エミール・ルー

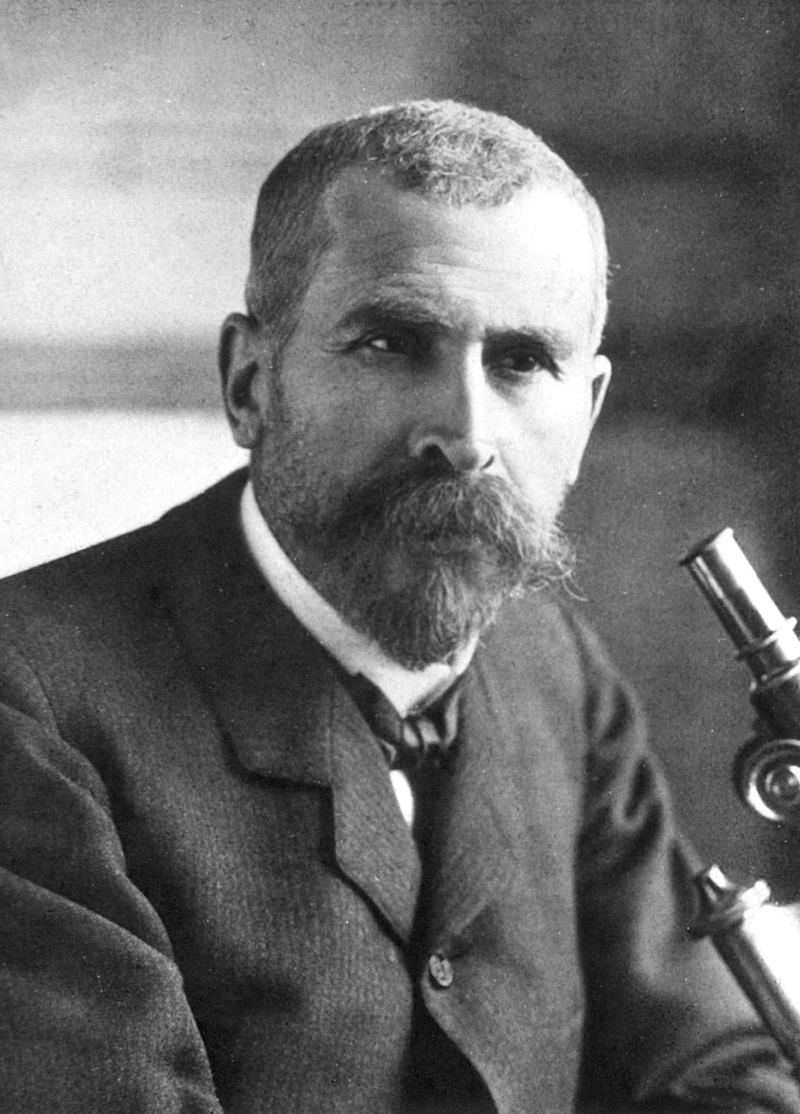

Pierre Paul Émile Roux, 1853-1933

☆

ピエール・ポール・エミール・ルー FRS[1](フランス語発音: [1853年12月17日 -

1933年11月3日)[2]は、フランスの医師、細菌学者、免疫学者である。パスツール研究所の共同設立者であるルイ・パスツール(1822-

1895)の最も親密な共同研究者の一人であり、この病気に対する最初の有効な治療法である抗ジフテリア血清の製造に携わった。さらに、コレラ、鶏コレ

ラ、狂犬病、結核の研究も行った。ルーは免疫学の創始者とみなされている[3]。

| Pierre Paul Émile Roux

FRS[1] (French pronunciation: [pjɛʁ pɔl emil ʁu]; 17 December 1853 – 3

November 1933)[2] was a French physician, bacteriologist and

immunologist. Roux was one of the closest collaborators of Louis

Pasteur (1822–1895), a co-founder of the Pasteur Institute, and

responsible for the institute's production of the anti-diphtheria

serum, the first effective therapy for this disease. Additionally, he

investigated cholera, chicken-cholera, rabies, and tuberculosis. Roux

is regarded as a founder of the field of immunology.[3] |

ピ

エール・ポール・エミール・ルー FRS[1](フランス語発音: [1853年12月17日 -

1933年11月3日)[2]は、フランスの医師、細菌学者、免疫学者である。パスツール研究所の共同設立者であるルイ・パスツール(1822-

1895)の最も親密な共同研究者の一人であり、この病気に対する最初の有効な治療法である抗ジフテリア血清の製造に携わった。さらに、コレラ、鶏コレ

ラ、狂犬病、結核の研究も行った。ルーは免疫学の創始者とみなされている[3]。 |

| Early years Roux was born in Confolens, Charente. It is believed that Roux had a fatherless childhood.[4] He received his baccalaureate in sciences in 1871 and started his studies in 1872 at the Medical School of Clermont-Ferrand. He worked initially as a student assistant in chemistry at the Faculty of Sciences, under Émile Duclaux. From 1874 to 1878, he continued his studies in Paris and was admitted as clinical assistant at Hôtel-Dieu. Between 1874 and 1877, Roux received a fellowship for the Military School at Val-de-Grâce, but quit it after failing to present his dissertation in due time. It is also believed that Roux may have been dismissed from the military for some form of insubordination.[4] In 1878, he started to work as an assistant to the course on fermentation given by his patron Duclaux at the Sorbonne University.[1] In 1878, Pierre Paul Emile Roux married Rose Anna Shedlock in London, but it was kept a secret.[5][6] Shedlock was a historical figure in her own right, being one of the first women medical students in Britain and Europe. Shedlock met Roux while both were in medical school in Paris. Shedlock died in 1879 of tuberculosis within days of Roux performing his critical experiments on chicken cholera vaccine.[7] In an inaccurate biography, Roux's niece stated that Shedlock contracted tuberculosis from Roux. However, this is unlikely, given that Shedlock had symptoms before marrying Roux.[8] According to his niece, Roux allegedly believed that marriage was an opportunity for women to satisfy their "deepest aspirations", while for men it was "mutilation".[4] |

幼少期 ルーはシャラント県コンフォランで生まれた。1871年に理学部のバカロレアを取得し、1872年にクレルモンフェランの医学部で学び始める。当初は理学 部で化学の助手としてエミール・デュクローの下で働いた。1874年から1878年までパリで勉強を続け、オテル・デューで臨床助手を務めた。1874年 から1877年にかけて、ルーはヴァル・ド・グラース陸軍士官学校の奨学金を得たが、論文発表が間に合わなかったため退学した。1878年、ルーはソルボ ンヌ大学でパトロンであったデュクローの発酵講座の助手として働き始める[1]。 1878年、ピエール・ポール・エミール・ルーはロンドンでローズ・アンナ・シェドロックと結婚したが、そのことは秘密にされていた[5][6]。シェド ロックは、ともにパリの医学部に在学中にルーと知り合った。シェドロックは1879年、ルーが鶏コレラワクチンの重要な実験を行った数日後に結核で亡く なった[7]。不正確な伝記の中で、ルーの姪はシェドロックがルーから結核をうつされたと述べている。しかし、シェドロックはルーと結婚する前から症状が あったことから、その可能性は低い[8]。姪によれば、ルーは、結婚とは女性にとっては「最も深い願望」を満たす機会であり、男性にとっては「切断」であ ると考えていたとされる[4]。 |

| Work with Pasteur Duclaux recommended Roux to Louis Pasteur, who was looking for assistants, and Roux joined Pasteur's laboratory as a research assistant from 1878 to 1883 at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. When Roux first began his career with Pasteur, he started as an animal inoculator. He performed well in the technical tasks, and became more involved with research.[4] Roux began his research on the microbiological causation of diseases, and in this capacity worked with Pasteur on avian cholera (1879–1880) and anthrax (1879–1890), and was involved in the famous experiment on anthrax vaccination of animals at Pouilly-le-Fort [fr].[1] In this vaccination experiment, Roux and Charles Chamberland injected 25 sheep with their anthrax vaccine, and the other 25 were unvaccinated.[9] A few weeks later, all 50 sheep were injected with the anthrax bacillus. When it was clear that all 25 vaccinated sheep would survive, and all 25 unvaccinated sheep would die, Pasteur arrived to great fanfare. Louis Pasteur and Émile Roux were sometimes in disagreement in their approach to disease. Pasteur was an experimental scientist, whereas Roux was more focused on clinical medicine. They also held different religious and political beliefs, with Pasteur being a right- leaning Catholic, and Roux being a left-leaning atheist. Given their many differences, they clashed often as they worked towards vaccines against anthrax and rabies. The main issues between Roux and Pasteur regarded the ethics of human experimentation, specifically, the amount of evidence from animal experimentation needed in order to justify giving the rabies vaccine to humans. Roux was more reluctant to give the vaccine to humans without further evidence that it was safe in animals.[4] In 1883, he presented a doctoral dissertation in medicine titled Des Nouvelles Acquisitions sur la Rage, in which he described his research on rabies with Pasteur since 1881, which led to the development of the first vaccination against this fearsome disease. Roux discovered the idea of intracranial transmission of rabies, which paved the road for many more Pastorian milestones in research.[4] Roux was now recognized as an expert in the nascent sciences of medical microbiology and immunology. With Pasteur's other assistants (Edmond Nocard, Louis Thuillier, who died while in Alexandria after contracting the disease, and Straus), Roux traveled in 1883 to Egypt to study a human cholera outbreak there, but they were unable to find the pathogen for the disease, which was later discovered in Alexandria by the German physician Robert Koch (1843–1910).[1] In 1883 and for the following 40 years, Émile Roux became closely involved with the creation of what was to become the Pasteur Institute. Roux is known for developing the concept of combining development, research, and application in a specialized hospital. The most distinctive feature of the Pasteur Hospital was free access to medical care. The hospital was also known for being very hygienic for the time period.[10] He divided his time between biomedical research and administrative duties. In 1888, an important year in his career, he accepted the position of Director of Services, joined the editorial board of the Annales de l'Institut Pasteur, and established the first regular course on microbiological technique, which would become extremely influential in the training of many important French and foreign researchers and physicians in infectious diseases.[11][1] |

パスツールとの仕事 デュクローは、助手を探していたルイ・パスツールにルーを推薦し、ルーは1878年から1883年までパリの高等師範学校の助手としてパスツールの研究室 に加わった。ルーがパスツールのもとでキャリアをスタートさせた当初は、動物用の接種器としてスタートした。ルーは技術的な仕事を順調にこなし、研究にも 携わるようになった[4]。微生物学的な疾病の原因に関する研究を始め、パスツールとともに鳥コレラ(1879-1880年)と炭疽菌(1879- 1890年)の研究を行い、プイイ=ル=フォール[fr]での有名な炭疽菌の動物へのワクチン接種実験に関わった。 [このワクチン接種実験では、ルーとシャルル・チェンバーランドは25頭のヒツジに炭疽ワクチンを注射し、残りの25頭はワクチン未接種とした[9]。ワ クチンを接種した25頭の羊はすべて生き残り、ワクチンを接種していない25頭の羊はすべて死亡することが明らかになったとき、パスツールが到着し、大騒 ぎになった。 ルイ・パスツールとエミール・ルーは、病気に対するアプローチで意見が対立することがあった。パスツールは実験科学者であったが、ルーは臨床医学に重きを 置いていた。パスツールは右寄りのカトリック、ルーは左寄りの無神論者であった。炭疽菌や狂犬病のワクチン開発に取り組む中で、2人はしばしば衝突した。 特に、狂犬病ワクチンを人間に投与することを正当化するために必要な動物実験の証拠の量についてである。ルーは、狂犬病ワクチンが動物実験において安全で あるというさらなる証拠がない限り、狂犬病ワクチンをヒトに投与することに消極的であった[4]。 1883年、ルーは「Des Nouvelles Acquisitions sur la Rage(狂犬病に関する新たな発見)」と題する医学博士論文を発表した。この論文では、1881年以来パスツールとともに行ってきた狂犬病の研究が述べ られており、この恐ろしい病気に対する最初のワクチン接種の開発につながった。ルーが発見した狂犬病の頭蓋内感染というアイデアは、パスツールにとってさ らに多くの画期的な研究への道を開くものであった。ルーはパスツールの他の助手(エドモン・ノカール、ルイ・トゥイリエ(アレクサンドリア滞在中にコレラ に感染して死亡)、ストラウス)と共に、1883年にエジプトで発生したコレラの調査を行ったが、コレラの病原体を発見することはできず、後にドイツ人医 師ロベルト・コッホ(1843-1910)によってアレクサンドリアで発見された。 1883年から40年間、エミール・ルーは後のパスツール研究所の設立に深く関わった。ルーは、専門病院において開発、研究、応用を組み合わせるというコ ンセプトを開発したことで知られている。パスツール病院の最大の特徴は、医療を無料で受けられることだった。また、この病院は当時としては非常に衛生的で あったことでも知られている[10]。彼は生物医学研究と管理業務を分担して行った。彼のキャリアにおいて重要な年であった1888年、彼はサービス部長 を引き受け、パスツール研究所の編集委員会に加わり、微生物学的技術に関する最初の定期講座を開設した。この講座は、感染症に関する多くの重要なフランス 国内外の研究者や医師の育成に極めて大きな影響を与えることになった[11][1]。 |

| Diphtheria research The development of a diphtheria anti-toxin serum was a race between researchers Emil Behring in Berlin, and Émile Roux in Paris. They both developed it nearly simultaneously. However, the serum was marketed differently in each country. In Germany, the serum was marketed in a private business setting, whereas in France, the serum was distributed through a communal health care system.[12] The race to develop the diphtheria anti-toxin serum was considered a national rivalry, although each team of researchers adopted each other's experimental practices and built off of each other.[13] In a controversy, the first Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine was given to Emil Von Behring for his work on the serum therapy for diphtheria. Roux had been nominated in 1888 for the isolation of the diphtheria toxin, but didn't win the prize in 1901 because his discovery was deemed to be too "old." Over the years, Roux came close to the Nobel Prize but never won.[14] Also in 1883, Roux published, with Alexandre Yersin, the first of his classical works on the causation of diphtheria by the Klebs-Loeffler bacillus, then an extremely prevalent and lethal disease, particularly among children. Diphtheria is contagious microbial disease marked by throat lesions, polyneuritis, myocarditis, low blood pressure, and collapse. He studied its toxin and its properties, and began in 1891 to develop an effective serum to treat the disease, following the demonstration, by Emil Adolf von Behring (1854–1917) and Kitasato Shibasaburō (1852–1931) that antibodies against the diphtheric toxin could be produced in animals. He successfully demonstrated the use of this antitoxin with Auguste Chaillou in a study with 300 diseased children in the Hôpital des Enfants-Malades and was henceforth hailed as a scientific hero in medical congresses throughout Europe.[1] |

ジフテリアの研究 ジフテリアの抗毒素血清の開発は、ベルリンの研究者エミール・ベーリングとパリの研究者エミール・ルーの間で競われた。二人はほぼ同時に開発した。しか し、この血清はそれぞれの国で異なる方法で販売された。ジフテリアの抗毒素血清の開発競争は、それぞれの研究者チームが互いの実験方法を採用し、互いに協 力し合いながらも、国民的なライバル関係であったと考えられている[13]。論争となったが、第1回ノーベル生理学・医学賞は、ジフテリアの血清療法に関 するエミール・フォン・ベーリングに贈られた。ルーは1888年にジフテリア毒素の単離で受賞候補に挙がっていたが、1901年には発見が「古すぎる」と いう理由で受賞を逃した。その後、ルーがノーベル賞に近づくことはあったが、受賞することはなかった[14]。 1883年、ルーはアレクサンドル・イェルサンと共に、クレブス・ロフラー菌によるジフテリアの原因に関する古典的著作の最初のものを発表した。ジフテリ アは、のどの病変、多発性神経炎、心筋炎、低血圧、虚脱を特徴とする伝染性の微生物病である。彼はジフテリアの毒素とその性質を研究し、1891年、エ ミール・アドルフ・フォン・ベーリング(1854-1917)と北里柴三郎(1852-1931)によって、ジフテリア毒素に対する抗体が動物で産生され ることが証明されたのを受けて、この病気を治療する効果的な血清の開発に着手した。彼は、オーギュスト・シャイユー(Auguste Chaillou)とともに、マラデス病院(Hôpital des Enfants-Malades)の300人の患児を対象とした研究で、この抗毒素の使用に成功し、以後ヨーロッパ中の医学会議で科学的英雄として賞賛さ れた[1]。 |

| Other research and later years In the following years, Roux dedicated himself indefatigably to many investigations on the microbiology and practical immunology of tetanus, tuberculosis, syphilis, and pneumonia. He was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1900. In 1904, he was nominated to Pasteur's former position as General Director of the Pasteur Institute.[1] In 1916, he moved to a small apartment in the Pasteur Hospital, where he died on 3 November 1933. |

その他の研究と晩年 その後の数年間、ルーは破傷風、結核、梅毒、肺炎の微生物学と実践的免疫学に関する多くの研究に精力的に取り組んだ。1900年にはスウェーデン王立科学アカデミーの会員に選ばれた。1904年、パスツールの前職であるパスツール研究所所長に指名される[1]。 1916年、パスツール病院の小さなアパートに移り、1933年11月3日に死去した。 |

| Awards and honors In 1917, he received the Copley Medal for his outstanding achievements in research.[15] Asteroid 293366 Roux, discovered by French amateur astronomer Bernard Christophe in 2007, was named in his memory.[16] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 12 March 2017 (M.P.C. 103971).[17] The Roux culture bottle, a flask for culturing cells, is named after him.[18] |

受賞と栄誉 1917年、研究での優れた業績に対してコプリーメダルを受賞した[15]。 2007年にフランスのアマチュア天文家ベルナール・クリストフによって発見された小惑星293366ルーは、彼を記念して命名された[16]。2017年3月12日に小惑星センターによって公式命名引用文が発表された(M.P.C. 103971)[17]。 細胞を培養するためのフラスコであるルー培養瓶は、彼にちなんで命名された[18]。 |

An injection against croup at the Hôpital Trousseau [fr] in Paris, with Roux observing, by P. A. A. Brouillet in 1893 |

1893年、パリのトルソー病院[fr]でのクループに対する注射(ルーが観察している)。 |

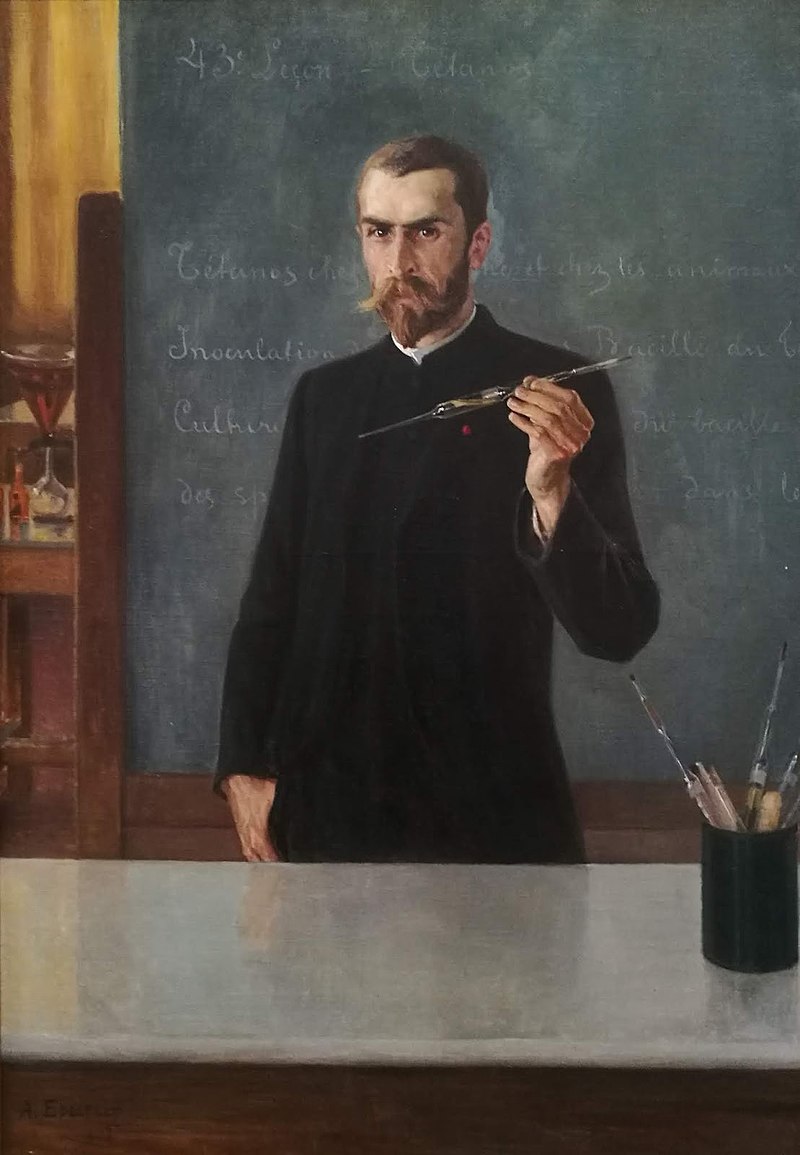

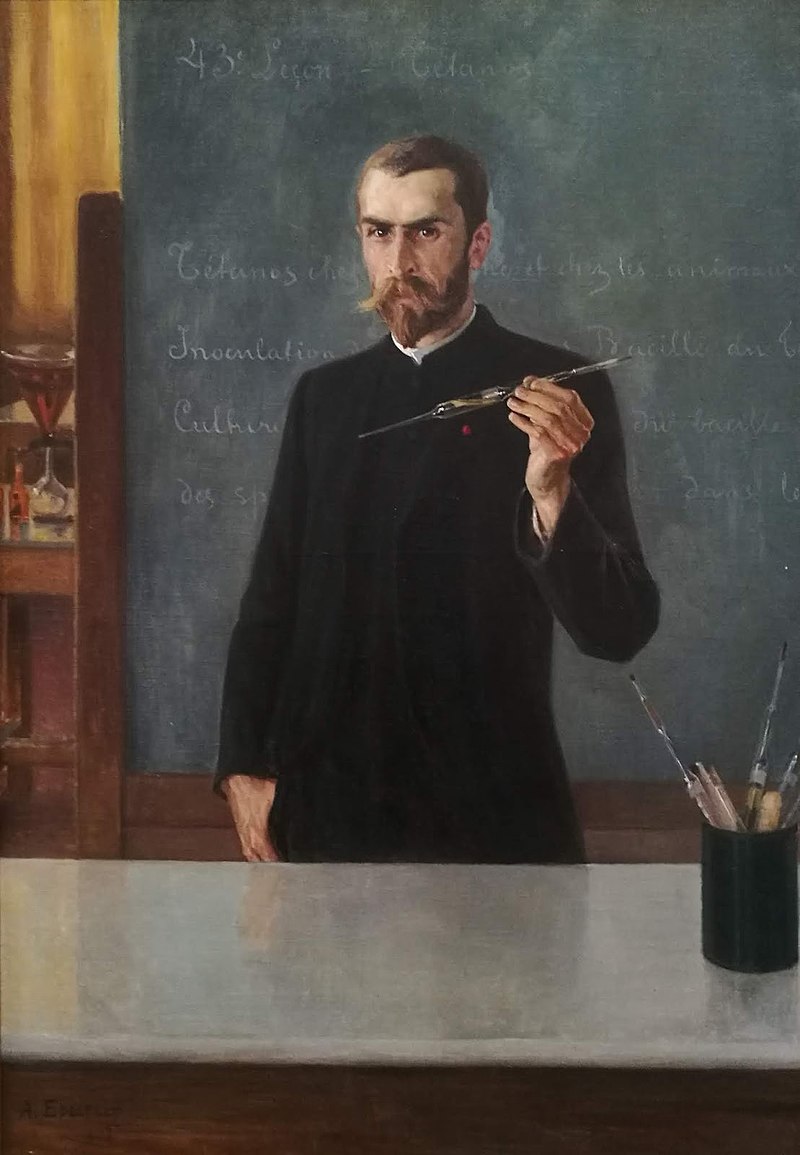

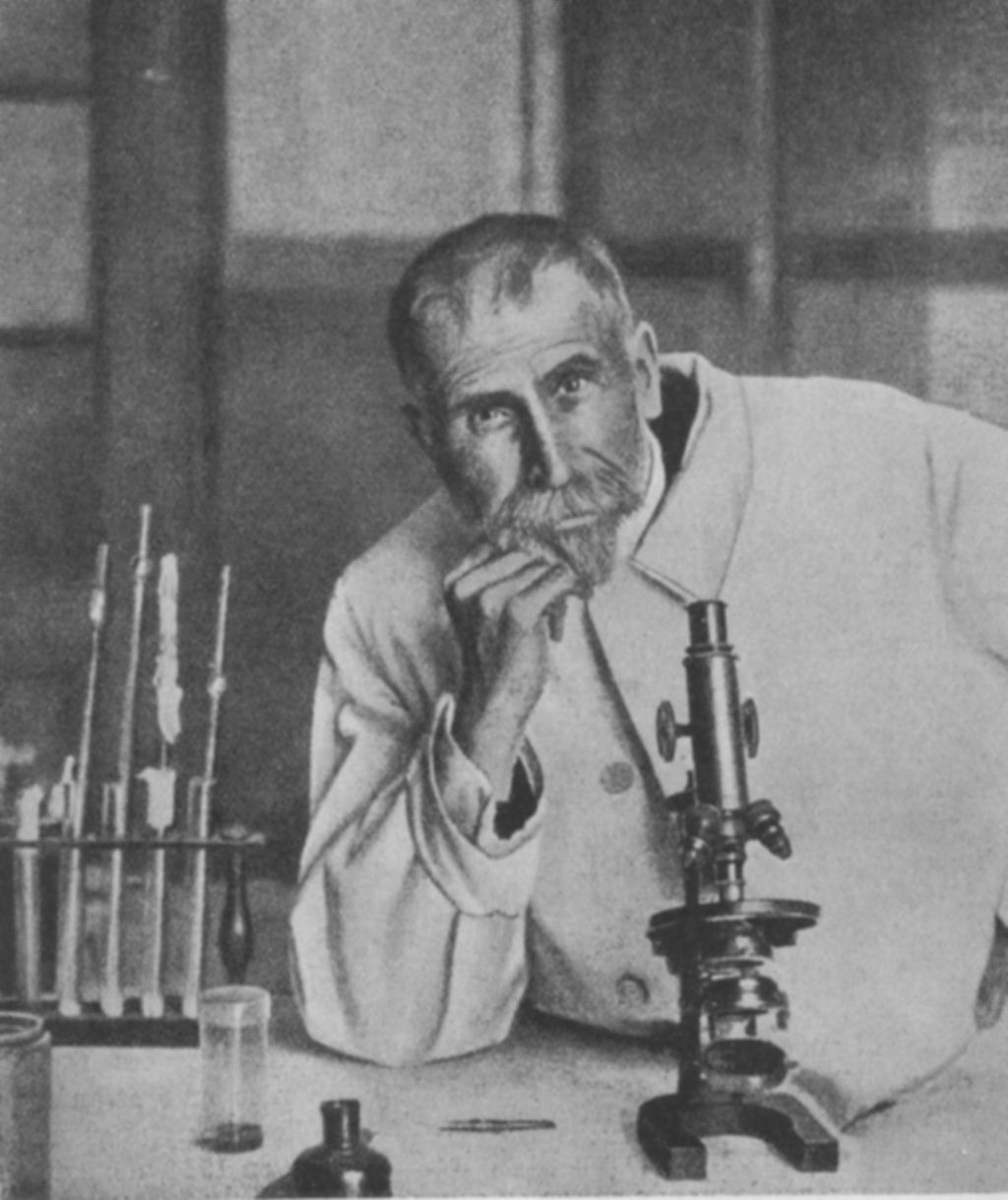

Dr. Emile Roux, Albert Edelfelt, 1896 |

エミール・ルー博士、アルベール・エーデルフェルト、1896年 |

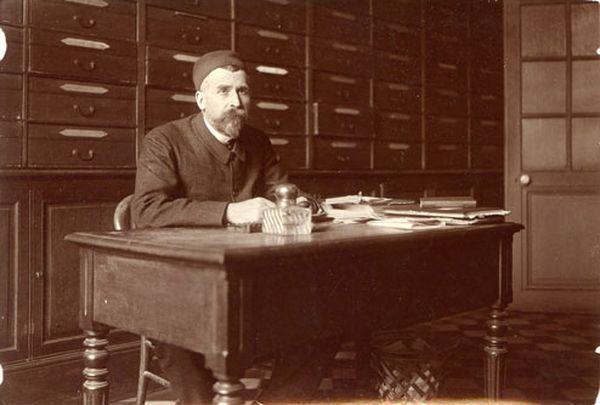

Office in 1906 |

Office in 1906 |

18th and 19th Century Medicine by Veloso Salgado in 1906, Pasteur at the center and Roux kneeling in front with the rabbit |

1906年、ヴェローゾ・サルガドによる18世紀と19世紀の医学、中央がパスツール、正面がウサギと膝をつくルー |

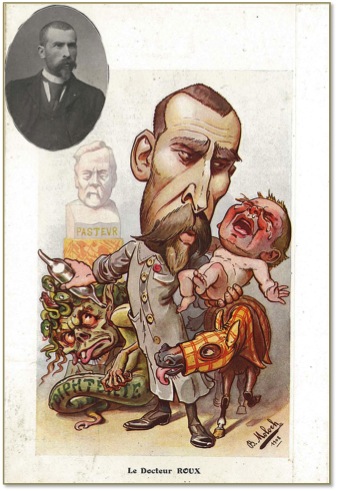

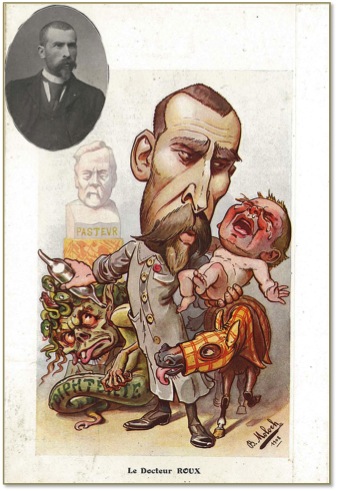

Friendly caricature of members of the Academy of Medicine designed by Hector Moloch [fr] and published in the journal Chanteclair in 1910 |

ヘクトール・モロク[fr]がデザインし、1910年に雑誌『シャンテクレール』に掲載された医学アカデミー会員たちの親しみやすい風刺画。 |

Roux, unknown date |

Roux, unknown date |

25th anniversary of the Pasteur Institute on 15 November 1913 |

1913年11月15日、パスツール研究所創立25周年記念日 |

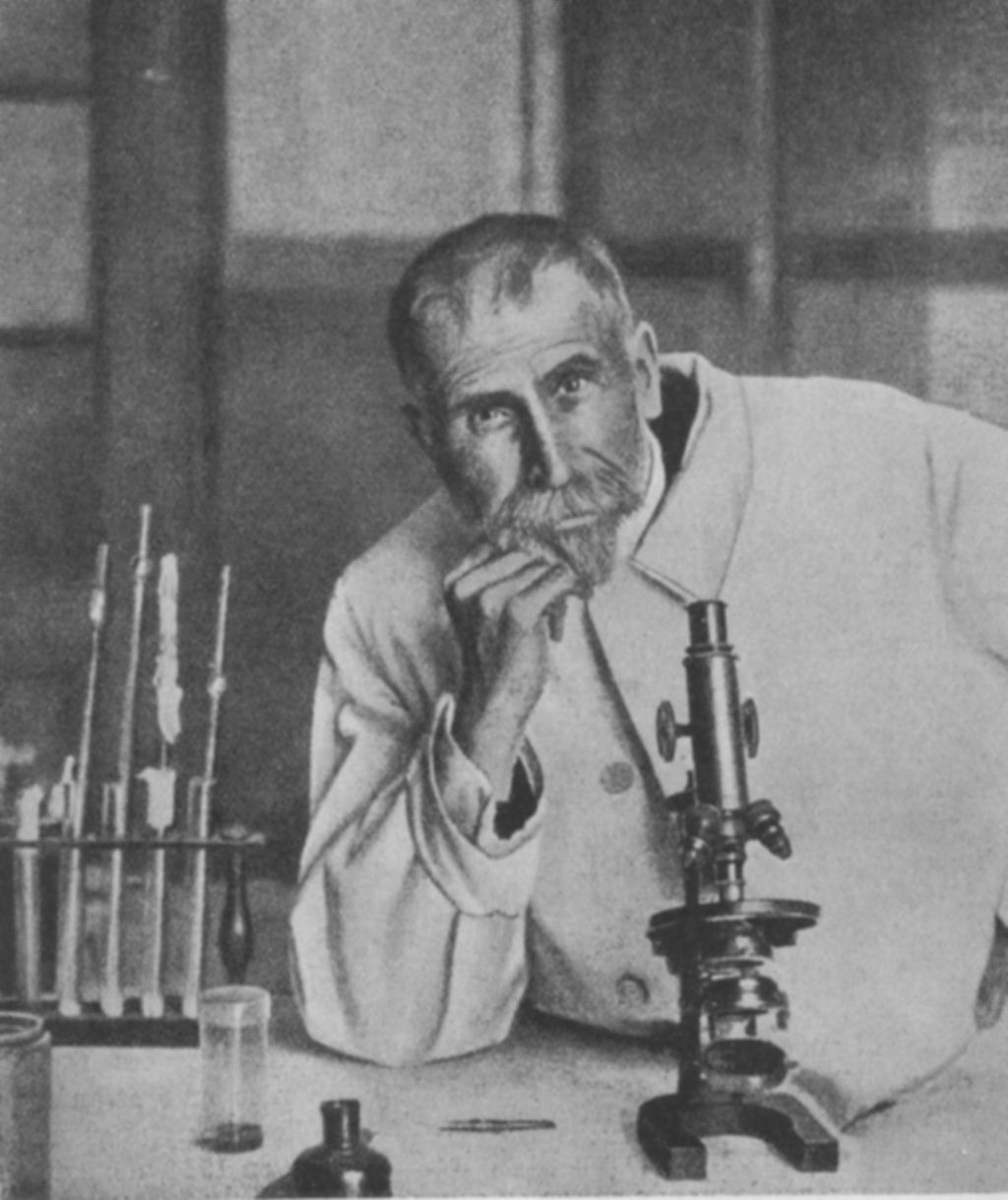

Roux in 1927 |

Roux in 1927 |

| References "Pierre Paul Emile Roux. 1853-1933". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 1 (3): 197–204. 1934. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1934.0005. Pierre Paul Émile Roux. Biographie. Institut Pasteur, Paris. a g, N. (1934). "Pierre Paul Emile Roux". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 30 (1): 70–71. PMC 403187. PMID 20319369. GEISON, GERALD L. (1990). "Pasteur, Roux, and Rabies: Scientific versus Clinical Mentalities". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 45 (3): 341–365. doi:10.1093/jhmas/45.3.341. ISSN 0022-5045. PMID 2212608. McIntyre, Neil (2016). "The marriage (1878) of Emile Roux (1853-1933) and Rose Anna Shedlock (b. c. 1850". Journal of Medical Biography. 24: 175–176. Murnane, John P; Probert, Rebecca (25 August 2024). "The relationship between Rose Anna Shedlock (c1850-1878) and Emile Roux (1853-1933)". Journal of Medical Biography. OnLine First: 1–8. Murnane, John P; Probert, Rebecca (25 August 2024). "The relationship between Rose Anna Shedlock (c1850-1878) and Emile Roux (1853-1933)". Journal of Medical Biography. OnLine First: 1–8. McIntyre, Neil (21 March 2014). "The fate of Rose Anna Shedlock (c1850–1878) and the early career of Émile Roux (1853–1933)". Journal of Medical Biography. 24 (1): 60–67. doi:10.1177/0967772013513992. ISSN 0967-7720. PMID 24658208. S2CID 43576406. Geison, Gerald L. (1995). The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 145–175. Opinel, Annick (May 2008). "The Emergence of French Medical Entomology: The Influence of Universities, the Institut Pasteur and Military Physicians (1890–c.1938)". Medical History. 52 (3): 387–405. doi:10.1017/s0025727300002696. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 2449474. PMID 18641790. "Emile Roux, pilies de l'aventure Pasteur". Pasteur. 9 November 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2020. Hess, Volker (June 2008). "The Administrative Stabilization of Vaccines: Regulating the Diphtheria Antitoxin in France and Germany, 1894–1900". Science in Context. 21 (2): 201–227. doi:10.1017/s0269889708001695. ISSN 0269-8897. PMID 18831137. S2CID 423178. Klöppel, Ulrike (June 2008). "Enacting Cultural Boundaries in French and German Diphtheria Serum Research". Science in Context. 21 (2): 161–180. doi:10.1017/s0269889708001671. ISSN 0269-8897. PMID 18831135. S2CID 23575164. Franz., Luttenberger. Excellence and chance : the Nobel Prize case of E. von Behring and E. Roux. OCLC 1147879148. "Notes and Records of the Royal Society". Royal Society Publishing. Retrieved 5 February 2009. "293366 Roux (2007 EQ9)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 12 September 2019. "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 12 September 2019. Erhard F. Kaleta (2006): "A Brief History, Modes of Spread and Impact of Fowl Plague Viruses". Asia-Pacific Biotech News, volume 10, issue 14, pages 717-725. doi:10.1142/S0219030306001236 |

参考文献 「ピエール・ポール・エミール・ルー 1853-1933」. Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 1 (3): 197-204. 1934. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1934.0005. Pierre Paul Émile Roux. Biographie. Institut Pasteur, Paris. a g, N. (1934). 「Pierre Paul Emile Roux」. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 30 (1): 70-71. PMC 403187. PMID 20319369. Geison, Gerald L. (1990). 「パスツール、ルー、そして狂犬病: Scientific versus Clinical Mentalities」. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 45 (3): 341–365. doi:10.1093/jhmas/45.3.341. ISSN 0022-5045. PMID 2212608. McIntyre, Neil (2016). 「The marriage (1878) of Emile Roux (1853-1933) and Rose Anna Shedlock (b. c. 1850)」. Journal of Medical Biography. 24: 175-176. Murnane, John P; Probert, Rebecca (25 August 2024). 「ローズ・アンナ・シェドロック(1850-1878)とエミール・ルー(1853-1933)の関係」. Journal of Medical Biography. OnLine First: 1-8. Murnane, John P; Probert, Rebecca (25 August 2024). 「ローズ・アンナ・シェドロック(1850-1878)とエミール・ルー(1853-1933)の関係」. Journal of Medical Biography. OnLine First: 1-8. McIntyre, Neil (21 March 2014). 「The fate of Rose Anna Shedlock (c1850-1878) and the early career of Émile Roux (1853-1933)」. Journal of Medical Biography. 24 (1): 60–67. doi:10.1177/0967772013513992. issn 0967-7720. PMID 24658208. s2cid 43576406. Geison, Gerald L. (1995). The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Opinel, Annick (May 2008). 「フランス医昆虫学の出現: The Influence of Universities, the Institut Pasteur and Military Physicians (1890-c.1938)」. 医学史。52 (3): 387–405. doi:10.1017/s0025727300002696. issn 0025-7273. PMC 2449474. PMID 18641790. 「Emile Roux, pilies de l'aventure Pasteur」. Pasteur. 9 November 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2020. Hess, Volker (June 2008). 「ワクチンの行政的安定化: フランスとドイツにおけるジフテリア抗毒素の規制、1894-1900年」. Science in Context. 21 (2): 201–227. doi:10.1017/s0269889708001695. issn 0269-8897. PMID 18831137. S2CID 423178. Klöppel, Ulrike (June 2008). 「Enacting Cultural Boundaries in French and German Diphtheria Serum Research」. Science in Context. 21 (2): 161–180. doi:10.1017/s0269889708001671. ISSN 0269-8897. PMID 18831135. S2CID 23575164. Franz., Luttenberger. 優秀さと偶然:E.フォン・ベーリングとE.ルーのノーベル賞受賞例。OCLC 1147879148. 「王立協会のノートと記録」. 王立協会出版. 2009年2月5日取得。 「293366 ルー (2007 EQ9)」. 小惑星センター。2019年9月12日取得。 「MPC/MPO/MPS アーカイブ」. マイナー・プラネット・センター. 2019年9月12日に取得された。 Erhard F. Kaleta (2006): 「A Brief History, Modes of Spread and Impact of Fowl Plague Viruses」. Asia-Pacific Biotech News、第10巻、第14号、717-725ページ。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89mile_Roux |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆