あらゆる形態の人種差別の撤廃に関する国際条約

International Convention on the

Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

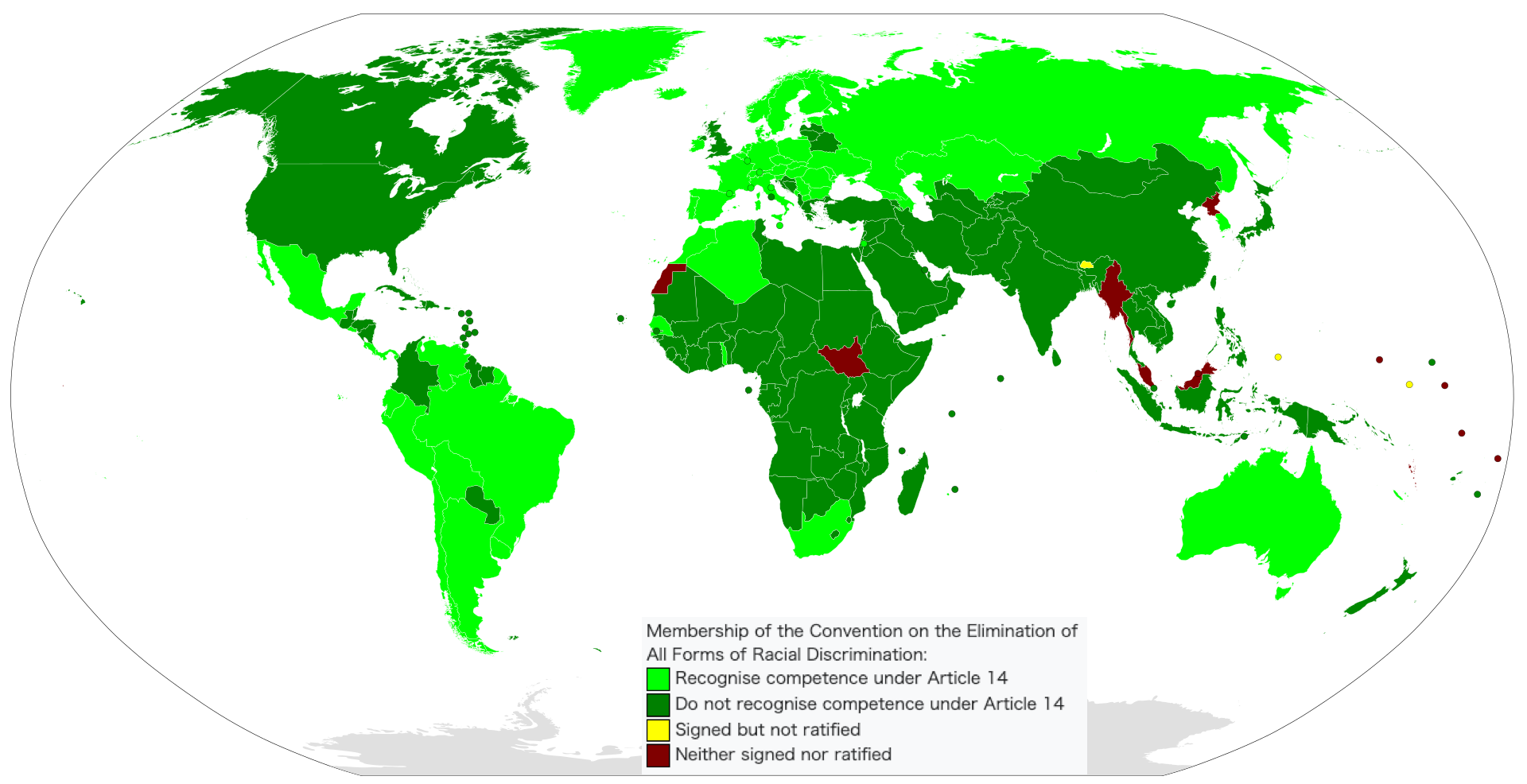

☆あらゆる形態の人種的差別撤廃に関する国際条約(ICERD)は、国連条約である。第三世代の人権文書であるこの条約は、加盟国に対し人種的差別の撤廃とあらゆる人種間の理解の促進を義務付けている[6]。また、この条約は、加盟国に対しヘイトスピーチの犯罪化と人種差別主義的団体の加盟の犯罪化を義務付けている[7]。 この条約には、加盟国に対する強制力を効果的に与える個人苦情処理メカニズムも含まれている。これにより、同条約の解釈と実施に関する限定的な判例法の発展につながった。 同条約は1965年12月21日に国連総会で採択され、署名のために開放された[8]。1969年1月4日に発効した。2020年7月現在、88カ国が署名国、182カ国が締約国(加入および継承を含む)となっている[2]。 この条約は人種差別撤廃委員会(CERD)によってモニターされている。

| The International

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

(ICERD) is a United Nations convention. A third-generation human rights

instrument, the Convention commits its members to the elimination of

racial discrimination and the promotion of understanding among all

races.[6] The Convention also requires its parties to criminalize hate

speech and criminalize membership in racist organizations.[7] The Convention also includes an individual complaints mechanism, effectively making it enforceable against its parties. This has led to the development of a limited jurisprudence on the interpretation and implementation of the Convention. The convention was adopted and opened for signature by the United Nations General Assembly on 21 December 1965,[8] and entered into force on 4 January 1969. As of July 2020, it has 88 countries as signatories and 182 countries as parties (including accessions and successions).[2] The Convention is monitored by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD). |

あらゆる形態の人種的差別撤廃に関する国際条約(ICERD)は、国連

条約である。第三世代の人権文書であるこの条約は、加盟国に対し人種的差別の撤廃とあらゆる人種間の理解の促進を義務付けている[6]。また、この条約

は、加盟国に対しヘイトスピーチの犯罪化と人種差別主義的団体の加盟の犯罪化を義務付けている[7]。 この条約には、加盟国に対する強制力を効果的に与える個人苦情処理メカニズムも含まれている。これにより、同条約の解釈と実施に関する限定的な判例法の発 展につながった。 同条約は1965年12月21日に国連総会で採択され、署名のために開放された[8]。1969年1月4日に発効した。2020年7月現在、88カ国が署 名国、182カ国が締約国(加入および継承を含む)となっている[2]。 この条約は人種差別撤廃委員会(CERD)によってモニターされている。 |

| Genesis In December 1960, following incidents of antisemitism in several parts of the world,[9] the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution condemning "all manifestations and practices of racial, religious and national hatred" as violations of the United Nations Charter and Universal Declaration of Human Rights and calling on the governments of all states to "take all necessary measures to prevent all manifestations of racial, religious and national hatred".[10] The Economic and Social Council followed this up by drafting a resolution on "manifestations of racial prejudice and national and religious intolerance", calling on governments to educate the public against intolerance and rescind discriminatory laws.[11] Lack of time prevented this from being considered by the General Assembly in 1961,[12] but it was passed the next year.[11] During the early debate on this resolution, African nations led by the Central African Republic, Chad, Dahomey, Guinea, Côte d'Ivoire, Mali, Mauritania, and Upper Volta pushed for more concrete action on the issue, in the form of an international convention against racial discrimination.[13] Some nations preferred a declaration rather than a binding convention, while others wanted to deal with racial and religious intolerance in a single instrument.[14] The eventual compromise, forced by the Arab nations' political opposition to treating religious intolerance at the same time as racial intolerance plus other nations' opinion that religious intolerance was less urgent,[15] was for two resolutions, one calling for a declaration and draft convention aimed at eliminating racial discrimination,[16] the other doing the same for religious intolerance.[17] Article 4, criminalizing incitement to racial discrimination, was also controversial in the drafting stage. In the first debate of the article, there were two drafts, one presented by the United States and one by the Soviet Union and Poland. The United States, supported by the United Kingdom, proposed that only incitement "resulting in or likely to result in violence" should be prohibited, whereas the Soviet Union wanted to "prohibit and disband racist, fascist and any other organization practicing or inciting racial discrimination". The Nordic countries proposed a compromise in which a clause of "due regard" to the rights Universal Declaration of Human Rights was added to be taken into account when crimininalizing hate speech.[18] The draft Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination was adopted by the General Assembly on 20 November 1963.[19] The same day the General Assembly called for the Economic and Social Council and the Commission on Human Rights to make the drafting of a Convention on the subject an absolute priority.[20] The draft was completed by mid-1964,[21] but delays in the General Assembly meant that it could not be adopted that year.[15] It was finally adopted on 21 December 1965.[8] |

はじまり 1960年12月、世界各地で反ユダヤ主義の事件が発生したことを受け[9]、国連総会は「人種、宗教、国家に対する憎悪のあらゆる表現や行為」を国連憲 章および世界人権宣言違反として非難し、すべての国家政府に対し「人種、宗教、国家に対する憎悪のあらゆる表現を防ぐために必要なあらゆる措置を講じる」 よう求める決議を採択した[1 0] 経済社会理事会はこれに続き、「人種的偏見と国家・宗教的不寛容の表れ」に関する決議案を起草し、各国政府に対して不寛容に対する国民の教育と差別的法の 撤廃を呼びかけた[11]。時間の不足により、1961年の総会では審議されなかった[12]が、翌年に可決された[11]。 この決議案の初期の議論において、中央アフリカ共和国、チャド、ダホメー、ギニア、コートジボワール、マリ、モーリタニア、およびウルバールを率いるアフ リカ諸国は 中央アフリカ共和国、チャド、ダホメー、ギニア、コートジボワール、マリ、モーリタニア、およびウルヴァルタが主導するアフリカ諸国は、この問題につい て、人種差別禁止条約という形でより具体的な行動を取るよう求めた[13]。一部の国は拘束力のある条約よりも宣言を望み、他の国は人種的・宗教的不寛容 を単一の文書で取り扱うことを望んだ[14]。最終的に、 これは、アラブ諸国の宗教的不寛容を人種的不寛容と同時に取り扱うことへの政治的反対と、宗教的不寛容はそれほど緊急性が高くないという他の国の意見に よって強要された妥協案であった[15]。 人種差別を扇動することを犯罪とする第4条も、草案作成段階で物議を醸した。この条文の最初の審議では、米国とソ連・ポーランドが提出した2つの草案が あった。米国は、英国の支持を受け、「暴力行為につながり、またはつながりかねない」扇動のみを禁止すべきだと提案したが、ソ連は「人種差別主義、ファシ ズム、および人種差別を助長または扇動するその他のあらゆる団体を禁止し解散させる」ことを望んでいた。北欧諸国は、ヘイトスピーチを犯罪とする際に考慮 すべき事項として、世界人権宣言の人権に「適切な配慮」を行うという条項を追加するという妥協案を提案した[18]。 あらゆる形態の人種差別の撤廃に関する宣言草案は、1963年11月20日に国連総会で採択された[19]。同日、総会は 経済社会理事会と人権委員会に対し、このテーマに関する条約の草案作成を最優先事項とするよう求めた[20]。草案は1964年中頃に完成したが [21]、総会での遅れにより、その年に採択されることはなかった[15]。最終的に採択されたのは1965年12月21日だった[8]。 |

| Core provisions Definition of "racial discrimination" Main articles: Racism and Discrimination Preamble of the Convention reaffirms dignity and equality before the law citing Charter of United Nations and Universal Declaration of Human Rights and condemns colonialism citing Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and also cites ILO Convention on Employment and Occupation (C111) and Convention against Discrimination in Education against discrimination. Article 1 of the Convention defines "racial discrimination" as: ... any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.[22] Distinctions made on the basis of citizenship (that is, between citizens and non-citizens) are specifically excluded from the definition, as are positive discrimination policies and other measures taken to redress imbalances and promote equality.[23] This definition does not distinguish between discrimination based on ethnicity and discrimination based on race, despite the following statement by anthropologists in the United Nations Economic and Social Council. 6. National, religious, geographic, linguistic and cultural groups do not necessarily coincide with racial groups; and the cultural traits of such groups have no demonstrated genetic connection with racial traits.[24] The clear conclusion in the report is that Race and Ethnicity can be correlated, but must not get mixed up. The inclusion of descent specifically covers discrimination on the basis of caste and other forms of inherited status.[25] Discrimination need not be strictly based on race or ethnicity for the Convention to apply. Rather, whether a particular action or policy discriminates is judged by its effects.[26] In seeking to determine whether an action has an effect contrary to the Convention, it will look to see whether that action has an unjustifiable disparate impact upon a group distinguished by race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin.[26] The question of whether an individual belongs to a particular racial group is to be decided, in the absence of justification to the contrary, by self-identification.[27] Prevention of discrimination Main articles: Anti-discrimination law, Equality before the law, and Institutionalized discrimination Article 1 of the Convention does not prohibit discrimination based on nationality, citizenship or naturalization but prohibits discrimination "against any particular nationality".[28] Article 2 of the Convention condemns racial discrimination and obliges parties to "undertake to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating racial discrimination in all its forms".[6] It also obliges parties to promote understanding among all races.[6] To achieve this, the Convention requires that signatories: Not practice racial discrimination in public institutions[29] Not "sponsor, defend, or support" racial discrimination[30] Review existing policies, and amend or revoke those that cause or perpetuate racial discrimination[31] Prohibit "by all appropriate means, including legislation," racial discrimination by individuals and organisations within their jurisdictions[32] Encourage groups, movements, and other means that eliminate barriers between races, and discourage racial division[33] Parties are obliged "when the circumstances so warrant" to use positive discrimination policies for specific racial groups to guarantee "the full and equal enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms".[34] However, these measures must be finite, and "shall in no case entail as a consequence the maintenance of unequal or separate rights for different racial groups after the objectives for which they were taken have been achieved".[34] Article 5 expands upon the general obligation of Article 2 and creates a specific obligation to guarantee the right of everyone to equality before the law regardless of "race, colour, or national or ethnic origin".[35] It further lists specific rights this equality must apply to: equal treatment by courts and tribunals,[36] security of the person and freedom from violence,[37] the civil and political rights affirmed in the ICCPR,[38] the economic, social and cultural rights affirmed in the ICESCR,[39] and the right of access to any place or service used by the general public, "such as transport hotels, restaurants, cafes, theatres and parks."[40] This list is not exhaustive, and the obligation extends to all human rights.[41] Article 6 obliges parties to provide "effective protection and remedies" through the courts or other institutions for any act of racial discrimination.[42] This includes a right to a legal remedy and damages for injury suffered due to discrimination.[42] Condemnation of apartheid Main article: Crime of apartheid Article 3 condemns apartheid and racial segregation and obliges parties to "prevent, prohibit and eradicate" these practices in territories under their jurisdiction.[43] This article has since been strengthened by the recognition of apartheid as a crime against humanity in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[44] The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination regards this article as also entailing an obligation to eradicate the consequences of past policies of segregation, and to prevent racial segregation arising from the actions of private individuals.[45] Prohibition of incitement Main articles: Hate speech, Hate crime, and Incitement to ethnic or racial hatred Article 4 of the Convention condemns propaganda and organizations that attempt to justify discrimination or are based on the idea of racial supremacism.[7] It obliges parties, "with due regard to the principles embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights", to adopt "immediate and positive measures" to eradicate these forms of incitement and discrimination.[7] Specifically, it obliges parties to criminalize hate speech, hate crimes and the financing of racist activities,[46] and to prohibit and criminalize membership in organizations that "promote and incite" racial discrimination.[47] A number of parties have reservations on this article, and interpret it as not permitting or requiring measures that infringe on the freedoms of speech, association or assembly.[48] The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination regards this article as a mandatory obligation of parties to the Convention,[49] and has repeatedly criticized parties for failing to abide by it.[50] It regards the obligation as consistent with the freedoms of opinion and expression affirmed in the UNDHR and ICCPR[51] and notes that the latter specifically outlaws inciting racial discrimination, hatred and violence.[52] It views the provisions as necessary to prevent organised racial violence and the "political exploitation of ethnic difference."[53] Promotion of tolerance Main article: Toleration Article 7 obliges parties to adopt "immediate and effective measures", particularly in education, to combat racial prejudice and encourage understanding and tolerance between different racial, ethnic and national groups.[54] Dispute resolution mechanism Articles 11 through 13 of the Convention establish a dispute resolution mechanism between parties. A party that believes another party is not implementing the Convention may complain to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.[55] The Committee will pass on the complaint, and if it is not resolved between the two parties, may establish an ad hoc Conciliation Commission to investigate and make recommendations on the matter.[56] This procedure has been first invoked in 2018, by Qatar against Saudi Arabia and UAE[57] and by Palestine against Israel.[58] Article 22 further allows any dispute over the interpretation or application of the Convention to be referred to the International Court of Justice.[59] This clause has been invoked three times, by Georgia against Russia,[60] by Ukraine against Russia,[61] by Qatar against UAE.[62] Individual complaints mechanism Article 14 of the Convention establishes an individual complaints mechanism similar to that of the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Parties may at any time recognise the competence of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination to consider complaints from individuals or groups who claim their rights under the Convention have been violated.[63] Such parties may establish local bodies to hear complaints before they are passed on.[64] Complainants must have exhausted all domestic remedies, and anonymous complaints and complaints that refer to events that occurred before the country concerned joined Convention are not permitted.[65] The Committee can request information from and make recommendations to a party.[65] The individual complaints mechanism came into operation in 1982, after it had been accepted by ten states-parties.[66] As of 2010, 58 states had recognised the competence of the Committee,[2] and 54 cases have been dealt with by the Committee.[67] |

中核条項 「人種的差別」の定義 主な項目:人種差別と差別 条約の前文では、国連憲章と世界人権宣言を引用し、法の下の平等と尊厳を再確認し、植民地主義を非難し、植民地諸国および人民の独立付与に関する宣言、あ らゆる形態の人種的差別の撤廃に関する宣言を引用し、また、ILO雇用及び職業に関する条約(C111)と教育における差別の撤廃に関する条約を引用し、 差別を非難している。 条約第1条では、「人種差別」を次のように定義している。 ... 人種、肌の色、家系、または民族的もしくは種族的出身に基づくあらゆる区別、排除、制限、または優先的取り扱いで、政治的、経済的、社会的、文化的、また はその他のあらゆる公共生活分野における人権および基本的自由の平等の立場での承認、享受、または行使を無効にする、または損なうことを目的とする、また はそのような効果をもたらすもの[22]。 市民権(すなわち、市民と非市民)を根拠とした区別は 市民権(つまり、市民と非市民)を基準とした区別は、定義から明確に除外されている。また、ポジティブ・ディシジョン(積極的差別是正措置)や、不均衡を 是正し平等を促進するためのその他の措置も定義から除外されている[23]。 この定義では、民族に基づく差別と人種に基づく差別が区別されていないが、国連経済社会理事会の人類学者による以下の記述がある。 6. 国家、宗教、地理、言語、文化的なグループは人種グループと必ずしも一致するわけではなく、またそのようなグループの文化的特徴は人種の特徴と遺伝学的に関連があるわけではない[24]。 報告書で明確に述べられている結論は、人種と民族性は相関関係にあるが、混同してはならないということである。血統の包含は、特にカーストやその他の遺伝 的地位に基づく差別をカバーする[25]。条約が適用されるためには、差別が厳密に人種や民族に基づく必要は無い。むしろ、特定の行動や政策が差別的であ るかどうかは、その影響によって判断される[26]。 ある行動が条約に反する影響をもたらすかどうかを判断する際には、その行動が、人種、肌の色、出身、または民族的もしくは種族的出身によって区別される集 団に対して、正当化できない不均衡な影響を与えているかどうかが検討される 、肌の色、家系、または民族的もしくは種族的出身による差別的影響があるかどうかが判断される[26]。 ある個人が特定の人種集団に属しているかどうかは、反対の正当な理由がない限り、自己申告によって決定される[27]。 差別の防止 主な項目: 反差別法、法の下の平等、制度化された差別 条約第1条は、国籍、市民権、帰化に基づく差別を禁止するものではないが、「特定の国籍に対する」差別を禁止している[28]。 条約第2条は人種的差別を非難し、 「あらゆる形態の人種的差別を撤廃するための政策を、あらゆる適切な手段を用いて、遅滞なく追求することを約束」することを義務付けている[6]。また、 すべての民族間の理解を促進することも義務付けている[6]。これを達成するために、この条約は加盟国に以下のことを求めている。 公的機関において人種差別を行わない[29]。 人種差別を「後援、擁護、支持」しない[30]。 既存の政策を見直し、人種差別を引き起こす、または助長する政策を改正または廃止する[31]。 管轄内の個人や組織による人種差別を、「立法を含むあらゆる適切な手段」で禁止する[32]。 人種間の障壁をなくし、人種的分断を助長しないような団体、運動、その他の手段を奨励する[33]。 締約国は、「 「状況がそのように正当化される場合」には、特定の人種グループに対して積極的差別政策を採用し、「人権と基本的自由の完全なかつ平等の享受」を保障する 義務がある[34]。ただし、これらの措置は限定的なものでなければならず、「いかなる場合においても、その措置が取られた目的が達成された後に、異なる 人種グループに対して不平等または分離した権利を維持する結果をもたらすものであってはならない」[34]。 第5条では、第2条の一般的な義務をさらに拡大し、特定の義務を定めている。「人種、皮膚の色、または民族的もしくは種族的出身」にかかわらず、すべての 人々の法の下の平等を保障することである[35]。さらに、この平等の適用対象となる具体的な権利を列挙している。すなわち、裁判所および法廷による平等 な扱い[36]、身体の安全および暴力からの自由[37]、国際人権規約で認められた市民的および政治的権利[38]、国際人権規約で認められた経済的、 社会的および文化的権利[39]、および 「交通機関、ホテル、レストラン、カフェ、劇場、公園など、一般市民が利用するあらゆる場所やサービス」[40] へのアクセスの権利。このリストは網羅的なものではなく、義務はあらゆる人権に及ぶ[41]。 第6条は、締約国に対し、人種差別的行為に対して裁判所やその他の機関を通じて「効果的な保護と救済」[42] を提供することを義務付けている。これには、差別による被害に対する法的救済と損害賠償を受ける権利が含まれる[42]。 アパルトヘイトの非難 メイン記事: アパルトヘイトの犯罪 第3条はアパルトヘイトと人種隔離を非難し、締約国に対し、その管轄下にある領域においてこれらの慣行を「防止し、禁止し、根絶」することを義務付けてい る[43]。この条項は、国際刑事裁判所ローマ規程においてアパルトヘイトが人道に対する罪として認定されたことにより、強化された[44]。国際刑事裁 判所ローマ規程でアパルトヘイトが人道に対する罪として認定されたことにより、この条文は強化された[44]。 人種差別撤廃委員会は、この条文は過去の隔離政策がもたらした結果を根絶し、個人の行動に起因する人種的隔離を防ぐ義務も伴うとみなしている[45]。 扇動の禁止 主な項目: ヘイトスピーチ、ヘイトクライム、民族または人種的憎悪の扇動 条約第4条は、差別を正当化しようとする宣伝や人種至上主義の思想に基づく団体を非難している[7]。締約国に対し、「世界人権宣言に具現化された原則に 十分な配慮を払いつつ」、これらの扇動や差別を根絶するための「即時かつ積極的な措置」を講じることを義務付けている[7]。具体的には、締約国に対し、 ヘイトスピーチ、ヘイトクライム、人種差別主義的活動の資金調達を犯罪化[46]し、人種差別を「助長し扇動」する団体の加入を禁止し犯罪化[47]する ことを義務付けている。 ヘイトスピーチ、ヘイトクライム、人種差別主義的活動の資金調達を犯罪化すること[46]、そして人種差別を「助長し扇動」する団体のメンバーシップを禁 止し犯罪化すること[47]を締約国に義務付けている。 人種差別撤廃委員会は、この条項を条約の締約国に対する義務的な義務とみなしている [49]、そして、締約国がこれを順守していないことを繰り返し批判してきた[50]。同委員会は、この義務は、世界人権宣言および国際人権規約で認めら れた意見および表現の自由と矛盾しない[51]とし、後者は特に人種差別、憎悪、暴力を扇動することを禁じている[52]と指摘している。同委員会は、こ の規定は組織的な人種的暴力を防止し、「民族的差異の政治的利用」を防ぐために必要であるとみなしている[53]。 寛容の促進 メイン記事: 寛容 第7条は、締約国に対し、人種的偏見と闘い、異なる人種、民族、国家集団間の理解と寛容を奨励するために、特に教育において「即時かつ効果的な措置」を講じることを義務付けている[54]。 紛争解決メカニズム 条約の第11条から第13条は、締約国間の紛争解決メカニズムを確立している。ある締約国が他の締約国が条約を履行していないと考える場合、人種差別撤廃 委員会に苦情を申し出ることができる[55]。委員会は苦情を両締約国に伝え、両者間で解決に至らない場合は、その問題について調査し勧告を行うための臨 時調停委員会を設置することができる[56]。この手続きは、2018年に初めてカタールがサウジアラビアとアラブ首長国連邦に対して[57]、パレスチ ナがイスラエルに対して[58]、それぞれ申し立てた。 2018年に、カタールがサウジアラビアとアラブ首長国連邦に対して[57]、パレスチナがイスラエルに対して[58]、初めてこの手続きを求めた。 第22条では、この条約の解釈や適用に関するあらゆる紛争を国際司法裁判所に付託することを認めている[59]。この条項はこれまでに3回、グルジアがロ シアに対して[60]、ウクライナがロシアに対して[ 61]、カタールによるアラブ首長国連邦に対するもの[62]である。 個人による苦情処理メカニズム 条約の第14条は、市民的及び政治的権利に関する国際規約の第1選択議定書、障害者権利条約の選択議定書、女性に対するあらゆる形態の差別の撤廃に関する 条約の選択議定書と同様の個人による苦情処理メカニズムを規定している。締約国は、いつでも、人種差別撤廃委員会が、条約に基づく権利が侵害されたと主張 する個人または集団からの苦情を検討する権限を有することを認めることができる[63]。このような締約国は、苦情が委員会に送られる前にそれを審理する 国内機関を設置することができる[64]。苦情を申し出る者は、国内救済手段をすべて尽くさなければならず、匿名の苦情や、当該国が条約に加盟する前の出 来事を指す苦情は認められない [65]。委員会は締約国に対して情報の提供を要求し、勧告を行うこともできる[65]。 個人通報制度は、10の締約国によって受け入れられた後、1982年に運用が開始された[66]。2010年現在、58カ国が委員会の権限を承認しており[2]、委員会が扱った事例は54件に上る[67]。 |

| Reservations A number of parties have made reservations and interpretative declarations to their application of the Convention. The Convention text forbids reservations "incompatible with the object and purpose of this Convention" or that would inhibit the operation of any body established by it.[68] A reservation is considered incompatible or inhibitive if two-thirds of parties object to it.[68] Article 22 Afghanistan, Bahrain, China, Cuba, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Israel, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Madagascar, Morocco, Mozambique, Nepal, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, Vietnam, and Yemen do not consider themselves bound by Article 22. Some interpret this article as allowing disputes to be referred to the International Court of Justice only with the consent of all involved parties.[2] Obligations beyond existing constitution Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, Thailand and United States interpret the Convention as not implying any obligations beyond the limits of their existing constitutions.[2] Hate speech Austria, Belgium, France, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Malta, Monaco, Switzerland and Tonga all interpret Article 4 as not permitting or requiring measures that threaten the freedoms of speech, opinion, association, and assembly.[2] Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Fiji, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, Thailand and United Kingdom interpret the Convention as creating an obligation to enact measures against hate speech and hate crimes only when a need arises. The United States of America "does not accept any obligation under this Convention, in particular under articles 4 and 7, to restrict those [extensive protections of individual freedom of speech, expression and association contained in the Constitution and laws of the United States], through the adoption of legislation or any other measures, to the extent that they are protected by the Constitution and laws of the United States."[2] Immigration Monaco and Switzerland reserve the right to apply their own legal principles on the entry of foreigners into their labour markets.[2] The United Kingdom does not regard the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 and Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968 as constituting any form of racial discrimination.[2] Indigenous people Tonga reserves the right not to apply the Convention to any restriction on the alienation of land held by indigenous Tongans. Fiji has significant reservations around Article 5, and reserves the right not to implement those provisions if they are incompatible with existing law on voting rights, the alienation of land by indigenous Fijians.[2] |

留保 多数の締約国が条約の適用について留保および解釈宣言を行っている。条約の本文では、「この条約の目的および趣旨に反する」留保や、条約によって設立され た機関の活動を妨げるような留保を禁じている[68]。留保が条約の目的や趣旨に反するか、あるいは条約によって設立された機関の活動を妨げるものである とみなされるためには、締約国の3分の2がこれに反対する必要がある[68]。 第22条 アフガニスタン 、バーレーン、中国、キューバ、エジプト、赤道ギニア、インド、インドネシア、イラク、イスラエル、クウェート、レバノン、リビア、マダガスカル、モロッ コ、モザンビーク、ネパール、サウジアラビア、シリア、タイ、トルコ、ベトナム、イエメンは、第22条に拘束されないとしている。この条文は、紛争を国際 司法裁判所に付託できるのは、関係するすべての当事者の同意がある場合のみであると解釈する国もある[2]。 現行憲法を超える義務 アンティグア・バーブーダ、バハマ、バルバドス、ガイアナ、ジャマイカ、ネパール、パプアニューギニア、タイ、米国は、この条約は、現行憲法の限界を超える義務を意味するものではないと解釈している[2]。 ヘイトスピーチ オーストリア、ベルギー、フランス、アイルランド、 イタリア、日本、マルタ、モナコ、スイス、トンガは、第4条が言論、意見、結社、集会の自由を脅かすような措置を許可または要求するものではないと解釈し ている[2]。アンティグア・バーブーダ、バハマ、バルバドス、フィジー、ネパール、パプアニューギニア、タイ、イギリスは、ヘイトスピーチやヘイトクラ イムに対する措置を制定する義務は、必要性が生じた場合にのみ生じるものと条約を解釈している。 アメリカ合衆国は、「この条約、特に第4条および第7条に基づく義務を一切受け入れない。すなわち、合衆国憲法および法律によって保護されている範囲にお いて、立法措置またはその他の措置の採用によって、合衆国憲法および法律によって保護されている(合衆国憲法および法律に規定されている広範な個人の言 論、表現、結社の自由)を制限する義務を一切受け入れない」[2]。 移民 モナコとスイス 自国の労働市場への外国人の入国について、独自の法的原則を適用する権利を留保している[2]。イギリスは、1962年英連邦移民法および1968年英連邦移民法を人種差別を構成するものとみなしていない[2]。 先住民 トンガは、先住民であるトンガ人が所有する土地の譲渡制限について、同条約を適用しない権利を留保している。フィジーは、第5条に重大な留保を置き、これ らの規定が、フィジー先住民による土地の所有権放棄や投票権に関する現行法と矛盾する場合は、それらの規定を実施しない権利を留保している[2]。 |

| Jurisprudence At the CERD The individual complaints mechanism has led to a limited jurisprudence on the interpretation and implementation of the Convention. As at September 2011, 48 complaints have been registered with the Committee; 17 of these have been deemed inadmissible, 16 have led to a finding of no violation, and in 11 cases a party has been found to have violated the Convention. Three cases were still pending.[69] Several cases have dealt with the treatment of Romani people in Eastern Europe. In Koptova v. Slovakia the Committee found that resolutions by several villages in Slovakia forbidding the residence of Roma were discriminatory and restricted freedom of movement and residence, and recommended the Slovak government take steps to end such practices.[70] In L.R. v. Slovakia the Committee found that the Slovak government had failed to provide an effective remedy for discrimination suffered by Roma after the cancellation of a housing project on ethnic grounds.[71] In Durmic v. Serbia and Montenegro the Committee found a systemic failure by the Serbian government to investigate and prosecute discrimination against Roma in access to public places.[72] In several cases, notably L.K. v. Netherlands and Gelle v. Denmark, the Committee has criticized parties for their failure to adequately prosecute acts of racial discrimination or incitement. In both cases, the Committee refused to accept "any claim that the enactment of law making racial discrimination a criminal act in itself represents full compliance with the obligations of States parties under the Convention".[73] Such laws "must also be effectively implemented by the competent national tribunals and other State institutions".[74] While the Committee accepts the discretion of prosecutors on whether or not to lay charges, this discretion "should be applied in each case of alleged racial discrimination in the light of the guarantees laid down in the Convention"[75] In The Jewish community of Oslo et al. v. Norway, the Committee found that the prohibition of hate speech was compatible with freedom of speech, and that the acquittal of a neo-Nazi leader by the Supreme Court of Norway on freedom of speech grounds was a violation of the Convention.[76] In Hagan v. Australia, the Committee ruled that, while not originally intended to demean anyone, the name of the "E. S. 'Nigger' Brown Stand" (named in honour of 1920s rugby league player Edward Stanley Brown) at a Toowoomba sports field was racially offensive and should be removed.[77] At the ICJ Georgia won a judgment for a provisional measure of protection at the ICJ over the Russian Federation in the case of Russo-Georgian War. |

法学 CERD において 個人苦情処理メカニズムにより、条約の解釈と実施に関する限定的な法学が生まれた。2011年9月時点で、委員会には48件の苦情が登録されており、そのうち17件は受理不可、16件は違反なし、11件は条約違反と認定された。3件は依然として保留中である[69]。 いくつかの事例では、東ヨーロッパにおけるロマ人の扱いについて取り上げられている。コプトヴァ対スロバキア事件において、委員会は、スロバキア国内のい くつかの村がロマ人の居住を禁じる決議を差別的であり、移動と居住の自由を制限するものであると認定し、スロバキア政府に対し、このような慣行を終わらせ る措置を講じるよう勧告した[70]。L.R.対スロバキア事件において、委員会は、スロバキア政府が、民族的理由による住宅建設計画の取り消し後にロマ 人が受けた差別に対して効果的な救済措置を講じなかったと認定した[71]。プロジェクトが民族的な理由により中止された後、ロマの人々が受けた差別に対 して、スロバキア政府が効果的な救済措置を講じなかったと委員会は判断した[71]。 L.K. v. Netherlands(オランダ対L.K.)やGelle v. Denmark(デンマーク対Gelle)などのいくつかのケースにおいて、委員会は、人種差別や扇動行為を適切に起訴しなかった当事国を批判している。 いずれの場合も、委員会は「人種差別を犯罪行為とみなす法律の制定自体が、条約に基づく締約国の義務を完全に遵守していることを示すいかなる主張も」 [73] 受け入れることを拒否した。このような法律は、「管轄の国内裁判所やその他の国家機関によって効果的に実施されなければならない」[74]。委員会は、起 訴するか否かの検察官の裁量を受け入れるが、この裁量権は「条約に定められた保障に照らして、人種差別が疑われる各事例に適用されるべきである」 [75]。「条約に定められた保障に照らして、人種差別が疑われる各事例に適用されるべきである」[75]。 「オスロ・ユダヤ人共同体対ノルウェー」事件において、委員会はヘイトスピーチの禁止は言論の自由と両立し、ノルウェー最高裁が言論の自由を理由にネオナチ指導者を無罪としたことは条約違反であると判断した[76]。 「ヘーガン対オーストラリア」事件において、委員会は、 誰かを貶める意図はなかったが、「E. S. 'Nigger' Brown Stand」(1920年代のラグビーリーグ選手、エドワード・スタンリー・ブラウンにちなんで名付けられた)というトゥーンバのスポーツ競技場の名称は 人種差別的であり、削除されるべきであると委員会は裁定した[77]。 国際司法裁判所 グルジアは、国際司法裁判所において、ロシア連邦に対する暫定的な保護措置を求める判決を勝ち取った。 |

| Impact The impact of an international treaty can be measured in two ways: by its acceptance, and by its implementation.[78][79] On the first measure, the Convention has gained near-universal acceptance by the international community, with fewer than twenty (mostly small) states yet to become parties.[2] Most major states have also accepted the Convention's individual complaints mechanism, signaling a strong desire to be bound by the Convention's provisions.[2] The Convention has faced persistent problems with reporting since its inception, with parties frequently failing to report fully,[80] or even at all.[81] As of 2008, twenty parties had failed to report for more than ten years, and thirty parties had failed to report for more than five.[82] One party, Sierra Leone, had failed to report since 1976, while two more – Liberia and Saint Lucia had never met their reporting requirements under the Convention.[83] The Committee has responded to this persistent failure to report by reviewing the late parties anyway – a strategy that has produced some success in gaining compliance with reporting requirements.[84] This lack of reporting is seen by some as a significant failure of the Convention.[85] However the reporting system has also been praised as providing "a permanent stimulus inducing individual States to enact anti-racist legislation or amend the existing one when necessary."[86] |

影響 国際条約の影響は、2つの方法で測定できる。すなわち、条約の受け入れと条約の実施である[78][79]。最初の基準では、この条約は国際社会からほぼ 普遍的に受け入れられており、まだ締約国になっていない国(ほとんどが小国)は20カ国未満である[2]。また、ほとんどの主要国は、この条約の個別苦情 処理メカニズムも受け入れている。これは、この条約の規定に拘束されることを強く望んでいることを示している[2]。この条約は 発効以来、締約国による報告には常に問題があり、報告が完全に行われないこともあれば、まったく行われないこともある[80]。2008年時点で、20の 締約国が10年以上報告を行っておらず、30の締約国が5年以上報告を行っていない[82]。シエラレオネは1976年以来一度も報告を行っていない。ま た、リベリアとセントルシアは、条約に基づく報告義務を一度も果たしていない[83]。条約の下で報告義務を果たしたことがない[83]。委員会は、この 報告義務の不履行に対して、遅れて参加した締約国についても審査するという対応をとってきた。この戦略は、報告義務の遵守を促す上で一定の成果を上げてい る[84]。報告義務の不履行は、条約の重大な欠陥であると見る向きもある[85]。しかし、報告制度は、「個々の国家が反人種差別法を制定したり、必要 に応じて既存の法律を改正したりすることを促す恒久的な刺激」を提供していると評価されている[86]。 |

| Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination is a body of human rights experts tasked with monitoring the implementation of the Convention. It consists of 18 independent human rights experts, elected for four-year terms, with half the members elected every two years. Members are elected by secret ballot of the parties, with each party allowed to nominate one of its nationals to the Committee.[87] All parties are required to submit regular reports to the Committee outlining the legislative, judicial, policy and other measures they have taken to give effect to the Convention. The first report is due within a year of the Convention entering into effect for that state; thereafter reports are due every two years or whenever the Committee requests.[88] The Committee examines each report and addresses its concerns and recommendations to the state party in the form of "concluding observations". On 10 August 2018, United Nations human rights experts expressed alarm over many credible reports that China had detained a million or more ethnic Uyghurs in Xinjiang.[89] Gay McDougall, a member of the Committee, said that "In the name of combating religious extremism, China had turned Xinjiang into something resembling a massive internment camp, shrouded in secrecy, a sort of no-rights zone."[90] On 13 August 2019, the Committee considered the first report submitted by the Palestinian Authority. A number of experts questioned the delegation regarding antisemitism, particularly in textbooks.[91] Silvio José Albuquerque e Silva (Brazil) also raised evidence of discrimination against Roma and other minorities, the status of women, and oppression of the LGBT community.[92] The Committee's report[93] of 30 August 2019 reflected these concerns.[94] On 23 April 2018 Palestine filed an inter-state complaint against Israel for breaches of its obligations under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD).[95][96] On 4 and 5 December 2019, the Committee considered the report submitted by Israel and in its conclusions of 12 December[97] noted that it is worried about "existing discriminatory legislation, the segregation of Israeli society into Jewish and non-Jewish sectors" and other complaints." The Committee also decided that it has jurisdiction regarding the inter-State communication submitted by the State of Palestine on 23 April 2018 against the State of Israel.[98] Israel's Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded by alleging bias by the committee members, noting that their "blatant anti-Israel posture, and reckless disregard for the welfare of Israelis, is a shocking neglect of the duties of the CERD Committee to act with impartiality and objectivity."[95] The Committee typically meets every March and August in Geneva.[99] The current (as of February 2024) membership of the Committee is:[100]  |

人種差別撤廃委員会 人種差別撤廃委員会は、条約の実施状況を監視する任務を負った人権問題の専門家で構成される機関である。 4年任期で選出される18人の独立した人権問題の専門家で構成され、2年ごとに半数の委員が改選される。委員は各政党の無記名投票により選出され、各政党 は自国民を1名ずつ委員会に推薦することができる[87]。 すべての加盟国は、条約を履行するためにとった立法、司法、政策、その他の措置の概要を記載した定期報告を委員会に提出することが義務付けられている。最 初の報告書は、その条約が発効してから1年以内に提出しなければならない。その後は2年ごとに、または委員会が要請するたびに提出しなければならない [88]。委員会は各報告書を検討し、懸念事項や勧告を「最終見解」という形で締約国に伝える。 2018年8月10日、国連人権専門家は、中国が新疆ウイグル自治区で100万人以上のウイグル族を拘束しているという多くの信頼できる報告について、懸 念を表明した[89]。同委員会の委員であるゲイ・マクドゥガルは、「宗教的過激主義との闘いという名目で、 宗教的過激主義との闘いという名目で、中国は新疆を秘密主義に覆われた大規模な収容所のような場所、いわば無権利地帯に変えてしまった」[90]。 2019年8月13日、委員会はパレスチナ自治政府から提出された最初の報告書を検討した。多くの専門家が、特に教科書における反ユダヤ主義について代表 団に質問した[91]。シルヴィオ・ジョゼ・アルブケルケ・エ・シルヴァ(ブラジル)も、ロマ族やその他の少数民族に対する差別、女性の地位、LGBTコ ミュニティへの抑圧の証拠を提示した[92]。2019年8月30日の委員会の報告書[93]には、これらの懸念が反映されていた[94]。2018年4 月23日、パレスチナは パレスチナは2018年4月23日、あらゆる形態の人種差別撤廃条約(ICERD)に基づく義務違反を理由にイスラエルを相手取り、国家間の苦情を申し立 てた[95][96]。 2019年12月4日と5日、委員会はイスラエルが提出した報告書を検討し、12月12日の結論[97]で、「既存の差別的な法律、イスラエル社会のユダ ヤ人と非ユダヤ人への分離」やその他の苦情について懸念していると指摘した。委員会はまた、パレスチナ国が2018年4月23日にイスラエル国に対して提 出した国家間通報についても管轄権を有すると決定した[98]。これに対し、イスラエル外務省は、委員会メンバーの偏りを指摘し、「あからさまな反イスラ エル姿勢と、 「イスラエル国民の福祉を無視した彼らの露骨な反イスラエル姿勢は、公平性と客観性をもって行動するというCERD委員会の義務を無視した衝撃的な怠慢で ある」[95]。 委員会は通常、毎年3月と8月にジュネーブで会合を開く[99]。2024年2月現在の委員会のメンバーは以下のとおりである[100]。  |

| Opposition In Malaysia On 8 December 2018, two of Malaysia's major right wing political parties – the Islamist Malaysian Islamic Party and the ethnonationalist United Malays National Organisation – organized a "Anti-ICERD Peaceful Rally" with the support of several non-government organizations on fears of the convention allegedly compromising bumiputera privileges and special positions of the Malay people and Islam in the country,[101] a major tenet held by both these parties. This rally was held in the capital of the country, Kuala Lumpur.[102] |

反対 マレーシア 2018年12月8日、マレーシアの主要な右翼政党であるイスラム主義政党のマレーシア・イスラム党と民族主義政党の統一マレー国民機構の2党は、非政府 組織数団体の支援を受け、同条約がマレー系住民とイスラム教徒の特権と地位を損なうという懸念から、「反ICERD平和 この集会は、同条約がマレー系住民とイスラム教徒の特権と特別な地位を損なうという懸念から、マレーシアの主要な右翼政党であるイスラム主義政党「マレー シア・イスラム党」と民族主義政党「統一マレー国民機構」が、複数の非政府組織の支援を受けて開催したものだった[101]。この集会は、同国の首都クア ラルンプールで開催された[102]。 |

| Anti-ICERD Rally in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Anti-racism Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination Discrimination based on nationality Environmental racism Environmental racism in Europe Racial Equality Proposal, 1919 World Conference against Racism |

マレーシア・クアラルンプールでの反ICERD集会 反人種差別 あらゆる形態の人種的差別撤廃宣言 国籍に基づく差別 環境人種差別 ヨーロッパにおける環境人種差別 1919年の人種的平等の提案 人種差別反対世界会議 |

| https://x.gd/ypoVP |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆