敵

Enemy

Duel between two enemies; here, the characters of Eugene Onegin and Vladimir Lensky from the novel, Eugene Onegin.

☆敵[enemy]

とは、力ずくで敵対的あるいは脅威と見なされる個人または集団である。敵という概念は「個人と共同体の双方にとって基本的」であることが確認されている

[1]。「敵」という用語は、特定の存在を脅威として指定し、それに対する強い感情的反応を引き起こすという社会的機能を果たす。[2]

敵を持つ状態、あるいは敵である状態は、敵意、敵対関係、敵対関係性と呼ばれる。

| An

enemy or a foe is an individual or a group that is considered as

forcefully adverse or threatening. The concept of an enemy has been

observed to be "basic for both individuals and communities".[1] The

term "enemy" serves the social function of designating a particular

entity as a threat, thereby invoking an intense emotional response to

that entity.[2] The state of being or having an enemy is enmity,

foehood or foeship. |

敵[enemy]

とは、力ずくで敵対的あるいは脅威と見なされる個人または集団である。敵という概念は「個人と共同体の双方にとって基本的」であることが確認されている

[1]。「敵」という用語は、特定の存在を脅威として指定し、それに対する強い感情的反応を引き起こすという社会的機能を果たす。[2]

敵を持つ状態、あるいは敵である状態は、敵意、敵対関係、敵対関係性と呼ばれる。 |

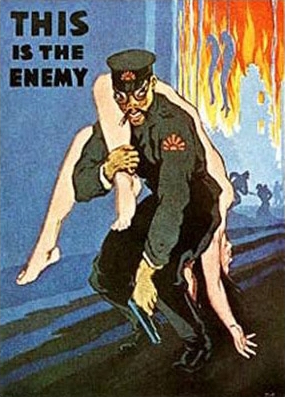

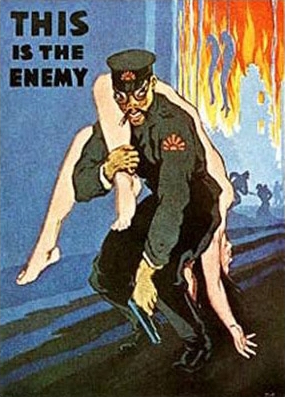

Terms War-time propaganda representation of the Japanese Imperial Army, an enemy of the United States at the time Enemy comes from the 9th century Latin word inimi, derived from Latin for "bad friend" (Latin: inimicus) through French.[3] "Enemy" is a strong word, and "emotions associated with the enemy would include anger, hatred, frustration, envy, jealousy, fear, distrust, and possibly grudging respect".[2] As a political concept, an enemy is likely to be met with hate, violence, battle and war. The opposite of an enemy is a friend or ally. Because the term "the enemy" is a bit bellicose and militaristic to use in polite society, informal substitutes are more often used. Often the substituted terms become pejoratives in the context that they are used. In any case, the designation of an "enemy" exists solely to denote the status of a particular group of people as a threat, and to propagate this designation within the local context. Substituted terms for an enemy often go further to meaningfully identify a known group as an enemy, and to pejoratively frame that identification. A government may seek to represent a person or group as a threat to the public good by designating that person or group to be a public enemy,[4] or an enemy of the people. The characterization of an individual or/and group as an enemy is called demonization. The propagation of demonization is a major aspect of propaganda. An "enemy" may also be conceptual; used to describe impersonal phenomena such disease, and a host of other things. In theology, "the Enemy" is typically reserved to represent an evil deity,[5] devil or a demon. For example, "in early Iroquois legend, the Sun and Moon, as god and goddess of Day and Night, had already acquired the characters of the great friend and enemy of man, the Good and Evil Deity".[5] Conversely, some religions describe a monotheistic God as an enemy; for example, in 1 Samuel 28:16, the spirit of Samuel tells a disobedient Saul: "Wherefore then dost thou ask of me, seeing the LORD is departed from thee, and is become thine enemy?" "The enemy," as the object of social anger or repulsion, has throughout history been used as the prototypical propaganda tool to focus the fear and anxiety within a society toward a particular target. The target is often general, as with an ethnic group or race of people, or it can also be a conceptual target, as with an ideology which characterizes a particular group. In some cases the concept of the enemy have morphed; whereas once racial and ethnic claims to support a call to war may later have changed to ideological and conceptual based claims. During the Cold War, the terms "Communists" or "Reds" were believed by many in American society to mean "the enemy," and the meaning of the two terms could be extremely pejorative, depending on the political context, mood, or state of fear and agitation within the society at the time. There are many terms and phrases that allude to overlooking or failing to notice an enemy, such as Trojan horse or wolf in sheep's clothing.[6] Generally, the counterpoint to an enemy is a friend or ally, although the term frenemy has been coined to capture the sense of a relationship wherein the parties are allied for some purposes and at odds with one another for other purposes.  |

用語 当時アメリカ合衆国の敵であった日本帝国軍の戦時プロパガンダ表現 敵(えき)という言葉は、9世紀のラテン語「inimi」に由来する。これはラテン語で「悪い友人」(ラテン語: inimicus)を意味する言葉がフランス語を経て派生したものである。[3]「敵」は強い言葉であり、「敵に関連する感情には怒り、憎悪、挫折感、羨 望、嫉妬、恐怖、不信、そして場合によっては渋々ながらの敬意が含まれる」[2]。政治的概念として、敵は憎悪、暴力、戦闘、戦争をもって迎えられがち だ。「敵」の対義語は友または同盟者である。「敵」という用語は社交界ではやや好戦的で軍国主義的であるため、非公式な代替語が頻繁に用いられる。代替語 は使用される文脈において蔑称となることが多い。いずれにせよ、「敵」という指定は、特定の集団を脅威として位置付け、その指定を地域文脈内で拡散させる ためだけに存在する。敵の代用語は、既知の集団を敵として意味ある形で特定し、その特定を貶める枠組みを与えることが多い。政府は個人や集団を「公敵」 [4]や「人民の敵」と指定することで、公共の利益に対する脅威として表現しようとする。 個人や集団を敵と規定する行為は悪魔化と呼ばれる。この悪魔化の拡散はプロパガンダの主要な側面だ。「敵」は概念的な存在となり得る。疾病のような非人格 的現象や、その他多くの事象を説明するために用いられる。神学において「敵」は通常、悪の神[5]、悪魔、あるいは悪霊を表すために留保される。例えば 「初期のイロコイ族の伝説では、昼と夜の神である太陽と月は、すでに人間の偉大な友であり敵である、善悪の神としての性格を獲得していた」[5]。逆に、 一神教の神を敵と描写する宗教もある。例えばサムエル記第一28章16節では、サムエルの霊が不従順なサウルにこう告げる: 「主はあなたから離れ、あなたの敵となられたのに、なぜ私に問うのか」 社会的怒りや嫌悪の対象としての「敵」は、歴史を通じて、社会内の恐怖や不安を特定の標的に向けるための典型的なプロパガンダ手段として用いられてきた。 標的は民族集団や人種のように一般的な場合もあれば、特定の集団を特徴づけるイデオロギーのように概念的な場合もある。場合によっては敵の概念は変容す る。かつては戦争への呼びかけを正当化する根拠が人種的・民族的であったものが、後にイデオロギー的・概念的な主張に変わることもある。 冷戦時代、アメリカ社会では「共産主義者」や「赤」という言葉が「敵」を意味すると広く信じられていた。これらの用語の意味は、当時の政治的文脈や社会の雰囲気、恐怖や動揺の状態によって、極めて蔑称的なものとなり得た。 敵を見逃したり気づかなかったりする状況を暗示する用語や表現は数多く存在する。例えばトロイの木馬や羊の皮を被った狼などだ[6]。一般的に敵の対極に は友や同盟国が位置するが、特定の目的では協力し合いながら別の目的では対立する関係性を表す「フレネミー」という造語も生まれた。  |

As a function of social science Unity of various countries against a common enemy The existence or perceived existence of a collective enemy tends to increase the cohesiveness of the group.[7] However, the identification and treatment of other entities as enemies may be irrational, and a sign of a psychological dysfunction. For example, group polarization may devolve into groupthink, which may lead members of the "in" group to perceive nonmembers or other groups as enemies even where the others present neither antagonism nor an actual threat.[8] Paranoid schizophrenia is characterized by the irrational belief that other people, ranging from family members and personal acquaintances to celebrities seen on television, are personal enemies plotting harm to the sufferer.[9][10] Irrational approaches may extend to treating impersonal phenomena not merely as conceptual enemies, but as sentient actors intentionally bringing strife to the sufferer. The concept of the enemy is well covered in the field of peace and conflict studies, which is available as a major at many major universities. In peace studies, enemies are those entities who are perceived as frustrating or preventing achievement of a goal. The enemy may not even know they are being regarded as such, since the concept is one-sided. Thus, in order to achieve peace, one must eliminate the threat. This can be achieved by: destroying the enemy changing one's perception of an entity as enemy achieving the goal the enemy is frustrating. Personal conflicts are frequently either unexamined (one's goals are not well defined) or examined only from one point of view. This means it is often possible to resolve conflict (to eliminate the cause of the conflict) by redefining goals such that the frustration (not the person) is eliminated, obvious, negotiated away, or decided upon. |

社会科学の一機能として 共通の敵に対する諸国の結束 集団的敵の存在、あるいはその認識は、集団の結束力を高める傾向がある。[7] しかし、他の存在を敵と特定し扱う行為は非合理的であり、心理的機能不全の兆候となり得る。例えば集団極化は集団思考に陥り、「内集団」のメンバーが、敵 対心や実際の脅威すら示さない非メンバーや他集団を敵と認識する事態を招きうる。[8] 妄想型統合失調症は、家族や知人からテレビの有名人まで、あらゆる他人を自身に危害を加えようとする個人的な敵と非合理的に信じる特徴を持つ。[9] [10] 非合理的なアプローチは、非人格的な現象を単なる概念上の敵として扱うだけでなく、意図的に苦悩をもたらす知覚可能な主体として扱うことまで及ぶ。 敵の概念は平和・紛争研究の分野で広く扱われており、多くの主要大学で専攻として提供されている。平和研究において敵とは、目標達成を妨げると認識される存在を指す。この概念は一方的なものであるため、敵とみなされている当の当事者はその事実すら知らない場合がある。 したがって平和を達成するには、脅威を排除しなければならない。その方法は以下の通りである: 敵を破壊する 敵と認識している対象への見方を変える 敵が妨害している目標を達成する 個人的な対立は、しばしば検証されていない(目標が明確に定義されていない)か、一方の視点からのみ検証される。これは、目標を再定義することで対立を解 決(対立の原因を排除)できる場合が多いことを意味する。つまり、妨害要因(人格そのものではなく)を排除し、明らかにし、交渉で取り除き、あるいは合意 によって解決するのだ。 |

| In literature Main article: Antagonist In literature, stories are often developed by presenting a primary character, the protagonist, as overcoming obstacles presented by an antagonist who is depicted as a personal enemy of the protagonist. Serial fictional narratives of heroes often present the hero contending against an archenemy whose capabilities match or exceed those of the hero, thereby establishing tension as to whether the hero will be able to defeat this enemy. The enemy may be displayed as an evil character who plans to harm innocents, so that the reader will side with the protagonist in the need to battle the enemy.[11] |

文学において 主な記事: 敵対者 文学において、物語はしばしば主人公という主要な登場人物が、敵対者によって提示される障害を克服する形で展開される。敵対者は主人公の個人的な敵として 描かれる。連続する英雄物語では、英雄が自らの能力に匹敵するかそれ以上の力を持つ宿敵と対峙する構図が頻繁に描かれる。これにより、英雄がこの敵を打ち 倒せるかという緊張感が生まれる。敵は無実の人々を傷つけようとする悪役として描かれることが多く、読者は主人公と共に敵と戦う必要性に共感するようにな る。[11] |

Treatment Former enemy rebel (on the left) forgiven by a police commander (on the right) Various legal and theological regimes exist governing the treatment of enemies. Many religions have precepts favoring forgiveness and reconciliation with enemies. The Jewish Encyclopedia states that "[h]atred of an enemy is a natural impulse of primitive peoples",[12] while "willingness to forgive an enemy is a mark of advanced moral development".[12] It contends that the teaching of the Bible, Talmud, and other writings, "gradually educates the people toward the latter stage",[12] stating that "indications in the Bible of a spirit of hatred and vengeance toward the enemy... are for the most part purely nationalistic expressions—hatred of the national enemy being quite compatible with an otherwise kindly spirit".[12] Religious doctrines According to the Dalai Lama, virtually all major religions have "similar ideals of love, the same goal of benefiting humanity through spiritual practice, and the same effect of making their followers into better human beings".[13] It is therefore widely expressed in world religions that enemies should be treated with love, kindness, compassion, and forgiveness. The Book of Exodus states: "If thou meet thine enemy's ox or his ass going astray, thou shalt surely bring it back to him again. If thou see the ass of him that hateth thee lying under his burden, and thou wouldest forbear to help him, thou shalt surely help with him."[14] The Book of Proverbs similarly states: "Rejoice not when thine enemy falleth and let not thy heart be glad when he stumbleth",[15] and: "If thine enemy be hungry give him bread to eat, and if he be thirsty give him water to drink. For thus shalt thou heap coals of fire upon his head, and the Lord shall reward thee".[16] The Jewish Encyclopedia contends that the opinion that the Old Testament commanded hatred of the enemy derives from a misunderstanding of the Sermon on the Mount, wherein Jesus said: "Ye have heard that it hath been said, Thou shalt love thy neighbor and hate thine enemy. But I say unto you, Love your enemies and pray for them that persecute you".[17] The Jewish Encyclopedia also cites passages in the Talmud stating: "If a man finds both a friend and an enemy requiring assistance he should assist his enemy first in order to subdue his evil inclination",[12] and: "Who is strong? He who converts an enemy into a friend".[12] The concept of Ahimsa, found in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism, also captures this sentiment, requiring kindness and non-violence towards all living things on the basis that they all are connected. Indian leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi strongly believed in this principle, stating that "[t]o one who follows this doctrine there is no room for an enemy".[18] In 1 Corinthians 15:25-26 in the New Testament, Saint Paul refers to Christ's reign with all his enemies under his feet, until finally death, the last enemy, is destroyed. Methodist writer Joseph Benson notes from this text that this enemy, death, "continues, in some measure, to hold the subjects of Christ under his dominion" until the end.[19] |

敵の扱い 元敵対反乱者(左)が警察指揮官(右)に赦される 敵の扱いに関する様々な法的・神学的枠組みが存在する。多くの宗教は敵への赦しと和解を推奨する教義を持つ。『ユダヤ百科事典』は「敵への憎悪は原始民族 の自然な衝動である」[12]と述べつつ、「敵を赦す意思は高度な道徳的発展の証である」と記す。[12] 同書は聖書、タルムードその他の文献の教えが「人民を後者の段階へ徐々に導く」と主張し[12]、「聖書に見られる敵への憎悪や復讐の精神は…大半が純粋 なナショナリスト的表現であり、国家の敵への憎悪はそれ以外の慈愛の精神と両立し得る」と述べている。[12] 宗教的教義 ダライ・ラマによれば、ほぼ全ての主要宗教は「愛という類似の理想、精神的修行を通じて人類に利益をもたらすという同一の目標、そして信者をより良き人間 へと変容させる同一の効果」を有している[13]。したがって、敵を愛と慈愛、思いやり、そして寛容をもって扱うべきだという考えは、世界の宗教において 広く表明されている。 出エジプト記にはこう記されている。「もし敵の牛や驢馬が迷っているのを見かけたら、必ず持ち主に返さねばならない。もし憎む者の驢馬が荷物の下で倒れて いるのを見かけて、助けるのをためらうなら、必ず彼を助けるべきである」。[14] 箴言も同様にこう述べている。「敵が倒れても喜ぶな。彼がつまずいても心を楽しませてはならない」[15]、そして「敵が飢えていればパンを与え、渇いて いれば水を飲ませよ。そうすれば、あなたは彼の頭に燃える炭を積むことになる。主はあなたに報いるであろう」。[16] ユダヤ百科事典によれば、旧約聖書が敵への憎悪を命じたとする見解は、山上の垂訓の誤解に由来する。そこではイエスがこう述べている:「『隣人を愛し、敵 を憎め』と言われたのを、お前たちは聞いた。しかし、私は言う。敵を愛し、迫害する者のために祈れ」。[17] ユダヤ百科事典はまた、タルムードの以下の記述を引用している。「友と敵の両方が助けを必要としている場合、人はまず敵を助けるべきである。それは悪の傾向を制するためである」[12]。また「強き者とは誰か。敵を友に変える者である」とも述べている。[12] ヒンドゥー教、ジャイナ教、仏教に見られるアヒンサーの概念も、この考え方を捉えており、すべての生き物はつながっているという考え方に基づいて、すべて の生き物に対して親切と非暴力を求めるものである。インディアンの指導者モハンダス・カラムチャンド・ガンディーは、この原則を強く信じ、「この教義に従 う者にとって、敵の存在の余地はない」と述べた。[18] 新約聖書のコリントの信徒への手紙一 15:25-26 で、聖パウロは、キリストがすべての敵をその足の下に置き、ついに最後の敵である死が滅ぼされるまで、キリストが君臨することについて言及している。メソ ジストの作家ジョセフ・ベンソンは、この文章から、この敵である死は、終わりまで「ある程度、キリストの臣民をその支配下に置き続ける」と指摘している。 [19] |

| Anti-fan Demonization Enemy combatant Frenemy Rivalry |

アンチファン 悪魔化 敵対戦闘員 敵であり味方 ライバル関係 |

| References 1. Mortimer Ostow, Spirit, Mind, & Brain: A Psychoanalytic Examination of Spirituality and Religion (2007), p. 73. 2. Martha L. Cottam, Beth Dietz-Uhler, Elena Mastors, Introduction to Political Psychology (2009), p. 54. 3. Robert Greene (3 September 2010). The 33 Strategies Of War. Profile Books. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-84765-142-6. Retrieved 29 August 2013. ...the word "enemy"—from the Latin inimicus, "not a friend"... 4. Journals of the House of Lords, Volume 5. H.M. Stationery Office. 1642. 5. Edward Burnett Tylor, Primitive culture (1873), p. 323-4. 6. Vũ, Hoàng Thảo. A study on techniques to learn English idioms and proverbs. Diss. Đại học Dân lập Hải Phòng, 2010. 7. Joan Ferrante-Wallace, Sociology: A Global Perspective (2006), p. 120. 8. Wayne Weiten, Psychology: Themes and Variations, p. 546. 9. Wayne Weiten, Psychology: Themes and Variations, p. 468. 10. Mortimer Ostow, Spirit, Mind, & Brain: A Psychoanalytic Examination of Spirituality and Religion (2007), p. 74. 11. Patrick Colm Hogan, What Literature Teaches Us about Emotion (2011), p. 294. 12. Kaufmann Kohler, David Philipson, Treatment of an Enemy, The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906). 13. The Dalai Lama, quoted in John Templeton, Agape Love: Tradition In Eight World Religions (2008), p. 2-3. 14. Exodus 23:4-5. 15. Proverbs 24:17. 16. Proverbs 25:21-22. 17. Matthew 5:43-44. 18. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, The Satyagraha Ashram, reported in The Gandhi Reader: A Source Book of His Life and Writings, 2nd ed. (Madras: Samata Books, 1984), p. 138. 19. Benson, J., Benson Commentary on 1 Corinthians 15, accessed 26 November 2023 |

参考文献 1. モーティマー・オストウ『精神、心、脳:精神性と宗教の精神分析的考察』(2007年)、73頁。 2. マーサ・L・コッタム、ベス・ディーツ=ウーラー、エレナ・マスターズ『政治心理学入門』(2009年)、54頁。 3. ロバート・グリーン(2010年9月3日)。『戦争の33の戦略』。プロファイル・ブックス。9頁。ISBN 978-1-84765-142-6。2013年8月29日閲覧。...「敵」という言葉はラテン語のinimicus(友ではない者)に由来する... 4. 『貴族院議事録』第5巻。英国政府刊行局。1642年。 5. エドワード・バーネット・タイラー『原始文化』(1873年)、323-4頁。 6. ヴー・ホアン・タオ『英語慣用句・諺学習技法に関する研究』。海防私立大学博士論文、2010年。 7. ジョアン・フェランテ=ウォレス『社会学:グローバルな視点』(2006年)、120頁。 8. ウェイン・ワイテン『心理学:主題と変奏』、546頁。 9. ウェイン・ワイテン『心理学:主題と変奏』、468頁。 10. モーティマー・オストウ『精神、心、脳:精神性と宗教の精神分析的考察』(2007年)、74頁。 11. パトリック・コルム・ホーガン『文学が教えてくれる感情について』(2011年)、294頁。 12. カウフマン・コーラー、デイヴィッド・フィリップソン『敵の扱い』、『ユダヤ百科事典』(1906年) 。 13. ダライ・ラマ、ジョン・テンプルトン著『アガペの愛:八つの世界宗教における伝統』(2008年)2-3ページで引用。 14. 出エジプト記 23:4-5。 15. 箴言 24:17。 16. 箴言 25:21-22。 17. マタイによる福音書 5:43-44。 18. モハンダス・カラムチャンド・ガンディー、『サティヤグラハ・アシュラム』、『ガンディー・リーダー:その生涯と著作の資料集』第 2 版(マドラス:サマタ・ブックス、1984 年)138 ページ。 19. ベンソン、J.、『1 コリント 15 章に関するベンソン注解』、2023 年 11 月 26 日アクセス。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enemy |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099