消去法的唯物論

Eliminativer Materialismus, Eliminative

materialism

☆ 消去法による唯物論(消去主義とも呼ばれる)は、心の哲学における唯物論の立場であり、フォークサイコロジーにおける精神状態の大半は存在しないという考 え方を示すものである。[1] 消去主義の支持者の中には、信念や願望など、日常的な心理的概念の多くは定義が曖昧であるため、首尾一貫した神経学的根拠は見つからないと主張する者もい る。行動や経験に関する心理的概念は、それが生物学的なレベルにどれだけ還元できるかによって判断されるべきであるという主張がある。[2] その他のバージョンでは、痛みや視覚知覚などの意識的な心理状態の存在を否定する。[3] ある種の存在に関する消去主義とは、その種の存在は存在しないという見解である。[4] 例えば、唯物論は魂について消去主義的であり、近代の化学者はフロギストンについて消去主義的であり、近代の生物学者はエラン・ヴィタルについて消去主義 的であり、近代の物理学者は光輝エーテルについて消去主義的である。消去法による唯物論は、信念、欲望、痛みの主観的な感覚など、常識が当然のことと考え る特定の精神的存在は存在しないという、比較的新しい(1960年代から70年代)考え方である。 [5][6] 最も一般的なものは、ポールとパトリシア・チャーチランドが表明した命題的態度に関する消去主義[7]、およびダニエル・デネット、ジョルジュ・レイ、 ジャシー・リース・アンティスが表明したクオリア(主観的経験の特定の事例に関する主観的解釈)に関する消去主義である。

| Eliminative

materialism (also called eliminativism) is a materialist position in

the philosophy of mind that expresses the idea that the majority of

mental states in folk psychology do not exist.[1] Some supporters of

eliminativism argue that no coherent neural basis will be found for

many everyday psychological concepts such as belief or desire, since

they are poorly defined. The argument is that psychological concepts of

behavior and experience should be judged by how well they reduce to the

biological level.[2] Other versions entail the nonexistence of

conscious mental states such as pain and visual perceptions.[3] Eliminativism about a class of entities is the view that the class of entities does not exist.[4] For example, materialism tends to be eliminativist about the soul; modern chemists are eliminativist about phlogiston; modern biologists are eliminativist about élan vital; and modern physicists are eliminativist about luminiferous ether. Eliminative materialism is the relatively new (1960s–70s) idea that certain classes of mental entities that common sense takes for granted, such as beliefs, desires, and the subjective sensation of pain, do not exist.[5][6] The most common versions are eliminativism about propositional attitudes, as expressed by Paul and Patricia Churchland,[7] and eliminativism about qualia (subjective interpretations about particular instances of subjective experience), as expressed by Daniel Dennett, Georges Rey,[3] and Jacy Reese Anthis.[8] In the context of materialist understandings of psychology, eliminativism is the opposite of reductive materialism, arguing that mental states as conventionally understood do exist, and directly correspond to the physical state of the nervous system.[9] An intermediate position, revisionary materialism, often argues the mental state in question will prove to be somewhat reducible to physical phenomena—with some changes needed to the commonsense concept.[1][10] Since eliminative materialism arguably claims that future research will fail to find a neuronal basis for various mental phenomena, it may need to wait for science to progress further. One might question the position on these grounds, but philosophers like Churchland argue that eliminativism is often necessary in order to open the minds of thinkers to new evidence and better explanations.[9] Views closely related to eliminativism include illusionism and quietism. |

消去法による唯物論(消去主義とも呼ばれる)は、心の哲学における唯物

論の立場であり、フォークサイコロジーにおける精神状態の大半は存在しないという考え方を示すものである。[1]

消去主義の支持者の中には、信念や願望など、日常的な心理的概念の多くは定義が曖昧であるため、首尾一貫した神経学的根拠は見つからないと主張する者もい

る。行動や経験に関する心理的概念は、それが生物学的なレベルにどれだけ還元できるかによって判断されるべきであるという主張がある。[2]

その他のバージョンでは、痛みや視覚知覚などの意識的な心理状態の存在を否定する。[3] ある種の存在に関する消去主義とは、その種の存在は存在しないという見解である。[4] 例えば、唯物論は魂について消去主義的であり、近代の化学者はフロギストンについて消去主義的であり、近代の生物学者はエラン・ヴィタルについて消去主義 的であり、近代の物理学者は光輝エーテルについて消去主義的である。消去法による唯物論は、信念、欲望、痛みの主観的な感覚など、常識が当然のことと考え る特定の精神的存在は存在しないという、比較的新しい(1960年代から70年代)考え方である。 [5][6] 最も一般的なものは、ポールとパトリシア・チャーチランドが表明した命題的態度に関する消去主義[7]、およびダニエル・デネット、ジョルジュ・レイ、 ジャシー・リース・アンティスが表明したクオリア(主観的経験の特定の事例に関する主観的解釈)に関する消去主義である。 唯物論的な心理学の理解においては、消去主義は還元主義的唯物論の対極に位置づけられ、従来から理解されているような精神状態は存在し、神経系の物理的状 態に直接対応していると主張する。[9] 中間的な立場である修正的唯物論は、問題となっている精神状態は常識的概念に若干の変更を加える必要はあるものの、物理現象にいくらか還元できることを証 明するだろうと主張することが多い。[1][10] 消去法による唯物論は、おそらく今後の研究ではさまざまな精神現象の神経学的根拠は見つからないと主張しているため、科学がさらに進歩するのを待つ必要が あるかもしれない。このような理由から消去法による唯物論に疑問を呈する人もいるが、チャーチランドのような哲学者は、消去主義は思想家の心に新しい証拠 やより優れた説明を受け入れる余地を残すためにしばしば必要であると主張している。[9] 消去法による唯物論と密接に関連する見解には、幻想説と静寂説がある。 |

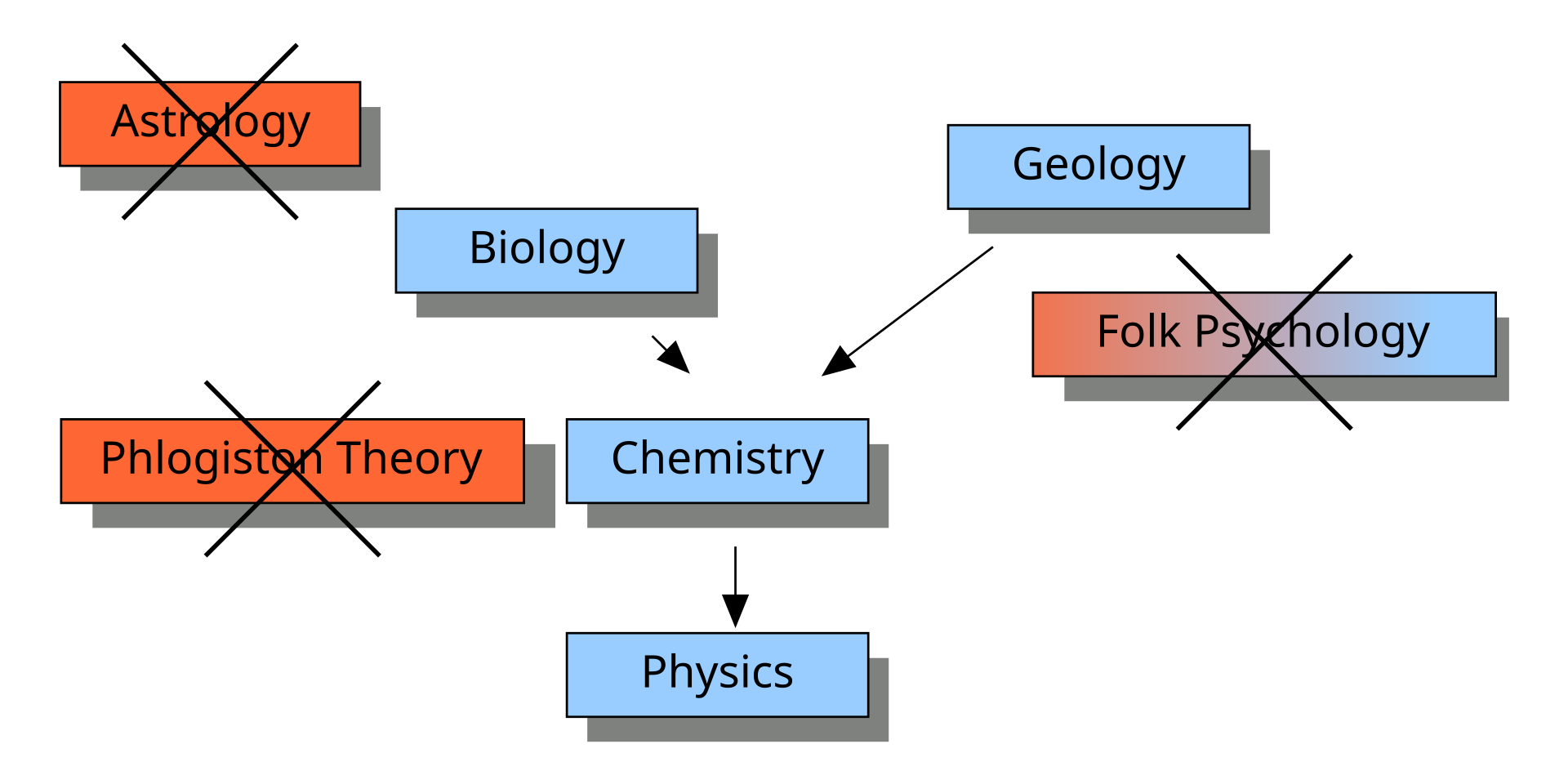

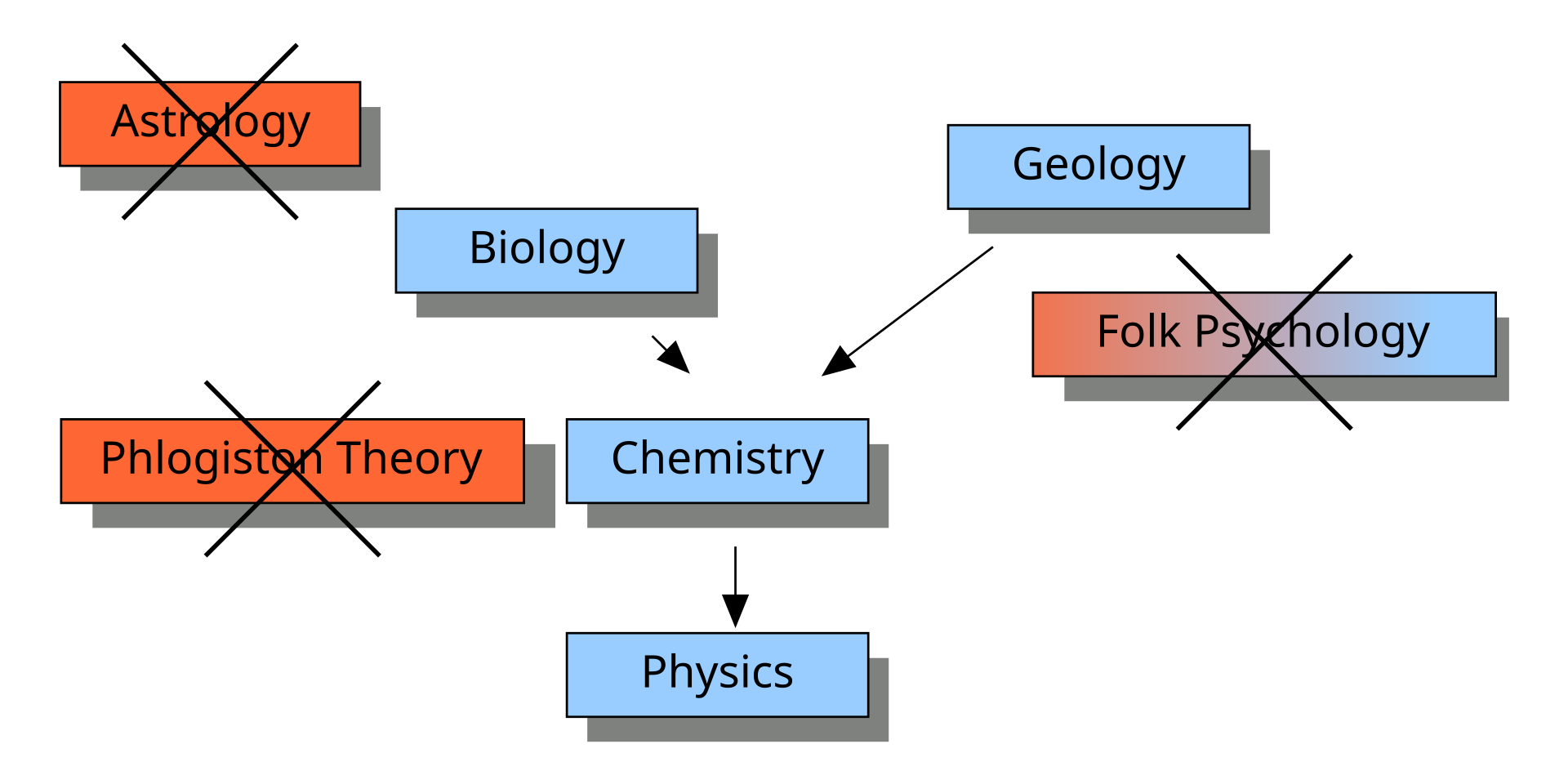

| Overview Various arguments have been made for and against eliminative materialism over the last 50 years. The view's history can be traced to David Hume, who rejected the idea of the "self" on the grounds that it was not based on any impression.[11] Most arguments for the view are based on the assumption that people's commonsense view of the mind is actually an implicit theory. It is to be compared and contrasted with other scientific theories in its explanatory success, accuracy, and ability to predict the future. Eliminativists argue that commonsense "folk" psychology has failed and will eventually need to be replaced by explanations derived from neuroscience. These philosophers therefore tend to emphasize the importance of neuroscientific research as well as developments in artificial intelligence. Philosophers who argue against eliminativism may take several approaches. Simulation theorists, like Robert Gordon[12] and Alvin Goldman,[13] argue that folk psychology is not a theory, but depends on internal simulation of others, and therefore is not subject to falsification in the same way that theories are. Jerry Fodor, among others,[14] argues that folk psychology is, in fact, a successful (even indispensable) theory. Another view is that eliminativism assumes the existence of the beliefs and other entities it seeks to "eliminate" and is thus self-refuting.[15]  Schematic overview: Eliminativists suggest that some sciences can be reduced (blue), but that theories that are in principle irreducible will eventually be eliminated (orange). Eliminativism maintains that the commonsense understanding of the mind is mistaken, and that neuroscience will one day reveal that mental states talked about in everyday discourse, using words such as "intend", "believe", "desire", and "love", do not refer to anything real. Because of the inadequacy of natural languages, people mistakenly think that they have such beliefs and desires.[2] Some eliminativists, such as Frank Jackson, claim that consciousness does not exist except as an epiphenomenon of brain function; others, such as Georges Rey, claim that the concept will eventually be eliminated as neuroscience progresses.[3][16] Consciousness and folk psychology are separate issues, and it is possible to take an eliminative stance on one but not the other.[4] The roots of eliminativism go back to the writings of Wilfred Sellars, W.V.O. Quine, Paul Feyerabend, and Richard Rorty.[5][6][17] The term "eliminative materialism" was first introduced by James Cornman in 1968 while describing a version of physicalism endorsed by Rorty. The later Ludwig Wittgenstein was also an important inspiration for eliminativism, particularly with his attack on "private objects" as "grammatical fictions".[4] Early eliminativists such as Rorty and Feyerabend often confused two different notions of the sort of elimination that the term "eliminative materialism" entailed. On the one hand, they claimed, the cognitive sciences that will ultimately give people a correct account of the mind's workings will not employ terms that refer to commonsense mental states like beliefs and desires; these states will not be part of the ontology of a mature cognitive science.[5][6] But critics immediately countered that this view was indistinguishable from the identity theory of mind.[2][18] Quine himself wondered what exactly was so eliminative about eliminative materialism: Is physicalism a repudiation of mental objects after all, or a theory of them? Does it repudiate the mental state of pain or anger in favor of its physical concomitant, or does it identify the mental state with a state of the physical organism (and so a state of the physical organism with the mental state)?[19] On the other hand, the same philosophers claimed that commonsense mental states simply do not exist. But critics pointed out that eliminativists could not have it both ways: either mental states exist and will ultimately be explained in terms of lower-level neurophysiological processes, or they do not.[2][18] Modern eliminativists have much more clearly expressed the view that mental phenomena simply do not exist and will eventually be eliminated from people's thinking about the brain in the same way that demons have been eliminated from people's thinking about mental illness and psychopathology.[4] While it was a minority view in the 1960s, eliminative materialism gained prominence and acceptance during the 1980s.[20] Proponents of this view, such as B.F. Skinner, often made parallels to previous superseded scientific theories (such as that of the four humours, the phlogiston theory of combustion, and the vital force theory of life) that have all been successfully eliminated in attempting to establish their thesis about the nature of the mental. In these cases, science has not produced more detailed versions or reductions of these theories, but rejected them altogether as obsolete. Radical behaviorists, such as Skinner, argued that folk psychology is already obsolete and should be replaced by descriptions of histories of reinforcement and punishment.[21] Such views were eventually abandoned. Patricia and Paul Churchland argued that folk psychology will be gradually replaced as neuroscience matures.[20] Eliminativism is not only motivated by philosophical considerations, but is also a prediction about what form future scientific theories will take. Eliminativist philosophers therefore tend to be concerned with data from the relevant brain and cognitive sciences.[22] In addition, because eliminativism is essentially predictive in nature, different theorists can and often do predict which aspects of folk psychology will be eliminated from folk psychological vocabulary. None of these philosophers are eliminativists tout court.[23][24][25] Today, the eliminativist view is most closely associated with the Churchlands, who deny the existence of propositional attitudes (a subclass of intentional states), and with Daniel Dennett, who is generally considered an eliminativist about qualia and phenomenal aspects of consciousness. One way to summarize the difference between the Churchlands' view and Dennett's is that the Churchlands are eliminativists about propositional attitudes, but reductionists about qualia, while Dennett is an anti-reductionist about propositional attitudes and an eliminativist about qualia.[4][25][26][27] More recently, Brian Tomasik and Jacy Reese Anthis have made various arguments for eliminativism.[28][29] Elizabeth Irvine has argued that both science and folk psychology do not treat mental states as having phenomenal properties so the hard problem "may not be a genuine problem for non-philosophers (despite its overwhelming obviousness to philosophers), and questions about consciousness may well 'shatter' into more specific questions about particular capacities."[30] In 2022, Anthis published Consciousness Semanticism: A Precise Eliminativist Theory of Consciousness, which asserts that "formal argumentation from precise semantics" dissolves the hard problem because of the contradiction between precision implied in philosophical theory and the vagueness in its definition, which implies there is no fact of the matter for phenomenological consciousness.[8] |

概要 消去法による唯物論については、過去50年にわたって賛否両論が展開されてきた。この見解の歴史は、印象に基づかないという理由で「自己」という概念を否 定したデイヴィッド・ヒュームにまで遡ることができる。[11] この見解に対する議論のほとんどは、人々の心の常識的な見方が、実際には暗黙の理論であるという前提に基づいている。その説明の成功、正確さ、未来予測能 力において、他の科学理論と比較対照されるべきである。 排除論者は、常識的な「フォーク」心理学は失敗しており、最終的には神経科学から導き出された説明に置き換えられる必要があると主張する。 したがって、これらの哲学者は神経科学的研究や人工知能の発展の重要性を強調する傾向にある。 消去主義に反対する哲学者たちは、いくつかのアプローチを取っている。シミュレーション理論家であるロバート・ゴードン(Robert Gordon)[12]やアルビン・ゴールドマン(Alvin Goldman)[13]は、フォークサイコロジーは理論ではなく、他者の内部シミュレーションに依存しているため、理論のように反証の対象にはならない と主張している。ジェリー・フォダー(Jerry Fodor)は、フォークサイコロジーは実際、成功した(不可欠な)理論であると主張している。別の見解としては、消去主義は「消去」しようとする信念や その他の実体の存在を前提としているため、自己矛盾しているというものがある。[15]  概略図:消去主義者は、一部の科学は還元可能(青)であるが、原理的に還元不可能な理論は最終的には消去される(オレンジ)と主張する。 消去主義は、心の常識的理解は誤りであり、神経科学がいつの日か、「意図する」、「信じる」、「欲する」、「愛する」といった言葉を用いて日常的な会話で 語られる心的状態は、実体のあるものを指していないことを明らかにするだろうと主張する。自然言語の不完全性により、人々は誤って、そのような信念や欲求 を持っていると考えるのである。[2] フランク・ジャクソンなどの消去法論者は、意識は脳機能の随伴現象としてのみ存在すると主張する。また、ジョルジュ・レイなどの消去法論者は、神経科学の 進歩に伴い、この概念は最終的に消去されるだろうと主張する。 [3][16] 意識とフォークサイコロジーは別個の問題であり、一方に対しては消去法による立場を取ることが可能であるが、他方に対してはそうではない。[4] 消去主義のルーツは、ウィルフレッド・セラーズ、W.V.O. クワイン、ポール・フェイヤーアーベント、リチャード・ローティの著作にさかのぼる。[5][6][17] 「消去法による唯物論」という用語は、1968年にジェームズ・コーンマンが、ローティが支持する物理主義の一形態を説明した際に初めて使用した。 また、後のルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインも消去主義にとって重要なインスピレーションの源であり、特に「私的な対象」を「文法上の虚構」として攻撃 した点においてそうである。[4] 初期の消去論者であるロルティやファイヤアーベントは、しばしば「消去法による唯物論」という用語が意味する2つの異なる概念を混同していた。彼らは、心 の働きについて最終的に正しい説明を与えることになる認知科学では、信念や欲求といった常識的な心的状態を示す用語は用いられないと主張した。 [5][6] しかし、この見解は心の同一説と区別できないという批判がすぐに寄せられた。[2][18] クワイン自身も、消去法による唯物論の何がそれほど消去的なのか疑問に思っていた。 物理主義は結局のところ心的対象の否定なのか、それとも心的対象の理論なのか? 物理主義は、苦痛や怒りの心的状態を否定し、その物理的随伴を支持するのか、それとも心的状態を物理的生物の状態(そして、物理的生物の状態を心的状態と 同一視する)と同一視するのか?[19] 一方、同じ哲学者たちは、常識的な心的状態は単純に存在しないと主張した。しかし、批判者たちは、消去論者は両方の立場を取ることはできないと指摘した。 すなわち、心的状態は存在し、最終的にはより低レベルの神経生理学的プロセスによって説明されるか、あるいは存在しないかのいずれかである。[2] [18] 現代の消去論者は、心的現象は単純に存在せず、最終的には、精神疾患や精神病理学に対する考え方から悪魔が排除されたのと同じ方法で、脳に対する考え方か らも排除されるという見解をより明確に表明している。 [4] 1960年代には少数派の見解であったが、消去法による唯物論は1980年代に注目を集め、受け入れられるようになった。[20] この見解の支持者であるB.F. スキナーなどの支持者たちは、過去の時代遅れとなった科学理論(例えば、4つの体液説、燃焼におけるフロギストン説、生命の活力説など)と比較することが 多い。これらはすべて、精神の本質に関する彼らの論文を立証しようとする試みにおいて、排除することに成功している。これらの場合、科学はこれらの理論の より詳細なバージョンや縮小版を生み出したのではなく、時代遅れとして完全に拒絶した。スキナーのような急進的な行動主義者は、フォークサイコロジーはす でに時代遅れであり、強化と罰の歴史の記述に置き換えるべきだと主張した。[21] このような見解は最終的に放棄された。パトリシアとポール・チャーチランドは、神経科学が成熟するにつれ、フォークサイコロジーは徐々に置き換えられてい くと主張した。[20] 消去主義は、哲学的考察のみに動機付けられているのではなく、未来の科学理論がどのような形になるかについての予測でもある。したがって、消去主義の哲学 者は関連する脳科学や認知科学のデータに関心を持つ傾向にある。[22] さらに、消去主義は本質的に予測的な性質を持つため、異なる理論家は、フォークサイコロジーの語彙からどの側面が消去されるかを予測することが可能であ り、実際によく行われている。これらの哲学者の誰もが消去主義者というわけではない。[23][24][25] 今日、排除論的な見解は、命題的態度(意図状態のサブクラス)の存在を否定するチャーチランド夫妻と、クオリアや意識の現象的側面について一般的に排除論 的であると考えられているダニエル・デネットと最も密接に関連している。チャーチランドの考えとデネットの考えの相違点を要約する一つの方法は、チャーチ ランドは命題的態度については排除論者であるが、クオリアについては還元論者であるのに対し、デネットは命題的態度については反還元論者であり、クオリア については排除論者であるというものである。[4][25][26][27] 最近では、ブライアン・トマシクとジャシー・リース・アンティスが消去主義のさまざまな論拠を提示している。[28][29] エリザベス・アーバインは、科学もフォークサイコロジーも心的状態を現象的特性として扱っていないため、ハード・プロブレムは「非哲学者にとっては(哲学 者にとっては明白であるにもかかわらず)真の課題ではないかもしれない」と主張している。また、意識に関する疑問は、特定の能力に関するより具体的な疑問 へと「粉々になる」可能性もある。 [30] 2022年、アンティスは『意識の意味論:意識に関する厳密な排除論的理論』を出版した。この本では、「厳密な意味論からの形式的な論証」が「哲学理論に 暗示される厳密性と定義のあいまいさの間の矛盾」を理由に、ハード・プロブレムを解消すると主張している。この矛盾は、現象学的意識には事実が存在しない ことを暗示している。[8] |

| Arguments for eliminativism Problems with folk theories Eliminativists such as Paul and Patricia Churchland argue that folk psychology is a fully developed but non-formalized theory of human behavior. It is used to explain and make predictions about human mental states and behavior. This view is often referred to as the theory of mind or just simply theory-theory, for it theorizes the existence of an unacknowledged theory. As a theory in the scientific sense, eliminativists maintain, folk psychology must be evaluated on the basis of its predictive power and explanatory success as a research program for the investigation of the mind/brain.[31][32] Such eliminativists have developed different arguments to show that folk psychology is a seriously mistaken theory and should be abolished. They argue that folk psychology excludes from its purview or has traditionally been mistaken about many important mental phenomena that can and are being examined and explained by modern neuroscience. Some examples are dreaming, consciousness, mental disorders, learning processes, and memory abilities. Furthermore, they argue, folk psychology's development in the last 2,500 years has not been significant and it is therefore stagnant. The ancient Greeks already had a folk psychology comparable to modern views. But in contrast to this lack of development, neuroscience is rapidly progressing and, in their view, can explain many cognitive processes that folk psychology cannot.[22][33] Folk psychology retains characteristics of now obsolete theories or legends from the past. Ancient societies tried to explain the physical mysteries of nature by ascribing mental conditions to them in such statements as "the sea is angry". Gradually, these everyday folk psychological explanations were replaced by more efficient scientific descriptions. Today, eliminativists argue, there is no reason not to accept an effective scientific account of cognition. If such an explanation existed, then there would be no need for folk-psychological explanations of behavior, and the latter would be eliminated the same way as the mythological explanations the ancients used.[34] Another line of argument is the meta-induction based on what eliminativists view as the disastrous historical record of folk theories in general. Ancient pre-scientific "theories" of folk biology, folk physics, and folk cosmology have all proven radically wrong. Eliminativists argue the same in the case of folk psychology. There seems no logical basis, to the eliminativist, to make an exception just because folk psychology has lasted longer and is more intuitive or instinctively plausible than other folk theories.[33] Indeed, the eliminativists warn, considerations of intuitive plausibility may be precisely the result of the deeply entrenched nature in society of folk psychology itself. It may be that people's beliefs and other such states are as theory-laden as external perceptions and hence that intuitions will tend to be biased in their favor.[23] |

消去主義の主張 民間説の問題点 ポール・チャーチランドやパトリシア・チャーチランドなどの消去主義者は、フォークサイコロジーは十分に発達しているが形式化されていない人間行動の理論 であると主張している。これは人間の精神状態や行動を説明し、予測するために用いられる。この見解は、認知されていない理論の存在を理論化しているため、 心の理論または単に理論理論と呼ばれることが多い。科学的意味での理論として、排除論者は、フォークサイコロジーは、心や脳の研究プログラムとしての予測 能力と説明の成功に基づいて評価されなければならないと主張している。[31][32] こうした排除論者は、フォークサイコロジーが重大な誤りを犯した理論であり、廃止されるべきであることを示すために、異なる論拠を展開している。彼らは、 フォークサイコロジーは、その守備範囲から除外しているか、あるいは伝統的に誤解している、現代の神経科学によって調査・説明できる多くの重要な精神現象 があると主張している。その例としては、夢、意識、精神障害、学習プロセス、記憶能力などがある。さらに、彼らは、過去2500年間のフォークサイコロ ジーの発展は著しいものではなく、停滞していると主張する。古代ギリシャ人はすでに、現代の見解に匹敵するフォークサイコロジーを持っていた。しかし、こ の発展の欠如とは対照的に、神経科学は急速に進歩しており、彼らの見解では、フォークサイコロジーでは説明できない多くの認知プロセスを説明できるとい う。[22][33] フォークサイコロジーには、現在では時代遅れとなった過去の理論や伝説の特徴が残っている。古代社会では、「海が怒っている」というような表現で自然界の 物理的な謎を精神状態に帰属させることで説明しようとしていた。徐々に、こうした日常的なフォークサイコロジーによる説明は、より効率的な科学的説明に 取って代わられるようになった。今日、排除論者は、認知に関する効果的な科学的説明を受け入れない理由はないと主張する。そのような説明が存在するなら ば、行動に関するフォーク心理学的な説明は不要となり、後者は古代人が用いた神話的説明と同じように排除されるだろう。 もう一つの論点は、消去法論者がフォーク理論全般の悲惨な歴史的記録とみなすメタ誘導に基づくものである。古代の非科学的なフォーク生物学、フォーク物理 学、フォーク宇宙論の「理論」はすべて根本的に間違っていることが証明されている。排除論者は、フォークサイコロジーの場合も同様であると主張する。排除 論者にとって、フォークサイコロジーが他のフォーク理論よりも長く続いており、より直感的または本能的に納得できるからといって、それを例外とする論理的 根拠はない。[33] 実際、排除論者は、直感的に納得できるという考察は、まさにフォークサイコロジーが社会に深く根付いていることの結果である可能性があると警告している。 人々の信念やその他の状態は、外部からの知覚と同様に理論に満ちている可能性があり、それゆえ直観はそれらに有利な方向に偏りがちになるのかもしれない。 [23] |

| Specific problems with folk psychology Much of folk psychology involves the attribution of intentional states (or more specifically as a subclass, propositional attitudes). Eliminativists point out that these states are generally ascribed syntactic and semantic properties. An example of this is the language of thought hypothesis, which attributes a discrete, combinatorial syntax and other linguistic properties to these mental phenomena. Eliminativists argue that such discrete, combinatorial characteristics have no place in neuroscience, which speaks of action potentials, spiking frequencies, and other continuous and distributed effects. Hence, the syntactic structures assumed by folk psychology have no place in such a structure as the brain.[22] To this there have been two responses. On the one hand, some philosophers deny that mental states are linguistic and see this as a straw man argument.[35][36] The other view is represented by those who subscribe to "a language of thought". They assert that mental states can be multiply realized and that functional characterizations are just higher-level characterizations of what happens at the physical level.[37][38] It has also been argued against folk psychology that the intentionality of mental states like belief implies that they have semantic qualities. Specifically, their meaning is determined by the things they are about in the external world. This makes it difficult to explain how they can play the causal roles they are supposed to in cognitive processes.[39] In recent years, this latter argument has been fortified by the theory of connectionism. Many connectionist models of the brain have been developed in which the processes of language learning and other forms of representation are highly distributed and parallel. This tends to indicate that such discrete and semantically endowed entities as beliefs and desires are unnecessary.[40] |

フォークサイコロジーの具体的な問題 フォークサイコロジーの多くは、意図状態(またはより具体的には、命題的態度というサブクラス)の帰属に関わっている。 排除論者は、これらの状態は一般的に、統語的および意味的特性が帰属されていると指摘している。その例として、思考言語仮説がある。これは、これらの精神 現象に離散的な組み合わせの構文やその他の言語的特性を帰属させるものである。排除論者は、活動電位、スパイク周波数、その他の連続的かつ分散的な効果を 語る神経科学には、このような離散的な組み合わせの特性は存在しないと主張する。したがって、フォークサイコロジーが想定する構文構造は、脳のような構造 には存在しない。[22]これに対しては、2つの反応があった。一方では、精神状態は言語的ではないと否定する哲学者もおり、これは藁人形論法であると見 なしている。[35][36] もう一方の見解は、「思考の言語」を支持する人々によって代表されている。彼らは、精神状態は多重的に実現可能であり、機能的特性は物理的レベルで起こる 事象の単に高レベルの特性であると主張している。[37][38] 信念のような心的状態の意図性は、それらが意味的性質を持つことを意味するというフォークサイコロジーに対する反論もなされている。具体的には、それらの 意味は、それらが関わる外界の事物によって決定される。このため、それらが認知プロセスにおいて想定される因果的役割を果たす仕組みを説明することが困難 になる。 近年、この後者の議論は、コネクショニズム理論によって強化されている。脳の多くのコネクショニストモデルが開発されており、その中では言語学習やその他 の表現形式のプロセスが高度に分散的かつ並列的に行われている。この傾向は、信念や欲求といった意味論的に付与された離散的な実体が不要であることを示唆 している。[40] |

| Physics eliminates intentionality The problem of intentionality poses a significant challenge to materialist accounts of cognition. If thoughts are neural processes, we must explain how specific neural networks can be "about" external objects or concepts. We can think about Paris, for instance, but there is no clear mechanism by which neurons can represent a city.[41] Traditional analogies fail to explain this phenomenon. Unlike a photograph, neurons do not physically resemble Paris. Nor can we appeal to conventional symbolism, as we might with a stop sign representing the action of stopping. Such symbols derive their meaning from social agreement and interpretation, which are not applicable to a brain's workings. Attempts to posit a separate neural process that assigns meaning to the "Paris neurons" merely shift the problem without resolving it, as we then need to explain how this secondary process can assign meaning, initiating an infinite regress.[42] The only way to break this regress is to postulate matter with intrinsic meaning, independent of external interpretation. But our current understanding of physics precludes the existence of such matter. The fundamental particles and forces physics describes have no inherent semantic properties that could ground intentionality. This physical limitation presents a formidable obstacle to materialist theories of mind that rely on neural representations. It suggests that intentionality, as commonly understood, may be incompatible with a purely physicalist worldview. This suggests that our folk psychological concepts of intentional states will be eliminated in light of scientific understanding.[41] |

物理学は意図主義を消去法によるものとする 意図主義の問題は、認知に関する唯物論的説明に大きな課題を突きつける。思考が神経プロセスであるならば、特定の神経ネットワークが外部の物体や概念を 「対象とする」ことができる仕組みを説明しなければならない。例えばパリについて考えることはできるが、ニューロンが都市を表現できる明確なメカニズムは 存在しない。 従来の類似性による説明では、この現象を説明することはできない。ニューロンは写真とは異なり、物理的にパリに似ているわけではない。また、停止の合図と して用いられる標識のように、従来の象徴主義に訴えることもできない。このような象徴は、社会的な合意や解釈から意味を導き出すものであり、脳の働きには 適用できない。「パリのニューロン」に意味を割り当てる別の神経プロセスを仮定しようとする試みは、問題を先送りするだけであり、解決にはならない。なぜ なら、この二次的なプロセスがどのようにして意味を割り当てることができるのかを説明する必要があり、無限後退が始まるからである。 この無限後退を断ち切る唯一の方法は、外部の解釈とは無関係に、本質的な意味を持つ物質を仮定することである。しかし、現在の物理学の理解では、そのよう な物質の存在はありえない。物理学が説明する基本粒子や力には、意図性を基礎付けることのできる固有の意味特性がない。この物理的な限界は、神経表現に依 存する唯物論的な心の理論にとって、大きな障害となる。これは、一般的に理解されているように、意図性は純粋な唯物論的世界観と相容れない可能性があるこ とを示唆している。これは、意図状態に関する我々のフォークサイコロジーの概念は、科学的理解に照らして消去法による排除の対象となることを示唆してい る。[41] |

| Evolution eliminates intentionality Another argument for eliminative materialism stems from evolutionary theory. This argument suggests that natural selection, the process shaping our neural architecture, cannot solve the "disjunction problem", which challenges the idea that neural states can store specific, determinate propositional content. Natural selection, as Darwin described it, is primarily a process of selection against rather than selection for traits. It passively filters out traits below a certain fitness threshold rather than actively choosing beneficial ones. This lack of foresight or purpose in evolution becomes problematic when considering how neural states could represent unique propositions.[43][44] The disjunction problem arises from the fact that natural selection cannot discriminate between coextensive properties. For example, consider two genes close together on a chromosome. One gene might code for a beneficial trait, while the other codes for a neutral or even harmful trait. Due to their proximity, these genes are often inherited together, a phenomenon known as genetic linkage. Natural selection cannot distinguish between these linked traits; it can only act on their combined effect on the organism's fitness. Only random processes like genetic crossover—where chromosomes exchange genetic material during reproduction—can break these linkages. Until such a break occurs, natural selection remains "blind" to the linked genes' individual effects.[44][45] Eliminativists argue that if natural selection—the process responsible for shaping our neural architecture—cannot solve the disjunction problem, then our brains cannot store unique, non-disjunctive propositions, as required by folk psychology. Instead, they suggest that neural states contain inherently disjunctive or indeterminate content. This argument leads eliminativists to reject the notion that neural states have specific, determinate informational content corresponding to the discrete, non-disjunctive propositions of folk psychology. This evolutionary argument adds to the eliminativist case that our commonsense understanding of beliefs, desires, and other propositional attitudes is flawed and should be replaced by a neuroscientific account that acknowledges the indeterminate nature of neural representations.[46][47] |

進化は意図主義を排除する 消去法による唯物論のもう一つの論拠は、進化論から生じている。この論拠は、神経構造を形成するプロセスである自然淘汰では、「論理和問題」を解決できな いことを示唆している。論理和問題とは、神経状態が特定の決定論的な命題内容を保存できるという考えに疑問を投げかけるものである。ダーウィンが述べたよ うに、自然淘汰は主に、形質に対して選択するプロセスというよりも、むしろ選択されるプロセスである。自然淘汰は、能動的に有益なものを選択するのではな く、受動的に特定の適合度閾値以下の形質を排除する。進化に先見性や目的がないということが問題となるのは、神経状態がどのようにして独自の命題を表現で きるかを考える場合である。 自然淘汰が重複する性質を区別できないという事実から、論理和問題が生じる。例えば、染色体上で近接する2つの遺伝子を考える。一方の遺伝子が有益な形質 をコードしている一方で、もう一方の遺伝子が中立的な、あるいは有害な形質をコードしている可能性がある。これらの遺伝子は近接しているため、しばしば一 緒に遺伝される。この現象は遺伝的連鎖として知られている。自然淘汰は、これらの連鎖した形質を区別することができない。自然淘汰が作用できるのは、生物 の適応度に対するそれらの複合効果だけである。遺伝子交差のようなランダムなプロセス、すなわち、生殖の際に染色体が遺伝物質を交換するプロセスだけが、 これらの連鎖を断ち切ることができる。このような断絶が起こるまでは、自然淘汰は連鎖した遺伝子の個々の効果に対して「盲目」のままである。[44] [45] 排除論者は、神経構造の形成に責任を持つプロセスである自然淘汰が、論理和問題を解決できないのであれば、フォークサイコロジーが要求するような、独特で 論理和ではない命題を脳が保存することはできないと主張する。その代わり、神経状態には本質的に論理和または不確定な内容が含まれていると彼らは提案す る。この主張により、排除論者は、神経状態にはフォークサイコロジーの離散的で論理和ではない命題に対応する、特定で決定的な情報内容があるという考えを 否定することになる。この進化論的議論は、信念、欲求、その他の命題的態度に関する我々の常識的理解は誤りであり、神経表現の不確定性な性質を認める神経 科学的な説明に置き換えるべきであるという、排除論者の主張を補強するものである。[46][47] |

| Arguments against eliminativism Intentionality and consciousness are identical Some eliminativists reject intentionality while accepting the existence of qualia. Other eliminativists reject qualia while accepting intentionality. Many philosophers argue that intentionality cannot exist without consciousness and vice versa, and so any philosopher who accepts one while rejecting the other is being inconsistent. They argue that, to be consistent, one must accept both qualia and intentionality or reject them both. Philosophers who argue for such a position include Philip Goff, Terence Horgan, Uriah Kriegal, and John Tienson.[48][49] The philosopher Keith Frankish accepts the existence of intentionality but holds to illusionism about consciousness because he rejects qualia. Goff notes that beliefs are a kind of propositional thought. |

消去主義に対する反論 意図性と意識は同一である 消去主義者の一部は、クオリアの存在は認めるが、意図性を否定する。また、消去主義者の一部は、意図性を認めるが、クオリアを否定する。多くの哲学者は、 意識がなければ意図性は存在し得ず、その逆もまた真であると主張しており、そのため、一方を認めて他方を否定する哲学者は一貫性を欠いていると主張してい る。彼らは、一貫性を保つためには、クオリアと意図性の両方を認めるか、あるいは両方を否定しなければならないと主張している。このような立場を主張する 哲学者には、フィリップ・ゴフ、テレンス・ホーガン、ウリヤ・クリーガル、ジョン・ティンソンなどがいる。[48][49] 哲学者のキース・フランクは、意図性の存在は認めるが、クオリアを否定しているため、意識については幻想説を主張している。ゴフは、信念は命題思考の一種 であると指摘している。 |

| Intuitive reservations The thesis of eliminativism seems so obviously wrong to many critics, who find it undeniable that people know immediately and indubitably that they have minds, that argumentation seems unnecessary. This sort of intuition-pumping is illustrated by asking what happens when one asks oneself honestly if one has mental states.[50] Eliminativists object to such a rebuttal of their position by claiming that intuitions often are mistaken. Analogies from the history of science are frequently invoked to buttress this observation: it may appear obvious that the sun travels around the earth, for example, but this was nevertheless proved wrong. Similarly, it may appear obvious that apart from neural events there are also mental conditions, but that could be false.[23] But even if one accepts the susceptibility to error of people's intuitions, the objection can be reformulated: if the existence of mental conditions seems perfectly obvious and is central to our conception of the world, then enormously strong arguments are needed to deny their existence. Furthermore, these arguments, to be consistent, must be formulated in a way that does not presuppose the existence of entities like "mental states", "logical arguments", and "ideas", lest they be self-contradictory.[51] Those who accept this objection say that the arguments for eliminativism are far too weak to establish such a radical claim and that there is thus no reason to accept eliminativism.[50] |

直感的な予約 消去主義の主張は多くの批評家にとって明らかに誤っているように思える。人々は自分が心を持っていることを即座に疑いなく認識していることは否定できない と考える批評家にとっては、その議論は不要である。このような直感的な推論は、自分が精神状態を持っているかどうかを自分に正直に問いかけたときに何が起 こるかを尋ねることによって説明される。[50] 消去主義者は、直感はしばしば誤っていると主張することで、このような立場に対する反論に異議を唱える。この主張を裏付けるために、科学史からの類推が頻 繁に引き合いに出される。例えば、太陽が地球の周りを回っていることは明白であるように見えるが、それでもそれは間違いであることが証明された。同様に、 神経事象とは別に心的状態もあることは明白であるように見えるが、それは間違いである可能性がある。 しかし、人々の直観に誤りやすいという性質があることを認めるとしても、この反対意見は次のように言い換えられる。精神状態の存在が完全に明白であり、そ れが我々の世界観の中心であるならば、その存在を否定するには非常に強力な論拠が必要である。さらに、これらの主張は首尾一貫しているためには、「心的状 態」、「論理的推論」、「観念」といった実体の存在を前提としない形で定式化されなければならない。さもなければ、自己矛盾を招くことになるからだ。 [51] この反論を受け入れる人々は、消去主義の主張はこのような急進的な主張を立証するにはあまりにも弱すぎるとし、したがって消去主義を受け入れる理由はない と主張する。[50] |

| Self-refutation Some philosophers, such as Paul Boghossian, have attempted to show that eliminativism is in some sense self-refuting, since the theory presupposes the existence of mental phenomena. If eliminativism is true, then eliminativists must accept an intentional property like truth, supposing that in order to assert something one must believe it. Hence, for eliminativism to be asserted as a thesis, the eliminativist must believe that it is true; if so, there are beliefs, and eliminativism is false.[15][52] Georges Rey and Michael Devitt reply to this objection by invoking deflationary semantic theories that avoid analyzing predicates like "x is true" as expressing a real property. They are instead construed as logical devices, so that asserting that a sentence is true is just a quoted way of asserting the sentence itself. To say "'God exists' is true" is just to say "God exists". This way, Rey and Devitt argue, insofar as dispositional replacements of "claims" and deflationary accounts of "true" are coherent, eliminativism is not self-refuting.[53] |

自己反駁 ポール・ボゴシアン(Paul Boghossian)などの哲学者は、消去主義が精神現象の存在を前提としている以上、ある意味で自己反駁的であることを示そうとしてきた。もし消去主 義が真実であるならば、何かを主張するためにはそれを信じなければならないと仮定すると、消去主義者は「真実」のような意図的特性を受け入れなければなら ない。したがって、消去主義が命題として主張されるためには、消去主義者はそれを真実だと信じなければならない。もしそうであれば、信念が存在することに なり、消去主義は誤りである。[15][52] ジョルジュ・レイとマイケル・デビットは、この反論に対して、「xは真である」のような述語を実在する性質を表現するものとして分析することを避ける、消 極的な意味論理論を援用することで反論している。それらは代わりに論理的な装置として解釈され、文が真であると主張することは、その文自体を引用した主張 の方法である。「『神は存在する』は真である」と言うことは、「神は存在する」と言うことと同じである。レイとデビットは、この方法では、「主張」の性質 論的置換と「真」の消去論的説明が首尾一貫している限り、消去主義は自己矛盾ではないと主張している。[53] |

| Correspondence theory of truth Several philosophers, such as the Churchlands and Alex Rosenberg,[43][54] have developed a theory of structural resemblance or physical isomorphism that could explain how neural states can instantiate truth within the correspondence theory of truth. Neuroscientists use the word "representation" to identify the neural circuits' encoding of inputs from the peripheral nervous system in, for example, the visual cortex. But they use the word without according it any commitment to intentional content. In fact, there is an explicit commitment to describing neural representations in terms of structures of neural axonal discharges that are physically isomorphic to the inputs that cause them. Suppose that this way of understanding representation in the brain is preserved in the long-term course of research providing an understanding of how the brain processes and stores information. Then there will be considerable evidence that the brain is a neural network whose physical structure is identical to the aspects of its environment it tracks and whose representations of these features consist in this physical isomorphism.[44] Experiments in the 1980s with macaques isolated the structural resemblance between input vibrations the finger feels, measured in cycles per second, and representations of them in neural circuits, measured in action-potential spikes per second. This resemblance between two easily measured variables makes it unsurprising that they would be among the first such structural resemblances to be discovered. Macaques and humans have the same peripheral nervous system sensitivities and can make the same tactile discriminations. Subsequent research into neural processing has increasingly vindicated a structural resemblance or physical isomorphism approach to how information enters the brain and is stored and deployed.[43][55] This isomorphism between brain and world is not a matter of some relationship between reality and a map of reality stored in the brain. Maps require interpretation if they are to be about what they map, and eliminativism and neuroscience share a commitment to explaining the appearance of aboutness by purely physical relationships between informational states in the brain and what they "represent". The brain-to-world relationship must be a matter of physical isomorphism—sameness of form, outline, structure—that does not require interpretation.[44] This machinery can be applied to make "sense" of eliminativism in terms of the sentences eliminativists say or write. When we say that eliminativism is true, that the brain does not store information in the form of unique sentences, statements, expressing propositions or anything like them, there is a set of neural circuits that has no trouble coherently carrying this information. There is a possible translation manual that will guide us back from the vocalization or inscription eliminativists express to these circuits. These neural structures will differ from the neural circuits of those who explicitly reject eliminativism in ways that our translation manual will presumably shed some light on, giving us a neurological handle on disagreement and on the structural differences in neural circuitry, if any, between asserting p and asserting not-p when p expresses the eliminativist thesis.[43] |

対応説における真理 チャーチランド夫妻やアレックス・ローゼンバーグなど、一部の哲学者は、神経状態が対応説における真理をどのように具現化できるかを説明できる構造的類似 性または物理的同型の理論を展開している。神経科学者は、例えば視覚皮質における末梢神経系からの入力の神経回路の符号化を特定するために「表現」という 言葉を使用する。しかし、彼らはその言葉に意図的内容を一切関連付けずに使用している。実際には、神経表現を、それらを引き起こす入力と物理的に対応する 神経軸索放電の構造という観点から説明するという明確な約束事がある。脳における表現の理解が、脳が情報を処理し保存する方法の理解をもたらす長期的な研 究過程において維持されると仮定しよう。 そうすると、脳が、追跡する環境の側面と物理構造が同一であるニューラルネットワークであり、これらの特徴の表現がこの物理的等価性から成り立っていると いう、かなりの証拠が存在することになる。 1980年代にマカク属のサルを対象として行われた実験では、指が感じる入力振動(1秒あたりのサイクル数で測定)と神経回路におけるそれらの表現(1秒 あたりの活動電位スパイク数で測定)との構造的な類似性が特定された。この2つの変数は簡単に測定できるため、このような構造的な類似性が最初に発見され たとしても驚くことではない。マカク属とヒトは末梢神経系の感度も同じであり、同じ触覚の識別を行うことができる。神経処理に関するその後の研究により、 情報が脳に入り、保存され、利用される方法に関する構造的類似性または物理的等価性アプローチがますます正当化されてきた。[43][55] 脳と世界の間のこの等価性は、現実と脳に保存された現実の地図の間の関係の問題ではない。地図が対象を写し取るものであるためには解釈が必要であり、消去 主義と神経科学は、脳内の情報状態とそれが「表象する」ものとの間の純粋に物理的な関係によって、アバウトネス(aboutness)の外見を説明するこ とに専心している。脳と世界との関係は、解釈を必要としない物理的な同形性、すなわち形態、輪郭、構造の同一性に関わるものでなければならない。 このメカニズムは、消去主義者が口にする、あるいは書く文章の消去主義を「理解」するために応用することができる。消去主義が真実であり、脳が独自の文 章、声明、命題、またはそれらに類する形式で情報を保存しないという場合、この情報を首尾一貫して伝達することに何ら問題のない神経回路が存在する。消去 論者が発声または記述するこれらの回路に、私たちを導き戻す翻訳マニュアルが存在する可能性がある。これらの神経構造は、消去主義を明確に否定する人々の 神経回路とは異なる。おそらく、この翻訳マニュアルは、pを主張することとpではないと主張することの間に構造的な違いがあるかどうか、また、pが消去主 義の論文を表現する場合、意見の相違と神経回路の構造的な違いについて、私たちに神経学的な理解をもたらすだろう。[43] |

| Criticism The physical isomorphism approach faces indeterminacy problems. Any given structure in the brain will be causally related to, and isomorphic in various respects to, many different structures in external reality. But we cannot discriminate the one it is intended to represent or that it is supposed to be true "of". These locutions are heavy with just the intentionality that eliminativism denies. Here is a problem of underdetermination or holism that eliminativism shares with intentionality-dependent theories of mind. Here, we can only invoke pragmatic criteria for discriminating successful structural representations—the substitution of true ones for unsuccessful ones—the ones we used to call false.[43] Dennett notes that it is possible that such indeterminacy problems remain only hypothetical, not occurring in reality. He constructs a 4x4 "Quinian crossword puzzle" with words that must satisfy both the across and down definitions. Since there are multiple constraints on this puzzle, there is one solution. Thus we can think of the brain and its relation to the external world as a very large crossword puzzle that must satisfy exceedingly many constraints to which there is only one possible solution. Therefore, in reality we may end up with only one physical isomorphism between the brain and the external world.[47] |

批判 物理的同形性アプローチは不確定性問題に直面する。脳内の任意の構造は、因果関係があり、さまざまな点で外部の現実の多くの異なる構造と同形である。しか し、それが表象しようとしているもの、あるいはそれが「~について」真であると想定されているものを識別することはできない。これらの表現は、消去主義が 否定する意図性そのものである。これは、消去主義が意図性依存の心の理論と共有する、過少決定または全体論の問題である。ここでは、成功した構造的表象を 識別するための実用的な基準のみを呼び起こすことができる。つまり、成功していない表象を真の表象に置き換えること、つまり、かつては偽と呼ばれていたも のを置き換えることである。 デネットは、このような不確定性問題はあくまで仮説上の問題であり、現実には起こりえない可能性があると指摘している。彼は、タテヨコの定義をともに満た す必要のある単語を使った4x4の「クイニアン・クロスワード・パズル」を作成した。このパズルには複数の制約があるため、解答は1つしかない。したがっ て、脳と外部世界との関係は、非常に多くの制約を満たさなければならない非常に大きなクロスワード・パズルであり、その解答は1つしかないと考えることが できる。したがって、実際には、脳と外部世界との間に物理的な同形が1つだけ存在することになるかもしれない。[47] |

| Pragmatic theory of truth When indeterminacy problems arose because the brain is physically isomorphic to multiple structures of the external world, it was urged that a pragmatic approach be used to resolve the problem. Another approach argues that the pragmatic theory of truth should be used from the start to decide whether certain neural circuits store true information about the external world. Pragmatism was founded by Charles Sanders Peirce and William James, and later refined by our understanding of the philosophy of science. According to pragmatism, to say that general relativity is true is to say that it makes more accurate predictions than other theories (Newtonian mechanics, Aristotle's physics, etc.). If computer circuits lack intentionality and do not store information using propositions, then in what sense can computer A have true information about the world while computer B lacks it? If the computers were instantiated in autonomous cars, we could test whether A or B successfully complete a cross-country road trip. If A succeeds while B fails, the pragmatist can say that A holds true information about the world, because A's information allows it to make more accurate predictions (relative to B) about the world and to move around its environment more successfully. Similarly, if brain A has information that enables the biological organism to make more accurate predictions about the world and helps the organism successfully move around in the environment, then A has true information about the world. Although not advocates of eliminativism, John Shook and Tibor Solymosi argue that pragmatism is a promising program for understanding advancements in neuroscience and integrating them into a philosophical picture of the world.[56] |

プラグマティックな真理理論 脳が物理的に外界の複数の構造と類似しているために不確定性問題が生じた場合、その問題を解決するにはプラグマティックなアプローチを用いるべきであると 主張された。別のアプローチでは、特定の神経回路が外界に関する真の情報を保存しているかどうかを判断するには、当初からプラグマティックな真理理論を用 いるべきであると主張している。プラグマティズムはチャールズ・サンダース・パースとウィリアム・ジェームズによって創始され、その後、科学哲学の理解に よって洗練された。プラグマティズムによれば、一般相対性理論が真であるということは、他の理論(ニュートン力学、アリストテレス物理学など)よりも正確 な予測ができるということである。もしコンピュータ回路が意図主義を欠き、命題を使用して情報を保存しないのであれば、コンピュータAが世界の真の情報を 持ち、コンピュータBがそれを欠いているという状況は、どのような意味で可能だろうか?もしコンピュータが自律走行車に実装されている場合、AまたはBが 長距離ドライブを成功裏に完了できるかどうかをテストすることができる。もしAが成功し、Bが失敗した場合、プラグマティストは、Aが世界の真実の情報を 保持していると言うことができる。なぜなら、Aの情報は、世界について(Bと比較して)より正確な予測を可能にし、環境をよりうまく動き回ることを可能に するからだ。同様に、脳Aが生物体に世界についてより正確な予測を可能にし、生物体が環境をうまく動き回ることを助ける情報を保持している場合、Aは世界 の真実の情報を保持していることになる。消去主義の支持者ではないジョン・シュックとティボール・ソルモシは、プラグマティズムは神経科学の進歩を理解 し、それを世界の哲学的概念に統合するための有望なプログラムであると主張している。[56] |

| Criticism The reason naturalism cannot be pragmatic in its epistemology starts with its metaphysics. Science tells us that we are components of the natural realm, indeed latecomers in the 13.8-billion-year-old universe. The universe was not organized around our needs and abilities, and what works for us is just a set of contingent facts that could have been otherwise. Once we have begun discovering things about the universe that work for us, science sets out to explain why they do. It is clear that one explanation for why things work for us that we must rule out as unilluminating, indeed question-begging, is that they work for us because they work for us. If something works for us, enables us to meet our needs and wants, there must be an explanation reflecting facts about us and the world that produce the needs and the means to satisfy them.[46] The explanation of why scientific methods work for us must be a causal explanation. It must show what facts about reality make the methods we employ to acquire knowledge suitable for doing so. The explanation must show that our methods work — for example, have reliable technological application — not by coincidence, still less miracle or accident. That means there must be some facts, events, processes that operate in reality and brought about our pragmatic success. The demand that success be explained is a consequence of science's epistemology. If the truth of such explanations consists in the fact that they work for us (as pragmatism requires), then the explanation of why our scientific methods work is that they work. That is not a satisfying explanation.[46] |

批判 自然主義がその認識論において実用的であることができない理由は、その形而上学から始まる。科学は、我々は自然界の構成要素であり、138億年の歴史を持 つ宇宙においては後発組であると教えている。宇宙は我々のニーズや能力に合わせて組織化されたものではなく、我々にとって都合の良いものは、別の可能性も あった偶発的な事実の集合に過ぎない。我々にとって都合の良い宇宙の事実が発見され始めると、科学はそれらがなぜそうなるのかを説明しようとする。私たち にとって都合が良い理由として、明らかに説明不足であり、疑問を提起するような説明は、私たちにとって都合が良いから、という理由である。もし何かが私た ちにとって都合が良く、私たちのニーズや欲求を満たすことができるのであれば、そのニーズやそれを満たす手段を生み出す私たち自身や世界の事実を反映した 説明がなければならない。 科学的手法が私たちに役立つ理由の説明は、因果関係を説明するものでなければならない。現実に関するどのような事実が、知識を得るために用いる手法を知識 獲得に適したものにするのかを示さなければならない。説明は、私たちの手法が機能していることを示さなければならない。例えば、信頼性の高い技術的応用な どである。偶然や奇跡、事故によって機能しているのではないことを示さなければならない。つまり、現実の中で機能し、私たちの実用的な成功をもたらしてい る事実、出来事、プロセスが存在しなければならない。成功を説明するという要求は、科学の認識論の結果である。もしそのような説明の真実性が、それが私た ちにとって役立つという事実にあるとすれば(プラグマティズムが要求するように)、私たちの科学的手法がなぜ役立つのかという説明は、それが役立つからで ある。それは納得のいく説明ではない。[46] |

| Efficacy of folk psychology Some philosophers argue that folk psychology is quite successful.[14][57][58] Simulation theorists doubt that people's understanding of the mental can be explained in terms of a theory at all. Rather they argue that people's understanding of others is based on internal simulations of how they would act and respond in similar situations.[12][13] Jerry Fodor believes in folk psychology's success as a theory, because it makes for an effective way of communication in everyday life that can be implemented with few words. Such effectiveness could not be achieved with complex neuroscientific terminology.[14] |

フォークサイコロジーの有効性 一部の哲学者は、フォークサイコロジーは極めて成功していると主張している。[14][57][58] シミュレーション理論の専門家は、人間の精神に対する理解が理論によって説明できるかどうかを疑っている。むしろ、彼らは、他者に対する人々の理解は、同 様の状況下でどのように行動し、反応するかを予測する内部シミュレーションに基づいていると主張している。[12][13]ジェリー・フォダーは、フォー クサイコロジーが理論として成功していると考えている。なぜなら、それは日常生活における効果的なコミュニケーションの方法であり、少ない言葉で実行でき るからだ。このような効果は、複雑な神経科学用語では達成できない。[14] |

| Qualia Another problem for the eliminativist is the consideration that human beings undergo subjective experiences and hence their conscious mental states have qualia. Since qualia are generally regarded as characteristics of mental states, their existence does not seem compatible with eliminativism.[59] Eliminativists such as Dennett and Rey respond by rejecting qualia.[60][61] Opponents of eliminativism see this response as problematic, since many claim that existence of qualia is perfectly obvious. Many philosophers consider the "elimination" of qualia implausible, if not incomprehensible. They assert that, for instance, the existence of pain is simply beyond denial.[59] Admitting that the existence of qualia seems obvious, Dennett nevertheless holds that "qualia" is a theoretical term from an outdated metaphysics stemming from Cartesian intuitions. He argues that a precise analysis shows that the term is in the long run empty and full of contradictions. Eliminativism's claim about qualia is that there is no unbiased evidence for such experiences when regarded as something more than propositional attitudes.[25][62] In other words, it does not deny that pain exists, but holds that it exists independently of its effect on behavior. Influenced by Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations, Dennett and Rey have defended eliminativism about qualia even when other aspects of the mental are accepted. |

クオリア 排除論者にとって、もう一つの問題は、人間は主観的な経験を経験し、それゆえ、彼らの意識的な精神状態にはクオリアがあるという考えである。クオリアは一 般的に心的状態の特徴とみなされているため、その存在は消去主義と両立しないように思われる。[59] デネットやレイなどの消去主義者は、クオリアを否定することでこれに応えている。[60][61] 消去主義の反対派は、クオリアの存在は明白であると主張する者が多いため、この回答は問題があると見ている。多くの哲学者は、クオリアの「消去」はありえ ない、あるいは理解できないと見なしている。彼らは、例えば、痛みの存在は否定できないと主張している。 クオリアの存在は明白であると認める一方で、デネットは「クオリア」という用語はデカルト主義的直観に由来する時代遅れの形而上学の理論用語であると主張 している。彼は、正確な分析によれば、この用語は長期的には空虚で矛盾に満ちていると論じている。消去主義のクオリアに関する主張は、命題的態度以上のも のとして考えた場合、そのような経験には偏りのない証拠は存在しないというものである。[25][62] つまり、痛みの存在を否定するものではないが、それは行動への影響とは無関係に存在すると主張する。ウィトゲンシュタインの『哲学探究』の影響を受け、デ ネットとレイは、精神の他の側面が受け入れられる場合でも、クオリアに関する消去主義を擁護している。 |

| Quining qualia Dennett offers philosophical thought experiments to argue that qualia do not exist.[63] First he lists five properties of qualia: They are "directly" or "immediately" graspable during our conscious experiences.[63] We are infallible about them.[63] They are "private": no one can directly access anyone else's qualia.[63] They are ineffable.[63] They are "intrinsic" and "simple" or "unanalyzable."[63] |

クオリアのクイニング デネットは、クオリアは存在しないと主張する哲学的思考実験を行っている。[63] まず、彼はクオリアの5つの特性を挙げている。 それらは、我々の意識的な経験において「直接」または「即座」に把握できる。[63] 我々はそれらについて絶対的な確信を持っている。[63] それらは「個人的」である。誰一人として他者のクオリアに直接アクセスすることはできない。[63] それらは言葉では表現できない。[63] それらは「本質的」で「単純」または「分析不能」である。[63] |

| Inverted qualia The first thought experiment Dennett uses to demonstrate that qualia lack the listed necessary properties to exist involves inverted qualia: consider two people who have different qualia but the same external physical behavior. But now the qualia supporter can present an "intrapersonal" variation. Suppose a neurosurgeon works on your brain and you discover that grass now looks red. Would this not be a case where we could confirm the reality of qualia—by noticing how the qualia have changed while every other aspect of our conscious experience remains the same? Not quite, Dennett replies via the next "intuition pump" (his term for an intuition-based thought experiment), "alternative neurosurgery". There are two different ways the neurosurgeon might have accomplished the inversion. First, they might have tinkered with something "early on", so that signals from the eye when you look at grass contain the information "red" rather than "green". This would result in genuine qualia inversion. But they might instead have tinkered with your memory. Here your qualia would remain the same, but your memory would be altered so that your current green experience would contradict your earlier memories of grass. You would still feel that the color of grass had changed, but here the qualia have not changed, but your memories have. Would you be able to tell which of these scenarios is correct? No: your perceptual experience tells you that something has changed but not whether your qualia have changed. Dennett concludes, since (by hypothesis) the two surgical procedures can yield exactly the same introspective effects while only one inverts the qualia, nothing in the subject's experience can favor one hypothesis over the other. So unless he seeks outside help, the state of his own qualia must be as unknowable to him as the state of anyone else's. It is questionable, in short, that we have direct, infallible access to our conscious experience.[63] |

反転クオリア クオリアが存在するために必要な特性を欠いていることを示すために、デネットが最初に用いた思考実験は、反転クオリアを伴うものである。異なるクオリアを 持ちながらも、外見上は同じ行動をとる2人の人物を想定する。しかし、今度はクオリアの支持者側が「個人内」のバリエーションを提示できる。脳外科医があ なたの脳を手術し、その結果、草が赤く見えるようになったとしよう。この場合、意識体験の他のあらゆる側面は変わらないまま、クオリアだけが変化したこと に気づくことで、クオリアの実在性を確認できるのではないか?そうではないと、デネットは次の「直観ポンプ」(直観に基づく思考実験を指す彼の造語)であ る「代替神経外科」で答えている。神経外科医が反転を達成した可能性は2つある。まず、何か「初期の」部分をいじって、草を見るときに目から送られる信号 が「緑」ではなく「赤」という情報を含むようにした可能性がある。これは真のクオリア反転となる。しかし、代わりに記憶をいじった可能性もある。この場 合、クオリアは変わらないが、記憶が変化し、現在の緑の体験が以前の草の記憶と矛盾することになる。それでも、草の色が変わったと感じるだろうが、この場 合、クオリアは変わっていないが、記憶は変わっている。あなたは、これらのシナリオのどちらが正しいか分かるだろうか?いいえ。知覚体験では何かが変化し たことは分かるが、クオリアが変化したかどうかは分からない。デネットは、2つの外科手術がまったく同じ内省効果をもたらす可能性がある一方で、クオリア を反転させるのはそのうちの1つだけであるという仮説を前提に、被験者の経験からどちらかの仮説を支持するものは何も得られないと結論づけている。そのた め、外部の助けを求めない限り、彼自身のクオリアの状態は、他の誰のクオリアの状態と同じように、彼にとって知ることができないものでなければならない。 つまり、要するに、私たちが意識経験に直接かつ絶対確実なアクセスを持っているかどうかは疑わしいのである。[63] |

| The experienced beer drinker Dennett's second thought experiment involves beer. Many people think of beer as an acquired taste: one's first sip is often unpleasant, but one gradually comes to enjoy it. But wait, Dennett asks—what is the "it" here? Compare the flavor of that first taste with the flavor now. Does the beer taste exactly the same both then and now, only now you like that taste whereas before you disliked it? Or is it that the way beer tastes gradually shifts—so that the taste you did not like at the beginning is not the same taste you now like? In fact most people simply cannot tell which is the correct analysis. But that is to give up again on the idea that we have special and infallible access to our qualia. Further, when forced to choose, many people feel that the second analysis is more plausible. But then if one's reactions to an experience are in any way constitutive of it, the experience is not so "intrinsic" after all—and another qualia property falls.[63] |

ビールをよく飲む経験豊富な デネットの第二の思考実験はビールに関するものだ。多くの人はビールを「慣れ親しんだ味」と考えている。最初のひと口は不快なことが多いが、徐々にその味 を楽しめるようになる。しかし、デネットは問いかける。「その『それ』とは何だろうか?最初のひと口の味と、今の味を比べてみよう。ビールは当時も今も まったく同じ味で、以前は嫌いだったが今は好きだというだけだろうか? それとも、ビールの味は徐々に変化し、当初は好きではなかった味が、今では好きな味になっているということだろうか? 実際、ほとんどの人はどちらが正しい分析なのかを判断できない。しかし、それはクオリアに特別な、そして絶対的なアクセス方法があるという考えを再び放棄 することになる。さらに、どちらかを選ばなければならない場合、多くの人は2番目の分析の方がより説得力があると感じる。しかし、もし経験に対する反応が その経験の構成要素であるならば、その経験はそれほど「本質的」なものではなく、クオリアの別の特性が当てはまることになる。[63] |

| Inverted goggles Dennett's third thought experiment involves inverted goggles. Scientists have devised special eyeglasses that invert up and down for the wearer. When you put them on, everything looks upside down. When subjects first put them on, they can barely walk around without stumbling. But after subjects wear them for a while, something surprising occurs. They adapt and become able to walk around as easily as before. When you ask them whether they adapted by re-inverting their visual field or simply got used to walking around in an upside-down world, they cannot say. So as in our beer-drinking case, either we simply do not have the special, infallible access to our qualia that would allow us to distinguish the two cases or the way the world looks to us is actually a function of how we respond to the world—in which case qualia are not "intrinsic" properties of experience.[63] |

上下逆さまのゴーグル デネットの3番目の思考実験は、上下逆さまのゴーグルを使用する。科学者たちは、上下が逆さまに見える特殊なメガネを考案した。装着すると、すべてが上下 逆さまに見える。被験者が初めて装着したときは、よろけずに歩くのがやっとである。しかし、しばらく装着していると、驚くべきことが起こる。適応して、以 前と同じように楽に歩けるようになるのだ。視界を再び上下逆さまにして適応したのか、それとも上下逆さまの世界で歩くことに慣れただけなのかと尋ねても、 被験者は答えられない。ビールを飲む場合と同様に、この2つのケースを区別できるような特別な、絶対確実なクオリアへのアクセスが私たちにはないだけなの か、あるいは、私たちが見ている世界は、実際には、私たちが世界にどう反応するかによって決まるものなのかもしれない。後者の場合、クオリアは経験の「本 質的」な性質ではない。[63] |

| Criticism Edward Feser objects to Dennett's position as follows. That you need to appeal to third-person neurological evidence to determine whether your memory of your qualia has been tampered with does not seem to show that your qualia themselves—past or present—can be known only by appealing to that evidence. You might still be directly aware of your qualia from the first-person, subjective point of view even if you do not know whether they are the same as the qualia you had yesterday—just as you might really be aware of the article in front of you even if you do not know whether it is the same as the article you saw yesterday. Questions about memory do not necessarily bear on the nature of your awareness of objects present here and now (even if they bear on what you can justifiably claim to know about such objects), whatever those objects happen to be. Dennett's assertion that scientific objectivity requires appealing exclusively to third-person evidence appears mistaken. What scientific objectivity requires is not denial of the first-person subjective point of view but rather a means of communicating inter-subjectively about what one can grasp only from that point of view. Given the relational structure first-person phenomena like qualia appear to exhibit—a structure that Carnap devoted great effort to elucidating—such a means seems available: we can communicate what we know about qualia in terms of their structural relations to one another. Dennett fails to see that qualia can be essentially subjective and still relational or non-intrinsic, and thus communicable. This communicability ensures that claims about qualia are epistemologically objective; that is, they can in principle be grasped and evaluated by all competent observers even though they are claims about phenomena that are arguably not metaphysically objective, i.e., about entities that exist only as grasped by a subject of experience. It is only the former sort of objectivity that science requires. It does not require the latter, and cannot plausibly require it if the first-person realm of qualia is what we know better than anything else.[64] |

批判 エドワード・フェイザーは、デネットの立場に対して次のように異議を唱えている。クオリアの記憶が改ざんされたかどうかを判断するために、第三者の神経学 的証拠に訴える必要があるという主張は、クオリア自体(過去または現在)が、その証拠に訴えることによってのみ知ることができることを示しているようには 思えない。たとえ昨日のクオリアと同じかどうか分からなくても、一人称の主観的な視点から自分のクオリアを直接的に認識している可能性はある。ちょうど、 それが昨日見た記事と同じかどうか分からなくても、目の前の記事を本当に認識している可能性があるのと同じだ。記憶に関する質問は、それが何であれ、必ず しも今ここに存在する対象に対するあなたの意識の本質に影響を与えるものではない(たとえそれが、あなたがそのような対象について正当に知っていると主張 できることに関係しているとしても)。デネットが主張する、科学的客観性は三人称の証拠のみに訴えることを要求するという主張は誤っているように見える。 科学的客観性が必要としているのは、一人称の主観的視点の否定ではなく、むしろ、その視点からしか把握できないことを主観的に伝える手段である。クオリア のような一人称の現象が示す関係的構造(カルナップが解明に多大な努力を傾けた構造)を考慮すると、そのような手段は利用可能であると思われる。クオリア について知っていることを、クオリア同士の構造的関係性という観点から伝えることができる。デネットは、クオリアが本質的に主観的でありながらも、相対的 または非本質的であり、したがって伝達可能であるという事実を見落としている。この伝達可能性により、クオリアに関する主張は認識論的に客観的であること が保証される。つまり、それらは経験の主体によってのみ把握される存在に関する主張であり、形而上学的には客観的ではないかもしれないが、原理的には有能 な観察者全員が把握し評価できるのである。科学が要求するのは、あくまでも前者の客観性である。後者は必要としないし、クオリアという一人称の領域が何よ りもよく知られているものであるならば、後者を必要とすることは妥当ではない。[64] |

| Illusionism Illusionism is an active program within eliminative materialism to explain phenomenal consciousness as an illusion. It is promoted by the philosophers Daniel Dennett, Keith Frankish, and Jay Garfield, and the neuroscientist Michael Graziano.[65][66] Graziano has advanced the attention schema theory of consciousness and postulates that consciousness is an illusion.[67][68] According to David Chalmers, proponents argue that once we can explain consciousness as an illusion without the need for a realist view of consciousness, we can construct a debunking argument against realist views of consciousness.[69] This line of argument draws from other debunking arguments like the evolutionary debunking argument in the field of metaethics. Such arguments note that morality is explained by evolution without positing moral realism, so there is a sufficient basis to debunk moral realism.[70] Criticism Illusionists generally hold that once it is explained why people believe and say they are conscious, the hard problem of consciousness will dissolve. Chalmers agrees that a mechanism for these beliefs and reports can and should be identified using the standard methods of physical science, but disagrees that this would support illusionism, saying that the datum illusionism fails to account for is not reports of consciousness but rather first-person consciousness itself.[71] He separates consciousness from beliefs and reports about consciousness, but holds that a fully satisfactory theory of consciousness should explain how the two are "inextricably intertwined" so that their alignment does not require an inexplicable coincidence.[71] Illusionism has also been criticized by the philosopher Jesse Prinz.[72] |

イリュージョニズム イリュージョニズムは、現象的意識を幻想として説明する消去法による唯物論の積極的なプログラムである。この理論は、哲学者のダニエル・デネット、キー ス・フランク、ジェイ・ガーフィールド、および神経科学者のマイケル・グラツィアーノによって推進されている。[65][66] グラツィアーノは意識の注意スキーマ理論を推進しており、意識は幻想であると仮定している。 [67][68] デビッド・チャルマーズによると、擁護派は、意識を幻想として説明できれば、実在論的な意識観を必要とせずに、実在論的な意識観に対する反証を構築できる と主張している。[69] この種の議論は、メタ倫理学の分野における進化論的論証のような反証論から引き出されている。このような議論では、道徳は道徳的実在論を仮定することなく 進化によって説明できると指摘しているため、道徳的実在論を論破するのに十分な根拠がある。[70] 批判 イリュージョニストは一般的に、人々が意識があると信じたり発言したりする理由が説明されれば、意識の難問は解消されると主張する。チャルマーズは、これ らの信念や報告のメカニズムは物理科学の標準的な方法を用いて特定できるし、特定すべきであるという点には同意するが、これがイリュージョニズムを裏付け ることには反対である。データイリュージョニズムが説明できないのは、意識の報告ではなく、むしろ一人称の意識そのものであると彼は言う。 [71] 彼は意識と意識に関する信念や報告を区別しているが、意識に関する完全に満足のいく理論は、この2つが「切っても切り離せないほど絡み合っている」ことを 説明すべきであり、その整合性が不可解な偶然の一致を必要としないようにすべきであると主張している。[71] 幻想説は哲学者のジェシー・プリンツ(Jesse Prinz)からも批判されている。[72] |

| Attention schema theory Blindsight Constructivist epistemology Cotard delusion Deconstructivism Epiphenomenalism Functionalism Mind–body problem Monism New mysterianism Nihilism Phenomenology Physicalism Principle of locality Property dualism Reductionism Scientism Substance dualism Vertiginous question |

注意スキーマ理論 ブラインドサイト 構成主義的認識論 コタール錯覚 脱構築主義 随伴現象説 機能主義 心身問題 一元論 新神秘主義 ニヒリズム 現象学 物理主義 局在性の原理 性質二元論 還元主義 科学主義 実体二元論 めまいがするような質問 |

| Further reading Baker, L. (1987). Saving Belief: A Critique of Physicalism, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02050-7. Broad, C. D. (1925). The Mind and its Place in Nature. London, Routledge & Kegan. ISBN 0-415-22552-3 (2001 Reprint Ed.). Churchland, P.M. (1979). Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind. New York, Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-33827-1. Churchland, P.M. (1988). Matter and Consciousness, revised Ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53074-0. Rorty, Richard. "Mind-body Identity, Privacy and Categories" in The Review of Metaphysics XIX:24-54. Reprinted Rosenthal, D.M. (ed.) 1971. Stich, S. (1996). Deconstructing the Mind. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512666-1. |

さらに読む ベイカー、L. (1987年)。Saving Belief: A Critique of Physicalism(信念の保存:物理主義批判)、プリンストン、ニュージャージー州:プリンストン大学出版。ISBN 0-691-02050-7。 ブロード、C. D. (1925年)。The Mind and its Place in Nature(心とその自然界における位置)。ロンドン、ルートレッジ・アンド・キーガン。ISBN 0-415-22552-3(2001年再版)。 Churchland, P.M. (1979). Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind. New York, Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-33827-1. Churchland, P.M. (1988). Matter and Consciousness, revised Ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53074-0. ロートリ、リチャード。「心身同一性、プライバシー、カテゴリー」『形而上学評論』第19巻、24-54ページ。再掲、ロゼンタール、D.M.(編)1971年。 スティッチ、S.(1996年)。『心を解体する』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 0-19-512666-1。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eliminative_materialism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆