エル・グレコ

El Greco

エ

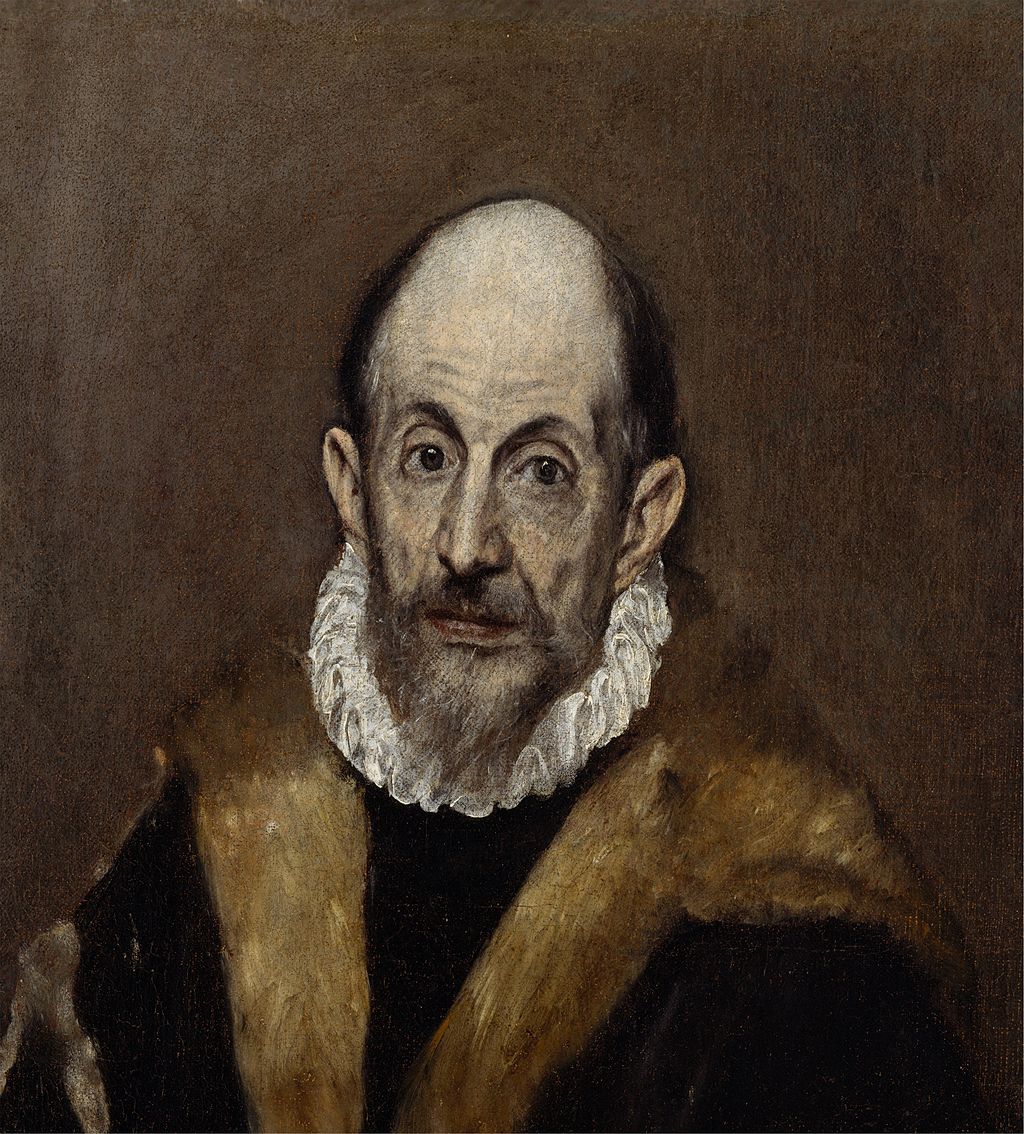

ルグレコと称される人の自画像(1500年ごろ)

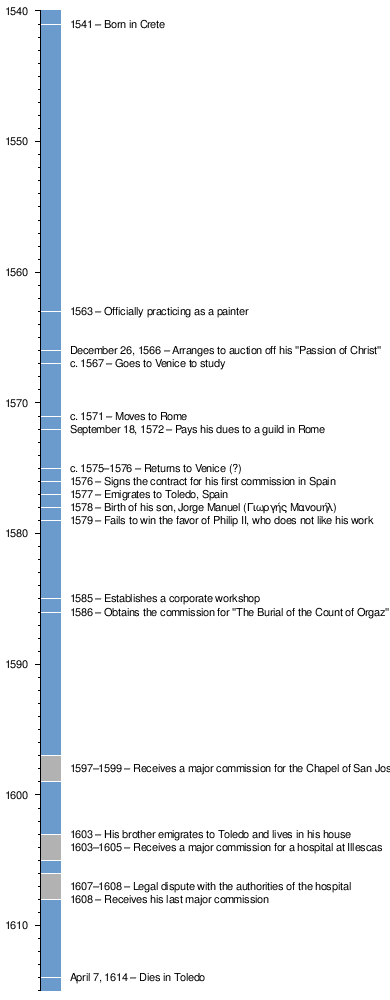

☆ ドメニコス・テオトコプーロス(ギリシア語: Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος、国際音声記号: [ðoˈminikos θeotoˈkopulos]; 1541年10月1日 - 1614年4月7日)は、ギリシャ出身のスペイン・ルネサンス期の画家、彫刻家、建築家である。エル・グレコは通称であり[a]、通常、ギリシャ文字でフ ルネームを署名し、古代ギリシャ語で「クレタ人」を意味する「Κρής(Krḗs)」という言葉を付け加えていた。 エル・グレコは、当時イタリアのヴェネツィア共和国の一部であり、ビザンティン後期美術の中心地であったカンディア王国(現在のクレタ島)で生まれた。 26歳でヴェネツィアに渡る前は、他のギリシャ人芸術家たちと同様に、その伝統の中で修行を積み、巨匠となった。[6] 1570年、彼はローマに移り、そこでアトリエを開き、一連の作品を制作した。イタリア滞在中、エル・グレコは、ティントレットやティツィアーノなど、当 時の偉大な芸術家たちからマニエリスムやヴェネツィア・ルネサンスの要素を取り入れ、自身のスタイルを豊かにした。1577年、彼はスペインのトレドに移 り住み、そこで生涯を終えるまで制作を続けた。トレドでは、エル・グレコはいくつかの主要な委託を受け、代表作である『トレドの眺望』や『第五の封印』な どを制作した。 エル・グレコの劇的で表現主義的なスタイルは同時代の人々には困惑をもって迎えられたが、20世紀には評価されるようになった。エル・グレコは表現主義と キュビズムの先駆者とみなされている。また、彼の性格と作品は、ライナー・マリア・リルケやニコス・カザンザキスといった詩人や作家たちにインスピレー ションを与えた。エル・グレコは、現代の学者たちからは、既存の流派に属さないほど個性的な芸術家であると評されている。[3] 彼は、ねじれたように長く伸びた人物像と、しばしば幻想的または幻影的な彩色で知られており、ビザンティン美術の伝統と西洋絵画の伝統を融合させている。 [7]

| Doménikos

Theotokópoulos (Greek: Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος, IPA: [ðoˈminikos

θeotoˈkopulos]; 1 October 1541 – 7 April 1614),[2] most widely known as

El Greco (Spanish pronunciation: [el ˈgɾeko]; "The Greek"), was a Greek

painter, sculptor and architect of the Spanish Renaissance. El Greco

was a nickname,[a] and the artist normally signed his paintings with

his full birth name in Greek letters often adding the word Κρής (Krḗs),

which means "Cretan" in Ancient Greek. El Greco was born in the Kingdom of Candia (modern Crete), which was at that time part of the Republic of Venice, Italy, and the center of Post-Byzantine art. He trained and became a master within that tradition before traveling at age 26 to Venice, as other Greek artists had done.[6] In 1570, he moved to Rome, where he opened a workshop and executed a series of works. During his stay in Italy, El Greco enriched his style with elements of Mannerism and of the Venetian Renaissance taken from a number of great artists of the time, notably Tintoretto and Titian. In 1577, he moved to Toledo, Spain, where he lived and worked until his death. In Toledo, El Greco received several major commissions and produced his best-known paintings, such as View of Toledo and Opening of the Fifth Seal. El Greco's dramatic and expressionistic style was met with puzzlement by his contemporaries but found appreciation by the 20th century. El Greco is regarded as a precursor of both Expressionism and Cubism, while his personality and works were a source of inspiration for poets and writers such as Rainer Maria Rilke and Nikos Kazantzakis. El Greco has been characterized by modern scholars as an artist so individual that he belongs to no conventional school.[3] He is best known for tortuously elongated figures and often fantastic or phantasmagorical pigmentation, marrying Byzantine traditions with those of Western painting.[7] |

ドメニコス・テオトコプーロス(ギリシア語: Δομήνικος

Θεοτοκόπουλος、国際音声記号: [ðoˈminikos θeotoˈkopulos]; 1541年10月1日 -

1614年4月7日)は、ギリシャ出身のスペイン・ルネサンス期の画家、彫刻家、建築家である。エル・グレコは通称であり[a]、通常、ギリシャ文字でフ

ルネームを署名し、古代ギリシャ語で「クレタ人」を意味する「Κρής(Krḗs)」という言葉を付け加えていた。 エル・グレコは、当時イタリアのヴェネツィア共和国の一部であり、ビザンティン後期美術の中心地であったカンディア王国(現在のクレタ島)で生まれた。 26歳でヴェネツィアに渡る前は、他のギリシャ人芸術家たちと同様に、その伝統の中で修行を積み、巨匠となった。[6] 1570年、彼はローマに移り、そこでアトリエを開き、一連の作品を制作した。イタリア滞在中、エル・グレコは、ティントレットやティツィアーノなど、当 時の偉大な芸術家たちからマニエリスムやヴェネツィア・ルネサンスの要素を取り入れ、自身のスタイルを豊かにした。1577年、彼はスペインのトレドに移 り住み、そこで生涯を終えるまで制作を続けた。トレドでは、エル・グレコはいくつかの主要な委託を受け、代表作である『トレドの眺望』や『第五の封印』な どを制作した。 エル・グレコの劇的で表現主義的なスタイルは同時代の人々には困惑をもって迎えられたが、20世紀には評価されるようになった。エル・グレコは表現主義と キュビズムの先駆者とみなされている。また、彼の性格と作品は、ライナー・マリア・リルケやニコス・カザンザキスといった詩人や作家たちにインスピレー ションを与えた。エル・グレコは、現代の学者たちからは、既存の流派に属さないほど個性的な芸術家であると評されている。[3] 彼は、ねじれたように長く伸びた人物像と、しばしば幻想的または幻影的な彩色で知られており、ビザンティン美術の伝統と西洋絵画の伝統を融合させている。 [7] |

|

|

| Life Early years and family  The Dormition of the Virgin (before 1567, tempera and gold on panel, 61.4 × 45 cm, Holy Cathedral of the Dormition of the Virgin, Hermoupolis, Syros) was probably created near the end of the artist's Cretan period. The painting combines post-Byzantine and Italian mannerist stylistic and iconographic elements. Born in 1541, in either the village of Fodele or Candia (the Venetian name of Chandax, present day Heraklion) on Crete,[b] El Greco was descended from a prosperous urban family, which had probably been driven out of Chania to Candia after an uprising against the Catholic Venetians between 1526 and 1528.[11] El Greco's father, Geṓrgios Theotokópoulos (Γεώργιος Θεοτοκόπουλος; d. 1556), was a merchant and tax collector. Almost nothing is known about his mother or his first wife, except that they were also Greek.[12] His second wife was a Spaniard.[13] El Greco's older brother, Manoússos Theotokópoulos (1531–1604), was a wealthy merchant and spent the last years of his life (1603–1604) in El Greco's Toledo home.[13] El Greco received his initial training as an icon painter of the Cretan school, a leading center of post-Byzantine art. In addition to painting, he probably studied the classics of ancient Greece, and perhaps the Latin classics also; he left a "working library" of 130 volumes at his death, including the Bible in Greek and an annotated Vasari book.[14] Candia was a center for artistic activity where Eastern and Western cultures co-existed harmoniously, where around two hundred painters were active during the 16th century, and had organized a painters' guild, based on the Italian model.[11] In 1563, at the age of twenty-two, El Greco was described in a document as a "master" ("maestro Domenigo"), meaning he was already a master of the guild and presumably operating his own workshop.[15] Three years later, in June 1566, as a witness to a contract, he signed his name in Greek as μαΐστρος Μένεγος Θεοτοκόπουλος σγουράφος (maḯstros Ménegos Theotokópoulos sgouráfos; "Master Ménegos Theotokópoulos, painter").[c] Most scholars believe that the Theotokópoulos "family was almost certainly Greek Orthodox",[17] although some Catholic sources still claim him from birth.[d] Like many Orthodox emigrants to Catholic areas of Europe, some assert that he may have transferred to Catholicism after his arrival, and possibly practiced as a Catholic in Spain, where he described himself as a "devout Catholic" in his will. The extensive archival research conducted since the early 1960s by scholars, such as Nikolaos Panayotakis, Pandelis Prevelakis and Maria Constantoudaki, indicates strongly that El Greco's family and ancestors were Greek Orthodox. One of his uncles was an Orthodox priest, and his name is not mentioned in the Catholic archival baptismal records on Crete.[20] Prevelakis goes even further, expressing his doubt that El Greco was ever a practicing Roman Catholic.[21] Important for his early biography, El Greco, still in Crete, painted his Dormition of the Virgin near the end of his Cretan period, probably before 1567. Three other signed works of "Domḗnicos" are attributed to El Greco (Modena Triptych, St. Luke Painting the Virgin and Child, and The Adoration of the Magi).[22] |

生涯 初期の時代と家族  エル・グレコの作と想像されている『聖母の被昇天』(1567年以前、テンペラと金彩、パネル、61.4×45cm、聖母の被昇天聖堂、ヘルモポリス、シ ロス島)は、おそらく画家のクレタ島時代末期に制作された作品である。この絵画は、ビザンチン後期とイタリア・マニエリスムの様式と図像学的な要素を組み 合わせたものである。 1541年にクレタ島のフォデレ村またはカンディア村(ヴェネツィア時代の名称はシャンダクス、現在のイラクリオン)で生まれたエル・グレコは、裕福な都 市部の家系の出身であった。おそらく、1526年から1528年にかけてのカトリックのヴェネツィア人に対する蜂起の後、ハニアからカンディアへと追われ た家系であった 1526年から1528年の間にカトリックのヴェネツィア人に対する反乱が起こり、おそらくハニアからカンディアへと追われたのであろう。[11] エル・グレコの父、ゲオルギオス・テオトコプーロス(Γεώργιος Θεοτοκόπουλος、1556年没)は商人であり、徴税人でもあった。母親や最初の妻については、ギリシア人であったということ以外はほとんど知 られていない。[12] 2番目の妻はスペイン人であった。[13] エル・グレコの兄マヌソス・テオトコプーロス(1531年-1604年)は裕福な商人であり、晩年(1603年-1604年)をエル・グレコのトレドの家 で過ごした。[13] エル・グレコは、ビザンチン後期芸術の主要な中心地であったクレタ派のイコン画家として初期の訓練を受けた。絵画に加えて、おそらく古代ギリシャの古典を 学び、ラテン語の古典も学んだと思われる。彼は130冊の蔵書を残してこの世を去ったが、その中にはギリシャ語の聖書や注釈付きのヴァザーリの著書も含ま れていた。カンディアは東西文化が調和的に共存する芸術活動の中心地であり、16世紀にはおよそ200人の画家が活躍し、 16世紀にはおよそ200人の画家が活躍し、イタリアのモデルを基に画家組合が組織されていた。[11] 1563年、22歳のとき、エル・グレコは文書の中で「巨匠」(「マエストロ・ドメニコ」)と記述されており、これはすでに組合の巨匠であり、おそらく自 身の工房を運営していたことを意味する。[15] その3年後、1566年6月には 1566年6月、ある契約の証人として、彼はギリシャ語で「マエストロ・メネゴス・テオトコポウロス・スグラフォス(maḯstros Ménegos Theotokópoulos sgouráfos;「マエストロ・メネゴス・テオトコポウロス、画家」)」と署名した。[c] ほとんどの学者は、テオトコプーロス「一族はほぼ間違いなくギリシャ正教徒であった」と信じているが[17]、一部のカトリックの資料では、彼が出生時か らカトリックであったと主張しているものもある[d]。ヨーロッパのカトリック地域に移住した多くの正教徒と同様に、一部では、彼が到着後にカトリックに 改宗し、スペインではカトリックとして信仰を実践していた可能性があると主張している。ニコラオス・パナイオタキス、パンドレリス・プレヴェラキス、マリ ア・コンスタンツォウダキといった学者たちが1960年代初頭から行ってきた広範囲にわたるアーカイブ調査では、エル・グレコの一族および先祖はギリシャ 正教であったことが強く示唆されている。彼の叔父のひとりは正教会の司祭であり、その名はクレタ島のカトリック教会の洗礼記録には記載されていない。 [20] プレベラキスはさらに踏み込んで、エル・グレコがローマ・カトリックの信者であったかどうかについて疑問を呈している。[21] 初期の伝記において重要なのは、エル・グレコはクレタ島に滞在していた時期に、おそらく1567年以前に、クレタ島時代最後の作品となる『聖母の眠り』を 描いたということである。 「ドメニコス」の署名入り作品として知られる3点(モデナ・トリプティク、聖ルカによる聖母子像、東方三博士の礼拝)は、エル・グレコの作品とされてい る。[22] |

Italy The Adoration of the Magi (1565–1567, 56 × 62 cm, Benaki Museum, Athens). The icon, signed by El Greco ("Χείρ Δομήνιχου", Created by the hand of Doménicos), was painted in Candia on part of an old chest.  Adoration of the Magi, 1568, Museo Soumaya, Mexico City It was natural for the young El Greco to pursue his career in Venice, Crete having been a possession of the Republic of Venice since 1211.[3] Though the exact year is not clear, most scholars agree that El Greco went to Venice around 1567.[e] Knowledge of El Greco's years in Italy is limited. He lived in Venice until 1570 and, according to a letter written by his much older friend, the greatest miniaturist of the age, Giulio Clovio, was a "disciple" of Titian, who was by then in his eighties but still vigorous. This may mean he worked in Titian's large studio, or not. Clovio characterized El Greco as "a rare talent in painting".[26] In 1570, El Greco moved to Rome, where he executed a series of works strongly marked by his Venetian apprenticeship.[26] It is unknown how long he remained in Rome, though he may have returned to Venice (c. 1575–76) before he left for Spain.[27] In Rome, on the recommendation of Giulio Clovio,[28] El Greco was received as a guest at the Palazzo Farnese, which Cardinal Alessandro Farnese had made a center of the artistic and intellectual life of the city. There he came into contact with the intellectual elite of the city, including the Roman scholar Fulvio Orsini, whose collection would later include seven paintings by the artist (View of Mt. Sinai and a portrait of Clovio are among them).[29] Unlike other Cretan artists who had moved to Venice, El Greco substantially altered his style and sought to distinguish himself by inventing new and unusual interpretations of traditional religious subject matter.[30] His works painted in Italy were influenced by the Venetian Renaissance style of the period, with agile, elongated figures reminiscent of Tintoretto and a chromatic framework that connects him to Titian.[3] The Venetian painters also taught him to organize his multi-figured compositions in landscapes vibrant with atmospheric light. Clovio reports visiting El Greco on a summer's day while the artist was still in Rome. El Greco was sitting in a darkened room, because he found the darkness more conducive to thought than the light of the day, which disturbed his "inner light".[31] As a result of his stay in Rome, his works were enriched with elements such as violent perspective vanishing points or strange attitudes struck by the figures with their repeated twisting and turning and tempestuous gestures; all elements of Mannerism.[26]  Portrait of Giorgio Giulio Clovio, the earliest surviving portrait from El Greco (1571, oil on canvas, 58 × 86 cm, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples). In the portrait of Clovio, friend and supporter in Rome of the young Cretan artist, the first evidence of El Greco's gifts as a portraitist are apparent. By the time El Greco arrived in Rome, Michelangelo and Raphael were dead, but their example continued to be paramount, and somewhat overwhelming for young painters. El Greco was determined to make his own mark in Rome defending his personal artistic views, ideas and style.[32] He singled out Correggio and Parmigianino for particular praise,[33] but he did not hesitate to dismiss Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel;[f] he extended an offer to Pope Pius V to paint over the whole work in accord with the new and stricter Catholic thinking.[35] When he was later asked what he thought about Michelangelo, El Greco replied that "he was a good man, but he did not know how to paint".[36] However, despite El Greco's criticism,[37] Michelangelo's influence can be seen in later El Greco works such as the Allegory of the Holy League.[38] By painting portraits of Michelangelo, Titian, Clovio and, presumably, Raphael in one of his works (The Purification of the Temple), El Greco not only expressed his gratitude but also advanced the claim to rival these masters. As his own commentaries indicate, El Greco viewed Titian, Michelangelo and Raphael as models to emulate.[35] In his 17th century Chronicles, Giulio Mancini included El Greco among the painters who had initiated, in various ways, a re-evaluation of Michelangelo's teachings.[39] Because of his unconventional artistic beliefs (such as his dismissal of Michelangelo's technique) and personality, El Greco soon acquired enemies in Rome. Architect and writer Pirro Ligorio called him a "foolish foreigner", and newly discovered archival material reveals a skirmish with Farnese, who obliged the young artist to leave his palace.[39] On 6 July 1572, El Greco officially complained about this event. A few months later, on 18 September 1572, he paid his dues to the Guild of Saint Luke in Rome as a miniature painter.[40] At the end of that year, El Greco opened his own workshop and hired as assistants the painters Lattanzio Bonastri de Lucignano and Francisco Preboste.[39] |

イタリア 東方三博士の礼拝(1565年-1567年、56×62cm、アテネのベナキ美術館)。エル・グレコの署名(「Χείρ Δομήνιχου」、ドメニコスの手による作品)のあるこのイコンは、カンディアで古いチェストの一部に描かれた。  東方三博士の礼拝、1568年、メキシコシティ、ソウマヤ美術館 1211年以降クレタ島はヴェネツィア共和国の領土であったため、若きエル・グレコがヴェネツィアでキャリアを追求するのは自然なことだった。[3] 詳しい年は不明だが、ほとんどの学者はエル・グレコが1567年頃にヴェネツィアに行ったことに同意している。[e] イタリア時代のエル・グレコに関する知識は限られている。彼は1570年までヴェネツィアに住んでいたが、当時すでに80歳代であったが依然として精力的 に活動していたティツィアーノの「弟子」であったと、はるかに年長の友人で同時代の最も優れた細密画家ジュリオ・クロヴィオが書いた手紙に書かれている。 これは、ティツィアーノの大きなアトリエで働いていたことを意味しているのかもしれないし、そうでないのかもしれない。クロヴィオはエル・グレコを「絵画 における稀な才能」と評している。 1570年、エル・グレコはローマに移り、そこでヴェネツィアでの徒弟時代の影響を強く感じさせる一連の作品を制作した。[26] ローマにどれだけの期間滞在したかは不明だが、スペインへ発つ前にヴェネツィアに戻った可能性もある(1575年から1576年頃)。 6年)にヴェネツィアに戻った可能性もあるが、スペインへ旅立つ前にローマを離れたかどうかは不明である。[27] ローマでは、ジュリオ・クロヴィオの推薦により、エル・グレコはファルネーゼ宮殿に招かれた。この宮殿は、枢機卿アレッサンドロ・ファルネーゼが芸術と知 的生活の中心地としていた場所である。そこで彼は、ローマの学者フルヴィオ・オルシーニを含む、この街の知識人エリートたちと接触した。オルシーニのコレ クションには、後にエル・グレコの絵画7点(シナイ山の眺め、およびクロヴィオの肖像画など)が加わった。 ヴェネツィアに移住した他のクレタ島出身の芸術家たちとは異なり、エル・グレコは自身のスタイルを大幅に変更し、伝統的な宗教的主題を新しい、奇抜な解釈 で表現することで、自身の独自性を際立たせようとした。[30] イタリアで描かれた彼の作品は、当時のヴェネツィア・ルネサンス様式の影響を受けており ティントレットを思わせる俊敏で細長い人物像と、ティツィアーノにつながる色彩の枠組みが特徴である。[3] ヴェネツィアの画家たちはまた、大気光に満ちた風景の中で、多数の人物を配置した構図を構成する方法も彼に教えた。クロヴィオは、エル・グレコがまだロー マに滞在していた夏の日に彼を訪問したと報告している。エル・グレコは、明るい光よりもむしろ闇の方が思考を促すと考え、部屋を暗くして座っていた。ロー マ滞在の結果、彼の作品には、消失点に向かって急激に広がる遠近法や、人物が何度も体をひねったり、荒々しい身振りをする奇妙な姿勢など、マニエリスムの 要素が取り入れられた。  エル・グレコの現存する最古の肖像画であるジョルジョ・ジュリオ・クローヴィオの肖像画(1571年、油彩画、58×86cm、ナポリ、カポディモンテ美 術館)。クレタ島の若き芸術家の友人であり、ローマでの支援者であったクローヴィオの肖像画には、エル・グレコの肖像画家としての才能の最初の兆候が明白 に表れている。 エル・グレコがローマに到着したときには、ミケランジェロとラファエロはすでに亡くなっていたが、彼らの作品は依然として最高峰であり、若い画家たちに とっては圧倒的な存在であった。エル・グレコはローマで独自の芸術的見解、アイデア、スタイルを主張し、独自の地位を築くことを決意していた。[32] 彼は特にコレッジョとパルミジャニーノを賞賛したが、[33] システィーナ礼拝堂のミケランジェロの『最後の審判』を批判することをためらわなかった。[f] 彼は教皇ピウス5世に 新しい、より厳格なカトリックの考え方に従って、作品全体に上塗りをするよう、教皇ピウス5世に申し出た。[35] 後にミケランジェロについてどう思うかと尋ねられた際、エル・グレコは「彼は良い人だったが、絵の描き方を知らなかった」と答えた。[36] しかし、エル・グレコの批判にもかかわらず、[37] ミケランジェロの その影響は、後のエル・グレコの作品である『神聖同盟の寓意』などに見られる。[38] エル・グレコは、ミケランジェロ、ティツィアーノ、クローヴィオ、おそらくラファエロの肖像画を自身の作品(『神殿の清め』)のひとつに描くことで、彼ら への感謝の意を表しただけでなく、彼らと肩を並べるという主張を推し進めた。彼自身の論評が示すように、エル・グレコはティツィアーノ、ミケランジェロ、 ラファエロを模範としていた。[35] 17世紀の年代記『クロニクル』の中で、ジュリオ・マンシーニは、ミケランジェロの教えを様々な形で再評価した画家の一人としてエル・グレコを挙げてい る。[39] 型破りな芸術的信念(ミケランジェロの技法を否定するなど)と性格により、エル・グレコはローマでたちまち敵を作った。建築家で作家のピッロ・リゴーリオ は彼を「愚かな外国人」と呼び、新たに発見された資料では、ファルネーゼとの小競り合いが明らかになっており、ファルネーゼは若い芸術家に宮殿からの退去 を命じた。1572年7月6日、エル・グレコはこの出来事について正式に苦情を申し立てた。数ヶ月後の1572年9月18日、彼はローマの聖ルカ組合にミ ニチュア画家として会費を納めた。[40] その年の終わりに、エル・グレコは自身の工房を開き、ラッタンツィオ・ボナストリ・デ・ルチニャーノとフランシスコ・プレボストという画家を助手として 雇った。[39] |

| Spain Move to Toledo  The Assumption of the Virgin (1577–1579, oil on canvas, 401 × 228 cm, Art Institute of Chicago) was one of the nine paintings El Greco completed for the church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo in Toledo, his first commission in Spain. In 1577, El Greco migrated to Madrid and then to Toledo, where he produced his mature works.[41] At the time, Toledo was the religious capital of Spain and a populous city[g] with "an illustrious past, a prosperous present and an uncertain future".[43] In Rome, El Greco had earned the respect of some intellectuals, but was also facing the hostility of certain art critics.[44] During the 1570s the huge monastery-palace of El Escorial was still under construction and Philip II of Spain was experiencing difficulties in finding good artists for the many large paintings required to decorate it. Titian was dead, and Tintoretto, Veronese and Anthonis Mor all refused to come to Spain. Philip had to rely on the lesser talent of Juan Fernández de Navarrete, of whose gravedad y decoro ("seriousness and decorum") the king approved. When Fernández died in 1579, the moment was ideal for El Greco to move to Toledo.[45] Through Clovio and Orsini, El Greco met Benito Arias Montano, a Spanish humanist and agent of Philip; Pedro Chacón, a clergyman; and Luis de Castilla, son of Diego de Castilla, the dean of the Cathedral of Toledo.[42] El Greco's friendship with Castilla would secure his first large commissions in Toledo. He arrived in Toledo by July 1577, and signed contracts for a group of paintings that was to adorn the church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo in Toledo and for the renowned El Espolio.[46] By September 1579 he had completed nine paintings for Santo Domingo, including The Trinity and The Assumption of the Virgin. These works would establish the painter's reputation in Toledo.[40] El Greco did not plan to settle permanently in Toledo, since his final aim was to win the favor of Philip and make his mark in his court.[47] Indeed, he did manage to secure two important commissions from the monarch: Allegory of the Holy League and Martyrdom of St. Maurice. However, the king did not like these works and placed the St Maurice altarpiece in the chapter-house rather than the intended chapel. He gave no further commissions to El Greco.[48] The exact reasons for the king's dissatisfaction remain unclear. Some scholars have suggested that Philip did not like the inclusion of living persons in a religious scene;[48] some others that El Greco's works violated a basic rule of the Counter-Reformation, namely that in the image the content was paramount rather than the style.[49] Philip took a close interest in his artistic commissions, and had very decided tastes; a long sought-after sculpted Crucifixion by Benvenuto Cellini also failed to please when it arrived, and was likewise exiled to a less prominent place. Philip's next experiment, with Federico Zuccari was even less successful.[50] In any case, Philip's dissatisfaction ended any hopes of royal patronage El Greco may have had.[40] |

スペイン トレドへ移る  『聖母被昇天』(1577年-1579年、油彩、キャンバス、401×228cm、シカゴ美術館)は、スペインで初めて受注したトレドのサント・ドミンゴ・エル・アンティグオ教会のために、エル・グレコが完成させた9点の絵画のうちの1点である。 1577年、エル・グレコはマドリードに移住し、その後トレドに移り住み、そこで円熟した作品を制作した。[41] 当時、トレドはスペインの宗教的中心地であり、人口の多い都市[g] であった。「輝かしい過去、繁栄する現在、そして不確かな未来」[43] を持つ都市であった。ローマでは、エル・ エル・グレコは一部の知識人から尊敬を集めていたが、一部の美術評論家からは敵意も向けられていた。[44] 1570年代、巨大な修道院兼宮殿であるエル・エスコリアルはまだ建設中であり、スペイン王フェリペ2世は、宮殿を飾るために必要な多くの大型絵画を描く 優秀な芸術家を見つけるのに苦労していた。ティツィアーノはすでに亡くなっており、ティントレット、ヴェロネーゼ、アントニス・モールはスペイン行きを拒 否した。フィリップは、才能は劣るものの、国王が認める「深刻さと品位」を備えたファン・フェルナンデス・デ・ナヴァレッテに頼らざるを得なかった。 1579年にフェルナンデスが亡くなると、エル・グレコがトレドに移るには絶好の機会となった。 エル・グレコは、クロヴィオとオルシーニを通じて、スペインの人文主義者でフェリペのエージェントであるベニート・アリアス・モンターノ、聖職者のペド ロ・チャコン、トレド大聖堂の主任司祭ディエゴ・デ・カスティーリャの息子ルイス・デ・カスティーリャと知り合った。カスティーリャとの友情は、トレドに おけるエル・グレコの最初の大型の委託を確保することとなった。1577年7月までにトレドに到着した彼は、トレドのサント・ドミンゴ・エル・アンティグ オ教会を飾る絵画群と、有名なエル・エスポリオのための契約に署名した。[46] 1579年9月までに、彼はサント・ドミンゴのために「三位一体」や「聖母被昇天」を含む9枚の絵画を完成させた。これらの作品は、トレドにおける画家の 名声を確立することとなった。[40] エル・グレコはトレドに永住するつもりはなかった。なぜなら、最終的な目的はフェリペ王の寵愛を受け、宮廷で名を成すことだったからである。[47] 実際、彼は国王から2つの重要な依頼を受けることに成功した。「神聖同盟の寓意」と「聖モーリスの殉教」である。しかし、国王はこれらの作品を気に入ら ず、「聖モーリスの殉教」の祭壇画を本来の礼拝堂ではなく集会室に置いた。その後、国王はエル・グレコに新たな注文を出すことはなかった。[48] 国王が不満を抱いた正確な理由は不明のままである。一部の学者は、フィリップが宗教的な場面の中に生きている人物が描かれることを好まなかったためだと指 摘している。[48] また、エル・グレコの作品が対抗宗教改革の基本原則に違反していたためだという説もある。すなわち、その原則とは、スタイルよりも内容が重要であるという ものである 。フィリップは芸術作品の注文に強い関心を示し、非常に明確な好みを持っていた。ベンヴェヌート・チェッリーニが長年かけて制作した「磔刑」も、到着した 時にはフィリップの気に入ることはなく、同様に目立たない場所に追いやられた。フィリップの次の試み、フェデリコ・ズッカリーとの共同作業はさらに成功し なかった。[50] いずれにしても、フィリップの不満により、エル・グレコが抱いていたかもしれない王室の後援への期待は打ち砕かれた。[40] |

Mature works and later years The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586–1588, oil on canvas, 480 × 360 cm, church of Santo Tomé, Toledo), now El Greco's best known work, illustrates a popular local legend. An exceptionally large painting, it is clearly divided into two zones: the heavenly above and the terrestrial below, brought together compositionally. Lacking the favor of the king, El Greco was obliged to remain in Toledo, where he had been received in 1577 as a great painter.[51] According to Hortensio Félix Paravicino, a 17th-century Spanish preacher and poet, "Crete gave him life and the painter's craft, Toledo a better homeland, where through Death he began to achieve eternal life."[52] In 1585, he appears to have hired an assistant, Italian painter Francisco Preboste, and to have established a workshop capable of producing altar frames and statues as well as paintings.[53] On 12 March 1586 he obtained the commission for The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, now his best-known work.[54] The decade 1597 to 1607 was a period of intense activity for El Greco. During these years he received several major commissions, and his workshop created pictorial and sculptural ensembles for a variety of religious institutions. Among his major commissions of this period were three altars for the Chapel of San José in Toledo (1597–1599); three paintings (1596–1600) for the Colegio de Doña María de Aragon, an Augustinian monastery in Madrid, and the high altar, four lateral altars, and the painting St. Ildefonso for the Capilla Mayor of the Hospital de la Caridad (Hospital of Charity) at Illescas (1603–1605).[3] The minutes of the commission of The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (1607–1613), which were composed by the personnel of the municipality, describe El Greco as "one of the greatest men in both this kingdom and outside it".[55] Between 1607 and 1608 El Greco was involved in a protracted legal dispute with the authorities of the Hospital of Charity at Illescas concerning payment for his work, which included painting, sculpture and architecture;[h] this and other legal disputes contributed to the economic difficulties he experienced towards the end of his life.[59] In 1608, he received his last major commission at the Hospital of Saint John the Baptist in Toledo.[40]  The Disrobing of Christ (El Espolio) (1577–1579, oil on canvas, 285 × 173 cm, Sacristy of the Cathedral, Toledo) is one of the most famous altarpieces of El Greco. El Greco's altarpieces are renowned for their dynamic compositions and startling innovations. El Greco made Toledo his home. Surviving contracts mention him as the tenant from 1585 onwards of a complex consisting of three apartments and twenty-four rooms which belonged to the Marquis de Villena.[9] It was in these apartments, which also served as his workshop, that he spent the rest of his life, painting and studying. He lived in considerable style, sometimes employing musicians to play whilst he dined. It is not confirmed whether he lived with his Spanish female companion, Jerónima de Las Cuevas, whom he probably never married. She was the mother of his only son, Jorge Manuel, born in 1578, who also became a painter, assisted his father, and continued to repeat his compositions for many years after he inherited the studio.[i] In 1604, Jorge Manuel and Alfonsa de los Morales gave birth to El Greco's grandson, Gabriel, who was baptized by Gregorio Angulo, governor of Toledo and a personal friend of the artist.[59] During the course of the execution of a commission for the Hospital de Tavera, El Greco fell seriously ill, and died a month later, on 7 April 1614. A few days earlier, on 31 March, he had directed that his son should have the power to make his will. Two Greeks, friends of the painter, witnessed this last will and testament (El Greco never lost touch with his Greek origins).[60] He was buried in the Church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo, aged 73.[61] |

円熟した作品と晩年 『オルガス伯爵の埋葬』 (1586年-1588年、油彩画、480×360cm、トレドのサント・トメ教会)は、現在ではエル・グレコの最も有名な作品であり、地元で人気の伝説 を描いている。非常に大きな絵画で、天上の部分と地上の部分の2つのゾーンに明確に分けられており、構図上は一体化されている。 王の寵愛を受けられなかったエル・グレコは、1577年に偉大な画家として迎え入れられたトレドに留まることを余儀なくされた。[51] 17世紀のスペインの説教師であり詩人でもあるオルテンシオ・フェリックス・パラビシーノによると、「クレタ島は彼に生命と画家としての技術を与え、トレ ドはより良い故郷となり、死を通して永遠の生命を獲得し始めた」[52] 永遠の命を手に入れ始めた」とある。[52] 1585年には、イタリア人画家フランシスコ・プレボストという助手を雇い、絵画だけでなく祭壇画や彫像も制作できる工房を設立したようだ。[53] 1586年3月12日には、現在では彼の最も有名な作品である『オルガス伯爵の埋葬』の制作依頼を受けた。[54] 1597年から1607年までの10年間は、エル・グレコにとって非常に活発な活動期間であった。この間、彼はいくつかの主要な委託を受け、彼の工房では さまざまな宗教施設のために絵画や彫刻の集合体が制作された。この時期の主な依頼には、トレドのサン・ホセ礼拝堂のための祭壇3点(1597年~1599 年)、マドリードのアウグスティノ修道院であるドニャ・マリア・デ・アラゴン学院のための絵画3点(1596年~1600年)、イレスカスのカリダッド病 院(慈善病院)の大祭壇、4つの側祭壇、聖イルデフォンソの絵画(1603年~1605年)などがある (1603年-1605年)の依頼を受けた。[3] 無原罪の聖母の委託(1607年-1613年)の議事録は、自治体の職員によって作成され、エル・グレコを「この王国とそれ以外の地域でも最も偉大な人物 の一人」と表現している。[55] 1607年から1608年にかけて、エル・グレコはイレスカスにある慈善病院の当局と、絵画、彫刻、建築などの仕事に対する報酬をめぐって長期にわたる法 的な争いに巻き込まれた。 この件やその他の訴訟が、晩年の経済的困難の一因となった。[59] 1608年、トレドのサン・ファン・バウティスタ病院で最後の主要な依頼を受けた。[40]  キリストの衣剥ぎ(El Espolio)(1577年-1579年、油彩、キャンバス、285×173cm、トレド大聖堂の聖具室)は、エル・グレコの祭壇画の中でも最も有名な 作品のひとつである。エル・グレコの祭壇画は、ダイナミックな構図と驚くべき革新性で知られている。 エル・グレコはトレドに居を構えた。現存する契約書には、1585年以降、彼はビジェナ侯爵の所有する3つのアパートメントと24の部屋からなる複合施設 の借主であったことが記載されている。[9] これらのアパートメントは彼の工房としても使用され、彼はそこで絵を描き、研究に没頭しながら残りの人生を過ごした。彼はかなり贅沢な生活を送り、時には 食事中に音楽家を雇って演奏させていた。 彼が結婚することはなかったと思われるスペイン人の女性仲間、ヘロニマ・デ・ラス・クエバスと暮らしていたかどうかは確認されていない。彼女は1578年 に生まれた彼の唯一の息子ホルヘ・マヌエルの母親であり、ホルヘ・マヌエルも画家となり、父親を手伝い、アトリエを継承した後も長年にわたって父親の作品 を模倣し続けた。[i] 1604年、ホルヘ・マヌエルとアルフォンサ・デ・ロス・モラレスの間にエル・グレコの孫であるガブリエルが誕生し、トレド総督で画家の友人でもあったグ レゴリオ・アングロによって洗礼を受けた。[59] タベーラ病院からの依頼を遂行している最中に、エル・グレコは重病にかかり、1か月後の1614年4月7日に亡くなった。その数日前の3月31日、彼は息 子に遺言を作成する権限を与えるよう指示していた。画家の友人である2人のギリシア人が、この遺言の証人となった(エル・グレコはギリシアのルーツを忘れ たことはなかった)。[60] 彼は73歳で、サント・ドミンゴ・エル・アンティグオ教会に埋葬された。[61] |

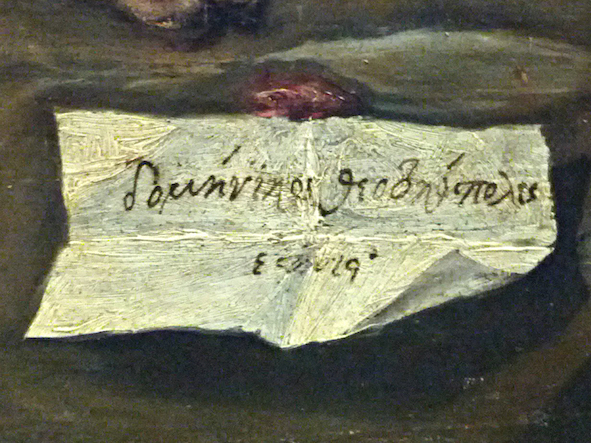

| Art Main article: Art of El Greco Technique and style The primacy of imagination and intuition over the subjective character of creation was a fundamental principle of El Greco's style.[36] El Greco discarded classicist criteria such as measure and proportion. He believed that grace is the supreme quest of art, but the painter achieves grace only by managing to solve the most complex problems with ease.[36] El Greco regarded color as the most important and the most ungovernable element of painting, and declared that color had primacy over form.[36] Francisco Pacheco, a painter and theoretician who visited El Greco in 1611, wrote that the painter liked "the colors crude and unmixed in great blots as a boastful display of his dexterity" and that "he believed in constant repainting and retouching in order to make the broad masses tell flat as in nature".[62] "I hold the imitation of color to be the greatest difficulty of art." — El Greco, from notes of the painter in one of his commentaries.[63] Art historian Max Dvořák was the first scholar to connect El Greco's art with Mannerism and Antinaturalism.[64] Modern scholars characterize El Greco's theory as "typically Mannerist" and pinpoint its sources in the Neoplatonism of the Renaissance.[65] Jonathan Brown believes that El Greco created a sophisticated form of art;[66] according to Nicholas Penny "once in Spain, El Greco was able to create a style of his own—one that disavowed most of the descriptive ambitions of painting".[67]  View of Toledo (c. 1596–1600, oil on canvas, 47.75 × 42.75 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is one of the two surviving landscapes of Toledo painted by El Greco.  Detail from St. Andrew and St. Francis (1595, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid), showing the artist's signature in Greek. In his mature works El Greco demonstrated a characteristic tendency to dramatize rather than to describe.[3] The strong spiritual emotion transfers from painting directly to the audience. According to Pacheco, El Greco's perturbed, violent and at times seemingly careless-in-execution art was due to a studied effort to acquire a freedom of style.[62] El Greco's preference for exceptionally tall and slender figures and elongated compositions, which served both his expressive purposes and aesthetic principles, led him to disregard the laws of nature and elongate his compositions to ever greater extents, particularly when they were destined for altarpieces.[68] The anatomy of the human body becomes even more otherworldly in El Greco's mature works; for The Immaculate Conception (El Greco, Toledo) El Greco asked to lengthen the altarpiece itself by another 1.5 ft (0.46 m) "because in this way the form will be perfect and not reduced, which is the worst thing that can happen to a figure". A significant innovation of El Greco's mature works is the interweaving between form and space; a reciprocal relationship is developed between the two which completely unifies the painting surface. This interweaving would re-emerge three centuries later in the works of Cézanne and Picasso.[68] Another characteristic of El Greco's mature style is the use of light. As Jonathan Brown notes, "each figure seems to carry its own light within or reflects the light that emanates from an unseen source".[69] Fernando Marias and Agustín Bustamante García, the scholars who transcribed El Greco's handwritten notes, connect the power that the painter gives to light with the ideas underlying Christian Neo-Platonism.[70] Modern scholarly research emphasizes the importance of Toledo for the complete development of El Greco's mature style and stresses the painter's ability to adjust his style in accordance with his surroundings.[71] Harold Wethey asserts that "although Greek by descent and Italian by artistic preparation, the artist became so immersed in the religious environment of Spain that he became the most vital visual representative of Spanish mysticism". He believes that in El Greco's mature works "the devotional intensity of mood reflects the religious spirit of Roman Catholic Spain in the period of the Counter-Reformation".[3] El Greco also excelled as a portraitist, able not only to record a sitter's features but also to convey their character.[72] His portraits are fewer in number than his religious paintings, but are of equally high quality. Wethey says that "by such simple means, the artist created a memorable characterization that places him in the highest rank as a portraitist, along with Titian and Rembrandt".[3] |

芸術 詳細は「エル・グレコの芸術」を参照 技法と様式 主観的な創造性よりも想像力と直観を優先させることは、エル・グレコのスタイルの根本的な原則であった。[36] エル・グレコは、尺度や比率といった古典主義の基準を捨てた。彼は、優美さが芸術の究極の探求であると信じていたが、画家が優美さを獲得するには、最も複 雑な問題を容易に解決することによってのみ可能であると考えていた。[36] エル・グレコは色彩を絵画において最も重要かつ最も制御しがたい要素と考え、色彩がフォルムよりも優先されるべきであると宣言した。1611年にエル・グ レコを訪れた画家であり理論家でもあるフランシスコ・パチェコは、 画家は「自分の腕前を誇示するかのように、粗野で混じりけのない色を大きな斑点状に塗ることを好んだ」と書き、「彼は、自然のままの平らな質感を表現する ために、絶え間なく塗り直し、手を加えることを信じていた」と述べている。[62] 「私は色彩の模倣を芸術における最大の難関であると考える。 — 画家の注釈のひとつより、エル・グレコの言葉。 美術史家のマックス・ドヴォルザークは、エル・グレコの芸術をマニエリスムと反自然主義と関連づけた最初の学者である。[64] 現代の学者たちは、エル・グレコの理論を「典型的なマニエリスム」と特徴づけ、その源流をルネサンス期のネオプラトニズムに求めている 。ジョナサン・ブラウンは、エル・グレコは洗練された芸術を生み出したと考えている。[66] ニコラス・ペニーによると、「スペインに渡ったエル・グレコは、絵画の描写的な野心のほとんどを否定する独自のスタイルを生み出すことができた」という。 [67]  『トレドの眺望』(1596年頃 - 1600年、油彩画、47.75 × 42.75 cm、メトロポリタン美術館、ニューヨーク)は、エル・グレコが描いた2点の現存するトレドの風景画のうちの1点である。  『聖アンドレアと聖フランシス』(1595年、油彩画、プラド美術館、マドリード)の一部。ギリシャ語で書かれた画家のサインが見える。 円熟期の作品では、エル・グレコは描写よりも劇的な表現を好む傾向が顕著に見られる。[3] 絵画から観客に直接的に伝わる強い精神的な感情。パチェコによると、エル・グレコの不安定で暴力的、時に無造作とも見えるような作品は、様式の自由を獲得 するための研究努力の結果であったという。[62] エル・グレコが、表現上の目的と美的原則の両方を満たす、非常に背が高く細長い人物像と細長い構図を好んだため、自然の法則を無視し、特に祭壇画のため に、構図をより一層細長く描くようになった。。人体の解剖学は、エル・グレコの成熟した作品においてさらに超世俗的なものとなる。無原罪の御宿り(トレ ド、エル・グレコ)では、エル・グレコは祭壇画自体をさらに1.5フィート(0.46メートル)長くするように依頼した。「なぜなら、この方法では形が完 璧になり、縮小されることがないからだ。これは、人物画にとって最悪の事態である」。エル・グレコの円熟期の作品における重要な革新は、形態と空間との織 り交ぜ方である。この2つの間に相互関係が生まれ、絵画の表面が完全に統一される。この織り交ぜ方は、3世紀後にセザンヌやピカソの作品に再び現れること になる。 エル・グレコの成熟したスタイルのもう一つの特徴は、光の使い方である。ジョナサン・ブラウンが指摘するように、「それぞれの人物は、自身の中に光を宿し ているか、あるいは見えない光源から発せられる光を反射しているように見える」のである。[69] エル・グレコの自筆のメモを書き写した学者であるフェルナンド・マリアスとアグスティン・ブスタマンテ・ガルシアは、画家が光に与える力をキリスト教新プ ラトン主義の根底にある考え方と結びつけている。[70] 現代の学術研究では、エル・グレコの円熟したスタイルの完成にトレドが果たした役割の重要性が強調されており、画家が周囲の環境に合わせて自身のスタイル を適応させる能力が強調されている。[71] ハロルド・ウェスリーは、「ギリシャの血筋であり、芸術的素養はイタリア的であるが、この芸術家はスペインの宗教的環境に深く浸り、スペイン神秘主義の最 も重要な視覚的表現者となった」と主張している。彼は、エル・グレコの円熟した作品では、「敬虔な情熱が、対抗宗教改革期のローマ・カトリックのスペイン の宗教的精神を反映している」と考えている。[3] エル・グレコは肖像画家としても優れており、被写体の特徴を記録するだけでなく、その人物の性格をも伝えることができた。[72] 彼の肖像画は宗教画に比べると数は少ないが、同様に高い品質を誇っている。 ウィーシーは「このようなシンプルな手段によって、ティツィアーノやレンブラントと並び、肖像画家として最高ランクに位置づけられるほど印象的な人物描写 を創り出した」と述べている。[3] |

| Painting materials El Greco painted many of his paintings on fine canvas and employed a viscous oil medium.[73] He painted with the usual pigments of his period such as azurite, lead-tin-yellow, vermilion, madder lake, ochres and red lead, but he seldom used the expensive natural ultramarine.[74] Suggested Byzantine affinities Since the beginning of the 20th century, scholars have debated whether El Greco's style had Byzantine origins. Certain art historians had asserted that El Greco's roots were firmly in the Byzantine tradition, and that his most individual characteristics derive directly from the art of his ancestors,[75] while others had argued that Byzantine art could not be related to El Greco's later work.[76] "I would not be happy to see a beautiful, well-proportioned woman, no matter from which point of view, however extravagant, not only lose her beauty in order to, I would say, increase in size according to the law of vision, but no longer appear beautiful, and, in fact, become monstrous." — El Greco, from marginalia the painter inscribed in his copy of Daniele Barbaro's translation of Vitruvius' De architectura.[77] The discovery of the Dormition of the Virgin on Syros, an authentic and signed work from the painter's Cretan period, and the extensive archival research in the early 1960s, contributed to the rekindling and reassessment of these theories. Although following many conventions of the Byzantine icon, aspects of the style certainly show Venetian influence, and the composition, showing the death of Mary, combines the different doctrines of the Orthodox Dormition of the Virgin and the Catholic Assumption of the Virgin.[78] Significant scholarly works of the second half of the 20th century devoted to El Greco reappraise many of the interpretations of his work, including his supposed Byzantinism.[4] Based on the notes written in El Greco's own hand, on his unique style, and on the fact that El Greco signed his name in Greek characters, they see an organic continuity between Byzantine painting and his art.[79] According to Marina Lambraki-Plaka "far from the influence of Italy, in a neutral place which was intellectually similar to his birthplace, Candia, the Byzantine elements of his education emerged and played a catalytic role in the new conception of the image which is presented to us in his mature work".[80] In making this judgement, Lambraki-Plaka disagrees with Oxford University professors Cyril Mango and Elizabeth Jeffreys, who assert that "despite claims to the contrary, the only Byzantine element of his famous paintings was his signature in Greek lettering".[81] Nikos Hadjinikolaou states that from 1570 El Greco's painting is "neither Byzantine nor post-Byzantine but Western European. The works he produced in Italy belong to the history of the Italian art, and those he produced in Spain to the history of Spanish art".[82] The English art historian David Davies seeks the roots of El Greco's style in the intellectual sources of his Greek-Christian education and in the world of his recollections from the liturgical and ceremonial aspect of the Orthodox Church. Davies believes that the religious climate of the Counter-Reformation and the aesthetics of Mannerism acted as catalysts to activate his individual technique. He asserts that the philosophies of Platonism and ancient Neo-Platonism, the works of Plotinus and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, the texts of the Church fathers and the liturgy offer the keys to the understanding of El Greco's style.[83] Summarizing the ensuing scholarly debate on this issue, José Álvarez Lopera, curator at the Museo del Prado, Madrid, concludes that the presence of "Byzantine memories" is obvious in El Greco's mature works, though there are still some obscure issues concerning his Byzantine origins needing further illumination.[84] |

絵画材料 エル・グレコは多くの絵画を上質なキャンバスに描き、粘度の高い油絵具を使用した。[73] 彼は、アズライト、鉛丹、朱、茜、黄土色、鉛丹といった当時の一般的な顔料を使用したが、高価な天然ウルトラマリンはほとんど使用しなかった。[74] ビザンティンとの関連性 20世紀初頭から、学者たちはエル・グレコのスタイルがビザンティン起源であるかどうかについて議論を交わしてきた。一部の美術史家は、エル・グレコの ルーツはビザンティン伝統にしっかりと根ざしており、彼の最も個性的な特徴は先祖の芸術から直接的に派生したものであると主張しているが、一方で、ビザン ティン芸術はエル・グレコの後の作品とは関連性がないと主張する者もいる。 「私は、どんなに贅沢なものであっても、美しい均整のとれた女性が、視覚の法則に従ってサイズが大きくなるために、あるいは、もはや美しくなく、実際には怪物のように見えるために、美しさを失うのを見るのは嬉しくないだろう。」 — エル・グレコ、ダニエレ・バルバロによるウィトルウィウスの『建築について』の翻訳本の余白に書き込んだ画家による注釈より。 クレタ島時代の画家による真正かつ署名入りの作品である『シロス島の聖母被昇天』の発見と、1960年代初頭の広範なアーカイブ調査が、これらの理論の再 燃と再評価に貢献した。ビザンチン様式のイコンの多くの慣例に従っているとはいえ、その様式の側面には確かにヴェネツィアの影響が見られ、聖母の死を描い た構図は、正教の聖母の眠りとカトリックの聖母の被昇天という異なる教義を組み合わせている。[78] 20世紀後半のエル・グレコに関する重要な学術的研究は、 彼の作品の解釈の多くを再評価し、その中には彼のビザンティン様式とされるものも含まれている。[4] エル・グレコ自身の筆跡によるメモ、彼の独特なスタイル、そしてエル・グレコがギリシャ文字で署名していたという事実に基づいて、ビザンティン絵画と彼の 芸術の間には有機的な連続性があると考えられている。[79] マリーナ・ランブラキ=プラカによると、「 イタリアの影響とはかけ離れた、知的な意味で彼の生まれ故郷であるカンディアに似た中立的な場所で、彼の教育におけるビザンチン的要素が浮上し、彼の成熟 した作品で私たちに提示されるイメージの新しい概念において触媒的な役割を果たした」と述べている。[80] この判断を下すにあたり、Lambraki-Plakaはオックスフォード大学の教授であるシリル・ 「異論はあるものの、彼の有名な絵画におけるビザンティン的要素は、ギリシャ文字で書かれた彼の署名だけである」と主張するオックスフォード大学の教授、 シリル・マンゴとエリザベス・ジェフリーズに反対している。[81] ニコス・ハジニコラウは、1570年以降のエル・グレコの絵画は「ビザンティン的でも後ビザンティン的でもなく、西欧的である」と述べている。彼がイタリ アで制作した作品はイタリア美術の歴史に属し、スペインで制作した作品はスペイン美術の歴史に属する」と述べている。[82] イギリスの美術史家デヴィッド・デイヴィスは、エル・グレコのスタイルのルーツを、ギリシャ・キリスト教の教育による知的源泉と、正教会の典礼や儀式から 想起される世界に見出している。デイヴィスは、対抗宗教改革の宗教的風潮とマニエリスムの美学が、彼の独自の技法を活性化させる触媒の役割を果たしたと考 えている。彼は、プラトン主義と古代ネオプラトン主義の哲学、プロティノスと偽ディオニシオス・アレオパギタの著作、教会の父祖たちの文章、典礼が、エ ル・グレコのスタイルを理解する鍵であると主張している。[83] この問題に関する学術的な議論を要約すると、マドリードのプラド美術館のキュレーターであるホセ・アルバレス・ロペラは、エル・グレコの円熟した作品には 「ビザンティン的な記憶」が明白に存在していると結論づけている。ただし、彼のビザンティン起源については、まだいくつかの不明瞭な問題があり、さらなる 解明が必要である。[84] |

| Architecture and sculpture El Greco was highly esteemed as an architect and sculptor during his lifetime.[85] He usually designed complete altar compositions, working as architect and sculptor as well as painter—at, for instance, the Hospital de la Caridad. There he decorated the chapel of the hospital, but the wooden altar and the sculptures he created have in all probability perished.[86] For El Espolio the master designed the original altar of gilded wood which has been destroyed, but his small sculptured group of the Miracle of St. Ildefonso still survives on the lower center of the frame.[3] His most important architectural achievement was the church and Monastery of Santo Domingo el Antiguo, for which he also executed sculptures and paintings.[87] El Greco is regarded as a painter who incorporated architecture in his painting.[88] He is also credited with the architectural frames to his own paintings in Toledo. Pacheco characterized him as "a writer of painting, sculpture and architecture".[36] In the marginalia that El Greco inscribed in his copy of Daniele Barbaro's translation of Vitruvius' De architectura, he refuted Vitruvius' attachment to archaeological remains, canonical proportions, perspective and mathematics. He also saw Vitruvius' manner of distorting proportions in order to compensate for distance from the eye as responsible for creating monstrous forms. El Greco was averse to the very idea of rules in architecture; he believed above all in the freedom of invention and defended novelty, variety, and complexity. These ideas were, however, far too extreme for the architectural circles of his era and had no immediate resonance.[88] |

建築と彫刻 エル・グレコは存命中、建築家および彫刻家としても高く評価されていた。[85] 通常、祭壇全体の構図をデザインし、建築家や彫刻家、画家として働いていた。例えば、ラ・カリダ病院などである。そこで彼は病院の礼拝堂を装飾したが、彼 が制作した木製の祭壇と彫刻は、おそらくすべて失われてしまった。エル・エスポリオのために、巨匠は金箔を施した木製のオリジナル祭壇を設計したが、それ は破壊されてしまった。しかし、聖イルデフォンソの奇跡を題材にした彼の小さな彫刻群は、フレームの中央下部に今も残っている。 彼の最も重要な建築上の功績は、サント・ドミンゴ・エル・アンティグオ教会と修道院であり、そのために彫刻や絵画も制作した。[87] エル・グレコは、建築を絵画に取り入れた画家とみなされている。[88] また、トレドの自身の絵画の建築的な額縁も評価されている。パチェコは、彼を「絵画、彫刻、建築の作家」と評した。[36] エル・グレコがダニエレ・バルバロによるウィトルウィウスの『建築について』の翻訳本の余白に書き込んだ注釈では、彼はウィトルウィウスの考古学的遺跡、 規範的な比率、遠近法、数学への固執を否定している。また、ヴィトルヴィウスが遠近の距離を補うために比率を歪めるやり方が、奇怪な形を生み出す原因と なっていると彼は考えた。エル・グレコは建築における規則という考えそのものを嫌悪し、何よりも発明の自由を信じ、斬新さ、多様性、複雑さを擁護した。し かし、これらの考えは当時の建築界にとってはあまりにも極端であり、すぐに共感を呼ぶことはなかった。[88] |

| Legacy Main article: Posthumous fame of El Greco Posthumous critical reputation  The Holy Trinity (1577–1579, 300 × 178 cm, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain) was part of a group of works created for the church "Santo Domingo el Antiguo". El Greco was disdained by the immediate generations after his death because his work was opposed in many respects to the principles of the early baroque style which came to the fore near the beginning of the 17th century and soon supplanted the last surviving traits of the 16th-century Mannerism.[3] El Greco was deemed incomprehensible and had no important followers.[89] Only his son and a few unknown painters produced weak copies of his works. Late 17th- and early 18th-century Spanish commentators praised his skill but criticized his antinaturalistic style and his complex iconography. Some of these commentators, such as Antonio Palomino and Juan Agustín Ceán Bermúdez, described his mature work as "contemptible", "ridiculous" and "worthy of scorn".[90] The views of Palomino and Bermúdez were frequently repeated in Spanish historiography, adorned with terms such as "strange", "queer", "original", "eccentric" and "odd".[91] The phrase "sunk in eccentricity", often encountered in such texts, in time developed into "madness".[i] With the arrival of Romantic sentiments in the late 18th century, El Greco's works were examined anew.[89] To French writer Théophile Gautier, El Greco was the precursor of the European Romantic movement in all its craving for the strange and the extreme.[92] Gautier regarded El Greco as the ideal romantic hero (the "gifted", the "misunderstood", the "mad"),[j] and was the first who explicitly expressed his admiration for El Greco's later technique.[91] French art critics Zacharie Astruc and Paul Lefort helped to promote a widespread revival of interest in his painting. In the 1890s, Spanish painters living in Paris adopted him as their guide and mentor.[92] However, in the popular English-speaking imagination he remained the man who "painted horrors in the Escorial" in the words of Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopaedia in 1899.[94] In 1908, Spanish art historian Manuel Bartolomé Cossío published the first comprehensive catalogue of El Greco's works; in this book El Greco was presented as the founder of the Spanish School.[95] The same year Julius Meier-Graefe, a scholar of French Impressionism, traveled in Spain, expecting to study Velásquez, but instead becoming fascinated by El Greco; he recorded his experiences in Spanische Reise (Spanish Journey, published in English in 1926), the book which widely established El Greco as a great painter of the past "outside a somewhat narrow circle".[96] In El Greco's work, Meier-Graefe found foreshadowing of modernity.[97] These are the words Meier-Graefe used to describe El Greco's impact on the artistic movements of his time: He [El Greco] has discovered a realm of new possibilities. Not even he, himself, was able to exhaust them. All the generations that follow after him live in his realm. There is a greater difference between him and Titian, his master, than between him and Renoir or Cézanne. Nevertheless, Renoir and Cézanne are masters of impeccable originality because it is not possible to avail yourself of El Greco's language, if in using it, it is not invented again and again, by the user. — Julius Meier-Graefe, The Spanish Journey[98] To the English artist and critic Roger Fry in 1920, El Greco was the archetypal genius who did as he thought best "with complete indifference to what effect the right expression might have on the public". Fry described El Greco as "an old master who is not merely modern, but actually appears a good many steps ahead of us, turning back to show us the way".[33] During the same period, other researchers developed alternative, more radical theories. The ophthalmologists August Goldschmidt and Germán Beritens argued that El Greco painted such elongated human figures because he had vision problems (possibly progressive astigmatism or strabismus) that made him see bodies longer than they were, and at an angle to the perpendicular;[99][k] the physician Arturo Perera, however, attributed this style to the use of marijuana.[104] Michael Kimmelman, a reviewer for The New York Times, stated that "to Greeks [El Greco] became the quintessential Greek painter; to the Spanish, the quintessential Spaniard".[33] Epitomizing the consensus of El Greco's impact, Jimmy Carter, the 39th President of the United States, said in April 1980 that El Greco was "the most extraordinary painter that ever came along back then" and that he was "maybe three or four centuries ahead of his time".[92] |

遺産 詳細は「エル・グレコの死後の名声」を参照 死後の批評的評価  『聖なる三位一体』(1577年-1579年、300×178cm、油彩画、プラド美術館、スペイン、マドリード)は、教会「サント・ドミンゴ・エル・アンティグオ」のために制作された作品群の一部である。 エル・グレコは、17世紀初頭に台頭した初期バロック様式の原則の多くの点で対立していたため、彼の死後、直後の世代から軽蔑された。初期バロック様式 は、すぐに 16世紀のマニエリスムの最後の生き残りの特徴をすぐに取って代わった。[3] エル・グレコは理解不能とみなされ、重要な追随者はいなかった。[89] 彼の作品の弱々しい模写を制作したのは、彼の息子と数名の無名の画家だけだった。17世紀後半から18世紀初頭にかけてのスペインの評論家たちは、彼の技 術を賞賛する一方で、非現実的な作風と複雑な図像を批判した。アントニオ・パロミーノやフアン・アグスティン・セアン・ベルムデスといった評論家たちは、 彼の円熟した作品を「卑しい」、「滑稽」、「軽蔑に値する」と評した。[90] パロミーノとベルムデスの見解は、 スペインの歴史学では、「奇妙」、「風変わり」、「独創的」、「奇抜」、「奇異」などの表現で飾られながら、パロミノとベルムデスの見解が繰り返し述べら れた。[91] このような文章でしばしば見られる「風変わりに没頭する」という表現は、やがて「狂気」へと発展した。[i] 18世紀後半にロマン主義の感情が到来すると、エル・グレコの作品は新たに評価されるようになった。[89] フランスの作家テオフィル・ゴーティエにとって、エル・グレコは奇妙なものを追い求め、極端なものを求めるヨーロッパのロマン主義運動の先駆者であった。 [92] ゴーティエは、 理想的なロマン派の英雄(「才能に恵まれた」、「誤解された」、「狂気じみた」)[j]と見なし、エル・グレコの後の技法に対する賞賛を明確に表明した最 初の人物であった。[91] フランスの美術評論家ザカリー・アストリュックとポール・ルフォーは、彼の絵画に対する関心を広範に復活させるのに貢献した。1890年代には、パリに住 むスペイン人画家たちが彼を師と仰ぐようになった。[92] しかし、英語圏の一般的な想像力の中では、1899年のエフライム・チェンバースの『百科事典』の言葉によれば、彼は「エスコリアル宮殿で恐怖を描いた」 人物のままであった。[94] 1908年にはスペインの美術史家マヌエル・バルトロメ・コッシオが、エル・グレコの作品の最初の包括的なカタログを出版した。この本では、エル・グレコ はスペイン派の創始者として紹介されている。[95] 同じ年、フランス印象派の研究者ユリウス・マイヤー=グレーフェは、ベラスケスを研究するためにスペインを訪れたが、代わりにエル・グレコに魅了された。 彼はその経験を『Span (スペインの旅、1926年に英語版出版)で、この本によって、エル・グレコは「やや狭いサークルの外側」にある過去の偉大な画家として広く知られるよう になった。[96] エル・グレコの作品には、近代性の萌芽が認められるとマイヤー=グレフェは考えた。[97] マイヤー=グレフェは、当時の芸術運動に与えたエル・グレコの影響について、次のように述べている。 彼は(エル・グレコは)新しい可能性の領域を発見した。彼自身でさえ、その可能性をすべて使い果たすことはできなかった。彼以降のすべての世代は、彼の領 域の中で生きている。彼と師であるティツィアーノとの違いは、彼とルノワールやセザンヌとの違いよりも大きい。しかし、ルノワールやセザンヌは、非の打ち どころのない独創性の持ち主である。なぜなら、もしエル・グレコの言語を使用するとしても、その言語を何度も何度も発明し直さなければ、その言語を利用す ることはできないからだ。 —ユリウス・マイヤー=グレーフェ、『スペインの旅』[98] 1920年、イギリスの画家であり批評家でもあるロジャー・フライ(Roger Fry)にとって、エル・グレコは、自身の考えた通りに描き、「それが一般大衆にどのような影響を与えるかということには全く関心を示さなかった」典型的 な天才であった。フライはエル・グレコを「単にモダンなだけでなく、実際には我々よりもかなり先を行き、我々を導くために振り返っているような巨匠」と評 した。 同じ時期に、他の研究者たちは、より代替的で、より急進的な理論を展開した。眼科医のオーガスト・ゴールドシュミットとヘルマン・ベリテンズは、エル・グ レコが細長い人物を描いたのは、視力障害(おそらく進行性の乱視または斜視)により、身体を実際よりも長く、垂直から斜めに見ていたからだと主張した。 [99][k] しかし、医師のアートゥーロ・ペレーラは、この様式をマリファナの使用に起因するものとしている。[104] ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の批評家マイケル・キンメルマンは、「ギリシア人にとって、エル・グレコは典型的なギリシア人画家であり、スペイン人にとっては 典型的なスペイン人である」と述べている。[33] エル・グレコの影響力に関するコンセンサスを象徴するものとして、第39代アメリカ合衆国大統領ジミー・カーターは1980年4月、エル・グレコは「当時現れた画家の中で最も非凡な画家」であり、「おそらく3、4世紀は時代を先取りしていた」と述べた。[92] |

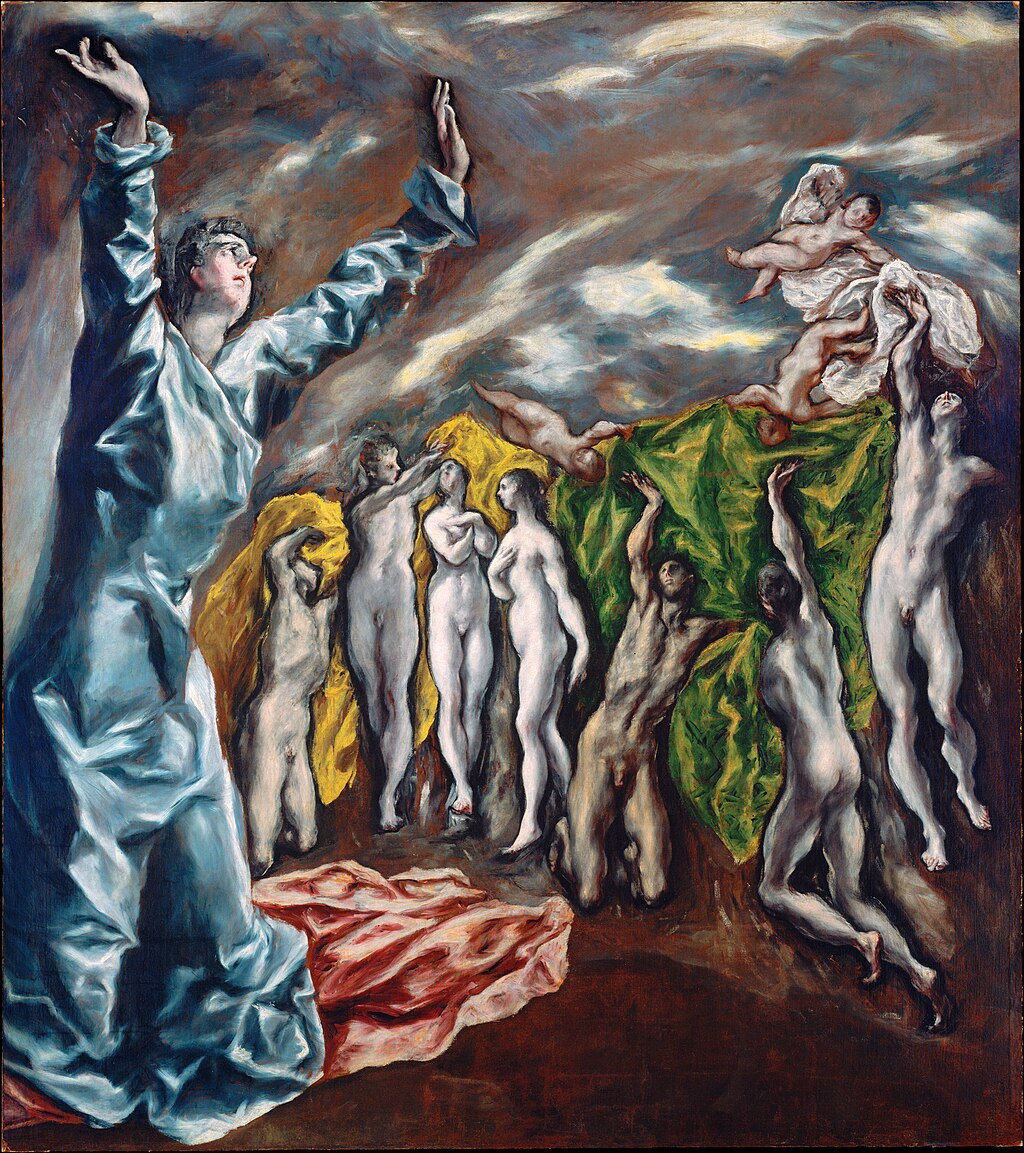

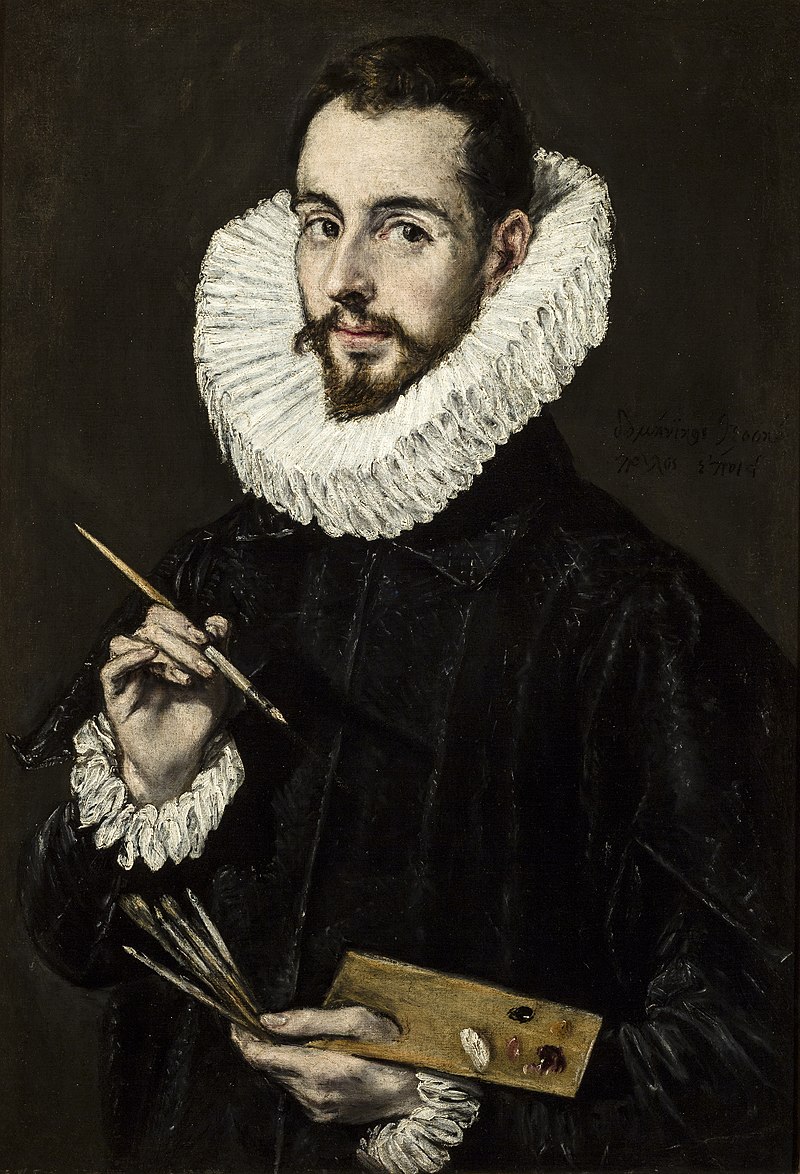

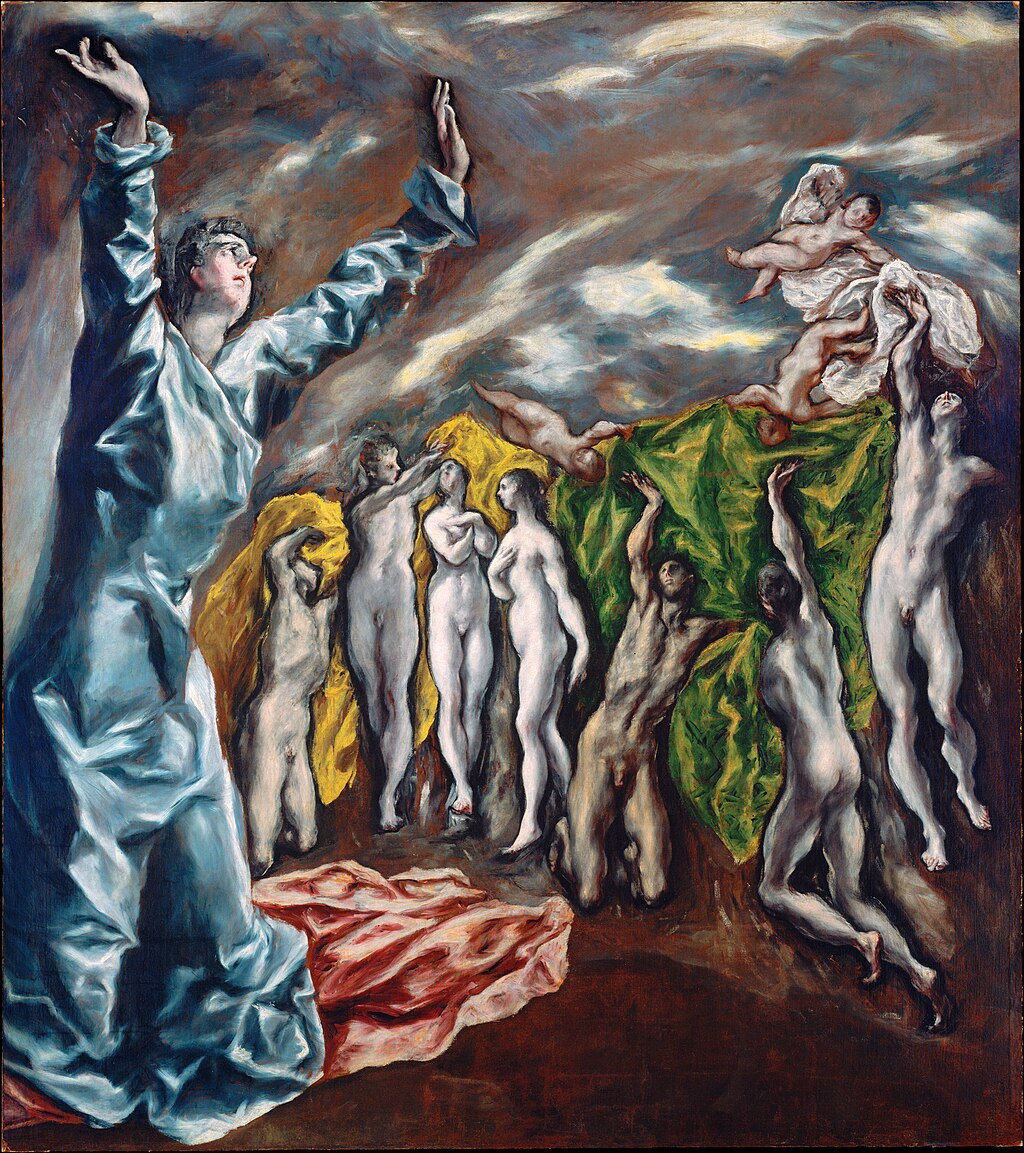

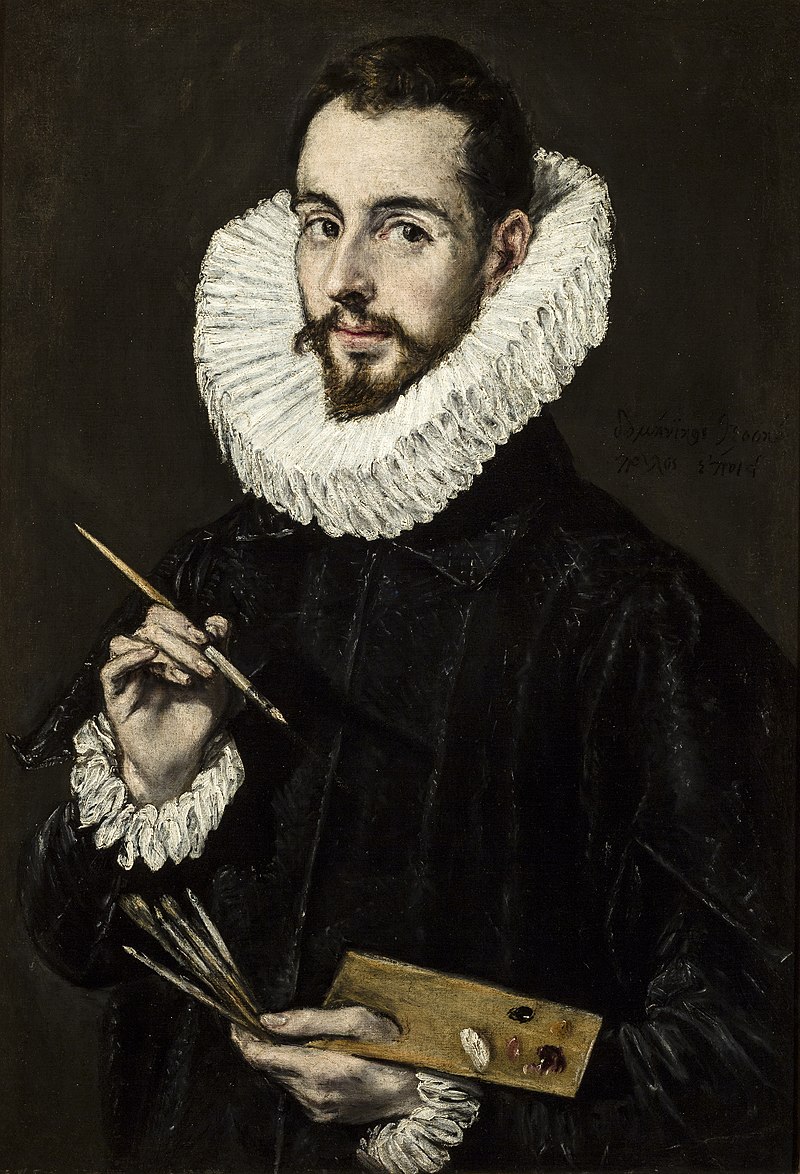

| Influence on other artists See also: Boy Leading a Horse  The Opening of the Fifth Seal (1608–1614, oil, 225 × 193 cm., New York, Metropolitan Museum) has been suggested to be the prime source of inspiration for Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.  Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907, oil on canvas, 243.9 × 233.7 cm., New York, Museum of Modern Art) appears to have certain morphological and stylistic similarities with The Opening of the Fifth Seal.  Portrait of Jorge Manuel Theotocopoulos (1600–1605, oil on canvas, 81 × 56 cm, Museo de Bellas Artes, Seville)  The Portrait of a Painter after El Greco (1950, oil on plywood, 100.5 × 81 cm, Angela Rosengart Collection, Lucerne) is Picasso's version of the Portrait of Jorge Manuel Theotocopoulos.  Weltenallegorie, 2009, Matthias Laurenz Gräff According to Efi Foundoulaki, "painters and theoreticians from the beginning of the 20th century 'discovered' a new El Greco but in process they also discovered and revealed their own selves".[105] His expressiveness and colors influenced Eugène Delacroix and Édouard Manet.[106] To the Blaue Reiter group in Munich in 1912, El Greco typified that mystical inner construction that it was the task of their generation to rediscover.[107] The first painter who appears to have noticed the structural code in the morphology of the mature El Greco was Paul Cézanne, one of the forerunners of Cubism.[89] Comparative morphological analyses of the two painters revealed their common elements, such as the distortion of the human body, the reddish and (in appearance only) unworked backgrounds and the similarities in the rendering of space.[108] According to Brown, "Cézanne and El Greco are spiritual brothers despite the centuries which separate them".[109] Fry observed that Cézanne drew from "his great discovery of the permeation of every part of the design with a uniform and continuous plastic theme".[110] The Symbolists, and Pablo Picasso during his Blue Period, drew on the cold tonality of El Greco, utilizing the anatomy of his ascetic figures. While Picasso was working on his Proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, he visited his friend Ignacio Zuloaga in his studio in Paris and studied El Greco's Opening of the Fifth Seal (owned by Zuloaga since 1897).[111] The relation between Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and the Opening of the Fifth Seal was pinpointed in the early 1980s, when the stylistic similarities and the relationship between the motifs of both works were analysed.[112] The early Cubist explorations of Picasso were to uncover other aspects in the work of El Greco: structural analysis of his compositions, multi-faced refraction of form, interweaving of form and space, and special effects of highlights. Several traits of Cubism, such as distortions and the materialistic rendering of time, have their analogies in El Greco's work. According to Picasso, El Greco's structure is Cubist.[113] On 22 February 1950, Picasso began his series of "paraphrases" of other painters' works with The Portrait of a Painter after El Greco.[114] Foundoulaki asserts that Picasso "completed ... the process for the activation of the painterly values of El Greco which had been started by Manet and carried on by Cézanne".[115] The expressionists focused on the expressive distortions of El Greco. According to Franz Marc, one of the principal painters of the German expressionist movement, "we refer with pleasure and with steadfastness to the case of El Greco, because the glory of this painter is closely tied to the evolution of our new perceptions on art".[116] Jackson Pollock, a major force in the abstract expressionist movement, was also influenced by El Greco. By 1943, Pollock had completed sixty drawing compositions after El Greco and owned three books on the Cretan master.[117] Pollock influenced the artist Joseph Glasco's interest in El Greco's art. Glasco created several contemporary paintings based on one of his favorite subjects, El Greco's View of Toledo.[118] Kysa Johnson used El Greco's paintings of the Immaculate Conception as the compositional framework for some of her works, and the master's anatomical distortions are somewhat reflected in Fritz Chesnut's portraits.[119] El Greco's personality and work were a source of inspiration for poet Rainer Maria Rilke. One set of Rilke's poems (Himmelfahrt Mariae I.II., 1913) was based directly on El Greco's Immaculate Conception.[120] Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis, who felt a great spiritual affinity for El Greco, called his autobiography Report to Greco and wrote a tribute to the Cretan-born artist.[121] In 1998, the Greek electronic composer and artist Vangelis published El Greco, a symphonic album inspired by the artist. This album is an expansion of an earlier album by Vangelis, Foros Timis Ston Greco (A Tribute to El Greco, Φόρος Τιμής Στον Γκρέκο). The life of the Cretan-born artist is the subject of the film El Greco of Greek, Spanish and British production. Directed by Ioannis Smaragdis, the film began shooting in October 2006 on the island of Crete and debuted on the screen one year later;[122] British actor Nick Ashdon was cast to play El Greco.[123] In reference to El Greco, the Austrian artist Matthias Laurenz Gräff created his large-format religious triptych "Weltenalegorie" (World allegory) in 2009, which contains various figures from El Greco's paintings. |

他の芸術家への影響 関連項目:馬を引く少年  第5の封印の扉(1608年-1614年、油彩、225×193cm、ニューヨーク、メトロポリタン美術館)は、ピカソの『アヴィニョンの娘たち』のインスピレーションの主な源であると示唆されている。  ピカソの『アヴィニョンの娘たち』(1907年、油彩画、243.9 × 233.7 cm、ニューヨーク近代美術館)は、『第五の封印』と形態や様式にいくつかの類似点があるように見える。  ホルヘ・マヌエル・テオトコプロスの肖像(1600年-1605年、油彩画、81×56cm、セビリア美術館)  「画家の肖像」(1950年、ベニヤ板に油彩、100.5 × 81 cm、アンジェラ・ローゼンガルト・コレクション、ルツェルン)は、ピカソによるテオトコプーロスの肖像画の解釈である。  「世界の寓意」、2009年、マティアス・ローレンツ・グラーフ エフィ・フンドゥラキによると、「20世紀初頭の画家や理論家たちは、新しいエル・グレコを『発見』したが、その過程で彼ら自身をも発見し、明らかにし た」という。[105] 彼の表現力と色彩は、ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワとエドゥアール・マネに影響を与えた。[106] 1912年のミュンヘンの青騎士グループにとって、 エル・グレコは、彼らの世代が再発見すべき神秘的な内面の構築を象徴していた。[107] 成熟したエル・グレコの形態学に構造上のコードがあることに最初に気づいたと思われる画家は、キュビズムの先駆者の一人であるポール・セザンヌである。 [89] 2人の画家の形態比較分析により、人体の歪み、 赤みを帯びた(見た目だけの)未加工の背景、空間の表現における類似性などである。[108] ブラウンによると、「セザンヌとエル・グレコは、隔たった世紀にもかかわらず、精神的な兄弟である」という。[109] フライは、セザンヌが「デザインのあらゆる部分に均一で連続的な造形主題が浸透しているという、彼の偉大な発見」から着想を得たと指摘している。 [110] 象徴主義者たちや青の時代(1901年から1906年)のパブロ・ピカソは、エル・グレコの冷たい色調や禁欲的な人物の解剖学を利用した。ピカソが原始的 キュビスムの『アヴィニョンの娘たち』に取り組んでいたとき、彼は友人のイグナシオ・スロアガのパリのスタジオを訪れ、1897年からスロアガが所有して いた『第五の封印』を研究した。 [111] 『アヴィニョンの娘たち』と『第五の封印』の関連性は、両作品の様式上の類似性とモチーフの関係性が分析された1980年代初頭に指摘された。[112] ピカソの初期のキュビスムの探求は、エル・グレコの作品における他の側面を明らかにすることとなった。すなわち、彼の構図の構造的分析、多面的な形態の屈 折、形態と空間の織り交ぜ、ハイライトの特殊効果などである。歪みや唯物論的な時間の表現など、キュビスムのいくつかの特徴は、エル・グレコの作品にも類 似している。ピカソによれば、エル・グレコの構図はキュビズム的である。[113] 1950年2月22日、ピカソはエル・グレコの『画家の肖像』を皮切りに、他の画家の作品の「パラフレーズ」シリーズの制作を開始した 。 ファンドゥラキスは、ピカソが「マネが着手し、セザンヌが引き継いだエル・グレコの絵画的価値の活性化プロセスを完成させた」と主張している。 表現主義者たちは、エル・グレコの表現上の歪みに注目した。ドイツ表現主義運動の主要な画家の一人であるフランツ・マルクは、「我々は喜びと確信を持って エル・グレコの事例に言及する。なぜなら、この画家の栄光は、我々の芸術に対する新しい認識の進化と密接に結びついているからだ」と述べている。 [116] 抽象表現主義運動の主要な推進者であったジャクソン・ポロックもまた、エル・グレコの影響を受けていた。1943年までに、ポロックはエル・グレコの模写 を60点描き上げ、クレタ島の巨匠に関する本を3冊所有していた。 ポロックは、画家ジョセフ・グラスコのエル・グレコ芸術への関心に影響を与えた。グラスコは、お気に入りの主題のひとつである『トレドの眺望』を題材に、いくつかの現代絵画を制作した。 キサ・ジョンソンは、無原罪懐胎のエル・グレコの絵画をいくつかの作品の構図の枠組みとして使用し、巨匠の解剖学的な歪みは、フリッツ・チェスナットの肖像画にいくらか反映されている。 エル・グレコの性格と作品は、詩人ライナー・マリア・リルケのインスピレーションの源となった。リルケの詩の一連(『聖母の被昇天』第1巻・第2巻、 1913年)は、エル・グレコの『無原罪の御宿り』を直接の題材としている。[120] ギリシャ人作家のニコス・カザンザキスは、エル・グレコに強い精神的な親近感を抱いており、自伝を『グレコへの報告』と名付け、クレタ島生まれの芸術家へ の賛辞を書いた。[121] 1998年には、ギリシャの電子音楽作曲家でありアーティストでもあるヴァンゲリスが、エル・グレコにインスピレーションを受けた交響アルバム『El Greco』を発表した。このアルバムは、ヴァンゲリスの以前のアルバム『Foros Timis Ston Greco』(『A Tribute to El Greco』、『Φόρος Τιμής Στον Γκρέκο』)の拡大版である。クレタ島生まれの芸術家の生涯は、ギリシャ、スペイン、イギリス共同制作の映画『ギリシャのエル・グレコ』の主題となっ ている。イオアニス・スマラグディスの監督作品であるこの映画は、2006年10月にクレタ島で撮影を開始し、1年後に公開された。[122] イギリス人俳優のニック・アシュドンがエル・グレコ役を演じた。[123] エル・グレコにちなんで、オーストリア人アーティストのマティアス・ローレンツ・グラーフは、2009年に大型の宗教的な3連祭壇画「Weltenalegorie(世界の寓話)」を制作した。この作品には、エル・グレコの絵画に登場するさまざまな人物が描かれている。 |

| Debates on attribution Further information: List of works by El Greco  The Modena Triptych (1568, tempera on panel, 37 × 23.8 cm (central), 24 × 18 cm (side panels), Galleria Estense, Modena) is a small-scale composition attributed to El Greco.  "Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος (Doménicos Theotocópoulos) ἐποίει." The words El Greco used to sign his paintings. El Greco appended after his name the word "epoiei" (ἐποίει, "(he) made it"). In The Assumption the painter used the word "deixas" (δείξας, "(he) displayed it") instead of "epoiei". The exact number of El Greco's works has been a hotly contested issue. In 1937, a highly influential study by art historian Rodolfo Pallucchini had the effect of greatly increasing the number of works accepted to be by El Greco. Pallucchini attributed to El Greco a small triptych in the Galleria Estense at Modena on the basis of a signature on the painting on the back of the central panel on the Modena triptych ("Χείρ Δομήνιϰου", Created by the hand of Doménikos).[124] There was consensus that the triptych was indeed an early work of El Greco and, therefore, Pallucchini's publication became the yardstick for attributions to the artist.[125] Nevertheless, Wethey denied that the Modena triptych had any connection at all with the artist and, in 1962, produced a reactive catalogue raisonné with a greatly reduced corpus of materials. Whereas art historian José Camón Aznar had attributed between 787 and 829 paintings to the Cretan master, Wethey reduced the number to 285 authentic works and Halldor Sœhner, a German researcher of Spanish art, recognized only 137.[126] Wethey and other scholars rejected the notion that Crete took any part in his formation and supported the elimination of a series of works from El Greco's œuvre.[127] Since 1962, the discovery of the Dormition and the extensive archival research has gradually convinced scholars that Wethey's assessments were not entirely correct, and that his catalogue decisions may have distorted the perception of the whole nature of El Greco's origins, development and œuvre. The discovery of the Dormition led to the attribution of three other signed works of "Doménicos" to El Greco (Modena Triptych, St. Luke Painting the Virgin and Child, and The Adoration of the Magi) and then to the acceptance of more works as authentic—some signed, some not (such as The Passion of Christ (Pietà with Angels) painted in 1566),[128]—which were brought into the group of early works of El Greco. El Greco is now seen as an artist with a formative training on Crete; a series of works illuminate his early style, some painted while he was still on Crete, some from his period in Venice, and some from his subsequent stay in Rome.[4] Even Wethey accepted that "he [El Greco] probably had painted the little and much disputed triptych in the Galleria Estense at Modena before he left Crete".[25] Nevertheless, disputes over the exact number of El Greco's authentic works remain unresolved, and the status of Wethey's catalogue raisonné is at the center of these disagreements.[129] A few sculptures, including Epimetheus and Pandora, have been attributed to El Greco. This doubtful attribution is based on the testimony of Pacheco (he saw in El Greco's studio a series of figurines, but these may have been merely models). There are also four drawings among the surviving works of El Greco; three of them are preparatory works for the altarpiece of Santo Domingo el Antiguo and the fourth is a study for one of his paintings, The Crucifixion.[130] |

帰属に関する議論 詳細情報:エル・グレコの作品一覧  モデナ・トリプティク(1568年、板にテンペラ、中央部分37×23.8cm、側面部分24×18cm、エステンセ美術館、モデナ)は、エル・グレコの作品とされる小規模な構図である。  「Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος (Doménicos Theotocópoulos) ἐποίει.」は、エル・グレコが自身の絵画に署名する際に用いた言葉である。エル・グレコは、自身の名前の後に「epoiei」(ἐποίει、 「(彼が)作った」)という言葉を付け加えた。「聖母被昇天」では、「epoiei」の代わりに「deixas」(δείξας、「(彼は)それを展示し た」)という言葉が使われている。 エル・グレコの作品の正確な数は、長年論争の的となってきた。1937年、美術史家ロドルフォ・パルッチーニによる影響力の高い研究により、エル・グレコ の作品として認められる作品数が大幅に増加した。パラッチーニは、モデナのエステンセ美術館にある小さな三連祭壇画を、中央パネルの裏側の絵画に署名が あったことを根拠に、エル・グレコの作品と認定した。(「Χείρ Δομήνιϰου」、ドメニコスの手による作品)[124] この三連祭壇画は、 確かに初期のエル・グレコの作品であるというコンセンサスが得られ、それゆえに、パルッチーニの著書が、その画家の作品の帰属を決定する基準となった。 [125] しかし、ウェッティはモデナの三連祭壇画がその画家とまったく関係がないと否定し、1962年には、大幅に削減した資料で反論的なカタログレゾネを制作し た。美術史家のホセ・カモン・アスナールは、クレタ島の巨匠による絵画を787点から829点と推定していたが、ウィーシーは真正な作品の数を285点に まで減らし、ドイツのスペイン美術研究家ハルドル・ソーンは スペイン美術の研究者であるハルドル・ソーンは137点のみを認定した。[126] ウィーティーや他の学者たちは、クレタ島が彼の形成に何らかの影響を与えたという考えを否定し、エル・グレコの作品群から一連の作品を排除することを支持 した。[127] 1962年以来、聖母被昇天の発見と広範なアーカイブ調査により、次第に学者たちは、Wetheyの評価が完全に正しかったわけではないこと、また彼の作 品目録の決定が、エル・グレコの起源、発展、作品の全体像に対する認識を歪めていた可能性があることに納得するようになった。聖母ドミティカの発見によ り、ドメニコスが署名した他の3作品(モデナ・トリプティク、聖ルカによる聖母子像、東方三博士の礼拝)がエル・グレコの作品であると認定され、その後、 署名のあるもの、ないもの(1566年に描かれた『キリストの受難(天使たちを伴うピエタ)』など)を含め、より多くの作品が真正なものと認められるよう になった。エル・グレコは現在では、クレタ島で形成期の訓練を受けた芸術家と見なされている。一連の作品は彼の初期の様式を明らかにしており、その中には クレタ島にいた時に描かれたもの、ヴェネツィアにいた時期の作品、ローマに滞在していた時期の作品がある。[4] ウェセイでさえ、「おそらく、 おそらく、クレタ島を離れる前に、モデナのエステンセ美術館にある論争の的となっている三連祭壇画を制作した」と認めている。[25] しかし、エル・グレコの真正な作品の正確な数については意見が分かれており、未だに決着がついていない。また、Wetheyのカタログレゾネの評価は、こ うした意見の相違の中心となっている。[129] エピメテウスとパンドラを含む数点の彫刻がエル・グレコの作品とされている。この疑わしい帰属は、パチェーコの証言に基づいている(彼はエル・グレコのア トリエで一連のフィギュアを目撃したが、それらは単なる模型であった可能性もある)。また、エル・グレコの現存する作品の中には4点のデッサンがあり、そ のうち3点はサント・ドミンゴ・エル・アンティグオの祭壇画の準備作品であり、4点目は彼の絵画『磔刑』の習作である。[130] |

| Nazi-looted art In 2010 the heirs of the Baron Mor Lipot Herzog, a Jewish Hungarian art collector who had been looted by the Nazis, filed a restitution claim for El Greco's The Agony in the Garden.[131][132] In 2015, El Greco's Portrait of a Gentleman, which had been looted by the Nazis from German Jewish art collector Julius Priester in 1944, was returned to his heirs after it surfaced at an auction with a fake provenance.[133] According to Anne Webber, co-chair of the Commission for Looted Art in Europe, the painting's provenance had been "scrubbed".[134] |

ナチスに略奪された美術品 2010年、ナチスに略奪されたユダヤ系ハンガリーの美術収集家、バロン・モール・リポット・ヘルツォークの相続人は、エル・グレコの『園の苦悩』の返還 請求を行った。[131][132] 2015年、 1944年にナチスがドイツ系ユダヤ人の美術収集家ユリウス・プリースターから略奪したエル・グレコの『紳士の肖像』は、偽の来歴が記載された状態でオー クションに出品された後、彼の相続人に返還された。[133] ヨーロッパ略奪美術品委員会の共同委員長であるアン・ウェバーによると、この絵画の来歴は「消去」されていたという。[134] |

| El Greco Museum, Toledo, Spain Museum of El Greco, Fodele, Crete |

スペイン、トレド、エル・グレコ美術館 ギリシャ、クレタ島、フィデル、エル・グレコ美術館 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Greco |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆