン(Edward Osborne

Wilson、1929年6月10日 -

2021年12月26日)は、社会生物学の分野を開拓したことで知られるアメリカの生物学者、自然主義者、生態学者、昆虫学者である。 アラバマ州で生まれたウィルソンは、幼い頃から自然に興味を持ち、アウトドアに親しんだ。7歳の時に釣り中の事故で視力を一部失明し、視力が低下したこと でウィルソンは昆虫学を研究することを決意した。アラバマ大学を卒業後、ウィルソンはハーバード大学に編入し、複数の分野で頭角を現した。1956年に は、性格転位理論を定義する論文を共同執筆した。1967年には、ロバート・マッカーサーとともに島嶼生物地理学説を展開した。 ウィルソンは、ハーバード大学有機体進化生物学部のペレグリン大学特別研究教授(名誉教授)であり、デューク大学の講師でもあった。また、懐疑的調査委員 会の研究員でもあった。スウェーデン王立科学アカデミーはウィルソンにクラフォード賞を授与した。彼は国際人文主義アカデミーの人文主義者賞受賞者であっ た。[3][4] 彼はピューリッツァー賞一般ノンフィクション部門を2度受賞している(1979年の『人間の本性について』、1991年の『蟻』)。また、『地球の社会的 征服』、『若い科学者への手紙』、『人間の存在の意味』はニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のベストセラーとなった。 ウィルソンの作品は、存命中から賞賛と批判の両方を集めた。彼の著書『社会生物学』は特に論争の火種となり、社会生物学研究会から批判を受けた。[7] [8] ウィルソンの進化論の解釈は、リチャード・ドーキンスとの論争として広く報道された。[9] 彼の死後、手紙の調査により、彼は心理学者のJ.フィリップ・ラシュトンを支持していたことが明らかになった。ラシュトンの人種と知能に関する研究は、科学界 では広く欠陥が多く人種差別的であるとみなされている。[10][11] |

| Early life Edward Osborne Wilson was born on June 10, 1929, in Birmingham, Alabama. He was the only child of Inez Linnette Freeman and Edward Osborne Wilson Sr.[12] According to his autobiography, Naturalist, he grew up in various towns in the Southern United States which included Mobile, Decatur, and Pensacola.[13] From an early age, he was interested in natural history. His father was an alcoholic who eventually committed suicide. His parents allowed him to bring home black widow spiders and keep them on the porch.[14] They divorced when he was seven years old. In the same year that his parents divorced, Wilson blinded himself in his right eye in a fishing accident.[15] Despite the prolonged pain, he did not stop fishing. He did not complain because he was anxious to stay outdoors, and never sought medical treatment. Several months later, his right pupil clouded over with a cataract. He was admitted to Pensacola Hospital to have the lens removed. Wilson writes, in his autobiography, that the "surgery was a terrifying [19th] century ordeal". Wilson retained full sight in his left eye, with a vision of 20/10. The 20/10 vision prompted him to focus on "little things": "I noticed butterflies and ants more than other kids did, and took an interest in them automatically." Although he had lost his stereoscopic vision, he could still see fine print and the hairs on the bodies of small insects. His reduced ability to observe mammals and birds led him to concentrate on insects.[16] At the age of nine, Wilson undertook his first expeditions at Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C. He began to collect insects and he gained a passion for butterflies. He would capture them using nets made with brooms, coat hangers, and cheesecloth bags.[16] Going on these expeditions led to Wilson's fascination with ants. He describes in his autobiography how one day he pulled the bark of a rotting tree away and discovered citronella ants underneath.[16] The worker ants he found were "short, fat, brilliant yellow, and emitted a strong lemony odor".[16] Wilson said the event left a "vivid and lasting impression".[16] He also earned the Eagle Scout award and served as Nature Director of his Boy Scouts summer camp. At age 18, intent on becoming an entomologist, he began by collecting flies, but the shortage of insect pins during World War II caused him to switch to ants, which could be stored in vials. With the encouragement of Marion R. Smith, a myrmecologist from the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, Wilson began a survey of all the ants of Alabama. This study led him to report the first colony of fire ants in the U.S., near the port of Mobile.[17] Education Wilson said he went to 15 or 16 schools during 11 years of schooling.[14] He was concerned that he might not be able to afford to go to a university, and he tried to enlist in the United States Army, intending to earn U.S. government financial support for his education. He failed the Army medical examination due to his impaired eyesight,[16] but was able to afford to enroll in the University of Alabama, where he earned his Bachelor of Science in 1949 and Master of Science in biology in 1950. The next year, Wilson transferred to Harvard University.[16] Appointed to the Harvard Society of Fellows, he could travel on overseas expeditions, collecting ant species of Cuba and Mexico and travel the South Pacific, including Australia, New Guinea, Fiji, and New Caledonia, as well as to Sri Lanka. In 1955, he received his Ph.D. and married Irene Kelley.[18][19] |

幼少期 エドワード・オズボーン・ウィルソンは1929年6月10日、アラバマ州バーミングハムで生まれた。 父親はイネス・リネット・フリーマン、母親はエドワード・オズボーン・ウィルソン・シニアで、彼は一人っ子であった。[12] 彼の自伝『ナチュラリスト』によると、彼はアメリカ南部のモービル、ディケーター、ペンサコーラなど、さまざまな町で育った。[13] 幼い頃から、彼は自然史に興味を持っていた。父親はアルコール依存症で、後に自殺した。両親は彼が黒後家蜘蛛を捕まえて家にもち帰ることを許し、ベランダ で飼うことを許可した。[14] 彼が7歳の時に両親は離婚した。 両親が離婚した同じ年に、ウィルソンは釣り中の事故で右目を失明した。[15] 長期にわたる痛みに苦しめられながらも、彼は釣りをやめようとはしなかった。屋外にいたいという思いが強かったため、彼は不満を漏らすことはなく、医療治 療を受けることもなかった。数ヶ月後、彼の右目の瞳孔は白内障で濁った。彼はレンズ除去手術を受けるためペンサコーラ病院に入院した。ウィルソンは自伝の 中で、その手術は「恐ろしい19世紀の試練」だったと書いている。ウィルソンは左目の視力は20/10で、完全な視力を保っていた。視力が20/10あっ たため、彼は「小さなもの」に注目するようになった。「他の子供よりも蝶や蟻に気づき、自然と興味を持つようになった。」立体視力を失ったものの、小さな 昆虫の体毛や小さな文字はまだ見ることができた。哺乳類や鳥類を観察する能力が低下したため、昆虫に集中するようになった。 9歳の時、ウィルソンはワシントンD.C.のロック・クリーク公園で最初の探検を行った。昆虫の収集を始め、蝶に夢中になった。彼はほうきや洋服掛け、 チーズクロス製の袋で作った網を使って蝶を捕まえた。[16] これらの探検がきっかけで、ウィルソンはアリに魅了されるようになった。彼は自伝の中で、ある日、朽ちた木の樹皮を剥がしたところ、シトロネラ蟻を発見し たことを記している。[16] 発見した働きアリは「背が低く、丸々と太っていて、鮮やかな黄色で、強いレモンのような匂いを放っていた」という。[16] ウィルソンは、この出来事は「鮮明で、長く心に残る印象」を残したと述べている。[16] また、彼はイーグルスカウト賞を受賞し、ボーイスカウトの夏キャンプでは自然担当ディレクターを務めた。18歳の時、昆虫学者になることを決意した彼はハ エの収集から始めたが、第二次世界大戦中の昆虫ピン不足により、ビンに保管できるアリに切り替えた。ワシントンにある国立自然史博物館の蟻学者マリオン・ R・スミス(Marion R. Smith)の勧めで、ウィルソンはアラバマ州の全アリの調査を開始した。この研究により、彼はアメリカ合衆国で初めて、モービル港付近にヒアリのコロ ニーを発見した。 教育 ウィルソンは、11年間の学校生活で15校から16校の学校に通ったと述べている。[14] 大学進学の費用が工面できないのではないかと心配した彼は、アメリカ合衆国陸軍に入隊し、その教育費をアメリカ政府から支援してもらおうとした。視力の低 下により陸軍の健康診断に不合格となったが[16]、アラバマ大学に入学する資金はあった。そこで1949年に理学士号、1950年に生物学の修士号を取 得した。翌年、ウィルソンはハーバード大学に転校した。 ハーバード大学の研究員に任命されたウィルソンは、海外探検に出かけ、キューバやメキシコの蟻の種を集め、オーストラリア、ニューギニア、フィジー、 ニューカレドニア、スリランカを含む南太平洋を旅した。1955年、ウィルソンは博士号を取得し、アイリーン・ケリーと結婚した。[18][19] |

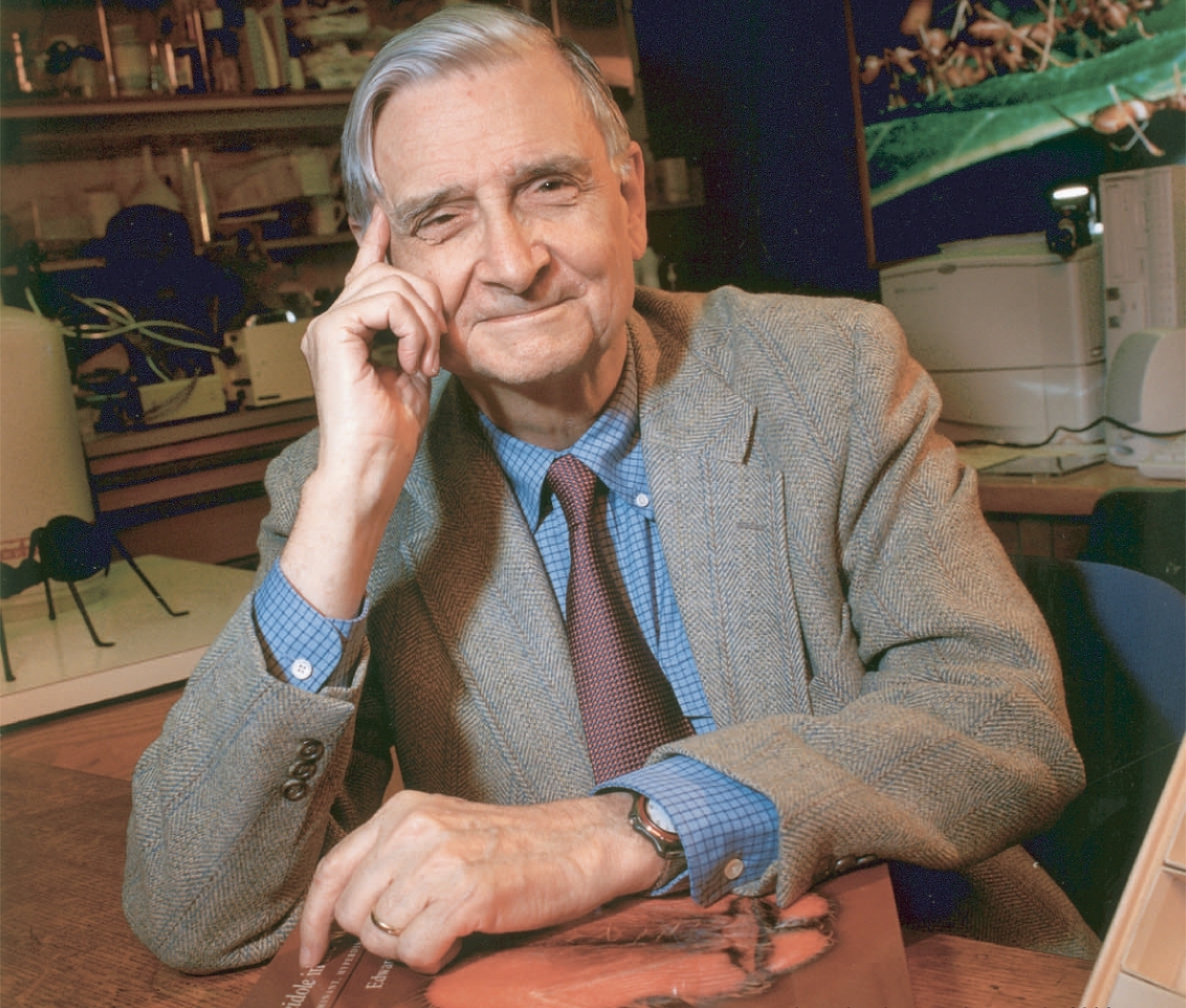

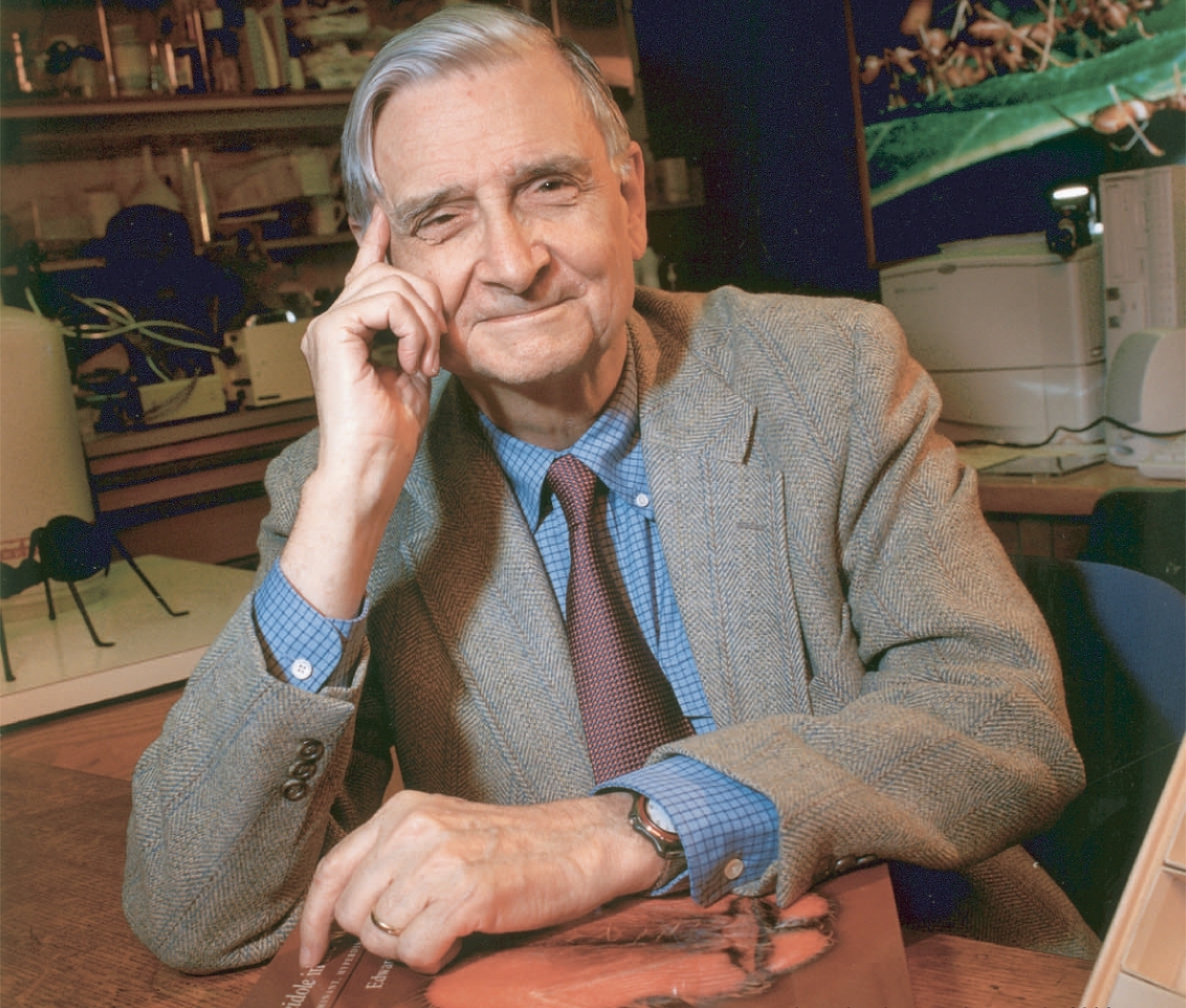

Career Wilson in 2003 From 1956 until 1996, Wilson was part of the faculty of Harvard. He began as an ant taxonomist and worked on understanding their microevolution, how they developed into new species by escaping environmental disadvantages and moving into new habitats. He developed a theory of the "taxon cycle".[18] In collaboration with mathematician William H. Bossert, Wilson developed a classification of pheromones based on insect communication patterns.[20] In the 1960s, he collaborated with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur in developing the theory of species equilibrium. In the 1970s he and biologist Daniel S. Simberloff tested this theory on tiny mangrove islets in the Florida Keys. They eradicated all insect species and observed the repopulation by new species.[21] Wilson and MacArthur's book The Theory of Island Biogeography became a standard ecology text.[18] In 1971, he published The Insect Societies, which argued that insect behavior and the behavior of other animals are influenced by similar evolutionary pressures.[22] In 1973, Wilson was appointed the curator of entomology at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.[23] In 1975, he published the book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis applying his theories of insect behavior to vertebrates, and in the last chapter, to humans. He speculated that evolved and inherited tendencies were responsible for hierarchical social organization among humans. In 1978 he published On Human Nature, which dealt with the role of biology in the evolution of human culture and won a Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.[18] Wilson was named the Frank B. Baird Jr., Professor of Science in 1976 and, after his retirement from Harvard in 1996, he became the Pellegrino University Professor Emeritus.[23] In 1981 after collaborating with biologist Charles Lumsden, he published Genes, Mind and Culture, a theory of gene-culture coevolution. In 1990 he published The Ants, co-written with zoologist Bert Hölldobler, winning his second Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.[18] In the 1990s, he published The Diversity of Life (1992); an autobiography, Naturalist (1994); and Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998) about the unity of the natural and social sciences.[18] Wilson was praised for his environmental advocacy, and his secular-humanist and deist ideas pertaining to religious and ethical matters.[24] Wilson was characterized by several titles during his career, including the "father of biodiversity,"[25][26] "ant man,"[27] and "Darwin's heir."[28][29][30] In a PBS interview, David Attenborough described Wilson as "a magic name to many of us working in the natural world, for two reasons. First, he is a towering example of a specialist, a world authority. Nobody in the world has ever known as much as Ed Wilson about ants. But, in addition to that intense knowledge and understanding, he has the widest of pictures. He sees the planet and the natural world that it contains in amazing detail but extraordinary coherence".[31] Disagreement with Richard Dawkins Although Dawkins defended Wilson during the so-called "sociobiology debate",[32] a disagreement between them arose over the theory of evolution.[9][33] The disagreement began in 2012 when Dawkins wrote a critical review of Wilson's book The Social Conquest of Earth in Prospect Magazine.[9] In the review, Dawkins criticized Wilson for rejecting kin selection and for supporting group selection, labeling it "bland" and "unfocused," and he wrote that the book's theoretical errors were "important, pervasive, and integral to its thesis in a way that renders it impossible to recommend".[34][35] Wilson responded in the same magazine and wrote that Dawkins made "little connection to the part he criticizes" and accused him of engaging in rhetoric.[33] In 2014, Wilson said in an interview, "There is no dispute between me and Richard Dawkins and there never has been, because he's a journalist, and journalists are people that report what the scientists have found and the arguments I’ve had have actually been with scientists doing research".[33] Dawkins responded in a tweet: "I greatly admire EO Wilson & his huge contributions to entomology, ecology, biogeography, conservation, etc. He's just wrong on kin selection" and later added, "Anybody who thinks I'm a journalist who reports what other scientists think is invited to read The Extended Phenotype".[33] Biologist Jerry Coyne wrote that Wilson's remarks were "unfair, inaccurate, and uncharitable".[36] In 2021, in an obituary to Wilson, Dawkins stated that their dispute was "purely scientific".[37] Dawkins wrote that he stands by his critical review and doesn't regret "its outspoken tone", but noted that he also stood by his "profound admiration for Professor Wilson and his life work".[37] Support of J. Philippe Rushton Prior to Wilson's death, his personal correspondences were donated to the Library of Congress at the library's request.[38] Following his death, several articles were published discussing the discrepancy between Wilson's legacy as a champion of biogeography and conservation biology, and his support of scientific racist pseudoscientist J. Philippe Rushton over several years. Rushton was a controversial psychologist at the University of Western Ontario, who later headed the Pioneer Fund.[38][39][40] From the late 1980s to the early 1990s, Wilson wrote several emails to Rushton's colleagues defending Rushton's work in the face of widespread criticism for scholarly misconduct, misrepresentation of data, and confirmation bias, all of which were allegedly used by Rushton to support his personal ideas on race.[38] Wilson also sponsored an article written by Rushton in PNAS,[41] and during the review process, Wilson intentionally sought out reviewers for the article who he believed would likely already agree with its premise.[38] Wilson kept his support of Rushton's racist ideologies behind-the-scenes so as to not draw too much attention to himself or tarnish his own reputation.[42] Wilson responded to another request from Rushton to sponsor a second PNAS article with the following: "You have my support in many ways, but for me to sponsor an article on racial differences in the PNAS would be counterproductive for both of us." Wilson also remarked that the reason Rushton's ideologies were not more widely supported is because of the "... fear of being called racist, which is virtually a death sentence in American academia if taken seriously. I admit that I myself have tended to avoid the subject of Rushton's work, out of fear."[38] In 2022, the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation issued a statement rejecting Wilson's support of Rushton and racism, on behalf of the board of directors and staff.[43] |

キャリア ウィルソン2003年 1956年から1996年まで、ウィルソンはハーバード大学の教授陣の一員であった。彼はアリの分類学者としてキャリアをスタートさせ、アリが環境上の不 利な条件を逃れて新しい生息地に移り住むことで、どのように新しい種へと進化するのかという、アリの微小進化の解明に取り組んだ。彼は「分類群サイクル」 の理論を展開した。[18] ウィルソンは数学者のウィリアム・H・ボッサートと共同で、昆虫のコミュニケーションパターンに基づくフェロモンの分類法を開発した。1960年代には、 数学者で生態学者のロバート・マッカーサーと共同で種の平衡理論を開発した。1970年代には、生物学者のダニエル・S・シムベロフとともに、フロリダ キーズの小さなマングローブの小島でこの理論を検証した。 彼らはすべての昆虫種を根絶し、新たな種による再繁殖を観察した。[21] ウィルソンとマッカーサーの著書『島嶼生物地理学説』は、生態学の標準的な教科書となった。[18] 1971年には『The Insect Societies』を出版し、昆虫の行動と他の動物の行動は同様の進化上の圧力によって影響を受けていると主張した。[22] 1973年、ウィルソンはハーバード大学比較動物学博物館の昆虫学部門の館長に任命された。[23] 1975年には『Sociobiology: 昆虫の行動に関する自身の理論を脊椎動物に適用し、最終章では人間にも適用した。彼は、進化によって受け継がれた傾向が人間社会の階層的な組織化の原因で あると推測した。1978年には『人間の本性について』を出版し、人間の文化の進化における生物学の役割について論じ、一般ノンフィクション部門でピュ リッツァー賞を受賞した。 ウィルソンは1976年にフランク・B・ベアード・ジュニア科学教授に任命され、1996年にハーバード大学を退職した後、ペレグリーノ名誉教授となった。 1981年、生物学者チャールズ・ラムズデンとの共同研究の後、遺伝子と文化の共進化論である『遺伝子、心、文化』を出版した。1990年には動物学者のバート・ヘルトドルファーとの共著『蟻』を出版し、一般ノンフィクション部門で2度目のピュリッツァー賞を受賞した。 1990年代には、『生命の多様性』(1992年)、自伝『自然主義者』(1994年)、自然科学と社会科学の統一に関する『コンシリエンス:知識の統 一』(1998年)を出版した。ウィルソンは環境保護の提唱者として、また宗教や倫理に関する世俗的ヒューマニズムや自然神論の思想家として賞賛された。 ウィルソンは、そのキャリアにおいて、「生物多様性の父」[25][26]、「蟻男」[27]、「ダーウィンの後継者」[28][29][30]など、い くつかの異名で呼ばれていた。PBSのインタビューで、デヴィッド・アッテンボローはウィルソンを「自然界で働く私たちの多くにとって、魔法のような名前 だ。その理由は2つある。第一に、彼は専門家の、世界的な権威の、傑出した模範である。エド・ウィルソンのように蟻について多くのことを知る人物は世界に 存在しない。しかし、その深い知識と理解に加えて、彼は最も幅広い視野を持っている。彼は地球と、その中に存在する自然界を驚くほど詳細に、しかし並外れ た一貫性をもって見ているのだ」[31]。 リチャード・ドーキンスとの意見の相違 いわゆる「社会生物学論争」の最中、ドーキンスはウィルソンを擁護したが、進化論をめぐって両者の意見の相違が生じた。[9][33] 意見の相違は2012年に始まり、ドーキンスがウィルソンの著書『The Social Conquest of Earth』を『Prospect Magazine』で批判的に論評したことによる。[9] ドーキンスは、ウィルソンが血縁淘汰を否定し、集団淘汰を支持していることを批判し 「平凡」で「焦点がぼやけている」と評し、その本の理論的な誤りは「重要で広範囲に及び、その論文の主張に不可欠なものであり、推奨することが不可能なほ どである」と書いた。[34][35] ウィルソンは同じ雑誌でこれに反論し、ドーキンスは「彼が批判する部分とほとんど関連性がない」と書き、ドーキンスが修辞に走っていると非難した。 [33] 2014年、ウィルソンはインタビューで「私とリチャード・ドーキンスの間には何の論争もないし、これまでにもなかった。なぜなら、彼はジャーナリストで あり、ジャーナリストは科学者が発見したことを報道する人々だからだ。そして、私が実際に論争してきたのは、研究を行っている科学者たちだ」と述べた。 [33] これに対してドーキンスはツイートで「私はEOウィルソンを非常に尊敬しており、彼の昆虫学、生態学、生物地理学、保全学などへの多大な貢献を称賛してい る。彼は近縁淘汰についてだけは間違っている」とツイートし、後に「私が他の科学者の考えを報道するジャーナリストだと思っている人は、『拡張表現型』を 読んでみるといい」と付け加えた。[33] 生物学者ジェリー・コインは、ウィルソンの発言は「不公平で不正確、かつ思いやりがない」と書いた。[36] 2 2021年、ウィルソンへの追悼文の中で、ドーキンスは2人の論争は「純粋に科学的」なものであったと述べた。[37] ドーキンスは、自身の批判的評価を支持し、「率直な論調」を後悔していないと述べたが、ウィルソン教授と彼のライフワークに対する「深い尊敬の念」も変わ らないと指摘した。[37] J.フィリップ・ラシュトンの支援 ウィルソンの死に先立ち、彼の個人的な書簡は、図書館の要請により米国議会図書館に寄贈された。[38] 彼の死後、生物地理学および保全生物学の擁護者としてのウィルソンの遺産と、彼が長年にわたって科学的人種差別主義者であるJ.フィリップ・ラシュトンを 支援していたこととの間の矛盾について論じた記事がいくつか発表された。ラシュトンは、ウェスタンオンタリオ大学の物議を醸した心理学者であり、後にパイ オニアファンドの代表となった人物である。[38][39][40] 1980年代後半から1990年代初頭にかけて、ウィルソンはルシュトンの同僚たちに、ルシュトンを擁護する複数の電子メールを送っている。ルシュトン は、学術的不正行為、データの誤った表現、確証バイアスなど、広範な批判に直面していたが、それらはすべて、ルシュトンが人種に関する個人的な考えを支持 するために利用したとされているものである。ウィルソンはまた、ルシュトンがPNASに投稿した論文のスポンサーも務めており[4]、 また、査読プロセス中、ウィルソンは、その前提にすでに同意していると思われる査読者を意図的に選んだ[38]。ウィルソンは、自身に注目が集まりすぎた り、自身の評判が傷ついたりしないよう、ラシュトンの人種差別的イデオロギーへの支持を水面下で続けていた[42]。ウィルソンは、ラシュトンから2本目 のPNAS論文のスポンサーになるよう依頼されたことに対し、次のように答えた。「私はあなたのことを様々な面で応援しているが、PNASに人種差異に関 する論文を後援することは、私たち双方にとって逆効果だ」とウィルソンは述べた。また、ウィルソンは、ラシュトンの思想が広く支持されていない理由につい て、「...人種差別主義者と呼ばれることを恐れているからだ。真剣に受け止められれば、それは事実上、米国の学術界における死刑宣告となる。私も、恐れ からラシュトンの研究テーマを避けてきた傾向があることを認める」と述べた。[38] 2022年、E.O.ウィルソン生物多様性財団は、理事会およびスタッフを代表して、ウィルソンがラシュトンと人種主義を支持していることを否定する声明を発表した。[43] |

| Work Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, 1975 Main article: Sociobiology: The New Synthesis  Wilson at the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 2007 Wilson used sociobiology and evolutionary principles to explain the behavior of social insects and then to understand the social behavior of other animals, including humans, thus establishing sociobiology as a new scientific field.[44] He argued that all animal behavior, including that of humans, is the product of heredity, environmental stimuli, and past experiences, and that free will is an illusion. He referred to the biological basis of behavior as the "genetic leash".[45]: 127–128 The sociobiological view is that all animal social behavior is governed by epigenetic rules worked out by the laws of evolution. This theory and research proved to be seminal, controversial, and influential.[46] Wilson argued that the unit of selection is a gene, the basic element of heredity. The target of selection is normally the individual who carries an ensemble of genes of certain kinds. With regard to the use of kin selection in explaining the behavior of eusocial insects, the "new view that I'm proposing is that it was group selection all along, an idea first roughly formulated by Darwin."[47] Sociobiological research was at the time particularly controversial with regard to its application to humans.[48] The theory established a scientific argument for rejecting the common doctrine of tabula rasa, which holds that human beings are born without any innate mental content and that culture functions to increase human knowledge and aid in survival and success.[49] Reception and controversy Sociobiology: The New Synthesis was initially met with praise by most biologists.[7][8] After substantial criticism of the book was launched by the Sociobiology Study Group, associated with the organization Science for the People, a major controversy known as the "sociobiology debate" ensued,[7][8] and Wilson was accused of racism, misogyny, and support for eugenics.[50] Several of Wilson's colleagues at Harvard,[51] such as Richard Lewontin and Stephen Jay Gould, both members of the Group, were strongly opposed. Both focused their criticism mostly on Wilson's sociobiological writings.[52] Gould, Lewontin, and other members, wrote "Against 'Sociobiology'" in an open letter criticizing Wilson's "deterministic view of human society and human action".[53] Other public lectures, reading groups, and press releases were organized criticizing Wilson's work. In response, Wilson produced a discussion article entitled "Academic Vigilantism and the Political Significance of Sociobiology" in BioScience.[54][55] In February 1978, while participating in a discussion on sociobiology at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Wilson was surrounded, chanted at and doused with water[a] by members of the International Committee Against Racism, who accused Wilson of advocating racism and genetic determinism. Steven Jay Gould, who was present at the event, and Science for the People, which had previously protested Wilson, condemned the attack.[60][57] Philosopher Mary Midgley encountered Sociobiology in the process of writing Beast and Man (1979)[61] and significantly rewrote the book to offer a critique of Wilson's views. Midgley praised the book for the study of animal behavior, clarity, scholarship, and encyclopedic scope, but extensively critiqued Wilson for conceptual confusion, scientism, and anthropomorphism of genetics.[62] On Human Nature, 1978 Wilson wrote in his 1978 book On Human Nature, "The evolutionary epic is probably the best myth we will ever have."[63] Wilson's fame prompted use of the morphed phrase epic of evolution.[24] The book won the Pulitzer Prize in 1979.[64] The Ants, 1990 Wilson, along with Bert Hölldobler, carried out a systematic study of ants and ant behavior,[65] culminating in the 1990 encyclopedic work The Ants. Because much self-sacrificing behavior on the part of individual ants can be explained on the basis of their genetic interests in the survival of the sisters, with whom they share 75% of their genes (though the actual case is some species' queens mate with multiple males and therefore some workers in a colony would only be 25% related), Wilson argued for a sociobiological explanation for all social behavior on the model of the behavior of the social insects. Wilson said in reference to ants that "Karl Marx was right, socialism works, it is just that he had the wrong species".[66] He asserted that individual ants and other eusocial species were able to reach higher Darwinian fitness putting the needs of the colony above their own needs as individuals because they lack reproductive independence: individual ants cannot reproduce without a queen, so they can only increase their fitness by working to enhance the fitness of the colony as a whole. Humans, however, do possess reproductive independence, and so individual humans enjoy their maximum level of Darwinian fitness by looking after their own survival and having their own offspring.[67] Consilience, 1998 In his 1998 book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, Wilson discussed methods that have been used to unite the sciences and might be able to unite the sciences with the humanities. He argued that knowledge is a single, unified thing, not divided between science and humanistic inquiry.[68] Wilson used the term "consilience" to describe the synthesis of knowledge from different specialized fields of human endeavor. He defined human nature as a collection of epigenetic rules, the genetic patterns of mental development. He argued that culture and rituals are products, not parts, of human nature. He said art is not part of human nature, but our appreciation of art is. He suggested that concepts such as art appreciation, fear of snakes, or the incest taboo (Westermarck effect) could be studied by scientific methods of the natural sciences and be part of interdisciplinary research.[69] |

仕事 『ソシオバイオロジー:ザ・ニュー・シンセシス』、1975年 詳細は「ソシオバイオロジー:ザ・ニュー・シンセシス」を参照  ウィルソン、2007年、ピーボディ自然史博物館にて ウィルソンは、社会生物学と進化論の原理を用いて社会性昆虫の行動を説明し、さらに人間を含む他の動物の社会行動を理解することで、社会生物学を新たな科 学分野として確立した。[44] 彼は、人間を含む動物の行動はすべて、遺伝、環境刺激、過去の経験の産物であり、自由意志は幻想であると主張した。彼は行動の生物学的な基礎を「遺伝的 鎖」と呼んだ。[45]:127-128 社会生物学の見解では、動物の社会行動はすべて進化の法則によって作り出された後天的な規則によって支配されている。この理論と研究は、画期的で、論争を 巻き起こし、影響力のあるものとなった。[46] ウィルソンは、選択の単位は遺伝の基本要素である遺伝子であると主張した。選択の対象は通常、特定の種類の遺伝子群を持つ個体である。真社会性昆虫の行動 を説明する際の血縁淘汰の利用に関して、ウィルソンは「私が提案する新しい見解は、それは最初から集団淘汰であったというもので、この考えはダーウィンに よって初めて大まかに定式化された」と述べている。 社会生物学の研究は、当時、人間への応用に関して特に論争を呼んでいた。[48] この理論は、人間は生まれながらにして何の精神的内容も持たず、文化は人間の知識を増やし、生存と成功を助けるために機能するというタブラ・ラーサの一般 的な教義を否定する科学的論拠を確立した。[49] 評価と論争 『ソシオバイオロジー:ザ・ニュー・シンセシス』は当初、ほとんどの生物学者から賞賛をもって迎えられた。[7][8] しかし、サイエンス・フォー・ザ・ピープルという組織に関連するソシオバイオロジー研究グループから同書に対する批判が本格的に展開されると、「ソシオバ イオロジー論争」として知られる大きな論争が巻き起こった。[7][8] ]ウィルソンは人種主義、女性嫌悪、優生学への支持を非難された。[50] ハーバード大学のウィルソンの同僚の何人か、[51] リチャード・ルウォンタンやスティーブン・ジェイ・グールドなど、グループのメンバーである両名は強く反対した。両者は主にウィルソンの社会生物学に関す る著作を批判の対象とした。[52] グールド、ルウォンタン、およびその他のメンバーは、ウィルソンの「人間社会と人間行動の決定論的見解」を批判する公開書簡で「『社会生物学』に反対す る」と書いた。[53] ウィルソンの研究を批判する公開講座、読書会、プレスリリースが開催された。これに対してウィルソンは、BioScience誌に「学問の自警主義と社会 生物学の政治的意義」と題する論説を発表した。[54][55] 1978年2月、アメリカ科学振興協会の年次総会で社会生物学に関する討論に参加していたウィルソンは、国際反人種主義委員会のメンバーに取り囲まれ、人 種主義と遺伝的決定論を擁護していると非難され、罵声を浴びせられ、水をかぶせられた。この場に居合わせたスティーブン・J・グールドや、以前からウィル ソンに抗議していた『サイエンス・フォー・ザ・ピープル』は、この攻撃を非難した。 哲学者メアリー・ミドゲリーは『野獣と人間』(1979年)を執筆する過程で『ソシオバイオロジー』に出会い[61]、ウィルソンの見解に対する批判を提 示するために同書を大幅に書き直した。ミドゲリーは同書を動物行動学、明晰さ、博識、百科事典的な広範さの研究として賞賛したが、ウィルソンの概念の混 乱、科学主義、遺伝学の人格視を広く批判した[62]。 『人間の本性について』、1978年 ウィルソンは1978年の著書『人間の本性について』で「進化論の大叙事詩は、おそらく我々が持つことになる最良の神話である」と書いた。[63] ウィルソンの名声により、進化の大叙事詩という合成語が使われるようになった。[24] この著書は1979年にピューリッツァー賞を受賞した。[64] 『蟻』(1990年 ウィルソンはバート・ホルドボーラーとともに、アリとアリの行動に関する体系的な研究を行い、[65] 1990年に『蟻』という百科事典的な著作を完成させた。アリ個体による自己犠牲的な行動の多くは、遺伝子の75%を共有する姉妹の生存に対する遺伝的な 関心に基づいて説明できるため(ただし、実際には一部の種の女王アリは複数の雄と交尾するため、コロニー内の一部の働きアリは25%しか血縁関係がな い)、ウィルソンは社会昆虫の行動をモデルとして、社会行動のすべてを社会生物学的に説明できると主張した。 ウィルソンはアリを例に挙げ、「カール・マルクスは正しかった。社会主義は機能する。ただ、彼が間違った種を想定していただけだ」と述べた。[66] 彼は、アリや他の真社会性動物は、生殖の独立性を持たないため、個体としてのニーズよりもコロニーのニーズを優先することで、より高いダーウィン的適応度 に達することができると主張した。アリは女王なしでは繁殖できないため、コロニー全体の適応度を高めるために働くことでしか、自身の適応度を高めることが できない。しかし、人間には生殖上の独立性があるため、個々の人間は自身の生存と自身の子供を育てることで、ダーウィン的適応度を最大限に高めることがで きる。[67] Consilience, 1998 1998年の著書『Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge』の中で、ウィルソンは科学を統合するために用いられてきた方法について論じ、科学と人文科学を統合できる可能性についても論じてい る。彼は、知識とは単一で統一されたものであり、科学と人文科学の探究の間で分割されるものではないと主張した。ウィルソンは、人間の努力における異なる 専門分野からの知識の統合を表現するために「consilience」という用語を用いた。彼は、人間の性質を後天的な規則の集合体、すなわち精神発達の 遺伝的パターンと定義した。彼は、文化や儀式は人間の性質の一部分ではなく、その産物であると論じた。芸術は人間の性質の一部ではないが、芸術に対する人 間の評価はそうであると彼は述べた。芸術鑑賞、蛇に対する恐怖、近親相姦のタブー(ウェスターマーク効果)といった概念は、自然科学の科学的手段によって 研究することができ、学際的研究の一部となりうる、と彼は示唆した。[69] |

| Spiritual and political beliefs Scientific humanism Wilson coined the phrase scientific humanism as "the only worldview compatible with science's growing knowledge of the real world and the laws of nature".[70] Wilson argued that it is best suited to improve the human condition. In 2003, he was one of the signers of the Humanist Manifesto.[71] God and religion On the question of God, Wilson described his position as "provisional deism"[72] and explicitly denied the label of "atheist", preferring "agnostic".[73] He explained his faith as a trajectory away from traditional beliefs: "I drifted away from the church, not definitively agnostic or atheistic, just Baptist & Christian no more."[45] Wilson argued that belief in God and the rituals of religion are products of evolution.[74] He argued that they should not be rejected or dismissed, but further investigated by science to better understand their significance to human nature. In his book The Creation, Wilson wrote that scientists ought to "offer the hand of friendship" to religious leaders and build an alliance with them, stating that "Science and religion are two of the most potent forces on Earth and they should come together to save the creation."[75] Wilson made an appeal to the religious community on the lecture circuit at Midland College, Texas, for example, and that "the appeal received a 'massive reply'", that a covenant had been written and that a "partnership will work to a substantial degree as time goes on".[76] In a New Scientist interview published on January 21, 2015, however, Wilson said that religious faith is "dragging us down", and: I would say that for the sake of human progress, the best thing we could possibly do would be to diminish, to the point of eliminating, religious faiths. But certainly not eliminating the natural yearnings of our species or the asking of these great questions.[77] Ecology Wilson said that, if he could start his life over he would work in microbial ecology, when discussing the reinvigoration of his original fields of study since the 1960s.[78] He studied the mass extinctions of the 20th century and their relationship to modern society, and identifying mass extinction as the greatest threat to Earth's future.[79] In 1998 argued for an ecological approach at the Capitol: Now when you cut a forest, an ancient forest in particular, you are not just removing a lot of big trees and a few birds fluttering around in the canopy. You are drastically imperiling a vast array of species within a few square miles of you. The number of these species may go to tens of thousands. ... Many of them are still unknown to science, and science has not yet discovered the key role undoubtedly played in the maintenance of that ecosystem, as in the case of fungi, microorganisms, and many of the insects.[80] From the late 1970s Wilson was actively involved in the global conservation of biodiversity, contributing and promoting research. In 1984 he published Biophilia, a work that explored the evolutionary and psychological basis of humanity's attraction to the natural environment. This work introduced the word biophilia which influenced the shaping of modern conservation ethics. In 1988 Wilson edited the BioDiversity volume, based on the proceedings of the first US national conference on the subject, which also introduced the term biodiversity into the language. This work was very influential in creating the modern field of biodiversity studies.[81] In 2011, Wilson led scientific expeditions to the Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique and the archipelagos of Vanuatu and New Caledonia in the southwest Pacific. Wilson was part of the international conservation movement, as a consultant to Columbia University's Earth Institute, as a director of the American Museum of Natural History, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund.[18] Understanding the scale of the extinction crisis led him to advocate for forest protection,[80] including the "Act to Save America's Forests", first introduced in 1998 and reintroduced in 2008, but never passed.[82] The Forests Now Declaration called for new markets-based mechanisms to protect tropical forests.[83] Wilson once said destroying a rainforest for economic gain was like burning a Renaissance painting to cook a meal.[84] In 2014, Wilson called for setting aside 50% of Earth's surface for other species to thrive in as the only possible strategy to solve the extinction crisis. The idea became the basis for his book Half-Earth (2016) and for the Half-Earth Project of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation.[85][86] Wilson's influence regarding ecology through popular science was discussed by Alan G. Gross in The Scientific Sublime (2018).[87] Wilson was instrumental in launching the Encyclopedia of Life (EOL)[88] initiative with the goal of creating a global database to include information on the 1.9 million species recognized by science. Currently, it includes information on practically all known species. This open and searchable digital repository for organism traits, measurements, interactions and other data has more than 300 international partners and countless scientists providing global users' access to knowledge of life on Earth. For his part, Wilson discovered and described more than 400 species of ants.[89][90] |

精神的・政治的信念 科学的ヒューマニズム ウィルソンは「科学的ヒューマニズム」という言葉を「現実世界と自然法則に関する科学の知識の増大と調和する唯一の世界観」として造語した。[70] ウィルソンは、それは人間の状態を改善するのに最も適していると主張した。2003年には、ヒューマニスト宣言の署名者の一人となった。[71] 神と宗教 神の存在について、ウィルソンは自身の立場を「暫定的な自然神論」と表現し[72]、「無神論者」というレッテルを明確に否定し、「不可知論者」という呼 称を好んだ[73]。彼は自身の信仰を、伝統的な信念から離れた軌跡であると説明した。「私は教会から離れただけであり、決定的な不可知論者でも無神論者 でもない。ただ、バプテスト派であり、キリスト教徒であることをやめただけだ」[45] ウィルソンは、神への信仰や宗教の儀式は進化の産物であると主張した。[74] それらを拒絶したり否定したりすべきではなく、むしろ科学によってさらに調査し、人間の本質に対するそれらの意義をより深く理解すべきであると主張した。 著書『創造』の中で、ウィルソンは科学者たちは宗教指導者たちに「友好の手を差し伸べる」べきであり、彼らと手を組むべきであると述べ、「科学と宗教は地 球上で最も強力な2つの力であり、それらは共に手を組んで創造物を救うべきである」と主張した。 ウィルソンは、テキサス州ミッドランド・カレッジでの講演会など、宗教界に向けて呼びかけを行い、「その呼びかけは『大きな反響』を得た」とし、協定が結ばれ、「パートナーシップは時が経つにつれ、かなりの程度まで機能するだろう」と述べた。[76] しかし、2015年1月21日に発行された『ニューサイエンティスト』誌のインタビューで、ウィルソンは宗教的信仰は「私たちを足止めしている」と述べ、 私は、人類の進歩のためには、宗教を衰退させ、最終的には排除することが最善の策だと考える。しかし、人類が持つ自然な憧れや、こうした大きな疑問を投げかけることを排除するつもりはまったくない。 生態学 ウィルソンは、もし人生をやり直せるなら、1960年代以来の自身の研究分野の再活性化について議論する際に、微生物生態学の分野で働きたいと述べた。 [78] 彼は20世紀の大規模な絶滅と現代社会との関係を研究し、大量絶滅を地球の未来に対する最大の脅威であると特定した。[79] 1998年には、議事堂で生態学的アプローチを主張した。 今、特に古代の森林を伐採するということは、たくさんの大きな木々や、樹冠を飛び回る少数の鳥類を除去するだけにとどまらない。数平方マイルの範囲内に生 息する広範な生物種を、極めて危険にさらすことになるのだ。それらの生物種の数は、数万種に上る可能性がある。... それらの多くは科学的に未だ知られておらず、科学は、菌類や微生物、多くの昆虫の場合のように、その生態系の維持に間違いなく重要な役割を果たしているも のを、まだ発見していない。[80] 1970年代後半から、ウィルソンは生物多様性の世界的保全に積極的に関わり、研究に貢献し、推進した。1984年には、人間が自然環境に惹きつけられる ことの進化論的および心理学的根拠を探求した著書『Biophilia』を出版した。この著書で、ウィルソンは「バイオフィリア」という言葉を導入し、現 代の保全倫理の形成に影響を与えた。1988年には、ウィルソンは生物多様性に関する最初の米国国民会議の議事録を基に『生物多様性』を編集し、この言葉 もまた言語として導入された。この作品は、生物多様性研究という現代の分野を創出する上で非常に大きな影響を与えた。[81] 2011年には、ウィルソンはモザンビークのゴロンゴサ国立公園と南西太平洋のバヌアツ諸島およびニューカレドニア諸島への科学探検を主導した。ウィルソ ンは、コロンビア大学地球研究所のコンサルタント、アメリカ自然史博物館、コンサベーション・インターナショナル、ザ・ネイチャー・コンサーバンシー、お よび世界自然保護基金の理事を務めるなど、国際的な自然保護運動の一翼を担っていた。 絶滅危機の規模を理解した彼は、森林保護を提唱するようになった。[80] これには、1998年に初めて提出され、2008年に再提出されたものの、可決されることはなかった「アメリカの森林を救うための法律」も含まれる。 [82] 「Forests Now宣言」は、 熱帯雨林を保護するための新しい市場ベースのメカニズムを求めた。[83] ウィルソンはかつて、経済的利益のために熱帯雨林を破壊することは、ルネサンス期の絵画を料理するために燃やすようなものだと述べた。[84] 2014年、ウィルソンは絶滅の危機を解決する唯一の戦略として、地球表面の50%を他の生物が繁栄するために確保することを求めた。この考えは、彼の著 書『Half-Earth』(2016年)と、E.O.ウィルソン生物多様性財団の「Half-Earth Project」の基礎となった。[85][86] ウィルソンの一般向け科学による生態学への影響については、アラン・G・グロスが『The Scientific Sublime』(2018年)で論じている。[87] ウィルソンは、科学的に認識されている190万種の情報を含む世界規模のデータベースを作成することを目的としたイニシアティブ「生命の百科事典 (EOL)」[88]の立ち上げに尽力した。現在、このデータベースには、ほぼすべての既知の種の情報が含まれている。この生物の特性、測定値、相互作 用、その他のデータを収めたオープンで検索可能なデジタルリポジトリには、300を超える国際パートナーと数えきれないほどの科学者が参加しており、地球 上の生命に関する知識を世界中のユーザーに提供している。ウィルソンは、400種以上のアリを発見し、その特徴を記述した。[89][90] |

| Retirement and death In 1996, Wilson officially retired from Harvard University, where he continued to hold the positions of Professor Emeritus and Honorary Curator in Entomology.[91] He fully retired from Harvard in 2002 at age 73. After stepping down, he published more than a dozen books, including a digital biology textbook for the iPad.[12][92] He founded the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation, which finances the PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award and is an "independent foundation" at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University. Wilson became a special lecturer at Duke University as part of the agreement.[93] Wilson and his wife, Irene, resided in Lexington, Massachusetts.[18] He had a daughter, Catherine.[84] He was preceded in death by his wife (on August 7, 2021) and died in nearby Burlington on December 26, 2021, at the age of 92.[12][92] |

引退と死 1996年、ウィルソンはハーバード大学を正式に引退し、同大学では名誉教授および名誉昆虫学キュレーターの地位を保持し続けた。[91] 2002年、73歳でハーバード大学を完全に引退した。引退後、iPad用のデジタル生物学教科書を含む1ダース以上の書籍を出版した。[12][92] E.O.ウィルソン生物多様性財団を設立し、ペン/E.O.ウィルソン文学科学執筆賞に資金援助している。また、デューク大学ニコラス環境大学院の「独立財団」でもある。ウィルソンは、この合意の一環として、デューク大学の特別講師となった。 ウィルソンと妻のアイリーンはマサチューセッツ州レキシントンに住んでいた。[18] 娘のキャサリンがいる。[84] 2021年8月7日に妻に先立たれ、同年12月26日にバーリントン近郊で92歳で死去した。[12][92] |

Awards and honors Wilson at a "fireside chat" during which he received the Addison Emery Verrill Medal in 2007  Wilson addresses the audience at the dedication of the Biophilia Center named for him at Nokuse Plantation in Walton County, Florida. Wilson's scientific and conservation honors include: Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, elected 1959[94] Member of the National Academy of Sciences, elected 1969[95] Member of the American Philosophical Society, elected 1976.[96] U.S. National Medal of Science, 1977[19] Leidy Award, 1979, from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia[97] Pulitzer Prize for On Human Nature, 1979[98] Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, 1984[19] ECI Prize, International Ecology Institute, terrestrial ecology, 1987[99] Honorary doctorate from the Faculty of Mathematics and Science at Uppsala University, Sweden, 1987[100] Academy of Achievement Golden Plate Award, 1988[101] His books The Insect Societies and Sociobiology: The New Synthesis were honored with the Science Citation Classic award by the Institute for Scientific Information.[102] Crafoord Prize, 1990, a prize awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences[103] Pulitzer Prize for The Ants (with Bert Hölldobler), 1991[104] International Prize for Biology, 1993[19] Carl Sagan Award for Public Understanding of Science, 1994[105] The National Audubon Society's Audubon Medal, 1995[19] Time magazine's 25 Most Influential People in America, 1995[104] Certificate of Distinction, International Congresses of Entomology, Florence, Italy 1996[106] Benjamin Franklin Medal for Distinguished Achievement in the Sciences of the American Philosophical Society, 1998.[107] American Humanist Association's 1999 Humanist of the Year[104] Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science, 2000[108] Nierenberg Prize, 2001[19] Distinguished Eagle Scout Award 2004[109] Dauphin Island Sea Lab christened one of its research vessel the R/V E.O. Wilson.[110] Linnean Tercentenary Silver Medal, 2006[111] Addison Emery Verrill Medal from the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 2007[112] TED Prize 2007[113] given yearly to "honor a maximum of three individuals who have shown that they can, in some way, positively impact life on this planet." XIX Premi Internacional Catalunya 2007[114] E.O. Wilson Biophilia Center[115] on Nokuse Plantation in Walton County, Florida 2009 video[116] The Explorers Club Medal, 2009[117] 2010 BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Award in the Ecology and Conservation Biology Category[118] Thomas Jefferson Medal in Architecture, 2010[119] 2010 Heartland Prize for fiction for his first novel Anthill: A Novel[120] EarthSky Science Communicator of the Year, 2010[121] International Cosmos Prize, 2012[122] Kew International Medal (2014)[1] Doctor of Science, honoris causa, from the American Museum of Natural History (2014)[123] 2016 Harper Lee Award[124][125] Commemoration in the species' epithet of Myrmoderus eowilsoni (2018)[126] Commemoration in the species' epithet of Miniopterus wilsoni (2020)[127] |

受賞および栄誉 2007年に「ファイヤーサイド・チャット」でアディソン・エメリー・ベリル・メダルを受賞したウィルソン  フロリダ州ウォルトン郡のノークセ・プランテーションに自身の名を冠したバイオフィリア・センターが献堂され、ウィルソンが聴衆に挨拶している。 ウィルソンの科学および保全に関する栄誉には以下がある。 アメリカ芸術科学アカデミー会員、1959年選出[94] 全米科学アカデミー会員、1969年選出[95] アメリカ哲学協会会員、1976年選出[96] アメリカ国家科学賞、1977年[19] フィラデルフィア自然科学アカデミーより1979年レイディ賞[97] 人間の本性』でピューリッツァー賞、1979年[98] 1984年 タイラー賞(環境業績部門)[19] 1987年 国際生態学研究所(ECI)賞(陸上生態学)[99] 1987年 スウェーデン・ウプサラ大学数学・科学部より名誉博士号[100] 1988年 アメリカ・アカデミー・オブ・アカチーブメント(Academy of Achievement)ゴールデン・プレート賞[101] 著書『昆虫社会』と『社会生物学:新しい総合』は、科学情報研究所から科学引用文献クラシック賞を授与された。 1990年、スウェーデン王立科学アカデミーからクラフォード賞を授与された。 1991年、『蟻』(バート・ホルドボーラーとの共著)でピューリッツァー賞を授与された。 国際生物学賞、1993年[19] カール・セーガン賞、1994年[105] 全米オーデュボン協会オーデュボン・メダル、1995年[19] タイム誌「アメリカで最も影響力のある25人」、1995年[104] 1996年 イタリア、フィレンツェで開催された国際昆虫学会議より「優秀賞」[106] 1998年 アメリカ哲学協会より「ベンジャミン・フランクリン・メダル」(科学分野における顕著な功績に対して)[107] 1999年 アメリカヒューマニスト協会より「ヒューマニスト・オブ・ザ・イヤー」[104] 2000年 ルイス・トマス賞(科学に関する著作に対して)[108] ニーレンバーグ賞、2001年[19] 2004年、優秀イーグル・スカウト賞[109] ドーフィン島海洋研究所は、その研究船の1隻に「R/V E.O. ウィルソン」と命名した。 2006年、リンネ生誕300周年記念銀メダル受賞[111] 2007年、ピーボディ自然史博物館よりアディソン・エメリ・ヴェリル・メダル受賞[112] 2007年、TED賞受賞[113](毎年、「何らかの形で地球上の生命にポジティブな影響を与えることができることを示した最大3人の個人を表彰する」ために贈られる賞) 第19回カタルーニャ国際賞 2007年[114] フロリダ州ウォルトン郡のノークス・プランテーションにあるE.O.ウィルソン・バイオフィリア・センター[115] 2009年のビデオ[116] エクスプローラーズクラブ・メダル、2009年[117] 2010年BBVA知識フロンティア賞、生態学および保全生物学部門[118] 2010年トーマス・ジェファーソン建築メダル[119] 2010年処女作『蟻塚:小説』でフィクション部門ハートランド賞[120] 2010年アーススカイ・サイエンス・コミュニケーター・オブ・ザ・イヤー[121] 2012年コスモス国際賞[122] キュー国際メダル(2014年)[1] アメリカ自然史博物館より名誉博士号(2014年)[123] 2016年ハーパー・リー賞[124][125] Myrmoderus eowilsoniの種小名に記念(2018年)[126] Miniopterus wilsoniの種小名に記念(2020年)[127] |

| Main works Brown, W. L.; Wilson, E. O. (1956). "Character displacement". Systematic Zoology. 5 (2): 49–64. doi:10.2307/2411924. JSTOR 2411924., coauthored with William Brown Jr.; paper honored in 1986 as a Science Citation Classic, i.e., as one of the most frequently cited scientific papers of all time.[128] The Theory of Island Biogeography, 1967, Princeton University Press (2001 reprint), ISBN 0-691-08836-5, with Robert H. MacArthur The Insect Societies, 1971, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-45490-1 Sociobiology: The New Synthesis 1975, Harvard University Press, (Twenty-fifth Anniversary Edition, 2000 ISBN 0-674-00089-7) On Human Nature, 1979, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-01638-6, winner of the 1979 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction. Genes, Mind and Culture: The Coevolutionary Process, 1981, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-34475-8 Promethean Fire: Reflections on the Origin of Mind, 1983, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-71445-8 Biophilia, 1984, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-07441-6 Success and Dominance in Ecosystems: The Case of the Social Insects, 1990, Inter-Research, ISSN 0932-2205 The Ants, 1990, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-04075-9, Winner of the 1991 Pulitzer Prize, with Bert Hölldobler The Diversity of Life, 1992, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-21298-3, The Diversity of Life: Special Edition, ISBN 0-674-21299-1 The Biophilia Hypothesis, 1993, Shearwater Books, ISBN 1-55963-148-1, with Stephen R. Kellert Journey to the Ants: A Story of Scientific Exploration, 1994, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-48525-4, with Bert Hölldobler Naturalist, 1994, Shearwater Books, ISBN 1-55963-288-7 In Search of Nature, 1996, Shearwater Books, ISBN 1-55963-215-1, with Laura Simonds Southworth Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, 1998, Knopf, ISBN 0-679-45077-7 The Future of Life, 2002, Knopf, ISBN 0-679-45078-5 Pheidole in the New World: A Dominant, Hyperdiverse Ant Genus, 2003, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-00293-8 The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth, September 2006, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-06217-5 Nature Revealed: Selected Writings 1949–2006, ISBN 0-8018-8329-6 The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies, 2009, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-06704-0, with Bert Hölldobler Anthill: A Novel, April 2010, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-07119-1 Kingdom of Ants: Jose Celestino Mutis and the Dawn of Natural History in the New World, 2010, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, with José María Gómez Durán ISBN 0-8018-9785-8 The Leafcutter Ants: Civilization by Instinct, 2011, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-33868-3, with Bert Hölldobler The Social Conquest of Earth, 2012, Liveright Publishing Corporation, New York, ISBN 0-87140-363-3 Letters to a Young Scientist, 2014, Liveright, ISBN 0-87140-385-4 A Window on Eternity: A Biologist's Walk Through Gorongosa National Park, 2014, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 1-4767-4741-5 The Meaning of Human Existence, 2014, Liveright, ISBN 0-87140-100-2 Half-Earth, 2016, Liveright, ISBN 978-1-63149-082-8 The Origins of Creativity, 2017, Liveright, ISBN 978-1-63149-318-8 Genesis: The Deep Origin of Societies, 2019, Liveright; ISBN 1-63149-554-2 Tales from the Ant World, 2020, Liveright, ISBN 978-1-63149-556-4[129][130] Naturalist: A Graphic Adaptation November 10, 2020, Island Press; ISBN 978-1-61091-958-6[131] Edited works From So Simple a Beginning: Darwin's Four Great Books, edited with introductions by Edward O. Wilson (2005, W. W. Norton) ISBN 0-393-06134-5 |

主な作品 ブラウン, W. L.; ウィルソン, E. O. (1956). 「性格の変位」。『体系動物学』5 (2): 49–64. doi:10.2307/2411924. JSTOR 2411924.、ウィリアム・ブラウン・ジュニアとの共著。1986年に「サイテーション・クラシック」として表彰された論文、すなわち、史上最も頻繁 に引用された科学論文の1つ。[128] 『島嶼生物地理学説』(The Theory of Island Biogeography)1967年、プリンストン大学出版(2001年再版)、ISBN 0-691-08836-5、ロバート・H・マッカーサーとの共著 『昆虫社会』(The Insect Societies)1971年、ハーバード大学出版、ISBN 0-674-45490-1 『ソシオバイオロジー:新しい総合』1975年、ハーバード大学出版局、(25周年記念版、2000年、ISBN 0-674-00089-7) 『人間の本性について』1979年、ハーバード大学出版、ISBN 0-674-01638-6、1979年ピューリッツァー賞一般ノンフィクション部門受賞作。 『遺伝子、心、文化:共進化の過程』1981年、ハーバード大学出版、ISBN 0-674-34475-8 プロメテウスの火:心の起源についての考察、1983年、ハーバード大学出版、ISBN 0-674-71445-8 バイオフィリア、1984年、ハーバード大学出版、ISBN 0-674-07441-6 生態系における成功と優位性:社会性昆虫の事例、1990年、インターリサーチ、ISSN 0932-2205 アリ、1990年、ハーバード大学出版局、ISBN 0-674-04075-9、1991年ピューリッツァー賞受賞、共著:バート・ホルドブラー 『生命の多様性』、1992年、ハーバード大学出版局、ISBN 0-674-21298-3、『生命の多様性:特別版』、ISBN 0-674-21299-1 『バイオフィリア仮説』、1993年、Shearwater Books、ISBN 1-55963-148-1、スティーブン・R・ケラートとの共著 『蟻への旅:科学探検の物語』、1994年、ハーバード大学出版局、ISBN 0-674-48525-4、ベルト・ホルドビラーとの共著 『ナチュラリスト』、1994年、Shearwater Books、ISBN 1-55963-288-7 『自然を求めて』、1996年、Shearwater Books、ISBN 1-55963-215-1、ローラ・シモンズ・サウスワースとの共著 Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, 1998, Knopf, ISBN 0-679-45077-7 The Future of Life, 2002, Knopf, ISBN 0-679-45078-5 『新世界のPheidole:優勢で超多様性アリ属』、2003年、ハーバード大学出版、ISBN 0-674-00293-8 『創造:地球上の生命を救うための訴え』、2006年9月、W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.、ISBN 978-0-393-06217-5 Nature Revealed: Selected Writings 1949–2006(自然の啓示:1949年から2006年の選集)、ISBN 0-8018-8329-6 『超個体:昆虫社会の美、優雅さ、奇妙さ』、2009年、W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-06704-0、バート・ヘルドビラーとの共著 『蟻塚:小説』2010年4月、W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-07119-1 『蟻の王国:ホセ・セレスティーノ・ムティスと新世界の博物学の夜明け』2010年、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学出版、ボルチモア、ホセ・マリア・ゴメス・ドゥランとの共著 ISBN 0-8018-9785-8 葉切アリ:本能による文明、2011年、W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-33868-3、バート・ホルドビラーとの共著 地球の社会的征服、2012年、Liveright Publishing Corporation、ニューヨーク、ISBN 0-87140-363-3 『若き科学者への手紙』、2014年、リバライト、ISBN 0-87140-385-4 『永遠への窓:生物学者がゴロンゴサ国立公園を歩く』、2014年、サイモン&シュスター、ISBN 1-4767-4741-5 人間の存在の意味、2014年、リヴァーライト社、ISBN 0-87140-100-2 半地球、2016年、リヴァーライト社、ISBN 978-1-63149-082-8 創造性の起源、2017年、リヴァーライト社、ISBN 978-1-63149-318-8 創世記:社会の深い起源、2019年、リバライト、ISBN 1-63149-554-2 アリの世界の物語、2020年、リバライト、ISBN 978-1-63149-556-4[129][130] 『ナチュラリスト:グラフィック・アダプテーション』2020年11月10日、アイランド・プレス、ISBN 978-1-61091-958-6[131] 編集作品 『とても単純な始まり:ダーウィンの4冊の偉大な本』エドワード・O・ウィルソン編、2005年、W. W. Norton、ISBN 0-393-06134-5 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._O._Wilson | |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆