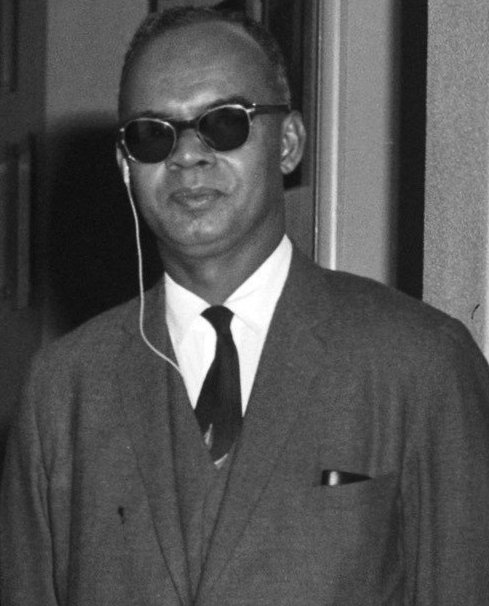

エリック・ウィリアムズ

Eric Eustace Williams, 1911-1981

☆ エ リック・ユースタス・ウィリアムズ TC CH(1911年9月25日 - 1981年3月29日)はトリニダード・トバゴの政治家である。[6] 彼は「国家の父」と評されており、[1][2][3][4][5] 1956年10月28日に多数派支配、1962年8月31日に独立、1976年8月1日に共和制へと導き、1981年に死去するまで、自身の政党である人 民国民運動とともに、総選挙での勝利を途切れることなく続けた。彼はトリニダード・トバゴの初代首相であり、またカリブ海地域の歴史家でもあり、特に著書 『資本主義と奴隷制』で知られている。

| Eric Eustace Williams TC

CH (25 September 1911 – 29 March 1981) was a Trinidad and Tobago

politician.[6] He has been described as the "Father of the

Nation",[1][2][3][4][5] having led the then British Colony of Trinidad

and Tobago to majority rule on 28 October 1956, to independence on 31

August 1962, and republic status on 1 August 1976, leading an unbroken

string of general elections victories with his political party, the

People's National Movement, until his death in 1981. He was the first

Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago and also a Caribbean historian,

especially for his book entitled Capitalism and Slavery.[7] |

エ

リック・ユースタス・ウィリアムズ TC CH(1911年9月25日 - 1981年3月29日)はトリニダード・トバゴの政治家である。[6]

彼は「国家の父」と評されており、[1][2][3][4][5]

1956年10月28日に多数派支配、1962年8月31日に独立、1976年8月1日に共和制へと導き、1981年に死去するまで、自身の政党である人

民国民運動とともに、総選挙での勝利を途切れることなく続けた。彼はトリニダード・トバゴの初代首相であり、またカリブ海地域の歴史家でもあり、特に著書

『資本主義と奴隷制』で知られている。 |

| Early life Williams was born on 25 September in 1911. His father Thomas Henry Williams was a minor civil servant and devout Roman Catholic, and his mother Eliza Frances Boissiere (13 April 1888 – 1969) was a descendant of the mixed French Creole Mulatto elite and had African and French ancestry. She was a descendant of the notable de Boissière family in Trinidad. Eliza's paternal grandfather was John Boissiere, a married upper-middle class Frenchman who had an intimate relationship with an African slave named Ma Zu Zule. From the union, Jules Arnold Boissiere, father of Eliza, was born.[8] He saw his first school years at Tranquillity Boys' Intermediate Government School and he was later educated at Queen's Royal College in Port of Spain, where he excelled at academics and football. A football injury at QRC led to a hearing problem which he wore a hearing aid to correct. He won an island scholarship in 1932, which allowed him to attend St. Catherine's Society, Oxford (later renamed St. Catherine's College). In 1935, he received a first class honours degree, and ranked first among history graduates that year. He also represented the university at football. In 1938, he went on to obtain his doctorate (see section below). In Inward Hunger, his autobiography, he described his experience of studying at Oxford, including his frustrations with rampant racial discrimination at the institution, and his travels in Germany after the Nazis' seizure of power. |

幼少期 ウィリアムズは1911年9月25日に生まれた。父親のトーマス・ヘンリー・ウィリアムズは下級公務員で敬虔なローマ・カトリック信者であり、母親のイラ イザ・フランシス・ボワシエ(1888年4月13日 - 1969年)はフランス系混血エリートの子孫で、アフリカとフランスの血筋を引いていた。彼女はトリニダードの著名なド・ボワシエール家の末裔であった。 イライザの父方の祖父はジョン・ボワシエールで、既婚の上流中流階級のフランス人であり、マ・ズー・ズーレという名の奴隷の女性と親密な関係にあった。こ の関係から、イライザの父ジュールズ・アーノルド・ボワシエールが生まれた。 彼はトランキリティ・ボーイズ・インターミディエイト・ガバメント・スクールで最初の学校生活を送り、その後ポート・オブ・スペインのクイーンズ・ロイヤル・カレッジで学んだ。QRCでサッカーの負傷を機に聴力障害を患い、補聴器を着用して聴力を補っていた。 1932年には島嶼奨学金を獲得し、オックスフォードのセント・キャサリン・ソサエティ(後にセント・キャサリン・カレッジと改称)に入学した。1935 年には優等学位を取得し、その年の歴史学部の卒業生の中で第1位となった。また、サッカーでは大学代表選手として活躍した。1938年には博士号を取得し た(下記参照)。自伝『Inward Hunger』では、オックスフォード大学での経験について、大学内での人種差別の横行に対するフラストレーションや、ナチスが政権を握った後のドイツで の旅行などを含めて記述している。 |

| Scholarly career In Inward Hunger, Williams recounts that in the period following his graduation, He was "severely handicapped in my research by my lack of money ... I was turned down everywhere I tried ... and could not ignore the racial factor involved". However, in 1936, thanks to a recommendation made by Sir Alfred Claud Hollis (Governor of Trinidad and Tobago, 1930–36), the Leathersellers' Company awarded him a £50 grant to continue his advanced research in history at Oxford.[9] He completed the D.Phil in 1938 under the supervision of Vincent Harlow. His doctoral thesis was titled The Economic Aspects of the Abolition of the Slave Trade and West Indian Slavery, and was published as Capitalism and Slavery in 1944,[10] although excerpts of his thesis were published in 1939 by The Keys, the journal of the League of Coloured Peoples. According to Williams, Fredric Warburg – a publisher of Marxist literature, who Williams asked to publish his thesis – refused to publish, saying that "such a book... would be contrary to the British tradition".[11] His thesis was both a direct attack on the idea that moral and humanitarian motives were the key facts in the success of the British abolitionist movement, and a covert critique of the established British historiography on the West Indies (as exemplified by, in Williams' view, the works of Oxford professor Reginald Coupland) as supportive of continued British colonial rule. Williams's argument owed much to the influence of C. L. R. James, whose The Black Jacobins, also completed in 1938, also offered an economic and geostrategic explanation for the rise of abolitionism in the Western world.[12] |

学術的な経歴 ウィリアムズは『Inward Hunger』の中で、卒業後の時期について次のように述べている。「私は金銭的な問題で研究に著しく支障をきたしていた。どこに行っても断られ、人種的 な要因を無視することはできなかった」と述懐しています。しかし、1936年には、アルフレッド・クロード・ホリス卿(1930年から1936年までトリ ニダード・トバゴ総督)の推薦により、オックスフォード大学で歴史学の高度な研究を継続するための助成金50ポンドがレザーセラーズ・カンパニーから授与 されました。 彼はヴィンセント・ハーロウの指導の下、1938年に博士号を取得した。彼の博士論文のタイトルは『奴隷貿易廃止と西インド諸島における奴隷制の経済的側 面』であり、1944年に『資本主義と奴隷制』として出版されたが、論文の抜粋は1939年に有色人種連盟の機関誌『ザ・キーズ』に掲載されていた。ウィ リアムズによると、マルクス主義の文献の出版者であるフレデリック・ウォーバーグは、ウィリアムズが自身の論文の出版を依頼した人物であるが、彼は「その ような本は...英国の伝統に反する」として出版を拒否したという。[11] 彼 の論文は、道徳的および また、英国の奴隷制度廃止運動の成功の鍵となる要因は道徳的・人道的な動機であるという考えに対する直接的な攻撃であり、また、英国の西インド諸島に関す る定説の歴史学(ウィリアムズの見解では、オックスフォード大学のレジナルド・クープランド教授の著作に代表される)が英国の植民地支配の継続を支持して いるという隠れた批判でもあった。ウィリアムズの主張は、C. L. R. ジェームズの影響を強く受けており、ジェームズの著書『黒人ジャコバン人』(1938年完成)もまた、西洋世界における奴隷制度廃止論の高まりを経済的お よび地政学的に説明している。 |

| Gad Heuman states: In Capitalism and Slavery, Eric Williams argued that the declining economies of the British West Indies led to the abolition of the slave trade and of slavery. More recent research has rejected this conclusion; it is now clear that the colonies of the British Caribbean profited considerably during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.[13] |

ガッド・ヒューマンは次のように述べている。 『資本主義と奴隷制』において、エリック・ウィリア ムズは、イギリス領西インド諸島の経済衰退が奴隷貿易と奴隷制度の廃止につながったと主張した。より最近の研究では、この結論は否定されている。英領カリ ブ海の植民地が、アメリカ独立戦争およびナポレオン戦争の間に多大な利益を得ていたことは明らかである。 |

| However,

Capitalism and Slavery covers the economic history of sugar and slavery

beyond just the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, and discusses the

decline of sugar plantations from 1823 until the emancipation of the

slaves in the 1830s. It also discusses the British government's use of

the equalisation of the sugar duties Acts in the 1840s to sever their

responsibilities to buy sugar from the British West Indian colonies,

and to buy sugar on the open market from Cuba and Brazil, where it was

cheaper.[14] In support of the Williams thesis, David Ryden presented

evidence to show that by the early nineteenth century there was an

emerging crisis of profitability.[15] Williams's argument about abolitionism went far beyond this decline thesis. What he argued was that the new economic and social interest created in the 18th century by the slave-based Atlantic economy generated new pro-free trade and anti-slavery political interests. These interacted with the rise of evangelical antislavery and with the self-emancipation of slave rebels, from the Haitian Revolution of 1792–1804 to the Jamaica Christmas Rebellion of 1831, to bring the end of Slavery in the 1830s.[16] In 1939, Williams joined the Political Science department at Howard University.[12] In 1943, Williams organized a conference about the "economic future of the Caribbean."[17] He argued that small islands of the West Indies would be vulnerable to domination by the former colonial powers in the event that these islands became independent states; Williams advocated for a West Indian Federation as a solution to post-colonial dependence.[17] |

し

かし、『資本主義と奴隷制』は、アメリカ独立戦争およびナポレオン戦争の時代を超えて砂糖と奴隷の経済史をカバーしており、1823年から1830年代の

奴隷解放までの砂糖プランテーションの衰退についても論じている。また、1840年代に英国政府が砂糖関税均等化法を利用して、西インド諸島植民地から砂

糖を買う責任を放棄し、より安価なキューバやブラジルから市場で砂糖を買うようになったことについても論じている。[14]

ウィリアムズの論文を裏付けるものとして、デイヴィッド・ライデンは19世紀初頭には収益性の危機が迫っていたことを示す証拠を提示した。[15] ウィリアムズの(奴隷)廃止論に関する主張は、この(経済)衰退論をはるかに超えるものであった。彼が主張したことは、18世紀に奴隷制に基づく大西洋経 済によって生み出された新しい経済的・社会的利益が、自由貿易推進派と奴隷制廃止派という新しい政治的利益を生み出したということである。これらは、 1792年から1804年のハイチ革命から1831年のジャマイカのクリスマス蜂起までの、福音主義的奴隷廃止運動の高まりや、奴隷反乱者の自己解放と相 互作用し、1830年代に奴隷制度の終焉をもたらした。[16] 1939年、ウィリアムズはハワード大学の政治学部に入学した。[12] 1943年、ウィリアムズは「カリブ海地域の経済的未来」に関する会議を主催した。[17] 彼は、西インド諸島が独立国家となった場合、これらの島々はかつての宗主国による支配を受けやすいと主張した。ウィリアムズは、植民地独立後の依存関係の 解決策として西インド諸島連邦を提唱した。[17] |

| Shift to public life In 1944, Williams was appointed to the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission. In 1948 he returned to Trinidad as the Commission's deputy chairman of the Caribbean Research Council. In Trinidad, he delivered an acclaimed series of educational lectures. In 1955, after disagreements between Williams and the Commission, the Commission elected not to renew his contract. In a speech at Woodford Square in Port of Spain, he declared that he had decided to "put down his bucket" in the land of his birth. He rechristened that enclosed park, which stood in front of the Trinidad courts and legislature, "The University of Woodford Square", and proceeded to give a series of public lectures on world history, Greek democracy and philosophy, the history of slavery, and the history of the Caribbean to large audiences drawn from every social class.[citation needed] |

公的生活への転身 1944年、ウィリアムズは英米カリブ委員会に任命された。1948年、カリブ研究協議会の副議長としてトリニダードに戻った。トリニダードでは、彼は教 育的な講演シリーズを行い、高い評価を得た。1955年、ウィリアムズと委員会との意見の相違により、委員会は彼の契約を更新しないことを決定した。ポー ト・オブ・スペインのウッドフォード・スクエアでの演説で、彼は「生まれ故郷の地に身を置く」ことを決意したと宣言した。トリニダードの裁判所と立法府の 前にあった囲い込み公園を「ウッドフォード・スクエア大学」と改名し、世界史、ギリシャの民主主義と哲学、奴隷制の歴史、カリブ海の歴史などについて、あ らゆる階層から集まった大勢の聴衆を対象に一連の公開講座を開講した。 |

| Entry into nationalist politics in Trinidad and Tobago From that public platform on 15 January 1956, Williams inaugurated his own political party, the People's National Movement (PNM), which would take Trinidad and Tobago into independence in 1962, and dominate its post-colonial politics. Until this time his lectures had been carried out under the auspices of the Political Movement, a branch of the Teachers Education and Cultural Association, a group that had been founded in the 1940s as an alternative to the official teachers' union. The PNM's first document was its constitution. Unlike the other political parties of the time, the PNM was a highly organized, hierarchical body. Its second document was The People's Charter, in which the party strove to separate itself from the transitory political assemblages which had thus far been the norm in Trinidadian politics. In elections held eight months later, on 24 September the Peoples National Movement won 13 of the 24 elected seats in the Legislative Council, defeating 6 of the 16 incumbents running for re-election. Although the PNM did not secure a majority in the 31-member Legislative Council, he was able to convince the Secretary of State for the Colonies to allow him to name the five appointed members of the council (despite the opposition of the Governor, Sir Edward Betham Beetham). This gave him a clear majority in the Legislative Council. Williams was thus elected Chief Minister and was also able to get all seven of his ministers elected. |

トリニダード・トバゴのナショナリスト政治への参入 1956年1月15日、ウィリアムズは、その公の演説の壇上から、自身の政党である人民国民運動(People's National Movement、PNM)を結成した。この政党は、1962年にトリニダード・トバゴを独立に導き、その後の植民地後の政治を支配することになる。それ までは、彼の講義は政治運動(Political Movement)の後援の下で行われていた。政治運動は、1940年代に公式の教員組合の代替組織として設立された教員教育文化協会(Teachers Education and Cultural Association)の一部門である。 PNMの最初の文書は党の憲法であった。当時の他の政党とは異なり、PNMは高度に組織化された階層的な組織であった。その第二の文書は『人民憲章』であ り、この党はそれまでのトリニダードの政治の常識であった一過性の政治結集から自らを切り離そうと努力した。 その8か月後の9月24日に行われた選挙では、人民国民運動は立法議会の24議席中13議席を獲得し、再選を目指した現職議員16名のうち6名を破った。 PNMは31議席からなる立法議会の過半数を占めることはできなかったが、植民地大臣を説得して、任命された5人の議員を指名することを認めさせた(総督 のエドワード・ベサム・ビータム卿の反対にもかかわらず)。これにより、立法議会でPNMは明確な多数派となった。ウィリアムズはこうして首席大臣に選出 され、7人の閣僚全員を当選させることもできた。 |

| Federation and independence After the Second World War, the Colonial Office had preferred that British colonies move towards political independence in the kind of federal systems which had appeared to succeed since the Canadian confederation, which created Canada, in the 19th century. In the British West Indies, this goal coincided with the political aims of the nationalist movements which had emerged in all the colonies of the region during the 1930s. The Montego Bay conference of 1948 had declared the common aim to be the achievement by the West Indies of "Dominion Status" (which meant constitutional independence from the British government) as a Federation. In 1958, a West Indies Federation emerged from the British Caribbean, which with British Guiana (now Guyana) and British Honduras (now Belize) choosing to opt out of the Federation, leaving Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago as the dominant players. Most political parties in the various territories aligned themselves into one of two Federal political parties – the West Indies Federal Labour Party (led by Grantley Adams of Barbados and Norman Manley of Jamaica) and the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) led by Manley's cousin, Sir Alexander Bustamante. The PNM affiliated with the former, while several opposition parties (the People's Democratic Party, the Trinidad Labour Party and the Party of Political Progress Groups) aligned themselves with the DLP, and soon merged to form the Democratic Labour Party of Trinidad and Tobago. The DLP victory in the 1958 Federal Elections and subsequent poor showing by the PNM in the 1959 County Council Elections soured Williams on the Federation. Lord Hailes (Governor-General of the Federation) also overruled two PNM nominations to the Federal Senate in order to balance a disproportionately WIFLP-dominated Senate. When Bustamante withdrew Jamaica from the Federation, this left Trinidad and Tobago in the untenable position of having to provide 75% of the Federal budget while having less than half the seats in the Federal government. In a speech, Williams declared that "one from ten leaves nought". Following the adoption of a resolution to that effect by the PNM General Council on 15 January 1962, Williams withdrew Trinidad and Tobago from the West Indies Federation. This action led the British government to dissolve the Federation. In 1961 the PNM had introduced the Representation of the People Bill. This Bill was designed to modernise the electoral system by instituting permanent registration of voters, identification cards, voting machines and revised electoral boundaries. These changes were seen by the DLP as an attempt to disenfranchise illiterate rural voters through intimidation, to rig the elections through the use of voting machines, to allow Afro-Caribbean immigrants from other islands to vote, and to gerrymander the boundaries to ensure victory by the PNM. Opponents of the PNM saw "proof" of these allegations when A. N. R. Robinson was declared winner of the Tobago seat in 1961 with more votes than there were registered voters, and in the fact that the PNM was able to win every subsequent election until the 1980 Tobago House of Assembly Elections. The 1961 elections gave the PNM 57% of the votes and 20 of the 30 seats. This two-thirds majority allowed them to draft the Independence Constitution without input from the DLP. Although supported by the Colonial Office, independence was blocked by the DLP, until Williams was able to make a deal with DLP leader Rudranath Capildeo that strengthened the rights of the minority party and expanded the number of Opposition Senators. With Capildeo's assent, Trinidad and Tobago became independent on 31 August 1962, 25 days after Jamaica. In addition to primeministership, Williams was also Minister of Finance from 1957 to 1961 and from 1966 to 1971.[18] |

連邦化と独立 第二次世界大戦後、イギリス植民地省は、19世紀にカナダを建国したカナダ連邦以来、成功を収めていると思われた連邦制のような政治的独立に向けて、イギ リス植民地が歩み寄ることを望んでいた。イギリス領西インド諸島では、この目標は1930年代にこの地域のすべての植民地で勃興した民族主義運動の政治的 目標と一致していた。1948年のモンテゴベイ会議では、西インド諸島が連邦として「ドミニオン・ステータス」(英国政府からの憲法上の独立を意味する) を達成することが共通の目標として宣言された。1958年、ジャマイカとトリニダード・トバゴが主導権を握る中、西インド諸島連邦が英国領カリブ地域から 誕生した。このとき、英領ガイアナ(現ガイアナ)と英領ホンジュラス(現ベリーズ)は連邦からの離脱を選択した。各領内のほとんどの政党は、西インド諸島 連邦労働党(バルバドスのグラントリー・アダムスとジャマイカのノーマン・マンリーが指導)と、マンリーの従兄弟であるアレクサンダー・バスタマンテ卿が 指導する民主労働党(DLP)の2つの連邦政党のどちらかに合流した。PNMは前者の政党と提携し、複数の野党(人民民主党、トリニダード労働党、政治進 歩グループ党)はDLPと提携し、その後まもなく合併してトリニダード・トバゴ民主労働党を結成した。 1958年の連邦議会選挙でのDLPの勝利と、それに続く1959年のカウンティ議会選挙でのPNMの不振により、ウィリアムズは連邦に幻滅した。また、 ヘイルズ卿(連邦総督)は、WIFLPが過半数を占める上院のバランスを取るために、PNMが指名した上院議員2名を却下した。 ブスタマンテがジャマイカを連邦から脱退させたことで、トリニダード・トバゴは連邦予算の75%を負担しなければならない立場に置かれながら、連邦政府の 議席数は半分以下という、耐え難い立場に置かれることとなった。 ウィリアムズは演説で「10人中1人が去っても、残りはゼロにはならない」と宣言した。1962年1月15日にPNMの一般評議会が同様の決議を採択した ことを受け、ウィリアムズはトリニダード・トバゴを西インド諸島連邦から脱退させた。この行動により、英国政府は連邦を解散した。 1961年、PNMは人民代表法案を提出した。この法案は、有権者の恒久的な登録、身分証明書、投票機、選挙区の境界の見直しなどを導入することで、選挙 制度を近代化することを目的としていた。これらの変更は、DLP(人民党)から、脅迫によって文盲の農村部の有権者の選挙権を剥奪し、投票機を使用して選 挙を不正に操作し、他の島々からのアフリカ系カリブ移民に投票を認め、PNM(トリニダードトバゴ労働党)の勝利を確実にするために選挙区の境界を細工す る試みであると見なされた。PNMの反対派は、1961年にA. N. R. ロビンソンがトバゴの議席で、有権者登録者数よりも多い票を獲得して当選したこと、および1980年のトバゴ議会選挙までPNMがその後のすべての選挙で 勝利を収めたという事実を、これらの主張の「証拠」と見なした。 1961年の選挙では、PNMは57%の票を獲得し、30議席中20議席を獲得した。この3分の2の多数派により、DLPの意見を聞かずに独立憲法を起草 することが可能となった。植民地省の支援を受けていたものの、独立はDLPによって阻止されていたが、ウィリアムズがDLP党首のルドラナート・カピル ディオと取引を成立させ、少数派の政党の権利を強化し、野党の上院議員の数を増やすことで、独立は実現した。カピルデオの同意を得て、トリニダード・トバ ゴはジャマイカから25日遅れの1962年8月31日に独立した。ウィリアムズは1957年から1961年、および1966年から1971年まで、首相職 に加えて財務大臣も務めた。 |

| Black Power Main article: Black Power Revolution Between 1968 and 1970 the Black Power movement gained strength in Trinidad and Tobago. The leadership of the movement developed within the Guild of Undergraduates at the St. Augustine Campus of the University of the West Indies. Led by Geddes Granger, the National Joint Action Committee joined up with trade unionists led by George Weekes of the Oilfields Workers' Trade Union and Basdeo Panday, then a young trade-union lawyer and activist. The Black Power Revolution started during the 1970 Carnival. In response to the challenge, Williams countered with a broadcast entitled "I am for Black Power". He introduced a 5% levy to fund unemployment reduction and established the first locally owned commercial bank. However, this intervention had little impact on the protests. On 3 April 1970, a protester was killed by the police. This was followed on 13 April by the resignation of A. N. R. Robinson, Member of Parliament for Tobago East. On 18 April sugar workers went on strike, and there was the talk of a general strike. In response to this, Williams proclaimed a State of Emergency on 21 April and arrested 15 Black Power leaders. In response to this, a portion of the Trinidad and Tobago Defence Force, led by Raffique Shah and Rex Lassalle, mutinied and took hostages at the army barracks at Teteron. Through the action of the Trinidad and Tobago Coast Guard the mutiny was contained and the mutineers surrendered on 25 April. Williams made three additional speeches in which he sought to identify himself with the aims of the Black Power movement. He reshuffled his cabinet and removed three ministers (including two White members) and three senators. He also proposed a Public Order Bill which would have curtailed civil liberties in an effort to control protest marches. After public opposition, led by A. N. R. Robinson and his newly created Action Committee of Democratic Citizens (which later became the Democratic Action Congress), the Bill was withdrawn. Attorney General Karl Hudson-Phillips offered to resign over the failure of the Bill, but Williams refused his resignation. |

ブラックパワー 詳細は「ブラックパワー革命」を参照 1968年から1970年にかけて、トリニダード・トバゴではブラックパワー運動が勢いを増した。この運動の指導部は、西インド諸島大学セントオーガス ティン・キャンパスの学部生組合内で形成された。ゲデス・グランジャーが率いる全国合同行動委員会は、石油労働者組合のジョージ・ウィークスや、当時若手 の労働組合弁護士兼活動家であったバスディオ・パンデイが率いる労働組合主義者たちと合流した。1970年のカーニバルの期間中にブラックパワー革命が始 まった。この挑戦を受けて、ウィリアムズ首相は「私はブラックパワーを支持する」と題する放送で反論した。失業率の低下を目的とした5%の課税を導入し、 初の地元資本による商業銀行を設立した。しかし、この介入は抗議活動にほとんど影響を及ぼさなかった。 1970年4月3日、抗議活動家が警察に射殺された。これを受けて、4月13日にはトバゴ東地区選出の国会議員A. N. R. ロビンソンが辞任した。4月18日には砂糖労働者がストライキに入り、ゼネストの噂も流れた。これを受けて、ウィリアムズは4月21日に非常事態を宣言 し、ブラックパワーの指導者15名を逮捕した。これに対して、ラフィーク・シャーとレックス・ラサールが率いるトリニダード・トバゴ防衛軍の一部が反乱を 起こし、テテロンにある軍の兵舎で人質をとった。トリニダード・トバゴ沿岸警備隊の活動により、反乱は鎮圧され、反乱軍は4月25日に降伏した。 ウィリアムズはさらに3度演説を行い、ブラックパワー運動の目標に自らを同調させようとした。彼は内閣を改造し、3人の大臣(うち2人は白人)と3人の上 院議員を解任した。また、デモ行進を規制するために市民の自由を制限する公共秩序法案を提出した。A. N. R. ロビンソンと彼が新たに結成した民主市民行動委員会(後に民主行動会議となる)が主導した世論の反対を受け、この法案は撤回された。法案の失敗の責任を取 り、カール・ハドソン=フィリップス司法長官は辞任を申し出たが、ウィリアムズ首相は辞任を拒否した。 |

| Death Prime Minister Eric Eustace Williams of Trinidad and Tobago, died on 29 March 1981 due to throat cancer at his official house in St. Anne, a Port of Spain neighborhood in Trinidad and Tobago. He was 69 years old at the time of his death.[19][20] |

死 トリニダード・トバゴの首相エリック・ユースタス・ウィリアムズは、1981年3月29日、ポート・オブ・スペイン近郊のセント・アンにある公邸で、喉頭癌のため死去した。享年69歳であった。[19][20] |

| Personal life Eric Williams had married Elsie Ribeiro, a music studies student born to a mother from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and a Portuguese Trinidadian father, on 30 January 1937, while he was a postgraduate student at Oxford University. He had known Ribeiro from Trinidad before he left for the United Kingdom and she was the sister of his roommate in England. The ceremony was private out of fear that the terms of his scholarship could have prohibited marriage and he did not want it to be terminated. After he graduated, they moved to Washington, D.C. in the United States where he obtained a position at Howard University. They had a son, Alistair Williams, in 1943 and a daughter, Elsie Pamela Williams, in 1947. However, Williams questioned the paternity of Elsie Pamela, thus leading to problems in the marriage. In May 1948, Williams left Washington, D.C. to go back to Trinidad, abandoning his wife and children. His reason for not financially supporting them after leaving was because Ribeiro refused to send their children to Oxford University in the future.[21][22] After returning to Trinidad in 1948, he met Evelyn Siulan Soy Moyou, a typist 13 years his junior of Chinese descent on her father's side and Chinese, African, and Portuguese descent on her mother's side, and she was a niece of Solomon Hochoy, the future Governor and Governor-General of Trinidad and Tobago during Williams's premiership. She worked at the Caribbean Commission where Williams had taken up a position. They began a relationship and he initiated divorce proceedings from Ribeiro in January 1950 on a Caribbean Commission trip to the U.S. Virgin Islands.[21][22] Ribeiro responded with an injunction restraining him from proceeding with his petition. After dropping the proceedings, in a letter of April 1950 submitted to the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia court, he agreed to abide by its decision and be bound by an order regarding alimony. However, a few months later while on a research holiday in the United States he reinitiated divorce proceedings in Reno, Nevada, known for its quick divorces, due to the fact that Moyou was pregnant with his child. However, Ribeiro obtained an injunction preventing Williams from making any attempt at divorce, on the grounds that he had earlier subjected himself to the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia court. Williams filed formal proceedings for a divorce on 24 November 1950. On 13 December 1950, Williams was ordered to appear in court, most likely because he had filed for a divorce in Reno, even though he had earlier submitted himself to the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia. Even though a lawyer had been assigned to him, he did not appear and on 22 December 1950 he was ordered to be taken into custody by a US Marshal. His lawyer in Reno pointed out that his divorce had been granted, though a search of the court records showed no entry for a final decree. Williams eventually met the six-week residential requirement to obtain a Nevada divorce and on 2 January 1951, he married Moyou in Reno, in a ceremony performed by The Rev. Munroe Warner of First Christian Church. Their daughter, Erica Williams, was born on 12 February 1951, in Reno. After his second marriage, Ribeiro obtained a divorce from him on 20 January 1951, on grounds of desertion. It was made effective on 21 July 1951 and he was ordered to pay a monthly alimony of US$250 for the maintenance of his first wife and two children. On 26 May 1953, Mayou died from Tuberculosis.[21][22] He later married Mayleen Mook Sang, his daughter's dentist.[23] She was of Chinese Guyanese origin.[24] They were married on Caledonia Island on 13 November 1957 by Rev. Andrew McKean, of Greyfriars Presbyterian Church on Frederick Street in Port of Spain.[25] However, the couple never lived together and the marriage was kept hidden by Williams. The marriage was exposed 18 months later when Mook Sang sent a copy of their marriage certificate to the Chronicle newspaper following rumors of Williams having an affair with a local beauty queen. They remained married till his death. After his death she filed to receive Willaims's benefits and pension from his premiership, however it was given to his daughter, Erica, who was named his heir in his will.[26] |

私生活 エリック・ウィリアムズは、セントビンセント・グレナディーン出身の母親とトリニダード・トバゴ出身のポルトガル人の父親を持つ音楽専攻の学生、エル シー・リベイロと1937年1月30日に結婚した。彼は英国に留学する前からトリニダードでリベイロと知り合っており、彼女は英国での彼のルームメイトの 姉妹であった。奨学金の規定が結婚を禁じており、それを理由に奨学金を打ち切られることを望まなかったため、式は内輪で執り行われた。卒業後、2人はワシ ントンD.C.に移り、そこでウィリアムズはハワード大学で職を得た。1943年に息子のアリスター・ウィリアムズ、1947年に娘のエルシー・パメラ・ ウィリアムズが誕生した。しかし、ウィリアムズはエルシー・パメラの父親が自分であるかどうか疑い、それが結婚生活に問題を引き起こした。1948年5 月、ウィリアムズは妻と子供たちを捨ててワシントンD.C.を離れ、トリニダードに戻った。彼が家族を経済的に支援しなかった理由は、リベイロが将来子供 たちをオックスフォード大学に入学させないことを拒否したためだった。 1948年にトリニダードに戻った後、彼は13歳年下のタイピスト、イヴリン・シウラン・ソイ・モイヨと出会った。彼女は父親が中国人、母親が中国人、ア フリカ人、ポルトガル人の混血であり、ウィリアムズが首相在任中にトリニダード・トバゴの総督および総督となったソロモン・ホチョイの姪であった。彼女 は、ウィリアムズが職を得たカリブ共同体で働いていた。2人は関係を持ち、1950年1月、カリブ共同体による米領ヴァージン諸島への出張中に、ウィリア ムズはリベイロとの離婚手続きを開始した。[21][22] リベイロは、彼が離婚の申し立てを進めることを差し止める命令を出した。訴訟を取り下げた後、1950年4月にコロンビア特別区裁判所に提出した書簡で、 彼はその判決に従うこと、扶養料に関する命令に従うことに同意した。しかし、数ヵ月後、休暇で米国に滞在中に、モユーが彼の子供を身籠もっていたことを理 由に、離婚手続きを迅速な離婚で知られるネバダ州リノで再開した。しかし、リベイロは、以前コロンビア特別区裁判所の管轄権に自らを服従させたことを理由 に、ウィリアムズが離婚を試みることを禁じる命令を得た。ウィリアムズは1950年11月24日に正式に離婚手続きを行った。1950年12月13日、 ウィリアムズは裁判所への出頭を命じられた。おそらく、それ以前にコロンビア特別区の管轄権に身を委ねていたにもかかわらず、リノで離婚を申請したことが 原因だったと思われる。弁護士が割り当てられたにもかかわらず、彼は出頭せず、1950年12月22日、連邦保安官によって身柄を拘束されるよう命じられ た。リノの弁護士は、離婚が成立したと指摘したが、裁判記録の検索では最終判決の記載は見つからなかった。最終的に、ウィリアムズはネバダ州での離婚に必 要な6週間の居住要件を満たし、1951年1月2日、リノでモヨと結婚した。結婚式は、ファースト・クリスチャン教会のモンロー・ワーナー牧師によって執 り行われた。二人の娘、エリカ・ウィリアムズは、1951年2月12日にリノで生まれた。二度目の結婚後、リベイロは1951年1月20日に彼から離婚を 言い渡された。理由は「遺棄」であった。1951年7月21日に成立し、彼は最初の妻と2人の子供たちの生活費として毎月250ドルの扶養料を支払うよう 命じられた。1953年5月26日、マヨウは結核により死亡した。[21][22] その後、娘の歯科医であるメイリーン・ムック・サンと結婚した。彼女は中国系ガイアナ人であった。[24] 1957年11月13日、ポート・オブ・スペインのフレデリック・ストリートにあるグレイフライアーズ・プレズビテリアン教会の牧師アンドリュー・マッ キーンによって、カリドニア島で結婚式を挙げた。[25] しかし、夫婦は同居することはなく、ウィリアムズは結婚を隠し続けた。結婚が暴露されたのは、それから18ヶ月後、ウィリアムズが地元のミスコン優勝者と 不倫関係にあるという噂が流れた後、ムック・サンが結婚証明書のコピーを新聞『クロニクル』に送ったときだった。 2人はウィリアムズの死まで結婚生活を続けた。 彼の死後、彼女はウィリアムズの首相としての給付金と年金を受け取るよう申請したが、それは彼の遺言で後継者に指名された娘のエリカに与えられた。 |

| Legacy Academic contributions Williams specialised in the study of slavery. Many Western academics focused on his chapter on the abolition of the slave trade, but that is just a small part of his work. In his 1944 book, Capitalism and Slavery, Williams argued that the British government's passage of the Slave Trade Act in 1807 was motivated primarily by economic concerns rather than by humanitarian ones. Williams also argued that by extension, so was the emancipation of the slaves and the blockade of Africa, and that as industrial capitalism and wage labour began to expand, eliminating the competition from wage-free slavery became economically advantageous. Williams' impact on that field of study has proved of lasting significance. As Barbara Solow and Stanley Engerman put it in the preface to a compilation of essays on Williams that was based on a commemorative symposium held in Italy in 1984, Williams "defined the study of Caribbean history, and its writing affected the course of Caribbean history.... Scholars may disagree on his ideas, but they remain the starting point of discussion.... Any conference on British capitalism and Caribbean slavery is a conference on Eric Williams." In an open letter to Solow, Yale Professor of History David Brion Davis refers to Williams' thesis of the declining economic viability of slave labor as "undermined by a vast mountain of empirical evidence and has been repudiated by the world’s leading authorities on New World slavery, the transatlantic slave trade, and the British abolition movement".[27] A major work which was written to refute Eric Williams' thesis was Seymour Drescher's Econocide, which argued that when the slave trade was abolished in 1807, Britain's sugar economy was thriving. However, other historians have noted that Drescher ended his study of the economic history of the British West Indies in 1822, and did not address the decline of the British sugar industry (something which was highlighted by Williams) which began in the mid-1820s, and continued until the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.[28] The majority of Eric William's thesis, which addressed the decline of the sugar industry in the 1820s, the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, and the sugar equalisation acts of the 1840s, has continued to influence the historiography of the 19th-century West Indies and it's connection to the wider Atlantic world as a whole.[29][30] In addition to Capitalism and Slavery, Williams produced a number of other scholarly works focused on the Caribbean. Of particular significance are two published long after he had abandoned his academic career for public life: British Historians and the West Indies and From Columbus to Castro. The former, based on research done in the 1940s and initially presented at a symposium at Clark Atlanta University, sought to challenge established British historiography on the West Indies. Williams was particularly scathing in his criticism of the work of Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle. The latter work is a general history of the Caribbean from the 15th to the mid-20th centuries. The work appeared at the same time as a similarly titled book (De Cristóbal Colón a Fidel Castro) by another Caribbean scholar-statesman, Juan Bosch of the Dominican Republic. Williams sent one of 73 Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages to NASA for the historic first lunar landing in 1969. The message still rests on the lunar surface today. He wrote, in part: "It is our earnest hope for mankind that while we gain the moon, we shall not lose the world."[31] |

遺産 学術的貢献 ウィリアムズは奴隷制の研究を専門としていた。多くの西洋の学者は奴隷貿易廃止に関する彼の章に注目したが、それは彼の研究のごく一部に過ぎない。 1944年に出版された著書『資本主義と奴隷制』の中で、ウィリアムズは1807年に英国政府が奴隷貿易法を可決した動機は、人道的なものではなく、主に 経済的な懸念であったと主張した。また、ウィリアムズは、奴隷解放やアフリカの封鎖も同様であり、産業資本主義と賃金労働が拡大し始めると、賃金が発生し ない奴隷制による競争を排除することが経済的に有利になるとも主張した。 ウィリアムズの研究分野への影響は、今なお重要な意味を持ち続けている。1984年にイタリアで開催された記念シンポジウムに基づくウィリアムズの論文集 の序文で、バーバラ・ソローとスタンリー・エンゲルマンは次のように述べている。「ウィリアムズはカリブ海地域の歴史研究を定義づけ、その著作はカリブ海 地域の歴史の流れに影響を与えた。学者たちは彼の考えに反対するかもしれないが、議論の出発点には変わりない。英国資本主義とカリブ海奴隷制に関する会議 は、すべてエリック・ウィリアムズに関する会議である」 ソロー教授宛ての公開書簡で、イェール大学の歴史学教授デビッド・ブライアン・デイビスは、奴隷労働の経済的持続可能性の低下に関するウィリアムズの論文 を「膨大な量の経験的証拠によって損なわれ、新世界における奴隷制、大西洋奴隷貿易、英国の奴隷廃止運動の分野における世界的な権威者たちによって否定さ れた」と述べている 大西洋奴隷貿易、および英国の奴隷廃止運動に関する世界的な権威者たちによって否定されている」と述べている。[27] エリック・ウィリアムズの論文に反論するために書かれた主要な著作に、シーモア・ドレシャーの『エコノサイド』がある。同書は、1807年に奴隷貿易が廃 止されたとき、英国の砂糖経済は繁栄していたと主張している。しかし、他の歴史家は、ドレシャーが1822年に英領西インド諸島の経済史の研究を終えてお り、1820年代半ばに始まり、1833年の奴隷制度廃止法成立まで続いた英領西インド諸島の砂糖産業の衰退(これはウィリアムズが強調した点である)に ついては取り上げていないことを指摘している。[28] エリック・ウィリアムズの 1820年代の砂糖産業の衰退、1833年の奴隷制度廃止法の成立、1840年代の砂糖平価法について論じたウィリアムズの論文の大半は、19世紀の西イ ンド諸島の歴史学に影響を与え続け、大西洋世界全体とのつながりにも影響を与えている。 資本主義と奴隷制』に加え、ウィリアムズはカリブ海地域に焦点を当てた学術的な著作を数多く発表した。特に重要なのは、学術的なキャリアを捨てて公人とし ての生活を始めた後に発表された2つの著作、『イギリスの歴史家と西インド諸島』と『コロンブスからカストロまで』である。前者は1940年代の研究を基 にしており、当初はクラーク・アトランタ大学でのシンポジウムで発表された。この著作は、西インド諸島に関するイギリスの定説的な歴史学に異議を唱えるこ とを目的としていた。ウィリアムズは特にスコットランドの歴史家トーマス・カーライルの業績に対する批判を痛烈に展開した。後者の著作は15世紀から20 世紀半ばまでのカリブ海地域の通史である。この著作は、同じカリブ海地域の学者であり政治家であるドミニカ共和国のフアン・ボッシュによる同タイトルの著 作(『クリストバル・コロンからフィデル・カストロへ』)と同時期に発表された。 ウィリアムズは、1969年の人類初の月面着陸を記念してNASAに送られた73通の「アポロ11号親善メッセージ」のうちの1通を書いた。そのメッセー ジは今もなお月の表面に残っている。彼は次のように書いた。「月を手に入れる一方で、世界を失わないことが人類にとっての切なる願いである」[31]。 |

| The Eric Williams Memorial Collection Main article: Eric Williams Memorial Collection The Eric Williams Memorial Collection (EWMC) at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago was inaugurated in 1998 by former US Secretary of State Colin Powell. In 1999, it was named to UNESCO's prestigious Memory of the World Register. Secretary Powell heralded Williams as a tireless warrior in the battle against colonialism, and for his many other achievements as a scholar, politician and international statesman. The Collection consists of the late Dr. Williams' Library and Archives. Available for consultation by researchers, the Collection amply reflects its owner's eclectic interests, comprising some 7,000 volumes, as well as correspondence, speeches, manuscripts, historical writings, research notes, conference documents and a miscellany of reports. The Museum contains a wealth of emotive memorabilia of the period and copies of the seven translations of Williams' major work, Capitalism and Slavery (into Russian, Chinese and Japanese [1968, 2004] among them, and a Korean translation was released in 2006). Photographs depicting various aspects of his life and contribution to the development of Trinidad and Tobago complete this extraordinarily rich archive, as does a three-dimensional re-creation of Williams' study. Dr Colin Palmer, Dodge Professor of History at Princeton University, has said: "as a model for similar archival collections in the Caribbean...I remain very impressed by its breadth.... [It] is a national treasure." Palmer's biography of Williams up to 1970, Eric Williams and the Making of the Modern Caribbean (University of North Carolina Press, 2008), is dedicated to the Collection. |

エリック・ウィリアムズ記念コレクション 詳細は「エリック・ウィリアムズ記念コレクション」を参照 トリニダード・トバゴの西インド諸島大学にあるエリック・ウィリアムズ記念コレクション(EWMC)は、1998年にコリン・パウエル元米国務長官によっ て設立された。1999年には、ユネスコの世界記憶遺産に登録された。パウエル長官は、ウィリアムズを植民地主義との戦いにおける不屈の戦士であり、学 者、政治家、国際政治家として数々の功績を残した人物と称賛した。 コレクションは、故ウィリアムズ博士の図書館と文書館から構成されている。研究者の閲覧に供されているコレクションは、その所有者の幅広い関心を十分に反 映しており、7,000冊の書籍、書簡、スピーチ原稿、歴史的文献、研究ノート、会議資料、各種報告書などから構成されている。この博物館には、当時の感 動的な記念品や、ウィリアムズの主要著作『資本主義と奴隷制』の7言語(ロシア語、中国語、日本語[1968年、2004年]、2006年には韓国語版も 出版)への翻訳版が収められている。 彼の生涯とトリニダード・トバゴの発展への貢献をさまざまな側面から描いた写真や、ウィリアムズの書斎を再現した3D模型も、この非常に貴重なアーカイブ を完成させている。 プリンストン大学の歴史学教授であるコリン・パーマー博士は、「カリブ海地域における同様のアーカイブコレクションの模範として...私はその広さに非常 に感銘を受けている。...これは国の宝である」と述べている。パーマーの著書『1970年までのエリック・ウィリアムズと近代カリブ海地域の形成』 (University of North Carolina Press、2008年)は、このコレクションに捧げられている。 |

| Film In 2011, to mark the centenary of Williams' birth, Mariel Brown directed the documentary film Inward Hunger: the Story of Eric Williams, scripted by Alake Pilgrim.[32] |

映画 2011年、ウィリアムズ生誕100周年を記念して、マリエル・ブラウンが監督したドキュメンタリー映画『Inward Hunger: the Story of Eric Williams』が公開された。脚本はアラケ・ピルグリムが担当した。 |

| Selected bibliography Capitalism and Slavery, 1944. Documents of West Indian History: 1492–1655 from the Spanish discovery to the British conquest of Jamaica, Volume 1, 1963. History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago, 1964. British Historians and the West Indies, 1964. The Negro In The Caribbean, 1970. Inward Hunger: The Education of a Prime Minister, 1971. From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean 1492–1969, 1971. Forged from the Love of Liberty: Selected Speeches of Dr. Eric Williams, 1981. |

主な著書 資本主義と奴隷制、1944年。 西インド諸島史の資料:1492年~1655年、スペインによる発見からイギリスによるジャマイカ征服まで、第1巻、1963年。 トリニダード・トバゴの人々の歴史、1964年。 イギリスの歴史家と西インド諸島、1964年。 カリブ海の黒人、1970年。 内なる飢え:首相の教育、1971年。 コロンブスからカストロまで:カリブ海の歴史1492年~1969年、1971年。 自由への愛から鍛えられた:エリック・ウィリアムズ博士の講演集、1981年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Williams |

|

| Eric Williams. 1944. Capitalism and Slavery Richmond, Virginia. University of North Carolina Press. Eric Williams. 1964. History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago. Port of Spain. ISBN 1-881316-65-3 Eric Williams. 1964. British Historians and the West Indies, Port of Spain. Solow, Barbara, and Stanley Engerman (eds). 1987. British Capitalism & Caribbean Slavery: the Legacy of Eric Williams. Cudjoe, Selwyn. 1993. Eric E. Williams Speaks: Essays on Colonialism and Independence. ISBN 0-87023-887-6 Drescher, Seymour. 1977. Econocide: British Slavery in the Era of Abolition Meighoo, Kirk. 2003. Politics in a Half Made Society: Trinidad and Tobago, 1925–2002. ISBN 1-55876-306-6 Rahman, Tahir (2007). We Came in Peace for all Mankind − the Untold Story of the Apollo 11 Silicon Disc. Leathers Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58597-441-2. |

エリック・ウィリアムズ著。1944年。『資本主義と奴隷制』。バージニア州リッチモンド。ノースカロライナ大学出版。 エリック・ウィリアムズ著。1964年。『トリニダード・トバゴ人民の歴史』。ポートオブスペイン。ISBN 1-881316-65-3 エリック・ウィリアムズ著。1964年。『英国の歴史家と西インド諸島』。ポートオブスペイン。 ソロー、バーバラ、スタンリー・エンゲルマン(編)著。1987年。『英国資本主義とカリブ海の奴隷制度:エリック・ウィリアムズの遺産』。 クドゥー、セルウィン著。1993年。『エリック・E・ウィリアムズの言葉:植民地主義と独立に関するエッセイ』。ISBN 0-87023-887-6 ドレスチャー、シーモア。1977年。エコノサイド:廃止時代における英国の奴隷制度 ミーグー、カーク。2003年。半ば作られた社会における政治:トリニダード・トバゴ、1925年~2002年。ISBN 1-55876-306-6 Rahman, Tahir (2007). We Came in Peace for all Mankind − the Untold Story of the Apollo 11 Silicon Disc. Leathers Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58597-441-2. |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆