身体化された認知

Embodied cognition

☆ 身体化された認知(認識)とは、認知が生物の身体の状態や能力によってどのように形成されるかを調査する、多様な理論のグループを指す。身体化された要因 には、運動系、知覚系、環境との身体的な相互作用(状況依存性)、生物の脳と身体の機能構造を形成する世界についての想定などが含まれる。身体化された認 知は、これらの要素が、知覚バイアス、記憶想起、理解、高度な精神構造(意味の帰属やカテゴリーなど)、およびさまざまな認知タスク(推論や判断)のパ フォーマンスなど、幅広い認知機能に不可欠であることを示唆している。 身体化された心理論は、認知主義、計算論、デカルト主義的二元論などの他の理論に異議を唱えている。[1][2] 拡張された心理論、状況的認知、非活性化説と密接に関連している。現代版は、心理学、言語学、認知科学、力学系、人工知能、ロボット工学、動物認知、植物 認知、神経生物学の最新の研究から得られた理解に基づいている。

| Embodied cognition

represents a diverse group of theories which investigate how cognition

is shaped by the bodily state and capacities of the organism. These

embodied factors include the motor system, the perceptual system,

bodily interactions with the environment (situatedness), and the

assumptions about the world that shape the functional structure of the

brain and body of the organism. Embodied cognition suggests that these

elements are essential to a wide spectrum of cognitive functions, such

as perception biases, memory recall, comprehension and high-level

mental constructs (such as meaning attribution and categories) and

performance on various cognitive tasks (reasoning or judgment). The embodied mind thesis challenges other theories, such as cognitivism, computationalism, and Cartesian dualism.[1][2] It is closely related to the extended mind thesis, situated cognition, and enactivism. The modern version depends on understandings drawn from up-to-date research in psychology, linguistics, cognitive science, dynamical systems, artificial intelligence, robotics, animal cognition, plant cognition, and neurobiology. |

身体化された認知(認識)とは、認知が生物の身体の状態や能力によって

どのように形成されるかを調査する、多様な理論のグループを指す。身体化された要因には、運動系、知覚系、環境との身体的な相互作用(状況依存性)、生物

の脳と身体の機能構造を形成する世界についての想定などが含まれる。身体化された認知は、これらの要素が、知覚バイアス、記憶想起、理解、高度な精神構造

(意味の帰属やカテゴリーなど)、およびさまざまな認知タスク(推論や判断)のパフォーマンスなど、幅広い認知機能に不可欠であることを示唆している。 身体化された心理論は、認知主義、計算論、デカルト主義的二元論などの他の理論に異議を唱えている。[1][2] 拡張された心理論、状況的認知、非活性化説と密接に関連している。現代版は、心理学、言語学、認知科学、力学系、人工知能、ロボット工学、動物認知、植物 認知、神経生物学の最新の研究から得られた理解に基づいている。 |

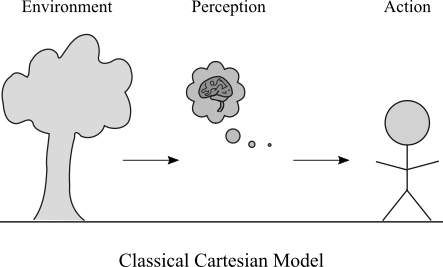

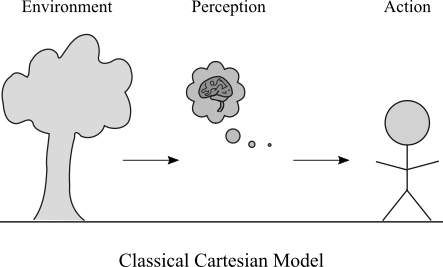

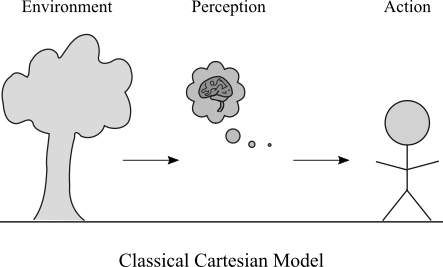

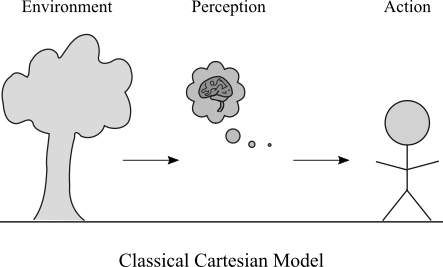

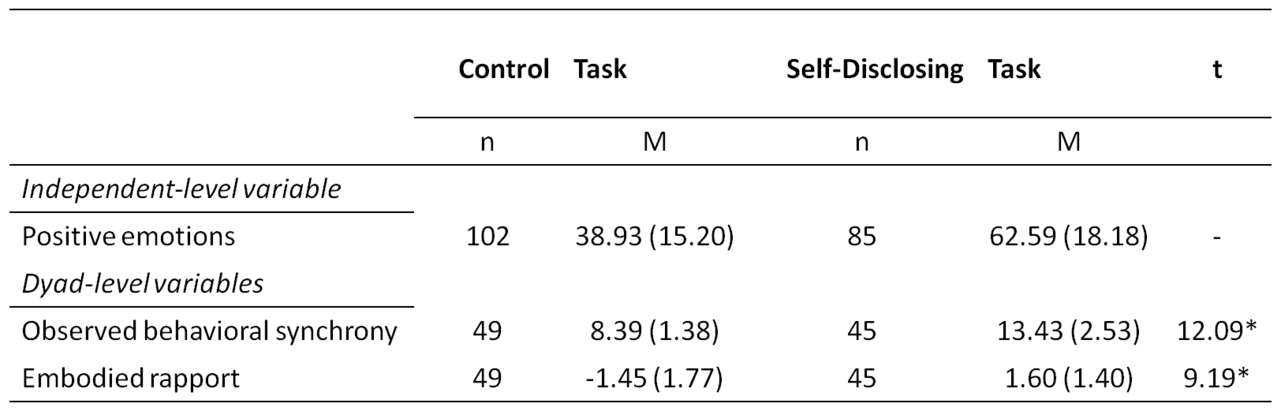

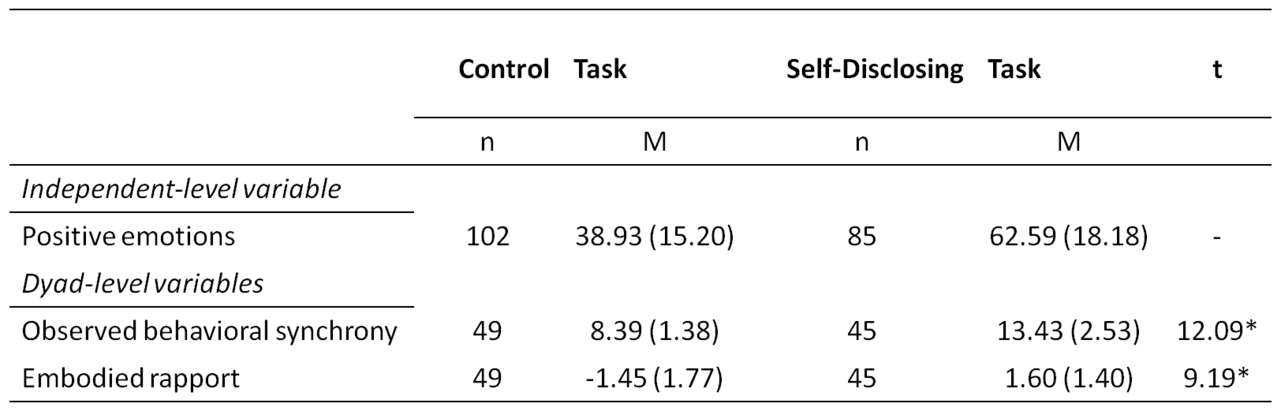

Theory The classical Cartesian model of the mind under which body, world, perception and action are understood as independent Proponents of the embodied cognition thesis emphasize the active and significant role the body plays in the shaping of cognition and in the understanding of an agent's mind and cognitive capacities. In philosophy, embodied cognition holds that an agent's cognition, rather than being the product of mere (innate) abstract representations of the world, is strongly influenced by aspects of an agent's body beyond the brain itself.[1][3] An embodied model of cognition opposes the disembodied Cartesian model, according to which all mental phenomena are non-physical and, therefore, not influenced by the body. With this opposition the embodiment thesis intends to reintroduce an agent's bodily experiences into any account of cognition. It is a rather broad thesis and encompasses both weak and strong variants of embodiment.[2][4][3][5][6] In an attempt to reconcile cognitive science with human experience, the enactive approach to cognition defines "embodiment" as follows:[2] By using the term embodied we mean to highlight two points: first that cognition depends upon the kinds of experience that come from having a body with various sensorimotor capacities, and second, that these individual sensorimotor capacities are themselves embedded in a more encompassing biological, psychological and cultural context. — The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience by Francisco J. Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch, pages 172–173. This double sense attributed to the embodiment thesis emphasizes the many aspects of cognition that researchers in different fields—such as philosophy, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, psychology, and neuroscience—are involved with. This general characterization of embodiment faces some difficulties: a consequence of this emphasis on the body, experience, culture, context, and the cognitive mechanisms of an agent in the world is that often distinct views and approaches to embodied cognition overlap. The theses of extended cognition and situated cognition, for example, are usually intertwined and not always carefully separated. And since each of the aspects of the embodiment thesis is endorsed to different degrees, embodied cognition should be better seen "as a research program rather than a well-defined unified theory".[5] Some authors explain the embodiment thesis by arguing that cognition depends on an agent's body and its interactions with a determined environment. From this perspective, cognition in real biological systems is not an end in itself; it is constrained by the system's goals and capacities. Such constraints do not mean cognition is set by adaptive behavior (or autopoiesis) alone, but instead that cognition requires "some kind of information processing... the transformation or communication of incoming information". The acquiring of such information involves the agent's "exploration and modification of the environment".[7] It would be a mistake, however, to suppose that cognition consists simply of building maximally accurate representations of input information...the gaining of knowledge is a stepping stone to achieving the more immediate goal of guiding behavior in response to the system's changing surroundings. — Marcin Miłkowski, Explaining the Computational Mind, p. 4. |

理論 心に関する古典的なデカルト主義モデルでは、身体、世界、知覚、行動は独立したものとして理解される。 身体化された認知論の支持者たちは、身体が認知の形成や、エージェントの心や認知能力の理解において果たす能動的かつ重要な役割を強調する。哲学におい て、身体化された認知とは、人間の認知は、単なる(生得的な)世界の抽象的表現の産物ではなく、脳そのもの以外の身体の側面からも強く影響を受けていると いう考え方である。[1][3] 身体化された認知モデルは、身体を排除したデカルト主義モデルに反対するものである。デカルト主義モデルでは、すべての精神現象は非物理的であり、した がって身体の影響を受けないとしている。この対立を踏まえ、身体化説は、認知に関するあらゆる説明に主体の身体経験を再び導入しようとするものである。こ れはかなり広義の説であり、身体化の弱い形態と強い形態の両方を包含している。[2][4][3][5][6] 認知科学と人間の経験を調和させる試みとして、認知に対する実行アプローチでは「身体化」を次のように定義している。 「身体化された」という用語を用いることで、次の2点を強調したい。第1に、認知はさまざまな感覚運動能力を備えた身体を持つことで得られる経験の種類に 依存しているということ、第2に、これらの個々の感覚運動能力は、より包括的な生物学的、心理学的、文化的な文脈に埋め込まれているということである。 —『The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience』(身体化された心:認知科学と人間経験)フランシスコ・J・ヴァレラ、エヴァン・トンプソン、エレノア・ロッシュ著、172- 173ページ。 この「二重感覚」は、身体化理論に起因するものであり、哲学、認知科学、人工知能、心理学、神経科学など、異なる分野の研究者たちが関与する認知の多くの 側面を強調している。身体化に関するこの一般的な特徴づけにはいくつかの問題がある。身体、経験、文化、文脈、そして世界におけるエージェントの認知メカ ニズムを強調する結果として、身体化認知に対する異なる見解やアプローチが重複することが多い。例えば、拡張認知と状況認知の理論は通常、複雑に絡み合っ ており、常に明確に区別されているわけではない。また、身体化理論の各側面は異なる程度で支持されているため、身体化認知は「明確に定義された統一理論と いうよりも、研究プログラム」として捉えるべきである。[5] 身体化理論を説明するために、認知はエージェントの身体とその環境との相互作用に依存していると主張する著者もいる。この観点から見ると、実際の生物学的 システムにおける認知はそれ自体が目的なのではなく、システムの目標や能力によって制約されている。このような制約があるからといって、認知が適応行動 (またはオートポイエーシス)のみによって決定されるというわけではなく、認知には「何らかの情報処理... 入力情報の変換または伝達」が必要である。このような情報の獲得には、エージェントによる「環境の探索と修正」が関わっている。[7] しかし、認知が入力情報の最大限に正確な表現を構築することのみで構成されていると考えるのは誤りである。知識の獲得は、システムの変化する環境に対応し て行動を導くというより直接的な目標を達成するための足がかりとなる。 — Marcin Miłkowski, Explaining the Computational Mind, p. 4. |

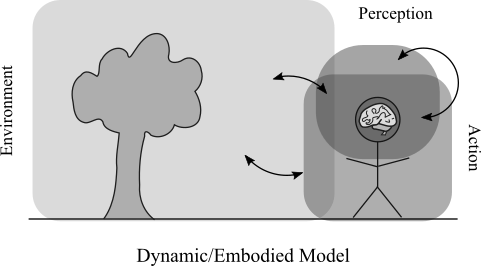

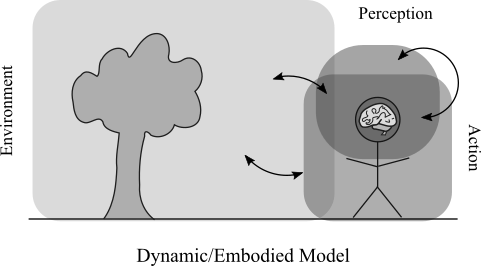

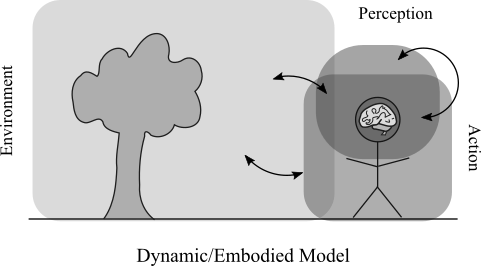

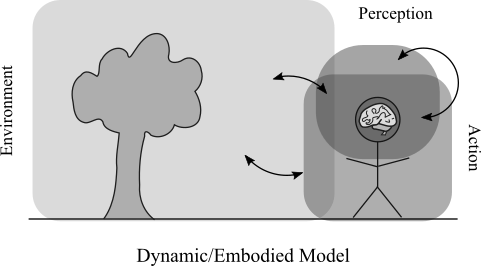

The embodied cognitive model of the mind under which body, world, perception and action are dynamically related with each other Another approach to understanding embodied cognition comes from a narrower characterization of the embodiment thesis. The following narrower view of embodiment avoids any compromises to external sources other than the body and allows differentiating between embodied cognition, extended cognition, and situated cognition. Thus, the embodiment thesis can be specified as follows:[1] Many features of cognition are embodied in that they are deeply dependent upon characteristics of the physical body of an agent, such that the agent's beyond-the-brain body plays a significant causal role, or a physically constitutive role, in that agent's cognitive processing. — RA Wilson and L Foglia, Embodied Cognition in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. This thesis points out the core idea that an agent's body plays a significant role in shaping different features of cognition, such as perception, attention, memory, reasoning—among others. Likewise, these features of cognition depend on the kind of body an agent has. The thesis omits direct mention of some aspects of the "more encompassing biological, psychological and cultural context" included in the enactive definition, making it possible to separate embodied cognition, extended cognition, and situated cognition. In contrast to the embodiment thesis, the extended mind thesis limits cognitive processing neither to the brain nor even to the body, it extends it outward into the agent's world.[1][8][9] Situated cognition emphasizes that this extension is not just a matter of including resources outside the head but stressing the role of probing and changing interactions with the agent's world.[10] Cognition is situated in that it is inherently dependent upon the cultural and social contexts within which it takes place.[11] This conceptual reframing of cognition as an activity influenced by the body has had significant implications. For instance, the view of cognition inherited by most contemporary cognitive neuroscience is internalist in nature. An agent's behavior along with its capacity to maintain (accurate) representations of the surrounding environment were considered as the product of "powerful brains that can maintain the world models and devise plans".[12] From this perspective, cognizing was conceived as something that an isolated brain did. In contrast, accepting the role the body plays during cognitive processes allows us to account for a more encompassing view of cognition. This shift in perspective within neuroscience suggests that successful behavior in real-world scenarios demands the integration of several sensorimotor and cognitive (as well as affective) capacities of an agent. Thus, cognition emerges in the relationship between an agent and the affordances provided by the environment rather than in the brain alone. In 2002, a collection of positive characterizations summarizing what the embodiment thesis entails for cognition were offered. Professor of Cognitive Psychology Margaret Wilson argues that the general outlook of embodied cognition "displays an interesting co-variation of multiple observations and houses a number of different claims: (1) cognition is situated; (2) cognition is time-pressured; (3) we off-load cognitive work onto the environment; (4) the environment is part of the cognitive system; (5) cognition is for action; (6) offline cognition is bodily-based".[13] According to Wilson, the first three and the fifth claim appear to be at least partially true, while the fourth claim is deeply problematic in that all things that have an impact on the elements of a system are not necessarily considered part of the system.[13] The sixth claim has received the least attention in the literature on embodied cognition, yet it might be the most significant of the six claims as it shows how certain human cognitive capabilities, that previously were thought to be highly abstract, now appear to be leaning towards an embodied approach for their explanation.[13] Wilson also describes at least five main (abstract) categories that combine both sensory and motor skills (or sensorimotor functions). The first three are working memory, episodic memory, and implicit memory; the fourth is mental imagery, and finally, the fifth concerns reasoning and problem solving. |

身体、世界、知覚、行動が動的に相互に関係している心の身体化認知モデル 身体化認知を理解するもう一つのアプローチは、身体化説のより狭義の特性によるものである。以下の身体化に関するより狭義の見解は、身体以外の外部ソース に対する妥協を一切排除し、身体化認知、拡張認知、状況認知の区別を可能にする。したがって、身体化説は以下のように特定できる。[1] 認知の多くの特徴は、エージェントの物理的身体の特性に深く依存している。そのため、エージェントの脳以外の身体は、そのエージェントの認知処理において 重要な因果的役割、または物理的構成的役割を果たしている。 — RA Wilson and L Foglia, Embodied Cognition in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. この論文は、エージェントの身体が知覚、注意、記憶、推論など、異なる認知の特徴を形成する上で重要な役割を果たすという核心的な考え方を指摘している。 同様に、これらの認知の特徴は、エージェントが持つ身体の種類に依存する。この論文では、エージェンシーの定義に含まれる「より包括的な生物学的、心理学 的、文化的文脈」のいくつかの側面について直接言及していないため、身体化認知、拡張認知、状況認知を区別することが可能となっている。 身体化理論とは対照的に、拡張心理論は認知処理を脳にも身体にも限定せず、エージェントの世界へと外へと拡張する。[1][8][9] 状況的認知論では、この拡張は単に頭の外にあるリソースを含めるという問題ではなく、エージェントの世界との相互作用を探り、変化させる役割を強調するも のであると強調している。 [10] 認知は、それが起こる文化的および社会的文脈に本質的に依存しているという意味で、状況依存的である。[11] 身体に影響される活動としての認知の概念の再構築は、重要な意味合いを持っている。例えば、現代の認知神経科学のほとんどが受け継いできた認知の考え方 は、本質的に内省的なものである。エージェントの行動と、周囲の環境の(正確な)表現を維持する能力は、「世界モデルを維持し、計画を考案できる強力な 脳」の産物であると考えられていた。[12] この観点では、認知とは孤立した脳が行うものとして考えられていた。これに対して、認知プロセスにおける身体の役割を受け入れることで、より包括的な認知 の概念を説明することが可能になる。神経科学におけるこの視点の転換は、現実世界のシナリオにおける成功した行動には、エージェントの複数の感覚運動およ び認知(および情動)能力の統合が必要であることを示唆している。したがって、認知は脳内のみで生じるのではなく、エージェントと環境が提供するアフォー ダンスとの関係において生じるのである。 2002年には、身体化理論が認知に及ぼす影響を要約した肯定的な特徴のまとめが発表された。認知心理学教授のマーガレット・ウィルソンは、身体化された 認知の一般的な見通しは「複数の観察結果の興味深い共変動を示し、異なる主張を数多く内包している」と主張している。すなわち、「(1)認知は状況に依存 する、(2)認知には時間的制約がある、(3)認知作業を環境に委ねる、(4)環境は認知システムの一部である、(5)認知は行動のためのものである、 (6)オフラインでの認知は身体に基づいている」という主張である。 [13] ウィルソンによると、最初の3つと5つめの主張は少なくとも部分的に正しいと思われるが、4つめの主張は、システムに影響を与えるものはすべてシステムの 一部として考慮されるとは限らないという点で、深刻な問題がある。 [13] 6番目の主張は、身体化された認知に関する文献では最も注目されていないが、これまで非常に抽象的であると考えられていた特定の人間の認知能力が、現在で はその説明に身体化されたアプローチが適しているように見えることを示しているため、6つの主張の中で最も重要な主張である可能性がある。[13] ウィルソンはまた、感覚と運動技能(または感覚運動機能)の両方を組み合わせた少なくとも5つの主な(抽象的な)カテゴリーについても説明している。最初 の3つは、作業記憶、エピソード記憶、潜在記憶であり、4つ目は心的イメージ、そして5つ目は推論と問題解決である。 |

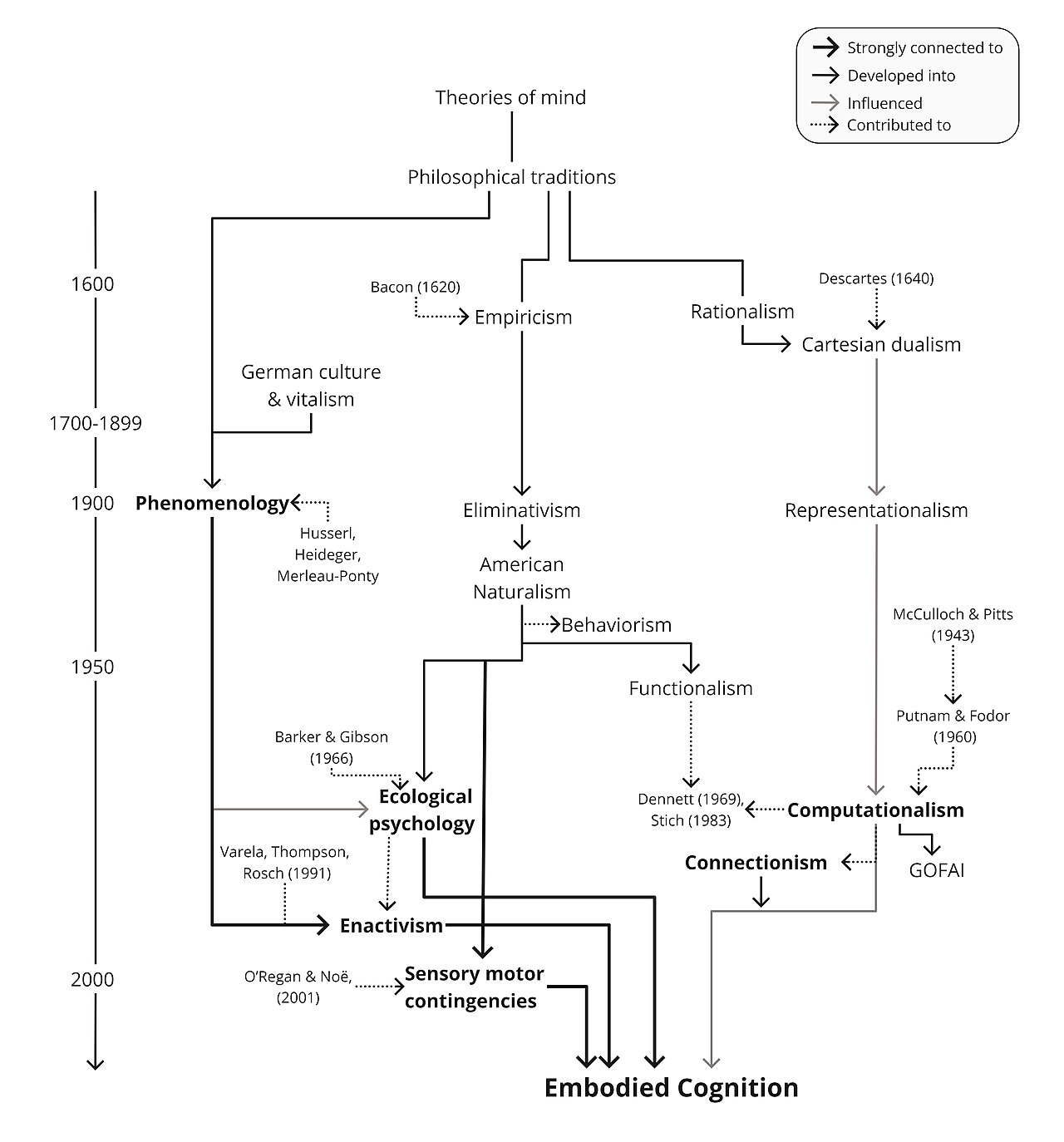

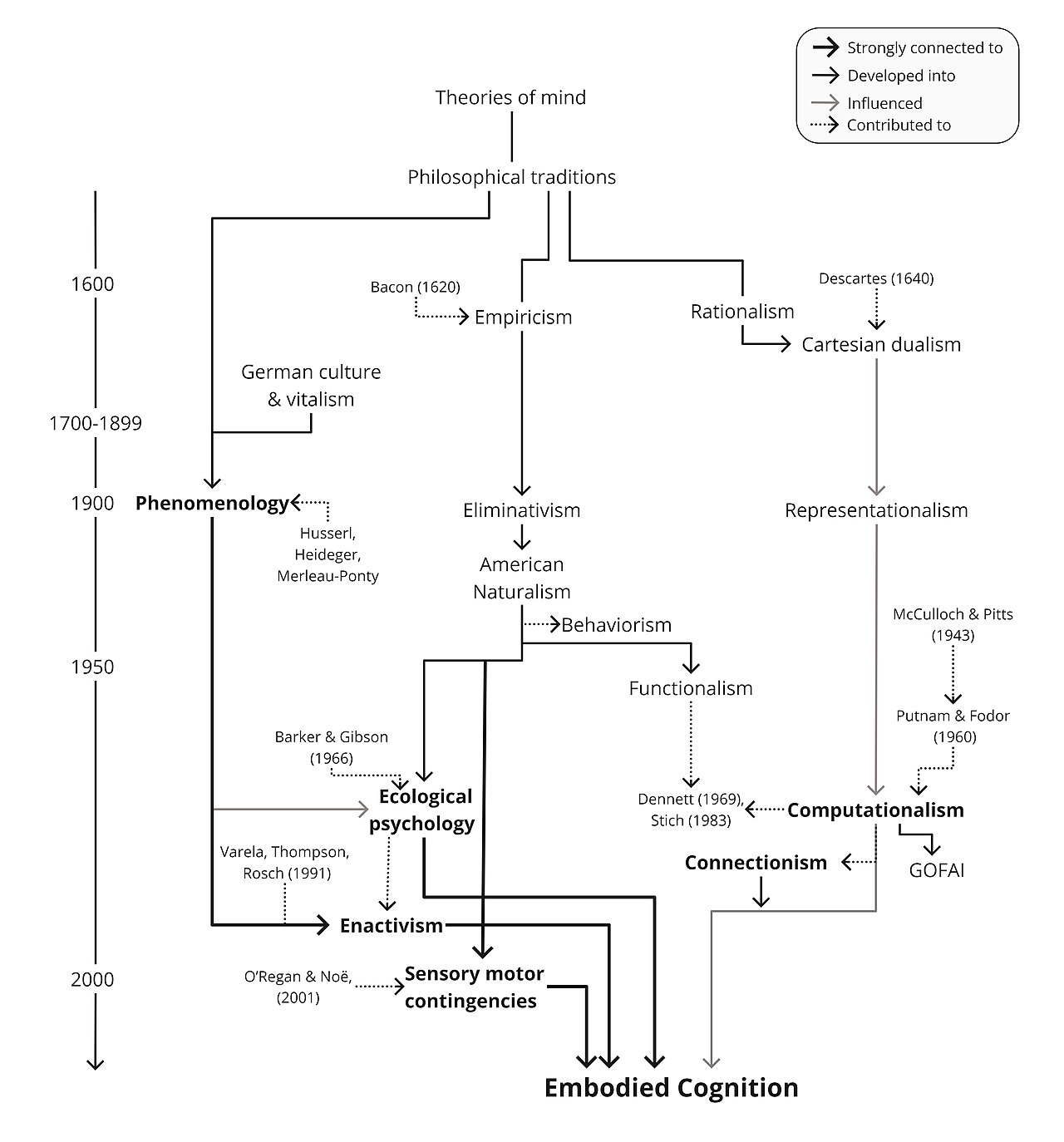

History A timeline graph reconstructing historically relevant developments and key contributions that influenced the growth of embodied cognition. To the left are the years in descending order. The legend on the top-right corner indicates how to interpret the connections made. The theory of embodied cognition, along with the multiple aspects it comprises, can be regarded as the imminent result of an intellectual skepticism towards the flourishment of the disembodied theory of mind put forth by René Descartes in the 17th century. According to Cartesian dualism, the mind is entirely distinct from the body and can be successfully explained and understood without reference to the body or to its processes.[14] Research has been done to identify the set of ideas that would establish what could be considered as the early stages of embodied cognition around inquiries regarding the mind-body-soul relation and vitalism in the German tradition from 1740 to 1920.[15] The modern approach and definition of embodied cognition has a relatively short history.[16] Intellectual underpinnings of embodied cognition can be traced back to the influence of philosophy and, more specifically, the phenomenological tradition, psychology, and connectionism in the 20th century. Phenomenologists such as Edmund Husserl (1850–1938), Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), and Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908–1962) served as a source of inspiration for what would later be known as the embodiment thesis. They stood up against the mechanistic and disembodied approach to the explanation of the mind by emphasizing the fact that there are aspects of human experiences (consciousness, cognition) that cannot simply be explained by a model of the mind as computation of inner symbols. From a phenomenological standpoint, such aspects remain unaccountable if, as in Cartesian dualism, they are not "deeply rooted in the physical nuts-and-bolts of the interacting agent".[17] Maurice Merleau-Ponty in his Phenomenology of Perception [transl. 1], for example, rejects the Cartesian idea that people's primary mode of being in the world is thinking [transl. 2][transl. 3] and proposes corporeity [transl. 4], that is, the body itself as the primary site for knowing the world, and perception as the medium and the pre-reflective foundation of experience. The body is the vehicle of being in the world, and having a body is, for a living creature, to be intervolved in a definite environment, to identify oneself with certain projects and be continually committed to them.[18] So stated, the body is the primary condition for experience since it comprises a collection of active meanings about the world and its objects. The body also provides the first-person perspective (a point of view) with which one experiences the world and opens up multiple possibilities for being.[18] The appreciation of the phenomenological mindset allows us to not overlook the influence that phenomenology's speculative but systematic reflection on the mind-body-world relation had in the growth and development of the core ideas which embodied cognition comprises. From a phenomenological perspective "all cognition is embodied, interactive, and embedded in dynamically changing environments".[19] These constitute the set of beliefs which proponents of embodied cognition such as cognitive scientists Francisco Varela, Eleonor Rosch, and Evan Thompson will revise later on and seek to reintroduce in the scientific study of cognition under the name of enaction.[2] Enactivism reclaims the importance of considering the biodynamics of the living organism to understand cognition by gathering ideas from fields such as biology, psychoanalysis, Buddhism, and phenomenology. According to this enactive approach, organisms obtain knowledge or develop their cognitive capacities through a perception–action relationship with a mutually determining environment. This basic idea of (qualitative) experience as the product of an individual's active perception–action interactions with its surrounding is also traceable to the American contextualist or pragmatist tradition in works such as Art As Experience by American psychologist John Dewey. For Dewey, experiences affect people's personal lives as they are the by-product of continuous and commutative interactions of a biological and organic self (an incarnated body) with the world. These lived (corporeal) experiences should serve as the foundation to build upon.[20] On the bases of empirical grounds, and in opposition to those philosophical traditions that belittled the importance of the body to understand cognition, research on embodiment have demonstrated the relationship between cognition and bodily process. Thus, understanding cognition requires one to consider and investigate the sensory and motor mechanism that enables it. Cognitive scientist George Lakoff, for example, holds that reasoning and language arise from the nature of bodily experiences and, thus, even people's own metaphors have bodily references.[21] Since the 1950s, encouraged by progress in informatics, researchers began to create digital models of the processes by which sensory input is selected by the brain, stored in the memory, connected to existing knowledge and used for elaboration.[22] These traditional computationalists views of cognition that were typical in the 1950s–1980s are now considered implausible because there is no continuity with the cognitive skills that would have been demanded and developed by the ancestors of the human species.[23] The earlier version of the concept of embodiment in cognition was offered in 1997-1999 by Irina Trofimova who called the experimentally proven effects of embodiment in meaning attribution as "projection through capacities".[24][3][25] Some researchers indeed argue that this algorithmic focus on mental activities ignores the fact that human beings engage with evolutionary pressures using their entire bodies.[26][27] Margaret Wilson considers the embodied cognition perspective as fundamentally an evolutionary one, viewing cognition as a set of abilities that built upon, and still reflects, the structure of physical bodies and how human brains evolved to manage those bodies.[23] The theory of evolution emphasises that thanks to their bipedal gait, early humans did not need their 'forepaws' for locomotion, facilitating them to manipulate the environment with the aid of tools. One researcher goes even further, positing that the multiple opportunities provided by human hands shape people's concepts of the mind.[27] One example is that people often conceive cognitive processes in manual terms, such as 'grasping an idea'. J.J. Gibson (1904–1979) developed his theory on ecological psychology that entirely contradicted the computationalist idea of understanding the mind as information processing which by that time had permeated psychology—both in theory and practice. Gibson particularly disagreed with the way his contemporaries understood the nature of perception. Computationalist perspectives, for example, consider perceptual objects as an unreliable source of information upon which the mind must do some sort of inference. Gibson view perceptual processes as the product of the relation between a moving agent and its relationship with a specific environment.[28] Similarly, Varela and colleague's argue that both cognition and the environment are not pre-given; instead, they are enacted or brought forth by the agent's history of sensorimotor and structurally coupled activities.[2] Connectionism also put forth a critique to the computationalist commitments yet granting the possibility of some sort of non-symbolic computational processes to take place.[29] According to the connectionist thesis, cognition as a biological phenomenon can be explained and understood through the interaction and dynamics of artificial neural networks (ANNs).[30][31] Given the traces of abstraction that remain in the inputs and outputs through which connectionist neural networks carry its computations, connectionism is said to be not so far from computationalism and unable to cope with both the challenge of dealing with the details involved during perceiving and acting and explaining higher level cognition.[32][33] Likewise, connectionism's take on cognition is biologically inspired by the behavior and interaction of single neurons, yet its connections to the embodiment thesis in general, and to perception–action interactions in particular, are not clearly outlined or straightforward. By early 2000, O'Regan, J. K. and Noë, A. provided empirical evidence against the computationalist mindset arguing that although cortical maps exist in the brain and their patterns of activation give rise to perceptual experiences, they alone are unable to fully explain the subjective character of experience. Namely, it is unclear how internal representations generate conscious perception. Given this ambiguity, O'Regan, J. K. and Nöe, A. put forth what would later be known as "sensorimotor contingencies" (SMCs) in an attempt to understand the changing character of sensations as actors act in the world. According to the SMC theory, The experience of seeing occurs when the organism masters what we call the governing laws of sensorimotor contingency.[34] Ever since the late 20th century and recognizing the significant role the body plays for cognition, the embodied cognition theory has gained (an ever increasing) popularity, it has been the subject of multiple articles in different research areas, and the mainstream approach to what Shapiro and Spaulding call the "embodied make-over".[19] A consequence of this widespread acceptance of the embodiment thesis is the emergence of 4E features of cognition (embodied, embedded, enacted, and extended cognition). Under 4E, cognition is no longer thought of as being instantiated in or by a single organism, rather: It assumes that cognition is shaped and structured by dynamic interactions between the brain, body, and both the physical and social environments.[35] |

沿革 身体化された認知の成長に影響を与えた歴史的に関連性の高い発展と主要な貢献を再構成した年表グラフ。左側には降順で年代が示されている。右上隅の凡例 は、つながりの解釈方法を示している。 身体化された認知の理論は、その多様な側面とともに、17世紀にルネ・デカルトが提唱した身体を伴わない心の理論の隆盛に対する知的懐疑主義の切迫した結 果とみなすことができる。デカルト主義的二元論によれば、心は身体とは完全に別個のものであり、身体やそのプロセスを参照することなく、うまく説明し理解 することができる。 1740年から1920年までのドイツの伝統における心身魂の関係や活力論に関する研究から、身体化された認知の初期段階と考えられるものの確立を目指し た一連のアイデアの特定に向けた研究が行われている。[15] 身体化された認知の現代的なアプローチや定義の歴史は比較的浅い。 [16] 身体化された認知の知的基盤は、20世紀の哲学、より具体的には現象学の伝統、心理学、コネクショニズムの影響にまで遡ることができる。 エドムンド・フッサール(1850-1938)、マルティン・ハイデガー(1889-1976)、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティ(1908-1962)と いった現象学者たちは、後に「身体化理論」として知られるようになるもののインスピレーションの源となった。彼らは、人間の経験(意識、認知)には、内的 シンボルの計算という心のモデルでは単純に説明できない側面があることを強調することで、心の説明における機械論的かつ身体を排除したアプローチに異議を 唱えた。現象学の観点では、デカルト主義的な二元論のように、そうした側面が「相互作用する主体の物理的な仕組みに深く根ざしていない」場合、そうした側 面は説明できないままである。 [17] 例えば、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティは著書『知覚の現象学』[1]において、デカルト主義的な考え方、すなわち、人間が世界で存在する主な方法は思考であ るという考え方を否定し[2][3]、身体性[4]、すなわち、身体そのものが世界を知るための主な場所であり、知覚は経験の媒体であり、反射以前の基礎 であると提唱している。 身体は世界における存在の乗り物であり、身体を持つことは、生物にとって、特定の環境に深く関わり、特定のプロジェクトと自己同一化し、それらに継続的に 献身することを意味する。 このように述べると、身体は世界とその対象物に関する能動的な意味の集合体であるため、経験の第一条件となる。身体はまた、世界を経験する一人称の視点 (観点)を提供し、存在の可能性を複数開拓する。 現象学的な考え方を理解することで、心身世界関係に関する現象学の思索的かつ体系的な考察が、認知を体現するコアなアイデアの成長と発展に与えた影響を見 落とさないようにすることができる。現象学的観点では、「すべての認知は体現され、相互的であり、動的に変化する環境に埋め込まれている」のである。 [19] これらは、認知科学者フランシスコ・ヴァレラ、エレオノーラ・ロッシュ、エヴァン・トンプソンといった身体化された認知の提唱者たちが後に修正し、エネク ションという名称で認知の科学的調査に再び導入しようとしている信念の集合を構成している。[2] エネクティヴィズムは、生物学、精神分析学、仏教、現象学などの分野からアイデアを集め、認知を理解するために生物の生体力学を考慮することの重要性を再 認識する。このエンアクティヴィズムのアプローチによると、生物は相互に決定し合う環境との知覚と行動の関係を通じて知識を得たり、認知能力を発達させた りする。 この基本的な考え方(質的)経験は、個人が周囲との能動的な知覚と行動の相互作用の産物であるという考え方は、アメリカのコンテクスチュアリズムやプラグ マティズムの伝統にも見られる。例えば、アメリカの心理学者ジョン・デューイの著書『経験としての芸術』などである。デューイにとって、経験とは、生物学 的かつ有機的な自己(肉体)と世界との継続的かつ相互的な相互作用の副産物であり、人格に影響を与えるものである。このような実存的(肉体的な)経験は、 その上に構築する基盤となるべきものである。 実証的な根拠に基づき、認知を理解する上で身体の重要性を軽視する哲学的な伝統に反対する形で、身体化に関する研究は認知と身体のプロセスとの関係を明ら かにしてきた。したがって、認知を理解するには、それを可能にする感覚と運動のメカニズムを考慮し、調査する必要がある。認知科学者のジョージ・ラコフ は、例えば、推論と言語は身体経験の性質から生じるものであり、したがって、人々が用いる比喩にも身体的な参照がある、と主張している。 1950年代以降、情報科学の進歩に後押しされ、研究者たちは感覚入力が脳によって選択され、記憶に保存され、既存の知識と結びつけられ、さらに詳細な情 報へと利用されるまでのプロセスをデジタルモデル化するようになった。 [22] 1950年代から1980年代にかけて典型的なものだった、こうした伝統的な計算論的認知観は、現在では考えにくいものと考えられている。なぜなら、人類 の先祖が要求し、発達させてきた認知能力との連続性がないからである。 [23] 認知における身体化の概念の初期のバージョンは、意味帰属における身体化の実験的に証明された効果を「能力を介した投影」と呼んだイリーナ・トロフィモワ によって1997年から1999年の間に提示された。[24][3][25] 実際、一部の研究者は、この精神活動に焦点を当てたアルゴリズムは、人間が全身を使って進化の圧力に対処しているという事実を無視していると主張してい る。 [26][27] マーガレット・ウィルソンは、身体化された認知の観点が基本的に進化論的なものであると考え、認知を身体の構造を基盤とし、またその構造を反映する一連の 能力と捉えている。また、人間の脳が身体を管理するために進化してきた方法でもあると見なしている。[23] 進化論では、初期の人類は二足歩行により「前足」を移動のために必要としなかったため、道具を使って環境を操作することが容易になったと強調している。あ る研究者はさらに踏み込んで、人間の「手」が提供する多くの機会が、人々の心に対する概念を形成していると主張している。[27] その一例として、人々はしばしば「アイデアを把握する」といったように、認知プロセスを手を使った言葉で表現する。 J.J.ギブソン(1904-1979)は、当時心理学の理論と実践の両面で浸透していた、心を情報処理として理解する計算論的考え方に完全に反する生態 心理学の理論を展開した。ギブソンは特に、同時代の知覚の本質に対する理解に反対した。計算論的視点では、知覚対象は信頼性の低い情報源であり、心はそれ に基づいて何らかの推論を行わなければならないと考える。ギブソンは知覚プロセスを、動く主体と特定の環境との関係の産物と見なしている。[28] 同様に、ヴァレラとその同僚は、認知も環境も先天的なものではなく、それらは主体の感覚運動と構造的に結合した活動の歴史によって生み出されると主張して いる。[2] コネクショニズムは、計算論的立場に批判的な見解を示しているが、何らかの非記号的な計算プロセスが起こる可能性を認めている。 [29] コネクショニストの論文によると、生物学的現象としての認知は、人工ニューラルネットワーク(ANN)の相互作用と力学によって説明され、理解できる。 [30][31] コネクショニストのニューラルネットワークが計算を行う際の入力と出力には抽象化の痕跡が残っているため、コネクショニズムは計算論からそれほど離れてお らず、知覚や行動に関わる詳細を扱うことや、高次認知を説明することの両方の課題に対処できないと言われている。 [32][33] 同様に、コネクショニズムの認知に関する見解は、単一ニューロンの行動と相互作用から生物学的に着想を得ているが、一般的に身体化説、特に知覚と行動の相 互作用との関連性については、明確に説明されておらず、単純なものではない。 2000年初頭までに、オリアンとノエは、大脳皮質地図が脳内に存在し、その活性化パターンが知覚体験を生み出すものの、それだけでは体験の主観的な性格 を完全に説明することはできないという計算論的考え方に対する実証的証拠を提示した。すなわち、内部表現がどのようにして意識的な知覚を生み出すのかは不 明である。この曖昧さを受け、O'Regan, J. K. と Nöe, A. は、俳優が世界で演じる中で感覚の性質が変化することを理解しようと試み、後に「感覚運動随伴性(sensorimotor contingencies: SMC)」として知られるようになる理論を打ち出した。SMC理論によると、 見るという経験は、生物が感覚運動随伴性の支配法則を習得したときに起こる。[34] 20世紀後半以降、身体が認知に果たす重要な役割が認識されるようになって以来、身体化認知理論は(ますます)人気を集め、異なる研究分野で多数の記事の 主題となり、シャピロとスポルディングが「身体化による改革」と呼ぶものへの主流のアプローチとなっている。 [19] 身体化理論が広く受け入れられた結果、4Eの認知機能(身体化認知、埋め込み認知、遂行認知、拡張認知)が誕生した。4Eでは、認知はもはや単一の生物に よって、あるいは単一の生物に具現化されるとは考えられていない。むしろ、 認知は脳、身体、物理的環境および社会的環境の間の動的な相互作用によって形成され、構造化されると想定されている。[35] |

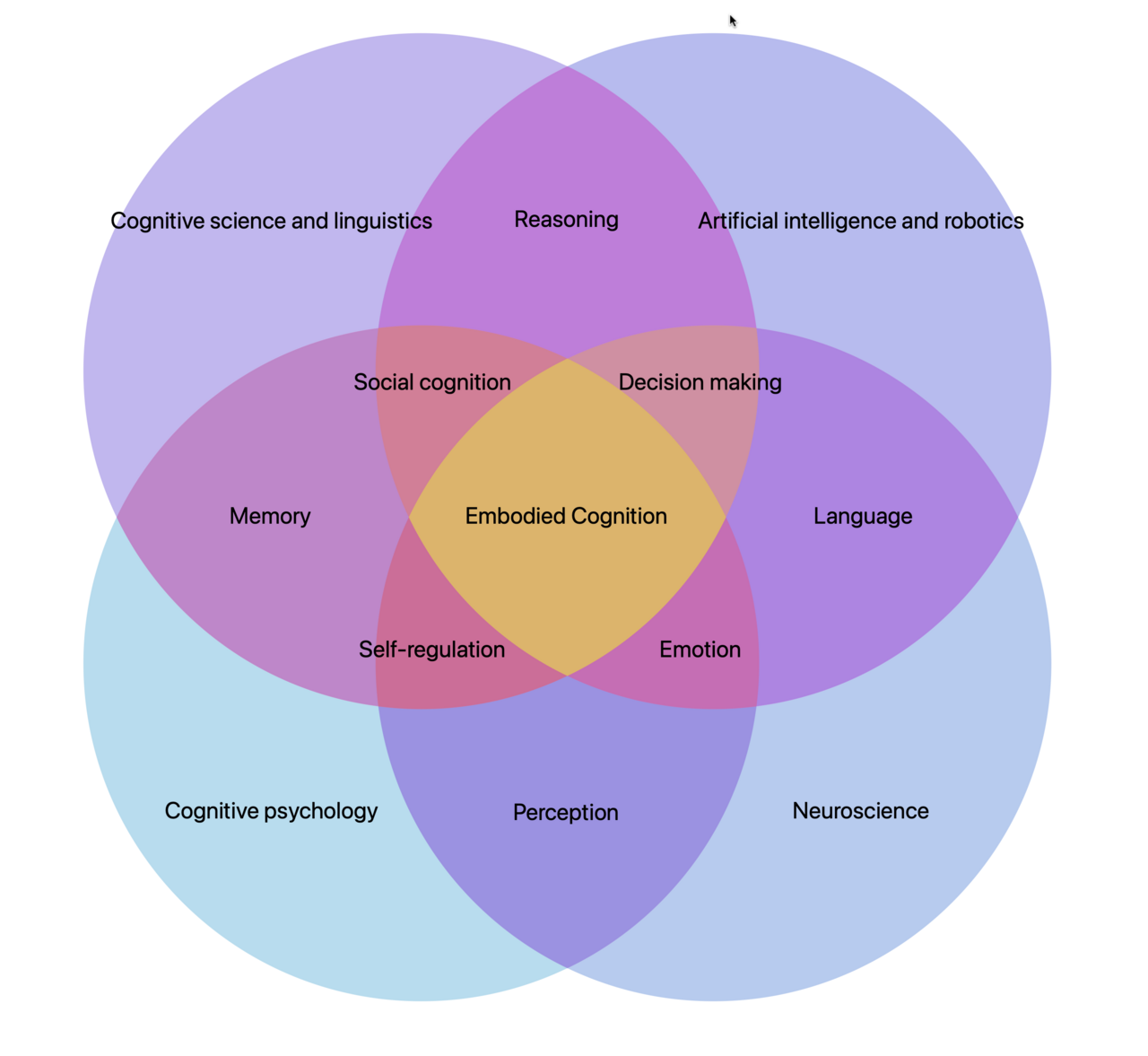

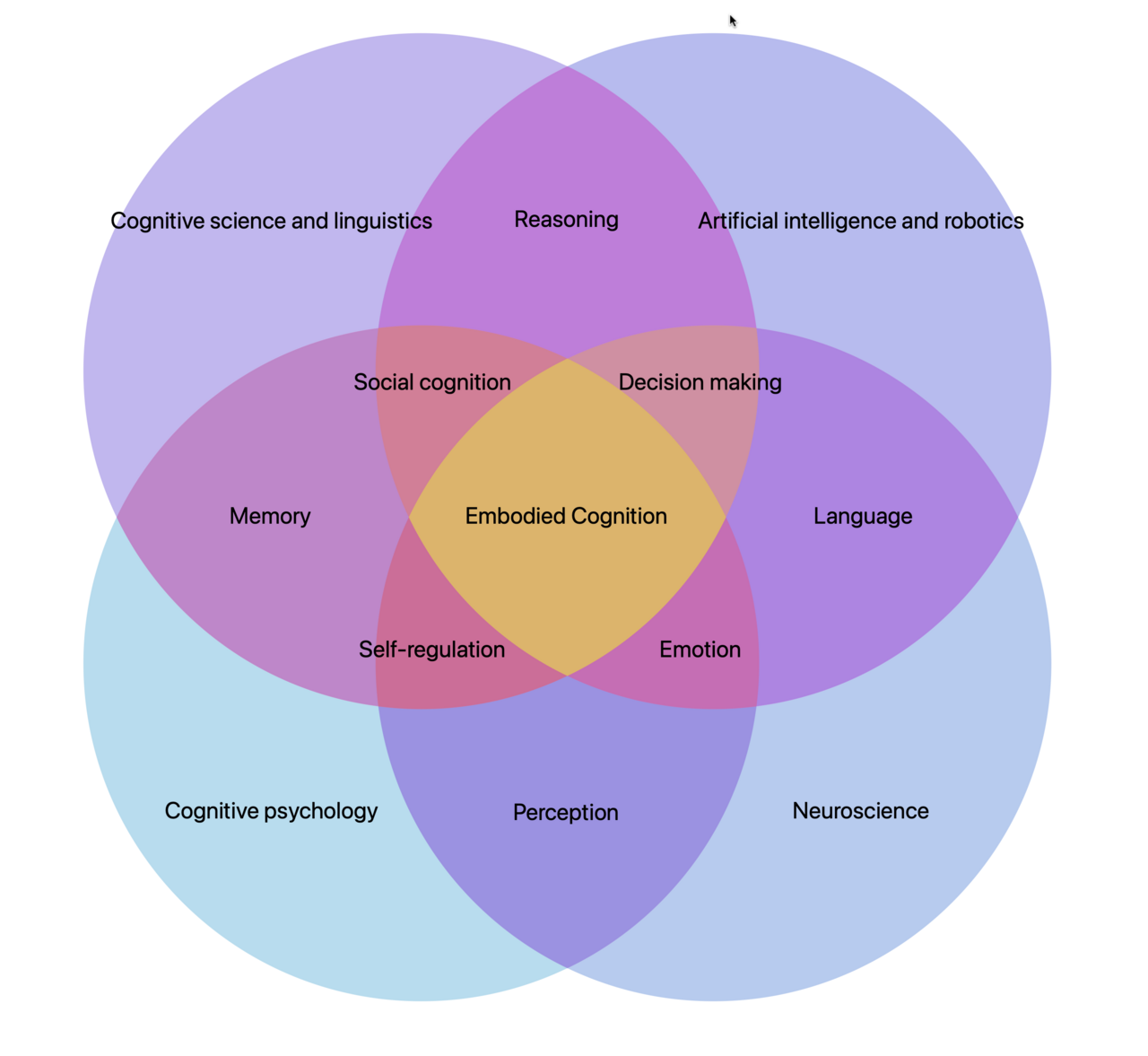

Scope The scope of embodied cognition and the intertwined relationship that arise between the sciences Embodied cognition argues that several factors both internal and external (such as the body and the environment) play a role in the development of an agent's cognitive capacities, just as mental constructs (such as thoughts and desires) are said to influence an agent's bodily actions. For this reason, embodied cognition is considered as a wide-ranging research program, rather than a well-defined and unified theory.[19] A scientific approach to embodied cognition reaches, inspires, and brings together ideas from several research areas, each with its own take on embodiment yet in a joint effort to (methodically) investigate embodied cognition. Research on embodied cognition comprises a variety of fields within the sciences such as linguistics, neuroscience, (cognitive) psychology, philosophy, artificial intelligence, robotics, etc. For this reason, contemporary developments on embodied cognition can be regarded as the embodied make-over of cognitive science offering new ways to look at the nature, structure, and mechanisms of cognition.[4] Embodying cognition requires the different features of cognition such as perception, language, memory, learning, reasoning, emotion, self-regulation, and its social aspects to be revisited and investigated through the lens of embodiment in order to ground its theoretical and methodological underpinnings.[36] Embodied cognition has gained the attention and interest of classical cognitive science (along with all sciences it comprises) to incorporate embodiment ideas into its research. In linguistics, George Lakoff (a cognitive scientist and linguist) and his collaborators Mark Johnson, Mark Turner, and Rafael E. Núñez have promoted and expanded the embodiment thesis based on developments within the field of cognitive science.[37][38][39][40][41] Their research has provided evidence suggesting that people use their understanding of familiar physical objects, actions, and situations to understand other domains. All cognition is based on the knowledge that comes from the body and other disciplines are mapped onto humans' embodied knowledge using a combination of conceptual metaphor, image schema and prototypes. The conceptual metaphors research have argued that people use metaphors all over [37] to be in charge of the conceptual level; in other words, they map one conceptual state into another one. Therefore, research has stated that there is a single metaphor behind various definitions. Several examples of conceptual metaphors from different fields were collected to explain how metaphors relate to other metaphors and often refer to body aspects.[37][39] The most common example given to this explanation is when people describe the concept of love, associating this love metaphor with physically embodied journey experiences. Another example of the language and embodiment of Lakoff and Mark Turner is visual metaphors. Accordingly, they argue that the positioning of these visual metaphors for upright and forward-moving creatures depends on body type and the characteristics of the body's interaction with the environment.[37] Another study from 2000 focused on the "image schema" to investigate how people understand abstract concepts.[41] Accordingly, abstract concepts are understood by considering basic physical situations. Abstract concepts, whose basic physical states are considered, are then interpreted by using sensory-motor and perceptual skills. Thus, it is shown that there is a spatial reasoning process that requires using the body even in reasoning over abstract concepts. In this context, the image schema is seen as a conceptual metaphor form. For example, spatial reasoning skills and the visual cortex tend to be used to understand a mathematical concept consisting of imaginary numbers that are purely abstract.[41] Thus, it has been shown how important the body plays in the image schema as in the conceptual metaphor in the interpretation of concepts. Another important factor in understanding linguistic categories is prototypes. Eleanor Rosch argued that prototypes play an important role in people's cognition. According to her research, prototypes are the most typical members of a category, and she explains this with an example from birds. The robin, for example, is a prototypical bird while the penguin is not a prototypical bird which shows that objects that are prototypical are more easily categorized, and therefore, people can find answers by reasoning about the categories they encounter through these prototypes.[42] Another study identified basic level categories that exemplify this situation in a more structured way. Accordingly, basic level categories are categories that can be associated with basic physical motions; they are made up of prototypes that can be easily visualized. These prototypes are used for reasoning about general categories.[43] On the other hand, Lakoff emphasizes that what is important in prototype theory, rather than class or type characteristics, is that the feature of the categories people use is a bodily experience.[38] Thus, as seen in the general of these approaches, it can be said that the most basic feature in understanding and interpreting linguistic concepts and categories is whether the concept or category has been experienced bodily. Neuroscientists Gerald Edelman, António Damásio and others have outlined the connection between the body, individual structures in the brain and aspects of the mind such as consciousness, emotion, self-awareness and will.[44][45] Biology has also inspired Gregory Bateson, Humberto Maturana, Francisco Varela, Eleanor Rosch and Evan Thompson to develop a closely related version of the idea, which they call enactivism.[2][46] The motor theory of speech perception proposed by Alvin Liberman and colleagues at the Haskins Laboratories argues that the identification of words is embodied in perception of the bodily movements by which spoken words are made.[47][48][49][50][51] In related work at Haskins, Paul Mermelstein, Philip Rubin, Louis Goldstein, and colleagues developed articulatory synthesis tools for computationally modeling the physiology and aeroacoustics of the vocal tract, demonstrating how cognition and perception of speech can be shaped by biological constraints. This was extended into the audio-visual domain by the "talking heads" approach of Eric Vatikiotis-Bateson, Rubin, and other colleagues. The concept of embodiment has been inspired by research in cognitive neuroscience, such as the proposals of Gerald Edelman concerning how mathematical and computational models such as neuronal group selection and neural degeneracy result in emergent categorization. From a neuroscientific perspective, the embodied cognition theory examines the interaction of sensorimotor, cognitive, and affective neurological systems. The embodied mind thesis is compatible with some views of cognition promoted in neuropsychology, such as the theories of consciousness of Vilayanur S. Ramachandran, Gerald Edelman, and Antonio Damasio. It is also supported by a broad and ever-increasing collection of empirical studies within neuroscience. By examining brain activity with neuroimaging techniques, researchers have found indications of embodiment. In an Electroencephalography (EEG) study researchers showed that in line with the embodied cognition, sensorimotor contingency and common coding theses, sensory and motor processes in the brain are not sequentially separated, they are strongly coupled.[52] Considering the interaction of the sensorimotor and cognitive system, a study from 2005 stresses how crucial sensorimotor cortices are for semantic comprehension of body–action terms and sentences.[53] A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study from 2004 showed that passively read action words, such as lick, pick or kick, led to a somatotopic neuronal activity in or adjacent to brain regions associated with actual movement of the respective body parts.[54] Using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a study in 2005 stated that the activity of the motor system is coupled to auditory action-related sentences. When the participants listened to hand–or foot-related sentences, the motor evoked potentials (MEPs) recorded from the hand and foot muscles were reduced.[55] These two exemplary studies indicate a relationship between cognitively understanding words referring to sensorimotor concepts and activation of sensorimotor cortices. Along the lines of embodiment, neuroimaging techniques serve to show interactions of the sensory and motor system. Next to neuroimaging studies, behavioral studies also provides evidence supporting the embodied cognition theory. Abstract higher cognitive concepts such as the "importance" of an object or an issue also seem to stand in relation to the sensorimotor system. People estimate objects to be heavier when they are told that they are important or hold important information in contrast to unimportant information.[56] Similarly, weight affects the way people invest physical and cognitive effort when dealing with concrete or abstract issues. For example, more importance is assigned to decision–making procedures when holding heavier clipboards.[57] What this suggest is that the physical effort invested in concrete objects leads to more cognitive effort when dealing with abstract concepts. The work of cognitive neuroscientists such as Francisco Varela and Walter Freeman seeks to explain embodied and situated cognition in terms of dynamical systems theory and neurophenomenology, rejecting the idea that the brain merely uses representations to cognise (a position also espoused by Gerhard Werner). There are several neuroscientific approaches to explain cognition from an embodied perspective as well as multiple methods such as neuroimaging techniques, behavioral experiments, and dynamical models that can be employed to support and further investigate embodied cognition. In the field of Robotics researchers such as Rodney Brooks, Hans Moravec and Rolf Pfeifer have argued that true artificial intelligence can only be achieved by machines that have sensory and motor skills and are connected to the world through a body.[6][58][59] The insights of these robotics researchers have in turn inspired philosophers like Andy Clark and Hendriks-Jansen.[60][61] In the light of these, a body is essential for cognition and, therefore, for intelligent behavior since the interaction between the body and the environment is fundamental for developing cognitive abilities.[62] This type of knowledge is grounded in physical embodiment–the relationship humans have with their bodies. It is the concept of "the idea that the mind is not only connected to the body but that the body influences the mind".[16] Embodied artificial intelligence and robotics is a method of applying this principle to artificial systems. |

スコープ 身体化された認知のスコープと、科学の間に生じる複雑に絡み合った関係 身体化された認知は、エージェントの認知能力の発達には、内部および外部の複数の要因(身体や環境など)が関与していると主張する。思考や欲求などの心的 構成がエージェントの身体行動に影響を与えると言われるのと同様に。このため、身体化された認知は、明確に定義された統一理論というよりも、幅広い研究プ ログラムとして考えられている。[19] 身体化された認知に対する科学的アプローチは、身体化に関する独自の考え方を持つ複数の研究分野からアイデアを取り入れ、触発し、統合する。 身体化された認知の研究は、言語学、神経科学、(認知)心理学、哲学、人工知能、ロボット工学など、科学のさまざまな分野にまたがっている。このため、身 体化認知の現代的な発展は、認知の性質、構造、メカニズムを新たな視点から捉える認知科学の身体化と捉えることができる。[4] 認知を身体化するには、認知の異なる特徴、例えば知覚、言語、記憶、学習、推論、感情、自己制御、およびその社会的側面を、理論的および方法論的基礎を確 立するために、身体化の観点から再検討し、調査する必要がある。[36] 身体化された認知は、古典的な認知科学(その一部を構成するすべての科学とともに)の注目と関心を集め、その研究に身体化の概念を取り入れるようになっ た。言語学では、認知科学者であり言語学者でもあるジョージ・レイコフ(George Lakoff)と彼の共同研究者であるマーク・ジョンソン(Mark Johnson)、マーク・ターナー(Mark Turner)、ラファエル・E・ヌニェス(Rafael E. Núñez)が、認知科学分野での発展を基に、身体化理論を推進し、拡大してきた。[37][38][39][40][41] 彼らの研究は、人々が身近な物理的対象、行動、状況についての理解を、他の領域の理解にも応用していることを示す証拠を提供している。すべての認知は身体 から得られる知識に基づいており、他の分野は概念的メタファー、イメージ・スキーマ、プロトタイプの組み合わせを使用して、人間の身体化された知識にマッ ピングされる。 概念的メタファーの研究では、人々はメタファーをあらゆる場面で使用して概念レベルを管理していると主張している[37]。言い換えれば、ある概念の状態 を別の概念の状態にマッピングしている。したがって、研究では、さまざまな定義の背後には単一のメタファーが存在すると述べている。異なる分野における概 念的メタファーの例がいくつか収集され、メタファーが他のメタファーとどのように関連しているか、また、しばしば身体的な側面を参照しているかが説明され ている。[37][39] この説明で最もよく挙げられる例は、人が愛の概念を説明するとき、この愛のメタファーを肉体的に具現化された旅の経験と関連付ける場合である。ラカフと マーク・ターナーの言語と身体化のもう一つの例は、視覚的メタファーである。彼らは、直立し前進する生き物に対する視覚的メタファーの位置づけは、体型と 環境との相互作用における身体の特性に依存していると主張している。 2000年の別の研究では、「イメージスキーマ」に焦点を当て、人々が抽象概念をどのように理解するかを調査した。[41] それによると、抽象概念は基本的な物理的状況を考慮することで理解される。基本的な物理的状態が考慮された抽象概念は、感覚運動能力や知覚能力を用いて解 釈される。このように、抽象概念の推論においても身体を使う空間的推論のプロセスが存在することが示されている。この文脈において、イメージスキーマは概 念的メタファーの一形態と見なされる。例えば、純粋に抽象的な虚数からなる数学的概念を理解する場合には、空間的推論スキルと視覚野が使われる傾向にあ る。このように、概念の解釈におけるイメージスキーマにおける身体の重要性が、概念的メタファーと同様に示されている。 言語カテゴリーを理解する上で、もう一つの重要な要素はプロトタイプである。エレノア・ロッシュは、プロトタイプが人間の認知において重要な役割を果たし ていると主張した。彼女の研究によると、プロトタイプとはカテゴリーの中で最も典型的なメンバーであり、彼女は鳥を例に挙げて説明している。例えば、ロビ ンは典型的な鳥であるが、ペンギンは典型的な鳥ではない。このことは、典型的なものはより簡単にカテゴリー化されることを示しており、したがって、人々は これらの典型的なものを通じて遭遇するカテゴリーについて推論することで答えを見つけることができる。[42] 別の研究では、この状況をより構造的に示す基本レベルのカテゴリーが特定された。したがって、基本レベルのカテゴリーとは、基本的な物理的な動きと関連付 けられるカテゴリーであり、容易に視覚化できるプロトタイプで構成される。これらのプロトタイプは、一般的なカテゴリーの推論に使用される。[43] 一方、ラカフは、プロトタイプ理論において重要なのは、クラスやタイプの特性ではなく、人々が使用するカテゴリーの特徴が身体的な経験であることであると 強調している。[38] したがって、これらのアプローチの一般的な傾向を見ると、言語的な概念やカテゴリーを理解し解釈する上で最も基本的な特徴は、その概念やカテゴリーが身体 的に経験されているかどうかであると言える。 神経科学者のジェラルド・エデルマンやアントニオ・ダマシオらは、身体、脳の個々の構造、意識、感情、自己認識、意志などの精神の側面との関連性を概説し ている。 [44][45] 生物学はまた、グレゴリー・ベイトソン、ウンベルト・マトゥラーナ、フランシスコ・ヴァレラ、エレノア・ロッシュ、エヴァン・トンプソンらにもインスピ レーションを与え、彼らはこの考えに密接に関連したバージョンを開発し、それを「非活性化説」と呼んでいる。[2][46] アルビン・リバーマンとハスケンス研究所の同僚たちが提案した「運動理論による音声知覚」では、単語の識別は、発話による音声が生成される身体の動きの知 覚に体現されていると主張している。 [47][48][49][50][51] ハスケイン研究所の関連研究では、ポール・マーメルシュタイン、フィリップ・ルービン、ルイス・ゴールドスタイン、および同僚らが、声道の生理学と空力音 響学を計算機モデル化するための調音合成ツールを開発し、音声の認知と知覚が生物学的制約によってどのように形成されるかを実証した。これは、Eric Vatikiotis-Bateson、Rubin、およびその他の同僚による「トーキング・ヘッズ」アプローチによって、オーディオビジュアルの領域に まで拡大された。 身体化の概念は、神経細胞集団の選択や神経の多様性などの数学的および計算モデルがどのようにして新たなカテゴリー化をもたらすかに関するジェラルド・エ デルマンの提案など、認知神経科学の研究から着想を得ている。神経科学的な観点から、身体化認知理論は感覚運動、認知、情動の神経系間の相互作用を検証す る。身体化された心に関する論文は、ヴィラヌール・S・ラマチャンドラン、ジェラルド・エデルマン、アントニオ・ダマシオなどの意識に関する理論など、神 経心理学で推進されている認知に関するいくつかの見解と一致している。また、神経科学における広範で増加し続ける実証研究のコレクションによっても裏付け られている。神経画像技術を用いて脳の活動を調査することで、研究者たちは身体化の兆候を発見した。脳波(EEG)の研究では、身体化された認知、感覚運 動の偶発性、共通コーディングの理論に沿って、脳内の感覚と運動のプロセスは順次分離されているのではなく、強く結びついていることが示された。[52] 感覚運動系と認知系の相互作用を考慮した2005年の研究では、身体と行動に関する用語や文章の意味理解において、感覚運動皮質がどれほど重要であるかが 強調されている。 [53] 2004年の機能的磁気共鳴画像法(fMRI)を用いた研究では、受動的に読まれた動作を表す言葉、例えば lick(舐める)、pick(選ぶ)、kick(蹴る)などは、それぞれの身体部位の実際の動きに関連する脳領域内またはその近傍で体部位特異的な神経 細胞の活動を導くことが示された。 [54] 経頭蓋磁気刺激(TMS)を用いた2005年の研究では、運動系の活動は聴覚による動作関連の文章と結びついていると述べている。参加者が手や足に関する 文章を聞いた場合、手や足の筋肉から記録された運動誘発電位(MEP)が減少した。[55] これらの2つの例示的研究は、感覚運動の概念を指す言葉を認知的に理解することと、感覚運動野の活性化との関係を示している。身体化という観点では、神経 画像技術は感覚系と運動系の相互作用を示すのに役立つ。 神経画像研究に次いで、行動研究も身体化認知理論を裏付ける証拠を提供している。 対象物や問題の「重要性」といった抽象的な高次認知概念も、感覚運動系と関係があるように思われる。 人々は、対象物が重要である、あるいは重要な情報を保持していると告げられると、重要でない情報と比較して、その対象物がより重いと推定する。[56] 同様に、重量は、具体的な問題や抽象的な問題に対処する際に、人が物理的および認知的努力をどのように投資するかに影響を与える。例えば、より重いクリッ プボードを持つと、意思決定手続きにより重点が置かれる。[57] このことから示唆されるのは、具体的な対象物に費やされる物理的な努力が、抽象的な概念を扱う際に、より多くの認知的努力につながるということである。 フランシスコ・ヴァレラやウォルター・フリーマンといった認知神経科学者の研究は、脳は単に表象を用いて認知するだけであるという考えを否定し(ゲアハル ト・ヴェルナーもこの立場を支持している)、力学系理論と神経現象学の観点から身体化された認知と状況依存的な認知を説明しようとしている。身体化された 視点から認知を説明するための神経科学的なアプローチはいくつかあり、身体化された認知を裏付け、さらに詳しく調査するために、神経画像技術、行動実験、 力学モデルなどの複数の方法が採用されている。 ロボット工学の分野では、ロドニー・ブルックス、ハンス・モラヴェック、ロルフ・ファイファーなどの研究者が、真の人工知能は感覚と運動能力を備え、身体 を通して世界とつながっている機械によってのみ達成できると主張している。[6][58][59] これらのロボット工学研究者の洞察は、アンディ・クラークやヘンドリクス=ジャンセンなどの哲学者にも影響を与えている。[60][61] これらの観点から、身体は認知にとって不可欠であり、したがって、身体と環境との相互作用は認知能力を発達させる上で基本的なものであるため、知的な行動 にとっても不可欠である。[62] この種の知識は、身体化、すなわち人間と身体との関係に根ざしている。それは「心は身体とつながっているだけでなく、身体が心に影響を与える」という考え 方である。[16] 身体化された人工知能とロボット工学は、この原理を人工システムに適用する方法である。 |

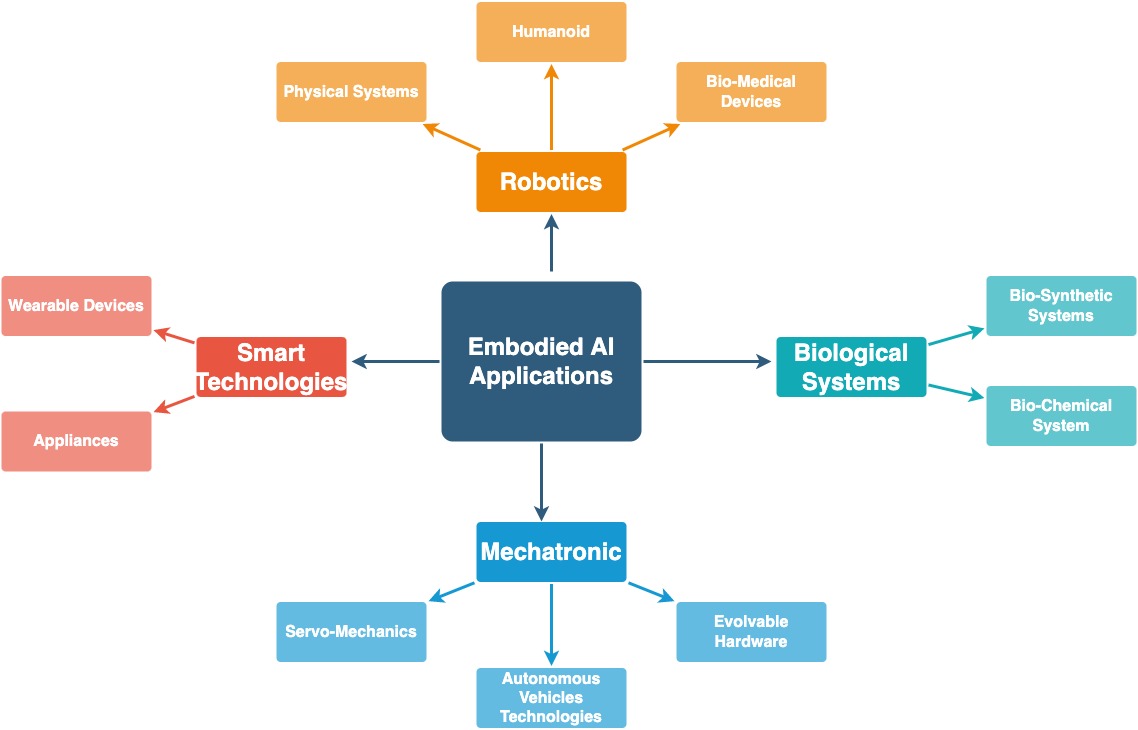

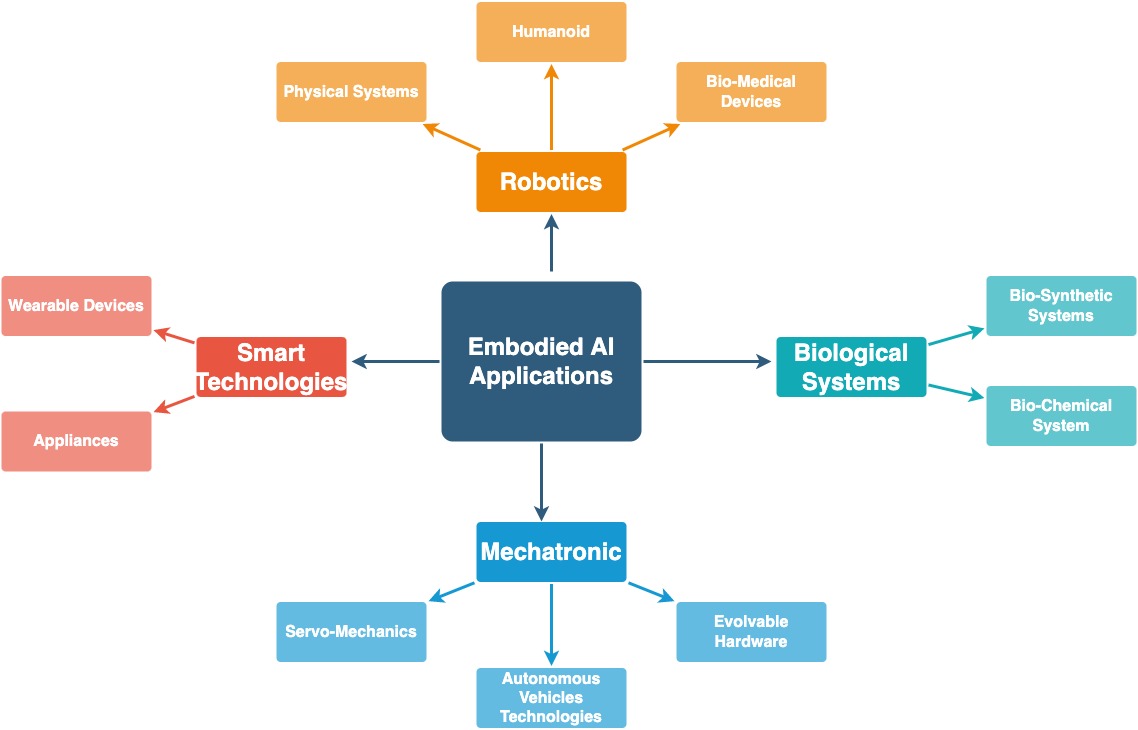

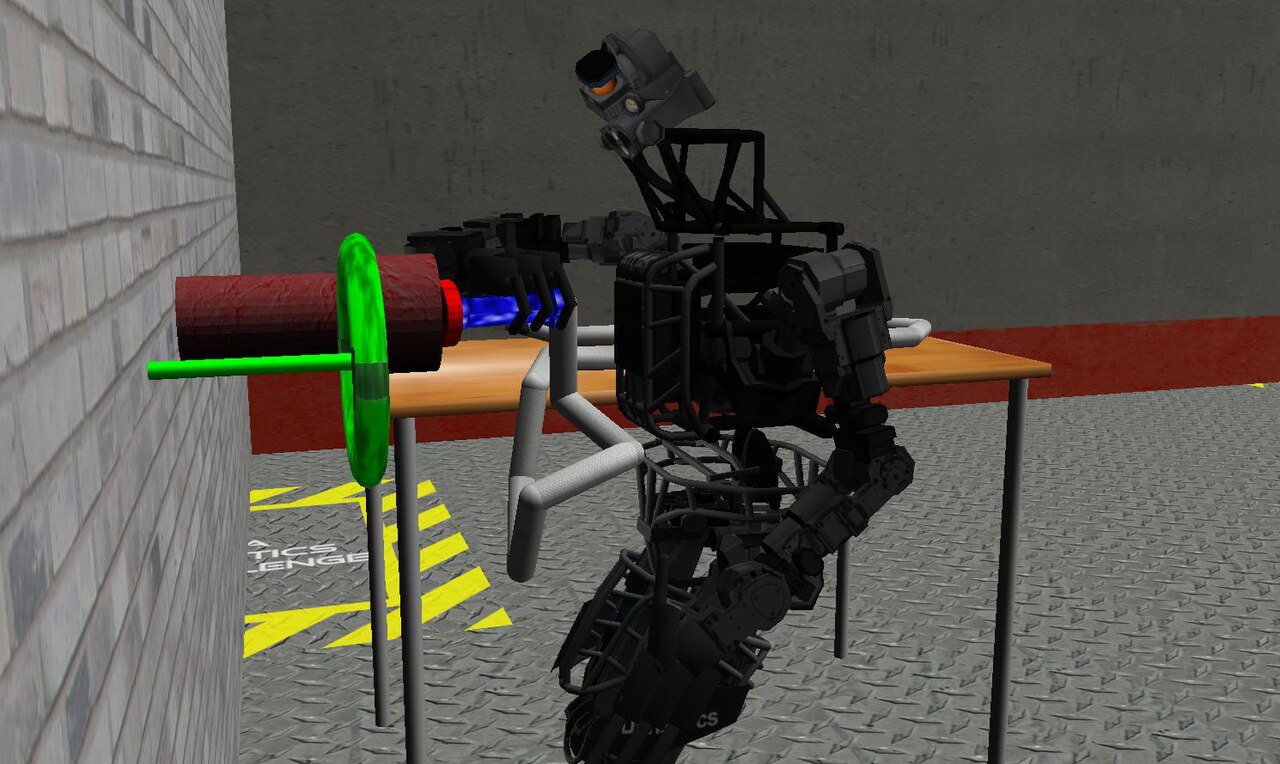

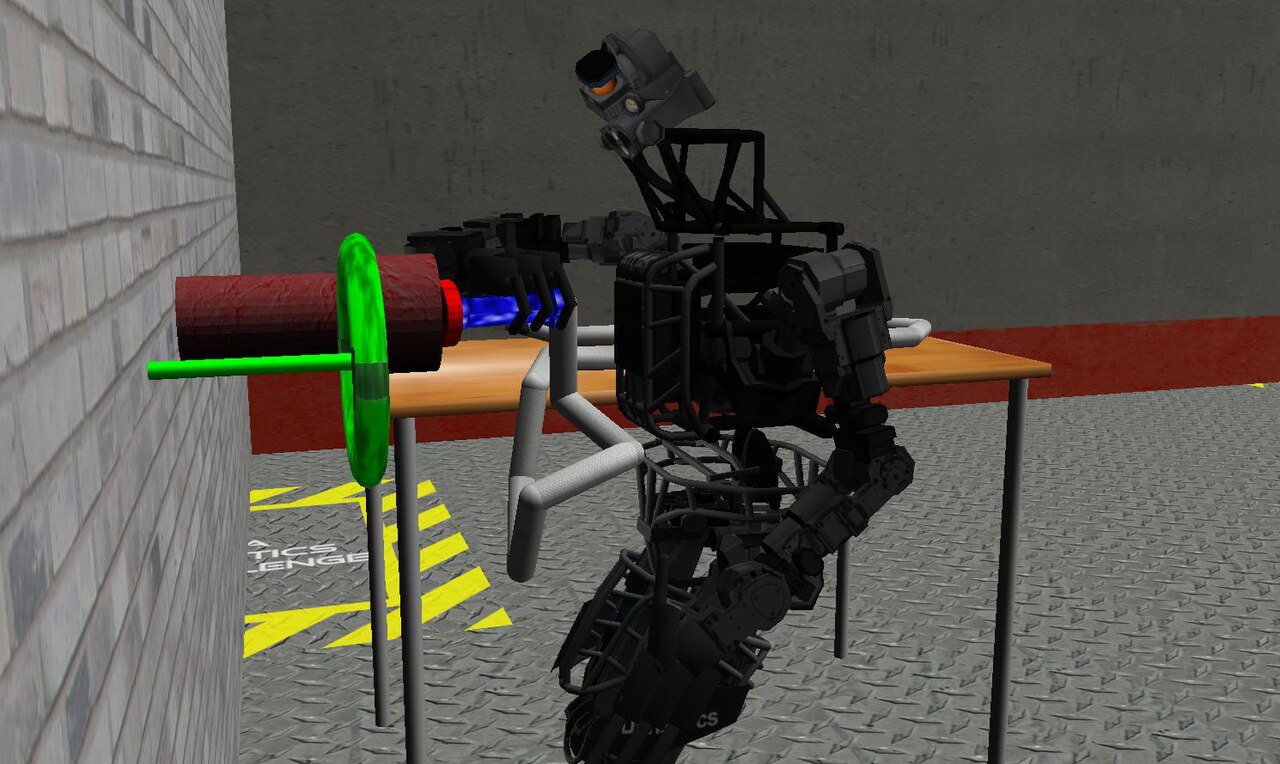

The applications of embodied cognition and artificial intelligence Traditional artificial intelligence involves a computational approach. This primary computational paradigm evolved to the embodied perspective with embodied cognition studies and brought more interdisciplinary research topics to artificial intelligence. Embodied perspective brings a necessity of working with the physical world and systems which came alongside robotics. Robotics are essential for the embodied artificial perspective due to their differing capabilities from computers; computers define the inputs; robots can interact with the physical world via their own body.[63] Researchers working on embodied AI are moving away from an algorithm-driven approach to robots interacting with the physical world.[64] Embodied Artificial intelligence tries to figure out how biological systems work first, then construct basic rules of intelligent behavior, and finally apply that knowledge to create artificial systems, robots, or intelligent devices.[65] Embodied artificial intelligence has a large scale of applications and research. For instance, the embodied artificial approach can be seen in micro- and nano-mechatronic systems and evolvable hardware, top-down bio-synthetic systems research, bottom-up chemo-synthetic systems, and biochemical systems.[66] The majority of embodied artificial intelligence focuses on robot training and autonomous vehicle technologies. Autonomous vehicles have a significant interest in embodied artificial intelligence applications because this technology allows driving and making possible judgments based on what they see as humans do.[67] |

身体化された認知と人工知能の応用 従来の人工知能は、計算論的アプローチを採用していた。この計算論的パラダイムは、身体化された認知研究により身体化された視点へと発展し、人工知能にさ らに学際的な研究テーマをもたらした。身体化された視点は、物理的世界やシステムと協働する必要性を生み出し、それはロボット工学の発展につながった。ロ ボット工学は、コンピュータとは異なる能力を持つため、身体化された人工知能の視点にとって不可欠である。コンピュータは入力を定義するが、ロボットは自 身の身体を介して物理的世界と相互作用することができる。 [63] 身体化AIの研究者は、物理的世界と相互作用するロボットに対するアルゴリズム主導のアプローチから離れつつある。[64] 身体化人工知能は、まず生物学的システムがどのように機能するかを解明し、次に知的行動の基本的なルールを構築し、最後にその知識を応用して人工システ ム、ロボット、またはインテリジェントデバイスを創り出すことを試みる。[65] 身体化人工知能は、応用と研究の両面で幅広い分野にわたっている。例えば、身体性人工アプローチは、マイクロおよびナノメカトロニクスシステムや進化可能 なハードウェア、トップダウン型のバイオ合成システム研究、ボトムアップ型の化学合成システム、生化学システムに見られる。身体性人工知能の大部分は、ロ ボットの訓練や自律走行車技術に焦点を当てている。自律走行車は、この技術によって人間が行うように、運転や目にしたものに基づく判断が可能になるため、 身体化人工知能の応用に大きな関心を寄せている。[67] |

Perception Example of the "change blindness" illusion. These two alternating images contain several differences that most people struggle to find right away. It emphasizes the fact that perception is active and demands attention. Traditional neuropsychological research widely acknowledged that when an internal representation of the outside world is activated somewhere in the brain, it leads to a perceptual experience. Embodied cognition challenges this claim by stating that the existence of cortical maps in the brain fails to explain and account for the subjective character of people's perceptual experiences.[34] For example, they cannot sufficiently explain the apparent stability of the visual world despite eye movements, the filling-in of the blind spot, or visual illusions such as "change blindness" which reveal apparent imperfections in the visual system.[34] From an embodied cognition perspective, perception is not a passive reception of (incomplete) sensory inputs for which the brain must compensate to provide us with a coherent picture. The brain interprets the outside world based on an individual's intentions, memories, and emotions, as well as the environment and the specific situation the individual is in. Perception involves more complex processes than simply receiving inputs (or visual stimuli) from the external world to output actions in response to them. Perception is an active process conducted by a perceiving agent (a perceiver);[68] it entails an engaged perceiver and is influenced by the agent's experiences and intentions, its bodily states, and the interaction between the agent's body and the environment around it. One example of such active interaction between perception and the body is the case that distance perception can be influenced by bodily states. The way people view the outside world can differ depending on the physical resources that individuals have such as fitness, age, or glucose levels. For instance, in one study, people with chronic pain who are less capable of moving around perceived given distances as further than healthy people did.[69] Another study shows that intended actions can affect processing in visual search, with more orientation errors for pointing than for grasping.[70] Because orientation is important when grasping an object, the plan to grasp an object is thought to improve orientation accuracy.[70] This shows how actions, the body's interaction with the environment, can contribute to the visual processing of task-relevant information. Perception also influences the perspective individuals to take on a particular situation and the type of judgments they make. For instance, researchers have shown that people will significantly more likely take the perspective of another person (e.g., a person in a picture) instead of their own when making judgements about objects in a photograph.[71] This means that the presence of people (as compared to only objects) in a visual scene affects the perspective a viewer takes when making judgements on, for example, relations between objects in the scene. Some researchers state that these results suggest a "disembodied" cognition given the fact that people take the perspective of others instead of their own and make judgments accordingly.[71] |

知覚 「変化盲」の錯視の例。この2つの交互に表示される画像には、ほとんどの人がすぐに発見できないいくつかの相違点がある。これは、知覚が能動的であり、注 意を要するという事実を強調している。 従来の神経心理学の研究では、外界の内部表現が脳のどこかで活性化されると知覚体験につながるということが広く認められていた。身体化された認知は、この 主張に異議を唱え、脳内の皮質地図の存在は、人々の知覚体験の主観的な性格を説明できないと主張している。[34] 例えば、眼球運動にもかかわらず視覚世界が安定しているように見えること、盲点の補完、あるいは「変化盲」などの視覚的錯覚は、視覚システムに明らかな欠 陥があることを示しているが、これらは十分に説明できない。 [34] 身体化された認知の観点から見ると、知覚とは、脳が補償して一貫したイメージを提供しなければならないような、(不完全な)感覚入力の受動的な受信ではな い。脳は、個人の意図、記憶、感情、および個人が置かれている環境や特定の状況に基づいて外界を解釈する。知覚は、外界からの入力(または視覚刺激)を受 け取り、それに応じた行動をアウトプットするよりも、より複雑なプロセスを伴う。知覚は知覚する主体(知覚者)によって行われる能動的なプロセスであり [68]、知覚者は関与し、その主体の経験や意図、身体の状態、その主体の身体と周囲の環境との相互作用の影響を受ける。 知覚と身体の間のこのような能動的な相互作用の例としては、距離知覚が身体の状態によって影響を受ける場合がある。フィットネス、年齢、グルコースレベル など、個人が持つ物理的リソースによって、外界の見え方が異なる可能性がある。例えば、ある研究では、慢性的な痛みを抱え、動き回る能力が低い人々は、健 康な人々よりも、与えられた距離をより遠く感じていることが分かった。[69] 別の研究では、意図した行動が視覚探索の処理に影響を与えることが示されており、把握よりも指示の方が方向エラーが大きい。 [70] 物体を把握する際には方向性が重要であるため、物体を把握する計画は方向性の精度を向上させると考えられている。[70] これは、行動、つまり身体と環境との相互作用が、課題に関連する視覚情報の処理にどのように貢献しうるかを示している。 知覚はまた、個人が特定の状況に対して取る視点や、下す判断の種類にも影響を与える。例えば、研究者は、写真内の物体について判断を下す際には、人は自分 自身の視点ではなく、他者(例えば写真内の人物)の視点に立つ可能性がはるかに高いことを示している。[71] つまり、視覚的な場面の中に人物がいる場合(物体のみの場合と比較して)、その人物の視点が、例えばその場面内の物体間の関係について判断を下す際に、見 る者の視点に影響を与えるということである。一部の研究者は、これらの結果は、人々が自分自身の視点ではなく他者の視点に立って判断を下すという事実を踏 まえると、「身体から切り離された」認知を示唆していると述べている。[71] |

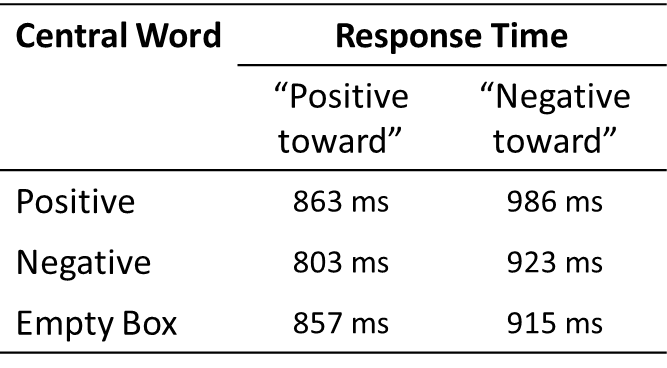

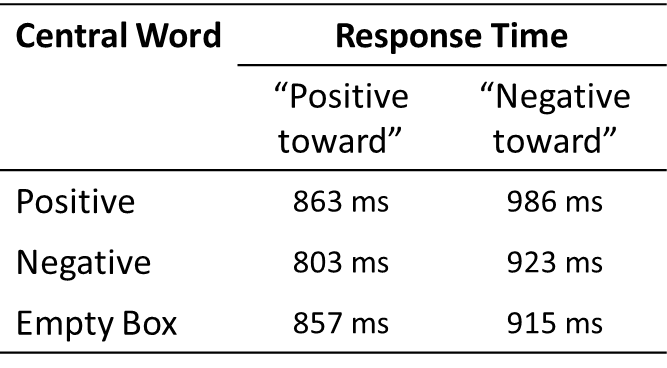

| Language See also: Embodied language processing Embodied cognition views on language describes how when humans comprehend words, sensorimotor areas are involved in interacting with the objects and entities the words refer to.[72] First experimental studies of the impact of body's sex, age and constitution (temperament) on language perception and use emerged in 1995-99 and expanded from 2010s [24] [3] [25] The embodiment effect initially was called "projection through capacities" and emerged as a tendency of people attribute meaning to common adjectives and abstract and neutral nouns depending on their endurance, tempo, plasticity, emotionality, sex or age.[3][73][25] For example, in these studies males with stronger motor-physical endurance estimated abstractions describing people-, work/reality- and time-related concepts in more positive terms than males with a weaker endurance. Females with stronger social or physical endurance estimated social attractors in more positive terms than weaker females. Both male and female temperament groups with higher sociability showed a universal positive bias in their estimations of social concepts, in comparison to participants with lower sociability. Over the last years, behavioral and neural evidence has shown that the process of language comprehension activates motor simulations[74] and involves motor systems.[75][76][77] Some researchers have investigated mirror neurons to illustrate the link between the mirror neuron systems and language suggesting that some aspects of language (such as part of semantics and phonology) can be embodied in the sensorimotor system represented by mirror neurons.[78] It is well known that language has a multi-component structure, one of which is language comprehension. Research on embodied cognition shows that language comprehension involves the motor system.[79][80] In addition, various studies explain that understanding linguistic explanations of actions is based on a simulation of the action described.[81] These action simulations also include evaluation of the motor system.[80] A study in which university students evaluated language comprehension and motor system with a pendulum swinging task while performing a "sentence judgment task" found significant changes in functions containing performable sentences. Another study used the mirror neurons perspective to illustrate the relationship between the motor system and several language components. Because mirror neurons are one of the essential parts of the motor system, researchers compared monkeys and humans in an anatomical framework; specifically, they made the comparison with respect to Broca's area.[78] Another study concerning the role of mirror neurons during learning via language usage stated that activations occurred in Broca's area even when participants watched other people's conversations without hearing the sounds.[82] An fMRI study examining the relationship of mirror neurons in humans with linguistic materials has shown that there are activations in the premotor cortex and Broca's area when reading or listening to sentences associated with actions.[83] According to these findings, researchers state that there is a connection between the motor system and language. They also argue that the motor system together with mirror neurons mechanisms can process certain aspects of language.[78] As of 2014, literature mainly focuses on the relation between language and embodied cognition on a motor system, more precisely by mirror neuron explanations. This relationship also extends to cognitive capabilities which involve a variety of language components. Studies have examined how embodied and extended cognition can help to reconceptualize and ground second language acquisition.[84] The nature of language acquisition extends cognitive capability itself due to the fact that it has multiple components which have embodied representations associated with language processing and provide a ground concept for language.[85] |

言語 関連情報:身体性言語処理 身体化認知の言語に関する見解では、人間が言葉を理解する際に、感覚運動野がその言葉が指し示す対象や実体との相互作用に関与していると説明している。 [72] 身体の性別、年齢、体質(気質)が言語の知覚と使用に与える影響に関する最初の実験的研究は、1995年から1999年に登場し、2010年代から拡大し ている。[24][3][25] 身体化効果は当初、「 能力による投影」と呼ばれ、持久力、テンポ、可塑性、感情性、性別、年齢に応じて、一般的な形容詞や抽象的・中性的な名詞に意味を帰属させる傾向として現 れた。[3][73][25] 例えば、これらの研究では、運動能力や身体能力の持久力が高い男性は、持久力の低い男性よりも、人間、仕事・現実、時間に関連する概念をより肯定的に評価 した。社会的または身体的持久力が高い女性は、低い女性よりも社会的概念をより肯定的に評価した。社交性の高い男性および女性の気質グループは、社交性の 低い参加者と比較して、社会的概念の評価において普遍的な肯定的なバイアスを示した。 ここ数年、行動学的および神経学的証拠から、言語理解のプロセスは運動シミュレーションを活性化し[74]、運動系に関与することが示されている[75] [76][77]。一部の研究者はミラーニューロンを調査し、ミラーニューロン系と言語の関連性を説明しようとしている。言語のいくつかの側面(意味論や 音韻論の一部など)は、ミラーニューロンによって表される感覚運動系において体現される可能性があることが示唆されている[78]。 言語には複数の構成要素からなる構造があることはよく知られており、その一つが言語理解である。身体化された認知に関する研究では、言語理解には運動系が 関与していることが示されている。[79][80] さらに、さまざまな研究により、言語による行動の説明を理解するには、説明された行動のシミュレーションが必要であることが説明されている。[81] これらの行動シミュレーションには、運動系の評価も含まれる。[80] 大学生を対象に、「文判断課題」を実行しながら振り子を振る課題で言語理解と運動系を評価した研究では、実行可能な文を含む機能に著しい変化が見られた。 別の研究では、運動系と複数の言語構成要素の関係を説明するのに、ミラーニューロンの観点が用いられた。ミラーニューロンは運動系に不可欠な要素であるた め、研究者は解剖学的枠組みの中でサルとヒトを比較した。具体的には、ブローカ領域に関して比較を行った。[78] 言語使用による学習におけるミラーニューロンの役割に関する別の研究では、参加者が音を聞かずに他者の会話を観察している場合でも、ブローカ領域で活性化 が起こることが示された。 [82] ヒトのミラーニューロンと言語資料との関係を調べたfMRI研究では、動作に関連する文章を読んだり聞いたりすると、前頭前野とブローカ野が活性化するこ とが示されている。[83] これらの知見によると、運動系と言語の間には関連性があるという。また、運動系とミラーニューロンのメカニズムが組み合わさることで、言語の特定の側面を 処理できるとも主張されている。[78] 2014年現在、文献では主に言語と運動系における身体化された認知の関係、より正確にはミラーニューロンの説明に焦点が当てられている。この関係は、言 語のさまざまな要素を含む認知能力にも及んでいる。研究では、身体化された認知や拡張された認知が、第二言語習得の再概念化と基礎付けにどのように役立つ かが検証されている。[84] 言語習得の本質は、言語処理に関連する身体化された表現を持つ複数の要素があり、言語の基礎概念を提供しているという事実により、認知能力そのものを拡張 する。[85] |

| Memory The body has an essential role in shaping the mind. So, the mind must be understood in the context of its relationship with a physical body that interacts in the world. These interactions can also be cognitive activities in everyday life, such as driving, chatting, and imagining the placement of items in a room. These cognitive activities are limited by memory capacity.[13] The relationships between memory and embodied cognition have been demonstrated in studies in different fields and through various tasks. In general, studies on embodied cognition and memory investigate how manipulations on the body cause changes in memory performance, or vice versa, manipulations through memory tasks subsequently lead to bodily changes.[86] Researchers have drawn attention to the relationship between memory and action from an embodied cognition approach where memory is defined as integrated patterns of actions limited by the body.[87] On the one hand, embodied cognition sees action preparation as a fundamental function of cognition. On the other hand, memory plays a role in tasks that do not occur in the present but involve remembering actions and information from the past and imagining events that may or may not happen in the future. Glenberg blurs this apparent dichotomy by arguing that there is a reciprocal relationship between memory, action, and perception. Accordingly, manipulations that can take place in the body or movement can lead to changes in memory.[86][87] Researchers have also investigated the influence of body position on ease of recall in an autobiographical memory study to examine the effect of embodied cognition on memory performance.[86][88] Participants were asked to take positions compatible or incompatible with their original body position of the remembered event during a recall event. Researchers found out that participants given compatible body positions compared to incompatible body positions showed faster responses in recalling memories during the experiment. Thus, they concluded that body position facilitates access to autobiographical memories.[88] The relationship between memory and body has also emphasised that memory systems depend on the body's experiences with the world. This is particularly evident in episodic memory because this type of memories in the episodic memory system are defined by their content and are remembered as experienced by the person who is remembering.[13] Research has also investigated the relationship between embodiment and memory by recalling collective and personal memories indicating how embodiment enriches the understanding of memory.[89] Embodied memory research through the recalling of personal traumas and violent memories has reported that people who have experienced trauma or violence re-feel their experiences in their narratives throughout their lives. In addition, memories that threaten a person's life by directly affecting the body, such as injury and physical violence, recreate similar reactions again in the body while remembering the event. For example, people can report feeling smells, sounds, and movements when remembering childhood trauma memories. A proper evaluation of those memories and the corresponding physical and physiological phenomena associated with them could describe how those set of recalled memories are embodied.[90] New perspectives on the neural structure and memory processes underlying embodied cognition, episodic memory, recall, and recognition have also been explored.[91][13] As experiences are received, neural states are reenacted in action, perception, and introspection systems. Perception includes sensory modalities; motor modalities include movement; and introspection includes emotional, mental, and motivational states. All of these modalities altogether constitute different aspects that shape experiences. Therefore, cognitive processes applied to memory support the action that is appropriate for a particular situation, not by remembering what the situation is, but by remembering the relationship of the action to that situation.[13] For example, remembering and identifying the party one attended the previous day is said to be related to the body because the sensory-motor aspects of the event that is being recalled (i.e., the party), along with the details of what happened, are being reconstructed.[86][92] |

記憶 心を形成する上で身体は重要な役割を果たしている。そのため、心は、世界と相互作用する物理的な身体との関係性という文脈で理解されなければならない。こ れらの相互作用は、運転や雑談、部屋の中の物の配置を想像するなど、日常生活における認知活動でもある。これらの認知活動は、記憶容量によって制限され る。[13] 記憶と身体化された認知の関係性は、異なる分野の研究やさまざまな課題を通じて実証されている。一般的に、身体化された認知と記憶に関する研究では、身体 への操作が記憶のパフォーマンスにどのような変化をもたらすか、あるいはその逆の、記憶作業による身体への変化が記憶パフォーマンスにどのような影響を与 えるかを調査している。[86] 研究者たちは、身体化された認知アプローチから、記憶と行動の関係に注目している。記憶は身体によって制限された行動の統合されたパターンとして定義され ている。[87] 一方で、身体化された認知は、行動の準備を認知の基本的な機能と見なしている。一方、記憶は、現在起こっていないが、過去の行動や情報を思い出すことや、 将来起こるかもしれない出来事を想像することを伴う課題において役割を果たす。グレンバーグは、記憶、行動、知覚の間には相互関係があるという主張によ り、この明白な二分法を曖昧にしている。したがって、身体や動きの中で起こりうる操作は、記憶の変化につながる可能性がある。 また、身体化された認知が記憶のパフォーマンスに与える影響を調査するために、自伝的記憶の研究において、身体の位置が想起のしやすさに与える影響につい ても研究者が調査している。[86][88] 参加者は、想起の際に、記憶している出来事のときの身体の位置と一致する、または一致しない位置を取るよう求められた。研究者は、一致する身体の位置を 取った参加者は、一致しない身体の位置を取った参加者よりも、実験中の記憶想起の反応が速いことを発見した。したがって、身体の位置は自伝的記憶へのアク セスを容易にするという結論に達した。[88] 記憶と身体の関係は、記憶システムが身体の世界での経験に依存していることを強調している。これはエピソード記憶において特に顕著である。なぜなら、エピ ソード記憶システムにおけるこのタイプの記憶は内容によって定義され、記憶している人格によって経験されたものとして記憶されるからである。 [13] また、集合的記憶や個人的記憶を想起することで、身体化と記憶の関係を調査する研究も行われている。これにより、身体化が記憶の理解をいかに豊かにするか が示されている。[89] 個人的なトラウマや暴力的な記憶を想起することで身体化された記憶を調査する研究では、トラウマや暴力を経験した人は生涯にわたって、その経験を物語の中 で再び追体験することが報告されている。さらに、負傷や身体的暴力など、人格に直接影響を及ぼしてその人格の生命を脅かすような記憶は、その出来事を思い 出す際に、再び同様の反応を身体に引き起こす。例えば、幼少期のトラウマを思い出す際に、匂いや音、動きを感じたと報告する人もいる。こうした記憶と、そ れに関連する身体および生理現象を適切に評価することで、想起された記憶の集合がどのように具現化されるかを説明できる可能性がある。 身体化された認知、エピソード記憶、想起、認識の根底にある神経構造と記憶プロセスに関する新たな視点も研究されている。[91][13] 経験が受け取られると、神経状態は行動、知覚、内省システムで再現される。知覚には感覚様式が含まれ、運動様式には動きが含まれ、内省には感情、精神、動 機づけの状態が含まれる。これらの様相はすべて、経験を形成する異なる側面を構成している。したがって、記憶に適用される認知プロセスは、特定の状況に適 した行動をサポートするが、その状況がどのようなものかを思い出すのではなく、その状況に対する行動の関係性を思い出すことによってである。 [13] 例えば、前日に参加したパーティーを思い出すことや特定することは、その出来事(すなわち、パーティー)の感覚運動的な側面が、起こった出来事の詳細とと もに再構成されるため、身体に関連していると言われている。[86][92] |

| Learning Research on embodied cognition and learning suggests that learning could occur and be triggered by perception-action interactions of the body with the surrounding environment. An embodied cognitive approach to child development provides insights into how infants attain spatial knowledge and develop spatial skills that allow them to (successfully) interact with the world around them.[93] Most infants learn to walk in the first 18 months of life, which draws on ample new opportunities for exploring things around them. In this exploration, infants learn spatial relations, and by carrying objects from one place to another, they may also learn affordances such as "transportability".[94] Thereafter, new phases in exploration may occur through which infants can discover other even more elaborate affordances.[93] According to Eleanor Gibson, exploration takes an essential place in cognitive development. For example, infants explore whatever is in their vicinity by seeing, mouthing, or touching it before learning to reach objects nearby. Then, infants learn to crawl, which enables them to seek out objects beyond reaching distance, learn basic spatial relations between themselves, objects, and others, and get an understanding of depth and distance.[93] This development of motor skills through the exploration of the physical and social world seems to play a central role in visual-spatial cognition.[93] Embodied perception-action experience may serve as a tool for learning that extends across the life span, from infancy to adulthood.[95] Research on the role of action in early as well as educational learning contexts demonstrates the importance of embodiment for learning. In one experiment, three-month-old infants who were not skilled in reaching were trained to reach for objects with velcro-covered mittens instead. Afterward, the assessments and comparison with the control group showed that infants can rapidly form goal-based action representations and view others' actions as goal-directed.[96] Further research indicates that mere observational experience by infants does not produce these results.[95] Similarly, research has shown how action and bodily movements can be used as scaffolds for learning. A study investigating whether infants at high risk for developing autism spectrum disorders (ASD) could benefit from action scaffolded interventions (reaching experiences) during early development indicates an increase in grasping activity following training. And thus, it provides evidence about the possibility for high-risk of ASD infants to learn and respond to action-based treatment interventions.[97] Another study investigates how teaching methods can benefit from embodiment and proposes that a professor's movements and gestures contribute to learning by growing students' embodied experiences in the classroom, leading to an increased capacity to recall.[98] The action-based language theory (ABL) states that aspects of embodiment are also relevant for language learning and acquisition. ABL proposes that the brain exploits the same mechanisms used in motor control for language learning. When adults, for example, call attention to an object and an infant follows the lead and attends to said object, canonical neurons are activated and affordances of an object become available to the infant. Simultaneously, hearing the articulation of the object's name leads to the activation of speech mirror mechanisms in infants. This chain of events allows for Hebbian learning of the meaning of verbal labels by linking the speech and action controllers, which get activated in this scenario.[99] The role of gestures in learning is another example of the importance of embodiment for cognition. Gestures can aid, facilitate and enhance learning performance,[100][101][102] or compromise it when the gestures are restricted[103] or meaningless to the content that is being transmitted.[104] In a study using the Tower of Hanoi (TOH) puzzle, participants were divided into two groups. In the first part of the experiment, the smallest disks used in TOH were the lightest and could be moved using just one hand. For the second part, this was reversed for one group (switch group) so that the smallest disks were the heaviest, and participants needed both hands to move them. The disks remained the same for the other group (no-switch group). After the experiment ended, participants were asked to explain their solution while researchers monitored their gestures when describing their solution. The results showed that using gestures affected the performance of the switch group in the second part of the experiment. The more they used one-handed gestures to depict their solution in the first part of the experiment, the worse they performed in the second part.[105] A study investigating the role of gestures in second language learning states that learning the vocabulary with self-performed gestures increases learning outcomes. The enduring benefits continued even after two and six months post-learning. In addition, the same study also investigated the neural correlates of learning a second language with gestures. The results indicate that left premotor areas and the superior temporal sulcus (a brain region responsible for visual processing of biological motion) were activated during learning with gestures.[106] Similarly, an fMRI study showed that children who learned to solve mathematical problems using a speech and gesture strategy were more likely to have activation in motor regions of the brain. The activation of motor regions occurred during scans in which children were not using gestures to solve the problems. These findings indicate that learning with gestures creates a neural trace of the motor system that goes beyond the learning phase and activates when children engage with problems they learned to solve with gestures.[107] Embodied cognition has also been linked to both reading and writing. Research shows that physical and perceptual engagements congruent with the content of the reading material can boost reading comprehension. Findings also suggest that the benefits accrued from handwriting as compared to typing in letter recognition and written communication result from the more embodied nature of handwriting.[108] |

学習 身体化された認知と学習に関する研究によると、学習は身体と周囲の環境との知覚と行動の相互作用によって引き起こされ、生じる可能性があることが示唆され ている。 身体化された認知アプローチによる子どもの発達に関する研究は、乳幼児が空間的な知識を習得し、周囲の世界と(うまく)相互作用できる空間的なスキルを習 得する方法についての洞察を提供している。[93] ほとんどの乳幼児は、生後18か月までに歩き方を習得するが、これは周囲のものを探索する新たな機会が豊富にあることを意味する。この探索において、乳児 は空間的な関係を学び、物体をある場所から別の場所へと運ぶことで、「運搬可能性」などのアフォーダンスも学ぶ可能性がある。[94] その後、探索の新たな段階が起こり、乳児はさらに精巧なアフォーダンスを発見できる可能性がある。[93] エレノア・ギブソンによると、探索は認知発達において重要な位置を占める。例えば、乳児は、近くにある物体に手が届くようになる前に、目で見て、口で真似 をして、触って、身の回りのあらゆるものを探索する。その後、乳児はハイハイを覚え、手の届かない距離にある物体を探したり、自分自身、物体、他者との基 本的な空間関係を学んだり、奥行きや距離感を理解したりできるようになる。[93] 物理的および社会的世界の探索を通じて運動技能が発達することは、視覚空間認知において中心的な役割を果たしているようだ。[93] 身体化された知覚と行動の経験は、乳児期から成人期まで生涯にわたって学習を促進するツールとなる可能性がある。[95] 初期の学習や教育的な学習の文脈における行動の役割に関する研究は、学習における身体化の重要性を示している。ある実験では、手を伸ばすことが上手ではな い生後3か月の乳児を対象に、マジックテープ付きの手袋を使って代わりに物体に手を伸ばす訓練を行った。その後、評価と対照群との比較により、乳児は目標 に基づく行動表現を迅速に形成し、他者の行動を目標指向的と見なすことができることが示された。[96] さらに研究を進めると、乳児が単に観察経験を積むだけではこのような結果は得られないことが示された。[95] 同様に、研究により、行動や身体の動きが学習の足場としてどのように利用できるかが示されている。自閉症スペクトラム障害(ASD)を発症するリスクが高 い乳児が、幼児期の行動支援介入(リーチング体験)から恩恵を受けられるかどうかを調査した研究では、トレーニング後に把握活動が増加したことが示されて いる。したがって、自閉症スペクトラム障害(ASD)のリスクが高い乳幼児が、行動に基づく治療介入を学習し、反応できる可能性を示す証拠となる。 [97] 別の研究では、教授法が身体化からどのような恩恵を受けられるかを調査し、教授の動きやジェスチャーが、教室での学生の身体化された経験を成長させ、想起 能力を高めることで学習に貢献するという提案を行っている。[98] アクションベース言語理論(ABL)は、身体化の側面は言語学習や習得にも関連していると主張している。ABLは、脳は言語学習に運動制御で使用されるの と同じメカニズムを利用していると提案している。例えば、大人が物体に注意を向け、乳児がその動きを追って同じ物体に注意を向けると、標準ニューロンが活 性化し、その物体の潜在能力が乳児に利用可能になる。同時に、物体の名称の明瞭な発音を聞くことで、乳児の音声ミラーリングのメカニズムが活性化する。こ の一連の出来事により、音声と動作のコントローラーがリンクされ、このシナリオで活性化されることで、言語ラベルの意味がヘブの学習によって習得される。 学習におけるジェスチャーの役割は、認知における身体化の重要性を示すもう一つの例である。ジェスチャーは学習の成果を向上させることができるが [100][101][102]、ジェスチャーが制限されたり[103]、伝えようとする内容に対して意味のないものであったりすると、学習の成果を損な う可能性もある[104]。ハノイの塔(TOH)パズルを用いた研究では、参加者は2つのグループに分けられた。実験の第1部では、TOHで使用される最 も小さい円盤は最も軽く、片手だけで動かすことができた。第2部では、1つのグループ(スイッチグループ)ではこれが逆転し、最も小さい円盤が最も重くな り、参加者は両手を使って動かす必要があった。もう一方のグループ(ノースイッチグループ)では円盤は同じままであった。実験終了後、参加者は自分の解決 策を説明するように求められ、研究者は彼らのジェスチャーを観察した。その結果、ジェスチャーを使用することで、実験の第2部におけるスイッチグループの パフォーマンスに影響が及ぶことが示された。実験の第1部で片手ジェスチャーを使用してソリューションを描写する回数が増えるほど、第2部のパフォーマン スは低下した。[105] 第二言語学習におけるジェスチャーの役割を調査した研究では、ジェスチャーを伴う語彙学習は学習成果を高めるとしている。その効果は学習後2ヶ月、6ヶ月 後も持続した。さらに、同研究では、ジェスチャーを用いた第二言語学習における神経相関についても調査している。その結果、ジェスチャーを用いた学習中に は、左の前運動野と上側頭溝(生物の動きの視覚処理を司る脳領域)が活性化することが示された。[106] 同様に、fMRIを用いた研究では、音声とジェスチャーの戦略を用いて数学の問題を解くことを学んだ子供たちは、脳の運動領域がより活性化しやすいことが 示された。運動野の活性化は、子どもたちがジェスチャーを使わずに問題を解くスキャン中に起こった。これらの知見は、ジェスチャーを使った学習が運動シス テムの神経痕跡を作り出し、学習段階を超えて、子どもたちがジェスチャーを使って解くことを学んだ問題に取り組む際に活性化することを示している。 身体化された認知は、読み書きにも関連している。研究によると、読んでいる内容と一致する身体的および知覚的な関わりは、読解力を高めることができる。ま た、手書き文字はタイピングよりも文字認識や文章作成に有益であるという結果も、手書き文字の身体性によるものであることが示唆されている。[108] |

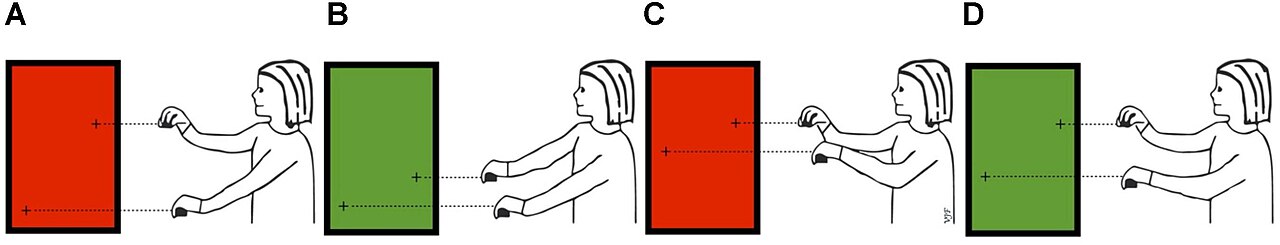

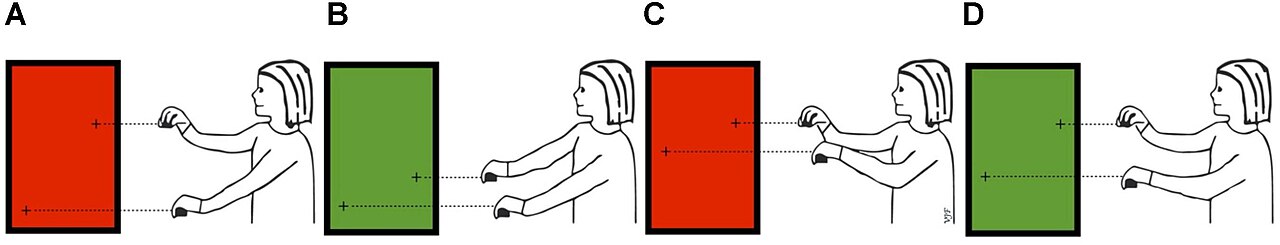

| Reasoning Experiments investigating the relation between motor processes and high-level reasoning have suggested that bodily action and sensorimotor experience are linked to various aspects of reasoning. A study indicated that even though most individuals recruit visual processes when presented with spatial problems such as mental rotation tasks,[109] motor experts (such as wrestlers) favor motor processes over visual encoding to manipulate the objects mentally, showing higher overall performance. Results indicate that motor experts' performance drops once the (hand) movement is inhibited.[110] A related study showed that motor experts use similar processes for the mental rotation of body parts and polygons, whereas non-experts treated these stimuli differently.[111] These results were not due to underlying confounds, as demonstrated by a training study that showed mental rotation improvements after a one-year motor training compared with controls.[112] Similar patterns were also found in working memory tasks, with the ability to remember movements being significantly disrupted by a secondary verbal task in controls and by a motor task in motor experts, suggesting the involvement of different mechanisms to encode movements based on either verbal or on motor processes.[113]  Demonstration of dynamic depictive gestures for the Triangle conjecture The role of motor experience in reasoning has also been investigated through gestures. The Gesture as Simulated Action theory (GSA) provides a framework for understanding how gestures manifest their connection.[114] According to GSA, gestures result from the embodied simulation of actions and sensorimotor states. Consequently, gesturing while expressing or reasoning ideas shows that embodied processes are involved in producing them. More significantly, gesturing heightens focus and increases activation of motor and perceptual information. Gestures are said to have a casual role in reasoning as gesturing leads to increased motor and perceptual information flow during the reasoning process. This does not necessarily translate into more effective reasoning, as such information is sometimes irrelevant for a specific problem.[115] The effects of gestures on reasoning are not limited only to speakers; they convey information that also affects listeners' reasoning. For example, listeners could produce similar simulations to those of the speaker by attending to the speaker's gestures.[115] More evidence for the embodied role of gestures during reasoning comes from studies on mathematical and geometric reasoning. Studies indicate that gestures and, more particularly, dynamic depictive gestures (i.e., gestures used to represent and show the transformation of objects) are linked to better performance in snap judgment (intuition), insight, and mathematical reasoning for proof.[116] Additionally, the use of dynamic depictive gestures are associated with better mathematical reasoning, and thus, directing learners to use such gestures facilitates justification and proof activities. Embodied cognition theory has been applied in behavioral law and economics theory to enlighten reasoning and decision-making processes involving risk and time, decisions, and judgment. Research has shown that the idea that mental processes are grounded in bodily states is not being captured in the standard view of human rationality and the link between them could be useful for understanding and predicting human actions that seem irrational. The concept of "embodied rationality" results from expanding such ideas into law and highlights how findings stemming from embodied cognition offer a more encompassing insight into human behavior and rationality.[117] |

推論 運動プロセスと高度な推論の関係を調査する実験により、身体動作と感覚運動経験が推論のさまざまな側面と関連していることが示唆されている。ある研究で は、ほとんどの人は、メンタルローテーション課題のような空間的問題を提示された際に視覚プロセスを利用するが、[109] 運動の専門家(レスリング選手など)は、視覚的エンコーディングよりも運動プロセスを好み、対象を頭の中で操作する際に全体的なパフォーマンスが高いこと が示されている。結果から、運動の専門家は(手の)動きが抑制されるとパフォーマンスが低下することが示されている。[110] 関連研究では、運動の専門家は身体の部位と多角形の回転を同様のプロセスで処理するが、専門家でない人はこれらの刺激を異なる方法で処理することが示され ている。[111] これらの結果は、基礎的な混同によるものではない。1年間の運動トレーニング後の回転能力の向上が、対照群と比較して示されたトレーニング研究によって実 証されている。 [112] 同様のパターンは作業記憶課題でも見られ、運動の記憶能力は、対照群では二次的な言語課題によって、運動の専門家では運動課題によって著しく阻害された。 これは、言語または運動処理に基づく運動の符号化に異なるメカニズムが関与していることを示唆している。[113]  三角形予想に対する動的な描写ジェスチャーのデモンストレーション 推論における運動経験の役割も、ジェスチャーを通じて調査されている。ジェスチャー・シミュレーション理論(GSA)は、ジェスチャーがどのように関連性 を示すかを理解するための枠組みを提供する。[114] GSAによると、ジェスチャーは、身体化された行動と感覚運動状態のシミュレーションの結果として生じる。したがって、アイデアを表現したり推論したりす る際に身振り手振りを用いることは、それらの生成に身体化されたプロセスが関与していることを示す。さらに重要なのは、身振り手振りによって集中力が高ま り、運動および知覚情報の活性化が促進されることである。推論プロセスにおいて、身振り手振りによって運動および知覚情報の流れが増加するため、身振り手 振りには推論において間接的な役割があると考えられている。ただし、こうした情報は特定の問題には無関係である場合もあるため、必ずしもより効果的な推論 につながるとは限らない。[115] ジェスチャーが推論に与える影響は話し手に限定されるものではなく、聞き手の推論にも影響を与える情報を伝える。例えば、聞き手が話し手のジェスチャーに 注意を払うことで、話し手と同様のシミュレーションを行うことができる。[115] 推論におけるジェスチャーの身体的な役割を示すさらなる証拠は、数学的および幾何学的推論の研究から得られている。研究によると、ジェスチャー、特に動的 描写ジェスチャー(すなわち、対象物の変化を表現し示すために使用されるジェスチャー)は、即断(直観)、洞察、証明のための数学的推論のパフォーマンス 向上と関連していることが示されている。[116] さらに、動的描写ジェスチャーの使用は、より優れた数学的推論と関連しているため、学習者にこのようなジェスチャーの使用を促すことで、正当化と証明活動 を促進することができる。 身体化認知理論は、行動法則や経済理論に適用され、リスクや時間、決定、判断を含む推論や意思決定のプロセスを解明するのに役立っている。研究により、精 神的なプロセスは身体の状態に根ざしているという考え方は、人間の合理性の標準的な見解では捉えられておらず、両者の関連性は非合理的に見える人間の行動 を理解し予測するのに役立つ可能性があることが示されている。「身体化された合理性」という概念は、このような考え方を法律に拡大適用した結果であり、身 体化された認知から得られた知見が人間の行動と合理性に対するより包括的な洞察をもたらすことを示している。[117] |