環境主義

Environmentalism

☆

環境保護主義ともいう。自然環境を保護することが重要であるという主義や主張。自然保護思想と深く関係して

いるが、自然保護が環境を人間にとって住み易く快適であるように維持管理すべきであるという考え方であるのに対して、環境主義はそこに住む人間よりも人間

以外の生物や環境の保護のほうが大切であるという考え方に主眼がおかれている。鬼頭秀一(1996)によると環境主義は、動物解放論、自然の権利論、

ディープエコロジーという3つ思潮に歴史的起源をもつが、これらはみな人間中心主義からの脱却をはかるものである。

| Environmentalism

or environmental rights is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social

movement about supporting life, habitats, and surroundings. While

environmentalism focuses more on the environmental and nature-related

aspects of green ideology and politics, ecologism combines the ideology

of social ecology and environmentalism. Ecologism is more commonly used

in continental European languages, while environmentalism is more

commonly used in English but the words have slightly different

connotations. Environmentalism advocates the preservation, restoration and improvement of the natural environment and critical earth system elements or processes such as the climate, and may be referred to as a movement to control pollution or protect plant and animal diversity.[1] For this reason, concepts such as a land ethics, environmental ethics, biodiversity, ecology, and the biophilia hypothesis figure predominantly. The environmentalist movement encompasses various approaches to addressing environmental issues, including free market environmentalism, evangelical environmentalism, and the environmental conservation movement. At its crux, environmentalism is an attempt to balance relations between humans and the various natural systems on which they depend in such a way that all the components are accorded a proper degree of sustainability.[2] The exact measures and outcomes of this balance is controversial and there are many different ways for environmental concerns to be expressed in practice. Environmentalism and environmental concerns are often represented by the colour green,[3] but this association has been appropriated by the marketing industries for the tactic known as greenwashing.[4] Environmentalism is opposed by anti-environmentalism, which says that the Earth is less fragile than some environmentalists maintain, and portrays environmentalism as overreacting to the human contribution to climate change or opposing human advancement.[5] |

環

境主義または環境権は、生命、生息地、環境を支援する広範な哲学、イデオロギー、社会運動である。環境主義は、環境や自然に関する緑のイデオロギーや政治

の側面により重点を置いているが、エコロジズムは社会生態学と環境主義のイデオロギーを組み合わせたものである。エコロジズムは、ヨーロッパ大陸の言語で

はより一般的に使用されているが、環境主義は英語でより一般的に使用されている。しかし、これらの言葉には微妙に異なる含みがある。 環境保護主義は、自然環境や気候などの重要な地球システム要素やプロセスの保全、修復、改善を提唱しており、汚染の抑制や動植物の多様性の保護を目的とし た運動であるともいえる。このため、土地倫理、環境倫理、生物多様性、生態学、バイオフィリア仮説などの概念が中心となっている。環境保護運動には、環境 問題への取り組みとして、自由市場環境主義、福音派環境主義、環境保護運動など、さまざまなアプローチが含まれる。 環境保護主義の根本は、人間と人間が依存するさまざまな自然システムとの関係を、すべての構成要素が適切な持続可能性を確保できる形でバランスさせる試み である。[2] このバランスを正確に測定し、結果を導き出すことは議論の余地があり、環境問題への懸念を実際に表明する方法は数多く存在する。環境保護主義や環境問題 は、しばしば緑色で表現されるが[3]、この関連性はマーケティング業界によって「グリーンウォッシング」と呼ばれる戦術として利用されている。 環境保護主義は、地球は一部の環境保護論者が主張するほど脆弱ではなく、環境保護主義は気候変動に対する人間の貢献に過剰反応している、あるいは人間の進歩に反対していると主張する反環境保護主義と対立している。[5] |

| Definitions Environmentalism denotes a social movement that seeks to influence the political process by lobbying, activism, and education in order to protect natural resources and ecosystems. An environmentalist is a person who may speak out about our natural environment and the sustainable management of its resources through changes in public policy or individual behaviour. This may include supporting practices such as informed consumption, conservation initiatives, investment in renewable resources, improved efficiencies in the materials economy, transitioning to new accounting paradigms such as ecological economics, renewing and revitalizing our connections with non-human life or even opting to have one less child to reduce consumption and pressure on resources. In various ways (for example, grassroots activism and protests), environmentalists and environmental organisations seek to give the natural world a stronger voice in human affairs.[6] In general terms, environmentalists advocate the sustainable management of resources, and the protection (and restoration, when necessary) of the natural environment through changes in public policy and individual behaviour. In its recognition of humanity as a participant in ecosystems, the movement is centered around ecology, health, and human rights. |

定義 環境保護主義とは、自然資源や生態系を保護するために、ロビー活動、活動、教育を通じて政治プロセスに影響を与えようとする社会運動を指す。 環境保護主義者は、公共政策や個人の行動の変化を通じて、自然環境やその資源の持続可能な管理について発言する人格である。これには、情報に基づく消費、 保全イニシアティブ、再生可能資源への投資、物質経済の効率性向上、生態経済学などの新しい会計パラダイムへの移行、人間以外の生命とのつながりの再構築 や活性化、あるいは消費や資源への圧力を減らすために子供を一人減らすという選択肢の支持などが含まれる。 環境保護活動家や環境保護団体は、さまざまな方法(例えば、草の根運動や抗議活動など)で、自然界が人類の活動により強い影響力を行使できるよう努めている。[6] 一般的に、環境保護活動家は、公共政策や個人の行動の変化を通じて、資源の持続可能な管理と自然環境の保護(必要に応じて修復)を提唱している。人間も生態系の一員であるという認識に基づき、この運動は生態学、保健、人権を中心に展開されている。 |

| History See also: Conservation movement and Timeline of history of environmentalism A concern for environmental protection has recurred in diverse forms, in different parts of the world, throughout history. The earliest ideas of environmental protectionism can be found in Jainism, a religion from ancient India revived by Mahavira in the 6th century BC. Jainism offers a view that is in many ways compatible with core values associated with environmental activism, such as the protection of life by nonviolence, which could form a strong ecological ethos for global protection of the environment. Mahavira's teachings on the symbiosis between all living beings—as well as the five elements of earth, water, air, fire, and space—are core to environmental thought today.[7][8] In West Asia, the Caliph Abu Bakr in the 630s AD commanded his army to "Bring no harm to the trees, nor burn them with fire," and to "Slay not any of the enemy's flock, save for your food."[9] Various Islamic medical treatises during the 9th to 13th centuries dealt with environmentalism and environmental science, including the issue of pollution. The authors of such treatises included Al-Kindi, Qusta ibn Luqa, Al-Razi, Ibn Al-Jazzar, al-Tamimi, al-Masihi, Avicenna, Ali ibn Ridwan, Ibn Jumay, Isaac Israeli ben Solomon, Abd-el-latif, Ibn al-Quff, and Ibn al-Nafis. Their works covered a number of subjects related to pollution, such as air pollution, water pollution, soil contamination, and the mishandling of municipal solid waste. They also included assessments of certain localities' environmental impact.[10] In Europe, King Edward I of England banned the burning and sale of "sea-coal" in 1272 by proclamation in London, after its smoke had become a prevalent annoyance throughout the city.[11][12] This fuel, common in London due to the local scarcity of wood, was given this early name because it could be found washed up on some shores, from where it was carted away on a wheelbarrow. |

歴史 関連情報: 環境保護運動、環境保護の歴史年表 環境保護への関心は、歴史を通じて、世界の異なる地域で、さまざまな形で繰り返し生じてきた。環境保護主義の最も初期の考え方は、古代インドの宗教である ジャイナ教に見られる。ジャイナ教は、非暴力による生命の保護など、環境保護活動の中心的な価値観と多くの点で共通する見解を提供しており、地球環境保護 のための強力な生態学的倫理観を形成する可能性がある。 マハーヴィーラの説く、すべての生物と地球、水、空気、火、空間という5つの要素との共生は、今日の環境思想の中心となっている。[7][8] 西アジアでは、630年代のカリフ、アブー・バクルが軍隊に「木々を傷つけることなく、火で燃やすこともしてはならない」こと、「敵の家畜を殺してはなら ない。ただし、食料として確保する場合は除く」ことを命じた。[9] 9世紀から13世紀にかけてのさまざまなイスラム医学論文では、環境保護や環境科学、汚染問題などが扱われた。そのような論文の著者には、アル・キン ディ、クスタ・イブン・ルカ、アル・ラジ、イブン・アル・ジャザール、アル・タミミ、アル・マシヒ、アヴィセンナ、アリ・イブン・リドワン、イブン・ジュ マイ、イサク・イスラエル・ベン・ソロモン、アブド・エル・ラティフ、イブン・アル・クフ、イブン・アル・ナフィスなどがいた。彼らの研究は、大気汚染、 水質汚染、土壌汚染、一般廃棄物の不適切な処理など、汚染に関連する多くのテーマをカバーしていた。また、特定の地域の環境への影響の評価も含まれてい た。 ヨーロッパでは、ロンドン市内で煙が大きな迷惑となっていたことを受け、1272年にイングランド王エドワード1世がロンドンで布告を発し、「海炭」の燃 焼と販売を禁止した。[11][12] この燃料は、木材が不足していたロンドンでは一般的であったが、海岸に打ち上げられることがあり、そこから手押し車で運び出されていたため、このような初 期の名称が付けられた。 |

Early environmental legislation Levels of air pollution rose during the Industrial Revolution, sparking the first modern environmental laws to be passed in the mid-19th century. At the advent of steam and electricity the muse of history holds her nose and shuts her eyes (H. G. Wells 1918).[13] The origins of the environmental movement lay in the response to increasing levels of smoke pollution in the atmosphere during the Industrial Revolution. The emergence of great factories and the concomitant immense growth in coal consumption gave rise to an unprecedented level of air pollution in industrial centers; after 1900 the large volume of industrial chemical discharges added to the growing load of untreated human waste.[14] The first large-scale, modern environmental laws came in the form of Britain's Alkali Acts, passed in 1863, to regulate the deleterious air pollution (gaseous hydrochloric acid) given off by the Leblanc process, used to produce soda ash. An Alkali inspector and four sub-inspectors were appointed to curb this pollution. The inspectorate's responsibilities were gradually expanded, culminating in the Alkali Order 1958 which placed all major heavy industries that emitted smoke, grit, dust and fumes under supervision. In industrial cities, local experts and reformers, especially after 1890, took the lead in identifying environmental degradation and pollution, and initiating grass-roots movements to demand and achieve reforms.[15] Typically the highest priority went to water and air pollution. The Coal Smoke Abatement Society was formed in 1898 making it one of the oldest environmental NGOs. It was founded by artist Sir William Blake Richmond, frustrated with the pall cast by coal smoke. Although there were earlier pieces of legislation, the Public Health Act 1875 required all furnaces and fireplaces to consume their own smoke. It also provided for sanctions against factories that emitted large amounts of black smoke. This law's provisions were extended in 1926 with the Smoke Abatement Act to include other emissions, such as soot, ash, and gritty particles, and to empower local authorities to impose their own regulations. It was only under the impetus of the Great Smog of 1952 in London, which almost brought the city to a standstill and may have caused upward of 6,000 deaths, that the Clean Air Act 1956 was passed and airborne pollution in the city was first tackled. Financial incentives were offered to householders to replace open coal fires with alternatives (such as installing gas fires) or those who preferred, to burn coke instead (a byproduct of town gas production) which produces minimal smoke. 'Smoke control areas' were introduced in some towns and cities where only smokeless fuels could be burnt and power stations were relocated away from cities. The act formed an important impetus to modern environmentalism and caused a rethinking of the dangers of environmental degradation to people's quality of life.[16] The late 19th century also saw the passage of the first wildlife conservation laws. The zoologist Alfred Newton published a series of investigations into the Desirability of establishing a 'Close-time' for the preservation of indigenous animals between 1872 and 1903. His advocacy for legislation to protect animals from hunting during the mating season led to the formation of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and influenced the passage of the Sea Birds Preservation Act in 1869 as the first nature protection law in the world.[17][18] During the Spanish Revolution, anarchist-controlled territories undertook several environmental reforms, which were possibly the largest in the world at the time. Daniel Guerin notes that anarchist territories would diversify crops, extend irrigation, initiate reforestation, start tree nurseries and help to establish naturist communities.[19] Once there was a link discovered between air pollution and tuberculosis, the CNT shut down several metal factories.[20] |

初期の環境保護法 産業革命の間に大気汚染のレベルが上昇し、19世紀半ばに最初の近代的な環境保護法が制定された。 蒸気と電気の出現により、歴史の女神は鼻をつまみ目を覆う(H. G. Wells 1918)[13]。 環境保護運動の起源は、産業革命期の大気中の煙による汚染の深刻化への対応に求められる。大規模な工場が現れ、それに伴って石炭消費量が大幅に増加したこ とで、工業地帯では前例のないレベルの大気汚染が発生した。1900年以降は、大量の産業化学物質が排出され、未処理の人間の排泄物による負荷がさらに増 加した。 [14] 初めての大規模で近代的な環境法は、1863年に可決された英国のアルカリ法であり、ソーダ灰の生産に使用されるルブラン法から排出される有害な大気汚染 (気体状の塩酸)を規制するものであった。 この汚染を抑制するために、アルカリ検査官と4人の副検査官が任命された。検査官の責任は徐々に拡大し、1958年のアルカリ法では、煙、砂、粉塵、ガス を排出するすべての主要重工業が監督下に置かれることとなった。 工業都市では、1890年以降、特に地元の専門家や改革者が環境悪化や汚染を特定し、改革を要求して実現するための草の根運動を率先して始めた。[15] 通常、最も優先順位が高かったのは水質汚染と大気汚染であった。石炭煙軽減協会は1898年に結成され、最も古い環境NGOのひとつとなった。同協会は、 石炭煙がもたらす暗い雰囲気に不満を抱いていた芸術家のウィリアム・ブレイク・リッチモンド卿によって設立された。それ以前にもいくつかの法律はあった が、1875年の公衆衛生法では、すべての炉や暖炉が自身の煙を消費することを義務付けた。また、大量の黒煙を排出する工場に対する制裁も規定した。この 法律の規定は、1926年の煙害防止法によって拡大され、煤煙、灰、砂塵などの他の排出物も対象となり、地方自治体が独自の規制を課す権限も与えられた。 ロンドンをほぼ麻痺状態に陥れ、6,000人以上の死者を出した可能性のある1952年のロンドン大気汚染事件をきっかけに、1956年の大気浄化法が可 決され、ロンドンにおける大気汚染への対策が初めて取られた。一般家庭に対して、石炭の直火ストーブを他のもの(ガスストーブの設置など)に交換する、あ るいは煙の少ないコークス(都市ガス製造の副産物)を燃やすことを奨励する金銭的インセンティブが提供された。一部の都市では「スモークコントロール地 域」が導入され、無煙燃料のみが使用可能となり、発電所は都市部から移転された。この法律は、現代の環境保護運動に重要な推進力を与え、環境悪化が人々の 生活の質に及ぼす危険性について再考を促した。 19世紀後半には、初の野生生物保護法も制定された。動物学者アルフレッド・ニュートンは、1872年から1903年にかけて、在来動物の保護を目的とし た「クローズタイム」の設定の必要性に関する一連の調査結果を発表した。交尾期の動物狩猟を禁止する法律の制定を提唱したことで、鳥類保護協会の設立につ ながり、1869年に世界初の自然保護法である海鳥保護法の成立に影響を与えた。[17][18] スペイン革命中、無政府主義者が支配した地域では、当時おそらく世界最大規模の環境改革が実施された。ダニエル・ゲランは、無政府主義者の支配地域では、 農作物の多様化、灌漑の拡大、森林再生の開始、苗木生産の開始、自然主義者のコミュニティの設立支援などが行われたと指摘している。[19] 一度、大気汚染と結核の関連性が発見されると、CNTは複数の金属工場を閉鎖した。[20] |

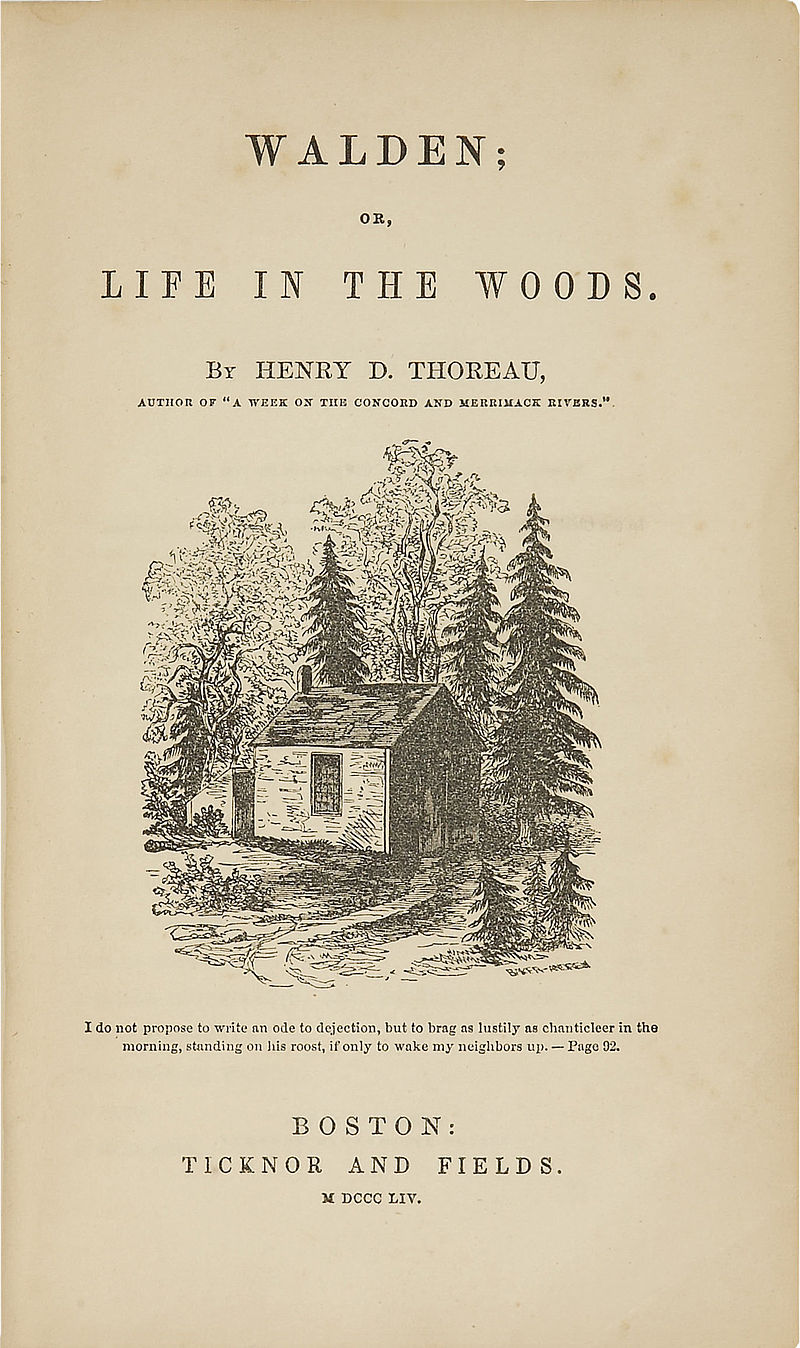

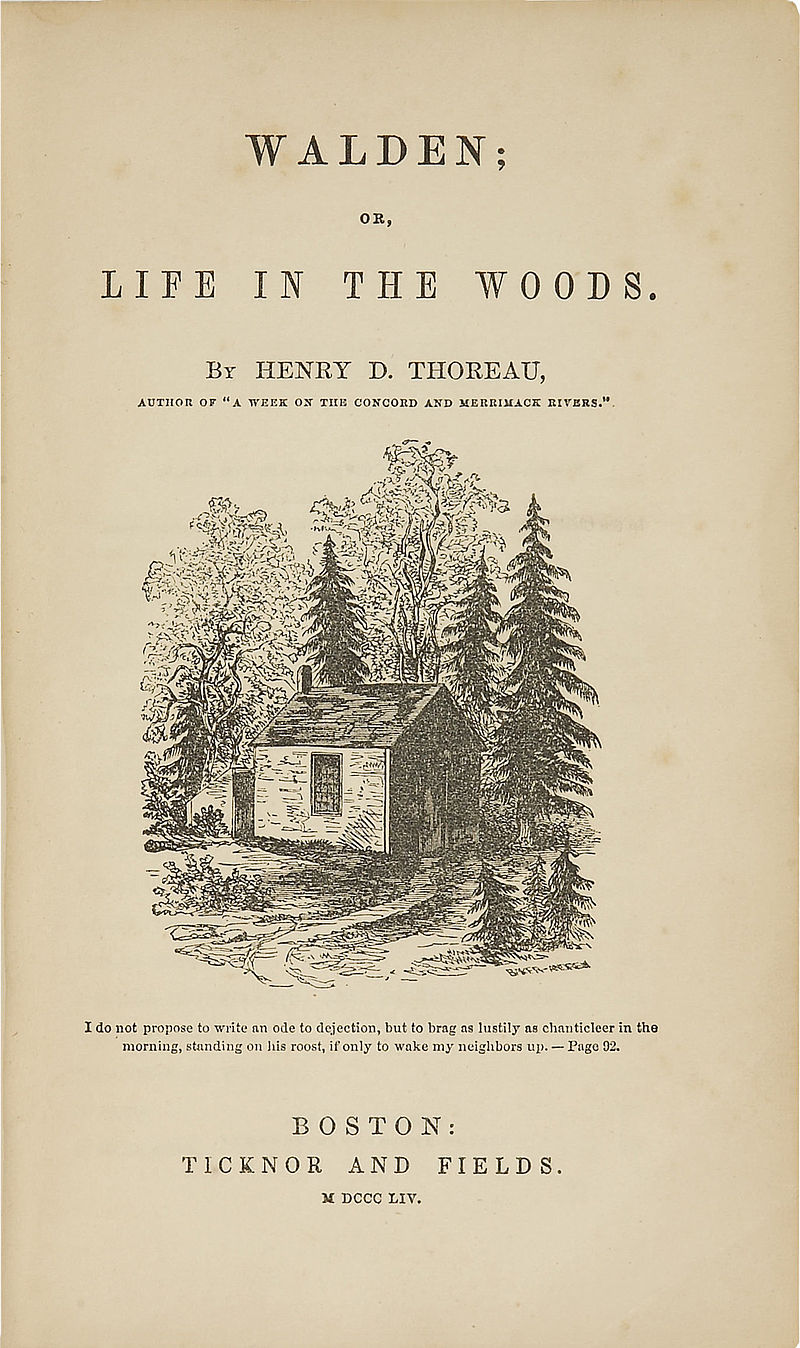

| First environmental movements Early interest in the environment was a feature of the Romantic movement in the early 19th century. In Britain the poet William Wordsworth travelled extensively in the Lake District and wrote that it is a "sort of national property in which every man has a right and interest who has an eye to perceive and a heart to enjoy".[21]  John Ruskin, an influential thinker who articulated the Romantic ideal of environmental protection and conservation Systematic efforts on behalf of the environment only began in the late 19th century; it grew out of the amenity movement in Britain in the 1870s, which was a reaction to industrialisation, the growth of cities, and worsening air and water pollution. Starting with the formation of the Commons Preservation Society in 1865, the movement championed rural preservation against the encroachments of industrialisation. Robert Hunter, solicitor for the society, worked with Hardwicke Rawnsley, Octavia Hill, and John Ruskin to lead a successful campaign to prevent the construction of railways to carry slate from the quarries, which would have ruined the unspoiled valleys of Newlands and Ennerdale. This success led to the formation of the Lake District Defence Society (later to become The Friends of the Lake District).[22] Peter Kropotkin wrote about ecology in economics, agricultural science, conservation, ethology, criminology, urban planning, geography, geology and biology. He observed in Swiss and Siberian glaciers that they had been slowly melting since the dawn of the industrial revolution, possibly making him one of the first predictors for climate change. He also observed the damage done from deforestation and hunting.[23] Kropotkin's writings would become influential in the 1970s and became a major inspiration for the intentional community movement as well as his ideas becoming the basis for the theory of social ecology. In 1893 Hill, Hunter and Rawnsley agreed to set up a national body to coordinate environmental conservation efforts across the country; the "National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty" was formally inaugurated in 1894.[24] The organisation obtained secure footing through the 1907 National Trust Bill, which gave the trust the status of a statutory corporation.[25] and the bill was passed in August 1907.[26] An early "Back-to-Nature" movement, which anticipated the romantic ideal of modern environmentalism, was advocated by intellectuals such as John Ruskin, William Morris, George Bernard Shaw and Edward Carpenter, who were all against consumerism, pollution and other activities that were harmful to the natural world.[27] The movement was a reaction to the urban conditions of the industrial towns, where sanitation was awful, pollution levels intolerable and housing terribly cramped. Idealists championed the rural life as a mythical utopia and advocated a return to it. John Ruskin argued that people should return to a "small piece of English ground, beautiful, peaceful, and fruitful. We will have no steam engines upon it ... we will have plenty of flowers and vegetables ... we will have some music and poetry; the children will learn to dance to it and sing it."[28] Practical ventures in the establishment of small cooperative farms were even attempted and old rural traditions, without the "taint of manufacture or the canker of artificiality", were enthusiastically revived, including the Morris dance and the maypole.[29] These ideas also inspired various environmental groups in the UK, such as the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, established in 1889 by Emily Williamson as a protest group to campaign for greater protection for the indigenous birds of the island.[30] The Society attracted growing support from the suburban middle-classes as well as support from many other influential figures, such as the ornithologist Professor Alfred Newton. By 1900, public support for the organisation had grown, and it had over 25,000 members. The garden city movement incorporated many environmental concerns into its urban planning manifesto; the Socialist League and The Clarion movement also began to advocate measures of nature conservation.[31]  Original title page of Walden by Henry David Thoreau |

最初の環境保護運動 環境に対する初期の関心は、19世紀初頭のロマン主義運動の特徴であった。英国の詩人ウィリアム・ワーズワースは湖水地方を広く旅し、「見る目と楽しむ心を持つすべての国民が権利と関心を持つべき、一種の国民的財産である」と記している。[21]  ジョン・ラスキンは、ロマン主義の環境保護と保全の理想を明確にした影響力のある思想家である 環境保護のための組織的な取り組みは19世紀後半になってようやく始まった。これは、産業化、都市の拡大、大気や水質の悪化への反発として1870年代に 英国で起こったアメニティ運動から発展したものである。1865年のコモンズ保護協会の結成を皮切りに、この運動は産業化の脅威から農村を守ることを目的 とした。協会の弁護士であったロバート・ハンターは、ハードウィック・ロウンズリー、オクタヴィア・ヒル、ジョン・ラスキンらと協力し、ニューランズやエ ンナーデールの自然のままの渓谷を台無しにしてしまうであろう採石場からスレートを運搬するための鉄道建設を阻止するキャンペーンを成功に導いた。この成 功により、湖水地方防衛協会(後に湖水地方友の会となる)が結成された。[22] ピーター・クロポトキンは、経済学、農業科学、保全、動物行動学、犯罪学、都市計画、地理学、地質学、生物学における生態学について執筆した。彼はスイス とシベリアの氷河を観察し、産業革命の黎明期から徐々に溶け始めていることを発見した。おそらく、彼は気候変動を予測した最初の人物の一人である。また、 森林伐採や狩猟による被害についても観察していた。[23] クロポトキンの著作は1970年代に影響力を持ち、意図的なコミュニティ運動の主要なインスピレーションとなった。また、彼の考えは社会生態学の理論の基 礎となった。 1893年、ヒル、ハンター、ロンスリーは、全国的な環境保護の取り組みを調整する組織を設立することに合意し、1894年に「歴史的または自然的美観を 有する場所のためのナショナル・トラスト」が正式に発足した。[24] この組織は、1907年のナショナル・トラスト法案によって確固たる地位を築いた。この法案は、トラストに法定法人の地位を与えた。 [25] 法案は1907年8月に可決された。[26] 近代環境保護主義のロマン主義的理想を先取りした初期の「自然回帰」運動は、ジョン・ラスキン、ウィリアム・モリス、ジョージ・バーナード・ショー、エド ワード・カーペンターといった知識人によって提唱された。彼らは皆、消費主義や公害、自然界に有害なその他の活動に反対していた。[27] この運動は、衛生状態が悪く、公害レベルが耐え難く、住宅がひどく手狭な工業都市の都市環境への反応であった。理想主義者たちは、田舎での生活を神話上の ユートピアとして賞賛し、そこへの回帰を提唱した。ジョン・ラスキンは、人々は「美しく、平和で、実り多い、イングランドの小さな土地」に戻るべきだと主 張した。そこには蒸気機関車は走らないだろう...そこには花や野菜が溢れるだろう...そこでは音楽や詩が生まれるだろう。子供たちはその音楽に合わせ て踊り、歌うだろう」[28] 小規模な協同農場の設立に向けた実用的な試みも行われ、また「工業の汚点や不自然さの弊害」のない昔ながらの田園の伝統、例えばモリスダンスやメイポールなども熱心に復活された。 これらの考えは、英国のさまざまな環境保護団体にも影響を与えた。例えば、1889年にエミリー・ウィリアムソンが、英国固有の鳥類の保護を訴える抗議運 動グループとして設立した英国鳥類保護協会(Royal Society for the Protection of Birds)などである。この協会は、郊外の中流階級からの支持を集めるとともに、鳥類学者のアルフレッド・ニュートン教授など、多くの有力者からの支持 も得た。1900年までに、この組織への一般市民の支持は拡大し、会員数は2万5000人を超えた。 ガーデンシティ運動は、都市計画のマニフェストに多くの環境問題への懸念を取り入れた。社会主義連盟とクラリオン運動もまた、自然保護の施策を提唱し始め た。  ヘンリー・デイビッド・ソロー著『ウォールデン』のオリジナルタイトルページ |

| The

movement in the United States began in the late 19th century, out of

concerns for protecting the natural resources of the West, with

individuals such as John Muir and Henry David Thoreau making key

philosophical contributions. Thoreau was interested in peoples'

relationship with nature and studied this by living close to nature in

a simple life. He published his experiences in the book Walden, which

argues that people should become intimately close with nature. Muir

came to believe in nature's inherent right, especially after spending

time hiking in Yosemite Valley and studying both the ecology and

geology. He successfully lobbied congress to form Yosemite National

Park and went on to set up the Sierra Club in 1892. The conservationist

principles as well as the belief in an inherent right of nature were to

become the bedrock of modern environmentalism. In the 20th century, environmental ideas continued to grow in popularity and recognition. Efforts were starting to be made to save some wildlife, particularly the American bison. The death of the last passenger pigeon as well as the endangerment of the American bison helped to focus the minds of conservationists and to popularise their concerns. In 1916, the National Park Service was founded by US President Woodrow Wilson. The Forestry Commission was set up in 1919 in Britain to increase the amount of woodland in Britain by buying land for afforestation and reforestation. The commission was also tasked with promoting forestry and the production of timber for trade.[32] During the 1920s the Commission focused on acquiring land to begin planting out new forests; much of the land was previously used for agricultural purposes. By 1939 the Forestry Commission was the largest landowner in Britain.[33] During the 1930s the Nazis had elements that were supportive of animal rights, zoos and wildlife,[34] and took several measures to ensure their protection.[35] In 1933 the government created a stringent animal-protection law and in 1934, Das Reichsjagdgesetz (The Reich Hunting Law) was enacted which limited hunting.[36][37] Several Nazis were environmentalists (notably Rudolf Hess), and species protection and animal welfare were significant issues in the regime.[35] In 1935, the regime enacted the "Reich Nature Protection Act" (Reichsnaturschutzgesetz). The concept of the Dauerwald (best translated as the "perpetual forest") which included concepts such as forest management and protection was promoted and efforts were also made to curb air pollution.[38] In 1949, A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold was published. It explained Leopold's belief that humankind should have moral respect for the environment and that it is unethical to harm it. The book is sometimes called the most influential book on conservation. Throughout the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and beyond, photography was used to enhance public awareness of the need for protecting land and recruiting members to environmental organisations. David Brower, Ansel Adams and Nancy Newhall created the Sierra Club Exhibit Format Series, which helped raise public environmental awareness and brought a rapidly increasing flood of new members to the Sierra Club and to the environmental movement in general. This Is Dinosaur, edited by Wallace Stegner with photographs by Martin Litton and Philip Hyde, prevented the building of dams within Dinosaur National Monument by becoming part of a new kind of activism called environmentalism that combined the conservationist ideals of Thoreau, Leopold and Muir with hard-hitting advertising, lobbying, book distribution, letter writing campaigns, and more. The powerful use of photography in addition to the written word for conservation dated back to the creation of Yosemite National Park, when photographs persuaded Abraham Lincoln to preserve the beautiful glacier carved landscape for all time. The Sierra Club Exhibit Format Series galvanised public opposition to building dams in the Grand Canyon and protected many other national treasures. The Sierra Club often led a coalition of many environmental groups including the Wilderness Society and many others. After a focus on preserving wilderness in the 1950s and 1960s, the Sierra Club and other groups broadened their focus to include such issues as air and water pollution, population concern, and curbing the exploitation of natural resources. The prevailing belief regarding the origins of early environmentalism suggests that it emerged as a local response to the adverse impacts of industrialization in Western nations and communities. In terms of conservation efforts, there is a widespread view that the conservation movement began as a predominantly elite concern in North America, focusing on the preservation of local natural areas. A less prevailing view, however, attributes the roots of early environmentalism to a growing public concern about the influence of Western economic forces, particularly in connection with colonization, on tropical environments.[39] Richard Grove, in a 1990 report, points out that little attention has been given to the significance of the colonial experience, particularly the European colonial experience, in shaping early European environmentalism.[39] Grove argues that as European colonization expanded, so did the European interaction with land and indigenous people, providing Europeans with an awareness of the destructive consequences of their economic and colonial activities on the newly "discovered" lands. As global trade expanded through colonization, the European concept of nature underwent a transformation, with the foreign tropical environments of their conquests evolving into romantic symbols of idyllic landscapes that required care and protection by Europeans. Examples of this impact of colonization on the Western mindset can be found in prominent cultural references, such as William Shakespeare's play "The Tempest" and Andrew Marvell's poem "Bermoothes."[39] Although this newfound self-awareness among Europeans about the destructive impacts of colonization on the environment did not halt the expansion of colonization itself, it did pave the way for a different approach to colonization – one focused on the preservation and protection of foreign natural resources. This phenomenon can be linked to the emergence of Edenic thinking, or the quest for Eden on Earth. This quest to locate Eden gained prominence in the 15th century, coinciding with colonization, and fostered the belief that newly "discovered" lands, especially tropical ones, had the potential to be heavenly paradises.[39] |

米国における自然保護運動は、西部の自然資源を保護する必

要性への懸念から、19世紀後半に始まった。ジョン・ミューアやヘンリー・デイビッド・ソローといった人物が、この運動に重要な哲学的な貢献を果たした。

ソローは、人々と自然との関係に関心を抱き、自然の近くで質素な生活を営むことで、この関係を研究した。彼はその経験を著書『ウォールデン』で発表し、人

々は自然と親密な関係を築くべきであると主張した。特にヨセミテ渓谷でハイキングを楽しみ、生態系と地質学の両方を研究したことで、ミューアは自然の固有

の権利を信じるようになった。彼は議会に働きかけてヨセミテ国立公園の設立に成功し、1892年にはシエラ・クラブを設立した。自然の固有の権利を信じる

という信念と自然保護の原則は、現代の環境保護主義の基盤となった。 20世紀に入ると、環境保護の考え方はさらに広く認知されるようになった。野生生物、特にアメリカバイソンの保護に向けた取り組みが始まった。最後のカラ スバトの死とアメリカバイソンの絶滅危惧は、自然保護論者の関心を自然保護に向けさせ、その懸念を広めるのに役立った。1916年、ウッドロウ・ウィルソ ン米国大統領により国立公園局が設立された。 1919年には、イギリスで植林および再植林用地の土地買収により国内の森林面積を増やすことを目的とした林業委員会が設立された。委員会は林業の振興と 木材の生産による貿易の促進も任務としていた。[32] 1920年代には、委員会は新たな森林の植林を開始するための土地の取得に重点的に取り組んだ。その土地の多くは以前は農業用に使用されていた。1939 年までに、林業委員会は英国最大の土地所有者となっていた。[33] 1930年代、ナチスには動物愛護や動物園、野生動物保護を支持する要素があり[34]、それらの保護を確実にするためにいくつかの措置が取られた [35]。1933年には政府が厳格な動物保護法を制定し、1934年には狩猟を制限する「帝国狩猟法」が制定された。 [36][37] ナチスの中には環境保護主義者もいた(特にルドルフ・ヘス)。種保護と動物福祉は、政権にとって重要な問題であった。[35] 1935年、政権は「自然保護法(Reichsnaturschutzgesetz)」を制定した。森林管理や保護などの概念を含む「ダウアーヴァルト (訳語として「永遠の森」が最適)」の概念が推進され、大気汚染の抑制に向けた取り組みも行われた。 1949 年には、アルド・レオポルドの著書『砂の国年鑑』が出版された。この本では、人間は環境に対して道徳的な敬意を払うべきであり、環境を傷つけることは非倫 理的であるというレオポルドの信念が説明されている。この本は、自然保護運動に最も影響を与えた本と呼ばれることもある。 1950年代、1960年代、1970年代、そしてそれ以降、土地の保護の必要性や環境保護団体への参加を促すために、写真が活用された。デビッド・ブラ ウワー、アンセル・アダムス、ナンシー・ニューホールは、シエラクラブ展示フォーマットシリーズを作成し、環境保護に対する一般市民の意識を高め、シエラ クラブや環境保護運動全般に、急速に増加する新規会員を呼び込むのに貢献した。ウォレス・ステグナーが編集し、マーティン・リットンとフィリップ・ハイド が撮影した『This Is Dinosaur』は、ソロー、レオポルド、ミューアの自然保護主義の理想と、強力な広告、ロビー活動、書籍の配布、手紙によるキャンペーンなどを組み合 わせた、環境保護主義と呼ばれる新しい形の活動の一部となり、ダイナソー国立記念物内のダム建設を阻止した。自然保護のための文章に加えて写真が効果的に 使われたのは、ヨセミテ国立公園の創設にまで遡る。美しい氷河が作り出した地形を永久に保存するよう、写真がエイブラハム・リンカーン大統領を説得したの だ。シエラクラブの展示形式シリーズは、グランドキャニオンにダムを建設することに対する国民の反対運動を活気づけ、その他多くの自然遺産を保護した。シ エラクラブは、ウィルダネス・ソサエティをはじめとする多くの環境保護団体と連携することが多かった。 1950年代と1960年代には原生地域の保護に重点的に取り組んだが、その後、シエラクラブやその他のグループは、大気や水の汚染、人口問題、天然資源の乱開発の抑制などの問題にも視野を広げた。 初期の環境保護主義の起源に関する一般的な考え方では、それは欧米諸国や地域における工業化の悪影響に対する地域的な対応として現れたとされている。 保全活動に関しては、環境保護運動は北米のエリート層が中心となって、地域の自然地域の保全に焦点を当てて始まったという見方が一般的である。しかし、あ まり一般的ではない見解では、初期の環境保護主義のルーツは、特に植民地化に関連して、西洋の経済力が熱帯環境に与える影響に対する一般市民の懸念の高ま りにあるとしている。[39] リチャード・グローブは1990年の報告書で、初期のヨーロッパの環境保護主義の形成において、植民地経験、特にヨーロッパの植民地経験の重要性がほとん ど注目されていないと指摘している。[39] グローブは、ヨーロッパの植民地化が拡大するにつれ、ヨーロッパと土地や先住民との交流も深まり、ヨーロッパ人たちは、新たに「発見」した土地における経 済活動や植民地活動が破壊的な結果をもたらすという認識を持つようになったと主張している。植民地化による世界貿易の拡大に伴い、ヨーロッパ人の自然観に も変化が生じ、征服した土地の外国の熱帯環境は、ヨーロッパ人の手入れと保護を必要とする牧歌的な風景のロマンチックな象徴へと変化した。植民地化が西洋 人の考え方に与えた影響の例は、ウィリアム・シェイクスピアの戯曲『テンペスト』やアンドリュー・マーヴェルの詩『バーモウセス』[39] などの著名な文化的な参照先に見出すことができる。 ヨーロッパ人による植民地化が環境に破壊的な影響を与えるという新たな自己認識は、植民地化の拡大そのものを止めることはなかったが、植民地化に対する異 なるアプローチへの道筋をつけた。それは、外国の天然資源の保全と保護に焦点を当てたアプローチである。この現象は、エデンの園的な思考、すなわち地上の 楽園を求める動きと関連している。この楽園探しの動きは、植民地化と時を同じくして15世紀に盛んになり、新たに「発見」された土地、特に熱帯の土地には 天国の楽園となる可能性があるという信念を育んだ。[39] |

| Post-war expansion See also: Steady-state economy § Post-war economic expansion and emerging ecological concerns  In the United States and several other countries, the boom was manifested in suburban development and urban sprawl, aided by automobile ownership. In 1962, Silent Spring by American biologist Rachel Carson was published. The book cataloged the environmental impacts of the indiscriminate spraying of DDT in the US and questioned the logic of releasing large amounts of chemicals into the environment without fully understanding their effects on human health and ecology. The book suggested that DDT and other pesticides may cause cancer and that their agricultural use was a threat to wildlife, particularly birds.[40] The resulting public concern led to the creation of the United States Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 which subsequently banned the agricultural use of DDT in the US in 1972. The limited use of DDT in disease vector control continues to this day in certain parts of the world and remains controversial. The book's legacy was to produce a far greater awareness of environmental issues and interest into how people affect the environment. With this new interest in environment came interest in problems such as air pollution and petroleum spills, and environmental interest grew. New pressure groups formed, notably Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth (US), as well as notable local organisations such as the Wyoming Outdoor Council, which was founded in 1967. From 1962 to 1998, the environmental movement founded 772 national organizations in the United States.[41] In the 1970s, the environmental movement gained rapid speed around the world as a productive outgrowth of the counterculture movement.[42] The world's first political parties to campaign on a predominantly environmental platform were the United Tasmania Group of Tasmania, Australia, and the Values Party of New Zealand.[43][44] The first green party in Europe was the Popular Movement for the Environment, founded in 1972 in the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel. The first national green party in Europe was PEOPLE, founded in Britain in February 1973, which eventually turned into the Ecology Party, and then the Green Party. Protection of the environment also became important in the developing world; the Chipko movement was formed in India under the influence of Mhatmas Gandhi and they set up peaceful resistance to deforestation by literally hugging trees (leading to the term "tree huggers"). Their peaceful methods of protest and slogan "ecology is permanent economy" were very influential. Another milestone in the movement was the creation of Earth Day. Earth Day was first observed in San Francisco and other cities on 21 March 1970, the first day of spring. It was created to give awareness to environmental issues. On 21 March 1971, United Nations Secretary-General U Thant spoke of a spaceship Earth on Earth Day, hereby referring to the ecosystem services the earth supplies to us, and hence our obligation to protect it (and with it, ourselves). Earth Day is now coordinated globally by the Earth Day Network,[45] and is celebrated in more than 192 countries every year.[46] The UN's first major conference on international environmental issues, the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (also known as the Stockholm Conference), was held on 5–16 June 1972. It marked a turning point in the development of international environmental politics.[47] By the mid-1970s, many felt that people were on the edge of environmental catastrophe. The back-to-the-land movement started to form and ideas of environmental ethics joined with anti-Vietnam War sentiments and other political issues. These individuals lived outside normal society and started to take on some of the more radical environmental theories such as deep ecology. Around this time more mainstream environmentalism was starting to show force with the signing of the Endangered Species Act in 1973 and the formation of CITES in 1975. Significant amendments were also enacted to the United States Clean Air Act[48] and Clean Water Act.[49] In 1979, James Lovelock, a British scientist, published Gaia: A new look at life on Earth, which put forth the Gaia hypothesis; it proposes that life on earth can be understood as a single organism. This became an important part of the Deep Green ideology. Throughout the rest of the history of environmentalism there has been debate and argument between more radical followers of this Deep Green ideology and more mainstream environmentalists. |

戦後の拡大 参照:定常経済 § 戦後の経済拡大と生態系への懸念  米国およびその他のいくつかの国々では、ブームは自動車の普及に後押しされた郊外開発とスプロール現象という形で現れた。 1962年には、アメリカの生物学者レイチェル・カーソンの著書『沈黙の春』が出版された。この本は、アメリカにおけるDDTの無差別散布が環境に与える 影響をまとめ、人体の保健や生態系への影響を十分に理解しないまま、環境中に大量の化学物質を放出することの論理を疑問視した。この本は、DDTやその他 の殺虫剤が発がん性を持つ可能性を示唆し、それらの農業利用は野生生物、特に鳥類にとって脅威であると主張した。[40] その結果、人々の間に懸念が広がり、1970年に米国環境保護庁が設立され、1972年には米国におけるDDTの農業利用が禁止された。 媒介生物の駆除を目的とした限定的なDDTの利用は、現在でも世界の特定の地域では継続されており、論争の的となっている。この本の功績は、環境問題に対 する認識を飛躍的に高め、人々が環境に与える影響に対する関心を喚起したことである。環境に対する新たな関心は、大気汚染や石油流出などの問題に対する関 心をも呼び起こし、環境への関心は高まった。新たな圧力団体が結成され、中でもグリーンピースやフレンズ・オブ・ジ・アース(米国)が有名である。また、 ワイオミング・アウトドア・カウンシル(1967年設立)のような地元の著名な組織もあった。1962年から1998年の間に、環境保護運動によって米国 で772の全国組織が設立された。[41] 1970年代には、環境保護運動はカウンターカルチャー運動の生産的な副産物として世界中で急速に広がった。[42] 環境保護を主な政策として掲げた世界初の政党は、オーストラリアのタスマニアにあるタスマニア連合(United Tasmania Group)とニュージーランドの価値党(Values Party)である。[43][44] ヨーロッパ初の環境保護政党は、1972年にスイスのヌーシャテル州で設立された環境のための人民運動(Popular Movement for the Environment)である。ヨーロッパで最初の全国的な緑の党は、1973年2月にイギリスで結成されたPEOPLEであり、最終的にエコロジー 党、そして緑の党へと発展した。 発展途上国でも環境保護が重要視されるようになり、インドではマハトマ・ガンジーの影響を受けて「チップコ運動」が起こり、文字通り木に抱きつくことで森 林伐採に平和的な抵抗を示した(「ツリー・ハガー」という言葉の由来となった)。彼らの平和的な抗議活動と「エコロジーは永遠の経済」というスローガン は、大きな影響を与えた。 この運動におけるもう一つの画期的な出来事は、「アースデイ」の創設である。アースデイは、1970年3月21日、春分の日にサンフランシスコをはじめと するいくつかの都市で初めて開催された。環境問題への意識を高めることを目的として創設された。1971年3月21日、国連事務総長ウ・タントはアースデ イの席上で「地球号」という表現を用いて、地球が私たちに提供している生態系サービスについて言及し、それゆえに私たちは地球を守る義務がある(そして、 それによって自分自身を守る義務がある)と述べた。アースデイは現在、アースデイ・ネットワークによって世界規模で調整されており、毎年192カ国以上で 祝われている。 国連による初の主要な国際環境問題会議である「国連人間環境会議」(ストックホルム会議とも呼ばれる)は、1972年6月5日から16日にかけて開催された。これは、国際環境政治の発展における転換点となった。 1970年代半ばには、人々は環境の破局の瀬戸際に立たされていると感じるようになった。バック・トゥ・ザ・ランド運動が形成され始め、環境倫理の考え方 がベトナム戦争反対の感情やその他の政治問題と結びついた。これらの人々は通常の社会から離れて生活し、ディープ・エコロジーのようなより急進的な環境理 論の一部を取り入れ始めた。この頃、1973年の絶滅危惧種法(Endangered Species Act)の署名や1975年のワシントン条約(CITES)の結成により、より主流派の環境保護主義が力を持ち始めていた。また、米国の大気浄化法 (United States Clean Air Act)[48]と水質浄化法(Clean Water Act)[49]にも大幅な改正が加えられた。 1979年には、イギリスの科学者ジェームズ・ラブロックが『ガイア:地球生命への新しい視点』を出版し、ガイア仮説を提唱した。これは、地球上の生命は ひとつの有機体として理解できるというものである。これがディープ・グリーン思想の重要な一部となった。環境保護運動の歴史を通じて、このディープ・グ リーン思想の急進的な支持者と、より主流派の環境保護主義者との間で、議論や論争が続いている。 |

| 21st century and beyond Environmentalism continues to evolve to face up to new issues such as global warming, overpopulation, genetic engineering, and plastic pollution. Research demonstrates a precipitous decline in the US public's interest in 19 different areas of environmental concern.[50] Americans are less likely to be actively participating in an environmental movement or organisation and more likely to identify as "unsympathetic" to an environmental movement than in 2000.[51] This is likely a lingering factor of the Great Recession in 2008. Since 2005, the percentage of Americans agreeing that the environment should be given priority over economic growth has dropped 10 points; in contrast, those feeling that growth should be given priority "even if the environment suffers to some extent" has risen 12 percent.[51] Nevertheless, a recent National Geographic survey indicated strong desire for commitment across a dozen countries, indicating a majority were in favour of more than half of the Earth's land surface being protected.[52] |

21世紀以降 環境保護主義は、地球温暖化、人口過剰、遺伝子組み換え、プラスチック汚染などの新たな問題に直面し、進化し続けている。 研究によると、米国国民の環境問題への関心は、19の異なる分野で急激に低下していることが明らかになっている。[50] 米国人は環境保護運動や環境保護団体に積極的に参加する傾向が弱まり、2000年よりも環境保護運動に対して「無関心」であると認識する傾向が強まってい る。[51] これは、2008年の大不況の余波である可能性が高い。2005年以来、環境よりも経済成長を優先すべきだと考えるアメリカ人の割合は10ポイント減少し ている。一方、「多少環境が悪化しても、経済成長を優先すべき」と考える人の割合は12%増加している。[51] しかし、ナショナルジオグラフィックの最近の調査では、12カ国で環境保護への強い要望が示され、地球の陸地の半分以上を保護すべきだと考える国民が多数 派であることが示された。 [52] |

New forms of ecoactivism Demonstrators in a tree at the Berkeley oak grove protest in 2008 Tree sitting is a form of activism in which the protester sits in a tree in an attempt to stop the removal of a tree or to impede the demolition of an area with the longest and most famous tree-sitter being Julia Butterfly Hill, who spent 738 days in a California Redwood, saving a three-acre tract of forest.[53] Also notable is the Yellow Finch tree sit, which was a 932-day blockade of the Mountain Valley Pipeline from 2018 to 2021.[54][55] Sit-ins can be used to encourage social change, such as the Greensboro sit-ins, a series of protests in 1960 to stop racial segregation, but can also be used in ecoactivism, as in the Dakota Access Pipeline Protest.[56] Before the Syrian civil war, Rojava had been ecologically damaged by monoculture, oil extraction, damming of rivers, deforestation, drought, topsoil loss and general pollution. The DFNS launched a campaign titled 'Make Rojava Green Again' (a parody of Make America Great Again) which is attempting to provide renewable energy to communities (especially solar energy), reforestation, protecting water sources, planting gardens, promoting urban agriculture, creating wildlife reserves, water recycling, beekeeping, expanding public transportation and promoting environmental awareness within their communities.[57] The Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities are firmly environmentalist and have stopped the extraction of oil, uranium, timber and metal from the Lacandon Jungle and stopped the use of pesticides and chemical fertilisers in farming.[58] The CIPO-RFM has engaged in sabotage and direct action against wind farms, shrimp farms, eucalyptus plantations and the timber industry. They have also set up corn and coffee worker cooperatives and built schools and hospitals to help the local populations. They have also created a network of autonomous community radio stations to educate people about dangers to the environment and inform the surrounding communities about new industrial projects that would destroy more land. In 2001, the CIPO-RFM defeated the construction of a highway that was part of Plan Puebla Panama.[59] |

新しい形のエコ活動 2008年のバークレーのオークグローブでの抗議活動で、木の上に座るデモ参加者 ツリーシッティングは、樹木の伐採を阻止したり、地域の破壊を妨害したりするために、抗議者が木の上に座るという活動形態である。最も長く、最も有名なツ リーシッターは、カリフォルニア州のレッドウッドの木に738日間座り込み、3エーカーの森林地帯を救ったジュリア・バタフライ・ヒルである。 [53] また、2018年から2021年にかけてマウンテンバレーパイプラインを932日間封鎖したイエローフィンチのツリーシットも注目に値する。[54] [55] 座り込みは、1960年に人種隔離政策を停止させるために行われた一連の抗議運動であるグリーンズボロ座り込みのように、社会変革を促すために用いられることもあるが、ダコタ・アクセス・パイプライン抗議運動のように、エコ活動にも用いられることがある。 シリア内戦以前、ロジャヴァは単一栽培、石油採掘、河川の堰き止め、森林伐採、干ばつ、表土の喪失、および一般的な汚染によって生態系が破壊されていた。 DFNSは「Make Rojava Green Again」(「Make America Great Again」のパロディ)と題したキャンペーンを開始し、地域社会への再生可能エネルギー(特に太陽光発電)の供給、森林再生、水源の保護、菜園の設置、 都市農業の推進、野生生物保護区の創設、水のリサイクル、養蜂、公共交通機関の拡充、地域社会における環境意識の啓発に取り組んでいる。 サパティスタ自治市は環境保護に強く、ラカンドン密林からの石油、ウラン、木材、金属の採取を中止し、農業における農薬や化学肥料の使用を中止した。 CIPO-RFMは、風力発電所、エビ養殖場、ユーカリ植林、木材産業に対する妨害行為や直接行動を行っている。また、トウモロコシやコーヒーの労働者協 同組合を設立し、学校や病院を建設して地元住民を支援している。さらに、環境への危険性について人々を教育し、より広範囲の土地を破壊する新たな工業プロ ジェクトについて周辺地域に知らせるために、自治コミュニティのラジオ局のネットワークを構築した。2001年には、CIPO-RFMはプエブラ・パナマ 計画の一部である高速道路の建設を阻止した。[59] |

| Environmental movement Main article: Environmental movement Before flue-gas desulfurization was installed, the air-polluting emissions from this power plant in New Mexico contained excessive amounts of sulfur dioxide. The environmental movement (a term that sometimes includes the conservation and green movements) is a diverse scientific, social, and political movement. Though the movement is represented by a range of organisations, because of the inclusion of environmentalism in the classroom curriculum,[60][61] the environmental movement has a younger demographic than is common in other social movements (see green seniors). Environmentalism as a movement covers broad areas of institutional oppression, including for example: consumption of ecosystems and natural resources into waste, dumping waste into disadvantaged communities, air pollution, water pollution, weak infrastructure, exposure of organic life to toxins, mono-culture, anti-polythene drive (jhola movement) and various other focuses. Because of these divisions, the environmental movement can be categorized into these primary focuses: environmental science, environmental activism, environmental advocacy, and environmental justice.[62] |

環境保護運動 詳細は「環境保護運動」を参照 排煙脱硫装置が設置される前、ニューメキシコ州のこの発電所から排出される大気汚染物質には、過剰な量の二酸化硫黄が含まれていた。 環境保護運動(環境保護運動やグリーン運動を含む場合もある)は、科学的、社会的、政治的な多様な運動である。この運動はさまざまな組織によって代表され ているが、環境保護主義が教育カリキュラムに組み込まれているため、環境保護運動は他の社会運動に比べて若い層が多い(グリーンシニアを参照)。 環境保護運動は、制度的な抑圧の幅広い分野をカバーしており、例えば、生態系や天然資源の浪費、恵まれない地域への廃棄物の投棄、大気汚染、水質汚染、脆 弱なインフラ、有機生命体の毒素への曝露、単一栽培、反ポリエチレン運動(ジョーラ運動)、およびその他のさまざまな焦点を含む。これらの区分により、環 境保護運動は、環境科学、環境活動、環境擁護、環境正義という4つの主要な焦点に分類することができる。[62] |

| Free market environmentalism Main article: Free-market environmentalism Free market environmentalism is a theory that argues that the free market, property rights, and tort law provide the best tools to preserve the health and sustainability of the environment. It considers environmental stewardship to be natural, as well as the expulsion of polluters and other aggressors through individual and class action. |

自由市場環境主義 詳細は「自由市場環境主義」を参照 自由市場環境主義とは、自由市場、財産権、不法行為法が環境の保健と持続可能性を維持する上で最良の手段であると主張する理論である。また、個人および集団訴訟によって汚染者やその他の加害者を排除することも当然のことと考えている。 |

| Evangelical environmentalism Main article: Evangelical environmentalism Evangelical environmentalism is an environmental movement in the United States in which some Evangelicals have emphasized biblical mandates concerning humanity's role as steward and subsequent responsibility for the care taking of Creation. While the movement has focused on different environmental issues, it is best known for its focus of addressing climate action from a biblically grounded theological perspective. This movement is controversial among some non-Christian environmentalists due to its rooting in a specific religion. |

福音派の環境保護主義 詳細は「福音派環境主義」を参照 福音派環境主義は、米国における環境保護運動であり、一部の福音派は、人間が管理者の役割を果たし、創造物を大切に扱うことに対するその後の責任につい て、聖書が命じていることを強調している。この運動は、異なる環境問題に焦点を当ててきたが、聖書に基づく神学的観点から気候変動への対策に焦点を当てて いることで最もよく知られている。この運動は、特定の宗教に根ざしていることから、一部の非キリスト教徒の環境保護主義者からは論争の的となっている。 |

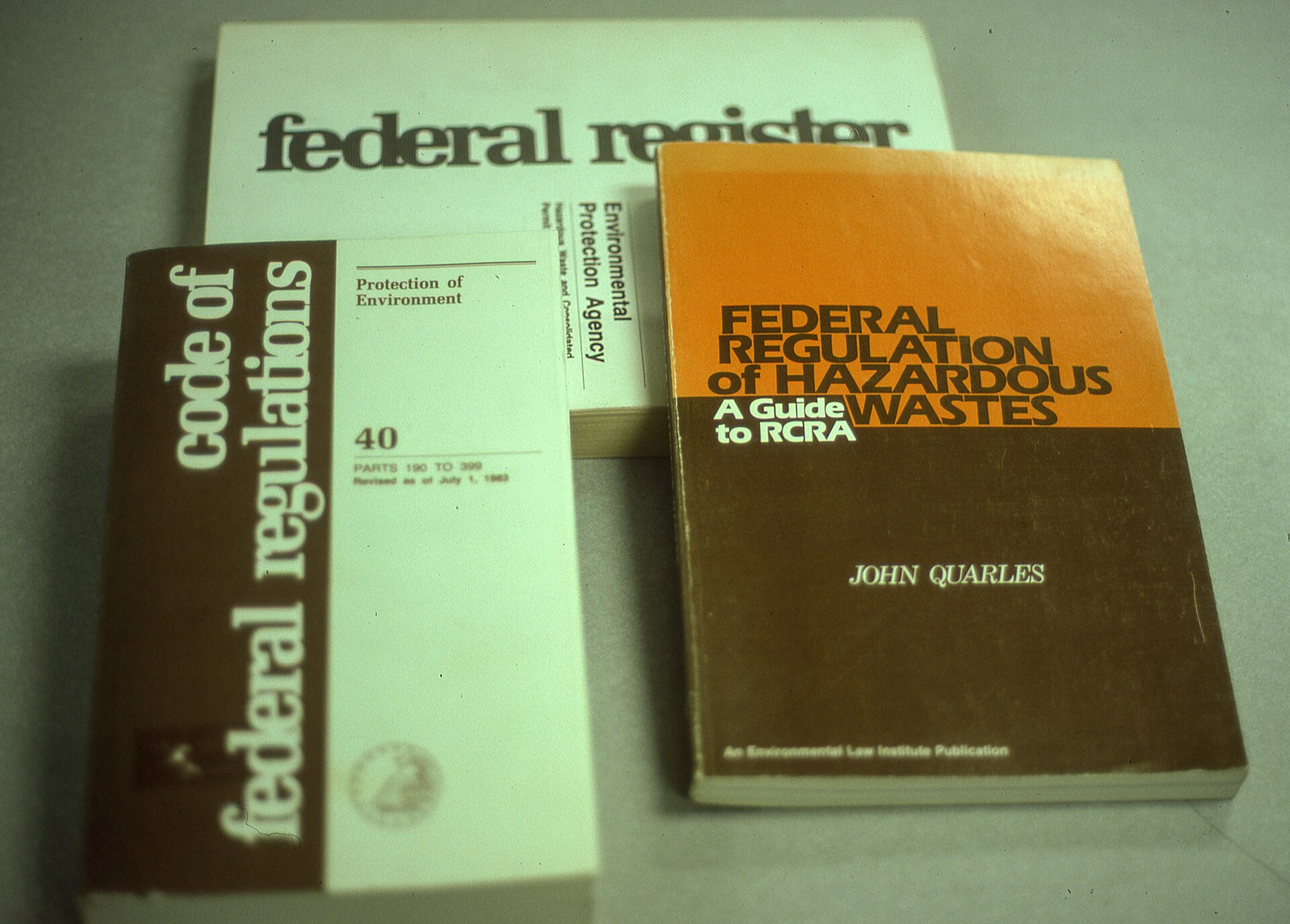

Preservation and conservation Federal Register documents and literature related to US environmental regulations, including the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), 1987 Main articles: Nature conservation and Conservation movement Environmental preservation in the United States and other parts of the world, including Australia, is viewed as the setting aside of natural resources to prevent damage caused by contact with humans or by certain human activities, such as logging, mining, hunting, and fishing, often to replace them with new human activities such as tourism and recreation.[63] Regulations and laws may be enacted for the preservation of natural resources. |

保全と保護 米国環境規制に関する連邦官報の文書および文献。これには、資源保全回収法(RCRA)1987年も含まれる 主な記事:自然保護と自然保護運動 アメリカ合衆国およびオーストラリアを含むその他の地域における環境保全は、人間との接触や伐採、採掘、狩猟、漁業などの特定の人間活動による被害を防ぐ ために自然資源を確保することと見なされており、多くの場合、観光やレクリエーションなどの新たな人間活動に置き換えることを目的としている。[63] 自然資源の保全を目的として、規制や法律が制定される場合がある。 |

| Exergy and availability of resources Thermodynamic derived environmentalism is based on the second law of thermodynamics, minimization of exergy disruption (or entropy generation)and the concept of availability. It moves from the milestone work of Jan Szargut who emphasized the relation between exergy and availability,[64] it is necessary to remember "Exergy Ecology and Democracy".[65] by Goran Wall, a short essay, which evidences the strict relation that relates exergy disruption with environmental and social disruption. More recently it has verified that governmental emissions and impacts balances underestimate the effective GHG production by means of human processes. In fact, they often neglects the impacts of import/export related emissions. In addition they have analyzed the UN SDGs and the methods which are suggested for verifying the advances of the countries. This activity has evidenced that objective and coherent parameters are missing. Therefore, they suggest the introduction of exergy analysis as the most effective method for estimating the environmental degradation.[66][67] Therefore, a novel fiscal model based on Exergy and availability disruption has been defined as the only possible way for overcoming the problems induced by the globalized markets. |

エクセルギーと資源の利用可能量 熱力学派の環境保護論は、熱力学第二法則、エクセルギーの撹乱(またはエントロピーの発生)の最小化、および利用可能性の概念に基づいている。エクセル ギーと利用可能性の関係を強調したヤン・シャルグットの画期的な研究[64]から発展したものであり、ゴラン・ウォールの短いエッセイ「エクセルギー生態 学と民主主義」[65]を想起する必要がある。このエッセイは、エクセルギーの撹乱と環境および社会の撹乱との厳密な関係を証明している。さらに最近で は、政府による排出量と影響のバランスは、人間活動による実質的な温室効果ガス排出量を過小評価していることが検証されている。実際、輸出入に関連する排 出量の影響はしばしば無視されている。さらに、国連の持続可能な開発目標(SDGs)と、各国の進捗状況を検証するために提案されている手法についても分 析している。この活動により、客観的かつ首尾一貫したパラメータが欠如していることが明らかになった。そのため、環境悪化を推定する最も効果的な方法とし てエクセルギー分析の導入を提案している。[66][67] したがって、エクセルギーと可用性破壊に基づく新しい財政モデルが、グローバル化した市場が引き起こす問題を克服する唯一の可能な方法として定義されてい る。 |

| Organisations and conferences Main article: List of environmental organizations This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Environmental organisations can be global, regional, national or local; they can be government-run or private (NGO). Environmentalist activity exists in almost every country. Moreover, groups dedicated to community development and social justice also focus on environmental concerns. Some US environmental organisations, among them the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Environmental Defense Fund, specialise in bringing lawsuits (a tactic seen as particularly useful in that country). Other groups, such as the US-based National Wildlife Federation, Earth Day, National Cleanup Day, the Nature Conservancy, and The Wilderness Society, and global groups like the World Wide Fund for Nature and Friends of the Earth, disseminate information, participate in public hearings, lobby, stage demonstrations, and may purchase land for preservation. Statewide nonprofit organisations such as the Wyoming Outdoor Council often collaborate with these national organisations and employ similar strategies. Smaller groups, including Wildlife Conservation International, conduct research on endangered species and ecosystems. More radical organisations, such as Greenpeace, Earth First!, and the Earth Liberation Front, have more directly opposed actions they regard as environmentally harmful. While Greenpeace is devoted to nonviolent confrontation as a means of bearing witness to environmental wrongs and bringing issues into the public realm for debate, the underground Earth Liberation Front engages in the clandestine destruction of property, the release of caged or penned animals, and other criminal acts. Such tactics are regarded as unusual within the movement, however. On an international level, concern for the environment was the subject of a United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972, attended by 114 nations. Out of this meeting developed the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the follow-up United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992. Other international organisations in support of environmental policies development include the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (as part of NAFTA), the European Environment Agency (EEA), and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). |

組織と会議 詳細は「環境保護団体一覧」を参照 この節には出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典のない項目は、削除される場合があります。 (2023年8月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 環境保護団体は、世界規模、地域、国民、あるいは地域レベルで活動する。政府運営の団体もあれば、民間(NGO)の団体もある。環境保護活動はほとんどの国で存在する。さらに、地域開発や社会正義に専念するグループも環境問題に焦点を当てている。 米国の環境保護団体の中には、自然資源防衛協議会や環境防衛基金など、訴訟を起こすことを専門とする団体もある(この戦術は米国では特に有効であると考え られている)。また、米国を拠点とする全米野生生物連盟、アースデイ、全米清掃の日、自然保護協会、ウィルダネス・ソサエティ、そして世界規模のWWF (世界自然保護基金)やFoE(国際環境保護連合)といったグループは、情報の普及、公聴会への参加、ロビー活動、デモの実施、保護のための土地購入など を行っている。ワイオミング・アウトドア・カウンシルなどの州全体の非営利団体は、これらの全国組織と協力し、同様の戦略を採用することが多い。 Wildlife Conservation Internationalなどの小規模なグループは、絶滅危惧種や生態系に関する研究を行っている。グリーンピース、アース・ファースト、アース・リベ レーション・フロントなどのより急進的な団体は、環境に有害であるとみなされる行動に直接的に反対している。グリーンピースは環境破壊の証人となること、 そして問題を議論の場に持ち出すことを目的として非暴力の対決に専念しているが、地下組織であるアース・リベレーション・フロントは、財産の秘密裏の破 壊、檻や囲いに入れられた動物の解放、その他の犯罪行為を行っている。しかし、このような戦術は、この運動の中では異例であるとみなされている。 国際レベルでは、1972年に114カ国の国民が参加してスウェーデンのストックホルムで開催された「人間環境会議」で、環境問題が議題となった。この会 議をきっかけに、国連環境計画(UNEP)が設立され、1992年には国連環境開発会議(地球サミット)が開催された。環境政策の策定を支援するその他の 国際機関としては、北米自由貿易協定(NAFTA)の一部である環境協力委員会、欧州環境機関(EEA)、気候変動に関する政府間パネル(IPCC)など がある。 |

Environmental protests Climate activists blockade British Airports Authority's headquarters for day of action.  "March Against Monsanto", Vancouver, Canada, 25 May 2013 Main article: List of environmental protests Notable environmental protests and campaigns include: 2010 Xinfa aluminum plant protest Anti-WAAhnsinns Festival Car-Free Days Camp for Climate Action Campaign against Climate Change Climate Rush Cofán people oil drilling protest (Ecuador) Earth Day Earth First! Earthlife Africa Extinction Rebellion Global Climate Strikes[68][69] Global Day of Action Gurindji Strike Hands off our Forest Homes before Roads Water Protectors Just Stop Oil Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta Love Canal protests March Against Monsanto Nevada Desert Experience Plane Mad Plane Stupid Qidong protest Save Manapouri Campaign Say Yes demonstrations Shifang protest Stop Climate Chaos |

環境保護運動 気候活動家が英国空港局の本社を1日封鎖。  2013年5月25日、カナダ、バンクーバーでの「マーチ・アゲインスト・モンサント」 詳細は「環境保護運動の一覧」を参照 著名な環境保護運動およびキャンペーンには以下のようなものがある。 2010年 新発アルミニウム工場抗議 反WAAhnsinnsフェスティバル カーフリーデー 気候変動対策キャンプ 気候変動反対キャンペーン クライメート・ラッシュ コファン族の石油掘削抗議(エクアドル) アースデイ アース・ファースト! アースライフ・アフリカ 絶滅の反乱 グローバル・クライメート・ストライキ[68][69] グローバル・アクション・デー グルンジ・ストライキ 森に手を出さないで 道路より家を ウォーター・プロテクターズ ジャスト・ストップ・オイル クパ・ピティ・クンガ・チュタ ラブ・キャナル抗議 マーチ・アゲインスト・モンサント ネバダ砂漠体験 飛行機狂 飛行機は愚かだ 啓東市の抗議 マナポウリを守ろうキャンペーン イエスと言おうデモ 什邡市の抗議 気候変動の混乱を止めよう |

| Environmentalists Notable advocates for environmental protection and sustainability include: Edward Abbey (author) David Attenborough (broadcaster, naturalist) John James Audubon (naturalist) Judi Bari (environmentalist) James Cameron (filmmaker and environmentalist) Frances Beinecke (environmentalist and former president of the Natural Resources Defense Council) David Bellamy (botanist) Wendell Berry (farmer, philosopher) Murray Bookchin (anarchist, philosopher, social ecologist) Erin Brockovich (environmental lawyer and activist) David Brower (writer, activist) Bob Brown (activist and politician) Lester Brown (environmental analyst, author) Carol Browner (lawyer and activist) Molly Burhans (faith-based environmentalist) Kevin Buzzacott (Aboriginal activist) Berta Caceres (environmental and indigenous rights activist) Helen Caldicott (medical doctor) Rachel Carson (biologist, writer) Majora Carter (urban revitalization strategist) Charles III (King of the United Kingdom) Barry Commoner (biologist, politician) Jacques-Yves Cousteau (explorer, ecologist) Herman Daly (ecological economist and steady-state theorist) Peter Dauvergne (political scientist) Laurie David (activist and producer) Marina DeBris (environmental artist) Leonardo DiCaprio (actor and environmentalist)[70] Sylvia Earle (marine biologist) Paul R. Ehrlich (population biologist) Hans-Josef Fell (German Green Party member) Jane Fonda (actor) Josh Fox (filmmaker, environmental activist) Mizuho Fukushima (politician, activist) Peter Garrett (musician, politician) Jane Goodall (primatologist, anthropologist, and UN Messenger of Peace) Lois Gibbs (Founder of the Center for Health, Environment and Justice) Al Gore (former Vice President of the United States) Daryl Hannah (activist) James Hansen (scientist) Garrett Hardin (ecologist, ecophilosopher) Denis Hayes (environmentalist and solar power advocate) Julia Butterfly Hill (activist) Robert Hunter (journalist, co-founder and first president of Greenpeace) Tetsunari Iida (sustainable energy advocate) Lisa P. Jackson (chemical engineer and former administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency) Naomi Klein (writer, activist) Winona LaDuke (environmentalist) Aldo Leopold (ecologist) A. Carl Leopold (plant physiologist) James Lovelock (scientist) Amory Lovins (energy policy analyst) Hunter Lovins (environmentalist) Caroline Lucas (politician) Wangari Maathai (activist and Nobel laureate) Jarid Manos (CEO of the Great Plains Restoration Council) Xiuhtezcatl Martinez (environmental activist, hip-hop artist) Bill McKibben (writer, activist) David McTaggart (activist) Chico Mendes (activist) Joni Mitchell (musician, environmental activist) George Monbiot (journalist) John Muir (naturalist, activist) Ralph Nader (activist) Gaylord Nelson (politician) Alan Pears (environmental consultant and energy efficiency pioneer) Gifford Pinchot (first chief of the USFS) Jonathon Porritt (politician) John Wesley Powell (second director of the USGS) Barbara Pyle (documentarian and executive producer of Captain Planet and the Planeteers) Phil Radford (environmental, clean energy and democracy advocate, Greenpeace Executive Director) Bonnie Raitt (musician) Theodore Roosevelt (former President of the United States) Habiba Sarobi (politician and activist) E. F. Schumacher (author of Small Is Beautiful) Vandana Shiva (ecofeminist and activist) Marina Silva (politician and activist) Alicia Silverstone (activist and author of The Kind Diet) Lauren Singer (activist and entrepreneur) Swami Sundaranand (Yogi, photographer, and mountaineer) Cass Sunstein (environmental lawyer) David Suzuki (scientist, broadcaster) Henry David Thoreau (writer, philosopher) Greta Thunberg (environmentalist) Stewart Udall (former United States Secretary of the Interior) Jo Valentine (politician and activist) Dominique Voynet (politician and environmentalist) Christopher O. Ward (water infrastructure expert) Alice Waters (activist and restaurateur) Gabriel Willow (environmental educator, naturalist) Howard Zahniser (author of the 1964 Wilderness Act) |

環境保護活動家 環境保護と持続可能性の著名な提唱者には以下が含まれる。 エドワード・アビー(作家 デヴィッド・アッテンボロー(放送者、自然主義者 ジョン・ジェームズ・オーデュボン(自然主義者 ジュディ・バリー(環境保護活動家 ジェームズ・キャメロン(映画製作者、環境保護活動家 フランシス・ベインチ(環境保護活動家、元天然資源防衛協議会会長 デイヴィッド・ベラミー(植物学者 ウェンデル・ベリー(農場経営者、哲学者 マレー・ブクチン(アナーキスト、哲学者、社会生態学者) エリン・ブロコビッチ(環境弁護士、活動家) デヴィッド・ブラウワー(作家、活動家) ボブ・ブラウン(活動家、政治家) レスター・ブラウン(環境アナリスト、作家) キャロル・ブラウナー(弁護士、活動家) モリー・バーハンズ(信仰に基づく環境保護主義者) ケヴィン・バザコット(先住民活動家) ベルタ・カセレス(環境および先住民の権利活動家) ヘレン・カルディコット(医師) レイチェル・カーソン(生物学者、作家) メイジャー・カーター(都市再生戦略家) チャールズ3世(イギリス王) バリー・コモナー(生物学者、政治家) ジャック=イヴ・クストー(探検家、生態学者) ハーマン・ダリー(生態経済学者、定常理論家) ピーター・ドゥーヴェルニュ(政治学者) ローリー・デイヴィッド(活動家、プロデューサー) マリーナ・デブリス(環境芸術家) レオナルド・ディカプリオ(俳優、環境保護活動家)[70] シルヴィア・アール(海洋生物学者) ポール・R・エーリック(人口生物学者) ハンス=ヨゼフ・フェル(ドイツ緑の党所属議員) ジェーン・フォンダ(俳優) ジョシュ・フォックス(映画製作者、環境保護活動家) 福島瑞穂(政治家、活動家) ピーター・ギャレット(ミュージシャン、政治家) ジェーン・グドール(霊長類学者、人類学者、国連平和大使) ロイス・ギブス(Center for Health, Environment and Justiceの創設者) アル・ゴア(元アメリカ合衆国副大統領) ダリル・ハンナ(活動家) ジェームズ・ハンセン(科学者) ギャレット・ハーディン(生態学者、エコフィロソファー) デニス・ヘイズ(環境保護活動家、太陽光発電の提唱者) ジュリア・バタフライ・ヒル(活動家) ロバート・ハンター(ジャーナリスト、グリーンピースの共同創設者および初代代表) 飯田哲也(持続可能なエネルギーの提唱者) リサ・P・ジャクソン(化学エンジニア、元米国環境保護庁長官) ナオミ・クライン(作家、活動家) ウィノナ・ラドゥーク(環境保護活動家) アルド・レオポルド(生態学者) A. カール・レオポルド(植物生理学者) ジェームズ・ラブロック(科学者) アモリー・ロビンス(エネルギー政策アナリスト) ハンター・ロビンス(環境保護活動家) キャロライン・ルーカス(政治家) ワンガリ・マータイ(活動家、ノーベル賞受賞者) ジャリド・マノス(グレートプレインズ修復協議会CEO) シウテツァル・マルティネス(環境保護活動家、ヒップホップアーティスト) ビル・マッキベン(作家、活動家) デビッド・マクタガート(活動家) チコ・メンデス(活動家) ジョニ・ミッチェル(ミュージシャン、環境活動家) ジョージ・モンビオ(ジャーナリスト) ジョン・ミューア(自然主義者、活動家) ラルフ・ネーダー(活動家) ゲイロード・ネルソン(政治家) アラン・ピアース(環境コンサルタント、エネルギー効率化の先駆者) ギフォード・ピンショー(初代米国森林局長官) ジョナサン・ポーリット(政治家) ジョン・ウェスレー・パウエル(米国地質調査所第2代所長) バーバラ・パイル(ドキュメンタリー制作者、『キャプテン・プラネットとプラネティアーズ』のエグゼクティブ・プロデューサー) フィル・ラドフォード(環境、クリーンエネルギー、民主主義の擁護者、グリーンピースの元エグゼクティブ・ディレクター) ボニー・レイット(ミュージシャン) セオドア・ルーズベルト(元米国大統領) ハビバ・サロビ(政治家、活動家) E. F. シューマッハー(『スモール・イズ・ビューティフル』の著者) ヴァンダナ・シヴァ(エコフェミニスト、活動家) マリーナ・シルヴァ(政治家、活動家) アリシア・シルバーストーン(活動家、『The Kind Diet』の著者) ローレン・シンガー(活動家、起業家) スワミ・スンダラナンダ(ヨギ、写真家、登山家) キャス・サンスティーン(環境弁護士) デヴィッド・スズキ(科学者、放送作家) ヘンリー・デイヴィッド・ソロー(作家、哲学者) グレタ・トゥーンベリ(環境保護活動家) スチュワート・ユドール(元米国内務長官) ジョー・バレンタイン(政治家、活動家) ドミニク・ボイニエ(政治家、環境保護活動家) クリストファー・O・ウォード(水インフラ専門家) アリス・ウォーターズ(活動家、レストラン経営者) ガブリエル・ウィロー(環境教育者、自然主義者) ハワード・ザニサー(1964年原生自然法の起草者) |

Assassinations Early American game warden Guy Bradley, who was killed in 1905 while attempting to stop a bird poacher near Flamingo, Florida See also: List of environmental activists assassinated Every year, more than 100 environmental activists are murdered throughout the world.[71] Most recent deaths are in Brazil, where activists combat logging in the Amazon rainforest.[72] 116 environmental activists were assassinated in 2014,[73] and 185 in 2015.[71] This represents more than two environmentalists assassinated every week in 2014 and three every week in 2015.[74][75] More than 200 environmental activists were assassinated worldwide between 2016 and early 2018.[76] A 2020 incident saw several rangers murdered in the Congo Rainforest by poaching squads. Occurrences like this are relatively common, and account for a large number of deaths.[77] |

暗殺 初期のアメリカの森林警備官、ガイ・ブラッドリーは、1905年にフロリダ州フラミンゴ近郊で鳥類の密猟者を止めようとして殺害された 参照:暗殺された環境活動家の一覧 毎年、世界中で100人以上の環境活動家が殺害されている。[71] 最近では、アマゾンの熱帯雨林での伐採と戦うブラジルの活動家が殺害されている。[72] 2014年には116人[73]、2015年には185人の環境活動家が暗殺された。これは、2014年には毎週2人以上、2015年には毎週3人以上の 環境活動家が暗殺されたことを意味する。[74][75] 2016年から2018年初頭にかけて、世界中で200人以上の環境活動家が暗殺された。 2020年にコンゴの熱帯雨林で、密猟者によって複数の森林警備隊員が殺害される事件が発生した。このような事件は比較的よく起こり、多数の死者を出して いる。 |

| In popular culture Further information: Climate change in popular culture and Environmentalism in music The U.S. Forest Service created Smokey the Bear in 1944; he appeared in countless posters, radio and television programs, movies, press releases, and other guises to warn about forest fires.[78] The comic strip Mark Trail, by environmentalist Ed Dodd, began in 1946; it still appears weekly in 175 newspapers. The children's animated show Captain Planet and the Planeteers, created by Ted Turner and Barbara Pyle in 1989 to inform children about environmental issues. The show aired for six seasons and 113 episodes, in 100 countries worldwide from 1990 to 1996.[79] In 1974, Spokane, Washington, became one of the smallest cities ever to host a World's Fair. From Saturday, 4 May, to Sunday, 3 November 1974, Spokane hosted Expo 74, the first world's fair to focus on the environment. The theme of Expo 74 was "Celebrating Tomorrow's Fresh New Environment." (In 1982, Knoxville, Tennessee, was another small city to host a world's fair: Expo '82, with the theme, "Energy Turns the World.") FernGully: The Last Rainforest is an animated motion picture released in 1992, which focuses exclusively on the environment. The movie is based on a book under the same title by Diana Young. In 1998, a sequel, FernGully 2: The Magical Rescue, was introduced. Miss Earth is one of the Big Four international beauty pageants. (The other three are Miss Universe, Miss International, and Miss World.) Out of these four beauty pageants, Miss Earth is the only international beauty pageant that promotes "environmental awareness." The reigning titleholders dedicate their year to promote specific projects and often address issues concerning the environment and other global issues through school tours, tree planting activities, street campaigns, coastal clean ups, speaking engagements, shopping mall tours, media guesting, environmental fair, storytelling programs, eco-fashion shows, and other environmental activities. The Miss Earth winner is the spokesperson for the Miss Earth Foundation, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and other environmental organizations. The Miss Earth Foundation also works with the environmental departments and ministries of participating countries, various private sectors and corporations, as well as Greenpeace and the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF). Another area of environmentalism is to use art to raise awareness about misuse of the environment.[80][81][82] One example is trashion, using trash to create clothes, jewelry, and other objects for the home. Marina DeBris is one trashion artist, who focuses on ocean and beach trash to design clothes and for fund raising, education. |

大衆文化 さらに詳しい情報:大衆文化における気候変動、音楽における環境保護 米国森林局は1944年に「スモーキー・ベア」を制作した。彼は無数のポスター、ラジオやテレビ番組、映画、プレスリリースなど、さまざまな形で登場し、森林火災の危険性を警告した。 環境保護主義者エド・ドッドによる漫画「マーク・トレイル」は1946年に始まり、現在も175の新聞に毎週掲載されている。 1989年にテッド・ターナーとバーバラ・パイルが制作した子供向けアニメ番組『キャプテン・プラネットとプラネティアーズ』は、子供たちに環境問題につ いて教えることを目的としていた。この番組は6シーズン、113エピソードが制作され、1990年から1996年にかけて世界100カ国で放映された。 1974年、ワシントン州スポケーンは、世界博覧会を開催した都市としては史上最小規模の都市となった。1974年5月4日(土)から11月3日(日)ま で、スポケーンでは環境に焦点を当てた初の万国博覧会であるエキスポ74が開催された。エキスポ74のテーマは「明日の新鮮な環境を祝う」であった。 (1982年には、テネシー州ノックスビルでも「エネルギーが世界を回す」をテーマに、小規模な都市としてはもう一つの万国博覧会であるエキスポ'82が 開催された。) 『ファーングリー:最後の熱帯雨林』(FernGully: The Last Rainforest)は、1992年に公開された環境問題に焦点を当てたアニメーション映画である。この映画はダイアナ・ヤング(Diana Young)の同名の書籍を原作としている。1998年には続編『ファーングリー2:呪術的救出』(FernGully 2: The Magical Rescue)が公開された。 ミス・アースは、世界四大ミスコンテストのひとつである(他の3つはミス・ユニバース、ミス・インターナショナル、ミス・ワールド)。この4つのミスコン テストのうち、ミス・アースは「環境意識」を推進する唯一の国際的なミスコンテストである。現役のタイトルホルダーは、特定のプロジェクトを推進するため に1年間を捧げ、学校訪問、植樹活動、街頭キャンペーン、海岸清掃、講演、ショッピングモールツアー、メディア出演、環境フェア、ストーリーテリングプロ グラム、エコファッションショー、その他の環境活動などを通じて、環境やその他の地球規模の問題に関する問題に取り組むことが多い。ミス・アースの優勝者 は、ミス・アース財団、国連環境計画(UNEP)、その他の環境保護団体のスポークスパーソンとなる。ミス・アース財団は、参加国の環境省や環境関連の省 庁、さまざまな民間部門や企業、グリーンピースや世界自然保護基金(WWF)とも協力している。 環境保護のもう一つの分野は、環境の悪用に対する意識を高めるために芸術を利用することである。[80][81][82] その一例がトラッシュ(trashion)であり、ゴミを使って洋服やアクセサリー、その他の家庭用品を作る。マリーナ・デブリスはトラッシュ・アーティ ストの一人であり、洋服のデザインや募金活動、教育のために海やビーチのゴミに焦点を当てている。 |

| Criticism and alternative views When environmentalism first became popular during the early 20th century, the focus was wilderness protection and wildlife preservation. These goals reflected the interests of the movement's initial, primarily white middle and upper class supporters, including through viewing preservation and protection via a lens that failed to appreciate the centuries-long work of indigenous communities who had lived without ushering in the types of environmental devastation these settler colonial "environmentalists" now sought to mitigate. The actions of many mainstream environmental organizations still reflect these early principles.[83] Numerous low-income minorities felt isolated or negatively impacted by the movement, exemplified by the Southwest Organizing Project's (SWOP) Letter to the Group of 10, a letter sent to major environmental organizations by several local environmental justice activists.[84] The letter argued that the environmental movement was so concerned about cleaning up and preserving nature that it ignored the negative side-effects that doing so caused communities nearby, namely less job growth.[83] In addition, the NIMBY movement has transferred locally unwanted land uses (LULUs) from middle-class neighborhoods to poor communities with large minority populations. Therefore, vulnerable communities with fewer political opportunities are more often exposed to hazardous waste and toxins.[85] This has resulted in the PIBBY principle, or at least the PIMBY (Place-in-minorities'-backyard), as supported by the United Church of Christ's study in 1987.[86] As a result, some minorities have viewed the environmental movement as elitist. Environmental elitism manifested itself in three different forms: Compositional – Environmentalists are from the middle and upper class. Ideological – The reforms benefit the movement's supporters but impose costs on nonparticipants. Impact – The reforms have "regressive social impacts". They disproportionately benefit environmentalists and harm underrepresented populations.[87] Many environmentalists believe that human interference with 'nature' should be restricted or minimised as a matter of urgency (for the sake of life, or the planet, or just for the benefit of the human species),[88] whereas environmental skeptics and anti-environmentalists do not believe that there is such a need.[89] One can also regard oneself as an environmentalist and believe that human 'interference' with 'nature' should be increased.[90] Nevertheless, there is a risk that the shift from emotional environmentalism into the technical management of natural resources and hazards could decrease the touch of humans with nature, leading to less concern with environment preservation.[91] Increasingly, typical conservation rhetoric is being replaced with restoration approaches and larger landscape initiatives that seek to create more holistic impacts.[92] In the 2000s, American author, film director, medical graduate and intellect Michael Crichton criticized environmentalism as being religiously motivated rather than grounded in empirical evidence, arguing that climate change was a natural part of Earth's history and had been occurring long before humans dominated the planet. Also claiming to argue from his minor education in anthropology, he stated that religion was a part of human social make-up and that if it was suppressed, it would simply re-emerge in another form. With the decline of Christianity and Church attendance in the Western world, environmentalism has become more popular according to him, which he termed as "the religion of urban atheists".[93][94][95][96] Others seek a balance that involves both caring deeply for the environment while letting science guide human actions affecting it. Such an approach would avoid the emotionalism which, for example, anti-GMO activism has been criticized for, and protect the integrity of science. Planting trees, for another example, can be emotionally satisfying but should also involve being conscious of ecological concerns such as the effect on water cycles and the use of nonnative, potentially invasive species.[97] |

批判と代替的な見解 環境保護主義が20世紀初頭に初めて広まった際、その焦点は荒野の保護と野生生物の保全に置かれていた。これらの目標は、当初の環境保護主義の支持者で あった主に白人の中流階級および上流階級の人々の関心を反映したものであり、その中には、環境破壊を緩和しようとしている入植植民地主義的な「環境保護主 義者」が、今まさに緩和しようとしている環境破壊を招くことなく暮らしてきた先住民コミュニティの数世紀にわたる努力を正当に評価しない視点から、保全と 保護を捉えることも含まれていた。多くの主流派環境保護団体の活動は、今でも初期の原則を反映している。[83] 多数の低所得のマイノリティは、この運動から孤立感や悪影響を受けたと感じており、その例として、南西部組織化プロジェクト(SWOP)が主要な環境保護 団体に送った「グループ10への手紙」がある。これは、地元の環境正義活動家数名が送った手紙である。 [84] この書簡では、環境保護運動が自然の浄化と保全にあまりにも熱心であるあまり、そのために近隣の地域社会に生じる負の副作用、すなわち雇用の減少を無視し ていると主張している。[83] さらに、NIMBY運動により、地元で望まれない土地利用(LULU)が中流階級の地域からマイノリティ人口の多い貧困地域へと移転している。したがっ て、政治的機会が限られている脆弱なコミュニティは、有害廃棄物や毒素にさらされることが多くなる。[85] これが、1987年のキリスト合同教会の研究で支持されたPIBBY原則、少なくともPIMBY(マイノリティの裏庭に立地する場所)という原則を生み出 した。[86] その結果、一部のマイノリティは環境保護運動をエリート主義的と見なしている。環境保護主義のエリート主義は、以下の3つの異なる形態で現れている。 構成 - 環境保護主義者は中流階級および上流階級出身である。 イデオロギー - 改革は運動の支援者に利益をもたらすが、非参加者にコストを強いる。 影響 - 改革は「逆進的な社会的影響」をもたらす。改革は環境保護主義者に不均衡な利益をもたらし、過小評価されている集団に害を与える。 多くの環境保護論者は、人類による「自然」への干渉は緊急の問題として制限または最小化されるべきであると考えている(生命のため、地球のため、あるいは 人類の利益のため)が、環境懐疑論者や反環境保護論者はそのような必要性はないと考えている。[89] また、自らを環境保護論者とみなす一方で、人類による「自然」への「干渉」は増やすべきだと考える人もいる。 [90] しかし、感情的な環境保護主義から自然資源や危険の技術的管理へとシフトすることで、人間と自然との触れ合いが減り、環境保全への関心が薄れるというリス クもある。[91] 典型的な保護主義的なレトリックは、より全体的な影響を創出しようとする修復アプローチや広域景観イニシアティブに置き換えられつつある。 2000年代には、作家、映画監督、医学博士であり、知性派としても知られるマイケル・クライトンが、環境保護主義は経験的証拠に基づくものではなく、宗 教的な動機に基づいていると批判し、気候変動は地球の歴史において自然なものであり、人類が地球を支配するはるか以前から起こっていたと主張した。また、 マイナーな人類学の教育から論じていると主張し、宗教は人間の社会構成の一部であり、それが抑制されたとしても、別の形態で再び現れるだけだと述べた。キ リスト教の衰退と西洋世界における教会への出席率の低下に伴い、環境保護主義がより人気が高まっていると彼は主張し、それを「都市部の無神論者の宗教」と 呼んだ。[93][94][95][96] また、環境への深い配慮と、環境に影響を与える人間の行動を科学が導くことの両方を求めるバランスを求める人もいる。このようなアプローチは、例えば遺伝 子組み換え作物に対する反対運動が批判されてきたような感情論を回避し、科学の整合性を守ることになる。例えば、植樹は感情的に満足感を得られるが、水循 環への影響や、外来種で潜在的に侵略的な種の利用など、生態系への懸念を意識することも必要である。[97] |

| Anti-environmentalism Bright green environmentalism Climate movement Conservation movement Ecomodernism Ecosia Ecotage Ecotechnology Environmental history of the United States Environmental planning Environmental, social, and governance Environmental studies Environmental technology Greening Green building Human ecology Human impact on the environment List of climate scientists List of women climate scientists and activists Nature conservation Outline of environmentalism Radical environmentalism Religion and environmentalism Sustainability Tree planting |

反環境主義 明るい緑の環境主義 気候変動運動 保全運動 エコモダニズム Ecosia Ecotage エコテクノロジー 米国の環境史 環境計画 環境、社会、ガバナンス 環境学 環境技術 緑化 グリーンビルディング 人間生態学 人間による環境への影響 気候科学者一覧 女性気候科学者および活動家一覧 自然保護 環境保護の概要 急進的な環境保護主義 宗教と環境保護 持続可能性 植樹 |

| Further reading Apps, Jerry, and Natasha Kassulke. Planting an Idea Critical and Creative Thinking about Environmental Issues (2023) online Borowy, Iris. "Before UNEP: who was in charge of the global environment? The struggle for institutional responsibility 1968–72." Journal of Global History 14.1 (2019): 87–106. Daynes, Byron W., and Glen Sussman, eds. White House Politics and the Environment: Franklin D. Roosevelt to George W. Bush (Texas A&M University Press; 2010) 300 pages; evaluates how 12 presidents helped or hindered the cause of environmental protection. Johnson, Erik W., and Scott Frickel, (2011). "Ecological Threat and the Founding of U.S. National Environmental Movement Organizations, 1962–1998," Social Problems 58 (Aug. 2011), 305–29. Lear, Linda (1997). Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-3428-8. Martell, Luke. "Ecology and Society: An Introduction". Polity Press, 1994. McCormick, John. 1995. The Global Environmental Movement. John Wiley. London. 312 pp. ISBN 9780471949404 OCLC 33832322 Palmer, Joy. Fifty Key Thinkers on the Environment (Routledge, 2001) de Steiguer, J. Edward. 2006. The Origins of Modern Environmental Thought. University of Arizona Press. Tucson. 246 pp. ISBN 9780816524617 Tooze, Adam, "Democracy and Its Discontents", The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 10 (6 June 2019), pp. 52–53, 56–57. "Democracy has no clear answer for the mindless operation of bureaucratic and [technological power. We may indeed be witnessing its extension in the form of artificial intelligence and robotics. Likewise, after decades of dire warning, the environmental problem remains fundamentally unaddressed.... Bureaucratic overreach and environmental catastrophe are precisely the kinds of slow-moving existential challenges that democracies deal with very badly.... Finally, there is the threat du jour: corporations and the technologies they promote." (pp. 56–57.) Verweij, Marco; Thompson, Michael (eds), 2006, Clumsy Solutions for a Complex World: Governance, Politics and Plural Perceptions, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-00230-2 Vogel, David. California Greenin': How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader (2018) 280 pp online review Woodhouse, Keith M. "The Politics of Ecology: Environmentalism and Liberalism in the 1960s," Journal for the Study of Radicalism, Volume 2, Number 2, 2009, pp. 53–84 World Bank, 2003, "Sustainable Development in a Dynamic World: Transforming Institutions, Growth, and Quality of Life" Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, World Development Report 2003, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and Oxford University Press. |

さらに詳しく Apps, Jerry, and Natasha Kassulke. Planting an Idea Critical and Creative Thinking about Environmental Issues (2023) online Borowy, Iris. 「Before UNEP: who was in charge of the global environment? The struggle for institutional responsibility 1968–72.」 Journal of Global History 14.1 (2019): 87–106. デイネス、バイロン・W.、グレン・サスマン編『ホワイトハウスの政治と環境:フランクリン・D・ルーズベルトからジョージ・W・ブッシュまで』(テキサ スA&M大学出版、2010年)300ページ。12人の大統領が環境保護の推進に貢献したか、あるいは妨げとなったかを評価している。 ジョンソン、エリック・W.、スコット・フリッケル、(2011年)。「生態系の脅威と米国の環境保護運動組織の創設、1962年~1998年」、『社会問題』58号(2011年8月)、305~29ページ。 リア・ラー(1997年)『レイチェル・カーソン:自然の証人』ニューヨーク:ヘンリー・ホルト・アンド・カンパニー。ISBN 978-0-8050-3428-8。 ルーク・マーテル(1994年)『エコロジーと社会:入門』ポリティ・プレス。 ジョン・マコーミック(1995年)『地球環境運動』ジョン・ワイリー。ロンドン。312ページ。ISBN 9780471949404 OCLC 33832322 Palmer, Joy. Fifty Key Thinkers on the Environment (Routledge, 2001) de Steiguer, J. Edward. 2006. The Origins of Modern Environmental Thought. University of Arizona Press. Tucson. 246 pp. ISBN 9780816524617 トゥーズ、アダム、「民主主義とその不満」、ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス、第66巻、第10号(2019年6月6日)、52-53、56- 57ページ。「民主主義は、官僚主義とテクノロジーの無分別な運用に対して明確な答えを持っていない。私たちは、人工知能やロボット工学の形で、その拡大 を目撃しているのかもしれない。同様に、数十年にわたって深刻な警告がなされてきたにもかかわらず、環境問題は依然として根本的には対処されていない。官 僚主義の行き過ぎと環境の破局は、まさに民主主義が非常に苦手とする、動きの遅い実存的課題である。最後に、今日的な脅威がある。企業と、それらが推進す る技術である。」(56-57ページ) Verweij, Marco; Thompson, Michael (eds), 2006, Clumsy Solutions for a Complex World: Governance, Politics and Plural Perceptions, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-00230-2 Vogel, David. カリフォルニアのグリーン化:ゴールデンステートが環境リーダーとなった経緯(2018年)280ページのオンラインレビュー ウッドハウス、キース・M. 「エコロジーの政治学:1960年代の環境保護主義と自由主義」『ラディカリズム研究ジャーナル』第2巻第2号、2009年、53-84ページ 世界銀行、2003年、「ダイナミックな世界における持続可能な開発:制度、成長、生活の質の変革」『世界開発報告書2003』、国際復興開発銀行およびオックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmentalism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆