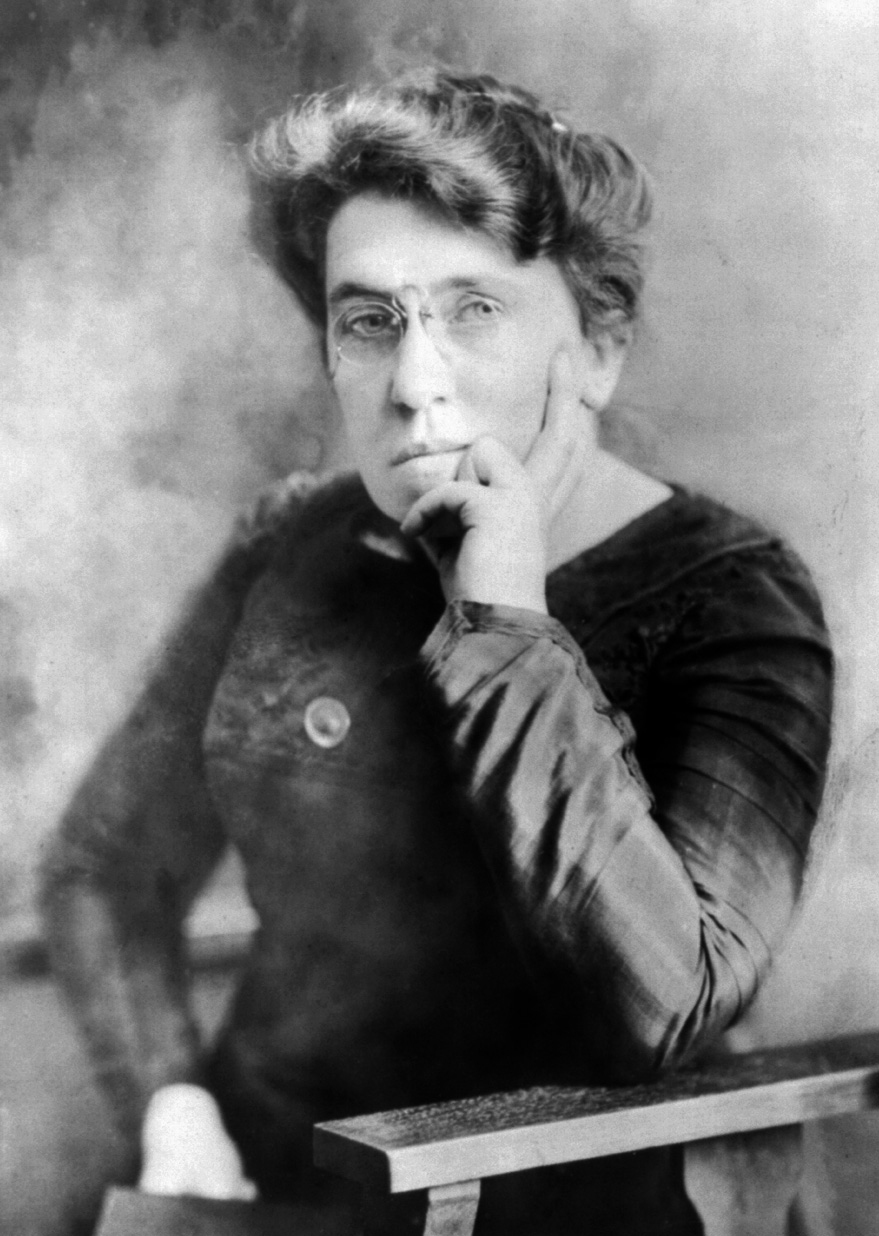

エマ・ゴールドマン・ジ・アナキスト

Emma

Goldman, the Anarchist, 1869-1940

☆エマ・ゴールドマン(1869年6月27日 - 1940年5月14日)はロシア生まれの無政府主義者、政治活動家、作家。20世紀前半の北米とヨーロッパにおけるアナキズム政治思想の発展に極めて重要な役割を果たした。

★Emma Goldman (June

27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist, political

activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of

anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first

half of the 20th century. Born

in Kaunas, Lithuania (then within the Russian Empire), to an Orthodox

Lithuanian Jewish family, Goldman emigrated to the United States in

1885.[2] Attracted to anarchism after the Chicago Haymarket affair,

Goldman became a writer and a renowned lecturer on anarchist

philosophy, women's rights, and social issues, attracting crowds of

thousands.[2] She and anarchist writer Alexander Berkman, her lover and

lifelong friend, planned to assassinate industrialist and financier

Henry Clay Frick as an act of propaganda of the deed. Frick survived

the attempt on his life in 1892, and Berkman was sentenced to 22 years

in prison. Goldman was imprisoned several times in the years that

followed, for "inciting to riot" and illegally distributing information

about birth control. In 1906, Goldman founded the anarchist journal

Mother Earth. Born

in Kaunas, Lithuania (then within the Russian Empire), to an Orthodox

Lithuanian Jewish family, Goldman emigrated to the United States in

1885.[2] Attracted to anarchism after the Chicago Haymarket affair,

Goldman became a writer and a renowned lecturer on anarchist

philosophy, women's rights, and social issues, attracting crowds of

thousands.[2] She and anarchist writer Alexander Berkman, her lover and

lifelong friend, planned to assassinate industrialist and financier

Henry Clay Frick as an act of propaganda of the deed. Frick survived

the attempt on his life in 1892, and Berkman was sentenced to 22 years

in prison. Goldman was imprisoned several times in the years that

followed, for "inciting to riot" and illegally distributing information

about birth control. In 1906, Goldman founded the anarchist journal

Mother Earth.In 1917, Goldman and Berkman were sentenced to two years in jail for conspiring to "induce persons not to register" for the newly instated draft. After their release from prison, they were arrested—along with 248 others—in the so-called Palmer Raids during the First Red Scare and deported to Russia in December 1919. Initially supportive of that country's October Revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power, Goldman changed her opinion in the wake of the Kronstadt rebellion; she denounced the Soviet Union for its violent repression of independent voices. She left the Soviet Union and in 1923 published a book about her experiences, My Disillusionment in Russia. While living in England, Canada, and France, she wrote an autobiography called Living My Life. It was published in two volumes, in 1931 and 1935. After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Goldman traveled to Spain to support the anarchist revolution there. She died in Toronto, Canada, in 1940, aged 70. During her life, Goldman was lionized as a freethinking "rebel woman" by admirers, and denounced by detractors as an advocate of politically motivated murder and violent revolution.[3] Her writing and lectures spanned a wide variety of issues, including prisons, atheism, freedom of speech, militarism, capitalism, marriage, free love, and homosexuality. Although she distanced herself from first-wave feminism and its efforts toward women's suffrage, she developed new ways of incorporating gender politics into anarchism. After decades of obscurity, Goldman gained iconic status in the 1970s by a revival of interest in her life, when feminist and anarchist scholars rekindled popular interest. |

エマ・ゴールドマン(1869年6月27日 - 1940年5月14日)はロシア生まれの無政府主義者、政治活動家、作家。20世紀前半の北米とヨーロッパにおけるアナキズム政治思想の発展に極めて重要な役割を果たした。 リ

トアニア(当時はロシア帝国内)のカウナスで正統派リトアニア系ユダヤ人の家庭に生まれたゴールドマンは、1885年にアメリカ合衆国に移住した[2]。

シカゴ・ヘイマーケット事件後にアナキズムに惹かれたゴールドマンは、作家となり、アナキズム哲学、女性の権利、社会問題についての著名な講演者となり、

何千人もの聴衆を魅了した。 [2]

ゴールドマンは、恋人であり生涯の友人であったアナーキスト作家のアレクサンダー・バークマンとともに、実業家であり金融業者であったヘンリー・クレイ・

フリックの暗殺を計画した。フリックは1892年の暗殺未遂事件で一命を取り留め、バークマンには22年の禁固刑が言い渡された。ゴールドマンはその後数

年間、「暴動の扇動」や避妊に関する情報を違法に配布した罪で何度も投獄された。1906年、ゴールドマンはアナーキスト雑誌『マザー・アース』を創刊。 リ

トアニア(当時はロシア帝国内)のカウナスで正統派リトアニア系ユダヤ人の家庭に生まれたゴールドマンは、1885年にアメリカ合衆国に移住した[2]。

シカゴ・ヘイマーケット事件後にアナキズムに惹かれたゴールドマンは、作家となり、アナキズム哲学、女性の権利、社会問題についての著名な講演者となり、

何千人もの聴衆を魅了した。 [2]

ゴールドマンは、恋人であり生涯の友人であったアナーキスト作家のアレクサンダー・バークマンとともに、実業家であり金融業者であったヘンリー・クレイ・

フリックの暗殺を計画した。フリックは1892年の暗殺未遂事件で一命を取り留め、バークマンには22年の禁固刑が言い渡された。ゴールドマンはその後数

年間、「暴動の扇動」や避妊に関する情報を違法に配布した罪で何度も投獄された。1906年、ゴールドマンはアナーキスト雑誌『マザー・アース』を創刊。1917年、ゴールドマンとバークマンは、新たに導入された徴兵制度に「登録しないよう誘導する」共謀の罪で、2年間の禁固刑を言い渡された。出所後、二 人は第一次赤狩り中のいわゆるパーマー襲撃で他の248人とともに逮捕され、1919年12月にロシアに強制送還された。当初はボリシェヴィキを政権に就 けた十月革命を支持していたゴールドマンだったが、クロンシュタットの反乱をきっかけに意見を変え、ソ連が独立派の声を暴力的に弾圧していることを非難し た。彼女はソ連を去り、1923年にその体験を綴った本『ロシアにおける私の幻滅』を出版した。イギリス、カナダ、フランスで暮らしながら、『わが人生を 生きる』という自伝を執筆。これは1931年と1935年の2冊に分けて出版された。スペイン内戦勃発後、ゴールドマンはスペインに渡り、同国の無政府主 義革命を支援した。1940年、カナダのトロントで70歳で死去。 彼女の著作や講演は、刑務所、無神論、言論の自由、軍国主義、資本主義、結婚、自由恋愛、同性愛など、さまざまな問題に及んだ。彼女は第一波フェミニズム や女性参政権獲得への努力とは距離を置いていたが、ジェンダー政治をアナキズムに取り入れる新しい方法を開発した。数十年間無名だったゴールドマンは、 1970年代、フェミニストとアナーキストの研究者が大衆の関心を再燃させたことで、彼女の人生への関心が高まり、象徴的な地位を獲得した。 |

| Family Emma Goldman was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Kovno in Lithuania, then within the Russian Empire.[4] Goldman's mother Taube Bienowitch had been married before to a man with whom she had two daughters—Helena in 1860 and Lena in 1862. When her first husband died of tuberculosis, Taube was devastated. Goldman later wrote: "Whatever love she had had died with the young man to whom she had been married at the age of fifteen."[5] Taube's second marriage was arranged by her family and, as Goldman puts it, "mismated from the first".[5] Her second husband, Abraham Goldman, invested Taube's inheritance in a business that quickly failed. The ensuing hardship, combined with the emotional distance between husband and wife, made the household a tense place for the children. When Taube became pregnant, Abraham hoped desperately for a son; a daughter, he believed, would be one more sign of failure.[6] They eventually had three sons, but their first child was Emma.[7] Emma Goldman was born on June 27, 1869.[8][9] Her father used violence to punish his children, beating them when they disobeyed him. He used a whip on Emma, the most rebellious of them.[10] Her mother provided scarce comfort, rarely calling on Abraham to tone down his beatings.[11] Goldman later speculated that her father's furious temper was at least partly a result of sexual frustration.[5] Goldman's relationships with her elder half-sisters, Helena and Lena, were a study in contrasts. Helena, the oldest, provided the comfort the children lacked from their mother and filled Goldman's childhood with "whatever joy it had".[12] Lena, however, was distant and uncharitable.[13] The three sisters were joined by brothers Louis (who died at the age of six), Herman (born in 1872), and Moishe (born in 1879).[14] When Emma Goldman was a young girl, the Goldman family moved to the village of Papilė, where her father ran an inn. While her sisters worked, she became friends with a servant named Petrushka, who excited her "first erotic sensations".[15] Later in Papilė she witnessed a peasant being whipped with a knout in the street. This event traumatized her and contributed to her lifelong distaste for violent authority.[16] At the age of seven, Goldman moved with her family to the Prussian city of Königsberg (then part of the German Empire), and she was enrolled in a Realschule. One teacher punished disobedient students—targeting Goldman in particular—by beating their hands with a ruler. Another teacher tried to molest his female students and was fired when Goldman fought back. She found a sympathetic mentor in her German-language teacher, who loaned her books and took her to an opera. A passionate student, Goldman passed the exam for admission into a gymnasium, but her religion teacher refused to provide a certificate of good behavior and she was unable to attend.[17] The family moved to the Russian capital of Saint Petersburg, where her father opened one unsuccessful store after another. Their poverty forced the children to work, and Goldman took an assortment of jobs, including one in a corset shop.[18] As a teenager Goldman begged her father to allow her to return to school, but instead he threw her French book into the fire and shouted: "Girls do not have to learn much! All a Jewish daughter needs to know is how to prepare gefilte fish, cut noodles fine, and give the man plenty of children."[19] Goldman pursued an independent education on her own. She studied the political turmoil around her, particularly the Nihilists responsible for assassinating Alexander II of Russia. The ensuing turmoil intrigued Goldman, although she did not fully understand it at the time.[20] When she read Nikolai Chernyshevsky's novel, What Is to Be Done? (1863), she found a role model in the protagonist Vera, who adopts a Nihilist philosophy and escapes her repressive family to live freely and organize a sewing cooperative. The book enthralled Goldman and remained a source of inspiration throughout her life.[21] Her father, meanwhile, continued to insist on a domestic future for her, and he tried to arrange for her to be married at the age of fifteen. They fought about the issue constantly; he complained that she was becoming a "loose" woman, and she insisted that she would marry for love alone.[22] At the corset shop, she was forced to fend off unwelcome advances from Russian officers and other men. One man took her into a hotel room and committed what Goldman described as "violent contact";[23] two biographers call it rape.[24] She was stunned by the experience, overcome by "shock at the discovery that the contact between man and woman could be so brutal and painful."[25] Goldman felt that the encounter forever soured her interactions with men.[25] |

家族 エマ・ゴールドマンは、当時ロシア帝国内にあったリトアニアのコヴノで、正統派ユダヤ人の家庭に生まれた[4]。ゴールドマンの母タウベ・ビエノヴィッチ は、以前にある男性と結婚しており、1860年にヘレナ、1862年にレナの2人の娘をもうけた。最初の夫が結核で亡くなったとき、タウベは大きなショッ クを受けた。後にゴールドマンは、「15歳で結婚した若い男との間に、彼女が抱いていた愛はすべて死んでしまった」と書いている[5]。 2番目の夫エイブラハム・ゴールドマンは、タウベの遺産を事業に投資したが、すぐに失敗に終わった。その後の苦難は、夫婦間の感情的な距離と相まって、子供たちにとって家庭を緊張した場所にした。タウベが妊娠したとき、アブラハムは必死に息子を望んだ。 エマ・ゴールドマンは1869年6月27日に生まれた[8][9]。彼女の父親は子供たちを罰するために暴力を使い、逆らうと殴った。最も反抗的であった エマには鞭を使った[10]。母親はほとんど慰めを与えず、アブラハムに殴る音を小さくするよう呼びかけることはほとんどなかった[11]。後にゴールド マンは、父親の激しい気性は少なくとも部分的には性的欲求不満の結果であったと推測している[5]。 ゴールドマンの異母姉であるヘレナとレナとの関係は対照的であった。長女のヘレナは、子供たちに欠けていた母親からの安らぎを与え、ゴールドマンの子供時 代を「どんな喜びでも」満たしてくれた[12]。しかし、レナはよそよそしく、無慈悲だった[13]。3人の姉妹には、兄弟のルイ(6歳で死去)、ヘルマ ン(1872年生まれ)、モイシェ(1879年生まれ)が加わった[14]。 エマ・ゴールドマンが幼い頃、ゴールドマン一家はパピレ村に移り住み、父親が宿屋を経営していた。姉たちが働いている間、彼女はペトルーシュカという名の 使用人と友達になり、「初めてのエロティックな感覚」を刺激された[15]。その後、パピレで彼女は、路上で農民が鞭で打たれているのを目撃した。この出 来事が彼女のトラウマとなり、暴力的な権威に対する嫌悪感を生涯抱くきっかけとなった[16]。 7歳のとき、ゴールドマンは家族とともにプロイセンのケーニヒスベルク(当時はドイツ帝国の一部)に移り、レアルシューレに入学した。ある教師は、言うこ とを聞かない生徒、特にゴールドマンをターゲットに、定規で手を叩く罰を与えた。別の教師は女生徒を痴漢しようとしたが、ゴールドマンが反撃したため解雇 された。ゴールドマンはドイツ語の教師という親身な指導者を見つけ、本を貸してくれたり、オペラに連れて行ってもらったりした。熱心な生徒であったゴール ドマンは、ギムナジウムの入学試験に合格したが、宗教の教師が素行不良証明書の提出を拒否したため、ギムナジウムに通うことはできなかった[17]。 一家はロシアの首都サンクトペテルブルクに移り住み、父親は次々と売れない店を開いた。10代の頃、ゴールドマンは学校に戻ることを父親に懇願したが、父 親は代わりに彼女のフランス語の本を火の中に投げ入れ、こう叫んだ: 「女の子は多くを学ぶ必要はない!ユダヤ人の娘に必要なのは、ゲフィルテフィッシュの調理法と麺の切り方、そして男にたくさんの子供を与えることだけだ」 [19]。 ゴールドマンは独学で教育を受けた。彼女は周囲の政治的混乱、特にロシアのアレクサンドル2世を暗殺したニヒリストについて研究した。ニコライ・チェルヌ イシェフスキーの小説『何をなすべきか?(1863)を読んだ彼女は、ニヒリストの哲学を取り入れ、抑圧的な家族から逃れて自由に暮らし、縫製組合を組織 する主人公ヴェラに模範を見出した。この本はゴールドマンを夢中にさせ、生涯を通じてインスピレーションの源であり続けた[21]。 一方、父親は彼女の家庭的な将来を主張し続け、15歳で結婚させようとした。コルセット店では、ロシア人将校や他の男性からの歓迎されない誘いをかわすこ とを余儀なくされた。ある男性は彼女をホテルの部屋に連れ込み、ゴールドマンが「暴力的な接触」と表現する行為を行った[23]。 |

Rochester, New York Emma Goldman in 1886 In 1885, her sister Helena made plans to move to New York in the United States to join her sister Lena and her husband. Goldman wanted to join her sister, but their father refused to allow it. Despite Helena's offer to pay for the trip, Abraham turned a deaf ear to their pleas. Desperate, Goldman threatened to throw herself into the Neva River if she could not go. Their father finally agreed. On December 29, 1885, Helena and Emma arrived at New York City's Castle Garden, the entry for immigrants.[26] They settled upstate, living in the Rochester home which Lena had made with her husband Samuel. Fleeing the rising antisemitism of Saint Petersburg, their parents and brothers joined them a year later. Goldman began working as a seamstress, sewing overcoats for more than ten hours a day, earning two and a half dollars a week. She asked for a raise and was denied; she quit and took work at a smaller shop nearby.[27] At her new job, Goldman met a fellow worker named Jacob Kershner, who shared her love for books, dancing, and traveling, as well as her frustration with the monotony of factory work. After four months, they married in February 1887.[28] Once he moved in with Goldman's family, their relationship faltered. On their wedding night she discovered that he was impotent; they became emotionally and physically distant. Before long he became jealous and suspicious and threatened to commit suicide lest she left him. Meanwhile, Goldman was becoming more engaged with the political turmoil around her, particularly the aftermath of executions related to the 1886 Haymarket affair in Chicago and the anti-authoritarian political philosophy of anarchism.[29] Less than a year after the wedding, the couple were divorced; Kershner begged Goldman to return and threatened to poison himself if she did not. They reunited, but after three months she left once again. Her parents considered her behavior "loose" and refused to allow Goldman into their home.[30] Carrying her sewing machine in one hand and a bag with five dollars in the other, she left Rochester and headed southeast to New York City.[31] Most and Berkman  Goldman enjoyed a decades-long relationship with her lover Alexander Berkman. Photo c. 1917–1919. On her first day in the city, Goldman met two men who greatly changed her life. At Sachs' Café, a gathering place for radicals, she was introduced to Alexander Berkman, an anarchist who invited her to a public speech that evening. They went to hear Johann Most, editor of a radical publication called Freiheit and an advocate of "propaganda of the deed"—the use of violence to instigate change.[32] She was impressed by his fiery oration, and Most took her under his wing, training her in methods of public speaking. He encouraged her vigorously, telling her that she was "to take my place when I am gone."[33] One of her first public talks in support of "the Cause" was in Rochester. After convincing Helena not to tell their parents of her speech, Goldman found her mind a blank once on stage. She later wrote, suddenly:[34] something strange happened. In a flash I saw it—every incident of my three years in Rochester: the Garson factory, its drudgery and humiliation, the failure of my marriage, the Chicago crime...I began to speak. Words I had never heard myself utter before came pouring forth, faster and faster. They came with passionate intensity...The audience had vanished, the hall itself had disappeared; I was conscious only of my own words, of my ecstatic song. Excited by the experience, Goldman refined her public persona during subsequent engagements. She quickly found herself arguing with Most over her independence. After a momentous speech in Cleveland, she felt as though she had become "a parrot repeating Most's views"[35] and resolved to express herself on the stage. When she returned to New York, Most became furious and told her: "Who is not with me is against me!"[36] She left Freiheit and joined another publication, Die Autonomie.[37] Meanwhile, Goldman had begun a friendship with Berkman, whom she affectionately called Sasha. Before long they became lovers and moved into a communal apartment with his cousin Modest "Fedya" Stein and Goldman's friend, Helen Minkin, on 42nd Street.[38] Although their relationship had numerous difficulties, Goldman and Berkman would share a close bond for decades, united by their anarchist principles and commitment to personal equality.[39] In 1892, Goldman joined with Berkman and Stein in opening an ice cream shop in Worcester, Massachusetts. After a few months of operating the shop, Goldman and Berkman were diverted to participate in the Homestead Strike near Pittsburgh.[40][41] |

ニューヨーク州ロチェスター 1886年のエマ・ゴールドマン 1885年、姉のヘレナは姉のレナとその夫のもとへ行くため、アメリカのニューヨークへ移住する計画を立てた。ゴールドマンは姉と一緒になりたかったが、 父親はそれを許さなかった。ヘレナが旅費を出すと言ったにもかかわらず、エイブラハムは二人の嘆願に耳を貸さなかった。絶望したゴールドマンは、行けな かったらネヴァ川に身を投げると脅した。父親はようやく同意した。1885年12月29日、ヘレナとエマはニューヨークのキャッスル・ガーデンに到着し た。 二人は州北部に定住し、レナが夫サミュエルと建てたロチェスターの家に住んだ。サンクトペテルブルグの反ユダヤ主義の高まりから逃れて、両親と兄弟が1年 後に合流した。ゴールドマンはお針子として働き始め、1日に10時間以上オーバーコートを縫い、週に2ドル半を稼いだ。彼女は昇給を求めたが拒否され、辞 めて近くの小さな店で働いた[27]。 新しい職場で、ゴールドマンはジェイコブ・カーシュナーという同僚の労働者に出会った。彼は、彼女の本、ダンス、旅行への愛と、工場での単調な仕事への不 満を共有した。4ヵ月後、2人は1887年2月に結婚した[28]。彼がゴールドマンの家族と同居するようになると、2人の関係は険悪になった。結婚式の 夜、彼女は彼がインポテンツであることを知った。やがて彼は嫉妬と疑心暗鬼に陥り、彼女が自分のもとを去らないように自殺すると脅した。一方、ゴールドマ ンは周囲の政治的混乱、特に1886年にシカゴで起きたヘイマーケット事件に関連する処刑の余波や、アナーキズムの反権威主義的な政治哲学に関わるように なっていた[29]。 カーシュナーはゴールドマンに復縁を懇願し、復縁しなければ毒殺すると脅した。カーシュナーはゴールドマンに復縁を懇願し、復縁しなければ毒殺すると脅し た。両親は彼女の行動を「ルーズ」とみなし、ゴールドマンを家に入れることを拒否した[30]。片手にミシン、もう片方の手に5ドルの入ったバッグを持っ て、彼女はロチェスターを離れ、南東のニューヨークへ向かった[31]。 モストとバークマン  ゴールドマンは恋人のアレクサンダー・バークマンと数十年にわたる交際を楽しんだ。1917-1919年頃の写真。 ニューヨークでの最初の日、ゴールドマンは彼女の人生を大きく変えた2人の男性に出会う。急進派が集うサックス・カフェで、彼女は無政府主義者のアレクサ ンダー・バークマンを紹介され、その夜の演説会に招待された。二人は、『フライハイト』という急進的な出版物の編集者であり、「行為のプロパガンダ」(変 革を促すために暴力を行使すること)の提唱者であるヨハン・モストの演説を聴きに行った[32]。モストは彼女を力強く励まし、「私がいなくなったら、私 の代わりをするように」と告げた[33]。「大義」を支持する彼女の最初の公の場での演説のひとつは、ロチェスターでのことだった。ヘレナに自分のスピー チのことを両親に言わないように説得した後、ゴールドマンはステージに立つと頭が真っ白になることに気づいた。彼女は後に、突然こう書いた[34]。 奇妙なことが起こった。ギャルソン工場、その苦役と屈辱、結婚の失敗、シカゴの犯罪......私は話し始めた。今まで聞いたこともないような言葉が、どんどん出てきた。聴衆は消え、ホール自体も消え、私は自分の言葉、恍惚とした歌だけを意識していた。 この体験に興奮したゴールドマンは、その後の活動で公の場での人格に磨きをかけた。彼女はすぐに、自分の独立をめぐってモストと論争することになった。ク リーブランドでの重要なスピーチの後、彼女は自分が「モストの意見を繰り返すオウム」[35]になったように感じ、舞台で自分を表現することを決意した。 ニューヨークに戻ると、モストは激怒し、彼女に言った: 私とともにいない者は、私に敵対しているのだ!」[36]。彼女はフライハイトを去り、別の出版社『ディ・オートノミー』に加わった[37]。 一方、ゴールドマンはバークマンと親交を深め、彼女は親しみを込めてサーシャと呼んでいた。やがて二人は恋人となり、ゴールドマンのいとこであるモデス ト・"フェディア"・スタインとゴールドマンの友人であるヘレン・ミンキンとともに42丁目の共同アパートに引っ越した[38]。二人の関係には数々の困 難があったが、ゴールドマンとバークマンは、無政府主義の理念と個人の平等へのコミットメントによって結ばれ、数十年にわたって親密な絆を共有することに なる[39]。 1892年、ゴールドマンはバークマンとスタインとともに、マサチューセッツ州ウースターでアイスクリーム店を開いた。数ヶ月間この店を経営した後、ゴールドマンとバークマンはピッツバーグ近郊のホームステッド・ストライキに参加することになった[40][41]。 |

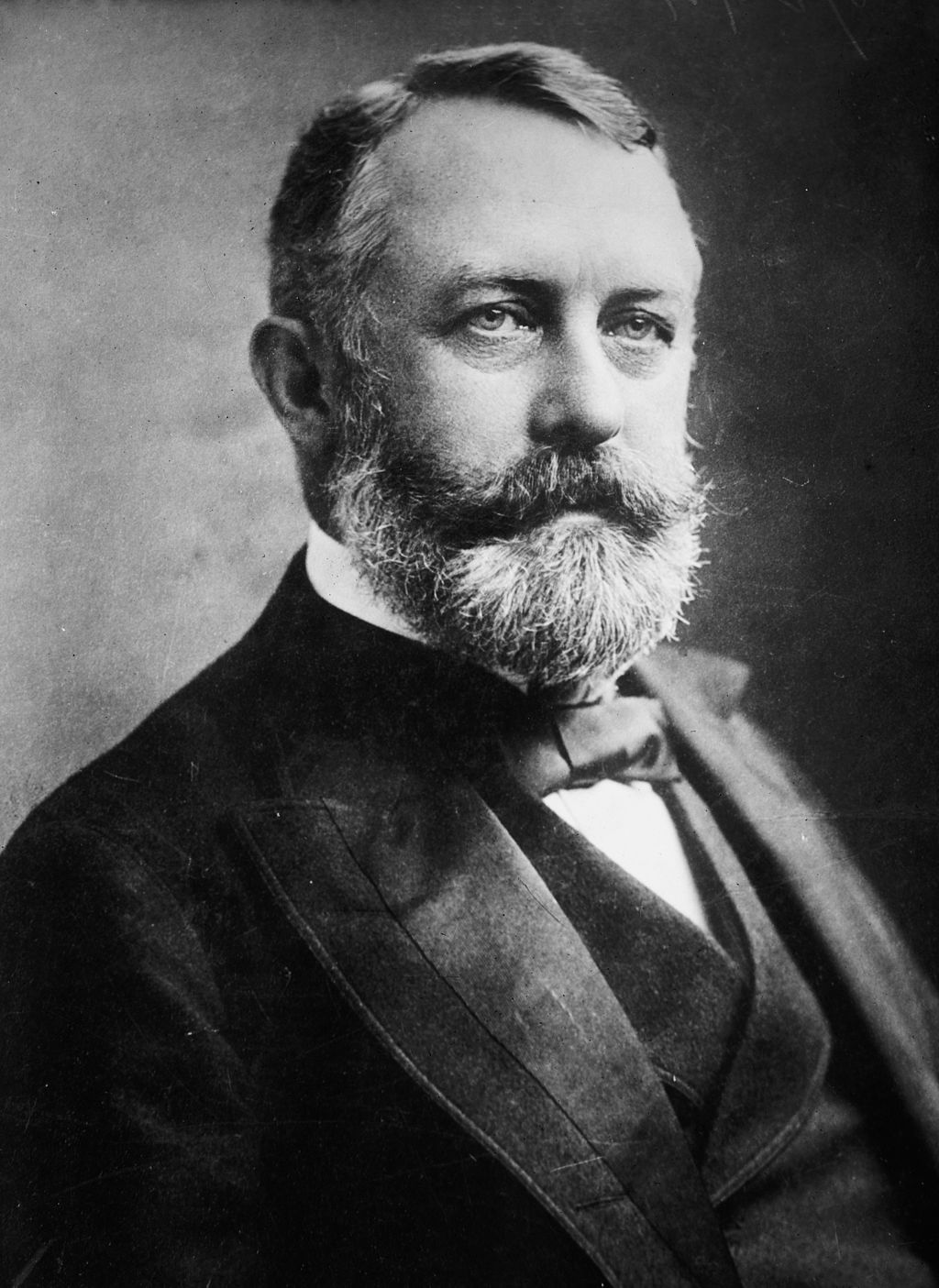

| Homestead plot Further information: Homestead Strike Berkman and Goldman came together through the Homestead Strike. In June 1892, a steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, owned by Andrew Carnegie became the focus of national attention when talks between the Carnegie Steel Company and the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers (AA) broke down. The factory's manager was Henry Clay Frick, a fierce opponent of the union. When a final round of talks failed at the end of June, management closed the plant and locked out the workers, who immediately went on strike. Strikebreakers were brought in and the company hired Pinkerton guards to protect them. On July 6, a fight broke out between 300 Pinkerton guards and a crowd of armed union workers. During the twelve-hour gunfight, seven guards and nine strikers were killed.[42]  Goldman and Berkman believed that a retaliatory assassination of Carnegie Steel Company manager Henry Clay Frick (pictured) would "strike terror into the soul of his class" and "bring the teachings of Anarchism before the world".[43] When a majority of the nation's newspapers expressed support of the strikers, Goldman and Berkman resolved to assassinate Frick, an action they expected would inspire the workers to revolt against the capitalist system. Berkman chose to carry out the assassination, and ordered Goldman to stay behind in order to explain his motives after he went to jail. He would be in charge of "the deed"; she of the associated propaganda.[44] Berkman set off for Pittsburgh on his way to Homestead, where he planned to shoot Frick.[45] Goldman, meanwhile, decided to help fund the scheme through prostitution. Remembering the character of Sonya in Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel Crime and Punishment (1866), she mused: "She had become a prostitute in order to support her little brothers and sisters...Sensitive Sonya could sell her body; why not I?"[46] Once on the street, Goldman caught the eye of a man who took her into a saloon, bought her a beer, gave her ten dollars, informed her she did not have "the knack," and told her to quit the business. She was "too astounded for speech".[46] She wrote to Helena, claiming illness, and asked her for fifteen dollars.[47] On July 23, Berkman gained access to Frick's office while carrying a concealed handgun; he shot Frick three times, and stabbed him in the leg. A group of workers—far from joining in his attentat—beat Berkman unconscious, and he was carried away by the police.[48] Berkman was convicted of attempted murder[49] and sentenced to 22 years in prison.[50] Goldman suffered during his long absence.[45] Convinced Goldman was involved in the plot, police raided her apartment. Although they found no evidence, they pressured her landlord into evicting her. Worse, the attentat had failed to rouse the masses: workers and anarchists alike condemned Berkman's action. Johann Most, their former mentor, lashed out at Berkman and the assassination attempt. Furious at these attacks, Goldman brought a toy horsewhip to a public lecture and demanded, onstage, that Most explain his betrayal. He dismissed her, whereupon she struck him with the whip, broke it on her knee, and hurled the pieces at him.[51][52] She later regretted her assault, confiding to a friend: "At the age of twenty-three, one does not reason."[53] "Inciting to riot" When the Panic of 1893 struck in the following year, the United States suffered one of its worst economic crises. By year's end, the unemployment rate was higher than 20%,[54] and "hunger demonstrations" sometimes gave way to riots. Goldman began speaking to crowds of frustrated men and women in New York City. On August 21, she spoke to a crowd of nearly 3,000 people in Union Square, where she encouraged unemployed workers to take immediate action. Her exact words are unclear: undercover agents insist she ordered the crowd to "take everything ... by force".[55] But Goldman later recounted this message: "Well then, demonstrate before the palaces of the rich; demand work. If they do not give you work, demand bread. If they deny you both, take bread."[56] Later in court, Detective-Sergeant Charles Jacobs offered yet another version of her speech.[57]  Goldman (shown here in Union Square, New York in 1916) urged unemployed workers to take direct action rather than depend on charity or government aid. A week later, Goldman was arrested in Philadelphia and returned to New York City for trial, charged with "inciting to riot".[58] During the train ride, Jacobs offered to drop the charges against her if she would inform on other radicals in the area. She responded by throwing a glass of ice water in his face.[59] As she awaited trial, Goldman was visited by Nellie Bly, a reporter for the New York World. She spent two hours talking to Goldman and wrote a positive article about the woman she described as a "modern Joan of Arc."[60] Despite this positive publicity, the jury was persuaded by Jacobs' testimony and frightened by Goldman's politics. The assistant district attorney questioned Goldman about her anarchism, as well as her atheism; the judge spoke of her as "a dangerous woman".[61] She was sentenced to one year in the Blackwell's Island Penitentiary. Once inside, she suffered an attack of rheumatism and was sent to the infirmary. There, she befriended a visiting doctor and received informal training in nursing, eventually being placed in charge of a 16-bed women's ward in the infirmary.[62] She also read dozens of books, including works by the American activist-writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau; novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne; poet Walt Whitman, and philosopher John Stuart Mill.[63] When Goldman was released after ten months, a raucous crowd of nearly 3,000 people greeted her at the Thalia Theater in New York City. She soon became swamped with requests for interviews and lectures.[64] To make money, Goldman decided to continue the medical studies she had started in prison, but her preferred fields of specialization—midwifery and massage—were unavailable to nursing students in the US. She sailed to Europe, lecturing in London, Glasgow, and Edinburgh. She met with renowned anarchists such as Errico Malatesta, Louise Michel, and Peter Kropotkin. In Vienna, she received two diplomas for midwifery and put them immediately to use back in the US.[65] Alternating between lectures and midwifery, Goldman conducted the first cross-country tour by an anarchist speaker. In November 1899, she returned to Europe to speak, where she met the Czech anarchist Hippolyte Havel in London. They went together to France and helped organize the 1900 International Anarchist Congress on the outskirts of Paris.[66] Afterward, Havel immigrated to the United States, traveling with Goldman to Chicago. They shared a residence there with friends of Goldman.[67] |

ホームステッド区画 さらに詳しい情報 ホームステッド・ストライキ バークマンとゴールドマンはホームステッド・ストライキを通じて知り合った。1892年6月、アンドリュー・カーネギーが所有するペンシルベニア州ホーム ステッドの鉄鋼工場は、カーネギー・スチール・カンパニーとアマルガム鉄鋼労働者組合(AA)との話し合いが決裂し、全米の注目の的となった。この工場の 経営者はヘンリー・クレイ・フリックで、組合に激しく反対していた。6月末に最終交渉が決裂すると、経営陣は工場を閉鎖して労働者を締め出し、労働者は直 ちにストライキに突入した。ストライキ要員が投入され、会社はピンカートンの警備員を雇って彼らを保護した。7月6日、ピンカートンの警備員300人と武 装した労働組合員の群衆との間で戦闘が勃発した。12時間に及ぶ銃撃戦で、7人の警備員と9人のストライカーが殺された[42]。  ゴールドマンとバークマンは、カーネギー・スチール・カンパニーの経営者ヘンリー・クレイ・フリック(写真)の報復暗殺が「彼の階級の魂に恐怖を与え」、「アナキズムの教えを世界に知らしめる」ことになると考えていた[43]。 全米の新聞の大半がストライキ支持を表明すると、ゴールドマンとバークマンはフリックを暗殺することを決意した。バークマンは暗殺を実行することを選択 し、ゴールドマンが刑務所に入った後に動機を説明するために残るよう命じた。バークマンはホームステッドに向かう途中、ピッツバーグに向けて出発し、そこ でフリックを射殺する計画を立てた[45]。 一方、ゴールドマンは売春によって資金を調達することにした。フョードル・ドストエフスキーの小説『罪と罰』(1866年)に登場するソーニャを思い出 し、彼女はこう考えた: 「敏感なソーニャは体を売ることができたのに、なぜ私はできないのだろう」[46]。路上でゴールドマンはある男の目にとまり、その男は彼女を酒場に連れ て行き、ビールをおごった。彼女は「驚きすぎて言葉が出なかった」[46]。ヘレナに手紙を書き、病気だと言って15ドルを要求した[47]。 7月23日、バークマンは拳銃を隠し持ってフリックのオフィスに侵入し、フリックを3発撃ち、足を刺した。バークマンは殺人未遂で有罪判決を受け[49]、懲役22年の判決を受けた[50]。 ゴールドマンが陰謀に関与していると確信した警察は、彼女のアパートに踏み込んだ。証拠は何も見つからなかったが、警察は大家に圧力をかけて彼女を立ち退 かせた。さらに悪いことに、アテンダットは大衆を奮い立たせることができなかった。労働者もアナーキストも同様に、バークマンの行動を非難した。労働者も アナーキストもバークマンの行動を非難し、彼らのかつての指導者であったヨハン・モストは、バークマンと暗殺未遂事件を非難した。こうした攻撃に激怒した ゴールドマンは、公開講座におもちゃの鞭を持ち込み、舞台上でモストに自分の裏切りを説明するよう要求した。彼は彼女を退席させたが、彼女はその鞭で彼を 殴り、膝の上で折ってその破片を彼に投げつけた[51][52]。後に彼女は自分の暴行を後悔し、友人にこう打ち明けた: 「23歳にもなって、人は理性を持たない」[53]。 "暴動の扇動" 翌1893年にパニックが起こると、アメリカは最悪の経済危機に見舞われた。年末には失業率が20%を超え[54]、「飢餓デモ」が暴動に発展することも あった。ゴールドマンはニューヨークで、不満を募らせた男女の群衆を前に演説を始めた。8月21日、彼女はユニオン・スクエアで約3,000人の群衆を前 に演説を行い、失業中の労働者たちに直ちに行動を起こすよう促した。彼女の正確な言葉は不明である。覆面捜査官は、彼女が群衆に「力ずくで......す べてを奪い取れ」と命令したと主張している[55]が、後にゴールドマンはこのメッセージをこう語っている: 「では、金持ちの宮殿の前でデモをしなさい。彼らが仕事を与えないなら、パンを要求せよ。もし彼らが両方とも拒否したら、パンを取れ」[56]。後に法廷 で、チャールズ・ジェイコブス巡査部長は、彼女のスピーチのさらに別のバージョンを提供した[57]。  ゴールドマン(この写真は1916年にニューヨークのユニオン・スクエアで撮影されたもの)は、失業中の労働者たちに、慈善事業や政府の援助に頼るのではなく、直接行動を起こすよう促した。 ゴールドマン(この写真は1916年にニューヨークのユニオン・スクエアで撮影されたもの)は、失業中の労働者たちに、慈善事業や政府の援助に頼るのではなく、直接行動を起こすよう促した。その1週間後、ゴールドマンはフィラデルフィアで逮捕され、「暴動を扇動した」罪で起訴され、裁判を受けるためにニューヨークに戻った。裁判を待つ間、 ゴールドマンは『ニューヨーク・ワールド』紙の記者ネリー・ブライの訪問を受けた。彼女は2時間かけてゴールドマンと話し、この女性について「現代のジャ ンヌ・ダルク」と表現する好意的な記事を書いた[60]。 このような好意的な宣伝にもかかわらず、陪審はジェイコブスの証言に説得され、ゴールドマンの政治におびえた。地方検事補はゴールドマンの無政府主義や無 神論について質問し、裁判官は彼女を「危険な女性」と評した[61]。刑務所に入ると、彼女はリウマチの発作を起こし、医務室に送られた。彼女はまた、ア メリカの活動家であるラルフ・ワルド・エマーソンやヘンリー・デイヴィッド・ソロー、小説家のナサニエル・ホーソーン、詩人のウォルト・ホイットマン、哲 学者のジョン・スチュアート・ミル[63]の作品など、何十冊もの本を読んだ。10ヵ月後にゴールドマンが釈放されると、ニューヨークのタリア劇場で 3000人近い騒々しい群衆が彼女を迎えた。彼女はすぐにインタビューや講演の依頼で押し寄せるようになった[64]。 お金を稼ぐために、ゴールドマンは獄中で始めた医学の勉強を続けることにしたが、彼女の希望する専門分野である助産とマッサージは、アメリカでは看護学生 が学ぶことができなかった。彼女はヨーロッパに渡り、ロンドン、グラスゴー、エディンバラで講義を行った。エリコ・マラテスタ、ルイーズ・ミシェル、ピー ター・クロポトキンといった著名なアナキストたちと知り合った。ウィーンで彼女は助産師の資格を2つ取得し、アメリカに戻ってすぐに活用した[65]。 講演と助産を交互に行いながら、ゴールドマンは無政府主義者による初の全国ツアーを行った。1899年11月、彼女は講演のためにヨーロッパに戻り、ロン ドンでチェコの無政府主義者ヒポリト・ハヴェルと出会った。その後、ハベルはアメリカに移住し、ゴールドマンと共にシカゴに向かった。二人はそこでゴール ドマンの友人たちと住居を共にした[67]。 |

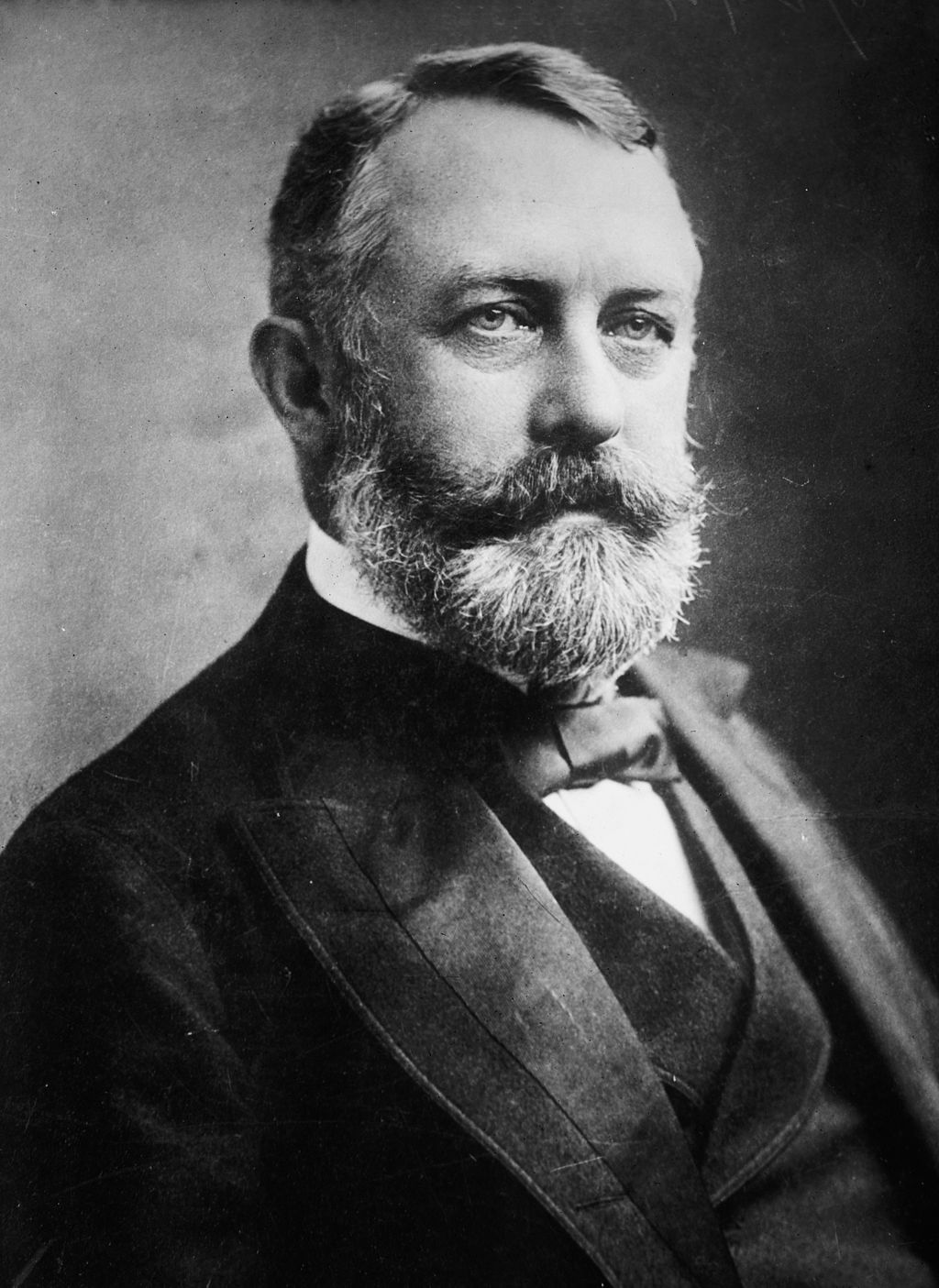

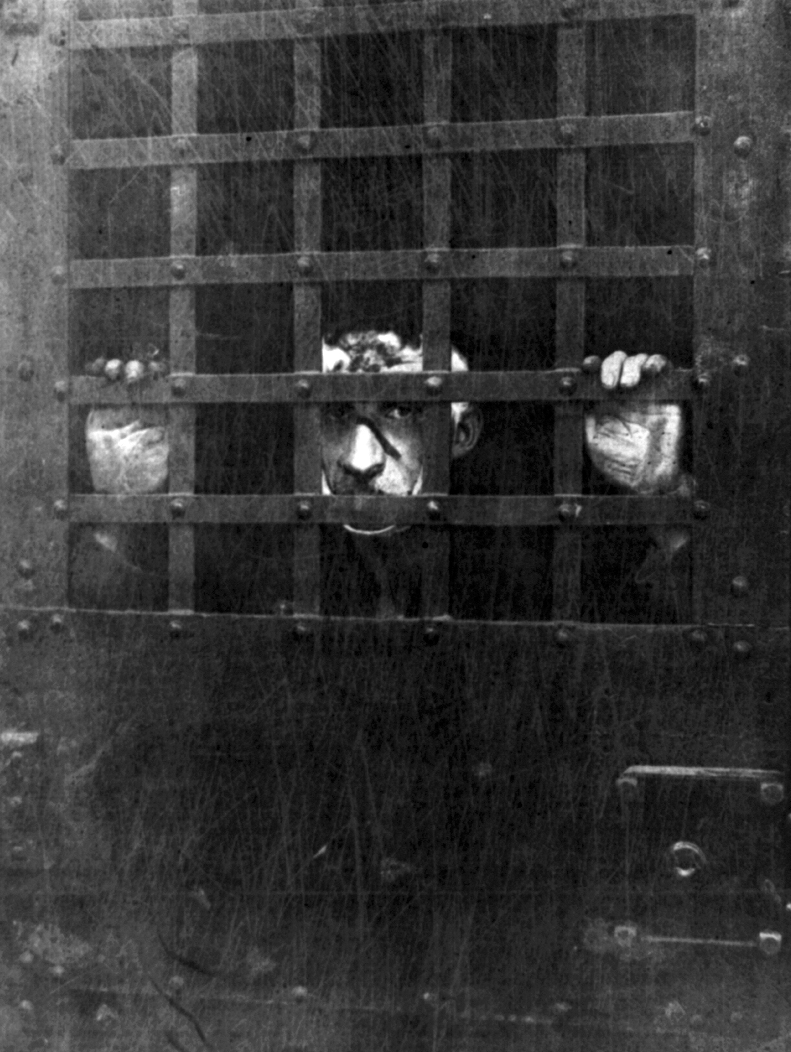

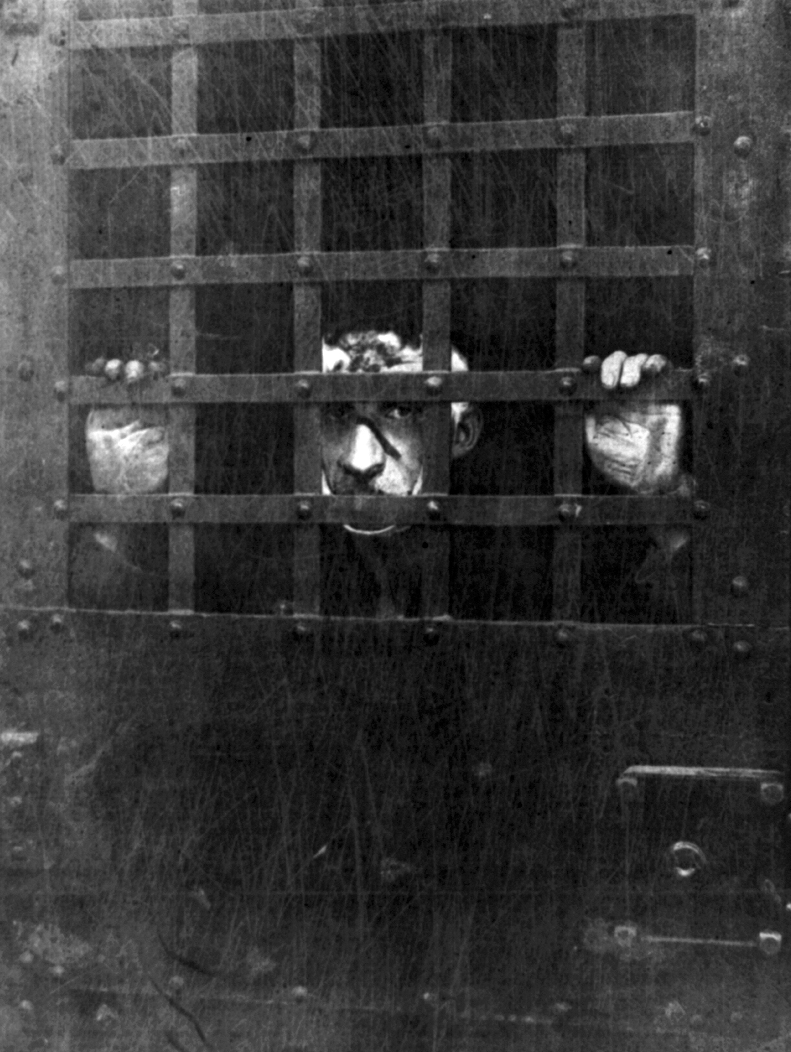

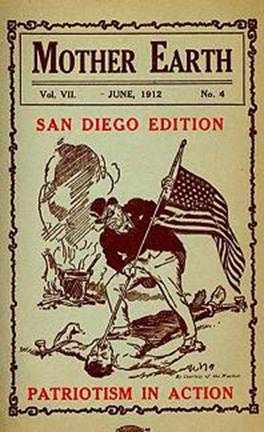

| McKinley assassination Further information: Assassination of William McKinley  Leon Czolgosz insisted that Goldman had not guided his plan to assassinate US President William McKinley, but she was arrested and held for two weeks. On September 6, 1901, Leon Czolgosz, an unemployed factory worker and anarchist,[68] shot US President William McKinley twice during a public speaking event in Buffalo, New York. McKinley was hit in the breastbone and stomach, and died eight days later.[69] Czolgosz was arrested, and interrogated around the clock. During interrogation he claimed to be an anarchist and said he had been inspired to act after attending a speech by Goldman. The authorities used this as a pretext to charge Goldman with planning McKinley's assassination. They tracked her to the residence in Chicago she shared with Havel, as well as with Mary and Abe Isaak, an anarchist couple and their family.[70] Goldman was arrested, along with Isaak, Havel, and ten other anarchists.[71] Earlier, Czolgosz had tried but failed to become friends with Goldman and her companions. During a talk in Cleveland, Czolgosz had approached Goldman and asked her advice on which books he should read. In July 1901, he had appeared at the Isaak house, asking a series of unusual questions. They assumed he was an infiltrator, like a number of police agents sent to spy on radical groups. They had remained distant from him, and Abe Isaak sent a notice to associates warning of "another spy".[72] Although Czolgosz repeatedly denied Goldman's involvement, the police held her in close custody, subjecting her to what she called the "third degree".[73] She explained her housemates' distrust of Czolgosz, and the police finally recognized that she had not had any significant contact with the attacker. No evidence was found linking Goldman to the attack, and she was released after two weeks of detention. Before McKinley died, Goldman offered to provide nursing care, referring to him as "merely a human being".[74] Czolgosz, despite considerable evidence of mental illness, was convicted of murder and executed.[75] Throughout her detention and after her release, Goldman steadfastly refused to condemn Czolgosz's actions, standing virtually alone in doing so. Friends and supporters—including Berkman—urged her to quit his cause. But Goldman defended Czolgosz as a "supersensitive being" and chastised other anarchists for abandoning him.[76] She was vilified in the press as the "high priestess of anarchy",[77] while many newspapers declared the anarchist movement responsible for the murder.[78] In the wake of these events, socialism gained support over anarchism among US radicals. McKinley's successor, Theodore Roosevelt, declared his intent to crack down "not only against anarchists, but against all active and passive sympathizers with anarchists".[79] Mother Earth and Berkman's release Main article: Mother Earth (magazine) After Czolgosz was executed, Goldman withdrew from society and, from 1903 to 1913, lived at 208–210 East 13th Street, New York City.[80] Scorned by her fellow anarchists, vilified by the press, and separated from her love, Berkman, she retreated into anonymity and nursing. "It was bitter and hard to face life anew," she wrote later.[81] Using the name E. G. Smith, she left public life and took on a series of private nursing jobs while suffering from severe depression.[82] The US Congress' passage of the Anarchist Exclusion Act (1903) stirred a new wave of oppositional activism, pulling Goldman back into the movement. A coalition of people and organizations across the left end of the political spectrum opposed the law on grounds that it violated freedom of speech, and she had the nation's ear once again.[83] After an English anarchist named John Turner was arrested under the Anarchist Exclusion Act and threatened with deportation, Goldman joined forces with the Free Speech League to champion his cause.[84] The league enlisted the aid of noted attorneys Clarence Darrow and Edgar Lee Masters, who took Turner's case to the US Supreme Court. Although Turner and the League lost, Goldman considered it a victory of propaganda.[85] She had returned to anarchist activism, but it was taking its toll on her. "I never felt so weighed down," she wrote to Berkman. "I fear I am forever doomed to remain public property and to have my life worn out through the care for the lives of others."[86] In 1906, Goldman decided to start a publication, "a place of expression for the young idealists in arts and letters".[87] Mother Earth was staffed by a cadre of radical activists, including Hippolyte Havel, Max Baginski, and Leonard Abbott. In addition to publishing original works by its editors and anarchists around the world, Mother Earth reprinted selections from a variety of writers. These included the French philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, and British writer Mary Wollstonecraft. Goldman wrote frequently about anarchism, politics, labor issues, atheism, sexuality, and feminism, and was the first editor of the magazine.[88][89]  Goldman's Mother Earth magazine became a home to radical activists and literary free thinkers around the US. On May 18 of the same year, Alexander Berkman was released from prison. Carrying a bouquet of roses, Goldman met him on the train platform and found herself "seized by terror and pity"[90] as she beheld his gaunt, pale form. Neither was able to speak; they returned to her home in silence. For weeks, he struggled to readjust to life on the outside: An abortive speaking tour ended in failure, and in Cleveland he purchased a revolver with the intent of killing himself.[91][92] Upon returning to New York, he learned that Goldman had been arrested with a group of activists meeting to reflect on Czolgosz. Invigorated anew by this violation of freedom of assembly, he declared, "My resurrection has come!"[93] and set about securing their release.[94] Berkman took the helm of Mother Earth in 1907, while Goldman toured the country to raise funds to keep it operating. Editing the magazine was a revitalizing experience for Berkman. But his relationship with Goldman faltered, and he had an affair with a 15-year-old anarchist named Becky Edelsohn. Goldman was pained by his rejection of her but considered it a consequence of his prison experience.[95] Later that year she served as a delegate from the US to the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam. Anarchists and syndicalists from around the world gathered to sort out the tension between the two ideologies, but no decisive agreement was reached. Goldman returned to the US and continued speaking to large audiences.[96] |

マッキンリー暗殺 さらに詳しい情報 ウィリアム・マッキンリー暗殺  レオン・チョルゴシュが、ゴールドマンはウィリアム・マッキンリー米大統領暗殺計画を誘導したのではないと主張したが、彼女は逮捕され、2週間拘留された。 1901年9月6日、失業中の工場労働者で無政府主義者のレオン・チョルゴシュ[68]は、ニューヨーク州バッファローでの演説イベント中にウィリアム・ マッキンリー米大統領を2発撃った。マッキンリーは胸骨と胃を撃たれ、8日後に死亡した[69]。取り調べ中、彼はアナーキストであると主張し、ゴールド マンの演説に出席した後に行動を起こす気になったと語った。当局はこれを口実に、ゴールドマンをマッキンリー暗殺計画で告発した。当局はゴールドマンをハ ベルと同居していたシカゴの邸宅まで追跡し、さらにメアリーとエイブ・イザークというアナーキスト夫婦とその家族まで追跡した[70]。ゴールドマンはイ ザーク、ハベル、その他10人のアナーキストとともに逮捕された[71]。 それ以前、ツォルゴシュはゴールドマンとその仲間たちと友達になろうとしたが失敗していた。クリーブランドでの講演の際、ゾルゴシュはゴールドマンに近づ き、どの本を読むべきかアドバイスを求めた。1901年7月、彼はアイザックの家に現れ、一連の変わった質問をした。彼らは、彼が急進派グループのスパイ として送り込まれた多くの警察諜報員のような潜入者だと考えた。彼らは彼と距離を置いたままであり、エイブ・イザークは「もう一人のスパイ」であることを 警告する通知を関係者に送った[72]。 ゾルゴシュはゴールドマンの関与を繰り返し否定したが、警察は彼女を厳重に拘束し、彼女が「三等兵」と呼ぶ拷問を加えた[73]。彼女は同居人がゾルゴ シュに不信感を抱いていることを説明し、警察は最終的に彼女が襲撃犯と重要な接触を持っていなかったことを認めた。ゴールドマンと襲撃を結びつける証拠は 見つからず、彼女は2週間の拘留後に釈放された。マッキンリーが亡くなる前、ゴールドマンは彼を「単なる人間」と呼んで看護を提供することを申し出た [74]。ゾルゴシュは、精神病の証拠がかなりあったにもかかわらず、殺人罪で有罪判決を受け、処刑された[75]。 勾留中も釈放後も、ゴールドマンは断固としてゾルゴシュの行動を非難することを拒否し、事実上一人でそうしていた。バークマンを含む友人や支持者たちは、 彼女に彼の大義をやめるよう促した。しかし、ゴールドマンは「超敏感な存在」としてゾルゴシュを擁護し、彼を見捨てた他のアナーキストを非難した [76]。 彼女は「アナーキーの高僧」としてマスコミで中傷され[77]、多くの新聞はアナーキスト運動が殺人の責任があると断言した[78]。 これらの事件をきっかけに、アメリカの急進主義者の間ではアナーキズムよりも社会主義が支持されるようになった。マッキンリーの後継者であるセオドア・ ルーズベルトは、「無政府主義者だけでなく、無政府主義者と積極的・消極的な同調者すべてを取り締まる」と宣言した[79]。 マザー・アースとバークマンの釈放 主な記事 マザーアース(雑誌) アナーキスト仲間から蔑まれ、マスコミから中傷され、愛するバークマンと離れ離れになった彼女は、匿名と看護の世界に引きこもった。「人生と新たに向き合うのは苦しく、つらかった」と彼女は後に書いている[81]。 E.G.スミスという名前を使って、彼女は公の場から離れ、重度のうつ病に苦しみながら、個人的な看護の仕事を次々と引き受けた[82]。 アメリカ議会がアナキスト排斥法(1903年)を可決したことで、反対運動の新たな波が巻き起こり、ゴールドマンは運動に引き戻された。この法律は言論の 自由を侵害するという理由で、政治的スペクトルの左端にわたる人々や組織の連合が反対し、ゴールドマンは再び国民の耳目を集めるようになった[83]。 ジョン・ターナーというイギリスの無政府主義者が無政府主義者排斥法に基づいて逮捕され、国外追放の危機にさらされた後、ゴールドマンは言論の自由連盟と 手を組み、彼の大義を擁護した[84]。同連盟は著名な弁護士クラレンス・ダロウとエドガー・リー・マスターズの助力を得て、ターナーの裁判を連邦最高裁 判所に持ち込んだ。ターナーとリーグは敗れたが、ゴールドマンはこれをプロパガンダの勝利と考えた[85]。「これほど気が重くなったことはありません。 「私は永遠に公共の財産であり続け、他人の命を気遣うことで自分の命をすり減らす運命にあるのではないかと恐れています」[86]。 1906年、ゴールドマンは「芸術と文学における若い理想主義者のための表現の場」である出版物の創刊を決意する。編集者や世界中のアナーキストによるオ リジナル作品の出版に加え、『マザー・アース』はさまざまな作家の作品を再版した。フランスの哲学者ピエール=ジョゼフ・プルードン、ロシアのアナキス ト、ピーター・クロポトキン、ドイツの哲学者フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、イギリスの作家メアリー・ウルストンクラフトなどである。ゴールドマンはアナーキズ ム、政治、労働問題、無神論、セクシュアリティ、フェミニズムについて頻繁に執筆し、雑誌の初代編集長を務めた[88][89]。  ゴールドマンの『マザー・アース』誌は、アメリカ中の急進的な活動家や文学的な自由思想家たちの拠点となった。 同年5月18日、アレクサンダー・バークマンが出所。薔薇の花束を持ったゴールドマンは駅のホームで彼に会い、やせ細った青白い彼の姿を見て「恐怖と憐れ みにとらわれた」[90]。二人とも言葉を発することができず、沈黙のまま彼女の家に戻った。数週間、彼は外の生活に適応しようともがいた: 講演ツアーは失敗に終わり、クリーブランドでは自殺するつもりでリボルバーを購入した[91][92]。ニューヨークに戻ると、ゴールドマンがゾルゴシュ について考えるために集まった活動家グループとともに逮捕されたことを知った。この集会の自由の侵害によって新たな活力を得た彼は、「私の復活が来た!」 [93]と宣言し、彼らの釈放の確保に乗り出した[94]。 1907年、バークマンが『マザー・アース』の編集長に就任する一方、ゴールドマンは『マザー・アース』を運営し続けるための資金集めのために全国を回っ た。雑誌の編集は、バークマンにとって活気を取り戻す経験となった。しかし、ゴールドマンとの関係は悪化し、彼はベッキー・エーデルソーンという15歳の アナーキストと関係を持った。ゴールドマンは、彼が彼女を拒絶したことに心を痛めたが、それは彼の刑務所での経験の結果だと考えた[95]。その年の暮 れ、彼女はアメリカからアムステルダム国際アナキスト会議の代表を務めた。世界中からアナキストとシンジカリストが集まり、2つのイデオロギーの間の緊張 を整理しようとしたが、決定的な合意には至らなかった。ゴールドマンはアメリカに戻り、多くの聴衆を前に講演を続けた[96]。 |

| Reitman, essays, and birth control For the next ten years, Goldman traveled around the country nonstop, delivering lectures and agitating for anarchism. The coalitions formed in opposition to the Anarchist Exclusion Act had given her an appreciation for reaching out to those of other political positions. When the US Justice Department sent spies to observe, they reported the meetings as "packed".[97] Writers, journalists, artists, judges, and workers from across the spectrum spoke of her "magnetic power", her "convincing presence", her "force, eloquence, and fire".[98]  Goldman joined Margaret Sanger in crusading for women's access to birth control; both women were arrested for violating the Comstock Law. In the spring of 1908, Goldman met and fell in love with Ben Reitman, the so-called "Hobo doctor". Having grown up in Chicago's Tenderloin District, Reitman spent several years as a drifter before earning a medical degree from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Chicago. As a doctor, he treated people suffering from poverty and illness, particularly venereal diseases. He and Goldman began an affair. They shared a commitment to free love and Reitman took a variety of lovers, but Goldman did not. She tried to reconcile her feelings of jealousy with a belief in freedom of the heart but found it difficult.[99] Two years later, Goldman began feeling frustrated with lecture audiences. She yearned to "reach the few who really want to learn, rather than the many who come to be amused".[100] She collected a series of speeches and items she had written for Mother Earth and published a book titled Anarchism and Other Essays. Covering a wide variety of topics, Goldman tried to represent "the mental and soul struggles of twenty-one years".[100] When Margaret Sanger, an advocate of access to contraception, coined the term "birth control" and disseminated information about various methods in the June 1914 issue of her magazine The Woman Rebel, she received aggressive support from Goldman. The latter had already been active in efforts to increase birth control access for several years. In 1916, Goldman was arrested for giving lessons in public on how to use contraceptives.[101] Sanger, too, was arrested under the Comstock Law, which prohibited the dissemination of "obscene, lewd, or lascivious articles", which authorities defined as including information relating to birth control.[102] Although they later split from Sanger over charges of insufficient support, Goldman and Reitman distributed copies of Sanger's pamphlet Family Limitation (along with a similar essay of Reitman's). In 1915 Goldman conducted a nationwide speaking tour, in part to raise awareness about contraception options. Although the nation's attitude toward the topic seemed to be liberalizing, Goldman was arrested on February 11, 1916, as she was about to give another public lecture.[103] Goldman was charged with violating the Comstock Law. Refusing to pay a $100 fine, she spent two weeks in a prison workhouse, which she saw as an "opportunity" to reconnect with those rejected by society.[104] World War I Although President Woodrow Wilson was re-elected in 1916 under the slogan "He kept us out of the war", at the start of his second term, he announced that Germany's continued deployment of unrestricted submarine warfare was sufficient cause for the US to enter the Great War. Shortly afterward, Congress passed the Selective Service Act of 1917, which required all males aged 21–30 to register for military conscription. Goldman saw the decision as an exercise in militarist aggression, driven by capitalism. She declared in Mother Earth her intent to resist conscription, and to oppose US involvement in the war.[105][106]  Goldman on a streetcar in 1917, perhaps during a strike or demonstration To this end, she and Berkman organized the No Conscription League of New York, which proclaimed: "We oppose conscription because we are internationalists, antimilitarists, and opposed to all wars waged by capitalistic governments."[107] The group became a vanguard for anti-draft activism, and chapters began to appear in other cities. When police began raiding the group's public events to find young men who had not registered for the draft, Goldman and others focused their efforts on distributing pamphlets and other writings.[105] In the midst of the nation's patriotic fervor, many elements of the political left refused to support the League's efforts. The Women's Peace Party, for example, ceased its opposition to the war once the US entered it. The Socialist Party of America took an official stance against US involvement but supported Wilson in most of his activities.[108] On June 15, 1917, Goldman and Berkman were arrested during a raid of their offices, in which authorities seized "a wagon load of anarchist records and propaganda".[109] The New York Times reported that Goldman asked to change into a more appropriate outfit, and emerged in a gown of "royal purple".[109][110] The pair were charged with conspiracy to "induce persons not to register"[111] under the newly enacted Espionage Act,[112] and were held on US$25,000 bail each. Defending herself and Berkman during their trial, Goldman invoked the First Amendment, asking how the government could claim to fight for democracy abroad while suppressing free speech at home:[113] We say that if America has entered the war to make the world safe for democracy, she must first make democracy safe in America. How else is the world to take America seriously, when democracy at home is daily being outraged, free speech suppressed, peaceable assemblies broken up by overbearing and brutal gangsters in uniform; when free press is curtailed and every independent opinion gagged? Verily, poor as we are in democracy, how can we give of it to the world? The jury found Goldman and Berkman guilty. Judge Julius Marshuetz Mayer imposed the maximum sentence: two years' imprisonment, a $10,000 fine each, and the possibility of deportation after their release from prison. As she was transported to Missouri State Penitentiary, Goldman wrote to a friend: "Two years imprisonment for having made an uncompromising stand for one's ideal. Why that is a small price."[114] In prison, she was assigned to work as a seamstress, under the eye of a "miserable gutter-snipe of a 21-year-old boy paid to get results".[115] She met the socialist Kate Richards O'Hare, who had also been imprisoned under the Espionage Act. Although they differed on political strategy—O'Hare believed in voting to achieve state power—the two women came together to agitate for better conditions among prisoners.[116] Goldman also met and became friends with Gabriella Segata Antolini, an anarchist and follower of Luigi Galleani. Antolini had been arrested transporting a satchel filled with dynamite on a Chicago-bound train. She had refused to cooperate with authorities and was sent to prison for 14 months. Working together to make life better for the other inmates, the three women became known as "The Trinity". Goldman was released on September 27, 1919.[117] |

ライトマン、エッセイ、避妊具 その後10年間、ゴールドマンは講演やアナーキズムのアジテーションのために、ひっきりなしに全国を飛び回った。無政府主義者排斥法に反対して結成された 連合は、彼女に他の政治的立場の人々に働きかけることへの理解を与えた。米国司法省がスパイを派遣して視察させたとき、彼らは会合が「満員」であったと報 告した[97]。あらゆる分野の作家、ジャーナリスト、芸術家、裁判官、労働者たちが、彼女の「磁力」、「説得力のある存在」、「力、雄弁、炎」について 語った[98]。  ゴールドマンはマーガレット・サンガーとともに、女性が避妊具を使えるようにするための運動を展開し、二人ともコムストック法違反で逮捕された。 1908年の春、ゴールドマンはいわゆる「ホーボー・ドクター」であるベン・ライトマンと出会い、恋に落ちた。シカゴのテンダーロイン地区で育ったライト マンは、シカゴ医師外科大学で医学の学位を取得するまでの数年間を流れ者として過ごした。医師として貧困や病気、特に性病に苦しむ人々を治療した。彼と ゴールドマンは不倫関係を始めた。二人は自由恋愛を信条とし、ライトマンはさまざまな恋人をつくったが、ゴールドマンはつくらなかった。彼女は嫉妬の感情 と心の自由への信念を調和させようとしたが、難しいことに気づいた[99]。 2年後、ゴールドマンは講演会の聴衆に不満を感じ始めた。彼女は、「面白半分に来る多くの聴衆ではなく、本当に学びたいと思っている少数の聴衆に届けた い」と切望していた[100]。彼女は、一連の講演や『マザー・アース』のために書いた項目を集め、『アナキズムとその他のエッセイ』という本を出版し た。さまざまなトピックを取り上げ、ゴールドマンは「21年間の精神と魂の闘い」を表現しようとした[100]。 避妊へのアクセスを提唱していたマーガレット・サンガーが、自身の雑誌『The Woman Rebel』の1914年6月号で「避妊」という言葉を作り、さまざまな方法についての情報を広めたとき、彼女はゴールドマンから積極的な支援を受けた。 ゴールドマンはすでに数年前から避妊の普及に積極的に取り組んでいた。1916年、ゴールドマンは公衆の面前で避妊具の使い方を教えたことで逮捕され [101]、サンガーも「わいせつ、みだら、淫らな記事」の流布を禁止するコムストック法で逮捕されたが、当局の定義では避妊具に関する情報も含まれてい た[102]。 のちに支援不足を理由にサンガーから離れたが、ゴールドマンとライトマンはサンガーの小冊子『家族の制限』(ライトマンの同様のエッセイとともに)を配布 した。1915年、ゴールドマンは避妊の選択肢についての認識を高めるためもあって、全国的な講演ツアーを行った。このテーマに対する国の態度は自由化し ているように思われたが、ゴールドマンは1916年2月11日、別の公開講演を行おうとしていたところを逮捕された[103]。100ドルの罰金の支払い を拒否した彼女は、社会から拒絶された人々と再びつながる「機会」と考え、刑務所の作業小屋で2週間を過ごした[104]。 第一次世界大戦 ウッドロー・ウィルソン大統領は1916年、「彼は我々を戦争から遠ざけてくれた」というスローガンを掲げて再選されたが、2期目の初めに、ドイツが無制 限潜水艦戦を展開し続けていることが、アメリカが第一次世界大戦に参戦する十分な理由であると発表した。その直後、議会は1917年選択服務法を可決し、 21歳から30歳までのすべての男性に徴兵登録を義務付けた。ゴールドマンは、この決定を資本主義による軍国主義的侵略の実践と見なした。彼女は『母なる 大地』で徴兵制に抵抗し、アメリカの戦争への関与に反対する意思を表明した[105][106]。  1917年、おそらくストライキかデモの最中、路面電車に乗ったゴールドマン この目的のために、彼女はバークマンとともにニューヨーク徴兵反対同盟を組織し、こう宣言した: 「私たちが徴兵制に反対するのは、私たちが国際主義者であり、反軍国主義者であり、資本主義政府によって行われるすべての戦争に反対しているからです」 [107] 。警察が徴兵登録をしていない若者を見つけるために、このグループの公的なイベントに踏み込むようになると、ゴールドマンと他の人々はパンフレットやその 他の著作物を配布することに力を注いだ[105]。たとえば婦人平和党は、アメリカが戦争に突入すると戦争への反対をやめた。アメリカ社会党は公式にはア メリカの参戦に反対する立場をとっていたが、ウィルソンの活動のほとんどを支持していた[108]。 1917年6月15日、ゴールドマンとバークマンは事務所を襲撃された際に逮捕され、当局は「無政府主義者の記録とプロパガンダを荷馬車に積んで」押収し た[109]。 ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、ゴールドマンがより適切な服装に着替えるよう求め、「王家の紫色」のガウンを着て現れたと報じた[109][110]。二人 は新しく制定されたスパイ活動法の下で「登録しないように人を誘導する」[111]共謀罪で起訴され、それぞれ25,000米ドルの保釈金で拘束された [112]。公判中、ゴールドマンは自身とバークマンを擁護し、憲法修正第1条を持ち出して、政府が国内で言論の自由を抑圧しながら、どうして海外で民主 主義のために戦うと主張できるのかと問いかけた[113]。 アメリカが世界を民主主義のために安全にするために戦争に参戦したのであれば、まずアメリカ国内で民主主義を安全にしなければならない。自国の民主主義が 日々蹂躙され、言論の自由が抑圧され、制服を着た威圧的で残忍なギャングたちによって平和的な集会が壊され、報道の自由が抑制され、あらゆる独立した意見 が封じ込められるとき、世界は他にどうやってアメリカを真剣に受け止めればいいのだろうか。本当に、民主主義が貧弱な私たちは、どうやって世界に民主主義 を提供できるのだろうか? 陪審員はゴールドマンとバークマンを有罪とした。ジュリアス・マーシュエッツ・メイヤー判事は、最高刑である禁固2年、罰金各1万ドル、出所後の国外追放 の可能性を課した。ミズーリ州立刑務所に移送されるとき、ゴールドマンは友人に手紙を書いた: 「自分の理想のために妥協しない姿勢を貫いたのに、2年の禁固刑。それは安いものだ」[114]。 刑務所の中で彼女は、「結果を出すために給料をもらっている21歳の少年のみすぼらしいガタースナイプ」[115]の目の下で、お針子として働くことに なった。二人は政治的な戦略で意見の相違があったが、オヘアは国家権力を獲得するために投票することを信じており、二人の女性は囚人たちの待遇改善を求め て共に活動するようになった[116]。ゴールドマンはまた、ルイジ・ガレアーニの信奉者でアナーキストであったガブリエラ・セガタ・アントリーニと出会 い、友人となった。アントリーニは、シカゴ行きの列車でダイナマイトを詰めたかばんを運んでいたところを逮捕された。彼女は当局への協力を拒否し、14ヵ 月間刑務所に送られた。他の受刑者の生活を改善するために協力し合い、3人の女性は「三位一体」として知られるようになった。ゴールドマンは1919年9 月27日に釈放された[117]。 |

Deportation Goldman's deportation photo, 1919 Goldman's deportation photo, 1919Goldman and Berkman were released from prison during the United States' Red Scare of 1919–20, when public anxiety about wartime pro-German activities had expanded into a pervasive fear of Bolshevism and the prospect of an imminent radical revolution. It was a time of social unrest due to union organizing strikes and actions by activist immigrants. Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer and J. Edgar Hoover, head of the US Department of Justice's General Intelligence Division (now the FBI), were intent on using the Anarchist Exclusion Act and its 1918 expansion to deport any non-citizens they could identify as advocates of anarchy or revolution. "Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman," Hoover wrote while they were in prison, "are, beyond doubt, two of the most dangerous anarchists in this country and return to the community will result in undue harm."[118] At her deportation hearing on October 27, 1919, Goldman refused to answer questions about her beliefs, on the grounds that her American citizenship invalidated any attempt to deport her under the Anarchist Exclusion Act, which could be enforced only against non-citizens of the US. She presented a written statement instead: "Today so-called aliens are deported. Tomorrow native Americans will be banished. Already some patrioteers are suggesting that native American sons to whom democracy is a sacred ideal should be exiled."[119] Louis Post at the Department of Labor, which had ultimate authority over deportation decisions, determined that the revocation of her husband Kershner's American citizenship in 1908 after his conviction had revoked hers as well. After initially promising a court fight,[120] Goldman decided not to appeal his ruling.[121] The Labor Department included Goldman and Berkman among 249 aliens it deported en masse, mostly people with only vague associations with radical groups, who had been swept up in government raids in November.[122] Buford, a ship the press nicknamed the "Soviet Ark", sailed from the Army's New York Port of Embarkation on December 21.[123][124] Some 58 enlisted men and four officers provided security on the journey, and pistols were distributed to the crew.[123][125] Most of the press approved enthusiastically. The Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote: "It is hoped and expected that other vessels, larger, more commodious, carrying similar cargoes, will follow in her wake."[126] The ship landed her charges in Hanko, Finland, on Saturday, January 17, 1920.[127] Upon arrival in Finland, authorities there conducted the deportees to the Russian frontier under a flag of truce.[128] Russia  Here, Emma Goldman delivers a eulogy at Peter Kropotkin's funeral procession. Immediately in front of Goldman stands her lifelong comrade Alexander Berkman. Kropotkin's funeral was the occasion of the last great demonstration of anarchists in Moscow—tens of thousands of people poured into the streets to pay their respects. Goldman initially viewed the Bolshevik revolution in a positive light. She wrote in Mother Earth that despite its dependence on Communist government, it represented "the most fundamental, far-reaching and all-embracing principles of human freedom and of economic well-being".[129] By the time she neared Europe, she expressed fears about what was to come. She was worried about the ongoing Russian Civil War and the possibility of being seized by anti-Bolshevik forces. The state, anti-capitalist though it was, also posed a threat. "I could never in my life work within the confines of the State," she wrote to her niece, "Bolshevist or otherwise."[130] She quickly discovered that her fears were justified. Days after returning to Petrograd (Saint Petersburg), she was shocked to hear a party official refer to free speech as a "bourgeois superstition".[131] As she and Berkman traveled around the country, they found repression, mismanagement, and corruption[132] instead of the equality and worker empowerment they had dreamed of. Those who questioned the government were demonized as counter-revolutionaries,[132] and workers labored under severe conditions.[132] They met with Vladimir Lenin, who assured them that government suppression of press liberties was justified. He told them: "There can be no free speech in a revolutionary period."[133] Berkman was more willing to forgive the government's actions in the name of "historical necessity", but he eventually joined Goldman in opposing the Soviet state's authority.[134] In March 1921, strikes erupted in Petrograd when workers took to the streets demanding better food rations and more union autonomy. Goldman and Berkman felt a responsibility to support the strikers, stating: "To remain silent now is impossible, even criminal."[135] The unrest spread to the port town of Kronstadt, where the government ordered a military response to suppress striking soldiers and sailors. In the Kronstadt rebellion, approximately 1,000 rebelling sailors and soldiers were killed and two thousand more were arrested; many were later executed. In the wake of these events, Goldman and Berkman decided there was no future in the country for them. "More and more", she wrote, "we have come to the conclusion that we can do nothing here. And as we can not keep up a life of inactivity much longer we have decided to leave."[136] In December 1921, they left the country and went to the Latvian capital city of Riga. The US commissioner in that city wired officials in Washington DC, who began requesting information from other governments about the couple's activities. After a short trip to Stockholm, they moved to Berlin for several years; during this time Goldman agreed to write a series of articles about her time in Russia for Joseph Pulitzer's newspaper, the New York World. These were later collected and published in book form as My Disillusionment in Russia (1923) and My Further Disillusionment in Russia (1924). The publishers added these titles to attract attention; Goldman protested, albeit in vain.[137] |

国外追放 ゴールドマンの国外追放写真(1919年 ゴールドマンの国外追放写真(1919年ゴールドマンとバークマンが刑務所から釈放されたのは、1919年から20年にかけてのアメリカの「赤狩り」の時期であった。戦時中の親ドイツ活動に対す る国民の不安が、ボルシェヴィズムへの恐怖と差し迫った急進革命の予感へと拡大した時期であった。労働組合の組織化ストライキや、活動的な移民による行動 によって社会不安が高まっていた時期である。アレクサンダー・ミッチェル・パーマー司法長官とJ・エドガー・フーバー米司法省総合情報部(現FBI)長官 は、無政府主義者排斥法とその1918年の拡張を利用して、無政府主義や革命の支持者であると特定できた非市民を国外追放することに躍起になっていた。 「エマ・ゴールドマンとアレクサンダー・バークマンは、間違いなく、この国で最も危険なアナキストであり、社会復帰は過度の害をもたらすだろう」 [118]。 1919年10月27日に行われた国外追放の審問で、ゴールドマンは自分の信条についての質問に答えることを拒否した。その理由は、彼女のアメリカ市民権 によって、アメリカの非市民に対してのみ施行することができるアナキスト排斥法に基づいて彼女を国外追放しようとする試みが無効になるからであった。彼女 は代わりに書面を提出した: 「今日、いわゆる外国人は強制送還された。明日はネイティブ・アメリカンが追放されるでしょう。すでに何人かの愛国主義者は、民主主義が神聖な理想である ネイティブ・アメリカンの息子たちを追放すべきだと提案しています」[119]。強制送還の決定について最終的な権限を持つ労働省のルイス・ポストは、 1908年に夫カーシュナーが有罪判決を受けた後にアメリカ市民権を剥奪されたことで、彼女の市民権も剥奪されたと判断した。当初は法廷闘争を約束してい た[120]が、ゴールドマンは判決を不服とすることを決めた[121]。 労働省はゴールドマンとバークマンを249人の外国人の中に含め、一斉に国外退去処分にした。報道陣が「ソビエトの方舟」とあだ名したビュフォード号は、 12月21日に陸軍のニューヨーク港から出航した[123][124]。58人の下士官と4人の将校が船旅の警備に当たり、乗組員にはピストルが配られた [123][125]。クリーブランド・プレーン・ディーラー紙(The Cleveland Plain Dealer)は、「より大型で、より日用品が豊富で、同様の積荷を積んだ他の船舶が、この船の後に続くことが期待される」と書いている[126]。 ロシア  ピーター・クロポトキンの葬列で弔辞を述べるエマ・ゴールドマン。ゴールドマンのすぐ前には彼女の生涯の同志であるアレクサンダー・バークマンが立っている。クロポトキンの葬儀は、モスクワにおけるアナキストの最後の大規模なデモの場となった。 ゴールドマンは当初、ボリシェヴィキ革命を肯定的にとらえていた。彼女は『母なる大地』の中で、共産主義政府に依存していたにもかかわらず、それは「人間 の自由と経済的幸福の最も基本的で、広範囲に及ぶ、包括的な原則」を表していると書いている[129]。彼女は、進行中のロシア内戦と、反ボリシェヴィキ 勢力に占領される可能性を心配していた。反資本主義とはいえ、国家もまた脅威であった。「ボリシェヴィキであろうとそうでなかろうと、私は国家の枠内で働 くことは生涯できませんでした」と彼女は姪に手紙を書いている[130]。 彼女はすぐに、自分の恐れが正当なものであったことを知った。ペトログラード(サンクトペテルブルク)に戻った数日後、彼女は党幹部が言論の自由を「ブル ジョアの迷信」と呼ぶのを聞いて衝撃を受けた。政府に疑問を呈する者は反革命分子として悪者にされ[132]、労働者は過酷な条件の下で労働していた [132]。彼らはウラジーミル・レーニンに会い、彼は政府が報道の自由を抑圧することは正当化されると断言した。彼は彼らに言った: 「ベルクマンは「歴史的必要性」という名目で政府の行動を許そうとしたが、最終的にはゴールドマンとともにソビエト国家の権威に反対した[134]。 1921年3月、ペトログラードでストライキが勃発し、労働者たちは食料配給の改善と組合の自治権拡大を求めて街頭に出た。ゴールドマンとバークマンはス トライキ参加者を支援する責任を感じ、こう述べた: 「今黙っていることは不可能であり、犯罪的ですらある」[135] 不安は港町クロンシュタットにまで広がり、政府はストライキを起こした兵士や船員を鎮圧するために軍事的対応を命じた。クロンシュタットの反乱では、反乱 を起こした約1,000人の水兵と兵士が殺され、さらに2,000人が逮捕された。これらの事件をきっかけに、ゴールドマンとバークマンは、この国に自分 たちの未来はないと決心した。「ますます」、「私たちはここで何もできないという結論に達した。そして、これ以上長く不活発な生活を続けることはできない ので、私たちは去ることにした」[136]。 1921年12月、彼らは国を出て、ラトビアの首都リガに向かった。同市の米国総監はワシントンDCの当局者に電報を打ち、同政府は夫妻の活動について他 国政府に情報提供を要請し始めた。ストックホルムへの短い旅行の後、二人はベルリンに数年間移り住んだ。この間、ゴールドマンは、ジョセフ・ピューリッ ツァーの新聞『ニューヨーク・ワールド』にロシアでの生活について一連の記事を書くことに同意した。これらは後に、『ロシアにおける私の幻滅』(1923 年)、『ロシアにおける私のさらなる幻滅』(1924年)として書籍化された。出版社は注目を集めるためにこれらのタイトルを付けたが、ゴールドマンは無 駄ではあったが抗議した[137]。 |

| England, Canada, and France Goldman found it difficult to acclimate to the German leftist community in Berlin. Communists despised her outspokenness about Soviet repression; liberals derided her radicalism. While Berkman remained in Berlin helping Russian exiles, Goldman moved to London in September 1924. Upon her arrival, the novelist Rebecca West arranged a reception dinner for her, attended by philosopher Bertrand Russell, novelist H. G. Wells, and more than 200 other guests. When she spoke of her dissatisfaction with the Soviet government, the audience was shocked. Some left the gathering; others berated her for prematurely criticizing the Communist experiment.[138] Later, in a letter, Russell declined to support her efforts at systemic change in the Soviet Union and ridiculed her anarchist idealism.[139]  The 1927 executions of Italian anarchists Nicola Sacco (right) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were troubling for Goldman, then living alone in Canada. In 1925, the spectre of deportation loomed again, but James Colton, a Scottish anarchist Goldman had first met in Glasgow whilst on a speaking tour in 1895,[140] had offered to marry her and provide British citizenship. Although they were only distant acquaintances, she accepted and they were married on June 27, 1925, Goldman's 58th birthday. Her new status gave her peace of mind and allowed her to travel to France and Canada.[141] The pair sporadically exchanged correspondence until Colton's death in 1936.[142][143] Life in London was stressful for Goldman; she wrote to Berkman: "I am awfully tired and so lonely and heartsick. It is a dreadful feeling to come back here from lectures and find not a kindred soul, no one who cares whether one is dead or alive."[144] She worked on analytical studies of drama, expanding on the work she had published in 1914. But the audiences were "awful," and she never finished her second book on the subject.[145] Goldman traveled to Canada in 1927, just in time to receive news of the impending executions of Italian anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in Boston. Angered by the many irregularities of the case, she saw it as another travesty of justice in the US. She longed to join the mass demonstrations in Boston; memories of the Haymarket affair overwhelmed her, compounded by her isolation. "Then," she wrote, "I had my life before me to take up the cause for those killed. Now I have nothing."[146][147] In 1928, she began writing her autobiography, with the support of a group of American admirers, including journalist H. L. Mencken, poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, novelist Theodore Dreiser and art collector Peggy Guggenheim, who raised $4,000 for her.[148] She secured a cottage in the French coastal city of Saint-Tropez and spent two years recounting her life. Berkman offered sharply critical feedback, which she eventually incorporated at the price of a strain on their relationship.[149] Goldman intended the book, Living My Life, as a single volume for a price the working class could afford (she urged no more than $5.00); her publisher Alfred A. Knopf released it as two volumes sold together for $7.50. Goldman was furious, but unable to force a change. Due in large part to the Great Depression, sales were sluggish despite keen interest from libraries around the US.[150] Critical reviews were generally enthusiastic; The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Saturday Review of Literature all listed it as one of the year's top non-fiction books.[151] In 1933, Goldman received permission to lecture in the United States under the condition that she speak only about drama and her autobiography—but not current political events. She returned to New York on February 2, 1934, to generally positive press coverage—except from Communist publications. Soon she was surrounded by admirers and friends, besieged with invitations to talks and interviews. Her visa expired in May, and she went to Toronto in order to file another request to visit the US. This second attempt was denied. She stayed in Canada, writing articles for US publications.[152] In February and March 1936, Berkman underwent a pair of prostate gland operations. Recuperating in Nice and cared for by his companion, Emmy Eckstein, he missed Goldman's sixty-seventh birthday in Saint-Tropez in June. She wrote in sadness, but he never read the letter; she received a call in the middle of the night that Berkman was in great distress. She left for Nice immediately but when she arrived that morning, Goldman found that he had shot himself and was in a nearly comatose paralysis. He died later that evening.[153] Spanish Civil War In July 1936, the Spanish Civil War started after an attempted coup d'état by parts of the Spanish Army against the government of the Second Spanish Republic. At the same time, the Spanish anarchists, fighting against the Nationalist forces, started an anarchist revolution. Goldman was invited to Barcelona and in an instant, as she wrote to her niece, "the crushing weight that was pressing down on my heart since Sasha's death left me as by magic".[154] She was welcomed by the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) organizations, and for the first time in her life lived in a community run by and for anarchists, according to true anarchist principles. "In all my life", she wrote later, "I have not met with such warm hospitality, comradeship and solidarity."[155] After touring a series of collectives in the province of Huesca, she told a group of workers: "Your revolution will destroy forever [the notion] that anarchism stands for chaos."[156] She began editing the weekly CNT-FAI Information Bulletin and responded to English-language mail.[157]  Goldman edited the English-language Bulletin of the Anarcho-syndicalist organizations Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) during the Spanish Civil War. Goldman began to worry about the future of Spain's anarchism when the CNT-FAI joined a coalition government in 1937—against the core anarchist principle of abstaining from state structures—and, more distressingly, made repeated concessions to Communist forces in the name of uniting against fascism. In November 1936, she wrote that cooperating with Communists in Spain was "a denial of our comrades in Stalin's concentration camps".[158] The USSR, meanwhile, refused to send weapons to anarchist forces, and disinformation campaigns were being waged against the anarchists across Europe and the US. Her faith in the movement unshaken, Goldman returned to London as an official representative of the CNT-FAI.[159] Delivering lectures and giving interviews, Goldman enthusiastically supported the Spanish anarcho-syndicalists. She wrote regularly for Spain and the World, a biweekly newspaper focusing on the civil war. In May 1937, Communist-led forces attacked anarchist strongholds and broke up agrarian collectives. Newspapers in England and elsewhere accepted the timeline of events offered by the Second Spanish Republic at face value. British journalist George Orwell, present for the crackdown, wrote: "[T]he accounts of the Barcelona riots in May ... beat everything I have ever seen for lying."[160] Goldman returned to Spain in September, but the CNT-FAI appeared to her like people "in a burning house". Worse, anarchists and other radicals around the world refused to support their cause.[161] The Nationalist forces declared victory in Spain just before she returned to London. Frustrated by England's repressive atmosphere—which she called "more fascist than the fascists"[162]—she returned to Canada in 1939. Her service to the anarchist cause in Spain was not forgotten. On her seventieth birthday, the former Secretary-General of the CNT-FAI, Mariano Vázquez, sent a message to her from Paris, praising her for her contributions and naming her as "our spiritual mother". She called it "the most beautiful tribute I have ever received".[163] |

イギリス、カナダ、フランス ゴールドマンは、ベルリンのドイツ人左翼コミュニティに馴染むのが難しいと感じた。共産主義者はソ連の弾圧について率直な彼女の発言を軽蔑し、リベラル派 は彼女の急進主義を嘲笑した。ベルクマンがベルリンに残ってロシアからの亡命者を助けている間、ゴールドマンは1924年9月にロンドンに移った。到着す ると、小説家のレベッカ・ウェストが彼女のためにレセプション・ディナーを用意し、哲学者のバートランド・ラッセル、小説家のH・G・ウェルズら200人 以上の招待客が出席した。彼女がソ連政府への不満を語ったとき、聴衆は衝撃を受けた。その後、ラッセルは手紙の中で、ソビエト連邦の体制変革に向けた彼女 の努力を支持することを拒否し、彼女の無政府主義的理想主義を嘲笑した[139]。  1927年のイタリアのアナーキスト、ニコラ・サッコ(右)とバルトロメオ・ヴァンゼッティの処刑は、当時カナダで一人暮らしをしていたゴールドマンにとって厄介なものだった。 1925年、国外追放の恐怖が再び迫ってきたが、ゴールドマンが1895年に講演旅行中にグラスゴーで初めて会ったスコットランドのアナーキスト、ジェー ムズ・コルトン[140]が彼女と結婚し、イギリスの市民権を提供すると申し出てきた。二人は遠い知人に過ぎなかったが、彼女はそれを受け入れ、ゴールド マンの58歳の誕生日である1925年6月27日に結婚した。1936年にコルトンが亡くなるまで、2人は散発的に文通をした[141][142] [143]。ロンドンでの生活はゴールドマンにとってストレスフルなものであった。講義から帰ってきて、気の合う人がいない、自分が死んでいようが生きて いようが誰も気にかけてくれないというのは、恐ろしい気分です」[144]。彼女は1914年に発表した仕事を発展させ、ドラマの分析的研究に取り組ん だ。しかし聴衆は「ひどい」もので、彼女はこのテーマに関する2冊目の本を完成させることはなかった[145]。 ゴールドマンは1927年にカナダに渡り、ちょうどボストンでイタリアのアナキスト、ニコラ・サッコとバルトロメオ・ヴァンゼッティが処刑されるという知 らせを受けた。この事件の多くの不正に憤慨した彼女は、これがアメリカにおける正義のもうひとつの茶番であると考えた。ボストンでの大規模なデモに参加し たいと切望していたが、ヘイマーケット事件の記憶が彼女を圧倒し、孤立感がさらに強まった。「ヘイマーケット事件の思い出が彼女を圧倒し、孤立した状態に 追い打ちをかけた。今、私には何もない」[146][147]。 1928年、彼女はジャーナリストのH.L.メンケン、詩人のエドナ・セント・ヴィンセント・ミレイ、小説家のセオドア・ドライザー、美術収集家のペ ギー・グッゲンハイムといったアメリカの崇拝者たちの支援を受けて自伝の執筆を開始し、彼女のために4000ドルを集めた[148]。ゴールドマンはこの 本『Living My Life』を労働者階級が買えるような価格(彼女は5ドルを超えないように要求した)で一冊にまとめるつもりだったが、出版社のアルフレッド・A・ノプフ はそれを2冊合わせて7.5ドルで発売した。ゴールドマンは激怒したが、変更を迫ることはできなかった。世界大恐慌の影響もあり、アメリカ中の図書館から 強い関心が寄せられていたにもかかわらず、売り上げは伸び悩んでいた[150]。批評は概して熱狂的で、『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙、『ニューヨー カー』紙、『サタデー・レビュー・オブ・リテラチャー』誌はいずれも、その年のトップ・ノンフィクションの一冊としてこの本を挙げている[151]。 1933年、ゴールドマンはアメリカでの講演許可を得るが、その条件は戯曲と自伝についてのみ話し、政治的な時事問題については話さないというものだっ た。1934年2月2日にニューヨークに戻ったゴールドマンは、共産主義者の出版物を除いて、おおむね好意的に報道された。間もなく、彼女は崇拝者や友人 たちに囲まれ、講演やインタビューの誘いに包囲されるようになった。ビザは5月に失効し、彼女は再度の渡米申請をするためにトロントに向かった。この2度 目の申請は却下された。彼女はカナダに留まり、米国の出版物に記事を書いた[152]。 1936年2月と3月、バークマンは前立腺の手術を受ける。ニースで療養し、同伴者のエミー・エクスタインが世話をしたが、6月にサントロペで行われた ゴールドマンの67歳の誕生日を欠席した。彼女は悲しみをこめて手紙を書いたが、ゴールドマンがその手紙を読むことはなかった。彼女はすぐにニースに向 かったが、その日の朝、ゴールドマンが到着すると、彼は拳銃自殺を図り、ほとんど昏睡状態に近い麻痺状態にあった。彼はその日の夜に亡くなった [153]。 スペイン内戦 1936年7月、スペイン第二共和国政府に対するスペイン軍の一部によるクーデター未遂の後、スペイン内戦が始まった。同時に、スペインの無政府主義者た ちは国民党軍と戦い、無政府主義革命を起こした。ゴールドマンはバルセロナに招かれ、姪に宛てた手紙にあるように、「サーシャの死以来、私の心に圧し掛 かっていた重圧は、一瞬にして魔法のように私のもとを去った」[154]。彼女は全国労働者連盟(CNT)とアナルキスタ・イベリカ連盟(FAI)の組織 に歓迎され、人生で初めて、真のアナーキストの原則に従って、アナーキストによって、アナーキストのために運営されるコミュニティで生活した。「私の人生 の中で、これほど温かいもてなし、同志愛、連帯に出会ったことはなかった」と彼女は後に書いている[155]。ウエスカ県の一連の集会を見学した後、彼女 は労働者のグループに言った: あなた方の革命は、アナーキズムが混沌の象徴であるという[概念を]永遠に破壊するでしょう」[156]。週刊の『CNT-FAI情報誌』の編集を始め、 英語のメールに返信した[157]。  ゴールドマンはスペイン内戦中、アナルコ・サンディカリスト組織であるCNT(Confederación Nacional del Trabajo)とFAI(Federación Anarquista Ibérica)の英語版『Bulletin』を編集していた。 1937年にCNTとFAIが連立政権に参加したとき、ゴールドマンはスペインのアナーキズムの将来を心配し始めた。1936年11月、彼女はスペインの 共産主義者と協力することは「スターリンの強制収容所にいる同志を否定すること」だと書いている[158]。一方、ソ連はアナキスト勢力に武器を送ること を拒否し、ヨーロッパやアメリカ全土でアナキストに対する偽情報キャンペーンが展開されていた。運動への信頼は揺るがず、ゴールドマンはCNT-FAIの 公式代表としてロンドンに戻った[159]。 ゴールドマンは講演やインタビューに応じ、スペインの無政府シンジカリストたちを熱心に支援した。内戦に焦点を当てた隔週刊の新聞『スペインと世界』に定 期的に寄稿。1937年5月、共産主義主導の軍隊がアナキストの拠点を攻撃し、農民集会を解散させた。イギリスやその他の国の新聞は、スペイン第二共和国 が提示した事件の時系列を額面通りに受け入れた。弾圧に立ち会ったイギリスのジャーナリスト、ジョージ・オーウェルは、「5月のバルセロナの暴動に関する 証言は......私がこれまで見てきた嘘の証言に勝るものだった」と書いている[160]。 ゴールドマンは9月にスペインに戻ったが、CNT-FAIは彼女にとって「燃えている家の中にいる」人々のように見えた。さらに悪いことに、世界中のア ナーキストやその他の急進派は彼らの大義を支持することを拒否した[161]。国民党軍は、彼女がロンドンに戻る直前にスペインでの勝利を宣言した。彼女 は「ファシストよりもファシスト的」[162]と呼ぶイギリスの抑圧的な雰囲気に苛立ち、1939年にカナダに戻った。スペインにおけるアナーキストの大 義に対する彼女の貢献は忘れ去られることはなかった。彼女の70歳の誕生日に、CNT-FAIの前事務総長マリアーノ・バスケスはパリから彼女にメッセー ジを送り、彼女の貢献を賞賛し、彼女を「私たちの精神的な母」と名づけた。彼女はこれを「これまで受け取った中で最も美しい賛辞」と呼んだ[163]。 |

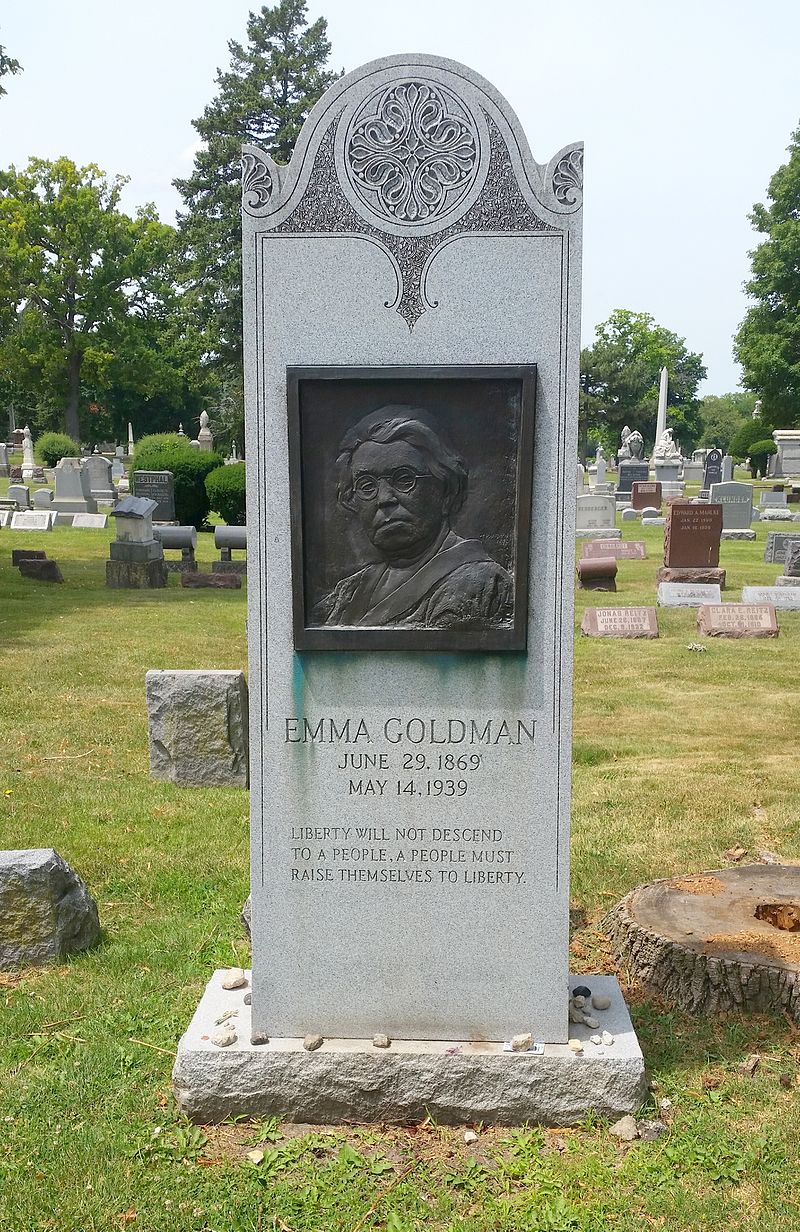

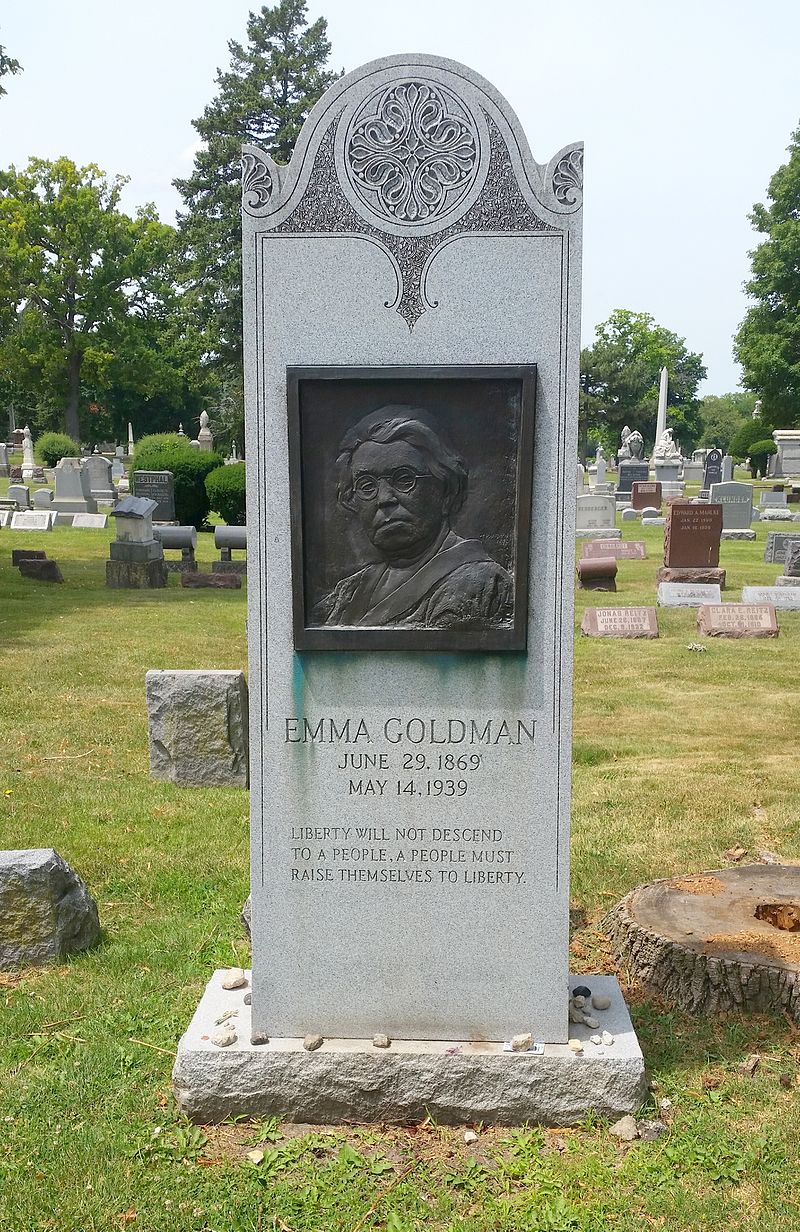

Final years Tombstone of Emma Goldman, Forest Home Cemetery, Forest Park, IL Goldman's grave in Illinois' Forest Home Cemetery, near those of the anarchists executed for the Haymarket affair. The dates on the stone are incorrect. As the events preceding World War II began to unfold in Europe, Goldman reiterated her opposition to wars waged by governments. "[M]uch as I loathe Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin and Franco", she wrote to a friend, "I would not support a war against them and for the democracies which, in the last analysis, are only Fascist in disguise."[164] She felt that Britain and France had missed their opportunity to oppose fascism, and that the coming war would only result in "a new form of madness in the world".[164] Death On Saturday, February 17, 1940, Goldman suffered a debilitating stroke. She became paralyzed on her right side, and although her hearing was unaffected, she could not speak. As one friend described it: "Just to think that here was Emma, the greatest orator in America, unable to utter one word."[165] For three months she improved slightly, receiving visitors and on one occasion gesturing to her address book to signal that a friend might find friendly contacts during a trip to Mexico. She suffered another stroke on May 8 and she died six days later in Toronto, aged 70.[166][167] The US Immigration and Naturalization Service allowed her body to be brought back to the United States. She was buried in German Waldheim Cemetery (now named Forest Home Cemetery) in Forest Park, Illinois, a western suburb of Chicago, near the graves of those executed after the Haymarket affair.[168] The bas relief on her grave marker was created by sculptor Jo Davidson,[169] and the stone includes the quote "Liberty will not descend to a people, a people must raise themselves to liberty". |

晩年 エマ・ゴールドマンの墓碑(イリノイ州フォレストパーク、フォレストホーム墓地) イリノイ州のフォレスト・ホーム墓地にあるゴールドマンの墓は、ヘイマーケット事件で処刑されたアナキストたちの墓の近くにある。石碑の日付は間違っている。 第二次世界大戦に先立つ出来事がヨーロッパで展開し始めると、ゴールドマンは政府による戦争に改めて反対を表明した。「ヒトラー、ムッソリーニ、スターリ ン、フランコが大嫌いな私としては、彼らに対する戦争や、結局のところファシストを装っているに過ぎない民主主義国家のための戦争を支持するつもりはな い」[164]と、彼女はイギリスとフランスがファシズムに反対する機会を逸してしまったと感じており、来るべき戦争は「世界に新しい形の狂気」をもたら すだけだと考えていた[164]。 死 1940年2月17日土曜日、ゴールドマンは衰弱性の脳卒中を起こした。右半身が麻痺し、聴力には影響がなかったが、話すことはできなかった。ある友人が こう語っている: 「アメリカで最も偉大な演説家であったエマが、一言も話すことができなかったと思うと」[165]。3ヶ月の間、彼女はわずかに回復し、訪問者を受け入れ たり、ある時には、友人がメキシコへの旅行中に友好的な連絡先を見つけるかもしれないことを知らせるために、アドレス帳を示す仕草をしたりした。彼女は5 月8日に再び脳卒中を起こし、その6日後にトロントで70歳で亡くなった[166][167]。 アメリカ移民帰化局は彼女の遺体をアメリカに持ち帰ることを許可した。ヘイマーケット事件後に処刑された人々の墓の近くにある、シカゴ西郊のイリノイ州 フォレストパークにあるドイツ系ヴァルトハイム墓地(現在はフォレスト・ホーム墓地と命名)に埋葬された[168]。彼女の墓標のベースレリーフは彫刻家 ジョー・デヴィッドソンによって制作され[169]、その石には「自由は民衆に降り注がない。 |