創 発

Emergence

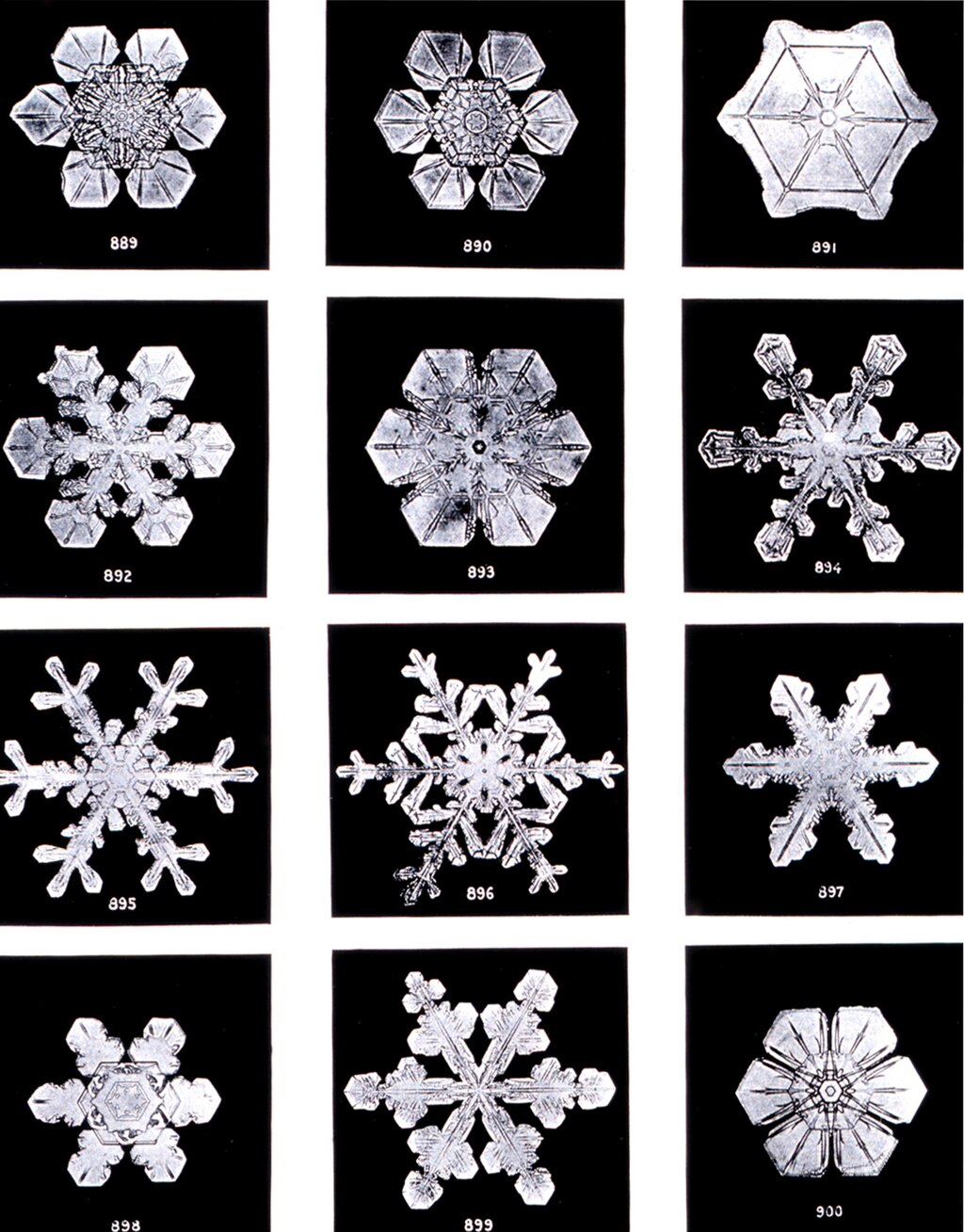

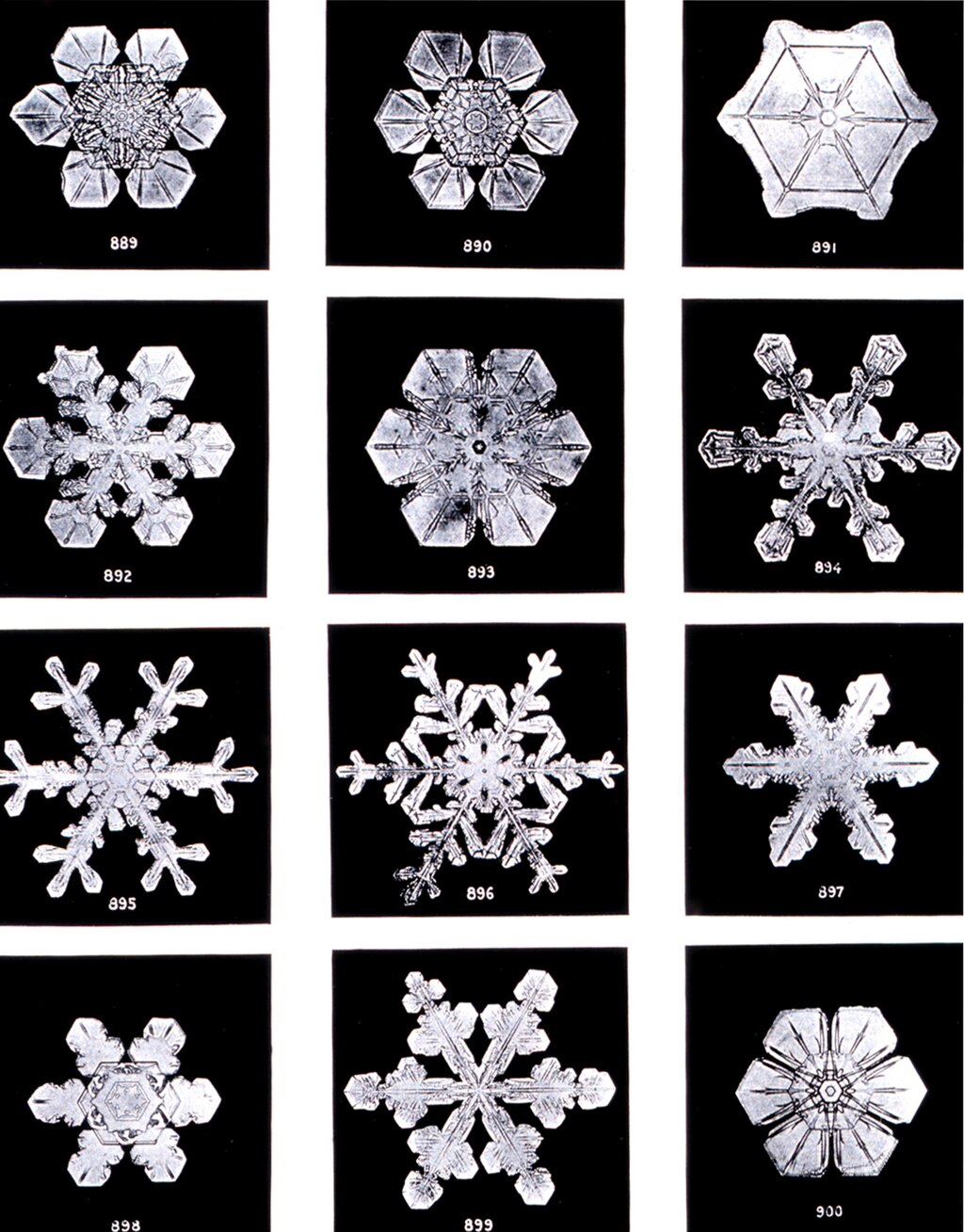

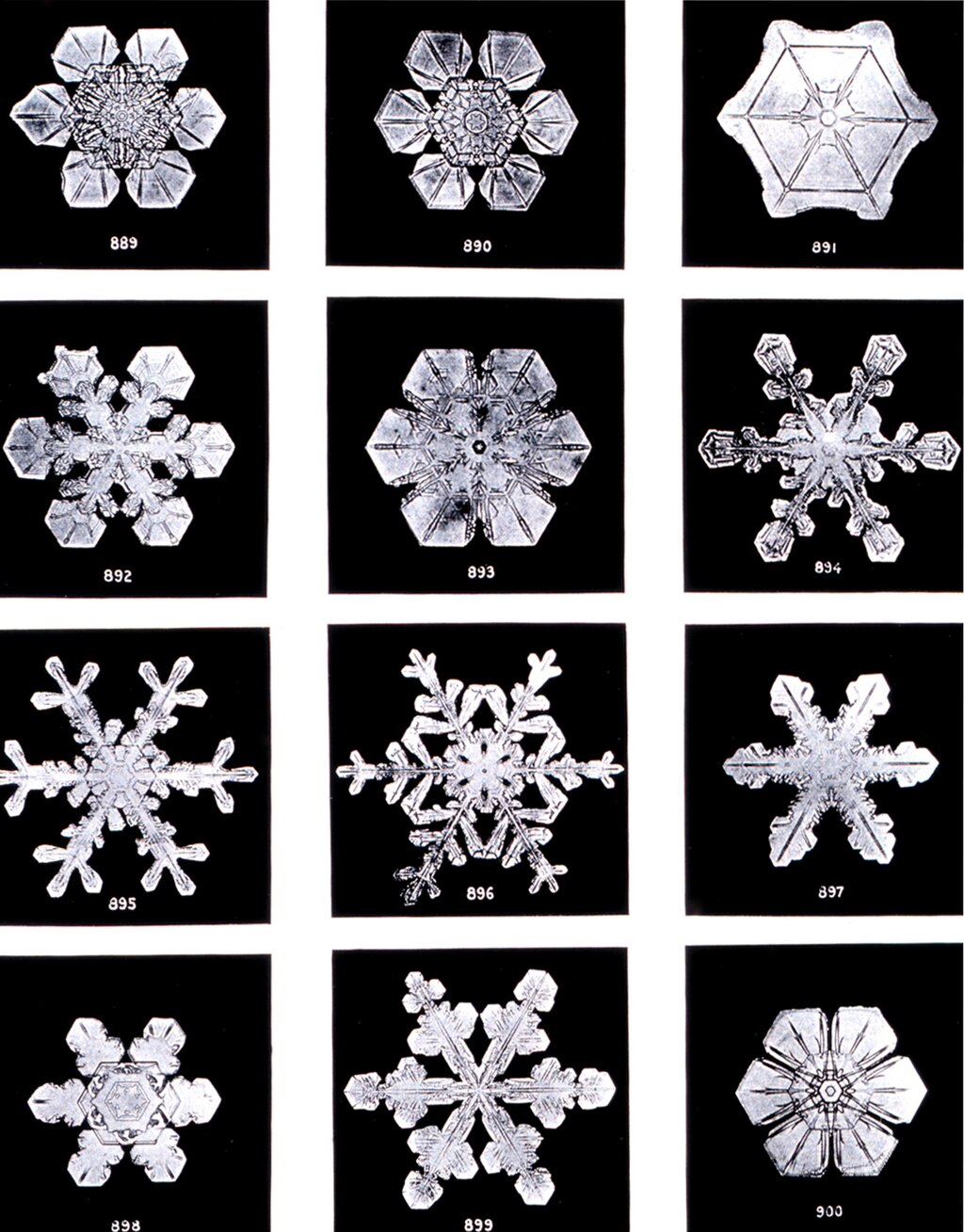

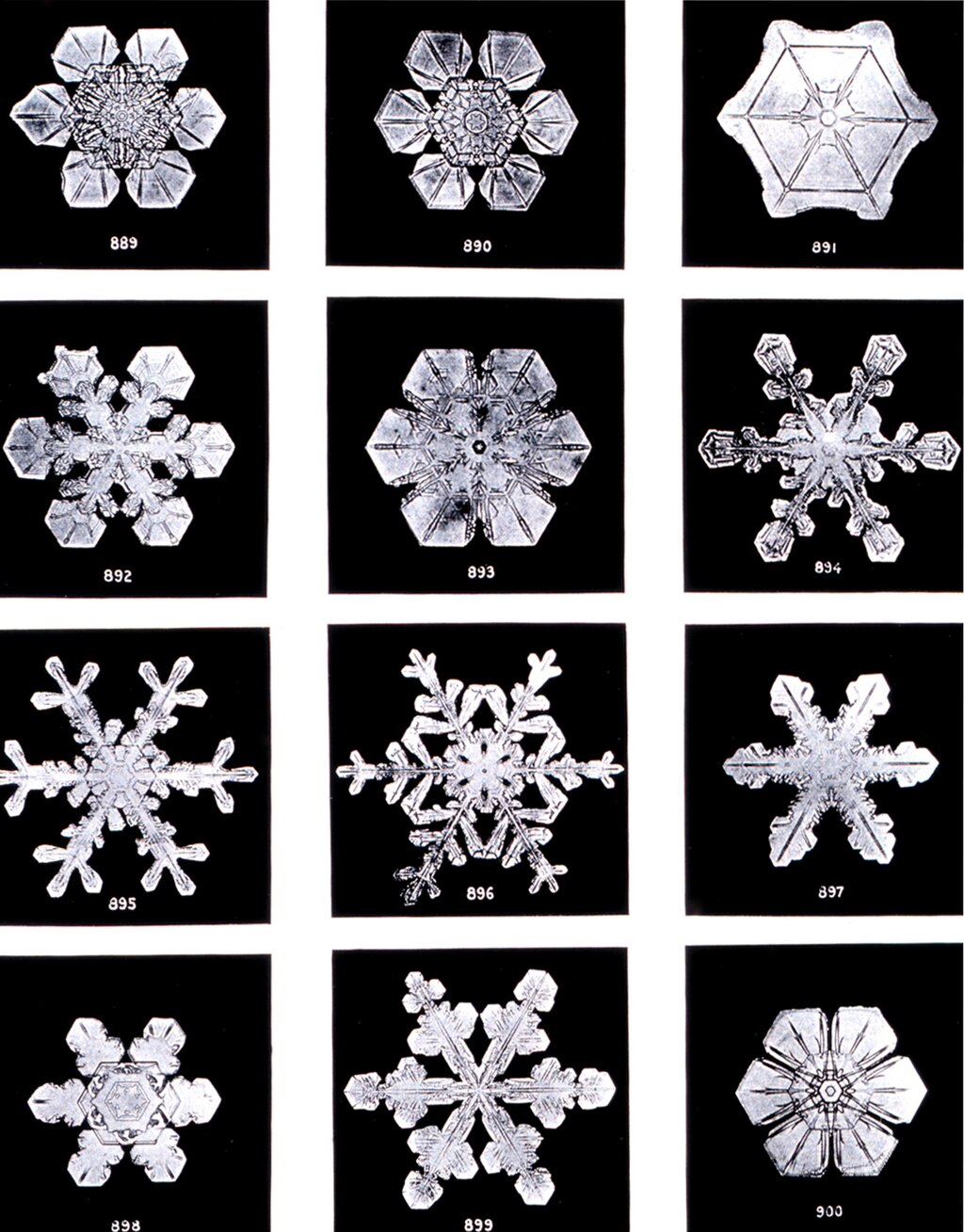

雪の結晶の複雑な対称パターンやフラクタルパターンの形成は、物理システムにおける創発を例証している

☆哲学、システム理論、科学、芸術において、出現は、複雑な存在が、その構成要素が単独では持たない性質や行動を持ち、より広い全体の中で相互作用するときにのみ現れる現象です。

出現は、統合的レベルや複雑系に関する理論において中心的な役割を果たしている。例えば、生物学で研究される生命の現象は、化学や物理学の出現的性質である。

哲学では、出現的性質を強調する理論は出現主義と呼ばれている。[1]

| In philosophy,

systems theory, science, and art, emergence occurs when a complex

entity has properties or behaviors that its parts do not have on their

own, and emerge only when they interact in a wider whole. Emergence plays a central role in theories of integrative levels and of complex systems. For instance, the phenomenon of life as studied in biology is an emergent property of chemistry and physics. In philosophy, theories that emphasize emergent properties have been called emergentism.[1]  The formation of complex symmetrical and fractal patterns in snowflakes exemplifies emergence in a physical system. |

哲学、システム理論、科学、芸術において、出現は、複雑な存在が、その

構成要素が単独では持たない性質や行動を持ち、より広い全体の中で相互作用するときにのみ現れる現象です。 出現は、統合的レベルや複雑系に関する理論において中心的な役割を果たしている。例えば、生物学で研究される生命の現象は、化学や物理学の出現的性質であ る。 哲学では、出現的性質を強調する理論は出現主義と呼ばれている。[1]  雪の結晶の複雑な対称パターンやフラクタルパターンの形成は、物理システムにおける創発を例証している。。 |

| In philosophy Main article: Emergentism Philosophers often understand emergence as a claim about the etiology of a system's properties. An emergent property of a system, in this context, is one that is not a property of any component of that system, but is still a feature of the system as a whole. Nicolai Hartmann (1882–1950), one of the first modern philosophers to write on emergence, termed this a categorial novum (new category).[2] |

哲学 主な記事 創発論 哲学者はしばしば、創発をシステムの特性の病因に関する主張として理解する。この文脈では、システムの創発的特性とは、システムのどの構成要素の特性でも ないが、システム全体の特徴であるものを指す。創発について書いた最初の近代哲学者の一人であるニコライ・ハートマン(1882-1950)は、これをカ テゴリアル・ノヴム(新しいカテゴリー)と呼んだ[2]。 |

| Definitions This concept of emergence dates from at least the time of Aristotle.[3] Many scientists and philosophers[4] have written on the concept, including John Stuart Mill (Composition of Causes, 1843)[5] and Julian Huxley[6] (1887–1975). The philosopher G. H. Lewes coined the term "emergent" in 1875, distinguishing it from the merely "resultant": Every resultant is either a sum or a difference of the co-operant forces; their sum, when their directions are the same – their difference, when their directions are contrary. Further, every resultant is clearly traceable in its components, because these are homogeneous and commensurable. It is otherwise with emergents, when, instead of adding measurable motion to measurable motion, or things of one kind to other individuals of their kind, there is a co-operation of things of unlike kinds. The emergent is unlike its components insofar as these are incommensurable, and it cannot be reduced to their sum or their difference.[7][8] |

定義 この創発の概念は、少なくともアリストテレスの時代からある[3]。ジョン・スチュアート・ミル(『原因の構成』1843年)[5]やジュリアン・ハクスリー[6](1887-1975年)など、多くの科学者や哲学者[4]がこの概念について書いている。 哲学者のG.H.ルイスは1875年に「創発(emergent)」という言葉を作り、単なる「結果的(resultant)」とは区別した: すべての結果は、共働する力の和か差であり、それらの和は方向が同じであるとき、それらの差は方向が反対のときである。さらに、すべての結果は、その構成 要素において明確に追跡可能である。測定可能な運動に測定可能な運動を加えたり、ある種類のものに他の種類のものを加えたりするのではなく、種類の異なる ものの協力があるとき、創発的なものはそうではない。創発的なものは、それらが共約不可能性である限りにおいて、その構成要素とは異なっており、それらの 和や差に還元することはできない[7][8]。 |

A termite "cathedral" mound produced by a termite colony offers a classic example of emergence in nature. |

シロアリのコロニーが作り出す「カテドラル」マウンドは、自然界における出現の典型的な例を示している。 |

| Strong and weak emergence Further information: Emergent materialism and Reductive materialism Usage of the notion "emergence" may generally be subdivided into two perspectives, that of "weak emergence" and "strong emergence". One paper discussing this division is Weak Emergence, by philosopher Mark Bedau. In terms of physical systems, weak emergence is a type of emergence in which the emergent property is amenable to computer simulation or similar forms of after-the-fact analysis (for example, the formation of a traffic jam, the structure of a flock of starlings in flight or a school of fish, or the formation of galaxies). Crucial in these simulations is that the interacting members retain their independence. If not, a new entity is formed with new, emergent properties: this is called strong emergence, which it is argued cannot be simulated, analysed or reduced.[9] David Chalmers writes that emergence often causes confusion in philosophy and science due to a failure to demarcate strong and weak emergence, which are "quite different concepts".[10] Some common points between the two notions are that emergence concerns new properties produced as the system grows, which is to say ones which are not shared with its components or prior states. Also, it is assumed that the properties are supervenient rather than metaphysically primitive.[9] Weak emergence describes new properties arising in systems as a result of the interactions at a fundamental level. However, Bedau stipulates that the properties can be determined only by observing or simulating the system, and not by any process of a reductionist analysis. As a consequence the emerging properties are scale dependent: they are only observable if the system is large enough to exhibit the phenomenon. Chaotic, unpredictable behaviour can be seen as an emergent phenomenon, while at a microscopic scale the behaviour of the constituent parts can be fully deterministic.[citation needed] Bedau notes that weak emergence is not a universal metaphysical solvent, as the hypothesis that consciousness is weakly emergent would not resolve the traditional philosophical questions about the physicality of consciousness. However, Bedau concludes that adopting this view would provide a precise notion that emergence is involved in consciousness, and second, the notion of weak emergence is metaphysically benign.[9] Strong emergence describes the direct causal action of a high-level system on its components; qualities produced this way are irreducible to the system's constituent parts.[11] The whole is other than the sum of its parts. It is argued then that no simulation of the system can exist, for such a simulation would itself constitute a reduction of the system to its constituent parts.[9] Physics lacks well-established examples of strong emergence, unless it is interpreted as the impossibility in practice to explain the whole in terms of the parts. Practical impossibility may be a more useful distinction than one in principle, since it is easier to determine and quantify, and does not imply the use of mysterious forces, but simply reflects the limits of our capability.[12] |

強いエマージェンシーと弱いエマージェンシー さらなる情報 創発的唯物論と還元的唯物論 創発」という概念の用法は、一般的に「弱い創発」と「強い創発」という2つの観点に分けられる。この区分について論じた論文に、哲学者マーク・ベダウによ る『弱い創発』がある。物理システムに関して言えば、弱い創発とは、創発的な性質がコンピュータ・シミュレーションやそれに類する事後分析に適しているタ イプの創発である(例えば、交通渋滞の形成、飛翔するムクドリの群れや魚の群れの構造、銀河の形成など)。これらのシミュレーションで重要なのは、相互作 用するメンバーが独立性を保つことである。もしそうでなければ、新たな創発的特性を持つ新たな実体が形成される。これは強い創発と呼ばれ、シミュレーショ ンや分析、縮小はできないと主張されている[9]。 デイヴィッド・チャルマーズは、強い創発と弱い創発は「全く異なる概念」であり、その区別がつかないために、創発はしばしば哲学や科学において混乱を引き起こすと書いている[10]。 この2つの概念に共通する点として、創発はシステムの成長に伴って生じる新しい性質、つまりシステムの構成要素やそれ以前の状態とは共有されない性質に関 するものであることが挙げられる。また、その特性は形而上学的に原始的なものではなく、むしろ超越的なものであると仮定されている[9]。 弱い創発は、基本的なレベルでの相互作用の結果としてシステムに生じる新しい特性を記述する。しかしベダウは、その特性はシステムを観察するかシミュレー ションすることによってのみ決定することができ、いかなる還元主義的分析のプロセスによっても決定することはできないと規定している。その結果、出現する 特性は規模に依存する。つまり、現象を示すのに十分な規模のシステムでなければ観測できないのである。カオス的で予測不可能な振る舞いは創発現象として見 ることができるが、ミクロなスケールでは構成部分の振る舞いは完全に決定論的であることもある。 ベダウは、意識が弱く創発的であるという仮説は、意識の物理性に関する伝統的な哲学的疑問を解決しないため、弱い創発は普遍的な形而上学的溶媒ではないと 指摘している。しかしベダウは、この見解を採用することで、創発が意識に関与しているという正確な概念を提供することができ、第二に、弱い創発の概念は形 而上学的に穏やかであると結論付けている[9]。 強い創発は、高レベルのシステムがその構成要素に直接因果的な作用を及ぼすことを説明している。なぜなら、そのようなシミュレーショ ンは、それ自体がシステムの構成部分への還元を構成してしまうからであ る。現実的な不可能性は、原理的な不可能性よりも判断や定量化が容易であり、神秘的な力の使用を意味するものではなく、単に我々の能力の限界を反映するも のであるため、より有用な区別であるかもしれない[12]。 |

| Viability of strong emergence One of the reasons for the importance of distinguishing these two concepts with respect to their difference concerns the relationship of purported emergent properties to science. Some thinkers question the plausibility of strong emergence as contravening our usual understanding of physics. Mark A. Bedau observes: Although strong emergence is logically possible, it is uncomfortably like magic. How does an irreducible but supervenient downward causal power arise, since by definition it cannot be due to the aggregation of the micro-level potentialities? Such causal powers would be quite unlike anything within our scientific ken. This not only indicates how they will discomfort reasonable forms of materialism. Their mysteriousness will only heighten the traditional worry that emergence entails illegitimately getting something from nothing.[9] The concern that strong emergence does so entail is that such a consequence must be incompatible with metaphysical principles such as the principle of sufficient reason or the Latin dictum ex nihilo nihil fit, often translated as "nothing comes from nothing".[13] Strong emergence can be criticized for leading to causal overdetermination. The canonical example concerns emergent mental states (M and M∗) that supervene on physical states (P and P∗) respectively. Let M and M∗ be emergent properties. Let M∗ supervene on base property P∗. What happens when M causes M∗? Jaegwon Kim says: In our schematic example above, we concluded that M causes M∗ by causing P∗. So M causes P∗. Now, M, as an emergent, must itself have an emergence base property, say P. Now we face a critical question: if an emergent, M, emerges from basal condition P, why cannot P displace M as a cause of any putative effect of M? Why cannot P do all the work in explaining why any alleged effect of M occurred? If causation is understood as nomological (law-based) sufficiency, P, as M's emergence base, is nomologically sufficient for it, and M, as P∗'s cause, is nomologically sufficient for P∗. It follows that P is nomologically sufficient for P∗ and hence qualifies as its cause...If M is somehow retained as a cause, we are faced with the highly implausible consequence that every case of downward causation involves overdetermination (since P remains a cause of P∗ as well). Moreover, this goes against the spirit of emergentism in any case: emergents are supposed to make distinctive and novel causal contributions.[14] If M is the cause of M∗, then M∗ is overdetermined because M∗ can also be thought of as being determined by P. One escape-route that a strong emergentist could take would be to deny downward causation. However, this would remove the proposed reason that emergent mental states must supervene on physical states, which in turn would call physicalism into question, and thus be unpalatable for some philosophers and physicists. |

強い創発の可能性 この2つの概念の違いを区別することの重要性の理由のひとつは、創発的性質とされるものと科学との関係にある。私たちの通常の物理学の理解に反するとして、強い創発の妥当性に疑問を呈する思想家もいる。マーク・A・ベダウはこう言う: 強い創発は論理的には可能だが、呪術的である。というのも、定義上、それはミクロレベルの潜在能力の集合体によるものではありえないからである。そのよう な因果の力は、私たちの科学的知見の範囲内にはないものである。このことは、それらが合理的な唯物論の形態をどのように不快にさせるかを示しているだけで はない。その不可思議さは、創発が無から有を得ることを違法に伴うという伝統的な懸念を強めるだけである[9]。 強い創発がそうであるという懸念は、そのような帰結が、十分理由の原理や、しばしば「無から有は生じない」と訳されるラテン語の訓辞ex nihilo nihil fitのような形而上学的原理と相容れないものでなければならないということである[13]。 強い創発は因果的な過剰決定をもたらすとして批判されることがある。典型的な例は、それぞれ物理的状態(PとP*)に重畳する創発的な精神状態(Mと M*)に関するものである。MとM*を創発的性質とする。M*が基本特性P*に重畳するとする。MがM*を引き起こすとどうなるか?Jaegwon Kim氏は言う: 上の模式的な例では、MはP*を引き起こすことによってM*を引き起こすと結論づけた。つまり、MはP*を引き起こす。さて、創発体としてのMは、それ自 体、創発の基礎となる性質、例えばPを持たなければならない。もし創発体であるMが基礎となる条件Pから創発されるのであれば、なぜPは、Mがもたらすと 考えられる効果の原因としてMを置き換えることができないのだろうか?なぜPは、Mの影響とされるものの原因としてMを置き換えることができないのだろう か?因果関係を名辞論的(法則論的)充足性として理解するならば、Mの発生基盤としてのPはMにとって名辞論的充足性であり、P*の原因としてのMはP* にとって名辞論的充足性である。もしMが何らかの形で原因として保持されるのであれば、(PがP*の原因であることに変わりはないため)下向きの因果関係 のすべてのケースが過剰決定を伴うという、非常にありえない帰結に直面することになる。さらに、これはどのような場合でも創発主義の精神に反する:創発者 は、独特で新規な因果的貢献をすることになっている[14]。 もしMがM*の原因であるならば、M*もPによって決定されると考えることができるので、M*は過剰決定である。しかし、これでは、創発的な精神状態が物 理的な状態を超越しなければならないという提案された理由を取り除くことになり、ひいては物理主義に疑問を投げかけることになり、一部の哲学者や物理学者 にとっては不愉快なことである。 |

| Carroll

and Parola propose a taxonomy that classifies emergent phenomena by how

the macro-description relates to the underlying micro-dynamics.[15] Type‑0 (Featureless) Emergence A coarse-graining map Φ from a micro state space A to a macro state space B that commutes with time evolution, without requiring any further decomposition into subsystems. Type‑1 (Local) Emergence Emergence where the macro theory is defined in terms of localized collections of micro-subsystems. This category is subdivided into: Type‑1a (Direct) Emergence: When the emergence map Φ is algorithmically simple (i.e. compressible), so that the macro behavior is easily deduced from the micro-states. Type‑1b (Incompressible) Emergence: When Φ is algorithmically complex (i.e. incompressible), making the macro behavior appear more novel despite being determined by the micro-dynamics. Type‑2 (Nonlocal) Emergence Cases in which both the micro and macro theories admit subsystem decompositions, yet the macro entities are defined nonlocally with respect to the micro-structure, meaning that macro behavior depends on widely distributed micro information. Type‑3 (Augmented) Emergence A form of strong emergence in which the macro theory introduces additional ontological variables that do not supervene on the micro-states, thereby positing genuinely novel macro-level entities. |

CarrollとParolaは、マクロ記述と根底にあるミクロダイナミクスとの関係によって創発現象を分類する分類法を提案している[15]。 タイプ0(特徴なし)創発 ミクロな状態空間Aからマクロな状態空間Bへの粗視化マップΦで、サブシステムへのさらなる分解を必要とせず、時間進化とコミュートする。 タイプ1(局所的)創発 マクロな理論がミクロなサブシステムの局所的な集合の観点から定義される創発。このカテゴリーは次のように細分化される: タイプ-1a(直接)創発: 創発マップΦがアルゴリズム的に単純(圧縮可能)であり、ミクロな状態からマクロな振る舞いが容易に推測できる。 タイプ1b(非圧縮性)創発: Φがアルゴリズム的に複雑な場合(すなわち非圧縮性)、ミクロの力学によって決定されるにもかかわらず、マクロの振る舞いがより新しく見える。 タイプ2(非局所的)創発 ミクロ理論とマクロ理論の両方がサブシステムの分解を認めるが、マクロの実体はミクロ構造に対して非局所的に定義され、マクロの振る舞いが広く分布したミクロの情報に依存することを意味する。 タイプ3(拡張)創発 強い創発の一形態で、マクロ理論がミクロ状態を超越しない付加的な存在論的変数を導入することにより、真に新しいマクロレベルの実体を仮定する。 |

| Objective or subjective quality Crutchfield regards the properties of complexity and organization of any system as subjective qualities determined by the observer. Defining structure and detecting the emergence of complexity in nature are inherently subjective, though essential, scientific activities. Despite the difficulties, these problems can be analysed in terms of how model-building observers infer from measurements the computational capabilities embedded in non-linear processes. An observer's notion of what is ordered, what is random, and what is complex in its environment depends directly on its computational resources: the amount of raw measurement data, of memory, and of time available for estimation and inference. The discovery of structure in an environment depends more critically and subtly, though, on how those resources are organized. The descriptive power of the observer's chosen (or implicit) computational model class, for example, can be an overwhelming determinant in finding regularity in data.[16] The low entropy of an ordered system can be viewed as an example of subjective emergence: the observer sees an ordered system by ignoring the underlying microstructure (i.e. movement of molecules or elementary particles) and concludes that the system has a low entropy.[17] On the other hand, chaotic, unpredictable behaviour can also be seen as subjective emergent, while at a microscopic scale the movement of the constituent parts can be fully deterministic. |

主体性か主観性か クラッチフィールドは、あらゆるシステムの複雑性と組織の主体性を、観察者によって決定される主観的な性質とみなしている。 構造を定義し、自然界における複雑性の出現を検出することは、本質的に主観的ではあるが、不可欠な科学的活動である。困難にもかかわらず、これらの問題 は、モデルを構築する観測者が、非線形過程に組み込まれた計算能力を測定値からどのように推測するかという観点から分析することができる。何が秩序で、何 がランダムで、何が複雑な環境であるかという観測者の概念は、その計算資源(生の測定データ量、メモリ量、推定と推論に利用できる時間)に直接依存する。 しかし、環境における構造の発見は、それらの資源がどのように組織化されているかによって、より決定的かつ微妙に左右される。例えば、観察者が選択した (または暗黙の)計算モデルクラスの記述力は、データの規則性を発見する上で圧倒的な決定要因となり得る[16]。 観察者は、根底にある微細構造(分子や素粒子の動き)を無視することで、秩序化された系を見ることができ、その系が低エントロピーであると結論付けることができる。 |

| In science In physics, emergence is used to describe a property, law, or phenomenon which occurs at macroscopic scales (in space or time) but not at microscopic scales, despite the fact that a macroscopic system can be viewed as a very large ensemble of microscopic systems.[18][19] An emergent behavior of a physical system is a qualitative property that can only occur in the limit that the number of microscopic constituents tends to infinity.[20] According to Robert Laughlin,[11] for many-particle systems, nothing can be calculated exactly from the microscopic equations, and macroscopic systems are characterised by broken symmetry: the symmetry present in the microscopic equations is not present in the macroscopic system, due to phase transitions. As a result, these macroscopic systems are described in their own terminology, and have properties that do not depend on many microscopic details. Novelist Arthur Koestler used the metaphor of Janus (a symbol of the unity underlying complements like open/shut, peace/war) to illustrate how the two perspectives (strong vs. weak or holistic vs. reductionistic) should be treated as non-exclusive, and should work together to address the issues of emergence.[21] Theoretical physicist Philip W. Anderson states it this way: The ability to reduce everything to simple fundamental laws does not imply the ability to start from those laws and reconstruct the universe. The constructionist hypothesis breaks down when confronted with the twin difficulties of scale and complexity. At each level of complexity entirely new properties appear. Psychology is not applied biology, nor is biology applied chemistry. We can now see that the whole becomes not merely more, but very different from the sum of its parts.[22] Meanwhile, others have worked towards developing analytical evidence of strong emergence. Renormalization methods in theoretical physics enable physicists to study critical phenomena that are not tractable as the combination of their parts.[23] In 2009, Gu et al. presented a class of infinite physical systems that exhibits non-computable macroscopic properties.[24][25] More precisely, if one could compute certain macroscopic properties of these systems from the microscopic description of these systems, then one would be able to solve computational problems known to be undecidable in computer science. These results concern infinite systems, finite systems being considered computable. However, macroscopic concepts which only apply in the limit of infinite systems, such as phase transitions and the renormalization group, are important for understanding and modeling real, finite physical systems. Gu et al. concluded that Although macroscopic concepts are essential for understanding our world, much of fundamental physics has been devoted to the search for a 'theory of everything', a set of equations that perfectly describe the behavior of all fundamental particles. The view that this is the goal of science rests in part on the rationale that such a theory would allow us to derive the behavior of all macroscopic concepts, at least in principle. The evidence we have presented suggests that this view may be overly optimistic. A 'theory of everything' is one of many components necessary for complete understanding of the universe, but is not necessarily the only one. The development of macroscopic laws from first principles may involve more than just systematic logic, and could require conjectures suggested by experiments, simulations or insight.[24] |

科学 物理学では、創発は、巨視的なシステムは微視的なシステムの非常に大きなアンサンブルとして見ることができるという事実にもかかわらず、巨視的なスケール (空間または時間)で発生し、微視的なスケールでは発生しない特性、法則、または現象を記述するために使用される[18][19]。 物理系の創発的な振る舞いは、微視的な構成要素の数が無限大になる極限においてのみ起こりうる定性的な特性である[20]。 ロバート・ラフリンによれば[11]、多粒子系では、微視的方程式から正確に計算できるものはなく、巨視的系は対称性の破れによって特徴づけられる。その結果、これらの巨視的系は独自の用語で記述され、多くの微視的細部に依存しない特性を持つ。 小説家アーサー・ケストラーは、ヤヌスの隠喩(開/閉、平和/戦争といった補完の根底にある統一の象徴)を使って、2つの視点(強対弱、全体主義対還元主 義)がいかに非排他的なものとして扱われるべきかを説明し、創発の問題に取り組むために協力し合うべきだと述べた[21]。理論物理学者フィリップ・W・ アンダーソンはこのように述べる: すべてを単純な基本法則に還元する能力は、それらの法則から出発して宇宙を再構築する能力を意味しない。構築主義者の仮説は、スケールと複雑さという2つ の難題に直面したときに破綻する。複雑さのレベルが上がるごとに、まったく新しい性質が現れる。心理学は生物学の応用ではないし、生物学は化学の応用でも ない。私たちは今、全体が単に部分以上のものになるのではなく、部分の総和とはまったく異なるものになることを理解することができる[22]。 一方、他の研究者たちは、強い創発の分析的証拠を開発することに 取り組んできた。2009年、Guらは、計算不可能な巨視的性質を示す無限物理系のクラスを提示した[24][25]。より正確には、これらの系の微視的 記述から、これらの系のある種の巨視的性質を計算することができれば、計算機科学において決定不可能であることが知られている計算問題を解くことができ る。これらの結果は無限系に関するものであり、有限系は計算可能であると考えられている。しかし、相転移や繰り込み群など、無限系の極限でのみ適用される 巨視的概念は、現実の有限物理系を理解しモデル化する上で重要である。Guらは次のように結論づけている。 巨視的概念は我々の世界を理解するために不可欠であるが、基礎物理学の多くは、『万物の理論』、すなわちすべての基本粒子の振る舞いを完全に記述する一連 の方程式の探求に費やされてきた。これが科学の目標であるという考え方は、そのような理論があれば、少なくとも原理的には、すべての巨視的概念の振る舞い を導くことができるという根拠に基づいている。我々が提示した証拠は、この見解が過度に楽観的である可能性を示唆している。万物の理論」は、宇宙を完全に 理解するために必要な多くの構成要素の一つではあるが、必ずしもそれだけではない。第一原理から巨視的な法則を発展させるには、体系的な論理以上のものが 必要かもしれないし、実験やシミュレーション、洞察によって示唆される推測が必要かもしれない[24]。 |

| In humanity See also: Spontaneous order and Self-organization Human beings are the basic elements of social systems, which perpetually interact and create, maintain, or untangle mutual social bonds. Social bonds in social systems are perpetually changing in the sense of the ongoing reconfiguration of their structure.[26] An early argument (1904–05) for the emergence of social formations can be found in Max Weber's most famous work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.[27] Recently, the emergence of a new social system is linked with the emergence of order from nonlinear relationships among multiple interacting units, where multiple interacting units are individual thoughts, consciousness, and actions.[28] In the case of the global economic system, under capitalism, growth, accumulation and innovation can be considered emergent processes where not only does technological processes sustain growth, but growth becomes the source of further innovations in a recursive, self-expanding spiral. In this sense, the exponential trend of the growth curve reveals the presence of a long-term positive feedback among growth, accumulation, and innovation; and the emergence of new structures and institutions connected to the multi-scale process of growth. [29] This is reflected in the work of Karl Polanyi, who traces the process by which labor and nature are converted into commodities in the passage from an economic system based on agriculture to one based on industry.[30] This shift, along with the idea of the self-regulating market, set the stage not only for another economy but also for another society. The principle of emergence is also brought forth when thinking about alternatives to the current economic system based on growth facing social and ecological limits. Both degrowth and social ecological economics have argued in favor of a co-evolutionary perspective for theorizing about transformations that overcome the dependence of human wellbeing on economic growth.[31][32] Economic trends and patterns which emerge are studied intensively by economists.[33] Within the field of group facilitation and organization development, there have been a number of new group processes that are designed to maximize emergence and self-organization, by offering a minimal set of effective initial conditions. Examples of these processes include SEED-SCALE, appreciative inquiry, Future Search, the world cafe or knowledge cafe, Open Space Technology, and others (Holman, 2010[34]). In international development, concepts of emergence have been used within a theory of social change termed SEED-SCALE to show how standard principles interact to bring forward socio-economic development fitted to cultural values, community economics, and natural environment (local solutions emerging from the larger socio-econo-biosphere). These principles can be implemented utilizing a sequence of standardized tasks that self-assemble in individually specific ways utilizing recursive evaluative criteria.[35] Looking at emergence in the context of social and systems change, invites us to reframe our thinking on parts and wholes and their interrelation. Unlike machines, living systems at all levels of recursion - be it a sentient body, a tree, a family, an organisation, the education system, the economy, the health system, the political system etc - are continuously creating themselves. They are continually growing and changing along with their surrounding elements, and therefore are more than the sum of their parts. As Peter Senge and co-authors put forward in the book Presence: Exploring profound change in People, Organizations and Society, "as long as our thinking is governed by habit - notably industrial, "machine age" concepts such as control, predictability, standardization, and "faster is better" - we will continue to recreate institutions as they have been, despite their disharmony with the larger world, and the need for all living systems to evolve."[36] While change is predictably constant, it is unpredictable in direction and often occurs at second and nth orders of systemic relationality.[37] Understanding emergence and what creates the conditions for different forms of emergence to occur, either insidious or nourishing vitality, is essential in the search for deep transformations. The works of Nora Bateson and her colleagues at the International Bateson Institute delve into this. Since 2012, they have been researching questions such as what makes a living system ready to change? Can unforeseen ready-ness for change be nourished? Here being ready is not thought of as being prepared, but rather as nourishing the flexibility we do not yet know will be needed. These inquiries challenge the common view that a theory of change is produced from an identified preferred goal or outcome. As explained in their paper An essay on ready-ing: Tending the prelude to change:[37] "While linear managing or controlling of the direction of change may appear desirable, tending to how the system becomes ready allows for pathways of possibility previously unimagined." This brings a new lens to the field of emergence in social and systems change as it looks to tending the pre-emergent process. Warm Data Labs are the fruit of their praxis, they are spaces for transcontextual mutual learning in which aphanipoetic phenomena unfold.[38] Having hosted hundreds of Warm Data processes with 1000s of participants, they have found that these spaces of shared poly-learning across contexts lead to a realm of potential change, a necessarily obscured zone of wild interaction of unseen, unsaid, unknown flexibility.[37] It is such flexibility that nourishes the ready-ing living systems require to respond to complex situations in new ways and change. In other words, this readying process preludes what will emerge. When exploring questions of social change, it is important to ask ourselves, what is submerging in the current social imaginary and perhaps, rather than focus all our resources and energy on driving direct order responses, to nourish flexibility with ourselves, and the systems we are a part of. Another approach that engages with the concept of emergence for social change is Theory U, where "deep emergence" is the result of self-transcending knowledge after a successful journey along the U through layers of awareness.[39] This practice nourishes transformation at the inner-being level, which enables new ways of being, seeing and relating to emerge. The concept of emergence has also been employed in the field of facilitation. In Emergent Strategy, adrienne maree brown defines emergent strategies as "ways for humans to practice complexity and grow the future through relatively simple interactions".[40] In linguistics, the concept of emergence has been applied in the domain of stylometry to explain the interrelation between the syntactical structures of the text and the author style (Slautina, Marusenko, 2014).[41] It has also been argued that the structure and regularity of language grammar, or at least language change, is an emergent phenomenon.[42] While each speaker merely tries to reach their own communicative goals, they use language in a particular way. If enough speakers behave in that way, language is changed.[43] In a wider sense, the norms of a language, i.e. the linguistic conventions of its speech society, can be seen as a system emerging from long-time participation in communicative problem-solving in various social circumstances.[44] |

人間性において も参照のこと: 自然発生的秩序と自己組織化 人間は社会システムの基本的要素であり、社会システムは永続的に相互作用し、相互の社会的結合を生み出し、維持し、あるいは解きほぐす。社会システムにお ける社会的結合は、その構造の継続的な再構成という意味で永続的に変化している[26]。社会形成の創発に関する初期の議論(1904-05)は、マック ス・ウェーバーの最も有名な著作『プロテスタントの倫理と資本主義の精神』に見られる。[最近では、新たな社会システムの創発は、複数の相互作用単位(こ こで複数の相互作用単位とは個人の思考、意識、行動である)の間の非線形の関係から秩序が創発することと結びつけられている[28]。グローバル経済シス テムの場合、資本主義の下では、成長、蓄積、革新は、技術的プロセスが成長を維持するだけでなく、成長が再帰的、自己拡大的なスパイラルにおいてさらなる 革新の源泉となる創発的プロセスと考えることができる。この意味で、成長曲線の指数関数的傾向は、成長、蓄積、イノベーションの間に長期的な正のフィード バックが存在すること、そして、成長のマルチスケール・プロセスに関連する新たな構造や制度が出現することを明らかにしている。[このことは、農業に基づ く経済体制から工業に基づく経済体制への移行において、労働と自然が商品に転換される過程をたどったカール・ポランニーの研究に反映されている。創発の原 理は、社会的・生態学的限界に直面する成長に基づく現在の経済システムの代替案を考える際にも持ち出される。脱成長経済学と社会生態経済学はともに、経済 成長への人間の幸福の依存を克服する変革について理論化するために、共進化の視点を支持することを主張している[31][32]。 グループ・ファシリテーションと組織開発の分野では、効果的な初期条件の最小セットを提供することで、創発と自己組織化を格律化するように設計された新し いグループ・プロセスが数多く存在している。これらのプロセスの例としては、SEED-SCALE、鑑賞的探究、フューチャーサーチ、ワールドカフェやナ レッジカフェ、オープンスペース・テクノロジーなどがある(Holman, 2010[34])。国際開発では、SEED-SCALEと呼ばれる社会変革理論の中で創発の概念が使用されており、文化的価値、コミュニティ経済、自然 環境(より大きな社会生態圏から生まれるローカルな解決策)に適合した社会経済的発展をもたらすために、標準的な原則がどのように相互作用するかを示して いる。これらの原則は、再帰的な評価基準を利用して、個々に特化した方法で自己組織化する標準化されたタスクのシーケンスを利用して実施することができる [35]。 社会とシステムの変化という文脈で創発を見ることは、部分と全体、そしてそれらの相互関係についての考え方を再構築することを私たちに促す。機械とは異な り、覚醒体であれ、樹木であれ、家族であれ、組織であれ、教育システムであれ、経済であれ、保健システムであれ、政治システムであれ、あらゆるレベルの再 帰性を持つ生命システムは、絶えず自分自身を創造している。それらは周囲の要素とともに絶えず成長し、変化しており、それゆえ部分の総和以上のものであ る。ピーター・センゲと共著者たちが『プレゼンス』で提唱しているように: 人民、組織、社会における深遠な変化を探求する」という本の中で、ピーター・センゲと共著者たちが提唱しているように、「私たちの思考が習慣に支配されて いる限り、特に、制御、予測可能性、標準化、「速いほどよい」といった工業的な「機械時代」の概念に支配されている限り、私たちは、より大きな世界との不 調和や、すべての生命システムが進化する必要性があるにもかかわらず、制度をこれまでと同じように作り直し続けるだろう。「変化は予測可能なほど恒常的な ものであるが、その方向性は予測不可能であり、多くの場合、システム的な関係性の二次、三次で発生するものである。 国際ベイトソン研究所のノラ・ベイトソンと彼女の同僚たちの研究は、これを掘り下げている。2012年以来、彼らは、何が生きたシステムを変化させる準備 を整えるのか?変化への予期せぬ準備態勢は育まれるのだろうか?ここでいう「準備ができている」とは、準備万端であることではなく、私たちがまだ知らない 柔軟性を養うことである。これらの問いかけは、変革の理論は、特定された望ましい目標や成果から生み出されるという一般的な見方に挑戦するものである。彼 らの論文『An essay on ready-ing: Tending the prelude to change』[37]で説明されているように、「変化の方向性を直線的に管理したり、コントロールしたりすることは望ましいように見えるかもしれない が、システムがどのように準備態勢に入るかに気を配ることで、以前は想像もつかなかったような可能性の道筋が可能になる」のである。これは、社会変化やシ ステム変化における創発の分野に新しいレンズをもたらし、創発前のプロセスに目を向けることになる。ウォーム・データ・ラボは彼らの実践の成果であり、ア ファニポエティックな現象が展開される、文脈を超えた相互学習のための空間である[38]。1,000人以上の参加者とともに何百ものウォーム・データ・ プロセスを主催してきた彼らは、文脈を超えた共有されたポリ・ラーニングのこうした空間が、潜在的な変化の領域、つまり目に見えず、語られず、未知の柔軟 性を持つ野生の相互作用の必然的に不明瞭なゾーンにつながることを発見した[37]。言い換えれば、この準備のプロセスは、何が出現するかを先取りしてい るのである。社会変革の問題を探求する際には、現在の社会的想像力の中で何が沈潜しているのかを自問することが重要である。そしておそらく、直接的な秩序 への対応を推進することにすべての資源とエネルギーを集中させるのではなく、自分自身と、自分たちの一部であるシステムの柔軟性を養うことが重要なのであ る。 社会変革のための創発の概念に関わるもう一つのアプローチは、セオリーUであ る。セオリーUでは、「深い創発」は、気づきの層を通してUに沿った旅に 成功した後の、自己超越的な知識の結果である。創発の概念はファシリテーションの分野でも採用されている。アドリアン・マリー・ブラウンは『創発的戦略』 の中で、創発的戦略を「人間が複雑性を実践し、比較的単純な相互作用を通じて未来を成長させる方法」と定義している[40]。 言語学では、テキストの構文構造と著者の文体との間の相互関係を説明するために、創発の概念が文体測定の領域で適用されている(Slautina, Marusenko, 2014)[41]。また、言語文法の構造と規則性、あるいは少なくとも言語の変化は創発的な現象であると論じられている[42]。各話者は単に自分自身 のコミュニケーション目標を達成しようとする一方で、特定の方法で言語を使用する。より広い意味では、ある言語の規範、すなわちその言語社会の言語的慣習 は、様々な社会的状況におけるコミュニケーション上の問題解決への長年の参加から生まれたシステムとして見ることができる[44]。 |

| In technology The bulk conductive response of binary (RC) electrical networks with random arrangements, known as the Universal dielectric response (UDR), can be seen as emergent properties of such physical systems. Such arrangements can be used as simple physical prototypes for deriving mathematical formulae for the emergent responses of complex systems.[45] Internet traffic can also exhibit some seemingly emergent properties. In the congestion control mechanism, TCP flows can become globally synchronized at bottlenecks, simultaneously increasing and then decreasing throughput in coordination. Congestion, widely regarded as a nuisance, is possibly an emergent property of the spreading of bottlenecks across a network in high traffic flows which can be considered as a phase transition.[46] Some artificially intelligent (AI) computer applications simulate emergent behavior.[47] One example is Boids, which mimics the swarming behavior of birds.[48] |

テクノロジー ユニバーサル誘電応答(UDR)として知られる、ランダムに配置された2値(RC)電気ネットワークのバルク導電応答は、このような物理システムの創発的 特性として見ることができる。このような配置は、複雑なシステムの創発応答に関する数式を導き出すための単純な物理的プロトタイプとして使用することがで きる[45]。インターネットのトラフィックも、一見創発的な特性を示すことがある。輻輳制御メカニズムでは、TCPフローがボトルネックにおいてグロー バルに同期し、同時に協調してスループットを増加させたり減少させたりすることがある。輻輳は、広く厄介なものと見なされているが、おそらくは、相転移と 見なすことができる高トラフィックフローにおいて、ネットワーク全体にボトルネックが広がることによる創発的な特性である[46]。 人工知能(AI)コンピュータアプリケーションの中には、創発的な振る舞いをシミュレートするものがある[47]。 その一例が、鳥の群れ行動を模倣したBoidsである[48]。 |

| In religion and art In religion, emergence grounds expressions of religious naturalism and syntheism in which a sense of the sacred is perceived in the workings of entirely naturalistic processes by which more complex forms arise or evolve from simpler forms. Examples are detailed in The Sacred Emergence of Nature by Ursula Goodenough & Terrence Deacon and Beyond Reductionism: Reinventing the Sacred by Stuart Kauffman, both from 2006, as well as Syntheism – Creating God in The Internet Age by Alexander Bard & Jan Söderqvist from 2014 and Emergentism: A Religion of Complexity for the Metamodern World by Brendan Graham Dempsey (2022).[citation needed] Michael J. Pearce has used emergence to describe the experience of works of art in relation to contemporary neuroscience.[49] Practicing artist Leonel Moura, in turn, attributes to his "artbots" a real, if nonetheless rudimentary, creativity based on emergent principles.[50] |

宗教と芸術 宗教では、創発は宗教的自然主義や総合主義の表現を根拠づけるものであり、より複雑な形態がより単純な形態から生じたり進化したりする、完全に自然主義的 なプロセスの働きの中に神聖な感覚が知覚される。その例は、アーシュラ・グッドナフ&テレンス・ディーコン著『The Sacred Emergence of Nature』や『Beyond Reductionism』に詳しい: 2006年のスチュアート・カウフマン著『聖なるものの再発明』、2014年のアレクサンダー・バード&ヤン・セーデルクヴィスト著『Syntheism - Creating God in The Internet Age』、『Emergentism』に詳しい: ブレンダン・グレアム・デンプシー著『メタモダン世界のための複雑性の宗教』(2022年)である。 マイケル・J・ピアースは、現代の神経科学との関連において、芸術作品の経験を説明するために創発を使用している[49]。一方、実践的なアーティストで あるレオネル・モウラは、彼の「アートボット」に、初歩的ではあるが、創発原理に基づく真の創造性を見出している[50]。 |

| Abiogenesis – Life arising from non-living matter Anthropic principle – Hypothesis about sapient life and the universe Connectionism – Cognitive science approach Dual-phase evolution – Process that drives self-organization within complex adaptive systems Emergenesis – The result of a specific combination of several interacting genes Emergent algorithm – Algorithm exhibiting emergent behavior Emergent evolution – Evolutionary biology Emergent gameplay – Aspect of gameplay Emergent gravity – Theory in modern physics that describes gravity as an entropic force Emergent organization Emergentism – Philosophical belief in emergence Externality – In economics, an imposed cost or benefit Free will – Capacity or ability to make choices without constraints Generative science – Study of how complex behaviour can be generated by deterministic and finite rules and parameters Irreducible complexity – Argument by proponents of intelligent design Langton's ant – Two-dimensional Turing machine with emergent behavior Law of Complexity-Consciousness – Idea that everything in the universe will converge to a final point of unification Libertarianism (metaphysics) – Term in metaphysics Mass action (sociology) – Simultaneous similar behavior of many people, without coordination Organic Wholes of G.E. Moore – English philosopher (1873–1958) Polytely – Problem-solving technique Society of Mind – Book by Marvin Minsky Superorganism – Group of synergistic organisms Swarm intelligence – Collective behavior of decentralized, self-organized systems System of systems – Collection of co-operating systems Spontaneous order – Spontaneous emergence of order out of seeming chaos |

自然発生 - 生物でない物質から生命が発生する 人間原理 - 有人生命と宇宙に関する仮説 コネクショニズム - 認知科学的アプローチ 二相進化 - 複雑な適応システム内の自己組織化を促すプロセス 創発 - 相互作用するいくつかの遺伝子の特定の組み合わせの結果である。 創発アルゴリズム - 創発的な振る舞いを示すアルゴリズム 創発的進化 - 進化生物学 創発的ゲームプレイ - ゲームプレイの一側面 Emergent gravity(創発的重力) - 現代物理学の理論で、重力をエントロピー的な力として記述する。 創発的組織 創発主義 - 創発に対する哲学的信念。 外部性 - 経済学において、課されるコストや利益。 自由意志 - 制約を受けずに選択を行う能力。 生成科学 - 決定論的で有限なルールやパラメータによって、複雑な振る舞いがどのように生成されるかを研究する。 不可逆的複雑性 - 知的デザイン支持者の主張 ラングトンのアリ - 創発的な振る舞いをする2次元チューリング機械 複雑性の法則-意識 - 宇宙のすべてが最終的な統一点に収束するという考え方 リバタリアニズム(形而上学) - 形而上学における用語 大衆行動(社会学) - 協調することなく、多くの人民が同時に同じような行動をとること。 G.E.ムーアの有機的全体 - イギリスの哲学者(1873年~1958年) ポリテリー - 問題解決のテクニック 心の社会 - マービン・ミンスキーの著書 スーパーオーガニズム - 相乗効果のある生物の集団 群知能 - 分散化された自己組織化システムの集団行動 System of Systems(システム・オブ・システムズ) - 協力するシステムの集合体 自発的秩序 - 一見カオスに見えるものから秩序が自然に出現すること |

| Bibliography Albert, Réka; Jeong, Hawoong; Barabási, Albert-László (9 September 1999). "Diameter of the World-Wide Web". Nature. 401 (6749): 130–131. arXiv:cond-mat/9907038. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..130A. doi:10.1038/43601. S2CID 4419938. Anderson, P.W. (1972), "More is Different: Broken Symmetry and the Nature of the Hierarchical Structure of Science", Science, 177 (4047): 393–96, Bibcode:1972Sci...177..393A, doi:10.1126/science.177.4047.393, PMID 17796623, S2CID 34548824 Bedau, Mark A. (1997). "Weak Emergence" (PDF). Philosophical Perspectives. 11: 375–399. doi:10.1111/0029-4624.31.s11.17. Bejan, Adrian (2016), The Physics of Life: The Evolution of Everything, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-1250078827 Bejan, Adrian; Zane, J. P. (2012). Design in Nature: How the Constructal Law Governs Evolution in Biology, Physics, Technology, and Social Organizations. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53461-1 Blitz, David (1992). Emergent Evolution: Qualitative Novelty and the Levels of Reality. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. Corning, Peter A. (1983), The Synergism Hypothesis: A Theory of Progressive Evolution, New York: McGraw-Hill Corning, Peter A. (2005). Holistic Darwinism: Synergy, Cybernetics and the Bioeconomics of Evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Huxley, J. S.; Huxley, T. H. (1947). Evolution and Ethics: 1983–1934. London: The Pilot Press. Koestler, Arthur (1969), A. Koestler; J. R. Smythies (eds.), Beyond Reductionism: New Perspectives in the Life Sciences, London: Hutchinson Laughlin, Robert (2005), A Different Universe: Reinventing Physics from the Bottom Down, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-03828-2 Steels, L (1991). "Towards a Theory of Emergent Functionality". In Meyer, J.-A.; Wiloson, S. W. (eds.). From Animals to Animats: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Simulation of Adaptive Behavior. Cambridge: MIT Press. pp. 451–461. |

書誌 Albert, Réka; Jeong, Hawoong; Barabási, Albert-László (9 September 1999). 「ワールド・ワイド・ウェブの直径". Nature. 401 (6749): 130–131. arXiv:cond-mat/9907038. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..130A. doi:10.1038/43601. S2CID 4419938. Anderson, P.W. (1972), 「More is Different: Broken Symmetry and the Nature of the Hierarchical Structure of Science」, Science, 177 (4047): この論文では、「科学とは何か」、について論じた。 Bedau, Mark A. (1997). 「弱い創発" (PDF). Philosophical Perspectives. 11: 375-399. doi:10.1111/0029-4624.31.s11.17. Bejan, Adrian (2016), The Physics of Life: The Evolution of Everything, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-1250078827 Bejan, Adrian; Zane, J. P. (2012). Design in Nature: How the Constructal Law Governs Evolution in Biology, Physics, Technology, and Social Organizations. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53461-1 Blitz, David (1992). 創発的進化: 質的新奇性と現実のレベル. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. Corning, Peter A. (1983), The Synergism Hypothesis: A Theory of Progressive Evolution, New York: McGraw-Hill Corning, Peter A. (2005). ホリスティック・ダーウィニズム Synergy, Cybernetics and the Bioeconomics of Evolution. シカゴ: University of Chicago Press. Huxley, J. S.; Huxley, T. H. (1947). Evolution and Ethics: 1983-1934. ロンドン: The Pilot Press. Koestler, Arthur (1969), A. Koestler; J. R. Smythies (eds.), Beyond Reductionism: New Perspectives in the Life Sciences, London: Hutchinson. Laughlin, Robert (2005), A Different Universe: Reinventing Physics from the Bottom Down, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-03828-2. Steels, L (1991). 「創発的機能の理論に向けて」. Meyer, J.-A.; Wiloson, S. W. (eds.). From Animals to Animats: 第1回適応行動のシミュレーションに関する国際会議議事録. ケンブリッジ: MIT Press. 451-461. |

| Alexander, V. N. (2011). The

Biologist's Mistress: Rethinking Self-Organization in Art, Literature

and Nature. Litchfield Park AZ: Emergent Publications. Bateson, Gregory (1972), Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-226-03905-3 Batty, Michael (2005), Cities and Complexity, MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-52479-7 Bunge, Mario Augusto (2003), Emergence and Convergence: Qualitiative Novelty and the Unity of Knowledge, Toronto: University of Toronto Press Chalmers, David J. (2002). "Strong and Weak Emergence" [2] Republished in P. Clayton and P. Davies, eds. (2006) The Re-Emergence of Emergence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Philip Clayton & Paul Davies (eds.) (2006). The Re-Emergence of Emergence: The Emergentist Hypothesis from Science to Religion Oxford: Oxford University Press. Felipe Cucker and Stephen Smale (2007), The Japanese Journal of Mathematics, The Mathematics of Emergence Delsemme, Armand (1998), Our Cosmic Origins: From the Big Bang to the Emergence of Life and Intelligence, Cambridge University Press Goodwin, Brian (2001), How the Leopard Changed Its Spots: The Evolution of Complexity, Princeton University Press Hoffmann, Peter M. "Life's Ratchet: How Molecular Machines Extract Order from Chaos" (2012), Basic Books. Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1979), Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid, Harvester Press Holland, John H. (1998), Emergence from Chaos to Order, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-7382-0142-9 Kauffman, Stuart (1993), The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-507951-7 Keller, Rudi (1994), On Language Change: The Invisible Hand in Language, London/New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-07671-5 Kauffman, Stuart (1995), At Home in the Universe, New York: Oxford University Press Kelly, Kevin (1994), Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, and the Economic World, Perseus Books, ISBN 978-0-201-48340-6 Krugman, Paul (1996), The Self-organizing Economy, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-55786-698-1, ISBN 0-87609-177-X Lewin, Roger (2000), Complexity - Life at the Edge of Chaos (second ed.), University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-47654-4, ISBN 0-226-47655-3 Ignazio Licata & Ammar Sakaji (eds) (2008). Physics of Emergence and Organization, ISBN 978-981-277-994-6, World Scientific and Imperial College Press. Marshall, Stephen (2009), Cities Design and Evolution, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-42329-8, ISBN 0-415-42329-5 Morowitz, Harold J. (2002), The Emergence of Everything: How the World Became Complex, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513513-8 Pearce, Michael J. (2015), Art in the Age of Emergence., Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 978-1-443-87057-3, ISBN 1-443-87057-9 Schelling, Thomas C. (1978), Micromotives and Macrobehaviour, W. W. Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-05701-0 Smith, John Maynard; Szathmáry, Eörs (1997), The Major Transitions in Evolution, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-850294-4 Smith, Reginald D. (2008), "The Dynamics of Internet Traffic: Self-Similarity, Self-Organization, and Complex Phenomena", Advances in Complex Systems, 14 (6): 905–949, arXiv:0807.3374, Bibcode:2008arXiv0807.3374S, doi:10.1142/S0219525911003451, S2CID 18937228 Solé, Ricard and Goodwin, Brian (2000) Signs of life: how complexity pervades biology, Basic Books, New York Jakub Tkac & Jiri Kroc (2017), Cellular Automaton Simulation of Dynamic Recrystallization: Introduction into Self-Organization and Emergence (Software) (PDF) Cellular Automaton Simulation of Dynamic Recrystallization: Introduction into Self-Organization and Emergence "Video - Simulation of DRX" Wan, Poe Yu-ze (2011), "Emergence à la Systems Theory: Epistemological Totalausschluss or Ontological Novelty?", Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 41 (2): 178–210, doi:10.1177/0048393109350751, S2CID 144965056 Wan, Poe Yu-ze (2011), Reframing the Social: Emergentist Systemism and Social Theory, Ashgate Publishing, archived from the original on 2013-03-11, retrieved 2012-02-13 Weinstock, Michael (2010), The Architecture of Emergence - the evolution of form in Nature and Civilisation, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-06633-1architectureofemergence.com Wolfram, Stephen (2002), A New Kind of Science, Wolfram Media, ISBN 978-1-57955-008-0 Young, Louise B. (2002), The Unfinished Universe, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-508039-1 |

アレクサンダー、V. N. (2011). 生物学者の愛人: 芸術、文学、自然における自己組織化を再考する。Litchfield Park AZ: Emergent Publications. Bateson, Gregory (1972), Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-226-03905-3. Batty, Michael (2005), Cities and Complexity, MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-52479-7. Bunge, Mario Augusto (2003), Emergence and Convergence: Qualitiative Novelty and the Unity of Knowledge, Toronto: トロント大学出版局 Chalmers, David J. (2002). 「強い創発と弱い創発」 [2] P. Clayton and P. Davies, eds. (2006) The Re-Emergence of Emergence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. フィリップ・クレイトン&ポール・デイヴィス編 (2006). The Re-Emergence of Emergence: The Emergentist Hypothesis from Science to Religion オックスフォード: Oxford University Press. フェリペ・カッカー、スティーブン・スメイル (2007), 日本数学会, 創発の数学 Delsemme, Armand (1998), Our Cosmic Origins: ビッグバンから生命と知性の出現まで, ケンブリッジ大学出版局. Goodwin, Brian (2001), How the Leopard Changed Its Spots: The Evolution of Complexity, Princeton University Press. Hoffmann, Peter M. 「Life's Ratchet: How Molecular Machines Extract Order from Chaos」 (2012), Basic Books. Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1979), Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid, Harvester Press. Holland, John H. (1998), Emergence from Chaos to Order, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-7382-0142-9. Kauffman, Stuart (1993), The Origins of Order: オックスフォード大学出版局、ISBN 978-0-19-507951-7 Keller, Rudi (1994), On Language Change: The Invisible Hand in Language, London/New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-07671-5 Kauffman, Stuart (1995), At Home in the Universe, New York: オックスフォード大学出版局 Kelly, Kevin (1994), Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, and the Economic World, Perseus Books, ISBN 978-0-201-48340-6. Krugman, Paul (1996), The Self-organizing Economy, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-55786-698-1, ISBN 0-87609-177-X Lewin, Roger (2000), Complexity - Life at the Edge of Chaos (second ed.), University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-47654-4, ISBN 0-226-47655-3. Ignazio Licata & Ammar Sakaji (eds) (2008). 創発と組織の物理学, ISBN 978-981-277-994-6, World Scientific and Imperial College Press. Marshall, Stephen (2009), Cities Design and Evolution, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-42329-8, ISBN 0-415-42329-5. Morowitz, Harold J. (2002), The Emergence of Everything: How the World Became Complex, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513513-8. Pearce, Michael J. (2015), Art in the Age of Emergence., Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 978-1-443-87057-3, ISBN 1-443-87057-9 Schelling, Thomas C. (1978), Micromotives and Macrobehaviour, W. W. Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-05701-0 Smith, John Maynard; Szathmáry, Eörs (1997), The Major Transitions in Evolution, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-850294-4. Smith, Reginald D. (2008), "The Dynamics of Internet Traffic: 自己相似性、自己組織化、複雑現象", Advances in Complex Systems, 14 (6): (1)インターネットトラフィックの自己相似性、自己組織化、複雑現象", Advances in Complex Systems, 14 (6): 905-949, arXiv:0807.3374, Bibcode:2008arXiv0807.3374S, doi:10.1142/S0219525911003451, S2CID 18937228 Solé, Ricard and Goodwin, Brian (2000) Signs of Life: How complexity pervades biology, Basic Books, New York. Jakub Tkac & Jiri Kroc (2017), Cellular Automaton Simulation of Dynamic Recrystallization: Introduction into Self-Organization and Emergence (Software) (PDF) Cellular Automaton Simulation of Dynamic Recrystallization: 自己組織化と創発への導入 「ビデオ - DRXのシミュレーション」 Wan, Poe Yu-ze (2011), "Emergence à la Systems Theory: 社会科学の哲学, 41 (2): 178-210, doi:10.1177/0048393109350751, S2CID 144965056 Wan, Poe Yu-ze (2011), Reframing the Social:Emergentist Systemism and Social Theory, Ashgate Publishing, archived from the original on 2013-03-11, retrieved 2012-02-13 Weinstock, Michael (2010), The Architecture of Emergence - the evolution of form in Nature and Civilisation, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-06633-1architectureofemergence.com. Wolfram, Stephen (2002), A New Kind of Science, Wolfram Media, ISBN 978-1-57955-008-0 Young, Louise B. (2002), The Unfinished Universe, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-508039-1. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergence |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099