ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育

Higher Education in Latin America

★ラ テンアメリカにおける高等教育は、過去40年間で3,000を超える高等教育機関に成長した。1,700万人の高等教育在籍者のうち、ブラジル、メキシ コ、アルゼンチンの3か国で1,000万人を占めている。ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育へのアクセスは、 ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育へのアクセスは、多くのラテンアメリカ諸国における所得分布に関して、大きな格差を示している。高等教育は、この地域では 新しいものではない。実際、多くの教育機関は数百年の歴史を持つが、高等教育分野における目覚ましい成長は、より最近のことであ る。2016/2017年の出願者調査によると、ラテンアメリカ人は一般的に高等教育を重視している、と言われる。

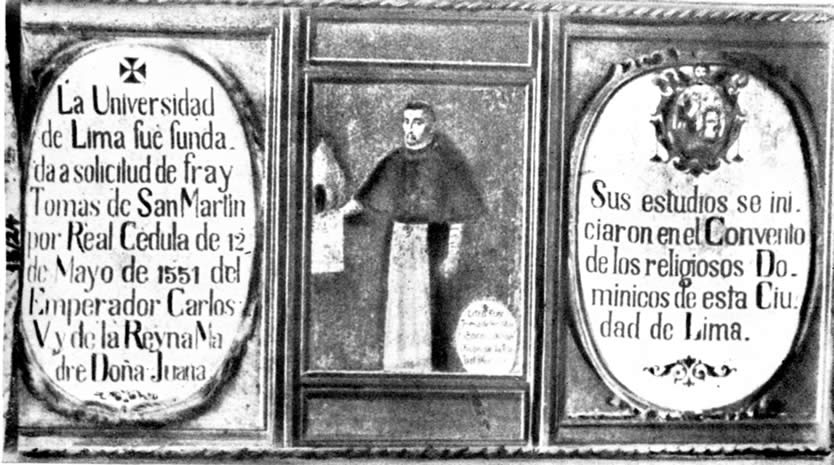

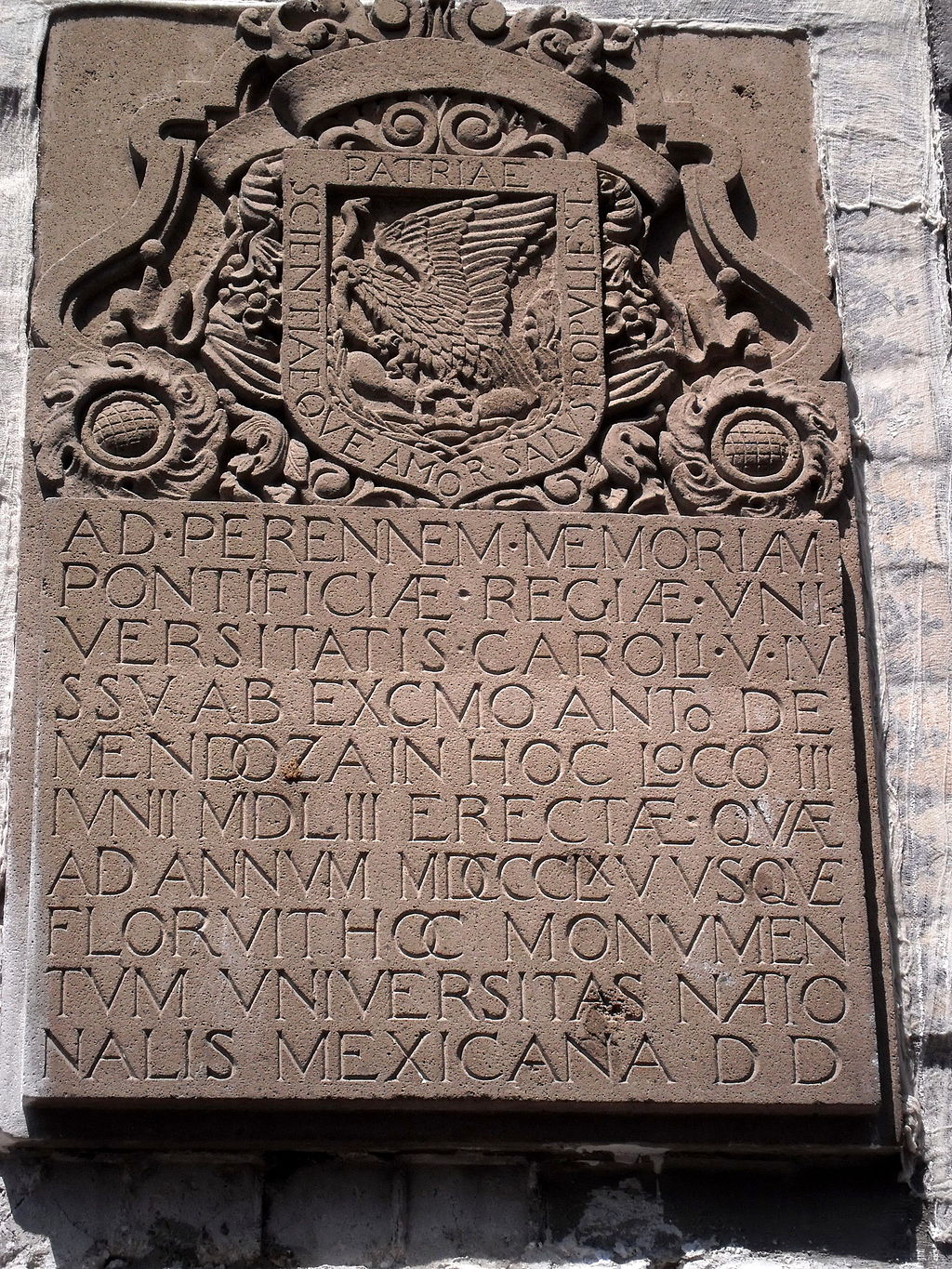

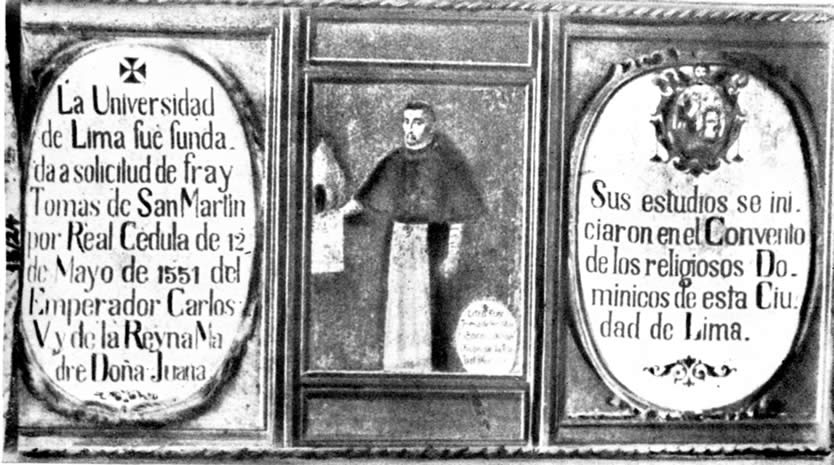

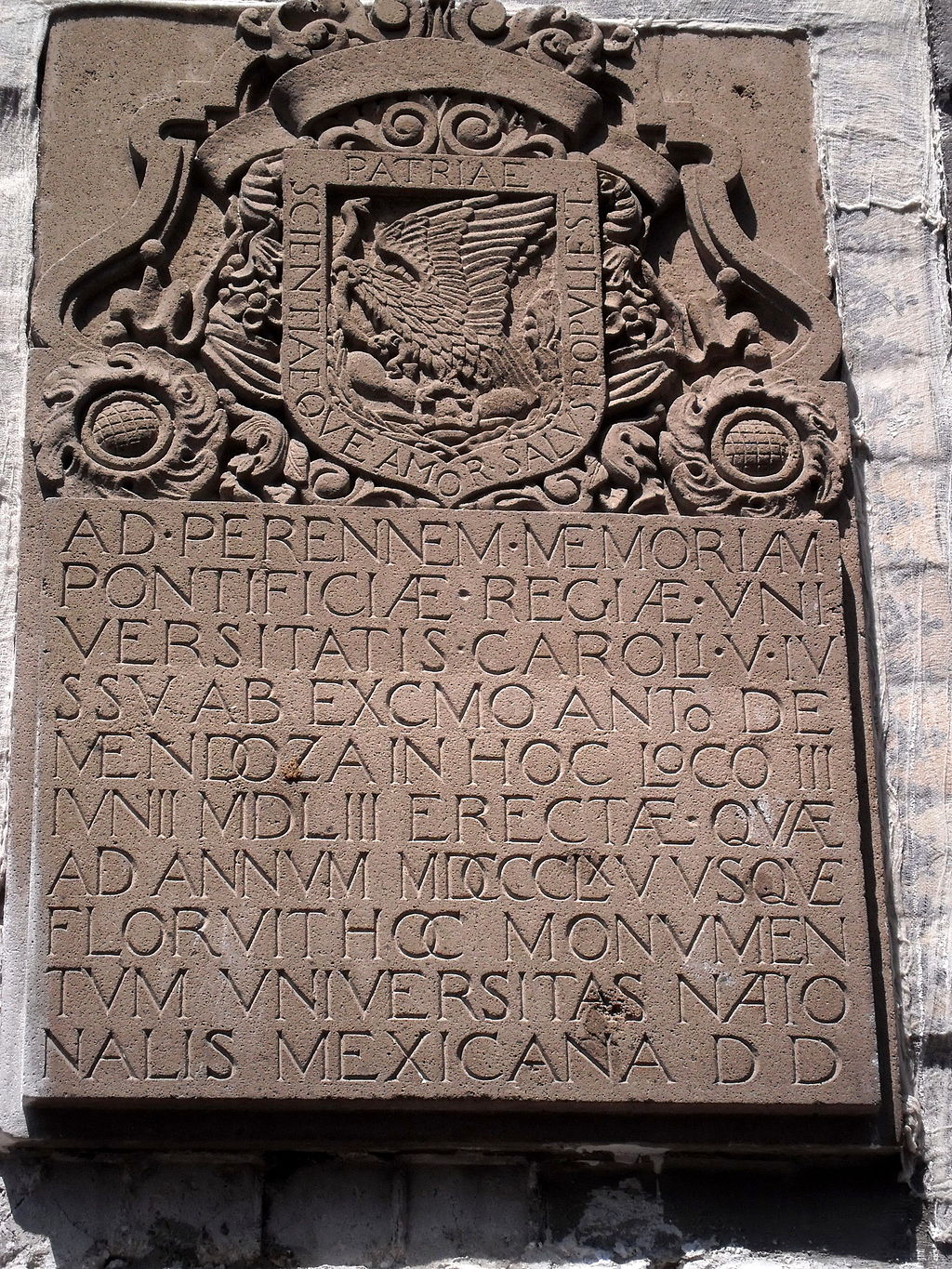

| Higher education This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. Please help improve it by rewriting it in an encyclopedic style. (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Overview Higher Education in Latin America has grown over the past forty years to comprise more than 3,000 higher education institutions.[21] Out of 17 million students in higher education, Brazil, Mexico and Argentina account for 10 million.[22] Access to higher education in Latin America shows a massive gap when it comes to income distribution in many Latin American countries.[23] Although higher education is not new to the region; indeed, many institutions date back hundreds of years, but the noticeable growth spurt in the area of higher education has been more recent. Latin Americans value higher education in general, according to the Applicant survey of 2016/2017.[24][25] The past four decades have been a time of tremendous change and growth for Higher Education in the region. Institutional growth has resulted in a diversification of degrees offered to include more graduate degrees (Master's degrees, professional degrees and doctorates) and less traditional areas of study.[22] This increase in graduate degrees has presented challenges related to funding, especially in the public sector of education. Budgetary limitations in the late 20th century saw a surge of private universities in many Latin American countries.[22] These universities sprung up all over the region during the time period and continue to serve a particular subset of the population. In general, Latin America is still subject to a developmental lag when it comes to education, and higher education in particular. The country of Brazil is the main exception to this "developmental lag".[22] Brazil boasts many of the top universities in Latin America, in some of the country's richest areas. Low amounts of money are invested into research and development in the region.[22] This creates a lack of competition with other areas of the world and results in less innovation coming from the region. History Colonial Period  Oil painting commemorating the foundation of the University of Lima Oil painting commemorating the foundation of the University of Lima (later named San Marcos), officially the first university in Peru and the Americas, and his manager Friar Tomas of San Martin Colonization was of great significance to the course of higher education in Latin America, and the spirit of the colonial period was interwoven in the Church. "In the 1800s, numerous countries, including Chile, Ecuador, and Colombia, signed contracts with the Catholic Church, or modeled their constitution on Catholic values, declaring themselves Catholic states."[26] As Spanish Christianity was reformed in the 16th century by Cardinal Jiménez de Cisneros, the Church was more under Crown control in Spain than any other European monarchy.[27]  Plaque relative to the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico Plaque relative to the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico. Latin: "Ad Perennem Memoriam Pontifical Regiae Universitatis Caroli V Ivssv AB ExcMo [Excellency] ENTO [NIO] de Mendoza In Hoc Crazy III [3] IUNII MDCCCLXV VSQVE FLORVIT HOC MONVMENTVM Universitas Nationalis Mexican. DD [Dedicavit or dedit Dedicavit] ". English: To perpetuate the memory of the Royal University and Pontifical University of Carlos V. By order of the Excellency Antonio de Mendoza, in this place was erected on June 3, 1553. Who until year 1865 here flourished. Monument to the National Mexican University. He has given the dedication. Higher education in Latin America was heavily affected by the relationship between Church and State. "Spanish America's universities were created to serve the Church and state simultaneously. They often functioned by the authority of papal bulls and royal charters. The first to receive the papal bull was the Dominican Republic's University of Santo Domingo (1538). First to receive the royal authorization was Peru's University of San Marcos (1551). And considered to be the first founded in North America, is the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico (1551).[28] The offerings of the three institutions were similar, including law, medicine, and economics, etc. "Spain enjoyed great success in transplanting its institutions and culture. These universities (Santo Domingo, San Marcos, and the Royal Pontifical) had state support but money was always a problem. The entering fees were small but rose the longer one stayed. This favored the rich upper class".[29] Entitlement and access to education continued to be an issue throughout the history of higher education in Latin America. From a global perspective on the inception of the university, the oldest existing, and continually operating educational institution in the world is the University of Karueein, founded in 859 AD in Morocco, the University of Bologna, Italy, was founded in 1088, and England's University of Oxford was founded in 1167.[30] Initially, the Church and State in Latin America granted authority to universities, and the position of maestrescuela was filled by one who served as a liaison among stakeholders. "Most of the universities were organized by religious orders, especially Jesuits and Dominicans, and these orders provided not only most of the administrators but also most of the teachers…Graduation was a religious as well as an academic event"; many students were trained to enter the clergy or to take on bureaucratic positions for the state.[28] Early Post-colonial Period At the time of the Spanish American wars of independence, approximately twenty-five universities were operating in Spanish America. These universities, influenced by the French Enlightenment, came to be regulated by government rather than cooperative interests or the Church. Growth and expansion of the university system was slowed due to political and financial instability; university life was regularly interrupted. In the 1840s Chile and Uruguay implemented an educational model that incorporated centralized Napoleonic lines which promoted the "base education for the future leaders of the nation, as well as members of the bureaucracy and the military".[31] In the time of post-colonialism, "[Gregorio Weinberg] defined three successive stages up until the twentieth century: "imposed culture", "accepted culture" and "criticised or disputed culture". The phase of 'imposed culture', which was of a functional nature for the metropolis, corresponds to the colonial era, while the second phase, that of the "accepted culture", is associated with the organisation of the national societies... [and the] assimilation of foreign cultural and philosophical tendencies by Latin American countries, which adopted them due to their usefulness for solving the theoretical and practical problems involved in organizing the new nations."[32] The export-led economic growth of the 19th and 20th centuries allowed for the increased availability of resources and urbanization, and together with the spirit of competition of the political elite, drove university expansion. Ultimately, control over university leadership, faculty, curriculum, and admissions led to the separation of state controlled and funded institutions from those which were privately run.[33] "Social demand, however, was not the only cause of the proliferation of universities. To provide educational opportunity for working class youth who held jobs during the day, night schools run for profit were established by enterprising educators. Some universities were started because many traditional institutions remained unresponsive to national needs for new kinds of training. But, by far the most important added stimulus can be traced to the lack of criteria for the accreditation of new programs and institutions."[34] Conflicts of power between liberals and conservatives and the promotion or opposition of secularism fueled the growth of separate public and private universities. The "philosophy of positivism powerfully reinforced the notion that scientific progress was inherently incompatible with religious interference".[28] The State's power and control continued to increase to the point that "the universities of Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua all held State monopolies on the authority to grant academic degrees and professional licenses".[28] An additional hurdle for education to overcome was the fact that "the early development of mass educational systems in Latin America reflected inequalities in the distribution of wealth, income, and opportunities that became barriers to the universalization of mandatory schooling. The gap between regions and between rural and urban areas within each country, strongly associated with those between social classes and ethnic groups, was not reduced through centralized educational policies that typically resulted in greater subsidies to the more advantaged groups".[34] Student Movements in the 20th Century University enrollment exclusiveness in favor of the wealthy began to change with rapidly increasing enrollment rates credited by Latin America's population and economic growth.[28] The University Reform Movement (UFM) in Argentina, or Movimiento de la Reforma Universitaria "emerged as a revolution ‘from below’ and ‘from inside’ against the ancien re´gime of a very old type of university".[35] "The widening political gap between the autonomous public universities and democratically elected governments was made more critical by a radicalized student activism in the Cold War climate of the latter half of the 20th century. The most visible confrontations took place in the late 1960s, a time of student mobilization worldwide. These protests were very frequent throughout the period in most countries in Latin America, reinforcing the image of a politically involved student movement, even if it was often fostered by the mobilization of a minority of student activists with representation in university governance and closely linked to national political movements and parties. In many cases, student confrontations with the authorities mixed radical demands for revolutionary change with more limited demands for organizational transformation and more generous funding".[34] Argentina, for example, had an increasingly robust middle class population which demanded access to university education. Argentina's university system quickly expanded with the demand. "Contemporary analysts have estimated that roughly 85 to 90 percent of Latin America's university students come from the middle class".[28] That growth and prosperity of Argentina's middle class along with electoral rights, an increased migration to urban areas, and the universal suffrage law of 1912 empowered students to challenge conservative systems and voice their demands. In December 1917, the University of Córdoba refused to concede to student demands for the university meet a perceived need. Students responded by organizing a mass protest; they refused to attend classes and hosted a demonstration on school grounds. They magnified the power of the student voice by including local politicians, labor groups, and student organizations. The primary goals of the student movement were to "secularize and democratize Córdoba University by expanding student and professor participation in its administration and modernizing the curricula", and to make university education "available and affordable by lifting entrance restrictions and establishing greater flexibility in attendance and examinations to accommodate low and middle-income students with work obligations". Students did not receive a response for nearly a year.[36] "The university reform movement in Argentina influenced university reform campaigns in Uruguay, Chile, and Peru, among others".[36] Student involvement has been credited with marked increased attention to and participation in politics as well as a redistribution of power on campus, however this was not always the case. A slowly changing system, students were met with a number of setbacks. "Some reforms... reduced student and professorial authority, giving it instead to administrators or even to the State".[28] In the case of Colombian students, the example of Argentina was nontransferable. "Unable to unify themselves, overly concerned with broad political issues, and the 'unholy alliance' of foreign imperialists and local oligarchs, Colombian students never won access to legitimate and effective means of influencing university policy."[37] The struggle for control of power within higher education has continued, however a number of reforms have attempted to address the problems. Examples of reforms in Colombia included following the North American Land Grant model, administrative reforms designed to target spending and asset waste, and employing more full-time professors.[37] The university systems have been criticized for reflecting the culture in which they are set as opposed to strategically guiding culture through the pursuit of intellectual ideals and educational and vocational advancement. Having come through a period of reform trial and error, "several Latin societies have already embarked on radical political paths and others exhibit willingness to explore novel alternatives."[37] Moving into the future, Latin America will continue to develop their higher education programs to increase academic and social success through increased availability to all people. Institutions in Latin American higher education  Central University City Campus of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) Central University City Campus of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) (Mexico City), inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List. According to The Economist, "Latin America boasts some giant universities and a few venerable ones: the University of Buenos Aires (UBA) and the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) enroll several hundred thousand students apiece, while Lima's San Marcos was founded in 1551. Even so, the region is hardly synonymous with excellence in higher education. Research output is unimpressive, teaching techniques are old-fashioned and students drop out in droves. These failings matter. Faster economic growth is driving a big rise in demand for higher education in the region and a large crop of new universities".[38] The Economist article lists the 2011 rankings of higher education institutions in Latin America. The article states, "Of the 200 top universities, 65 are in Brazil, 35 in Mexico, 25 apiece in Argentina and Chile and 20 in Colombia. The University of São Paulo (USP), the richest and biggest university in Brazil's richest state, came top".[38] Higher education institutions in Latin America are private, public and federal colleges and universities. Most experts agree that there is no typical Latin American university as the universities must reflect the vast differences found within each country and region within Latin America.[39] Most Latin American countries started from a European model (mostly modeled after the French or Spanish) and have adopted their own educational models differently in each region.[39] Most models appeared to be Napoleonic which has historically been vocationally oriented and nationalistic in nature.[39] Even now, students pursuing higher education in Latin America are asked to find a field of study and adhere to the prescribed major path within their college or university. Latin America is facing many issues in the ever-expanding era of globalization. Their enrollments and their students must be prepared to participate in a more globalized world than ever before and they must have the institutions to support a more international mission. Scholars believe that there is tension among countries that defined modernity differently. Modernity within education will allow for progress with educational policy and research and particularly in comparative education. Defining modernity differently in each country does not allow for consensus on what a modern educational system could and should look like.[40]  University of São Paulo seen from Torre do Relógio, São Paulo. University of São Paulo seen from Torre do Relógio, São Paulo. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico and Peru represent about 90 percent of the Latin American region's population.[41] It's important to acknowledge that higher education in Latin America really only reflects on the elite few Latin American countries that can and do offer higher education options for their citizens. More research must be done in this area to bolster the information on some of the smaller countries in parts of Latin America that do not have higher education options. Or who do have higher education options but are limited in number and scope. In a 2002 publication on higher education institutions in Latin American and Caribbean Universities, including Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Uruguay, Venezuela, Mexico, Peru, Brazil and the Dominican Republic, 1,917 of them were considered private universities.[39] In some countries, such as Brazil, there are state and federal higher education institutions in each state. Federal universities in Brazil make up an enrollment of 600,000 student in 99 institutions throughout the country.[42] More information on higher education specific to Brazil can be found here: Brazil.  University City of Buenos Aires (Argentina). September 2008. University City of Buenos Aires (Argentina). September 2008. Alternatively, 1,023 universities are considered public in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico and Peru. There are about 5,816 institutes that are considered private or public and even some were not deemed identifiable. Of both regions, Latin America and the Caribbean, there are nearly 14 million students enrolled in some type of higher education institution. Roughly 13,896,522 students are enrolled at institutions in Latin American where not quite 95,000 are enrolled in the Caribbean.[43] Participation in higher education has seen an increase in enrollment from 1998 to 2001. In developed countries, the gross enrollment rate jumped from 45.6% to 54.6% in 2001.[44] Additionally, female participation in enrollment jumped from 59.2% in 1998 to 64.3% in 2001. (unEsCo, 2005). Transitional and developing countries also saw a jump in gross enrollment rates from 1998 to 2001. Of the Latin American countries analyzed, Brazil, Mexico and Argentina had the highest distribution of enrollments. These top three countries accounted for about 60% of total enrollment in higher education.[44] Brazil led the Latin American countries by holding 28% of higher education enrollment in all of Latin America. Shortly behind Brazil is Mexico with 17% of the total enrollment and Argentina at 14%.[44] Sets of countries also distribute their enrollment among private and public universities differently as well. For example, Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic students are mostly enrolled in private sector higher education universities and institutions.[44] Between 50% and 75% of total enrollments in the previously mentioned countries are within the private sector. Conversely, Ecuador, Mexico, Venezuela, Paraguay, Peru and Guatemala see between 50% and 75% of their enrollments within the public sector. Cuba, Uruguay, Bolivia, Panama, Honduras and Argentina see the vast majority of their total enrollment within the public sector as well. These countries see about 75% to 100% of their total enrollment attend public institutions.[44] There has been a clear trend in higher education in Latin America towards the commercialization and privatization of higher education.[44] This is a trend that is evident throughout the world when it comes to higher education. An increase in private schools meaning more private money which introduces more flexibility when it comes to funding programs and beginning innovation initiatives. Since 1994, enrollment in private institutions has increased nearly 8% to 46% (from 38%) of total enrollment in 2002. Public institutions have seen a decline, however, losing that 8% in total enrollments. Public institutions are down to 54% in 2002.[44] Throughout the 1990s, the Inter-American Development bank altered its focus to the introduction of community colleges and other short-cycle colleges in the region. Then, its lending programs for more traditional higher education declined.[39] During this time, the World Bank became a major player in making large investments in several countries. The countries where the largest investments were made were Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela.[39] The World Bank has also increased its funding efforts in Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Venezuela in the areas of science and technology research. The efforts by the World Bank are intended to support the modernization of higher education in major countries throughout Latin America. The funding was used for student aid, university grants, research grants and much more. The granting amounted to more than $1.5 billion since its initiative started.[39] Areas of study vary widely amongst institutions in Latin America. The majority of students’ fields of study are in social sciences, business and law. 42% of enrolled students are studying in social sciences, business and law. Whereas 14% are focusing on engineering, industry and construction. Just 10% are pursuing degrees in Education followed by sciences and health and social welfare each of which are at 9%.[44] A 2015 report from the OECD pointed out that Latin American professionals are over-schooled and underpaid, due they don't have access to the right type of education.[24] Since the 1980s and into the 1990s, there have been many attempts to reform education in Latin American in direct response to the increased interested in globalization. Although globalization has significantly affected Latin American countries, Latin America as a whole remains out the outskirts of the global research and knowledge centers.[39] One of the more recent efforts established by a Latin American country to increase globalization and an interest in the STEM (Science Technology Engineering and Math) fields is the Brazil Scientific Mobility Program. The initiative focuses on sending Brazilian undergraduate and graduate students to study in the United States for a limited period of time.[45] Students must be majoring in a Brazilian institution in a STEM field in order to participate in the program. Participants are awarded a grant/scholarship that allows them to student in the United States for up to one year at a university with a focus in STEM-related areas. The initiative hopes to grant scholarships to Brazil's 100,000 best students in STEM fields.[45] The Brazilian Scientific Mobility Program also allows Brazilian students to master the English language by offering them time to take intensive English language courses before moving onto STEM content classes. Since its conception, more than 20,000 Brazilian students have been placed at universities through the United States.[46] Additionally 475 U.S. host institutions have been involved in hosting either academic or intensive English students or in some instance providing both programs. The primary area of study for Brazilian scholarship grantees is engineering where 65% of program grantees are engineering majors.[46] The program goals complement the goals and areas of improvement from all of Latin America. The goals are to: "To promote scientific research; To invest in educational resources, allocated both within Brazil, and internationally; To increase international cooperation within science and technology and To initiate and engage students in global dialogue.[45] In order for Latin American countries to bolster their higher education efforts, they must work to massify their higher education system and make their scientific and technological capability more robust.[47] Additionally, more outreach must be obtained amongst nearby societies and countries in order to build rapport and relationships that extend to higher education. This could improve teacher training, collaboration in curriculum development and support schools in difficult student and teacher interactions. Finally, Latin America must be able to compete with the increased demands that globalization places upon higher education. Latin America must adapt their higher education institutions to reflect the globalization trend affecting higher education throughout the entire world.[47] The trend is already affecting higher education in Latin American countries with initiatives such as the Brazilian Scientific Mobility Program but those programs are few. Providing more opportunities for Latin American students to study abroad even to other Latin American countries could really benefits students to change their worldviews. Eventually, such programs could affect education policy in many Latin American countries providing a strong partnership across the world. To learn more about education systems specific to a particular Latin American country, find their webpages here: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Bahamas, Dominican Republic, Haiti, etc. Higher education funding Latin American countries have developed a strong economic growth during the 2000s- the first time since the debt crisis of the 1980s. In addition, with a "demographic bonus", in which the proportion of children declines and thus the older generation has increased the size of the working-age population. Thus, for aging societies, it is essential to invest in advanced human capital for the quality and productivity of a smaller work force. So, the expanding regional growth increases the financial resources to train more and better-qualified higher education graduates.[48] In Latin American countries, nearly half of enrollment in tertiary education is concentrated in institutions whose main source of funding is tuition and fees. Therefore, students and their parents are already contributing heavily to finance higher education institutions. Moreover, some of these countries charge tuition and fees to students at public universities; a prime example is Chile's public university sector. In other countries where undergraduate programs in public institutions are free of charge and the majority of the enrollment is concentrated in the public sector (as in Argentina and Uruguay), the government is the principal source of funding. However, this is not the case with graduate degrees as students usually pay the tuition and fees at graduate schools. In most Latin American countries, with the exception of Chile, negotiating the funding model is still the most relevant mechanism to distribute core higher education funding to institutions.[49] Additionally, since the late 1980s and 1990s, many of these governments have been allocating a small proportion of the total budget via formulas and funds to achieve specific objectives. Several Latin American countries took advantage of the boom years and raised their public and private investment in higher education. This also contributed to improving low-income students’ access to these institutions. The complexity of Higher Education in the region can be viewed in a series of historical and emerging trends, in its heterogeneity, its inequality, but above all in the role that public universities and some very outstanding institutions of higher education can assume to construct a new scenario that can aid in significant improvement in the living conditions of its populations, and provide the possibility of greater well-being, democracy, and equality coming from science, education, and culture. The rest of this section will take a look at how Higher Education institutions in Latin America are funded. Changes have been occurring and the funding models appear to be moving targets. Latin America is diverse with twenty sovereign states that stretch from the southern border of the United States to the southern tip of South America. With this much space and diversity, the funding for higher education can vary from state to state. There seem to be four prevalent models for the financing of higher education in Latin America. These four models apply indiscriminately and in different combinations in the countries of the region, thus reflecting the diversity one observes in the region in terms of financing and policies and outcomes.[49] The four prevalent models for financing Higher Education in Latin America are: 1. Direct public financing, provided to eligible institutions through the regular state budget, usually through legislative approval and through the respective ministry responsible for financial matters. The receiving institutions are state universities; this is, formal dependencies of state authority, which academics contracted through the public service, and with the application of management norms being those that are applicable to the public sector in general. Exceptions to this are the cases of Chile and Nicaragua, where for historical reasons, private institutions also receive this kind of public financing. In many states various conditions have been established for the use of the funds, thus restricting the autonomy of their institutional management. Some countries have attempted to make this fixed-base form of providing resources to Higher Education more flexible through budgetary review based on academic results.[49] 2. Policy objective-based public financing. This treats resources that are usually not recurrent, included in special funds of a transitory nature or for attaining specific objectives or achievements of universities or institutions of Higher Education that those funds help to finance. Many of the objectives or goals established have to do with teaching, especially taking into account the numbers and quality of students (the case of the Indirect Fiscal Contribution in Chile), or with achievements in the area of research (funds in the case of Venezuela), or for graduate training (The CAPES model of Brazil). Less progress has been made in terms of programs that include negotiations with the state and competition between institutions to obtain funds based on management commitments. The Chilean experience regarding MECESUP (improvement of quality and equity in Higher Education) funds fostered this purpose, but the results in terms of sustainable achievements are still to be seen. In Argentina, the case of FOMEC (implemented competitive funds) is alike, with resources aimed at real investment programs. It is important to mention Brazil in this regard. The Ministry of Education established a program called PROUNI in 2005 with the purpose of optimizing the use of enrolment places offered by private universities. In effect, the excess of unused enrolment places, which tends to diminish efficiency in the provision of private education leads to an offer by the public sector to acquire them at a tuition cost below that originally charged. In this regard, the incentive for universities to fill their places and foster a greater absorption of students in the Higher Education system, giving preference for grants to student with the greatest financial need. In the short term, the government seeks to have some 400,000 students participating in this system, a figure that in 2006 was 250,000 students.[49] 3. Private financing occurs through the payment of tuition on the part of families, by companies that finance research and graduate programs, or thorough private individuals or companies that make donations to institutions of Higher Education. The charging of student tuition is not only a practice carried out by multiple new universities that have emerged throughout the region. Charging for the cost of education has also been transformed into a practice that increasingly occurs in state universities as well- a situation that Chile is notorious for. Tuition charges and the ways in which this takes place is a controversial political theme in most countries, since it tends to reserve Higher Education for an elite, and has a negative long-term impact on the distribution of income. However, it is clear without greater financial commitment from states, further expansion of Higher Education can only be attained, once existing residual resources of the institutions have been used, only through a reduction of quality. This has placed in relief the emergence of accreditation institutions and procedures aimed being used as an instrument of control or at least of information, regarding private expansion and the progressive privatization of the state sector. In regard to the existence of private donations as a financing mechanism for Higher Education, the regulatory structure for doing so is extremely fragile in most Latin American countries. There is also a culture of distrust toward the public sector and academia in general terms, which also affects the possibility of establishing private company-university strategic alliances for financing and execution of projects with productive applications. From the university side, there is an anti-capitalist sentiment that sees the desire for profit as a negative influence on scientific and technological research.[49] 4. A mixed model, that combines state financing, both fixed and by objectives and goals, with private financing based on the direct payment from students or through other mechanisms or private funding. The Chilean case is one of these (in which the state university sector collects monthly charges). The Mexico system is trying to grow the public resources allocated by objectives and goals. In Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru and the Dominican Republic, countries for which information exists, between 10% (Costa Rica) and 38% (Peru) of the incomes of institutions of Higher Education come from their own resources generated by private activities.[49] Tuition charges have progressively become a reality in institutions of Higher Education in Latin America. Public and state universities face serious structural financial problems, especially because their resources embrace teaching, research, and extension, including the production of public goods that do not necessarily have an explicit financial counterpart. These universities also obey a number of public regulation which often raise their costs significantly. Financial restrictions oblige them to cover at least part of their costs based on student fees. This has led to profound and sustained conflicts. The conversations around funding Higher Education in Latin America are ongoing. Overall, Latin American countries have made great progress in improving their education systems, particular in the last two decades. The governments have increased spending on education, expanded cooperation with the United States, the World Bank, and other donors, and pledged to achieve certain educational milestones established through the Organization of American States' Summit of the Americas process. However, despite these recent improvements, Latin America's education indicators still lag behind the developed world and many developing countries of comparable income levels in East Asia.[50] Student opportunities and future challenges Organizations which link higher education between Latin America and Europe include AlßAN (now ERASMUS Mundos), ALFA and AlInvest. The ALFA Program of co-operation between Higher Education Institutions (HEI's) of the European Union and Latin America "began in 1994 and sought to reinforce co-operation in the field of Higher Education. The program co-finances projects aimed at improving the capacity of individuals and institutions (universities and other relevant organizations) in the two regions".[51] AlßAN provided scholarships to Latin American students, but was replaced in 2010 by ERASMUS Mundos, which provides avenues for Latin American students to study in Europe. ERASMUS Mundos also fosters community and cooperation between Latin America and the European Union. The program provides joint masters and doctoral programs, including a scholarship scheme. It has the aim of "mobility flows of students and academics between European and non-European higher education institutions [and the] promotion of excellence and attractiveness of European higher education worldwide...The European Commission informs potential applicants about funding opportunities through a program guide and regular calls for proposals published on the Erasmus Mundus website".[52] Organizations exist to foster cooperation between Latin American and North American higher education, as well. The Ibero-American University Council (CUIB) and the Latin American Network for the Accreditation and Quality of Higher Education are two such organizations. "Latin American and North American cooperation is often labeled inter-American and is exemplified by organizations such as the Inter-American Organization for Higher Education (IOHE) and the Organization of American States (OAS )".[53] According to the World Bank, the Latin American region is "defined in a cultural and geographical sense. It includes all the countries from Mexico to Argentina. Organizations such as the Latin American Universities Union and the Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and Caribbean are good examples of regional organizations. Sub-regional organizations include the Montevideo Group University Association (AUGM), the Association of Universities of the Amazon (UNAMAZ), and the Council of University presidents for the Integration of the West-Central Sub-Region of South America (CRISCO)".[53] |

高等教育 【注意書き】この節は、ウィキペディア編集者の個人的な感想や、トピックに関する独自の論点などを述べた個人的なエッセイ、または論説文のようなスタイル で書かれている。百科事典的なスタイルに書き直すことで、この節を改善できる。 (2021年10月) (このメッセージの削除方法とタイミングについてはこちらをご覧ください。) 概要 ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育は、過去40年間で3,000を超える高等教育機関に成長した。[21] 1,700万人の高等教育在籍者のうち、ブラジル、メキシコ、アルゼンチンの3か国で1,000万人を占めている。[22] ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育へのアクセスは、 ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育へのアクセスは、多くのラテンアメリカ諸国における所得分布に関して、大きな格差を示している。[23] 高等教育は、この地域では新しいものではない。実際、多くの教育機関は数百年の歴史を持つが、高等教育分野における目覚ましい成長は、より最近のことであ る。2016/2017年の出願者調査によると、ラテンアメリカ人は一般的に高等教育を重視している。[24][25] この40年間は、この地域の高等教育にとって、大きな変化と成長の時期であった。 機関の成長により、提供される学位の多様化が進み、より多くの大学院学位(修士号、専門職学位、博士号)や、より伝統的でない分野の学位が含まれるように なった。[22] この大学院学位の増加は、特に教育の公共部門において、資金調達に関する課題をもたらした。20世紀後半の予算の制約により、多くのラテンアメリカ諸国で 私立大学が急増した。[22] これらの大学は、この期間に地域全体にわたって次々と誕生し、現在も特定の人口層にサービスを提供し続けている。一般的に、ラテンアメリカは教育、特に高 等教育に関しては依然として発展の遅れをとっている。ブラジルは、この「発展の遅れ」の主な例外である。[22] ブラジルは、国内でも富裕な地域に、ラテンアメリカ屈指の大学を数多く有している。 この地域では研究開発への投資額が少ない。[22] そのため、世界の他の地域との競争が生まれず、この地域から生まれるイノベーションが少ないという結果につながっている。 歴史 植民地時代  リマ大学創立を記念する油絵 リマ大学(後にサンマルコスと改名)創立を記念する油絵、ペルーおよびアメリカ大陸で最初の大学、および経営者のサンマルティン修道士 ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育の進展にとって、植民地化は大きな意味を持っていた。植民地時代の精神は教会に織り込まれていた。「1800年代には、チ リ、エクアドル、コロンビアを含む多数の国々がカトリック教会と契約を結んだり、憲法をカトリックの価値観に準拠させたりして、自らをカトリック国家であ ると宣言した。」[26] 16世紀にヒメネス・デ・シスネロス枢機卿によってスペインのキリスト教が改革されたことで、スペインでは教会が他のどのヨーロッパの君主国よりも王権の 支配下に置かれるようになった。[27]  メキシコ王立・教皇立大学に関する銘板 メキシコ王立・教皇庁立大学に関する銘板。 ラテン語:「教皇カルロス5世の王立大学を末永く記憶するために、アントニオ・デ・メンドーサ閣下によって、1553年6月3日、この地に建立された。 DD [献呈する、献呈した]」。英語訳:メキシコ国立大学に、カルロス5世の王立・教皇庁立大学の記憶を永遠のものとする。アントニオ・デ・メンドーサ閣下の 命により、1553年6月3日、この地に建立された。1865年まで、この場所で栄えた。メキシコ国立大学への記念碑。献呈された。 ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育は、教会と国家の関係に大きく影響された。「スペイン領アメリカにおける大学は、教会と国家の両方に奉仕するために創設さ れた。それらはしばしば、教皇勅書や王権の認可による権限に基づいて機能した。教皇勅書を受けた最初の大学は、ドミニカ共和国のサント・ドミンゴ大学 (1538年)である。最初に王の認可を受けたのはペルーのサン・マルコス大学(1551年)である。そして、北米で最初に設立されたとされるのはメキシ コ王立・教皇庁立大学(1551年)である。[28] これら3つの教育機関の提供科目は、法律、医学、経済学など、類似していた。「スペインは、自国の制度や文化を移植することに大成功を収めた。これらの大 学(サント・ドミンゴ大学、サン・マルコス大学、王立教皇庁大学)は国家の支援を受けていたが、常に資金不足の問題を抱えていた。入学金は少額だったが、 在学期間が長くなるほど高額になっていった。このため、富裕層の上流階級が優遇されていた。[29] 権利と教育へのアクセスは、ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育の歴史を通じて、引き続き問題となっていた。世界的な視点から大学の始まりを考えると、現存す る世界最古の教育機関であり、現在も運営されているのは、西暦859年にモロッコで創設されたカルウィーン大学、1088年に創設されたイタリアのボロー ニャ大学、1167年に創設された英国のオックスフォード大学である。 当初、ラテンアメリカでは教会と国家が大学に権限を与え、maestrescuelaの役職は利害関係者間の連絡係を務める者が就いていた。「ほとんどの 大学は宗教団体によって運営されており、特にイエズス会やドミニコ会が運営の多くを担っていた。また、これらの宗教団体は管理者の大半だけでなく、教員の 多くも提供していた。卒業は学術的なイベントであると同時に宗教的なイベントでもあった。」多くの学生は聖職者になるか、国家の官僚になるための教育を受 けていた。[28] 初期のポストコロニアル時代 スペイン系アメリカ独立戦争の頃には、スペイン語圏アメリカにはおよそ25校の大学が存在していた。これらの大学は、フランス啓蒙思想の影響を受け、共同 体の利害や教会ではなく政府によって規制されるようになった。政治的・財政的不安定により、大学システムの成長と拡大は鈍化し、大学の日常は度々中断され た。1840年代には、チリとウルグアイがナポレオン流の中央集権的な教育モデルを導入し、「国家の将来の指導者、および官僚や軍人となるべき者」のため の基礎教育を推進した。[31] ポストコロニアルの時代には、「グレゴリオ・ワインバーグは、20世紀までの3つの連続した段階を定義した。すなわち、「押し付けられた文化」、「受け入 れられた文化」、そして「批判された、あるいは論争の的となった文化」である。「押し付けられた文化」の段階は、大都市にとって機能的な性質のものであ り、植民地時代に相当する。一方、2番目の段階である「受け入れられた文化」は、国民社会の組織化と関連している。また、ラテンアメリカ諸国による外国の 文化的・哲学的傾向の同化は、新しい国家の組織化に伴う理論的・実践的な問題の解決に役立つものとしてそれらを採用したことによるものである。 19世紀と20世紀の輸出主導型の経済成長により、資源の入手が容易になり、都市化が進んだ。また、政治エリートの競争心も相まって、大学の拡大を後押し した。最終的には、大学のリーダーシップ、教員、カリキュラム、入学選抜の管理が、国が管理・出資する機関と民間運営の機関の分離につながった。[33] 「しかし、大学が急増した原因は社会的需要だけではなかった。日中仕事を持つ労働者階級の若者にも教育の機会を与えるため、進取の気性に富む教育者たちに よって営利目的の夜間学校が設立された。多くの伝統的な教育機関が新しいタイプのトレーニングに対する国家のニーズに応えようとしなかったため、いくつか の大学が設立された。しかし、最も重要な追加刺激は、新しいプログラムや機関の認定基準の欠如に起因するものである。」[34] リベラル派と保守派の間の権力闘争や、世俗主義の推進派と反対派の対立が、公立大学と私立大学の増加に拍車をかけた。実証主義の哲学は、科学の進歩は本質 的に宗教的干渉と相容れないという考えを強力に補強した」[28]。国家の権力と支配は増大し続け、「コスタリカ、グアテマラ、ホンジュラス、ニカラグア の大学はすべて、 学位や専門免許を授与する権限を国家が独占していた」のである。[28] 教育が克服すべきさらなる障害は、「ラテンアメリカにおける初期の大衆教育システムの展開は、富、収入、機会の不平等を反映しており、義務教育の普遍化の 障壁となった」という事実であった。地域間や、各国内の農村部と都市部の格差は、社会階級や民族集団間の格差と強く関連しており、一般的に恵まれた集団へ の補助金増額につながる中央集権的な教育政策では、その格差は縮小されなかった」[34]。 20世紀の学生運動 富裕層に有利な大学入学の排他性は、ラテンアメリカにおける人口増加と経済成長による入学率の急速な上昇により、変化し始めた。アルゼンチンの大学改革運 動(UFM)またはMovimiento de la Reforma Universitariaは、「 。「自治権を持つ公立大学と民主的に選出された政府との政治的な溝は、20世紀後半の冷戦下で急進化した学生運動により、より深刻化した。最も顕著な対立 は、世界中で学生が動員された1960年代後半に起こった。これらの抗議活動は、ラテンアメリカ諸国のほとんどで、この期間を通じて非常に頻繁に行われ、 政治に関与する学生運動というイメージを強化した。ただし、それはしばしば、大学の運営に参画し、国の政治運動や政党と密接に結びついた少数の学生活動家 の動員によって促進されたものであった。多くの場合、学生と当局の対立は、革命的な変化を求める急進的な要求と、組織改革やより手厚い資金援助を求めるよ り限定的な要求が混在していた」[34]。例えばアルゼンチンでは、大学教育へのアクセスを求める中流階級の人口が増加していた。アルゼンチンの大学制度 は、その需要とともに急速に拡大した。「現代の分析家たちは、ラテンアメリカの大学生のおよそ85~90パーセントが中流階級出身であると推定している」 [28]。アルゼンチンの中流階級の成長と繁栄、それに選挙権、都市部への人口流入の増加、1912年の普通選挙法により、学生たちは保守的な体制に異議 を唱え、自らの要求を訴える力を得た。1917年12月、コルドバ大学は学生たちの要求を退け、大学が認識しているニーズに応えることを拒否した。学生た ちはこれに反発し、大規模な抗議活動を実施。授業をボイコットし、大学構内でデモを行った。地元の政治家や労働組合、学生団体も参加し、学生たちの声の力 を大きくした。学生運動の主な目的は、「学生と教授陣の大学運営への参加を拡大し、カリキュラムを近代化することで、コルドバ大学を世俗化し民主化するこ と」、そして「入学制限を撤廃し、勤労学生にも対応できるよう出席や試験に柔軟性を持たせることで、大学教育を『利用しやすく、手頃な価格』にすること」 であった。学生たちは約1年間、何の返答も得られなかった。[36] 「アルゼンチンの大学改革運動は、ウルグアイ、チリ、ペルーなどにおける大学改革運動に影響を与えた」[36]。 学生の関与は、政治への注目と参加の顕著な増加、およびキャンパス内の権力の再配分につながったと評価されているが、常にそうであったわけではない。ゆっ くりと変化するシステムの中で、学生たちは多くの挫折を経験した。「一部の改革は...学生と教授の権限を縮小し、代わりに管理職や国家に権限を与えた」 [28]。コロンビアの学生の場合、アルゼンチンの例は適用できなかった。「団結できず、広範な政治問題に過剰に懸念し、外国の帝国主義者と地元の寡頭制 勢力との『不浄な同盟』に気を取られたコロンビアの学生たちは、大学の政策に影響を与えるための合法的かつ効果的な手段を手に入れることはなかった」 [37]。高等教育における権力闘争は続いているが、多くの改革が問題の解決を試みてきた。コロンビアにおける改革の例としては、北米の土地補助金モデル を参考にしたもの、支出と資産の浪費をターゲットとする行政改革、常勤教授の増員などが挙げられる。[37] 大学制度は、知的理想の追求や教育・職業上の進歩を通じて文化を戦略的に導くのではなく、その文化を反映しているとして批判されてきた。改革の試行錯誤の 時期を経て、「ラテンアメリカのいくつかの社会はすでに急進的な政治路線に乗り出しており、また、他の社会も新たな選択肢を模索する意欲を示している」 [37]。将来に向けて、ラテンアメリカは、高等教育プログラムをさらに発展させ、すべての人々への高等教育の機会を拡大することで、学問的成功と社会的 な成功を増加させていくであろう。 ラテンアメリカの高等教育機関  メキシコ国立自治大学(UNAM)の中央大学都市キャンパス メキシコ国立自治大学(UNAM)中央大学都市キャンパス(メキシコシティ)は、ユネスコの世界遺産リストに登録されている。 エコノミスト誌によると、「ラテンアメリカには巨大な大学や由緒ある大学がいくつかある。ブエノスアイレス大学(UBA)とメキシコ国立自治大学 (UNAM)にはそれぞれ数十万人の学生が在籍しており、リマのサンマルコス大学は1551年に設立された。それでも、この地域は高等教育の卓越性と同義 語とは言いがたい。研究業績は印象的なものではなく、教授法は時代遅れで、学生は大量にドロップアウトしている。これらの欠点は重要である。経済成長の加 速により、この地域では高等教育に対する需要が大幅に増加しており、新しい大学が数多く誕生している」[38]。エコノミスト誌の記事では、2011年の ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育機関のランキングが掲載されている。記事には、「上位200校のうち、65校がブラジル、35校がメキシコ、25校ずつが アルゼンチンとチリ、20校がコロンビアに位置している。ブラジルで最も裕福なサンパウロ大学(USP)がトップに輝いた」とある。[38] ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育機関は、私立、公立、連邦立の大学である。ほとんどの専門家は、ラテンアメリカには典型的な大学というものは存在しないと いう点で一致している。なぜなら、ラテンアメリカ内の国や地域ごとに大きな違いがあるため、大学もそれらを反映していなければならないからである。 [39] ほとんどのラテンアメリカ諸国はヨーロッパのモデル(主にフランスまたはスペインのモデル)から出発し、地域ごとに異なる独自の教育モデルを採用している 。そのほとんどはナポレオン時代のもので、歴史的に職業志向で、かつ国家主義的な性質を持つものであった。現在でも、ラテンアメリカで高等教育を受ける学 生は、大学内で専攻分野を見つけ、規定された専攻課程を遵守することが求められる。ラテンアメリカは、拡大を続けるグローバル化時代において、多くの問題 に直面している。入学希望者および学生は、これまで以上にグローバル化された世界に参加する準備ができていなければならず、より国際的な使命を支援する機 関も必要である。学者たちは、近代を異なる形で定義する国々間に緊張関係があると考えている。教育における近代性は、教育政策や研究、特に比較教育の進歩 を可能にする。近代性を各国で異なる形で定義することは、近代的な教育システムがどのようなものになり得るか、また、どのようなものになるべきかについて のコンセンサスを許さないのである。  サンパウロの時計塔から見たサンパウロ大学。 サンパウロの時計塔から見たサンパウロ大学。 アルゼンチン、ブラジル、チリ、コロンビア、キューバ、メキシコ、ペルーの人口は、ラテンアメリカ地域の人口の約90パーセントを占めている。[41] ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育は、実際に高等教育の選択肢を自国民に提供できる、また提供しているラテンアメリカ諸国のエリート層の一部にしか反映され ていないことを認識することが重要である。高等教育の選択肢を持たないラテンアメリカの一部の小規模な国々に関する情報を強化するためには、この分野での さらなる研究が必要である。あるいは、高等教育の選択肢はあっても、その数や範囲が限られている国々についてもである。アルゼンチン、ボリビア、チリ、コ ロンビア、コスタリカ、キューバ、エクアドル、エルサルバドル、グアテマラ、ホンジュラス、ニカラグア、パナマ、ウルグアイ、ベネズエラ、メキシコ、ペ ルー、ブラジル、ドミニカ共和国を含むラテンアメリカおよびカリブ海地域の高等教育機関に関する2002年の出版物では、1,917校が私立大学とされて いる。[39] ブラジルなどの国々では、各州に州立および連邦立の高等教育機関がある。ブラジルの連邦大学は、全国に99校あり、60万人の学生が在籍している。 [42] ブラジル特有の高等教育に関する詳細は以下を参照のこと:ブラジル。  ブエノスアイレス大学都市(アルゼンチン)。2008年9月。 ブエノスアイレス大学都市(アルゼンチン)。2008年9月。 あるいは、アルゼンチン、ブラジル、チリ、コロンビア、キューバ、メキシコ、ペルーでは、1,023校の大学が公立とされている。私立または公立とされる 教育機関は約5,816校あり、一部は特定できないと判断された。ラテンアメリカとカリブ海地域を合わせた両地域では、何らかの高等教育機関に約 1,400万人の学生が在籍している。ラテンアメリカでは約1,389万6,522人の学生が高等教育機関に在籍しており、カリブ海地域では約9万 5,000人である。[43] 高等教育への参加は、1998年から2001年にかけて在籍者数が増加している。先進国では、総就学率が2001年には45.6%から54.6%へと急増 した。[44] さらに、女性の就学率は1998年の59.2%から2001年には64.3%へと急増した。(ユネスコ、2005年)。移行国および発展途上国でも、 1998年から2001年にかけて総就学率が急上昇した。分析対象となったラテンアメリカ諸国のうち、ブラジル、メキシコ、アルゼンチンの3カ国が最も高 い就学率を示した。この上位3カ国で高等教育の総就学率の約60%を占めている。ブラジルに次いでメキシコが全体の17%、アルゼンチンが14%となって いる。[44] また、これらの国々では、私立大学と公立大学への入学も異なる割合で分布している。例えば、ブラジル、チリ、エルサルバドル、コロンビア、コスタリカ、ニ カラグア、ドミニカ共和国では、学生のほとんどが私立の高等教育機関に入学している。[44] 先に挙げた国々では、総入学数の50%から75%が私立セクターである。一方、エクアドル、メキシコ、ベネズエラ、パラグアイ、ペルー、グアテマラでは、 50%から75%の学生が公立の教育機関で学んでいる。キューバ、ウルグアイ、ボリビア、パナマ、ホンジュラス、アルゼンチンでも、学生の大多数が公立の 教育機関で学んでいる。これらの国々では、総在籍数の約75%から100%が公立機関に通っている。[44] ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育では、商業化と民営化の明確な傾向が見られる。[44] これは、高等教育に関して言えば、世界中で明らかな傾向である。私立学校の増加は、プログラムへの資金調達や革新的な取り組みの開始に関して、より柔軟性 を導入する民間資金の増加を意味する。1994年以来、私立機関への入学は2002年の総入学数の38%から46%(8%増)に増加した。しかし、公立機 関への入学は減少しており、総入学数で8%を失っている。公立機関への入学は2002年には54%に減少している。[44] 1990年代を通じて、米州開発銀行は地域におけるコミュニティ・カレッジやその他の短期大学導入に重点を移した。その後、より伝統的な高等教育に対する 融資プログラムは減少した。[39] この時期、世界銀行は複数の国々への大規模な投資を行う主要なプレイヤーとなった。最も多額の投資が行われた国々は、アルゼンチン、チリ、コロンビア、メ キシコ、ベネズエラであった。[39] 世界銀行は、ブラジル、チリ、メキシコ、ベネズエラにおける科学技術研究分野への資金援助も増加させた。世界銀行の取り組みは、ラテンアメリカ全域の主要 国における高等教育の近代化を支援することを目的としている。資金は、学生支援、大学助成金、研究助成金など、さまざまな用途に充てられた。助成金総額 は、取り組み開始以来、15億ドル以上に上る。 ラテンアメリカでは、教育機関によって専攻分野が大きく異なる。学生の専攻分野の大半は、社会科学、ビジネス、法律である。在籍学生の42%が社会科学、 ビジネス、法律を専攻している。一方、工学、産業、建築を専攻しているのは14%である。教育の学位取得を目指しているのはわずか10%で、科学と保健・ 社会福祉がそれぞれ9%で続いている。[44] 2015年のOECDの報告書では、ラテンアメリカの専門家は過剰な教育を受けており、低賃金であると指摘されている。その理由は、 適切な教育を受けられないことが原因であると指摘している。[24] 1980年代から1990年代にかけて、グローバル化への関心の高まりを受けて、ラテンアメリカでは教育改革の試みが数多く行われた。グローバル化はラテ ンアメリカ諸国に大きな影響を与えたが、ラテンアメリカ全体としては、依然としてグローバルな研究・知識センターの周辺にとどまっている。[39] ラテンアメリカ諸国がグローバル化と科学・技術・工学・数学(STEM)分野への関心を高めるために最近打ち出した取り組みのひとつに、ブラジル科学モビ リティ・プログラムがある。この取り組みは、ブラジルの学部生および大学院生を米国に一定期間留学させることに焦点を当てている。参加者は、STEM関連 分野に重点を置く米国の大学で最長1年間学ぶための助成金/奨学金が支給される。このイニシアティブでは、ブラジルのSTEM分野の優秀な学生10万人に 奨学金を支給することを目指している。[45] ブラジル科学人材交流プログラムでは、STEM科目の授業に着手する前に集中的な英語コースを受講する時間を設けることで、ブラジルの学生が英語を習得す ることも可能にしている。構想以来、2万人以上のブラジル人学生が米国の大学に入学している。[46] さらに、475の米国の受け入れ機関が、学術または集中英語コースの学生を受け入れたり、あるいは両方のプログラムを提供したりしている。ブラジル人奨学 生の専攻分野は工学が中心で、プログラム奨学生の65%が工学専攻である。[46] プログラムの目標は、ラテンアメリカ全体の目標と改善分野を補完するものである。目標は次の通りである。「科学的研究を促進する。教育資源に投資し、ブラ ジル国内および国際的に配分する。科学技術における国際協力を強化する。学生にグローバルな対話を開始させ、参加させる。」[45] ラテンアメリカ諸国が高等教育への取り組みを強化するためには、高等教育制度の大衆化を図り、科学技術能力を強化する必要がある。さらに、高等教育にまで 広がる信頼関係と関係を構築するためには、近隣の社会や諸国との連携を強化しなければならない。これにより、教師の研修やカリキュラム開発における協力体 制が改善され、生徒や教師間の交流が難しい学校への支援が強化される可能性がある。最後に、ラテンアメリカは、グローバル化が高等教育に課す高まる需要に 競争力を持たなければならない。ラテンアメリカは、世界全体で高等教育に影響を及ぼしているグローバル化の傾向を反映するように、高等教育機関を適応させ なければならない。[47] この傾向は、ブラジルの科学者移動プログラムなどのイニシアティブにより、すでにラテンアメリカ諸国の高等教育に影響を及ぼしているが、そのようなプログ ラムはまだ少ない。ラテンアメリカの学生が、他のラテンアメリカ諸国へ留学する機会を増やすことは、学生の世界観を変える上で非常に有益である。最終的に は、このようなプログラムは、世界中で強力なパートナーシップを提供することで、多くのラテンアメリカ諸国の教育政策に影響を与える可能性がある。 特定のラテンアメリカ諸国の教育制度についてさらに詳しく知りたい場合は、以下のリンクから各国のウェブページを参照のこと:アルゼンチン、ボリビア、チ リ、コロンビア、エクアドル、ベネズエラ、グアテマラ、メキシコ、パナマ、バハマ、ドミニカ共和国、ハイチ、その他 高等教育への資金 ラテンアメリカ諸国は、1980年代の債務危機以来初めて、2000年代に力強い経済成長を遂げた。さらに、「人口ボーナス」により、子供の割合が減少 し、高齢者の割合が増加したため、労働年齢人口の規模が拡大した。そのため、高齢化社会においては、より少ない労働力で質と生産性を向上させるために、高 度な人的資本への投資が不可欠である。そのため、地域経済の成長拡大により、より多くの有能な高等教育修了者を育成するための財源が増加している。 [48] ラテンアメリカ諸国では、高等教育への入学者のほぼ半数が、授業料と手数料を主な財源とする教育機関に集中している。そのため、学生とその親はすでに高等 教育機関の財政に大きく貢献している。さらに、これらの国々の中には公立大学の学生にも授業料や手数料を課しているところもあり、その代表例がチリの公立 大学セクターである。公立機関の学部課程が無料で、入学者の大半が公立機関に集中している国々(アルゼンチンやウルグアイなど)では、政府が主な資金源と なっている。しかし、大学院課程では学生が通常、授業料や手数料を支払うため、この限りではない。 チリを除くほとんどのラテンアメリカ諸国では、高等教育の主要な財源を教育機関に分配する仕組みとして、資金調達モデルの交渉が依然として最も適切な方法 である。[49] さらに、1980年代後半から1990年代にかけて、これらの政府の多くは、特定の目標を達成するために、予算総額のわずかな割合を公式や資金を通じて割 り当ててきた。ラテンアメリカ諸国のうち数カ国は好景気の波に乗って、高等教育への公的および民間投資を増額した。このこともまた、低所得層の学生が高等 教育機関へのアクセスを改善する一因となった。 この地域の高等教育の複雑性は、歴史的および新たなトレンドの数々、その不均質性、不平等性、そして何よりも、公立大学や非常に優れた高等教育機関が、そ の地域の生活水準の大幅な改善を支援し、科学、教育、文化から生まれるより大きな幸福、民主主義、平等性の可能性を提供できるという新たなシナリオを構築 する役割を担っているという点に見て取れる。このセクションでは、ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育機関の資金調達方法について見ていく。変化が起こってお り、資金調達モデルは動く標的のように見える。 ラテンアメリカは、米国の南の国境から南米の南端まで広がる20の主権国家から成る多様性に富んだ地域である。これほど広大な地域で多様性があるため、高 等教育の資金調達は国によって異なる。 ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育の資金調達には、主に4つのモデルがあるようだ。この4つのモデルは、この地域の国々で無差別に、また異なる組み合わせで 適用されており、資金調達や政策、成果の面でこの地域に見られる多様性を反映している。[49] ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育の資金調達で一般的な4つのモデルは以下の通りである。 4. 通常は立法府の承認と財務を担当する各省庁を通じて、通常の国家予算から適格機関に提供される公的資金による直接的な資金調達。 資金を受け取る機関は国立大学であり、これはすなわち、国家権力の正式な下部組織であり、公務員として雇用された教員が、公共部門一般に適用される管理基 準を適用して運営されている。 これには例外があり、チリとニカラグアでは歴史的な理由から私立機関もこの種の公的資金を受け取っている。多くの国では、資金の使用に関してさまざまな条 件が設けられており、それによって機関の経営の自主性が制限されている。一部の国では、学術的成果に基づく予算の見直しを通じて、高等教育への資源提供の 固定ベース方式をより柔軟なものにしようとしている。 2. 政策目標に基づく公的資金。これは通常、経常的支出ではない資金を対象とするもので、一時的な性質を持つ特別基金に組み込まれたり、高等教育機関が特定の 目標や成果を達成するために、その資金が財政支援を行う。設定された目標や目的の多くは、特に学生数や学生の質を考慮した教育(チリの間接的財政貢献の場 合)、または研究分野での成果(ベネズエラの資金)、または大学院生の研修(ブラジルのCAPESモデル)に関係している。国家との交渉や、経営上のコ ミットメントに基づく資金獲得をめぐる機関間の競争などを含むプログラムに関しては、それほど進展していない。MECESUP(高等教育の質と公平性の向 上)資金に関するチリの経験は、この目的を促進したが、持続可能な成果という観点での結果はまだ出ていない。アルゼンチンでは、FOMEC(競争的資金の 実施)の事例が同様であり、実際の投資プログラムに資源が向けられている。この点において、ブラジルについて言及することは重要である。教育省は2005 年に、私立大学が提供する入学定員の最適利用を目的としたPROUNIと呼ばれるプログラムを設立した。実際、私立教育の効率性を低下させる傾向にある未 使用の入学定員の過剰分は、公立部門が本来の授業料よりも低い授業料でそれらを取得するよう促すことになる。この点において、大学は定員を埋め、高等教育 システムへの学生の吸収を促進するインセンティブが与えられ、経済的に最も困窮している学生に優先的に助成金が支給される。短期的には、政府は40万人の 学生がこの制度に参加することを目指しており、2006年には25万人の学生が参加していた。 3. 【私費による運営】学費の支払いは、家庭からの授業料の支払い、研究や大学院プログラムへの資金提供を行う企業、または高等教育機関への寄付を行う個人や企業を通じて行われ る。学生への授業料の徴収は、この地域に新たに誕生した多数の大学のみが行っている慣行ではない。教育費の徴収は、公立大学でもますます行われる慣行へと 変化している。これはチリが特に悪名高い状況である。授業料の徴収とその方法については、高等教育がエリート層に独占され、所得分配に長期的な悪影響を及 ぼす傾向があるため、ほとんどの国々で政治的な論争の的となっている。しかし、国からの財政的支援が拡大しない限り、高等教育のさらなる拡大は、既存の教 育機関の資源が利用された後、質の低下によってのみ達成できることは明らかである。そのため、民間部門の拡大や、国家部門の段階的な民営化を管理する手 段、あるいは少なくとも情報を得る手段として、認定機関や認定手続きの設立が促進された。高等教育の資金調達メカニズムとしての民間からの寄付の存在に関 しては、そのための規制構造はほとんどのラテンアメリカ諸国において極めて脆弱である。また、公共部門や学術界全般に対する不信感も存在しており、生産的 な応用を伴うプロジェクトの資金調達や実施を目的とした企業と大学の戦略的提携の可能性にも影響を与えている。大学側には、利益追求を科学技術研究に悪影 響を与えるものとして捉える反資本主義的な感情がある。 4. 固定費および目的別予算の両方による国家財政と、学生からの直接支払い、またはその他のメカニズムや民間資金による民間財政を組み合わせた混合モデル。チ リのケースは、このモデルの1つである(州立大学部門が月謝を徴収している)。メキシコのシステムは、目的と目標別に割り当てられた公的資源の拡大を試み ている。アルゼンチン、ボリビア、コロンビア、コスタリカ、ペルー、ドミニカ共和国など、情報のある国々では、高等教育機関の収入の10%(コスタリカ) から38%(ペルー)が、民間活動によって生み出された独自の資源によるものである。 ラテンアメリカでは、高等教育機関における授業料徴収が徐々に現実のものとなっている。公立大学や州立大学は、特に、その財源が教育、研究、普及(必ずし も明確な財政的見返りをもたらさない公共財の生産を含む)を包含しているため、深刻な構造的財政問題に直面している。これらの大学はまた、多くの公共規制 に従う必要があり、そのことがしばしば大幅なコスト増につながっている。財政的制約により、少なくとも一部の費用を学生の授業料で賄うことを余儀なくされ ている。これが深刻かつ持続的な対立を生み出している。ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育の財源に関する議論は現在も続いている。 全体として、ラテンアメリカ諸国は、特に過去20年間で、教育システムの改善において大きな進歩を遂げた。政府は教育への支出を増やし、米国、世界銀行、 その他のドナーとの協力を拡大し、米州機構の米州サミットプロセスを通じて確立された特定の教育目標の達成を誓約した。しかし、こうした最近の改善にもか かわらず、ラテンアメリカの教育指標は依然として先進国や、同等の所得水準にある東アジアの多くの開発途上国に遅れをとっている。 学生の機会と将来の課題 ラテンアメリカとヨーロッパの高等教育を結びつける組織には、AlßAN(現在のERASMUS Mundos)、ALFA、AlInvestがある。欧州連合とラテンアメリカの高等教育機関(HEI)間の協力プログラムであるALFAは「1994年 に始まり、高等教育分野での協力を強化することを目指した。このプログラムは、両地域の個人および機関(大学やその他の関連組織)の能力向上を目的とした プロジェクトに共同資金を提供する」[51]。AlßANはラテンアメリカ人学生に奨学金を提供したが、2010年にERASMUS Mundosに置き換えられた。ERASMUS Mundosはラテンアメリカ人学生がヨーロッパで学ぶ道を開くとともに、ラテンアメリカと欧州連合(EU)間の共同体意識と協力を促進する。このプログ ラムは共同修士課程・博士課程を提供し、奨学金制度を含む。その目的は「欧州と非欧州の高等教育機関間の学生・研究者の流動性の促進」ならびに「欧州高等 教育の世界的な卓越性と魅力の向上」にある。欧州委員会は、エラスムス・ムンドゥス公式サイトで公開されるプログラムガイドと定期的な公募を通じて、資金 提供の機会を潜在的な応募者に通知している。[52] ラテンアメリカと北米の高等教育間の協力促進を目的とした組織も存在する。イベロアメリカ大学評議会(CUIB)とラテンアメリカ高等教育認証・品質ネッ トワークがその例である。「ラテンアメリカと北米の協力はしばしば米州間協力と呼ばれ、米州高等教育機構(IOHE)や米州機構(OAS)などの組織がそ の例である」。[53] 世界銀行によれば、ラテンアメリカ地域は「文化的・地理的に定義される。メキシコからアルゼンチンまでの全ての国々を含む」。ラテンアメリカ大学連合やラ テンアメリカ・カリブ高等教育研究所などの組織は、地域組織の良い例だ。準地域組織には、モンテビデオ大学連合(AUGM)、アマゾン大学協会 (UNAMAZ)、南米中西準地域統合大学学長評議会(CRISCO)などがある。」[53] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Education_in_Latin_America |

☆ 大きな進歩にもかかわらず、ラテンアメリカでは教育が依然として課題となっている。この地域では教育の普及において大きな進歩を遂げ、ほとんどの子供たち が小学校に通い、中等教育へのアクセスも大幅に増加している。子供たちは親の世代よりも平均で2年多く学校に通っている。この地域のほとんどの教育システ ムでは、90年代初頭には教育サービスへのアクセスがなかった地域やコミュニティにも手が届くよう、さまざまな管理および制度上の改革を実施している。 しかし、この地域には、4歳から17歳までの2,300万人の子供たちが、正規の教育システムから取り残されている。推定によると、就学前年齢(4歳から 5歳)の子供の30%が学校に通っておらず、最も脆弱な集団である貧困層、農村部、先住民、アフリカ系住民では、この割合は40%を超える。小学校就学年 齢(6歳から12歳)の子供たちの間では、ほぼ全員が教育を受けているが、それでも初等教育システムに500万人の子供たちを組み入れる必要がある。これ らの子供たちは主に遠隔地に住み、先住民またはアフリカ系であり、極度の貧困状態にある。13歳から17歳までの人々では、教育システムに登録しているの は80%のみであり、そのうち中等教育に通っているのは66%のみである。残りの14%は依然として小学校に通っている。これらの割合は、社会的弱者層で はさらに高くなり、13歳から17歳までの最貧困層の若者の75%が学校に通っている。高等教育の普及率は最も低く、18歳から25歳までの教育システム 外の人の割合は70%にとどまっている[明確化が必要]。現在、低所得層の子供や農村部に住む人々の半数以上が、9年間の教育を修了できていない。

| Despite significant

progress, education remains a challenge in Latin America.[1] The region

has made great progress in educational coverage; almost all children

attend primary school and access to secondary education has increased

considerably. Children complete on average two more years of schooling

than their parents' generation.[2] Most educational systems in the

region have implemented various types of administrative and

institutional reforms that have enabled reach for places and

communities that had no access to education services in the early 90s. However, there are still 23 million children in the region between the ages of 4 and 17 outside of the formal education system. Estimates indicate that 30% of preschool age children (ages 4 –5) do not attend school, and for the most vulnerable populations – poor, rural, indigenous and afro-descendants – this calculation exceeds 40 percent. Among primary school age children (ages 6 to 12), coverage is almost universal; however there is still a need to incorporate 5 million children in the primary education system. These children live mostly in remote areas, are indigenous or Afro-descendants and live in extreme poverty.[3] Among people between the ages of 13 and 17 years, only 80% are enrolled in the education system; among those, only 66% attend secondary school. The remaining 14% are still attending primary school. These percentages are higher among vulnerable population groups: 75% of the poorest youth between the ages of 13 and 17 years attend school. Tertiary education has the lowest coverage, with only 70% of people between the ages of 18 and 25 years outside of the education system[clarify]. Currently, more than half of low income children or people living in rural areas fail to complete nine years of education.[3] |

大きな進歩にもかかわらず、ラテンアメリカでは教育が依然として課題と

なっている。[1]

この地域では教育の普及において大きな進歩を遂げ、ほとんどの子供たちが小学校に通い、中等教育へのアクセスも大幅に増加している。子供たちは親の世代よ

りも平均で2年多く学校に通っている。[2]

この地域のほとんどの教育システムでは、90年代初頭には教育サービスへのアクセスがなかった地域やコミュニティにも手が届くよう、さまざまな管理および

制度上の改革を実施している。 しかし、この地域には、4歳から17歳までの2,300万人の子供たちが、正規の教育システムから取り残されている。 推定によると、就学前年齢(4歳から5歳)の子供の30%が学校に通っておらず、最も脆弱な集団である貧困層、農村部、先住民、アフリカ系住民では、この 割合は40%を超える。小学校就学年齢(6歳から12歳)の子供たちの間では、ほぼ全員が教育を受けているが、それでも初等教育システムに500万人の子 供たちを組み入れる必要がある。これらの子供たちは主に遠隔地に住み、先住民またはアフリカ系であり、極度の貧困状態にある。[3] 13歳から17歳までの人々では、教育システムに登録しているのは80%のみであり、そのうち中等教育に通っているのは66%のみである。残りの14%は 依然として小学校に通っている。これらの割合は、社会的弱者層ではさらに高くなり、13歳から17歳までの最貧困層の若者の75%が学校に通っている。高 等教育の普及率は最も低く、18歳から25歳までの教育システム外の人の割合は70%にとどまっている[明確化]。現在、低所得層の子供や農村部に住む人 々の半数以上が、9年間の教育を修了できていない。[3] |

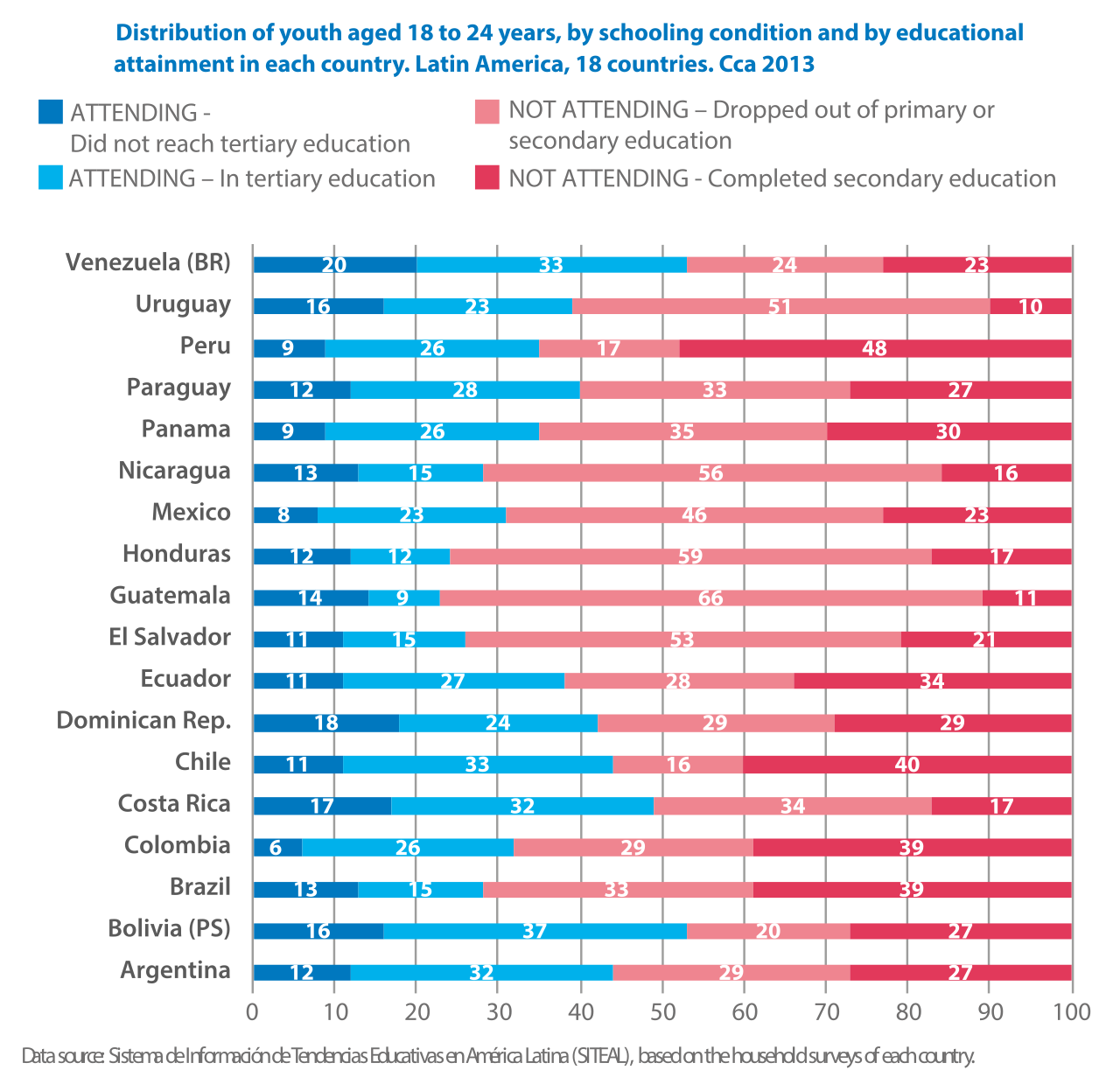

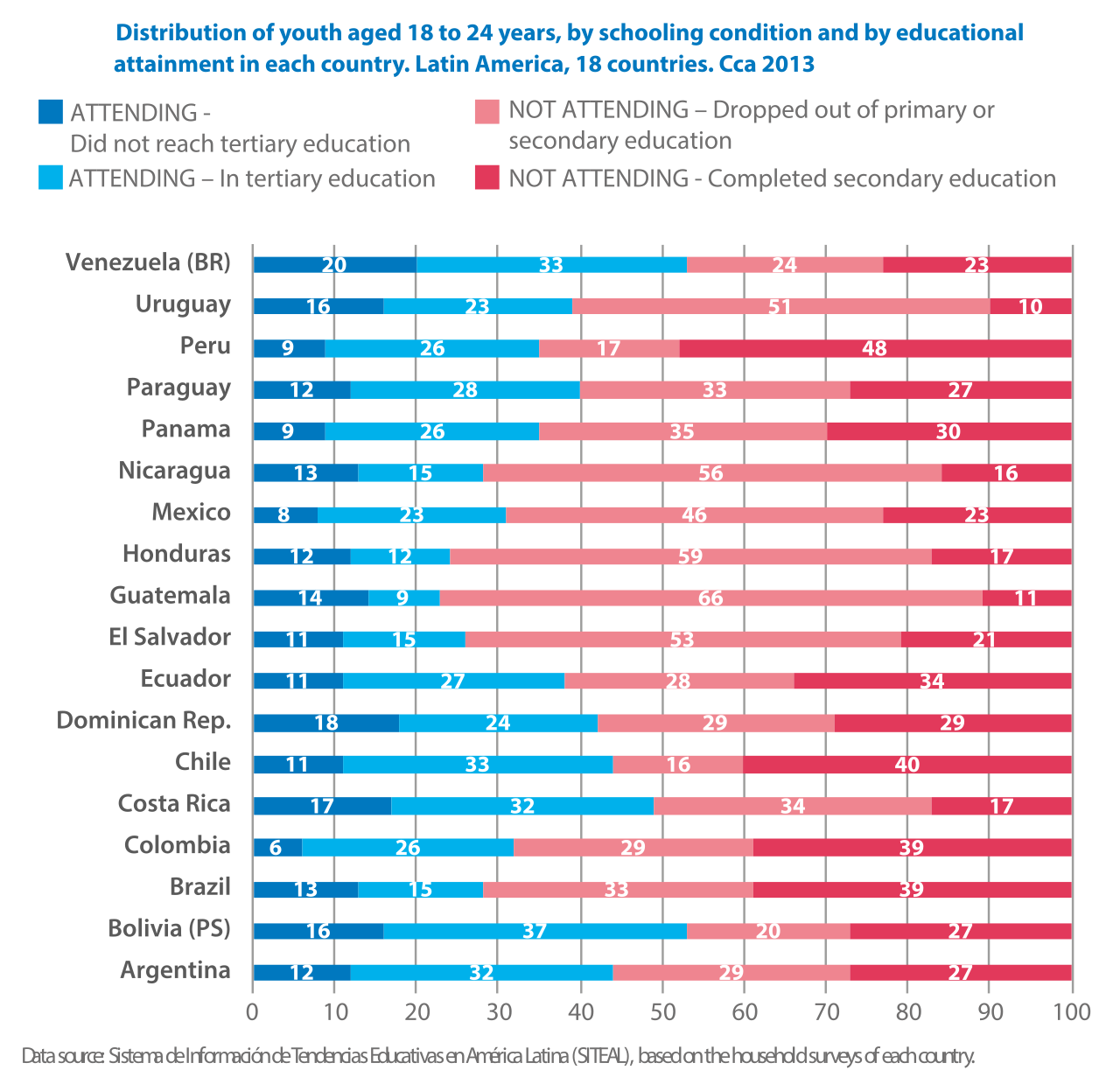

Retention and completion Distribution of youth by schooling condition and educational attainment in Latin American countries In Mexico, access to education has increased with 87% of the population today completing their primary schooling compared to 46.6% in 1980.[4] The countries of the region show wide differences in their averages and gaps in completion rates, especially at the secondary level. While on average 55% of youth in the region complete the first cycle of secondary education, in countries such as Guatemala and Nicaragua this estimation falls to 30%. In Chile, it approaches 80%. Desertion is also a challenge for Latin America. According to Inter-American Development Bank studies, 20% of students enter primary school with one or more lagging years. During this cycle, about 10% repeat 1st and 2nd grade, and 8% repeat grades 3 and 4. Only 40% of children enter secondary school at the expected age. At the secondary level, approximately 10% of youth in each grade level repeat their grade. On average, a child who attends 7.2 years of school completes only 6 years of education (primary), while a person attending 12 years of school only completes 9 years of education (high school).[3] By the age of 18, only 1 in every 6 rural men and women are still in school. Therefore, only a small number or poor rural youth have the chance to attend a university.[5] A study published by the Inter-American Development Bank also revealed that school dropout rates in Latin America can be significantly reduced by improving the quality of school's infrastructure, such as access to clean water and electricity.[6] The study shows that, in Brazil, a universalization program focused on providing electricity to rural and indigenous schools (Light for All), reduced 27% the dropout rates of schools treated by the program when compared to schools without electricity. School-based feeding programs are widely used in Latin America to improve access to education, and at least 23 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean region have some large-scale school feeding activity. Altogether, 55% of school-age children (and 88% of primary school-age children) in the region benefit from school meal programs. This is the highest rate of school feeding coverage seen in any region of the world.[7] In El Salvador, a reform known as the EDUCO (Educación y Cooperación Para el Desarrollo) system has been implemented by the El Salvadorian government with the support of the World Bank and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. This system was put in place to improve retention rates and student outcomes. EDUCO is a form of community-managed schools, in which the community is in charge of school administration, including the hiring and firing of teachers and decisions such as how long the students go to school for and for how many days. A study conducted from 1996 to 1998 found that students in EDUCO schools were 5% more likely to continue their education than those in traditional schools and that weekly visits by the community and parent organizations that run the schools increased probability of school retention by 19%.[8] |

就学率と修了率 ラテンアメリカ諸国における学齢期の若者の就学状況と教育達成度 メキシコでは、教育へのアクセスが増加し、現在では人口の87%が初等教育を修了しているが、1980年にはその割合は46.6%であった。[4] この地域の国々では、平均値と修了率の格差に大きな違いが見られ、特に中等教育レベルで顕著である。この地域の若者の平均55%が中等教育の第一段階を修 了している一方で、グアテマラやニカラグアなどの国々ではこの割合は30%にまで落ち込む。チリでは80%に迫る。中退もラテンアメリカにとっての課題で ある。米州開発銀行の調査によると、1学年またはそれ以上の遅れをもって小学校に入学する生徒は全体の20%に上る。この期間に、約10%が1年生と2年 生を、8%が3年生と4年生を繰り返している。 期待される年齢で中等教育に入学する生徒は全体の40%に過ぎない。中等教育レベルでは、各学年の約10%の生徒が留年している。平均すると、7.2年間 学校に通った子供は6年間(初等教育)しか教育を受けておらず、12年間学校に通った人は9年間(高校)しか教育を受けていないことになる。[3] 18歳までに、農村部の男女のうち、学校に通っているのは6人に1人だけである。そのため、農村部の貧しい若者で大学に通うチャンスがあるのは、ごく一部 に限られている。[5] 米州開発銀行が発表した研究報告書では、ラテンアメリカにおける退学率は、学校のインフラの質を改善することで大幅に削減できることが明らかになってい る。例えば、清潔な水や電気へのアクセスなどである。[6] この研究では、ブラジルでは、農村部や先住民の学校への電気供給に焦点を当てた普遍化プログラム(Light for All)により、電気のない学校と比較して、プログラム対象校の退学率が27%減少したことが示されている。 教育へのアクセスを改善するために、学校給食プログラムがラテンアメリカで広く利用されており、ラテンアメリカおよびカリブ海地域の少なくとも23カ国で 大規模な学校給食活動が行われている。この地域の学齢期の子供たちの55%(小学校就学年齢の子供たちの88%)が学校給食プログラムの恩恵を受けてい る。これは、世界中のどの地域よりも学校給食の普及率が高いことを示している。 エルサルバドルでは、エルサルバドル政府が世界銀行とユネスコの支援を受けて、EDUCO(Educación y Cooperación Para el Desarrollo)と呼ばれる教育改革を実施している。このシステムは、留年率と生徒の成績を改善するために導入された。EDUCOはコミュニティ管 理型の学校の一形態であり、教師の採用や解雇、生徒が学校に通う期間や日数などの決定を含む学校運営はコミュニティが担当する。1996年から1998年 にかけて実施された調査では、EDUCO方式の学校に通う生徒は、従来の学校に通う生徒よりも5%以上教育を継続する可能性が高いことが判明した。また、 学校を運営するコミュニティや保護者組織が毎週学校を訪問することで、退学率が19%低下した。[8] |

| Education inputs The 2007 Teacher Evaluation Census in Peru and Chilean Teacher Evaluation System (DocenteMás), indicated that teacher quality in the region is very low.[9] Other education inputs and services are equally inadequate. School infrastructure and access to basic services such as water, electricity, telecommunications and sewage systems are very poor in many Latin American schools. Approximately 40% of elementary schools lack libraries, 88% lack science labs, 63% lack a meeting space for teachers, 65% lack computer rooms, and 35% lack a gymnasium. On the other hand, 21% of schools have no access to potable water, 40% lack a drainage system, 53% lack phone lines, 32% have an inadequate number of bathrooms, and 11% have no access to electricity. The conditions of schools that hold students from the poorest quintile are highly unsuitable: approximately 50% have electricity and water, 19% have a drainage system and 4% have access to a telephone line; almost none have science labs, gymnasiums, computer rooms, and only 42% have libraries.[10] Additionally, students who migrate to cities from rural areas generally live cheaply on the periphery of urban centers where they have little to no access to public services.[11] Few schools can count on education inputs like textbooks and educational technologies. Second Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (SERCE) data indicate that, on average, 3rd and 6th grade students have access to only three books per student in the school library. Students from lower socioeconomic status have access to an average of one book per student, while students from higher socioeconomic status have access to eight books per student. A school's location is a high determinant of the number of books that a student will have, benefitting urban schools over rural schools.[12] With regards to educational technologies, while there has been an increase in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) access for Latin American children and adolescents in the last decade, along with a widespeard interest in One-to-One (1–1) computing models in the past 4 years, its access and use is still too limited to produce sufficient changes in the educational practices of teachers and students. Students in the region are reaching a rate of 100 students per computer, indicating that each student has access to a few minutes of computer time a week.[13] The majority of Latin American countries have a shorter school year than Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries: while the school year in Japan lasts 240 days, it lasts 180 days in Argentina and only 125 days in Honduras.[14] Furthermore, the average instruction time in the region is also short: two thirds of students in the region have less than 20 hours of instruction time per week (on average only 10% of Latin American students at the primary level attend school full-time). Student and teacher absence rates in the region are also high. |

教育への投資 2007年のペルーの教師評価国勢調査とチリの教師評価システム(DocenteMás)によると、この地域の教師の質は非常に低いことが示されている。 [9] その他の教育への投資やサービスも同様に不十分である。多くのラテンアメリカの学校では、学校のインフラや、水、電気、通信、下水設備などの基本的なサー ビスへのアクセスが非常に悪い。小学校の約40%には図書館がなく、88%には理科実験室が、63%には教師の打ち合わせスペースが、65%にはコン ピューター室が、35%には体育館がない。一方、21%の学校では飲料水へのアクセスがなく、40%では排水設備がなく、53%では電話回線がなく、 32%ではトイレの数が十分ではなく、11%では電気へのアクセスがない。最貧困層に属する生徒が通う学校の状況は、極めて不適切である。電気や水道があ る学校は約50%、排水設備がある学校は19%、電話回線がある学校は4%である。理科室、体育館、コンピューター室がある学校はほとんどなく、図書館が ある学校は42%にすぎない。 体育館、コンピューター室もほとんどなく、図書館があるのはわずか42%である。[10] さらに、農村部から都市部へ移住した生徒は、都市部の周辺部に安価に住むことが一般的であり、公共サービスへのアクセスはほとんどないか、まったくない。 [11] 教科書や教育テクノロジーといった教育への投資を当てにできる学校はほとんどない。第2回地域比較・説明研究(SERCE)のデータによると、平均して、 小学校3年生と6年生の生徒が学校の図書館で利用できる本は、生徒一人当たりわずか3冊である。低所得層の生徒は生徒一人あたり平均1冊の図書しか利用で きないのに対し、高所得層の生徒は生徒一人あたり平均8冊の図書を利用できる。学校の所在地は、生徒が利用できる図書数の決定要因として大きく影響してお り、都市部の学校が地方の学校よりも有利である。[12] 教育技術に関しては、ラテンアメリカの子供や青少年の情報通信技術(ICT)へのアクセスは、 過去4年間で一対一(1対1)コンピューティングモデルへの関心が広がっているものの、教師や生徒の教育実践に十分な変化をもたらすには、そのアクセスと 利用はまだ限定的である。この地域の生徒は1台のコンピューターを100人で共有している計算となり、生徒一人当たり週に数分間しかコンピューターを利用 できないことを示している。 ラテンアメリカ諸国のほとんどは、経済協力開発機構(OECD)諸国よりも学校年度が短い。日本の学校年度は240日であるのに対し、アルゼンチンでは 180日、ホンジュラスでは125日である。 14] さらに、この地域の平均授業時間も短い。この地域の学生の3分の2は、週20時間未満しか授業を受けていない(初等教育レベルでは、ラテンアメリカではフ ルタイムで学校に通う学生は平均でわずか10%である)。この地域の学生と教師の欠席率も高い。 |

| Learning The results of the Second Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (SERCE) indicate that almost two-thirds of Latin American students do not achieve satisfactory reading and math scores. There is a significant learning gap between students from different socio-economic backgrounds, those who live in rural areas and those who belong to indigenous and Afro-descendant groups. Research indicates that student in 3rd grade belonging to the poorest quintile has a 12% probability of obtaining a satisfactory reading score while a student in the wealthiest quintile has a 56% probability of doing so. In mathematics, the probability differs between 10% and 48%.[12] From 2000 to 2012 the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) tracked test scores on international math tests among 15 years, and revealed that several Latin American countries had mixed or declining trends over time, with Brazil and Chile being the only positive trending countries.[1] Data from surveys conducted to employers in Argentina, Brazil and Chile developed by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) show that a significant proportion of employers face difficulties in finding workers with relevant skills for good job performance, especially behavioral skills. |

学習 第2回地域比較・説明調査(SERCE)の結果によると、ラテンアメリカの生徒のほぼ3分の2が、読解力と算数において満足のいく成績を収めていないこと が明らかになっている。社会経済的背景の異なる生徒、農村部に住む生徒、先住民やアフリカ系ラテンアメリカ人の生徒の間には、著しい学習格差がある。調査 によると、最貧困層に属する小学3年生の生徒が満足な読解力のスコアを獲得できる確率は12%であるのに対し、最富裕層に属する生徒の獲得確率は56%で ある。数学では、その確率は10%から48%の間で異なる。[12] 2000年から2012年にかけて、国際的な学力テストであるPISA(生徒の学習到達度調査)は15歳を対象とした国際的な数学テストの成績を追跡調査 し、ラテンアメリカ諸国のいくつかでは、成績に混合傾向または低下傾向が見られることを明らかにした。ブラジルとチリは唯一の成績上昇傾向の国である。 [1] 米州開発銀行(IDB)がアルゼンチン、ブラジル、チリの雇用主を対象に実施した調査の結果、かなりの割合の雇用主が、適切なスキル、特に行動スキルを備 えた労働者を見つけるのに苦労していることが明らかになった。 |

| PISA The 2009 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) results reveal that countries in the region have a low performance and high inequality level compared with other countries. 48% of Latin American students have difficulty performing rudimentary reading tasks and do not have the essential skills needed to participate effectively and productively in society (not achieving level 2), as measured by the 2009 PISA Assessment, compared with only 18% of students in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. This percentage is even more pronounced for low-income students in the region, where 62% do not demonstrate these essential skills.[15] According to the Inter-American Development Bank's (IDB) analysis of the 2009 PISA Results, Chile, Colombia and Peru are among the countries that displayed the largest advancements when compared to previous versions of the test. Despite this, countries in the region are ranked among the lowest performing countries. Chile, which achieved the best reading scores at the regional level, is ranked number 44 out of 65 while Panama and Peru are located at numbers 62 and 63, respectively. The poor performance of Latin American students is also evident when compared to countries of similar income levels. The gap between the results obtained by the countries in the region and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (excluding Mexico and Chile) is enhanced when taking into account the level of income per capita of the countries in the sample. Latin America received systematically worse results than what their level of per capita income or expenditure on education would predict.[15] |

PISA 2009年の生徒の学習到達度調査(PISA)の結果によると、この地域の国々は他の国々と比較して成績が低く、格差が大きいことが明らかになった。 2009年のPISA評価によると、ラテンアメリカの生徒の48%が初歩的な読解課題をこなすのに困難を感じており、社会に効果的かつ生産的に参加するた めに必要な基本的スキルを身につけていない(レベル2に達していない)。これに対し、経済協力開発機構(OECD)諸国の生徒では、この割合は18%にと どまっている。この割合は、同地域の低所得層の学生ではさらに顕著であり、62%がこれらの必須スキルを身に付けていない。[15] 米州開発銀行(IDB)による2009年のPISA結果の分析によると、チリ、コロンビア、ペルーは、過去のテスト結果と比較して最も大きな進歩を示した 国のひとつである。にもかかわらず、同地域の国々は最低ランクに位置づけられている。地域レベルで読解力テストの最高得点を獲得したチリは65カ国中44 位、パナマとペルーはそれぞれ62位と63位である。ラテンアメリカの生徒の成績不振は、同程度の所得水準の国々と比較しても明らかである。サンプル対象 国の1人当たりの所得水準を考慮すると、この地域における各国の成績と経済協力開発機構(OECD)加盟国(メキシコとチリを除く)の成績との格差はさら に広がる。ラテンアメリカは、1人当たりの所得水準や教育支出が予測するよりも、一貫して悪い成績を収めている。[15] |

| School bullying Central America According to consistent PISA data collected in 2015 in Costa Rica and Mexico, globally, the Central America sub-region has the lowest prevalence of bullying, at 22.8% (range 19%–31.6%) and there is little difference in bullying prevalence between the sexes.[16] Sexual bullying is the most frequent type of bullying for both boys (15.3%) and girls (10.8%). Physical bullying is the second most frequent type of bullying for boys (13.3%) and psychological bullying is the second most frequent type of bullying for girls (8.2%).[16] Girls are far less likely to report physical bullying (4.5%) than boys. Overall, students in Central America report a higher prevalence of psychological bullying than the global median of 5.5%.[16] Data from the Third Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (TERCE), conducted in 2013 in four countries in the sub-region, show that students report more psychological bullying than physical bullying.[16] Physical appearance is reported to be the main driver for bullying by both boys (14.2%) and girls (24.2%), although the proportion of girls reporting this is far higher.[16] Boys (11.2%) are more likely than girls (8.4%) to report that bullying is related to race, nationality or colour, while girls (4.8%) are more likely than boys (2.2%) to report that bullying is related to religion.[16] The prevalence of physical violence in schools in Central America is low compared to other regions. The overall prevalence of physical fights, at 25.6% is the second lowest of all regions – only Asia has a lower prevalence. Central America also has the lowest proportion of students reporting being involved in a physical fight four or more times in the past year (4.9%).[16] There is a significant difference in prevalence between the sexes. Boys (33.9%) are twice as likely to report involvement in a physical fight as girls (16.9%). The overall prevalence of physical attacks in schools in Central America, at 20.5%, is the lowest of any region.[16] The difference between the sexes is less significant than for physical fights, with boys reporting only a slightly higher prevalence of physical attacks (21.7%) than girls (18%). In terms of trends, Central America has seen an overall decrease in bullying in schools.[16] South America The prevalence of bullying in South America, at 30.2% (range 15.1%–47.4%), is slightly lower than the global median of 32%. The prevalence of bullying is similar in boys (31.7%) and girls (29.3%). Data collected through PISA in 2015 in five countries in the sub-region reveal a lower prevalence of bullying, ranging from 16.9% in Uruguay to 22.1% in Colombia.[16] Physical bullying is the most frequent type of bullying reported by boys who have been bullied (13.6%), followed by sexual bullying (10.8%), and psychological bullying (5.6%). The situation is different for girls. Sexual bullying (9.4%) and psychological bullying (9.4%) are the most frequent types of bullying reported by girls who have been bullied, followed by physical bullying (5.4%).[16] Students in South America report a higher prevalence of psychological bullying than the global median of 5.5%.[16] The Third Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (TERCE), 2013 data from eight countries in the sub-region show that students report more psychological bullying than physical bullying.[16] The most frequent driver of bullying is physical appearance. Differences between the sexes are small, with 14% of boys and 15.8% of girls reporting that they were bullied because of their physical appearance.[16] Boys (8.4%) are more likely than girls (5.6%) to report that bullying is related to race, nationality or colour. Only 3.7% of boys and 3.9% of girls report that it is related to their religion.[16] The overall prevalence of physical fights, at 31.3% (range 20.2%–39.4%), is below the global median of 36%, but this masks significant differences between the sexes. The prevalence of being involved in a physical fight is 45.3% among boys compared with 20.8% among girls.[16] The overall prevalence of physical attacks, at 25.6%, is below the global median of 31.4%, and is the second lowest prevalence of any region. South America has an overall decrease in bullying in schools. Only one country, Uruguay, has shown a significant decline in bullying, physical fights and physical attacks.[16] |

学校でのいじめ 中米 2015年にコスタリカとメキシコで収集された一貫したPISAデータによると、世界的に見て、中米の小地域ではいじめの発生率が最も低く、22.8% (範囲19%–31.6%)であり、いじめの発生率に男女間でほとんど差異はない。[16] 性的ないじめは、男子(15.3%)と女子(10.8%)の両方にとって最も多いタイプのいじめである。男子(13.3%)にとっては身体的ないじめが2 番目に多いタイプのいじめであり、女子(8.2%)にとっては心理的ないじめが2番目に多いタイプのいじめである。[16] 女子生徒が身体的いじめ(4.5%)を報告する可能性は男子生徒よりもはるかに低い。全体として、中米の生徒は、世界平均の5.5%よりも心理的いじめの 発生率が高いと報告している。[16] 2013年に中米の4か国で実施された第3回地域比較・説明調査(TERCE)のデータによると、生徒は身体的いじめよりも心理的いじめを多く報告してい る。[16] 身体的特徴が主な要因となっていじめが行われていると報告しているのは、男子生徒(14.2%)と女子生徒(24.2%)の両方であるが、女子生徒の割合 がはるかに高い。[16] 男子生徒(11.2%)は、 いじめが人種、国籍、肌の色に関連していると報告している割合は、女子(8.4%)よりも男子(11.2%)の方が高く、いじめが宗教に関連していると報 告している割合は、男子(2.2%)よりも女子(4.8%)の方が高い。[16] 中米の学校における身体的暴力の発生率は、他の地域と比較すると低い。全体的な身体的喧嘩の発生率は25.6%で、これは全地域の中で2番目に低い。発生 率がこれより低いのはアジアのみである。中米では、過去1年間に4回以上身体的喧嘩に関わったと報告した生徒の割合も最も低い(4.9%)。[16] 男女間では、いじめの発生率に著しい差がある。男子生徒(33.9%)は女子生徒(16.9%)の2倍の割合で、いじめに遭ったと報告している。中米の学 校における身体的攻撃の全体的な発生率は20.5%で、これはどの地域よりも最も低い数値である。[16] 男女間の差は身体的喧嘩ほど顕著ではなく、男子の身体的攻撃の発生率(21.7%)は女子(18%)よりもわずかに高い程度である。傾向としては、中米で は学校でのいじめが全体的に減少している。[16] 南アメリカ 南アメリカにおけるいじめの発生率は30.2%(範囲15.1%~47.4%)であり、世界平均の32%をやや下回っている。いじめの発生率は、男子 (31.7%)と女子(29.3%)でほぼ同じである。2015年のPISAを通じて収集された、この地域内の5か国におけるデータでは、ウルグアイの 16.9%からコロンビアの22.1%までと、いじめの発生率はより低いことが明らかになっている。[16] 身体的いじめは、いじめられた経験のある男子生徒(13.6%)が報告した最も多いいじめの種類であり、性的いじめ(10.8%)と心理的いじめ (5.6%)がそれに続いている。女子生徒の場合は状況が異なる。いじめられた経験のある女子生徒が報告した最も多いいじめの種類は、性的いじめ (9.4%)と心理的いじめ(9.4%)であり、身体的いじめ(5.4%)がそれに続いている。[16] 南米の生徒は、世界平均の5.5%よりも心理的いじめの割合が高いと報告している。[16] 2013年の第3回地域比較・説明調査(TERCE)による8か国のデータでは、生徒は身体的いじめよりも心理的いじめを多く報告している。[16] いじめの最も多い原因は外見である。男女間の差は小さく、外見を理由にいじめられたと報告した男子生徒は14%、女子生徒は15.8%であった。 男子生徒(8.4%)の方が女子生徒(5.6%)よりも、いじめが人種、国籍、肌の色に関係していると報告する可能性が高い。男子生徒の3.7%、女子生 徒の3.9%だけが、いじめが宗教に関係していると報告している。 全体的な身体的暴力の発生率は31.3%(20.2%~39.4%の範囲)であり、世界平均の36%を下回っているが、これは男女間の大きな違いを覆い隠 している。男子では45.3%であるのに対し、女子では20.8%である。[16] 身体的な攻撃の全体的な発生率は25.6%であり、これは世界平均の31.4%を下回り、地域別では2番目に低い発生率である。南米では、学校でのいじめ が全体的に減少している。いじめ、身体的喧嘩、身体的攻撃が大幅に減少したのは、ウルグアイ1カ国のみである。[16] |

| Education and growth When regions of the world are compared in terms of long run economic growth, Latin America ranks at the bottom along with Sub-Saharan Africa. This slow growth has been a puzzle, because education and human capital is frequently identified as an important element of growth. Yet, the relatively good performance of Latin America in terms of access and school attainment has not translated into good economic outcomes. Economic inequality was decreasing during the 20th century, while it was still extremely high during the first phase of globalization in the 18th and 19th century.[17] For these reasons, many economists have argued that other factors such as economic institutions or financial crises must be responsible for the poor growth, and they have generally ignored any role for education in Latin American countries.[18] On the other hand, Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann argue that the slow growth is directly related to the low achievement and poor learning that comes with each year of school in Latin America.[19] Their analysis suggests that the long run growth of Latin America would improve significantly if the learning in schools were to improve. |

教育と成長 世界の地域を長期的な経済成長の観点で比較した場合、ラテンアメリカはサハラ以南のアフリカとともに最下位にランク付けされる。教育と人的資本が成長の重 要な要素として頻繁に指摘されているため、この低成長は不可解である。しかし、ラテンアメリカは教育へのアクセスと学校での達成度という観点では比較的良 好な成績を収めているが、それが良好な経済結果には結びついていない。経済的不平等は20世紀には減少傾向にあったが、18世紀と19世紀のグローバリ ゼーションの初期段階では依然として極めて高かった。[17] これらの理由から、多くの経済学者は、経済制度や金融危機といった他の要因が低成長の原因であると主張し、ラテンアメリカ諸国における教育の役割を概ね無 視してきた 。 一方、エリック・ハヌセクとルドガー・ヴェスマンは、ラテンアメリカにおける低成長は、学校教育の成果の低さと学習の質の低さに直接関係していると主張し ている。 |

| Primary and secondary education Primary education is compulsory throughout the region. The first phase of secondary education – or lower secondary according to UNESCO's International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) – is compulsory in all Latin American countries except in Nicaragua, while the final phase of secondary education (i.e. upper secondary) is compulsory in 12 of the 19 Latin American countries.[20] At present, it is expected that all individuals gain access to and remain within the education system at least until completion of the secondary level. However, during the first years of the 2010s, there was a schooling deficit – understood as the gap observed between the theoretical and the actual school trajectory – corresponding to 2.5% among children aged 9 to 11 years; 21% among adolescents aged 15 to 17 years; 37% among youth aged 21 to 23 years; and around 46% among adults aged 31 to 33 years.[20] Indeed, data show that 2.5% of boys and girls aged 9 to 11 years never entered the primary level or, in any case, do not attend school, with no considerable Gender Differences. In rural areas, this proportion is even higher. Yet, the biggest divide is associated with socio-economic levels, where the lack of schooling impacts the most underprivileged sectors hardest. The situation is most critical in Nicaragua, where this proportion rises to 8% and in Guatemala and Honduras, where more than 4% of the boys and girls are out of school.[20] |

初等・中等教育 初等教育は、この地域全体で義務教育となっている。中等教育の第一段階(ユネスコの国際標準教育分類(ISCED)では前期中等教育)は、ニカラグアを除 くすべてのラテンアメリカ諸国で義務教育となっているが、中等教育の最終段階(後期中等教育)は、ラテンアメリカ19カ国のうち12カ国で義務教育となっ ている。 現在、すべての個人が少なくとも中等教育修了までは教育システムにアクセスし、そのシステム内に留まることが期待されている。しかし、2010年代の最初 の数年間には、理論上の学校進路と実際の学校進路の間に観察されるギャップとして理解される就学不足が、9歳から11歳までの子供たちの2.5%、 15歳から17歳の青少年では21%、21歳から23歳の若者では37%、そして31歳から33歳の成人では約46%に達している。[20] 実際、9歳から11歳の男女の2.5%が初等教育段階に入学していないか、あるいは何らかの理由で学校に通っていないことがデータから示されているが、男 女間の差はほとんどない。農村部では、この割合はさらに高くなる。しかし、最大の格差は社会経済レベルに関連しており、学校教育を受けていないことが最も 恵まれない層に最も深刻な影響を与えている。この割合が8%にまで上昇しているニカラグア、および男子生徒・女子生徒の4%以上が学校に通っていないグア テマラとホンジュラスでは、状況は最も深刻である。[20] |

| Higher education - above |

ラテンアメリカにおける高等教育 → 冒頭に掲示 |