エマーソンと奴隷制

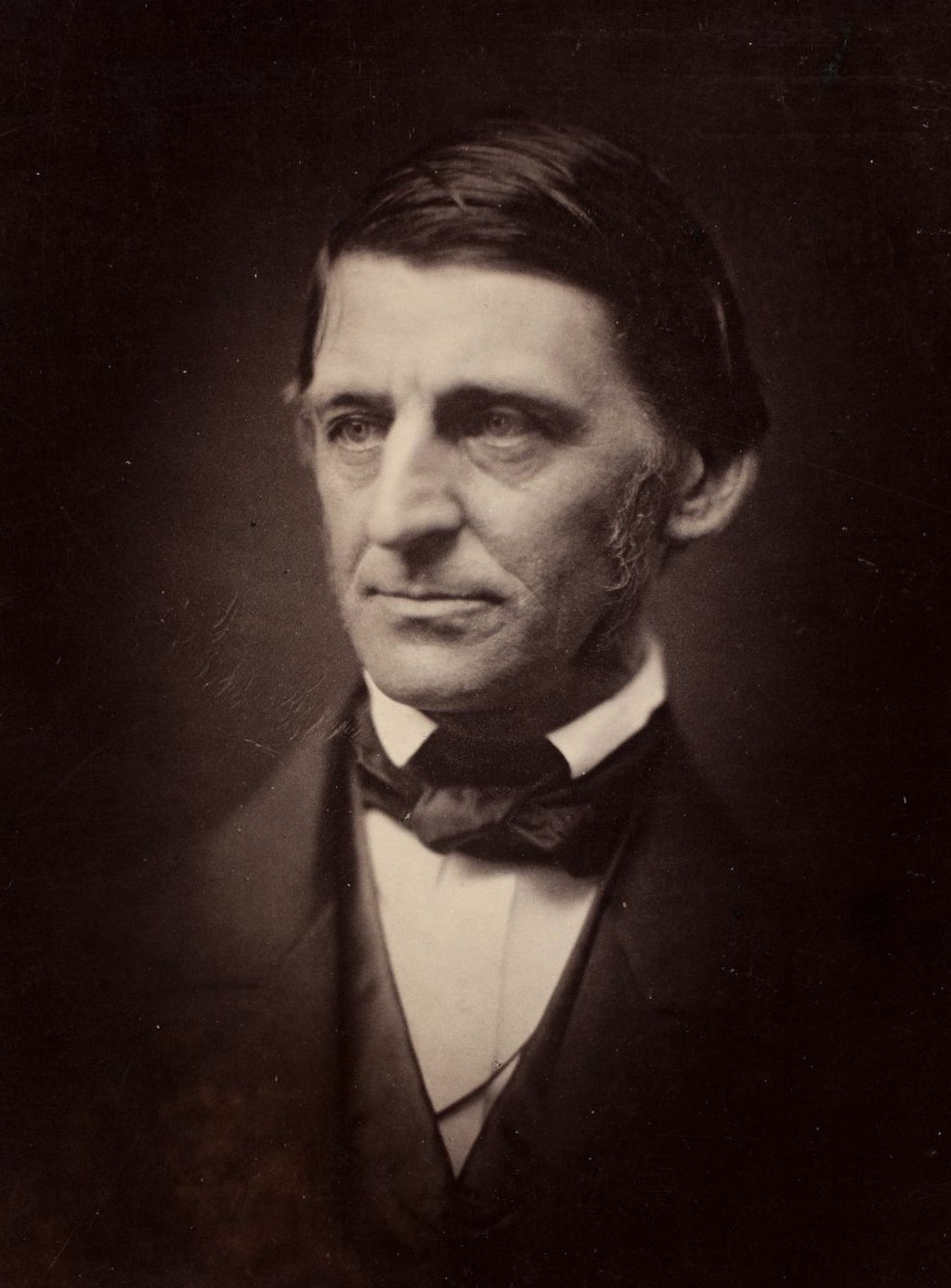

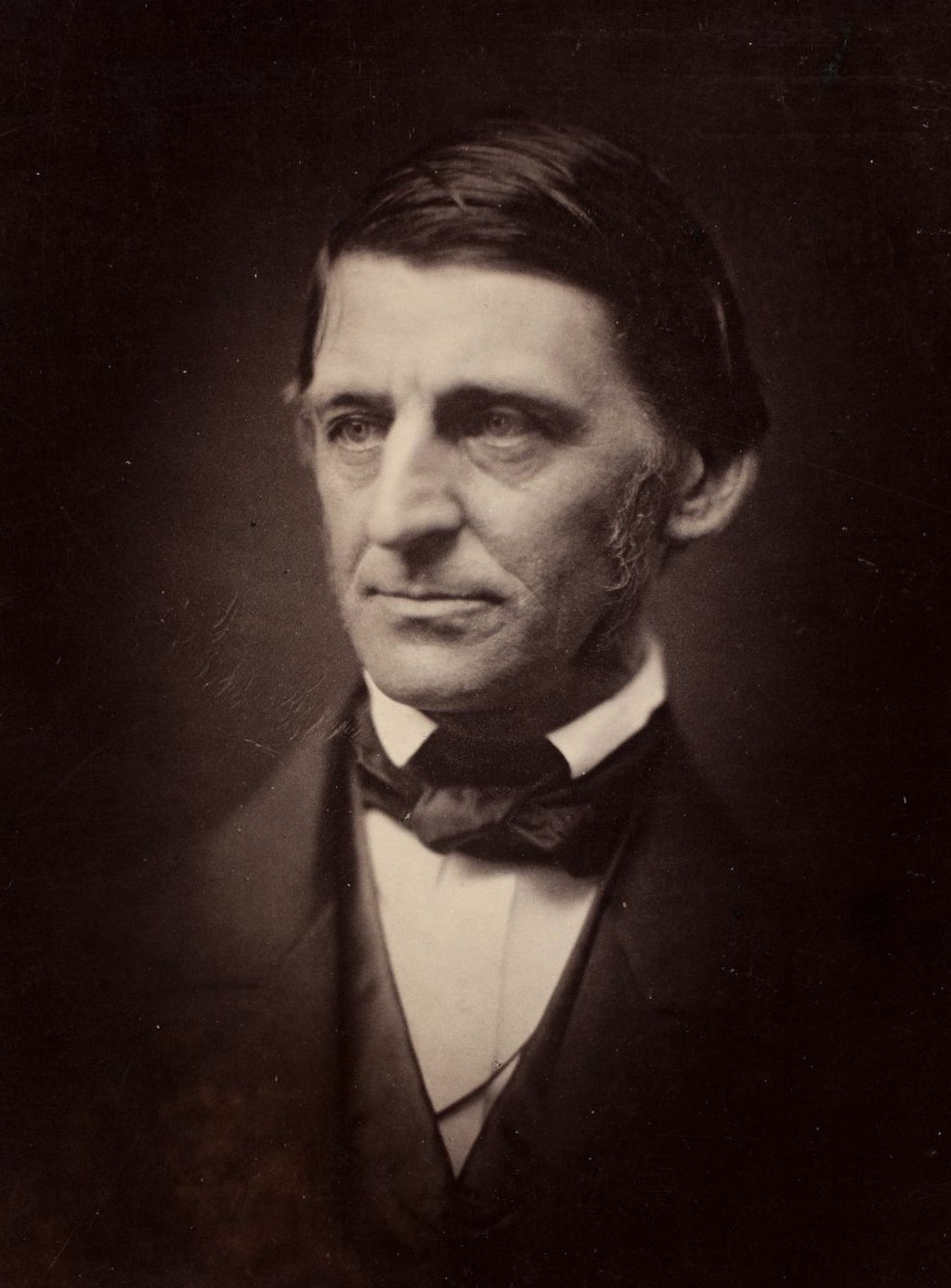

Emerson

and Slavery

☆

エマーソンが熱心な奴隷廃止論者になったのは1844年のことだが、彼の日記によれば、若い頃から奴隷制度に関心を持ち、奴隷解放の手助けをすることを夢

見ていたようだ。1856年6月、合衆国上院議員のチャールズ・サムナーがその熱心な奴隷制度廃止論者としての見解のために殴打された直後、エマーソン

は、自分自身が奴隷制度廃止運動に熱心でなかったことを嘆いた。

| Race and slavery Emerson did not become an ardent abolitionist until 1844, though his journals show he was concerned with slavery beginning in his youth, even dreaming about helping to free slaves. In June 1856, shortly after Charles Sumner, a United States Senator, was beaten for his staunch abolitionist views, Emerson lamented that he himself was not as committed to the cause. He wrote, "There are men who as soon as they are born take a bee-line to the axe of the inquisitor. ... Wonderful the way in which we are saved by this unfailing supply of the moral element".[184] After Sumner's attack, Emerson began to speak out about slavery. "I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom", he said at a meeting at Concord that summer.[185] Emerson used slavery as an example of a human injustice, especially in his role as a minister. In early 1838, provoked by the murder of an abolitionist publisher from Alton, Illinois, named Elijah Parish Lovejoy, Emerson gave his first public antislavery address. As he said, "It is but the other day that the brave Lovejoy gave his breast to the bullets of a mob, for the rights of free speech and opinion, and died when it was better not to live".[184] John Quincy Adams said the mob-murder of Lovejoy "sent a shock as of any earthquake throughout this continent".[186] However, Emerson maintained that reform would be achieved through moral agreement rather than by militant action. By August 1, 1844, at a lecture in Concord, he stated more clearly his support for the abolitionist movement: "We are indebted mainly to this movement, and to the continuers of it, for the popular discussion of every point of practical ethics".[187] |

人種と奴隷制度 エマーソンが熱心な奴隷廃止論者になったのは1844年のことだが、彼の日記によれば、若い頃から奴隷制度に関心を持ち、奴隷解放の手助けをすることを夢 見ていたようだ。1856年6月、合衆国上院議員のチャールズ・サムナーがその熱心な奴隷制度廃止論者としての見解のために殴打された直後、エマーソン は、自分自身が奴隷制度廃止運動に熱心でなかったことを嘆いた。彼はこう書いている。「生まれるとすぐに、審問官の斧に向かう人がいる。... サムナーの攻撃の後、エマーソンは奴隷制について発言し始めた。「奴隷制をなくさなければ、自由をなくさなければならないと思う」と、彼はその夏にコン コードで開かれた集会で述べている[185]。エマーソンは、特に牧師としての役割において、奴隷制を人間の不正義の例として用いていた。1838年初 頭、イリノイ州アルトンのイライジャ・パリッシュ・ラブジョイという奴隷制度廃止論者の出版社が殺害された事件をきっかけに、エマーソンは初めて公の場で 奴隷制度反対の演説を行った。彼は、「勇敢なラブジョイは、言論の自由と意見の権利のために暴徒の銃弾にその胸を捧げ、生きていない方がましだというとき に死んだのは、つい先日のことである」と述べた[184]。 ジョン・クインシー・アダムズは、ラブジョイの暴徒殺害について、「この大陸全体に地震のような衝撃を与えた」と述べている[186]。 しかし、エマーソンは、改革は過激な行動によってではなく、道徳的な合意によって達成されると主張した。1844年8月1日、コンコードでの講演で、彼は 奴隷廃止運動への支持をより明確に表明した: 「私たちは主にこの運動とその継続者たちに、実践的な倫理のあらゆる点についての大衆的な議論について恩義を感じている」[187]。 |

| Emerson is often known as one of

the most liberal democratic thinkers of his time who believed that

through the democratic process, slavery should be abolished. While

being an avid abolitionist who was known for his criticism of the

legality of slavery, Emerson struggled with the implications of

race.[188] His usual liberal leanings did not clearly translate when it

came to believing that all races had equal capability or function,

which was a common conception for the period in which he lived.[188] Many critics believe that it was his views

on race that inhibited him from becoming an abolitionist earlier in his

life and also inhibited him from being more active in the antislavery

movement.[189] Much of his early life, he was silent on the

topic of race and slavery. Not until he was well into his 30s did

Emerson begin to publish writings on race and slavery, and not until he

was in his late 40s and 50s did he became known as an antislavery

activist.[188] |

エマソンは、民主主義のプロセスを通じて奴隷制を廃止すべきだと信じ

た、当時最もリベラルな民主主義思想家の一人としてよく知られている。奴隷制の合法性を批判したことで知られる熱心な奴隷廃止論者であった一方で、エマソ

ンは人種が持つ意味合いに苦慮していた[188]。彼の通常のリベラルな傾向は、彼が生きた時代には一般的な考え方であった、すべての人種が等しい能力や

機能を持つと信じることに関しては、明確に反映されなかった。 [188]多くの批

評家は、彼が人生の早い段階で奴隷廃止論者になることを阻害し、また反奴隷制運動でより積極的に活動することを阻害したのは、人種に関する彼の見解であっ

たと考えている[189]。エマーソンが人種と奴隷制に関する著作を発表し始めたのは30代に入ってからであり、反奴隷制活動家として知ら

れるようになったのは40代後半から50代になってからである[188]。 |

| Emerson is often known as one of

the most liberal democratic thinkers of his time who believed that

through the democratic process, slavery should be abolished. While

being an avid abolitionist who was known for his criticism of the

legality of slavery, Emerson struggled with the implications of

race.[188] His usual liberal leanings did not clearly translate when it

came to believing that all races had equal capability or function,

which was a common conception for the period in which he lived.[188]

Many critics believe that it was his views on race that inhibited him

from becoming an abolitionist earlier in his life and also inhibited

him from being more active in the antislavery movement.[189] Much of

his early life, he was silent on the topic of race and slavery. Not

until he was well into his 30s did Emerson begin to publish writings on

race and slavery, and not until he was in his late 40s and 50s did he

became known as an antislavery activist.[188] |

エマソンは、民主主義のプロセスを通じて奴隷制を廃止すべきだと信じ

た、当時最もリベラルな民主主義思想家の一人としてよく知られている。奴隷制の合法性を批判したことで知られる熱心な奴隷廃止論者であった一方で、エマソ

ンは人種が持つ意味合いに苦慮していた[188]。彼の通常のリベラルな傾向は、彼が生きた時代には一般的な考え方であった、すべての人種が等しい能力や

機能を持つと信じることに関しては、明確に反映されなかった。

[188]多くの批評家は、彼が人生の早い段階で奴隷廃止論者になることを阻害し、また反奴隷制運動でより積極的に活動することを阻害したのは、人種に関

する彼の見解であったと考えている[189]。エマーソンが人種と奴隷制に関する著作を発表し始めたのは30代に入ってからであり、反奴隷制活動家として

知られるようになったのは40代後半から50代になってからである[188]。 |

| Emerson is often known as one of

the most liberal democratic thinkers of his time who believed that

through the democratic process, slavery should be abolished. While

being an avid abolitionist who was known for his criticism of the

legality of slavery, Emerson struggled with the implications of

race.[188] His usual liberal leanings did not clearly translate when it

came to believing that all races had equal capability or function,

which was a common conception for the period in which he lived.[188]

Many critics believe that it was his views on race that inhibited him

from becoming an abolitionist earlier in his life and also inhibited

him from being more active in the antislavery movement.[189] Much of

his early life, he was silent on the topic of race and slavery. Not

until he was well into his 30s did Emerson begin to publish writings on

race and slavery, and not until he was in his late 40s and 50s did he

became known as an antislavery activist.[188] |

エマーソンは、当時最もリベラルな民主主義思想家の一人として知られ、

民主主義のプロセスを通じて奴隷制は廃止されるべきだと考えていた。奴隷制の合法性を批判したことで知られる熱心な奴隷廃止論者であった一方で、エマソン

は人種が持つ意味合いに苦慮していた[188]。彼の通常のリベラルな傾向は、彼が生きた時代には一般的な考え方であった、すべての人種が等しい能力や機

能を持つと信じることに関しては、明確に反映されなかった。

[188]多くの批評家は、彼が人生の早い段階で奴隷廃止論者になることを阻害し、また反奴隷制運動でより積極的に活動することを阻害したのは、人種に関

する彼の見解であったと考えている[189]。エマーソンが人種と奴隷制に関する著作を発表し始めたのは30代に入ってからであり、反奴隷制活動家として

知られるようになったのは40代後半から50代になってからである[188]。 |

| Emerson saw himself as a man of

"Saxon descent". In a speech given in 1835 titled "Permanent Traits of

the English National Genius", he said, "The inhabitants of the United

States, especially of the Northern portion, are descended from the

people of England and have inherited the traits of their national

character".[192] He saw direct ties between race based on national

identity and the inherent nature of the human being. White Americans

who were native-born in the United States and of English ancestry were

categorized by him as a separate "race", which he thought had a

position of being superior to other nations. His idea of race was based

on a shared culture, environment, and history. He believed that

native-born Americans of English descent were superior to European

immigrants, including the Irish, French, and Germans, and also as being

superior to English people from England, whom he considered a close

second and the only really comparable group.[188] |

エマーソンは自らを「サクソン系」の人間だと考えていた。1835年に

行われた「イギリスの国民的天才の永続的な特質」と題された演説の中で、彼は「アメリカ合衆国の住民、特に北部の住民はイングランドの人々の子孫であり、

彼らの国民性の特質を受け継いでいる」と述べた[192]。

彼は国民的アイデンティティに基づく人種と人間の本質的な性質との間に直接的な結びつきがあると考えた。アメリカ生まれでイギリス人の祖先を持つアメリカ

白人は、彼によって別の「人種」として分類され、それは他の国々よりも優位な立場にあると考えられていた。彼の考える人種とは、共有する文化、環境、歴史

に基づいていた。彼はイギリス系の生粋のアメリカ人はアイルランド人、フランス人、ドイツ人などのヨーロッパからの移民よりも優れており、またイギリス出

身のイギリス人よりも優れていると考えていた。 |

| Later in his life, Emerson's

ideas on race changed when he became more involved in the abolitionist

movement while at the same time, he began to more thoroughly analyze

the philosophical implications of race and racial hierarchies. His

beliefs shifted focus to the potential outcomes of racial conflicts.

Emerson's racial views were closely related to his views on nationalism

and national superiority, which was a common view in the United States

at that time. Emerson used contemporary theories of race and natural

science to support a theory of race development.[191] He believed that

the current political battle and the current enslavement of other races

was an inevitable racial struggle, one that would result in the

inevitable union of the United States. Such conflicts were necessary

for the dialectic of change that would eventually allow the progress of

the nation.[191] In much of his later work, Emerson seems to allow the

notion that different European races will eventually mix in America.

This hybridization process would lead to a superior race that would be

to the advantage of the superiority of the United States.[193] |

その後、エマソンは人種差別撤廃運動により深く関わるようになると同時

に、人種と人種階層が持つ哲学的な意味をより徹底的に分析するようになり、人種に関する考え方が変化した。彼の信念は、人種間の対立がもたらす潜在的な結

果に焦点を移した。エマソンの人種観は、当時のアメリカで一般的だったナショナリズムや民族の優越性に関する彼の見解と密接に関連していた。エマーソンは

現代の人種論と自然科学を用いて、人種発展論を支持した[191]。

彼は、現在の政治的な戦いや他民族の奴隷化は不可避な人種的闘争であり、その結果として必然的に合衆国が統合されると考えていた。このような対立は、最終

的に国家の進歩を可能にする変化の弁証法にとって必要なものであった[191]。エマーソンは、晩年の著作の多くにおいて、異なるヨーロッパ人種が最終的

にアメリカで混血するという考え方を認めているようである。この混血のプロセスは、アメリカの優位性に有利な優れた人種を生み出すことになるだろう

[193]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Waldo_Emerson#Race_and_slavery |

|

| Literary career and

transcendentalism Emerson in 1859 On September 8, 1836, the day before the publication of Nature, Emerson met with Frederic Henry Hedge, George Putnam, and George Ripley to plan periodic gatherings of other like-minded intellectuals.[79] This was the beginning of the Transcendental Club, which served as a center for the movement. Its first official meeting was held on September 19, 1836.[80] On September 1, 1837, women attended a meeting of the Transcendental Club for the first time. Emerson invited Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Hoar, and Sarah Ripley for dinner at his home before the meeting to ensure that they would be present for the evening get-together.[81] Fuller would prove to be an important figure in transcendentalism. Emerson anonymously sent his first essay, "Nature", to James Munroe and Company to be published on September 9, 1836. A year later, on August 31, 1837, he delivered his now-famous Phi Beta Kappa address, "The American Scholar",[82] then entitled "An Oration, Delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Cambridge"; it was renamed for a collection of essays (which included the first general publication of "Nature") in 1849.[83] Friends urged him to publish the talk, and he did so at his own expense, in an edition of 500 copies, which sold out in a month.[9] In the speech, Emerson declared literary independence in the United States and urged Americans to create a writing style all their own, free from Europe.[84] James Russell Lowell, who was a student at Harvard at the time, called it "an event without former parallel on our literary annals".[85] Another member of the audience, Reverend John Pierce, called it "an apparently incoherent and unintelligible address".[86] In 1837, Emerson befriended Henry David Thoreau. Though they had likely met as early as 1835, in the fall of 1837, Emerson asked Thoreau, "Do you keep a journal?" The question went on to be a lifelong inspiration for Thoreau.[87] Emerson's own journal was published in 16 large volumes, in the definitive Harvard University Press edition issued between 1960 and 1982. Some scholars consider the journal to be Emerson's key literary work.[88][page needed] In March 1837, Emerson gave a series of lectures on the philosophy of history at the Masonic Temple in Boston. This was the first time he managed a lecture series on his own, and it was the beginning of his career as a lecturer.[89] The profits from this series of lectures were much larger than when he was paid by an organization to talk, and he continued to manage his own lectures often throughout his lifetime. He eventually gave as many as 80 lectures a year, traveling across the northern United States as far as St. Louis, Des Moines, Minneapolis, and California.[90] On July 15, 1838,[91] Emerson was invited to Divinity Hall, Harvard Divinity School, to deliver the school's graduation address, which came to be known as the "Divinity School Address". Emerson discounted biblical miracles and proclaimed that, while Jesus was a great man, he was not God: historical Christianity, he said, had turned Jesus into a "demigod, as the Orientals or the Greeks would describe Osiris or Apollo".[92] His comments outraged the establishment and the general Protestant community. He was denounced as an atheist[92] and a poisoner of young men's minds. Despite the roar of critics, he made no reply, leaving others to put forward a defense. He was not invited back to speak at Harvard for another thirty years.[93] The transcendental group began to publish its flagship journal, The Dial, in July 1840.[94] They planned the journal as early as October 1839, but did not begin work on it until the first week of 1840.[95] Unitarian minister George Ripley was the managing editor.[96] Margaret Fuller was the first editor, having been approached by Emerson after several others had declined the role.[97] Fuller stayed on for about two years, when Emerson took over, using the journal to promote talented young writers including Ellery Channing and Thoreau.[87] In 1841 Emerson published Essays, his second book, which included the famous essay "Self-Reliance".[98] His aunt called it a "strange medley of atheism and false independence", but it gained favorable reviews in London and Paris. This book, and its popular reception, more than any of Emerson's contributions to date laid the groundwork for his international fame.[99] In January 1842 Emerson's first son, Waldo, died of scarlet fever.[100] Emerson wrote of his grief in the poem "Threnody" ("For this losing is true dying"),[101] and the essay "Experience". In the same month, William James was born, and Emerson agreed to be his godfather. Bronson Alcott announced his plans in November 1842 to find "a farm of a hundred acres in excellent condition with good buildings, a good orchard and grounds".[102] Charles Lane purchased a 90-acre (36 ha) farm in Harvard, Massachusetts, in May 1843 for what would become Fruitlands, a community based on Utopian ideals inspired in part by transcendentalism.[103] The farm would run based on a communal effort, using no animals for labor; its participants would eat no meat and use no wool or leather.[104] Emerson said he felt "sad at heart" for not engaging in the experiment himself.[105] Even so, he did not feel Fruitlands would be a success. "Their whole doctrine is spiritual", he wrote, "but they always end with saying, Give us much land and money".[106] Even Alcott admitted he was not prepared for the difficulty in operating Fruitlands. "None of us were prepared to actualize practically the ideal life of which we dreamed. So we fell apart", he wrote.[107] After its failure, Emerson helped buy a farm for Alcott's family in Concord[106] which Alcott named "Hillside".[107] The Dial ceased publication in April 1844; Horace Greeley reported it as an end to the "most original and thoughtful periodical ever published in this country".[108] In 1844, Emerson published his second collection of essays, Essays: Second Series. This collection included "The Poet", "Experience", "Gifts", and an essay entitled "Nature", a different work from the 1836 essay of the same name. Emerson made a living as a popular lecturer in New England and much of the rest of the country. He had begun lecturing in 1833; by the 1850s he was giving as many as 80 lectures per year.[109] He addressed the Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge and the Gloucester Lyceum, among others. Emerson spoke on a wide variety of subjects, and many of his essays grew out of his lectures. He charged between $10 and $50 for each appearance, bringing him as much as $2,000 in a typical winter lecture season. This was more than his earnings from other sources. In some years, he earned as much as $900 for a series of six lectures, and in another, for a winter series of talks in Boston, he netted $1,600.[110] He eventually gave some 1,500 lectures in his lifetime. His earnings allowed him to expand his property, buying 11 acres (4.5 ha) of land by Walden Pond and a few more acres in a neighboring pine grove. He wrote that he was "landlord and water lord of 14 acres, more or less".[106] Emerson was introduced to Indian philosophy through the works of the French philosopher Victor Cousin.[111] In 1845, Emerson's journals show he was reading the Bhagavad Gita and Henry Thomas Colebrooke's Essays on the Vedas.[112] He was strongly influenced by Vedanta, and much of his writing has strong shades of nondualism. One of the clearest examples of this can be found in his essay "The Over-soul": We live in succession, in division, in parts, in particles. Meantime within man is the soul of the whole; the wise silence; the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related, the eternal ONE. And this deep power in which we exist and whose beatitude is all accessible to us, is not only self-sufficing and perfect in every hour, but the act of seeing and the thing seen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject and the object, are one. We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree; but the whole, of which these are shining parts, is the soul.[113] The central message Emerson drew from his Asian studies was that "the purpose of life was spiritual transformation and direct experience of divine power, here and now on earth."[114][115] In 1847–48, he toured the British Isles.[116] He also visited Paris between the French Revolution of 1848 and the bloody June Days. When he arrived, he saw the stumps of trees that had been cut down to form barricades in the February riots. On May 21, he stood on the Champ de Mars in the midst of mass celebrations for concord, peace and labor. He wrote in his journal, "At the end of the year we shall take account, & see if the Revolution was worth the trees."[117] The trip left an important imprint on Emerson's later work. His 1856 book English Traits is based largely on observations recorded in his travel journals and notebooks. Emerson later came to see the American Civil War as a "revolution" that shared common ground with the European revolutions of 1848.[118] In a speech in Concord, Massachusetts on May 3, 1851, Emerson denounced the Fugitive Slave Act: The act of Congress is a law which every one of you will break on the earliest occasion—a law which no man can obey, or abet the obeying, without loss of self-respect and forfeiture of the name of gentleman.[119] That summer, he wrote in his diary: This filthy enactment was made in the nineteenth century by people who could read and write. I will not obey it.[120] In February 1852 Emerson and James Freeman Clarke and William Henry Channing edited an edition of the works and letters of Margaret Fuller, who had died in 1850.[121] Within a week of her death, her New York editor, Horace Greeley, suggested to Emerson that a biography of Fuller, to be called Margaret and Her Friends, be prepared quickly "before the interest excited by her sad decease has passed away".[122] Published under the title The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli,[123] Fuller's words were heavily censored or rewritten.[124] The three editors were not concerned about accuracy; they believed public interest in Fuller was temporary and that she would not survive as a historical figure.[125] Even so, it was the best-selling biography of the decade and went through thirteen editions before the end of the century.[123] Walt Whitman published the innovative poetry collection Leaves of Grass in 1855 and sent a copy to Emerson for his opinion. Emerson responded positively, sending Whitman a flattering five-page letter in response.[126] Emerson's approval helped the first edition of Leaves of Grass stir up significant interest[127] and convinced Whitman to issue a second edition shortly thereafter.[128] This edition quoted a phrase from Emerson's letter, printed in gold leaf on the cover: "I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career".[129] Emerson took offense that this letter was made public[130] and later was more critical of the work.[131] Philosophers Camp at Follensbee Pond – Adirondacks Ralph Waldo Emerson, in the summer of 1858, would venture into the great wilderness of upstate New York. Joining him were nine of the most illustrious intellectuals ever to camp out in the Adirondacks to connect with nature: Louis Agassiz, James Russell Lowell, John Holmes, Horatio Woodman, Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar, Jeffries Wyman, Estes Howe, Amos Binney, and William James Stillman. Invited, but unable to make the trip for diverse reasons, were: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Charles Eliot Norton, all members of the Saturday Club (Boston, Massachusetts).[132] This social club was mostly a literary membership that met the last Saturday of the month at the Boston Parker House Hotel (Omni Parker House). William James Stillman was a painter and founding editor of an art journal called the Crayon. Stillman was born and grew up in Schenectady which was just south of the Adirondack mountains. He would later travel there to paint the wilderness landscape and to fish and hunt. He would share his experiences in this wilderness to the members of the Saturday Club, raising their interest in this unknown region. James Russell Lowell[133] and William Stillman would lead the effort to organize a trip to the Adirondacks. They would begin their journey on August 2, 1858, traveling by train, steamboat, stagecoach, and canoe guide boats. News that these cultured men were living like "Sacs and Sioux" in the wilderness appeared in newspapers across the nation. This would become known as the "Philosophers Camp".[134] This event was a landmark in the nineteenth-century intellectual movement, linking nature with art and literature. Although much has been written over many years by scholars and biographers of Emerson's life, little has been written of what has become known as the "Philosophers Camp" at Follensbee Pond. Yet, his epic poem "Adirondac"[135] reads like a journal of his day-to-day detailed description of adventures in the wilderness with his fellow members of the Saturday Club. This two-week camping excursion (1858 in the Adirondacks) brought him face to face with a true wilderness, something he spoke of in his essay "Nature", published in 1836. He said, "in the wilderness I find something more dear and connate than in streets or villages".[136] Civil War years Emerson was staunchly opposed to slavery, but he did not appreciate being in the public limelight and was hesitant about lecturing on the subject. In the years leading up to the Civil War, he did give a number of lectures, however, beginning as early as November 1837.[137] A number of his friends and family members were more active abolitionists than he, at first, but from 1844 on he more actively opposed slavery. He gave a number of speeches and lectures, and welcomed John Brown to his home during Brown's visits to Concord.[138][page needed] He voted for Abraham Lincoln in 1860, but was disappointed that Lincoln was more concerned about preserving the Union than eliminating slavery outright.[139] Once the American Civil War broke out, Emerson made it clear that he believed in immediate emancipation of the slaves.[140] Around this time, in 1860, Emerson published The Conduct of Life, his seventh collection of essays. It "grappled with some of the thorniest issues of the moment," and "his experience in the abolition ranks is a telling influence in his conclusions."[141] In these essays Emerson strongly embraced the idea of war as a means of national rebirth: "Civil war, national bankruptcy, or revolution, [are] more rich in the central tones than languid years of prosperity."[142] Emerson visited Washington, D.C, at the end of January 1862. He gave a public lecture at the Smithsonian on January 31, 1862, and declared, "The South calls slavery an institution ... I call it destitution ... Emancipation is the demand of civilization".[143] The next day, February 1, his friend Charles Sumner took him to meet Lincoln at the White House. Lincoln was familiar with Emerson's work, having previously seen him lecture.[144] Emerson's misgivings about Lincoln began to soften after this meeting.[145] In 1865, he spoke at a memorial service held for Lincoln in Concord: "Old as history is, and manifold as are its tragedies, I doubt if any death has caused so much pain as this has caused, or will have caused, on its announcement."[144] Emerson also met a number of high-ranking government officials, including Salmon P. Chase, the secretary of the treasury; Edward Bates, the attorney general; Edwin M. Stanton, the secretary of war; Gideon Welles, the secretary of the navy; and William Seward, the secretary of state.[146] On May 6, 1862, Emerson's protégé Henry David Thoreau died of tuberculosis at the age of 44. Emerson delivered his eulogy. He often referred to Thoreau as his best friend,[147] despite a falling-out that began in 1849 after Thoreau published A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.[148] Another friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne, died two years after Thoreau, in 1864. Emerson served as a pallbearer when Hawthorne was buried in Concord, as Emerson wrote, "in a pomp of sunshine and verdure".[149] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1864.[150] In 1867, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[151] |

文学者としてのキャリアと超越主義 1859年のエマーソン 1836年9月8日、『自然』が出版される前日、エマーソンはフレデリック・ヘンリー・ヘッジ、ジョージ・パットナム、ジョージ・リプリーと会い、志を同 じくする知識人たちの定期的な集まりを計画した[79]。これが運動の中心となる超越クラブの始まりであった。その最初の公式会合は1836年9月19日 に開かれた[80]。1837年9月1日、超越クラブの会合に初めて女性が参加した。エマーソンは、マーガレット・フラー、エリザベス・ホアー、サラ・リ プリーの3人を会合の前に自宅に招き、夜の懇親会に出席できるようにした[81]。フラーは超越主義において重要な人物となる。 エマーソンは、1836年9月9日に出版される最初のエッセイ「自然」をジェームズ・マンロー社に匿名で送った。その1年後の1837年8月31日、彼は 今では有名なファイ・ベータ・カッパの演説「アメリカの学者」[82]を行った。当時は「ケンブリッジのファイ・ベータ・カッパ協会で行われた演説」と題 されていたが、1849年にエッセイ集(「自然」の最初の一般出版を含む)に改題された[83]。 [当時ハーバード大学の学生であったジェームズ・ラッセル・ローウェルは、この演説を「我々の文学史においてかつて類例のない出来事」と呼んだ[85]。 また聴衆の一人であったジョン・ピアース牧師は、この演説を「明らかに支離滅裂で意味不明な演説」と呼んだ[86]。 1837年、エマーソンはヘンリー・デイヴィッド・ソローと親しくなる。二人が出会ったのは1835年のことであったと思われるが、1837年の秋、エ マーソンはソローに "日記をつけているか "と尋ねた。87]エマソン自身の日記は、1960年から1982年にかけて発行されたハーバード大学出版局の決定版として、16巻の大冊で出版された。 この日記をエマーソンの主要な文学作品とみなす学者もいる[88][要出典]。 1837年3月、エマーソンはボストンのメーソン寺院で歴史哲学に関する一連の講義を行った。この連続講演の収益は、団体から報酬を得て講演するよりもは るかに大きく、エマソンは生涯を通じてたびたび自らの講演会を運営し続けた。彼は最終的に年間80回もの講演を行い、セントルイス、デモイン、ミネアポリ ス、カリフォルニアまでアメリカ北部を旅した[90]。 1838年7月15日[91]、エマーソンはハーバード大学神学部のディヴィニティ・ホールに招かれ、「神学部の演説」として知られるようになった同校の 卒業式の演説を行った。エマーソンは聖書の奇跡を否定し、イエスは偉大な人物ではあったが神ではなかったと宣言した。歴史的キリスト教はイエスを「東洋人 やギリシャ人がオシリスやアポロを表現するような半神」に変えてしまったと彼は言った。彼は無神論者[92]、若者の心を毒する者として非難された。批評 家たちの咆哮にもかかわらず、彼は何も答えず、他の人たちが弁明することになった。彼はその後30年間、ハーバード大学で再び講演に招かれることはなかっ た[93]。 超越論的グループは1840年7月にその代表的な雑誌である『ザ・ダイアル』を発行し始めた[94]。彼らは1839年10月には早くもこの雑誌の企画を 立てていたが、1840年の第1週まで制作を開始しなかった[95]。 [96]マーガレット・フラーが最初の編集者となり、他の何人かがその役割を辞退した後にエマソンから声をかけられた[97]。フラーはエマソンが引き継 いだ後、約2年間在籍し、エラリー・チャニングやソローを含む才能ある若い作家を宣伝するために雑誌を利用した[87]。 1841年、エマーソンは有名なエッセイ「自立」を含む2冊目の著書『エッセイ集』を出版した[98]。叔母はこの本を「無神論と偽りの自立の奇妙な寄せ 集め」と呼んだが、ロンドンやパリでは好意的な批評を得た。この本とその好評は、これまでのエマソンのどの寄稿よりも、彼の国際的名声の基礎を築いた [99]。 1842年1月、エマソンの長男ウォルドが猩紅熱で死去[100]。エマソンはその悲しみを詩「Threnody」(「この喪失は真の死である」)とエッ セイ「Experience」に記した[101]。同じ月にウィリアム・ジェームズが誕生し、エマーソンは彼の名付け親になることに同意。 ブロンソン・オルコットは1842年11月、「良い建物、良い果樹園と敷地のある、素晴らしい状態の100エーカーの農場」を探す計画を発表した [102]。チャールズ・レーンは1843年5月、マサチューセッツ州ハーバードに90エーカー(36ヘクタール)の農場を購入し、超越主義に触発された ユートピア的理想に基づく共同体「フルーツランズ」となる。 [103]この農場は共同作業に基づいて運営され、労働には動物を使わず、参加者は肉を食べず、羊毛や皮革を使用しない[104]。エマーソンは、自分自 身がこの実験に参加しなかったことを「心底悲しい」と感じたと述べている[105]。それでも彼は、フルーツランズが成功するとは感じていなかった。「彼 らの教義はすべて精神的なものだ」と彼は書いているが、「彼らはいつも、多くの土地と金をよこせと言って終わる」[106]。オルコットでさえ、フルーツ ランドの経営が困難であることを覚悟していなかったことを認めている。「私たちの誰も、夢見ていた理想的な生活を実際に実現する準備ができていなかった。 だから私たちはバラバラになった」と書いている[107]。その失敗の後、エマーソンはオルコットの家族のためにコンコードに農場を購入するのを援助し [106]、その農場をオルコットは「ヒルサイド」と名付けた[107]。 ホレス・グリーリーはこれを「この国で出版された中で最も独創的で思慮深い定期刊行物」の終焉と報じた[108]。 1844年、エマーソンは2冊目のエッセイ集『Essays: セカンド・シリーズ)。このエッセイ集には、「詩人」、「経験」、「贈り物」、そして1836年の同名のエッセイとは別の作品である「自然」と題された エッセイが含まれていた。 エマーソンは、ニューイングランドをはじめ全米で人気の講演家として生計を立てていた。1833年から講演を始め、1850年代には年間80回もの講演を 行っていた[109]。ボストン有用知識普及協会(Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge)やグロスター・リセウム(Gloucester Lyceum)などで講演を行った。エマーソンはさまざまなテーマで講演を行い、彼のエッセイの多くは講演から生まれたものであった。講演料は1回につき 10ドルから50ドルで、典型的な冬の講演シーズンには2,000ドルもの収入を得た。これは他の収入よりも多かった。ある年には6回の講演で900ド ル、またある年にはボストンでの冬の講演で1,600ドルの収入を得た[110]。その収入によって彼は所有地を拡大することができ、ウォールデン池のほ とりに11エーカー(4.5ヘクタール)の土地を購入し、さらに近隣の松林に数エーカーの土地を購入した。彼は「多かれ少なかれ、14エーカーの地主であ り水主であった」と書いている[106]。 1845年、エマーソンはバガヴァッド・ギーターとヘンリー・トーマス・コールブルックの『ヴェーダについてのエッセイ』を読んでいたことがエマーソンの 日記に記されている[111]。その最も明確な例のひとつが、彼のエッセイ『オーバー・ソウル』にある: われわれは連続し、分裂し、部分し、粒子して生きている。人間の内には全体の魂があり、賢明な沈黙があり、普遍的な美があり、すべての部分と粒子が等しく 関係している。そして、私たちが存在し、その至高がすべて私たちに通じるこの深い力は、自己充足的で、どんな時も完全であるだけでなく、見る行為と見られ るもの、見る者と見るもの、主体と客体は一体である。われわれは世界を、太陽、月、動物、樹木のように断片的に見ているが、それらが輝く部分である全体が 魂である。 エマーソンがアジアの研究から引き出した中心的なメッセージは、「人生の目的は、霊的な変容と神の力の直接的な経験であり、今ここで地上にある」というも のであった[114][115]。 1847年から48年にかけて、彼はイギリス諸島を旅行した[116]。到着したとき、彼は2月の暴動でバリケードを形成するために切り倒された木の切り 株を見た。5月21日、彼はシャン・ド・マルスに立ち、和合、平和、労働のための大規模な祝典の真っ只中にいた。彼は日記に「この年の終わりに、革命が木 々に値するものであったかどうか、勘定してみよう」[117]と記している。1856年に出版された彼の著書『English Traits』は、主に彼の旅行記やノートに記録された観察に基づいている。エマーソンは後に、アメリカの南北戦争を1848年のヨーロッパの革命と共通 する「革命」とみなすようになった[118]。 1851年5月3日、マサチューセッツ州コンコードでの演説で、エマーソンは逃亡奴隷法を非難した: この議会法は、あなた方の誰もが早い機会に破ることになる法律であり、自尊心を失い、紳士の名を失うことなくして、従うことも、従うことを幇助することも できない法律である」[119]。 その年の夏、彼は日記にこう書いた: この不潔な法令は、読み書きのできる人々によって19世紀に作られたものだ。私はそれに従わない」[120]。 1852年2月、エマーソンはジェイムズ・フリーマン・クラークとウィリアム・ヘンリー・チャニングとともに、1850年に亡くなったマーガレット・フ ラーの著作と書簡を編集した[121]。 [122]マーガレット・フラー・オッソリの回想録(The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli)というタイトルで出版されたが[123]、フラーの言葉は大幅に検閲されたり、書き直されたりした[124]。 3人の編集者は正確さにはこだわらず、フラーに対する世間の関心は一時的なもので、歴史上の人物として生き残ることはないと考えていた[125]。 それでも、この伝記は10年間で最も売れた伝記となり、世紀末までに13版を重ねた[123]。 ウォルト・ホイットマンは1855年に革新的な詩集『草の葉』を出版し、そのコピーをエマーソンに送って意見を求めた。エマソンは肯定的な反応を示し、ホ イットマンに5ページにわたるお世辞たっぷりの手紙を送った[126]。エマソンの承認によって『草の葉』初版は大きな関心を集めることになり [127]、ホイットマンはその後まもなく第2版を出版することになった[128]: 「エマーソンはこの手紙が公開されたことに腹を立て[130]、後にこの作品に対してより批判的になった[131]。 アディロンダック、フォレンスビー池での哲学者キャンプ 1858年の夏、ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソンはニューヨーク州北部の大自然の中に飛び込んだ。 彼と行動を共にしたのは、アディロンダック山脈で自然と触れ合うキャンプをした最も著名な知識人9人であった: ルイス・アガシズ、ジェームズ・ラッセル・ローウェル、ジョン・ホームズ、ホレイショ・ウッドマン、エベネザー・ロックウッド・ホアー、ジェフリーズ・ワ イマン、エステス・ハウ、エイモス・ビニー、ウィリアム・ジェームズ・スティルマンである。招待されたものの、さまざまな理由で来日できなかったのは以下 の通り: オリヴァー・ウェンデル・ホームズ、ヘンリー・ウォズワース・ロングフェロー、チャールズ・エリオット・ノートンは、いずれもサタデー・クラブ(マサ チューセッツ州ボストン)の会員だった[132]。 この社交クラブはほとんどが文学会員で、毎月最終土曜日にボストン・パーカー・ハウス・ホテル(オムニ・パーカー・ハウス)で会合を開いていた。ウィリア ム・ジェームズ・スティルマンは画家であり、「クレヨン」という美術雑誌の創刊編集者でもあった。スティルマンはアディロンダック山脈のすぐ南に位置する シェネクタディで生まれ育った。後に彼は、大自然の風景を描き、釣りや狩りをするためにこの地を訪れるようになる。彼はこの荒野での体験をサタデークラブ の会員に伝え、この未知の地域への関心を高めた。 ジェームズ・ラッセル・ローウェル[133]とウィリアム・スティルマンは、アディロンダックへの旅を組織するための活動を率いることになる。彼らは 1858年8月2日に旅を開始し、列車、蒸気船、駅馬車、カヌーのガイドボートを乗り継いで旅をした。この教養ある男たちが荒野で「サックとスー」のよう な生活をしているというニュースは、全米の新聞に掲載された。これは「哲学者キャンプ」として知られるようになる[134]。 この出来事は、自然を芸術や文学と結びつける、19世紀の知的運動における画期的な出来事であった。 エマソンの生涯については、学者や伝記作家によって長年にわたって多くのことが書かれてきたが、フォレンスビー池での「哲学者キャンプ」として知られるよ うになったことについては、ほとんど書かれていない。しかし、彼の叙事詩『アディロンダック』[135]は、サタデークラブの仲間たちとの荒野での冒険を 日々詳細に描写した日記のように読める。この2週間のキャンプ旅行(1858年、アディロンダック)で、彼は1836年に出版されたエッセイ 『Nature(自然)』の中で語っていた、真の荒野と対面することになる。彼は、「荒野には、街や村よりももっと親密で結びつきの強いものがある」と 語っている[136]。 南北戦争時代 エマーソンは奴隷制度に断固反対していたが、世間の脚光を浴びることを好まず、このテーマで講演することをためらっていた。しかし、南北戦争に至るまでの 数年間、彼は1837年11月頃から多くの講演を行っている[137]。彼の友人や家族の中には、当初は彼よりも積極的な奴隷制度廃止論者が多かったが、 1844年以降、彼はより積極的に奴隷制度に反対するようになる。1860年にはエイブラハム・リンカーンに投票したが、リンカーンが奴隷制の撤廃よりも 連邦の維持を重視していたことに失望した[139]。 アメリカ南北戦争が勃発すると、エマーソンは奴隷の即時解放を信じていることを明らかにした[140]。 この頃、1860年にエマーソンは7冊目のエッセイ集『The Conduct of Life』を出版した。このエッセイ集は「その時々の最も茨の道ともいうべき問題に取り組み」、「奴隷廃止運動における彼の経験が、彼の結論に決定的な影 響を及ぼしている」[141]: 「内戦、国家破産、革命は、[中略]繁栄の気だるい年月よりも中心的な色調において豊かである」[142]。 エマーソンは1862年1月末にワシントンを訪れた。彼は1862年1月31日にスミソニアンで公開講演を行い、こう宣言した。私はそれを窮乏と呼ぶ.奴 隷解放は文明の要求である」[143] 翌2月1日、友人のチャールズ・サムナーは彼をホワイトハウスでリンカーンに会わせた。リンカーンは以前、エマソンの講演を見たことがあり、エマソンの作 品に親しんでいた[144]。1865年、彼はコンコードで行われたリンカーンの追悼式でスピーチを行った: 「歴史は古く、その悲劇は多岐にわたるが、この死がその発表の際に引き起こした、あるいはこれから引き起こすであろう、これほど多くの痛みを引き起こした 死があっただろうか」[144] エマーソンはまた、国庫長官のサーモン・P・チェイス、司法長官のエドワード・ベイツ、陸軍長官のエドウィン・M・スタントン、海軍長官のギデオン・ウェ ルズ、国務長官のウィリアム・スワードなど、多くの政府高官にも会っている[146]。 1862年5月6日、エマソンの弟子ヘンリー・デイヴィッド・ソローが結核のため44歳で死去。エマソンは弔辞を述べた。ソローが『コンコード川とメリ マック川の一週間』を出版した後の1849年に始まった不仲にもかかわらず[147]、彼はしばしばソローを親友と呼んだ[148]。エマーソンは、ホー ソーンがコンコードに埋葬された際、喪主を務めた。エマーソンが「陽光と緑に満ちた華やかな中で」と書いている[149]。 1864年にはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された[150]。1867年にはアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された[151]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Waldo_Emerson |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099