経済学・哲学草稿、あるいはパリ手稿

Ökonomisch-philosophische Manuskripte, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844

経済学・哲学草稿、あるいはパリ手稿

Ökonomisch-philosophische Manuskripte, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844

「1844年の経済哲 学手稿(Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844)」=ウィキペディア(日本語):「『1844年の経済哲学手稿』( Ökonomisch-philosophische Manuskripte aus dem Jahre 1844)、またはパリ手稿[1](Pariser Manuskripte)、1844年手稿[1]は、ドイツの思想家、カール・マルクスが1844年4月から8月に書いた一連のメモで、死後1932年に 出版された。/このノートは、マルクスの生前から数十年後に、モスクワのマルクス・エンゲルス・レーニン研究所の研究者がソビエト連邦でオリジナルのドイ ツ語で編集したものである。1932年にベルリンで発表された後、1933年にソ連(モスクワ・レニングラード)でドイツ語版として再出版された。その出 版は、それまでマルクスの信奉者が知らなかった理論的な枠組みの中に彼の仕事を位置づけ、マルクスに対する評価を大きく変えることになった。」

1)総論

2)疎外された労働

3)共産主義

4)ヘーゲル批判

5)ニーズ、生産、分業とお金

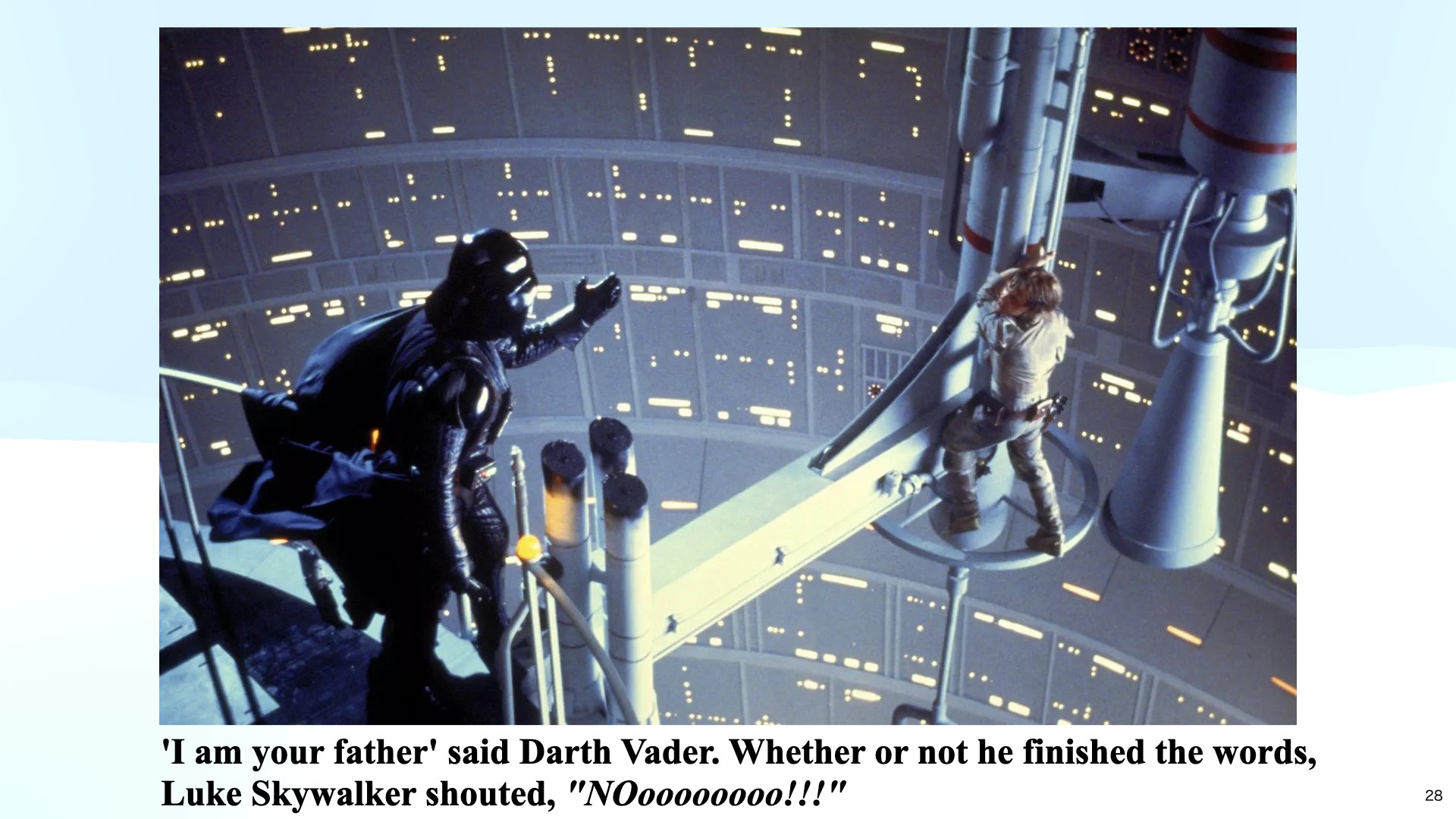

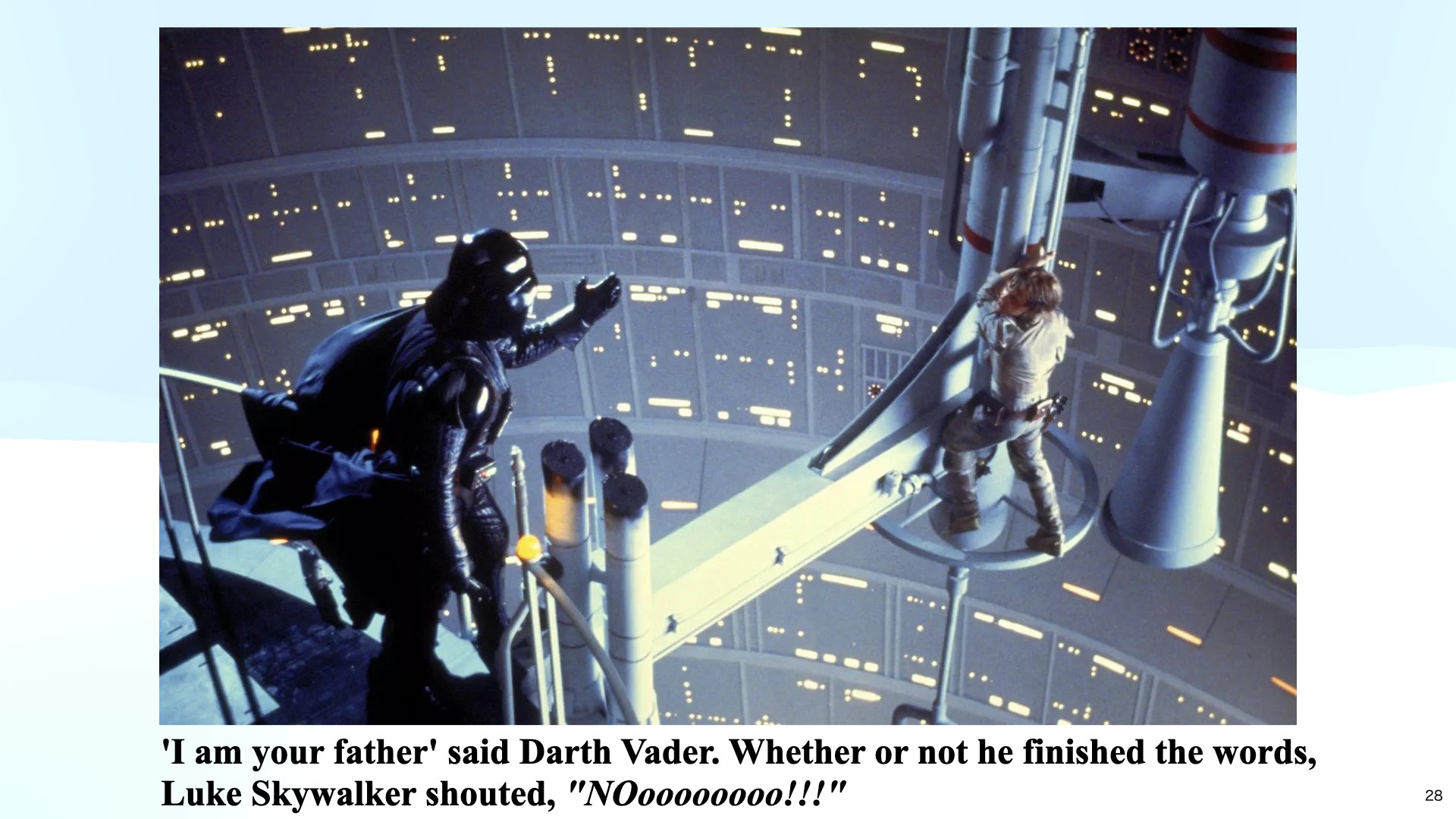

| 1)総論 マルクスは『手稿』の中で、経済的なカテゴリーを、自然におけ る人間の位置づけに関する哲学的な解釈と関連付けて説明しています。マルクスのノートでは、政治経済の基本概念である資本、家賃、労働、財産、貨幣、商 品、欲求、賃金について、一般的な哲学的分析がなされている[11]。その重要な概念は、マルクスが哲学的な用語を用いて「疎外」に基づく資本主義社会へ の批判を進める際に登場する[1]。マルクスの理論は、ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』(1807年)とフォイエルバッハの『キリスト教の本質(英語版)』 (1841年)から(変更がないわけではないが)転用されたものである[20]。疎外は単なる記述的な概念ではなく、世界の根本的な変革を通じて、脱疎外 を求めるものである[21]。 2)疎外された労働 マルクスの第一次草稿は、その大部分が、『原稿』執筆当時にマルクスが読んでいたアダム・スミスなどの古典派経済学者の著作からの抜粋や言い換えで構成さ れている[14]。ここでマルクスは、古典派政治経済学に対して多くの批判を加えている。マルクスは、経済学的概念が人間を人間として扱うのではなく、 家、商品を扱うように、人間の大部分を抽象的労働に還元していると主張する。マルクスは、資本を労働とその生産物に対する命令権であるとするスミスの定義 に従う[22]。彼は、スミスの言う地主と資本家の区別に反対し、土地財産の性格は封建時代から変質し、社会は労働者と資本家の2つの階級にしか分かれな い(ようになっている)と主張している。さらに、古典派経済学者に見られる労働観は、表面的で抽象的であると批判している[23]。マルクスは、古典派経 済学者が、私有財産、交換、競争といった概念を事実としてとらえ、それらを説明する必要を見出さない、架空の原初的状態から出発していると主張する [24]。マルクスは、これらの要因の関連性と歴史に対処する、より首尾一貫した説明を提供したと考えている[25]。 マルクスは、資本主義がいかに人間を人間性から疎外しているかを説明している。人間の基本的な特性は、労働、すなわち自然との取引である[26]。以前の 社会では、人間は自然そのものに依存して、「自然の欲求」を満たすことができた。しかし、現代社会では、土地所有が市場経済の法則に従うので、人はお金に よってのみ生きていくことができる。労働者の労働と生産物は、彼自身から切り離された存在になっている。彼の生産力は、他の商品と同じように、最低維持費 によって決定される市場価格で売買される商品である。労働者は、働く必要を満たすために働くのではなく、ただ生き延びるために働く[27]。「労働者は、 労働の対象、すなわち、仕事を受け取ること、そして、第二に、生計の手段を受け取ることで、労働の対象を受け取る。これによって彼は、第一に労働者とし て、第二に肉体的主体として存在することができる。この隷属の高さは、彼が肉体的主体として自らを維持できるのは労働者としてだけであり、彼が労働者であ るのは肉体的主体としてだけである」ということである[28]。 彼の仕事が資本階級のために富を生み出す一方で、労働者自身は動物のレベルにまで落とされる[27]。社会の富が減少しているならば、最も苦しむのは労働 者であり、増加しているならば、資本は増加し、労働の産物はますます労働者から疎外される[14]。 現代の生産プロセスは、人間の本質的な能力の発達と展開を促進しない。したがって、人間は、自分の人生が意味や充足感を欠いていると感じる。彼らは、現代 の社会的世界に「疎外されている」と感じ、家にいるような気がしないのである。マルクスは、労働者が4つの点で疎外されていると論じている。 彼が生産する製品から 彼がこの製品を生産する行為から 彼の性質と彼自身から 他の人間から 労働者とその生産物との関係は、彼の貧困化と非人間化の主要な原因である[29]。労働者の労働によって生産される対象は、異質なものとして、その生産者 とは独立した力として存在する[30]。労働者が生産すればするほど、彼は仕事を失い、飢餓に近づく[29]。人間は、もはや自分の外の世界との交流の主 導者ではなく、自分自身の進化の制御を失っている[31]。マルクスは、宗教との類似を描いている。宗教では、神が歴史的プロセスの主体であり、人間は依 存状態にある[32]。人間が神に帰属すればするほど、人間は自分自身の中にとどまることができなくなるのである。同様に、労働者が自分の生命を対象物の 中に外在化させるとき、彼の生命は対象物に属し、彼自身に属さない。対象は敵対的で異質なものとして彼に対峙している[29]。彼の性質は、他の人や物の 属性となる[31]。 対象物の生産行為は、疎外感の第二の次元である。それは強制労働であり、自発的なものではない。労働は労働者の外部にあるもので、彼の本性の一部ではな い。労働者の活動は他者に属し、自己を喪失させる[29]。労働者は、食べること、飲むこと、子孫を残すことという動物的な機能においてのみ安らかであ る。人間的な機能において、彼は動物のように感じさせられる[33]。 マルクスが論じる疎外の第三の次元は、人間がその種から疎外されていることである[34]。マルクスはここで、フォイエルバッハの用語を用いて、人間を 「種的存在」と表現している[35]。人間は、無機的自然の全領域を自分のために利用することができる自己意識的な被造物である。他の動物は生産するが、 すぐに必要なものだけを生産する。一方、人間は、普遍的かつ自由に生産する。彼は、いかなる種の基準にも従って生産することができ、対象物に内在する基準 を適用する方法を常に知っている[34]。このように、人間は美の法則に従って創造する[36]。このような無機的自然の変容こそ、マルクスが人間の「生 命活動」と呼ぶものであり、人間の本質である。人間は、その生命活動が単なる存在の手段に転化されたために、種としての存在を失ってしまったのである [37]。 疎外の第四の、そして最後の次元は、疎外の他の三つの次元から引き出されたものである。マルクスは、人間は他の人間から疎外されていると考えている [37]。マルクスは、労働者の労働の産物は異質なものであり、他の誰かに属していると主張している。労働者の生産活動は、労働者にとって苦悩であり、そ れゆえ、それは他の者の快楽でなければならない[38]。マルクスは、この他者とは誰なのか、と問う[37]。人間の労働の生産物は自然にも神々にも属さ ないので、この二つの事実は、人間の生産物と人間の活動を支配しているのは他の人間であることを指摘している[39]。 マルクスは、疎外の分析から、私有財産は外在化した労働の産物であり、その逆ではない、という結論を導き出した。資本家の労働に対する関係を生み出すの は、労働者の労働に対する関係である[40]。マルクスは、このことから、社会的労働が、今度は、すべての価値の源泉であり、したがって、富の分配の源泉 であることを導き出そうとする[41]。彼は、古典派経済学者が労働を生産の基礎として扱う一方で、労働には何も与えず、私有財産にすべてを与えていると 主張する。マルクスにとって、賃金と私有財産は、ともに労働の疎外がもたらした結果であり、同一である[41]。賃金の増加は、労働をその人間的な意味と 意義に回復させない[41]。労働者の解放は、普遍的な人間的解放の達成となる。なぜなら、労働者の生産に対する関係には、人間的隷属の全体が関与してい るからである[42]。 3)共産主義 マルクスは第3稿で共産主義の概念について論じている[43]。マルクスにとって、共産主義とは「私有財産の廃止の積極的表現」である[44]。マルクス はここで、それまでの社会主義作家は、疎外の克服について部分的で不満足な洞察しか提供してこなかったと主張する[43]。彼は、資本の廃止を唱えたプ ルードン、農業労働への復帰を唱えたフーリエ、工業労働の正しい組織化を唱えたサン=シモンについて言及している。 マルクスは、不適切と考える2つの共産主義の形態を論じている[43]。第一は、「粗野な共産主義」-私有財産の普遍化-である[43]。この形態の共産 主義は、労働者というカテゴリーを廃止するのではなく、すべての人間にそれを拡大するため、「あらゆる領域で人間の人格を否定する」ものである[45]。 それは、「文化と文明の世界全体を抽象的に否定するもの」である[45]。ここでは、唯一の共同体は、(疎外された)労働者の共同体であり、唯一の平等 は、普遍的資本家としての共同体によって支払われる賃金のものである[46]。 マルクスが不完全と見なす共産主義の第二の形態は、次の二種類に分けられる。 依然として政治的性格をもち、民主的または専制的なもの。 国家を廃止したもの いずれも依然として本質的に不完全で、私有財産、すなわち人間の疎外に影響されたものである[47]。デイヴィッド・マクレラン(英語版)はここでマルク スが、エティエンヌ・カベ(英語版)のユートピア的共産主義を民主主義、グラックス・バブーフの信奉者が唱えたプロレタリアートの独裁を専制的共産主義、 そして国家の廃止をテオドール・デザミー(英語版)の共産主義としていることを指摘している[43]。「粗雑な共産主義」の本質を論じた上で、マルクスは 自らの共産主義の考えを次のように述べている。[48] 共産主義は、「人間の自己離反」としての「私有財産」、したがって、人間を通じて、人間のための「人間」の本質の真の「占有」に積極的に取って代わること である。それは、人間が「社会的」、すなわち人間として完全に自己回復すること、意識化した回復、以前の発展期の富全体の中で行われる回復なのである。こ の共産主義は、完全に発展した自然主義としてヒューマニズムに等しく、完全に発展したヒューマニズムとして自然主義に等しい。それは、人間と自然、人間と 人間の間の対立の「真の」解決、存在と存在、対象化と自己肯定、自由と必要、個人と種の間の対立の真の解決なのである。それは歴史の謎の解決策であり、自 分自身が解決策であることを知っている。 マルクスは、共産主義の概念について、その歴史的基盤、社会的性格、個人への配慮という三つの側面を深く論じている[49]。 マルクスはまず、自分の共産主義と他の「未発達な」形態の共産主義を区別する。彼は、私有財産に反対した歴史的な共同体の形態に訴えて自らを正当化する共 産主義の例として、カベやヴィレガルデルの共産主義を挙げる[50]。この共産主義が過去の歴史の孤立した側面やエポックに訴えるのに対し、マルクスの共 産主義は、「歴史の全運動」に基づいている[48]。それは、「私有財産の運動、より正確に言えば、経済の運動にその経験的および理論的基礎を見出す」の である[48]。人間生活の最も基本的な疎外は、私有財産の存在に表れており、この疎外は、人間の実生活-経済的領域-において生じるものである [50]。宗教的な疎外は、人間の意識の中にのみ生じる[50]。したがって、私有財産の克服は、宗教、家族、国家など、他のすべての疎外感の克服になる のである[50]。 マルクスは、第二に、人間が自分自身に対して、他の人間に対して、また、非独占的な状況において生産するものに対しての関係は、労働の社会的性格こそが基 本であることを示していると主張する[51]。マルクスは、人間と社会との間には、社会が人間を生産し、人間によって生産されるという相互関係があると考 える[51]。人間と社会との間に相互関係があるように、人間と自然との間にも相互関係がある。 「したがって社会は、人間と自然との本質的な完全な統一であり、自然の真の復活であり、人間の実現した自然主義であり、自然の実現した人間主義である。 [52]」 人間の本質的な能力は、社会的な交わりにおいて生み出される。孤立して働くとき、彼は人間であることによって社会的な行為を行い、言葉を使う思考さえも社 会的な活動である[51]。 このように人間の存在の社会的側面を強調することは、人間の個性を破壊するものではない[51]。 「人間は、どんなにそれゆえ特定の個人であろうとも-まさにこの特殊性こそが彼を個人とし、真の個々の共同体的存在とするのであるが-それと同じくらい全 体性、理想的全体性、思考の主観的経験、それ自体のための社会を経験したものである[53]。」 マルクスの第3稿の残りの部分は、全体的な、全面的な、無権利の人間についての彼の観念を説明している[54]。見る、聞く、嗅ぐ、味わう、触る、考え る、観察する、感じる、欲望する、行動する、愛する、これらすべてが現実を充足する手段となるのである[54]。私有財産が人間を条件づけ、実際に使用す るときだけ自分のものであると想像できるようにしているので、疎外された人間にとってこれを想像することは困難である[54]。その場合でも、その対象 は、労働と資本の創造からなると理解される生活を維持するための手段としてのみ使用される[54]。マルクスは「すべての身体的、知的な感覚が、一つの疎 外-持つということ-に取って代わられたと考えている。私有財産に取って代わられることは、人間のすべての感覚と属性が完全に解放されることである [54]。したがって必要性や満足はエゴイスティックな性質を失い、自然は「その利用が人間の利用になったという意味において」単なる有用性を失うだろ う」と主張している[55][55]。人間がある対象に没頭しなくなると、彼の能力がその対象に適合する方法が全く異なるものになる[56]。無権利者が 充当する対象は、彼の本性に対応するものである。飢えた人間は、純粋に動物的な方法でしか食べ物を評価できないし、鉱物の商人は、その品物に美ではなく価 値しか見出せない。私有財産を超越することによって、人間の能力は解放され、人間的な能力となる[56]。主観主義と客観主義[57]、精神主義と物質主 義[56]、活動と受動性[57]といった抽象的な知的対立が消滅し、人間の文化的潜在能力が完全かつ調和的に発展することになるのである。「人間の実践 的なエネルギーが、人生の真の問題に取り組むことになる[56]。 マルクスは次に、宗教、政治、芸術の歴史ではなく、産業の歴史こそが人間の本質的な能力を明らかにするものであると、後のマルクスによる史的唯物論の詳細 な説明を先取りする一節を述べている[58]。産業は人間の能力と心理を明らかにするものであり、したがって、人間に関するあらゆる科学の基礎となるもの である。産業の巨大な成長は、自然科学が人間の生活を一変させることを可能にした[58]。マルクスは、先に人間と自然との間に相互関係を確立したよう に、自然科学がいつの日か人間の科学を含み、人間の科学が自然科学を含むようになると考えているのである[59]。マルクスは、フォイエルバッハが述べた ような人間の感覚-経験が、一つの全面的な科学の基礎を形成しうると考えている[59]。 4)ヘーゲル批判 共産主義についてのマルクスの議論に続く『手稿』の部分は、ヘーゲルに対する批判に関するものである[60]。マルクスがヘーゲルの弁証法を論じる必要が あると考えるのは、ヘーゲルが古典派経済学者には隠されていた形で人間の労働の本質を把握したからである[61]。ヘーゲルは、労働について抽象的で精神 的な理解をしているにもかかわらず、労働が価値の創造者であることを正しく見抜いているのである[60]。ヘーゲルの哲学の構造は、人間の労働過程におけ る現実の経済的疎外を正確に反映している[60]。マルクスは、ヘーゲルが非常に現実的な発見をしたが、それを「神秘化」してしまったと考える。彼は、 フォイエルバッハが、ヘーゲルに対して建設的な態度をとる唯一の批評家であると主張している。しかし、彼はまた、フォイエルバッハのアプローチの弱点を照 らすために、ヘーゲルを利用するのである[62]。 ヘーゲルの弁証法の偉大さは、疎外を人類の進化に必要な段階と見なすところにある[63]。人類は、疎外とその超越が交互に起こるプロセスによって自らを 創造する[11]。ヘーゲルは、労働を人間の本質を実現する疎外過程と見ている。人間は、自分の本質的な力を対象化された状態で外在化し、それを外部から 自分の中に同化させるのである[11]。ヘーゲルは、人間の生活を秩序づけているように見える対象-宗教、富-は、実際には人間に属するものであり、人間 の本質的な能力の産物であることを理解している[63]。それにもかかわらず、マルクスは、ヘーゲルが労働を精神活動と同一視し、疎外を客観性と同一視し ていると批判している[11]。マルクスは、ヘーゲルの間違いは、人間に客観的、感覚的に属する実体を精神的な実体にすることだと考えている[64]。 ヘーゲルにとって、疎外の超越は、対象の超越、つまり、人間の精神的本性に再吸収されることである[11]。ヘーゲルの体系では、異質なものの充当は、意 識の領域で行われる抽象的な充当でしかないのである。人間は経済的、政治的疎外に苦しんでいるが、ヘーゲルの関心は経済と政治の思考にあるにすぎない [64]。人間と自然との統合は、精神的なレベルで行われるので、マルクスは、この統合を抽象的で幻想的なものとみなしている[11]。 マルクスは、フォイエルバッハこそ、ヘーゲルの弟子の中で、師匠の哲学を真に征服した唯一の人物であるとする[62]。フォイエルバッハは、ヘーゲルが、 宗教と神学の抽象的で無限の視点から出発し、これを哲学の有限で特殊な態度に取って代わった後、この態度に代わって、神学特有の抽象性を回復したことを示 すことに成功した。フォイエルバッハは、この最終段階を退歩と見なし、マルクスもこれに同意している[65]。 ヘーゲルは、現実とは精神が自己を実現することであり、疎外とは、人間が自分たちの環境と文化が精神の発露であることを理解しないことにあると考える。精 神の存在は、それ自身の生産活動においてのみ、またそれを通じてのみ構成される。自己を実現する過程で、精神は世界を生産するが、それははじめは外的なも のと信じていたが、次第に自分自身の生産物であることを理解するようになる。歴史の目的は自由であり、自由は人間が完全に自己意識的になることにある [66]。 マルクスは、ヘーゲルの精神という概念を否定し、人間の精神活動、すなわち彼の考えは、それ自体では社会的、文化的変化を説明するには不十分だと考えてい る[66]。マルクスは、ヘーゲルは人間性が自己意識の一つの属性であるかのように語っているが、実際には自己意識は人間性の一つの属性に過ぎない、と述 べている[67]。ヘーゲルは、人間は自己意識と同一視できると考えているが、自己意識は対象として自分自身しか持っていないからである[66]。さら に、ヘーゲルは、疎外を客観性によって構成されるものと考え、疎外の克服を主として客観性の克服と考える。これに対して、マルクスは、人間が単なる自己意 識であるならば、自己意識に対して独立性のない抽象的な対象を自分の外部に設けることしかできない、と主張する[67]。すべての疎外が自己意識の疎外で あるとすれば、実際の疎外、すなわち自然物に対する疎外は、見かけだけのものである[67]。 マルクスはその代わりに、人間を客観的で自然な存在としてとらえ、彼の本性に対応する本物の自然物を持っていると考えている[67]。マルクスはこの考え 方を「自然主義」「人文主義」と呼んでいる。彼は、この見解を観念論や唯物論と区別しながらも、両者において本質的に真であるものを統一していると主張し ている。マルクスにとって、自然は人間と対立するものであるが、人間はそれ自体、自然のシステムの一部である。人間の本性は、彼の欲求と衝動によって構成 されており、これらの本質的な欲求と衝動が満たされるのは、自然を通してである[68]。そのため、人間は、自分の客観的な性質を表現するために、自分か ら独立した対象を必要とする。対象そのものでもなく、対象を持たない存在が、唯一の存在者-非対象的な存在-である[69]。 この人間性の議論に続いて、マルクスはヘーゲルの『現象学』の最終章についてコメントしている。マルクスは、ヘーゲルが疎外と客観性を同一視し、意識が疎 外を超越したと主張していることを批判する。マルクスによれば、ヘーゲルは、意識はその対象が自らの自己疎外であることを知っている、つまり、意識の対象 と意識そのものとの間には区別がない、と考えている。人間が、精神世界を自分の真の存在の特徴であると信じ、その疎外された形において精神世界と一体であ ると感じるとき、疎外は超越されるのである[70]。マルクスは、「超越」(Aufhebung)の意味について、ヘーゲルと根本的に異なっている。私有 財産、道徳、家族、市民社会、国家などは、思想において「超越」されたが、依然として存在する[71]。ヘーゲルは、無神論が神を超越して理論的ヒューマ ニズムを生み出し、共産主義が私有財産を超越して実践的ヒューマニズムを生み出すという、疎外のプロセスとその超越に関する真の洞察に到達しているのであ る[72]。しかし、マルクスの考えでは、ヒューマニズムに到達しようとするこれらの試みは、それ自体が超越され、自己創造的で積極的なヒューマニズムを 生み出さなければならないのである[73]。 5)ニーズ、生産、分業とお金 マルクスは、「原稿」の最後の部分で、私有財産の道徳と貨幣の意味について考察している。この議論は、賃金、家賃、利潤に関する最初のセクションと同じ枠 組みで行われている。マルクスは、私有財産は、人間を依存させるために、人為的に欲求を作り出すと主張している[74]。人間とその欲求が市場の意のまま になるにつれて、貧困が増大し、人間の生活条件は動物のそれよりも悪くなる。これに沿って、政治経済学は、徹底した禁欲主義を説き、労働者の欲求を悲惨な 生活必需品にまで低下させる[74]。政治経済は、疎外によって活動が異なる領域に分けられ、しばしば異なる矛盾した規範を持つため、独自の私法を持って いる[75]。マルクスは、古典的経済学者が人口を制限することを望み、人間さえも贅沢品だと考えていることに触れている[76]。そして、共産主義の話 題に戻る。イギリスの状況は、ドイツやフランスの状況よりも、疎外感の超越のための確かな基礎を提供すると主張している。イギリスの疎外感の形態は、実際 的な必要性に基づいているが、ドイツの共産主義は、普遍的な自己意識を確立しようとする試みに基づいており、フランスの共産主義の平等性は、単に政治的基 盤を持っているだけである[76]。 マルクスは、この章の後半で、資本の非人間的な作用に立ち戻る[76]。彼は、利子率の低下と地代の廃止、さらに分業の問題を論じている[77]。次の貨 幣の項では、マルクスはシェイクスピアやゲーテを引用して、貨幣が社会を破滅させるものであることを主張する。貨幣は何でも買うことができるので、あらゆ る欠乏を改善することができる。マルクスは、すべてのものが明確な、人間的な価値を持つようになる社会では、愛だけが愛と交換されるようになる、などと考 える[78]。 |

★経済学・哲学草稿(1844)本文の英訳

《序言》→タグジャンプ(Preface)

| First Manuscript Wages of Labour Profit of Capital 1. Capital 2. The Profit of Capital 3. The Rule of Capital Over Labour and the Motives of the Capitalist 4. The Accumulation of Capitals and the Competition Among the Capitalists Rent of Land Estranged Labour Second Manuscript Antithesis of Capital and Labour. Landed Property and Capital Third Manuscript Private Property and Labour Private Property and Communism Human Needs & Division of Labour Under the Rule of Private Property The Power Of Money Critique of the Hegelian Dialectic and Philosophy as a Whole and Hegel’s Construction of The Phenomenology, November 1844 Plan for a Work on The Modern State, November 1844 |

| 第一草稿 |

Wages of Labour |

Wages are

determined through the antagonistic struggle between capitalist and

worker. Victory goes necessarily to the capitalist. The capitalist can

live longer without the worker than can the worker without the

capitalist. Combination among the capitalists is customary and

effective; workers’ combination is prohibited and painful in its

consequences for them. Besides, the landowner and the capitalist can

make use of industrial advantages to augment their revenues; the worker

has neither rent nor interest on capital to supplement his industrial

income. Hence the intensity of the competition among the workers. Thus

only for the workers is the separation of capital, landed property, and

labour an inevitable, essential and detrimental separation. Capital and

landed property need not remain fixed in this abstraction, as must the

labour of the workers. The separation of capital, rent, and labour is thus fatal for the worker. The lowest and the only necessary wage rate is that providing for the subsistence of the worker for the duration of his work and as much more as is necessary for him to support a family and for the race of labourers not to die out. The ordinary wage, according to Smith, is the lowest compatible with common humanity [6], that is, with cattle-like existence. The demand for men necessarily governs the production of men, as of every other commodity. Should supply greatly exceed demand, a section of the workers sinks into beggary or starvation. The worker’s existence is thus brought under the same condition as the existence of every other commodity. The worker has become a commodity, and it is a bit of luck for him if he can find a buyer. And the demand on which the life of the worker depends, depends on the whim of the rich and the capitalists. Should supply exceed demand, then one of the constituent parts of the price – profit, rent or wages – is paid below its rate, [a part of these] factors is therefore withdrawn from this application, and thus the market price gravitates [towards the] natural price as the centre-point. But (1) where there is considerable division of labour it is most difficult for the worker to direct his labour into other channels; (2) because of his subordinate relation to the capitalist, he is the first to suffer. Thus in the gravitation of market price to natural price it is the worker who loses most of all and necessarily. And it is just the capacity of the capitalist to direct his capital into another channel which either renders the worker, who is restricted to some particular branch of labour, destitute, or forces him to submit to every demand of this capitalist. The accidental and sudden fluctuations in market price hit rent less than they do that part of the price which is resolved into profit and wages; but they hit profit less than they do wages. In most cases, for every wage that rises, one remains stationary and one falls. The worker need not necessarily gain when the capitalist does, but he necessarily loses when the latter loses. Thus, the worker does not gain if the capitalist keeps the market price above the natural price by virtue of some manufacturing or trading secret, or by virtue of monopoly or the favorable situation of his land. Furthermore, the prices of labour are much more constant than the prices of provisions. Often they stand in inverse proportion. In a dear year wages fall on account of the decrease in demand, but rise on account of the increase in the prices of provisions – and thus balance. In any case, a number of workers are left without bread. In cheap years wages rise on account of the rise in demand, but decrease on account of the fall in the prices of provisions – and thus balance. Another respect in which the worker is at a disadvantage: The labour prices of the various kinds of workers show much wider differences than the profits in the various branches in which capital is applied. In labour all the natural, spiritual, and social variety of individual activity is manifested and is variously rewarded, whilst dead capital always keeps the same pace and is indifferent to real individual activity. In general we should observe that in those cases where worker and capitalist equally suffer, the worker suffers in his very existence, the capitalist in the profit on his dead mammon. The worker has to struggle not only for his physical means of subsistence; he has to struggle to get work, i.e., the possibility, the means, to perform his activity. Let us take the three chief conditions in which society can find itself and consider the situation of the worker in them: (1) If the wealth of society declines the worker suffers most of all, and for the following reason: although the working class cannot gain so much as can the class of property owners in a prosperous state of society, no one suffers so cruelly from its decline as the working class. (2) Let us now take a society in which wealth is increasing. This condition is the only one favorable to the worker. Here competition between the capitalists sets in. The demand for workers exceeds their supply. But: In the first place, the raising of wages gives rise to overwork among the workers. The more they wish to earn, the more must they sacrifice their time and carry out slave-labour, completely losing all their freedom, in the service of greed. Thereby they shorten their lives. This shortening of their life-span is a favourable circumstance for the working class as a whole, for as a result of it an ever-fresh supply of labour becomes necessary. This class has always to sacrifice a part of itself in order not to be wholly destroyed. Furthermore: When does a society find itself in a condition of advancing wealth? When the capitals and the revenues of a country are growing. But this is only possible: (a) As the result of the accumulation of much labour, capital being accumulated labour; as the result, therefore, of the fact that more and more of his products are being taken away from the worker, that to an increasing extent his own labour confronts him as another man’s property and that the means of his existence and his activity are increasingly concentrated in the hands of the capitalist. (b) The accumulation of capital increases the division of labour, and the division of labour increases the number of workers. Conversely, the number of workers increases the division of labour, just as the division of labour increases the accumulation of capital. With this division of labour on the one hand and the accumulation of capital on the other, the worker becomes ever more exclusively dependent on labour, and on a particular, very one-sided, machine-like labour at that. Just as he is thus depressed spiritually and physically to the condition of a machine and from being a man becomes an abstract activity and a belly, so he also becomes ever more dependent on every fluctuation in market price, on the application of capital, and on the whim of the rich. Equally, the increase in the class of people wholly dependent on work intensifies competition among the workers, thus lowering their price. In the factory system this situation of the worker reaches its climax. (c) In an increasingly prosperous society only the richest of the rich can continue to live on money interest. Everyone else has to carry on a business with his capital, or venture it in trade. As a result, the competition between the capitalists becomes more intense. The concentration of capital increases, the big capitalists ruin the small, and a section of the erstwhile capitalists sinks into the working class, which as a result of this supply again suffers to some extent a depression of wages and passes into a still greater dependence on the few big capitalists. The number of capitalists having been diminished, their competition with respect to the workers scarcely exists any longer; and the number of workers having been increased, their competition among themselves has become all the more intense, unnatural, and violent. Consequently, a section of the working class falls into beggary or starvation just as necessarily as a section of the middle capitalists falls into the working class. Hence even in the condition of society most favorable to the worker, the inevitable result for the worker is overwork and premature death, decline to a mere machine, a bond servant of capital, which piles up dangerously over and against him, more competition, and starvation or beggary for a section of the workers. The raising of wages excites in the worker the capitalist’s mania to get rich, which he, however, can only satisfy by the sacrifice of his mind and body. The raising of wages presupposes and entails the accumulation of capital, and thus sets the product of labour against the worker as something ever more alien to him. Similarly, the division of labour renders him ever more one-sided and dependent, bringing with it the competition not only of men but also of machines. Since the worker has sunk to the level of a machine, he can be confronted by the machine as a competitor. Finally, as the amassing of capital increases the amount of industry and therefore the number of workers, it causes the same amount of industry to manufacture a larger amount of products, which leads to over-production and thus either ends by throwing a large section of workers out of work or by reducing their wages to the most miserable minimum. Such are the consequences of a state of society most favourable to the worker – namely, of a state of growing, advancing wealth. Eventually, however, this state of growth must sooner or later reach its peak. What is the worker’s position now? (3) “In a country which had acquired that full complement of riches both the wages of labour and the profits of stock would probably be very low [...] the competition for employment would necessarily be so great as to reduce the wages of labour to what was barely sufficient to keep up the number of labourers, and, the country being already fully peopled, that number could never be augmented.” [Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, Vol. I, p. 84.] The surplus would have to die. Thus in a declining state of society – increasing misery of the worker; in an advancing state – misery with complications; and in a fully developed state of society – static misery. Since, however, according to Smith, a society is not happy, of which the greater part suffers – yet even the wealthiest state of society leads to this suffering of the majority – and since the economic system [7] (and in general a society based on private interest) leads to this wealthiest condition, it follows that the goal of the economic system is the unhappiness of society. Concerning the relationship between worker and capitalist we should add that the capitalist is more than compensated for rising wages by the reduction in the amount of labour time, and that rising wages and rising interest on capital operate on the price of commodities like simple and compound interest respectively. Let us put ourselves now wholly at the standpoint of the political economist, and follow him in comparing the theoretical and practical claims of the workers. He tells us that originally and in theory the whole product of labour belongs to the worker. But at the same time he tells us that in actual fact what the worker gets is the smallest and utterly indispensable part of the product – as much, only, as is necessary for his existence, not as a human being, but as a worker, and for the propagation, not of humanity, but of the slave class of workers. The political economist tells us that everything is bought with labour and that capital is nothing but accumulated labour; but at the same time he tells us that the worker, far from being able to buy everything, must sell himself and his humanity. Whilst the rent of the idle landowner usually amounts to a third of the product of the soil, and the profit of the busy capitalist to as much as twice the interest on money, the “something more” which the worker himself earns at the best of times amounts to so little that of four children of his, two must starve and die. Whilst according to the political economists it is solely through labour that man enhances the value of the products of nature, whilst labour is man’s active possession, according to this same political economy the landowner and the capitalist, who qua landowner and capitalist are merely privileged and idle gods, are everywhere superior to the worker and lay down the law to him. Whilst according to the political economists labour is the sole unchanging price of things, there is nothing more fortuitous than the price of labour, nothing exposed to greater fluctuations. Whilst the division of labour raises the productive power of labour and increases the wealth and refinement of society, it impoverishes the worker and reduces him to a machine. Whilst labour brings about the accumulation of capital and with this the increasing prosperity of society, it renders the worker ever more dependent on the capitalist, leads him into competition of a new intensity, and drives him into the headlong rush of overproduction, with its subsequent corresponding slump. Whilst the interest of the worker, according to the political economists, never stands opposed to the interest of society, society always and necessarily stands opposed to the interest of the worker. According to the political economists, the interest of the worker is never opposed to that of society: (1) because the rising wages are more than compensated by the reduction in the amount of labour time, together with the other consequences set forth above; and (2) because in relation to society the whole gross product is the net product, and only in relation to the private individual has the net product any significance. But that labour itself, not merely in present conditions but insofar as its purpose in general is the mere increase of wealth – that labour itself, I say, is harmful and pernicious – follows from the political economist’s line of argument, without his being aware of it. In theory, rent of land and profit on capital are deductions suffered by wages. In actual fact, however, wages are a deduction which land and capital allow to go to the worker, a concession from the product of labour to the workers, to labour. When society is in a state of decline, the worker suffers most severely. The specific severity of his burden he owes to his position as a worker, but the burden as such to the position of society. But when society is in a state of progress, the ruin and impoverishment of the worker is the product of his labour and of the wealth produced by him. The misery results, therefore, from the essence of present-day labour itself. Society in a state of maximum wealth – an ideal, but one which is approximately attained, and which at least is the aim of political economy as of civil society – means for the workers static misery. It goes without saying that the proletarian, i.e., the man who, being without capital and rent, lives purely by labour, and by a one-sided, abstract labour, is considered by political economy only as a worker. Political economy can therefore advance the proposition that the proletarian, the same as any horse, must get as much as will enable him to work. It does not consider him when he is not working, as a human being; but leaves such consideration to criminal law, to doctors, to religion, to the statistical tables, to politics and to the poor-house overseer. Let us now rise above the level of political economy and try to answer two questions on the basis of the above exposition, which has been presented almost in the words of the political economists: (1) What in the evolution of mankind is the meaning of this reduction of the greater part of mankind to abstract labour? (2) What are the mistakes committed by the piecemeal reformers, who either want to raise wages and in this way to improve the situation of the working class, or regard equality of wages (as Proudhon does) as the goal of social revolution? In political economy labour occurs only in the form of activity as a source of livelihood. ||VIII, 1|“It can be asserted that those occupations which presuppose specific talents or longer training have become on the whole more lucrative; whilst the proportionate reward for mechanically monotonous activity in which one person can be trained as easily and quickly as another has fallen with growing competition, and was inevitably bound to fall. And it is just this sort of work which in the present state of the organization of labour is still by far the commonest. If therefore a worker in the first category now earns seven times as much as he did, say, fifty years ago, whilst the earnings of another in the second category have remained unchanged, then of course both are earning on the average four times as much. But if the first category comprises only a thousand workers in a particular country, and the second a million, then 999,000 are no better off than fifty years ago – and they are worse off if at the same time the prices of the necessaries of life have risen. With such superficial calculation of averages people try to deceive themselves about the most numerous class of the population. Moreover, the size of the wage is only one factor in the estimation of the worker’s income, because it is essential for the measurement of the latter to take into account the certainty of its duration – which is obviously out of the question in the anarchy of so-called free competition, with its ever-recurring fluctuations and periods of stagnation. Finally, the hours of work customary formerly and now have to be considered. And for the English cotton-workers these have been increased, as a result of the entrepreneurs’ mania for profit. ||IX, 1| to between twelve and sixteen hours a day during the past twenty-five years or so – that is to say, precisely during the period of the introduction of labour-saving machines; and this increase in one country and in one branch of industry inevitably asserted itself elsewhere to a greater or lesser degree, for the right of the unlimited exploitation of the poor by the rich is still universally recognized.” (Wilhelm Schulz, Die Bewegung der Production.) “But even if it were as true as it is false that the average income of every class of society has increased, the income-differences and relative income-distances may nevertheless have become greater and the contrasts between wealth and poverty accordingly stand out more sharply. For just because total production rises – and in the same measure as it rises – needs, desires and claims also multiply and thus relative poverty can increase whilst absolute poverty diminishes. The Samoyed living on fish oil and rancid fish is not poor because in his secluded society all have the same needs. But in a state that is forging ahead, which in the course of a decade, say, increased by a third its total production in proportion to the population, the worker who is getting as much at the end of ten years as at the beginning has not remained as well off, but has become poorer by a third.” (op. cit., pp. 65-66) But political economy knows the worker only as a working animal – as a beast reduced to the strictest bodily needs. “To develop in greater spiritual freedom, a people must break their bondage to their bodily needs – they must cease to be the slaves of the body. They must, above all, have time at their disposal for spiritual creative activity and spiritual enjoyment. The developments in the labour organism gain this time. Indeed, with new motive forces and improved machinery, a single worker in the cotton mills now often performs the work formerly requiring a hundred, or even 250 to 350 workers. Similar results can be observed in all branches of production, because external natural forces are being compelled to participate to an ever-greater degree in human labour. If the satisfaction of a given amount of material needs formerly required a certain expenditure of time and human effort which has later been reduced by half, then without any loss of material comfort the scope for spiritual activity and enjoyment has been simultaneously extended by as much.... But again the way in which the booty, that we win from old Cronus [Greek God associated with time.] himself in his most private domain, is shared out is still decided by the dice-throw of blind, unjust Chance. In France it has been calculated that at the present stage in the development of production an average working period of five hours a day by every person capable of work could suffice for the satisfaction of all the material interests of society.... Notwithstanding the time saved by the perfecting of machinery. the duration of the slave-labour performed by a large population in the factories has only increased.” (Schulz, op. cit., pp. 67, 68.) “The transition from compound manual labour rests on a break-down of the latter into its simple operations. At first, however, only some of the uniformly-recurring operations will devolve on machines, while some will devolve on men. From the nature of things, and from confirmatory experience, it is clear that unendingly monotonous activity of this kind is as harmful to the mind as to the body; thus this combination of machinery with mere division of labour among a greater number of hands must inevitably show all the disadvantages of the latter. These disadvantages appear, among other things, in the greater mortality of factory workers.... Consideration has not been given ... to this big distinction as to how far men work through machines or how far as machines.” (op. cit., p. 69.) “In the future life of the peoples, however, the inanimate forces of nature working in machines will be our slaves and serfs.” (op. cit., p. 74.) “The English spinning mills employ 196,818 women and only 158,818 men. For every 100 male workers in the cotton mills of Lancashire there are 103 female workers, and in Scotland as many as 209. In the English flax mills of Leeds, for every 100 male workers there were found to be 147 female workers. In Dundee and on the east coast of Scotland as many as 280. In the English silk mills ... many female workers; male workers predominate in the woollen mills where the work requires greater physical strength. In 1833, no fewer than 38,927 women were employed alongside 18,593 men in the North American cotton mills. As a result of the changes in the labour organism, a wider sphere of gainful employment has thus fallen to the share of the female sex.... Women now occupying an economically more independent position ... the two sexes are drawn closer together in their social conditions.” (op. cit., pp. 71-72.) “Working in the English steam- and water-driven spinning mills in 1835 were: 20,558 children between the ages of eight and twelve; 35,867 between the ages of twelve and thirteen; and, lastly, 108,208 children between the ages of thirteen and eighteen.... Admittedly, further advances in mechanisation, by more and more removing all monotonous work from human hands, are operating in the direction of a gradual ||XII, 1| elimination of this evil. But standing in the way of these more rapid advances is the very circumstance that the capitalists can, in the easiest and cheapest fashion, appropriate the energies of the lower classes down to the children, to be used instead of mechanical devices.” (op. cit., pp. 70-71.) “Lord Brougham’s call to the workers – ‘Become capitalists’. ... This is the evil that millions are able to earn a bare subsistence for themselves only by strenuous labour which shatters the body and cripples them morally and intellectually; that they are even obliged to consider the misfortune of finding such work a piece of good fortune.” (op. cit., p. 60.) “In order to live, then, the non-owners are obliged to place themselves, directly or indirectly, at the service of the owners – to put themselves, that is to say, into a position of dependence upon them.” (Pecqueur, Théorie nouvelle d’économie soc., etc..) Servants – pay: workers – wages; employees – salary or emoluments. (loc. cit., pp. 409, 410.) “To hire out one’s labour,” “to lend one’s labour at interest,” “to work in another’s place.” “To hire out the materials of labour”, “to lend the materials of labour at interest”, “to make others work in one’s place”. (op. cit., p. 411.) “Such an economic order condemns men to occupations so mean, to a degradation so devastating and bitter, that by comparison savagery seems like a kingly condition.... (op. cit., pp. 417, 418.) “Prostitution of the non-owning class in all its forms.” (op. cit., p. 421 f.) “Ragmen.” Charles Loudon in the book Solution du probleme de la population, etc., Paris, 1842[8], declares the number of prostitutes in England to be between sixty and seventy thousand. The number of women of doubtful virtue is said to be equally large (p. 228). “The average life of these unfortunate creatures on the streets, after they have embarked on their career of vice, is about six or seven years. To maintain the number of sixty to seventy thousand prostitutes, there must be in the three kingdoms at least eight to nine thousand women who commit themselves to this abject profession each year, or about twenty-four new victims each day – an average of one per hour; and it follows that if the same proportion holds good over the whole surface of the globe, there must constantly be in existence one and a half million unfortunate women of this kind.” (op. cit., p. 229.) “The numbers of the poverty-stricken grow with their poverty, and at the extreme limit of destitution human beings are crowded together in the greatest numbers contending with each other for the right to suffer.... In 1821 the population of Ireland was 6,801,827. In 1831 it had risen to 7,764,010 – an increase of 14 per cent in ten years. In Leinster, the wealthiest province, the population increased by only 8 per cent; whilst in Connaught, the most poverty-stricken province, the increase reached 21 per cent. (Extract from the Enquiries Published in England on Ireland, Vienna, 1840.)” (Buret, De la misère, etc., t. 1, pp. 36, 37.) Political economy considers labour in the abstract as a thing; labour is a commodity. If the price is high, then the commodity is in great demand; if the price is low, then the commodity is in great supply: the price of labour as a commodity must fall lower and lower. (Buret, op. cit.) This is made inevitable partly by the competition between capitalist and worker, partly by the competition amongst the workers. “The working population, the seller of labour, is necessarily reduced to accepting the most meagre part of the product.... Is the theory of labour as a commodity anything other than a theory of disguised bondage?” (op. cit, p. 43.) “Why then has nothing but an exchange-value been seen in labour?” (op. cit., p. 44.) The large workshops prefer to buy the labour of women and children, because this costs less than that of men. (op. cit.) “The worker is not at all in the position of a free seller vis-à-vis the one who employs him.... The capitalist is always free to employ labour, and the worker is always forced to sell it. The value of labour is completely destroyed if it is not sold every instant. Labour can neither be accumulated nor even be saved, unlike true [commodities]. “Labour is life, and if life is not each day exchanged for food, it suffers and soon perishes. To claim that human life is a commodity, one must, therefore, admit slavery.” (op. cit., p. 49, 50.) If then labour is a commodity it is a commodity with the most unfortunate attributes. But even by the principles of political economy it is no commodity, for it is not the “free result of a free transaction.” [op. cit.] The present economic regime “simultaneously lowers the price and the remuneration of labour; it perfects the worker and degrades the man.” (op. cit., pp. 52-53.) “Industry has become a war, and commerce a gamble.” (op. cit., p. 62.) “The cotton-working machines” (in England) alone represent 84,000,000 manual workers. [op. cit., p. 193.]. Up to the present, industry has been in a state of war, a war of conquest: “It has squandered the lives of the men who made up its army with the same indifference as the great conquerors. Its aim was the possession of wealth, not the happiness of men.” (Buret, op. cit.) “These interests” (that is, economic interests), “freely left to themselves ... must necessarily come into conflict; they have no other arbiter but war, and the decisions of war assign defeat and death to some, in order to give victory to the others.... It is in the conflict of opposed forces that science seeks order and equilibrium: perpetual war, according to it, is the sole means of obtaining peace; that war is called competition.” (op. cit., p. 23.) “The industrial war, to be conducted with success, demands large armies which it can amass on one spot and profusely decimate. And it is neither from devotion nor from duty that the soldiers of this army bear the exertions imposed on them, but only to escape the hard necessity of hunger. They feel neither attachment nor gratitude towards their bosses, nor are these bound to their subordinates by any feeling of benevolence. They do not know them as men, but only as instruments of production which have to yield as much as possible with as little cost as possible. These populations of workers, ever more crowded together, have not even the assurance of always being employed. Industry, which has called them together, only lets them live while it needs them, and as soon as it can get rid of them it abandons them without the slightest scruple; and the workers are compelled to offer their persons and their powers for whatever price they can get. The longer, more painful and more disgusting the work they are given, the less they are paid. There are those who, with sixteen hours’ work a day and unremitting exertion, scarcely buy the right not to die.” (op. cit., pp. 68-69.) “We are convinced ... as are the commissioners charged with the inquiry into the condition of the hand-loom weavers, that the large industrial towns would in a short time lose their population of workers if they were not all the time receiving from the neighbouring rural areas constant recruitments of healthy men, a constant flow of fresh blood.” (op. cit., p. 362.) |

賃

金は資本家と労働者の拮抗的闘争を通じて決定される。勝利は必然的に資本家にもたらされる。資本家は、労働者なしでも、資本家なしの労働者よりも長く生き

ることができる。資本家の間の結合は慣習的で効果的であるが、労働者の結合は禁止されており、労働者にとって苦痛を伴う。そのうえ、地主と資本家は、産業

上の利点を利用して収入を増やすことができるが、労働者には、産業上の収入を補うための賃借料も資本利子もない。それゆえ、労働者間の競争が激しくなるの

である。このように、資本、土地所有、労働の分離は、労働者にとってのみ、必然的、本質的かつ有害な分離である。資本と土地所有は、労働者の労働と同様

に、この抽象的なものに固定されている必要はない。 資本、地代、労働の分離は、このように労働者にとって致命的である。 最低で唯一必要な賃金は、労働者が労働している間、その労働者の生活を賄い、さらに労働者が家族を養い、労働者の種族が滅びないために必要なだけの賃金で ある。スミスによれば、通常の賃金とは、人類共通の生活水準 [6]、すなわち家畜のような存在と両立しうる最低の賃金である。 他のあらゆる商品と同様に、人間の需要は必然的に人間の生産を支配する。供給が需要を大幅に上回れば、労働者の一部は乞食か飢餓に陥る。こうして労働者の 存在は、他のあらゆる商品の存在と同じ条件下に置かれることになる。労働者は商品となったのであり、買い手が見つかるかどうかは、彼にとってはちょっとし た幸運なのである。そして、労働者の生活が依存する需要は、金持ちと資本家の気まぐれに左右される。供給が需要を上回れば、価格の構成要素の一つである利 潤、家賃、賃金がその率を下回って支払われることになり、したがって[これらの]要素の一部がこの適用から外され、こうして市場価格は中心点としての自然 価格に向かって[引き寄せられる]のである。しかし、(1)かなりの分業が行われているところでは、労働者が自分の労働力を他の経路に向けることは最も困 難である。 このように、市場価格が自然価格へと引き寄せられる中で、必然的に最も損をするのは労働者である。そして、資本家がその資本を別の経路に向かわせることが できるのは、ある特定の労働分野に限定されている労働者を貧困に陥れるか、この資本家のあらゆる要求に服従させるかのどちらかである。 市場価格の偶発的で突発的な変動は、価格のうち利潤と賃金に分解される部分よりも賃借料に打撃を与えないが、賃金よりも利潤に打撃を与える。たいていの場 合、賃金が上昇するごとに、賃金が据え置かれるものと下落するものがある。 資本家が利益を得るとき、労働者は必ずしも利益を得る必要はないが、資本家が損失を被るとき、労働者は必ず損失を被る。したがって、資本家が、ある製造上 もしくは取引上の秘密によって、または独占もしくはその土地の有利な状況によって、市場価格を自然価格より高く維持しても、労働者は得をしない。 さらに、労働の価格は、糧食の価格よりもはるかに一定している。両者はしばしば反比例する。ある年の賃金は、需要の減少によって下落し、糧食価格の上昇に よって上昇する。いずれにせよ、多くの労働者がパンを手にすることができない。安い年の賃金は、需要の増加によって上昇するが、糧食価格の下落によって低 下する。 労働者が不利になるもう一つの点がある: さまざまな種類の労働者の労働価格は、資本が適用されるさまざまな部門における利益よりも、はるかに大きな差異を示している。労働においては、個人の活動 の自然的、精神的、社会的な多様性がすべて現れ、さまざまに報われるのに対して、死んだ資本は常に同じペースを保ち、個人の真の活動には無関心である。 一般に、労働者と資本家が等しく苦しむ場合、労働者はその存在そのものに、資本家はその死んだ金もうけに苦しむのである。 労働者は、自分の肉体的な生活手段のために闘わなければならないだけでなく、仕事を得るために、すなわち、自分の活動を行う可能性、手段を得るために闘わ なければならないのである。 社会が陥りうる3つの主な条件を取り上げ、その中での労働者の状況を考えてみよう: (1) 社会の富が減少した場合、労働者が最も苦しむが、その理由は次のとおりである:労働者階級は、社会が繁栄している状態では、財産所有者階級が得ることがで きるほどの利益を得ることはできないが、労働者階級ほどその減少によって無残に苦しむ者はいない。 (2) 次に、富が増加している社会を考えてみよう。この状態は、労働者にとって唯一有利なものである。ここで資本家間の競争が始まる。労働者の需要は供給を上回 る。しかし: 第一に、賃金の引き上げは労働者に過重労働をもたらす。稼ごうとすればするほど、労働者は自分の時間を犠牲にしなければならず、貪欲のために、完全に自由 を失って奴隷労働をしなければならない。そうすることで、彼らは命を縮める。このように寿命が縮まることは、労働者階級全体にとって好ましい状況である。 なぜなら、その結果、常に新鮮な労働力の供給が必要となるからである。この階級は、完全に破壊されないために、常に自らの一部を犠牲にしなければならな い。 さらに 社会が富を増大させる状態になるのはどんなときか。一国の資本と歳入が増大するときである。しかし、それが可能なのは (a)多くの労働の蓄積の結果として、資本は労働を蓄積したものである。したがって、労働者の生産物がますます多く労働者から取り上げられ、労働者自身の 労働が他人の所有物としてますます多く労働者に直面し、労働者の生存と活動の手段がますます資本家の手に集中しているという事実の結果として。 (b) 資本の蓄積は分業を増大させ、分業は労働者の数を増大させる。逆に、労働者の数は、労働の分業が資本の蓄積を増大させるのと同様に、労働の分業を増大させ る。一方では分業が進み、他方では資本の蓄積が進むにつれて、労働者はますます労働に、それも特殊な、きわめて一方的な、機械のような労働にのみ依存する ようになる。こうして労働者は、精神的にも肉体的にも機械の状態に落ち込み、人間であることから抽象的な活動や腹になるように、市場価格のあらゆる変動、 資本の利用、金持ちの気まぐれにますます依存するようになる。同様に、労働に全面的に依存する階級の増加は、労働者間の競争を激化させ、その結果、労働者 の価格を引き下げる。工場制度では、労働者のこの状況は頂点に達する。 (c)ますます豊かになる社会では、金持ちの中の金持ちだけが、金の利子で生活し続けることができる。それ以外のすべての人は、自分の資本で事業を営む か、貿易で資本を投じなければならない。その結果、資本家間の競争が激化する。資本の集中が進み、大資本家が小資本家を破滅させ、かつての資本家の一部が 労働者階級に転落し、この供給の結果、労働者階級は再び賃金の下落にある程度苦しみ、少数の大資本家への依存をさらに強めることになる。資本家の数が減っ たので、労働者に対する彼らの競争は、もはやほとんど存在しなくなり、労働者の数が増えたので、彼ら自身の間の競争は、いっそう激しく、不自然で、暴力的 になった。その結果、労働者階級の一部は、中間資本家の一部が労働者階級に転落するのと同じように、必然的に乞食や飢餓に転落する。 それゆえ、労働者にとって最も有利な社会の状態であっても、労働者にとって避けられない結果は、過労と早死にであり、単なる機械、資本の束縛的下僕に成り 下がり、それが彼の上に、彼に対して危険なほど積み重なり、競争が激化し、労働者の一部が飢餓や乞食に陥るのである。 賃金の引き上げは、労働者に資本家の一攫千金マニアを興奮させるが、労働者は、自分の精神と肉体を犠牲にすることでしか、そのマニアを満足させることがで きない。賃金の引き上げは、資本の蓄積を前提とし、また、資本の蓄積を伴うものであり、したがって、労働の生産物を、労働者にとってますます異質なものと して、労働者に突きつけるものである。同様に、分業は、労働者をますます一方的で依存的なものにし、人間だけでなく機械との競争ももたらす。労働者は機械 のレベルにまで沈んでしまったので、競争相手として機械と対決することができる。最後に、資本の蓄積は産業の量を増やし、したがって労働者の数を増加させ るので、同じ量の産業がより多くの製品を製造するようになり、過剰生産につながり、その結果、労働者の大部分を失業させるか、彼らの賃金を最も悲惨な最低 賃金にまで引き下げることによって終わる。 このようなことは、労働者にとって最も有利な社会の状態、すなわち、富が増大し、前進している状態の結果である。 しかし結局、この成長状態は遅かれ早かれピークに達しなければならない。今、労働者の立場は? (3)「そのような富を完全に獲得した国では、労働の賃金も株式の利潤もおそらく非常に低いであろう[...]雇用のための競争は、労働者の数を維持する のにかろうじて十分なものまで労働の賃金を引き下げるほど必然的に大きくなるであろう。[アダム・スミス『国富論』第一巻、84ページ)。 余剰人員は死ぬしかない。 このように、社会が衰退している状態では、労働者の不幸が増大し、社会が進歩している状態では、複雑化した不幸が増大し、社会が完全に発展した状態では、 不幸は静止する。 しかし、スミスによれば、社会は幸福ではなく、その大部分は苦しんでいるのであり、しかし、社会の最も豊かな状態でさえ、大多数のこの苦しみをもたらすの であり、経済システム[7](そして一般に私利私欲に基づく社会)はこの最も豊かな状態をもたらすのであるから、経済システムの目標は社会の不幸であると いうことになる。 労働者と資本家の関係については、資本家は労働時間の減少によって賃金の上昇を補って余りあるものであり、賃金の上昇と資本利子の上昇は、それぞれ単利と 複利のように商品価格に作用することを付け加えておく。 ここで、われわれを完全に政治経済学者の立場に置き、彼にならって労働者の理論的主張と実際的主張とを比較してみよう。 彼は、元来、理論的には、労働生産物全体が労働者のものであると言う。しかし、同時に彼は、実際のところ、労働者が手にするのは、生産物のごくわずかで、 まったく欠くことのできない部分であり、人間としてではなく、労働者として、また、人類ではなく、労働者という奴隷階級の増殖のために、労働者が存在する ために必要な分だけである、と言う。 政治経済学者は、すべてのものは労働によって買われ、資本は労働の蓄積にほかならないと言う。しかし同時に、労働者はすべてを買うことができるどころか、 自分自身と人間性を売らなければならないと言う。 怠け者の地主の家賃は通常、土地の生産物の三分の一に達し、多忙な資本家の利潤は貨幣の利子の二倍にも達するが、労働者自身が最良の時に稼ぐ「それ以上の 何か」は、4人の子供のうち2人が飢えて死ななければならないほどわずかなものである。 政治経済学者によれば、人間が自然の産物の価値を高めるのは、もっぱら労働を通じてであり、労働は人間の積極的な所有物であるのに対して、この同じ政治経 済学によれば、地主と資本家は、地主と資本家としては特権的で無為な神々にすぎないが、いたるところで労働者より優位にあり、労働者に法を定めている。 政治経済学者によれば、労働は物事の唯一の不変の価格であるが、労働の価格ほど偶然的なものはなく、より大きな変動にさらされるものはない。 分業が労働の生産力を高め、社会の富と洗練を高める一方で、労働者を貧しくし、機械に貶める。労働が資本の蓄積をもたらし、これによって社会の繁栄が増大 する一方で、労働者を資本家への依存をますます強め、新たな激しさの競争へと導き、過剰生産とそれに続く対応する不況の真っ逆さまへと駆り立てる。 政治経済学者によれば、労働者の利益は、社会の利益と対立することはないが、社会は、常に、必然的に、労働者の利益と対立する。 政治経済学者によれば、労働者の利益は社会の利益と対立することはない。(1) なぜなら、賃金の上昇は、上に述べた他の結果とともに、労働時間の減少によって十二分に補われるからであり、(2) なぜなら、社会との関係においては、総生産物全体が正味の生産物であり、私的個人との関係においてのみ、正味の生産物が意味を持つからである。 しかし、労働そのものが、単に現在の状況においてだけでなく、その目的が一般に富の増大である限りにおいて、つまり、労働そのものが有害で悪質であるとい うことが、政治経済学者の主張の筋書きから、彼が意識するまでもなく、導かれるのである。 理論的には、土地の賃貸料と資本の利潤は賃金の控除である。しかし、実際には、賃金は、土地と資本が労働者に支払うことを認める控除であり、労働生産物か ら労働者、労働への譲歩である。 社会が衰退状態にあるとき、労働者は最も深刻な苦しみを受ける。その負担の具体的な厳しさは、労働者としての立場に負うものであるが、そのような負担は社 会の立場に負うものである。 しかし、社会が進歩の状態にあるとき、労働者の破滅と困窮は、彼の労働と彼によって生み出された富の産物である。したがって、不幸は現在の労働の本質その ものから生じる。 最大の富の状態にある社会は、理想ではあるが、ほぼ達成されているものであり、少なくとも市民社会と同様に政治経済の目標であるが、労働者にとっては静的 な不幸を意味する。 プロレタリア、すなわち、資本も賃借料も持たず、純粋に労働によって、しかも一方的で抽象的な労働によって生活する人間が、政治経済学では労働者としてし か見なされないことは言うまでもない。したがって、政治経済学は、プロレタリアは、他の馬と同じように、働くことができるだけのものを手に入れなければな らないという命題を唱えることができる。しかし、そのような配慮は、刑法、医者、宗教、統計表、政治、貧民院監督に委ねられている。 それでは、政治経済学のレベルを超えて、政治経済学者の言葉をほとんどそのまま使った上記の説明をもとに、2つの質問に答えてみよう: (1)人類の進化において、人類の大部分を抽象的労働に還元することの意味は何か? (2)賃金を引き上げ、それによって労働者階級の状況を改善しようとしたり、(プルードンのように)賃金の平等を社会革命の目標と考えたりする断片的な改 革者が犯した過ちは何か。 政治経済においては、労働は生活の源泉としての活動というかたちでのみ発生する。 ||特定の才能や長い訓練を前提とする職業は、全体として、より有利になったと断言することができる。一方、ある人が他の人と同じように簡単かつ迅速に訓 練することができる機械的で単調な活動に対する比例報酬は、競争の激化とともに下落し、必然的に下落することになった。そして、労働組織の現状では、この 種の仕事が依然として圧倒的に多いのである。したがって、第一のカテゴリーに属する労働者の収入が、たとえば50年前の7倍であるのに対して、第二のカテ ゴリーに属する別の労働者の収入が変わっていないとすれば、当然、両者とも平均して4倍の収入を得ていることになる。しかし、ある国において、第一のカテ ゴリーに属する労働者が1,000人で、第二のカテゴリーに属する労働者が100万人だとすると、99万9,000人は50年前より恵まれていないことに なる。このような表面的な平均値の計算によって、人々は人口の最も多い階級について自分自身を欺こうとする。さらに、賃金の大小は、労働者の所得を推定す る際の一要素にすぎない。なぜなら、労働者の所得を測定するためには、その期間の確実性を考慮に入れることが不可欠だからであり、これは、絶えず変動と停 滞が繰り返される、いわゆる自由競争の無政府状態では、明らかに論外である。最後に、以前と現在の慣例的な労働時間を考慮しなければならない。イギリス人 綿労働者の労働時間は、企業家の利潤追求マニアの結果、増加した。||そして、このような労働時間の増加は、ある国、ある産業分野においては、必然的に、 他の場所でも、多かれ少なかれ主張されるようになったのである。(ヴィルヘルム・シュルツ『生産の運動』)。 「しかし、社会の各階層の平均所得が増加したことが嘘のように真実であったとしても、所得格差や相対的所得格差はより大きくなり、富と貧困のコントラスト はより鮮明になる。というのも、総生産高が上昇すればするほど、ニーズや欲望や要求も増大するため、絶対的貧困が減少する一方で、相対的貧困が増大する可 能性があるからである。魚油と腐った魚を食べて暮らすサモエドは貧しくはない。なぜなら、彼の人里離れた社会では、すべての人が同じニーズを持っているか らだ。しかし、たとえば10年の間に、人口に比例して総生産が3分の1に増加したような、前進を続ける国家では、10年後に当初と同じだけの所得を得てい る労働者は、裕福なままではなく、3分の1も貧しくなっている。(前掲書、65-66頁) しかし、政治経済学は、労働者を働く動物としてしか知らない。 「より精神的に自由に発展するためには、人々は肉体的欲求への束縛を解かなければならない。そして何よりも、精神的な創造活動と精神的な楽しみのために自 由に使える時間を持たなければならない。労働器官の発達は、この時間を獲得する。実際、新しい原動力と改良された機械によって、綿工場では、以前は100 人、あるいは250人から350人の労働者を必要としていた仕事を、今では一人の労働者がこなすことがよくある。同じような結果は、あらゆる生産分野で観 察することができる。というのも、外的な自然の力が、人間の労働にこれまで以上に大きく関与せざるを得なくなっているからである。一定量の物質的な欲求を 満たすために、以前は一定の時間と人間の労力が必要であったが、それが後に半分に減らされたとすれば、物質的な快適さを失うことなく、精神的な活動や享受 の範囲も同時に同じくらい拡大されたことになる......。しかし、クロノス[ギリシャ神話で時間と結びついた神]の最も私的な領域から勝ち取った戦利 品が、どのように分配されるかは、今もなお、盲目的で不公正な偶然のサイコロ投げによって決められている。フランスでは、生産の現段階では、労働能力のあ るすべての人が1日平均5時間働けば、社会のすべての物質的利益を満たすことができると計算されている......。機械の完成によって時間が節約された にもかかわらず、工場で多数の人々が行う奴隷労働の時間は長くなるばかりである」。(シュルツ、前掲書、67、68頁)。 「複合的肉体労働からの移行は、後者を単純作業に分解することにかかっている。しかし、最初は、一様に繰り返される作業の一部だけが機械に委ねられ、一部 は人間に委ねられる。物事の本質から見ても、またそれを裏付ける経験から見ても、この種の単調な作業が延々と続くことは、身体と同様に精神にも有害である ことは明らかである。こうした欠点は、とりわけ工場労働者の死亡率の高さに現れている......。人間はどこまで機械を通して働くのか、それともどこま で機械として働くのか、この大きな区別については......考慮されていない。(前掲書、69ページ)。 「しかし、諸民族の将来の生活においては、機械で働く自然の無生物の力は、われわれの奴隷であり、農奴であろう。(前掲書、74ページ) 「イギリスの紡績工場では196,818人の女性を雇用しているが、男性は158,818人にすぎない。ランカシャーの綿工場では、男性労働者100人に 対して女性労働者が103人、スコットランドでは209人もいる。リーズの亜麻工場では、男性労働者100人に対して女性労働者は147人であった。ダン ディーやスコットランドの東海岸では280人にものぼる。イギリスの絹織物工場では......多くの女性労働者がいたが、より体力を必要とする毛織物工 場では男性労働者が優勢であった。1833年には、38,927人以上の女性が北米の綿工場で18,593人の男性とともに雇用されていた。このような労 働組織の変化の結果、有給雇用のより広い領域が女性の占有するところとなった......。女性は今や経済的により独立した地位を占め......両性は その社会的条件においてより接近している」(前掲書、pp. (前掲書、71-72頁)。 「1835年にイギリスの蒸気および水力紡績工場で働いていたのは、以下の通りであった: 8歳から12歳までの子供は20,558人、12歳から13歳までの子供は35,867人、そして最後に13歳から18歳までの子供は108,208人で あった。確かに、機械化のさらなる進歩は、単調な仕事を人間の手からますます取り除くことによって、この弊害を徐々になくす方向に作用している。しかし、 このような急速な進歩の妨げとなっているのは、資本家が、最も簡単で最も安価な方法で、下層階級のエネルギーを子供に至るまで、機械装置の代わりに利用で きるようにしているという、まさにそのような事情である。(前掲書、70-71頁)。 ブロアム卿の労働者への呼びかけ-「資本家になれ」。... 何百万人もの労働者が、肉体を打ち砕き、道徳的にも知性的にも不自由にするような激しい労働によってしか、自分たちの最低限の生計を立てることができない ということである。(前掲書、60ページ)。 「非所有者は、生きるために、直接的または間接的に、所有者に奉仕する、つまり、所有者に依存する立場に身を置かざるをえない。(ペクール『社会経済新理 論』など)。 使用人-給与:労働者-賃金、被雇用者-給与または報酬。(loc. cit., pp. 409, 410.) "労働力を貸す"、"利子をつけて労働力を貸す"、"他人の代わりに働く" "労働の材料を貸し出すこと"、"労働の材料を利子で貸すこと"、"他人を自分の代わりに働かせること"。(前掲書、411ページ)。 「このような経済秩序は、人間をあまりに卑しい職業に就かせ、あまりに破滅的で辛辣な堕落へと追いやる。(前掲書、417、418頁) "あらゆる形態の非所有階級の売春"。(op. cit., p. 421 f.) "Ragmen". チャールズ・ルードン(Charles Loudon)は、『人口問題の解決』(Solution du probleme de la population, etc., Paris, 1842[8])という本の中で、イングランドの売春婦の数は6万人から7万人であると発表している。貞操観念の疑わしい女性の数も同様に多いとされてい る(p.228)。 「これらの不幸な生き物が悪の道に足を踏み入れてからの平均余命は6、7年である。6万人から7万人の娼婦の数を維持するためには、三国には毎年少なくと も8千人から9千人の女性がこの忌まわしい職業に身を投じているはずであり、毎日およそ24人の新しい犠牲者が出ていることになる。(前掲書、229ペー ジ)。 貧困に苦しむ人々の数は、その貧しさとともに増加し、困窮の極限に達した人々は、苦しみを受ける権利をめぐって互いに争うために、最大限の数でひしめき 合っている......」(前掲書、p.229)。1821年、アイルランドの人口は6,801,827人だった。1831年には7,764,010人に なり、10年間で14%も増加した。最も裕福なレンスター州では人口の増加はわずか8%であったが、最も貧困にあえぐコノート州では増加率は21%に達し た。(1840年ウィーン、アイルランドに関するイングランドでの調査報告書からの抜粋)」。(ビュレ、De la misère, etc., t. 1, pp. 36, 37)」。 政治経済学は労働を抽象的にモノとして考える。価格が高ければ、その商品は大きな需要があり、価格が低ければ、その商品は大きな供給がある。(このこと は、部分的には資本家と労働者の間の競争によって、また部分的には労働者間の競争によって避けられない。 労働の売り手である労働者は、必然的に、生産物のごくわずかな部分を受け入れるしかなくなる......」。労働を商品とする理論は、偽装された束縛の理 論以外の何ものでもないだろう。(前掲書、p. 43.) "ではなぜ労働には交換価値しか見いだされないのか。(前掲書44頁)。 大工房は女性や子供の労働力を買うことを好む。(前掲書) 「労働者は、彼を雇用する者に対しては、自由な売り手の立場にはまったくない......。資本家はつねに自由に労働を雇用し、労働者はつねに労働を売ら ざるをえない。労働の価値は、瞬時に売らなければ完全に破壊される。労働は、真の[商品]とは違って、蓄積することも保存することさえできない。 「労働は生命であり、もし生命が毎日食べ物と交換されなければ、生命は苦しみ、やがて滅びる。人間の生命が商品であると主張するには、奴隷制を認めなけれ ばならない。(前掲書、49、50頁)。 労働が商品であるとすれば、それは最も不幸な属性を持つ商品である。しかし、政治経済学の原則に照らしても、労働は「自由な取引の自由な結果」ではないの だから、商品ではない。[現在の経済体制は 「現在の経済体制は、労働の価格と報酬を同時に引き下げ、労働者を完成させ、人間を劣化させる。(産業は戦争となり、商業はギャンブルとなった。(前掲 書、62ページ) 「イギリスの)綿花製造機械だけで、8,400万人の肉体労働者が働いている。[前掲書、193ページ)。 現在に至るまで、産業は戦争状態、征服戦争状態にある: 「産業は、その軍隊を構成する人々の命を、偉大な征服者と同じように無関心に浪費してきた。その目的は富の所有であって、人間の幸福ではなかった」。(こ れらの利益」(すなわち、経済的利益)は、「自由放任のままでは......必然的に衝突する。科学が秩序と均衡を求めるのは、対立する力の衝突のなかに ある。科学によれば、永続的な戦争こそが平和を得る唯一の手段であり、その戦争は競争と呼ばれる」。(その戦争は競争と呼ばれる。) 「産業戦争が成功裏に遂行されるためには、一箇所に集結して大量に壊滅させることのできる大軍が必要である。この軍隊の兵士が自分に課せられた労苦に耐え るのは、献身からでも義務からでもなく、ただ飢餓というつらい必要から逃れるためである。彼らは上司に愛着も感謝も感じないし、部下を博愛の感情で縛るこ ともない。彼らは彼らを人間としてではなく、できるだけ少ないコストでできるだけ多くの収穫を得なければならない生産の道具としてしか知らない。これらの 労働者の集団は、ますます混み合っているが、常に雇用されているという保証さえない。労働者を呼び集めた産業は、彼らを必要とする間だけ生かし、彼らを追 い出すことができるとすぐに、少しも気兼ねすることなく彼らを見捨てる。より長く、より辛く、より嫌な仕事を与えられれば与えられるほど、彼らの賃金は下 がる。1日16時間の労働と絶え間ない努力で、死なない権利をほとんど買えない労働者がいる」(前掲書、pp. (前掲書、68-69頁)。 「手織り機織り工の状態に関する調査を担当した委員と同様に、大規模な工業都市が、近隣の農村地域から常に健康な男性、つまり新鮮な血液の絶え間ない流入 を受けなければ、労働者の人口を短期間で失うことになると、われわれは確信している」(前掲書、68-69ページ)。(前掲書、362ページ)。 |

|

| Profit of Capital |

||||

| 1. Capital |

||I, 2| What is

the basis of capital, that is, of private property in the products of

other men's labour? “Even if capital itself does not merely amount to theft or fraud, it still requires the cooperation of legislation to sanctify inheritance.” (Say, Traité d'économie politique.)[9] How does one become a proprietor of productive stock? How does one become owner of the products created by means of this stock? By virtue of positive law. (Say, t. II, p. 4.) What does one acquire with capital, with the inheritance of a large fortune, for instance? “The person who [either acquires, or] succeeds to a great fortune, does not necessarily [acquire or] succeed to any political power [.... ] The power which that possession immediately and directly conveys to him, is the power of purchasing; a certain command over all the labour, or over all the produce of labour, which is then in the market.” (Wealth of Nations, by Adam Smith, Vol. I, pp. 26-27.)[10] Capital is thus the governing power over labour and its products. The capitalist possesses this power, not on account of his personal or human qualities, but inasmuch as he is an owner of capital. His power is the purchasing power of his capital, which nothing can withstand. Later we shall see first how the capitalist, by means of capital, exercises his governing power over labour, then, however, we shall see the governing power of capital over the capitalist himself. What is capital? “A certain quantity of labour stocked and stored up to be employed.” (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 295.) Capital is stored-up labour. (2) Fonds, or stock, is any accumulation of products of the soil or of manufacture. Stock is called capital only when it yields to its owner a revenue or profit. (Adam Smith, op. cit., p. 243) |

||資本、すなわち他人の労働生産物に対する私有財産の基礎とは何か? 「資本それ自体が単に窃盗や詐欺に相当しないとしても、相続を神聖化するための立法による協力が必要である。(セイ『政治経済学綱要』)[9]。 人はどのようにして生産的ストックの所有者になるのだろうか。このストックによって生み出された生産物の所有者になるにはどうすればよいのか。 実定法によってである。(セイ、t. II、p. 4)。 資本によって、たとえば巨額の財産を相続することによって、人は何を獲得するのか。 「莫大な財産を[獲得する、あるいは]継承する者は、必ずしも政治的権力を[獲得する、あるいは]継承するわけではない。(アダム・スミス著『国富論』第 一巻、26-27頁)[10]。 このように、資本は労働とその生産物を支配する力である。資本家は、その個人的または人間的な資質によってではなく、資本の所有者である以上、この力を所 有している。彼の権力は、資本の購買力であり、何ものもそれに耐えることはできない。 後で、まず資本家が資本によって、労働に対する支配力をどのように行使するかについて見てみよう。次に、資本家自身に対する資本の支配力について見てみよ う。 資本とは何か? 「使用されるためにストックされ蓄積された一定量の労働力」。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第一巻、295ページ)。 資本とは蓄積された労働である。 (2)フォンド(ストック)とは、土壌の生産物や製造物の蓄積のことである。ストックは、所有者に収益や利益をもたらす場合にのみ資本と呼ばれる。(アダ ム・スミス、前掲書、243ページ)。 |

||

| 2. The Profit of

Capital |

2. The Profit of

Capital The profit or gain of capital is altogether different from the wages of labour. This difference is manifested in two ways: in the first place, the profits of capital are regulated altogether by the value of the capital employed, although the labour of inspection and direction associated with different capitals may be the same. Moreover in large works the whole of this labour is committed to some principal clerk, whose salary bears no regular proportion to the ||II, 2| capital of which he oversees the management. And although the labour of the proprietor is here reduced almost to nothing, he still demands profits in proportion to his capital. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 43)[11] Why does the capitalist demand this proportion between profit and capital? He would have no interest in employing the workers, unless he expected from the sale of their work something more than is necessary to replace the stock advanced by him as wages and he would have no interest to employ a great stock rather than a small one, unless his profits were to bear some proportion to the extent of his stock. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 42) The capitalist thus makes a profit, first, on the wages, and secondly on the raw materials advanced by him. What proportion, then, does profit bear to capital? If it is already difficult to determine the usual average level of wages at a particular place and at a particular time, it is even more difficult to determine the profit on capitals. A change in the price of the commodities in which the capitalist deals, the good or bad fortune of his rivals and customers, a thousand other accidents to which commodities are exposed both in transit and in the warehouses – all produce a daily, almost hourly variation in profit. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 78-79.) But though it is impossible to determine with precision what are the profits on capitals, some notion may be formed of them from the interest of money. Wherever a great deal can be made by the use of money, a great deal will be given for the use of it; wherever little can be made by it, little will be given. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 79.) The proportion which the usual market rate of interest ought to bear to the rate of clear profit, necessarily varies as profit rises or falls. Double interest is in Great Britain reckoned what the merchants call a good, moderate, reasonable profit, terms which mean no more than a common and usual profit. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 87.) What is the lowest rate of profit? And what the highest? The lowest rate of ordinary profit on capital must always be something more than what is sufficient to compensate the occasional losses to which every employment of stock is exposed. It is this surplus only which is neat or clear profit. The same holds for the lowest rate of interest. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 86) ||III, 2| The highest rate to which ordinary profits can rise is that which in the price of the greater part of commodities eats up the whole of the rent of the land, and reduces the wages of labour contained in the commodity supplied to the lowest rate, the bare subsistence of the labourer during his work. The worker must always be fed in some way or other while he is required to work; rent can disappear entirely. For example: the servants of the East India Company in Bengal. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 86-87) Besides all the advantages of limited competition which the capitalist may exploit in this case, he can keep the market price above the natural price by quite decorous means. For one thing, by keeping secrets in trade if the market is at a great distance from those who supply it, that is, by concealing a price change, its rise above the natural level. This concealment has the effect that other capitalists do not follow him in investing their capital in this branch of industry or trade. Then again by keeping secrets in manufacture, which enable the capitalist to reduce the costs of production and supply his commodity at the same or even at lower prices than his competitors while obtaining a higher profit. (Deceiving by keeping secrets is not immoral? Dealings on the Stock Exchange.) Furthermore, where production is restricted to a particular locality (as in the case of a rare wine), and where the effective demand can never be satisfied. Finally, through monopolies exercised by individuals or companies. Monopoly price is the highest possible. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 53-54) Other fortuitous causes which can raise the profit on capital: The acquisition of new territories, or of new branches of trade, often increases the profit on capital even in a wealthy country, because they withdraw some capital from the old branches of trade, reduce competition, and cause the market to be supplied with fewer commodities, the prices of which then rise: those who deal in these commodities can then afford to borrow at a higher rate of interest. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 83) The more a commodity comes to be manufactured – the more it becomes an object of manufacture – the greater becomes that part of the price which resolves itself into wages and profit in proportion to that which resolves itself into rent. In the progress of the manufacture of a commodity, not only the number of profits increases, but every subsequent profit is greater than the foregoing; because the capital from which ||IV, 2| it is derived must always be greater. The capital which employs the weavers, for example, must always be greater than that which employs the spinners; because it not only replaces that capital with its profits, but pays, besides, the wages of weavers; and the profits must always bear some proportion to the capital. (op. cit., Vol. I, p. 45) Thus the advance made by human labour in converting the product of nature into the manufactured product of nature increases, not the wages of labour, but in part the number of profitable capital investments, and in part the size of every subsequent capital in comparison with the foregoing. More about the advantages which the capitalist derives from the division of labour, later. He profits doubly – first, by the division of labour; and secondly, in general, by the advance which human labour makes on the natural product. The greater the human share in a commodity, the greater the profit of dead capital. In one and the same society the average rates of profit on capital are much more nearly on the same level than the wages of the different sorts of labour. (op. cit., Vol. I, p. 100.) In the different employments of capital, the ordinary rate of profit varies with the certainty or uncertainty of the returns. The ordinary profit of stock, though it rises with the risk, does not always seem to rise in proportion to it. (op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 99-100.) It goes without saying that profits also rise if the means of circulation become less expensive or easier available (e.g., paper money). |

2. 資本の利潤 資本の利潤は、労働の賃金とはまったく異なる。第一に、資本の利潤は、使用される資本の価値によって完全に調整されるが、異なる資本に関連する検査と指示 の労働は同じであるかもしれない。さらに、大規模な事業所では、この労働のすべてが何人かの主要な事務員に委ねられており、その給与は、彼が管理を監督す る資本に対して正規の比率を占めていない。そして、所有者の労働はここでほとんどゼロになるが、所有者は依然として資本に比例した利潤を要求する。(アダ ム・スミス、前掲書、第一巻、43頁)[11]。 なぜ資本家は利潤と資本の間にこのような比率を要求するのか。 資本家は、労働者を雇用することに何の関心も持たないが、それは、労働者の仕事の販売から、賃金として資本家が提供した在庫に代わる必要以上のものを期待 するのでなければならないし、また、利潤が資本家の在庫の程度にある程度比例するのでなければ、小さな在庫よりも大きな在庫を雇用することに何の関心も持 たないからである。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第一巻、42ページ)。 こうして資本家は、第一に賃金に対して、第二に原材料に対して利潤を得る。 それでは、利潤は資本に対してどのような割合を占めるのであろうか。 特定の場所と特定の時間における賃金の通常の平均水準を決定することがすでに困難であるとすれば、資本の利潤を決定することはさらに困難である。資本家が 取引する商品の価格の変動、彼のライバルや顧客の吉凶、商品が輸送中や倉庫の中でさらされる千差万別の事故-これらすべてが、利潤に毎日、ほとんど毎時の 変動をもたらすのである。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第一巻、78-79頁)。 しかし、資本の利潤を正確に決定することは不可能であるが、貨幣の利子から、その利潤を推測することは可能である。貨幣の使用によって多くの利益が得られ るところでは、貨幣の使用に対して多くの利益が与えられ、貨幣の使用によってほとんど利益が得られないところでは、ほとんど利益が与えられない。(アダ ム・スミス、前掲書、第一巻、79ページ)。 通常の市場利子率が明瞭な利潤率に占める割合は、利潤の増減に応じて必然的に変化する。イギリスでは、商人たちが「良い」「適度な」「妥当な」利益と呼ぶ 二倍の利子が計算される。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第1巻、87ページ)。 最低の利潤とは何か。また、最高利潤率とは何か。 資本に対する通常の利潤の最低率は、常に、株式のすべての雇用が時折さらされる損失を補うのに十分なもの以上のものでなければならない。この余剰のみが、 適正な利潤あるいは明確な利潤である。最低利子率についても同様である。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第一巻、86ページ)。 ||通常の利潤が上昇しうる最も高い利潤率とは、商品の価格の大部分において、土地の賃料の全部を食いつぶし、供給される商品に含まれる労働の賃金を、労 働者が労働している間の裸の生活費という最も低い利潤率にまで低下させる利潤率である。労働者は、労働を要求されている間、常に何らかの方法で食べさせら れていなければならない。例えば、ベンガルの東インド会社の使用人などである。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第1巻、86-87頁)。 この場合、資本家が利用することができる限定的な競争によるあらゆる利点のほかに、資本家は極めて礼節をわきまえた手段によって、市場価格を自然価格より 高く維持することができる。 ひとつには、市場がそれを供給する人々から大きな距離にある場合、取引上の秘密を保持することによって、つまり価格変動を隠すことによって、その自然水準 以上の上昇を維持することができる。この隠蔽は、他の資本家がこの産業や貿易の分野に資本を投下する際に、彼に追随しないという効果をもたらす。 また、製造上の秘密を保持することによっても、資本家が生産コストを削減し、より高い利潤を得ながら、競争相手と同じかそれよりも低い価格で商品を供給す ることを可能にする。(秘密を守ることによって欺くことは不道徳ではないのか?証券取引所での取引)。さらに、生産が特定の地域に限定され(希少なワイン の場合のように)、有効需要を満たすことができない場合。最後に、個人または企業による独占。独占価格は可能な限り高い。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第一 巻、53-54頁)。 資本の利潤を増大させるその他の僥倖: 新しい領土の獲得や新しい貿易分野の獲得は、豊かな国であっても、しばしば資本利潤を増加させる。それは、古い貿易分野から資本が引き抜かれ、競争が減少 し、市場に供給される商品の数が減り、その商品の価格が上昇するからである。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第一巻、83ページ)。 商品が製造されるようになればなるほど、つまり製造の対象になればなるほど、賃借料に転化する価格に比例して、賃金と利潤に転化する価格の部分が大きくな る。商品の製造が進むにつれて、利潤の数が増えるだけでなく、その後に生じる利潤はすべて、それ以前のものよりも大きくなる。例えば、織工を雇用する資本 は、紡績工を雇用する資本よりも常に大きくなければならない。なぜなら、紡績工はその資本を利益で置き換えるだけでなく、織工の賃金も支払うからである。 (前掲書、第1巻、45ページ) このように、自然の産物を自然の製造物に変えるという人間の労働による進歩は、労働の賃金ではなく、部分的には、利益をもたらす資本投資の数を増やし、部 分的には、前述の資本と比較して、後続のあらゆる資本の規模を増大させるのである。 資本家が分業から得る利点については、後で詳しく述べる。 資本家は二重に利益を得る。第一に、分業によって、第二に、一般に、人間の労働が自然の産物にもたらす進歩によってである。商品における人間の取り分が大 きければ大きいほど、死んだ資本の利潤は大きくなる。 一つの同じ社会では、資本の平均利潤率は、さまざまな種類の労働の賃金よりもはるかにほぼ同じ水準にある。(前掲書、第1巻、100ページ)資本のさまざ まな使用において、通常の利潤率は、リターンの確実性や不確実性に応じて変化する。 株式の通常の利潤は、リスクとともに上昇するとはいえ、必ずしもリスクに比例して上昇するとは限らない。(前掲書、第一巻、99-100頁)。 流通手段が安価になったり、入手しやすくなったりすれば、利益も上昇することは言うまでもない(たとえば紙幣)。 |

||

| 3. The Rule of

Capital Over Labour and the Motives of the Capitalist |

3. The Rule of

Capital over Labour and the Motives of the Capitalist The consideration of his own private profit is the sole motive which determines the owner of any capital to employ it either in agriculture, in manufactures, or in some particular branch of the wholesale or retail trade. The different quantities of productive labour which it may put into motion, ||V, 2| and the different values which it may add to the annual produce of the land and labour of his country, according as it is employed in one or other of those different ways, never enter into his thoughts. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 335.) The most useful employment of capital for the capitalist is that which, risks being equal, yields him the greatest profit. This employment is not always the most useful for society; the most useful employment is that which utilises the productive powers of nature. (Say, t. II, pp. 130-31.) The plans and speculations of the employers of capitals regulate and direct all the most important operations of labour, and profit is the end proposed by all those plans and projects. But the rate of profit does not, like rent and wages, rise with the prosperity and fall with the decline of the society. On the contrary, it is naturally low in rich and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin. The interest of this class, therefore, has not the same connection with the general interest of the society as that of the other two.... The particular interest of the dealers in any particular branch of trade or manufactures is always in some respects different from, and frequently even in sharp opposition to, that of the public. To widen the market and to narrow the sellers' competition is always the interest of the dealer.... This is a class of people whose interest is never exactly the same as that of society, a class of people who have generally an interest to deceive and to oppress the public. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 231-32) |

3. 労働に対する資本の支配と資本家の動機 資本の所有者が、それを農業に、製造業に、あるいは卸売業や小売業の特定の部門に使用することを決定する唯一の動機は、自己の私的利潤を考慮することであ る。資本が動かすことのできる生産労働の量や、その国の土地と労働の年間生産高に加えることのできる価値の違いは、資本がこれらの異なる方法のいずれか、 あるいは他の方法で使われることに応じて、彼の思考に入ることはない。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第一巻、335ページ)。 資本家にとって最も有用な資本の使用とは、リスクが同じであれば、彼に最大の利潤をもたらすものである。この雇用は必ずしも社会にとって最も有用な雇用で はない。最も有用な雇用とは、自然の生産力を利用する雇用である。(セイ、t. II、130-31頁)。 資本の使用者の計画と思惑は、労働の最も重要な業務のすべてを規制し、方向づけるものであり、利潤はこれらの計画と思惑が提案するすべての目的である。し かし、利潤率は、家賃や賃金のように、社会の繁栄とともに上昇し、社会の衰退とともに下降するものではない。それどころか、富める国では当然低く、貧しい 国では当然高くなる。したがって、この階級の利益は、他の2つの階級の利益ほどには、社会の一般的利益とは関係がない......。貿易や製造の特定の部 門における販売業者の特定の利益は、常にいくつかの点で一般大衆の利益とは異なっており、しばしば鋭く対立することさえある。市場を広げ、売り手の競争を 狭めることは、常に販売業者の利益である......。これは、その利益が社会の利益とまったく同じであることはない人々の階級であり、一般に大衆を欺 き、抑圧する利益を持つ人々の階級である。(アダム・スミス、前掲書、第一巻、231-32頁)。 |

||

| 4. The

Accumulation of Capitals and the Competition Among the Capitalists |

4. The